CATHEDRAL MUSIC

We offer four brands of organ each with their own identity, sounds, appearance, technology and style. All our brands share valuable characteristics such as technological innovation and the best sound quality, which is never a compromise. All provide the player with a unique playing experience. A great heritage and tradition are our starting points; innovation creates the organ of your dreams. Contact us for tickets for our ‘Autumn Shades’ concert at Shaw on Saturday 3rd October 2020

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus | Rodgers

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November.

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2020

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ editor@fcm.org.uk

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon pm@fcm.org.uk

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

DT Design,

4 Bedern Bank, Ripon HG4 1PE 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: +44 20 3637 2172 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 4 Bedern Bank, Ripon HG4 1PE 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

Receive your first year membership of the Royal College of Organists FREE, with your home practice organ purchase

Sonus instruments, based on the very successful ‘Physis’ physical modelling sound platform, additionally incorporate an enhanced internal audio system to generate an exciting moving sound field for increased enjoyment in a home environment. Speakers above the keyboards and to the organ sides create a truly sensational and immersive sound field.

Starting at £11,700 inc VAT for a 34 stop 2 manual, the instrument pictured here is the Sonus 60 with 50 stops at £16,900 inc VAT. Neither words nor recordings can do justice to the sound of these instruments; you just have to experience it in the flesh.

Multiple speaker locations create a uniquely authentic sound

To play one of our instruments call us to book a visit to our showroom, or contact one of our regional retailers listed below.

Soundtec Irvine

Rimmers Music Edinburgh

Promenade Music Morecambe

Pianos Cymru Porthmadog

Henderson Music Londonderry

Keynote Organs Belfast

Cookes Pianos Norwich

Jeffers Music Bandon

Cotswold Organ Company Worcester

Viscount Organs Wales Swansea

Wensleigh Palmer Crediton

South Coast Organs Portsmouth

Viscount Classical Organs Ltd

Tel: 01869 247 333

E: enquiries@viscountorgans.net

www.viscountorgans.net

Sonus 60One of my favourite remarks of recent weeks is, ‘I wish we could go back to “precedented” times…’. Don’t we all? But since we can’t, and onward is the only option, in our area of support we must concentrate our efforts on offering whatever assistance we can to musicians of all kinds who have lost huge swathes of their incomes to – as my aged uncle refers to the virus – ‘Corvid’. Mass cancellations of concerts, events and services, and the closure of churches over the most important festival in the Christian year have had an enormous effect on the finances of all involved, but in the musicians’ world where so many are self-employed and a large proportion exist on erratic incomes, it is more important than ever that we give whatever aid we can. For those who can afford it, donating back the price of concert tickets bought, even if a drop in the ocean, can give a little relief to struggling churches and musicians. For those on low, restricted or immoveable incomes themselves, maybe the best way forward is to resolve, once lockdown is ended, to attend more events, buy – and encourage others to buy – more tickets for rearranged concerts etc, and thus help to swell the coffers of the – what? – endangered? afflicted? stricken? All of those, perhaps. We must all do what we can, as soon as we can.

To this end you will find included with this magazine a letter from FCM’s Chairman Peter Allwood which gives details of two very important developments, one of which concerns the formation of an emergency fund to support those choral foundations which will struggle to survive once lockdown restrictions are lifted due to loss of income from concerts and venue hire. If any member is missing this insert, it can be found on the FCM website or obtained by email from me.

Most of us currently have more time on our hands than heretofore, of course, and so hopefully this magazine will be a welcome arrival on your doormat. (It would be nice to think that it is always well received, but perhaps a little more so in these strange times.) What you will see first is thoughts about our president, Sir Stephen Cleobury. His death came as CM 2/19 went to press – doesn’t November seem a long time ago now? So much has happened since then – so this coverage had to wait. Mark Williams, who first met Sir Stephen as an undergraduate and who was Director of Music at Jesus College in Cambridge before moving to Magdalen in Oxford, has gathered comments from a wide circle of people who worked with him in different capacities and at various stages of his life. Without exception, those who knew Sir Stephen well all speak of his unfailing courtesy, his adherence to the highest of standards, and his true generosity of spirit to those around him, which at FCM we also recognise; he was always anxious to be involved in our initiatives, and gave most willingly of his time until sadly he was no longer able to do so.

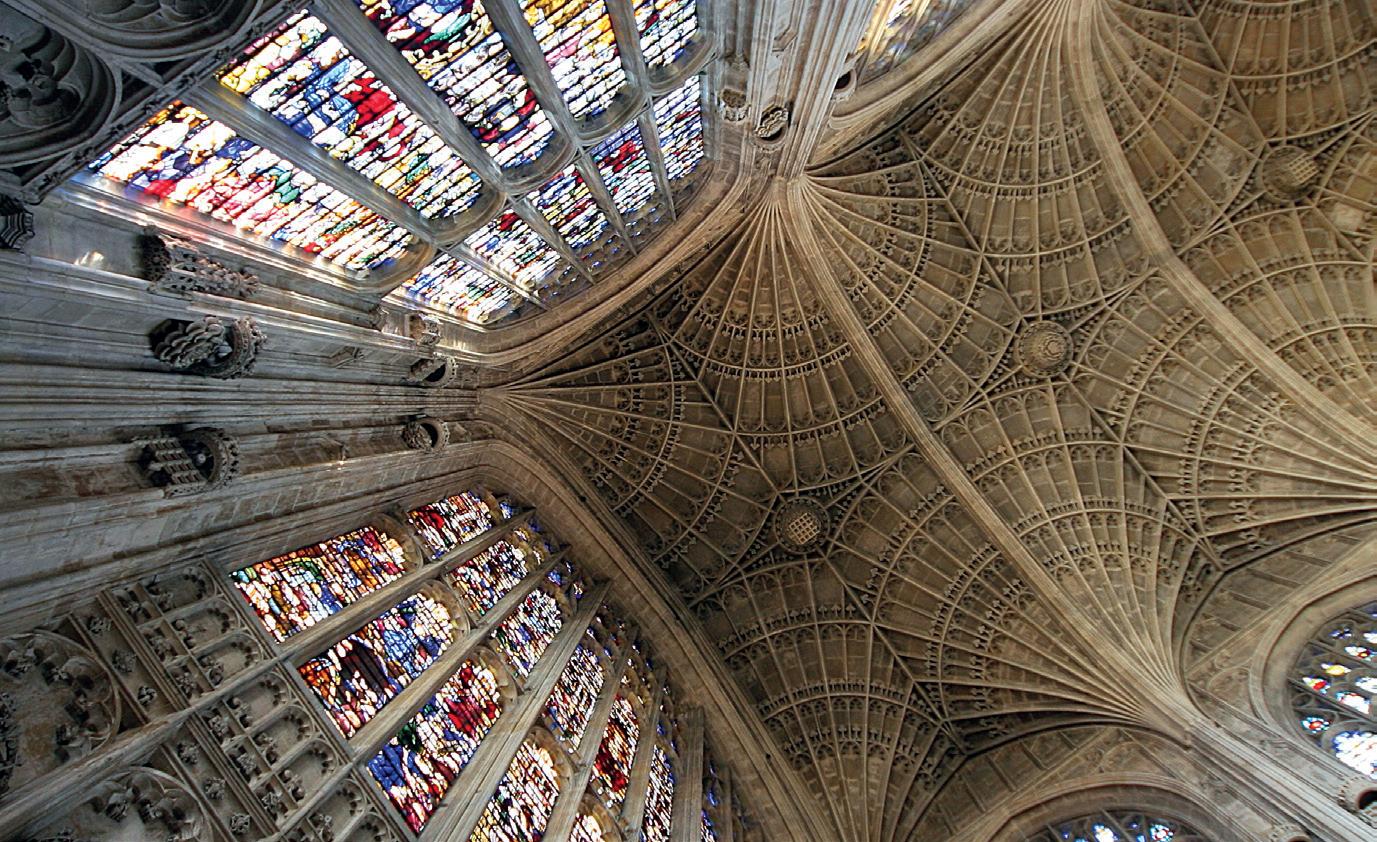

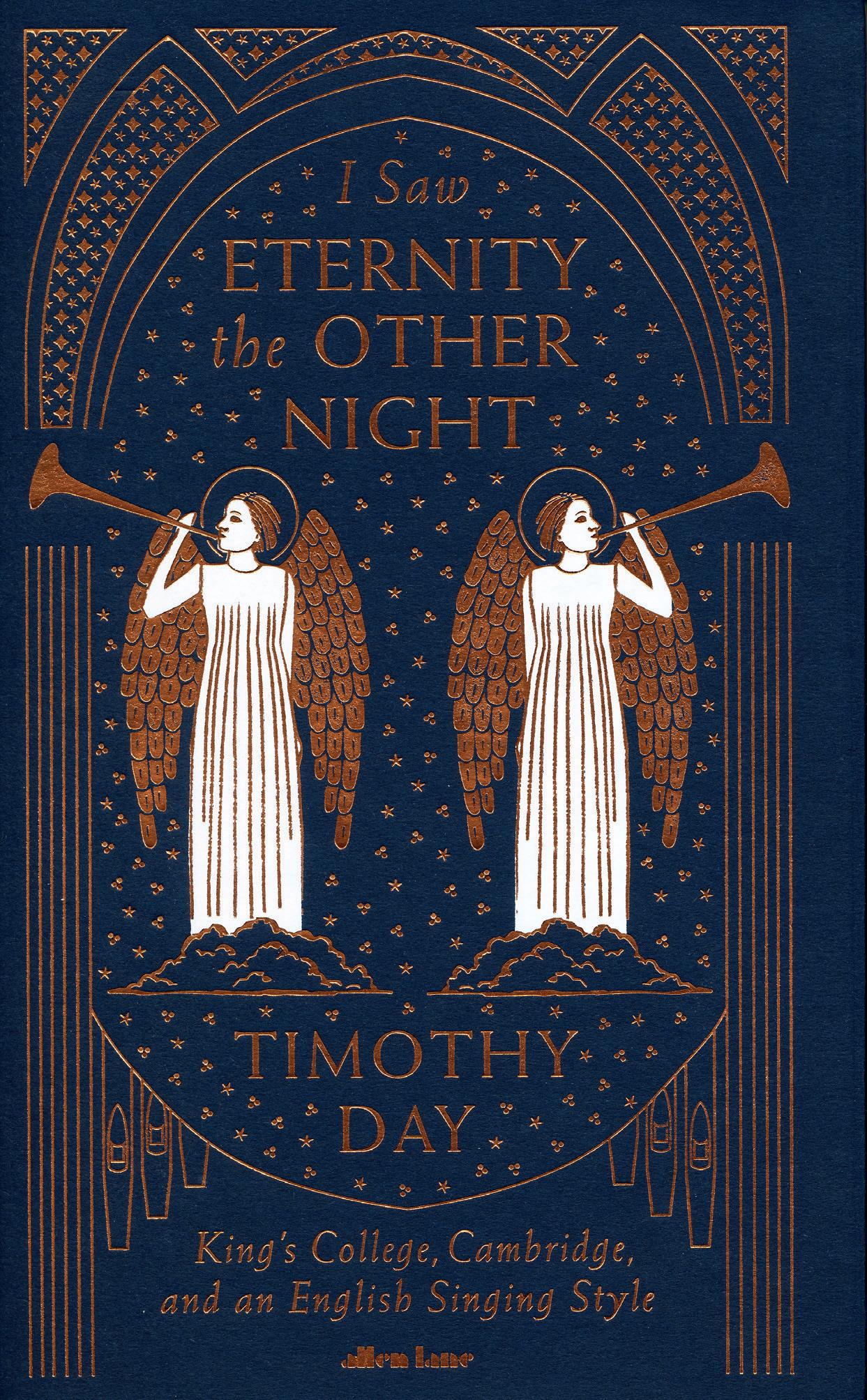

Further into the magazine you can discover more about the famous ‘King’s sound’, identified all over the musical world, and Sir Stephen’s role in the continuance of this widely recognised trademark, and how it came about, in Tim Storey’s review of Timothy Day’s recent book I Saw Eternity the Other Night

And you can read about the fulfilment of David Flood’s long held-dream – a new organ at Canterbury. Normally I would say, let us rejoice him in his achievement. But how strange it must have been – as for all our churches and cathedrals but in particular for the iconic Canterbury – to have had a totally silent Easter. A new organ, but no music from it, and no prayers, no singing, no choir, no clergy – as for all of us, of course, but somehow much underlined by stillness at the heart of the Church of England. Our mission, our raison d’etre – sustaining a living heritage – has become more important than ever it was.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free full-length CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to

increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over£4 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

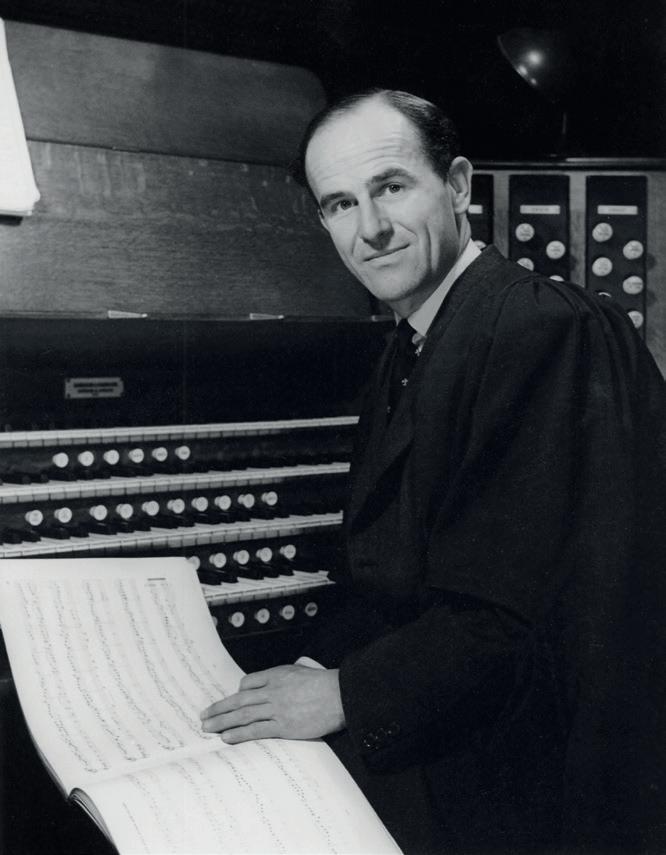

MW: My own first encounter with Stephen was as an undergraduate, not at King’s College but at Trinity, just down the road. Stephen asked me to play for a series of rehearsals with the chorus of the Cambridge University Musical Society. As a fresh-faced student, I was rather nervous about having to play for such a legendary figure in the choral world. And he was indeed demanding, with an ear and sense of rhythm that left nowhere for a sloppy accompanist to hide, but, within minutes of the rehearsal starting, I also saw the humour and kindness that brought humanity to his music-making. A raised eyebrow indicated that he knew exactly how he expected his seemingly gentle criticism of tuning or rhythm to be taken, and I was particularly struck by how quickly the rehearsal seemed to pass, owing to the execution of what I knew was a perfectly planned 90 minutes. In the years since my undergraduate days, I became increasingly aware not only of the magnitude of Stephen’s influence, but also of the depth of respect and affection for him across the musical world.

Thedeath of Sir Stephen Cleobury (1948-2019) on St Cecilia’s Day last year shook the musical world, coming so soon after his retirement from King’s College Cambridge following 37 years as Director of Music. Mark Williams, Informator Choristarum and Organist at Magdalen College Oxford, talks to colleagues, friends, former students and choristers about Stephen’s influence on generations of musicians.

ANDREW STAPLES was a choral scholar at King’s between 1998 and 2001. He has gone on to pursue a career as an internationally renowned tenor, appearing in major roles at the Royal Opera House, the Metropolitan Opera, New York, the Deutsche Staatsoper, Berlin and the Lyric Opera of Chicago, as well as in the Proms and on the stages of the world’s major concert halls.

AS: For all of us at King’s, Stephen was the ultimate benchmark of musicianship. He was someone you wanted to impress and, more than anything, he was someone you never wanted to let down. He inspired this ardent service without employing any tactics or high-handed methods, he simply made you want to sing better and try harder, work faster and learn more by setting a clear, humble and humbling example. His was a dedication to a cause that extended far beyond what was professionally required. Stephen knew that what he was asking of us wasn’t easy, but he believed it was worth it, and that the rewards would lead to a real sense of achievement and fulfilment. He enjoyed building teams and making them

into the best they could be. He was loyal and thoughtful, and, thankfully for me, he was patient and forgiving. He would rehearse a psalm in the same way that he rehearsed a Bach Passion, striving to make every sound, thought and gesture a matter of corporate responsibility and collective care.

As I entered my final year at King’s some 25 years ago, it occurred to me that I would never experience anything like that choir again and I’m yet to be convinced that I was wrong. Not so much Christmas and the glamorous tours as the wet Tuesday Evensong rehearsals when, in an empty, candle-lit chapel, Stephen would guide us through centuries of music, a quaver at a time, carefully instilling in us his sense of dedication to a higher purpose, all in the service of crafting music worthy of its surroundings and intention.

After three years under that kind of productive pressure we emerged able to sight-read anything, blend perfectly, and confident that our pristine text could be heard at the back of any concert hall on the planet, skills that have got me out of many a jam since.

JAMES VIVIAN has held the post of Organist and Director of Music at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle since 2013, directing the choir for the weddings of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex and Princess Eugenie and Jack Brooksbank. Prior to moving to Windsor, he was Assistant Organist and subsequently Director of Music at the Temple Church in London. He held the organ scholarship at King’s between 1993 and 1997:

JV: To encapsulate Stephen’s influence on me and my career is difficult to do in a few words. ‘Demanding but fair’ is a phrase that comes to mind when I think of my time as Organ Scholar at King’s, but that doesn’t adequately convey his generosity and his real desire to support his organ scholars. Particularly in my second year, when I was his only organ scholar, he was avuncular; he understood the pressures his organ scholars were under, and he always made a point of telling us when he thought we had played particularly well. Of course, we were left in no doubt when he thought we hadn’t played particularly well, too, but we knew that he was not demanding standards of us that he did not demand of himself every single day.

During my time at King’s I learned a great deal from him that I still put into use every day – the value of meticulous preparation, integrity and courtesy, attention to detail, and of how to organise and run an efficient rehearsal.

RICHARD GOWERS was a chorister at King’s 2003-2008 and Organ Scholar 2014-2017. He went on to study piano at the Royal Academy of Music and performs as a pianist and organist. He has appeared at the BBC Proms, Aldeburgh Festival, Wigmore Hall, Toulouse Les Orgues, and in collaboration with the Aurora Orchestra, BBC Singers, CBSO, LPO and several other ensembles. In 2018, the King’s label released his debut disc of Messiaen, which became a Gramophone Editor‘s Choice:

JOD: The prospect of my becoming Assistant Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral was both an exciting and a daunting one as I reached my final term at Cambridge. I was absolutely overawed by Stephen Cleobury, the cathedral’s Master of Music, who seemed utterly authoritative and almost incredibly competent. In the end, I worked with him for only a few months, as his appointment as Director of Music at King’s was announced just before I was appointed. In that short time, I found him an exacting boss but also a very supportive one. His comments were always constructive and I learned a huge amount from him, especially about the importance of being properly prepared (Stephen was never caught unprepared –for anything).

RG: My days as a chorister under Stephen were defined by his total leadership, authority and precision. In short, thanks to his demands, we were obsessed with what we did and gave all we could. It is hard to look back and conceive the amount of work we must have done to reach his expectation, but it is easy to see how much it shaped our lives.

A good rapport with Stephen was everything. The chorister system is praised for demanding a professional standard from children, and we all recognised that and took pride in it. We all tried to impress him. At the end of instrumental practice, just before the 8.10am chorister rehearsal, I would bash out choir music I’d picked up by ear to try and demonstrate an interest. “Was that you playing the Buxtehude Magnificat, Gowers?” he would ask. “A bit too fast, wasn’t it?”

In the end, trying to impress Stephen as an individual was missing the point. It was a choir: 16 choristers singing one musical line. Stephen loved recounting his predecessor Philip Ledger’s point that ‘a choir is only as good as its worst singer’. The system of apologising to him for any mistakes you made in a service was something that baffled outsiders, but felt entirely reasonable to us. Nothing was under-rehearsed on his watch.

Not all choristers went on to become musicians, but invariably we recognised what he had given us: a standard of discipline, group mentality and above all a profound love of music.

JAMES O’DONNELL took up his first post as Assistant Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral, on graduating from Jesus College Cambridge in 1982. He went on to become the Master of Music there in 1988, moving to his current post as Organist and Master of the Choristers at Westminster Abbey in 2000:

Playing for Stephen could be terrifying. This was partly because, when I arrived at the cathedral, the organs were in a poor state of repair and quite unpredictable. But it was also because you really wanted to play well for him and knew that any under-preparation or carelessness would be noticed. In that sense he was an inspiring master and encouraged you to give your best at all times.

CHRISTOPHER ROBINSON was Director of Music at St John’s College Cambridge between 1992 and 2003, having previously held positions at St George’s Windsor, and Worcester Cathedral:

CR: I first came across Stephen in 1962 in Worcester, where he was Head Chorister in the cathedral choir. He was quite small, always tidily dressed, polite, unassuming, yet totally au fait with everything that was going on. He always seemed wise beyond his years –precocious without being precious.

Along with a group of other talented boys (which included his brother Nicholas) I gave him piano lessons. A year later I also taught him the organ. Progress was rapid, and it was not long before he was fulfilling the role of organ scholar. He was an exceptionally diligent and determined pupil and if, at first, his style was inclined to be cautious, by the time of his audition for the St John’s organ scholarship at Cambridge he was playing the Toccata, Adagio and Fugue with considerable panache. As a pianist, I recall a fine account of Mozart’s G major Concerto K453.

Following his chorister days, he developed a pleasing light baritone voice and I encouraged him to join a madrigal group which I ran at the Alice Ottley School. This marked a significant step forward in his social life! In due course, he directed a similar group of his own. He also sang in the Festival Chorus and encountered a wide variety of choral works by such composers as Berlioz, Poulenc, Stravinsky, Britten (the War Requiem) and, of course, Elgar. From time to time he came with me to Birmingham to act as accompanist

for the City Choir. Nothing seemed to faze him, not even the Glagolitic Mass

After Cambridge he returned to Worcester to marry Penny. I remember this occasion vividly. George Guest conducted the combined choirs of Worcester and St John’s, and I played the organ. I was glad was quite something.

SUZI DIGBY is a renowned choral director and music educator. Founder of The Voices Foundation and director of The London Youth Choir and the professional ensemble, ORA Singers, amongst others, she lives in Cambridge with her husband, the Lord Eatwell, President of Queens’ College:

SD: I first met Stephen when I arrived at Queens’ College Cambridge in 2006. As the ‘hers’ college to King’s ‘his’ college (ours was co-founded by Margaret of Anjou, the wife of Henry VI), our colleges enjoyed a natural pairing. As a big choral person, the significance to me of being next door to King’s was immense. Over the next 13 years, Stephen was an unfailing support and a gracious friend. Perhaps the most abiding personal memory was Sir David Willcocks’ 90th birthday party, which I hosted in the Tudor Long Gallery at Queens’. We surprised Sir David with a performance of John Rutter’s specially commissioned Birthday Ode and Sir David’s wartime song, which we all sang under his direction. Seeing Stephen singing heartily alongside a distinguished gathering of musicians was a sight to behold!

JOHN RUTTER is one of the world’s leading composers, particularly celebrated for his many and muchloved contributions to the choral repertoire. Amongst pieces written for the King’s choir and Stephen Cleobury are two of his most famous carol settings, ‘What sweeter music’ and ‘Dormi Jesu’:

instead? We’ve got a slot after the eighth lesson this year.” I wrote the carol – What sweeter music – and Stephen championed it ever afterwards. It was always hard to find the right words to thank him; he was embarrassed by overt expressions of feeling, but the occasional private note from him showed that it meant a lot to know that he and his work were appreciated.

JOD: Stephen’s achievements during his short period at Westminster Cathedral were extraordinary and, in my view, have not been fully acknowledged. On his arrival he found in the cathedral choir a disorganised and somewhat demoralised group. Through methodical and dedicated work he rapidly transformed it into a top professional ensemble with a growing international reputation. He provided the foundations on which his successors have been able to build. Always musically demanding and disciplined, he was also courteous and goodhumoured and deeply respected by all his colleagues.

Stephen and I got on well, and we stayed in touch when he went to King’s. As I moved on to more senior positions, he seemed to me obviously the best person to ask for advice on tricky professional matters, and he always generously gave his attention despite the many other pressures on his time. His guidance was always balanced, wise and sensible, and totally discreet. Confidences were never broken.

JV: Stephen was genuinely delighted when his organ and choral scholars went on to succeed in later life, and he and Emma followed their careers with interest. I vividly remember coming out of a recent televised royal event to find a text message – sent during the broadcast – from him and Emma complimenting the choir on something they had just sung. That meant a great deal. It also meant a great deal that I could pick up the phone and ask for advice at any time. There was almost nothing in the world of professional music-making that Stephen hadn’t experienced, and his invaluable counsel was always wise and measured. I, and many others, will greatly miss being able to tap into that vast well of knowledge.

JR: Stephen’s professional and public life is well documented. His personal acts of kindness and thoughtfulness are less well known; he didn’t advertise them. Whether it was a kind word to a chorister parent suffering bereavement, dealing sensitively with a choir member battling serious illness, remembering a distinguished colleague in retirement, or spending extra time with a struggling organ scholar, his humanity was always there alongside his musicianship. I have particular reason to be grateful for this side of his nature: in 1987 he asked me to write a substantial choral work for the King’s choir’s annual concert at the Barbican. Illness forced me to renege on this commitment, and I felt terrible about it. He threw me a lifeline. “John,” he said, “I realise a big piece would be too much, but could you manage a carol for the Christmas Eve service

SD: We all know about Stephen’s peerless contribution to choral music at King’s. I feel most indebted to him for the outstanding series of 35 new commissions for Nine Lessons and Carols – an unparalleled contribution to the choral repertoire. What most people are less aware of is Stephen’s extraordinary generosity with respect to his work with other choirs and groups around the world. If he could make himself available, he would accept every invitation to work with community and school choirs. He also brought his daughter to one of my Kodály musicianship classes, such was his interest in music education in general. Stephen was tireless, ego-less and unfailingly gracious. And a superb musician.

GABRIEL JACKSON is one the United Kingdom’s most prominent and highly regarded composers, known in particular for his prolific output of choral music:

MW: On returning to Cambridge, as Director of Music at Jesus College, in 2009, Stephen was the first of the Cambridge directors of music to write inviting me to dinner. He was an exceptionally gracious host and a tremendous conversationalist. Personal friendships and the exchange of ideas with colleagues meant a great deal to him, and he worked tirelessly to nurture both, always taking time to send a handwritten note, or latterly a text message or email, whether after catching a broadcast or on learning of some difficult personal news. He offered warm encouragement and sage advice as our relationship evolved from teacher–student to colleagues. With his wife, Emma, he extended the hand of friendship to many of his colleagues across the university and the musical profession, and I was fortunate to be one of those. Like a large number of others, I am grateful for the many kindnesses he showed me over the years.

GJ: Stephen was a meticulous, conscientious interpreter of new works. He had total respect for what was in the score (if he thought you knew what you were doing!) and his instincts for all those little nuances of performance that can’t be notated were incredibly sure. There was never anything to say to Stephen in a rehearsal. Any observations one might make, if asked – and, of course, he always did ask – had already been made by him.

When I wrote The Christ-child for the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols in 2009, he invited me up to a rehearsal at King’s a week or so before Christmas Eve. We had a very nice lunch, went over to the chapel, he introduced me to the choir, they sang through the piece – beautifully – a couple of times, I said “Thank you very much, Stephen, that’s great!” and went home. That’s how Stephen was – quietly, efficiently professional, and so immaculately musical.

CR: In 1991, Stephen and I were reunited, now as colleagues as I was appointed to direct the choir of his alma mater. I have been proud to admire his long and distinguished reign at King’s which – more recently – I witnessed at close quarters. The plans for his final year were as ambitious and challenging as one would have expected. In view of his failing health, it is astonishing that he was able to summon up enough strength to carry them through. Music-making seemed to invigorate him in a miraculous way.

It is cruel that the long years of retirement which he so richly deserved were denied him. However, it would certainly have been a busy retirement. As Emma, his wife and constant support for almost 20 years so neatly put it, ‘time off’ was not really a concept which Stephen understood, and although he seemed to thrive on hard work, we should not forget that he was, above all, a deeply sensitive human being.

DAVID BUTCHER has been Chief Executive and Artistic Director of Britten Sinfonia since the orchestra’s foundation in 1992. The orchestra collaborated with Stephen Cleobury and the King’s choir regularly, including in a number of critically acclaimed recordings:

DB: Immediately following any project with Stephen – a concert, tour or recording – there would be a letter or email of thanks to Britten Sinfonia musicians and the management team. These thanks typically never contained superficial platitudes but were thoughtful, heartfelt, precise and instructive, whether praising particular musician contributions or thanking our percussionists for putting up with a long journey from van to stage. Stephen was a true gentleman as well as a brilliant musician. His preparation and attention to detail were as legendary as his musical precision and brilliance. Like the great Oliver Knussen, Stephen could unerringly detect any intonation or balance issue requiring further enlightenment at 50 paces during the most complex of musical passages, and this with his courtesy and inspiring musicianship made him one of the orchestra’s favourite collaborators. Over the years he got to know our players personally. Occasionally if, say, a different 2nd clarinet or 4th cello was in for the first time he would make a point of knowing their name and welcoming them individually. We were all so honoured and touched that he asked us to join him for his retirement concert in King’s chapel. It was probably the easiest event we’ve ever had to book musicians for as all our players wanted to be there for him. Although obviously unwell, he somehow transcended earthly physical frailties to inspire and illuminate a never-to-be-forgotten performance of Britten’s Saint Nicolas, creating a night that will live long in our collective musical memory. We will miss him so very much and the orchestra is privileged to have played a small part in his unique musical legacy – one that lives on through his multitudinous recordings and many commissions, and through the countless lives he touched.

JOD: Stephen’s work over more than four decades has been an inspiration to me and to so many. He has trained countless young musicians and thereby made an inestimable contribution to the musical world, especially to choral music. It is very cruel that he died so soon after stepping down from his long and distinguished tenure at King’s, but I know I am amongst countless others in remembering him with gratitude, respect and deep affection.

AS: A generous and selfless musician, Stephen transformed the lives and careers of innumerable choristers, choral scholars and organ scholars, teaching us that if a job is worth doing, it’s worth doing to the best of our abilities. We thank him for nurturing, training and teasing out talents and performances that otherwise simply wouldn’t have emerged; for sharing with us a wealth of opportunity and experience, for sharing with us his love of music and its power, and for leading us into a deeper and more humble appreciation of it. I hope he felt the depth of the affection and respect that we all had for him; it’s often easier to demonstrate the latter without dipping into the vast pool of the former.

JR: In an age when we tend to gush in public and trumpet our achievements all over social media, Stephen stood as a reminder of old-fashioned gentlemanly restraint and courtesy. We shall all miss him.

The Edington Festival of Music within the Liturgy (the Edington Music Festival) is marking its 65th birthday with the launch of a new annual award to support choristers at those cathedrals, colleges and greater churches which have applied to FCM for financial support.

The Edington Festival Award has been made possible by a recent bequest to the Edington Music Festival Association (EMFA), which has been ethically invested. Working in collaboration with FCM’s Diamond Fund for Choristers, the award will most likely be allocated for choral training or as support for choristers.

The EMFA executive committee has agreed to support boy and girl choristers at choral foundations whether or not they have an existing relationship with the festival.

The inclusion of greater churches as potential beneficiaries of the Edington Festival Award means that funds will also

be available to support a grassroots level of choral training within the rich and historic tradition of music inspired by religious texts. This sacred music is at the heart of the eight days of services which comprise the Edington Music Festival, exploring the full panoply of composition from plainchant through to new commissions.

Richard Pinel, Director of the Edington Music Festival and Director of Music at Jesus College Cambridge, comments, “We know that sometimes for financial reasons talented young singers and choirs are unable to undertake professional vocal training to enable them to progress within the particular niche that is church music.”

He continues, “The Edington Music Festival has been a launchpad for both junior choristers and senior musicians for 65 years; a large number of the UK’s most respected and talented oratorio and operatic soloists and organists, and members of the most well-known vocal ensembles have

participated in the eight-day festival since 1956. Our three choirs are selected annually from cathedrals and collegiate choirs all over the UK, and the Festival provides an opportunity for more than 80 musicians from the age of 9 or 10 upwards to sing familiar and new music from this complex and beautiful repertoire. We hope that the Edington Festival Award will enable more talented musicians and choirs to experience the joy and fulfilment of singing this extraordinary music.”

The world-famous vocal ensemble The King’s Singers has included many singers over the years who have come through the Edington Festival. Julian Gregory, tenor, and Pat Dunachie, countertenor, two of their latest Edington Festival alumni, have added their support for the initiative: “Church music is in the blood of The King’s Singers, so we are delighted to hear that the Edington Music Festival, through this new award, will be working to increase access to training at all levels of church music-making. The Edington Music Festival has been a formative experience for many members of The King’s

Singers, past and present, and the more people who are able to experience the kind of music celebrated by this wonderful festival, the richer the world of choral music will be.”

The nearby Wiltshire parish of St John’s in Devizes, where former Assistant Festival Organist Chris Totney is Director of Music, has added its support to the scheme. “The benefits of singing have been well documented in recent years. As well as being good for physical and mental wellbeing, it has all sorts of wider benefits such as the development of reading, mathematical and leadership skills to name but a few – and you make friends for life,” says Chris. “The English choral tradition is the envy of the world and the Edington Music Festival is one of the most iconic snapshots of this every summer. In an age where we hear all too frequently about cuts in arts funding, it’s wonderful that this new award will empower choral foundations to provide more sustainable support for future generations of choristers.”

calling to each other from the highest possible locations – one placed in the octagon lantern and the other at clock level at the west end of the building.

In the context of the long history of Ely Cathedral, three decades of responsibility for the music in such a glorious place is a mere flash in the pan, and any reflections must inevitably be highly selective. What follows here aims to identify what has stayed the same and what has changed during that time.

When I first arrived, the overwhelming impressions were of the scale, beauty and mystery of the building. Externally, the mystery is certainly still striking. A particularly impressive time of year in Ely is the autumn, when the mists shroud the octagon and west tower. Internally, I worry about some erosion of mystery caused by a preoccupation with tourism and a determination to cater for all kinds of worship. Both are understandable and laudable developments, in step with contemporary times and views about the role of cathedrals, but in order to really appreciate the essence of Ely Cathedral it’s probably best to come early in the morning, or at evensong time on a cold, dim day when the visitors have gone and the busy, often rather noisy events of a typical day do not intrude. When entering the cathedral to take the daily boys’ rehearsal at 8am I nearly always made a point of coming in from the west end. This enabled me to take in the view of the whole length of the building and remind myself of the privilege of working in such an exceptional setting. It is especially wonderful when there is no seating in the nave. The huge size of the cathedral, with all its galleries and other performing spaces (including the fabulous 14th century Lady Chapel) has been a constant source of inspiration to composers throughout the centuries – including Christopher Tye and John Amner, whose music has been included on a number of CDs recorded over the past 30 years. The marvellous performing spaces have also inspired me to write extensively for the Ely choir, including a setting of the Advent Responsory which features two soloists

The chorister rehearsals were always the highlight of my day. At 8 in the morning children are fresh and lively. Seldom has anything yet gone wrong with their day, and their enthusiasm and energy shines through. It just needs to be harnessed and channelled into the task of concentrating and singing. If the work is not properly done at that stage of the day it is likely that there will be difficulties later on, when a day at school will have taken its toll. So the early morning work has to be intense and determined, but this can only be achieved by teamwork and dedication to task. Enjoyment and humour are equally crucial ingredients – especially the latter. Boys are usually capable of achieving almost anything we might expect of an adult if they are told they can do it. Equally true, they are also mischievous and the cause of much amusement. They say daft things (!) and it’s good to take time out of a rehearsal to enjoy that, however much pressure there may be to get through the notes and turn them into worship.

Many of my favourite memories concern the laughter. April Fool pranks are an ideal example, and there have been many of them over the years. In my final year I decided to introduce the boys to John Cage’s infamous silent work 4’33”, arguing that silence is an important element of worship. Some of the boys were appropriately dubious; others seemed at least partially convinced. A few minutes later I discovered that the tables had been turned. The song school piano had been ‘prepared’ in John Cage style (I believe by other staff) and I had to remove combs, loo paper and other items from the inside of the instrument before practice could continue!

My initial task at Ely was to preserve and develop the musical standards of the cathedral’s only choir, which consisted at that time of 18 boys and six lay clerks. My credentials at the time of my appointment were related to the unusual task I had undertaken in my previous appointment as DoM at St Edmundsbury Cathedral. My job there had been to find a way of changing a mixed-voice line of trebles back to a boys-only line. This was a controversial challenge. Many times I had to point out that the cathedral policy had been decided before I was appointed to make it happen and that it did not reflect my own feelings about girls in cathedral choirs. It required sensitivity to the parents and to the girls, none of whom were required to leave prematurely. It therefore took several years to achieve, and involved intensive recruitment of boys from various schools. The experience I gained of working with girls as well as with boys during the period of change at St Edmundsbury proved invaluable to me later on at Ely.

I find it interesting to compare this initial task of my own at Ely with that of my successor, Edmund Aldhouse, who took over after Easter 2019. Edmund’s task is much more varied and it reflects the changes that came about during my tenure. There are now five ‘in house’ choirs at Ely Cathedral – too many for one person to direct, of course, but nonetheless all to be taken into account, developed and appreciated. The five choirs are:

» Boys and men

(six lay clerks plus a large pool of extra singers)

» Girls

(who also frequently sing with the men)

» Children’s Choir (young boys and girls)

» Adult Voluntary Choir (Ely Cathedral Octagon Singers. Membership by audition)

» Cathedral Community Choir (Adults. Any level and no audition)

The Friends of Cathedral Music are well aware that the recruitment of boys is a challenging task in this day and age. When I began my time at Ely there was a constant stream of enquiries from parents of potential choristers. Although many of them were relatively local, some came from as far away as Scotland. Numbers have dropped off significantly, and much work and thought has been required to tackle this problem, and with mixed success. The question of boarding has been only part of the issue; more flexibility has proved necessary and wise. Trickier still has been adapting to 21st century lifestyle – especially at weekends. Again, the response has been more flexibility. Boys are now recruited from Year 3 onwards, as opposed to from Year 5 onwards, but at the other end of the system the problem of voices changing earlier is unlikely to go away. The costs of choristership are a serious matter both for parents and for chapters, both of which have so many other matters to juggle. In this, the work of FCM

becomes more and more essential and their support has always been hugely appreciated. Long may it continue!

Another frequent agenda item has been the payment, conditions and turnover in the lay clerk ranks. Somehow, somebody has always turned up to fill gaps as and when they arise, and thankfully the quality and standard of the altos, tenors and basses has been mercifully high during my time at Ely. As these observations begin to move towards the biggest musical change of all, it is pleasing to make special mention of the fact that Ely can now boast its first female lay clerk in the ranks.

The girls’ line was added to the music department in 2006. I thought it wise to resist any temptation to ‘jump onto the bandwagon’ in immediate response to the Salisbury initiative, preferring to watch how others would go about this in order to learn from their successes (and mistakes). Incidentally, the introduction of girls at St Edmundsbury by Harrison Oxley preceded the Salisbury scenario by many years – a fact which is frequently overlooked. In 2006 I felt the personalities and conditions were right to proceed at Ely, and girls were recruited from the senior department of King’s Ely (rather than from the junior department where the boy choristers are educated).

A crucial ingredient was the school’s generous offer to pay for the girls as well as for their Director of Music and organist, thereby avoiding any necessity for the cathedral chapter to find the necessary funds. The girls were an instant success and in recent years younger recruits from the top two year groups in the junior school have been added, allowing the older girls to concentrate more easily on their public exams. The girls and boys have often combined for various services and concerts, to great effect. One fascinating aspect of this is that they blend so well together. They just create the sound themselves; very little work seems to be needed to ensure that neither the boys nor the girls dominate the sound. So many treble singers do of course need more lower voices to balance them, and the pool of (mixed voice) extra singers which has been a feature of weekend worship for many years, known as the ‘expanded choir’, has come into its own on these occasions.

Ely’s children’s choir, ‘The Ely Imps’ was also founded in 2006. Initially intended as a concert choir, the boys and girls now frequently sing in special services either alone or with the choristers. For the first 10 years of its existence I had the pleasure of directing this choir, but they now have their own director who has also contributed much to singing outreach projects.

The Cathedral Community Choir is the most recent addition to the choral picture. This was founded by Canon Victoria Johnson, who took responsibility for them in her own very special and effective way. Canon Johnson has recently been appointed Canon Precentor at York Minster. She will be sorely missed at Ely – and not just by the singers!

the questions asked about its future. It has been a privilege to be able to observe how choristers thrive and succeed at King’s Ely when they leave the choir.

I hope I have managed to put worship (Opus Dei) first, even though so much work has to be done to facilitate concerts, tours, broadcasts and special events (which I like to call ‘the icing on the cake’). Some of my fondest concert memories relate to my earlier days when, for example, the cathedral choir gave several performances both in the cathedral and in London of Handel’s Messiah and Bach’s St John Passion. In more recent times our home concerts have had to be more popular in style and content, and I have often been required to come out of my comfort zone in order to meet the demands of unusual concert projects. For example: a swing concert combining the choir with a big band, and a Science Festival concert (where I found myself having an argument with a dalek in front of the choir and audience!)

Obviously, there have been many other changes at the cathedral over the years. Some of them are exclusively concerned with music, but others are not. Here are a few that immediately spring to mind:

Bishops, deans, other clergy and chapter members have come and gone. Tempted though I am to comment on individual clergy contributions I have experienced over the years I think it wise to resist, other than to say that it has been a pleasure to work with some of them.

At some point, school pupils became ‘students’ and the School Head became the Principal. The number of cathedral office staff increased approximately tenfold. All choristers have been required to have individual singing lessons, and lay clerks have been encouraged to do likewise. There is no such thing as a Canon Treasurer any more, but there is a cathedral administrator. There has been a gigantic increase in the number of meetings needed to make the cathedral function as smoothly as it does. Safeguarding eats up days – if not weeks – of time and attention. We are all aware of how important it is to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the children in our care, but I’m not convinced that the endless round of training and, more recently, ‘audits’ associated with these concerns is ideally conceived or delivered, despite best intentions. Similarly, I wonder about the volume of risk assessment required of us all, and about the tick-box procedures sometimes involved. Hours of sitting in front of a computer screen are the result for cathedral Directors of Music and some clergy. I worry that matters such as this put young and talented people off working for the church when they contemplate which direction their career might take.

I hope that high choral standards and the traditional makeup of the English cathedral choir (boys and men) has been maintained during my watch, and also enhanced. I reiterate that I think it a good thing that choristers are still expected to be boarders here, with plenty of flexibility incorporated into the system. It’s a very special and positive experience when associated with demands of the choral tradition – despite all

I think some of the most memorable services I have experienced have been the ones which some might think ordinary. I have much preferred such occasions to the more ceremonial ones attended by the great and good. Of the many larger-scale services which preoccupy us around Christmas and Easter my favourite has always been the Advent Procession.

Foreign tours have been a rewarding part of cathedral choir life. Each and every one of those has been an adventure and I have many happy memories of them all. Two trips to Poland were definite highlights, likewise a trip to northern Italy where the concerts always began late but where the huge audiences were particularly appreciative (when they eventually decided to turn up!). After singing in northern Italy, the choir went on to Rome where all our planned concerts did happen – but not necessarily on the day or at the time planned! It was very moving to sing in the Church of St Paul without the walls in such close proximity to the resting place of my favourite saint. A particularly fine tour was to France, following part of Via Podiensis – one of the famous pilgrimage routes. Although that tour had its challenges in terms of travel and accommodation, we all had great fun and it was spiritually especially rewarding.

What do I miss most of all after 12 months out of post? That’s easy. It’s the special rhythm of life which utterly dominated not just my time at Ely, but also my years at Worcester as assistant organist, those I spent at St Mary’s Warwick, and those spent at St Edmundsbury Cathedral as Director of Music.

Finally, I must add that my career doing what I love most in so many inspirational places has always been a double act. Entertaining choir members (young and older) in our various homes has always been an essential and delightful part of the job. My wife, Sally, and I have decided to stay put in Ely where we will continue to worship. Proximity to Cambridge is a great asset, enabling great choral experiences in the college chapels and allowing me to accept some teaching opportunities in the university. We are currently looking forward to using a newly acquired ‘bolt-hole’ in Worcester (where we met back in the 1970s.) All being well, that will enable to us enjoy some other passions we share: the Malvern Hills, proper cricket – and our grandchild, Poppy.

When I first arrived, the overwhelming impressions were of the scale, beauty and mystery of the building.

I’m sitting at the computer in my office at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Fort Worth, Texas. It’s February. Yesterday it was 26oC outside, and tomorrow it will be -2oC; Texas weather changes dramatically at this time of year, but in the summer it will remain at around 40oC, which I love!

I moved here in September 2018, to be Organist and Choirmaster at All Saints’. The church seats around 400 people, and we have around 2000 parishioners. Obviously not all of them come at once – we have several services each Sunday, and of course there are some who don’t come every Sunday anyway. The organ was built by Garland Pipe Organs, Inc., in 2001, and it has 5 manuals, 207 stops and 4759 pipes. It’s in a Romantic/Symphonic style, very different to the Classical style of the Rieger organ I used to play in Oxford. On the Rieger, Bach’s preludes and fugues sounded wonderful; on the Garland, I’m particularly enjoying playing pieces by composers such as Howells, Elgar, Mulet and Reger.

Before I moved here, I lived mainly in Oxford from 1996 until 2018, first as an undergraduate, then a graduate, and then as Sub-Organist at Christ Church Cathedral. I loved it in Oxford, but I had been wanting to move on for a number of years. I applied for various jobs without success, at Westminster Abbey, St Paul’s Cathedral, and Jesus College in Cambridge. I decided to leave Christ Church in the summer of 2018 (at the same time as Stephen Darlington retired), whether or not I had another job to go to! I thought about changing career, and had a wonderful opportunity to do some work experience in Dubai, thanks to Paul Griffiths, CEO of Dubai International Airports. I also thought about trying to be a freelance musician in London, or finding an organist position on the Continent. But the idea of moving to the States seemed the right one, because I had travelled to the States so many times for concerts – about twice a year since 2001 – and I always enjoyed it. So I started letting lots of American friends and colleagues know that I was looking for a job over here. Several mentioned that the American Guild of Organists and the Association of Anglican Musicians were good sources of job listings; I was already a member of the AGO, and I decided to join AAM too. In the end, I found my job here by another route – a recommendation from a friend in Philadelphia, who said that there was a church in Fort Worth looking for a new organist. I wondered whether it was All Saints’, because I’d given three recitals here (2007, 2011, 2014), and I knew that my friend Rick Grimes (my predecessor at All Saints’) was thinking of retiring soon. So I had several conversations with the rector at All Saints’ in January 2018, and in February I started the arduous process of applying for a work visa –six months later, in August, the visa was stamped in my passport, just in time! … which reminds me that it runs out next year (it’s a three-year visa, from 2018 to 2021), so I must start thinking about applying for a Green Card, for Legal Permanent Residency.

There are two choirs here, the Family Choir and the All Saints’ Choir. The Family Choir sings at the 9am service on Sundays. There is no commitment to being in the Family Choir, so anyone can attend the 8.30am rehearsal, and the purpose of the choir is to lead the congregation in the singing of the hymns, psalm, and service music. Usually only five or six people sing in the Family Choir, which makes it a little small, but I’m hoping this number will increase over time. The size isn’t a problem at the moment because the choir doesn’t sing anthems on its own. It’s perfect for those who enjoy singing in a group but who don’t have the time to commit to all the rehearsals of the main choir.

The All Saints’ Choir is the main choir. We rehearse every Thursday evening and Sunday morning, and sing at the 11.15am service on Sundays. We prepare two anthems each week (an Offertory Anthem and an Ablutions Anthem), and we sing a wide variety of music – from Byrd and Tallis to Howells and Stanford, as well as lots of lovely American choral music. I don’t have an assistant – I can conduct when the anthem is unaccompanied, but if it’s accompanied, the choir has a good view of me sitting at the organ, and either they follow my body movements, or I play with my right hand and pedals, and try and conduct with my left hand … but it’s rather hard to coordinate! My predecessor, Rick Grimes, chose reasonably similar music, and I’m gradually introducing one or two new pieces as I go along, such as Peccantem me quotidie by Morales, which we sang on Ash Wednesday.

The All Saints’ Choir also sings for one evensong a month, and there are a few Sundays during the year when it sings for both the 9am and 11.15am services: All Saints’ Sunday, Palm Sunday, Easter Day, Pentecost, and the Sunday in January each year when the Bishop visits. It also sings for two services on Christmas Eve (at 7pm and 10pm), and the liturgies on Ash Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Easter Eve.

Unlike the Family Choir, there is a commitment to being in the All Saints’ Choir. Everyone is a volunteer, and everyone is expected to attend at least 80% of the rehearsals and services during the choral season, which runs from late August to early July. When I arrived, there were 19 singers, and I’m pleased to report that there are now 27, including some new younger members, which means that the average age has come down a little! A few members have sung in the choir for over 30 years, about half have sung in the choir for over 10 years, and the remainder are relatively new.

I’m working on inviting some choral scholars to join us next season, from local universities such as TCU (Texas Christian University). We also have plans for starting a children’s choir – they will rehearse on Wednesday evenings, and sing a little piece at the 9am service on one Sunday a month – probably the YOS (Youth Oriented Sunday) when kids are more involved with various parts of the service, such as reading the lessons and saying the prayers.

Looking after the choir library is another of my duties here – putting out music, making sure we have enough copies, repairing old copies, ordering new copies, preparing booklets of psalms and anthems, putting away music, and updating the catalogue when I order new anthems. Managing the various budgets is an additional task – the seven accounts are Worship

Commission Professional Expenses, Music Program, Organ and Piano maintenance, Sub Musicians, Choir Vestments, Music Program Assistants, and the Choirmaster Discretionary Fund. (There is a separate fund for choral scholars.)

We have a number of concerts at All Saints’ each season –mostly organ recitals, and a Christmas concert with the choir and a small orchestra of local musicians. Next year will be our 75th anniversary year, so we’re planning a few special events for that, including two concerts in collaboration with Fort Worth Opera, which is also celebrating its 75th anniversary.

When I first moved over here, I stayed with a delightful family (and two dogs, two cats, one turkey, one parrot, two ducks, and several chickens!) for a month, and then rented an apartment for a year, and now I’ve bought a house in Westworth Village, about 6 minutes drive from All Saints’. I’ve also bought a piano (a Steinway model B), and I have a dog too – a chocolate labrador called Daisy.

There are many similarities between my job in Oxford and my job here, not least because American Episcopal liturgies are similar to the Anglican services I played for in Oxford. But of course there are differences. One is that I am now working with a volunteer choir, rather than the boys, choral scholars (academical clerks) and professional singers (lay clerks) in the cathedral choir at Christ Church; I much prefer the volunteer choir here, because the atmosphere is fun and relaxed, although I do miss working with the kids.

the ‘Gloria’ during Easter. In Oxford, only the choir sang these movements – for example, Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli or Byrd’s Mass for 5 voices. I do miss those beautiful Renaissance Mass settings, as well as the wonderful choral repertory for Mattins, such as Britten’s Te Deum in C major.

We have four services here on Christmas Eve, and no services on Christmas Day (actually there is a service at 10am on Christmas Day, but as there is no music, I’m not required to be there!). In Oxford, by contrast, we always had a festive Mattins and Eucharist on Christmas Day morning. The four services here on Christmas Eve are at 2pm, 4pm, 7pm and 10pm – quite an exhausting day! The first two services are more oriented towards families and children.

It’s very nice here at All Saints’ to feel part of a large church family, and I know most of the hundreds of parishioners who come to church every Sunday. Back at Christ Church, there were one or two regular members of the congregation, but most people were tourists or occasional visitors.

Aside from my work at All Saints’, I continue to give a few recitals – last year mostly around the US, but also in Hungary and Taiwan. I’m lucky that there is some flexibility in my job here, so I can arrange for a substitute, and I’m allowed to take a certain amount of time off each year. In fact, it’s rather easier to give recitals in the US now, because I can just fly to another city for one concert, and then come straight home to Fort Worth – whereas when I was living in Oxford, I had to make sure that I had a few concerts in a row, in order to make a transatlantic tour worthwhile. Talking of flying, it’s convenient that my local airport, DFW (Dallas Fort Worth), is one of the biggest in the country, so I can often fly somewhere directly, without having to change planes.

When I travel for concerts in other states, and say that I live in Texas now, the response is usually either, “Oh, I’m so sorry” (because plenty of Americans make fun of Texas and Texans) or “How’s the wall with Mexico going?”! But I love the lifestyle here in Texas – it’s quite relaxed and easygoing, and everyone I’ve met is warm and friendly. I used to ride horses when I was younger, so of course I’ve been on horses out here, wearing my cowboy hat and cowboy boots … although I’m not very good with a lasso or a gun yet! If I don’t say anything, I might pass as a Texan, but as soon as I open my mouth, my accent gives me away!

Another difference is that I choose all the music, including the hymns, for the services here; I did help Stephen (Darlington) choose the choral music at Christ Church, but the Precentor chose the hymns, so I had never chosen a hymn before I moved here! I enjoy choosing anthems and hymns which connect to the readings, and I like making certain links, such as playing a postlude based on one of the hymn tunes. And the organ voluntary before a service here is called the prelude; after a service it is the postlude.

A further difference is that here there are congregational settings of the ‘Kyrie’, ‘Gloria’, ‘Sanctus’, ‘Benedictus’ and ‘Agnus Dei’. We don’t sing all those movements each Sunday, but normally two or three, depending on the liturgical season; for example, we sing the ‘Kyrie’ and ‘Agnus Dei’ in Lent, and

There are many wonderful museums in the Metroplex (Dallas and Fort Worth are 30 miles apart, but the two cities have gradually grown together, and the whole area is now known as the Metroplex), including the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth. There’s a Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, and a Dallas Symphony Orchestra, as well as thriving chamber music societies in both cities. Last night, I heard the wonderful pianist Stephen Hough give a solo recital, and the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition takes place here every four years.

Oxford to Fort Worth was a big change, and many friends here can’t understand why I left the Dreaming Spires, but I don’t regret it for a second. If you like wide open spaces, hot weather, ‘the most prestigious classical piano contest in the world’ (Chicago Tribune), and rodeos, please come and visit!

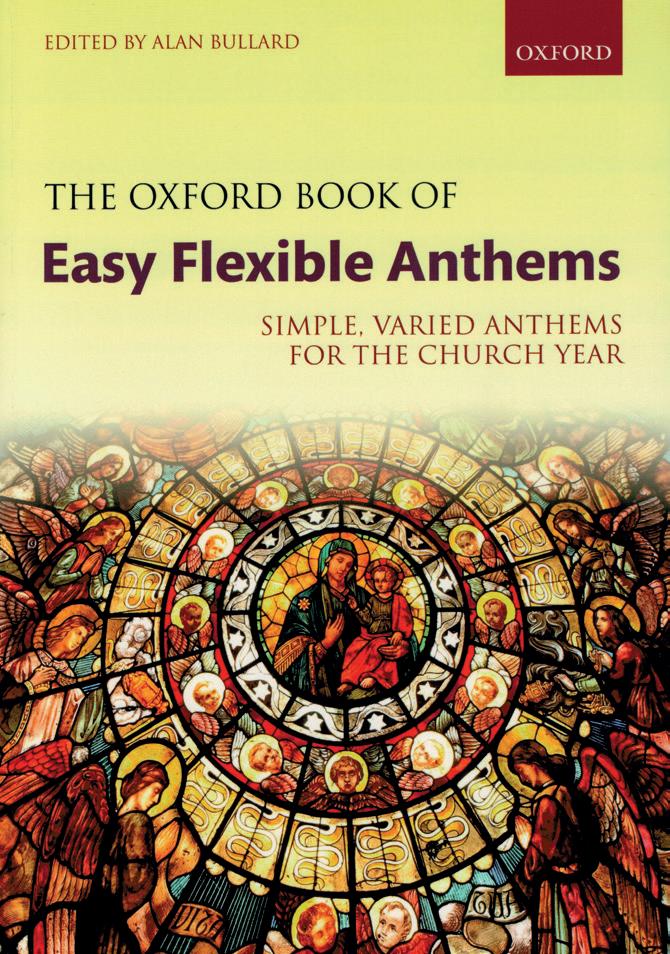

What a remarkably self-effacing and personable man Alan Bullard is! Once, at a northern venue, the premiere of his new composition was the first item in the programme. After going up on stage to acknowledge the applause, Alan found he couldn’t remember exactly where he had been sitting – in fact, the hall seemed completely full. He later realised that, while he was on stage, ushers had admitted late-comers, one of whom had been shown to Alan’s seat. Never one to make a fuss, he stood uncomplainingly at the back of the hall for the rest of the concert!

Bullard has a significant catalogue of work in all genres, including orchestral and chamber music, but it is for his choral and educational output that he is particularly known. His compositional style might be called ‘approachable’ in the best sense, i.e. without compromise in its musical idiom. He has a practical outlook in terms of performability, catering for non-professional performers and allowing flexibility in his choral and instrumental scorings. When asked how his choral style has changed over the years he says, “I suppose my music has become more simplified – particularly in terms of a greater focus on the text.”

Seeking to identify works which illustrate this change in approach from complexity to relative simplicity, he volunteers his four settings of the evening canticles, conveniently spread throughout his compositional career. His first setting of the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (1992) is scored for unaccompanied SATB with divisions. It is quite a complex work and challenging to bring off but, as always, the musical language is attractive and rewarding for the singers.

His second Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis is The Selwyn Service, written for Sarah MacDonald and the choir of Selwyn College Cambridge. This dates from 2012 but is still firmly in the chapel choir’s repertoire, being performed as recently as the first Sunday in Lent this year. It is quite difficult technically, but there is also evidence of Alan’s later preoccupation with flexible scorings in that, unusually, it is designed to work equally well unaccompanied or with an organ accompaniment.

Alan’s third setting of the canticles is his Essex Service, which was commissioned for the RSCM Essex and East London Area Choral Festival at Brentwood Cathedral in 2015. It was originally written as a two-part service for sopranos/trebles and altos, with – optionally – tenors doubling the soprano part and basses doubling the altos, a layout which one wag has rather unkindly called (not, I hasten to add, in relation to this piece) ‘Bryan Kelly scoring’! In 2016, Alan recast the work as a genuine four-part SATB service and this version was

recorded by James Davy and the Chelmsford Cathedral choir. In this work there is a less discursive approach to setting the text and the musical style is cleaner and more concise, though not, as Bullard is quick to point out, ‘dumbed down’ in any way.

Bullard then went to the Royal College of Music, where he was taught composition by no less a figure than Herbert Howells. He has fond memories of Howells as a teacher – ‘A lovely man who was wonderfully supportive’, though his methods were not very pro-active, leaving it to Bullard to decide what to bring to show him, then carefully erasing or substituting a few notes to improve the proffered composition. Alan says: “It might not have suited everyone, but it was fine for me – I suppose I learnt from him through osmosis.” When Howells was unwell, Bullard was taught for a term by the formidable Ruth Gipps, always known as ‘Wid’ – “Though I wouldn’t have dreamt of calling her that!” he laughs. She was something of a shock after the laid-back Howells, but she encouraged Bullard to compose an orchestral work which she performed with her London Repertoire Orchestra. (Incidentally, it is strange that her really fine Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis for Westminster Abbey (1959) are hardly ever performed.) Gipps was quite unreceptive to any hint of modernism, such as sketches in 12-tone style, which she would dismiss out of hand, whereas Howells, who was clearly well aware of this music, would gently recommend Berg as a model rather than Webern!

After MA studies with Arnold Whittall at Nottingham University, a succession of part-time jobs followed before, at the age of 27, Bullard moved to Colchester Institute in Essex, where he was to stay from 1975 for 30 years. This time brought a new range of performance opportunities for him, such as writing for the Institute’s orchestras, choirs and chamber ensembles as well as for local groups like the Colchester Choral Society (Dance of the Universe, 1979) and the Colchester Chamber Orchestra (Sinfonietta, 1987), and for visiting groups such as Gemini (Lament, 1990) and the Vega Quintet (Dances for Wind Quintet, 1982).

Alan’s fourth service is his Colchester Service, which is included in The Oxford Book of Easy Flexible Anthems (2017), and flexibility is indeed the key factor here, with the music working as a unison service, hence it uses a narrow vocal range of only an octave, in two parts or for SATB, bringing the music within the capabilities of more modest church choirs. The text is changed too in that it is the Common Worship text that is used, not the words of The Book of Common Prayer, and the musical language, with its sensitive response to the words and easy, melodic flow, is altogether much simpler.

Bullard does not come from a musical family, although both his parents, Paul and Jeanne, were artists. He was born in London in 1947, and studied piano with Geoffrey Flowers at the Blackheath Conservatoire of Music before attending St Olave’s Grammar School, then near Tower Bridge, where he sang in the good school choir which performed ambitious works such as Messiah, the St John Passion – a lifelong love (in fact, a Dutch academic recently sent Bullard a detailed analysis of influences of the Passion in Bullard’s cantata Wondrous Cross – something the composer was unaware of!) – and more modern works like Vaughan Williams’ In Windsor Forest, and Delius’s On Craig Dhu. A particular influence was George Dyson’s In Honour of the City, of which Alan said, “It was thrilling for an 11-year-old to be part of such a huge sound, and the harmony really excited me!’

In terms of Bullard’s more extended works, five largerscale cantatas also conveniently illustrate his development. Wondrous Cross (2011) is a 30-minute Passiontide cantata, written for Lion Walk United Reformed Church in Colchester. The concept here was to provide something shorter than traditional Passions that the average church choir could attempt with relative ease. The thread binding the 16 short movements is the Seven Last Words and, perhaps unusually, the words of Christ are assigned to the full choir rather than a soloist. The congregation is actively involved too throughout the course of the work, rather in the manner of Britten’s Saint Nicolas perhaps, by joining in the singing of hymns (a familiar trait of Bullard’s longer works) such as ‘There is a green hill far away’ and ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’. Again, Bullard’s flexibility of scoring is apparent, with various combinations of strings, piano and organ allowed.

Wondrous Cross was later taken up by the choir of Selwyn College, and this led to a second cantata specifically written for them: O Come, Emmanuel (2012) – another substantial

Bullard does not come from a musical family, although both his parents, Paul and Jeanne, were artists.

work lasting some 35 minutes, this time on an advent theme and using the ‘O Antiphons’ as a connecting thread. Original plainsong melodies and, again, congregational hymns, are incorporated.

Alan’s third cantata, A Light in the Stable (2016) has a Christmas theme and this 35-minute work was written for Philip Brunelle and VocalEssence, Philip’s choir in Minneapolis, USA. Here again there is flexible scoring, for chamber orchestra and/or piano, and there are some congregational carols. Bullard mentions his delight at discovering that the two tunes usually sung to ‘Away in a manger’ will obligingly combine contrapuntally, as will the tunes of ‘While shepherds watched’ and ‘Go tell it on the mountain’, and those of ‘The first nowell’ and ‘Of the Father’s love begotten’ – an interest and facility in counterpoint which surprises me not at all, having been in receipt of delightful Christmas cards from Alan over the years which invariably featured an ingenious seasonal round or canon!

in 2008. Needless to say, this generated huge international interest in Alan’s music, particularly in the USA, from where he has received many commissions.

Alan feels a rather different style of church music is preferred in the USA, with an inclination towards short, text-focused works which do not ‘get in the way of the worship’, rather than the more traditional European discursiveness of, say, Palestrina or the lengthy fugues in Mozart masses. Many of his works have proved very popular there, and recent American commissions include two short works: This is the key and Song to the moon. Again, these pieces show a typically attractive, folklike melodicism, while their unison textures can be optionally expanded to two parts to cater for choirs of different sizes and abilities. They have also been taken up by UK choirs, and Bullard, still actively involved in writing for youth choirs, is currently working on a commission on a conservation topic for the Romsey Festival.

The fourth cantata, Psalmi Penitentiales (2016) is a 20-minute work for choir and organ written for Chelmsford’s Waltham Singers. More serious in tone, this work has a Passiontide text in Latin and is based on the Ubi caritas plainsong. Despite being more complex than some of Bullard’s other works, its striking harmonic design and easy lyricism make it very rewarding to sing.

Alan’s fifth work is the recent, shorter (15-minute) unaccompanied cantata, Images of Peace (2018), commissioned by Colchester Choral Society, in which the text, encouraging peace and understanding, is taken from a variety of sources, not focusing on any one particular creed or belief.

A significant moment occurred for Alan when Stephen Cleobury programmed his Glory to the Christ Child in the King’s College Service of Nine Lessons and Carols in 2007, and again

Alan is very well known for his educational music and he is enthusiastic about encouraging young people at all levels of ability. His compositions for both young and adult learners of piano and other instruments are widely known, for instance the Joining the Dots sight-reading course (eight volumes for piano, and five for each of guitar, violin, and singing) for ABRSM. There is also Pianoworks (2007-14), written jointly with his wife Janet, a series aimed at adult learners, now running to as many as nine volumes. As with all his educational work, there is an acute awareness of the exact technical requirements for each particular grade, but no sense of the patronising ‘writing down’, and no compromise in compositional integrity. As Alan says: “There is as much satisfaction in writing a really

Alan is very well known for his educational music and he is enthusiastic about encouraging young people at all levels of ability. His compositions for both young and adult learners of piano and other instruments are widely known, for instance the Joining the Dots sight-reading course (eight volumes for piano, and five for each of guitar, violin, and singing) for ABRSM.

good Grade 1 piano piece as in writing something for a professional performer.”

There are also more advanced piano compositions, of course, for instance his wittily titled 12 or 13 Preludes for Piano (Book 1, 2017) consisting of a prelude in all the major keys (number 1 may be repeated at the end, hence 12 or 13!) and Book 2 contains the same in all the minor keys. The idea was to limit each prelude to only two pages of music, to include plenty of contrast, and ‘to ensure I could just about play them myself!’ – which, knowing Alan’s huge facility as a pianist, is perhaps a slightly daunting prospect for the more humble!

Bullard has composed relatively little for solo organ apart from contributions to Oxford Hymn Settings for Organists (2014-20) – a six-volume series of treatments of well-known hymn melodies in a variety of styles, and a welcome practical resource for organists. However, many of his choral works do feature large-scale organ accompaniments of course, as in the recent anthem Make a joyful noise unto the Lord (2019), written for the re-dedication of the organ of St Guthlac’s in Lincolnshire after a rebuild.

Alan Bullard is certainly a composer who has made a hugely significant contribution to church music. He is always concerned that his compositions should be eminently practical in performance, approachable in idiom and, most importantly, enjoyable for the performers – what a charmingly modest man, and what a fine composer too!

Originally from Flintshire, MARK BELLIS was appointed music lecturer at Colchester Institute in 2005, taking over from Alan Bullard on his retirement. He was Course Leader there for the BA Music programme, also teaching composition and music history for 13 years before retiring in 2018. He obtained a PhD in Composition from Durham University and subsequently taught at sixth-form colleges in Sheffield and Bournemouth before moving to Colchester. Mark is still active as a composer and choir trainer, conducting the Colne Singers, a Visiting Choir now in its 11th year, and Cambridge’s Erasmus Chamber Choir. He is FCM Diocesan Representative for Chelmsford.

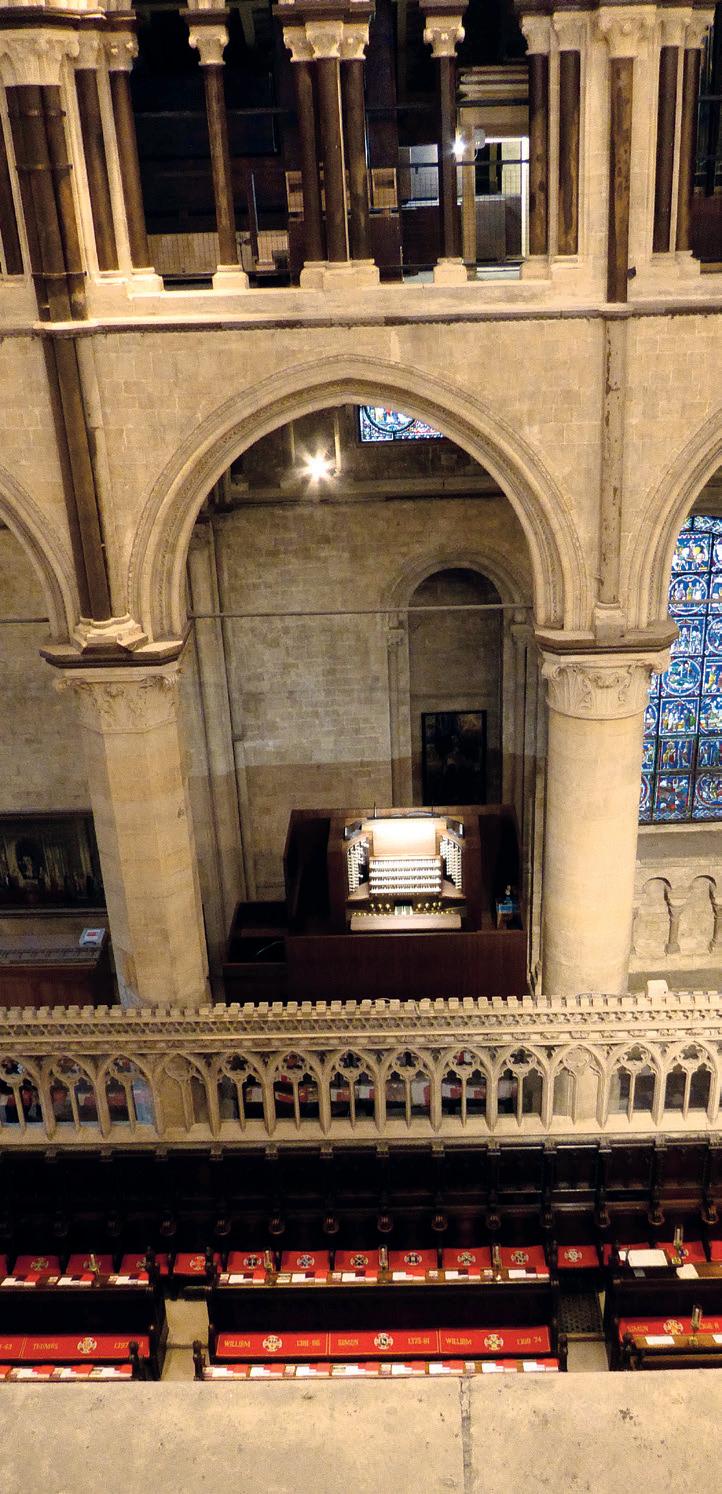

‘Dream on,’ I was told, some 15 years ago, when the question of revitalising the organ was raised. In 1979 the organ had been reduced in size from four to three manuals and situated at the west end of the quire triforium; the thinking was that this might help the sound to carry to the nave. It was, however, found to be less effective than expected and, just in time for the Enthronement of Archbishop Runcie in 1980, the small nave organ was added. The console remained on the pulpitum screen, giving a good vantage point both east and west but with little contact with the choir in the choir stalls. So, the dream began in 2005 and over the next five or six years a scheme was refined.

As Canterbury Cathedral is really two acoustic spaces, we were faced with the choice of either a huge project – to address both the quire and the nave – or something more manageable. It soon became obvious that we should address the quire organ first and allow the nave to be a second project in its own right. We needed to make the organ more versatile and more able to serve the needs of the daily programme of sung services in a more colourful way, as befits such a large and internationally important building. Because the choir stalls face towards the centre of the long quire space, the organ needed to be positioned to blend with and support the choir in the same area. The Swell, situated at the western end of the quire, i.e. the area furthest away from the choir stalls, needed to be moved so that it could be used for psalm-singing and the large amount of choir accompaniment that takes place in the cathedral. At the same time, substantial congregations

regularly require support over a longer space, rather than have the organ sound reaching towards them from a distance. The famously unobstructed architecture of the quire could not be disturbed, so the organ had again to be placed in the triforium, but this time it would be incorporated in the north side, as well as the south, for the first time.

Harrison & Harrison were appointed to undertake the work, following a fascinating tender process. Three firms of organ-builders produced detailed designs which took into account the strict limitations of the spaces available and also considered the impact on the liturgical and musical life of the cathedral. There were of course some similarities between the submissions, but all three firms approached the challenges with such imagination and energy that it was hard to choose a ‘winner’!

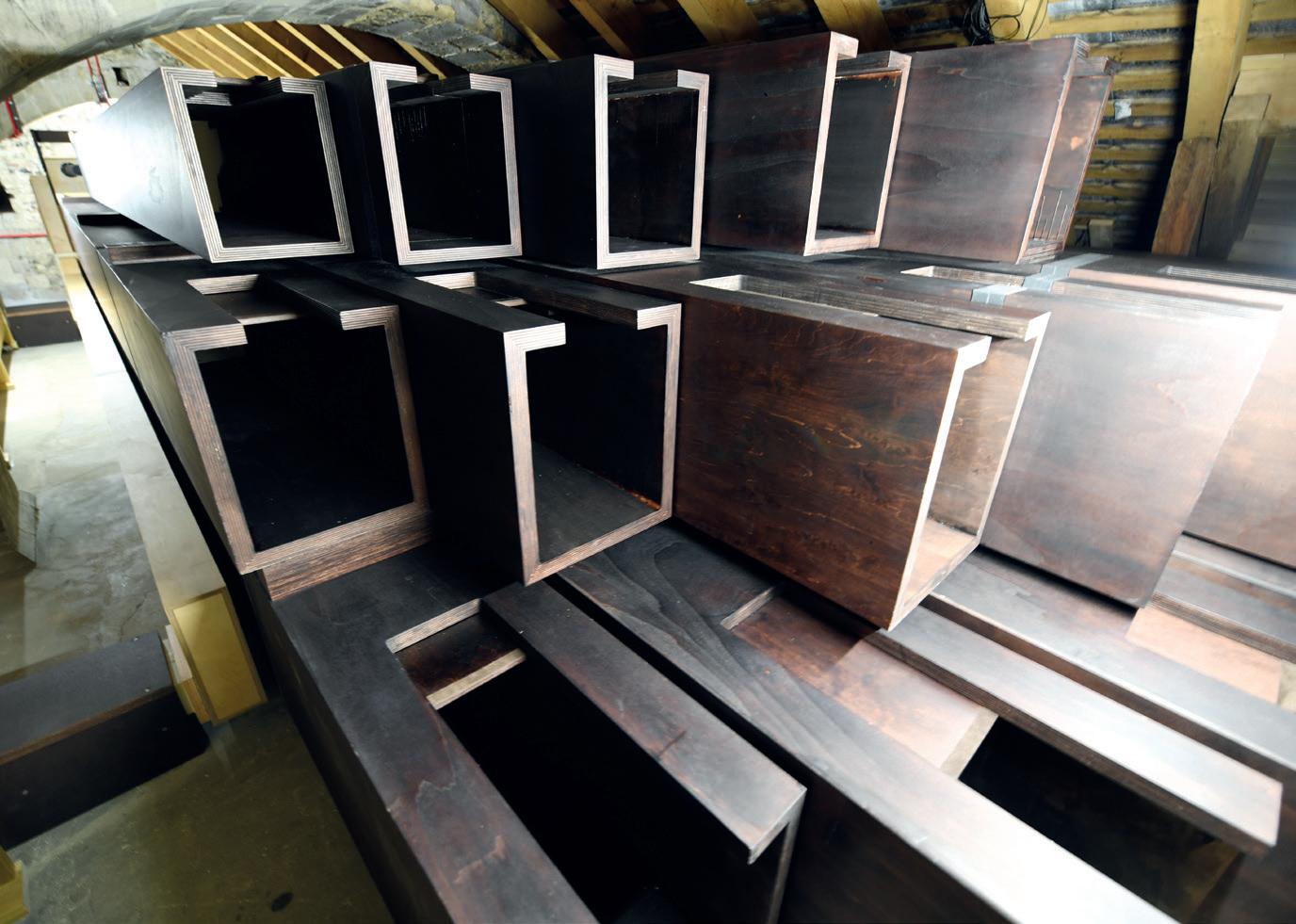

The disposition of the departments of the organ was quite easily refined, and using both sides of the triforium allowed the design much more space, even though the north side has a lower roof height. More than a year of temperature surveys gave everyone full confidence that the organ would work well in this new shape, with most of the new work placed in the departments on the north. All of the Willis pipework contained in the 1979 organ was retained and new ranks were added, keeping true to the Willis model throughout. A new Solo organ was built and the fine 1886 Tubas incorporated. These have been separated and moved, however, from the west (nave) end of the organ to the opposite east end and

enclosed in a box to give greater expressive possibilities. A new unenclosed Choir organ (as Willis provided) allowed some of the former ranks to be re-modelled but, essentially, it is new. At the western end of the north triforium a new Transept Great chorus allows core organ tone to reach the congregation at that end of the quire. One of the biggest (literally) additions to the organ has been the re-establishment of the 32’ Double Open Wood, now lying on its side in the north-west bays of the triforium. In addition to this, seeking to provide as much breadth as possible, we added a stopped 32’ Sub Bourdon on the south side for the soft, low rumble so often an essential element of a cathedral sound. The photograph in the cathedral archives of the previous open 32’ pipes being sawn up in the 1960s remains a harrowing sight! We have been without a full-length 32’ flue since that time, relying only on Willis’s tremendous 32’ reed.