CATHEDRAL MUSIC FCM 60 YEARS

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2016

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon grahamhermon@lineone.net

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Tatton Media Solutions, 9 St Lawrence Way, Tallington, Stamford PE9 4RH 01780 740866 / 07738 632215 wesley.tatton@btinternet.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

In the summer of 2016, the Selby Abbey Trust has arranged a series of Celebrity Organ Recitals to be performed on the Custom Built Regent Classic Organ by Viscount installed especially for this concert series, while the historic William Hill organ undergoes restoration by Principal Pipe Organs of York.

Win a £10,000

Take part in our Digital vs Pipe Organ online aural test to win the Envoy 35-F

www.viscountorgans.net/theorgan

June 7th Roger Tebbet, Selby Abbey

June 14th Paul Derrett, Hull

June 21st Joshua Stephens, Sheffield Cathedral

June 28th Graham Barber, St Bartholomew’s, Armley, Leeds

July 5th Colin Walsh, Lincoln Cathedral

July 12th John Scott Whiteley, Organist Emeritus, York Minster

July 19th Franz Hauk, Ingolstadt Minster

July 26th Charles Harrison, Chichester Cathedral

August 2nd D’Arcy Trinkwon, Worth Abbey

All recitals commence in the Abbey at 12.30

This prestigious series of concerts will feature cathedral and concert organists from the UK and from Europe who are among the most distinguished performers in the world.

For further information and a complete programme itinerary, please visit www.viscountorgans.net

This year FCM celebrates 60 years since its inception in the St Bride’s Institute, the building next to the church (which was being rebuilt after the war) off Fleet St. Ronald Sibthorp, precentor at Truro Cathedral and writer of the original letter to The Times and other papers, bemoaned the paucity of weekday services in UK cathedrals and suggested, to combat the severe drop in standards caused by two world wars, the formation of a new society to be known as The Friends of Cathedral Music.

From small acorns grow large oaks. FCM’s 60th year promises to be its most glorious, and with two magnificent concerts in London, at St Paul’s and St Martin-in-the-Fields (the St Paul’s concert was on 27th April; the St Martin’s one is 24th June – details can be had from the SMF website) and many National, Regional and Local Gatherings taking place, there is no chance that our aims will go uncelebrated. In addition, the St Paul’s concert is a fund-raising event for the Diamond Fund for Choristers, which has been set up in order to provide bursaries for choristers and to relieve hardship with targeted grants. The intention is to raise £10 million by 2020. Of course, the fund needs all the monetary support it can get, but one of the most valuable ways in which members can help is by recruiting more members. Try bringing a friend to Evensong, or invite people to a London or Liverpool concert, or pass on your copy of this magazine to an interested party (spare copies can always be obtained from me for this purpose. They are generally available at the Gatherings too.)

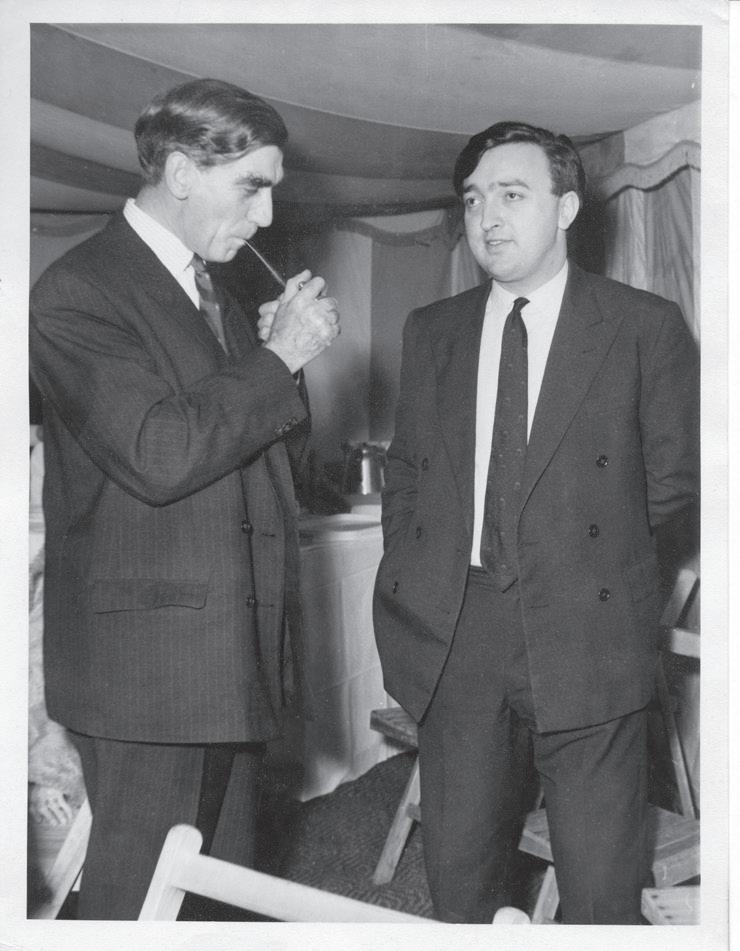

One of the conductors at the concert at St Martin-in-theFields is to be the FCM President, Christopher Robinson, who retires this year after 12 years in post. Well known, of course, for his fine music-making at Worcester Cathedral, St George’s Windsor and St John’s College Cambridge, Dr Robinson’s remarkable career has been encapsulated in these pages by Roger Judd, a reviewer for CM and a colleague of Dr Robinson’s at St George’s. We shall miss Dr Robinson sorely when he leaves us in June.

I have remarked in the past on the extraordinary sway that the cathedral music world holds over its denizens. For a demonstration of this you should read the article by Richard Shephard on his fifty years – so far – spent at Gloucester, Salisbury and York. Although a teacher, and latterly headmaster of the Minster School at York, his life has encompassed a happy mixture of singing, composing and music-making (and, of course, teaching...) Matthew Martin is a few years behind Richard, but has already made a considerable stir with his compositions. His colleague at Edington, Jeremy Summerly, has snatched a moment from his own busy schedule to talk to Matthew about getting published, compositional inspiration, about Matthew’s new life at Keble, and .... Michael Jackson!

Lastly, the wonderful organs of Cavaillé-Coll. Their development in the latter half of the 19th century is a fascinating story of the dominance of one man, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. Without him, the world of cathedral music would undoubtedly be a very different universe. For those to whom his organs are an unexplored landscape, this article is a revelation.

Sooty Asquith• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

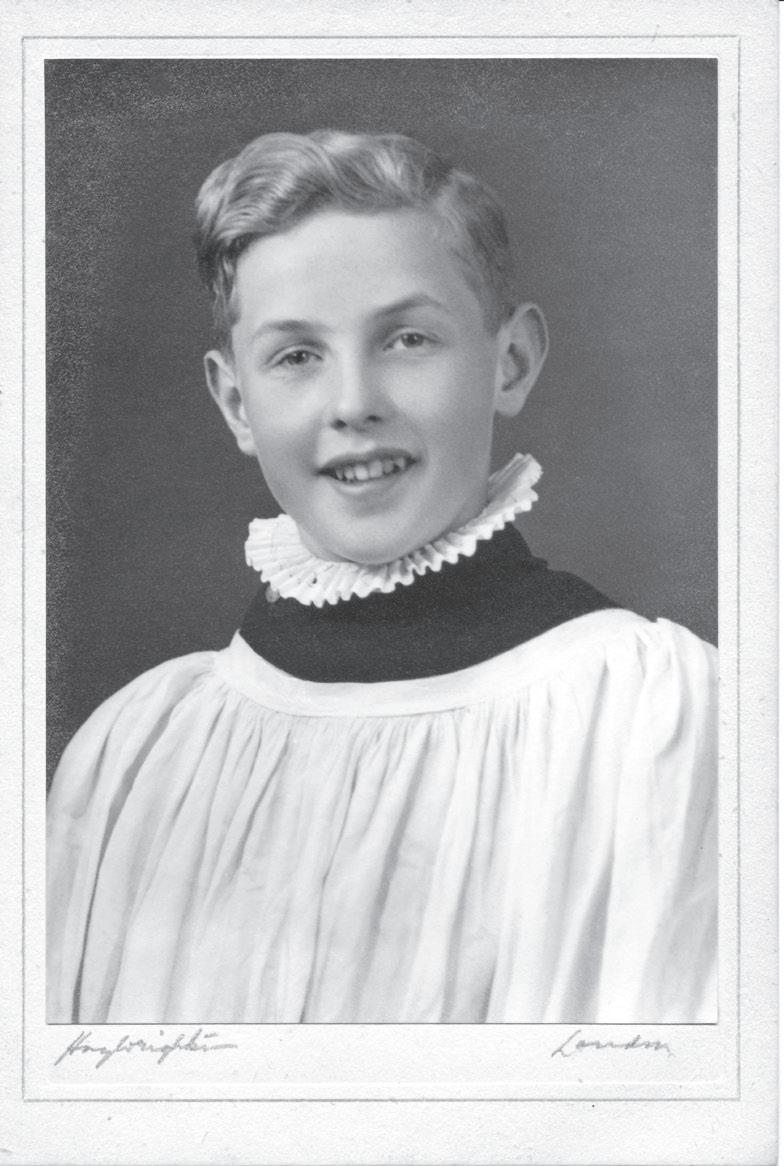

Christopher Robinson was born in April 1936, in Peterborough, where his father was a minor canon in the cathedral. Henry Coleman, the cathedral organist, was his godfather. His father had a good voice to sing the services, and he also played the violin, while his mother played the piano and also sang. She was a gifted teacher, and a fine cook.

When Christopher was about 18 months old, his father moved the family to the parish of Quatt, a small village in Shropshire between Kidderminster and Bridgnorth, to be nearer to his wife’s family. Around the age of four Christopher started to have piano lessons with Mamie Carter in Kidderminster. “I didn’t care much for practising,” Christopher remembers, “so, to encourage me, from an early age my father used to take me to his church in Quatt. There I was allowed to play the organ, a 2-manual Bevington which was hand-blown by my father.” Christopher was able to play hymns which his father had simplified for small hands (but as yet no feet!).

The young Christopher went to school at St Michael’s, Tenbury, which had come to his parents’ attention through one of his mother’s relatives who lived in Tenbury. At the age of seven (1943) he was taken to Maurice Bevan, of the famous musical family, who lived at nearby Quatford Castle, where he was given a lesson or two by way of preparation. Then he was taken to sing to Sir Sydney Nicholson, who was running the music at the college for a time during the war, and joined the college in May that year. By then C E S Littlejohn, an avuncular figure, had taken over as director of music and composer of an anthem, Lord, I am not high-minded, which Christopher particularly remembers amongst his compositions that were sung.

St Michael’s was a happy place for Christopher: not only was he able to play a great deal of music, but cricket filled his summers! The Warden (headmaster) when he started was Dr Billen, a scholarly man who taught the top forms all the major subjects. At Tenbury Christopher took most of the Associated Board exams, passing Grade VIII before leaving.

The return from war service of the choirmaster, Maxwell Menzies, was an important moment, and Christopher absorbed a lot from him. Menzies was a strong disciplinarian and improved the choir no end. He introduced many of the boys to all sorts of music, which, armed with miniature scores, they listened to on gramophone records. Christopher learnt the piano and organ with him, though for some time

he still couldn’t reach the pedals. He worked his way through the bound copies of ARCO score-reading and transposition exercises that were on the shelves, and started playing the organ in the church for services. By singing in the choir he 5-part Mass (sung in English, as was the way then), Harris’s Faire is the heaven, VW’s Te Deum in G, and of course Dering’s Factum est silentium at Michaelmas. The BBC made several programmes with the choir, and Christopher remembers the Warden singing Love bade me welcome very beautifully. Tenbury was also where Christopher realised that he had perfect pitch, which was a bit of a trial there as the organ was significantly sharp!

After Tenbury, what next? “The examiner for my Grade VII piano was Kenneth Stubbs, who was Director of Music at Rugby School. It’s possible that he put the idea of Rugby as a next step into my parents’ heads,” Christopher goes on. “Winning a music scholarship there opened up new horizons. An early memory is of listening to rehearsals of the excellent school orchestra, whose programme in my first term was Elgar Cello Concerto, Sibelius’s 2nd Symphony, and Borodin’s Prince Igor Overture. This really blew me away.” Whatever the reason, the school’s very fine orchestral repertoire made a big impact on him. In order to immerse himself in this new soundworld

he took up the cello, and joined Richard Lloyd (later at Hereford and Durham Cathedrals), an excellent trombonist, in the orchestra. Cricket also featured strongly in the summer term and eventually he made it into his house first team.

The Director of Music deemed that Christopher couldn’t play the organ for two years as it would spoil his piano technique, which, in retrospect, Christopher thinks was probably a good thing. When he did resume playing he soon passed his ARCO (in 1952), and the playing part of the FRCO in 1953. Though success in the paperwork eluded him, there was an amusing spin-off. One of the tests was to write a part-song. “I thought mine was quite good, so I took away my rough workings after the exam, and not long afterwards Novello’s published it!” Christopher recalls. His father arranged lessons in the paperwork with Ambrose Porter (Lichfield Cathedral), which saw him through to the full FRCO before leaving Rugby.

Christopher played for many of the chapel services, including the ‘big’ occasions like the carol service, helped take sectional rehearsals, and memorably put on a performance of The Mikado with the late Rodney Milnes, a contemporary of his, and later to become a distinguished opera expert and critic; Christopher arranged the orchestral part for two pianos.

When Christopher went up to Oxford in 1954, the organist was Thomas Armstrong, a distinguished figure with a wideranging musical and scholarly mind. Latin Masses were sung every Sunday, and for these the choir used to sing near the altar where the acoustic was kinder. The senior scholar at Christ Church was Harrison (Fred) Oxley, and Christopher and he quickly became very good friends. In the faculty, harmony and counterpoint were no problem, but the history of music brought on despair. During his first year he sang in the Oxford Bach Choir (OBC), which Armstrong conducted. “Armstrong was very good on the educational aspect of this job,” Christopher says now. “He wanted to share his enthusiasm and love for the music being worked on, even getting the choir to sing the arias en masse so they immersed themselves in the whole work.”

After Christopher’s first year, Armstrong became Principal of the Royal Academy of Music and Sydney Watson, who also conducted the OBC, took his place. Watson too had a great enthusiasm for what he was doing, and was both a good tutor and a good conductor. He stammered, and that, coupled with a superb sense of humour and brilliant timing, led to some hilarious moments. As was the way at the time, Watson did much of the organ playing, only leaving the loft when unaccompanied music needed to be conducted. Christopher took every opportunity he could to make music, playing the piano, working with chamber choirs and playing cello in various instrumental groups.

A significant change in his musical life occurred with the arrival of Meredith Davies as organist of New College in 1956. For the first time, when he played in a performance of Bach’s Third Brandenburg Concerto, Christopher saw a professional conductor at work. Davies took over the City of Birmingham Choir (CBC) from David Willcocks. “I often attended his rehearsals,” says Christopher, “and this got me involved playing keyboards in the CBSO, which started a relationship with the orchestra and choir that lasted many years.” He saw at first hand Davies’s work with the New College Choir – he didn’t care for undergraduate organ scholars, preferring a slightly older, more experienced musician, so in his fourth (BMus) year Christopher played at New College and attended his rehearsals. Davies worked hard on the boys, getting them to breathe properly and form ‘correct’ vowel sounds, and shape musical lines.

Oxford was also where Christopher met his wife, Shirley. The professor, Sir Jack Westrup, conducted the university orchestra, and Christopher played cello and then double bass. Westrup put on a performance of Verdi’s Macbeth in which the young Heather Harper was the lead soprano. “Shirley was one of the witches!” Christopher laughs. “She was in the year above, also reading music, and because she sang (alto) in lots of choir groups, our paths often crossed. She did her Dip. Ed. and then got a job in the Midlands as Director of Music at Bilston Girls’ High School, which was very convenient!”

After he graduated, Christopher also did a Dip. Ed., but in Birmingham – by then Shirley had joined the CBC. Meredith Davies got him involved with the choir, taking rehearsals and playing sundry keyboards in the CBSO. Then he took his first job, which was as an assistant music master at Oundle School with Robin Miller (DoM) – Graham Smallbone (later at Eton College) taught the cello – and he was there for three years.

Thereafter he left schoolwork, mainly because he had always wanted to work in the cathedral world. A letter arrived one day from Douglas Guest saying that Edgar Day was retiring, and would he like to go to Worcester Cathedral for an interview, which he did, becoming Assistant Organist in 1962. The boys at the cathedral were excellent, and the Festival Choral Society was huge – almost 300 singers – and Christopher really liked Douglas, who became a very good friend. “He was an adventurous programme planner,” Christopher remembers. “One of the earliest performances of Britten’s War Requiem was conducted by him as well as Stravinsky’s Canticum Sacrum and the Poulenc Gloria, which was then very new.” Christopher was very much involved with the preparation of all these. A new opportunity arose when he became Assistant Conductor of the CBC in 1963.

After that, things changed somewhat, as Guest was appointed to Westminster Abbey, and Christopher was promoted at Worcester (1963). The first thing he had to do was appoint his own assistant – Harry Bramma, who had been a contemporary of his at Oxford, and was at that time DoM at Retford Grammar School. They had a great rapport, as can be heard on some of the recordings they did together with the choir (Elgar and RVW especially), and Bramma had many wonderful musical enthusiasms which he enjoyed sharing with his students. Christopher’s choristers and pupils, many of whom are now familiar names in musical circles, were “a great lot”.

Part of the job, of course, at Worcester, was planning and directing the Three Choirs Festival (TCF), which he did in 1966, 1969 and 1972. When he started at Worcester, his colleagues were Melville Cook at Hereford, and Herbert (John) Sumsion at Gloucester, both of whom welcomed him warmly, and did not treat him as the novice he obviously was. After a few years, Cook and Sumsion stood down and were replaced by Richard Lloyd (Hereford) and John Sanders (Gloucester). Christopher’s programming policy was, as much as possible, to include pieces that hadn’t previously been performed at the TCF. For example, Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts, Tippett’s A Child of Our Time, Penderecki’s Stabat Mater and Janacek’s Glagolitic Mass. There were also commissions like Jonathan Harvey’s Ludus Amoris

One of the problems with the TCF at that time was that there was too much music and too little time to rehearse it properly. Pre-1950 there was so-called ‘Black Monday’ at the beginning of the festival week when everything for the whole week had to be rehearsed in a day, which was crazy! They would try and cover the ‘novelties’ in some detail, while pieces like Gerontius and Elijah would have had scant attention – a situation difficult to imagine today. Gradually things improved, but getting adequate rehearsal time on days when there were two concerts was never easy.

Work with the CBSO continued, and he had a good rapport with them. “Conducting was something I just picked it up ‘on the hoof’, although Meredith Davies at the CBC gave me a lot of help, as did Sir Adrian Boult, and I learnt a great deal just by watching them,” Christopher says. His early keyboard work with the CBSO meant that he knew the players personally, so standing up in front of them when he took over the CBC from Meredith Davies was less daunting than it might have been. “Also, I was aware that orchestral players are critical of choral conductors who give all their attention to the choir and ignore the players. I wanted to have the choir sufficiently well rehearsed so that I could attend to the orchestra, who may be seeing the music for the first time,” Christopher remembers. He gained greater artistic freedom with the CBC and the CBSO than he would ever have done with the TCF, and couldn’t, for example, have done Tippett’s A Mask of Time and Messiaen’s La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jesus-Christ in a TCF programme; there just wouldn’t have been enough rehearsal time. The CBC also did Delius’s Mass of Life several times, once jointly with the OBC.

Although not necessarily looking for a move, in 1975 Christopher went to Windsor Castle as Organist of St George’s Chapel following the death of Sidney Campbell. “The invitation to apply was too good to ignore!” he recalls. Initially he was worried that he might miss the TCF, but having taken over as conductor of the OBC some months earlier, he was not going to be short of outside work. “The St George’s choir was not in very good shape, and a great deal of work had to be done, especially as 1975 was the quincentenary year of the chapel. A number of special concerts had been arranged, masterminded by David Willcocks: a special service was to be broadcast live on radio and TV which included a commissioned Te Deum by Phillip Cannon, which wasn’t straightforward; shortly after that, Field Marshall Lord Montgomery died and his funeral was at Windsor, so these two high profile events were quite challenging. Luckily Stephen Verney, the Precentor, was particularly supportive of my endeavours.”

The lay clerks fell into two distinct categories: half were the ‘old stagers’, and the others were younger, ex-choral scholars who were making their futures outside the castle, and who were regarded with some suspicion by the older team. The choir suffered from a lack of rehearsal time, so the two sung Mattins had to be sacrificed for this. Christopher organised for the men to come in for a 20-minute rehearsal before Evensong, which immediately bore dividends, and gradually things turned around so that he can now look back on many events with great pleasure. Notable among these are the series of CDs made with Hyperion, especially the Parry disc with the Songs of Farewell, and a concert given in Great St Mary’s as part of the 1987 International Congress of Organists in Cambridge. The highlight there was William Mundy’s Vox patris cælestis

When George Guest retired from St John’s College in 1991, Christopher succeeded him. It was unexpected: a Sunday lunchtime phone call came from the Master of the College, and although Christopher was thrilled to be asked, he was slightly daunted by the prospect of stepping into George’s shoes. Indeed, it wasn’t easy to begin with – the back rows were short of two choral scholars and two volunteers, and there were no dates in the diary, and no recordings or tours planned. Also, the choir was regarded with suspicion by some of the Fellows, but nevertheless he received great support from the Master.

A new Master, Peter Goddard, brought about a great change in attitude when he said that the vital thing was for the choir to be well known, and that royalties and fees were of secondary importance (under Guest, the college had done very well out of recording royalties, but these were drying up, and huge recording fees were becoming a thing of the past.) “The series of CDs for Naxos helped hugely in that regard, as did a good word from John Rutter at a crucial moment. There wasn’t much money in the contract, but it brought in massive publicity,” Christopher says. The result was a series of splendid tours to Australia, Japan, the USA, Canada and, nearer to home, to Sweden, France, the Netherlands and Germany.

Retirement from St John’s came in 2003, but Christopher remains busy in the choral world. “And I feel lucky still to be wanted!” he says. Firstly, he ran the music at Clare College Cambridge for a year for Tim Brown, during which time he took the choir to St Michael’s Tenbury to record a CD of S S Wesley’s music. Again, he was grateful to John Rutter – this

time for engineering as well as producing this recording. Now he is mentoring the organ scholars at Downing College, and he occasionally directs services at Selwyn and Trinity Colleges for Sarah Macdonald and Stephen Layton respectively. He’s been over to Saint Thomas, Fifth Avenue to direct the Choirmasters’ Week several times, most recently for the late John Scott, and also the Yale University Schola Cantorum.

In addition to all the above he serves on the committees of the Leith Hill Festival, the Ouseley Trust, the Howells Trust, and of course he is FCM’s President. He is also Patron of the Ely Cathedral Girls’ Choir and involved with the Archdiocese of Cologne, advising the publisher, Carus Verlag, on an anthology of English anthems. In addition, he goes over to Herning in Denmark several times a year to the Danish Singing School, which was set up some years ago by Mads Bille to foster singing in young people. The enterprise has the support of the Danish Ministry of Culture and, as there is no tradition in Denmark for this sort of thing, it’s a brave venture, but it’s working. There are around 100 youngsters attending after school, and they learn to sing, do theory, and play instruments. Christopher works with the singers and the choirs that have blossomed under Bille’s guidance, spending a week or so with them each visit.

To conclude, I ask Christopher about how he would characterise the identifiable ‘Robinson sound’ that the boys at Worcester, Windsor and Cambridge all had. He replies that he wanted a sound that is exciting, engaging and expressive. This boils down to having boys who are themselves lively and receptive, and who are prepared to take risks. “Telling them that something is difficult should be avoided,” he says. “Boys have to feel that singing is physically enjoyable, and they need to communicate that to the listener. The words are terrifically important too, in the formation of sounds and in the shape and length of phrases.” These are Christopher’s main

his teacher Alexandre Böely was dismissed from his post for playing too many fugues!

With French organ art at its lowest point, revolution of a different kind was not slow in coming. Over the next 20 years, two distinct organ schools evolved, one headed by Saint-Saëns and César Franck, and the other by Guilmant and Widor, with Cavaillé-Coll’s organs providing inspiration and challenge in equal measure: ‘Our school owes its creation – I say it without reservation – to the special, magical sound of these instruments.’ Charles-Marie Widor (1932)

The legacy of the French organist-composers, as exemplified by the masterworks of Franck, the organ symphonies of Widor, and the deeply spiritual sound world of Messiaen, is one of the most significant achievements in organ culture of the last 150 years. The thread which connected all these was the great organ-builder, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. But go back 100 years from there, and the parlous state of French organ music at the start of the 19th century might come as a surprise to some.

The Revolution of 1789 touched all areas of French life. The Church was secularised, its buildings used as barracks, stabling, or storerooms, and organs were often vandalised or destroyed. As the glories of the classical organ waned, the Grand Siècle of Titelouze, Couperin, and Clérambault seemed lost for ever. In addition, the opening of the Paris Conservatoire in 1795 heralded a form of musical liberation in the city, with opera and ballet its main beneficiaries. The style of the opéra comique soon found its way into the Mass, but a simpler, pianistic style of organ performance then emerged, allied with the barcarolle, gallop or even the valse. The composer and organist Camille Saint-Saëns rebuked his contemporaries as ‘musicians without brains, performers without fingers’, and

Aristide Cavaillé-Coll was born in 1811 in Montpellier into a family of organ-builders. His paternal grandfather, Jean-Pierre Cavaillé, had built organs in France and Spain, and Aristide’s father, Dominique Cavaillé-Coll (whose mother’s name had been added to her husband’s in the Spanish tradition), was Jean-Pierre’s apprentice, partner and successor. Craftsmanship and integrity, hallmarks of Aristide’s life and work, were learned from father and grandfather at an early age. By the time Aristide was 14, he had begun his apprenticeship, helping in the Toulouse workshop, and at 18 he had completed his first organ unsupervised.

Such talent couldn’t remain in Toulouse for long, and it was the composer Rossini, making a visit to the town, who suggested it was time to move the family business to Paris. The Cavaillé-Colls disembarked in the capital on 21 September 1833, and within three days Aristide had submitted a proposal to build a new 84-stop organ for the Royal Basilica of Saint Denis.

Aristide, still in his twenties, became head of the firm in all but name. His genius for invention saw the introduction of a succession of innovations. Steady wind at varied pressures was now supplied to accommodate the needs of pipes of different timbres and pitches. The system of ventil pedals was extended to enable ingenious shifts of registration. The pneumatic Barker lever was introduced, and instruments grew in size and power. The Clicquot echo division was enlarged and enclosed, making possible an unprecedented dynamic range. And it was Aristide who perfected individual tone colours that blended into an ensemble characterised by luminosity and fire.

A succession of truly magnificent organs followed:

La Madeleine 1846

St Clotilde 1859

St Sulpice 1862

Notre Dame 1868

The Trocadéro 1878

St Etienne, Caen 1885

St Sernin, Toulouse 1889

St Ouen, Rouen 1890

What makes these organs so magical, so special? A key aspect is that certain stops spoke with the same voice in every instrument bearing the Cavaillé-Coll name, irrespective of size or date. The foundation stops at St Denis were close to those of Notre Dame, even though 25 years came between the two designs. Another great skill was Cavaillé-Coll’s ability to scale pipes to the building while staying true to his ideals of tone. Consoles became models of convenience, with most facing the nave, the draw-stops within easy reach, and with German pedal boards beginning at bottom C, and not F or A, as in the past. Crucially, this allowed for the performance of the music of J S Bach.

In northern Europe in the early 19th century a tradition still survived of organ playing centred around the music of Bach. The year 1844 saw the first French performances of the works of Bach by the German organist Adolph Friedrich Hesse. In a recital at St Eustache, Hesse brought to Paris a style he had learned from Rinck, who had been trained by Kittel, who had been taught by Bach himself. Those who were accustomed to organists conjuring up shipwrecks at sea found Hesse intolerably boring, but a few found it significant – including Cavaillé-Coll. When Hesse’s most famous pupil, the Belgian Jacques-Nicolas Lemmens, visited Paris in 1852 and 1854, he further impressed with truly virtuoso performances of Bach. His playing would inspire a new generation of organists, and his tutor, the 1862 Ecole d’Orgue, would contribute to an expanded playing style in France. ‘He is a giant,’ wrote Berlioz.

In the autumn of 1844, Cavaillé-Coll visited Alsace where he met Jean Widor, a long-time employee of the organ builder Callinet. A friendship evolved which would link the organbuilder and his art to three generations of the Widor family. But most significant of all was the birth on 21 February 1844 of a composer and teacher who, more than anyone, caused Bach to be venerated by a succession of young musicians: Charles-Marie Widor.

Cavaillé-Coll knew that his organs required organists who could fully exploit their tonal and mechanical innovations. Widor was to tell Dupré that, when staying with his parents in Lyon in 1858, Aristide had said: ‘After Charles-Marie finishes school, he must go and study in Brussels with the great organist Lemmens. I shall introduce him. I have already sent him young Guilmant.’ Widor studied privately with Lemmens for several months in 1863, and Lemmens’s ideas and personality were to have a profound effect on French organ teaching and composing for decades to come.

‘Not a person who heard Lemmens will forget the lucidity, the strength, the grandeur of his playing: the smallest details given weight, but always in proportion with the piece as a whole.’ His agility looked the more astonishing for his height and powerful build. ‘One thought of an animal tamer confronting the beast… classic posture, knees and ankles together, player motionless, hands and feet near as possible to the keys… the minimum of movement.’ (Widor)

By the end of the 1860s, thanks to the influence of CavailléColl, the young Widor had been transformed from student to serious artist. Widor had also begun to write music of his own, including chamber and piano works. His career as a virtuoso and composer was therefore well launched when, on New Year’s Eve 1869, while deputising at La Cavaillé-Coll at his side, the 25-year-old Widor learned of the sudden death of the inimitable Lefébure-Wély, organist of St Sulpice. In Dupré’s telling of the tale, Cavaillé-Coll nudged the younger man and said, “I’m thinking”. Within a few days, Widor was installed as temporary organist, with responsibility for Cavaillé-Coll’s largest masterpiece.

Presiding over this amphitheatre of a console had a profound effect on Widor. He later remarked ‘one will never write for the orchestra in the same way as the organ. But from now on, one will have to be as careful managing tone colour in an organ work as in an orchestral one.’ He wasted no time. Within two years of his appointment at St Sulpice, Widor had dispatched to his publisher no fewer than four of his eventual ten organ symphonies.

What of our second organ school, that headed by Franck & Saint-Saëns? The influence of Bach is still integral, but that of Lemmens less so.

ability during the arid years of the early 1850s. Cavaillé-Coll included Saint-Saëns amongst the organists recommended to clients for the inauguration of new organs, and his prize in 1857 (at the age of just 22) was the sought-after post of

La Madeleine was the richest and most fashionable church in Paris, with an inspirational 4-manual Cavaillé-Coll organ and a generous salary. Though neither a true classicist nor a great innovator, Saint-Saëns exerted a far-reaching influence from his organ bench. His opinion of liturgical music was certainly an oddity in Paris at the time, with him asserting that it should be ‘grand in style, serene in spirit, and aloof from all that was worldly’. He abhorred the singing of operatic airs in church, and denounced the mixing of styles which often led to the juxtaposition of one composer’s Gloria with another’s Credo. He even judged Bach ‘inapt for the meditative purpose of the church’. The Mass in B Minor was considered concert music, and the organ preludes, toccatas, and variations were ‘unfitted for Catholic liturgy by their essential virtuosity’. And we won’t mention the ‘egregious Protestantism’ of the chorale preludes!

Though their names are often mentioned in the same sentence, Saint-Saëns and Franck were anything but friends. In almost every respect – origins, experience, aesthetic ideas – the two composers differed greatly. Saint-Saëns was urbane, sophisticated, conservative, and fastidious in attire. Franck was gauche, liberal, absent-minded, and according to Vincent d’Indy, rather shabby – often seen in ‘a coat a size too big, and trousers a size too short’.

Camille Saint-Saëns’s passionate attachment to music of the 18th century, his dexterity as a pianist, and his organ studies with Alexandre Böely signalled him as a performer of rare

César Franck had shared the platform with Lemmens at his Paris concert in 1854. A pianist of prodigious ability, who achieved a premier prix at the age of just 11, Franck set about mastering Lemmens’s techniques himself. But his primary contribution to the evolving organ culture was as a composer. Franck’s output includes a mere dozen large-scale organ works; Six Pièces, Trois Pièces and Trois Chorals. Like Saint-Saens, he more often wrote for the voice, orchestra or piano, leaving a masterwork in almost every genre, from the string quartet to the symphony. Yet to the organ, week after week for 40 years, he confided some of his deepest thought, and the Six Pièces were epoch-making, setting precedents on which others would build.

repertoire from roughly the time of Henry Purcell to the early 20th century – but I knew next to nothing of the music of the composers mentioned by the reviewers: Herbert Howells, Edward Bairstow, Charles Wood, Samuel Sebastian Wesley and so on. My family was then living in West Kensington, and Harrods, with its excellent record department, was just a short bus ride away. I decided to go there without delay to explore matters further.

and knew a fair number of the major works of the classical

The first few long-playing records had just been issued, but this was still mainly the world of the 78rpm disc. Most record

completing my National Service. In 1956-57 Philip Taylor, the Informator, was in what was to be his final year. He was a fine organist and a capable teacher of the instrument, but his choir practices were rumoured to be very chaotic. His musical tastes, too, seemed in many ways to belong to a bygone age, and to many of us he seemed a rather sad, lonely, withdrawn figure. It was hard to escape the feeling that the choir was living on its past reputation.

The changes in the choir’s fortunes after his successor, Bernard Rose, arrived at the college were immediately apparent. Almost overnight the choir became far more disciplined. Within three weeks the rather ‘dead’ sound of the treble line under his predecessor began to be replaced by an altogether crisper, more sparkling sound which echoed round

Though I was not in the choir and not even a music student, I soon came to know Bernard Rose rather well. One day I

rooms equipped with record players where one could listen ad lib to those records which were of interest, and reject any where either the recording or the performance was of poor quality.

summoned up the courage to ask him if I might perhaps make some recordings of the choir. To my relief he was happy for me to go ahead, and I thus became the first person to make a whole series of Magdalen recordings. Tape recorders for domestic use had appeared on the market only a year or two earlier, though the BBC and similar organisations had presumably had them before that. At this date, very few people other than celebrities had much idea of what their voices sounded like to others, and the first few playback sessions in any student or family circle usually led to expressions of surprise or horror, and much hilarity. These early tape recorders were large, unwieldy, rather expensive machines, full of valves, and as heavy as small refrigerators, and on one train journey a railway official even insisted that mine should travel in the guard’s van “since it clearly was not part of my personal luggage”.

Tape recorders were, however, indispensable for anyone seriously interested in exploring the 15th, 16th and 17thcentury English choral repertoire. By the mid-1950s a few of the major works by William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons were, it is true, available on LP records, but there was very little Thomas Tallis on disc, or music by figures such as Thomas Tomkins and Thomas Weelkes. It is doubtful if a single piece by Magdalen composers such as Richard Davy, John Sheppard, John Mason, Richard Nicholson or Daniel Purcell would then have been available. English pre-Reformation church music hardly figured at all in the record catalogues, although the occasional BBC Third Programme broadcasts of early music did provide some compensation, and it was now at last possible to record these.

Making off-air recordings of BBC broadcasts was one thing; making recordings of the choir during a chapel service was a very different matter, and I have to admit that my first attempt was not at all successful. I well remember sitting in the organ loft during one Evensong with the tape recorder beside me. I had simply dangled the microphone loosely over the organ loft balustrade and hoped for the best. This microphone, which had come with the tape recorder as part of the package, was clearly a budget model, as the lead from the microphone to the recorder was very short, and I wasn’t sure if the microphone would pick up anything at all. It did, in fact, work surprisingly well, but only in the quieter passages. Whenever the organ was playing loudly the sound was wildly distorted.

It was clear to me that I needed to make any future recordings at a far greater distance from the organ, and preferably with the help of a better microphone. At this point the Oxford recording engineer Harry Mudd came to my rescue. He found me an excellent microphone, with yards and yards of cable attached. Mr Talboys, the verger, produced a ladder from somewhere, though I was never sure if he fully approved of my activities. I ran the cable along the chapel wall and above the wooden panelling, from the organ loft to a point roughly in line with the cantoris choir stalls and high above them, and attached the microphone to the panelling. There it stayed for at least a year, secure and almost invisible.

The recordings I made with the microphone in its new position were mostly reasonably good by the standards of the 1950s, when even professionally made recordings were still mainly in mono. The chapel services at this time were

mildly ‘low church’, and choral services other than Evensong were rare. I sometimes recorded the whole service, but more often just the introit (if there was one), the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis, and the anthem. Almost anything from the 16th and 17th centuries interested me, but I also recall recording pieces by Haldane Campbell Stewart, Charles Wood, and Samuel Wesley. It is a matter of pure luck that a few of the recordings which I made in 1958-59 have survived to this day despite numerous removals and 55 years of storage in attics, garages and garden sheds. Much of the material I recorded has sadly been lost over the years, or may even have been deleted by me in my undergraduate days to make room for fresh recordings.

Although I was the first person to make a large number of recordings of the choir, Harry Mudd had a year earlier already made one very short private (non-commercial) recording. This took place in July 1957, a few days before Philip Taylor’s retirement after 14 years as Informator, and it is the earliest known recording of the choir singing in the chapel. The idea of making a record almost certainly came from the chorister parents. One of the choristers chose his favourite Mag-andNunc setting (Sumsion in G) for the disc, and for the reverse side Philip Taylor selected Handel’s Let the bright seraphim – an unwise choice as it was never part of the choir’s normal repertoire and the piece was clearly badly under-rehearsed. The music was issued on a 10-inch LP record, and an alternative pressing on two 78rpm discs was made for parents who had as yet no equipment for playing LP records. The trebles and the six lay clerks sang for the recording, but the two academical clerks (choral scholars) were not invited to take part. There were at this date just two academicals in the choir – not two per year, but a total of two in the choir -- at any one time. This had been the pattern for roughly a century, but was soon changed under Bernard Rose, so that at the Evensong which was broadcast almost exactly two years later there were, rather ironically, no fewer than seven academicals in the choir, with just one surviving lay clerk.

Two very short pre-war recordings of the choir singing from the top of the Great Tower have come down to us – recordings whose main aim was evidently to capture the atmosphere of the May Day celebrations rather than to ‘showcase’ the choir. The earlier of these comes from a 1931 Pathé newsreel entitled: ‘Oxford: Ye Merrie Monthe of Maye. Centuries-old custom of ushering in May Day at dawn with old English songs & dances, filmed for first time.’ The filming crew did rather well to carry their heavy equipment to the top of the tower, but their film was then cruelly truncated in the cutting room. On the film the choir is hardly shown at all, and Benjamin Rogers’s Hymnus Eucharisticus is reduced to just one-and-ahalf verses. The editors were seemingly more interested in the Morris Dancing and the crowds below. The tiny soundtrack fragment, with the singers accompanied by the dawn chorus

on top form, is the earliest recording we have of the full choir. Four years later the BBC made a rather similar recording (now in the National Sound Archive) of the start of the May Day ceremony.

The college also has a few even earlier recordings, from 1906-07, when the battle of the formats, flat discs versus cylinders, was at its height. (Flat discs eventually won, though cylindrical records continued to be manufactured till 1929, and a few are still made today for what must surely be a minuscule number of cylinder enthusiasts.) Recording techniques in the pre-electric period (before 1925) were extremely primitive, and only studio recordings were possible, but these are nevertheless recordings of very great historical interest and, despite their limitations, they give

us some indication of the excellence of the men’s voices at this time. They were all made by singers from the choir, not by the full choir, which is probably just as well. Early recordings made with solo singers or by very small groups were usually much more successful than those made by larger groups of singers. On these recordings John Lomas, a celebrated Oxford bass who sang in the choir from 18901930, performed two arias by Gounod, with an orchestral accompaniment, and four current or former academical clerks, ‘the Magdalen Glee Singers of Oxford University’, sang two carols. Spoken introductions on records were quite common at this period, and their spoken announcements included what may well be the earliest recordings in sound of the name ‘Magdalen’.

The recordings from 1906-07, 1931 and 1957 mentioned in this article are now available on a recently released Archive CD (reviewed by Timothy Storey CM 1/13). The CD also includes the best of my own recordings from undergraduate days, and off-air recordings of parts of the first two Evensong broadcasts from Magdalen, in 1959 and 1960. Many of these recordings were until recently in danger of being lost, and none of this material has previously been available on either LP records or CDs. The CD also includes a brief introductory talk about the college and its chapel by John Betjeman, and it comes with a 40-page booklet which has nine photographs, and much historical information about the choir and its organists. Copies can be bought from the Magdalen College Bursary (celia.brown@magd.ox.ac.uk) or from www.oxrecs.com They are being sold in aid of the Choir Fund and the Student Support Fund.

1998, we were taken to King’s chapel for a recital by David Goode. Afterwards I told Sarah Baldock that my goal was to go to King’s, to which she replied, ‘You will have to work very hard!’

What did you enjoy most about being an organ scholar at King’s, and at Westminster Cathedral?

These were two very different places (one being a Church of England foundation and the other being Roman Catholic), and I learned different but very complementary things at both. When I first went to King’s my experience of choral music was extremely limited and I had to learn a great deal of repertoire. During my first year, I was fortunate to work with world-class professional musicians on a daily basis at both King’s and Westminster Cathedral, and with many soloists, instrumentalists and orchestras, and I performed in many amazing places, taking part in big services and concerts as well as experiencing the discipline of the daily round of chapel and cathedral worship. All of this was scary and nerve-racking but also very fulfilling.

Education Details: Tonbridge School, Kent; King’s College, Cambridge

Career details to date:

2003 – 2004 Organ Scholar, Tonbridge School (the first ever)

2004 – 2007 Organ Scholar, King’s College, Cambridge

2007 – 2008 Organ Scholar, Westminster Cathedral (and Acting Director of the Choir School)

2008 – 2009 Assistant Director of Music and Organist, Felsted School, Essex and Director of Music, St Philip’s Church, Earl’s Court Road, London

2009 – 2011 Assistant Organist and Assistant Director of Music of the Chorister School, Durham Cathedral

2011 – 2015 Assistant Director of Music, St Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney, Australia

Were you a chorister, and if so, where?

No, I went to a preparatory school at an early age, and my parents were not musical.

Then what or who made you take up playing the organ? Having started piano lessons I went to the school chapel at Tonbridge with my teacher, heard the organ, and loved the sounds it made. This led to me having organ lessons with Sarah Baldock from the age of 11 to 18.

When at school, did you ever dream of achieving all that you have?

I did not really think about my future until, during my first visit to Oundle for the ‘Pulling Out the Stops’ course in

What do you think you have gained from your experience as a cathedral musician in Australia, and what has Australian cathedral music gained from you?

Understandably, music in Australian cathedrals and churches does not have the long and rich choral tradition of England, and it has been very rewarding to bring some of that to Australia and particularly to St Mary’s Cathedral. Since Director of Music Thomas Wilson and I arrived, the number of weekly choral services has grown from a handful to up to 13 per week during term-time (including Sung Vespers and Mass every day apart from Fridays). It has been very rewarding to introduce the choristers to life as a busy singer and to make them aware that being involved on a daily basis is very special and is something which they will remember for the rest of their lives. A bonus has been training the ex-chorister teenagers as the ‘Cathedral Scholars’ (who sing ATB services at least once per week) and to teach them to perform Gregorian chant and polyphony, something which they are very privileged to achieve. To see a small group of 13 teenagers performing 5part Palestrina offertory motets to a high standard has been very special.

You have had an enormously varied role during your time in Sydney. What has that role included?

Playing the organ at all regular choral services plus special services such as concerts, recitals, state and other funerals, memorial services and weddings. Assisting in training the choristers, probationer choristers and professional lay clerks and running the special ‘Cathedral Scholars’ programme. Directing the St Mary’s Singers (the cathedral’s amateur adult choir). Teaching organ and piano at St Mary’s Cathedral College (from which the choristers are drawn). Overseeing

and coaching the cathedral’s two assistant organists/organ scholars. Giving Sunday afternoon and Grand Organ Recital Series performances on the cathedral’s Letourneau main organ.

Do you have time to do anything else in your spare time apart from eat and sleep?!

Not always!

What organ pieces have you learned recently and why?

The complete Vierne Symphony No. 6 which I performed during my last Grand Organ Recital in St Mary’s Cathedral. I had played the Finale after the Easter Vigil Sung Mass in 2014 and wanted to learn what is one of the most wonderfully rich and challenging pieces in the Romantic repertoire.

Do you listen to recordings of new pieces as you learn them?

If so, whose interpretations have helped you?

Not really. I may have heard them in the past but I like to steer clear of the influence of others’ interpretations until I have formed my own, after which I may go to recordings by others and perhaps ‘steal’ some ideas which are an improvement on mine!

Has any particular recording inspired you?

Not so much the recordings as the instruments on which I have played, which include many Cavaillé-Coll organs in Paris. I try to emulate their sounds for French Romantic music. Likewise, when playing Bach, with the organs I have played in Germany and Holland.

Which was the last CD you bought?

A Wagner recording by Jonas Kaufman!

Which fellow organists and choir directors do you admire most?

Top of my list has to be Stephen Cleobury for his attention to detail, professionalism and sheer musicianship. Others I have worked with include James Lancelot at Durham (his playing is electric), and Martin Baker at Westminster Cathedral for his training methods and the sound he achieves from his choir. I learned a great deal about performing plainchant from Matthew Martin, and organ lessons from David Briggs (one of my favourite organists) have been extremely inspiring. Receiving lessons most recently from Dame Gillian Weir has been enlightening. She really is a musician first and foremost and an organist second.

What are some of the places where you have given recitals?

With King’s choir on tour at Concertgebouw, Amsterdam; Seoul Arts Centre, South Korea; Esplanade Concert Hall, Singapore; Istanbul International Music Festival; Festival of Sacred Music in Ecuador.

Venues across the USA including: St Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue and St Mary the Virgin, Times Square, New York; Washington National Cathedral; Kansas City Cathedral;

In England: King’s College Chapel, Cambridge; Westminster Abbey; cathedrals of Westminster, St Albans, Truro, Worcester, Lichfield, Durham.

In Australia: St Mary’s and St Andrew’s Cathedrals, Sydney; St John’s Cathedral, Brisbane; Sydney Town Hall (on the

gigantic 5-manual William Hill instrument – the largest organ in Australia); St Mary’s Cathedral, Hobart.

Have you made any organ recordings?

My first CD has just been released (recorded in St Mary’s Cathedral) on the Organism label (ORG019) and is entitled ‘From Bach to Bingham’. It contains some of my favourite pieces which span the last 300 years. Its production has been enabled by the support of the St Mary’s Cathedral music foundation, known as the ‘Palestrina Foundation’.

Does any event at which you have played particularly stand out in your memory?

Many do, but I have really enjoyed my recent collaboration with the terrific principal trumpeter of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, David Elton, with whom I have played music for trumpet and organ at such venues as Sydney Town Hall.

How do you cope with nerves?

I find that I can control nerves more easily when I have to rely on myself alone (as in organ playing) than when I have to perform with a choir which I have rehearsed. My nerves centre more on worrying about how I have prepared the choir – particularly when they have had to learn a large amount of music in a short space of time – when you think about it, it is actually quite extraordinary what we are asking our young choristers to do.

What are your hobbies?

Running. I started at school and ‘got the bug’. After school, the running fell by the wayside, but Sydney is such a beautiful city and seems made for running, so I took it up again when I arrived in Australia and in 2013 I ran my first half marathon and later that year the full Sydney marathon, which was one of the best experiences of my life. I have now completed my third marathon and am planning my fourth. I have also grown to love Australian sport and particularly AFL (known to we English as Australian Rules Football!). Well-known Sydney organist David Drury (Sydney University and Sydney Symphony Orchestra organist) took me on a few occasions to Sydney Swans AFL matches at the famous Sydney Cricket Ground and I have been hooked ever since!

Would you recommend life as an organist and church musician and what are the drawbacks to this life?

I would definitely recommend such a life to serious young musicians. It is very much a way of life and not a ‘9 to 5’ job – if you want to be a cathedral musician it has to be something you really love as you cannot leave your work behind you at the end of the day or even on a rare day off.

What should be the role of FCM in these times and in the future?

To support professional church and cathedral musicians and their choirs both financially and through publicity for our wonderful heritage of church music. Many music lovers are unaware of the great quality and quantity of music performed to a consistently high standard in our cathedrals. In my experience here at St Mary’s, many people express both surprise and delight when they chance upon the music when visiting the cathedral.

This profile was researched and compiled by David Seward, FCM’s representative in Australia, just before Oliver left Sydney to return to England in November 2015.

Jeremy Summerly talks to Matthew Martin

JS: What was the first musical experience you can remember?

MM: I have a very clear memory of attempting to play our piano at home when I was about four years old. I used the black notes to invent tunes, finding their sounds more interesting than those of the white notes. And it wasn’t just Chopsticks. I think there’s a case for allowing children to experiment musically and improvise before teaching them how to read printed music.

JS: So when did you stop playing only the black notes?

MM: I began to have violin and piano lessons when I was about six, but I wasn’t especially interested in the substance of the lessons because I preferred to make up my own tunes. Practising scales was a total bore – although I now wish I had. When I was eight I joined the choir at Dean Close School. The choirmaster, Ian Little (who had been a cathedral organist at Coventry), fostered my interest (despite describing me as a sack of potatoes), and when I sang a piece that I liked, I’d scoot over to the piano after rehearsal to see if I could replicate the music under my fingers. My piano teacher was not impressed with this casual approach.

JS: And when you began to listen to music, was that just classical?

MM: Not by any means. I enjoyed much 1980s pop music – I think that was my first experience of modality in music. It’s interesting how much some Michael Jackson songs fit the Dorian mode! And I was deeply affected by some of the incidental music for television composed by Patrick Gowers – Sherlock Holmes, Smiley’s People etc. I have since written a trumpet sonata in his memory, which was put on at the Cheltenham Festival last year.

JS: What was the first piece that you committed to manuscript paper?

MM: When I was eleven I wrote a couple of organ pieces, which are now thankfully ‘lost’. I wasn’t having organ lessons but I’d taught myself how to find some basic sounds and how to operate the pedals enough to play a simple hymn tune. I could barely reach them, however. The encouragement of a local parishioner led to a visit to Gloucester Cathedral (which has a very cool and edgy organ designed in the 1970s by Ralph Downes) and I was able to spend some time in the organ loft with the legendary Dr John Sanders. In a later incarnation (2011) I was asked to write a piece for Gloucester Cathedral choir in his memory (A Song of the New Jerusalem). I remember clearly the great man’s tweed suit, and I waited nervously as he thumbed through my organ pieces, which he described as ‘reminiscent of the Widor Toccata’. I’m not sure he was all that impressed, although he was gracious, nevertheless. But I still wasn’t allowed organ lessons because I wasn’t deemed good enough at the piano. My mother remonstrated with the school, and organ lessons were grudgingly granted.

JS: So this was a turning point?

MM: The real turning point came when Paul Derrett, then organist of Christ Church, Cheltenham, heard me play and offered to give me weekly lessons on the 4-manual instrument there. It had a Tuba. Paul was the first person who took a serious interest in my development and was (is) a fantastic player and musician. He was impressed with my sight-reading ability and I guess he was able to spot a reasonably natural musician hiding behind a timid little boy. Unbeknown to my school, for £6 every Sunday evening I’d learn with Paul, which I did up until the point where I was offered an organ scholarship at Oxford. In my sixth-form year I had some sessions with Stephen Farr (when he was Assistant at Christ Church Oxford) and we are still talking. In those early days (apart from in my lessons with Paul Derrett, and later perhaps with Stevie Farr), I don’t think I was ever told I was ‘good’ or even could be. But in a way I’m thankful for that as it gave me focus and determination.

JS: You applied to Magdalen College.

MM: I wasn’t going to apply there. I was worried it might be unrealistic to apply to a choral foundation, so I settled on Hertford College, where my headmaster had been an undergraduate. But when I was in the Lower Sixth I went on a course in France, and one of the teachers was Magnus Williamson, who had himself been an organ scholar at Magdalen. Magnus said that if I applied to Magdalen I might well be in with a chance. I remember Magnus as the most erudite, charismatic, funny person

I’d met up to that point. So I did what Magnus advised, and I’ve been for ever grateful for his encouragement.

JS: When you arrived at Magdalen as an undergraduate, what sort of musician did you consider yourself to be?

MM: A player with some natural facility and, I suppose, a bit of a conductor (I had formed my own band of singers at school). Not really a composer. The Informator Choristarum, Bill (Grayston) Ives, was very demanding of me as an organ scholar and I wasn’t allowed to get away with anything. Good for him. And Bill encouraged me to write for the choir. He’d ask the choir to sing some of my music and we’d talk about the various ways of writing singable lines and how to space the voices – all good practical stuff. And I developed a sound that I think of as a ‘frosty – even angular – English style’, which was based on gestures that I liked in the music of Kenneth Leighton, Lennox Berkeley, Arthur Wills, and John Joubert, rather than in the music of Howells and Vaughan Williams. I was also heavily influenced by earlier composers: Byrd, Sheppard, Tallis etc, and I enjoyed writing in those ‘old’ styles, too. So I began to write to order. A psalm chant here, an Alleluia there, then some men’s voice pieces – liturgical fodder. I was writing for the moment: functional, serviceable (literally) music. I’m not sure I regarded any of it particularly highly.

JS: Do any of those early compositions survive?

MM: A few, but nobody’s going to see them. Although they may still be in the Magdalen Choir library…

JS: So what’s the earliest piece we can hear?

MM: In 1997, with Bill Ives’s help, I had an Ave Maria for choir and organ published by Novello. I will always remain grateful for the opportunity to have a work published when I was a young man, but if I’m honest I don’t like the piece much. I wonder about the wisdom of having too much published too early – once in print it never goes away.

JS: And then in 1998 you arrived as a postgraduate student at the Royal Academy of Music. At that point your focus was definitely the organ.

MM: Yes, it was organ for a couple of years, partly because I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, so becoming an ‘expert’ in something seemed like a good plan. Lots of technical exercises and detailed work followed, and then some private study in France with Marie-Claire Alain. Then in 2000, New College Oxford held a composition competition. The prize was £1,000 and a BBC Radio 3 broadcast. I sent in my anthem Veni, Sancte Spiritus for choir and organ, and jointly won it with Tarik O’Regan. This led to a delightfully informal offer from Edward Higginbottom to become Assistant Organist at New College. I took him up on it. We didn’t often speak of the winning piece, however, which had thankfully been dropped from the repertoire.

JS: In 2000 you also wrote an 8-voice choral piece Ecce concipies for Andrew Smith and the Choir of St Peter’s, Eaton Square.

MM: And that Advent anthem is probably the earliest piece of mine that I still regard with affection. It’s fast, spikey, and contrapuntal – quite unlike a lot of slow

music that’s much in vogue at the opening of the 21st century. I like music with edge; music that’s acidic and goes on a journey. I’m a great fan of Stravinsky. I remember as a child loving the soundworld of the Dumbarton Oaks Concerto, the Symphony of Psalms, and particularly the bleakly affecting Symphonies of Wind Instruments. Learning one’s counterpoint really is one of the keys to becoming a good composer (and indeed musician).

JS: And from then on you’ve established yourself as a voice in the British choral scene.

MM: I’ve certainly been asked to write music for an increasing number of prestigious performers and events, and I’ve been published by OUP as well as Novello, and more recently by Faber Music, which is my now main publisher. I’ve written for the CBSO and Chorus, The Cardinall’s Musick, Westminster Cathedral, Gloucester Cathedral, The Gabrieli Consort, Westminster Abbey, York Minster, the Exon Singers, the St Endellion Easter Festival, and for the 2015 St Cecilia Service in St Paul’s Cathedral. In 2014, Daniel Hyde and the Magdalen College choir made a disc of my music for Opus Arte, the Royal Opera House label.

JS: You’re now Director of Music at Keble College Oxford – a post that allows you to continue composing.

MM: Yes, although the regular commitments at the college and university mean I need to be especially focused about working to a deadline – which can make composition easier. In a sense, I’m now a fully signed-up portfolio musician with varied interests. I conduct, teach (academic and composition), play, and compose – not to mention the administration! Alongside running the choir at Keble and teaching my students, I’m writing a Magnificat for Paul McCreesh and the Gabrieli Consort, a set of Lamentations for Peter Phillips and The Tallis Scholars, a choral piece for Edward Higginbottom for performance in the USA this summer, some Petrarch Sonnets for my friend Marcus Farnsworth for the Three Choirs’ Festival, and an Advent piece for Uppsala Cathedral choir in Sweden. A congregational Mass setting has also been requested! Westminster Abbey choir featured a Jubilate of mine in the Commonwealth Service in March, which was broadcast live on TV in the presence of HM The Queen herself, I gather. I’ve spent my life working towards a time when I can get paid to write music to order, and now it’s properly happening...

Jeremy Summerly is Director of Music at St Peter’s College Oxford, a position which involves conducting the chapel choir and teaching the keyboard skills module of the Music degree. He founded Oxford Camerata in 1984 and conducted Schola Cantorum of Oxford from 1990-96. He founded the Royal Academy Consort, was Head of Academic Studies at the RAM, and is one of the conductors of the Choir of London. He is also Director of Music at St Luke’s, Chelsea, and co-artistic Director of Oxford Baroque. He has made over 50 commercial recordings, and has given concert tours throughout Europe, the Middle East, and the USA. His wife gave birth to their first child hours after the St Peter’s Advent Carol Service in 2015: Jeremy managed to attend both events.

Matthew has for many years also been involved at the annual Edington Festival of Music within the Liturgy where he directs the Nave Choir. He won the Liturgical category in the 2013 British Composer Awards and a CD of his choral music was released by the choir of Magdalen College Oxford to critical acclaim (there is an excellent short film of the making of this CD on the Magdalen website on the ‘Choir’ page). Matthew was Assistant Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral from 2004-2010.

The RSCM is committed to promoting the study, practice and improvement of music in Christian worship. Through training programmes, courses, publications, advice and encouragement, we support church music today and invest in the future.

We have now expanded our range of organ courses and are pleased to offer “Survival Kit! A Course for Appointed Cathedral Organ Scholars 2016/17”. Full details can be found online.

Derek Perry

Derek Perry

The first week of June 1942 incorporated a milestone. The letter my mother had written to Westminster Abbey had failed to prompt any sort of reply, but she had received a letter from St Paul’s Cathedral explaining that the Westminster Abbey choir had been disbanded on account of the war and her letter had been handed over to them. Would she please bring her son to a voice trial and academic test at the choir school, Carter Lane, London EC4 on the first Saturday in June at, I think, 9 am.

Duly scrubbed and alongside about 30 other boys and their parents (mostly just the mothers), I reported. The written examination was in several parts and presided over by the headmaster, the Revd A. Jessop Price. The vocal audition was undertaken by one boy at a time, alphabetically, and he was put through his paces by the cathedral organist, Dr John Dykes Bower, and the sub-organist, Dr Douglas Hopkins. Apart from the candidates and these three men, the school was deserted; the other staff and pupils had been evacuated to Truro when the war began.

After this, the parents and candidates crowded into the headmaster’s study (a room of generous proportions), and I can remember the exact words of his first sentence. It went, “Will the parents of the following boys please stay behind –Beale1, Howlett2, Pearcey, Perry, Pitkin and Wilkinson.” Jessop Price then explained some of the administrative arrangements which would enable us to join the school. Despite being located 300 miles from London, we were to remain the boys of St Paul’s Cathedral choir school, though we were integrated with Truro Cathedral School. We kept our own distinctive uniform and,

except on Sundays, sang different services to Truro Cathedral Choir.

From my mother’s standpoint, there were both advantages and disadvantages in what was happening. Without me in daily attendance she felt able to rent out our home and take lodgings in Mill Hill where she now worked. That eased her financial problems, but she did not know what provision she could make for my care during school holidays. There were neither school nor boarding fees to be paid, and the train journey between Paddington and Truro was free in both directions, but music lessons and haircuts were compulsory and had to be paid for. Some formal provision of pocket money was also deemed necessary. Buying the uniform presented more than a financial problem: clothing coupons were nobly given by most of the family so that I could be properly kitted out. The school outfitters was a firm with an evocative name, Isaac Walton. They should have sold fishing tackle. The shop was near the top of Ludgate Hill and, armed with a uniform list, we went there when dismissed by Jessop Price. The shopping was uneventful except that, even aged nine, I had an unenviably large head, and there was not a cap in the shop to fit me. One was specially made and available before term started in September.

While we were still evacuated, every term started at Paddington Station at 11 am when the School Special left for the West Country. A number of public schools – for girls as well as boys – in the south-east had found temporary homes with other schools west of Reading, and we were all carried to our various destinations by the one train. Each school was allocated its required number of compartments; we needed only three.

The headmaster travelled with us, and the newest boys, the probationers, were required to travel in his compartment. In those days the trip to Truro took eight hours so we arrived at Truro Station at 7 pm with a mile uphill walk ahead of us, no fun for a nine-year-old with a small but heavy case to carry.

Most of my belongings were sent on ahead in a trunk, PLA (Passenger Luggage in Advance) to our exact location, Trewinnard Court. This was the boys’ boarding house for Truro Cathedral School and also the prep department. That prep department had two classes and therefore two teachers – Miss Quiney and Miss Bennett. The former took the senior class. She was a sour woman and, along with a number of other staff, had a dislike and resentment of St Paul’s boys who, throughout the school, up to and including the fifth form, were significantly more successful than the Truro boys. I learned all the swear words in my first year in Truro; and I learned also that you did not use the words in grown-up company. It was something of a surprise, then, to overhear by chance Miss Q tell Miss B that “all the Paulines (meaning the St Paul’s boys) are b*gg*rs”. She was the first woman I had heard swear.

There is a real excitement for a nine-year-old going away to boarding school which sustained one in those first few days when everything was new and there was much to learn. But routine soon is established, and then came homesickness. We all suffered from it, and it hurt, especially at bedtime. The routines of school are pretty much the same all over the world, but being a member of a cathedral choir is not quite so common. I started as a probationer; during this time I did not wear a cassock or surplice, and neither did I sit in the choir stalls for services. It was indeed a period of probation, and the powers that be were entitled to dispense with you if you did not come up to scratch.

My own probation lasted only until late May 1943 when, along with two others, I was made a chorister. This involved

a ceremony during a weekday Evensong conducted by the headmaster. (If it had been at St Paul’s it would have been the dean.) A particular psalm was sung (Ps. 16 verses 5-6); and also an appropriate hymn (‘Fair waved the golden corn’, verses 4-6). At the conclusion I received a copy of the Book of Common Prayer suitably inscribed. The choristers, of whom there should have been 32, had a hierarchy. On entry into the ranks I became a member of the back desk (about a third of the total of choristers). There were no specific desks at which one sat, but the desk you were in had real significance. The only electors were the choristers and the only criterion for promotion was vocal contribution, which is more than singing ability. It is also to do with musicality, with co-operation and with confidence.

You never knew beforehand when elections would be held. They were announced and conducted immediately, generally by Douglas Hopkins, at the start of choir practice. There were no ballot forms. DH would say: “There are three vacancies

Despite being located 300 miles from London, we were to remain the boys of St Paul’s Cathedral choir school, though we were integrated with Truro Cathedral School. We kept our own distinctive uniform and, except on Sundays, sang different services to Truro Cathedral Choir.

in the front desk. Nominations, please,” whereupon a short discussion took place between front desk members who would then call out names. Unless there were objections, the first three names called out were promoted. A similar procedure moved boys from the back to the middle desk. Apart from status, the big bonus was in reaching the front desk, where the eight members were allowed to take any hardback book into choir practice and read it after the choirmaster announced, “Back desk and middle desk only”, which he did frequently when a well-known piece was to be rehearsed. I moved to the middle desk in the summer of 1944 and to the front a year later.

One way in which we maintained the repertoire of cathedral music was for boys to sing the three men’s parts, tenor and bass transposed an octave up, the altos remaining at pitch. Even so it was impossible to perform much of the music sung in normal times3. The day-to-day work with the choir was the responsibility of Sydney Lovatt, who had been brought out of retirement. He was a journeyman musician who had the deplorable habit of clearing his throat, spitting the result on the floor and rubbing it into the ground with the sole of his shoe. The musical highlight of each term in Truro was the week-long visit from Douglas Hopkins. I have, subsequently, sung under many conductors but none as inspirational as DH, who was himself a former head boy of the school. This gave him a dramatic advantage over anyone else who had anything at all to do with the choir school. He could sing well (which Dykes Bower could not); he was amusing and indiscreet. But, most of all, he knew what it was like.

My first year’s schooling in Truro was in the prep department under the foul-mouthed Miss Q. After a year we moved down to the main school beside the cathedral in the centre of the town about a mile from Trewinnard Court, to which we had daily to return for lunch – four miles walking to school and back every day. In September ’44 there were two significant changes. First, with Tony Pitkin and Peter Beale, I moved from form 1 to form 3. We had occupied three of the first four places in form 1 and were clearly misplaced, and I left Trewinnard Court with no regrets, moving to a house in Carvosa Road. Already billeted there was Alistair Cairns, a senior boy in the choir. By now I no longer suffered homesickness -- in fact I was generally happier when at school. Why then was I so pleased to leave Trewinnard Court? It was an attractive building in an attractive setting – but its adult inhabitants were an unpleasant gang with little or nothing to commend them. We had not fed well at Trewinnard Court and it is the only time in my life that I can remember feeling really hungry with no prospect of relieving that craving. The situation in Carvosa Road was very different. We had a substantial roast dinner on Sundays at lunchtime, and on Tuesdays a true Cornish pasty. The first one I received overlapped both sides of a dinner plate!

It would be a mistake to fail to record something of the power and influence of our headmaster, Jessop Price. Before his appointment as head of the choir school he had been on the staff of Chester Cathedral as Precentor, and he had a pleasant, full-bodied and accurate baritone voice. His relationship with the Truro head was one of mutual dislike. Price was unbending, and determined that the integration of the choir school into the Truro scene should never betray the integrity of St Paul’s and its independence. Thus, for example, we took no part in organised games, (although, for instance, Alistair

Again, please,” was the reply, and so it would continue for half an hour until I could say, to his satisfaction, “How now, brown cow”! I have never been sure whether I should be angry or amused or pleased or ashamed about these episodes. I do know that my speech had improved significantly by the time I left the choir school.