NEWS: UCUP Demands

Dean of Students Reverse Student Eviction

2

NEWS: UCUP Demands

Dean of Students Reverse Student Eviction

2

By NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | Senior News Reporter

On October 21, an unnamed undergraduate student was placed on an involuntary leave of absence and removed from on-campus housing after being arrested by the Chicago Police Department (CPD) during the pro-Palestine protest on October 11, according to the student’s lawyer.

The incident was first made public in an October 22 UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP) Instagram post describing the event. The student was referred to as “A.” in the post to protect his identity.

“2 Deans and 2 UCPD officers showed up at student A.’s door. They gave him

just minutes to pack up a backpack before removing him from his dorm, leaving him homeless,” the post read. “Admin informed him that if he returns to campus, he will be arrested.”

The Maroon spoke with Megan Porter, a lawyer supporting the student in navigating the University’s disciplinary proceedings, about the situation.

Porter explained that the student was first contacted on October 16 by an individual “in the Dean’s office, essentially requesting that they schedule an appointment.”

“The student, when they got the email, it looked to them like a spam

email… and so they just didn’t think anything of it,” Porter said.

According to Porter, the student received no further communication from the University before October 21, when University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) officers and deans-on-call showed up at the student’s on-campus residence with a letter informing him that he was being placed on involuntary leave.

Porter declined to share the email or letter with the Maroon

“The deans had made a decision that [the student was] being placed on involuntary leave of absence, and also that they would be barred from campus, and because of that, would have to leave

their dorm,” Porter said. “They were given just a little bit of time to pack a backpack in order to leave, told that they could arrange at a different date [to get] their stuff, but they were told that they would not be able to come back on campus without risking arrest.”

Porter told the Maroon that the University’s decision to place the student on involuntary leave was based on the student’s presence at the October 11 protest, where he was arrested by CPD.

“The allegation against the student is that they were present at this protest, and also that they were arrested at the protest by the Chicago Police Department,” Porter said. “But the specifics CONTINUED ON PG. 8

By NOAH GLASGOW | Senior News Reporter

Kenzi Bustamante began the summer of 2024 as president of the Chicago Thinker. The Thinker, the University of Chicago’s conservative newspaper, was—for its supporters—a remarkable success story. It had built a strong Twitter base, with nearly 35,000 followers. Its writers had been launched onto Fox News and Real America’s Voice. According to internal documents obtained by the Maroon, it had around $62,000 in grant money and private donations ready to carry it into the fall. And it had achieved all this while denouncing the campus “mob” that, in 2020, it had been founded to resist.

But Bustamante (A.B. ’24) would not

NEWS: Uncommon Interview: Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression Director Tom Ginsburg PAGE 3

end the summer with her role as president. In fact, both of the Thinker ’s lead editors— Bustamante and Publisher Ben Ogilvie (J.D., M.B.A ’25)—would be expelled by the Thinker ’s founding editors in what Ogilvie, a law student, described as a “coup of the Thinker.”

The struggle for control over the Thinker plays out across dozens of internal emails and documents obtained by the Maroon this fall. Conflict over “juvenile” editorial decisions and the status of the Thinker ’s affiliated nonprofit, the Chicago Thinker Foundation, spiraled into a bitter struggle that left the masthead bare and the website

NEWS: Updated Event Policy Alters Long-Standing “Art to Live With” Tradition

PAGE 5

VIEWPOINTS: What Are They Scared of?

ARTS: Sigur Ros: A Love Letter to the Ensemble

10

By OLIVER BUNTIN | Senior News Reporter

A fourth-year student was arrested by the Chicago Police Department (CPD) at the October 11 pro-Palestine protest on campus and charged with aggravated battery of a peace officer under 720 ILCS 5.0/12-3.05-D-4. In Illinois, aggravated battery of a peace officer is a Class 2 felony, punishable by three to seven years in prison, up to 30 months of probation, and/ or fines up to $25,000.

The student was released on October 12, according to his CPD arrest record.

CPD documents obtained by the Maroon through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request state that an officer felt the student “shove him, kick him in the legs, and strike him with an open hand to the left side of the face.” The officer sustained “blunt trauma” and “abrasion” injuries, described as “minor.” The student also sustained a “minor” scrape on his left knee and was treated while in custody.

This information is corroborated by photographs captured by the Maroon

during the protest, which show the student kicking a CPD officer in the back of the leg. Subsequently, three CPD officers attempted to restrain the student, who fled but tripped and fell against a parked car. He continued to flee, with officers hitting his arms and legs with a baton. According to the police report, officers observed a bystander stick their leg out and trip the student, allowing CPD to detain and handcuff him.

During the October 11 protest, pro-Palestine demonstrators locked Cobb Gate and graffitied the “Nuclear Energy” sculpture before University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) officers entered the crowd and detained one individual. The detainment sparked physical confrontations between protesters and police, who pepper-sprayed demonstrators surrounding a UCPD vehicle. According to a University spokesperson, three individuals were arrested at the protest.

The Maroon independently verified

the arrested student’s identity and affiliation with the University by cross-referencing his CPD arrest log, photos captured by the Maroon at the protest, FOIA documents, as well as details and

By SABRINA CHANG | Deputy News Editor

Pro-Palestine protesters delivered a petition to the Office of the Dean of Students on October 29, urging the University to reverse the involuntary leave of absence on which a student was placed after being arrested at the October 11 protest. After being placed on leave, the student was ordered to immediately vacate student housing in accordance with the University’s involuntary leave of absence policy.

The rally, led by UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP), began at approximately 11:40 a.m. with around 40 protesters gathered outside Harper Memorial Library. It started with chants of “Free, free Palestine!” followed by speakers reading the petition aloud, referring to the student as “A.” to protect his identity.

“October 11 was A.’s first time going to a protest at UChicago. Now the university has forced him out of his home, threatened

him with arrest if he returns to campus, and cut off his access to his meal plan— imposing an unjust, unlawful sanction on this student in violation of its own policies and state law,” the petition read.

The Maroon has verified that the petition to reverse the involuntary leave of absence gathered over 1,500 individual signatures, including students, faculty and staff, community members, and various organizations.

During the rally, speakers demanded that the student be permitted to return to campus and resume his education immediately. “An attack on one of us is an attack on all of us,” a speaker said, which was followed by cheers from the crowd.

According to University policy, the decision to place a student on involuntary leave of absence is up to the discretion of

“An attack on one of us is an attack on all of us,” a speaker said, which was followed by cheers from the crowd.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 2

the dean of students. The student may request a review; however, once the dean reaches a final decision, it is “final and unreviewable within the University.”

Four University of Chicago Police Department officers, eight Allied Universal Security officers, and two deans-on-call were present at the protest.

At approximately 11:52 a.m., the protesters entered Harper. The group continued chanting, “Hey deans, what do you say, how many kids did you bomb today?” and “UChicago loves investments, UChicago hates its students,” as they moved toward the Office of the Dean of Students.

The protesters gathered briefly in the hallway outside Dean of Students Philip

Venticinque’s office, where the speakers reiterated the petition’s demands. The rally ended at approximately 11:56 a.m.

The Maroon later confirmed that the protesters handed the petition to Patricia Maloney, the executive assistant to the dean of students in the College. They also posted a copy of the petition on a bulletin board outside Dean Venticinque’s office.

In a statement to the Maroon, the University wrote, “The Office of the Dean of Students in the College received the petition. We don’t have any other updates beyond the statement we shared last week.” UCUP declined a request for comment.

Eva McCord contributed reporting.

By OLIVER BUNTIN | Senior News Reporter

Tom Ginsburg is the Leo Spitz Distinguished Service Professor of International Law at the University of Chicago Law School and has been the faculty director of the Chicago Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression since its launch in 2023. The Chicago Forum recently received an anonymous $100 million donation. The Maroon sat down with Ginsburg to discuss his hopes for the Forum and his thoughts on campus speech.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Chicago Maroon: At a very basic level, how do you define free expression?

Tom Ginsburg : Let me say what it is not. Free expression is not that anyone can say anything, anytime, without constraint. That’s a naive view of what it is, and in particular, in a university, we have all kinds of constraints on speech. In the broader constitutional order, free expression basically stands for the idea that the government cannot constrain a speaker from expressing any idea. But of course, you can be constrained by your company, your business, your colleagues, social pressure.... Constraints happen a lot in the real world, notwithstanding our very broad protection for free speech in this country. So that’s kind of the background condition against which

American universities operate. And I do think, in an academic context, free speech stands for something a little bit different. Free speech stands for our willingness to challenge each other’s ideas, which is essential for the production of knowledge.

CM: What’s the distinction between free inquiry and free expression?

TG : So we’re the Forum [of] Free Inquiry and Expression, and the reason we use that as the name is because, in [an] academic context, we’re not expressing things just for the heck of it. We’re expressing things towards inquiry. The purpose of the university is to discover knowledge and to help people learn how to inquire… so our free expression policies should be subservient to that. In some sense, they should be towards the purpose of the university as a place for knowledge and discovery, and that’s why we put inquiry first.

I say inquiry before expression because expression is subordinate to inquiry. So I’ll give you [an] example of the kind of constraint we have. I am a law professor. I can’t go into my classroom and… teach molecular engineering. If I was doing that, the University could fire me because I’m not doing the job which I was hired to do, and I wouldn’t be able to say, “Oh, I have free speech. I get to say whatever I want in the classroom. I have academic free -

dom.” No, that’s not how it works. It’s also the case that even though we have free speech in the University, a student can’t just get up in the middle of a classroom and start giving a speech

[because] there’s all kinds of structure, and those structures are there because we have a purpose, and that purpose is learning and teaching.

CONTINUED ON PG. 4

Eva McCord & Kayla Rubenstein, Co-Editors-in-Chief

Anushree Vashist, Managing Editor

Zachary Leiter, Deputy Managing Editor

Allison Ho, Chief Production Officer

Kaelyn Hindshaw & Nathan Ohana, Co-Chief Financial Officers

The Maroon Editorial Board consists of the editors-in-chief and select staff of the Maroon

NEWS

Tiffany Li, head editor

Peter Maheras, editor

Katherine Weaver, editor

GREY CITY

Rachel Liu, editor

Elena Eisenstadt, editor

Evgenia Anastasakos, editor

VIEWPOINTS

Sofia Cavallone, co-head editor

Cherie Fernandes, co-head editor

ARTS

Noah Glasgow, head editor

SPORTS

Shrivas Raghavan, editor

Josh Grossman, editor

DATA AND TECHNOLOGY

Nikhil Patel, lead developer

Austin Steinhart, lead developer

PODCASTS

Jake Zucker, head editor

CROSSWORDS

Henry Josephson, co-head editor

Pravan Chakravarthy, co-head editor

PHOTO AND VIDEO

Emma-Victoria Banos, co-head editor

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon, co-head editor

DESIGN

Elena Jochum, design editor

Haebin Jung, design editor

Kaiden Wu, deputy designer

Marlene Ma, design associate

Aditi Menon, design associate

Clementine Zei, design associate

COPY

Coco Liu, copy chief

Maelyn McKay, copy chief

SOCIAL MEDIA

Max Fang, manager

Jayda Hobson, manager

NEWSLETTER

Sofia Cavallone, editor

Amy Ma, editor

BUSINESS

Jack Flintoft, co-director of operations

Crystal Li, co-director of operations

Arjun Mazumdar, director of marketing

Ananya Sahai, director of sales and strategy

Executive Slate editor@chicagomaroon.com

For advertising inquiries, please contact ads@chicagomaroon.com

Circulation 2,500

“ But I do think Twitter has been a challenge for our democracy because it creates a kind of a culture of anger and a culture of censorship.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 3

CM : Could you explain how the Forum was founded and what your role is?

TG : So first of all, I’m a scholar of democracy around the world, mainly outside the United States. That’s my expertise. And I work on constitutions all over the world. And when you work on constitutional democracy, you come to appreciate that free expression and free speech are essential to the definition of democracy. Really, you can’t have a democracy unless people can criticize the government freely and such.

So that’s just been something I’ve been interested in, and I’ve been a little bit concerned about the United States in the last few years—the state of our democracy, the state of free expression, and such. The president of the University came to me, Paul Alivisatos. The Forum is his creation.

And I said yes immediately because when the president asks you to do something, usually you should say yes. And also because I think it was an interesting opportunity to think about how to advance our tradition of free expression at this university in the 21st century.

CM : What was your reaction when you learned about the recent $100 million donation?

TG : I was very pleased. And it’s an anonymous donation, which I think is extraordinary. Most people with that amount of money… they want credit. So it’s an extraordinary individual who was giving the money, basically because the person wanted to honor our long tradition and to help us go forward. And it’s for all of us. There’s no strings on the gift. It’s just for free expression.

CM : How do you hope to put this money to use?

TG : We’ve been giving grants to researchers all around the University for research that’s in related areas. We had an event this last summer, a pilot event we called the Academic Freedom Institute, where we brought people

from 20-something universities to the University of Chicago for a three-day workshop on academic freedom and free expression in the university.

The purpose was not so much to be missionaries but to show that we ourselves don’t always have the answers. We’re wrestling with these things, you know, and it was helpful for administrators from other schools to learn how our people were wrestling with the ideas. We also talked about the history of academic freedom. So that’s something.

We also want to have fellowships. So you can imagine that would include everyone from a scholar who’s writing a book on free expression or someone looking at the neurobiology of it, to someone who’s a dissident in another country who is being punished for their free expression. We might have some of those people here too. So we have to ramp up a fellowship program. We also want to expand orientation so that every person who comes into the University, including faculty, students, [and] staff… get[s] exposed to our tradition of free expression.

CM : How have the [pro-Palestine] protests of the past year intersected with your work?

TG : [When] you have protests, that’s a slightly different form of speech…. The Strauss report actually says that protest is part of a university culture. We should have some protest. But from my point of view, [there] obviously have to be limits on the kind of actions you can take.

At the end of the day, [the encampment] was disbanded. And I know there are people, or some people, [who were] really angry about it on both sides of the issue, but at the end of the day, it was disbanded peacefully, and I consider that a kind of cooperative act between the protesters and the University administration. They might not characterize [it] like that, but they were cooperating in a performance about what protest is like, and this is very different from what happened in some other universities.

I do think it would be helpful in our orientations to tell students how to protest, what things they can do, and what they can’t. Obviously, you can, in our university, put up signs in the quad. You get permission to do that. You can have demonstrations when events arise, but you can’t desecrate the Henry Moore sculpture. That’s not allowed, and if you do that, you’re going to be punished, and you shouldn’t be surprised by that. That’s just basic, but one of the things we do in the Law School is we have had sometimes controversial speakers, and we said, “This is what you can do: you can stand with your posters that are insulting the speaker, but you just can’t block the view of anyone who wants to see him.” [So] we can channel protest in a healthy direction in which everyone can express their anger in situations, but without disrupting the ability of those who want to hear from being able to do so.

CM : What do you see as the most significant contemporary threats to free expression?

TG : The biggest thing is, can free expression survive the age of social media? And I think the answer is yes. But social media has created a lot of challenges. It creates a culture of insult. I’m talking specifically about Twitter here. Twitter, to me, is a highly problematic form of social media because it’s not really free speech. It’s owned by one guy who regularly censors things that he doesn’t like, and I happen to disagree with his view, so I don’t spend much time on Twitter. But I do think Twitter has been a challenge for our democracy because it creates a kind of a culture of anger and a culture of censorship. I think that’s really a bad side of social media. On the good side, social media allows all kinds of democratization of communication channels. And one of our speakers at our launch, Josh Cohen, used the analogy [of] the printing press. You know, the printing press was invented, and they started making Bibles. But it took a few decades before people really worked out how to use

that technology. And then they created mass literature and pamphlets and all kinds of political discourse. And in some sense, his analogy is that we’re just in the early years of trying to figure out social media. We don’t really understand what its power is and how to use it responsibly, in some sense.

Now, the challenge in universities is a different one. We’re under pressure from all kinds of sides, and one of them, of course, is the state, the government. You have state legislatures now passing bills that restrict what universities can do, who they can hire, and things like this. And I think that’s generally not helpful. [There’s] I think 14 bills in various states that are trying to limit DEI in particular. The Indiana bill is a free speech bill, but it requires the evaluation of state professors and state universities on the basis of their ability to foster discussion in the classroom. I’m just not sure that the state is very helpful. So that’s a major challenge. Second challenge, of course, there’s always a challenge from donors. But I think, to be honest, at the University of Chicago, I think we’ve had 100-something years of dealing with this. Very early on in the University’s history, there was a challenge from donors, and the response of the University President, William Raymond Harper, was to say, look, if a professor says something you don’t like, that’s not us speaking, that’s just the professor speaking in their own capacity, and it’s not our problem. We are a community of scholars, and we don’t speak ourselves.

CM : Are you concerned about academic or intellectual self-censorship based on social or career-related pressure?

TG : I think that’s a huge problem…. There’s a survey that was conducted by FIRE [Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression] in 2022 or 2023, and I actually replicated it. I can’t give you a copy, but I did this exact same survey for our faculty because I wanted a baseline when we were launching the Forum. And one

CONTINUED ON PG. 5

“ We have to be willing to let people express themselves and not treat everything as if it’s an existential challenge.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 4

of the things that [the survey] showed is that our faculty were less willing to self-censor in the classroom than the national average by a significant amount. So that’s good, but I think it is a pervasive problem in the culture. And I even hear from my junior colleagues, “Oh, I might not want to say that; it might get [me] canceled.” Even senior colleagues. That’s bad. We have to be willing to let people express themselves and not treat everything as

if it’s an existential challenge. We’ve got to be able to have discussions and trust each other that we’re going to kind of keep it in the discussion room, if you will. So that’s a big challenge.

CM : What advice would you give to students who want to foster a culture of free inquiry on campus?

TG : First of all, the Forum has a mailing list. We’re going to be doing a lot of events. We have a student advisory board that we just put together, and we’re eager to engage with stu -

dents through the board or on it. We’re also going to, probably, in the winter or spring, announce funds for student activities that advance free expression. So if you and your friends in the dorm want to start a debate club or something like that, you can get money from us to do that.

[But] it doesn’t have to be through us. Ideally, we want this stuff to be going on everywhere. And of course, the free expression issues are very different in biological sciences as they

are in anthropology and stuff. So we need it to be really widely distributed throughout the school. But I think the most important thing students can do is speak your mind and be willing to make arguments that you might not even agree with, just for the opportunity to make the argument. That kind of playing around with the ideas as distinct from your own position is a really healthy thing. And I think it’s up to us, [and] also the University, to provide opportunities for that as well.

By AMY MA | Deputy News Editor

This fall, changes to the University of Chicago’s campus policies following last year’s protests impacted the Smart Museum’s long-running “Art to Live With” program. The event, which allows students to borrow artworks from the museum’s collection for a year, had to adapt to the University’s updated guidelines for on-campus activities, particularly regarding overnight camping.

Originally based on a 120-work collection donated by alumnus Joseph R. Shapiro (EX ’34), “Art to Live With” has been a hallmark of student engagement at the Smart Museum since 1958. Though the program became defunct in the 1980s, it was revived in 2017 through the support of Gregory Westin Wendt (A.B. ’83).

In past years, committed students have camped outside the Smart Museum for days, eager to claim coveted works by renowned artists like Picasso, Goya, and Chagall. Lauren Payne, associate registrar of art in public spaces, recalled that “some die-hard enthusiasts [started camping] as early as four days before the event.”

However, on September 24, Interim Dean of Students Michael Hayes informed the campus community of sev-

eral policy revisions via email. Among the updates was a prohibition on staying overnight in outdoor structures on campus and the requirement that any erected structures, such as tents, receive prior approval. Additionally, amplified sound is now restricted to certain times of the day. These changes are part of the University’s ongoing efforts to “support free expression while restricting individuals from using violence, threats, or harassment while expressing their opinions,” Hayes wrote.

For the “Art to Live With” program, the ban on overnight camping altered a key aspect of student participation. “This year, we were already considering revising the camping guidelines due to safety concerns,” Payne said. “However, when we were informed of the University’s policy changes two weeks before the event, we had to clarify these updates in our communications and promotions.”

In response to student feedback, the museum introduced earlier check-in times on Saturday and improved accessibility to event information through an expanded website. These changes aimed to create a smoother, more enjoyable experience while complying with the new restrictions.

“Our check-in events… featured DJs from WHPK as well as lawn games and classic Chicago hotdogs. The enthusiasm and energy [were] high,” Payne said. “Overall, the number of participants was slightly down from previous years, but there was not a significant decrease.”

Student participants had mixed reactions to the new format. Marcus Kuo, a second-year student who participated in “Art to Live With” this year and last year, reflected on the differences.

“Last year, people camped out as early as Thursday,” he said. “There was a competitive element to it, where those who were willing to stay outside longer would secure a better position in line. This year, because camping was not allowed, people started lining up at 3 a.m. instead.”

Kuo acknowledged that while the new rules made the process less intense, it also diminished some of the “camaraderie” associated with overnight camping.

“This year, we were finished with check-ins by 8 p.m., and it didn’t feel like we were really waiting overnight for a piece of art,” Kuo said. “That said, I think the new format was more manageable for many students.”

Another second-year student, Na -

talie Sauer, echoed similar sentiments. Sauer, who participated in “Art to Live With” for the second time, felt that the lack of camping took away from the community-building aspect of the event. “Last year, camping out with friends created an opportunity to meet and interact with other students who shared a passion for art,” Sauer said. “This year, it felt more impersonal. People just lined up, checked in, and then left.”

Though Sauer expressed a preference for the event’s previous format, she acknowledged that the Smart Museum’s hands were tied by the University’s new regulations. “I would love to see camping return in the future, but I realize the Museum can’t control the University’s policies,” she said. “The event was still enjoyable, but it lacked the social engagement that camping fostered.”

Looking ahead, Payne emphasized that the “Art to Live With” program is constantly evolving, and student feedback remains a crucial element of its success. “We always prioritize the student experience,” she said. “We are already brainstorming ideas for next year, and I’m excited about the potential for further enhancements to the event.”

“ They used their control of the login credentials to take control of the Thinker from Kenzi, me, and Declan.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

dark for months.

Trouble began in late June, when Bustamante and Ogilvie turned their attention away from the paper’s daily operations and toward one of its longstanding goals: financial independence from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI), a conservative think tank that funds independent student publications across American universities.

The Thinker had begun to secure independence two years before. In the spring of 2022, the Thinker ’s founding editors, Evita Duffy-Alfonso (A.B. ’22) and Audrey Unverferth (A.B. ’22), had set up a nonprofit corporation—the Chicago Thinker Foundation, a 501(c)(3)—which could shelter the Thinker ’s money if the decision was ever made to separate from the ISI. Duffy-Alfonso, Unverferth, and Declan Hurley (A.B. ’24), their successor as editor-in-chief, were all named to the Foundation’s board of directors.

In late June 2024, Hurley wrote to Duffy-Alfonso and Unverferth asking them to name the Thinker ’s new editorial leadership to the board of the Foundation.

“Kenzi and I want the Thinker to financially separate from the Collegiate Network,” the ISI’s network of campus publications, Hurley wrote. But this would be nearly impossible if the Thinker’s day-today leadership did not have control over the Foundation designed to shelter the paper’s money.

“It would make much more sense for the people running the Thinker to have legal oversight over the publication,” Hurley wrote.

A week later, Unverferth responded. It was clear that a transition would not be forthcoming.

Since becoming publisher, Ogilvie had made several changes to the website that Unverferth found tasteless, she wrote.

“The Chicago Thinker is not ‘right-leaning,’ nor is it some mere ‘free speech experiment’ sharing ‘spicy’ (juvenile!) ‘hot takes,’” Unverferth wrote, quoting Ogilvie’s changes. “The Thinker is conservative and libertarian or it is not the Thinker.”

Unverferth further accused the Thinker ’s leadership of mismanaging their finances, leaving an invoice from their legal

counsel’s office unpaid. Unverferth wrote that she could not “in good conscience” name Ogilvie to the board of the Thinker Foundation. She also declined to extend a board invitation to Bustamante.

In a string of emails, Bustamante assured Unverferth that she would undo Ogilvie’s website changes but asked that she still be appointed to the board of the Thinker Foundation. Unverferth ignored this appeal while requesting further minor changes to the website, a complete inventory of the Thinker ’s finances, and the immediate payment of all outstanding legal bills.

According to expense sheets Bustamante provided to the Maroon, these legal bills only listed charges associated with the Thinker Foundation, like filing tax forms and drafting bylaws. Since the Foundation had been set up by Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso, it had accrued over $5,000 in legal fees, with the Foundation’s lawyer billing at over $500 per hour, emails show.

At the end of July, Bustamante, still refused a seat on the Thinker Foundation’s board, told Unverferth that she would not be using the funds of the Thinker publication, provided by the ISI, to pay the Thinker Foundation’s 2024 501(c)(3) annual registration fees.

“I do not see the legal connection between the two entities, or the benefit of spending Chicago Thinker funds on Chicago Thinker Foundation fees,” Bustamante wrote.

Bustamante told the Maroon that, during this period, the Foundation had failed to fulfill its original purpose of securing the Thinker ’s financial independence from the ISI.

Within three days of informing Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso that she would not be paying the Foundation’s filing fees, Bustamante found that the passwords to the Thinker ’s website, Gmail, and social media accounts had all been changed. She no longer had access.

“Everything has been changed to Audrey’s phone number and email. I was hoping you all could let me know what’s going on,” Bustamante wrote to Unverferth, Hurley, and Duffy-Alfonso.

The changes caught Hurley by surprise as well. He wrote urgently to Unverferth

and Duffy-Alfonso: “To put matters lightly, I am concerned that Kenzi does not have access to the Thinker accounts.… Can you please confirm that you had no role in signing Kenzi out?”

But Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso had indeed played a role in signing Bustamante out, Ogilvie told the Maroon

“They used their control of the login credentials to take control of the Thinker from Kenzi, me, and Declan,” Ogilvie said.

On August 18, after nearly three weeks of silence, Bustamante and Ogilvie received nearly identical emails informing them that they had been fired from the Thinker

“We no longer believe that the Chicago Thinker is a good fit for you,” Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso wrote Ogilvie. “The Board of the Chicago Thinker Foundation has decided to remove you as acting Managing Editor of the Chicago Thinker newspaper, effective immediately.”

Bustamante and Ogilvie refused to accept that the Foundation had any authority to fire them. Bustamante told the Maroon that the Thinker Foundation’s articles of incorporation did not authorize the board of directors to dismiss the publication’s staff.

“They never answered the question of how they have authority over the paper, because they don’t have authority,” Bustamante told the Maroon

In a statement to the Maroon, Duffy-Alfonso and Unverferth wrote that the “Chicago Thinker Foundation is a Section 501(c)(3) nonprofit media organization that owns the Chicago Thinker student publication and funds and oversees its operations.”

“The Foundation, through its publication, provides UChicago student volunteers with extraordinary opportunities for leadership and public commentary. As with any organizations made up of volunteers, at times, volunteers may be dismissed when deemed appropriate,” Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso wrote.

Bustamante maintains that the Thinker Foundation and the Thinker publication were and remain legally separate entities.

Although she had been dismissed by Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso, Bustamante filed a claim with SiteGround, the host of the Thinker ’s website, requesting con-

trol over the domain. She also contacted the ISI and requested their help restoring the Thinker ’s digital accounts to its student editors.

Two weeks later, Bustamante received a cease-and-desist letter from the same law firm whose legal fees she had refused to pay.

“[W]e ask that you please immediately refrain from making further representations that you have any authority to make decisions for [the] Foundation and the Chicago Thinker,” the letter read. It instructed Bustamante to “take appropriate corrective measures as directed by the Foundation Board.”

Bustamante would not have time to contest the letter. Just weeks before the start of autumn quarter, Bustamante decided to take a corporate job rather than return to the University to complete the final year of her four-plus-one master’s program.

Bustamante told the Maroon that the controversy at the Thinker played no role in her decision to leave the University.

Bustamante’s decision not to return to campus left Ogilvie alone to contest control over the Thinker. In the days before the start of the academic year, Ogilvie wrote to the Thinker staff that, assured of the support of the ISI, he would be reestablishing the Thinker with an entirely new digital presence.

“I like the Thinker brand, and I am not eager to leave it behind,” Ogilvie wrote. “This means that the Thinker will continue on campus next year, which is what I care about most: I want to continue mentoring students and producing good writing.”

Just hours later, a post on the Thinker ’s X account—controlled by Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso—announced that fourthyear Christopher Phillips had been appointed the publication’s editor-in-chief. Rather than further contest control of the paper, Ogilvie decided to hand over the reins to Phillips.

In a final email to the Thinker ’s alumni, Ogilvie denounced Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso for taking control of the publication.

“Audrey and Evita have barely been involved with the Thinker since they graduated,” Ogilvie wrote. “I do not recommend do-

CONTINUED ON PG. 7

“ In short, Unverferth, Duffy-Alfonso, and Phillips had carried out a ‘coup of the Thinker,’” Ogilvie told the Maroon.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 6

ing favors for the Thinker, participating in Thinker events, or recommending current UChicago students write for the paper.”

In short, Unverferth, Duffy-Alfonso, and Phillips had carried out a “coup of the Thinker,” Ogilvie told the Maroon.

“I don’t say that they carried out a coup to give them a hard time,” he said. “A coup is basically a power takeover by insiders, and that’s basically what happened here.”

“It’s just something people who are

managing an organization should be aware of,” Ogilvie added.

Phillips did not reply to the Maroon’s request for comment.

In a conversation with the Maroon, Bustamante said she was unsure who now controls the Thinker ’s website and funds.

Since June, no new articles have appeared on the website. When Ogilvie decided to hand the publication over to Phillips, he was able to update the masthead to reflect his departure, he said.

Ogilvie believes Unverferth, Alfonso-Duffy, and Phillips now have editorial control over the website.

Neither Ogilvie nor Bustamante knew whether the ISI had agreed to hand the outstanding funds over to the Thinker ’s new leadership. Ogilvie believes they have.

The ISI did not respond to the Maroon’s request for comment.

Ogilvie and Bustamante both maintain that Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso had no authority to dismiss them from their edi-

torial roles.

Unverferth and Duffy-Alfonso see things differently.

“The Foundation supports and protects the student publication by providing financial oversight, safeguarding the paper’s intellectual property, and defending its mission[,]” they wrote in their statement. “The Foundation operates the Thinker so that strong conservative and libertarian voices may flourish on UChicago’s campus for generations to come.”

By BRIDGET JINGLEI YE | News Reporter

A 30-foot inflatable dog, accompanied by a petting pen of puppies from a local animal shelter, appeared for just one day on the University’s main quad on October 17. The installation advertised the NOMO: No Missing Out app, which launched its two-week anti-social media challenge, “Less Social Media, More Real Life,” on October 20.

Saieh Family Professor of Economics Leonardo Bursztyn, the app’s developer, explained in an interview with the Maroon that launching NOMO’s pilot on campus is an attempt to address the mental health of the University community.

“It’s an opportunity to help students, especially first-years just starting, to spend more time connecting with each other in real life, because students spend four or five hours a day on TikTok and

Instagram,” he said. “Those are hours that could be spent on really connecting, having real, meaningful connections and interactions in real life.”

The app challenges users to reduce their social media use to less than one hour per day for two weeks. Users who succeed have the chance to win prizes, including two free Starbucks drinks and entry into a raffle for tickets to Billie Eilish’s sold-out Chicago show.

For each person who completes the challenge, NOMO will also donate money to local animal shelters and climate change organizations, which is what inspired the inflatable dog advertisement. By encouraging reduced social media use, NOMO aims to address mental health struggles among teenagers and young adults.

The app also provides a schedule of on-campus activities that are available for students to take advantage of. Bursztyn explains that this provides students the opportunity to form meaningful connections offline.

Additionally, NOMO is a way to help improve academic performance on college campuses. “Digital media, like cell phones, specifically, really affect test scores and education,” he said. By removing digital distractions, NOMO hopes to help students focus and perform better in their academic work.

The creation of NOMO was inspired by Bursztyn’s research on “social media traps.” According to his work, a social media trap occurs when consumers’ experience with a platform is largely negative but quitting the platform would lead to even greater drawbacks.

His research showed that young

adults, despite using social media daily, often wished these platforms didn’t exist. “The average student needs to be paid $59 to deactivate TikTok for four weeks but is willing to pay $28 to remove TikTok from their campus for four weeks,” he said.

Beyond NOMO, Bursztyn serves as the founder and director of the Normal Lab at UChicago and the co-director of the Becker Friedman Institute Political Economics Initiative. His research focuses on how social pressure and norms shape individual decisions. He studies these influences in areas like education, labor markets, and politics across both developing and developed countries.

Currently in its pilot phase, NOMO is available only to UChicago students. The team behind NOMO aims to expand the app to campuses across the country by December 2024.

By GRACE BEATTY | News Reporter

University Church installed 56 solar panels on its roof this May using fund -

ing from the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in 2021.

Since the installation began generating electricity, the church—located across from Bartlett Dining Commons on East 57th Street and South University Ave -

nue—has cut its carbon emissions by approximately 16 tons and eliminated nearly all of their electrical costs.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 7

From the date of installation to October 17, the solar panels have produced over 20 kilowatt hours. As a result, the Church’s annual electrical bill, previously over $3,000, is now projected to drop to around $200. The carbon dioxide saved so far as a result of the switch to renewable energy is equivalent to planting 240 trees.

At the start of the project, University Church Treasurer Stephanie Weaver worked with Illinois Solar for All—a state program that makes solar installations more affordable for eligible residents and organizations—to apply for funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed

by President Biden in November 2021.

According to Weaver, while the Infrastructure Bill offers funding for private homes and businesses, it prioritizes accessibility for nonprofit organizations like University Church.

“[EPA Renewable Energy Cost payments] covered at least the portion of our cost to put the solar panels on,” Weaver said. “With the passing of the infrastructure bill, that was more money available to cover the cost.”

With numerous organizations using the Church’s space on a weekly basis, including counseling and psychotherapy groups and an amateur theater troupe, Weaver said the Church easily “me[t] the criteria for funding.” After securing

permission from the City of Chicago—a process that took about a year and a half and included “an architectural survey of the Church”—Ailey Solar was able to proceed with the solar panel installation.

“They installed enough panels to cover electricity that you use monthly, daily—all your electric needs,” Weaver said. When necessary, the panels can also “pull electricity off the grid.”

The panels are expected to last nearly 25 years, and the Church anticipates minimal additional upkeep investments during this period. In the meantime, University Church is continuing to explore other ways to reduce their climate impact.

“The thermostats are set to 60 degrees. We turn it up a little on Sunday and then turn it back down,” Weaver said.

The church is also implementing “smart thermostats” and a full substitution of their current light bulbs with more energy-efficient LEDs. In the future, they hope to transition entirely to electrically operated heating and cooling.

“I think everyone—individuals in their houses, businesses, the University of Chicago—should think about and explore pursuing a solar option,” Weaver said, adding that Augustana Lutheran Church is already planning to follow in their footsteps.

“ They gave him just minutes to pack up a backpack before removing him from his dorm, leaving him homeless,” the post read.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

about who made the report… none of that was provided to the student.”

Porter also said the University’s decision left the student “functionally homeless,” as his family lives out of state.

The University declined to comment on the specifics of the student’s situation, citing federal privacy laws.

In a statement to the Maroon, the University reiterated its commitment to free expression and explained how student disciplinary procedures are applied in the statement.

“The University of Chicago is fundamentally committed to upholding the rights of protesters to express their views on any issue. At the same time, University policies make it clear that protests cannot jeopardize public safety, disrupt the University’s operations, or involve unlawful activity, including vandalism or criminal assault.”

The statement continued: “The University’s involuntary leave of absence policy can be found here and sets forth the bases for its application. The Univer-

sity also adheres to Student Disciplinary Systems, which are applied to individual cases based on factors such as the nature of the alleged offense and in which area of the University a student is enrolled. Student discipline is reserved for allegations that a student has violated University policies.”

According to University policy, a student may be placed on involuntary leave of absence when:

“A Dean of Students (or designee) determines, after conducting an individualized assessment, that: (1) there is a reasonable basis to believe the student has engaged, or threatened to engage, in conduct that has caused or is likely to cause serious disruption to the learning, extra-curricular and/or living activities of members of the community or others, including by impeding the rightful activities of others; and/or (2) the student is unable to function as a student; and/ or (3) the student’s continued presence on campus poses a serious threat to the physical safety of any person or property.”

“A student who has been placed on

an involuntary leave of absence or emergency interim leave must promptly vacate University housing, leave campus, cannot participate in student activities or use any University facilities, and may not return until authorized to return from the leave and/or reenroll,” the policy continues. The University spokesperson also directed the Maroon to an earlier statement regarding the October 11 protest. In the October 11 statement, the University stated that three arrests had been made.

In May, several hours after the pro-Palestine encampment had been cleared, protesters were handed cards informing them that their continued presence on the main quad could escalate to an invocation of the emergency interim leave policy. However, no student was ever subjected to it. Before the October 11 protest escalated, the University passed out similar cards to demonstrators on the main quad stating that their protest violated University guidelines and that individual students may be subject to University discipline or arrest.

Denis Hirschfeldt, a professor in the Department of Mathematics, member of Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine (FSJP), and a former member of the Council of the Faculty Senate, expressed concerns to the Maroon about the transparency of University disciplinary systems as they have been applied to student protesters.

“Right now, absent this kind of detailed information on why [the University] did what they did, and why they believe it was legal within their statutes, legal within the law… I think that it’s going to be very hard for us to know whether there is some procedure being followed,” Hirschfeldt said. “I think that we also need to know it, not just obviously for the sake of this particular student and other students who might have the same thing happen to them, but also to know whether [University administration] is trying to wrest control of these disciplinary systems.”

Oliver Buntin and Zachary Leiter contributed reporting.

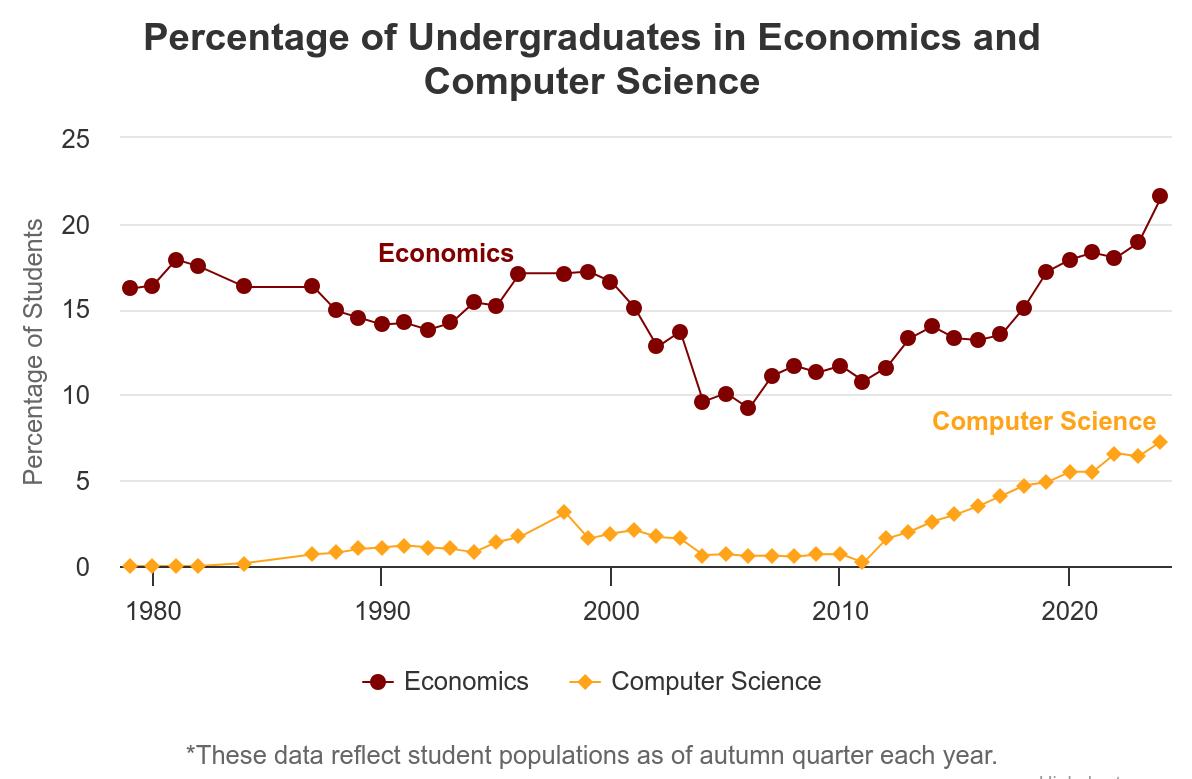

The University of Chicago remains a leading institution for economics, with growing student interest, especially after introducing the business economics specialization.

By ERIKA LENHARDT | Associate Developer

How much of an economics school is UChicago? In 2018, John List, now the Kenneth C. Griffin Distinguished Service Professor in Economics and the College, introduced a new specialization called business economics. The specialization is tailored towards students interested in pursuing careers in the private, nonprofit, and public sectors. Although this specialization is tailored toward students aiming for industry careers, it has attracted a wide range of students, including those planning to attend graduate school. One possible reason for its growing popularity is the low number of course requirements as compared to other economics specializations. The rising interest in business economics raises the question: Has UChicago always been an “economics school,” or has its reputation in this field

only recently surged?

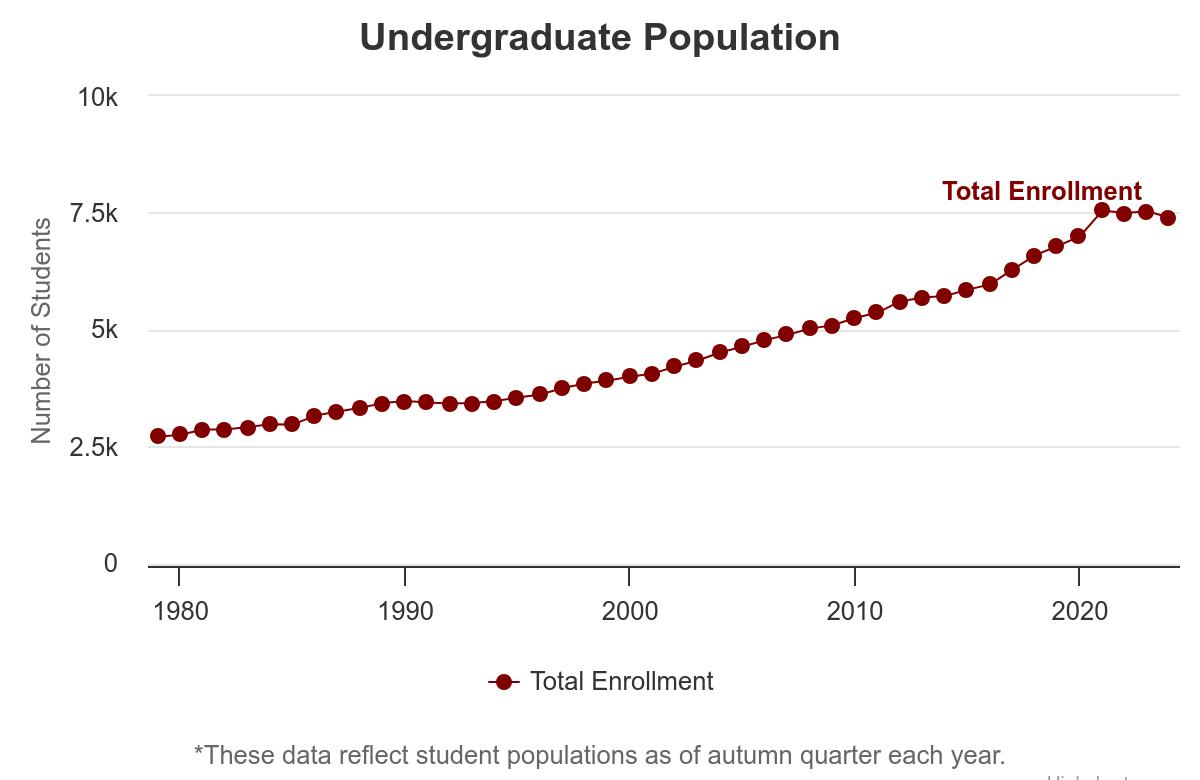

To preface, UChicago’s demographics have shifted over the past 45 years. The undergraduate population has grown by an astounding 172.5 percent, from 2,715 students in 1979 to 7,398 in 2024. The extreme growth of the student body prompts a question about how the economics program has responded: Has it expanded, remained stable, or declined in relation to the increasing undergraduate population?

As shown on the graph, the percentage of students interested in the field of economics has ranged from as low as 9.2 percent to as high as 21.6 percent since 1979. With an average of 14.7 percent of students studying economics per quarter, the economics presence at UChicago has been strong since the 1970s. It remains one of—if not the—most pop -

ular fields at the University. Though its popularity declined slightly in the early 2000s, economics remains one of the most favored fields at UChicago. Additionally, 2024 has had the highest percentage of students pursuing economics. In the years leading up to 2024, the percentage of students in economics had been in the high 15–18 percent range, steadily increasing toward the 20 percent mark. This increase may be attributed to the newly introduced business economics specialization mentioned above.

In comparison with other fields, such as computer science, economics has displayed more consistency in popularity over the decades. Computer science, on the other hand, experienced a rapid rise from near obscurity to being the second-most popular major at UChicago. Its growth is striking, with a 42.6 percent increase in students majoring and minoring in computer science be -

tween 1984 and 2024. To put this in perspective, only five students were declared computer science majors in 1984, compared to 486 economics majors, a 1:97 ratio. By 2024, these numbers had grown to 541 students in computer science and 1,595 in economics, a much closer 1:3 ratio.

To respond to the question of whether UChicago is an economics school, the answer is yes. While the recent introduction of the business economics specialization may have contributed to the program’s growth, it only builds on the historical strength of UChicago’s economics program, which has remained prominent since at least the 1970s (and perhaps before too, as the data is limited to 1970 and later). As the world shifts toward more technology-driven fields, economics is likely to remain a significant presence at UChicago.

The data and the trade-offs that the president and trustees don’t want you to see.

By CLIFFORD ANDO

On October 23, President Alivisatos will deliver his annual report to the University’s Senate—loosely speaking, all tenure-stream faculty, plus the president, provost, and vice presidents—and “discuss matters of University interest” (Statutes of the University, amended 5/1/2013, §12.4.2.1). What information should he provide, in order to enable an informed and critical conversation? What does he owe the community in an age of transformation?

Two models are available for how to talk about the University’s policies, priorities, and ambition among engaged, committed insiders. One is offered by the University’s institutions of faculty governance, with which I have over a decade of personal experience. There, decisions are presented as discrete acts of judgment on academic matters alone, shorn of financial data and therefore without any holistic discussion of trade-offs or opportunity costs.

A second model is offered by the University’s Board of Trustees, who discuss whether to advance or weaken units amidst a sea of data: in particular, historical, current, and projected budgets for operational expenses; numbers of faculty and staff in each governing body; trends in enrollment and revenue; and historical, current, and projected capital expenditures. This I know because, just after Labor Day, I received (from an anonymous benefactor) briefing books from the annual meetings of the Board, as well as supplementary

materials—booklets of data and a manual on “The University’s strategic approach to risks and opportunities”—going back to 2009.

To my mind, the importance of the enterprise, and the gravity of the moment, together urge that the president adopt the second model in conversations with the faculty, as well.

The context of this year’s report is one of achievement and promise, but also change and loss. Starting very nearly from scratch, the University has achieved remarkable excellence in molecular and geoengineering and is a central player in an emerging regional ecology in quantum computing. At the same time, the University’s financial troubles and their consequences—its great debt burden; its layoffs; the decline in the rank of its College; its faltering commitment to need-blind admissions—have received coverage in newspapers across the nation. What is noise and what merits sustained reflection among those charged with thinking about the health and direction of a great university?

The temptation is strong to think about the many individuals, research groups, and projects of the University in isolation. Nor is this unreasonable. As an intellectual matter, one could map life at the University partly and properly on the model of toddlers on the playground, engaged in so-called “parallel play.” (Something like this is the false premise for the budgetary model increasingly adopted by mostly private universities, that of “Responsibility Center Management,” but that is a story

for another day.) As I have said, this is very much how matters are generally brought before the institutions of faculty governance—as isolated academic matters, shorn of financial data. The faculty should not concern themselves with money, it is implied; no trade-offs are necessary. Indeed, when I sat on the Committee of the Council many years ago and the question of the acquisition of the Marine Biological Laboratory was raised, I inquired about the opportunity costs of an initiative on that scale and was advised—by a fellow member of the faculty— that “at the University of Chicago, all good ideas get funded.” We segued rapidly to the acclamation phase of the proceedings.

The news that the University might spend as much as $100 million on a single cluster of projects and hires related to geoengineering raises (again) the question of opportunity costs. At what point—at what scale—does a

commitment to one person, area, or field crowd out the University’s ability to pursue excellence to the same degree in other areas?

That said, consideration of “opportunity costs” seems to me insufficient to the scale of change and the vast shift in priorities that the University is undergoing. Here it is useful to recall that the context for the University’s debt crisis, layoffs, and so on, is vastly increasing revenue. According to the University’s public financial statements, the combined revenue of the University and Biological Sciences Division (without the Medical Center) was $1.916 billion in 2013, $2.425 billion in 2018, and $2.901 billion in 2023. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI inflation calculator, inflation from January 2013 to January 2023 was 29.92 percent. Revenue growth of 51.4 percent was therefore markedly greater than inflation. How does this figure into the mix of facts that

I cited above? If we are making so much more, why are we deeply in debt? Why are programs being closed and the arts decimated? What is the larger context of priorities, choices, and institutional change in which this all makes sense?

The simple facts of the matter are that the University has been spending far, far more than it takes in, in order to invest in select fields of research, and we never actually existed in a world in which trade-offs did not need to be made. To see this, one needs something other than pablum about how much President Alivisatos enjoyed the Core when he was a student or how the University aspires to excellence across the board. We need to follow the money.

Broadly speaking, we need two bodies of information. The first is a history of the budget of the so-called governing bodies

a

person, area, or field crowd out the University’s ability to pursue excellence to the same degree in other areas?

(Booth, Divinity, Humanities, Law, etc.) in terms of gross operating expenses, presented alongside numbers of tenure-stream faculty, other academic appointees, staff, etc. in each unit, as well as gross undergraduate enrollment and aggregate numbers of majors. Have we enabled research and teaching to flourish in the many fields that we study? And have we sustained those communities with a reasoned and appropriate commitment to the efficiency, dignity, and safety of research and learning in all those fields? To understand the future to which we are being led, we need those figures for the last 15 years and projected at least three years into the future.

The second body of information that we require is a history and projection of capital expenditures—essentially building new stuff or investing in the renewal, refurbishment, or replacement of old stuff—over the same time period, including the crucial matter of what portion of capital expenditures over that period in

any given unit has been funded by restricted funds, as well as what percentage, for each governing body, has been funded via unrestricted funds. The point is that while attracting restricted funds in support of a given project might seem to free up unrestricted funds for other purposes, it very much appears that restricted funding exercises a powerful gravitational pull on all other forms of funding. And we would want this laid out in a way that expenditure per member of the Senate (and perhaps per unit of undergraduate enrollment) is clear. A back of the envelope calculation suggests a ratio of capital investment from unit to unit of hundreds to one.

Are these requests for budgetary information unreasonable or difficult? One answer is: this is more or less exactly the information that is already supplied to the trustees when they discuss the present and future condition of the University and vote on policy and priorities. It is in the briefing books.

That the University’s lea -

dership is making trade-offs and starving some units in order to pay for others is explicitly part of the briefings received by the trustees. They are told that we are eliminating programs and weakening some units to pay for others. They get an explanation, or perhaps, an interpretation, of what the consequences of budgetary acts are likely to be. During the liquidity crisis of FY2016, for example, the library eliminated 14 vacant positions, laid off 13 persons, and cut $1.35 million from the budget for collections. The trustees were told, “These actions will result in a reduction in library hours, reduced services to faculty and staff”—perhaps “students” were intended—“and may impact statistics related to national rankings.” (The negative impact on the library’s national ranking, due to the disfavor to which it has been subject, is now well known.)

In the same year, the Divisions of Humanities and Social Sciences together eliminated 35 positions, “reducing support to affiliated centers and cutting

non-compensation costs. The impact of these actions will be to reduce the support given to faculty.” You don’t say.

But in that same planning session, it was announced that the Department of Economics would hire seven additional faculty in FY2017 alone, and it was envisioned that the Institute of Molecular Engineering (as it was then known) would soon expand by nearly 50 percent, from 17 faculty to 25. In the trustees’ meeting a year later, $25 million was allocated for renovations to office space to accommodate “incremental IME faculty.”

This raises the question of how explicitly the connection between choices made this past year will be made in future briefing books to the trustees: Did we eliminate German and shrink middle school sports at the Lab School, did we shrink spending in humanities, did we fire staff from the Smart Museum, did we, as I am told, momentarily suspend our commitment to need-blind admissions to pay for geoengineering (say) on a scale greater than

The Spirit that Self-Negates A data science major reflects on AI.

By NICOLAS POSNER

I was heartened to read the Maroon ’s coverage of Professor Ben Zhao. His project, Glaze, employs developments in AI to both hinder and attack the ability of image models to recognize and catalog faces. It’s the kind of technology that is going to make

the lives of some people—namely, image and video model developers—a little more difficult for a while to come. It seems perverse, that this technology is now being deployed against itself. And yet, this was the first AI-related story I’ve read in months that genuinely excited me.

As a graduating senior in the

Data Science Institute (DSI), I’m in an unusual position. While the DSI curriculum covers a wide range of topics, AI undeniably constitutes a significant portion that has only grown in the last few years, as the creation of the major was followed by the release of ChatGPT and the subsequent ascension of AI in the public consciousness.

In what feels like an overnight change, AI went from sci-fi to staple. Concerns like AI safety transformed from fringe speculation into the subjects of mass controversy. Every old product is getting an AI-enhanced makeover, which is probably good news for DSI graduates. But in the face

we can afford?

At some level, this is as it should be—if by that one intends that universities should not remain static and must respond to the development of new fields of knowledge. It is also the norm, here undergirded by the University’s statutes, that the president and provost should determine the direction and priorities of the institution.

But why should these choices be a secret? If the president, provost, and trustees are secure and confident about their vision, why not discuss in public their reasoning about which departments, divisions, and majors are to be privileged, and which are being encouraged to decline?

Provide the data, to be checked against what the trustees were told. Then we can discuss “matters of university interest” together.

Clifford Ando is the David B. and Clara E. Stern Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of Classics and History and in the College.

of all this development, much of it professionally and academically fascinating, I can’t help but feel deeply ambivalent about AI. Some detachment is inevitable while in the weeds of a given field. When your exposure to machine learning includes linear algebra and notebooks full of SciPy, it’s CONTINUED ON PG. 12

hard not to look at flashy news stories speculating on future AI capabilities without thinking, ‘It’s matrices. It’s just a gigantic stack of matrices.’ You lose a lot of the starry-eyed enthusiasm.

But you can leave aside science journalism (a domain which can never live up to the expectations of scientists in the same field) and find real, compelling papers that push the boundaries of the possible, like Anthropic’s October paper on monosemanticity, which explores methods for interpreting the internal processes of AI models. Yet, my ambivalence does not abate.

On reflection, I can’t seem to conjure a vision of an AI-enabled future which is better at the human level. I don’t necessarily disbelieve projections that claim AI will have such-and-such impact on GDP, improve existing technology, or finally ensure that our children are learning, but none of these professed outcomes compel

me on an intuitive level. I recently interviewed with a fund that is feverishly seeking out startups that use retrieval augmented generation (RAG)—the new hotness for language models, which connects a large language model (LLM) to a database in order to improve accuracy and value in specific domains. RAGs for your dentistry practice! RAGs for your smart fridge! It’s part of the same bubble of AI-enabled services I expect will pop in five to ten years, and I can’t help but look across this vast and WiFi-enabled landscape and wonder what it’s all for. When I look at the problems our world faces, the ones I expect to get worse as time goes on, they’re broadly problems I expect AI to aggravate, not solve. The scarcity of the written word was not a problem before 2020 and it certainly isn’t a problem now. My inability to draw so much as a stick figure is not a problem. The fact that social relations increasingly migrate into virtual spaces,

that language has begun to shape itself around content moderation, and that even the bottomless pit of entertainment has been displaced by mere doomscrolling, however, are problems.

Technologies like Glaze, I believe, are the first tremors of a rising backlash against the decomposition of the human into the mechanical. It feels a bit like studying aerospace engineering on the cusp of the First World War, knowing my chosen field will be the nexus of a vast contest of offensive and defensive ability in which my own contributions, however small, cannot be innocent. This conflict, however, despite having humans on both sides, will be fought to negotiate the frontier between human and machine.

This is why I take pleasure in technology that is, formally speaking, perverse. It delays and obstructs the straightforward goal of AI, which is to make the world more legible, categorizable, and processible. It cuts out a little more space for the human. In the face of my former ambivalence, I am struck with inspiration: there is a possibility for this technology not to clarify and illuminate but to obscure and to mystify. It is a possibility that is strange and capricious but also genuinely exciting in a way that new applications of AI to online advertising are not.

We’ll always reject your racist neutrality.

This is also great news for the major. Engineers don’t go hungry in war. You might think what I’ve written here is pure humanities babble, but if you see me across the trenches in a few years, have some mercy—we’re probably keeping each other employed.

Posner is a 2024 alum of The College.

By HASSAN DOOSTDAR

Because I refused to cooperate with UChicago’s disciplinary hearings against me in relation to the Popular University for Gaza encampment last May, I have been suspended for the autumn quarter. Or, as the official letter from UChicago puts it, I have been “placed on an administrative leave of absence.”

Upon reading the suspension letter, my mind went to Israel’s practice of “administrative detention.” Not because there is any comparison between the severity of being blocked from attending classes for nine weeks

and the dystopian Israeli military court system. It is because the words chosen made me think of Layan Kayed, a brave Palestinian student organizer who was brutally arrested by the Israeli Occupation Forces on April 7, 2024, and today remains (as do 10,000 other Palestinians) in Israeli prison. In 2022, along with other UChicago and McGill students, I had a conversation over Zoom with Layan. She described how, during the first time she was incarcerated by Israel, she and other Palestinian women created a covert school within the prisons for each other so that the jailers could not disrupt

their education. I believe conversations like this one planted the seeds which sprouted into the Popular University on our campus this year, as they taught us about Palestinian legacies of popular education rooted in grassroots solidarity and resistance.

The phrases “administrative leave of absence” and “administrative detention” are abstract, detached, and bureaucratic. They don’t immediately evoke University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) cops in riot gear or soldiers with assault rifles and tear gas—though this is the reality for the encampments

and the occupied West Bank.

But that’s enough of my analysis—just read Layan’s article! As a reminder to those who have extended their support to student protesters in the U.S. and not yet to those organizing in Palestine, it is even more urgent to do the latter. Now, if you’re still reading my essay instead of Layan’s, let me explain.

If I had decided to once again work with the excellent lawyers from Palestine Legal and the National Lawyers Guild who have supported anti-genocide students through every instance of repression thrown at us, from the sit-in to the most recent mass

pepper spray attack by UCPD, I probably wouldn’t be in this situation today.

When I demanded of Jeremy Inabinet, the associate dean of students at the “Center for Student Integrity,” that he say my late friend Elijah’s name in his next email as a condition for my participation in the disciplinary procedures, I fully expected him to follow the playbook of racist gaslighting framed as “neutrality” that his colleagues and higher-ups like Paul Alivisatos and Ravi Randhava have perfected throughout their careers. This essay is a tiny act of resistance

CONTINUED ON PG. 13

detention” are abstract, detached, and bureaucratic.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 12

against the mirage of “neutrality” that UChicago policy tries to create, which I view as a central part of this institution’s racist, genocidal complicity.

In spring 2024, I filed for a voluntary leave of absence, expecting to return to classes this autumn quarter. I intended to take those nine weeks to grieve and spend time with my friends and family, then return after the summer to finish my degree in history and Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity.

One factor that influenced me to file for leave was the ongoing U.S.–Israeli genocide of Palestinians. This genocide, and the barbaric, indiscriminate war on all resistance to it, has imposed death, injury, starvation, disease, and deep emotional wounds across occupied Palestine, Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. In the process of protesting this genocidal war, which is led by the U.S. government, I have witnessed friends be threatened and sanctioned by their universities and employers and be brutalized, harassed, and detained by the police and other racists. I’ve personally experienced many of these forms of violence over the past year.

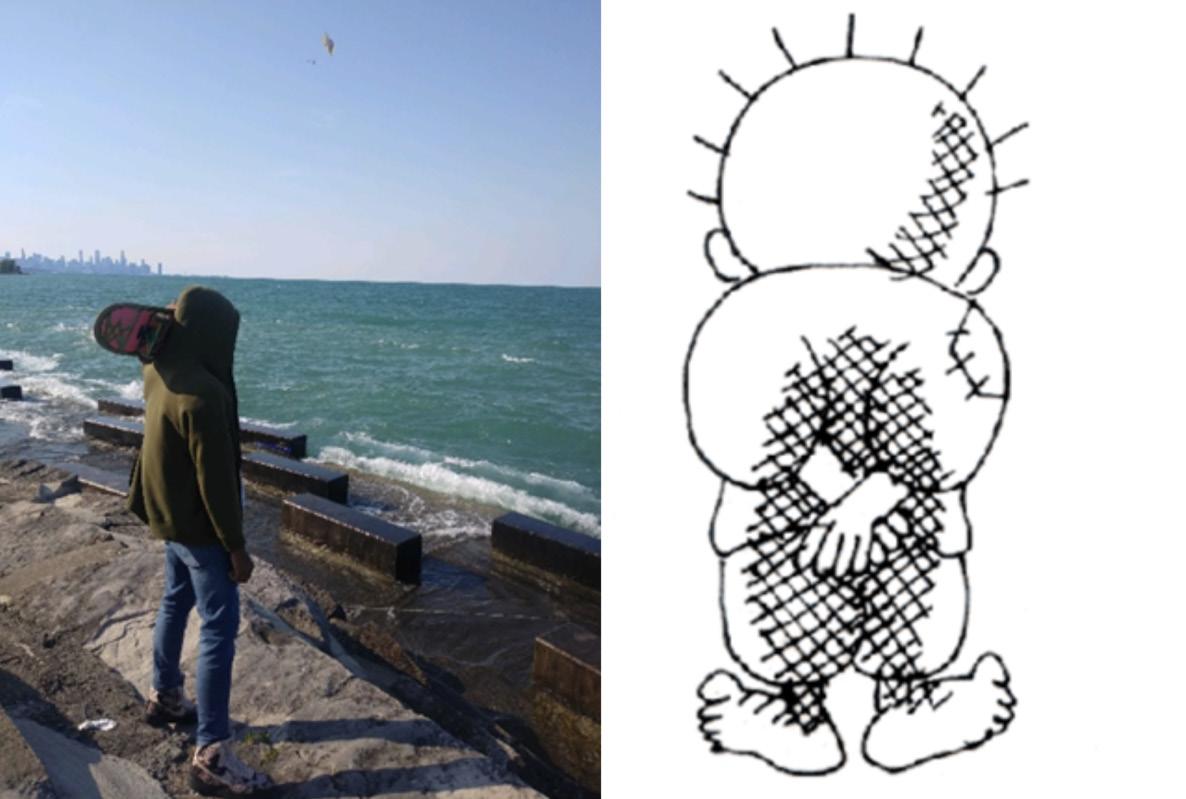

The second reason I decided to file for a leave of absence was that in February 2024, the life of my best friend, Elijah, came to an end. The picture at the top of this article is Elijah looking out at the lake. The picture on the right is Naji al-Ali’s immortal Handala, which deserves some research from you. Elijah has his back to us—he sees something in the lake that we cannot. Handala has his back to us because Naji al-Ali would not draw his face until Handala, like other refugees, was able to return home to Palestine.

Elijah and I attended Lindblom Math and Science Academy, located in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, together for seventh and eighth grade. We stayed the closest of friends even as I changed schools. Elijah attended Lindblom for high school, while I reluctantly attended Jones College Prep in downtown Chicago, something my parents encouraged me to do because it’d give me a better chance to be admitted to an elite university like this one. By my third year at UChicago, Elijah was struggling with mental, spiritual, and physical conditions that one psychiatrist called schizophrenia. In November 2023, he departed unannounced from the transitional housing center he stayed at, which led me, his other friends, and family to search the city for him.

The skills I learned organizing and struggling for Palestine were the same skills I used in searching for Elijah. Putting up flyers around the city, staying disciplined and active in the face of deep uncertainty and pain, sharing tips and resources in a group chat…

But in the end Elijah was discovered near Lake Michigan—he had drowned. During his beautiful life, he was one of the most intellectually and artistically influential people for me. Our long phone conversations are what drove me to study the dynamics of racial capitalism here, and our shared experiences continue to be a big factor in my desire to become a Chicago Public School teacher.

Elijah taught me how to listen and think outside the box, which I believe are some of the most valuable things anyone could teach. I’d text him a quote by Frantz Fanon, and he’d reply with a video by Bobby Hemmitt.

Elijah with his back to us (left) and Naji al-Ali’s depiction of a young Palestinian refugee, who refuses to grow up until he can return to his homeland (right). hassan doostdar .

One of my last memories with him was at the apartment of a Palestinian friend in Chicago, where he freestyled smoothly over Fairuz songs.

It was during my voluntary leave of absence, and after Elijah’s passing, that the UChicago Popular University for Gaza encampment took place. One of the key stances of those who participated in the encampment was that the struggles of the working class in the U.S., particularly diaspora and Black people, are inseparable from the struggle of the Palestinian people against Zionist occupation and U.S. imperialism. I saw this very directly in my friendship with Elijah.

He was always skeptical of UChicago as an institution. I remember sitting in Hutchinson Commons and dying of laughter with him because of all the pretentious paintings of (white) “important UChicago-ans” staring down at us. Having grown

up in Chicago, he knew from experience about Black people being displaced because of the University’s expansionism. He wasn’t surprised to hear what I learned in classes like “The Philosophy of Civic Engagement”—that Black academics at UChicago were put through real indignities due to the systems of racially restrictive covenants and segregation that the institution perpetrated.

Beyond his critical eye for white supremacist nonsense, Elijah saw the value of education as inherently tied to self-knowledge, both of himself as an individual Black man and through a collective practice of overcoming colonialism. I think that his struggle against the psychiatric system boxing him into dehumanizing definitions, whether as “a schizophrenic” or otherwise, was a sign of real strength in this regard. When, during my second year at UChicago, he at-

tended “Counterterrorism and Empire,” an event organized by SJP in protest of Israeli general Meir Elran’s class “Security, Counterterrorism and Resilience: The Israeli Case,” I was really proud. He wasn’t a “registered student,” but he came to dinner with all the panel participants afterwards and talked to students and professors alike. Without his jokes and insight by my side, it would not have been the same.

I easily get lost in storytelling about Elijah, so let me return to the discussion of the current disciplinary case against me, in the context of the Palestine solidarity movement on campus. The protests against UChicago’s complicity in the genocide of Palestinians have clear, coalition-based demands, which developed over years of student and community organizing. The simplest of these demands,

CONTINUED FROM PG. 13

which in November 2023 the UChicago administration preferred to arrest 26 students (including myself) and two faculty over, rather than acquiesce to, was a public meeting about divestment.

After our mass arrests and quick release, a large number of cultural organizations on campus co-wrote and signed a statement in support of UCUP’s demands, denouncing repression by UChicago administration and the UCPD. I personally met with Randhava, executive director of the “Center for Identity + Inclusion (CI+I),” which houses the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs (OMSA), to see what OMSA was willing to do in collaboration with the organized “students of color” whom it serves. There I got an initial taste of the racist gaslighting framed as neutrality that I have named above.