Cathedral MUSIC

ISSUE 1/09

For many years organists throughout the land have aspired to playing a Makin organ. Now with the unsurpassed sampled technology within the Westmorland Custom range, designed by organists for organists; there has never been a better time to own one. Don’t expect gimmicks because you won’t find them here.

Design your own specification, with motorised drawstop or illuminated tab control, with 2, 3 or 4 manuals in sumptuous consoles. These organs are for people who are serious about music, with a discerning taste for the best in sound and build quality. People like you.

Makin is renowned for excellence in after sales service and our highly competitive prices. As the UK’s leading manufacturer, we install at least two Makin and Johannus organs each week at churches, schools, halls, homes and crematoria throughout the British Isles. Visit our web site for customer testimonials, lists of forthcoming and recent installations, sample specifications and much, much more. Contact us today and take your first step to becoming a member of the Makin Family.

You don’t buy a Makin Organ; you invest in one ... Why settle for less? Custom

Westmorland For more details & a brochure please telephone 01706 888100 sales@makinorgans.co.uk Visit our web site www.makinorgans.co.uk

Organs

Cathedral Music

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2009

Editor

Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace Ripon North Yorkshire

HG4 2QS

ajpalmer@lineone.net

Assistant Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon

FCM e-mail info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road

LONDON SW4 8AR

Tel:0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

Friends of Cathedral Music

Membership Department

27 Old Gloucester Street London WC1N 3XX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087

E-mail: info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT Tel: 0113 255 6866

info@mypec.co.uk

www.mypec.co.uk

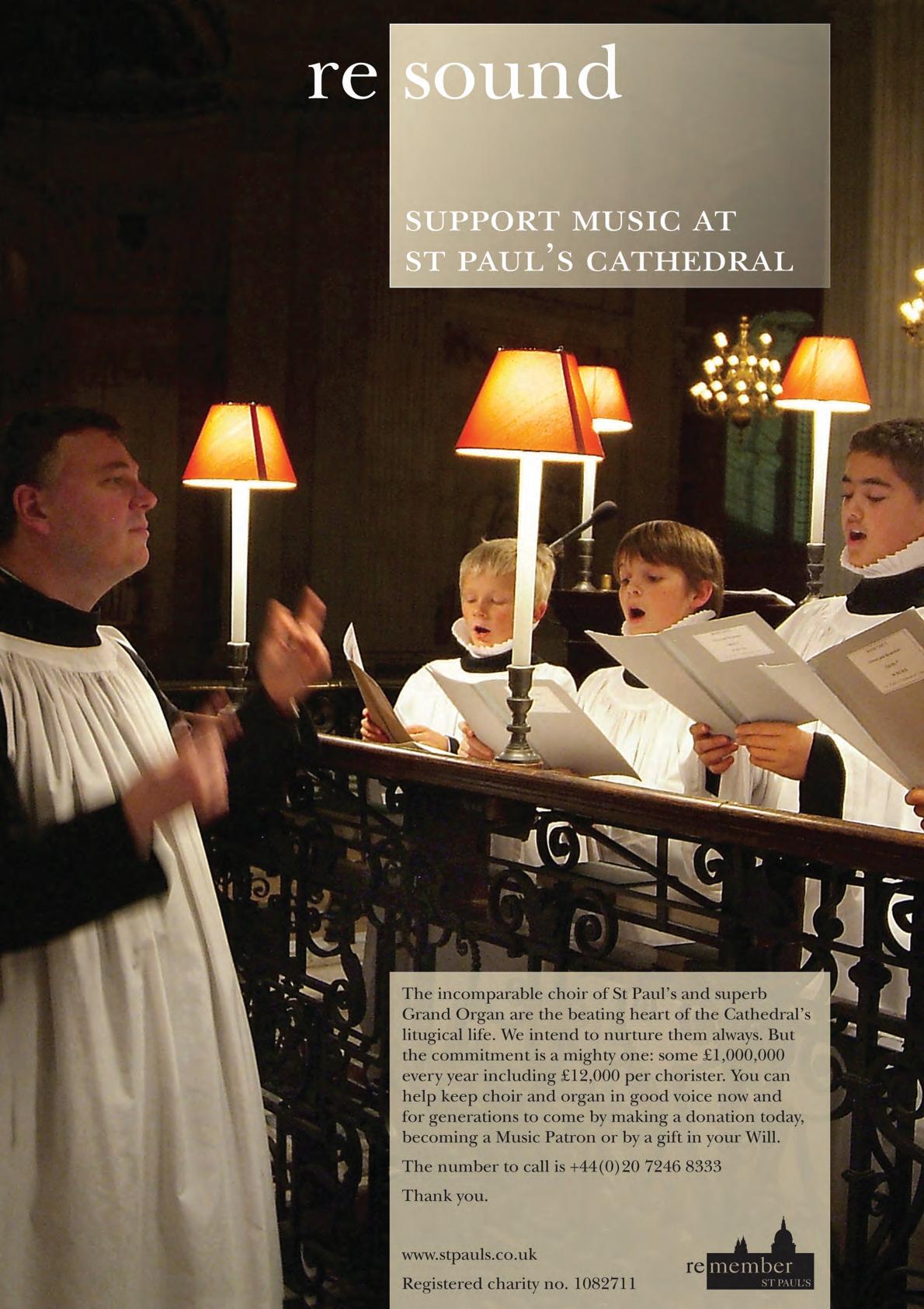

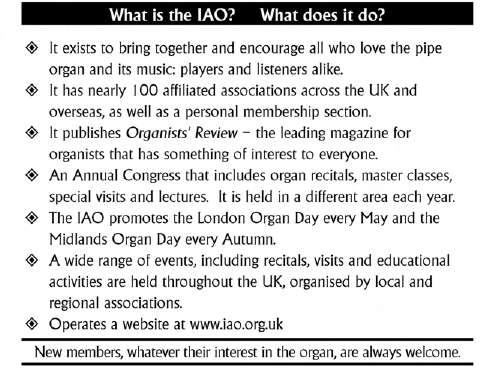

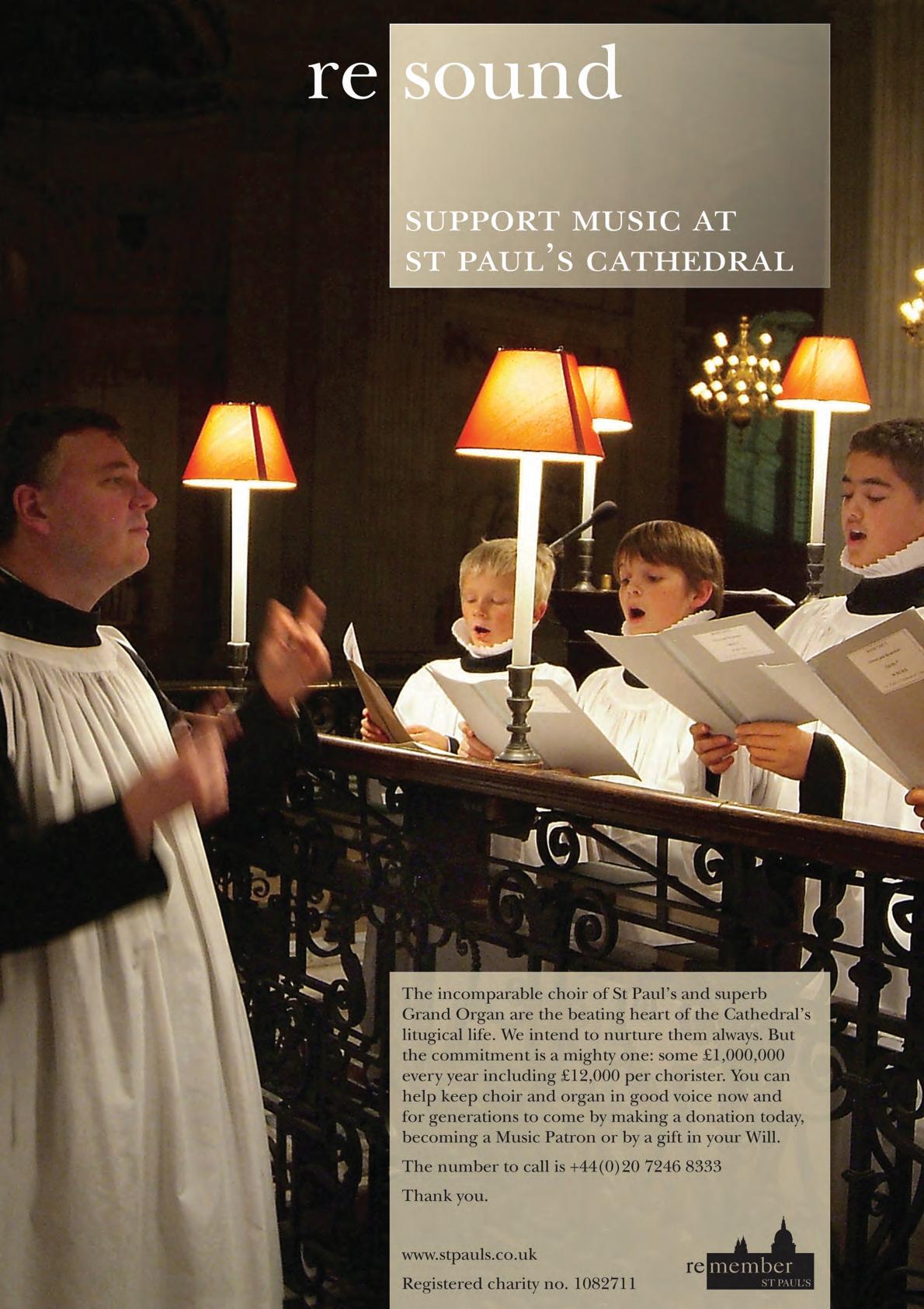

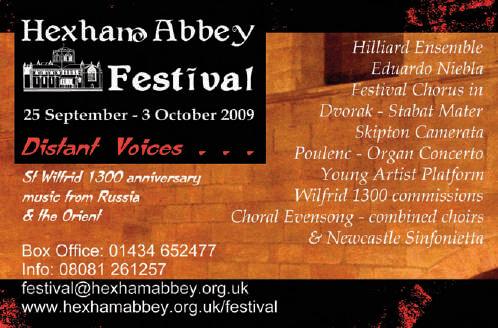

Cover Photographs Front Cover Bristol Cathedral Photo: © Neil Hobbs Back Cover The Nave and Organ Screen at Beverley Minster Photo: © Craig Wilkinson The Magazine of the Friends of Cathedral Music CM Comment 4 Andrew Palmer Chorister Days with Alan Spedding 5 Graham Hermon A Personal Reflection 6 Alan Spedding reflects on forty-two years as Organist and Master of the Choristers at Beverley Minster Just for the Record 12 Christopher Humphries talks about his recording experiences Stephen Darlington 16 60 Seconds in Music Profile Safeguarding this Priceless Heritage –Bristol Cathedral Choir School 18 Canon Wendy Wilby, Precentor Liverpool’s Year as Capital of Culture 2008 22 Timothy Noon Simon Johnson 24 60 Seconds in Music Profile The Singingmen’s Supper 26 Bristol Cathedral’s Lay Clerks’ Tune Singingmen & Drinkingmen 28 A Lay Clerks Tale –Andy Marshall The Klais Organ of Bath Abbey 30 Peter King Whose Music is it Anyway? 38 Revd Martin Eastwood –Liturgy and Music at St Paul’s between the Wars The King’s Singer 42 Tim Rogerson Clergy, Organists & other Disharmonies 46 A talk given at the conference ‘Cathedral Voices across half a Millennium’ BBC Proms Preview 53 Roger Tucker Sounds New Contemporary Music Festival in Canterbury 54 Paul Edlin Cambridge Choirs Today 56 Geoffrey Webber –Cambridge University celebrates its 800th Anniversary Letters 59 Your views Book & Music Reviews 60 The latest books and recordings Cathedral Music 3 Payment of a donation of £3 to the distributor of this magazine is invited to cover the cost of its production and distribution Cathedral

MUSIC Cathedral MUSIC

CM Comment Andrew Palmer’

lost all their singing boys.

In this edition we are publishing a letter from FCM member Lynda Collins, which indicates her disquiet over what she sees as the erosion of the pre-eminence of the traditional all-male cathedral choir by the slow but sure march of girl choristers into our cathedral choir stalls. In my last Comment [2/08] I dared to suggest that this had not undermined the all-male tradition in the way that was predicted by a minority of its supporters.

The whole complex interaction that has followed from the formation of the first girls’ top line at Salisbury in 1991 is difficult to unravel. I use the term ‘top line’ rather than ‘choir’, because these groups were never intended to be freestanding choirs of girls’ voices.

The concern which Lynda Collins expresses is that girls will eventually replace the tradition of boys singing the top line in our cathedrals; so that is the case that has to be proved.

I recall the response of Alan Thurlow, our immediate past chairman, when this matter was raised in FCM Council: “show me an example of this happening and I will take the threat seriously.” It has to be said that we never could.

The Campaign for the Traditional Cathedral Choir (CTCC) was predicated on this perceived threat. As part of their service they now produce a leaflet (advertised in our last edition) which shows how many all-male choirs are still around in cathedrals and churches, which seems to belie their basic fear. In the latter category it is certainly true that many churches have

The CTCC predict the demise of the boys’ top line but they also have never adduced the hard evidence that Dr Thurlow called for. I know of no Anglican cathedral, where boys have always sung the top line, from which they have now disappeared; in fact there are several where boy choristers have been restored e.g. at St Davids and St Edmundsbury and, incidentally, both St Anne’s and St Peter’s Cathedrals in Belfast have introduced a boys’ top line. It is interesting to note that Dublin’s three cathedrals each offer a different model. Of the two Anglican foundations, St Patrick’s has an all-male choir fed with boys from the only choir school in Ireland, whereas Christ Church closed its choir school in 1972 and now has an adult choir. At the RC Pro-Cathedral there is the wonderful Palestrina Boys’ Choir, which as well as singing Solemn Mass with the cathedral’s main choir, performs as a free-standing concert ensemble.

The truth is that there are arguments and pressures both ways: yes, there are those who want girls to have more opportunities to sing in cathedrals and there are those opposed to this, although it is politically incorrect to reveal it. Some deans and chapters are in favour, others are against, because of financial, practical or musical traditional reasons. A director of music cannot initiate such an innovation because he or she wants to, nor can they do the reverse but they can advise their deans & chapters. One assumes no professional cathedral music directors would want to lose their boys’ top line and they work very hard to go out and recruit good voices, especially in cathedrals where there is no choir school. It is interesting to note that some of the major English foundations still do not have a girls’ top line, although a few have an alternative girls’ group on a quite different footing from the main choir. There are clearly signs that most cathedrals want to strike a balance between giving girls their longawaited opportunity and keeping the

all-male tradition strong. The CTCC can claim some of the credit for opening up this debate by highlighting the dangers. The resulting scrutiny of this divisive issue from all sides, not least from the parents of both the boys and the girls, has all helped.

My point is that it is a mistake to exaggerate the trend, so implying the battle is lost. I believe that we shall not know the outcome for many years and the trend may be less total than Collins and other members of the CTCC fear. The truth is that, on the evidence, the all-male tradition is not dying but coexisting peacefully. At Salisbury, the recruitment of boys is stronger than ever. The real danger is that the practice of mixing boys and girls singing the top line might increase, because then the unique qualities of each will be submerged in a homogenised and undistinctive vocal timbre. It is pleasing to note that this has not happened and there is still only one Anglican cathedral in England with a mixed top line. The majority of cathedrals are not in favour of mixing.

Another threat to the traditional sound is the temptation to use women to sing the alto line, because of the lack of male counter-tenors, the unique feature of the English cathedral choir. Indeed the loss of boys from the top line will lead eventually to a shortage of altos, tenors and basses. Always remember that the majority of lay clerks are ex-cathedral choristers who have been hooked on the traditional repertoire as boys.

In criticising FCM, Lynda Collins makes the mistake of confusing the messenger with the message. It is an exaggeration to say that ‘the makeup of choirs is far removed from those in existence when the FCM was founded’, the alto, tenor and bass lines are still sung by men and in the majority of services in cathedrals there is still a boys’ top line. The inclusion of women in cathedral choirs is extremely rare. At all events, the traditional repertoire is still sung in our cathedrals: and it was to safeguard this that our founder, Ronald Sibthorp, set up the FCM.

Cathedral Music 4

‘

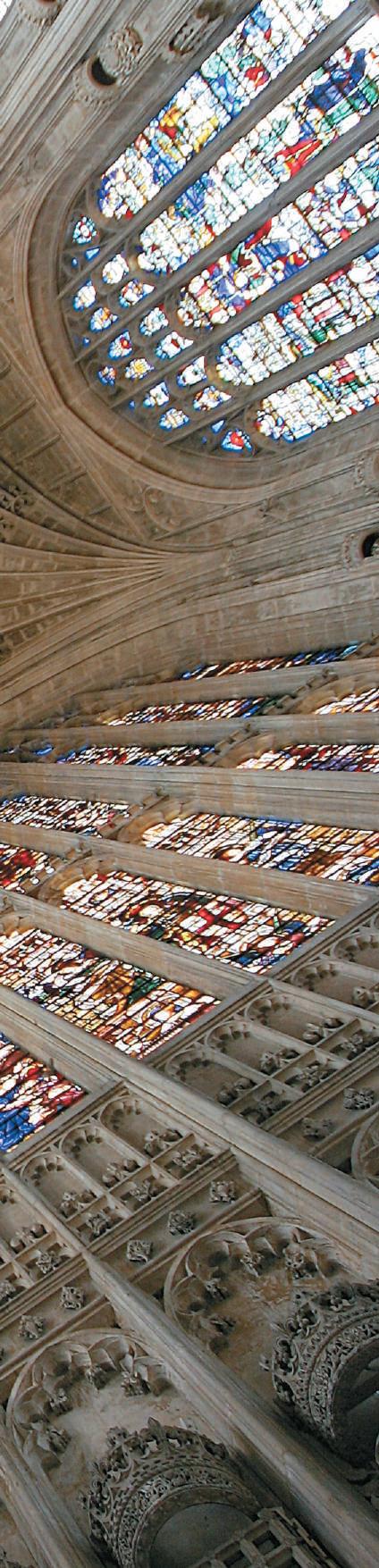

The CTCC predict the demise of the boys’ top line but they also have never adduced the hard evidence that Dr Thurlow called for.

Chorister Days with Alan Spedding

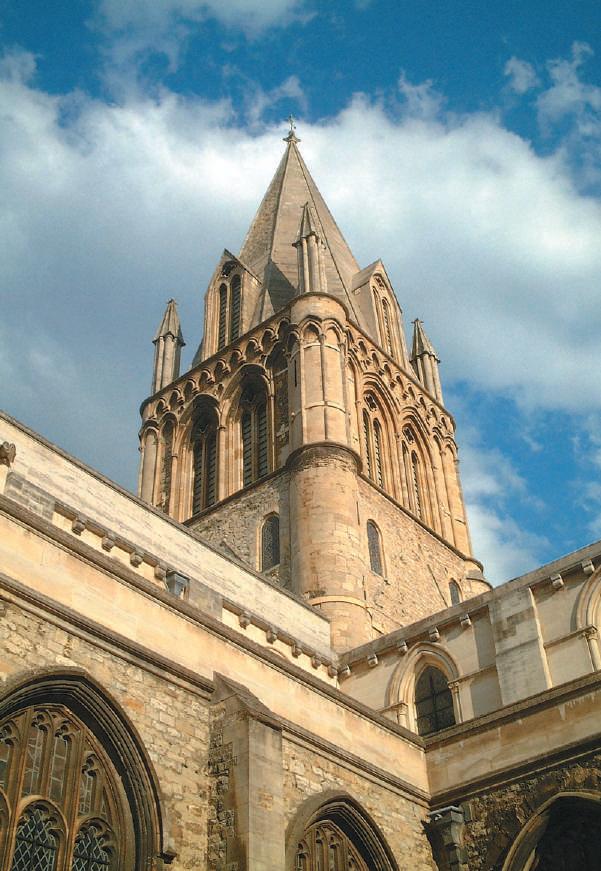

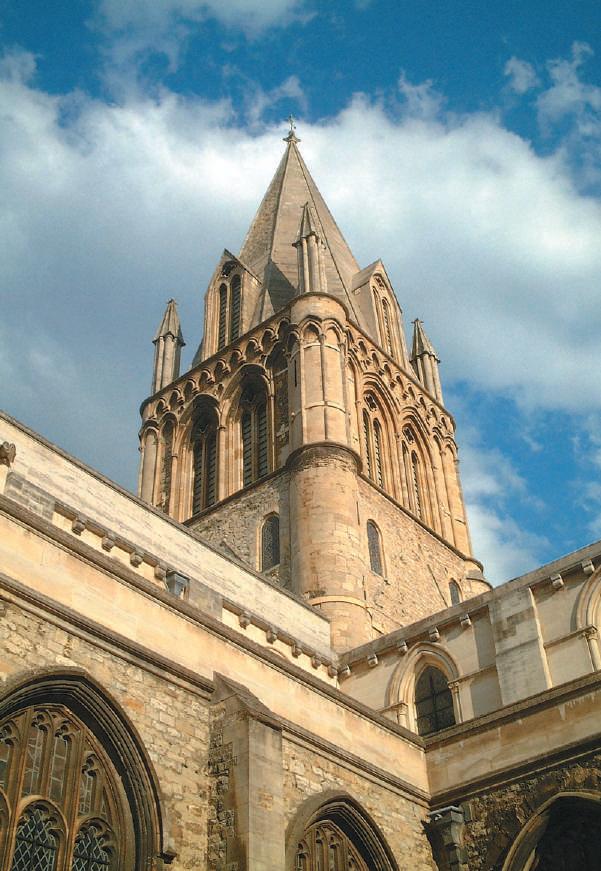

The photograph above is pretty much the view I saw as a boy from the bathroom of our family home in Wilbert Lane, Beverley. I was fortunate in that my mother attended church and out of the two fine churches in Beverley, we lived in the parish of the Minster, often referred to as one of the finest Gothic church buildings in Europe. When Alan Spedding started at the Minster in 1967 he was looking for new choristers. Speaking to my mother after one service to enquire if my two elder brothers might be interested in joining the choir, my mum declared: “I have a third boy at home who loves singing”. This was the start of my chorister days at Beverley Minster and what a kickstart it was. I was in awe of the building, its beauty, the organ and the new Master of the Choristers, Alan

Spedding. Alan had a clear idea of what he expected from us choristers, and had the skill and expertise to get exactly what he wanted. Thursday night Evensong was a highlight for me and I will never forget those dark winter nights where we would sing this wonderful service in a building of such beauty and magnificence. Historically, the organists of Beverley Minster have tended to have long tenures –Alan Spedding has been no exception to that rule. If you have seen this building you will understand, like me, why this should be the case. For those of you who have not visited Beverley Minster, you should put it on your ‘To Do’ list. You will not be disappointed!

Sadly my chorister days at the Minster were cut short due to a family move to North Yorkshire, but I never lost contact with Alan. Some years later as an adult,

I sang under his direction for a few years on a summer course at Salisbury Cathedral. With a love for cathedral music I went on and became a lay clerk at Ripon Cathedral and sang there for seventeen years. Such has been Alan’s inspiration to not just me, but many choristers, organ scholars, and song men. Alan retired from the Minster directing his last service on March 12th 2009. A service was held on Sunday 1st March 2009, at which Alan’s retirement presentation was made. A very large congregation attended and a former Vicar of the Minster, now the Bishop of Chester preached. Dr Peter Foster gave a light-hearted sermon and cited the happy days he had served at the Minster and spoke of the excellent working relationship he had enjoyed with Alan.

Graham Hermon

CATHEDRAL MUSIC Production Manager

Cathedral Music 5

I am enormously proud to write this foreword to Alan’s article and am certain that I am amongst hundreds of people who send Alan our very best wishes in his retirement, though I have no doubt he will still be very much involved in music-making.

Beverley Minster, north view © Jonathan Tait, 2008 www.flickr.com/photos/jontait2002

Alan Spedding A Personal Reflection

Cathedral Music 6

Beverley Minster from the east © Michael Briggs

In 2002 I was invited to contribute an article in CATHEDRAL MUSIC to mark my thirty-five years as Organist and Master of the Choristers at Beverley Minster. The Editor has been kind enough to ask me to write again now that my retirement, after forty-two years in the post, is imminent –a post which I expected originally to occupy for five years at the most. As I had covered my Beverley years fairly fully in 2002 I thought I might reflect on my earlier musical experiences, however self-indulgent an exercise this may be and for which I apologise at the outset.

I can remember the day I joined the choir of St Mary’s, Wimbledon at the age of eight. It was a Sunday and I was an insignificant probationer among about thirty other boys. (The church is situated just above the famous All-England tennis courts and is visible in many TV relays during Wimbledon fortnight.) I remember nothing of the morning service (Matins, of course), but the Evening Canticles were sung to Noble in A minor. I soon found that sight-singing came naturally to me and I rose, eventually, to the dizzy heights of solo boy and head chorister.

My piano teacher, Horace Collins, sang in the choir and felt, rightly, that singing would widen my musical horizons. He had already given me a thorough musical training which covered, in addition to piano playing, theory, aural training, sight-reading, piano accompaniment, listening to records (he had a vast collection of 78s), playing piano duets and so on. He and my father also took me to orchestral concerts and piano recitals. My Thursday evening lesson took three hours, 6.00pm to 9.00pm, all for the princely sum of two shillings. We were a poor family and I owe him so much for giving me such a foundation.

Our choir had its own rules and customs, some set by the

choirmaster, others by the boys themselves, among which were some initiation rites which would appall the current health and safety lobby. One of these involved jumping off a wall at the bottom of the churchyard and another consisted of climbing to the top of the monument to the great Victorian engineer Bazalgette, removing the top tile, presenting it to the head boy and returning it whence it came as quickly as possible. Our elders and betters were blissfully unaware of any of this, I’m sure.

The choir was affiliated to the special choirs of Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral respectively. Both these choirs attracted boys and men from parish choirs all over London and gave us the opportunity of singing some exciting repertoire. I revelled in discovering such works as Gibbons’s O clap your hands and Weelkes’s and Gibbons’s Hosanna to the Son of David in performances in the Abbey under William McKie, at which the purists might turn up their noses in the light of modern scholarship, but which inspired a whole generation of young singers. On one occasion we sang Parry’s I was glad as Queen Elizabeth and Princess Margaret processed through the Abbey. This was 1951 and King George VI was prevented from attending through illness from attending the service and, sadly, he was dead within a year.

At St Paul’s we sang Messiah on the first Tuesday in Advent and a truncated version, in English, of Bach’s St Matthew Passion, on Tuesday in Holy Week, conducted by John Dykes Bower. The large choir sang under the dome to a packed congregation and I can still remember the thrill, not only of taking part in such awe-inspiring surroundings, but also in listening to some of the superb soloists from the cathedral

Cathedral Music 7

Alan Spedding and his wife with the choir after a service of celebration for his work, March 1st 2009 © Michael Hopps

choir who sang in these performances. These included Alfred Deller, Gerald English, Norman Allin, Thomas Helmsley, Alpha Newby and many more. The St Paul’s trebles sang some of the arias together and the effect of hearing Have mercy, Lord from the Passion, with its heartwrenching violin solo (played, I think, by Marie Wilson) has never left me. There was an interval in the Advent Messiah when the collection would be taken from the vast congregation during just four verses of the hymn, Lo! He comes, with clouds descending taken at a most majestic tempo and accompanied on the cathedral Willis, by Harry Gabb. We made friends with the cathedral choristers and used to smuggle food for them, especially jars of Marmite because they claimed to be half-starved –so much for Maria Hackett!

St Paul’s had been bombed in the war and both the north transept and the high altar were blocked off until the work of restoration could be completed. Outside the cathedral the bombs had done their worst and the ground to the north was flattened and derelict.

During this time I made friends with a German boy of my own age who came to my primary school as part of a scheme to help children badly affected by the war. He came from Hamburg which had been badly blitzed and many of us could sympathise as we had been bombed out ourselves (twice in my case). He introduced me to a delightful, highly cultured German-speaking lady who invited us to string quartet parties in her house, where she entertained many Jewish refugee musicians from Viennese orchestras who had sought asylum in London from the Nazis in the thirties. There I heard much of the standard Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert repertoire played in a style which has long been superseded, but which may still be heard in archive recordings. This was another valuable musical experience beyond the narrow confines of church music.

A further experience was my introduction to orchestral music. The London Philharmonic Orchestra came to our local town hall about once a quarter and my father and my teacher took me to my first concert when I was about eight. The main work was Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherezade. I had had the work explained to me in advance, so that I knew what to expect. What I had not expected, however, was the flamboyant conducting style of Sergiu Celibidache who at that time had long black hair, which flew about wildly during the livelier passages but hung like a curtain in front of his eyes when the music quietened down. The leader of the orchestra, David Wise, spotted me in the audience, sought me out during the interval and took me backstage to meet the players –a kind gesture on his part and a great excitement for me. At another concert in the Royal Albert Hall the programme featured music by Brahms and Richard Strauss. The main work in the second half was Till Eulenspiegel and I was mystified to see that most of the audience had evaporated during the interval. It was explained to me that this was a protest against Strauss (who was still alive) because he was believed, unjustly, to have been a Nazi sympathiser during the war. On another occasion I was taken to a Saturday afternoon concert in the Albert Hall where I heard Honegger’s King David with Margaretta Scott as narrator and what was possibly the first London performance of Hymnus Paradisi by Howells.

When I was about eleven, the organist of our church, Leonard Morris, showed me the rudiments of organ playing and then allowed me the use of the organ. I could play the manuals, but was determined to use the pedals and I remember forcing myself to play a Bach fugue very slowly and deliberately one afternoon for about three hours, until I achieved some measure of independence of hands and feet. My parents could not afford organ lessons and I learned much by watching some of the best London players of the day. On more than one occasion I was

Cathedral Music 8

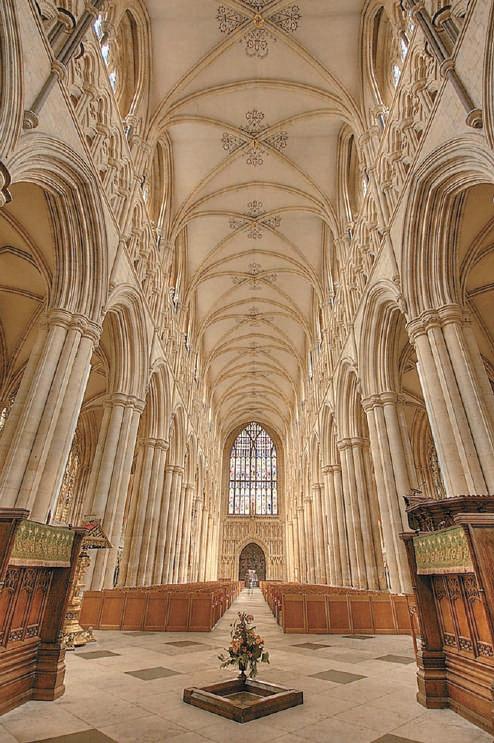

Beverley Minster Nave looking west © Craig Wilkinson

Beverley Minster Font © Lez Slack

invited into the loft at the Temple Church by the great George Thalben-Ball, who allowed me to stay on and play after the morning service. I was also invited to turn pages for recitalists at one of our local churches where I met a number of great musicians, including GTB, William Harris and Francis Jackson, all of whom were extremely kind to me.

Aged thirteen I became assistant organist of a church in Tooting Bec where the organ has since been described as the worst in London. To add to its inadequacies as an instrument, the blower was in the crypt where it picked up the coke fumes from the boiler and blew them into the organ loft. At sixteen I was appointed to St John’s, Wimbledon, with a fine threemanual Hill, Norman and Beard organ to play. I recruited the church youth club to sing in the choir and had a very happy time with good friends of my own age. The church had had a number of illustrious organists, including Alfred W Ketèlbey of In a Monastery Garden fame, who was also appointed at the age of sixteen.

Then came National Service in the army where, at the end of ten weeks’ basic training, I passed out with the champion recruit’s medal to the utter amazement of my father and many of my friends. Posted to Aldershot, I played in one or two of the local churches and gave the opening recital on the new organ in the garrison church.

On demobilisation I gained a place at the Royal College of Music where at last I had regular organ lessons with the brilliant John Birch. Cello was my second study, with Harvey Phillips, another fine musician. My harmony professor was Phillip Cannon, whose lessons were always stimulating and interesting and his own compositions were written in an individual, personal language which I find most sympathetic. His works deserve to be much better known.

1963 was a very significant year. Early in the year I took over as conductor of a choral society within a few weeks of their

performance of Bach’s B Minor Mass. In April I was appointed organist of the Parish Church of Kingston-upon-Thames. In July I graduated and, most importantly of all, my wife and I were married in August prior to my taking up my first full-time teaching post as Head of Music at a new school in Kingston. The Vicar of Kingston, Evan Pilkington, was an inspiring preacher and a pastor of great warmth and kindness and congregations were very large. He was most encouraging to the choir and would join us socially for visits to the pub after choir practice and occasional forays into the curry houses of the town.

In 1967 my wife and I, together with our first son, aged six months, took steps into the unknown when I was appointed to Beverley Minster. The north was not altogether new to us and indeed my father’s roots were in the Lake District, but we had always lived in London. Nevertheless, it was something of a culture shock at first and the pace of life was slower.

Re-reading my earlier article for CATHEDRAL MUSIC I am struck by the variety of musical experiences I have enjoyed in common, no doubt, with many other church musicians. The round of activities connected with music in the Minster has included Sunday services, mid-week evensongs, weddings, funerals, occasional services and civic events, concerts, recitals, broadcasts, lectures, rehearsals and choir practices.

Beverley Minster is a parish church and not a cathedral and I have always had parish church resources to work with. There is no choir school and recruitment of singers has never been straightforward, in spite of a large congregation. A high standard of music is expected by visitors to the church who enter a magnificent building of European significance and we do our best to meet their expectations. We are blessed with an organ of national importance which is a constant joy to play for both service accompaniment and recital work.

In addition to my work at the Minster I have needed other employment to supplement my income. The church is not an

Cathedral Music 9

The staircase to the organ loft at Beverley Minster © Craig Wilkinson

Beverley Minster Great West Door © Craig Wilkinson

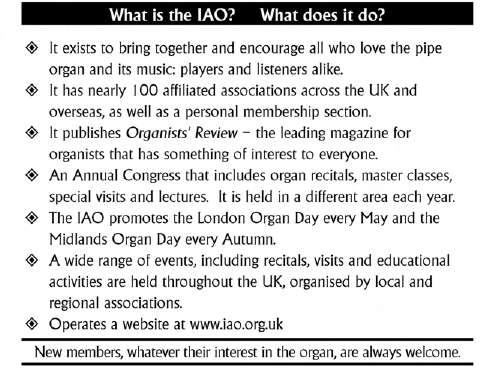

over-generous employer. For four years I was Head of Music at a large comprehensive school in Hull before becoming Music Master at Beverley Grammar School. I taught there for about twenty years, after which I taught part-time at Hull University. I have conducted two large choral societies, made recordings, broadcast on radio and television, adjudicated in music festivals, worked as an examining member of the council of the RCO, directed many RSCM courses, festivals and other events and served as an Associated Board examiner. I have also published choral and organ music. For nine years I was coeditor of Organists’ Review.

As I leave the Minster I shall miss so much that has been a significant part of my life. I shall miss my friends in the choir and my musical colleagues. I have been privileged to have shared so many spiritual and musical experiences with them, not to mention being involved in many aspects of their personal and family lives. I shall miss the young singers and the sheer enjoyment in exploring music together and I shall miss the wonderful Minster organ. I am looking forward to having a little more time in which family life is not always dominated by the church timetable. I couldn’t help comparing the organist’s lifestyle with that of the clergy when I read an obituary in The Times recently of a prominent Anglican priest who summed up the clerical life as, ‘We like what we do and, by and large, we do what we like!’ I have already enjoyed some innocent fun in quoting the remark to chosen clergy friends. After all, in the words of Alexander Pope it is, ‘What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d’!

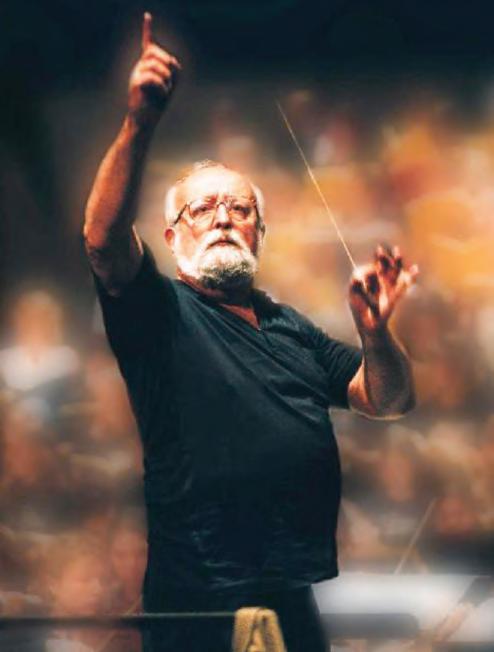

Alan Spedding

Alan Spedding

Cathedral Music 10

© Michael Hopps

The Queen meets Alan Spedding during her Golden Jubilee Tour to Beverley

Photo: Hull Daily Mail

Tewkesbury abbey

Music sacred to god performed within a Liturgical setting

Monday 27th July to Sunday 2nd August 2009

Tewkesbury Abbey Church Street

Tewkesbury Gloucestershire GL20 5RZ 01684 850959

E-mail: office@tewkesburyabbey.org.uk

Dean Close Preparatory School Lansdown Road Cheltenham

Gloucestershire GL51 6QS

www.deanclose.org.uk

Tel:(01242) 258001

Cathedral Music 11

CHORISTER SCHOLARSHIPS & BURSARIES TEWKESBURY ABBEY SCHOLA CANTORUM OF DEAN CLOSE PREPARATORY SCHOOL CHELTENHAM Voice Trials for boys aged between 6 and 11 ■ Usually weekday/term time commitments only ■ Worldwide concerts and recordings ■ Broadcasts for TV and Radio ■ Co-educational Aged 2+ - 18 ■ Boarding and Day School T EWKESBURY A BBEY S CHOLA C ANTORUM No Christmas or Easter commitments

W`âá|vt f xÉ tvÜt

Just for THE RECORD

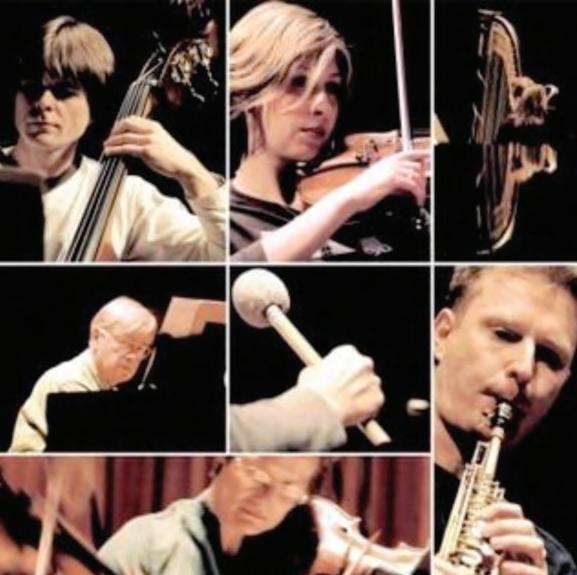

Ex-chorister and aspiring recording engineer Christopher Humphries talks about his experiences at recording sessions in Canterbury, Oxford and Huddersfield.

Since I started doing Music Technology at AS-level at school I knew I wanted to be a classical music recording engineer as it would be a perfect combination of my two passions. However, my love of sacred choral music emerged long before, as a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral under David Flood. During my tenure I was lucky enough to take part in several BBC Choral Evensong broadcasts and record two CDs: A Canterbury Christmas (1998) and Easter at Canterbury (2000). Recording a CD was a little out of the ordinary for us as choristers as we were used to single performances, one chance at getting it right and no ‘take 2’ if it wasn’t quite up to scratch. Nevertheless, I remember I was more fascinated than most by the technology involved, and took every opportunity to visit the engineer and his equipment situated in the crypt during the breaks. I’m sure this is one of the factors that has led me to the classical recording industry, and my future career.

This year I heard that Canterbury Cathedral Choir was planning to record another CD and thought that it would be a wonderful opportunity to see how it all worked from the other side and how a professional CD recording worked in the real world. David kindly agreed to let me sit in and observe the sessions, and put me in contact with the engineer, who seemed very happy for me to be there and to have me ‘on the team’.

The main work featured on the disc was to be Britten’s Ceremony of Carols (hence the album title Ceremony), but it also includes some favourites, works that have won a special place in the hearts of both choir and congregation. These include such gems as Stanford’s Canticles in G and Mendelssohn’s Lift Thine Eyes, as well as his well-known anthem Hear My Prayer Also featured is a piece that is particularly close to my heart; Tim Noon’s Evocation to a Friend was a commission for the Canterbury Cathedral Choristers at the time I was a chorister and so I was consequently a part of its very first performance, so to be a part of its first recording too was something special.

I had the feeling that David had been saving this specific selection of works for a special group of choristers, because although there are some full choir pieces on the CD, as a whole it is very much a showcase for the choristers, with over

half the disc using boys’ voices, with seven treble soloists featured throughout.

The engineer for the sessions was Brendan Hearne of York Ambisonic who, during David Flood’s twenty years as Organist and Master of the Choristers at Canterbury, has recorded eleven CDs of the choir and two of the organ. Both the CDs I took part in (as well as Ceremony), boast on the cover: ‘STEREO/AMBISONIC UHJ SURROUND SOUND RECORDING’. Every time I listened to them I wondered what this meant, and at these sessions I finally got the chance to ask the man himself.

It turns out that Ambisonics is the name for a surround-sound recording system developed in Britain by which a complete sound field, including reverberant as well as direct sound, is recorded in one environment (the recording location) and reproduced in another, such as your home or car.

The sound is often captured through a Soundfield microphone whose four capsules are arranged to sample from the surface of a sphere, as it were. The signals omnidirectional, front and back, left and right and up and down are labelled W, X, Y and Z respectively and are collectively known as ‘Bformat’. They contain all the necessary information to build a complete 3D image of a performance.

The signals from those four capsules can then be encoded to two channels in such a way that they will sound good through headphones or stereo loudspeakers. This encoding system is based on collaborative work between the inventors of Ambisonics and the BBC and represents a fusion of the Ambisonic 45J encoding system and the BBC’s Matrix H encoding system. Further, since that encoding known as stereo UHJ encoding also contains surround-sound information, that additional information can be extracted using a special UHJ decoder and played through four loudspeakers.

B-format is now most often used to create 5.1 surround recordings, but this is not its only use. Ambisonics was the undeserving loser in a format war many years ago, much the same as VHS vs Betamax or even Blu-ray vs HD DVD today, but technically, Ambisonics was, and still is, far superior. Ambisonics encodes using complex algorithms that allow the decoding to

Cathedral Music 12

Canterbury Cathedral

Merton College, Oxford HuddersfieldUniversity concert hall

be more versatile, meaning that where 5.1 is bound to be only played in six channels, Ambisonics can be decoded into four or more, dispersing itself equally around the speakers, providing a much more effective surround experience.

Even though most people will not have UHJ decoders on their home hi-fis, the side effect of using the Soundfield’s multichannel output and the multitude of algorithmic encoding is that, because of the inherent inter-channel phase relationships, a UHJ-encoded stereo recording gives the listener the experience of a stereo image that is significantly wider and deeper than that of a standard stereo recording.

Stereo UHJ encoding can either take place live in the signal chain directly after the microphone preamplifier or in postproduction if additional manipulation or ‘tweaking’ is required. With a UHJ hardware encoder, Brendan took the first approach and used its circuitry to encode the data in real time, converting the B-format signal to a stereo UHJ signal which he then recorded onto two DAT machines simultaneously, to be safe. The last thing you want is to be doing the best take of the night and the tape machine suddenly breaks down!

Despite the complex encoding, Brendan favored a very simplistic approach to micing, opting to continue with the preferred method of using solely one microphone, a Soundfield Mk4, placed with ultimate precision. This provides a very natural sound obviously, and captures both the direct sound of the choir, as well as the acoustic of the environment. Although 5.1 currently dominates the commercial market, exciting things are happening in the world of Ambisonics, and people like Brendan are gradually making it increasingly well known to the public.

We used different parts of the cathedral for different items on the CD; the Quire for pieces with Organ, and the Nave for those without. In the Quire the choir stood on the Decani side in front of the pews next to the choir stalls with the microphone in the first row of the Cantoris side, about 10 ft high. In the Nave the mic was placed about 20ft away from the choir, also raised to a height of about 10ft. Great care was taken during both set-ups to ensure the mic was placed in exactly the same position, height and direction, so as to minimize the difference in sound from session to session. There were four sessions overall, two-and-ahalf in the Nave, and one-and-a-half in the Quire. They were all evening sessions, 7.00pm-10.00pm, as this was the only time that the boys, lay clerks and the cathedral itself are all free. Before these intensive sessions the boys will have had an 8.00am-9.00am rehearsal, a full day of school, followed immediately by a rehearsal and evensong service, leaving only an hour to eat and do homework before they are back in the cathedral. When you consider this, it is quite incredible how fresh and bright the sound is.

Whilst recording the well-known O for the wings of a dove section of Mendelssohn’s Hear My Prayer, some of the perspex panels in the building began to resonate in sympathy with one of the notes of the organ. In the full-choir sections this would not be as perceptible, but in a pp section with a solo treble, it becomes surprisingly dominant! To prevent this, a number of lay clerks volunteered to place their hands on the panels to keep them quiet while another few takes were recorded. Being in the makeshift control room in the crypt, I unfortunately missed this spectacle, but when I listen to that section now, I can’t help but picture them there hugging the walls while the soloist sings!

In the summer I was fortunate enough to be present at a different choral recording session, this time with the choir of New College, Oxford in their own chapel in the city. This time the music being recorded was all six of Bach’s Motets (BWV 225-230), which required a full SATB choir with a chamber

organ accompaniment. These sessions, which were engineered (and produced) by Adrian Hunter, were quite different from those at Canterbury in many aspects.

Adrian prefers to have a selection of microphones around the space to allow for more control over the sound in postproduction, in order to get the optimum sound from the environment as well as the performers.

For the main sound from the choir, he used a pair of DPA 4003 omnidirectional microphones, placed in a similar position to Brendan’s, but with a pair of AKG 414s alongside, in cardioid pattern. Also, to pick up the ambience and reverberation of the chapel, he placed a pair of AKG C4000Bs facing into the wings. Also a pair of Røde NT55s were put near the chamber organ, just in case its sound was buried too much in the fuller sections and needed to be reinforced.

During the early part of the first session, it became clear that, through the microphones, the sound of the trebles was slightly overpowering that of the lay clerks. To try and restore the balance we decided to rearrange the choir into a more unorthodox arrangement, placing the boys behind the men, standing on benches. This movement of only a few feet made a remarkable difference to the sound, and gave a much better sense of balance to the sound.

Since these sessions I have returned to the University of Huddersfield to study for an MA by research degree, and am taking the opportunity to record as many ensembles as will let me, to gain such experience. The first of these this year was conveniently similar to those I witnessed – Huddersfield’s local parish church choir in the University’s church-turnedconcert hall. The choir wanted to record some of their favourite motets from their repertoire, as well as some hymns. We have a Soundfield mic mounted in the hall for general concert recording, which I used for ambience, and I set-up two AKG 414s closer to and above the choir to get the more direct sound. In the a cappella sections this worked quite well, giving a good balance of direct to ambient sound, but during the hymns the choir were a little overpowered, and in hindsight I would have changed the set-up. However, the choir seemed very happy with the result, and have asked me to do another CD with them later in the year.

Also at the end of last year I was invited back to Oxford to record the debut concert of a new concert choir, Voxabilis. This gave me a golden opportunity to record in the marvellous space that is Merton College Chapel. As it was a concert I had to be conscious of where I placed microphones so that it did not detract from the audience’s view of the choir, or enjoyment of the concert. I used a pair of DPA 4011s placed just behind the conductor slightly above head height to get a good close sound from the choir, and a pair of AKG 414s half way down the chapel, about 20ft further back and high up to capture the reverb of the building. The difference between the two was quite striking, and when mixed together gave a nice representation of both the choir and the space.

I feel privileged to have been present at these recording sessions and I hope I have given you a glimpse into the process of choral CD recording –watch out for my name on albums in years to come!

‘Ceremony’ (York CD 202) is available now from the Canterbury Cathedral Shop (www.cathedral-enterprises.co.uk). Reviewed on page 61.

New College Choir’s ‘Bach Motet’ CD is scheduled for release later this year.

For more information about Ambisonics, please visit www.ambisonic.net

Cathedral Music 13

NEWS BITES

NEW E-MAIL NEWSLETTER FOR SACRED MUSIC LOVERS

A free e-mail newsletter to keep aficionados of church and sacred music up to date with latest news and information has been launched by the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM). It will be distributed by e-mail six times a year and is available through the RSCM website at www.rscm.com where anyone can sign up for it, whether a member of the RSCM or not. The newsletter will include news and information from the RSCM, including ideas, inspiration and recommendations for the best use of music in worship, new publications, and information about forthcoming events and courses. It will also contain details of forthcoming broadcasts and other news such as key church music appointments and reflect wider issues. To view the first issue and sign up for the newsletter go to www.rscm.com/newsletter

CHOIR SCHOOLS ASSOCIATION FESTIVAL

140 choristers from choir schools across the South West descended on Wells on the 4 March when Wells Cathedral School hosted the annual Choir Schools Association Festival. The girl and boy choristers from choir schools at Winchester, Hereford, Llandaff and Truro, arrived midmorning, and following a munificent lunch, enjoyed taking part in the competitively-fought annual soccer and netball tournaments in the afternoon sunshine. St John’s College, Cardiff, won the netball tournament, the Pilgrims’ School, Winchester, won the soccer, and a special award was given to Connor Harris from The Cathedral School, Llandaff, for outstanding sportsmanship. The visiting Head of Xinghai Music School in Guangzhou, China, Professor Li JiWu, who is staying at Wells Cathedral School with five of his talented musical students, as part of the British Council School Linking Exchange with Wells, was delighted to present the trophies to the choristers.

After a high tea of sandwiches, cake and buns, all choristers joined in a splendid Evensong in Wells Cathedral, where they sang Psalm 23, Magnificat, set to music by Timothy Byram-Wigfield, and Nunc Dimittis set to music by Geoffrey Burgon. Pupils loved the fact they were competing against other choristers and that all who were involved were coming from the same experiences and musical background.

Head of Wells Cathedral Junior School, Nick Wilson, said: “The day was a marvellous opportunity for so many talented choristers to come together from over a wide area of the country to share experiences on the sports fields and also in the cathedral. Despite a morning of snow, the sun came out and the event was competed for in bright sunshine. The choristers are extremely competitive and they thoroughly enjoyed doing ‘battle’ in their respective sports. The Evensong was an uplifting experience with the sound of 150 voices filling the cathedral.”

CANTERBURY FESTIVAL CELEBRATES 25 YEARS IN 2009

This October Canterbury Festival - Kent’s International Arts Festivalcelebrates 25 years of bringing the best in classical music and opera to the city in this annual celebration of the arts, which attracts over 70,000 visitors each year. A multi-arts Festival that includes over two hundred events in two weeks each October, at the core of the Festival’s activity is its extensive classical music programme, which takes places in venues across the city, including the stunning Nave of Canterbury Cathedral. This year’s Canterbury Festival takes place between Saturday 17 – Saturday 31 October 2009. Tickets are available to Festival Friends from Monday 20 July and the general public on Monday 10 August. To become a Festival Friend or to receive a free Canterbury Festival brochure go to www.canterburyfestival.co.uk or contact the Canterbury Festival Office on 01227 452853.

PRINCE OF WALES TO BE PATRON FOR A FURTHER FIVE YEARS

HRH The Prince of Wales has announced that he is to renew his Patronage of Hereford Cathedral Perpetual Trust for a further five years. The announcement came at the end of the very successful visit of The Prince and The Duchess of Cornwall to Hereford Cathedral, to mark the beginning of work on the Cathedral Close. The Prince of Wales, who became Patron of the Trust in February 2004, launched the major restoration of the Close, which is substantially funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. “We are delighted with the news,” said Robert Rogers, Chairman of Hereford Cathedral Perpetual Trust. “The Prince of Wales has been a great supporter of our work for many years; indeed his first visit to the Cathedral was in the early 1980s. We are thrilled that he will remain as our Patron as the works to the Cathedral Close proceed and, in due course, as we start to look at the projects which will follow.” During their visit, Their Royal Highnesses had the opportunity to tour the Close and meet those who had been involved in the development of the project and its funding. The Prince of Wales and The Duchess of Cornwall spent some time in the Cloister Café and Cathedral Shop, with The Duchess buying some chocolate brownies and two Hereford Cathedral teddy bears. The Prince also took the opportunity to take a look at the stone carved to mark his 60th birthday last year, which has now been placed high above the windows on the south side of the building.

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL 20 NOVEMBER 9 FEBRUARY 2009

Emily Young, one of Britain’s greatest contemporary sculptors, brought seven-and-a-half newly sculpted Angel Heads to Salisbury Cathedral from 20 November 2008 to 8 February 2009 as the final and most spectacular temporary art installation celebrating the iconic building’s 750th Anniversary. Taking her inspiration from the word ‘angel’ and from the architecture of the Cathedral itself, these heads emit a profound spirituality, humanity and optimism.

The Angel Heads, one for each century of the Cathedral’s history, have been installed in three different locations. All are sculpted from the same Purbeck stone as the Cathedral itself, seven in Purbeck freestone and the small ‘half’ head in blue Purbeck marble. The expressions on the individual faces reveal a sense of deep contemplation which develop from the stone itself as Young works with the surface scars, revealing the ancient beauty created by the elements over unimaginable time scales. There is also a musical sound scape, composed by Arthur Jeffes, inspired by the sounds of the cathedral and its surroundings. This can be heard at specific times each day.

The four largest heads, up to one metre square and weighing almost a ton, are positioned in the main nave surrounding and reflecting in the much celebrated new living water font by William Pye. One smaller head and the blue ‘half’ head are situated in the Trinity Chapel adjacent to the blue Purbeck marble pillar. The remaining two stand illuminated in the cloisters looking towards the cathedral’s soaring spire.

Cathedral Music 14

News from Choirs and Places where they sing

Prof Li JiWu presents a trophy

by World Renowned artist

Carlo Curley

Romsey Abbey

Friday 22nd May

Ealing Abbey

Friday 5 June

All Saints’ Parish Church, Leamington Spa

Saturday 27th June

Norwich RC Cathedral

Friday 24th July

Ripon Cathedral

Tuesday 8th September

Salford RC Cathedral

Friday 9th October

Viscount Organs are delighted to announce the launch of a revolutionary new development in pipe organ sound generation, that takes digital organs to a new level of authenticity and excitement.

So that you can evaluate the wonderful sounds of we are offering you the opportunity to experience one of the new instruments for yourself within the venue.

To book an appointment or for further information, please call Viscount Organs on 01869 247333 or email sales@viscountorgans.net

ome and ear the ifference D

C ome and ear

ifference D

C

elebrity Recital Programme

H

the

H

C

www.viscountorgans.net www.physisorgans.comwww.prestigeorgans.com

60Seconds in Music Profile Stephen Darlington

Age: 56

Education details:

King’s School Worcester, Christ Church Oxford (Organ Scholar 1971-74)

Career details to date:

Assistant Organist, Canterbury Cathedral (1974-1978)

Master of the Music, St Albans Abbey (1978-1985)

Artistic Director, St Albans International Organ Festival (1979-1985) Organist and Official Student in Music, Christ Church, Oxford (1985-present)

What do you enjoy most about working in a cathedral like Oxford?

The combination of maintaining the choral tradition of the Church of England within the context of a centre of academic excellence.

What have been some of the highlights during your career?

Actually there are too many to name! Sometimes they occur in surprising ways: a perfectly balanced performance of a Palestrina motet in a service features in my memory as much as conducting in Sydney Opera House or the Royal Festival Hall. The wonderful thing about music is that there are always new discoveries to be made.

Briefly tell us about a typical day at Christ Church?

The day starts with a rehearsal of the choristers from 7.55am - 8.55am. Some days are spent teaching undergraduates and graduates or lecturing in the Music Faculty, and others are spent in research. The afternoon rehearsal is at 5.00pm with Evensong at 6.00pm.

Do you still play much and if so, which organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

Sadly I do not have time to play very much these days.

What or who made you take up the organ?

I was a pupil at King’s School Worcester when Christopher Robinson was in charge of the music in the Cathedral and Harry Bramma his assistant and Director of Music in the School. It was because of them that I was inspired to take up the organ.

Cathedral Music 16

Which organists do you admire the most?

The list of organists I admire is long! It surely includes of the older generation, Peter Hurford, Simon Preston and Gillian Weir, and of the younger generation Thomas Trotter, David Goode and my own assistant, Clive Driskill-Smith.

What was the last CD you bought?

Verdi’s Aïda.

What was the last recording you were working on? Music from the Eton Choirbook

What is your favourite organ to play? Sydney Town Hall.

What is your favourite building? Canterbury Cathedral.

What is your favourite anthem? I don’t really have one. If pressed I would say Laudibusin Sanctis by William Byrd or The Twelve by William Walton.

What is your favourite set of canticles? Byrd’s Great Service.

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants? Psalm 84 (O how amiable are thy dwellings) to the chant by Thomas Armstrong.

What is your favourite organ piece? Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor BWV582 by J S Bach.

Who is your favourite composer ? Mozart.

Any forthcoming appearances of note?

Daily services at Christ Church are top of my list, but there are a few highlights in our busy concert diary, such as the launching concert of our two most recent recordings, (More Divine than Human: Music from the Eton Choirbook and Howard Goodall’s Eternal Light: A Requiem in Christ Church Cathedral on Saturday 13 June. Also, Handel’s Acis and Galatea (in a speciallycommissioned edition of Mendelssohn’s arrangement) in the Sheldonian Theatre on Friday 3 July and our Christmas Festival concert in St John’s Smith Square on Monday 14 December.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

Undoubtedly the highlight of my organ solo career was giving a recital in St Bavo in Haarlem. The thought that Mozart and Mendelssohn had touched the same keys was truly inspiring.

Has any particular recording inspired you?

Soile Isokoski conducted by Marek Janowski in a recording of songs by Richard Strauss: sumptuous singing and playing.

What are your hobbies?

Reading novels, walking, French wine.

Do you play any other instruments? Violin and piano.

What was the last book you read? White Tiger by Avarind Adiga.

What are your favourite radio and television programmes? Just a Minute and Blackadder.

What Newspapers and magazines do you read?

I have a rather eclectic taste in journalism ranging from the Daily Telegraph for sport, The Times for News and The Observer for weekend reflection.

What makes you laugh?

I see humour in almost everything: an ability to laugh is probably the most important aspect of life.

If you could have dinner with two people, one from the 21st century and the other from the past, who would you include?

William Shakespeare and Nelson Mandela. An unlikely combination but one which might produce an interesting outcome and menu!

What should be the role of the FCM in the 21st century?

At a time when choral music is more widely disseminated than ever before, it is comforting to know that there is an organisation devoted to the fostering of music in cathedrals. Its work in providing financial support is invaluable, as is its ability to focus discussions about the role of music in cathedral worship and the prospects for the future.

Cathedral Music 17

registrar@cccs.org.uk www.cccs.org.uk (01865) 260650 3 Brewer Street, Oxford OX1 1QW Christ Church Cathedral

Oxford Voice trials by arrangement for boys aged 7

School

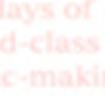

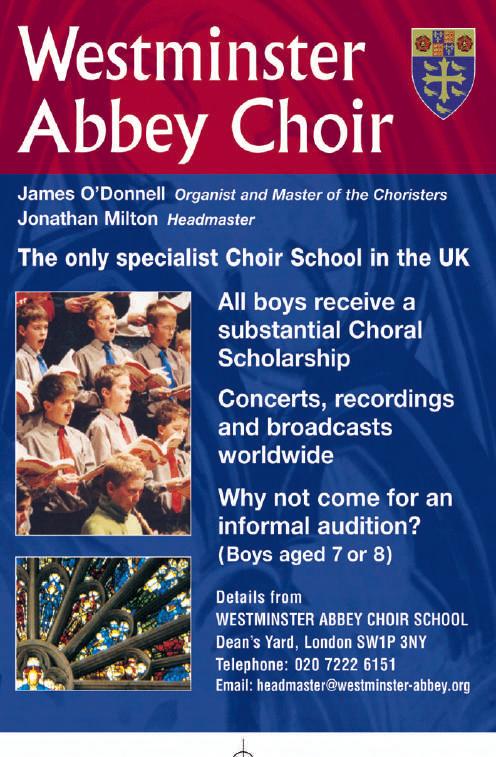

SAFEGUARDING THIS PRICELESS HERITAGE

Bristol Cathedral Choir School –a Faith Academy

by Canon Wendy Wilby Precentor

by Canon Wendy Wilby Precentor

‘The choir is the lifeblood; the animating factor that turns a cathedral from a beautiful but silent place into one that reverberates with glory’. These words, found on the homepage of The Friends of Cathedral Music website, are embedded in the hearts of precentors everywhere who recognise just how extremely vulnerable cathedral choirs can be.

As Precentor of Bristol Cathedral, I too see this vulnerability. We precentors become like trained guarddogs! Our eyes and ears are open, listening out for attacks from without, and even, God preserve us, from within. We recognise the difficulties of recruitment, especially where boy choristers are concerned, we know how tight the budgets are for music, we observe the decline of the robed choir in parish churches and we struggle with colleagues about mission priorities. Perhaps we become a little bit on the defensive as we recognise all these external factors, and there is no doubt that we must always be open to change to serve our people under God. That said, we precentors do know the truth –of course, we know that the choir is the cathedral’s lifeblood.

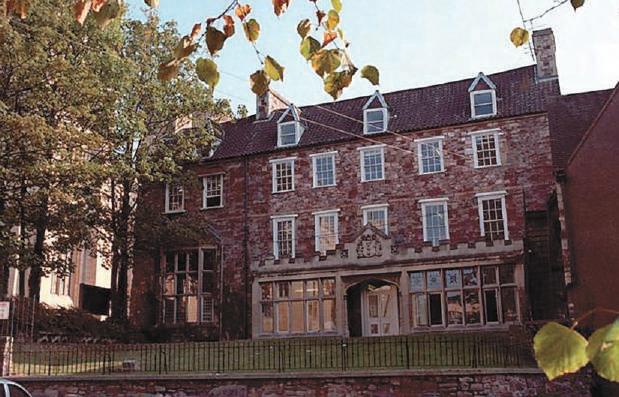

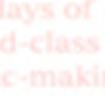

Cathedral Music 18

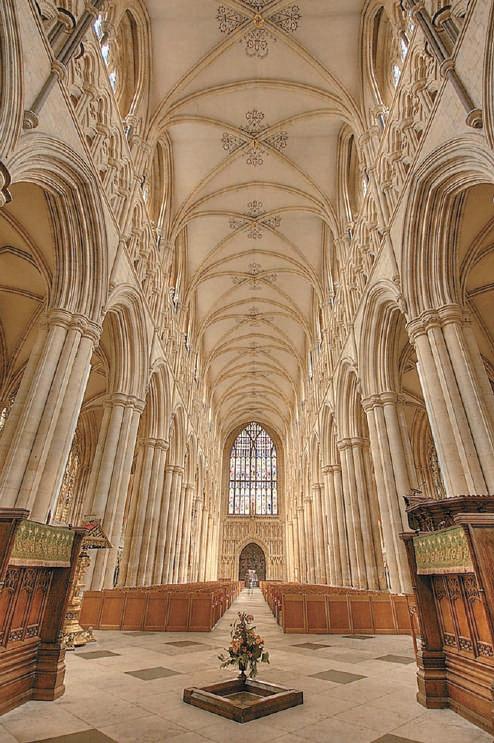

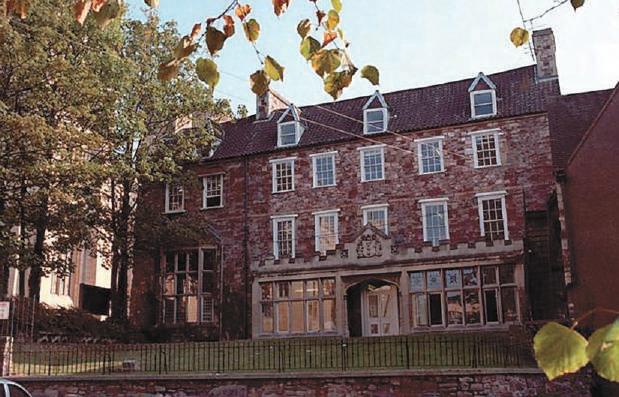

Let me first of all draw you a picture of Bristol Cathedral. There is no doubt that this place of worship really is a ‘hidden treasure’ to be discovered and explored –found just a little way out of the city centre, but close to Bristol Harbourside, giving it, as Pevsner remarked: ‘The saltiest history of any in England.’ Its colourful history encompasses eight centuries. Its buildings range from the Chapter House, erected in the reign of Henry II, to the nave built in the reign of Queen Victoria and right through to the development at the north end in the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Bristol is one of those six former abbey churches which became cathedrals at the Reformation under Henry VIII’s ‘New Foundation’. Before that it was an Augustinian Abbey run by the ‘black’ canons –ordained monks who led their lives according to the Rule of St Augustine of Hippo. There is certainly evidence of a school here, perhaps even a good number of centuries before the Reformation. Anyhow, the Henrician statutes stipulated that there should be six boy choristers supervised by one schoolmaster and one under-master, and amongst the offices of the Dean (Statute IV) was the duty that the boys ‘be faithfully instructed’. Statute XXVI provided for the boys’ education in grammar. Even though standards gradually declined, and by the time of Archbishop Laud’s visitation in 1634 the boys only had one master and there was an official complaint that the grammar boys never even turned up for religious services, yet there is no reason to think that these educational prerogatives were not adhered to. The Dean therefore seems to have had a duty of care for the choristers and grammar school boys. It is likely that the dormitory above the Deanery buildings was occupied by young male students, some of whom were involved in cathedral life as choristers.

This ancient story has taken us through the centuries and into the modernity of the 21st century now with a choir of six lay clerks, four choral scholars and several choristers which, in several combinations, sings six or seven services a week. Bristol Cathedral School has provided us with these boy choristers since records began, adding girl choristers to the choir only three-anda-half years ago when this independent school became coeducational. So we now have two separate top lines –boys and girls. The school itself has premises which adjoin the Cathedral creating a cloister garth. The buzz and bustle of young people joining the visitors and clerics is a constant feature .

Apart from our own choir, we are also blessed at our cathedral to be able to host many visiting choirs in the school holidays –they seem to enjoy coming to the city and our building, and we ourselves enjoy them very much. However, just occasionally we have had a silent week. These sorts of weeks are refreshing at first, but too many of them, and I get to musing about the vulnerability of our choir… or perhaps even the school. How could we possibly manage without this ‘lifeblood’? If the school ceased to function, the choristers, as we know them, rehearsing

daily at 8.15am and 4.15pm would stop.

Well, it was on 24 December 2006 that Frank Field MP wrote his article in The Times ‘The silence of the choirs’. I have to say that it was to be transformative for us at Bristol as we planned for our future during the next year. This is a little of what he said:

‘The future of Westminster Abbey’s choir is assured. But we have no such guarantee for most of our other great cathedral choirs. Some deans must be driven to despair about how future bills are to be met. But, to contradict one of Margaret Thatcher’s great sayings, there is an alternative that can secure the future of cathedral choirs while making a huge contribution to the serious teaching of music.

‘One reason why some choirs cost so much is that they are full-time and are nurtured in special choir schools. The schools are small because each cathedral needs only the best couple of dozen boys or, increasingly, girls in its area. It is this smallness that makes for their extraordinary cost. Smallness also involves elitism. If cathedral choirs are to survive it is important to break out of this elitism and return cathedral choir schools to what they once were: great schools educating significant numbers of pupils.

‘The government’s academy scheme could be the basis for establishing a series of music schools open to boys and girls who have an interest and aptitude in music. The cathedral choir schools could become the driving force behind this transformation by offering to convert into academies.

‘In return for receiving state funds, cathedrals would offer to spread their excellence through these new musical academies to a huge group of young people, many of whose musical talents remain starved of development. Local education authorities would play a part in ensuring that the academies strengthened music in other state schools.

‘The sound of this music would herald a great change in English education. Music would begin to regain its rightful place in the curriculum. And taxpayers’ attention would be drawn to how the excellence of a few is spread to many schools up and down our country.’

The Dean, the Headteacher, the Chair of Governors and the Precentor all agreed that this would be a wonderful step forward for our particular partnership of cathedral and choir school, and the ‘Short ride in a fast machine’ (to quote the title of a piece by John Adams) began! And this really was a rapid journey. We were fast-tracked towards Academy-status, opening in September 2008 as Bristol Cathedral Choir School. It is a new legal title to describe what we are, and the addition of the word ‘choir’ in the name gave it a permanence that would have warmed any precentor’s heart. The name of the school was even carved in stone over the archway of our new three million pound buildings. The Choir Academy is here to stay.

Journeys involving change are never easy and this one was no exception. There were times when I wondered just exactly what

Cathedral Music 19

Bristol Cathedral School

we were changing into. The government was adamant that we needed to have a different mindset. To train a handful of children to be choristers is not only elitist but totally against the inclusive nature of academies. To be an academy, the school needed to have singing at the very heart of its existence, not just as a bolt-on extra in the form of choristers. Of course, that latter statement is such a laudable aim. We are certainly not there yet, but now with a new Principal who has been a lay clerk at the Chapel Royal and a new Head of Specialism (music of course) who is a member of the Senior Leadership Team, we are well on the way to putting music as a high priority in the life of the school whilst maintaining the standard of excellence in the Cathedral Choir. Our successful Chorister Outreach Project, ‘Bristol Voices’, includes a junior choir made up of local primary school children that meets at the Academy weekly and we are gradually transforming and gradually looking outwards. Outreach is such a buzzword in our faith programmes that this direction just has to be right. Cathedrals, Bristol included, need to be outward looking if they are going to survive. The school itself used to be grant aided, offering free places to a number of boys, so this reversal to free education suits us very well also. What could be better than to offer the opportunity to sing in a cathedral choir to any child regardless of economic status? Anyone with musical aptitude can have a voice trial.

We are in the extraordinary, if not unique, position for a choir school of being an 11-18 secondary school. This means that boys and girls do not become full choristers until they begin Year 7. Our probationers, at the stage before we converted, were beginning to dry up and this placed a huge and worrying strain particularly on the boy choristers. Now we are absolutely full of probationers. We have developed our probationer programme until we have eight Year 5s and eight Year 6s plus one or two Year 4s. All these children have to fulfil an exacting programme that is strictly monitored before they can gain a place at the Academy in Year 7. Because they have attended worship at the cathedral on such a regular basis, eight probationers can enter the school each year. They are a mixture of boys and girls of course, but now each separate line is strengthening. The workload is divided equally between girl choristers and boy choristers.

To summarise; we at Bristol Cathedral are most grateful for the government initiative that has led us into working with a 21st century Choir Academy. We feel that we have indeed 'safeguarded this priceless heritage.

Cathedral Music 20

The future of Westminster Abbey’s choir is assured. But we have no such guarantee for most of our other great cathedral choirs. Some deans must be driven to despair about how future bills are to be met.

TALLEST CATHEDRAL SPIRE IN BRITAIN TURNS INTO A LARGE RED NOSE FOR COMIC RELIEF 2009

Salisbury Cathedral took part in Comic Relief’s Red Nose Day by turning its 404ft soaring spire red each night from Monday, 9 March through to Red Nose Day on Friday, 13 March. The Dean of Salisbury, the Very Revd June Osborne, said: “We’re very pleased to be taking an active role to support Comic Relief and being in a position to use our profile and sheer size to help. We are one of a number of iconic buildings in different parts of the country invited to ‘paint the town red’ to help raise awareness for the charity and its important work of addressing global poverty and injustice aspirations which match those of the cathedral. Salisbury Cathedral is also donating 20% of its income from visitors on Red Nose Day to the charity.

PANCAKES, PALMS AND PROBATIONERS

The young probationers (trainee choristers) of Salisbury Cathedral Choir learnt about the meanings of Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday when they enjoyed cooking, tossing and eating delicious pancakes for breakfast with Canon Precentor, Jeremy Davies, before helping him burn last year’s Palm Sunday crosses to create the ash to be used in Ash Wednesday’s services in the cathedral.

They heard that ‘Shrove’ comes from the early English word ‘shrive’, meaning to forgive. It is also a Carnival (literally a ‘farewell to meat’) when all the fats and flesh are eaten up to prepare for the forty-days’ fast of Lent. The event is much looked forward to by the probationers. Jeremy Davies said: “I’ve hosted this special ‘pancake and palms for probationers’ breakfast on Shrove Tuesday for many years now and find it a perfect way of having a bit of fun whilst also explaining the true meaning of the day and the start of our preparation for Lent. This year for the first time we are ending with a pancake race outside the cathedral before the children rejoin their classmates for the school day!” During services in the cathedral throughout Ash Wednesday, the ashes prepared by the probationers are placed, in the shape of the cross, on the recipients’ foreheads as the priest says the words: “Remember that you are dust and to dust you will return. Turn away from sin and be faithful to Christ.’’

SOUTHERN CATHEDRALS FESTIVAL

2009 Salisbury Cathedral 15-18 July.

Southern Cathedrals Festival (SCF) 2009, the annual festival of choral music featuring the choirs of Chichester, Salisbury and Winchester Cathedrals, is hosted by Salisbury Cathedral from 15-18 July.

News from Choirs and Places where they sing

Celebrating the anniversaries of Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn and Purcell, the choirs are joined by guest performers in a Festival which includes fourteen concerts, nine services, a choral masterclass and world premières by Barry Ferguson and Will Todd.

NEWS BITES

David Halls, Director of Music at Salisbury, is Festival Director. “It has been my privilege to watch the Festival develop over the past 25 years and my colleagues at Chichester and Winchester have helped me put together a dynamic programme which will undoubtedly deliver an exciting and forward-looking Festival. At its heart is the daily round of services that have been central to the Anglican church for centuries, here shared amongst the three cathedrals’ boys’ choirs and the girl choristers of Salisbury & Winchester. The choirs also join together in various combinations for three major concerts, ending with a performance of Mozart’s sublime Mass in C minor with Sarum Orchestra on the Saturday evening.”

The Festival opens at 4.30pm on Wednesday, 15 July with Choral Evensong sung by Salisbury’s girl choristers with Martin Ings on trumpet and Daniel Cook on organ and is followed by the Festival Launch Reception. Booking brochures, which include further information about the Festival and how to become a Patron, are now widely available. Full details can be found at: www.southerncathedralsfestival.org.uk or telephone the Department of Liturgy & Music, Salisbury Cathedral, 33 The Close, Salisbury SP1 2EJ –Telephone: 01722 555125 or e-mail: s.flanaghan@salcath.co.uk

NEW RECORDING FOR HEREFORD CATHEDRAL

A new CD of music by Herbert Howells has been recorded by the Choir of Hereford Cathedral ready for release during the summer. “It’s a couple of years since the Choir last made a CD –a highly acclaimed disc of music by the Tudor composer William Byrd,” said Geraint Bowen, organist and director of music at Hereford Cathedral. “This time we have gone for a complete contrast with the music of Herbert Howells [1892-1983]. The cathedral’s wonderful acoustic and world-renowned Willis organ are perfect partners for the choir in this kind of music. With a composer so closely identified with the three cathedral cities of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester, and with their Three Choirs Festival, this seemed an obvious choice, especially as Hereford is hosting the Three Choirs Festival this August. Among the pieces that we have recorded are the three service settings that Howells wrote for each of the Three Choirs’ cathedrals, including the Hereford Service, which was first performed in 1970. Further information can be obtained from Hereford Cathedral Perpetual Trust (01432 374261; e-mail perpetual.trust@herefordcathedral.org).

Cathedral Music 21

Photo: © Ash Mills

Choristers listening to recorded extracts. Left to right: Oliver Layton, Anthony Mansfield and Rory Turnbull

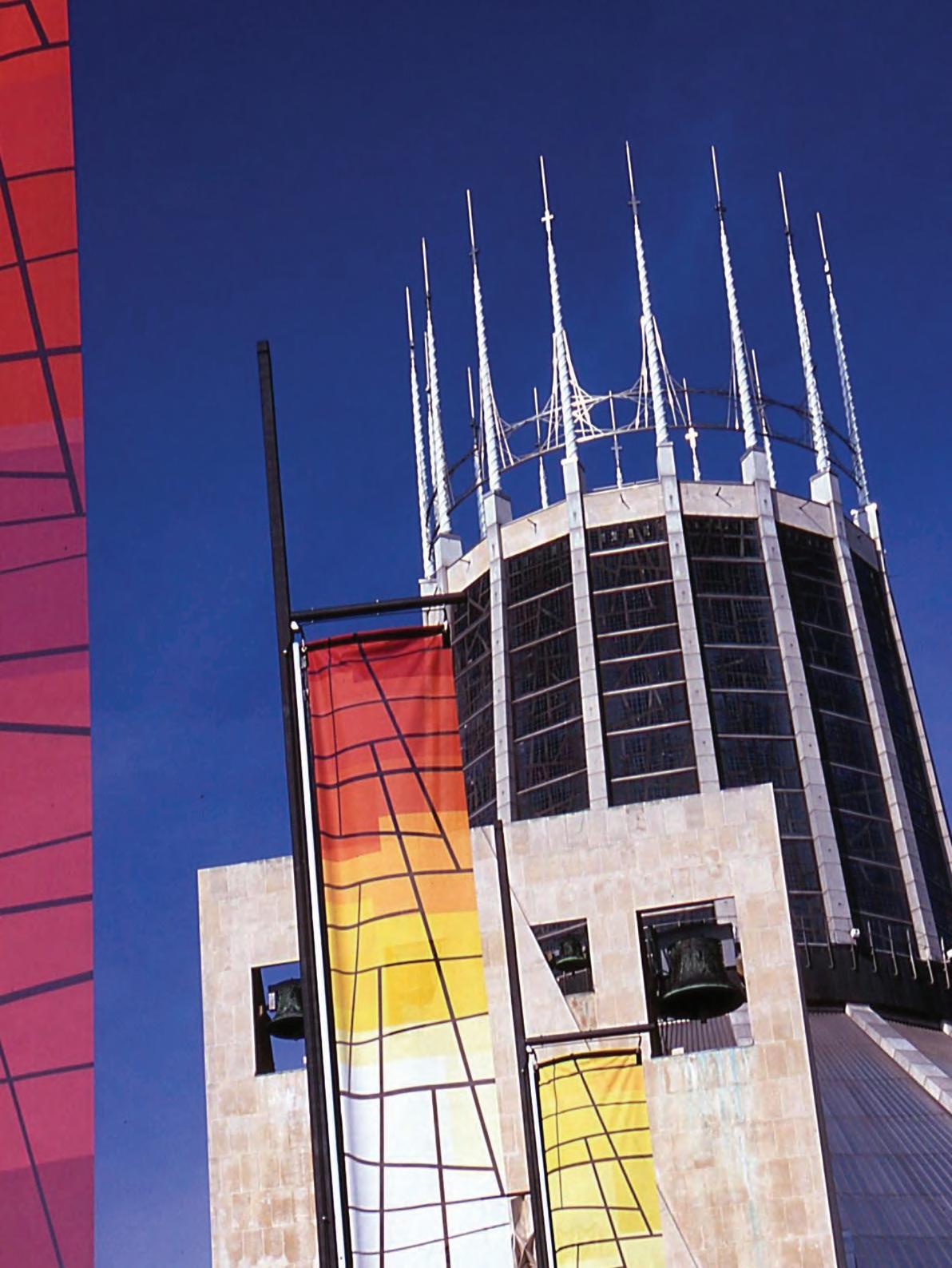

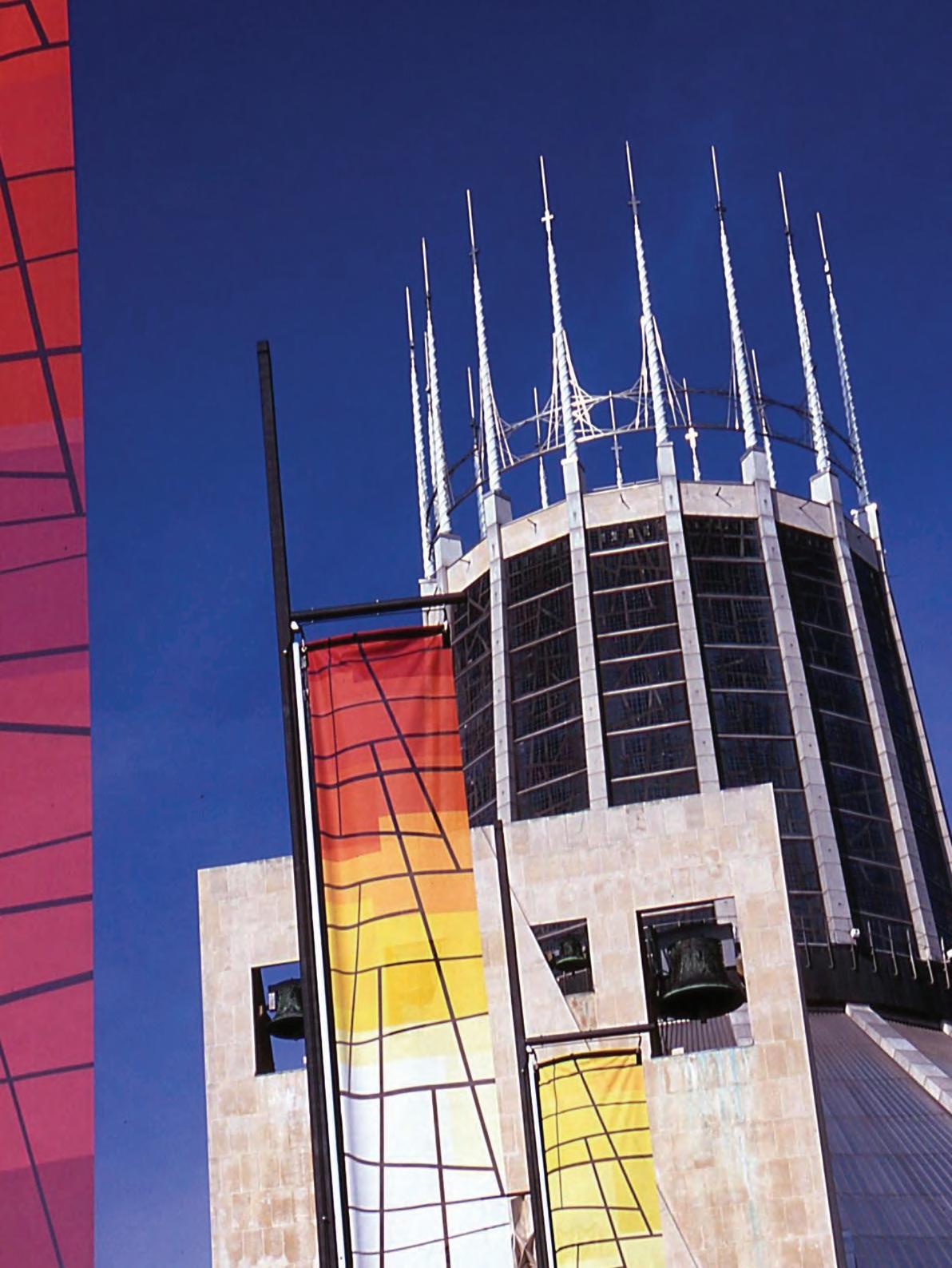

LIVERPOOL’S YEAR as Capital

Timothy Noon

Cathedral Music 22

of Culture 2008

When Prof Peter Toyne addressed the FCM National Gathering in St Davids several years ago, he spoke engagingly of how he had led Liverpool’s bid to become European Capital of Culture. I remember being struck by his assertion that the European bureaucrats had been particularly impressed when he took them to an ordinary, weekday Choral Evensong at the Anglican Cathedral. They had not encountered church music like that before and were especially amazed when he explained that a similar act of worship was taking place, simultaneously, at a cathedral at the other end of the street!

I am sure that there were far greater reasons of politics to account for Liverpool’s success in winning the bid but I do like to think that the contributions to the city’s cultural life offered by its cathedrals’ choirs might have helped a little.

Whatever the case, being European Capital of Culture in 2008 threw the spotlight onto Liverpool throughout the year and both cathedrals relished every opportunity this presented.

In January, the Archbishop of Canterbury visited the city and, during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, preached a moving sermon at Choral Vespers in the Metropolitan Cathedral to a congregation of about 2,000. The two cathedrals’ choirs joined forces for the occasion, the first of several collaborations throughout the year.

In May, Liverpool hosted the RSCM’s national Celebration Day and the two cathedral choirs were joined by over 500 singers from the North West, under the expert guidance of Brian Kay. Then, at Pentecost, the ‘Two Cathedrals’ service began at the Metropolitan Cathedral, with the choirs and congregation then processing –in glorious sunshine! –all the way down Hope Street, to Liverpool Cathedral, where the service concluded. At the halfway point, the procession paused for the blessing and unveiling of a marvellous new sculpture. Symbolising Christian Unity and paying tribute to the pioneering work of Bishop David Sheppard and Archbishop Derek Worlock, this monument takes the form of two open doors pointing down the street.

In June the choirs were together again for a performance of Britten’s War Requiem in which singers from Liverpool’s twin city, Cologne, were involved. Including choristers from all three cathedrals, a boys’ choir of about one hundred was assembled, together with the combined forces of the Liverpool Philharmonic Chorus and the voluntary choirs and lay clerks of each cathedral. Many of the performers were able to go to Cologne, the following week, to repeat the concert.

During the year, both cathedral choirs also collaborated with other singers, keen to experience Liverpool in its special year. In May, the Metropolitan Cathedral hosted the conferences of the Choir Schools’ Association and the Cathedral Organists’ Association at the same time. A concert was held to highlight the work of choristers within choir schools and to showcase some of the outreach work currently being undertaken across the country. One hundred and fifty choristers came from as far afield as Rochester and Edinburgh, Lincoln and Winchester, and they made a magical sound in the resonant space of the Metropolitan Cathedral.

Later in the summer, the city welcomed the Choristers of Wells Cathedral and the Schola Cantorum of the London Oratory School, the latter group performing Roxanna Panufnik’s Westminster Mass with the Metropolitan Cathedral Choir.

The BBC paid close attention to Liverpool’s cathedrals during 2008, broadcasting Sunday Worship on Radio 4 from Liverpool Cathedral on Holocaust Memorial Day and on Easter Day and from the Metropolitan Cathedral at Pentecost, and Midnight Mass. Both cathedrals have been featured on Songs of Praise and BBC1’s Easter Morning television broadcast came live from the Metropolitan Cathedral. Radio 3 broadcast Choral Vespers live in November, at the start of a symposium of bishops from Europe and Africa, featuring a homily from the Archbishop of Abuja, and music by James MacMillan and Kenneth Leighton.

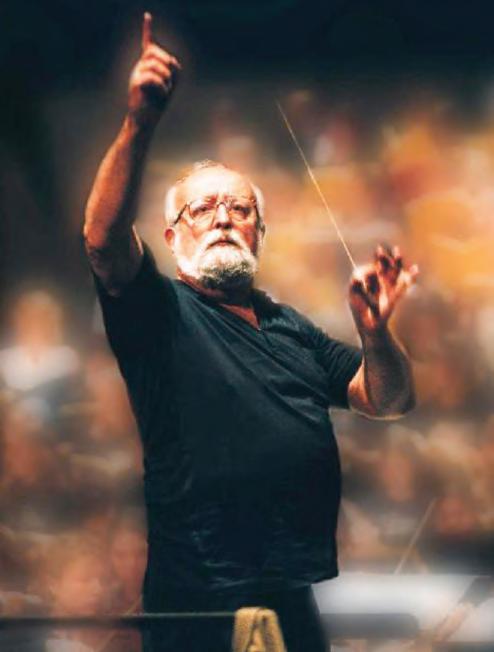

There was more contemporary music from Scotland at the end of the year, as the Metropolitan Cathedral’s Concert Society bravely undertook to commission Sir Peter Maxwell Davies to compose a substantial work in celebration of the city’s status. Hymn to the Spirit of Fire is scored for two choirs and organ, and loosely based on the ancient hymn, Veni creator. The fifteen-minute work was dedicated to Sir Paul McCartney and received its first performance, in the presence of the composer, at the Metropolitan Cathedral on Saturday, 13 December 2008, bringing the year to a glorious conclusion.

Cathedral Music 23

60Seconds in Music Profile Simon Johnson

Age: 33

Education details: Chorister, Peterborough Cathedral; Music Scholar, Bloxham School; University of East Anglia. Organ teachers: Malcolm Tyler, David Sanger, Anne Page and Marie-Claire Alain.

Career details to date:

Organ Scholar, Rochester Cathedral; Organ Scholar, Norwich Cathedral; Organ Scholar, St Paul’s Cathedral; Director of Music, All Saints’ Church, Northampton; Assistant Master of Music & Director of the Abbey Girls’ Choir, St Albans Cathedral; Organist & Assistant Director of Music, St Paul’s Cathedral.

What do you enjoy most about working in a cathedral like St Paul’s?

The building: a wonderful and immense statement of architectural purity.

What did you enjoy most at St Albans?

The people who I was working with; it is a very happy place.

Briefly tell us about the organ work at St Paul’s?

The Director of Music, Andrew Carwood, is a wonderful choir trainer, but doesn’t play the organ. So basically I have responsibility for anything to do with organs and organ playing in the Cathedral. Obviously, the Grand Organ is sizeable and gets some pretty heavy usage so it takes a fair amount of maintaining and I’m regularly in contact with the builders and tuners. There are other organs under my care too: the legendary Willis on Wheels, a Jennings Organ in the Choir Practice Room, the Tickell Chamber Organ and, soon, a new organ by William Drake in the OBE chapel. In terms of playing there is nominally a set pattern for the week but I don’t think there has yet been a normal week, since I’ve been here. I’m usually to be found playing the organ for the weekend choral services as a minimum. I am very ably assisted by a sub-organist and an organ scholar and have some responsibility in their development, but they are both so good that I hardly think that they need my help. There is some educational work and I’m also responsible for engaging recitalists.

Cathedral Music 24

How do you cope with the reverberation?

In many ways I’m still finding out. I think the key is giving space to everything. That doesn’t necessarily mean playing slower, though sometimes that can help.

At which cathedral would you most like to be the Director of Music?

I have an amazing job at the moment and am not thinking too far ahead. I’ve run choirs before so I’m not feeling any pressure to go out and prove any points either to myself or anyone else. If/when the time comes, I’ll go wherever will have me!

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

I’ve just learned the Three Preludes & Fugues Op 37 of Mendelssohn. They are dedicated to Attwood, who was Organist at St Paul’s and a good friend of the composer, so it seemed appropriate for me to learn them in the anniversary year.

Have you been listening to recordings of them and, if so, is it just one interpretation or many, and which players?

Generally I prefer to find my own way when I’m learning new music. I have John Scott’s recording of the Mendelssohn and will put that on if I start getting above myself!

What or who made you take up the organ? Being a chorister.

Which organists do you admire the most?

Too many to mention by name. I certainly have a great admiration for those who are able to pursue broader musical interests outside of the cathedral organ loft, whether that be as outstanding choir trainers, recitalists, orchestral conductors or composers, whilst maintaining a high standard of playing.

What was the last CD you bought?

Abbado’s Brahms Symphonies.

What was the last recording you were working on? Pèlerinage, a CD by the St Albans Abbey Girls’ Choir.

What is your favourite organ to play? St Paul’s.

What is your favourite building?

Peterborough Cathedral.

What is your favourite anthem?

Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb.

What is your favourite set of canticles?

Gibbons 2nd Service

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants? 131 (Knight).

What is your favourite organ piece?

Reubke Sonata.

Who is your favourite composer?

J S Bach.

Any forthcoming appearances of note?

Winchester Cathedral 5 May, St Paul’s Cathedral 6 August, Nôtre-Dame de Paris 25 April 2010.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

The installation of Jeffrey John as Dean of St Albans was a very special occasion.

Have any particular recordings inspired you?

Piet Kee’s Bach recordings at Haarlem. I used the word ‘space’ when talking about organ playing in a previous answer and I think that those recordings are a supreme example of how it can be achieved.

How do you cope with nerves and pressure?