CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Not only do we supply the best in digital organs from four leading organ builders, but we now publish our own organ music and carry the largest stock of sheet organ music with over 1,500 volumes on our shelves from a catalogue of over 10,000 titles. Why not visit us in Shaw (OL2 7DE) where you can park for free, browse, have a coffee, play and purchase sheet organ music or use our online shop at www.sheetorganmusic.co.uk.

ChurchOrganWorld … the one stop shop for organists

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November.

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2019

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ editor@fcm.org.uk

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon pm@fcm.org.uk

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:

DT Design, 4 Bedern Bank, Ripon HG4 1PE 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 020 3637 2172

International: +44 20 3637 2172 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by:

DT Design, 4 Bedern Bank, Ripon HG4 1PE 07828 851458

d.trewhitt@sky.com Cover

Receive your first year membership of the Royal College of Organists FREE, with your home practice organ purchase

Sonus instruments, based on the very successful ‘Physis’ physical modelling sound platform, additionally incorporate an enhanced internal audio system to generate an exciting moving sound field for increased enjoyment in a home environment. Speakers above the keyboards and to the organ sides create a truly sensational and immersive sound field.

Starting at £11,700 inc VAT for a 34 stop 2 manual, the instrument pictured here is the Sonus 60 with 50 stops at £16,900 inc VAT. Neither words nor recordings can do justice to the sound of these instruments; you just have to experience it in the flesh.

Multiple speaker locations create a uniquely authentic sound

To play one of our instruments call us to book a visit to our showroom, or contact one of our regional retailers listed below.

Soundtec Irvine

Rimmers Music Edinburgh

Promenade Music Morecambe

Pianos Cymru Porthmadog

Henderson Music Londonderry

Keynote Organs Belfast

Cookes Pianos Norwich

Jeffers Music Bandon

Cotswold Organ Company Worcester

Viscount Organs Wales Swansea

Wensleigh Palmer Crediton

South Coast Organs Portsmouth

Viscount Classical Organs Ltd

Tel: 01869 247 333

E: enquiries@viscountorgans.net

www.viscountorgans.net

Sonus 60There are two Royal Peculiars celebrated in this magazine. One, St Stephen’s Chapel, once situated in the Palace of Westminster, is no longer extant, but the other, St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London, is a busy and much used amenity (its evocative name, St Peter in Chains, refers to the saint’s imprisonment under Herod Agrippa in Jerusalem). As well as catering to many City bodies and livery companies, St Peter’s is a regular parish church, with Sunday Matins and Eucharists, concerts, carol services and other special services. Colm Carey, whose group Odyssean Ensemble has recently released its first CD, has been associated with this chapel –and, indeed, with the second chapel based at the Tower, the Chapel of St John – for almost 25 years. He, and Elizabeth Biggs, who writes wonderfully knowledgeably on St Stephen’s (the full title of which chapel is ‘St Stephen the Protomartyr within the Palace of Westminster...’), bring a much loved part of the cathedral music world to vivid life.

All those who have read CD reviews in Cathedral Music over the last few years will be acquainted with Roger Judd’s incisive and informed comments on choral and organ performances. In this issue he recalls his time spent at St Michael’s Tenbury, the school set up by Frederick Ouseley in 1856, and contemplates the legacy left by Ouseley, not simply financially but, of course, musically. The school was deliberately sited in a remote location so as to insulate it from ‘the influence of London’... and was founded in reaction to the decline of Anglican church music in the Victorian period. How much Ouseley would have had in common with FCM’s

own founder! Roger’s piece, originally a talk presented to the Association of Assistant Cathedral Organists, has sadly had to be shortened due to space constraints, but there is plenty left that will undoubtedly be of great interest to readers.

A confession next. I occasionally say to people when things go wrong, ‘I am my own secretary, and often not a good one...’, and any mistakes which occur in this magazine are generally my own. So, in the article about the Cathedral Organists’ Association (COA) which appeared in the last magazine, I inadvertently published the first draft of Michael Nicholas’s article instead of his later, corrected, one, which was unfortunate because some of the facts in that draft were subsequently changed. Thus the article should have said that Elizabeth Stratford at Arundel was the first woman to be appointed Organist and Master of the Choristers at a UK cathedral, and that Katherine Dienes-Williams was the first woman to join the COA upon her appointment to the post of Director of Music at St Mary’s Collegiate Church in Warwick in 2001. Heartfelt apologies to both of them, and also to Sarah MacDonald, whose name I spelt incorrectly. I am pleased to say that you can read about Sarah’s activities with the Ely Girls’ Choir, and her thoughts about changing the age range of the choir, later on in these pages.

Those who came to the Cathedral Choristers of Great Britain extravaganza in Liverpool in June will know how successful it was, and will have enjoyed the glorious sound the expanded group of choristers produced in front of a fine collection of people, including HRH The Duchess of Gloucester, patron of the Diamond Fund for Choristers, our president Stephen Cleobury, and John Rutter, who gave a brilliant speech in support of the DFC. The Anglican cathedral was a fantastic backdrop for the occasion, and it is hoped that the event may be repeated in a year or two’s time.

Sooty AsquithLog onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free full-length CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to

increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over£4 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

London’s Tate Modern gallery has recently become the most visited tourist attraction in the UK. Together with several iconic new buildings and facilities, such as Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, the Millennium Bridge, Cutty Sark, Borough Market and the Shard, it is one of the many developments in recent decades that have transformed the previously rundown South Bank of the Thames in Southwark into a bustling, vibrant and popular commercial and cultural area much frequented by tourists.

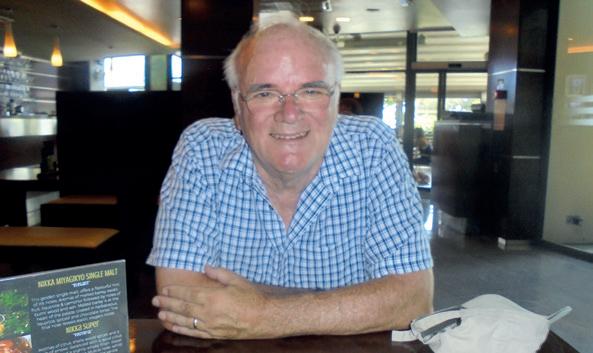

During his 30 years as Organist and Director of Music at Southwark Cathedral (the former St Saviour’s church dating back to monastic times that became a cathedral when the diocese was created in 1905), Peter Wright has witnessed this amazing regeneration, whether from his sitting room window on Bankside overlooking the Thames and St Paul’s Cathedral or on his daily walk to the cathedral. “It’s all quite remarkable,” he says. “When I first came here the only place to dine out was Garfunkel’s at London Bridge station, but now it’s almost a gastronome’s heaven with so many good places to choose from.”

During this period of impressive local regeneration, music at the cathedral has grown and developed equally impressively under Peter’s skilful direction. Building on the sure

foundations laid by his predecessor (Harry Bramma, who went on to be Director of the RSCM and Director of Music at All Saints Margaret Street), as well as nurturing both the long-established boys’ choir and the Thursday Singers (a voluntary choir drawn from the local community, which sings at weekday Festival eucharists and occasionally at Choral Evensong), he has overseen the development of two new choirs: the Merbecke Choir, founded in 2003 as a youth choir for the cathedral’s former choristers, which now attracts 2530 young singers from various backgrounds; and the girls’ choir, founded in 2000, which he entrusted to his Assistant Organist Stephen Disley, and which now has 27 choristers singing regularly at weekday evensongs and once a term at Sunday services.

Passionate about the cathedral’s famous 1897 T C Lewis organ, Peter organised its comprehensive restoration by Harrison & Harrison in 1991 and oversaw the installation of a new console in 2018. Regular Monday lunchtime organ recitals, given by visiting organists as well as the ‘home team’, continue to attract increasingly sizeable audiences.

Organ scholarships were established in 2000, since when a succession of outstanding scholars have been appointed, all of whom have gone on to major posts in cathedral music –

Daniel Cook (now Director of Music at Durham Cathedral), Ian Keatley (until recently at Christ Church Cathedral Dublin), Martin Ford at The Guards’ Chapel, David Pipe at Leeds Cathedral, Timothy Wakerell at New College Oxford, Tom Little at Croydon Minster, Jonathan Hope at Gloucester Cathedral, Martyn Noble at the Chapel Royal in St James’s Palace, Edward Hewes at St Dominic’s Priory in North London and Alexander Binns, who is now Director of Music at Derby Cathedral. The roll-call bears glowing testimony to the tremendous success of Peter’s initiative as well as to his outstanding talent in teaching and nurturing his scholars, and Peter is especially pleased that Ian Keatley has been appointed as his successor at Southwark.

By any standards, it is a remarkable transformation. With characteristic modesty, preparing for his retirement at the end of August, Peter says, “Throughout my time here, I’ve been wonderfully supported by lay clerks, assistants and clergy, and this has enabled us to achieve high standards and to convey the Christian message through the incomparable language of music. It has been a delight and a privilege, and I’m very pleased with everything we’ve been able to do – though I do wish I could have evangelised more about our wonderful organ and put it more firmly on the map!”

Peter was born in Hertfordshire and brought up mainly in Finchley. His first musical inspiration, when he was only four years old, was Russ Conway, the then very popular and muchloved pianist with a missing finger, who regularly appeared on The Billy Cotton Band Show in the early days of television He experimented on the family piano and started lessons three years later with Dorothy Fryer who, he says, was, “Just fantastic – a true saint who started me off and with whom I stayed until I was 17 when I went up to the Royal College of Music (RCM), having done my A Levels and gained my ARCO. I owe her such a lot.”

There were, however, plenty of other experiences en route from Russ Conway to the RCM. While still at his prep school

(Holmewood, North London) he sang in the chorus for their annual Gilbert & Sullivan productions and, in his final year, played the piano accompaniment for The Mikado, with his twin brother Nigel singing the part of Pitti-Sing.

After that he went to Highgate School where not only was his love of choral music fostered (inter alia, by singing the War Requiem under Britten and Willcocks), but his passion for the organ was sparked as he followed in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps by taking lessons, and then playing for services in the school chapel. At 13 he was appointed Assistant Organist of the United Reformed Church in Finchley, becoming Organist two years later. Then at 17 he became Organist at St Michael’s Church, Highgate where, he says, “I was responsible for the boys’ choir and started to learn my craft as a choir trainer – largely through trial and error – but throughout my formative teenage years I always had a great love of the organ, and knew the way I wanted to go.”

He then spent two years as Organ Exhibitioner at the RCM, studying with Richard Popplewell (Organ) and Angus Morrison (Piano) and gaining various prizes and diplomas, including his FRCO. It was just before his first term there that he went to Truro for an RSCM cathedral course led by Gerald Knight, with Roy Massey playing the organ. He was so ‘wowed’ by it all that he realised then that he really wanted to be a cathedral organist – even though he’d never been a cathedral chorister, as was the normal expectation at that time.

In 1973, he went up to Emmanuel College Cambridge as Organ Scholar where he continued his organ studies with Dame Gillian Weir, as well as with Flor Peeters in Belgium. While at Cambridge, George Guest, then Organist at St John’s College, took him under his wing and, with John Scott also there as Organ Scholar, it was, he says, “the most wonderful opportunity. Occasionally they were both away, so I had to do the lot! Also, having my own choir at Emmanuel meant I had the best of all possible worlds.”

Four years later, at the age of 23, he was appointed SubOrganist at Guildford Cathedral, under Philip Moore and, subsequently, Andrew Millington. Within three years of starting there, he made his first recording, since when he has been much in demand as an organ recitalist, playing regularly with the country’s leading orchestras, and performing widely in Europe, Japan, South Africa, USA, Bermuda, Australia and New Zealand.

It was in 1989 that he was appointed Organist at Southwark, where, he reflects, “I arrived ‘home’ as a London boy by birth, full of inspiration and determined to build further on Harry Bramma’s remarkable achievements. It had not been the easiest of times for Harry, but he ‘got it’ at every level, bringing about a minor miracle in achieving high musical standards, despite having very limited rehearsal time and no choir school (the school from which most of the boys had previously come moved from the area in 1968). Many often said, ‘It shouldn’t work!’ (the title of a talk I give about the choir…), but it did, thanks to Harry’s determination and dedication.”

Thirty years later, Southwark is still without a choir school and still has very limited rehearsal time, but Peter has had the same missionary zeal as his predecessor in extending and transforming the musical life of the cathedral. “The thing I’m most proud of is that we’ve maintained a standard that holds its own against places with a lot more on their side. While maintaining and developing further the Opus Dei, we’ve performed at the Proms, made several recordings (including the theme tune, Ecce homo qui est fava for the TV series Mr Bean!), done many broadcasts of Choral Evensong for the BBC, made three tours to the USA and several to Europe, and

put on many special national services including one in the aftermath of the London Bridge attack last year, and those for the national launch of Choirbook for the Queen in 2011 (the year of Her Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee) and the celebration of FCM’s Diamond Jubilee in 2016.

Musicians (FGCM) in 2000, and awarded the prestigious Fellowship of the Royal School of Church Music (FRSCM) in 2011. In order to mark his 25 years of service at Southwark, he was made an honorary lay canon of the cathedral five years ago.

As he now heads off into ‘retirement’, staying in London but well away from the noise of the Bankside buskers and tourists which has at times been the bane of his life, Peter is looking forward to having more time to pursue his other interests, which include opera (his favourite is Tosca which gave him the opera bug when he was 16), jazz, theatre-going, poetry, long walks in the countryside (but only in the knowledge that he’ll be returning home to London!), and fine dining, as well as great French wines. He will, however, be doing all he can to avoid his pet dislikes – Muzak, and anything by his most disliked composer, Berlioz, for whom he says he has a total blind spot!

...

“It’s been a wonderful experience, though it’s got harder over the last five years or so. Almost all cathedrals now find chorister recruitment and retention more challenging, choristers tend to be less self-reliant and possibly less able to commit than once they were – not least because the demands made on them for a wide range of activities in order to get into schools of their choice have increased hugely. Finances are increasingly tight, fund-raising is tougher, and some of the fun has gone out of it all, BUT I still get a kick out of enabling our choristers to make music to standards that might not have been thought possible.

“Of course, there’s a huge pastoral responsibility in all this, and it’s especially rewarding when choristers ‘go the extra mile’ in displaying their commitment to the choir. Shortly after I came to Southwark, there was a Tube and train strike. I wasn’t surprised when one boy was absent for rehearsal and evensong, because he lived in Highgate (six miles away), but with only five minutes to go before the service he turned up breathless, having walked all the way! ‘They’re my family,’ he said, ‘I couldn’t let them down!’ It’s that kind of dedication that makes the job so totally rewarding, and why I’ve always been there for them.”

Also ‘totally rewarding’ for any cathedral organist must surely be being able to perform works by your favourite composers. For Peter, Philip Moore is top of the list of living cathedral music composers – his music features regularly on Southwark’s music lists (as he says, “his music is original, well-constructed and practical”); of earlier composers, Bach is his real passion, closely followed by Byrd, especially his anthem Civitas sancti tui, while his favourite setting of the evening canticles is the Howells St Paul’s Service which he chose for his last service at Southwark on 14 July 2018.

After serving on FCM Council from 2001 to 2004, Peter became President of the Royal College of Organists from 2005 to 2008, and is now one of its vice-presidents. For his outstanding service to cathedral and church music nationally, he was made an Honorary Fellow of the Guild of Church

Southwark will not be the same without Peter Wright. It’s the end of an era, throughout which he has done so much, so successfully, to develop and transform the musical heritage of the cathedral, at a time when the neglected area to which he came in 1989 has been similarly transformed. He will be much missed, though he knows he leaves the cathedral in very capable and inspiring hands.

Also ‘totally rewarding’ for any cathedral organist must surely be being able to perform works by your favourite composers. For Peter, Philip Moore is top of the list of living cathedral music composers –his music features regularly on Southwark’s music lists

Francis Pott (b. 1957) is one of this country’s most distinctive and original composers, with a distinguished corpus of works which represents an individual artistic voice, honed over 35 years through a lifetime of performance and the study of music. Pott’s compositional style is multilayered: on the one hand instantly recognisable, with a distinctive thumbprint to each work which shows the hand of both a master technician and a craftsman; on the other, his work can often be elusive and ephemeral, with beautifully wrought choral miniatures vying with grand oratorios which interrogate the very nature of human existence. His music asks important questions of the contemporary world and doesn’t shy away from tackling difficult issues, but conversely it is through the synthesis and assimilation of previous models, styles and philosophies that Pott seeks to engage with modern society. His music may be viewed as traditional, conservative or perhaps even reactionary when considered alongside that of some of his contemporaries, but there is an eclecticism and a ‘re-encountering’ of tradition that make his work anything but regressive, and these showcase a composer very much in the zeitgeist of contemporary British music.

Pott’s musical upbringing is steeped in the tradition in which his work now sits: a chorister at New College Oxford in the 1960s, he was then a scholar at Winchester College and followed this with a degree at Magdalene College Cambridge. Although this background could have been stifling for some composers, it is not true of Pott, who found the experience of being a chorister ‘the cornerstone of my development as a composer, having first awakened my awareness both of composers in general and of composition as a pursuit’. It was whilst at New College that Pott was initiated into the mix of ancient and modern that characterises his later aesthetic, both through the regular services the choir undertook (with the repertoire from Byrd to Leighton and everything in between) and through the artworks present in the chapel and antechapel. Here, El Greco’s St James the Greater rubs shoulders with Jacob Epstein’s Lazarus (1947-48), which has a contorted angularity but this, with its conventional form, was an obvious influence to the nascent composer. However, the regular performance of English Renaissance masters such as Tallis and Byrd had the greatest effect on Pott; they engendered the beginnings of the complex modal polyphony that characterises his mature output.

The early 1980s saw Pott’s first tangible successes on a national stage. There were two competition wins by two different works for organ (the instrument has been a prominent part of the composer’s oeuvre throughout his career): Mosaici di Ravenna won the 1981 Gerald Finzi Trust National Composition Award and Empyrean won the 1982 Lloyd’s Bank National Composition Award. Both these works are still part of Pott’s recognised output, with the composer acknowledging them as ‘beginning to develop something approaching a personal idiom’. The 1980s also found Pott embarking on his first commissioned work, Nunc natus est altissimus (‘Now the most high is born’), a four-movement sequence for soprano voices and harp that was premiered by the choristers of Christ Church Oxford at St John’s Smith Square in 1983. The work was commissioned as a companion piece to Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols and, despite some striking deviations from the earlier piece, Britten’s offering is never far away and looms over the newer work like a benevolent ghost. However, Nunc natus est altissimus had a lasting impact on Pott’s later work

in two ways: first, that the text of the second movement (an anonymous 14th-century offering) was re-acquisitioned and re-used to great effect in the much more substantial A Song on the End of the World from 1999, and secondly, that it was the first instance of the composer collating, combining and interpolating different texts for dramatic and narrative effect, something that characterises his later, mature output.

Another facet of Francis Pott’s musical development was encountered in the late 1980s when he became a lay clerk in the choir of the Temple Church, London, a position he held from 1987-1991. Unlike many composers of his generation, Pott has been a prominent performer throughout his career, either as a choral singer (he followed his spell at the Temple with a decade in the Winchester Cathedral choir) or as a pianist, and this has had an impact on his artistic life both practically and philosophically. Today, he is most well known for his choral music, honed by his years of singing, and this has given him access to some of the country’s leading choirs and organists, including performers with whom he has regularly collaborated from his earliest works to current commissions. Like his experiences as a chorister, Pott’s years as a lay clerk have had a strong bearing on the direction and development of his work – what he refers to as ‘a long process of osmosis and critical reaction’ – refining his compositional aesthetic and his technical prowess with every subsequent piece. Alongside his work as a performer, Pott has juggled academic commitments with his compositional career (like many contemporary composers), first as the John Bennett Lecturer in Music at St Hilda’s College Oxford (a position he held from 1992-2001) then as Lecturer and later Professor of Music at London College of Music (a position he holds to this day).

Pott’s music is characterised primarily by its polyphonic and contrapuntal textures, not merely as surface-level decoration to a simpler underlying progression but as the very fabric of each composition: a thorough, almost compulsive procedure that moves beyond the ambitious to a tour de force of compositional technique. The effects are often bewildering in both their technical complexity and their artistic beauty, with works from the briefest motet to the grandest statement all exhibiting the same expertise and attention to detail. Pott is aware of how important the polyphonic aspect of his work is to his music in general and how it distinguishes him from his contemporaries: ‘Counterpoint is important, but it is partly a matter of looking around and thinking, “This is an area where I can be me because there aren’t too many other people jostling for space.”’ Certainly, with the current

vogue for contemporary choral music to be slow, static and homophonic, Pott’s music feels of another age: not necessarily of a distant era of complex polyphony, but of a time when the horizontal aspect of a work was as important as the vertical, and composers gave credence to the technical rigour underpinning even the shortest piece. Like many aspects of his compositional voice, Pott’s love and mastery of counterpoint sprang from his earliest musical experiences, filtered again though his career as a performer: from the singing of Byrd’s Laudibus in sanctis to the playing of Bach’s Orchestral Suites at the piano and the early introduction to the adroit polyphony of Kenneth Leighton, all these pointing in the direction of a renewed, contrapuntal musical language.

The 1990s found Pott writing more and more intricate and expressive works for the Anglican Church, many as commissions from some of the leading cathedral choirs and choral foundations. Two of the most impressive were substantial anthems for double choir and organ: Turn our captivity, O Lord (1993) and Bring us, O Lord God, at our last awakening (1995). These two works (and a host of other motets, carols and anthems from the period) could easily paint the picture of Francis Pott as a parochial Anglican composer, found mostly in the choir stalls or the organ loft, but this wouldn’t do justice to the aesthetic and philosophical journey that the composer was beginning to undertake in the late 1990s. This journey reached its culmination in one of his most significant works, the oratorio The Cloud of Unknowing from 2005.

The late 1990s saw the composition of arguably Pott’s most high-profile commission to date, the oratorio A Song on the End of the World that was the Elgar Commission for the 1999 Three Choirs Festival in Worcester. This hugely ambitious work, scored for large choir, orchestra, and soprano, mezzosoprano and baritone soloists, traverses seven substantial

movements in its 70-minute span. Although the piece is greatly indebted to the English oratorio tradition (including Elgar’s own contributions), it is a work that is focused in a much more contemporary way than an august commission from a venerable festival might suggest: it is a sacred piece at its heart, but one that asks difficult yet pertinent questions about faith, suffering and redemption. It is one of many pieces in the composer’s oeuvre in which carefully chosen texts are combined to create a powerful narrative that underpins a composition, a theme that has carried on in Pott’s work to the present.

If one piece represents most fully Francis Pott’s work, philosophy and aesthetic it is his oratorio The Cloud of Unknowing, which was premiered by the Vasari Singers (tenor James Gilchrist, organist Jeremy Filsell), and conducted by Jeremy Backhouse at the 2006 London Festival of Contemporary Church Music. The piece draws together many of Pott’s experiments and discoveries from the previous 20 years in a dramatic and affecting form, asking deep questions of performers and audience alike in its 90-minute arch. Originally conceived as a more modest offering, it quickly swelled to something much more substantial and epic: by negotiated agreement it would end up four times the length of the original commission proposal! As in A Song on the End of the World, sacred texts form the framework of the narrative, but again these are augmented by judiciously chosen secular fragments and poems which shine a light on the darker recesses of man’s inhumanity to his fellow man. It is a work of great significance in the composer’s output, and one that continues to speak to its audiences nearly 15 years after its premiere.

Pott’s stock has continued to rise in the years after The Cloud of Unknowing, with more performances, recordings, publications and commissions creating an impressive corpus of works.

Though his reputation may seem to hang on his larger, weightier compositions, it may well be on his slighter works that his legacy depends. In recent years Pott’s expanding collection of Christmas carols has found a place in the repertoire of many choirs across the country, with multiple recordings of pieces paying testament to the lasting success of this. Perhaps the most successful has been Balulalow, probably best known in Britten’s setting from A Ceremony of Carols. Pott’s Balulalow was written in 2009 for long-term collaborators Judy Martin and the choir of Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral. Over the last ten years it has had countless performances, and seven commercial recordings from the likes of leading groups such as Voces8, the Gabrieli Consort and Commotio. Although short, the work acts as a microcosm of Pott’s style and compositional concerns, as The Gramophone remarked in 2016: ‘A minutely wrought harmonic structure combined with an ingenious use of compositional techniques … to construct a piece that stands up to rigorous technical scrutiny, while retaining a strong appeal to the human side of any listener thanks to the warm tonality of its melodies and their harmonisations.’

As Francis Pott enters his seventh decade, his creativity and ambition show no sign of abating. Semi-retirement from an academic post in September 2018 has given the composer more time for some large-scale projects that have been gestating for over a quarter of a century. In a musical climate where choral music is enjoying a renaissance and sacred texts are almost a work has an engaged audience and is an important voice to be heard. With ‘tradition’ no longer being a dirty word to

artists and ensembles, composers who look to embrace and assimilate traditional models, forms and ideas are increasingly in vogue and it is to be hoped that the work of Francis Pott will continue to resonate with contemporary audiences for a long time to come.

Today, Edgar Bainton is only known for his anthem And I saw a new Heaven. But he also completed three symphonies, three tone-poems and other orchestral works, two surviving operas, and 11 extant choral works. There are also three chamber-music works and over 100 songs, 114 part-songs and some piano music, including a fine ConcertoFantasia for piano and orchestra which won a Carnegie Prize in 1920. This prompts the question: why are so few of these works heard today? Particularly as the vast majority were published in the UK and many of his songs and part-songs were heard frequently in concerts, broadcasts and competitive festivals during the inter-war years. Could part of the reason be that, like several other prominent British musicians of his time such as Healey Willan (Canada), Thomas Tertius Noble (USA), Peter Racine Fricker (USA) and Erik Chisholm (South Africa), Edgar Bainton emigrated, in his case, to Australia in 1934 and remained there until his death in 1956? In the process he perhaps became more recognised as an Australian composer.

Edgar Leslie Bainton was born in Hackney in February 1880. His father, the Revd George Bainton, was a Congregational minister, and early in Edgar’s life the family moved to Coventry where George was appointed to West Orchard Congregational Chapel. Edgar made his first public appearance as a pianist at the age of nine, and at 16 won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music to study piano with Franklin Taylor, and counterpoint and theory with Walford Davies. The choice of piano teacher was to be especially fortunate – Edgar had

developed an absorbing interest in the music of J S Bach very early and would play Bach on the piano every morning throughout his life. In her published memoir of her father, Helen Bainton claims that young Edgar knew all the 48 by heart by the age of 16; whatever the case, Franklin Taylor (1843-1919) was a renowned Bach scholar. Later on, Edgar gained the Wilson Scholarship to study composition with Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, and became one of the rising generation of composers at the centre of a developing British musical renaissance. Bainton’s love of Bach emerges in his Op. 1 – a Prelude and Fugue for piano, dating from 1898.1

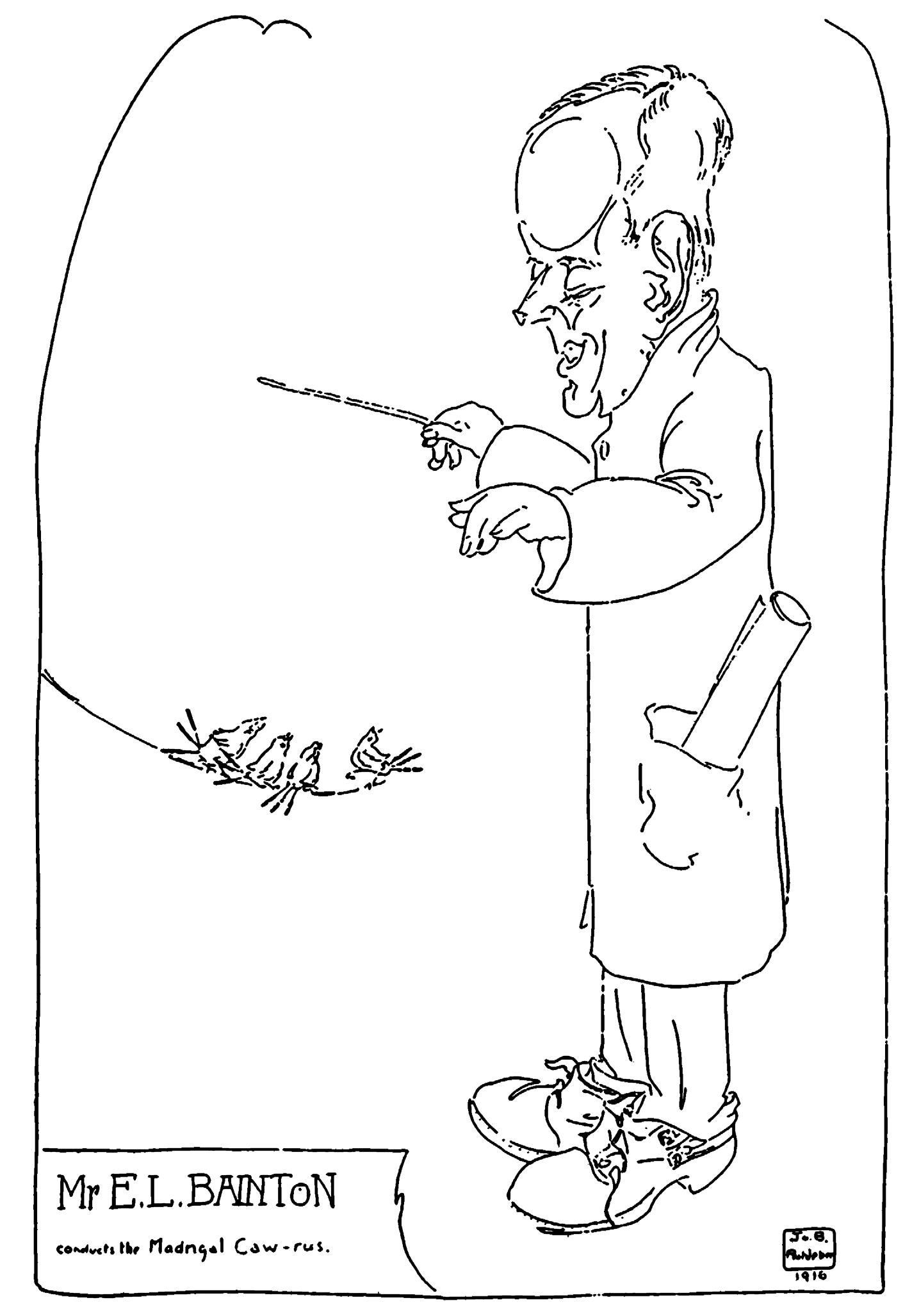

Bainton graduated from the RCM in 1901 with both the Tagore Medal and the Hopkinson Gold Medals under his belt, and that same year was appointed to the staff of the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Conservatoire of Music – a privatelyrun institution established some 40 years earlier. Ethel Eales, an accomplished violinist, pianist and singer and one of his students, became his wife in 1905 and they had two daughters. Bainton was much involved with local music-making –conducting the local Philharmonic Orchestra (invaluable for learning orchestration) and serving as accompanist and programme-annotator to the Chamber-Music Society. He conducted the Newcastle and Gateshead Choral Society in the premiere of his first full-scale choral work The Blessed Damozel in 19072 and in 1912 became Principal of the Conservatoire.

The November 2018 edition of Cathedral Music contained an article about Percy Hull and his internment at Ruhleben Camp during the First World War. Edgar and Ethel Bainton suffered a similar fate – they were arrested en route to the Bayreuth Festival in 1914. Ethel was soon repatriated and it was left to her to keep the Conservatoire open throughout the war while Edgar spent the next four years interned in

Ruhleben. Being placed in charge of music in the camp, he formed an orchestra and gave regular concerts (Bainton played piano concertos by Mozart and Chopin). In addition, plays by Shakespeare (such as Twelfth Night and The Merry Wives of Windsor) were performed for the 1916 tercentenary celebrations, for which Bainton wrote theatre music, re-worked in 1919 as Three Pieces for Orchestra. 3 In the last year of the war Bainton, along with B J Dale, Percy Hull and others, was invalided out to Scheveningen in The Hague for convalescence after a breakdown in health, and composed his song Twilight (John Masefield)4 there. Before being allowed to return home, Bainton had one more deed to perform – he was asked to take Sir Edward Elgar’s place to conduct the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra for two concerts of British music in 1918 – the first British conductor to receive this honour.

– SATB a cappella). Both were published by Oxford University Press. Of the other publications: The Heavens declare thy Glory is harder to obtain – a copy is held in the British Library.

There is one highly effective organ piece, Vexilla Regis (1925), lasting around four minutes. This was published in Australia in 1973, but has been out of print for many years; however, I am very grateful to Culver Music in the UK for issuing a reprint; every copy sold generates a royalty to the Edgar Bainton (UK) Society.

Bainton’s 11 extant choral works fall into three categories. Firstly, there are three that exist in MS vocal score form only: The Transfiguration of Dante Op. 18 (author unknown), To the Name above every Name (Richard Crashaw), and The Veteran of Heaven (Francis Thompson). The last two have been typeset and deserve to be heard, but would need orchestrating (Bainton marks occasional instrumental cues in his MSS). Secondly, Bainton’s secular choral works include: Symphony No. 1 ‘Before Sunrise’ (Swinburne, 1907) which won a Carnegie Award in 1917 and is an extended four-movement depiction of the Creation from a more agnostic point of view (‘Glory to Man in the Highest’!). Other works in this category, Sunset at Sea (Geoffrey Buckley), The Vindictive Staircase (W W Gibson) and A Song of Freedom and Joy (Edward Carpenter), were originally published in vocal score, but no longer have surviving full scores and parts. Of the remaining works: The Dancing Seal (W W Gibson), The Blessed Damozel (D G Rossetti) and the two works described below have extant full orchestral scores from which parts could be created.

During much of the 1920s Bainton continued with his Conservatoire activities in Newcastle, and became part of a core group of musicians at the centre of musical life in the North East. In the early 1930s he undertook many trips abroad, both as an examiner for the Associated Board and for lecture-tours of the USA, Canada and the Far East. It must have been on one of these, in Australia, that he was considered for the post of Director of the New South Wales Conservatorium in Sydney. Helen relates that in 1933 her father received a telephone call – not from the Conservatorium but from the Sydney Morning Herald (‘paparazzi’ are not new!) informing him of his appointment! And so it was that in 1934 Edgar and his family emigrated to Australia, where he became an important part of the musical and cultural life, including as a staff conductor of the then-new ABC Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Bainton was to remain in Australia (even after retirement from the ‘Con’ in 1946) until his death in December 1956.

Now let us examine And I Saw... a little more closely. Why has it proved to be the ideal work to be performed at major church services reflecting on tragic events? For example, it has taken pride of place in special services for: Hillsborough (Liverpool Cathedral, 1989), the 9/11 attacks (St Paul’s, 2001), and more recently, Grenfell Tower (2017). Perhaps in his own special way Bainton is able to lift us above the raw emotions of the occasion and lead us towards an awareness of a higher realm of existence than our own – achieved by a perfect balance of restrained emotion and technical skill which, in my opinion, is the hallmark of his best work and in its finest form lifts us up to a heightened state of imagination.

Of Bainton’s other church music: Open thy Gates (Robert Herrick – SATB a cappella) is a short and beautiful motet, ideal as an introit; as is Christ in the Wilderness (Robert Graves

As mentioned earlier, Bainton had known Percy Hull from their time in Ruhleben – they are even photographed side by side in one of the camp’s orchestra pictures, and when Hull was appointed to succeed George Sinclair at Hereford Cathedral on his return in 1918 he was instrumental in having works by some of the Ruhleben composers featured in future Three Choirs Festivals. Bainton’s Three Pieces for Orchestra were performed at the 1921 Festival, alongside works by B J Dale, Frederick Keel and Percy Hull himself, and Bainton’s orchestral poem Epithalamion was premiered at the Worcester Festival in 1929. Edgar and Ethel regularly attended these festivals and there is a photograph, taken in Percy Hull’s garden in 1927, in which they are pictured standing beside Elgar [see illustration].

Of Bainton’s choral works, The Tower (Robert Nichols) was composed for the 1924 Hereford Festival. It evokes the mood before the Last Supper and Gethsemane and is written for

double choir (no soloists) and orchestra and lasts for around 15-20 minutes. The opening atmosphere of expectancy is created by open chords of fifths in A minor [see illustration], setting the mood for the first choral entry. The vocal score was originally published in 1924; Bainton’s full score is in the British Library but would need typesetting for future performance.

A Hymn to God the Father (John Donne) was written for the 1926 Worcester Festival. This is a six- or seven-minute tour de force for double choir and orchestra and originally preceded Elgar’s The Kingdom. Starting in D minor, the work gradually gains in intensity until by the time we reach ‘I have a sin of fear’ the choir bursts out with a rising cascade of canonic entries across all eight parts [see illustration], building to a great climax, and then subsides to a peaceful D major close. Again, there are no orchestral parts at present, but the full score has already been typeset by the Edgar Bainton (UK) Society and it is hoped that both works will be revived in time for their centenaries in Hereford in 2024, and Worcester in 2026.

Finally, what happens to the royalties generated by And I Saw...? In the past these went to Bainton’s two daughters in Sydney, but when I researched Bainton’s works during the late 1980s Helen Bainton expressed the wish that all future royalties should help to promote and make available many of her father’s other works. After Helen’s death in 1996 this became a reality when the Edgar Bainton (UK) Society was established in 1997. The royalties generated since have helped to typeset and record a sizeable number of important works, including the second and third symphonies, the three tonepoems Pompilia, Prometheus and Paracelsus, the String Quartet and numerous songs – 20 of which appeared on a NAXOS CD in 2017.4 All these works can be heard on CD, as well as the Sonata for Viola and Piano, Sonata for Cello and Piano, Two Songs (Edward Carpenter) for Baritone and Orchestra, Concerto-Fantasia

and Genesis (from the First Symphony), Three Pieces for Orchestra, the suite The Golden River and Pavane, Idyll and Bacchanal for strings. The work goes on, and typesetting the choral works’ surviving full scores will be a future priority before royalties cease in 2026. By setting these pieces it is to be hoped that many other works of Edgar Bainton will be more widely heard again, alongside the works of those of his contemporaries who are also currently being re-discovered as an essential part of our musical heritage.

MICHAEL JONES is a professional pianist and organist who graduated from what is now the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire in 1974 with prizes for Piano, Advanced Harmony, and Musical Distinction. He is also a historian, lecturer, musicologist and independent concert-giver noted for his unusual and innovative programming. His CD recordings include Romantics in England (with cellist Joseph Spooner) and For Joyance (with oboist Mark Baigent). He is the music executor/trustee for the Edgar Bainton estate in the UK.

1 Original MS, dated “5/July 1898” is in the Mitchell Library, Sydney.

2 The original MSS full score and parts are in the Mitchell Library. A complete set of copies are kept here, as the work was performed by the Broadheath Singers and Windsor Sinfonia, conducted by Robert Tucker, in Eton School Hall in 1998.

3 This and other works listed can be heard on 3 Chandos CDs, played by the BBC Philharmonic on CHAN 9757, 10019 and 10460 (conducted by Vernon Handley, Martyn Brabbins and Paul Daniel).

4 This is one of Bainton’s unpublished songs which can now be heard on Naxos 8.571377, released in 2017.

During the morning of 26 December 1547 the Royal College of St Stephen the Protomartyr within the Palace of Westminster celebrated the feast day of their patron saint for the last time. With the canons lined up in their stalls in the quire, the lay clerks and choristers sung the lavish Latin polyphonic mass for St Stephen composed by their verger and organist, Nicholas Ludford. Even after the many religious changes imposed by not-quite-20 years of Reformation in the English Church, the Latin mass was still – just – in use. Those present at that mass that day, including Ludford himself and the long-serving dean, John Chamber, who had been dean since 1514 and a canon before that, were aware that the end was near. The College was unlikely to be spared from the new law which had received Royal Assent from Edward VI two days earlier on Christmas Eve. This Second Chantries Act abolished all institutions – secular colleges, hospitals, and chantries – that had as their primary religious function to pray for the dead in purgatory. St Stephen’s was to be no exception, unlike St George’s Windsor and the university colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, which were the subject of an intense lobbying campaign. St Stephen’s mounted no such campaign.

By Easter 1548, not quite 200 years of royal musical tradition at St Stephen’s had ended. The community was broken up and pensioned off. The expensive vestments and altar plate were confiscated by the king’s uncle, Protector Somerset, and the College’s lands sold to a range of opportunists. The clerks and choristers went to work elsewhere, including some at Westminster Abbey. John Chamber, already in his late seventies, outlived the College by just a year before he died and was buried at St Margaret’s, Westminster. Nicholas Ludford stayed in Westminster and continued to be active at St Margaret’s until his own death in 1557.

The musical tradition that ended with Ludford and his colleagues in 1548 had been started by Edward III in 1348. He had founded St Stephen’s Westminster and St George’s Windsor as sister institutions to pray for the royal dead and to ensure that the main chapels at his two favourite palaces were the home to a constant round of religious music and services. He wanted these chapels to have an equivalent round

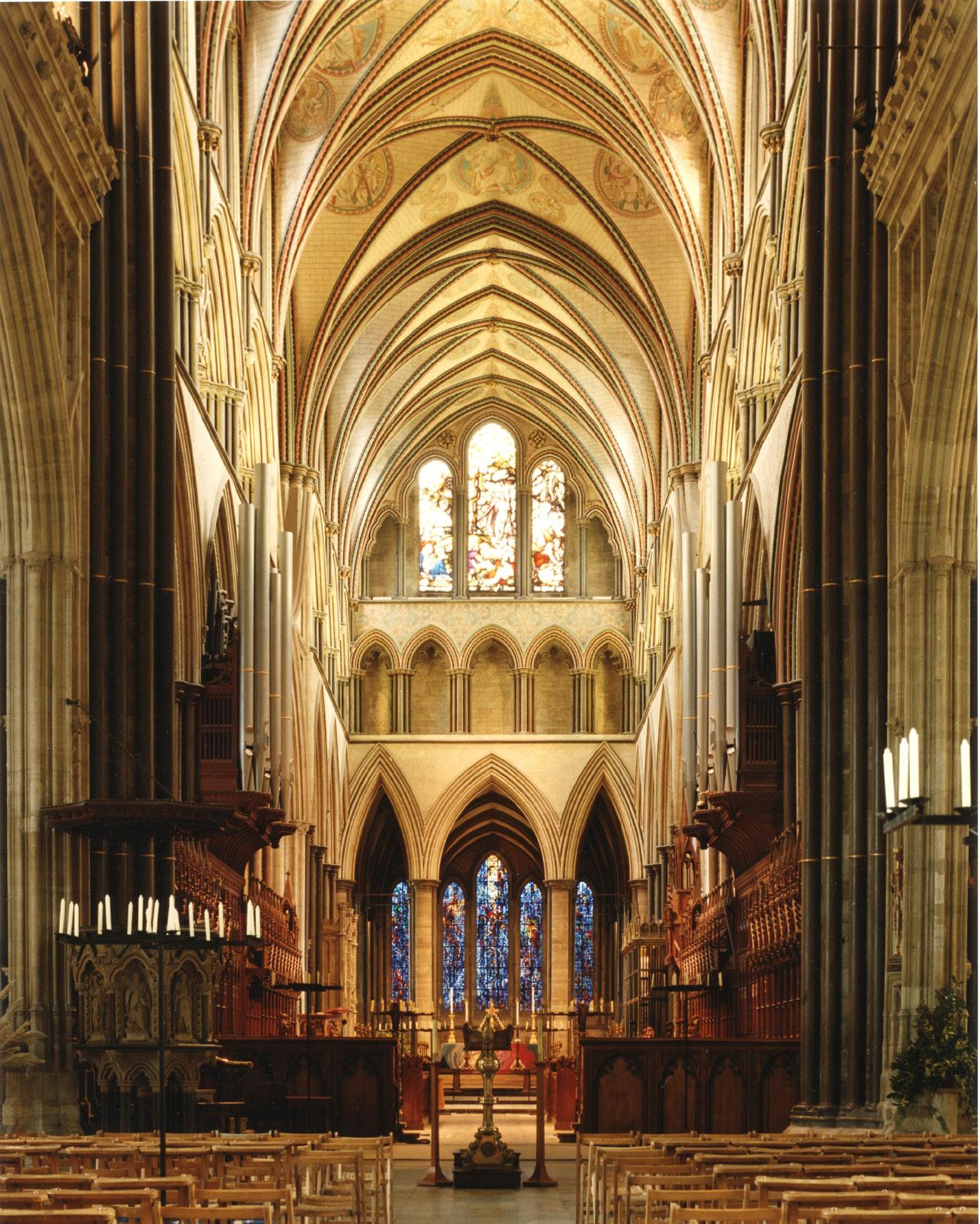

of services to the great cathedrals, particularly the services at Salisbury Cathedral. At Westminster, the new St Stephen’s was responsible for the main chapel dedicated to St Stephen, for St Mary Undercroft beneath it, and the small chapel with a cult image known as St Mary le Pew.

Of the College’s three chapels, St Mary Undercroft alone survives today. Edward gave both new colleges lands and revenues to pay wages, maintain the buildings and buy candles, incense, service books and vestments. Each college was headed by a dean and twelve canons who made up the chapter, supported by 13 vicars. Like any cathedral today, musical staff were also needed. By the standards of the 14th century, St Stephen’s was ridiculously elaborate, with four lay clerks and six choristers to serve as the choir. Unlike the canons and vicars, the clerks’ and choristers’ job was to focus on singing at all the services held in the chapels. The vicars also had to have good singing voices, while the canons had no obligations other than to show up at the main mass of the day to receive their residence payments of a shilling a day.

St Stephen’s College took pride in its musical abilities from the start. Edward’s foundation charter emphasised that the clerks and choristers were there to ensure that the music was polyphonic rather than the usual plainchant, which explains the high level of specialised musical staffing he provided. In the 15th century, other choirs were founded with the same

or larger numbers of musical specialists. The cathedrals especially expanded their use of positions that came to be known as singing men, and made them the backbone of their musical staff as they started to develop the English polyphonic and choral traditions. The challenge seems to have been set by St Stephen’s and St George’s; other institutions responded.

We don’t know much at all about the men who were clerks in the early days, but we do know that there were distinguished musicians among the canons. A celebratory motet, probably written and performed by the Chapel Royal to glorify Edward III as a new King Arthur for his victories in France in either 1358 or in the 1360s, talks of the knighthood, the priesthood and the people joining together to give thanks for the king’s successes. It praises 12 leading musicians around the king and his sons for their skills. Among the men named are two canons of St Stephen’s, William Tideswell and John Corby. Corby, according to the music, ‘shone out true-heartedly’ among the Chapel Royal. He had come to St Stephen’s in 1363 and probably stayed until his death around 1368. William Tideswell is identified by a Latin pun and he too was one of the singers of the Chapel Royal and played the lyre, according to the lyrics of the motet. We sadly do not know if either Tideswell or Corby composed any music that might have been used in St Stephen’s Chapel around this time. They might well have done so in working collections that did not survive the Reformation or which had become outmoded in the 15th century.

In the mid-15th century we also find Nicholas Sturgeon at St Stephen’s. He was a composer for the Chapel Royal, and a canon at Exeter and Wells cathedrals. His music survives in the Old Hall manuscript in the British Library, the most important source for late medieval English music. Sturgeon was later precentor at St Paul’s and thus was responsible for maintaining its musical tradition. How much time he actually spent at St Stephen’s and on the music there is unknown, although he did at least involve himself with the College’s land dealings in London and Westminster.

The clerks and choristers, the musical specialists of the College, are sadly very shadowy indeed. We know that usually one of the clerks served as Master of the Choristers. In 1544, Thomas Wallys was appointed clerk and Master of the Choristers. We also know that in 1452 one of the clerks was running a school in St Mary le Pew, probably as Master of the Choristers, when a careless schoolboy started a fire. The repairs were to take about 20 years, so there must have been very severe damage.

A few documents giving the duties of a clerk in the 1540s survive, but are annoyingly vague. According to his contract, William Pampion was to have a salary of £6 13s 4d in return for ‘serving and busying himself… around divine offices and behaving himself honourably in the … service’. If he was ill or infirm, it was his duty to organise a deputy. Pampion can be found living near to the College on Long Woolstaple Street in Westminster in 1544, when he paid 20 shillings in tax for that year. His neighbour there was Nicholas Ludford, who paid only 4s 5d in tax. These two paid similar amounts in the following years. After 1548, William Pampion’s colleague Alexander Perryn, who seems to have only joined St Stephen’s in its last two or so years, moved over to Westminster Abbey as a clerk there. Perryn’s processional from his Abbey days, in which he has added polyphony in the margins, survives in Paris.

The Missa lapidaverunt Stephanum or the ‘They have stoned Stephen’ Mass that would have been used on Boxing Day in 1547 is one of a whole series of elaborate masses composed by Nicholas Ludford for the College that survive in the Gonville and Caius Choirbook and in a set of partbooks for a weekly cycle of Lady Masses which are now in the British Library. These masses show the possibilities of the musical tradition at St Stephen’s and the Chapel Royal, where the composers, including Robert Fayrfax and William Cornish, are also represented in the Caius Choirbook. All the masses assume great familiarity and specialisation in singing elaborate multipart (five voices) music. The Lady Masses in particular also reflect the College’s daily commitment to saying services for the Virgin Mary, which was specified in 1348 and is clearly still being honoured 200 years later.

Ludford came to St Stephen’s in 1527 as the verger/organist, following in an established tradition. The composer John Bedyngham, whose work survives in continental manuscripts, had held the same position in the mid-15th century. Ludford’s work at St Stephen’s was not to organise the music — that was the task of the canon-precentor — and not to look after the choristers, but to play the organ and ensure that the chapel was kept in good repair. As a bonus, the College took advantage of his compositional skills.

The inventory of the chapels in 1548 includes three choirbooks, identified as ‘pricksong’ (i.e. music sung from notation rather than by ear), or polyphonic music, which would have formed the basis of the College’s musical repertoire. Two of the books cannot now be identified, but the third is known. It is almost certainly the Caius Choirbook, because there is a decorated initial showing the sexton of the chapel, John Coke, beating a pan, and other figures who are not identified but probably represent some of the men who worked at St Stephen’s in the late 1510s and 1520s. In addition, the Caius Choirbook was commissioned by Edward Higgons, canon at St Stephen’s, who also gave cloth of gold and crimson velvet altar hangings for the high altar. It would thus make sense that the choirbook was also Higgons’ gift to St Stephen’s, and that it may have returned to his family after the College’s dissolution before being given to Caius in the late 16th century.

Higgons’ canonry in 1518 was very much a retirement post after a long and active career as a lawyer in Westminster, but he seems to have taken great care of the musical and liturgical tradition at the College, and at Arundel College in Sussex, where he was Master. Although not a composer himself, he continued the tradition of musically-engaged canons that had started with Tideswell and Corby two centuries earlier.

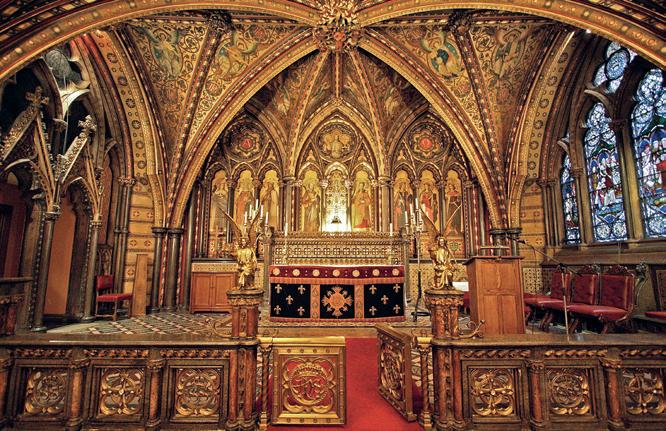

Today St Mary Undercroft is the chapel for the Houses of Parliament and hosts regular concerts and services. It is one of the few reminders left within Parliament of St Stephen’s Chapel and College, the other being the 16th-century cloisters next door which are now used as offices. It has been many things, including the Speaker’s State Dining Room in the early 19th century, when it was full of red hangings and gilded furniture. There is a story that Oliver Cromwell stabled his horses there, but because it would have been impossible to get horses into the building, and we know that it was used for storage around that time, the story is sadly not true. Since the 1850s it has once again been a chapel and used by members of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords for weddings and baptisms. Barry and Pugin, as part of their work on the current palace of Westminster, rebuilt and redecorated it to reflect its medieval splendour, including the roof bosses first carved in the 1320s. But in 1548 St Mary Undercroft was probably little used, as it was much less lavishly furnished than St Stephen’s Chapel above it. The upper chapel was where the College and visitors to the palace were more likely to be found. The inventory says that it had a ‘hearse’ and old black vestments for use at funerals, while upstairs were sets of vestments of velvet worked with silk thread, and the three great books of polyphonic music.

Unlike St Stephen’s Chapel, which became St Stephen’s Hall, St Mary Undercroft continues a distinguished and influential royal medieval musical tradition that was modelled on the cathedrals of the 14th century. Because Westminster is still a royal palace, the chapel is a Royal Peculiar and the Speaker’s chaplain, currently The Revd Rose Hudson-Wilkin, is responsible for services.

ELIZABETH BIGGS is an academic and researcher who has spent the last five years working on St Stephen’s College and the Palace of Westminster during the Middle Ages. Her book on the College is forthcoming with Boydell & Brewer next year. She has held post-doctoral research positions at Durham and York, where her work on the surviving 16th-century cloisters was funded by the Leverhulme Trust as part of Dr Elizabeth Hallam Smith’s Emeritus Fellowship.

Stephen Timpany

All photos Ian Maginess

On Sunday 23 September 2018 a festival service of Choral Evensong marked the 750th anniversary of the present building of St Patrick’s Cathedral (Church of Ireland) in Armagh. The anthem for the occasion was O Thou, the central orb by Charles Wood, a former chorister of the cathedral, who was born a few years shy of the building’s 600th anniversary. Wood subsequently became Professor of Music at Cambridge and a prolific composer of liturgical music.

Armagh, a small city of around 15,000 inhabitants situated 40 miles to the south-west of Belfast and 83 miles to the north-west of Dublin, has been the seat of the Church of Ireland and Roman Catholic primates in a succession traced to St Patrick himself. In the mid-fifth century St Patrick founded a monastery in Armagh (predating Canterbury by 150 years) and in 1005 Brian Boru, the first High King, confirmed the tradition that the saint had granted it preeminence over all churches in Ireland. The church built by St Patrick suffered many burnings and sackings in the succeeding centuries at the hands of various raiders, and the present building was begun by Archbishop O’Scanaill

in 1268. The building is cruciform in shape, and, although modest in scale when compared to many English cathedrals, has a unified architectural style and an aura of timelessness, with an excellent acoustic for organ and choral music. It sits prominently on top of the Hill of Armagh, above the busy streets of the city below.

Armagh has the oldest choral tradition in Ireland, dating from the days of St Patrick. In the ninth century the priests and monks were joined by the Culdees (usually translated as ‘companions of God’) who devoted themselves to the singing of daily services in the quire. This community of singers was disbanded at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. In 1634 a royal warrant established the ‘College of King Charles in the Cathedral of St Patrick’s, Armagh’ consisting of eight vicars choral and an organist. Later Archbishop Lindsay provided further funds which allowed for the addition of four boys’ voices. Like many similar institutions, the fortunes of the choir waxed and waned over the years, with its height in the mid-19th century when Armagh had a choir school, 12 salaried choir men and an assistant organist, in addition to the position of Organist and Master of the Choristers. Some of the choir men lived in tied houses opposite the cathedral, and daily services were sung. The disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1871 led to a reduction in the choir’s finances, with the result that the salaried men were reduced to four and the assistant organist was made redundant. The choir school closed in 1947 and salaried choir men ceased in the 1960s, after which the choir became entirely voluntary, and remains so to this day.

The position of Organist and Master of the Choristers is part-time, and the cathedral is possibly unique in having an assistant organist who is a parish priest and a member of its chapter! I was appointed Organist in 2015, and I am also a post-primary schoolteacher. My assistant, appointed in 2011, is Canon Dr Peter Thompson, who is also Rector of Castlecaulfield. There are two choral services on Sunday (Sung Eucharist or occasionally Matins at 11am and Choral Evensong at 3.15pm) from September to June, as well as to festivals and other special occasions, and two rehearsals per week – a full choir practice on Wednesday and boys only on Fridays, in addition to a 40-minute practice before each service. There is also a post-Evensong practice for young men whose voices have recently changed, an innovation which has proved beneficial. The choir has the usual half-term breaks, as well as days off on the Sundays following Christmas Day and Easter Sunday. Usually the organist accompanies and directs the choir on Sunday mornings, while the organist directs

the choir and the assistant organist accompanies on Sunday afternoons and for special services. This latter arrangement is much more satisfactory, as, although a CCTV system enables the organist to see the choir from the console, any meaningful communication and direction are difficult. The cathedral is lucky to have Peter, who is able to skilfully accompany services, give organ recitals, intone the Office or sing a missing choir part as and when required. Cathedral music in Armagh is run on a very slender budget and the cathedral was delighted recently to receive a grant from the Friends of Cathedral Music. This was used to increase the endowment, which provides the salary of the Organist and Master of the Choristers, and to purchase a ‘new’ secondhand grand piano for the choir rehearsal room. The cathedral is most grateful for this support.

At full strength this year, the choir has 30 voices (20 boys and 10 men). All of the present choir men have been choristers in the choir, which engenders a great sense of collegiality, continuity and tradition. Most boys make a commitment to attend regularly either the morning or afternoon service, with some attending both, although all are flexible if required. Since my appointment I have been fortunate in establishing good relationships with local primary schools, and two of these schools have provided the majority of choristers in recent years. I find it useful to have two intakes per year, in October and February. Following a month’s trial period, the boys join the choir as probationers for one year. Although one or two boys have joined the choir during their first year at post-primary school, most join at age 8 or 9. I have found that approaching schools directly works much better for recruitment than invitations in the local press or media, although the latter do help to raise awareness of the choir’s activities.

Social gatherings and outings are important events in the annual choir calendar. There are at least three social events

per annum for the choir’s extended family (boys, siblings, parents, choir men and partners) and there are also termly outings for the boys, which they enjoy immensely. No choristers live within walking distance of the cathedral, so parents have to transport their sons. The cathedral is fortunate in having such supportive and committed parents who also help with the supervision and organisation of choir activities. We are greatly indebted to them. Without their wholehearted support, music-making in the cathedral would be extremely challenging.

I was appointed Organist and Master of the Choristers in September 2015, having been acting director during the illness of my predecessor, Theo Saunders. I had organ lessons for seven years with Martin White, also one of my predecessors, after which I studied Music and French at Queen’s University, Belfast. I then completed teacher training and started work as a post-primary teacher. I had been organist and choirmaster in three different parishes, latterly in Holy Trinity Parish

Church, Banbridge, where the choir undertook regular cathedral visits and made two CD recordings. I have always been interested in cathedral music and about 15 years ago I resumed my musical studies and passed the ARCO diploma. I am also a past president of the Ulster Society of Organists and Choirmasters.

My immediate predecessor Theo Saunders was responsible, together with the cathedral choir and the Children and Gentlemen of Her Majesty’s Chapels Royal, for the music at the Royal Maundy in 2008, which was one of the most impressive services in the cathedral’s history. Theo pioneered three important ventures during his tenure as Organist (2002-2015): firstly, the ‘Morning on the Hill’ visits whereby local school children spend a morning exploring the cathedral, Robinson Library and former Diocesan Registry, thus introducing many to the cathedral for the first time, and secondly, the establishment of a monthly organ recital series from September to June. Theo also formed a voluntary choir which sings at weekday festivals of the church, such as Epiphany, Candlemas and Ascension. It also sings at the celebration of the Eucharist which precedes a meeting of an ‘Electoral College’, the Church of Ireland’s particular way of choosing a new bishop.

Martin White served as Organist from 1968 to 2002 and was influential in the lives of many young people through his work at the cathedral and as organiser of Craigavon Music Centre. Martin deserves great credit for maintaining the men and boys’ choir through the worst years of the Troubles, when the choir could very easily have been disbanded, and when ordinary everyday life in Ulster was almost impossible. With the notable exception of Dr Joe McKee, who was Assistant Organist from 1975 to 1985, Martin accompanied services and directed the choir single-handedly, as well as finding time to undertake re-leathering of the Roosevelt soundboards to ensure the organ remained playable. Shortly after his retirement, Martin was made a lay canon of the cathedral and received the title of Organist Emeritus in 2017.

One of the treasures of Armagh Cathedral is its wonderful organ. The present instrument was originally built by J W Walker in 1840, with alterations in 1928, 1941 and 1951. The instrument stood on a screen before it was moved to its present position. The firm of Wells-Kennedy (Lisburn, Co. Antrim) completed a substantial and very successful rebuild in 1996, which included the installation of new slider soundboards and underactions, rewiring, refurbishment of the console, the installation of a new solid-state switching system and various tonal modifications and additions. Tonal egress was greatly enhanced by raising the soundboards of the manual divisions by eight feet, and the two original organ cases, which were hidden inside the chamber, were placed to face each other under the arches at the north and south sides of the crossing. The organ is essentially a Romantic instrument with full and balanced choruses and a wealth of solo and accompanimental voices. The instrument is very well resourced for recital work and is ideal for accompaniment with two divisions under expression. Two 32’ stops, a splendid Tuba and a wonderful acoustic add to the excitement. It is without doubt one of Ireland’s most successful organs.

A welcome addition to music in the cathedral was the establishment of the Armagh Diocesan Singers in 2018. The

mixed-voice ensemble of 28 voices, under the direction of Peter Thompson, sings a monthly Choral Evensong in the cathedral and complements the work of the cathedral choir. The Diocesan Singers also cover the cathedral choir’s halfterm holidays and ensures that there is choral music in the cathedral every Sunday from the start of September to the end of June. The cathedral is always happy to welcome visiting choirs during July and August This year choirs have come from St Mark’s, Portadown, St Paul’s Cathedral (Buffalo, USA), and King’s College School, Wimbledon. Budget youth hostel accommodation and hotels are available within walking distance and there is always a warm welcome in Armagh.

For one week in August each year the Charles Wood Festival and Summer School takes places in Armagh, under the artistic direction of Dr David Hill. It presents a feast of vocal and choral music in various churches around the city, alongside vocal masterclasses. The festival has become a major event in the Irish cultural landscape and has undoubtedly put Armagh into the consciousness of those interested in liturgical music in a way that would not have been possible before the festival began.

The Northern Ireland International Organ Competition (NIIOC), founded in 2011 by Richard Yarr, has now become the world’s leading competition for players aged 21 and under. NIIOC runs concurrently with the Charles Wood Festival and is now partnered with the St Albans International Organ Competition. It is fitting that both the festival and NIIOC perpetuate the names of two musicians associated with the cathedral – the Theo Saunders Scholarship and the William Lauder Scholarship – for organists and singers respectively.

St Patrick’s, Armagh was once described to me as ‘an English cathedral set in the middle of the Irish countryside’ and indeed the city’s rural location does mean that there is a limited pool of part-singers who have the skills to sing in the cathedral choir, and most of them are associated with the choir already. There are limited employment opportunities in the city, so that many choir members leave Armagh following A levels, and do not return. Although the city hosts many cultural activities, Armagh does suffer from being an hour’s drive from greater Belfast, where the majority of Northern Ireland’s population live. I often think, too, that few people realise the preciousness of cathedral music, or of the unique English tradition of cathedral men and boys’ choirs. The cathedral’s music needs to be placed on a firmer financial foundation than at present, and we are currently investigating how this might best be done. Although so many choir members leave Armagh for higher education and employment, often outside Northern Ireland, the cathedral is keen to build links with its former choristers, and this April held a Past Choristers’ service, something we plan to repeat.

It is a privilege to be Organist and Master of the Choristers in such a beautiful and historic place, and to belong to a very long tradition of musicians in the cathedral. I receive great support from the boys, their parents and the choir men, and have an excellent working relationship with Dean Gregory Dunstan, who was a chorister under Sir William Harris at St George’s Chapel, Windsor. I hope that the tradition of the men and boys’ choir will continue for many years to come on the Hill of Armagh.

The construction of the castle that became known as the Tower of London was begun in 1078 by Bishop Gundulf of Rochester, on the instructions of William the Conqueror. Once a place of incarceration, torture and execution, the Tower’s history encompasses many other less gruesome facets and at various times has been an armoury, a treasury, a menagerie, the home of the Royal Mint (run for a period by one Isaac Newton, who lived in the Tower), a public record office, and the home of the Crown Jewels of England. It is also the home to two very fine chapels.

Today, both chapels are fully functioning places of worship, and are very much living organisms within the giant museum of the Tower of London. The Chapel of St John the Evangelist, within the great White Tower itself, is one of the oldest Norman chapels in Britain and is a very fine example of early Norman architecture. It was the monarch’s private chapel when in residence at the Tower, and it was here that the Knights of the Bath kept an all-night vigil, having had their ritual bath in the adjoining room, before escorting the monarch to Westminster to be crowned, a custom that ran from Henry VI’s time to that of Charles II. This is also the chapel in which Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales, married Catherine of Aragon in 1501.

In the shadow of the Tower sits the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula (St Peter in Chains), aptly named for a place of

worship within a prison. This chapel was completed in 1520 and was built on the instructions of Henry VIII. Sir Richard Cholmondeley, Lieutenant of the Tower at the time, was given the task of overseeing the construction of the chapel, and he included for himself and his wife a rather large tomb. A careful inspection of the tomb reveals that the date of death is blank. Cholmondeley had fallen out with Henry VIII and fled to the north of England so as not to lose his head. When the tomb was relocated within the chapel in the 19th century, it was found not to contain human remains, but the chapel’s font! (It is thought that this may have been hidden during the Commonwealth by the then chaplain of the Tower, but he took the secret to the grave with him.) The font, dating from around 1490, was probably part of the previously chapel, which was destroyed by fire in 1512.

The rather simple, but elegant, roof of the chapel is made of Spanish chestnut. The timbers were brought all the way from Spain and may be considered a gesture from Catherine of Aragon’s second husband, Henry VIII (Catherine was, of course, Henry’s first wife).

The very fine organ case was created by the renowned English woodcarver Grinling Gibbons. The instrument, dating from c1699, was originally built for use in the Banqueting House in Whitehall, and was moved to the Tower in 1890. Gibbons, like many craftsmen of the time, was illiterate, so he used a

peapod by way of signature. If the peapod was open, it meant he had been paid for the work; if it was closed, he had not. On the Tower’s organ the peapod is open... and can be seen just above the console to the right.

The inner workings of the organ, and the façade pipes, date from 1999. Having been through various rebuilds since it began its life, by the late 1990s the organ had become increasingly unreliable, so the choral foundation of the Tower took the decision to commission an instrument to be built within the existing historical casework. Orgues Létourneau of Quebec in Canada won the tender and, as well as building a very fine 2-manual organ, they renovated the Gibbons case.

As the primary role of the organ is to accompany the liturgy in the chapel, it was important that a new instrument should have the appropriate colour and sound to do this to the highest quality. The new organ fulfils this task admirably. In addition, much of the solo repertoire can be played on it with enormous integrity.

There is great deal of fascinating history associated with the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula, but perhaps what it is best known for are those people who are buried in it. Anyone who has read Hilary Mantel’s historical novel Wolf Hall will be interested to know that the main protagonists of her book are all buried there. A brass plaque (which reads like a Who’s

Who of Tudor England) on the west wall of the chapel carries the name of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s enforcer. Three Queens of England – Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard, and Lady Jane Grey – were executed within the walls of the Tower and are buried by the altar. Two saints of the Roman Catholic church are buried in the crypt area, beside the chapel rather than under it – John Fisher (another Bishop of Rochester) and Thomas More. These last both lost their lives for not accepting Henry VIII’s Act of Supremacy.

Today, the chapel is staffed by a chaplain, assistant chaplain, a chapel clerk and sextons, all of whom are drawn from the body of yeoman warders who live and work in the Tower. While primarily a Chapel Royal, St Peter’s also serves as the local church of the Tower of London. There is a choir of 12 professional singers and myself as Organist and Master of Music who provide music not just for Sundays and feast days through the year, but for many visiting charitable organisations and livery companies. The chapel uses the 1662 Book of Common Prayer and the King James Bible for all its services, with Matins three times a month and a Sung Eucharist once a month.

My own association with the Chapels Royal in the Tower goes back almost 25 years. I first played the organ for a service there in 1994 while a student at the Royal Academy of Music, and enjoyed ten years of accompanying the choir under

Stephen Tilton, before becoming Master of Music myself in 2004. Since then I have worked to develop the musical life of the chapels in a variety of guises. The repertoire has grown enormously. Shortly after I took over we started singing Viennese masses, which had never been done before at the Tower, and they are now a regular part of our musical offerings for Eucharists, often incorporating a small orchestra for major festivals such as Easter Day. We revel in performing Tudor music as part of our services – the building especially suits this era of composition, allowing the grandeur of the music to speak forth while enabling all the detail to be heard. I am very proud that we are one of the few places in the country that performs parts of William Byrd’s Great Service for the liturgy, as we do the major services of Gibbons, Tomkins and Weelkes. We regularly commission new music, including a carol each year, performed at our ‘State’ Service of Nine Lessons and Carols. The Chapel of St John has no organ, but this, coupled with the nature of the space, makes it ideally suited to a cappella Renaissance masses, as well as the odd offering from the Eton Choir Book and some carefully chosen contemporary pieces.

The choir performs a number of concerts each year, often with a small band, and individual members of the choir mount their own projects to perform Dowland and Purcell songs, or Bach cantatas, all well suited to the building.

I have found that the chapels at the Tower weave a wonderful thread through what has been a nomadic life as a freelance