Cathedral MUSIC

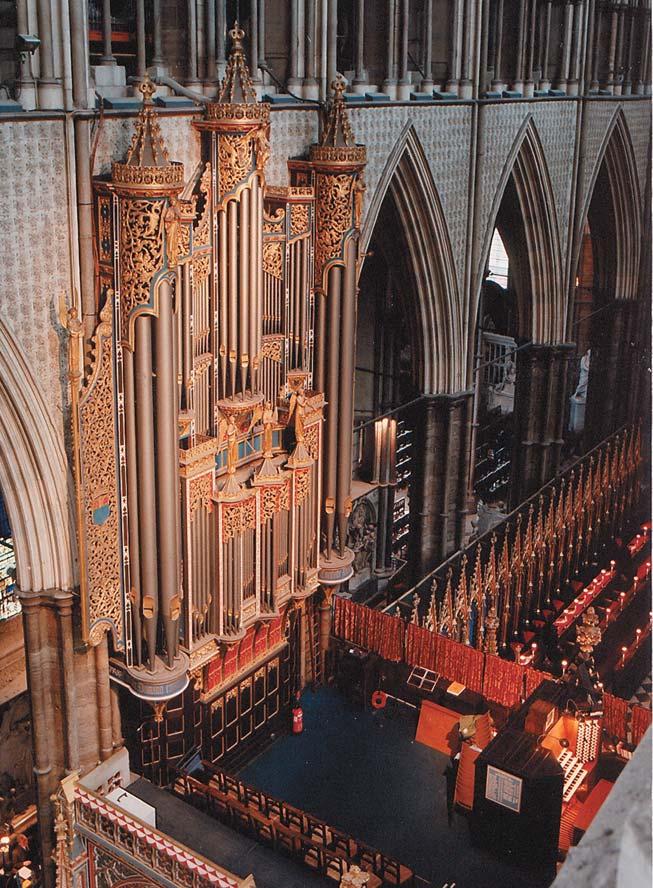

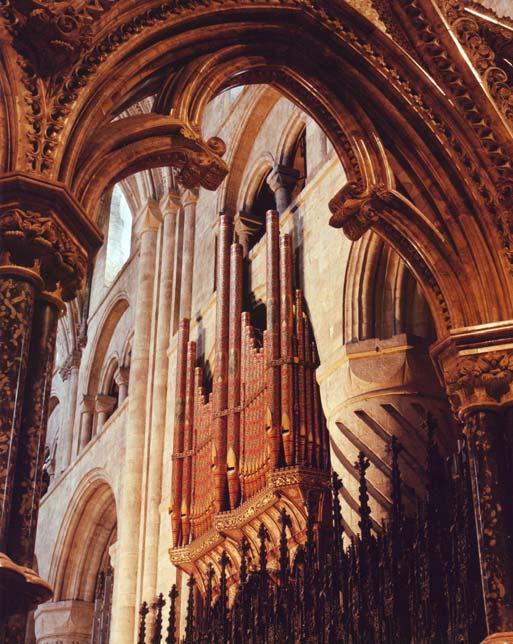

Designed and built by organists for organists

Simply the best in sampled digital sound, with no gimmicks. This is a Makin Westmorland organ.

the difference. Our Westmorland Custom instruments use a separate sound-sample for every note of every rank, and the realism is simply breathtaking! You are actually listening to the sound of organ pipes themselves, and not to something artificially-generated by computer, or based on only a few individual samples. What’s more, Makin uses genuine English pipe samples, from the finest organs in the country, to create that true English sound for which we are renowned. Experience our top-quality consoles, bespoke speaker systems, and unrivalled customer service. You will soon understand why customers choose Makin, rather than settle for second-best. to us. Together we can draw up your own unique specification today. our website for customer testimonials, details of installations, events local to you, and much, much more.

Makin Westmorland. Serious organs for the discerning musician. Someone like you.

You don’t buy a Makin Organ … you invest in one.

For more details and a brochure please telephone www.makinorgans.co.uk

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2010

Editor Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace Ripon North Yorkshire

HG4 2QS

ajpalmer@lineone.net

Deputy Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon

FCM e-mail info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road

LONDON SW4 8AR

Tel:0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership

27 Old Gloucester Street

London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087

E-mail: info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT

Tel: 0113 255 6866

info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

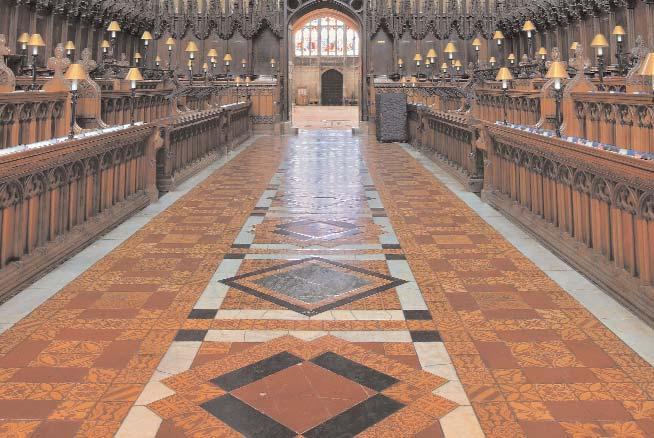

Cover Photographs

Cover

Are you a tweeter? Are you on Facebook or LinkedIn? When was the last time you read a blog on the subject of cathedral music? I thought about this recently when I was asked yet again why can we not keep our choristers interested in cathedral music, once they have left their cathedral choir. We live in a fast pace social media world and we must all keep up with these innovative developments.

When I look back, there was not much that separated our grandparents from us but over the past decades, as the Internet and e-mail have taken off, there is an ever-widening gap between, for example, my 11-year-old nephew and myself.

When I was at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, New York, last November I was struck by the opening remarks of the Rector, welcoming everyone to the office of Evensong, including, those listening and viewing on the webcast. Indeed it is happening here, as Andrew

Nethsingha pointed out on Radio 3’s In Tune; that his chapel choir at St John’s College, Cambridge, is the first to broadcast on-line. This is amazing! How long will it be before we all watch webcasts of services in our studies or living rooms? I am sure the majority of readers would find there is no substitute for the live audio-visual experience. We should recognise the power of the new media by just comparing what is available today, for example, BBC Radio 3’s Choral Evensong and the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols from King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, with the Internet experience. If there is a thirst for television and radio, think about the possibilities we are missing. How does this all contribute to holding the younger listener?

I have not yet heard of a cathedral organist who tweats. Think what could be achieved if, on a Saturday afternoon, the message came out “Cracking Evensong tonight Howells’s St Paul’s 5.30pm at Ripon.” Or for people like me, who commentate on cathedral music, to tweat: “Another excellent Evensong at York tonight”. The beauty of a tweat message is that it is picked up by hundreds of people at the same time.

We all have to become aware of this powerful force operating. For cathedral organists and FCM, I think these multimedia social networking sites should now be recognised for their ability to communicate with younger age groups.

To what extent will this damage corporate worship? Is it too late? If not how does it all work hand-in-hand?

Some of you will argue that is damage proof because the tradition has lasted centuries. I beg to disagree. Whereas the 19th century was clearly the age of the Industrial Revolution, the 20th, the century of the car, aviation and textiles, the 21st is certainly the period of knowledge transfer and the information age, where everything has become faster and more widespread. The acme of this is the Internet, the ultimate global market, the final triumph of knowledge over physical strength, the chance to create perfect competition and high productivity across the board. The modern economy has become the New Economy.

And there is so much on offer for us to capitalise on, by developing the FCM and our field of cathedral music, so as to make it more powerful than in the Golden Age of English polyphony. We should remember that disruptive though the Reformation may have been to the liturgy, there was no interruption to musical creativity. Tallis and Byrd, for example, continued writing in the same style. Let’s strive to achieve new heights; to mix my metaphors, we cannot afford to stand at the crossroads for too long on the verge of a new dawn. In this way we may find many newcomers who have never sung in a choir or attended Choral Evensong, listening to the music.

We live in a social media world, that’s fast pace and it’s up to us to keep motivated.

CM: How did your studies at the RCM compare with those as Organ Scholar at King’s College, Cambridge?

AP: I enjoyed the Royal College of Music but my life was dominated by being concurrently Organ Scholar at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, where I learned much from Christopher Robinson (FCM President) –the finest cathedral choir trainer of his generation and Christopher’s assistant, the late John Porter, who was an accompanist of genius. At the RCM I also learned much from John Barstow, my piano teacher (I was a ‘First Study’ pianist), who had me playing music I never dreamed I could such as Liszt and Rachmaninov. He kept telling me that I should “leave the cloisters and those noisy bells” and become a concert pianist! My organ teacher was Richard Popplewell, whose knowledge, repertoire and technique were immense. He had been Organ Scholar at King’s College, Cambridge, so we spent much time talking about King’s. We also did The Times Crossword together each lesson! I don’t remember learning much from the other classes but I enjoyed singing in the College Chorus under David Willcocks, from whom I learned a huge amount about dealing with large choruses.

CM: You studied with FCM Vice-President Herbert Howells. What was he like?

AP: It was a privilege to study with Herbert Howells. I found him quiet, thoughtful and occasionally passionate. I was supposed to be studying stylistics but we talked about other things most of the time. His memories of Ralph Vaughan Williams, Holst and so on were priceless. So were his written comments and reports and a note congratulating me on my awards at Cambridge. These are things I treasure.

CM: You have been out of cathedral music for sometime. How did you keep your hand in?

AP: I was out of cathedral music for 18 years. After St George’s, King’s College, Cambridge and Worcester, where I was Assistant Organist, I was ready to do something else. I had been on several cathedral organist post shortlists but had not landed a job and I was fed up! In my ‘years away’ I worked for the CBSO, playing in the orchestra, starting a youth choir with Simon Halsey, and being Associate Chorus Master (to Simon Halsey) to the CBSO Chorus. I taught at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, and conducted their chorus and was Artistic Director of the BBC National Chorus of Wales, serving the Chief Conductors successively, Richard Hickox and Thierry Fischer. I also worked for Welsh National Opera conducting community operas.

During this time I kept my hand in as an organist by giving occasional recitals and making many CDs for Priory records. Although I did not ‘keep my hand in’ around liturgical issues, I missed some cathedral music but I missed no other aspect of life in the cathedral world.

CM: A wealth of experience. How has this impacted on your training of the Gloucester Cathedral Choir?

AP: All musical experience is valuable, particularly in the choral conducting world. I have been privileged to work with some fantastic musicians: Rattle, Elder, Haitink, Abbado, Otaka and I have learned from them all. I have also learned much from many singing teachers, Robert Dean, David Lowe, Hilary llystyn Jones, Miriam Bowen and so on. I try to make all of my choirs sing with a sound technique and attend to details. I am blessed at Gloucester with some bright boys, some great

As Adrian Partington prepares for this year’s Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester he took time out of his very busy schedule to talk to CATHEDRAL MUSIC about his career.Photo © Chris Smith

lay clerks, and an acoustic which must rank with the best in the world. Good choral directing is about giving your singers confidence and discipline, but also making them feel relaxed and good about themselves. I try to make the choir at Gloucester feel comfortable but I keep raising the bar to make them achieve more. My many out-of-cathedral experiences simply help me to help them. I have started, with Simon Halsey, a choral conducting course at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, which is innovative and highly successful.

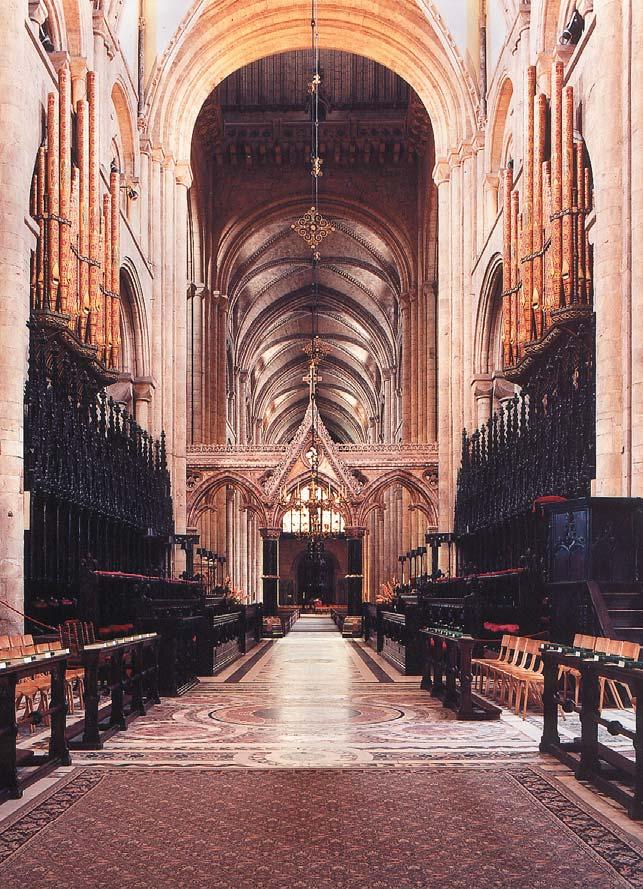

CM: So why did you come back to a cathedral post?

AP: I came back to cathedral music for two reasons: to give my family more stability (I was so often working away) and secondly, to enjoy having the experience of running the Three Choirs Festival. Also, Gloucester had always been one of my favourite cathedrals, with its unsurpassable architecture, great musical tradition and convenient geographical position. I would not have been tempted to go to most other cathedrals. Gloucester is special, and the longer I’m here, the more I enjoy it.

CM: How difficult is chorister recruitment and outreach?

AP: To take recruitment first. We are all involved with the recruitment of choristers here. Most of them come from local primary schools, or are already at the King’s School. I see boys regularly through the year, and thus far there seems to be no shortage of good boys coming for audition.

Our outreach programme, of course, helps recruitment. Each term one of our lay clerks, Russell Burton and his colleagues go into a cluster of different Gloucestershire Primary Schools, occasionally accompanied by groups of choristers, to prepare the schools for a termly concert in the cathedral, at which the cathedral choir performs with, and separately from, the school choirs. It is a fantastic scheme (started by my predecessor, Andrew Nethsingha),and we are doing all we can to maintain it, now that the Government is withdrawing its financial support.

CM: Tell us about the job at Gloucester.

AP: My job at Gloucester involves me with many different things: the Three Choirs Festival, which is a huge amount of work but very exciting; Gloucester Choral Society, which gives five choral-orchestral concerts a year, and all the administration which these jobs require. I have a first rate PA, Helen Sims, who takes a lot of the strain off my shoulders, and an excellent Chorister Tutor, Bill Armiger who deals with many chorister issues. I can’t speak highly enough of my assistant, Ashley Grote, who must have claims for being the best young organist in the country, and the current Organ Scholar, Robert Dixon, who has a phenomenal work rate and maturity for a teenager.

CM: Picking up on the money side of things. What are the financial constraints you find yourself under at the moment?

AP: I think about money as little as possible, but all cathedral departments at Gloucester have been asked to make a 5% cut to their budgets. This is easily achieved and I am currently not having to compromise. We have access to some generous benefactors and trusts at Gloucester. We are not ‘flush’ with money but we are not poor, either.

CM: A question that exercises us in FCM is how can we market cathedral music?

AP: The glory of cathedral music is that it is there when people want it. I’m not sure that it needs to be ‘marketed’. I think the cathedrals themselves need to make their marketing more sophisticated, but a large proportion of the population regard cathedrals as tourist sites and wander in when they feel like it. I fear that the Church of England is not highly regarded by most of the population and until that particular tide turns, all the marketing in the world will make little difference to people’s perceptions of cathedrals or their music.

CM: So, to the Three Choirs. How is the new central Festival administration working?

AP: The new central administration of the Three Choirs Festival is the most important innovation for decades. It is making the festival more organised, more cost effective, more modern; Paul Hedley, the first General Manager is taking a lot of administrative responsibility off the shoulders of the three cathedral directors of music. Richard Hickox said to me 20 years ago that the festival needed central administration if it was to survive; and now it’s got it, and it’s brilliant.

CM: What are this year’s highlights?

AP: The highlights at Gloucester 2010 are: Elgar’s The Kingdom, Mahler’s Second Symphony , the Joubert Requiem (first performance), the 100th anniversary performances of RVW’s Tallis Fantasia and the Elgar Violin Concerto (Roger Norrington conducting),the three cathedral choirs singing Gabrieli and Monteverdi with His Majesty’s Sagbutts and Cornetts; the first concert to be given by the Festival Singers –this is a ‘Youth’ Three Choirs Chorus which I have formed to try to ensure the future of the Festival Chorus, which, whilst still very good, is rather elderly (although the average age this year is rather lower than recently!).

CM: Are you introducing anything significantly new this year?

AP: My innovations for 2010 are as follows: the Festival Singers (see above); and the shifting of the chorus rehearsals to later in the year. There has always been the practice of rehearsing from April to early July, then stopping for a month! By the time the choir reassembled for the Festival, they had forgotten much detail. This has always sent my predecessors, and my colleagues at Worcester and Hereford mad and sent me crazy at my first festival in 2008. So last year, I rehearsed the Gloucester contingent without a break and found that many Worcester and Hereford singers came voluntarily to my rehearsals. This year I am doing the official rehearsing without a break, and my colleagues are kindly doing the same. I have also increased the number of ‘massed’ rehearsals, and put these later in the year. I wouldn’t have had the courage to do this without my experience of preparing choruses for BBC Promenade concerts. The idea of the BBC Symphony Chorus having a month’s break between rehearsing and performing would be viewed as ridiculous. I am trying to make our chorus operation here as efficient as theirs! I am not popular now but have received no direct complaints, because you cannot argue with the logic of the new arrangements!

CM: You’re a busy man, what drives you?

AP: I am driven by my love of music and the need to pay twice-yearly Income Tax and quarterly VAT bills! I ‘relax’ by spending time with my five children!

Scotland’s second most senior judge has been appointed as Chairman of Council of the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM). The Rt Hon Lord Gill (68), the Lord Justice Clerk, takes up the role in the summer. He succeeds Mark Williams, a senior partner in an international investment company, whose term of office is about to come to an end. Brian Gill has had a lifelong interest in church music, ever since singing as a treble in the choir at St Aloysius’s College, Glasgow. He has subsequently held several organist positions, most recently at St Columba’s Roman Catholic Church in Edinburgh, where he and his wife run an annual music festival. He is Chairman of the Friends of the Music of St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh. As Chairman of RSCM Council, Lord Gill will lead a team of trustees comprising experienced church musicians, senior clergy and distinguished business figures. Lindsay Gray, Director of the RSCM has welcomed Lord Gill’s appointment. “Brian brings an excellent combination of qualities; as well as his work as a church musician, he brings an extensive understanding of the music education scene, along with expert knowledge of the law and procedure as it affects charitable organisations like the RSCM.”

The Royal School of Church Music is offering organ scholarships to two young organists at the 2010 Bath Summer Course for Young People. The successful candidates will have the opportunity to play the four-manual Klais organ in the city’s splendid Abbey Church; the setting for some of the choral services. They will assist the Course Organist in playing for rehearsals and services during the popular week-long event, which is based at Kingswood School and runs from 23-29 August.

The Bath Summer Course for Young People, directed by international church musician Geoff Weaver, draws many young singers from RSCMaffiliated choirs around the UK who return year after year for its mix of specialist teaching, the chance to sing services and concerts in some lovely venues, and plenty of fun and friendship. The music-making reaches a high standard accompanied by experienced tutor and Course Organist Steven Grahl.

The scholarships will be awarded to young organists aged 16-21, at Grade 8 standard or thereabouts. “This is an excellent opportunity to learn with the Course Organist and gain valuable experience in accompanying large groups of singers,” says Sue Snell, the RSCM’s Head of Education. There will also be opportunities to direct choir rehearsals in some of the course’s wide range of repertoire. Full details of the course and scholarships can be found on the RSCM website www.rscm.com/courses or by calling 01722 424843. The closing date for scholarship applications is 14 May 2010.

The Royal School of Church Music begins 2010 with a major boost to its work: an annual grant of £100,000 is to be made by the Liz and Terry Bramall Charitable Trust for the next five years. The funding will be used to finance regional adviser posts throughout England and staff the work of the education department at the RSCM’s main office in Salisbury.

The RSCM supports and promotes church music in its affiliated churches, choirs and schools with a comprehensive range of training programmes, courses and inspirational events for singers of all ages, organists, music directors and instrumentalists. The new funding will secure an existing Regional Adviser post in the North of England, and enable the creation of three similar roles elsewhere in England; their work will include liaison with volunteer area committees and a programme of visits to affiliated churches to support musicians and clergy. In addition, the RSCM will make a new full-time and a part-time appointment in its expanding Education Department, which oversees training programmes such as Voice for Life and Church Music Skills

“This gives us a truly amazing start to the new decade,” said Lindsay Gray, Director of the RSCM. “We are hugely grateful to Liz and Terry Bramall for their splendid support, which will have a significant impact on our work, not least in enabling closer direct contact with and support for our affiliates and members in their own churches.”

The Liz and Terry Bramall Charitable Trust already funds and sponsors a number of arts organisations and events including the Leeds International Piano Competition and Opera North. Terry Bramall, who has now retired following a long and successful career in the construction industry, is a director of Doncaster Rovers Football Club. What is not so well known is that Terry Bramall himself is a lover of church music and an organist. “At the age of sixteen I was harangued by the local archdeacon into playing the organ at a nearby village church. I agreed, so long as I could choose the hymns!” His wife Liz sings in a small church choir. “Together we are delighted to support the work of the RSCM, especially when it comes to bringing young people to church music and keeping them involved. We are pleased that our grant will be used to support and enable church musicians; we know at first hand how useful and invaluable that can be.”

Three Regional Music Adviser posts will be advertised in the press and on the RSCM website in early January.

The Royal School of Church Music has launched Music Sunday 2010, bringing together a celebration of music with fundraising. Participating churches will be able to celebrate and affirm the work of their musicians, and combine it with a fundraising campaign to be split on a 50:50 basis, between the church itself and RSCM, an international charity that promotes and supports music in all styles of Christian worship. The date has been set as 13 June 2010. Music Sunday is an opportunity to give thanks for the dedication and work of church musicians, whether choristers, instrumentalists, cantors, organists, or choir directors. “Church musicians play an important part in church worship, and along with clergy they are often the ‘first-in and last-out’ on a Sunday, with a lot more preparation going on behind the scenes at other times,” says Lindsay Gray. “Music Sunday is an excellent opportunity to give thanks for the ‘craftsman’s art and music’s measure.’” Suggested prayers, readings and music for the occasion can be found on the RSCM website www.rscm.com/musicsunday. The Music Sunday campaign shares proceeds between the participating church, choir, or school and the Royal School of Church Music. The overall target for 2010 is to raise £100,000. The RSCM website includes fund-raising ideas, ranging from a coffee morning or barbecue to a music marathon or sponsored ‘sing’. There is also guidance on how to promote an event and deal with issues such as Gift Aid.

Tuesday 11 May, 2010 –5.30 pm St Paul’s Cathedral

The choirs of St Paul’s and Lincoln Cathedrals and Westminster Abbey will take part.

Free tickets are available on the door or from

The Registrar, Corporation of the Sons of the Clergy, 1 Dean Trench Street, Westminster, London, SW1P 3HB

Charity No: 207736

Tel: 020 7799 3696 www.clergycharities.org.uk

It is appropriate in this bicentenary year to celebrate the life and achievements of Samuel Sebastian Wesley. His distinguished career as a composer, organist and choirmaster was widely admired in his lifetime and many of his anthems have been in the repertory of cathedral and church choirs now for a very long time.

He has also been admired as a composer of hymn tunes and it is this aspect of his work that is the focus of the present article. Wesley’s most significant contribution to the hymn tune repertory is contained in the large volume that he published in 1872. The elaborate title page of this volume ran as follows:

‘The European Psalmist: Dedicated by permission, to Her Majesty The Queen. A collection of hymn tunes; selected from British and foreign sources, supplying, it is believed, music for every metre in common use in English churches. To which are added chants, an easy service, short anthems, etc, etc. The whole revised, and where necessary, rearranged, and much of the new portion composed, by Samuel Sebastian Wesley, Mus. Doc. London: Novello Boosey, Hamilton Adams, 1872, (562pp).

The massive volume contained 733 items. There are 615 hymn tunes, some settings of the Sanctus, and a large number of double chants. At the end there were some short anthems and canticle settings. Some of the anthems include music by Samuel Wesley, père.

The volume had a subscription list of some five to six hundred names, and these included many musicians, organists and clergymen. The Hereford Dean and Chapter ordered twelve copies while Winchester College requested eight. The well-known individuals who subscribed included Rev Sir F G Ouseley Bart etc, St. Michael’s College, Tenbury, Henry Willis, Organ Builder and Joseph Barnby.

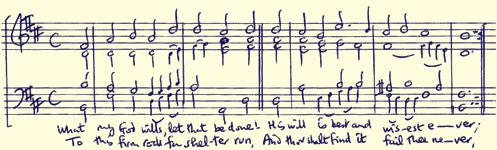

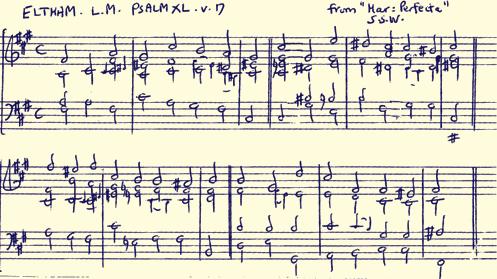

Of the 615 hymn tunes in the book well over 100 were by Wesley himself. All of them were set out on four staves. This may seem a curious and rather extravagant method of presentation, but at the time it was probably thought helpful to give the alto and tenor parts of a tune on separate staves above the four-part layout underneath. The words of the first verse of each hymn were inserted in the middle. An illustration from the first item in the book demonstrates the usual plan (see example 1 above).

It will be noticed that the stems of some of the notes go in two directions when a particular note is common to two parts. It is also to be noticed that Wesley put the time signature at the head of the tunes in his book.

One or two comments may be offered with respect to certain tunes, some well known and others now long forgotten.

The famous Hereford (54, in F major) was set to a metrical version of Psalm 103 – The Lord abounds with tender love –its first association with O thou who camest from above was in the 1904 edition of Hymns A&M.

After a series of tunes in LM (1-84), CM (85-240) and SM (241-269) metres, Wesley included a selection of German chorales. Some of these appeared in more than one version,

and in one instance (425) Wesley suggested that a bar could be omitted so as to allow the tune to fit words in a different metre. The harmony of tunes that appear in more than one version is usually different and so sometimes is their metre. Landsberg, for instance, appears as an eight-line tune (295) or a six-line tune (348). The former was taken from J S Bach’s Cantata 144 where the chorale text is Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh allzeit. Wesley’s words are a translation of this text (see example 2 above).

It is perhaps surprising to find that there are three versions here of the chorale Herzliebster Jesu (325, 330 and 394) but only one of the Passion Chorale (393). By 1872, however, J S Bach’s uses of these chorales in the St Matthew Passion and elsewhere was not widely known in England.

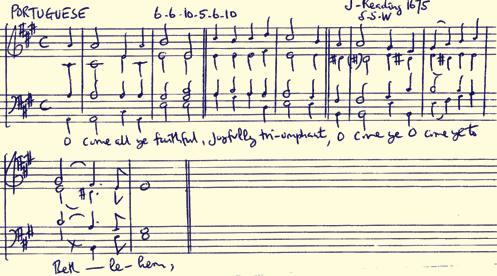

The source of Adeste Fideles (313) words and music, has puzzled many for some time(see example 3 overleaf). I have a suspicion that Wesley was correct in supposing or noticing that the tune was Portuguese in origin. His source for it was 17th century rather than 18th and he does not refer to J F Wade, the Catholic priest who lived and worked in France for many years and who may have ‘discovered’ the tune to associate with his Latin text. The history of the tune is full of interest and may be discovered in some detail in one or two references1. In any case its origins date back to well before the 17th century in more than one form.

Two of the tunes in Wesley’s book are better known today as

the basis of two of Hubert Parry’s organ pieces. Hampton(8) is an LM tune set to words based on Psalm 139/14. ‘I’ll praise thee from whose hands I came’. Wesley’s D major tune is given in example 4. Its four staves are given in full as there are one or two interesting details to notice in its presentation if the separate middle parts are compared with the ‘score’.

The third piece in Parry’s first set of chorale preludes (1912) is based on this melody and is in F major. Parry liked to associate the tune with the hymn O love, how deep, how broad, how high, a 15th century Latin hymn translated by Benjamin Webb that is now usually sung to Eisenach. Wesley’s fine tune has not survived in modern hymn books and Parry’s prelude is rarely heard nowadays, owing, no doubt, to the fact that the tune is not much recognised or known.

Eltham (68) is an LM tune in the unusual key of F sharp minor. Why F sharp minor? The tune was taken from

Harmonia Perfecta, a book of tunes of 1730, where it appeared in G minor with the melody in the tenor. Since Wesley’s day the tune has appeared in Hymns A&M (1904. No 322), Congregational Praise (1951 No 129) and the Anglican Hymnal (No 1965 No 156). Its presentation in lower keys in more

Grapes are blended to produce the Grand cru.

Materials and Spirit are also blended in the age-old way to produce the Grand Orgue for the discerning palate.

recent times clearly aids its use –it has now got down as far as E minor! Parry discovered the tune and used it as the basis of a chorale fantasia (1915). The tune there was quoted in F minor and associated with Watts’s hymn When I survey the wondrous cross. This splendid organ piece was much admired by Gerald Finzi, who made an arrangement of it for string orchestra (1950). Wesley’s Eltham is shown in example 5 above.

Wesley clearly spent much time and gave much thought to the compilation of his collection and its progress had been pursued over many years. As he said in his Preface, he had been asked to make such a collection ‘long ago’ and to include in it psalm and hymn tunes that were ‘most commonly used in public worship’.

His contribution to the existence and development of hymn tunes in the 19th century was substantial and his work deserves to be noticed and consulted perhaps a little more often when new hymn books and tunes are under consideration.

1See John Julian A Dictionary of Hymnology. 1892. Pages 20-22 for a discussion of what was known of Adeste Fideles up to the end of the 19th century. A more recent study is by Dom John Stephen OSB The Adeste Fideles –A Study of its Origins and Development. Buckfast Abbey Publications. (1947). Published in both English and French (42pp xiii pp of music examples). The tune existed formerly in various different forms, and there are references to its Iberian origins in Dom John’s fascinating booklet.

A short list of references in connection with some of the more important aspects of SS Wesley’s life and work:

S S Wesley. A Few Words on Cathedral Music. 1849 Reprinted in facsimile. Hinrichsen 1961b. London. 1961. 78pp with supplementary music.

E Routley The Musical Wesleys. London. 1968.

B Matthews S S Wesley 1810-1876 A Centenary Memoir. Bournemouth. 1976.

P Chappell Dr S S Wesley 1810-1876 Portrait of a Victorian Musician. Great Wakering 1977.

D Gedge The Reforms of S S Wesley. The Organ. July and October 1988 and January 1989.

Two volumes in Musica Britannica have been devoted to S S Wesley’s Anthems, edited by Peter Horton. MB 57 (1990) and 63 (1993). The latter includes versions of The Wilderness and Ascribe unto the Lord with orchestral accompaniment.

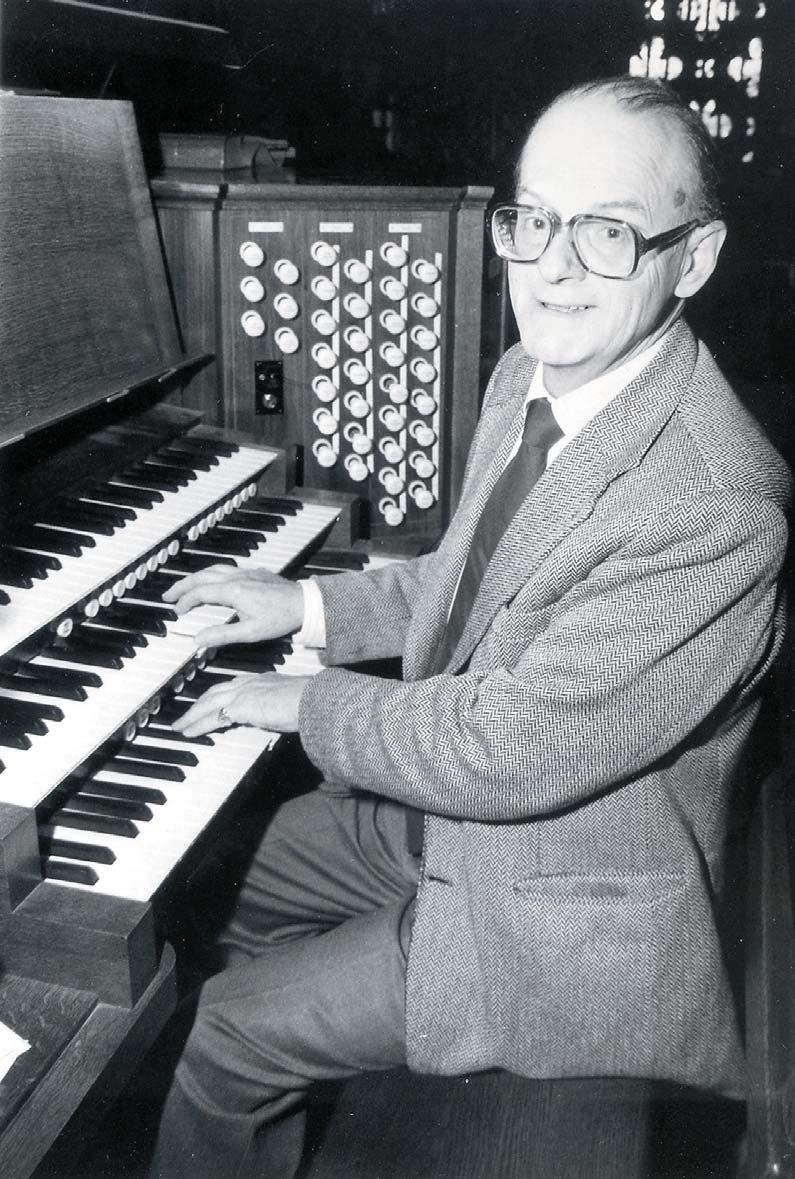

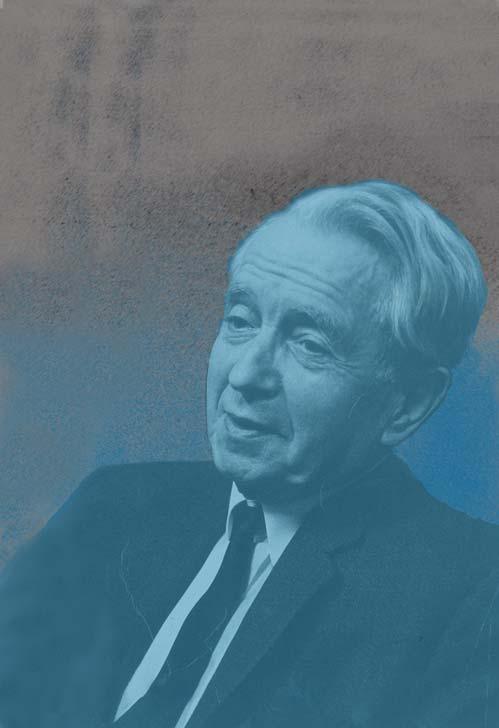

It is a rare event to be able to celebrate the musical life and work of a new centenarian, but we are privileged this year to mark, with respect and acclaim, the great achievements of Stanley Vann, who died on 27th March 2010 aged 100. William Stanley Vann –Stanley to those around him, and (daringly) ‘Stan’ to us choristers when we thought he wasn’t listening – reached the zenith of his career as Master of the Music at Peterborough Cathedral from 1953 to 1977, and my two brothers and I were privileged to experience cathedral music-making under a director at the height of his powers during the final eight years of his tenure. His time at Peterborough is rightly regarded as the period which most defined Stanley Vann as a choir-trainer, but a long and varied apprenticeship had preceded the Peterborough appointment, providing him with a host of experiences upon which he was eventually able to draw in so masterly a way.

Stanley Vann was born in Leicester in 1910, and showed early musical promise that even included some embryonic composition from the age of seven. His passion for church music, fuelled by regular church-going, gradually developed and he eventually, aged 15, became an organ pupil of Victor Thomas, who was chorusmaster for the Leicester Philharmonic. By the age of 20, Stanley had obtained his ARCM, ARCO and FRCO diplomas, and become Assistant Organist at Leicester Cathedral under Dr George Gray. Soon afterwards, on the retirement of Victor Thomas, Stanley succeeded him as Leicester Philharmonic chorusmaster, which brought him into early contact with one of the giants of English music-making, their conductor Sir Henry Wood, who by all accounts had unwavering confidence in Stanley’s ability to prepare the singers (and who had indeed requested Stanley for the post). By now it was clear that Stanley was not going to pursue a career in building and architecture with the family firm, and it was no surprise when he started accumulating directorships of various choirs himself, in particular that of organist and choirmaster at Gainsborough Parish Church in 1933, a post he would retain for six years while he also

directed the music at two Gainsborough schools (and still continued as Leicester Philharmonic chorusmaster, Sir Malcolm Sargent becoming their conductor).

This period of his life saw his marriage to Frances in 1934 and his first taste of live BBC broadcasts, with two Choral Evensongs in 1938.

A move to take up the reins at Holy Trinity, Leamington Spa coincided with the outbreak of war, and his early mechanical drawing experience led to his working on airframe drawings at the Rover car works in Coventry –though he had also found time to inaugurate the Leamington Bach Choir in 1940. Later he rose to the rank of Captain in the Royal Artillery, and suffered a perforated eardrum while involved in anti-aircraft defences on the south coast. His legendary keen ear for pitch and tuning is consequently to be considered even more remarkable, and few were ever aware of the damage to his hearing. While serving overseas Stanley conducted the Garrison Orchestra in Osnabrück, broadcast an organ recital from Hamburg on the British Forces Network and recorded an orchestral concert from Bruges.

On returning to Leamington in 1947 he founded the Warwickshire Symphony Orchestra and obtained an external BMus from London University after studying with Sir Edward Bairstow and Dr George Oldroyd (hence no doubt the frequent outings of the Oldroyd in D Communion Service during his Peterborough days). Then in 1949 he made his first permanent move into cathedral music when he became Organist and Choirmaster at Chelmsford Cathedral; even then there was another orchestra to be founded (the Essex Symphony Orchestra, of which Stanley was made President in 1990), and he was also appointed Professor at Trinity College, London, whence he received an honorary FTCL four years later. Finally, in 1953, Stanley was appointed Master of the Music at Peterborough Cathedral, a post he held until his retirement 24 years later and which would form the basis of his national and, indeed, international reputation. I think it would be fair to say that few of the UK’s cathedral musical directors of the last 50

Peterborough Cathedral Choir between 1969 and 1976, looks back over a century.

years can have had such varied and all-embracing preparation for the position for which they are most remembered; part of Stanley’s success at Peterborough was clearly due to his amazingly diverse and eclectic musical apprenticeship, and to the knowledge he gained from countless musicians, young and old, of every kind of ability under the sun, whom he encountered in sometimes extraordinary circumstances during the first 20 years or so of his adult life.

At Peterborough Stanley led a full musical life, elements of which included conducting the Peterborough Philharmonic, teaching singing, adjudicating and composing (of which more anon). But it was the Cathedral Choir that was from the outset the particular focus of his attention, especially since his predecessor Douglas Hopkins admitted to Stanley that it was, to put it mildly, in a less than satisfactory state. Stanley at once set about rectifying the situation, and one of the first things he did was to reduce the repertoire so as to concentrate on creating the ‘Peterborough sound’ which was to become so characteristic. That he had basically achieved this by the end of the ‘fifties is a tribute to his abilities, determination and vision; and perhaps Stanley was exactly the right man in the right place at the right time.

Although one of England’s greatest medieval buildings, Peterborough Cathedral in the 1950s was a provincial establishment with a situation that included some unpromising features. However historically significant, the city itself had become an industrial, manufacturing centre that had owed its expansion to the railways, and it suffered architecturally, socially and culturally in comparison with Cambridge and Ely, for example, both about 30 miles away. The Cathedral had a reputation for being one of the country’s most unvisited masterpieces, since Peterborough as a whole did not have the old-world charm of many other typical cathedral cities. These drawbacks must inevitably have dissuaded certain potential lay clerks from applying for posts in the cathedral choir over the years. The situation regarding the choristers was also potentially unpromising, as the

cathedral had no self-contained choir school as such; many choristers attended the King’s School (the city grammar school) from the age of 11, but even in my time in the early 1970s several of my chorister colleagues went to other city schools, which made things administratively less easy than at most other British cathedrals, and thus further added to the Master of the Music’s challenges. How, therefore, was he to achieve heights of musical excellence to compare with, say, King’s College, Cambridge down the road?

His solution was to turn these apparent weaknesses into strengths through a mixture of many remarkable qualities. Stanley had that ability to communicate to those around him the feeling that what he, and we, were doing was significant, worthwhile, and probably unique. The point was that this feeling was, of course, absolutely genuine: Stanley believed entirely in his calling, and basically strove to do everything as perfectly as possible: if you were singing to God, nothing less was admissible. If you sang in Stanley’s choir, you signed up to this manifesto by default –maybe consciously as an adult, or perhaps unconsciously as a boy chorister. He had spent enough years in secular life to appreciate that young boys in a bustling city were not necessarily going to spend every waking hour contemplating what they were going to sing for Evensong that night; but he was never slow to remind us of John Stainer’s habit of kneeling in the organ loft at St Paul’s before he played for a service, and we were encouraged to be on duty from the moment we arrived at the song school for rehearsal, maybe after a hair-raising bicycle race through the traffic-dense city streets (few health and safety considerations then!). If you sang a wrong note in rehearsal (heaven forbid it happened in a service!) you came to feel that it mattered for reasons that went beyond the obvious fact that it ruined that particular musical moment. One quickly came to share Stanley’s vision of the value of perfection, and a combination of leading by example and charismatic influence brought its results. Even as boys, we felt instinctively, and then empirically, that we were in the presence of a great man.

An associated quality Stanley imbued in his singers was loyalty, which manifested itself in particular in his lay clerks, many of whom stayed at Peterborough for many years. Aspiring soloists, by and large, went elsewhere and whilst some lay clerks were deservedly in demand locally for solo work, those who stayed were usually happy for Stanley to mould their voices into a choral unit designed for the building –and this remained the height of ambition for the majority. Stanley was, of course, not unaware of individual singers’ needs, and was always very generous when it came to offering visiting singers opportunities to sing with the choir; but they had to conform quickly to the exacting demands for precision, long diminuendos, and shading off at the ends of phrases to a degree that taxed even the most advanced vocal techniques. Boys, lay clerks and supernumeraries alike soon learned that a voice that stood out in any way was quickly subject to the famous Stanley glare, usually accompanied by an air-drawn ‘hairpin’ that brooked no repeat of the felony!

By the time I arrived Stanley’s method of teaching us boys was the relatively simple expedient of having probationers learn from experiencing the perfection surrounding us. There was a little bit of probationers’ ‘note-bashing’ once a week, but mostly new recruits were placed strategically between two more senior boys and learnt most of their trade from them. A few mantras from Stanley usually sufficed: head tone, precise vowels and consonants, absolutely no edge to the voice, and that inevitable shading off at the end of a phrase, particularly in the psalms which became Stanley’s especial trademark. Vocally, what he aimed for was blend: no voice was to stand out, you were all part of something greater than the sum of its parts. The words were important: diction was paramount, and to aid this Stanley insisted on bright tone; old-fashioned hootiness or anything that sounded remotely lugubrious (a favourite word) was to be avoided. It is clear that he had achieved something akin to his goal by the time John Betjeman, who used to attend Evensong incognito, wrote in his mid-1960s script for English cathedrals and their music: ‘You will now hear the choir of Peterborough Cathedral sing… and I think you will agree that they are a matchless choir.’

Although there was an underlying cautiousness about Stanley, which I’ll come to below, a mixture of necessity, pragmatism and trust somewhat belied this where the choristers were concerned. He was loath to have a boy sing full-time until he was sure he had totally absorbed the Vann ethos; on the other hand many boys came to him at the relatively advanced age of eleven, so they had to learn quickly. A result was that Stanley usually had a set of fully-fledged choristers who were smaller in number than in other cathedral choirs, and also older –average age maybe thirteen, with some fourteen and even fifteen year olds. Given his ability to mould us in his image, however, we were in absolutely no doubt as to what was required in order for the appropriate standard to be achieved. Stanley repaid this consensus by placing a high degree of confidence in his choristers; the Head Boys sometimes conducted the psalms, for instance (rather than one of the men), and for someone usually averse to any form of risk, Stanley’s liking for a lot of treble solo work was noteworthy. I think he knew the boys would just cope: we were mini-Stanleys (minivanns?)! The first live BBC broadcast Evensong I took part in from Peterborough featured Weelkes’s For Trebles service as the setting of the canticles, with two boys taking the two extensive solo parts: by any normal yardstick a risky venture, but marvellously vindicated. For

another live Evensong a couple of years later Stanley felt I could “do a job” (as football managers are wont to say; he didn’t quite put it like that) in Wise’s Prepare ye the way: at the age of 14, there was every chance my voice might have given way under the strain, but again there was no problem. This confidence in his trebles stretched at least as far back as 1961, when Stanley’s pioneering LP for Argo featured boys duetting in Dering’s Gaudent in coelis and Duo Seraphim

By the time John Betjeman was making his comments Stanley’s Peterborough choir had become a touchstone for others to be measured by. In particular, it had become known for its singing of the psalms, which for Stanley lay at the heart of Evensong. There is, of course, no one way to sing the psalms ‘correctly’, but for many Stanley’s approach to psalmody summed up his achievements: not too fast, not too slow, a feel for an overall phrase rather than a need to point each individual word; a sense of a journey yet with time to reflect (that shading off at the end of each half-line). There was to be no jerkiness, so the accompanist played through pauses and other punctuation, keeping any registration changes subtle at the half-verse, and (usually) only taking the hands off at the end of a double chant. Choir and organ naturally came in together at a change of chant. Stanley tended to see psalms as elements of a sequence, and thus the chants to a particular evening’s psalms tended to embody a satisfying sense of structure, rather than just having the feel of three or four psalms randomly tacked together. Stanley’s own chants began to make their way into the Peterborough chantbook during the 1960s; he wanted them initially to remain ‘special’ to Peterborough, and was loath to publicise them more widely; latterly, many have made their way around the country, and can be heard by now in most of our cathedrals. A small number of them have an austere, spiky quality, whereas the majority have an essential warmth and an unerring feel for form and melody, with some exhibiting a profundity that almost defies description, such as the following examples.

Stanley had always enjoyed composition, and all sorts of pieces in addition to psalm chants continued to flow from his pen, and indeed did so unstintingly during his extensive ‘retirement’. Although, in the manner of many 20th century cathedral organists, his music is essentially diatonic with elements of the English pastoral school popularised by Vaughan Williams (whom Stanley knew), it has enough individual features to lend it a distinct individuality. It is always carefully crafted, and a lifetime of working with choirs and organs of all shapes and sizes means it is always singable, playable and bears its intended performers very much in mind. That has not stopped some of his pieces being quite difficult to perform and, for singers, to tune: a liking for pentatonic colouring and enharmonic change can offer challenges to the most able performers. The quality of

Stanley’s music has nevertheless long been recognised, underlined by a plethora of publications, the sets of canticles he has written for any number of cathedrals and a host of commissions for professionals and amateurs alike. It is impossible in an article of this length to offer more than a glimpse of the scope of Stanley’s oeuvre, and a visit to www.stanleyvannmusic.org.uk will make up for the relatively brief remarks possible here. Of more than 200 available works, the following will give an all-too-brief introduction to his output. For Christmas, Jesu thou art welcome is a masterfully simple carol arrangement, and Come listen to my story a gloriously tuneful piece with an affecting treble solo and exciting organ accompaniments. General anthems include the relatively wellknown Behold, how good and joyful, with another lingering treble solo, and the more straightforward Praise to God, Immortal Praise that church choirs will find attractive. Of many settings of the evening canticles the haunting Chichester Service has recently been republished, while for many the essential Stanley Vann is his Evening Service in E minor, a modally-inspired masterpiece of minimalism that stresses the Virgin’s awe at being chosen for her divine role. Of many works for organ that Stanley wrote largely in retirement, the quiet, contemplative Choral and the al fresco Fêtes are good examples of the contrasting ends of Stanley’s spectrum. Two striking settings of the mass include the Missa Sancti Pauli for double choir, written for St Paul’s Cathedral, and the remarkable 30-minute Billingshurst Mass, scored for soli, choir and full orchestra. This last was written for Billingshurst Choral Society in 2000, and has had several performances. Its most memorable features include some lovely lyrical solo work and some well-crafted and at times impressionistic orchestration that shows how much Stanley absorbed from working on and

around the concert platform for so many years. All the above can be obtained by visiting the aforementioned website, which also gives details of available recordings.

As Stanley’s confidence that the Peterborough choir could maintain his standards of performance grew over the years, the choral repertoire gradually began to expand, and although it remained conservative in comparison with some foundations, it was by the 1970s comparable with that of most British cathedrals. It took a little longer for the repertoire of

Communion settings to receive Stanley’s attention, and a rare blind spot was his barnacle-like championing of an unremarkable modal setting by Woolley that most of us would have gladly used for kindling, given the chance. On the whole Stanley was not a fan of the flamboyant occasion, and he did not perform most of the longest anthems that featured in some other places. Thus he would do Travers’s Ascribe unto the Lord , instead of Wesley’s, and preferred a small piece performed exquisitely to a long one sung unevenly. He occasionally took these precepts somewhat to extremes, especially on Mondays when there was a post-Evensong rehearsal: the Precentor would announce something like “For the anthem, O Lord, turn not away thy face by John Bull” (the piece would be barely a page long), a tiny running joke that for several years successfully evaded even Stanley’s eager antennae. On the other hand, there was innovative material, and commissions that other cathedrals didn’t do, such as Monteverdi’s Cantate Domino and Adoramus Te, Tony HewittJones’s At the round earth’s imagined corners and Howells’s through-composed anthem Thee will I love. But his cautious instincts remained, and a new piece would lie on the song school table for weeks or even months before we got to rehearse it. In particular, his preparations for BBC broadcasts were legendary: he would record his own rehearsals, and then send the assistant organist and each lay clerk a personalised checklist of minutiae to work on before the big day; details included which notes would benefit from being tuned slightly sharper, where an individual singer might sing a touch louder or softer to achieve better balance, and so on. What one can at least say is that the ends justified the means, and all his broadcasts inevitably gleaned much complimentary comment from general listener and professional colleague alike.

Although obviously a competent organist, Stanley rarely played for services, preferring to be down below directing the choir – a practice that will seem commonplace today, but was by no means universal 50 years ago. He was nonetheless a quietly effective influence in organ-playing matters, as Barry Ferguson, Stanley’s assistant from 1964-71 recalls: “He offered few bits of advice, leaving me to sort things out on my own,

which on reflection was confidence-building and enabling for a young assistant. One was: ‘Never use the mixtures for a hymn play-over; it can muddle the ear and cloud the tune.’” Barry also remembers page-turning for Stanley when he recorded a short recital for the BBC. “His performance of Howells’s Sarabande for the Morning of Easter was confident, stirring, sonorous, full of varied colours and ebb-and-flow, and masterly in his organ management.” Douglas Fox later confided to Barry that he had heard many performances of the Lizst B.A.C.H. Fantasia, some flashy, some very fast, but none as musical as Stanley’s. A memory that stays with me is when Stanley did once play the organ for Evensong, the assistant being away: as we processed in on a dark winter evening he produced an extraordinary shimmering soundscape the like of which I have not heard before or since. Absolutely magical.

Whilst valuing the daily cathedral round, and even preferring cold February Evensongs when there might be nobody in the congregation, Stanley was also proud of notable achievements that belonged to the other end of the scale. He had directed the Cathedral Choir in many radio and television broadcasts by the time he retired, and was amongst the first to undertake foreign tours. In 1975

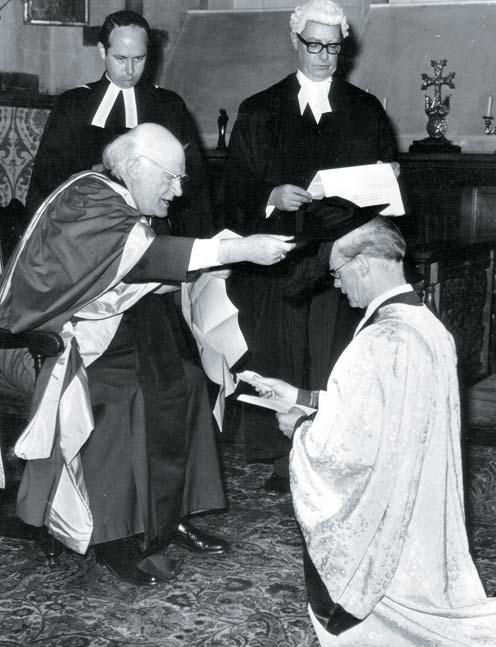

Peterborough Cathedral Choir was the first Anglican choir to sing High Mass in Notre Dame, Paris. He directed as many LP recordings as any other comparable choir, including a version of Stainer’s Crucifixion that remains a high watermark 35 years later. In 1972 the Archbishop of Canterbury conferred on him the Lambeth DMus for services to cathedral music (the ‘W’ on the organists’ plaque in the cathedral conveniently gave way to ‘Dr’), and in 1975 Stanley directed the music for the Royal Maundy Service in Peterborough Cathedral. On his retirement in 1977 an LP exclusively devoted to his music was recorded, which has been drawn upon in the recent production of a centenary CD featuring the current Choir of Peterborough Cathedral, directed by Andrew Reid.

Had Stanley not left us such a rich musical legacy, he would still be remembered as the quintessential English gentleman (complete with customary felt hat and umbrella). If, in a cut-

and-thrust world, “nice guys come second”, then Stanley was a glorious exception to the rule, rising to the top of his profession by being thoroughly decent, even-tempered and reasonable. If he felt the need to criticise, then he would find a way of making his point without disturbing the atmosphere. “Gentlemen, what are we doing?” was about the worst it ever got when some particularly heinous musical crime was being perpetrated during rehearsal. A remark such as ‘A pity about bar 7’ had, in consequence, the force of a devastating blow! Many found this tendency to euphemism amusing, but it was amusement born of deep affection and respect. A rare extreme moment, witnessed by both Barry Ferguson and myself, occurred after a rehearsal of Stanley’s Missa Brevis, a difficult piece full of discords, awkward intervals and tuning issues, had not gone especially swimmingly.

“What shall I do with the copies, Dr Vann?” asked Bill Lloyd, the senior lay clerk.

Came the reply: “Oh… shove ’em up a drainpipe!”

Otherwise even the most irritating moments were greeted largely with equanimity, and if anyone could transform the adequate into the well-nigh perfect by sheer force of personality, then Dr Stanley Vann was your man.

Stanley retired to Wansford, just off the A1 west of Peterborough, to indulge in music-making of various kinds, composition and setting up his substantial model railway layout. Frances sadly died in 1993, and a handful of years later Stanley moved to Richmond, Yorkshire, to be close to his family. In February this year he was treated to a 100th birthday serenade by choristers, old choristers and old friends, and Choral Evensong, featuring Stanley’s music, was broadcast on 24 February 2010 on BBC Radio 3 from Peterborough Cathedral.

On behalf of countless old choristers and music-lovers everywhere, may I offer my heartfelt thanks for the life of Dr W Stanley Vann: teacher, organist, composer, choir-trainer, officer and gentleman.

The author acknowledges with gratitude information supplied in connection with this article by Barry Ferguson and Gary Sieling (sometime Assistant Organists of Peterborough Cathedral), David Lowe (sometime Peterborough Cathedral chorister) and Martyn Vann.

22 April

A battle of three organs with the St Paul’s organists

SIMON JOHNSON

TIMOTHY WAKERELL TIM HARPER

A series of recitals by world-renowned organists

6 May HANS FAGIUS Sweden

3 June

SIMON JOHNSON

St Paul’s Cathedral

1 July

TIMOTHY WAKERELL

St Paul’s Cathedral

5 August DAVID SANGER UK

2 September

ROBERT QUINNEY

Westminster Abbey

Tuesday 22 June, 8pm

Monteverdi: Vespers (1610) with the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral, conducted by Andrew Carwood £5, £10, £15, £25, £35

Tuesday 29 June, 8pm

Haydn: The Creation with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, BBC National Chorus of Wales, conducted by Thierry Fischer £5, £10, £15, £25, £30

Thursday 8 July, 8pm

Beethoven: Symphony No 9 with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Monteverdi Choir, conducted by Sir John Eliot Gardiner

£5, £10, £20, £30, £40

Early evening series in City churches, including ‘Discoveries’ from the BBC New Generation Artists

www.colf.org

For the latest news and special offers join our Facebook fanpage at www.facebook.com Follow us on Twitter: twitter.com/CoLFestival

this vibrant city, one finds a haven of quiet contemplation. Close to the south end of Central Park the first thing that one notices on entering St Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue is how dark and brooding it is. Designed by the distinguished architectural firm of Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson and completed in 1913, St Thomas Church is built in the French High Gothic style, with stone ornamentation of the later Flamboyant period in the windows, small arches of the triforium, and stonework surrounding the statuary in the reredos. The flat wall behind the altar is reminiscent of some English cathedrals, and the magnificent reredos, the tallest in the world. Except for its length, St Thomas is of cathedral proportions, with the nave vault rising 95 feet above the floor.

My first visit last October before running the New York marathon was for Evensong sung by the Gentlemen of the Choir –beautifully sung in an oasis of calm and serenity. I was struck, however, by the stained glass on the triforium as it could hardly be seen and reminded me of a child’s kaleidoscope where a finger has been put over one end of it so the light cannot get through. The church has begun a huge, multi-year project to restore its 33 magnificent stained glass windows. Over the course of the next four years, each window in turn will be removed and taken to one of four chosen stained glass artisan studios for complete restoration. No daylight punctuates the church except from the doors at the west end. I was, however, here to interview John Scott.

John has been in New York for the past six years, having left St Paul’s Cathedral, so I started by asking him about the differences he found early on in the job. I certainly found some things very different here from what I had been used to at St Paul’s. The Gentlemen of the Choir were not as fluent sight-readers as their English counterparts, largely due to the fact that they had not been ‘through the mill’ as choristers. It did demonstrate to me just how special the English cathedral model is and how

the training received over four or five years as a cathedral or collegiate chorister equips children to be such fine readers as adults.

So what I inherited here was a team of mostly very fine voices but as choral singers, they were not quite as quick at reading. Fortunately, the rehearsal provision was generous –an hour before each service with the full choir (as opposed to just 25 minutes at St Paul’s) but they certainly improved during my first year. They had to, really, as I introduced something like 150 new pieces in that first year which presented them all with quite a challenge! I’m glad to say that the whole choir responded magnificently, and nothing was changed or cancelled. I also inherited a 9am full choir rehearsal in church every Saturday morning which I scrapped after two weeks as I felt I needed more time rehearsing just the boys only and working on developing the sound and securing the notes. The men were delighted not to have to come in on a Saturday morning, and we agreed that we would have a 75-minute rehearsal just for the men on a Thursday evening after Evensong, in its place. This also helped in creating a more cohesive and blended sound and building up a ‘house style’. Over the five years I’ve been here, this has certainly paid dividends.”

We have moved to his tiny office on ground level and the hustle and bustle and noise of the outside world permeates through. In fact it is like being in some American drama. On the walls are certificates and lots of music and CDs are spread throughout the study.

“My predecessor here, Gerre Hancock, did a wonderful job over 33 years, building up the choir’s repertoire and reputation. When I arrived, I felt I wanted to introduce more early and contemporary music, though there were very few obvious gaps in the repertoire. I’m very fond of the early English composers,

such as Tallis, Sheppard and Tye, so we’ve added a number of works by them. There was already quite a lot of Byrd in the library, and Gerre had even done a very fine recording of the Great Service back in the 1980s.”

With so many contemporary composers around is this a field, I ponder, that may have been neglected?

Emphatically ‘no’. We do more contemporary music now and have commissioned some composers to write works for us, such as a highly original Bright Mass with Canons by New York composer Nico Muhly, a protégé of John Adams, who also recently wrote the music for the film The Reader. We recorded Nico’s Mass on our last CD, called American Voices, along with works by Bernstein, Copland, Barber, Rorem and Hancock. Bryan Kelly has also written a Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis for us, and we gave the US premiere of Sir John Tavener’s Mass in 2008.”

What about the big oratorio works?

“We have a concert series which is supported by our Friends of Music (Patrons). We perform five or six concerts each season, presenting sacred choral repertoire which we can’t always perform liturgically. There are the annual two Messiah performances in December which completely pack the church, and Britten’s Ceremony of Carols is another feature of the Christmas season. Last season we performed the St Matthew Passion in which our own period-instrument orchestra, Concert Royal, combined with The English Concert, who were over here on tour. That was a particular highlight of my time here. In recent years, though, we’ve sung some of the cornerstones of the oratorio repertoire such as Haydn’s Creation and the NelsonMass , the Mozart Requiem and Coronation Mass as well as some rather less

well-known works. Last year, we gave the US premiere of Missa Hyemalis by Franz Xavier Richter, a contemporary of Mozart. This season we have the Monteverdi Vespers to look forward to in March, plus an all-Britten concert in May.”

In the UK the thorny issue of chorister and lay clerk recruitment never goes away, so what’s it like in New York? John Scott is proud of what he has at St Thomas.

“The boys here come from a wide geographical network though the majority are from the tri-state areas of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Curiously, given its population, we only have three boys currently who live in Manhattan. Some are from further afield –a few from Massachusetts, a couple from North Carolina, one from Minnesota and one from Florida. We recruit widely but it’s always a challenge, as it is everywhere these days. Each year I write to a network of churches and choir directors who have been kind enough to send us boys in the past, in the hope that they will encourage parents with musical children to send them along to audition and look at the school. The alumni (old chorister network) is also another source of recruitment, of course, and we have one boy at the moment whose father was a chorister here. We also go on tour each year, by courtesy of our concert agent, Karen McFarlane and in March we’ll be heading out to give four concerts in Texas and Tennessee. We always hope that there may be parents with young children who are attracted to what they see and hear.

These tours have always involved the full choir of men and boys, though last fall, we began a new strategy of taking just the boys out to sing. We gave three concerts of treble-only repertoire, sacred and secular and sang in schools and joined with other children’s choirs in New Haven (Connecticut) and Massachusetts. This was quite successful as a recruitment tactic, and we shall certainly repeat the format this year.” As a result, the choir is up to full strength with 38 boys in school and John says he is indeed fortunate to have such good material.

All choristers in the choir attend St Thomas Choir School, the only church-affiliated residential choir school in the United States, and one of only a handful of such schools remaining in the world. The prospectus says that St Thomas

Choir School ‘offers extensive musical training and a rich curriculum for boys in grades three through eight, with class sizes averaging just eight students’. The Choir School was close to my hotel and near Carnegie Hall and Central Park in a block purpose-built in 1988. The school was founded by T. Tertius Noble in 1919. He had been Organist of York Minster and only accepted the job in New York on the condition that the Church founded the school ‘after the ancient English cathedral model’. The St Thomas authorities agreed. “As the only church with a residential choir school here in North America I find it strangely moving to be part of this little pocket of Anglican excellence in the midst of the crazy, exhilarating city that is New York! The school has survived because the Church is very proud of its choral tradition. Over the years, parishioners have been extraordinarily generous in supporting the school through private donations. When I first went to St Paul’s, the choir school there was just for the choristers only, but that all changed in the 1980s owing to financial pressures. The Dean and Chapter felt that they had no choice but to open up the school to fee-paying day boys, who were not choristers. Of course, when this happened, the ethos of the school changed overnight, and something was definitely lost, even though the financial future of the school was secured and there may have been many educational and social benefits to having a larger school and ‘classroom dynamic’. Most significantly, though, the relationship between the school and cathedral changed overnight, and it was never the same again. I’m happy to turn to a school such as we have here at St Thomas, where all the boys in school are choristers, with a clear understanding of their role in leading the worship in church. It’s a wonderful establishment, and the Headmaster, Fr Charles Wallace and his teaching staff are all incredibly dedicated and supportive of the boys and their work in the choir. Most significantly, this is a church with a choir school, not a school with a choir.

As for lay clerks, the Gentlemen of the Choir, they are all professional singers, though New York does not perhaps offer the same opportunities for singers that might exist in London, for instance. There are fewer, smaller, mixed vocal ensembles

or specialist groups. One or two of the men have day jobs and some augment the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera, from time to time. Others have solo careers, although John points out that, unlike the UK, there is not enough solo concert work in NYC for singers.”

When vacancies arise he doesn’t need to advertise –although there is no equivalent of The Church Times but he has a deputy list, although not an extensive one. There are good fees for rehearsals and services and though he would not divulge how much the salary was, he maintains that fees are comparable to London rates, if not slightly better.

‘There are fewer choral services here; we don’t sing every day. At St Paul’s there were nine choral services a week; here there are five. At St Paul’s it was relentless: the high profile made it an exacting job, with the downside being there was just so much music to prepare. The day-to-day stuff was often not rehearsed as thoroughly as one would like, simply owing to pressure of time with the sheer volume of repertoire needed for that number of services each week. At St Thomas, the ratio of rehearsal time to performance is more generous, with the result that one can work in more detail. The schedule is more manageable, with the boys rehearsing before school from 8-9.15 every day except on Mondays. At St Paul’s we had a morning rehearsal and also a boys’ voices Evensong on a Monday, so everyone was tired after the rigorous round of Sunday services. There was simply not enough recovery time for the boys, I felt.”

Of course, I point out that St Paul’s was unique. “Yes, St Paul’s is the nation’s cathedral and so services of national importance take place, full of pomp and ceremony, whether

of a royal nature or to do with the City of London or other institutions. There were many extra events during the course of each year and it was wonderful. There is much less of that here, for sure, so the rhythm of day-to-day liturgy is less interrupted here.”

He explains that there was never such a thing as a routine week at St Paul’s. “In my last few years in London, I’m sure the diary became busier each year, and I began to feel the frustration of yet another Evensong being cancelled owing to a special service, or sung by just the men if the boys had sung earlier in the day. Here at St Thomas, I rather like the fact that there are few variations to our liturgical routine, except in the run-up to Christmas and Easter.” John Scott appreciates this and feels that everything is more manageable, giving him the opportunity for being more creative, adventurous and imaginative with the choir’s liturgical repertoire and Church’s concert series.

I ask him does he then miss the UK?

“There are aspects of St Paul’s that I miss, certainly –the building itself, the organ, and of course the acoustic. I feel very privileged to have been part of it. It was a wonderful place to be, overwhelming in so many ways, but like all cathedrals these days, there’s the constant pressure to find new ways of reinventing themselves and to minister to a more secular age. At times, the politics of the institution were very challenging.”

Would he then go back?

“I don’t think so. I have no reason to want to go back to cathedral life in the UK, I’m very happy doing what I do here. It’s very fulfilling.”

I can’t help wondering why did he come out to Manhattan.

“Why did I come here? Well, when I was appointed to St Paul’s in 1990 to succeed FCM Chairman Christopher Dearnley, the then Dean, Eric Evans, a wise and counselled man, called me to his office and said ‘I want you to do the job’. I was only 33 at the time and I had some feeling of apprehension – was I too young and would I be up to the job? I was also worried that I might still be in post there when I was 65 which would not be right for the cathedral, the choir or me.

I aired these concerns to Dean Evans, whose reply was ‘John, this is not a job for life’. It was prudent advice.”

John continues, “I totally agreed and I told the Dean that I would give him 15 years, to which he responded, ‘That seems absolutely right’. But how come he went to New York? “Ah! The link with Gerre Hancock comes in here. He ran an annual Choirmasters’ Conference at St Thomas which was always led by an external guest director, often from the UK. It all began in 1973 with Francis Jackson and the greats like George Guest and Barry Rose who each came out eight times to direct the course. In 1998 I was invited to lead the Conference and I accepted because I had been to St Thomas once before and l remember that I enjoyed the atmosphere of the church and the liturgy. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I directed the course, despite the inevitable difficulties of working with someone else’s choir. There was a really positive atmosphere and I came away with an equally positive feeling. I was asked back again in 2003 and I found the experience even more enjoyable.

“Then Gerre announced his retirement at the end of 2003 and I was already beginning to think that the 15 years that I’d allotted myself as Organist and Director of Music at St Paul’s were almost up, and what would I do next? I really thought, well, it’s now or never, so I decided to apply. I’d always thought that New York is an incredible city, full of energy and buzz, and with a similar cultural richness to London, so I threw my hat into the ring. I was interviewed twice: the second time when I was with the St Paul’s Cathedral Choir when we were on tour in October 2003, giving a concert at St Thomas. I remember feeling very torn on the day of the interview.”

So I ask if it was like going into the unknown.

“I did not know what to expect and I was fearful of not living up to expectations. Yes, there was some apprehension on my part, but I’ve never regretted the move. It was the right time for me to do something else, and everyone here was so very welcoming and friendly.”

What of the future? Dean Evans had said there was a finite time to stay at St Paul’s, so what of St Thomas?

“I have not given myself a set time to be here; my contract does

not specify a retirement age. Will I stay here or go back to the UK when I eventually retire? Who knows? I return three or four times a year to the UK, and it’s nice to catch up with friends and family, of course. I am able to do more recital work in the summer months than previously, as we break up in the second week of June and I’m basically free until early September, which gives me the opportunity to travel and play recitals. I was on the jury of the St Albans Festival last year and I gave five recitals in Germany and four in Australia, so it has worked out well. I love living in New York – my apartment is at the Choir School with a nice view towards Central Park from one of my outside terraces. I don’t have a car, and have not driven since I left the UK, but, who in their right mind would drive in New York? Although New York is certainly iconic America, it is perhaps not like living in the rest of the States. It’s far more cosmopolitan.

I miss the BBC radio and television as well as English beer. The Anglican choral tradition in the US is still quite strong and there are many parish churches running fine music programmes. John tells me that there are several good parish church choirs singing cathedral-type repertoire in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Many churches in Manhattan have adult, mixed, professional choirs which are very fine – places such as Trinity, Wall Street, or St Ignatius Loyola. Like St Thomas, they are fortunate to have a financial endowment set up in the 19th/20th centuries which have been well looked after.

At St Thomas, the Church is run by the Rector who is equivalent to a Dean but there is no recourse to a chapter of canons.”

So how is the Church managed?

“The stewardship is devolved around the Vestry which consists of the Rector and clergy, and an elected body of lay people from the parish who bring commitment, experience and financial expertise from their professional backgrounds. So we have people on the Vestry like Jon Meacham, who recently won a Pulitzer Prize for his book about the wartime cooperation between FDR and Churchill; he is the Managing Editor of Newsweek magazine. Others work for great corporate institutions, such as Morgan Stanley, etc. The Vestry meets once a month and is a high-powered group of people. The meetings are dispatched with great efficiency and care. Our Music Committee meets three times a year and is essentially a support group for the matters of collective concern such as fundraising and advertising. So I can use them as a soundingboard for any concerns I may have about policy such as ticket prices for the concert series and the day-to-day running of the music department as well as future plans.”

Because St Thomas is in the heart of Manhattan, I ask where do the congregation come from?

“The congregation is mostly New York City-based but there are plenty of visitors, too, so Sunday congregations can be up to 400-500 in the summer months but there is a strong core of regulars week-in, week-out. It is a parish situation, so one gets to see the same people each week.”

Like anywhere, John still has the same administrative roles and budgets to contend with and he is as busy as he ever was. He does all the conducting and his two excellent assistants do the playing, except for the Tippett St John’s Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis which he plays for old times sake and he also

plays the voluntary after the Sunday morning Eucharist.

John also likes to give himself annual projects, so he has just played the complete works of Messiaen and in 2010 will turn his attention to the six symphonies of Vierne. In 2007 he played the complete organ works of Buxtehude on the Gallery Organ, which was built in 1996, inspired by the North European 18th-century style of organ building. He is working up to another complete Bach series.

One project that he will be fundraising for is the AeolianSkinner front organ in the Chancel, which needs to be replaced. Hopefully it will be completed for the church’s centenary in 2013. The present building, replaced the 19thcentury church which burnt down. “We have a very exciting

scheme from Dobson Organs – one of the best US builders at the present time. Everyone thinks we are well off over here but the streets are not paved with gold. Our investment was badly hit, as was everyone, by last year’s crash and I’ve had to oversee a 20% cut in the music budget.”

He does make recordings with the choir each year and I am aware that not many of them arrive over here.

“We have worked with US companies for our recordings, but the returns are low, so we’ve experimented with making CDs on our own in-house label, in the hope that the sales will eventually pay for the projects. I’m aware though that our distribution is currently limited to sales through the church website and shop. We’re looking into how this can be turned into something more global. Perhaps he should investigate iTunes. ” Quite rightly, he wants to hold on to his own product for marketing. He wants to get the choir better known worldwide and is proud that the choir has broadcast for BBC Choral Evensong