CATHEDRAL MUSIC

We offer four brands of organ each with their own identity, sounds, appearance, technology and style. All our brands share valuable characteristics such as technological innovation and the best sound quality, which is never a compromise. All provide the player with a unique playing experience. A great heritage and tradition are our starting points; innovation creates the organ of your dreams.

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November.

ISSN 1363-6960 MAY 2021

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ editor@fcm.org.uk

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon pm@fcm.org.uk

To contact FCM enquiries@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

020 3151 6096 (office hours) www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of the Cathedral Music Trust. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by CMT.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

DT Design,

1 St Wilfrid’s Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3151 6096

International: +44 20 3151 6096 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrid’s Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

‘What is it you miss most?’ This question, if asked of those who have recently retired from the daily round of the Opus Dei, frequently gets a very straightforward answer: ‘The psalms’. Of course, many of us find the psalms a particularly appealing part of a church or cathedral’s offering – the simplicity, the wisdom, the glorious language (the smiting of cattle with hailstones, the cloudy pillars, the froward hearts, the rooting out of wicked doers…), their timeless quality – but apparently all the more so do departing DoMs and organists who have been steeped in this culture sometimes since boyhood. Girlhood, too, increasingly now. Try testing a regular singer or player of the psalms on the final word of ‘The sparrow hath found her an –––’ and the answer is more than likely to be accurate (Psalm 84, if you were unsure): for those who have sung more than 1000 psalms before they are 14, the evocative words are ingrained. And it’s not just the language. The accompaniment of psalms is a true art, one absorbed by years of listening and innumerable hours of practice in otherwise silent churches late at night, for the simplicity of the singing does not allow for any false notes. Colin Walsh and Katherine Dienes Williams in these pages have laid out their considerable thoughts behind this very desirable skill –not too much, not too little, a restrained use of the pedals – and how to teach young choristers the ‘code’ behind when to move to a different note, for example. But what pleasure it gives to the listener, even perhaps one who is not a regular attender at church, when everything is in its right place.

Some places are clearly very ‘right’ in the cathedral world, if David Flood’s extraordinary length of service at Canterbury is anything to go by – not just his 32 years in the top job but also his further eight spent as assistant to Allan Wicks (who served at Canterbury himself for nearly 30 years). And while long service can be a feature of organists and DoMs, 40 years and the overseeing of the music for four archiepiscopal enthronements is probably unparalleled. Certainly Allan Wicks was only responsible for three! David has also nobly served as an advisor to this magazine for more than 20 years, always providing invaluable support, guidance, advice – and

• Enjoy invitations to our Gatherings as part of our events programme

• Receive our acclaimed magazine Cathedral Music twice a year

articles too. Canterbury will surely miss him greatly, and to move on from such a position as his during a pandemic can only be a particular sadness.

A second ‘lifer’, or almost, who died in October and in whose memory Roger Judd has gathered many tributes, was Arthur Wills, who arrived in Ely as assistant in 1949 and didn’t retire (from his later position as DoM) until 1990. When asked once by the Duke of Edinburgh what his most important task as cathedral organist was, he replied, ‘Appointing a brilliant assistant!’ and this was clearly true: as several of his assistants remarked, Wills was frequently absent from the cathedral, either giving recitals or teaching in London, so a great deal fell to his assistant’s lot. At least two of them said, ‘Fortunately, neither he nor I were ever ill!’

And presumably Jonathan Rennert, at St Michael’s in Cornhill, is never ill either – once at St John’s in Cambridge, he has now been at St Michael’s for 42 years (only just beginning to approach Harold Darke, who clocked up 50 years there), curating the longest-running series of weekly organ recitals, many of which he has played himself. These have even continued through the pandemic, broadcast on YouTube, and with discussions afterwards on Zoom. Not one to let the world pass him by, Jonathan is also a great champion of new music, recently commissioning St Michael’s composer in residence, Rhiannon Randle, to write an anthem for choir and erhu. (It’s a Chinese stringed instrument; in my ignorance I had to look this up.) The choir’s CD, which includes this anthem, is reviewed later in the magazine.

Let it not be said either that we at Cathedral Music Trust are letting the world pass us by – we have held a virtual AGM (still available to watch on our shiny new website) – and there have been virtual gatherings, a virtual compline and of course Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor played by 54 cathedral organists, which raised considerable sums for the Cathedral Choirs’ Emergency Fund. The Church Commissioners matchfunded the £1m with another £1m of their own, the whole of which was distributed in grant form to 43 cathedrals across the UK in December.

Our way of communicating with readers is also evolving –the newsletter Cathedral Voice will be moving to an electronic version from 2022. There will be further information about this in the next newsletter itself, in August, but before then –ideally, now -- do remember to sign up to the mailing list on the CMT website if you have not already done so.

Sooty Asquith• Delve deeper into the heart of cathedral music with our Friends newsletters and journals

• Help us nurture the next generation of cathedral musicians and enrich more lives through the power of music

To enjoy a year’s worth of insights and Friendship, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk or call 020 3151 6096

We ask for a suggested subscription of £25 per year to be a Friend of Cathedral Music, and all Friends are asked to consider donating over and above this to assist us in developing our work and increasing the funds we have available to award as grants to choral foundations.

When I think back, I was very lucky. From the age of about 18 my aim was to be a cathedral organist and my first job was as Assistant Organist at Canterbury Cathedral, straight from university. Allan Wicks appointed me, he said, because I was ‘green’ and someone he could shape into the colleague he wanted. If that was indeed the process, I enjoyed it very much!

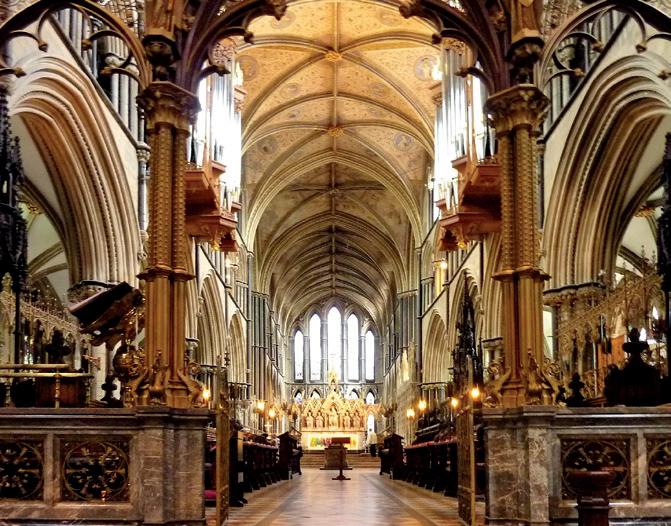

And then to be appointed Organist at such a magnificent cathedral as Lincoln before I was 30 I also thought very fortunate. I had a wonderful two years there and still maintain great friendships. When I came back to Canterbury in 1988 it was a thrill to be back but definitely daunting to think of what lay ahead. But I did have some experience of what life at the Mother Church could be like, and I also had ideas about

how things might develop. I am very grateful to the dean at that time, John Simpson, along with Sir David Lumsden who advised him, for having the courage to appoint me.

It was a challenge in a lot of ways, especially to make sure that the journey would not be more of the same: I had to go in a different direction – but the bright light which always shines on Canterbury as the focus for the worldwide Anglican Communion was consistent. It was important that we ‘flew the flag’ all the time, and the team (most of whom I knew well, of course) were certainly committed and ready for a new energy. In particular, I am so grateful to Michael Harris, who had succeeded me as Assistant Organist two years earlier, because he then became an ideal colleague in every way. For the choristers, it was a happy thing for them to have a familiar face returning (so they said!). And in order to make things feel fresh and instantly and unmistakably different, I changed the direction of the desks and piano in the practice room through 90 degrees. When they came in for the first rehearsal it certainly made an impression!

Evensong at Canterbury is sung every day of the week and rehearsal is always short, owing to the demands on the building and the number of visitors. Choristers and lay clerks were always excellent sight-readers but the amount of time we had to prepare back then was just too tight, so it was agreed that we should expand the time allowed to give us some time as a full choir before every service, and a little longer at our one weekly opportunity after Evensong on a Monday (as it settled to be). The repertoire was wide and we regularly introduced new works and revived others which had not been sung for a while. Our former colleagues, Anthony Piccolo and Gabriel Jackson, have contributed much to the music library and, of course, in 1988 Alan Ridout lived just a few yards from the cathedral. When the BBC were looking to record some short morning services, I asked Alan for some suitable boysonly anthems and these arrived after just a few days, in his inimitable spidery handwriting. Alan’s music was always very appropriate and eminently singable.

Before long, a ‘major occasion’ was on the horizon as Archbishop Robert Runcie (for whose enthronement I had played in 1980) retired, and George Carey was enthroned on 19 April 1991. The coordination of the music for the service was exciting as, following the practice of so many previous enthronements, we were able to commission a new setting of the Te Deum. For this I turned to Grayston Ives, who responded with his Canterbury Te Deum, a wonderfully exciting piece including astonishing parts for brass – played on that occasion by the fanfare team from the Royal Marines. That was quite a sound, with the amazing trumpets in a gallery just above the choir. We welcomed Noel Tredinnick and some of his musicians from All Souls, Langham Place to bring a different colour to the programme. It was a joy to make new friends and share the occasion with them.

We had a fruitful relationship with the Royal Marines School of Music in Deal, especially after the dreadful attack in September 1989. I was delighted to be invited to join them as the organist for the Mountbatten Festival in the Royal Albert Hall the following year, an occasion which brought such poignant memories as they remembered lost colleagues. Playing the Widor Toccata with the massed bands joining in for the last few pages was one of the occasions I will never forget!

The enthronements of Archbishops Rowan Williams and Justin Welby were wonderful, unforgettable occasions, each with the opportunity to add different colours, whether it was new music commissions or the inclusion of an African dance group. With guests from around the world and the need to support the Archbishop in every way, the focus was always on the liturgy and the central part which the music played. We are lucky to have enjoyed the most rewarding relationships with the Archbishops and involvement with them has been a pleasure. It was Archbishop Justin who recently observed that few people had known as many of his predecessors as I had!

The awareness of Canterbury across the world was brought home whenever we had the chance to travel. We couldn’t ‘leave home’ very often as our responsibility towards the large numbers of pilgrims and visitors in the cathedral every day was very significant. When people make such a huge effort to visit the Mother Church, they expect to hear the choir in situ. But we did occasionally travel. Our first US tour in 1994 took us right across the continent, starting in the middle and moving west and then east, ending in Canada. It taught me so

much about planning a tour and looking after the singers, but what was particularly heartwarming was the reception for the people from Canterbury, which was always astonishing.

I took the choir across the Atlantic six times, and each visit was so memorable and great fun. Tours are a wonderfully cathartic event for a choir, not least because they bring the community closely together for a long time, but also because it is very satisfying to have the time to rehearse, polish the repertoire and share all the normal things – communal meals, airport lounges, coach journeys – which bring the team together in a very special way. To mention all the notable occasions would take a book, but moments such as participating in a concert in Washington National Cathedral with the National Cathedral choir and the choir of St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, is one of the highest points. The joint performance of the Allegri Miserere, when ‘my’ solo quartet was in the far west gallery watching me on a CCTV screen, was such a thrill. Singing for former President George H Bush and his wife Barbara, who were so generous, was an amazing occasion.

Rehearsing a young chorister for his first solo, seeing the beam on his face when it goes well and building on that for the next time: that’s one of the great treasures too. Helping young musicians achieve something which, a few years or even months before, they had no idea they could do, is very fulfilling.

Choosing repertoire for a daily programme is a fascinating thing but it can also be demanding; you need to weigh up the calendar, how much rehearsal time you have, and whether a piece is in the consciousness or not. It is helpful to look at a two-week span of music a bit like one might choose something from a restaurant menu: you select pieces with which other people can identify. I would endeavour not to overload the diet with any one type of repertoire, and when it came to a particular season I would look back to previous years to see – mainly – what to avoid and which changes it would be beneficial to bring. Of course, we would all then say, ‘… When will we have…?’ and the pieces which mean so much to people, those that carry the real essence of a season, had to be included; not least for me too!

I was and am so grateful for constant support from the Chapter and especially the Dean, Robert Willis, a gifted musician and prolific author. It was so good to be able to introduce the congregation to a new hymn that he had written for a particular occasion and to know that all our highs and lows were understood. I also had the joy of a sequence of very talented colleagues, both as assistants and as organ scholars. The success of a performance lies very firmly in the dedication of the performers, from the youngest chorister to a long-serving lay clerk and the first-rate accompanist. They all brought so much to what we did, and I will always be very thankful for them.

As Canterbury is just a few miles from the coast, it is of course easier to visit European destinations. We did concerts in France on day-trips and used to go to the Netherlands for just a few days. We were delighted to visit Rome to support the Archbishop when on an ecumenical visit to the Pope, and there is no doubt that the impact that can be brought by the full choir on occasions such as that is enormous. A trip to Norway in 2017 was accompanied by a BBC TV crew, when we visited the site of the most northern relic of St Thomas of Canterbury in a beautiful village on the side of a fjord. The crew became great friends and the programme has since been aired quite a few times, including the electrifying trip to that fjord-side venue by high-speed ‘RIB’ boats!

I have always thought, though, that the daily sequence of services, the Opus Dei, was the most important part of the job. To give an exhilarating performance on a Tuesday in February or a Friday in November for whoever might be present is the vital thing. You never know who might be there, and in Canterbury there are rarely fewer than 50, and someone could well be attending for the first or even the only time in their life. We always hope that people leave uplifted by the experience and that it lives with them for a long time. Then there are the regular members of the community who keep coming because it means so much to them and with whom we make good friendships, and the members of the cathedral foundation, the ‘core family’ which has reinforced the continuity over the centuries.

Canterbury lives in the spotlight and never more than at the time of a Lambeth Conference, when literally hundreds of bishops from around the world gather. To know that news of the cathedral and its liturgy would be delivered first-hand all over the world was very exciting. Visiting the Mother Church was an emotional occasion for many and they wanted to make as much of their time as possible. Planning took literally years, and while we welcomed our pilgrims and made them feel at home, we also wanted to show the world what we had been doing, with such care, on a daily basis for hundreds of years.

All this then, but Canterbury is not a large city and it stands at one end of the country. This is a really small catchment area from which to draw singers. Fifty years ago I knew that choristers had come from distant areas of the country (until 1972 Canterbury had 60 boys in the choir, 30 dayboys and 30 boarders) but increasingly the preference for families has been to stay more local. Yes, we have wonderful families who travelled many miles to bring their boys and who spent hours (and lots of fuel!) on the road and we are so grateful to them. It was vital, though, to enthuse families within the SE corner of the country with the great experience of choristership and encourage them to join the journey. For lay clerks too, I was always in admiration of the commitment which families would make, sometimes to start a new life in Kent when London seems so close but in fact is not, when it comes to being present in time for a 5pm rehearsal. The dedication of these people is amazing and so greatly valued. It was just the same, if not more intense, for my long-suffering wife and family who were so tolerant of the commitment we all made – “Where’s Daddy…? In the cathedral, of course!”.

When I think back, I was very lucky. From the age of about 18 my aim was to be a cathedral organist and my first job was as Assistant Organist in Canterbury Cathedral, straight from university.

In recent months attention was focused on the need to revisit both the role and the state of the cathedral organ. Since the building is now used more than ever (except during current problems) and the variety of occasions when music is required is much wider, the need to update and expand the organ became very urgent.

Based on quality Henry Willis work of 1886, and having undergone four rebuilds since then, the organ had much to offer but needed liberation. It was in 2005 that the Dean invited me ‘to dream about what we could do’. That could have been a risky invitation but it led to a deep exploration of what we needed and what we could actually achieve. Canterbury Cathedral is a tricky acoustical space since it is effectively two separate areas, so at first the dream led to the idea that we needed two substantial organs, one for the nave and one for the quire. Acoustic surveys and a lot of strong advice led to the realisation that, while this would be a wonderful thing to achieve, it was not actually feasible as one project. So we embarked on the plan to provide an instrument which would serve the quire (where 90% of the services take place) in the very best way, with colour and flexibility, to which, eventually, a sizable nave organ could be added.

The organ, after a stunning re-construction by Harrison & Harrison (completed last March), is now just what I had planned for and which I hope will serve the cathedral for a very long time to come. I must record deep gratitude to William McVicker for his level-headed advice and also to the Cathedral Trust and other donors, without whom it would never have happened.

Yes, I have been very lucky and I have had a wonderful time: a total of 42 years in cathedral music. I trust that Canterbury and all her sister cathedrals will continue in strength, long into the future, so that we can look forward as far as we can look back.

John Robinson writes:I was not the only one of David’s organ scholars to return for a second innings! Having been at Canterbury and experienced various ‘baptisms of fire’ in my gap year, the pull of David’s music department proved again too strong to resist, and I was delighted to become his assistant.

Bubbling beneath the always cheerful surface there was something of the ‘boy in a sweet shop’ about David’s approach. A deeply humble man, David knew that Canterbury Cathedral is any church musician’s ‘heaven on earth’, and he revelled in that, every day, which meant that we all did too – singers and organists alike. I remember one occasion when I fell down some steps (probably not the

practice room steps, which were in any case legendary!) and David offered to play so that I could conduct with my working hand. While we were processing in, we heard what sounded like really good Bairstow emanating from the pipes high up in the south triforium. The then organ had never sounded convincing played in repertoire like that, and I was sufficiently curious afterwards to ask him what it was – “Oh, I was just improvising,” he said. “I rarely get the chance.”

David’s generosity is legendary, and he and Alayne always made the most of the splendid organist’s house in the Precincts. David created a unique world around the music at the Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, and his legacy will long remain, not least in the remarkable new organ he campaigned for, over so many years, and finally saw through to completion. David will also be remembered very fondly by generations of choirboys who found a humane and kindly champion of the world’s greatest church music as their mentor, in their most formative years. Thank you, David, for all you have done.

Tim Noon writes:

“And what does it mean to you?” asked the television journalist.

Solemn thoughts clearly filled David’s mind, for the normally genial smile left his face and his eyes took on a misty appearance. His voice, generally imbued with self-confidence, seemed to tremble slightly as he answered, “Well, … everything.”

That tiny moment from the BBC 2014 series Canterbury Cathedral stuck in my mind at the time, and whilst I was looking for it recently on YouTube I came across a multitude of documentaries about Canterbury, with David and his boys seeming to feature in them all.

Over the years charted by these glimpses into the Song School, David’s hair might have progressively become slightly greyer, but clearly his absolute commitment to, and enthusiasm for, the gloriously never-ending task of training up the choristers and delivering the ‘daily round’ has been utterly undiminished.

There is no wonder that the documentary makers have been so fascinated! In every moment, David holds the boys’ attention in the palm of his hand, and they hang on his every word. The rehearsals move at 90 miles an hour with not a second wasted: there is no fat to trim. Gently pushing, warmly encouraging, working hard by example, literally leading from the front, David instils in

his choristers a profound self-belief that they know will last them a lifetime, and for which they will be for ever grateful.

It would be no over-statement to say that David has given his life to Canterbury Cathedral. Having been appointed Assistant Organist there in his early twenties in 1978, he become Organist and Master of the Choristers just ten years later (immediately after a five-term sojourn at Lincoln Cathedral), and has spent the subsequent 32 years leading his very happy and successful team.

David is one of the most generous and loyal people I have ever met; he is definitely the first person I would call in a crisis. He is dependably cheerful and always full of energy, and somehow he manages to transmit this to everyone else when leading a group. He has great wisdom and a quick wit, but is also empathetic and unfailingly kind. It is no coincidence that so many of his lay clerks have sung for him for so long.

It is typical of David’s magnanimity that when Covid put paid to his plans for an ‘end of academic year’ celebration of his tenure last year he agreed to stay on for another –albeit, very uncertain – term. Though I can only imagine the frustration felt by not being able to begin one’s retirement as planned, or to finish one’s working life under ‘normal’ circumstances, nevertheless, David was there, being professional, ‘keeping the show on the road’, making wonderful music to the greater glory of God.

Because, well, it means everything.

Have a long and happy retirement, David – you deserve it! I am sure all readers of this magazine will want to join with me in expressing sincerest gratitude for all that you have given to cathedral music over the past 40-plus years.

When I was appointed Dean of Canterbury in 2001 David had already been Organist and Master of the Choristers for 15 years. Not only that, for one could add on the eight years that he had spent as Assistant Organist to Allan Wicks which gave him 23 years of experience not only of the music of Canterbury Cathedral but also of the large resident cathedral community and the people of Canterbury and Kent. I was to be his third Dean and, not knowing him then, I was slightly nervous when coming to his study in the Precincts to plan my installation. My first impression when the front door opened was that I was entering a family home of enormous warmth and hospitality and that reality was carried into the study itself with its windows looking out onto the busy Precincts where tourists, citizens, pilgrims and cathedral staff were happily mingling on that fine spring morning. David was completely relaxed in the lively atmosphere and anxious to make me feel equally at home. As we exchanged initial thoughts about the service, I began to appreciate for the first time the constant energy, the boundless enthusiasm, the broad experience and the willingness to create a service which I would enjoy and which he would feel worthy of Canterbury.

I soon perceived that for David this position of being Organist and Master of the Choristers was not simply a profession in which his skills were used to their utmost, it was a vocation and a way of life which involved not only him and Alayne but his family, all of whom musical, and the widest circle of friends and acquaintances worldwide.

I was to receive in the almost 22 years that we worked together so much hospitality and also musical advice from that home but also, always, the constant readiness to throw every ounce of energy, knowledge and skill at every task that we had to accomplish at however short notice. This energy and enthusiasm was evident as much on choir tours to the United States or to the Vatican, aside from the many other places toured, as it was for the huge services of the Lambeth Conference or the enthronement of archbishops. Even in the holidays his readiness to conduct the International Children’s Festival and to travel across the world to hold courses for choirs like the Tacoma Youth Chorus demonstrated the same deep love of music in general but choral music in particular.

At the heart of all this lay his loyalty to the daily rhythm of the cathedral and its worship. Day by day as I walked early to Matins our paths would usually cross as he left his house for morning practice, and his cheerful greeting would set the tone for the day. His love of the daily psalms and cathedral repertoire for Evensong and Sung Eucharist was everything to him and no one could doubt that.

It is sad that the restrictions of the pandemic caused so much to be paused or cancelled, and also prohibited a large gathering of friends and former choristers from coming together to give a huge musical farewell to David and Alayne. Christmas, though, still gave the full choir a chance to sing before the fierce lockdown began again, and there was a glorious new dimension to that Christmas music, for David’s longed-for project had been, thanks to his efforts, completed. The rebuilt and much enlarged Henry Willis organ was accompanying the choir in full glory for a last grateful ‘Hurrah’ for David’s long years of service, and I was aware that the boundless energy, enthusiasm and enjoyment was still the hallmark of his musicianship, and something that the Canterbury community and I personally will give such thanks for and miss over the years to come as his legacy lives on in so many ways in this place.

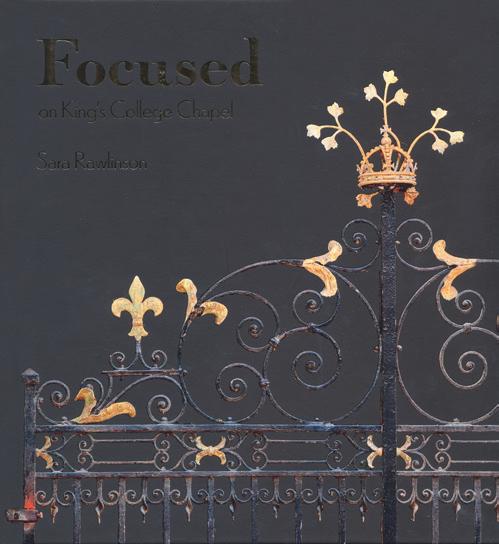

A collection of annotated photographs and poems Available from www.sararawlinson.com

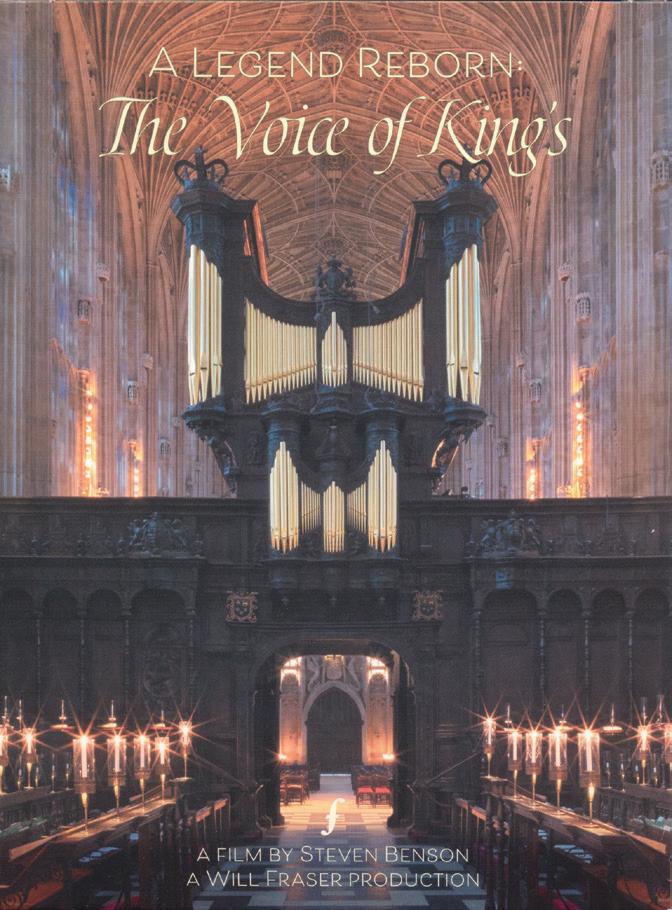

For the many who have listened to the pure sound of the choir of King’s College Cambridge at Christmas or other times throughout the year but only seen brief glimpses of the chapel on the television screen, here is the perfect gift. Taken over several years, the photographer Sara Rawlinson, resident now in Cambridge but something of a nomad, having lived in the USA, Australia and Scotland, has amassed a stunning selection of images concentrating on the interior of this famous chapel. The photographs are illuminated by the photographer’s own text, minimal in content, allowing the pictures to speak for themselves. Several are taken from a celestial cherry-picker (despite Rawlinson’s fear of heights!), allowing the reader to experience over-arching views of the space, and to appreciate the rainbow hues of the massive stained-glass windows. Most will surely be familiar with the quire, nave and organ; now is the chance to absorb the finer elements of stonework, carvings, ironwork, gargoyles and fan-vaulting displayed here in glorious detail. A labour of love, and much to be admired.

by the combination of the words and music. The Psalms of David, as translated by Coverdale, enrich our lives with some of the most beautiful religious writings of all time. The psalms are a fountain of hope and inspiration in an uncertain world.

For 32 years I have been blessed with the fine ‘Father’ Willis organ at Lincoln Cathedral. The quality of the voicing is second to none and the organ’s position on the central screen and in the triforium places the instrument at a certain distance from the choir, increasing the adaptability and subtleness of the whole. It is indeed possible to allow the organ to ‘float’ around the building, which can be magical.

The choir’s role is to sing in four-part harmony and tell the story. My job as organist is to inspire and enable them to give of their best, without too much interference or ‘taking over’. I have to adapt to the strength and confidence of the choir at a given moment; a rigid and set plan of registration is not really possible. Divisional pistons are used sparingly; I prefer hand registrations, and certainly avoid general pistons which can interrupt the flow with an audible ‘thud’ when activated.

Orchestrating the psalms is an art peculiar to the Anglican tradition. There are moments which call for reeds e.g. ‘The Lord thundered out of heaven... Hailstones and coals of fire’ (Ps 18 v13), and those where a more reflective approach is appropriate e.g. ‘He shall receive the blessing from the Lord’ (Ps 24 v5). For the louder moments it can be effective to use the reeds lower down the keyboard and tempered by the swell box; for the softer moments maybe the flutes at a higher register. A strategy I use a lot is to leave the choir to sing alone for the first three or four words and then to creep in discreetly – ‘He shall receive the (+org) blessing from the Lord’, or make one’s presence felt – ‘The Lord also (+org) thundered out of heaven’. Equally colourful is to start a verse with just one or two notes in the lower registers and add more as the verse proceeds, with you moving up the keyboard.

‘What do you miss most?’ is a question I have asked colleagues who have recently retired or moved away from cathedral music. The response is, more often than not, ‘The psalms, the beauty of the text and the chant’. Whether one is accompanying, conducting or singing, the psalms are, to me, the cornerstone of choral Matins and Evensong. We are at once guided and educated

Use of the pedals can be tedious if overdone. One or two unaccompanied verses can, again, produce a different texture (and make the choir listen to themselves!). The reappearance of the organ as the text becomes more affirmative –’Thou hast turned my heaviness into joy’ (Ps 30 v12) – can be very effective. An inspired descant has to be handled carefully; following the top line around seems pointless, unless the singers are in need of some help, but a well-shaped solo upper part on a flute – ‘Yea, the sparrow hath found her an house’ (Ps 84 v3) – is both colourful and

Colin Walsh

‘Therefore will I praise thee and thy faithfulness, O God, playing upon an instrument of musick’

enhances the text. Equally pointless would be following the alto or tenor line around.

The use of mutation stops can be harmonically confusing, but maybe the sound you want to portray is the grasshopper – ‘And am driven away as the grasshopper’ (Ps 109 v22). Mixtures can be used for special effect e.g. ‘He cast forth lightnings and destroyed them’ (Ps 18 v14).

All of this sounds fine if you are an experienced accompanist, have a professional choir to work with and a versatile organ. When welcoming new young organists to the cathedral I have always advised a simple and safe approach to start with. Getting to know the text and the chant from memory is important, so it is best to play the four vocal parts as written, with a limited number of registration changes. Slowly and with confidence and experience the novice can build upon this strong foundation, perhaps beginning by providing contrast and a bit of colour by playing the upper parts an octave higher for a verse or two, and leaving the pedals out. The important

thing is to help and encourage the choir; an organist trying to embellish the psalms before he or she is ready does nothing to help the choir or worship.

I am immensely grateful to my mentors in my organ scholar days – Sidney Campbell at St George’s Windsor and Simon Preston at Christ Church Oxford. Both were brilliant accompanists who have been a constant source of inspiration and education throughout my career, and like most of their colleagues at that time, they would play the psalms. It was a rare event if the psalms were conducted; the choir would watch and listen to one another.

As I write this during lockdown, having not played a service for some time, I am reminded of what my colleagues have said to me. And it is indeed the psalms that I miss the most.

Each month, Anglican cathedral choirs adhering to the evening psalms as allocated by the Book of Common Prayer anticipate the approach of the 15th evening, when Psalm 78, the longest psalm appointed to be sung in an office of prayer, makes its monthly appearance with its ‘frogs’ and ‘lice’, its smiting of cattle with thunderbolts – hot thunderbolts, not just any old thunderbolts – its ‘smiting in the hinder parts’ etc. Here there are endless opportunities for the organist to go beyond the mere chordal harmonies, to describe the poetry of the psalm whilst playing the chant – using registrations to depict sheep, goats, rain, sea and so on. In an Anglican cathedral, one might also hear the beauty and simplicity of the plainsong tones of psalmody sung unaccompanied, or even with simple accompaniment, as they are in monastic foundations throughout the Christian world.

For all probationer choristers and apprentice organists, it is the psalms which are the most difficult to sing and to accompany. Singers must learn to decipher a code: a text grouped and held together by bar-lines, colons, syllables and dots is like a form of code. And there is much code to be found in the psalms themselves – for example, Psalm 119, the longest psalm, where each of its 22 sets of eight verse sections begins with a letter of the Hebrew alphabet, thus forming an acrostic; or Psalm 46, where it is possible that the 46th word from the start of the psalm, and the 46th word from the end of the psalm indicate a code name for someone who may have been working with Miles Coverdale on his translation of the psalms in 1539 – it is asserted that this is how he left his signature – the 46th word from the start is ‘shake’ and the 46th word from the end is ‘spear’.

Coupled with language used in our familiar Coverdale translation, in which some words, people and places themselves need explanation to the modern reader (for example, Og, the King of Bashan), the psalms are where each of my chorister rehearsals begin – such is the importance that I place on their positioning within any service. Cathedral choirs are known for their ability to sing the psalms well, with sensitivity to the poetic language, clear diction, shaping and interest, and people buy and listen to recordings of the psalter. The words of the psalms are the beating heart of the prayer that is the daily office.

To learn to sing or play Anglican chant well, it is first necessary to memorise the chant appointed to that text. Each establishment has its own psalter with different types of pointing (that is to say, the division of words and syllables in the text based on their rhythmic stresses of speech). Some establishments have their own particular style of chanting the psalms, which has grown into a tradition. Other methods

generally use the stress of the spoken word to give rhythmic impetus to the text. By way of example, what you might see as a bar-line in between words indicates a change of notes, with a dot also indicating the same. Sometimes this can be in the middle of a syllable. Likewise, at a colon (at the end of a line of text), the note changes. Sounds and looks complicated? It is! But it’s quite quick to learn and understand once you get the pattern of it.

Playing the organ to accompany Anglican psalm chants is, however, a different story. When I first arrived at Winchester Cathedral, I would practise the psalms for up to four hours every day. First, there is the memorising of the chant. Then the colours, or the registrations that you must choose to use. Then there is the actual rehearsal – breathing, moving and balancing with the choir. Jumping from stop to stop, from manual to manual, re-harmonising, solo-ing out a melody and so on. Finally, the performance. All such practice was, in my career, made worthwhile when the late Dr George Guest, who attended an evensong at Winchester Cathedral at which I was accompanying the psalms, met me for the first time afterwards and announced: “Katherine, you play the psalms like an angel!” – before our discussions moved on to the merits of the Welsh rugby team and the All Blacks…

The music of the psalms speaks to us all, and continues to excite me to this day in whatever form it appears. It connects us, unlike any other way can, to the earliest members of the Church, and links us inextricably through the ages with an unbroken line of prayerful lament, praise and hope. The words of the psalter are those which have resonated with me the most through events that may have happened during the course of a day – events sometimes of great sadness, but likewise events of great joy, hope and encouragement. Music heightens the emotions, as Augustine rightly pointed out, but it also elevates our prayers and, often, when the music of Anglican chant is coupled with the whole human experience described in these 150 poetic masterpieces we know and reiterate every month of the year, we are transcended. It is the singing of psalmody which continues to be one of my great musical loves, well deserving of the utmost care and attention.

Singers must learn to decipher a code: a text grouped and held together by bar-lines, colons, syllables and dots is like a form of code. And there is much code to be found in the psalms themselves.Katherine Dienes-Williams is Organist and Master of the Choristers at Guildford Cathedral. The above is an extract from a Lent talk.

The tradition of metrical psalm singing arose from the aspiration of the Reformation movement to render the Bible and liturgy accessible to the congregation, achieved by translation into the vernacular, and, in the case of the psalms, into a rhyming and strophic form. Thomas Sternhold is remembered as the originator of the first metrical version of the Psalms. The Book of Common Prayer (1549) did not sanction the use of metrical psalms, ignoring the attempts of early publications such as Myles Coverdale’s Goostly Psalms and Spirituall Songs (London, c.1536) and John Hopkins’ Certayne Psalmes (London, 1547) to prompt liturgical reform and introduce congregational hymnody on the same lines as Lutheran practice. Hopkins’ Certayne Psalmes included 19 psalms. A second collection published in 1549 shortly after Sternhold’s death, Al Such Psalmes of Daivid (London, 1549), included 18 more psalms by Sternhold and seven by Hopkins. These 44 psalms were added to by Hopkins and other writers in several more publications, and culminated in The Whole Booke of Psalmes (London, 1562; a 1747 copy of this book is available on the internet).

However, while ‘it is true that [congregational] hymnody was not prescribed [in The Book of Common Prayer]... neither was it proscribed’ (Goostly Psalmes), and Elizabeth I’s Royal Injunctions of 1559 permitted ‘that in the beginning, or in the end of Common Prayers, either at morning or evening, there may be sung an hymn, or suchlike song, to the praise of Almighty God, in the best sort of melody and music that may be conveniently desired, having respect that the sentence of the hymn may be understanded and perceived’. The translation into metre of the whole psalter and canticles suggests that these versions were used as alternatives to the official prose versions. The psalm collections were also intended for domestic use, with books with four parts arranged so that singers could perform from a single copy, and some editions provided lute or cittern accompaniment.

The practice of congregational psalm singing was not officially recognised until 1644 in Parliament’s A Directory for the Publique Worship, where it is recommended that psalms be sung ‘before

‘While dealing with the expression of the words in the psalms, a timely warning must be given against exaggeration in the direction of ‘word painting’. No doubt many in the congregation may have heard organists attempt to portray ‘birds singing among the branches’ (generally depicted by means of the shrillest flute in the organ). The author has a vivid recollection of attempts to

or after the reading’ and before the Dismissal. With the benefit of hindsight, and in the context of the Directory, these metrical psalm settings became associated with the Puritan reforms of Parliament; in reality, however, the Directory was reflecting a custom established in cathedrals (such as Worcester and York) and parish churches before the Civil War. Indeed, the suppression of congregational psalms in some cathedrals by High Church divines in the 1620s heightened worries that the Anglican Church was set on a course back to Rome. Peter Smart (author of A Sermon Preached in the Cathedrall Church of Durham 1628) spoke vehemently when John Cosin, canon at Durham and Chaplain to Charles I, abolished the practice of psalm singing at Durham Cathedral: Lastly, why forbid they singing of Psalmes, as all the people may sing with them, and praise God together, before and after Sermons, as by authority is allowed, and heretofore hath been practised both here and in all reformed churches. How dare they in stead of Psalmes, appoint Anthems, (little better than profane Ballads some of them) I say, so many Anthems to be sung, which none of the people understand, nor all the singers themselves, which the Preface to the Communion booke, and the Queenes Injunctions, will have cut off, because the people is not edified by them. Is it for spite they beare to Geneva, which all Papists hate, or for the love of Rome, which because they cannot imitate in having Latine service, yet they will come as neer it as they can, in having service in English so said and sung, that few or none can understand the same? I blame not the singers, most of which mislike these prophane innovations, though they be forced to follow them.

The language of Sternhold’s translations is governed but never constrained by the self-imposed structure of the metre and rhyme schemes. Sternhold developed the Common Metre (8686) from the so-called Ballad Metre and within this ‘repetition of sound, word and idea’ are important aspects of his style.

Taken from 12 Psalms ‘to comon tunes’ by William Lawes (1602-45), edited by Paul Gameson.

represent ‘the heavens dropping’ and ‘the word running very swiftly’, the former by a startling staccato chord on the lowest octave of the Great organ while the right hand sustained the harmony on the Swell, and the latter by a run up the keyboard of surprising rapidity. Ideas such as these would not, it is believed, occur to any organist of refined taste.’

The William Lawes pieces referred to above are available from www.resonusclassics.com on Music for Troubled Times: TheEnglishCivilWar&SiegeofYork, a CD sung by The Ebor Singers and conducted by Paul Gameson.

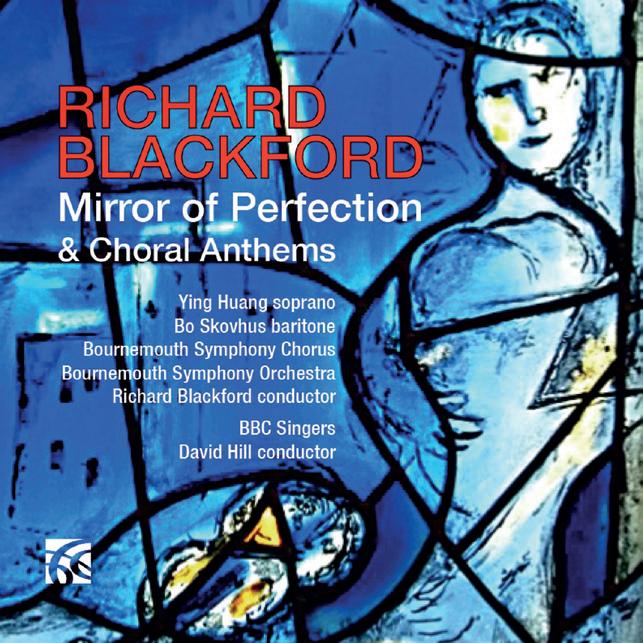

Pietà is my third major choral commission from the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus, but our association goes back to 1996, when Sony Classical invited me to record Mirror of Perfection with them. If I were to try to identify threads that run through the four works, I would say that the themes of spirituality, loss, ecstasy and yearning are, to some extent, found in all four.

Mirror of Perfection sets little-known poems of St Francis of Assisi that describe the poet’s ardent love of his Creator. It was the universal appeal of the poems, Francis’s love of the natural world, his profound inner need to celebrate life through

despair, his capacity for joy, that attracted me. In the sixth movement, the astonishing poem features the word amore no less than 48 times. Though a secular cantata, Mirror has been performed frequently in churches and cathedrals, including both the Upper and Lower Basilicas of Assisi by different choirs. Of all my choral works it is the most widely performed, having achieved over 120 performances in nine countries.

The first of the Bournemouth commissions, Voices of Exile, was written for the choir’s 90th anniversary. In conversation with the secretary, Carolyn Date, and her late husband Sandrey, we found that we had in common a commitment to the

work of Amnesty International. Carolyn and Sandrey were also aware of my music drama, King, which is based on the life of Martin Luther King, with lyrics by Maya Angelou. King was recorded by Decca, starring the legendary baritone Simon Estes, and performed at President Clinton’s Re-inauguration in Washington DC with an introduction by Angelou. One of my most treasured mementos from that project is an inscribed copy of Coretta Scott King’s biography My Life with Martin Luther King Jnr that reads, ‘To Richard Blackford, with appreciation for your efforts toward the fulfilment of the dream’.

After months of research and discussion with the Dates, I decided to set to music 17 poems on the subject of refugees and displacement. Voices of Exile (2001) is scored for mixed chorus, children’s chorus, three soloists and an ensemble of 17 players. It was premiered under the direction of Neville Creed at The Lighthouse, Poole. Like Mirror, the texts are high octane expressions of love, loss, grief and hope. Two further poems by the poet Tony Harrison, with whom I had collaborated on 12 film and theatre projects, frame the refugee texts, by way of Prologue and Epilogue. At 65 minutes it is almost twice the length of Mirror of Perfection. Shortly after the premiere, the eminent conductor of the Bach Choir, David Hill, urged me to re-orchestrate it for full symphony orchestra. It was in this format that he recorded it with the Bach Choir and the Philharmonia Orchestra. Voices of Exile broke new ground for me. It’s like a large solo and choral song-cycle that also incorporates tape playback of some of the poets’ actual voices declaiming and singing their texts. This lent a degree of authenticity to a work that was trying to bear witness to their experiences of displacement and their journeys to rebuild their lives. Indeed, Voices also has passages of tenderness and hope, such as the duet between tenor and mezzo-soprano

My Wish, by the Kurdistan poet Mohamed Khaki, and the aria Yemma by the Algerian poetess Samia Dahnaan.

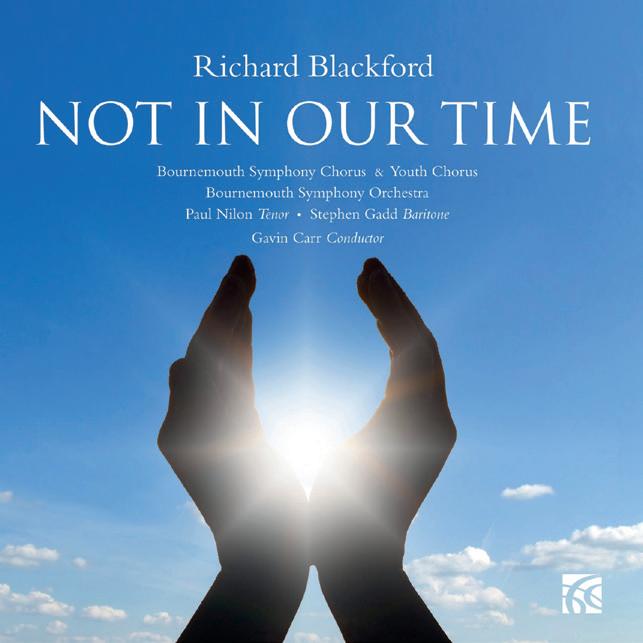

Ten years later the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus premiered my next commission, Not in our Time, for its centenary Of all my works, the subject matter is the most challenging, and begins with a response to the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Centre. In reading the ensuing Al Qaeda statements about how, in their opinion, the crusades against them had never ceased, I noticed the similarity of language between their words and those of both Christian and Muslim incitements to war during the First Crusade. Consequently, I chose words by Pope Urban II, AbulMuzzafar Al-Abyurdi, George Bush Jnr, Barack Obama, and the poem Not in our Time by the American poet Hilda Doolittle. Scored for mixed chorus, children’s chorus, tenor and baritone soloists and orchestra, its 13 sections last 55 minutes. My approach to the music is more symphonic, more organic than in Voices of Exile. Motifs permeate many of the movements, and the work is conceived much more like a dramatic cantata than the poem-cycle format of the earlier work. The two sections, ‘The First Crusade’ and ‘The Fall of Jerusalem’, are a sustained building of tension that are propelled at first by the crusader hymn Vexilla Regis prodeunt, then the sublime Lucis largitor splendide, which erupts after the victorious crusaders enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The juxtaposition of the horrors of war with the sublime expression of spirituality is a recurring feature. A year after the premiere, it was performed before an audience of 4000 in the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago’s Millennium Park. The ovation left me in no doubt that many Americans had connected with the subject of the work and especially with Obama’s plea for peaceful co-existence in its final section.

I had not expected a third commission from the BSC, but was delighted when I was once again approached by Carolyn and Sandrey Date. We knew each other well by now, and some years previously I had been invited to be president of the chorus. I knew that, as far as subject matter went, they expected another work that had strong contemporary resonance and was a further exploration of the themes of their previous two commissions. But things had changed. In 2016 I embarked on a PhD degree at Bristol University under the supervision of the composer John Pickard. My three-year course of research and study focused on poly-rhythm and multiple simultaneous tempi, as reflected in my second violin concerto Niobe. My rhythmic and harmonic language had advanced and I was fascinated by new possibilities of musical structure and form. I worried whether these stylistic developments could be compatible with writing another major work for amateur singers, even the superb BSC. Throughout my life I’ve kept in my head Benjamin Britten’s dictum that a composer, as well as expanding the range and technique of his musical style, should also be ‘useful’. In accepting the commission I determined to build on what I had learned and yet keep the technical standard of the choral and orchestral writing within the grasp of any good amateur chorus and orchestra.

In 2017 my wife Clare and I visited Rome, and I took her to see Michelangelo’s incomparable statue ‘Pietà’ in St Peter’s. What fascinated me was how something so sad could also be so beautiful. I recalled settings of the Stabat Mater that I had known for years (Pergolesi, Dvořák, Szymanowski) and went back to the Latin text that describes the grief of Mary, mother of Jesus, as she cradles her son after the crucifixion. The poem is largely bleak, though there are moments of light, especially the hope of attaining paradise towards the end. When I mentioned to a friend that I was considering setting the Stabat Mater, he remarked that one of the pitfalls is that of creating ‘six slow movements in succession’. Around that time I was also aware on news bulletins of the attacks against civilians in Syria and saw images of mothers cradling their dead or wounded children. But it was only when I re-read Anna Akhmatova’s poem cycle, Requiem, that I believed I had found the solution to the work’s structure. Akhmatova, whose husband had been ‘disappeared’ by Stalin’s KGB, saw her son taken away and believed she would never see him again. She pleaded with the authorities, and in her poem she wrote, ‘For 17 months I’ve pleaded, pleaded that you come home, flung myself at the hangman’s feet for you, my son –for you, my horror.’ This seemed less like the contemplation of the grieving mother but more of an expression of her rage, and it lent an entirely new dimension to the Stabat Mater theme.

As the composition progressed it became clear that my setting would be very far from ‘six slow movements’. Pietà contains much fast music that is dramatic, defiant and passionate, not merely a mediation on grief: the Pro peccatis suae gentis, the graphic description of Christ’s flagellation, is marked furioso; the first Akhmatova poem is marked Allegro assai; the Flammis ne urar succensus is marked Vivo, then Allegro molto. Even the Andante movements contain rapid accelerandi and huge choral climaxes, such as the unison cry of ‘Eia’ at the end of Eia mater, fons amoris

Scored for mixed chorus, children’s chorus, mezzo-soprano and baritone soloists, soprano saxophone and string

orchestra, Pietà lasts 45 minutes. I decided early on to write an obligato part for soprano saxophone, as the instrument feels to me halfway between the human voice and an instrument. At times it’s like a keening, ancient shawm, at others a third vocal soloist. It brings a warmth and tenderness to many of the key movements of the work, as well as concluding it.

I divided the combined Stabat Mater and Akhmatova texts into three main parts, preceded by an intense string prelude that sets the tone for what is to come. The predominantly dark tone of Part I is contrasted with the gentler children’s chorus that opens Part II and the four Akhmatova poems that follow. The turning point, at which light and hope begin to suffuse the work, occurs in Part III, in the middle of Mov. VIII Fac me tecum pie flere, where the saxophone introduces a soft melisma that is taken up contrapuntally by the choir with added solo violin and solo cello parts interweaving with the saxophone, strings and singers.

When I started composing the Stabat Mater text I realised how hard it is to set. The poem is tough, the images are raw, it

is unrelenting in its evocation of grief. Yet the poem offers moments of great tenderness and beauty. It is the delicate balance of emotional extremes, of crisis and the hope of salvation, that I tried to reconcile in the course of the composition. I was asked at the premiere how different the work would have been if I had not taken the PhD. Though its language is undeniably tonal and chromatic, the organic development of ideas is very far from Mirror of Perfection. Even in the opening muttered entry: ‘Stabat mater dolorosa’, as if the chorus is afraid to even pronounce those words, the musical attention is on the searing cello line that cuts through it, not on the chorus. This would not have occurred to me earlier in my career.

Pietà was premiered at The Lighthouse, Poole with the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus, Bournemouth Symphony Youth Chorus, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, soloists Jennifer Johnstone, Stephen Gadd, Amy Dickson and conductor Gavin Carr, to whom the work is dedicated. Its London premiere was given at Cadogan Hall. It was jointly commissioned by the St Albans Choral Society, and the

premiere by them in 2020 had to be postponed due to the COVID pandemic. This will now take place in St Albans Cathedral in 2022, and further performances are scheduled at Winchester Cathedral next year.

I will always be grateful to my friends at the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus for having the faith to commission not one, but three major choral works. When Pietà won the 2020 Ivor Novello Award in the Choral Category the BSC was in the middle of a Zoom rehearsal. When they heard the news of the award there was a whoop of joy, and I was delighted that our long association had been acknowledged with this honour.

It was with great sadness that I learnt of the death from breast cancer of our director of music and organist, Catherine Ennis, on Christmas Eve last year.

Catherine was the most amazing person and colleague. After college at Oxford, she was appointed assistant organist at Christ Church, the first woman to hold such a post at an English Anglican cathedral. She was also Director of Music at St Marylebone Parish Church for over a decade and for the last 35 years has been Director of Music and Organist at St Lawrence Jewry.

She was known throughout the organ world as a dynamic personality, both as an organist and as a mover and shaker. She was an energetic force in the creation of four organs here in London, at St Marylebone Parish Church in 1987, St Lawrence Jewry in 2001, at Trinity College of Music in 2003 and The Queen’s Organ in the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey. She was also involved in other projects in the past year. She founded the London Organ Concerts Guide and was President of the Incorporated Association of Organists 2003-2005, the Royal College of Organists from 2013-15 and was a trustee of the Nicholas Danby Trust. In 2018 she was awarded the medal of the Royal College of Organists, its most prestigious award. Most recently she became a patron of The Society of Women Organists. She also had a highly successful international recital career which continued throughout her musical life.

also curated a series of concerts each year showcasing the emerging talent of those beginning their international careers as professional organists. I have seen many tributes to her from now well-established organists who say that she was a formative influence on them in their early years.

In 35 years at St Lawrence Jewry she played at civic services for 35 Lord Mayors of the City of London, and there is probably not a single past Master of the 110 livery companies who has not heard her play at major events. She was also ever-present at weddings, memorial services and special events for so many people over those three and a half decades.

One of her great passions was to nurture young organists. In recent years, St Lawrence hosted a series of sixth-form student recitals, allowing young performers to give a major London recital with support and encouragement from such an inspirational member of the organ world. Catherine

But such CV material does not tell the whole story. Catherine was a true giant of the organ world but was also a wife and daughter and mother who gave loving attention to her whole family while continuing her professional career.

She was also a supportive colleague to me. I came to St Lawrence Jewry with little musical knowledge and no professional music background. I was privileged to work with someone who understood the relationship that needs to exist between clergy and organists. She had an instinctive awareness of the dynamics of the Anglican choral tradition as director, conductor, organist or all three at the same time!

Catherine was never one to push herself forward. Her high-profile roles, such as President of the Royal College of Organists, were for her all about service, not self. Her commitment to young organists and to organ-building was about the future of the organ in the wider musical world. Her desire for nothing but the best was deep in her heart.

I was honoured to have her as a colleague, and I will miss her greatly.

Reverend Richard McLaren adds:

Catherine, as Director of Music at Marylebone Parish Church, was a female leader in a decidedly male milieu, and being also a Roman Catholic in an Anglican church she was distinctly exotic. But she understood the making of Christian worship to her fingertips. She was brilliant at interpreting the spirit of the liturgy with her particular combination of discipline and spontaneity which brings all good music-making to life. She understood perfectly how to frame sequences of words and music, silence and movement, the emphasis of minor and major keys, diminuendo and crescendo. She knew just what settings of the repertoire would work and for what occasion – for intimate private occasions, major public ones, ordinary Sundays, special Sundays. You can imagine what a rare professional gift this was to a priest or team preparing worship with her. A gift of heart, emotional intelligence, as well as learning – in fact nothing less than her soul. St Irenaeus, a Church Father in the 2nd century, wrote a perfect line for her: ‘The glory of God is a human being fully alive’. That is Catherine. I, and many others in the church’s life, thank God for her.

After college at Oxford, she was appointed assistant organist at Christ Church, the first woman to hold such a post at an English Anglican cathedral.

“You’ve come all the way from Canterbury. You poor sods, a hell of a bloody way.” These warm words from the dean greeted Philip Moore on arriving for his interview to replace Barry Rose as Organist and Master of the Choristers of Guildford Cathedral.

It was 1974. Fifteen years earlier Barry had himself arrived and set up the choir in time for the cathedral’s consecration on 17 May 1961, quickly building it up to a level of sustained excellence before moving on to St Paul’s Cathedral: his successor would be facing a daunting task. As Philip later put it, ‘[Barry’s choir] sang everything exceedingly well’.

Philip was at that time assistant to Allan Wicks at Canterbury Cathedral, having earlier studied organ, piano, composition and conducting at the Royal College of Music before being

appointed Assistant Music Master and Organist at Eton College. He had been at Canterbury since 1968 but, keen to run his own show, he had for some while been applying for cathedral posts as they became vacant: Exeter, Wells and Winchester. But, ‘I wasn’t shortlisted for any of those. Then Hereford and Guildford came up at the same time. I had always admired Guildford and had been very impressed not only with the choir but also with Tony Bridge, the dean. He had come to Canterbury to conduct the Holy Week services, and he was unforgettable and riveting ... (Also) one of the canons, Frank Telfer, had been chaplain of the University of Kent at Canterbury, and I knew and liked him.’

The appointment was announced at the beginning of April 1974 and Philip moved into Cathedral Close in time for September. Barry had thoroughly briefed him before handing over, but it was, as Philip later recalled, ‘Daunting indeed … succeeding someone who had not only built a fine choir more or less into the very fabric of the building, but who had also sustained its excellence.’ Philip did, however, have a clear idea of how he wanted to develop the music at Guildford. ‘I wanted to broaden the repertoire, especially over the selection of communion and Mass settings. I may have gone over the top to begin with but eventually we came to a happy medium. … (but) generally the choir sang so well that I wasn’t out to change anything drastically. I think (overall) I just wanted to make the daily offering as good as it could possibly be.’

One thing Philip found difficult was the system by which the men operated. ‘There were those who came to every service, and those who attended on certain days of the week. All were paid. One man, for example, would appear on Mondays and Tuesdays. At the weekend, several others would appear –usually an alto, two basses and a tenor. It was a difficult system to operate because I would sometimes want to look ahead to weekend music, the setting of the Mass especially, and all sorts of balances would be thrown out by this influx of singers. Eventually we began a system of choral scholarships with the University of Surrey, which was close by. This worked well and produced some fine singers, who eventually made their names in the London singing world.’ Another burden ‘was having to drive some of the boys home after Evensong. Simon Deller drove some in the minibus in one direction and I went in another. With Evensong at 5.45pm, this made for a very late arrival home. It was not easy, especially as our three children were aged between ten months and four years old.’

Philip was helped to settle by being welcomed warmly into the cathedral community. ‘The precentor, Robert Gibbin, was a very caring man, a good musician and a good flautist. It was quite clear from the very beginning that the dean and chapter and the parents were completely behind me in everything. The sub-organist, Tony Froggatt, was also there to help and not to hinder. If things had not gone according to plan, he would give an honest and unbiased opinion about why.’

Inevitably, though, there were some who struggled with the new arrangements. Peter Wright, who took over from Tony Froggatt in 1977, later remembered that when he arrived, ‘The ghost of Barry Rose (was) still very much in evidence. There were some who simply refused to believe that anybody after Barry could run the choir. As one lay clerk put it, “Even if St Cecilia herself had taken over there would still be some who would moan.”’ However, Philip ‘brought his own experience

of working with Allan Wicks at Canterbury and his own strong musical personality to bear on the choir,’ says Peter.

Philip was to stay at Guildford for nine years, before succeeding Francis Jackson at York Minster in 1983. There were many highlights in that time. He is particularly proud of his first broadcasts. ‘Barry wrote and said how impressed he was – and that the first was better than any previous ones that had come from Guildford. I treasured that, having taken over his baby!’ Other highlights included, ‘Evensong, especially in the depths of winter. Starting Advent Procession services, and instituting a sung Requiem on All Souls’ Day, my last Duruflé Requiem being especially memorable.’ And the funniest moment? ‘Tony Bridge, the dean, saying, after the Magnificat, “I believe in one God…” I went over to him and whispered, “The second lesson comes next.” He replied: “Terribly sorry, everybody. Sit ye down.”’

St Paul’s, Gloucester and Winchester. I will never forget the combined choirs singing the Howells St Paul’s Magnificat under the dome. It was quite overwhelming. By contrast, some of the most satisfying moments were at Evensong in the gloom of winter with very few people in attendance. A simple piece of Tallis or a pianissimo ‘Gloria’ to a psalm might just touch a spot when building, organ and singers were in perfect sympathy with each other.’

Since 1983, three organists have been in post in Guildford with the present holder, Katherine Dienes-Williams, the first woman to hold the most senior musical post in a Church of England cathedral, arriving in 2007. Andrew Millington took over from Philip in 1983 and stayed until 1999 and Stephen Farr was in post between 1999 and 2007.

Before being appointed to Guildford, Andrew Millington was assistant organist at Gloucester Cathedral. He was well aware of what he was taking on. ‘Initially I was anxious that we could keep the ship afloat as I realised that the cathedral was going through a precarious time financially. We couldn’t afford to employ a precentor for the first three years of my time. Secondly, I was acutely aware of the reputation and high standard of the Guildford choir. My immediate ambition was to maintain the quality which had been a hallmark under Philip and Barry. It can be more of a challenge to maintain a level of excellence than to build things up from a lower level.’

There were many highlights: ‘I recall a very moving performance of Bach’s St John Passion which the choir gave one Good Friday, and a trip to St Paul’s in London for the Festival of the Sons of Clergy, where we joined the choirs of

After 16 years Andrew moved on to Exeter Cathedral, and was succeeded by Stephen Farr, who had been sub-organist of Winchester Cathedral, and before that at Clare and Christ Church. It was Stephen who oversaw the introduction of girl choristers into the choir in 2002.

Stephen arrived with plenty of ideas, as he later remembered: ‘I had some big ambitions, yes, being a green 30-something sub-organist – repertoire, projects, commissions etc. It’s true to say they were shelved pretty fast when I arrived, and I’ll leave it at that – my first two or three years were not at all easy.’ These years include what Stephen regards as his biggest challenge: ‘An Easter Day with only six choristers singing out of a full complement of nine. Two were ill, one was on a family holiday. And consequent to that, finally grasping the nettle of changing the routine to make some sort of normal family life possible for chorister parents. It was difficult, and caused upset and even hostility, but it was increasingly clear that the proposition we were offering to children and parents had become untenable. A seven-day week (Monday-Friday school and/or cathedral, then cathedral all weekend) for 8-13 year olds in a day-school infrastructure is not a healthy thing. I know that because every single family we offered a chorister place to that year turned us down, and I asked them to tell us why. I took some flak for it, but noticed that several other foundations followed suit not long afterwards. Our chorister numbers doubled within three years.’

There were some notable musical highlights for Stephen, though. ‘Probably my most memorable individual service was a Lady Chapel Tallis Lamentations with the gents on a proverbial foggy Monday in Lent – a non-clerical congregation of precisely no one, but exquisitely sung; it could have gone straight on to a CD. Advent carol services would be next on the list – something about the occasion always inspired the boys to raise their game several notches. Curiously, the big things like the Royal Maundy left less of a mark on me musically.’

Highlights for other reasons include, ‘The new sound system picking up the calls from a local takeaway driver’s radio. “The

Lord be with you; two chicken bhunas and a garlic naan to No. 5”!’ Also, ‘The sense of everyone pulling very hard to make it work, and the delight and satisfaction all round when it did. People are really invested in the place.’ And his lasting memory? ‘Being alone in the building on sunny evenings – just beautiful. When I left, a member of the clergy sent me a very kind letter saying that I had created a choir which punched way above its weight, so I’ll happily settle for that!’ Stephen moved on from Guildford to combine a freelance career with posts as Director of Music at St Paul’s Knightsbridge and Music Consultant of Worcester College Oxford.

Stephen was followed by Katherine Dienes-Williams in January 2008. Katherine was born and educated in Wellington, New Zealand, and studied for a BA in Modern Languages and a BMus at university there. She was organ scholar and then assistant organist at Wellington Cathedral. Prior to arriving at Guildford she had been Director of Music at St Mary’s Warwick for seven years. Her time at Guildford has not been without its challenges.

‘The profile of the cathedral sounded like a good fit. I knew of Stevie Farr’s excellent musicianship and his work with the choir and that there were both boy and girl choristers, which appealed.’ Katherine was the first female appointed to direct the music at an Anglican cathedral although, for her, her appointment to Warwick seven years previously had seemed the more pioneering moment. But, ‘the smashing of the glass ceiling did feel like a huge, vastly important moment at the time and utterly thrilling. It was always a case for me not of “Why” but rather of “Why not?”’

As with every Guildford Cathedral music director, a constant challenge has been the transportation of choristers. ‘We are heavily reliant on the goodwill of our chorister parents in collecting and dropping their children off here, whilst depending on a bus service to transport our boy choristers from Lanesborough School and the Royal Grammar School to the cathedral after school on Tuesdays and Thursdays. There are days when the bus doesn’t turn up, the bus is late, there is snow mid-Evensong, a traffic jam on the A3 etc. and one has to make alternative arrangements, very often at the last minute.’ And of course Katherine also has had to negotiate the choir

through Covid, including the death of a deputy singer, Tim Pride, former countertenor lay clerk at Winchester, who last sang with the choir in one of the final fully choral services in March 2020.

Katherine is full of ambitions for the development of music at the cathedral. ‘I think we should have someone from the music and education departments to really harness musical outreach so that we become a centre of musical opportunity and learning for all generations. This needs to work right from toddler music groups to local primary schools to the cathedral choir to the Guildford Cathedral Singers (adult voluntary choir) to links with our ex-choristers to music for people in care homes / people with special needs – we need to just harness it all together. We should be a hub of excellence and be proud to be ‘elite’ – just as one would be proud of being an elite athlete.’

Barry Rose’s ‘baby’ is clearly in safe hands.

Simon Carpenter works part time in the NHS and has recently completed an MA on Herbert Brewer and his pupils at the University of Gloucestershire. This has led to him achieving his dream job of joining the Three Choirs Festival team as a voluntary archivist and historian.

It was autumn 1995 and we had just moved to Southport. Within the first few weeks of starting at my new school there was an opportunity to audition to sing in a choir. At the end of an assembly, a man entered the room and proceeded to sit down at the school piano; he listened to us all sing a scale (although I didn’t know what that was at the time) and then, at the end, handed a letter out to those who had impressed, inviting us to a meeting at Holy Trinity Church.

And that was my introduction to a lifelong love of an interest in singing, music and the great buildings in which these are heard – supported (thankfully) by my parents, who still to this day are actively involved in the church, my mother as churchwarden, and my father as a member of the choir.

Holy Trinity Southport is and remains my home parish church. There has always been a rich musical heritage, one which was established by David Bowman in the early 1960s. Some readers might recognise his name from Ampleforth Abbey, where he formed the Schola Cantorum. The legacy was carried on by the appointment of David Williams in 1965 – he remained in post for almost 40 years, working alongside three different incumbents, most notably Revd Canon Dr Rod Garner, who retired in 2008. Ian Wells from Liverpool Anglican Cathedral took over the role on David’s departure, and John Hosking, formerly organist at St Asaph Cathedral, replaced Ian a few years ago.

There are too many memories to talk about as a chorister, from evensongs in the depth of winter where sometimes only your breath could be seen, the great patronal celebrations, concerts a-plenty – the opportunities were so many! The greatest was the annual ‘Choir Holiday’ where we packed our musical bags and travelled off to a cathedral and sang the services whilst the resident cathedral choir went on their summer holidays. This was, and still is, a valuable part of what goes on not only at Holy Trinity, but also across the country in other parish church choirs. My first holiday was in 1996 when we visited Llandaff Cathedral and in future years we visited Peterborough, St George’s Windsor, Bristol, Southwell Minster, Norwich, Exeter and Chichester. In all, I sang on 22 choir holidays, and they remain some of my foremost memories of my life as a chorister. The opportunity to sing in these great spaces filled me with a great sense of pride –a tradition unrivalled in the world. And I enjoyed the social elements as I got a bit older!

An undergraduate degree at the University of Huddersfield offered more opportunities – the course was a varied one that encompassed many different elements of music, and it opened my eyes to specific subjects such as small ensemble singing, and the Renaissance and Baroque periods in detail. I greatly appreciated the chance to sing in a small choir at St Peter’s Church, and I latterly filled the post of acting Director of Music in my final months in Huddersfield, working

alongside the Very Revd Catherine Ogle, currently Dean of Winchester. Another revelation in the final months was an introduction to the City of York by a good friend who had become involved in the renowned York Early Music Festival, an organisation I am still involved with to this day. Dr Delma Tomlin MBE, the director, is a constant inspiration to the arts world, especially in these trying times we currently are living in. I had never considered studying for a Master’s degree, but the more I thought about the prospect of living in York, the more the idea became attractive. I was very aware of the musical heritage the city had to offer.