CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Whichever organ you buy from us, you can be assured of top sound and build quality, our technical expertise, great attention to detail and the best in customer service. We invest in our instruments so you can invest in your future. These are serious instruments for serious people, people like you. Explore our websites and then fall in love with the organ of your dreams in our showrooms.

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus | Rodgers

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus | Rodgers

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2017

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon grahamhermon@lineone.net

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Tatton Media Solutions, 9 St Lawrence Way, Tallington, Stamford PE9 4RH 01780 740866 / 07738 632215 wesley.tatton@btinternet.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by: DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

Cover photographs

Front Cover Stunning ceilings at Peterborough Cathedral

Photo: Richard Scott

Back Cover Chapelle Royale, Versailles

Photo: rowhider@live.fr

See

Irvine Soundtec Organs

Edinburgh Key Player

Morecambe Promenade Music

Porthmadog Pianos Cymru

Leigh A Bogdan Organs

Swansea Music Station

Norwich Cookes Pianos

Bandon Jeffers Music

Exeter Music Unlimited

Ballymena Nicholl Brothers

Londonderry Henderson Music

Belfast Keynote Organs

First things first: if you have not already bought a copy of the every-chorister-CD, please do seek one out (you can order them online – just type into Google ‘Decca chorister CD’ and a link will come up). Those who attended the gala concert last year in St Paul’s Cathedral, where one chorister from almost every cathedral in the UK joined with the choir of St Paul’s, will know how exceptional the choir sounded then. The new CD, Jubilate, encapsulates that sound beautifully, and copies have been flying off the shelves of cathedral and other shops. It’s top of the classical chart at the time of writing and you can see the promotional video on YouTube if you type in ‘Jubilate’. Buy as many as possible as presents – the CD is the perfect example of what FCM exists to support, and the repertoire on it is very approachable, particularly to those who are not familiar with cathedral music – and spread the word by recommending it to all your friends.

Next: a departure. Sadly, our much-appreciated, unique and very effective chairman Peter Toyne is standing down at the June AGM in Bristol, and I know I speak for all of us when I say we will be very sorry to see him go. He has been a fantastic chairman, promoting FCM with great energy and enthusiasm, and – as our first article in this magazine says – he will be a hard act to follow. But... when one door closes another opens, and we are very lucky that Peter Allwood is standing by to take over, having been in close collaboration with Peter T for some months. Peter A has had a varied career in and around cathedral music for most of his life. He was a choral scholar at

King’s Cambridge before – amongst other things – becoming director of the National Youth Music Theatre for many years. He is also a highly regarded composer and conductor. Read more about him in the November 2017 magazine.

We also say a more profound farewell to Cathedral Music’s one-time deputy editor, Roger Tucker, who died at the end of February. Roger, a long-time member of FCM, was a real stalwart of the summer cathedral festivals, where he would run the FCM stall, handing out magazines to all interested parties (and some not so interested!) and working hard at recruiting new members. Those readers with a good memory will remember his magazine reports on the Proms and the Three Choirs Festivals, always to the point and wellconstructed, even if delivered at the twelfth hour – ‘deadline’ and ‘time-keeping’ were not words in Roger’s vocabulary! His knowledge was extensive on many subjects, and he had a very acute eye for detail, an attribute much valued by editors. A longer tribute to Roger can be found in the forthcoming issue of Cathedral Voice

On page 10 we celebrate 90 years of the Royal School of Church Music, to which FCM has very strong links. The education, courses and help it supplies are wide-ranging and extensive; without these, music at many parish churches and cathedrals would be greatly at risk – the RSCM offers training on conducting, repertoire and professional development for church musicians, runs summer schools for singers and organists, has structured courses for choristers (Voice for Life) and is happy to provide advice to affiliated members throughout the world. It is a brilliant, supportive and up-todate organisation which deserves great credit.

And finally, keep your eyes open for two things: the new FCM website and the FCM gift voucher. Both should be available shortly.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

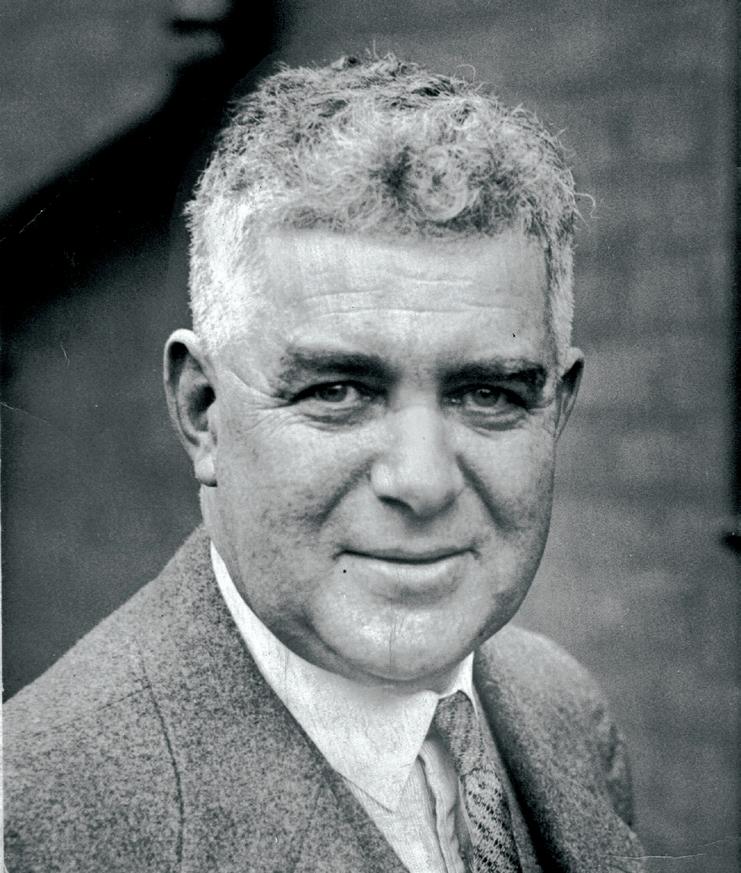

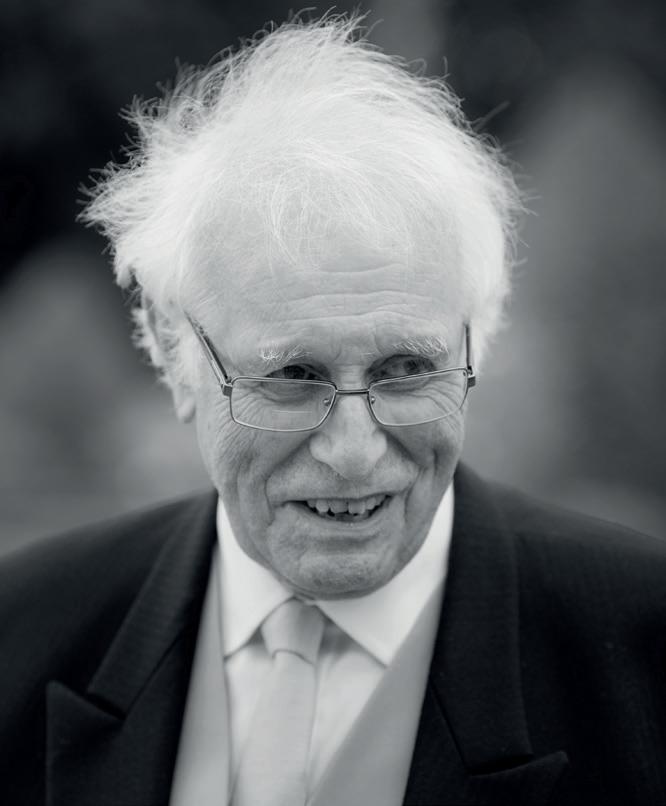

When this edition of Cathedral Music is published, FCM will (still) be 60 years old and Professor Peter Toyne CBE, its fourth chairman, will have been in post for 15 years, which makes him (at least in terms of time served) an ‘average’ chairman. In reality, of course, his chairmanship has not in any way been average

It is often said of headmasters – and the saying can be applied to those in chief-executive-type positions – that their most important function is to recruit good senior staff, and for FCM (a charity largely run by volunteers) this has been crucial. Alan Thurlow, Peter’s predecessor, had appointed Peter Smith as National Gatherings Manager, an excellent appointment, as anyone who has attended a National Gathering over the past 16 years will be able to testify. Michael Cooke, who had served diligently as Honorary Secretary for many years, signified his intention to stand down from that post soon after Peter’s appointment, and an extremely competent replacement was found in the form of Roger Bishton, who is a local government clerk by profession. Roger was not able to take on the whole of Michael’s work, so Michael agreed to stay on for a few years as Grants Secretary. Peter then lined up Michael’s replacement in the form of Christopher Gower, who had recently retired as Master of the Music at Peterborough Cathedral. Christopher has managed this part of the charity’s affairs with great efficiency, commitment and a very dry sense of humour. In 2005 a new treasurer was needed and Peter (tipped off by Michael Cooke) wasted no time in tracking down the present writer (a chartered accountant, who specialises in charity accounts) and offered him the post, which appointment seems (for the most part) to have been welcomed. What else...? The role of DR Co-ordinator had been undertaken by a number of individuals, each only for a short time, until Peter lit upon the idea of a job-share, appointing Terry Duffy (at the time at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral) and Michael Wiles, DR for York. Finally, a few years ago a new editor was required for Cathedral Music, and Peter offered the position to Sooty

Asquith, a book publisher of many years standing, who ably stepped into the role in succession to Andrew Palmer, the founding editor.

Peter’s life before FCM was full of remarkable activity. His interest in cathedral music was, perhaps, first sparked by his position as head chorister at Ripon. His son Simon continued the tradition at Exeter Cathedral, and remains a professional musician. Peter, in rapid advancement up the academic food chain, became the first Vice Chancellor of John Moores University in Liverpool, and was made a CBE for his work in regenerating Liverpool. Those who attended the Liverpool gathering in 2016 will remember his attachment to and great enthusiasm for that remarkable city.

Shortly before his appointment to FCM, Peter had been a pivotal figure in the city of Liverpool’s successful bid to become European Capital of Culture for 2008, with a wonderfully staged PR stunt in which he was photographed climbing into a helicopter, apparently with an envelope containing the bid on his way to London to deliver it. It turned out that after taking off he had, in fact, landed only a few miles away, the bid having been safely delivered the previous day – but the publicity was invaluable. This appetite for publicity has been used to good effect for FCM with frequent letters to national newspapers and a willingness to ‘bang the drum’ for cathedral music whenever possible.

During Peter’s time as chairman there have been several FCM firsts: record payments of grants, particularly in 2016; the first ‘overseas’ gathering (Northern Ireland) in 2008; the first nonUK gathering (the Netherlands) in 2015; the commissioning of an anthem (from Philip Moore); the ability to join FCM through the website; the first Festal Dinner at a Gathering in a cathedral (Manchester) in 2009; a singing workshop for FCM members (Tewkesbury) in 2007, and the establishment, initially under the editorship of Trevor Godfrey, of the FCM twice-yearly newsletter, Cathedral Voice. A significant change in the governance of the charity has been the establishment of a small number of subcommittees. As both the responsibilities of running a charity and the size of FCM have increased, so has the amount of business needing to be transacted by the trustees (Council) of the charity. Accordingly, its four subcommittees now undertake much of the business, which makes Council meetings run rather more neatly than would

otherwise have been the case. Whilst there is the risk that a committee structure takes responsibility away from the main board (Council), Peter has always encouraged those present at meetings to express their opinions and the full Council discusses all significant decisions in depth.

Two of the most significant successes of the past 12 years have been the saving of the choirs at Tewkesbury and Llandaff. Whilst it would be an exaggeration to suggest that FCM was solely responsible for saving these two choirs, the extent of Peter’s own involvement in working (with other agencies) to ensure that regular ‘cathedral’ services have been maintained cannot be underestimated, as those of us who have been on the receiving end of evening phone calls made from trains know only too well. The 50th and 60th anniversaries of the founding of FCM have been celebrated in grand style, with much of the planning of the latter being undertaken by Peter alone.

In all of this, Peter has been supported by his wife, Angela, and this has meant that in addition to being generous with his time for FCM business, Peter has also been extremely hospitable.

When a National Gathering took place in Chester, Peter and Angela invited all Council members and officers to their home in the Wirral for supper, and since moving to London they have hosted countless FCM subcommittee meetings. There was also the occasion on which Peter was awarded the Freedom of the City of Liverpool when several FCM colleagues were invited to the ceremony, which was followed by a dinner hosted by Peter for all who had attended. The main course was, of course, scouse, a Liverpool speciality. All of this has been done whilst maintaining an impressive schedule of holidays, to all manner of unexpected destinations.

Taking over from Alan Thurlow meant that Peter had a hard act to follow, and so it will be for his successor Peter Allwood, for, during Peter’s time as chairman, FCM has again become much more widely known and has subsequently gained a good deal from its increased membership. History appears to have repeated itself to the great benefit of FCM, but it is to be hoped that the paths of FCM and our retiring chairman will cross frequently in the years to come.

Ifirst met Peter on a snowy afternoon in February 2004 in the cafeteria at Bristol Temple Meads railway station. I’d seen an advertisement for the position of Secretary to the Friends of Cathedral Music and, in what was a somewhat reckless moment, decided to put myself forward as a possible candidate. Arrangements were made for me to meet Peter on his way to an engagement at Gloucester Cathedral and so with a certain amount of trepidation I made my way to Bristol for our meeting.

I needn’t have worried because as soon as I met Peter I was warmed by his charm and friendliness, and I can quite truthfully say that I had never previously experienced such an enjoyable interview. That is not to say that it wasn’t carried out

in a business-like manner, because all the necessary interview questions were thoroughly explored; fortunately, Peter seemed to think that I would be suitable. This was verified when Council subsequently appointed me without any further interview.

During our initial discussions I realised that our views about FCM were rather similar, and I was confident that we could work well together. Peter is an exceptional person. He has just the right balance of looking to the future with good and sound fresh ideas but at the same time is sensitive to those with differing views; he also has the ability and patience to steer everyone gently in the direction which will ultimately result in the best solution. This is a rare attribute and so much appreciated.

Peter was born in Rotherham and educated at Ripon Grammar School where he sang in the cathedral choir and became head chorister. He studied geography at Bristol University, during which time he attended St Mary Redcliffe Church, where he became a server. Although our paths did not cross, I received my early organ lessons at about that time from the organist, Garth Benson. After lecturing at the university Peter moved to Exeter, where he was appointed senior lecturer in geography and more importantly met and subsequently married Angela, who was studying theology. In 1978 he and his family moved to Chichester where he became Head of Bishop Otter College and subsequently was appointed Rector of North East London Polytechnic (now University of East London). In 1992 he was appointed the founding Vice-Chancellor of John Moores University, Liverpool.

During his time in Liverpool, Peter demonstrated both his interest in a large number of different subjects, and also his enormous energy in giving of his time so generously to these causes. One would imagine that steering a new university during its initial years would be more than enough work for anyone, but not so with Peter. Having always been very interested in cathedral music and liturgy, he became a

member of the Church of England Synod and also a member of the Archbishops’ Council, taking a special interest in the publishing arm of Church House, Westminster. He became a Council member of Liverpool Cathedral and played a major part in planning the installation of Justin Welby as Dean of Liverpool in December 2007.

That Peter was High Sheriff of Merseyside in 2001-2 can be seen from a marvellous photograph of him (in his home) in full uniform, mounted on an impressive-looking horse! He has held too many appointments to list, but I would mention that he is Life President of Liverpool Organists’ Association and was awarded the freedom of the City of Liverpool in 2010.

Now, what of his time as Chairman of FCM? Succeeding Dr Alan Thurlow in 2002, his period as chairman has seen much activity and growth. Highlights include our Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2006 with a gala reception in the House of Commons organised for us by our member Robert Key, when he was still the Member of Parliament for Salisbury. We were delighted to welcome our senior Vice-President, Dr Francis Jackson, who recounted stories about his time at York Minster and also his more recent adventures travelling around the UK by coach, giving organ recitals.

Ten years later we celebrated our Diamond Jubilee, about which much has been written elsewhere. Suffice it to say that one of the highlights of the year’s celebrations must surely have been the gala concert at St Paul’s Cathedral in April when a chorister from almost every cathedral choir in this country joined with the choir of St Paul’s Cathedral under the baton of their Director of Music, Andrew Carwood, to give a breathtaking concert of cathedral music. These choristers have all met once again in St Paul’s Cathedral to record some of the music performed at the concert, and a CD of this has just been launched (see p5 for order details).

During Peter’s time as chairman we have seen the membership of FCM increase to almost 4,000 and our grant-giving rise to almost £4m since its inception in 1956. Last year we gave a record £600,000. Mention must also be made of Peter’s talent as an editor. During the last few years he has more than ably taken over the editorship of Cathedral Voice and it has now expanded to 20-24 pages per issue, all in full colour.

Peter is an excellent after-dinner speaker and he has the rare ability to be able to deliver a serious speech with just the right amount of humour, thus keeping the attention of his audience. He is such delightful company and, together with his lovely wife, Angela, they are the perfect host and hostess. We shall all miss Peter very much indeed and wish him every success and pleasure in his future endeavours, which, knowing him, will continue to be many.

Roger BishtonWe provide all types of new instruments

New Organs

Restoration

Rebuilding

Tuning

Maintenance

We can give unbiased advice for all your requirements

Hillside Organ Works

Carrhill Road, Mossley, Lancashire OL5 0SE Tel: 01457 833 009

www.georgesixsmithandsonltd.co.uk

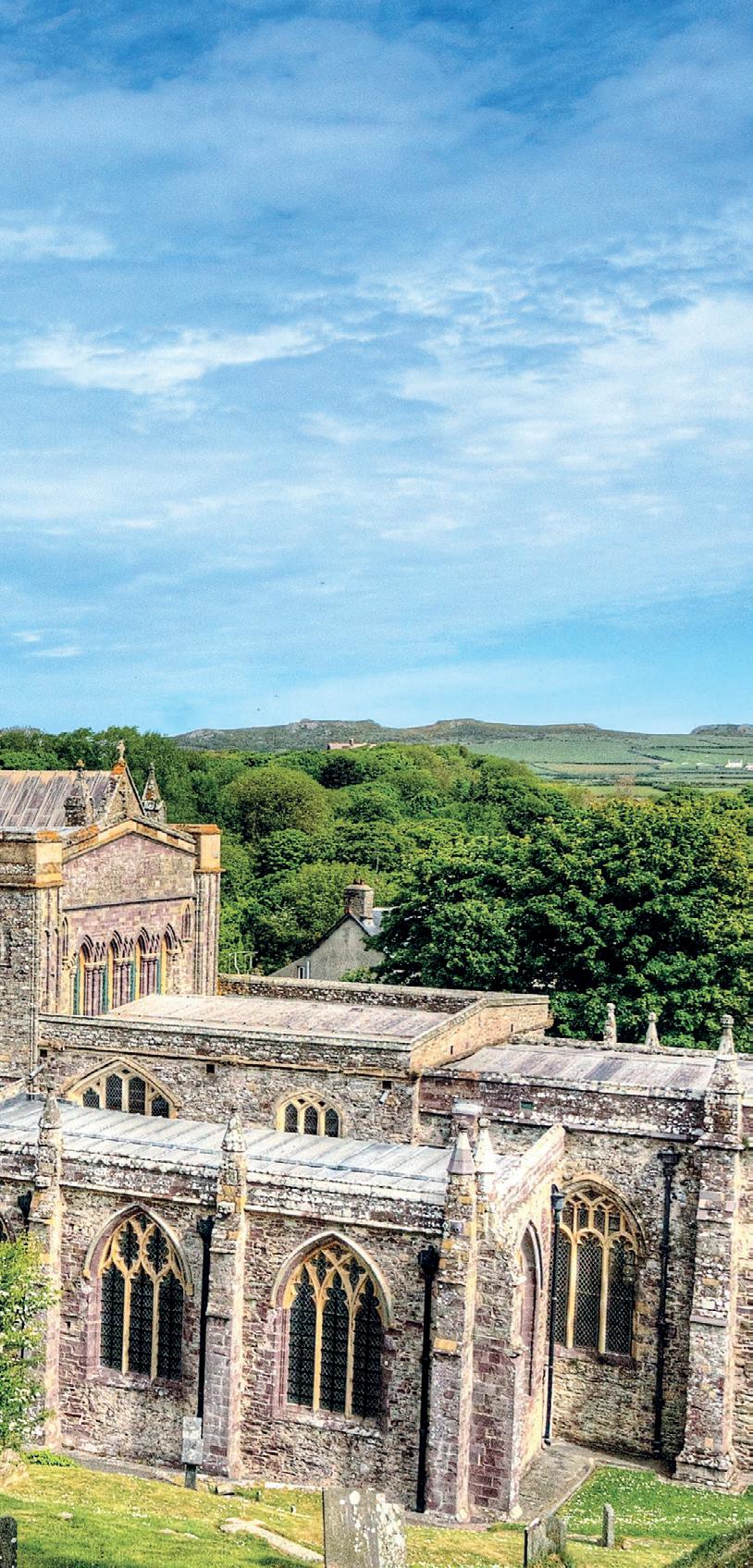

Ninety years is a good position from which to look back and recall the highs and lows of any life or institution. For the RSCM it is remarkable that we still exist at all, given the financial crises that have regularly threatened the organisation, but we are currently somewhat better placed financially and certainly still imbued with that strong vision of our founder, Sir Sydney Nicholson: a desire to improve the standards of church music and musicians.

Lower Chapel, and at Carlisle and Manchester Cathedrals before appointment to Westminster Abbey in 1918 at the age of 43. Nicholson was an energetic character and, with his slightly aristocratic background and a diplomacy inherited from his politician father, he moved in highly placed social circles where he was well known in the upper echelons of the clergy, especially through his connections at the Athenaeum Club in Pall Mall. He found that the music at Westminster was in a pretty poor state – the responses and psalms were never rehearsed and the twelve regular lay vicars were abusing the deputy system. Within a few years he successfully turned all this round and, using two teams of boys, was able to provide sung services on 365 days a year.

The first hint of Nicholson’s practical concern for the state of music in parish churches came in 1924 when he formed what he called a ‘model’ choir. Using members of his Westminster Abbey Special Choir, this choir went on tour to demonstrate at a parish level how things should or could be done. This initiative was in response to the Archbishops’ report published two years earlier entitled Music in Worship

Over the next couple of years Nicholson formulated his own double plan: a training college with a resident choir so that church musicians could hone their choir-training skills, and also a national network providing advice at a parish level.

After much discussion with eminent musicians and church leaders, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, Nicholson tendered his resignation from the Abbey in 1927 and arranged a meeting with the Dean of Westminster in order to explain his plans. Following this, both the School of English Church Music and the College of St Nicolas were born, opening just over a year later at Bullers Wood in Chislehurst. It was very fortunate that Nicholson had a private income for, after leaving the Abbey, he never again had a regular salary, and indeed the Chislehurst property for the College was bought by him and donated to the School.

Over the next ten years the College and an international network of musicians grew so much that, by 1939, around 1500 parish choirs were affiliated to the SECM and many were using the various publications issued during that decade.

Major church music festivals were held in 1930 at the Royal Albert Hall and in 1933 and 1936 at the Crystal Palace, involving thousands of singers (Westminster Abbey was too small!), but the onset of WWII caused an abrupt end to the work of the College as most of the students were called up for military duty and the school premises were taken over for other uses. Sir Sydney (he had been knighted for his work at the Coronation in 1937) moved to be acting organist at St Michael’s, Tenbury, and he ran the College of St Nicolas from there until the School moved to Leamington Spa in 1943.

The SECM remained active during the war but there was a shift in emphasis towards courses for boys and the publishing of music for upper voices. Choirs all over the country were devastated by the haemorrhage of men into the armed services and many parishes were suddenly reduced to a boysonly status. Even before the move to Leamington in 1943, the dean and chapter of Canterbury Cathedral had offered accommodation to the College and so it re-opened after the war in January 1946 in the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral. The previous year the organisation had changed its name from the SECM to the Royal School of Church Music. At face value this might seem like promotion and recognition, but in fact it had been applied for by SECM Council in 1944. Nicholson’s

death in 1946 was a great blow to the RSCM; it was his energy and funds that had been both the backbone and the driving force of the organisation. There was no money to employ another director and so three honorary ‘Associate Directors’ were appointed – Gerald Knight, organist at Canterbury, John Dykes Bower of St Paul’s Cathedral, and William McKie from Westminster Abbey. They guided the RSCM in various ways until it settled in Croydon at Addington Palace.

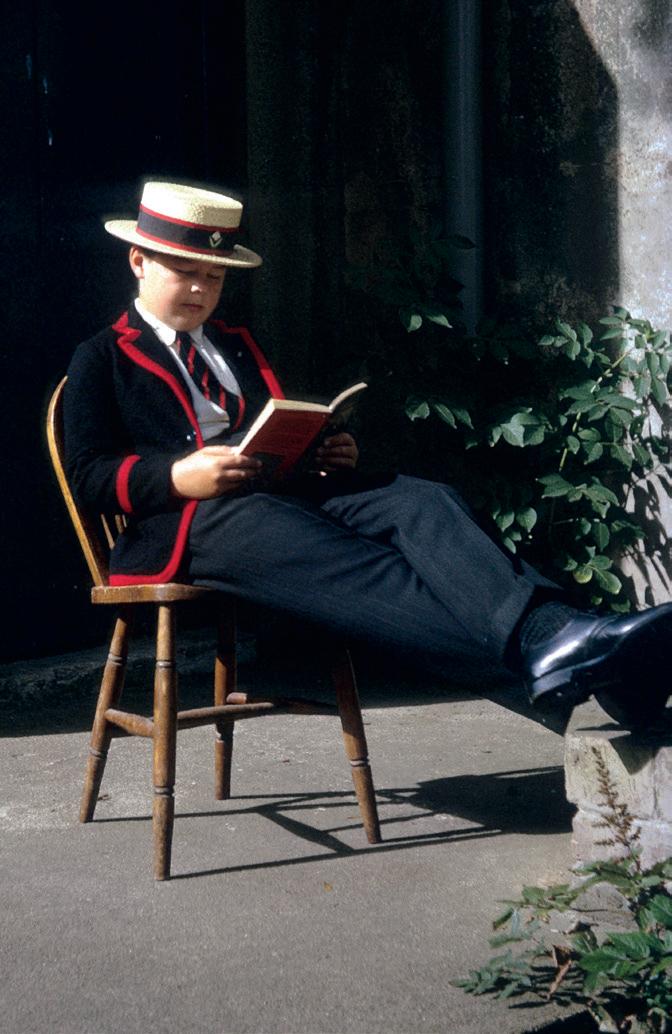

Although not wishing to portray it as some sort of ‘Golden Age’, those Addington years, from 1953 until 1996, were really the glory years of the RSCM, with a gradual increase in the number and scope of the courses offered both at Addington and around the country, and a burgeoning influence on parish churches through the diocesan network and publications. Liaison at a diocesan level has always been a key feature of the RSCM’s work and, for most of our existence, relationships with cathedrals have been both close and vital. The RSCM’s work extended worldwide, notably to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada and the USA. Naturally there were many courses arranged for boys, often up to 140 at a time, and also courses for choirmasters (both town and country – their needs were perceived as quite different). The prestigious courses for boys were the summer cathedral

courses where 40 boys and 40 young men would sing services at a major cathedral for two weeks with a BBC broadcast Evensong during the second week. Judging by our recordings, the standard was staggeringly high. Then there were courses for organists taking the advanced Archbishop’s Diploma in Church Music (ADCM), and other diplomas for lay readers, ordinands and newly ordained clergy – indeed, training the clergy was always as much a priority as training the musicians. Ordinands from many of the Anglican training colleges were sent to Croydon three times a year until the 1970s, when the budgets of those colleges became so tight that musical training was seen as something of a luxury rather than a necessity. In later years, director Lionel Dakers made a positive effort to visit training colleges (at the RSCM’s expense) to scratch the surface of educating prospective clergy, but he gradually found the colleges to be less and less enthusiastic. Many clergy are now being ordained with virtually no knowledge of hymnody or sung liturgy. With the recent appointment of a full-time RSCM Head of Ministerial Training the RSCM is seeking to address that problem.

According to the 1958 annual report, during the previous ten years nearly 2500 students had attended courses at Addington and Canterbury, including 1000 ordinands, junior clergy and lay readers and, during the first four years at Addington, 700 organists, choirmasters and singers had attended. A major educational milestone in 1965 was the introduction of the Chorister Training Scheme (CTS) by RSCM Headquarters Commissioner Martin How. This structured course featured graded attainment levels, with medallions and ribbons, record cards and training materials for both choristers and choirmasters. Taken up with enthusiasm all around the world, the CTS was re-launched as the ‘Sing Aloud’ scheme in 1989 and then replaced by the current ‘Voice for Life’ training programme (which also now includes adult singers) in 1999.

During the first half of the Addington era there were full-time residential students, many working for their ARCO, FRCO or also attending the London music colleges. They usually stayed for one or two years. The list of famous names is enormous and so I mention just a few – Gillian Weir, James Lancelot, Peter Phillips and Paul Spicer. The residential college closed

in 1974 because it was no longer financially viable. We did not confer degrees or diplomas and, with universities offering these together with choral and organ scholarships, the best candidates were generally pursuing that route into a musical career.

In 1953 the RSCM took out a 50-year lease at Addington at £1000 a year. It became clear during the inflationary 1990s, however, that any new lease would not be at such a peppercorn rent and it was necessary to look elsewhere. Cleveland Lodge, the house in Dorking belonging to concert organist Lady (Susi) Jeans was bequeathed to us. The idea of owning our home in the idyllic setting of Box Hill with a railway station outside the front door was, on the face of it, very attractive, but unfortunately the property was in a bad state. It needed rebuilding, during which part of it fell down, but with a substantial drain on RSCM reserves and a lottery grant of over £1 million, this was achieved.

time of particular financial crisis. Many cuts were made and publishing almost ground to a halt in the early Noughties. Allowing for inflation, the cost of the upkeep of Cleveland Lodge and its grounds had escalated to be more of a drain on resources than looking after Addington Palace had been, and so a move, with a tightening of the belt, was necessary. In 2006 we decamped to Sarum College in Salisbury.

Since then, publishing has flourished and now includes a wide range of material in different styles and ‘photocopiable’ resources, which provide an inexpensive source of high quality music. One of the major successes of the RSCM has been our quarterly Sunday by Sunday magazine issued along with Church Music Quarterly; indeed, some churches join us specifically to obtain this members-only benefit. Introduced in 1996 on the initiative of Harry Bramma, and coming of age this year with its 84th issue, we offer guidance based on the major lectionaries for all those who choose music for parish worship. Using a wide range of ecumenically based sources, we suggest hymns, songs, chants, anthems, children’s music, organ music and psalms, together with a brief theological thumbnail based on the readings set for the day. The musical choices offered are designed to be relevant to churches both with or without choirs and organists, and they encompass many musical styles including the music of Iona and Taizé. In our recommendations we also recognise and try to take into account the different skill levels available in parishes. The magazine has a training element too, with regular workshops on specific choral pieces, hymns, songs and organ music.

90 years and counting – for the RSCM there is still work to do and much to look forward to, but these reflections on its work over the decades surely show how much has been achieved, starting with the vision of one man.

We moved into Cleveland Lodge in 1996 under the directorship of Harry Bramma. Harry was instrumental in ensuring that the RSCM embraced more fully both the idea of girls in choirs, and the diversity of musical styles in worship. On his retirement his successor, Professor John Harper, combined the dual role of director and chief business executive. With the liturgical changes at the introduction of Common Worship in 2000, it was valuable to have an experienced liturgist such as John (who was also on the Church of England Liturgical Commission) to oversee the provision of music for the new liturgy; just as earlier, from 1980 onwards, during the years of experimenting with Series Three and the ASB, the RSCM had anticipated the changes and commissioned composers to write for the new liturgies. So it was to be for Common Worship, but the new music for this century necessarily had to encompass a rather greater range of musical styles than before and the cost of these publications was considerable. The RSCM has never been flush with funds but this was a

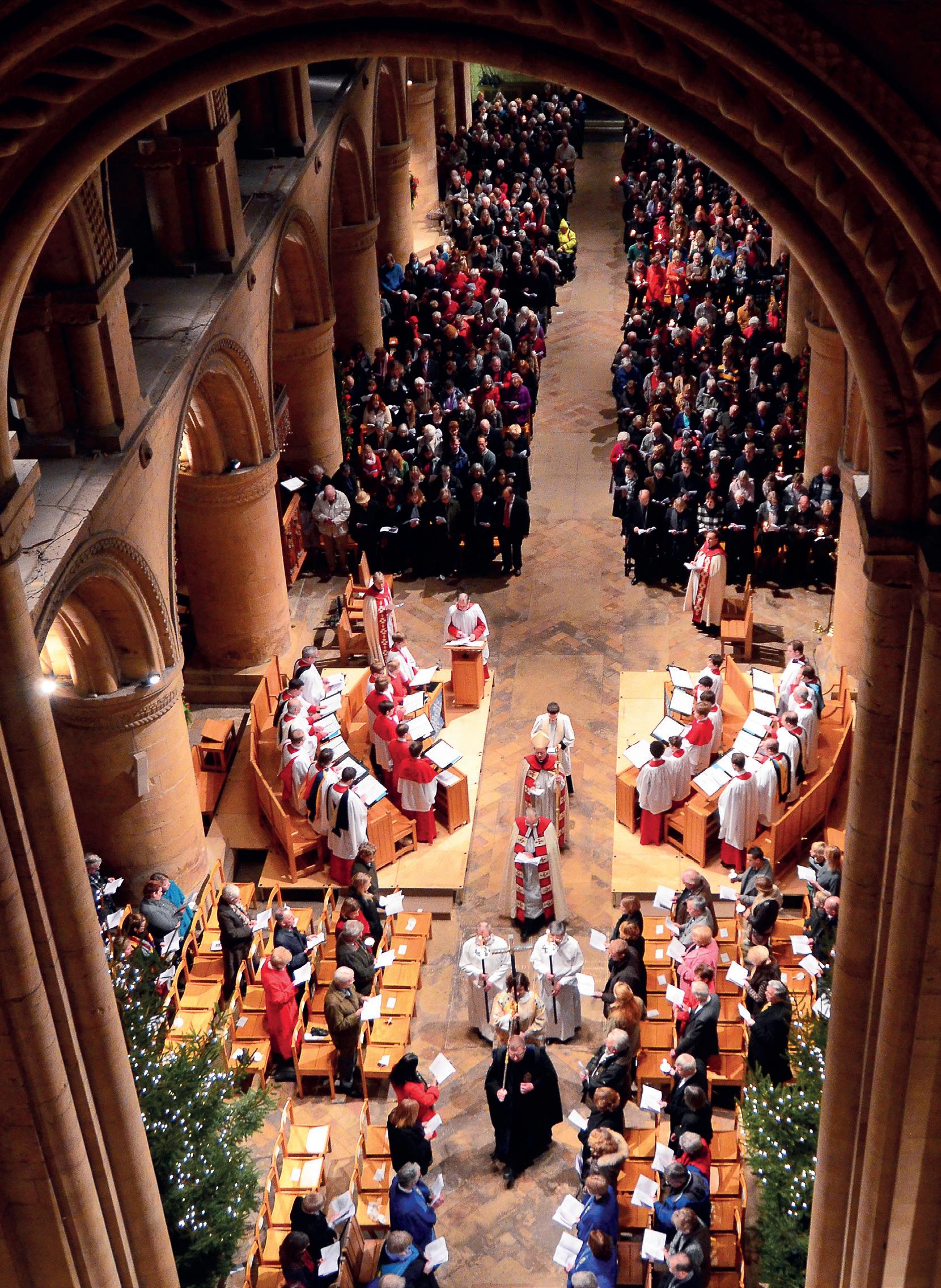

In terms of age, the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King in Liverpool is a mere infant but, nonetheless undaunted, it has great plans to celebrate its Golden Jubilee in 2017 on the Feast of Pentecost, Sunday 4 June, with a festival lasting two weeks. Many other events will take place during the year.

The present building, designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd, is in fact the fourth attempt to build a cathedral for the Liverpool diocese, the largest Catholic diocese in the UK. After the restoration of the hierarchy in 1850, when Pope Pius IX recreated the diocesan chain of command which had been extinguished with the death of the last Catholic bishop in the reign of Elizabeth I, plans were laid to build a cathedral in Everton, with Edward Welby Pugin being the architect selected. He designed a cruciform building with a huge steeple to be dedicated to St Edward. Work began on the Lady Chapel and was completed within three years. The attention of the diocese then became concentrated on more pressing needs – parish churches, schools and orphanages – as the Catholic population rapidly increased, in large part due to the dramatic effects of the Irish potato famine, and the completion of the cathedral was abandoned. The Lady Chapel served as a parish church until the 1950s, when it was demolished.

A second attempt was made in the 1930s when the diocese bought the site of the present cathedral. It seems very fitting that a cathedral should replace what previously had been the largest workhouse in Europe; this had housed 4000 inmates and closed finally in 1928. Archbishop Richard Downey commissioned Edwin Lutyens, the foremost architect of the time, to build the largest cathedral in the world with a design which incorporated an enormous dome. The completed building would have eclipsed Liverpool Cathedral (the largest Anglican cathedral in the UK), for which the foundation stone had been laid in 1904. An idea of the scale can be envisaged from the dimensions: the Lutyens building was intended to reach 158 metres high whilst the Anglican cathedral is a mere 101 metres tall! The foundation stone was laid on Whit

Sunday 1933. A model of Lutyens’ cathedral, constructed to help raise funds, is now displayed in the Liverpool Museum on the Mersey waterfront. It stands about four metres high and is over five metres long (and is well worth a visit).

World War II interrupted the construction work, and by the 1950s the final cost had escalated to £27m. Archbishop William Godfrey, instructing Adrian Gilbert Scott (brother of Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect of the Anglican cathedral) to reduce both the proportions and the costs, found that the new design pleased few people. Archbishop John Carmel Heenan, appointed to Liverpool in 1957, realised that drastic action was needed and had the Lutyens crypt roofed over and opened, supplanting the nearby Pro-Cathedral. He then scrapped Scott’s plans and set up an international design competition for an entirely new building with a budget of £1m for the main structure. About 300 entries were received. Of these, one by Frederick Gibberd was chosen, and building began in 1962. The new cathedral was opened and consecrated at Pentecost just five years later, by which time Heenan had been translated to Westminster as a cardinal. He returned for consecration as the Papal Legate.

So this year, the cathedral, now a much loved iconic feature of the Liverpool skyline situated on the same high ridge as its sister cathedral at the far end of Hope Street, will celebrate its 50th birthday. Both cathedrals are both dedicated to Christ; neither is geographically aligned in the normal liturgical manner – east to west – but both are on the north–south axis. Somewhat Tardis-like, the exterior of the Metropolitan Cathedral disguises the vastness of its interior; it seats over 2,000, in pews arranged in concentric circles around the sanctuary and high altar, so that no one is very far away

from the liturgical action. A series of side chapels round the perimeter and between the buttresses, each framed by blue glass, were originally intended for the celebration of mass by individual priests, but these have been adapted for alternative uses after concelebrations rendered them redundant. The great lantern window, the largest in the world, was designed by John Piper with the execution being carried out by Patrick Reyntiens. Two thousand tons of coloured glass and concrete hover above the sanctuary without obvious means of support. The colours of the spectrum in rotation represent the glory of God, with three bursts of white light recalling the Trinity. Artists whose works adorn the great internal space include Elizabeth Frink, William Mitchell, Robert Brumby, Sean Rice, George Mayer-Marton, Stephen Foster and Arthur Dooley.

The choir stalls and organ console are situated behind the Archbishop’s chair at nave level with the fine 4-manual Walker organ of 108 stops and its distinctive and striking display of brass trumpets set on a projecting shelf above the entrance to the Blessed Sacrament Chapel. The Lady Chapel with its ceramic Madonna is sited to the left.

Outside the main porch an impressive and huge flight of steps, flanked by two coloured glass panels standing like sentries, leads up to the main entrance where four bells hang above bronze sliding doors. Named Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, they provide an unforgettable visual spectacle and an impressive aural experience when tolling. The vestries, song room, music library and offices are at ground level; an internal processional ramp offers a dramatic entry route into the cathedral.

The Lutyens crypt is enormous, sometimes overwhelming visitors with its four vast spaces. The Pontifical Hall houses

a splendid treasury exhibition and has displays documenting the history of the cathedral, including a video presentation during which the Lutyens building is superimposed on the Liverpool skyline with alarming results. There is a chapel which serves as the local parish church; a concert room seating over 300, and the Crypt Hall which can seat up to 350 for formal dinners, with its own state-of-the-art kitchen. Apart from the chapel, these spaces are used by the two nearby universities as examination halls at various times of the year, and the Crypt Hall annually houses the CAMRA beer festival, the best attended in the country! The crypt roof serves as a great piazza with an external altar.

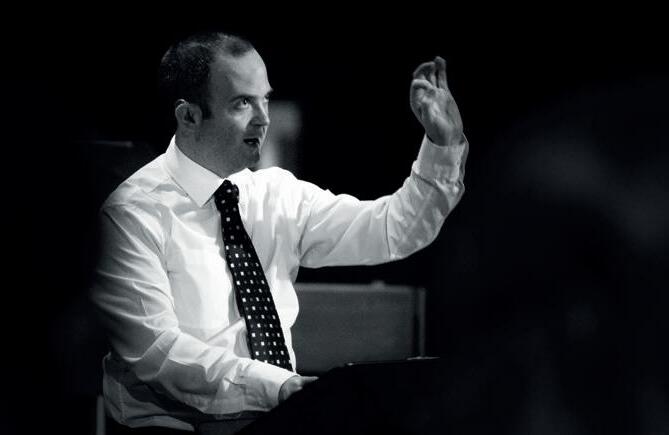

The choir of boys and men was founded in 1960, services then being held in the Lutyens crypt, while the girls’ choir came later, in 2008. The choirs’ repertoire includes Gregorian chant and a wide range of Latin and English church music composed throughout the ages up to the present day. The music of the cathedral has an international reputation and choral services are sung each day except on Saturdays during choir terms. All the choristers are pupils at the cathedral’s choir schools, St Edward’s College & St Edward’s School, which are situated not far from the cathedral in West Derby and where daily rehearsals take place each morning for an hour before school. The lay clerks are supplemented by choral scholars and the organ scholarship was established in 1975, the first such in the Catholic church. The first organ scholar was David Saint, who in 2016 retired as the Principal of the Birmingham Conservatoire (see CM 2/16). A number of former choristers have gone on to singing careers and many other posts in the music world. The current director of music, Dr Christopher McElroy, has been in position since 2012. He is ably supported by the Assistant Director, James Luxton (see CM 1/16).

Although Liverpool was the European City of Culture in 2008, I prefer to cite it as the Capital of Ecumenism. After a history of religious strife in the city, the work done by Bishop David Sheppard and Archbishop Derek Worlock in the 70s and 80s did much to replace antagonism with cooperation: their maxim was ‘Better Together’, also the title of a book they co-wrote. Today the cathedrals work alongside each other on various levels, from a joint food bank to ecumenical services and musical events such as Messiah, and the choristers enjoy an annual sports day together. A high point of this sharing is the Pentecost Service which begins in one cathedral and ends in the other; the congregation, choirs and clergy all process along Hope Street.

The Jubilee Festival, besides the Solemn Choral Mass, Evening Prayer on Pentecost Sunday and other events during the year, will include a grand dinner following the singing of the First Vespers of the feast the day before, and a flower festival. A performance of an electronic setting of the mass by the French composer Pierre Henry, originally intended to be choreographed as part of the secular events at the opening of the cathedral in 1967 and which was not completed in time, will this year be promoted in May in conjunction with the Bluecoat Creative Centre, which is celebrating its 300th birthday. A concert by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society Orchestra and Chorus together with the Metropolitan Cathedral choirs will perform a new Gloria composed and to be conducted by Sir James MacMillan, with tenor soloist Ian Bostridge. The programme also includes music for brass, and Poulenc’s Gloria. In July, Benjamin Britten’s Noyes Fludde will be performed by local school children, and there will be four organ recitals by top-class organists: Johann Vexo (Notre Dame, Paris), Martin Baker (Westminster Cathedral), Ian Tracey (Liverpool Cathedral) and James Luxton (Assistant

Director of Music, Metropolitan Cathedral). Each recitalist has been asked to include a work performed in one of the four recitals at the opening of the cathedral when the recitalists then were Flor Peeters, Fernando Germani, Jeanne Demessieux and Noel Rawsthorne. The choirs of Westminster Cathedral and the Metropolitan Cathedral will combine to sing Mozart’s Requiem together with the Liverpool Mozart Orchestra in November. Another choral concert will feature the Liverpool Welsh Choral Union which also sang in the festival at the opening of the cathedral. The Sixteen, who visit the cathedral each year, will be welcomed to perform their Choral Pilgrimage 2017 programme in September. An exhibition showing some of the unsuccessful designs for the cathedral is also planned. A project entitled ‘Fifty Years of Memories’ for which local folk are invited to record their own memories from 1967 onwards will then be available to be heard in listening booths in the city.

We hope to welcome as many visitors as possible to explore this remarkable cathedral and its stunning crypt as well as enjoying the celebratory events.

Magdalen College, Oxford in the summer of 1964. Someone had pulled out at the very last minute so I was summoned as a late possibility. The voice trial still seems like yesterday, and my hopeless preparation drew Dr Rose’s merciless mockery, but nevertheless I did take in his warmth and extraordinary charisma. I’d just about do, I felt. Soon I found myself as a probationer at age 11, older than most but at least I had learnt the ropes during some happy terms at Exeter under Christopher Herrick.

Through the 60-a-day blue haze, the Song School was a survival exercise in enduring Dr Rose’s endless derision and sarcasm, yet our deep affection, respect and loyalty knew no bounds. His choral direction was effortless and a joy. By contrast we rebelled at his organ scholars, particularly those who stopped and nitpicked at every bar. We were sorely disappointed when Dr Rose delegated a choir practice, sadly all too often.

But he had so much else to do. Even at that tender age, I was deeply impressed that Dr Rose could go hunting for an ancient manuscript and then appear with all the parts handwritten and ready to go. What an immense privilege it was to witness the likes of Tomkins Sixth emerge for the first time in centuries!

I recall that some choristers were true-born musicians, but certainly not me. I was Cantoris material and best avoided if there were a solo to be done. I seemed to evolve another quality, that of reliability. At a sudden entry or change in tempo, I would always be there, maybe not prettily but at least something would happen. I think Bernard appreciated that.

My career as a treble ended abruptly in 1967 when we returned for the Michaelmas term. There was always a glorious fortnight before the university term started, and then it was

To see Dr Rose at work, calmly absorbing a complete orchestral score while his fingers and feet apparently moved all on their own, was unbelievable.

out of the Indian summer and straight into the cool solemnity of the Song School. Within minutes it became obvious that my voice was breaking. Just as I luxuriated in the boundless joy of, at last, a life without commitments, Dr Rose alighted upon a plan. There was no way that he was going to pay me for an entire term of doing nothing, so instead I would become his PA. Right up to Christmas Eve, I prepared and carried his music, turned the pages and ran errands. My reliability had returned to haunt me.

How I loved that organ loft! To see Dr Rose at work, calmly absorbing a complete orchestral score while his fingers and feet apparently moved all on their own, was unbelievable. I have spent the entire intervening half-century hoping to wake up tomorrow as a ready-made cathedral organist. It would not of course require any effort on my part – after all, Bernard never seemed to expend any. His music just ‘happened’.

Sunday Evensong was the big event of the week and there was always a superb organ voluntary to look forward to –particularly by me, crouched right next to Dr Rose, pulling stops and awaiting the page-turning nods. One dark night, Bernard was right at the height of something immense when he stopped dead in his tracks. From the antechapel beneath, the congregational chit-chat roared on. Bernard selected the largest book I have ever seen, leaned over the edge and dropped it cleanly between the heads beneath. It landed flat with a noise like a cannon-shot. There was instant silence. After a few seconds the voluntary continued and nobody dared breathe even a whisper. That was Bernard.

I’ll never be sure if Dr Rose actually liked me, but we certainly worked well together over hundreds of hours of close contact. I may be the only chorister to have ever been awarded this extraordinary privilege, and I think it significant that chance delivered it to an appreciative amateur rather than a blasé prima donna. In the long run, Bernard probably had a more positive impact on my life than literally anyone else. Thank you so much, Dr Rose.

Robert went on to a career as an airline pilot, where the chorister’s habits of accuracy, timing and long concentration proved invaluable. His musical heart has been in Venice ever since 1966, when Magdalen sang a Gabrieli Magnificat in Westminster Abbey. In Monmouthshire, Robert sings several times a week at local level. He is a Friend of Newport Cathedral Choir, where choral music is blossoming under the dedicated directorship of Dr Emma Gibbins.

Do you know a musical boy who dreams of becoming a Cathedral Chorister? If so, please bring him along for an informal voice trial.

Please contact the Registrar, Clare James, at registrar@cccs.org.uk or on 01865 242561.

www.cccs.org.uk

Highlights include...

FESTIVAL

13-29 July 2017

Bach and Vivaldi with the Academy of Ancient Music, the Aurora Orchestra playing from memory, the Festival Chorus singing Mozart’s Requiem in King’s College Chapel, Tenebrae performing Talbot’s Path of Miracles, a silent film with organ improvisation by Richard Hills, organ works by Bach, Couperin, Daksagmüller & Byrd

Booking now open online and via

The main function of the FAC, which is ultimately responsible to the Cathedral Fabric Commission for England (CFCE), is to advise, review and, when called upon to do so, approve decisions made by the dean and chapter which might be regarded as affecting national heritage items (and our distinguished organ certainly comes into that category). None of us had any doubt that the request to alter the pitch of the organ, so that it could perform all the tasks required of it in today’s world, should and would be accepted without difficulty.

We were in the unusually happy position of having the financial resources to pay for the change from a small part of the hugely successful appeal that had been launched in 1996. Not only that, but as part of the devastation wrought by the fire on 22 November 2001, the organ was severely damaged by fire, smoke, chemical residue from the burning plastic chairs, and water, and it was necessary to dismantle, clean and rebuild the instrument completely. With the organ unusable and large sections of it needing to be taken back to the organbuilders’ workshops in Durham, this was the moment to seize the opportunity to convert the organ to standard pitch for which the reasons were compelling.

In 1990, Dean Randolph Wise invited me to become a founder member of the Peterborough Cathedral Fabric Advisory Committee (FAC). 24 hours before the first meeting he told me he was expecting me to be the chairman; I protested that my only relevant specialist knowledge of the task envisaged was that I knew a certain amount about organs.

Little did I suspect at the time that this knowledge was to be sorely tested in our attempts to alter the pitch of our magnificent organ, attempts which were to exceed in length and acrimonious negotiations anything else that has been on the FAC agenda during the last 20 years. Consider the time and effort committed to major work that has been done to the fabric of the cathedral during this period: the restoration of the nave ceiling, the renovations necessary after the fire, and developments in the precincts as a whole.

Why does the pitch of the organ matter so much? In the 1890s there was no generally accepted measure of standard pitch. Organ-builders had been free to choose a level with which they were comfortable. In Hill’s instrument of 1894 this was around a quarter-tone sharp of what became standard pitch very soon afterwards. The international agreements that were more or less established around the turn of the century resulted in a general consensus that the pitch of the A above what we recognise as middle C on a keyboard instrument should vibrate at 440 cycles per second (cps), the standard tuning fork pitch with which most are familiar from the tuning-up of orchestras. A variation of two or three cps makes no effective difference – even 445 cps does not worry most people – but the Peterborough organ, depending on the temperature in the building at any given time, has A in the region of 452cps or more. This creates a situation in which modern wind instruments cannot tune to it, so performances with orchestras or other groups are impossible.

Orchestras and bands ceased to use sharp pitch instruments soon after the organ was built – they have become museum pieces, or in most cases have been scrapped. Even today’s most highly skilled professionals cannot match Peterborough’s very sharp pitch, and for amateurs and schoolchildren it is impossible. The difficulty cannot be solved by organists’ wellrecognised ability to transpose – that simply puts them flat to a degree that cannot be accommodated! Fundamentally then, there is an overwhelming reason to make the instrument playable in all normal circumstances and not have its use confined to recitals and accompanying services – though here too there are urgent reasons to accommodate to standard pitch. To be in a position where we cannot use the cathedral organ, one of the most costly items in the building, for all services, concerts and other events, or to make its full impact felt on special occasions, such as outreach with schools bringing their musicians to make music in the cathedral, would be very unsatisfactory.

Large cathedral organs are complicated, expensive to build and to maintain so cost is always a major influence on what can be achieved at any stage – parts wear out and substantial refurbishment is required from time to time; this might happen in the normal course of events after periods of 30 to 50 years. Fundamentally, the Peterborough organ dates from 1894, though it was based in part on an earlier instrument and incorporated pipes from 1868 and some from c1735. Some wind pressures had been increased in 1912, major rebuilds were undertaken in 1930 and again in 1981, and thus the instrument we know today evolved over time. .

As with most instruments of this kind, the opportunity to make some changes is nearly always taken at the time of a rebuild. There may be a wish to alter wind pressures, add, delete or re-voice ranks of pipes, install new action, move the console to a more practical position and so on. Some of these changes are undertaken for practical reasons, some to

adjust to a new fashion and just occasionally some as a result of a passing whim! On each occasion at Peterborough the cathedral organist had wanted to lower the pitch of the organ to something close to what had by then been established as standard pitch, but the cost of such a change, which involves lengthening and altering large numbers of pipes, made it an impossibility.

In years past, the only stumbling block to rectifying this situation – not so this time, of course – had been that there was never enough money to do so. A while after the 1981 rebuild, however, a new problem arose. The establishment of the CFCE has been a boon in terms of making it possible to maintain the fabric of the nation’s cathedrals, as access to Government and other funding was not available previously, and without it many cathedrals would be struggling even more than they are now. Funding is monitored and to a certain extent controlled through the CFCE, and anyone visiting Peterborough Cathedral will know just how decisive and influential the system has proved in maintaining and improving the quality of our heritage, a task that would be well nigh impossible without such practical help and guidance. We are all profoundly grateful for this help. Quite rightly, we all have to argue our case for support, and justify all applications (and needless to say the published rules and requirements are onerous!). An important part lies in the hearing of possible objections, and that is where we ran into difficulties.

There is a powerful conservationist lobby that believes it is rarely acceptable to change any aspect of an original concept, and considers any change as an assault on the integrity of the item in question – preservation is everything. Usually this approach is thoroughly justified, but when applied to an organ which has to perform a fully functioning practical role, and has in any case been subject to much alteration and addition that has changed its nature over the years, it makes no sense to preserve those aspects that prevent it from fulfilling the task

for which it exists. In essence, the arguments at Peterborough revolved around disagreements as to whether the organ was to be viewed as an historic piece of furniture or as an essential functioning instrument capable of satisfying all reasonable needs.

In 2002, the first attempt to secure approval for changing the pitch resulted in an abrupt rejection. It stated that, ‘Adequate justification for an extensive material alteration to the historic fabric of the organ has not been provided’ and ‘The proposals are likely to result in an alteration to the tonal character of the instrument’. It was our view that the extensive changes to the instrument did not justify their determination to put such emphasis on the historic fabric, which had already undergone so many changes. We were also convinced that the tonal character of the instrument, as it stood, would not suffer, and that there was ample evidence to support this contention by referring to the experience of Westminster and Southwark Cathedrals and the Royal Albert Hall, where such changes had been very successful.

Following the rejection, a letter to the dean from the CFCE made a number of recommendations about how the cathedral should consider tackling the problem. Included were suggestions such as acquiring a second pipe organ, using an electronic instrument, and seeking advice from those who thought they knew how to cope in such circumstances (it was rather dismissive of the evidence and experience of those who actually worked in Peterborough Cathedral and were fully familiar with the difficulties). This did not go down well and led to a second application.

David Painter, Canon Residentiary of Peterborough at the time, undertook the unenviable task of masterminding the second application, which was presented in 2003. It was a very thorough and carefully researched process. First of all, it gave reasoned objections to the proposals put forward by

the Commission, not the least of which was that they would relegate the Hill organ to a situation in which it would be used very rarely. A meeting was arranged with members of the CFCE and held at Peterborough so that all matters could be thoroughly discussed. Our case was put forward in detail and there were almost no contrary views expressed by members of the Commission. Ian Bell, our organ consultant, whose work had included advisory positions for St Paul’s Cathedral, the Royal Festival Hall, the Royal College of Organists, Eton

College and many others, presented a report that dealt comprehensively with matters of historical authenticity, technical detail and the tonal quality to be expected. Dr Christopher Robinson, who had been a consultant at the time of the 1981 rebuild, spoke eloquently and from the heart about the importance of promoting and maintaining the highest achievable standards of performance and chorister training. Such standards could not be achieved when boys and girls learnt to play their instruments and perform unaccompanied anthems at one pitch and were then asked to achieve similar results when singing at a different pitch with the organ.

These views were strongly supported by Dr Peter Hurford: “It must be extremely confusing for a youngster’s development of relative (let alone ‘perfect’) pitch,” he said. In addition we submitted a letter of support from ten of the most respected, skilled and publicly recognised cathedral organists and directors of music in the country – King’s College Cambridge, Christ Church Cathedral Oxford, Westminster Abbey and Cathedral and St Paul’s Cathedral amongst them. They said, amongst other things: “We are sensitive to the need to respect the fundamental integrity of distinguished instruments. At the same time, we are aware of the more important obligation to distinguish between musical instruments in use as part of a living tradition, serving a specific purpose, and those valued as museum pieces”.

It was all in vain! As a special exception to normal practice, the dean was invited to attend a CFCE meeting in London at which a decision was to be made (organ experts were not allowed to attend). He found himself faced with considerable opposition, which concentrated on technical questions about degrees of sharpness that he could not be expected to answer with authority: for instance, another dean wanted to know why Salisbury Cathedral’s musicians did not have any difficulty in coping with their sharp pitch, so what was

the fuss about? The answer was in the submission – Salisbury pitch was 445cps as opposed to Peterborough’s 452 and the difference was ruinous – but alas, no one seemed to have read or understood the evidence. The application was rejected for the second time.

At Peterborough it was resolved that the matter could not be allowed to rest, but that there should be a delay before an unprecedented third application was submitted. Meanwhile the organ was restored so that it could be used again when the ravages of the fire had been dealt with.

Our final application went to the CFCE at the start of 2009. In January I wrote on behalf of the FAC: ‘The documentation makes it absolutely clear that this magnificent organ must be available to support the cathedral’s mission, outreach, educational and community roles, and services. It will look the same, sound the same, and at long last be able to fulfil its true function… We will be totally failing in our essential purpose if we do not make this change possible, and ask you to approve the application.’

Our then director of music, Andrew Reid, had brought his scholarly mind and total efficiency to bear on all the available information and produced a new and impressively comprehensive submission. In the course of his research he had discovered that when the legendary Stanley Vann was the organist, he had wanted to resolve the problem by disposing of the instrument altogether, so much was he dismayed by the difficulties the pitch presented. Various small loose ends were tied – Sir David Willcocks, who had at one time been organist of Salisbury Cathedral and is renowned for his sensitivity to pitch and tuning, gave us his written support. Ian Bell and Christopher Robinson agreed once more to do all in their power to help. The dean, Charles Taylor, exercised his formidable diplomatic skills. Significantly, Frank Field MP, who had become chairman of the CFCE, immediately demonstrated his commitment to a thorough assessment.

This time, nothing was left to chance. Andrew Reid and the dean organised a special meeting in the cathedral to which Frank Field and Ian Bell were willing to come, together with a technical representative from the CFCE – there was an abundance of goodwill being offered. On the appointed day there was appalling weather which prevented Mr Field and me from reaching Peterborough, so we missed the revealing and amusing demonstration that took place. Andrew and his assistant, Francesca Massey, demonstrated the scale of the problem the choir faces in being obliged to perform at two different and unrelated pitches. First, Andrew played the main organ and then Francesca repeated what he had played on the chamber organ (at 440cps). To make the point even more forcefully, they then repeated the exercise in what should have been unison... There followed a guided tour inside the organ case during which Ian Bell revealed that most of the pipework had been altered over the years.

But it still remained for us to convince the main body of the CFCE. Thanks to the dean’s persuasive powers, we were permitted to take a deputation to the CFCE meeting on 26 February 2009, following which the decision would be made. The CFCE emphasised its obligation to protect and preserve, subjects on which several members spoke with conviction. The

dean put the case for a fully functioning instrument, Ian Bell gave an entertaining and professional description of what the inside of the organ really looked like and how it had altered over the years, Christopher Robinson spoke purposefully about the obligation of cathedrals to produce the highest standards of performance, and Andrew Reid testified to the practical obstacles that the current pitch put in the way of his team. To our relief and delight, the case was won.

And now that Harrison & Harrison have finished their labours, we can look ahead to concerts where instruments of all kinds can join in with the organ’s mighty sound, and singers do not have to adjust their pitch. Check out the Peterborough Cathedral website for more details on the repitching journey – or, much better, visit the cathedral and see for yourself what a difference has been made by the combined efforts of musicians, clergy and organ-builders.

Graham Smallbone read Music at Oxford, was successively Director of Music at Dean Close School, Marlborough College, Precentor and Director of Music at Eton College, and Headmaster of Oakham School. He has been President of the Music Masters’ Association and Warden of the Incorporated Society of Musicians School Music Section, has extensive musical and educational involvement as a governor of the National Youth Orchestra and the Yehudi Menuhin School, and was Chairman of Governors of the Purcell School 1998-2010. He has been Chairman of the Peterborough Cathedral Fabric Advisory Committee since 1990.

not designed necessarily for people of faith but is for anyone who has a hunger for something sacred, and is seeking classical music at its most soul-searching and haunting. It draws on well-researched theology, history, biography, literature, art and the liturgical calendar to place the selection of music in the context of education and information. In his approach to this music Stephen explores the faith that inspired it and the diversity of musical approaches which express it, and the wider context in which he presents the music talks to a broader audience than simply those wishing for a beautiful spiritual journey or a sacred end to a Sunday.

Although the programme deals predominantly with the Christian tradition underpinning much of western classical music, Stephen aims to present theology, culture, politics, history and the passions and musicianship of composers and performers in a way that acknowledges that listeners may not share or be familiar with those religious traditions or their context.

F.or The God Who Sings (FTGWS) on Australia’s ABC Classic FM is a dedicated weekly programme of sacred western classical music presented by Stephen Watkins. The two-hour programme has an established niche nationally and internationally, providing music and thought that audiences aren’t getting elsewhere. Stephen’s role as producer/presenter requires passion for and knowledge of two specialisms – religion and music – plus production skills, and the technical skills for studio operation and the online programme webpage. Stephen and the programme are held in high regard in the arts and the broader community nationally and internationally.

The programme is unique in the domestic and international market, and feedback has indicated that it attracts international online listeners, reaching into Canada and North America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The age range also appears diverse, with a younger audience listening more to the latenight broadcasts. A recent postcard from one young listener says, ‘The music is not something I always enjoy sensually, but there is a rigour to it; perhaps intellectual, perhaps something else. I’ve loved the lessons or precepts you have imported that have stayed with me. Thank you so much for your teaching.’

In its 12th year under Stephen’s stewardship, the audience in the late Sunday night 10pm-midnight slot is relatively small but the programme consistently achieves Classic FM’s 1st or 2nd highest weekly share.

Over the years Stephen has transformed the programme from what some may have considered a ‘choir fest’ into something intentionally closer to an exploration of high art and ideas

The aim of FTGWS is to take the listener on a spiritual voyage inspired by the history and festivals of the world’s religions. It’s

Stephen has a deep knowledge of the recorded repertoire, history and new directions in composition and recordings and is widely regarded in Australia and beyond as a leading expert in the field. The programme demonstrates the depth, context and complexity which a presenter with Stephen’s breadth of knowledge can bring to the music, to the ABC and to its audiences.

Sir James MacMillan, whose work often features on FTGWS, has written of the hunger in composers and audiences that Stephen appeals to: ‘In spite of the retreat of faith in Western society, composers over the last century or so have never given up on their search for the sacred…. One constantly hears talk of transcendence, mystery and vision. Visionary mysticism is much in vogue in discussion about the arts these days. “Spirituality” is held to be a positive factor by many, especially among the non-religious, or those who pride themselves on their non-conventional unorthodoxy in religious matters. Music can be described as the most spiritual of the arts by those who proclaim their atheism and agnosticism.’

Jane Jeffes, Content Director of Religion and Ethics programmes for Australia’s national broadcaster, ABC, finds FTGWS ‘a beautiful end to the week, a counterpoint to the prevailing darkness, chaos and tensions of the world in which we find ourselves in 2017. To paraphrase T S Eliot, the programme provides a still place in the turning world; its opening sounds are a reminder of what George Herbert called “Church-bells beyond the stars heard, the soul’s blood…. something understood”.’

‘For the God who Sings’ can be heard live on Sunday evenings at 10pm (Australian time) or streamed on www.abc.net.au then go to /classic/program/forthegodwhosings/ (each weekly programme is available for one month by clicking on ‘Listen Again’).

ABC’s Religion and Ethics Department supports FCM through Corporate Membership of FCM.

Education details:

Townsend C of E School, St Albans (1997-2002)

Christ’s Hospital (2002-2004)

Selwyn College, Cambridge University: MA in Music (2005-2008) FRCO (2009)

Career details to date (and dates):

Assistant Organist, Winchester College & Music Assistant, The Pilgrims’ School (2004-2005)

Organ Scholar, Selwyn College, Cambridge (2005-2008)

Organ Scholar, Peterborough Cathedral (2008-2010)

Tutor to Choristers, Magdalen College School & Associate Organist, Magdalen College, Oxford (2010-2011)

Assistant Organist, Lincoln Cathedral (2011-2014)

Assistant Director of Music, Rochester Cathedral (2014-present)

Were

Yes, at St Albans Cathedral, where I was a founder member, and Head Chorister in my final year. Being a chorister is why I am a musician now: it was an incredible, immersive formative experience, and I loved every minute. There is probably no musical experience that can give a child such expertise and musical learning as being a chorister.

Being a chorister! Listening to the colours that the organists used, especially in the psalms, was really inspiring, and I have to admit the sheer power that you can unleash was also a contributing factor. My mother is an organist, and, though I went on an Oundle course aged 12, and thoroughly enjoyed it, I didn’t want to follow in my Mum’s footsteps, so didn’t start then. However, by the time I was 16, the call was too great, and I could resist no longer – so I suppose I started fairly late in the end.

Is anyone else in your family musical?

See previous answer! My whole family. Both my sisters also work in the music industry, in London, my Dad sings in every choir in his area, and my Mum is a piano teacher. She actually taught me all the way up to Grade VIII (and both my sisters). Growing up, my sisters and I formed a piano trio with our first study instruments (piano, violin, cello), and my Mum and I have now performed many concerts as a professional duo, in piano duet (Brahms Requiem) and recitals of organ duets – we wonder whether we are the first mother and daughter duo in this country?!

What stands out from your time as Asst Organist at Winchester College?

It was my first experience working in a school, and with choristers (and ‘quiristers’ as they’re called at the College), and I realised I loved working with children.

Are there any big differences between your positions at Lincoln, and Rochester?

Huge. At Lincoln I was part of a team of four organists, where I played for many services, did lots of work with the choristers and directed the cathedral’s chamber choir, Lincoln Cathedral Consort. At Rochester I direct the girl choristers, and have responsibility for them, as well as playing for services for the boys.

How long have you been a member of the Holst Singers?

Just over two years now, I auditioned as soon as I moved down to Rochester, where I am so close to London. I absolutely love singing with such a brilliant choir, and working with Stephen Layton is fascinating, and incredibly fulfilling. In March we came to Rochester to perform Rachmaninov’s Vespers, and our next concert is at St John’s Smith Square, where we continue our Handel oratorio series with Jephtha on 20 May.

How do you fit all your commitments (sporting, cathedral, singing) into your daily life?!

Hmm, with difficulty. It is a real problem in life wanting to do both music and sport, and this is something I first encountered as a chorister and have been battling with ever since! Cycling or walking to work helps me stay active (which is important for productive work in my case), and I do manage to play hockey for a local club, Gillingham Anchorians, though am able to attend training far more often than actually play matches.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

I have been working on some Bach trios, as I felt I wanted something that I could really engage with on a cerebral level. I recently broke my right little finger (playing hockey – oops!), and it turns out it is rather key to the majority of organ music and accompaniments. This was another reason for the trios, as they do not have any big chords to negotiate.

Have you been listening to recordings of them and if so, is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

Contrary to what many people do, I actually don’t listen to recordings until after I have learnt a piece of music. I feel I want to interpret it using my own resources first, and then use a variety of recordings as a secondary level of learning.

How much conducting do you do?

I do more conducting now than I do playing, given that I direct the girl choristers. At Rochester we alternate weekends between the treble lines, so I have a full weekend to conduct once a fortnight, plus weekday services.

What was the last CD you bought?

‘Three Wings’ – it is a fusion of plainsong sung by the Winchester College quiristers, with contemporary music backing tracks by David Lol Perry. It is not at all what you would expect with plainsong, and has an eerie beauty to it.

(See review on p54)

What was the last recording you were working on?

We are currently just about to record a new disc of favourite anthems at Rochester Cathedral, with dates booked in April, featuring the boys, girls and men.

What is your

a) favourite organ to play?

Lincoln Cathedral, I do miss it at times!

b) favourite building?

Peterborough Cathedral, such a friendly building, with the stunning mediaeval ceiling paintings, and unique in being able to see from one end to the other.

c) favourite anthem?

It is hard to choose one, but Britten: Rejoice in the Lamb would be high up there, as would many Renaissance anthems

d) favourite set of canticles?

Mathias: Jesus College Service (not because it is great music, but because it was my favourite as a chorister, and I have never stopped enjoying it)

e) favourite psalm and accompanying chants?

Andrew Reid’s quadruple chant for the nasty bits in Psalm 78

f) favourite organ piece?

I most enjoy playing Tournemire Victimae Paschali and Eben Moto Ostinato, and Messiaen La Nativité

g) favourite composer?

For the organ: Messiaen. Favourite composers overall: Rachmaninov and Britten. And Bach, of course.

Which pieces are you including in your next organ recital?

Probably Alain Deuxième fantaisie and I have only ever given one recital that didn’t include any Bach. Beyond that I am still experimenting with my healing finger to see what works.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

Performing Giles Swayne’s virtuosic Stations of the Cross at Lincoln Cathedral. Swayne taught me composition at Cambridge, and he actually came to the performance (it doesn’t get done very often). The movements are fiendishly difficult, and it was a huge project, but it was a great moment. I did once play Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony at the Royal Albert Hall, that was pretty cool!

How do you cope with nerves?

Ensuring that I have done sufficient practice before performing, that really helps calm you down. Concentration, especially as you begin, as it is normally 30 seconds into a performance that it suddenly hits you that there are people listening.

What are your hobbies?

Playing (and watching) sport: I play hockey for Gillingham Anchorians, play squash, and I have a road bike. I have even done one triathlon.

Other than that I also enjoy walking (mountains and hills, preferably in Scotland), reading (fantasy and historical fiction best), and socialising with friends (often involving good food and drink).

Do you play any other instruments?

The piano (as a pianist, not as an organist!) and I sing, which is something that I am trying to do more of at the moment.

What are the drawbacks to life as an organist?

Playing the organ can be a very isolating experience, and most humans are social creatures, so I think it is important for organists to ensure they do not spend too much time holed up in organ lofts.

As a young English cathedral chorister visiting the great northern French cathedrals on holiday, I was amazed to find that there were no choirs to fill these incredible buildings. This inspired me, and by about the age of twelve I knew what I wanted to do for a career. The ambition was still there when I reached my final year at university. But how to go about it? The answer appeared as if by magic in the form of a note addressed to all organ scholars from Edward Higginbottom. It was an advertisement for ‘organ scholar / assistant’ at the Maîtrise de Caen. Five minutes after reading it I wrote a letter of application.

Sometime later, in September 2000, I was met off the Portsmouth–Caen night ferry by a man with long grey hair and a beard, smoking a pipe and driving a battered Renault Twingo. He was wearing big brown leather boots. He didn’t look like a cathedral organist, though older readers will no doubt remember similarities with Robert Weddle, formerly Organist of Coventry Cathedral. And so I found myself spending two wonderful years living in Caen, working as Robert’s assistant, training the choristers of the Maîtrise de Caen at the town’s Conservatoire and accompanying their weekly concerts in the church of Notre Dame de la Gloriette.