CATHEDRAL MUSIC

We offer four brands of organ each with their own identity, sounds, appearance, technology and style. All our brands share valuable characteristics such as technological innovation and the best sound quality, which is never a compromise. All provide the player with a unique playing experience. A great heritage and tradition are our starting points; innovation creates the organ of your dreams.

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November.

ISSN 1363-6960 201

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Tatton Media Solutions, 9 St Lawrence Way, Tallington, Stamford PE9 4RH 01780 740866 / 07738 632215 wesley.tatton@btinternet.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by: DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

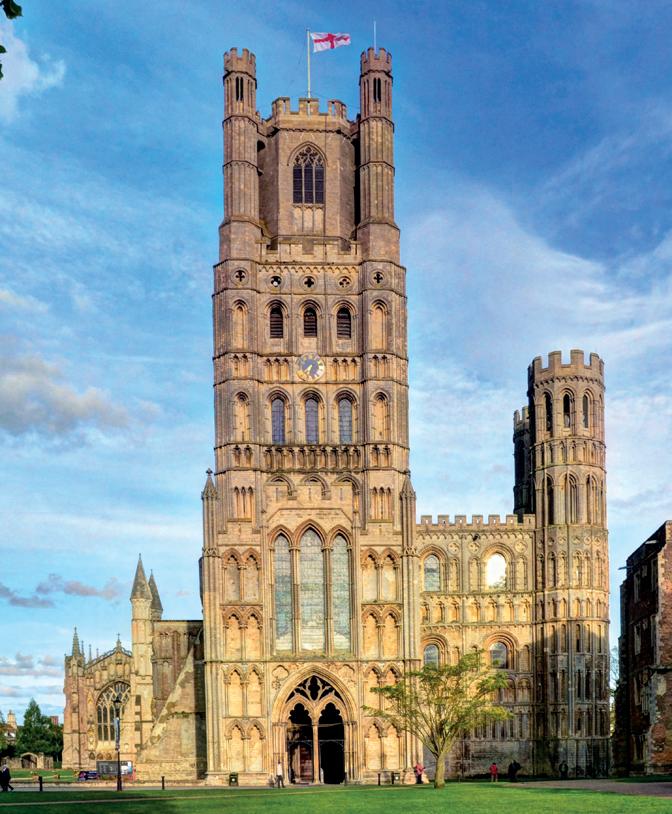

Cover photographs

Front Cover Christ Church Cathedral

Back Cover

Bath Abbey

51

52

56

Receive your first year membership of the Royal College of Organists FREE, with your home practice organ purchase

Our new range of sampled sound instruments offer: More internal speakers More detailed sampling with a greater number of sample points Internal solid state recording facility

See and play the new range in Bicester or at regional dealers

Irvine ......................Soundtec Organs

Orchestral voices on all models A full range of models starts from £6000

To learn more or book an appointment to play, contact us on

01869 247 333

Edinburgh ..............Key Player

Morecambe ...........Promenade Music

Porthmadog ...........Pianos Cymru

Leigh ......................A Bogdan Organs

Swansea ................Music Station

Norwich .................Cookes Pianos

Bandon ..................Jeffers Music

Exeter ....................Music Unlimited

Ballymena ..............Nicholl Brothers

Londonderry ............Henderson Music

Belfast ......................Keynote Organs

Just before the May edition of this magazine was printed, the new FCM website went live (www.fcm.org.uk). Take a look: it is worth your time and attention, with a more contemporary feel, frequently updated information pages, and a list of all Gatherings taking place round the country. Christmas cards and other FCM merchandise (pens, tote bags, notelets, ties, CDs etc) may also be purchased without hassle, and there are easy links for those wishing to join or donate.

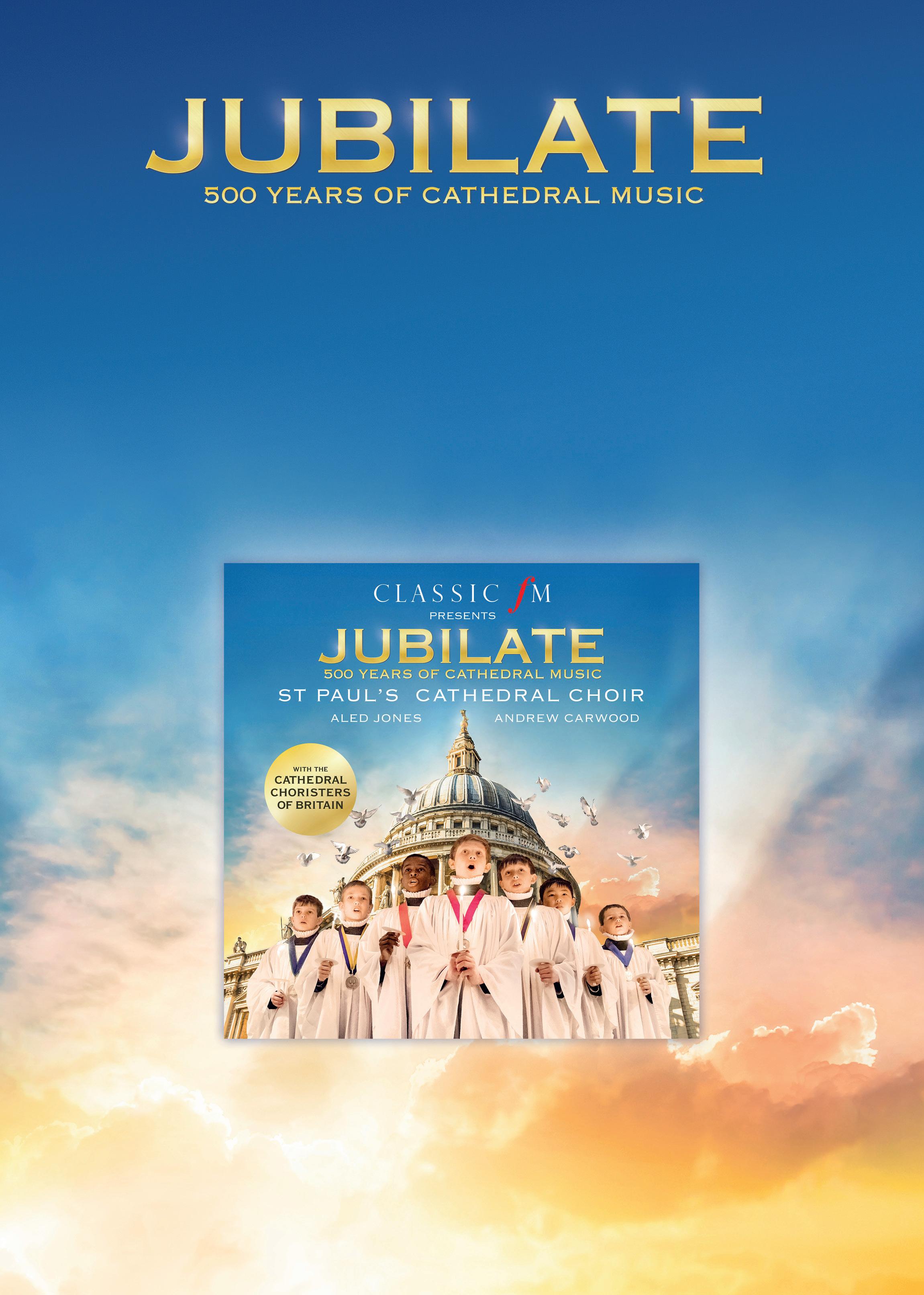

Many FCM members will have already bought copies of the Jubilate CD for their friends. Those who have not, please do so if you can, either through the website or at a Gathering or via the insert that comes with this magazine. Alternatively, you can type ‘Jubilate 500’ into Google, which will bring up various alternatives. The CD is currently No. 2 in the classical music bestseller albums and has sold over 10,000 copies worldwide. We would very much like to sell many more copies, however, since some of the royalties will help to swell the coffers of FCM and the Diamond Fund for Choristers, and also because the disc is a perfect example of the music we exist to support. If you Google ‘Jubilate 500 YouTube’ you can watch the excellent promotional video.

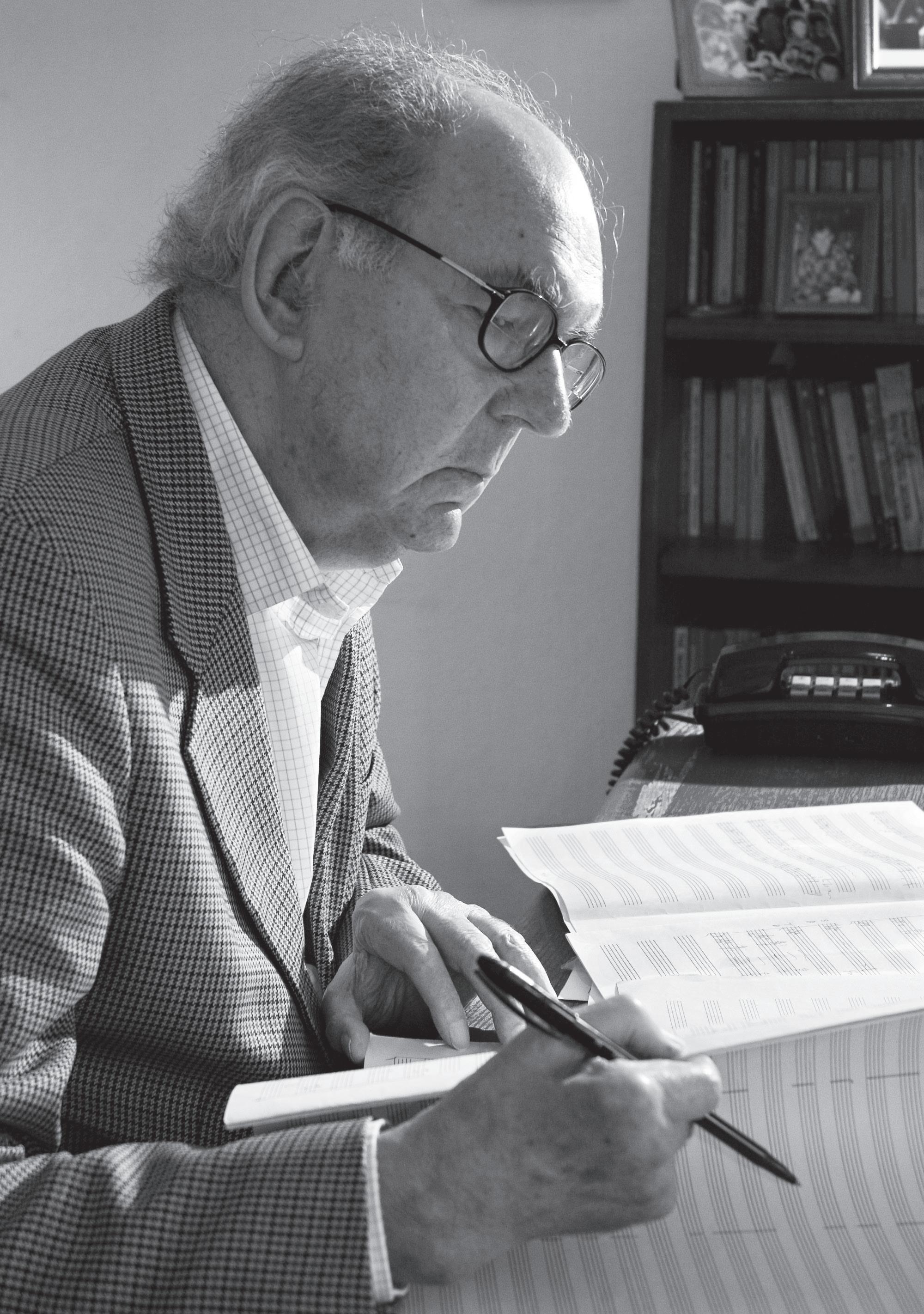

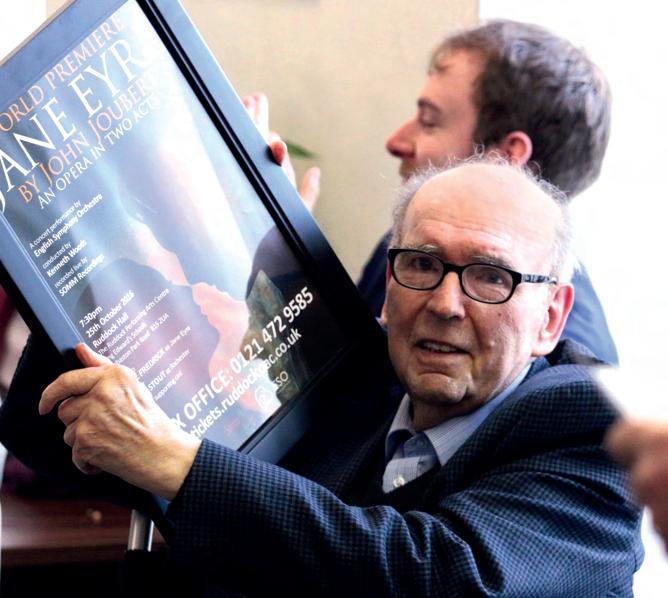

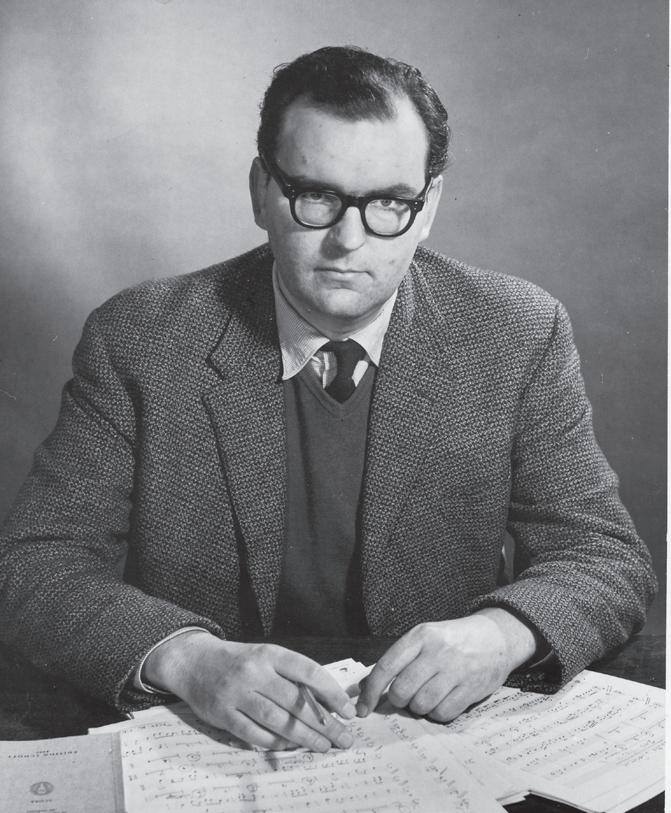

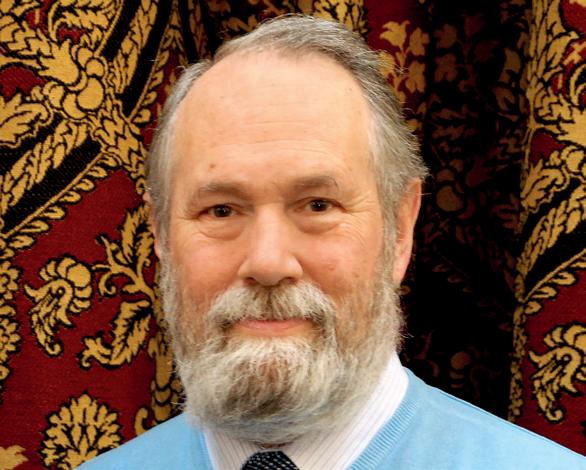

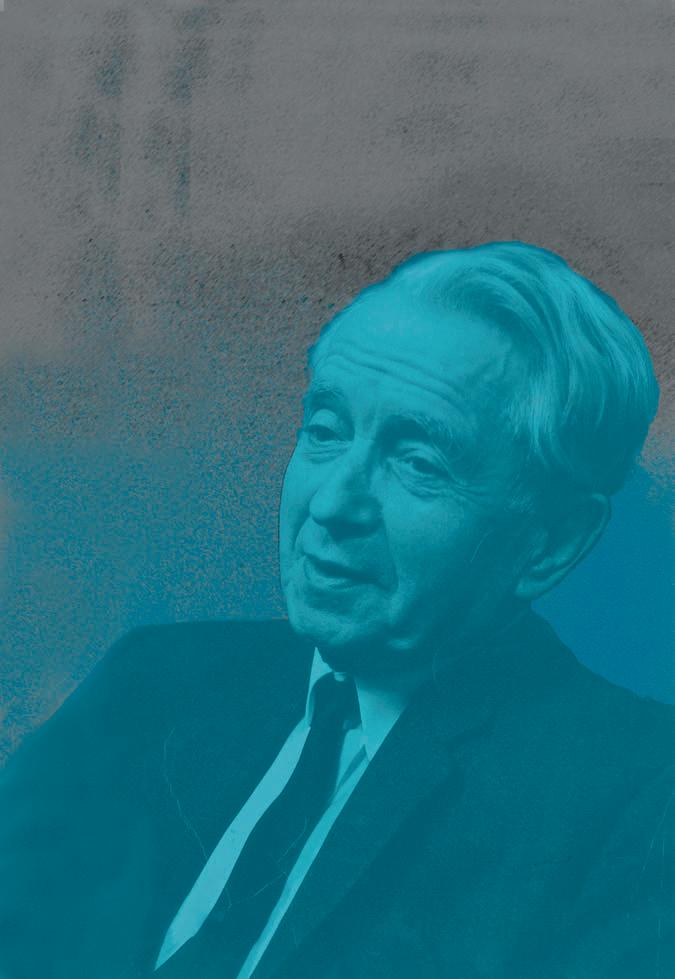

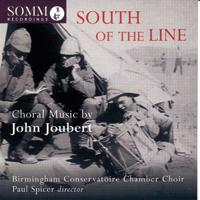

Many people, if asked to name a work by John Joubert, will mention his immaculate carol There is no rose, or perhaps Torches (both in the Carols for Choirs series). Not so many are aware of his other works (two symphonies, four concertos, four oratorios, seven operas, and more). The recording of his most recent opera, Jane Eyre, was released on his 90th birthday earlier this year, and he is still composing. Howard Friend, his long-time publisher, writes of Joubert’s life and musical

development, both in South Africa (where he was born and grew up) and then in the UK; Joubert’s style has many echoes of the Anglican choral tradition in which he immersed himself as a young man, but his voice is decidedly his own and his works greatly repay further listening.

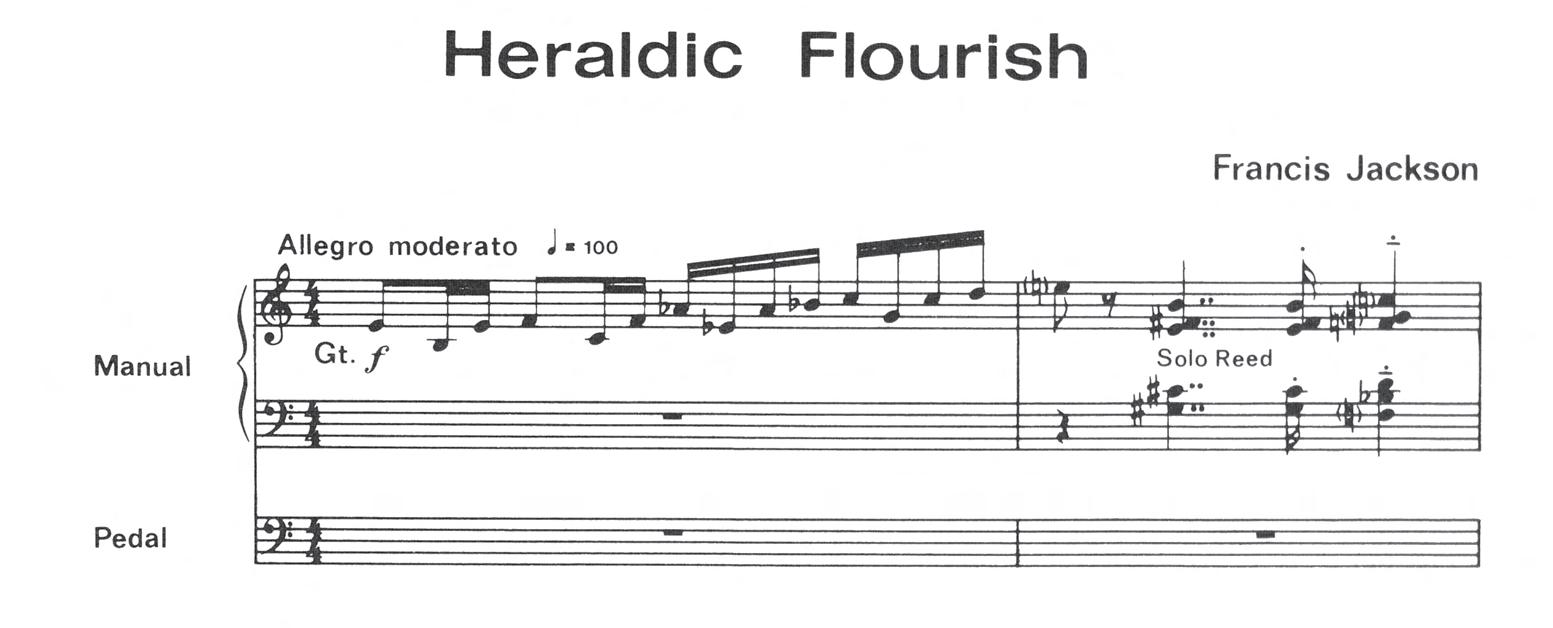

Another composer, another celebration: Francis Jackson was 100 in October 2017. Through the pages of his autobiography, Music for a Long While, and through his organ works, Andrew McCrea examines the influences on Jackson (amongst others Sir Edward Bairstow, his predecessor, mentor and teacher) and his evolution as a composer, in particular of organ sonatas, a genre which survives in Britain in no small part thanks to Professor Jackson’s contribution.

What would music in cathedrals have been like when FCM was in its infancy? Timothy Storey on FCM’s behalf has researched many old recordings to find out. If you follow his guidance you can hear much of what he has been listening to, and may be amused to note the differences between then and now, not least, of course, in terms of pronunciation. As with HM Queen, so with choirboys: ‘handmaiden’ is no longer pronounced ‘hendmaiden’! And, presumably, no longer do Masters of the Choristers interpret their titles literally and decline to rehearse the ‘back row’.

An offer: the Institute of British Organ Building is offering at a reduced price to FCM members (10% off the list price of £10 or £12) past copies of its signature magazine, Organ Building, the highly acclaimed publication written by organ-builders, consultants and players. Order through ‘administrator@ibo.co.uk’, having looked at (but not ordered through) their website, www.ibo.co.uk/webStore/index.php.

And if magazines don’t appeal as a Christmas present, why not hand to a fortunate recipient an FCM membership gift voucher, available through the website?

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

•welcome pack

•twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

•‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

•attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

•meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music •enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £ million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

me through the key inspirational moments: his early desire to follow in the footsteps of his father, who was a gifted artist and draughtsman, and then his interest in music, which came later. His mother, a talented pianist and student of Harriet Cohen, played duets with him, a useful but limited early introduction to classical music. There was little or no exposure to chamber music or opera in South Africa before and during the war years. This was an interest pursued during evenings of sitting around the gramophone at a music club, with John being 13 or 14 years old at the time. These gatherings of enthusiasts, which inspired in him the urge to write, were conducted by Austrian émigrés in Cape Town. There were other epiphanies: I felt a moment of recognition when he described how thrilling it was to see a page of full score, whatever the work was, an illustration in Arthur Mee’s The Children’s Encyclopaedia, the multi-volume book that for half a century influenced generations of sons and daughters of the Empire with its extraordinary images. These made an understandably deep impression on the junior Joubert, even in distant Cape Province.

Returning to meet John Joubert in his Birmingham home of the past 54 years was in itself an experience for me, having last crossed that threshold as an undergraduate in the early 1970s. To students of the rebellious sit-in years, John always seemed an elder statesman, his discussion calm and succinctly expressed. Never one to race to a remark not fully considered, that part of his personality remains unchanged in this year of his 90th birthday. Mobility may be more limited (so that he no longer trails clouds of silent glory for us as he once did around the Barber Institute Music Department), but there is no mistaking the man, his appearance, his speech. Not only are Mary and he long settled in Moseley, but they have been together for over 60 years. Their two children are both in the arts, his daughter, Anna, a cellist, very much in evidence, also living in the West Midlands. Such stability is hardly the standard image of a professional composer who can number almost 200 works in his output. But one so outwardly internalised may simply carry reserve into all aspects of his life, preferring to express himself through his musical creations.

During our meeting, he was willing to talk to me about his early life and formative years in Cape Town and after. He took

As so often, separation from fellow youngsters was a catalyst for creativity; thus, six weeks of quarantine confinement at home with a younger sister who had caught scarlet fever encouraged in him a need both to listen to more music and to write, himself, in more concentrated fashion. The disadvantage was that he had to rule his own manuscript paper, even for the resultant orchestral work. Duly impressed with the endeavour, however, his mother took the score to W H Bell, a composition teacher whom she had known in London before 1914, the year he had emigrated to South Africa. Without commenting on the musical content, Bell was sufficiently convinced of a talent, by the sheer creative urge in the teenager, to recommend a more formal study of music at school. The price to pay was the doubtless welcome dropping of mathematics in favour of what was to be his vocational subject.

Joubert’s compositional gift matured fast and he heard his works performed even before leaving Cape Town after the War. Following his PRS scholarship to the Royal Academy, he arrived in London, memorably for him, aboard SS Winchester Castle, still then tricked out as a troop ship. His composition teachers included Howard Ferguson and Alan Bush, the latter he recalls more for his powerful instruction than his radical politics.

His first string quartet was heard by Basil Ramsey at Novello, to which publisher Joubert was subsequently signed, as he is to this day (their longest surviving relationship with a composer). That was in 1950, in their grand Edwardian offices in Wardour Street, the atmosphere of which at the time he described as being that of a high-class undertaker!

John’s early compositional background is surprisingly diverse, even stretching to one or two film scores from the 1950s: a public information documentary on the Orange River District of South Africa, and another about the materials needed for making furniture. Joubert relates such things with his customary detachment, while allowing pregnant pauses.

It seems that a distinguished but little explored conducting career began with his appointment to a lectureship at Hull University in 1950, with the provision of a choir all to himself. He was not, however, entirely new to the game, having conducted in a less regular way at the Royal Academy. A generation of undergraduates, myself included, at Birmingham University will recall the weekly, more or less obligatory Motet Choir rehearsals, not, as I look back over four years, conducted by anyone but Mr Joubert – it wouldn’t have worked! – though occasionally there would be a distinguished eavesdropper: a youthful Gordon Crosse sat in on our Laetabundus exsultet. Eclectic indeed, we sang not only his own succession of new choral works (‘an occupational hazard’, as he put it) but anything from Handel to Vaughan Williams, Poulenc, Copland, Hindemith, Britten, Tippett, Maxwell Davies, Richard Rodney Bennett, Williamson… Fellow composer Peter Dickinson has commented on the fact that the Birmingham Motet Choir sang his The Dry Heart as proof of what a high-quality choral conductor Joubert must have been, working with an unauditioned undergraduate choir, something that is clear also in that choir’s performance on record of Joubert’s Four Latin Motets.

What about his music? Joubert’s reputation rests largely upon his output of small-scale choral settings, through which the reach of his popularity is considerable, even international. But I feel that the soul of Joubert is found in his less-often performed, more sustained works. As a result, as with many other composers (think of Bruckner or Schubert), he applies a symphonic-scale sensibility to his choral miniatures. He is a composer of considerable range. Rather than the miniature choral gems we should look to the larger-scale works for a more personal statement. There is a predominantly angry feel in works like South of the Line (see the review on p59), as

you would expect for settings of Thomas Hardy’s (essentially) war poems with a strong link to the Anglo-Boer War. But it is there, too, in the symphonies: the relentless, driving rhythms, the motifs repeated over and over across the orchestra, to an almost obsessive degree, even in the accompanied choral works, an organ part that seems often to contradict rather than support the chorus, an added layer to an already involved vocal counterpoint. This comes across at odds with the softspoken, gentle giant whom we meet, almost a dichotomy in his personality that lends it a fearsome authority.

Of great interest are his stage works, including five fulllength operas. His response to questions on his choice of work tends to the professional rather than strictly intellectual – perhaps he is too much the essential musician and man of the theatre, more a Richard Strauss than a Wagner. Or perhaps it is the noticeable reserve and unwillingness to leave clues or to explain. Certainly, his themes display a catholic and heavyweight choice for opera, taken from Conrad and Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot, even Tolstoy, or an old friend in that denizen of the TLS, Adolf Wood.

Interestingly, one opera that never made it was an intended setting of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, the distinguished

He took me through the key inspirational moments: his early desire to follow in the footsteps of his father, who was a gifted artist and draughtsman, and then his interest in music, which came later.

novel set in South Africa, which foreshadowed many of the dramas later to become manifest in the apartheid years. Joubert had long ago approached the author for his consent to write it but he was pipped at the post by Kurt Weill, who created Lost in the Stars from it within a year of its publication. Paton’s novel eventually found expression for Joubert in his Second Symphony of 1971, along with outrage at other iniquities of the era in South Africa, not least the infamous Pass Laws. If its political message attracted little attention in the UK, it was certainly noted by the authorities in Pretoria.

Despite the once red-hot topic of South Africa and apartheid which dominated the headlines for much of his life, Joubert could not be considered a political commentator. If there is rage or indignation, it is only occasionally spelt out. Even the overtly South African theme of his short opera, In the Drought (1955, libretto by Adolf Wood), has a more universal message. Joubert would most likely argue that Under Western Eyes, though written half a century ago, with its themes of uprising, betrayal and human weakness in the face of a hostile regime, is a work which still has resonance today. He does suggest that it was inspired by the situation in his home country in the 1960s: subversion under the spotlight. Tangentially, he adds that he first got to know of it, and consider his own setting, through

a French film version (Sous les yeux d’Occident) with a score by Georges Auric, which he saw in Cape Town in 1936. And yet, diffuse though the sources may be, there are common themes in Under Western Eyes, Silas Marner, In the Drought, even Jane Eyre, less apparent in Antigone, his first opera. The unwritten Joubert Cry, the Beloved Country may hold the key: it could be broadly summarised as decency and sacrifice being both destructive and redemptive in a hostile or irrational society. Only someone with a love for their country in crisis could grasp the full meaning of such concepts.

There is no doubting the importance for him of a lifetime of teaching and supervision. Of his many years of university teaching, he comments: “It is an excellent way of learning”. The range was considerable as was the requirement of degree courses of the period: I recall his enthusiastic lectures on the likes of Bellini, Rossini, Lassus and Mahler. With his seemingly insouciant delivery of dictums, things tended to stick in the mind: for example, Joubert was greatly surprised by the Austrian/Italian composer Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975), who dismissed late Stravinsky serialism as ‘rule-breaking’.

Joubert is no advocate of serialism. His anthem Let there be light starts with all 12 notes of the chromatic scale spread over

SATB, but that is as far as it goes. Twelve-note music is not so much the shibboleth today that it was in the less pluralistic academic music world of 50 years ago, but Joubert has called it ‘a reach-me-down technique devised by someone who wanted to suppress tonality…but you can’t’. It is, he says, ‘the opposite of creativity’. For a composer of the same generation as Berio, Boulez, Feldman, Henze, Kurtág, Ligeti, Nono and Stockhausen, it is hardly surprising, then, that, among such attention grabbers, Joubert, beavering away far from Darmstadt and Donaueschingen, has had to be patient in order be heard or appreciated generally.

Yet nothing is that simple. He gives me a salutary lesson about William Glock, who, from the late 1950s to early ’70s as the BBC music supremo and Controller of the Proms, gained a reputation for excluding a generation or two of home-grown composers in preference for the European avant-garde or representatives of a radical younger generation, like Birtwistle and Maxwell Davies: “All I can say is that, during the Glock years, I had more broadcasts on the BBC than ever before or since”.

When, in 2007, marking an earlier milestone birthday, a string of new pieces, performances and commemorative interviews took place, Joubert observed that turning 80 was one of his best career moves. Well, a 90th birthday year that has seen the issue of five CDs of hitherto unrecorded work, a third symphony, several choral commissions and a presence in the celebrations of the Hull UK City of Culture 2017 feels neither

Ifirst had the privilege of working with John Joubert in 2012 when I approached him about commissioning two works from him through our ‘Cathedral Commissions’ scheme. He readily agreed to an unaccompanied Latin Mass (Missa Wellensis) and, after some deliberation, to an unaccompanied setting of Locus iste – the shadow of Bruckner’s beautiful setting initially making him hesitant.

The following year Joubert was our featured composer during our festival new music wells 73-13, and was present for the premieres of Missa Wellensis and Locus iste. These works are incredibly demanding to sing, being almost symphonic in scale, but very welcome additions to the repertoire. Joubert also attended a concert featuring his chamber music (he was interviewed by Howard Skempton in our ‘Composer Conversations’ series), and he gave a composition masterclass at Wells Cathedral School. His modest, warm, and generous presence left a deep impression on all those who met and heard him.

The success of this led me to commission another work from him, a setting of the St Mark Passion. This followed on from Bob Chilcott’s St John Passion which we had

like a falling off of inspiration or public neglect. How enviable he is amongst men!

John Joubertpremiered in 2013 and subsequently recorded. Joubert’s setting is a dramatic and very moving one, using traditional Passiontide hymns from the English Hymnal – in contrast to Chilcott’s setting which incorporated familiar hymn texts with new tunes – and is scored for soloists (including two very extensive and demanding parts for the Narrator and Christ), solo cello, organ, and choir. The contributions required from the choir are relatively modest but most effective. The St Mark Passion was premiered on Palm Sunday in 2016, which also happened to be the composer’s 89th birthday. It is an easily programmable work that deserves to be in the repertoires of cathedral and collegiate choirs, and I hope that our recording of it will encourage choir directors to explore this Passion setting of one of the UK’s most significant composers, and perhaps the other works as well.

Ifounded Siglo de Oro while I was a student at King’s College London. At the start it was really just a group of friends, most of whom were choral scholars in the college’s chapel choir. We were inspired by the experience of singing Renaissance polyphony under the choir’s director, the late David Trendell, to the extent that we wanted to rehearse and perform even more of this repertoire – in our own time! In recent years we have moved from being a student group to becoming a fully-fledged ensemble: in 2014 we made our professional debut at the Spitalfields Festival (the Financial Times said that we ‘performed with vivacity and poise’). We’ve since been invited to give concerts at festivals across the UK, as well as further afield, in Finland and Malta, and have sung live several times on BBC Radio 3’s In Tune. Occasionally we take on other, more unusual projects: in 2016 we worked with composer Emily Hall on her opera-installation ‘Lost and Found’, at the Corinthia Hotel in London. We were praised for our role in the production as ‘the superb a cappella chorus’ by the Observer

Over time, the identity of the singers in the group has gradually changed – although we still have four former King’s College London choral scholars singing regularly in the group – and we now have quite a mix of backgrounds, from singers who have come to us via collegiate choirs or choral schemes, such as the Genesis Sixteen, to those who are simultaneously pursuing vocal training as soloists at one of the London conservatoires.

Drop Down, Ye Heavens is our debut CD, and is the result of an ongoing collaboration with classical saxophonist Sam Corkin. It features new settings of the eight Advent antiphons that we commissioned from eight different composers, alongside Renaissance and contemporary pieces that share a sense of mystery and expectation. BBC Music magazine made it a ‘Christmas Choice’ and called it ‘a debut with a difference… a novel, ungimmicky project, vividly executed’, while Gramophone described it as ‘so invigorating... this one hits you with its character and depth’.

In September 2017 we recorded our second disc, again with Delphian Records. This time we focused entirely on early music, and in particular the world premiere recording of Hieronymus Praetorius’ Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum. It’s an exceptionally colourful setting of the Mass, written at the end of the Renaissance and influenced by the very best music emanating from the Low Countries, Northern Germany, and above all, Venice. We’re hugely looking forward to introducing this exciting repertoire into the world in March next year.

In 2018 we have lots of other exciting plans, including two performances at the Barber Institute in Birmingham, our French debut, and a special concert at the Royal Society of Physicians to mark their 500th anniversary.

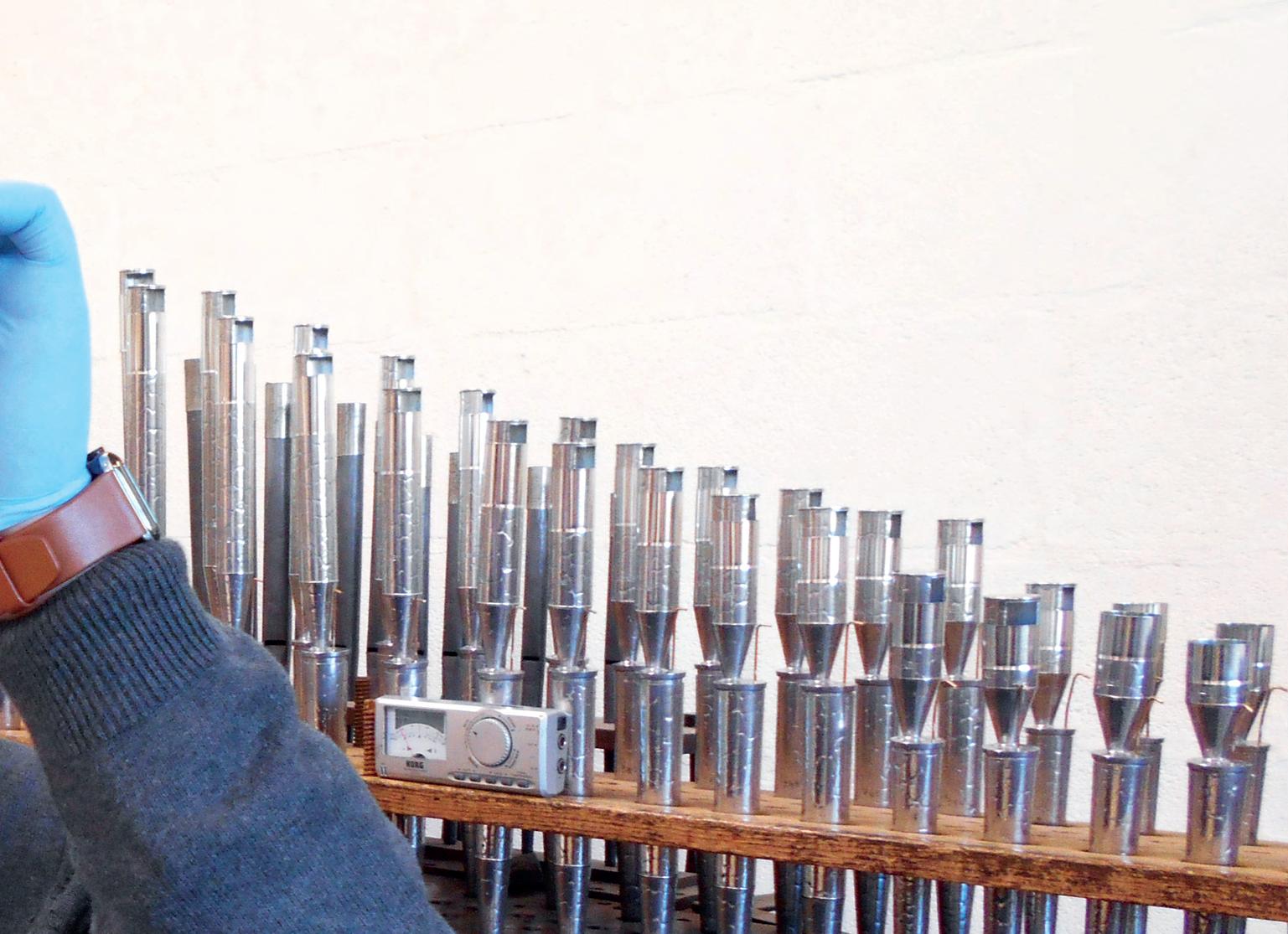

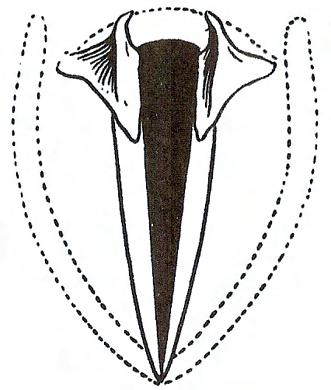

The pipe organ sits right at the heart of liturgical music in cathedrals, churches and chapels around the world but, like all complex mechanical instruments, over time many thousands of individual components wear out, leather perishes and mechanical defects occur.

When work is required it tends to be an expensive, once-ina-generation operation, and it is generally to a professional organ-builder that any delicate and exacting work is entrusted. It is easy, by checking internet and social media, to follow those companies who photograph and film aspects of their craft and post them online, but who knows where the people behind the specialist craft of organ-building come from, and how does a person interested in a career in this unique craft get started?

The education system today is one that encourages further education, and it seems that fewer people leaving school after GCSEs are actively looking for a job. Many people who graduate with a degree have no job to go to, or perhaps are unsure as to what career they want to pursue. I have long thought that one of the best ways to encourage people into organ-building is to catch them when they are young.

Thanks to the Industrial Revolution during the 19th century, religious feeling in Britain grew as the Church of England

regained energy and many churches were built. These churches required new organs to lead the singing, with the result that there was a huge boom in organ-building. An 1851 survey showed that about 40% of the population went to church, which in a similar survey 30 years later had declined to 33%, and by the late 19th century this had sunk even further. Come the late 20th century, and only a small minority of the population attended church regularly. Now church attendance in the UK stands at 6%, and it is predicted that by 2020 attendance will be down to around 4%. This decline has forced a large number of churches to close, and many fine pipe organs are therefore being left to face an uncertain future (should they be rehomed? Demolished?). And although there is now a steady increase in cathedral attendance, the closure of churches impacts particularly on parish church musicians, many of whom no longer have the volume of people joining their church choirs. This has an obvious knock-on effect, as the children who form the front row of church choirs today would normally -- in the past -- have gone on to form the back row of the future, with their children becoming tomorrow’s front row, and so on. What was once a self-perpetuating circle is now fragmented. This is evident from travelling around the world whilst working on organs: in the various choir photographs that adorn vestry walls there are fewer people in evidence year upon year. Of course some parish churches do buck this trend, but these tend to be the more established

civic churches which perhaps have more financial resources with which to employ musicians.

A similar trait is perhaps also evident in organ-building. Many people active in the trade today initially took an interest through exposure to the instrument as choristers, or through having been pointed towards a career in organ-building by a schoolteacher who knew of a local company and the many different skills involved. Some came into the trade by following in the footsteps of their own family members (we have an organ-builder at Harrison & Harrison (H&H) who is the third generation of his family to work there). But whichever way people came into the trade past and present, general knowledge of the art of organ-building has undoubtedly diminished. A new or restored pipe organ is perhaps now considered to be an expensive luxury. Indeed, a pipe organ is to many an unknown instrument.

Gareth Malone, the charismatic TV choirmaster, has revolutionised the number of people who sing in secular choirs throughout the country. He – of course – is not alone in so doing, but the number of people who commit to singing in sacred church choirs does not increase, and thus exposure to the pipe organ also diminishes further. Today, people only really come into contact with ‘the king of instruments’ in their school chapel (if they are fortunate to have an organ

at school), or at weddings, funerals or town/concert halls. Exposure is perhaps most often through a holiday visit to a cathedral where the organist or choir may be practising, and this is not sufficient to draw someone towards wanting to learn to play the organ, or to find out how the instrument works, and then ultimately to discover that there is an exciting and varied career to be had.

I was introduced to the electronic organ at a young age by my father, who had a Hammond organ at home (he still has it), and on this I learnt. It was through learning to play the electronic organ in a wholly secular environment that an interest in music was generated which ultimately was the catalyst to my joining the local parish choir at the invitation of a school friend. I was already 12 by then, and therefore hugely late to the game as a chorister, but it was there that I was to find my love for the organ. This led quickly to a desire to understand instruments with pipes and wind, and to the discovery of a more classical repertoire. Shortly after joining the choir, the encouragement of the Director of Music and Newcastle diocesan organ adviser, Russell Missin (Organist of St Nicholas Cathedral, 1967-1987) began to rub off on me. I accompanied Russell to the H&H workshop for an open day in 1992 where I first met the Chairman and then Managing Director, Mark Venning, and decided then, at the age of 14, that a career in organ-building was what I wanted to pursue.

“In my eyes and ears the organ will ever be the king of instruments.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791

I was never an academic, and the thought of further study after school was unappealing. Aged 15, I wanted to apply to H&H for an apprenticeship, but my parents insisted that I should first apply for a position with our local firm in Tynemouth – H&H being some 25 miles away in Durham. Only after something closer to home was not available was I allowed to write to H&H asking to be considered. At the time, this was a complete punt on my part as H&H were not actively looking for apprentices, but I got a favourable response to my letter and was interviewed on a cold January morning in 1994, in the old workshop in Hawthorn Terrace where, having done a written test, woodwork test and sit-down interview (scary stuff for a 15-year-old), I secured a four-year apprenticeship to begin straight after leaving school.

to highlight someone who may have a flair for a certain skill; having served their time as general apprentice, that person may then specialise within the larger team picture. As an organist, I was always very interested in tuning and voicing, but these two specialist aspects formed the last year of an apprenticeship, although I still thought it worthwhile to let my boss know that I was interested. Mark Venning had a word with then Head Voicer, Peter Hopps, and I was taken into the voicing room, where alongside continuing with all other aspects of my training on the bench I was fully immersed into the ‘dark art’ of tuning and voicing.

Training at H&H gives the apprentice a wide exposure to all aspects of the craft, such as woodwork, metalwork and leatherwork. This holistic approach allows for the development of good all-round knowledge, and it also helps

By the age of 18 I was being sent out to local tuning and maintenance visits, often taking another younger apprentice with me to hold notes. The frequency of local tuning gradually increased to covering tuning rounds while more established tuners were on holiday. An apprenticeship in organ-building is infinite but, having served my time, I became a qualified organ-builder in September 1998 and was offered a full-time job. As I had already spent a lot of time in the voicing room I made a very natural move to full-time voicing, where alongside workshop voicing I would find myself onsite, finishing jobs with Peter and Duncan, and also continuing to assist with tuning visits. After a few more years, at the age of 22, I moved to London to succeed David Chapman as London Tuner. For the next 12 years, around my tuning commitments, I continued to play an active role in the voicing team, and upon Peter Hopps’ retirement in 2012 I was appointed Head Voicer. I combined this with my role as London Tuner, but in order to give my full attention to the increasing voicing programme, after 16 years as London Tuner I handed over to a colleague who was running a smaller round in Bristol. He pretty much learnt on the job with no previous bench experience.

Back in the 1970s, around 5% of the workforce at H&H could play the organ. Today we have a much larger proportion of

organists, including seven of our nine nationwide tuners, totalling 35% of the workforce. Although many people think that organ-builders are a dying breed, there are more opportunities for people to get involved than one might first think. Being a casual keyholder for a local tuner may lead to discovering someone who can tune, or work experience in a workshop can lead to a continuing interest. Organs are more than just pipes and wind: there are many elements and different skills which people bring together as a team to build an organ. These range from general woodworking and cabinet-making to leatherwork, metalwork, electrical systems, mechanics, design, tuning and voicing. For those who want to know more about what goes on ‘under the bonnet’, it is likely that your local organ-builder would be delighted to offer advice on where to find such opportunities if they are unable to offer them themselves.

The Institute of British Organ Building (IBO) publishes a fascinating annual journal, Organ Building, which features pipe organs built, rebuilt or restored throughout the year. It is an excellent, full-colour publication, where amongst articles on topics relating to the pipe organ there is an invaluable map and directory of accredited members and their contact details. Visit the IBO website for more details: www.ibo.co.uk

Having been an organ builder for 23 years, I can say with hand on heart that every day is different and you never stop learning. My job has taken me all around the world and given me access to many amazing places where I have met some fascinating people. I still have to pinch myself that amongst the many instruments I have been privileged to work on, to date I can include 26 UK cathedral organs, and 32 cathedral organs worldwide.

Andrew Scott joined H&H as an apprentice in 1994. In 2000 at the age of 22 he succeeded David Chapman as London Tuner. Andrew was appointed Head Voicer in April 2012, and since taking up the role he has been responsible for leading the voicing on many projects, including the Royal Festival Hall, Exeter Cathedral and King’s College Cambridge, alongside new organs for Edington Priory, Hakadal Kirke (Norway) and Bedford, St Andrew. He serves as a board member for the International Society of Organbuilders, and in addition to his work at H&H he is an accomplished organist and choir trainer, currently holding the posts of Director of Music at St Michael & All Angels, Croydon, and director of the chamber choir Amici Coro.

Parts of this article were first published in the quarterly newsletter of the Institute of British Organ Building (No.74, June 2014) and in Organists’ Review (June 2015) and are reproduced here with kind permission.

To borrow a description first applied to Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London 1828-56, the Revd Ronald Sibthorp had ‘an ungovernable passion for business’ which might unkindly be characterised as a penchant for doing other people’s work. At Peterborough and Truro, the first two cathedrals at which FCM’s revered founder served as a minor canon, he was glad to obtain from the organist a complete list of the choir’s repertoire, and thereafter to take over from him the complete responsibility for choosing the music to be sung by the cathedral choir in the daily services. At Lichfield, his third and last minor canonry, he administered the Friends of the Cathedral, and in all three he ran the bookstall.

Sibthorp was a dedicated and single-minded lover of cathedral music and worship, and it was quite in character that in 1949 he should found an Association of Cathedral Minor Canons which he ran single-handed for well over a decade. It was this body which became alarmed by a (perceived) threat posed to cathedral choirs by the implementation of the 1944 Education Act which, it was feared, might restrict the amount of time choristers would have available for services and rehearsals. The real heart of the problem, however, seemed to lie not with the Act, but that it seemed to be no one’s business to

ensure that wartime reductions in the number of choral services were made good, and also that the new generation of deans and canons perhaps had not been brought up in a tradition that valued and enjoyed daily choral services. Most of the ‘parish church cathedrals’ had been content with at most a couple of weekday choral services and were not greatly affected, though Birmingham’s five weekday Evensongs had dwindled to only two.

The near-extinction of weekday choral Mattins was deplored, but it was sadly unrealistic to hope for the revival of the prewar conditions when this office was sung on at least a couple of weekdays in most ancient cathedrals. Exceptionally, at Lichfield and Wells it had been sung on every weekday, but in neither place did this provision survive the war. Only at St Paul’s was a daily morning service resumed, in the special circumstances of a large and fully professional choir with a school solely devoted to the needs of the choristers; and even then two of these ‘morning services’ had been replaced by a ‘hymn-sandwich’ at 12:30.

In any case, the days of the tiny choir school which took no pupils other than the cathedral choristers seemed to be numbered. At Ely and Worcester the boys could join the

as a minorPeterborough Cathedral Photo: Hans Davis Photography Truro Cathedral Photo: Brian Snelson Lichfield Cathedral Photo: Michael O’Donnell

King’s School as junior pupils, but at Durham, Lichfield and York the choir school eventually became a much-expanded preparatory school which included non-singing pupils as well as the choristers. Conversely, at Lincoln and Ripon new choir and preparatory schools were founded because an ancient grammar school was no longer willing or able to accommodate the special demands of the choristers’ routine. Other examples might be adduced, if only to illustrate the point that there was no typical solution to the problem of housing and educating a cathedral’s choristers. Another consideration was that cathedrals could no longer regard their adult singers as full-time employees and pay them to sing weekday morning services. The cathedral might find additional work for some in the chapter office or works department or choir school, but such sympathetic employers did not always exist. At Durham, where Mattins was sung on Tuesdays and Thursdays until the late 1960s, one of the lay clerks was a highly qualified engineer who had taken a menial job as a college handyman in order to be free to sing in the choir. Such enthusiasm and dedication were by no means uncommon.

As a response to these concerns, the Association of Minor Canons proposed that five of their number should join with

five each from the Cathedral Organists’ Conference, the Church Music Society and the Royal School of Church Music to form a committee of 20 that would act as a kind of OFSTED, visiting cathedrals to report on the state of the music and to take deans, canons and organists to task for any shortcomings that might be found. Unsurprisingly, the idea was dropped as being potentially embarrassing and probably ineffective. What cathedral music really needed was Friends, those who loved to worship at cathedral services, who could spread the word to those who did not know what they were missing and needed more information. If such Friends became sufficiently numerous they would constitute a body of opinion which could not be ignored if a cathedral’s music were to come under threat; but they could assume a positive role both by their presence at services and by their help with publicity and fundraising. So in 1956 the Friends of Cathedral Music came into being.

What is the purpose of a cathedral choir? It is to assist a cathedral’s clergy in their obligation to recite the whole psalter each month in more or less equal portions each day, both morning and evening; and to recite the canticles at Morning and Evening Prayer daily. Over the centuries a

distinctly Anglican repertoire of chant has evolved, and a rich treasure-house of music for the Morning Prayer (Mattins) canticles Te Deum, Benedicite, Benedictus and Jubilate, and for Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis at Evening Prayer (Evensong). The anthem is almost an optional extra, there being no proper texts provided in the Book of Common Prayer (BCP). A worshipper at Mattins or Evensong 60 years ago would have heard the complete introduction: ‘Dearly beloved brethren...’ in full, with the general confession and absolution perhaps intoned rather than spoken. The Preces and Responses would be sung to a home-grown setting, or perhaps ‘Tallis’s Festal’ or, on special occasions, Byrd, Smith or Tomkins. The creed would have been intoned, and in some places even the state prayers after the anthem. The organist would have been for the most part invisible, only emerging from his loft to conduct unaccompanied music, while the psalms, canticles and anthem were led by a skilfully played organ accompaniment. The assistant organist was someone who played on the organist’s day off.

There was a stable and immutable repertoire of anthems common to most cathedrals, though some favoured the Tudors and Stuarts and others the Georgians. The works of the best Victorians, such as Goss, Mendelssohn, Walmisley and S S Wesley, were universally sung, but Gounod and Stainer seemed to have had their day. The music of Bairstow, Stanford, Wood and their pupils was greatly admired and was sung everywhere. So settled was the repertoire that many establishments had thought it worthwhile to provide the congregation with a book containing the words of all the anthems in regular use, with a translation of Latin texts. A ‘Rolls-Royce’ of such books was compiled for King’s College Cambridge and subsequently adopted for Gloucester, Salisbury and York, with substantial additions to suit the particular requirements of those cathedrals. Novello’s Words of Anthems was rather more of a Morris Minor, but useful enough to be specially printed and bound for Lichfield Cathedral with a number of additional texts.

At many cathedrals a choral celebration of the Holy Communion was a relatively infrequent event, replacing or following Sunday Mattins once a month or on great festivals. It would have been sung complete by the choir, creed and all. The singing of Latin Masses was virtually unknown, but in a few places one might hear Byrd, Palestrina or Schubert in English by way of a change from Harwood, Stanford and Whitlock. A choral celebration on a saint’s day would take place in the morning, never (well, hardly ever) replacing Evensong.

FCM’s founder was a single-minded if perhaps uncritical enthusiast for his cause, and he longed to share his enthusiasm with others. But what was the quality of the product he was selling around 1956 and the subsequent ten years? Drs James Bowman, Harry Bramma and Francis Jackson have been generous in sharing their recollections, and the memoirs of Lionel Dakers, David Gedge, Frederic Hodgson, Michael Howard, Dennis Townhill and Arthur Wills may also be regarded as primary sources. Archive recordings of the choirs of Magdalen College Oxford, Salisbury Cathedral and York Minster have been reissued on CD in recent years, and an exciting reservoir of material is to be found on the internet. Type in, for example, Evensong, Worcester, Willcocks, and up will come someone’s recording of a radio broadcast. This is an actual example, and you will be rewarded by part of a 1955

Evensong in which the Worcester boys’ singing of The souls of the righteous (Nares) is most beautiful, just as one would expect from choristers trained by the legendary David Willcocks in the years immediately preceding his return to King’s. Harry Bramma confirmed that Worcester had some very talented choristers at this time.

In 1956 a number of cathedral organists had been in office since before the war; their attitudes and methods inevitably were of their generation, but with rare exceptions they were musicians of quality and dedication. Conrad Eden’s choristers at Durham were aware and proud of the skill in sight-reading which he imparted to them; and at Lichfield Ambrose Porter (soon to retire) was a noted trainer of boys’ voices and was famed for his accompaniment of the cathedral service; John Dykes Bower (St Paul’s) was immensely respected as a player and choirmaster. Heathcote Statham had been at Norwich since 1928; James Bowman, an Ely chorister, encountered the Norwich choir at joint Evensongs and was distinctly unimpressed; and a tale is told of a disastrous performance of a Byrd anthem at Lincoln, of which the organist (Gordon Slater) is said to have remarked to a visitor that he would ‘not often hear a performance like that’. The visitor felt compelled to agree! In a class of his own was the famously eccentric Guillaume Ormond, immortalised by A L Rowse as the Disorganist of Truro Cathedral.

The post-war generation included such luminaries as Sidney Campbell, (Ely, Southwark, Canterbury and Windsor), Douglas Guest (Salisbury, Worcester and Westminster Abbey), Francis Jackson (York), Alwyn Surplice (Bristol and Winchester), Stanley Vann (Peterborough), David Willcocks (Salisbury, Worcester and King’s) and Arthur Wills (Ely). Yet to come were John Birch (Chichester) and Christopher Dearnley (Salisbury and St Paul’s). And we should not forget

the organists of the Oxford and Cambridge colleges, George Guest, Meredith Davies, Boris Ord, Bernard Rose and others. For further recordings by many of the above, type in (say) Evensong King’s Ord; in this case you will be rewarded with a very fine performance of Howells’s St Paul’s Service, broadcast in 1956. You might try Evensong, Durham, Eden, or Evensong, New College, Davies, or Evensong, Wells, Pouncey; i.e. Evensong + place + organist. We are rightly proud of the standard attained by our best choirs nowadays, but there are lessons to be learned from these primitive old recordings. What is immediately obvious is that everywhere the boys were well trained to sing beautifully and freely, sometimes without absolute precision of ensemble but always confidently and clearly, with every word audible. Would that this were always true of today’s professional singers! The vowel sounds now seem somewhat dated, with the much-derided ‘megnify’, ‘end heth’, ‘hendmaiden’ etc. by no means unique to King’s! Francis Jackson used to make his boys practise saying, ‘That bad lad has had an accident’. The only examples of anything approaching ‘continental tone’ were provided by King’s (1956) and Ely; try Evensong, Ely, Howard 1958

Evensong, Salisbury, Guest shows what a good choir Douglas Guest bequeathed to his successor Christopher Dearnley, but we hear rather too much of an alto soloist who may have been good by the standards of the day but would hardly pass muster in even the least of today’s choirs.

Some choirmen had grown very old but could not be forced to retire, having been appointed before the Cathedrals Measure of 1931 abolished freeholds for all singers who came thereafter. Freddy Hodgson’s delightful Choirs and Cloisters records that a number of his friends sang most beautifully into their eighties, as they were fully entitled. Freddy himself went on to a ripe old age at the Chapels Royal of St James’s and Hampton Court Palaces. A St Paul’s chorister recalls how ‘in 1962 I was … on Decani, positioned in front of three altos who seemed, to my young eyes and ears, to have already made it to the departure lounge but not quite to the gate!’ Evensong, St Paul’s, Dykes Bower is illuminating!

In a class of their own are the broadcasts from Peterborough, where Stanley Vann (Organist since 1953) raised an ordinary provincial choir to a standard fit to be compared with the best in the land. Even as a chorister, James Bowman thought that his own choir at Ely, good though it was, suffered in the comparison. In his words, ‘the secret was that Stanley persuaded the men to blend’. Unfortunately, it has to be admitted that only in the chapels of King’s and St John’s Colleges in Cambridge did the men sing as to the same standard as the boys. If you track down Evensong, Durham, 1960 you will hear a verse anthem by Wise in which the alto, tenor and bass soloists seem only concerned to outdo each other in volume. Evensong, Chichester, Birch 1965 proves that although the boys sang extremely well, it was taking John Birch some time to bring the men up to the same standard!

In some places, relations between organist and choir were less than harmonious. When Ambrose Porter arrived at Lichfield, the organist was also technically a lay vicar. He naturally assumed that as organist he would take the chair at a lay vicars’ meeting; but he was bluntly informed that he was the junior person present and had no right to do so. He had nothing more to do with them until he retired. One of the lay clerks at Durham, having no great opinion of Conrad Eden’s abilities, kept in his stall a notebook in which he recorded the organist’s every mistake. The atmosphere at Windsor was notoriously unpleasant. Not a few organists interpreted literally their title of Organist and Master of the Choristers, with no specific obligation to rehearse the men, whom they regarded as a necessary evil about whom nothing much could be done. In any case, there was often only one rehearsal of the full choir each week, and it is a tribute to the thorough training of the boys, and the professionalism of the men, that in most cathedrals the services were decently, even well, sung. The old ways persisted until the 1960s and beyond, but a new generation of organists, many of them formerly organ scholars in the ancient universities, was now applying a rigorous training to the whole choir, not just the boys. A leaflet issued in 1966 by the Church Music Society reveals that this was something of a Golden Age for cathedral and collegiate choirs, with Evensong on at least five weekdays in the ancient cathedrals, and even a few weekday Mattinses. It warns that ‘at some cathedrals, services are not sung during August’, for it was still quite usual for the choir to remain in residence for a number of days after Christmas and Easter, the men perhaps singing on their own for a few more days. Look for Evensong, Durham, Eden 1965, a live broadcast on 29 December, no less!

FCM’s founder built better than he knew. In 1956 and the following decade, or even 20 years later, the world of cathedral music was in better shape than he had feared, but by the 1980s the Friends were growing into a body powerful and wealthy enough to help the nation’s choirs face a whole host of new challenges, social, ecclesiastical and financial. Not that one was ungrateful for the more modest help of the Friends’ earlier days. In the writer’s years at Birmingham Cathedral (1979-84) the copies of Purcell in G minor, skilfully bound into cardboard covers by Sibthorp’s own fair hand, were a tangible reminder of the Friends’ existence and generosity. Long may it continue.

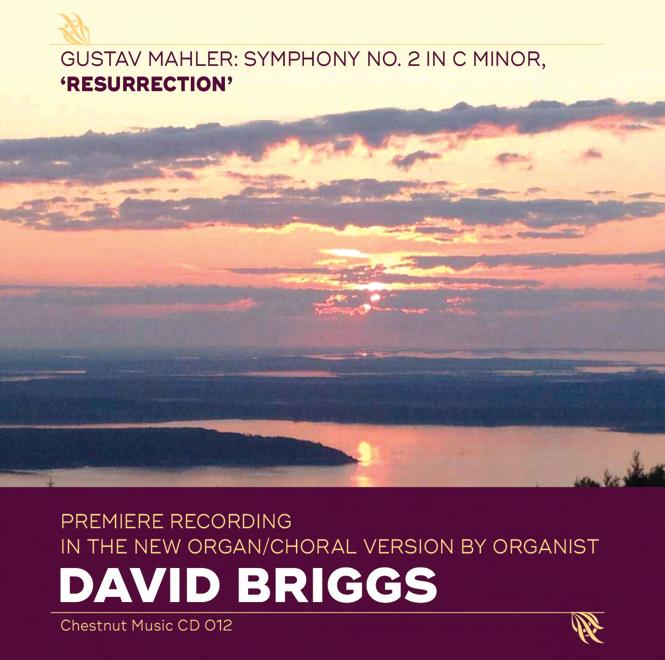

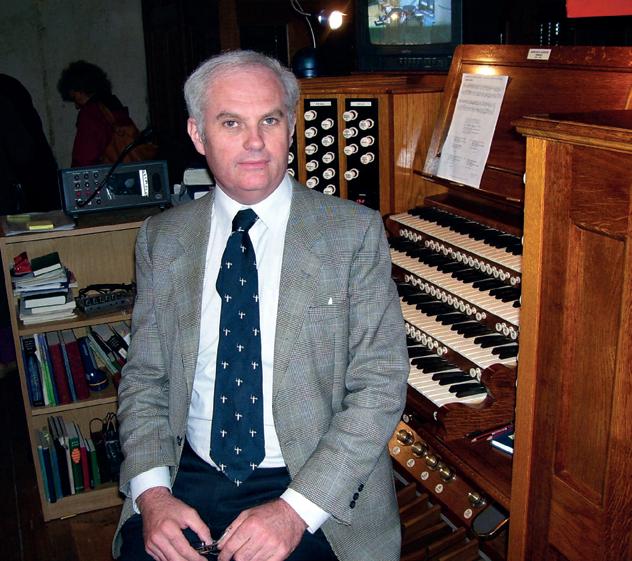

With his late-Romantic, bombastic sound, Gustav Mahler is a composer known for his ability to write for huge instrumental forces. He’s also known for being uniquely able to build those forces up to key musical moments, shape a denouement that is never sudden, and allow a contemplation that washes over listeners in an often profound manner. But the Herculean efforts required for most Mahlerian symphonies have made it next to impossible to imagine an effective staging of the symphonies in intimate venues or anything less than a grand hall. What instrument and single player could possibly invoke and create the effect of a massive orchestra?

of reproduction was fairly rudimentary. The playing of orchestral transcriptions in organ concerts therefore gave the general public virtually their only regular opportunity to experience the great orchestral and operatic repertoire, firsthand.

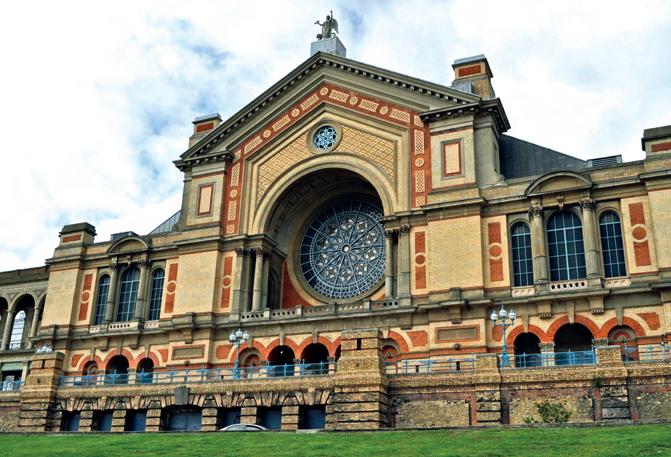

Because I have always been rather obsessed by the great corpus of orchestral music from the 19th and 20th centuries, it has been refreshing to observe the pendulum swinging more towards the mid-point in terms of programming for organ concerts and recordings over the last three decades or so. At the beginning of the 20th century it was not difficult to find recital programmes consisting almost entirely of orchestral transcriptions. Players such as E H Lemare and W T Best brought great skill and integrity to the playing of this repertoire and, in that very different sociological era, audiences were often huge. At the Alexandra Palace in the 1930s so many people came to recitals by Harry Goss Custard that he was obliged to have two sessions every Sunday afternoon. The choice of repertoire was, of course, also related to the evolution of the recording industry. 78 rpm records were the order of the day – and inevitably the quality

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Organ Reform Movement (which sought to recapture the baroque instrument over the then current trend for ‘Romantic’ organs) arrived and the playing of transcriptions and arrangements went completely out of fashion. The rationale suddenly became centred on historic performance practice and trends in organ-building mirrored the movement (although this could have been the other way round!). Audiences could expect to hear a very different type of recital – invariably Bach, a plentiful supply of early repertoire and then, bypassing the 19th century, works by Messiaen or one of his contemporaries. There was a definite tendency towards specialisation, and as a result members of the general public, who were often entirely unfamiliar with this repertoire, became perplexed and to some extent ostracised.

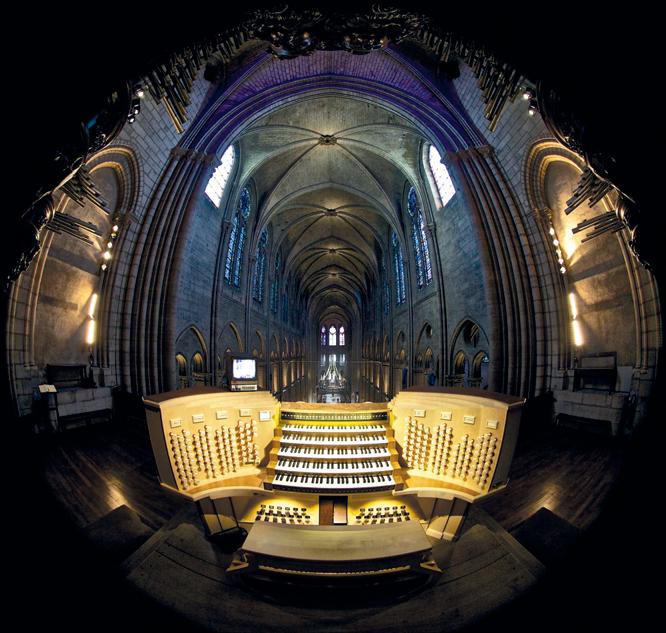

The current trend towards recapturing both the enthusiasm and the size of the audience is very refreshing. There is no doubt that organists have benefited from the increased breadth of historical knowledge inherited from the reform movement in terms of touch, fingering, articulation and rhetoric, but now there is an increasing realisation amongst many players that the crucial thing is not to play for oneself but, principally, for the enjoyment of others. Louis Vierne at Notre-Dame, in describing his attitude towards performance, said: ‘Il faut rigoler les gens’ [You must entertain people].

Of course, the idea of presenting music in transcription is a very old one – indeed, transcriptions have been made throughout musical history. J S Bach frequently made arrangements of both his own and other composers’ music, crossing instrumental boundaries. The 1746 Schübler chorales and the arrangements of the Vivaldi concertos are obvious cases in point. Bach’s frequent use of the word Klavier in his keyboard music implies that his attitude towards specific keyboard instruments was quite liberal – the music was made to be played on whatever instrument was to hand. There is no doubt that really great music speaks for itself and can be effective in different guises. Many other great composers have also made transcriptions of their own music (e.g. Ravel’s La Valse, and The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky, which exist in piano duet form). Liszt made transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies for piano solo and Maurice Ravel famously orchestrated Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, a work that was originally written for piano. Having said that, of course, a transcription is by its very nature something of an illusion and must be made to sound effective in its new guise. A poor transcription, or a good transcription badly played, can easily turn into a travesty of the original. However, a good transcription, interpreted well, can heighten our awareness of the message behind the music – we can listen with new ears. A new artistic dimension is given to the original. Perhaps it’s rather like seeing a painting in a new frame in a different gallery and under different lighting conditions. It is basically the same concept but the variation in approach can affect the observer in an entirely different way.

Over the past couple of decades, a number of very largescale organ transcriptions have been made and recorded. At the reopening of the organ in Notre-Dame de Paris, Olivier Latry played his brilliant transcription of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Lionel Rogg has transcribed and recorded Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 on the new Van den Heuvel organ at Victoria Hall, Geneva. Pierre Pincemaille has made staggering arrangements of two other Stravinsky ballet scores, The Firebird and Petroushka and recorded them on the Gonzalez/Dargassies organ of Radio France in Paris. My own transcription and recording (for Priory in 1997) of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 became Priory’s best-selling organ disc, emphasising that transcriptions are very much coming

back into fashion. Interestingly, none of the above composers left any original music for organ. Neither, sadly, did Debussy, Ravel, Bartok, Prokofiev or Rachmaninov. Maybe this is due to the technological evolution of the instrument. Today’s computerised control of registration offers the player much more possibility for rapid changes of colour, timbre and dynamic. Is it not likely that to Debussy, for whom colour was paramount, the instruments of the time seemed somewhat intractable?

Transcribing major orchestral works like Mahler symphonies is an extremely stimulating, if somewhat lengthy, experience. Because the organ is rather like a self-contained orchestra, the transcription could be, at best, rather like presenting an object in an entirely new light. I have been very much in love with Mahler No. 5 since playing it as a 15-year-old violist in the National Youth Orchestra under Sir Charles Groves. Inevitably, in making an arrangement for organ, one is obliged to make many choices – principally for those passages where there is simply so much going on in the orchestra that it is impossible to play it all with two hands and two feet. Working out exactly what is essential and what can remain ‘implied’ is a delicate procedure. In some ways, streamlining the orchestral texture doesn’t necessarily mean impoverishment of the musical content. The advantage of inputting the transcription directly into the excellent ‘Sibelius 7’ software is that it is possible to make modifications very easily after trying the music out on an organ, (in this case, the organ of Gloucester Cathedral

huge Mahlerian climaxes have an even more awesome quality. Since then I have also transcribed and recorded Mahler’s Sixth, Second, Eighth and Fourth symphonies.

where I was Director of Music from 1994-2002). These changes were generally registrational but sometimes involved structural reorganisation of counterpoint, including making octave transpositions etc. in order to make the music lie more comfortably under the fingers. Very many passages were completely reworked until the final result became convincing as an organ piece. If the transcription is too complicated, too difficult, the musical content will suffer anyway because the performance will sound awkward. That means that it is important to reach a clear and natural transcription of as many passages as possible. Registrational integrity and smoothness is essential in this symphonic repertoire. When I recorded Mahler Five I made extensive use of registrational ‘camouflage’ in order to try and cover up the stop changes. The generous Gloucester Cathedral acoustic helped, too! The transcription I made does not attempt to be a slavish imitation of the original Mahler orchestration, rather more of an adaptation. My aim was to give the organ the sonic character of a large orchestra. The organ, moreover, has a unique ability to sustain, particularly fortissimo, and thus the

Several important ingredients go into both the making and the performance of successful organ transcriptions. I always start from the full orchestral score and not a piano reduction. It’s perhaps surprising that, with Mahler’s symphonies, it’s not necessary to reduce too much, or to leave too much out. If you look at the sketches, things are often quite clear (and written for piano over three staves). The magic with Mahler comes, of course, from the subtlety of the orchestral colour, but with modern organ console technology and a degree of imagination it’s possible to replicate (or more accurately translate) this in a new medium. It’s important, too, not to make the transcription unplayable. I tend to find ways, through octave transpositions, reorganising of the voicing of the harmony, and so on, to make the music lie well under the hands and both feet.

Processing each note is a very time-consuming (and rather therapeutic) exercise – each bar requires a large amount of thought and this is a perfect way to get to know a score very intimately. The organist, of course, has four main advantages over the pianist, when it comes to performing orchestral transcriptions: a) the ability to incorporate either single or double pedal parts; b) more expressive potential through registrational colour and swell boxes; c) more possibility for sustaining intense orchestral crescendos; and d) very often performing in great cathedrals, where the acoustic and aesthetic ambience can add so much to the emotional impact of this music. Playing the last movement of Mahler Three at York Minster a while back, the effect of that matchless building on the music was breathtaking.

In making the transcriptions, I’m quite disciplined about including the composers’ original intentions for phrasing, articulations, and dynamic parameters. More than that, though, I leave to the integrity and free will of the performer. From the performance point of view, I always endeavour to adopt a registration scheme that has as much colour and vivacity as the orchestra, but not necessarily the same explicit colours. There are certain instruments we just don’t have, but I think with care it’s possible to create registrations that have the same emotional ambience, clarity, and contrast. One should try to imagine what Mahler would say if he were looking over your shoulder as you played.

My profound hope is that people will enjoy playing and hearing these re-castings of Mahler’s originals. This is highly

Processing each note is a very time-consuming (and rather therapeutic) exercise – each bar requires a large amount of thought and this is a perfect way to get to know a score very intimately.The quire and organ of Gloucester Cathedral

charged, emotional music that shows Mahler’s complete genius for creating a completely original soundscape, one which is instantly recognisable and completely inimitable –but still translatable.

The CDs of David’s transcriptions of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 and Symphony No. 8 are available from www.david-briggs.org

David Briggs obtained his FRCO (Fellow of the Royal College of Organists) diploma at the age of 17, winning all the prizes and the Silver Medal of the Worshipful Company of Musicians. From 1981-84 he was Organ Scholar at King’s College Cambridge, during which time he studied organ with Jean Langlais in Paris. The first British winner of the Tournemire Prize at the St Albans International Improvisation Competition, he also won the first prize in the International Improvisation Competition at Paisley. Subsequently David held positions at Hereford, Truro and Gloucester Cathedrals. He is currently Artist-inResidence at St James Cathedral, Toronto.

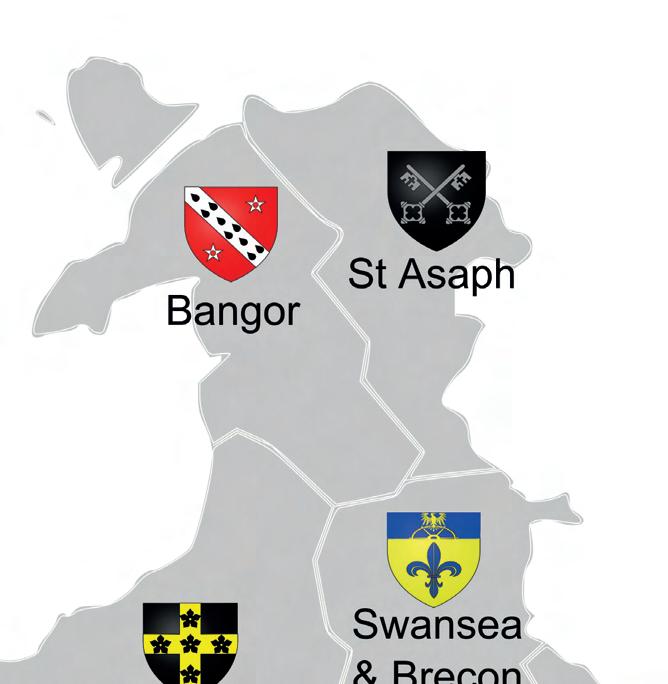

St Asaph is the smallest medieval cathedral in the UK, located in one of the six dioceses of the Church in Wales. More than 200 Anglican churches make up the family of the diocese of St Asaph – Teulu Asaph – which covers a large area of the North Wales coast, meeting the diocese of Bangor to the west, Chester and Hereford to the east and reaching south to mid-Wales and the diocese of Swansea and Brecon.

Saint Kentigern built his church here in AD560, returning to Strathclyde in AD573, leaving Asaph as his successor. Since that time the cathedral and diocese have been thus dedicated. With a population of around 3400, it was an honour for St Asaph to be awarded city status as part of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 2012. The present cathedral building, begun in the 13th century, is home to the William Morgan bible and has record of a cathedral choir as far back as the late 13th century. The roll call of organists begins in 1620 and for those who like a statistic or two, the current Bishop of St Asaph is the 76th Bishop, while I am the 26th cathedral organist. I have been based in Wales since 1999, serving first as Assistant Organist for five years and as Organist and Director of Music from 2004.

My time at St Asaph has been varied and creative, not least because I have striven to sustain and develop our musical

offering in what has been and continues to be a challenging time for the wider church. When I first arrived here as a parttime assistant organist, fresh from an organ scholarship at Liverpool’s iconic Metropolitan Cathedral, there was a choir of boys and men and the cathedral’s 4-manual Hill organ had just undergone a £250,000 major rebuild by David Wood of Huddersfield.

The dean and chapter at that time were bold in their keenness to offer the same musical opportunity to girls and so, as Assistant Organist, it fell to me to establish a cathedral girls’ choir. It has been fulfilling to see this project evolve and flourish over successive years, not least when one of our girls, who has subsequently returned recently to sing regularly as an alto lay clerk, reached the 2008 finals stage of BBC Radio 2’s Young Chorister of the Year held at St Paul’s.

I’m sure that I’m not alone among my fellows in saying that the most affirming part of being Director of Music is to witness the many talented boy and girl choristers achieve so much during their time in the choir stalls, seeing them grow musically and spiritually as individuals. In April 2016 one of our girl choristers, Hannah, thoroughly enjoyed her time representing St Asaph as part of the Diamond Choir in concert at St Paul’s and also taking part in the 2017 Decca recording.

Many of our choristers have gone on to further studies at university, achieving places on music degree courses at the Royal Academy of Music, Royal Northern College of Music and Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama.

I am often asked, “What have been the musical highlights experienced in your time at St Asaph so far?” and of course there have been many. Surprisingly, these high points can be often be when you least expect them, during a weekday Evensong in the depths of winter with a small congregation, for example, when they can occur quite spontaneously. These distinctive glimpses truly affirm the words of St Augustine: “Those who sing pray twice”, and encourage a renewed freshness in our roles.

My job description as Director of Music is broad, but in real terms I have always viewed it as ‘enabler and encourager’. To see our cathedral choirs involved in commercial CD recording ventures, live and recorded broadcasts for BBC national radio, as well as appearing in two televised broadcasts for BBC TV’s Songs of Praise from St Asaph, has been a real cause for celebration. Whilst helping the choir to reach a broader listening base, these occasions have applauded the gifts of our musicians and have been exciting, unforgettable experiences for each of our singers.

Reaching a wider community, whilst retaining a positive choir profile, has been vital for our continual recruitment of singers. It has been wonderful to see the choir relish concert opportunities to appear with The King’s Singers as part of the North Wales International Music Festival, with Russell Watson as part of his Candlelight Cathedral Tour, and recently with Aled Jones as part of his UK tour.

The composer Sibelius (1865-1957) stated simply that, ‘Music begins where the possibilities of language end’. No better phrase sums up so perfectly why music has been such an influence in helping people to worship, or clarifies this

essential need to continue in our music-making, despite the difficult and ever-prevalent challenges of finance and recruitment – worship is rightly so at the heart of our cathedral choir’s mission here.

We have two separate groups of boy and girl choristers who are drawn from all over the North Wales area, not just St Asaph itself: our youngest is seven and our eldest is 14. Tuition in reading musical notation and vocal production is built into our weekly training schedule, this latter being tailored to the progress of each individual child, and our repertoire ranges widely from Gregorian chant to music written by contemporary composers.

St Asaph’s doesn’t have its own choir school, which means that our choristers currently attend 11 different schools. Because of this geographical spread we are heavily reliant on our chorister parents to organise lift-sharing, and to battle the traffic on the A55 ‘expressway’ (what a misnomer...). As I’m sure is the case in many other music departments countrywide, it is their generous goodwill which enables us to continue.

It’s important for the choirs to have some well-earned downtime and to socialise, and we are lucky to have an active cathedral choir association which organises events for the choirs and their families and helps to raise valuable funds throughout the year to support our growth and development. It has generously funded the cost of many essential items including CD recordings and musical scores, purchase of choir robes, cloaks and polo shirts, and a piano for the song school.

This year we are celebrating 40 years since the formation of the association, so to mark this milestone we have commissioned a new Christmas carol for the cathedral choir, composed by Will Todd and to be premiered in December 2017.

We now have a well-equipped song school building which has recently undergone a £25,000 restoration, with new systems to replace the aged heating and lighting. The choir itself was pro-active in helping to raise these funds, which have made a significant improvement to our rehearsal and meeting facilities, administrative and robing areas, and the building is home to our music library.

As cathedral Organist, another question I’m often asked is, “How and when did you start to play the organ?” Undoubtedly, my principal early exposure to the sound of the instrument and subsequently my desire to learn to play it were from influences at school. The Liverpool Blue Coat School was fortunate in having two versatile pipe organs; each morning the Head would invite all students to sit for the organ voluntary. This daily time to remain quiet and hear some great playing, and a variety of colour, dramatic styles and textures, all had a huge influence on my musical development, as did the access to the great teaching staff there (in 2016 the school was ranked as the best school in the country based on its GCSE results).

cathedral choirs to parishes within the Teulu Asaph – some 30 visits to date, and we continue to promote our annual Evening Organ Recital series, which has attracted players and listeners from both the UK and abroad.

I’m certain that strong musical partnerships are vital to the outreach of church music and to secure growth for the future. During my time here I have always been keen to work collaboratively with other organisations, whether directing the cathedral choir at the inauguration and installation of the First Chancellor of Glynd r University, training choristers for the Mid-Wales Opera Company’s performance of Britten’s Noyes Fludde or a continuing involvement in the work of the RSCM.

Having then gone on to the RNCM to study organ, and receiving tremendous opportunities to learn from the teachers and performers there which went hand in hand with that, I have some concerns that in many places a lack of exposure to the organ must be detrimental in inspiring and securing future players. This point could easily also be made in respect of today’s young singers being exposed to the sound of our choirs; however, we should feel encouraged by the words of St David, who told his monks to ‘do the little things’ when attempts are made by us to redress the balance.

Our St Asaph response to St David’s words has included devising and delivering organ workshops for visiting Key Stage 2 and 3 pupils, in partnership with the cathedral’s School Visits Service, as well as co-ordinating regular visits of the

As I am chairman of the RSCM North Wales Area, I have many special memories of planning and directing all-age practical workshops and choral festivals, and also of serving as an examiner. In North Wales we have been able to welcome many very experienced musicians to direct events, such as Bob Chilcott, Mervyn Cousins, Andrew Reid, Barry Rose, John Rutter and Paul Leddington Wright.

Throughout my career I have been fortunate in having received a solid musical training. In September 2011, I became an Associate Lecturer at Canterbury Christ Church University and was able to share my skills as mentor. I taught both as part of the university’s BMus (Hons) degree course in Church Music studies and the joint RSCM foundation degree in Church Music studies. This involved maintaining regular contact with assigned students, visiting and assessing them in their placement parishes, preparing individuals for practical

Over the years we have received £24,500 in grants from the FCM, 1992 – £2,500, 1999 – £7,000, and 2009 – £15,000, all of which have been put to very good use.

performance at the residential schools and helping students with their selection of relevant repertoire choices and research study materials. All of this focused on excellence in choral directing, composition, organ performance, improvising, liturgy content and advanced performance skills.

It has been a great delight to be Diocesan Representative of FCM, helping to promote and support the essential national work of FCM within the St Asaph diocese, and to have been able to host a National Gathering of the organisation here in 2007. Over the years we have received £24,500 in grants from the FCM, 1992 – £2,500, 1999 – £7,000, and 2009 – £15,000, all of which have been put to very good use.

Being a chorister is a tremendous musical opportunity for a young singer, proven to assist in all-round educational development. The confidence that choristers gain through their committed service and through being part of a team who regularly perform together is well documented, and each will take pleasure in their friends’ successes.

In terms of my own service, I still have some way to go to match St Asaph’s longest-serving cathedral organist, Dr Harold Stocks. My mere 13 years at the console cannot match his healthy 39 years in post until his retirement in 1956, but the challenge of nurturing a creative environment to enable a weekly round of meaningful worship to continue offers a constantly renewing daily focus which I value enormously.

At St Asaph I have been very blessed.

choir training. At age ten, 12 of us were shortlisted for a trial and three of us were successful and joined the probationers. Dieter Pevsner, son of Professor Nikolaus Pevsner, Andrew Martindale and myself. As probationers we were placed next to senior choristers to learn the ropes. Among these experienced persons were Christopher Reason, later a notable bassoonist and organist, Professor of Harmony and Aural Training and finally Dean of the Royal Academy of Music, and Michael Mitchell, who was later a viola player with the LSO.

How fortunate we were to have such a wonderful director of music in Dr (later Sir Thomas) Armstrong, whose interest in us continued long after we left the choir. He had a profound influence on all of us. For a while Gavin Brown was his assistant (an ex-head chorister). He was later organist at Brighton Parish Church when my father was vicar of Brighton just after the war. He subsequently joined the staff at the Royal Academy. Allan Wicks was the organ scholar and later became Organist and Master of the Choristers at Canterbury after distinguished service at other cathedrals. One thing I will always remember about him was his ability as a jazz pianist!

At the outset of WWII my father, who had served as an infantry officer on the Somme on WWI, was recalled – this time as a chaplain – and sent to France. I was then seven and a half years old. My parents decided to send me away from London to Christ Church Cathedral Choir School in Oxford. It was a wise decision as our house was flattened during the Blitz. Needless to say, I was the youngest boy in the school, but I took to life there like a duck to water. It was quite clear that it would be a year or two before I would be given a trial to join the choristers, and there was no guarantee that I would be successful in gaining a place. However, we were all taught a musical instrument, the violin in my case, and given