C CATHEDRAL MUSIC

With the recent acquisition of Copeman Hart & Company Ltd by Makin Organs, as a combined company we now offer the best of both worlds with the foremost sampled sound technology from Makin and Johannus and real-time computing from Copeman Hart. No other company offers such a broad range of products covering all technologies. Our customers are now in a unique position in that they can choose anything from a simple home practice instrument through to the largest of cathedral organs. Please take the time to visit us and browse our websites, we don’t think you will be disappointed.

www.makinorgans.co.uk

www.copemanhart.co.uk

For more details and brochures please telephone 01706 888100

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2012

Editor Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Deputy Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon FCM email info@fcm.org.uk Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

Roger Tucker, 16 Rodenhurst Road, London SW4 8AR

0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London, WC1N 3AX Tel: 0845 644 3721 International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

Beech Hall, Knaresborough, HG5 0EA 01423 796262 info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

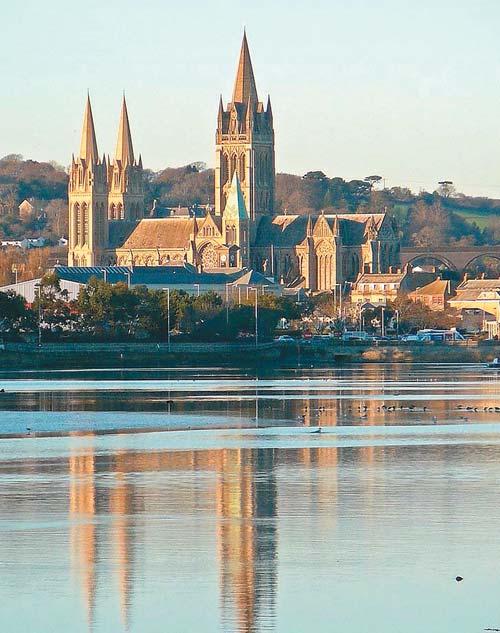

Cover photographs Front Cover Truro Cathedral ©

5

6 Two Choirs under one Roof: Music at Cambridge’s Jesus College Mark Williams talks to Sooty Asquith

12

16

22

26

At the recent Lincoln gathering in October this year I took note that there were one or two grey heads present, and it occurred to me that the following might be relevant. Did you know that since April 2012 a reduced rate of inheritance tax (36% instead of 40%) can now apply to most people who leave 10% or more of their estate to charity? The maths is compelling and straightforward: your beneficiaries will only be slightly out of pocket, but your good cause will be significantly better off. If you are not already leaving this amount to charity (and few, it seems, are) you would of course need to update your will or add a codicil. Apparently 35% of people say they’d happily leave a gift to charity in their will once family and friends have been provided for, but only 7% actually do. Writing a will isn’t something one does very often, is it? And when even looking up the solicitor’s name and telephone number seems to cost money, it becomes less attractive still. But consider perhaps the good and continuing use to which a legacy can be put by FCM – supporting choristers, lay clerks, choral foundations, organists etc – even after you are no longer present; it would be worth the effort, wouldn’t it?

There is frequently talk about the hugely important subject of increasing our membership, and of how we can make

people more aware of FCM and its purpose. Cathedral Voice recently listed a collection of useful ways in which others could be recruited to the cause, and I would particularly like to emphasise the passing on of this magazine when you have finished with it. Don’t simply recycle it but hand it on to friends, to anywhere with a waiting room, leave it on the table at the back of a church you’ve never been to before, or offer it to the manager of your local cathedral shop in the hope that they may take extra copies to sell. Widen the circle. Future members will thank you.

And now Christmas approaches. The organised souls will have already bought their cards, but for those whom Life occasionally ambushes from behind – don’t forget that you can still buy FCM cards in a fine choice of different designs.

You will also find included in the pages of this magazine a brand new FCM recruitment leaflet. Please do consider carefully how best you can make use of this and do not simply ignore it or consign it to the waste paper bin. Encourage your friends to join, or, perhaps, give FCM membership to a lucky person as a Christmas present.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

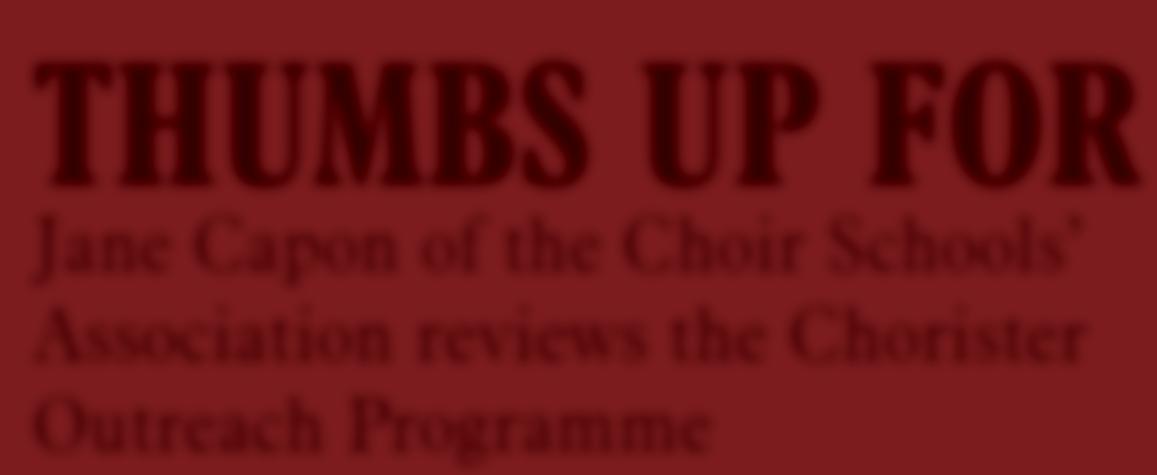

Dating back to the foundation of Jesus College at the end of the fifteenth century, the choir of men and boys has a long history. The chapel and its worship had fallen into a parlous state by the middle of the nineteenth century and Augustus Pugin was employed to restore the building (which in parts dates back to the twelfth century) while Sir John Sutton, a Fellow Commoner, commissioned J C Bishop to build a new organ, and re-established a school for the education of choristers. In due course the choristers came to be recruited from local schools, and that remains the case to this day. When, in 1979, the college admitted women undergraduates for the first time, it was felt that they ought to be given the opportunity to play their part in the chapel worship. Nobody wished to see the choir of men and boys dissolved, and so the chapel became the first of any Cambridge college to have two choirs; they share the weekly services between them, and come together for occasional special events, concerts and tours. Today, the Chapel Choir of men and boys sings Evensong on a Thursday and Saturday whilst the College Choir of male and female undergraduates sings the services on a Tuesday and Sunday.

There are currently 23 boys singing as probationers and choristers at Jesus. They come from fourteen different schools in the Cambridge area and a number travel from quite far afield. It is, of course, unusual to have so many choirs of men and boys in such a small area (Ely is very close by too) but King’s and St John’s, equally long-standing choral foundations, offer a very different experience, with their choristers boarding and rehearsing daily, performing to an extraordinarily high standard day in day out, broadcasting regularly both nationally and internationally. They are not seen as competition: Jesus offers boys the chance to become a part of the life of a Cambridge college whilst still living at home and attending their own schools. Boys come to choir in the way that they might go to football practice, and Mark Williams, Director of Music at Jesus since 2009, hopes that they feel as passionate about singing as they might feel about sport or any other activity pursued outside the school walls. Beyond the musical benefits, which are selfevident, parents appreciate the emphasis on teamwork, discipline, personal presentation and commitment that are intrinsic to what Jesus Chapel Choir does, whilst the boys themselves value the opportunity to perform at a high level with

talented students in a beautiful and ancient building. One of the most rewarding aspects of the job for Mark is seeing the boys arrive at a rehearsal straight from school or a football match and watching their faces light up as he announces that the first anthem is by Tallis. Of course their faces light up even more when they receive their termly pocket money! As one of the smallest ones said to Mark with surprising honesty when he was asked why he’d joined the choir, “I was really only interested in the spending money, but I have to admit I do quite like singing now!” On recruitment Mark says, “We have been fortunate to have good numbers auditioning in recent years, but there’s no relying on that, and so we continue to work on recruitment and outreach, holding Singing Days and visiting local primary schools.”

Funding for tours (to the USA, France, Germany and the Ukraine in the three years that Mark has been at the college), recordings and major concerts with orchestra comes mainly from donations. The choir has performed with the Britten Sinfonia and other highly regarded ensembles, and there are plenty of other exciting projects planned for the future. A number of former students of the college and others have chosen to support the chapel in this way, and – thanks to the kindness of a former student – choristers receive contributions towards the cost of instrumental tuition.

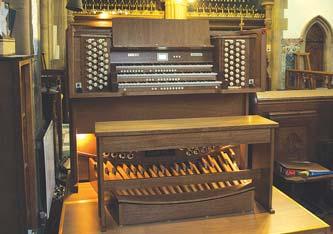

Jesus is blessed with no fewer than three organs. The Sutton Organ was installed in 1849 and the case, painted by Pugin, is extremely beautiful. It has recently been restored to its original state by William Drake and is a wonderful historic instrument, used from time to time in repertoire from the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Hudleston Organ was built in 2007 by Orgelbau Kuhn of Switzerland and is a triumph of modern organ building. It is used for the majority of service accompaniment and is a versatile instrument, well suited to repertoire from all periods and countries. In 2010, a third member of the organ family arrived: the Rawlinson organ, built by Kenneth Tickell, is a chamber organ of just three stops which can be wheeled into the choir stalls to enable the organ scholars to accompany the choir ‘at ground level’. Mark believes this gives them invaluable experience in listening and in understanding ensemble issues, particularly in music from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to which the instrument is best suited. Furthermore, the college has recently commissioned and taken delivery of a magnificent double harpsichord after Zell (1728), built by Bruce Kennedy in Tuscany.

Mark himself spent a year as Organ Scholar at Truro under Andrew Nethsingha and Simon Morley. He much enjoyed having unlimited practice time on the magnificent Father

Willis organ and, beyond the many benefits of spending a year focusing on his playing without administrative or academic responsibilities, also learnt a great deal about working with children through living at Polwhele House, the cathedral’s choir school. He went on to be Organ Scholar of Trinity College Cambridge which, with its choir of male and female students trained by Richard Marlow, was a very different kettle of fish. The choir’s vast and varied repertoire, its exciting touring and recording schedule, and the peerless Metzler organ made for a highly rewarding three years.

After Cambridge he spent six years at St Paul’s Cathedral, combining his role in the cathedral with the post of Director of Music at the cathedral school. It was a demanding but fulfilling period in his career: “I have many happy memories of my time working in that great building and playing that magnificent organ for national occasions and for daily services, learning so much from the peerless John Scott and his distinguished successor, Malcolm Archer,” he comments. He gave up the post in 2006 and for three years pursued a varied and busy freelance career, travelling around the world performing with orchestras, giving recitals, recording, playing for film scores, teaching music to opera singers and writing arrangements for pop groups. “That was thrilling,” he says, “but the post at Jesus has given me the opportunity to pursue

some of this freelance work as well as my work with the choirs, my teaching and my playing.”

Both choirs are in Mark’s care at Jesus, which he views as “the most challenging and the most rewarding aspect of being Director of Music here”. The two choirs have developed their own characteristic sound and repertoire and he enjoys the variety a great deal. Bringing the two together for recordings, concerts, tours and special occasions makes for a very exciting sound and a special sense of community. There are also two organ scholars at any one time and Jesus boasts a long and distinguished list of these, including numerous cathedral organists such as Peter Hurford, Richard Lloyd, Malcolm Archer, James O’Donnell, Geraint Bowen and Charles Harrison. The two current incumbents – Robert Dixon and Benjamin Morris – are both talented musicians and fine players. In addition to accompanying and, from time to time, directing the choirs, the organ scholars assist in the training of the choristers, working regularly with the probationers and teaching music theory to all the boys.

All the adult members of the choir, including the organ scholars, are students at Cambridge University, studying a wide array of subjects including Classics, Engineering, English, History, Medicine, Modern Languages and, of course, Music. There is a small number of choir members who are graduates

or volunteers from other colleges, but of the 28 members of the choir, 22 are undergraduates at Jesus College. The workload for the gentlemen is twice that of the ladies, but Mark feels that the men enjoy the opportunity to sing separately with both boys and with women – the two experiences are very different. Equally, the female choral scholars enjoy the chance to be part of a thriving musical scene whilst also having time to pursue other activities, musical or otherwise.

It was in 1998 that the college appointed its first Director of Music, Timothy Byram-Wigfield, who was followed by Daniel Hyde, and it was under these two distinguished musicians that the choirs began to record for Priory, Regent and Naxos. The choirs’ first recording for Signum Classics – Journey into Light (released in September 2012) – is a disc of music from Advent to Candlemas, with a number of pieces sung by the combined choirs, including a work commissioned for a recent visit to the USA by the talented New York-based composer, Nico Muhly. Earlier this year, the choir recorded a disc of music for Remembrance, including favourites by Ireland, Vaughan Williams, Harris and Parry, alongside less familiar pieces by James MacMillan, Matthew Martin and Arvo Pärt.

Mark says that he enjoys performing as much as possible outside the confines of the university, and believes that spending time practising solo repertoire and, perhaps more importantly, performing as a continuo player, organist or conductor with professional ensembles broaden his experience in a way that can only be valuable to his work with the students and the choristers. “It’s a teacher’s way of learning, and so I am delighted that I still have the opportunity to perform with a number of early music ensembles as organist and harpsichordist. I also play voluntaries regularly after services in the chapel here, and from time to time accompany services directed by the organ scholars, as a reminder to myself of what I put them through on a daily basis! My next organ recital is in the USA, but I enjoy performing nearer to home too.”

Mark teaches harmony, counterpoint and keyboard skills to students from Jesus and a number of other colleges at undergraduate level and is also involved in some teaching for

the graduate M.Mus course in Choral Studies. “It’s a real pleasure,” he says, “to be able to play a part in the growth of these young musicians academically as well as practically. It would be easy to treat them as young professionals during rehearsals and services, but it is to study for a degree that should be their priority, and teaching both choir members and other students reminds me of that. It also fills me with great admiration for choral and organ scholars across the university who perform at a high level academically whilst also singing beautifully, preparing their music, performing with jazz bands, playing for the hockey team, acting on the stage of the Arts Theatre, baking cakes, doing yoga and leading full and busy social lives. I don’t know when they sleep!”

The combined choirs have, as readers of Cathedral Voice may remember, recently visited the USA. Their successful concert tour of the East Coast of the USA in December 2010 was overshadowed by snow at Heathrow, which meant spending an extra few days in Washington DC, most of which was taken up with giving interviews to American and international news channels! “It is perhaps that part of the tour that will stay with all of us,” Mark thinks, “in particular the generosity and warmth of so many people who looked after us in the week before Christmas when they had plenty of other things to do.” Singing in St Thomas Fifth Avenue, in St Bartholomew’s Park Avenue (which the choristers recognised from several films) and performing impromptu carols for the Governor of Virginia and his cabinet at George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon were just some of the highlights of a memorable trip. This Christmas the combined choirs return to the USA, visiting the West Coast to perform in Seattle, Portland (Oregon) and San Francisco. Is Mark tempting fate? “I certainly hope not,” he replies.

Any final thoughts? “It is an extraordinary privilege to live and study in this beautiful place, in the presence of so many great minds and with former students such as Cranmer and Coleridge looking down on you from their portraits on the walls,” Mark says. “It’s an environment that fosters creativity, intellectual curiosity and sociability in a unique and special way, making it an exciting place in which to make music and a wonderful community in which to live and work.”

“Collier, would you like to join the choir?” were among the first words I encountered upon joining Berkhamsted School at the age of 10. They were spoken by the Director of the Chapel Choir, Philip Coates, somebody who proved to be a huge influence on the rest of my life. “No, sir, thank you, I don’t. I want to play football and cricket on Sundays when you have choir practice.” Well, the upshot of all this was that I did join the choir, I thoroughly enjoyed it, and Philip Coates, realising I had potential, trained my voice to a remarkable standard. The drug had been taken, initially as a bitter pill, but eventually leading to my life’s work when Priory Records was formed in 1980. Previous to this (upon leaving school) I had gone straight into industry to train in sales and marketing, and again this was a vital step in securing a successful long-term future for Priory.

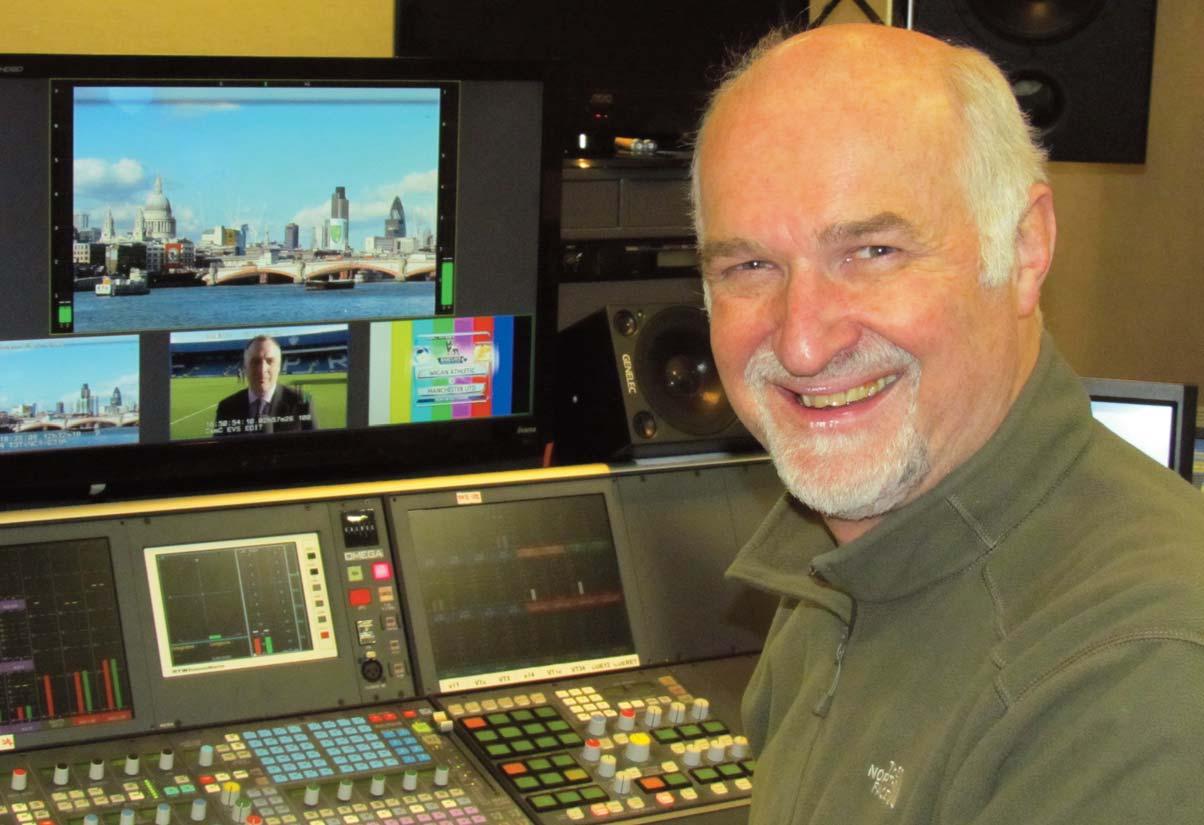

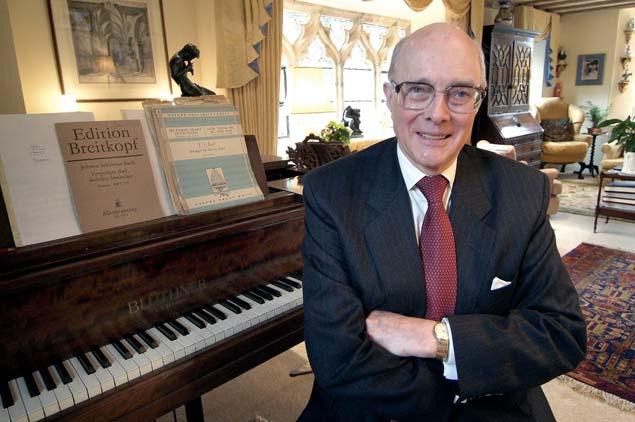

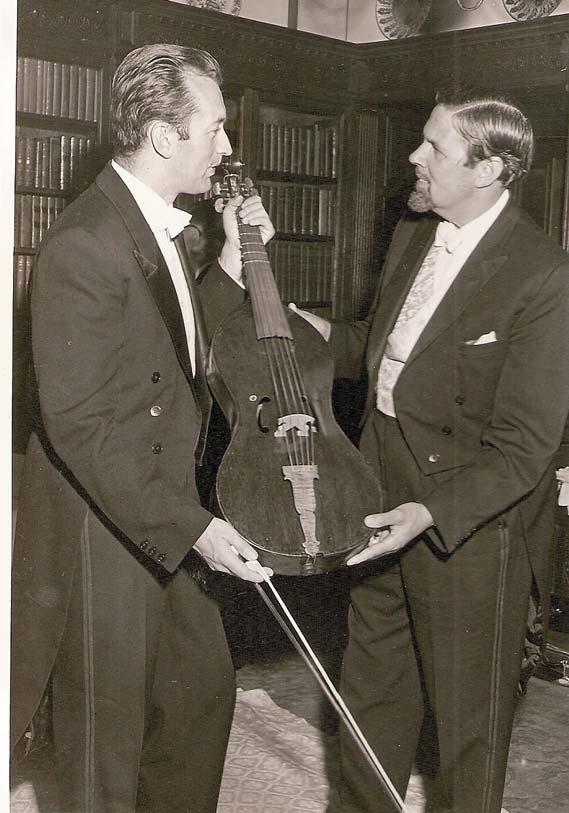

The formation of the company was quite by chance. I met Paul Crichton (pictured above), who was head of sound at Central Television, in a pub, and after discovering our mutual interest we decided we would dip our toes in the water and try

to make some private recordings. He emphasised, though, that he only wanted to make the recordings and that I would have to find the business. It was very hard work; no contacts, just a typewriter, and visits to local churches to obtain contact details of choirmasters and organists. I wrote to as many as I could, in between working for a furniture company as my full-time job. Slowly but surely in those days of the vinyl LP (yes, the black round object that clicked and popped and suffered from end of side distortion) we managed to get a few local recordings, pressing 250 or 500 discs. Recorded on a Revox A77 tape recorder, we edited the master (only managing this within pauses in the music), designed the sleeve, cleared the copyright and pressed the LPs. We enjoyed a certain amount of success, and ploughed back any small profit into the business.

Fast forward to 1988 (not on a tape recorder, though, but on much smaller digital FI equipment). The business had developed quite markedly, in that we were making commercial recordings for CD. The LP had all but disappeared, and having sat through countless recording

sessions with Paul Crichton, he could not cope with the amount of editing he was undertaking for Priory and combining it with his TV work. He therefore said to me that, if we were to continue, I would have to make the recordings as well as sell the product, while he just did the editing. This is what happened and still does today. However, a similar problem to Paul’s also faced me. A full-time job and the development of Priory all at the same time. Something had to give, and with great relish I quit my sales job.

We have never really looked back. The new regime of my running the company, selling the product and making the recordings worked well. Until this time, product had been stored at my home, at my aunt’s home and indeed any ‘home’ I could find. Again, it was time for change and I rented premises to store the expanding catalogue, and also some offices not far away. The business was developing at a fast rate and by 1995, at the height of the CD boom, I had seven people working for me.

Perhaps at this point I should explain why we had not appointed a distributor to sell our products in order to leave us time for marketing. When Priory made its first commercial recording in 1982, I went to a leading distributor at that time proudly brandishing the first two releases. Sadly I was informed that I would be considered when I got a minimum of 12 in the catalogue! Help! That would take ages and how was I to sell what I had already? Quite simply, I put the boxes in the boot of my car and visited all the classical music shops I could find countrywide, combining this with the selling visits of my fulltime job. With this excellent coverage of the country, I was approached by other labels to distribute for them. We took them all on when I left my job and became distributors as well as having our own label. This we still do today.

By 1991 the CD was motoring. We were distributing for over 30 labels and it was necessary to move again, this time close by to new offices and warehouse facilities in Wingrave, Buckinghamshire. We employed a salesman, who called on retail outlets and cathedral shops, a designer for CD booklets, a warehouse supervisor and packer and, of course, an accounts and marketing person (Callum Ross joining me in 1997) as well as maintaining Paul on the editing and post- production.

We recorded a best-selling set of all the psalms with 10 different cathedral choirs, a comprehensive set of 21 CDs featuring settings of the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, and another of Great Cathedral Anthemsas well as many, many more. Now this sounds as if Priory Records is all about choral music, but, of course, we were famed for our Great Cathedral Organ series and for recording music for the very first time, music that was completely new to the organ music catalogues. Priory became an international company and is recognised as such. We have recorded all over the world and brought organ music to the homes of thousands of people in such diverse places as Singapore, the USA, Iceland, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, the Canary Islands, Malta and the Balearic Islands, as well as countless venues across Europe. No other specialist company in this field has ever come close to providing the wealth of traditional church music recorded by Priory. We are often asked how we record organs and choirs. The answer is simple – with a single point microphone, which has four capsules pointing in different directions. We aim, and I think succeed, in providing the listener with the best seat in the house. If this means stringing him up 50 feet in the air or placing her in the front pew of the church we will achieve this. We work on the proviso that we only have one pair of ears and therefore multi-miking is not necessary or ideal, as long as the organ or choir balance. The results are what one might call an organic sound that is honest and faithful to the ambience of the building, and captures the artist(s) naturally. It is strange how many choirmasters are still impressed by the engineer who has a vast array of buttons before him, flashing lights, multiple microphones and stands, and cables running to every point of the building. When these are unnecessary Priory does not use them. We are proud of how we capture our sound, and have won numerous engineering prizes and accolades, as well as supplying many CDs to top-end hi-fi shops for optimum sound demonstration.

Perhaps now is the time to look at the years from 1995 to the present day. Where have things changed and have they changed for the better? Where does the future lie and how are we planning for the years ahead?

Gone are the days of editing where the music had its natural breaks and we cut with a razor blade. Today our organists expect us to edit in the middle of a quaver, or at any point that they demand. We piece together the cathedral echo so that nobody can detect the breaks.

It is fair to say that the industry knew that the CD would not maintain its high volume of sales. However, we continue to offer music on CD, including a set of 542 hymns which make up The Complete New English Hymnal, our ever-expanding series of Great European Organsand the complete organ works of nearly all the major British composers who wrote for the instrument. Our catalogue also includes comprehensive complete cycles and rare or unrecorded music by French and German composers, including the complete organ works of Sigrid Karg-Elert, (probably 15 CDs by the time the series is finished) currently being recorded with Professor Stefan Engels, primarily in Germany.

Due to the early success of the Psalms of David, we are also presently recording a new set, in day/evening sequence but using different cathedral choirs and not (hopefully) duplicating any of the chants used before, either by us or by St Paul’s Cathedral in their own series.

Yes, the sales of CDs are falling, but we do not see the end of this medium just yet. After all, there is so much more to record – and I do not mean yet another cycle of the complete Bach or Franck organ works! Are recordings better today that when we started 32 years ago? Perhaps. The digital age has helped us. Computers dominate our lives, so much so that six hours of recordings can be stored on a flash card and around seventy on the internal hard drive. Gone are the days of editing where the music had its natural breaks and we cut with a razor blade. Today our organists expect us to edit in the middle of a quaver, or at any point that they demand. We piece together the cathedral echo so that nobody can detect the breaks. Indeed, the average listener today would have no idea just how many edits certain CDs have had! Clicks can be eradicated, hisses (from re-mastered LPs) can be lessened and extraneous noise greatly reduced or jettisoned. Almost nothing is beyond today’s editing wizards!

The future? Three years ago two things were decided at Priory. The first was that we would make our entire catalogue, currently standing at around 600 commercial CDs (we never delete any title), available for download. It took about two years to complete the required data spreadsheets, but now our music is available via iTunes, Amazon, Spotify and countless others. We have seen remarkable sales of downloads, but is this to the detriment of the CD? Are we robbing Peter to pay Paul? I do not know, but I have to say that this is not a medium I like. I prefer to see CDs on shelves, ready to hand. Sadly, quality seems to count for nothing these days. I still listen to my music on state-of-the-art equipment via loudspeakers, but for the younger generation this is not the case, as quality is of secondary importance. Compressed sound seems to be fine for most, listened to through cheap headphones.

The second major decision we made was to create a series of DVDs, not just featuring an organ recital but also including a demonstration of the organ and a visual tour of its environs.

There was only one place to start and that was with Professor Ian Tracey at Liverpool Cathedral! He was the ideal person to kick the series off. And so it proved, with his superb playing and wonderful commentary about the organ. Wow, did we see some sales! Indeed, all the releases to date (eight in total) – York, King’s College Cambridge, Lincoln, St Paul’s, Canterbury, Exeter and Salisbury – have been tremendous successes. Accolades have followed, King’s being DVD of the Month for August in Gramophone magazine – beating Leonard Bernstein’s latest reissue! It will come as no surprise that these DVDs cost five figure sums to make. We are recording them in stereo and 5.1 surround sound and they are filmed in high definition. This is where our technology is now ahead of the market, the problem being that in order to realise the potential of high definition pictures, they should be viewed on a BluRay player. Sadly, few of our customers have this technology, so they are not enjoying the picture quality to the full.

Priory is optimistic about the future. Our emphasis will still be on CDs, but we will also offer all our recordings for download. Our market has dramatically changed over the years: gone are those wonderful shops where you could browse and chat. However, Priory now has a presence in virtually every British cathedral shop in the UK, offering its own recordings as well as other CDs that interest tourists. This trade is buoyant and should be for the foreseeable future.

Finally – and we cannot get away from it – the internet. Priory enjoys healthy sales via the web. My son, whose company specialises in website-building, web design and ecommerce, has created a new site for us, unrecognisable from the previous version. As well as Facebook and Twitter, we now have our own internet radio station (Priory Radio) where a good selection of our recordings can be heard 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. This has been very successful, particularly because, as we all know, Radio 3 and Classic FM broadcast virtually nothing of this precious heritage of ours. So get listening, enjoy it all and please post any comments on our site as well as letting us have your suggestions on any related matter. We look forward to many more years of success, preserving the treasured national heritage that so many in the church seem to want to forget.

At school, Neil Collier’s fortes were sport and music – specifically singing, although he also played the violin and French horn (until his singing teacher decreed the latter incompatible with the development of properly rounded vocal chords). He became a keen record collector and sang in various choirs in the area. His first jobs were well away from music, though, in sales and marketing – first with Thorn Lighting, then Dreamland (makers of electric blankets) and finally Lancelot Furniture, where he became national sales manager. Singing with a choir in Hemel Hempstead during this period he met Paul Crichton, a sound engineer working for Central Television. The two found a common interest, became friends and started Priory Records

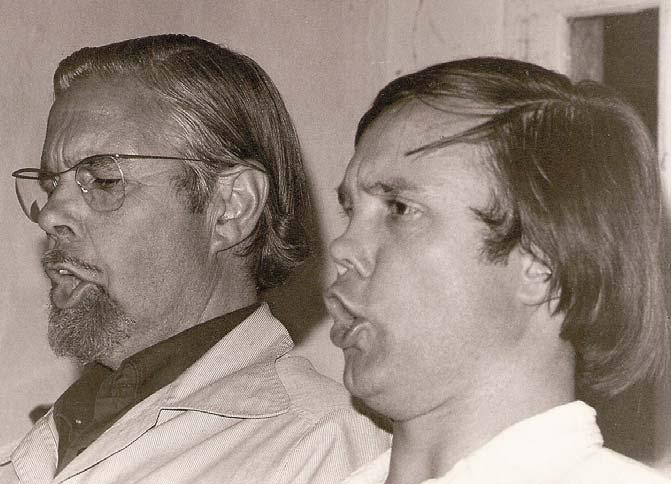

Simon Lindley pays tribute to Carlo Curley, who died in August just a few days before his sixtieth birthday.

Cathedral music appears in many guises – instrumental as well as choral. The greatest churches in our land regularly host concerts or recitals utilising the often magnificent instruments situated within their walls. Natural acoustics and the general ambience usually enhance the music produced, and the whole experience becomes the more memorable in consequence.

For exactly four decades following his first arrival here in 1972 from the USA where he was born, concert virtuoso Carlo Curley embellished such occasions and the lives of so many of us beyond measure by his playing, his entrepreneurial skill as a presenter, and – possibly most significantly of all – by virtue of the friendships he established and sustained for so long within the cathedral communities of so many foundations. The organists, of course, definitely; but vergers, stewards and clergy too all felt the easy warmth of his personality. He had many clerical friends and appreciated greatly the chance for conversation with them as well as with his musical colleagues –these valued occasions were often augmented by considerable quantities of good food and accompanied by gales of laughter, though perhaps they became rather more thoughtful and reflective as the years went by.

Notwithstanding the challenges of his health, Carlo was seen, and more importantly, heard on top form at Liverpool Cathedral with Ian Tracey in June and at the thirtieth anniversary recital on his friend Peter Collins’s organ at Cardiff’s St David’s Hall in July. He died not many days later, in Melton Mowbray, the Leicestershire town that he had adopted and that had taken him to its heart.

Looking back, his friendship with and tutelage from the legendary Sir George Thalben-Ball early established Carlo’s musical credentials with the general, as well as the musical, public, and memorable concerts often involving experiences with a touring organ in tandem with the building’s resident instrument became very popular. Co-operation with musicians of the calibre of Liverpool’s masterly Noel Rawsthorne, the mercurial Ronald Perrin of Ripon and concert organist Jane Parker-Smith were valued and vital components of the musical scene of the day; in recent years, his links with international artists of the calibre of Thomas Trotter and David Briggs have proved similarly fruitful.

Big-hearted and of substantial build, Carlo became known as the ‘Pavarotti of the organ’. There are not many organists whose deaths have made the editorial as well as the obituary pages of the national press, but Carlo made a big impact wherever he went. An Anglophile, certainly, but he was also a

great lover of Scandinavia and Australasia – Melbourne inhabitants, for example, proclaim him as the saviour of their Town Hall instrument.

His playing was enriched by formidable skill, a devilishly accurate pedal technique, a gentle touch, the ability to discover precisely the most piquant registration and by phrasing that was the envy of many colleagues. The formula for a Curley concert involved what was often a fairly set pattern; in that respect, he was rather like a master chef with the musical equivalent of table d’hôte spiced by an aural sauce or two. Bach he played in the grand manner, and Reger chorale fantasias similarly.

Carlo presented challenges for those who refuse to countenance the production of organ sound by anything other than wind-blown pipes. As a significant champion of digital instruments and artist of choice for Allen Organs for many years, he pushed out the boundaries of the instrument and virtually invented what has become known as the ‘organ gala’ or the ‘Battle of the Organs’ – one wonders how much valuable income for cathedrals and their music has been made by such means over the years of his playing on these occasions.

Listening to his detractors made one wonder whether perhaps criticism rode in tandem with a degree of envy at the measure of his public acclaim. For every twenty detrimental comments within and without the profession, there were probably twenty thousand souls who would provide a rapturous response to his artistry, commitment and brilliance. Furthermore, his autobiography In the Pipeline is a very good read and the well-thumbed pages of copies in public libraries provide their own testament to its popularity.

He embraced the video age and its potential wholeheartedly, and expanded our musical lives by means of a wide-ranging discography. Carlo was, too, a great lover of the Big Screen video that enabled distant audiences far away from cathedral lofts to see, as well as hear, him play. In recent years, fellow concert organist and friend Keith Hearnshaw worked indefatigably and highly effectively at Curley concerts with such installations.

Mention of his name invariably brought a broad smile to people’s faces. Did any personality you know ever have so expansive a signature? Carlo enlarged our lives beyond measure, delighted his audiences wherever he played, and was a very real ‘Friend of Cathedral Music’ – cathedrals here in Britain, of course, but also around the globe too.

We all miss him and, to use a term employed often by him about others, he was a treasure.

Iwas privileged to spend three years as one of George Howell Guest’s organ scholars towards the end of his 40year reign at St John’s College Cambridge. I know that hundreds of other former choristers and organ and choral scholars share my feelings of gratitude at the extraordinary experience of learning and performing with George. He was not only a great musician, but also a hugely inspiring teacher. His passion for and commitment to cathedral music transferred itself to ensuing generations, and it is no coincidence that many of Britain’s finest choir trainers were George’s pupils – Stephen Cleobury, David Hill, Andrew Lumsden, John Scott and the tragically short-lived Brian Runnett, to name but five. So many other professional musicians speak of the seminal influence that George had on them, from the international operatic baritone Simon Keenlyside to the Philharmonia Orchestra viola player Michael Turner.

The influence on me was equally powerful. When hearing the finest musicians, one sometimes feels that the music couldn’t possibly be performed any other way. Of course I was young and naïve, but when I worked with GHG it seemed to me strange that those of George’s protégés who now ran their own choirs didn’t attempt to make them sound exactly like George’s choir! Later, of course, I realised that there are many other styles and approaches which are equally valid – but such was the strength and conviction of George’s musical personality that this seemed unimaginable whilst I was working with him.

So what made up this distinctive personality? He created a unique treble sound which has never quite been recreated by anyone else (except that our current FCM President developed his own equally wonderful version of the Guest timbre, and David Hill later continued the tradition). Two of George’s influences were Boris Ord (at King’s) and George Malcolm (the originator of the ‘continental’ sound at Westminster Cathedral). Added to this mix was a red-blooded passion and insistence on emotion, perhaps related to George’s love of Welsh hymn-singing. George’s approach to phrasing was utterly his own and had a great influence on tone-colour and vibrato – every single note in a phrase had to have a sense of direction. He imbued an almost unbelievable musicality and sense of line in the choristers. I will never forget once being privileged to conduct George’s choir in Bruckner’s Christus factus est on a big occasion in 1990. In the last few bars I gave a particular gesture to the Decani boys, who responded with the most wonderfully musical vibrato on a particular B flat – all totally unrehearsed – and I marvelled that music-making could surely not come better than this. I remember thinking that conducting George’s choir on top form must be like conducting the Berlin Philharmonic! George showed genius in instilling such sophistication in young boys, and many other aspects of his sound were also distinctive: the Gents were always encouraged to sing out in an uninhibited way, and a very strong deep rich bass line was a particular feature.

GHG used to talk about the importance of using the eyes and the whole body in one’s conducting. He had the gestures and the rapport with his singers necessary to create moments of breathtaking beauty and spontaneity in performance. I remember occasions when one was reduced to tears in a concert by some rubato which he engendered in the whole choir, without it having happened in rehearsal. It is fashionable to say that a performer should simply be the vessel through

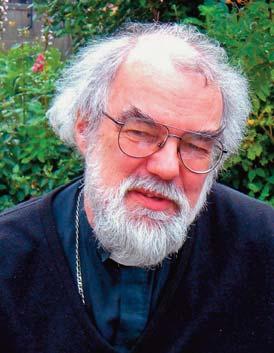

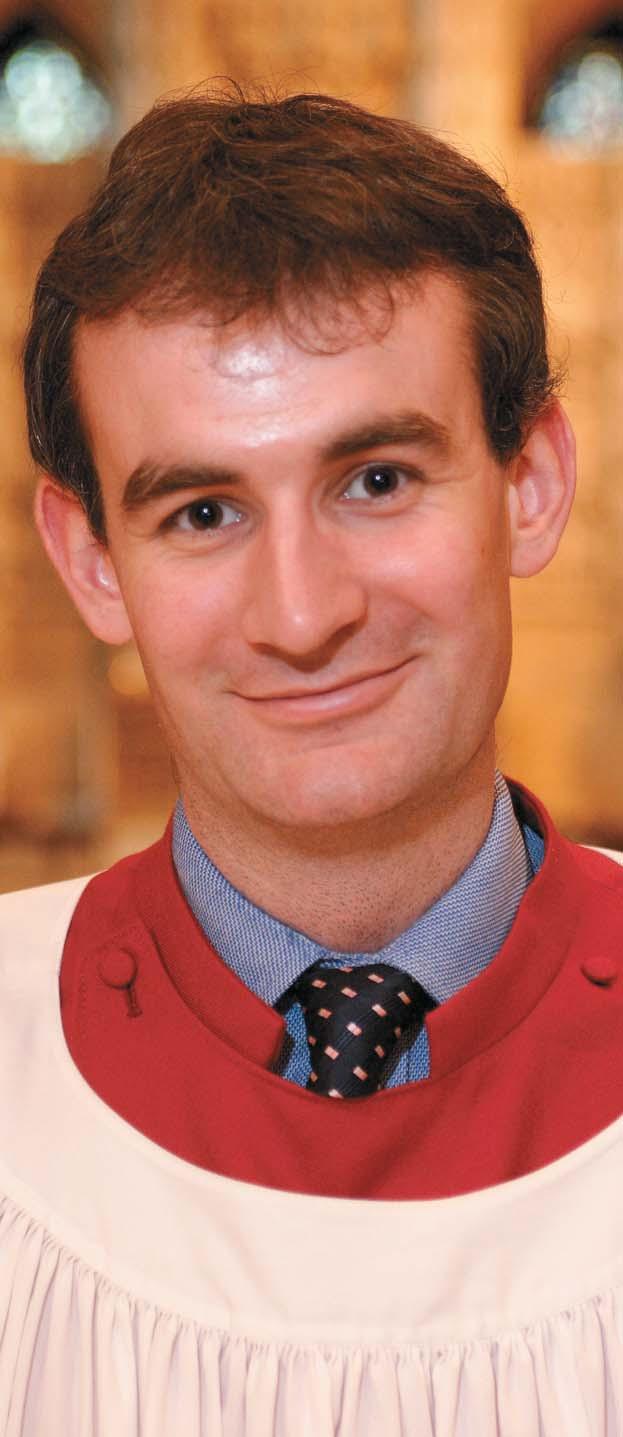

November 20th marks the tenth anniversary of the death of distinguished former FCM President, Dr George Guest, one of the greatest choir trainers of the twentieth century.Andrew Nethsingha © Paul Marc Mitchell

which the music passes between the printed page and the listener, and of course this is an admirable and important maxim, but I confess to loving performances which are full of the personality not only of the composer but also of the performer (if it is a great performer!). It was another part of George’s genius that he could bring such exquisite shape and beauty to even the simplest music, such as Psalm 23 or a plainsong Credo, and he also had the ability to make secondrate music sound much better than it deserved (!).

In some choirs one might learn the necessity of getting every detail in tune, in time, minutely balanced, every vowel sound unified, etc. All these things were taught at St John’s too, but we also realised that by far the most important aims were to communicate emotionally with people, to express the inner meaning of the words (George could recite the entire psalter from memory from an early age), to move the listeners, and to bring them closer in their relationship with God.

Two further inspirations were George’s sheer determination and his powers of persuasion. He knew exactly what he wanted and he wouldn’t take no for an answer! In 1955 the College was planning to undertake a substantial rebuild of the chapel organ. George told the College Council that every organ that was any good had an en chamade trumpet stop. The College eventually asked where the closest example of such a stop was, so that they could go and hear it. They were expecting an answer like Ely or Peterborough, but were surprised to be told it was Madrid!

Early in George’s tenure the St John’s choir school was seriously threatened with closure. After various interventions – including a telegram from Vaughan Williams – the school

was saved, but the College Council declared that there were to be no boarders. Nevertheless, George went ahead and appointed boys from far-flung parts of the UK, and had them lodging with various people around the town. After a respectable lapse of time he quietly suggested that, rather than having all these choristers living in different places, it might make sense to house them under one roof.... Some fifty years later St John’s boasts one of the finest choir schools in the country (GHG would urge me to write the finest!), complete with a state-of-the-art new boarding house.

In taking St John’s from very humble beginnings to being one of the most highly regarded choirs in the world, George showed that anything was possible. With him, the choir toured to the US, Brazil, East Germany, Japan, Australia and dozens of other countries. His hundred or so LPs and CDs are still cherished by hundreds of thousands around the world. He had a ground-breaking approach to repertoire, whether through his famous recordings of Haydn masses, French music such as Fauré, Duruflé and Poulenc, his commitment to new music (one thinks of the works he commissioned from Howells, Tippett, Berkeley and Langlais for example), or his re-discovery of so much sixteenth-century repertoire. George used to boast that the choir had over seventy Latin settings of the mass in its repertoire.

One of George’s tenets was that the music published on the termly list should never be changed for any reason. I remember two stressful days when the main organ broke down and George insisted that I accompany Howells in G and Stanford in G on the chamber organ (one manual and no pedals!). I protested (mildly – it was not a good idea to fall out with

George), only to be told, “Andrew, I haven’t changed the music since the day the King died.” I was amused by this response and related the story to Stephen Cleobury, who told me that he had had exactly the same response from GHG twenty years earlier!

Of course, George had his idiosyncrasies – the Cymbelstern* was, for example, painted with Chester City football colours (indeed, the mood of a Saturday rehearsal had a strong correlation to the result of the match that afternoon!). His love for Welsh meant that our concert programmes abroad often included music in that language. A whole CD was recorded of music sung entirely in Welsh (including VW Five Mystical Songs!). And a recording of Charpentier’s Messe de Minuit was rendered more difficult than necessary because the choir and orchestra were positioned in the ante-chapel (the orchestra asking all sorts of difficult questions about notes inégales which got short shrift from George!) with the chamber organ being some seventy yards away. It could easily have been moved, but George had had wooden boards attached to the base of the instrument to cover up the wheels (to avoid paying VAT), and because he remained unconvinced by our assertions that the taxman was hardly likely to appear in the middle of a recording session while the chapel was locked, the organ remained in its place. And then George was a wonderful raconteur. If you get any two ex-GHG choral or organ scholars together, they will immediately break into affectionate George impressions and start sharing the anecdotes they heard from him in the Baron of Beef!

George’s widow, Nan, continues to be a wholehearted supporter of the St John’s choir. His daughter Elizabeth teaches violin at St John’s College School. His son David, himself a former chorister and choral scholar, is also highly successful in the choral music world. As his family reflect on this anniversary, I hope they will take comfort in knowing that George’s legacy will always live on through his recordings, his teaching and his inspiration.

How might one sum up the music-making of George Howell Guest? I can think of no better way than to use the words which Beethoven inscribed at the top of the autograph score of his Missa Solemnis: ‘From the heart, may it in turn go to the heart’.

Footnote

*A ‘toy’ stop consisting of a metal or wooden star or wheel on which several small bells are mounted. When the stop is engaged, the star rotates, producing a continuous tinkling sound. The star was often visible on the exterior of the organ case. It was common in northern Europe, Germany in particular, throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. After 1700 the bells were sometimes tuned to particular notes. The name Cymbelstern means ‘cymbal star’.

Andrew Nethsingha was a chorister at Exeter Cathedral, where his father was organist, and organ scholar at St George’s Windsor and St John’s College Cambridge before becoming Assistant Organist at Wells Cathedral. He was subsequently Organist and Master of the Choristers at Truro and Gloucester Cathedrals before returning to St John’s as Director of Music in 2007. His innovations there have included the weekly service webcasts and a termly Bach cantata series. Andrew has worked with several of the UK’s leading orchestras and performs regularly as a conductor and organist in North America, South Africa, the Far East and throughout Europe. He is enthusiastically committed to passing on his love of cathedral music to future generations.

Career details to date:

Organ Scholar, Worcester Cathedral (2001-2)

Organ Scholar, St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle (2002-3)

Organ Scholar, King’s College Cambridge (2003-6)

Assistant Sub-Organist (title later changed to SubOrganist) at St Paul’s Cathedral (2006-8)

Assistant Master of the Music and Director of the Abbey Girls’ Choir at St Albans Cathedral (since 2008)

Were you a chorister, and if so, where?

I was a chorister at York Minster under Philip Moore. It was an enjoyable time, and has undoubtedly been the impetus for my career in church music. My last year was particularly memorable with CD recordings, the Enthronement of an Archbishop, and a televised Choral Evensong recording.

What did you enjoy most about being Sub-Organist at St Paul’s?

I enjoyed putting into practice the skills (accompanying and choral directing) that I’d developed working at King’s with Stephen Cleobury and the choir (and earlier at Eton, Worcester and Windsor). I also enjoyed working with professional singers, having responsibility for specific tasks within the music department, and of course playing a world-famous organ in a wonderful space!

What or who made you take up the organ?

The combination of learning the piano from a young age and, as a chorister, hearing John Scott Whiteley’s wonderful solo playing, accompaniments and improvisations.

When you were at school, did you think you might end up where you are now?

No, I don’t think I was thinking much further ahead than the possibility of an Oxbridge organ scholarship. The girls’ choir at York was formed the term after I left the Minster Choir, in the same year as the girls’ choir was formed at St Albans. Directing

the Abbey Girls’ Choir is one of the most rewarding parts of my present job, and it’s interesting to see just how much the advent of girls’ choirs has reinvigorated the cathedral music scene since I was at school.

You won First Prize and the Audience Prize at the 2008 Miami International Organ Competition. What difference has this made to your career, do you think?

There are a great many organ competitions, and I was very fortunate to be selected to take part in the final of the Miami competition. Organ playing in Britain is predominantly bound up in the English cathedral and collegiate tradition, which can make for a busy (often hectic!) schedule of work each week. I think this explains why there are relatively few British applicants for international competitions, which can require a huge investment of time (and necessitate time off from church duties). The Miami competition was excellent experience for me: of course prizes are important on a CV, but in reality my cathedral duties (which I find extremely rewarding) have to come before freelance recital work, so in that sense it perhaps hasn’t always been possible to maximise the benefit which that recognition could bring.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

I have recently begun tackling parts of the Organ Symphony by Malcolm Williamson. It’s a remarkable work which was well received in the 1960s and 1970s, when it was premiered and then recorded, but like most of Williamson’s music it has since fallen into neglect.

Have you been listening to recordings of it? Is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

Yes – the recording made by Allan Wicks on the Coventry Cathedral organ, issued in 1978.

Which organists do you admire the most?

My teachers John Scott Whiteley, Alastair Sampson, Thomas Trotter and Johannes Geffert. Also John Scott, Robert Quinney, David Briggs and Dame Gillian Weir.

What was the last CD you bought?

Who are these angels? – New Choral Music by James MacMillan (Cappella Nova).

What was the last recording you were working on?

Earlier this summer I made a solo recording of organ music by Lennox and Michael Berkeley for Resonus Classics (a download-only label), due for release next year. Last year I directed the St Albans Abbey Girls’ Choir in a recording of Mendelssohn Choral Works for Naxos, released in September.

What is your favourite organ to play?

Three very different instruments, but all equal favourites: King’s College Cambridge, St Paul’s Cathedral and St Albans Cathedral.

What is your favourite building? My house!

What is your favourite anthem?

Viri Galilei – Gowers, but many others, too

What is your favourite set of canticles?

Howells – Collegium Regale (Evening)

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants? I can’t decide on a chant, but certainly Psalm 139

What is your favourite organ piece?

Too many to choose from, but amongst favourites I would definitely include plenty of Bach, plus the Reubke Sonata and the Poulenc Organ Concerto.

Who is your favourite composer? Too many to choose from!

What is your most recent organ recital? Which pieces are you including?

King’s College Chapel on 13th October. I’m planning to play part of the Williamson Symphony plus the Bach/Ernst Concerto in G and the Dupré Cortège et Litanie.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols, which I accompanied twice whilst at King’s, is always a very special occasion for the choir, for which everyone prepares extremely hard. Also performing with St Paul’s Cathedral Choir at the American Guild of Organists’ National Convention in St Paul, Minnesota, was a great privilege, if rather nerve-wracking!

Has any particular recording inspired you?

Peter Hurford’s complete Bach recordings for Decca. Also Thomas Trotter’s Alain, Liszt and Reubke recordings and John Scott playing Dupré.

How do you cope with nerves?

I try to make sure that I am as well prepared as possible, and then to concentrate in performance.

What are your hobbies?

Eating, sleeping and watching television.

Do you play any other instruments?

Not any more. I enjoy playing the piano but don’t find the time to learn new repertoire.

Would you recommend life as an organist?

If you are prepared to practise hard, be organised, and keep focused by learning new repertoire, then yes.

What are the drawbacks?

Access to organs for practice can be difficult, even though some unsociable hours are to be expected. I think that many organists working in cathedrals find that clear evenings available for organ practice are increasingly hard to come by as there is ever greater pressure on the buildings for activities such as guided tours, concerts and extra services. It can be a difficult juggling act to organise practice around these constraints and one’s other cathedral and freelance duties, and I worry that this discourages some very fine players from pursuing careers in cathedral music.

What do you think should be the role of the FCM in the twenty-first century?

To continue to support cathedral music, in all its forms, giving opportunities to enable everyone to perform to the highest standards.

Every cathedral choir is, of course, unique. Even a superficial knowledge of the tradition is enough to indicate that, whatever similarities there are in choirs’ duties and conditions, nevertheless each one is different and each foundation has its own particular challenges.

Cathedral choirs fall broadly into the two categories of those with choir schools, and those where the boys and/or girls are drawn from a number of schools in the area. Newport is firmly in the latter category, the great majority of our boys coming from state junior or comprehensive schools, with a handful from two independent schools in the diocese, Monmouth School and Rougemont School. Thanks to the generosity of the Royal Masonic Trust we do now have two scholarships to offer boys at Rougemont School, but all our other choristers are voluntary.

Our choir sings four times a week, on Wednesdays (boys only), Fridays and Sundays (morning and evening). In addition there is a Training Choir of younger boys, which meets weekly on Mondays and sings a simplified form of Evensong approximately once a month. For the choristers, the time commitment is substantial of course, as it is in any cathedral choir; they regularly give up ten to twelve hours a

week for the choir – and all this on a totally voluntary basis for the great majority of them. The great question is, ‘Why do they do it?’ and I shall consider this later.

The men of the choir are also unpaid; sadly the cathedral, despite its unequivocal support for the choral foundation, simply does not have the financial resources even to pay travel expenses. We are enormously blessed with our gentlemen, in two ways in particular. Firstly, a great majority of our boys, when their voices change, choose to stay on in the choir to sing a lower part; these teenagers we designate choral scholars – although again there is no scholarship attached! Secondly, we have a small number of unpaid lay clerks of working age who somehow manage to juggle their choir, work and family lives – but we also have a good number of recently retired lay clerks, many of them from the educational sphere. Indeed, our back rows at present include one current teacher, one recently retired deputy head, and three retired headteachers. I definitely have to watch my step! It goes without saying that having this amount of professional educational experience is of untold benefit to the choir, not least in giving us a good number of highly experienced colleagues to help pastorally on choir tours and trips.

Newport Cathedral Choir is, like all cathedral and similar choirs, a very precious organisation. Like many choirs it is, too, quite a fragile flower. It is a flower I have tended for well over thirty years.Christopher Barton

The choral scholars, who have all come through the treble ranks, are a wonderful bunch too. We believe it is very important to keep these teenage boys singing, and indeed many of them go on to choral scholarships at university. There are, naturally, vocal difficulties as the voices change; we do have to review constantly that each boy is singing the right part for where his voice is in the process of the change, and we do have to make sure that they do not strain or damage their voices. The potential vocal weaknesses of certain individual voices in certain ranges are covered, though, by their colleagues. For example, we have seven teenage altos at present, and we can be sure that if one of them cannot manage a certain part of the range, several others will. Realistically, the biggest problem is the tessitura of alto verses in the Renaissance repertoire; much of it lies low, and that is the weakest and most unreliable part of changing voices. We get around this by sometimes having a tenor who is also a skilled alto singing the verse, or sometimes even a treble. This flexibility enables us to sing most of the repertoire.

Over the ups and downs of over 33 years here, the trebles have never ceased to amaze me. I continually give thanks that there is a stream of boys willing to give so much time to learn the skills of high-quality choral singing. Numbers inevitably fluctuate, but we have never been seriously low in forces. There are always scare stories around about the demise of boys’ voluntary choirs, the Jeremiahs often say, “You can’t get boys to sing or give the commitment these days”, but that has not been the case here – so why do they do it?

Personally I think there are two key words: enjoyment and respect. While things cannot always go as one might wish, I do always try, as much as is humanly possible, to ensure that the boys enjoy every single attendance. On the rare occasions I am away, the advice I always give to whoever covers for me is to try as hard as possible to send the boys home happy. If they have

enjoyed themselves, the chances are they will have sung well! Respect – well, I do expect the boys to respect me, but it is totally a two-way process. Each individual boy in the choir, from the youngest to the Head Chorister, knows (I hope) how much I respect him. This engenders an underlying warmth and happiness in the choir which carries us through the times when a service may not have gone as well as we might have wished.

For everybody in our, and any, choir, careful choice of repertoire is essential for happiness. No one, whether eight or eighty, will find fulfilment in singing music they dislike, and in a voluntary choir like ours they could easily vote with their feet. I do sometimes (not infrequently) have to ‘sell’ new music to the choir, but they do generally trust my judgement, and in most cases familiarity with a new work brings a genuine joy in singing it. I am extremely careful in my choice of contemporary repertoire, though. There will be readers of this article who have been kind enough to write music for us, and to whom I will have always said the same thing: please give us a decent amount of counterpoint so that all voices in the choir have music of interest to sing. I cannot imagine why so much boringly chordal, supposedly ‘atmospheric’ music is offered to choirs (and congregations); there are occasional exceptions, of course, but this style generally offers little of interest to altos, tenors, basses or listeners. At Newport Cathedral we have been deeply honoured by the people who have written music for us over the last 33 years, including Robert Ashfield, Michael Barlow, Mervyn Burtch, Richard Roderick Jones, Ronny Krippner, William Mathias, Simon Mold, Philip Moore, Elis Pehkonen, Paul Ritchie, John Sanders, Andrew Seivewright, Richard Shephard, Herbert Sumsion, Adrian Williams and Jeremy Winston, with a new work promised soon from Martin Neary. This is a varied group, some old friends, some new friends, some local composers and, of course, some world-famous names. Since

the majority of these composers are still happily very much with us, I prefer not to mention specific works, but believe me, there is music of exceptionally high quality that has been written for our choir, and which we are privileged to perform. It is an ambition of mine before too long to make a recording of some of the music that has been composed for our choir over the last decades; only a little of it is published, but the great majority of it deserves wider dissemination.

Like many choirs we tour regularly, although the costs and other restrictions of this are worrying us more and more. 2012 was the first year that we have not had either a formal tour or a choir holiday (which we tend to have about every four or five years in place of a singing tour). The choir has sung in Ireland, Holland, Belgium, and Canada, and has also made three tours to Germany, as well as occasional weeks in many UK cathedrals. Some years ago we used to visit York Minster regularly; although we have not been there for a long time now, I suspect that it is still the cathedral at which (apart, obviously from Newport) we have sung most services – although it may have been overtaken by Westminster Abbey where we have sung a lot in recent years, either for residential visits or just for day trips. One great asset of Newport as a geographical location is that it is so well placed for visiting cathedrals; we have been on day trips to sing at most of them within a 100-mile radius or more, including Bristol, Christ Church Oxford, Gloucester, Worcester, Hereford, Brecon, Salisbury, Wells, Exeter, St Paul’s, Winchester, Chichester, Chester and Lichfield – some of these on several occasions. These tours and day trips are of real value to the choir in so many ways, not least in encouraging family and congregational support, as we take many guests with us on day trips, and many families come to join us for parts of tours. If tours become financially unviable, we hope at least to continue and perhaps increase the day trips.

We also have quite a lot of non-singing trips for the choir, especially the boys: theme parks, seaside, walking (lots of wonderful walking countryside within easy reach of Newport), city visiting, attractions like Cheddar Caves, all sorts of things are really popular and excellent for morale. The boys also have an annual sports day, Decani and Cantoris competing against each other, which they greatly enjoy! As they get older we might take them further afield; one recent trip for Senior Choristers and Choral Scholars was to Amsterdam – just for one night, but two whole days with early departure and late return flights from Bristol.

What have been the best and the worst things over my years

with the choir? Well, the worst is easy. On a tour to Belgium we were involved in quite a nasty coach crash, which resulted in a dozen or so boys being taken to four different hospitals. Although only four were kept overnight, and there were no serious injuries, it was a horrible few hours, and one is always thinking how close we were to utter disaster. The choir’s sense of community and mutual support shone through that difficult time though, and was commented on extensively by the superb Red Cross and emergency services who helped us. The best thing – well, there are obviously so many highlights over such a long period. As a single service I would have to say the invitation for the choir to sing at Archbishop Rowan’s enthronement as Archbishop of Canterbury in 2001. Archbishop Rowan had, of course, been our diocesan bishop, and it was an amazing experience for the choir to go to Canterbury and sing live to all the millions of people watching all over the world. The anthem we sang, Come, my way had been composed by John Sanders a few years earlier for the then Bishop Rowan’s enthronement as Archbishop of Wales in Newport Cathedral, so it was most fitting that he should have chosen it for us to sing at Canterbury, especially as the service was held on the day of commemoration of George Herbert. Over a longer period of time, the whole choir has been enjoying the relationship we have been developing over the last six or seven years with Westminster Abbey; we now sing there at least once every year and often more frequently, and we are always made so welcome. To have the privilege of singing in that incredible building, surrounded by all that history, is one which we all cherish greatly.

I earlier described the choir as a ‘fragile flower’. Its future seems secure, with a supportive dean and no significant recruitment problems, but I am constantly aware that things could change very quickly – apart from two scholarshipholding boys, there is no absolute requirement on any of the members to continue coming, so this brings me back to our determination to make it as positive an experience as possible for each and every member. We are also massively aided now by the Friends of Newport Cathedral Choir, a support group set up four years ago. FNCC has itself become extremely successful, raising money for the choir but also with its own social programme ranging from treasure hunts to an Annual Lecture given so far by Philip Moore, Barry Rose and Martin Neary – a distinguished group indeed!

For more information about the choir, please visit its website: www.newportcathedralchoir.org

CHRISTOPHER BARTON was, from 1975 to 1978, Organ Scholar of Worcester College Oxford. He also studied organ with Richard Popplewell and James Dalton, and composition with Edmund Rubbra.

Since 1979 he has been Organist and Master of the Choristers at Newport Cathedral, where he indulges to the full his passionate love of choir training with the traditional male choir. Christopher was for thirteen years also Music Director of the Dyfed Choir, one of the finest mixed-voice choirs in Wales, and he has given recitals in cathedrals and churches all over the country including in recent years Wells Cathedral, St Davids Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, Malvern Priory, St Paul’s Cathedral and St Mary’s Church on Alderney. He has been awarded the honorary diplomas ARSCM, AWACM and FGCM in recognition of his outstanding contributions to church and cathedral music in and beyond Wales. Christopher teaches a considerable number of private pupils, and in any spare time he enjoys the theatre, reading and walking. He is married with two children, both of whom show musical promise.

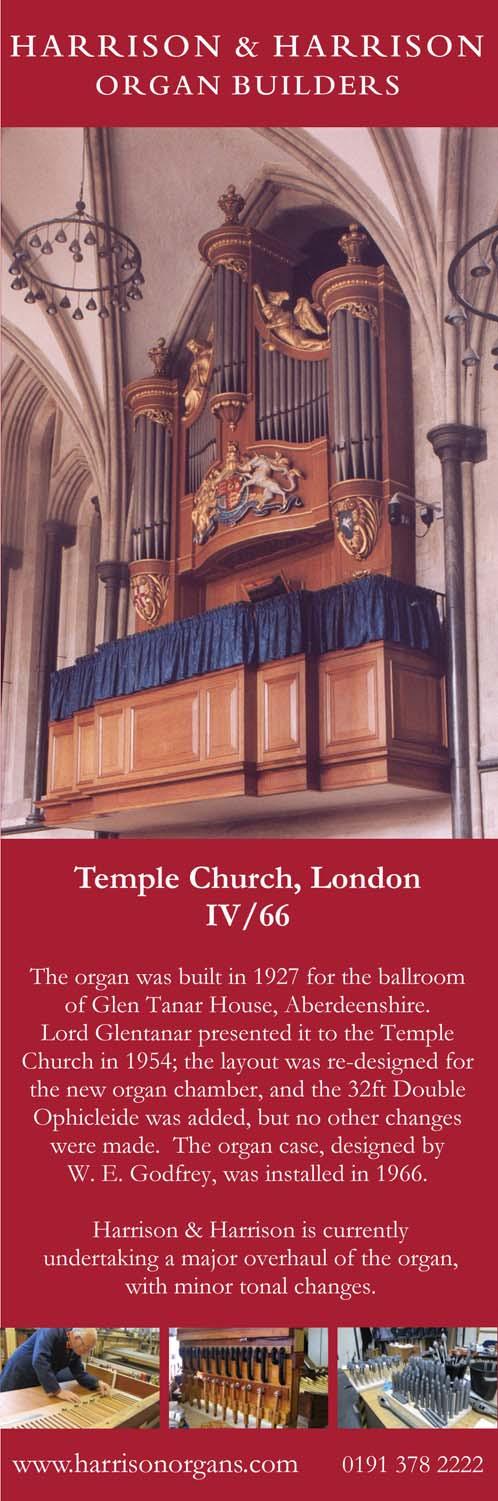

When a traditional pipe organ begins to cause serious problems, it’s usually time for a major overhaul. However, whilst refurbishment should be explored before considering a replacement, this may not be in the best interests of the church if:

• The original organ was of poor quality

• The organ cannot meet the changed musical needs of the church

• A major re-ordering is planned, requiring the organ to be re-sited in a limited space

• The cost of an overhaul is beyond the financial resources of the church

Usually, if a new organ is necessary, it should be a traditional instrument although, when the availability of space and/or finance is limited, an electronic organ may be seen as the only viable option, especially for cash-strapped smaller churches. There is also a third option: a combination organ, which combines speaking pipes with digital pipes, and provides some of the tonal attributes of the traditional organ along with the benefits of a digital instrument (space and economy). Many combination instruments have been installed outside the UK; here, the idea has only recently begun to catch on.

Electronic organs date back to the 1890s, but by far the most effective early instrument was invented in 1934 in the United States by Laurens Hammond. The success of this led to a complaint to the US Federal Trade Commission by organ manufacturers, who said that Hammond was fraudulently claiming that their instrument could replicate the sound of a pipe organ. In addition, they felt that the sound was so different that the instrument should not even be called an organ. The case backfired on the organ manufacturers as, whilst the FTC required Hammond to cease claiming equivalence to a pipe organ, it did state that the instrument was definitely an organ, and that ‘Hammond Organ’ should be a legally accepted term.

An electronic organ speaks by generating fluctuating electric currents, either mechanically or electronically; these are then amplified and made audible by a loudspeaker. The simplest method is electro-acoustic sound generation, where a vibrating element such as a reed or string is part of an electronic circuit or is amplified by a microphone or pickup (for example, the Orgatron (1934): air is blown by a fan over reeds, then the vibrations are detected electro-statically and amplified).

Electro-mechanical sound generation occurs when rotating discs with imprinted wave patterns (‘tone wheels’) pass close to electro-magnetic, electro-static or photo-electric sensors. The Compton and Hammond organs of the 1930s are examples of instruments using this technology.

Before the 1950s, vacuum tubes were used as electronic oscillators but, following the invention of the transistor in 1947, solid state systems were developed. The first transistorised church organ was introduced by Rodgers in 1958. This was also the year the integrated circuit was invented (by Texas Instruments) which eventually led to the introduction of the first digital organ by Allen in 1971. The continued development of the integrated circuit has led to the almost universal use of computer-based systems for electronic organs, with the first software-based instrument being introduced in 1990. The ready availability of computer power and memory has led to electronic organs increasingly using stored samples of recordings of existing pipe organs rather than synthesised sounds.

Whilst there were some earlier combinations of electronic pipes with speaking pipes, the first combination organ that was musically successful and had a lasting impact was developed by Rodgers in 1972. One of its key attributes was the incorporation of a tuning control so that the electronics could follow the natural changes in the tuning of the pipes caused by changes in humidity and temperature. Since then, the company has installed over 4000 combination organs in the USA.

Although existing organs may be improved by adding speaking pipes to an electronic organ or digital pipes to a traditional organ, the best combination organs will be conceived as a single instrument. Electronic pedal pipes are also used as components of new traditional organs by some organ builders to reduce costs and to overcome space constraints. As with a traditional organ, however, the combination organ should be designed as a unique instrument, taking into consideration both the range of music to be used to support worship and the acoustics of the church.

The benefits of a combination organ (reduced costs and space) are of little value if the organ does not perform well as a musical instrument. Some will argue that a combination organ can never be successful because the two elements of the instrument are so different, possibly even incompatible. However, if the considerations listed above are taken into account, an excellent outcome can result. A medium-sized reasonably traditional Anglican parish church may use the organ for:

• leading congregational hymn singing

• leading the choir for anthems and solos

• supporting the congregation during funerals and marriages

• providing quiet musical interludes and voluntaries

• providing appropriate pre- and post-service music

• wider community use in concerts and recitals

Priorities need to be established to prevent the organ being badly compromised by trying to be too broad in scope or by attempting to meet all possible requirements and thus becoming unwieldy in terms of stop requirements. Equally, a rigid adherence to a particular style of organ design could severely restrict the music available to the church. A balance must be found so that the church can obtain the most benefit from the organ at an acceptable cost.

The musical core of an organ is the Principal Chorus, which is made up of pipes in the Diapason, Principal, Fifteenth and Mixture stops. These tend to be selected as the main speaking pipes for a combination organ. Tonal decisions for other stops will be linked back to the Principal Chorus to provide an integrated instrument.

One of the often-stated incompatibilities of speaking pipes and electronic pipes is that the vibration of air generated in a pipe is different from the equivalent vibrations from a speaker, which means that pipes give a fuller, rounder sound that is less directional than that from speakers. Whilst this may be valid in a side-by-side comparison of a single speaking pipe with the equivalent digital pipe, such differences are difficult to detect with electronic and speaking pipes in combination. A welldesigned combination organ will have several high-quality speakers carefully placed to overcome directionality issues. Also, many traditional organ designers effectively create speakers by putting pipes into cases.

The importance of high-quality components for the amplifier and speaker system is critical if there is not to be distortion of the resultant sound. Any weakness will be particularly noticed during large choruses and in the build-up to the deployment of a large number of stops. The problems of distortion arise due to mechanical imperfections of speakers combined with the mixing of the different pipe tones being fed through the speaker. The key requirements of a successful combination organ are to have sufficient speakers and sufficient amplifier channels with the necessary controls for the routing of the digital signals to specific speakers, thus avoiding situations where distortion could occur.

The belief that electronic and speaking pipes are incompatible leads to the view that the voicing of the two sets of pipes is so different that the combination can never be seamless. This is not the case. The organ voicer will exercise the same experience, skill and judgement to determine the precise sound required from a particular pipe independently of whether it is electronic or speaking. The only difference is how the voicer’s wishes are implemented. The speaking pipes will be modified by physical changes to the pipe whereas the sound of the electronic pipes will be modified by changing the waveform of the stored sound for the pipe.

There have been concerns about the different effects of temperature and humidity on electronic and speaking pipes, but these are also without foundation. To allow for environmental changes, modern electronic organs can incorporate an automatic tuning adjustment so that the electronic pipes stay in tune with the speaking pipes.

Traditional organs can be very long-lived, with lifetimes in excess of 100 years being cited. Whether this applies to most organs or a minority is uncertain, as comprehensive records are not readily available. Assessing the potential lifetime of electronic organs is also difficult, but it is possible to extrapolate from existing records and analyse the failure modes of individual components to provide a reasonable estimate. This leads to an expected lifetime of 25 years. Certainly, the major electronic organ manufacturers all report an ability to supply spare parts and also service any of their organs, some of which are over 50 years old. The figure of 25 years before a major failure is not dissimilar to the frequency of major overhauls that would be expected for a traditional organ.

It is possible to argue that the long lifetime of a traditional instrument means that the initial outlay can be spread over many years to offset the high cost. A very low annual depreciation rate of 1% is sometimes quoted, but since a traditional 3-manual organ with 40 stops may cost £400,000, this is still a significant £4,000 per annum. An equivalent digital organ may be £40,000 for a high-quality customised instrument, while a standard model could be half this. A combination organ will be somewhere between these figures: not a very useful statement, but more specific costs relate to the particular combination of electronic and speaking pipes.

One difference between digital and traditional organs is that the former do not need regular tuning and service, whereas the reverse is true for the latter, at an annual cost of 0.2 - 0.3% of the replacement cost of the organ. The cost of a

major overhaul of a traditional organ may occur every 25 years or so, with a cost of perhaps 5% of the replacement price.