C CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Simply the best in sampled digital sound, with no gimmicks. This is a Makin Westmorland organ.

the difference. Our Westmorland Custom instruments use a separate sound-sample for every note of every rank, and the realism is simply breathtaking! You are actually listening to the sound of organ pipes themselves, and not to something artificially-generated by computer, or based on only a few individual samples. What’s more, Makin uses genuine English pipe samples, from the finest organs in the country, to create that true English sound for which we are renowned. Experience our top-quality consoles, bespoke speaker systems, and unrivalled customer service. You will soon understand why customers choose Makin, rather than settle for second-best. to us. Together we can draw up your own unique specification today. our website for customer testimonials, details of installations, events local to you, and much, much more.

Makin Westmorland. Serious organs for the discerning musician. Someone like you.

You don’t buy a Makin Organ … you invest in one.

For more details and a brochure please telephone 01706 888100

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2011

Editor Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London, SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Deputy Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon FCM email info@fcm.org.uk Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

Roger Tucker, 16 Rodenhurst Road, London, SW4 8AR 0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London, WC1N 3AX Tel: 0845 644 3721 International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, LS28 8NT 0113 255 6866 info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

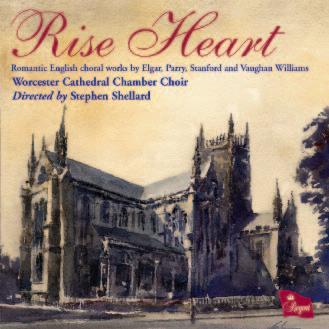

Cover

In the last issue of CATHEDRAL MUSIC Andrew Reid at Peterborough talked about the contentious issue of female lay clerks in the traditional cathedral choir, which article sufficiently moved Peter Giles to put pen to paper in support of the all-male tradition. His response may cause you to have second or even third thoughts about the right way forward for music foundations in our great cathedrals. Two forthcoming publications may also make you look ahead: the fifth book in the much loved and world-famous Carols for Choirs series, and the remarkable tribute to Queen Elizabeth II in her diamond jubilee year, Choirbook for The Queen, to be launched at a special evensong service on November 22 at Southwark Cathedral. FCM chairman Peter Toyne (see page 5) is a member of the committee responsible for the inception and development of this project, which will see copies of the Choirbook made available to every cathedral and most college choirs throughout the country. You

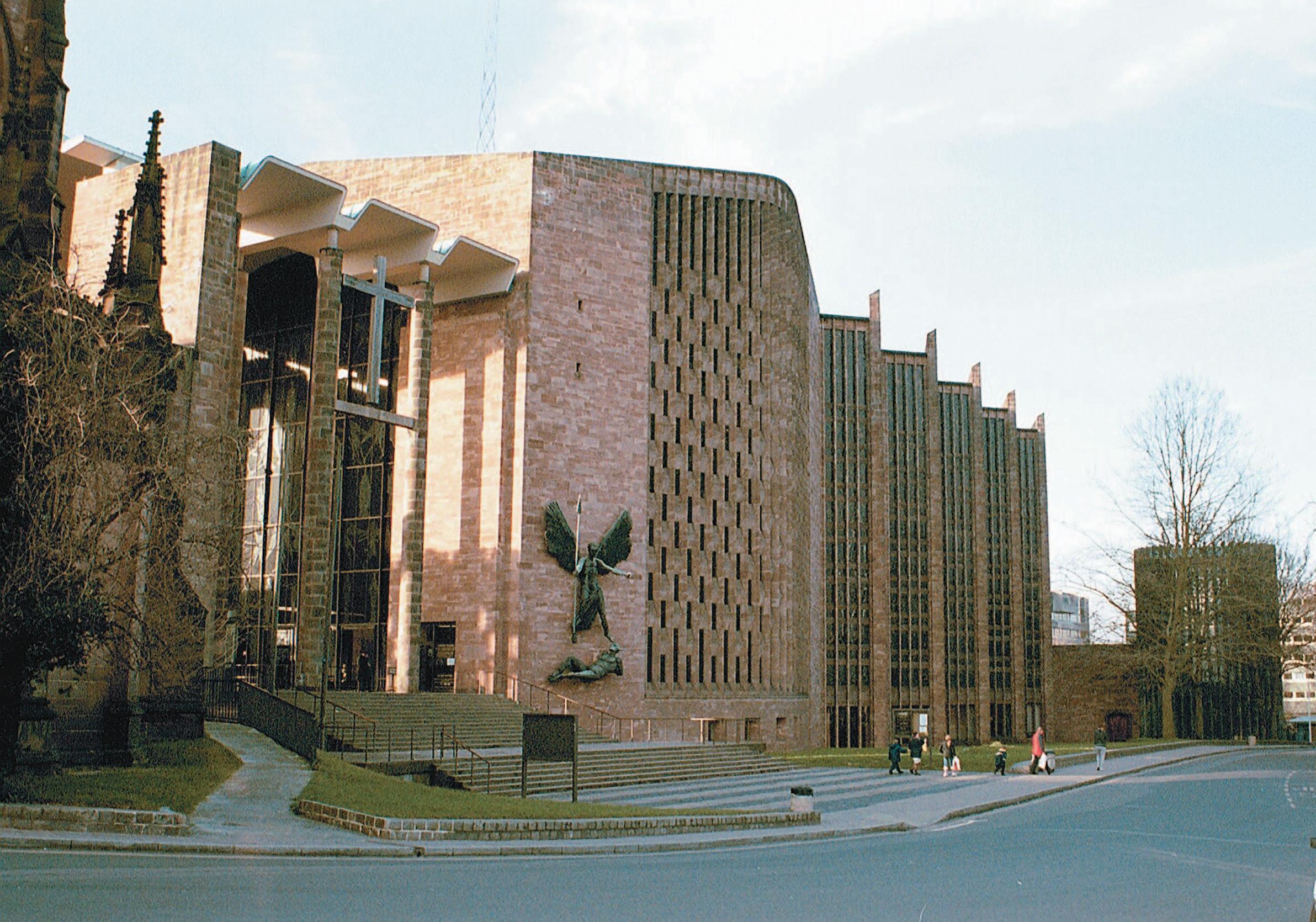

will find a full list of anthems included in this historical volume, partially funded by a £20,000 grant from FCM, on page 6. In this issue we are celebrating several long-serving and wonderful musicians; what is it that encourages people to stay in the same place for a long time? What are the challenges, and the rewards? You might ask the same of Andrew Palmer, editor of this magazine for the last 20 years. An extraordinary achievement, and a true labour of love; for more about Andrew, read Roger Tucker’s piece –one of the most difficult he has ever had to write, he says. And as well as our usual reviews, profiles and items of news of general interest, there is an in-depth report on the state of cathedral music in Australia, some thoughts on being a Precentor from the current and previous incumbents at St Paul’s Cathedral, and notes on running a Golden Jubilee celebration for one of our newest cathedrals, Coventry.

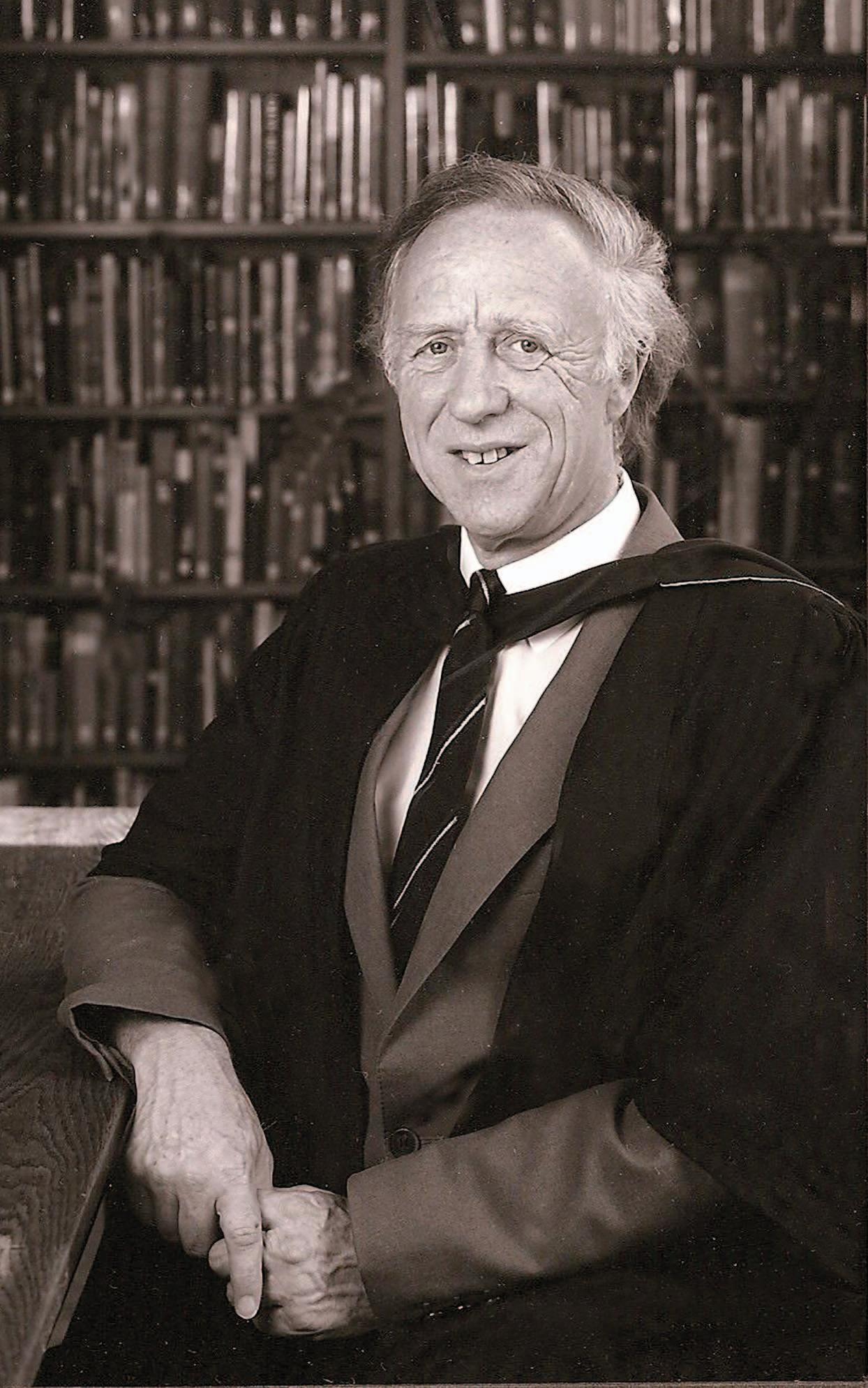

Sooty AsquithThe overworked cliché ‘what you see is what you get’ could not be less true of Andrew Palmer. He does not wear the credentials of his personal qualities on his sleeve; he is a very private, rather shy person – an unlikely choice for the editorship of FCM’s Annual Report at a time of change in 1991. The previous editor had just died, as well as our founder, the Revd Ronald Sibthorp. His successor as chairman, the Organist of St Paul’s Cathedral, Christopher Dearnley, had emigrated to Australia. The decision of the succeeding chairman, Alan Thurlow, to invite Andrew at the age of 26 to become editor can now be seen as an inspired choice: he handed him a blank slate, with no strings attached, other than budgetary limits. This was a huge challenge to someone whose only experience of the field had been as a cathedral chorister.

The contents of those early editions in the 1990s shows a clear-headed plan for developing the Annual Report into a magazine, with high quality paper and printing and the capacity to sustain advertising. The first challenge was to persuade the contributors that he wanted them to write significant articles for no payment. It was the success with which he did this that is one of his major achievements, given that the magazine was not going to achieve a circulation much outside the membership of FCM, in 1991 no more than 3000. Quite quickly, Andrew’s chosen contributors were not only delivering the goods but avidly reading one another’s thoughts on a very specialised range of topics – and thus swelling the pool of expertise to which

they were all contributing. The first UK magazine in the specialised field of cathedral music was rapidly gaining a reputation for well-informed writing, with new names appearing alongside familiar ones. The catalogue of articles over the twenty years tells the story very clearly.

In 1997 Andrew persuaded Council to agree to publish two editions per year and then a year later to switch to A4 size and thereby come into line with most of our competitors. This was widely welcomed and lifted the magazine onto a more competitive level. Over the years, it has never been necessary to defend or justify it, which is a testimony to Andrew’s judgement about content.

I was invited on board back in 1993, as a result of marking up all the typos and solecisms in the first of the new format editions (in a size in between A5 and A4). Andrew nailed me as proofreader on the spot and since then we have developed a kind of literary dialectic, our unique way to better expression of our ideas. This has operated in the writing of Comment, our

individually authored reviews and the Newsbites. On the rare occasions when a contributor’s article is over length, the method quickly achieves agreement about cuts.

Of course there have been ruffled feathers due to the critical tone of some of our reviews. Andrew refused to accept the view of one well-known chapel choir director that because FCM exists to support all the choirs and musicians in our field, the magazine should only hand out bouquets, not criticisms, in any reviews of their performances. To do that, he believes, would weaken the value of all our critical writing and be a disservice to our readers, who have a right to expect truthful comment on a professionally responsible level.

The well-produced and illustrated magazine you receive today is a tribute to the tenacity and self-belief of its founding editor. Although it is now sent to all cathedral foundations in the UK and therefore, we hope, read by the ‘managements’, it deserves a wider circulation than the FCM membership of around 4000. The marketing of such a universally praised publication to all aficionados of cathedral music is long overdue and that should be one of FCM’s goals for the coming decade. There is a readership out there beyond the membership, and those of us who sell back copies at the cathedral festivals are very gratified by the enthusiasm with which they are snapped up and the wide approval they receive. The magazine is indeed a huge asset in supporting our cause.

Roger Tucker, Deputy Editor

For all who love and support cathedral music, there could scarcely be a more fitting tribute to Her Majesty The Queen in the Diamond Jubilee year of her accession than the publication of a collection of anthems composed in the decade since her Golden Jubilee in 2002.

The performance of all those anthems during her jubilee year by the choirs of cathedrals, colleges and other major music foundations throughout the land, and the knowledge that the collection should become an essential resource base for generations of choirs to come would, however, make it all the more special.

Yet that is precisely what the Choirbook for The Queen will be –a collection of 44 contemporary anthems, including eleven new commissions, that is set to become part of the continuing repertoire not only of the eighty choirs formally participating in the year-long celebration, but also of many other choral foundations throughout the world.

It can therefore be seen as a latter-day equivalent of The Eton Choirbook that was produced 500 years ago in the reign of King Henry VII and which is still in use today.

The original idea of producing such a choirbook came from Robert Ponsonby (BBC Controller of Music from 1972 to 1985) who explains: “I inherited from my father, Noel Ponsonby, a love of what I have always thought of as ‘Cathedral Music’. On retirement I took to thinking about the glories of our ‘English’ choral traditions – Anglican, primarily – and I pictured the possibility of a nationwide celebration of such music. So, in 2004, I wrote to Peter Maxwell Davies, who liked the idea, and it was taken forward by a number of wonderfully dedicated people who shaped my simple notion into what is now our Choirbook for The Queen.”

That ‘shaping’ began with the setting-up of a steering group with Sir Peter Maxwell Davies as its Artistic Adviser and Ian Ritchie (Director of the City of London Festival) as its chairman. Together with Robert Ponsonby, its members were

Stephen Cleobury (Director of Music at King’s College Cambridge), Christopher Robinson (FCM President and formerly Director of Music at St John’s College Cambridge), Timothy Hone (Head of Liturgy & Music at Salisbury Cathedral), Andrew Nethsingha (Director of Music at St John’s College Cambridge), Andrew Kurowski (Producer, BBC Radio 3), Richard White (Choir Schools’ Association), Lucy Winkett (then Precentor at St Paul’s Cathedral, London) and me (as Chairman of FCM). Carol Butler, the Director of the Winchester Festival, was appointed as Chief Executive.

Deciding on the content of the book was delegated to a smaller editorial group (Stephen Cleobury, Christopher Robinson, Tim Hone, Andrew Kurowski and Lucy Winkett, with Ian Ritchie as its chairman). That was never going to be an easy task but, as Ian Ritchie explains, “We needed a crosssection of anthems that would represent a broad church of composers, including those who had never previously written for this genre, as well as those who had already contributed significantly to the development of British church music.

“We also wanted to have anthems set to a wide range of texts which could be performed either at particular times or on any occasion throughout the church year, which would be challenging but also satisfyingly within the capability of good amateur choirs as well as professionals.”

As work on selecting and commissioning the anthems progressed, the directors of music of cathedral choirs and major college and music foundations throughout the UK were invited to participate in the project by agreeing to perform at least one anthem from the Choirbook during the course of the year and thereafter to keep it in their repertoire. Their response was overwhelming, with eighty choirs from Anglican and Roman Catholic foundations enthusiastically agreeing to take part.

In the end, thirty-three existing anthems were chosen for inclusion in the book, together with ten commissioned from

Richard Allain Cana’s guest

Julian Anderson My beloved spake

Richard Baker To keep a true Lent

Sally Beamish In the stillness

David Bedford May God shield you on every step *

Richard Rodney Bennett These Three

Judith Bingham Corpus Christi carol *

Diana Burrell O joyful light *

John Casken In the bleak midwinter

Richard Causton Cradle song

Bob Chilcott The heart in waiting

Peter Maxwell Davies Advent Calendar *

Jonathan Dove Vast ocean of light

Michael Finnissy Sincerity *

Alexander Goehr Cities and thrones and powers *

Francis Grier Prayer for the Church’s banquet *

Jonathan Harvey The royal banners go forward

Cheryl-Frances Hoad Psalm 1

Robin Holloway Psalm 121

Francis Jackson Te lucis ante terminum

Gabriel Jackson To morning

John Joubert Seek the Lord

James MacMillan Canticle of Zachariah

Colin Matthews The angel’s carol

David Matthews Psalm 23

John McCabe The last and greatest herald

Cecilia McDowall Ave Regina caeolorum

Philip Moore As the Father hath loved me

Tarik O’Regan Beatus auctor saeculi

Nigel Osborne Prayer for Africa *

Roxanna Panufnik Joy at the sound *

Anthony Payne Betwixt Heaven and Charing Cross

Julian Philips Church music *

Francis Pott O Lord, grant The Queen a long life

John Rutter I my best-beloved’s am

David Sawer Wonder *

Robert Saxton O living love

Andrew Simpson Sing unto the Lord

Howard Skempton Ave Virgo sanctissima

Giles Swayne Ave verum corpus

John Tavener Take him, earth, for cherishing

Mark-Anthony Turnage Miserere nobis

Judith Weir True blue dream of sky

John Woolrich Earth grown old

* Choirbook Trust commission

leading composers and one specially composed by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies as Master of The Queen’s Music. The new anthems will be given their broadcast premieres throughout next year during BBC Radio 3’s relays of Choral Evensong.

Clearly, the cost of commissioning new works and of producing and publishing such a large volume (actually it’s going to be published as a two-volume set) was always going to be significant, but Penny Jonas (the project’s Fundraising Consultant) was hugely successful in securing grants from a number of foundations and charities.

“The response to our appeals for funds to realize this ambitious idea was highly rewarding,” she said. “Seed money to commission new works and start the project was generously provided by a number of donors including the Allchurches Trust, the Astor Foundation, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, the G C Gibson Trust, the Ouseley Trust and the Friends of Cathedral Music who made a grant of £20,000.” Carol Butler, commenting on this grant said, “FCM agreed a very generous donation relatively early on in the planning of the Choirbook At that point we had a clear idea of what we wanted to achieve but we needed a funder to take a leap of faith with a major donation. FCM came forward at just the right point, giving us the time to develop the project knowing that we had the money to underpin the work. There’s also no doubt that the donation was a great encouragement to other potential sponsors that we approached.”

“Other benefactors in kind were solicitors Charles Russell, bankers C Hoare & Co. and publishers Canterbury Press, and the major and very significant grant which ensured the publication came with immense generosity from The Foyle Foundation.

“Once we had been successful in securing the funds for the commissioning, the collection of the works and the publication of the book, a further endeavour to seek support for the participating choirs to be provided with full sets of the books was launched.” Penny Jonas takes up the thread: “Individuals were approached and invited to ‘partner’ a choir or cathedral with which they had some personal affinity or relationship by becoming a Diamond Subscriber. Very many came with a memory or a delightful story to tell about each association.”

As a result, all the participating choirs will be presented with a set of the books, each of which will be inscribed with the name of their Diamond Subscriber.

Commenting on the outcome, Carol Butler said: “There have certainly been some difficult moments en route but it has been an enormous privilege and joy to have been involved in it from the very beginning.” And there is no doubt at all in my mind, as Chairman of The Choirbook Trust that was established to oversee the financial, production and publication arrangements for the project, that it is Carol who, because of her tenacity and dedication to the project, has been the real ‘Diamond’ who made it all happen.

FCM’s significant role in contributing to the funding of the project is being recognised by its being named as the commissioning sponsor of the new anthems by Judith Bingham and Francis Grier, and also by being the Diamond Subscriber for twenty-one choirs.

Given that our aim is ‘supporting a living tradition’, what more fitting way could there have been than this for us to be

doing just that in these two ways and, at the same time, to be paying tribute to Her Majesty in her Jubilee Year?

The Choirbook will be published by Canterbury Press and launched at a special service of Choral Evensong on St Cecilia’s Day (22 November) in Southwark Cathedral. Peter Wright, Director of Music at Southwark, says: “The publication of Choirbook for The Queen marks a highly significant moment for church music in this country. It is a great privilege that the launch is taking place at Southwark and an honour indeed for the cathedral choir to have the opportunity to sing the premiere of Peter Maxwell Davies’s masterly anthem Advent Calendar – serendipitously appropriate for this time of year.”

FCM President Christopher Robinson, reflecting on the way

Francis Grier was a chorister at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, organ scholar at King’s College Cambridge and organist at Christ Church Cathedral Oxford, where he commissioned numerous works from John Tavener, William Mathias, Giles Swayne and others. He now combines his work as a psychoanalyst with composing and performing. He has been commissioned to write numerous works for the BBC and for various cathedral and collegiate foundations in this country and abroad, including, in 1996, a setting of Psalm 150 as a birthday present for The Queen, and, in 2006, a large-scale setting of the Passion for the BBC Singers, King’s College, Cambridge and Vocal Essence in Minneapolis.

in which the project has come to fruition, has no doubts about its significance. “It will be an important historical indicator of the flourishing state of church music in the year 2012,” he says. “The contents will not only be a welcome challenge but also an encouragement to composers whom one hopes will continue to write for our choirs.”

Robert Ponsonby’s ‘simple notion’ has thus become not just a reality but a major landmark in the continuing development of church music. With characteristic humility, he simply says: “I am astonished, elated – and very grateful.”

Peter ToyneFurther information about The Choirbook, including interviews with some of the composers, can be obtained from the official website at: www.choirbookforthequeen.org.uk/book/

Judith

Judith Bingham studied composing and singing at the Royal Academy of Music. For many years she was a member of the BBC Singers; between 2004 and 2009 she was their ‘Composer-inAssociation’, during which time, in addition to several works for the BBC Singers, she wrote pieces for professional, amateur and collegiate choirs including King’s College Cambridge and the BBC Symphony Chorus at the Proms. In addition to her choral works, Bingham has written for brass band, for solo instruments, symphonic wind bands, chamber groups and large orchestra and a substantial number of pieces for organ.

James Thomas

James Thomas

All photographs by John Williams

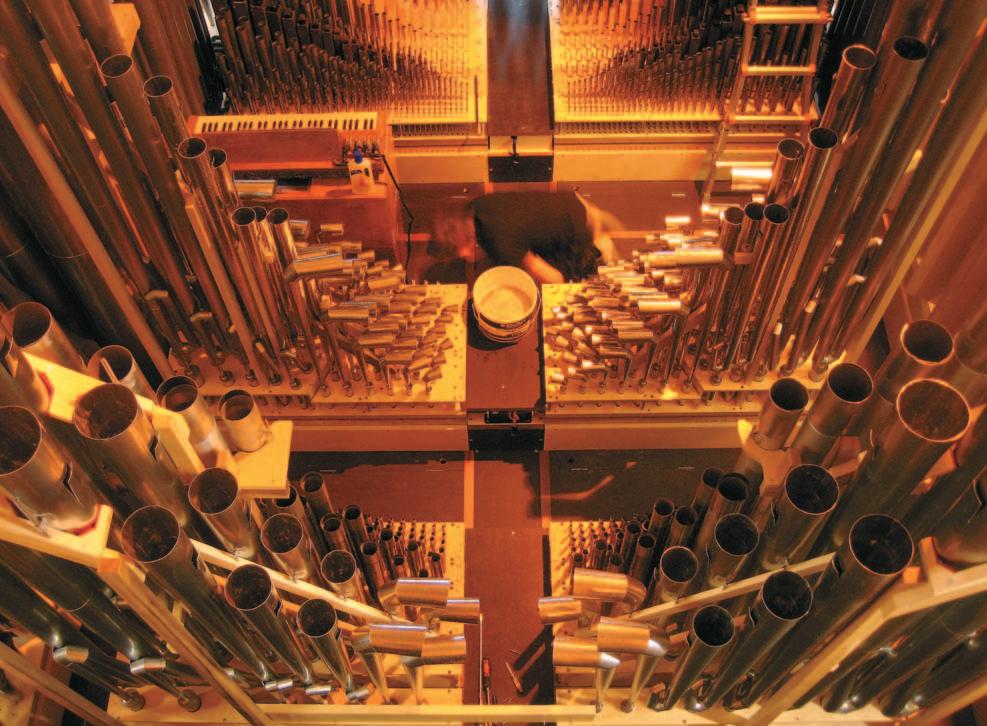

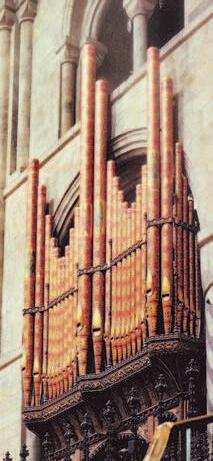

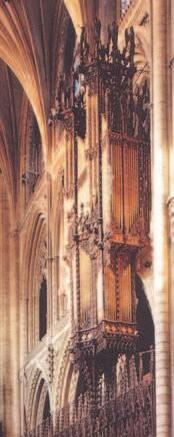

The idea from the outset was to create a musical instrument which sings with a unified voice. I have long been convinced that a choir which has a good blend of voices will make its music travel far more easily and efficiently in a building than an ensemble with lumps and bumps. It is similarly true for the organ.

Our previous instrument was installed in a new chamber high up on the north-west side of the quire in 1970. My predecessor but three, the late Harrison Oxley, had created an ingenious scheme, mixing old and new pipework. The instrument was built by Nicholsons on a very tight budget, meaning that there were certainly insufficient funds to design and build the two large cases which the organ so desperately needed. The instrument produced a wide variety of tone colours but in its crucial role of getting the sound into the nave for congregational singing it was less successful. There were pipes with too many different origins to be able to blend effectively, and the organ was also becoming increasingly unreliable mechanically and electrically.

In contrast, our new Harrison & Harrison has been brilliantly voiced so that, with each increase in volume, the stops added blend beautifully with their neighbours, and the ranks we have retained from previous instruments have all been revoiced to a certain extent to ensure that they fit well into the overall musical scheme. Indeed, it is possible to use any combination of stops throughout the whole tonal range secure in the knowledge that the blend will create a new musical timbre. This means that the fifty-nine speaking stops supply an almost inexhaustible variety of combinations.

The instrument therefore possesses its own musical character of great integrity and this, allied to an ingenious stop-list, means that not only can music as diverse as Sweelinck, Couperin, Franck, Bach, Howells and Messiaen all be performed credibly

As any organist knows, a cathedral organ has to be able to perform a wide variety of tasks. Obviously it would be inappropriate in a British cathedral to build an instrument perfectly suited to, say, German Baroque, since the choir’s repertoire is bound to include composers like Howells and Stanford. There are thus some instruments, in an attempt to be all things to all men, which lose their musical integrity and identity and are generally not much of a pleasure to listen to, nor to play. Not so here at Bury St Edmunds!

and compellingly, but also the many and varied demands of the Anglican choral tradition are coped with effortlessly.

The organ’s position in the building means that the player has to think very carefully about where his congregation and choir are sitting. The Great and Solo box speak very strongly to the west, but sitting at the console one is not aware of the true impact of these divisions in the nave. Sited just above the player’s head is the Choir division, which speaks beautifully in the quire and, for the choral offices of Evensong and Mattins there, it performs the role of the Great organ. The Swell division is enclosed in a box with two independently controlled sets of shutters: one speaking west, the other south. Thus for quire services the west shutters remain closed and only the south shutters are employed. For services in the nave, the Great organ comes into its own, along with the west-facing swell shutters. Even here the organ has several roles to perform: accompanying the choir in the nave; accompanying large congregations; and providing suitable liturgical ceremonial music. For the latter, the two high pressure solo reeds, situated well above the player’s head in the quire, sound splendidly in the nave (but are quite shattering in the quire and have to be used sparingly!).

The voicing of the Great and Swell choruses, both flue and reed, is warm, vigorous and compelling; there is a wealth of

colour on the Choir, Solo and Swell divisions and no lack of support from the firm yet promptly-speaking Pedal department. The Open Wood has a real presence in the tutti, as do both the magnificent new Ophicleide and, underpinning the whole ensemble, the full-length 32’ Double Trombone.

The Solo and Swell Octave, Sub-octave and Unison Off couplers provide even more variety of colour. On the Solo, for example, there are three 8+4’ flute combinations: the obvious one, the Harmonic Flute + octave, and the 4’ Flute + Sub octave – all equally lovely. One can have great fun experimenting with other timbres on Solo and Swell in a similar way.

Needless to say the craftsmanship is of the highest order, and the internal layout quite brilliantly planned, allowing the organ tuners easy access to every pipe.

Since Advent Sunday 2010 David Humphreys – the Assistant Director of Music, now at Peterborough – and I have been discovering ways in which this extraordinarily versatile instrument can be played, and we have also been fascinated to hear how our recitalists have tackled it. David uses the organ very effectively for accompanying our choral repertoire and has produced memorable performances of English music (such as Howells and Stanford) which are not in my repertoire. By a curious coincidence (or is it?) the organ is

also ideally suited to the music of Olivier Messiaen, which I love and play frequently.

When I arrived here nearly fifteen years ago, I inherited a file marked ‘Organ Project’ which was then several years old, but lack of funds had prevented much progress. I encouraged colleagues to start thinking again about the project and formed the Cathedral Organ Working Party. I think we would have achieved our goals sooner than we did had it not been for the opportunity that arose to build the glorious tower: of course the organ project had to take a back seat for that, as it did when further opportunities arose to build the new Chapel of the Transfiguration, the Crypt Treasury and a new row of cloisters!

Raising the money for such a project was a huge undertaking, requiring much patience, tenacity and hours of often fruitless labour. The lion’s share was carried out by members of the Cathedral Organ Working Party, a body that existed for over a decade and was chaired at first by the former Dean, the Very Revd James Atwell, and then (for a crucial phase leading to the signing of the contract) by the late Brigadier Denis Blomfield-Smith. Many people contributed countless hours of work for the COWP and many, many generous people made donations, ranging from £5 to over £500,000. I must also mention the sterling work (pun intended) of the (then) Cathedral’s Finance Manager, Kate Morris and her colleagues for their excellent handling of the financial side of a very complex operation.

The resulting instrument is a triumph of collaboration between many different parties – Harrison & Harrison, who are, I know, very proud of their creation in this their 150th anniversary year; Pennys Mill (case makers); Campbell Smith (the specialist decorators of the spectacular cases); John Bucknall (the architect who realised the decoration and instructed the painters); and the scaffolders, electricians and, of course, many colleagues at the cathedral itself. Members of the cathedral community too had to put up with a great deal of disruption, especially since the organ’s installation followed immediately upon the completion of the vaulted ceiling of the tower. I cannot thank all those involved sufficiently.

The Inaugural Recital was given by Nicolas Kynaston on March 5, 2011 to a very large and enthusiastic audience. The organ and vaulted ceiling were dedicated the previous day by the Bishop of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich in the presence of HRH the Prince of Wales.

James Thomas has been Director of Music at St Edmundsbury Cathedral since 1997. He was organ scholar at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and Assistant Director of Music at both Blackburn and Chichester Cathedrals.

DF: Congratulations on twenty-five years as Organist of Durham Cathedral. You will have seen many wonderful occasions and have lots of great recollections; can you describe some of them and how you look back on them now?

JL: Out of so many, I suppose the ones which stand out most are the 1987 celebration service on the 1300th anniversary of the death of St Cuthbert, for which we commissioned a new work from John Tavener; the memorial service for Sir Bobby Robson in 2009; and, most movingly of all, the admission of the first twenty girl choristers on All Saints’ Day 2009, for which the cathedral was full.

DF: Durham is famous not just for its choral foundation but also for the organ. What are your experiences of playing it over the years? Have you overseen any changes?

JL: I shall never forget the first hour I spent on it after I had heard of my appointment here. It is a sublime instrument which despite being a liturgical English Romantic organ in excelsis nevertheless manages to recreate several other completely different sound worlds. Many listeners have commented on the way in which it seems so perfectly at one with the building. I would not dream of making alterations which would change its character; Harrison & Harrison did make some sensitive but useful improvements to the Pedal

Chorus in the 1990s, and at the same time added a steady, gentle Tremulant to the Choir organ.

DF: Have you managed to achieve ambitions during this time? Do you have further ambitions for the cathedral’s music?

JL: I think the ambition of any cathedral organist during these challenging times is to keep the precious tradition alive, developing and in good heart; we are each of us small links in a long and valuable chain. I am grateful for having been able to help do that, having started here with a music foundation which was clearly flourishing under Richard Lloyd, the most sensitive and supportive predecessor one could wish for. The music here is greatly valued; the Chapter is open and generous in its appreciation, and I like to think that the ministry of music plays a valuable role in the life of the city, the diocese and the region. I am in no doubt that the advent of the girls here is an enrichment and strengthening of that tradition (the two teams of choristers are clearly supportive and proud of each other); my ambition is to see at least the first generation of girl choristers through their time in the choir. I hope also that we shall be able to expand the amount of orchestral accompaniment in the liturgy – the cathedral’s development plan includes instrumental scholarships in the long term, and that is a step I would be keen to see us take when it becomes possible.

DF: Which have been the most telling changes? Which have been the areas of your life that you have found demanding?

JL: The most telling change is, of course, the expansion in the number of choristers now that we have two teams. Before that, the inauguration of Durham Cathedral Consort of Singers in 1997 was a milestone; I had been very aware of the lack of opportunity for women undergraduates to sing in the cathedral as part of a cathedral choir (I should add that the Consort is not exclusively composed of students, however). Because all choristers now leave in July, rather than at the end of the term before their 14th birthday, we lose them on average eight months earlier – and when they come to us they tend to have considerably less experience of singing than was formerly the case. So the learning curve each September is that much steeper.

DF: The north-east is a wonderful place to live; is it a great place to make music?

JL: Oh yes – quite apart from the University (see below), the Sage Centre Gateshead is a major promoter of performance, outreach and education, as well as being a magnificent home for the wonderful Northern Sinfonia. And then there is a great deal of music-making going on, both town and gown, in the region.

DF: Have you managed to maintain your own solo performance career at the same time? This can be an anxiety for some, where the office draws so much time. Can you reflect on some of the most memorable places you have played?

JL: Yes, I’ve been very fortunate in being given the freedom to travel and give recitals – inevitably many of the foreign trips are outside choir terms. Finding time for personal practice can be a battle, but it’s a battle I’ve never had any intention of losing; playing is vitally important to me, and I have been keen to emphasise the role that the organ can play in the liturgy –for example we have extended voluntaries before Sunday Evensong and a middle voluntary after the sermon in the Sung Eucharist. I have been lucky to play so many wonderful instruments; it’s hard to choose, but the cathedrals of Riga, Nidaros and Notre-Dame de Paris stand out especially. But this week I played at Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow – an amazing organ in a simply sensational building.

DF: What do you regard as the greatest challenges for us in cathedral music in the 21st century?

JL: Recruitment – particularly, I think, of boys. This is down to

several factors – a lack of singing in schools for boys especially (which the outreach programmes of our cathedral and very many others seek to ameliorate); difficulty or unwillingness on the part of families with regard to making the commitment to the travel involved for day choristers or alternatively to making the sacrifices involved in boarding (especially at a distance); the decline in the number of churchgoers countrywide, and the encroachment of so many leisure activities onto Sundays. These are challenges, and provided we are prepared to rise to them rather than regard them as obstacles, we shall win. At the end of the day (dare I say this), if God wants to be worshipped by Anglican SATB choirs He will make it possible.

DF: The cathedral is surrounded by a world-famous university. How have you evolved the relationship between it and the cathedral? Is this an area where you can foresee further development?

JL: I found myself teaching Fugue and String Quartet in my first week in Durham; the university music department is nearer the cathedral than my house in the Close is! That proximity (on a world heritage site) is very valuable – the experience of reading Music at the university and being a choral scholar at the cathedral is very special. I took over conductorship of the University Choral Society in 1987 and since then have moved to inviting the University Orchestral Society to accompany our concerts. I see this as a valuable part of the cathedral’s outreach; each year more than a hundred students have the experience of singing or playing in the great works of the oratorio repertoire in unforgettable surroundings. I am sure that with a world-class music department and with the cathedral’s musical life – and its enviable collection of music manuscripts – we shall continue to explore openings and opportunities in collaboration with each other. Outside music, the cathedral has become more and more aware of the creative opportunities open to it by virtue of being effectively surrounded by university colleges. It is something we value and take seriously.

DF: I am nearing this landmark myself and I am sometimes asked “What next?”: how do you feel about that question?

JL: After twenty years in Durham, our outstanding suborganist Keith Wright has moved on, and Francesca Massey has taken up the post. I look forward to seeing her grow into the role and into the community, and to seeing the girl choristers firmly established. There’s still quite a lot of organ music lurking in the organ-stool at home waiting to be tackled – I’ve just learnt Vierne’s Sixth Symphony this summer. After that, who knows? I try not to think about the day when I shall have to say goodbye to the cathedral organ here.

DF: We know your love for railways: do tell us about some of the journeys you’ve enjoyed from Durham over the years.

JL: Well, who told you that?! I had some wonderful days out on steam excursions with Tony Davies (whose photographs of Harrison & Harrison organs your readers will have seen) before his too-early death. Sylvia and I celebrated my 40th birthday with a wonderful midwinter Luxury Land Cruise from King’s Cross to Mallaig and Oban. At a simple level there have been lovely days out in the Tyne Valley or along the incomparable line up to Berwick and Edinburgh. The pièce de résistance though was in celebration of our twenty-five years here; the Chapter generously gave me time off, and we visited Switzerland with the Railway Touring Company – steam engines, vintage rolling stock, everything organised for us. Superb!

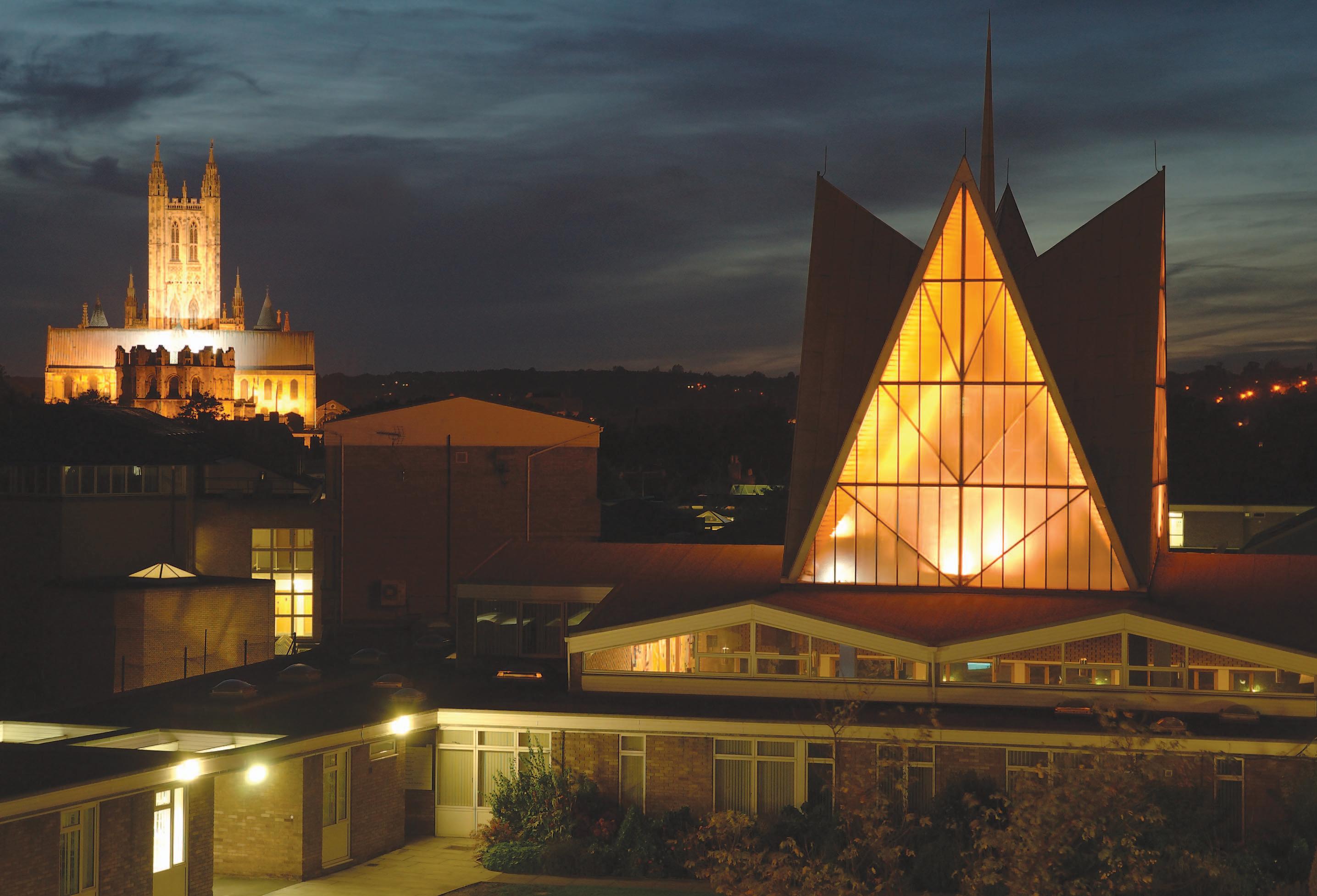

Every week, thousands of people up and down the country devote many hours to preparing and leading music for worship, as choir directors, singers, organists, instrumentalists or music group leaders. Now, a remarkable collaboration between two institutions –Canterbury Christ Church University (CCCU) and The Royal School of Church Music –has been developed to try and support this work.

The Foundation Degree in Church Music is inspired by the belief that many church musicians would like to deepen their knowledge and understanding of what they do. The course offers an opportunity to do so using the combined expertise of a university with a developing specialism in Church Music and the RSCM’s track record of work at all levels of church music in the UK (and abroad), supported by a formidable network of advisors and volunteers across the country. At this point I need to pay tribute to the woman who has been my opposite number in the development of the course: the RSCM’s Head of Education, Sue Snell, who has recruited the most remarkable team of mentors to work with students right across the country, from Aberdeen to St Davids. (She has now handed over to Huw Morgan, who will provide the crucial link between the RSCM and the university.) The commitment of the RSCM has been ever more impressive as the idea became reality over the last nine months, and nowhere was this more clearly demonstrated than at the recent start-of-year staff meeting of the Music and Performing Arts Department: as a group, they’re a sceptical bunch (it goes with the territory in academic life; you tend to view everything as if it were a dodgy PhD proposal) but when I offered my colleagues a brief introduction to the RSCM staff we now have in the field, the respectful silence which descended upon this contentious gathering was eloquent testimony to the expertise in church musicianship that the RSCM has been able to command.

Like all foundation degrees, the Church Music degree course is grounded in practical, work-based study – ie much of the work is carried out in the student’s own church or place of worship. So an important aspect of the work is the use of that home base for the objective evaluation and development of the student’s thinking about, and practice of, their musical ministry. It’s a two-year undertaking if you hurl yourself at it

for what we call ‘full-time’ study, though you can go part-time and take four, but it’s worth noting that students have almost complete control over when and how they work, since they are at home for the vast majority of their time.

A major strength of the course is the way in which the university and the RSCM are working together. Throughout the year, the RSCM’s extensive network of practising church musicians will support and mentor students in their musical home base, while CCCU will provide tuition at three four-day Residential Study Schools, in the autumn, winter and spring of each academic year, imparting the specialist knowledge and understanding which underpins music for worship.

For the rest of the year, university tutors are only a phone call or an email away, and much of the study should be done using online resources. Students have access to CCCU’s Virtual Learning Environment, ‘Blackboard’, and all the learning materials originated by the module tutors are there. The e-library includes the Grove Online Dictionary of Music, and the Naxos online music library, and access to the RSCM’s Colles Library in Salisbury can also be arranged.

For Christ Church, this new degree course is an obvious development which fits with the specialism it is developing in Church Music. Christ Church is a Church of England foundation; the cathedral is just across the road from the Canterbury campus; the organist of the cathedral, Dr David Flood, is a Fellow of the university and a visiting lecturer in the department; I am a lay clerk in the cathedral choir; and many undergraduates are already active in the chapel choir and in local church music groups –often going on to lead those groups when they’ve graduated. We thought it was time to turn that energy and enthusiasm into something more substantial, and we were delighted that the RSCM is joining forces with us. It made the long, tortuous process of ‘validating’ the degree –normally as much fun as a tooth extraction without anaesthetic – much easier, and the visiting luminaries who came to the university to scrutinise the finished product (the last and most invasive part of the process before the course is unleashed upon a cohort of students) complimented us on the quality of that collaboration. That sort of feedback in university life is about as common as a burning bush, and just as significant. Suffice it to say that we were heartened. The course is suitable

for students of all ages, whether or not they are inexperienced or proficient musicians.

At the time of writing, the first Residential Study School in Canterbury has just taken place. Because students spend plenty of time in the cathedral, our thinking was for them to get the best out of it –not only is it an inspiring building which offers artistic and spiritual nourishment, but it also serves as an opportunity to practise the kind of semi-detached reflection we’re asking of the students back at their home churches as part of their studies. So students attended an open rehearsal with the boys of the cathedral choir (food for thought for later practical sessions on choir training), an Evensong, Eucharist on the Sunday morning –and we all sang Compline, very monastically, just to ourselves, in the Eastern Crypt (yes, we have two crypts!) on the Saturday evening. I’ll also admit to a little apprehension here: we knew the mix of students included everything on the ecumenical spectrum from Free Church, Scottish Presbyterian, and Zimbabwean Methodist to Roman Catholic –with all points of Anglicanism (whatever that means) dotted about in between –so it wasn’t entirely impossible that some might object to this apparent emphasis on C-of-ECathedral. But fortunately no one has –at least, not so far; a typical comment was: “A real treat!... An unexpected bonus to the course, an opportunity I am so pleased to have had. The Compline service was a special occasion and the highlight of the week for me.”

There are other collaborations at Christ Church which, we hope, will serve as an inspiration for the students: the university has a long-established relationship with two of our country’s leading composers, Peter Maxwell Davies and Paul Patterson, who are visiting professors at the university, and CCCU is also the foremost provider of training for the lay ministry in the south east, and will capitalise on this depth of expertise in the future study schools.

This is a course which, in time-honoured university tradition, is less concerned with the answers than with the quality of the questions. We’re hoping that as our students take a couple of years to walk around the issues which we’ve parcelled up conveniently (universities think in boxes, I’m finding, however often we exhort our students to think outside them) into bundles called ‘Ministry and Worship’, ‘Music and Liturgy’, and even (in the first year) the nuts-andbolts ‘Church Music Management’, they will learn to ask better questions.

Sometimes, they have to set themselves their own questions, and the quality of these is crucial to the success or otherwise of their study. In each of the two years of (full-time) study, students do a project. It’s worth a sixth of their marks in Year 1, and a third in Year 2, so it’s quite significant. The project gives them a chance –we hope –either to scrutinise one aspect of their own practice or develop in some new direction. They’ve already started thinking about their projects for this year, and it looks as if they’re eager for the intellectual fray. We might

have known this would happen, but it’s taken me slightly by surprise; perhaps I hadn’t really realised how self-reliant an awful lot of church musicians have to be.

I’ve left till now the brief comments about what, for many, will be the heart of the matter. The module called ‘Practical Church Musicianship’ expects our students to choose two areas of practical work in which they will submit assessments where the student can specialise as a singer, voice trainer, choir trainer, music leader, organ/keyboard player/instrumentalist or composer/ arranger. There is also help in the practical management of church music, including legal issues and copyright. It’s a neat example, I think, of one of the ways in which the course is both supportive and developmental: we all know what we’re good at, but it might be nice to have a critical friend (i) to tell us how we might improve, and (ii) to help us see if we can get better at something else as well. I have every confidence that members of the RSCM Mentor Team will be very well qualified to be those critical friends.

This degree is a new venture, and there couldn’t be a worse time, in the world of Higher Education, to be launching one of them. I’ll leave the last word to one of our students, but I’ll offer a personal point of view first: if I look back to the 18-yearold I was, in that tiny Yorkshire village in which I spent my teenage years, and consider how likely I would be to go to university in today’s economic climate, given my family background and my mother’s pathological worry about debt, bless her, I think today’s version of me would have ended up being the accountant she wanted me to become though I still think I would have hated it. So at the risk of being hopelessly

anecdotal, I’ll just point out that if this course enables other young people who love their work in parish churches up and down the country to study at degree level, it will have been worth the effort.

We next meet our students in January, here in Canterbury. We’re not at all sure how many will make it across the country through the freezing fogs and snows of a British winter, and we may have to re-think that particular part of the schedule –but if this participant is in any way speaking for the group, I have no worries: “Feel utterly mind-blown by the whole experience. It’s been a wonderful sojourn and a marvellous opportunity, thanks so much! Really looking forward to the next session and hope to do the course justice. I am feeling much more confident and am keen to put new ideas into practice... Can’t wait till January!”

More information is available on both the CCCU and RSCM websites: www.canterbury.ac.uk/studyhere/church-music and www.rscm.com/fdcm

Precentor has changed over the centuries. Despite being styled the primary cantor, the Precentor at St Paul’s Cathedral has not traditionally done any singing. That is left to three Minor Canons who lead the daily worship at Mattins and Evensong, and who sing the Eucharist on a Sunday.

Moving within St Paul’s in 2003 from being a Minor Canon to a Canon meant that bizarrely, by following tradition, I would have stopped singing and this didn’t make sense to anyone. One of the main reasons that I enjoyed being part of the music foundation at St Paul’s was my background in music: I trained as a soprano at the Royal College of Music and sang with groups such as Polyphony and the Cambridge Singers before I was ordained. So it was wonderful to continue to sing the Eucharist despite being a member of the Chapter!

The music foundation, in modern terms the music and liturgy departments, was a thrilling and challenging place to work with so many outstanding clergy, professional musicians and such able administrators to bring together. Our monthly planning meetings, which we called LAMP (liturgy and music

planning) were a mixture of ‘what worked well last time’ and “how can we bring this theme to life this time”, and it was exhilarating to have to keep in mind the impact of public liturgy on a million and a half visitors each year. The shape of daily evensong, the rhythm of Sunday and the observance of festivals combined in a discipline that moulded our responses to big national events such as 9/11, 7/7, the end of the operations in Iraq or Northern Ireland, and the South Asian tsunami. The location and history of St Paul’s meant that we dealt often with government departments and national organisations, and we were able to make a difference to how national events were commemorated. But daily services on the proverbial ‘wet Tuesday in February’ were equally important and we often said to one another that it was because the choir sang Evensong every day to such a high standard that we were

able to think of responding to national events with large-scale services at such short notice.

St Paul’s itself is a cathedral that was in the end a compromise between the building Christopher Wren wanted to build and the one that was politically acceptable to a cautious Chapter in the late seventeenth-century Church of England. It has therefore an inherent architectural tension in it; one’s eye is drawn to the High Altar, yes, but also to the dominant feature: the inspirational dome. The dome was not designed for any liturgy to be held under it at all, but despite its size it is an intimate space that lends itself to, for example, an evening Eucharist in the round with the natural light from Wren’s windows streaming in as the sun sets. It was a challenge attempting to think through these tensions: which altar to use for the liturgical focus at any given service, the position of the choir or the organist, and the importance of the organ supporting congregational singing in such a vast space. The famous acoustic beat everyone who thought they could defeat it, but the imagination of successive Directors of Music and Minor Canons who placed choristers, cellists, trumpeters, shofar players, etc up in the galleries and high in the dome meant that evocative sound was a regular feature of our liturgical diet. For the service to commemorate the death of 300,000 people in the South Asian tsunami, we released 300,000 petals from flowers grown around the Indian Ocean from the dome galleries and their silent falling reduced everyone, including the Thai fiddle player, to tears. Using the height, depth and width of such an extraordinary building was a wonderful opportunity to invoke the sense of God transcendent and if I’m honest, we were more able to do this than invoke the sense of God imminent. The church needs both aspects of God to be proclaimed in our liturgy; God incarnate and also God unconfined. It strikes me that as yet again cathedrals are reporting a growth in their attendance, our population is yearning for a sense of God beyond ourselves in a world where everything is more or less immediate and disposable.

Now I am serving in another Wren building, the only church in London that was built by Wren outside the City, and I revel again in his vision of the church: light, wide, open and elegant. The acoustic at St James’s Piccadilly is absolutely superb, particularly for chamber music and unaccompanied voice, and our six concerts a week, three at lunchtime and three in the evening, ensure that much wonderful music is made and heard here almost every day. Being in the West End makes the contrast between the outside and inside of the building starker than ever. Traffic, roadworks, sirens and crowds mean that our environment is relentlessly noisy but the

peace that somehow is preserved within the building is very special. The standard of music-making in the regular concerts is superb and the range from Miles Davies to Shostakovich guarantees large and varied audiences –in 2012 we will be taking part in a festival of Bach and the London Jazz Festival for example.

On Sundays, a volunteer choir drawn from the congregation sings a range of music from Taizé chants and responsorial psalms to Mozart and the occasional Tallis during the Eucharist, and I have been struck by the unaccompanied singing of the congregation in parts for the Sanctus, Benedictus and during the hymns. I have never heard better unaccompanied congregational singing in a church before coming to St James’s. This is a big contrast to the cathedral style of participation I was used to; listening and praying through the choir’s offering on our behalf.

Another musical issue, despite a magnificent case in the gallery with carving by Grinling Gibbons, is that there is no working pipe organ at St James’s. As a modern rector’s life will inevitably include fund-raising, this will be on the agenda for the future. I feel honoured to have served in two such elegant buildings which by their grace dignify those of us who pray and sing in them. I live, with 10 million others of every culture and race, in a gloriously historic city full of contemporary commotion. The phrase, ‘It’s like Piccadilly Circus round here’ is acutely brought to life where I am now; and the vision that Wren bequeathed here at St James’s, as well as at St Paul’s, is one that resonates with the movement of the Spirit in the Book of Genesis; one that brings order out of chaos and one that calls harmony out of all who make music within its walls.

...I have been struck by the unaccompanied singing of the congregation in parts for the Sanctus, Benedictus and during the hymns. I have never heard better unaccompanied congregational singing in a church before coming to St James’s

Michael

When St Edmundsbury Cathedral built its great gothic lantern tower, completed in 2005, it made a very bold statement of confidence about the Christian faith and about what it means to be a cathedral.

Christopher Wren was doing something similar when he built St Paul’s Cathedral, completed 300 years ago this year. And no doubt the unknown Norman French architect of the abbey at Durham was also thinking along these lines when he began work on his church of God in 1093.

As someone said to me recently, I’ve been knocking around cathedrals for quite a while. St Paul’s is my third precentorship (the first was Durham, the second was Bury St Edmunds). It would be tempting to say that I’ve pretty much got the measure of cathedrals by now but that would be to miss one of the most exciting points about these places: that, while the rhythm of daily worship is identical in every cathedral worth its name, the capacity of these sacred places to surprise knows no bounds.

I am not a professional musician although I’ve sung solo, as it were, alongside professional musicians for fourteen years. I reckon I’ve sung ‘O Lord, open thou our lips’ about 2,500 times if my memory and my maths serve me right. Having said that, at St Paul’s – rather like the distinguished person who has his toothpaste squeezed onto his toothbrush for him – the words are now sung for me by our admirable Minor Canons. Perhaps they’ll all have a cold on the same day one day and I’ll be able to see if I can remember how it goes.

I arrived at St Paul’s in March of this year to find a series of new structural arrangements in place concerning the way in which the cathedral’s musical forces are disposed: a reorganisation in the working practices of the Vicars Choral and a different way of making use of deputies (of which there are about 150). The new system works well and, whether 40 singers (including boys) are performing Evensong in the Quire or four singers are performing a four-part mass at lunchtime under the Dome, the quality of the sound is remarkable, despite the vast space and enormous acoustic.

The acoustic presents challenges for the delivery of the liturgy: does the minister wait for the acoustic to die every time he or she is about to speak after the music or does this break the pace of the liturgy at its more dramatic moments? How does the organist prevent the acoustic from dictating the speed of hymn accompaniment? And how does one do ‘intimate’ in so vast a deep?

The daily pattern of worship feels no different here from Durham or St Edmundsbury – except that Morning Prayer is at 7.30 am as opposed to 8.45 am in the other two places (I use two alarm clocks now...). That, a daily Eucharist, Evensong sung most days of the week, and three major choral services on Sunday are really the hallmark of worship in an English cathedral regardless of its location, size, age, or resources. And that’s how it should be.

One very particular difference between St Paul’s and St Edmundsbury is, of course, the presence here of a choir school. At St Edmundsbury Cathedral, the choristers are drawn from a variety of different state and independent schools in the locality. This is tricky in terms of co-ordination, especially when choristers are needed for special services during school time, and the delivery and collection of children from and to diverse locations, but it does mean that a significant cross-section of the local community through its schools enjoys a significant association with their cathedral. Nevertheless, a school community which is also well and truly part of the cathedral community is a great blessing and

provides a significant ‘resident’ community as a balancing antidote to the somewhat transient nature of the worshipping community of St Paul’s.

Which is, of course, another significant contrast: all cathedrals enjoy the presence of visitors at most of their acts of worship but St Paul’s almost only enjoys the presence of visitors. There is a core of regular worshippers here and the liturgical community of clergy and lay staff is a very significant part of the regular worshipping community, but is nevertheless a small percentage of the whole. This adds an edge to the preparation of our worship and the crafting of our sermons and the leading of our worship: nothing can be taken for granted and our ‘guests’ who may only have one opportunity to be inspired by what they encounter at St Paul’s must not be let down.

But I suppose that if anything provides a contrast between my experiences at St Paul’s and elsewhere, it is the location and the size. It’s London and everything is ‘writ large’. I remember attending a lecture under the Dome in my first week here and the organiser was disappointed because there were only 700 people at it. I understand that we were slightly disappointed that only 1,500 people attended the Holy Week offering of Bach’s St John Passion. But, as I write, we’re busy considering whether we’ll be able to broadcast our carol services out into Paternoster Square as we did last year, to cater for the many thousands of people who won’t be able to get inside the building at Christmas.

And, of course, the profile of the place means that you have to think even more carefully than usual about the wisdom of what you might say or do about God and the world because the platform upon which we’re privileged to speak and act sits under a very sharply focused spotlight and comes in for very clear scrutiny. That’s nothing to be afraid of – what a wasted opportunity if it scared us – but we must never forget the implications for us and for our fellow Christians elsewhere –and perhaps more pertinently the implications for God: not unto us, O Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give the praise.

And as for any more contrasts? Before my first three months here were up, I had been presented to HRH the Duchess of Gloucester, HRH the Princess Royal, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh, and HM the Queen. Nothing particularly new in that: I’d met all four of them before – at St Edmundsbury Cathedral!

Michael Hampel

Precentor, Durham Cathedral, 1997-2002

Senior Tutor, St Chad’s College, Durham, 2002-2004

Precentor, St Edmundsbury Cathedral, 2004-2011 (Sub-Dean from 2008)

Of the twenty-three Anglican dioceses in Australia, fewer than half have the resources to maintain any kind of cathedral music tradition. The cathedrals of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth have choirs of high standards with professionally trained church musicians in charge, even if not all are employed full-time. The cathedrals of many regional dioceses also employ professional organists or choir directors but work with amateur choral resources. Most regional cathedrals double up as country parish churches but many take their music seriously. Other cathedrals in more remote dioceses have minimal music resources and rely on volunteer, perhaps even reluctant, organists.

For example, Holy Cross Cathedral, Geraldton is the cathedral church for the diocese of North West Australia, the largest land-mass Anglican diocese in the world, covering two million square kilometres, a quarter of the continent. But the population of the diocese is only about 150,000 people with just eighteen Anglican parishes, mostly small farming, fishing and mining communities. The cathedral is no less significant than any other in the world, but its music ministry is essentially geared to a transient population.

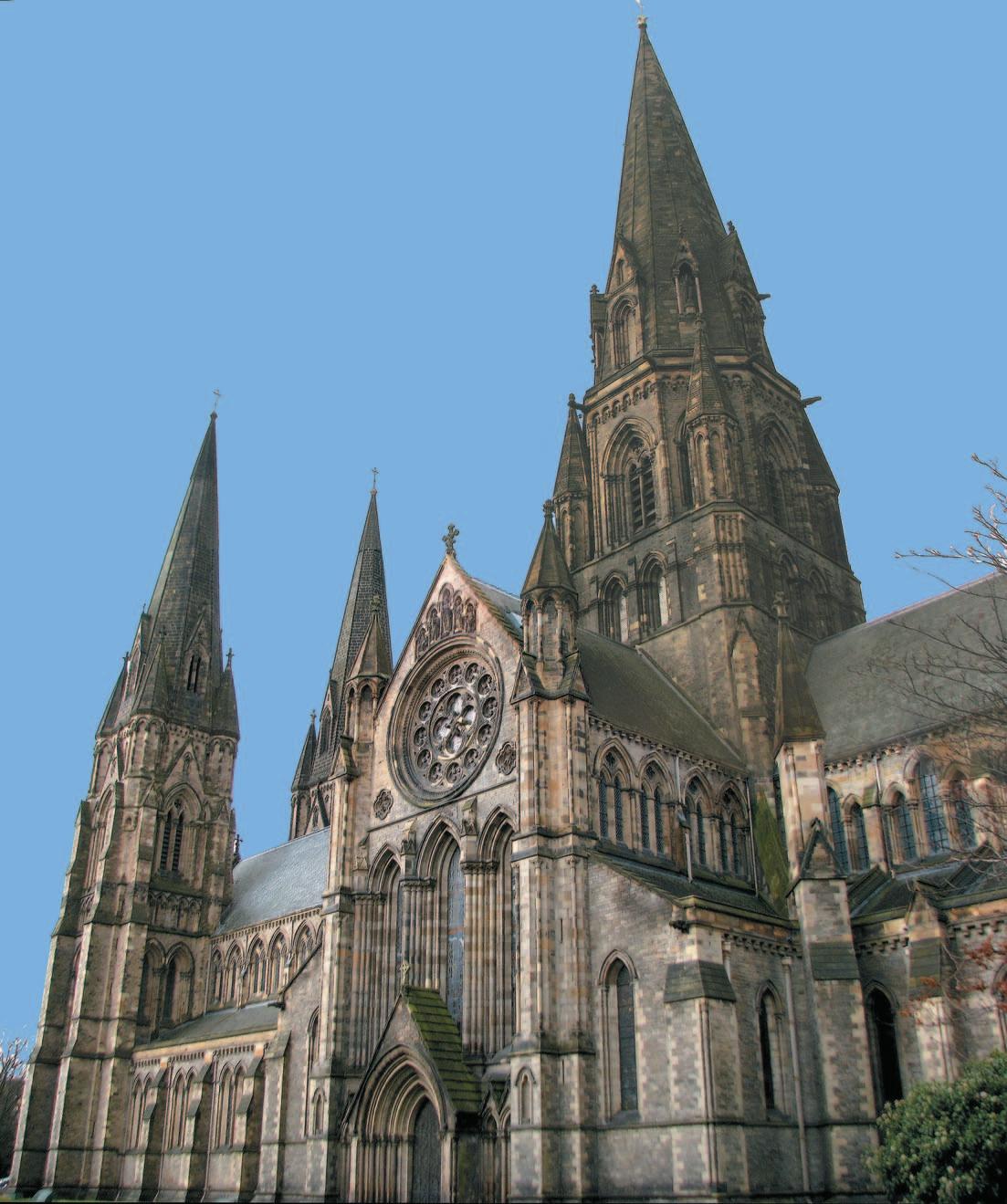

Architecturally, the high profile Australian cathedrals are products of the Gothic Revival style; William Butterfield being responsible for Melbourne and Adelaide, Edmund Blacket for Sydney, Perth and Goulburn, and John Pearson (of Truro fame) for Brisbane. As usual in high profile cathedrals there is

always tension, mostly financially induced, but also often in the area of priorities. Some, like Melbourne, try to emulate what happens in English cathedrals while others have little interest in being replicas of their English counterparts and prefer to forge their own Australian identities or, as in the case of Sydney, its ideological identity.

The oldest cathedral in Australia is St Andrew’s in Sydney, NSW, which is the only cathedral that has its own adjacent choir day school, founded in 1885, just eighteen years after the consecration of the cathedral. Today the school has over a thousand pupils, aged 5-18. Girl pupils were introduced over a decade ago and sing a weekly service. Weekday Evensong is no longer sung almost daily but on Thursdays only, with two Mattins services a week and a choral service on Sunday morning.

St Andrew’s Cathedral Choir is the only Australian choir to have sung on BBC Choral Evensong, which coincided with the Sydney Olympics in 2000. The current director of music, Ross Cobb, is the cathedral’s eleventh organist, recruited from Christ Church, Clifton, Bristol six years ago. Ross has continued the international tours begun in 1985, which have seen the choir sing in as many as sixteen English cathedrals, Westminster Abbey and St George’s Windsor, plus cathedrals in Europe and New Zealand. Popular publicity that the cathedral choir became defunct after the arrival of a new dean in 2003 is totally false! What is true, however, is that the cathedral interior has been re-ordered to resemble a meeting

There is a story of a bishop in an Australian outback diocese who always carried his chair (cathedra) in the boot of his car. Whichever church he was visiting in his vast diocese, that church became his cathedral for the day because that was where his chair was set up. Whether this is literally true or just folklore, it tells a story of extremes in the Australian cathedral world.Choristers in front of St George’s, Perth Photo © Russell Barton

hall rather than a place of worship. Fortunately, the majestic exterior is immune from ecclesiastical vandalism.

Probably the hardest working cathedral choir in the country is that of St Paul’s in Melbourne, Victoria. Since its formation in 1888, the choir has had only five directors of music and still maintains a daily Evensong, the only cathedral in Australia to do so. This is all the more remarkable since the choristers are educated at Trinity Grammar School, Kew, a considerable distance from the cathedral, and come in for practice after school by bus, train or tram. The current director of music, Dr June Nixon, was appointed in 1973 and has so far been responsible for the music at more than 11,500 choral services.

St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane, Queensland has recently adopted the model of two part-time positions, director of choral music, Graeme Morton and organist, Michael Fulcher. The choir of men and boys is sustained by offering 50% scholarships at the Church of England grammar school which is some suburbs away from the cathedral. The boys rehearse at the school three mornings a week at 7.30am plus a Friday afternoon rehearsal and the usual pre-service rehearsals. Their training is enhanced by having two female tutors, one being a vocal teacher and speech therapist, the other a primary school music educator. The weekly routine of Sunday morning Choral Eucharist and Evensong is maintained, and there are also two other choirs: a mixed-voice choir, the Cathedral Singers, and a chamber choir that provides more specialized repertoire and non-liturgical performances.

The music at St George’s Cathedral, Perth, Western Australia has always benefited from the policy of its dean and chapter to search the world for the best possible music director, even if such appointments are not expected to be long term. Since the arrival in 2008 of Joseph Nolan, formerly of Her Majesty’s Chapels Royal, St James’s Palace, the standard of music at St George’s has grown exponentially. The cathedral choir has twenty boy choristers with a substantial waiting list and sixteen paid professional lay clerks, a rarity for Australian cathedrals. St George’s probably has the largest budget for music of any cathedral in Australia. There is no tradition of daily Evensong but the choir has a very full

schedule. It now broadcasts regularly and records for the ABC. There is also the Cathedral Consort, a group of twenty professional singers which shares the load of Sunday Evensongs with the men and boys’ choir. Such has been the impact of St George’s music on the city of Perth that the cathedral holds a major annual concert series with the cathedral choirs and guest artists, featuring at least two orchestral oratorios a year with players from the West Australian Symphony Orchestra. This is supported financially by the cathedral chapter, private sponsors and the cathedral’s Foundation for the Arts. In 2008 the choir travelled to France and sang in Amiens Cathedral and St Sulpice, Paris.

For all TV watchers of test cricket, St Peter’s Cathedral, Adelaide, South Australia, will be a familiar sight. Indeed at the end of every other over at the Adelaide Oval the commentator tells us that the ball is being bowled from the cathedral end.

The cathedral choir has been in existence for over 130 years, although is no longer exclusively a men and boys’ choir. In fact it is the only choir of children and adults of its type in Adelaide. The children have performed with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and the State Opera, while the lay clerks are amongst Adelaide’s best choral singers. The choir now sings at three services a week, two on Sunday and a Wednesday Evensong. Music education is taken very seriously and the trebles are fully involved with the RSCM Voice for Life scheme. The emphasis on sight-reading enables the choir to learn repertoire quickly and allows time for work on choral and vocal technique. For many years St Peter’s Cathedral has had a separate choir director, Leonie Hempton and organist, Shirley Gale. Recently the choir made its second international tour, to the south of England and to Rome, singing in St Peter’s Basilica.

The capital city of Tasmania, Hobart, has the beautiful St David’s Cathedral. It once had an all-male tradition but the boys’ choir was disbanded in 1998 and now is a mixed adult SATB choir of up to twenty singers, with a current age range of seventeen to seventy-eight years. This includes the longestserving chorister who has contributed sixty-eight years of unbroken service, man and boy. There is a Choral Eucharist each Sunday morning, with Evensong on the fourth Sunday

and Choral Mattins on the fifth. The organist, Andrew Bainbridge, is part-time, so the cathedral frequently relies on other local organists to play for funerals and occasional services.

Moving on to the regional cathedrals, All Saints Cathedral, Bathurst, in the central tablelands of NSW, is blessed with one of the finest acoustics in the world for choral music and is a favourite venue for visiting overseas choirs. Bathurst was also the centre for the most recent RSCM National Summer School, directed by Matthew Owens from Wells Cathedral. Choral Eucharist on Sundays is at the early hour of 8.00am, and there is a monthly Sunday Evensong at 4.30pm. For this Evensong, the regular core membership of about sixteen adults swells to around twenty-four, with talented and dedicated singers travelling from far afield to rehearse midafternoon and then to sing a full choral service. Working with limited financial resources, the Precentor/Liturgist Michael Deasey is also principal organist and director of music, which has the advantage of avoiding any policy disagreements. A recent innovation has been the introduction of a choral scholarship to a tertiary or secondary student, the first recipient being a very welcome young tenor, an endangered species in most country towns.

Also in New South Wales is Christ Church Cathedral, Newcastle, an imposing building overlooking the city, where the choir maintains a schedule of Choral Eucharist and Evensong every Sunday, as well as other special diocesan and civic occasions. It is a volunteer choir of around forty members (aged between thirteen and eighty-five), but averages about twenty-five choristers for services. In this mixed choir, a limited number of scholarships are offered to those studying at secondary or tertiary level. The organist and music director is Peter Guy, who maintains a large and varied repertoire. Like most Australian cathedral music positions, he is classified as part-time, but of course that is a reality only in terms of remuneration, not in actual time. Also, like many provincial cathedrals, the assistant organist is totally voluntary but there is minimal funding in Newcastle for an organ scholar.

In the far north of tropical Queensland is St James’s Cathedral, Townsville, the seat of the Bishop of North

Queensland. It is an impressive edifice but struggling financially, with most clerical and lay positions being filled by dedicated honoraries. This includes the director of music Sam Blanch, whose day job is Head of Music at Townsville Grammar School. The cathedral choir which sings at the 9am Sunday Eucharist has about eight regular members. It is only for the festival Sundays that the choir is robed and sits in the choir stalls. For ordinary Sundays the choir sits in the midst of the congregation from where it leads the congregational setting of the Eucharist and gathers together for the psalm and motet. However, like so many cathedrals in Australia, even the struggling ones, there is recognition that Evensong is one of the great liturgical creations of all time, and the choir sings it regularly, usually on the first Sunday of each month. For large diocesan events, choirs from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island congregations come to sing, and the cathedral is also the venue for concerts and school choral festivals.

The stunningly beautiful St Saviour’s Cathedral, Goulburn is the seat of the Bishop of Canberra and Goulburn, with the cathedral city being an hour’s drive from the nation’s capital. The cathedral choir is small, currently about ten members, but in the process of expanding, and sings at the Sunday Eucharist (where its solo contribution is the communion motet), Holy Week services, and provides the music for major diocesan events. Greg Oehm (Director of Music) and Robert Smith (Organist) are both professional musicians in their own right but have to work with limited resources. A highlight of 2011 was to combine with the choir of Christ’s College Cambridge to sing Choral Evensong in celebration of four hundred years of the King James Bible; the 1604 version of the Prayer Book was used, together with period music and readings.

Similar stories with local variations can be told of the thirteen cathedrals not discussed in this article, most seeing their principal role as a parish church and only going into ‘cathedral mode’ for diocesan occasions. But cathedrals great and small, city or country, regional or remote, share the one great common cause, which is to worship God – not because He needs it, but He knows that we need it, to transform us, inspire us and to humble us.

Age: 37

Education details:

Ysgol Dyffryn Ogwen, Bethesda, North Wales; Eton College (Sixth Form Music Scholar); Magdalen College, Oxford and Yale University.

Career details to date (and dates):

Organ Scholar, Magdalen College, Oxford (1992-5); Assistant Organist, St Asaph Cathedral (1995-8); Organ Scholar, Hampstead Parish Church (1998-9); Fellow in Church Music, Christ Church, New Haven, CT, USA (19992001); Assistant Organist, St Philip’s Cathedral, Atlanta, GA, USA (2001-2); Director, Atlanta Schola Cantorum (2001-3); Sub Organist and Director of Guildford Cathedral Girls’ Choir (2003-9); Assistant Director of Music, Exeter Cathedral (2010).

Were you a chorister, and if so, where? Did you enjoy the experience? Sadly, no, I wasn’t a chorister. In retrospect I wish I had been as I’m sure it makes one a better choir trainer when working with children, simply from being able to empathise with the chorister’s lot.

What did you enjoy most about being an organ scholar at Magdalen?

It was a privilege to live in a college of such architectural beauty: the scale of intimacy and splendour of the college chapel remains (for me) one of its glories. Working with Bill Ives made a lasting impression: having a singer of that calibre standing in front of a choir always made me wish I didn’t have a voice like a corncrake!

What or who made you take up the organ?

Two of my sisters are organists: a combination of their example and encouragement together with spending most Sundays in church did it for me. My earliest memory is of hearing Swell to Mixture at our local church, with the box half open. Should I go and get my anorak now?

When you were at school, did you think you might end up where you are now? Why or why not?

No, not at all, I think one soon learns the truth of John Lennon’s line that life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans! Equally, I think that seeking out high-powered jobs becomes less attractive as one gets older when one realises that they are often far less glamorous than they appear (and highly stressful!).

What was different about studying in America? Why did you go there?

I went to America because I met Thomas Murray (through Geoffrey Morgan) and applied for the Master’s course in organ performance at Yale, where Tom is the professor of organ. I then stayed in the USA for four years: like most Brits who go there I was mesmerised by the vitality of the organ scene, the fact that people actually go to church, and by the salaries. Studying in America is wonderful because pedagogy is considered de rigueur from the undergraduate level. The experience cleaned up my very sketchy technique! In general, American organ studies look far more towards Europe than they do towards the UK, so they provide a good contrast with our home-grown Anglican approaches.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

I heard someone play Guilmant’s Fifth Sonata recently so I’m hawking that around a bit at the moment, especially as this is a Guilmant centenary year. I’m one of those people who learns the first two pages of pieces then loses interest, but a piece that I’ve enjoyed learning is Miroir by Ad Wammes.

Have you been listening to recordings of them and if so is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

I’ve not listened to the Guilmant, but Andrew Canning’s recording of the Wammes is firmly in the iPod.

Which organists do you admire the most?

It would be a huge list! I guess it depends on the repertoire, but André Isoir, Nathan Laube and Tom Murray jump to mind. I am captivated by Cameron Carpenter, although, like Jean Guillou, his interpretations can be a little too outré for my Luddite tastes. And I’m envious of his wardrobe.

What was the last CD you bought?

The album ‘Swim’ by Caribou

What was the last recording you were working on?

The girls and men of Exeter Cathedral Choir have just recorded a CD of anthems for the liturgical year

What is your favourite organ to play?

Bristol Cathedral

What is your favourite building?

(sacred) Notre-Dame de Fontgombault, France; (secular)

Bilbao Guggenheim

What is your favourite anthem?

Media vita – John Sheppard

What is your favourite set of canticles?

Dyson in F

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants?

Psalm 53, Robert Ashfield

What is your favourite organ piece?

Sicilienne – Duruflé

Who is your favourite composer?

Jehan Alain

When is your next organ recital? Which pieces are you including? The diary is empty! Any takers?

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

One Good Friday at Guildford Cathedral, during the singing of ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’, something happened in that the entire congregation seemed to be completely involved with the words and we accompanied each other rather than there being any sense of leading. Once we got to the line ‘demands my soul, my life, my all’ I think we all felt we had gone above and beyond a normal hymn sing, even though I know we should be aspiring to that all the time!

Has any particular recording inspired you?

The Simon Rattle/Andrei Gavrilov recording of the Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand inspires me to practise the piano harder.

How do you cope with nerves?

I try to convince myself that nerves are a hindrance; getting that balance between inertia and adrenalin can be tricky.

What are your hobbies?