There are sailboats, and there are Skerry Cruisers. With their spectacular elegance and with a peppered history as only boat types that tend to extremes can have. This also applies to this unique SK30 Tre Sang. The legendary Englishman Colonel “Blondie” Hasler, for example, bought her in November 1945 and sailed the ship from the south coast west wards around Land’s End into the Bristol Channel in a ‘mild if wet November’. Between November 1945 and August 1946, Tre Sang left more than 2,600 nautical miles in her wake on the open sea without any significant difficulties, winning race after race. Tre Sang was built in Sweden in 1934 according to plans by Harry Becker, but certainly not for this purpose. How

ever, even in her early years in Sweden, she was one of the fastest and most successful 30’s until she was sold to England in 1938, the first ever Skerry Cruiser to do so. She sailed with various owners in Sweden, Eng land and Wales as well as with her current owner, first on the Bavarian lakes, then in Uruguay and, since 2009, on the Baltic Sea with her home port in Flensburg at Robbe & Berking Classics. This boat was never renamed; the name means something like “a particularly good hand at cards” in Swedish. Even as developments in yacht building continued, the “Skerry Cruiser” remained as they were: long, narrow, elegant, wet and fast. Timeless and always popular, even today.

It seems unbelievable that we have never to my knowledge – in 35 years of publishing – really tackled the subject of yacht interiors. There have been interviews with designers over the years and we once gave an award for the best interior as part of our annual awards in 2015, to the schooner Altair. Given that the interior of a seagoing yacht is by far its largest liveable space, contains nearly all the boat’s volume and is the place where a crewmember will spend at least half his or her time at sea, and given how much effort and expense goes into creating a good interior, and how much sailors love them, this seems quite an amazing omission. Just as amazing is the fact that no reader has ever asked us to tackle the subject of yacht interiors. Not one! Well, like it or not, we’ve dived into it this month, with a brief look at the history of yacht interiors, and a list of guiding principles from experienced bluewater sailor Roz Cunliffe. And on the subject, you might like the cosy below-decks of our lead yacht this month, Constance (page 4). A cosy bolthole for when autumn skies thicken...

COVER STORY

. CORNISH NEW BUILD

new 34 wooden yacht in the manner of a Falmouth quay punt

. 12-M CLASS CLASH

from Flensburg, Germany

. CORK WEEK

yacht racing in Ireland

. YORKSHIRE ROSE

19th-century Voluta, once the cock of the eet in Yorkshire

. KEEPING THE HERITAGE

Gail McGarva and her mission to preserve working boat history

. BOSUN’S BAG

the diesel

. POLYMATH OF POTTERING

story of Victorian yachtsman and

the proli c FB Cooke

STORY

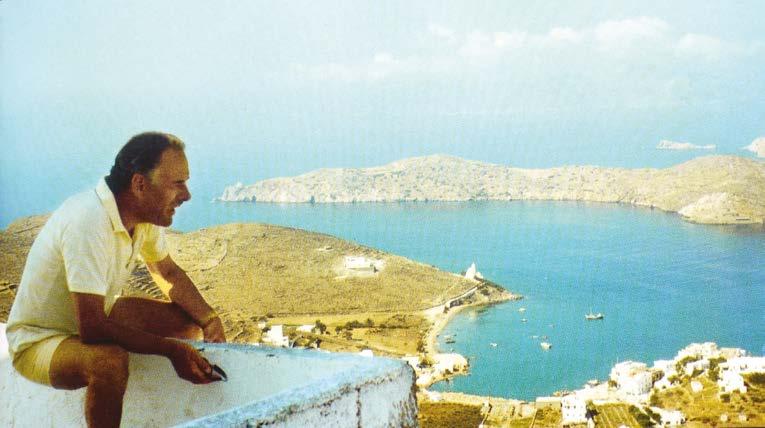

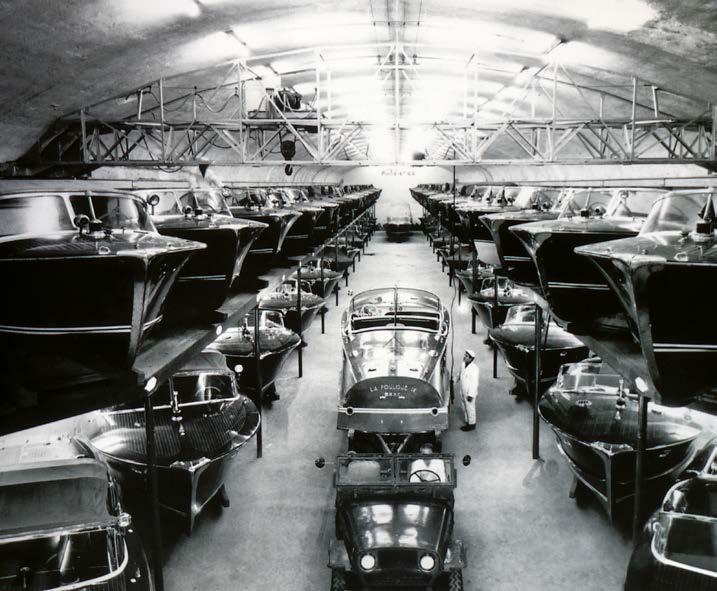

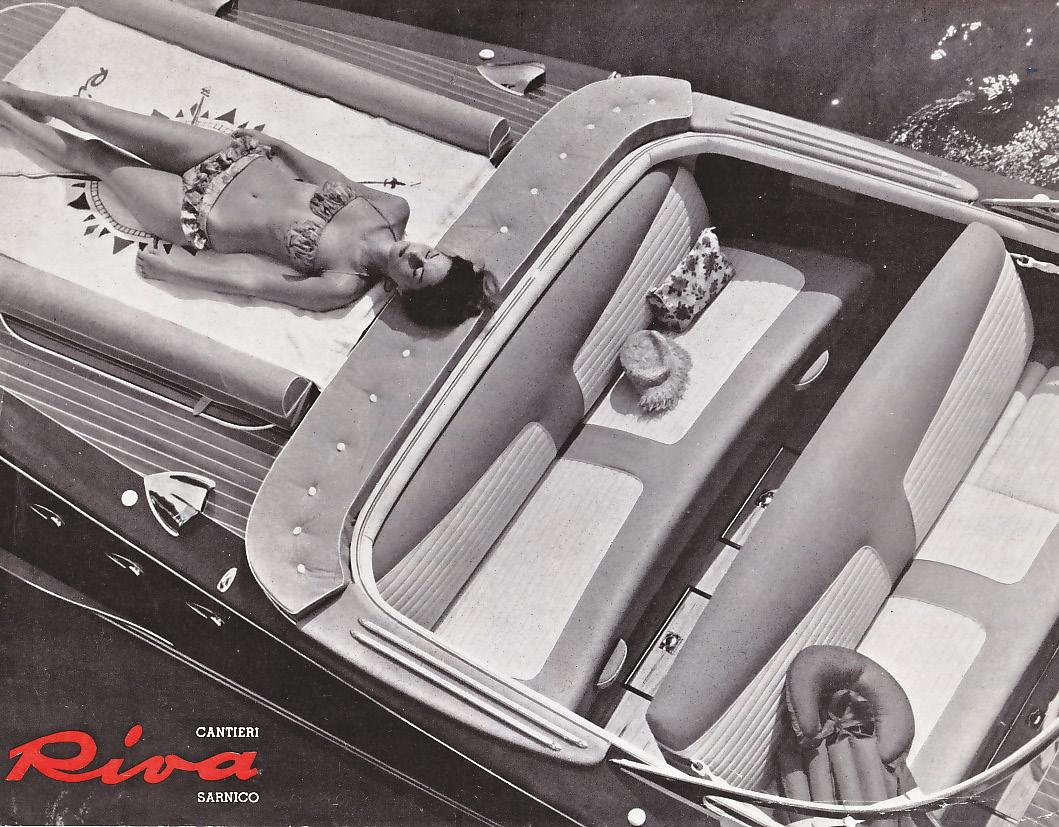

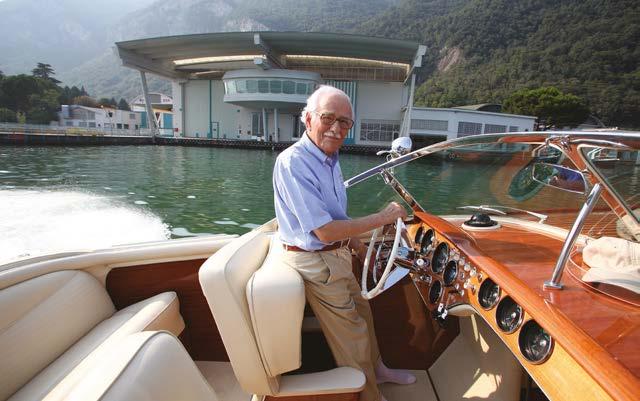

. RIVA CENTENARY

legacy of Carlo Riva and his fabulous boats, a century a er his birth

STORY

. YACHT INTERIORS

inside story

TOM CUNLIFFE

. PARTY TIME

rum to stun a bu alo, followed

a WW2 commemorative sail

. FATHER-AND-SON TEAM

Riva’s yard in Maldon, Essex

TELL TALES

SALEROOM

OBJECTS OF DESIRE

CLOSE QUARTERS

WORDSAND PHOTOS NIGEL SHARP

WORDSAND PHOTOS NIGEL SHARP

have to have a passion for wooden boats and be slightly mad to commission a brand-new one these days,” said Simon Wisker, owner of the new gaff cutter Constance. “You are making a personal investment in preserving traditional skills without getting it back in financial terms.”

Simon began sailing in the early 1970s when his father built a Mirror dinghy. For several years he and his family sailed this boat, and then later a Wayfarer, in Poole harbour near their home, and also on family holidays on the Percuil River, near St Mawes in Cornwall. Having continued to sail a bit at university in Exeter and then in Aberdeen, he built a 14ft (4.26m) clinker dinghy and took his own children sailing in the Lake District and on the west coast of Scotland. Ten years ago, retirement brought him back to Exeter, from where he went on holiday to St Mawes, which is where his interest in gaff cutters began.

Seeing the 1895 Falmouth working boat Florence on the harbour beach having a scrub in readiness for Falmouth Sailing Week about 10 years ago, he chatted to one of her skippers, Bill Handley. Florence belongs to a syndicate, and when it became apparent that there was a share available, Simon agreed to buy one. This resulted in frequent journeys between Exeter and St Mawes, and Simon often found himself leaving his crew mates to enjoy a post-race beer or two in St Mawes Sailing Club while he drove home.

He and his wife Kay briefly considered buying a small holiday cottage in St Mawes until he began to think that the answer might be to have a boat, maybe even to build a new one. He initially envisaged a boat small enough to sail on his own, something like a 20ft (6m) Mevagissey tosher, and camping on board under a boom tent. “But Kay said that she didn’t really want to camp on a boat,” said Simon. “She wanted something bigger that was really comfortable for her and the dog.” Although he started to look at the possibility of buying a secondhand boat – including, at one stage, a Bristol Channel pilot cutter – it wasn’t long before he found himself going in a different direction.

Below: Constance under construction at Gweek Classic Boatyard

Facing page: Constance under sail o St Anthony’s Lighthouse

Inset: Ben Harris making the point that Constance can sail herself

For some time Simon had been following the career of boatbuilder Ben Harris, and might have been interested in his appeal for volunteers to help build the Ed Burnett gaff cutter Panacea (CB366 to 372) were it not for the distance between Exeter and his workshop near Falmouth. Simon contacted Ben who told him that Alva, the gaff cutter, which he had built for himself in 2011 (CB286) was for sale. “We went to look at her and could see that she was a lovely boat,” said Simon, “but Ben convinced us that she would be no use to us at all and what we really needed was a brand-new boat, which he could build.”

Some time ago Ben took the lines off Curlew, the Falmouth Quay Punt made famous by the ambitious exploits of Tim and Pauline Carr, and had made no secret of his desire to build a boat to these lines. But at 28ft (8.5m) LOD she was quite a bit smaller than the boat that Simon and Kay now envisaged – it was becoming apparent that their accommodation needs would necessitate a hull more like 34ft (10.4m) – and so naval architect Jack Gifford was brought in to help with the project. Jack put Curlew’s lines on his computer, and analysed some of her key parameters such as her shape, ballast ratio, and centre of buoyancy coefficients “just to try to see why this boat had proved herself as such a well-behaved sea boat, and to try to characterise her shape,” he told me. When he initially scaled up the lines to 34ft he found that this resulted in too heavy a boat. “So she required a bit of pairing down in the mid body section to bring her back to around 12 tonnes, which is what you would want a non-working gaff cutter of that size to displace,” he said. He also used various characteristics of Alva and the Ed Burnett Ivy Green, which were reference boats that Simon admired. Jack drew the sail plan but with input from both Simon and Ben, “with no particular reference yachts but just trying to pull in ideas from various rigs we had seen.”

The question of where to build the new boat soon resolved itself when Ben found out that the shed at Gweek Classic Boatyard, in which he had been temporarily storing Alva, was available for a longer term.

During Simon’s earliest discussions with Ben, he made it clear that he would like to play a hands-on role in the build of the boat. It took a little while before they agreed how that should work, but then Simon’s involvement began at the very beginning, with the lofting. Initially Jack thought that he would provide CAD drawings for the moulds and so on, and so it wouldn’t be necessary to do any lofting, but Simon was particularly keen to do much of this himself, albeit under Ben’s close supervision. As it turned out, it was of great benefit, because Ben, Jack and Simon were able to look down at the full-size lofted lines from a mezzanine floor, from which they could see some small imperfections and from which they all agreed that it would be advantageous to make small modifications to the sheer and the freeboard. “It was definitely a collaborative process of design, which was very enjoyable,” said Ben. “It was a real pleasure to do that,” added Jack. “It isn’t always possible but, as Ben must be

the absolute closest boatbuilder to my house, it was quite easy to do so!”

Constance’s hull was built from oak and larch. Oak was used for the keel, stem, sternpost, deadwoods, sawn frames, steamed timbers, the garboards and the next four planks up, and the sheer strake and next plank down; the remaining 14 planks are larch, all of them full length.

Ben had sourced the oak for the keel (max width 22in x 8in) about three years previously from SH Somerscales in Grimsby, and much of the other oak had been sourced even earlier than that, locally from the Tregothnan Estate on the banks of the Truro River. About three quarters of the sawn frames are in single futtocks. “We had exactly the right shapes to be able to do that,” said Ben. “So that makes her lighter as well as stronger.”

Throughout most of the length of the boat there are three steamed timbers (2in x 1¼in) between each pair of sawn frames but in the mast area, where there is a greater concentration of sawn frames, there is just one. Simon remembers going to Somerscales “with a tape measure and rough drawings on the hottest day in 2019” to select the larch to be used for the planking. The majority of planking is 1¼in thick and the sheer strake is 1½in. Everything was fastened with aluminium bronze bolts or copper clenches.

Ben and his team cast the five-tonne lead keel themselves, pouring the molten lead into a wooden mould bound with steel “to make sure it wasn’t going to burst open or anything – it looked like some kind of Gothic horror sarcophagus buried in the ground.” They happened to do it on a really hot day and Ben said “it was like being in the pits of hell.” Afterwards they complied with a long-standing boatbuilding tradition by rewarding themselves with a barrel of beer. The ballast keel was bolted to the wood keel with 10 x ¾in aluminium bronze bolts into galleries in the lead.

The beamshelf (6in x 2in amidships and tapering at the ends) and the deck beams (laminated for the coachroof and solid for the foredeck and side decks) are all oak. The deck itself consists of two layers of ½in yellow cedar (the lower one fore-and-aft, the upper one at 45 degrees, and glued together with resorcinol), sealed on top with glass and epoxy, and then with a 5/16in

Above: Fitting the shutter plank

Below: Finishing the deck details

Facing page, clockwise from top left: The teak for the decking was reclaimed from a 1920s cruise ship; Ben Harris’s builder’s plate; Traditional teak skylight over the saloon; The Fife rail around the mast; The forepeak; View of the galley from the chart table; Mainsheet block; Goosenecks

thick laid teak deck with oak covering boards. Ben favours this sort of subdeck rather than plywood as cedar is “more or less impervious to rot, and if you have any water ingress, it is always localised. It doesn’t spread through the solid wood, unlike plywood which tends to wick moisture through its many layers.”

The teak for the decking, the 1½in thick coamings and for the traditional skylight on the coachroof, had been reclaimed from a 1920s cruise ship which had been scrapped. “I chanced upon a local chap who had been bequeathed a load of it by his dad,” said Ben. “He had used most of it to floor his entire house and I offered to remake his floors in oak in return for the teak, but he said it was too much hassle.” But he still had a number of unused 15ft x 5½in x 2½in boards, which Ben was able to buy from him, albeit with some former fastening holes and ingrained iron stain in them, some of which is now visible in the skylight. “But I think that’s fine,” said Ben, “because it tells a story of where it came from.”

Although Jack produced comprehensive drawings for the interior design, “quite a few alterations were made in situ with Simon just holding up bits of wood in different places and just sketching it out on bits of wood,” said Ben, “to make sure that everything would be comfortable just for them.” The layout from the companionway going forward consists of the chart table to port (with an oilskin locker aft of it) and galley to starboard; seating to port and starboard with a folding table between, a pilot berth outboard to port and bookshelves outboard to starboard; a wood-fired heater to starboard and then a passageway with the heads compartment to port; and then the fo’c’s’le with a berth to port and a wide shelf to starboard. All of the interior joinery is made up of oak and white painted tongue-and-groove larch, and has a light airy feel to it. Constance’s interior generally feels surprisingly spacious for her length and has comfortable standing headroom throughout.

The engine is a Beta 35hp diesel; the engineering and electrical installation was done by Andrew Cox Marine, the instrumentation by BT Marine (Electronics); the stainless steel water and fuel tanks were fabricated by Keefe Engineering, and the Hobbit stove was supplied by Salamander Stoves in Devon.

Ben and his team also made the spars, all in Douglas

fir with a hollow gaff and the others solid. John Albrecht made up the rigging and many of the stainless steel fabrications; Colin Frake supplied much of the galvanised hardware and the blocks; the self-tailing winches are from Australian company Hutton Arco and many other deck and rig fittings came from Davey & Co and Toplicht. The sails are by Ratsey & Lapthorn. Throughout the build of the hull, Simon spent two or three days a week working with Ben and his core team of Pete Paxton, James Pardo and Josh Neely “doing whatever I was told to do”. But 11 days after the shutter plank was fitted the first Covid lockdown began and, as Simon’s circumstances then put him in a medically vulnerable category, that forced the end of his hands-on involvement. “As I am a perfectionist I was initially concerned that I would be frustrated not being involved in the build,” he said. “But whenever I managed to visit I was never disappointed with the workmanship or the decisions Ben had made. I completely trusted the way he and his team worked.” With the intention of remaining at least remotely involved, Simon planned to build Constance’s clinker tender but, after losing his workshop when he and Kay sold their house, he was unable to do so. The tender was then built by Josh, alongside Constance. Constance’s build started in September 2019 with an original plan to launch sometime in 2021. However, Covid restrictions and consequent increases in lead times for materials and equipment held things up, and

Above, left: Launching at Gweek in the rain

Above, right: Early sea trials

Below, left: Simon (grey tee) on the helm with son George (yellow tee) and boatbuilder Ben

Below, right:

Under way in light winds

so a decision was made to “slow down and get her done properly,” said Simon. She was eventually launched on a rainy day in May 2022.

When I asked him about his plans for Constance, Simon seemed embarrassed – and unnecessarily so – to admit that he hasn’t got anything particularly ambitious in mind, at least not in the immediate future. He sensibly realises he has little experience handling a boat of this sort – Florence is about half the size in displacement terms and, although he regularly crews on her, he only occasionally takes the helm on the way to and from races – and so he sees the first season or two as a time to slowly get to know Constance before he starts thinking about going further afield. He is mindful of the fact that Kay “isn’t a super keen sailor” and so, in addition to sailing plans, he is looking forward to “just being aboard – with the wood burner on it is fabulous to be in that cabin,” he said.

What will be of great benefit in getting to know Constance is that Ben has gone to great lengths to make her as easy as possible to sail shorthanded. She is a well-balanced boat and so it is possible to carefully tie the tiller to a windward winch and then leave her to sail herself in a straight line for significant periods. Tacking singlehanded is relatively straightforward with a little practice and Simon’s confidence with that is already growing. One thing is for absolute certain, and that is that wherever he takes her, near or far, he can hold his head high – very high – with pride.

A total of 10 of the best 12-Metre yachts on the Baltic circuit, including nine classics and one modern 12-M turned out in Flensburg for the annual Robbe & Berking Sterling Cup recently.

Besides the 12-Metres, the organisers always invite a selection of other yachts such as Dragons, 6-Ms and 8-Ms but this year in addition, thirteen 5.5-Ms sailed the class Open German Championships, and a dozen classic Rivas provided an extra classic atmosphere.

For years, the top five or six of the Baltic 12-M fleet has been a fairly evenly matched group but with the Olin Stephens-designed Vim from 1939 regularly topping the list as the winner. However, this year newcomer Northern Light not only shook up the competition but has also given fresh impetus to the already immensely popular 12-M scene in the Baltic.

Together with the tune-up races in Dyvig, Denmark the weekend before, no fewer than 16 races were sailed. With so many closely-matched yachts in this class, the lead changed constantly throughout the races, but over the course of the event it became clear that Northern Light had somehow found an edge in boat speed and tactics, resulting in four firsts, two seconds and one third.

Like Vim, she was built by Nevins in New York and designed by Olin Stephens. She is a year older than Vim, but clearly already steeped in Stephens’ design genius. She was only the second 12-M designed by Stephens, the first being her almost identical sister ship Nyala. Another newcomer that performed well was Nini Anker, formerly known as Siesta and built in 2015 by Robbe & Berking to a design by Johan Anker.

Part of the strength of the growth of the Baltic 12-Metre fleet is because racing is mainly done with amateur sailors and the owners helm the boats themselves. The support of Patrick Howaldt (the owner of Vim and vice-president of the International Twelve Metre Association) and Oliver Berking over the years in various projects has of course contributed significantly to the growth of the class.

The racing for the Sterling Cup was much more exciting than the Low Points Scoring System indicates. In the final results for example, four of the nine yachts had scored a first place. In many races the di erence between first or second place was a matter of seconds. But there is no doubt that Northern Light was the deserved winner with only 13 points over nine races. Nini Anker was on her heels with 17 points and Vim in third place with 28 points. It should be mentioned that Vim’s end result was seriously hampered by the fact that a crew member was injured in race two and she withdrew and did not start the third race that day.

The 2022 edition of Volvo Cork Week held in July in Crosshaven saw 192 boats taking part in a full five-day programme of racing inside and outside Cork Harbour.

Racing took place on five separate courses with 14 di erent classes taking part, including the Classic Class, which enjoyed tremendous sailing in Mediterranean conditions on a series of windward/leeward courses o Roaches Point. A total of 18 classic yachts attended the regatta with nine entering the racing including two Cork One-Designs: Elsie owned by Patrick Dorgan and Jap, which was helmed by Harold Cudmore for the week.

The 2022 classics regatta was the result of the postponed Cork 300 event, which had been scheduled for 2020. Colin Moorhead the Admiral of Royal Cork Yacht Club at the time felt there was an opportunity to capitalise on a burgeoning classic scene in southern Ireland. “The Atlantic Yacht Club in France had committed to a ‘Go to Cork’ initiative for 2020 and were keen to finally make it happen in 2022. “Our event in 2022 was very much a toe in the water but it was a great success and certainly bodes well for the future. We hope to make an announcement soon about a stand alone Cork Classic Regatta for 2025.”

JJ Ollu’s French classic Bilou-Belle, from Atlantic YC, won the Classic Class by just two points from Patrick Dorgan’s Cork Harbour One-Design Elsie. Third was Dafydd Hughes’ Welsh S&S 34 Bendigedig, which also won the Prince of Wales 300th Anniversary Trophy. “The Prince of Wales Trophy is going to Wales!” commented Dafydd Hughes. “If the weather systems allow me, I will be racing Bendigedig around the world in the 2023 Global Solo Challenge.”

Other notable yachts at the regatta included local boat Lady Minn from Schull Harbour Sailing Club owned by Simon O’Keefe and Erin from the Royal Cork Yacht Club owned by Terry Birtles. Although not o cially in the Classic Class, the imperious Ron Holland-designed IMP looked glorious all week.

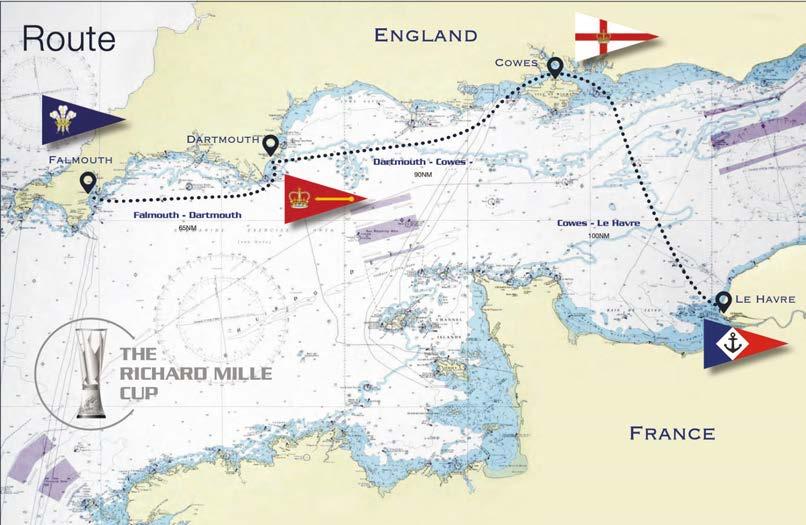

The first Richard Mille Cup will take place in 2023, with racing for classic yachts on both sides of the English Channel.

Entry will be open to “invited owners and charterers of yachts built before 1939 or faithful replicas of such yachts. The minimum size of any yacht eligible to enter will be 10m length at the waterline”.

It will be raced under the CIM handicap system, one of the first times CIM has been used on the English side of the Channel. All yachts entering will have to provide a valid CIM certificate.

There is also a new cup being prepared for the event. The Richard Mille Cup is a perpetual trophy standing a metre high. The winner will be presented with a 40cm high replica also made by Garrard.

The announcement comes after the setting up of a classic boat hub in Brest, France, earlier this year, with impetus coming from the new owner of Moonbeam IV (1920), Richard Mille, the owner of Mariquita (1911), Benoit Couturier, together with the owner of Moonbeam III (1903), who have all moved those boats to the Breton port, with French sailor Jack Caraes as team manager. William Collier, managing

director of GL Watson & Co, who was instrumental in the boats changing hands, is consulting on refit and restoration issues.

Luxury watchmaker Richard Mille sponsored the Fife Regatta earlier this year and this new event was inspired by the port-to-port nature of the Fife Regatta, as well as by the 'Fife at the Squadron' event that followed it, with spectacular racing in the challenging conditions of the Solent.

“The driving motivation is to create a challenging sporting event with competition through a range of inshore and o shore races," organisers said. "It is being created by a classic yacht owner for qualifying yacht owners. It is recognised that the di ering racing formats will provide very di erent challenges for the yachts and the Cup will recognise all-round performance through the whole series."

This inaugural series is being organised with the Royal Yacht Squadron, the Royal Cornwall Yacht Club, Royal Dart Yacht Club and the Société des Régattes du Havre. Entry will be by invitation and expressions of interest are welcome. richardmillecup.com

Falmouth, inshore racing: Royal Cornwall YC reception on Sat 10 June, with three days of inshore racing.

O shore race, Falmouth to Dartmouth, 65nm: depart Wed 14 June, Dartmouth dinner on Thurs 15 June.

O shore race, Dartmouth to Cowes, 90nm: depart Fri 16 June. Break in racing in Cowes. Cowes: Royal Yacht Squadron reception Mon 19 June, then three days' Solent racing, possibly with a race around Isle of Wight.

Cowes to Le Havre, 100nm: Société des Régattes du Havre welcome + prize-giving.

British-flagged Kismet (pictured above) won the 11th edition of the Gstaad Yacht Club's Centenary Trophy, the rendez-vous at Les Voiles de Saint-Tropez for classic yachts aged 100 years or more. Kismet, built in 1898 and famously one of the houseboats pulled from a mud berth on the English east coast, was skippered by owner Richard Matthews. The boat is the first Fife design to have won the race, having entered twice before, each time making the podium. Second was the Herresho Bar Harbor 31, Scud (1903), owned by Patrizio Bertelli, with Torben Grael calling tactics, while third was another Herresho , the NY30 Oriole (1905), sailed by a Spanish crew.

An elated Matthews said: “We are very happy. The boat went perfectly we never had her going so fast windward. The course was perfect and we had enough wind. It was just a perfect sail. We were looking back and kept saying: ‘Where are they?’. We saw Scud coming up fast but we thought we had enough time. The key moment was when we decided to change the small jib to a bigger one. We have got a great crew, very good sailors.”

Kismet is coming up for her 125th birthday next year and Matthews said he would love to return to defend the title.

The Centenary Trophy is raced in a pursuit format, with the

'slowest' boats setting o first. Consequently the finish is often close. However, this year Kismet, after starting seventh out of 22, was ahead of the rest in three minutes and remained so for the 9nm course.

The Gstaad Yacht Club event welcomed some newcomers this year, including: the oldest boat on the water at Saint-Tropez, the pilot cutter Madcap, built in Cardi , Wales, in 1874; a German ketch from 1920 designed by Herbert Wustrau, Wiki; and what is almost certainly the Mediterranean's only regularly competing Solent Sunbeam, Dainty, from 1922 (see below).

The 22 entrants also included the two boats that enjoyed an epic tussle for first last year, the William Gardner-designed P-Class, Olympian, of 1913, and the Herresho , Spartan, of 1912, the last remaining NY50. The biggest participant was the the 177ft (54m) three-masted topsail schooner Shenandoah of Sark launched in 1902. Further centenarians in this remarkable fleet were the P-class, Chips, of 1913, the Fife ketch Sumurun of 1914, the Fife Jap of 1897, the Liljegren design for the 1912 Olympics, Marga, and the Thomas Rabot-design, Lulu, from 1897.

Participants saw a film celebrating the first decade of the Centenary Trophy, comprising images by Juerg Kaufmann, as well as a new film about the race, made by Shirley Robertson and Vertigo films.

A newcomer to the Gstaad Yacht Club’s Centenary Trophy in September was the Solent Sunbeam Dainty, qualifying for the race as she turns 100 this year, along with the class that she spawned – Dainty was the first Sunbeam designed by Alfred Westmacott in 1922. Bosham-based Peter Nicholson has owned Dainty since he was 19, racing and winning in many Cowes Weeks as well as countless other regattas. The boat is maintained at Haines Boatyard in Itchenor, where the classic wooden Sunbeam keelboat fleet is now being bolstered by GRP replicas, 11 so far. Dainty has been trailed to the Mediterranean regattas each summer for the last 17 years, and although she has been refused entry to some events for her 27ft (8.2m) LOA, when entered she has raced against the most famous classics afloat – Anna Boulton's shot here shows her passing Elena of London. At the Gstaad Yacht Club’s Centenary Trophy this year Peter Nicholson was presented with a commemorative book by Bruno Troublé. solentsunbeam.co.uk

JUERGThe wooden boat area at the Southampton International Boat Show in September proved a highlight of the event, with craft displayed by members of the Wooden Boatbuilders Trade Association and others.

A centrepiece of the area was Jubilee, pictured above centre, one of only 17 Deben Cherubs designed and built by Woodbridge Boatyard on the Deben River in Su olk. She dates from 1935, the year of King George V’s silver jubilee, hence the name, which had added poignancy during the boat show week. Woodbridge Boatyard joined many exhibitors in marking the death of Queen Elizabeth II by flying Jubilee's flag at half mast (right).

Woodbridge is trialling a biocide-free antifoul on this and other boats it looks after, and Jubilee’s topsides are coated with organic linseed oil-based paint, tinted with natural pigment to a custom colour – aiming for an environmentally friendly and a low-maintenance way of coating the boat.

A century ago, a Deben Cherub would have cost £160. Today the yard has other Cherubs and similar dayboats and small cruisers, waiting for the right owner to instigate a revamp.

Another boat built by Woodbridge was being proudly displayed by owner Vicki, pictured below right, who commissioned her to the lines of a clinker dinghy that used to be built by Everson & Son, the famous yard from which Woodbridge grew. Vicki said: “To own a clinker dinghy like this is a childhood dream come true.”

Among other new wooden boats on show was the lug-rigged Mystery 14 (above right), which Nic Compton wrote about in our April issue. The boat is built by Colin Evans of Evans Boatwork in Pembrokeshire, Wales.

Meanwhile the International Boat Building College in Lowestoft and the Boat Building Academy in Lyme Regis were both fielding enquiries

from interested punters. IBTC Lowestoft put on a well-attended demonstration of how to steam-bend a piece of oak.

Boat Building Academy director Will Reed was showing o the first student-built boat at BBA that was also designed by a student (below left), as well as examples of what BBA students have made in the college’s short furniture-making courses.

The award-winning work of Star Yachts in Bristol is a Southampton Boat Show staple. Pictured below centre is yard owner Win Knoops with colleague Olly and the Bristol 6.0, an electric launch that we featured in our March issue.

Over on the marina, Spirit Yachts' all-electric Spirit 44CR and Spirit 30 were on display, easy to spot among the many GRP yachts on the pontoon. The 30ft (9.15m) Spirit 30 is the first Spirit hull to have flax lay-up and bio resin incorporated into its build, the hull constructed from responsibly sourced, FSC-certified sapele ringframes and Douglas fir planking. The boat has a Torqeedo Cruise 4.0 FP electric drive system powered by lithium ion batteries and a Torqeedo 650W battery charger, giving a range of around 16nm at five knots.

Older, and also attracting a steady stream of visitors, was the Nicholson 31, with the class association keen to celebrate 'the original bluewater cruiser', first built in 1976 by Camper & Nicholsons in Gosport.

Meanwhile the masts of the tall ship Morgenster (top left) towered over the show. Visitors could tour and book evening sails on the 157ft (48m) clipper brig, a sail training ship built in 1919.

Making its world premiere was the Dale Classic 37 motorboat, based on the widely respected Arthur Mursell semi-displacement Dale 40 design, this boat fitted with a wealth of modern features.

A design by Charles Sibbick from 1899, and launched in April 1900, SAUNTERER has understated beauty and simple pre-WW1 elegance, which hides her immensely strong and original construction, being an extremely seaworthy, fast and very English vintage yacht. A wooden yawl of 47’ on the deck, SAUNTERER has undergone a substantial, well recorded and complete restoration undertaken by people who know and have a deep understanding of this vessel, maintaining the atmosphere of a 1900’s yacht. Now for sale a er several years cruising on the South Coast, she is ready to be enjoyed as a contemporary classic yacht by her next owner. Her previous owners include Captain Oates of Antarctic fame, who owned her when he died in 1912, and for whom she is a living memorial.

The OGA (Association for Ga Rig Sailing) is planning its 60th birthday party next year, with a series of events around Ipswich and the River Orwell as well as a Round Britain cruise. Hosted by the East Coast OGA, up to 150 boats are expected at the River Orwell events from 2-6 August 2023.

The four days will encompass class racing, cruising in company, shoreside excursions and entertainment for all ages. The celebrations will be held in Ipswich Dock and Su olk Yacht Harbour, both on the Orwell.

The event will include the first Ga ing 4.1 Championships for the Andrew Wolstenholmedesigned OGA dinghy, followed by the East Coast Areas’ Annual Cruise, to which all are welcome.

Coordinator Alison Cable said: “Between them, the River Orwell, Stour and Walton Backwaters provide sheltered sailing in most weathers and for the larger boats there are the open waters of the Harwich approaches. A range of sailing events will be organised to suit the di erent groups of boats and the conditions."

For those without a boat, the OGA is aiming to provide cruises on a local smack or Thames Barge.

The Round Britain Cruise fleet is scheduled to finish at Su olk Yacht Harbour just before the celebrations. Registrations are being taken and skippers are encouraged to o er crew spaces on one or more legs of the trip. Email oga60@oga.org.uk.

The idea was successful for the OGA’s 50th anniversary in 2013, when more than 200 boats took part in at least some of the round Britain challenge.

Alison said: “In 2023 we hope to repeat that success. We already know there will be celebrations in Cowes, Plymouth, Milford Haven and Dublin, as the fleet sails clockwise round the coast. Other gatherings will be decided as the event takes shape, culminating with a final party at Su olk Yacht Harbour on the first weekend of August 2023. We intend to make this final event suitable for all OGA members and boats from yachts to dinghies, and everything between.”

The round Britain fleet will assemble in Ramsgate on 27-29 April, ready to set o towards Cowes, to be there for the early May bank holiday. Then the fleet will head on to Pymouth for 10-12 May. There will be 10 days to get round Land’s End before arriving in Neyland Marina in Milford Haven for a gathering on 20-21 May.

Dublin Bay will be hosting an OGA party the following weekend. The Scottish area OGA will host a party on 17-18 June, probably at Kerrera Marina or Oban.

At this point the fleet will probably split to go through the Caledonian Canal or round the top of Scotland, before rejoining to travel down the English east coast towards the jubilee party on the River Orwell.

The OGA is looking for partners and supporters for the Ipswich and Orwell events. Interested companies can contact Pete Thomas on pete.m.thomas@btinternet.com.

For further information see oga.org.uk

Light winds greeted a varied fleet of wooden boats for the August edition of the Albert Race, held in Rossö, a seaside town south of Strömstad in Sweden, writes Erik Norlander.

Sixteen boats started in northern Bohuslän’s classic wooden boat meeting, but none of them could threaten the course record of 54 minutes.

The boats sail to a local handicap, called RYS, which loosely interpreted means Rossö Yard Stick. Regatta organisers set a boat's RYS number arbitrarily, largely basing it on last year’s results.

The start at Killingholmen was taken elegantly by Bengt Jansson who, with his Tango, an Olle Enderlein-drawn Ballerina, had

the pleasure of leading the field out through Rossöhamn. There the wind dropped and so did the boat, allowing more easily powered boats to pass.

Race tactics include choosing the best route at Vadbodskäret – sometimes it pays to lead the fleet through, but if you stall in a wind hole, they will sail around you!

The winner was a former fishing boat, Frifararen, recently restored to working condition by owner Johan Goksöyr, and probably the only boat of its kind left.

Albert Olsson, after whom the Albert Race is named, was a fisherman and chairman of SVC, the Swedish Fishermen's Central Association.

Not many sailing clubs can claim to be 150 years old, but the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club celebrated its 150th birthday with more than 60 boats on display, plus a family fair and regatta, on its home waters of Sydney Harbour. sass.com.au

1962. Refit 2022. Designed by the Scottish naval architects G.L. Watson & Co. and built along traditional lines to Lloyds class by Ailsa Shipbuilding, Scotland. She has a top speed of 11 knots and boasts a maximum range of 4,000 NM, thanks to her twin Gardner engines. She has cruised extensively in all latitudes including a circumnavigation. She was also a support vessel for the filming of Luc Besson’s Atlantis. Her interior has been rebuilt using varnished mahogany, in a timeless style, with modern details for comfort.

2010.

After owning, restoring, rebuilding and recreating a number of famous yachts, her owner built her with his vast experience, and has once again constructed a yacht that no-one thought would ever sail again. Her original lines were honoured to the finest detail, and her sail plan is identical to that of her victorious 1905 Transatlantic Race, which immortalised her in yachting history. Above all, she is again breathtakingly beautiful, turning heads wherever the wind takes her.

Her dimensions are simply incredible; 65 m overall, 56 m over deck and 42 m at waterline. Thanks to her spars, which tower some 45 meters above the waterline and support a staggering area of 1,750 m² of sail, she performs at unmatched speeds under sail.

1952. Designed & steel built by Koser & Meyer in Germany. She is a very nice ketch with a special character. She is ideal for long cruising periods while easy to manage, even with just one crew member. She accommodates up to 6 guests in 3 cabins and up to 3 crew members in 2 cabins.

2004 From a Joubert Nivelt Design, LAZY DAYS is a new classic jewel, of which only 5 units sail across the oceans. She is spacious, comfortable and luxurious with a special character. The interior is built around a spacious saloon with beautiful dark woodwork and a galley to starboard. She offers 4 double cabins and two shower rooms, both with electric toilets.

1930. Refit 2017. Built as Falcon by George Lawley & Sons (Boston, USA) and designed by famous naval architect Mike Paine. She is optimised for racing. Since she became JOUR DE FÊTE in 2011, she has campaigned very successfully in the Mediterranean classic circuit, earning a name for herself, due to her immaculate level of maintenance and outstanding beauty on the water, as well as her ability to win.

Thestory of Voluta begins with her first owner

George MacAndrew, a businessman who took his holidays at Seaview on the Isle of Wight and who wanted a boat that could be moored close inshore. MacAndrew was a serial boat owner and astute yachtsman who had already commissioned boats and yachts from several Solent boatbuilders. In his notebook ‘Notes Relating to my Sea Boats and Yachts, 1886-1902,’ he describes his adventures in said craft and his dealings with the boatbuilders, in a charming glimpse back into a distant age, when yacht cruising was still a fledgling sport. A yachtsman could walk into a boatyard through the wood shavings and sawdust, see the craftsmen at work and stop and talk through his conception for a new yacht build with the boatbuilder and/or designer, who would then add his expertise to those ideas to create a unique new yacht.

In 1886, MacAndrew commissioned a 15ft (4.6m) open centreboard boat from Picket of Southampton, before taking on and finishing to his requirements Snowbird, a 35-footer (10.7m) in 1890. That same year, he commissioned Lukes of Hamble to build a 17ft (5.2m) “scientifically designed miniature yacht” –Cyproea. He was very taken with Cyproea’s sea keeping and speed, and it led to the conception of Voluta. In 1893, with his family of an age to take more involvement

with his yachting, he commissioned Ianthina, a 34ft (10.4m) yacht, choosing Stow and Sons of Shoreham over Paynes of Southampton to build her, the quotes given being £300 versus £450 respectively, leading him to conclude that “one has to pay for contracting a fashionable firm!”

He had no regret in choosing Stows, as he was highly impressed with their quality, and even more so with the boat’s punctual delivery – compared to the “vexatious slackness” of other boatbuilders! In 1898 he commissioned a Redwing from Camper and Nicholsons, and in 1899, he contracted Stows again to build him Voluta.

“I had often thought when sailing the Cyproea, what a fine cruising yacht would result from multiplying each dimension of her by two; this was my guide in deciding dimensions, but the waterline length was increased 4ft 6in (1.4m) beyond twice the Cyproea and, above water, the length was further extended by a long counter – on the whole, the model and characteristics seemed very similar to the smaller boat with all her excellent qualities.”

By early June 1900, Voluta was first under canvas in Shoreham Harbour, before leaving on 9 June for her summer base at Seaview on the Isle of Wight.

“Though the Voluta was of rather light draft and fitted with a centreplate, she was very far removed from

the ‘skimming dish’ type of boat usually associated with this contrivance and which is neither suitable nor safe for open sea work. On the contrary she was an excellent hard weather yacht, of great initial stability, and a constantly increasing righting power as she heeled to the pressure of the wind, having sufficient draft of water and ballast to make her a powerful sea boat; indeed she never showed to better advantage compared with other yachts we met sailing, than when beating against a strong wind and hammering into a sea. Of course, when on the wind, the grip of the centreplate was a great aid, but it was not an absolute necessity, as she beat to windward very fairly without its use, and we often did not lower it for short spells of this point of sailing. Indeed during our first season we sailed the ship constantly for about six weeks without the use of the plate, having by mismanagement had to spend two or three hours at low water upon a gravel bank, when the slot became jammed with small stones, and the plate could not be lowered.” The MacAndrews used Voluta for three seasons in all, laying her up at Lukes yard after the 1902 season and offering her for sale.

“My contract price with Messr Stow for building this vessel in 1900 had been £900, and I spent some £40 more on her full inventory. I sold her, after being laid up for over a year in the beginning of 1904, for £480, times then being rather unfavourable for selling.”

Clockwise from top left: Captain Sharpe seated and Dr TC Jackson in suit at Bridlington; Capt JF Sharpe –picture from RYYC centenary handbook, 1947, (although photo would have been pre-war); Commodore’s flagship at the Bridlington Regatta (note bunches of flowers at bowsprit end and mizzen boom)

The remarkable survival of MacAndrew’s notebook paints Voluta’s early years in beautiful vivid colour, fleshing out hazy details and bringing to life the Solent sailing community at the turn of the last century. In the days when yacht sailing was still a new sport, and great diligence had to be applied to every part of the craft sailors ventured forth in, MacAndrew had conceived and had a yacht built, which through her peculiar and unique qualities, would still be sailing 120 years on.

Voluta was bought by a yachtsman who was to go on to be one of the leading figures of Yorkshire yachting over the next 40 years. Dr TC Jackson, Royal Yorkshire YC member, along with his skipper of over 20 years, JF ‘Pez’ Sharpe, would race Voluta consistently until World War Two, making her probably the best known yacht in the area – I have found more than 200 articles mentioning her in the local press from this era – and after his rise to commodore of the club in 1922, Voluta was the RYYC’s flagship. After the RYYC’s move to Bridlington in 1901, its prestige grew. Large yachts like L’Esperance, Rosalind, Cariad and Adelaide sailed the waters of Bridlington Bay competing for valuable trophies, and spectators would line the quays for Regatta Week. Voluta competed every year, winning many prizes, and presiding over the annual

Regatta Review, when the fleet would sail by the town dressed overall in what sounds like quite a spectacle. Dr Jackson was a great yachtsman, commodore of the RYYC for over 20 years, a leading member of the Humber Yawl Club, member of the Yacht Racing Association and, it seems, a passionate supporter of all things sailing and all things Yorkshire! Skipper Sharpe was a respected skipper, having crewed in the Shamrock II America’s Cup challenge, and he kept Voluta in top order.

Here is an excerpt from a letter by the late Commander Robert Blythe OBE, formerly of the RYYC. “I met Capt John Frederick Sharpe a few times when he was skipper of Voluta. He was known locally as Pez Sharpe (but not by me), lived on board Voluta with a youth as paid deck hand during the summer and sailed Voluta back to the Crouch where she was laid up by him and fitted out in the spring and sailed back to Bridlington. At that time, the 1920s, practically all the yachts at Bridlington had paid skippers or paid hands even the one designs. Voluta was then the largest yacht in the harbour and was kept in immaculate condition although, apart from Regatta Week, she did not often go to sea. You might say she set the standard of what a gentleman’s yacht should be.”

As the years passed towards World War One, the number of large yachts making the annual trip up to Bridlington for the regatta dwindled, and as yachting restarted after the war they had stopped coming altogether.

After losing her rig in a fire while laid up ashore in World War Two, it seems Voluta was re-rigged as a bermudan yawl, as attested to by photos taken in the 1950s under George Miller’s ownership. She shows up in the race results a few times after the war at the RYYC, but then is mentioned in an intriguing newspaper article describing her imminent trip from Goole to North Wales! She was then bought by Sir Hugh Bell and I M Pease in 1959, and in 1964 she drops off the Lloyds register. The trail goes cold now for 10 years or so when it comes back with various accounts of her being in the Falmouth and Helford area under the ownership of Frank Lang, a local character who owned and kept Voluta going, in what seems an ageing state of repair during the 1970s and 80s. She appeared in the BBC documentary ‘Under Sail - A Lady of Leisure’ in 1986, by which time she was working out of Newton Ferrers as a charter boat. The trail goes cold again then for a while.

I found her on the hard in Rhodes, Greece, where she’d been baking under the hot sun for five years and was in a poor state. I made a low offer reflecting her condition, which was refused. I thought no more of it until two years later when the yard manager Giles got in touch to say she was going to be on eBay that month. I bit the bullet and flew out for a look. She was a strange sight, with an ugly doghouse, massive gaps and splits in the planking, a failing keel repair and filthy inside. Despite all that you could see that this was an old lady of great character who had lived a life and was still holding her head up, although the end could have been perilously near. Little did I know when clicking ‘bid now’ how much influence this boat would have on my life, but also what a story, which has come slowly to me in bits and bobs, this lady of leisure had to tell.

Facing page, clockwise from top left: Carrick Roads; Original Reids of Paisley capstan windlass; Florence towing the boys; A fine bow wave; Lots of varnish

My own 17 years of ownership have involved more rebuilding than sailing! The initial delivery trip from Rhodes to La Ciotat, where I was to start the renovation, was when I properly fell for her. I got a crew together including my brother Graham and best mate Kevin Burns to refit, launch, and sail her the 1,200 miles to France.

Overleaf, page 28, clockwise from top left: Fastening planks in La Ciotat; Finishing the counter in Gweek; Voluta doing what she does best; Fair topsides and a great paintjob in Gweek

Through three full gales in a windy November Mediterranean, she performed superbly: seakindly, fast, biddable, and like all my favourite boats, one who looks after you rather than vice versa. In more moderate winds she kept up good speeds with a very kindly motion. As MacAndrew said back in 1900, she is a boat of great initial stability, slow to spill the G&T!

In La Ciotat, over three years, I embarked upon the first large refit I did. In 2007 I moved back to Cornwall, so launched Voluta in a part-finished state, and she came home up the Rhone, through Paris and into the Channel at Honfleur. The French canals are beautiful and make a wonderful trip, this certainly highlights the advantages of a shallow draught vessel – you would be pushed to get another 50ft (15.25m) classic to the Med by this route.

In 2009 I had my second big push at restoring her and was lucky be helped by Nathan Puttock, a fantastic shipwright who really boosted the project. My old ship mate Andy Mongan, along with Matt and Chris, also helped out doing an incredible job of fairing and painting the topsides: a shinier boat never came out of Gweek.

During these years, the family lived aboard and we sailed in severall Falmouth Classics, winning our class twice, although it was while racing in a good breeze one year that I contrived, by mismanagement, to snap the bowsprit and topmast. Although catastrophic at the time – I had not the time nor finances to rectify this damage, so we didn’t do much sailing for a while – it turned out for the best, as the topmast rig, which I had put on her believing it to be close to the original, turned out to be completely wrong. When I bought her I received two historical photos, one showing her in Shoreham sporting a topmast. I copied this rig to be close to the original, but as my research advanced and I unearthed more and more historical photos of her pole-masted, it became clear I had made an error. To correct it, Ashley Butler built a mast to dimensions similar to the original, and Jay Redman-Stainer worked his magic splicing up the traditional standing rigging.

Anyone who knows wooden boats will agree it does not take long for problems to arise if you take your eye off the ball. During the period I was busy sailing another gaff yawl home from Canada (Anne Marie, CB passim), Voluta’s 30-year-old plywood subdeck rotted, another blow to time and funds; but in November 2019 I hauled her out in Flushing and started the third, and last, big stage in her renovation. I redecked reusing the old teak, so once again she is looking pretty, structurally sound, and in a state I hope MacAndrew and Jackson would approve of!

In my journey with Voluta, I have been constantly amazed by the wealth of her history, of which there is doubtless more to learn, and the physical survival of this boat that was built with the best materials available at the time, by wonderfully skilled craftsmen, to a unique design, one that has proved so very successful for so very long.

Removed rusted solid steel centreplate and steel centreboard box which was leaking badly

Fixed the keel issue, at the same time closing the centreboard slot in a way that it is a simple procedure to open again and restore the centreboard, if so desired Replaced the stern post Replaced the stern knee

Did large hook scarf repair to the stem Replaced the rudder Started rebuilding the counter Repaired the horn timbers Removed doghouse, lowering it to original height, tied it in with the rest of the coachroof by laminating 18mm ply on top of the existing tongue and groove pine Removed the engine and replaced it under a new part of raised deck at the front of the cockpit with a V drive box, improving interior space

Removed, cleaned up and replaced all the original wrought Iron floors, replacing a couple where it was necessary, and refastened with bronze bolts Replaced one dozen or more frames

Replaced the garboards, stealers and half a dozen more planks, (iroko) Refastened the boat entirely under the water with silicone bronze screws Refastened the boat where necessary above the water with silicone bronze screws Replaced all centreline bolts with new bronze bolts Removed and restored the original Reid and Sons capstan windlass New forehatch matching historical photograph

Replaced one dozen or so frames

Rebuilt counter stern

Fitted new bulwark stanchions, bulwarks and cap rail Installed rudder trunk tube

Fitted coaming cladding and deck margins

Built new topmast rig

Built new boom

Built new bumkin

Renovated existing spars

Took boat back to wood and repainted – traditional paint below waterline and Awlgrip above

Re-formed scarf at front end of lead keel by cutting and recasting Replaced approximately 50 per cent of bilge stringer each side and refastened with copper bar riveted and silicone bronze screws

Refaired and repainted coachroof top with non-skid Awlgrip

Fitted samson posts

Fitted new stem ironwork incorporating lifting bowsprit system with twin forestays New ironwork for masts and booms (MINOR) FLUSHING REFIT 2016

Replaced oak mast step

Replaced 1in bronze keel bolts

Refaired and replaced forward deadwood

Repaired forward knee

Fitted new mast built by Ashley Butler, standing rigging by Traditional Rigging of Bristol

Removed plywood subdeck and replaced with 2 x 9mm Robbins marine plywood epoxied together and glued and screwed to deckbeams

Re machined and replaced 17mm thick teak deck epoxied and screwed to ply subdeck, caulked with TDS to full depth of planks. Screws plugged to give minimum 10mm wear

New aft king plank

New bronze rudderstock bearing New tiller

New cockpit ply and teak

Fitted 4 Gibb 9CR sheet winches

Repainted Awlgrip topsides

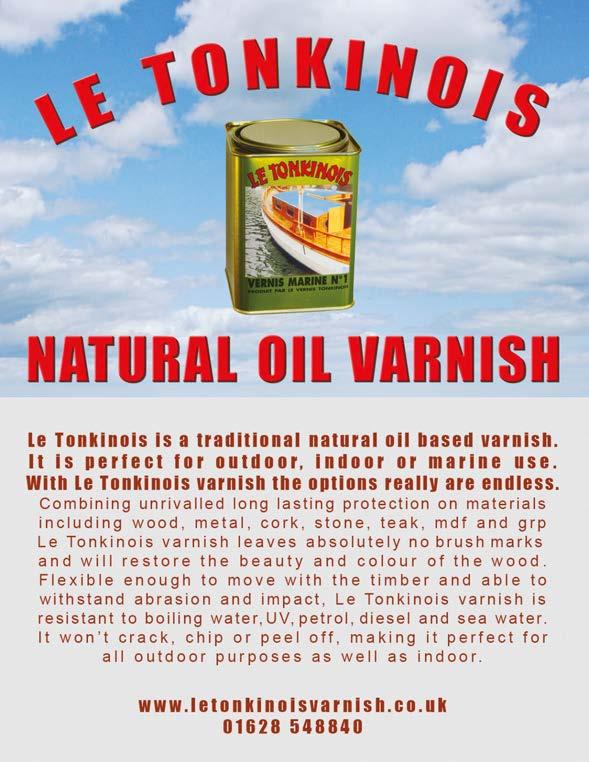

Revarnished everything at least 10 coats Le Tonkinois and Epifanes

Repainted and decorated interior

Rewired and serviced engine

New water pump for engine

Fitted new 200 Ah batteries x 2 and new wiring for DC panel

Fitted new 12v submersible bilge pump

Fitted Taylors para n 30 cooker

Fitted restored antique tip up sink in head New Jabsco head and pipework

Fitted diesel heater – Eberspacher ducting, copper exhaust

New mainsail made by Katie Allan and Simon Palmer

New hatch and sail covers by Katie Allan New fuel tank

New flexible water tank New mizen ga

Many new elm blocks with bronze bindings

Nearly all new running rigging

New interior upholstery by Katie Allan

37’ Percy Crossley Bermudan Sloop built by the Ponsharden Shipyard, Falmouth in 1934. Pitch pine on oak hull with a Kauri pine laid deck. Major refit in 2018 including all new keel bolts and strap floors plus a new interior, rigging and sails. Superbly elegant yacht in good structural shape, full of pedigree and charm.

Hants £49,500

39’ Looe Lugger built in 1907, now dandy rigged with gaff main and lug mizzen. Detailed maintenance records since 2016, a well cared for and up together yacht. Recent sails and rigging, new keel bolts and recent hull repairs. The last of the sailing fishing boats from Looe, a yacht with a long and rich history.

Devon £75,000

62’ motor yacht designed by Archibald MacMillan and built by the Fairlie Yacht Slip Ltd in 1968. An elegant yacht built for a wealthy Scottish couple. Mahogany hull with solid teak decks. Aluminium superstructure. 4 sleeping cabins with 10 berths and 7’ headroom. Twin Gardner 6LX diesels with new 2021 generator. An excellent yacht with plenty of pedigree and class.

25’ Itchen Ferry design built by Berthons as a yacht in 1926. Pitch pine hull with all bronze and copper fastenings. Major rebuild in 1990’s, very nicely maintained since. Vetus 16hp diesel installed 2009. Very smart boat with varnished teak interior and 2 single berths plus heads and galley.

Hants £19,750

25’ Laurent Giles Vertue built by Elkins of Christchurch in 1954. Teak and mahogany planking with lead keel and bronze keel bolts. Yacht laid teak deck and varnished teak coamings. Nanni 21hp diesel new in 2015. New rigging in 2014 with a full sail wardrobe. Very nice quality yacht with recent survey and detailed history.

35’ Sole Bay motor sailer ketch designed by Francis Jones and built by Porter and Haylett in 1968. 2021 refit by Harbour Marine Services. BMC Commodore 66hp diesel. 5 berths with 6’3” headroom and 2 heads with a shower. Comfortable saloon and very nice wheelhouse for sailing in wet weather. Ideal cruising boat for UK sailing.

Suffolk £32,000

36’ Kim Holman Bermudan Sloop built by Kimber and Blake in 1961. Successful offshore racing boat in her day with numerous Fastnet finishes and survivor of the infamous 1964 Santander Race. Fallen on hard times in recent years she now needs a full refit but he delightful lines and sailing provenance mean she is a yacht well worthy of the effort. Cornwall £10,000

16’ Paul Gartside rowing skiff built by Adrian Morgan in 2019. Used only a handful of times, she comes with 2 pairs of oars, as new road trailer and a fitted all over cover. Planked in Vendia, a processed timber board, she weighs only 60kg in total. A delight to row and in superb condition.

Suffolk £6,500

As the glassfibre revolution gathered momentum companies like Chris Craft and Riva entered a transitional period, still producing vessels in mahogany but making them look like glassfibre so as not to appear behind the times.

The 40mph 1966 Riva Junior, billed as “the young people’s rocket,” was on that very cusp. Though its white-painted hull mimicked polyester, the entry-level 18ft 6in (5.7m) sports boat was the last all-new Riva model

to be built of mahogany in the traditional way. And while the immortal Aquarama endured into the 1990s, when Carlo Riva sold out in 1969 all new models introduced by US owner Whittaker were of glassfibre, including the 1972 Riva Rudy, which was basically a revamped Junior.

Pretty much the only mahogany element of the Rudy was the grab rail. But it also lacked something else: glamour. Brigitte Bardot and actor Peter Sellers were among

More than 150 years of British yachting history –much of it with royal associations – is coming on to the market on 1 November as Portsmouth’s combined Royal Naval Club and the Royal Albert Yacht Club closes its doors for good.

Approximately 100 lots, o ered on behalf of the administrators, trace a path through the pantheon of yachting from 1864, including: silver trophies named in memory of Charles Nicholson; mementos from GL Watson’s 1892 Britannia, which was so beloved by King George V that on his death in 1936 the famed racing cutter was stripped and sacrificed to the sea o the Isle of Wight; photographs, books and historical archive material.

For collectors and historians it’s a rare opportunity. For those lacking in history it’s an opportunity to line a library or den with all the ephemera you need to suggest that your family has pedigree and once achieved something.

A circa 1800 naval tin and horn lantern might command a low four-figure sum on a good day, but when its provenance confirms that it was on the gun decks as Nelson fought and died at Trafalgar, that considerably ups the ante.

Not only is the lantern accompanied by a letter confirming it was on board HMS Victory in

the run-up to Trafalgar and was later presented to Admiral Sir Roger Keyes in 1929, this exact form of lantern is depicted in a celebrated early 19th century painting by Arthur William Devis, who was given access to the exact location where Nelson was treated. The result at auction was £47,880.

the jet-set Junior owners, but you’ll find no such A-list roll-call for the Rudy.

This 2014-restored 1967 Junior, fitted with 5.7-litre Riva Crusader 190hp V8, recently sold for £41,400; that’s considerably more than a comparable plastic Rudy would fetch. And here’s another pleasing irony. The hand-built Junior notched up 626 sales from 1966 to 1972, while the “mass-produced” Rudy found only 364 customers over its 14-year life. Wood, it seems, won the day.

Perfect provenance: (above) A racing flag from George V’s Britannia comes with a letter from Buckingham Palace stating “I am commanded by The King and Queen Mary to send you these flags” Top left: a Beken of Cowes photograph of Charles Nicholson at the helm of CandidaBottom left: a circa 1910 yachtsman’s pocket dispute set adds a touch of decorum in di erences of opinion about who rammed whom

“The world belongs to those who enjoy it,” says the Robbe & Berking brochure and we’re sure we wouldn’t disagree, especially after knocking back a shot from these fine silver receptacles, which you can find in the German silversmith’s Dante Bar Collection.

“The high thermal conductivity of the silver allows every drinking vessel to immediately assume the temperature of the beverage,” they say. Reason enough to pour another. €248 (around £212) for the 90g silverplated model; €357 (around £305) to have it gold-plated inside

Built to go anywhere, they say. Fully waterproof, best in class optics and coming with a lifetime warranty. US binocular manufacturer Nocs make some bold claims. They also make the point that these compact binoculars are undeniably stylish. Nocs say: “We began our search for the perfect travel binocular: great optics in a compact, rugged housing, at a price that didn’t break the bank. They didn’t exist, so we built them.”

models available, from $95 (around £80)

We’ve had a number of requests as to where sailors can find this fine gin, which has been spotted at various English south coast regattas this summer including British Classic Week and the U a Fox 50 event. Both events, indeed, have been supported by Dartmouth Gin, with finishers at a very hot British Classic Week rewarded by a fresh bottle as they crossed the line – the bottle presented by the distiller himself, Lance Whitehead, shown here. Lance is a lifetime sailor and the owner of the Cockwells pilot cutter, Merlin. His Dartmouth Gin was named Craft Gin of the Year 2020 and is distilled in Dartmouth, Devon, “very slowly” to produce a remarkably smooth, full-flavoured spirit. It comes in a handsome bottle, carved to depict a replica of the wrought-ironwork on St Saviour’s Church door in Dartmouth. Also available to US and other non-UK readers.

This chunky ocean blue chronograph from Hugo Boss is made with sailors in mind, water-resistant, and complete with a rugged fabric strap and solar-powered movement.

Building rare and near-extinct traditional wooden working boats may seem a niche and isolated occupation but when Gail McGarva takes on a new project, she likes to get everyone involved.

Rowing crews are involved in the riveting and oiling of their Cornish pilot gigs; workers from the sawmill join the launch of her replica Shetland boat; and the elderly men who once went to sea in the original lerret boats she replicated, share their memories as oral histories.

“I have a very strong philosophy that if you involve people in the building process, they will have a connection with the boat and then they will ultimately become custodians of it,” she says.

These days Gail also shares the skills, history and stories of regional working boats by touring museums and heritage centres with her programme called Disappearing Lines. Participants learn the key processes of boatbuilding and are taught how to steam-bend oak ribs, creating what Gail calls ‘ghost ships’.

“They’re a symbol of the craft that is disappearing,” she says. “I hope to raise awareness and help prevent boats from being lost, reigniting people’s passion for their local maritime history, and for the sea.”

Gail’s own passion for traditional clinker craft was sparked at the outset of a nine-month course at the Lyme Regis Boatbuilding Academy in 2004. She’d had no formal experience of woodwork and was changing direction after careers in theatre and education, and as a sign language interpreter. Having lived on boats for many years, she felt now was the time for them to be her focus. Gail was 39 when she gained a City and Guilds bursary to do the course and “knew immediately as soon as I walked in the door that this is what I wanted to do,” she says.

Her initial project was to create a replica of a Shetland fishing boat she’d read about in an article in this magazine –Classic Boat. The Gardie dated back to 1882 and was housed in the Boat Haven Museum in Unst. Willie Mouat had been responsible for its conservation so Gail asked him to be her guide for the build.

Having completed the boat, she made the enormous journey back to Unst with the boat (a 14-hour ferry from Aberdeen) to launch it among the community from where it originated. It was an emotional moment and confirmed for Gail that she wanted to specialise in creating replicas of boats in danger of extinction.

“Working boats are rarely given a status or profile,” she says. “They’re not so well documented as other boats, with no designer drawings or construction plans. The skills to build them would have been passed down from generation to generation.”

In order to preserve these craft, Gail takes the lines of an existing endangered ‘mother’ boat and replicates it, calling it a ‘daughter’ boat. She speaks of them with fondness and

reverence, as if they are living, breathing entities each with their own particular characters.

“Working boats have a strong sense of the weaving of form and function and, alongside the oral history attached to a craft,” she says, “you can look at the shape of the boat and it tells you its past, its job, its shoreline, the way it’s launched. Every working boat has a different story to tell in the shape of its hull.”

Although Gail is commissioned to build boats by individuals, groups or heritage organisations, she hopes that they aren’t static museum pieces. Her goal is for them to find a place in the modern context. The revival of the building of Cornish pilot gigs shows how this can be possible.

“I was very fortunate that when I completed my training there was an explosion of interest in Cornish pilot gigs and clubs were commissioning new boats,” she says.

These 32ft (9.8m) clinker craft were formerly used to guide ships into harbour, but are now popular as racing boats, rowed by six oarsmen and a cox. Around 160 vessels line up at the Scilly Championships.

As Gail’s passion for her subject grew, she learned more about the history of boatbuilding and the different types of working boats, and started to give talks on the subject.

“I’ve been invited everywhere from the WI to the V&A,” she says. “People realised I wanted to communicate the stories, sharing the narrative of the boats and where they sit in our cultural heritage, as well as showing how they have been created.”

She constructed a ‘story boat’ to host events for children, transforming Vera, a 100-year-old lerret she had been given, into a mobile maritime museum – upturned and mounted on wheels – to travel around schools.

“It was common in island communities, when a boat is no longer seaworthy, to use it as something constructive on land,” Gail says. “On Unst, I came across an upturned boat used as a sheep shelter. I’d crawled inside and the structural ribcage of the boat as the roof was enchanting.”

Her passion and commitment are infectious, and Gail has been recognised with several awards including the British Empire Medal for her services to clinker boatbuilding and heritage crafts. She’s a trustee of the Boatbuilding Academy and is also working with the Heritage Craft Association to heighten awareness and gain support for traditional boatbuilding.

“It’s not only the vessels that are teetering on the edge,” she says, “it’s the skill base that’s available to do it.”

It all seems very different from Gail’s earlier life and career but she believes her skills and experiences all come together in this new role.

In her concluding note, Gail says: “Working with communities, focusing on heritage, writing songs and stories, I feel there’s an integration of all the past threads interwoven in the work that I do as a boatbuilder.”

“Working boats are rarely given a status or profile”

Gail McGarva

When a boat stays in the water all winter, there are two choices for preparing her engine for long periods of rest. The obvious solution is to make a pact with oneself to visit the vessel at least once a fortnight and run the motor under load for an hour or so every time. Running it in neutral gear is bad news because it will take ages to warm up and diesels love to work. Too much of this will cause deterioration to the cylinder bores among other things so, if she’s alongside, make sure the stern line and the head spring are well set up, then select ahead and give it half revs. The engine will enjoy its outing and the batteries will love a good old jolt from the alternator.

The downside of this policy is that it’s easy to put off until the spring doing the basic engine service we all can manage. After a diesel has run for a season, or 100 hours, or whatever you’ve decided is to be the oil-change interval, the oil absorbs undesirable extras that worry away at the metal parts inside the engine. Changing the oil and filter removes the lion’s share of these. If you’re content to leave them doing their nasty work all winter long, that’s up to you, but an oil change at lay-up time is by far the better solution. Since you are going to that trouble, why not change the fuel filters at the same time, and do what needs to be done with the gearbox oil too. Even if you plan on the fortnightly run to keep things working, fresh oil will be a bonus. The guarantee of clean fuel will be another, and there’s also the psychological advantage that you’ve done the jobs already when fit-out time comes around.

Whether the boat is stored ashore or afloat, if she’s outside, or even inside, in an unheated shed, the fuel in the tanks will be subject to big temperature and humidity changes. Any air above the fuel will carry moisture in it, replenished via the tank breathers. An abrupt fall in temperature condenses this and that’s a few more drops of the dreaded water in your diesel. Pressing the tanks up full at lay-up time is the best way around this. The less air in the top of the tank, the less water in the diesel next year and, of course, you’ve taken the hit in the wallet six months ago when you’re having to stump up for antifouling, a new sail and all the rest of the new-season commitments.

Whether a boat is going ashore for the winter, or staying afloat but will be left alone for months, there’s one more job that will save you a lot of money in the end. Corrosion in the heat exchanger, exhaust elbow and piping in general are going on quietly all winter long if they are left full of salt water. Here’s what to do.

The engine’s internal system is already full of coolant with the required concentration of antifreeze – or it should be. It’s the raw water system we’re interested in. First, buy a gallon or so of

eco-antifreeze. Mix 50/50 with fresh water in a watering can with no rose on the spout. Warm up the engine. Diesels don’t like being left after running for only a couple of minutes. Now, stop the engine and close the inlet seacock. Open the top of the water strainer and stand by with the watering can. Start the engine and watch the level in the strainer. As soon as it drops, top it up with the antifreeze and go on until you’ve none left. Shut the engine down immediately and replace the lid on the strainer. Leave the seacock closed. All the parts that count are now protected against frost, but equally importantly, the anti-corrosion and lubricating qualities are beyond price. Come spring, open the seacocks and start up. The eco antifreeze will do no harm as it’s ejected, and away you go.

When is a halyard not a halyard?

Answer: When it’s a gantline.

The last rope left aloft when stripping a rig is always called a gantline. It’s best if this has its turning sheave as high as possible so that anyone in a bosun’s chair bringing the halyard blocks down for the winter can reach them all without stretching. A gaffer’s topsail halyard is favourite for this because it is set in a sheave on a pin through the mast and has no block of its own that would otherwise have to be left aloft. On a bermudan mast it will be the main halyard or a topping lift.

Blocks left aloft in the weather all winter long suffer horribly. By spring, they are always the worse for wear, with cracks appearing in the wooden joints as well as having their varnish wrecked by the wind, rain and snow. It’s so much better to bring them home. Then you can service them in comfort instead of slumping on the sofa to study the latest grim tidings from Albert Square.

If muscle for getting aloft is a problem and you have a power windlass, try this: lead the halyard that will become the gantline through a turning block at the base of the mast and take it to the windlass. You may need a second block near the hauling drum to ensure a fair lead. Otherwise riding turns may follow, which you don’t want with little Jimmy halfway up the stick. Sitting on deck with the heel of a boot on the windlass switch is the best way to operate the system, because you can watch what’s going on. And when the job’s done, take off all the turns except the last two so you can surge the rope smoothly. Nobody enjoys a jerky ride down to the deck.

MARTYN MACKRILL Son of a marine engineer and grandson of a trawlerman, Martyn is Honorary Painter of the Royal Thames Yacht Club and the Royal Yacht Squadron. His depictions of classic boats, from clinker rowing boats to Edwardian schooners, have made him one of the most sought-after marine artists, and his work forms part of major collections worldwide. He and his wife, Bryony, sail the restored 1910 ga cutter Nightfall (Classic Boat 328).

MARTYN MACKRILL Son of a marine engineer and grandson of a trawlerman, Martyn is Honorary Painter of the Royal Thames Yacht Club and the Royal Yacht Squadron. His depictions of classic boats, from clinker rowing boats to Edwardian schooners, have made him one of the most sought-after marine artists, and his work forms part of major collections worldwide. He and his wife, Bryony, sail the restored 1910 ga cutter Nightfall (Classic Boat 328).

Francis B Cooke owned 19 boats which spawned 34 books, hundreds of articles, and the founding of a sailing club and a yacht insurance business. He counted Uffa Fox, Thomas Lipton and Major Wykeham-Martin among his friends. Now, 150 years after his birth, Dick Durham takes a look at the unpublished autobiography

Hewatched Britannia sail her first race in the Thames Estuary in 1893; observed Kaiser Wilhelm II board Meteor off Cowes in 1906 and reported on the challenge for the America’s Cup by Sopwith’s Endeavour in 1934. Yet Francis Bernard Cooke never sailed a boat bigger than what he himself described as a ‘pocket cruiser.’

FBC, as he signed off his 100s of articles, pontificated on ocean passage-making; deep sea cruising and the Fastnet Race, yet he spent his 76 years cruising mostly between Harwich and the Thames and competing in handicap races on a few miles of the upper Crouch in Essex.

Cooke wrote with great authority on the evolution of the modern yacht; singlehanded cruising and the luffing rule yet was equally at home advising on how to poach an egg on board, preventing a dinghy nosing your stern and placing a pig of ballast in the right place.

Above left: Portrait of FB Cooke with pipe

Above right: Tiercel is dismasted by a Thames barge

If ever anyone epitomised the valuable training that sailing on the East Coast provides the small-boat novice, with its shoal waters; fast-running tides and shifting sandbanks it is Francis B Cooke.

Apart from the yachting press and every national newspaper in the UK, and some from the USA and Europe, editors from every journal in Britain called upon FBC’s expertise. From The Tatler, Country Life and The Spectator, to the Pall Mall Gazette, Sporting Life and Blackwood’s Magazine, they kept his Blick typewriter ribbons rolling.

It is no wonder his late son-in-law, Sandhursttrained Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Miller, said of him: “He lived a sort of cocooned life; he spent his day in his study writing into the small hours. He made periodic visits to the post box at the end of the road and he appeared for meals. He indulged in no social life… and he seemed to erect a wall of isolation.” And, as an unpublished typescript handed to Classic

Boat magazine by his granddaughter, Faith Egan proves, Cooke kept writing well into his centenary.

My Early Years At Sea, which FBC describes as a 10-year ‘apprenticeship’ was, Faith tells me, bashed out in his 100th year.

FBC was born, one of seven children to Alfred and Harriette in a Georgian house on St George’s Terrace in London’s Regents Park on 12 June 1872. His father was a lobby correspondent for the Daily News and a devout churchgoer.

A self-taught clarinetist and composer of music, FBC attended a concert in London by the global phenomenon Franz Liszt in 1886, but it was sailing that captured his soul.

The young Francis swapped a broken rollerskate, catapult and pet mouse for a model schooner that he sailed on Kensington’s Round Pond until it sank. He had little better luck with his first boat, Fat Boy, a 12ft (3.6m) lugsail dinghy which he and a school pal capsized off Kingston-Upon-Thames, when he was 17.

His first cruise was in March 1890 aboard a pal’s boat, Tiercel , a 30ft (9.1m) converted ship’s lifeboat moored at Hole Haven, Canvey Island in Essex which, in those far-off times was connected to the mainland only by ferry which was ‘rather like an enlarged shooting punt.’ Once on the island side of Benfleet Creek, they had a three-mile walk to Hole Haven carrying stores over an ice-bound road. They did not reach the Lobster Smack Inn until after closing time, but the landlord had left bread and beer for them on his doorstep.