CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Rodgers is proud to present the next generation of home and church organs from our Inspire Series. Born from the dream of enhancing spiritual experiences at churches all over the world… Born from the dream of homes filled with exquisite musical sounds... Born from the dream of bringing this experience within reach of anyone... All created because we believe in that dream.

Rodgers is proud to present the next generation of home and church organs from our Inspire Series. Born from the dream of enhancing spiritual experiences at churches all over the world… Born from the dream of homes filled with exquisite musical sounds... Born from the dream of bringing this experience within reach of anyone... All created because we believe in that dream.

The Rodgers Inspire 233 and the smaller 227 are designed for those who believe in dreams.

The Rodgers Inspire Series 227 and 233 organs are designed for those who believe in dreams. www.rodgersinstruments.com

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November.

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2019

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ editor@fcm.org.uk

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon pm@fcm.org.uk

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding adver tising should be addressed to:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: +44 20 3637 2172 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by: DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

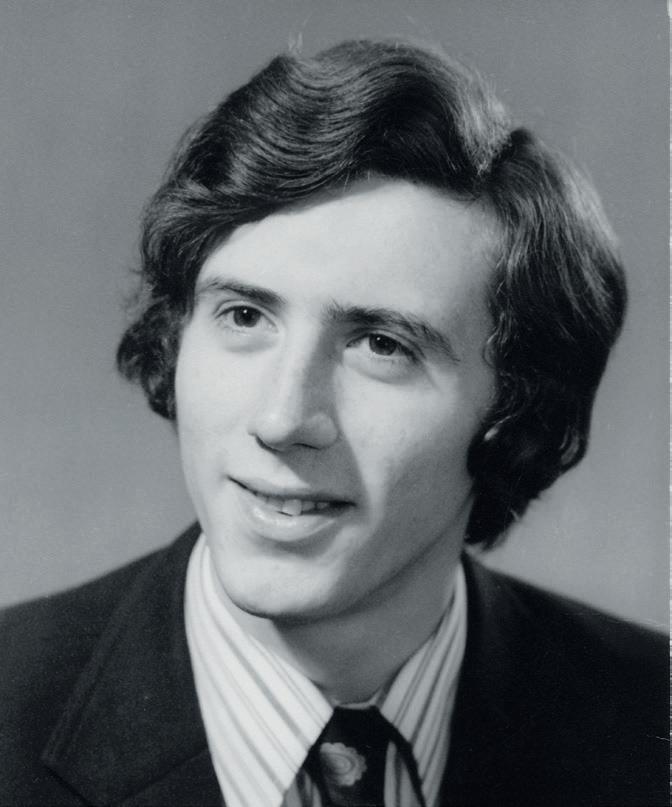

There is a slightly reflective feel to the articles in this magazine, brought on by the recent deaths of two notable figures in the cathedral music world, Peter Hurford and Noel Rawsthorne. Their lives make interesting reading, and their influence on several generations of organists can clearly be measured not just by their own great achievements but also by those of their pupils. Readers will also have spotted the recent death in January of the revered South African-born composer John Joubert, who featured in these pages for his 90th birthday a couple of years ago. His name is to be inscribed in the book at a triumphal evensong at the musicians’ church, St Sepulchre’s, this month. His compositions, of course, were not limited to church music, but encompassed concertos, operas, oratorios and symphonies. A more unexpected remembrance is of David Lepine, less well known perhaps but esteemed nonetheless for inculcating in his pupils a genuine and lifelong love of music. John Harding, a former pupil, has joined with several others to pay tribute to a man of great charm who died unexpectedly and far too young.

Looking outside the UK, Donald Hunt (once at St Mary’s Edinburgh and now at Christ Church in Victoria, BC, and not the Worcester elder statesman) has been instrumental in bringing an English-cathedral-style education to the youngsters of a small part of Canada – though with a difference. Not many UK choristers are likely to have fitted in ice hockey practice before their morning rehearsals! His ‘program’ is still in its infancy, but he has already enlisted a fine selection of young musicians.

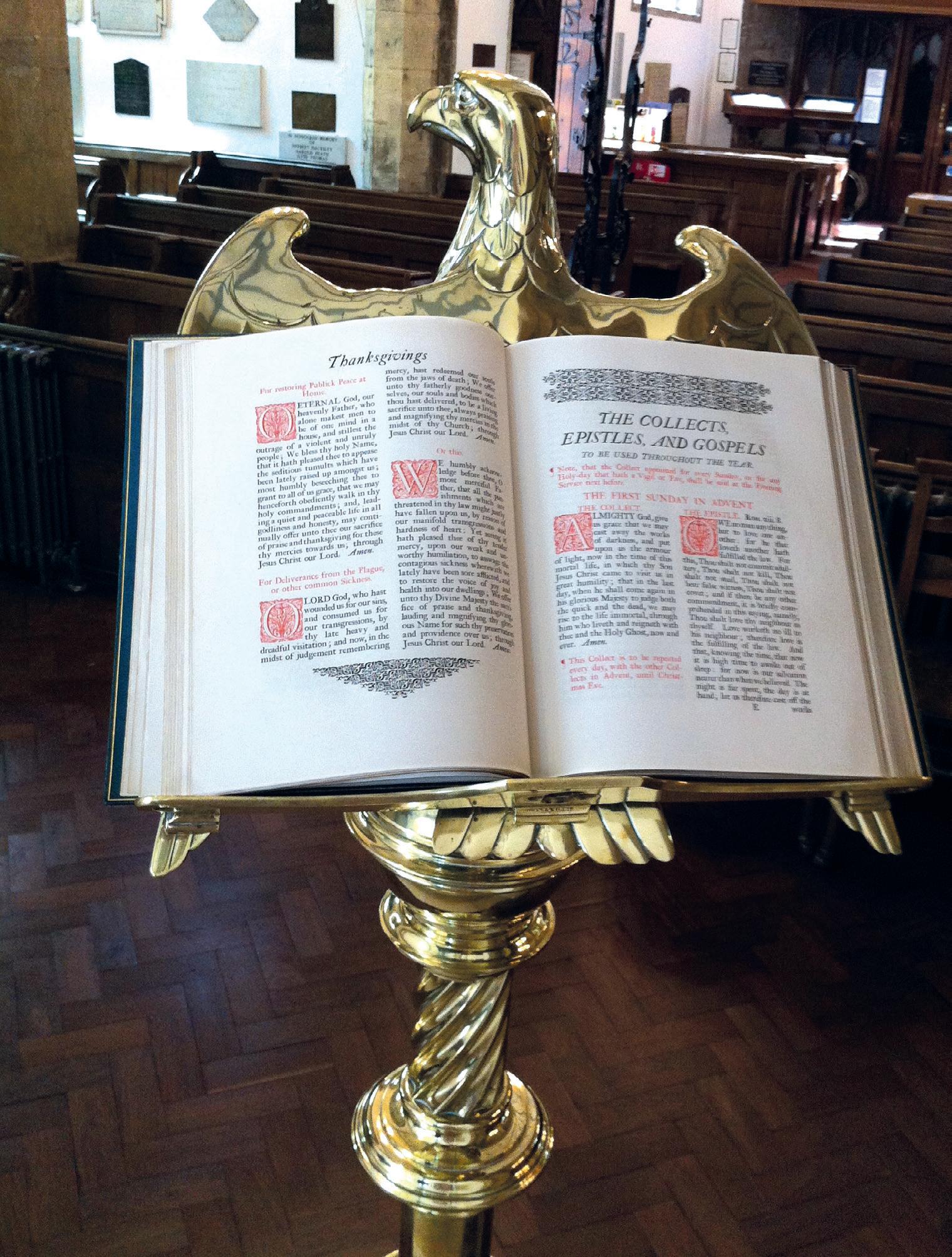

Amongst the readers of CM are likely to be found many enthusiasts for the Book of Common Prayer, with its beautiful cadences and glorious language (yes, I’m a fan too). There may, indeed, be many FCM members who also belong to The Prayer Book Society, which was founded shortly before the introduction of Series 3 into our churches, in 1972. For those who are less aware of it and would like to know more, Prudence Dailey, Chairman of the PBS and editor of The Book of Common Prayer, Past, Present and Future, writes compellingly about the society’s aims and achievements, and about this year’s Cranmer Awards.

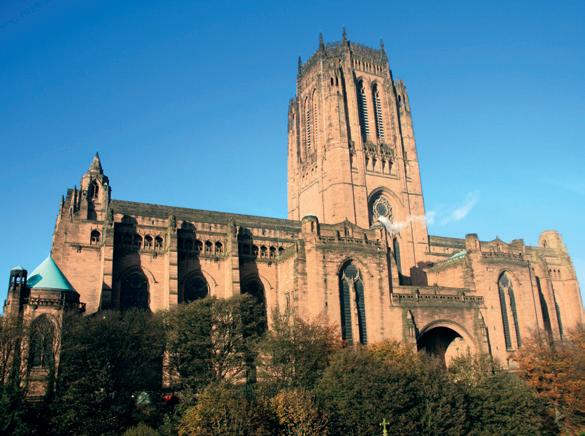

In 2016, as part of FCM’s Golden Jubilee celebrations and to help launch the new fund-raising initiative The Diamond Fund for Choristers, a magnificent gala evening in the presence of HRH the Duchess of Gloucester was held at St Paul’s. It was a memorable occasion, not least for the presence of one chorister from almost every cathedral or choral foundation in the UK, together with the choir of St Paul’s. Later on this year, on 13 June 2019, there is to be a further celebration of choristers and their music, this time to be held at Liverpool (Anglican) Cathedral; if there is a chance that you can get to Liverpool for this, then do so: it promises to be an outstanding event at a remarkable venue. Liverpool Cathedral is the fifth largest cathedral in the world and, at 189m, the longest. Thus there should be no shortage of space – it can seat up to 3000 people!

Celebrating a long career in church music, 33 years of which were spent at the helm of Christ Church Oxford, is Stephen Darlington, who also spent time there as organ scholar and who retired last year. His guiding principle for musical performance at Oxford’s cathedral has always been to be ‘the best possible advocate for liturgical music at the highest possible standard’, which is something we can wholeheartedly support, and with gratitude for such dedication to duty.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

•welcome pack

•twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

•‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

•attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

•meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music •enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £4 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

Of all the expressions I find most evocative of what it means to have a vocation, this poem by W H Auden from his Horae Canonicae is particularly compelling:

You need not see what someone is doing To know if it is his vocation, You have only to watch his eyes: A cook mixing a sauce, a surgeon Making a primary incision, A clerk completing a bill of lading, Wear the same rapt expression, Forgetting themselves in a function. How beautiful it is, That eye-on-object look.

This ‘forgetting themselves in a function’ has been one of the delights of my career in cathedral music, 33 years of which were spent at Oxford’s Christ Church Cathedral: it has been there in performance, in the choirstalls, in the singing, and in the tutorials and lectures. I have been very fortunate to have had this experience.

Both my parents were musical and devout Christians, so I was surrounded by music from a young age. I well remember my first vinyl record, Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto played by Yehudi Menuhin, a Christmas present from my grandmother: I still have it, in fact. So it was no surprise that as I developed as a violinist and pianist, and then organist, I felt drawn towards a musical career. However, the seeds of my ambition to pursue a career in the field of church music were sown at school (The King’s School, Worcester), where I was influenced by two wonderful musicians, Harry Bramma and Christopher Robinson; the latter introduced me to an incomparable level of musicianship to which I have aspired throughout my life. Both men helped me to fulfil an ambition to become Simon Preston’s first organ scholar at Christ Church Oxford. Here I encountered a different style of music-making, one which was electrifying and obsessive. At the time we all knew we were witnessing a meteoric rise in standards: Simon had an absolutely clear vision of what he wanted, and he wouldn’t stop until he had achieved it. My other tutor at Oxford was the musicologist, Edward Olleson, a brilliant academic who also had a profound influence on me, and who helped me develop a love of the study of music alongside its performance.

My first job thereafter was as Assistant Organist at Canterbury Cathedral. Those who worked alongside Allan Wicks would confirm that he was a brilliant and inspirational figure. Here was a cathedral organist who loved listening to the string quartets of Bartók, playing the piano, commissioning contemporary composers, widening the repertoire to include Monteverdi and other Early Music composers whose music rarely appeared on cathedral music lists at that time. He was

just as towering a figure in the musical world as Christopher Robinson and Simon Preston, and all three of them were gifted in different ways. I feel very lucky to have been guided by them in my formative years.

Much to my surprise, I was appointed Master of the Music at St Albans Abbey in succession to Peter Hurford in 1978, at the age of 25. The Dean, Peter Moore, was a brilliant man, a more than competent musician who really cared about music in worship, but also a maverick: perhaps that is why he appointed me! This wonderful cathedral provided me with the perfect environment in which to explore liturgical music of all types and continue Peter Hurford’s outstanding tradition. I worked with tremendous singers young and old, an excellent colleague, my assistant Andrew Parnell, and established an organ scholarship: everyone seemed to relish the breadth of music we performed. I also ran the St Albans International Organ Festival and the competition which lies at its core, which remains the most important one in the world.

I had loved Christ Church as Organ Scholar, but never imagined I would return to run its academic music as a university lecturer and be director of the cathedral choir. My formal role was ‘Organist and Official Student in Music’ and I later became the university’s Choragus. These days it is only a nominal title, but it is an important historic one, originating from Greek theatre: the choragus was the leader of the chorus in ancient Greek drama, and when the professorship of music at Oxford was established in the 17th century, the position of Choragus was also created, its holder acting as an enabler of music-making in the wider university.

My guiding principle in performance at the cathedral has remained unchanged: to be the best possible advocate for liturgical music at the highest possible standard. I believe strongly that there is something profoundly unique about performing choral music in a sacred space and as part of the liturgy. It is self-evidently the case that music has the power to evoke deep spiritual responses in people: sacred choral music is probably more widely disseminated now than at any stage in history. Obviously for this to work, standards must be high: no one wants to listen to second-rate performances.

I have avoided the word ‘quality’ so far, not least because writing about the subject in the sphere of liturgical music is fraught with problems. Such a label is often perceived as élitist. In case you thought this was a new phenomenon, here is Parry writing in 1899: ‘It can hardly be denied by anyone who calls himself a musician that a very considerable proportion of the hymn-tunes in many popular modern collections are as vile as it is possible for anything to be that has an excuse for calling itself artistic.’ I agree with Parry: we owe it to worshippers to be uncompromising in the projection of ‘good’ music. That this is not straightforward is graphically illustrated by several of my own experiences. For example, I once chose to broadcast a contemporary setting of the evening canticles on BBC Radio 3. This provoked one of the most amusingly aggressive letters I have ever received. The correspondent complained that the job of those trying to advance the cause of church music was hard enough without people like me broadcasting cacophonous rubbish like that!

So much for the quality of the music itself, but what of the quality of performance: why on earth should it matter that this should be good too? After all, it would be naïve to assert that the best performances are always those which are technically most accomplished. The philosopher Simone Weil wrote at length about education and religion. One of her most powerful themes is on the topic of attention. ‘Attention consists of suspending our thought, leaving it detached, empty and ready to be penetrated by the object ... We do not obtain the most precious gifts by going in search of them but by waiting for them.’ On the face of it, that may seem rather an odd notion, but I think it is that sentiment which unites performers and listeners, whatever their age, through the emptying of the mind and the intensity of concentration, both of which are fused as a creative and liberating force.

If my guiding principles have not changed, neither has my approach to highlights. The most satisfying aspect of my career has been taking vicarious pleasure in the success of my pupils, some of whom are now music lecturers and teachers, some conductors or singers or solo artists, some active in church music and others in a variety of other professions to which their musical education has made a significant contribution. There are so many of them that it is invidious to single out individual names, but such a list definitely includes Laurence Cummings, Timothy Noon, Elizabeth Burgess, Christian Wilson and Ben Sheen amongst the keyboardists. At the time of writing, three of the current King’s Singers were in the Christ Church choir, as were several regular members of consort groups such as The Sixteen, the Tallis Scholars

and The Cardinall’s Musick, to name just a few. Others such as John Mark Ainsley, Timothy Mirfin, George Humphreys and Stuart Jackson are having very successful opera careers. I have also had a succession of brilliant assistant organists as colleagues including Stephen Farr, David Goode and Clive Driskill-Smith, and it has been a privilege to work with them.

My own performance highlights have been countless. Perhaps most satisfying are those which have appeared unexpectedly in a cathedral service, when sometimes an intangible dimension has entered into the music-making, one which defies verbal description. In a sense, every one of the more than 60 commercial recordings with Christ Church has been a highlight. More than 40 of them have featured première performances of Early Music or more contemporary compositions. I am particularly proud of the 8-CD set of Early Music on the Nimbus label and the 5-CD set of Eton Choirbook music on the Avie label.

I have been fortunate in taking the Christ Church choir on many tours overseas, often performing in some of the world’s famous concert halls such as the Sydney Opera House. On most tours I have made a point of engaging in collaborative projects, so I have vivid memories of joint concerts in Jamaica, Portugal, Bermuda, China and the USA, for example. Particularly memorable also is a televised concert in Prague in 1989, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, with Iliana Cotrubas and Placido Domingo. Václav Havel had just been elected President of Czechoslovakia and was sitting close to me. This was an extraordinary historic event when there was

a tangible air of optimism in the building. The accompanying orchestra consisted entirely of dissident players who had refused to join the Party, so were forbidden from membership of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra – it was profoundly moving.

In the field of contemporary music, I have also been fortunate in being able to commission many new sacred compositions from composers as diverse as Howard Goodall, Francis Grier, Edward Harper, Gabriel Jackson, William Mathias, Robert Saxton, Mark Simpson, John Tavener and Judith Weir.

In an interview on his appointment as principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Kurt Masur commented that as a teenager he told his father he wanted to be an organist like Bach (not the electrician his father hoped he would become!). Masur said: “I wanted to be an organist, not a conductor. I didn’t want to be glamorous.” A career as an organist may not seem glamorous these days, but there was a time when its value was surprisingly high: in 1546, the organist at Christ Church was the highest earning member of the community, being paid twice as much as the tutors, in fact. Regrettably this is no longer the case, either at Christ Church or anywhere else: the rewards of the profession have to be calculated in other ways.

Nationally the general standard has risen hugely during my lifetime, and the awareness of choral music is much more widespread. However, financial constraints are bringing pressure to bear on all aspects of the ministry of cathedrals, and of course, music is an obvious target when institutions face difficult financial decisions. It is crucial that the clergy recognise the power of music to act as a spiritual vehicle for worshippers of all ages in a powerful and unique way. This tradition is too precious to abandon and deserves to be properly resourced. It may be comforting to know that such pressures are not new, however: cathedral music was at a very low ebb in the first half of the 19th century and underwent a distinctive revival in the hands of reformers such as Ouseley, whose establishment at St Michael’s College in Tenbury was part of a deliberate attempt to raise standards. Let us hope that similarly enlightened figures will emerge in our own time.

I end this article where I began, with more words by W H Auden, one of Christ Church’s most famous alumni. In his Christmas Oratorio, entitled ‘For the Time Being’, there is a reflective chorale which was set to music by Benjamin Britten and more recently, at my request, by Robert Saxton. The final stanza could be interpreted as a prayer as well as a cry for action. If I needed a motto for my life as a church musician then it would be hard to improve on the final three words: ‘Adventure, Art, and Peace’.

Inflict Thy promises with each Occasion of distress, That from our incoherence we May learn to put our trust in Thee, And brutal fact persuade us to Adventure, Art, and Peace.

a centre for music within the confines of an environment that had seemed dangerously near to becoming something of a cultural white elephant.

His work with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra included supervision of the refurbishment of the Rushworth organ in the splendid Philharmonic Hall and he sustained substantial friendships, personal and professional, with successive ‘Phil’ conductors. A particularly creative partnership with Sir Charles Groves is, happily, evidenced for us all in a number of very fine recordings.

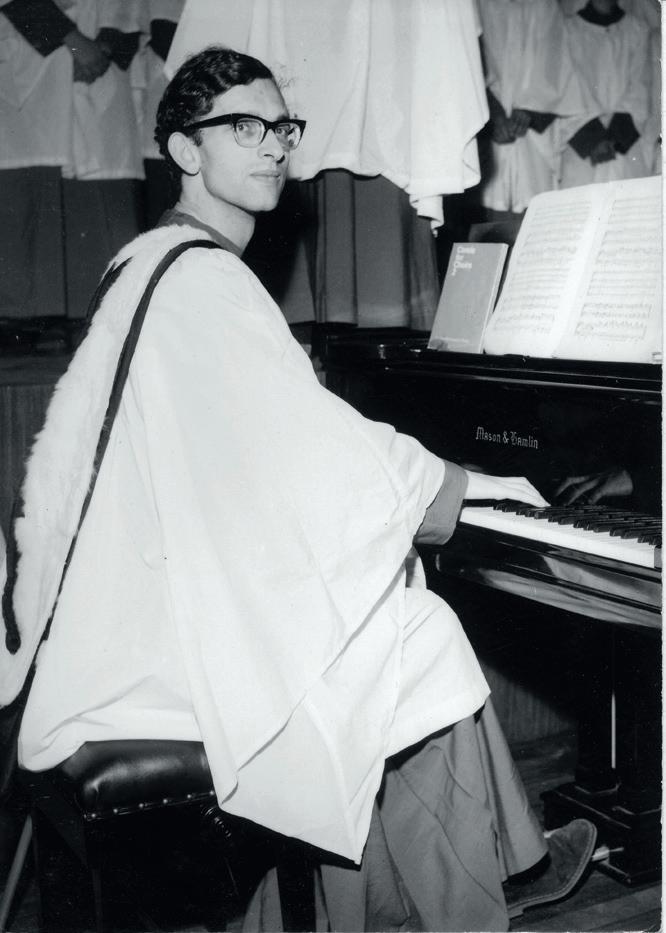

For long the master of the mightiest Mersey sound of all, Noel Rawsthorne – Liverpool Cathedral organist for a quarter of a century and, truly, a legend over the course of his long lifetime – died on 28 January in his home city of Liverpool at the age of 89.

Pupil of Germani in Italy, Dupré in Paris and Harold Dawber at the Royal Manchester College, Rawsthorne’s own list of pupils reads like a Who’s Who on musical Merseyside. His successor as cathedral organist, Ian Tracey, is but one of many; this extensive band of musicians also includes the brothers Duffy, Philip & Terence, once colleagues at the other end of Hope Street in music-making at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King.

Yet Noel’s teaching was far more a matter of service rather than status. Generations of students have had cause for considerable gratitude on account of his creative instruction and individual coaching – especially in keyboard skills – for classroom rather than cathedral.

The award of an honorary doctorate in music from the University of Liverpool was not only richly deserved but gave much pleasure to admirers and colleagues alike.

Rawsthorne’s commitment to the music-making of his home city – not least through his long service to St Katherine’s College (now absorbed within Liverpool Hope University) as a music lecturer – has been total.

The cathedral, though for years his main centre of activity, formed only part of the story.

On retirement from the console of the grandest Willis of them all in 1980, his energies were wholeheartedly directed to reviving the fortunes of music-making at St George’s Hall. There he served as City Organist until 1984 and revitalised that building’s recital programme, raising once again its profile as

It is well known that his best-selling solo discography, especially his recordings on the cathedral organ, is, without a shadow of doubt, one of the most distinguished of such post-war catalogues. Many of his performances are widely acknowledged as benchmark interpretations against which others are measured. His superb and trail-blazing Great Cathedral Organs recording – the very first in that splendid and hugely historic EMI series – included what was probably the first recorded interpretation of the original version of the Duruflé Toccata by a British player.

For listeners the world over, Noel as an interpreter of the keyboard repertoire represented the very best in English organ-playing.

A vivid and unerring sense of colour, warmly eloquent phrasing and sturdy rhythm pervaded all his performances. Having for much of his life played one of the world’s finest instruments, he was also particularly well known for getting the very best out of rather more modest (even quirky) musical resources. Add to such already substantial musical virtues the extraordinary fusion of artist and craftsman that has proved such a source of constant admiration to his colleagues, and it is possible to glean something of this special master’s strength of character and depth of influence.

On the choral scene, he was thoroughly at home when composing for ‘all sorts and conditions’ of choirs. Interestingly, the considerable number of pieces designed specifically for the Liverpool Cathedral choir, while fitting that most individual of ambient acoustics like a glove, do not rely for their effect on rich resonance alone but are happily at home in less generously proportioned surroundings. Of the liturgical items, the fine two sets of Responses and the Liverpool Mass claim particular attention. The more modestly conceived Festive Eucharist composed for the completion of the cathedral in 1978 is very widely sung, as are some of his vividly etched miniatures – God be in my head, Like as the hart and I will lift up mine eyes spring at once to mind.

Organists, choristers, congregations and audiences everywhere have considerable cause to be thankful that the

manuscript page has been so much the recipient of his most recent energies.

Script, scoring and musical layout – all these aspects are firm, focused and gloriously secure. There are no spare notes, no musical equivalent of verbal waffle; everything lies beautifully under hands and feet and encapsulates so much of the clarity and sense of direction which are such significant elements of his character.

Among original compositions for the king of instruments, the substantial Dance Suite (written to celebrate the re-opening of the Huddersfield Town Hall organ after major work and dedicated, like a number of his recent works to Dr Gordon Stewart, the long-serving Borough Organist who became a close personal friend of Noel’s) and the hilarious Hornpipe Humoresque claim particular attention. But maybe the heart of his muse is enshrined in the lovely Aria – elegant, fluent, pulsing with heartfelt emotion but not with the heart on the sleeve: above all, memorable.

For the organist, he rehabilitated some of music’s most attractive works by providing eminently practical arrangements and transcriptions (from other musical media) that, while challenging the professional, do not remain beyond the scope of those for whom recitals and recordings are not within their regular experience.

Rawsthorne’s repertoire enhancement includes a number of ‘musts’ – volumes which are in every self-respecting player’s music cupboard: Music for the Bride, Music of Remembrance and, particularly, Encore! lead the field among his many anthologies.

Noel Rawsthorne, by his playing, teaching and composing, was an exemplar of admirable purpose and strength of character. He will be hugely missed by so very many.

Teaching was but one of the many skills of this great polymath, and one which was very dear to his heart; he was an inspirational teacher and in some 60 years in the profession must have taught thousands of organists, both amateur and professional. The organ world has to be a richer place for his presence, and greatly the poorer for his passing.

Suave, well spoken, immaculately dressed, a total perfectionist in everything he did, and excelling in pretty much anything he turned his hands to – organist, teacher, composer, arranger, organ designer, harpsichord maker, cook, angler, gardener, French polisher, watercolour artist and IT boffin... the list could go on! There was no end to his many talents, nor to his capacity to study each of them to expert level, thereafter adding his own particularly original perspective.

As an organist he was at the forefront of his generation, a most eloquent player; many of his recordings are still the benchmarks for subsequent generations of exponents. His immaculate technique and effortless console management were honed by a scholarship with Fernando Germani in Siena, which he always said was ‘like having a knife in one’s back the whole time’ but musically, incredibly energising.

The first time he played in front of Germani, a large-scaled Bach prelude and fugue, (rather brilliantly, he thought), there were no interruptions whatsoever, but after a pause, the maestro declaimed: “Now, we must learn to look pretty at ze console, we must sit up straight, head straight, back straight, arms straight...” and absolutely nothing about the work at all. Noel always held that this was a most humbling experience for him; it was right back to basics, and all about general deportment at the console, which was to be the raison d’etre of the immaculate console management and playing position which became one of his hallmarks.

He would not suffer wrong notes: “We are not paid to play wrong notes,” he would always say. We were all chastised for

even dropping one. In my youth, after a Bach prelude and fugue in the Lady Chapel, where a couple had ‘gone astray’, he came up to the loft and said, quietly but firmly: “Sort them out please... I have just been down in the Lady Chapel with a brush and pan, and with all the wrong notes I have swept up off the floor, I could write a new fugue....” followed by his wry smile and codicil: “‘And so they collected them and filled twelve baskets with the fragments thereof!’” I was to learn that he was a great quoter of scriptural passages at salient moments.

When at the console of his Boeing 747 (as he affectionately referred to it), he was supremely in control, but he had a recurring nightmare about oversleeping and running up Bold Street towards the cathedral in his underwear with his briefcase full of music. A policeman, appearing from one of the shop doorways, in stentorian tones says: “You can’t go up there, sir, there’s a big service on.” Having convinced the policeman of his identity, he finally gets to the loft, but all the stops are in the wrong place, much of the organ non-operational, and all the hymns he needs are missing from the hymn book. He plays one tune and the congregation sing another; at this point he always awoke in a cold sweat to find that he was not at the console and that there were several hours to go! This probably explained the fact that he would always leave for the cathedral in enough time to be able to change a wheel, should he get a puncture on the way.

On one notable occasion, during a sermon from one of our aged canons (always destined to be a lengthy one), he sat down in a comfy red armchair in the sitting room behind the console, cup of coffee to his side, and... drifted off. In the dream which followed he definitely heard people singing, and woke suddenly to find that the choir, congregation and clergy were indeed engaged in the final hymn but down a minor 3rd.... In true NR fashion, he slid onto the bench and came in quietly, crescendo-ing to complete the hymn. The dean came up after the concluding voluntary and said, “Noel, we didn’t see you, and reckoned the organ was playing up again, so we thought we’d better start the hymn.” Cool as a cucumber, Noel replied, “Quite right, Mr Dean, thank you very much.” Thereafter there was a written edict in the loft: ‘If you are alone, without an organ scholar, do not sit in this chair. NR’, and he kept to that, as, subsequently, have we all.

With his love of order in all things, the coffee percolator was always filled with coffee and water before a service, and would

“I don’t see it that way ...” usually followed by,

“Move over and play it like this ...” – two of the golden catch-phrases which will be instantly recognised by any and all of Noel’s many students.Ian Tracey Photo: Maureen McLaughlin

be turned on with the console electrics, in order that it was nicely percolated by the sermon. However, on one occasion, one of my predecessors as assistant forgot to put the water in, and so, as the eastward procession of Cross Guild and clergy entered, they did so with noses in the air, smelling the overwhelming odour of burning coffee throughout the building! With true NR aplomb, the post-Gospel improvisation took as its theme, “Whence is that goodly fragrance flowing?”

Noel loved his recital work, and especially that in USSR where he was the first British organist ever to be invited, making several subsequent returns. I always packed his music into the various files, in programmes A, B, C, D etc. However, I once inadvertently sent him senza the back page of Howells Set 1 No. 1. As Western music was nigh on impossible to obtain in Russia at that time, he was unable to acquire a copy and had to do his best to remember it (memory-playing not being one of his strengths). He jotted down what he could recall of it on a piece of manuscript paper and penned me a postcard: ‘Where is the back page of HH Set 1 No. 1...? I have given a different performance of it every evening; last evening in a ‘Festival of British Music’ with Sir William Walton and André Previn in the audience!...’. I went up aloft, and there, to my horror, was said back page. I dreaded the return of the maestro, but he just laughed it off and commanded that the music librarian go through all his music and ensure that all copies were intact.

recital that evening. The stops being numbered, he was pencilling in +58, +62, -61, -83, + IIIrk, +IVrk etc. He was aware of the white-mackintoshed KGB man just across from him; he had followed him in and had been subsequently watching him intently. Finally, the man stood up, pointing a gun at him and saying, “You vill now come vis me, please.” Noel obeyed, and to his horror, found himself in a cell being interrogated as to what these codes were and on whose behalf he was spying. His attempts to explain were met with disbelief, and finally all his music was taken away and the cell door closed. Just at the point of despair, when he thought he might never see his family again, a huge man in Russian uniform appeared, completely filling the doorway (‘This is it,’ he thought...). The man had the copy of the K608 in his hand. Smiling, he said: “Mr Rostorn, you ere now free to go... ve haf dis Wolfgang Mozart in custody... and he hav confess-ed all,” .... and, beaming, he added, “I apologiz for my colleague.... and I vill be at your consert too-night!”

Mercifully, they did let him out, and we had another 45 years of this amazingly creative and loving man who did so much for the organ, its followers and for his students. The Prayer Book puts it so well when it says, ‘Our hearts are unfeignedly thankful’ for all he gave and for the huge legacy he leaves, both at the cathedral and in the organ world as a whole.

His mortal remains will be interred in the north choir aisle of Liverpool (Anglican) Cathedral underneath the organ, alongside those of his predecessor Harry Goss-Custard at the 3pm Evensong preceding the 93rd Anniversary Recital on 19th October 2019. Organists from all over the world have already signified their intention to attend; all are welcome, and as the cathedral has a seating capacity of some 3000, there should be plenty of room.

Some words written by Bessie Stanley in the Lincoln Sentinel of 1905 in an essay entitled ‘What Constitutes Success?’ could almost have been written about Noel as they express, so well, all that he was, and also something of his legacy to us all.

He has achieved success who has lived well, laughed often and loved much;

Noel had always steered clear of memory-playing after one instance of playing the Bach Great G minor, the final pedal entry of which, he realised to his horror, turned out to be that of the Little G Minor. In his own words: “I have no idea at which point the one seamlessly became the other!”

Things in Russia didn’t always go smoothly; one night in Yerevan in Armenia, playing to a packed house, he went on, set his combinations, put down the first chord and absolutely nothing happened. He turned to his assistant and, out of the corner of his mouth, said, “Will you switch the organ on, please?” (using, in this case, an ignition key). The assistant replied, “I’m sorry, there’s no key.” Not speaking any Russian, they both went off, to the astonishment of the now silent audience, doing a mime Marcel Marceau would have been proud of. Finding the organ-builder drinking wine in the basement with a set of keys in his pocket, they returned, brandished the key to thunderous applause, and started all over again.

On another occasion, Noel was sitting in a coffee shop in Moscow, putting registration into his Mozart K608 for the

Who has gained the respect of intelligent men and the love of little children;

Who has filled his niche and accomplished his task;

Who has left the world better than he found it…

Who has never lacked appreciation of earth’s beauty or failed to express it;

Who has always looked for the best in others and given the best he had;

Whose life was an inspiration; and whose memory, a benediction.

May he rest in peace and may his memory be for ever bright.

Noel excelled in pretty much anything he turned his hands to – organist, teacher, composer, arranger, organ designer, harpsichord maker, cook, angler, gardener, French polisher, watercolour artist and IT boffin...

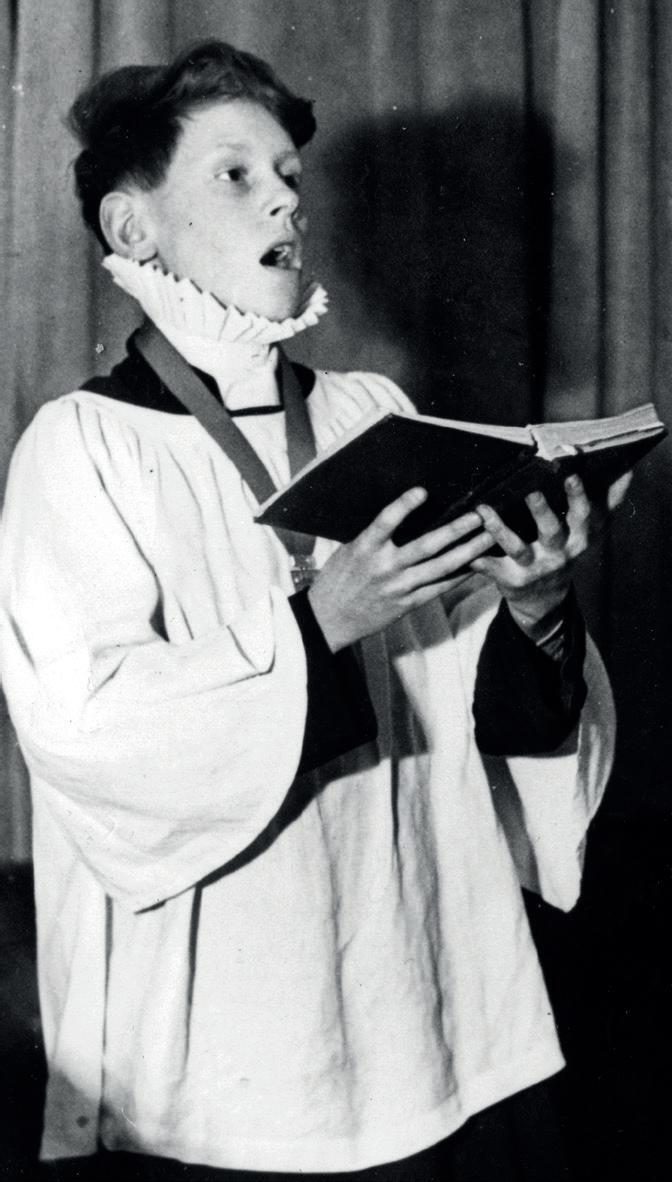

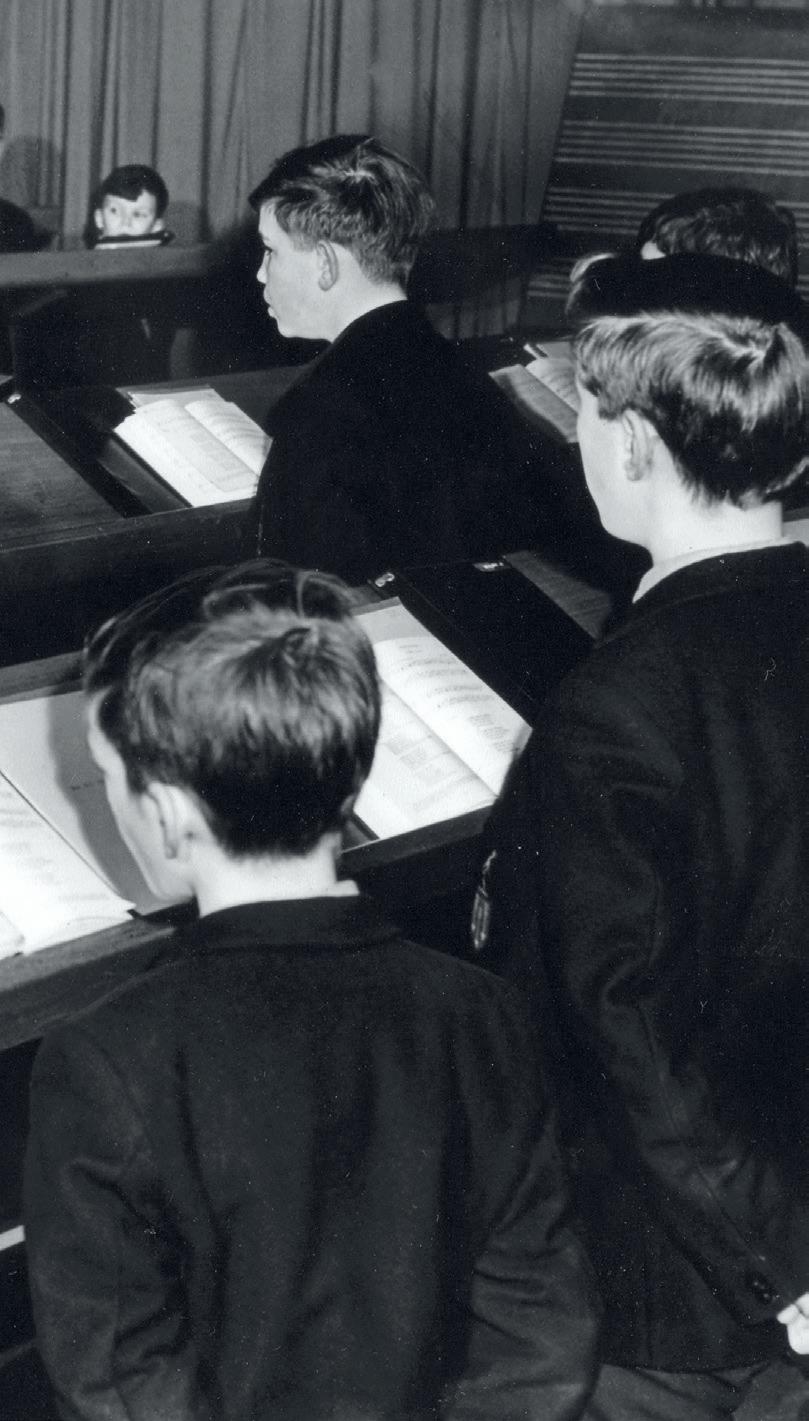

those days, the singing being led from the organ, so the assistant organist’s function was to deputise for the organist as required, and be generally helpful. A pupil-assistant would deputise under close supervision at first, but be left on his own when he had grown in confidence and skill. So, try to picture a young boy travelling on his own to a place where he knew no one, to join a cathedral community in which he was younger than the senior choristers, who might be as old as 16. The choristers sang Mattins every weekday at 8.30am on their way to the National School, where they usually arrived a few minutes late; they left a few minutes early to sing Evensong at 4pm, and after a boy had left school a sympathetic employer might allow him to continue in the choir until his voice broke. Evensong was followed by an hour’s rehearsal, and a boy might be persuaded to return in the evening to blow the organ for Harris to practise. The men of the choir hardly feature in this account, so one must assume that they only sang on Sundays.

Imust begin by exploding a myth. You will read in many places that Harris grew up in Fulham and was a chorister at Holy Trinity, Tulse Hill. This is very unlikely, as it would be a rotten journey today, and particularly so for a young boy in the age of steam trains and horse buses. In fact, William Henry Harris, the eldest of three children of William Henry Harris, a postman, was born not in Fulham but in Brixton Hill on 28 March 1883. Young William was baptised in May at the nearby St Saviour’s Church where he joined the choir at a very young age. He decamped to the neighbouring parish, Holy Trinity, where the organist was a professional musician of some repute, and so from the age of eight William came under the influence of Dr Walmsley Little, who taught him so well that he rapidly became a capable organist.

What was to be done with this talented youngster when he left school just before his 14th birthday? One of the curates, the Revd H Sinclair Brooke, raised the funds to send him as an articled pupil-assistant to St Davids Cathedral, where the newly-appointed organist, Herbert Charles Morris, happened to be a friend. Cathedral choirs were never conducted in

The published reminiscences of John Miles Thomas, a chorister in the 1890s, give an unflattering picture of the organist. ‘Morris…was a small man, unsmiling, cynical and distant. There were times when he got annoyed without apparent reason, and he would take hold of a boy and flog him with his walking stick.’ That aside, he was a good musician, who took his responsibilities seriously. The articlessystem was one of apprenticeship, offering, in spite of its limitations, a great deal that was admirable. By the time Harris had completed this apprenticeship, begun before he was 14, he was a good player, a good extemporiser, able to transpose anything at sight, to read from a full score, and to improvise from an 18th century figured-bass an effective continuo part. He was also well grounded in fugue, canon and counterpoint. Morris, only ten years older than his pupil, taught Harris so well that in July 1898 William gained the diploma of ARCO (Associate of the Royal College of Organists). In the following January he was one of the 13 (out of 78) who were awarded the College’s very much more difficult Fellowship (FRCO), the virtual equivalent of a university degree. He was but 15 years and ten months old, perhaps the youngest-ever FRCO, and he had already been awarded a scholarship to the Royal College of Music (RCM). Morris and St Davids had done him proud, and left him with ‘an almost monastic devotion to the daily offices of the Anglican Church’.

The move to Fulham had taken place by now and with Kensington and the Royal College of Music not far away William would have been able to live at home. He studied the organ with the legendary Walter Parratt, Organist of St George’s Windsor, who must have been surprised at so wellqualified a pupil but had much to teach him about style and repertoire and the wider world of music. William would have studied composition with Stanford and Charles Wood, for Parry’s responsibilities as Director of the College left him no time for teaching, though he retained a close and benevolent interest in all his students.

Then, and for another half-century, universities offered degrees in music but did not teach it, whereas colleges such as the RCM taught music but did not award degrees. The degrees of Bachelor and Doctor of Music were offered by Durham and Oxford (and a few others) to non-resident students who had to submit an ‘exercise’ and pass a written examination. William’s FRCO already stood him in good stead, so immediately on leaving the RCM he formally joined the University of Oxford by matriculating at Queen’s College. In 1903 he passed the examination and submitted his exercise, a setting of Dryden’s paraphrase of the Veni Creator He graduated Bachelor of Music on 10 November 1904. A doctorate was more of the same, only more so, and required a few years’ further study. In 1909, the written examination duly passed, he submitted his exercise, a substantial setting for double choir, soloists and large orchestra of Milton’s Ode on the morning of Christ’s Nativity. He graduated Doctor of Music on 1 December 1910, and so became ‘Doc H’ to generations of choristers. It is surely not without significance that his chosen texts were religious but non-biblical, for he was developing a discerning taste in literature.

It is time to explode another myth: William was not taught by Henry Walford Davies, who was on the staff of the RCM but did not teach composition; however, Davies had just been appointed Organist of the Temple Church and was glad to make use of such a capable and experienced assistant as William. Davies also employed him as accompanist to the London Church Choir Association, and to the Bach Choir which Davies directed for a few years before being succeeded by Hugh Percy Allen, a man who would have a profound influence on William’s future career.

He had by now played in a number of London churches, but he longed to be back in a cathedral. Lichfield needed an assistant organist to help with the choristers’ training and play for some of the twice-daily weekday services. There were no regular Sunday duties, so he was also able to be Organist of the large and wealthy St Augustine’s Church, Edgbaston, inheriting his predecessor’s teaching at the Birmingham and Midland Institute, the forerunner of today’s Birmingham Conservatoire. There he came under the powerful influence of Granville Bantock. He took up these positions in 1911, and in 1913 he married Kathleen Doris Carter (‘Dora’), who bore him two daughters. With war imminent he joined the 28th Battalion of the London Regiment volunteer light infantry unit, but nothing is known of any active service until the very last year of the war. He did find time to compose a substantial work for choir and orchestra. The Hound of Heaven, a setting of Francis Thompson’s poem, had its first performance in December 1918, by the Birmingham Festival Choral Society

and Orchestra, and its second in 1920 by the same forces. It was well received by the local critics and accepted for publication by Stainer & Bell with a subsidy from the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, but it did not prosper.

Hugh Allen, William’s friend of Bach Choir days, had been chosen to follow Parry as Director of the RCM after Parry’s death. Harris succeeded Allen in his post as Organist of New College in 1919, and was further rewarded with a professorship of organ and harmony at the RCM. Unfortunately a mere Doctor of Music was not a senior member of the university, for the only degree that mattered was that of Bachelor of Arts (BA), awarded at the end of a residential undergraduate course, and from which one proceeded without further examination, and a minimum of 21 terms from matriculation, to the degree of Master of Arts (MA) and the status of Senior Member of the university. Someone, possibly Allen, found a solution to this problem.

Oxford was then still the world of the Bertie Woosters, for whom an undemanding ‘pass’ degree was offered, and William accomplished this by 1923. He was exempt from any further examinations as he had passed the second examination for the degree of Bachelor of Music, and having matriculated in 1902 he had been a member of the university for the prescribed 21 terms and could proceed to the degree of MA as soon as his BA had been conferred. Thus Dr Harris became a Senior Member of the university.

He began to include his own music in the chapel services, and November 1925 saw the first performance of his most celebrated work, Faire is the heaven for unaccompanied double choir. King of glory, King of peace, for three-part trebles and organ, was sung on 16 occasions between 1924 and 1929. One of his happiest inspirations, its printed copy immortalises the names of Cullis and Gooderson, the best of a remarkably fine set of choristers. It is noteworthy that he chose to set Edmund Spenser and George Herbert rather than the Bible or Prayer Book. To these years also belongs his best-known hymn tune, for Lead, kindly Light. Harris named it ‘Alberta’ after the Canadian province where, during an examination tour, he found himself stranded at a remote railway station. This experience obviously left its mark!

Harris was running the famous Balliol Sunday Evening Concerts and was also involved in a pioneering revival of Monteverdi’s operas, but he was a cathedral musician at heart and was glad to move to Christ Church, Oxford’s cathedral as well as the chapel of Cardinal Wolsey’s mighty college. Its organist, Noel Ponsonby, died suddenly in 1929, and so William left New College to spend four years at the cathedral. A splendid anthem from those years was O what their joy and their glory must be (1931). For full choir with organ or orchestra, it is a set of variations on that hymn’s noble melody.

Then history seemed to repeat itself with a sudden death, this time at St George’s Windsor, where cathedral-style choral services were sung daily, morning and evening. Walford Davies had served for only four years, and had been followed by Charles Hylton Stewart who died most tragically in 1932 after only six weeks in post. The invitation to Dr Harris was almost a royal command, and from 1933 until his retirement in 1961 he was the chapel’s organist, renowned for his skill as a trainer of choristers and in increasing demand as a most

useful and versatile composer. He inherited the new tradition, only ended by the war, of an annual Festival of Church Music in which the Windsor choir took the major but by no means sole share. The demands of these festivals may have prompted Harris to compose a number of motets and anthems, the best of which is Love of love and Light of light, (1934). He was enjoying a burst of compositional activity, and a large-scale festival cantata, Michael Angelo’s Confession of Faith, was commissioned for the 1935 Three Choirs Festival at Worcester. The 1937 Coronation called forth an Offertorium, O hearken thou; and the revival of the Garter Day ceremonies later that same year was marked with a Te Deum in B flat. He even turned his hand to a couple of short orchestral works: an overture Once upon a Time was performed at the Proms on 5 September 1940, and a Heroic Prelude on 4 August 1942.

Life at Windsor continued much as usual, with the full round of chapel services maintained throughout the war, for the boys had not been sent elsewhere and most of the men were too old for military service. Doc H gave music lessons to Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, who together with various residents of the castle and the wider community formed a madrigal group which he directed. Thus Princess Elizabeth was able to take an informed interest in the music for her wedding in Westminster Abbey, in which six of the Windsor choristers and their choirmaster played a vital part. By November 1947 the boys’ choirs of the Abbey and the Chapel Royal, disbanded early in the War, were only in the early stages of being rebuilt; but the Windsor choristers’ training had continued without interruption and so the Abbey’s organist, William McKie, was glad to enlist the support of such experienced singers. Harris accompanied some of the singing, and McKie left an amusing account of the famous treble solo in S S Wesley’s Blessed be the God and Father. ‘William Harris had been slow, which hadn’t helped the [Abbey] boy who was trying the solo, so I gave it to my top eight, saying privately to them, “You come along with me and never mind Doc H.” – so they did. And William Harris, the perfect gentleman, came along too, but against his better judgement.’ Another observer commented that ‘while Doc H played, he looked more like the White Rabbit than ever, rocked slightly to and fro, and kept saying to himself in a sad little voice “Too fast, too fast”.’

The choir, however, was in poor shape owing to the men’s inadequacies, and the recordings issued by Columbia between 1949 and 1953 did nothing to enhance its reputation. It still sang nobly on state occasions: at the funerals of George V in 1936 and George VI in 1952, and in 1953 there was the coronation of H M Queen Elizabeth II, for which Harris composed a Gradual, Let my prayer come up, for choir and orchestra. By the following year he had been knighted for his part in the ceremony.

Lionel Dakers, Assistant Organist 1950-53, was impressed and a little surprised by ‘Doc H’ who ‘was in some respects a person of marked contrasts. He was as original and at times venturesome in much of his composition as he was instinctively traditional in his organ-playing. Freddy Hodgson, an enthusiastic and notably kind-natured lay clerk, recorded a somewhat rose-tinted impression of Doc H, who ‘maintained a rigid discipline with his choir and drove himself as hard as he drove his singers. Full attendance was demanded, and he was rarely absent. There were many tense early-morning practices with Doc H, often in critical mood, and everyone had to be on

his toes. On occasion an aggrieved lay clerk would retaliate, with the inevitable fireworks.’ The boys, who adored Harris,

It’s still dark outside as 14 boys and girls assemble in front of two long rows of choir stalls to start their vocal exercises. With hands on their hips and their Christ Church Cathedral School uniforms variously tucked in, they continue the centuries-old tradition of Anglican church choristers, warming up their young voices.

But this isn’t a scene in a British cathedral city. This choir practice is held on the far reaches of Canada’s West Coast, in Victoria, British Columbia, where the city’s Christ Church Cathedral has launched Canada’s first and only fully immersive chorister program based in a cathedral school.

“I fell in love with this tradition in the UK and always wanted to start a similar program in Canada,” says Donald Hunt, a Canadian who was recruited as Director of Music at the cathedral from Edinburgh, where he was Assistant Organist at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral.

As the youngsters hit their high notes, the soaring vaulted ceiling in the cathedral’s Chapel of the New Jerusalem amplifies even the most tentative of voices. “The children are developing the sound that I was aiming for much more quickly than I thought they would,” says Hunt. “Perhaps it has something to do with this wonderful space.”

The scene invokes a centuries-old tradition, but it is illuminated by the dawning sun shining through striking

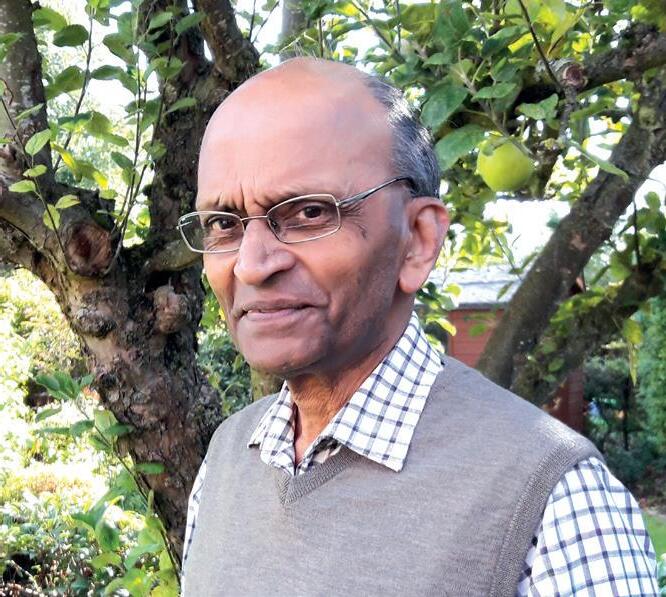

While cathedral chorister programs in North America are few and far between, a flourishing new program on Canada’s West Coast proves the exception.Christ Church Cathedral choristers with Donald Hunt far right Christ Church Cathedral Victoria, British Columbia Photo: Chris Thrackray

stained glass of modern design in a chapel less than 30 years old. And while the year-old chorister program pays tribute to its musical and spiritual roots, its location and the modern lifestyles of its Canadian choristers and their families are also taken into account.

Where British choristers’ lives are likely to revolve mostly around their cathedral and education schedules, Canadian participants often combine their music practices and study with various extra-curricular sports and other outdoor activities. One young chorister, Elysse, arrived at a recent 7.30am practice having already played ice hockey at a regional rink, while fellow singer Alyssa balances singing with dance classes. Alyssa recently took part in a performance by the visiting Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s production of The Nutcracker undertaking, among other roles, ‘a fuzzy-wuzzy polar bear’.

Despite their busy schedules, the youngsters arrive for practice “charged up”, says Hunt, who has gradually introduced his choristers to the cathedral congregation once or twice a month at its Wednesday Evensong service. He says there’s a different feel to the service as the choristers’ families now mingle with the regular congregation. “One of the chorister’s grandmothers shed tears of joy after an evensong. People get quite emotional when they consider what it means to the future of our church.”

The chorister program is also attracting interest in the adjacent cathedral school. “We were hoping that the program would be a draw to the school, and we’re delighted to have had five or six new applications already,” says Stuart Hall, the Head of School. With the growth of interest in the school, which is nearing capacity, and in the chorister program, Hall is hoping to increase scholarships to reward qualified children and encourage new applications to the school (which already has a music program). “We hope to raise the level of music tuition, which in turn will give Donald a larger talent pool to work with,” says Hall.

Sarah McDonald, Canadian-born Director of Music at Selwyn College Cambridge, and Director of the Girls’ Choir at Ely Cathedral, spent much of her youth in Victoria and knows the cathedral well. She’s always believed the cathedral school had tremendous untapped potential for a chorister program. “I’m delighted to see this going ahead,” she enthuses.

Successful applicants to the chorister program currently receive scholarships to help offset the cost of their school tuition. All but one of the current crop of choristers are students at the kindergarten to Grade 8 (age 13-14) cathedral school, which was founded in 1989.

Aspirations to establish a chorister program have been percolating for several years among the cathedral’s leadership. Now that it has finally been realised, Christ Church Cathedral is reaping the benefits – according to the present dean, The Very Revd Ansley Tucker, who herself sang for 25 years in a semi-professional choir specialising in Early Music.

“The people who come are elated to see the children singing, and the children themselves are in an activity they enjoy. It’s so enlivening for people to hear children making music of this quality.” She praises the youngsters’ ability to learn difficult music quickly, which in turn expands their knowledge of liturgical music and its history. “You’ve got nine-year-olds memorising magnificats and being introduced to texts of scriptures and prayers through music, and this strengthens a musical and spiritual tradition.”

Sarah McDonald would concur. “It is fantastic to have a new generation of children learning to love the great choral repertoire. Choral singing is hugely important to so many people, and it seems obvious to be training [children] up from a young age so that it will thrive into the future.” Sarah sees this as the cradle of the next generation of choral singers and church musicians, and an engine of growth for the church.

“There is a regeneration of Choral Evensong [in England], with cathedral congregations rising during the week, despite a decline on Sundays.”

Apart from belting out the national anthem at sporting events, Canadians are a reticent bunch when it comes to public singing, and are becoming less vocal at mainstay church services, such as Christmas Eve carol services, says Tucker. But she feels that engaging a new generation in a chorister program is a step towards changing that. “The fact that we’re teaching children, especially boys, that music is important and requires skill and ardour is a bonus all round.”

“I smile a lot more now,” says Jude, who sang in the Victoria Children’s Choir and the cathedral school’s choir before becoming a cathedral chorister. While both children enjoy the repertoire of the program, Alan says he likes to “switch it up every once in a while” and sing non-church-related music on occasion. Both boys will be encouraged to join the cathedral’s back row when their voices change, and their participation in a chorister program will provide lifelong benefits.

“There is no better foundation for the musical development of a young person than to sing in a good liturgical choir that has a wide repertoire with excellent leadership and direction,” says Matthew Larkin, one of Canada’s leading Anglican choral directors, also a concert organist and the conductor of Caelis Academy Ensemble in Canada’s capital Ottawa, a choir he founded after he left his post as music director at that city’s Christ Church Cathedral. While not a church choir, Caelis follows the cathedral practice of using boys and/or girls in the treble line. “I have lived the tradition of cathedral music almost all my life. It’s part of who I am, not just as an artist but as a person,” Larkin says. He admits, though, that it’s increasingly difficult to establish that kind of lifelong influence on today’s children, given the increasing competition for their attention. When he was a child, “It would have been unfathomable for a game [of ice hockey] to be scheduled on a Sunday morning”, whereas now Canadian choir directors must consider chorister families’ desire to pack as many activities, often outdoor, into a weekend as they can.

Two of the boy choristers, Alan and Jude, both 12, were already keen choir members when they joined the program, and they play various musical instruments in addition to singing. Both particularly enjoyed a recent road trip to nearby Shawnigan Lake boarding and day school where a video recording was made of the service they sang in the chapel. This recording clearly influences how they sing:

Larkin also acknowledges that “the administration aspect of a cathedral type of choir is substantial” which is further challenged by a diminishing volunteer base of parents who are less likely to have sung in a church choir themselves and are therefore generally less motivated to enrol their children in one.

All those challenges makes Victoria’s chorister program all the more impressive, according to Larkin. “If Christ Church Cathedral Victoria can buck this trend ... it sends a compelling and exciting message. There is no stronger community than a choir. It builds confidence, expressive ability and a sense of collegiality in which friendships are made and sustained.”

Larkin’s thoughts are echoed by Matthew White, the acclaimed Canadian counter-tenor and Artistic Director of Early Music Vancouver, who now makes Victoria his home. He recognises the importance of the cathedral’s chorister initiative and credits his early chorister days with setting him on his life’s path. “It gave me the opportunity to appreciate really great music. And it provides an opportunity, especially for boys, to nurture a part of themselves that’s different.”

Like many Canadian boys, he juggled music with ice hockey, but it was his time in the choir that shaped his character. “You notice that different people have different talents, which can all be useful to the whole. Choral singing teaches children how to appreciate beauty and I can’t imagine a higher endeavour.”

Tucker agrees that the lessons learned in a chorister program extend well beyond the musical. “The great value of singing in a choir is that it’s a team sport and you learn when to support and when to let someone else shine.”

Internationally recognised tenor Benjamin Butterfield, now a professor of voice at the University of Victoria, spent several years at Christ Church Cathedral as a chorister along with his four brothers and sister. He thinks his university voice students would benefit from having the same liturgical music foundation that he received. “You develop an ear and discipline,” he says. “In church you have to be present and listen before you get up and sing. The church repertoire teaches different aspects of music, such as a sense of structure,

music history, language and sight-reading skills. Children don’t receive that breadth of training and experience in the average school choir. I also love the idea that, with church music, kids are singing about something a bit bigger than they are.”

The chorister program has also engaged University of Victoria students as choral scholars to serve as mentors to the choristers and leaders to the cathedral choir sections. And while he’s passionate about challenging children to expand their musical skills beyond the latest pop culture songs, Butterfield is aware of the competition for the choristers’ time – but he is not dismissive of doing both. “Singing and sports can coexist,” says Butterfield. “That’s what creates well-rounded kids. The children are looking for experiential direction from their parents and it’s up to them to provide it.”

Although both the cathedral school and the chorister program are nearing capacity, there is always room for expansion, says Hunt. “There’s a wonderful base of support from the cathedral community, and strong interest from parents for activities where children can reach their full potential.” He sees a bright future and believes that any child with the desire, musical interest and aptitude can succeed.

“We are moving to a steady state of 20 children, and in the future I think building two full treble lines for boys and girls is quite achievable,” says Hunt. “There’s also potential to expand the chorister scholarship scheme, offering greater reductions in cathedral school tuition, widening the reach of the program so that more families can explore this magnificent opportunity for their children.”

As the morning practice wraps up, the choristers grab their backpacks and head out in the morning chill for the short walk to their school. Watching them, Hunt sees the embodiment of an ancient tradition but with a new generation of choristers who require a new approach. “To create something of enduring quality, it’s important to build something that works for this culture,” he says in appreciation of the challenges and opportunities ahead of him. “Yes, we have a deep cultural connection (to Britain) but we’re also Canadians.”

Perhaps no one embodies this philosophy better than Elysse. “I want to stay in this program,” she beams. “I like singing Evensong — and then I go and play hockey!”

As every cathedral musician knows, acoustics vary from one building to another, and even from one position to another within the same building. The effect may depend on the overall size of the space, the surface materials, the configuration of the architecture, the type of ceiling and the number of people in the building. Buildings are multisensory environments in which the dimensions of sound, not to mention smell, ritual, and even flickering candles and air temperature, affect religious sensibilities just as much as the visual setting. What is more, the experience of the listener is not the same as that of the performer.

As an architectural historian, I first became interested in the relationship between architecture and music in Venetian churches as a PhD student in the early 1970s. I realised

that sacred architecture cannot be studied solely in visual terms. It was in 16th-century Venice that the tradition of the coro spezzato, or divided choir, took root, pioneered by Flemish composer Adrian Willaert in St Mark’s between 1527 and 1562. But where in the churches did the divided choirs sing? Ceremonial books of the period are singularly unhelpful about their positions (‘the singers were in the usual place’), and musicologists have suggested various different alternatives. One solution in St Mark’s was to gather all the singers together in the raised hexagonal pulpit known as the bigonzo outside the choir-screen, but this offered no spatial separation. During Willaert’s term as maestro di cappella, the architect Jacopo Sansovino created two new raised singing galleries or pergoli on either side of the chancel, perhaps to accommodate the divided choirs.

Some 30 years later, still hoping to investigate this subject, I found the ideal research collaborator: a young architect and historian called Laura Moretti who was also a professional cellist. Together we devised a research project to explore the relationship between architecture and music in Renaissance Venice and in 2005 were lucky to win funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. We assembled a team of acousticians and musicologists to help us, and held our first conference in Venice in 2006. To our surprise the various experts got on together splendidly, and they became our advisers and supporters as we devised our various investigations and experiments.

First of all, we selected 12 Venetian churches of various types and dates. The ducal chapel of St Mark’s took pride of place

as the mainspring of musical invention. We also looked at two monastic churches, three friaries, three parish churches, and three of the state hospitals, famous for their choirs of female orphans. Some were medieval buildings included for comparison, but the main focus was the work of the 16thcentury architects Jacopo Sansovino and Andrea Palladio.

Throughout the whole three-year duration of the project, Laura and I were busy with historical research in archives and libraries, so that we could integrate the musical information into the building histories, liturgical developments and religious events of the period. In particular, the Council of Trent (1542-63), which ushered in the Counter Reformation, promoted a new emphasis on intelligibility and decorum in church music. Meanwhile, the rapid growth of music printing in 16th-century Venice complicated the relationship between musical composition and specific locations. After the publication of Willaert’s Psalmi spezzati in 1550, for instance, the composer lost control over where, and by how many voices, the pieces would be performed.

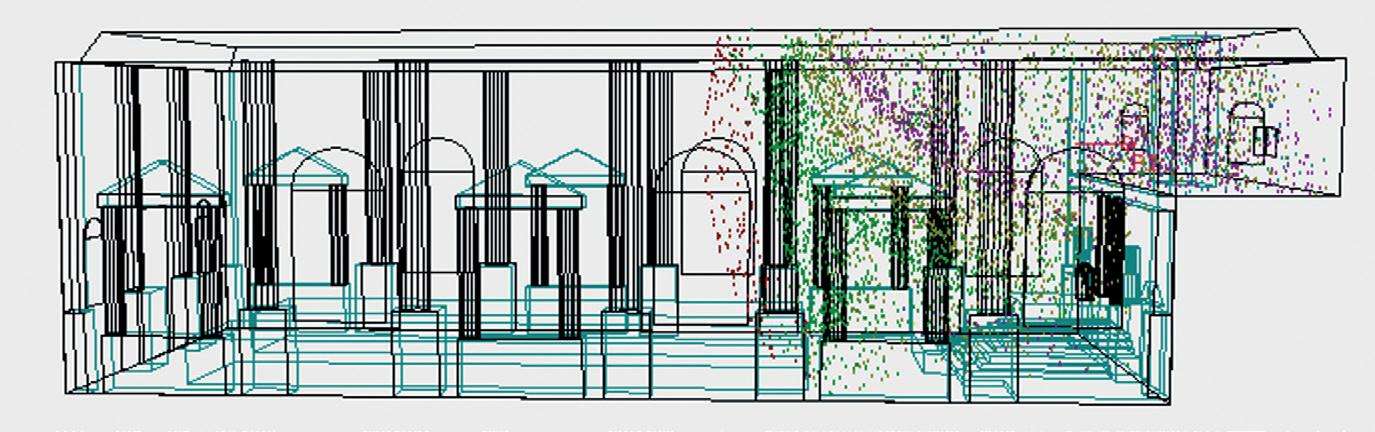

The initial stage of the research involved making complex scientific measurements of the acoustics of each church, using the expertise of Davide Bonsi, then based at the acoustic laboratory at San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. We hired a boat to transport the equipment all over the city, and in each church we selected various possible places where musicians might have performed, as well as a selection of listener positions (fig. 1). Because the sound at various frequencies was emitted by a siren-like instrument we had to place signs to warn the public of the potentially alarming noise.

To our amazement there was a very close correlation between the subjective and objective results, indicating that even untrained listeners are able to distinguish different acoustic properties.

The next stage was to record live liturgical music in the same spaces. Sadly, in Italy most Catholic churches have abandoned traditional sacred music since the second Vatican Council (1962-5). We needed an expert choir which could sing complex Renaissance polyphony at sight, ideally one which included children as the hospital churches had done. Luckily the choir of St John’s in Cambridge was willing to come to Venice for a week in April 2007 to carry out the choral experiments. I was thrilled when David Hill, the then Director of Music, agreed to take on the challenge. During the tour the choir gave only two proper concerts, one in the church of the Frari (fig. 2) and one in Santo Stefano, as the rest of their time was needed for our research.

We worked the choir extremely hard. Numerous recordings were made in every church to experiment with different positions of singers and listeners, often repeating the same piece over and over again to compare the various locations. Yet the commitment and involvement of the whole choir amazed me. Only the very smallest boys were given some time off to play on the beach at the Lido. With the help of our musicological advisors, especially Iain Fenlon, we chose a range of pieces from the repertoire of the time: elaborate polyphonic psalms and motets by composers such as Willaert, Giovanni Gabrieli and Monteverdi, as well as plainchant, falso bordone (simpler polyphony) and organ works. In St Mark’s our experiments confirmed that the Sansovino pergoli offered the ideal setting for coro spezzato, from the point of view of both performers and listeners. All the same, it was important to recognise that the situation was very fluid – all the composers at St Mark’s would have experimented with different singing positions. We also needed to find out how these innovative pieces sounded in other kinds of spaces.

We put posters up all over Venice inviting the public to come to hear the choral tests. Our listeners were a mixed bunch – they included ladies of the parish, local enthusiasts, tourists, our friends and colleagues, and parents or friends of the singers. The audience had to work too, for we circulated questionnaires in both English and Italian inviting assessments of various acoustic parameters, such as clarity, loudness, the direction of the sound, and envelopment Even the singers (both the boy choristers and the choral scholars) completed their own questionnaires in every church, giving their personal impressions of the acoustics.

Among the many memorable experiences during that week, a few stand out. We usually invited the priest of the church to read a text so that we could record the acoustics of the spoken word, but in one parish church the priest unexpectedly went home. The College’s Dean came to the rescue by delivering an impromptu mini-sermon on the theme of Mary Magdalene (just right for Easter Monday) from the beautiful marble pulpit. The most transcendental moment was when we were exploring the acoustics of the octagonal domed burial chapel on the corner of San Michele in Isola. The chapel is lined with marble reliefs of the life of the Virgin and has a white stone dome constructed like an igloo. Spontaneously the choir decided to sing Mouton’s Nesciens Mater, although it was not on our list of chosen pieces, and the result was unforgettably evocative.

We came back to Cambridge with 16 CDs of recordings, made by expert sound engineer Matthew Dilley, and a suitcase full of questionnaires. The next few months were spent analysing all the acoustic data and the listeners’ responses. Because the audience questionnaires invited numerical answers on a scale of one to ten, we could quantify their assessments of clarity, reverberation, loudness etc and compare these with the measured acoustic parameters. To our amazement there was a very close correlation between the subjective and objective results, indicating that even untrained listeners are able to distinguish different acoustic properties. We believe this is the first time that a systematic comparison has been made between objective acoustic measurements and subjective audience perceptions of the same phenomena.

One of the most notable results was the clear division of acoustic properties according to the type of church. The driest acoustics were found in the parish churches, which were small, compact spaces, mainly used for family rites of passage such as baptisms, marriages, funerals and commemorative masses. As our experiments took place in the week after Easter, every church had brought out its best carpets and hangings, making the acoustics even drier – and not at all pleasant for the singers.

At the opposite extreme, the large monastic churches had very long reverberation times, which gave plainchant a rich spiritual resonance, but made complex mensural polyphony dissonant and indistinct. The most difficult acoustics were

those of the two Palladio churches, the Redentore and San Giorgio Maggiore, with their high, smooth domes, huge interiors and hard surface materials. This seemed surprising for two reasons. One was Palladio’s known interest in musical harmony and proportion, and the other was the fact that each of these churches was visited annually by the Doge in a great ceremonial festivity, using the choir and liturgy from St Mark’s.

In between were St Mark’s and the hospital churches. St Mark’s, with its five golden mosaic domes and marble panelling, remained the paradigm, but it had very different acoustics from those of other churches. As the private chapel of the doge and the burial place of the Evangelist, this was the centre of state ceremonial (St Mark’s has only been the cathedral of Venice since 1804). Certainly within the chancel, where the doge, visiting ambassadors, and high state dignitaries had their pews, the listening experience was extremely good. By the early 17th century, when instrumentalists joined the singers on festive occasions, even more positions were found for musicians in niches and raised galleries around the chancel, to give this privileged space even more benefit. It should be noted that John Eliot Gardiner’s famous video recording of the 1610 Vespers, performed to an audience in the nave in 1989, arranged musicians and singers around the crossing in a configuration that had never existed in Monteverdi’s time.

The optimal acoustic for the new polyphony was found in the hospitals. As these foundations relied on donations from the public to sustain their institutions, they had to ensure that their churches offered the best possible acoustics. The most beautiful was that of the church of the Ospedaletto, where the female orphans would have sung from the raised gallery above the high altar. Listening to the choristers of St John’s singing from that position, our audience remarked on the strange and moving effect of angelic voices descending from

above. Interestingly, our scientific acoustic measurements confirmed this effect of the vertical transmission of sound.

Giving more detail to all of the above, in 2009 we published the book Sound & Space in Renaissance Venice: Architecture, Music, Acoustics, by myself and Laura Moretti, and set up a website with selected music tracks www.djh1000.user.srcf.net/ soundandspace/. In fairness to St John’s choir, it should be stressed that none of the music was rehearsed, and tracks with poor acoustics as well as those that worked well musically have been included. The technical appendix, which explained and interpreted the results assembled by acousticians Davide Bonsi and Raf Orlowksi, was written by Cambridge physicist Malcolm Longair.

As a coda I should mention a fascinating extension of our project carried out in 2009-10 by a young MPhil student in Cambridge called Braxton Boren, using the specialised Danish acoustic software Odeon© to make virtual reconstructions of several of our chosen churches. At the Ospedaletto, for example, he was able to illustrate graphically the effect of sound seemingly falling from the ceiling like rain (fig. 3) His virtual acoustic model of the Redentore showed sound rising into the dome on its high cylindrical drum, and swirling around for some time before descending to the crossing to mix with the sounds emitted later on. At the same time, other sound waves bounced off the façade wall of the church. This cacophony of delayed sound led to the performance difficulties that we had experienced. However, when Braxton filled our virtual model with the wooden stands, draperies and hangings that would have been erected for the annual ducal festivity, and added hundreds of virtual spectators in heavy ceremonial robes, the reverberation time dropped to a remarkable degree. Thus we were able to confirm our suspicions that the large number of spectators on the annual Festa del Redentore would have allowed excellent audibility.

Deborah Howard is Professor Emerita of Architectural History at Cambridge University, where she is a Fellow of St John’s College. During her career spanning more than four decades, her research has focused especially on the art and architecture of Venice and the Veneto; the relationship between architecture and music; and cultural exchange in the eastern Mediterranean. Apart from the book Sound&Spacein Renaissance Venice (2009), she and Laura Moretti co-edited TheMusicRoominEarlyModernFranceandItaly (2012). Her latest book is TheSacredHomeinRenaissanceItaly (2018, with Mary Laven and Abigail Brundin).

Laura Moretti is now a Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of St Andrews.

Braxton Boren is now Assistant Professor of Performing Arts at the American University, Washington DC.

Members of FCM will be delighted to know that there is to be a second ‘Cathedral Choristers of Britain’ concert, this time at Liverpool Cathedral on 13 June 2019. The first such concert, at St Paul’s Cathedral on 26 April 2016, launched FCM’s Diamond Fund for Choristers and brought together choristers from 63 choral foundations – one from each establishment, representing the greatest number of cathedral choirs ever under one roof – together with the choir of St Paul’s Cathedral, in a remarkable and unforgettable performance, prompting some in the media

to call it ‘the world’s first cathedral supergroup’. Readers of Cathedral Music with keen memories will recall Alexander Armstrong’s excellent speech extolling the benefits of being a chorister in the November edition of that year.

The intention behind these concerts, which are now planned to take place at three-yearly intervals at different cathedrals throughout the United Kingdom, is to showcase the talent of Britain’s cathedral choristers and the directors of music who train them; to raise awareness of this jewel in the UK’s cultural,

educational and heritage crown against a background of increasing pressures on cathedral finances; and to generate income to safeguard and strengthen Britain’s world-renowned choral tradition.

The Liverpool concert will feature choristers from cathedrals all over the UK, both boys and girls, and music from the 17th to the 21st centuries, including a new work by former Gloucester Cathedral chorister and Chamberlain of York Minster Richard Shephard. The concert, organised by FCM’s Diamond Fund for Choristers, will be conducted by Lee Ward and Christopher McElroy, Directors of Music at the city’s Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedrals. Dr John Rutter, the internationally acclaimed composer, will speak at the concert about the value of choristership