CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Whichever organ you buy from us, you can be assured of top sound and build quality, our technical expertise, great attention to detail and the best in customer service. We invest in our instruments so you can invest in your future. These are serious instruments for serious people, people like you. Explore our websites and then fall in love with the organ of your dreams in our showrooms.

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus | Rodgers

Makin | Copeman Hart | Johannus | Rodgers

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2016

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon grahamhermon@lineone.net

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Tatton Media Solutions, 9 St Lawrence Way, Tallington, Stamford PE9 4RH 01780 740866 / 07738 632215 wesley.tatton@btinternet.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

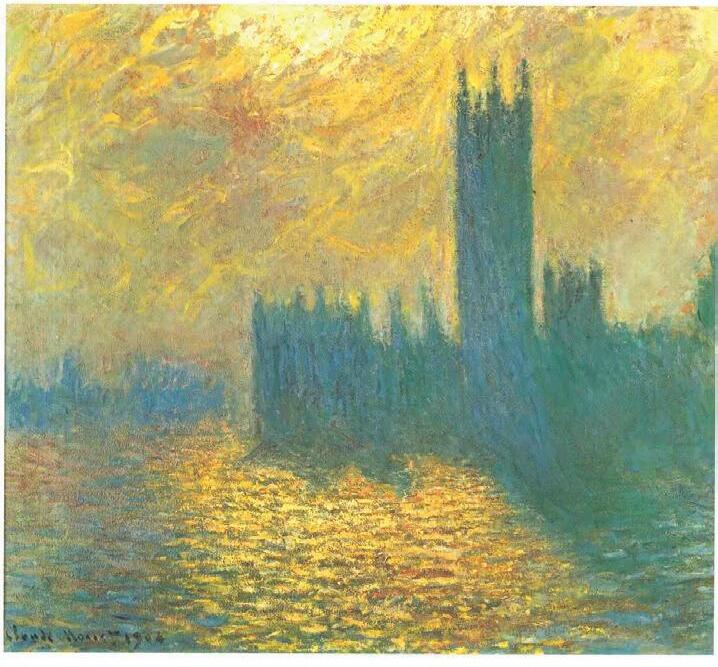

Cover photographs

Front Cover

Romsey Abbey interior

Photo: James Guppy

Back Cover

St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street

Photo: Brent Flanders

To play one call us to book a visit to our showroom, or contact one of our regional retailers listed below.

Irvine Soundtec Organs

Edinburgh Key Player

Morecambe Promenade Music

Porthmadog Pianos Cymru

Leigh A Bogdan Organs

Swansea Music Station

Multiple speaker locations create a uniquely authentic sound

Sonus instruments, based on the very successful ‘Physis’ physical modelling sound platform, additionally incorporate an enhanced internal audio system to generate an exciting moving sound field for increased enjoyment in a home environment. Speakers above the keyboards to the organ sides create a truly sensational and immersing sound field.

Starting at £9500 inc vat for a 34 stop 2 manual the instrument pictured here is the Sonus 60 with 50 stops at £13700 inc vat. Neither words nor recordings can do justice to the sound of these instruments; you just have to experience it in the flesh.

Norwich Cookes Pianos

Exeter Music Unlimited

Bandon Jeffers Music

Ballymena Nicholl Brothers

Londonderry Henderson Music

Belfast Keynote Organs

Receive your first year membership of the Royal College of Organists FREE, with your home practice organ purchase

Pictured above: Sonus 60

Pictured above: Sonus 60

This year has been a glorious one for FCM. All those who have attended the Diamond Jubilee celebrations in St Paul’s and St Martin in the Fields, in York in March, and in Liverpool just recently, will surely have felt uplifted by what has been achieved in the cathedral world since our inception in 1956. Of course there have been many changes – no longer does Matins play a central part in the life of a cathedral, for example, and it is becoming increasingly rare for a cathedral not to have a girls’ choir – but greatly to be welcomed now is the notable increase in cathedral congregations, in particular since the turn of the century. In large part this welcome growth must stem from the widespread excellence of the music offering, and thus – amongst other reasons -- in (very small) part from FCM’s own efforts. As an organisation we punch well above our collective weight; we all work very hard to bring what we value so highly to prominence, to draw in those who are hovering in the wings of support, and to publicise our cause more widely. There remains much more to do but, given the manpower, what FCM has achieved is remarkable.

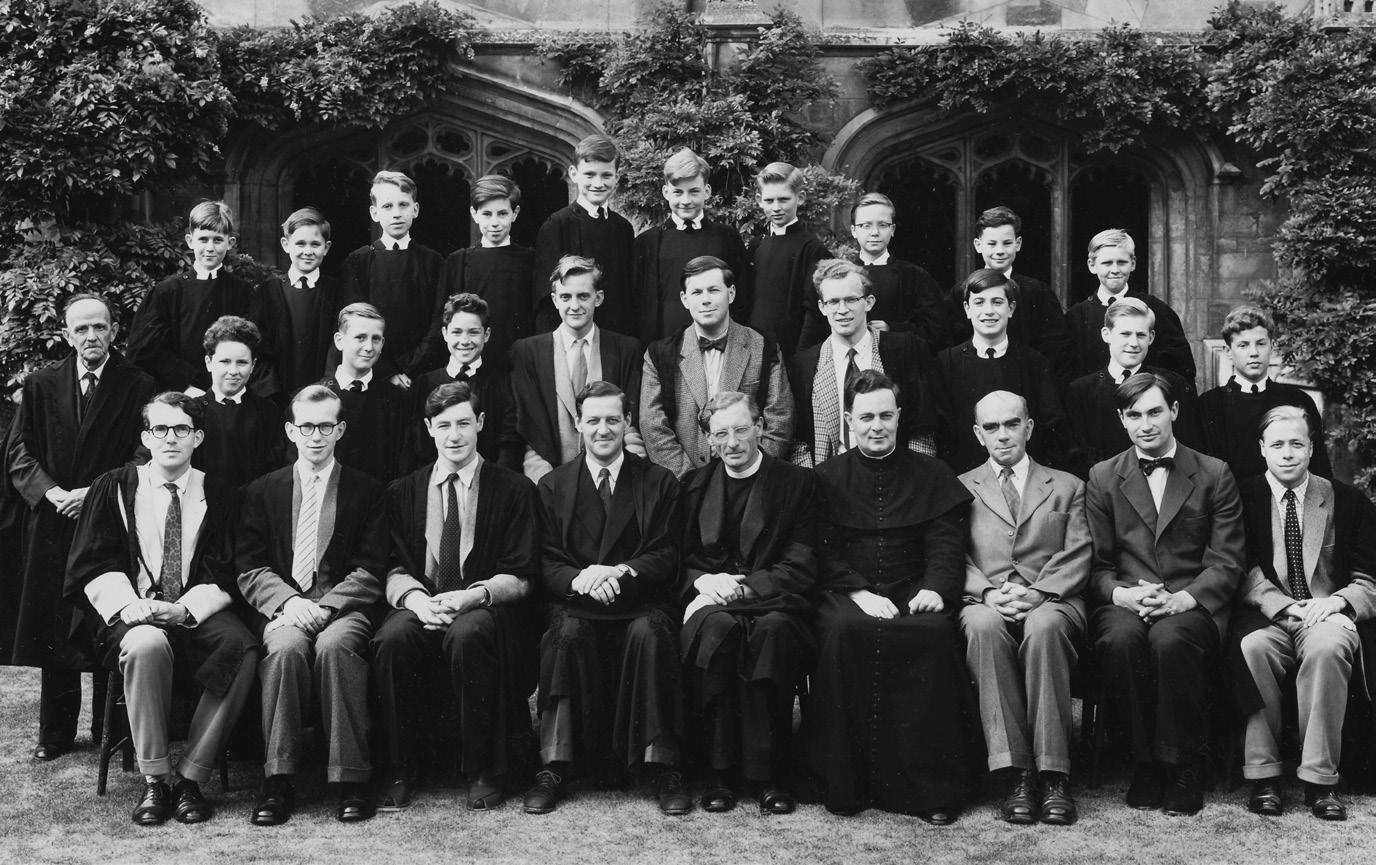

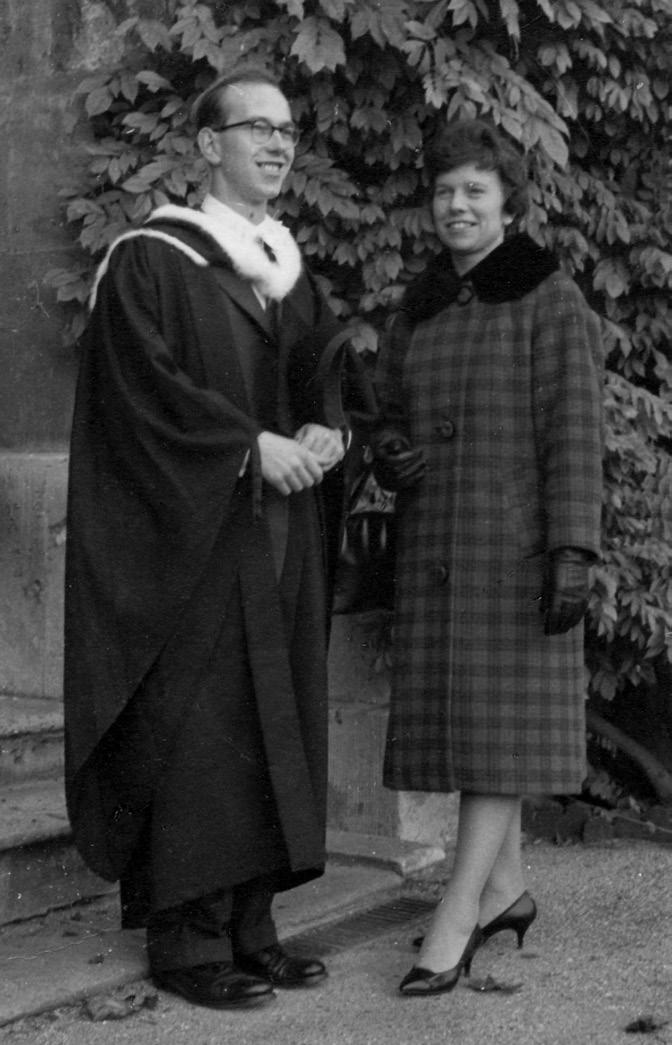

In the last issue of this magazine we said farewell to Christopher Robinson, who is handing over the president’s baton to Stephen Cleobury. Whilst there will be few amongst us who are unfamiliar with the latter’s achievements at King’s, many will know less of his life before Cambridge. Peter Toyne, somehow finding time in his own and Stephen’s busy schedules, talks to him about his experiences as a chorister at Worcester and as director of music at St Matthew’s, Northampton.

We have another departing soul to thank also: our redoubtable gatherings manager, Peter Smith, who, along with his doughty and indomitable wife Gina, has handled FCM’s weekend (and some longer) excursions to so many cathedrals over the years, throughout the UK and even to the Netherlands. The excellence of these weekends and the enjoyment gained by so many from them is attributable to Peter and Gina’s forethought and forward planning, and also to their unfailing good humour whatever the circumstance. We hope for their continued presence, despite their ‘retirement’, and look forward also to the next gathering, in March in Carlisle, which comes under the jurisdiction of the new gatherings manager, Rosemary Downey.

Most of us are keen followers of Choral Evensong, the BBC’s longest running series ever. You may be surprised to learn about some of the issues involved, technical, trivial and traditional, from its producer, Stephen Shipley, who reviews the programme as it reaches its 90th anniversary. Did you listen to the Blues Evensong from the University Church in Oxford, or the jazz Choral Vespers in 2002? Or did you, perhaps, like some, switch the radio off in fury and ring the BBC to complain? Life as a producer, even as a producer of such a ‘quiet’ programme as Choral Evensong, clearly has its ups and downs.

And for a piece of good news, enter ‘Why cathedrals are soaring’ into your search engine to read an article from the Spectator written by Simon Jenkins, the author of England’s Thousand Best Churches. FCM can’t claim full responsibility for the resurgence of cathedrals across the country, but few would argue that our contributions have not given a considerable helping hand towards this happy outcome. Let us hope for many more successful years for FCM.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

Stephen Cleobury was born in Bromley. His father, John, was a keen musician who had always wanted to be a professional musician, but John’s father wouldn’t allow it, so he went into medicine and began a career as a GP.

When Stephen was eight years old, his father decided that he wanted to work in psychiatry and moved to take up a post at Rubery Hill Hospital in Birmingham. While he was there, one of his colleagues, a lady doctor, noted that his two boys seemed musical and suggested that they might be good enough to become choristers at nearby Worcester Cathedral. Enquiries were duly made, and that was the beginning of Stephen’s career in music.

He says: “When I started at Worcester, I had no idea what was involved. My parents had been regular churchgoers, so I knew what Sunday Matins and Evensong were like, but I was more than a little surprised to find that there was much more to it than that at the cathedral!

“It was at Worcester that I experienced a wide range of music and, through the Three Choirs Festival, I began to appreciate that there was music beyond the choir stalls. I have great memories of my time there, learning the value of the daily offices and that something really excellent can happen on an otherwise dull Tuesday afternoon in mid-February.

“With the benefit of hindsight, these were obviously exciting times. Douglas Guest was Organist in succession to David Willcocks, who had just gone on to King’s Cambridge, and shortly afterwards the first Carols for Choirs came out, and I remember Douglas introducing us to ‘the green book’, which saved using lots of different books at the carol services.

“But it wasn’t just about singing in the choir. Douglas started me off on the organ (I was the William Dore Organ Scholar) and he taught me a real love of music, especially of the Tudor repertoire and Thomas Tomkins (a former Worcester organist), in particular.

“Christopher Robinson followed on from Douglas, with Harry Bramma as his assistant. These two were inspirational teachers, and were extremely important in my musical formation. Christopher taught me organ and piano, and Harry introduced me to a wide range of music including the Mozart piano concertos, Haydn string quartets, and Wagner’s Ring Cycle. They were just fantastic teachers! As a result, towards the end of the 1960s, there were six or eight of us winning major organ scholarships to Oxbridge colleges; the quality of music in the school was transformed by Harry. Christopher taught me the organ and piano and Harry dealt with the academic side of my education at ‘O’ and ‘A’ level, but as there were no such classes timetabled, we did them out of school. We used to go to Harry’s house at 4 o’clock a couple of afternoons a week, stopping off at the shop on the way to buy cakes with money he had given us, then we would come back and do our harmony or whatever. Harry was dedicated to getting us interested in good music and would play recordings for us, but sadly there was no orchestral activity at the school, and

only later did I learn to play the viola a little. I deeply regret never having had the opportunity to play in an orchestra.

“The Three Choirs Festival also meant a lot and made a tremendous impression on me – by the time I was about 12 I’d heard or even sung in many of the great choral works, such as Messiah, Elgar’s great oratorios, Brahms’s Requiem, and the Verdi Te Deum. I also well remember being amazed by Alan Loveday’s playing of the Beethoven Violin Concerto (a work I’ve loved ever since and that I’ve been lucky enough to conduct on a number of occasions).

“Then it was on to St John’s as Organ Student where George Guest was Director of Music. David Willcocks, who by then was Director of Music at King’s College, also took an interest in what I was doing. I accompanied rehearsals of the Cambridge University Musical Society chorus under David, and occasionally took rehearsals in his absence. He kindly invited me to the King’s organ loft for Sunday evensongs. I thus had a wide exposure to a range of music. George and David were formative influences for me. George was very interested in the music of the Roman church. He had visited Spain and was a devotee of George Malcolm, who had done enormously good work in bringing Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony into the repertoire of Westminster Cathedral. Guest copied a lot of that so that St John’s choir at that time was probably the only Anglican choir singing any significant amount of Gregorian chant. I remember finding it inexpressibly beautiful when I first heard it, and I also remember Terry Allbright inspiring me to learn Messiaen. Terry was an organ scholar at Jesus and had just bought Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie. Hearing this inspired me to do a complete performance of La Nativité du Seigneur.”

Stephen’s next appointment was as Director of Music at St Matthew’s Northampton, a lavishly-built church with a 4-manual organ, which had been paid for with money put up by the local brewery. “There was a men and boys voluntary choir, which was completely different from anything I had experienced before, and the boys were local children, often coming from quite poor families, whom I had to recruit. Perhaps a main reason for wanting to go to St Matthew’s was because it was known as a good jumping-off ground for aspiring cathedral organists (such as Robert Joyce who went on to Llandaff, John Bertalot to Blackburn and Michael Nicholas to Norwich). Of course, under its inspired

vicar, Walter Hussey, it had enjoyed a huge reputation for commissioning new music – Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb was the first in 1943, and in my time we had a splendid Missa Brevis by William Mathias in 1973. Hussey also commissioned works of art: there was a wonderful Sutherland ‘Crucifixion’ behind the altar which must have been a model for what he eventually did in Coventry Cathedral; and there was a Henry Moore ‘Madonna and Child’.

“I have never regretted going there because it gave me more strings to my bow (after a really quite sheltered life up to that point). For the first time, one learned about parish life, recruiting choristers, dealing with adults, beginning to realise that the whole operation is more than just about the music, and developing personal skills, administrative abilities and the qualities of leadership needed to enable people to realise their potential.

“I taught at Northampton Grammar School, though I was completely unqualified, and I also took over from Michael Nicholas as Director of the Northampton Bach Choir and Chamber Choir. I’ve never worked so hard as I did then!”

Next it was to London and Westminster Abbey as Sub-Organist under Douglas Guest, who had been appointed Organist there on leaving Worcester in 1963. “It was here that I experienced, for the first time, working with a choir of professional singers, and as the post was only part-time (and part-salary!) I had to engage in freelance activities – and, of course, being part of the ‘London scene’ meant there were plenty of new learning opportunities available. At the Blackheath Conservatoire I taught piano and theory; I accompanied for the BBC Singers and for John Eliot Gardiner’s Monteverdi Choir. It was here that my horizons were widened further.”

After that, in 1979, Stephen moved along Victoria Street to be Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral, a move that perplexed some of his friends. “I went for reasons of ecumenism and I was really excited by the repertoire. It was very much a broadening experience, learning Gregorian chant for example, and an immensely exciting time. Ecumenical hopes were high, there was a new inter-denominational spirit, and

Cardinal Hume was an inspiriting leader. Among my duties was to direct the music for the Pope’s visit to the cathedral and Wembley Stadium in 1982.”

Stephen’s final move was to King’s later the same year. When the post came up and a friend encouraged him to apply, he asked himself, “Am I too young for this?” But, of course, he did apply and looking back on his appointment, he says, “Nobody would take on this position without being conscious of the historic reputation of the choir, and it took me a while to feel at ease with myself in seeking to maintain the tradition, and to seek to develop it. I feel privileged to have had the opportunities it has presented for over 30 years.”

So, looking back over his career so far, which of the many skills he has learned and developed does he think are the most significant in enabling him to carry out his responsibilities at King’s? “Dedication to making sure that every day’s experience is the best it can be, and leadership that shows respect for those under my direction, a clear understanding of the didactic role, and a wide experience of performing a varied repertoire. The job is enormously rewarding but it is with you all the time; six days a week you are conducting a choir service and you want it to be good. When I wake on a Monday morning and know there is to be no service, there is a different feel to the day. The acoustic of the building is beautiful but of course it is also very resonant, so the chief challenge is to achieve a clarity of texture. Another challenge is the motivation of, and the psychological approach to the members of the choir, particularly the choral scholars, because they have to be prepared to spend 20 hours a week singing, as well as carrying out their academic work; there are times when some need a bit of motivating and I have come to realise how this can be approached from a psychological point of view, and what I do in that respect can be be formative for them. Naturally, that increases my sense of responsibility!”

“I was delighted when Christopher Robinson came to Cambridge, and equally, I am honoured to be succeeding him as President of FCM.”

Alexander Armstrong is an actor, comedian, presenter and singer. He was a chorister in Edinburgh and a choral scholar at Cambridge. At the FCM Diamond Jubilee celebrations at St Paul’s Cathedral, where the audience was treated to some marvellous music sung by a choir composed of a chorister from every UK cathedral, he gave the following speech.

Iam delighted to have the opportunity to talk to you briefly about the tremendous privilege of choristership: the single greatest leg-up a child can be given in life.

I’m sure that sounds overblown and, yes, it is a bold claim, but the more I think about it the truer I realise it is. Someone made the mistake of asking me during an interview the other day what the benefits are of being a chorister. The interview ended up over-running by half an hour, and I was barely halfway through my list!

The most obvious benefit is the total submersion in music. This is a complete musical education by process of osmosis. When you come to hang up your cassock for the final time at the age of 13 you will – without even having realised it was happening because you were just having a lovely time singing – have personal experience of every age and fashion of music from the ancient fauxbourdons of plainchant to the exciting knotty textures of anthems so contemporary that the composers themselves might very well have conducted you. You will have breathed life into everyone from Buxtehude to Britten to Bach to Bridge to Bax to Brahms to Byrd to Bairstow to Bruckner to Bliss (and that’s just the Bs I can think of off the top of my head). But you will know them, know them and love them in the way only a performer truly can. Choral music, to this day, has the power to move me so profoundly that I can lose myself in it for hours and just ride out the happy contemplations it evokes. It is a constant and lifelong tiding of comfort and – euphoric – joy.

Then there is the musicianship you absorb as a chorister, not just the music theory, the maths (the Italian!) all of which is very useful, but elegant musical phrasing, the projection of good diction, the shaping of beautiful vowel sounds for optimum tone, the careful precision-singing of a psalm which can only be achieved by listening intently to those around you and blending your tone and rhythm with theirs – all of these skills and sensitivities become second nature and all of them have strange and unexpected use and resonance in later life.

And I must not forget the language – and I don’t mean the salty badinage of the vestry but the liturgy you’re immersed in, the psalms, the collects, the canticles – the poetry you get to sing (Herbert, Donne, Milton, Shakespeare, Hardy and Auden are all poets I first learnt to love – Christopher Smart

I owe my entire career to my experience as a chorister. It was where I learnt to perform, where I learnt to use the full range of my voice; where I learnt to listen, where I learnt to write comedy, where I learnt to carry a pencil at all times...

even – by singing and performing their words). Your lexicon at the age of 13 is astounding, as is your turn of phrase, taught by endless psalms and hymns, and not just the range of your vocabulary but also your innate sense of the poetic. You will have come to know only too well the powerful quiet of an Evensong, or the sumptuous echo of a final amen sung from an ante-chapel but rolling around the clerestory like wine in a taster’s glass.

And let’s not overlook the discipline of choristership; the order it brings to a young person’s often chaotic life, the friendship, the focus. Punctuality is one of the first lessons you learn: the ignominy of arriving even a minute late is something no chorister wants to experience twice. Then selfpossession, decorum and grace are all attributes you quickly learn to fake – in the first instance – before adopting them for real as you gradually mature. But where else in the modern world is a child taught gravitas? Where else is a child taught, for example, to bow with proper dignity and humility?

I owe my entire career to my experience as a chorister. It was where I learnt to perform, where I learnt to use the full range of my voice; where I learnt to listen, where I learnt to write comedy, where I learnt to carry a pencil at all times – but most importantly it was where I learnt the wonderful truth that something exceptional, something as beautiful as anything anywhere, can be created just by you and your friends. I remember on a choir tour to Salamanca (oh – travel! There’s another benefit!), exploring the old cathedral with a couple of friends and, finding ourselves alone in some sort of chapter house, we fired off a Boyce three-part canon just to test the acoustics. A terrible, toe-curlingly self-indulgent thing to do,

but what a sound we made! And what a thing to discover: that we three – children, essentially – carried between us all the components of something so joyous, so perfect, so complete. (And Boyce! There we are, there’s another B for my list.)

I was lucky enough to be a chorister at St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh, which had a good mix of boy and girl choristers as is now fairly typical in cathedrals up and down the country. And both there and at Trinity College Cambridge, where I ended up as a choral scholar, I sang with people from all walks of life (many of whom had their entire educations – at some of the country’s best schools, I might add – paid for by the music they had first learnt as choristers). I sang alongside some people of different faiths and plenty of none at all. And I am always heartened by the ethnic diversity in our cathedral and college choir rooms.

So you see, you don’t need to be a boy to be a chorister, you don’t need to be a toff to be a chorister, you don’t need to be religious, you don’t even need to be Christian. Although, as I say, I’m aware that there is a certain spirituality that all choristers come to know well – something that lurks in the silences of a darkening nave while rush-hour traffic chugs about just yards outside the West door. A spirituality that is wrapped up in the ritual, the mystery and the beauty of this ancient tradition we have become part of. And I’m going to call that spirituality ‘the privilege of choristership’. That is what we must celebrate, and preserve for the future, ‘throughout all generations’.

The Royal School of Church Music supports the work of cathedral musicians at every level under Director Andrew Reid and Head of Choral Studies Adrian Lucas.

In addition to a broad programme of parochial support, ministerial training, and related publications, the RSCM is responding to cathedrals’ requests by training organ scholars-elect in a latesummer Survival Kit course. Also, ex-chorister boys and girls may audition for the Millennium Youth Choir which offers high-calibre and context-based learning to older teenagers and young adults.

To find out more about suitable courses and opportunities, visit our website at www.rscm.com/learn-with-us

Cathedral Music is also now an imprint of RSCM Press – see the catalogue at https://www.rscmshop.com/cathedral-music.html

been

and

Iwas brought up in Jarrow, on Tyneside. My mother was a teacher and my father an electrical draughtsman at Swan Hunters. I owe my mother many wonderful things but I think she would not have been hurt to be described as ‘unmusical’. My father, on the other hand, was a keen amateur musician who enjoyed jazz and big band music. His father, Robert, was also a musician who composed the hymn tune Gresford, known for many years now as ‘the Miners’ Hymn’. This has stirred up a good deal of interest in the last ten or so years with a BBC Radio 4 Soul Music programme devoted to it, a book by Peter Crookston (The Pitmen’s Requiem) which interweaves the life of my grandfather with the story of the demise of the mining industry, and the unveiling of a blue plaque at my grandfather’s home by Tony Benn in 2011.

Whilst my background was not the traditional one of a church musician, a strong musical thread ran throughout my childhood. When I was three or four years old, my mother would take me to a children’s service on Sunday afternoons and I do remember clearly my fascination with the organ, even at that age: I would watch for the appearance of the organist in the gallery and enjoy his ritual of turning on the motor and light, finding the hymnbook and drawing some stops. (My recollection of the content of the services is a little less

Music at St Chad’s Cathedral, Birmingham, since 1978 and was Principal of Birmingham Conservatoire until 2015. One year after his retirement from the Conservatoire, he reflects on his career to date.

sharp...) When I was eight, I joined the parish choir and also began piano lessons with Jarrow’s formidable but wonderful Madam Annie Hall Rankin. Five years later, I began organ lessons with the excellent Clifford Hartley in Sunderland. He took me to ARCO before I left him to go to university.

I was fortunate to gain the organ scholarship at Hull University, which proved to be perfect for me. As a Catholic, I simply did not have the experience to undertake a role at a major (Anglican) choral foundation, but Hull gave me the opportunity to cut my teeth through recruiting and directing the chapel choir which sang once a week. I was very green, and I remain grateful to the singers who indulged and tolerated me! Hull also gave a recital each term on the then very new Walker organ in the Middleton Hall, and offered me lessons with Alan Spedding at Beverley Minster.

A meeting with Terry Duffy, Organist of Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral, when I was still at school led, indirectly, to my becoming the first organ scholar there. I held the post from 1975 to 1977 and I loved it – that building, that organ, that acoustic, Terry’s marvellous accompanying, and working, for the first time really, with a professional and inspiring choir director, Philip Duffy. By this time, I was also

having lessons with Gillian Weir and, looking back, I can see all the more what an amazing and critical period this was for my professional formation.

Leaving Liverpool was very difficult, but after five years of being a student options were running out and so I took a teaching job in Newcastle. Very early on, the Head ordered an organ for the school hall on the basis of my being there, so it probably came as a bit of blow when I accepted the post at St Chad’s in Birmingham only a few months later. Not that the decision to move to Birmingham was an easy one: if only we could know in advance the rightness or otherwise of a decision! This is how it all happened.

The scene: it’s November 1977 and I am sitting in my parents’ house, reading the Musical Times

Me: “Hey, listen to this! They’re advertising the Organist and Director of Music post at St Chad’s Cathedral!”

Reaction: strangely muted. My parents were enjoying having me back in the north east, and I liked it too. However, after the intense musical activity in Liverpool I was beginning to be frustrated that there was no outlet for deep interest in church music in Newcastle. I knew St Chad’s from a visit in 1969 with my church choir for a Pueri Cantores festival and

had been thrilled to be shown the new organ by Roger Hill, then Cathedral Organist.

And so it was that I went for an interview. A few months later, my parents looked on with a mixture of pride and anxiety as I resigned from my school job and moved to Birmingham in the summer of 1978 to take up the post. Thirty-eight years later...!

I remember feeling slightly underwhelmed, to be honest, when I walked into the cathedral on the day of my interview. After Liverpool, St Chad’s seemed rather small, and I wasn’t immediately certain that the very part-time job would be sufficiently attractive to warrant the major upheaval of giving up my full-time teaching post and moving from Newcastle. As someone who dislikes change anyway, this was a consoling thought and one which helped me relax for the interview. On the other hand, my competitive spirit pushed me to perform to the best of my ability and later in the day, ambivalence gave way to ambition when I rehearsed the choir and realised both its potential and the glorious acoustic of the building.

I already knew that the choir had been endowed in 1854 by cantor/choirmaster John Hardman. St Chad’s was the first Catholic cathedral to be built in this country after the Reformation and the choir was the country’s oldest endowed

Catholic cathedral choir in the country. Hardman also drew up a set of choir rules designed to foster the singing of plainsong and polyphony.

The situation seems to have been stable for over 100 years, with the choir singing high mass and vespers – full Latin, of course – every Sunday, and in place for all the major festivals. Sadly, by the 1960s things were not so rosy, and the closure of the cathedral in 1967 for a major restoration sounded the death knell for the choir. The difficult task of re-establishing the choir was begun in the early 70s and taken on by John Harper, my immediate predecessor. Thanks to John’s efforts, the choir of men and boys was once again in a fairly healthy state when I arrived and he had done much to develop a local tradition which was neither the full-blown Catholic tradition of pre-Vatican II days, nor, thankfully, did it embrace the lowest common denominator approach prevalent at that time.

The move to Birmingham was financially a little risky for me, and so I had to look for other sources of income. The job was, after all, very part-time. One of the areas suggested to me for investigation was the then Birmingham School of Music and I went there to meet John Bishop, who offered me some organ teaching and theory classes. The BSM was a very small

institution compared with what it is today. I believe it had around 180 students, offered only graduate diploma courses and operated from a half-completed building in the middle of a deserted building site.

I suppose I really expected to be in Birmingham for only a few years, just sufficient time for the world to discover my precocious talents. (I was a super-confident 23-year-old.) What actually happened is that my work at the BSM increased year on year and in 1981 I became a part-time, salaried tutor. Subsequently, and as the school grew, I became Head of Organ following the retirement of George Miles and John Bishop, Director of the Chamber Choir, and then full-time member of staff in 1992.

By this time, the School of Music had been renamed Birmingham Conservatoire and it was leading the way in its sector with the introduction of Bachelor awards, and then Masters and PhD programmes. The Conservatoire is part of a university, unlike other free-standing UK conservatoires, but it has always punched somewhat above its weight and offered a less formal, innovative alternative to those august institutions. These days, it is definitely considered by applicants to be on at least an equal footing with sister colleges and in several disciplines the ‘go to’ place!

When I retired, plans for a new building were well under way. The present building will be used for one more year but vacated during summer 2017 at which point staff and students will move to new premises in the middle of the vibrant Birmingham City University main campus in the city’s new ‘learning quarter’. The opportunity to build a new conservatoire does not occur very often, and Birmingham’s will be the first – and possibly the last – to be built from scratch this century; and with a brand new facility, it is so much easier to build in digital technology resources as well as incorporating the latest thinking on concert hall design and soundproof studios. The Conservatoire will have five public performance spaces: a concert hall, recital hall, jazz studio, a black box experimental music space, and an organ studio.

I am particularly pleased to note the success of the organ department, under the inspirational stewardship of Henry Fairs. Currently, the organ in St Chad’s, of which more later, is the main teaching and examining instrument, but mediumterm plans include the commissioning of new organs built in particular historical styles which will complement the city’s stock of wonderful eclectic organs. I feel that in the next few years Birmingham will become a major European centre for organ studies. The postgraduate choral conducting programme with Paul Spicer also makes it an attractive place for budding choral directors. I know that my successor, Julian Lloyd Webber, shares my interest in the organ department, not least because his own father was, of course, an organist.

whether I should stay at St Chad’s when an unexpected opportunity arose in the form of an appeal for the restoration of the cathedral fabric. Whilst replacing the ‘cast-iron rainwater goods’ and re-leading the windows were both necessities, I felt the appeal lacked a certain... how shall I say?.... glamour. At the same time, the organ – an impressive, 4-manual Nicholson with a second organ in the chancel – was becoming less reliable, and I realised that unless I managed to have some major work to it included in the appeal, it would probably be another ten years before anything might be considered. What I had not expected was the reaction to my proposal of Archbishop Maurice Couve de Murville, who decided that we should build a new instrument in a new west gallery. (He was particularly interested in the case, designing some of the pipe shades himself.) Nicolas Kynaston was appointed to be our consultant and after an exhaustive tendering process, Walkers were given the contract.

From my point of view, this was just the stimulus I needed and the years from 1989 to 1993 were terrifically exciting. Nicolas was determined that the organ would be versatile and fullblooded and through his formidable negotiating skills the initial scheme of 22 stops grew to 40. The handsome case was designed by David Graebe and painted in the colours Pugin had chosen for the cathedral. The result was, and remains, stunning. The combination of vibrant voicing, generous acoustic and gorgeous casework makes this one of the most successful recent organs in the country.

Reinvigorated as I was, I could not ignore the fact that it was becoming more and more difficult to maintain numbers and standards in the cathedral choir. When I first took up my post, parents would put the choir ahead of other activities for their sons, but by this point it was more usual for parents to apologise to me for their sons’ absences due to football/ swimming/chess etc etc. With the support of the cathedral authorities, we introduced choral scholars from both the Conservatoire and Birmingham University with the idea that they would work with the boys but, really, the writing was on the wall, and by 2003 the choir had become an entirely adult one.

I am sorry that the demise of the boys’ choir occurred on my watch, but I am also certain it was the right course of action. Today, we have a choir of some 22 singers and are able to be ambitious in our repertoire choices and to explore less mainstream composers such as Maissano, de Monte and Padilla.

Retirement from the ‘day job’ does mean that I can now devote the time to St Chad’s that I want and that it deserves. Much has happened in the years since my appointment, but I would highlight two events as particularly significant: the building of a new organ in 1993 and the transition to a professional adult choir in the early noughties.

By the late 1980s, I had been at St Chad’s for ten years. The Conservatoire had unexpectedly become the focus of my professional life and the challenge of running a voluntary boys’ and men’s choir was less stimulating than it had been. I was certainly thinking about what I wanted to do next and

Retirement from a job which occupied most of my waking thoughts and, indeed, time, has not meant that I am not busy. The difference, as all retirees know, is that I am able to be selective – I am busy doing things that I have chosen to do. I enjoy the challenges of being Executive Vice President of the IAO and trustee of various charities; I enjoy practising and playing the organ in a way I haven’t for years; and I am enjoying exploring fresh repertoire with my choir. It’s a delightful point to reach in one’s life. My ambition now is to continue along the same lines and see just how good a player I can become at this late stage. At the same time, I hope never to reach the point where I am the only person not to realise it is time to give up!

as well as including stimulating features, a wealth of educational material and reviews of organrelated music, CDs, DVDs, books and much, much more.

TO

Director of Music George Richford writes about an almost forgotten abbey and a different choral tradition in a hidden corner of Hampshire.

Perhaps because it is situated off the beaten track, not quite in the New Forest – although not far from the city of Southampton – or because it lies equidistant between the architectural marvels of Winchester and Salisbury Cathedrals, or because the distractions of Peppa Pig World lure the great majority away from it in a different direction, one can forgive those who ask, ‘Where is Romsey?!’

The Abbey in Romsey is an enormous Norman masterpiece. It has a foundation dating back to around 907 AD, when King Edward the Elder established a community of Benedictine nuns in the town, and it is the largest surviving medieval nunnery anywhere in the British Isles (the nuns have long since departed). To the west, and eventually running into Southampton Water, lies the River Test, a world-renowned chalk stream and trout river and, as legend has it, the one in which the Abbey’s patron, St Ethelflaeda, used to stand naked to recite the psalms.

Choral music is thriving here. Excluding school choirs, there is approximately one choir per thousand people in the town (there are 14,000 inhabitants). It is not a case of ‘Do you sing in a choir?’ but ‘Which choir do you sing in?’. There are youth choirs, bands and orchestras that contribute to the rich and varied musical life of this extraordinary town, and the Abbey choirs are no exception.

After my initial drive for choristers earlier this year, we have 25 girl choristers (aged between 11 and 18), 28 boy choristers (aged between seven and 13), 14 regular altos, countertenors, tenors and basses forming the back row, several choral scholars from Southampton University, a training choir of around 20 boys and girls who are on the waiting list to join the Abbey top lines, and now an Abbey Consort which is for adults, former choristers, and students from Southampton. All in all, we have over 120 singers.

The Abbey congregation on a Sunday morning regularly tops 300, with up to 800 in attendance for the usual Christmas and Easter celebrations. There are often 100 in attendance for Choral Evensong on Sunday evenings. Romsey Abbey choirs are a testament to the fact that choral worship is still relevant, alive and well in the 21st century. Despite the pessimism and the apocalyptic forecasts of empty choir-stalls and tumbleweedstrewn naves, it is possible to ‘survive and thrive’ as a parish choir in today’s world. What are we doing differently?

Firstly – the role of Director of Music is one of politician, administrator, manager, strategist, librarian, organiser, pastoral assistant, helper, someone to talk to, email replier, tidy-up-er and… musician – in that order! Being DoM at any large, active church is a multi-faceted job, and those who undertake the role have to be flexible. There may be

no administrative staff or other employees; often musicians end up doing jobs that they may not want to do, but which nevertheless need doing. Central to the musicians’ role at the Abbey is being a part of the community, living in the town, and taking the time to talk to people.

Secondly – the relationship of the choirs: ‘Tradition’ is a much-used word in church music circles. It can be used as a defence mechanism, a justification or a cause worth fighting for, and it can also be loaded with politics. The tradition of Romsey Abbey is that there are sung services. This is apart from, but not divorced from, our peculiar history (in Romsey, girls and women were worshipping and singing for 500 years before boys and men arrived to lead choral worship). Girls are a central part to that tradition in the Abbey; this year we celebrate 20 years since their re-establishment by Di Williams, and their first CD, Adoration, is being released this November.

I hugely value the history of boys singing and also the importance of boys singing today. Without it, the flow of young men into back-row positions in chapels, cathedrals and churches across the country would be endangered. When I arrived in Romsey I had 11 boys on the books, which for a church the size of Romsey (and with a chancel wide enough to park a bus), was both terrifying and unsustainable. Thirdly, then, and very importantly, is recruitment.

Our campaign took two months of hard slog, 28 schools visited, 984 emails, 47 miles of walking (to visit potential choristers at school and at home), 1000 flyers, 500 posters, a specially devised SMS text service, a taster day and all the accompanying sweat and tears. We were rewarded with 18 new boys in the choir, and a further 16 eager boys on the waiting list, happy to sing in our newly established training choir. All in all, we now have 40+ boys ‘on the books’. It was very hard work. There are no shortcuts, and no secrets!

Next came the even harder work of training the choir up to standard. For us, this was a matter of meticulous, but flexible, strategy. Before Easter 2016 I had ten boys remaining and my task was to make them able to absorb 18 new boys. I had to

engender responsibility, and a work ethic that was conducive to accepting so many new boys who varied in age from seven to ten years old. I needed to be able to use my existing boys to model singing, blend, musicality and behaviour in a way that made for a happy and controlled expansion. We had only six months to achieve this.

The boys’ rehearsal schedule now gives us 1½ hours each Monday and Thursday. To maximize the chances of retaining the new ones, it was pointless to continue rehearsals as if nothing was different, so I streamed them: Mondays became the day for all the boys to sing together. We focused on learning repertoire and the techniques of singing, general churchmanship and everything else that old hands do without thinking. I devised games and methods whereby the new boys could absorb these techniques by ‘doing’ music, not just being ‘told’ music. ‘Sound before symbol’ was and is the mantra. These sessions were differentiated accordingly but also succeeded in engaging the more experienced boys through responsibility as well as firming up good practice.

Thursdays continued as usual for the more experienced boys and, crucially, the brave and determined new choristers who were hungry for the challenge. These rehearsals were almost identical to the ‘old’ Thursdays, and so the new boys were thrown in at the deep end. Good old osmosis and the fundamentals of ‘listening before doing’ governed these rehearsals, but they brought more advanced learning, much like having an accelerated group at school.

To begin with, the complete boys’ section sang only one or two services a month. This was a gradual immersion but it works well if started straight away. From September onwards, the boys have been singing everything together as one homogenous top line. Music is generally straightforward, with Early Music and Victoriana being the staple repertoire. Our girls, on the whole, sing contemporary and baroque repertoire, to complement the boys’ repertoire and to ensure they have a sense of individuality and specialism. The aim is to have an appropriate number of choristers to sing choral services at the Abbey to a high standard within two years.

Fifth: it has to be admitted that church music and choral singing isn’t ‘cool’. Don’t try to make it something it isn’t. It is an art form that is fundamentally expressive, meaningful, beautiful, and sometimes exciting, and it should always be engaging. The trick is to make this super-subtle and expressive medium valuable and satisfying to 21st century kids with 21st century eyes and ears and distractions. Personally, I don’t try to do things that are immediately catchy or unanimously loved by everyone. I find and demonstrate value in everything we do, and assign repertoire by the challenge it presents. We do lots of verse-anthems and Early Music – and yes, the boys love it! We do the big, fat, English repertoire from c. 1850-1950 for a different kind of challenge. I also schedule music that I personally dislike, but the value of which I appreciate. After all, it isn’t only the music itself that will determine whether or not a boy or girl stays in the choir – it is the way it is delivered.

But as with other church choirs like ours, we need support. There is an abundance of support for smaller parishes through the RSCM, Church Music Futures and other trusts and organisations. Then there are mechanisms that share knowledge and resources for cathedrals – the Cathedral Organists’ Association, the Choir Schools’ Association, etc. But what about us – the forgotten middle: the larger parishes, the greater parish churches and those of a similar ilk? We do not have the practical resources of most cathedrals and colleges – and I am not speaking just about money. I, and others like me, do everything ourselves and rely on the support of our parents, choir associations and ‘willing’ volunteers.

It isn’t that many of the resources aren’t relevant to us – they are. But I think that there can be an assumption that the larger parish churches and those like them just get on with it – ‘play cathedral’, or make this all happen by magic. It is backbreaking work where every conceivable aspect of running a music department falls on our own shoulders. I deal with, on average, 140 emails, text messages or phone calls every day. I am at work from the moment I open my eyes in the morning to when I fall asleep at night. When all is well, it’s a worthy reward. If things go pear-shaped, it is your own head on the block!

Romsey Abbey may look like a cathedral, the choir may dress like a cathedral choir and may even sound like a cathedral choir, but it isn’t one, and it doesn’t pretend to be. Running departments like ours in Romsey, and in other large parish churches, requires enormous effort, even just to bring in the requisite number of people to sing for a single service. We recruit and train cathedral-sized choirs with tiny budgets, with few if any employed staff, and little or no shared resources.

So, what of the future? I would like to see a Greater Churches Music Conference or similar, something that offers collaboration, the sharing of ideas and resources, and an arena in which the bigger church music departments can participate. I should like to see a pre-existing trust or organisation take the lead in this initiative. It could or should be open to those larger musical foundations which provide two or more full choral services each week, not just those in the ‘greater church network’. Practical issues could be addressed, such as ordering music storage boxes, choir medals, new music and cassocks etc, and also advising on marketing, advertising, and things like finding the best psalters. But it would also be a place where like-minded musicians can discuss different initiatives that have worked for them. Recruitment must surely be top of everyone’s list – for without it, we have no choirs and thus no music in our churches.

I’m not complaining, though it may sound like it! I love my job and, like other places, we are lucky in that we have a fantastic team, a wonderful choir, and great parents and supporters around us that make this ministry possible, week after week. I am certain that more can be done to help foundations like ours; our musicians, clergy and all the people that make things happen need support.

So, don’t forget about places like Romsey Abbey – those Norman churches or gothic priories that continue to echo with choral worship. Visit them, worship in them, and support them where you can – or what you value most may not be there when you next look.

There’s no doubt that Choral Evensong has a dedicated and growing following on the radio in the UK – and many weeks bring us grateful feedback from internet listeners abroad too. Such is the increasing awareness of Choral Evensong’s therapeutic properties – sublime music performed to the glory of God in magnificent surroundings – that there’s even a website which will tell you the nearest venue where you can hear and see it sung if you input your postcode (www.choralevensong.org).

As Giles Fraser commented in the Guardian, Choral Evensong can become ‘an emotional anchor, a way of patterning our lives with time and quietness. Our internal clocks are readjusted to tick along to a rhythm that is at once slower and yet also more expansive than the one that regulates our souls throughout the rest of the day. It becomes a sort of cradling.’

So wrote an appreciative listener to BBC Radio 3’s Choral Evensong ten years ago on its 80th anniversary. And I quoted those same words at the end of a Cathedral Music article around the same time. It’s worth then reiterating straightaway, as we celebrate the programme’s 90th anniversary – happily coinciding with the 70th anniversary of the launch of the Third Programme, established in 1946 – that Choral Evensong is the BBC’s longest running series ever. Indeed, there’s no other programme in broadcast history which can match its longevity. Apart from a brief blip in 1970, it’s been broadcast weekly since October 1926 – firstly on the National Programme from Westminster Abbey, then from St Paul’s Cathedral and York Minster. It continued on the Home Service (which became Radio 4 in 1967) and Radio 3 took it over in 1970. During the war, from 1940-1942, the live locations of Choral Evensong weren’t revealed – simply from ‘a northern cathedral’ or ‘a western cathedral’ or occasionally ‘a public school chapel’. Since then, over 80 different venues have been visited in this country and abroad – cathedrals and abbeys, parish churches, college chapels and monasteries – and, having experimented with two services a week and for a brief period a live transmission on a Sunday, the service now goes out live on a Wednesday afternoon and is repeated the following Sunday afternoon. It’s a very satisfactory arrangement and it attracts around a quarter of a million listeners each week if you add together those who listen on Wednesdays or Sundays (or both). It’s also available via the BBC Radio 3 website for 30 days after the initial broadcast.

So what are the issues involved in putting together a weekly schedule of a worship programme which will nourish the soul as well as sit comfortably alongside the rest of Radio 3’s high quality output?

Most importantly, Choral Evensong is an opportunity to promote what cathedrals offer on a daily basis. The programme can be a snapshot of a particular place on a particular day. But there are inconsistencies in following that argument too closely. How many cathedrals put on a sung Evensong lasting a full hour in the middle of a weekday afternoon? A perfectly legitimate comment has been made more than once to me that the BBC encourages the ‘out of the ordinary’ by, for example, allowing bidding for dates to coincide with, say, patronal festivals. This could be said to ignore the ferial nature of much of cathedral worship – the Opus Dei – the daily round. But it seems to me that the listener likes to hear what happens in specific places on their special festal occasions – provided that not every week is a festival!

An hour is a long time to fill. Is it too long for a ferial service in ‘ordinary time’? I would say it isn’t, because it allows a decent amount of psalmody and, if required, the opportunity to sing an extended setting of the canticles or a long anthem. And the organ voluntary has sometimes been known to last a full quarter of an hour. Why not? Sadly in so many cathedrals, the voluntary at the end of the service isn’t given the proper attention it deserves. We try never to fade a piece of music unless it is absolutely necessary – which is why listeners regularly express their appreciation at being able to hear

‘You could call it calm or spirituality. You could call it holiness – but it’s very precious.’

a complete organ piece uninterrupted by congregational chatter…

Mention of psalmody raises a concern that many cathedrals are reducing the amount of psalms the choir sings at Evensong. It’s a worrying trend because the psalms surely lie at the core of the Daily Office. They are the essence of the Jewish synagogue worship that Jesus himself would have known so well, and they shouldn’t be glossed over. I must admit to a particular enthusiasm for the 15th evening (Psalm 78 with its 73 verses) when it falls on a Wednesday. Indeed, there have been some very fine interpretations recently of its epic qualities, clearly relished by both the choir and the organist, who has plenty of opportunity to add colour to the drama with imaginative registration. But cut down the psalmody to a mere handful of verses and one of the highest expressions of the Anglican choral tradition, with an order of service rooted in Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, is lost.

Any discussion of the content of Choral Evensong and how a broadcast is planned raises the sensitive question of the quality of the speech. Of course Choral Evensong is highly musiccentred, but the speech needs just as much attention, so that it blends into a network which prides itself on thoughtful and dignified presentation. It concerns me a lot when I arrive at a broadcast venue to discover the readings haven’t yet been allocated or, even worse, the prayers or intercessions haven’t been written. Perhaps it’s worth saying that we receive just as much praise and criticism of the spoken word as for the sung portions of the liturgy. Fortunately, there are still many imaginative and enterprising clergy who are prepared to take a few risks in creating the shape of a broadcast service. The time after the three collects can be said to be outside the structure of the set liturgy, so there’s space for perhaps the inspirational juxtaposition of prayers and a short anthem. Further reflection on the theme of the lessons may be offered – especially if the Additional Weekday Lectionary is used, the purpose of which is primarily aimed at those who only attend Evensong occasionally. Above all, here’s an opportunity to hold before God our sometimes mixed-up feelings and translate them aesthetically into something worthy of wonder.

It’s often said that music takes us deeper into the heart of God. So, bearing in mind that it’s in the hands of the musicians that the Church is at its most emotionally compelling, probably the most important issue in broadcasting a regular weekly worship programme must be the choice of repertoire. Anecdotal evidence suggests that listeners particularly enjoy the more

familiar pieces. But the Radio 3 audience – indeed the Choral Evensong congregation – don’t shy away from something more adventurous that may have been chosen to showcase the choir’s abilities. They expect to be challenged – though it’s worth remembering that it doesn’t take much longer than a few seconds at the beginning of any programme for people to switch off the radio if they don’t like what they’re hearing. So if the introit is a tortuous motet setting some obscure words, it’s hardly likely to encourage the listener to stay with it, let alone find it an inspiration to worship.

While I’ve been producing Choral Evensong, the opening of the service has been changed on several occasions – although I suppose the most dramatic time when that didn’t happen was when we broadcast a jazz Choral Vespers with the Big Buzzard Boogie Band from Clifton Cathedral in 2002, incorporating some of the pieces composed by Duke Ellington in the last years of his life. We had nine calls to the Broadcasting House duty office during that transmission. Five were strongly in favour and the others said they didn’t tune in ‘to listen to a pop concert’. One left a message hoping that the ghost of Lord Reith would haunt me for the rest of my days!

Four years later, we followed it with another jazz service, a ‘Blues Evensong’ from the University Church in Oxford, brilliantly conceived and composed by the renowned baritone, Roderick Williams, and sung by a very talented student choir, Schola Cantorum of Oxford. The broadcast was repeated this year in October as part of the archival celebration of the 90th anniversary of Choral Evensong. When it was first transmitted, live on the day of the Encaenia ceremony in June, the university was in festive mood, awarding honorary degrees to distinguished men and women and commemorating its benefactors. The carnival atmosphere was very much reflected in the style of the broadcast and the response in general was encouragingly positive – although inevitably there were one or two listeners who weren’t so impressed.

Radio 3 aims to promote and encourage new music whenever it can, and through Choral Evensong, we’re able to demonstrate that the tradition of composing for the Church’s liturgies is still alive. That has been well established in the regular broadcasts from the annual Festival of Music within the Liturgy at Edington Priory on the edge of Salisbury Plain. For many years now, every May, we’ve visited the London Festival

of Contemporary Church Music in St Pancras Church for some excellent services where the music is sung with real flair and precision and the worship led with care and sensitivity. We were also able to broadcast in the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee year, 2012, 12 newly commissioned anthems from the Choirbook for the Queen, a collection brought together during the ten years since the Golden Jubilee of Her Majesty’s accession to the throne.

Yes, occasionally I’ve heard people say that the complexity of some modern music doesn’t enhance the worship at all, especially if the spoken parts of the liturgy haven’t been carefully prepared. But a challenging anthem, which may be criticised for just being there to show off the virtuosity of

the choir, can be integrated into the worship so much more effectively if the prayers that follow it pick up both its mood and its text. It’s a question of balance: is it better to choose the tried and tested as far as the music is concerned or present the listener with something more daring? Whatever the decision, it’s worth remembering that the inevitable extra nervousness brought on by a red transmission light isn’t the time for experimenting with less experienced soloists or an unfamiliar piece which hasn’t had a good run-in.

The essence of a broadcast Choral Evensong must always be its spiritual dimension. It must sit within the tradition of regular worship which goes on day by day in so many cathedrals, churches and chapels all over the country. And it should have

the flexibility to live and breathe and change according to what’s happening in the world for which it prays.

And that brings us neatly back to where we started: the appreciation of the precious calm that Evensong can create. The beauty of the music and the spoken word unlocks the spirit and allows it to soar – without confrontation, without the demands of affiliation – rather, an encouragement to seek truth at an individual’s own pace, in his or her own way. The regular broadcasting of Choral Evensong has been described as a ‘spiritual lifeline’ by many a listener. Long may it continue.

The choir has been through many changes over the years. It began as an all-male choir, developed into an all-adult choir, and now it numbers around 35-40 adults (SATB) and 20 children, the ‘Choristers’, who I re-formed in 2007. For a short time, from 1909 when St Mary’s became a cathedral, the choir sang every day, but now they only sing on Sundays (two services) and also on high days and holy days, although a midweek Choral Evensong was still being sung into the 1970s. We maintain a huge and varied repertoire, from the most ancient to the most modern, incorporating new music from all over the world: Europe, Scandinavia, Iona, Africa, the USA, and even a jazz mass!

New music is something I pursue vigorously, and over the years of my tenure we have had no fewer than 30 new pieces written for us by composers such as David Bednall, Malcolm Archer, Richard Shephard and Martin Dalby, as well as young and local composers such as John Gormley, Oliver Searle and Robert Allan.

They say time flies when you are enjoying yourself, and certainly it is difficult to believe that for 20 years I have been Director of Music at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral in Glasgow (not, incidentally, to be confused with either St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh or with Glasgow Cathedral, which is St Mungo’s and hasn’t technically been a cathedral since 1690, given that it is Presbyterian).

I took over from Bernard Porter, who was instrumental in bringing the choir and music back from the brink of extinction. He instilled into his singers a new sense of purpose, and pride in high standards, and it was on this foundation that I began to develop the next phase of the cathedral’s musical life.

The Scottish Episcopal Church is a minority denomination in Scotland, but it is the nearest thing to an Anglican Church you will find here. Consequently, while there are not many members of the church, they travel far and wide to experience the worship we offer. That being said, St Mary’s is thriving like never before, with a congregation of around 200 on a Sunday morning, and upwards of 400 on special occasions.

Entirely voluntary, with a current age range of 7 – 60+, the choir is made up of people from all walks of life and varying musical experiences and expertise. Whilst most of them live in the Glasgow area, many of them travel quite some distance to come and sing with us; we have two singers who even come regularly from Dundee! People come to audition because they have been to a service and heard us, or have heard us on the radio, or, if they’ve moved up from the south, by recommendation from my church music colleagues. There is

It was hugely heart-warming to celebrate my 20-year tenure on Sunday 3rd July this year, with a Choral Mass in the morning, and a huge Choral Evensong which was attended by many alumni of the choir, some of whom came from all over the country, and even from Barcelona and the USA!

a student body, too; in term-time we have students who are studying in Glasgow, and when they go away in the holidays, former choristers who are studying away return to sing with us! Although the turnover of personnel can be quite high, we claim that membership of St Mary’s is for life, and many returning or visiting choristers can often be found donning a cassock and surplice during their visit. They are all bound together by their love of music, and by their desire to offer their musical skills to enhance our worship. This is a very warm-hearted, nurturing group of people who thrive on a challenge, and are immensely supportive of each other, musically and socially. In real terms, our singers are very much a big family.

Recruiting choristers is difficult and haphazard; schools won’t allow me in to recruit, as we are a) a church, and b) a non-established church in their eyes, so we have occasional ‘Come and be a chorister’ events, and I send out flyers and information to schools, in the hope that music teachers might spread the word anyway. Otherwise it is done by word of mouth and through social media.

The Choristers are trained using the RSCM Voice for Life scheme which, along with quantities of pizza, fruit and cake, we have found to be a huge incentive, although it is timeconsuming to deliver. They have achieved many Bronze and Silver Awards, and St Mary’s also has the first two Gold Awards in Scotland, one given to a chorister, and one to an adult member. Many of our young singers go on to choral

scholarships at major universities, including Trinity, Gonville and Caius, and Jesus Colleges in Cambridge, and Durham, Aberdeen, St Andrew’s and Glasgow University Chapel Choirs, and the choir of Gloucester Cathedral. Some have also gained places to study singing at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) here in Glasgow, and at the Guildhall and the Royal Academy of Music in London.

The choir now represents the cathedral and diocese at many special events, either those of its own or those organised by other churches in the diocese, as well as taking part in fundraising concerts. Over the years, the use of instruments in worship at St Mary’s has developed from the occasional solo obbligato to strings, brass, and sometimes a whole symphony orchestra. This has led me to writing many arrangements for them, and the occasional new work.

Another branch to the choir’s life has been recordings and broadcasts. The choir has broadcast more than 50 radio and TV programmes including the Daily Service and Morning Worship on BBC Radio 4, Sunday Half-hour on Radio 2, and a wide variety of special programmes on BBC Radios 2, 4, Scotland and the World Service. St Mary’s Cathedral Choir has also appeared many times on BBC Television’s Songs of Praise, and has recorded four CDs to critical acclaim.

And we have some rather ‘wackier’ projects too! We have been an art installation (!) – and the backing choir to the BMX

Bandits! One of our current projects is a flexible composition called Memorial Ground, which was commissioned by the East Neuk Festival and 14-18 Now (a major cultural programme taking place across the UK to mark the centenary of WWI). Memorial Ground recalls the Battle of the Somme, and is written by Pulitzer prize-winning composer David Lang. St Mary’s was chosen to record the videos for the website – where the score and resources can also be found – demonstrating how the work can be used in a liturgical context.

Our summer cathedral residency is something else I have introduced, and is now an established part of the choir’s life. Lately we have sung in Durham, Lincoln, Chester, and Carlisle Cathedrals, as well as Beverley Minster and Tewkesbury Abbey and, this year, Ripon Cathedral.

The post of Director of Music has developed in many ways since I was appointed, but although it is still very much a part-

time post, it is now at least a professional one. I was only paid a very small ‘honorarium’ when I was appointed.

The post of Assistant Organist has also been very piecemeal, with frequent changes. There were times when I was without any help for years at a time, or simply had an organist who could play for evensongs and nothing else. We have occasionally had organ scholars, but these have all been on a precarious year-to-year basis and provision depended on who was around to fill the posts and whether I could get funding for them. For many years we have only been able to appoint to these positions due to the generosity of a single benefactor.

But things are currently looking up, largely due to a very generous grant of £30,000 from FCM, coupled with some active fund-raising and some exceedingly valuable donations from church and choir members, including our ongoing

benefactor. We have been able to establish a Music Endowment Fund which has secured the post in perpetuity.

Some of our assistant organists and organ scholars have gone on to very exciting posts at the RCS, Manchester Cathedral (Assistant Organist), Downing College Cambridge and Canterbury Cathedral (Organ Scholars), and Director of Music at the Swiss Church in London. It is very much my hope that in the future we too will be able to offer choral scholarships and an organ scholarship.

Other sidelines – for we don’t rest on our laurels! – have been to establish links with other choirs, fostering relationships with the many universities in Glasgow, and with the RCS. We recently sang an Evensong celebrating the FCM’s Diamond Jubilee, for which we were joined by the choir of Glasgow Cathedral and the chapel choir of Glasgow University. I have also launched a successful series of lunchtime concerts

featuring local musicians and young artists looking for a platform in the city, and have run organ workshops for schools.

As the post of Director of Music at St Mary’s is part-time, I have always needed other activities to help me make a living.

I teach three days a week in the High School of Glasgow, where I am responsible for much of the choral programme, including their acclaimed chamber choir which has made several radio and TV appearances, and which holds the title of ‘BBC Songs of Praise Senior School Choir of the Year 2013’. I also founded and conduct the RSCM’s Scottish Voices, direct the Changed Voices of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra (RSNO) Junior Chorus, the Changed Voices of the National Youth Choir of Scotland Boys’ Choir, and am frequently invited to conduct the RCS Chamber Choir.

I run choral workshops for the RSNO Learning and Engagement department, and do the same for festivals and choirs throughout Scotland. I have worked with most of Scotland’s top choirs, for five years was Music Director of Bearsden Choir, an established choral society, and am also a visiting examiner for the RCS, and for the RSCM.

Part of my job is to play the organ at St Mary’s, of course, and I also give recitals all over Britain and beyond. Recent venues include Westminster Cathedral, Chester Cathedral, the Caird Hall in Dundee, Ayr Town Hall, Brechin Cathedral, St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh and over fifty recitals at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. I have also played continuo for the RSNO, and recently accompanied the RSNO Chorus on their tour to Prague.

I have been very fortunate in having a hugely appreciative congregation (that also sings very well), and also, appreciative clergy who understand the importance of music in worship, and a choir which is both dedicated and huge fun to work with.

There is still much to achieve. I would eventually like to expand the number of sung services, develop a proper outreach and recruiting strategy with local schools, expand our links more with further educational establishments, take the choir abroad on tour, and – now becoming quite urgent – replace the cathedral organ. There are plans afoot too to improve our accommodation. This is much needed, as we have but one small hall, so choir practice has to take place in the cathedral all year round.

It was hugely heart-warming to celebrate my 20-year tenure on Sunday 3rd July this year, with a Choral Mass in the morning, and a huge Choral Evensong which was attended by many alumni of the choir, some of whom came from all over the country, and even from Barcelona and the USA! There were so many kind words, generous gifts and a lovely party!

I love my ministry here in Glasgow, and the years have just flown by! I count myself very fortunate to work in such a vibrant church in such a lively city, and I hope I have managed to help put St Mary’s Cathedral, Glasgow on the musical map.

And, as long as there’s so much to do, here’s to many more years!

Sir, From time to time concern is expressed at the difficulty of maintaining full weekday choral services in our cathedrals, and it is only too true that this great tradition has been sadly mutilated, chiefly as a result of two world wars. The degree to which this has taken place varies from cathedral to cathedral and depends on local conditions. Thus while at some cathedrals Matins is still sung on certain weekdays, at others it has been abandoned. Even the number of weekday Choral Evensongs has been reduced in several cathedrals, and in at least two has altogether disappeared.

It seems to us unfitting that the survival and continuity of this glorious musical tradition – which has so often been described as a national heritage – should be governed by purely local conditions, and that any individual cathedral should be allowed to suffer the loss or curtailment of its weekly choral services because those conditions happen to be unfavourable. Some measure of coordination would seem to be desirable, and to this end we suggest that all who love and value this heritage, whether clergy or lay, professional musicians or amateur, should unite to form a new society, to be known as ‘The Friends of Cathedral Music’.

The main objects of such a society would be to widen general interest in the subject; to serve as a coordinating link between the individual choral foundations, thus strengthening the tradition as a whole and helping to prevent the further curtailment of choral services in the future; and to consider the possibility of extending the tradition to those new cathedrals which are still without adequate choral foundations.

Within six months of the above letter to The Times being published, a meeting was held at St Bride’s Fleet Street on 2 June 1956 to consider what could be done about the dire situation that had been described.

By then, it had become clear that it was not just about the number of weekday choral services being reduced – there were difficulties in recruitment and retention of choristers and lay clerks, the musical standard of many choirs was low, and there were pressures to increase congregational singing at the expense of choral settings at Matins and Evensong.

Michael Cooke, a founder member of FCM, was at the St Bride’s meeting:

“In 1955 I was a tenor in a choir of boys and men in Leicester, singing cathedral-type services every Sunday, both morning and evening. I enjoyed my role in that choir and had no idea that the cathedral music tradition was under threat until I read the letter from Ronald Sibthorp and others expressing their concern. I was one of some 240 who replied, and one of the 40 who subsequently attended the meeting at St Bride’s.

“I do not remember too much about the discussion, except that it was decided to go ahead with the foundation of the proposed new organisation. Mr Ronald Lockwood, headmaster of a boys’ school in Kidderminster, offered his services as secretary and I offered mine as his assistant. Ronald Sibthorp was elected as chairman; Dr Martin Shaw, the wellknown church music composer of, amongst others, Fanfare for Christmas Morning, was elected as president; and the Bishop of Truro was made patron.”

Only a year after the St Bride’s meeting, Martin Shaw died and Herbert Howells became president. By then there were 276 members and FCM’s income totalled £171.

A number of initiatives soon followed. Ronald Sibthorp, as precentor, moved from Truro to Lichfield where he gathered about 15-20 members and held an informal conference –an event that marked the beginning of regular meetings at different cathedrals by which the local Friends were able to offer their support, advice and encouragement; FCM representatives for each diocese were appointed; and each year the AGM was held at a different cathedral. By 1962, so strong had the support and enthusiasm for these various meetings become, that twice-yearly ‘Gatherings’ were initiated (with the AGM being held at one of them) and the charismatic figure of Tony Harvey became FCM’s ‘tour operator’ who planned the kind of action-packed weekends that our members have enjoyed ever since.

Naturally, in these early years any financial help that FCM could give to cathedrals was limited because of its small membership. The first grant, in 1960, was a gift of £10 to Coventry Cathedral to purchase copies of Stanford in C, and £450 was raised to endow a head chorister’s prize at Lincoln, but it wasn’t until 1968 that more significant grants to cathedrals began to be made when £750 (payable over four years) was earmarked to help save the choir school at St Mary’s, Edinburgh.

It was in that same year that FCM took up Sibthorp’s proposed ‘watchdog’ role for the first time, by leading the public outcry that followed the BBC’s announcement of its intention to discontinue regular Wednesday afternoon live broadcasts of Choral Evensong. In the face of such strong opposition the BBC relented and FCM gained widespread recognition as a national hero.