Assured.

Whichever organ you buy from us, you can be assured of top sound and build quality, our technical expertise, great attention to detail and the best in customer service. We invest in our instruments so you can invest in your future. These are serious instruments for serious people, people like you. Explore our websites and then fall in love with the organ of your dreams in our showrooms.

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus

CATHEDRAL MUSIC

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2015

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon grahamhermon@lineone.net

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Tatton Media Solutions, 9 St Lawrence Way, Tallington, Stamford PE9 4RH 01780 740866 / 07436 791353 wesley.tatton@btinternet.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by: DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

Cover photographs

Front Cover

Exeter Cathedral

© Alan Soper (nalamanpics@gmail.com)

Back Cover

The quire and organ pipes at King’s College Cambridge

© Hugh Taylor

Technology bringing tradition to life

Instruments for all budgets, settings and performers

Recent large commissions include:

Rebuild of early Bradford Organ at St Mary’s, Witney

Replacement of Allen Organ at Sutton Valence School

Replacement of Copeman Hart Organ at St Peter’s, Caversham

New Instrument for the Great Hall, Swansea University

For a free, full information pack on custom built and standard instruments including a complementary DVD, please do call or email us.

From the EDITOR

The sound of music. No, not the film or the musical, but the science of acoustics. Who knew that large stainedglass windows absorb bass notes, while in a reverberant environment (such as most cathedrals) the extreme treble is affected by the atmosphere? That Father Willis’s most famous saying was, ‘The most important stop on the organ is the sound of the building’? Today’s organ designers are able to work round the awkward shapes and the soundabsorbing structures of cathedrals and churches, but since the construction teams of our intriguingly shaped cathedrals were not able to benefit from modern-day technology and 21st-century know-how, acoustical challenges play a large part in John Norman’s informative article on p28

There is challenge of a different sort as the reader ventures further into the magazine: the trials faced by those who are beguiled or coerced into turning pages for their keyboardplaying colleagues. Practitioners of page-turning – long a neglected and undervalued profession – will welcome recent proposals to encourage the development of increased skills in all aspects of this art, with the ultimate goal of a universally recognised qualification. See p36 for more details.

In August and September of this year we lost two giants of the cathedral music world, two people who had spent all but their very earliest years working in and enhancing the

remarkable tradition of English choral music, John Scott (59) and David Willcocks (95). Readers of this magazine are by their allegiance to this tradition and to FCM confirmed supporters of our exceptional cathedrals, but those who choose to work in the profession, who frequently live in the glorious cloisters and who spend so much of their lives surrounded by the magnificent architecture of these special buildings are very often the finest exponents of an esoteric art. Our world is poorer for the loss of these two talented men, both consummate musicians and in so many ways the inspiration to so many people, but our thoughts will perhaps dwell more heavily and in greater sadness on the death of John Scott, a man at the top of his profession, and one whose third child was born very shortly after his death. We mourn the passing of both, but there is consolation in knowing that their work, their recordings, and their enormous contribution to the world of music will endure.

Next year is the 60th anniversary of the founding of Friends of Cathedral Music at St Bride’s Fleet St, following a meeting led by Ronald Sibthorp at which some 40 people came together to discuss their concerns over the quality of music in post-war cathedrals. In addition to two National Gatherings (Gloucester in May, Liverpool in October), there will be a Diamond Jubilee Gathering in London (24-25 June) with a celebration service at St Bride’s, and Evensong at Southwark Cathedral followed by a reception. It is to be hoped that as many members as possible will attend these events, bringing with them legions of friends to convert to the cause! Please spread the word as widely as you can.

Sooty AsquithJOINING FRIENDS OF CATHEDRAL MUSIC JOINING FRIENDS OF CATHEDRAL MUSIC

How to join Friends of Cathedral Music

Log onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

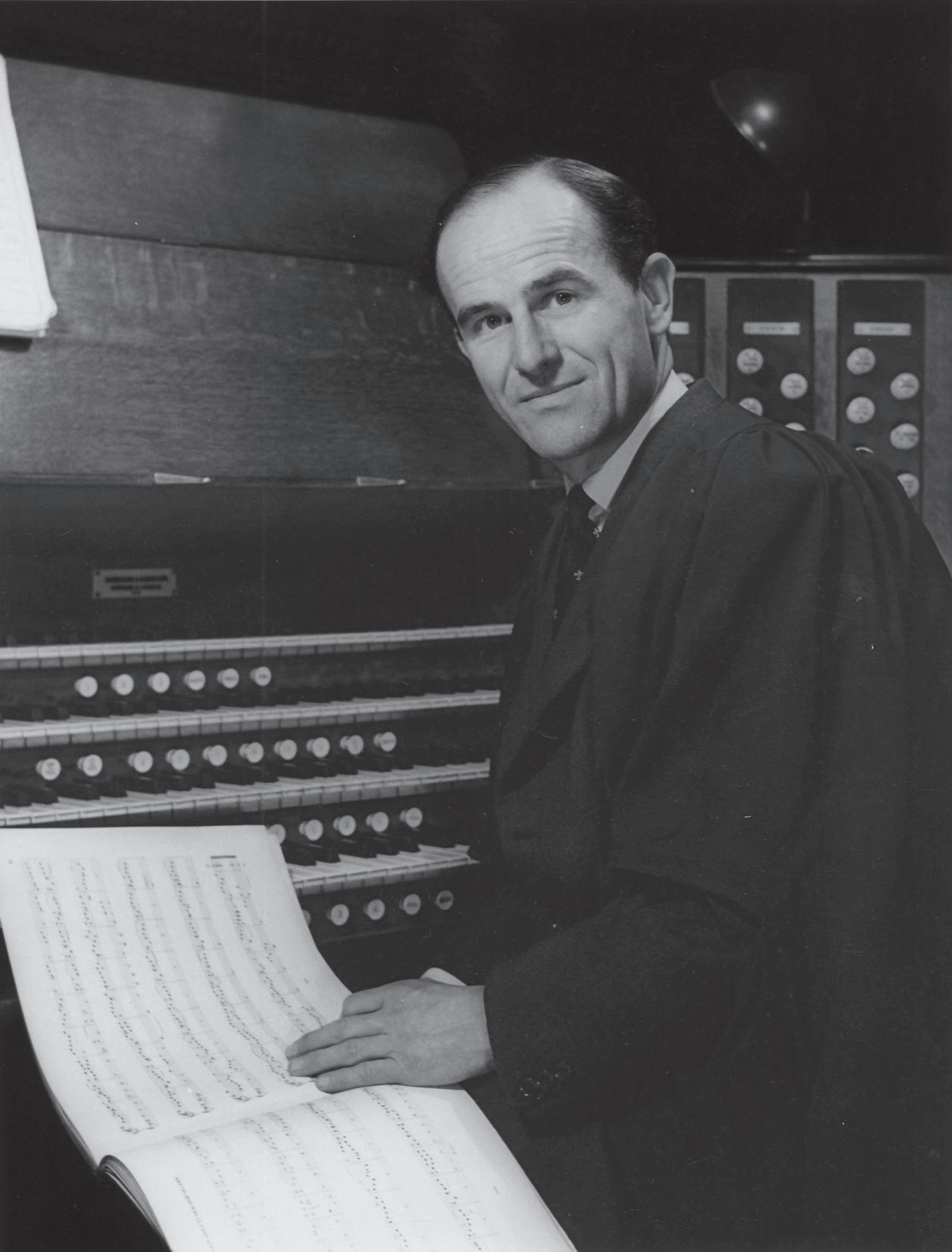

JOHN SCOTTAn appreciation

The sudden death of John Scott (1956-2015) in August was a profound shock to the world of church music. Mark Williams, Director of Music at Jesus College Cambridge, who worked with John as Assistant Organist at St Paul’s Cathedral, London between 2000 and 2004, discusses one of the towering figures in the organ world with those who encountered him professionally and personally.

y first day at St Paul’s Cathedral was a memorable one. It was a Sunday in early October and I had no responsibilities – I simply turned up to watch what happened. I was fresh out of Cambridge, with its intimate chapels and comfortable familiarity, and I found myself somewhat intimidated by the scale of the building, let alone what might be expected of me in the months and years ahead. I was also a little daunted by the prospect of working with somebody whose recordings I had listened to from an early age. Legend had it that John simply never played a wrong note and that his own pursuit of perfection made him quite a taskmaster – I subsequently discovered both to be true. During Evensong, I sat under the dome and was taken aback by the acoustic – the first hymn started and a great sound washed over me – overwhelming, but challenging from a musical point of view, and I wondered how the choir and organ could ever hope to achieve any kind of clarity in a more complex repertoire. And then the cathedral choir began to sing. I was immediately captivated, not only by the extraordinary expressivity of the ensemble (in particular the trebles) but also by the refined elegance of John Scott’s conducting. His gestures were controlled yet poetic and the acoustic, which had seemed to swallow everything up, suddenly revealed colours and shapes that I had never heard before, even in something as mundane . Following Evensong, John gave a recital as part of a series in which he was performing the complete organ works of J S Bach. It was revelatory. I had never heard anything quite like it. On a Romantic organ, in a building with an eight-second echo, I heard every note with crystal clarity. I knew then that I was encountering firstclass musicianship of a rare kind. There was a spontaneity that was somehow contained within – yet not constrained by – considered and disciplined playing, the sum of which was an experience that was both uplifting and deeply moving. For the next four years, it was a privilege to

Jonathan Bielby, under whom John sang as a chorister at Wakefield Cathedral and who was John’s first organ teacher, observes that, “John, in this age of specialism, was supremely a non-specialist. Even as a teenager at Wakefield his breadth of knowledge and style was amazing. As my Assistant Organist he would play Frescobaldi, Titelouze and du Mage, but also Patrick Gowers and Kenneth Leighton; he played fistfuls of notes in Reger’s Hallelujah, Gott zu loben and Dupré, and revelled in the Baroque figuration of Buxtehude and Bach. What he learnt at Wakefield he was proud to share with the world.”

Benjamin Sheen was a chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral under John, and at the age of 13 the youngest person ever to give an organ recital at St Paul’s. He went on to study at Christ Church Oxford and, in 2012, took up the post of Assistant Organist at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue: “To say that there was no greater influence than John in my musical career thus far is no exaggeration. From my first days as a chorister at St Paul’s, John’s enthusiasm, dedication and constant striving for perfection were humbling to all of us who worked with him. In the last few years, I have been privileged to become part of

his musical legacy in St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, where he was loved and revered by all. A shining light in the musical world has gone out but, despite passing from this life, he will never be forgotten and will remain one of the greatest mentors and influences in my life.”

Geraint Bowen, Director of Music at Hereford Cathedral, studied the organ with John in the early 1980s, and his two sons were later choristers at St Paul’s Cathedral. He invited John to give the celebrity recital at the 300th anniversary of the Three Choirs Festival at Hereford in July 2015, which sadly turned out to be his last UK concert and included the premiere of O Gott, du frommer Gott by Anthony Powers, part of the Orgelbüchlein Project. Geraint recalls: “I’ll always be grateful for the musical insights which I learnt from John at a formative stage in my musical development, which have stayed with me ever since. More recently, watching him work with the choir at St Paul’s was always an inspiration: there was a wonderfully relaxed elegance in his conducting which conveyed such a strong sense of line to the singers. He was as friendly and modest as ever on his last visit to Hereford – always a gentleman.”

Jonathan Bielby

Benjamin Sheen

Geraint Bowen

Photo: Harrison Linsey

Jonathan Bielby

Benjamin Sheen

Geraint Bowen

Photo: Harrison Linsey

David Hill, Chief Conductor of the BBC Singers and former Director of Music at St John’s College Cambridge, Winchester Cathedral and Westminster Cathedral, arrived at St John’s in 1976, as John’s junior organ scholar: “We were aware of each other even prior to meeting: he had been in Wakefield whilst I was at Chetham’s in Manchester across the Pennines. We had much in common, shared a benign rivalry, and Jonathan Bielby taught us both the organ. It was immediately clear to me that John’s capacity to absorb music was nothing short of astonishing, as was his ability to communicate, very clearly, what he expected from himself and others. We worked well together and have been close friends ever since. We grew to understand our similarities and differences: I owe him so much and rejoice in having known him.”

Canon Lucy Winkett, Minor Canon and later Canon Precentor of St Paul’s, remembers the profound impact John’s musicmaking had on her in her daily experience of Evensong: “John could be both spectacularly kind and protectively fierce in his pursuit of musical excellence. He always placed his incomparable skill at the service of the liturgy and I feel immensely privileged to have seen this, day after day, at first hand. What I found especially inspiring was his commitment to take the choir with him somewhere new, in the middle of Evensong, during, say, a Howells Magnificat or an Elgar anthem. The energy would change, the pace would quicken and the piece would simply take off in a way that was breathtaking. Musically, he had an intense commitment to the tradition at the same time as being daring in his interpretation of even the simplest psalm chant. He expressed something very profound about the spiritual life in his utter commitment to the piece in front of him; the ever-new and renewing presence of God within the context of the ancient wisdom of the centuries. John’s faith underpinned his performance of music in the liturgy and, by his skill, he helped others believe.”

James O’Donnell, who, for almost 20 years, worked alongside John in London, firstly as Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral and then as Organist and Master of the Choristers at Westminster Abbey, reflects: “In the early 1990s, St Paul’s and Westminster Cathedrals began an ecumenical exchange during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity that continues to this day. The two choirs sang an evening office from their own tradition in the other church. John saw this as an important

opportunity on many levels – not least social. The parties after these services were legendary and truly ecumenical! As I got to know John better and better, his profound commitment to the importance of making excellent music in a liturgical context, and his love of the Anglican choral tradition, became ever clearer. John was also deeply supportive of, and generous towards, other musicians, in his characteristically understated way. He often made the effort, in his busy schedule, to attend organ concerts given by others – including me. To know that he would be in the audience at your recital was not necessarily the most calming of prospects, but you knew that he was there solely to support you and appreciate the performance. He was a masterful musician with astonishing facility. His every gesture as a conductor, and every note as a player, was considered, and effective: his performances always had a sense of authority and inevitability, yet also a compelling freshness and vitality. He was never ‘flashy’. I consider having known this gentle man to be one of the great privileges of my life.”

John Rutter CBE composed works for the choir of St Paul’s when John Scott was Organist and Director of Music. The two also worked together on a number of seminal recordings with the Cambridge Singers: “John always said ‘yes’ to anything he was asked to do if he possibly could; his work with me sometimes led to encounters with occasionally less than perfect organs, which he somehow turned into tonal jewels. He was a solid-gold professional and a lovely man, with an obliging-ness, a sense of duty, and a relish for musicmaking that was breathtaking in its reach. In addition to his extraordinary skills as a soloist, he was a perfect chamber musician who became part of any ensemble he played in. I remember a Fauré Requiem recording where he seemed to phrase and breathe at one with singers and instrumentalists alike.”

New York-based composer, Nico Muhly, knew John well, writing for the choir of St Thomas and for John as a solo recitalist. John’s choir at St Thomas became one of the finest ecclesiastical ensembles in the world, and Nico reflects on slipping into Evensong on Fifth Avenue: “To watch him conduct the choir for a random Thursday Evensong was to watch an essay in simultaneous restraint and spontaneity: centuries of performance practice reanimated, stylised, and tightened. I think of his influence as a form of epidemic:

David Hill Canon Lucy Winkett James O’Donnell Photo: Clare Clifford

St German’s Cathedral is the newest created cathedral in the British Isles, and the mother church of what is believed to be the oldest diocese in the Church of England (founded in 447). The original Cathedral of St German, inside the walls of Peel Castle, fell into ruin in the 18th century. The Bishop consecrated his chapel at the Bishop’s Palace as the pro-cathedral and instituted a chapter of canons with himself as Dean. The Bishop’s Palace was sold in 1980 and the Victorian Kirk German in Peel was elevated to the Island’s cathedral. More recently, in October 2011, Canon Nigel Godfrey, vicar and sub-dean, was officially installed as the Dean of the new cathedral.

Upon my arrival in 2012 there was only one service with music a week, sung by an ad hoc choir, which often consisted of only three parts (S, A, and men). For the ‘cathedral services’ (ordinations, Christmas Day, Easter Day) my predecessor had

invited a variety of Island singers to form a special choir. But in anticipation of change, a group of people had established the St German’s Cathedral Music and Arts Foundation, and I was appointed as Organist and Director of Music.

Initially, it was tempting to start with a blank sheet, but because the Island works in a very unusual and close-knit way, it was clearly more sensible to develop the status quo. So the ad hoc choir were rehearsed and regularised into a traditional SATB group of singers, and the repertoire was expanded slowly until they were singing a simple anthem each week. At the same time I was keen to bring in a group of child choristers. The city of Peel has a large primary school and that was to be my first port of call. My first visit proved fruitless – lots of interested children, but very uninterested parents! Not one to give up easily, I persisted with the local school, but also targeted two other smaller satellite schools, visiting each one armed with

AN ISLAND CATHEDRAL’S MUSICAL RENAISSANCE Peter Litman

a PowerPoint presentation and something to sing, hoping it might interest the children. It worked, and before long I had six boys and three girls interested in singing regularly.

In May the cathedral was to host a service of celebration for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee to be attended by the Lieutenant Governor. I wanted to include the new child choristers whose job it was simply to lead the hymns. For the occasion, I also formed the ‘Jubilee Singers’ (a community singing endeavour) which numbered around 60 amateur singers drawn from the Island’s choirs. They joined with the cathedral’s adult singers and sang Handel’s Zadok the Priest. The accompaniment was provided by the organist at King William’s College, allowing me to direct the choirs in a rousing service as befitted Her Majesty the Queen.

Success breeds success, they say, so the nine children decided they wanted to be the ‘Cathedral Choristers’ and a weekly

rehearsal was fixed, separate from the adult singers. To develop an identity for the children, the adult choir was renamed the Nave Choir and the children got their wish.

Up to this point Evensong on Sundays had been a said service, attended by the Dean and occasional members of the congregation. My suggestion was to introduce sung elements to this service by the new choristers, and happily the Dean agreed. So, gradually, using plainchant responses, single chants (for canticles and psalms) and simple melody songs for anthems, the choristers were taught music alongside literacy and meaning. As a result of introducing music to the evening service, the congregation began to embrace the concept of Choral Evensong and numbers slowly began to increase.

The next step was to propose a new pattern of music at Sunday services to the Dean and Precentor, and this was agreed for the

new academic year. The Nave Choir were to sing on two Sunday mornings a month, with the choristers singing Evensong every Sunday. The plan also included a new SATB quartet of trained singers which would sing one Sunday morning service a month. By what I believe to be divine intervention, at this stage I received an email from a professional bass-baritone in Canada; it revealed that he and his family (all choristers) were moving to the Island for a year, and this family turned out to be absolutely pivotal in the development of the cathedral music programme.

With the start of the new choir year, the Dean and I launched our new proposed service pattern, and with the Canadian duo, now augmented by a soprano and a tenor, the first Sunday service of each month featured a Renaissance choral setting of the Eucharist. Meanwhile, the cathedral choristers, growing in confidence and ability, had started to produce a strong sound, although one or two had dropped out owing to the increased commitment. So I planned the first big outreach activity for October. I invited five of the local primary schools into the cathedral for a workshop/performance of a popular children’s cantata. Each school would have the opportunity to showcase their own choir before a massed performance of the cantata. This was very successful and caused a flurry of interest in the choristers, and by November I had six boys and seven girls, all now resplendent in brand new probationer-purple cassocks. A head chorister was voted in, and because this was a boy, we also appointed a head girl.

All energy was diverted to preparing the combined choirs (Nave, choristers and Schola) for the first serious Nine Lessons and Carols service in the cathedral. To ensure success, we adopted the traditional format with the descants and carols people wanted to hear, and generated a great deal of publicity.

The newly adopted service structure continued into 2013 although up to this point the cathedral choristers were

all probationers. Then in February 2013 five boys and five girls were formally admitted as full choristers, a significant historical event, since these were the first child choristers to be recorded in St German’s Cathedral since 1755, when the Island’s Bishop Hildesley recruited ten girls and ten boys to sing at the pro-cathedral. He also clothed and fed them. It is now generally believed that this act was more likely social philanthropy than musical education as they did not last very long! But could it be that Sodor and Man was the first diocese to have encouraged girls to be cathedral choristers, as early as 1755?!

Shortly after being admitted to the Peel choir, the son of the Canadian duo expressed an interest in becoming a professional chorister and, with my encouragement, he was auditioned and accepted by the Schola Cantorum at Tewkesbury Abbey.

In the summer term of 2013 the choristers received an invitation from the Mananan International Festival asking them to sing a Choral Evensong in the Summer Festival. This gave me the opportunity I needed to platform the new choristers, and also to add alto, tenor and bass lay clerks behind them. During the service we sang the Stanford in C canticles and Bairstow’s wonderful anthem Save us, O Lord. Sadly, this was to be the swansong for the Canadian family, who were returning home (minus the Tewkesbury chorister). With them they had brought stability and great musicality, and had opened up a network connection to other singers across the Island, all of which became integral to the development of the cathedral’s music department.

We are the only cathedral and indeed children’s choir (outside the school choirs) on the Isle of Man, and as such the choristers have little idea of what it is to be a cathedral chorister. To try to address this, I contacted Liverpool Cathedral and requested a joint venture. The result was that we were invited to join with their choir for a service of Choral

Evensong. The whole experience gave my young choristers increased confidence and a great boost, so much so that in September the Nave Choir was finally dissolved.

At this time Bishop Robert informed me of a proposed visit from the BBC’s Songs of Praise team, who had asked to film two programmes featuring the cathedral choir. I was very cautious but agreed to the challenge, and the project was to become a catalyst for another recruitment strategy. My move was to retain a few of the former Nave Choir, combine them with members of the expanding Schola, and with two newly initiated choral scholars, form a new Schola of 12-16 singers who would also act as the back row for the choristers. With a grant from the Bishop’s funds, we purchased purple cassocks and white surplices just in time for Songs of Praise. Finally, the formal cathedral choir was now established.

The choristers now number 18 boys and girls (11 choristers and seven probationers) and recently, our boy head chorister has achieved RSCM Bronze with commendation, which is excellent considering he has no formal musical or vocal training. This year we have also formed a Key Stage 1 choir at the local primary school, which not only acts as a feeder for the cathedral choir, but also ensures a continuous involvement with the local school and the wider community. It rehearses each week and sings Evensong once a term. The back row numbers a total of 17 singers who sing on rotation. Though amateur, they are of sufficient ability to sight-sing quickly.

Easter Sunday 2015 saw the departure of a girl chorister to Durham Cathedral’s choir, and whilst challenging for me as choir director to lose talented recruits, I believe it does testify that the training, nurture, environment and experience created here enables children to take on professional choristerships, and potentially change their lives.

Being the only cathedral on the Island, we are also the national cathedral. In July earlier this year, we sang for the Tynwald Day church service (the ancient Manx Parliament)

in St John’s Chapel which was streamed live across the world, and in addition, we had a Royal visit from HRH The Princess Royal (Patron of the Cathedral Development Campaign). Such events are not only important for the expansion of the choir and music department, but I believe shape our unique identity as the Manx cathedral.

Of course, as other cathedrals well know, funding a developing music programme is a major task, and this is the ongoing objective of the St German’s Cathedral Music and Arts Foundation. Up until now, apart from initial funding for my own salary, the music department has been run on a shoestring. It is now the role of the Music Foundation to ensure that the department is permanently endowed so that in future the focus can be, as it should be, upon growth and development. But I can now say with confidence that any visitor to the cathedral would find a developing musical department similar to other cathedrals in the British Isles. My work here involves researching, testing and implementing innovative and creative ways to develop the cathedral’s music programme, and to encourage and re-examine the priceless heritage of Anglican church music alongside the Island’s talented children.

Peter Litman originally trained at Canterbury Christ Church College where he was organ scholar from 1996-1999. In 2003, he was appointed Director of the MA Choral Education course at Roehampton University. In 2009 he returned to church music and was appointed Organist and Choirmaster at St Peter’s Collegiate Church, Ruthin (North Wales), continuing his organ studies with Organist Emeritus of Chester Cathedral, Roger Fisher. Outside his cathedral work, Peter also conducts the Island’s premier chamber choir, the Tallis Consort, and is an assisting organist at King William’s College.

Cathedral choristers

SIR HERBERT BREWER (1865-1928) John Morehen

This year marks the sesquicentenary of the birth of Sir Herbert Brewer, one of the most energetic and versatile church musicians of his generation, and one of the most gifted of those whose professional lives were spent exclusively in the provinces. Herbert Howells, a pupil of Brewer, described him as ‘the greatest organist I have ever known’. Brewer was equally renowned as a composer, choirtrainer, adjudicator, examiner and teacher.

While still in his early teens Brewer was already undertaking organist engagements at such diverse locations as Gloucester Prison, Painswick Church, and Highnam Court (the Parry family seat). His first professional appointment, aged 15, was at St Catherine’s Church, Gloucester, for the choir of which he composed his first published setting of the evening canticles. Shortly afterwards, he moved to Gloucester’s medieval church of St Mary de Crypt. During these formative years he studied organ with C H Lloyd at Gloucester Cathedral, where he was head chorister.

When Lloyd was appointed Organist at Christ Church Oxford, he invited Brewer – still only 17 – to be his assistant. The following year, Brewer won an organ scholarship to the Royal College of Music, where he studied organ with Parratt, counterpoint with Bridge and composition with Stanford. His health was precarious, however, and the commuting between Oxford and London quickly took its toll. He was awarded the organ scholarship at Exeter College Oxford, enabling him to relinquish his RCM scholarship and concentrate his activities in Oxford.

In 1885 the Bristol Cathedral organist, George Riseley, was dismissed following disputes with the Bristol chapter, and Brewer, now aged 20, was appointed to succeed him. Unfortunately for Brewer, Riseley took the chapter to court, where he won his case and was reinstated. After only two months at Bristol Brewer was unemployed; he returned to Oxford to resume his recently vacated organ scholarship at Exeter College.

In 1886 Brewer was appointed organist of St Michael’s, Coventry, which later became Coventry Cathedral. He supervised the installation of a new Willis organ, and spent six happy years before being appointed music master at Tonbridge School. At Tonbridge, as at Coventry, his immediate priorities were securing a new organ (again from ‘Father’ Willis), improving the chapel choir, and founding a local choral society. After four years at Tonbridge, Brewer eventually gained the position which he so earnestly coveted – Organist of Gloucester Cathedral. He was still only 31, and was to occupy the post until his death in 1928.

Brewer’s early years at Gloucester were largely preoccupied with the celebrations for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee (1897), the completion of the cathedral organ (1899), and the founding of the Gloucestershire Orchestra Society (1901). He was also steadily composing and, as his reputation grew, he became increasingly involved in examining and adjudicating.

The most high-profile and demanding aspect of the Gloucester organist-ship was the responsibility every three years for planning and directing the Three Choirs Festival, the annual music meeting which takes place in rotation in the cities of Gloucester, Worcester and Hereford. Brewer oversaw eight such festivals, where he set out to champion new music, both British and continental.

At his first festival (1898), Brewer directed the English première of three of Verdi’s Quattro pezzi sacri, while ColeridgeTaylor, whose ethnicity created a sensation, conducted his newly commissioned orchestral Ballade. The commission was almost entirely due to Elgar, who interceded with Brewer on Coleridge-Taylor’s behalf. Its success prompted Brewer to offer Coleridge-Taylor a commission for the 1901 festival too, which also included premières of music by Parry and Bridge.

Brewer’s projected programme for the 1904 festival included Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, but this was roundly vetoed by the dean of Gloucester (although it had already been performed at both Hereford and Worcester). Brewer invited Richard Strauss and Parry to compose new works for the 1907 festival, though both declined. He also invited Glazunov to conduct his Symphony No. 6, but the Russian composer was unable to obtain leave from his post at the St Petersburg conservatory. The only première at this festival was Bantock’s Christ in the Wilderness, part of a projected (but uncompleted) larger work.

This year marks the sesquicentenary of the birth of Sir Herbert Brewer, one of the most energetic and versatile church musicians of his generation, and one of the most gifted of those whose professional lives were spent exclusively in the provinces.

The talking point of the 1910 Gloucester Festival was the legendary première of Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia In a rare lapse of judgment, Brewer described the piece to Herbert Howells as ‘a queer, mad work by an odd fellow from Chelsea’.

The 1913 festival was notable for the presence of Saint-Saëns who, nigh on 80, not only conducted his new oratorio The Promised Land but also performed a Mozart piano concerto. This festival was noteworthy, too, for the first performance of Sibelius’s tone poem Luonnotar, which Brewer conducted. There was also the première of Stanford’s substantial unaccompanied double-choir work Ye Holy Angels Bright

Brewer resolved to make the Gloucester Festival of 1922 essentially British, and there were 27 such pieces. The scale of some concerts was breathtaking. One comprised Scriabin’s The Poem of Ecstasy, Parry’s Ode to Music and There is an old belief, Bliss’s Colour Symphony (first performance), Eugene Goossens’ Silence (choir/orchestra, first performance), Holst’s Two Psalms, and – to round off the programme – Verdi’s Requiem!

The 1925 Gloucester Festival was destined to be Brewer’s last. Dame Ethel Smyth took up the baton for two of her own compositions, in the first festival concert to be conducted by a female. Regrettably Sibelius failed to fulfil his commission, which should have been his elusive Symphony No. 8. Following the festival, Brewer’s health began to fail, and although he had provisionally planned the 1928 festival – including invitations to Ravel and Honegger to write new works – he died on 1

commissioned for the 1895 Gloucester Festival, when it was performed with orchestral accompaniment. This was the year before Brewer’s appointment to Gloucester, and its reception may well have been influential in securing his appointment.

Brewer wrote only about ten bona fide anthems, some of which might more appropriately be described as introits. However, three anthems – Blessing, Glory, Wisdom and Thanks, the Easter anthem O death, where is thy sting, and God is our hope and strength – are more substantial. Brewer’s most extended anthem, God within, was one of his last compositions, and he was never to hear it performed. It was composed for the 1928 Festival of the Sons of the Clergy in St Paul’s Cathedral. Scored for full orchestra and organ, its style is redolent of Elgar, whose favourite performance direction – nobilmente – it carries.

Brewer is particularly comfortable when writing for his own instrument, the organ, where his 20 or so pieces show him to be equally adept at diatonic and chromatic writing and in both free and strict forms. He is perhaps at his best in the more extrovert postludes, such as his Triumphal Song, A Thanksgiving Processional, and Marche héroïque, though several of his reflective character pieces, such as Interlude in F and Cloister garth, have an undeniable charm. Special mention might be made of the Meditation on the name of BACH, which has an unusual harmonic adventurousness in keeping with the chromaticism of the BACH motif itself.

and part-songs. His most substantial works are his cantata Emmaus and his oratorio The Holy Innocents, written for the Gloucester Festivals of 1901 and 1904 respectively. Much of the orchestration of Emmaus is the work of Elgar, who at the time was concerned about Brewer’s health. Brewer later modestly admitted that ‘… what measure of success Emmaus has attained is largely due to the effective orchestration’.

Surprisingly, only a small proportion of Brewer’s music is for regular church use. As a church composer his reputation rests today upon his canticles in E flat and D, the latter written the year before his death for the 1927 Hereford Festival. Both are sturdy pieces, and fully deserve their place in the repertory. Of the remaining three Evening Services, the early setting in C major is perhaps undeservedly neglected. It was

Although Brewer was not a composer of the top flight, he was certainly more than merely competent. He is a master of the grand ceremonial style, very much at ease when writing for the ‘big occasion’. Much of his church music demonstrates the potential of unison and octave writing, though he also exploits imaginative choral textures. His church compositions are well structured, and are marked also by a strong sense of tonal direction, imaginative modulations, and an effective use of sequences. In his word-setting he avoids the tyranny of the four-bar phrase, and he is rarely guilty of false accentuation. His organ introductions and interludes are never routine, but invariably have something to say.

Brewer’s informal autobiography, Memories of Choirs and Cloisters, was published three years after his death. This retrospective collection of reminiscences was assembled towards the end of his life, probably in the early 1920s. Brewer recalls S S Wesley’s amusing eccentricities, and he also provides an absorbing account of his relationship with Elgar and Parry. From Brewer’s reflections emerges a scrupulous and warm-hearted musician who was also a keen practical joker; his text is enlivened by countless anecdotes which reveal him as one whose natural seriousness is frequently relieved by mischievous touches of humour.

This is an edited version of a talk given to the Church Music Society in September 2015.

Herbert Howells, a pupil of Brewer, described him as ‘the greatest organist I have ever known’.

St Mary de Crypt, the church outside Gloucester where Brewer was organist while still a teenager

John Morehen was Organ Scholar at New College Oxford, and a research postgraduate at King’s College Cambridge. In 1967 he joined the music staff of Washington National Cathedral, and he also taught at the American University in Washington DC. He returned to England in 1968 on his appointment as SubOrganist at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where he played the organ for many royal and state occasions. From 1973-2002 he was on the staff of the music department of Nottingham University, where he is now Emeritus Professor of Music. He was a regular BBC Radio 3 continuo player and recitalist for 25 years. His main area of scholarly expertise is English church music of the 16th and 17th centuries. He is a past president of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, and he was Master of the Worshipful Company of Musicians in 2012-13. John’s new edition of Brewer’s Memories of Choirs and Cloisters is published by Stainer & Bell at £14.99 plus p&p.

Informal Pre-auditions any time by arrangement

All children are educated at Salisbury Cathedral School Scholarships and Bursaries available

COME & SING L ANGLAIS HE WAS BORN Brenda Dean

40 years, and also taught at the Schola Cantorum in Paris, where between 1961 and 1976 he helped both French and foreign students. His reputation as a pedagogue, important composer and concert artist drew pupils and audiences of many nationalities, especially from the USA, where he gave 300 recitals and countless masterclasses.

In 1945 he became organist at the church of Sainte-Clothilde in Paris, the successor to César Franck and Charles Tournemire. He remained there as titular for 42 years, retiring at the age of 80. He died four years later.

A prolific composer, his catalogue of works comprises vocal and instrumental sacred music (among them the famous Missa salve regina, the Messe solennelle and the Missa in , very often performed in concert), secular music and numerous organ pieces, some of which are considered

Langlais went blind from glaucoma at the age of two, despite this handicap, became one of the most respected organists and composers of the 20th century.Jean Langlais at the house of his birth 1984 Photo reproduced courtesy of Marie-Louise Langlais

IN THE TOWN WHERE writes on the annual Langlais Festival

How the Langlais Festival started

In 2002 I bought my house in La Fontenelle, a village halfway between the Mont St Michel and Rennes. It was un coup de foudre – I just fell in love with it. The house dates from the 17th century and possibly at one time belonged to a nobleman. It certainly has lots of character and I spent about eight years renovating it. Now there are excellent facilities for groups of up to 40 people in a large rehearsal room, with other rooms around it which can be used for small group work etc. Two months after I’d bought the house, I discovered that the village was Jean Langlais’s birthplace. There was a plaque on the wall of the little cottage in which Jean Langlais was born, just round the corner from my house, and I recognised the name because I’d heard organists playing his music in cathedrals in England. It was, as the French would say, un hasard heureux.

I sang then (and still sing) with the Wingrave Singers, a Buckinghamshire choir which replaces cathedral choirs when they are on holiday. When I went back to the UK and spoke to our choir director, Colin Spinks, he was very interested because

he’d trained with David Briggs at Gloucester Cathedral and Briggs had been one of Langlais’s pupils. Between us, Colin and I devised the idea of a Langlais Festival, the first of which, a series of three concerts by the Wingrave Singers, took place in August 2005. The mayor and town council of La Fontenelle were enthusiastic because they wanted to raise the profile of both Langlais and their village, and also because the centenary of Langlais’s birth was fast approaching. They wanted to mark the occasion in an appropriate way – why should this not be the solution? The festival was an immediate success as it both met with the approval and support of the Langlais family and also began an enduring collaboration with the local French population.

Shortly after this, the Association Les Amis de Jean Langlais was created and I became its first president, a position which I continue to hold. Subsequent festivals have also had the financial support of the Communauté de Communes, la Region de Bretagne and the EU, as well as sponsorship by local businesses.

How the choral course evolved from this

It was Colin’s idea to involve David Bednall, who’d been a colleague of his at Gloucester Cathedral. Colin invited him to provide organ accompaniment for the Wingrave Singers in the first three Langlais Festivals, and David, having been assistant to Malcolm Archer at Wells, then suggested that Malcolm might be interested in directing a choral course. I was thrilled when Malcolm accepted my invitation and came on board in 2008. Since then there have been eight annual choral weeks, and Malcolm, David and Colin have continued to be pivotal in making them the huge success that they are. The focus is on a mixture of French and English choral music: Jean Langlais to be sure, but also those who influenced him, including Franck, Fauré, Widor, Vierne, Duruflé, Poulenc, Guy Ropartz (1864-1955) and Villette, and music from the Anglican tradition including works by Malcolm and David. In 2008 Daniel Roth attended the festival to hear us sing his Messe brève. We also usually sing a little Handel, because it goes down well with our French audiences!

Rehearsals are held in my house and in the church just across the road. On the second day of the course, participants sing a church mass in La Fontenelle together with the local French choir, and there are two concerts at the end of the week, the first in a prestigious venue, e.g. the Basilique de Pontmain, l’Abbatiale de Saint-Melaine in Rennes, the church of SainteCroix, Saint Servan (St Malo) and the Abbaye aux Hommes in Caen, with the final concert in La Fontenelle.

listened to each section in turn and moved the singers around until the balance sounded right. Finally, she assembled all the sections and handed over to Malcolm a choir, not just a collection of disparate voices. This was particularly instructive to the choir conductors who were participating as singers.”

There are normally 45–52 singers aged between 18 and 80, mainly from the UK (and a few from France), but there have also been participants from Hong Kong and Morocco. Reasonable sight-reading skills are expected, and a singing reference is essential. The music is issued two months in advance so that people are generally able to arrive note-perfect. The course recruits through Brittany Music Workshops in the UK, and there are many regulars who have attended all eight courses. Of course we also recruit and welcome new singers every year. We are able to provide choral scholarships for young singers – this year there were nine choral scholars – and this certainly improves the quality of the sound. These young people have generally had previous choral experience in cathedral or university college choirs, but any young person over the age of 18 is welcome to apply if they have a good reference from their musical director or singing teacher.

Accommodation and food

The choral week also works well socially. Every year is like a big family reunion and there is ample opportunity for convivial gatherings. There is a friendly restaurant in La Fontenelle where we have lunch. Most people stay in B & Bs or gites in La Fontenelle or neighbouring towns, and many of the local French population are happy to provide accommodation for the week. Indeed, the Association’s French committee and the local choir, la Chorale Les Amis de Jean Langlais, have made good friendships with the choral week’s participants, particularly at Association lunches and at the mayor’s vin d’honneur which follows the final concert every year.

Other events in the Langlais Festival

What makes the Langlais choral week unique

Apart from a series of entertaining lectures which Malcolm, David and Colin give every year, and the fact that participants are able to work with highly regarded composers on their own pieces, a further and very special addition to the choral week is vocal coach Hilary Jones, who gives all the singers an individual lesson and runs a solo singing masterclass with Colin as accompanist. Hilary is widely known as a trainer of cathedral choristers in the south of England, and she is expert at improving the quality of the choir’s sound. As Rupert Street, a participant in 2010, says in his appreciative report: “Everybody was intrigued by Hilary ‘voicing’ the choir. She

Malcolm Archer’s choral week is only one half of the festival’s activities and there is always a further week of concerts. The festival has attracted top quality international organists over the years, e.g. Marie-Claire Alain, who gave one of her final organ recitals in Dol Cathedral in 2007 to honour the memory of her friend Jean Langlais, Marie-Louise Langlais, widow of the composer, French organists Sylvie Mallet, Véronique Le Guen, Loïc Georgeault and Florence Rousseau, Luca Massaglia from Italy, Martina Ziegert from Germany, Frantisek Vanicek from the Czech Republic, Jane Watts from the UK and of course Malcolm and David, who give annual recitals of French and English music as well as their own inimitable improvisations. Malcolm also brings his very talented organ pupils from Winchester College to take part in his recitals. Among them this year was Henry Websdale, who will take up his position as organ scholar at King’s College Cambridge in October 2016.

In 2012 Colin gave a memorable concert of music by Langlais and Dupré for organ and piano with Claude Langlais, Jean Langlais’s son, and choirs and orchestras have come from Spain, Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK to pay homage to the memory of Jean Langlais. The men of Royal Holloway sang for us with Rupert Gough in 2007, Malcolm Archer brought his quiristers from Winchester College to visit us in December 2012, and we welcomed Katherine Dienes-Williams and the girls’ choir of Guildford Cathedral last summer.

Pontmain, the church of Saint-Léonard, Fougères and the church of Saint-Méen in Cancale. More modern organs can be found at the church of Saint-Martin in Vitré, the church of La Bouëxière and the church of Notre Dame in Pontorson.

What participants have said about the choral workshops…

There is no doubt that so many singers return to La Fontenelle because they have such a good time. They love the countryside, the fresh air, the food and drink, and the welcome from the local population. They like the marriage of English and French music. They enjoy singing both with the local choir in La Fontenelle, and also in the prestigious and beautiful churches and cathedrals in the surrounding area. They really appreciate the quality of the musical experience they have under Malcolm’s expert guidance,

Hilary’s encouraging teaching and David’s and Colin’s superb accompaniments. As one participant said recently: “The workshop is exceptionally well planned and organised. The bringing together of a choir of people who have not sung together before and shaping them into concert standard after five days is a remarkable achievement, and it was hugely rewarding to be a participant.”

And the icing on the cake? This July, for helping to make Jean Langlais more widely known and for putting La Fontenelle on the map, I was made a citoyenne d’honneur (honorary citizen) of La Fontenelle, and presented with a medal by the mayor!

For further details about the festival and the choral week, please see www.brittanymusicworkshops.eu and www.jeanlanglais.eu. For Rupert Street’s report see choralsociety.org.uk/html/rupertstreet1.html.

SIR DAVID WILLCOCKS Thoughts and Reminiscences

WILLCOCKSReminiscences by Stephen Cleobury

With the death in September of David Willcocks, the world of cathedral music lost one of its finest musicians, one whose achievements made him a legend in his own lifetime, and one whose influence will continue to be felt for a very long time. His broadening of repertoire, and his broadcasting, recording and touring, helped to bring sacred choral music to a much wider and larger audience than ever before; the quality of his performances inspired a widespread rise in standards and expectations.

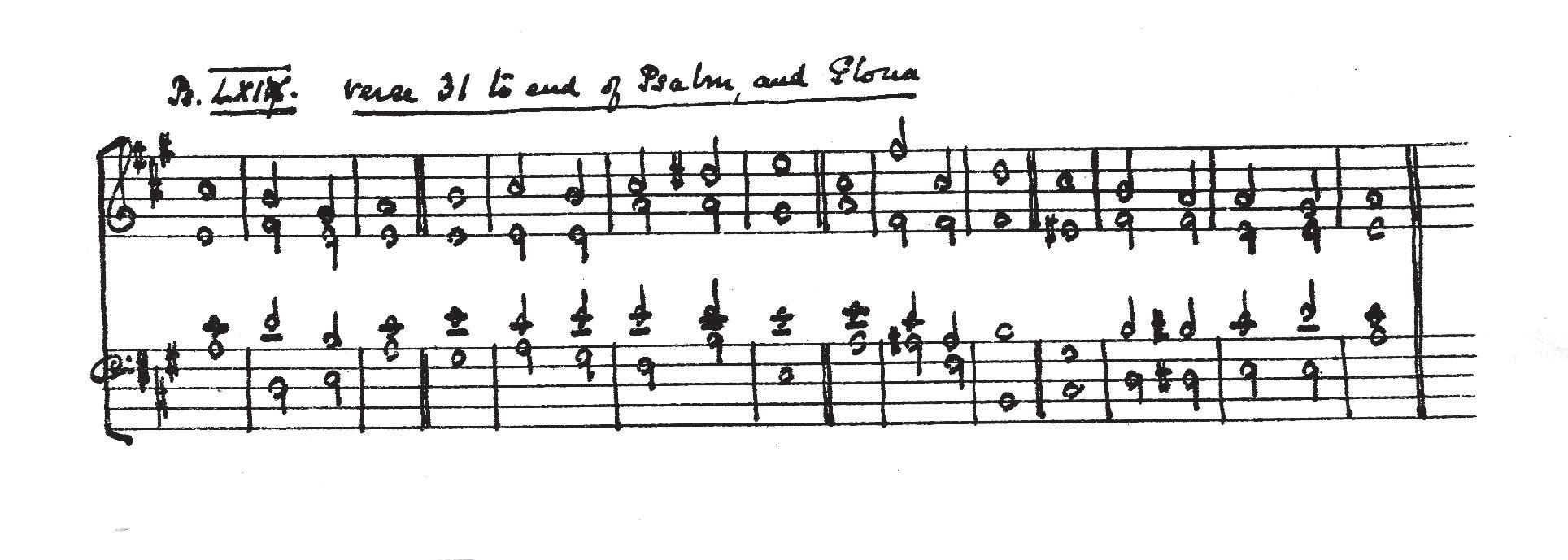

I first heard his name in Worcester, where I became a chorister in 1958. This was shortly after David had relinquished his position as Organist there to return to King’s College Cambridge. He had become Organ Scholar of King’s in 1939 under Boris Ord, and was now to succeed him as Organist and Director of Music. I could not possibly have imagined then that I would become one of his successors at King’s, that he and I would become colleagues, and that he would be such a huge support and inspiration to me. I often wonder, when reflecting on a performance I have given, what David would have thought of it. I always hope that it will have to some degree approached his own exacting technical standards, but also that it might have communicated something of his ever-present desire to convey the meaning of the text in a choral work. Like so many of the 20th-century composers with whom he was associated, Vaughan Williams, Howells and Britten, for example, David was not a religious man in any conventional sense, but he had the keenest response to words (and was clever with words too, Scrabble being something he excelled at – as undergraduates, we often found ourselves playing this game in French after a lunch party at the family home). In particular, he valued the psalms of David (appropriately named), and his own copy of the psalms was heavily annotated with marginal notes. He found in them, I think, poetic depictions of ‘all sorts and conditions of men’ which informed many of his personal relationships.

Since his death, very many of his former pupils have spoken of his sympathetic and understanding approach to them, and of the ways in which he was supportive of their needs in whatever situation they found themselves. He had a strong sense of justice and fair play. He was also possessed of a joie de vivre, an enthusiastic and energetic approach to all that he did, which inspired those who sang under his direction. He had an enviable ability to produce a quick-witted response to a given situation or remark. Upon receiving a letter complaining that his choral scholars wore their hair too long, he replied that he had it on the best authority that Jesus Christ had had long hair. When the Dean and Chapter of Worcester tried to forbid a performance of Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast on account of its

alleged profanity, he observed that the libretto was drawn from the Old Testament which was read out in services; and when the Dean of Salisbury complained that David was, during Holy Week, rehearsing the hymn ‘Jesus Christ is risen today’ with its ‘Alleluia’, he immediately asked the choir to replace that word with ‘fa-la-la-la’.

These days there is much more specialisation than there used to be. David came from that great tradition of the all-rounder. The expression ‘jack-of-all-trades’ has a pejorative aspect, but it can be truly said that David was not just a ‘jack’ but a master of them all. As a musician, he possessed an acute perception of pitch and an unerring rhythmic sense. These qualities enabled him, as a conductor, to place the achievement of excellent intonation, good balance, blend and ensemble at the top of his technical agenda, to which was added that special expression and enunciation of text that made his performances so compelling.

He was a fine administrator and leader, as his work as Director of the Royal College of Music showed. He was an excellent organist too, capable of giving impeccable performances of Bach from memory. He worked with professionals, amateurs and the young alike in orchestras and choirs, drawing the best from them with appropriate combinations of encouragement and cajolery. He could be demanding, but always with a twinkle in his eye, and with a humorous remark never far away. Everyone performing for him knew that if he was tough on them, he applied the same rigorous standards to himself.

I remember listening to the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols from King’s in my chorister years. I once heard David

With the death in September of David Willcocks, the world of cathedral music lost one of its finest musicians, one whose achievements made him a legend in his own lifetime, and one whose influence will continue to be felt for a very long time.

interviewed about his work with a choir. His answers to the various questions imparted the wisdom, experience and insight of a master musician, and I remember in particular

is something all of us do well to heed.

Each Christmas at Worcester, the cathedral choir took part in a seasonal concert with the Festival Choral Society, and I remember the enjoyment we all derived from using the ‘green book’ for the first time. This, of course, is now known as Carols for Choirs I. David was to publish many more arrangements of carols and hymns, but already in this book his seemingly effortless ease in producing soaring descants and skilfully varied harmonies was plain for all to hear. He also had great facility in writing these. Members of King’s choir from his time have told me how a descant would often be written in the lunch break on a recording day, something which he wished to conceal from the record producer. The choral scholars would readily go along with David’s little deception when he handed out copies of music they had never seen before, saying, ‘Now, gentlemen, you will recall when we were rehearsing this yesterday….’!

The Worcester years were highly formative for me, and we were lucky in that the Three Choirs Festival introduced us to most of the major choral works with orchestra. One of the early performances of Britten’s War Requiem was given in the 1963 festival (Douglas Guest, David’s predecessor as Organ Scholar at King’s, and then Organist at Worcester and another great mentor to me, was very ‘up to date’ in his programming), and, if memory serves correctly, David conducted the chamber orchestra on that occasion, with Douglas directing the main forces. David subsequently conducted this work many times, and I was later to be involved in some of these, mainly during my time at Westminster Cathedral, playing the organ and providing the boys’ choir.

those visits to Evensong gave me a chance to experience his expertise in that area, too. In those days, of course, organists accompanied their choir far more often than is the case now, and David was a superbly sensitive psalm-player, as the famous recording of The Psalms of David from King’s shows, and his highly developed sense of rhythm was a feature of his anthem accompaniments.

During my second and third years as a student at Cambridge I was the accompanist to the CUMS chorus. David was a superb trainer of large amateur choruses, and seemed especially to relish this side of his work. He was particularly concerned that singers should not bury their heads in the copy, and he had two games which he played to try to catch out the inattentive. If he placed his handkerchief on his head while he was conducting, you certainly wanted to be among the first to raise your hand to show you had noticed. Behind him in the rehearsal hall was a blackboard, and he was often able to complete the matrix of a noughts and crosses board before everyone had become aware of this. These rehearsals were my main opportunities to see David at work, and I learned a huge amount from them. His acute ear enabled him to spot errors quickly and to rectify them speedily, this ability being one of the most important for the conductor to cultivate. In those days many of the organ scholars sang in the chorus, and through this, as well as his work at King’s, David’s methods and skills were passed on to future generations of organists and choir directors.

After Cambridge, I next encountered David in my time as Sub-Organist at Westminster Abbey, he being an old chorister of the Abbey. By that time Douglas Guest was Organist there, and I remember a concert given jointly by the Abbey choir and

Street. He was always most welcoming. I also played for Bach Choir concerts, of which he was Musical Director. One of the most memorable experiences for me was to play the keyboard continuo in a performance of Bach’s St John Passion which was to be the last occasion on which Peter Pears sang the role of Evangelist. To be in such close proximity to an artist of that calibre is a huge privilege. The Bach Choir connection continued through my time as Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral. Another aspect of David’s musical prowess was on show at after-concert parties, when he would play Chopin’s Minute Waltz, hands crossed, lying underneath the piano.

Then, for me, King’s. No pressure at my first Evensong. That day there was a dinner in Hall for alumni from the ’30s and ’40s, and Douglas and David had both been invited. The reader can only imagine my feelings as I directed the choir for the first time under their watchful eyes! But they were wholly behind me and, as they say today, affirming. And that was the case with David for over thirty years. Others can, and do with great affection, often very amusingly, retell countless stories about David. For me the outstanding thing was his unstinting support over this long period in what is a not unchallenging job. Always willing to advise, never interfering, he was the perfect predecessor.

He is generous in his encouragement of other performers: my wife (a former member of his Bach Choir) and I treasure his verdict on her singing of the responses when she was chaplain of King’s – ‘exactly an octave sharp’. Notice that word ‘exactly’. No greater compliment could have come from that source.

I join the musical world and countless others in paying tribute to this remarkable man, whose memory we revere.

MATCHING THE ORGAN TO THE BUILDING

ACOUSTICS - THE VITAL INGREDIENT John Norman

A major difficulty is that visual issues usually receive priority attention. This is at least partly caused by a general ignorance of acoustic principles, not only in the general public but also, sadly, amongst architects. In the Royal Festival Hall, the distinguished musician Ralph Downes fought a long battle over the location of the organ, where original proposals put the instrument in the roof-space! It took support from Sir Malcolm Sargent for him to win the day.

The organ has the widest range, from soft to loud, of any musical instrument. It is also the only instrument to have its design varied according to the acoustic of the building where it is housed. Other instruments either rely on some temporary method of adjusting their sound, such as the raising of the lid of a grand piano, or are present in greater or smaller numbers, as in the contrast between a string quartet and a full orchestra. Not for nothing does St Paul’s Cathedral, with its enormous dome taking sound from the nave, have more choristers than any other English cathedral. And the notorious acoustic of the Royal Festival Hall, before it was altered, required leading orchestras to augment their double-bass players to 12 – the original acoustic designer, Hope Bagenal, once explained to my father that he had a horror of bass sound!

Organ Position

As the largest piece of furniture in the building, the placement of an organ is subject to both liturgical and architectural fashion. In the 17th and 18th centuries the standard position for an organ in Anglican churches was at the west end and, in cathedrals, on a screen between quire and nave. After 1850, it became the fashion in parish churches to dress the choir in cassocks and surplices and to seat the singers in the chancel instead of at the back, which led to organs being moved from the west end to positions at the east end. As a result, many organs were placed sideways, often in separate organ chambers with poor acoustical projection.

To some extent, the problem lies in the organ’s very wide range. Cathedral instruments typically go down to 32ft C. This pitch will ‘go round’ most obstacles in the interior of a building without significant loss, but the musically important higher notes will be seriously reduced unless redirected by a hard reflective surface. That is why organ position is less important in a very reverberant building, where much sound is heard by reflection anyway. On the other hand, organ position is all-important in a non-reverberant venue with a low ceiling and where reflected sound is absorbed by soft furnishings and carpets. In such surroundings most sound has to be direct.

Player Position

Although the location of the player has no direct effect on the sound of an organ, it may well affect the way in which it is played. It is practical to have the player located close to the choir, which can give rise to a conflict between visual and architectural considerations on the one hand and musical requirements on the other. Developments in organ mechanism towards the end of the 19th century allowed the separation of the player from the body of the instrument, leading to the possibility of placing the organ at the opposite end of the building from the player.

This arrangement proved highly unsatisfactory. God’s physical laws decree that it takes nearly a tenth of a second for sound to travel 100ft (30m). Try playing a really fast piece such as the final bars of the William Tell overture with that amount of lag! But the real problem is one of balance. If a player, however experienced, hears the organ too softly, he will tend to make more sound than really required. If the congregation is placed between player and instrument, one can almost guarantee that they will think he plays too loudly. The problem is less acute in reverberant buildings, such as most cathedrals, where the sound level diminishes less with distance. It has also been found that a 40ft (12m) separation of pipes and keyboard is

acceptable when combined with a fast all-electric key action, as in the new organ in the quire of Worcester Cathedral.

Reverberation

It was the distinguished Victorian organ-builder Father Willis who coined the phrase, ‘The most important stop on the organ is the sound of the building’. And it is obviously more satisfactory to perform music in the same acoustic ambience as was expected by its creator: listening to a Bach cantata in Leipzig’s St Thomas’s Church is an unforgettable experience.

Acoustic absorption is the other side of the coin of reverberation. The greater the absorption, the louder the organ will have to be to create the same musical effect, since the direct sound will have less reflected sound to back it up. This can cause problems. In the case of new buildings, late changes in the specifications of surfaces can upset the design of organs already under construction. At the Royal Festival Hall the ceiling proved to be more absorbent than the acoustician had originally planned.

The opposite phenomenon can result from a change to the building many years after construction. The large and cavernous chapel of the Royal Hospital School, Holbrook, Ipswich, has a cathedral-sized organ with a considerable reputation for its abilities in the performance of late 19th and early 20th-century music. The chapel was originally lined with an acoustic finish, which has become clogged up with paint. We may all love the five-second reverberation, but the organ tutti is now overwhelming. The musical problem is that one cannot have the artistically favourable five-second reverberation without the reduction in sound absorption that has led to the organ needing to be played with discretion.

One also has to think about the relationship between treble and bass. Organ-builders have long known that large leaded windows absorb bass; the better organ-builders have allowed for this in their calculations. A different problem is that caused by the 1970s’ fashion of covering tiled or wooden parish church floors with carpet, particularly if this is placed immediately in front of the choir and organ. This reduces the reinforcement of sound by reflection, and also introduces a substantial skew to the treble-to-bass balance. The problem normally affects organs already installed, where there is no corrective action that can be applied to the organ itself. The only solution is the removal of the offending carpet! Since the carpet at St John’s Church, Notting Hill, was removed, the church has been used for rehearsal by the Monteverdi Choir.

There is an important but more subtle effect on the tone of an organ which results from the absorption of sound in the extreme treble by the atmosphere. The effect of this ‘top note’ filter is virtually absent from venues with a dry acoustic, but very significant in buildings with long reverberation times such as cathedrals. The musical result is that a style of voicing appropriate to a reverberant cathedral will sound hard and aggressive in a more intimate environment. This occurred in the 1972 organ in the tiny chapel of St Mary Undercroft in the Palace of Westminster. Unpleasant at Westminster, the instrument proved perfectly satisfactory in a more reverberant church elsewhere. The replacement organ at Westminster was designed to have a deliberately less aggressive sound and has been widely praised.

What can the organ designer do to achieve the best result?

THE EFFECT OF A CASE ROOF

Organ-builders design cases with the minimum of panelling in order to maximise sound transmission, which can result in difficulties: one hardly dare place a ladder against Dr Arthur Beverley Minster. The equally solid-looking case designed by Father Smith 300 years ago for the Chapel Royal at Windsor (now in St Mary’s, Finedon, Northants) is much more open when looking out from the inside. Architect-designed cases are

Up to about 1820, it was usual for organ cases to be roofed in. Although originally provided more to keep out dust than for have been found to have important acoustical effects when an organ is freestanding. For this reason some present-day organ-builders now provide case roofs whenever possible and replace them on old organs where they have been removed. The roof provides early reflection of sound emitted vertically from the tops of the pipes, eliminating the time delay of sound travelling up to the ceiling structure and then down again. For example, the Oxford retains the Victorian appearance of its predecessor and thus has no case roof. Sound travelling up nearly 10m to be reflected from the arch above will arrive at the ears of the listeners on the floor below about 1/15th of a second after sound coming directly through the front pipes. This considerably reduces the precision of sound in a building with a long reverberation time and where the ratio of direct to reflected sound is quite low. Better for Bruckner than for Bach.

Beverley Minster. Organ case designed in 1916 by Dr Arthur Hill (of Hill & Son, organ-builders). Drawing by Herbert Norman.

Drawing: John Norman

Beverley Minster. Organ case designed in 1916 by Dr Arthur Hill (of Hill & Son, organ-builders). Drawing by Herbert Norman.

Drawing: John Norman

Voicing

In a reverberant building like a cathedral, the acoustic absorption of the air starts to become significant in the treble, so an organ needs to put out extra energy in the upper range, whereas in an acoustically ‘dead’ building one needs to hold back the upper harmonics or they will ‘scream’. A skilled voicer does this in two ways. Firstly by varying the ‘scale’ (diameter) of the pipes and secondly by varying the

height of the pipe mouth, the ‘cut-up’. A low cut-up gives a ‘sweet’ but non-aggressive sound, suitable for intimate and non-reverberant venues. A higher cut-up gives a harder sound which seems better able to cut through in a more reverberant environment. This can lead to trouble when an organ-builder used to reverberant abbeys on the Continent fails to modify his technique when confronted with a less reverberant venue in this country.

Out of tune-ness of major thirds with differing tuning temperaments.

Graph: John Norman

Tuning temperament

The musical scale poses a problem with major thirds, which particularly affects the organ because an Equal Tempered third is 1/7th of a semitone sharp, creating a dissonance in chords that incorporate a major third – the ‘Angry Thirds’ dissonance. Unequal temperaments reduce the dissonance in the common keys, but Equal Temperament is favoured by organ tuners in cathedrals where the treble filter imposed by the absorption by the air tends to blunt the aggressiveness of the chord. On the other hand, organ-builders whose main work is in more intimate buildings find the Angry Thirds intolerable and refuse to use Equal Temperament.

Number of stops

When John Goss was appointed organist of St Paul’s Cathedral in 1838, he had the temerity to enquire about the possibility of adding another stop to the 1697 Father Smith organ. Sir Sydney Smith, a very grand canon, was determined to put down the young upstart: “What a strange set of creatures you organists are! First you want the bull stop, then you want the tom-tit stop; in fact you are like a jaded cab-horse, always asking for another stop.” The plain fact is that the more stops there are, the more fun the instrument is to play. But, in practice, we also need to relate the size of the organ stop-list to the acoustic power needed.

The ideal size of an organ can be roughly calculated by relating the number of stops to the total acoustic absorption of the building. The latter figure can be calculated from the volume of the building and the measured reverberation time – the time required for a loud chord to die away to inaudibility. Additional manuals add tone possibilities and flexibility in

performance but relatively little volume. An organ in an open position needs less power than one entombed in an ‘organ chamber’. Only the number of stops on the Great organ are counted.

To sum up, the acoustic space inhabited by an organ can vary within very wide limits, and these variations will have a major effect on the musical result. Some effects can be taken into account in the design of the instrument but bad placement, for example, is difficult to mitigate, especially if poorly placed absorbent surfaces (i.e. carpets) are added after the organ has been made. Knowledge of the effect of atmospheric sound absorption at high frequencies on pipe scales, voicing treatment and tuning temperament is a relatively new development. Hopefully, however, improved acoustical knowledge amongst professionals will help to avoid future mistakes.

The above article has been adapted from a lecture given by John Norman at the Royal Academy of Music for the Institute of Acoustics in 2014 and repeated this year at Winchester Cathedral.

John Norman studied organ under H A Roberts and acoustics under Dr R W B Stephens, the latter as part of his degree at Imperial College London. He studied voicing and tonal design under Robert Lamb and Mark Fairhead at Hill, Norman & Beard. John has been consultant for 17 new organs and is a former member of the Cathedrals Fabric Commission. He now sings bass at Friern Barnet Parish Church.

A MAN OF MANY PARTS

Carl Turner writes on Andrew Millington, who retires after 16 years at Exeter Cathedral

“How do I get into the boys’ vestry, Andrew?”

“You need the code – it’s 1957–Y.”

“Is that a significant date?”

“Yes, it’s the last time Aston Villa won the FA cup!”

Thus began my 13 very happy years working with Andrew Millington at Exeter Cathedral.

Andrew is a man who never takes things lightly. Not only does he prepare the choir for every service as if it were the first he has ever directed, he can also be moved even to tears by the simplest and most beautiful of things, such as a particular hymn tune in procession. He has an eye for detail and a breadth of experience. To put it simply, Andrew Millington lives and breathes music and, because his whole life is immersed in it, others capture and are inspired by his energy and enthusiasm.

Andrew is also extremely modest; he is the first to admit that he came from humble beginnings, and it is clear that he has worked hard throughout his life. Born in 1953, he grew up with village life and then the family moved to Malvern where he attended a local grammar school. Perhaps that is where his love of walking and of the countryside comes from. The bass section of many a choir has heard their singing described as ‘distinctly agricultural’. His father was a good singer and the young Andrew joined Malvern Priory Choir as a boy, thus beginning his long association with church music.

He first studied the organ under Harry Bramma and Christopher Robinson at Worcester Cathedral. Because of his exceptional ability he gained a special place at the King’s School, Worcester, in the sixth form, where he first met Madeleine, the daughter of a priest, his wife and lifelong soul mate. Madeleine remembers her first encounters with Andrew – the ‘quiet, shy boy clutching his organ scores’. King’s School, at that time, was producing some fine musicians and it was there that Andrew studied alongside Stephen Cleobury and Stephen Darlington. Although there was some friendly rivalry, they became close friends and Stephen Darlington later on became his best man when Andrew married Madeleine in 1978.

Cleobury, Darlington and Millington were taught in Cambridge by John Rutter, where their obvious talent was noticed by a number of people. Andrew was organ scholar of Downing College. The trio continues to encourage each other: when I asked them what they thought of Andrew the response came swiftly:

“Andrew Millington has been outstanding in his career in cathedral music. He is a modest, unpretentious person with

Andrew Millington lives and breathes music and, because his whole life is immersed in it, others capture and are inspired by his energy and enthusiasm.

a true generosity of spirit, but above all he is a brilliant allround musician, whose devotion to church music has enabled him to touch the lives of vast numbers of people,” said Darlington.

Whilst Andrew was in Malvern he began his conducting career with the Aldwyn Consort of Voices, which competed in the European competition ‘Let the People Sing’. Other ensembles included the St Cecilia Singers in Gloucester, the Birmingham Bach Society and the Kidderminster Choral Society. Madeleine recalls that when they were first married he had choir rehearsals every night of the week. “I wondered when he had time to perform the concert!” she said.

Andrew has a hearty appetite for large-scale choral works and loves the music of Elgar and Mendelsohn, with performances of Elijah in particular thrilling him. He also has quite an appetite for sandwiches and many a choir member remembers the shout when they take a break, “Get to the sandwiches before Mr Millington!”. One of his favourite phrases is, “I can’t stand waste”, but this is also translated into his musical expertise: as a cathedral director of music he is methodical, careful in his choice of repertoire. He knows how to get the best from a group of singers in rehearsal regardless of how much time is left.