C CATHEDRAL MUSIC

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2012

Editor Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Deputy Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager

Graham Hermon FCM email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

Roger Tucker, 16 Rodenhurst Road, London SW4 8AR 0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London, WC1N 3AX Tel: 0845 644 3721 International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, LS28 8NT 0113 255 6866 info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

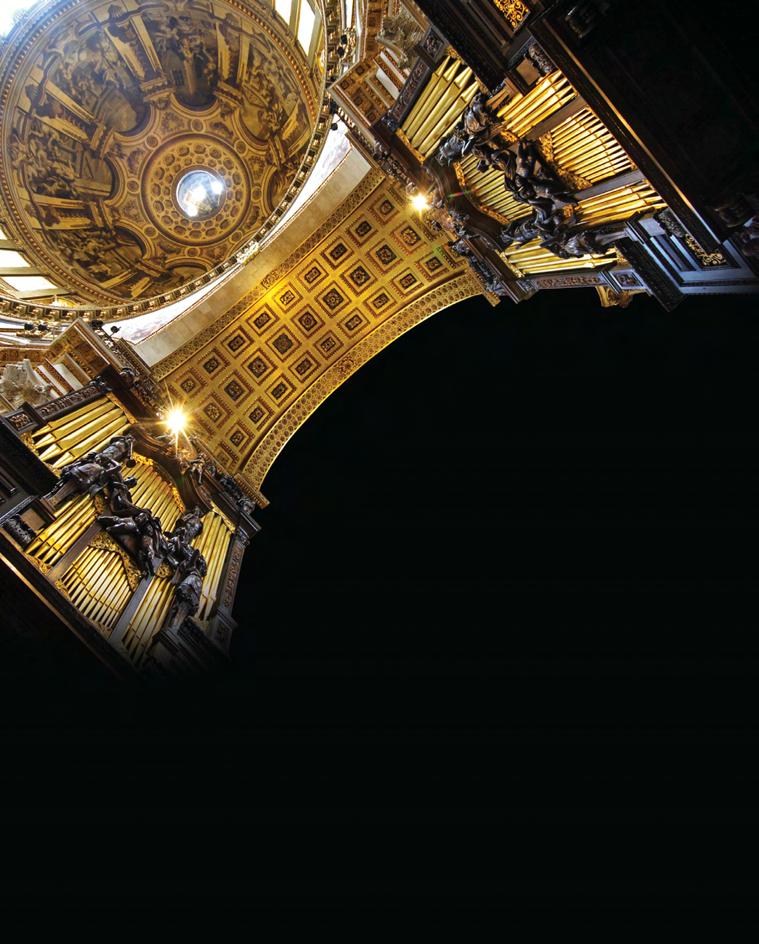

Cover photographs

Front Cover

Winchester

Technology bringing tradition to life

New Cadet organs designed exclusively for the UK market

See and play the new range in Bicester or at regional dealers

Irvine ...............Soundtec Organs

Edinburgh .......Key Player

Morecambe ....Promenade Music

Porthmadog ...Pianos Cymru

Leigh ...............A Bogdan Organs

Swansea .........Music Station

Norwich ..........Cookes Pianos

Bandon ...........Jeffers Music

Highbridge......WM Organs

Exeter ..............Music Unlimited

Ballymena.......Nicholl Brothers

Prices starting at just £3,000 (including VAT)

EDITOR From the

his month’s magazine is full of good things. We have thoughts by New College’s excellent Edward Higginbottom on the training of boy choristers; a primer on improvisation by Trinity Laban Conservatoire and Birmingham Conservatoire’s Ronny Krippner; and a panoramic view of choir schools by the one-time head of the Choir Schools’ Association Dr Brian Rees. Another Winchester stalwart, Andy Lumsden, is in conversation with FCM member and occasional CM contributor Richard Osmond. Of course our AGM and Gathering in June are based in Winchester –perhaps these latter articles will inspire you to come to both!also negotiated a discount of 20% off their recent recording for its members (details on p65).

You can read about the Leeds cathedral approach to musicmaking – wide ranging and diverse – from Ben Saunders and Thomas Leech, and David Davies writes on Léon Boëllmann, a composer who deserves to be known for more than the Toccata from his Suite gothique.

Also in June, for those of you who require something a little different, is a Chicago-based organ crawl (p49), at which FCM member Constance Bradley is offering tea to those brave souls willing to make a pilgrimage across the Pond for the occasion. She can be reached through the Editor’s office, should you decide to take up the invitation.

For pilgrimages of a different sort, Harry Christophers’ group The Sixteen is making its annual national tour of English cathedrals from York to Canterbury. These journeys have been so successful that they are now central to The Sixteen’s annual artistic programme of pre-Reformation sacred music. FCM has

On another subject altogether, it will most likely seem odd to you that I am already thinking of Christmas. But the next magazine will not be published until November, of course, so I would like to urge you all now to consider buying your cards from FCM this year. We will have our usual excellent and varied selection (details will be available towards the end of summer), and all the money raised goes towards our grants programme.

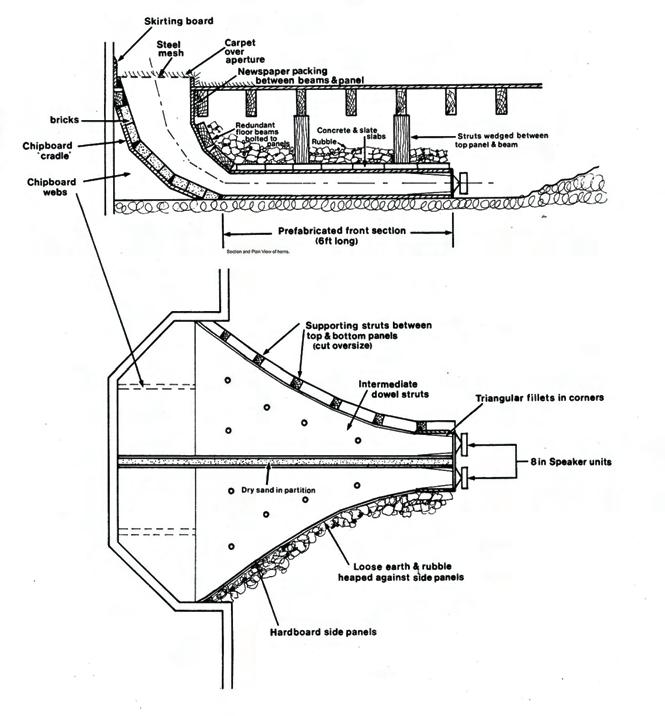

Looking ahead a little less far, do not forget to book tickets to one of the many festivals of music around the country – see what to expect from this year’s Proms, the City of London Festival and the Southern Cathedrals Festival on p55. Support for these festivals is always welcome, and you will hear very good music besides.

Sooty Asquith

ARRANGED BY REBECCA GROOM TE VELDETwo books of 28 practical settings for the church’s year

wo books of 28 prac T forthechurch’syear

CCA TE VELDE s tical chs year for the chur

These books o ove in hymn tunes will pr

services. The short easy e based ar e ideal for use as serv ar communion meditation e postludes. The styles ar

e of miniatur oughout nvaluable thr e to en epertoir esh r for fr pieces 30 seconds on well-known hymn tun od vice interludes, intr fertorie eludes, of s, short pr varied some a

These delightful books of miniature arrangements of hymn tunes will prove invaluable throughout the church year to organists looking for fresh repertoire to enhance services. The short easy pieces (each 30 seconds to a minute long) are based on well-known hymn tunes and are ideal for use as service interludes, hymn introductions, communion meditations, short preludes, offertories, and postludes. The styles are varied some settings are meditative, others more lively.

of church hance to a es and uctions, es, and are e meditative, others mor eface sug Includes a pr gical in es, a litur miniatur

gesting th dex, and an index of first

Includes a preface suggesting how best to use the miniatures, a liturgical index, and an index of first lines. £11.95 each

Book 1: 978-0-19-537712-5, Book 2: 978-0-19-338141-4

Book 1: om music shop vailable fr A Av or

Book 2: 978-0-19-338141-4

Available from music shops or direct from OUP, phone (0)1865 452630, or email music.orders.uk@oup.com

e lines om www.oup

www.oup.com/uk/music

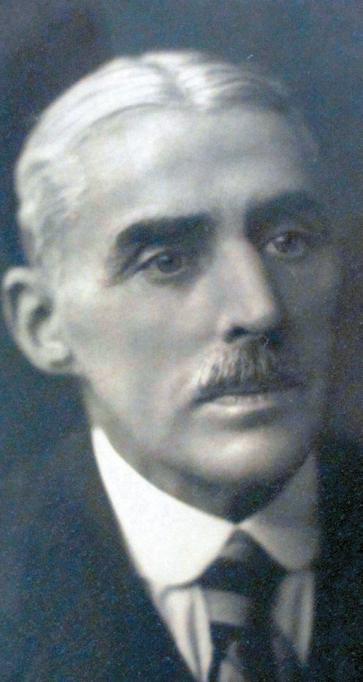

David Davies

David Davies

The year 2012 marks the sesquicentennial anniversary of the birth of the Alsatian composer and organist Léon Boëllmann (1862-1897). Very much a product of his time, yet a gifted exponent of his art, his life and work reveal a man of many parts.

Boëllmann’s legacy comes to us most notably in the form of his Suite gothique for organ, the concluding Toccata of which has associated him (somewhat unfairly) with any number of ‘one-hit wonder’ composers. The quality of his output suggests that his place in the eyes of history might have been anchored more firmly had he not died so tragically young, at the age of 35. Both his relatively short creative lifespan and his adoption of a conservative musical language have meant that his life was never quite brilliant and interesting enough to warrant an exhaustive biography; this, perhaps not least, because he lived at a time in the history of French composers that was dominated by giants upon whose shoulders several less distinguished – although mightily competent – musicians were to stand. Thus he belongs to that group of specifically Parisian musicians who stood at the juncture of late-Romantic and Impressionist styles.

The reaction against Wagnerian tendencies in the last years of the nineteenth century which heralded a new age of musical expression failed to interest Boëllmann, whose adoption of the comfortable style of the Belle Époque (with his cap set more towards the world of Wagner rather than towards the emerging, daring modernism of the time) went hand in hand

with his sense of progressing an established tradition. In his music one only hears occasionally the kind of chromaticism that challenged the tonal ear, and his harmonic language is, for the most part, rooted in the mould. It is tantalizing to speculate whether he would have ploughed a musically progressive or reactionary furrow had he lived longer; certainly, many of his melodies are shot through with the same sense of elegance and nobility one hears in Edwardian music, although, of course, his tone world cannot come from anywhere other than south of the English Channel.

Boëllmann’s chronology is reasonably straightforward: he was one of fourteen children born to Antoine Boëllmann and Marie-Hortense Brazis in the Upper Rhine. In 1875 he was admitted to L’École de Musique classique et religieuse, an academy

more ordinarily named after its founder, Louis Niedermeyer (1802-1861). This would have been a period of some personal challenge for Boëllmann who, having lost his father in 1870 and his mother in 1878, moved to Paris against the backdrop of advancing bellicose unrest in Europe, an unrest that ultimately led, of course, to the outbreak of the First World War.

Boëllmann’s tenure at the Niedermeyer sealed both his professional and personal life. It was here that this ‘quiet and accommodating youth’ – in the words of the Principal – came into contact with Eugène Gigout, and their names would afterwards be forever linked. Initially, Boëllmann studied harmony and piano with Gigout, le maître, and received organ tuition from Clément Loret. Composition lessons were taken

with the then director of the Niedermeyer, Gustave Lefèvre, who described Boëllmann’s talent as ‘giving promise of a brilliant career’. Ever the outstanding student, he was awarded the Premier Prix in organ, counterpoint, fugue, plainsong and composition, and was described as Gigout’s disciple favori In 1885 he married Louise Lefèvre, Gustave’s eldest daughter, and became a notable figure on the Parisian musical scene, connecting himself via marriage and professional ability to a network of powerful musicians.

Upon graduating from the Niedermeyer on 27th July 1881, Boëllmann assumed the assistant organist position at the church of SaintVincent-de-Paul, that impressive basilical church in the tenth arrondissement by the architects Lepère and Hittorff. The titulaire at Saint-Vincent at the time was Henri Fissot, one of whose predecessors was Louis Braille, inventor of the Braille system. In 1887 Boëllmann succeeded Fissot on the recommendation of Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, Charles Gounod, and Léo Delibes. The church contained two fine organs by Cavaillé-Coll: the 1853 orgue de chœur with 20 speaking stops, and the large, three-manual grand orgue of 1852 with 47 stops, its distinctive façade having been designed in collaboration with Hittorff. Cavaillé-Coll was particularly proud of his grand orgue in Saint-Vincent, the immaculate and beautiful engravings of this instrument prepared by his firm bearing testimony to that (see lower picture). The inaugural concert was given by the Belgian organist, Jacques Lemmens, the founder of a method of virtuoso pedal playing that is still taught to this day.

Unusually, the main organ at SaintVincent was spread across a classical arch, and had shutters for the expressive division made from glass rather than wood; it also featured a particular kind of wind-chest action more commonly found in Walcker organs in Germany. The aesthetic changes in organ design in the next half century were to be considerable, and so in 1894 Cavaillé-Coll rebuilt the instrument. Fissot had supported the need for renovation and rebuild much earlier, but the vicissitudes of the Paris Commune had forced prices to inflate, and it was only latterly that the parish authorities could afford the work. The inaugural concert on the restored instrument took place in 1894, with Boëllmann performing alongside Widor, Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant. Now listed as an historic monument, the organ case remains one of the glories of the Parisian organ scene, and is an outstanding example of nineteenth-century engineering. Both organs at Saint-Vincent were sources of inspiration to Boëllmann, whose first organ

works clearly specify registrations pertaining to the orgue de choeur there. He was known as a talented improviser, and was described as ‘a sensitive executant who coaxed pleasing sounds out of recalcitrant instruments’.

Boëllmann’s output for the organ spans his whole career, a career launched when his Offertoire sur des Noëls won first prize in December 1882 at the Societé internationale des organistes et maîtres de chapelle. The competition was judged by Dubois, Franck and Guilmant, among others; the citation at the adjudication stated ‘l’unanimité, avec félicitations, du jury’ Dedicated to Gigout, the work combines two Christmas melodies, and it is here that one sees the tendency towards homage that seems to inform so much of Boëllmann’s music. Some writers cite Mendelssohn as an influence, and, overall, it is easier to trace a line from the past as far as Boëllmann than it is to suggest anything particular about his style that was to break new ground. At most, one can see in Les Heures Mystiques (two volumes, 1896), how Boëllmann’s lighter movements might, perhaps, prefigure the scherzos of Vierne and the intermezzos of Widor. Nevertheless, his Suite gothique, a work whose longevity has placed it firmly in the repertoire, deserves some closer discussion.

Boëllmann published the work in 1895, the term gothique carrying with it a faintly pejorative air in the sense that it evoked a conscious resurrection of the past. Just as the distinction between ‘gothic’ and ‘gothick’ was so critical in British architecture of the period, so, too, is there a sense of the weight of history when the term is used in musical titles. Satie’s Danses gothiques of 1893, and Widor’s Symphonie gothique of 1895 raise the same ideological issues. It has been suggested that the title was an afterthought put forward by the publisher Auguste Durand, as a strategy to make the hitherto-named Suite pour orgue more marketable. Whatever the reason, the relationship between the title and the work was most aptly described by d’Indy, who wrote ‘ce n’est pas le style qui est ancien, mais seulement la forme, ce qui est bien different’.

The French musicologist and organist Norbert Dufourcq (who coined the title of this article) makes reference to the impressions left upon Boëllmann by the music of others: he proposes, for example, that the first movement of the Suite fuses the worlds of J S Bach and Franck, and that the second movement looks over its shoulder at Gigout’s Grand Chœur Dialogué, but also recalls, in its clean, classical proportions, the worlds of Marchand and Clérambault. This second movement was written with the antiphonal capabilities of the grand orgue at Saint-Vincent in mind, and the composer intended a spatial effect inspired by a particular instrument in a particular place. The third movement, a beautiful, limpid and delicate Prière à Nôtre-Dame evokes the vast space of Nôtre-Dame in Paris: a common misconception is that it is a prayer to the Virgin, yet this movement pays homage more to the French architect and theorist Viollet-le-Duc than it does to Our Lady. The final movement is a tightly-coiled spring: a little aggressive and menacing, maybe, but a piece whose formal symmetry is faultless, and whose consistency of harmonic language is a perfect model for study.

Boëllmann cannot have been immune to the stylistic musical soundscapes of his time, and the years 1850-1900 saw a hugely significant shift in French music. His own music was played at the Societé Nationale de Musique alongside that of Alkan, Chabrier, Chausson, Debussy, Dukas, Duparc, Fauré, d’Indy, Lalo, Ravel and others, the most far-reaching effects of whose music would stretch well into the new century. The

main items of Boëllmann’s works are six sacred motets, eighteen songs and four vocal works, five orchestral pieces, five chamber pieces and some fifteen works for the piano. His complete organ works comprise some 180 pages of music, of which – in addition to those already mentioned – the most substantial works are the Douze Pièces (1890), the Deuxième Suite (1896) and the Fantaisie (published 1898). Some of the orchestral pieces can be seen as taking their inspiration from other contemporary works: his 1893 Variations symphoniques for cello and orchestra (op. 23) holds up a mirror to Franck’s Variations symphoniques for piano and orchestra written eight years previously, and the organic, through-composed aspects of composition that were beginning to alter the formal precedent of multi-movement works at the time were clearly of

interest to Boëllmann. His opus 24 Symphonie en fa was given its premiere at the conservatoire in Nancy in 1894, directed by the renowned musician Guy Ropartz, and his Fantaisie dialoguée for organ and orchestra was performed to acclaim in Paris, London (at the Queen’s Hall) and Holland. The manuscript of an unpublished, two-act opéra comique exists in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, demonstrating his versatility as a composer for whom the organ was clearly important, although not exclusively so.

As a figure about town, Boëllmann enjoyed the salon life of Paris, his sharp wit and humour making him an attractive and popular guest. Just as others in his musical circle were known for their pithy commentary on life and music, with many a scathing bon mot, so, too, was Boëllmann recognised for his observational talent. He wrote for the journal L’art musical, either under the pseudonym le Révérend Père Léon or un garçon de la Salle Pleyel. His writings also appeared in Le guidemusical and La vérité. That he was referred to occasionally as Grand Léon speaks for itself.

Boëllmann’s death in 1897 was quite unexpected in one so young. Some sources give the cause of death as ‘une maladie pulmonaire’, while others suggest tuberculosis. And it was to be another nine years after Boëllmann’s death before an effective vaccine against TB was to be developed in Europe; he had, however, contracted pleurisy some years before, and it is, perhaps, most likely that it was this condition, left untreated, that led to the complications resulting in his death. His widow only survived him by one year, dying at the age of 32 in 1898, with their three children being adopted by Gigout thereafter. The eldest, Marie-Louise Boëllmann-Gigout, a music teacher

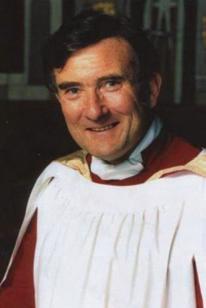

OBE, FRAM, FRSCM

Organist & Master of the Choristers at Chester, and then, Gloucester Cathedral

With a foreword by Dr Roy Massey

Now in paperback

15 illustrations –Price £12 p&p FREE

The Revd Alan Charters

Crescent House Church Street

TALGARTH

Brecon LD3 OBL

and coach, lived through the horrors of the Vichy government until her death in 1977. She was six when her father died.

With the relatively recent appearance of an Urtext edition of his complete organ works, perhaps we can hope to hear some of Boëllmann’s lesser-known pieces played this year. Certainly he deserves to be known for more than the Suite gothique.

David Davies is Assistant Director of Music at Exeter Cathedral. Having been organ scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford, he took a Master’s degree in organ performance at Yale University, and subsequently spent six years as Sub-Organist and Director of the Girls’ Choir at Guildford Cathedral. During this time he was adjunct faculty at the University of Surrey, where he taught techniques of musical composition.

The only specialist Choir School in the UK

James O’Donnell Organist and Master of the Choristers

Jonathan Milton Headmaster

All boys receive a substantial Choral Scholarship

Why not come for an informal audition?

(Boys aged 7 or 8)

Details from:

Westminster Abbey Choir School

Dean’s Yard, London SW1P 3NY

Telephone: 020 7222 6151

Email: headmaster@westminster-abbey.org

www.westminster-abbey.org

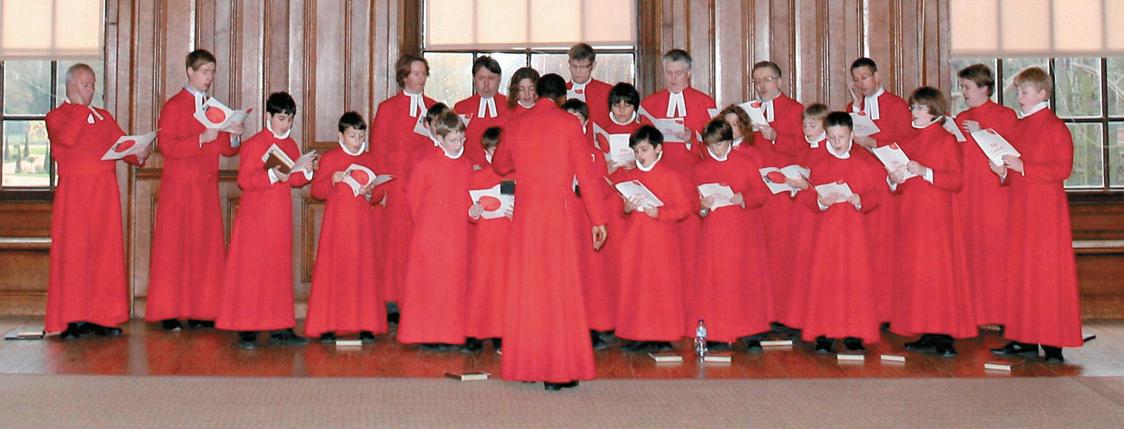

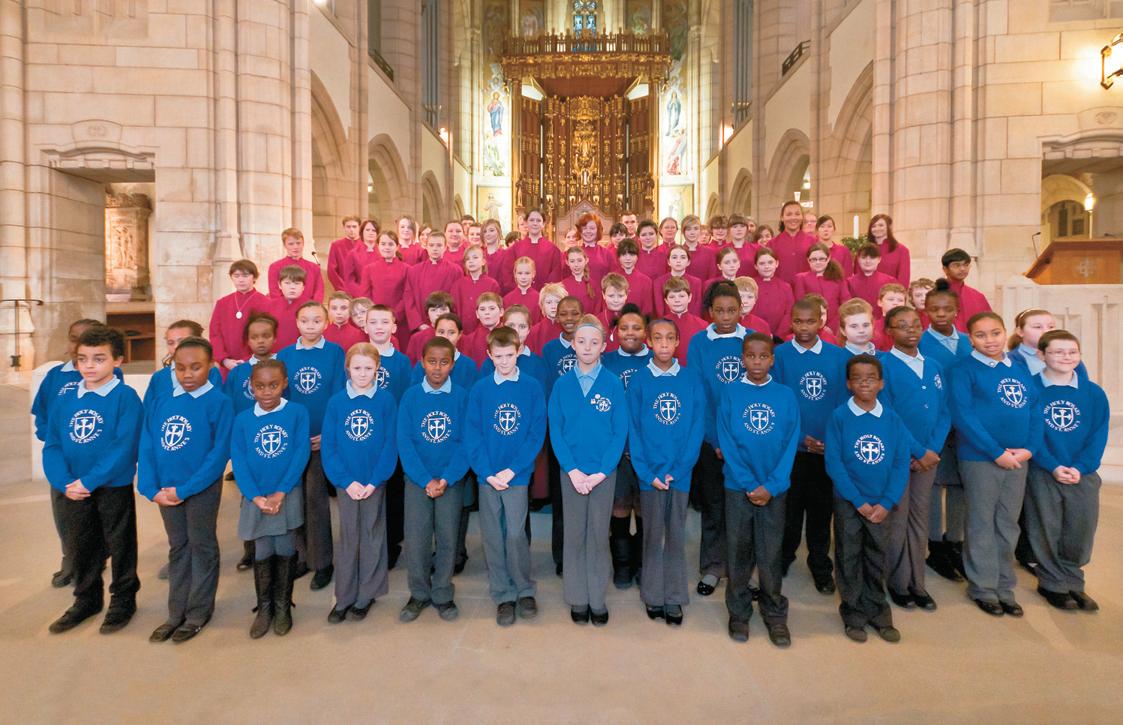

After many months of planning and preparation, 17 choristers and 19 adults of the Gloucester Cathedral Choir left Gloucester for the start of a tour to Cape Town.

All our arrangements were made by our tour company, Norman Allen Group Travel, which co-ordinated accommodation, food and visits to the tourist attractions as well as offering free public liability insurance for our group leaders (something very necessary in this day and age). Arriving in Cape Town, we were met by Father Nolan Tobias, rector of St Francis Church, Simonstown, and Ashley Grote, our Assistant Director of Music, who had flown out three days ahead of the group.

The gentlemen of the choir had host accommodation in Cape Town and the choristers and chaperones, including the Director of Music, settled into the somewhat basic dormitory-style accommodation at ‘Water’s Edge Pre-Primary Accommodation Centre’ for the first 3 nights. The ‘Rocklands Adventure Centre’, for the remaining six nights was still dormitory style but practical and comfortable and engendered a good team spirit.

During the 10 days in the Cape peninsula there was only one day without a concert or a service. The audiences, diverse in their background and cultures, greeted the choir warmly and with generous hospitality, and showed a keen interest and enthusiasm for the music. The cathedral choir sang at St Andrew’s Church, Cape Town; St Francis’ Church, Simonstown; St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town; Endler Hall, Stellenbosch University; St Clare’s Church, Ocean View and in the community hall in Lwandle township. Canon Neil Heavisides, Precentor, preached at the Eucharist in St Francis’ Church and led Evensong in St George’s Cathedral. A number of the concerts were joint ventures with local choirs, enabling contact and integration for the children and adults of each choir.

The informal concert in Lwandle, where the Uzuko Gospel Choir sang and listened to us in turn, was followed by a tour of the museum. Learning about the township’s recent history gave a good background to the walk around the area. This was one of the most profound experiences of the tour for many of our group, one which left the Director of Music wishing to create a link with their choir to support their musical endeavours.

When not singing, the boys and gentlemen visited many of the attractions in the Cape peninsula, including Table Mountain, the National Botanical Gardens, Hout Bay seal island, Cape Point, Boulders Beach penguin colony and Cape Town waterfront. Whilst the choir gentlemen and Precentor were tasting wine at the Spier Estate, the choristers visited the estate’s own highly successful Cheetah Project, where they enjoyed being filmed as part of National Geographic’s TV series Cheetah Diaries!

Although the choir only undertake a major tour once every three years and each one is memorable in different ways, this one will stay with us all for many years to come.

Helen Sims, Choir Tour Manager, Gloucester Cathedral

It is probably true to say that improvisation is one of the most challenging and, at the same time, most fascinating disciplines of the organist’s art: being able to make up music on the spot, seemingly off the cuff, instantaneously. Once part of every professional musician’s training, the art of musical improvisation disappeared almost entirely towards the end of the nineteenth century, and it is arguably organ and jazz music which kept it alive until today.

How does the concept of improvisation work? Is it really just like a Monopoly game (as Charles Waters suggested1) where ‘success’ is only a question of luck and/or talent, or is it a skill which everybody can learn? In short, improvisation can be studied and can be practised, but first let us look at organ improvisation in general and its role in Britain in particular.

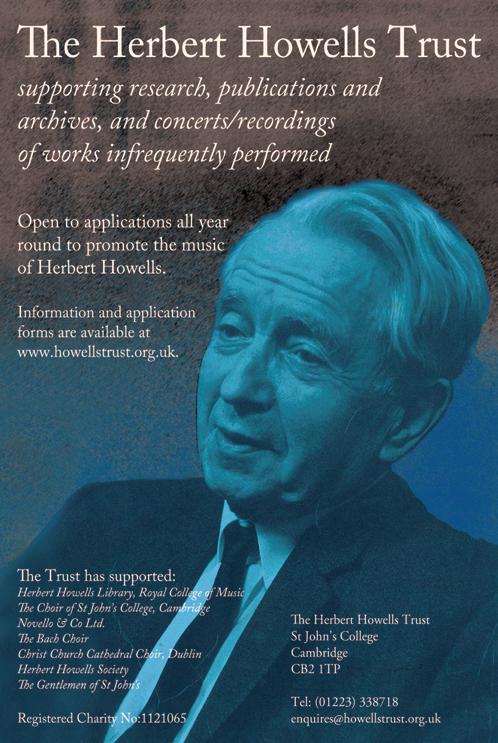

Over the centuries, different national schools of improvisation have developed, probably due to the specific liturgical requirements of each country. Organists in Catholic France, for instance, tend to improvise on Gregorian chant in a variety of contrasting modal styles whereas Lutheran organists in Germany focus primarily on chorale improvisation techniques. In the English cathedral tradition, there is an emphasis on ‘atmospheric’ improvisations before Evensong (as exemplified in Herbert Howells’s organ output), Gospel fanfares and hymn extensions, all of which have the power of lifting people’s minds and enhancing the beauty of the Anglican liturgy. Over recent years, improvisation styles seem to have become much more varied and ‘international’ in flavour in Britain. Globalisation and the development of recording technologies have had a huge impact on the way British organists improvise today and may well have helped initiate what could be considered a renaissance of organ improvisation in the UK.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, British organists regarded improvisation as a useful tool to cover gaps in church services, but certainly not as an art form. There was a common understanding that young organists would naturally ‘pick up’ the know-how of improvisation if they had the talent.

Some even suggested that improvisation is not meant to be studied at all as ‘the principal object of improvisation is the giving scope to the personal mood of the moment.’2 It doesn’t really come as a big surprise, therefore, that the standard of improvisation in general was not very high – although there were some noteworthy exceptions (Sir John Stainer, for instance, used to extemporise voluntaries in sonata form at St Paul’s Cathedral!). The French organist-composer Camille Saint-Saëns tells us why improvisation was at such a low ebb in Britain during the first half of the twentieth century: ‘You have many fine organists in England, but few good improvisers. It is an art you do not sufficiently practise or study, and it requires to be practised or studied... you have not worked on it as we have in France, where the art of improvisation has always been a feature of the organ class.’3

Today, more than a hundred years later, it is amazing to see how dramatically things have changed for the better. The majority of British conservatories now offer tuition in organ improvisation as a discipline in its own right. SophieVéronique Cauchefer-Choplin, titulaire adjointe of the GrandOrgue at Saint-Sulpice in Paris, has recently been appointed Professor of Organ at the RCM and teaches improvisation there regularly. The fine tradition of improvisation teaching at the RAM continues under Gerard Brooks (Director of Music at Westminster Central Hall) and the writer of these lines takes great pleasure in passing on this crucial skill to the organ students at Birmingham Conservatoire and Trinity Laban College of Music, London. The RCO, as well as the RSCM, regularly run courses for organists of all ages and abilities which focus either entirely, or at least partially, on developing ex tempore playing skills.

Improvisation as a form of music-making without any premeditation seems to mean different things to different people. For those who allow absolutely no preparation, the concept of practising improvisation doesn’t make any sense either as this is already a way of preparing one’s performance. Others, on the other hand, see no problem in applying prepared building blocks, amongst them J S Bach. Like all musicians in the Baroque period, Bach regarded improvisation as an extemporaneous composition: he ‘quilts together thorough-bass, composition, and improvisation as part of the same fabric of musicianship.’4 Bach’s Arnstadt Chorales are a perfect example of sketched-out improvisations and I believe that using blueprints is a very effective way of learning improvisation, albeit not the only one.

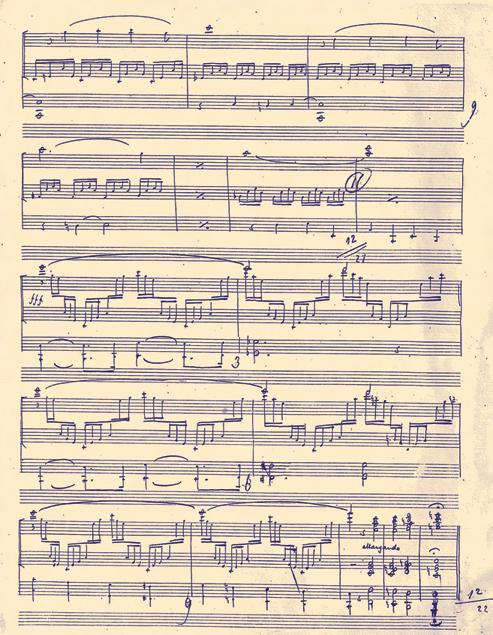

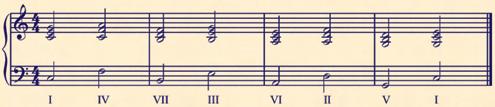

As a teacher of organ students at both school and conservatory level, I have come to realise more and more that learning improvisation starts with practical harmony, or in other words: harmonising hymns (Bach would have also added figured bass here). The Victorian improviser Frank Joseph Sawyer (1857-1908) states that students should ‘take the melodies of a thousand hymn tunes, and harmonise them at piano or organ. In this way you will learn how to use chords. It is this knowledge which is so necessary in extemporising.’5 However, a profound knowledge of keyboard harmony, counterpoint and musical form doesn’t automatically produce a good improviser. What this needs is a gradual merging of all these disciplines. The following ‘improvisation lessons’ are designed as initial guidelines for those teaching organ students as well as those who wish to further their own skills, or those who simply want to understand how improvisation can work.

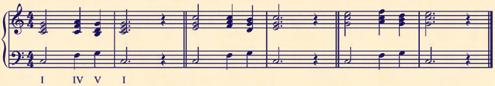

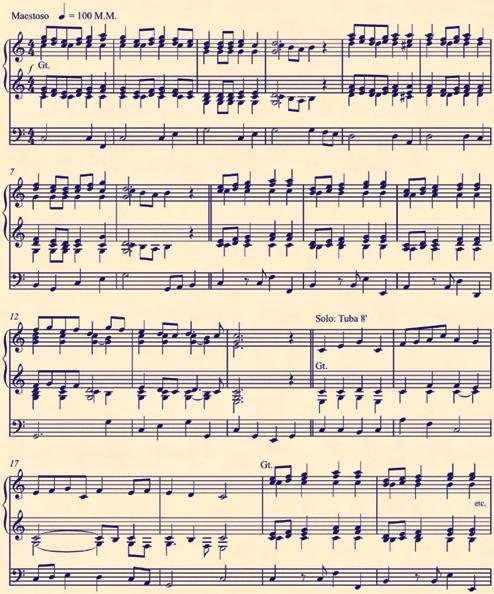

The quickest way of getting started with tonal improvisation is by getting to grips with playing cadences. Start with the most common cadence (I-IV-V-I) and practise it in all major and minor keys. Make sure you practise with manuals only (LH bass, RH triad) as well as manual and pedal (bass in the pedal; chords shared between both hands)

a short motific idea in the bass – otherwise, steady minims in the pedal quickly become tiresome on the ears:

This already gives you enough harmonic vocabulary for improvising short preludes. Important: always have the particular character of the piece you are going to improvise in mind (martial, sorrowful, cheerful, majestic, etc.) – it helps to get the creative juices flowing! Here is an example of the first four bars of an improvised Festive Prelude in C, based on the previous cadence exercise:

You will find that placing a one-bar pattern such as this on top of your cycle of fifths will come naturally to you very quickly. And what a great way of extending your Festive Prelude from Lesson 1!

The asterisks indicate passing notes which help to keep the voices moving. Listen carefully to your playing and try to memorise this phrase as quickly as possible. By doing that, you automatically develop two crucial key skills for improvisation: a creative inner ear and a good memory. If we think of the first four bars as being a ‘question’, then make up the ‘answer’ by repeating the first four bars but changing the ending slightly so that it finishes on the tonic:

Any church organist worth his salt needs to be able to improvise on hymn tunes. Creating an introductory voluntary before the service based on the opening hymn or making up an ‘emergency’ extension after the offertory hymn are just two of many possible situations where the organist has to engage creatively with hymns. The importance of being able to harmonise hymns has already been mentioned. However, there are ways of using the written-out harmonies of hymn books as blueprints for your improvisation (this is particularly useful for students who still struggle with harmonising at sight). For example, soloing-out the melody with your right hand on a separate manual whilst the left hand is playing the alto and tenor part on a softer manual together with the bass being played in the pedal. Take the hymn Jesus Christ is risen today (NEH 110) and have a go:

Both phrases together make up a simple, yet convincing prelude in the Baroque style! Now try transposing it up a tone to D major – it helps consolidate what you have just learned and makes you a more flexible improviser.

There are a number of useful chord progressions well worth memorising, and one of the most commonly found in Baroque music is the cycle of fifths. Again, practise the following example in different keys on manuals only as well as manual + pedal. Once you have completely mastered and internalised this chord progression, it will serve you well as a safety net in your improvisations:

This in itself is already of great practical use as you can easily liven-up your hymn playovers by bringing out the melody with a strong 8-foot Trumpet, for instance. Once you are comfortable with this way of playing, you can take things a step further: try and vary the melody by applying passing notes and auxiliary notes (the accompaniment is identical to the previous example):

Next, try and figurate the chords by ‘breaking’ them or creating passing notes between them. If possible, also include

Although you may not necessarily want to embellish the tune in your improvisations all the time, it is an important skill which requires regular practice. And again – if used with care –this can add some extra sparkle to your playovers.

Having mastered cadences (I-IV-V-I), cycles of fifths and hymn improvisation techniques, a world of possibilities in improvisation opens up. Here is the outline of a Ceremonial March on Jesus Christ is risen today which could be used, let’s say, before the service on Easter Sunday: starting off with a free section based on cadences and cycles of fifths, the first line of

the hymn is then stated (slightly varied) on the Tuba, followed again by a cycle of fifths:

I hope this article has given some helpful insights on what improvisation is, how to practise this particular art form and how to prepare your extemporaneous compositions for services or, indeed, concerts. It is a skill well worth acquiring, and a constant source of inspiration and enjoyment!

1 Waters, C., 1930. An Organist’s Monopoly: Extempore-Playing (Musical Times, Vol. 71, No. 1045 (Mar. 1, 1930), pp246-247)

2 Harding, H., 1907. Musical Form: its influence upon the art of Improvisation. (Royal College of Organists: Lectures 1907, p52)

3 Henderson, A., 1937. Memories of some distinguished French Organists. Saint-Saëns. (Musical Times, Vol. 78, pp534-536)

4 Ruiter-Feenstra, P., 2011. Bach and the Art of Improvisation. Vol. 1 (Ann Arbor: CHI Press, p8)

5 Sawyer, F., 1907. An Organist’s Voluntaries with special reference to those that are improvised. (Royal College of Organists: Lectures 1907, p45)

Ronny Krippner is Assistant Director of Music at St George’s Church, Hanover Square and teaches improvisation at Birmingham Conservatoire and Trinity Laban Conservatoire London. The DVD ‘ Ex Tempore – the Art of Organ Improvisation in England’ (2011), featuring improvisations by Ronny Krippner, was met with high critical acclaim (‘A phenomenally successful release,’ International Record Review) and can be purchased online at: www.fuguestatefilms.co.uk

This blueprint also lends itself to improvising hymn extensions and therefore may be of interest to all those preparing for organ scholarship auditions. A word of advice, though: do consider well the tempo of the hymn before starting out on your improvisation! It is easy to misjudge the tempo of the free section in relation to the hymn, something which is a most frustrating experience (for both player and congregation!).

It takes considerable effort to practise improvisation regularly on top of everything else, and by regularly I mean every day for at least 10-20mins. There is, alas, no quick fix: like all other skills, improvisation needs time to grow and develop.

Tuesdays at 7.00 pm

17 July Stephen Farr

24 July James O’Donnell

31 July Robert Quinney

7 August Colin Walsh

Further information available from: www.westminster-abbey.org

The 57th Festival of Church Music within the Liturgy at the Priory Church of St Mary Edington (near Westbury in Wiltshire)

Information from John d’Arcy, The Old Vicarage, Edington, Westbury, Wiltshire BA13 4QF Tel: 01380 830512

www.edingtonfestival.org

and teaching in a school – just as any organ scholar might hope to do on a gap year over here. Many things about the cathedral in Cape Town are similar to what one might expect to find in this country: a beautiful building, a cathedral choir singing familiar repertoire, and a fine Hill organ which was moved from St Margaret’s Westminster to Cape Town in 1909. However, as any cathedral must ask itself how it should best respond to the needs of the community it serves, St George’s in Cape Town faces a particularly interesting and challenging task, namely to combine tradition with a relevance to the new South Africa with all its opportunities and difficulties.

What or who made you take up the organ?

Age: 29

Education details:

Chorister, King’s College School, Cambridge 1990-95

Music Scholar, Uppingham School 1995-2000

Organ Scholar, King’s College Cambridge, 2001-4

Career details to date (and dates):

Organist in Residence, Tonbridge School 2004-5

Assistant Organist, Westminster Abbey 2005-8

Assistant Director of Music, Gloucester Cathedral 2008-present

Did you enjoy the experience of being a chorister?

I was a chorister at King’s College Cambridge and I loved it. I don’t come from a musical family, so am indebted to Stephen Cleobury for giving me that opportunity at an early age. The training and experiences that I was fortunate to receive at King’s as a boy have, without doubt, moulded me into the musician I am now.

What was different about being an organ scholar at St George’s, Cape Town?

When I came to think about a ‘gap’ year, my priority was of course to develop and maintain a high standard of organ playing prior to going to King’s. However, at the ordination of my former choir school housemaster, the Revd Chris Chivers,

I took up the piano at the age of seven when my older sister began lessons. I became interested in the organ at church. I grew up in a Baptist Church, and on Friday evenings I was allowed to play the church organ (or at least the manuals) whilst my mother and sister were at Girls’ Brigade in the Church Hall and my father was on the way home from work! When I started as a chorister at King’s, I was desperate to take organ lessons and was allowed to do so in my penultimate year once I had reached a sufficient standard on the piano.

When you were at school, did you think you might end up where you are now?

When I went for a music scholarship audition at Uppingham School at the age of thirteen, I told the Director of Music that I wanted to return to King’s as an organ scholar. I was never swayed from that ambition, and am fortunate in that I have never wanted to do anything other than pursue a career in cathedral music. So, to answer your question, I aspired to get to where I am now, and I hope that I haven’t ‘ended up’ quite yet!

In December, I learnt W T Best’s transcription of Mendelssohn’s overture to the oratorio St Paul for an Adventthemed recital I was giving. I remember turning pages for Robert Quinney playing it at Westminster Abbey and thinking what an exciting piece it is, especially when the chorale melody Wachet auf returns triumphantly at the end.

Have you been listening to recordings of it, and, if so, is it just one interpretation or many, and which players?

I have a recording of Simon Preston playing it at the Royal

Albert Hall, and spent a lot of time wishing I could play it as quickly and accurately as he does!

Have you entered any organ competitions? What do you think their relevance is to your work as a cathedral musician?

I was a finalist in Dublin in 2005 and a semi-finalist in St Albans in 2007. My honest opinion is that organ competitions have no relevance to work as a cathedral musician. They are worthwhile things to undertake if one has ambitions as a concert organist and if the prescribed repertoire is music that one aspires to learn. However, I think that all too often, in order to succeed in competitions, one has to play in a safe and uncontroversial style that will not offend the tastes of any given member of the jury, rather than being able to express one’s own interpretation of the music (and how dull it would be if all of us played in exactly the same way!). As a cathedral organist, an interesting, varied and liturgically relevant repertoire is important, but success in organ competitions is not.

What do you like most about Gloucester (the town or the cathedral)?

I am enormously privileged to work in a building as glorious as Gloucester Cathedral. The high vaulted quire, huge Norman pillars in the nave and the wonderful acoustic are inspiring. Outside the cathedral, Gloucester is an ordinary city that is very proud of its cathedral – it is certainly not a ‘chocolate box’ cathedral city that is only for the well-to-do. We are surrounded here by a very happy, supportive and encouraging community which is wonderful for both work and family life.

Apart from your work at the cathedral, do you run or sing in any other choirs?

As part of my role at the cathedral I direct the Cathedral Youth Choir and accompany Gloucester Choral Society and the Three Choirs Festival Chorus. I also direct Ross-on-Wye Choral Society and the St Cecilia Singers, a Gloucester-based chamber choir founded by Donald Hunt in 1949, and the Edington Festival of Music within the Liturgy (www.edingtonfestival.org).

Which organists do you admire the most?

There are two that spring to mind: David Goode, who was organ scholar at King’s when I was a chorister and my first organ teacher. His technical brilliance at the organ is combined with an inspiring sense of musicianship which in turn inspired me as I started the organ. The second is Nicolas Kynaston, with whom I have studied since I started at university. Nicolas’s imaginative and musical playing have given me the confidence to be true to myself as an organist and not feel bound by the interpretations of others all the time.

What was the last CD you bought?

Berlioz Te Deum and Requiem performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus under Sir Colin Davis.

What was the last recording you were working on?

The Cathedral Choir made a live recording of a concert that included the Duruflé Requiem prior to our tour of South Africa in October last year.

What is your favourite organ to play?

Gloucester Cathedral, for solo repertoire certainly.

What is your favourite building?

King’s College Chapel, Cambridge

What is your favourite anthem?

Too many to choose from, but perhaps Parsons Ave Maria or Elgar Great is the Lord

What is your favourite set of canticles? Howells Gloucester Service

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants? Psalm 84 to Bairstow

What is your favourite organ piece?

Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor by Bach

Who is your favourite composer? J S Bach

Where is your next organ recital? Which pieces are you including? Bristol Cathedral. I am playing Vierne’s Symphony No 2 in preparation for a recording I am making of it soon.

Have you played for an event/recital that stands out as a great moment? Playing for the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols at King’s is a special experience, something I often wish I could do again with the benefit of ten years’ experience!

Has any particular recording inspired you?

We made a recording of Bach’s St Matthew Passion when I was a chorister, and I still listen to that a lot, in particular the aria Erbarme dich sung by Michael Chance with the violin solo played by Roy Goodman.

How do you cope with nerves?

I find I am nervous mostly if I feel under-prepared or am not able to concentrate fully, so careful preparation and focus are crucial.

What are your hobbies?

Spending time with my wife and daughter and in particular walking in the beautiful Gloucestershire countryside with our dog. I also enjoy cooking.

Do you play any other instruments?

I used to play the French horn a lot at school and university, but it rarely comes out of the case these days!

Would you recommend life as an organist?

Wholeheartedly.

What are the drawbacks?

Long hours, often at anti-social times. Your heart has to be in it, and in that sense it is as much a vocation as a job, in my opinion.

What do you think should be the role of the FCM in the 21st century?

To continue the excellent work they do on a regional basis, with each branch supporting the needs of the music department in their local cathedral. These will almost certainly be different in each place, but ensuring the future music in all cathedrals is important and we are grateful to the FCM for all that they do to support us in that aim.

Since writing this piece, Ashley Grote has been appointed Master of Music at Nor wich Cathedral. He takes up this position in September 2012.

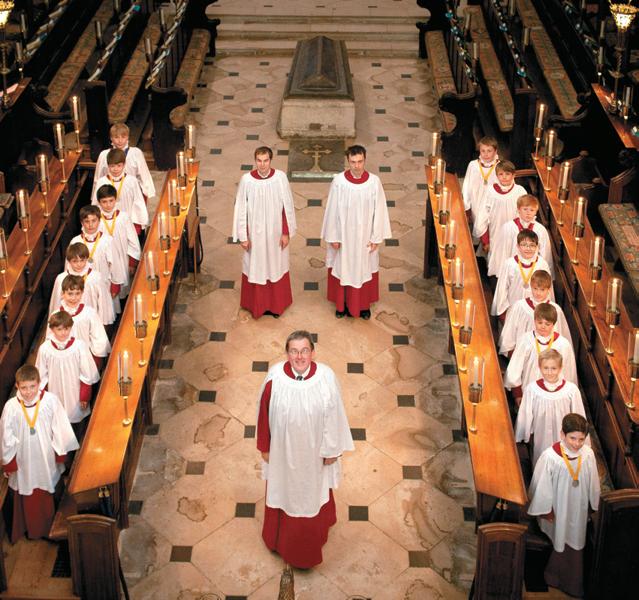

The FCM has chosen a significant year to hold its AGM in Winchester. Apart from the Olympics and the Diamond Jubilee, 2012 is the tenth anniversary of the appointment as cathedral organist of Andrew Lumsden (almost universally known as Andy). It is also his twentieth year as a cathedral organist (“You get less for murder,” he commented – but for murder there is the question of remission for good conduct...) and the latter part of the year sees his 50th birthday.

So how did it all begin? Andy was a chorister at New College Oxford, where his father, Sir David Lumsden, was organist. Andy claims he ‘got some stick’ from his fellow choristers for this apparently privileged position! He also tells me that his mother has a very good ear and was ‘a good pianist’. His brother and sisters are, he says, musical, so I sense a musical home with little effective rebellion. He took his Grade VIII piano exam at the age of 12, being warned by his piano teacher to work more on his scales to have any chance of success. “After my last lesson before the exam, my teacher was heard to say, “It’ll be a ****** miracle if he passes!” Imagine the mixed feelings when his teacher opened the notification of Andy’s distinction (his teacher was his father).

Aged seven, Andy was fascinated by the installation of the new Grant, Degens & Bradbeer organ in New College chapel and it was this that started his love of church music. Whilst still a chorister, he had organ lessons with Paul Hale, then organ scholar at the college and one of his father’s successors at Southwell Minster, and also Nicholas Danby.

After New College, he carried on under the William of Wykeham umbrella by moving to Winchester College, and got his first taste of Winchester and its cathedral (and presumably his first experiences of Martin Neary, his predecessor but one at Winchester and for whom he was later to work in London), being taught the organ by Christopher Tolley, another of his father’s former organ scholars. “Chris was excellent for me as a teacher,” he says, “as he tolerated no nonsense and really pushed me to learn more repertoire.” On returning to Winchester decades later, he found himself passing dons from the college in the street and saying, “Good morning, sir”, a habit he kicked quite quickly! Incidentally, he picked up his ARCO at the age of 17, with all the playing prizes.

Gap years were less fashionable in those days, so his was more rigorous than they sometimes appear now. He spent a year at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama as a repetiteur on the opera course, which he says broadened his outlook, both musically and more generally (and who says there is no connection between prima donnas and lay clerks?).

He then went up to Cambridge as organ scholar at St John’s, under the legendary George Guest (FCM’s one-time President). He was fascinated by Guest’s apparently effortless success in producing tonal quality, and the way in which performances would suddenly ‘take off’. I asked about the reputed rivalry between John’s and King’s; on the whole he played this down but did recall Guest’s barely-

restrained glee when a John’s man (Stephen Cleobury) was appointed as organist of ‘the other place’. While at Cambridge he had organ lessons from Peter Hurford, who travelled up from St Albans (where he had founded the legendary International Organ Festival and was for twenty years Master of the Music at the Abbey).

After six months as assistant organist to Catherine Ennis at St Marylebone Church (“some wonderful music making and lots of very loud laughter!”), Andy became assistant organist at Southwark Cathedral, working with Harry Bramma. Being a ‘parish church’ cathedral, it was a real eye-opener for him as the kids came from many different south London schools (as they still do). “Even though the musical standard was not necessarily in the same league as John’s, the sense of achievement with these boys was even greater. They were wonderful kids who were superbly encouraged by Harry, and there was a real family atmosphere in the place.”

In 1988, he moved as sub-organist to Westminster Abbey, where there were the inevitable and amazing special services. Andy played for the memorial service for Lord Olivier (“As this was televised live, it was rather fun watching Douglas Fairbanks Jnr, Michael Caine and Ronnie Corbett singing Jerusalem”), and the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Britain. In 1991 he played the organ for a live Songs of Praise at the start of the Gulf War, which had to be put together at three days’ notice.

He recalls an amusing incident when the Prince of Wales was unable to attend a service for the Order of the Bath, the Queen appearing instead. Apparently this led to much comment and discussion among the lay clerks about the advisability of sending in one’s stead a deputy more esteemed than oneself.

His first appointment as a cathedral organist came in 1992, at Lichfield. He describes this move as a cultural change and recalls the importance of teamwork with (successive) headmasters (a notable feature of his time at Lichfield). There was also a frantic period which saw nine broadcasts in less than four weeks, the then dean, Tom Wright, being commissioned by the BBC and insisting that they came to him, with the result that they wanted to make the most of

their investment of time and equipment.

Thinking that the ‘county’ pressures were a particular feature of Hampshire life and society, I asked about this aspect of his time at Lichfield. Andy sharply reminded me that the diocese of Lichfield serves two counties (and thus two Lords Lieutenant), Shropshire as well as Staffordshire (where Michael Scott-Joynt was Bishop of Stafford before preceding Andy to Winchester), causing double the load of county events.

He tells the story of an evensong when, without giving the precentor any warning, he deputed the head chorister to conduct the anthem (Mendelssohn Lift thine eyes). A rather surprised-looking precentor had to be encouraged by hand signals to get on with the announcement! This cleric, a sharp-witted and amusing man (and now a distinguished dean), was also leading the prayers that evening. As they all knelt down for these, the anthem having gone very well, the precentor was heard to say, “We pray for all those recently made redundant...”

At Lichfield, Andy began to direct, as opposed to accompanying, recordings, which of course continued when he moved to Winchester. Over subsequent years and because my repeated annual requests to him for a particular anthem had failed to bear fruit, I asked a major CD company to suggest a disc containing the anthem. After a short delay, I was duly chagrined to be told, “We recommend Lichfield under Lumsden.”

So when in 2002 the Chapter of Winchester needed to look for an organist, the then precentor, Charles Stewart, set off on a soft-shoe-shuffle round some of the choicest closes of England. Thank heavens Lichfield was on his itinerary.

Winchester’s stock was high when David Hill announced

that he was moving on (after a short break ending up at St John’s Cambridge), so there was a degree of uncertainty about future standards, even though Sarah Baldock was already making great strides with the recently formed girls’ choir.

There was no need to worry. The transition appeared almost seamless and Andy now seems to have been here forever (not sure he’ll thank me for that). The repertoire has changed gradually, not in a dramatic way, but there is a stream of new compositions. Andy’s watchword, which came up several times in our conversation, is ‘standards’, to which the size of the repertoire is secondary. He often wishes visiting choirs would not over-reach themselves just because they are in a cathedral (others might be tempted to think the same of visiting preachers). “Hearing a piece sung badly ruins worship.”

I asked him whether the way in which he allowed other members of the organ team to have their opportunity to conduct at services and take choir practices came from his own cathedral upbringing. Without saying ‘no’, he made it clear that he felt it was important to ensure that when they moved on they would be as well prepared as possible. He wishes he could accompany more, but accepts that this is the main job of others, and he certainly takes his turn on the voluntary rota.

I asked him what he thought of the practice in some cathedrals of having an organist and a choir director. He felt this could work, provided it was clear who was ultimately in charge, and instanced at least one case where this had not been so – with adverse results. “Whoever is the No. 1 must have a thorough knowledge and love of how a choir works. Being a good technician or a well-respected name simply isn’t enough for this job.”

In slightly the same vein I asked him whether he would like to be a member of Chapter, as are some directors of music in several other cathedrals. He rather thought not, despite a rueful comment that he might know a bit more about what was going on.

I asked about his favourite composer(s) and the immediate response was Brahms, with Bach as a close

second. In terms of performing he rates the Reubke Sonata He is less ready to nominate a ‘favourite’ organ, though he clearly remembers with fondness playing the organs in Sydney Opera House and Liverpool Cathedral, and Handel’s organ in the Marktkirche in Halle (Germany).

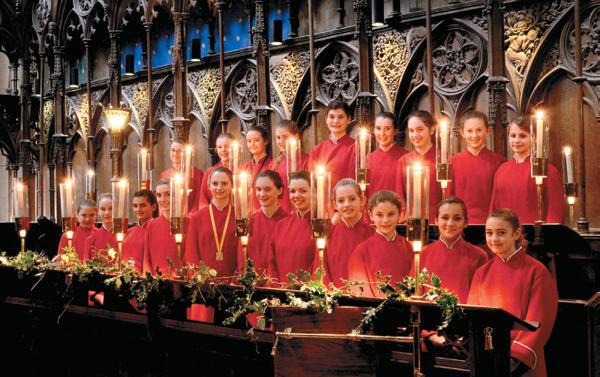

In terms of ‘coming home to Winchester’, he said that the girls’ choir had made a big difference, adding a new dimension to worship and a range of pastoral opportunities, with girls coming from ten different schools locally. Their higher age range also brings its own perspective. “I certainly can’t complain about the variety of problems we have to deal with!” For the boy choristers, many of whom live locally, the presence of the girls’ choir enables them to spend more Sunday afternoons with their families, a distinct advantage. He paid tribute to the Friends of Winchester Cathedral for meeting the running costs of the girls’ choir. The girls had raised Winchester’s profile, but he again stressed the importance of the relentless pursuit of standards.

I asked whether there was much time for hobbies. Andy enjoys flying and had some basic lessons in America (“where it would have been easier to make an emergency landing!”). Following the theme of excellence he admits to a modest interest in (and intake of) wine and enjoys travel, though, surprisingly perhaps, he does not pursue an extensive recital programme.

Recordings continue to take up time in the schedule and he hopes to build on the recently re-established link with Hyperion. The choir recorded a CD of Finzi and Holst with Regent in March 2012 (release date uncertain) and there are other plans in the pipeline – recordings do help the income stream of the choir.

I asked how he saw the Southern Cathedrals Festival, given its impact on workload and schedules. He values the opportunity it provides for commissioning some larger scale works (incidentally, often paid for by the minute!) and the scope for working with a bigger choir, and is pleased that a BBC broadcast or recording appears to be becoming a regular feature. The advent of girls at two of the cathedrals has changed the nature and make-up of programmes, and with two relatively recently appointed cathedral organists at

Salisbury and Chichester, there is currently a certain amount of re-thinking and re-grouping.

As to commissions or new works, he especially values having been involved with two in particular. He cited Philip Moore’s recent SCF commission At the Round Earth’s Imagined Corners (the composer having been given a free choice of text and taking the opportunity to make a setting he had long hoped to do, with four trumpets and the soloist placed in different parts of the building) and James MacMillan’s Laudi alla Vergine Maria. He was also glad to have premiered Roger Steptoe’s Organ Concerto at Peterborough Cathedral, having advised on some aspects of its composition. Harking back to his Westminster days, he recalled the Missa Trinitatis Sanctae by Francis Grier – “very difficult but breathtaking”. Overall, he is cautiously optimistic about the future of cathedral music, though a bit wary financially. “Grants like those from FCM help enormously and spread the word, which is so important to the future of cathedral music. Recruitment remains a problem. The quality of chorister is still out there, but the numbers coming forward are fewer and the outreach work that we all do is vital to bring the

undoubted benefits of cathedral music to a new generation.” Ongoing commitment is crucial, encouraged, as ever, by high standards. So the FCM visit in June will be very welcome and a chance to say thank you tangibly. Although Andy appears self-effacing and laid-back, in performance the intensity of his feelings and commitment shine through. When I asked about his own choir-training techniques he modestly replied, “It’s amazing how much you can do by the way you play it on the piano in rehearsal”. That distinction in Grade VIII at the age of 12 has been worth its weight in gold.

Richard Osmond co-ordinated for some years the ‘ In Quires and Places’ column in this magazine and has contributed CD and book reviews. He admits to being a cathedral music junkie since his student days at Exeter (reading Modern Languages), so Exeter Cathedral is a special place for him. He moved to Winchester on retirement and, as well as attending the cathedral, helps out with organ playing ‘at some of the more despairing villages, who are kind enough to say that the alternative is worse’. He is also a freelance translator and reviewer.

The Wells Cathedral Choir, accompanied by the school chamber orchestra, gave a special concert in the presence of HRH the Countess of Wessex and several other distinguished guests. In aid of the Wells Cathedral Chorister Trust and conducted by Matthew Owens, the concert included music by Mozart, Rachmaninov, Richard Allain, Howard Goodall and John Rutter. The Countess of Wessex, who is the Royal Patron of the Trust, had the opportunity to meet the players, singers and organisers afterwards.

Lindsay Gray, the Director of the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM), has announced his decision to move on from the post of Director during the autumn of 2012; he plans to pursue other professional interests over the next few years.

Mr Gray says: “When I leave in the autumn, it will be five years since my appointment and I consider it a wonderful privilege to have held the post of Director; I have thoroughly enjoyed my time leading the RSCM, and believe it is currently in a position of some considerable strength. I would still like to do other things at this stage of my career and, with the organisation in very good heart, I feel that now is the right time to move on.”

Lindsay Gray became Director of the RSCM after 14 years as headmaster of the Cathedral School, Llandaff in Cardiff. Much of his professional life has been connected with church music as a choir trainer, organist and singer. He studied Music at Cambridge where he was also a counter-tenor choral scholar at King’s under David Willcocks and Philip Ledger. He subsequently took an education diploma at Durham University, where he was also organist and choirmaster at St John’s Neville’s Cross and a choral scholar in the cathedral choir under Richard Lloyd.

In October the new Bishop of Salisbury, the Rt Revd Nicholas Holtam, was welcomed to the cathedral. Like so many, Bishop Nicholas sang in a church choir in his youth. Also at that time the Assistant Director of Music, Daniel Cook, left to become Director of Music at St Davids Cathedral. His replacement is to be John Challenger, currently Assistant Organist at St

John’s College Cambridge; he will not, however, be arriving in Salisbury until September. In the interregnum, David Halls is being ably assisted by an accomplished trio of organ scholar Matthew Jorysz, Tim Hone, Head of Liturgy and Music, and Ian Wicks, Director of Music at the Cathedral School. Jeremy Davies, Canon Precentor for over a quarter of a century, retired at the beginning of January. He will be much missed for his innovative liturgy. His successor, the Revd Tom Clammer, was installed in April. Many FCM members will, of course, have seen the excellent BBC Four documentary Angelic Voices, aired in March/April, featuring Salisbury’s two sets of choristers.

Bangor Cathedral, founded in the year 546 AD and the oldest cathedral in the United Kingdom, has had a choir certainly since the year 1360.

It is now about to introduce a girls’ choir, which will sing on separate occasions to the boy choristers, who will also increase their numbers. The purpose is to meet the demands on family life and create a balance between the two choirs.

Linked with this historic move is the creation of chorister scholarships which will be worth £950 a year. They will pay for instrumental lessons, singing and music lessons as well as help towards music exam fees. This development will create in the cathedral a music school which will be an enormous asset for Bangor and the surrounding district.

Bangor’s most famous choristers are Dr George Guest, who became Director of Music at St John’s College Cambridge and the broadcaster Aled Jones. While Aled’s later career cannot be promised, choristers will be given the same musical foundation which he received.

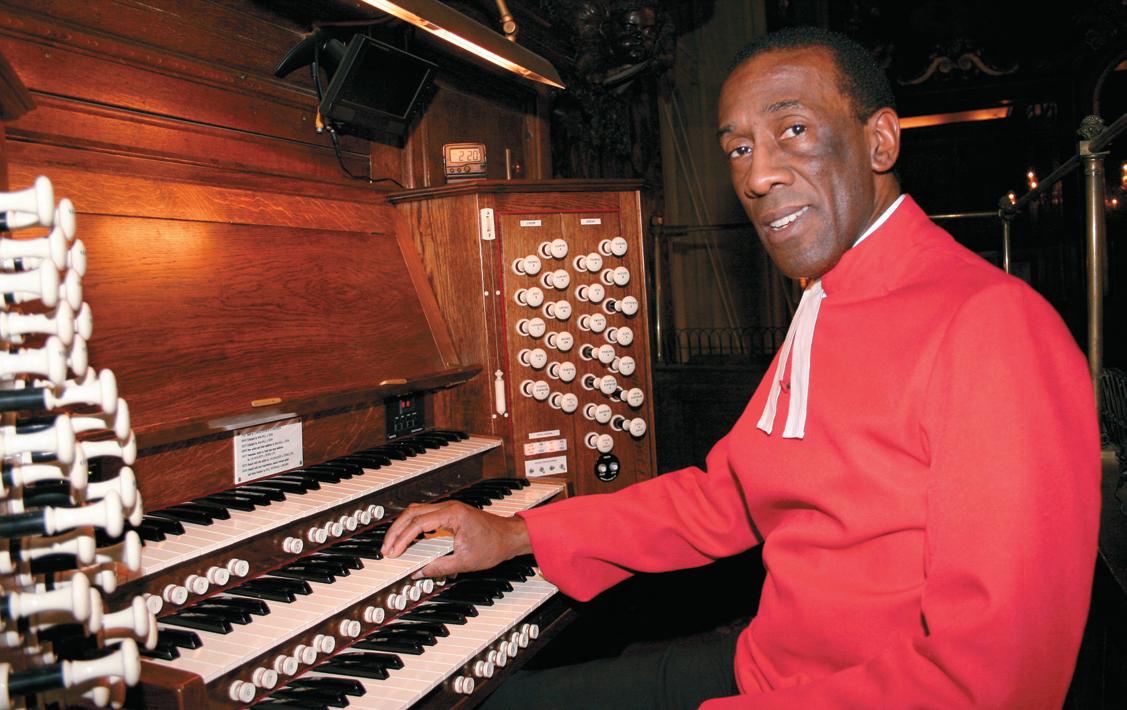

The launch last December of the choral foundation of the Chapel Royal, Hampton Court Palace, to ensure the security of the choral establishment, is a significant milestone in the history of the chapel and its choir.

With the Bishop of London (who is also Dean of the Chapels Royal) and the Master of the Queen’s Music among its patrons, the foundation’s objective is to secure £1.5 million to safeguard its choir and, in time, to create a sizeable fund, the income from which will ultimately be sufficient to finance future endeavours. Far too few people are aware that the Chapel Royal, currently based at St James’s Palace, and its two daughter establishments at HM Tower of London and Hampton Court Palace, are all resourced in different ways, in a reflection of the history of the three choirs. The choir based at St James’s Palace is a part of the Royal Household, with six salaried Gentlemen and ten boys (or

Children) who all hold choral scholarships at the City of London School. At the Tower of London, it wasn’t until 1965 that the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula had its status as a royal peculiar restored by Robert Stopford, the then Bishop of London, Dean of the Chapel Royal. With the help of the chaplain, Stanley Michael, who led financial appeals from the pulpit, a choral foundation to support the newly-formed adult choir was established under the patronage of HRH Princess Margaret. Its inaugural concert in 1966 was attended by

figures such as Sir Arthur Bliss, Sir Malcolm Sargent and Sir Adrian Boult. By contrast, Hampton Court’s choir has never enjoyed support from any form of endowment, but relied solely on the collections from the congregation. The Privy Purse Charitable Trust pays a modest contribution towards the overall running costs of the Chapel, but this will not last forever. The background to this can be summarised as follows. Hampton Court Palace was part of the royal circuit until the reign of George III. Services were regularly sung by the itinerant Chapel Royal whenever the monarch was in residence. With the departure of the court from Hampton Court in 1737, no other monarch lived there. Eventually, the palace was sub-divided into grace and favour apartments, and the growing number of residents led to the continuing use of the Chapel Royal building (which by now had its own chaplain) and the eventual appointment in 1831 of William H Fitzgerald, a local man, as the first permanent organist. By1845, he had been succeeded by William Christian Sellé. It is evident that there was an ad hoc choir of volunteers; however, the standard was poor – no doubt a reflection on the general state of church music at the time, as in the following year, the chaplain wrote to the Board of Works, enclosing a letter from his deputy, objecting to ‘the very inefficient manner in which the singing and Choral portions of Divine Service are performed at the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court’. The chaplain’s letter stated that it was ‘very unfit that the performance of Divine Service in a Royal Chapel should be wholly dependent upon voluntary sources’, and suggested that a small annual sum of about £50 for choral provision ‘would materially conduce to the respectability of the Establishment of the Chapel Royal’. The Treasury turned down

this and subsequent requests, and it wasn’t until 1868 that a choir was eventually established. This new choir also included exiled gentlemen from the choir of Kingston Parish Church, where an unusually high choral standard had been enjoyed until the appointment of a musically unsympathetic incumbent.

During the tenure of Fitzgerald and Sellé, services in the chapel were entirely private, and visitors to the Palace were not admitted to them until 1886. By this time, however, standards had slipped. With services now open to the public, the next organist, Basil Philpott, who had been appointed that same year, made strenuous efforts to restore the music to something like its former glory. His hard work paid off, but the choir still had no significant financial base, as he himself noted: ‘The choir is entirely without endowment, but it has now what it never had before, a library of music properly bound. Many things have been obtained to facilitate the practice as well as the performance of the music. ... My hope is that an endowment may be obtained for the boys some day, and that whatever excellence which may have been gained in the past may be maintained and exceeded in the future by those who will come to carry on the work we have tried to establish.’ His successors who did so include William James Phillips from 1930-1956, a greatly respected disciplinarian; Norman Askew (1956-1966) who, not long before his untimely death, struck one of those patches when the recruitment of boys becomes difficult and augmented the treble line with ladies; the well-known broadcaster, writer and reviewer Gordon Reynolds (1967-1995); and Richard Hill, who was training for a legal career on coming down from

Cambridge, and so held the post briefly from 1995 to 1996. So it has taken until the twenty-first century for Philpott’s hope to be realised because, from the beginning of the spring term 2012, the Foundation began to meet the cost of instrumental/vocal tuition for the choristers. These boys are drawn from a variety of day schools in the area. They rehearse twice a week (their parents often having to contend with diabolical rush-hour traffic), and sing at the two choral services held on Sundays and other Holy Days. They follow in the steps of former choristers such as the musicologist Professor Thurston Dart; the actor David Hemmings (who sang the part of Miles in the premiere of Britten’s The Turn of the Screw); the baritone Robert Hayward; the composer Antony Pitts; and conductors Nicholas Jenkins and Timothy Burke. In recent years, a small but steady stream of choristers have found themselves filling parts for boys’ voices in operas for both English National Opera and the Royal Opera, and having to carefully juggle their stage and choirstall commitments.

Hampton Court’s location at the outer edge of Greater London has sometimes made it difficult to retain Gentlemen, a disadvantage which was as much of a headache for Philpott at the beginning of the last century as it can be today. He noted then that ‘the other voices too – tenors and altos especially –came for a year or two years and then went to appointments where the fees were larger and the expenses of travelling less. In this way, a large number of younger men have passed through the choir without any unpleasant feeling except regret at the necessity of moving on.’ Today, Hampton Court is forced to remain competitive with the London churches and cathedrals in the fees payable to the men, and raising money for this has become one of the foundation’s targets.

The style of worship has always been – and is set to remain – traditional. The Authorised Version of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer are still used at all services; the Litany is sung at the beginning of Advent and Lent, and on Rogation Sunday. Matins remains the main Sunday morning service,

with the Eucharist being sung on the first Sunday of the month, as well as on Easter Day and on Whitsunday. This has led to the expansion and invigoration of a forgotten part of the Anglican repertoire with the introduction of settings of the morning canticles by contemporary composers such as Francis Jackson, William Mathias, Philip Moore and Robert Walker. The traditional language of other services sits side-byside with music by other composers such as Nicholas Jackson, Peter Maxwell Davies, James MacMillan, Judith Bingham and Jonathan Dove, and while the Choirbook for the Queen will provide further fare in the years to come, works by the Chapel Royal’s rich heritage of composers from previous centuries form the backbone of the choir’s repertoire.

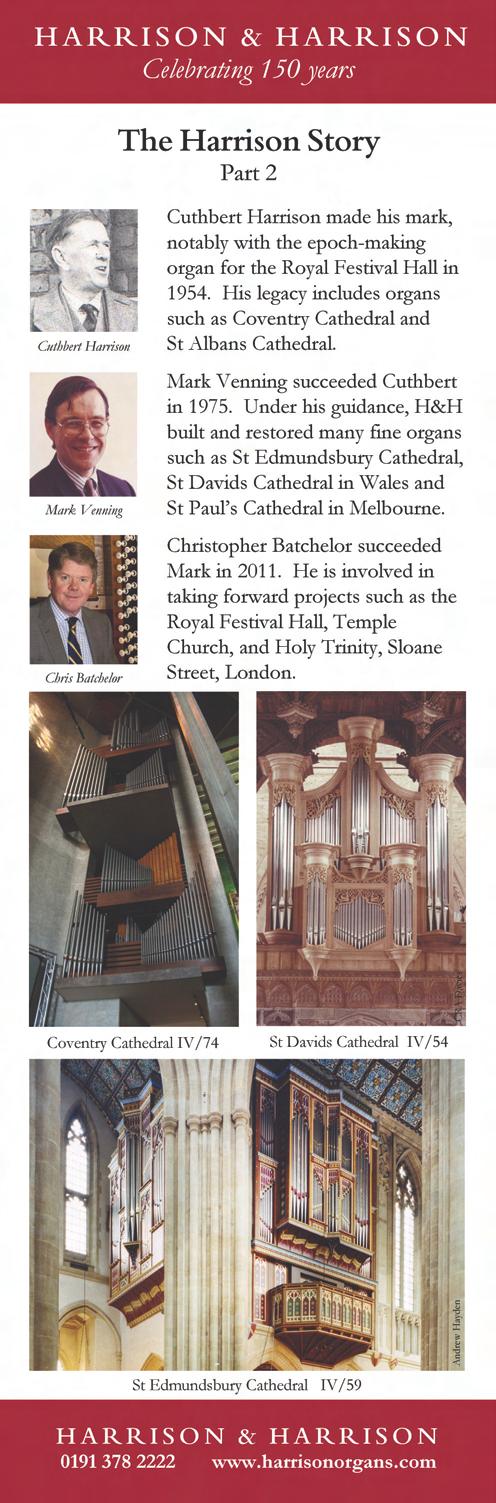

The choir’s fortunes and exposure have grown considerably in the past decade. In 2002, it marked the Queen’s Golden Jubilee with a tour to the Czech Republic, its first ever overseas tour, and probably the first time that a Chapel Royal choir had been heard outside the country since 1520 when it accompanied King Henry VIII to the Field of the Cloth of Gold near Calais. In May 2004, HM The Queen and HRH The Duke of Edinburgh attended a service of Matins at Hampton Court to mark the 400th anniversary of the Hampton Court Conference, the first time that a sovereign had worshipped there since the eighteenth century. Her College of Chaplains and the entire Chapel Royal establishment were also in attendance. Barely two months later, the choir found itself at Abbey Road Studios providing the backing track for the short animation film The Unsteady Chough. Future plans include a joint evensong in May of the choirs of the three Chapels Royal to mark the Diamond Jubilee, and the autumn sees the start of a series of concerts (some with orchestral accompaniment) to continue to highlight the support of the Choral Foundation and to enable the musical and vocal development of the choristers to be heard in music other than that for the liturgy. Next year, the historic Shrider/Hill organ will receive some much-needed attention and reconfiguration by Harrison & Harrison.

These are exciting times for the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court. There is a good-sized congregation of about three hundred regular worshippers, of which only a bare handful are nowadays residents of the Palace. The chaplain provides a daily ministry of the offices of Morning Prayer and the Eucharist, and as in other cathedrals and churches, volunteers from the congregation act as stewards during the opening hours of the Palace, presenting the chapel’s history and its continuing ministry to all who are interested. The choir’s role in enhancing the worship there remains highly valued and, almost 150 years after it was established, the choral foundation will enable the boys to develop their musical talent to the full, and with the men, to provide, in the words of the Dean, ‘the beauty, peace and inspiration to the congregation and visitors... and to the wider world for many years to come’.

The research of Stephen Willis and Alan Kendall is gratefully acknowledged.

CARL JACKSON has been Director of Music at Hampton Court since 1996. He was born in London and studied at the Royal Academy of Music as a Junior Exhibitioner and as an Intermediate Student. He also held an organ scholarship at the Chapel Royal, Hampton Court Palace under Professor Gordon Reynolds before proceeding to an organ scholarship at Downing College Cambridge where he was a pupil of Peter Hurford. Prior to his appointment at Hampton Court, he held appointments at Croydon Minster and (as Asst Director of Music) at St Peter’s Church, Eaton Square. He has also combined his career as a church musician with that of a school teacher, and has held posts in Huntingdon, Croydon, St Paul’s Girls’ School and Kingston Grammar School. Over the years, he has given organ recitals in –amongst others – Berkeley (California), Westminster Cathedral and Alexandra Palace. As an accompanist he has worked with Sir Willard White, and with the Elysian Singers of London with whom he appears on their CD of the music of James MacMillan (Signum). He was appointed MVO in the 2012 New Year’s Honours list.

In 2011 the Christ Church Cathedral Choir toured the US and Canada for nearly two weeks. We visited eight venues. We used no agent. We spent almost no money on marketing. We spent almost no money on hotels. We paid nothing for our visa advice. We had full houses, standing ovations, an energised choir and we returned with money in the bank. How did we do it?

The choir members arrived by air in Charlotte, NC on 28 March. They stayed in local people’s homes and we enjoyed a wonderful welcome party hosted in a mansion by the community. Charlotte is the home of our tour sponsor, WDAV, the classical public radio station in Charlotte whose general manager is Ben Roe, a friend of an alumnus. You will see later on what a large role WDAV and public radio played in our tour.

We began our series of concerts by singing in two churches in North Carolina: Covenant Presbyterian in Charlotte on 29 March and in St Alban’s Episcopal in Davidson the following day.

In all venues except for the cathedral in Washington we sang a programme that took the audience from the very beginnings of the choral tradition to the modern day, and because we had brought three organists with us – Michael Heighway, Ben Sheen and Clive Driskill-Smith – we were able to interleave the singing with recitals. Here is a typical programme from St Alban’s:

• De Profundis –Orlando de Lassus

• Organ solo: (Clive Driskill-Smith) – Fantasia in G Minor BWV 542 – J S Bach

• Leroy Kyrie – John Taverner

• Ave Maria – Robert Parsons

• Organ solo: (Clive Driskill-Smith) – Fugue in G Minor BWV 542 – J S Bach

• Miserere – Gregorio Allegri

• Jesus autem hodie – Peter Maxwell Davies

• Song of Simeon: Lord’s Prayer – John Tavener

• The Lord is my shepherd – Lennox Berkeley

• Organ Solo: (Michael Heighway) – Praeludium in F sharp minor – Dietrich Buxtehude

• Te Deum in C – Benjamin Britten

• Veni sancte spiritus – Howard Goodall

• Jubilate – William Walton

Throughout the trip, all the way to Toronto, the choir travelled in a bus driven by the redoubtable Larry. Looking back, it seems obvious now why so many bands/choirs/groups use a bus – it’s a bonding process. More importantly, we chose a bus because it gave us more control over stress. Many things can go wrong with flying. Flight delays are hell on tour. Flight schedules are unyielding. Our itinerary was also designed to keep our travel days reasonably short: our only long haul was from Boston to Toronto and on that journey we stopped off in Niagara Falls for a break.

We were all nervous about Washington. The cathedral is an immense space of 83,000 square feet, about the same size as St Paul’s in London. Would we fill it and how we would we sound? Luckily, we first gave a chamber concert at the British Embassy which helped a lot – a rapt audience and a great party to follow!

In order to fill the space in the cathedral we had to offer more of a show programme than we had sung in North Carolina, so we included Allegri’s Miserere (always a favourite) and ended with the Fauré Requiem. Thankfully, the cathedral was packed and we were given a standing ovation.

At this point our confidence increased, just at the right time, for our next venue was St Barts in New York, another vast space. Here we sang a variation on our full programme, as we had in Charlotte. It was another sell-out and, although we got a standing ovation, there was a coolness about the evening, not the same community support that we’d had in Charlotte and in Washington. Maybe it was just the Big City Effect. We still managed to troop off to our accommodation in a cheerful mood.

Thanks to our alumni, the men were put up in a boutique hotel and the boys in one of the smart New York men’s clubs. Fortunately the boys did not disturb the club members and had a quiet night. But New York is New York and there are rumours that the men escaped the bounds of their hotel and enjoyed the town.

Boston was our next stop, and we were all looking forward to staying in a beachside home belonging to an alumnus. Their ‘cottage’ was able to accommodate us all! On the way there, our only travel hiccup took place – it turned out that the bus could not get nearer than a full mile away from the house because the lane was too narrow – and it was raining! So imagine our re-creation of the retreat of the Grande Armée from Moscow – a long chain of boys, men and the school matron all

trundling their bags along a path in the dark and the rain for more than a mile. Of course we survived, but our troubles were not over. The next day, scheduled to perform live on radio at WGBH in Boston, we took a wrong turning, got lost in the Boston traffic and arrived in the studio with only minutes to go to air time! Frantic mobile phoning by us. Total calm by Ben Roe, who was now at WGBH’s classical station in Boston. He was used to performers arriving late. The bottom line was a mini concert by us and the most thoughtful interview on the tour. You would never have known that we nearly missed this. We also sang at Trinity in Boston – Evensong, not the full programme, including a couple of anthems by Tallis and Stanford. After the travel issues and the radio broadcast and the two previous large-scale performances, the shorter programme was a relief.

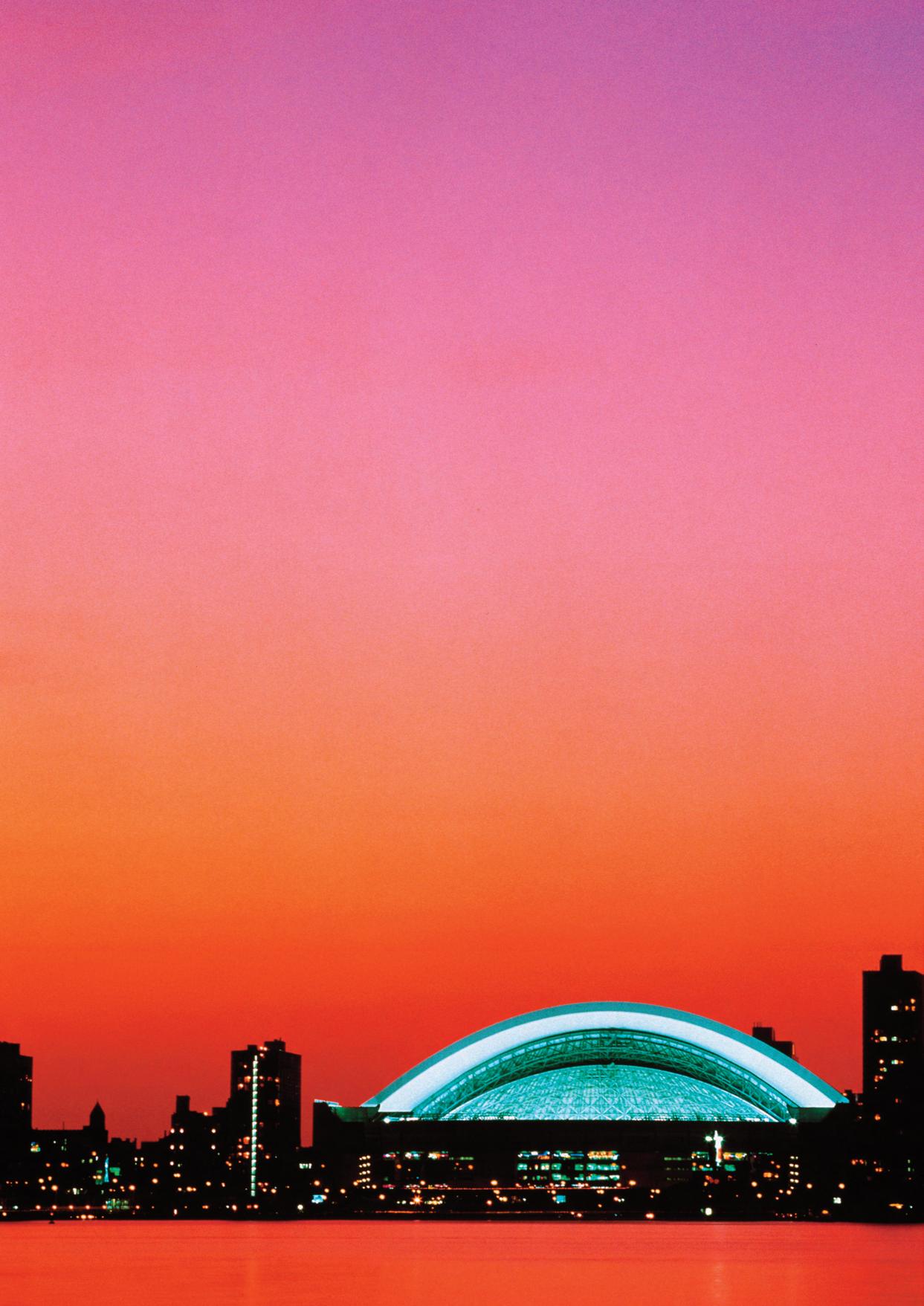

We had put on seven performances in seven days and with a lot of travel. We were tired. We now had a two-day journey to Toronto in Canada, but anticipating this we had planned a day’s break in Niagara Falls, which is just over the border. It’s easy to laugh at Niagara. It is, after all, splendidly tacky, but the Falls themselves conquer all cynics by their sheer magnitude, and the day off we had there rejuvenated us for the last performance at Grace Church in Toronto on 8 April.

As in North Carolina, in Toronto the entire local community combined together to host us and we all stayed in the local choir families’ homes. The church was packed with people who had come to support us. We had a wonderful response in every venue, but here there was a particular warmth which was very special.