CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Rodgers is proud to present the next generation of home and church organs from our Inspire Series. Born from the dream of enhancing spiritual experiences at churches all over the world… Born from the dream of homes filled with exquisite musical sounds... Born from the dream of bringing this experience within reach of anyone... All created because we believe in that dream.

Rodgers is proud to present the next generation of home and church organs from our Inspire Series. Born from the dream of enhancing spiritual experiences at churches all over the world… Born from the dream of homes filled with exquisite musical sounds... Born from the dream of bringing this experience within reach of anyone... All created because we believe in that dream.

The Rodgers Inspire 233 and the smaller 227 are designed for those who believe in dreams.

The Rodgers Inspire Series 227 and 233 organs are designed for those who believe in dreams. www.rodgersinstruments.com

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November.

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2018

Editor Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ editor@fcm.org.uk

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon pm@fcm.org.uk

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: +44 20 3637 2172 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

Cover photographs

Front Cover

Interior of Hereford Cathedral showing the corona

Photo: Doug Betts

Back Cover

Guildford Cathedral

Photo: David O Photo

Most CM readers know that 2018 marks the centenary of the death of Hubert Parry, an outstanding figure in the musical world, an inspiration to his students and a free-thinker of some note. His outlook, remarks Michael Trott, a lifelong enthusiast and author of Hubert Parry: A Life in Photographs, was characterised by a perpetual quest to ‘understand life in its complexity and a sense of the spiritual beyond orthodox religion’. This calls to mind another composer featured in these pages, James MacMillan, whose 60th birthday approaches next year. Phillip Cooke, himself an important composer and most likely familiar to many from recordings made of his music by the college choirs of Selwyn (Cambridge) and Queen’s (Oxford), looks at MacMillan’s early life and at his prodigious choral output. As with Parry, MacMillan’s secular works are as numerous and important as his sacred compositions, though it has to be said that no piece of Parry’s was ever live-streamed from the Sistine Chapel, as happened to MacMillan’s Stabat Mater

One of the Gatherings planned for 2020 is to be in Dublin, and it is hoped that a myriad FCM members will make the journey to the Fair City and enjoy St Patrick’s and Christ Church cathedrals, the surrounding Georgian architecture and the brilliant museums and libraries. Stuart Nicholson, Master of the Music at St Patrick’s, discusses the joys of musicmaking in Dublin, the lusty singing of his boy (and girl) choristers, and the different tunes for Hark! the herald Angels

sing... (Whilst writing about Christmas, may I remind you to buy your FCM Christmas cards now – one of the designs is of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin – all proceeds from sales of the cards will, as always, help to support choirs and cathedrals in need.)

Greg Morris, Associate Organist at Temple Church, has recently been entertaining London audiences with his series of 28 concerts in some of the capital’s most iconic ecclesiastical buildings. Entitled ‘Complete Bach’, the concerts have encompassed all the surviving music written by the great composer for the organ. Read how Greg decided what pieces to include, what to play with what and which organ would best suit which music. Which would be the most suitable churches to choose...? Temple was the base, of course, even though the organ only dates back to the 1920s, but thanks to Harrison & Harrison it copes with Bach remarkably well. Other churches included Southwark Cathedral, St Martin-in-the-Fields, St Paul’s and the relatively tiny St Matthew’s Westminster.

In September I went to marvel at an extraordinary library of books and manuscripts gathered over the years by a great enthusiast of such things, Gervase Duffield. Amongst the literary tomes of a recent purchase were collections of various canticles for morning and evening services specially bound many years ago for use by the choir at St Asaph’s Cathedral. Their condition could be described as ‘used’, but since one of the library’s specialities is rebinding old and valuable books, any parties interested in purchasing these volumes could take advantage of this option at a favourable price. Email editor@fcm.org.uk if you would like to know more; there are approximately 50 identical volumes, with composers ranging from Jeremiah Clark to Stainer.

Enjoy the magazine.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

•welcome pack

•twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

•‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

•attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

•meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

•enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £4 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

Amajor anniversary seems as good a reason as any to assess the life and work of a composer, with a 60th anniversary perhaps the most auspicious celebration: it is not bound up with youth, nor early promise, nor is it the grand retrospective that comes with much later birthdays. James MacMillan, who will be 60 in July 2019 and who holds an enviable position at the forefront of British music, is one of our most successful, most recognisable and most gifted composers. It seems an appropriate time to evaluate his career, his oeuvre and his impact on the wider world.

MacMillan was born in Kilwinning, Ayrshire, in south-west Scotland on 16 July 1959 to a teacher and a carpenter, with the family moving to the larger nearby town of Cumnock in 1963. Music was always present in the MacMillan household, largely because of James’s maternal grandfather, the young composer’s first musical influence, who took MacMillan to brass band rehearsals and bought him his first instrument, a cornet, in 1968. There was a wide variety of music-making taking place in Cumnock which MacMillan was directly or indirectly involved with, ranging from visiting professional ensembles (such as the Berlin Octet) to local amateur operatic and oratorio societies which gave performances of Handel and Gilbert & Sullivan, amongst other standard fare. MacMillan attended St John’s Roman Catholic primary school in the centre of the town before moving to Cumnock Academy for secondary education in 1973, and it was at this latter school that his musical abilities began to take shape. Under the watchful eye of the Head of Music, Bert Richardson, MacMillan began to flourish as a composer, drinking in Richardson’s own interests in Renaissance church music as well as his teacher’s espousal of the leading Anglican composer of the time, Kenneth Leighton (who was a friend of Richardson). It was whilst at secondary school that MacMillan’s first choral work was performed, the Sanctus from the Missa Brevis of 1977, with a more public performance at Paisley Abbey by the choir and their legendary director of music, George McPhee, coming shortly after.

MacMillan’s interest in Leighton took him to Edinburgh University in 1977 to study for a bachelor’s degree, and during his study there numerous choral works began to appear. Many of these early pieces (which the composer has recently rediscovered and had published) show his commitment to the Catholic faith, one of the most significant influences on his life and works, and something that has become synonymous with him as his career has progressed. However, like many composers studying at the time, choral music was not the primary concern, and MacMillan’s chamber and instrumental works of the period show the influence of Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle, then at the vanguard of British contemporary music.

Following his time in Edinburgh, MacMillan ventured south of the border to study for a PhD with John Casken at Durham University, Casken being one of the foremost composition teachers of his generation and a strong influence on MacMillan’s future works.

Perhaps the most pivotal moment in MacMillan’s career was in 1988 when, following PhD success and a short tenure as a part-time lecturer at Manchester University, he returned to his homeland and to married life in Glasgow. Soon after his return to Scotland some of his most exciting early

works came into being, including Into the Ferment, Tryst, Búsqueda and Cantos Sagrados (one of the first mature works of MacMillan’s to feature a choir). He began to form strong links with Scottish orchestras and ensembles, gaining his ‘big break’ from a commission from the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra for the 1990 Proms. The work which thrust him into the compositional spotlight was The Confession of Isobel Gowdie, a piece which is still his calling card to this day. The mix of dramatic and violent orchestral eruptions with softly unfolding modal lines, all carrying the influence of Scottish traditional music, was an instant hit with audiences, and this mixture has characterised MacMillan’s music ever since. He followed Isobel Gowdie with other notable pieces, such as The Berserking (a piano concerto inspired by a Glasgow Celtic match, football being one of his great passions), Tuireadh (dedicated to the victims of the Piper Alpha disaster in 1988), and the percussion concerto Veni, Veni, Emmanuel, his most performed orchestral work. By the mid-1990s MacMillan was one of the most prominent composers in the UK, with major commission following major commission for many of the country’s top orchestras and ensembles.

It is a work from 1993 that has perhaps had the greatest impact on his future compositions and which is a rival to Isobel Gowdie for the composer’s most significant piece: his cantata Seven Last Words from the Cross that was commissioned by BBC Television for Holy Week in 1994. Recognised by many to be MacMillan’s masterpiece, Seven Last Words has long since outlived its initial broadcast to be one of the most enduring of the composer’s works, constantly finding new admirers and devotees on both sides of the Atlantic, and further afield. MacMillan’s combination of the traditional gospel texts that form Jesus’s last words with specially chosen passages (largely from the Good Friday liturgy) to emphasise and comment is a masterstroke, and gives the work a greater depth and nuance than other settings. From the plangent opening chords to the declamatory outbursts of the second movement, to the violence of the sixth and the ultimate redemption through an instrumental threnody in the final movement, Seven Last Words from the Cross is MacMillan at his finest, and it is rightly lauded as one of his best pieces.

MacMillan’s Catholicism has influenced all aspects of his composition from the smallest choral work to the largest orchestral statement, with the grandest potentially being the Triduum: three inter-connected orchestral works relating to the narrative of the Easter sequence that was written between 1995 and 1997. Maundy Thursday is expressed through a concertante cor anglais work, The World’s Ransoming, where this

MacMillan is somewhat unusual in the British music scene for having success and respect across different genres, from intense chamber works to heartfelt songs to vivid orchestral tableaux.

melancholy woodwind instrument weaves its way to a forceful denouement. Good Friday is represented by a spiky cello concerto with echoes of Shostakovich, and Easter Sunday sees MacMillan embracing symphonic form for the first time in a bold and powerful end to the triptych. Further large-scale works followed, including the oratorio Quickening (1999, with shades of Britten’s War Requiem), a Second Symphony (also 1999) and the dazzling tone-poem for orchestra and optional chorus The Birds of Rhiannon for the 2001 Proms.

The new millennium found MacMillan beginning to explore choral music in earnest for the first time since his Edinburgh days, the result of this being an outpouring of works for choir. There are some colourful and dramatic liturgical works, including a through-composed Mass for Westminster Cathedral choir from 2000, and a set of evening canticles that was commissioned for the first Choral Evensong of the new century. There are two books of The Strathclyde Motets that MacMillan composed between 2005 and 2010, which are mainly settings of communion motets for choirs of differing abilities but feature also one of his most easily achievable choral works, O Radiant Dawn. Much of the groundwork for the motets took place during MacMillan’s time as director of music at St Columba’s Church in Maryhill, Glasgow, where he worked with singers of little or no musical training to bring new and beautiful music to the weekly liturgy. His most popular works for choir are a trio of pieces from before this choral epiphany which represent some of his most successful and heartfelt offerings in the medium: Christus Vincit (1994), A Child’s Prayer (1996) and A New Song (1997). These three works show MacMillan at his most intimate and direct, from the long, floating lines of Christus Vincit to the poignant memorial that is A Child’s Prayer (it was written in memory of the victims of the Dunblane Massacre) to the unleashing of heavenly glory at the end of A New Song: all three works have

found a place in the repertoire of both church and chamber choirs and will no doubt remain there.

MacMillan’s works for choir haven’t been solely reserved for smaller-scale, unaccompanied pieces – he has also written a succession of oratorios and other grand choral works in the past 15 years. Perhaps the most celebrated are his two Passion settings, St John (2007) and St Luke (2013), which have carried on the dramatic and visceral world of Seven Last Words with no less energy or impact. The St John is more traditional and bigboned, with a baritone soloist pitted against semi-chorus, large choir and orchestra in a colourful narrative. The St Luke is more concise; the soloist of its predecessor is replaced with an ethereal children’s choir and a reduced orchestra, reflecting the composer’s desire for the work to appeal to amateur choirs and societies. It is MacMillan’s intention to complete the quartet of gospels in his later years with a St Mark for choir and organ, and a St Matthew for unaccompanied voices. But his oratorios haven’t been reserved for Passion settings only. A highly acclaimed Stabat Mater, using the same forces as Seven Last Words and beginning to garner some of the same praise as its predecessor, received its premiere in 2016. The piece recently had the accolade of being the first work to be ‘live-streamed’ from the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, in a spell-binding performance by The Sixteen and the Britten Sinfonia.

MacMillan is somewhat unusual in the British music scene for having success and respect across different genres, from intense chamber works to heartfelt songs to vivid orchestral tableaux. Recent successes, aside from those for choral forces, have included the grand opera The Sacrifice (a Welsh National Opera commission from 2007), the more intimate retelling of Abraham and Sarah in the chamber opera Clemency (2010), and a host of characterful concertos for violin, viola, oboe,

trombone, saxophone and percussion that have appeared in the past ten years. His works (all issued by MacMillan’s longterm publisher, Boosey & Hawkes) range from the purely abstract to the vividly programmatic, with multiple recordings and broadcasts accompanying each one.

Much of the composer’s recent energies have been directed towards the foundation of The Cumnock Tryst, a music festival taking place in and around his home town which began in 2014. This has also led to MacMillan returning to south-west Scotland to live. The festival has brought many of the world’s leading performers to this unheralded part of the country to give performances of pieces old and new, including works by composers from the area supported by MacMillan. Naturally there are concerts of MacMillan’s work aplenty too, performed by, amongst others, Nicola Benedetti, The Sixteen and Westminster Cathedral choir, who have all recently given highly memorable performances.

As he reaches his 60 birthday, plaudits will no doubt appear from around the globe to celebrate MacMillan and his

continued success on the compositional stage, both at home and abroad. He is a visible presence not just as a composer but as a conductor, an educator, an artistic director and a powerful voice on the arts and faith in the wider media. Perhaps the greatest accolade that can be given to MacMillan is that he is someone who people actually listen to, not just as a successful composer but as an important voice in society, who holds the political classes to account and supports injustices in equal measure. In a world where contemporary classical music becomes more and more marginalised, it is important to recognise the achievements of those individuals who make a difference, and in this regard, as in so many others, James MacMillan is a composer of true importance. Dr Phillip Cooke is active as a

regular

Sixteen, the

Singers

many

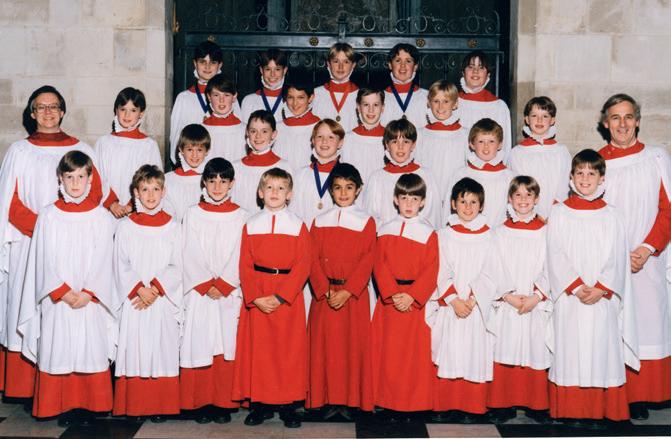

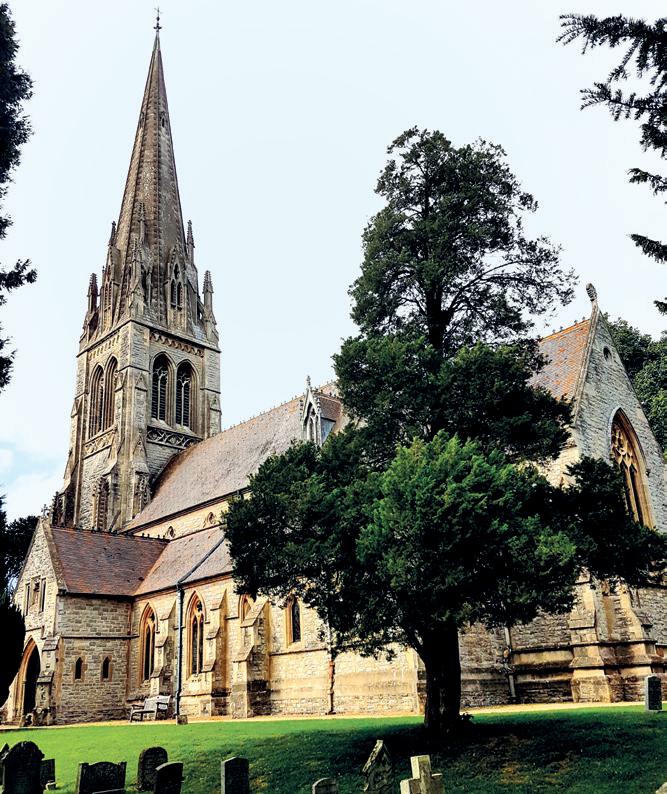

St Andrew’s Cathedral in Aberdeen is the seat of the Bishop of Aberdeen and Orkney and is one of seven cathedrals in the Province of the Scottish Episcopal Church. The current building (the nave of the cathedral) was completed in 1817. The roots of the present congregation go back to the time when they were forced out of the two ancient churches, the Borough Church of St Nicholas and the Cathedral Church of St Machar, for their loyalty to the deposed King James VII (James II of England). A number of meeting houses were used before John Skinner built a house in the Long Acre in 1776, the upper room of which was used as a secret chapel. It was in Aberdeen on 14 November 1784 that Samuel Seabury of Connecticut was consecrated Bishop for America, the first bishop outside the British Isles of what we now call the Anglican Communion. St Andrew’s became the cathedral church of the diocese in 1914.

There has always been a strong musical tradition in the cathedral but as the Scottish Episcopal Church is only the third largest church after the Presbyterians and the Roman Catholics, funding has always been tight. There are modest salaries and honoraria for myself as Organist and Master of the Choristers, the Organ Scholar or Assistant Organist and choral scholars, and pocket money for the choristers. Funding for new music is agreed by the cathedral trustees on an ad hoc basis. Other than this, the choir is run by unpaid volunteers and helpers, keeping the entire annual budget (excluding tours) to under £10,000.

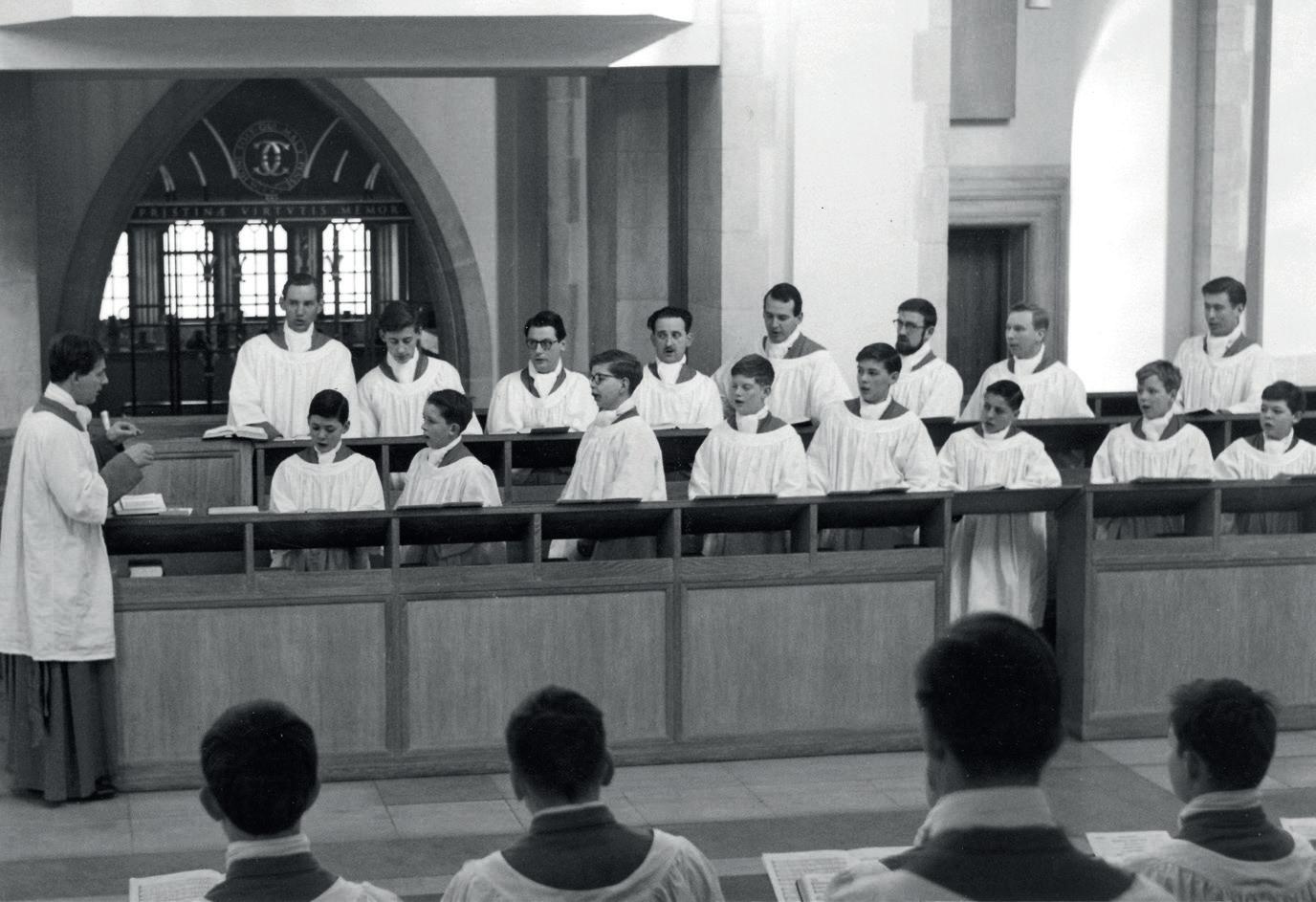

The pinnacle in recent times was when John Cullen was Director of Music in the 1960s. John was Head of Music at Aberdeen Grammar School and therefore had a ready supply

Morrisson

Morrisson

of boy choristers. He was given excellent support by the then Provost Patrick Shannon, and elements such as the use of Russian Orthodox liturgical music and the very popular Advent carol service were introduced for the first time. There are a number of excellent recordings of music for upper voices from that era.

After John Cullen’s departure a few organists came and went, and the choir waned somewhat. It was given a new lease of life by my predecessor Geoffrey Pearce, and it was Geoffrey who invited me to become his assistant. I had studied the organ with Dr Edgar Brice at Brentwood School in Essex where there was a fine 2-manual Willis organ. Music took a back seat while I studied for a chemistry degree at Imperial College. A plan to stay on for a doctorate took an unlikely turn when my supervisor announced he had accepted a new appointment in Aberdeen. A quick consultation of the atlas revealed that Aberdeen was on the north-east coast of Scotland, quite a long way north of Edinburgh. I followed him to do my doctorate, but a proposed three-year stay in the Granite City has lasted slightly longer!

When Geoffrey moved to Bridlington Priory in 1983, I was appointed to take over as Organist and Master of the Choristers. By careful befriending of those in charge of the lecture timetable I was able to combine lecturing in chemistry at Robert Gordon’s Institute of Technology (now Robert Gordon University) with my role at the cathedral. The choral pattern was two trebles practices during the week and a Sung Eucharist and a Choral Evensong on a Sunday. Midweek sung services were confined to major feast days. This pattern has remained largely constant over the years but has expanded as resources have allowed. Additional Wednesday Choral Evensongs and Friday Sung plainsong Complines have been a feature recently.

During the 1990s the choir thrived as a boys’ and men’s choir with over two dozen choristers and a full back row. This was a golden age for cathedral music in Scotland with fine boys’ and men’s choirs also in Dundee, Perth and Inverness, the flagship being St Mary’s Edinburgh where daily services are the pattern. The Scottish cathedral organists were given great support by Dr Dennis Townhill from St Mary’s who met us regularly and arranged joint services in Edinburgh.

After 2000, the number of boy choristers began to decline. The usual pattern of school recruitment visits continued to

engender enthusiasm, but without parental backing this effort proved increasingly fruitless. Help was around the corner when a link was established with a local private school with the support of the charismatic head of music, Adam Kirkcaldy. I took weekly evening rehearsals at the school and he bussed the choristers in on a Sunday. There were some excellent singers and this worked well until he moved on.

I had always fought to maintain the traditional boys and men set-up, but it was clear that there were a number of girls eager to become involved. It was agreed that they should be given an opportunity, and a girls’ choir was formed in 2003. Initially one or two services a month were designated for girls’ voices, but as they became more proficient this increased.

A decline in the number of boys meant that to maintain standards, the boys and girls were combined in 2007. Although this was a reluctant move on my part, it has proved a successful strategy. Numbers are buoyant, the balance of boys to girls has been largely maintained and the quality has seen a step change in achievement.

One interesting feature resulting from Aberdeen’s oil industry has been the increasing population of West Africans in the city. Many of these come from an Anglican background and they form a significant proportion of the cathedral congregation. It means that recruitment of choristers now comes almost exclusively from the congregation. Parental support is strong,

although their concept of timekeeping can be a little different from mine!

When I was appointed there was a thriving music department in Aberdeen University run by Reginald Barrett-Ayres. For ten years I was spoiled with assistant organists of high calibre, two of whom are now directors of music in English cathedrals in their own right. The university’s music department subsequently closed due to cutbacks in funding, which meant more unaccompanied music was required, and willing members of the back row conducted while I played.

Happily, the music department has reopened and has even seen a resurgence in recent years. I have had some excellent organ scholars/assistant organists who have moved on to greater things. The acclaimed composer Paul Mealor is a strong supporter and his music features widely in the repertoire. This includes his Seabury Mass written for the choir which is a strong favourite with the trebles and congregation and can be heard on YouTube.

A highlight of the choir year throughout my tenure has been the tours. These focus mainly on singing the week’s services at cathedrals across the UK. Over the years we have sung in more than 40 cathedrals in the British Isles as far afield as Truro, St Davids and Canterbury. We have just returned from a most enjoyable week at Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford. We are very grateful to the FCM Diamond Fund for Choristers for

financial assistance for some of our choristers to participate in this tour. The tours serve a number of functions. As we do not meet daily, they perform a vital role in team-building among the trebles and help to integrate the newer members. They also serve as an alumni event, allowing former members to either join the singing or attend the services. Tours abroad to the United States, Germany, Holland and Sweden have also taken place but cost has limited these opportunities.

The organ is modest in proportions but is one of the oldest in Scotland in regular use for worship. It was built by Muir, Wood & Co. of Edinburgh and opened on 30 August 1818. It has since been rebuilt and enlarged, most recently by Hill, Norman & Beard in 1983. We are in the middle of a series of recitals to commemorate the bicentenary.

Over 15 years ago my then assistant proposed a series of lunchtime recitals on Saturdays at noon. Although I was sceptical at first, after these had been running for a few weeks it became apparent that there was an appetite for such events. The series was extended and now runs every Saturday of the year (including Christmas Day if it falls on a Saturday!). The concerts’ main aim is to give performing opportunities to students, and they feature a variety of performers focusing mainly on organ and vocal music.

waiting list for next summer’s visits. We are again grateful to the FCM Diamond Fund for Choristers for financial support towards our chorister outreach.

Over time, the choir’s repertoire has changed. In the early years, settings by old favourites prevailed: Stanford, Noble, Sumsion, Harwood. In more recent years, my tastes have altered, and you are just as likely to hear Byrd, Gibbons, Weelkes and Tomkins with anthems by Victoria, Palestrina or Lobo. Also, many contemporary works are performed, as opportunities are given to students to showcase their compositions.

Aberdeen University recently moved its main weekly Chapel service from Sundays to Wednesdays. This has meant that university students are now available to sing at the cathedral on Sundays. Three years ago, the cathedral agreed to fund six choral scholarships and we have benefited enormously from the choral scholars’ input.

One feature that has been introduced in the last few years is the use of the RSCM Voice for Life training scheme for the trebles. Optional drop-in sessions are held prior to trebles practices where help is available as the choristers track their way through the Voice for Life workbooks. This is also good preparation for choristers wishing to take the RSCM bronze, silver and gold awards. We have recently received a grant from FCM’s Diamond Fund for Choristers which will enable us to provide additional vocal tuition for the choristers.

Another recent innovation has been to take Evensong into the diocese during the summer months. On every Sunday for five or six weeks we sing a Choral Evensong in one of the country churches. Congregations are large and enthusiastic, and the singers are rewarded richly with tea and cake. There is even a

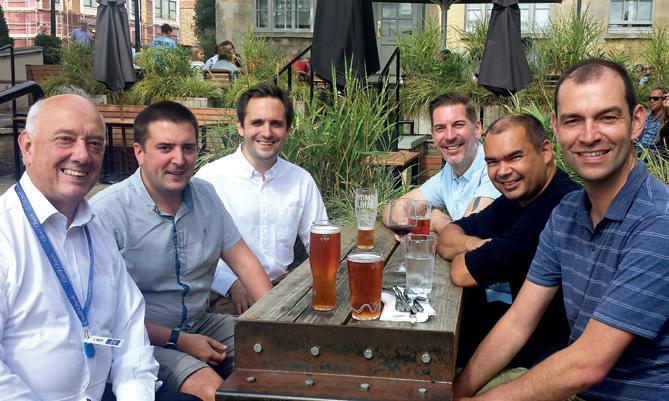

The lay clerks are all voluntary and there is a long list of deputies that I draw from to try to ensure that the back row is full. Countertenors are few and far between in the area and about ten years ago the decision was taken to invite ladies to sing alto. This has been a very positive move and they have integrated well, both musically and socially. As with most cathedral choirs, beer is an essential ingredient, both to restore the vocal cords and also socially – lay clerks’ ‘meetings’ are held after every Evensong in the Old Blackfriars across the Castlegate from the cathedral.

Our Head Chorister, Lewa Olaosebikan, has immensely enjoyed participating in the FCM Cathedral Choir of Britain events: the concert and subsequent recording in St Paul’s Cathedral, under the directorship of Andrew Carwood. Being so far from other cathedrals with treble choirs, it was an excellent opportunity to meet other choristers and compare notes.

In recognition of the importance of music in the cathedral, an outbuilding which was previously leased as a visual arts studio has been designated as a new Song School. The building requires significant work to upgrade the heating, electrics and the decoration and we are desperately trying to raise money towards it. I am particularly grateful to FCM and also choir alumni for their financial support in this venture.

As I complete 35 years in post, I look to the future and to my potential successor. We are grateful to FCM and anonymous benefactors for three years of bridge funding to enable the cathedral to increase the salary of the Director of Music post for my successor. Being Organist and Master of the Choristers has been a most fulfilling experience with endless opportunities and I have received excellent support from the clergy and congregation. I hope that the cathedral music will thrive for decades to come.

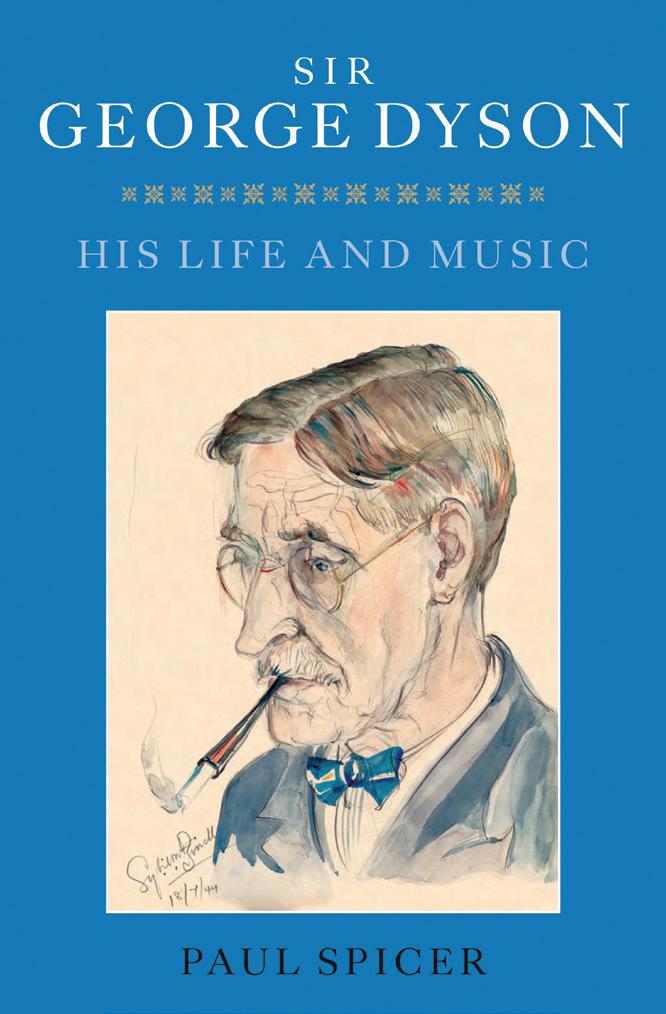

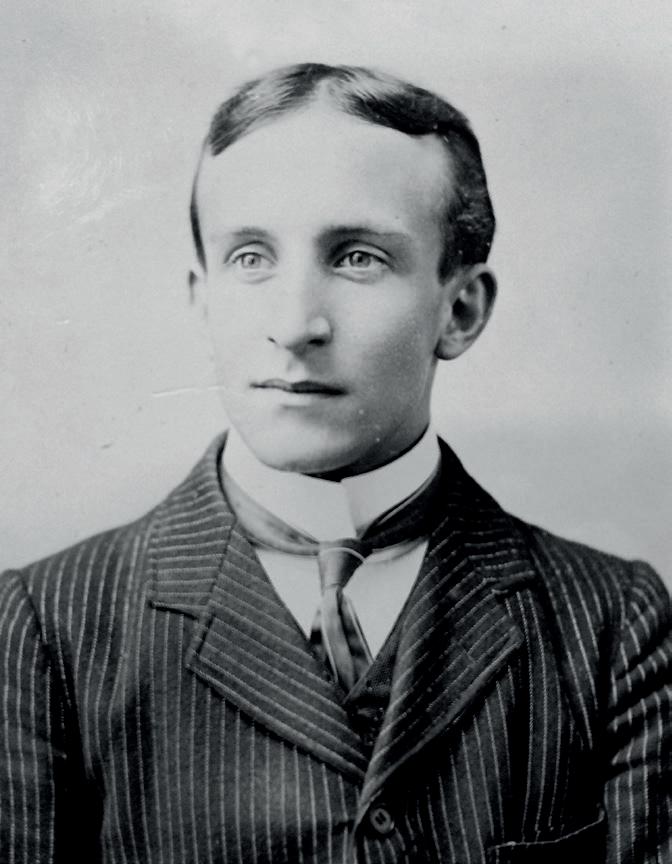

George Dyson (1883-1964) was a highly influential composer, educator and administrator whose work touched the lives of millions. Yet today, apart from his Canterbury Pilgrims and two sets of canticles for Evensong, his music is little known. He rose from humble beginnings to become the voice of public school music in Britain and, while a scholarship student at the RCM, he met and studied with some of the leading musicians of the day, including Charles Villiers Stanford and Hubert Parry. He went on to work in some of the country’s greatest schools, where he established his reputation as a composer, particularly of choral and orchestral works, of which Quo Vadis (a choral cycle of poems) was his most ambitious. A member of the BBC Brains Trust panel, Dyson was also the ‘voice of music’ on the radio for a number of years and helped to educate the nation through his regular broadcasts.

A fascinating, controversial man, George Dyson touched almost every sphere of musical life in Britain and helped to change the face of music performance and education in this country.

Dyson was born in Halifax in 1883 and was one of the most important British musicians of his day. Coming from a solidly working-class family (his father was a blacksmith carrying out his trade in one of the great Halifax engineering companies), George had his first musical experiences at the local Baptist church where his parents were regular members. His early talent was quickly recognised and he won a Foundation Scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London aged only 16 to study organ, first, and composition later (with Stanford). After this he returned to the college as the first alumnus to become its director (1938-1952).

Following a highly formative Mendelssohn Scholarship period in Italy and Germany, he came back to England to begin a long career as a school teacher. Sir Hubert Parry recommended him for his first appointment at the Royal Naval College, Osborne, which had been founded to double

the number of cadets entering the Navy in prevision – though this was not known at the time – of the world hostilities to come. Dyson’s appointment was something of an experiment as music was the last thing on most people’s minds in such an establishment. In reality, he had quite a lot of time to himself and he determined to use it profitably. He knew that if he wanted to progress to the greater public schools he would need a degree in music, preferably from Oxford or Cambridge, so he enrolled as a non-collegiate student at Oxford and took his BMus successfully in 1909, moving straight on to the DMus which was conferred in 1917. It was for this examination that his Choral Symphony was written. The work was unknown before the research I undertook for his biography, and it was a remarkable and exciting discovery in the Bodleian Library at Oxford (see review on p62).

Dyson called the symphony Psalm CVII Symphony (for solo, chorus and orchestra) and Overture. Psalm 107 is a dramatic telling of the expulsion of the Jews from Israel by the Babylonians. The Jews had been imprisoned for 70 years before being able to return home. The psalm tells the story of their wrongdoing, their prayers for forgiveness, God’s mercy, their treacherous journey home by sea, their rehabilitation in their homeland, and their praise to God for safe deliverance.

What is remarkable in this work is Dyson’s obvious command of a really large-scale structure. In all likelihood he chose Psalm 107 because of its variety of dramatic images and its suitability for breaking down into a four-movement format. The first movement opens with a lengthy orchestral overture which sets the scene and presents the thematic material for the whole first movement. The main choral movement follows without break. Here he presents some of the trademarks which make his later works so attractive: the sense of musical line; the Parry-like use of strongly contrapuntal interplay between voices; an inherent sense of drama, especially his ability to work a long paragraph up to an exciting climax, often using constantly increasing tempi to build tension;

and his ingenious use of imaginative harmony at key points. There are extended sections scored for double choir in two formations: SSAATTBB and SATB/SATB.

The last movement begins as a seascape, taking its cue from the words: ‘They that go down to the sea in ships, and occupy their business in great waters; these men see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.’

Dyson so often came into his own when setting sea-related texts, as can be seen in another work of his, St Paul’s Voyage to Melita. In this last movement he sets out with a figure instantly recognisable as a ‘turbulent sea’ motif and closely related to the third movement of Debussy’s La Mer – Dialogue du vent et de la mer. The movement builds to an incandescent climax close to the end with a wonderful breadth of expression, and ends emphatically with two linked but declamatory orchestral chords.

The second movement is in C minor, which is a big aural leap from the E major ending which precedes it. It is an uneasy Allegro agitato ma no troppo in 6/8 which takes its cue from the text (verses 4-8): ‘They went astray in the wilderness out of the way, and found no city to dwell in.’

The third movement moves to A minor and is marked Largo. It begins with a plangent theme for violins which play in unison for the first 16 bars, pianissimo or ppp. The music reflects the darkness of the image: ‘Such as sit in darkness and in the shadow of death’. The final section is a remarkable transformation into a broad, triumphant progression in the major before subsiding into a quiet ending.

By the 1930s Dyson had enjoyed considerable success with two very different choral works: In Honour of the City and The Canterbury Pilgrims. This last, hugely enjoyable work was performed all over the world and was conducted at least 35 times by Dyson himself. It was inevitable that after these successes the Three Choirs Festival would ask Dyson to compose a new work for them. He responded with St Paul’s Voyage to Melita for the 1933 Festival at Hereford and conducted the performance himself. Dyson chose the dramatic story from chapter 27 of the Acts of the Apostles which tells of St Paul’s remarkable journey to Rome up to the point of his shipwreck on the island of Malta (Melita). Paul had been warned about possible trouble if he visited Jerusalem, but he insisted on going, even if it led to his death. On his arrival, word had spread that he preached to both Gentiles and Jews, which led to a riot which caused his arrest. Paul invoked his right to be judged by Caesar himself in Rome, and so his long journey began. The irony was that King Agrippa had had a mind to release him had Paul not appealed to Caesar in this way. But the die was cast and so began the journey which ended in shipwreck but the miraculous saving of all hands.

These two major choral works show Dyson’s originality and mastery of the form. In following this path he gave us a whole series of dramatic choral and orchestral works including Nebuchadnezzar, The Blacksmiths, Agincourt, Sweet Thames run softly, Hierusalem, and biggest of all, Quo Vadis?Royal College of Music, Photo: Jeffery Johnson

Here, then, was another dramatic text for Dyson to set. The critics were bemused by Dyson’s choice and The Times noted that, ‘His music is neither oratorio in the accepted English sense of the term nor anthem, but narrative without comment.’ Audiences at these festivals were used to oratorios with a moral to be preached rather than simple drama for its own sake. They found the new approach difficult to understand or accept. But Dyson, who was not a religious man, loved vivid texts from which he could conjure Technicolor musical images. Also, as found in the early Choral Symphony, he could create large-scale structures which unfolded seamlessly through a rare ability to navigate long paragraphs with great strength of purpose. Additionally, his imagination as an orchestrator was second to none (his Oxford doctoral orchestration exercise was returned to him by the professor of music because it was so highly regarded) and is put to the greatest test in this work.

St Paul’s Voyage is scored for normal symphony orchestra with wind doublings, tenor solo and chorus. Ominous brass chords open the work and a semi-chorus delivers a choral recitative which begins the story: ‘And when it was determined that we should sail into Italy, they delivered Paul and certain other prisoners unto one named Julius, a centurion of Augustus’s band.’

Mournful seagull calls set a bleak scene and seem to be a portent of disaster to come. But the unexpected warmth of the arrival at Fair Havens, a harbour on the south coast of Crete, is reflected in Dyson’s richly coloured harmony. The weather was now becoming increasingly uncertain as it was late in the season, but the decision was taken to sail on and soon the dreaded name of the north-easterly hurricane-force wind, Euroclydon, was on everyone’s lips. The storm music begins – violent waves, eddies, troughs and peaks. The ship begins to break up, and ropes are passed underneath to bind it together. Dyson very effectively uses augmented chords to describe the crew’s sense of panic. Paul assures them, in a passage of dramatic recitative, that all will be well and that no one will be lost. Land nears, and in an almost imperceptible change of rhythm from 3/4 into 9/8, Paul urges them to eat so that they have energy for the final scene. The ship is run aground but the guards want to kill the prisoners in case they escape. Dyson’s use of jagged, stuttering chords mirrors the terror of the moment. Finally, the centurion orders everyone to save themselves and the choir rises to an exultant, climactic moment in the phrase, ‘And so it came to pass that they escaped all’, and the music subsides to end on a unison C for strings and bells.

These two major choral works show Dyson’s originality and mastery of the form. In following this path he gave us a whole series of dramatic choral and orchestral works including Nebuchadnezzar, The Blacksmiths, Agincourt, Sweet Thames run softly, Hierusalem, and biggest of all, Quo Vadis? All deserve to be reinvestigated and to become once more an important part of our choral landscape. More than this, the Choral Symphony should be widely taken up and performed as an alternative to the other great maritime work of the period, Vaughan Williams’s A Sea Symphony

The CD of these two pieces, sung the Bach Choir and soloists, with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra and David Hill, is available on the Naxos label.

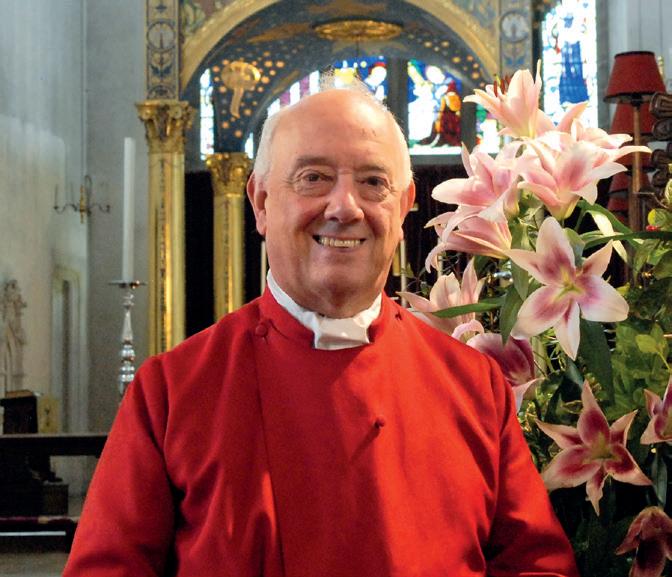

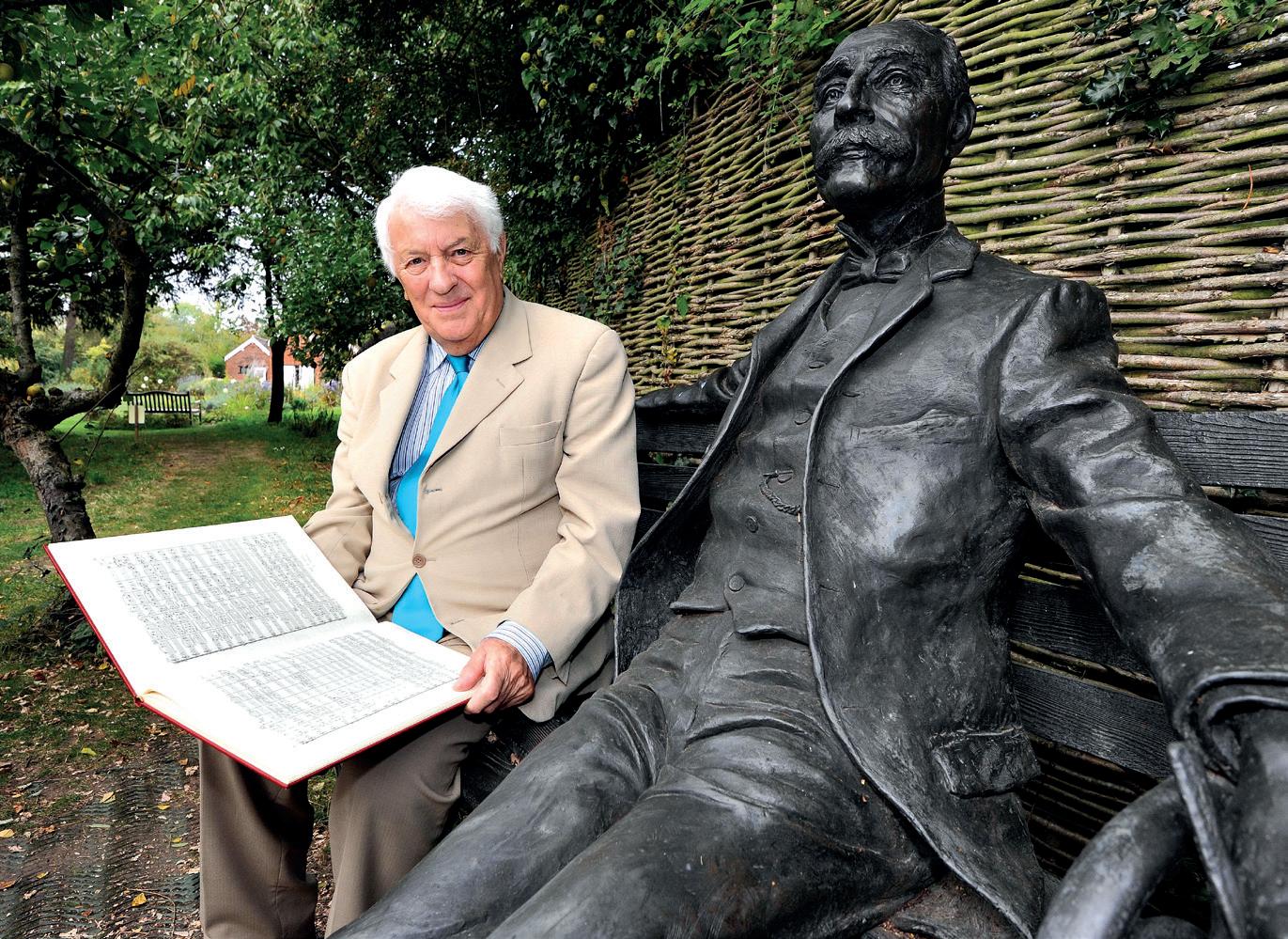

Paul Spicer was a composition student of Herbert Howells, whose biography he wrote in 1998. He is well known as a choral conductor especially of British music of the 20th century onwards, a writer, composer, teacher, and producer. He is a regular guest conductor with the BBC Singers and he taught at the Royal College of Music until 2008. He now teaches choral conducting at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, and at Oxford and Durham universities. He runs choral workshops all over the world and is in considerable demand as a composer and recording producer. His biographies of Howells and Dyson were received to great acclaim, and he is now working on a biography of Sir Arthur Bliss.

From the very beginning, the church had a fine musical tradition. It had an ambitious parish choir directed by excellent professional organists, and an in-house orchestra (comprised mostly of nuns!). There were up to 12 Masses per weekend, of which at least three were choral. Early music lists show that as well as Gregorian chant, music by composers such as Haydn, Mozart, Gounod, and Spohr were standard fare. Music clearly mattered to the church, and over time some of the many boys serving at the Masses were developed into a choir. By the 1940s the boys were singing alone, and had a developing local reputation for excellence.

St Paul’s Church in Harvard Square was finished in 1923. Designed by T P Graham in opulent Siena and Travertine marble, it is an architectural homage to San Zeno Maggiore Verona, T S Eliot’s favourite church. Although now standing in the middle of modern-day Harvard, the church was built with funds raised in door-to-door collections from members of the immigrant Irish community who originally lived around this area. By good fortune it is now at the confluence of the ‘Red Line’ (part of Boston’s underground rail network), the ‘No. 1 Bus’, and the River Charles, and has always been a meeting point for tourists, students and parishioners alike. Today it is perhaps best known as the home of St Paul’s Choir School, the only Catholic boys’ choir school in America.

That St Paul’s came to have a fully-functioning choir school singing at daily services in the church is surprising. The year of the choir school’s foundation, 1963, came right at the start of the Second Vatican Council, the outworkings of which in the USA were to have a significant (and at least temporarily chaotic) effect on Catholic church music. The roll-out of the Council in the USA often saw the wholesale jettisoning of Gregorian chant and polyphony at parish level, and a struggle with setting texts to English with not enough time, experience or training to do so effectively. Rancorous arguments about the nature of ‘congregational participation’ and about what constitutes ‘musical excellence’ were probably an echo of 1540s England, to some extent! Several years earlier in

Harvard Square, however, the decision had been made to launch a choir school, in answer to the 1947 encyclical ‘Mediator Dei’. This message from the Vatican had suggested that all major city-centre churches should have their own singing schools, and though few places took this suggestion seriously, St Paul’s was one of them. By this time, Theodore Marier had become Director of Music, and he undertook the extremely complex work of planning the transformation of the existing parish school into a choir school. It’s worth mentioning that Marier was very much part of ‘the resistance’ against losing the church’s musical heritage. He made sure that the congregation continued to sing Gregorian chants, and he was able to use his new choir school intake to sing polyphonic church music. It is said that at times he was the only person keeping Catholic music alive in America.

Having toured to the US with various cathedral choirs, and as an organ soloist, I was very excited to see what I could do with so much choral potential. It was not at all easy to leave Canterbury, where I was Assistant, particularly as I loved the daily routine of Evensong in that magnificent building, and had so much fun and great music-making working with Dr David Flood, but the St Paul’s job seemed so unique an opportunity that I nevertheless went ahead.

In the early days the school was tuition-free since the academic staff were all nuns, and the costs of employing a Director of Music, Assistant Director, and purchasing music were all covered by the parish. Things got off to an excellent start, with local schools sending promising boys into the choir school to audition. After a relatively short period of development the boys were singing to a high standard in the church, and able to provide the boys’ parts in orchestral repertoire with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The men of the choir were paid, and included both Harvard students and singers from local music colleges (of which there are at least three nationally renowned examples). Theodore Marier continued to direct the choir until 1986, over 50 years after he had first arrived as Assistant Organist in 1934. At the same time, he built a national reputation as a devotee of Gregorian chant, and was president of the Church Music Association of America. He was good friends with Jean Langlais and, through him, brought a number of Parisian organists to Boston over the years. Though recordings were made of the choir, revealing some very fine treble soloists, (especially Dennis Crowley, who went on to sing boys’ roles in several Britten opera US premieres,) the reputation of the choir remained relatively local. The long-time Assistant Director of Music, John Dunn, took over as Director in 1986.

When I saw the job of Director of Music advertised in 2010, I was greatly attracted by the prospect of directing a boys’ choir with a choir school, in a beautiful acoustic, in the US.

By the time I arrived, a number of factors had developed which created major challenges for the school. Recruitment had changed greatly towards the end of the 20th century, so that schools which once had been proud to get a boy into the choir were now closely guarding pupils for fear of losing revenue. My challenge was to find ways to reach new demographics, while also maintaining ties with historically supportive communities. Then discussions about the size of the choir were long overdue. In a situation where every boy is a chorister, it’s very tempting for those managing the accounts to make the school too big for the choir, unless non-singing pupils are admitted. So work was needed to help people understand why the size of the choir really needs to take into account the size of the building, and of course the repertoire being sung, if there is to be an excellent result. Another challenge was that, in the north-east of the USA, boys’ voices are breaking well over a year earlier than they were 20 years ago, so whilst in 1963 it was very unusual for an 8th grader (boy in Year 9) to have a broken voice, by 2010 I was seeing most boys in 7th grade experience ‘voice change’ during the year, and even some in 6th grade. In response to these factors, a number of developments were essential. We began to recruit in different ways: we used each of our concerts as a recruitment event, encouraged our parents to run ‘at homes’, partnered with local children’s choirs and engaged the media as much as possible, following recordings. We brought in ‘rolling admissions’ with a very flexible and streamlined approach to voice trials, and academic testing to suit the candidates and their families. We brought in two new grades at the bottom of the school. In addition, to help balance the competing claims of the economics of the school with the need to regulate the size of the choir, instead of taking ‘non-singers’ the choir school has formed a track for trebles who want a lesser singing commitment but the same excellent academic experience of the choir school. This works very well for the boys whose voices are breaking too, as the ‘Chorus’ (as it’s known) serves the additional purpose of helping the older boys start to find baritone/tenor ranges in preparation for high school choirs. The Chorus sings in the church twice monthly, while rehearsing a couple of times each week. At the same time, I introduced probationer training, run by the Assistant Director of Music. The probationers gain experience singing with the school Chorus initially before they are worked into the choir. Of course, the boys come from all over the spectrum of singing/musical experience, so this training period is essential to help teach the basics of sight-reading, posture and vocal technique. All the boys are prepared for ABRSM Theory and Piano exams. The Theory course is part of a general ‘musicianship’ course that includes some conducting, sight-singing and rhythmic components, especially early on. The ABRSM, with its long-established use in choir schools, is the perfect counterpart to choir rehearsals.

The school has always included the usual range of academic subjects, and for many parents this is probably more

We received an impressive amount of media interest in TV specials, news reports and radio (including Classic FM, which made the CD one of their recommended Christmas albums), which not only raised the profile of the choir in the US but helped greatly with our recruitment.St Paul’s choir

important than the music. Admission to excellent high schools is much prized in the vicinity. We have boys from every social background, including those whose parents work at Harvard, so there is a certain sense of academic aspiration which is valued by all. My work in the rehearsal room is made much easier because of the strong ethos and the firm sense of discipline in the school, although there are few discipline issues: the boys tend to be fascinated, and pretty engaged.

The choristers now sing six services a week: daily Mass on Tuesday to Friday, Vespers on Thursdays, and Mass on Sunday. The men of the choir are only present at weekends and for a mid-week rehearsal, so most of the repertoire is for treble voices. This has been an eye-opener to me, as it results in a very secure treble line that is extremely happy on its own. It’s certainly true that we miss the sense of cohesion with the men that comes from daily singing together, but having assembled an excellent group of men from local music colleges such as New England Conservatory, Boston Conservatory and Longy, it is no trouble to put things together for weekends and concerts. Repertoire selection has been another voyage of discovery, since we are mostly singing Mass. Vespers on Thursdays has been easy enough to find magnificats for, with classics such as Dyson in C Minor, Stanford in D, and the Sumsions, but Masses have been more challenging. Once the Britten, Fauré and Langlais had been done, I wasn’t sure where to go next, initially. But it turns out there are some amazing Rheinberger

Masses for 3-part treble choir, as well as effective Mass settings by Flor Peeters, Sauget, Chaminade, Andrew Carter and many more. At weekends anything is do-able, and this year we’ve been able to sing Byrd’s Laudibus in Sanctis and Bach’s Komm, Jesu, Komm for the first time. And having been able to extend our outreach with media appearances and recordings, we’ve had more families travelling across the USA to join the school. This year we had three fluent German-speaking boys, two from Germany, and so we scheduled a concert of German choral music at our spring concert.

Over my time at St Paul’s there have been many memorable musical moments. Making recordings for Decca and Sony Classical by AimHigher recordings was certainly a real high for all involved, and we knew they would be really well promoted by the brilliant Monica Fitzgibbons. We received an impressive amount of media interest in TV specials, news reports and radio (including Classic FM, which made the CD one of their recommended Christmas albums), which not only raised the profile of the choir in the US but helped greatly with our recruitment. Other recent highlights have included rekindling our relationship with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. This last year the boys were able to sing the ‘boys’ choir’ parts in Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust, and in Bernstein’s Kaddish Symphony. These were both amazing experiences; to be on stage with one of the world’s great orchestras, sublime soloists (Susan Graham’s ‘Marguerite’ was something to remember) and a well-known Maestro at age 10 is pretty special. And our

boys sang solos with the Boston Pops Orchestra at Christmas time, as well as performing concerts all around the area. Our now annual tradition of singing Britten’s Ceremony of Carols continues to grow each year, and this last year we paired it with John Rutter’s Dancing Day

When the boys leave St Paul’s they go on to a range of high schools, including ‘historic’ American schools such as Roxbury Latin and Andover. Wherever they go, they are greatly in demand for their singing and their academic preparedness. We have so far produced a number of professional organists, and in my time we’ve encouraged some highly talented organ scholars, the most recent of whom (Blake Chen) was head chorister at St John’s Cambridge until last year, so he’s still

very young. Our alumni miss the choir so much that we have created a range of options for them – an alumni chorus that sings weekly, and choral scholarships with the men and boys. Having been raised as a chorister myself in Roy Massey’s fabulous choir at Hereford, I’m so glad I have helped bring something of this tradition to the USA. Hearing the way in which the choir has changed so many lives makes my job perpetually rewarding and fulfilling, and I’m especially grateful to all the singers who have passed through the choir at St Paul’s during my time.

The choir’s two CDs, ‘Christmas in Harvard Square’ and ‘Ave Maria’, can be obtained from Amazon.

became friends, as George later recalled: ‘I was invited to visit the church of St Anne, Chingford Hatch on behalf of the Royal School of Church Music …. The music sung on that occasion was of a standard seldom attained in cathedrals let alone parish churches, and it became immediately clear that it was being accompanied by an instinctive director, one who, whilst having the utmost regard to technique, was at the same time able to bring the music to life by the subtlety of his interpretations.’

Ifirst met Barry Rose in about 1965, as a small child. I was taken out of lessons at my primary school one day by my mother, much to my excitement and the jealousy of the other children, and delivered to a strange young man in a strange building and asked to sing to him. I now know that the man was Barry Rose, and that I was auditioning for a place in the treble line of his recently established Guildford Cathedral choir. Being rather young at the time, I was invited back for another audition and also a school entrance exam the following year; I was later admitted into the choir and the de facto choir school, Lanesborough.

Just ten years before these events, my parents were not yet married, Guildford Cathedral was still being built, with no date set for its consecration, and Barry Rose was working in insurance in London. Up to then his church music experience consisted of accompanying the singers at his local Sunday school in Chingford and playing the Compton electronic organ in the newly built church of St Anne’s, Chingford Hatch. It was at Chingford that he and George Guest, Director of Music at St John’s Cambridge,

In 1956 Barry joined Martindale Sidwell’s choir at Hampstead Parish Church, an experience he later would say was the most influential of his early musical life (at this time the Hampstead choir was widely regarded as the finest church choir in the country). After nearly two years at Hampstead he was appointed Organist and Choirmaster of St Andrew’s Kingsbury, a church with an already strong choral tradition, whilst also setting up his own chamber choir, The Jacobean Singers, around the same time. He was also the accompanist for Bruno Turner’s Pro Musica Sacra chamber choir. Barry and Bruno shared a flat, and years later Bruno recalled, ‘I always felt that of the two of us Barry was the gifted instinctive musician. He knew what he liked and how he wanted it.’

Both Barry and Bruno were influenced by Michael Howard’s pioneering Renaissance Singers, and Barry was also much taken by Boris Ord’s choir at King’s College Cambridge, Stanley Vann’s choir at Peterborough Cathedral, and most of all George Guest’s St John’s College Cambridge choir. Barry used to go to Ely Cathedral to watch Michael Howard training the boys. In Michael’s obituary in the Guardian in 2002, it was reported that Howard ‘concentrated on the

Over the next 14 years, with a lot of hard work and a slowly growing repertoire, Barry led the Guildford choir to the forefront of choral music singing of the time, and the choir achieved widespread recognition through its several bestselling recordings for EMI.

production of pure, open, Italianate vowels consistent from the bottom to the top notes … Diction was perhaps Howard’s greatest preoccupation, and his legacy of recordings demonstrates the extent to which he demanded that his singers project their consonants. He was a hard taskmaster and, after a few months, the “Ely sound” began to develop, making itself heard with increasing regularity on the BBC Third Programme.’ This, to a Barry chorister, sounds a familiar narrative.

On the recommendation of Felix Aprahamian, then music critic of the Sunday Times, Barry auditioned for a place at the Royal Academy of Music to study organ with C H Trevor. Despite not possessing any of the required entry qualifications, he was offered a place by the college principal, Sir Thomas Armstrong, in March 1958. Whilst there, he spotted an advertisement for an organist for the new cathedral at Guildford, and was one of the 140 or so who applied. He hitched a lift to the interview on the back of a friend’s

motorbike and took with him a tape recorder so he could play the panel some recordings of his St Andrew’s choir.

Against all the odds he was appointed, and aged 25 in September 1960 he became the youngest cathedral organist in the country. He moved down to Guildford and started putting a new choir together. A supply of boy singers was the priority, and he looked at various local prep schools, eventually settling on Lanesborough. Barry auditioned the boys there and chose 16. He was, however, keen that membership of the choir should be open to any local boy with talent, so he also set up what he termed the Town Boys Choir. This was unfortunately short-lived. The plan was that these boys would sing Evensong on Friday and Sunday evenings, but this idealistic ambition did not survive to the end of the summer term. However, once assembled, all the recruited boys started rehearsing for the Consecration service, which was to be attended by the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and other members of the Royal Family – the date had been set for 17 May 1961. The day after,

however, was probably the more significant day in the choir’s history as it was then that the first daily Evensong took place. The canticles were sung to chants and the anthem was Charles Wood’s God omnipotent reigneth.

After a bit of to-ing and fro-ing, Barry had been offered No 1 Cathedral Cottage to live in. This was one of a pair of small houses designed by the cathedral architect Sir Edward Maufe, at the foot of Stag Hill. It also became home to some of the early men of the choir. At various times up to Barry’s marriage to Elizabeth (Buffie) Ware in 1965, Colin Wykes, Roger Lowman, Robert Hammersley, Michael Barry and Clifford Mould all lived there. Much of the choir’s life and humour originated in this bachelor pad, described years later by a visiting Alan Ridout: ‘I have never seen anything quite like it before or since and it reminded me somewhat of those drawings of the way Beethoven lived. The mess was from floor to ceiling, as if a bomb had just gone off.’ A lot of the choir’s early humour emerged from this set-up and its inhabitants, from any food found in the kitchen being fair game for anyone to consume, to any letters likewise being read by anyone. Clifford Mould later recalled, ‘I had a girlfriend who used to come and stay for weekends and she really became most upset when she discovered that her letters to me had obviously been read by everybody else, and she caused a tremendous sensation by writing a letter saying that since I had been in the cottage, it was as if a black cloud had descended over our life. This became known as the “black cloud” letter. When anyone else’s girlfriend complained, everyone would chorus “black cloud, black cloud!”’

Over the next 14 years, with a lot of hard work and a slowly growing repertoire, Barry led the Guildford choir to the forefront of choral music singing of the time, and the choir achieved widespread recognition through its several bestselling recordings for EMI. These now iconic (if you are an Old Guildfordian) recordings led to the choir being awarded a platinum, a gold and two silver discs. In addition, the choir acted as a backing group for a Peter Skellern track and on a couple of other ‘pop’ recordings, the link to these being through one of Barry’s former St Andrew’s choristers, Andrew Jackman, who became a freelance arranger and conductor. Barry and his brother-in-law, Nicolas Ware, a professional sound engineer, set up a recording company, Guild Records, recording and releasing several discs of the choir. Over the years they recorded the choir on numerous other occasions, these recordings now being available on the YouTube channel Archives of Sound.

Some of the choir’s sound attributes remained constant throughout the whole of Barry’s time, in particular the diction, the exuberance of the top notes, the moments of tender beauty and the overwhelming musicality. But other characteristics evolved.

During the first few years the confidence and skill of the initial batch of ten- and eleven-year-olds chosen to start the choir from Lanesborough had grown steadily, although ‘the blend was achieved by some breathy sounds – anyone with vocal clarity would stand out,’ as Barry later acknowledged. However, there was then a mass exodus in 1963 when nine boys left, including six of the originals.

By the time the next generation had bedded in, a more musical and less breathy sound was evident, from 1965

onwards. The choir was at its most ensemble-like from 1967, but soon after, around 1970, a little of that character had been sacrificed to an increase in vocal power. Three years further on, the choir sounded almost ‘continental’, with a thinner, more ‘romantic’ sound with more vibrato than would have been permitted earlier. The final generation of boys, from 1974, had a mellow, fluid sound with much less vibrato and no ‘edge’, a much more positive sound. By the time Barry left in 1974 the choir had become much more characterful and emotional than it had been for some years. The changes were partly to do with Barry’s changing tastes but were also prompted by the boys themselves, because the trick at a place like Guildford was to work with what you had, and Barry was not afraid to do this.

In May 1973 Barry was approached about a possible move to St Paul’s Cathedral. Two years earlier he had been appointed to the BBC as Music Adviser to the Head of Religious Broadcasting, in succession to George Thalben-Ball. This involved directing the BBC Singers and playing the organ in the live broadcast of the BBC Radio 4 Daily Service each weekday from All Soul’s Langham Place, as well as editing and often producing the weekly Choral Evensong broadcasts. After about a year of doing this alongside his Guildford responsibilities, it became clear that the arrangement would not be sustainable in the long run, and the possibility of a move to London looked attractive.

The post at St Paul’s was officially that of sub-organist and had become available through the retirement of Dr Harry Gabb. Barry auditioned in November 1973. It was agreed that he would stay at Guildford until July 1974, and in September of that year Philip Moore, then Allan Wicks’s assistant at Canterbury Cathedral, was given the unenviable job of taking over from Barry.

Barry started at St Paul’s in September 1974, and was to stay until an acrimonious and much publicised departure in July 1984. To start with, the signs were encouraging. He had been

brought in so that Christopher Dearnley, who was planning the 1977 rebuild of the cathedral organ, could have a full-time assistant. The unwritten agenda was that Barry would, in time, take over the training of the boys, and three years later he was formally appointed to the specially created post of Master of the Choir in time for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee service on 3 June 1977. Over the next seven years he led the choir through several State occasions and also a highly successful tour of the USA and Canada in 1980. However, much to the chapter’s displeasure and also that of Christopher Dearnley, he introduced the choristers to the world of pop music, just as he had at Guildford. Following a highly acclaimed appearance on the BBC Television Arena programme, the choristers made a Gold Disc recording of My Way, a Christmas single with another of Barry’s former St Andrew’s choristers (Chris Squire of the band Yes), together with several backing tracks and solos for other songs of a similar style, including Paul McCartney’s Rupert and the Frog Song. Boy soloists from the choir were also featured on television and radio; these included Paul Phoenix (Geoffrey Burgon’s Nunc Dimittis for Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) and Peter Auty (the original recording of We’re walking in the air for Howard Blake’s The Snowman).

Another point of conflict was the proposal by the cathedral to re-draw the employment contracts in order to assign various musical responsibilities to the Dean and Chapter. This was totally unacceptable to Barry (and also to the vicars choral) and, with no solution in sight, Barry was asked to resign as from July 1984. The anthems during his last week consisted of several settings of There is no Rose

From St Paul’s, Barry moved to Canterbury and took up the post of Master of the Choirs at the King’s School. This was a role specially created for him by the headmaster Canon Peter Pilkington. He was to stay there for three years. In April 1988 he was approached by the Dean of St Albans, Peter Moore, seeking advice on recruiting a successor to Colin Walsh who had just been appointed to Lincoln Cathedral. As a result,

Barry came away from St Albans having been persuaded to consider an offer to become the Abbey’s Master of Music. It was a difficult decision to leave Canterbury, but in the end Barry accepted and he, Elizabeth, and their three children moved to St Albans in August 1988.

Since then, apart from a brief spell at Chelmsford Cathedral between Graham Elliott’s departure and Peter Nardone’s arrival, he has officially been retired. However, he is still much in demand as a freelance musician and has links with several choirs in the United States.

To be reminded of and to listen to Barry’s legacy, and that of Michael Howard, Boris Ord and the others referred to in this article, one only has to search on YouTube. Within this vast archive, for Barry’s time at Guildford, the Archives of Sound channel as mentioned above is the definitive source, and for a more general look at cathedral and Anglican church music the Archive of Recorded Church Music channel is wideranging and fascinating.

Barry was to stay at St Albans for nine very happy and productive years before retiring in 1997. His role was to maintain and develop a choir that had already made its name through the work of Peter Hurford and Stephen Darlington. Throughout his time at the Abbey Barry worked alongside his colleague Andrew Parnell, and led the choir in several radio and television broadcasts, CD recordings and no fewer than five visits to the USA.

Barry was awarded the OBE in 1998 for ‘services to cathedral music’.

So what was new has now become a tradition. Peter Wright, who arrived at Guildford as Assistant Organist in 1977, 20 years later wrote: ‘No tradition can survive in aspic, and it is right that each successive director should bring a new facet to the music of Guildford Cathedral. The legacy of Barry Rose lives on but it is constantly evolving. The excitement of newness has now been replaced by a sense of tradition and continuity, and perhaps the greatest compliment to the pioneering days is that Guildford has now taken its place in the mainstream of cathedral music.’

As well as having a full-time job with the NHS, Simon Carpenter is also a part-time student of the University of Gloucestershire researching for an MA on Herbert Brewer of Gloucester Cathedral and his pupils.

as well as including stimulating features, a wealth of educational material and reviews of organrelated music, CDs, DVDs, books and much, much more.

TO

St Patrick’s Cathedral, or the National Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St Patrick, Dublin, to give it its full title, has been part of Dublin life since 1191. One of three cathedrals in the city, St Patrick’s serves as the national cathedral for the Church of Ireland. Our neighbouring Christ Church Cathedral (also Protestant – much to the bewilderment of many of our visitors) serves as the diocesan cathedral for Dublin & Glendalough, and St Mary’s pro cathedral on the north side of the city serves the Roman Catholic archdiocese of Dublin.

Following years of neglect, St Patrick’s was lovingly restored by Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness (of brewing fame) in the late 19th century and today, though primarily a house of prayer, it is also one of Dublin’s top tourist attractions with over 600,000 visitors a year. Those visiting are charged an entrance fee and it is from this revenue that the cathedral continues to be kept in the best possible health, thus ensuring its survival for both worshippers and visitors alike for centuries to come. It also means that thanks to the continuing support of the cathedral board, the music department is well resourced, and quite a department it is too: 21 boy choristers, 18 girl choristers (also aged 8-13), 14 girl scholars (aged 14-18), 4 Martin Scholars (aged 16-18), 4 choral scholars (male and female – all in tertiary education), an organ scholar, an organist & assistant master of the music, eight lay vicars, two Sunday men, five visiting instrumental staff, one singing coach, two music theory tutors, four chorister supervisors, a Keeper and Assistant Keeper of the Music, a music archivist, a cook, and of course the Master of the Music.

The offices of Mattins & Evensong are sung daily (Monday to Friday in termtime), making us somewhat unique in these

islands, along with either Eucharist or Mattins and Evensong on Sundays. Thanks to the ever-increasing numbers of visitors as well as a resurgence of popularity in the Anglican choral tradition, especially in cathedrals, numbers in the congregation are well above average and continue to grow. Of course, there will still be the odd wet and windy morning when the choristers sing the Office to an empty cathedral, but we are now also making the most of modern technology and broadcasting all our choral services via the cathedral website, and we have an ever-growing online congregation.

The biggest change to the choir in recent times is the introduction of girls to the front row of the choir stalls. Originally founded by Barbara Dagg and affectionately known as ‘the Daggetts’, the girls’ choir in its current form was re-established by Organist & Assistant Master of Music David Leigh in 2000. Over the last few years, the girls’ choir, or as

they are formally known, Schola Patricii, has become an integral part of the life of the cathedral. In addition to singing twice weekly for Evensong with the lay vicars, Schola, the members of which are all students at the cathedral grammar school, also sing a number of major services throughout the year including our Advent Procession, Evensong on Easter Day, the annual Act of Remembrance, and have made their own ‘new’ traditions of the now-annual liturgical performances of Britten’s Ceremony of Carols at Candlemass, and Bach’s St John Passion with orchestra on Palm Sunday.

In September 2016, another girls’ choir was established to cater for younger singers – ie those of a similar age to the boy choristers. Much like the boy choristers, these girls are all educated at the choir school, which – established in 1432 – is the oldest school in the country, as well as the last remaining choir school. Along with the boys, the younger girls also receive generous bursaries for instrumental lessons, and weekly singing and music theory tuition. Once a week the girls sing Mattins, and Evensong twice a month. Much like their older colleagues in Schola, we hope that as time goes on they will share more widely in the worship offered in the cathedral.

The boy choristers continue to go from strength to strength and still sing the lion’s share of the cathedral’s liturgical offering including a large portion of the 12 weekly choral services, regular broadcasts, termly concerts, recordings and annual tours – and all before their 13th birthday – or, God willing, their 14th or even their 15th. To the casual observer, and indeed to any prospective parents, this seems like an awful lot for such young singers – but it wasn’t that long ago when the boys would have been expected to sing the vast majority of the choral services throughout the school term (including those now sung by Schola and the girl choristers) and beyond,

throughout the summer months rather than enjoying a much needed break from both school and cathedral during July and August. No peace for the wicked indeed, and very wicked they must have been. There’s a great story from by Charlie Reede, ex-chorister and former Tower Captain (sadly no longer with us) – he told me how during the long summer months he, along with his chorister cohorts, would slip past the Precentor after Mattins and escape onto the cathedral roof to while away the hours until called back in for Evensong. There are even (rather more alarmingly) stories concerning choristers shimmying up the spire – thankfully these days the choristers are properly supervised, and access up the tower is limited!

It would be remiss of me not to mention the back row – or more accurately, the middle row, the back row being reserved

Speaking of Christmas: the festive season and St Patrick’s, especially for those born and raised in Dublin, are very much synonymous with each other, largely due to our annual radio broadcast of Nine Lessons and Carols, the unbroken record of which dates back to the 1940s.Choristers at St Patrick’s, Dublin Photo: Tristan Hutchinson

for the members of the cathedral chapter. The ‘Gentlemen of the Cathedral Choir’ comprise eight lay vicars choral (recently increased from six), two ‘Sunday men’ (until recently both called Victor and affectionately known as the ‘lay Victors choral’) as well as several choral scholars. It wasn’t so long ago that the lay vicars would hold down ‘real’ jobs, i.e. the 9-5 variety, and Evensong was so timed as to allow a quick dash from office to stalls and then home to the family, via a swift pint in the ‘Frog and Loincloth’, of course – length of psalm permitting. These days most if not all of the lay vicars make their living from music, whether by teaching it, writing it or performing it, and we are fortunate to be able to attract such talented signers as and when a vacancy arises.

Recording has become a regular part of the choristers’ schedule. We have recently released our third and fourth CDs under the watchful eyes (and ears) of Gary Cole at Regent Records, the fourth of which marked the girl choristers’ recording debut (not bad for their first year). These recordings have not only helped raise a considerable amount of money, they have also contributed to raising the profile of both the cathedral and its choir well beyond the city limits via broadcasts and, I’m pleased (and a little relieved) to say, some very favourable reviews. To date my favourite was for our Christmas in Dublin disc released back in 2013 when the boys of St Patrick’s were likened to those of King’s College Cambridge but whilst the boys of King’s were described as ‘angelic’, ours were described as ‘lusty’, and I’m happy to take that as a compliment.