MAKING

Sophistication, grace, and exclusivity—these simple words describe the power of Mainbocher’s couture; they were the foundation of his acclaim that spanned a career of more than forty years. And yet they fail to capture fully Mainbocher’s vision of clothing and his impact in the world of fashion.

Mainbocher in his New York studio, 1940s.

Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library.

“Certainly he has been the only leader in Paris couture who clearly hails, unchanged, from the Middle West.”

— Janet Flanner, New Yorker , 1940

By many accounts, Main Rousseau

Bocher should not have prospered as a couturier. He had little formal training, opened his Parisian salon in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929, and was an American working within the tightly guarded tradition of French couture. Despite his humble roots and the obstacles he faced, Mainbocher’s ambition and relentless drive led him to create an international fashion house serving royalty, Hollywood, and the social elite.1 His journey was both long and complex. Ultimately, the highly influential designer balanced his exclusive brand by designing uniforms for some of the United States’ most significant organizations for women—including the Naval Reserve’s WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and the Girl Scouts of America. While the name Mainbocher may not be as well know as it was in its prime, the work of this American couturier profoundly influenced the growing fashion industry of the early to mid-twentieth century.

THE CHICAGO YEARS (1890–1909)

“I’ve always been a West Sider at heart.” —Mainbocher, Chicago Tribune, 1940

Mainbocher grew up as Main Rousseau Bocher. Born in Chicago on October 24, 1890, Main lived on the city’s West Side at 1552 West Monroe Street with his parents, George Bocher and Luella Main Bocher, and older sister Lillian. Mainbocher expressed an interest in the arts at an early age. His talents were nurtured by his parents, and by age seven he was drawing and playing piano skillfully. He did well at his neighborhood high school, John Marshall, where he spent time playing the piano before class debates and serving as the water boy for the baseball team. During those early years though, neither fashion nor design was a consideration for the budding artist.

In 1907, he enrolled in the Lewis Institute, a relatively new vocational school,2 where he pursued memberships with the academy’s drama and glee clubs and provided piano accompaniments for student productions.3 His study of music was paramount. In journals composed

as an adult, he noted that to obtain a part-time job as a curtain operator at the Auditorium Theatre he pleaded with the stage manager to give him “any job that will help me hear the music.”4

After earning a degree from Lewis in 1908, Mainbocher enrolled at the University of Chicago. But, shortly thereafter, his father died at age fifty-three. While the Bochers owned their home, they were not wealthy5 and Mainbocher realized that he would need to help support his mother and sister: “I knew my university days were over,” he wrote, “so I looked for a job.”6 At the advice of his alderman, Mainbocher secured a position in the complaint department at Sears, Roebuck & Co.,7 where he fielded letters and responded to errors in fulfillment. Years later, he credited the experience as having taught him the value of good customer relations and solid business

practices. In 1909, after a short stint studying illustration at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts,8 Mainbocher and a classmate left Chicago to study in Manhattan.9 While he would never again live in Chicago, Mainbocher did not disconnect himself from his hometown or his experiences there. The skills and work ethic he gained as a young man in Chicago provided him with a resourcefulness that became essential to the foundation on which he built his successful business.

AN ARTIST IN THE MAKING (1909–20)

“A refined individuality was show in the [work] by Mons. Bocher.” —E. A. Taylor, The Studio, 1913

For the next eleven years, Mainbocher lived a rather bohemian lifestyle, bouncing between

Main R. Bocher, 1909. (ICHi-89063) The young student attended John Marshall High School, located at 3250 West Adams Street, which had opened in 1895. Louis J. Block served as its first principal. ICHi-71966.

In February 1940, the designer returned to his alma mater. The Chicago Tribune described his visit: “Mainbocher, the noted Paris stylist of women, found many willing listeners among the girls interested in the latest fashions today when he made a visit to Marshall High School.”

This Lewis Institute registration form (above) notes that Mainbocher’s father was a dry goods salesman. Right top: In the spring of 1907, the young student received an ‘F” in math; for the teenager, artistic and musical study were paramount. Right bottom: The front page of this 1908 Lewis Institute publication featured a charming illustration by the young artist. Note his signature in the lower right. Images courtesy of University Archives and Special Collections, Illinois Institute of Technology.

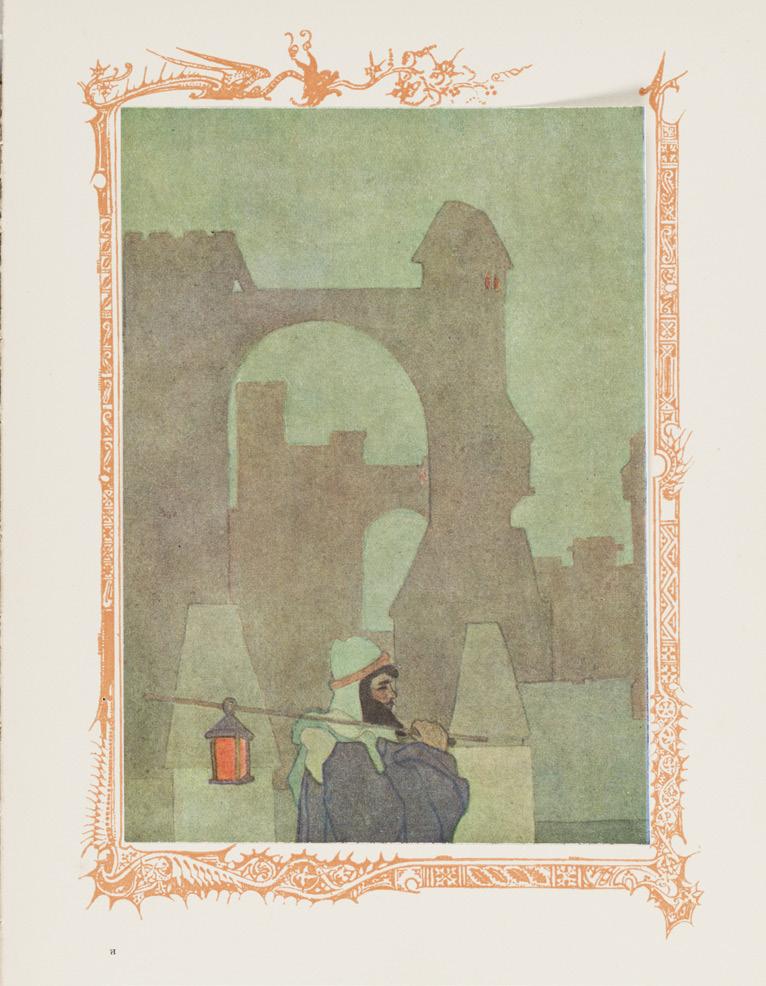

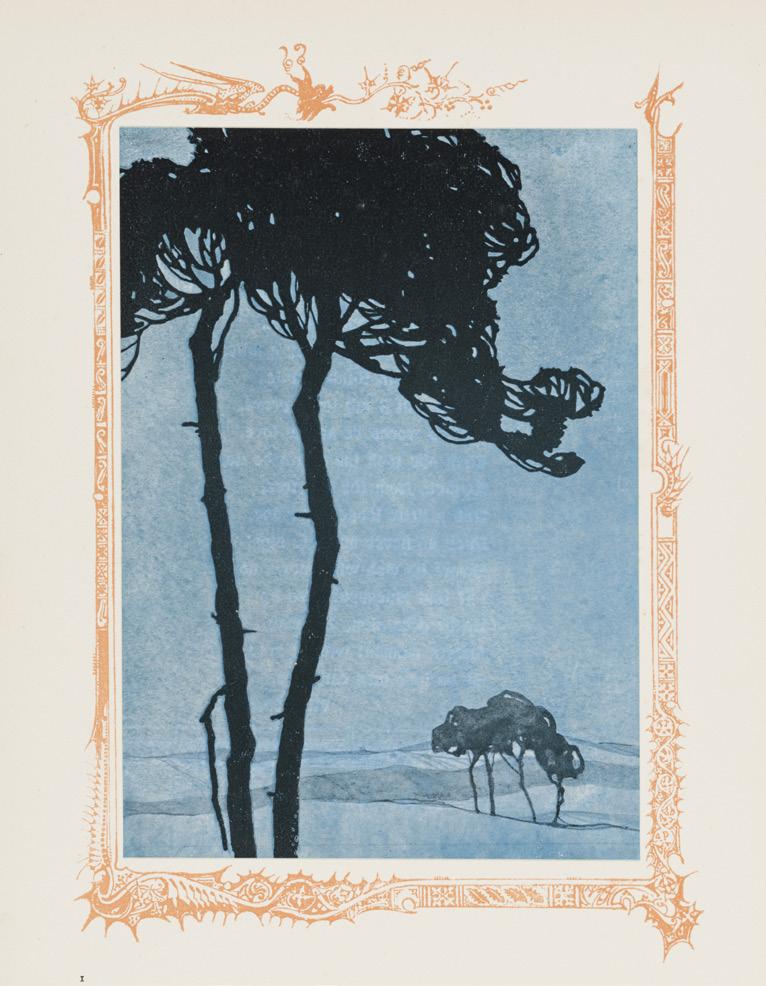

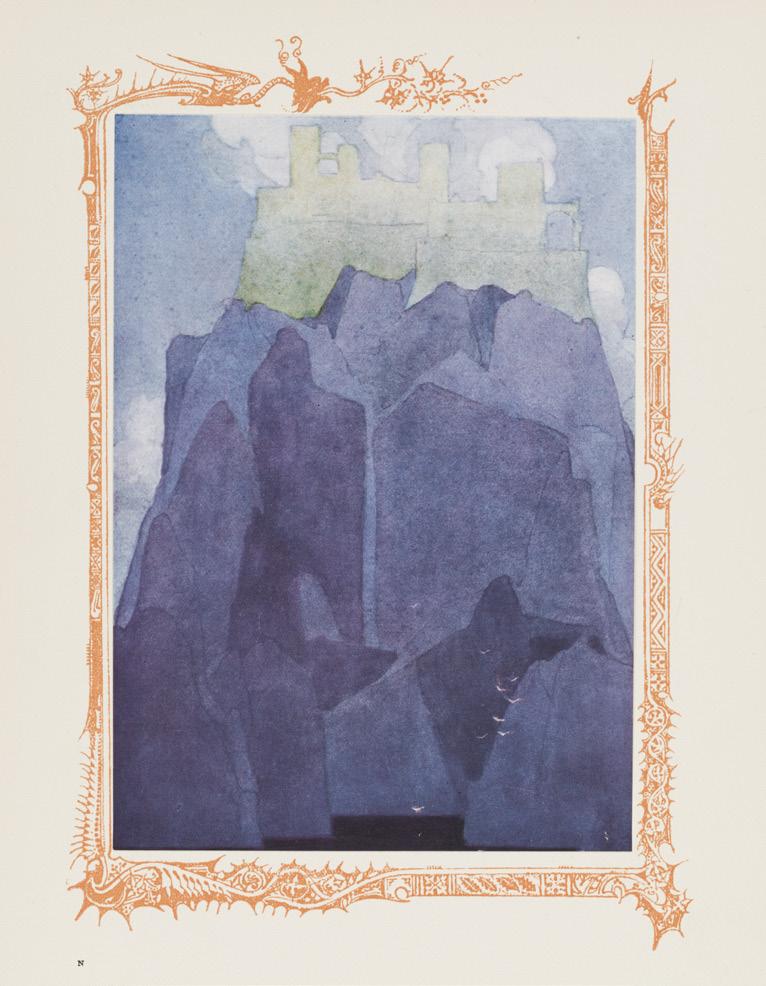

various studies and jobs in New York, Munich, Paris, and London. In Manhattan, he enrolled at the Art Students League of New York to study figure drawing.10 There, the owner of American Lithographic Company saw his work in a student show and offered Mainbocher a job designing cigar-box labels. “I didn’t have that kind of talent or mind,” he later admitted,11 so it was not a surprise that he was fired almost immediately. But it mattered little, as he had convinced his mother and sister to sell their house in Chicago and join him in New York. The family then traveled throughout Europe, landing for a time in Munich. In 1912, he moved to Paris to study with E. A. Taylor, a Scottish artist known for his focus on naturalism.12 Mainbocher returned to New York in 1913 with his mother, where he soon learned that his work had been selected for inclusion in the prestigious Eighth Salon of the Société des artistes décorateurs.13 Eager to see the installation, he managed a return trip to Paris by acting as tour guide and baggage handler for a group of thirty wealthy tourists. Eventually, he found himself in England, again studying with Taylor. After a few lean months, he finally received a break when the London department store Harrods commissioned him to create colored plates for the publication of the medieval poem, Aucassin and Nicolete. 14 He wired his mother: “Am a success! Come at once.”15 But 1914 saw the outbreak of World War I, forcing the artist and his mother to return to New York.

To make ends meet, he produced fashion renderings for E. L. Mayer, a fellow Chicago transplant who owned a major clothing

manufacturing house.16 At the time, he also took music lessons with Frank La Forge, an American composer17 and began forming valuable connections within New York’s arts circles. In early 1917, the musicologist Dr. Sigmund Spaeth,18 an accomplished musician, author, and critic for the New York Times, recommended Mainbocher to dancer Thomas Rector, who along with his partner, Hazel Allen, had popularized the “Hawaiian Waltz” in the United States: Bocher is “an exceedingly clever artist. He needs publicity and needs it badly.” Spaeth later featured Mainbocher’s painting of the two in costume in his article in the New York Times, providing the burgeoning artist with his first substantial bit of American press.19 But in 1917, with the United States’ entry into the war, Mainbocher was again on a boat to France.20

Mainbocher enlisted on March 7, 1918, serving as a sergeant in the Intelligence Corps. A fluent speaker of French and German, he worked as a plainclothes agent using “music student” as his cover. His assignment was to trail individuals suspected of supplying narcotics to American pilots. When suspicious of being followed, Mainbocher would duck inside his music teacher’s home. He was honorably discharged in Paris on May 12, 1919, and chose to stay in the city, dedicating himself to music full time. A friend, Mrs. Britten, encouraged Mainbocher to keep studying, telling him, “You ought to study. Your voice is too good to sing as an amateur.”21 She introduced him to F. S. Terry of General Electric, who financed Mainbocher’s studies with Henri Albers of the Opéra-Comique22 and later

In 1913, Mainbocher’s work was displayed at the Eighth Salon of the Société des artistes décorateurs in Paris. A review published in the Studio stated, “A refined individuality was shown in the four water-colors by Mons. Bocher; each reveals an uncommon sense of balance and fitness in the decorative adaptation of nature.”

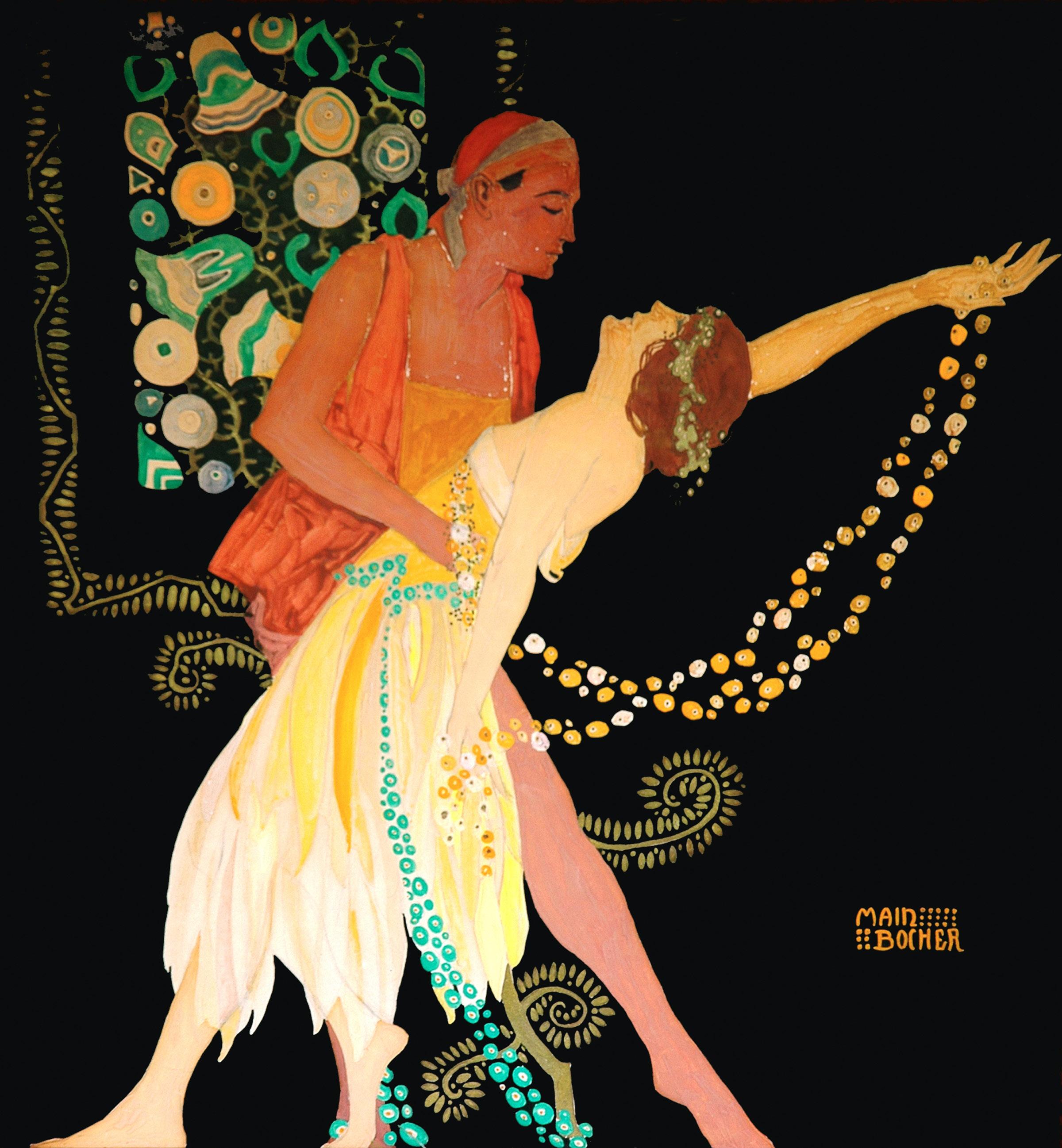

Mainbocher’s illustration of Thomas Rector and Hazel Allen in their “Hawaiian Waltz” costumes, c. 1917. Oil pastel on canvas. Courtesy of Thomas and Laura Wayland-Smith Hatch.

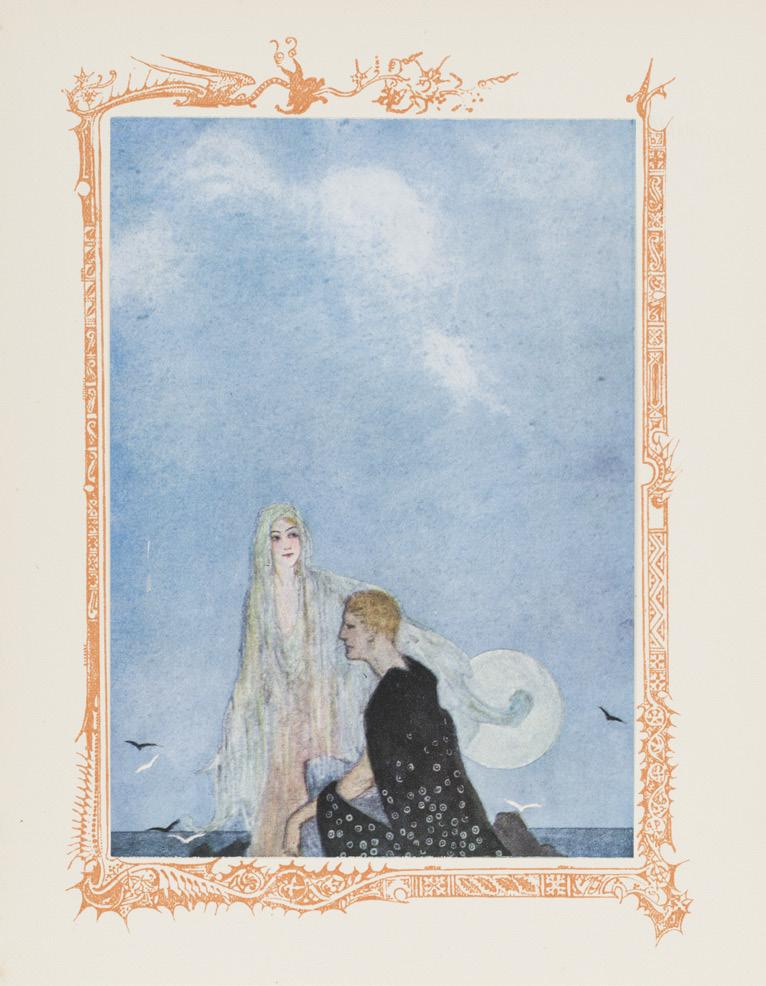

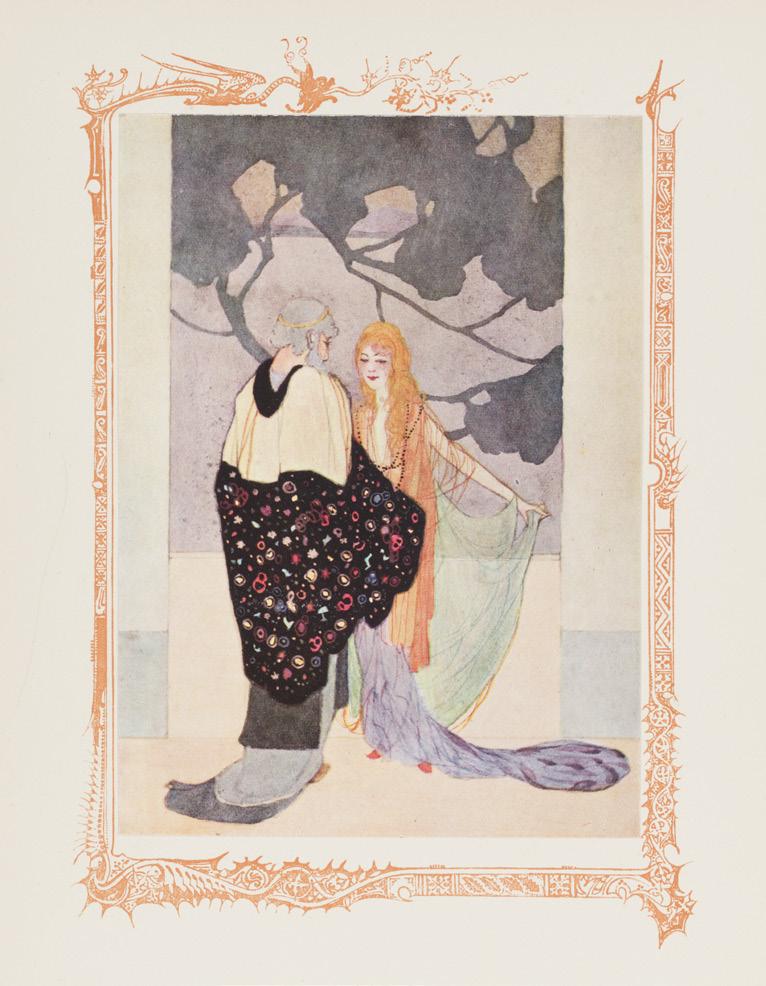

In 1914, while in London and desperate for money, Mainbocher finally received a break. Harrods department store commissioned him to create a series of colored plates to illustrate a printing of the medieval poem, Aucassin and Nicolete

with Olga Valda Kavaner, popularly known as Madame Valda.23 Because he overtrained, however, his singing career came to abrupt halt in 1921. On the night of his debut, he couldn’t produce a sound. It was a devastating blow.

MAKING MAINBOCHER (1921–39)

“There I was in Paris, with my family, with very little money saved.” —Mainbocher

The would-be designer, now in his early thirties, found himself at another crossroad. With few job prospects, he returned to fashion illustration. His first interview, a meeting with the couturier Captain Edward Molyneux, did not go well; they could not agree on his salary. But as he left, he received a tip that Harper’s Bazaar was looking for an artist. Mainbocher got the job, drawing for Harper’s for two years. The experience proved indispensable: “My first interest in clothes was as a fashion artist during the years that I drew in Paris for Harper’s Bazaar and learned to appreciate ‘chic.’” Then, in 1923, Edna Woolman Chase,24 the iconic editor in chief of Vogue, 25 selected Mainbocher for a position at the magazine’s Paris office. He wrote his first fashion editorial in 1924, at thirty-four years old.

Mainbocher’s seven-year tenure with Vogue was significantly productive for both the publication and the editor. Among other innovations, he initiated Vogue’s opening editorial “Eye View,” a concept the magazine used for the next fifty years. Through

“Eye View,” he promoted established and emerging artists, designers, illustrators, and photographers, including the fashion illustrator Eric26 and photographer George HoyningenHuene.27 Both artists benefited from their association with Mainbocher and went on to achieve considerable success. Eric especially became well known for his work for Vogue, regularly featured in the magazine from 1925, while Hoyningen-Huene became one of the most influential fashion photographers of the 1920s and 1930s.

A skilled writer and an astute arbiter of style, Mainbocher was promoted to editor in chief of French Vogue in 1927. He did not wait to be told what was popular but personally selected the designers and looks to publish in the magazine. He had a perfect eye—choosing styles that consistently became top sellers in the American market. He is also credited for moving the magazine’s look and feel to a more contemporary standard and for coining now well-known terms such as “off-white.”

But by 1929, he had hit a ceiling. Of his time at Vogue, Mainbocher wrote, “One of the important responsibilities I had as editor was to forecast coming fashions. After I had successfully for seven years been able to do this . . . I began to have an ambition to say something about clothes myself, so I decided to resign from Vogue and open a dressmaking house of my own.”28

In June 1929, he abruptly and rather fearlessly left his position to become a custom dressmaker. Mainbocher later recalled, “It was nothing that crept up on me. . . . It was an immediate and very agreeable

Mainbocher was honorably discharged on May 12, 1919, and paid $84.45 ($1176.63 today) for the extent of his service. According his army papers, his vocation was “musician” and his character, “excellent.” Main R. Bocher’s Army card, 1919. Ancestry.com, World War I cards, box 52.

explosion. . . . The whole idea was born and in 24 hours became absolutely right.” Not only had he not apprenticed under any couturiers, he had not really designed anything but a few dresses for friends. Halted by the collapse of Wall Street four months later, Mainbocher spent the time immersing himself in the study of fabrics—their weight, drape, and hand—and teaching himself “something of the craft of dressmaking.” Confident he would succeed; he relied on his sense of style and what he knew about good tailoring from his time at Vogue

Self-assured and well-connected, Mainbocher raised 900,000 francs ($560,000 in 2016) with the help of his mother, two countesses, and Mrs. Gilbert Miller, an American art collector and philanthropist,29 to incorporate his own salon. When it came time to open, he combined his first and last names, Main and

Bocher, to form the name of his company—a convention he borrowed from two French fashion houses he greatly respected— Augustabernand and Louiseboulanger. The result was the more sophisticated and French-sounding Mainbocher. Shortly thereafter, the man and his brand became widely known by the same name.

When the designer finally opened his salon, he was forty years old. He chose a quiet, residential location, opening at 12 avenue George V. 30 Most well-established couture salons of the day were situated along the bustling rue Royale or rue de la Paix. His was the only salon on George V, purposely located on the third floor so passersby could not peer inside. Despite a few lean months, he persevered. He recalled, “We did not sell

any dresses for two or three days. Strangely enough, no one was discouraged. We felt so sure of the ultimate success we lived in the future.” 31 By the late 1930s, he employed up to 350 people and was producing four collections per year, each including as many as one hundred different styles. Every garment was created in house by hand, with each workroom a “complete unit unto itself.” His business earned $2.5 million by 1939 ($43 million in 2016). As a result, he bought out all of his investors at a profit and transferred the stocks into his name.

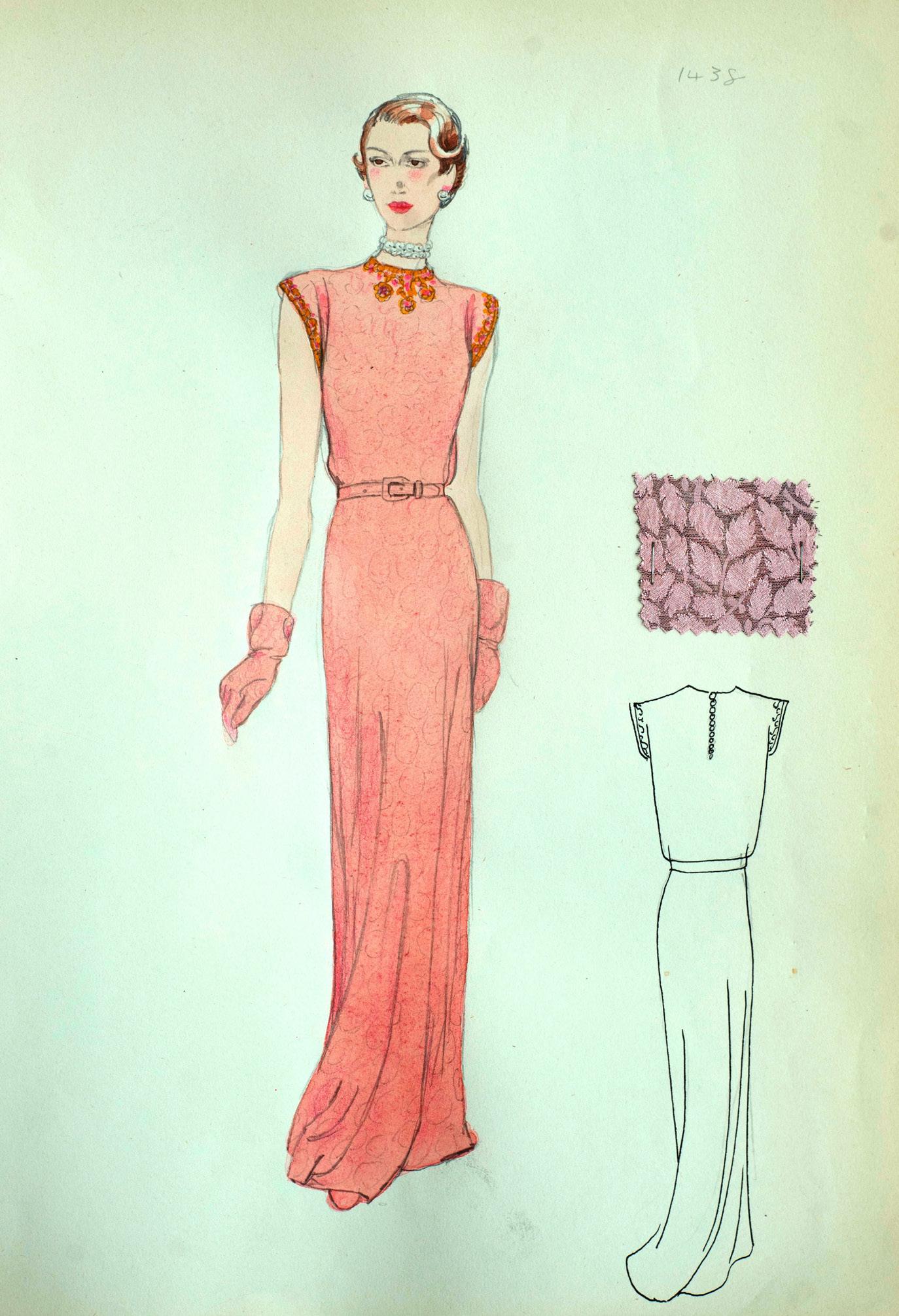

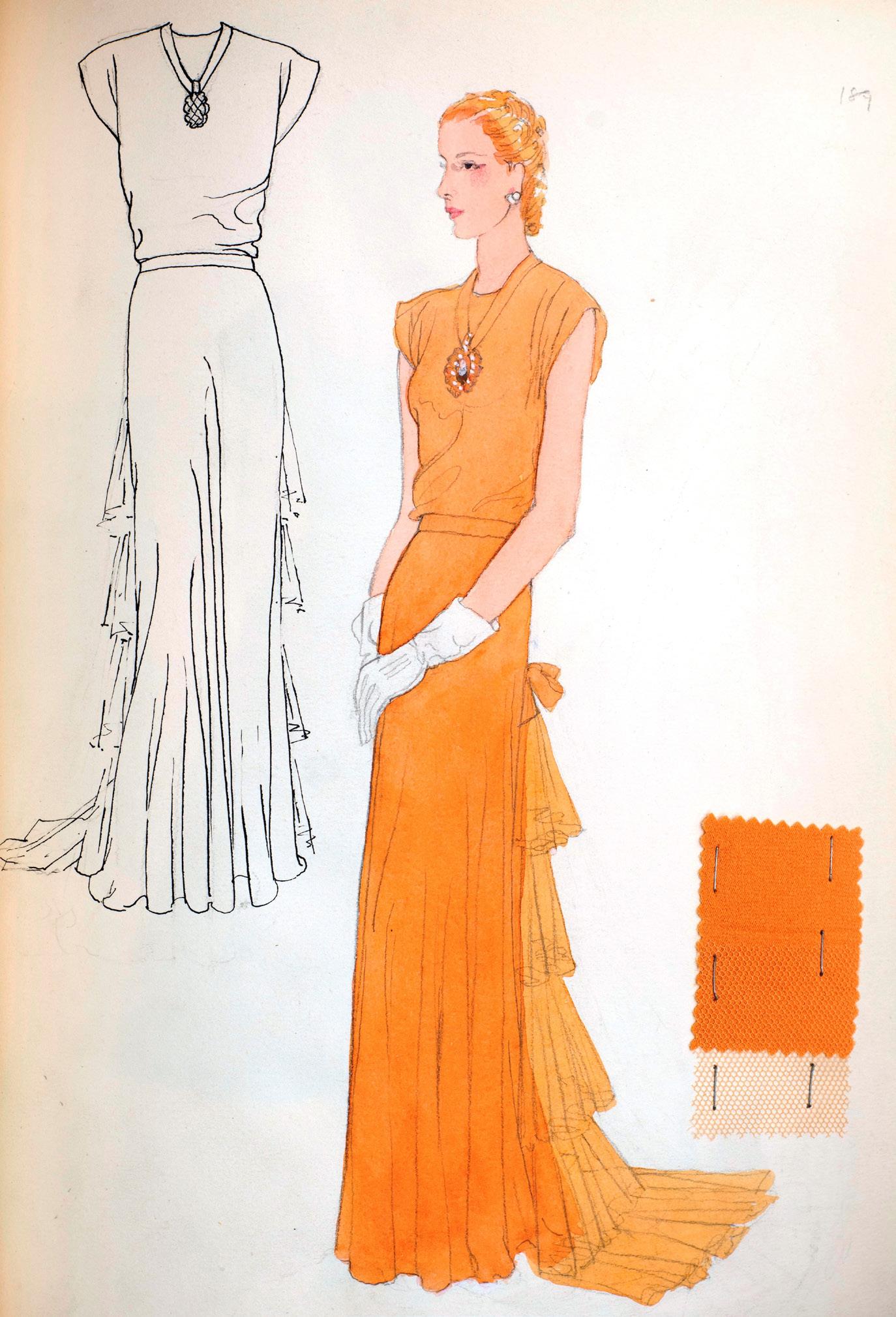

From the start, Mainbocher set out to create simple, subtle, luxurious, and, above all, elegantly feminine garments

of the highest quality. His intuition and meticulous nature served him well. In the 1930s, the house gained international fame and a reputation for creating sophisticated, perfectly constructed garments made to last. Mainbocher designed what he wanted and screened his clients with care. He had no interest in conforming to trends or creating fussy or over-the-top clothing. He was both prudent and scrupulous in his process, qualities upon which his clients began to rely.

Over the next forty years, the name Mainbocher became synonymous with sophistication, grace, and exclusivity. He created formal garments of complex cut and simple lines and contributed greatly to the fashion lexicon by introducing new styles,

The designer chose an unusual location for his salon—the quiet, residential avenue George V—and he selected the third-floor space, to ensure privacy for his clients. Photograph by Henri Daniels, 1930s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library.

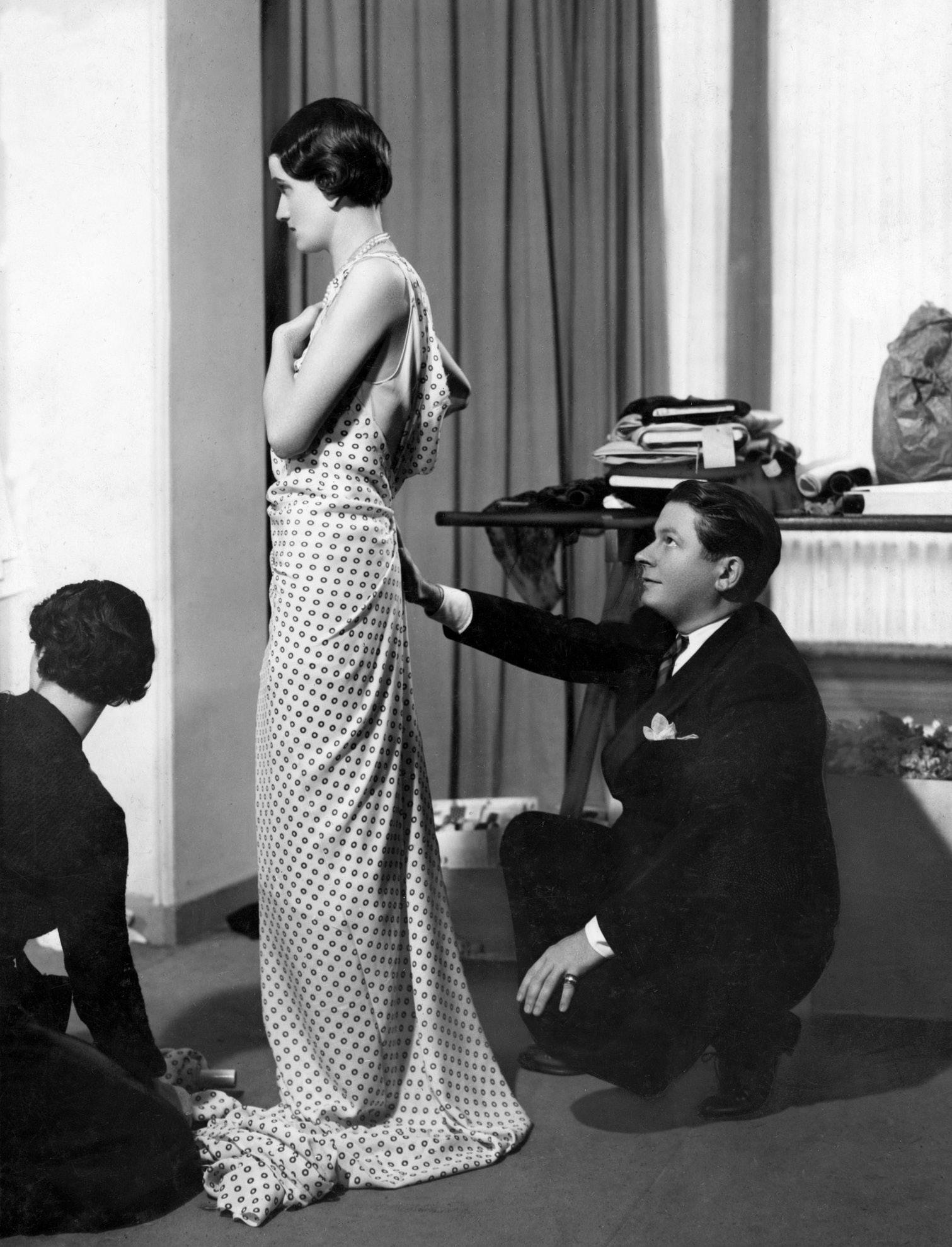

With no formal training, Mainbocher taught himself dressmaking by draping, cutting, and fitting muslin on models and mannequins. He once said, “I work on my dresses until they look right to me.”

by Bal Bernard, 1930s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library.

Photograph

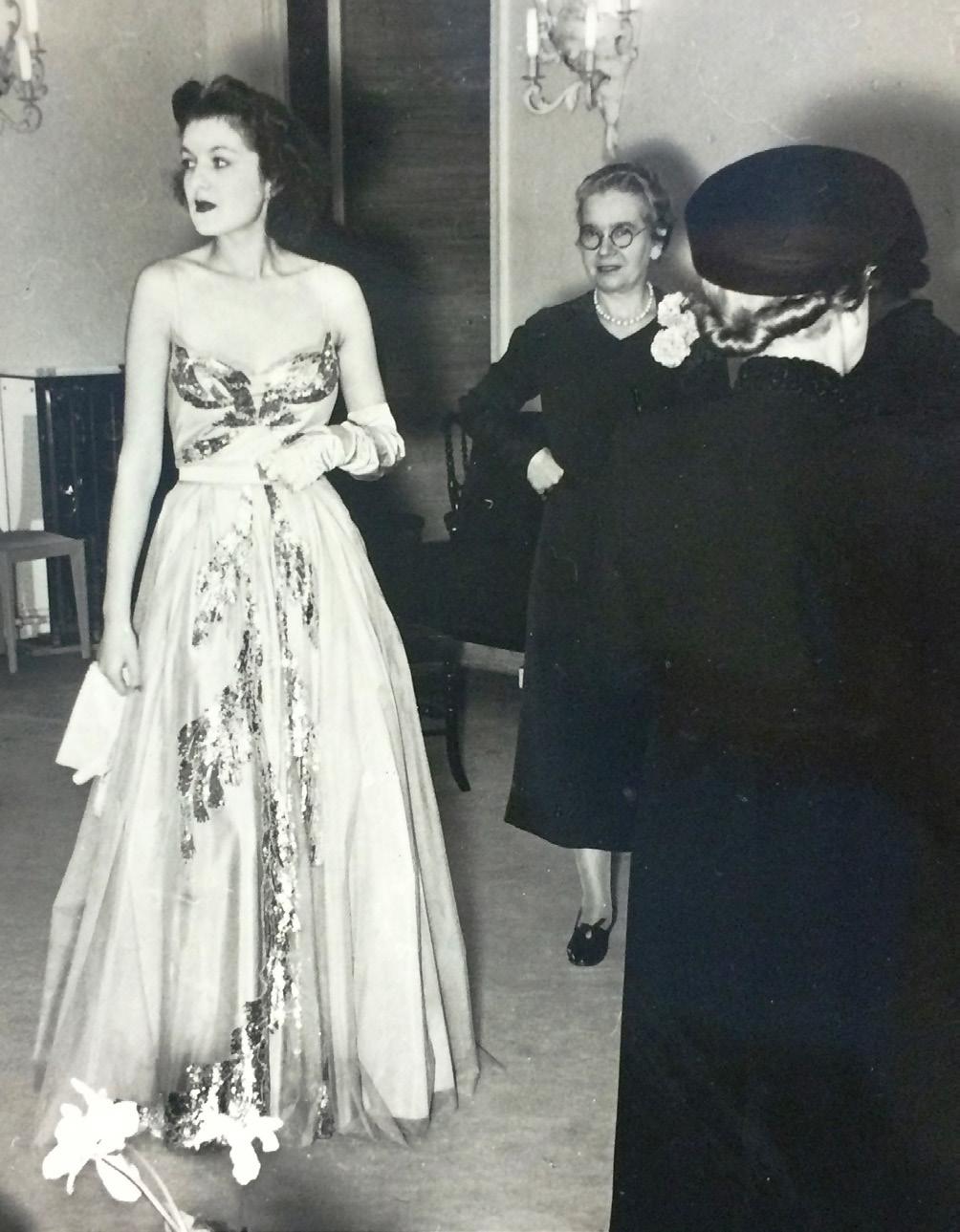

Mainbocher was very particular about the presentation of his clothing: “I wanted attention to be on the clothes.” He insisted his models wear gloves and refused to serve food or champagne, as was the standard at other houses, so his clients would not be distracted. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library.

Mainbocher seamstresses working on the Duchess of Windsor’s trousseau, France, 1937.

Photograph by Bal Bernard, 1930s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor photographed after their wedding in the Château de Candé at Monts, France, 1937. For the dress, Mainbocher selected a silk-crepe made in a custom blue, dubbed Wallis Blue, to match her eyes. ICHi-89056.

including the strapless dress, short cocktail dress, beaded cashmere sweater, and furlined coat, all while maintaining a reputation for impeccably constructed garments.

The house’s client list of the 1930s reads like a who’s who of the world’s best dressed, but in 1937, the designer acquired his most famous patron. King Edward VIII of England abdicated his throne in December 1936 to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American socialite. The couple’s scandalous love affair caught the world’s attention, and when the duchess wore a Mainbocherdesigned wedding dress, the couturier solidified his place among the fashion elite. Chanel and Schiaparelli had also submitted sketches for Simpson’s consideration, but she selected Mainbocher. Perhaps because they were alike: two Americans living among the European elite, pursuing elegance, sophistication, and improbable fame. Though he immediately destroyed the pattern for the duchess’s wedding dress, it became one of the most copied dresses of all time.32

The gown elevated the international appeal of Mainbocher, making him the couturier of moment, and the pair worked together for many years following her wedding. Mainbocher also become the premier choice of brides-to-be, designing dresses for a number of wealthy and renowned women, such as Babe Paley33 and Sharon Percy Rockefeller,34 for the duration of his career.

Due to earlier experiences within the fashion industry, Mainbocher was well acquainted with how easily designs were

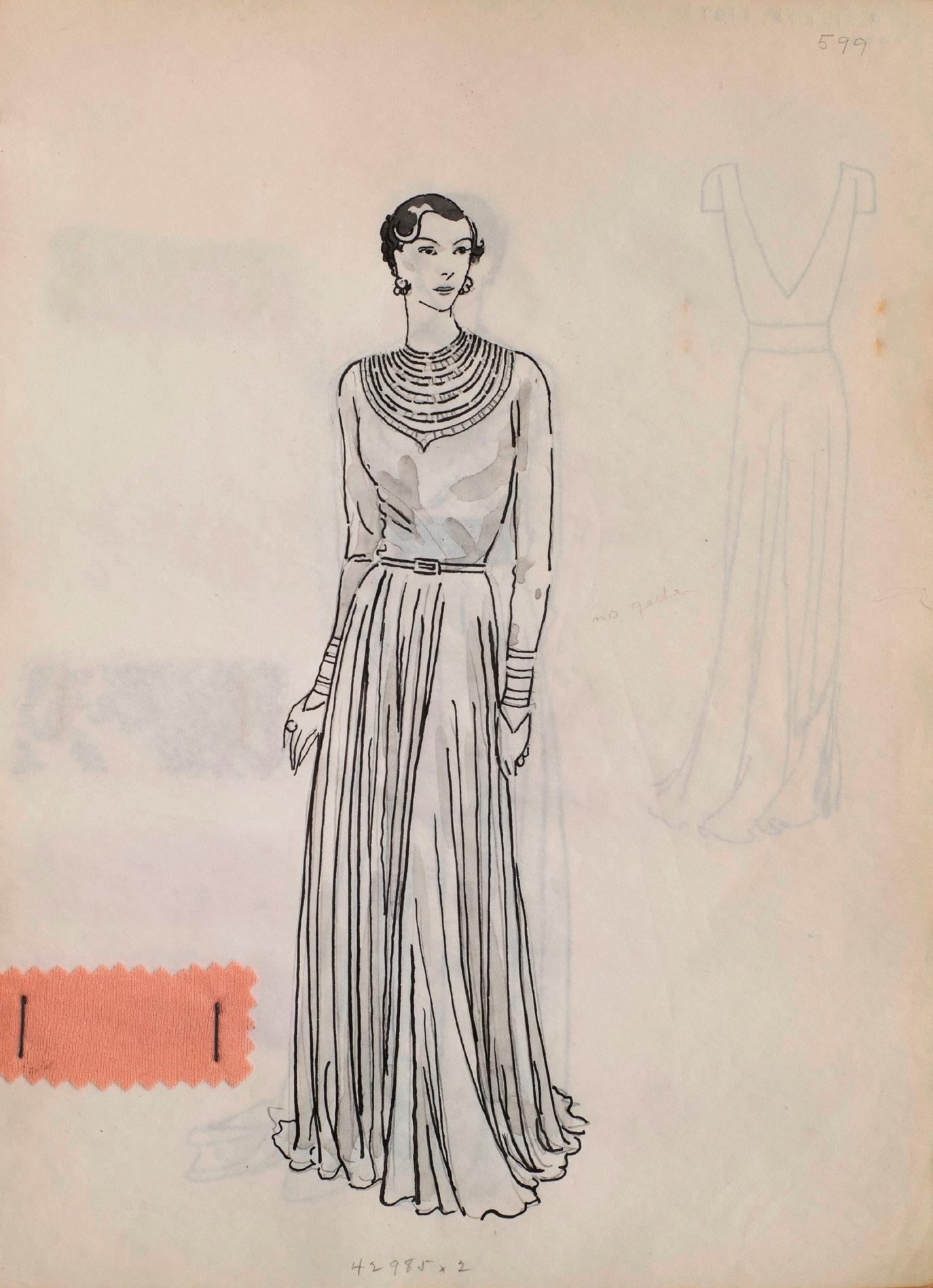

poached and reproduced. A shrewd and savvy businessman, he introduced a practice not yet seen in couture. He charged a fee to attend his fashion presentations, known as a “caution,” equaling the least expensive item featured. The fee was applied to discourage copyists, mainstream manufacturers, and others looking to duplicate his designs—and it worked. Not only did other couturiers adopt the caution, Mainbocher’s designs are also noticeably absent among collections of copies. In the Stephen Sondheim sketches housed in the archives at New York’s Parsons School of Design for example, copies of work by other houses such as Chanel, Rochas, Molyneux, Worth, Paquin, Goupy, and Schiaparelli are numerous, while nestled within the grouping are but a few examples of work by Mainbocher.

MAINBOCHER, INC. (1940–71)

“Mainbocher is really in advance of us all, because he does it in America.” — Christian Dior, 1956

The onset of World War II forced Mainbocher out of Paris. He had been living abroad since 1917. After paying off his staff and vacating his salon, Mainbocher and his partner, Britishborn fashion illustrator Douglas Pollard, sought refuge in New York. Mainbocher and Pollard met in Paris in the early 1920s and lived together from that point forward, maintaining both a personal and professional relationship. Pollard was originally employed by Captain Molyneux and then worked as a staff artist with Vogue. He left Vogue with the

establishment of Mainbocher Couture to work exclusively with the house until it closed in 1971. Of their years at Vogue, celebrated editor in chief Edna Woodman Chase recalled, “They made a good team, Main selecting the clothes and Douglas drawing them.”35

Fortunately, Mainbocher’s last French collection offered him an entry into the American market. Presented in August 1939 and immortalized by famed fashion photographer Horst P. Horst, the “wasp waist” collection reintroduced the corset and caused a furor—rejected by some who saw the corset as an unwelcome, backward step in women’s fashion. But Mainbocher had grown tired of what he referred to as the “debutante slouch” and wanted to see another silhouette emerge. His revival of the corseted waist anticipated Dior’s New Look by eight years. Regardless of reception, the style offered him a great opportunity. Low on cash, he partnered with Warner Brothers Corset Company and streamlined his design. The Mainbocher–Warner line of corsets debuted in the Grand Ballroom at the Hotel Astor on January 16, 1940, with the designer providing commentary.

At forty-nine years old, Mainbocher was again starting over. In a 1940 interview with the New York Times, he said, “I’m glad to be back, you know, and I am very proud of my American citizenship. I went abroad to be an artist with a capital A. Since 1930, I have been in business for myself doing the work that I like most. I hope to continue doing it here.” Sustained by his Warner contract,

Mainbocher reopened his house in New York, this time as Mainbocher, Inc. He chose 6 East Fifty-Seventh Street, neighboring Tiffany & Company, for his location and recreated his salon in the image of his Parisian atelier. Mainbocher presented his first New York collection on October 30, 1940, in a small room with a few devoted and influential guests. From that moment forward, there was little need for concern: the American social registry clamored for a fitting.

Mainbocher’s challenge was to secure a place in the American fashion industry and stand out in a country that did not readily embrace haute couture. He maintained the traditions and formal operations of a French salon, including appointments issued by invitation or introduction only. Chicagoan Jean Harvey Vanderbilt remembers visiting Mainbocher, Inc. with her husband, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, who told her, “I’m going to take you someplace where we’ll make you look marvelous. ” He was right—and she did.

Mainbocher had presented many new styles to fashion during his tenure in Paris, including the strapless bodice and the cinched waist, and his career in the United States proved to be equally prolific. Three hallmarks of his career—the jeweled sweater, the cocktail apron, and uniforms for the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), an auxiliary of the United States Naval Reserve—were presented in the early 1940s. The sweater and apron designs stemmed from a desire to create beautiful clothing during wartime fabric rationing. The stylish wool evening sweater adorned with intricate

Mainbocher introduced the nipped-in corseted waist in August 1939, a style which predated Christian Dior’s New Look by eight years. A month later, Parisians, anticipating the fall of their city, mobilized for war. This iconic image, captured by photographer Horst P. Horst, reflects the unsettling moment. Of the shoot, Horst recalled, “It was a tense and sad time. [The model] was crying.”

Photograph by Horst P. Horst/Conde Nast Collection/Getty Images.

beading particularly suited the American taste for casual but sophisticated attire, while the cocktail aprons allowed women to easily alter the look of an existing dress.

While many of his contemporaries readily embraced the ready-to-wear market of the post–World War II era, Mainbocher refused. Rather than mass producing or licensing his brand, he continued working exclusively in the couture tradition, serving private clients out of his studio. By the mid-1950s, Mainbocher was creating the most exclusive and luxurious clothes in the world with a price tag to match. “I simply felt I should be paid for my efforts,” he said. Because of the quality and timelessness of his designs, Mainbocher rightfully and unabashedly viewed his creations as sound investments that would remain relevant for years. And he frequently looked to his own creations for inspiration, revisiting the same silhouette again and again. By the late 1960s, however, he had grown weary of the rapid changes and trends in fashion, so he simply ignored them. Remarkably, his clients remained loyal.

Although he had witnessed two world wars and much professional uncertainty, Mainbocher was not prepared for the embezzlement scandal that rocked his business. In 1964, the New York Times reported that an employee of Mainbocher, Inc. had stolen $225,000 ($1.7 million in 2016) from the company. Stunned but not defeated, Mainbocher immediately gave up travel, theater, and his beloved daily fresh flowers in an effort to recoup his losses. He sold his car, moved into a smaller apartment, and cut his own

salary. He did not, however, reduce the salaries of his employees. After rectifying the balance, his financial situation evened out, but by 1971, he declared, “I just can’t do it anymore.” The fashion industry had changed, many of his colleagues were gone, and he was finally ready to retire. At the age of eighty-one, Mainbocher closed the doors to his renowned fashion house. He and Douglas sold their belongings and traveled across the Atlantic once more. The pair spent their remaining years together in Paris and Munich. Mainbocher passed away on December 27, 1976, at age eighty-six.

A LIFE AND LEGACY

“At 72, the short, round little man with the synthetic name can boast that his clothes are the most carefully made, the slowest to change, and among the most expensive in the world.” —Time magazine, 1963

In 2002, Mainbocher was honored among his American peers with a bronze plaque on New York City’s Fashion Walk of Fame in the legendary Garment District. It reads:

Mainbocher was known for the understated elegance of his clothing. Among his innovations were short evening dresses, jeweled sweaters, and a revival of the corset that anticipated Dior’s New Look. Most famous for designing the Duchess of Windsor’s trousseau in 1937, he also designed uniforms for the WAVES, the Red Cross, and the Girl Scouts.

Mainbocher’s distinguished legacy is also celebrated among European fashion houses such as Vionnet, Lanvin, Chanel, Dior, and

In this image published in Vogue in 1964,

Mrs. Alfred Vanderbilt modeled a highwaisted gown with crossed bodice by Mainbocher and jewels by Van Clef & Arpels.

Photograph by Horst P. Horst/Conde Nast Collection/Getty Images.

Mainbocher’s most influential and pervasive design of the 1940s was the stylish wool evening sweater adorned with intricate beading. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library.

Balenciaga. His work was shaped through a prism of precision, French sophistication, and American ambition. Yet Mainbocher stands for so much more. His is a story of a determined, self-assured man driven to succeed. Each step he took was a step toward

the mastery of what came next. For more than fifty years, against many odds, he successfully navigated the rocky terrain of the fashion industry, where he excelled as a fashion artist, a well-respected and accomplished editor, and a world-renowned couturier.

1. In 1929, Main Bocher combined his first and last names to form the name of his brand and company, Mainbocher. The designer is most commonly referred to by his company name.

2. The Lewis Institute was a vocational school founded in 1896 to help students from lower-income families develop technical skills for professional careers. In 1940, Lewis merged with the Armour Institute to form the Illinois Institute of Technology.

3. The Bohemian Girl and Iolanthe

4. Mainbocher’s journals are housed in the Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

5. George Bocher worked at 103 Wabash Avenue as a dry goods salesman at D.B. Fisk & Company.

In New York, Mainbocher continued his practice of creating clothing in unconventional fabrics, such as gingham and painted leather.

6. Mainbocher journals.

7. Sears, Roebuck & Co. is an American chain of department stores. Mainly known for its appliances, hardware, and clothing, the company was founded by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck in 1886. In the early 1900s, construction started on a forty-acre, $5 million mail-order plant and office building on Chicago’s West Side. When it opened in 1906, the mail-order plant, with more than three million square feet of floor space, was the largest business building in the world.

8. Chicago Academy of Fine Arts was founded in 1902 by Carl N. Werntz and was based on a “learning by doing system” which bypassed some of the theoretical work which traditionally had been required of art students. (Chicago Daily Tribune, February 15, 1948). A number of well-known illustrators attended this school, including Carl Oscar Augustus Erickson and Walt Disney.

9. Mainbocher moved to New York City with classmate Harold Speakman. They lived in Brooklyn but worked and studied in Manhattan.

10. The Art Students League of New York, an art school located on West Fifty-Seventh Street in Manhattan, was founded in 1875.

11. Mainbocher journals.

12. Ernest Archibald Taylor (1874–1951), better known as E. A. Taylor, was a Scottish artist, oil painter, watercolorist, and etcher as well as a designer of furniture, interiors, and stained glass.

13. The Societé des artistes décorateurs was a French society of designers of furniture, interiors, and decorative arts that was active from 1901 until the 2000s. It sponsored an annual exhibition in which its members displayed their new work.

14. Aucassin and Nicolete is an anonymous medieval French chantefable, a combination of prose and verse that is meant to be sung.

15. Mainbocher journals.

16. Edward L. Mayer was a highly regarded maker of women’s fashions in the early part of the twentieth century. His clothes were famed for their quality and fit.

17. Frank La Forge (1879–1953) was an American pianist, vocal coach, teacher, composer, and arranger of art songs.

18. Sigmund Gottfried Spaeth (1885–1965) was an American musicologist who traced the sources and origins of popular songs to their folk and classical roots. He was also an arranger, conductor, performer, author, educator, and longtime music critic for the New York Times

19. Wayland-Smith Hatch, page 198

20. Mainbocher sailed to Bordeaux, France, with fellow volunteers, including composer Cole Porter, architect Whitley Warren, and fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie. They docked on July 14, 1917.

21. Mainbocher journals.

22. Henri Albers, born Johan Hendrik Albers (1866–1926), was a Dutch opera singer who later became a French citizen.

23. Madam Giulia Valda (1850–1925) was born in Boston as Julia Wheelock. She went on to gain international fame as an opera singer.

24. Edna Woolman Chase (1877–1957) was editor in chief of Vogue from 1914 to 1952. She knew Mainbocher from his early days working as a fashion artist for E. L. Mayer in New York.

25. Vogue was founded as a weekly newspaper in the United States in 1892. It was purchased by Condé Montrose Nast in 1905 and grew significantly under his direction. Vogue’s Paris office opened in 1920.

26. American illustrator Carl Oscar August Erickson, popularly known as Eric, was born in Joliet, Illinois, in 1891 to Swedish immigrant parents. He studied at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts with Mainbocher.

27. Baron George Hoyningen-Huene was a Russian-born fashion photographer, whose prolific career produced some of the most iconic fashion photography of the twentieth century.

28. Mainbocher journals.

29. Kathryn Bache Miller (1896–1979) was an American art collector and philanthropist.

30. Cristóbal Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy followed Mainbocher’s lead, opening their own houses along the avenue George V in subsequent decades.

31. Mainbocher journals.

32. The Windsor wedding took place on June 3, 1937, and by August, copies were available in stores from Bonwit Teller’s to Klein’s department store. (Life, August 9, 1937)

33. Barbara “Babe” Cushing Mortimer Paley (1915–1978) was an American socialite and style icon, whose second husband, William S. Paley, was the founder of CBS.

34. Sharon Lee Percy Rockefeller (born 1944) is the wife of former West Virginia Senator John Davison “Jay” Rockefeller IV.

35. Laura Jacobs, “The Mark of Mainbocher,” Vanity Fair, 1998.

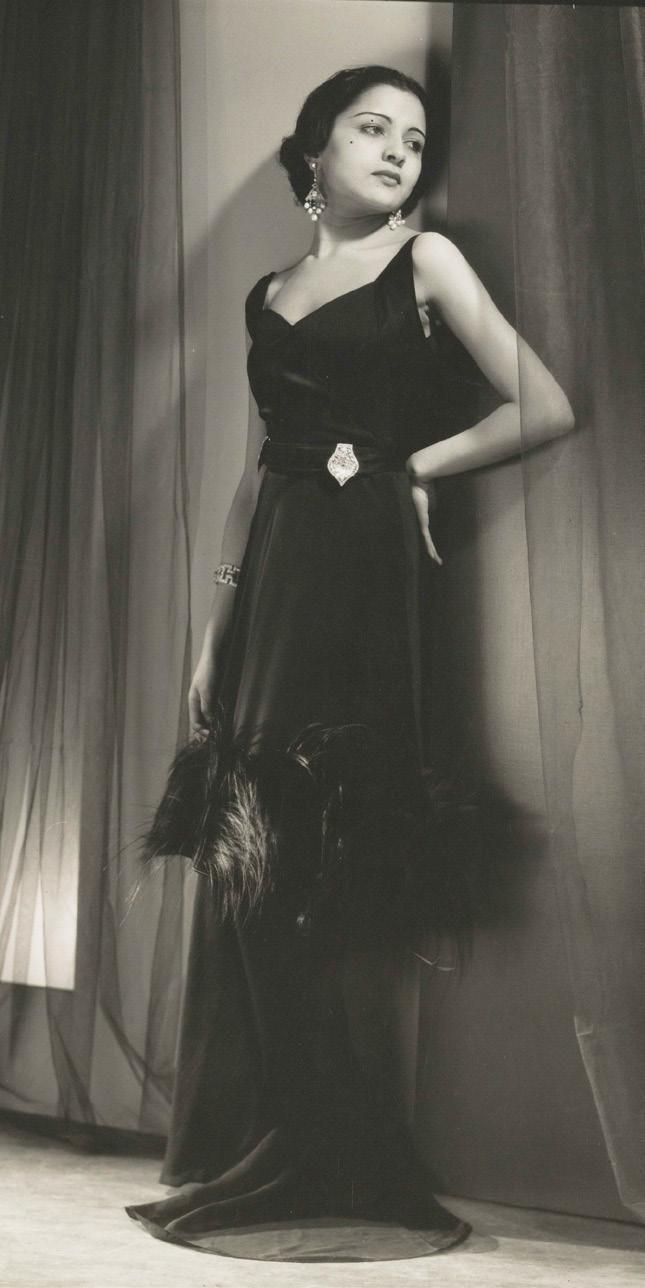

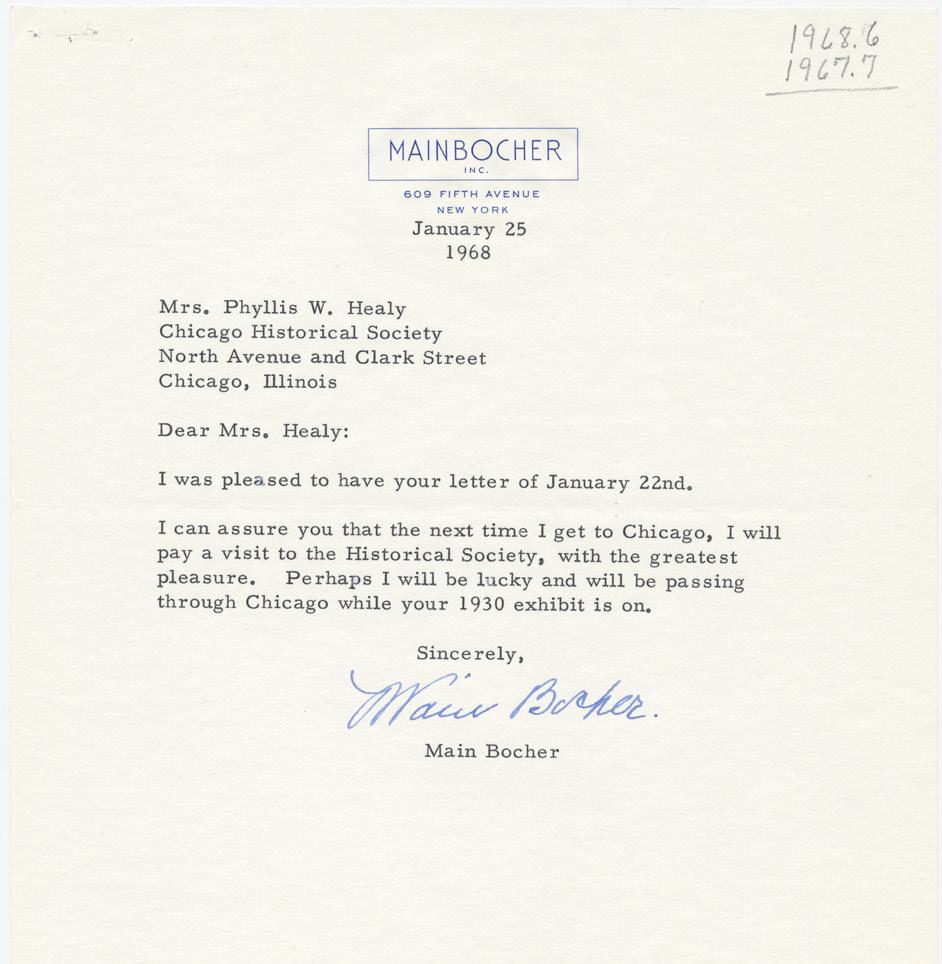

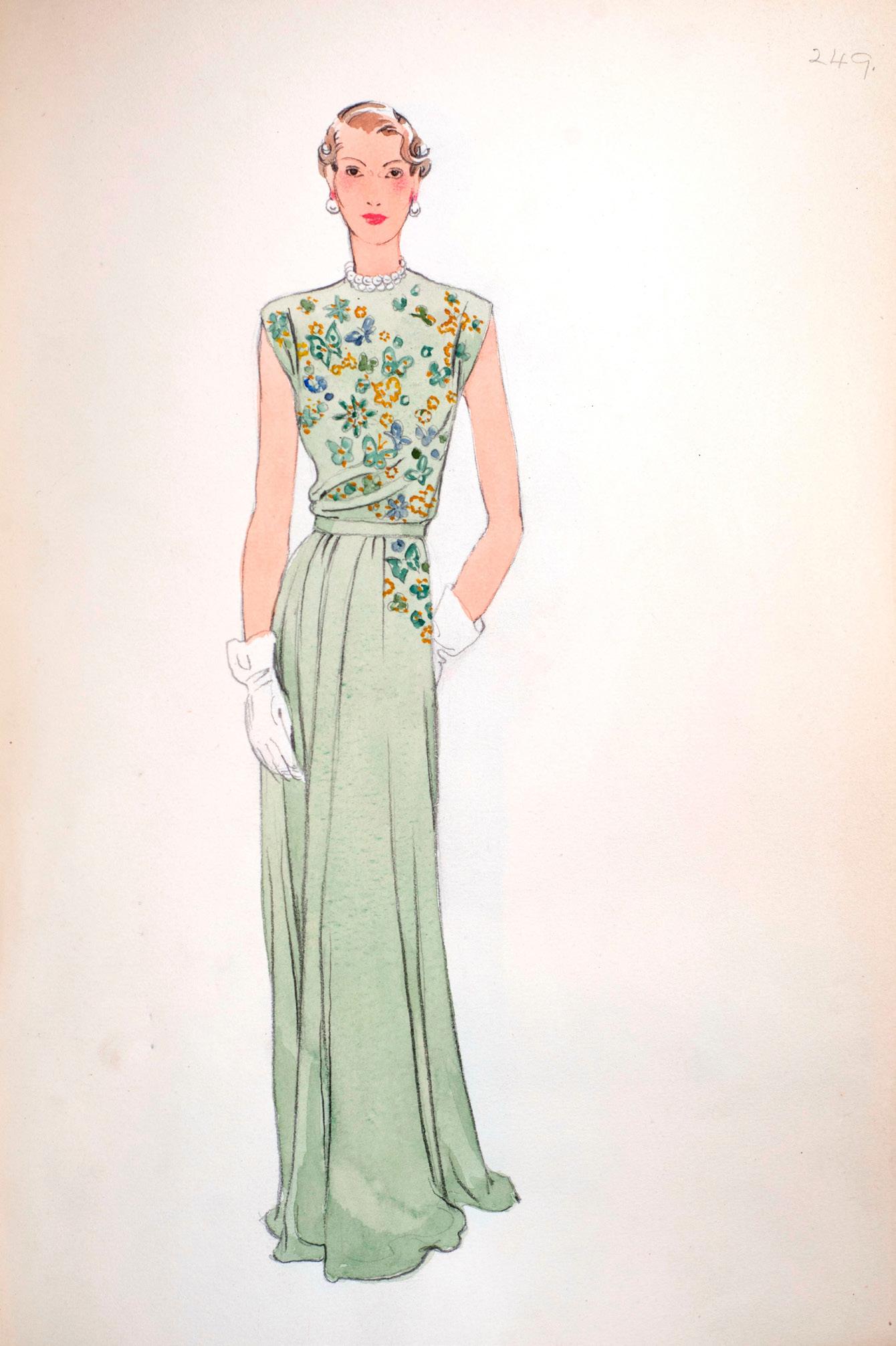

EVENING DRESS, SPRING 1937

Two-piece dress consisting of sleeveless tunic worn over matching slip-style gown

Gift of Mr. Main Bocher, 1968.6

Sponsored by Luvanis

ICHi-88999

In November 1930, at the age forty, Mainbocher opened his Paris studio. By 1931, his designs were presented in the fashion press alongside those by Vionnet, Molyneux, and Chanel. The two-tiered style was one of his favorite silhouettes.

ICHi-88998

EVENING COAT, SPRING 1937

Plaid wool long-sleeve double-breasted coat Gift of Mr. Main Bocher, 1968.7

ICHi-88895

Chicago philanthropist Mrs. Otto Madlener prompted Mainbocher to donate two garments—a two-tiered dress and plaid wool evening coat—to the Museum in 1968 for inclusion in an exhibition on 1930s fashion. The original receipts and a letter addressed to the curator at the time accompanied the donation.

ICHi-88606

ICHi-88602

In the 1930s, Mainbocher introduced cloth evening coats to wear instead of furs. This coat is among the earliest examples of Mainbocher’s work in the Museum’s collection.

ICHi-88891

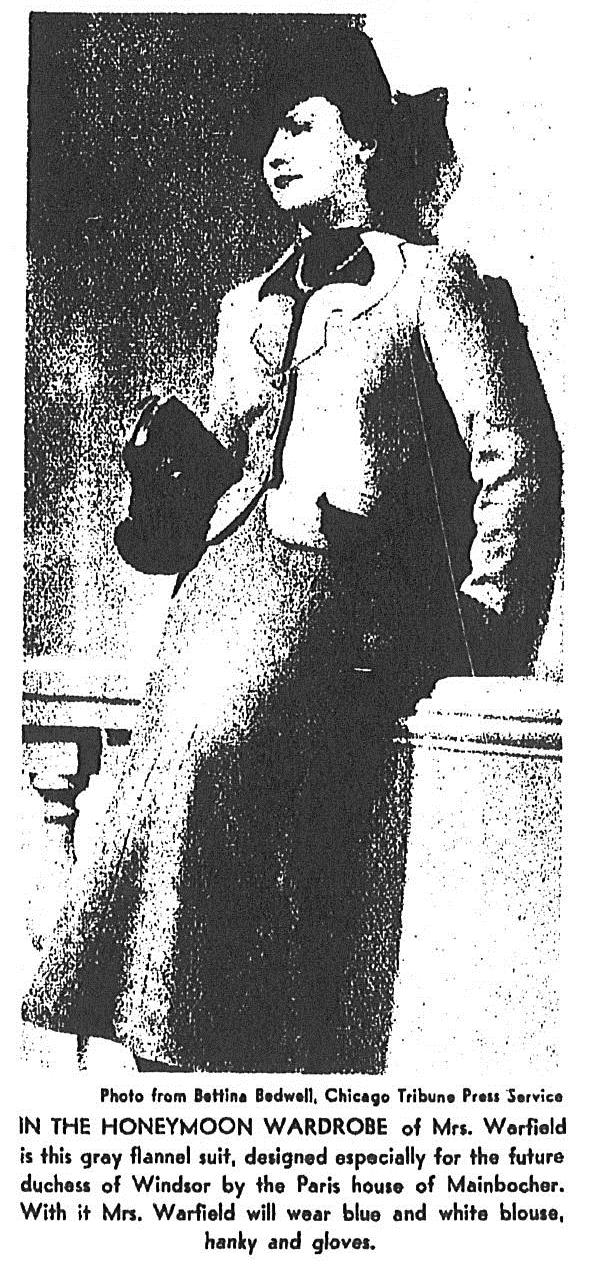

SKIRT SUIT, SPRING 1937

Wool flannel suit with silk printed blouse and handkerchief

Gift of Mrs. Stephen L. Ingersoll, 1983.622.4

Fashion and Photo Preliminaries to Windsor’s Wedding, Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1937

Mainbocher not only designed the Duchess of Windsor’s wedding dress, but many ensembles in her trousseau. Other clients of the house requested copies of the designs she favored, such as this suit worn by Chicagoan Mrs. Stephen L. Ingersoll, wife of the president of Ingersoll Steel. Mrs. Ingersoll’s ensemble has a brown and white blouse and handkerchief, while the duchess’s accessories were blue and white.

ICHi-88813

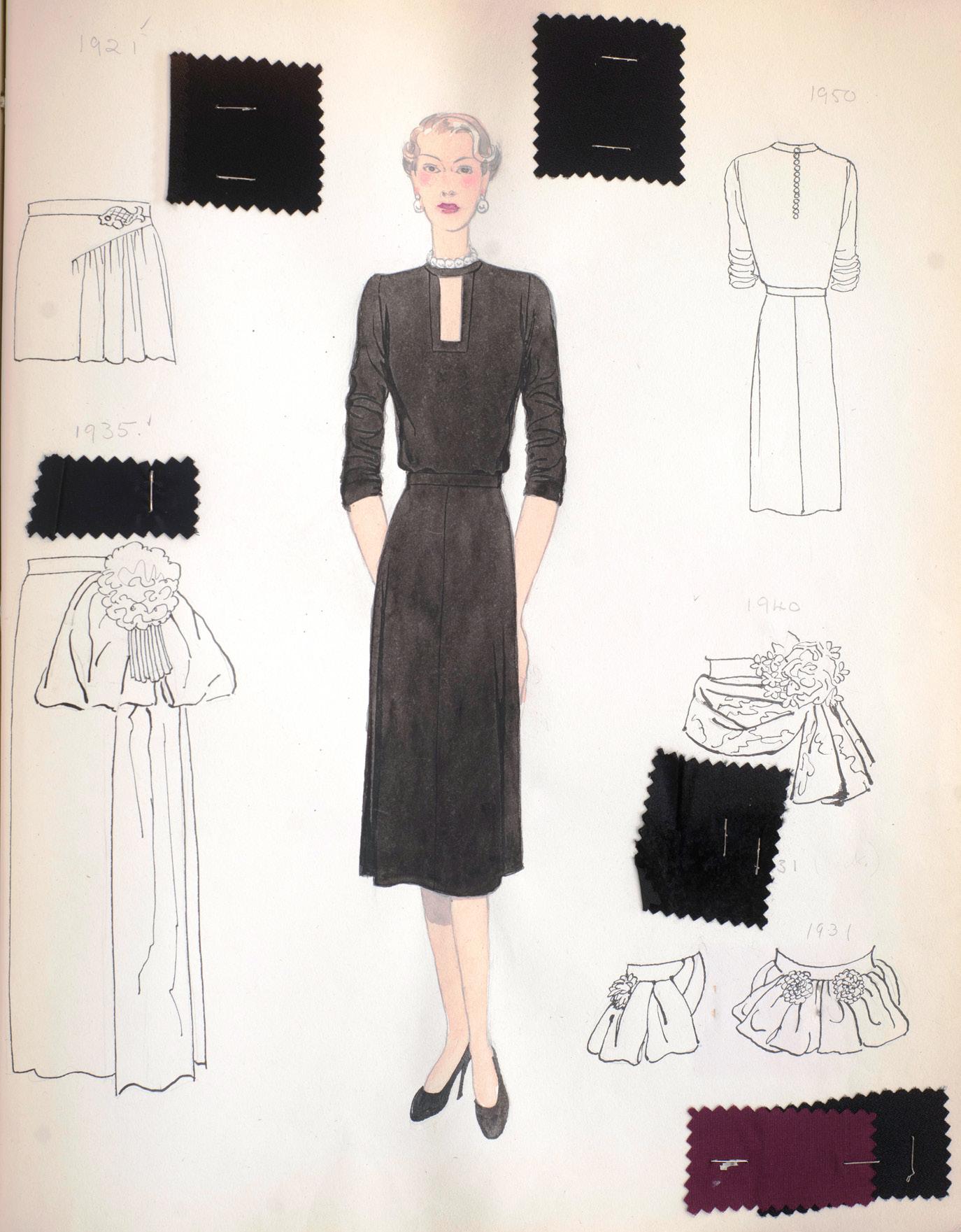

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1944

Gift

Sponsored by Marci and Ronald Holzer

Silk floral brocade dress trimmed with beads and sequin

of Mrs. A. Watson Armour III, 1959.348

During World War II and its aftermath, Mainbocher revisited the same silhouette repeatedly, updating the look with the use of restrained embellishments. He once remarked, “The war is over, but I can’t design flippant dresses as though its shadows have vanished.”

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1945

Gift of Mrs. A. Watson Armour III, 1959.354

Sponsored by Mr. and Mrs. Gregory Shearson

Silk crepe dress trimmed with paillete butterflies

Mainbocher worked with each client to create designs best suited for her. He made an earlier version of this dress in yellow, but Mrs. A. Watson Armour III requested it in a pale gray-green.

ICHi-88875

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1945

Knit jersey long-sleeve dress embellished with bands of silver beads and rhinestones and a matching belt Gift of Mrs. A. Watson Armour, III 1959.346

With an exacting vision, Mainbocher frequently added embellishments to his clothing so little to no jewelry would be required.

ICHi-88883

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1946

Silk crepe dress with faux jeweled medallion and tulle layers in a bustle effect topped by two crepe bows Gift of Mrs. A. Watson Armour III, 1959.355

Sponsored by David and Nancy Connelly

Speaking to the Fashion Group of Chicago in 1940, Mainbocher said, “What you don’t do with a dress is at least [as] important as what you do, do. Too many gadgets can spoil the dress, just as surely as too many cooks, the broth.”

ICHi-88888

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1946

Tulle dress with three-quarter sleeves, cuffs trimmed with silver and glass beads, faux pearls, sequins, and keyhole limpet shells

Gift of Mrs. Clive Runnells, 1967.218ab

Unlike many other couturiers, Mainbocher designed every item himself, at times even cutting the fabric. Throughout his career, he set out to create simple, subtle, and, above all, elegant garments—a philosophy that never wavered.

EVENING DRESS, SPRING 1947

Crepe sleeveless dress with an inverted V-shaped apron-like drape at front embellished with two-inch bands of brass-colored findings and small white and brown beads and a matching belt

Gift of Miss Peggy Stanley, 1979.91.1

During World War II, the United States government applied restrictions on the types and amount of fabrics that could be used in clothing manufacturing. Fashion designers adapted their designs accordingly. Mainbocher created a collection of interchangeable “dress aprons,” which were worn over simple cocktail or evening dresses to change up the look.

Mainbocher updated his concept of the dress apron in later designs. This garment from 1947 illustrates how he looked to his past work for inspiration. He integrated the apron style into the design of the dress, thus introducing a new silhouette.

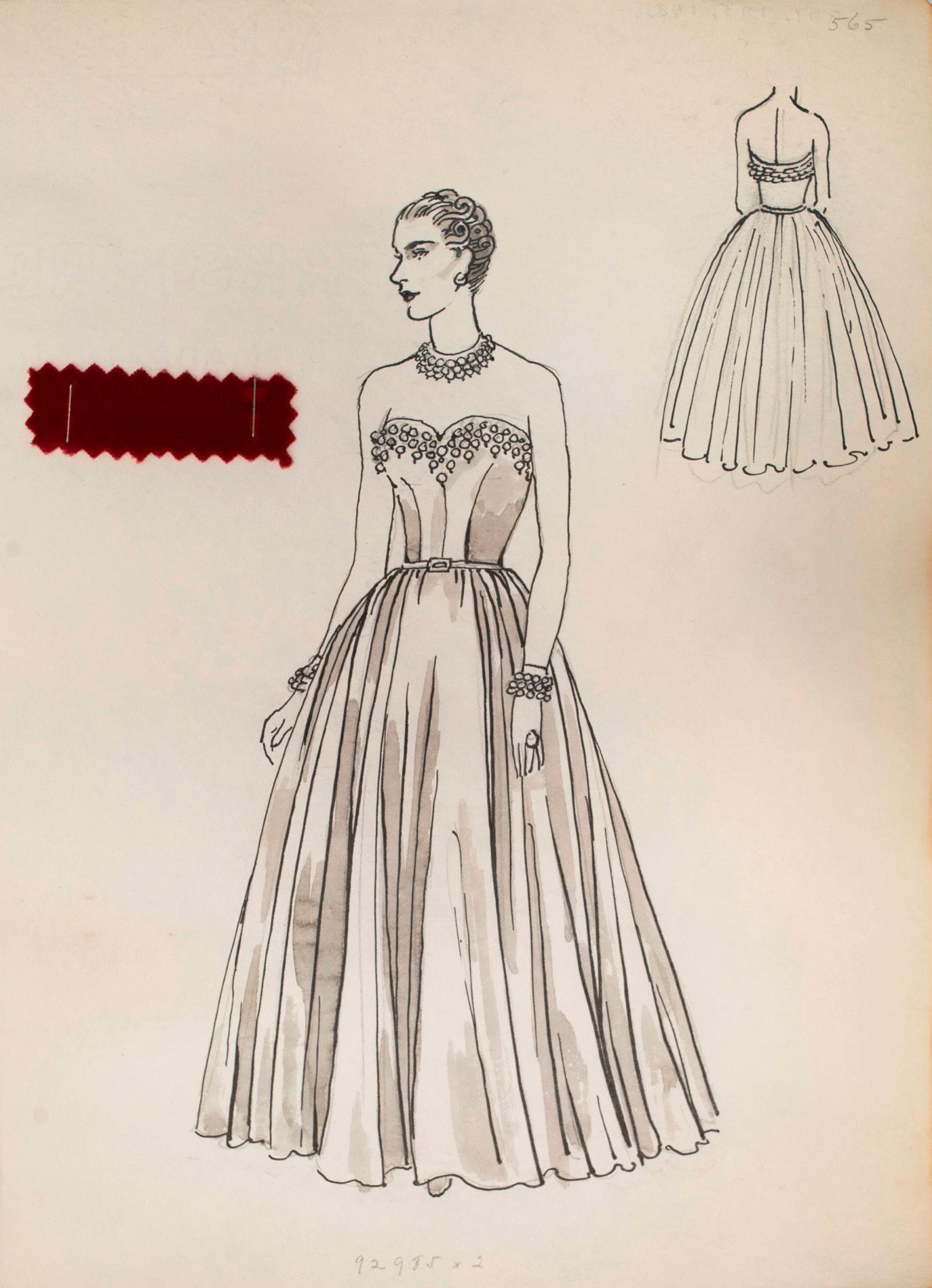

BALL GOWN WITH ACCESSORIES, FALL 1947

Velvet strapless evening gown trimmed with velvet-covered balls dotted with beads and sequins with a matching red velvet belt, choker, and bracelets

Gift of Mrs. A. Watson Armour, III 1959.345a-d

Mrs. A. Watson Armour III with William Douglas at a “400” party on December 10, 1948 in Chicago’s private club, The Casino.

In 1934, Mainbocher introduced the strapless dress; by the late 1940s he was regularly using the silhouette in his evening wear. The style has since become a fashion staple.

SKIRT SUIT, SPRING 1948

Wool suit with cropped jacket and plastic buttons

Gift of Miss Peggy Stanley, CC1971.145ab

Cosponsored by Victoria Fesmire, Vicki and Bill Hood, Dr. Katherine B. Klehr

The donor of this suit, Peg Stanley, was an interior designer at the renowned Chicago department store, Marshall Field & Company. In 1973, she told the Chicago Tribune, “I have always loved [Mainbocher’s] things, especially his suits.”

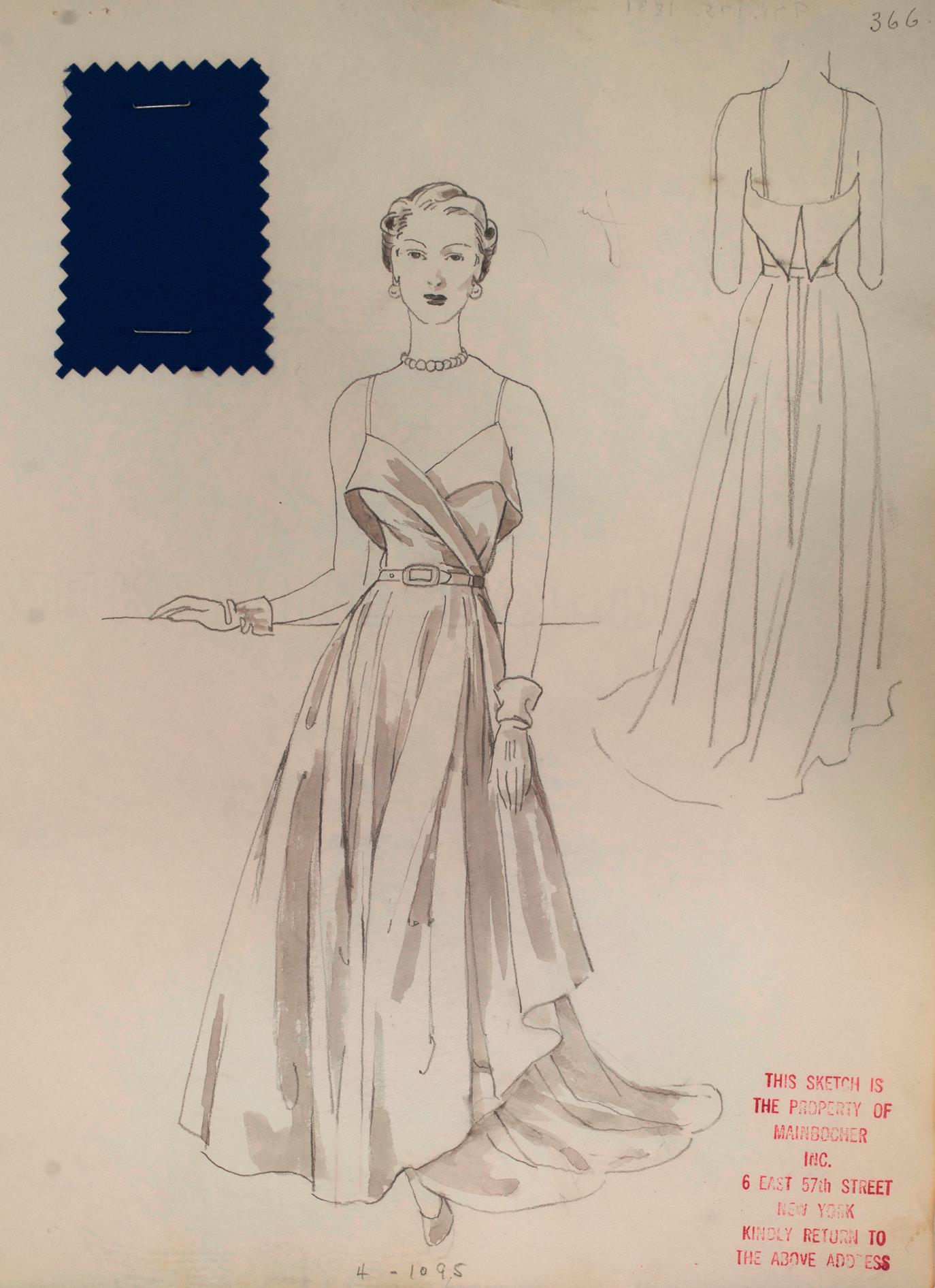

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1949

Silk taffeta wraparound dress with hook-and-eye closures at the left side of the waist

Gift of Mrs. Jo Hopkins Deutsch, 1975.210.1

The quality and timelessness of Mainbocher designs enabled him to rightfully and unabashedly view his creations as sound investments that would remain relevant for years. As Jo Hopkins Deutsch, the donor, recalled in an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 1973,“I lucked into my Mainbochers. A friend of my mother’s gave me three. . . . She couldn’t wear them anymore and thought, ‘They would fit Jo beautifully’ and they did.”

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1949

Satin dress with one shoulder strap, draped and tucked bodice, and matching belt Gift of Mrs. Donald Deutsch, 1986.571.1a-c

Mainbocher had reintroduced an hourglass silhouette in the late 1930s, but the style did not take hold immediately. Here, Mainbocher fused an austere military look, likely inspired by his styling for the US Navy, with that of Christian Dior’s famous 1947 New Look collection.

EVENING DRESS, FALL 1950

Satin dress with fitted bodice, V-neckline, and semicircular skirt

Gift of Mr. John Runnells and Mr. Clive Runnells, 1978.25.6

Originally designed to be cocktail length, Chicagoan Mrs. Clive Runnells requested a floor-length gown instead. This collaboration between client and designer is the hallmark of couture.

ICHi-88823

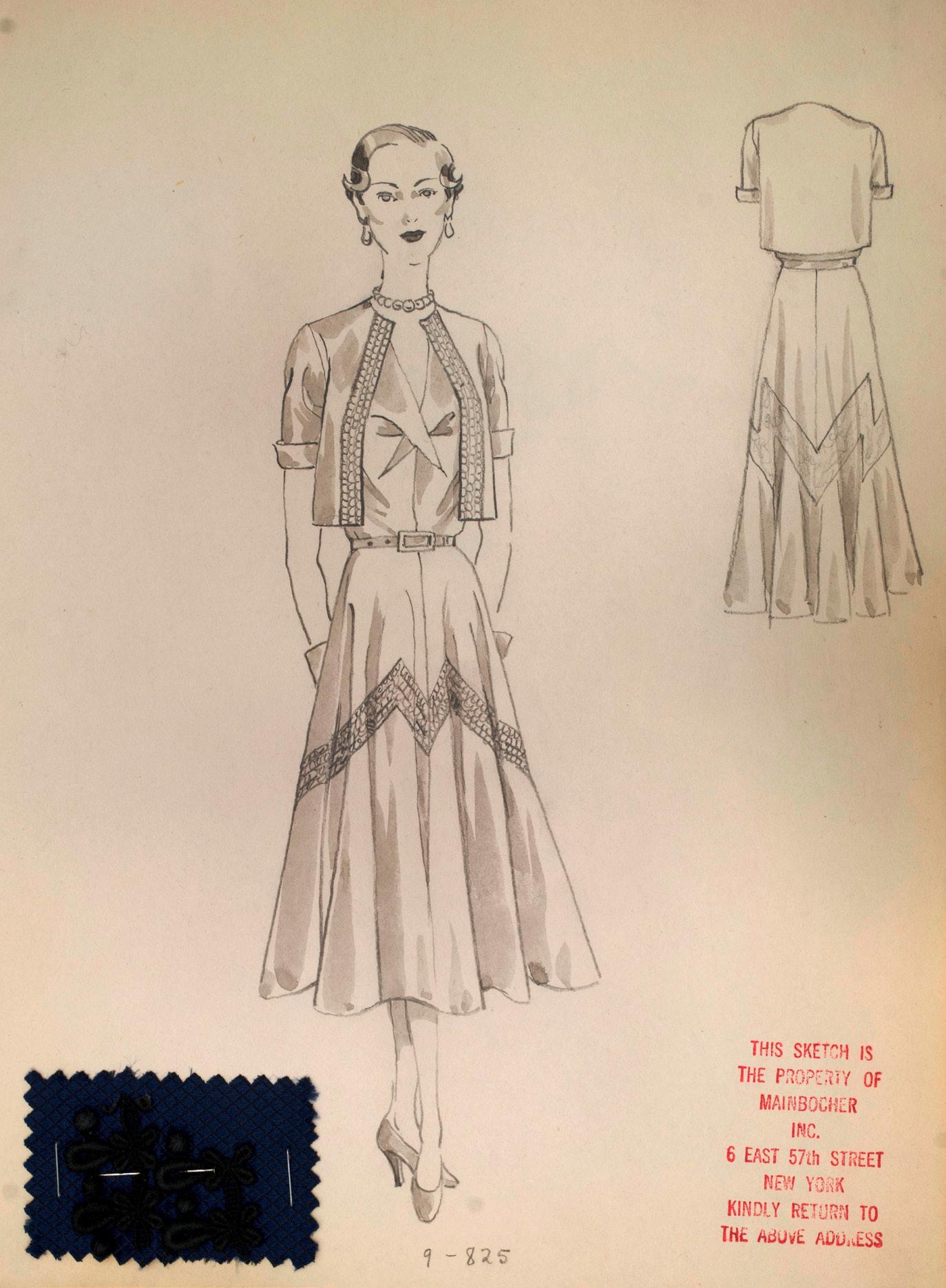

EVENING ENSEMBLE, FALL 1950

Silk dress and bolero-style jacket trimmed with soutache and lace

Gift of Mr. John Runnells and Mr. Clive Runnells, 1978.25.5ab

Cosponsored by Erica C. Meyer, Joan and Charles Moore, Neiman Marcus

Mrs. Runnells wore this custom gown to her son’s wedding in 1951. Mainbocher once stated, “How you look influences the way you feel, how you feel influences the way you act, how you act influences how many other people act.”

ICHi-88917

ICHi-88915

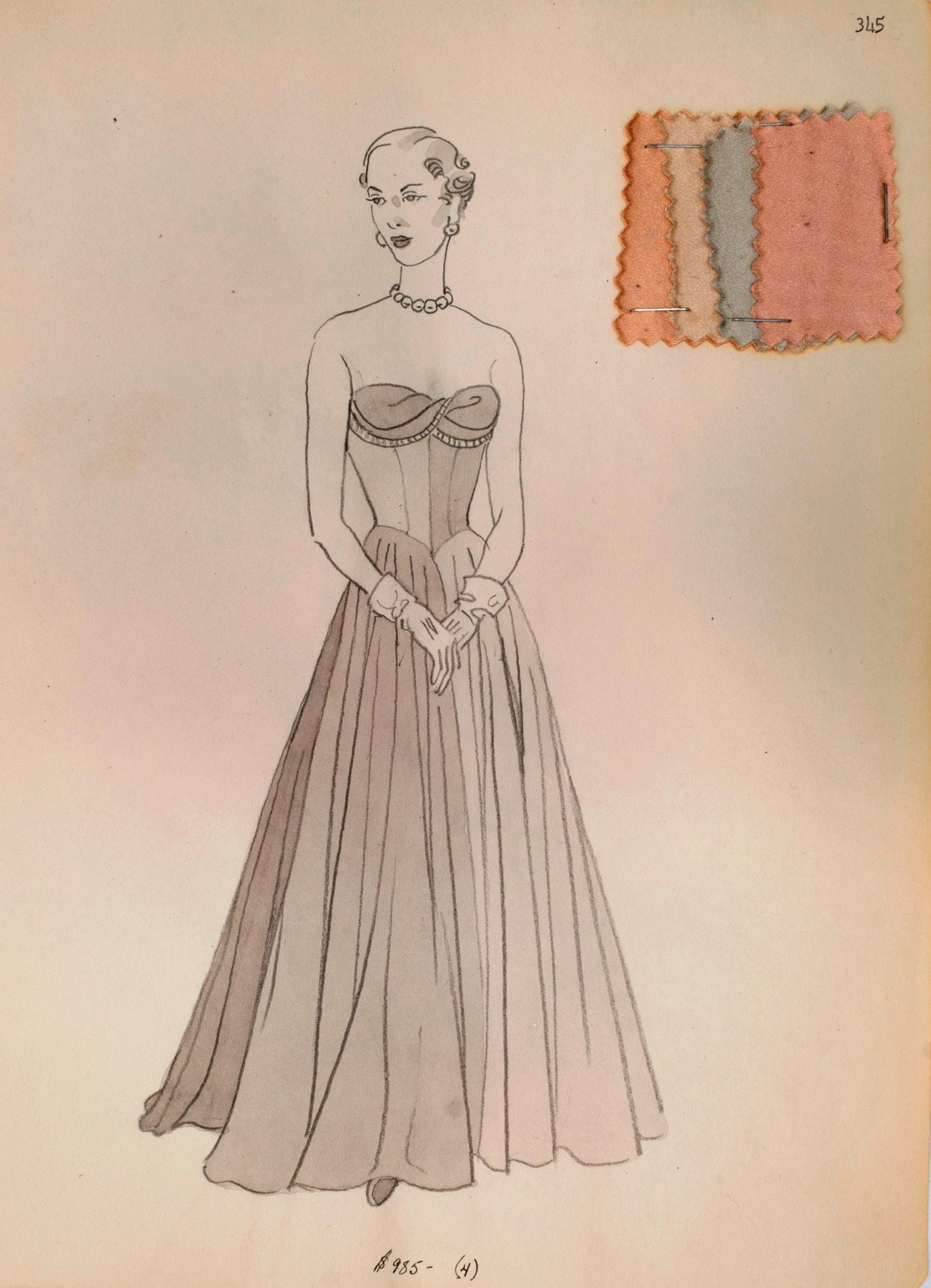

BALL GOWN, FALL 1951

Silk satin strapless evening gown constructed of four panels (pale pink, beige, gray, and champagne) embellished with 7/8-inch-wide curving bands of faux pearls and rhinestones

Gift of Mrs. A. Watson Armour, III 1962.294

Sponsored by Liz Stiffel

Today, all over the world, the strapless style is incorporated in the creation of wedding gowns, formal attire, and cocktail dresses. This gown was worn by Chicagoan Mrs. A. Watson Armour III (née Jean Schweppe) who was regular client of Mainbocher’s. The granddaughter of John G. Shedd, the second president of Marshall Field & Company, she was considered a connoisseur of fashion.

ICHi-88618

tweed suit overlaid with off-white silk at the collar and cuffs

Gift of Miss Peggy Stanley, CC1971.144ab

SKIRT SUIT, SPRING 1954

Wool

Mainbocher specialized in smart, well-tailored skirt suits, constructed of men’s suiting fabrics. Eleven clients purchased a version of this garment at the time of creation.

ICHi-88790

EVENING DRESS, SPRING 1954

Satin dress embroidered with sequins and rhinestones in a floral motif with a matching belt Gift of Mrs. Katherine W. Field, 1965.399

One of Mainbocher’s most notable styles was the short evening dress. To elevate its elegance, he adorned this dress with sequined flowers and skillfully crafted the belt so as not to disrupt the meandering floral pattern.

OPERA COAT, FALL 1955

Velvet floor-length cape trimmed with dark brown mink or sable Gift of Mrs. Charles W. Byran Jr. in memory of Mrs. Worth Faulkner, 1975.22.1

This sumptuous opera cape is one of the most expensive of Mainbocher’s designs at the time of purchase. According to records, the cape sold for $3,750.00 at the time of creation. That same year (1955), a Rolls Royce cost $5,700.00.

ICHi-88901

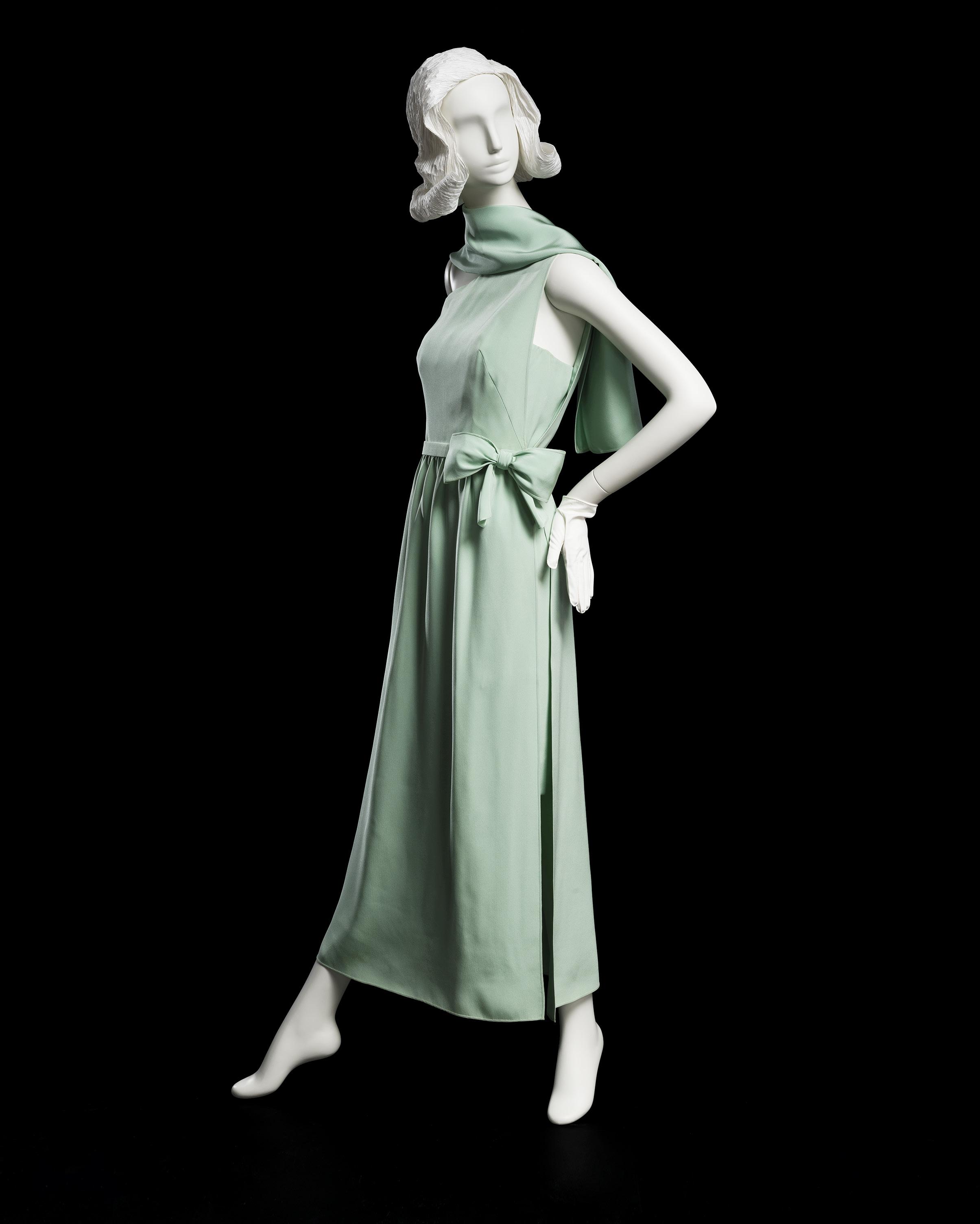

DRESS AND STOLE, SPRING 1964

Allover floral-patterned silk sleeveless dress with matching stole Gift of Mrs. Dorothy H. Rautbord, 1980.88.6

Mainbocher designed what he wanted, for whom he wanted. In 1963, Time magazine described him as “the great loner . . . [who] disregards the feverish pitch of the Paris houses and shows his collections at his own dignified pace.”

ICHi-88933

EVENING DRESS, SPRING 1965

Floral-patterned silk chiffon one-shouldered dress

Gift of Mrs. Dorothy H. Rautbord, 1980.88.5

Having worked as a fashion illustrator, magazine editor and couturier, Mainbocher was considered an authority on all matters of style.

ICHi-88925

EVENING DRESS, SPRING 1966

crepe two-piece dress with matching stole Gift of Mrs. Dorothy H. Rautbord, 1980.88.7

Cosponsored by Thom Pegg, D. Elizabeth Price, Karen Zupko

Silk

The 1960s saw hemlines rise and fall and rise again. Mainbocher designed this dress in spite of both. The slit in the long overskirt reveals the shorter underdress.

ICHi-88940

COUTURIER COSTUMES

MAINBOCHER’S THEATER WORK

TThe doors to Mainbocher’s New York couture salon had been open for less than a year when he was hired by producer John C. Wilson to design costumes for the Broadway premiere of Noel Coward’s latest play, Blithe Spirit. An exclusive custom designer dismayed by theatricality in clothes, Mainbocher seemed a curious choice for the task. But Leonora Corbett and Peggy Wood, his two Broadway stars in this very British comedy, were delighted with their classically elegant costumes, which had been adapted from the couturier’s fall 1941 collection. By the time the play closed two years later, Mainbocher had become the costume designer for some of Broadway’s great leading ladies, his work coveted for its high quality and taste.

The Chicago-born couturier had been forced to close his Paris house at the outbreak of World War II and returned to the United States in September 1939. He reopened his salon in October 1940 at 6 East Fiftyseventh Street in New York, just around the corner from Tiffany & Co. An adoring fashion press lauded his homecoming, relieved to discover his collection maintained the same strict attention to haute couture detail and craftsmanship as before, and his former customers flocked to his door in droves. They had yearned for the famed Mainbocher style of exquisite, classical dressmaking, the epitome of simple, quiet luxury with a whisper of confidence and wealth. By migrating to New York, America’s theatrical capital, Mainbocher was perfectly placed to create high fashion for the stage, preserving a long-standing European tradition exemplified by Parisian and London houses such as Worth, Redfern, and Lucile. Europe’s couturiers and dressmakers had once competed for attention using stage actresses to display their fashionable costumes. Now that war had severed Paris’ connection to the fashion pipeline, American designers seized their chance for the limelight. It was good

business for Broadway producers to call on Mainbocher should a leading lady’s costumes require the prestige of haute couture, and it was good business for the designer, who added American theater stars to his growing client list. A Mainbocher suit or gown worked as an expressive dramatic metaphor, embodying all the qualities his name might conjure in the public’s imagination. Mainbocher the designer made an easy cultural leap between the couture salon and the stage.

The theater season of 1942–43 found Mainbocher creating costumes for great actresses in unsuccessful plays that closed “out of town” and did not reach Broadway. These included Rose Burke, which starred the actress/ producer Katharine Cornell as a sophisticated artist, and A Lady Comes Home, with Ruth Chatterton playing one of the world’s bestdressed women. Both productions typified the formula for Mainbocher’s theatrical work: costumes designed solely for the leading lady, often in a role as a wealthy woman with a successful career and a bespoke wardrobe. The costumes usually were based on models featured in the designer’s current collection and were modified to suit the particular character in the play. Mainbocher, who did not follow trends, always worked with a silhouette featuring a long torso and natural shoulders, and his stage clothes gave each star a distinctive, graceful look. Constructed by his skilled staff employing stringent couture techniques, the Mainbocher costumes utilized beautiful fabrics and treated the actress to hand-stitched details and a custom fit. To costume the remaining cast members, a play’s producers would engage an additional

professional costume or fashion designer. This successful approach allowed Mainbocher to continue his stage work for the rest of his career.

During World War II, all designers and garment manufacturers in the United States were required to conform to Order L-85, the governmental regulations limiting the use of certain textiles and the amount of fabric a garment might have. The fashionable silhouette was frozen in 1941, unable to expand in volume or length. Mainbocher was often cited for his clever solutions to these restrictions, such as substituting rayon for silk or nylon, stitching ease into skirt fronts at the waist, and using unrestricted materials such as sequins and beads for sparkle and theatricality.

The production that established Mainbocher as a major Broadway figure was 1943’s One Touch of Venus. A musical fantasy boasting a powerhouse creative team (including songs by composer Kurt Weill and poet Ogden Nash), the satirical show was loosely based on the myth of Pygmalion. The musical starred Mary Martin as the goddess Venus, and she became one of Mainbocher‘s greatest friends and a lifelong customer. Martin’s stage charisma melded with the otherworldliness of the goddess of love, inspiring the designer’s topnotch costumes and triggering a sensation in the press. Two particular pieces in her wardrobe stood out. The first, Venus’ goddess gown, was made of chiffon dyed to a special Mainbocher-created shade he named “Venus pink”: a soft seashell color blended to give Martin a glow like the sea-born goddess. It sparked a fashion trend for “Venus pink”

Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in The Great Sebastians, a melodramatic comedy by Howard Lindsey and Russel Crouse. Mainbocher created Fontanne’s dresses and received a Tony award nomination. Mainbocher designed stage costumes the way he designed couture. The sumptuous clothing was said to make an actress feel empowered on stage. ICHi-89065, ICHi-89064

clothes and accessories, and helped establish pink as a gender-specific color for girls. The second costume, a black satin evening dress, caused so much excitement it received its own three-page spread in Life magazine. Featuring a deep-V halter front, the gown’s rear plunge revealed Martin’s supple back, and Mainbocher tied a thin ribbon choker of black satin around her neck to break up the long line of bare skin. “The slit in the skirt,” he told Life, “is a concession to the fact that after all, Venus is never a clothed lady. So often as possible, I exposed as much of Miss Martin as I could.”1 Both long, fluid garments harkened back to the generous, romantic draping of the years before the war and reminded many of how much had been lost to the conflict.

Following the success of One Touch of Venus, Mainbocher’s work was featured in nearly every Broadway season throughout the 1940s and 1950s. His clients, including Ruth Gordon, Talullah Bankhead, Betty Field, Libby Holman, Judy Holliday, Rosalind Russell, and Lynn Fontanne, were among the most famous names in theater. In 1950, producer Leland Hayward asked him to costume Ethel Merman, considered by some to be America’s greatest musical comedy star, for her role as a brash heiress-turned-ambassador in Irving Berlin’s Call Me Madam. Mainbocher presented Merman with nine costumes, including some of the most modern, elegant styles she’d ever worn, causing her to react, “My gawd, you’ve made a lady of me!”2 Her wardrobe included a negligee

of sheer pink point d’esprit net embroidered in gold sequins, an ankle-length yellow tulle strapless evening gown with a cascade of taffeta flowers and rhinestones, and a formal court presentation gown of ice-blue, silver, and gold brocaded satin with a long train featured in some onstage slapstick comedy.

The Sound of Music is the show for which Mainbocher may be best remembered. Written expressly for Mary Martin by Rodgers and Hammerstein, it is often identified today with Julie Andrews, who starred in the film version. Focused on the story of the von Trapp family children and their singing governess Maria in pre-war Austria, the production offered no opportunities for Mainbocher high fashion. It did, however, showcase many dirndl dresses, a Mainbocher couture style favorite for many years. For Maria’s wedding dress, the designer created a spectacular trained gown of white tulle and satin panels, topped with a veiled headpiece modeled on the wimple and veil of Benedictine nuns. Mary Martin received the 1960 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for this role, and she collected her award onstage dressed in a huge, buoyant gray tulle gown with a red bandeau bodice, originally created for her appearance in a 1955 Noel Coward TV special—a gown designed for her by Mainbocher.

Becky Lorberfeld is an independent fashion scholar and curator from New York City. She was the contributing curator of the Museum of the City of New York’s online exhibition, Worth/Mainbocher: Demystifying the Haute Couture

1. “Mary Martin’s Dress: Mainbocher’s Streamlined Creation Steals a Scene in New Broadway Hit.” Life Magazine 15, No. 21 (November 22, 1943): 58.

2. James Poling, “Smile When You Call Merman.” Collier’s Magazine, October 21, 1950. FIT Special Collections, Mainbocher Publicity Scrapbooks, Box 8-9: 59.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“A Corset Steals the Show as Paris Dressmakers Exhibit Fall Fashions,” Life, August 28, 1939, (1617.)

“A Uniform by Mainbocher,” Life, June 10, 1946

Baker, Therese Duzinkiewicz. “Mainbocher.” www.fashionencyclopedia.com/Le-Ma/Mainbocher. html

Barry, Edward. “Artists Learn by Doing,” Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1948.

Bates, Christina. A Cultural History of the Nurse’s Uniform. Gatineau, QC: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2012.

Bedwell, Bettina. “Mainbocher is Rediscovering His Homeland,” Chicago Tribune. January 14, 1940.

Bocher, Main. “Mainbocher by Main Bocher,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 1938, 102-103.

Bocher, Main Rousseau, Miscellaneous ephemeral material. The Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bocher, Main Rousseau, Scrapbooks. Gladys Marcus Library, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York.

Bowles, Hamish et al. Vogue: The Editor’s Eye. New York: Abrahams, 2012.

Boyer, G. Bruce and Patricia Mears eds. Elegance in an Age of Crisis Fashions of the 1030s. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

Braggiotti, Mary. “Mainbocher Presents First American Collection,” New York Post, January 1940.

Cass, Judith. “Nurses Thrilled by Passavant’s New Uniforms,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1949.

Davis, Ronald. Mary Martin: Broadway Legend. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Devlin, Polly. Vogue: Book of Fashion Photography 1919-1979. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979.

“Dressmaking a Real Hand Craft,” Women’s Wear Daily, February 9, 1940

“Duchess of Windsor Tours Shops in Paris,” New York Times, September 28, 1937.

Ewing, Elizabeth. History of 20th-Century Fashion. London: Batsford, 1974.

“Fashion and Photo Preliminaries to Windsor’s Wedding,” Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1937.

Fitzpatrick, Rita. “Mainbocher Tells Girls How to Be Well Dressed,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1948.

Flanner, Janet. “Pioneer,” New Yorker, January 13, 1940.

Gardner, Laura. “Mainbocher and the Decline of the Socialite,” Harper’s Bazaar, July 1949, 62–63.

Gilbert, Helen, “Okay, Girls—Man Your Bunks!”: Tales from the Life of a WWII Navy WAVE, Toledo, OH: Pedestrian Press, 2006.

Guttman, Stephanie. “The Wedding Gown: Revealing the Nation’s Mood,” New York Times, June 15, 1997.

Hill, Daniel Delis. As Seen In Vogue: A Century of American Fashion in Advertising. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2004.

Holme, Bryan, Katharine Tweed, Jessica Daves, Alexander Liberman. The World In Vogue. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

Howell, Georgina. In Vogue: Sixty Years of International Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. New York: Schocken Books, 1976.

Jacobs, Laura. “The Mark of Mainbocher,” Vanity Fair, October 2001, 86-93.

Lobenthal, Joel. Radical Rags: Fashions of The Sixties. New York: Abbeville Press, 1990.

Magidson, Phyllis. Worth/Mainbocher: Demystifying the Haute Couture. Museum of the City of New York. http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNYMN3_4.

“Mainbocher Show Offers Innovations,” New York Times, September 13, 1944.

“Mainbocher Shifts Here,” New York Times, September 20, 1940.

“Mainbocher Opens In New York,” Harper’s Bazaar, November 1940, 72–73.

“Mainbocher at His Best,” New York Times, November 22, 1969.

“Mainbocher Adds WAVES To Clients,” New York Times, August 15, 1942.

“Mainbocher is Critical,” New York Times, October 14, 1952.

“Mainbocher, Designer for 20th Century,” Women’s Wear Daily, June 18, 1942.

Marshall News (Chicago), February 14, 1940.

“Mary Martin’s Dress,” Life, November 22, 1943, 57-58, 60.

McConathy, Dale. “Mainbocher.” In American Fashion: The Life and Lines of Adrian, Mainbocher, McCardell, Norell, and Trigère, edited by Sarah Tomerlin Lee, 111–208. New York: Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co., 1975.

Mears, Patricia. American Beauty: Aesthetics and Innovation in Fashion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009. Published in association with the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York.

Morris, Bernadine. “Mainbocher, Fashion Designer for Notables Since 1930s, is Dead in Munich at 85,” New York Times, December 29, 1976.

Mulvagh, Jane. Vogue: History of 20th-Century Fashion. London: Penguin Group, 1998.

Polan, Brenda and Roger Tredre. The Great Fashion Designers. Oxford: Berg, 2009.

Pope, Virginia. “Mainbocher Opens First Salon Here,” New York Times, November 1, 1940.

— — —. “Mainbocher Holds Second Show Here,” New York Times, March 13, 1941.

— — —. “Mainbocher Hails New Fashion Era,” New York Times, March 10, 1947.

— — —. “Wasp Waist and Bustles Feature of Paris Winter Fashions Showings,” New York Times, August 2, 1939.

— — —. “Mainbocher Keeps Style Simplicity,” New York Times, September 7, 1945

Rachline, Sonia. Paris Vogue Covers. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2010.

Rector, Thomas Allen. The Singing Heart: The Autobiography of Thomas Allen Rector. Williamson, NY: Salmon Creek Publishing, 2010.

Resnikoff, Shoshana. “Sailors in Skirts: Mainbocher and the Making of the Navy WAVES.” MA thesis, University of Delaware, 2012. http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/11718.

Robinson, Julian. Fashion in The Forties. London: St. Martin’s Press, 1976.

Samek, Susan M. “Uniformly Feminine: The ‘Working Chic’ of Mainbocher.” Dress 20, no. 1 (2013): 33–44. doi: 10.1179/036121193805298264.

“Scouting a New Look,” Women’s Home Companion, 1948.

Steele, Valerie. Women of Fashion: Twentieth-Century Designers. New York: Rizzoli International, 1991.

Stemlow, Colonel Mary V. A History of the Women Marines, 1946-1977, Washington, DC: History and Museum Division Headquarters US Marine Corps, 1986.

“Still a West Sider at Heart,” Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1940.

Stitz, Marylin. “Mainbocher’s Designs Pass Fashion’s Test of Time,” Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1977.

Taylor, E. A. “The Exhibition of the Société des artistes décorateurs, Paris,” The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art, June 14, 1913, 51–58.

“Coals to Newcastle: Buy American in Paris,” The Chicagoan, April 1, 1933.

“The ‘Cheapest’ Dressmaker,” Life, May 20, 1946.

“The Descent of the “Wally” Dress,” Life, August 9, 1937, 57.

“The First Girl Scout.” Life, November 22, 1948, 71.

“The Lasting Look at Mainbocher,” Life, April 18, 1955, 92-93, 96-97.

“The Main Line,” Time, September 27, 1963.

“Underlining the Long Torso,” Vogue, March 15, 1940, 80–81.

University Archives & Special Collections, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Vogue, March 1, 1940, 27.

Walford, Jonathan. 1950s American Fashion. Shire Library 695. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2012.

“Waves Uniform,” Life, September 21, 1942, 49-52.

Weber, Ronald. News of Paris: American Journalists in the City of Light between the Wars. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

Winn, Marcia. “A Dress Must Fit Life, Is Plan of Main Bocher,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 7, 1940.

Wolfe, Sheila. “The Percy-Rockefeller Wedding in Color,” Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1967.