CM

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2014

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager

Graham Hermon grahamhermon@lineone.net

FCM email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 01765 605864

07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 01765 605864

07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

Cover photographs

Front Cover

Beverley Minster nave

© Craig Wilkinson

Back Cover

St Lawrence Jewry by Jon Reid © travelphoto.co

52

56

58

We were delighted to be commissioned to provide a custom built instrument for the new concert hall at the Guildhall School. This is part of the exciting multi million pound development of extensive new facilities for the school situated in Silk Street near the Barbican.

“The Regent Classic organ at Milton Court is ������������������������������������������� uncompromising quality to our wonderful new concert hall. Only recently it played a starring role in a poignant and moving performance of the Fauré Requiem. The Guildhall School is delighted with the organ not only to enhance its own student performances but also to offer a ������������������������������������������������ ���������������������������������������������� to Milton Court.”

Jonathan Vaughan, Director of Music, Guildhall School of Music & Drama

Jonathan Vaughan, Director of Music, Guildhall School of Music & Drama

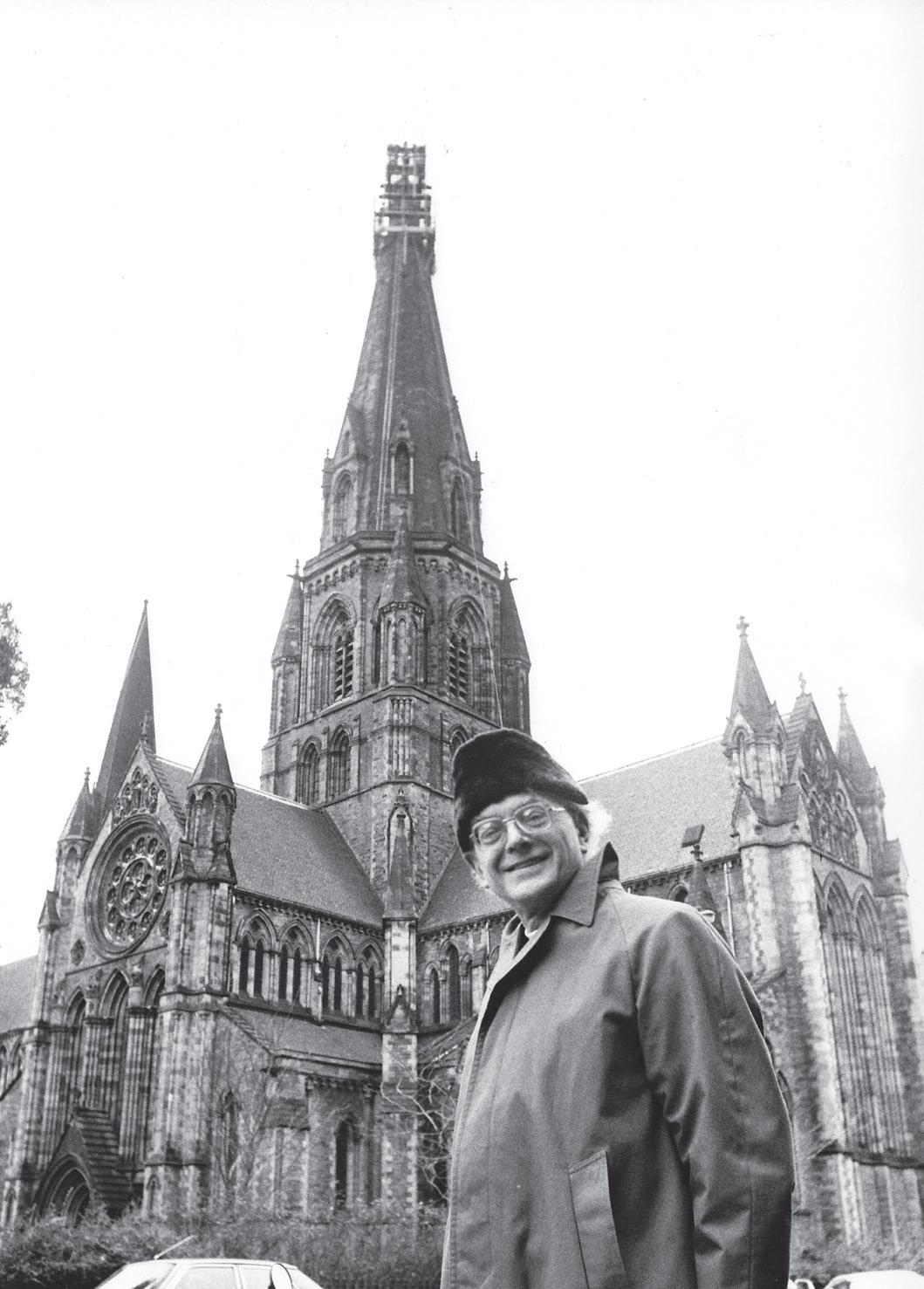

News will by now have reached most of our readers of the recent death of Dr Alan Spedding, who was Organist and Master of the Choristers at Beverley Minster for 42 years. A true gentleman with wide-ranging skills as composer, organist and choir trainer, he influenced generations of young musicians in his time, and was among other things a highly respected reviewer for this magazine. You can read more about him, his early life and his time at Beverley -- where he thought he would stay for a mere five years! -- on p52

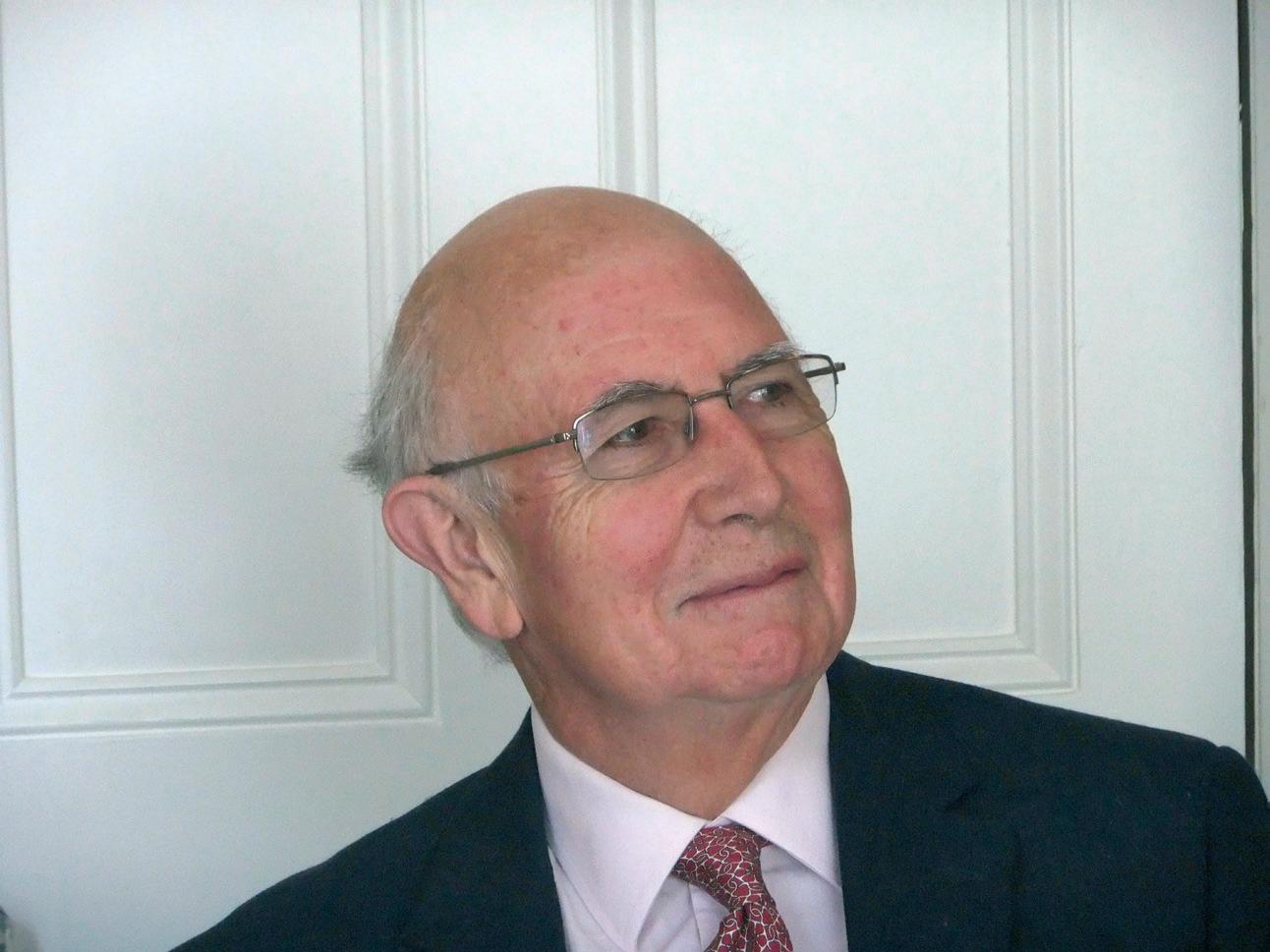

The year 2014 marks the end of Dr Higginbottom’s extraordinary reign at New College Oxford, a place he has made his own for the past 38 years. CDs from Novum, New College’s own record label inaugurated in 2010 by Dr Higginbottom, must surely be required listening for cathedral music enthusiasts. In characteristically forthright fashion Dr Higginbottom contemplates the distinctive sound of the countless trebles he has trained, their tone inspired initially by continental boys’ choirs, and speculates on what he will miss most as he moves on to fresh woods and pastures new.

Other new things impress: two very different but remarkable organs. One, with the unusual commission that firstly, the organ had to be moveable; secondly, it should fit into a particular space at the Mansion House; and thirdly,

it would have as its final resting place the Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey, was designed and built by Mander Organs to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of HM The Queen. One of its quirks is a Nightingale stop, which when drawn causes two small stuffed birds to rise above the organ’s cornice, and revolve. This caused much mirth when deployed at the grand reception in honour of 150 years of the Royal College of Organists towards the end of last year!

The other organ is a splendid and imposing construction by Dobson of Iowa now installed at Merton College Oxford. Commissioned by Merton to celebrate the 750th anniversary of the college’s founding, coupled with the rejuvenation of its choir, it is a magnificent instrument which adds lustre to the already beautiful chapel. The choir -- which has eighteen choral scholars and now sings three services a week, a significant increase since 2008 when only one service was sung per week -- has risen rapidly to the front ranks of Oxford and Cambridge collegiate choirs, and has produced several highly regarded CDs. The review of a recent one, The Merton Choirbook, a collection of pieces all related in some way to the college, can be seen on p59. Visit Merton this year if you can -- there are celebrations continuing throughout the year, and many recitals on the new organ.

Enjoy the magazine.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

Catherine Ennis is this year’s President of the Royal College of Organists, which was given its royal charter in 1893. She is the 60th president, only the second female to hold that august position, and not so much a new broom as a person prepared to bang the drum in a noble cause. Founded in 1863, the RCO is now a modern, dynamic charity dedicated to the promotion and advancement of organ playing and choral directing. It also, through the RCO Academy, runs scores of events aimed at nurturing and supporting the talents of organists and choral directors of all ages, backgrounds and levels of attainment. The RCO is unique in that there is no other charity which seeks to raise the standards of performance on a single musical instrument.

Catherine is naturally very proud of the RCO and its activities, in particular its educational programme. “The RCO Academy offers the opportunity to play at organs all over London and the UK. Courses explore diverse subjects -- for example, the ornamentation of Couperin or how to improve pedal technique -- and the roster of teachers is extraordinary.” These latter include Anne Marsden Thomas, who founded and directed the St Giles International Organ School from 1992 until January 2012, when it became part of the RCO Academy. There is a wide range of classes for which all players may sign up, regardless of age or aspiration. So if you occasionally play the organ at your local church and feel your technique needs improvement, why not consider an RCO course or class? Booking is online or by post, and class preparation sheets are also posted on the website. Most sessions (e.g. Playing the Psalms; How to Manage a Large Console; Sight-reading; Six Essentials for Starter Organists etc) are restricted to six active participants, to facilitate the best uptake of knowledge

The RCO Summer Course for Organists, which takes place at St Giles Cripplegate in the City of London in August, is also run by Anne Marsden Thomas and is always greatly oversubscribed. Student organists, split into seven levels of study from beginner to advanced, are able to play on a number of different organs and are each given a personal assessment. Participants can study accompaniment and keyboard skills, improvisation, technique, etc and there are performance and practice opportunities for everyone on up to 20 pipe organs.

The RCO also has a full-time Education Officer, Simon Williams, who with his colleague James Parsons organises courses in the Easter and summer holidays, again covering all standards. For teenagers preparing for university or cathedral organ scholarships, the RCO Academy offers The Organ Scholar Experience, which takes place in Oxford or Cambridge in alternate years.

The College of Organists, as it was first called, was founded by Richard Limpus, organist of St Michael’s, Cornhill, and a group of fellow organists who convened to discuss improving the professional skills and status of organists. From the start, activities were directed towards the encouragement of the composition of new church and organ music, and there was an energetic programme of lectures. The establishment of the famous examinations came in 1866, with the practical element taking place in St Michael’s, Cornhill. The familiar two-tier structure of Associateship (ARCO) and Fellowship (FRCO) diplomas followed in 1881 and has been in use ever since. A choir-training (now choral directing) diploma was introduced in 1909, and much more recently a foundation certificate (CertRCO) has been introduced to cater for the amateur player or developing student.

The first President of the RCO was the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Longley, in 1865. Subsequently, the office of Patron was created, and the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, and the Bishop of London, became Patrons of the College. From that time on, the office of President became an elective one. Nowadays, the President of the RCO spends the year before his or her term of office shadowing the existing incumbent. Catherine’s immediate predecessor was the Westminster Abbey Organist, James O’Donnell.

The presidential two-year office runs from July to July and in 2013 encompassed the high-profile celebration at the Mansion

House, enhanced by the presence of the Lord Mayor of London, Alderman Sir Roger Gifford, himself an enthusiastic musician and supporter of musical charities. That event was held with the intention of raising the public’s awareness of the RCO’s mission, one part of which is to educate young organists (and, indeed, those who are not so young, since courses are held for those longer in the tooth also), to which end the audience was treated to four performances by existing pupils of the RCO, the youngest being only twelve. In between the musical performances were speeches from those associated with the College, including one from the new chairman, Christopher Wood, a surgeon with an unusual trait: he has written, and had performed at St John’s Smith Square, a requiem, surely one of very few non-professional musicians to do so.

Like most charities, the RCO is not a rich organisation, but relies on the generosity of its approximately 2300 members and a few benefactors. In raising its profile through this 150th year it is hoped that those with an interest in the organ and in organ and choral music will consider supporting its work, in particular to continue finding and nurturing talented organists and choral directors. As part of the 150th anniversary celebrations the College is hosting the ‘150 for 150 Recital Challenge’, a spectacular year-long programme of concerts all listed on the RCO website. It features players of all standards, from the past and current presidents to others less elevated -- anybody who plays the organ can take part, and you don’t even have to be an RCO member. By filling in a form on the website your recital programme and date will be added to the nationwide recital programme and to the RCO Facebook page. All recitalists will be sent a ‘150 for 150’ recital pack containing templates for posters, press releases, and ideas and materials for using the recital to raise money in support of the College’s anniversary appeal. The culmination of this celebration will be on December 10th, when Martin Baker plays at the Royal Festival Hall.

RCO Anniversary events can be found at rco.org.uk, as can more details about both the RCO appeal, and in particular The Anniversary Circle, a group of supporters (both corporate and individual) who can help create a strong platform for the RCO’s work across education, outreach, examination and scholarship.

As well as being President of the RCO, Catherine Ennis is also Organist and Director of Music at St Lawrence in Jewry, a fine Wren church near the former medieval Jewish ghetto rebuilt in 1677 after the Great Fire of London and then again in 1957 after suffering extensive damage during the Blitz. It is now a guild church and the official church of the City of London Corporation. Like most Wren churches, few walls are at right angles, but the ‘sumptuous barn’ white interior with its gold leaf and chandeliers is spectacular.

Catherine has been in position for over 27 years, not in itself totally unusual in a profession where it is almost the norm to serve over 25 years as a cathedral director of music; what is considerably more unusual is that at the time she was appointed there was no female director of music at a UK cathedral. And although the list now includes such distinguished musicians as Sarah Baldock at Chichester and Katherine Dienes-Williams in Guildford, the balance is very heavily weighted in favour of the male sex. She is the founder of The London Organ Concerts Guide, which reaches many thousands of music lovers all over the UK and abroad, and the custodian at St Lawrence of a series of Tuesday lunchtime recitals which continue a century-long tradition of organ music as midday respite for all. She is one of the most distinguished organists in the UK and gives numerous recitals both here and abroad.

The St Lawrence organ is a fine Klais, installed under Catherine’s supervision in 2001. Retaining only the fine oak cases of the 1957 Mander organ, the new instrument replaced pipework which had been recycled from war-reclaimed organs, and action which had all but worn out. It majestically fulfils its requirements on the many civic occasions which occur at St Lawrence, the Lord Mayor’s church, and provides a rich tonal palette for the many different styles of repertoire which feature every Tuesday in the recital series. In recent years the church has acquired a reputation for assisting young musicians, with the Tuesday series hosting three discrete

opportunities each year: in June, the John Hill series features international young artists; in November, young UK organists who are being supported by the Eric Thompson Trust give recitals; and in March, top teenagers from across the country join forces to put the Klais through its paces in the Sixth Form series. The instrument is a unanimous hit with visiting organists and educates many of the young players in matters of sound and touch.

Fundraising for the church and its ministry can often be a struggle, so all areas of sponsorship are minutely explored. On one occasion, dogged by building works in the environs and unwilling to let a useful opportunity pass by, St Lawrence’s vicar was able to persuade the building firm involved to donate a substantial sum to offset the disruption caused.

St Lawrence has a small choir of professional singers, and there are no Sunday services. The church is unusual in that it is a guild church, not a parish church, and therefore congregations for its services are generated by its many associated organisations. These include charities, regimental associations, livery companies, local businesses, and some with Commonwealth ties, including the New Zealand Association. All special services and events are organised individually, including many carol services in December. Throughout the rest of the year an eclectic variety of musical activities takes place: lunchtime organ recitals, school concerts, piano recitals etc, and in August there is a summer festival aimed at those who have not departed the City for sunnier climes.

Catherine has had a long and respected career as an inspirational teacher, regularly gives organ recitals throughout the country, and has helped create four major new organs in London (St Marylebone, where she was director of music until 1990, the William Drake organ for Trinity College in Greenwich, The Queen’s Organ formerly at Mansion House and now in Westminster Abbey Lady Chapel, and of course St Lawrence).

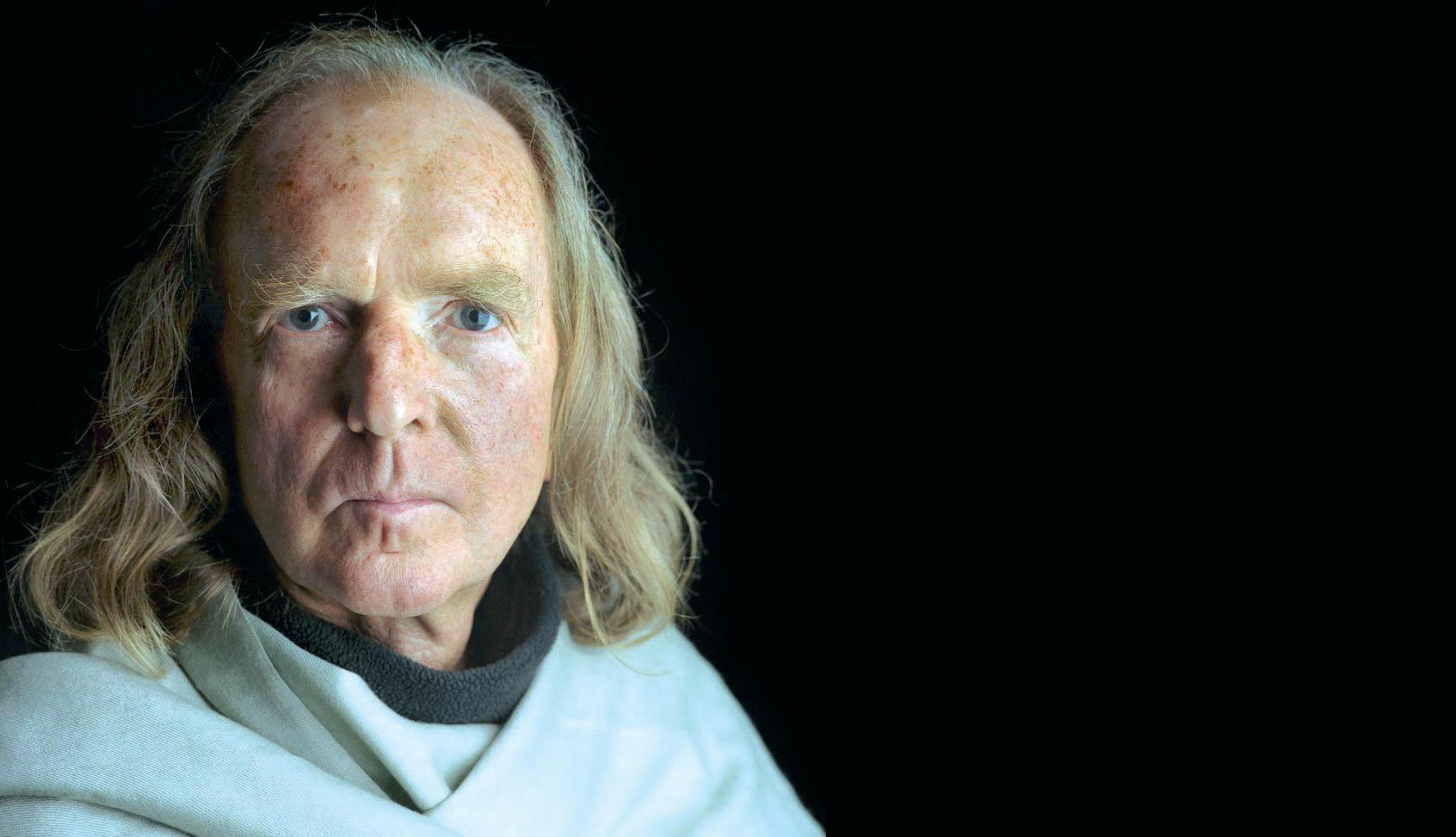

by Martin Neary 1944-2013

by Martin Neary 1944-2013

Sir John Tavener was a passionate believer who, when composing, clearly felt the hand of God. For a time in his thirties he had the confidence and determination to renounce several centuries of our musical inheritance, as he turned to the basic simplicity and repetition of Orthodox chant. From what some critics saw as a limited base, he could produce almost spontaneously (or so it seemed) some of the most moving scores of the past fifty years, touching the hearts of millions. From an early age he was absorbed by a sense of mortality -- I can hardly conceive how many requiem-type texts he must have set -- yet this serious side to his nature could not conceal his essential impishness, and certainly, in his youth, a certain wildness. His company was always entertaining and often hilarious, while his unashamed love of the sun, of wine and of flamboyant cars was legendary.

My earliest memories of John date back to 1972, when he came to Winchester to hear rehearsals for the first of his works I conducted, Little Requiem for Father Malachy Lynch. Winchester choristers remember how the long-legged composer in his white suit would arrive at the cathedral close in his white Bentley and, ignoring instructions to keep off the grass, lie down on the hallowed turf and sun himself.

At that point John was still in his modernist (Stravinskian) phase. It is easy to forget that his initial impact on the musical scene had been colourful, to say the least, with provocative works such as The Whale, which included a variety of cacophonous sounds (snorts and other violent expressions!). There were also his links with the Beatles, whose Apple label recorded The Whale and Celtic Requiem. The latter work, which

John Tavenerwe performed in Winchester Cathedral in May 1973, has a remarkable mixture of simple children’s songs, such as Jenny Jones is dead, is dead, alongside dissonant choral and orchestral writing and an ethereal arrangement, in the form of a very slow-moving canon of Lead, kindly light, John’s favourite hymn tune at the time. Despite protests from at least one parent about the violence of the language, we went ahead with the performance, and I shall never forget the ending, when the children, singing Jenny Jones, moved slowly down the long nave with sunlight streaming in through the West End window.

This was truly a marriage of music and ritual; and indeed several reviews around this time described John’s music as ‘cathedral music theatre’, notably after performances in Winchester and Bristol Cathedrals of his large-scale work, Ultimos ritos. John loved big sacred buildings and at the Winchester Cathedral UK première in 1975, he felt we came close to his original vision, with four choirs and string orchestras, four horns and four sets of timpani positioned in the four corners of the nave, trumpeters high up on the screen and the audience somehow accommodated in between! Ultimos ritos was inspired by the Crucifixus from Bach’s B minor Mass, and at the end a tape of the Bach movement gradually drowns out Tavener’s music, until all we hear are the last extraordinary chords of Bach’s Et sepultus est, seeming to chime in so well with John’s mantra of ‘dying unto oneself’.

Another crucial element of John’s compositional life was devotion to what he called ‘The Eternal Feminine’, and our next Tavener event, in 1977, was the first broadcast performance of Canticle of the Mother of God, given by Elise Ross and the Waynflete Singers. This demanding work, alternating melismas sung by a solo soprano in Modern Hebrew with responses from the unaccompanied choir in Modern Greek, was a huge challenge for the choir, and after the final rehearsal and balance test the BBC producer, Philip Moore, and I were pretty worried. However, thanks to my commandeering a young Winchester chorister named Stephen Layton, whose sense of pitch enabled him to hum the note for the sopranos before each entry, the performance was transformed, much to Philip Moore’s amazement!

The first Tavener setting clearly rooted in Orthodox chant to be heard in Winchester was the Great Prayer of Saint Andrew of Crete in 1981. John’s note, revealing so much of his belief at the time, began by quoting Mother Thekla, who was to become such a strong influence as well as his librettist and translator:

“We must repent from minute to minute, person by person. My wretched soul. The person alone is here important, because the Day of Judgement is at hand, and there we can only be alone, face to face, alone with the judge . . . ”

John continued:

“The work was inspired by my feelings of penitence during the first days of the Great Lent earlier this year and was finished on the Sunday of The Last Judgement.”

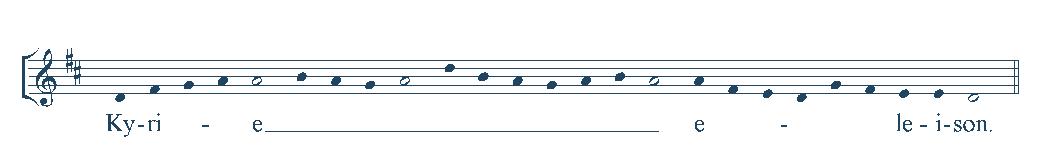

The music is a very slow chromatic descent – a musical prostration in fact – using all the chromatic scales, major and minor. It begins and ends with Irmos. In between are twentythree Troparia sung by a single male voice, and the choir responds to each Troparion respectively in English, Greek

and Slavonic, with the words ‘Have mercy upon me, O God, have mercy upon me’. The homophonic chord sequences were deceptively subtle, and the dense triads created an extraordinary effect. Such sequences became very much a part of John’s musical language, as can be heard in the Hymns to the Mother of God, and indeed in his unique cello concerto The Protecting Veil first performed at the 1989 Proms. The title itself shows how even his instrumental pieces were so often inspired by spiritual texts and chants.

By then an astonishing flow of pieces, some of which he would say came upon him ‘in a flash’ had poured forth, from the gargantuan to the apparently simplest of miniatures -- a supreme example being The Lamb, written for his nephew Simon’s third birthday, in which John found a wonderful way of matching the innocent symmetry of Blake’s verse with his own musical symmetry through the use of patterns such as inversion and retrograde. What made his music unique was that these patterns so often produced quite ravishing musical harmonies. But he could still be bold and even deliberately shocking, as when the organ thunders in with a clashing chord of C# minor in A Christmas Acclamation – God is with us (kindly commissioned to mark my time as Organist and Master of the Music at Winchester).

Virtually all these settings were influenced by Orthodox chant, and Orthodox texts. Interestingly, John anticipated the move to greater ecumenism with the inclusion of Orthodox antiphons in the Evening Canticles for King’s College Cambridge. In recent years, and particularly after his life-threatening heart attacks, his musical language had become simpler – I did not say less difficult! – but the inspiration was undoubtedly there, as can be heard in the Nunc Dimittis (2010) commissioned by the National Youth Choirs of Great Britain. And John’s own ecumenism led him to absorb the beliefs of a host of religions, even though his spiritual home was undoubtedly the Orthodox Church. It therefore felt so appropriate that his funeral in Winchester Cathedral, thanks to the gracious invitation of the Dean and Chapter, should have been essentially an Orthodox service. The Winchester Cathedral Choir, on top form under Andrew Lumsden, used the building in a way John would have loved, with stunning echoes in As one who has slept from the South Transept. That service, which lasted over two hours, was followed by his burial in the churchyard at Childe Okeford in Dorset, beside the lovely house (adorned with icons) where John and the family lived.

John was still composing at the time of his death, and many of the pieces written in the last years of his life deserve to be better known. One such is Miroir des Poèmes with words by Jean Biès, which was composed in 2006, but had to wait until January 2014 for its UK première. Performed at what

He could produce almost spontaneously (or so it seemed) some of the most moving scores of the past fifty years, touching the hearts of millions.

was to have been a 70th birthday celebration at St John’s Smith Square, but which sadly took the form of a memorial tribute, Miroir, scored for two choirs, two string quartets and double bass, is chorally extremely challenging, but ultimately very rewarding. Full of sharp contrasts and engaging rhythms, there are traces of John’s early style as he continued to create, often contrapuntally, some stunning harmonies around his haunting melodies. And the response of the performers, audience and critics was tremendous.

As Canon Lucy Winkett said when she ended her ‘Thought for the Day’ on BBC Radio 4, shortly after John’s death: “There are many, many people for whom he did just that.”

I will end by adapting the words from Hamlet in John’s bestknown work, Song for Athene, which made such an impact at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997, not least for

I also think of They are all gone into the world of light (dedicated to the memory of the wife of John’s heart surgeon, Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub, who had looked after him for thirty years), in which a deceptively simple alternation of major and minor tonality is especially haunting; and The peace that passeth understanding, commissioned for Remembrance Day 2009 in honour of the passing of the World War I generation. Once again there is the inspiring combination of music (full of the short phrases and dramatic key changes much favoured by John in his later works) and liturgy. Here is the composer’s note: ‘In this setting of St Paul’s great statement, I have tried in a simple and primordial manner to suggest majesty, solemnity and a radiance of peace and bliss. I have also given the music a ceremonial nature by inserting “Allelouias” (sic) sounding from “Heaven” (semi-chorus) -- which he called “The Celestial Realm” -- gradually rising in pitch until they are answered by “Allelouias” from “The World” (main choir). The music forms a gradual crescendo reflecting the meaning of the words. At the musical and spiritual climax, the full organ sounds four chords which represent the Four Angels before the Throne of God. The final chord then transforms into the sacred monosyllable OM, which hums around the building, representing the Peace and Beatitude of God’s Presence.’

For more than forty years I had the privilege of directing many Tavener premières in the UK, as well as conducting some of his largest works abroad, including Apocalypse (in Athens) and the seven-hour long Veil of the Temple (in Amsterdam). Our last foreign expedition was in 2011 to Switzerland when John, who by then was too frail to direct himself, asked me to deputise for him, at an atelier (workshop) in Fribourg dedicated to his choral, orchestral and chamber music. With John’s wife, Maryanna, we spent a fascinating week, having the luxury of five days’ rehearsal with the talented students, with whom John struck up an immediate rapport. The principal work was The Protecting Veil, and we took the opportunity to rearrange some of the orchestral string writing to enhance the beautiful antiphonal effects. It was also very moving to perform in the same concert the Hymn to the Mother of God, on which so much of The Protecting Veil is based.

John once commented, “I think there are an awful lot of artists around who are very good at leading us into hell. I would rather someone would show me the way to paradise.”

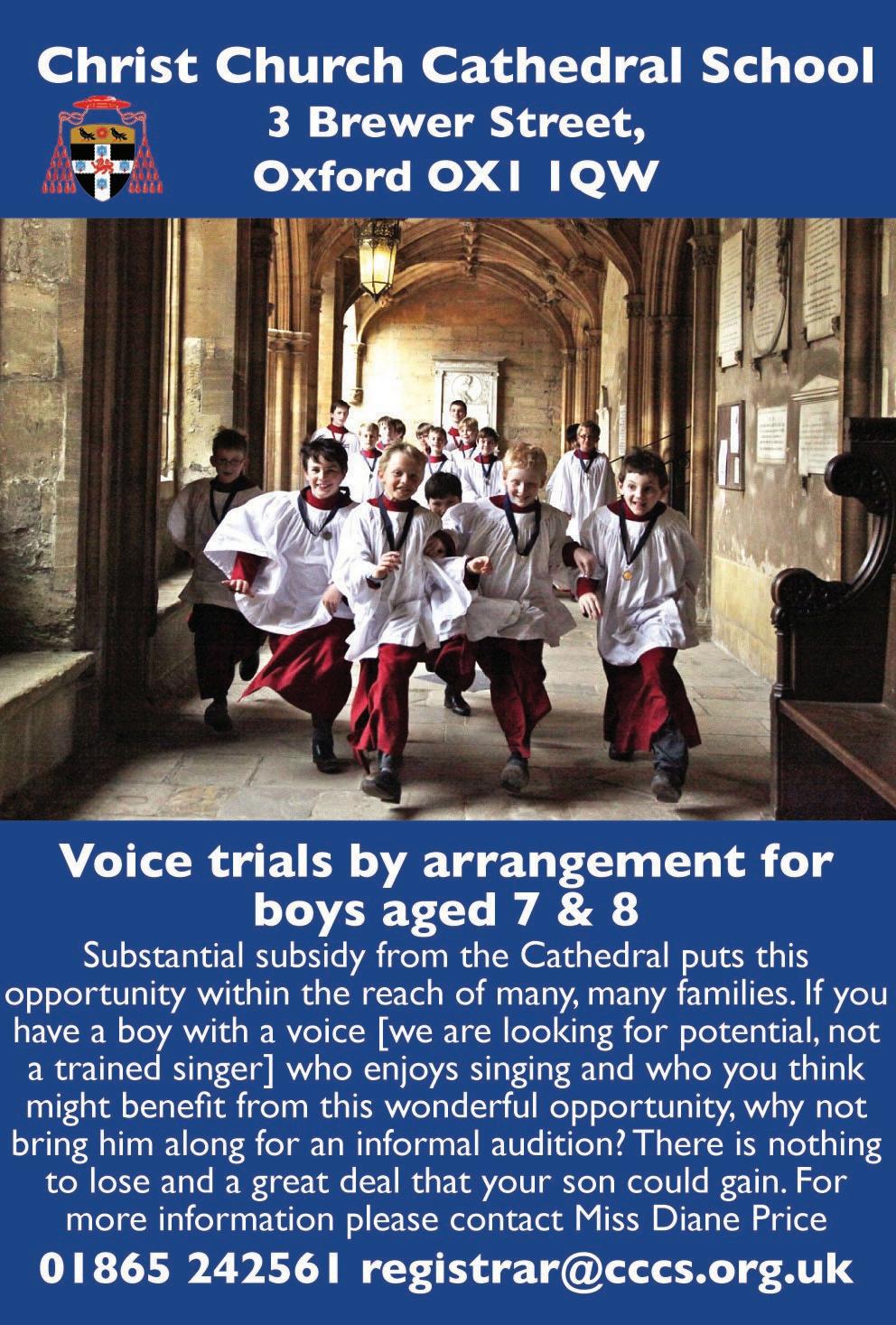

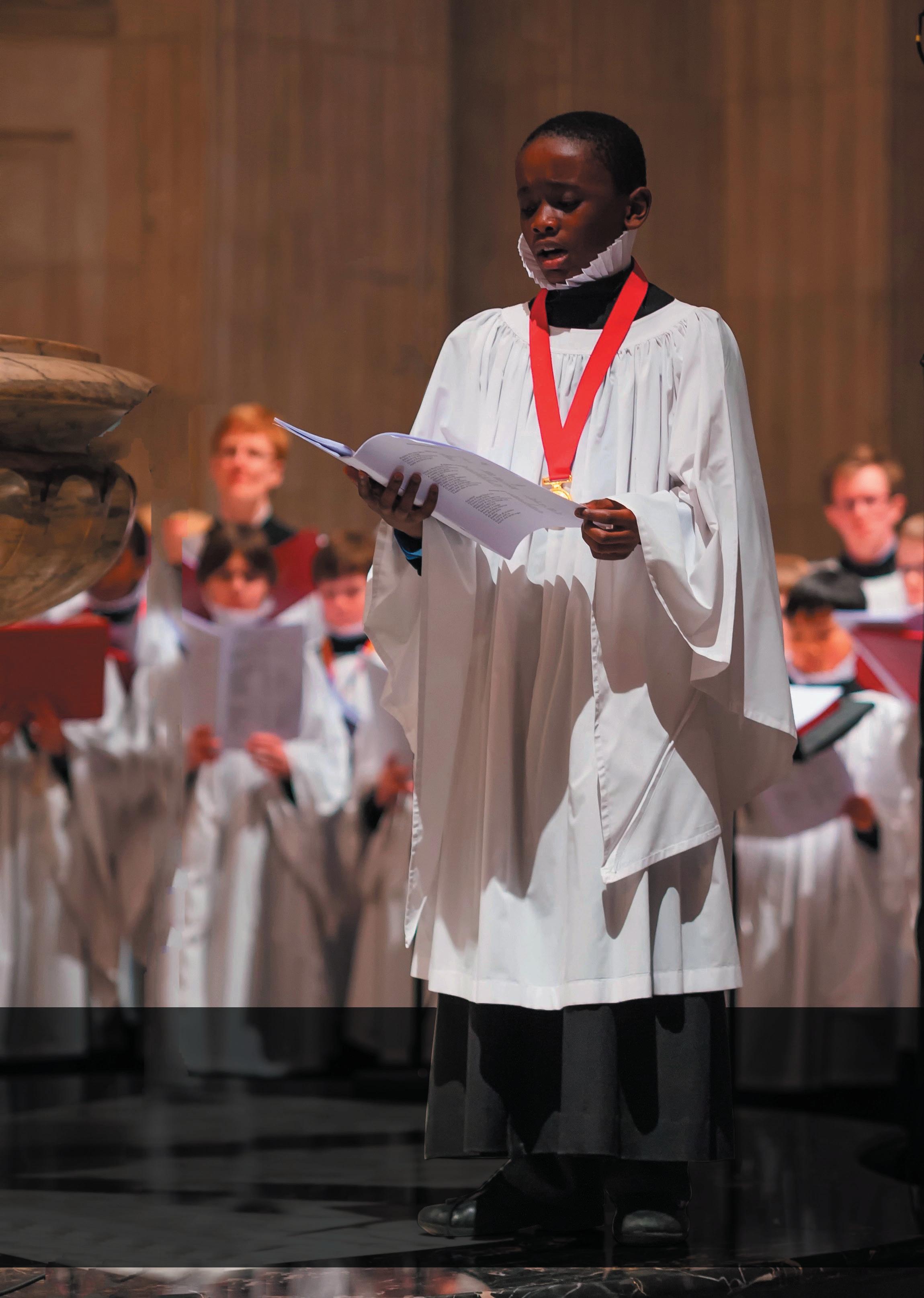

Substantial subsidy from the Cathedral puts this opportunity within the reach of many, many families. If you think you have a boy with a voice [we are looking for potential, not a trained singer] who ������������������������������������������������������������������ opportunity, why not bring him along for a formal audition? There is nothing to lose and a great deal that your son could gain. For more information please contact Laura Kemp.

01865 242561 registrar@cccs.org.uk

John was still composing at the time of his death, and many of the pieces written in the last years of his life deserve to be better known.Martin Neary was Organist and Master of the Music at Winchester Cathedral, and Organist and Master of the Choristers at Westminster Abbey.

I’d often passed Chelmsford on the train to Suffolk, but the cathedral didn’t really register with me, beyond a brief glimpse from the train window. I was baptised in Shenfield, just down the road, but grew up in Suffolk, from where I went to Southwell Minster as a chorister. After a varied career to date enjoying different positions around the country, it’s nice to be back in my home region and it’s a privilege to be working in this vibrant and positive atmosphere where the music is hugely valued, but never taken for granted.

Chelmsford was chosen as the cathedral for the new diocese of Essex and East London in the 1910s, fighting off competition from bigger but more remote churches in the county, and has seen a number of renowned organists over the last 100 years. Roland Middleton, Stanley Vann, Derrick Cantrell and Peter Nardone all spent valuable time here, and Philip Ledger, John Jordan and Graham Elliott also did a great deal to foster the musical establishment at Chelmsford. None has matched the longevity of Frederick Frye, organist at the time that Chelmsford Parish Church became the cathedral, who notched up 66 years of service!

Although small, the building is warm, light and welcoming, and as a result of the reordering and restoration, full of colour (there are striking icons and other artworks and the main ceilings are painted). It’s a world away from the dark, cluttered atmosphere that characterised the cathedral at its founding.

We marked the beginning of the cathedral’s centenary celebrations with a commissioned work from Jonathan Willcocks. The Temple involved the girls’ choir singing in procession along the length of the building, accompanied by brass, timpani and both organs (played from the chancel console). In May, a four-day music festival will showcase choral and big band music, silent films with organ accompaniment and more.

In November, as the climax of the choral foundation’s centenary celebrations, we are performing Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 with Canzona, a terrific Baroque ensemble that I’ve had the privilege of working with before. Also involved are the Chelmsford Singers, a secular choir in the city that I direct. I am intending to spread the performers out around the whole of the cathedral to create some spatial effects that we don’t often get to hear.

In addition, we will be broadcasting Choral Evensong on BBC Radio 3 – our first broadcast since my arrival -- and we also have a number of other exciting ventures planned for the months in between. (At the time of writing, the boys have just been invited to sing in Owen Wingrave at the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals.)

Our typical concert programme here is comprehensive. As well as performing larger works (and a regular performance

of Messiah), we take the opportunity to sing works with instruments that we might encounter in the liturgy. For example, in July last year we gave a performance of music by Britten which included Saint Nicolas, Rejoice in the Lamb (orchestrated by Imogen Holst) and his well-loved Te Deum in C in Britten’s own orchestration for string orchestra. To perform well-known choral works in this way can really change the way that one hears them and the sound world can be so different, as it was when we gave a concert of music from seventeenth-century Venice. Beatus vir sounds so much more exciting with period instruments, and although we can’t have them at Evensong all the time, the choristers don’t have to think too hard to remember what the cornets sounded like! It’s a valuable experience for choristers and audiences alike, and something that I remember well from my own time as a chorister at Southwell. I hope that our choristers will take the same inspiration from what we’re doing now.

The annual ‘Come and Sing’ events which the choral foundation holds – this year featuring Vivaldi’s Gloria and Pergolesi’s Magnificat -- have proved highly successful, partly from a fundraising point of view, but most importantly because they give the opportunity for large-scale choral singing to people who can only take part in such things on an occasional basis. Our many singers come from the west, north and east of London and thoroughly enjoy a good musical experience in a beautiful building like ours, working with professional musicians.

All this has to begin somewhere, so we hold two recruitment sessions a year for the cathedral choir (in spring and summer) and offer boys a taster session where they get to join a choir practice and then sing in the choir stalls with the choristers, with their parents watching. It seems to be a good hook: boys

here are clearly still keen to take part in voice trials, and the take-up figures are encouraging.

Recruitment would be much harder without the support of our schools and their teachers, particularly the two choral foundation schools that supply the majority of our boys at junior school age. I’m able to go into schools before the taster session and hear a selection of prospective singers and the more promising get a letter inviting them to attend the session in the cathedral. That said, we welcome auditions at any time of the year, and the girls’ choir operates on this basis. The bulk of the auditioning is done in the summer to replace leaving girls, but the occasional space opens up at other times and both ‘front row’ choirs are flourishing.

By far the hardest part of the chorister recruitment process for us is retention across the change to senior school. Chelmsford has excellent schools, but there are also a number of good selective schools just slightly too far away to allow boys who go there to attend morning rehearsals, so annually we lose at least one Year Six boy, which from the boy’s musical and developmental point of view is sad and frustrating. That’s the next challenge for us to tackle.

The timetable has developed well over the past few decades: Monday and Tuesday Evensongs are sung by boys and girls respectively. Every other Thursday is a men’s voices Evensong and the boys then have a 90-minute rehearsal; otherwise, services from Thursday to Sunday are sung by the boys and men, with occasional Saturday services and Mattins once a month. The girls’ workload is developing steadily: they have a morning practice before school, as well as another after Evensong, enabling them to look ahead through the term for the various extra services that they sing. There are sixteen girls, aged 10 – 18.

The back rows of the choir comprise a mixture of paid and volunteer singers. We have a flourishing choral scholarship scheme, taking gappies and post-graduates, and last year took the decision to double the number of choral scholars. There are tremendous benefits to being so close to London: it means that scholars are able to undertake further studies at music college or university and still get back here to sing, and it’s also very handy for lessons and concert work. We’ve had a great crop of past organ scholars, some of whom have gone on to become assistant directors of music in other cathedrals, which (I think) means that we have an important part to play in training future generations of organists and choir directors.

As if the back rows weren’t quite full enough, Chelmsford offers places to Junior Choral Scholars who, although still at school, are expected to fulfil the same obligations as the men. There is real value in this scheme as it offers a rigorous preparation for a gap year or university choral scholarship, in addition to the social benefits of learning to work with more senior and professional choir men. Past choristers are natural candidates for these scholarships, and although most tend to have a break of a year or two before re-auditioning, some have gone straight to the back row from the front. A very positive move has been to enlist a vocal coach for the choral scholars; this, combined with our geographical location and rent-free accommodation, allows us to offer young singers a valuable year (or two) to learn or refine their craft.

All of this excellent work takes a good deal of money to support and FCM have been very generous in their assistance, particularly of the choral scholars. At my installation service in September 2012, FCM presented a cheque for £20,000 towards the junior choral scholarship scheme. While this

doesn’t happen every day, it’s a sign of the great positivity that surrounds the music here, and we’re most grateful to all those who invest in the talents of our musicians.

Christmas is as busy and exciting as anywhere, but because Chelmsford is essentially a ‘one-room’ cathedral (i.e. it’s difficult to set the building for both Evensong and a carol service), the week is divided into two: Monday – Wednesday is given over to external carol services, and choral services resume on Thursdays. The girls’ choir joins the cathedral choir for the Advent Procession and a Christmas concert and then after Christmas sings for the Epiphany and Candlemas service. The cathedral choir sings at two Festivals of Nine Lessons and Carols, owing to our small size and the popularity of the event. The morning service on Christmas Day combines the parish and cathedral services, so it is packed and has a terrific atmosphere, but we’re all ready for a break by the end of it!

Perhaps a little unusually, we have a covenant with the Roman Catholic cathedral at Brentwood and enjoy good ecumenical relations, sharing a service at Pentecost every year, alternating venues and liturgies. Thus Evensong is held at Brentwood and Vespers at Chelmsford. A member of the visiting clergy team preaches and their choirmaster directs the joint choirs. It’s a great sign that both cathedrals are so committed to the covenant, and the RSCM locally mirrors the partnership: events are organised for churches in both dioceses and the Area Festival also alternates between the two

cathedrals, letting singers from both traditions experience something from the other. It’s easy to enjoy and even take that opportunity for granted as part of the cathedral’s mission, but it’s important for members of parish choirs to experience the same ecumenical opportunities and it underlines the good relationship enjoyed between the diocese of Chelmsford and its cathedral.

To cover choir holidays the cathedral has also a voluntary choir which gives an annual (and hugely well-attended) performance of Stainer’s Crucifixion on Good Friday evening and sings an evening service in the cathedral on Remembrance Sunday. There is a strong relationship with the Chelmsford Singers (mentioned above): the cathedral organist traditionally directs them, the organ scholar is the accompanist and several singers are also members of the voluntary choir.

All in all, the scale of the musical enterprise here is both impressive and realistic, given our resources. We have a very full choir diary, although there is usually just enough space for the occasional exciting ‘extra’. All our musicians (and their families) are so keen to make the most of the opportunities we enjoy that everything is approached with enthusiasm and care, whether we’re preparing for a concert, carol singing in the town, or a simple unaccompanied Evensong. I think that the devotion to maintaining a good musical tradition here must be one of the outstanding legacies of the last hundred years in Chelmsford and one that will surely last as a memorial to all those people who have contributed to it since 1914.

Education details:

Chetham’s School of Music, Manchester (2003-5)

Organ Scholar, King’s College, Cambridge (2006-10)

Career details to date:

Organ Scholar, St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle (2005-6)

Organ Scholar, Westminster Cathedral (2010)

Assistant Master of Music, Westminster Cathedral (2011-present)

What were your early music experiences?

My dad is a keen guitarist, and a big Status Quo fan – listening

to his record collection gave me a good grounding in functional harmony! Sunday Mass was the musical highlight of the week, so I’ve been interested in church music for as long as I can remember.

What or who made you take up the organ?

I remember being fascinated by the sound of the organ when I was a small boy. I always looked forward to the one Sunday a month when it was played at our local Catholic church for Mass, and I’d go upstairs to watch the organist at work. My father had a small half-size keyboard at home, and I began having lessons at a local music shop.

What stands out about your time at King’s? Did your commitments ever threaten to overwhelm you?

King’s is the best possible education for a church musician. Working with Stephen Cleobury every day was a privilege. I can’t think of anywhere else where you can have so great a range of musical experiences in one place – I remember playing second continuo in the Bach St Matthew Passion, the organ part of the Dvořák Stabat Mater, and the celeste part in Messiaen’s Trois Petites Liturgies, all within the space of a week, and on top of the regular round of services! Juggling all that with a degree is very challenging, but it certainly teaches you to organise your time and work efficiently. The big occasions like Christmas Eve and the Advent Procession were always extraordinary, but my favourite services were the quiet weekday Evensongs in January and February – a small congregation gathered in a dark chapel, with contemplative music on the list. I found the chapel at its most atmospheric on those evenings.

What are the particular challenges of the Edington Music Festival?

The Edington Festival has a very special atmosphere about it, as all the participants are there for the love of church music. They form three choirs – the Nave Choir of men and boys; the Consort of mixed voices; and the Schola, made up of men who sing Gregorian chant. For three years I was Festival Organist, and it could be tough to prepare all the music in a short space of time. The organ in Edington Priory was a twomanual Henry Jones instrument, which made some very nice sounds, but had no playing aids and was never designed to accompany large-scale choral music! Happily, the Henry Jones organ is now on its way to a new home in Tallinn, and a brandnew Harrison & Harrison organ is being installed before this year’s festival. Last year I became Director of the Schola, and I thoroughly enjoyed my first year with them. There’s a vast amount of chant to get through, as Mattins and Compline are sung each day by the Schola alone, and more complex chants are sung at Eucharist and Evensong. Having said that, performing great music in the heart of rural Wiltshire is a lovely way to spend a week in the summer!

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

I’m currently enjoying learning Bach’s C minor Trio Sonata BWV 526, which I’ll be playing at St Paul’s Cathedral as part of a series of recitals for the Sundays of Lent.

Have you been listening to recordings of them and if so is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

I’ve been listening to a number of different recordings, including those by Robert Quinney, John Butt, Simon Preston and Olivier Latry.

Do you do any conducting or teaching?

I conduct twice a week at the cathedral, and I’ve enjoyed taking occasional rehearsals for choral societies. Whilst I don’t do any regular teaching, I’ve found giving organ lessons very interesting – it really makes you think about your own playing and musical instincts.

What was the last recording you were working on?

The cathedral choir’s CD of James MacMillan’s choral music, including a number of pieces with brass and organ accompaniment.

What was the last CD you bought?

Two CDs of British organists of the early twentieth century.

What is your

a) favourite organ to play? I’d have to say the Grand Organ of Westminster Cathedral!

b) favourite building? Gloucester Cathedral

c) favourite anthem? It’s a tough choice, but I’d probably say Byrd Ne irascaris

d) favourite set of canticles? Howells St Paul’s

e) favourite psalm and accompanying chants? Am I allowed to say Dixit Dominus to Mode 1d ?!

f) favourite organ piece? Duruflé’s Prélude, Adagio et Choral Varié sur le Veni Creator

g) favourite composer? J S Bach

When was your most recent organ recital? Which pieces are you including?

I gave a recital at Westminster Cathedral on the last Sunday before Lent, when I played the Prelude and Fugue in A minor BWV 543 by J S Bach, Mozart’s Fantasia in F minor K 594, and the last movement of Vierne’s Symphony No. 6

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

Playing for the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols at King’s is a unique experience – no words can describe sitting on that organ bench at 3pm on Christmas Eve and seeing the BBC red light start to flash! A special privilege was playing for some of Pope Benedict XVI’s Mass at Westminster Cathedral in September 2010, a fortnight into my time as Organ Scholar. With the cathedral choir I’ve also taken part in two trips to Rome, including the Consistory in February 2014, during which I’ve had the opportunity to meet two Popes! As a Roman Catholic organist, there’s no greater honour.

What would be your Desert Island CD?

Probably Olivier Latry’s recording of the complete organ works of Messiaen. It’s such fascinating music, and I’m sure listening to it would keep one’s mind active on a desert island!

How do you cope with nerves?

Careful preparation is the only way to survive.

What are your hobbies?

I enjoy visiting monasteries and hearing Gregorian chant sung in its proper context. I’m interested in astronomy, although the centre of London isn’t the best place to observe the night sky! I also have a model railway, which is currently expanding at an alarming rate…

Do you play any other instruments?

I never learned an orchestral instrument, sadly, although over the last few years I’ve enjoyed playing the harpsichord, celeste and harmonium in different ensembles.

Would you recommend life as an organist? Absolutely.

What are the drawbacks?

Long hours of solitary work, often late at night in a cold building. But on the other hand, it’s wonderful to have a great building to oneself!

When I was appointed to New College at the age of 29, I could not believe my luck. In the scorchingly hot summer of 1976, as college lawns turned to stunted cornfields, I was coming to the end of a Cambridge junior research fellowship, and casting around for more permanent employment in the higher education sector. I had always kept up my music-making: lots of choral direction in Cambridge, two years in Paris studying organ with Marie-Claire Alain, a couple of organ LPs under my belt, and various publishing projects relating to performance. Some of this was likely to disappear on entering the HE sector, but I was able to wait for New College to make up its mind on its Organist vacancy. It duly did, more on a wing and a prayer, I sense, but a perfect decision for me. To be required by my employer to run a first-class college choir, with a reputation firmly established by H. K. Andrews and then Sir David Lumsden, to say nothing of Sir Hugh Allen, and then to contribute to the teaching of music undergraduates in a world-class university, was both a daunting and exhilarating prospect. I gave myself 10 years to do what I wanted to do. But I have stayed 38. I was having too much of a good time!

The first thing I noticed about the place was how different it was from Cambridge. New College was a much more formal, even abstract, place compared with my paternalistic Corpus Christi in Cambridge. And I was a greenhorn. It took me several weeks to persuade the domestic bursar of the day that I needed a telephone link in my flat, partly because he was a former naval Commander, and I a rating. Since then I have crawled my way up the ladder, and end now as Senior Fellow of the college. The great virtue of my cautious welcome was that I was left to get on with things. I had to contend with the then Dean of Divinity, who made the place feel at times glacial, and I’m not sure as a young man I knew how to deal with that. Most likely by getting drunk together, but we never did. The clerks of the day were fantastically patient as I got up to speed. And I recall sensing that the chapel operation was so well-drilled that it would look after itself. But I addressed the training of the treble voices immediately. I came in with all the bluff assurance of someone who had never done time in such an establishment, and didn’t really know, much less appreciate, what he might be overturning. David Lumsden had left me with a rising generation of choristers of great distinction, including the young James Gilchrist (I think I can say that I’m doing the same to my successor). So I was able quickly to produce from these boys the sound I wished to hear.

What about that sound? It’s been loved, liked, tolerated, contested. My objective was to have a top line (indeed a whole choir) robust enough to work on equal terms against an orchestra in concert halls (not simply engineered in the studio), and to have every boy in his last two years capable of singing a good solo, not just a bit of verse, but an aria. It didn’t always happen, of course, but it happened enough to allow me to make some early recordings for CRD Records with exceptionally demanding solo treble roles (notably the Western Wynde masses of Taverner and Tye). I’ve remained faithful to this ambition over my whole time here. Anyone who knows our recent recordings on the Novum label will know that our choristers take all the solo soprano roles, in works such as the Monteverdi Vespers, Mozart Requiem and Vespers, Couperin motets and Haydn Nelson Mass. This is

an approach I’ve extended also to the men of the choir. For me, New College Choir is an ensemble of solo voices, who (if you’re lucky) have the tact and discipline also to sing together -- in time, in tune, in balance. To get to that point with children, you need to give them some individual attention. Was New College the first such place to give its choristers regular solo singing lessons? I would be interested to know. But it was at least unusual in the late 1970s (whereas now of course it is commonplace). I also took lessons myself, and still do, with our present singing teacher, the wonderful Bronwen Mills, who followed the equally wonderful Colin Baldy. So New College trebles have vocal technique, and some of them turn out to be as accomplished as adult professionals.

An additional spur to finding a particular sound-world for New College was my experience of continental boy choirs. In the 1980s and early 1990s I led an International Academy of Children’s Choir Direction in Grasse (France). I heard at close quarters the work of Heinz Hennig (Hanover Boys), Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden (Tölz Boys), and Victor Popov (Moscow Boys). I encountered also the Escolania of Montserrat under the great Dom Segarra. One can’t hear these choirs and not be influenced. But one thing did strike me forcibly, particularly as a result of my work for the French government in its bid to re-establish choir schools in France: that the English system presented the perfect pedagogical tool for musical training. Such that, with its huge turnover of repertory, its daily routines and tasks, its selected numbers, its professionalised and supportive back rows, its frequent public performances, it was possible to echo in our work the purpose of choir schools so clearly articulated in the past: to provide an allround musical education for children. So, our boys know why they transpose certain pieces, they understand incipit clefs, they can turn a tremblement appuyé, they can hear a dominant ninth, they can appreciate the metrical and counter-metrical tread of a melodic line, and some of them compose descants -- to mention a few things at random. All New College trebles of my time will have inwardly digested their ‘Mini-mind’ (a comprehensive list of musical jargon for junior choristers), the most exotic datum being: ‘Direct – a sign looking like a worm that has hit a brick wall, signifying the pitch of the next note’. They never forget it! And that’s why I think a lot of them sing with real understanding, not only the understanding of which the famous RSCM prayer speaks, but the understanding that illuminates musical performance. If you need convincing of this, listen to what New College choristers can understand and then convey of the subtleties of the music of the esoteric Nicholas Ludford, their expertise quite rightly recognised in a Gramophone Award. No puppets on strings here.

This plays into what we choose to sing in our offices. We regard the whole of the Western European tradition of sacred music as relevant to our work. We can take an inclusive view of pre-Reformation music, and indeed of music written for other Christian denominations. And we don’t have to sing in English if the composer set Latin, French, German, Slavonic, or even Dutch texts. The size of our choir library has grown exponentially, as we continue to mine the riches of the Christian choral tradition. This makes us as much a cultural endeavour as a religious one, and as much an educational as a liturgical one.

These days, views on accessibility have greatly changed. On arriving at New College, it took me a little while to persuade

my colleagues that we might have a notice at the college gates cordially inviting visitors into our services: the prevailing view was that it was a private chapel. The choir rarely sang outside the chapel, but under David Lumsden’s guidance had begun the business of spreading its wings through recordings. Little by little it has not only become accepted that the choir should spread its wings, but highly desirable. These days we go on tour four or even five times a year (assisted in this regard by our relatively short – though intense – singing terms), and in my time we have made countless recordings (some 120 and rising). In the last few years we have started regular webcasts of our Evensongs. And of course the choir has a web identity, a Facebook presence, a Twitter moment. Taking our work out into the world at large is one of the most significant of the changes I have noted over the last 38 years. For some it will seem irrelevant, even perhaps questioning our core activity (singing the daily office); to others it is precisely what makes our singing connect with the modern world. Whatever the truth of these two views, I know that Christian faith and its liturgy lie at the heart of what we do. This is our irreducible asset. I also know that the experience of singing Messiah in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, followed the next morning by lively conversation around some van Goghs, is an indispensable enrichment.

Why should I give up doing this job, scarcely a job, more a way of life? A good question. It is the university’s policy to move us on ‘at a certain age’. I’m not opposed to that, arbitrary and wasteful though it may seem. I now have time to diversify, and to freelance, with plenty of active years of musical engagement ahead of me, and the opportunity to share the experience accumulated in my New College post. But, undeniably, I shall miss my daily routine with fine and motivated singers, and that indescribable privilege of singing John Taverner in a candle-lit medieval chapel when things do not simply ‘go to plan’ but transcend time and place. I have to accept that this is not likely to be a daily experience in the future!

Edward Higginbottom retires in July 2014. Robert Quinney is to be Associate Professor, and Organist and Tutorial Fellow in Music at New College. Robert is currently Director of Music and Organist at Peterborough Cathedral, where he directs the choir with both boy and girl choristers. He was previously Sub-Organist at Westminster Abbey. He was organ scholar at King’s College Cambridge (1995-98), and will be familiar to many for his performance in the organ loft at the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.

with a favourable acoustic. The Mansion House, designed by George Dance the Elder, was completed in 1752. It was built to occupy a very restricted site on what had once been a livestock market over the River Walbrook. It is now used as the Lord Mayor’s official residence and offices, and is therefore on a more domestic scale than Westminster Abbey’s Lady Chapel.

From the designer’s point of view, the more difficult of the two locations proved to be the Mansion House. Here, the organ was to be kept in the Salon, but when in use it was to be moved to the Egyptian Hall. The Salon is a large room

The Mander organ at the Mansion House and (inset) the bands of inlay to the sides of the keys

The Mander organ at the Mansion House and (inset) the bands of inlay to the sides of the keys

subdivided by many rows of columns, the spacing of which established the width of the case. The height was restricted by the need to avoid the very large chandeliers! Space was less of a problem in the Egyptian Hall, but clearly the organ had to be moveable.

The initial design of the organ showed a higher centre section with curved roofs to the sides, but this was not well received at Westminster Abbey. Mander therefore came up with a rectangular design which turned out to be more practical, especially when accommodating some later additions. The Surveyor of the Fabric at Westminster Abbey, Ptolemy Dean, reviewed the design and asked that the Bourdon pipes at the back of the organ be enclosed; as a compromise, an opening was left in the lower part of the back panelling to expose the pipe mouths of the lowest eight notes of the Bourdon and give them sufficient room in which to speak.

It’s a small organ (1280x1785x2720mm), with 11 stops. Given this size and the restrictions on the specification, the eighteenth-century chamber organ seemed to be a suitable model for the case, and the eighteenth-century influence is also evident in the two keyboards, which are designed with short keys and no overhangs. The key cheeks (the wooden pieces which sit alongside each end of the keyboards) copy early organ profiles but, in addition, have inlays made of various coloured timbers. The inlay work is based on that on a small G P England organ of 1806 which Mander restored recently. Baumgartner, who made the keys, suggested mitring the bands of inlay to the bottom of the lower manual only. The bands run down the edge of both of the key cheeks (see photograph on opposite page) and then return at the bottom edge of the lower keys. The result is colourful and looks very smart.

The pedalboard is flat with a narrow spacing, and the pedal sticks are kept short. The result neatly fits just within the width

There is one particularly unusual feature: a Nightingale stop. John Mander had considered adding both this and a Drum stop to the organ. In July 2012 he attended the International Society of Organbuilders’ Congress in Switzerland where he heard an organ which has a Rossignol stop. On this organ the stop activated three birds, which appeared bobbing up and down at an opening in the casework. Inspired by this, it was decided to include the birds on the Nightingale stop, and a mechanism was created. The revolving birds are fixed to a fan, which is blown by wind when the stop is drawn on. In addition, the wind inflates a small bellows, which raises the birds so that they can be seen above the cornice. For the sound there is the usual arrangement of pipes inserted upside down in a container of liquid. This is mounted low down in the case for ease of access. The Thunder or Drum stop is activated by a hitch-down pedal to the bass side of the case above the pedalboard; this moves a steel trundle with a wide slotted plate, which progressively pulls on the trackers for the bottom six notes of the Pedal.

(Alderman Roger Gifford) at a special workshop concert given by William McVicker. Further recitals were given by organists of the Chapels Royal and the Royal Peculiars. All proceeds were donated to the Lord Mayor’s Appeal 2013, which aimed to secure the future for the next generation by supplying more music, lifting children out of poverty, safeguarding the environment, and protecting and enabling access to art in all its forms. The principal beneficiary of the Lord Mayor’s Appeal 2013 is the City Music Foundation, a charity established to give new opportunities to aspiring professional musicians in the early stages of their careers, both financially and through mentoring.

Playing the opening recital on the new Mander organ in the Mansion House was a real pleasure. The tone matches the elegance and character of the beautiful case. The heart of the organ, the Diapason chorus, is rich, bold and characterful. The Mixture is well balanced, adding both brightness and strength to the chorus. The Diapason is warm and forthright, and the flute is colourful and expressive.

On Manual II the Recorder is especially beautiful. The Trumpet has a lively response with a good bass which is useful in adding depth to the tutti. I played the Adagio from Mendelssohn’s Second Sonata on the Sesquialtera, which provides good colour with a rich tone in the lower register and a singing elegance in the upper register. The Chimney Flute 4 sounded a little unsteady in legato music, but it was excellent for Daquin’s The Cuckoo (which I played as an encore), having a real clarity of touch and good expression.

The Pedal Bourdon is a clever stop, able to play quietly with clarity but also support the fuller chorus in louder tuttis Inevitably the Pedal division is a little restricted -- from the player’s standpoint it would have been useful to have the Trumpet and/or other stops available separately on the pedals to give more independence to the bass line.

The action is even and responsive, giving a very expressive connection with the note. At times I found it just a little light though no doubt this is inevitable with a smaller organ. Occasionally I coupled Manual II to Manual I as this extra depth was just a little more satisfying to play with and easier to control. The Nightingale stop is very effective and enjoyable and caused quite a few chuckles! Generally the instrument is very pleasing, although the organist must make allowances for its size and historically-informed mechanical design. At 5’8” -- average height for a man in the 21st century -- I did find the drawstops and the drum effect lever somewhat difficult to reach comfortably while playing.

Overall, the organ belies its small specification; it was a joy to play and easy to make music on. There was singing tone in the Thiman, for instance, and a transparency in the flutes which was very engaging. The organ was at its best playing Bach and Handel, and the Mendelssohn (Sonata No. 2) was also very convincing. Congratulations on the wonderful craftsmanship and artistry to all who were involved in the making of this beautiful instrument.

Overall, the organ belies its small specification; it was a joy to play and easy to make music on.Huw Williams is Sub-Organist at Her Majesty’s Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace, London. Lower console area showing brass toe pedals for the playing aids

There can be few organ lofts or organists’ music cases which have not, over the past eighty odd years, been graced by one or more volumes of Percy Whitlock’s attractive music. The various collections of shorter pieces have withstood the vagaries of fashion particularly well, perhaps because the wide-ranging usefulness of these organ miniatures means that they serve just as happily as voluntaries as recital items.

Whitlock’s sacred choral music has, on balance, fared less well. How often is his Solemn Te Deum performed these days, despite its fine construction and strong motivic development? The Three Introits, however, are regularly sung, making highly effective Communion motets, with their blend of sensitive word-setting, warm textures and gentle modulations. The early Jesu, grant me this, I pray and the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis – Fauxbourdons also make regular appearances on the service lists of those Anglophone ‘quires and places where they sing’.

Whitlock was, of course, writing for a fairly crowded market. Church choir libraries were already well filled with copious amounts of Bairstow, Boyce, Ireland, Purcell, Stainer, Stanford, Walmisley, S S Wesley, Charles Wood, and even early Howells (one hopes!). Whitlock’s earliest publications were exclusively choral: a set of canticles and a Motet for a Saint’s Day for SPCK, and a host of Anglican canticles and anthems published in the late ’20s and early ’30s by OUP, following in the footsteps of his ‘musical father’, Charles Hylton Stewart, who had done so much to train and encourage the youngster during his tenure as Organist of Rochester Cathedral from 1916-30. Hubert Foss (OUP’s founding music-department manager) had first refusal on anything Whitlock composed, taking several important orchestral scores (in manuscript) into the Hire Library, in addition to the longer recital organ works such as the Two Fantasie Chorals and the magnificent Organ Sonata (Whitlock’s longest composition). By the late 1960s these last pieces had fallen out of print. They were rescued from neglect in the early 1980s through the support of the Percy Whitlock Trust, the brainchild of Robert Gower, which – since 1983 – has done so much to restore Whitlock’s musical reputation by bringing little-known compositions into print and by subsidising recordings, concerts, organ scholarships and bursaries, exhibitions and the like.

The Whitlock Trust’s first patron was Percy’s widow, Edna (1901-93), who outlived her husband by 47 years. The Trust

was fortunate in having the late Christopher Dearnley, Organist of St Paul’s Cathedral, as its chairman; his energy and enthusiasm ensured that the Trust was put on a firm footing. The Trust has also been fortunate in having had the active support of so many fine musicians over the years, some – like Leslie Barnard – who knew the composer well, as well as those of the younger generations who recognised in his music a kindred spirit and began to promote it through broadcasts, recitals and recordings.

Long-lost manuscripts resurfaced. Many of them have subsequently been lodged in the British Library. The rediscovery of Whitlock’s personal diaries in 1990 was another major breakthrough, especially to the present author who, since his undergraduate days, had pondered the possibility of writing a book on Whitlock. This volume eventually appeared in 1998 and was launched at the May Festival held each year in St Stephen’s Church, Bournemouth, where Whitlock served as Director of Music from 1930-5 (and indeed there is an annual Whitlock Recital). Further musicological and editorial work produced a volume of the surviving piano and harpsichord music (published by Animus), and a set of Four Transcriptions for Organ (made by the present author) from original orchestral scores, as well as a Percy Whitlock Companion, which gathered together much of his surviving correspondence and organrelated articles for the Musical Times and Musical Opinion

Whitlock’s music continued to appear in broadcast recitals by (among others) George Thalben Ball, Francis Jackson, Philip Dore, Ernest Maynard, Douglas Hawkridge and Roger Fisher, providing a welcome extra trickle of PRS-derived income for Edna Whitlock. The tide seemed to turn decisively for the better in the late 1970s with the release of Graham Barber’s pioneering Sonata recording from Coventry Cathedral for Vista, and Robert Gower’s all-Whitlock Wealden Studios disc from St Stephen’s Church, Bournemouth, which included both Fantasie Chorals, played on the same instrument for which they had been conceived.

All three of Whitlock’s major organ works now became available in authoritative stereo recordings. The advent of the compact disc released a flood of new digital recordings, including Jennifer Bate’s recording of The Plymouth Suite for Hyperion, and Roderick Elms’ all-Whitlock disc from Rugby School chapel. Graham Barber went on to record the complete organ works for Priory Records over three CDs, whilst Roger Sayer guided Rochester Cathedral Choir through a wide

selection of the sacred choral music, including the hauntingly simple setting of O Gladsome Light, composed whilst Percy was still a boy treble at Rochester.

Bournemouth’s Food Control Office, as well as fulfilling night-time fire-watching duties.

All of this took its toll. In his last years he aged rapidly, suffering from increasingly high blood pressure and a ‘groggy’ lung. His death, just a month short of his forty-third birthday, came on 1 May 1946 (the same day as Bairstow). To his RCM contemporary, Robert Featherstone, Whitlock was a ‘musician and composer of rare quality’; to his friend Leslie Barnard, ‘a composer of very real merit’. Felix Aprahamian considered him the ‘Roger Quilter of the organ world’ – a rather limited description, perhaps, given the range and scale of his musical expression. Certainly, there is a great deal which is song-like about Whitlock’s melodic gift. He also distilled much from Handel (the lovely Poem for organ and orchestra of 1937 is a homage to the Baroque master’s celebrated Largo, which Whitlock recorded with the Bournemouth Orchestra under Godfrey in 1934 -- his only commercial recording with them), as well as Delius, Elgar, Rheinberger and Rachmaninov, whose ‘gorgeous’ Second Symphony bowled him over and provided the stimulus for his own organ Sonata

Whereas the financing of a solo organ or choral recording is usually readily achievable, subsidising orchestral recordings takes one into a higher and tougher league. It was, therefore, a great boon when the opportunity arose to record Whitlock’s lighter orchestral scores in Dublin with the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, conducted by the indefatigable Gavin Sutherland. This disc (now on the Naxos label) revealed not just how skilled Whitlock was at capturing a mood or a scene but how assured he was as an orchestrator.

From the late 1930s Whitlock often adopted the nom-de-plume Kenneth Lark for his non-organ music. Having relinquished (with great relief) his church position at the end of 1935, he relished the wider opportunities afforded him in his new fulltime position as Bournemouth’s Municipal Organist. From his perch at the console of the Compton organ, situated to the side of the orchestra pit in the Bournemouth Pavilion, he was able to spend many hours absorbing a wide range of music. Although he never broadcast as a theatre organist (referring to them as ‘denizens of the underworld’), he venerated such giants as Sidney Torch and the mighty Quentin Maclean. His fruitful association with Bournemouth’s Municipal Orchestra led to several commissions from the orchestra’s first three conductors, Sir Dan Godfrey, Richard Austin* and Montague Birch. Whitlock also played at various times for Dr Adrian Boult, Dr Malcolm Sargent, Sir John Barbirolli, Sir Thomas Beecham and Sir Henry Wood, who invited him to the Proms in 1942 as soloist in Handel’s Organ Concerto in B flat major. This performance, together with some other 120 BBC broadcasts (60 of which were solo recitals) meant that Whitlock’s name as a player stretched far and wide.

Quite how he managed to fit all of this into a busy life is still a puzzle. Despite a history of delicate health (which included a spell in Midhurst’s TB sanatorium in 1928), Whitlock found time to write a great deal of musical journalism (including three years as music critic for the Bournemouth Daily Echo), to teach privately and to collect and restore clocks. Much energy was spent on the construction from Meccano of a multipurpose chronometer and the installation of a 3-manual pipe organ in his Bournemouth home. Declared unfit for military duty, he served for the first two years of the war in

Percy Whitlock had a versatile and essentially gentle musical spirit. Just a few bars of his music can summon up the ambience of a lofty English parish church or cathedral or the ozone-laden salty air of the seaside. Such versatility is a rare gift.

*Whitlock can be seen briefly playing with the Municipal Orchestra conducted by Austin in six short musical features made by the Pathé Film Company in 1937. These have been posted on YouTube.

Programme to include:

Bach B Minor Mass

Britten War Requiem

Elgar The Apostles

Mahler Symphony No 2

Rasch A Foreign Field (World Premiere)

Guest artists:

Sarah Connolly

Håkan Hardenberger

Tenebrae

The King’s Singers

John Wilson

Percy Whitlock had a versatile and essentially gentle musical spirit. Just a few bars of his music can summon up the ambience of a lofty English parish church or cathedral or the ozone-laden salty air of the seaside. Such versatility is a rare gift.

Until 2008, there was one sung service a week in the chapel, and the choir was directed by the organ scholar. The success of the music over these years is partly attributable to a partnership between Organ Scholar and Chaplain; the two chaplains who have served the college since 1963 are both fine musicians and experienced organists. Then in 2006 Peter Phillips, already known to the college through his regular visits with The Tallis Scholars, made the suggestion that a chapel of the significance and size of Merton’s should have a more developed choral scene. The then warden, Dame Jessica Rawson, and the chaplain, the Revd Dr Simon Jones, were receptive to this idea and the college agreed to fundraise to endow eighteen choral scholarships along with the posts that Peter Phillips and I now hold. In October 2008, the new college choir sang its first services (initially on Wednesday and Sunday evenings) and in 2012 I left Tewkesbury and Dean Close to work full-time at Merton, which is when the pattern of singing on Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday (with a termly Compline on Mondays) was established. In addition to leading the worship in the chapel, the choir undertakes the usual activities of touring (Sweden and the USA this year), recording (for Delphian) and broadcasting (most recently on and Radio 3’s Britten 100th

The number of applicants for choral scholarships has steadily risen since 2008. Visits by the National Youth Choir and the Eton Choral Courses along with various open days have inspired potential candidates to consider Merton, and now our choir includes a number of former boy and girl cathedral

anniversary of the college has been on the horizon since I started working at Merton, and it has proved to be a tremendous opportunity for the choir. At the heart of the , the brainchild of former

Many of the leading composers of the day are represented in

Organ Scholar and BBC producer, Michael Emery. The idea of a collection of choral music is not a new one: early Tudor anthologies, pre-eminently the late fifteenth-century Eton Choirbook, were substantial musical monuments in their own right and also created a rich legacy that defined the characteristic sound and style of English church music. More recently, the coronation of HM The Queen in 1953 inspired the collection A Garland for The Queen. Ten composers –including Vaughan Williams, Howells, and Mertonian Lennox Berkeley – contributed mainly secular songs for mixed choir. For the sixtieth anniversary of The Queen’s accession to the throne, Peter Maxwell Davies and Robert Ponsonby had the idea of presenting Choirbook for The Queen. This collection of 44 pieces, including 11 commissions, not only celebrates the reign of Queen Elizabeth but also the British choral tradition. Merton College Choir was one of eighty cathedral and collegiate choirs asked to sing from this collection during the course of 2012.

Many of the leading composers of the day are represented in The Merton Choirbook They include Sir Harrison Birtwistle, who has set a text by Sir Geoffrey Hill, Oxford’s Professor of Poetry, James MacMillan and Jonathan Dove. Within the collection there are some particularly interesting groups of pieces. Four female composers, including Judith Weir, have each set one of the Marian antiphons; seven composers have each written one of the Advent antiphons, with John Tavener and Cecilia McDowall heading the list. Music for Choral Evensong is also included within the Choirbook, with Preces and Responses by Matthew Martin, a hymn by John Joubert, and numerous new Anglican chants from composers who principally write for the church. Peter Moger, Precentor of York Minster and an Old Mertonian, has composed responsorial chants for all

of the psalms set for the college Eucharists throughout 2014. The evening canticles appear both in Latin and in English, and a number of anthems suitable for the different seasons of the liturgical calendar make this collection something that we will draw on through the year. The new Dobson organ has inspired some of the music, including David Briggs’s Messe Solennelle and Chorale Preludes by John Caldwell and Gabriel Jackson, composed as part of William Whitehead’s Orgelbüchlein Project