Cathedral MUSIC Cathedral MUSIC

For many years organists throughout the land have aspired to playing a Makin organ. Now with the unsurpassed quality of the enhanced Westmorland Custom range, designed by organists for organists with no gimmicks, there has never been a better time to own one.

Built to your own specification, with drawstop or illuminated tab control, from small single manual up to large four manual instruments, they are for people who are serious about music, want the best in sound and build quality, excellence in after sales service and all at a highly competitive price.

As the UK’s leading manufacturer, Makin installs at least two organs each week at churches, schools, halls and homes throughout the British Isles. Visit our web site for an up to date list of recent installations, sample specifications and much, much more. Contact us today and take your first step to becoming a member of the Makin Family. You don’t buy a Makin Organ; you invest in one.

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is produced twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2007

Editor

Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace

Ripon North Yorkshire

HG4 2QS

ajpalmer@lineone.net

Assistant Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager

Graham Hermon

FCM e-mail FCM@netcomuk.co.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM. All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:-

Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road

LONDON SW4 8AR

Tel:0208 674 4916

cathedralmusic@supanet.com

inQuire Editor

Richard Osmond

10 Hazel Grove, Badger Farm, Winchester, Hants SO22 4PQ

Tel/Fax:01962 850818

Friends of Cathedral Music

Membership Department

27 Old Gloucester Street

London WC1N 3XX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087

E-mail: info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by Mypec

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT

Tel: 0113 255 6866 info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

there was no consultation with cathedrals about the change of day? Is it because in many cathedrals there is a sermon at Evensong on Sundays? I cannot understand why this has to happen; changing the day seemed acceptable but to alter the nature of the service right away alters the balance between the choral part of the service and the clergy. I will give Radio 3 the benefit of the doubt though. Perhaps the homilies at the moment are to coincide with Lent.

Communicating outside the precincts

There wasn’t quite the outcry I was expecting when BBC Radio 3 swapped the broadcast day for Choral Evensong from Wednesday to Sunday. Knowing our members I was taken by surprise. That said, there have been a couple of letters (see page ***) bemoaning the move. I, and I’m sure many of you do not appreciate the new element of a homily in the middle of the service. Why has Stephen Shipley seen fit to ask cathedral chapters to include this in the broadcast? Is it a sweetener because

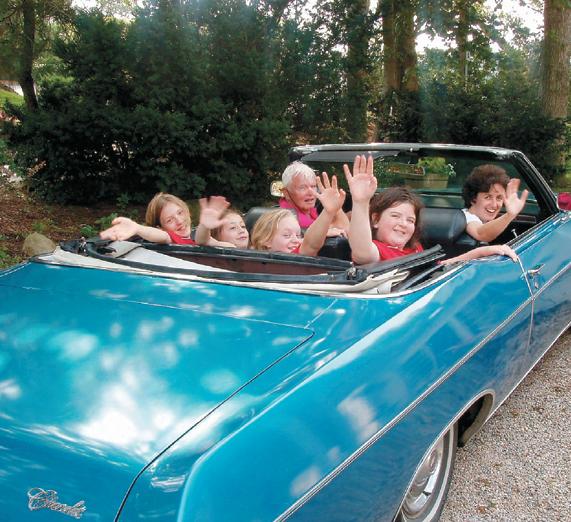

Elsewhere in this magazine Frank Field MP discusses the cost of running a cathedral music department and writes about the Government’s academy scheme, which could be the basis for establishing across the country a series of music schools open to boys and girls. As he states, the cathedral choir schools could become the driving force behind such a move. This is to be welcomed and is something that the choir schools should run with to help the continuation of the choral tradition in this country. One place that has started on its outreach initiatives is St Peter’s Collegiate Church, Wolverhampton and the imaginative ‘Singing Together’ initiative’ run jointly by Salisbury Cathedral School and its Cathedral. This is all commonsense and if it helps to fill the choir stalls then we should embrace these initiatives.

Running short of finance

A worrying trend is emerging: a

number of cathedral festivals are running short of cash. I understand that Chelmsford may not be able to run another festival in future. It was touch and go with this year’s St Albans International Organ Festival but fortunately it has been underwritten once more by John Stocker Holdings, which has sustained it in the past. These festivals play an important part in the life of a cathedral city; not only do they raise the profile of choirs, music and culture but have an economic impact too. For example The Three Choirs Festival is big business in each of the three cities in turn. There is a ninth day of charismatic gospel and modern church music adding one day to the 2007 Gloucester Three Choirs. This was viable purely because all the expensive staging and other facilities brought in would still be in position. Whether this is the right kind of music for this traditional Three Choirs Festival remains to be seen. Business sponsors a lot of the national big art exhibitions or single celebrations of composers, say at the Tate Britain or Barbican, and when it comes to sporting events there are massive amounts of money poured into them. Music and in particular the English choral tradition has played an enormous role in shaping our culture and psyche. I appeal to those of you who can influence corporate donations to do so. Where would we be without the Three Choirs, St Albans IOF, Southern Cathedrals Festivals or the Border Cathedrals Festival, if they were all to disappear? Inconsolable!

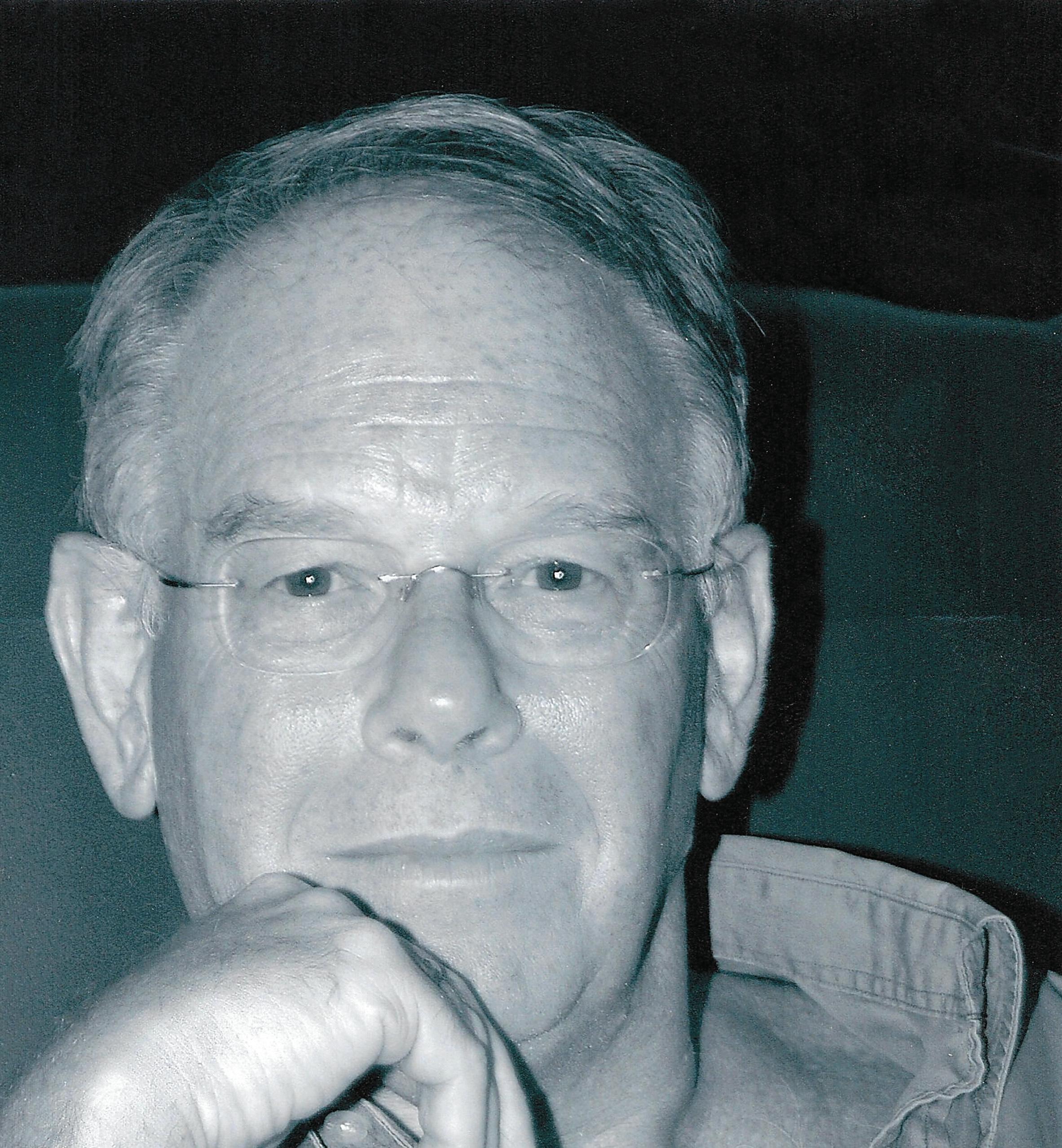

‘Music and in particular the English choral tradition has played an enormous role in shaping our culture and psyche. I appeal to those of you who can influence corporate donations to do so.’Rt Revd Gordon Mursell

Those who sing in cathedral choirs, as well as those who attend Choral Evensong, must sometimes ask themselves: why are we singing the Psalms? Why bother with this grumpy, partisan, obscure and preChristian collection of texts which often feel about as relevant to the 21st century as those medieval monuments to knights in armour that clutter up side aisles? Why can’t we write our own prayers and say or sing them instead?

Well (to answer the last question first) we can, of course, and do. But they’re no substitute for the Psalms. Let me suggest a few reasons why this is so.

First, and like Mount Everest, the Psalms are there. We didn’t choose them. They are part of what three thousand years of Jewish and Christian prayer and worship have entrusted to us. We could ignore them if we want, as we could ignore all of what is handed down to us. But (quite apart from the intrinsic riches they contain) there is a spiritual question here: if our worship consists only of things which we happen to choose and like, are we not simply imposing our own personal agendas on others? And if we insist on customising every act of worship and leaving out what we don’t like, how will we cope with those areas of our life where we can’t choose, and where we aren’t in control? There is a danger, in the age of New Labour, in forgetting that too much choice in life is just as disabling as too little. If we can make something constructive out of psalms we didn’t choose and don’t much care for, we may be better able to do the same when we find ourselves in situations where we have little or no choice. Furthermore, many (perhaps most) of the Psalms are themselves clearly written out of situations where the person praying was not in control. Taken as a whole, they are the mirroropposite of committee-produced collections of prayers or liturgies where everything awkward is carefully smoothed away. If the Psalms

‘There is a danger, in the age of New Labour, in forgetting that too much choice in life is just as disabling as too little.’

sometimes come across as tetchy or ill-tempered, it’s because they are the prayers of people who were struggling to come to terms with what is happening to them in the light of their faith in God. They can help us to do the same.

Which brings us to a second reason why they matter. The Psalms are full of question-marks. Most prayer collections or orders of service, from the Book of Common Prayer onwards, contain nothing but statements. The result is that all we feel able to bring to God is our certainties, not our questions. But what kind of God are we praying to if we can’t share our doubts and anxieties as well as our hopes and convictions?

The God of the psalms is a God deeply concerned about every aspect of our lives, a God who longs for us to be as honest and truthful in our praying as we possibly can be. All too often, Anglican worship leaves you with the impression that your doubts and secret failures, your sudden rages and hidden envies, have to be left at the door of the church. The psalms allow us to pray with them, and with our questions as well.

Let’s suppose it’s the fourth evening of the month and you are singing (or hearing someone else sing) the 22nd Psalm, which begins ‘my God, my God, look upon me; why hast thou forsaken me: and art so far from my health, and from the words of my complaint?’ What can you do with such a prayer? You may want to pray it for yourself: not everyone comes to choral evensong, or cathedral worship generally, feeling confident and cheerful, and it’s good to allow your own feelings, or sense of God’s absence, to find expression in the timeless words and music of the Psalms. But you may feel perfectly happy; in which case you can pray those words for the millions in our world who will, at that very moment, be feeling exactly like the psalmist did – people with terminal illness, or whose courageous attempts to live good lives seem to have pitched them into tragedy after tragedy. And if you can’t at once think of anyone else, then simply by singing or

mouthing these words you are caught up into that cosmic community of Jews and Christians who have used them in gulags and amphitheatres and countless places in between –and supremely into the presence of the person who prayed these very words as he hung on the cross at Calvary. You never pray a psalm on your own.

This brings us to the third point, which is that the Psalms make possible a kind of imaginative intercession all too rare in modern worship. It’s easy – too easy – to pray, in cathedrals or anywhere else, for the starving, the marginalised, the vulnerable, the oppressed, and the poor and then to move hastily on to the more congenial terrain of the diocese and the organ appeal; and just occasionally one might be forgiven for wondering whether the person leading such prayers has ever actually met someone who is starving, marginalised, vulnerable, and so on. There can be just a hint of a de haut en bas loftiness in Anglican prayer, which is utterly alien to the Bible. There, prayer is vigorous exercise, hard work – notice (to take just one of many examples) the reference in the Letter to the Colossians to someone called Epaphras, who is described as ‘always wrestling in his prayers on your behalf, so that you may stand mature and fully assured in everything that God wills’ (Col.4:12 NRSV). That’s the kind of prayer that will change our world.

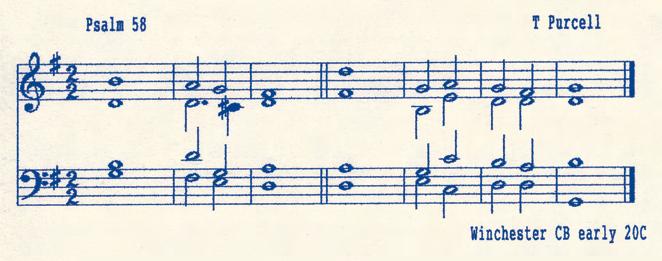

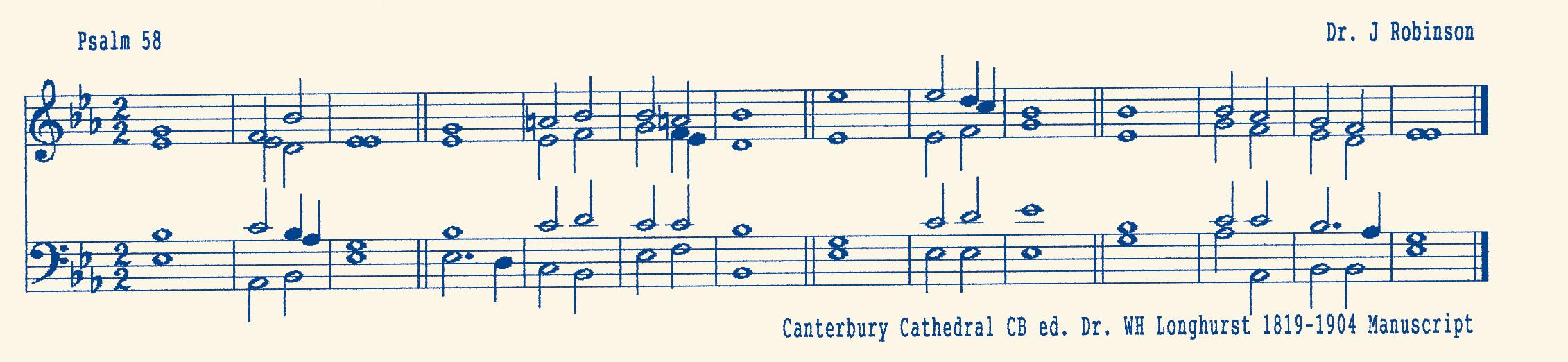

And it’s exactly that kind of prayer which we find in the Psalms. You may not have come across Psalm 58, partly because in the Prayer Book it is prescribed for use on the 11th morning, so never features in choral evensong, partly because in the revised 1928 Prayer Book and 1980 Alternative Service Book it has prim little square brackets round it, as though to say ‘this simply won’t do in polite Anglican circles – leave well alone.’ Even in the new Common Worship lectionary, it never appears. True, when you read it through, you may well feel the sentiments are ferocious and not very Christian: will the

righteous really ‘wash his footsteps in the blood of the ungodly?’ But this is to miss the point. The terrible 58th Psalm is palpably the prayer of someone who has been brutalized by appalling injustice. It could be the prayer of a survivor of Auschwitz, or of a prison camp in North Korea. It could be the way you or I would pray if we were to find ourselves thrown into prison and tortured for something we didn’t do. Psalms such as this remind us that, in most cases, evil does not sanctify its victims: it degrades them. By praying these words, we are given an opportunity to take our intercessions to a far deeper level than the easy canter round the world’s trouble spots that is all we usually manage – to imagine how it must feel to be victims of evil, in Pyongyang or Baghdad or Chechnya, and to pray with them for God to heal our world.

This stress on imaginative intercession is important for other reasons too. The great medieval cathedrals and churches were, and for the most part still are, stocked with a vast cornucopia of images, in stained glass and stone and memorial brasses, many (probably most) being more secular than religious – images of war, like the knights in armour mentioned earlier; images of work, or of play, or of family life, of birth and death, of trees and castles and stars and lakes. All the world can be found here. It doesn’t always find a place in our worship. Despite the enormous improvements in recent years, our modern liturgies are still often overpoweringly churchy, preferring the abstract language of concept to the far more accessible language of image. Jesus used almost exclusively the language of image. When someone asked him what the kingdom of heaven was like, he didn’t answer in terms of an incoming eschatological power; he said ‘it’s a bit like that mustard seed over there, that grows up into a big tree’. I have never seen a mustard seed. But I can imagine what he’s talking about, because I have an imagination. And so have you.

Exactly the same thing is found in the Psalms. They are a collection of 150 anonymous prayer-poems, some attributed (with varying degrees of likelihood) to King David. They breathe the air, not of a committee or synod but of the world ‘out there’, in all its vivid and sometimes violent (but also beautiful) reality. When the psalmists struggle to express what they want to say, they draw on images – ‘he shall be like a tree planted by the water-side’, or ‘my days are consumed like smoke’, or ‘I am even as it were a sparrow that sitteth alone upon the housetop’, or ‘I am as glad of thy word as one that findeth great spoils’ Some of these images are immediately and completely accessible to us, others demand time and reflection if they are to achieve their full power. But the images themselves demand no special learning or religious decoding. They allow us to bring the world into the chancel or pew, and to pray for it with all the imaginative wonder of which we are capable.

It may be worth concluding by reflecting very briefly on the most famous psalm of all, the 23rd, appointed to be sung on the fourth evening of the month in the Prayer Book. It consists of only six verses, and if you look closely at them you will see that only two of them (verses 4 and 5) are actually prayer, in the sense of an address directed to God. The psalm begins and ends with a kind of theological reflection or testimony (‘The Lord is my shepherdÖ and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever’). Theology (talking about God) and prayer (talking to God) are inseparably linked. The same thing happens constantly in the Bible – prayer is not some special and specialist activity, hygienically separated from everyday life, but something rooted in the very heart of the secular

world, something we can turn to and step out of again whenever we feel like it. The God of the psalms is the God of all life, not just of a narrowly religious piece of it.

Notice something else. The imagery of the 23rd Psalm is entirely secular: green pasture, still waters, the valley of dark shadows, the shepherd’s rod and staff, the picnic table, the glass full of wine. Many of this psalm’s translators appear to have disapproved of this, and so have given it a more conventionally religious tone: St Augustine turned the ‘still waters’ into the ‘waters of baptism’; H.W.Baker, in his famous paraphrase ‘The King of Love my Shepherd is’, introduced ‘food celestial’ and ‘my ransomed soul’, neither of which appear in the original, and turned the glass of wine at a picnic into something much more churchy: ‘O what transport of delight from thy pure chalice floweth!’ The price paid for this is that both the earthiness and the sheer defiant boldness of the original is lost. For this is the prayer of someone who lives and works in the countryside, someone who is exposed to terrible dangers, and yet who pictures God both as a caring shepherd and as the genial host at a picnic who prepares a table and charges our glasses precisely in the midst of our greatest stresses and worries (‘against them that trouble me’). In the presence of this God, there is nothing I need fear; and the psalm ends by defying our proneness to apathy and selfpity and encouraging us to look forward to the day when we shall dwell in the house of the Lord for ever. Now that really is a faith worth living and dying for.

Gordon Mursell is the Bishop of Stafford

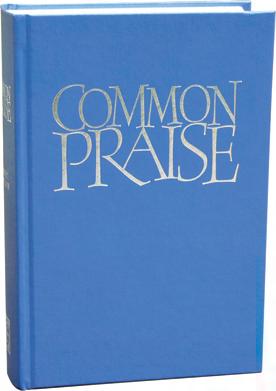

Main features include: Familiar words set to new and different alternative tunes. New musical arrangements. Tunes and words in new combinations which put both into fresh perspective.

Twentieth century words and music included for the first time.

Five editions available.

Full Music Edition

978-1-85311-264-5

216 x 135mm · hardback

1400pp · Ref. No 49

Usual Price £23.00

With 25% Grant*£17.25

Melody Edition

978-1-85311-265-2

171 x 114mm · hardback

1056pp · Ref. No 47

Usual Price £13.50

With 25% Grant*£10.13

Words (cased)

978-1-85311-266-9

165 x 110mm ·hardback

736pp · Ref. No 45

Usual Price£9.50

With 25% Grant*£7.13

Words (paperback)

978-1-85311-267-6

165 x 110mm · paperback

736pp · Ref. No 43

Usual Price£5.00

With 25% Grant*£3.75

Large Print Words

978-1-85311-467-0

171 x 114mm · hardback

544pp · Ref. No 41

Usual Price£19.00

With 25% Grant*£14.25

All editions are in hardback blue cloth, except for the words paperback which has an attractive full colour cover.

To order/request a grant application form: Tel: 01603 612914

Fax: 01603 624483 SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd, St Mary’s Works, St Mary’s Plain, Norwich NR3 3BH E-mail: orders@scm-canterburypress.co.uk

*To qualify for a GRANT OF 25% an order for a minimum of 20 COPIES, in any combination, of Common Praise hymn books, together with a completed grant application form (available on request from SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd) must be received.CMCP07

There was a time when Dieterich Buxtehude was almost always referred to as ‘an important precursor of J.S. Bach’. That he certainly was, and the young Bach learned much from the older master when he travelled from Arnstadt to Lübeck in 1705 to hear him play the impressive organ in the great Marienkirche. But it is now recognised that Buxtehude’s ever-inventive and compelling music should be heard, played, sung and studied in its own terms, and not simply as some sort of preparation for Bach. This tercentenary year of Buxtehude’s death will offer many opportunities to hear his music: articles are being written, new recordings made and many concerts planned throughout the country. Buxtehude’s organ music has long been familiar and widely-played, but we must remember that he composed also a quantity of vocal and instrumental music. Before we have a closer look at some of this, let us investigate what we know of the man and his life.

Early details of Buxtehude’s life, including the place of his birth, are sketchy; but a contemporary document tells us that he ‘recognised Denmark as his native country’, and he spent part of his early life in Helsingborg where his father Johannes was organist of the St Maria Kyrka. He moved to Lübeck in April 1668, at the age of 31, to take up the prestigious post of organist of the St Mary’s Church, in succession to Franz Tunder. Shortly after, he

married Tunder’s daughter, which may well have been a condition of the employment. (Four years before Buxtehude’s death, in 1703, the 21-year-old Johann Mattheson and the 18year-old Handel travelled together to Lübeck passing the time in their coach by composing double fugues! with a view to succeeding Buxtehude. He was still in post at that time, but was seeking a successor, not to mention husbands for his three unmarried daughters. However, Mattheson and Handel turned on their heels pretty quickly when they discovered that marriage “for which neither of us expressed the slightest inclination” was part of the deal) Buxtehude in fact remained in post until his death in 1707, having served the church for nearly 40 years.

His duties included playing the organ for the main Sunday morning and afternoon services; playing on feast days, of which the Lutherans had retained several from the Roman church; and for Saturday Vespers. Organ music would also have been required for weddings and funerals, which no doubt then, as now, provided some welcome extra income. Buxtehude was actually very well paid, however, having an annual salary of 709 Lübeck marks. He received further payment for his duties as Werkmeister, that is, church administrator and treasurer; and he seems to have been responsible for routine maintenance of the organs. In addition to all this, he received an allowance of beef, wine and clothing. His total salary was much larger than that of any of his fellow musicians.

A Kantor directed the choir, but it is not entirely clear how the various duties were assigned. The musicians in St Mary’s, of whom there were 14 on the regular payroll, were distributed in various balconies in the church, and direction of the various musical parts of the service must have been a shared responsibility as distances were quite considerable. There was also a certain amount of moving around in the course of the service; it would appear that the musicians used the space imaginatively. Buxtehude would certainly have spent much of the service at the main west-end organ. It is documented that his improvised introductions to the congregational chorales were very elaborate no mundane British play-over here. His extant discant organ chorales (that is, those with the melody elaborated in the soprano voice to be played on a solo stopcombination) presumably give some idea of what his improvised preludes were like. We must remember that, in earlier Lutheran practice, the organ alternated with the singing of the chorale, rather than accompanying it. However, in the course of the 17th century this was gradually changing,

and Buxtehude probably accompanied the singing at least some of the time. Solo organ music preludes, interludes and postludes would also have been required at certain points in the service, most of it improvised. Buxtehude’s free (that is, not chorale-based) praeludia, and his lengthy chorale fantasias, may well have been played at the close of the service. Works like the two Magnificat setting presumably had their place in the Vespers service.

In addition to congregational singing and organ music, there was an important place for choral works such as psalmsettings, solo arias, motets and cantatas, mostly with German texts but sometimes with Latin. These were performed with instruments and organ continuo; there was a small organ in the choir loft for this purpose, which someone else would have played. Although Buxtehude’s post as organist did not require him to write vocal works (unlike Bach’s position as Kantor at Leipzig which required him to provide weekly cantatas) he did in fact leave quite a corpus of sacred vocal music which was no doubt performed at St Mary’s. There was also a place for instrumental ensemble music, played during the distribution of the communion. (A contemporary chronicler tells us that the musicians generally left the church during the hour-long sermon, partly because it was so cold, and the whole service lasted three hours. We must not assume, however, that the entire congregation was present from beginning to end. Recent scholarship has shown that, in Bach’s day at Leipzig, worshippers came and went throughout the three-hour period, although most were present for the sermon. The practice was probably similar in Buxtehude’s day).

Buxtehude was renowned for the series of concerts he promoted known as the Abendmusiken, consisting of vocal and instrumental music, and forming what seems to have been regarded as a sort of sacred if un-acted opera. Concerts of sacred music are very familiar to us, but they were virtually unknown in Buxtehude’s day and aroused much interest and admiration. He was in fact building on a tradition established by his predecessor Tunder, but his concerts were more ambitious. They took place specifically on the last two Sundays of Trinity and on Advent 2, 3 and 4; they began at 4pm and lasted about an hour. Buxtehude set the chosen biblical texts to music, had the parts copied (without ‘Sibelius’ or photocopiers), fixed the singers and instrumentalists, raised funds, then rehearsed and directed the whole enterprise. Although the concerts were much praised, not everyone was in total sympathy with Buxtehude’s efforts. Writing some years after Buxtehude’s death, Kantor Caspar Ruetz complained that it was a bit much to have to go back into a freezing church in December, having already spent three hours there earlier in the day. And he was shocked by “the atrocious noise of the mischievous young people and the unruly running and romping about behind the choir”, not to mention “the sins and wickedness that take place under cover of darkness and poor light”. The Abendmusiken continued in the form devised by Buxtehude until 1810. They still continue today, although now in the summer months.1

It is hoped that this tercentenary year will make familiar some of Buxtehude’s vocal works; an increasing number are available in modern editions and many pieces are of modest length and for small forces, making them appropriate for liturgical (or concert) performance today. An excellent example is the delightful Jubilate Domino, for solo voice and continuo. A more ambitious work, already quite well-known and available on CD, is Membra Jesu Nostri, a cycle of seven

‘

This tercentenary year of Buxtehude’s death will offer many opportunities to hear his music: articles are being written, new recordings made and many concerts planned throughout the country.’

short, meditative cantatas which were possibly intended as a Holy Week or Good Friday devotion. This is fervent, introspective, devotional music, pietist in tone, and illustrating a side of Buxtehude’s musical genius very different from the confident flamboyance of some of the organ works.

The enterprising Dutch musician, Ton Koopman, is of course well-known for his electrifying performances of Buxtehude’s solo organ music. Having now completed his complete Bach cantata recordings, Koopman has just launched a new project which aims to record Buxtehude’s entire output organ music, harpsichord suites (already released), instrumental works and all the vocal music. This will take a few years to realise, but will doubtless introduce us to much more of this marvellous music.2

Most of us are familiar with a range of Buxtehude’s organ works, which encompass both chorale-based and ‘free’ works. The chorale-based works include the discant chorales mentioned above, as well as large-scale chorale fantasias and other such works. The free works include quite a lot of shorter contrapuntal pieces canzonas, fugues and so on as well as the three celebrated ground-bass pieces, the two Ciaconnas in C minor and E minor, and the Passacaglia in D minor. Some of these pieces were possibly intended as teaching material, rather than for liturgical use. The main body of free works consist of the praeludia (some entitled ‘toccata’). One should not refer to these as ‘preludes and fugues’ as very few are in two clear-cut movements; most are one-movement works, alternating rhetorical writing with stricter fugal sections. Many are characterised by the so-called stylus phantasticus, a welldocumented style of playing and composing that is calculated to surprise, astound and delight. In such music we find much variety in tempo, texture, gesture and (presumably) registration. It is a characteristic of much late 17th-century German music, and can be found in the instrumental works of composers such as Biber, Schmelzer and others, as well as in the organ music of Buxtehude’s contemporaries and pupils, such as Vincent Lübeck (who lived and worked not in Lübeck but in Hamburg), Nikolaus Bruhns, Georg Leyding and others. We are lucky that so much of Buxtehude’s organ music was written down, generally in organ tablature, by his pupils; it is salutory to be reminded that not a note of these works has come down to us in the composer’s own autograph. A number of his north German contemporaries are now known by only a few pieces, such as the long-lived Adam Reinken from Hamburg (to whom the young Bach also played). Had it not been for his pupils’ efforts we might have only two or three organ pieces by Buxtehude. (The

same, to a lesser extent, can be said of Bach).

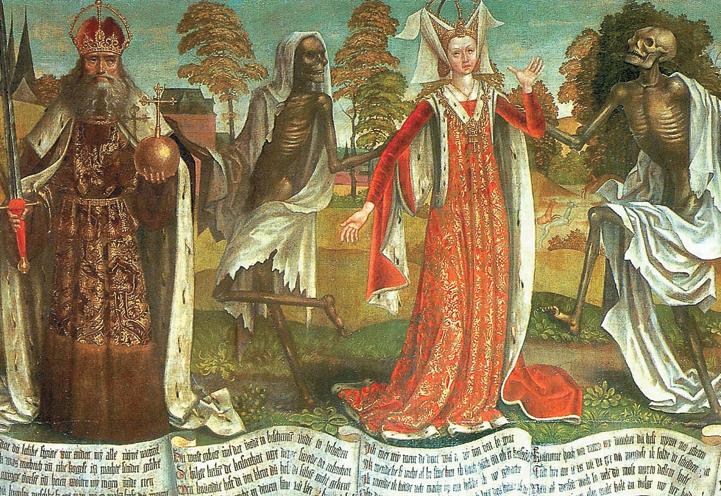

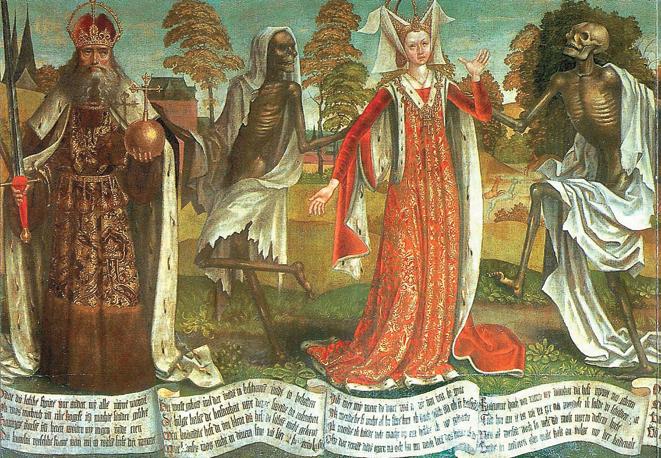

Finally, what of the organs which Buxtehude played? The large west-end organ was one of the largest and most comprehensive instruments known anywhere at that time, reflecting the wealth and prosperity of Lübeck. The instrument had been rebuilt and expanded at various times since 1516 enlarging and remodelling organs to suit changing tastes was not then frowned upon as it now is in some quarters! and by Buxtehude’s day it was a large instrument of three manuals and pedal, the latter comprising 15 stops including two 32’ ranks. There was also a smaller, yet still substantial organ in a side chapel, the ‘Totentanz Organ’. It was so called because of the famous painting, The Dance of Death, which adorned the chapel; this was painted in 1463, following a serious epidemic of plague. Although the large organ was much changed in the 19th century, the Totentanz organ remained virtually unchanged until the fateful night of 28-29 March 1942 when the whole church, and everything in it, was destroyed in the dreadful bombing of Lübeck by the Allied forces. During the period 1947-1959 the church was rebuilt; a large five-manual organ was installed in 1968 at the west end of the church by Kemper and Son, and in 1986 Führer built a new Totentanz organ. Neither organ, however, sets out to be a historic copy of the instruments from Buxtehude’s day.

There is no doubt that the 20-year-old Bach’s visit to Lübeck in the autumn of 1705 was pivotal in his musical development. His main purpose was to hear Buxtehude play the organ, and this must indeed have been a thrilling experience; but he also experienced the Abenmusiken of that year, and probably participated in the performances, perhaps as a violinist. Bach had permission from the church authorities at Arnstadt, where he was then organist, to make this 280-mile trip, but he had been given leave of absence for a month and got into trouble when he eventually returned for having stayed away “about four times as long”. We can sympathise with the church authorities, of course the young Bach was very headstrong but who can blame him for wanting to make the most of his visit, given the musical experiences which Buxtehude could provide?3

JOHN KITCHEN is a Senior Lecturer in Music and University Organist in the University of Edinburgh. He also directs the Edinburgh University Singers, is organist of Old Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church and Edinburgh City Organist. He gives many solo recitals both in the UK and further afield, and is much in demand as a continuo player, accompanist, lecturer, writer and reviewer.

1A number of websites provide information about St Mary’s Lübeck, both its history, and what is happening at the present time. Simply google ‘St Mary’s Church, Lübeck’.

2 The CDs are being released on the Antoine Marchand label, published by Challenge Records: website www.challenge.records.com.

3For further reading, see Kerala Snyder Dieterich Buxtehude, Organist in Lübeck (Schirmer Books, 1987). This is a magisterial account of the composer’s life and work (to which present article is indebted). It contains also a number of fascinating pictures and photographs, including some of the Marienkirche before its destruction. Unfortunately, I believe that the book is out of print, but it should be available from good libraries.

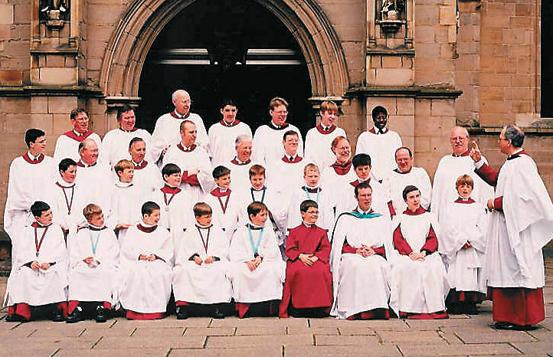

Patrick Dunachie from Ludlow and Max Foster from near Ledbury are sharing the office of head chorister at Hereford Cathedral after they were formally installed by the Dean during the Cathedral. It is the first time for a number of years, if not the first time ever, that this senior choir post has been shared between two boys. ‘Patrick and Max joined the choir around the same time’, said organist and director of music, Geraint Bowen. ‘They have given us exceptional service both in and out of the choir stalls and have developed a variety of skills during their time as choristers over the past five years’.

‘Normally we only have one head chorister but it would have been impossible to choose one of these two and not the other. They are also great friends and one of the tremendously important skills that boys also learn while singing with us is that of teamwork and therefore it seemed even more important to acknowledge how Patrick and Max have supported each other over the years’.

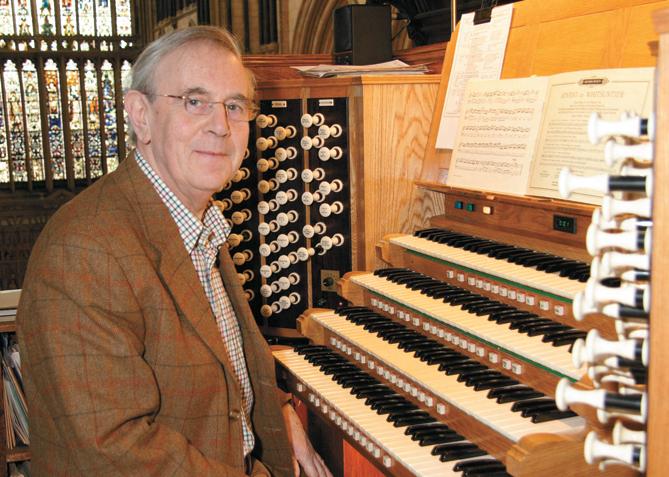

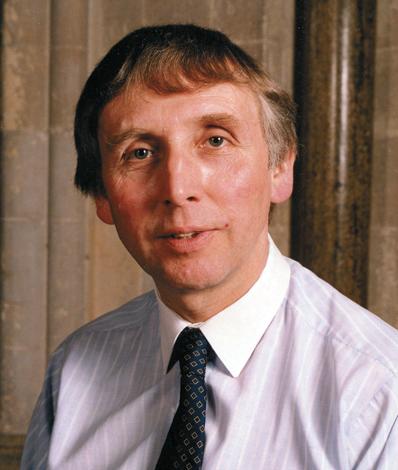

Dr Alan Spedding MBE celebrated 40 years as organist of Beverley Minster in January. We at FCM send him our heartiest congratulations in his anniversary. Alan studied organ and ‘cello at the Royal College of Music. He was appointed Organist and Master of the Choristers at Beverley Minster in 1967, after three years as organist of the Parish Church, Kingston upon Thames. He was musical director of the Hull Choral Union for twenty six years and has conducted the East Riding County Choir since 1969. He was music master at Beverley Grammar School for eighteen years and has taught part-time in the University of Hull where he is Organ Curator. The university made him an honorary Doctor of Music in 1994. He has also served as an examining member of the council of the Royal College of Organists and as Associate Editor of Organists’ Review. He was awarded the MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours in 2003 and was made an Associate of the Royal School of Church Music in May.

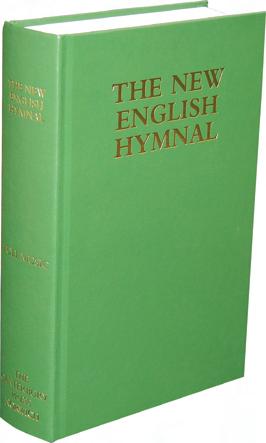

Main features include:

500 of the best hymns from English Hymnal, English Praise and from other sources.

Further 42hymns covering Advent, Holy Week and major feasts. Proper hymns, including new ones, for all red-letter Saints Days. Office hymns for the Christian year. Enlarged Eucharistic Section.

Selection of Responsorial psalms. Current printings include useful indexes together with an Appendix of Hymns suggested for Sundays and some Holy Days according to the Common Worship Lectionary. Available in the 4 editions.

Full Music and Words

978-0-90754-751-8

210 x 140mm

hardback· 1312pp

Ref. No 54

Usual Price£22.00

25% Grant* £16.50

Melody and Words

978-1-85311-097-9

171 x 114mm

hardback · 920pp

Ref. No 52

Usual Price £11.50

25% Grant* £8.62

Words Only

978-0-90754-749-5

157 x 105mm

hardback · 616pp

Ref. No 50

Usual Price £9.50

25% Grant* £7.12

To order/request a grant application form: Tel: 01603 612914

Large Print Words Only

978-1-85311-002-3

240 x 160mm

hardback · 544pp

Ref. No 56

Usual Price £17.50

25% Grant* £13.13

Fax: 01603 624483 SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd, St Mary’s Works, St Mary’s Plain, Norwich NR3 3BH. E-mail: orders@scm-canterburypress.co.uk

*To qualify for a GRANT OF 25% an order for a minimum of 20 COPIES, in any combination, of New English Hymnal hymn books, together with a completed grant application form (available on request from SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd) must be received.CMNEH07

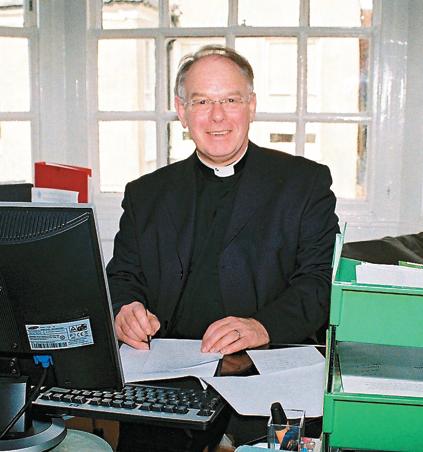

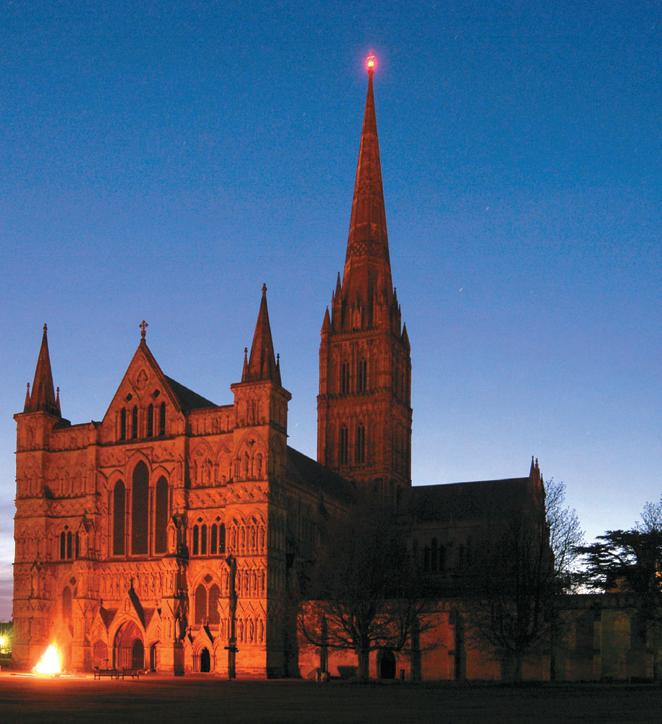

The word ‘Precentor’ is a combination of two Latin words, preces meaning prayers and cantor meaning singer. The Precentor is the singer of the prayers and that gives a clue to what a Precentor has done at Salisbury since 1091, when the second Bishop of Old Sarum, St Osmund, constituted the governance of an English secular cathedral on the French model with a Dean, Precentor, Chancellor and Treasurer.

First of all the prayers. A priest’s life is framed by prayer and indeed sustained by it, as is the case with all Christians. And in a cathedral, Morning Worship with morning prayer and Eucharist, and Evensong usually sung by the Cathedral choir led by the Precentor, are the fixed points in the day which inform the rhythm of the cathedral’s life. There are other fixed points of course during the week, mainly to do with meetings (a department meeting for the Liturgy & Music Department; a staff meeting with the wider cathedral staff; a monthly meeting of the Cathedral Chapter, the governing body of the Cathedral; the Cathedral Council which meets twice a year and to whom the Chapter is accountable and various other monthly meetings which the Precentor at Salisbury at any rate chairs, the Music Policy Committee and the Worship Committee. But all these meetings take place within the daily fixed points of the morning and evening offering of prayer and worship, which are the raison d’être of the Cathedral.

And then the singing of the prayers, which has to be interpreted in a wider context than simply singing, although Precentors at Salisbury (though not always at every cathedral) have tended

to be singers. For singing, read responsibility for the musicianschoristers, lay vicars, organists who for 900 years, both at the present Cathedral and its Norman predecessor, have maintained the fabric of worship and continue to do so, now with a girls’ choir as well as a boys’ choir. Involvement with the musicians includes the planning of liturgies and services and worship events in which music inevitably plays an enormous part. It also includes social, pastoral, occasionally disciplinary, interventions by the Precentor. One of the ancient titles for the Precentor is custos puerorum, guardian of the boys, and now the girls, and that includes not only looking after their moral and intellectual welfare, which is well catered for in the Cathedral School but also their spiritual welfare. To this end the Precentor meets regularly once a week for a couple of terms with the probationer choristers before they are admitted into the choir, in order to introduce them to aspects of a chorister’s life and their ministry as singers within the worshipping life of the Cathedral, which might otherwise be forgotten or glossed over. This weekly dialogue comes to an end usually on Shrove Tuesday, when the probationers meet in the Precentor’s house to have a pancake breakfast followed by the burning of the palm crosses to make the ash in readiness for the Ash Wednesday ceremonies on the following day.

The Precentor’s task of singing the prayers or leading the worship involves the wider remit of preparing, overseeing and directing the course of services in the Cathedral. This liturgical

role is the most time consuming of the Precentor’s tasks, which of course he does not do alone. At Salisbury, as at every cathedral, there is a team of liturgists and musicians involved in preparing and conducting worship. Clergy of course but also key musicians, servers, eucharistic administrants, acolytes, stewards and those who work in the office preparing service sheets and much of the minutiae of the liturgical rhythm. The exciting part of this work is creating a service for a special occasion tailored to the needs of a particular group or individual, or national or diocesan event. This often starts with a blank piece of paper and one or two ideas, which then have to be fleshed out. The whole process from paper to production will go through many further discussions and refinements until the final liturgy is celebrated. Very often those who attend such services are totally unaware, as they should be, of the immense amount of work and team co-operation and nervous energy that has gone into creating the service they are attending.

Of course a Precentor is also a priest and, in addition to these important and particular functions, a Precentor as a priest is maintaining a round of pastoral engagements with the sick and the dying; preparing people for marriage and baptism; with often a great deal of spiritual direction and retreat leading thrown in. Inevitably there is the round of preaching both in the Cathedral and away in the parishes and the diocese or further afield. It makes for a heady mix and is a busy and varied life in which there is no time at all to be bored but in which a Precentor, like every priest, needs time to stand still.

A week in the life of is a new series where we chart the week of an individual and ask them to tell us what their job involves.

The ancient city of St Albans lies just 24 miles north of the centre of London. The great Abbey Church is the only surviving building (along with its ancient gatehouse) of the great monastery founded back in the early ninth century by King Offa to house the relics of St Alban the first Christian martyr in Britain. This enormous church dominates the centre of the city and can be seen from quite a distance on both the railway line from London and the M25. After its dissolution in 1539 the Abbey Church became the parish church of the town and, since 1877 is also the cathedral church of the then newly created diocese of St Albans. So this great church has a thriving parish congregation and large wider community as well as the expected collegiate foundation of priests, and a large musical foundation led by the cathedral choir of boys and men, and totalling four choirs, who sing the daily choral services.

St Albans has the feel of a prosperous market town and the cathedral, like the old monastery, retains a sense of being the hub of the community. It is a place for all town, county and diocese and, with its ecumenical chaplaincy holding services for Roman Catholics, Free Church, German Lutherans and Russian Orthodox congregations, and the large of number of concerts and other events each year there is a buzz and liveliness about this busy and yet calm and spiritual place. Music is also an important part of community life in St Albans. Many professional musicians from London live here so it is really no surprise that the cathedral is the home to a thriving International Organ Festival, now in its forty-fourth year.

Peter Hurford came to be the Master of the Music of the Cathedral in his late twenties in 1958 and immediately began to energise musical life in the city. He and his wife Pat had experienced organ competitions in Europe in the ‘50s and lamented that we had nothing here in Britain to encourage and promote young organists to be good players. They also saw that a competition held in isolation from other musical events was a rather dull affair for the audience members who support these events as well as reinforcing in the mind of the general musical public the reputation that organ music and its association with church music in general are really musical backwaters.

The International Organ Festival at St Albans was conceived whilst the Hurfords were on a walking holiday and when they returned home the germ of an idea for an organ competition that was part of a wider festival of organ music, using the instrument in all sorts of musical contexts, had been fully developed.

The first IOF came in 1963 – one year after the new Harrison & Harrison organ had been installed. It lasted five days and made a profit of ten shillings – a tidy sum in 1963 –

the equivalent of 50p in modern currency. There were Festivals in ’64 and ’65 and thereafter every other year – the Festival in 2007 will be the 24th. The IOF at St Albans is now the longest running organ festival in the world.

At its heart are two internationally renowned competitions, the Interpretation competition and an Improvisation competition (formerly known as the Tournemire Prize). The competitions are considered very prestigious. Winners of these can be assured exposure on an international concert circuit, representation by an American agent and a solo CD with Priory Records as well as winning a generous cash prize. Former winners in interpretation include Dame Gillian Weir, Susan Landale, David Sanger, Thomas Trotter, Kevin Bowyer and most recently Andrew Dewar in 2005; and Guy Bovet, André Isoir, Naji Hakim, Jos van der Kooy, David Briggs and Martin Baker are all winners of the improvisation competition.

The Jury for the competitions always consists of renowned organists from around the world (the five juries included Marie-Claire Alain, Ralph Downes, Piet Kee and Anton Heiller). In 2007 the Jury will include two former winners of St Albans competitions: Lynne Davis (France/USA) and Martin Baker (Master of Music, Westminster Cathedral), and three internationally renowned recitalists and teachers of organ: Ludger Lohmann (professor of organ in the Musikhochschule in Stuttgart, Germany), David Titterington (head of organ studies at the Royal Academy of Music, London) and the young American organist, Paul Jacobs (chairman of the organ department at the Julliard School, New York). They will all perform in concerts throughout the ten day Festival. The competitions during the Festival are in three rounds after a recorded audition has been assessed earlier in the year.

The city of St Albans now has three excellent organs to host these competitions – originally the festival was partly conceived by Hurford to celebrate the building of the new organ in the Cathedral by Harrison & Harrison. The main competitions are still conducted on this instrument, its eclectic style and modern electro-pneumatic action now complemented by a new Mander organ with mechanical action in St Peter’s Church and the organ built for and owned by the IOF in St Saviour’s Church – a Peter Collins instrument designed and based on the style of the 18th century organ builder, Andreas Silbermann, in sound, specification, action and appearance.

The rest of the Festival incorporates or complements the organ in the world of music in general. There is at the heart of all these events the usual round of services in the Cathedral, with daily Evensong sung by the Cathedral Choir and the Abbey Girls Choir and festival services on the Sunday, which articulate the week and put the organ in its traditional and conventional

liturgical context. But there are also concerts with the organ (and without) in other contexts and musical styles with other instruments and for other groups, orchestras and choirs. Alongside the main organ festival there is an exhibition of organs, principally by the major British organ builders, and during the week demonstration recitals are played on these.

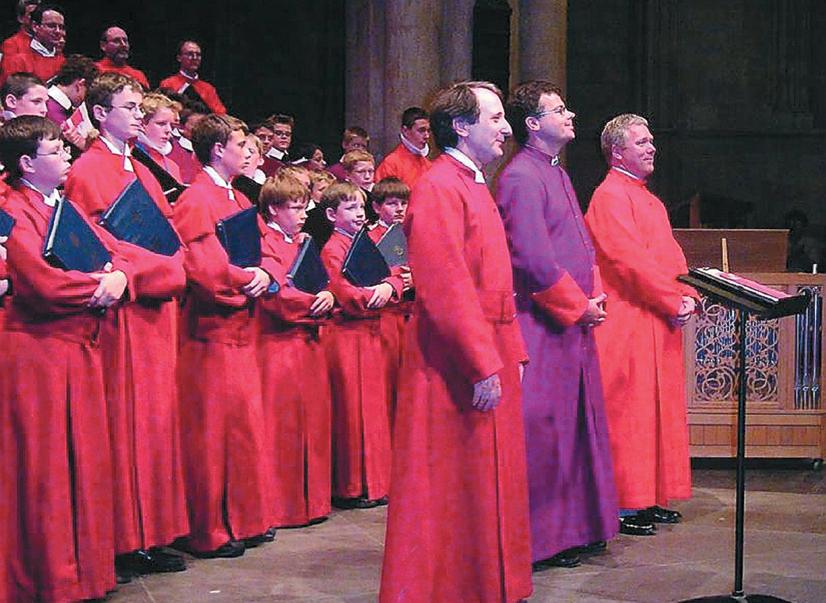

To date (February) the programme of events for the 2007 Festival includes such highlights as a jazz concert with John Dankworth and Cleo Lane, a fantastic gospel choir from London, Voices 2000, with organ, the internationally renowned Hilliard Ensemble perform and evening concert in the cathedral, and on another evening the soprano and presenter of Radio 3’s Early Music Show, Catherine Bott, will perform with a small consort. There will also be a performance of Elgar’s The Kingdom and, for aficionados of the English Cathedral choral tradition, a three choirs concert for the choirs of St Albans Cathedral, St John’s College, Cambridge (director, David Hill), and St Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue, New York City (director, John Scott) and an ‘awayday’ to some interesting and historical organs in Essex. We hope that it includes something for everyone.

The real success of the International Organ Festival over the last 44 years has been that all of its basic structures and support mechanisms are supplied by the local community. The Festival Society is largely a volunteer organisation – there are only three permanent paid staff and none are full-time employees. So all the box office staff, stewards at concerts, hosts of the competitors, the compilers and editors festival souvenir brochure and the managers of the organ competitions, for

example, are done by local people in their own time and largely at their own expense. This has been an invaluable asset in various ways, not least that it means the festival can run on a much lower budget than would be the case if all these were provided by paid staff. It has been interesting to see other competitions and festivals around the world come and then go after a brief flourishing, largely due to the loss of a major sponsor or the withdrawal of financial backing from a local authority. The financing of festivals never has been, nor ever will be, an easy task. We rely on sponsorship to make up the shortfall of expenditure over income from concert ticket sales, but without the support of all our volunteers the amount needed from corporate sponsors would be so much greater.

And a wonderful spin-off from the involvement of so many local people is the wonderful atmosphere that pervades the 10 days of the festival. All who come to experience the competitions in particular comment of this and feedback from competitors is unanimous – they feel very well supported and cared for by their hosts and others and affirmed in their musical contributions to the festival as a whole so that, whether a prize-winner or not, the whole experience is a good and positive one.

In mid-July St Albans is a lovely place to be. The city is beautiful with its mix of mediaeval and modern, there are great restaurants, large open spaces and green lawns adjacent to the cathedral, ancient roman ruins to visit just a stones throw away across a park and central London is only 20 minutes from Kings Cross by train. So with all this and the heady mix of the excitement of an international competition and wonderful concerts to attend in the evenings it is something to be experienced. This is also the last chance to hear the fabulous Harrison and Harrison organ designed by Hurford and Ralph Downes before its restoration and enhancement later this year and scheduled for reinstatement in time for the next festival in 2009. We hope to see you there.

Andrew Lucas is Artistic Director, The International Organ Festival at St Albans and Master of the Music, St Albans Cathedral

David Leeke reports that a service was held at St Michael’s, Croydon, on Saturday 3 February 2007 to commemorate the life of Michael Fleming. Michael Paschal Marcon Fleming (1928-2006) was an eminent church musician, for many years working at the Headquarters of the RSCM at Addington Palace and Director of Music at several well-known London churches. When he died in January 2006 he was Master of the Music at S Michael’s, Croydon, where he ran a choir of the highest standard singing a wealth of the cathedral repertoire. The window (see photograph) was commissioned in his memory. It is set in the south aisle replacing plain glass placed there after enemy action in 1944. The main figure is that of S Gregory the Great in recognition of Michael’s long association with plainsong and Gregorian Chant. Above this central figure is the west front of Canterbury Cathedral; Michael was educated at S Edmund’s School, Canterbury and was ‘Hymns Ancient and Modem Scholar’ at the RSCM when it was in the Cathedral Precincts. Michael himself features conducting three girl choristers who represent his choir at St Michael’s and girls from the RSCM Girls’ Choir which Michael established during his time at Addington. He is depicted wearing the hood of his Lambeth degree awarded to him for services to church music and liturgy. Here there is also a scroll of plainsong Victimae Paschali, the Easter Sequence (Michael was born on and named after Easter Day), with sections of the great Father Willis organ behind. In the border of the window there is more plainsong fragments of the office hymn for Michaelmas Christe sanctorum decus angelorum (Christ the fair glory of the holy angels). The dedication panel at the base of the window not only marks Michael Fleming’s name and dates, but includes words from the hymn for which he is best known for the fine tune Palace Green: To Cod all praise and glory’.

The Trustees of The Wells Cathedral Girl Chorister Trust have announced that HRH The Countess of Wessex has become the Royal Patron of the Trust. The girls’ choir was formed in 1994 and its contribution to the music of the cathedral is constantly being praised. The Trust was established in 2002 to ensure that there is proper bursary provision for the eighteen girl choristers to match that already in place for the boy choristers.

A special concert was held in November to mark two new recordings by the girl choristers. These are the first to be made by Matthew Owens [Organist and Master of Chorister] since he took up his post in January 2005. The recording of Geoffrey Burgon’s music now released includes the beautiful setting of the Nunc dimittis. The Gramophone review says “this immensely appealing music is superbly sung by the Wells Cathedral Choir who prove to have excellent soloists”. The second recording will be released in January 2007 and features the work of David Bednall, the Assistant Organist at Wells Cathedral.

Dr Alan Thurlow, FCM’s last Chairman and Organist and Master of the Choristers at Chichester Cathedral since 1980 has been awarded Fellowship of the RSCM, awarded for contributions to church music. He was presented with his award at the RSCM’s annual Celebration Day service in Llandaff Cathedral on 12th May by Mark Williams, Chairman of the RSCM Council. “Each year the RSCM has the pleasure of conferring awards on individuals and sometimes organisations who make outstanding contributions to the musical life of our communities”, he said.

Timothy Noon Organist of St Davids Cathedral was honoured with an Associateship, for the development of the cathedral choir and the St Davids Cathedral Festival.

DR ROBERT ASHFIELD RIP

Douglas Henn-Macrae a lay clerk at Rochester Cathedral writes: Robert (“Bobby” or “Doc”) Ashfield (as he is affectionately known in Rochester), was the first cathedral organist under whom I sang as a very new supernumerary lay clerk in the autumn of 1970, learning the job by singing alongside one of the six regular men. He was born in Surrey in July 1911 but his family moved to the village of Eynsford in Kent in 1912. His first practical musical experience was blowing the organ in the village church while his mother played and sometimes they reversed the roles. As a young teenager he attended Tonbridge School, where he excelled both at the organ and on the sports field. In 1928 he entered the Royal College of Music in London to study with Ernest Bullock (then Organist of Westminster Abbey). Having gained his ARCO diploma in 1931 and FRCO the following year, Bullock invited Robert to be his Organ Scholar at the Abbey. In 1934 he was appointed Organist of St John’s, Smith Square in London (now a concert hall) and in 1936 he became Music Master at Westminster Abbey Choir School, gaining his BMus from London University the same year. In 1940 he returned to Tonbridge School as Assistant Music Master, and obtained his DMus the following year, before being called up for war service. After the war, in 1946, he went to Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire as Organist and Rector Chori. He moved to Rochester Cathedral as Organist in 1956 and the following year was also appointed a Professor for Theory and Composition at the Royal College of Music. Robert retired in 1977 but remained active until very recently as a composer and concert promoter, and was a regular attender at the Cathedral Eucharist on Sunday mornings. We last saw him in church on Christmas morning. The Cathedral Special Choir had already scheduled some of Robert’s music for this weekend (as we often do). As I write, the Introit at Evensong today was his processional setting of Of the Father’s love begotten, and this is repeated at tomorrow’s New Year Carol Service; at Mattins we will sing Fairest of morning lights (17th century text by Thomas Pestel); and as an extra valedictory item at the end of the Eucharist we will sing his best-known anthem, written for a Diocesan Choirs’ Festival at Southwell in 1949 to a text by Lionel Johnson, based on Revelation 17: ‘Ah, see the fair chivalry come, the companions of Christ! White horsemen, who ride on white horses, the Knights of God! They, for their Lord and their Lover who sacrificed all Save the sweetness of treading where He first trod! These, thro’ the darkness of death, the dominions of night, Swept, and they woke in white places at morning tide: They saw with their eyes and sang for joy at the sight, They saw with their eyes the Eyes of the Crucified. Now, whithersoever He goeth, with Him they go: White horsemen, who ride on white horses, Oh, fair to see! They ride where the rivers of paradise flash and flow, White horsemen, with Christ their Captain, for ever He!’ May he rest in peace and rise in glory.

Ithink I’ve always been a bit on the outside: as a Scot we went to the ‘English’ church, and when working in England I never felt I had Dickens, brandy butter and all the other English traditions in my bones. So in a sense it was natural, having served Coventry Cathedral for eight years as Director of Music, to seek fresh challenges. In July 2005 I became the first serving cathedral organist in several centuries to become an Anglican minister. Despite having three years to come up with a plan, the management at Coventry were not

imaginative enough to see how music/ministry could be combined and the chance to contribute to a church where creativity is valued seemed too good to miss.

By coincidence the Dean of Brisbane had sung at Coventry Cathedral’s consecration (as a treble), and the international dimension of ministry (involving real engagement with other faiths and other Anglicanisms, as well as other languages) is something I value very much. Whereas the Sydney diocese has a problem with anything other than English in their liturgies,

A year ago, I wrote a little piece for CATHEDRAL MUSIC, and it’s great to be given the opportunity to reflect more on what life is like for church music here.

we positively relish other languages as a truer reflection of the multi-cultural status of Australia. Australia has a wonderful multi-cultural channel (SBS) and it is fascinating to see the church/state dynamic at work.

My post at St John’s is Director of Music, but it has been especially rewarding to see how I can bridge the perceived gap between the various aspects of music ministry and the many other pastoral matters. Being able to articulate the place of music is important, and because I am also rostered for sermons, prayers, offices, etc, people get to see a little of how integrated worship can work. In a funny way I had been doing that for years in Coventry, though because I wasn’t ordained it was often remarkable how that disadvantaged what needed doing. The church is particularly prone to clericalism, especially when its leaders are not very secure intellectually or emotionally, and it’s good to see that there are grounds for hope at least in Australia.

The previous organist at Brisbane had been appointed in 1960: inevitably the horizon nowadays is different from what it was then. For instance tight ensemble really matters (in most music), as does thorough training of boys to read music fluently. To sing a wide repertoire (which is pretty much a sine qua non in a cathedral) the music reading has to be pretty secure, and if you add to that the expected range of musical styles we need to access it means that focussing on reliable vocal technique and good rehearsal techniques (to maximise the time) are all important. Keeping up with music journals, the web, broadcast and recordings is important, as is having occasional visits from musicians. We had Colin Walsh playing a stunning recital on his way back to the UK (form a tour to NZ), and the choir of Girton Cambridge were out for a few weeks. Singing Kodaly Missa Brevis together was a delight, and it was good for the boys to see a mixed choir and hear sopranos sans wobble!

St John’s is by a large stretch the most comfortable cathedral to work in that I have known - there is none of the Barchester Towers nonsense that seems to be a parlour game for some English places. We forget that cathedral communities constantly need inspiring since they are a mix of transient, tourist, disaffected, explorers, snobs, nice people and those who also come for the music! The congregation has responded rather imaginatively to the various initiatives and after many years of things being the same, there was a hunger to change things so that has helped. That said, the idea of congregational involvement (eg responsorial psalms, and even sung acclamations etc) is still rather new and we have things to work on. I make a point of writing a page of notes about music, theology, and politics for each service sheet, which at the very least becomes reading matter if a sermon is below par! At the same time it shows a willingness to engage and inform so people know what it is we are about.

The choristers all attend the prestigious Anglican Church Grammar School, and the lay clerks are drawn from the area –the demographics of Brisbane are interesting, because there are so few ‘cathedral-style’ choirs, some folk travel huge distances to belong, and this is heartening that some folk value it that much. The pool of lay clerks has expanded in the last year, and this has given us a greater degree of flexibility. It simply isn’t true to say that Australia is uncultured (funny how UK folk assume that it is - Queensland has obligatory class music, while the UK can’t even pay peripatetic teachers!) but it is true to say that some folk do not quite know how committed one has to be to make music at the highest level. I am so lucky to have a superbly imaginative assistant in Christopher Cook –

he brings a wealth of experience and dynamism to the projects we do and the choristers would not have developed as fast as they have without his care and attention too.

The most pleasing comment I had was from Peter Kneeshaw (the organist at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney) who was impressed that the boys now make a large sound. Certainly, if every boy projects properly (especially with fairly straight walls, and a high stone ceiling) it is not that difficult to make a decentsized noise. I am also pleased that the Psalm-singing is now more developed. For instance, the ‘dramatisation’ of Anglican chant is quite important, and it is hugely satisfying (and better worship) to sense the journey and the emotion inside them.

It doesn’t of course take an outsider to do this - but sometimes (certainly in the UK) things can be rather in-bred: I was the first organist at Coventry in 35 years who hadn’t been the assistant organist! Valuing different approaches is really the key to good music-making as in church. The danger of ‘indifference’ is two-fold - one that we don’t care enough to make things better, but also we don’t value the differentness that worship offers. People forget that the word ‘holy’ is related to a type of differentness, a set-apartness. Stepping into choral worship is like dipping your toe in a stream that has been going on for hundreds of years. And the current rash or panic to call everything mission is a huge example of how the church can misunderstand its calling. God calls us to be faithful, which means worshipping God above all else. Until the church realises that worship is the most important thing we can do we are bound to struggle!

We are investigating the idea of the choir coming to the UK in 2009 (it takes a long time to get the finances straight for a big trip), and this is in the light of a lovely trip to New Zealand. The choristers in particular benefited from having to raise their game, and singing in Wellington Cathedral reminded me of Coventry (large acoustic) and also the same glass windows by the Kiwi John Hutton!) where clarity was allimportant. I think the FCM does a good job in keeping folk informed: becoming blinkered is one of the chief dangers of working in your own furrow!

‘Despite having three years to come up with a plan, the management at Coventry were not imaginative enough to see how music/ministry could be combined and the chance to contribute to a church where creativity is valued seemed too good to miss.

Age: 44

Education details:

Harrogate Grammar School 1977-1981

Worcester College, (Organ Scholar) Oxford 1981-1984

Career details to date:

Winchester Cathedral Organ Scholar 1984-1985

Salisbury Cathedral Assistant Organist 1985-2005

Salisbury Cathedral Director of Music 2005-

You have been assistant at Salisbury and now the No1. What has changed, if anything? And, what do you want to achieve?

I am enjoying being in overall control of the choirs here and particularly being able to rehearse them on a daily basis. The more experience I get, the more I rely on my musical instincts to produce what I hope are quality performances at a consistent standard. I want to build on the strong foundations laid by my predecessors and make Salisbury Cathedral a byword for excellence in liturgy and music.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

Although I do not play the organ as much as I should these days, I really enjoy learning music by the French School, as it suits the Willis organ so well. I have recently been tackling Vierne’s Third Symphony and movements from Widor’s symphonies.

Have you been listening to recordings of them and if so is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

I must confess that generally I do not listen to CDs of organ music as my main interests lie in choral and orchestral music.

What new repertoire will you be introducing to the choir?

I am keen to expand the repertoire of the choir in several directions. We currently do not sing enough music by Byrd, Gibbons and Tallis, and also we do not make significant inroads into the contemporary scene. Although perhaps not strictly new repertoire, a great deal of my energy over the past year has been in making the change from the Revised Psalter to Coverdale, something I had been wanting to do for a decade or so.

What or whom made you take up the organ?

Not sure really. I remember listening to a friend playing the organ and I reckon I was hooked from that moment.

Which organists do you admire the most?

I admire and am grateful to all the organists who have had an influence on me. Certainly Adrian Selway, my first teacher in Harrogate, then Ronald Perrin of Ripon Cathedral, James Lancelot, my patient mentor at Winchester, and finally Thomas Trotter, who took my playing to a new level.

What was the last CD you bought?

Erich Korngold’s Symphony with the LSO and Previn. Magnificent, underrated work, brilliantly performed.

What was the last recording you were working on?

My first in charge at Salisbury, The Virgin Mary’s Journey, recorded last year.

What is your:

(a) favourite organ to play?

St Paul’s Cathedral, London

(b) favourite building?

Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

(c) favourite anthem

Gibbons O thou the central orb – perfection

(d) favourite set of canticles

Stanford in C

(e) favourite psalm and accompanying chants?

Psalm 84 (Walter Alcock)

(f) favourite organ piece

Bach’s Passacaglia & fugue in C minor

(g) favourite composer

Brahms

What pieces are you including in an organ recital you are performing?

Mendelssohn’s 3rd Sonata, Walter Alcock’s Toccatina, Bach’s Prelude & fugue in B minor, Franck’s Choral 1 in E major.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

I enjoyed playing the organ part in the Saint-Saens Organ Symphony for a huge Salisbury Spire Appeal Event, when I was on the organ inside the cathedral, and the orchestra was on a stage, outside on the green at the West End.

Has any particular recording inspired you?

I still have an ancient LP of Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra

playing Elgar’s Symphony No. 1 and I reckon it beats all other versions I have heard. All the tempi are just right.

How do you cope with nerves? They don’t really bother me.

What are your hobbies?

Wine, beer, football, cricket, reading.

Do you play any other instruments? Cello – very, very badly.

What was the last book you read?

Vikram Seth’s An Equal Music.

What are your favourite radio and television programmes? I’m sorry I haven’t a clue and Match of the Day

What Newspapers and magazines do you read? The Week and Private Eye.

If you could have dinner with two people, one from the 21st century and the other from the past, who would you include?

Dinner with Humphrey Lyttleton and Mozart could be fun.

What should be the role of the FCM in the 21st century? To continue to encourage cathedral musicians in cherishing the past, nurturing the present and building for the future.

Saturday 20 January – boys

Saturday 3 February – girls

Do you know a child in Year 3 or 4 who loves singing and would like to be in Salisbury Cathedral Choir? A fantastic opportunity for children in a spectacular setting

Salisbury Cathedral Choir’s open day

Saturday 11 November 2006

There will also be a special workshop for prospective voice trial candidates and their parents on Saturday 9 December

The Director of Music, David Halls, is always happy to meet prospective choristers and their parents and advise on how best to prepare for voice trial

For further details about any of the above please telephone

A talk given to the FCM Oxford Gathering in March.

When Dr Higginbottom asked me to speak today he said that it would be fitting if your meeting in Oxford could be marked by some local colour in the shape of a talk on the Oxford Movement and its influence on church music in this country.

Let me start with a definition. The Oxford Movement is the name given to a stirring in the spirit of Anglican Churchmen, beginning in the first part of the 19th century, whose impact was to affect the whole of the Church of England. It is forever associated with Oxford because three Oxford dons were leading figures in this movement, each of them being at some point a fellow of Oriel College. I am referring to John Keble, after whom Keble College is named; John Henry Newman, who surely needs no introduction; and Edward Bouverie Pusey, in whose memory Pusey House here in Oxford was founded, where I have the privilege of working.

Now it is a pleasant irony, but an instructive one, to remember that the Oxford Movement began with politics and then got caught up with matters of theology and Church life. Also, as with so many important issues in English political affairs, you will not be surprised to learn that it involved Ireland. Put briefly, the problem was this: following the parliamentary union of England and Ireland in 1800 objections began to be raised to the system whereby in Ireland nonconformists and Roman Catholics were required to support financially the established Anglican Church. To assist the Church of Ireland financially in the wake of the changes which were coming about the English Government decided to amalgamate several Irish bishoprics, meaning that certain of them would cease to exist as independent dioceses. On purely utilitarian grounds this was reasonable, but for those who held a particular view of the nature of the Church the proposal was outrageous.

It helps to remember that the Oxford Movement did not spring from nowhere. Its roots were in that outlook on Anglican matters which we loosely call High Church. Those who hold to this position have a high opinion of the nature of the Church. They see the Church as a divine society, one instituted by God in Christ through his apostles. Its structures are therefore not accidental, but formed under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Its bishops are successors to the Apostles, who guarantee the orthodoxy of the Church’s doctrine and teaching. God’s own life is given to His people through the Sacraments of His Church. This is a school of opinion going back to the early days of Anglicanism, and with its foundations in an older Catholic tradition.

To those who thought in this way the plan to scrap bishoprics was highly offensive because it suggested that the

State had the right to decide the practical affairs of the Church. John Keble was one such High Churchman, and he took the opportunity to say why he objected to the Irish bishoprics scheme when he preached before the Judges of Assize meeting here in Oxford in 1833. He called his sermon National Apostasy. In it he intended to ask the vital question, ‘Is the Church merely a human institution, or is it indeed of Divine origin with its structures and hierarchy approved by God?’ If the latter was true, then the State had no right to tinker with things pertaining to the Church’s organisation.

Keble effectively put a lighted match to the proverbial blue touch-paper. Of those who responded to his challenge none was more important than John Henry Newman. It was Newman whose energy and enthusiasm drew a group of supporters together to see what might be done to reawaken a torpid Church of England to a sense of her God-given nature and her mission. Rather than bother with meetings and petitions, Newman sat down and wrote the first of what became the Tracts for the Times, recalling members of the clergy in particular to a sense of the sacredness of their office. Remember that this was a period when it was relatively easy and inexpensive to get a pamphlet set up and printed. All you had to do then was to distribute it. The Tracts, which became lengthier and weightier when Dr Pusey joined the Movement, spread the challenge of their writers far beyond the confines of Oxford, though the Movement has always kept its Oxford name. So famous did the Tracts become that those who supported the initiative of Keble, Newman and Pusey became known as Tractarians – the term I shall use to refer to them.

As might be expected, the Tracts stirred up a hornets nest. Accusations were rife that their writers wished to smuggle Popery into the Church of England, yet despite hostility and opposition – not least from bishops – the Tractarians steadily gained ground among those who wished to see the Church of England as more than just the shell of an Established Church. Even the massive blow they received in 1845, when Newman left for the Roman Catholic communion, did not destroy their influence. I would mention two areas in which they made particularly important contributions to the life of the Church of England.

In the first place, by reminding Anglicans of their Catholic heritage, the Oxford Movement inspired a renewed awareness of the importance of the Sacraments in Christian life. The Tractarians were anxious to follow the quest for personal devotion and holiness of life. It was partly this which led them and their followers to share in Dr Pusey’s deep concern for the poor. The willingness of Tractarian priests to minister the sacraments in the worst slums of Victorian England’s burgeoning cities was heroic. However, the Tractarian pursuit of

‘

...the Oxford Movement inspired a renewed awareness of the importance of the Sacraments in Christian life.’

holiness had another consequence, which was a conviction that if the sacraments of the Church were to be celebrated more frequently they must also be celebrated with fitting dignity and reverence. From this it could only be a small step to a desire to transform the conduct of worship in churches, and to have new churches built which would be suitable for solemn services.

This is leading us to the influence of the Tractarians on the music of the Church of England, but I must make one thing clear. The development of reverent worship which led, especially in the slums, to the colourful and ornate style of liturgy which became known as Ritualism was certainly an offshoot of Tractarianism, but not one which would have appealed much to the original Tractarians. The concern of Keble, Newman, Pusey and their like was first and foremost sound doctrine. Get your doctrine right and teach it rightly and a desire for good conduct of life and devotion in church will follow. This desire to instil sound teaching into people led to one of the most significant musical results coming from Tractarian influence, of which I shall say more in a moment.

From this point on I am going to have to be even more selective in giving illustrations. I must therefore ask you to accept that if the impact of the Oxford Movement on English Church life was sometimes the cause of contention, it was also widespread and surprisingly rapid. Even the cathedrals were not immune from it. As priests influenced by the Tractarian outlook were promoted to cathedral posts, so the effect on how things were done in cathedrals was felt; and given the dismal standard of worship existing in many cathedrals before the Oxford Movement, the change could only be for the better. One of the most striking examples of change

concerned one of the most striking cathedrals, St Paul’s.