IN-DEPTH BRIEFING // #88

AUTHOR

Lt Col Ollie Major British Army Liaison Officer to the German Army for Force Development

The Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research is the British Army’s think tank and tasked with enhancing the conceptual component of its fighting power. The views expressed in this In Depth Briefing are those of the author, and not of the CHACR, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, Ministry of Defence or British Army. The aim of the briefing is to provide a neutral platform for external researchers and experts to offer their views on critical issues. This document cannot be reproduced or used in part or whole without the permission of the CHACR. www.chacr.org.uk

WHICH country was Europe’s biggest financial contributor to NATO in 2024?1 And is also the producer and user of the most modern and most exported tank in NATO and owns the most sophisticated infantry fighting vehicle; has a reference army for European Allies that is a genuine player at the corps and divisional level; boasts a rapidly developing experimentation programme and an aggressive digitisation roll out; and has the most forward leaning plans for NATO Front Line Forces after the USA?

One could be forgiven for thinking these words applied to the British Army but in this case they refer to a long-standing and historically constant partner of the UK – Germany. Despite the long shadow of the 20th century in the public consciousness, Germany is arguably the NATO nation which is most closely aligned with the UK in terms of

military culture, foreign policy aims and approaches to force development. Following the historic Trinity House Agreement signed by the Secretary of State for Defence John Healey in October 2024, it is clear that the UK government recognises the importance of Germany and intends to do more with it in the military sphere. This In-Depth Briefing will examine the current UK-Germany land military relationship and make the case that the Stille Allianz (Silent Alliance) remains essential for the British Army and that Trinity House offers a vital opportunity. It will set out the ways in which UK and German interests are likely to converge in the land domain in any future conflict; the importance of Germany as the host nation for all our land deployment planning, and the fact that our industrial base is dependent on Germany and linked to the Bundeswehr.

The 1st German Panzer Division

recently held its first Waterloo Dinner, and the event is a fixture at the Führungsakademie in Hamburg; so the UK and Germany fighting side by side in a coalition of equals to defeat an over-mighty landgrabbing dictatorship clearly resonates today. Although the two World Wars have cast a long shadow over our common consciousness in recent times, we have historically been the best of Allies – we just didn’t shout about it, because until 1900-ish it was simply a fact and neither the British nor the Germans are given to such declarations.

We should not forget the roots of the term ‘Anglo-Saxon culture’ –the tribes that give its name were German (there are three states

1NATO Press Release Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2024) as at 12 Jun 2024 showing DEU financial contribution in raw currency as greater than the UK’s but including the time-limited Special Fund. Available at 20240618-Defence_Expenditure_of_ NATO_Countries_2014_2024_NATO-O. pdf (sharepoint.com)

in Germany called Saxony and many British soldiers lived in Lower Saxony), our language is Germanic and we are culturally far closer to Germany than other European nations. Germans recognise this and are often frustrated when we seem not to. German and British military cultures are far more closely aligned than we might think and have been ever since the Hannoverian succession in 1714.

German commanders were essential partners for Marlborough;2 Hougoumont Farm would not have been held without the efforts of German Jäger; and much of Wellington’s success in Spain and Belgium was due to the King’s German Legion. It was only in the early 20th century that the long-standing relationship shifted. Despite the impact of the post-war settlement on Germany’s willingness to use hard power, it maintained strong land forces alongside the British Army of the Rhine throughout the Cold War. Right up until the final UK withdrawal in 2019, the stationing of the bulk of the British Army’s armoured forces in Germany and the Bundeswehr training presence in Castlemartin created significant and deep military links between the nations. Even after the return to the UK, the senior mentor to the Commander Allied Raid Reaction Corps was General (Retd) Helge Hansen – a former German Chief of the General Staff and Commander in Chief, Allied Forces, Central Europe (NATO), who was an adviser to Bagnall’s reforms and a man who could both impress with his thoughtful, practical approach and terrify senior leaders with his displeasure.

2Some of them, at least - Bavaria has a history of being on the “wrong” side.

3Observation drawn from personal discussions with German Army officers from across the BLO (G) experience.

4Officially translated by the Federal Government as “watershed” but carrying a far more epoch-changing resonance in German – the last Wende was reunification in 1990.

“IT WAS THE INVASION OF UKRAINE WHICH GAVE GERMANY THE CONFIDENCE TO DO WHAT MANY IN THE FOREIGN POLICY ESTABLISHMENT HAD BEEN RECOMMENDING FOR SOME TIME – START TO RE-ESTABLISH ITSELF AS A FRONTLINE MILITARY POWER WITHIN NATO.”

Today, German colleagues recognise the similarity of approach of the two armies and are keen to work with the UK where appropriate.3 Recent work by the exchange officer in the 1st German Panzer Division to re-establish a formal process for partnership and exchange with the German Army has been warmly welcomed by the Germans, and the Chief of the Army, recognising our common approach, recently had ‘Serve to Lead’ translated, Germanified as ‘Offizier Sein’, and distributed across the Army.

Despite its robust position during the Cold War, Germany was quick to draw on the so-called peace dividend of the 1990s. German strategic culture has long preferred to invoke soft power rather than hard; it has also focused on a highly multilateral approach to military activity. This does not mean that Germany has not supported hard power – recollections of Iraq in 2003 tend to overshadow the support given by Germany to NATO in Kosovo in 1999 (under Green Party foreign minister Joschka Fischer), which marked the start of a shift in approach. Germany has increasingly ventured into UN operations and has a small but significant and growing presence in the Indo-Pacific region, including a fledgling China strategy. But as a central European power, it was the invasion of Ukraine which gave Germany the confidence to do what many in the foreign policy establishment had been recommending for some time – start to re-establish itself as a front-line military power

within NATO. With Chancellor Scholz’s Zeitenwende speech, in which he stated “we will do what is necessary to assure peace in Europe”, the government demonstrated a clear and distinct break with the recent past and a will and determination to transform Germany’s defence profile quickly and decisively.4

Although the €100 billion Special Fund dedicated to the re-equipping of the Armed Forces was the most high-profile measure and the one that caught international interest, it was only one of a series.

In June 2023, Germany published its first national security strategy focused on three pillars – wehrhaftigkeit (roughly translated as military robustness), resilience and sustainability. The importance of this step should not be underestimated, and nor

should the impact this has had on the German security discussion. The fact that the strategy directly links big international challenges to the day-to-day lives of citizens is an approach not seen in Germany since the Cold War. For the first time since 1945, Germany identified critical national interests – Germany had always seen itself, at least officially, as part of the wider European order and sought international solutions. Critically, and in line with the Zeitenwende, it identified Russia as the greatest threat to Germany national security (albeit with some caveats on whether this is an enduring fact) and was focused on the need for a psychological and societal change in German approaches to defence. The National Security Strategy effectively solidified the cultural change which Chancellor Scholz had called for in 2022 while seeking to address the uncomfortable truth that Germany’s Energiewende, the defining ecological policy for the ruling Green Party and cornerstone of the current

depended largely on – now unavailable – Russian gas in bridging to renewables. Loss of this access has strategic cost implications for Germany which are still playing out but, in contrast to Angela Merkel, the government was prepared to make that break.

Security and defence are, probably for the first time since the formation of the Bundeswehr, mainstream areas of discussion in a country which had effectively dedicated its armed forces to peace support operations outside Europe. Defence Minister Boris Pistorius is the only minister with positive approval ratings – with cross party support – and had to repeatedly deny any ambition to replace Scholz as the Chancellor candidate for the SPD in the 2025 election. Indeed, the whole discourse has changed.

The German education minister has called for training in civil defence, and for education on the role of the Bundeswehr in society – unthinkable five years ago.5 There is a live and open discussion about military service, levels of recruiting and potentially a return to conscription (still legal but suspended) in the face of demographic challenges; driven by the opposition CDU and likely to be an election issue. Pistorius, appointed from relative obscurity after Christina Lambrecht’s woefully inadequate response to the new challenges, has repeatedly discussed the importance of Kriegstüchtigkeit (war readiness), argued for the reintroduction of conscription in a modern form, and argued for Defence to be exempted from Federal Budget rules set in the constitution – this issue was one of the key factors driving the failure of Scholz’s government in November 2024. Even three years ago, any of these comments would almost certainly have led to dismissal. Scholz’s refusal to deploy Taurus missiles to Ukraine

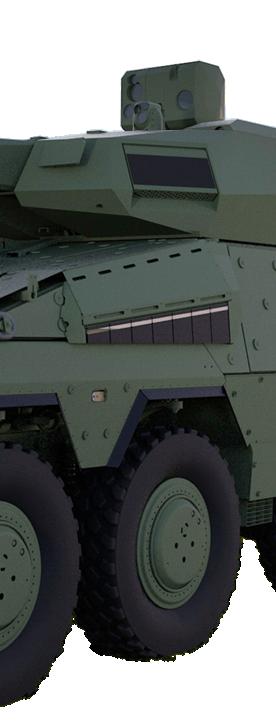

The Bundeswehr has ordered Skyranger 30 airdefence systems mounted on Boxer armoured vehicles Picture: Rheinmetall

“DAS DEUTSCHE HEER HAS HAD TO REVIEW ITS COMPLETE HOLDINGS. IT IS UPGRADING ITS LEOPARD TANKS, PUMA ARMOURED FIGHTING VEHICLES AND PANZERHAUBITZE 2000 TRACKED ARTILLERY. IT IS TRANSFORMING ITS BOXER FLEET FROM ONE PROCURED FOR PEACE SUPPORT TO ONE FOCUSED ON COLLECTIVE DEFENCE.”

has been deeply unpopular across the establishment. And at the NATO Washington Summit, Chancellor Scholz agreed the re-stationing of long-range US missiles on German soil for the first time since the IntermediateRange Nuclear Forces Treaty in 1987. Recent regional elections saw defence policy a critical issue for the first time in decades, and Ukraine will be a key pillar of this month’s election.

For das Deutsche Heer (the Army), the Zeitenwende has meant a period of rapid adaptation in terms of both capability and of culture with the Bundeswehr as a whole aiming to return to a level of capability last seen in the 1980s. In 2018, the German Chief of the Army told his generals that they had to prepare for collective defence as their core mission,6 and the subsequent change in approach has been rapid. The Special Fund is limited to four years, meaning that recapitalisation and new procurement has had to move fast – a new Special Fund was one of the coalition. Das Deutsche Heer is now focused on delivering two

armoured divisions to NATO,7 on enhancing the offer of a third rapid forces division (which contains Germany’s paratroopers and mountain infantry as well as a special forces element), and on ensuring that 1. German Netherlands Corps (1 GNC) can take its place at the heart of NATO operations. Netherlands Land Forces are now almost completely integrated into the German command system – not just as affiliations but as operational control units essential to the functioning of the wider force. German officers are entirely focused on Kriegstüchtigkeit – reinvesting in divisional and corps artillery; developing a new class of forces (based on Boxer) to fill a deployment gap between NATO Front Line Forces in Lithuania and those based in Germany; and on permanently basing a full armoured brigade, complete with families and domestic support, in Lithuania by 2027.

To do this, das Deutsche Heer has had to review its complete holdings. It is upgrading its Leopard tanks, Puma armoured fighting vehicles and Panzerhaubitze 2000 tracked artillery. It is transforming its

Boxer fleet from one procured for peace support to one focused on collective defence – Boxer infantry fighting vehicles and fire support variants with 30mm cannons; Boxer artillery; Boxer joint fire support team variants; a repair and recovery variant; and a new 120mm mortar for all troops. It also means new bridges, new rocket artillery and a comprehensive digitisation programme which will network the entire fleet. We should also be clear that in many areas, the scale of procurement places us at best on a level with and often behind Germany; discussions with German industry often reveal that they do not see us a market mover in procurement because we do not buy enough.8

5The Bundeswehr is the Armed Forces as a whole, including the procurement agency. Das Heer is the Army, die Marine the Navy and die Luftwaffe (Air Force, as opposed to Lufthansa – air trade), the air force. Germany also has a fourth Front Line command, the Cyber and Information Domain Service.

6Gen Lt Jörg Vollmer, Inspekteur des Heeres, speaking at the Informationslehrübung des Heers at Bergen Hohne in 2018.

7Each with a Dutch Brigade integrated into it as the third manoeuvre unit.

8BLO G discussions with German industrial figures. We are, however, a quality mark which they welcome as a signal to others.

But it means the prospects for cooperation are significant.

Germany is thinking operationally and strategically. It is working hard to remain genuinely capable of fielding a corps on a national basis and, as such, has significant common ground in concepts and development with the UK. Whatever our operational affiliation – Trinity House focuses on Forward Land Forces – the ability to cooperate with Germany at the higher tactical level will be essential to success. And Germany is rapidly becoming the reference Army for NATO’s central region alongside Poland – Hungary, for example, now uses entirely German land doctrine; the Netherlands has almost entirely integrated its land forces; and Czechia, Slovakia and other states are heavily engaged in partnerships in logistics; chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defence and other areas of cooperation. Germany has also started drafting a comprehensive operations plan for Germany as a transit nation, merging its operations and domestic commands, and seeking to integrate all elements of society, from emergency services to social affairs and transport. We will need to understand this plan and be able to work within Germany’s emerging framework.

Finally, the Zeitenwende and related changes to procurement to make it faster and more responsive to front line command needs have allowed das Deutsche Heer

9German procurement remains affected by rules designed to prevent Front Line Commands from developing their own independent approach to development and acquisition. Based on historical precedent, they are now outdated and much work is being done to reform the process.

10Discussion with the German Head of Delegation to the NATO Land Operations Working Group and author’s own experiences as the Deputy Chair and Chair of the Land Doctrine Panel.

“THE WAY IN WHICH THE UK AND GERMANY SEE THE LAND FIGHT WILL BE A CRITICAL ELEMENT IN SHAPING NATO’S APPROACH... IF WE COOPERATE AND ALIGN, THE EUROPEAN ARM OF NATO WILL BE SIGNIFICANTLY BETTER PLACED TO DEVELOP.”

to start to develop its own experimentation programme – a source of light friction with the procurement agency which had historically owned this role.9 This programme has clear instructions from the Chief of the Army to focus on delivering rapid acquisition which can help increase lethality and speed now – this is, of course, closely focused on the brigade in Lithuania. These changes are allowing the procurement system, which remains logical and responsive to top-down direction from the National Armaments Director who is located in the MOD and reports to a minister who has been doing the job ten years, to demonstrate significant agility.

There should be little doubt that Germany is rapidly becoming, once again, a peer and a partner in the land domain – and this requires a different approach. The final shape of the NATO force model (NFM) is beyond the scope and classification of this Briefing, but it is reasonable to assume, given the rhetoric and the information in the public domain, that the German Army will be focused on Joint Force Command Brunssum’s area of operations. The NFM also drives new approaches to the construction of forces – Germany

is focused on fighting the plan with the forces that will be there. The need for British brigades to be able to integrate into German divisions on an enduring basis, and the reverse, is therefore much lower than it was before NATO changed its approach. Similarly, German divisions are focused on 1 GNC and Multi-national Corps Northeast as their likely command chain.

Such an approach, however, would ignore the conceptual and procedural aspects of interoperability. We often talk about the technical aspects – command and control, for example – but it is the physical and cultural proximity that we have taken for granted and is just as great a currency. Certainly, our ability to deploy through Germany and to take advantage of NATO Forward Holding Base Sennelager relies on support from the Bundeswehr as a whole; Op Linotyper demonstrated that we no longer understand instinctively how to operate within and through Germany in the way we used to – Brexit, the move of the front line and loss of institutional memory have all played a part. If we do not understand Germany, we cannot deploy.

As two of the only allies who can genuinely claim to be effective at the corps level within NATO,

the way in which the UK and Germany see the land fight will be a critical element in shaping NATO’s approach. If we diverge, the ability of NATO commanders to fight across a coherent force will be severely impacted. But if we cooperate and align, the European arm of NATO will be significantly better placed to develop. That in turn will provide a virtuous counterbalance to US approaches such that the Alliance is better able to operate in a way which is aligned with its means. And the idea that the UK’s land forces will definitely not have to fight in JFC Brunssum’s area, and therefore alongside Germany, is not really credible.

The way forward is set out at the highest level in the Trinity House Agreement communiqué Cooperation should focus on key issues such as long-range fires; the use of artificial intelligence and digitalisation to reduce sensor-shooter-effector times; the conceptual approach to the role of the division and corps in the face of modern technology; and to the integration of multidomain forces across the breadth of a European, Allied collective defence. Trinity House is broad and should not necessarily be definitive – rather both nations will be best served by a spirit of constant cooperation and mutual support, so that each can review and comment on the others thinking, can adopt and adapt and between them produce a single set of views which can be presented to NATO for adoption by the Alliance.

This last point is perhaps the most important – when looking at the land domain, NATO’s conceptual development is driven by four nations: the UK, Germany, the Netherlands and the US.10 The more coherence we can create between these nations, the easier it will be to convince NATO. Once again, the UK can act as a vital connector and mediator across the Atlantic.

We should also recognise the inevitable links we have with Germany’s industrial base, the scale of UK investment through German companies and the level of consequent investment by them into the UK. Simply put, as the UK seeks to grow its Land Industrial Base, the German defence industry plays a critical part given the dependencies for systems which are essential to the enhancement of lethality on companies such as Rheinmetall, MBDA or KNDS. It rapidly becomes clear that German industry is key to UK modernisation.11 As Ed Arnold identified in 2023, this is not a position which has arisen by intent – it is a simple result of procurement going where the market takes it. It is, however, a fact, and one which must be considered when shaping UK approaches to Germany. His conclusion, that “the UK and Germany should commit to a joint high-level statement to make the case for a cooperative strategy to industry, which outlines the associated benefits, to provide the demand signal to industry and best prepare them for any change of approach”, took a vital step with Trinity

House Defence and will be developed through the coming years. Exports may remain a challenge, though this has been reduced significantly by the German decision to allow export of Typhoon, and the issue now is the very different control mechanisms employed by Germany (though trade and foreign ministries) and the UK to control this activity. It is, however, something which German colleagues understand and are sympathetic to – and it helps their industrial base as well, even if indirectly. Once again, the common ground is clear.

Such cooperation cannot just be focused on German industry; cooperation with das Deutsche Heer creates mass with a partner whom German industry cannot afford to annoy. The Bundeswehr does not buy German simply because it is German – like us, it buys because the product is the right one. German industry research and development is likely to respond far better to demand signals based on multinational approaches including Germany than to single models and we will all benefit from greater cooperation. Understanding German research and development (an underrated

resource in some circles) and collaborating and sharing development will, in turn, allow clearer and more consistent demand signals to industry.

This power of national influence has been shown recently by developments in the Main Ground Combat System, the Franco-German project for a future armoured solution. The level of political engagement to work together has driven both French and German industry to reshape and to make agreements on workshare before the project has even matured. This has happened because the Federal Government and the French Government have presented a line to their national industry (and, to an extent, to their militaries) which could not be ignored.

There is also a practical side to this. Like us, das Deutsche Heer is absolutely focused on greater lethality, preparedness and resilience, including significant investment in infrastructure. This will drive greater cooperation with industry, not least as we develop our models for deployment across Germany in the event of war. In the future, we will, based solely on current programmes, operate a broad

range of common systems with das Heer; cooperation and alignment, where appropriate on force development, will provide the basis for an optimised procurement programme. The greater our cooperation on procurement, future development and support contracts, the more efficiently we can deal with industry (to everyone’s benefit) – and the more effectively we will be able to achieve agreement for work to be conducted in the UK.

The UK and Germany have a depth of relationship which goes back centuries – far longer than any other European alliance aside from Portugal. Both politically and militarily, the two nations share interests, approaches and culture, and the potential for cooperation at the conceptual and industrial levels is significant. This In-Depth Briefing does not seek to present the Silent Alliance as being the most important, or to place it in a relative position compared to other European partners. It does, however, show that the scope for fruitful cooperation between the two nations is significant, if approached properly, and that the challenges of collective defence, of modernisation, of increased lethality and of innovative technology present significant opportunities for cooperation on a peer-to-peer level. The British Army already enjoys strong relationships with das Deutsche Heer, albeit one based on recent history rather than on actual practice. Trinity House marks a critical opportunity to turn up the volume of the Silent Alliance so it can once again play its full and proper role in our defence against common threats for mutual and wider benefit.

11This assertion is based on analysis conducted by BLO G. However, the analysis contains significant commercially sensitive elements and cannot therefore be included.