BLACKBEARD’S DEMISE

THE ROAD TO REVOLUTION

CHOCOLATE’S CURRENCY

BLACKBEARD’S DEMISE

THE ROAD TO REVOLUTION

CHOCOLATE’S CURRENCY

In the 18th century, global connections shaped daily life in unexpected ways. One artifact that tells this story is a mineral water bottle made in Germany and used in Williamsburg between 1760 and 1790. Bottled water, like today, was a symbol of health and status. This particular bottle, marked with a seal from the spring at Pyrmont, was a prized import for British consumers. Its journey across oceans to reach colonial America mirrors the global exchange of goods and ideas that defined the era.

Visit the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg to explore objects that connect past and present, and discover how global influences shaped everyday life in ways that still resonate today.

Visit the “Worlds Collide: Archaeology and Global Trade in 18th-century Williamsburg” exhibition – Now Open.

1

4 BUILDING ON A FOUNDATION

6 ON THE WEB

7 IN REMEMBRANCE: DR. BARBARA B. OBERG

10 READYING THE BRAY SCHOOL

Collaborative efforts prepare The Bray School to welcome guests

16 IN FOCUS

What did it mean to be famous in the 18th century?

24 CHRONICLES OF THE COLLECTION

Loyalist Mary Orange Rothery By Paul Aron

26 PHILANTHROPY AT WORK

Video creates maximum impact in the digital age By Corey Stewart

31 AT THE MUSEUMS

34 IN RETROSPECT

Beyond architecture: expanding research to tell a more complete story By Paul Aron

ON THE COVER: Katie McKinney, the Margaret Beck Pritchard Curator of Maps and Prints, discusses a new exhibition on 18th-century fame Page 16. PHOTOGRAPH BY

By Corey Stewart

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION TRUSTEES

Carly Fiorina, Chair, Mason Neck, Va.

Cliff Fleet, President and CEO, Williamsburg, Va.

Kendrick F. Ashton Jr., Arlington, Va.

Frank Batten Jr., Norfolk, Va.

Geoff Bennett, Fairfax, Va.

Catharine Broderick, Lake Wales, Fla.

William Casperson, Bronxville, N.Y.

Mark A. Coblitz, Wayne, Pa.

Walter B. Edgar, Columbia, S.C.

Neil M. Gorsuch, Washington, D.C.

Conrad Mercer Hall, Norfolk, Va.

Antonia Hernandez, Pasadena, Calif.

John A. Luke Jr., Richmond, Va.

Walfrido J. Martinez, New York, N.Y.

Leslie A. Miller, Philadelphia, Pa.

Steven L. Miller, Houston, Texas

Joseph W. Montgomery, Williamsburg, Va.

Steve Netzley, Carlsbad, Calif.

Walter S. Robertson III, Richmond, Va.

Gerald L. Shaheen, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Larry W. Sonsini, Palo Alto, Calif.

Sheldon M. Stone, Los Angeles, Calif.

Y. Ping Sun, Houston, Texas

Hon. John Charles Thomas, Richmond, Va.

Jeffrey B. Trammell, Washington, D.C.

Alex Wallace, New York, N.Y.

Charles R. Longsworth, Royalston, Mass.

Thurston R. Moore, Richmond, Va.

Richard G. Tilghman, Richmond, Va.

Henry C. Wolf, Williamsburg, Va.

TREND & TRADITION

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Catherine Whittenburg

ART DIRECTOR Katie Roy MANAGING EDITOR Jody Macenka PRODUCTION

DESIGNERS

PHOTOGRAPHER

EDITOR/WRITER

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Paul Aron, Ronald L. Hurst, Eve Otmar, Rachel West

COPY EDITORS Patricia Carroll, Amy Watson

Angela C. Taormina

PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR

Grenda Greene

DONORS Please address all donor correspondence, address changes and requests for our current financial statement to: Signe Foerster, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776 or email sfoerster@cwf.org, telephone 888-293-1776.

Donations support the programs and preservation efforts of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, a not-for-profit, tax-exempt corporation organized under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, with principal offices in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Address changes & subscription questions: gifts@cwf.org or 888-293-1776

Editorial inquiries: editor@cwf.org

Advertising: magazineadsales@cwf.org or 757-259-5907

Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg (ISSN 2470-198X) is published quarterly in winter, spring, summer and autumn by the not-for-profit Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 301 First Street, Williamsburg, VA 23185. A one-year subscription is available to Foundation donors of $50 a year or more, of which $14 is reserved for a subscription. Periodical postage paid at Williamsburg, VA, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg, Attn: Signe Foerster, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776. © 2025 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All rights reserved.

NOTE Advertising in Trend & Tradition does not imply endorsement of products or services by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

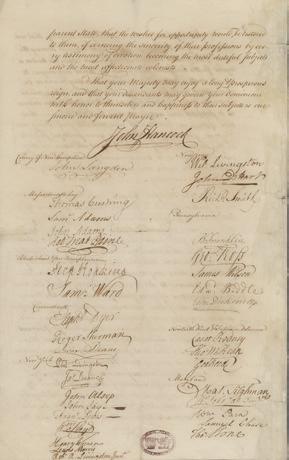

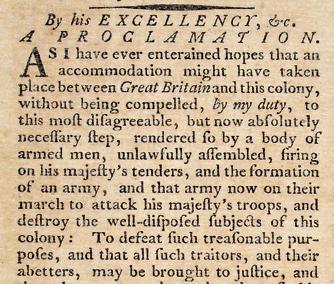

Commemorative events capture critical moments on the road to independence

“Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace but there is no peace. The war is actually begun!

The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field!

PATRICK HENRY, MARCH 23, 1775, AT THE SECOND VIRGINIA CONVENTION

It was damp and cloudy outside St. John’s Church in Richmond when Patrick Henry galvanized his likeminded counterparts and shocked his more conciliatory ones with his thunderous oratory at the Second Virginia Convention. No transcription of his speech exists; our closest approximation comes from his biographer years later, based on eyewitness accounts, including the final, fiery passage that has immortalized Henry in the minds of Americans:

I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

While revolutionary sentiment had been intensifying for more than a decade prior to 1775, all-out war was not a foregone conclusion. Even in the face of Patrick Henry’s eloquent ferocity at the Second Virginia Convention, his conservative colleagues continued to press for restraint. By week’s end, they had even passed a resolution of appreciation thanking Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, for his campaign against Native American tribes to the west the previous year. But Henry’s blistering words proved prescient. Less than a month later, the first shots of the American Revolution rang out at the battles of Lexington and Concord.

Nearly 250 years later, we are busily planning to commemorate the semiquincentennial of American independence. 2026 will be a historic year, drawing together people of all beliefs and backgrounds to remember and reflect on America’s extraordinary and extraordinarily complicated journey through history.

But if 1776 marked America’s birth as a sovereign

nation, 1775 marked the start of the Revolutionary War that gave rise to it. As I write this, my colleagues in the Historic Area are finalizing new programming to observe the anniversaries of key events that occurred in 1775, when a collective yearning for freedom transformed a movement of protest into one of armed rebellion.

Virginia had a central role in these developments. Two days after Lexington and Concord, on April 21, 1775, Lord Dunmore seized the gunpowder stored at the Magazine in Williamsburg. This bold act inspired a militia in Hanover County led by Patrick Henry himself to march on Williamsburg to demand the powder’s return.

Cooler heads ultimately prevailed, but the month of June brought the commissioning of George Washington as commander in chief of the Continental army. Less than a week later, a band of colonists seized the Governor’s Palace. And on October 26, British naval vessels attacked the city of Hampton, Virginia. The Revolutionary War had come to Virginia, more than six months before the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence.

Just as the tumultuous events of 1775 and 1776 are intertwined, so too are our plans for 2025 and 2026. This spring we will again welcome hundreds of planners, educators and museum professionals from around the country to prepare for 2026. This year’s Common Cause to All is the third and final event in this series, which last year brought more than 400 people from 34 states and Washington, D.C., to Williamsburg.

The Foundation’s leadership in this effort is only natural not only because we are the world’s largest U.S. history museum, but also because of Williamsburg’s

historical importance as the colonial capital city throughout the revolutionary era. 2026 offers an unparalleled opportunity to reflect on the democratic principles that evolved here, and a chance for us to demonstrate Williamsburg’s “power of place,” the guiding light of our campaign to share America’s story.

In preparation, our preservation teams have been hard at work including at the Williamsburg Bray School, which we dedicated with the descendant community and William & Mary in November and plan to open to the public this spring following completion of its restoration. We are also hard at work at the Magazine, where research in 2021 indicated that the structure does not reflect some key details of the original, including a clay tile roof and different window configurations. The most visible difference will be the perimeter wall, which is being lowered from 10 feet to 7 feet to more accurately reflect the building’s appearance in colonial times. With this restoration, we will be ready to observe the 250th anniversary of the Gunpowder Incident this spring.

In October, we will partner with William & Mary and the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture to host the fourth installment of For 2026:

Fleet

A Five-Year Conference Series. Each year, this conference connects the public with leading history scholars and their research. In the process, we are initiating powerful conversations about America’s past and the importance of sharing it with the world.

In a remarkably fitting coincidence, 2026 is also the 100th anniversary of Colonial Williamsburg’s founding, which we will also commemorate next year. The Foundation’s origins date to the Rev. W.A.R. Goodwin’s persuasion of John D. Rockefeller Jr. to restore Williamsburg to its colonial-era appearance in 1926 and more specifically to Rockefeller’s cryptic telegram to Goodwin on December 7 authorizing the Bruton Parish rector to purchase the Ludwell-Paradise House for restoration, thus launching what would become The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

As we prepare to celebrate our centennial, the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are planning an exhibition exploring the Foundation’s first 100 years.

We will also publish an expansive history of the Foundation in early 2026. And we will complete the Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Archaeology Center, an exciting project that truly befits the commemoration of the largest U.S. history museum in the world. The Foundation broke ground in 2023 on this state-of-the-art facility that will be home to the thousands of artifacts our archaeologists have collected over decades of excavations. When we open the center in 2026, guests will be able to observe archaeologists at work and participate in hands-on activities as well as view through a glass floor the preserved remains of a 17th-century building discovered on the site during the early stages of construction. With all of this and much more in the offing, 2025 and 2026 both promise to be exciting years. I hope you will be able to join us in Williamsburg soon to explore the start of America’s revolution in 1775, and that you return next year to commemorate 250 years of American independence. As diverse a community as Williamsburg was in the revolutionary era as the capital city of such a politically and economically vibrant colony, we are fortunate to have a rich, engaging and deeply researched origin story to share. It is because of your generosity that we continue to unearth fascinating new chapters of this story.

As Patrick Henry also said 250 years ago this March, “I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience. I know of no way of judging of the future but by the past.” Thank you for your unwavering commitment to our educational mission. Together, we can ensure that the bright lamp of experience continues to light the way for us all.

Sincerely,

Cliff Fleet President & CEO

Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Distinguished Presidential Chair

Children use critical thinking skills to discover who’s backing whom colonialwilliamsburg.org/loyalties

What does it mean to be an American citizen?

colonialwilliamsburg.org/civics

Learn about the historic trade of engraving colonialwilliamsburg.org/engraver

Dr. Barbara B. Oberg, a distinguished scholar of early American history who served on The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Board of Trustees from 2006 to 2015, died on Sept. 14.

“Barbara believed deeply in the work we do here to uncover and share a complete history of our nation,” said Cliff Fleet, president and CEO of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. “She applied her insights and many talents to the work of the Development, Human Resources, and Educational Programs and Policies committees. Her intellectual integrity, thoughtful leadership and steadfast commitment to the Foundation’s mission helped chart the course for our current success.”

Dr. Oberg’s long career as a professor of history at Princeton University included her celebrated work on The Papers of Benjamin Franklin as an editor and senior research scholar and as general editor of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson from 1999 –2014. She shepherded more than 20 volumes of Jeffer-

son’s public and private writings into print. The extensive collection, which begins with writings that predate the completion of Jefferson’s education, is ultimately expected to encompass more than 60 volumes.

Her scholarly interests included women’s history. She edited Women in the American Revolution: Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World, a collection of essays published in 2019 that explored issues of age, race, education and social class in the 18th century.

Dr. Oberg was especially devoted to organizations that support American history. She served as chair of the executive board of the Omohundro Institute and chair of the Committee on Library at the American Philosophical Society, to which she was elected for membership in 1998. She was a past president of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR) and a reviewer and panelist for the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The future of teaching is with the Bob and Marion Wilson Teacher Institute. Through our onsite, online and offsite programs, we are building a national community of passionate educators leading the way in innovative education.

Onsite Sessions

18 Sessions Summer Institute

What Teachers Are Saying...

Of the Bob and Marion Wilson Teacher Institute at Colonial Williamsburg Found the learning

5 Customized Workshops Hosted Throughout The Year

"My students will benefit greatly from my week-long educational training at Colonial Williamsburg. The firsthand experiences and in-depth knowledge I gained will allow me to bring history to life in the classroom." - A Returning Teacher from 2024

Expanded their American history content knowledge 99%

Felt stimulated to improve their teaching methods and appreciated the inclusive narratives they learned 1OO%

Became more comfortable using primary sources in the classroom

Developed in partnership with Colonial Williamsburg and iCivics, students explore Williamsburg in 1774 to see if rumors of rebellion are true. Students engage with young people across different social classes and life experiences to identify clues, balance opinions, and determine if loyalties in colonial America stay true to Britain or lie with soon-to-be-American patriots.

Scan here to learn more about the Bob and Marion Wilson Teacher Institute.

EXPLORE COLONIAL SITES AND HISTORY . PEEK BEHIND THE SCENES . PURSUE AND PLAN

p. 16

18th-Century Fame

Deconstruction was the first step to returning the historic school to its original state

Restoring The Williamsburg Bray School, America’s oldest surviving school for Black children, meant peeling away layers of 19th and 20th century additions, from plumbing to plaster. Underneath these modern revisions, researchers found valuable clues related to how the 18thcentury building that housed the school looked.

“There was a tremendous amount of evidence telling us what the building looked like in 1760,” said Matt Webster, executive director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research. “It was incredible, with everything from dormer evidence and the shape of shingles to the finishes on woodwork and depth of the plaster on the walls. We had to work to find and understand the clues, but all of the information was there to inform the restoration.”

Parts of the building that had to be stripped away included additions, bathrooms, and new floors, doors and walls. What was uncovered was sometimes dramatic. In 2021, members of Webster’s team found parts of the original rafters while working in the attic. The following year, they uncovered the entire 1760 chimney, which had been concealed

for nearly a hundred years. In 2023, they pulled up a small section of flooring from around 1925 and found part of the building’s original 1760 handsawed pine floor.

Even smaller discoveries held important clues as to how the building used to look: An original chair rail had been repurposed to hold up some plaster. Hidden in a wall was an original roof shingle, which had been reused to repair a door sill.

Deconstructing a building, Webster stressed, is not the normal way to demolish or renovate a building. It is a far more meticulous and careful process.

Senior conservator Chris Swan removed paint to allow for accurate molding profiles. (Bottom): Original chair rails helped researchers understand how the interior of the building initially looked.

Coordinating the work at the site fell to Dale Trowbridge, construction manager for architectural projects and engineering. Trowbridge’s work started well before the restoration.

“Back in 2021, I took a walk with Matt Webster,” said Trowbridge. “He said, ‘Don’t look now, but you’re going to move that building.’”

Once the building was moved, employees from many departments pitched in, with everyone from landscapers to security officers lending a hand. Especially crucial were members of the Building Trades department. The department’s members normally work behind the scenes, maintaining the Foundation’s 600-plus buildings. That work includes repairing and painting about 75 buildings each year.

To make sure the building was ready for its November 1 dedication ceremony, Building Trades brought their expertise to the Bray School, including the classroom, where they installed baseboard, chair rail, doors and drywall. They also installed the siding and painted it, ensuring the whole building was watertight.

Trowbridge coordinated the work of more than 20 outside contractors as well. Precision Services handled site work; Hercules, the fencing; National Turf Irrigation, the sprinkler system; and Hertzler & George, the sod, gravel paths and garden beds.

“There are so many groups that contribute to these projects,” said Webster. “The groups in maintenance and architecture and engineering are critical to a project’s success. The project managers, carpenters, masons, painters, millwork and mechanical maintenance workers, as well as so many others, work closely with us to make sure these places are preserved.”

“You have to pay attention to all the details,” said Webster. “We had parts from 1760 reused to build a 1940 wing. Those reused pieces were critical to understanding what the building originally looked like. Also, the history of the building did not stop in 1765,” Webster said, referring to the school’s move to a new building in 1765, nine years before it closed permanently. “We documented everything to assure that the information and the stories were preserved.”

Careful analysis was sometimes required to determine what was original and what was not. Architectural historians, for example, were not sure at first whether the building’s stairs were from the 18th century. By looking at construction techniques, nails and saw marks, they were able to determine that the staircase had been modified over time, but the framing, treads, risers and newel posts are original.

The discoveries continued even during the final stages of the building’s restoration.

“Two months ago, I was preparing to attach new siding, carefully going over frame and wall studs,” said Steve Chabra, the architectural preservation project supervisor. “I found what looked like old split firewood nailed to the side of the wall. Most of it was just split wood, but there was also a piece of backband the trim that goes around a wall or window. We have to look at everything to make sure we don’t lose anything.”

The pieces of the original building uncovered by Chabra and Scott Merrifield, architectural preservation technician, were key to the work of architectural historian Jennifer Wilkoski. From some of the surviving 18th-century window frames, for example, Wilkoski could

tell how many window sashes the pieces that hold the glass to include on new windows for the building. Historic tradespeople and the Foundation’s millwork shop used Wilkoski’s construction drawings to re-create the missing pieces, which ranged from closets to cellar entrances.

For a mantel over the fireplace or chimneypiece, as it was known in the 18th century Wilkoski based her drawings on the building’s one surviving original chimney. “I looked at the framing and the brickwork to determine the size of what the chimneypiece would have been, and I looked at comparable examples from other buildings,” Wilkoski said. “The design reflects both the physical evidence and the status of the building as a rental tenement.”

The original pieces taken from the building remain in the Foundation’s collections under the care of Dani Jaworski, manager of architectural collections.

“Chair rails from the original building showed us much about the design and how they were used in the rooms,” Jaworski said. “They’ll stay in our collection, and I hope they will be displayed someday.”

Discoveries like these took a lot of the guesswork out of the restoration work. Some of the pieces of the chair rails, for instance, even retain their original nails, and studs on the wall indicate where trim, like chair rails, might have been. Pieces of the original rafters show they had been made of oak, and they also provided clues as to how the original roof was framed.

Still, restoring the building presented all sorts of challenges. Historic carpenters, for example, had to patch holes in the 18th-century floor, making sure the patches match the original wood in width, thickness, height and quality. Like so much of the work on the building, attention to detail was paramount.

based her construction drawings of the fireplace on the surviving chimney and comparable examples from other buildings. (Below): This repurposed original roof shingle helped determine how new shingles should look.

SPEAKING AT THE NOVEMBER 1 dedication of the restored Bray School, Lonnie Bunch, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, called the event “one of the most important historic moments of the last decade.”

“This is not just a story locally,” Bunch told the crowd gathered at the school. “This is a story that transforms the country as we think about how do we understand, how do we embrace, how do we learn from, how are we made better by our history.”

Bunch said he was impressed by the work and commitment of both Colonial Williamsburg and William & Mary, who collaborated on the project along with the community of descendants of Bray School students.

Other speakers also noted how important it was to remember and research what happened at the Bray School.

“This is not just a building,” said the Hon. John Charles Thomas. “This is part of the very fabric of our nation.” Thomas, a Colonial Williamsburg Foundation trustee, was appointed to the Supreme Court of Virginia in 1983 at the age of 32, becoming the first African American member of the court, as well as the youngest justice in the court's history.

“This school, this building, and this structure is a window. It’s a window into lives of the children,” said Colonial Williamsburg President and CEO Cliff Fleet. “Today we want to remember them. We want to think about them. We want to bring their memories and their voices forward because they have been silenced, and they no longer are.”

Speakers included William & Mary President Katherine Rowe, Virginia state senator Mamie Locke, delegate Cliff Hayes and Dr. Rex Ellis. Ellis was the first African American vice president of Colonial Williamsburg, overseeing all of the Foundation’s educational programs, before becoming associate director of curatorial affairs at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“There are lots of people out there who are afraid that Americans cannot come together and confront difficult truths and remain united,” said Carly Fiorina, chair of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Board of Trustees.

“Today is proof positive: Yes, we can.”

The dedication ceremony concluded with members of the descendant community reading the names of known Bray students.

For more than 300 years, historic Williamsburg has been home to extraordinary artisans and craftsmen. At The Precious Gem, you’ll find master goldsmith and jewelry designer Reggie Akdogan, creating his one-of-akind handcrafted treasures since 1980. Dreams are made here.

Call 1-800-644-8077 or email info@thepreciousgems.com to talk about your jewels for a lifetime. Private appointments available.

Merchants Square, Williamsburg • 757-220-1115 • Mon - Sat 10am - 5:30pm, Sun by appointment. thepreciousgems.com • Like us on Facebook

What constituted notoriety in the 18th century?

IN 18TH CENTURY TERMINOLOGY, “fame” described great achievement or notable works. It was an aspirational concept, a goal to strive for that granted a person a degree of immortality. With the rise of print media and the dissemination of words and images via newspapers, broadsides, and biographies, ordinary citizens could at last attach a face to a famous name.

“The accessibility of printed material in the 18th century is at the root of modern celebrity,” said Katie McKinney, the Margaret Beck Pritchard Curator of Maps and Prints. “As print media’s reach expanded, so did the concept of fame. Writers, actors, criminals, politicians and military leaders could achieve celebrity status sometimes against their own wishes or best interests.”

Wilhelmus III (King William III) Engraved by Pieter Van Gunst after work by Jan Hendrik Brandon 1694

In the 18th century, portraits of royals were expressions of loyalty as well as reminders of the power of monarchs. King William III and his wife, Queen Mary II, took the throne of England in 1688 in a moment known as the Glorious Revolution. They ruled as comonarchs and reunited Britain after a period of upheaval. William & Mary was named for these monarchs, who issued the charter that established the college in 1693.

This likeness of King William III was considered a masterful example of engraving and would have been unaffordable for most people. Yet William’s and Mary’s images were also used on everyday household objects like dishes and mugs, as well as coins. Fragments from vessels bearing the royal likenesses or monograms have been discovered in Maryland and Massachusetts and at Jamestown.

17101712

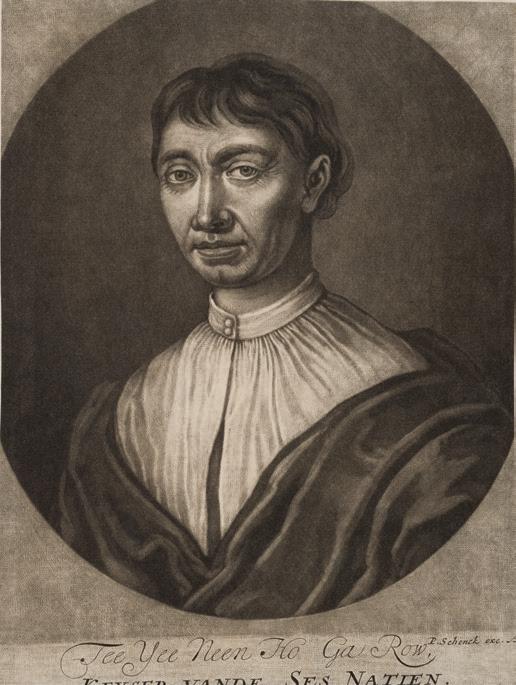

Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row (Hendrick Tejonihokarawa)

On Nee Yeath Tow no Riow (Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row or Johannes/John Onekaheriako)

Engraved by Pieter Schenk after work by John Faber

When a diplomatic envoy of four Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) representatives arrived in London in 1709, their appearance caused a sensation. Plays, ballads and even fashion trends arose from their visit. Numerous portraits of the delegation, dubbed “The Four Indian Kings,” were made and copied by engravers, who sold their work in a variety of sizes and price points. Queen Anne commissioned full-length portraits of the men, and engravers produced mezzotint copies to send back to the New York colony.

Mezzotint engravings are created when a copper plate is textured with a serrated tool. The textured areas hold ink, and the image is created by burnishing or smoothing the textured surface. Mezzotint engravings of the Haudenosaunee were sent to colonial centers of government. The engravings sent to Williamsburg were displayed in the Council Chamber at the Capitol.

Engraved by Valentine Green after work by Thomas Gainsborough

David Garrick (1717–1779) was the most famous and influential actor and playwright of the 18th century. Although he never visited America, his plays were staged throughout the colonies, including in Williamsburg. Garrick was instrumental in repopularizing the works of William Shakespeare, whose bust tops the pillar on which Garrick is leaning.

Thomas Gainsborough painted the portrait that serves as the inspiration for the engraving. The portrait hung in the town hall of Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s birthplace. Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette reported that Garrick was involved in planning Shakespeare’s 1769 jubilee, which helped make Stratford-upon-Avon a tourist destination. As Garrick’s fame grew, newspapers advertised printed copies of the portrait for sale.

17501753

Bow Porcelain Manufactory

1749

William Ansah Sessarakoo

Engraved by John Faber Jr. after work by Gabriel Mathias

William Ansah Sessarakoo’s father, Eno Baisie Kurentsi (“John Currentee”), was a powerful Fante diplomat and slave trader. Their home city in Ghana was a strategic port in the transatlantic slave trade. To strengthen his position with Europeans, William Ansah Sessarakoo’s father sent him to study in England in 1744. When the ship’s captain died at sea, Sessarakoo was sold into slavery in Barbados.

Eno Baisie Kurentsi petitioned English officials to return his son, and in 1749 Sessarakoo was sent to London. He became an instant celebrity, and his wrongful enslavement and visit to London inspired ballads, plays, memoirs and art.

Mr. Woodwarde in Character of ye Fine Gentlemen in Lethe

Engraved by James MacArdell after work by Francis Hayman

Henry Woodward (1714–1777) was an English actor known for his comedic performances. This print shows Woodward portraying “The Fine Gentleman,” one of his most celebrated roles, from David Garrick’s play Lethe: or Esop in the Shades. In the play, Woodward’s character is dressed in an absurd outfit. He pokes fun at the custom of the time in which wealthy Englishmen traveled throughout Europe on the grand tour and, once home, adopted foreign dress, customs and tastes. Although Woodward never came to the colonies, performances of Lethe appeared in New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis and Charleston.

Prints were not only a way to possess an image of a favorite actor; they also served as inspiration for decorative arts like this porcelain figure.

Elizabeth Dutchess of Hamilton & Brandon and Dutchess of Argyll (Elizabeth Gunning, Duchess of Hamilton and Brandon and Duchess of Argyll)

Engraved by John Finlayson after work by Catherine Read

Elizabeth Gunning, a noted beauty, was one of the most frequently depicted women in Britain during the mid-18th century. Born in Ireland to a family of minor nobility, Elizabeth (1733–1790) and her sister Maria became instant celebrities when they were presented to London society in 1751. The Duke of Hamilton was so taken with 17-yearold Elizabeth that they married that same evening, sealing the nuptials with a bed curtain ring. After the Duke of Hamilton’s death several years later, Elizabeth married John Campbell, who became the 5th Duke of Argyll. Both Elizabeth and Maria suffered from the white lead in the cosmetics they wore. Elizabeth recovered, but her sister died from lead poisoning at the age of 27. The modern-day tabloid has its roots in the 18th century. Broadsides, magazines and periodicals containing the latest news, political stories and scientific discoveries were published. In addition, readers could learn about society figures and their scandals.

17551760

Portrait Plaque of Elizabeth Canning

Lead-glazed earthenware

On New Year’s Day 1753, teenager Elizabeth Canning (1734–1773) left her mother’s home. When she returned almost a month later, Canning was injured and dirty and claimed to have been kidnapped and held in a hayloft. Press coverage of the story led to immense public support for Canning, and her alleged captors, Mary Squires and Susannah Wells, were tried and convicted. However, newspapers, the public and the courts soon began to question Canning’s tale. Witnesses recanted their testimony, and alibis changed. Canning was found guilty of perjury and sent to the Connecticut colony. To this day, it remains unclear what really happened to Elizabeth Canning.

17701790

Shoe

Silk, linen, leather and wood

Just as they do today, famous people in the 18th century influenced fashion. Print media helped trends spread quickly. When Princess Frederica of Prussia married King George III’s second son, Frederick, in 1791, her footwear caused a sensation. Her low-heeled, pointed-toed shoes inspired a style known as the “York heel,” a notable change from the taller heel that was fashionable in the early 1770s. Some women adapted the shoes they already owned to stay current with the trend. These shoes, which were made circa 1770 and then remade in the 1790s, had their formerly high heels cut down to mimic Frederica’s look.

1754

Elizabeth Canning

Etching and letterpress

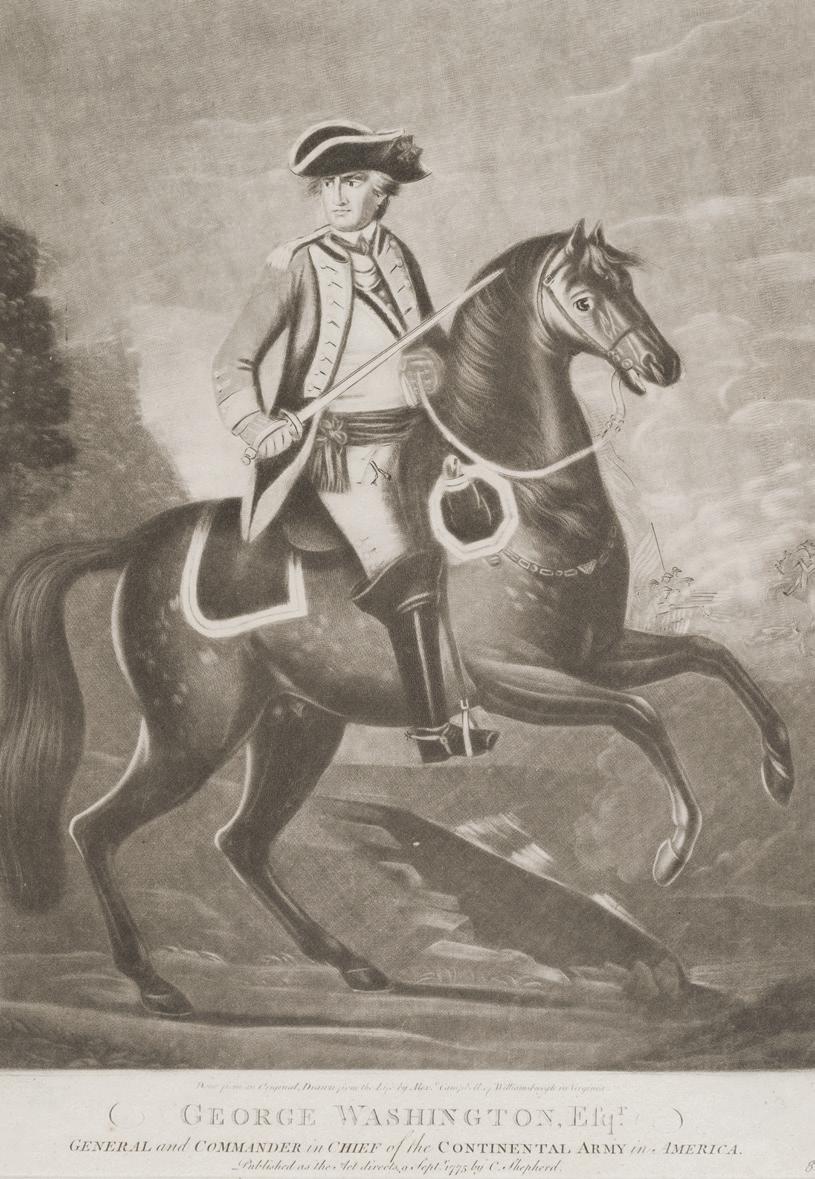

George Washington, Esqr.

Possibly published by John Sayer and John Bennett

English print publishers were eager to profit from the public’s interest in the war in America. They published a series of portraits of military officers, including this one of George Washington (1732–1799).

Although the print says it is “Drawn from the Life by Alex’r. Campbell of Williamsburgh in Virginia,” the artist’s name is fictitious. The true artist’s identity is unknown.

Lt. Col. Joseph Reed sent a copy of the print to Martha Washington. In a 1776 letter to Reed, George Washington, at the behest of his wife, thanked Reed. Washington added, “Mr Campbell whom I never saw (to my knowledge) has made a very formidable figure of the Commander in Chief giving him a sufficient portion of Terror in his Countenance.”

This exhibit is funded through the generosity of Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara. Celebrity in Print is on view in the Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara Gallery of the Dewitt Wallace Decorative Art Museum, part of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

DATE 1773

PLACE Norfolk, Virginia

MEDIUM Oil on canvas

DIMENSIONS 30 inches by 25 inches (unframed)

BY PAUL ARON

Like patriots, loyalists could be motivated by many factors, ranging from ideological to economic to personal. In the case of Mary Orange Rothery, clues to her motives can be found in testimony hers and others’ when she petitioned a British commission for reimbursement of the losses she suffered after leaving America as war with the Crown approached.

Rothery was a 26-year-old widow in 1773 when she sat for a portrait for traveling artist John Durand. A year later, she and her son, David, left Norfolk to join her father who had left Norfolk in the late 1760s in Liverpool.

In her 1784 petition, Rothery claimed that she left America because of “the Storm which she saw coming on.”

The coming storm, by which she meant the Revolution, did indeed destroy much of her property when parts of Norfolk burned in 1776. The property she had inherited after the 1771 death of her husband, the Norfolk merchant Matthew Rothery, included a large brick house, several warehouses, a wharf and a blacksmith’s shop. She also enslaved seven men and women.

Rothery’s petition for compensation described why she felt she had to leave America: “The Tea had been thrown into the Sea [and] the town of Norfolk was in great Divisions.” The petition added that “she has often blamed the Americans in Conversation.”

To make her case, Rothery had to overcome the commission’s reluctance to compensate anyone who had not actually fought for the British. Moreover, she left America in 1774, before war broke out. And her father, William Orange, had left Norfolk in part because he had advocated inoculations for smallpox, a controversial position at the time that could invoke hostility. Opponents of inoculations burned down one doctor’s home. This hostility might have extended to Rothery and influenced her decision to leave. “There was at that time no Appearance of rebellion [in Norfolk in 1774] but there was a Dispute about Inoculation & several Mobs assembled about it,” Robert Gilmour Sr., a successful Baltimore merchant, said in testimony before the commission.

The commission recognized Rothery as a loyalist, but questions remain. What is known is that she returned to America before leaving again for England.

“The story of Mary Rothery is still unfolding as we continue to learn about her life, travels and the complexities surrounding her departure,” said Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg’s Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. “How much compensation was awarded to her is still unknown, and what happened to her after her second return to England has yet to be discovered.”

Like many painters during the 1760s and 1770s, John Durand traveled for commissions, making stops in Connecticut and New York as well as Virginia. He probably apprenticed with Charles Catton in London, where he trained in coach and heraldic painting before coming to America. Within a year after his arrival in late 1766 or 1767, Durand visited southeastern Virginia. Bringing with him British precedents for composition and poses, the artist rendered the likenesses of numerous subjects throughout the region until about 1782. Durand advertised his services on several occasions in the Virginia Gazette, seeking “GENTLEMEN and LADIES that are inclined to have their pictures drawn.” He offered portrait painting at their homes or where he lived on Nicholson Street off Courthouse Square.

By Corey Stewart

Stories can help us make sense of our lives. Through them, we can build connections to one another and to the world around us. To make the principles, concerns and conflicts of American history more widely known, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation uses a variety of storytelling mediums. All are designed to create relatable connections between a 21st-century audience and the 18thcentury ideas on which our nation was founded.

Increasingly, video is the means by which these stories are told.

Video combines impactful images with meaningful words to help a viewer decide within seconds

whether a story engages them and whether they are interested in learning more.

People of all ages are using video as an access point to learning, whether it is a 30-second spot that leads to a longer text or a brief demonstration of how to accomplish a task.

HubSpot, a leading software company that tracks how consumers interact with content, reports that today’s audiences spend an average of 17 hours per week watching videos, and 94% of them watch videos to learn about an organization and its products and services.

According to a study

PHILANTHROPY AT WORK

Educational resources, including video, are vital to the Foundation’s mission to tell the early American story. The multiyear Power of Place Campaign aims to protect, strengthen and enhance Colonial Williamsburg’s ability to create engaging American history content for audiences of all ages.

Gifts of all amounts to the Foundation support the Campaign and the work of promoting history education and telling the American story.

To contribute to Colonial Williamsburg and advance its mission, please visit colonialwilliamsburg.org/give. If you would like more information on how you can support this work, contact us at campaign@cwf.org

by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a picture really is worth a thousand words. A human brain can process an image in only 13 milliseconds and retain that image for a long time. Video, then, makes for an impactful and efficient way to deliver information.

But video is not all about information. It is also about emotion. A successful video conveys the spirit of a place or group of people, showcasing their passion, excitement and, hopefully, their interest.

“As we think about how we most effectively advance Colonial Williamsburg’s mission to reach as many people as we can, video is the key,” said Mia Nagawiecki, the Royce R. and Kathryn M. Baker Vice President for Education Strategy and Civic Engagement. “In 2023, our educational

reach was over 20 million. Our digital content strategy, of which video is a core component, will enable us to continue to grow that number.”

Research by Colonial Williamsburg has shown that the No. 1 interest for all ages is stories of everyday life in the 18th century.

“As any visitor to the Historic Area knows,” Nagawiecki said, “this is what we do best. We give our guests an understanding of what life was like during the founding of our nation. What were citizens’ daily concerns and customs? What were their hopes and dreams and fears? These are the elements that allow us to understand the importance of what happened here and how we arrived where we are today as a nation. Video allows us to share that information with a much wider audi-

ence, increasing both our reach and our impact.”

Younger elementary school children can begin to engage with history through a collection of videos called “What the Huzzah is That?” With colorful animation and age-appropriate narration, these videos present an object from 18th-century life and connect it to its modern equivalent. The slate used in the 1700s, for example, was the forerunner to a 21st-century electronic tablet.

Nagawiecki and her colleagues are currently working to produce 500 animated videos to get children engaged with history through history. org . The website is being reimagined as the essential resource for K-12 teachers and students, with primary sources, videos and learn-

ing activities to make history and civics engaging.

For viewers with a special interest, Colonial Williamsburg’s YouTube page includes playlists for exploration. Want to learn more about historic trades? Trades Tuesday videos show what a wheelwright or bookbinder does, why their work matters to history, how the trade was learned in the 18th century and what tools are used.

For those seeking an introduction to Colonial Williamsburg, videos offer a glimpse of the Historic Area.

“What we’re finding is that people enjoy watching a short video introducing Colonial Williamsburg, and then they want to learn more and go to our website,” Nagawiecki said. “They might be planning a visit or simply seeing what the world’s largest living history museum is

PHILANTHROPY AT WORK

all about. Either way, they have now joined our community and increased their awareness of what we offer, both online and in person.”

If a visitor wants to learn more about a particular subject, they will soon be able to access a variety of related material.

“If a viewer is satisfied with a short video, they can move on to a new topic,” said Leslie Clark, executive producer of video at the Foundation. “But if they would like to really engage with the material, the pathways on the new website will allow them to easily discover related written texts, primary sources, relevant objects from the Foundation’s collections and longer videos.”

“One of the things we’re most excited about is the objects series,” Nagawiecki said. “This is where we showcase an item from archaeology or the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library’s Special Collections or the Art Museums and explain its historical context, relevance and importance to Colonial Williamsburg.”

The object series, called “Tales from the Collection,” will offer viewers an opportunity to go behind the scenes in many cases,

accessing items from archives and collections that are not available to the public, as well as items that are on public display such as museum pieces. “This really helps us expand our global reach,” said Carol Gillam, executive director of Foundation marketing and engagement. “You can be anywhere in the world and still benefit from the research being done here.”

Videos related to the

(Top): Nation Builder Stephen Seals portrays James Armistead Lafayette, an enslaved man who spied for America during the Revolution. (Left): Colonial Williamsburg’s YouTube channel features programming for both general and niche interests. (Right): Children identify historic items and make connections to the 21st century in this popular online series.

250th anniversary of the nation’s founding are also on tap, as well as 3D experiences that will allow guests to visit sites virtually across the Historic Area, including the Palace and Capitol.

“Our mission is to make our stories accessible to all ages in all corners of the globe,” Nagawiecki said. “Our nation began right here, but learning takes place everywhere.”

From utility pottery for a particular use to decorations that are singularly beautiful

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON COPES

“I made this...”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum

While oysters are available year-round, the tastiest emerge from winter’s cold seawater. What better time, then, to celebrate the oystermen and the underappreciated implements they use to harvest these savory mollusks? One example comes from Thomas Commeraw. Born into slavery, Commeraw became a free Black artisan and owned a successful pottery business in New York in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was one of the most prolific Manhattan potters to supply New York City’s oystermen with stoneware jars for preserving and shipping the pickled or brined oysters. Sometimes oyster jars were stamped with the names of the oystermen’s businesses. This Commeraw pot, on display in the Miodrag and Elizabeth Ridgely Blagojevich Gallery, is stamped “D · J · AND · CO No 24 / LUMBERSTREET / N · YORK” for New York oysterman Daniel Johnson.

This exhibition is made possible through a generous grant from The Americana Foundation.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

While winter’s chill conjures thoughts of wrapping up in a warm quilt, some quilts are solely works of art. In the last quarter of the 19th century, the interest in show quilts, including wildly patterned crazy quilts, reached its zenith. Most of these decorative quilts, intended for display, are smaller than bed-size quilts and usually composed of fine fabrics ornamented with decorative stitches. The crazy quilt shown here is composed of 20 squares of asymmetrical silk textiles and fan shapes, all overlaid with embroidery stitches forming names and initials, flowers, butterflies, a raised-work mouse and insects. The choice of decorative materials adds to the explosion of pattern and color. The quilt was made in 1886 by the ladies of the Presbyterian Missionary and Aid Society of Reedsburg, Wisconsin, for the pastor of the church. Twenty women joined forces to create the quilt, but it was never finished with a backing. This quilt is on view in the Foster and Muriel McCarl Gallery.

This exhibition is generously funded by the June G. Horsman Family Trust.

Peter Scott is Williamsburg’s earliest known cabinetmaker. Born in Scotland in the late 1600s, he likely trained in London before moving to Williamsburg by 1722. Highly successful, Scott plied his trade locally for a remarkable 53 years until his death in 1775 at age 81. Like many furniture makers trained at the beginning of the 18th century, he focused on tables and case furniture and left chair-making to others. Scott’s Williamsburg workforce included two enslaved cabinetmakers whose names are unknown. Scott’s products appeared in the homes of many prominent Virginians, including Washingtons, Jeffersons, Carters and others. His shop was prominently located on Duke of Gloucester Street directly across from Bruton Parish Church. He rented the

structure from the Custis and Washington families for 43 years. It provided housing for Continental army troops in the early months of the Revolution.

One of Scott’s earliest known works, this elegant desk and bookcase was made about 1725 for the Baytop family of nearby Gloucester County. Currently on view as part of A Rich and Varied Culture: The Material World of the Early South at the Art Museums , it was a recent gift to Colonial Williamsburg from the William & Mary Foundation.

Thanks to generous donors, Colonial Williamsburg will begin an archaeological investigation of the Peter Scott shop site in 2025.

Colonial Williamsburg’s Pooled Income Fund provides you with tax savings and income for life, while also providing a meaningful gift to The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. What better way to make history for you and generations to come. Contact us at 1.888.293.1776 or legacy@cwf.org today or reply with the attached card to get started.

A 60-year-old couple who gives $5,000 would receive a $1,400 tax deduction and estimated initial income of 4.0–4.5%.*

BY PAUL ARON

From its earliest days, Colonial Williamsburg was dedicated to research. Only gradually, however, did that research come to encompass the history of the town and the nation.

At first, Foundation officials thought of a “historian” as someone who, as Kenneth Chorley put it in 1929, “would keep track of everything that was done in Williamsburg... so that when the Restoration was completed we would have a complete document which would be a record of the work done.” Chorley, who later became the organization’s president, put “historian” in quotes.

In March 1930, Colonial Williamsburg hired Harold Shurtleff as “recorder and historian.” His contract, as well as his title, made clear that his primary responsibility was to record what was happening in 20th-century Williamsburg. His background as an architect seemed

Harold Shurtleff suggested that researching Williamsburg history would create an “appreciation of early American life, crafts and culture.”

to make him the perfect candidate for the focus on the town’s buildings rather than its early history.

Within months, however, Shurtleff was lobbying to expand his department and the type of research it would do. He had as an ally Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, the rector of Bruton Parish Church, who had dreamed of restoring Williamsburg and who had convinced John D. Rockefeller Jr. to fund it. Goodwin envisioned peopling Duke of Gloucester Street with scenes that “would show ancient modes of life and costume and would appeal to many who will not understand the

fine points of architecture.” In addition to many other projects, Goodwin also hoped to establish an archaeology laboratory.

In December 1931, Shurtleff weighed in with a report in which he presented the different directions that research could go. The first was “restricting the Department to its present function as a purely architectural and allied data gathering organization.” The second would entail “changing the Department so as to equip it to do research work on the historical side of Williamsburg and its vicinity in both the 17th and 18th centuries.” Shurtleff made clear

his strong preference for the second direction.

Shurtleff and Goodwin faced some resistance. Most of the experts working in Williamsburg were architects. This may seem strange for an organization that later came to pride itself on employing a range of experts, including archaeologists, architectural historians, conservators, curators and historians. But in the early years, architects controlled the direction of the research. Archaeologists, for example, focused on figuring out where buildings once stood and what shape they had. Only later would they give equal value to

the artifacts they uncovered and see them as clues to how the people of Williamsburg once lived.

The organization’s benefactor was also reluctant to change direction. While acknowledging the value of history, Rockefeller worried that expanding the scope of the organization’s research and programming would divert funds and attention needed for the restoration and reconstruction of the town’s buildings.

Shurtleff persisted, sometimes with Goodwin’s help and sometimes with the help of Rutherfoord Goodwin, who had joined his father at the organization in 1928.

Gradually, the organization expanded the scope of its research and its programs. In December 1934, soon before he became president of Colonial Williamsburg, Chorley delivered a speech in which he described the restoration of Williamsburg as the organization’s initial purpose. But with much of that accomplished, he continued, the organization’s objective was also to teach.

“What is it that we are to teach?” Chorley said. “It is history in its real and broader sense.”

From then on, research reports focused on the history of the site, not just its architecture or archaeology. These reports provided invaluable information about the community, which interpreters who later presented the history could employ. Indeed, in the decades following the early research, a wide range of research came to be recognized as important for its own sake and also as the framework for all Foundation programming.

“Today, looking back at the sheer

amount of historical research that has gone before us, along with the number of highly skilled researchers it took to create it, it can be a daunting prospect to develop on this work,” said Peter Inker, the Foundation’s current director of historical research. “But it is important to note that history is never fixed. There is always some new piece of evidence, some new question that has never been asked, that can completely change the way we look at what has been written, and how we interpret the past.

“Colonial Williamsburg has always been ready to ask questions, and we are continuing to seek information that has been overlooked or uninvestigated in the past,” Inker continued. “If we are going to tell the story of the people of Williamsburg, we need to tell everyone’s story and not be afraid to confront taboos or discomfort. Williamsburg is a place where people can find the stories that speak to them and a place where they feel comfortable enough to ask hard questions.”

Leather pocketbooks, such as the one above, were used to keep track of accounts and other vital information.

LEATHERWORK IDEAS FROM WILLIAMSBURG’S BEGINNINGS ARE REBORN IN A SERIES OF NEW PRODUCTS

by COREY STEWART

Charles Taliaferro was wellknown in 18th-century Williamsburg for creating equestrian goods in his shop on the southeast corner of Duke of Gloucester and Nassau streets. He promised that his work would be done “on the most reasonable terms, expeditiously, and warranted to be good.”

That good work served as an important reference point for a design team that has created modern leather accessories inspired

by craftsmanship practiced more than two centuries ago.

Taliaferro mainly produced riding chairs and harnesses, but advertisements in the Virginia Gazette from the 1760s and 1770s show that he also sold beer, candles, nails and shoes in his store.

Many of the modern bags created in partnership with Colonial Williamsburg for the CRAFT AND FORGE product line feature brass fittings that were influenced by the durable closures Taliaferro used. The shape of his equestrian saddlebags guided the design of the collection’s backpack and phone pouch.

The collection’s tote bag was also inspired by saddlebags Taliaferro produced. The straps and closures were inspired by items in Colonial Williamsburg’s textile archives, which house over 15,000 pieces, including waistcoats, bed linens, pocketbooks and wallets.

In the 18th century, “pocketbook” did not refer to a woman’s purse as it does today but rather to a collection of pages on which a gentleman could keep track of business matters such as purchases or accounts. The word “wallet” also meant something different in the 18th century, said Neal Hurst, curator of textiles and historic dress at Colonial Williamsburg.

“At that time, a wallet was a type of cloth sack that could be folded down the middle to keep its contents safe,” Hurst explained. “Paper money was not terribly common at the time because the Spanish, who had large supplies of gold and silver, were producing coins that were widely used as currency. But as the nation began to print paper currency, the meaning of the word evolved, and a ‘wallet’ began to more closely resemble what we have today.”

To produce the bags in the CRAFT AND FORGE collection, Colonial Williamsburg’s brand and licensing team

partnered with Mission Mercantile, a group of artisans in Mexico and Texas whose goods stand the test of time, according to Noreen O’Rourke, contract creative director of the Craft and Forge brand.

Many of the pieces in Colonial Williamsburg’s textile archives are made of leather that was embossed or stamped with the owner’s name, date or place of origin. Embossing is also a feature in several of the pieces.

“The level of craftsmanship, skill and care evidenced in Taliaferro’s work, which is common to all of the historic trades in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area, is reflected in these bags,” O’Rourke said. “Each piece embodies the tradition and heritage that underlies the mission of Colonial Williamsburg, updated to reflect modern aesthetics and needs.”

Sales of CRAFT AND FORGE products support the preservation, research and educational programs of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. To learn more, visit craftandforgebrand.com or shop.colonialwilliamsburg.com

(Above left): The Colonial Williamsburg collections include several 18th-century leather pocketbooks. (Above right and below): Taliaferro’s 18th-century designs included a three-strap closure. The modern bag features a single brass closure for ease of use.

New stores and restaurants coming soon!

The Carousel Children’s

Aromas Coffeehouse,

Bakery & Café

Baskin-Robbins

Berret’s Seafood Restaurant

& Taphouse Grill

Blink

Blue Talon Bistro

Brick & Vine

Campus Shop

Colonial Williamsburg

Bookstore

Boutique T

The Cheese Shop

Chico’s

The Christmas Shop

Danforth Pewter

DoG Street Pub

Everything Williamsburg

Eleva Coffee Lounge

Fat Canary

FatFace

French Twist Boutique

illy Caffé

J Fenton Gallery

J.McLaughlin

Kimball Theatre

lululemon athletica

Mellow Mushroom

Pizza Bakers

Monkee of Williamsburg

The Peanut Shop

The Precious Gem

Penny and a Sixpence

Precarious Beer Project

R. Bryant Ltd.

R. P . Wallace & Sons

General Store

SaladWorks

Scotland House Ltd.

Secret Garden

Sole Provisions

The Shoe Attic

The Spice & Tea Exchange of

Williamsburg

Talbots

Three Cabanas: A Lilly

Pulitzer Signature Store

The Williamsburg Winery

Tasting Room & Wine Bar

Walkabout Outfitter

William & Harry

Wythe Candy & Gourmet

Shop

The Revolutionary hero visited Williamsburg in 1824 and 2024

The Marquis de Lafayette visited Williamsburg on October 20, 1824, as part of a triumphant return to America. William & Mary bestowed an honorary degree of law on him as part of the celebrations. Two hundred years later, Colonial Williamsburg commemorated the 1824 visit and William & Mary once again presented an honorary degree to the marquis, portrayed by Colonial Williamsburg Nation Builder Mark Schneider.

Schneider spoke to the crowd as Lafayette about the importance of education. “All of the answers to

the future can be found in the past if you study your history,” he said. “Through educating yourself about the past, you become a better citizen of the future.”

Carriages brought Schneider as Lafayette, along with members of France’s NATO delegation, Williamsburg Mayor Douglas Pons and officials of the American Friends of Lafayette, down Duke of Gloucester Street. A salute to the AmericanFrench alliance included a flyover by the Escadron de Chasse 2/4 La Fayette, a squadron of the French Air and Space Force.

(Left): William & Mary President Katherine Rowe presented Mark Schneider, portraying the Marquis de Lafayette, with a facsimile of the honorary degree Lafayette received in 1824. (Below): The original degree is the property of the Chambrun Foundation, which preserves and maintains Lafayette’s estate.

The Kimball Theatre presented Once Upon a Time, featuring Schneider as Lafayette along with Colonial Williamsburg Nation Builders portraying George Washington, Martha Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and James Armistead Lafayette. Schneider described Once Upon a Time, in which Revolutionary figures reflected on their experiences with Lafayette, as “without a doubt the most emotional program I’ve ever performed.”

James Armistead Lafayette,

portrayed by Stephen Seals, joined Schneider for programs in Yorktown. He was born an enslaved Virginian and worked for the Marquis de Lafayette as a double agent during the Revolution. He took Lafayette’s name in tribute.

The Celebrity in Print exhibition at the Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara Gallery of the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Art Museum began with a discovery made by Katie McKinney, the Margaret Beck Pritchard Curator of Maps and Prints for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

“While working on a plan to install reproduction prints and maps in the King’s Arms Tavern,” McKinney said, “I discovered that the tavern keeper, Jane Vobe, purchased several prints in 1765. Most of the prints were land and seascapes, but Vobe also bought a print of the Duchess of Ancaster, one of Queen Charlotte’s ladies-in-waiting.”

McKinney wondered what Vobe might have known or admired about the Duchess of Ancaster that compelled her to purchase the print. She considered how the availability of printed material increased the influence of notable personages of the time.

“Being ‘famous’ meant something different in the 17th and 18th centuries than it does today,” McKinney said,

“but there were many people whose names were known beyond their immediate circles for their political views, fashion choices, beauty, social standing or scandalous behavior.”

Due to their appearance in printed media such as newspapers, broadsides and biographies, these early “celebrities” could influence the thoughts and practices of people far away for the first time. London newspapers, for instance, regularly covered the rich and famous, and the Virginia Gazette often picked up these stories.

The exhibition contains 30 works that explore the impact celebrities had on the material culture of the time. It includes portraits and prints, as well as ceramics, textiles and even tableware. The exhibition will eventually undergo a second presentation featuring new material and will be displayed through Nov. 8, 2025.

This exhibition is funded through the generosity of Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara.

While Lafayette was delivering remarks during the 1824 visit, he recognized the former spy in the audience and embraced him. In 2024, Schneider and Seals reenacted that moment.

“The marquis was a man of his time,” Seals said, “and still, he knew slavery was wrong and fought against it.”

Lafayette’s 1824 tour of the United States was the result of an invitation extended by President James Monroe, who hoped the visit would revive patriotic sentiment among Americans. Williamsburg and Yorktown are among 200 U.S. cities taking part in the re-created tour.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation partnered with The Richmond Forum in October to launch a speech and debate event for high school students. The event, sponsored by Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, inspired students to emulate the civic engagement of America’s founders.

In Williamsburg, students competed in debate and oratory competitions at the Capitol and other historic buildings. Their topics related to events that occurred between 1770 and 1775, offering students a unique opportunity to practice their skills where colonial leaders once debated questions of freedom and independence.

Colonial Williamsburg’s mission encourages critical thinking and civil discourse about historical people and events. The Richmond Forum welcomes subject matter experts to speak on public policy, arts, science, law and business. In 2018, the forum launched an

initiative to establish debate and speech programs in public schools throughout Richmond.

“There is incredible power in place, which is why Colonial Williamsburg has spent nearly a century preserving the spaces and stories connected to the birth of American democracy,” said Cliff Fleet, president and CEO of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

“Revolutionary Rhetoric provides students with the unique opportunity to experience the past in the present, inspiring them to apply what they learn to the future.”

William Casperson has joined the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Board of Trustees.

Casperson retired in 2023 from Oaktree Capital Management, where he served as co-portfolio manager for Oaktree’s U.S. private debt strategy and led the investment professionals, portfolio construction and strategic management. He is currently an adjunct assistant professor of business at Columbia Business School.

“William Casperson brings a wealth of financial expertise to the board. His insights deepen the board’s already excellent pool of financial experts, and his passion for our mission furthers our ability to expand Colonial Williamsburg’s educational impact on the eve of America’s 250th anniversary,” said Carly Fiorina, board chair.

Casperson’s appointment complements the board’s leaders who drive the Foundation's strategy and mission.

“Mr. Casperson is a welcome addition to the board. I’m eager to tap into his expertise to help us bring stories of America’s founding generation to life on-site and online for students of history wherever they live,” said Cliff Fleet, president and CEO of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Stones now permanently mark the grave sites of 62 people buried at the African Baptist Meeting House and Burial Ground on Nassau Street in the Historic Area. The remains were found during excavations of the site of one of the earliest African American churches, which was founded by enslaved and free worshippers.

In 2023 experts from Colonial Williamsburg, William & Mary and the University of Connecticut analyzed the remains of three of the individuals buried there and confirmed that they were ancestors of the First Baptist Church community. The current church is located just outside the Historic Area. The condition of the bones was too poor to get as much information from them as experts had hoped, and the community agreed with Executive Director of Archaeology Jack Gary’s recom-

mendation that no additional burials be disturbed.

Gary and his colleagues next presented the community with suggestions for commemorating the lives of the people buried there.

Archaeologists found an espe-

cially appropriate example at the Alexandria Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery. Hundreds of African Americans had fled to Alexandria in search of freedom during the Civil War. Just as at the Williamsburg site, it was impossible to identify the individuals buried there. And just as the Williamsburg site had been paved over for a parking lot, the Alexandria site had been covered over with a gas station and office building.

At the Alexandria cemetery, the graves are now marked by stones placed just as the graves were found, not lined up neatly. The First Baptist community endorsed a similar approach. The Foundation commissioned 62 stones in three sizes, each inscribed with the word “adult,” “child” or “infant.”

“It’s really powerful to see the stones exactly as people were buried,” said Gary. “This project is not a restoration, not a re-creation, not a memorial. It’s all those things.”

The John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Library is moving The Virginia Gazette and Colonial Williamsburg research reports into the Foundation’s digital asset management system. This initiative, supported by the Bloomberg Philanthropies Digital Accelerator, will make these resources more accessible to researchers.

“We are very excited to enhance access to The Virginia Gazette and Colonial Williamsburg research reports by making them available through the new digital collections platform,” said Emily Guthrie, executive director of the library. “Many of the over 2,000 research reports were not previously digitized. They provide deep documentation of the social, archaeological and architectural

history of Williamsburg and are now searchable on one public platform.”

The Virginia Gazette was the official newspaper of Virginia and was printed in Williamsburg from 1736 until 1780. The research reports cover a wide array of topics and reflect the evolution of scholarship over many decades. The new site will be publicly accessible in January 2025.

The Bloomberg Philanthropies Digital Accelerator supports leadership development and technological infrastructure investment that builds audiences, increases fundraising, drives revenue, delivers dynamic programming and helps develop best practices to share across a network of nonprofit cultural organizations.

Florida: Registration #CH10673. A COPY OF THE FOUNDATION’S OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE 1-800-HELP-FLA WITHIN THE STATE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE. Maryland: THE FOUNDATION’S CURRENT FINANCIAL STATEMENT IS AVAILABLE ON REQUEST AT THE ADDRESS LISTED ABOVE. FOR THE COST OF COPIES AND POSTAGE. DOCUMENTS AND INFORMATION SUBMITTED ARE AVAILABLE FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE, STATE HOUSE, ANNAPOLIS, MD 21401 New Jersey: INFORMATION FILED WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL CONCERNING THIS CHARITABLE SOLICITATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY BY CALLING (973) 504-6215. REGISTRATION WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT. Pennsylvania: THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION OF THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF STATE BY CALLING TOLL FREE WITHIN PENNSYLVANIA 1-800-732-0999. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT. Virginia: A FINANCIAL STATEMENT IS AVAILABLE FROM THE STATE DIVISION OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES UPON REQUEST. Washington: ADDITIONAL FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE CHARITIES DIVISION, OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE, OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON, BY CALLING 1-800-332-4483. West Virginia: WEST VIRGINIA RESIDENTS MAY OBTAIN A SUMMARY OF THE REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE, SOLICITATION LICENSING BRANCH, AT 1-800-830-4989, STATE CAPITOL, CHARLESTON, WEST VIRGINIA 25305. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT.

California: Not yet able to issue charitable gift annuities.

New York: Upon request, a copy of the latest annual report may be obtained from the address listed above for the foundation or from the Charities Bureau, Department of Law, Attorney General of New York, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

North Carolina: Financial information about the foundation and a copy of its license are available from the State

Solicitation Licensing Branch at (919) 807-2214. The license is not an endorsement by the state.

Oklahoma: A charitable gift annuity is not regulated by the Oklahoma Insurance Department and is not protected by a guaranty association affiliated with the Oklahoma Insurance Department. South Dakota: Charitable gift annuities are not regulated by and are not under the jurisdiction of the South Dakota Division of Insurance.

The Foundation does not issue charitable gift annuities in Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii, and Washington. In California — we are not yet able to issue charitable gift annuities.

Colonial Williamsburg’s educational travel program offers groups of 20 donors unusual access to sites around the world, some of which are rarely if ever open to the public or to private groups. Along with Director of Educational Travel and Conferences Tom Savage, guest co-hosts often include internationally celebrated specialists in their field, Colonial Williamsburg curators and senior leadership, and past and future speakers from Colonial Williamsburg’s educational conferences.

“India was truly a life-changing experience,” said Curator of Textiles and Historic Dress Neal Hurst, who co-hosted a 2024 tour that included ancient and modern sites throughout the country. “From the hustle and bustle of Asia’s largest spice market in Old Delhi to the sunset over the Taj Mahal, I gained so much insight and respect for the Indian culture and way of life.”

For Hurst, who curates many block-printed fabrics from England and India, witnessing block printing in Jaipur was a highlight of the trip.

Senior Curator of Furniture Tara Gleason Chicirda was especially excited to view the furniture of Gerrit Jensen, one of the most significant London cabinetmakers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. British furniture scholar Adam Bowett, who recently completed a book on Jensen’s work and was the keynote

speaker for the 2023 annual Antiques Forum, accompanied the group.

“The access one has to both the collections on the tour and the specialists that accompany the group is spectacular,” said Chicirda, who participated in the 2024 tour of great English country house collections.

Another 2024 tour covered historic Philadelphia and the Brandywine Valley and included the gala opening of the Delaware Antiques Show, America’s premier show for Americana. In the same year, a group traveled to Sicily, where the tour included meals with ancient noble families in private palaces.

For 2025, three tours are scheduled, the first of which is to Morocco and is sold out. A tour of Cambridge University and country houses of the West Midlands will take place in June, and a tour of Berlin and Dresden is scheduled for October.

Laura Pass Barry, the Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, has joined three travel programs. She noted that Savage has a Rolodex that can open any door.

“His tours are defined by unparalleled access to private homes, behind-the-scenes visits and oncein-a-lifetime memories shared by Colonial Williamsburg donor participants,” said Barry. “Whether the trip is to Boston or to Morocco, the influences of historic events and cultural trends are universal, always making their way back to the pivotal role our colonial capital continues to play.”

For more information, go to colonialwilliamsburg.org/travel . To request a space on a Colonial Williamsburg educational tour, email educationalconferences@cwf.org or call 800-603-0948.

by JEFFREY ROSEN

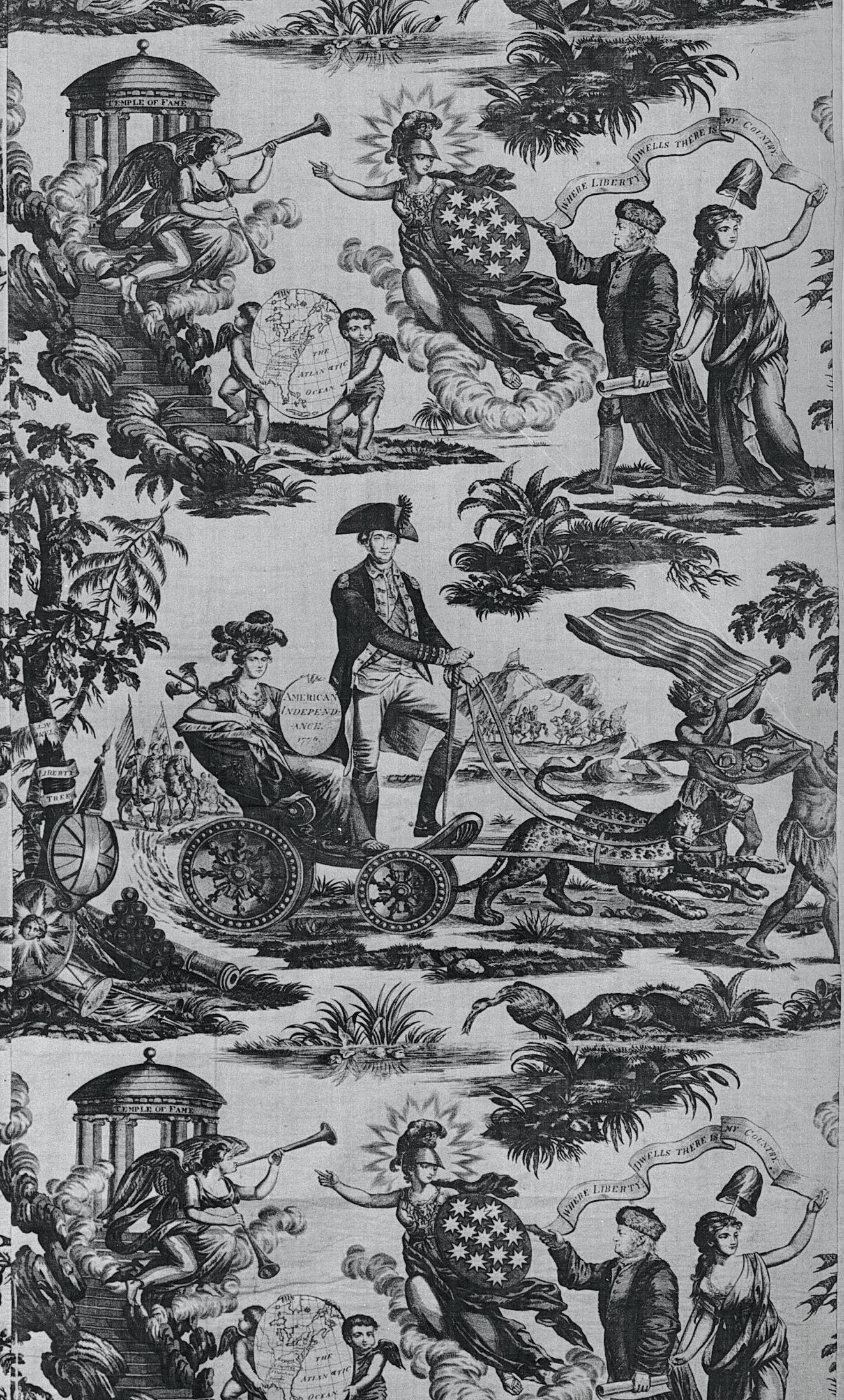

A fabric display includes depictions of liberty symbols including a banner that reads: Where Liberty Dwells, There is My Country.

IN MAY 1776 , the Continental Congress in Philadelphia asked the colonies to form new governments, and the Virginia Convention appointed George Mason, James Madison and others to draft a constitution and bill of rights for Virginia.

Writing in the Raleigh Tavern, Mason produced the first draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, whose preamble contains language that Thomas Jefferson would include in the Declaration of Independence almost word for word:

That all Men are born equally free and independant, and have certain inherent natural Rights, of which they can not by any Compact, deprive or divest their Posterity; among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty, with the Means of acquiring and possessing Property, and pursueing and obtaining Happiness and Safety.

Jefferson closely mirrored this language in his rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, before it was edited by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin:

We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.

Jefferson was sensitive to the charge of plagiarism. Nearly 50 years later, he wrote to a correspondent who, like many readers, was surprised by the similarities between Jefferson’s and Mason’s bills of

particulars against King George III. Jefferson said that he had sent his own draft constitution for Virginia from Philadelphia to Williamsburg in 1776, along with a preamble justifying separation from Great Britain. Although Jefferson’s constitution arrived too late, he said, the Virginia House liked his preamble and inserted it into the final document.

“Thus my Preamble became tacked to the work of George Mason,” Jefferson explained defensively, while praising Mason as “one of our really great men and of the first order of greatness.”

Classical Greek and Roman moral philosophers, including Cicero, Seneca and Plutarch, influenced the Founders’ understanding of the pursuit of happiness as being good, not feeling good the pursuit of long-term virtue rather than shortterm pleasure. For the Founders, personal self-government was necessary for political self-government. And the influence of classical writings extended beyond the political realm, inspiring the Founders to a personal search for the good life on their own terms.