A TOP SECRET

SEAT OF POWER

ART from the HEART

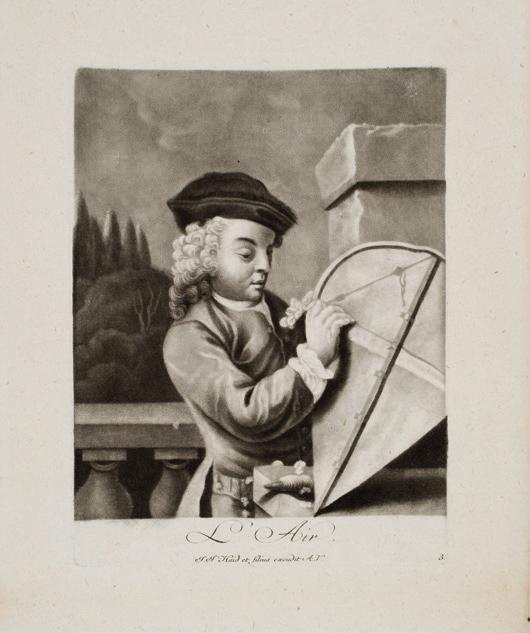

Behind every collection in the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg is an amazing story, beautifully told. Embark on a journey into the world of 18th-century fashion. Explore the intricate craftsmanship of crewel or wool embroidered jumps, offering women a lighter and more flexible alternative to traditional stays. Step into history as you discover the evolution and significance of these garments. Explore our collections, visit the Museum Store for unique treasures, and unwind at the Café, open daily to enhance your journey into the past.

4

6

10

25

By Paul Aron31 MODERN HISTORY

36

18

Paul Aron

Paul Aron

42 CHRONICLES OF THE COLLECTION

The Governor’s Chair symbolized the sovereignty of the Crown

By Paul Aron46 COMING UP

Conferences and events for the coming seasons

48 250 YEARS AGO: GETTING ATTENTION

The curious origins of an explosive essay

By Jon Kukla56

65

ART DIRECTOR

Katie Roy

DESIGNERS

Katherine Jordan

Lauren Metzger

PHOTOGRAPHER

Brian Newson

Carly Fiorina, Chair, Mason Neck, Va.

Cliff Fleet, President and CEO, Williamsburg, Va.

Kendrick F. Ashton Jr., Arlington, Va.

Frank Batten Jr., Norfolk, Va.

Geoff Bennett, Fairfax, Va.

Catharine Broderick, Lake Wales, Fla.

Mark A. Coblitz, Wayne, Pa.

Neil M. Gorsuch, Washington, D.C.

Antonia Hernandez, Pasadena, Calif.

Conrad Mercer Hall, Norfolk, Va.

John A. Luke Jr., Richmond, Va.

Walfrido J. Martinez, New York, N.Y.

Leslie A. Miller, Philadelphia, Pa.

Steven L. Miller, Houston, Texas

Joseph W. Montgomery, Williamsburg, Va.

Steve Netzley, Carlsbad, Calif.

Walter S. Robertson III, Richmond, Va.

Gerald L. Shaheen, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Larry W. Sonsini, Palo Alto, Calif.

Sheldon M. Stone, Los Angeles, Calif.

Y. Ping Sun, Houston, Texas

John C. Thomas, Richmond, Va.

Jeffrey B. Trammell, Washington, D.C.

Alex Wallace, New York, N.Y.

Colin G. Campbell, Williamsburg, Va.

Charles R. Longsworth, Royalston, Mass.

Thurston R. Moore, Richmond, Va.

Richard G. Tilghman, Richmond, Va.

Henry C. Wolf, Williamsburg, Va.

TREND & TRADITION

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Catherine Whittenburg

MANAGING EDITOR Jody Macenka

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Paul Aron, Ronald L. Hurst, Eve Otmar, John Wallace, Rachel West

COPY EDITORS

W. Hewlett Stith, Amy Watson

PRODUCTION MANAGER

Angela C. Taormina

PUBLICATIONS

COORDINATOR

Grenda Greene

MEDIA COLLECTIONS Tracey Gulden, Jenna Simpson, Brendan Sostak

RESEARCH Carl Childs, Erin Lopater, Marianne Martin, Douglas Mayo

DONORS Please address all donor correspondence, address changes and requests for our current financial statement to: Signe Foerster, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776 or email sfoerster@cwf.org, telephone 888-293-1776.

Donations support the programs and preservation efforts of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, a not-for-profit, tax-exempt corporation organized under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, with principal offices in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Address changes & subscription questions: gifts@cwf.org or 888-293-1776

Editorial inquiries: editor@cwf.org

Advertising: nfrey@cwf.org or 757-259-5907

Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg, Attn: Signe Foerster, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776. © 2024 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All rights reserved.

NOTE Advertising in Trend & Tradition does not imply endorsement of products or services by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

It’s hard to imagine a stronger start to the new year for Colonial Williamsburg and the news just keeps get ting better.

We began with our exciting year-end fundraising results for 2023. Thanks to your incredible generosity and commitment, the Foundation raised more than $103 million in philanthropic contributions last year, surpassing all previous fundraising records. This new milestone, which reflects our successful launch of The Power of Place campaign last fall, positions the Foundation among the nation’s preeminent institutions of American history, at the site where so much of America’s founding story took place.

Given Williamsburg’s leadership in 18thcentur y America, it is only fitting that today we lead the nation’s commemoration of America’s 250th anniversary in 2026. On March 18, shortly after this issue of Trend & Tradition goes to press, Colonial Williamsburg will host A Common Cause to All, a unique gathering of civic and educational leaders from around the country who

are planning for America’s 250th anniversary in 2026. This is the second consecutive year we are hosting this important event in partnership with the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission (VA250), which places Virginia and Colonial Williamsburg in lead roles at the center of the 2026 planning effort. We are excited to welcome more than 400 civic and educational leaders from at least 40 states to this uni fying event.

One of our many initiatives in support of 2026 is our research and restoration of the Williamsburg Bray School building, which is made possible thanks to your support. Believed to be America’s oldest surviving school building for Black children, enslaved and free, our research and preservation teams are working hard to prepare this original 18th- centur y building for its public opening this fall so we were thrilled when NBC’s Today show chose to share its moving, complicated story with the world in February.

Today show host Craig Melvin traveled to Williamsburg on Jan. 23 with a film crew to tour

this historic building and interview members of Colonial Williamsburg’s expert staff, the director of the William & Mary Bray School Lab and descendants of the very children who studied at the Bray School. Today ’s airing of not one but two segments about the school on Feb. 1 marked the second time in the span of a year that Melvin has personally covered our work, having previously filmed a segment in May 2023 about the Historic First Baptist Church excavation. With a daily viewership approaching 3 million, Today ’s thoughtful coverage of these groundbreaking programs has profoundly magnified their impact, engaging new audiences in our mission to share a more complete story of our nation. You can read more about the filming on Page 31.

independence approached, Monroe had looked to Lafayette, last surviving general of the American Continental army, to remind the nation of its struggle for freedom.

In the coming months, we will also introduce millions of Americans to an important but underrepresented Founding Father of our nation: the Marquis de Lafayette, a champion for liberty who joined the fight for America’s independence at just 19 years of age and quickly became a close ally and confidant of Gen. George Washington. Together, they would lead America’s troops to victory at the siege of Yorktown.

Many people know Lafayette’s name thanks to the number of streets, parks, schools and even towns that bear his name. Fewer know that many of these places took Lafayette’s name when he made his whirlwind return tour of the United States in 1824 at the invitation of President James Monroe. As the 50th anniversary of American

Later this year we will partner with the American Friends of Lafayette to commemorate the marquis’ return tour in 1824. Mark Schneider, who has skillfully portrayed Lafayette at the Foundation for decades, will reprise his role in locations across the country, beginning with an appearance in Staten Island on Aug. 15. On that day 200 years ago, the marquis disembarked from the American merchant ship Cadmus in the New York harbor after more than a month at sea. This tour is a timely reminder that the ideals that America was built upon are as meaningful today as they were nearly 250 years ago.

And there is much more to come, which I look forward to sharing with you in the coming months. 2024 is going to be a truly exciting year thanks to you, our wonderful friends, who are making it happen.

In gratitude,

Cliff Fleet President & CEO

Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Distinguished Presidential Chair

Cliff Fleet President & CEO

Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Distinguished Presidential Chair

Videos for kids that explain some everyday parts of early American life that may not look familiar colonialwilliamsburg.org/learn/what-thehuzzah-is-that/

There’s so much to know about the building that was the seat of early Virginia politics colonialwilliamsburg.org/locations/capitol/

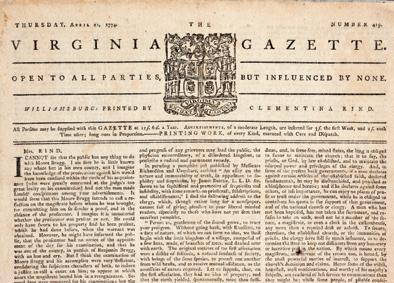

Explore the clues to 18th-century life contained in the Virginia Gazette colonialwilliamsburg.org/gazettes/

Precious Gem rings are handcrafted in 18K gold or platinum and may be made with your choice of gemstones and size stones; priced accordingly.

Call 1-800-644-8077 or email info@thepreciousgems.com to talk about your jewel for a lifetime.

If

p. 18

Maintaining the Town

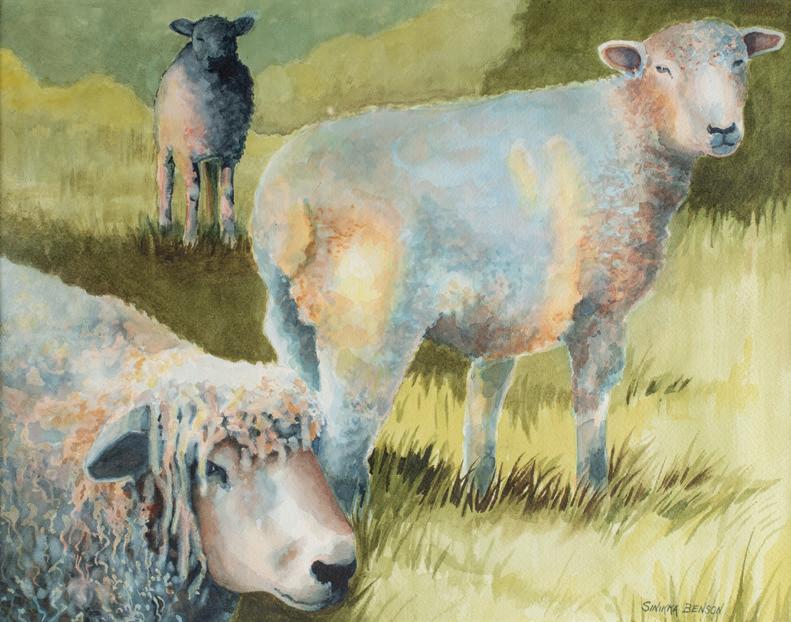

When visitors use their artistic talents to show their appreciation of the Historic Area, the living history museum comes to life in a new light. What follows are examples of how people, places and even animals moved these artists to share their love of Colonial Williamsburg.

“Walking through Colonial Williamsburg one spring day, I noticed some female interpreters working in this beautiful garden. It was a ‘slice of life’ that could have been taking place in colonial times. I am continually inspired by Colonial Williamsburg... the buildings and other structures, the interpreters dressed as citizens of another time, the livestock, even the trees. I am proud to live in such a special place.”

“My wife, Cheryl, and I are donors and volunteers we serve as ambassadors. I’m pretty much a self-taught artist. I credit my mother for passing along the creative genes. The field of beautiful yellow/orange flowers caught my eye some years ago. I wanted to capture a portion of the Art Museum with the beauty of the wild flowers covering the Custis field. I chose acrylic paint to help express the vibrancy of t he flowers.”

ARTIST PHILLIP MONTGOMERY

REPURPOSED WOOD AND PAINT MEDIUM

“We love Colonial Williamsburg and have stayed several times in the little rental houses. The architecture and the gardens and seeing the colonial trades draw us back over and over. We even got engaged to be mar ried there.”

“What caught my eye was the composition with so many of the objects that are reminiscent of this great ‘living history’ place. In today’s busy and sometimes frantic times, it’s so refreshing to just step back in time, slow down and enjoy the beautiful lessons that Colonial Williamsburg has to offer. We have been coming since 1969 and will continue to come here because there is always something new to explore!”

“My wife and I come often to Williamsburg and have been doing so for years. The depth and authenticity of Williamsburg has always inspired me. My work reflects this love and a love for historic al costume.”

“My daughter Amanda was determined to hoop and stick all over the Historic Area during our visit. The expression on Amanda’s face and her determination impart the joy she was feeling. Our family continued to return and experience our stay in a colonial home. Amanda would even bring back her hoop and stick on the airplane.”

Sandy Smith submitted the work of her friend Sinikka Benson, a middle-school art teacher who was her traveling and painting partner. On visits to Williamsburg, they searched for the sheep. “Sometimes they seemed as curious about us as we were about them,” said Smith, recalling her friend, who passed away in 2022, as modest about her talent and tireless in pursuing i mprovement.

“In this busy world, is there a more delightful escape than walking in the gardens of Colonial Williamsburg? The Taliaferro-Cole House garden has lovely paths that usually display some color with straw flowers its serenity is soothing. This garden will be featured for the Historic Garden Day Tour in Williamsburg on Tuesday, April 23. There are many other wonderful gardens in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area to explore, and they each offer so many more surprises.”

“Coming up slowly on Nicholson Street pulling one of the lovely carriages ending a long day, all looking for rest. I’ve been part of the Colonial Williamsburg Teacher Institute for 20+ years, working as a teacher facilitator and curriculum writer. I also went to art college and I’m now a watercolor painter, so everything came together!

“I love CW’s excitement of always striving for accuracy, improvement and passion! What’s not to love?

“I taught fifth grade for 22 years. I can honestly say over the 300 students I taught, every one of them loved American colonial history, courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg.”

ARTIST DON GORE WATERCOLOR MEDIUM

“I love to paint and draw on our travels across the country. My primary medium is watercolor and this particular scene at Colonial Williamsburg caught my attention. I think it tells a lot about the place and history in one image.

“My wife loves history and I love architecture and art. Colonial Williamsburg provides the perfect setting for both of us. We typically visit at least once a year and find it peaceful and inspiring each and every time. It doesn’t disappoint.”

Every day, there are the particulars the largely unseen details that demand attention. These routine and seemingly mundane tasks are so important that, if left undone, the experiences of the Historic Area would be vastly d ifferent.

Caring for buildings, tending gardens, protecting valuable artifacts these are only a few of the many examples of managing the moving parts of the world’s largest U. S. history museum. Much of that work happens behind the scenes, but the absence of

that work would be quite noticeable. These are just a few examples from across The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation which relies on donations to the Colonial Williamsburg Fund to support its daily operations.

Undra Jeter thinks a lot about grass. As Colonial Williamsburg’s Bill and Jean Lane Director of Coach & Livestock, Jeter heads a depart-

(Above):

(Opposite page): Bolts of wool fabric line the shelves at Historical Clothing & Dress. Information on the tags hanging from each bolt include the amount of material that remains.

ment responsible for the well-being of more than 100 animals, including horses, cattle and sheep. These animals lend their own 18th- centur y interpretation to the historical landscape. And like any animal from any era, they are hungry.

Jeter and his team must manage the vegetation on 62 acres of pasture that is both living space and sustenance for the large animals. Filling many stomachs can quickly consume copious amounts of forage, so pasture management is a

key element in the maintenance plan. “We rotate the animals on a weekly basis so they don’t overgraze the fields,” Jeter said.

Good grass begins with good soil, and Colonial Williamsburg regularly sends samples to Virginia Tech for analysis. Based on the deficiencies identified, the team chooses a commercial fertilizer that works in concert with the natural manure the animals provide. The combination with various types of seasonal seeds orchard grass, perennial rye and fescue provides a lush buffet from spring to fall.

That ensures that the livestock stay well-fed and there’s enough grass for the lean winter months.

those garments must be cleaned a job that also falls to this department. So the 20 employees who work there are in constant motion.

No one size fits all, said Mathew Gnagy, who manages the department. Garments fall into three categories:

“When we put down the grass seed, keep animals off, get it up good and high, we can get what we need which is that root depth,” Jeter said.

During busy times, Colonial Williamsburg employs more than 400 historical interpreters and other staff members who help to create the museum’s immersive experience. The Department of Historical Clothing & Dress helps them look the part.

Historical interpreters require historical dress, whether they have one role or several, and all

Historic Area employees whose jobs involve rugged work think brickmakers, foodways interpreters or tavern servers need more durable clothing with resistance to wear and tear. Historical outfits for most tradespeople and the Fifes & Drums of Colonial Williamsburg are built for active use but incorporate features such as handstitching to balance historical accuracy with the demands of a working museum professional. And finally, the department produces clothing for the actor-interpreters who

portray specific individuals and whose clothes are handsewn with elaborate flourishes.

In fact, Gnagy recently sewed an outfit for Mark Schneider, who portrays the ornately dressed Marquis de Lafayette.

“It took me 40 hours, and I didn’t use a sewing machine,” he said.

Every year, Colonial Williamsburg’s Department of Landscape and Horticulture plants bare-root trees ahead of the spring season. This year, it ordered more than 60 trees.

The Colonial Williamsburg Arboretum comprises trees and woody plants that would have been prevalent in the 18th century. Currently a Level 2 arboretum, the Foundation is working toward the expanded inventory required to attain Level 3 status. In addition, Foundation arborists plant trees to enhance the streetscape and to replace those that are removed because of old age or sickness, according to Landscape Manager Jon Lak.

It was common for lots in 18th- centur y Williamsburg to have small orchards that provided fruit for people and animals. These were

not varieties familiar to the modern palate. Instead, fruit trees that grew behind colonial homes bore types that are now considered heirloom or rare.

While growing these cultivars today requires a great deal more attention than those now grown in modern orchards, Landscape and Horticulture has a passion for planting that is rooted in authenticity.

“These are authentic types that have not been bred over hundreds of years to have resistance to pests and diseases,” said Melissa Sharifi, a department manager. “They are not very attractive or productive. Commercial fruit trees have highly intensive chemical needs, but that’s not something we can do in a public setting.”

Colonial Williamsburg curates a collection of 60 million artifacts from nearly a century of archaeological excavations. Each artifact tells its own story about the founding of America.

But carefully collecting these objects from the ground is just one step in the learning process. Working in conjunction with Colonial Williams-

burg’s conservators, archaeologists clean, catalog, study and store each item recovered during exc avations.

And when it comes to storage, no run-of-the-mill box will do.

“These aren’t just bankers boxes,” said Director of Archaeology Jack Gary. “These are acid-free curatorial boxes, which are the highest- qualit y environment that we can provide.”

Acid from traditional boxes could damage or even destroy artifacts. Other materials such as plastic also have drawbacks that make them unsuitable for storage.

Yet even these specialized boxes lose their ability over time to keep harmful elements at bay. With a special pen, conservators mark boxes so that they know when it is time to

move the items to new storage boxes for safekeeping.

And because the archaeologists are so busy digging these days, the size of the collection is constantly expanding. Gary estimates that his team easily requires 200 boxes a year. “We don’t see demand changing,” he said. “There will be a continual need long into the future.”

That future includes the completion of the Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Archaeology Center, which is expected to open in 2026. The new building will afford additional display and storage space

for the discoveries already made and those that are yet to come.

Special

Ben Swenson is a freelance writer living in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Every year some of the Historic Area buildings close so that experts can tackle specific maintenance issues. Exhibition buildings, trades shops and retail shops get this treatment every two to three years with the exception of the Capitol and the Governor’s Palace, both of which require annual maintenance, said Manager of Architectural Collections Dani Jaworski.

A couple weeks before a building is scheduled

Contributions to the Colonial Williamsburg Fund can be used for a variety purposes, including the day-to-day necessities that maintain this 18th-century town. It makes the immersive experiences of the Historic Area possible. The multiyear Power of Place fundraising campaign supports the people and

to be closed, Jaworski walks through with painters, carpenters, electricians, masons to carefully inspect the building. There are the usual suspects on the to-do list. Door and window hardware often declines with age, and repainting is constant. “You can see places where people naturally touch things, and that’s a visual intrusion because it begins to stain and doesn’t look good,” Jaworski said.

But there are often surprises, too. The team may find a loose board or a leak problems that can cascade if not promptly addressed.

The maintenance inspection is about ensuring that the buildings and the objects inside of them remain in good shape for generations to come. “We want to protect everything that the Foundation owns,” Jaworsk i said.

the infrastructure that bring early American history to life.

To contribute to Colonial Williamsburg and advance its mission, please visit cwpowerofplace.org .

If you would like more information on how you can support this work, contact us at campaign@ cwf.org .

A patch of ordinary ground. But beneath it, the foundation of one of the oldest Black churches in America. The excavation of the First Baptist Church is a new chapter in our understanding of what life was like in the time of our nation’s founding. Come visit. And see for yourself why here, history is never finished.

Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

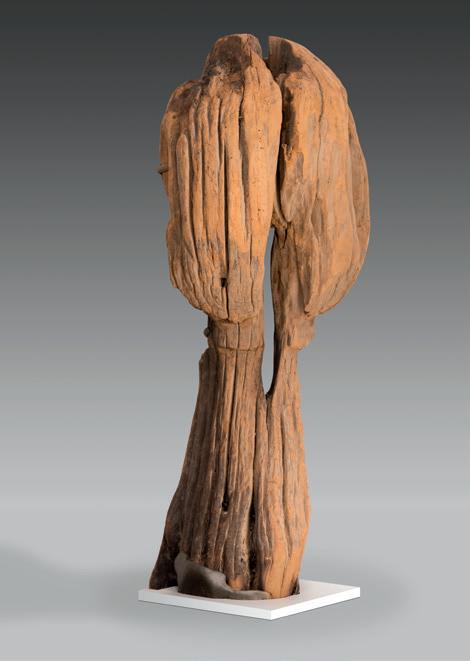

With spring comes an abundance of new life to enjoy. And while the Art Museums and the Historic Area have lovely outdoor gardens, the beauty of nature can also be found inside the galleries. Images of plants decorate ceramics, appear in backgrounds in paintings and are stitched into needlework. The natural world held great interest to many people in the 18th century. In the exhibition Revolution in Taste , on view in the Henry H. Weldon Gallery at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, numerous pieces depict trees and flowers. While many are stylized images, others are recognizable as specific species. A pressmolded and slip-traile d earthenware dish, dating from the early 18th century, displays a tree providing a resting spot for two large birds amid sprouting flowers. Nearby are plates adorned with detailed botanical images of flowers, leaves and insects. Trees are also featured in a work by Texan Eddie Arning in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum exhibition Eddie Arning: Artist . The drawing features a series of colorful birds instead of leaves place d in a tree.

Products of the natural world, such as wood, feature prominently as well, in furniture and even in some of Colonial Williamsburg’s iconic buildings. In Restoring Williamsburg , on view in the James Boswell and Christopher Caracci Gallery at the DeWitt Wallace Museum, architectural fragments of historic buildings from the Foundation’s architectural collection demonstrate the types of woods used to construct the town from cypress shingles to walnut molding to yellow pine doors. Two large pieces of oak stand out in the exhibition. One is a portion of the original gutter from the Peyton Randolph House. The other is a weathered acorn-shaped finial that topped the Magazine and served as the base of the weather vane.

These exhibitions are a reminder that the colonists who built and furnished early Williamsburg made beautiful and durable choices from the inspiration that nature provided.

Mary Virginia E. and Charles F. Crone have generously funded the Eddie Arning: Artist exhibition, and Restoring Williamsburg is made possible by Thomas L. and Nancy S. Baker.

Objects fashioned by early American artisans frequently bear details of form, construction and decoration that echo their makers’ cultural backgrounds and the commercial patterns of the communities in which they worked. This handsome black walnut chest of drawers is a case in point. Made about 1800 in northern Kentucky’s Mason County, it is a mixture of influences from widely disparate parts of North America. The case houses four drawers of graduated size, each ornamented with delicate line inlays. It closely follows Anglo-American chests made in port cities along the Atlantic coast. Artisans from Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania likely brought the concept to new settlements in Kentucky when they migrated west through Pittsburgh

and down the Ohio River.

On the other hand, the short cabriole legs that support this chest are of purely French form. They appear on a number of pieces made in and around Mason County but are unknown on furniture from the Atlantic coast. The design likely came to Kentucky by way of the river trade with French- controlled New Orleans, where such legs were common. Kentucky-made stoneware and agricultural crops were shipped in quantity down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers for sale at New Orleans, and ideas about furniture design clearly came back upstream.

This chest was a gift of Calder Loth. Look for it in a future exhibition at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

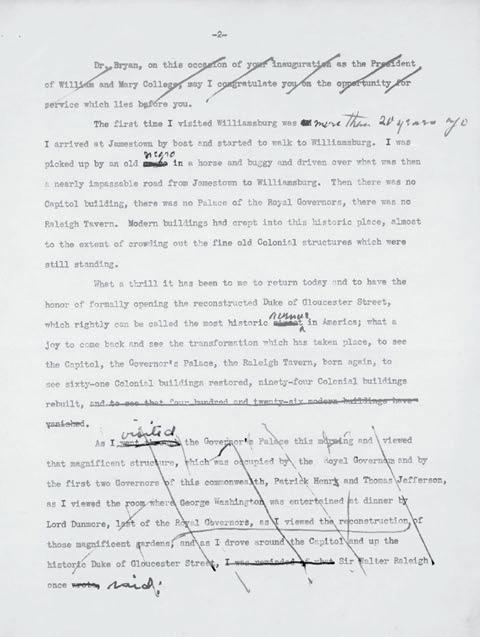

n Oct. 20, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Williamsburg. Just weeks before facing a reelection bid, he delivered a speech that featured praise and promises, as well as a call for Americans to emulate the nation’s founders a nd pioneers.

Roosevelt came to Williamsburg for the inauguration of John Stewart Bryan, who became the 19th president of William & Mary. Roosevelt told the inauguration audience he was thrilled to be in Williamsburg and to have the “honor of formally opening the Duke of Gloucester Street, which rightly can be called the most historic avenue in America.”

He also announced that the federal government would help fund preservation of Jamestown Island and the Yorktown battlefields. “When the work in these three places is completed,” he said, “we shall have saved for future generations the nation’s birthplace at Jamestown, the cradle of liberty at Williamsburg, and the seal-

ing of our independence at Yorktown.”

Roosevelt praised the transformation of the Historic Area, with its 61 restored buildings, its 94 reconstructed buildings and its gardens, marveling at how “the atmosphere of a whole glorious chapter in our history has been recaptured.”

The president’s visit delivered on Colonial Williamsburg’s hope for national attention to the restorat ion efforts.

Preparations for Roosevelt’s visit included not just the usual arrangements for a presidential trip but also some strategizing on the part of officials of the Restoration (as Colonial Williamsburg was then generally known). They wanted to make sure the organization made the most of the visit.

In August, Kenneth Chorley, a vice president who would soon become president of the Restoration, sought help from Raymond Fosdick. Fosdick was a friend of both Roosevelt and

the Restoration’s benefactor, John D. Rockefeller Jr.

“We thought that we ought not pass up the presence of the President on October 20th,” Chorley wrote Fosdick. “It is then our hope that he would make an address at the end of the Duke of Gloucester Street with reference to the Restoration in general.”

Chorley noted that Roosevelt was scheduled to arrive just two weeks before the election, so he suggested “the chance of tying up the ‘New Deal’ with the political history of Williamsburg seems to me to give him a great opportunity.”

Some opponents of the New Deal considered it too close to socialism, and Chorley saw this, too, as an opportunity. Roosevelt could praise Rockefeller for his support of the work in Williamsburg. Roosevelt, Chorley wrote Fosdick, “has talked so much about the privileged class and special interests that here is an opportunity for him to say something about how wealth can be construct ively used.”

Restoration officials also liked the idea of Roosevelt taking a carriage ride but worried about whether the partial paralysis due to polio would make it too difficult for the president to get in and out of the coach. They settled on a procession of cars.

Colonial Williamsburg officials had to be pleased with the results of t he planning.

In his speech during Bryan’s inauguration ceremony, Roosevelt described a “spiritual relationship between the past, the present and the future” and praised Rockefeller for his “fine vision and example...in recreating Wi lliamsburg.”

In less formal and extemporaneous

remarks after the mayor of Williamsburg presented him with a scroll, Roosevelt said, “I have not been here for two years but, as you know, I have often been here before in the past and every time that I come here I see renewed evidences of the restoration of Williamsburg to its high estate.” The president added that “the good people of Williamsburg have maintained the traditions of the past maintained them for the benefit of the Nation of today and the Nation of tomorrow.”

He was very happy, he added, “to be made today, in a sense, a citizen of Wi lliamsburg.”

Roosevelt’s more formal speech also included much that he himself wrote. It was not uncommon for multiple people, including the president, to mark up a draft of a speech. In this case, for example, the draft of the Williamsburg speech called Duke of Gloucester the most historic street in America, and “street” was then replaced by “avenue.” That edit appears to be in Roosevelt’s own handwriting.

Nationally, the press picked up on a variety of themes. The Great Falls (Montana) Leader headlined its story “Restoration of historic city lauded” and “Roosevelt praises efforts of young Rockefeller in Williamsburg.” The Nevada State Journal ’s headline was “Roosevelt asks people to emulate forefathers.” The Kearny (Nebraska) Daily Hub went with “New economic conditions to be met with spirit of the pioneer.” Many newspapers stressed that Roosevelt talked about Thomas Jefferson’s support for education and used headlines such as, in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Roosevelt urges broad education for civic service.”

NBC’s Today aired two segments in February about the Williamsburg Bray School, where enslaved and free Black children were educated during the 18th century.

Today show host Craig Melvin, who traveled to Williamsburg to record the segments, called the project “a construction site unlike any other” before recounting the school’s history of providing a religious education to some 300 Black children. The building was moved from the William & Mary campus last year and is currently undergoing meticulous reconstruction.

“We think this is critically impor-

tant work to make sure we can tell history in a way that brings us together as Americans and makes all people recognize that this country belongs to all of us,” Colonial Williamsburg President and CEO Cliff Fleet told Today show i nterviewers.

Janice Canaday, the Foundation’s African American Community Engagement manager, learned that her ancestors were among the students educated in the building. She described the emotions of entering the building and being able to “walk where they possibly walked.”

“They’ve planted those seeds,”

Canaday said. “They cast our seeds to the wind. The wind picked them up and took them everywhere. And we are everywhere. We’ve impacted this nation. It shows how powerful we are, how we thrive. That’s why the story is so important.”

Florida: Registration #CH10673. A COPY OF THE FOUNDATION’S OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE 1-800-HELP-FLA WITHIN THE STATE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE. Maryland: THE FOUNDATION’S CURRENT FINANCIAL STATEMENT IS AVAILABLE ON REQUEST AT THE ADDRESS LISTED ABOVE. FOR THE COST OF COPIES AND POSTAGE. DOCUMENTS AND INFORMATION SUBMITTED ARE AVAILABLE FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE, STATE HOUSE, ANNAPOLIS, MD 21401 New Jersey: INFORMATION FILED WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL CONCERNING THIS CHARITABLE SOLICITATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY BY CALLING (973) 504-6215. REGISTRATION WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT. Pennsylvania: THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION OF THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF STATE BY CALLING TOLL FREE WITHIN PENNSYLVANIA 1-800-732-0999. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT. Virginia: A FINANCIAL STATEMENT IS AVAILABLE FROM THE STATE DIVISION OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES UPON REQUEST. Washington: ADDITIONAL FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE CHARITIES DIVISION, OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE, OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON, BY CALLING 1-800-332-4483. West Virginia: WEST VIRGINIA RESIDENTS MAY OBTAIN A SUMMARY OF THE REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE, SOLICITATION LICENSING BRANCH, AT 1-800-830-4989, STATE CAPITOL, CHARLESTON, WEST VIRGINIA 25305. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT.

Matt Webster, executive director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research, described how the building was identified as the Williamsburg Bray School and the restoration efforts his team has undertaken. Melvin noted Colonial Williamsburg’s expertise in such reconstructions.

William & Mary Bray School Lab Director Maureen Elgersman Lee and Tonia Merideth, an oral historian at the Bray School Lab, were also featured on the show. In addition to discussing the history of the school, they described their work with descendants of t he students.

The nationally broadcast segments reached more than 2 million viewers. The segments can be seen at colonialwilliamsburg.org/ brayschool/ in the Williamsburg Bray School News Coverage section.

California: THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE. ANY PROSPECTIVE DONOR SHOULD SEEK THE ADVICE OF A QUALIFIED ESTATE AND/OR TAX PROFESSIONAL TO DETERMINE THE CONSEQUENCES OF HIS OR HER GIFT. Annuities are subject to regulation by the State of California. Payments under such agreements, however, are not protected or otherwise guaranteed by any government agency or the California Life and Health Insurance Guarantee Association.

New York: Upon request, a copy of the latest annual report may be obtained from the address listed above for the foundation or from the Charities Bureau, Department of Law, Attorney General of New York, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

North Carolina: Financial information about the foundation and a copy of its license are available from the State Solicitation Licensing Branch at (919) 807-2214. The license is not an endorsement by the state.

Oklahoma: A charitable gift annuity is not regulated by the Oklahoma Insurance Department and is not protected by a guaranty association affiliated with the Oklahoma Insurance Department. South Dakota: Charitable gift annuities are not regulated by and are not under the jurisdiction of the South Dakota Division of Insurance.

The Foundation does not issue charitable gift annuities in Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii and Washington state.

Work began in February to lower the wall surrounding the Magazine, the iconic building that housed weapons and ammunition the theft of which sparked the Revolution in Virginia.

New research indicates that the wall, which was constructed around 1755 and pulled down in the mid-19th century, was originally a few feet shorter than the 10-foot wall reconstructed in 1934-1935. Documentary evidence for the lower wall includes a letter from 1892 and a sketch that historian Benson J. Lossing made around 1850.

“We kept trying to visualize what the wall would look like,” said Matt Webster, executive director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research. “Once the first section came down,

all of a sudden there was the view that L ossing saw.”

The cap on the wall, which was based on an 18th- centur y design, has been preserved and will become part of t he new wall.

Reconstructing the wall is the first step toward creating a more accurate restoration of t he Magazine.

Just before the Revolution, the Magazine was the site of a pivotal event. In April 1775, British marines, following orders from Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, broke into the Magazine and removed 15 half-barrels of powder. An angry crowd gathered on Market Square. Calm was eventually restored, and Dunmore stated that he would “remain here until I am forced out,” but the situation remained uneasy. On June 8 he fled Williamsburg, and

on Nov. 7 he declared Virginia to be in a state of rebellion.

Before its restoration, the Magazine served at times as a market house, a Baptist church, a dancing school a nd a stable.

The Magazine wall is being lowered, allowing a view much like Benson J. Lossing’s 1850 view.

2024 marks the 350th anniversary of the founding of Bruton Parish Church. As part of the festivities, the congregation plans to host events that include its neighbors William & Mary and Colonial W illiamsburg.

In February, the church offered a walking tour of the William & Mary campus that included stops at Hearth: Memorial to the Enslaved and at the Brafferton, the building that once housed a school for American Indians. Nicole Brown, who interprets the Williamsburg Bray School teacher Ann Wager for Colonial Williamsburg, also shared the church’s role in the education of enslaved and free Black children at the school.

More events will be added for the yearlong celebration at the church, located in the heart of Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Records indicate that the church’s vestry named the Rev. Roland Jones on April 18, 1674, as the first rector. In 1677, a plan to build a new brick church to serve the consolidated parish was approved. John Page donated a plot of land in 1678, and a church measuring 60 feet by 24 feet was erected to the northwest of the present structure. It was completed in 1683 and dedicated the following year at t he Epiphany.

Donors propel fundraising to new heights in 2023

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation received a record $103 million in gifts during 2023 thanks to an outpouring of generosity from donors who are supporting key preservation, education and civic engagement initiatives.

The successful fundraising year builds on strong performances in 2021 and 2022, which along with 2023 comprise the top three fundraising years in Colonial Williamsburg’s 97-year history.

In October 2023, the Foundation also publicly launched The Power of Place The Centennial Campaign for Colonial Williamsburg, a comprehensive fundraising initiative advancing projects and operations leading up to the nation’s 250th anniversary and Colonial Williamsburg’s centennial in 2026. Through the campaign, which officially began in 2020, the Foundation has secured more than $350 million toward the overall $600 million goal.

“We named our campaign The Power of Place because so many of the ideas and events leading to the American Revolution happened in and around Williamsburg,” said Cliff Fleet, president and CEO of Colonial Williamsburg. “Today, as a direct result of our remarkable donors, the Foundation is making a significant impact on the nation as we enhance our ability to present authentic historical accounts and

engage in lessons and conversations around history and civic engagement, subjects that are critically needed in American education.”

During 2023, the restoration of the Williamsburg Bray School building, which was moved to its permanent location in the Historic Area, and the groundbreaking on the Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Archaeology Center were among the Foundation’s ambitious projects. The Foundation also convened the first annual A Common Cause to All conference, bringing together hundreds of representatives from 34 states to begin planning for the US 2026 semiqui ncentennial.

“We will continue to work closely with our donors so Colonial Williamsburg can lead the way up to and beyond the 250th anniversary of the United States,” Fleet said.

New research is the basis for a new look for Thomas Everard’s most stylish roomby PAUL ARON

An auction of a royal governor’s belongings proved to be a bonanza for a bookkeeping apprentice from London who rose to prominence in the Williamsburg community and for the researchers and curators who now study his house.

After Lt. Gov. Francis Fauquier died in 1768, his successor in the Governor’s Palace, Lord Botetourt, agreed to buy

many of the building’s furnishings. But other items were purchased by wealthy members of the community, including Thomas Everard, whose public offices included the positions of mayor and clerk of York County.

“The day of the Fauquier estate auction brought out all of the town’s most prominent men, such as Robert Carter, George Wythe, Peyton Randolph, James Southall, Robert Carter Nicholas, Benjamin Powell and many more, as they purchased items listed on the inventory, including 17 people enslaved men, women and children who were also sold that day,” said Amanda Keller, Colonial Williamsburg’s manager of historic interiors and associate curator of household accessories.

“We can see everything Thomas Everard purchased that day.”

In a presentation at last year’s Antiques Forum, Keller described the records of those purchases that provided impor-

tant clues to what Everard kept in the parlor of his Palace Green home, which is now being refurbished. The purchases included lump sugar, tea, wine, beer glasses, kitchen equipment like whisks, and large quantities of paper. More relevant to the refurbishing were ivory chess pieces and backgammon tables. Both games were popular during the period in many gentry households and often played in parlors.

Keller has also pored over Everard’s correspondence with John Norton, a London merchant from whom he bought many goods as he renovated and updated his house. Like his neighbors on Palace Green, Everard was intent on making his house fashionable. Everard may have been even more fashion conscious than his neighbors because, unlike most of them, he did not inherit his wealth.

Everard was born in London in 1719 and orphaned by the age of 10, after which he attended a school for impoverished children. From there, he was apprenticed to Matthew Kemp, a Williamsburg merchant and clerk of the General Court. Everard ultimately prospered, becoming clerk of the York County courts for four decades, and in 1756 he moved into what had been gunsmith John Brush’s house. Everard became mayor of Williamsburg twice, a vestryman of Bruton Parish Church, a trustee for the Public Hospital and the owner of besides his house in Williamsburg hundreds of acres of tobacco plantations.

The parlor, as a room visitors would see, was central to Everard’s efforts to make the house as fashionable as those of his neighbors. Its appearance evolved not only during his lifetime but also over the past 75 years as generations of Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeologists, conservators and curators uncovered new evidence.

Archaeologists have excavated the Everard property three times. The first excavation, in 1947, helped restore the building’s 18th- centur y architecture, which had been obscured by later additions. The second, in 1967, led to the restoration of the kitchen. The third, in 1987, focused on the lives of the enslaved men, women and children who lived and worked on t he property.

The artifacts uncovered, especially during the later digs, provided evidence about Everard’s possessions and the evolution of his preferences.

“We rely on artifacts to reflect Thomas Everard’s tastes, aspirations, apprehensions and strategies,” Senior Archaeologist Meredith Poole told the Antiques Forum audience last year. “And because

25 years of occupation resulted in two layers of Everard household trash in the ravine [on the north end of the property], we can compare the artifacts to see how his tastes, aspirations and strategies changed.”

Fragments of ceramics, for example, reveal that Everard especially liked tin-glazed earthenware known as delft. And after 1770, Everard could not resist fashionable products made by Josiah Wedgwood.

“Everard cultivates and emulates the tastes and the style of the gentry,” Poole noted, “and as those styles expand and change, the London orphan keeps pace.”

While archaeologists have uncovered artifacts and curators have studied records, Kirsten Moffitt, Colonial Williamsburg conservator and materials analyst, has focused on finishes such as paint, wallpaper and carpet.

“To find this evidence, we don’t need to dig a trench or pore over documents,” Moffitt told an Antiques Forum audience. “Everard actually left it behind. Microscopic traces of it anyway.”

In the conservation department’s laboratory, Moffitt analyzed recently discovered paint layers, wallpaper scraps and ca rpet fibers.

In her latest paint analysis, using various new techniques including cross-section microscopy, Moffitt found that Everard’s green paint was darker and less glossy than that used in 1995, and the parlor’s woodwork ultimately will be repainted with a richer, deeper hue of green.

When the house closed in autumn 2020 because of the pandemic, researchers took the opportunity to look for evidence of wallpaper. Since the original plaster walls had been demolished during the

house’s restoration during the early 1950s, this was no easy task. But debris on the tops of some doors and windows revealed, when studied under a microscope, a few small scraps of paper with a coating on one side. When examined in the lab, the coating turned out to be wheat starch paste used for hanging wallpaper, an indication that the parlor’s plaster walls had been papered.

Alas, the scraps were not sufficient to determine the color or pattern of the wallpaper, so curators will have to base the wallpaper on other factors, such as the trim color in the room and what was fashionable in the 18th century.

With the house closed, researchers also removed some of the reproduction carpet. To their surprise, they found some early carpet tacks with red fibers attached. The red dye used may have been cochineal, which was sourced from an

insect native to sout hern

“How did we get from Everard’s parlor to a Mexican cactus patch?” asked Moffitt. “Analysis, in hand with the Foundation’s traditional avenues of research, strongly guides our efforts to replicate the paint, wallpaper and carpet in Everard’s parlor but also informs how these decorative materials were intrinsically linked to the wider 18th- centur y world beyond Wi

Keller noted that red and green were often used together during the 18th century, making red carpets and green wallpaper logical choices for the parlor.

Curators have been working closely with Cynthia Decker Deuell, an architectural research associate, to create 3D models that show how the new paint

color and potential wallpapers will look i n the space.

No date has yet been set for reopening the Thomas Everard house. But, Keller said, once the testing of the carpet’s wool fibers is complete, curators can start acquiring the appropriate fabric for the carpet, wallpapers and chairs. The archaeological record and comparable probate inventories, including from Everard ’s neighbors, will help them select antique objects that likely reflect Everard’s taste.

“This is a work in progress,” Moffitt said. “Thanks to new discoveries and new technologies, we know more than ever before about the parlor’s past and we can set the stage for its future.”

The Thomas Everard House remains closed while research and refurbishing continues.

The chair on which the royal governor sat in Williamsburg’s Capitol was quite literal ly a throne.

The most striking feature of the armchair is the height of its seat about 26 inches above the ground. A footstool was provided so the governors’ feet would not dangle. King George III’s throne had similar proportions, so it was no accident that the governor, as the representative of the king, was placed high above his subjects. The chair may have been placed on a platform, raising it further, and it was probably situated under a canopy.

A family history by David Meade, who had been a member of the House of Burgesses, included a report on the appearance of Lord Botetourt, Virginia’s royal governor between 1768 and 1770, in the Council chamber. The account made clear the symbolic importance of the chair. “The Governor’s deportment was dignified and his delivery was solemn,” Meade reported. “It was said by those who had heard and seen George III speak and act on the throne of England, that his Lordship on the throne of Virginia was true to his prototype.”

Because of the high seat on the chair, governors would have rested their feet on a footstool. This reproduction was created as a companion to the chair, based on surviving 18th- century examples.

When the capital moved from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780, the chair followed. In 1866, it appeared in an illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper where it was described as the “Chair of the Speaker of the Senate.” After Virginia declared independence, the commonwealth’s Senate took over some of the functions that once belonged to the royal governor’s Council.

The chair later landed in

Colonial Williamsburg curator

Wallace Gusler, in his 1979 book Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710-1790, attributed the Governor’s Chair to Anthony Hay, a Williamsburg furniture maker. More recently, curators have thought it more likely that the chair was imported from England. In their 1997 book, Southern Furniture 1680-1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown noted that carvings as accomplished as those found on the chair, including lions’ heads and paw feet, were more likely to have been done in England and that the use of beech wood for parts of the chair was also more consistent with British practices. In 2012, Colonial Williamsburg acquired two upholstered back stools with identically carved front legs and paw feet and the same unusual brass nailing, suggesting they were likely two of the governor’s councilors’ chairs for the Capitol. One of the two chairs has a piece of Scotch pine, further evidence of the English origin for the chairs that Hurst and Prown ha d suggested.

MAKER: Unknown

DATE: circa 1750

PLACE: England, probably London

MEDIUM Mahogany and beech

DIMENSIONS: 49 inches high by 21½ inches wide by 24½ inches deep

This chair, which was used by the speaker of the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg, is similar to one used by the speaker of the House of Commons in London during the 18th century.

the hands of an antiques dealer, who in 1927 offered it to the Rev. Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, whose vision and persistence led to the restoration of Williamsburg. Goodwin immediately recognized the significance of the chair, and so did John D. Rockefeller Jr., who allocated $1,00 0 to buy it.

“It is incredibly fortuitous that the Foundation’s founders recognized the importance of this chair and were able to acquire it in order to share it with our visitors,” said Tara Chicirda, Colonial Williamsburg’s curator of furniture. “The chair is a visual reminder of the English throne that American patriots rebelled against in the Revolution. Even so, it was retained and reassigned to the Senate after the Revolution for the democratic governance of Virginia, subverting its original intent so that it came to be part of a government based on the will of the people.”

The chair is on display at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Remarkably, another 18th- centur y ceremonial chair has also survived from the Capitol, though this one from the start symbolized elected rather than royal authority. Known as the “Speaker’s Chair,” this was the seat from which the speaker presided over the Virginia House of Burgesses. Speakers sat in this chair from sometime before 1747, as evidenced by scorched sections of its underside presumably from the fire that destroyed the first Capitol that year.

The Speaker’s Chair sat in the Capitol when Patrick Henry protested the Stamp Act of 1765 by reportedly proclaiming, “If this be treason, make the most of it.” And it was there, 11 years later, that Virginia’s representatives severed their ties with Great Britain and adopted a Declaration of Rights and a constitution establishing a new government. Unlike the Governor’s Chair, which was made in London, the Speaker’s Chair was appropriately made in Williamsburg, probably by cabinetmaker Peter Scott.

Like the Governor’s Chair, when the capital moved from Williamsburg to Richmond, this chair went too. And it was pictured in the same 1866 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

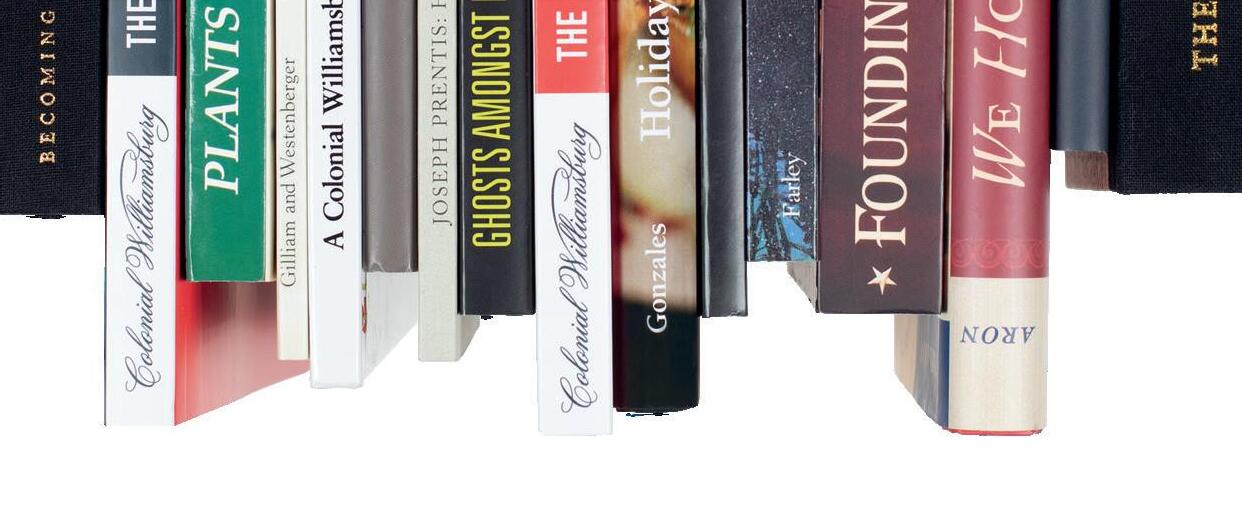

From historic feats to historic trades, from art to archaeology, from scholarly books to kids’ titles, you can take the stories of America’s beginnings — and a bit of Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area — home with you. 440

Drummers Call

Annual Garden Symposium

April 27-29

Explore the historic garden methods that can inspire a more sustainable future. colonialwilliamsburg.org/ garden-symposium/

Drummers Call

May 17-19

Visiting units from around the country join our own Colonial Williamsburg Fifes & Drums for performances of military field music throughout the Historic Area. colonialwilliamsburg.org/drummers-call/

Memorial Day Weekend

May 25-27

Join us for a variety of weekend events, including a traditional wreath-laying ceremony on Palace Green on May 27 as we honor the men and women of the United States military who sacrificed their lives to defend our nation.

colonialwilliamsburg.org/memorial-day/

Juneteenth

June 19

Commemorate the day in 1865 that federal troops arrived in Texas to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation. colonialwilliamsburg.org/juneteenth/

Fourth of July

July 4

Enjoy a full day of patriotic festivities, including public readings of the Declaration

Juneteenth

of Independence, musical performances and a dazzling fireworks display. colonialwilliamsburg.org/july4/

Elegance, Taste and Style Exhibition: The Mary D. Doering Fashion Collection

Currently Open

This Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg exhibition documents 50 years of one woman’s passion to create one of the greatest private collections of early textiles, accessories and costumes assembled in the United States. colonialwilliamsburg.org / elegance-taste-style/

For more information on programs and events, please visit colonialwilliamsburg. org/events- calendar/

p. 70

Who Was Agent 355?

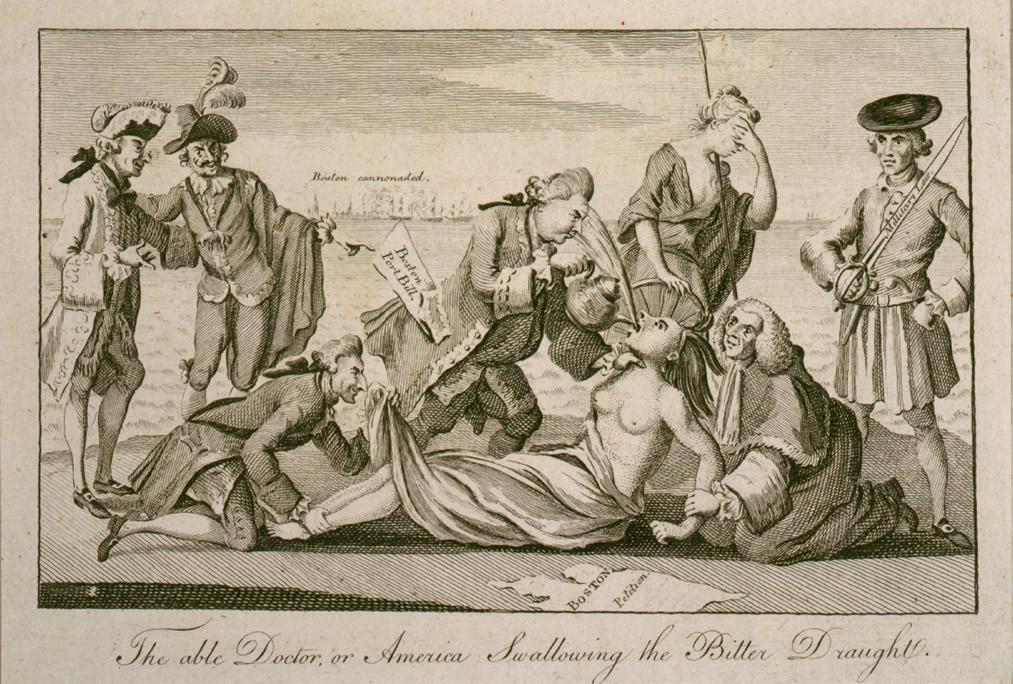

THE CURIOUS ORIGIN OF A SUMMARY VIEW OF THE RIGHTS OF BRITISH AMERICA

BY JON KUKLA

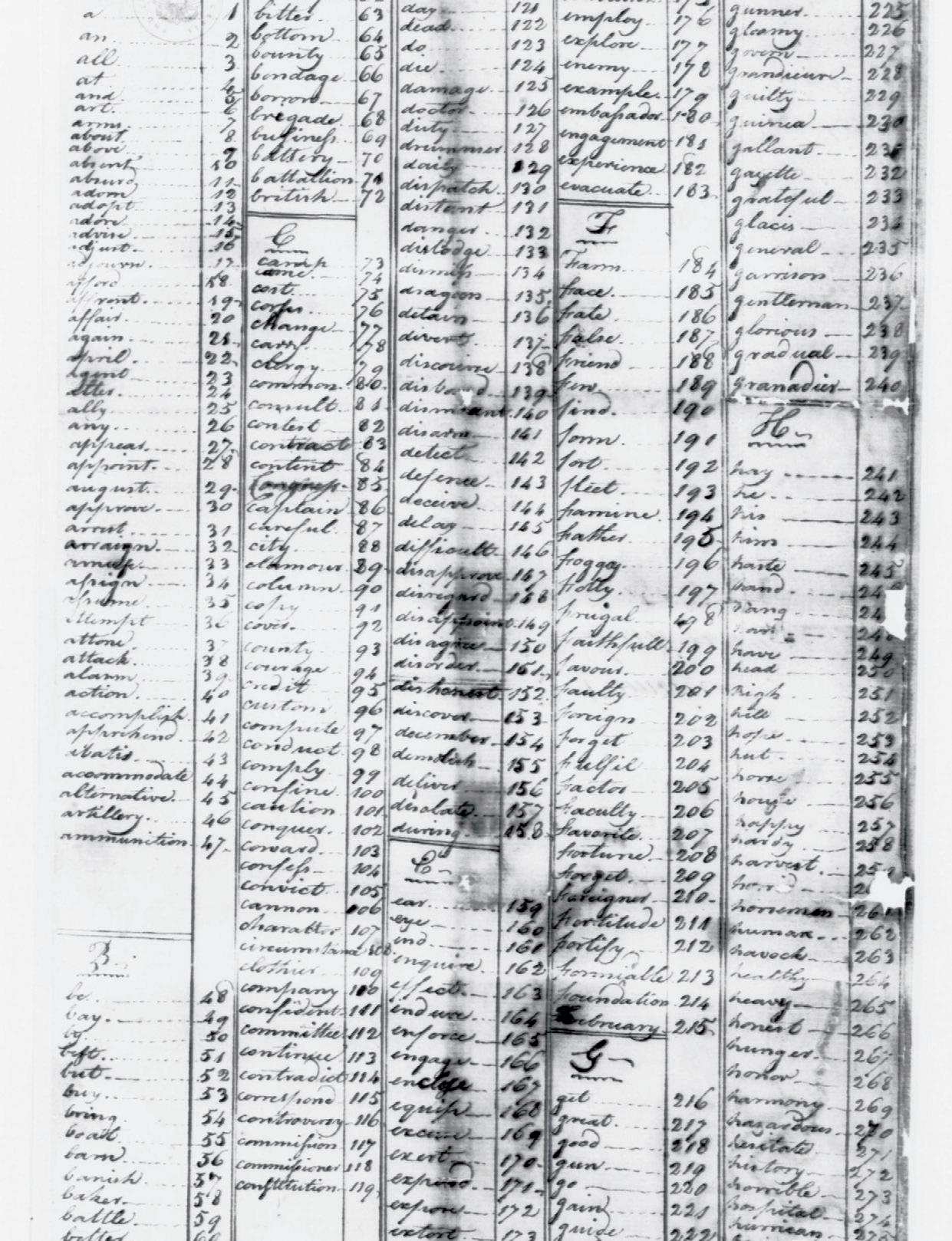

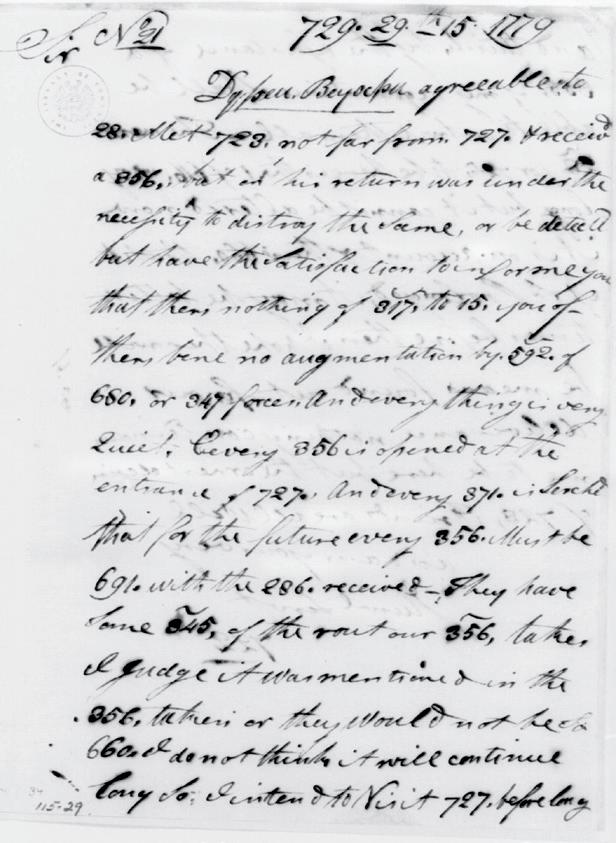

As he recalled the eventful summer of 1774 nearly half a century later, Thomas Jefferson was still annoyed. He had devoted many hours to a 7,000-word essay in advance of the revolutionary convention that met in Williamsburg that August. Although it was later celebrated as a significant expression of American principles, Jefferson was greatly disappointed when the convention declined to adopt his essay as formal instructions for the delegates Virginia sent to Philadelphia for the First Continental Congress i n September.

Elected to represent Albemarle County in the convention, Jefferson recalled more than 40 years later that he had “prepared a draught of instructions...which I meant to propose at our meeting.”

But before reaching Williamsburg he “was taken ill of a dysentery on the road, and unable to proceed.”

While Jefferson returned to Monticello, according to his recollections, his enslaved travel companion, Jupiter, rode on to Williamsburg with two copies of the essay “the one under cover to Peyton Randolph, who I knew would be in the chair of the convention, the other to Pat rick Henry.”

Like many of Jefferson’s late-in-life recollections, his tale of an interrupted trip to Williamsburg was accepted by generations of scholars as a reliable account of the creation of A Summary View of the Rights of Brit ish America.

Reliable, that is, until the late Julian Boyd, founding editor of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson project at Princeton University, reexamined the story and found it fraught with contradictions and unwarranted suppositions. While the document marks a bold moment in early discussions of freedom and independence, Jefferson’s intentions in writing it

and its connection to his much shorter, unpublished “Declaration of Rights” not to be confused with the Virginia Declaration of Rights written by George Mason have become fodder for speculation. His cloudy memories have deepened the mystery.

The essay that became A Summary View was not the only significant text Jefferson wrote in the summer of 1774. After a decade of tension, the imperial crisis felt like it was reaching a tipping point with the Intolerable Acts, the closing of the port of Boston and the arrival of British Gen. Thomas Gates with a fleet and four redcoat regiments.

Earlier, the American campaign to repeal the Stamp Act had demonstrated the effectiveness of economic pressure. When the colonies had employed nonimportation agreements against the Townshend Duties, however, their efforts had collapsed amid the regional rivalries of merchants in Boston, New York and Philadelphia.

The final hope for peacefully reversing British policy short of armed resistance seemed to be a

Continental Association a program of rigorous economic sanctions upheld by oaths of allegiance enforced by local committees in every city, township and county from Maine to Georgia. “Arms,” as George Washington remarked to George Mason, “should be the last resource.”

The flurry of Jefferson’s compositions began early in July 1774 when he and his boyhood friend John Walker, who represented Albemarle in the House of Burgesses, composed an announcement calling their constituents to a special countywide meeting about Britain’s “hostile invasion of a sister colony.” Then he penned the “Resolutions of the Freeholders of Albemarle County” that his neighbors adopted at their meeting on July 26. In line with the more famous Fairfax Resolves and similar pledges adopted by more than 30 Virginia counties between June 1 and Aug. 4, 1774, these resolutions laid the groundwork for the trade restrictions and boycott of British goods enacted first by Virginia’s upcoming convention and then by the First Continent al Congress.

With the Williamsburg convention in mind, Jefferson also drafted a succinct “Declaration of Rights” possibly meant to accompany Albemarle’s resolutions. But then for some reason, he set it aside. Its text, later discovered among his papers, advocated an almost complete immediate cessation of trade with Great Britain until Parliament repealed “the act for blocking up the harbor of Boston” and the other Intolerable Acts.

In many respects, his abandoned “Declaration of Rights” paralleled the formal instructions that Virginia’s convention adopted in Williamsburg on Aug. 6. In contrast to the essay later published as A Summary View, the arguments expressed in his discarded declaration scarcely differed from those expressed in the other county resolutions. Nor did they differ much from those advanced by Thomson

Mason, George Mason’s younger brother, in the six essays by “A BRITISH AMERICAN ” that he published that summer in Clementina Rind’s Virginia Gazette. Nor from the instructions the convention finally adopted for its congressional delegation.

Still, the connection between Jefferson’s “Declaration of Rights” and the essay published as A Summary View remains as puzzling today as it was for Jefferson’s learned editor, Julian Boyd, 50 years ago. Why did Jefferson abandon the 600-word “Declaration of Rights” in favor of the sprawling and digressive 7,000-word essay he sent to Peyton Randolph and Patrick Henry? And who was that essay’s intended audience?

Consulting Jefferson’s account books for detailed information about his travels and whereabouts in the summer of 1774, Boyd cast doubt on Jefferson’s years-later recollection of a journey to Williamsburg interrupted by sudden illness. In mid-June, he had returned to Monticello after settling his accounts for lodging and laundry while attending several clients’ cases before the General Court. Aside from a brief trip to Payne’s Ordinary in Goochland County July 17-19 too early for an interrupted trip to the convention Jefferson remained at Monticello into mid-August . On July 29, however, he dispatched Jupiter to the capital city with 21 pounds 6 shillings to buy paint from William Holliday, a Williamsburg coachmaker. The account books shed no light on Jefferson’s health at that moment, but Boyd was surely correct to conclude that Jupiter was the courier who delivered Jefferson’s essay to Henry a nd Randolph.

But, Boyd wondered, why two copies? Why, as Jefferson wrote in 1804, “one under cover to Peyton Randolph, who I knew would be in the chair of the convention, the other to Patrick Henry.” If Jefferson intended to present his Summary View to the convention in person and support it in debate,

In parliamentary practice, the tactic of laying something on the table could thwart a measure by postponing its consideration indefinitely.

why bring two copies of the lengthy essay?

On the other hand, if a sudden attack of dysentery, either on the road or at home, forced his last-minute decision to send duplicate copies to Randolph and Henry, how had Jefferson so quickly acquired the second copy a lengthy manuscript in the handwriting of Anderson Bryan, his father’s old clerk that Jupiter delivered to Williamsburg?

To resolve this mystery, Boyd chose to follow the manuscripts recognizing that nothing in Jefferson’s subsequent recollections could derive from firsthand knowledge of events at a convention he did not attend.

Three or four decades later, Jefferson drew on his familiarity with legislative procedure regarding one copy of the essay. “Peyton Randolph,” Jefferson surmised, “informed the Convention he had received such a paper from a member prevented by sickness from offering it in his place, and he laid it on the table [emphasis added] for perusal [where] it was read generally by the members, approved by many, but thought too bold for the present state of things.”

In parliamentary practice, the tactic of laying something on the table could thwart a measure by postponing its consideration indefinitely. In this instance, however, an eyewitness account written by Peyton Randolph’s nephew shows that his uncle was not hostile to Jefferson’s essay.

“I distinctly recollect the applause,” Edmund Randolph wrote in his History of Virginia, when

Jefferson’s essay was “read to a large company at the house of Peyton Randolph.”

Tracking the fate of Henry’s copy of the essay is more complicated especially because Jefferson’s later recollections were skewed by a hostility toward Henry that he had not felt in 1774. If Julian Boyd’s hunch is correct, Jefferson’s early admiration for Henry’s oration skills magnified this later perceived slight of A Summary View. In a brief account sent to an Italian correspondent, Jefferson maintained that “no more was ever heard or known” of the manuscript sent to Henry, who “probably thought it too bold.”

Jefferson’s opinion had soured further by the time he wrote his memoir: “Whether mr Henry disapproved the ground taken,” he complained in 1821, “or was too lazy to read it (for he was the laziest man in reading I ever knew) I never learnt. But he communicated it to nobody.”

Jefferson’s admiration for Henry began in 1765. As a law student, Jefferson stood in the lobby of the House of Burgesses during the momentous debates about the Stamp Act “and heard the splendid display of mr Henry’s talents as a popular orator.” Hinting at the envy that accomplished writers can feel toward actors and orators whose virtuosity bring words to life, Jefferson wrote that Henry’s talents “were great indeed; such as I have never heard from any other man. He appeared to me to speak as Homer wrote.”

Nine years later, with American liberties at greater risk and redcoats patrolling the streets of Boston, perhaps another burst of oratorical lightning was needed for the upcoming convention. Unable to promote his draft “Declaration of Rights” in person, Jefferson, Boyd speculated, abandoned it “with the great orator in mind” and expanded his arguments in the elevated rhetorical style that he could achieve “on paper but not at all in public debate.”

Boyd’s speculation helps to explain several peculiar aspects of the essay that became A Summary View. At more than 7,000 words it was much longer than needed. The convention’s actual instructions for the Virginia delegation comprised only 900 words that focused on immediately “stopping all Imports whatsoever from Great Britain” and adopting a plan of “Non- export ation” for the fol lowing year.

Aside from a paragraph denouncing British Gen. Thomas Gage, the convention endorsed economic sanctions using the same constitutional arguments that Americans had voiced since the Stamp Act and the same arguments that Jefferson abandoned along with the draft of his “Declaration of Rights.”

In A Summary View, Jefferson vaulted beyond justifications for nonimportation. He denounced Parliament almost in passing and focused instead on the king’s shortcomings “as chief magistrate of the British empire.” Citing example after example, Jefferson pointedly blamed George III for a long list of “unwarrantable encroachments and usurpations, attempted...by the legislature of one part of the empire.”

Recalling the tremendous impact of Henry’s Caesar-Brutus speech in the successful campaign against the Stamp Act, Jefferson “must have realized,” in Boyd’s words, that Virginia once again needed “all of the impassioned eloquence that a Patrick Henry cou ld provide.”

What then happened to Henry’s manuscript? Jefferson’s complained that he “was too lazy to read it...[and] communicated it to nobody,” but two account book entries resolve this final puzzle. According to Jefferson’s account books, Jupiter left Monticello on Friday, July 29, and he probably delivered the essays to Henry and Randolph about Monday, Aug. 1, with the convention scheduled to begin on Thursday, Aug. 4.

According to George Washington’s account books, on Saturday, Aug. 6, the last day of the convention, he paid 3 shillings 9 pence for “Mr. Jeffersons Bill of Rights” a sum too small to be a contribution toward printing costs but about right for copies of A Summary View.

This evidence suggests that during the first week of August, while Peyton Randolph’s copy of the essay was being read aloud at his house at the corner of Nicholson and North England streets, Henry’s copy was in the hands of Clementina Rind and her typesetters less than a block away in a rented space in the Ludwell-Paradise House on Duke of Gloucester Street that was home to her printing business. Henry had arranged for the publication and discussion of important drafts of legislation on other occasions as well. The prompt publication of A Summary View suggests that he recognized the merits of Jefferson’s essay and helped to secure its immediate publication.

Although Jefferson’s name did not appear on the title page of A Summary View probably because it was rushed into print without his knowledge or permission his authorship was an open secret. Henry and other Virginia delegates carried freshly printed copies to distribute among members of the First Continental Congress. It was promptly reprinted in Philadelphia and London, and by demonstrating Jefferson’s written eloquence, A Summary View helped win him a leading role in writing the Declaration of Independence.

As it turned out, support for economic sanctions was so widespread among the Virginia populace and their delegates to the August convention that the association passed almost unanimously and without need for Henry’s eloquence. By the following spring, however, when the question was whether to take up arms in support of American liberties, Jefferson was in good health and present in Richmond when Henry responded to the worsening of the crisis by calling for liberty or death.

Nine years later, with American liberties at greater risk and redcoats patrolling the streets of Boston, perhaps another burst of oratorical lightning was needed for the upcoming convention.

One theory about Thomas Jefferson’s A Summar y View suggests that he shared a copy with Patrick Henry to spark his characteristic fiery oration during the First Continental Congress.

Jon Kukla , a historian who lives in Richmond, Virginia, is at work on a book about the Stamp Act. His most recent book is the prizewinning Patrick Henry: Champion of Liberty

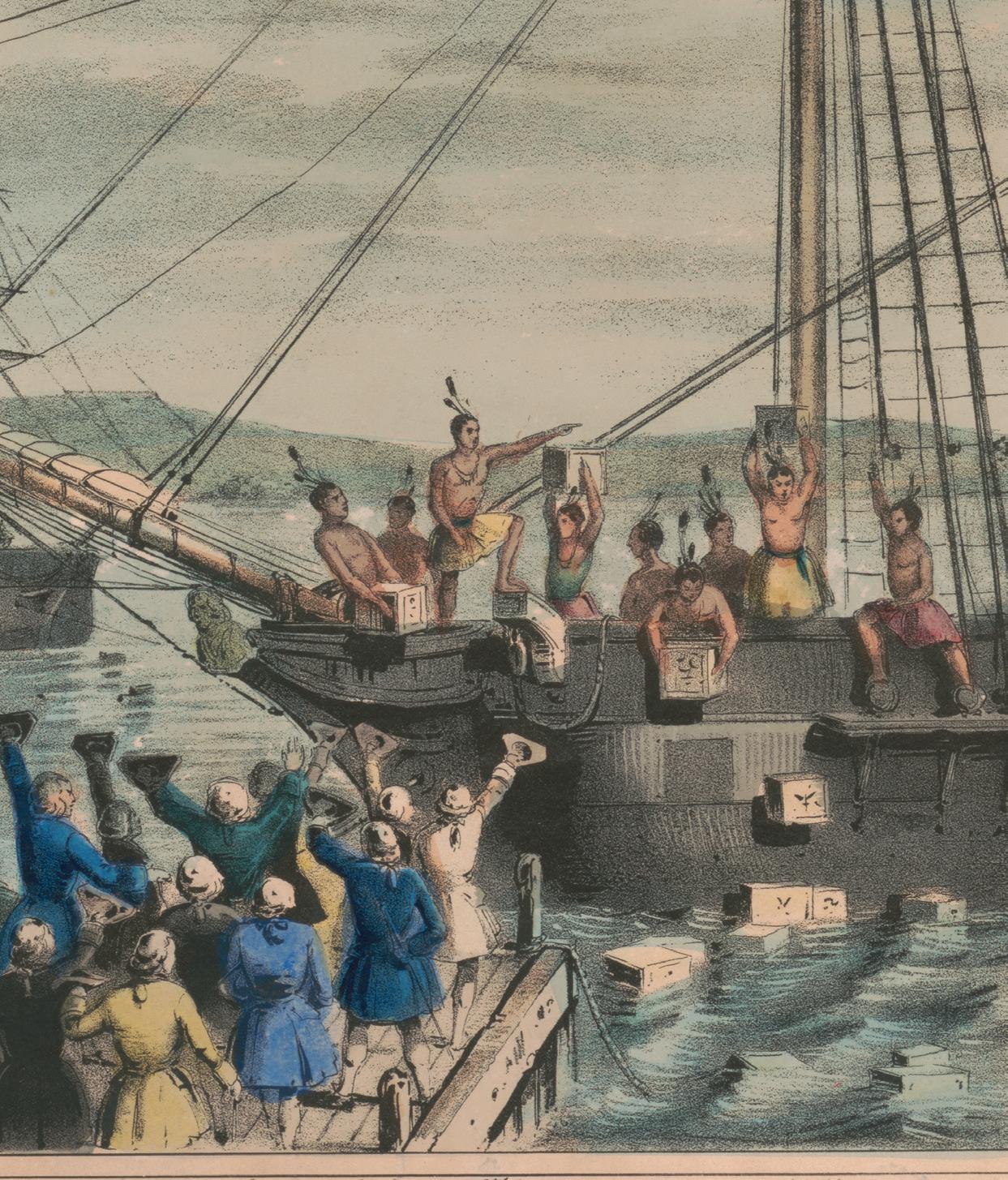

The story of the Boston Tea Party is a familiar one to most Americans.

On the night of Dec. 16, 1773, a group of colonists, some imitating the dress of Indigenous Mohawk people, left a meeting at the Green Dragon Tavern and made their way to Boston Harbor. There they boarded three ships dispatched by the British East India Company the Dartmouth, the Eleanor and the Beaver and, after unloading approximately 342 chests of tea, cast their contents into the harbor.

The legacy of actions taken that night encompasses political, social and cultural dimensions that still resonate through American communities today. Flinging the tea into the harbor was not merely the destruction of property. It was a symbolic protest against the Tea Act, designed

to bail out the financially strapped East India Company and the British policies that increasingly looked to the colonies to ra ise revenue.

The Tea Act, like the Stamp Act before it, energized a clandestine group known as the Sons of Liberty that drove much of the resistance in the city. Composed of local merchants, artisans and other activists, the Sons of Liberty used various means to challenge British authority and rally colonial support. They invoked their “rights as Englishmen” and argued that they should not be taxed by a distant government in which they had no representation.

At the time of the Boston Tea Party, Europeandescended communities in the American colonies had been grappling with a growing sense of discontent over British colonial policies. The British government, facing mounting debts from the Seven Years’ War, sought ways to raise revenue from the colonies to help shoulder future financial burdens. The Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765, which imposed duties on a variety of printed materials, were particularly contentious. In 1767 came the Townshend Acts, a series of measures aimed at taxing various imports into the colonies, such as glass, lead, paint and tea. These acts were also met with resistance, leading to boycotts and renewed tensions.

The imposition of the Tea Act of 1773 kindled in Massachusetts colonists a move to more overt action.

In political terms, the Boston Tea Party had an immediate and far-reachi ng impact on both the colonies and the British government. Some Bostonians celebrated it as a bold statement of resistance; others feared that British retaliation would inevit ably follow.

That retaliation came swiftly with a series of measures known as the Coercive Acts, or the Intolerable Acts, in 1774. These acts were intended to punish Boston and bring it under tighter British control. The Boston Port Act, for example, closed Boston Harbor until the colonists paid for the destroyed tea, which served only to further escalate tensions and unite the colonies against British oppression.

THE IMPOSITION OF THE TEA ACT OF 1773 KINDLED IN MASSACHUSETTS COLONISTS A MOVE TO MORE OVERT ACTION.

Rather than subduing the colonists, the British response ignited a renewed sense of solidarity among the colonies as they recognized that punitive measures against one colony could easily be applied to others.

The sense of solidarity and shared purpose that emerged from this event galvanized colonial leaders when they convened on Sept. 5, 1774, for the First Continental Congress, which aimed to coordinate responses to the Intolerable Acts and other British policies and also explore ways to peacefully address colonial grievances.

Today, the Boston Tea Party’s legacy transcends its immediate importance and consequences. For some it has become a potent symbol of freedom, resistance, courage and the quest for self- determ ination; for others, it is simply an act of vandalism.

THE SYMBOLIC WILLINGNESS TO MAKE SACRIFICES FOR PRINCIPLES AND THE GREATER GOOD HAS...INSPIRED ACTS OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE AND NONVIOLENT PROTEST.

The symbolism of the Tea Party has been described as “carnivalesque.” The spectacle of a mock tea ceremony was described by Joshua Wyeth, a teenage blacksmith who joined in the destruction of the tea, as “making so large a cup of tea for the fishes.”

The actions of Dec. 16 demonstrated a willingness to take a stand against perceived tyranny by sending a powerful message that these colonists were prepared to sacrifice economic comforts in the pursuit of their principles. Moreover, the Boston Tea Party further solidified the image of the Sons of Liberty and other colonial activists as champions of liberty and defenders of colonial rights. The affair has been used to capture the imagination of Americans to this day and to exemplify the spirit of resistance that characterized the colonial struggle for i ndependence.

The symbolic willingness to make sacrifices for principles and the greater good has, even in recent years, inspired acts of civil disobedience and nonviolent protest. The idea of resistance against unjust authority resonated during critical moments in American history, including the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi invoked the spirit of the Boston Tea Party as they advocated for social justice and equality, highlighting its timeless relevance in the fight against oppression. More recently, the Tea Party movement, whose name comes from “taxed enough already,” took the Boston Tea Party as its inspiration for a political and grassroots organization of conservatives, libertarians and populists.

The historic Boston event plays an important role in shaping the narrative of America. It provides a powerful example of popular action that galvanized public sentiment against British policies. Colonial newspapers, pamphlets and speeches spread the story of the Boston Tea Party, turning it into a compelling narrative of courage and defiance that rallied colonists to the cause of i ndependence.

The event fueled the development of an American identity and a growing sense of American nationalism. As colonists increasingly saw themselves as united in their resistance against British rule, they began to envision a future separate from the British Crown. The Boston Tea Party contributed to the forging of a common American identity, transcending the boundaries of individual colonies and laying the groundwork for the establishment of a new nation.

And while Boston’s protest is often cited as one of the fuses that ignited revolution, Boston was not the only city to take action in response to the Tea Act.

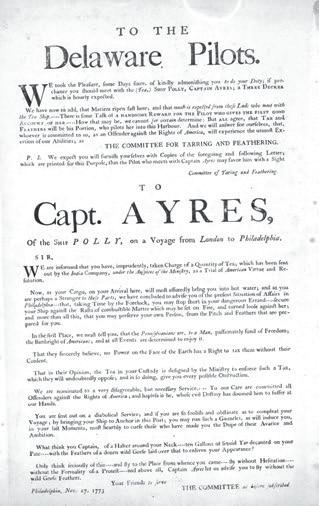

At a town meeting on Oct. 16, 1773, two months before the Boston Tea Party, Philadelphians drafted a public statement opposing the Tea Act, and their resolutions were used as a model by the Bostonians. As 697 chests of tea headed from London toward Philadelphia aboard the Polly, the Committee for Tarring and Feathering posted hand-

bills, including one addressed to the ship’s captain.

“We are informed that you have, imprudently, taken Charge of a Quantity of Tea; which has been sent out by the India Company,” the committee told a Captain Ayres. “Now, as your Cargo, on your Arrival here, will most assuredly bring you into hot water; and as you are perhaps a Stranger to these Parts, we have concluded to advise you [so that] you may stop short in your dangerous Errand secure your Ship against the Rafts of combustible Matter which may be set on Fire, and turned loose against her.”

The committee specified the consequences the captain would face if he ignored the warning: “ten Gallons of liquid Tar decanted on your Pate with the Feathers of a dozen wild Geese laid over that.”

“Fly to the Place from whence you came,” the handbill concluded, “let us advise you to fly without the wild Geese Feathers.”

After the Polly docked, Ayres was escorted to Philadelphia’s State House, where thousands gathered to protest the Tea Act. It is not known whether he read the handbill, but Ayres got the message. He set sail for England with the tea sti ll on board.

The London, captained by Alexander Curling, arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, on Dec. 1, 1773. There, too, patriots protested, in this case threatening to set the ship on fire. But in Charleston, the tea made it to shore, where customs officials locked it in a basement. There it sat for three years, to the frustration of the patriots who wanted to destroy it and the merchants who wanted to sell it.

New Yorkers learned of the Boston Tea Party in December 1773 when none other than Paul Revere arrived on horseback with the news. In April 1774, two ships with tea arrived in New York the Nancy, captained by Benjamin Lockyer, and the London, this time captained by John Chambers. Facing protests similar to those elsewhere, Lockyer agreed to return to England with his cargo. Chambers at first denied the London was carrying any tea but under pressure confessed.