Administrative Team

Charles D. Baldecchi, Head of School, P ’21, ’23, ’25

Todd Ballaban, Head of Middle School, P ’32

Joanne O. Beam, Director of Philanthropy, P ’22

David Gatoux, Director of Athletics

James Huffaker, Chief Technology Officer

Beth Lucas, Director of Human Resources, P ’35

Robert McArthur, Chief Financial and Operations Officer

Erica Moore, Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Mary Yorke Oates, Director of Enrollment Management, ’83 P ’12, ’15, ’18

Kristin Paxton-Shaw, Director of Marketing & Communications

Mark Tayloe, Head of Lower School, P ’15, ’20

Sonja L. Taylor, Associate Head of School

Lawrence Wall, Head of Upper School

Board Of Trustees

Rael Gorelick, Chair, P ’24, ’26, ’27, ’29

John Comly, Vice Chair, P ’28, ’30

Phil Colaco, Treasurer, P ’19, ’22, ’26

Dave Shuford, Secretary, P ’28, ’30

Mike Freno, Immediate Past Chair, P ’23, ’25, ’28

Mackenzie Alpert P ’30, ’32

Irm Bellavia P ’19, ’20, ’22, ’25

Mary Katherine DuBose P ’24, ’26

Paige Ford ’06

Don Gately P ’98, ’04 GP ’30, ’32, ’33, ’35

Stacy Gee P ’19, ’21, ’22

Anna Stiegel Glass ’01 P ’33, ’35, ’36

Donnie Johnson P ’33, ’33

Karim Lokas P ’24, ’26

Ed McMahan ’93 P ’22, ’24, ’30

Katie Morgan P ’21, ’24

Uma O’Brien P ’28, ’30, ’33

Jack Purcell P ’30, ’32

Christian Robinson P ’32, ’34, ’36

Jan Sweetenburg P ’98, ’00, 07 GP ’32, ’34, ’34, ’37

Charles Thies ’90 P ’32, ’35

Ex-Officio

Charles D. Baldecchi, Head of School, P ’21, ’23, ’25

Robert McArthur, Chief Financial and Operations Officer

James McLelland, 2024-25 Alumni Governing Board President, ’17

Kimber Morgan, 2024-25 Parents’ Council President, P ’25, P ’27, P ’29

Charlotte Latin School | Fall 2024

Editorial Director

Gavin Edwards P ’27

Associate Editor

Tricia Tam

Contributors

Lea Fitzpatrick P ’31, ’38

Alex Kern ’11

Meredith Kempert

Nunn ’98 P ’31, ’33

Athena Woodward ’25

Senior Graphic Designer

Monty Todd

Photography

William Dauska P ’24, ’27

Global Studies Department

Abbe McCracken P ’22, ’25

Lauren Putnam

St. John Photography

Angel Trimble

Sara Weiers P ’25, ’27

Rusty Williams

On the cover: Taking flight in Transitional Kindergarten

Please send address corrections to: Office of Philanthropy

Charlotte Latin School 9502 Providence Road Charlotte, NC 28277 Or email to cory.hardman@charlottelatin.org

Correction to the spring issue: Marsha Ashcraft served 26 years at Charlotte Latin.

Dear Friends of Charlotte Latin School:

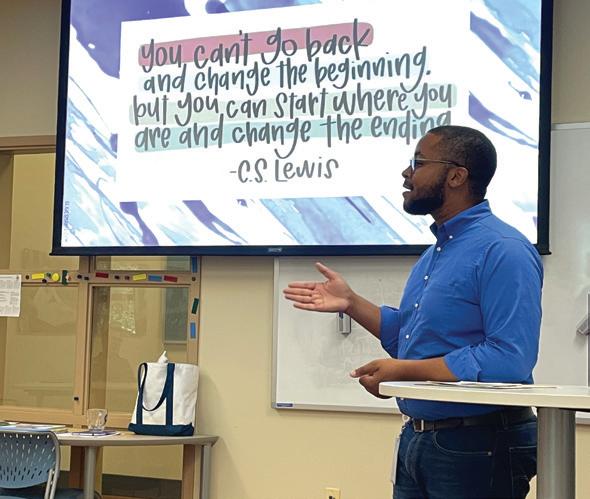

When we read a book together, it binds us more deeply. Reading requires individual focus on each page and private intellectual rigor as we grapple with an author’s ideas. But when we share our thoughts about that book, we also share the best parts of ourselves with the people around us: our insights, our passions, our disparate perspectives. That elevated conversation happens in Charlotte Latin School’s classrooms every single day, changing the lives of our students, one page at a time — and it happened on a larger scale this summer when our faculty, staff, and seniors all read David Brooks’ How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen.

Our All-Community Read couldn’t have come at a better moment. Brooks’s book offers a salve for alienation and bickering: his prescription is the willingness to recognize the complicated humanity of the people around us and to illuminate them by being curious about them. Shortly before Latin’s students returned to campus, our faculty and staff met in small groups to discuss the book. Engaging with each other in our classrooms mirrored the work of being an illuminator; it also anticipated the conversations with our students that began a few days later in those rooms.

I’m grateful to David Brooks for inspiring the people of Charlotte Latin School to think more deeply about what it means to be a community. I know that it’s not always easy to connect with the people around us: asking questions can be uncomfortable. Overcoming bias and preconceptions can be hard work, but it’s worth doing. That’s why the theme for Charlotte Latin this year is “illuminate”: the word reminds us of the value of shining the light of our attention on the people around us.

That value has always been deeply held at Latin: it’s the covalent bond between our faculty and our students. Illumination means that our teachers see the whole child, not only guiding them through their classroom work, but being there for their setbacks and their triumphs.

This issue of Latin puts a spotlight on some of the extraordinary people on the Latin campus. I want to particularly call your attention to the interview with Dr. Sonja L. Taylor, our Associate Head of School, on p. 14. She has the most elegant mind I have ever worked with and her understanding of how a curriculum works is second to none. She can take complex problems, explain them in a way that everybody in the room understands, and then find a solution that is not only adequate, but excellent.

The motto of Charlotte Latin School is Inlustrate Orbem, or “Enlighten the World.” We shine our light as brightly as we can on the people who spend their days at Latin, confident in the knowledge that they will then illuminate the world far beyond our 128 acres.

With gratitude for the light that you bring to Latin,

Chuck Baldecchi Head of School

The

John Adams versus Thomas Jefferson (1800). Abraham Lincoln versus Stephen Douglas (1858). Middle School students can now add one more election to the list of classic American democratic contests: the Oreo versus the chocolate chip cookie (2024).

This fall, in the weeks before Election Day, the halls of the Middle School were festooned with posters touting the virtues of Oreos or, alternatively, the merits of chocolate chip cookies. On November 5, the same day that their parents headed to the polls, students cast their ballots for one of

the two confections. But the mechanics of the cookie election echoed the real-world Electoral College: classrooms delivered their votes in a winner-take-all bloc, determined by a majority vote. And students needed to register to vote, signing up via a QR code — if they neglected to do so, like 118 of the 359 MS students did, they had to sit out the election and live with the consequences.

“That was the teachable moment,” said teacher Lauren Putnam, the Middle School history curriculum lead. Years from now, the memory of not getting to pull the lever for

a cookie might remind some of those students to register to vote.

The Middle School has run elections and straw polls in previous election years, trying to teach the basics of American democracy and to reinforce the connection between the Charlotte Latin campus and the larger world. Putnam said, “The students see their parents going to the voting booths, they see signs in their neighborhood, and the components of civics and history they’ve learned come to life.”

Charlotte Latin School has never dictated partisan politics to its students

— the longstanding goal has been to teach them how to think, not what to think — but this year, the school wanted to make doubly sure that real-world sectarian conflict didn’t infect the classroom. So the Middle School didn’t even conduct an informal straw poll of students’ opinions on the presidential race. Conversations about political issues, like the value of the Electoral College in the 21st century, were run on a “fishbowl” basis: students were randomly assigned a point of view and had to be ready to articulate arguments either that the system was outdated or that its merits endured. The shift from debate to discussion was a conscious effort to elevate civil discourse.

“There’s a time and a place for debate,” Putnam said. “But when students are debating, they’re promoting their argument, ready to refute the other side. We want our students to be open to new evidence, a new understanding, a nuanced way of thinking about questions.”

That approach went hand-in-hand with a broad consideration of the real-world body politic. “We’re emphasizing the importance of the ladder of voting,” Putnam said. “There’s local representation, there’s state representation, and then there’s your national federal representation. It all matters. They’re going to see

an authentic Mecklenburg County ballot: on Election Day, we’ll unpack that ballot rung by rung.”

Before they got their hands on that ballot, the Middle School got used to a new slogan: “Tuesdays We Vote.”

Three weeks out of the month, students voted through Google Classroom on a fun issue: beach or mountains, vanilla or chocolate. The last week of the month, students chimed in on a real-world issue like the legal driving age or the minimum wage. On a recent Tuesday, Putnam’s classroom voted on one of the fundamental questions of American history: whether the colonies should have seceded from Great Britain.

The plebiscite was preceded by a town-hall discussion set on the day of May 15, 1776, with seventh-grade students playing assigned roles of Massachusetts colonists, some loyalists, some patriots, some undecided.

“If we decide to go to war against the British soldiers, we’re very weak,” said one concerned landowner.

Another student, given the role of a Church of England clergyman, immersed himself in his character with an appeal to the divine blessing the Church had given the British empire: “If you believe that God is wrong,

you can leave the country, but if God is wrong, then what is right?”

“We are fine with paying taxes,” said one advocate for rebellion. “Our issue is taxation without representation.”

Reflecting either the persuasive arguments of the patriots or the historical inevitability of the United States of America, the class voted ten to five (with two abstentions) in favor of starting a new nation.

With the course of history affirmed and their own democratic skills honed, the students flooded out into the Middle School hallways, passing by cookieadvocacy posters as they hustled off to their next class. “They’re using the most powerful tool Americans have,” Putnam said. “The vote may not go their way, but on Tuesdays we vote.”

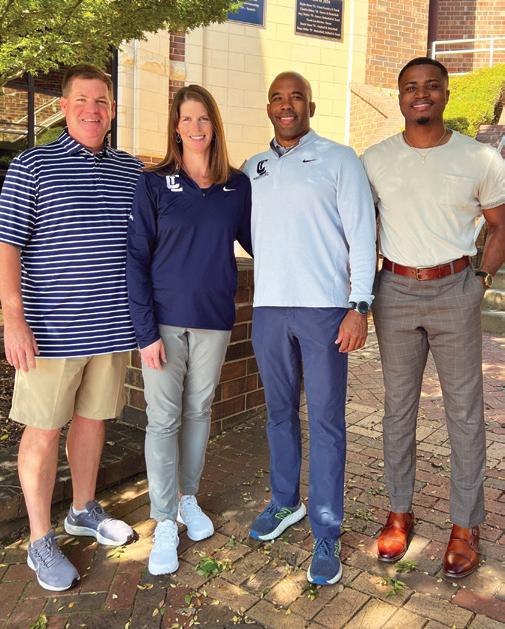

A roundtable conversation with the coaches of Latin’s varsity winter sports

Winter starts in November, at least when it comes to Charlotte Latin sports. To kick off the season, we sat down with the four head coaches of the school’s five varsity sports teams: Chris Berger (Boys’ Basketball), Giavonni Mack (Girls’ Basketball), David Paige (Wrestling), and Angel Trimble (Boys’ Swimming and Girls’ Swimming). They shared their thoughts on their new seasons, how they make teams out of multitasking Latin student-athletes, and how they like to celebrate after a big win.

What’s going to make this season different from last season?

Berger: Well, we lost some seniors who are off doing great things in their first year of college. But we’ve got five seniors returning with great experience and great leadership skills. We also have some young guys: we say that they come to us as puppies and we want to turn them into adult dogs. Trimble: We graduated 17 seniors, so our leadership is going to look very different this year. It varies every year, but I think we’ll have a spirited group — this team has traditions and a legacy. One tradition is the Tough Nut award, which was started by Patty Waldron, who was the head coach from 2008 to 2022. She went to the hardware store and would literally give hex bolts to swimmers who overcame a challenge or showed guts in a race. It’s a coveted thing and we take it very seriously: some of our kids keep their nuts on their keychains or on a backpack for years. Sometimes before a meet, I

check my inventory and realize I have to make a trip to Lowe’s.

Mack: I think the team is going to have a bit more toughness. They’ve been lifting weights, they’ve been doing speed training, they’ve been in the gym three or four days a week. At the end of the day, hard work breeds confidence. Paige: Every year is different. There’s some good competition — state championships are not guaranteed.

I’ve been here 20 years, and for 15 of them, I’ve been preparing my own son to wrestle for Charlotte Latin. When he was a baby, he’d come to practice in a stroller. He’s gone through our program and that attracted his friends and classmates, so we have a great group of freshmen coming in with a lot of wrestling experience.

Tell us how your approach to coaching has changed over the years.

Paige: When I was younger, I put more importance on winning. Over time, what I’ve learned is that the importance is in the journey, in the relationship that you have with the kids and the relationships that they have with each other. When you foster those things, the winning takes care of itself. And when you’ve coached long enough, you see kids coming back as adults, as leaders in their fields.

Mack: I’m a lot more patient. I want to help as many kids as I can, but I’ve learned to meet kids where they are and take what they can give me in availability and ability. Some kids want instant gratification: I have to reassure them that they’re doing a great job and I’m proud of them, because sometimes they don’t see the growth that they’ve gone through over the last three months.

Trimble: This is my first year as head, so I feel an increased sense of

responsibility, helping kids achieve their specific swimming goals and making sure their experience with the team is as positive as possible. I’m delegating some of the organizational parts of the job so I can give myself space to focus on the heart of coaching.

Berger: Experience is so valuable, and I didn’t know that when I was younger. All the things I’ve gone through have shaped who I am as a coach. But I’ve

always said that if the fire ever went out in my belly and I lost the desire to compete and help young studentathletes, then I’d find something else to do.

If we visited a practice, what phrase would we be most likely to hear you say?

Mack: “No one likes a quiet gym.” Or “It needs to sound like a volleyball team in here.” I’m big on constant communication. I’ve never met a team that was good and didn’t communicate.

Trimble: “Streamline” and “Don’t breathe off the wall.” Any time you’re leaving a wall in a swimming pool, you should be in a streamlined position, which means you have one hand over the other, your thumbs locked, and your elbows squeezed behind your head. You are stretched as lean and long and arrow-pointed as you can be. And when you come into the wall, we’ve trained you not to breathe into the wall, so you’re in a little bit of an oxygen deficit, and the instinct is to turn your head and get a big old gulp of air. Well, you immediately lose all your momentum. Whatever stroke you’re doing, you’re faster underwater than you are on the surface.

Berger: “Defense wins.” Or “Waste my money, don’t waste my time.” If we have a 120-minute practice, every one of those minutes is accounted for. A whistle goes off, let’s get to the next drill.

Paige: There’s usually a phrase a year. The first couple of years I was coaching, Richard Fletcher, who was the head coach, had the seniors read this book, Gates of Fire, about the Battle of Thermopylae. I thought it was a terrible idea, but when I finally sat down to read it, I couldn’t put it down. I’ve probably read that book ten times. So in 2021, I told the guys, “We’re going to burn these ships.” And when the team said that, I knew they were ready to battle.

How do you get your players to trust each other?

Berger: Spending time together establishes that trust. I love for my student-athletes to play different sports, so summertime is a great time to establish those relationships. It’s kind of clichéd, but I say that you’ve got to love each other and that I’ll do anything for you. It’s about letting young men know that it’s okay to say “I love you” — you can show your emotions in a good way.

Paige: It starts with believing in the program and trusting me. I tell them it’s going to be physically demanding. We’re going to have some bloody faces and bodies, but it hardens their will and toughens them up — and at the same time, we show them a lot of love. It’s a transformational experience.

Mack: I’m big on selflessness. Treat others how you would like to be treated, because this program is bigger than you. As a high school player, I thought the world revolved around me, and when I got to the college level, that was quickly stripped away from me. I don’t care how good you are, there is going to

come a time when you’re going to have to put your success and your accolades to the side and just worry about the team.

Trimble: Swimming’s an individual sport: it’s not like basketball, where they have to have a connection and a flow on the court. So it’s not as much about getting the kids to trust each other as it is getting them to be invested in one another’s success. If they’re supportive and attentive teammates, that energy lifts everybody up.

What’s the hardest part of coaching?

Mack: Getting these kids to believe in themselves. I see so much in these kids, and it’s not a naive thing. They sell themselves short all the time — I think at times they just don’t want to fail. I try to get them to understand that failure is fine. When you fail, you learn and you grow from it.

Trimble: It’s super-rewarding when you can help a kid get over a hump: maybe they’ve had a growth spurt and their bodies have changed, so their times are not aligning. Maybe their best stroke is not their best stroke anymore,

so you need to help them navigate that with a positive outlook. But it’s really tough when you can’t quite figure out that puzzle.

Berger: Not every day is cherries and rainbows, but you keep your head on a swivel and expect anything. There’s nothing really hard, because I love being flexible. I love helping a young man who comes to me and says, “Coach, I’m having an issue.”

Paige: In 2021, we won our tenth state title. And for probably 15 years before that, every day I envisioned winning that tenth championship. Latin volleyball had won nine in a row, and I knew that was the state record for independent schools in any sport, so I wanted to win ten. And the year after, we lost. When you’re a competitor, every year the pressure builds. It wasn’t the school putting pressure on me, or parents putting pressure — it’s the pressure I put on myself. I thought I was going to have a heart attack. That’s why I have a fish tank in the office.

Do you ever get nervous before a competition?

Paige: Always. I think that’s human nature: right before a battle, the nerves

make you feel alive. You hate it and love it at the same time.

Mack: No. Maybe some butterflies, but not in the sense of doubting myself. I’m just so thrilled and excited to get these girls ready.

Trimble: Definitely. I have a really hard time sleeping the night before states. I get nervous for the kids — I feel the anxiety for them.

Berger: Never. I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to lie. I don’t get nervous; I get anxious. There’s no reason to be nervous if you’re prepared. I don’t get vampire bats in my belly, but there might be one little butterfly floating around.

How do you work with Latin student-athletes who are doing five things at once?

Trimble: It’s a challenge. It really needs to come from the student: they need to take ownership of their schedule and communicate with their teacher, their coach, and whatever extracurricular responsibilities they may have. We’ve had some kids who do the musical and some very talented musicians in the Charlotte Youth Orchestra. As long as they plan ahead and show effort and a commitment to swim, then

we work with them. You want them to experience all those wonderful enrichment opportunities.

Mack: I ask my kids to communicate with me, and when you’re here, give me your best. If you’re not mentally and physically ready to go, let me know, even if it’s 10 minutes before practice: “I didn’t sleep at all last night, coach.” I’ll meet you halfway — I understand that a lot of these kids are not trying to play at the college level. Let’s have fun, let’s compete, let’s win some games — but not if I have to stress your mental or physical health. Communication is a life skill: you’ll have to communicate with your spouse, your kids, your boss, your employees. Berger: Flexibility, and understanding what the student-athlete is going through. When we were growing up, we had things on our plate, but not as much as kids today. In this day and age, you’ve got to make sure they’re doing okay.

Paige: I worked under a great head coach, Richard Fletcher, for 10 years. He taught me to love the school and understand all the different opportunities that kids have here. I had a kid last year who basically

took the year off because he was doing Fab Lab. That’s an incredible opportunity for a kid! You need to not only understand that, but celebrate it. When a kid has the lead in the play and he’s also doing everything he can to be at practice once or twice a week, that brings something to the table for your program. Everyone else understands, “Man, if this dude’s doing all he can to come in here and get his butt kicked, let me show up to practice.”

How do you celebrate a big victory?

Trimble: I get very emotional. I hug a lot. And then because I’m the Sports Information Director, I get to send results to the media, so I brag and post the results online and bore my husband with tales of success.

Mack: Just a lot of praise to the kids. I have a photographic memory with basketball because I’m such a fan, so I love to point out certain things that happened during the game, like a big play that changed the whole shape of the game. Helping the team remember certain things that happened so they feel confident about themselves. And I like to follow with some type of team bonding event, like laser tag or bowling: what memories can you build with them?

Paige: I can’t remember the last time I celebrated, to be honest. When we win the state championship, it’s a relief — at least I can breathe for a couple of weeks until the process starts again. I would say that I enjoy winning, but really what I enjoy is how it makes my guys feel.

Berger: I dance. If we do something well, let’s celebrate. Let’s play some of that music you like, and hopefully it’s PG-13. Do I know how to dance? Not really, but I just move my hips and I dance around and the kids seem to enjoy it.

Over the summer, the Inlustrate Orbem Building welcomed a new resident: six feet tall, piercing brown eyes, 20-foot wingspan. It’s a red-tailed hawk, rendered by Scott Nurkin ’95 for a mural titled Sky’s the Limit in the second-floor atrium Permanently in flight over the staircase to the third floor, the hawk has already become a favorite backdrop for group photos and a daily object lesson on the virtues of defying gravity.

Nurkin is a full-time muralist based in Chapel Hill, best known for his NC Musicians Murals Project. He’s merged his twin obsessions of art and music by painting murals of the giants of North

Carolina music in their hometowns: 25 so far, including jazz saxophonist John Coltrane in Hamlet, NC; singer Nina Simone in Tryon, NC; and country star Randy Travis in Marshville, NC.

“It’s a passion project for sure,” a paint-spattered Nurkin said in July, after coming down from the ladder where he had been spending his day rendering hawk feathers. “The passion is educating people on the fact that we are so lucky to have these awesome players in our backyard. It blows my mind that John Coltrane and Dizzy Gillespie were born 30 minutes away from each other.”

The idea for a series on North Carolina musicians had been germinating with Nurkin since 2006, when he painted a wall of Tarheel musical heroes in a Chapel Hill restaurant called Pepper’s Pizza, doing the work in exchange for free pizza for life. By 2019, the idea felt like a fire inside him: “I knew it was a great idea, but it was now or never — I had to make it happen or somebody else was going to do it.”

Nurkin painted many of the murals during the Covid-19 pandemic: some small North Carolina towns had extra money in the cultural budget that they could no longer spend on festivals or parades, but that could

finance tributes to their hometown heroes. (Also, it’s hard to get more socially distanced than being on a ladder 30 feet in the air.) The biggest name still on Nurkin’s wishlist: funk legend George Clinton, who was born in Kannapolis, North Carolina.

Nurkin arrived at Charlotte Latin School in his eleventh grade year. “I wasn’t a terrible kid or a terrible student at Myers Park, but I was losing interest in the things that mattered academically,” he remembered. He looked at a dozen different schools but was drawn to Latin because of the strength of its art program. “In a place like Latin, it’s not cool to have terrible

grades. You’ve got to keep up with the pack. There was a desire to learn how to take notes correctly and read and show up on time. Without Latin, I wouldn’t have gotten into the colleges I did — I know it sharpened my focus.”

He described the process of painting murals as a constant exercise in problem-solving. “There’s thousands of obstacles that seem to appear with any given mural,” he said. What were the challenges with Sky’s the Limit, which was financed by gifts from the classes of 2022 and 2024? “The staircase is completely unlevel ground,” he pointed out, “so I have to reposition myself every three feet,

which means I’m working on nine square feet at a time. And I typically work in aerosol spray paint on outdoor pieces, but I don’t want to gas out the entire building, so I’ve been using paintbrushes at the same time.”

So what does Nurkin think makes for a good mural? “Obviously, interesting subject matter, but also finding a way to use the space in an interesting way. I’m not saying that a mural of a flower on the side of a building is boring — it can be done really dynamically. But what I like to see is stuff I’ve never seen before.” He grinned. “That’s getting harder and harder to find, but it still happens constantly.”

The office of Dr. Sonja L. Taylor, Associate Head of School at Charlotte Latin School, has largely bare walls — but what keeps it from looking purely utilitarian are the bursts of royal purple upholstery throughout the room, splashes of her favorite color that double as tributes to her Louisiana heritage. That room reflects Taylor’s personality on the job: a no-nonsense, razor-sharp administrator who keeps dozens of committees and task forces on campus moving forward through all obstacles, but who nevertheless regularly erupts with joy.

Taylor has been at Charlotte Latin since 2017: her previous titles were Director of Diversity and Inclusion and Assistant Head of School for K–12 Curriculum and Instruction, Equity, and Strategic Initiatives. Before Latin, she worked as a writer, curriculum developer, and project manager in educational publishing, held diverse teaching and leadership roles at schools in Florida, Massachusetts, and South Carolina, and had a career as a professional chemist.

She’s happy to discuss her bird feeder or her grandchildren, but the conversation quickly moves to fundamental questions about the future of Charlotte Latin, which includes work on redesigning the schedule and an examination of the Lower School curriculum.

How would you describe the role of Associate Head of School?

The AHOS role is a perfect fit for my interests and skills — it allows me to serve as a thought partner to the Head of School and to help implement his vision for Latin through strategic planning, curriculum and instructional practices, and by creating relevant and engaging programming and experiences for students. I also work with the senior leadership team and our Board on

initiatives to help the school prepare for the future of education, build sustainable structures, and solve problems.

What is your day-to-day like?

It’s a bit of a frenzy, but I thrive in such environments. Like most school administrators, I spend a good portion of my day in meetings: in one moment, I may be collaborating with a division head to craft a parent communication or discussing budgets

with the CFOO; in another, I am planning a professional development day for faculty or talking to a student about how to approach a teacher about a challenge he is facing.

What are you working on now?

Lots of tasks! We are two years into Latin Leads, our strategic plan. This is an important milestone in the school’s accreditation cycle: we report on our progress and learning at the end of the second year. I am knee-deep in strategic plan implementation, working closely with our division heads and with Dr. David-Aaron Roth [Director of Student Leadership Development] and Michele King [Director of Student Support and Wellness]. David-Aaron and Michele are both relatively new to Latin and they are doing amazing work to prepare students to lead and thrive in an academically challenging environment. I am also partnering with Isa Stokes [Director of Academic Transition & Student Success] and others to design a summer bridge program that supports students as they transition to Latin from nonindependent school settings. And there’s the ongoing work of teaching and learning: curriculum planning, maintaining Latin’s commitment to excellence in the classroom, and pushing the limits of our daily schedule.

What prompted the redesign of the schedule?

Before we launched Latin Leads, we invested two years in talking to everyone — students, parents, employees, and alumni — to understand our strengths and opportunities. Over and over, across all constituencies, we learned that students needed fewer transitions and more balance in their day. Current students and alumni also expressed

As a TK-12 school, we have the luxury of establishing our foundation in Lower School and building on it. We will always seek out opportunities to improve our teaching and learning practices at all grade levels.

a desire for more advanced topics courses (distinct from Advanced Placement) that would allow them to explore interests and solve societal problems. We also learned that teachers often needed more time in class to engage in deeper learning — that the schedule could create pathways for a richer experience through advisory, plus increased access to interesting elective courses, community engagement, and other activities that complement the academic experience.

Schools examine their schedules regularly to meet student and employee needs. This practice is an essential part of our commitment to excellence and our desire to foster a culture of intellectual curiosity among all community members. Regardless of where we land with the modified schedule, the school’s prioritization of academic excellence won’t change.

When will the modified schedule go into effect?

It will be implemented at the start of the 2025-26 school year. We still have quite a bit of work to do before then.

Did anything surprise you about the process of working on the schedule?

I wouldn’t say “surprise” — I’ve been in schools for a long time and seen lots of things. Schedule changes, however, are a reminder of the

complexity of leading in schools. I am grateful for the thoughtful and creative work of our schedule design team. One of their tasks was to shadow Middle and Upper School students for an entire day. After that process was completed, one team member told me, “I was wiped out by midday!”

What motivated the examination of the Lower School curriculum?

Learning needs change over time: it’s common practice to regularly evaluate what you teach (curriculum), how you teach (instructional practices), and how you measure student progress (assessment). As a TK-12 school, we have the luxury of establishing our foundation in Lower School and building on it. We will always seek out opportunities to improve our teaching and learning practices at all grade levels. We want to ensure that our curriculum is vertically aligned and that students are prepared to meet the challenges of each grade level and from one division to the next.

How important is it that teachers get to express their own personalities?

That’s crucial. I know from experience that teachers thrive when they have the essentials: competence, confidence, a sense of belonging, and a degree of autonomy. It’s important that teachers are able to draw upon their creativity and

interests as they teach. That said, autonomy and the expression of unique personalities shouldn’t get in the way of creating a consistent learning experience for students. Individual creativity allows teachers to design fun and engaged learning journeys with reliable outcomes. As a chemistry and physics teacher, there were certain topics that I loved and others that were not as exciting. If I only focused on my preferred content, then I would have unfairly denied a student preparation for the next level of learning. As educators, we have to beware our biases.

What did you learn from the Lower School curriculum review?

We always learn a lot from a review. We had not engaged in a full audit of our practices in some time, so we were due for a deep dive. We have dedicated teachers who want students to thrive. We also have an opportunity to establish structures that position both students and teachers for success.

Part of the review encouraged teachers to evaluate their levels of competence and confidence in a number of areas. Consequently, we are considering how standards can help us achieve consistency in the classroom, without losing autonomy, and we made some modifications to our faculty performance review to more effectively measure progress toward instructional goals.

We also incorporated professional learning communities, PLCs, as a way for teachers to learn with and from each other. The Middle School successfully implemented PLCs a few years ago and our Upper School faculty use a regular gathering called Talking about Teaching as a way to engage in meaningful conversations about their practice.

Will a Lower School parent see a landmark moment when suddenly things are different?

No, not if we are doing our jobs well. Good teaching is best exemplified by joyful students who are excited about school.

Have aspects of your job overlapped with each other in ways that you didn’t expect? Everything overlaps! I can’t think of anything that I do that doesn’t have implications for various constituents. I am reminded of this fact each year when we begin work on the next year’s academic calendar. When we start and end school, when we plan breaks and professional development days, when we schedule testing and athletic events — that affects everyone.

When you were a chemist, what type of work were you doing?

I was focused on analytical and organic chemistry, particularly involving volatile organic compounds

(VOCs) and gas chromatographymass spectrometry (GC-MS) techniques. I worked with a midsize consulting firm with a diverse client base. My clients included well-known energy companies, a semiconductor fabricator that has since been absorbed by a large technology corporation, and a pharmaceutical giant. I really enjoyed that work because it allowed me to use my training as a chemist and my technical writing skills, which came in handy when I was preparing reports for both corporate clients and government agencies.

So how did you end up in education?

My employer encouraged volunteerism and I chose to spend Wednesday afternoons teaching chemistry in a local high-needs public school. Many of the students were from immigrant backgrounds and had limited exposure to professional scientists. The first time I showed up, they were like, we have never met a woman chemist, and certainly

never a black woman chemist. After numerous visits, the principal of that school asked if I had ever considered teaching as a career. I said, “My mother and almost every woman in my family teach. That’s not my path.” The principal persisted and admitted that although she could not match my salary as a scientist, the students were always talking about me on Thursdays.

My husband convinced me to seriously consider the opportunity. He said, “You’re excited about your lab, but when you come home on Wednesday, you can’t stop talking about these kids.” I decided to make the change, and it was the best professional and personal decision I’ve ever made.

My experiences as a scientist, classroom teacher, and department chair served me well when I began working in publishing. My first assignment was as a content writer on a high school chemistry textbook. Over time, I contributed to numerous science textbooks for both middle and high school students, authored several teachers’ guides, wrote biographical pieces about well-known scientists, and created standardized assessments. The publishing environment also introduced me to project management and exposed me to science curriculum design in major K-12 education markets including Texas, California, Georgia, and Florida. I eventually began my own business and still occasionally take on curriculum and assessment projects or provide strategic consulting to education clients.

When you’re hiring somebody, what qualities do you look for?

Oh, that’s easy — a balance of competence and warmth. Competence is necessary to do the job and warmth, especially as

an expression of one’s empathy for others and commitment to high ethical standards, is ideal. If a person is ethical and loves people, then they are going to always do what is in others’ best interest. I need employees who are equally committed to doing an excellent job and honoring others’ humanity.

What haven’t you done yet in your life that you would like to?

Be a college professor. That’s how I’d like to end my career.

What books have you read lately that you’ve loved?

I read multiple books at once, because something’s wrong with me, and one of them is always a memoir because I love hearing other people's life stories. I recently completed Lovely One by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. Her personal history is amazing and I appreciate how her participation in speech and debate as a high school student played such an important role in her journey to college, law school, and the Supreme Court. I also think Justice Jackson’s story resonated because my childhood desire was to become an

Justice Jackson’s debate experience was competing in science fairs at the local, state, and international level: looking back, I can see how that shaped my career.

I also recently completed Hidden Potential by Adam Grant and James by Percival Everett. I am currently finishing up Ina Garten’s memoir, Be Ready When the Luck Happens, which is fabulous!

When you go home to Louisiana, how do you reconnect?

Louisiana is my happy place! It is where I am my most authentic self. I love our culture: the language, the food, the music, the people, their energy, the stories, and the way of being. No matter how long I’ve been away, the moment I step back into that space I know that I am home. The older I get, the more I appreciate and feel connected to my ancestral heritage and that French Creole culture.

Although my grandparents were capable English speakers, their preferred (and first) language was Creole French. When I was growing up, that’s what I heard all day every

I need employees who are equally committed to doing an excellent job and honoring others’ humanity.

attorney, although my father didn’t support that career path. He believed that I needed to prove my worth as a mathematician or scientist because those careers embodied academic excellence, provided solid earnings, and defied expectations of women. He often told me, “You are an excellent math student and a good thinker. Men don’t think women are capable in that way, but you are. Do the thing that no one expects you to do.” My equivalent of

day. It wasn’t only conversational but in the church and the zydeco music that served as the soundtrack of my childhood. My cooking style is greatly influenced by the culture, especially by my mother’s family who are from the region of southwestern Louisiana known as Acadiana. I can still make gumbo, etouffee, and maque choux. However, those dishes are not the healthiest choices, so I have learned to be content with a nice, hearty salad.

By Athena Woodward ’25

Rows of seats stretch endlessly into the shadows. An empty coliseum is swallowed by an inky pool of darkness. Then with a sudden flicker, the stadium is alive and night itself has been stripped away.

At this moment, we can see the multiple meanings of the word illuminate: on a practical level, the 750-watt, 277-volt light fixtures over Patten Stadium allow the Charlotte Latin community to see each other and enjoy the action on the field. But the lights also illuminate qualities outside the visible spectrum: how our Hawks gather to support their peers, the swell of Latin pride, the way the lights make us feel when we bask in them.

For people at a Friday-night football game, from the players on the field to the fans in the stands, the massive lights mean something more than what they physically provide. Troy Logan ’27, ranked the eighthbest quarterback in North Carolina by The Charlotte Observer, explains that when the lights come on, so does his confidence, so he can “put on a show for the fans.”

Under a spotlight, we are all brought into sharp focus: our moves and expressions become magnified for the rest of the world to see. Cheerleader Darby Collins ’25 considers how the Patten Stadium lights shape her team’s performances. “We have an entirely different atmosphere

under the lights,” she says, her eyes flickering around the Quad. “Once that spotlight comes onto us, everyone is focused and ready to perform their absolute best for the audience.” She says that the cheer team’s energy changes between practice, during daylight, and at night: “Something slides into place when we are under Patten’s lights.”

With all eyes on us, we can discover new depths of confidence and display our best selves for the rest of our community. Walker Simerville ’26, baritone saxophone player, says the lights distinctly change the band’s performance. “When those lights come on, I feel like everything I am doing is important,” he says. “The atmosphere under the lights cannot be compared to anything else. They bring a unique excitement that a game at 4 o’clock could never bring.”

The lights connect us, highlighting our physical presence and emotional spirit. In shared community spaces, we can celebrate our talents, our triumphs, and most importantly, one another. But now this illumination is not limited to just one venue: Field #2, also known as “the turf field,” will soon receive high-wattage lighting of its own. The funding comes from the ongoing Honor & Glory capital campaign — but when the field was built as part of the Vision2020 campaign, Latin

laid the necessary wiring underneath the turf. That foresight will allow the school to install the lights in advance of the spring athletics season.

In the Patten Stadium press box, a room not much larger than a refrigerator, Coach Chris Berger points out how the Patten Stadium lights are identical to those in the Bank of America Stadium where the Carolina Panthers play home games (just less numerous). Set atop the press box’s platform of creaking, navystained wood is a long countertop, home to various microphones and scattered athletic papers.

Rifling through his pockets, Bob Searles, the Varsity Soccer PA announcer, pulls out a small bronze key that unlocks the Patten Stadium lighting system. “We had to hide this before, from Coach [Lee] Horton,” he says, sliding his chair toward a dark corner on the right side of the room. “He used to come in here early and want to turn the lights on, but we had to make him wait.”

Coach Berger laughs affectionately and watches Searles, who is stretching his arm into the darkness. Inserting the key into a small hole in the wall, he swiftly turns the switch just below it — and the stadium is suddenly flooded with illumination. A half hour from now, the Charlotte Latin Hawks will run out of the brick fieldhouse, through the twilight, and into the light.

Professional athlete, cybersecurity expert, public-health advocate: each graduate of Charlotte Latin School charts their own life path. We spoke to six 21st-century graduates about the work that they’re doing — in public schools and coffee shops and the farms of Virginia — and how Latin prepared them for their jobs, the unpredictable challenges of life, and the vagaries of the modern world.

E.C. Myers ’16, public relations coordinator for Conservation Partners, which helps Virginia landowners use the state’s land-preservation tax credit, lives in Lexington, VA.

When you were a kid, what did you want to do with your life?

Back at Latin, I probably wanted to be a teacher. When I was little, I wanted a pet pig, but my interest in an outdoorsy job awakened my senior year, during the “Observe and Serve” program, when I worked on a farm in Monroe [NC] for three days. I realized how much I admired and appreciated farm life. And then at Washington and Lee, I took an environmental service learning course, which was inspired by my AP Environmental Studies class at Latin. Through that, I spent time doing hands-on work at a small dairy farm outside of Lexington, Virginia. I ended up becoming great friends with the farmer and continued working and spending time there through my four years of college.

Why do you think you connected with farms?

I’m the fifth generation to grow up in our family home in Charlotte, which is super special, and so I relate to how farmers have a connection to their land.

So what does Conservation Partners do?

We’re consultants on the conservation easement process: we work with landowners to help them protect the land they love. Whether that’s farmland, a place of scenic views, a place where they like to go and hunt or fish or just spend time with their family, we help them preserve a conservation easement that protects the land from inappropriate development in perpetuity. Even if they sell the property, it will always be protected by that easement. So about half my experience at Conservation Partners is out in the field: at a podium presenting at cattlemen’s associations, or at town hall events, or at farm service agency meetings.

How receptive are those audiences to the notion of easements?

If people want to maximize the value of their property, we’re going to lose to developers every time. Developers are always going to be able to pay top dollar. If you look at Mecklenburg County, there’s only 6% of the open space left. But at those presentations, most of the time they’re there because they love their land. It’s not the right fit for some people, but there’s financial benefits: in Virginia, when you donate the development rights, you get a federal tax deduction and tax credits that people can sell for cash, while you

can continue to do the things they do on the property that they love. Earlier this week, I was visiting some landowners who were scraping by to keep their farm operating before the easement and now they’re in zero debt. Some people tell us that it paid for new tractors, or for their daughter’s wedding.

Do the Core Values of Latin still resonate with you?

Absolutely. I have such a hard time with AI and ChatGPT: it’s like using CliffsNotes. So I feel like I’m breaking the code of “Honor Above All” and it freaks me out. “Commitment to Excellence” is certainly important to me. And “Moral Courage” too: I don’t know if it’s necessarily courageous, but I’m certainly in a career where I feel like what I’m doing is for the general population, not just myself.

Why do you think you’re doing this job instead of being a farmer? I’m far too social to be a farmer, I think. I still have my dream of having pigs and cows. But if somebody isn’t out there protecting farmland, that’s not going to be an option for me or my children or future generations.

Mitchell Adams ’13 is a cybersecurity advisor at GuidePoint Security, the founder and president of Charlotte Young Professionals Group (CYPG), and a Charlotte resident.

How did you learn cybersecurity?

I did programming at Latin and then I was an MIS [management information systems] major at Alabama. When I graduated, I went to work for Goodman, and they had an opening on the cybersecurity team. I spent the first three and a half years of my career as an ethical hacker. We would drive to our clients — let’s say they’re community banks or regional hospital systems in the southeast — plug our laptops into the wall and see what we could hack into. It was a great way to learn a lot of industries really fast.

Once my boss and I visited a multinational steel company in eastern Texas. We were in a steel smelting factory, wearing hard hats. After an hour, we found something from China living in an old laptop or desktop that was on the smelting line. You can’t

update those computers because they might be mission-critical to the success of the business. We had to tell the client that we had found a nationstate threat actor in their network, and couldn’t pull the plug because they might have hooks throughout the network. We had to call in an incident response team to do the rest.

What’s the origin story of the Charlotte Young Professionals Group?

I saw there was a gap in the market for an organization that focuses on its members, run by its members. We wanted to focus on professional development, networking, giving back to the community. Our first event was the night the NBA canceled their season due to Covid. The timing could not have been more unfortunate: all we wanted to do was gather a bunch of young professionals and shake hands in the same room.

Do any of the core values of the CYPG map directly to your time at Latin?

One core value of the CYPG is community: I think about the positive impact the Latin community had on my life. That’s exactly what we’re trying to do: build strong relationships and have a positive impact on somebody’s life.

Is there a point where you’ll age out of the CYPG because you’re no longer a young professional?

We now have about 340 active dues-paying members, about 50-50 male-female. I’ve heard of a few folks getting jobs from connections they’ve made and there have been a couple of weddings too. I was doing a lot of the work at first, but we now have a board of 13 people, so I’m more of an advocate and ambassador for the program. Our black-tie charity ball is a big event: I would welcome any young professional Latin alumni to come join us. It’ll be on December 6 at the Mint Museum Uptown.

Well, our bylaws say 21 years old to 36, but we’ve never kicked anybody out for being too old.

Maggie Savage ’05, chief operating officer at EYElliance, which works to increase global access to eyeglasses, lives in Durham, NC.

Do you get more bang for your public-health buck with eyeglasses than, say, drugs for malaria?

It’s difficult to compare because the way we do cost effectiveness for malaria is you’re saving a life and so you’re valuing the full life. Whereas when we look at cost effectiveness for eyeglasses, we’re looking at the return on investment in terms of keeping people in the workforce and keeping them engaged with family. But we’re seeing returns that are almost as good as what you see with a deworming program, which is considered the most cost-effective intervention out there.

How much do you rely on the cooperation of the governments of the countries where the people who need eyeglasses live?

There have been NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] that have been working effectively for a long time on this problem. But when EYElliance was first founded, we looked at how much of the issue NGOs were really solving, and it was about 3%. So what are we talking about in terms of the other 97%? The private sector and governments, who can deliver reading glasses through their community health programs and their schools. Our approach is “How are we building the capacity of the government and the systems they already have in place?”

What’s an unexpected challenge with this work?

People don’t know how to categorize it. And there’s the assumption that this is a solved problem. So it falls through the cracks when we talk about the larger disability agenda. Most people who wear glasses don’t consider themselves within the category of being disabled or using an assistive product. But if I don’t have

my contacts or glasses, then the world is one big color cloud. I’m not quite legally blind, but I am not useful to society.

How do you think Latin prepared you for this life?

I am so grateful for the perspectives that Latin — and if we’re going to pinpoint it, the Latin History Department — provided. Having a mentor and teachers who cared, having teachers who pushed me to think about the drivers of inequities that existed in the world, and being able to have open and honest conversations about it, I was really appreciative of that. The summer after my junior year, I participated in an organization called Where There Be Dragons that gave me the opportunity to backpack with other students through rural Mexico. And visiting a camp for kids with disabilities, I saw for the first time the stark contrast where even minimal medical care wasn’t available. I remember coming back and having conversations with teachers about what it meant to grapple with those issues as you craft your own narrative and life.

What was your path after that?

I went to Duke and did my undergrad in public policy with a focus on global health policy. Following that, I took a meandering tour of domestic US health policy and worked on the rollout of Obamacare. Then I did my master’s in health policy and economics with a focus on low-income countries, a joint degree from the London School of Economics

and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. I went to work at the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and from there moved to Ethiopia for two and a half years, supporting the government on everything you need to design a functioning health-insurance system.

Tell me about a favorite day on the job.

The most joyous days are when you get the stories back about kids getting glasses. There’s nothing greater than a kid getting to see for the first time. But my favorite day happened last year at an international symposium, when we got to present a lot of the work that we were doing with community health workers in Liberia. It was incredibly validating having that panel, where an elder told her story of how she was able to reenter community, to be able to read her Bible, to text with her children, to sew for her grandkids because she could now thread the needle. And then that story reached folks in decision-making roles at ministries of health: they came to us and said, “Okay, we’re redesigning our community health package of services and we want to make sure that delivery of reading glasses is included.” That’s why we do this work. It’s not about our individual organization with the seven of us sitting at our desks, it’s about having an outsized impact by getting others to take this on in a sustainable way.

Daniel Hoilett ’11 lives in Greenville, SC, where he is an active participant in community theater and a counselor in the public school system.

Why did you switch from being a teacher to a school counselor?

During Covid, I taught second grade online and it opened my eyes to so many things happening in the home: among other things, how many grandparents were the primary caregivers. I started thinking about all the stress in families’ lives and I just wanted to help. This opportunity opened up in Greenville, South Carolina, because their ratio was one counselor for every 700 students and they were trying to lower that. They paid for our master’s degrees in school counseling: I graduate from Clemson in May, so this is technically my internship year.

Tell me about a kid who you had a rewarding relationship with. When I taught fifth grade, I tended to get a lot of students who had a bad rep. My principal said he knew that I’d be patient with them rather than just shoving them off somewhere. And one of them was a student who had a lot of very loud behaviors. If he was super-happy, he was going to make it known. And if he was super-angry, everyone knew it. But he benefited from the relationships in the classroom. I’ve always been very intentional about how we start our day. I tell my kids that if we start crazy, the day’s going to go crazy, but if we start calm, cool, and collected, then we’ll have a good day moving forward.

The last day of the year, I always read the same book to my students: The Runaway Bunny, with the message “Wherever you go, my love will find

you.” And one of the last things I let them do is what I call “final thoughts”: some of them are going to different middle schools, so I let them share anything they want.

He stood up and looked at me first and then turned to the entire group and said, “I just wanted to say thank you. I never felt more connected than I did this year.” And he apologized for some of the things he’d done and said, and I was just weeping.

As an undergraduate at Furman, you started as a theater major. What’s the overlap between theater and education?

I love that question. My first master’s is in literacy education and one of the things I like to share is how to make books come alive in the classroom and help kids want to learn and want to engage with you — and a lot of that comes with the theater arts.

Did you start doing theater at Latin?

My first show was in the sixth grade, The Best Christmas Pageant

Ever. I don’t think anyone else at Latin will remember that show, but I will never forget it. And choir was just bliss. Everybody could be having the worst day, but we came into choir for second period, and life was so much better.

How did the Core Values shape you?

The older I get, the more I have conversations with my mom where she explains some of her thought processes. Recently we talked about why she chose Latin in the first place. Without getting too religious, she felt like the fact that “Honor Above All” was at the top of every classroom door — that showed that the school was following what we believed as a family. Latin was the best way to launch me into who I am right now. Responsibility and what it means to be a good person: that’s what Latin cares about.

What’s the best advice you ever got?

Make the life that you want to live, not the life that you have to live.

After five years playing professional soccer in Australia, Cannon Clough ’14 returned to Charlotte for the inaugural season of the USL Super League as a member of the Carolina Ascent FC.

What were the pros and cons of living in Australia?

The only major con was being so far away from my family and everyone I’ve ever known. The pros, I could go on for days — that’s why I turned a one-year adventure into five years. My favorite memory is when I was in Newcastle, playing for the Newcastle Jets: my older brother Carson [’12] had a triathlon race in Tasmania, and my younger brother Cole [’18] was living in Australia for six months, and my parents came to visit. So my whole family was sitting on the beach in Australia, watching a surf competition, and I was looking around, thinking it was pretty cool and pretty surreal.

What do you think sets you apart as a player?

I’m a communicator: I like to be really vocal with my teammates and let them know what’s going on around them to make it easier for them. And on the field, I’m a workhorse. I’ve got a lot of grit and I’m never going to give up.

What’s it like playing in the first year of a new league?

When I got wind that we might have a pro team in Charlotte, it was definitely something I wanted to be part of. It’s a super-cool opportunity, and it’s also a bit of a leap of faith for all of us to commit to something like this. There’s definitely teething phases, but a lot of people involved really did the work beforehand to see what has and hasn’t worked in other leagues.

What’s a typical day like during the season?

We’re usually at the stadium from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. They have breakfast

set up there and we’ll have a team meeting that can be as short as five minutes or as long as 30 minutes, depending on how close we are to game day. They’ll tell us what our objectives are, what we’re learning at training, and then we’ll go out on the pitch and train. At the end of training, we usually celebrate somebody: we’ve got girls going through cool stuff like youth national team call-ups. Then back to the shed, shower, and we’ll usually sit around and hang out with each other; they have lunch catered for us every day. We do whatever else we need to do, whether that’s medical or speaking to coaches or going over film. And then two days a week we have a gym session in the afternoon. A game day is totally different: we don’t report until an hour and a half before game time.

How did your time at Latin form the path that you’re on?

Looking back, I’m really thankful for the structure and the focus on our academics: at a bare minimum, we’re well educated and we can have a good conversation with someone.

And the emphasis they put on being connected with the alumni is pretty special. It’s not like they produce people and spit them out in the world and never want to see them again.

Are the Core Values still relevant in your life?

“Honor Above All” sits in the front of my brain at all times, but especially if I’m making a big decision or need to have a hard conversation. It’s such a simple three-word phrase, but it speaks to being honest, trying your hardest, and doing the best you can. I know that’s not exactly what it mentions, but what it means for me is just to be a good person.

Carson Clough ’12, the CEO and cofounder of the Giddy Goat Coffee Roasters, a coffee shop in Charlotte (where he lives), won a silver medal competing in the triathlon at the 2024 Paralympic Games in Paris.

Why coffee?

It’s a social industry, a scalable industry, and an industry that has passed the test of time. I entered with little to zero experience, but the first aspect of it that I got to be part of was roasting coffee. It took my science background and my enjoyment in using my hands and put them together. As soon as I got my hands on a roaster, I was stoked. I was learning the chemistry of what a coffee bean is and figuring out how that translates into a flavor that I originally thought was just dirty water, but now I was tasting blueberry notes and things like that.

How has the experience of running the Giddy Goat differed from your expectations?

I had a huge learning opportunity, and I can genuinely say that I enjoy every aspect of the industry. I’ve had to learn how to manage, how to hire, how to keep up with inventory. I had worked in a bar and in a kitchen, but when you go from having set tasks to waking up and having to choose which things to do on your list of a hundred things to do, it threw me for a loop for a little while.

Your sister Cannon [’14] told us she was amazed at how you kept pushing ahead with this business, even when you were in your hospital bed after your right leg was amputated below the knee. While I was developing my roasting skills, I was living up at Lake Norman. It was August 2019 when I got into my boat accident. Rhyne and Lisa Davis

are the owners of the Giddy Goat, and Rhyne is the one who tapped me on the shoulder to help them get it started up. They stuck with me the whole time. I saw Rhyne the day after the accident and I said, “Hey, I’m going to be back to work soon, but I got to take a few days off.”

He said, “That’s the last thing I’m worried about right this second, Carson.”

Did competing in the Paralympics give you a more positive outlook?

From day one after my accident, I was fine. It was my job to make sure everyone understood that I was fine. I let people have their own time to grieve over my leg if they wanted to, but they only had a certain amount of time because I was ready to get back to it.

Somebody recently asked me what my one-legged life would tell my two-legged life. And the answer is that two-legged man was a wuss and I could have gotten in a lot better shape. What I’ve learned about how my body can adapt and what it can handle is very cool. I feel more limitless now with one leg than I ever did with two legs. And being on Team USA: I can’t say it was a dream, because I never thought it would happen. One of my favorite movies is Miracle on Ice. I used to watch that and visualize what it would be like to put on a USA jersey.

Do you have a favorite memory from Paris?

When I saw my family right after the race, I got to give my mom a very big hug and then my brother handed me a Busch Light and I got to shotgun my first beer in two months. Not even an hour later, I showed up at a bar and

all 50 people who had bought plane tickets from the U.S. to come watch me were there. That was way better than standing on the podium.

How did Latin color the person you are today?

Latin was the first people to give me a chance — and they gave me multiple chances. The amount of red cards I pulled in the Lower School, I don’t know why they didn’t say “You’re out of here.” It’s the ultimate shaper of me, with all the time I spent there, from the sports field to the classroom to the timeout chair. Some things that I thought were unnecessarily repetitive, now they’re good habits that have become second nature, and I am forever grateful for that.

An abridged list of the notable people who have collaborated with musician Peter Gabriel: Performance artist Laurie Anderson. Former South African president Nelson Mandela. Drummer and singer Phil Collins. And Charlotte Latin School senior Adam Stone ’25.

Gabriel, who started his career as lead singer of Genesis, is probably best known for his 1986 album So and its singles “Sledgehammer” and “In Your Eyes.” The leadoff track on his 2023 album I/O was a song called “Panopticom,” about what he called “an infinitely expandable accessible data globe,” or as he sang, “the motherlode tentacles around you.” (The title was a pun on “panopticon,” an 18th-century prison design.) The song wasn’t just a flight of musical fancy: Gabriel wanted to make the Panopticom a reality.

MIT professor Neil Gershenfeld, director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, connected Gabriel with Adam, whom he knew because of Adam’s work in the Fab Academy program. (Charlotte Latin School, through its Fab Lab, is the only high school in the world to participate in Gershenfeld’s Fab Academy, which teaches digital fabrication and prototyping skills, alongside dozens of colleges and graduate programs.)

“When I took Fab Academy my sophomore year, I came across a challenge on a global scale,” Adam says. “A big part of this course is building off each other’s work and not reinventing the wheel, but I couldn’t

really figure out which of the thousands of students had good documentation that I could reference. So I created this tool called the Expert Network Map.” Employing artificial intelligence, it classified the work of Fab Academy students into subject areas like 3D printing or molding and casting, elevating those whose work was most often referenced by their peers: this past year, it was used by over 400 students from more than 20 countries.

Building on his previous experience with worldwide data networks, Adam coded an initial version of Panopticom, visually rendering the global flow of information. “Peter was very excited with the prototype,” Adam says. “He had this idea that the personal stories were like DNA tattooed into the earth.”

The Pantopticom database emphasizes the worldwide connections of the human race. If you query it on a topic, rather than spitting out a scattered list of links like a Google search result, Pantopticom steers you to the global connections underpinning

your question. One of Adam's favorite examples: people living in Massachusetts who hear about glaciers melting in Iceland can use Panopticom to learn more about how rising sea levels will affect them in New England. But Panopticom would also inform them about how climate change has affected impoverished communities in Bangladesh — and the human stories of women there who are responding to that crisis.

In August, accompanied by a Latin coterie that included Tom Dubick, Chair of the Innovation and Design Department, Adam attended the twentieth International Fab Lab Conference and Symposium, held

at the Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla in Mexico. He attended a workshop about growing leather from cellulose, climbed the Great Pyramid of Cholula, and presented the Pantomicom prototype along with project manager JMM Molenaar and (in a recorded video) Peter Gabriel.

Topics of feedback after the presentation: how to make sure the Panopticom doesn’t become a conduit for misinformation, how to make sure people will be able to pick out meaningful threads from the tapestry of global information, how to use the software to track supply chains, both for Fab Labs and for disaster relief. The response was positive enough that Adam is already working on version 2.0.

Presenting to a thousand people in a packed auditorium might have been nerve-wracking, but Adam explains that he was well-prepared by his experiences at Latin, both on the speech and debate team and acting in plays. It’s easy to believe, given that he says it confidently, with plenty of eye contact, and in a well-formed sentence. His notable onstage roles at Latin include Lord Farquaad in Shrek the Musical and Admetos in the recent production of the Euripides play Alkestis. In college, he hopes to major in computer science and engineering, with a minor in musical theater. Where do his interests overlap? “A big part

Building on his previous experience with worldwide data networks, Adam coded an initial version of Panopticom, visually rendering the global flow of information.

of engineering and computer science is being able to present your ideas and your thoughts in a clear way.” Those are also necessary skills for public advocacy. “I have Tourette’s,” Adam says. “It’s on the mild side, but it was more prominent when I was younger.” (Tourette syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by involuntary verbal or physical tics.) For the last five years, Adam’s gone to Capitol Hill as a youth ambassador for the Tourette Association of America, lobbying members of Congress for funding into research and support for telemedicine.

“I learned about the challenge when people who have more severe Tourette’s are at a traffic stop,” Adam says. “If they’re jerking their arm or making a loud noise, the officer can think they’re intoxicated or aggressive and that can really escalate.” The current solution to that problem is to carry a card in your wallet describing Tourette syndrome — but reaching into your pocket at a traffic stop may be difficult or can be

misinterpreted by a police officer.

So for his final Fab Academy project, Adam came up with an electronic device that a driver can mount in the rear window of a car and turn on at a traffic stop to display the message “Driver Has Tourette Syndrome” — preserving their privacy in a way that a bumper sticker wouldn’t. He calls it the Tourette Syndrome Automobile Kit, or the disability forewarning system. “I created 20 free units of the lowercost version and I’ve shipped out 16 of those so far to people in North Carolina and South Carolina who want to use them,” he says. “I’m excited to hear feedback on how they’re working and what I can do to revise it and help people who need it.”

And in the long term? “I’m really passionate about making these assistive technologies to help people,” Adam says. “I want to be a thought leader in creating cutting-edge technologies to help better the lives of people with disabilities.” He grins. “And I want to keep exploring.”

Standing under a tessellated sky of brightly colored ceiling tiles and speaking over the soundtrack of a student-composed Spotify playlist, Upper School art teacher Richard Fletcher welcomes students to his classroom. They flow in from the hallway, retrieve their works-inprogress, and perch on wooden stools around the room. Without being told, they eagerly resume work on their sculptures, their drawings, and their paintings.

As a lifelong artist and a teacher for over 30 years, Fletcher has put creativity first in his own life. “One of the things that bothered me most was going to an art school and seeing painters sit in front of a painting and try to copy it,” he says. “The intention is to master a technique, but you might be killing the creativity and curiosity!” He understands the temptation for

schools to set up a rigid curriculum, but he and his colleagues at Charlotte Latin believe it’s best to awaken students’ creativity first and then teach them the techniques necessary to tap into it: “The biggest frustration that an artist can have is when they have a vision, but lack the skill to achieve it.”

His eyes flicker to the left: a student has approached his desk, holding up her painting of a jellyfish in the depths of an ultramarine ocean, “So right now if you squint your eyes, you see it’s all the same values,” he tells her. “All mid-tones, yes?” Through narrowed eyes, she nods in agreement. “If you pop that with highlights and lowlights,” he says, gesturing at the thin tentacles, “you’ll get the three-dimensional effect that you were wanting.”

Charlotte Latin School is hallowed ground for Fletcher, and not just because his room in the Science, Art, and Technology Building is an enclave of creativity. He graduated from the school in 1985; he began his professional career here; he has been a coach in the Latin wrestling program for many years; he met his wife Tiffany (an Upper School English teacher) on campus; their two children now attend Latin. Tiffany affectionately calls him a “renaissance man”: his roots at Latin are deep, but he has traveled widely and his interests span the globe.

Although Fletcher has deeply immersed himself in art for many years, it wasn’t originally the direction he had planned. “I was in college and had finished my Ancient History degree my junior year, and I was like, ‘Dad, I’m the worst historian who’s ever graced the halls of

Chapel Hill,’” Fletcher recalls. He pauses to laugh mercilessly at his younger self. “I was terrible. I really was! And my dad said, ‘Why don’t you get your studio art degree? You always loved studio art.’”

He stops cold. “And that’s where everything changed. It was like I had been swimming upstream for so long — now, the pressure of the world was off.”

That semester, Fletcher signed up for a class with professor Marvin Saltzman, a renowned American painter and printmaker. At a loss for subject matter, he labored for weeks over his first canvas: “A hobbit sitting on a tree stump.” When he displayed it at the class’s first critique, Saltzman walked by the painting, dismissed it with three words (one of which was an expletive), and continued without breaking his stride.

“This portly 60-something-yearold man,” Fletcher exclaims, “who was bald on top with crazy white hair that stuck out to the sides like Bozo The Clown!” He remembers how Saltzman’s cutting, matterof-fact criticism reduced many of his classmates to tears. So for his next painting, he found a new subject: Saltzman himself, angry and finger-pointing. Fletcher twists his expression and contorts his face, mimicking how he painted Saltzman those years ago.

Saltzman loved it. “Loved it,” Fletcher reports.

It would have been easy for Fletcher to abandon his new commitment to painting, but Saltzman had stoked his determination. “As a wrestler, it was a confrontation. Like,

‘I’m not gonna lose this one,’” he recalls. Was Saltzman testing his resilience? His reaction to adversity? Decades later, Fletcher thinks it was nuanced: Saltzman was assessing his openness to new information and his willingness to learn.

While Fletcher’s early work was more figurative, employing symbols and weaving iconography from his interest in ancient history, his new work is the opposite.

At the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, his friend and former student Justin Rivenbark ’99 came to him with a manifesto, which detailed six principles of “Rootist” philosophy: for example, “With each mark made the creator is encoding information about their subjective experience onto a surface.” The most important principle of all? The use of symbols is prohibited.

Fletcher was intrigued. Quarantined at home with surplus time, something he had been lacking, he

gleefully leaned into the unknown. “You just start making marks,” Fletcher says, “making marks and making marks. Do I like that here? Does it go there? What if I add this color? Does it go here? Do I want to subtract that?”

Through countless presentmoment decisions — a technique that differentiates Rootism from automatism, intuitive painting, or the action painting of abstract expressionism — a visual map of the artist’s consciousness emerges. “This is data. Data about me.” Fletcher says, “It’s a snapshot of me in a moment of time.”

As a two-way communication, Rootist art extends an invitation to observers to be fully aware and willing to feel. It’s not art for art’s sake, but art as communication between creator and viewer.

“It’s totally an internal analysis and you can’t be worried about anything else,” says

By Richard Fletcher