BURYING the HATCHET CUTTING-EDGE PORTRAITURE

BURYING the HATCHET CUTTING-EDGE PORTRAITURE

That

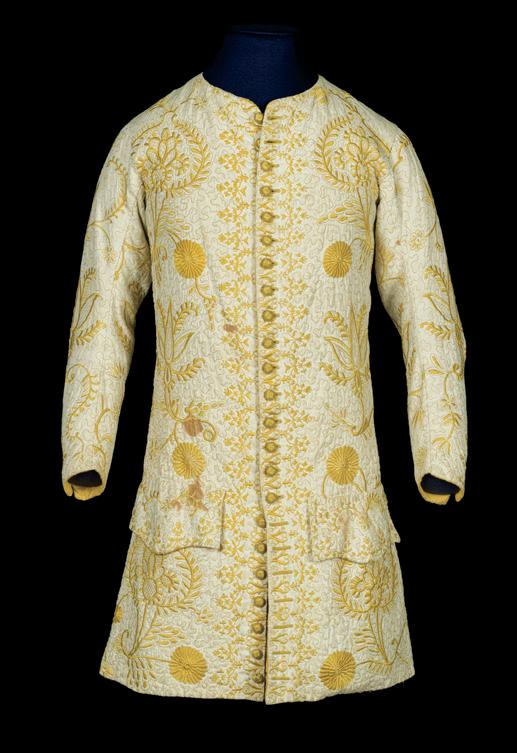

Behind every collection in the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg is an amazing story, beautifully told. Dating to the first quarter of the 18th century, this piece is fully embroidered in yellow silk with a popular vermicelli pattern (like the pasta) for the ground. Early waistcoats tended to be long with ball-like buttons from neck to hem. Step into history as you discover the evolution and significance of these garments. Explore our collections, visit the Museum Store for unique treasures, and unwind at the Café, open daily to enhance your journey into the past.

Paul Aron

Carly Fiorina, Chair, Mason Neck, Va.

Cliff Fleet, President and CEO, Williamsburg, Va.

Kendrick F. Ashton Jr., Arlington, Va.

Frank Batten Jr., Norfolk, Va.

Geoff Bennett, Fairfax, Va.

Catharine Broderick, Lake Wales, Fla.

Mark A. Coblitz, Wayne, Pa.

Walter B. Edgar, Columbia, S.C.

Neil M. Gorsuch, Washington, D.C.

Conrad Mercer Hall, Norfolk, Va.

Antonia Hernandez, Pasadena, Calif.

John A. Luke Jr., Richmond, Va.

Walfrido J. Martinez, New York, N.Y.

Leslie A. Miller, Philadelphia, Pa.

Steven L. Miller, Houston, Texas

Joseph W. Montgomery, Williamsburg, Va.

Steve Netzley, Carlsbad, Calif.

Walter S. Robertson III, Richmond, Va.

Gerald L. Shaheen, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Larry W. Sonsini, Palo Alto, Calif.

Sheldon M. Stone, Los Angeles, Calif.

Y. Ping Sun, Houston, Texas

Hon. John Charles Thomas, Richmond, Va.

Jeffrey B. Trammell, Washington, D.C.

Alex Wallace, New York, N.Y.

CHAIRS EMERITI

Colin G. Campbell, Williamsburg, Va.

Charles R. Longsworth, Royalston, Mass.

Thurston R. Moore, Richmond, Va.

Richard G. Tilghman, Richmond, Va.

Henry C. Wolf, Williamsburg, Va.

TREND & TRADITION

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Catherine Whittenburg

ART DIRECTOR Katie Roy

MANAGING EDITOR Jody Macenka PRODUCTION MANAGER Angela C. Taormina DESIGNERS

EDITOR/WRITER

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

PHOTOGRAPHER

PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR Grenda Greene

Paul Aron, Ronald L. Hurst, Eve Otmar, Rachel West

COPY EDITOR Amy Watson

DONORS Please address all donor correspondence, address changes and requests for our current financial statement to: Signe Foerster, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776 or email sfoerster@cwf.org, telephone 888-293-1776.

Donations support the programs and preservation efforts of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, a not-for-profit, tax-exempt corporation organized under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, with principal offices in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Address changes & subscription questions: gifts@cwf.org or 888-293-1776

Editorial inquiries: editor@cwf.org

Advertising: nfrey@cwf.org or 757-259-5907

Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg (ISSN 2470-198X) is published quarterly in winter, spring, summer and autumn by the not-for-profit Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 301 First Street, Williamsburg, VA 23185. A one-year subscription is available to Foundation donors of $50 a year or more, of which $14 is reserved for a subscription. Periodical postage paid at Williamsburg, VA, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg, Attn: Signe Foerster, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776. © 2024 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All rights reserved.

NOTE Advertising in Trend & Tradition does not imply endorsement of products or services by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

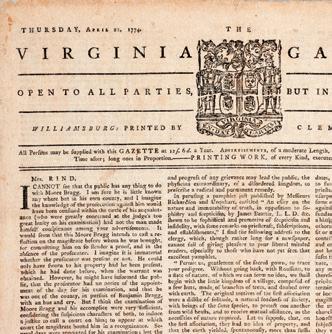

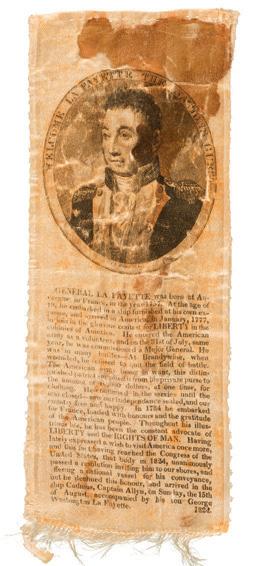

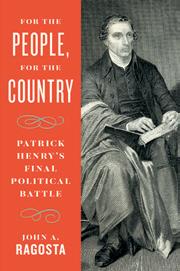

The 200th anniversary of Lafayette’s return comes at a critical time

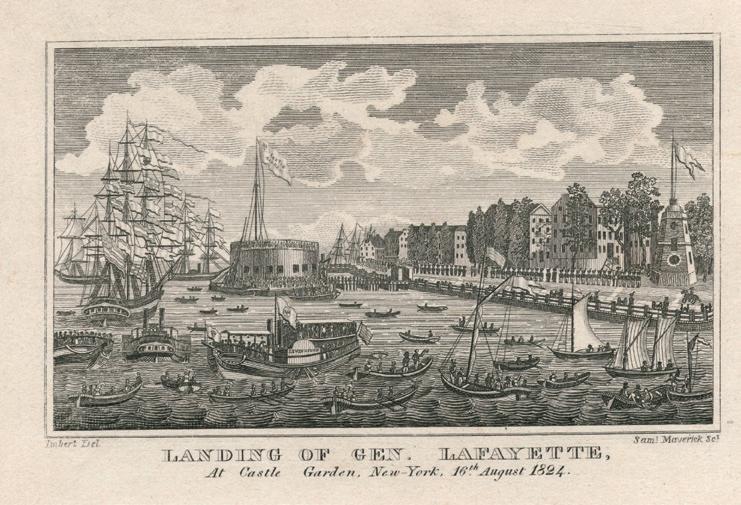

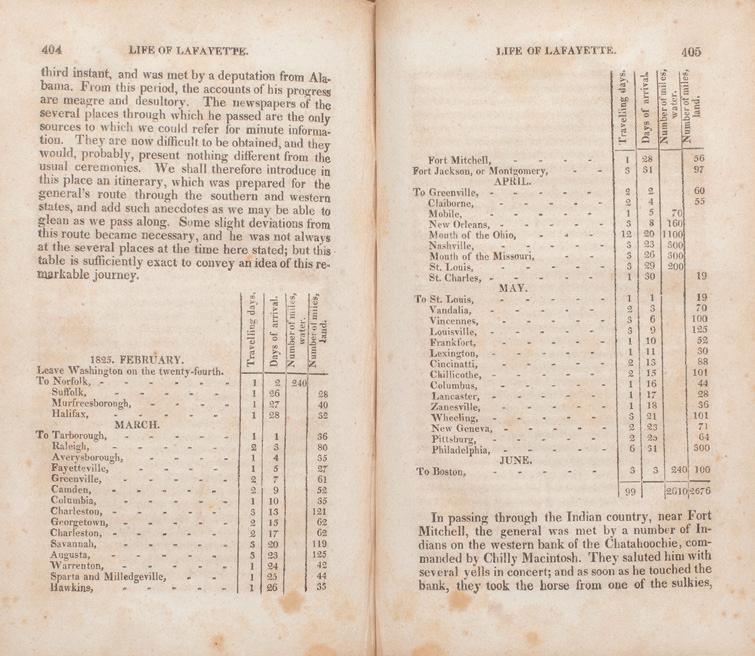

More than 80,000 people lined the streets of Manhattan on Aug. 16, 1824, to welcome a French hero of the American Revolution back to the country he had fought to liberate. Four decades had passed since the Marquis de Lafayette had helped lead the Continental army to victory at Yorktown but the cheering throngs reassured the 66-year-old Frenchman that he was far from forgotten. Over the next 13 months, thousands more Americans would turn out in the 24 states that then made up the union to thank him for his valiant role in their nation’s fight for independence.

This year Lafayette returns to New York on Aug. 16 docking in New York Harbor, where he arrived exactly 200 years before to launch a re-creation of his legendary U.S. tour. As I write these words, Colonial Williamsburg is working with the American Friends of Lafayette, a historical society dedicated to studying and preserving his legacy, to make possible this remarkable, yearlong event. Headlining much of the tour is Mark Schneider, who has so brilliantly portrayed Lafayette for the Foundation for decades. You can read more about this initiative beginning on page 23.

Why re-create this historic tour? While less wellknown than his American counterparts, Lafayette represents the very best of our nation’s founding ideals. His belief in the people and underlying principles of the United States was unwavering, and in 1824 his return proved to be a tonic for the nation at a politically fraught time in our history. Today, as we prepare to commemorate the United States’ 250th anniversary in what is yet again a politically tense environment, Lafayette’s legacy remains a beacon for all Americans, reminding us of the unifying principles that gave rise to a new nation that forever changed the world.

Liberty has had fewer champions more passionate than Lafayette, who left France in secret to join the Continental army. The idealistic 19-year-old nobleman fell in love with the country almost at first sight, at one point

writing to his wife, Adrienne: “The welfare of America is intimately connected with the happiness of all mankind; she will become the respectable and safe asylum of virtue, integrity, tolerance, equality, and a peaceful liberty.” Lafayette, who served in the army as a volunteer, would come to look upon America as his second country, and upon Washington as a second father.

An ardent advocate for human rights, Lafayette held fast to a belief that freedom extended well beyond the cause of independence. Lafayette was profoundly frustrated that the United States persisted in enslaving Black Americans and he expressed his disappointment openly to both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Lafayette became an abolitionist, joining the Society of the Friends of the Blacks in France and actively participating in antislavery movements on both sides of the Atlantic. He also remained a lifelong friend to Native Americans, in particular the Oneida Nation, with whose troops he fought during the Revolutionary War.

Lafayette also advocated for religious toleration in France, and while far from a modern definition of feminist, he supported women’s causes as well. In 1789 he drafted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in consultation with Jefferson, a document that both abolitionists and suffragists would invoke, along with the legacy of the author himself, in their continuing struggles.

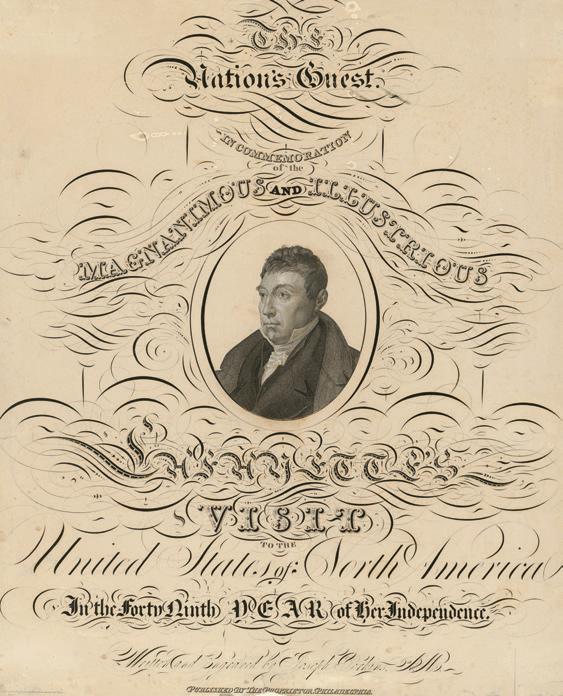

When President James Monroe and the U.S. Congress invited Lafayette to the United States in early 1824 to be the “Nation’s Guest,” this country’s 50th anniversary lay just over the horizon. But as the generation of the Revolutionary War was fading away so was Americans’ collective memory of that defining struggle. Monroe, who had served with Lafayette in the Continental army, wanted to honor his old comrade in arms for his courageous efforts during the war. But he also hoped Lafayette’s return could rekindle a patriotic reverence for all those who had fought and sacrificed so much to create a new nation.

Monroe’s hopes were not misplaced. But with the political turmoil that would coincide with his friend’s arrival that August, it became clear that Americans would need Lafayette in 1824 more than the president realized.

The early years of Monroe’s presidency were characterized by a sense of unity that the press dubbed the “Era of Good Feelings.” A Democratic-Republican, Monroe, in his election in 1816 dealt a fatal blow to the beleaguered Federalist Party and, for a time at least, ended the political warfare of America’s two-party system. In 1820 Monroe overwhelmingly won reelection, but the “Era of Good Feelings” was waning. An economic crisis in 1819 triggered a depression that persisted into Monroe’s second term as sectional divides sharpened largely over questions of slavery and states’ rights. By the time Lafayette stepped back on American soil in August 1824, the country was thoroughly fractured and barely two months away from what even today is considered one of the most contentious presidential elections in U.S. history.

“Lafayette’s arrival happened to land in the middle of one of the most contentious presidential elections in a generation which made the collective embrace by the Americans even more remarkable,” history author and podcaster Mike Duncan writes in Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution. “Though the election of 1824 was a brutal exercise in scorched-earth hyperpartisanship, Lafayette was something all Americans shared in common.”

The United States was still a one-party country, but infighting among Monroe’s Democratic-Republicans had split the party’s presidential ticket that year among four major candidates. None of the four received a majority of the vote, leaving the final decision to the U.S. House of Representatives which ultimately chose John Quincy Adams, though Andrew Jackson had won the most votes. When Adams named House Speaker Henry Clay as his secretary of state, Jackson and his supporters were outraged, denouncing the election as a “corrupt bargain” between the two men.

Lafayette dropped anchor in New York just as this political firestorm was building to full strength. But even as the candidates and their factions fiercely attacked one another, the rancor could not dim the nation’s excitement over the return of the Revolution’s last surviving major general. The arrival of America’s hero inspired a frenzy of patriotic excitement and celebration that transcended every political, geographic and generational divide so much so that the tour itself, envisioned initially as a three-month undertaking, quickly ballooned into an epic 13-month trek to cities and towns both large and small.

It’s not hard to see the parallels between 1824 and today. Just two years away from America’s Semiquincentennial, we are also experiencing a time of political polarization, with an approaching election that promises to showcase those divisions. We are also living through a time when Americans’ knowledge of their own history is hazy at best, a deficit that only widens the divides between us.

Lafayette’s tour in 1824 did not mend the nation’s rifts, per se. But it revived America’s appreciation for its history, revealing that its founding ideals run deeper than its fractures. Now, as this Foundation prepares to lead the nation’s commemoration of its 250th anniversary, retracing Lafayette’s steps will extend our work to bring all Americans closer to their own history, and to one another in the process.

This historic tour is a chance for all of us to rediscover and celebrate our nation’s most deeply held principles, which continue to light our best way forward together. It may be characterized, perhaps, as the best of history repeating itself and we are glad for the opportunity to make it happen. I hope many of you will be able to join us along the way.

Sincerely,

Cliff Fleet President & CEO

Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Distinguished Presidential Chair

Emily James’ moving portrayals in more than a dozen interpretive roles most notably as Edith Cumbo, a free Black woman negotiating an enslaved 18th-century society educated countless visitors to Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

“I get the privilege to tell the story of my ancestors to a modern-day audience not only of their sufferings but of their contributions to the making of America,” she said in an interview for the 2016 book The Art and Soul of African American Interpretation. “When I do my interpretation, I feel the strength of their African blood flowing through my veins.”

James, who was a fixture in the Historic Area for some 35 years, died on March 6. She was 76.

Born in Jamaica, James came to the United States in 1983 and joined the Foundation in 1987 as a character interpreter, sometimes working alongside her husband, Gregory, who died in 2013. She was often seen in the Historic Area carrying her husband’s period clothing in a basket she balanced on her head. Her accent contained a soft hint of her homeland.

In 2011, she joined the Nation Builder program to portray Cumbo, one of a very few free Black persons living in 18th-century Williamsburg. Cumbo headed her household, likely using her sewing

and laundry skills to earn a living.

James felt a special connection to Cumbo: “I compare her character traits with mine. They just blend together; it’s like having compatible DNA.”

Colleagues, some of whom James mentored, noted that her curiosity drove her to do extensive research, piecing together clues from primary sources.

“When you have a character, it’s like a marriage,”

James told The Washington Post in 2021, a year before she retired. “It takes five years to really become that person.”

“You cannot have American history without Native American history, without African history, because bringing [together] all these diverse cultures and ways, this is what becoming an American really means,”

James said in a 2020 interview. “We all built America.”

“It wasn’t just history that Emily taught us. She taught us about ourselves,” said Beth Kelly, the Foundation’s Theresa A. and Lawrence C. Salameno Vice President for Research, Training and Program Design. “With kindness, wit and a beaming smile, she would greet strangers as well as old friends. We were enveloped into her world, and when we parted from her, our minds were opened with a deeper understanding of our humanity.”

The realization of the Rev. Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin’s vision of this powerful place is shared today by hundreds of thousands of annual visitors, and supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of people who, as John D. Rockefeller, Jr., did – contribute to sustaining Dr. Goodwin’s dream. Become a Goodwin Society member today by naming The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in your estate plan. To learn more, please contact our gift planning team at 1.888.293.1776 or legacy@cwf.org.

EXPLORE COLONIAL SITES AND HISTORY . PEEK BEHIND THE SCENES . PURSUE AND PLAN

The increasingly rare skill of ‘freehand’ silhouette artistry

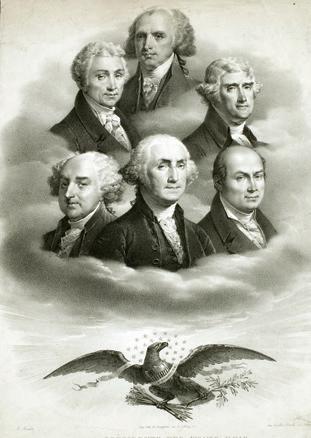

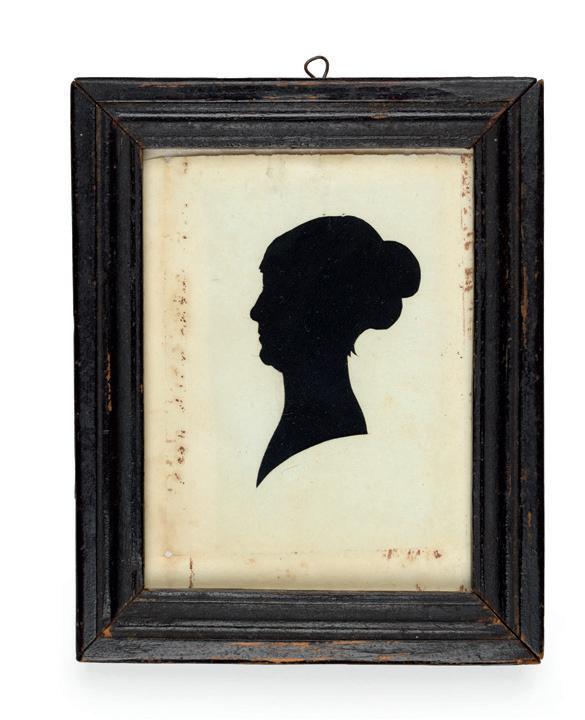

Asilhouette was a popular form of portraiture in late 18th- and early 19thcentury America. Generally appearing as a black profile on a light-colored background, a silhouette is stark and simple compared to a painted portrait. For many Americans, silhouettes conjured up the ideals of classical Greece and Rome, where they were also popular. And in an era before photography was invented, silhouettes were especially popular among those who could not afford to have costly portraits painted.

Still, there were not many silhouette artists in 18th-century America, partly because travel was difficult and so was the technique. There are even fewer today: Only about 20 in the world work

BY PAUL ARON PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRIAN NEWSON

“freehand,” meaning using just scissors and paper, without the aid of shadows, drawings or photographic devices.

One of those freehand artists is Lauren Muney, who is based in Baltimore and who spent time during the winter and spring researching and demonstrating her craft in Williamsburg. Muney came to Williamsburg thanks to a joint fellowship of the Foundation and EXARC: The International Society for Experimental Archaeology and Open-Air Museums.

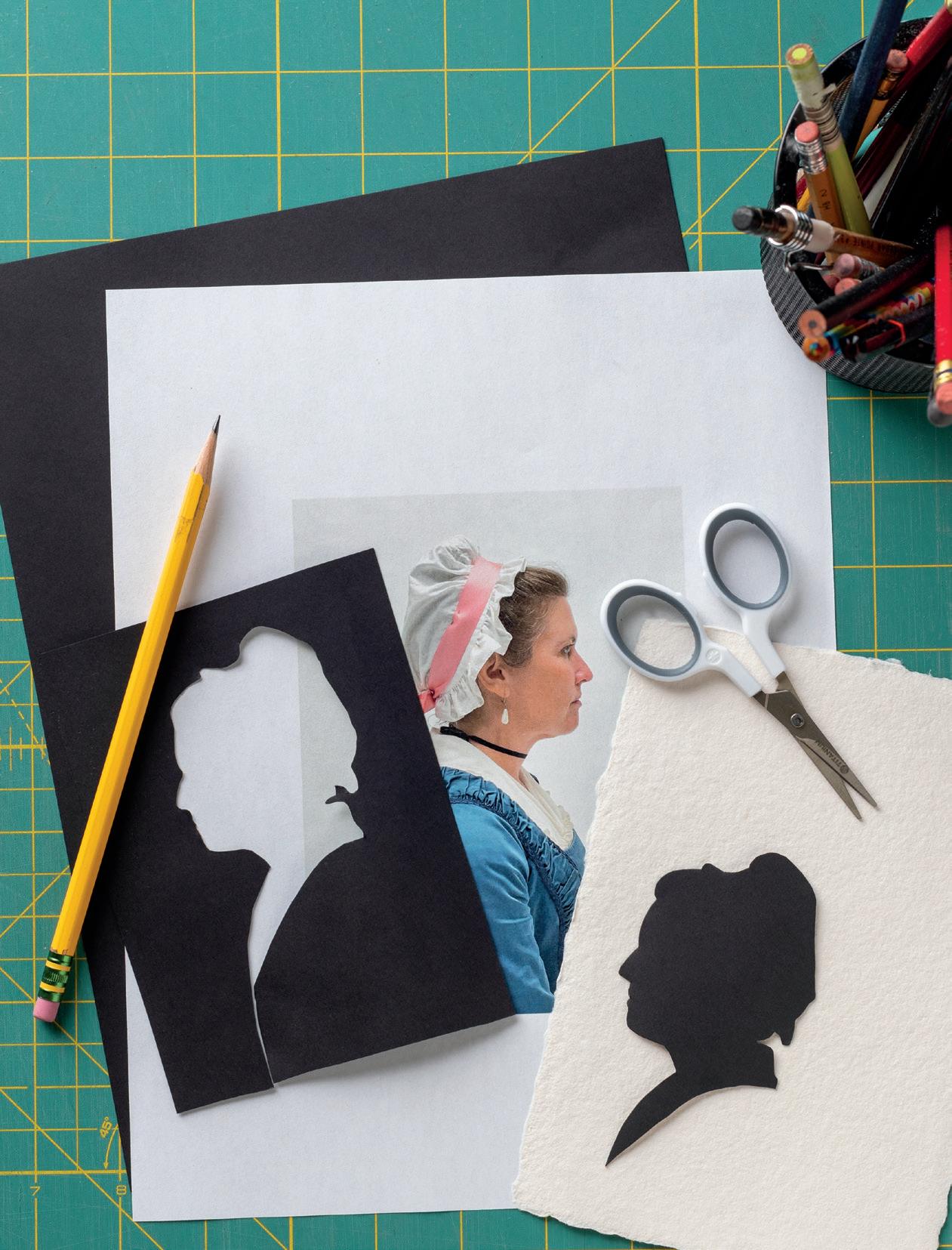

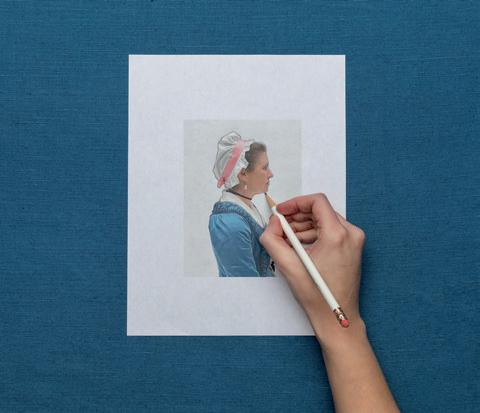

Though she carries with her a box of tools and materials, Lauren Muney creates silhouettes with just scissors and paper.

“Silhouette portraiture is deceptively difficult.”

— Lauren Muney

Experimental archaeology involves testing theories of how things were made in the past.

“I was excited to see Lauren’s application,” said Peter Inker, the Foundation’s director of Historical Research. “She is working in a field that we don’t often see at Colonial Williamsburg. Her research will help us to understand the conditions, networks and supplies of itinerant silhouette makers.”

“Not only that,” Inker added, “it let guests to the Historic Area experience a silhouette maker.”

Muney was first drawn to silhouettes when she saw one in an antiques store.

“I couldn’t afford to buy the antique, but I went home to study up on it, to perhaps make myself one for my wall,” she said. “Little did I know how difficult it was. It took me over a year just to work out the basic skills. Trying to teach myself to cut silhouettes was incredibly challenging.”

Years of anatomy drawing classes for her bachelor’s degree in illustration had given her a deep understanding of the human body. Still, Muney admits her initial efforts resulted in awful silhouettes.

“Silhouette portraiture is deceptively difficult,” she said. “I’ve now been working almost 17 years as a silhouette artist,

yet I think that I have only been excellent at cutting silhouettes in the last five years. It’s an incredibly intricate and personal portrait form that takes a long time to master.”

Cutting silhouettes freehand requires a range of skills, from a knowledge of anatomy to an ability to talk to people and to talk to them in a range of venues. Muney works so quickly that observers sometimes do not realize how much skill is involved. But it is hard not to be impressed by the results.

“It’s very hard to get a good portrait with any medium,” Muney said. “Using only scissors is definitely a superpower where I keep the hardship a secret.

“Although I am only using scissors, without being able to erase, I can get incredibly precise and detailed. And these silhouettes can give the sense of humanity and detailed character.”

Silhouettes offered Muney an opportunity to engage visitors in history.

“During the time I was discovering silhouettes, I was also noticing that the public seemed to be just observers in museums,” she said. “Sometimes they were walking through museums without connecting with anything. I wanted to give visitors something to connect with. I thought sitting for a silhouette was the perfect opportunity a little bit of experiencing history without too much effort on their part. Easing into history, one might say.”

The Colonial Williamsburg- EXARC fellowship was especially satisfying to

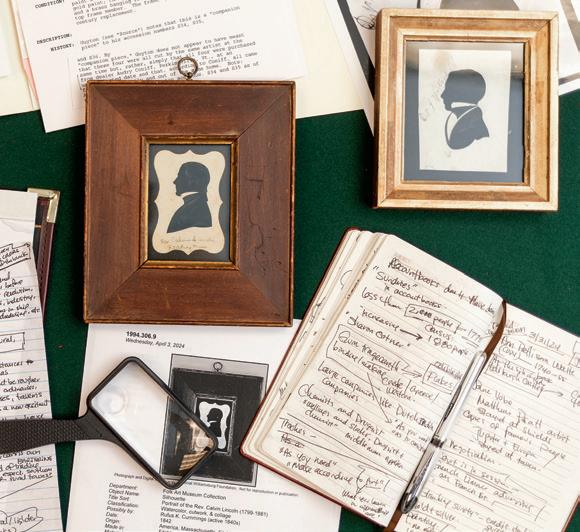

Lauren Muney kept notes about materials from Colonial Williamsburg's collections, including records and silhouettes. The two pictured here are from New England.

Muney since it gave her the opportunity to delve into the origins and evolution of her craft.

“My conception of being a resident researcher couldn’t even touch the exciting reality of being surrounded by so

many experts, researchers, tradespeople, historians, conservators, curators,” she said. “What is so amazing about Colonial Williamsburg are the intertwined resources and knowledgeable people.”

In Williamsburg, Muney explored how silhouette artists created their black paper. Museum experts have long wondered how this paper was made. To reproduce the mysterious black coatings, Muney experimented with materials like lampblack (soot that can be produced by candles and oil lamps) and beer. She even joined in the process of brewing traditional beer at the Palace kitchen to understand how beer’s ingredients could be used to blacken paper.

She also studied how itinerant artists traveled. She talked to wheelwrights about carts and wagons, and she researched everything from the condition of roads to tavern fees.

“To get a big picture of a subject, one must put many little subjects together,” she said. “Nowhere else except Colonial Williamsburg could I come to one location to find so many experts and so many resources.”

Some early 19th-century silhouette makers did not use the traditional scissor method but instead relied on what were known as physionotrace machines to trace a profile outline of a subject’s face.

Raphaelle Peale, the son of famous artist Charles Willson Peale, and William Bache were among the best-known silhouette artists to visit the Tidewater and Richmond areas. Both used these machines to create profiles.

Bache was known to have made silhouettes for a number of familiar Williamsburg names, including George Wythe and Mary Stith.

“References to silhouettes and their makers provide a tantalizing clue to the popularity of the form and help us to better understand the larger context of portraiture in Virginia,” said Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg’s Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture.

Join us this summer for a transformative educational experience in the Bob and Marion Wilson Teacher Institute’s online courses! Enhance your teaching toolkit and connect with peers as we engage with industry experts and master teachers who lead a deep dive into historical topics and our digital resources. With limited spots available, secure your free Zoom “seat” now.

July 29 to August 2, 2024 | 4 PM - 6 PM EDT

Explore American values through history and today in this five-day course. Dive into pairs of values like unity and diversity, and discover how they’ve shaped historic events and are balanced over time. Limited to 75 participants, suitable for teachers of upper elementary school level and above.

July 15 to July 19, 2024 | 4 PM - 6 PM EDT

Examine the diverse lives of women in the 18th century and how their perspectives shaped the American Revolution. Attend individual webinars or join us for the whole series via Zoom.

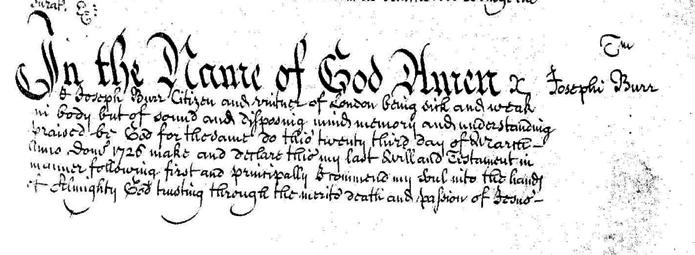

Joseph Burr died in 1727, leaving his 6-year-old daughter an orphan, but his will gave her some financial independence as an adult.

by PAUL ARON

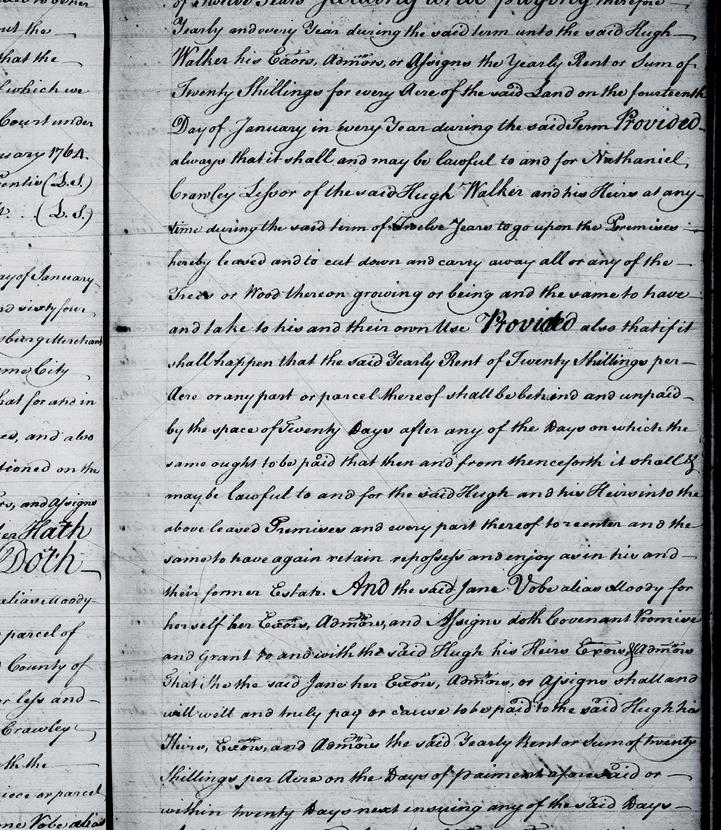

To prepare to portray Williamsburg tavern keeper Jane Vobe, Sharon Hollands started her research last year into the life of Colonial Williamsburg’s newest Nation Builder and she encountered a problem that many Historic Area interpreters know well. Much is known about such famous Founders as Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry and George and Martha Washington. The historical record for lesser-known figures, especially those who did not belong to the gentry, is often much skimpier.

For Hollands, the record offered a special challenge: It included references that could apply to two or even three people. Or perhaps the references all trace back to a single person. And each instance referred to events that could help shape Hollands’ portrayal.

London and Virginia records mention three names: Jenny Burr Vobe, Jane Vobe of Williamsburg and “Jane Vobe alias Moody.” Put the three together, and there was enough, albeit just barely, for Hollands to understand something about the woman who kept the King’s Arms Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street.

Jenny Burr (sometimes noted as Jane) appears in London records. Burr was the daughter of a wine merchant and tavern keeper. She was born in 1720 and orphaned when she was 6. Her father’s will divided his property among his five children. In 1739, Jenny married Thomas Vobe, also a wine merchant and tavern keeper.

York County records refer to Jane Vobe alias Moody, suggesting Vobe may have had a relationship with Mathew Moody after her husband died or disappeared.

The London records indicate that Thomas Vobe went bankrupt, and his creditors wanted the money his wife inherited as payment for his debts. But a court determined that since she had married before she was 21 and without the permission of her guardians, Thomas and his creditors could have access to only half of her inheritance. The rest would remain invested for Jenny and her children.

So far, no record of the Vobes in London after 1742 has been found. They may well have left England. In 1744, the name Thomas Vobe shows up in Williamsburg. This Thomas Vobe opened a tavern and then fell into bankruptcy for a second time, assuming this was the same Thomas cited in the London records.

A Mrs. Vobe appears in Williamsburg records in 1747, and within a few years a Jane Vobe appears in all sorts of Wil-

liamsburg records, including those of the courts, Bruton Parish and the Bray School as well as newspaper ads and other people’s account books.

Was this Jane Vobe the same person as Jenny Burr Vobe? Had she been able to weather her husband’s latest financial ruin because of her experience with his first business failure? This certainly could inform Hollands’ portrayal.

Similarly, Hollands found in the 1764 York County records a “Jane Vobe alias Moody,” which, along with other evidence, suggests Vobe may have had a commonlaw relationship with a Mathew Moody. What became of Thomas Vobe is not clear. He may have died by then and indeed, Jane Vobe is sometimes referred to as a widow or he may have left his wife. This, too, would help inform Hollands’ portrayal.

Hollands’ research demonstrates the challenge of creating a rounded character from limited historical references.

“Sometimes there are holes in interpreting,” she explained. “Sometimes I’ve found handwriting that’s difficult to read or portions of a page eaten away. But you have to reasonably infer. Even when we sometimes are imagining, our imagining is always based on our research.”

Interpretations can evolve as more is learned, and Hollands remains open to the possibility that newly uncovered evidence might change the nature of her portrayal of Vobe. There may be, for example, records in London that have not yet been digitized and that will offer a clearer picture of the woman who operated taverns in Williamsburg for some 30 years.

Hollands has portrayed other historical figures since coming to Williamsburg in 1998. She has a degree in theater but always had an interest in history and

“Even when we sometimes are imagining, our imagining is always based on our research.”

embraced playing many characters in the Historic Area. Before she began interpreting Vobe in the spring, her most recent role was Elizabeth Braxton, the wife of a signer of the Declaration of Independence who was also the daughter and sister of British loyalists.

“It’s interesting to do a range of characters and challenging to flip that switch, but I wanted to portray a Nation Builder,” she said. So when the decision was made to add Jane Vobe to Colonial Williamsburg’s Nation Builders, Hollands saw her opportunity and applied.

Vobe’s addition to the list of Nation Builders that includes George Washington and Thomas Jefferson is part of an effort to show that a range of people and not just the famous Founding Fathers helped build the new nation.

“Women filled surprising roles in the past,” said Beth Kelly, Colonial Williamsburg’s Theresa A. and Lawrence C. Salameno Vice President for Research, Training and Program Design, “and we

have an opportunity with Jane Vobe to bring to our audiences the story of a very successful business owner who worked hard moving from tavern to tavern, building her clientele, and was well connected to all levels of society and happens to be a woman. We chose this historical figure because Jane frames for subsequent generations an identity of focused hard work, excellence and compassion that becomes a work ethos for our national identity.”

For Hollands, portraying Vobe offered autonomy and the chance for a deep dive into research. “All first-person interpreters do tons of research, but the Nation Builder position gives me the chance to focus on one name,” she said. “A deep dive is exciting, even if it’s a deep dive into a shallow pool.”

Sharon Hollands discusses her research in Performance: Finding Jane Vobe , which is scheduled at the Hennage throughout the summer.

Much of Jane Vobe’s tenure as a tavern keeper took place in Williamsburg. When she began doing business on her own is not clear, but records indicate that she had an establishment on Waller Street until 1771. George Washington’s records show that he stayed there.

Vobe announced in 1772 that she had opened a tavern “at the Sign of The King’s Arms,” which she operated with the help of enslaved people, including Gowan Pamphlet, who led secret religious gatherings of enslaved and free Black congregants. She sent two enslaved children, Sal and Jack, to the Williamsburg Bray School, and four of the people she enslaved were baptized at Bruton Parish Church.

Vobe’s death was reported in 1786, a year after she left Williamsburg to open a tavern in Chesterfield County, Virginia, near the new seat of the commonwealth’s government in Richmond. An obituary printed in the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser described a woman “who, for many Years, kept a very genteel Public House at Williamsburg.”

Introducing the Revolutionary War major general to students on the 200th anniversary of his tour of America

by PAUL ARON ⋅ Photography by BRIAN NEWSON

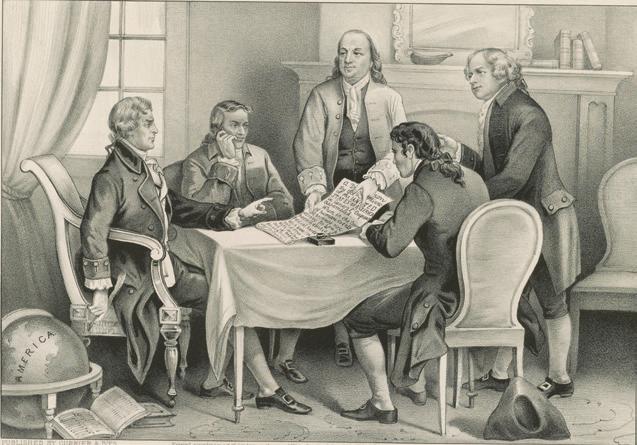

Colonial Williamsburg’s Nation Builder Mark Schneider visited three Washington, D.C.-area schools in May to introduce students to the Founder he interprets, the Marquis de Lafayette. This summer marks the 200th anniversary of the Revolutionary War hero’s triumphant return to the United States in 1824.

Sixth, seventh and eighth graders from Jefferson-Houston PreK-8 IB School in Alexandria, the Lab School of Washington in D.C. and St. Patrick’s Episcopal Day School in D.C. had the opportunity to pepper Schneider with questions about Lafayette. At St. Patrick’s, students wanted to know:

“Why should Americans remember you?”

“Why did you leave your wife to come to America?”

“How did you die?”

“What do you think of Alexander Hamilton?”

“How has the United States changed since the Revolution?”

In advance of the visit, Colonial Williamsburg produced a video that detailed five important facts about the marquis. Students were encouraged to ask Schneider, in costume and answering as Lafayette, to

elaborate on the information.

Schneider’s school visits grew out of discussions within a Colonial Williamsburg donor advisory group called the President’s Council, which seized on the anniversary of Lafayette’s return visit to America as a way to extend the Foundation’s educational mission. The council originally supported events for donors and then broadened the initiative to include school events, which staff members of Colonial Williamsburg’s Bob and Marion Wilson Teacher Institute helped arrange.

“One of the council’s principal interests has been to support the Foundation’s educational mission,” said Teresa Wood, who with her husband, Ken, sits on the council.

Lafayette’s school visits were designed to teach students about more than the marquis. Students also learned about other Revolutionary figures, including George Washington and James Armistead Lafayette, an enslaved man who spied on British forces at Yorktown. James Armistead worked primarily for Lafayette, and when he later gained his freedom, he took the name of the marquis.

As Lafayette, Schneider spoke to the students about his “grand tour” of America,

Students at St. Patrick’s Episcopal Day School were encouraged to ask questions about the Marquis de Lafayette.

Mark Schneider, who interprets the Founder, answered in character.

which spanned the years 1824 and 1825, covering all 24 of the existing states. The tour included visits with President James Monroe and former President Thomas Jefferson.

“With tremendous energy and great ease in answering questions, the Marquis’ presentation piqued our students’ interest in more fully exploring the concepts of freedom and democracy for all,” said Catherine Welch, a middle school learning specialist at St. Patrick’s. “We are confident that this experience, and others like it, will help our students evaluate and later participate in the great American experiment of democracy.”

the Marquis

A video about the Marquis de Lafayette that was shared with students of these three schools can be seen here: colonialwilliamsburg. org/lafayette5things

Schneider joined Colonial Williamsburg in 1997 in the Historic Trades department, after a stint in the U.S. Army. Two years later, he took on the role of Lafayette, for which he is ideally suited. He has a passion for military history, he is a skilled horseback rider and, because his mother was French, he is fluent in her native language.

Still, like all of Colonial Williamsburg’s Nation Builders, Schneider continued to study his subject. “All the while I was learning about the character,” he said, “but also about the world of the 18th century and the landscape what did Paris look like when there was no Eiffel Tower, no

Arc de Triomphe?”

For his school performances, Schneider wears a military uniform even though he would have worn civilian clothes during his 1824-1825 travels. “It’s better theatrically,” he admitted. “The uniform screams out Lafayette.”

As he does when performing in the Historic Area, Schneider stays in character when performing in schools. Since Lafayette’s return visit came decades after the Revolution, he is able to talk about the years that have passed. Here is what he told the students:

Asked why Americans should remember Lafayette, Schneider spoke not only of his participation in the Revolution but of his continuing efforts to end slavery and to be a friend to Native Americans.

Asked how Lafayette could leave his wife, Schneider noted that she was not only the most beautiful woman in the world but also the most understanding.

Asked how Lafayette died, Schneider remained in the year 1824 but told a “precautionary tale” about how attending a friend’s funeral might lead to catching a cold that turns into pneumonia.

Asked about Hamilton, he described him as a “dear friend” and spoke of how Hamilton “covered himself in glory” at Yorktown leading a surprise assault on a British redoubt.

Asked how America had changed since the Revolution, he spoke about the nation’s achievements but also about how, “unfortunately, the institution of slavery still remains.”

“I think America has much to do in the future,” he told the students.

Nation Builder Mark Schneider will make more school visits during the course of the year. These visits are made possible by generous support of Colonial Williamsburg’s President’s Council.

“My heart was enlisted and I thought only of joining the colors.”

Marquis de Lafayette

The Duke of Gloucester’s complaints did not have the desired effect on the Marquis de Lafayette.

The young marquis attended a dinner in 1775 at which the younger brother of King George railed against the North American colonists who were rising up against British rule. As the duke ridiculed the right of people to rule themselves, he struck a revolutionary chord in Lafayette. The young Frenchman’s heart told him to join the Continental army and fight alongside the Americans.

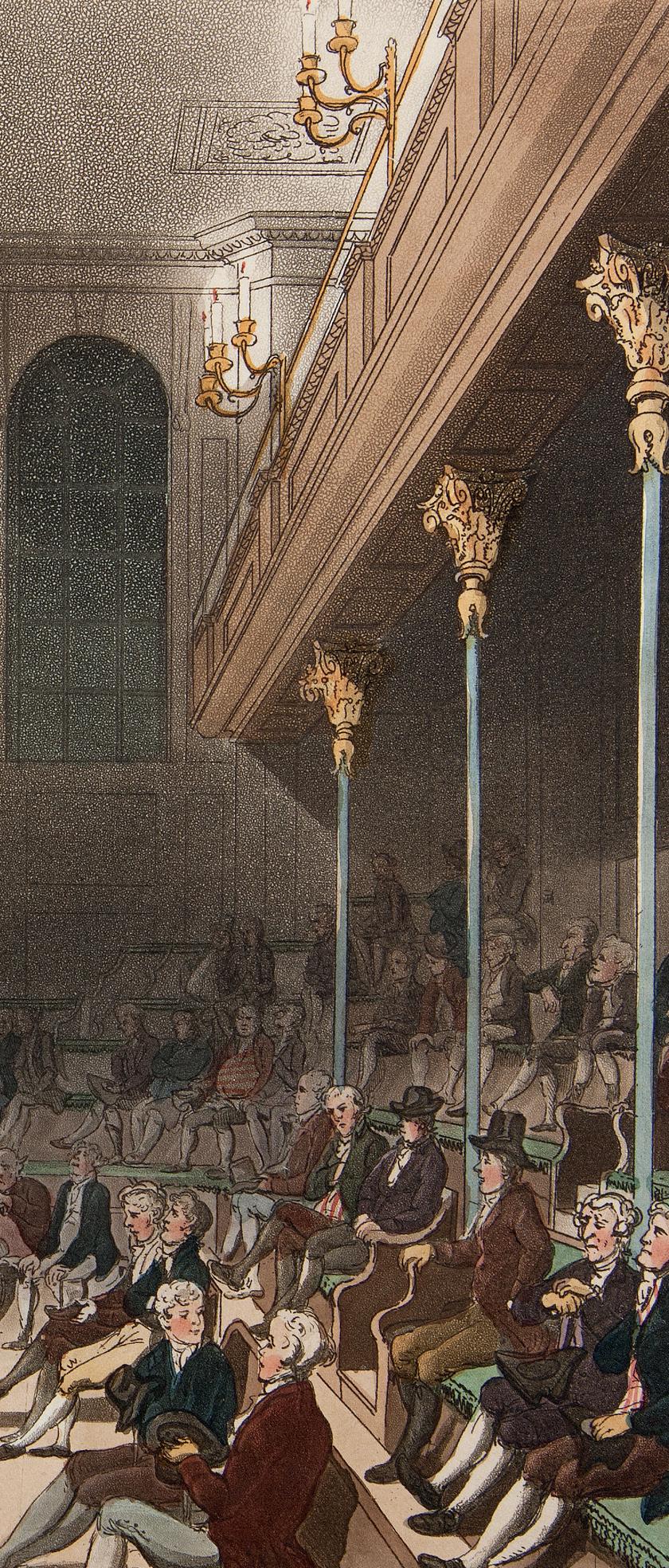

Lafayette was one of three division commanders in the American army during the siege at Yorktown in 1781 when the British surrendered, effectively ending the Revolutionary War.

Some 40 years later in 1824

Lafayette made a triumphant return to America at the invitation of President James Monroe, with whom Lafayette

endured a bitter winter at Valley Forge. During a 13-month tour, Lafayette reminded Americans of the reasons they fought for independence and freedom. The United States was about to celebrate its 50th birthday, and Monroe hoped to instill the spirit

Lafayette was heralded as the Nation’s Guest during his 1824 visit to America.

LAFAYETTE SCHOOL VISITS

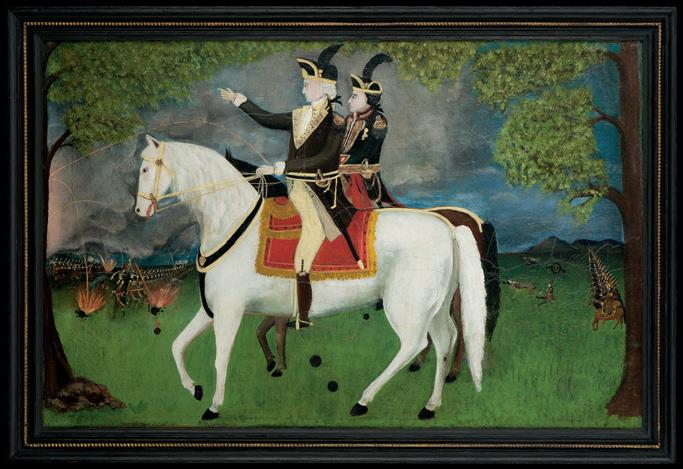

(Above): A flotilla of decorated boats greeted Lafayette’s arrival at Castle Garden in New York. (Opposite page): Lafayette is said to have commissioned this portrait of himself during his 1824 visit, likely as a gift to his host, President James Monroe.

of 1776 in a generation that did not experience the Revolutionary War. Traveling by steamboat, barge, stagecoach and horseback, Lafayette was greeted by crowds of well-wishers.

Beginning in August, the 200th anniversary of the French major general’s return will be celebrated with a tour organized by the American Friends of Lafayette, in partnership with Colonial Williamsburg and other cultural institutions. It retraces Lafayette’s steps across the 24 states that made up the United States in 1824 and offers opportunities to celebrate not just Lafayette’s military intelligence but also his support of human rights for the enslaved, for American Indians and for women. He also advocated for religious tolerance and opposed solitary confinement of prisoners, having been a political prisoner himself for five years after the deposition of Louis XVI.

Colonial Williamsburg Nation Builder Mark Schneider, who has interpreted Lafayette for decades, will take part in the tour, including its kickoff in New York on

Aug. 15. On that date in 1824, Lafayette and his son Georges Washington de Lafayette arrived in American waters on the Cadmus and stayed overnight at the Staten Island home of Minthorne Tompkins, the son of then U.S. Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins.

The following day, a steamship carried Lafayette to New York Harbor, where he was greeted by thousands of well-wishers. The modern tour is scheduled to include a 13-gun salute from Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, where a ceremonial troop review is planned, followed by a trip up Broadway to New York’s City Hall with reenactments of speeches given there 200 years ago.

The Virginia stops on the 2024 tour include Yorktown this fall, coinciding with the celebration of the victory over the British in 1781. On Oct. 18, Schneider will appear with fellow Nation Builder Stephen Seals in a re-creation of Lafayette’s reunion with an enslaved Black man who was a spy for the American cause. James Armistead Lafayette took Lafayette’s name in tribute, and the two men saw each other for the first time in more than 40 years when the Frenchman returned as the “Nation’s Guest.”

The tour comes to Williamsburg on Oct. 20-21 and includes programs recalling the ceremony in which Lafayette received an honorary degree from William & Mary, as well as events in the Historic Area and at the Kimball Theatre. More commemorations are planned for Charlottesville on Nov. 15 and Montpelier on Nov. 16-17. Events at Mount Vernon are scheduled for Aug. 29-Sept. 1, 2025.

Schneider said he is looking forward to future tour stops and to continuing to tell stories about Lafayette and his times. “I’m a firm believer that all the answers to the future can be found in the past,” he said.

For more information about the tour, visit lafayette200.org

Holy Water Font

MAKER John Swann

DATE 1820 - 1825

PLACE Alexandria, Virginia

MEDIUM Salt-glazed stoneware

DIMENSIONS 11 ₁ ⁄₈ inches high by 10

inches from handle to handle with a diameter of 9

inches

BY PAUL ARON PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON COPES

Colonial Williamsburg recently acquired a font believed to have been made for the first Catholic church in Virginia. This vessel held holy water, a sacramental reminder of baptism used for many forms of blessing in the Catholic Church.

Virginia was not welcoming to Catholics in its early years. In 1570, decades before the English settled at Jamestown, Spanish Jesuit priests established a small mission not far from the site of what would become Yorktown. Less than a year later, however, Native Americans killed the missionaries, sparing only an altar boy.

The House of Burgesses formally established the Church of England in Virginia in 1619, which meant that colonists of any religion were required to attend its services and support its ministers. But in 1776, Virginia’s Declaration of Rights asserted that “all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion.” French troops, many of whom were Catholic, played a crucial role in securing America’s independence and, after the decisive victory at Yorktown, even celebrated Mass at Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg.

Construction of the first Catholic church in Virginia, the Church of Saint Mary in Alexandria, began in 1795 and was completed a year later. According to a church history, George Washington contributed to the building fund. The current church, now known as the Basilica of Saint Mary, opened in 1826.

The incised letters on the font IHS a monogram, or Christogram, for Jesus, is often found on worship furnishings. A cross is flanked by doves with halos symbolic of the Holy Spirit and what are possibly pomegranates, a common image in Christian and other religious art.

“Objects that speak to the religious diversity of early America are rare, and ceramic objects even more so,” said Angelika Kuettner, Colonial Williamsburg’s associate curator of ceramics and glass.

Kuettner added that the font is one of only two known stoneware objects with potter John Swann’s mark and also decorated with intricately incised motifs neatly filled with cobalt blue decoration. The church may have commissioned Swann to make the font.

The font bears the maker’s mark of stoneware potter John Swann. An orphan from Maryland, Swann was apprenticed to Alexandria potter Lewis Plum and was the founder of Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Pottery. He advertised himself as a manufacturer of stoneware by 1815. Impervious to liquids, stoneware was a perfect means for food storage and for centuries had been touted for its durability. Germany and England were the initial sources of the stoneware in this country, but New England and New York had thriving domestic production centers by the mid- to late 18th century. Swann sold jugs, pots, pitchers, milk pans, churns, chamber pots and a variety of other useful wares.

FUELED

BY COREY STEWART

This year, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum marks 85 years since Abby Rockefeller gave her collection of folk art to Colonial Williamsburg as a permanent gift.

Having grown up the well-traveled daughter of a Rhode Island senator in a world that appreciated fine and decorative arts, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller was no stranger to beautiful things. However, unlike many of her peers who prized tradition, Rockefeller was determined to embrace the changing world around her.

Her views on social issues, for instance, were notably progressive. In a 1923 letter to three of her sons, she referred to the oppression of Black Americans as an “everlasting disgrace” and anti-Semitism as a “cruel injustice.” She urged the boys to “stand firmly for what is best and highest in life.”

Rockefeller saw art as an important part of social evolution, writing that it not only “enriches the spiritual life” but also makes a person “more sane and sympathetic, more observant and understanding.”

The desire to support what was new and good in the world extended to Rockefeller’s own art collection. A longtime collector of modern art and co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art in the late 1920s, Rockefeller became interested in folk art partly because of what the seemingly dissimilar art forms shared. Just as modern art bucked the conventions of fine art and experimented with shape, form and composition, folk art exhibited a similar aesthetic that appealed to Rockefeller. As biographer Bernice Kert, author of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family, explained in a documentary, Rockefeller “was attracted by the unusual, adventurous, inner-directed art. She liked experimentation.”

Folk art, like modern art, relies on the

artist’s own conception, expression and execution of its subject matter. But while a formally trained modern artist like Pablo Picasso is deliberate in his rejection of perspective and proportion in much of his work, an untrained folk artist might be aware of these traditional artistic conventions but simply lack the knowledge of how to execute them.

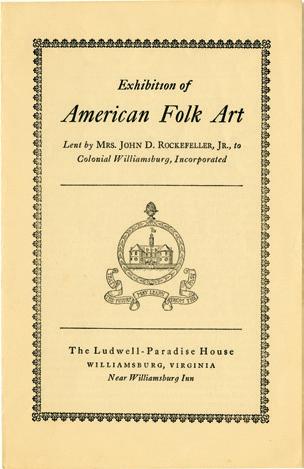

By 1932, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s folk art collection had become substantial enough to constitute a loan of 175 pieces, which she made anonymously to the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750-1900, was then loaned to several other museums.

At the same time, Rockefeller’s husband, John D. Rockefeller Jr., was helping steward the development of Colonial Williamsburg. Once The Art of the Common Man completed its traveling tour, Abby Rockefeller’s folk art collection was installed in the Ludwell-Paradise House on Duke of Gloucester Street.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (above) gave her folk art collection to The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1939. Her collection, which included Baby in Red Chair, was first housed at the Ludwell-Paradise House (opposite page and below).

The folk art proved so popular with visitors that in 1939 Rockefeller made her collection a permanent gift. By 1948, the year she died, her folk art collection had outgrown the Ludwell-Paradise House, and her husband initiated construction of a new, purpose-built building. Other pieces of her collection, which were on display at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, were brought to Williamsburg in 1955.

inheritance which was theirs without strings and without ideas borrowed from abroad....a grass roots America which was a part of our common experience.”

Over the years, the museum’s curators have been careful and deliberate in expanding the collection, ever faithful to the goal of telling the American story.

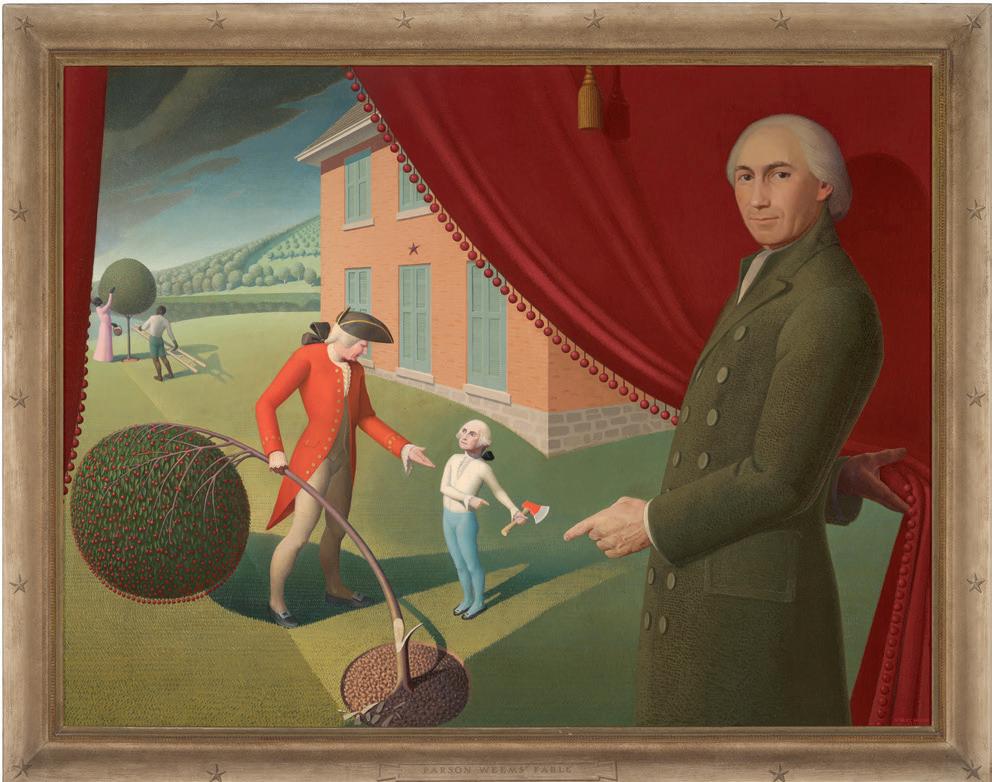

(Top, left): Holger Cahill, who served as national director of the Federal Arts Project, commented that the 1935 exhibition of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s collection at the Ludwell-Paradise House was one of “the best examples of this rare and uniquely American art.” (Top, right): The collection included Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown by Massachusetts folk artist Reuben Law Reed.

Historically, while some folk art arose from business transactions, such as portraits painted by traveling artists, much of it was made for everyday use, such as trade signs, whimsical decorations and children’s toys. These pieces reveal a great deal about the domestic lives, circumstances, concerns and interests of their creators. And while folk art exists in some form in every country, Abby Rockefeller’s collection was uniquely American, helping to tell the American story.

As Mitchell Wilder, director of the folk art museum in 1957, said, viewers of Rockefeller’s collection “saw for the first time the

“Growth has focused on two major areas,” said Laura Pass Barry, Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. “We have expanded the collection in different medias, such as pottery and textiles, and we have expanded our geographic and cultural footprint to show a more complete picture of America.”

Curators assess the aesthetic qualities of a piece, but also what the piece says about the context in which it originated and the circumstances of its creator.

When selecting a piece for the museum, Barry said, “We want to know its story.”

The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum is located at 301 S. Nassau St. and open seven days a week from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

New stores and restaurants coming soon!

The Carousel Children’s

Aromas Coffeehouse,

Bakery & Café

Baskin-Robbins

Berret’s Seafood Restaurant

& Taphouse Grill

Blink

Blue Talon Bistro

Brick & Vine

Campus Shop

Colonial Williamsburg

Bookstore

Boutique T

The Cheese Shop

Chico’s

The Christmas Shop

Danforth Pewter

DoG Street Pub

Everything Williamsburg

Eleva Coffee Lounge

Fat Canary

FatFace

French Twist Boutique

illy Caffé

J Fenton Gallery

J.McLaughlin

Kimball Theatre

lululemon athletica

Mellow Mushroom

Pizza Bakers

Monkee of Williamsburg

The Peanut Shop

The Precious Gem

Penny and a Sixpence

Precarious Beer Project

R. Bryant Ltd.

R. P . Wallace & Sons

General Store

SaladWorks

Scotland House Ltd.

Secret Garden

Sole Provisions

The Shoe Attic

The Spice & Tea Exchange of

Williamsburg

Talbots

Three Cabanas: A Lilly

Pulitzer Signature Store

The Williamsburg Winery

Tasting Room & Wine Bar

Walkabout Outfitter

William & Harry

Wythe Candy & Gourmet

Shop

Bob and Marion Wilson Teacher Institute

June-August

Education programs for teachers are available on-site and online beginning in June.

colonialwilliamsburg.org/ teacherinstituteprograms

Fourth of July

July 4

The annual reading of the Declaration of Independence is just one highlight of this patriotic day.

colonialwilliamsburg.org/july4

Homeschool Days

Sept. 7-22

Homeschool groups are invited to explore the historic sites where revolutionary ideas were shaped.

colonialwilliamsburg.org/homeschool

Constitution Day

Sept. 17

Celebrate the document signed by delegates to the Constitutional Convention on Sept. 17, 1787.

colonialwilliamsburg.org/constitutionday

Finding the clues and reading the evidence Williamsburg’s 18th-century magazine left behind by Jody Taylor

During his tenure as royal governor of the Virginia colony, from 1710 to 1722, Alexander Spotswood initiated a number of architectural projects in Williamsburg. Bruton Parish Church and a market house were built under his direction, and the stalled governor’s palace project was completed. Another Spotswood brainchild became one of the town’s architectural curiosities a building to store and safeguard the colony’s

arms and ammunition. Williamsburg’s octagonal-shaped magazine, which was completed in 1715, was located in the center of the infant town. Why Spotswood, who favored a Georgian architectural style, chose to give the edifice eight sides is unclear. There are scattered examples of octagonal buildings in Scotland and Germany during this period, but the use of this architectural style was not widespread.

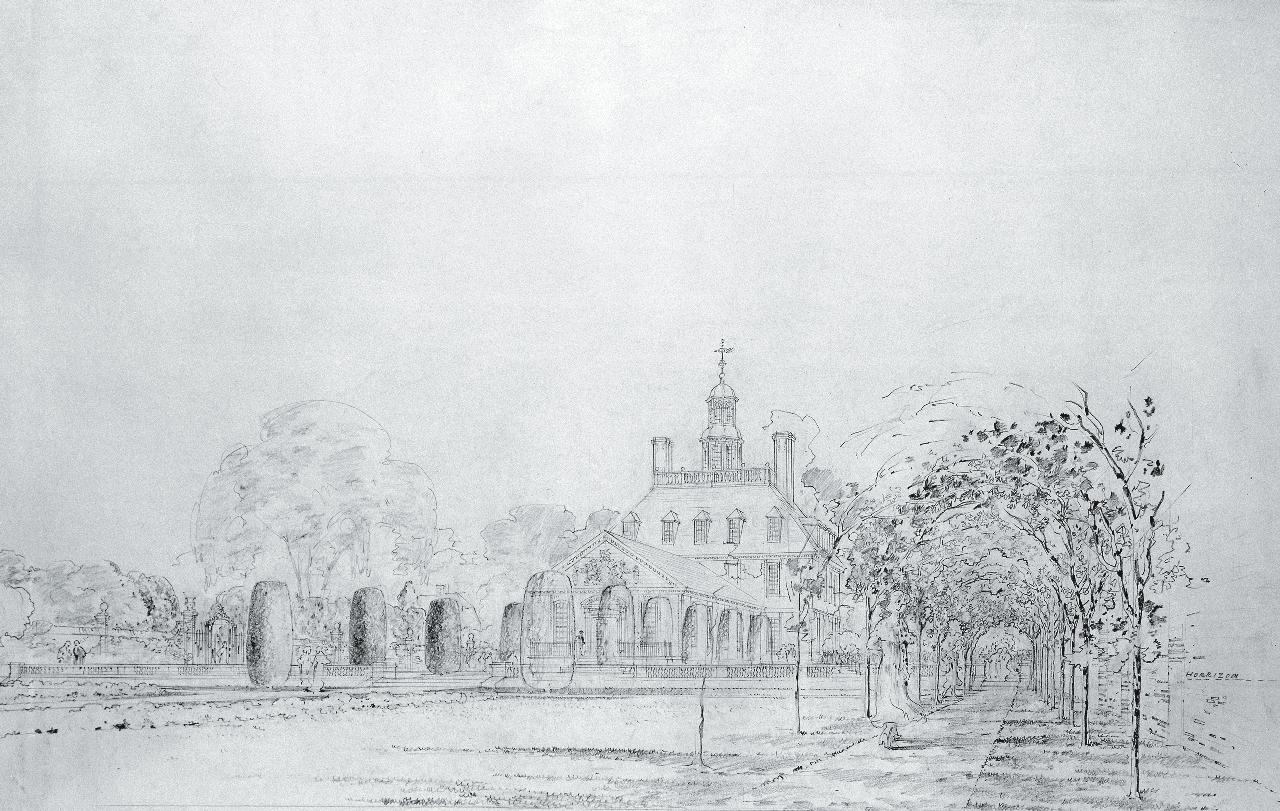

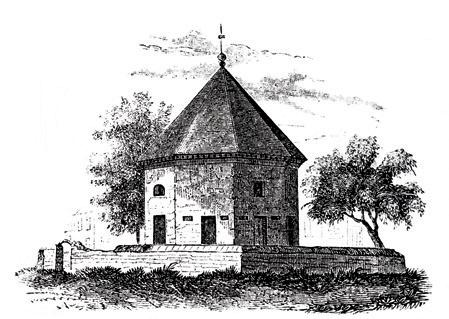

Benson J. Lossing’s 1850 drawing (above) was one piece of evidence for determining that the Magazine’s wall should be lowered (opposite page).

Matt Webster, Colonial Williamsburg’s executive director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research, ponders the choice. “What were the influences that prompted Spotswood to make the building octagonal? It’s a mystery we’re still trying to solve.”

But the building stands out for more than its eight sides.

The magazine became the center of a revolution-

PHILANTHROPY AT WORK

ary firestorm in 1775 when Lord Dunmore, citing rumors that a group of enslaved people was planning an insurrection, ordered the seizure of gunpowder from the building. Under Dunmore’s orders, Lt. Henry Collins, who captained the armed schooner Magdalen, left the ship anchored in the James River on the night of April 20 and entered the magazine with 20 royal marines. The squad returned to the ship very early the next morning with 15 half-barrels of gunpowder.

Anger over the removal of the gunpowder spurred calls among the colonists for armed resistance. The unrest prompted Patrick Henry some two weeks later to lead a militia on

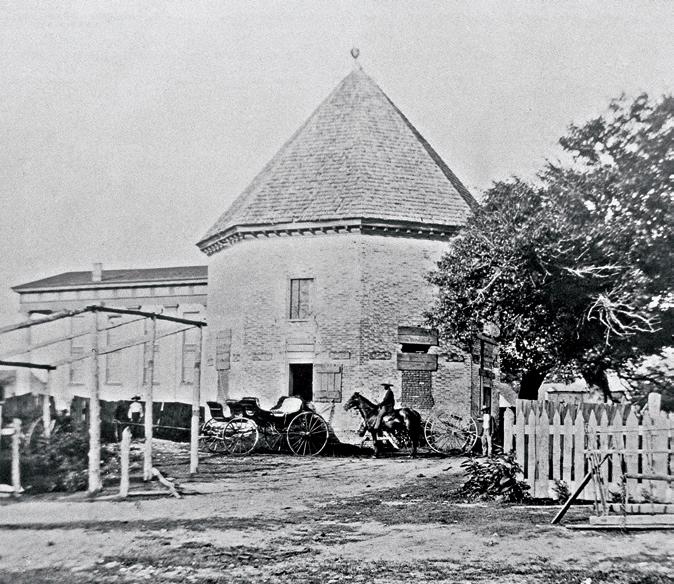

(Below, left): The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (today’s Preservation Virginia) bought the Magazine in 1889, repaired its crumbling walls and opened it as a museum. (Below, right): The Magazine served as a livery stable in the post-Civil War era.

a march from Hanover County to Williamsburg to demand the gunpowder’s return. A confrontation was averted when Carter Braxton, a well-connected planter who served in the House of Burgesses, negotiated a compromise that called for a royal reimbursement for the gunpowder.

As the 250th anniversary of that event draws closer, the Magazine is undergoing a transformation. Thanks to new research, the work will return the building’s appearance to something closer to how it looked on that April morning when

colonists discovered that their gunpowder was gone.

“The building has had a really rough life,” Webster said. “There have been so many changes, and then there was a pretty aggressive restoration in the 20th century. It’s difficult to pick through all this evidence. We have only four walls of the eightwall magazine that are intact enough to get information from.”

The magazine was used in a variety of ways between 1715 and Colonial Williamsburg’s initial restoration in the early 1930s. When Virginia’s government moved to Richmond

in 1780, the magazine had less and less value to the military. Over time it served as a market house, a Baptist meetinghouse, a Confederate arsenal, a dancing school and a stable. The changes made it difficult to ascertain its original appearance.

Much has been learned since the initial restoration was completed in 1934.

Webster and his team are getting a clearer vision of the original 18th-century appearance of the site.

Drawing on evidence and technologies not available for that 1930s restoration,

coupled with findings from a recent archaeological dig, they are piecing together the puzzle.

Earlier this year, the 10-foot perimeter wall was lowered by some 3 feet a noticeable change.

The French and Indian War had prompted the construction of a “high and strong brick wall” in 1755 in order to protect the building from the “designs of evil minded persons,” but in the 1850s it was torn down. The rebuilt one, as it turned out, was too high.

The 1930s restorers had relied on a book written by

(Top): Archaeologist Jessie Dick was part of a dig at the magazine that began in 2021. It was the first time archaeologists had excavated around the base of the building since the foundation was uncovered in the 1930s. (Above): Clay roofing tiles were among the latest dig’s discoveries.

a William & Mary professor who cited recollections of a 10-foot-high wall. The lowered wall now offers the same view that historian Benson J. Lossing saw in 1850 when he visited Williamsburg and made a sketch that played a prominent role in

determining how the wall should look.

Some 30 years after Lossing’s depiction, the magazine literally began to crumble due to neglect.

The building’s eastern and northeastern walls fell in 1888, exposing the interior to the elements. Two years later, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities paid $400 for the deed to the magazine and made plans to turn it into a museum. By 1935, the association had partnered with Colonial Williamsburg to restore the building, and the Foundation ultimately took ownership.

Research continues into the type of windows that would have been used in the original structure. Recent finds point to case-

ment windows with lead dividers. Evidence also specifies more windows on the ground floor than visitors see now.

One discovery during a recent dig indicates that the building was covered by fireproof clay tiles rather than more flammable shin-

Architectural preservation and the research that goes into ensuring its accuracy is fundamental in Colonial Williamsburg’s mission to tell complete stories of 18th-century life.

The Mary Morton Parsons Foundation has challenged Colonial Williamsburg to raise $300,000 in support of the Magazine’s restoration. Once the funding is secured the foundation will award

gles. Based on the quality of the tiles they found, Webster believes they may have been made in Europe.

As the architectural research continues, the Foundation is working on plans for programming that will commemorate the anniversary of the Gunpowder Incident. Along with exploring issues of resistance and personal freedoms, guests may also get insight into the work that historians, curators and tradespeople are doing to bring the Magazine back to its 18thcentury appearance.

“We’re constantly learning and adapting to the information we’re getting,” Webster said. “The building continues to tell us stories. We will take that information and implement it. The building tells us where to go.”

another $300,000 for the Magazine project. For more information on how you can contribute to this matching grant challenge, contact us at campaign@cwf.org

The multiyear Power of Place fundraising campaign supports the people and the infrastructure that bring early American history to life. To learn more, please visit colonialwilliamsburg. org/power-of-place/

Exhibitions highlight a craft and the furniture created to accommodate the work

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON COPES

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum CURRENTLY OPEN

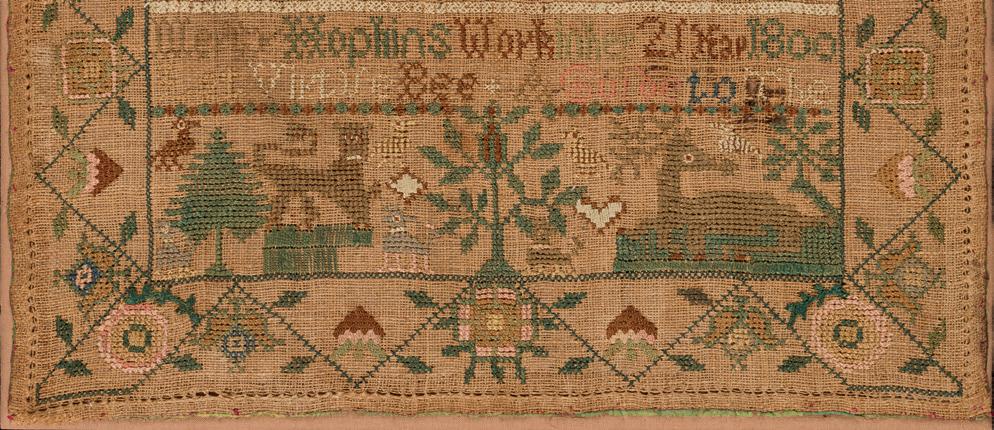

The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are filled with remarkable objects that offer rich histories and equally rich stories. Some represent the lives of famous people or great artists, but others highlight less familiar individuals. Though Mary Chicken, Mercy Hopkins and Martha Tabb Tompkins are not household names, their work opens a window into their lives and times. These young girls stitched samplers, proudly including their names. While samplers were mostly worked as school projects, the girls learned valuable needlework skills. Stitched in Time , an exhibition of American needlework, pays tribute to girls and women through the needlework they left behind.

Though this exhibition has been on view for more than a year, it recently got a makeover and includes new items such as a display of women’s worktables. By the end of the 18th century, cabinetmakers were making various types of tables tailored to the needs of the housewife. These worktables were small and could be easily moved around. They included a variety of drawers to hold thimbles, scissors, threads and other accessories as well as needlework projects like a pocket, sewing case or petticoat border. Woman with Sewing Box, which is featured in We the People , illustrates the importance of needlework. The large portrait, painted around 1840, prominently features sewing accessories.

Specialized tables were not just for sewing. The museums feature exhibitions with card, tea, dining, writing and sideboard tables. There is even an impressive stone-top chess table on view in A Rich and Varied Culture . Virginian John Hipkins Bernard ordered the “mosaic” tabletop while on a tour of Europe in 1819. Once it arrived in Virginia, the Bernards had the base of the table constructed by a local cabinetmaker. Jane Gay Bernard, who died in 1852, bequeathed the table to their daughter Helen Struan Bernard: “To dear Helen, her Father and myself think as she is the only chess Player she will most use the marble chess Table.”

Stitched in Time is generously funded by the Leonard J. and Cynthia L. Alaimo Endowment for Colonial Williamsburg’s Art Museums, the Jeanne L. Asplundh Textile Exhibitions Endowment and the George Cromwell Trust. We the People: American Folk Portraits is made possible through the generosity of Don and Elaine Bogus, and a gift from Carolyn and Michael McNamara funded A Rich and Varied Culture: The Material World of the Early South

Made by London’s William Cafe in 1763, these ornate silver candlesticks were likely first owned by Virginian John Page and his wife, Frances “Fanny” Burwell Page. Considering that wealthy Virginians of the mid-18th century often ordered luxury goods from England in association with a marriage, these candlesticks may have been procured for the couple’s 1765 wedding. A few years after that event, John and Fanny Page moved to Rosewell, a plantation complex near the York River in Gloucester County, Virginia. Begun by John’s grandfather in 1725, the brick, three-story, 12,000-square-foot house at Rosewell was one of the largest and most elaborate

residences in colonial America. With imported marble mantles and carved mahogany woodwork, it was an apt setting for the couple’s silver. Sadly, the house was destroyed by fire in 1916. Its evocative ruins are today open to the public and cared for by the Fairfield Foundation.

The Pages sold Rosewell in 1837, but a number of the furnishings remained in the family. Marked with the Page crest, these candlesticks descended through eight generations until they were given anonymously to Colonial Williamsburg “in loving memory of Mann Page.” They will appear in a new exhibition at the Art Museums in 2025.

Preparation for the new Campbell Archaeology Center uncovers a 17th-century home

As the excavator began preparing the ground for the more than 200 concrete pilings to underpin the Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Archaeology Center, construction came to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Not because of equipment failure or human error, but because the on-site member of Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeology team spotted something the corner of a brick foundation. The team quickly stepped in and uncovered the footprint of a 32-by-24 building. As it turns out, the new Campbell Archaeology Center is itself an

archaeological site. “Only in Colonial Williamsburg,” said Jack Gary, executive director of archaeology. “It’s so wonderfully ironic, and it’s exactly what makes this such a fascinating place. Imagine what else is out there!”

Brick analysis on the excavated foundation indicates that the large home dates to the late 17th century, when Williamsburg was still known as Middle Plantation. Bones, eggshells, oyster shells, pipe stems, a leaded windowpane, Chinese porcelain and numerous wig curlers have been recovered, suggesting that the

Small glass phials such as this one have been used to hold medicine or medicinal ingredients.

home belonged to affluent owners. The house likely stood until the late 1730s when it was demolished. These items will be incorporated into the new Campbell Archaeology Center, located on Nassau Street across from the Art Museums. The center will feature large, two-story exhibits to display some of the 60 million artifacts that have been discovered in Williamsburg over the years, as well as a glass floor in the main public hallway to allow visitors to see the newly discovered homesite below. “Archaeology is about seeing the layers of life below the surface. By incorporating the glass floor,

we’re really encouraging visitors to consider the history of this place and ask themselves what else they might be walking on when they’re here,” Gary said.

The Campbell Archaeology Center, scheduled to open to the public in 2026, will bring all of the archaeology team’s functions under one roof and provide state-of-the-art space for interactive workshops, exhibits and presentations. “There’s a saying in archaeology that excavation is only 40% of the work,” Gary explained. “Now visitors will be able to see what goes on in the lab, where we analyze, preserve and catalog artifacts. That’s

(Left): In addition to the foundation, the excavation uncovered the home’s well. (Below): The discoveries included numerous household items, such as the base of a Delft punch bowl.

where the stories begin to emerge, where we learn not just what the artifacts are but also what role they played in the everyday lives of the people here before us.”

For now, teams of Colonial Williamsburg archaeologists continue to carefully excavate, preserve and sift through the construction site while their future workspace takes shape around them. Gary, who visits the site every day, is excited about the find, as well as the future. Not only are there constant discoveries to be made by his teams, but the work itself is valued by visitors, supporters and The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

“What we are doing here is uncovering the story of this nation, and there are so many stories we can’t see yet, still waiting to be discovered,” Gary said. “We’re not even close to being done.”

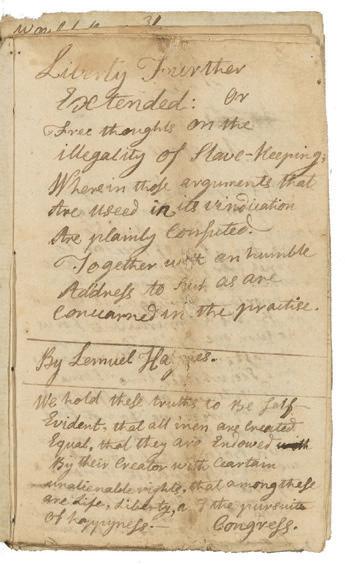

Foundation hosts planning sessions for the nation’s 250th birthday

More than 400 participants from 37 states gathered March 18-20 in Williamsburg for the second Common Cause to All, a gathering hosted by Colonial Williamsburg to plan commemorations for America’s 250th birthday.

“Our common cause and our worthy purpose are to unite Americans in a shared understanding of who we are, how we came to be a nation and to our commitment to our role as American citizens,” said Carly Fiorina, who chairs Colonial Williamsburg’s board of trustees and the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission.

Presenters during the threeday conference underscored the importance of telling the complete

story of Amer ican history. Speakers included the Hon. John Charles Thomas, retired Virginia Supreme Court Justice, National Constitution Center President Jeffrey Rosen, NBC journalist Harry Smith and Harvard professor Dr. Danielle Allen.

The Declaration of Independence “said something that reaches into our souls,” Thomas said. “And it was being repeated through time. Abraham Lincoln repeated some of those words in the Gettysburg Address. Martin Luther King repeated those words. If you look at the accounts of the students at Tiananmen Square in China, they repeated these words.”

Allen said the Declaration of Independence tells a story one that details how people decided to

Common Cause to All attendees had access to a variety of presentations, including “fireside chats” on multistate collaboration and reaching underserved communities. Carly Fiorina, Colonial Williamsburg’s board of trustees chair, delivered keynote remarks at the March 19 dinner.

change their lives. “They surveyed their circumstances, they found the wanting and they set a new course, a new direction.”

But there are those who do not see themselves represented in that founding document. The Founders, she said, did great things that were both brilliant and beautiful. They created a document that emphasizes both humility and responsibility. The philosophical mistake, she said, was attempting to protect the rights of all without all having a share in power.

The third and final Common Cause to All event is being planned for spring 2025.

As this issue of Trend & Tradition headed to press, Colonial Williamsburg announced the discovery by its archaeologists of evidence indicating the remains of a Revolutionary War barracks near the Colonial Williamsburg Regional Visitor Center.

Eighteenth-century maps and other documents from the period reference a barracks constructed in 1776-1777 to accommodate up to 2,000 soldiers and 100 horses. The barracks are thought to have been destroyed by fire in 1781 by Gen. Charles Cornwallis’ troops on their route to Yorktown.

Archaeological evidence of Continental army barracks is rare in Virginia. This site, which was occupied for five years, is particularly valuable because it was built and served only one purpose, and a large portion has been largely undisturbed since the barracks were destroyed. More information about this discovery will appear in the Autumn issue.

To read about it now and see artifacts from the site, visit colonialwilliamsburg.org/barracks

Florida: Registration #CH10673. A COPY OF THE FOUNDATION’S OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE 1-800-HELP-FLA WITHIN THE STATE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE. Maryland: THE FOUNDATION’S CURRENT FINANCIAL STATEMENT IS AVAILABLE ON REQUEST AT THE ADDRESS LISTED ABOVE. FOR THE COST OF COPIES AND POSTAGE. DOCUMENTS AND INFORMATION SUBMITTED ARE AVAILABLE FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE, STATE HOUSE, ANNAPOLIS, MD 21401 New Jersey: INFORMATION FILED WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL CONCERNING THIS CHARITABLE SOLICITATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY BY CALLING (973) 504-6215. REGISTRATION WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT. Pennsylvania: THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION OF THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF STATE BY CALLING TOLL FREE WITHIN PENNSYLVANIA 1-800-732-0999. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT. Virginia: A FINANCIAL STATEMENT IS AVAILABLE FROM THE STATE DIVISION OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES UPON REQUEST. Washington: ADDITIONAL FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE CHARITIES DIVISION, OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE, OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON, BY CALLING 1-800-332-4483. West Virginia: WEST VIRGINIA RESIDENTS MAY OBTAIN A SUMMARY OF THE REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE, SOLICITATION LICENSING BRANCH, AT 1-800-830-4989, STATE CAPITOL, CHARLESTON, WEST VIRGINIA 25305. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT.

California: THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE. ANY PROSPECTIVE DONOR SHOULD SEEK THE ADVICE OF A QUALIFIED ESTATE AND/OR TAX PROFESSIONAL TO DETERMINE THE CONSEQUENCES OF HIS OR HER GIFT. Annuities are subject to regulation by the State of California. Payments under such agreements, however, are not protected or otherwise guaranteed by any government agency or the California Life and Health Insurance Guarantee Association.

New York: Upon request, a copy of the latest annual report may be obtained from the address listed above for the foundation or from the Charities Bureau, Department of Law, Attorney General of New York, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

North Carolina: Financial information about the foundation and a copy of its license are available from the State Solicitation Licensing Branch at (919) 807-2214. The license is not an endorsement by the state.

Oklahoma: A charitable gift annuity is not regulated by the Oklahoma Insurance Department and is not protected by a guaranty association affiliated with the Oklahoma Insurance Department. South Dakota: Charitable gift annuities are not regulated by and are not under the jurisdiction of the South Dakota Division of Insurance.

The Foundation does not issue charitable gift annuities in Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii and Washington state.

Exploring ways the students and the community intersected

During the spring, Colonial Williamsburg introduced a tour of Historic Area landmarks that highlight how the Williamsburg community was connected to the Bray School, an institution dedicated to the education of enslaved and free Black children in the 18th century.

The Bray School Walking Tour brings to light the complicated legacy of the school and examines what is known about the lives of the children who attended. Over the school’s 14 years of operation, from 1760 to 1774, upwards of 300 students, mostly between the ages of 3 and 10, were taught by Ann Wager, the school’s sole teacher.

The search continues for additional documentation that will create a more complete picture of the school, which offered instruction

in the tenets of the Anglican church and in subjects including reading, behavior and sewing. Key sites in the Historic Area have already been connected to the school, and the one-hour tour introduces guests to these connections, as well as to what is known about the students and how education, religion and community intersected.

The tour, which covers about a half mile, begins in front of the Taliaferro-Cole Stable and is available daily at 10:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. An admission ticket is required.

This fall, the restored Bray School building, which was relocated from the campus of William & Mary to the Historic Area in 2023, will open to the public with interpretation that explores the experience of the children educated there.

Visitors to the Historic Area on April 8 when a partial solar eclipse temporarily darkened Virginia’s skies had the chance to get a science lesson from George Wythe.

Robert Weathers, a Nation Builder who portrays Wythe, used the occasion of the moon’s shadow partially blocking the sun to set up two telescopes at Market Square. One telescope offered the 18th-century view, projecting the image of the eclipse on paper. A modern telescope, equipped with a solar filter, allowed direct viewing.

Though Williamsburg did not experience a total eclipse the moon covered about 80% of the sun in eastern Virginia visitors still needed special glasses to safely view the astronomical event.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Williamsburg just two weeks before a congressional election. The In Retrospect feature that began on page 28 of the Spring 2024 issue incorrectly stated the type of election.

CHALLENGE YOUR PERCEPTIONS . DISCOVER FOOD FRESH FROM THE GARDEN . GET TO THE ART OF IT p. 73

Rediscovering the Broad Bean

By WOODY HOLTON

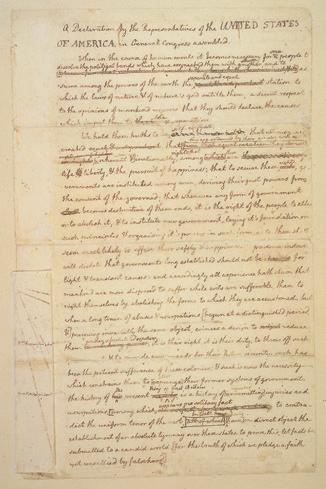

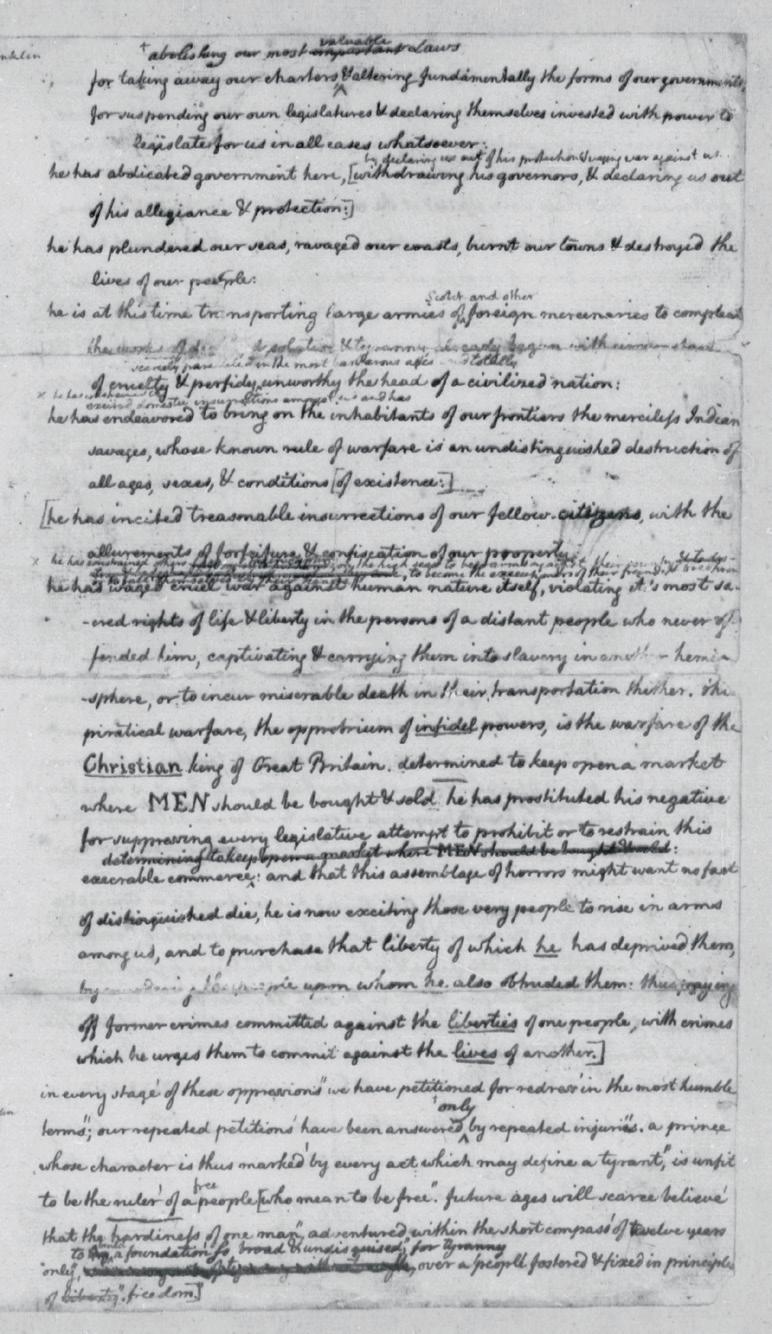

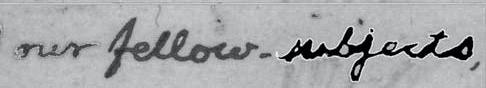

After “the,” “and” and “for,” the most common word in the Declaration of Independence is “he.”

And we all know who “he” is: George III, the king of Britain. Congratulations! You may have just answered one of history’s easiest trivia questions: “Whom does the Declaration of Independence declare independence from?”

But not so fast! There is a hidden enemy in the Declaration never actually named from whom the Americans were actually trying to get away. George III wielded more power than Charles III does today, but already by 1760, when George ascended to the throne, the nation’s true executive was plural: the king’s cabinet.

Then as now, cabinets survived only with the constant approval of the House of Commons. Theoretically the monarch enjoyed a comparable check on Parliament: a veto over its legislation. But no king or queen had dared to use the veto since 1708 when Queen Ann declined to arm the Scottish militia. Really, Parliament’s supremacy over the king went back to the Glorious Revolution and the accession of William and Mary in 1689. Even George III’s speeches to Parliament, like Charles’ today, were ventriloquist

WHAT BETTER WAY for Congress to reinforce Parliament’s irrelevance to the colonies than to never even mention that body by name?

acts, dictated to him by the very people he was speaking to.

But how can Parliament be the Declaration’s target? The word does not appear there. Actually, you can find the British legislature in the document if you look hard enough.

By far the longest section of the Declaration with nearly as many words as the other four combined is Congress’ list of British “Oppressions.” Two-thirds of these abuses, as Jefferson called them, start with “He,” but the others open with “For” and list such British aggressions as “For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent.”

This formulation seems strange until you look back at the introduction to the “For” paragraphs: “He has combined with others...giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation.”

“Others” means Parliament. Their “Acts of pretended Legislation” refer to parliamentary legislation respecting the colonies.

If Parliament adopted anti-American laws and kept an anti-American cabinet in power, why does the Declaration of Independence hide Parliament and hoist up George III? I once thought the Continental Congress focused on the king

in order to tap into Enlightenment antimonarchism. But, as Julian Boyd, the founding editor of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, pointed out in 1945, the Declaration “bore no necessary antagonism to the idea of kingship in general” only to George III.

Congress had another, more pressing reason to focus its ire on George III rather than Parliament. The way the delegates in Philadelphia saw it, the colonies did not need to rebel against Parliament because Parliament already exerted no power over them and in fact never had. That is why Congress refers in the Declaration to laws like the Stamp Act and the Tea Act as “pretended Legislation.” The situation would be comparable, for example, to the Virginia House of Burgesses adopting laws for Massachusetts: The burgesses too would be playing make-believe. What better way for Congress to reinforce Parliament’s irrelevance to the colonies than to never even mention that body by name?

By instead referring to the rulers of an empire upon which the sun never set as simply “others,” Congress delivered not only a sick burn but a bold constitutional claim one that most Britons found absurd, and indeed most modern historians do as well, since Americans had long accepted Britain’s monopoly

of their trade, control over their post offices and so on.

The principal sources for the Americans’ claim were pamphlets published in 1774 by two attorneys, James Wilson of Pennsylvania and Thomas Jefferson. In essence Wilson and Jefferson invented a new constitutional history of the relationship between the mother country and the colonies.

Jefferson originally composed his pamphlet as instructions for the Virginia delegates to the First Continental Congress. He (or possibly his printer) entitled it A Summary View of the Rights of British America. In the Declaration, Jefferson reinforced his claim against Parliament by using some very clever word choices. Those unnamed “others” had empowered themselves to adopt “pretended” laws only by asserting a jurisdiction “foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws.” Foreign. Jefferson was suggesting that, at least legislatively, Britain was a foreign country. Only American assemblies could legislate for Americans. Since the colonists’ only constitutional tie was to the king, that was the only one they needed to break.

By asserting that Parliament had never ruled them, white colonists could also plausibly reject the mother country’s favorite epithet for them: rebels. Citizens of India and slaves and the Irish might rebel, they could say, but we are simply ending our alliance of equals with Britain by replacing their monarchical figurehead with...an abstraction, “the united States of America,” a term that had never before appeared in print.

But denying that Parliament had any authority over the colonies was still new territory, even for Jefferson, and he sometimes lost his footing. For example, in one