Cathedral MUSIC

ISSUE 2/10

Cathedral Music

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2010

Editor

Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace Ripon

North Yorkshire HG4 2QS

ajpalmer@lineone.net

Deputy Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon

FCM e-mail info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road

LONDON SW4 8AR

Tel:0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership

27 Old Gloucester Street

London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087

E-mail: info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT

Tel: 0113 255 6866

info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

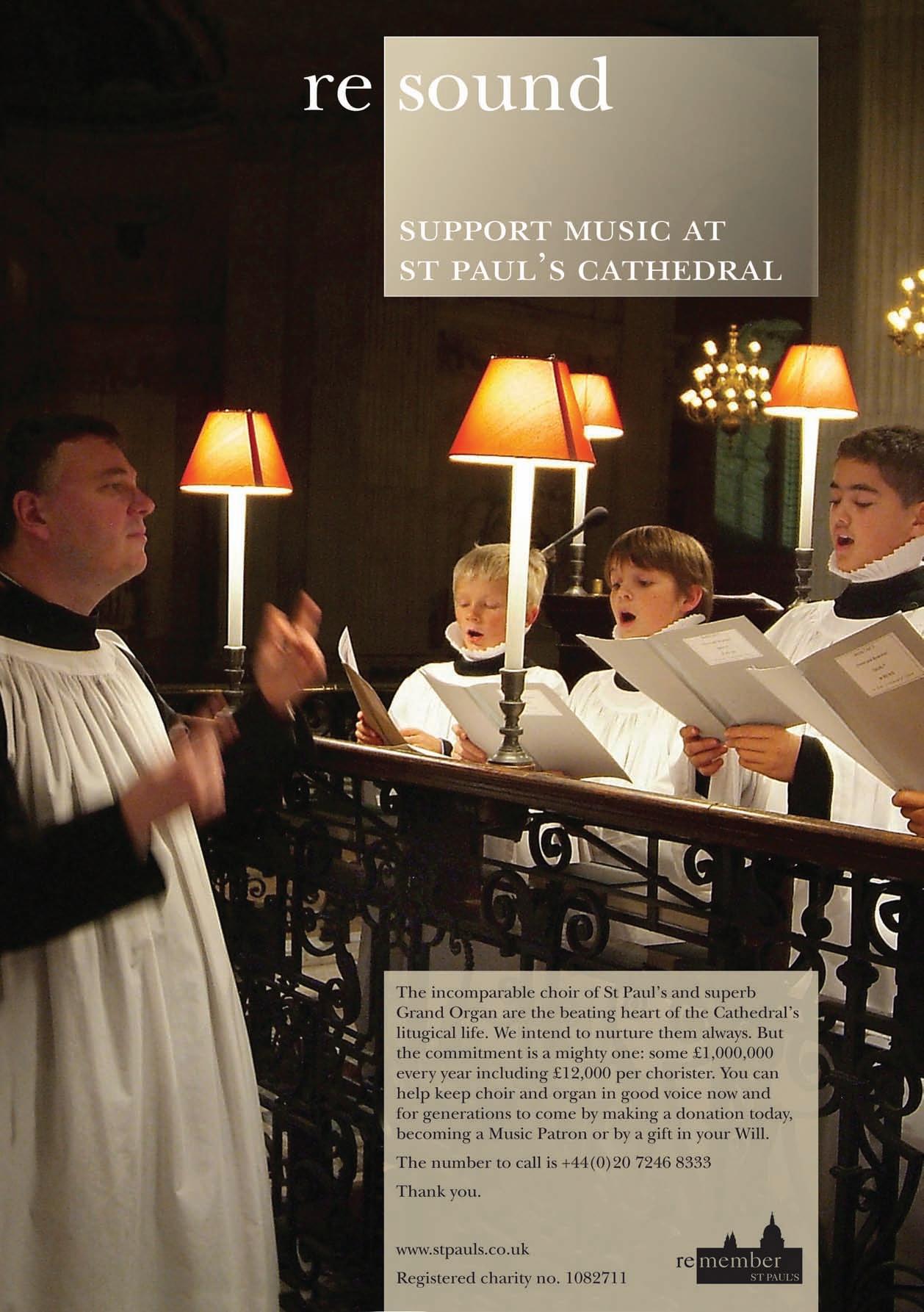

Cover Photographs

Front Cover Westminster Cathedral © Alex Ramsay Photography

Back Cover

Mgr Richard Moth, former Vicar-General of the Archdiocese of Southwark is Ordained Catholic Bishop of the Forces at Westminster Cathedral. 29 September 2009.

© Catholic Church (England & Wales)

Cathedral MUSIC Cathedral MUSIC

The Magazine of the Friends of Cathedral Music

Cathedral Music 3 Payment of a donation of £3 to the distributor of this magazine is invited to cover the cost of its production and distribution

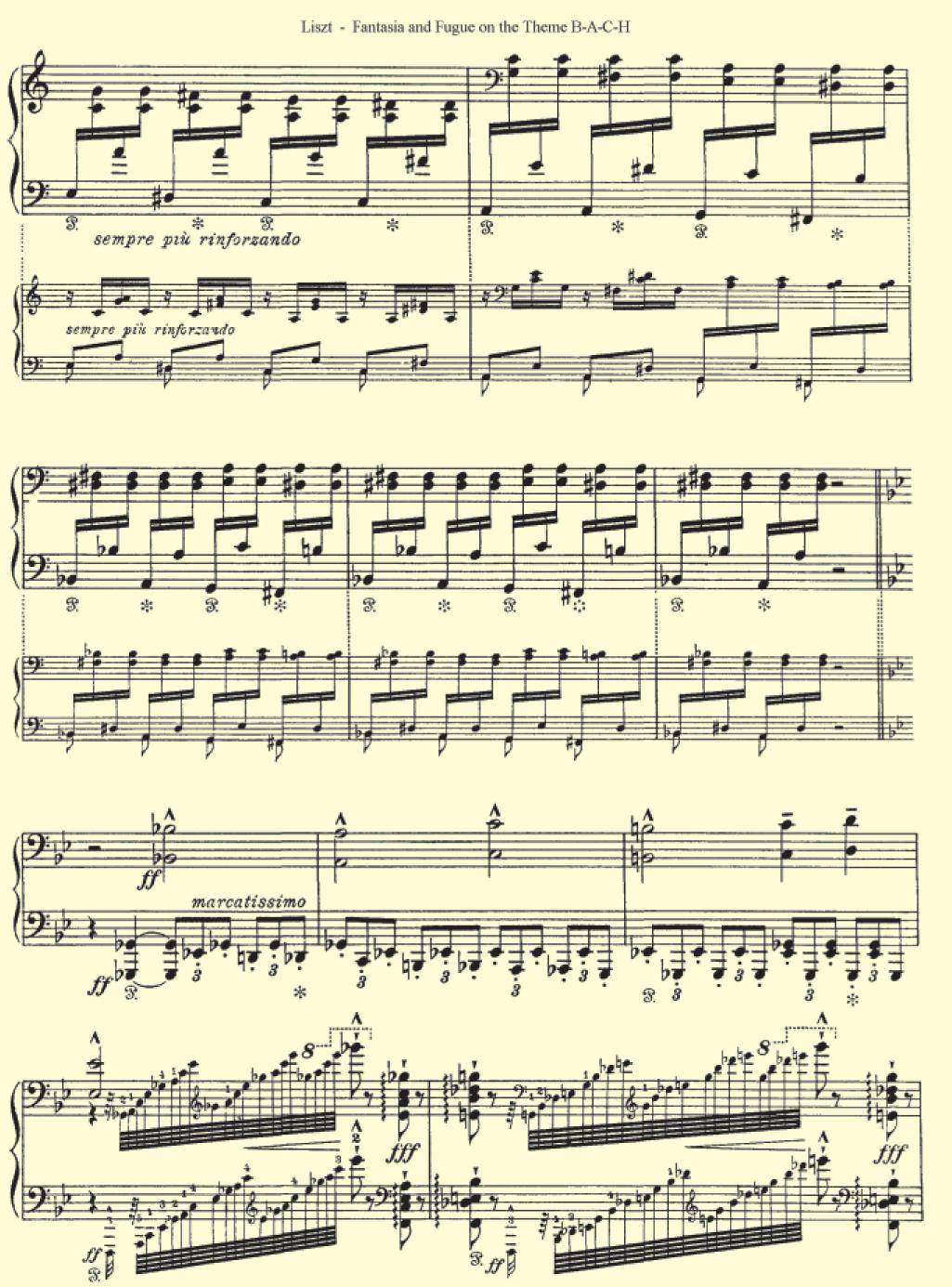

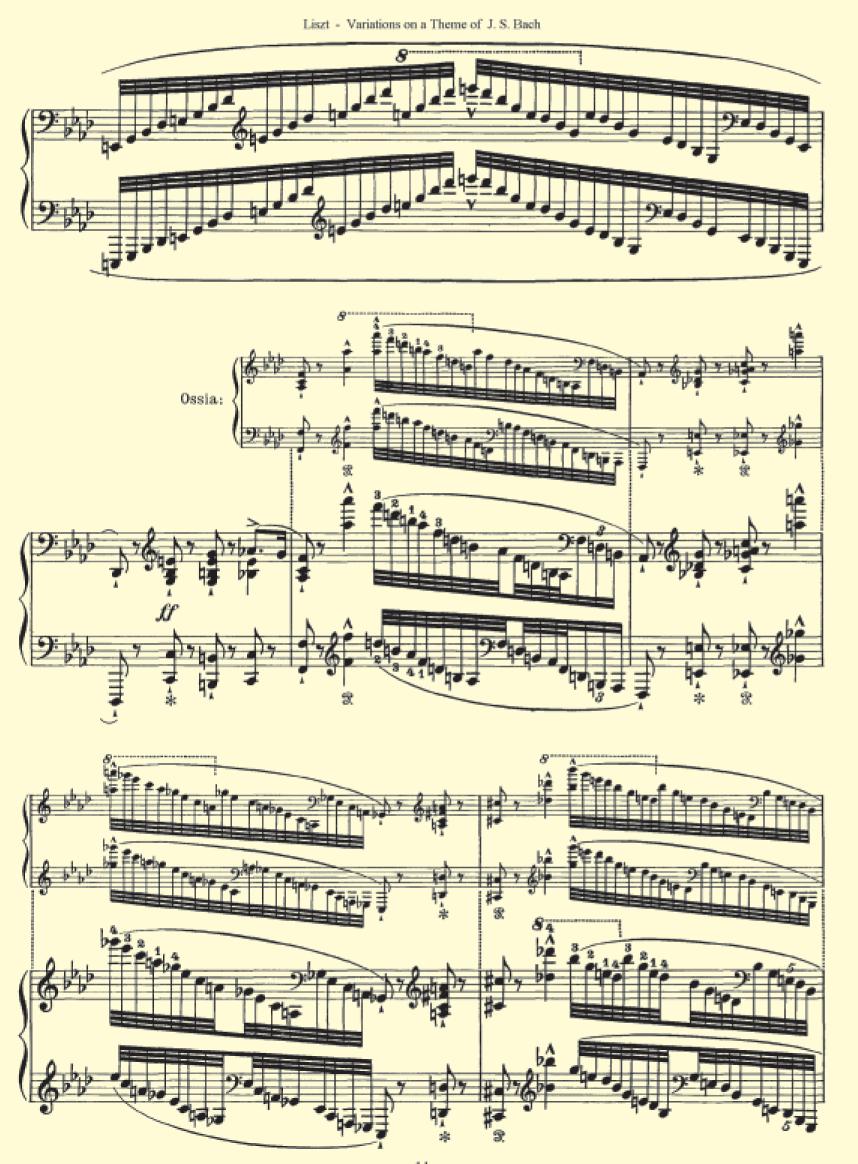

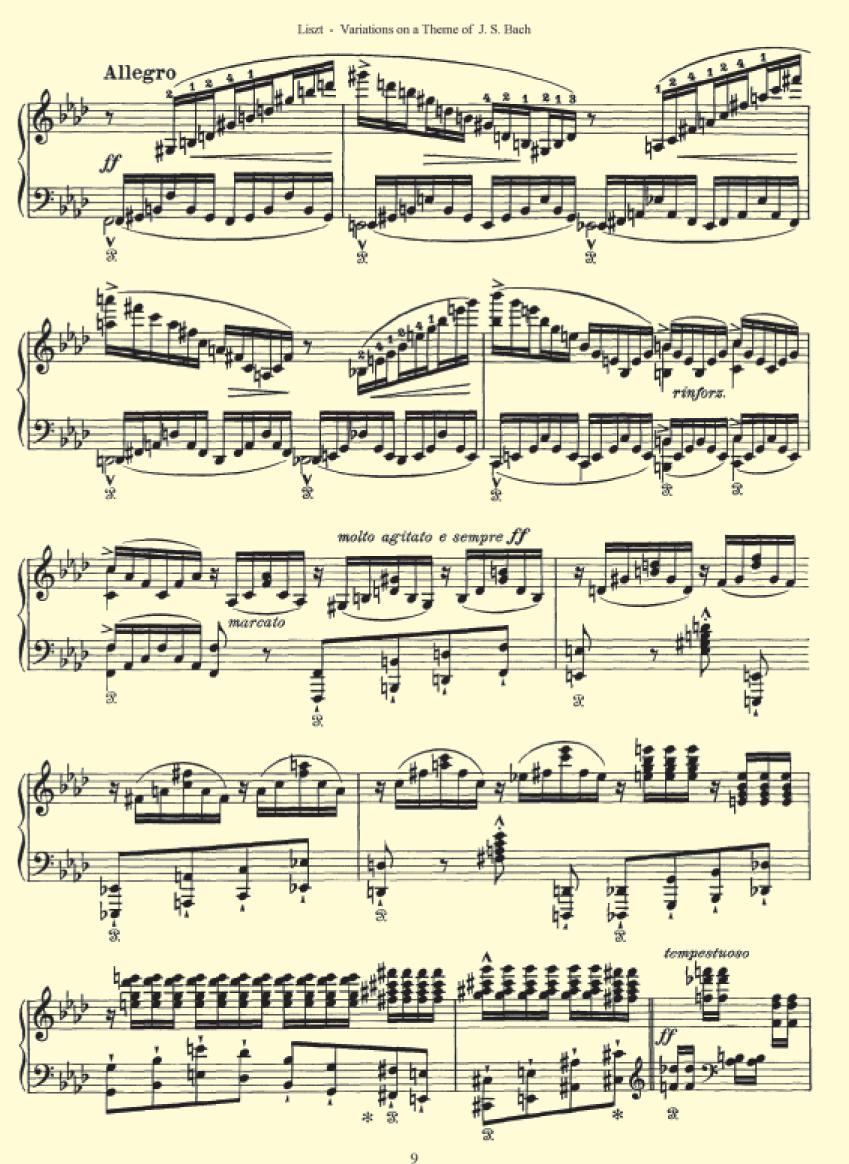

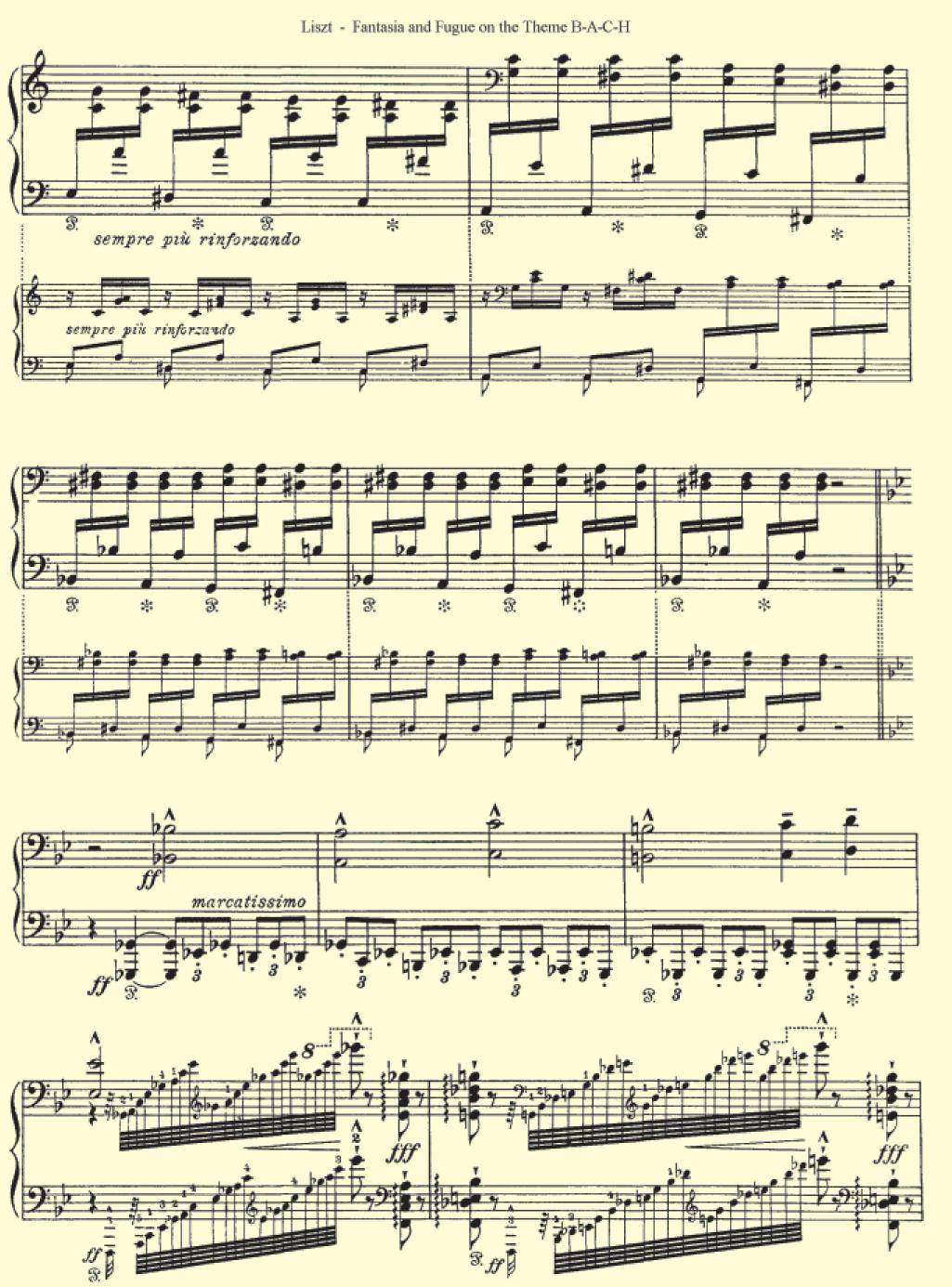

CM Comment 4 Andrew Palmer George Malcolm & the Westminster Cathedral Sound 5 Patrick Russill Some Reflections on my association with Westminster Cathedral 10 Stephen Cleobury CBE –Director of Music, King’s College, Cambridge An Interview with Jonathan Dove 12 Timothy Hone Philip Rushforth 18 60 Seconds in Music Profile From the Vaults of Westminster Cathedral 20 Sooty Asquith talks to Martin Baker about musical life at Westminster Cathedral Westminster Memories 24 David Hill recollects his time at Westminster Cathedral Celebration & Refreshment 26 The Chorister Outreach Programme and its effect on cathedral singing –David Lowe Geoffrey Burgon 29 Obituary Organs and choirs in the English Cathedral 32 Talk given to the FCM by Nicholas Thistlethwaite Palestrina For Tuppence 38 Timothy Storey A Short Tour of London Churches 40 Leigh Hatts Life After Bach 42 An Exploration of the organ music of Franz Liszt –Peter King Sibthorp makes The National Archive of Anglican Chants 2010 47 Peter W J Kirk Regent Records –Past, Present and Future 48 Gary Cole Letters 51 Your views Festivals Overview 2010 52 Roger Tucker Book & Music Reviews 54 The latest books and recordings DVD Reviews 65 Recent DVDs

CM Comment Andrew Palmer’ ‘

music in England, particularly by Tallis, Byrd and Taverner and Mass at the Cathedral was soon attended by inquisitive musicians as well as the faithful. The performance of great Renaissance Masses and motets in their proper liturgical context remains the cornerstone of the choir’s activity and formed the focus of the music for the Pope’s visit to Westminster. Terry also commissioned works by great Anglican musicians such as Howells, Stanford and Vaughan Williams.

This edition celebrates the music of the Catholic Church, especially at Westminster, on the occasion of the state visit to the UK by Pope Benedict XVI.

We know that the Pope was impressed and delighted by the quality of the singing he heard from both the Choir of Westminster Cathedral under Martin Baker and the Choir of Westminster Abbey under James O'Donnell, who is the first Catholic Organist and Master of the Choristers at the Abbey since the Church of England broke with Rome in 1536. The Pope heard for himself that the quality of cathedral singing is surely the highest it has been in 475 years. It has survived suppression during the Commonwealth, which attempted to destroy the high musical traditions of the Church and stringency during two world wars.

The work of the Friends of Cathedral Music since its foundation in 1956 has played a part in this quest for everhigher standards.

Cardinal Vaughan (1892-1903), the founder of Westminster Cathedral, recruited the outstanding cathedral music director of the time, Richard Runciman Terry from Downside Abbey, to be the first Master of Music for his new cathedral thereby setting the very high standard which has been maintained ever since. Richard Terry built up Westminster Cathedral Choir and was instrumental in reviving the music of the Golden Age of Renaissance

The Pope also heard a new commission composed for the occasion by FCM Vice-President James MacMillan, titled Tu es Petrus, which attracted huge praise and attention. This is highly significant: MacMillan is in my opinion currently the most important Catholic composer in the UK. His faith has inspired him to compose many sacred works. In a recent interview MacMillan told CATHEDRAL MUSIC that he was getting ‘more and more interested in what liturgy is, and exploring what might work best for Mass, either in the music that I write or the music that I use’.

It was interesting, too, that Byrd’s Mass for Five Voices was sung at Westminster Cathedral. Byrd never really abandoned his Catholic faith and lived through a time of religious persecution and his music was the fruit of deeply-held belief expressed against a back-drop of danger, but due to the tolerance of Elizabeth I he survived this turbulent period in our religious history.

In the same interview James MacMillan was also asked if these intense levels of persecution which may be a thing of the past, could still be significant obstacles put in the path of a Roman Catholic composer today. His reply was that: “It’s not just an issue for Roman Catholic artists, but we live in a time of renewed secular aggression about religion and a lack of understanding of the nuances of religion born out of perceived fundamentalism in a number of different religions. We live in a time of religious fanaticism as well, and the mainstream churches: Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian etc, are taking

the brunt of this, not just in the world of the arts but also in the wider world, and there is a kind of secular fundamentalism, almost as a counterpart to the religious fundamentalism, which has taken root in the public debate. This is very worrying and it doesn’t make for a complex and nuanced understanding or even discussion about religious matters.” This was a theme that Pope Benedict expanded on during his insightful and thoughtful address to the politicians in Westminster Hall.

MacMillan’s voice is an important one for us and should be listened to as his messages are so obviously relevant to today’s secular society.

Cathedral music had an important role in the Pope’s visit, not least because of its congruence between the Roman and Anglican Churches.

We can rejoice in the fact, unlike in France where first the Revolution and then two world wars disrupted the cathedral music tradition, in these Isles it has survived.

The millions who watched the services on television and listened on radio will have been struck by the indications of our growing ecumenical rapprochement being so well served by two of our leading choirs.

We at the FCM have continued to foster strong ecumenical links. We invited the Archbishop of Westminster to join the Archbishop of Canterbury as Joint Patron and James MacMillan and the Bishop of Brentwood to become Vice-Presidents.

Monsignor Philip Whitmore, who shared his bird’s-eye view of the Westminster Abbey service on Vatican Radio said: “...the beautiful liturgy that is so characteristic of English cathedrals goes back to the days when so many of them were monastic foundations and certainly Westminster Abbey was a Benedictine monastic foundation.”

Millions will have heard and seen James O’Donnell and Martin Baker conduct their choirs and we really should give plaudits to them and to the BBC for its excellent television broadcast coverage of the visit.

Cathedral Music 4

We know that the Pope was impressed and delighted by the quality of the choral singing he heard...

GEORGE MALCOLM

& the Westminster Cathedral Sound

Patrick Russill

Patrick Russill

It was only in 1981 that I first met George. This was more than 20 years after he had relinquished his post as Master of the Music at Westminster Cathedral, and though it was the autumn of his career he was still fairly active as a harpsichordist, pianist (often as a chamber music partner), conductor and even as an organist (including recordings of the Poulenc Concerto and the complete Handel Organ Concertos).

Ihad been drafted in as a replacement for Nicholas Kynaston to accompany a performance of Mendelssohn’s Lauda Sion at the Spode House Music Week, near Rugby, an annual post-Easter course for Catholic families, which George had been instrumental in founding. With some trepidation I introduced myself to this legendary figure. Then in his mid-sixties, Gauloise in hand as was his invariable custom, looking very thin and gaunt, but with a strikingly penetrating gaze, George was charmingly self-deprecating, courteous, keenly alert and intelligent, and flatteringly interested in who I was and what I did. Almost immediately, he sat me down at a piano and insisted we played some Mozart. Clearly this was intended to find out straightaway what sort of a musician I was. We started with the duet Variations in G major (K.501). He made me play primo, but it was impossible not to respond to the grace and finesse of George’s influence from the secondo part. At the end he said: “I’m so glad you don’t play like an organist!” – so all was well! Working with him on the Mendelssohn was wonderful. He was appreciative, encouraging, insightful and inspiring – he was in fact a great

natural teacher. Happily the performance went well and from then we became good friends.

He asked me to play continuo for him in concerts he conducted with the English Chamber Orchestra and the Philharmonia Chorus and to assist him as pageturner/registrant for a couple of remarkable organ recitals he gave in the Royal Festival Hall three or four years later (wonderful musicianship allied to minimal regard for ‘authenticity’). On these and other occasions we talked a lot about music and music-making in general, about his early musical formation and his time at Westminster Cathedral. For the last 15 years of his life he would always come to the London Oratory for Mass on Christmas and Easter mornings, a tell-tale whiff of Gauloise betraying that he had just come into the organ gallery and was just behind my shoulder as I played Messiaen’s Dieu parmi nous or the organ solo from Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass. And I was privileged to play the organ for his funeral in the Sacred Heart Church, Wimbledon.

There are very distinguished musicians who could describe (as I cannot) the first-hand experience of working under George at

Cathedral Music 5

Westminster Cathedral: Michael Berkeley, John Elwes, Colin Mawby and Nicholas Kynaston amongst his choristers, and Ian Partridge amongst his lay clerks. Yet, like everyone who made music with George I imagine, I retain the strongest impressions of one of the great musicians, whose character was entirely subsumed in the process of communication through music.

That introductory experience of playing Mozart with George made it clear his music-making was driven by scrupulous attention to imaginative gradation of tone colour and dynamic – not just what it said on the score, but lots, lots more. Phrasing was lifeblood. For all the brilliance of his passagework and rhythmic energy, the bedrock of his approach was lyrical, generously romantic but extremely elegant too. He gave a revealing response to Sir Hugh Allen at the Royal College of Music when he was auditioned there as a seven year old: on being asked who his favourite composers were, he replied “Mendelssohn and Gounod”. ‘I think that’s almost true now’ he added when he told me the story.

In my experience, the word he used in rehearsals more than any other was (in a rather high nasal intonation and decisively drawn-out) ‘...slight-ly...’. Whether the request was for louder/softer, faster/slower, higher/lower you knew that that ‘...slight-ly...’ was absolutely vital. Like all great musicians there was a compulsion in his music-making that was completely part of his character. It galvanized his singers, alternately captivated and terrorized his choristers and certainly bemused and terrified many of the clergy. That compulsion draws its power from different sources in different musicians: in George it was significantly fuelled by colourful Celtic aspects of his temperament, but also by religious devotion, discipline and courage. He had been a heavy drinker, to the extent that it threatened his career and even his life – in 1949 he fell through a second-floor window and suffered appalling facial injuries which required reconstructive surgery. He eventually became an absolute teetotaller with the assistance of the well-known radio voice of Catholicism in the 1950s and 1960s, Fr Agnellus Andrew. Nicholas Kynaston, who was a Westminster Cathedral chorister from 1949 to 1955 (and of course Organist there 1961-71), recalls that that however did nothing to alter George’s essential musical volatility.

George’s approach to choral sound, especially the sound of boys, was profoundly influenced by the work of a charismatic Jesuit priest, Fr John Driscoll, who from 1904 was choirmaster at the Sacred Heart Church, Wimbledon, right next door to the Jesuit Wimbledon College where George was a pupil. Driscoll’s Wimbledon Choir collaborated with Terry’s Westminster Cathedral Choir for the liturgical premiere of

Cathedral Music 6

Vaughan Williams’s Mass in G minor in 1923. Then from 1928 until his death in 1940 Driscoll was choirmaster at the Jesuit Church, Farm Street. According to George, who observed Driscoll’s rehearsals at first hand, the Farm Street boys were taught bel canto technique by a tenor from one of the London theatres, and combined with Driscoll’s iron discipline and musical drive, the resulting sound, as George heard it in the 1930s, was the inspiration for his own ‘Westminster Cathedral sound’. It was not an attempt to import a preconceived Continental style, but rather to exploit and control the natural open quality of a boy’s voice and character (‘just like you hear in the playground’ George said) within a Latinate vowel spectrum, a sound that he regarded as being entirely characteristic of Irish and Scottish traditions as well as Mediterranean traditions – an inherently Catholic mix. ‘The Farm Street choir’s entry in the first chorus of Mendelssohn’s Lauda Sion was terrific – they were the most exciting boys’ choir in London’: his emphasis used the same intonation as ‘...slightly...’. Driscoll was undoubtedly one of George’s heroes.

The Westminster Cathedral sound in 1947, when George arrived as Master of the Music there, was entirely at the other end of the spectrum from the Farm Street sound. Exactly what the sound of Terry’s choir was like, up to his resignation in 1924, is difficult to tell from the crude acoustical recordings that survive, but in the 1930s when the choir was run for a time by Fr Lancelot Long and by William Hyde (who in the 1930s, and on into the Malcolm regime, was a faithful, unsung assistant and more at the Cathedral) the boys’ sound was notably covered and hooty. Ralph Downes (who heard them after he returned to London as Organist of the Oratory in 1936 after a period in the USA) assured me that the boys were exercised to ‘lu – lu- lu’, and a 1931 recording (HMV C2256) of Howells’s Salve Regina and Philips’s Regina caeli bears this out. All the vowels are unbelievably ironed-out, the tone heavily covered: all is dull, unnatural and inexpressive.

George himself had a reedy baritone voice, with (as so many choirmasters do) an element of exaggeration added for teaching effect, in George’s case an over-bright production of vowels and relish of consonants. Ralph Downes attended a Christmas concert by the choristers in the Cathedral Hall in 1947, only months after George had taken over. According to Ralph every boy sang a solo ‘and they all sounded like little Georges’ – testament to George’s force of vocal and musical personality and his investment of trust in each chorister.

The development of the Westminster sound during George’s time can be glimpsed in tantalisingly short snippets on British Pathé newsreels. A collection of out-takes from a Mass in 1950 celebrating the centenary of the re-establishment of the English Catholic hierarchy is at www.britishpathe.com/ record.php?id=82916. Already one can dimly make out the passion and atmosphere typical of George, though perhaps not the full measure of tonal zest to be heard later in his tenure. Nonetheless, the decidedly mixed bunch of men whom George (for various reasons) had to make do with, and to whom he was characteristically loyal, are unmistakeable. On a later newsreel of the 1957 enthronement of Archbishop Godfrey at www.britishpathe.com/record.php?id=32655 we can hear the choir briefly and in full flight (I can’t identify the piece). The sound and delivery is instantly familiar: as on the famous recordings of Victoria’s Tenebrae Responsories and Britten’s Missa Brevis everyone is singing as if their lives depended on it.

George insisted that his sound was inherently healthy and was produced by a basis in good technique. During my first encounter with him at Spode House he explained some of his coaching techniques to a group of us. How was he able to get his boys to produce ‘that sound’ while singing high and piano,

and how was he able to cover the passaggio between chest and head voice? He said he encouraged his boys to imagine their singing to be like two counter-balanced lifts, as one (pitch) goes down, the other (resonance) rises. So high notes are produced with low, rich resonance and support, while low notes are produced with high, bright resonance. Nicholas Kynaston remembers George using this image and adds that correct breathing was also fundamental, together with absolute insistence on pure Latinate vowels (as is patently obvious from his recordings). He also remembers that once George’s essentials were absorbed, singing felt natural with no sense of forcing. Ian Partridge recalls he certainly was the first choirmaster he had come across who taught proper breath support. George himself said that he couldn’t remember any case of vocal health problems (nodules or the like). An amusing side effect was the boys singing of English (only at Christmas) when vernacular vowels had to be reintroduced to avoid ‘I saw three sheeps’ and the like!

Part and parcel of George’s Westminster Cathedral sound –and of course it has changed somewhat over the years, reflecting the musical character of successive Masters of the Music – was the intensity of expression that derived from his direction and exhortation. Nicholas Kynaston (again) remembers the boys being lined up after a performance of Victoria’s Requiem and George berating them for sounding like ‘a class of convent girls complaining about their rice pudding’: the next performance had rather more passion. When displeased, George could be witheringly and personally critical; when pleased, his praise was uplifting, the ultimate accolade being taken out for a cream tea in Victoria nearby.

Were it not for the survival of just a handful of recordings (both of the choir and also of some solo boys, especially John

The Choir of Westminster Abbey

The only specialist Choir School in the UK

James O’Donnell Organist and Master of the Choristers

Jonathan Milton Headmaster

All boys receive a substantial Choral Scholarship

Why not come for an informal audition?

(Boys aged 7 or 8)

Details from: Westminster Abbey Choir School

Dean’s Yard, London SW1P 3NY

Telephone: 020 7222 6151

Email: headmaster@westminster-abbey.org

www.westminster-abbey.org

Cathedral Music 7

Hahessy, now known as the tenor John Elwes) the remarkable instrument he created at Westminster Cathedral would be a matter of hearsay only, but thankfully the recorded legacy is uniquely vivid. The Victoria Responsories for Tenebrae recorded by Argo were put down in Holy Week 1959, at exactly the time the choir was performing them liturgically. In the ancient liturgy the responsories alternate with dry-as-dust patristic readings. The effect is like switching from black and white to vivid colour: academic meditation is contrasted with raw emotion and drama. George’s approach is unashamedly romantic, with huge interpretative interventions in tempo, rubato, agogics, dynamics and articulation, many of them, including re-touched scorings, inherited from Fr Driscoll’s edition. (The fine Bruno Turner edition for Chester was to appear a few years later.) The tonal and textual colouration is searing – it is not just that the pronunciation is ultra-Latinate, but that the meaning of the texts seem to completely possess the singers emotionally. If the boys occasionally tend to sharpness that is understandable given that the traditional Catholic Holy Week is gruelling enough musically without adding an LP recording to the schedule. The men, with the exception of a very young Ian Partridge (then, as ever, perfectly cultured and poised) and the counter-tenor Jonathan Steele, are wayward in intonation and vocal quality, though they are heroic in intent. But despite the variability of the men, the whole choir is forged into a single expressive unit by the heat of George’s inspiration, the communicative intensity making caveats seem trivial, even endearing. Ian Partridge recalls that, subsequently, George wished that his direction had been less excitable and more calm. Wildly dramatic it may be, but every gesture is justified by the words and their religious significance, projected by a blazing corporate response, which no subsequent recording has dared to approach.

Even by his own standards of lucidity and economy, Victoria’s directness of utterance in the Responsories is unique in his output, his motivic simplicity and formal clarity making possible a very detailed and varied interpretative approach – just as in the Italian madrigal repertoire of the same period. As I have found in my own annual experience of conducting the Responsories, variations of tempo and dynamic (even extreme ones), underlining the text and drama, are extraordinarily easy to negotiate with a choir. The texts are actually very curious, none more so than Animam meam dilectam which is an emotional switchback ride, with at least three different narrators (the Victim, the Oppressors and Onlookers as it were). Every aspect of George’s interpretation makes this clear, as a more objective approach would not. Other highlights are the extraordinary rage of Tamquam ad latronem (complete with Driscoll’s rescoring of the opening for tenors and basses rather than altos and tenors) and the exquisite grief of Caligaverunt oculi mei with its sublime setting of ‘si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus’ (‘if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow’), where the boys’ breathcontrol superbly supports the aching melodic line.

By the time the Victoria Responsories were recorded George had already decided that he would leave the Cathedral to pursue a freelance career. He told me that following sessions in Abbey Road studios sometime after Easter (he thought it was early May), he bumped into Benjamin Britten near Lord’s Cricket Ground, and told him he had resigned. ‘But what about my Mass?’ was Britten’s response, who had been bowled over by a performance of the Ceremony of Carols by George and his boys the previous Christmas. A fortnight later the score of the Missa Brevis arrived (it is dated ‘Trinity Sunday, 1959’, that is 24 May 1959). George said the boys learnt it in one rehearsal. The Decca recording (currently sadly unavailable), was made live at Mass on 22 July, with the boys singing from the organ gallery, necessarily stretched out in one long line in

the cramped space along the organ front and unconducted. In the heat of the moment, George makes a pedal slip at the start of the Gloria, and not surprisingly, ensemble is not always immaculate, but the corporate and individual confidence of the boys, the flair of the sound and the sweep of the performance are exhilarating. The solo boys were the same as on the Victoria recording: Michael Ronayne, John Hahessy and Kenneth Willes. About five years ago I heard the same qualities from the Cathedral choristers when they improvised (yes, improvised) a Missa Brevis, standing in the same layout along the organ front, unconducted yet brilliantly masterminded by Martin Baker at the console. The sense of mutual trust, confidence and liturgical understanding was just the same – deeply impressive and moving.

In case it may be thought that all George’s choral work was similarly red in tooth and claw, it is fascinating to hear his work from around the same time outside the Cathedral. In early 1961 he recorded Britten’s Cantata Academica and some smaller unaccompanied choral works, including an outstanding performance of the Hymn to St Cecilia for Decca. The choral group, though called the London Symphony Chorus, is clearly a hand-picked team of professionals. The Hymn is given a fabulously poised performance within the ensemble style of the time: scrupulous in intonation, blend and balance, totally clear in enunciation, written dynamics minutely observed. The opening section is leisurely, cool and witty; the scherzo is lightening fast and as clean as a whistle; the twists and turns of the final sections are flawlessly negotiated.

Professional adult choral sound has moved on in the past half-century, but for me, this is interpretatively still the benchmark recording of the Hymn to St Cecilia. Its knowing elegance and technical finesse is a world away from the risky passion of the Victoria and Britten recordings. Why then was this fan of Mendelssohn and Gounod – and consummate Mozartean – such an incendiary liturgical musician? For George, the mysteries enshrined in the Catholic liturgy, because elemental truth, had to be articulated in music with convinced passion, or not at all. A 17th century Oratorian, Blessed Juvenal Ancina, described Victoria as ‘servus Christi ardens’ – ‘an ardent servant of Christ’: George was no saint, yet he burned with the same zeal and is fully worthy of the same epithet.

A footnote about George’s liturgical compositions: he never claimed any originality as a composer, but nevertheless wrote fluently and suitably to order. The very first time I heard the Cathedral Choir live was Wednesday of Holy Week in 1969 – the boys only, under Colin Mawby, singing George’s turba choruses for the Luke Passion, beautifully tailored to the famous sound (which Mawby skilfully maintained), to the acoustic and the liturgical context. Kevin Mayhew has published a few other short high voice motets, as well as two more substantial works for Christmas: the Responsories for Matins of Christmas, which preceded Midnight Mass, their sense of joy and expectation wistfully recalled by those that heard and sang them in the 1950s, and the Missa ad praesepe which adopts a folkloric style with great charm. It is very appropriate that the current Cathedral Choir has recorded movements from this Mass on its recent Hyperion CD From the Vaults of Westminster Cathedral.

Patrick Russill is Director of Music of the London Oratory, Head of Choral Conducting at the Royal Academy of Music and Chief Examiner of the Royal College of Organists.

Cathedral Music 8

THREE GREAT PROCESSIONAL SERVICES MARK ADVENT, CHRISTMAS & EPIPHANY IN SALISBURY CATHEDRAL

Salisbury Cathedral is the setting for three great processional services which celebrate the special time of Advent, Christmas and Epiphany. This year for the first time The Advent Procession ‘From Darkness to Light’ takes place on three consecutive evenings, Friday 26, Saturday 27 and Sunday 28 November. The Christmas Procession is on Saturday 18 and Sunday 19 December and The Epiphany Procession on Sunday 23 January 2011. All these services begin at 7.00pm and finish at 8.15pm.

The Advent Procession – From Darkness to Light is one of the most popular services of the liturgical year. It begins with the Cathedral in total darkness and silence before the Advent Candle is lit at the West End. The service is a mix of beautiful music and readings during which two great processions move around the different spaces in the building which is, by the end, illuminated by almost 1300 candles.

The Christmas Procession is the Cathedral’s carol service with readings interspersed between carols. Here the focus of the procession is the Christmas Crib and the story of the birth of Jesus.

The Epiphany Procession commemorates the journey of the Magi travelling from the East to worship the baby Jesus, and follows Him through His early life and into manhood.

Many hundreds of people from throughout the diocese and beyond are expected to attend one or more of these imaginative and spectacular services, devised by the Canon Precentor Jeremy Davies. “I see Advent, Christmas and the Epiphany as the ideal time of year for using the Cathedral as it was originally envisaged, as an arena for processions and the great tradition of ‘worship on the move’. However these processions also invite us on an interior spiritual journey as we try to find the meaning and purpose of life.”

Those who wish to arrive early will be able to queue under cover in the Cloisters where seasonal refreshments are available before the Advent and

Christmas services. Doors open at 6.00pm when access to the Cathedral will be via the Cathedral Cloisters. Admission is free and no tickets are required for any of these services except for the Advent Procession on Friday 26th November for which entry is by ticket only. Tickets may be obtained from the Cathedral Shop after 18 October or by postal application to the Department of Liturgy and Music, 33 The Close, Salisbury SP1 2EJ enclosing an sae (maximum of 6). All tickets will be for a designated area of seating, not for individual reserved seats. On Saturday 27 and Sunday 28 November the services will be open to all on a first-come, first-served basis.

Please note there can be no admission once all seats are taken. There is no public parking in The Close, however parking is available for Disabled Blue Badge holders. For further information visit the Cathedral’s website: www.salisburycathedral.org.uk

A WONDERFUL DAY OF CELEBRATION AT SALISBURY CATHEDRAL FOR THE BISHOP OF SALISBURY

Salisbury Cathedral hosted a day of joyful celebration in July marking the immense contribution of the Bishop of Salisbury, Dr David Stancliffe. Hundreds of well-wishers from all over the diocese and beyond came to show their affection and respect for the Right Reverend Dr Stancliffe at his farewell events in the Diocese.

The Dean of Salisbury, the Very Revd June Osborne, said: “Blue skies and all-day sunshine set the seal on a day of joy and heartfelt thanks to Bishop David for seventeen years of inspiring and devoted service to the diocese. In the morning he ordained 23 men and women, the largest number ordained in a single service here since his first ordination in 1994 when he ordained the first women in the diocese and a truly fitting culmination of his work here. For David, there is no greater gift to leave the diocese than ensuring the continuity of the Church’s life through these new priests and their future ministry.”

After a gathering and presentation at 4.30pm to the Bishop and his wife Sarah, he then preached at his final Evensong as Bishop. In his address he thanked everyone in the Salisbury Diocese for “allowing me to enjoy the privilege [of being Bishop of Salisbury] these seventeen years, your partnership in the gospel, and your care and friendship.”

The Right Reverend Dr David Stancliffe gave up his full duties after attending the summer session of the Church of England’s legislative body, the General Synod, from 9-13 July. Rather than retiring, he intends to concentrate on teaching, writing, music and the arts.

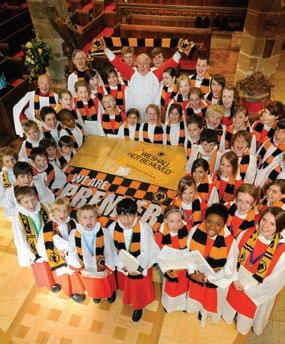

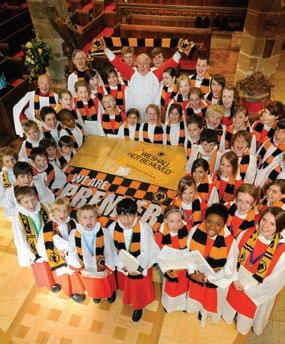

KEEPING WOLVES FROM THE DOOR

St Peter’s Wolverhampton had a very successful launch concert for the £300 000 needed to restore the 1860 Willis organ. The process of giving the first performance of a short football chant written by Elgar in support of the Wolves brought together the church choirs, Wolverhampton Symphony Orchestra, the Wolverhampton Wanderers Vice-Presidents Rachael Heyhoe-Flint and rock legend Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin, and the Elgar Society, and choristers were involved in local TV and 26 radio interviews (including the BBC World Service).

The all-Elgar concert, included the Enigma Variations Dorabella (Variation 10) was the daughter of the Rector of St Peter’s –hence the Wolves connection and the composition of the football chant ‘He banged the leather for goal’) The attractive photo shows some of the choir members in full Wolves regalia reproduced with acknowledgement to Tim Thursfield (Express & Star).

Cathedral Music 9

NEWS BITES News from Choirs and Places where they sing

Some Reflections on my association with WESTMINSTER CATHEDRAL

One of the most moving of the special (as distinct from statutory) services that I played for as Sub-Organist of Westminster Abbey (1974-1978) was the celebration of Vespers on the evening of 9 February 1976. Earlier that day, at the other end of Victoria Street, George Basil Hume, hitherto Abbot of Ampleforth, had been consecrated and enthroned as Archbishop of Westminster. It was a striking, and typical, act of ecumenical friendship by the then Dean of Westminster, Dr Edward Carpenter, to invite the monks of Ampleforth to celebrate Vespers in the Abbey which had been inhabited by their Benedictine forebears. Whether it was on this occasion, or another, that Basil Hume, surveying the Abbey from the pulpit, is said to have observed, ‘this used to be ours’, I do not recall. (He would have said this half jokingly, half seriously, with a characteristic twinkle in his eye). My task was to play before and after the service, while one of the monks was entrusted with the accompaniment of the Gregorian chant. At that time I would have had little ability in the art of harmonizing plainsong melodies, and no inkling that I was soon to have to acquire competence in this art very rapidly. I still remember seeing, through the mirror in the organ loft (no CCTV in those days), the procession, from the West Door through the Nave into the Quire, of the monks in their black habits, and realising that such a procession would last have taken place before the Reformation. It was a moving sight, indeed.

Perhaps this experience sowed a seed in my mind, for when, in 1978, I was encouraged by George Guest (under whom, as Organ Student at St John’s College, Cambridge, I had been privileged to learn, and come to love, a certain amount of plainsong) to apply for the position of Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral, George seemed to be pushing at an open door. He had been strongly influenced by the style of choral singing which George Malcolm had cultivated at the Cathedral, as well as by visits to Spain, where he heard monastic plainsong, and, incidentally, was excited by the Trompeta Real, a notable feature of many Spanish organs (he later commissioned such a stop for the St John’s organ) and had passed on his passion for these things to me.

To Archbishop (later Cardinal) Hume we owe the continued existence of the magnificent choral tradition of Westminster Cathedral. He inherited a situation in which financial and other pressures were threatening the Choir School and the choral liturgies. One of his first decisions was

to set about raising money for the School, with the aim of making it independent of diocesan funding. He appointed a fine Headmaster, the first layman to fulfil this role, Peter Hannigan, and I was appointed Master of Music. I was the first Anglican to hold this position, the Archbishop having apparently told the Administrator, who officially made the appointment, that he would rather have as Master of Music, ‘a practising Anglican than a lapsed Catholic’.

So it was that on the eve of the Epiphany, 5 January 1979, I found myself seated at the chamber organ to accompany First, and my first, Vespers in the Lady Chapel. The next day, a Saturday morning, two lay clerks, a tenor and a bass, appeared to sing at the Mass of Epiphany, for which I had, cautiously, I thought, programmed Byrd Mass for Three Voices. Not to be defeated, I decided to sing alto myself. This was not something that I did again, as someone said at the end of the service that, although tenor and bass were fine, ‘who was that alto?’. The tenor and bass were Clive Wearing and Trevor Ling, stalwarts of the choir, who showed me the redundancy notices they had been served by Hume’s predecessor, Cardinal Heenan. (These had been rescinded.) Once Clive and Trevor had satisfied themselves that I had prepared myself for my new job, they gave me the greatest support, and became good friends. Clive opened the bowling at my first rehearsal, asking a question about the interpretation of an obscure marking in the plainsong. Fortunately, I had taken the precaution of studying with the late Dr Mary Berry in the period between my appointment and taking up the post. Mary taught me the history of chant interpretation, how to transcribe it, how to conduct it, and, importantly, alerted me to newly emerging ideas about performance practice. Thus, I was well prepared for Clive’s yorker. I was pressed by Canon Oliver Kelly, the Administrator, to acquaint myself fully with the Roman liturgy, and especially to read the relevant documents of the recent Second Vatican Council. This enabled me better to understand and serve the Cathedral liturgies, and to be ready for the opposition or indifference to the choral tradition which I inevitably encountered in some circles. The fact that Basil Hume was known to be totally committed to the choir was an ultimate safeguard in this regard. This study also gave me an understanding of liturgy, of realising what was done in 1549, 1552 and 1662, and in more recent times, which was to

Cathedral Music 10

Director of Music King’s

be invaluable to me when I returned to work in the Anglican Church. (The prediction of some friends whose advice I sought at the time that I would, by going to Westminster Cathedral, ‘burn my boats’ in terms of obtaining an Anglican appointment in the future and/or be subject to attempts to ‘convert me to Rome’, proved unfounded.)

One of the difficulties, in my experience, of working for the two great foundations of the Abbey and the Cathedral, which I was thrilled to do in the 1970s, is that people can become obsessed with the grand occasions. There were plenty of these at the Abbey, of course, but also at the Cathedral, notably, in my time, the visit of Pope John Paul II to the UK. (An interesting, though worrying, feature of the planning of the music for this was the degree of ignorance displayed by many involved of the rich inheritance of Catholic liturgical music from pre-Reformation England: it would be tragic if this music were to cease to be heard in its proper liturgical context.) But the essence and raison d’être of a choral foundation is the daily singing of the liturgy, the Opus Dei. Basil Hume often reminded us of Augustine’s dictum – ‘qui cantat, bis orat’, and it is the inspiration of this idea which drives and should be the true motivation of those of us who work in these great institutions.

It would be fair to say that not all was well when I began work at the Cathedral. I have referred to financial pressures, and, indirectly, to tensions surrounding the continuing existence of traditional choral liturgies in which much of the music used Latin texts. These things could be dealt with: money was raised for the School, and Peter Hannigan’s outstanding work was supported by a fine set of governors, under the inspired chairmanship of the late Sir Paul Wright, and the choral liturgies survived. I was particularly pleased to be successful in resisting moves for the abolition of Vespers in Latin. The impoverished level of English and much of the new music written for contemporary vernacular liturgy (the Second Vatican Council did not, of course, abolish the use of Latin, as is popularly supposed) is depressing in the extreme. But there were three other areas which I set out to tackle, and these seemed fundamental to me.

First, I tried to encourage, and in some cases restore, good relations between clergy, school and lay clerks. People can only give of their best in a comfortable environment, where the contribution of each person is valued. Next, the organ.

This was flat in pitch, and badly in need of restoration. I did not see how the choir could achieve consistently good intonation in these circumstances. Fortunately, I was able to concentrate the institutional mind in respect of the need for restoration by presenting a (not too) hypothetical scenario of the organ’s breaking down as the Pope proceeded up the central aisle on his forthcoming visit. I remember Basil Hume’s coming to my office one day (that in itself tells something of the man he was – my not being summoned to see him) waving a cheque for £50,000 which a well-wisher had sent, saying ‘shall we start an organ fund with this?’.

Finally, and most important of all, was my attempt to achieve as consistent a standard of performance on a daily basis as possible. The daily liturgies, as distinct from the special services, are the lifeblood of a cathedral choir. There is no short cut to success here. Just as in any professional or academic sphere, constant attendance, hard work, and leadership by example, are required. The value of successful integration of music, sensitively chosen and well executed, with fine liturgy, properly celebrated, is enormous, and I was so excited and moved by the new experiences I was having. I hope this helped me to achieve something of what I set out to do. I was very lucky in having the assistance of Andrew Wright, who has since done excellent work at Brentwood Cathedral, and the benefit of some very fine singers, men and boys. The experiences and what I learned during my short time at the Cathedral have informed my work ever since, and it is wonderful that the Cathedral has been so immensely well served by my three successors, David Hill, James O’Donnell, and now, Martin Baker.

Cathedral Music 11

Stephen Cleobury CBE

College Cambridge

Stephen Cleobury CBE.

Timothy Hone interviews

JONATHAN DOVE

Last year, the Cathedral Organists’ Association commissioned a setting of the Missa Brevis from Jonathan Dove. The work received its first performance at their spring conference at Wells Cathedral in May 2009 and the work is included on a new disc dedicated to Jonathan Dove’s church music, performed by the Choir of Wells Cathedral, directed by Matthew Owens. The composer was recently interviewed by Timothy Hone, Head of Liturgy and Music at Salisbury Cathedral.

TH: I wondered about your first musical influences and the point at which you knew music was something you wanted to explore.

JD: The piano was my first love. I started playing the piano about four or five. I started to play by ear anything I heard my mother playing. Often it was the last thing I would hear when I was drifting off to sleep.

TH: So there was music in the home?

JD: My mother was a good pianist, although by profession she was an architect, as was my father. Once the children were in bed she would sit down and play Clair de lune or Handel’s Largo or bits of Oklahoma, and the next day I would then go and try and play those.

TH: And that was a perfectly natural thing for you to do?

JD: Yes, I think children often try and imitate their parents and this was just a way of doing that. I guess quite early on, I got into the way of making stuff up at the piano, sort of thinking

aloud at the piano. Also at the age of eight or nine I think, I was singing in the church choir. My mother was Catholic, although my father wasn’t really a churchgoer, so I started singing in church and around the age of twelve I started playing the organ.

TH: So had you had any formal instruction at this point?

JD: Oh, I certainly had piano lessons. In fact from the age of eleven, I went on Saturdays to the ILEA Centre for Young Musicians, in Pimlico, where I had weekly piano and violin lessons, though these had started while I was at primary school. Organ lessons came later when I went to secondary school. I got up to Grade 8 by the time I left school. The school also had a choir and there was a reasonable amount of music-making. There wasn’t an awful lot of instrumental music-making but I remember singing the Pie Jesu from the Fauré Requiem as a solo treble and I think I sang in the Vivaldi Gloria and Messiah

Cathedral Music 12

Photo © Dylan Collard

TH: So was music always the direction in which you were going to go? Or did you ever think perhaps of following your parents into architecture?

JD: No, it never occurred to me that I was going to do anything else. Though I didn’t know what form this was going to take. Composing always seemed to me the only thing that was really worth doing but it never occurred to me that I would be able to make a living out of that.

TH: So when did you start to write pieces down, as opposed to making them up?

JD: Pretty late. I only really wrote a handful of pieces in my teens. I remember writing something for two friends who were both violinists. But for the church I wrote at least one Mass, which probably would have technically been a Missa Brevis since I can’t remember setting a Credo. While none of these attempts was published, I’ve actually had several trial goes at the text, and this was probably significant in terms of the piece that was the recent result of the commission from the Cathedral Organists’ Association.

TH: So, pre-university, there seems to be a lot of different kinds of music-making going on. What sort of music made a big impact on you at that time?

JD: Well, I was always a sucker for piano concertos and would attempt to play them. The Beethoven Emperor Concerto was one of my first loves, and I would crash through the Rachmaninov Second Piano Concerto without ever actually practising it and getting it right, but giving an impression of it, which is all the fun! I can remember amusing myself with the Shostakovich Concerto and then lots of orchestral music. What I would tend to do is listen to the same piece over and over again every day for about three months – it was like having an affair with Mahler’s Ninth Symphony or Elgar’s Second. I didn’t absorb that much contemporary music, although at the Centre for Young Musicians there was an enterprising chap called Howard Rees, who would play us Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony or bits of Stockhausen as part of our general musicianship classes. I think on one occasion he got a whole room full of us to play In C, the minimalist piece by Terry Riley. So actually already I was introduced to quite a lot of what was actually going on at the time.

TH: Do you still recognize your own pieces at that time as being in the style that you’re now writing in? Or were you exploring lots of different styles?

JD: They’re certainly not what I am writing now and I think I would say that as a composer I really found my voice very late. I think I was nearly thirty before I wrote something that I thought was definitely me.

TH: The late 1970s and early 1980s were interesting years to start developing as a composer because the received wisdom was still that you had to write discordant, challenging music – the idea that you could write in a more accessible, tonally-influenced way, was not as respectable then as it is now.

JD: No, completely not. It was a ludicrous idea – to write even an octave, let alone a triad, was extremely suspect behaviour. And it certainly was when I was at university!

TH: When you were at Cambridge you studied with Robin Holloway?

JD: Yes, in my last year I had a few lessons with him and I think

probably the most important lesson was the first, in which I brought along a 20-page serial organ piece and on page two he said “I’m bored already”. And I realised that he was right and it was not an exciting piece. But I suppose I was trying to behave well, in a way that would be considered respectable.

TH: What was the influence of Robin Holloway’s teaching?

JD: The nature of Robin’s teaching, and the reason I think he was a great teacher, is that he was able to see the possibilities in the material you were already producing or attracted to. He didn’t try and make you write in any particular idiom, he just tried to make you write better.

TH: So you learned to respect the structure, how to develop your material, and how to maintain some consistency of intention?

JD: Yes, just seeing how many more possibilities there are in an idea than you might have thought. I still hadn’t really got into my stride. I think there was still a distance between the music that I could imagine, but perhaps a little vaguely, or music that I could improvise, and the music that I knew how to write. So I was continually impelled to produce great stretches of music, and did so every day, but I could never see a way of turning it into something more formed. And I suppose the big influences that really made that possible were from American minimalism, in particular, the music of Steve Reich. What was very attractive there was that he was writing white-note harmony that was rather like my hero Stravinsky, with diatonic clusters and chords, while the music had pulse, also like Stravinsky, but unlike most of what was then acceptable.

TH: You were talking a few minutes ago about the world of imagination, the world of improvisation compared with the world of written music. I’ve always found that one of the challenges of composition is holding the idea in the mind for long enough to write it down. In the attempt to grasp that idea it’s easy to lose the magic of where it might lead. On paper, there’s a different kind of process where you start to develop what you’ve already written rather than trying to capture the sounds you can hear in your imagination.

JD: I think that exactly captures the dilemma I faced through most of my twenties. Eventually what I would do is record myself playing, so I would simply keep a tape recorder on the piano and if I had an idea that felt it had a future, then I would record it so that it could be notated later. Actually what I still tend to do is get the piece as finished as I can in my mind before I write any of it down.

TH: So you can keep a lot of it in your head?

JD: I suppose I try and only work with material I can remember. So if it’s not catchy enough to remember, then I can’t work with it. If I can remember it, I should be able to feel my way through a whole movement before writing it down, so I can map out the journey. I guess later on it dawned on me that singing and dancing were the essential purposes of music and if you’re going to dance you’ve got to know where the next beat’s going to land. I had something of a breakthrough with a dance piece that I wrote when I was nearly thirty. I found great freedom in knowing that the audience was coming to watch the dancers and wasn’t primarily interested in the music. So I felt free to do whatever I liked – that was liberating. But also the idea that there was going to be movement was exciting and made me feel able to write pulsed music.

Cathedral Music 13

TH: So when you came down from Cambridge you then had a freelance career including some piano accompaniment and répétiteur work and this led you to working at Glyndebourne.

JD: That’s right. I worked as assistant chorus master to Ivor Bolton, for a year. Then, just around that time there was enough work suddenly to keep me busy composing. In the summer of 1989, I was musician-in-residence for the Salisbury Festival and wrote several pieces for that.

TH: So we have music with voices, music with movement and now music involving the community. All of those seem to be strands which resonate quite deeply. Writing church music seems to fit alongside them quite naturally.

JD: Actually there was a return to church music because, although I continued to play the organ at my local church during the holidays from Cambridge, I was no longer really a church goer. In my Cambridge years I was a bit of a night owl so I tended not to be up in time for any services, and have to admit that I didn’t actually attend any choral services while I was in Cambridge. So I missed out on an incredible repertoire and an extraordinary opportunity. I was therefore never properly exposed to the Anglican choral tradition and when I was in my twenties I had utterly lapsed as a Catholic.

A significant moment came in 1993, when Jeremy Davies, Precentor of Salisbury asked if I would write an extended setting of the Benedicite for the Creation Festival. This would involve dancers, as well as choir, steel pans and organ. At the beginning were words from Genesis. When these arrived I immediately went to the piano and music just came pouring out – which was a surprise, to be honest. I now realize that religious imagery still had a great hold on my imagination. Of course some of these were words that I had first heard as a young child so they were almost part of my DNA. ‘And the spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters’ – you know it’s an amazing idea, an amazing image, and I found these kind of giant cosmic

images with which the text was packed irresistible. Here was a story I wanted to tell. Another text was ‘In the beginning was the Word’ – again, this is powerful, resonant language. But I also realized that there was something both emotionally and musically important to me, even though to this day I have great difficulty with any organised religion. Awe and wonder and mystery are incredibly important human experiences and I suppose alongside that there was a sense of communion. These are experiences which music could enhance and they are also experiences which are not so easily accessed in other contexts. I suppose those are really the experiences which have drawn me back to writing church music, which I have continued to do since 1993, including at least one more piece for Salisbury – Into Thy Hands

TH: All the texts you have set seem incredibly strong, very poetic. Were the texts suggested to you or did you find them yourself?

JD: It was a mixture of the two. I think I was actually in a bookshop reading through a collection of metaphysical poets, and came across Welcome all wondersin one sight! I remember being immediately struck by it getting a tingly feeling. On the other hand, Ecce beatam lucem was suggested to me as a text by Ralph Allwood. Sometimes I’ve tried to find texts that have particular images, which was how I came to find the text Seek him that maketh the seven stars

TH: With the texts you have just mentioned, the strong images about light or transcendence almost suggests a particular kind of musical world. When you come to the words of the Missa Brevis, there is a different kind of challenge because the text has been set many hundreds of times before.

JD: To some extent I was shielded by my ignorance because I didn’t get up in time to go to all those services in Cambridge, so I simply hadn’t heard lots of those settings. The setting I knew as a child was the Britten Missa Brevis. I suppose that and the Stravinsky Mass served as models. The Stravinsky setting, although it has a Credo, is terse, making it perfectly useable in a liturgical context. My teenage attempts to set the text helped me to realise what the journey through the different Mass sections might involve. I think we must have played or sung Masses that I found unsatisfactory, though I can’t remember what they were. I remember that the settings used in the parish were quite popular and lightweight. I expect my own teenage pieces were in this idiom because they were written for choirs whose reading skills were modest, so the music was certainly pretty diatonic. However, it was something of a breakthrough for me to realise in about 1991 that really I had diatonic ears and that I was much happier not trying to write music which was chromatic or serial.

TH: Most of the people who listen to it have diatonic ears as well, so, if you are writing music with tonal references, you perhaps can be more expressive.

JD: In fact, I would say that my choral music is not tonal but modal. Around 1991, I realised I was writing pieces in which there were no accidentals. This modal language combined with a danceable rhythm was important for me.

TH: How did you determine the moods of the movements of the Mass? You seem to suggest that you wanted the piece to fit together while being aware of the different moods of the individual parts of the Mass.

JD: I didn’t have any scheme and I wasn’t trying to do anything

Cathedral Music 14

Photo © Hugo Glendinning

clever. While all the movements have the same key signature, I use different groups of notes in each movement to create a feeling of different modes out of the same scale.

TH: The terms of the commission were quite tight because we wanted a piece that could be used in the liturgy and that people would actually keep in the repertoire. We were delighted with the result because it also has a freshness and immediacy about it, which I think struck everyone. From other things you have said, it seems that you find some restrictions actually quite helpful.

JD: Yes, always, I find. The main thing is that you have the text and with it the drama that it implies. Alongside that, the particular thing about the nature of the Mass is that you are speaking for the people – the choir is singing on behalf of the congregation. It seems to me that the nature of the Mass is that it has to speak for everyone because these are the sentiments that everyone is endorsing at that moment. So I suppose that means that it does need to connect, and for that reason it’s helpful to have some kind of shared musical language. It’s got to be more than intelligible, the congregation needs to be able to relate to it and say, yes, that’s what I was feeling, and that’s what I wanted to say.

TH: Are there major non-musical influences on what you do – from your parents’ architectural background, for instance?

JD: I think that probably is only expressed in terms of sensitivity to the acoustics of different kinds of buildings and thinking what will sound well in a church as opposed to what will sound well in a concert hall. Really the lion’s share of my output now is operatic, so I would say that mostly I’m behaving as a musical storyteller. I’m certainly animated by voices and I’m animated by drama. And fortunately church music does involve some pretty dramatic stories, so there’s plenty for me to do.

TH: Presumably your operatic experience makes you very realistic, if you’re going to write pieces that go into production quite quickly. JD: Also, I’ve done a lot of work with community groups, where pieces are written collectively, with perhaps a group of people around the piano making something together. So you get a sense of what kind of musical vocabulary everyone shares and when you’re going beyond that. So you have a bit of a sense of what’s easy to pick up straight away and what is going to take that bit of extra rehearsal but will be worth the extra effort involved. Simplicity for me also means clarity, it means you are communicating clearly and avoiding doing something that’s simply clever. So it helps to think about what is really essential. But in the end there will always be moments where you feel the music is developing in a particular way and if it’s going to be a little bit tricky, I know it’s going to be worth it. So I think most of what I write would be a little bit of a stretch for choirs but a stretch that they’re happy to make.

Cathedral Music 15

Jonathan Dove, Julian Millard, Hyperion Sound Engineer and Matthew Owens listening back to a recording session with Wells Cathedral. Choir for their new CD see page 56.

WINNERS OF INSPIRED PHOTOGRAPHY COMPETITION AT SALISBURY CATHEDRAL ANNOUNCED

Over 250 inspired photographers from across the world submitted images to Salisbury Cathedral’s first photography competition. There was a huge originality of entries as people interpreted the theme ‘My Salisbury Cathedral’ using a wide range of cameras from the simple to sophisticated in the hope of winning one of the six great prizes. The judges were Edward Probert (Canon Chancellor Salisbury Cathedral), Ash Mills (Salisbury Cathedral’s official photographer), Roger Elliott (Chief Photographer, Salisbury Journal) and Ceri Hurford-Jones (Managing Director, Spire FM). David Coulthard, Director of Marketing and Communications at the Cathedral, said:

“We were delighted by the number of entries, interested to see the cathedral from new angles and amazed at the extraordinarily high quality of so many images. About half the entries were submitted by people living locally and the remainder from addresses all over the UK, Northern European countries, the USA, South Africa, and Russia. We are extremely grateful to our judges for their time and expertise and to all those who donated the superb prizes. The judges had a wonderful morning adjudicating and are pleased to announce the overall winner was Peter Nunn. His photograph Rejuvenation will be printed onto a large canvas and displayed in the Cathedral Refectory where it will be seen and enjoyed by many thousands of visitors to Salisbury Cathedral.

ROYAL MASONIC TRUST FOR GIRLS AND BOYS CHORAL BURSARY SCHEME

As money gets tighter in this age of austerity, and many cathedrals feel the double pinch of a drop in charitable donations and lower returns on their endowments, it is heartening to know that support for cathedrals throughout England and Wales is growing from one, perhaps surprising, quarter.

In 1995, the Royal Masonic Trust for Girls and Boys (RMTGB) launched their Choral Bursary Scheme to help children from low income families who would not otherwise be able to join the choir for financial reasons. The choristers and their families usually have no other connection with Freemasonry, and candidates are identified by the cathedral during voice trials.

At first, funding was only available to those cathedrals that had a designated choir school. Although cathedrals usually offer bursaries towards the fees of their partner schools to help talented children from less well off families to cope with the cost of fee-paying education, parents are often left with a portion of fees to pay themselves. This, along with the cost of incidental extras, can soon add up and create a significant barrier to the child taking up his or her place. The Choral Bursary Scheme provides support to one youngster at each cathedral involved and it covers the cathedral’s portion of the fees in full, freeing-up funds to be allocated to another chorister.

The scheme also assists parents with their portion of the fees, according to a financial test; this means that the highest level of support goes to those who need it most. The parents complete a form, giving details of their financial situation/household income and the family is visited by a member of the RMTGB’s Welfare Team. All grants are agreed by the RMTGB grants committee which meets four times a year. When the existing choral bursary recipient leaves the school, the cathedral starts the search for a suitable replacement at voice trials.

More recently however, the scheme has begun to open up to cathedrals that draw their choir from a number of surrounding schools. This recognises that even when school fees are not involved, costs like extra music lessons and the additional trips between home and the cathedral can still make joining the choir very difficult. In these instances a Choral Bursary of between £1,500 and £3,000 pa is given to the cathedral to use to help young choristers who would not otherwise be able to join the choir.

The Choral Bursary Scheme is now in its sixteenth year and at a recent grants committee meeting the number of cathedrals involved was expanded to a record 28. To date the scheme has made grants worth in excess of £2.3 million.

The benefits of the scheme are summed up by Linda Lawrence, the head teacher from the Chorister School, Durham, who states: “There is no doubt that support from the Royal Masonic Trust has meant a great deal to the school, the chorister involved and his family. It has meant that he has been able to access the academic teaching and support he needed, while allowing him to develop his musical talents as a cathedral chorister. The award has also meant that we, as a school, have had the benefit of having such a special young man as a pupil. In addition, his incredibly supportive parents are a very positive and valuable addition to our community.”

The scheme currently has vacancies at Guildford, Ripon, Windsor, Peterborough and Grimsby, so if you know of a family whose child is considering applying to become a chorister and who may benefit from the RMTGB Choral Bursary Scheme, please do advise them to talk to cathedral staff about the possibility of applying for this support.

The Choral Bursary Scheme is administered by Sarah Hale at the RMTGB and if you would like more information please contact: shale@rmtgb.org

THREE CHOIRS CHORISTERS PERFORM IN CARDIFF

The choristers of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester cathedrals joined the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and former winner of BBC Cardiff Singer of the World, Katarina Karnéus, for a performance of Mahler’s Third Symphony at the start of October in St David’s Hall, Cardiff, recorded for later broadcast on BBC Radio 3.

The choristers, all of whom last sang together at this year’s Three Choirs Festival, which is believed to be the oldest music festival in Europe, will be joining the massed voices of the BBC National Chorus of Wales for this epic work.

“This will be a wonderful opportunity for all the boys,” said Geraint Bowen, Director of Music at Hereford Cathedral, during a break from rehearsals for the performance. “The experience of being on stage amongst the vast orchestral forces assembled for this epic work will be unforgettable.”

The distinguished Japanese conductor Tadaaki Otaka, the orchestra’s Conductor Laureate, conducted the concert and his exceptional insight into Mahler’s music created a remarkable and memorable occasion.

Cathedral Music 16

NEWS BITES News from Choirs and Places where they sing

Offering extraordinary home practice versatility and value, the Vivace 40 model is priced at £4,700 inc VAT.

With over 5000 instruments sold worldwide each year, we have a growing group of satisfied customers, and when you hear a Viscount, you’ll want to join them.

For more information on our regional distributor network where you can play an instrument, contact Viscount Organs on 01869 247333 or email sales@viscountorgans.net

Experience the superior sound of the Viscount Vivace series of Organs.

Before deciding on your next organ purchase, be sure to listen to the new Vivace series from Viscount. Our versatile Vivace 40 model features:

2 Manuals

30 Note Pedal Board

31 Stops

110 voice sample library

5 selectable organ styles

Console voicing controls

8 Memory Levels

earing iselievingHB

Vivace 40

www.viscountorgans.net www.physisorgans.comwww.prestigeorgans.com . vis www scountorgans . net ysisorgans .ph www s . com . pres www stigeorgans . com

Vivace 30Vivace 60 deluxe

60Seconds in Music Profile

PHILIP RUSHFORTH

Age: 37

Education details: Chorister and Organ Scholar, Chester Cathedral 1981 – 1991 and a pupil of Abbey Gate College, Chester 1984-1991. Trinity College, Cambridge 1991-1994.

Career details to date: Assistant Organist, Southwell Minster and Director of the Southwell Minster Chorale 19942002. Assistant Director of Music, Chester Cathedral 2002-2007. Director of Music, Chester Cathedral 2007 to the present.

Cathedral Music 18

Photo © Alice Capper

You started as a chorister at Chester Cathedral and now you are Director of Music. What do you enjoy most about working in a cathedral like Chester?

Working on a daily basis with the choristers and maintaining the Opus Dei. I never tire of walking into Chester’s beautiful Quire stalls on a daily basis.

What was it like as a chorister at Chester Cathedral?

It was life-changing. The best experience a young boy can have. I had no idea what would be involved and sang Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer as my audition piece!

What or who made you take up the organ?

I first heard Chester’s organ as a probationer at the age of eight. Something clicked with me, even at that age. Roger Fisher, who was my choirmaster, was an inspiration on the organ. He eventually became my teacher – exacting but very generous and a brilliant organist and pianist.

At which cathedral would you most like to be the Director of Music?

I’m quite happy for the moment, thank you.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently & why?

Widor’s Eighth Symphony. I heard Alexander Ffinch play some of it in St David’s last year and thought what fine music it contains. Also, David Sanger persuaded me to learn Oskar Lindberg’s Sonata in G minor, which is like Rachmaninov for the organ!

Have you been listening to recordings of them and if so is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

I remember hearing Jane Parker-Smith playing the Final to Widor’s Eighth Symphony on a tape of wedding music which was one of the first organ recordings I owned.

Which organists do you admire the most?

The late David Sanger, whose encyclopaedic knowledge of the organ repertoire was seemingly endless; David Briggs, who introduced me to Cochereau and also the historic recordings of Louis Vierne and Edwin H Lemare, which are electrifying.

What was the last CD you bought?

Choral Music by Paweł Łukasweski from Trinity, Cambridge.

What was the last recording you were working on?

I recently recorded Whitlock’s immense Sonata in C minor and his Six Hymn Tune Preludes, together with former Chester organist Charles Hylton Stewart’s organ music. They were colleagues in Rochester and Whitlock played in Chester in 1931.

Has any particular recording inspired you?

Roger Fisher’s 1971 The Organ at Chester Cathedral recording, Vladimir Horowitz’s return to Moscow in 1986 and Simon Rattle’s recording of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius

What is your favourite organ to play? Chester’s.

What is your favourite building?

Spiritually, Chester. Architecturally, Southwell.

What is your favourite anthem?

So much glorious music from each century... When David Heard by Thomas Weelkes or Crucem tuam by Paweł Łukasweski.

What is your favourite set of canticles?

Perhaps the St Paul’s Service by Herbert Howells.

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants? Psalms 42 and 43 to Edward Bairstow.

What is your favourite organ piece?

Impossible to choose, but Healey Willan’s Introduction , Passacaglia and Fugue in E flat minor is a masterpiece.

Who is your favourite composer?

Again, impossible to say, but I do love Edward Elgar’s music.

What pieces are you including in an organ recital you are performing?

Dupré’s Second Symphony; Alcock, Introduction and Passacaglia; Karg-Elert’s Valse Mignonne and Lindberg’s Organ Sonata in G minor.

Any forthcoming appearances of note?

All Saints, Northampton and Hull City Hall.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

Playing in Cantu, Italy, the evening after Pope John Paul II died.

How do you cope with nerves?

Sufficient preparation. Slow and deep breathing, thinking about a calm place.

What are your hobbies?

The Titanic and her sister ships. I love intricate watches and own a few timepieces. Walking the coast of Anglesey. I find the life and work of Tony Hancock fascinating. Stanley Kubrick and the way he uses music in his films.

Do you play any other instruments?

I have a hundred-year-old Steinway at home and I habitually work through Bach, Haydn and Mozart on it. I also enjoy accompanying English and German Song.

What was the last book you read?

How to bring up your parents by Emma Kennedy.

What are your favourite radio and television programmes?

Hancock’s Half Hour; Breakfast on 3; Coast; Top Gear.

What Newspapers and magazines do you read?

The Sunday Telegraph; Radio Times.

What makes you laugh?

My sons! Tony Hancock. Dudley Moore playing Variations on Colonel Bogey in the style of Beethoven makes me laugh out loud!

If you could have dinner with two people, one from the 21st century and the other from the past, who would you include?

My wife, Louise, and Tony Hancock.

What do you think should be the role of the FCM in the 21st century?

George Dyson said: “If a man would live again in the musical history of 1000 years, let him sit in the choir of a cathedral and listen.” FCM undoubtedly endorses this, and should continue to do so in the exemplary way it already does.

Cathedral Music 19

From the vaults of WESTMINSTER CATHEDRAL

‘The strikingly Byzantine Westminster Cathedral has stood for barely 100 years and yet its musical tradition is rooted several centuries before, in plainchant and Renaissance polyphony, sung in spectacular style by its superb choir.’

(The Observer)

Sooty Asquith talks to Martin Baker about musical life at Westminster Cathedral.

Sooty Asquith talks to Martin Baker about musical life at Westminster Cathedral.

20 Cathedral Music

Not content with one centenary, or even two, Westminster Cathedral, in a style all its own, has this June celebrated its third centenary. The first, in 1995 (under the then Master of Music, James O’Donnell) commemorated the laying of the foundation stone; the second, eight years later, acknowledged 100 years of services at the Cathedral, and the third, in June 2010, celebrated the consecration of the Cathedral in 1910. Although the cathedral had by then been fully operational for seven years, under the laws of the Catholic Church at the time, no place of worship could be consecrated unless free from debt with its fabric complete, so the consecration ceremony did not take place until 28 June, 1910. The second centenary, perhaps the most elaborately planned, harked back to the opening service at the cathedral, a Requiem Mass for Cardinal Vaughan, the driving force behind the building of the cathedral.

Martin Baker, Master of Music at the cathedral since 2000 (and its organ scholar from 1988-90) was in charge for the latter two events. An early thought had been to replicate the music sung a hundred years ago, but the music for the consecration was perhaps a little too simple for such an important event: an everyday Gregorian chant, and a mass by Lassus, Missa quinti toni There were also two motets, Elegiabiectus esse (Philips) and Palestrina’s Tu es Petrus. The choir did sing the Philips as a communion motet in June this year, and one other, Bruckner’s Locus iste – which translates as “this place was made by God” – but Martin chose to bring in an orchestra for Haydn’s Missa Sancti Nicolai, and Parry’s I was glad There were some small doubts about the latter but it was also sung at the 1995 centenary, and, like the Bruckner, the text was appropriate. Also, Bruckner, a devout Roman Catholic, used the modal chords and long, Gregorian chant-like lines of the Renaissance masters, making him a particularly suitable choice for this cathedral.

A unique event of 2010, however, was the visit from the Pope for a Votive Mass of the Precious Blood, which took place in September. The choir sang Byrd’s 5-part Mass (used at the original consecration and with a strong connection to the Reformation – Byrd was and remained a Roman Catholic despite writing music for the Anglican church) and another Bruckner motet, Christus factus est. There was also some music for brass, organ and percussion – and some James MacMillan to provide contrast.

It was James MacMillan who provided the impetus to Martin’s recording career at Westminster Cathedral in 2000, the year that he took over from James O’Donnell. The choir was already rehearsing a new commission from MacMillan, a mass written in the vernacular, his third such piece but the only one written for a professional choir. The programme of recordings of the Mass by Hyperion had been started by David Hill in 1985, and Martin, on a visit to the late Ted Perry, in charge at Hyperion at the time, asked if