135 ISSUE 7: BLACK HISTORY

VOL.

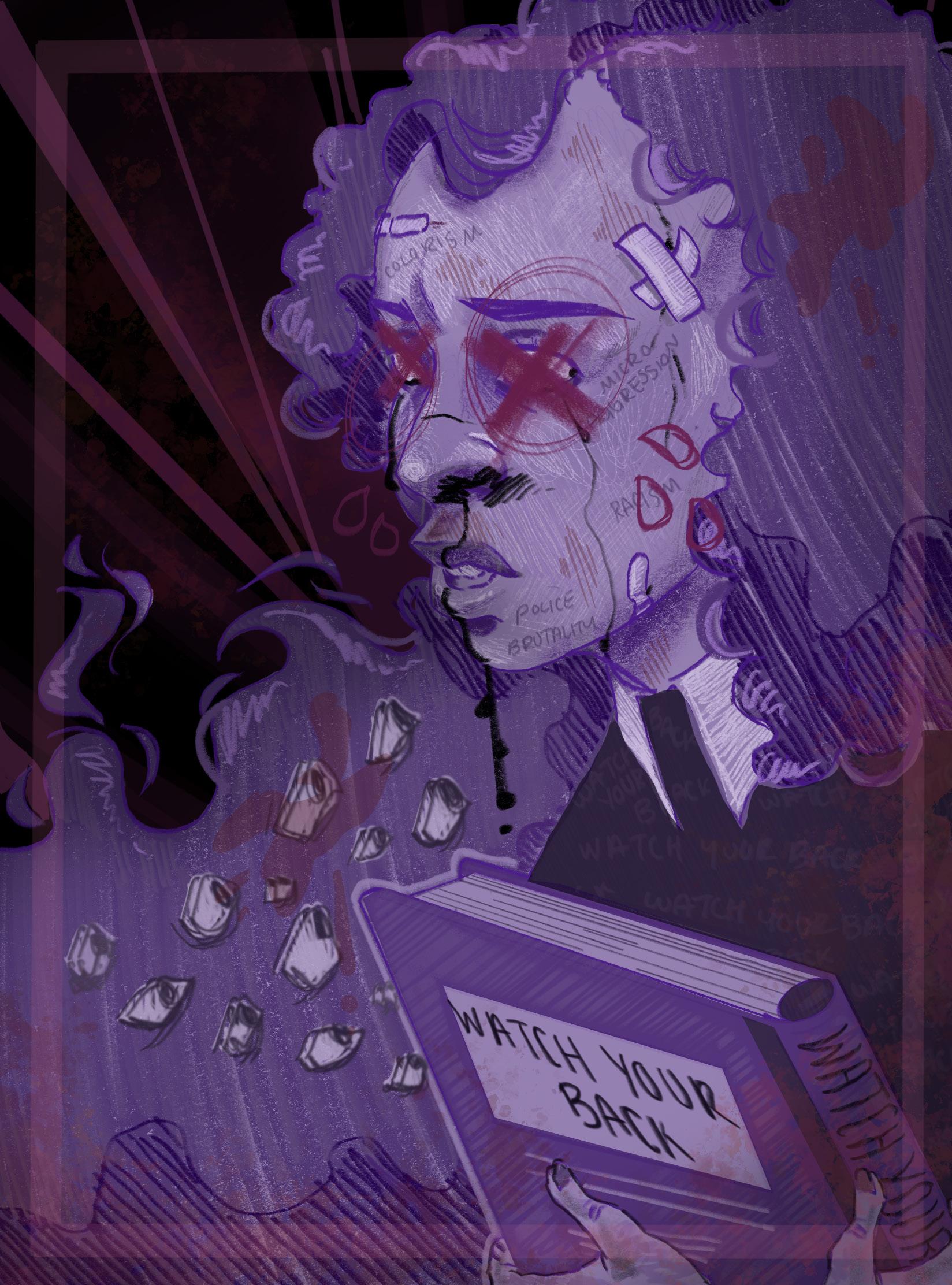

MONTH SPECIAL ISSUE CHIMAOBIAMANCHUKWU

SOLANA ADEDOKUN

Hello! What you’re holding in your hands (or reading online) is something very special. This 30-or-so page labor of love is the inaugural The C hi C ago M aroon Black History Month Issue, made in collaboration with the Organization of Black Students (OBS), the African and Caribbean Students Association (ACSA), Blacklight Magazine, and the Georgiana Rose Organization (GRO).

A lot of you might be thinking the same thing: Is this really the first Black History Month Issue The M aroon has done? Why has it taken so long? At least, those are the questions I asked myself before I pitched this idea to the current editor in chief! Historically, The M aroon has sorely lacked not only coverage of Black people and the South Side community, but diversity in all

Foreword

aspects of production, making it difficult to actually have enough momentum to create an issue like this.

Though I’m not as involved in each Black RSO as much as I would like to be, this issue is a love letter of sorts to the Black UChicago community. Coming from a predominantly white institution K-12 school, I never really had the chance to develop strong friendships with other Black students. Now, I know, no matter how much you’re involved, the Black community here will accept you with open arms.

This issue is not The M aroon ’s “I’m sorry” letter to the UChicago and South Side Black communities. Rather, it is mine and almost 30 other primarily-Black contributors’ from these partner RSOs platform to celebrate and empower the Black community while also educating non-Black

Editors

Solana Adedokun, head editor

Destin Bundu, design editor

Cameron Drake, social media editor

Simone Gulliver, editor

Tomás Miriti Pacheco, editor

Meghfira Mohammed, editor

Adesuwa Obasuyi, editor

Victoria (Tori) Harris, copy editor

Mia Rimmer, copy editor

Malaz Nour, copy editor

community members about the struggles and successes that Black people face everyday in our own community.

After the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, we stand at a watershed moment in our lives for Civil Rights issues: being keenly aware of the injustices that have (and continue to) plague Black people for centuries, but also implementing and creating tools to change the future for Black people. Change can start anywhere, and, right now, I want this magazine to be a place in our community where change can start.

This Black History Month, do more, be better.

Without further ado, welcome to the very first The M aroon Black History Month Magazine! Here’s to (hopefully) many more in the future.

Special Thanks

Organization of Black Students (OBS)

African Caribbean Students Association (ACSA)

Georgiana Rose Organization (GRO)

Blacklight Magazine

Caitlin Lozada

Tejas Narayan

Arianne Nguyen

2

GRO Page: Talking about the History of the Org and Dr. Georgiana Simpson

GRO

The Georgiana Rose Organization (GRO) is a mental health-focused student organization dedicated to the individual, social, cultural and political advancement of Black women at UChicago. Our aim is to create a community for people who identify with the Black ethnicity and femininity to feel safe in their identities and to develop platforms and tools for their voices to be heard, amplified, and validated on campus.

GRO was founded in June of 2020 by Marla Anderson (B.A. ’22), Dayo Adeoye (B.A. ’22) and Gabby Mahabeer (B.A. ’22). GRO was designed to bring together Black women from all parts of campus through a non-exclusive registration process and engage them with a variety of activities that promote personal and communal self-care; priorities that are sometimes left on the backburner while balancing and acclimating to life on campus.

Our organization is committed to the highest standards of inclusion and respect. While our mission is specific to the advancement of Black women and people who identify with Black femininity, we strive to maintain a welcoming atmosphere in everything that we endorse as an organization. Therefore, we aspire to participate in and adapt to contemporary conversations surrounding womanhood and open our space to all, regardless of their particular gender expression.

Our founders were inspired by the story of Dr. Georgiana Rose Simpson, the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in the United States. Simpson received her doctorate in German from the University of Chicago on June 14, 1921, just a few weeks after the Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma, evidence of the period’s broader racial

attitude. While on campus, Simpson briefly lived in Green Hall while it was a women’s dormitory at the time. Protesting from her white Southern peer forced Simpson out. Despite these challenges, Simpson remained committed to her studies and left behind a groundbreaking legacy as the first Black woman to achieve the highest level of formal education offered in the US education system. Our organization is

named after Dr. Georgiana Rose Simpson to pay homage to her life, work, and resilience, and embrace the collective history and experience of Black womanhood at UChicago.

Since GRO was founded during the pandemic, our first events were held online. This included the first annual Dr. Georgiana Rose Simspon Day event on March 31, 2021 where GRO’s former

3

President Marla Anderson, Vice-President Dayo Adeoye, and Advisors Dr. Melissa Gillliam and Candace Hairston shared their experiences as members of UChicago’s Black woman community. Our organization continues to reserve this day to uplift and highlight the experiences of Black women at UChicago.

GRO’s first in-person event took place on May 9, 2021, a trip to see the Bisa Butler: Portraits exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago, works from Black quilt artist Bisa Butler that celebrate Black life. The exhibit included her I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings portrait named after Maya Angelou’s 1969 memoir depicting four Black women attending college during the Jim Crow era. As Black women attending a predominant-

ly white institution, the group resonated with the confidence and resilience depicted by the young women in the portrait and took a photograph with the piece.

Since then, GRO has taken further inspiration from Maya Angelou by adopting language from one of her famous quotes as focuses for our organization and its four committees.

“My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.” — Maya Angelou

Our four committees and their focuses are:

1. Passion Committee - desires, inspirations, enthusiasms and creativities

2. Compassion Committee - mental health and self-care

3. Humor Committee - fun and entertainment

4. Style Committee - newsletters, social media, marketing and branding

If you’re interested in connecting with us, joining a committee, participating in leadership, or signing up for our newsletter to get updates about future events (including our third annual Dr. Simpson Day!), please send us an email at gro.uchicago@ gmail.com.

Instagram: @gro.uchicago | Website: grouchicago.wixsite.com/website

4

Climbing the Ivory Tower: Views From the Top

MARLA FIONA ANDERSON, BA ‘22

MARLA FIONA ANDERSON, BA ‘22

The Entrance - Getting Accepted to the University of Chicago

For most of my life, I didn’t even know that the University of Chicago existed. This changed during my senior year of high school, when I received a letter in the mail from QuestBridge, a non-profit helping high-achieving, academically motivated students from low-income backgrounds gain access to some of the nation’s “top institutions.” At first, I thought it was a scam, but after taking a leap of faith and completing a lengthy application process, I got matched to UChicago, the school with a reputation for diversity, in a city with a reputation for violence.

Why did UChicago accept me? Well, I was diverse and a high achiever. I graduated high school in the top five percent of my class of 250 students, the only Black student that year to do so. I was also involved as President of the Speech and Debate Team, President of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and Students, and member of the Marching and Concert Bands. I volunteered heavily with the American Red Cross, won several awards and earned multiple distinctions as the “first” person to do fill-in-the-blank-thing in each organization. In fact, I’m the only person that has ever attended UChicago from my high school.

My application essay was a letter to my mom titled Dear Mom: Jamaican Me Crazy. In the first line, I wrote “I’m 17 years old and I’ve never been to a birthday party.” I went on to talk about all the things I missed out on growing up due to being raised in an overprotected household and eventually came to the conclusion that my mom was “sending me into a tornado where I [would] be flung around by the underlying truths

of life. And there’s nothing I can do but hope and pray that I fall into the right ring of debris, and land safely on the ground.” I was right, but I would later consider it weird that I had to put my traumas on the line to gain acceptance, and I often wonder what my peers wrote about.

I was socially, emotionally and culturally unprepared for what I would face in the next four years. Though I grew up surrounded by mostly white Southern influences and, at the time, felt very comfortable in majority white spaces, it wasn’t the white community that welcomed me when I came to campus. In fact, my first ever party was in a Black student’s dorm room during UChicago’s 2018 Admitted Students Weekend, where I got crossed, lost, and thankfully redirected by a campus security guard. I didn’t know then that this would become the theme for the rest of my four years—trying new things, making mistakes, losing myself, and with guidance and support from others, coming out on the other side better for it.

The Climb - Navigating the Institution

First Year

Turns out, there were no tornadoes involved, but there were lots of stairs. Thankfully, I didn’t have to climb the first few alone. I was one of 50 students accepted to the Chicago Academic Achievement Program (CAAP), a bridge program for students from low-income, and rural backgrounds. On the first night, June 24, 2018, we all sat on the stairs of Behar House lounge in Campus North and introduced ourselves. I introduced myself as the severely overprotected girl looking forward to independence and exploring Chicago. Because of CAAP, I felt safe, connected, and prepared for matriculation in the fall. While there, I also posted the first video to

my new YouTube channel, where I would eventually become the first Black student to post videos about race matters at UChicago.

A few months later, I started getting to know the rest of my peers. According to a census on UChicago’s Inclusive Pedagogy site, in Fall 2018 the undergraduate student population was 39.3 percent White, 19.2 percent Asian, 14 percent International, 13.7 percent Latinx, 6.5 percent Multiracial, 5.2 percent Black, 2.1 percent not specified, 0.1 percent American Indian, and 0.01 percent Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. This site uses this information to encourage professors to “be proactive” and “consider including course materials written or created by people of different backgrounds and/or perspectives.”

As an Anthropology major, most of my classes relied on knowledge surrounding different backgrounds and perspectives. After taking my first few social science classes, I was attracted to the concepts I was learning and would come to love discussions surrounding race and the African diaspora. Systemic racism started making more sense to me, and I started seeing it in even more places than before.

I was friends with a faculty member from my high school who was posting anti-immigration propaganda to her news feed. As a first-generation Jamaican immigrant, who had a decent relationship with this person, I was hurt. The concept that all teachers love all their students quickly dissipated for me. I would later guard who I would trust pedagogically. I decided to share some of my perspectives on my own feed, with an audience that included many of my white peers from home. One person said that college was turning me into a “liberal snowflake” while another suggested that instead of using welfare benefits to get me a plane ticket, it might be easier to send me back on the boat I came on. Despite the

5

fact that I didn’t know what either a liberal snowflake or Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) was and that I entered the country via airplane, these messages hurt.

Around the same time I learned about the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) shooting Charles Soji Thomas, a Black student who was experiencing a mental health crisis in 2018. Due to a combination of my genetic history with mental illness, experiencing direct racism for the first time, and understanding more about systemic issues through my coursework, there was a period where I would walk around campus actively fearing for my life because my white peers or police officers might try to harm me. After sitting with these anxieties for some time, I decided to make an appointment with Student Counseling Services (SCS). By the time I got a chance to meet with SCS, I was paired with a non-Black, male therapist. Though my racial trauma needed the most psychological attention at the time, given the therapist’s identity, I didn’t know where to start or the best way to explain. I remember talking, crying, then leaving and feeling less hopeful than I did when I first walked in. After that, I went to one more session with SCS but after coming to the same result, I did not go back again.

While all this was happening, the love I had for my Black identity and community became stronger as I spent more time around Black students, professors, staff and culture. I fueled my needs for social interaction by joining the Organization of Black Students (OBS), the African and Caribbean Students Association (ACSA), Black Professional Society, and the Society of Scientists of Color. I even ran for firstyear representative in OBS and ACSA, and even though I wasn’t elected, I continued to attend as many events as I could. I would eventually sit in several leadership positions in multiple organizations, on and off campus, where I was tasked with planning and executing the same types of events which I enjoyed attending and benefitted from.

Second Year

Towards the end of my first year, I learned that since I was an Odyssey scholar, if I moved off campus and found an apartment with rent that was low enough, I would get a refund every quarter that would be enough to cover my housing and living expenses with a little bit left over. The alternative to this was staying in the dorms and continuing to pay the school a few hundred dollars every quarter. For myself and many other low-income students, this was an easy choice, so about a week after the end of my first year, I moved into my first apartment with two of my friends as roommates. The best part about moving off-campus is that when the pandemic happened, I didn’t have to pack all my belongings up or leave Chicago. Aside from the fact that doing remote classes from my mom’s studio apartment in New York would be nearly impossible since we would be sharing a small space and she was also working from home, after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, I didn’t need to ask her for permission to go out and protest. Instead I got to be right there in the middle of it. In fact, I attended one on May 30, 2020, the same day when Provost Ka Yee Lee made an announcement about our community and events in Minneapolis and Chicago. In this announcement, she stated that “The vitality of the South Side is fundamentally linked with that of the University, and we esteem the deep relationships and partnerships that the residents of the South Side and members of the University community have built together.” This phrasing was extremely inappropriate given that it portrayed the university’s relationship with the South Side as one built together in the spirit of collaboration, when historically, it has been one of oppression. We received another email a few days later from the Dean of Students office along the same lines as Lee’s announcement. My first reaction upon reading it was, “Why did they say people of color when the experience being talked about is exclusively Black?” It wasn’t until a later announcement on June 26, after students identified this gross lack of acknowledgement, that the university named anti-Black

violence for what it is. In 2021, the university released this announcement: Opposing Racism and Acts of Violence Against People of Asian Descent. Aside from the direct acknowledgement of the issue and stance in its title, in the latter announcement, the Provost says “we must rededicate ourselves as a community to oppose violence, racism, and bias. We stand together on behalf of all people who are vulnerable to acts of violence and bias.” Though I’m glad to see the University learning from its mistakes, I would have felt a lot more supported if those sentiments and commitments were shared with the Black community in 2020 as well.

On the social side, I dedicated a significant portion of my time to attending events hosted by one of the Black sororities that are active on campus. I was attracted to the idea of a community of Black women dedicating time and energy to building and uplifting themselves, each other and their communities and having fun doing so. I wanted in. Some time later, after submitting my application, I received the call I’d been waiting for, but not the news I was expecting. I was informed that my application was not accepted, and while I was encouraged to reapply in the future, I was not invited to be a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. at that time.

Disappointed with this news, I still wanted to engage in a community like this. I knew I needed more space to grow. My only options at the time were to either wait until their next rush cycle, or rush a graduate chapter. I chose to instead create my own space, by starting a new organization. On June 14, 2020, less than 4 months after receiving that rejection call, I was meeting with my friends, Gabby Mahabeer and Dayo Adeoye on our first Zoom call to discuss the establishment of what would become the Georgiana Rose Organization, a mental-health focused student organization for Black women on the UChicago campus. Our organization would be non-exclusive and open to all, and we would build the space to accommodate each person as they were, and prioritize the healing and support of each individual and

6

their social, cultural and political growth.

Third Year

Starting a new RSO while balancing other executive board commitments, quarantine requirements and social limitations, racial violence, internship hunting, and my first romantic relationship, my life commitments were once again taking a toll. I decided to reach out to SCS again, and this time I asked specifically for a Black woman therapist. On June 22, 2020 after successfully, getting through SCS’s external referral process, I had my first appointment with my first ever Black woman therapist. Finally, I had the space I needed to begin my healing journey.

Despite the widespread and demanding nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and related social issues, expectations for student academics and involvement were still high. However, the remote learning format offered some forms of escape. I remember a few times being in class and getting triggered by comments made by both professors and other students, and being thankful for the ability to turn my camera off and physically take a break. I could roll out of bed right before classes and meetings, listen to a lecture while taking a walk, and sometimes even be in two calls at once. I could be involved in more activities without getting physically overwhelmed.

At the end of winter quarter, I started a new work study position as a Student Centers Building Manager. Part of my job was to remind students to wear their masks and ask them to leave the building when it was time to close. I cannot count the amount of times I was either disrespected or undermined by white and international students, alumni and visitors. While I enjoyed this position otherwise, it exposed me to how shamefully some people treat the staff members, most of whom are Black, and it makes me sad. They do so much to keep our lives comfortable and deserve the utmost respect and care. Without them, the university would not be able to run!

Fourth Year

I’d learned enough about the finance world by my third year to receive a career track internship offer as an investment banking summer analyst at UBS Financial Services, Inc. After a summer on Wall Street, I found that I was more concerned with the mental health of the employees and the firm’s strenuous working environment than I was with investment banking. I decided to drop Economics, focus on my Anthropology major, and take as many Psychology-related classes as I could to begin pursuing a career in the Behavioral Sciences.

Right before the quarter started, Parul Kumar, former President of Undergraduate Student Government (USG), reached out to me about an open spot on the Executive Slate. She thought I might be a good addition to the space due to my connectedness with campus communities and my willingness to voice “radical ideas.” After running on a platform of supporting mental health initiatives and marginalized student voices, the College Council elected me as the new College Council Chair.

At this point, I was also preparing for grad school applications. After spending time with my family during the summer, I

was inspired to write my B.A. Thesis about how mental health is talked about in Black Caribbean student communities, so I could include my research in my application. However, I needed more experience. After one of my professors invited us to a virtual Lab Night event, I was drawn to the Chicago Center for Youth Violence Prevention (CCYVP) because of its focus on reducing youth violence and improving Black lives. After a conversation with the Program Manager, I was offered the role, and accepted it. Since I was financially unstable and both roles allowed me to do schoolwork in my downtime, I decided to continue being a Building Manager and aim for 15 hours of work each week between the two.

At first, this all seemed doable, then it wasn’t. My mental health plummeted. On the night of May 11th, while sitting in Ex Libris Cafe, I sent an email to the head of my department explaining that “[u]nfortunately, due to overcommitting myself with my spring quarter schedule, I did not finish my thesis in time and will not be submitting a BA Thesis for Anthropology. Instead, I hope to finish it as an MA thesis or other scholarly work at a later date.” I felt like I let down myself, my parents, my research participants, and my advisors. I felt like a failure.

The next day, I received the results of my MAPSS application. I was accepted to the program, but not to the Psychology track, so I wouldn’t get a lab placement. According to every person I spoke with in the field, lab experience was a necessary requirement for acceptance into a PhD program. While I was exposed to Behavioral Science Research as a Research Assistant with the CCYVP, it wasn’t a lab. Still, even with a lab placement, I would not have been able to accept this offer since the scholarship I was offered would only cover $30,000 of expenses, and I would be responsible for the remaining $40,929. What more could I have done?

This was my breaking point. I decided that I would no longer be graduating that quarter anymore and even told my family that they could cancel their flights. I tried to

7

“I could roll out of bed right before classes and meetings, listen to a lecture while taking a walk, and sometimes even be in two calls at once. I could be involved in more activities without getting physically overwhelmed.”

explain to them how I was feeling in terms of a battery: I was no longer recharging fast enough to have the energy needed to produce any fruitful results, and I needed rest. I planned to take an incomplete on either one or two of my finals, and use the next year to complete my thesis, achieve the other goals I’d set for myself that remained unaccomplished, and revolt against credentialism and elitism in academia.

After sharing my plans with my therapist, she suggested that I meet with my trusted mentors to hear their recommendations and that I follow them. My mentors reminded me of the violence I’d experienced in my time at the university, and that it might be easier for me to speak up about them as a non-student of the institution since I would be protected from direct retaliation. I left those meetings more focused on the idea of finally being free from UChicago, and recharged with the energy and support I needed to get there. I ended the quarter with my first ever 4.0.

Top - Conversations with Administration

Following the death of Shaoxiong ‘Dennis’ Zheng on November 9th, 2021, conversations on safety increased around campus. As a high-ranking member of USG, I was involved in many of these. On November 16, 2021, a week later, the university announced a permanent increase in policing and surveillance and an expansion of the shuttle program and Lyft Ride Smart Program. These came before Zheng’s memorial service on Thursday, November 18, at Rockefeller Chapel.

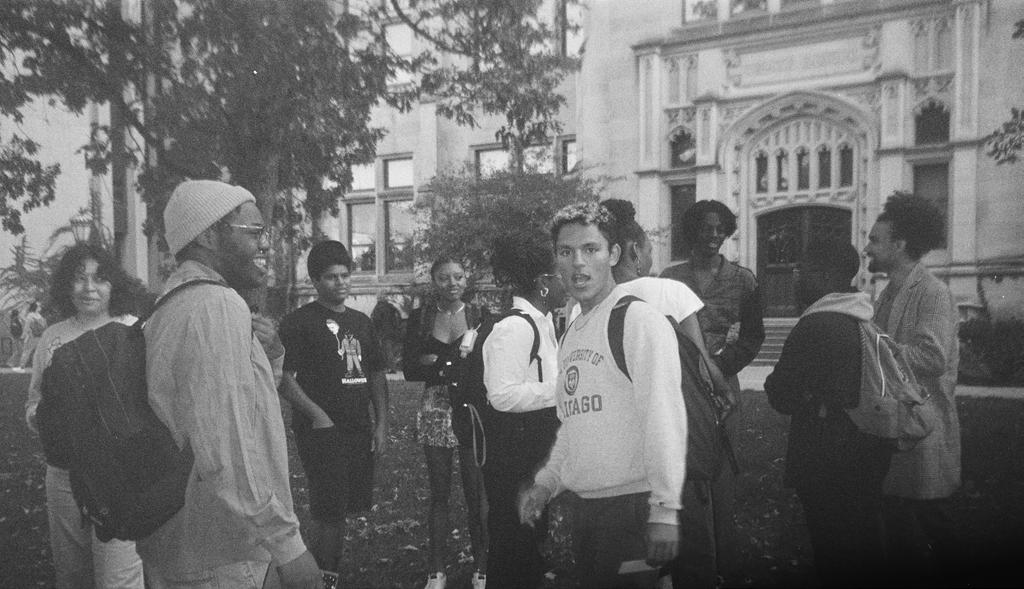

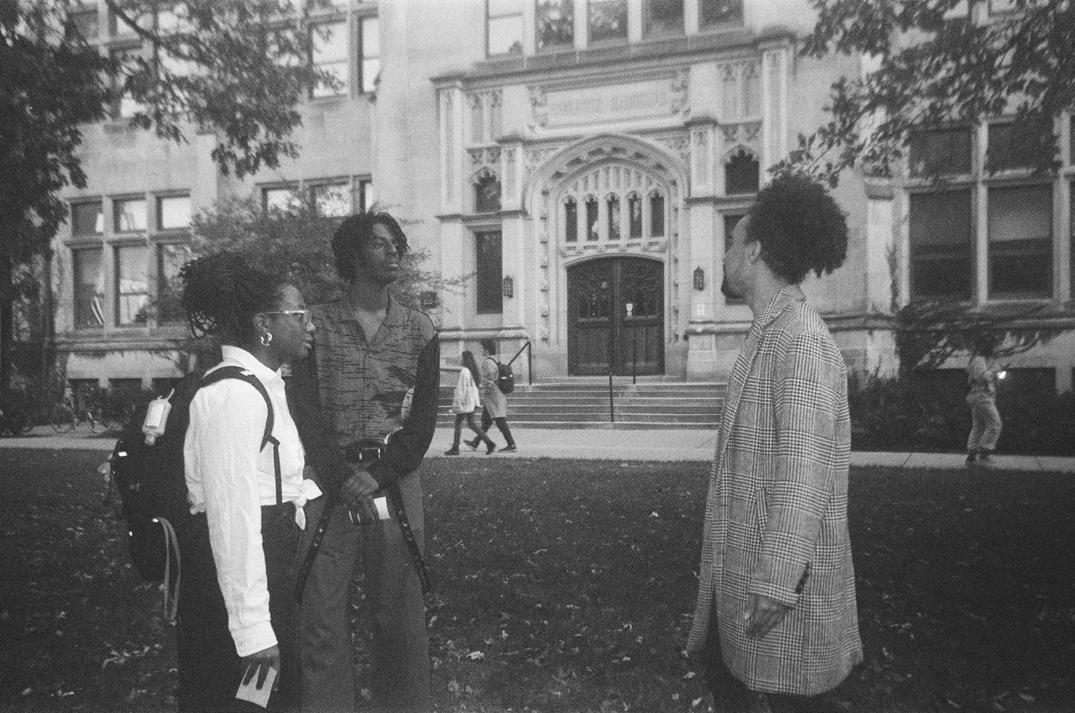

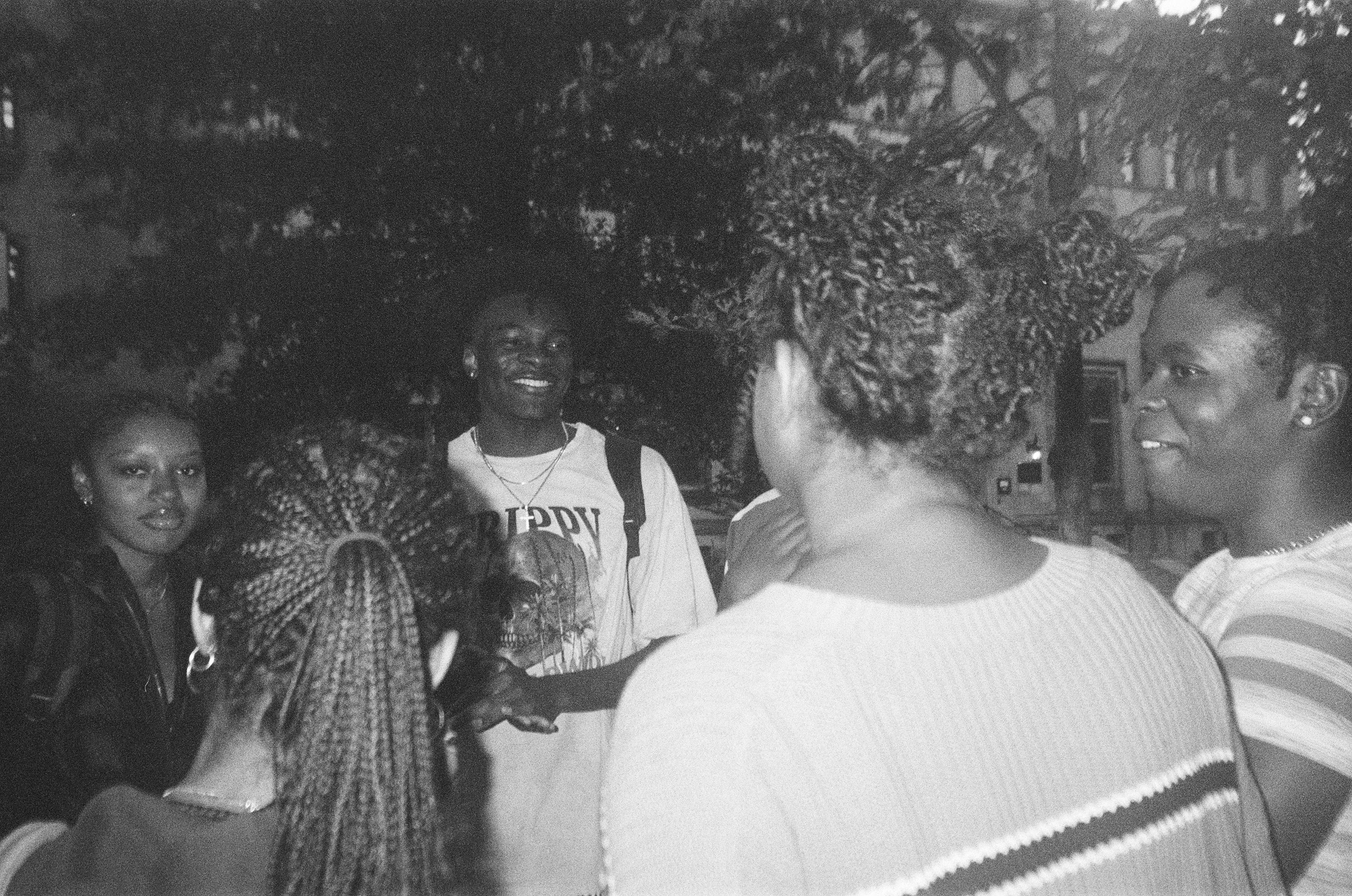

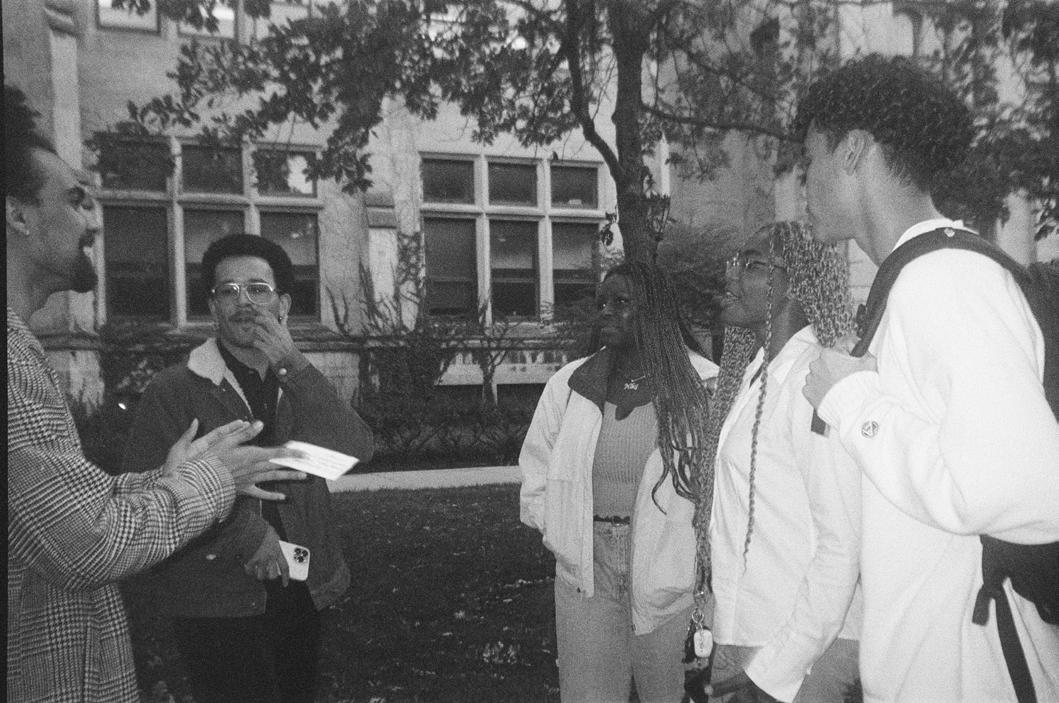

I met President Paul Alivisatos in person for the first time at the Campus Discussion on Safety and Security on November 17th, 2021, where they discussed with the Chicago Police Department (CPD) the steps they’d taken and would continue to take to enhance safety and security on campus. In fact, those are my locs in the cover photo—I was one of the few student leaders invited to attend in person. Alivisatos shared that the university “invite[s] all parents and current students to be part of the conversation about what will help them

feel like they can be safe and do their best work here” (stated at 32:30). However, we were immediately excluded from this since both recent history and this discussion promote further violence in our communities.

Among many other macroaggressions, I was most offended when David Brown, Superintendent of the Chicago Police Department, made multiple jokes in response to the question on racial bias in their policing of Black and Brown communities (35:15 - 37min). What’s funny? After this, I started experiencing symptoms of a panic attack. As the only non-police Black person present in the room, I felt it was my duty to say something, to fight. At the end of the discussion, I raised my hand. After no recognition, I stood, and I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I began to speak. Audience members started rushing to leave and one person even told me that this wasn’t the time or place. I asked why since this was the current topic of discussion, and insisted that my voice be heard. Physically shaking and extremely emotional, I did my best to explain our systemic crisis, demanded that more voices (including those of Black students) be included in further decision making, cursed at the president and the university for their continuation of the violence, and stormed out in a fit of frustration. This wasn’t my proudest speech, but I believed it was necessary to speak up about the flaws and injustices of what had been said. If I could’ve done things differently, I would’ve still said “this is absolute bullshit,” but then I would’ve went on to calmly ask the unanswered question I wrote on the provided Q&A sheet an hour before: How does the university plan to prioritize the voices and experiences of students, faculty, staff and community members from marginalized groups in its decision making?

On March 4th, 2020, in USG’s first private meeting with Alivisatos and my second interaction with him, Tyler Okeke, who was Vice President of Advocacy at the time, asked the president if he would support measures to improve the transparency of UCPD, ranging from adopting the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to releasing the budget. The president’s

response was that they use UCPD how they want to use UCPD, and would not be adopting FOIA because the university is a private entity. However, in the November discussion, Eric M. Heath, Associate Vice President for Safety & Security and Superintendent Brown made it clear that the two departments agreed to collaborate on “long term strategic plans to address crime in the neighborhoods surrounding campus” (7:20). Shouldn’t a private entity (UCPD) that shares camera footage, license plate readers and other data while engaging in joint patrols and traffic missions with a public entity (CPD) be held to the same standards as that public entity (7:05)? I mentioned in this meeting that USG, elected representatives for the entire undergraduate student body, had a firm stance against increasing police and questioned why that, along with stances from other student groups about the negative effects of policing and anti-Black rhetoric like OBS and #CareNotCops were not being taken into account in their decision making. The president responded by saying that while our personal opinions on this matter differed, what he was interested in was creating wealth in the community. It’s always about the money.

You know that phrase, “It’s lonely at the top”? My four years at UChicago taught me that getting to the top isn’t about gaining popularity or climbing the ladders of some imaginary hierarchical system. It’s about taking our backgrounds and experiences and gaining as much perspective as we can in the spaces and conversations that we find important. As a first generation, low-income student with a need for safe spaces to grow socially, emotionally, and culturally, things like mental health and supporting marginalized student voices are important not only for my platform, but also for me. I was able to sit across the table from the highest ranking members of university administration, the people with the power to make substantial changes, share my story and discuss recommendations for future improvements. In terms of this, I can’t imagine many other students, specifically Black students, getting the amount

8

of exposure to the university, its administration, and its violence like I did. Still, I left campus with the sense that my voice, experiences and immediate communities were not administrative priorities.

At some point, I realized that the administration, members of USG, and other student leaders had very similar roles: sourcing information on university life to make it better. The caveat is that some of us are getting paid millions to do, care, and listen less. If the university administration was listening like they say they do, they would hear what students, faculty, and community members have been saying for decades: the only way to ensure a reality of safety, rather than simply a “sense” of it is to radically heal our communities and end systemic violence. The success of this relies on all of us, on campus and off, working together to investigate, understand, unlearn and rebuild each facet of our current system to change it for the better.

View - Processing this Information

Around the same time, I saw that some of my closest peers were celebrating the completion of their theses. Did I do college wrong? What could I have done differently? What could I have deprioritized?

If I didn’t commit to exploring social spaces, I wouldn’t have gained the social and emotional learning skills that I missed growing up. If I had quit any of my jobs, I’d be even more in debt than I am now, and lacking the experience necessary to move into my desired field. If I’d quit Student Government, I wouldn’t have the knowledge I have now about administration. And if I’d quit GRO, I would have done a disservice to myself and the people I believe will benefit from the organization in the future. The leadership experiences I had have molded me into the best leader I’ve ever been. And the external financial, familial, and other things that came up were out of my control. Every single one of my experiences was necessary for me to develop this detailed view of university matters. I can’t pinpoint what exactly I could’ve done differently, but there’s more the university

could have done to support me, and by extension, other first generation, low-income, and Black students, in my identity and experiences.

Firstly, the university needs to hold themselves accountable to their part in the violence instead of gaslighting Black and brown communities. The original University of Chicago was founded in 1856, but closed in 1886 due to financial issues. Among the Old University’s incorporators were:

Stephen A. Douglas - slave owner and Illinois senator who argued for the continuation of slavery in the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. Douglas donated the initial land and financial endowment to fund the Old University.

William B. Ogden - the first mayor of the City of Chicago.

John H. Kinzie - the second president of the Town of Chicago and the son of John Kinzie. John Kinzie purchased (some believe forcefully) the house and lands of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable in 1800 through his frontman, Jean La Lime. Du Sable was the first permanent non-Indigenous settler of Chicago, and was of African descent. John Kinzie later murdered La Lime, who was also an interpreter between the Indigenous People and Fort Dearborn in Chicago. This is known as the first murder in Chicago.

John C. Burroughs - the first President of the Old University who served as Assistant Superintendent of Schools for the Chicago Board of Education from 1884 until his death. In 1889, Burroughs also supported fundraising efforts for the erection of the current University of Chicago.

On July 7th, 2020, the university announced the Removal of Stephen A. Douglas Plaque and Stone which was mounted in the wall of the Classics building. According to the announcement, “As John Boyer, Dean of the College and author of The University of Chicago: A History, notes, Douglas died in 1861 and had no connection to the University of Chicago that was founded in 1890 as a new institution with a distinct mission.” How does a stone memorial of a man with no connection to a

university find its way to that university’s campus? In fact, according to the same book by Boyer which is quoted here, more than half of the new university’s trustees and donors (including John D. Rockefeller) had a relationship to the University of Chicago prior to 1890. This is the UChicago legacy, built on murder, theft, and lies, and while it’s not a legacy to be proud of, it’s a legacy that belongs to the university and one that it should own up to.

Secondly, they should provide students with the full extent of support they need to succeed. On June 3, 2022, I attended the Odyssey Senior Celebration at the Rubenstein Forum. There, President Alivisatos stood on stage and promised a room full of Odyssey graduates and their families, including me and mine, that the university would support us throughout the rest of our post-graduation journeys. I thought about my dreams of pursuing a career in the Behavioral Sciences, possibly returning to the university in the future to teach in its non-Black Psychology department, and bringing a missing perspective to the next generation of Black psychologists. I thought about how I received the results of my MAPSS application the day after our last meeting with the president in which I shared that I applied and he suggested that more could be done to prepare students for graduate school applications. I thought about how UChicago had the resources to make my dreams a reality and didn’t. This promise had already been broken to me.

Thirdly, the university needs to better support students’ individual and communal needs. Inclusive pedagogy doesn’t stop at expanding course materials. It also requires substantial effort in building and maintaining quality resources and spaces to accommodate and nurture the different backgrounds and perspectives that students come in with. Since application essays notoriously include information on these, I wonder what would it look like if the university used that information not only as a basis of application-based decision making, but also as a tool to provide personalized resources and support to each incoming first year. While there are some

9

students who come here only to learn, and don’t need much additional university support, some students, like me, will rely almost completely on university resources, and to make sure every student can truly thrive here, it’s important to fully meet each student where they are. Historically, students have recognized these needs and taken it into their own hands to meet them, but there is an entire department of Campus and Student Life that is tasked with doing this and needs to do more.

Fourthly, they need to do all this while encouraging a more true culture of collaboration with the South Side community. For instance, in 2022, South Side residents ranked mental health as the area’s top concern for both children and adults in a study done by UChicago’s Medical Center. Given this, and the nationwide shortage of professionals trained to provide mental health support, there’s room for UChicago to strengthen its commitments to diversity and inclusion in SCS and its Behavioral Science departments, to ensure that interested students, like me, receive all the training and support they need to best prepare them for future positive change within these fields. What would it look like if the university supported faculty and student research and innovation initiatives that directly benefit the South Side community, radically? Or accepting more students from surrounding communities who are committed to their communities, in mass? UChicago has been here for over 166 years and refers to itself as an “anchor institution on the South Side.” If the scholarship produced was being transformed into community impact from day one, both the university and the surrounding communities would be much better off today. Instead, the community has faced decades of divestment and now carries the burdens of poverty, violence, and low educational and vocational opportunity. As the largest employer and most violent institution on the South Side, the university is responsible for making amends.

Exit - Life after UChicago

Transitioning from UChicago has been incredibly difficult for me. Many of the resources I was dependent on are now gone. I graduated job-free and debt-secured with no solidified plan for post-graduation. Most of my peers have gone on to work or study either at UChicago or other institutions, and are breaking new ground and doing amazing things. I am so proud of them.

After months of job searching, surviving on SNAP and Medicaid benefits, I once again found myself seeking a space that didn’t really exist and became motivated to create it. I am now walking in my divine purpose as founder of Mickle Muckle, a

I will end with this:

Black and Brown students, faculty and staff : Don’t be complicit, make your voices heard. Find your people and free yourself. Learn about this institution and its history and keep the administration accountable for their actions and policies. Stop trying to meet other people’s standards for you, especially when many of them are rooted in oppression. Make your mistakes and learn from them. If you knew better you wouldn’t have made the mistake in the first place.

White and International students, faculty and staff : Remember every day that people have suffered and continue to suffer to keep your life comfortable. If you continue to be impartial to that, you are part of the problem. Seek guidance on what a microaggression is and stop committing them.

non-profit organization which aims to cultivate spaces of healing, learning, and mutual aid to enhance the lives of Black youth and prepare them to make positive and sustainable impacts in their communities and the world. With the knowledge, experiences, and relationships that I have built and sustained so far, both on campus, on the South Side, and in my other communities,

I am excited and optimistic about what the future will hold. All things considered, I can truthfully say I feel blessed and honored to have attended the University of Chicago.

The University Administration : At the recent colloquium celebrating the the 25th anniversary of the Pozen Center for Human Rights, Ayça Çubukçu, associate professor in Human Rights stated: “We’re living in a moment when international organizations are unable or unwilling to hold the most powerful states accountable. As far as the future of human rights is concerned, we need to think beyond these institutions and critique them at their roots.” The university is not exempt from this. President Alivisatos, my question remains: Will you go down in university history as another white man that endorsed systemic racism? Or are you prepared to do something different? Is UChicago prepared to make radical change? Since its founding, the University has participated in and benefited from the commodification of the lives, labor, land, knowledge, education, health, culture and experiences of Black and brown people, on the South Side and beyond. There is a debt that is owed, and I can imagine that investing each university resource and every penny of the endowment for the next 25 years will only begin to make a dent.

10

“Remember every day that people have suffered and continue to suffer to keep your life comfortable. If you continue to be impartial to that, you are part of the problem. Seek guidance on what a microaggression is and stop committing them.”

11

What It Means to Be Black (Who Gets to Claim It)

IBUKUN ODELEYE this argument is invalid.

Black. Is it the description of a phenotype? Is it the definition of an individual who comes from a particular background? Is it a culmination of experiences? Does possessing Black genes make one Black?

In our current society, there are many ways people define Black, and many different opinions on what qualifies a person to be considered so. Some may argue that a person is Black because their physical features present that way, while others may argue a person is Black simply because they have Black ancestry. Some may say that one can be Black by proximity, whether that is growing up in a Black community, or being raised by Black parents. Some may say they are Black because they have been treated as such their whole life. But what does it really mean to be Black, and who gets to claim it?

One argument is that being Black isn’t based simply on appearance but also on one’s personal characteristics. Some people argue that even if a person is Black-presenting, if they have alternative interests to what is stereotypical to Black people, then they aren’t “truly Black”. The problem with this argument is that it limits the potential of Black people as individuals, characterizes us as a monolith, and reduces the characteristics of Black people to a set of actions instead of a physical identity shared by a variety of people who have varying personalities. Being Black is not merely liking rap music, dressing a certain way, using African American Vernacular English (AAVE) every time you speak, being athletic, growing up in a low-income environment, or any of the other stereotypes used to categorize Black people. If that were true, it is then possible for a non-Black person to “act Black” and by default feel as though they partake in the Black experience. It is not possible to be Black by proximity. Relating to Black experiences doesn’t make you Black, so

However, while being Black is not simply a set of character traits, I do believe it is possible to be out of touch with one’s Blackness. There is an experience, a culture that surrounds being Black; though there are many variations based on nationality and ethnicity, as Black people, we can relate to a certain culture that is unique to us. This culture means different things to different people, but in the same way that many other racial and ethnic groups relate to each other on the basis of race or ethnicity, the Black Diaspora is connected through cultural awareness, which can be described as a knowledge of one’s traditions, customs, heritage, and history.

other Black people. Because of this, many choose to assimilate themselves to Eurocentricity. They begin to despise the things that socially make one identifiable as a Black person: their hair, their culture, and even connections with other Black people. This assimilation causes one to be “out of touch”: When they go into the world where race is first base in categorizing a person, they cannot cope because they don’t understand what it means to be Black outside of the physical traits. Many of them struggle to find solace in other Black people because their whole lives they have been deprived of their Black identity.

This cultural awareness is a part of what it means to be Black.

Oftentimes, when a Black person is not raised around this cultural awareness, they do not develop the inclination that many Black people share. This can cause a feeling of disconnect due to being sheltered by their family, social status, or environment from the struggles, culture, and experiences that Black people face as a community. This lack of exposure deprives one of a safe space and community that can only be found among

On the flip side of this, there are people who think because they grew up in a Black community, or possess some Black genes, they by default they must be Black too. We live in a society where your phenotypical race plays a huge role in your treatment. There are so many struggles the Black community faces on the basis of phenotype. If a person is to go into an interview for a corporate job and the interviewer is racist, they are going to be treated based on what the interviewer can infer from how they look. White-presenting or racially ambiguous people are somewhat free from the stigma and stereotypes that come with being Black because they are not identifiable to the potentially racist others. There is a certain level of privilege that a white-presenting or racially ambiguous person is granted because, without any prior knowledge of background, they are not mistreated the way a Black person would be, regardless of whether or not they possess Black genetics. If a person has to actively validate or prove their Blackness with their grandma’s pictures, it is because they are not phenotypically Black, and they should probably take a step back and reevaluate what they think qualifies a person as Black.

Many people still use the one-drop rule and other harmful ideologies to categorize

12

“There is an experience, a culture that surrounds being Black; though there are many variations based on nationality and ethnicity, as Black people we can relate to a certain culture that is unique to us.”

someone as Black. The only mixed-race people in the 1950s that were able to pass were the ones that the white people could not identify. This proves the point that society treats (treated) you based on your phenotype. And who can blame them for doing so? No one wants the burden that comes with being Black. It is a privilege to be able to decide when and where you want to be Black, and many people knowingly or even unknowingly use it to their advantage. If you are half Black genetically but you phenotypically present as something else, no one is looking at you and judging you as a Black person because your genetic makeup is not present in your looks. You may be part of a minority community, but if you have pale skin and loose, blond hair, the world does not discriminate against you in the same way. Your natural hair is not being called unprofessional, you are less likely to be called slurs, your intelligence is not being questioned, and the stereotypes that a Black person has to deal with do not apply to you on the basis of race. The only way you would be associated with the Black community is if you were seen with your Black/mixed family members or if you showed a photo. You have the ability to deny your Blackness when it is convenient, and no one would bat an eye. You are absolved from a lot of the race-based discrimination the Black community faces because you are not a Black person. Now that doesn’t mean you don’t feel the effects of racism and the impact it has on the Black community, like a lack of significant resources, but your societal image is not compromised because of your physical appearance.

There are people who feel that because phenotypically Black people are affected by issues like employer discrimination (on the basis of race) and can therefore relate with Black people from this shared experience, they get to categorize themselves as Black. This is harmful because it reduces Blackness to a set of “universal” experiences and struggles, treating Black people as a monolith. When a person who is not a part of a minority claims to be part of the marginalized community, it undermines the struggle that that minority goes through. There is a distinct difference between culture and experience. Relating to the experiences of a Black person

doesn’t make you, yourself, Black if you too are not also phenotypically Black. There is no such thing as being Black by proximity to experiences because if that were the case, many other minority groups could claim Blackness since the issues they face are comparable, which doesn’t make any sense.

This is not by any means an argument that mixed-race people should not acknowledge their heritage, but one can never fully understand the Black experience without possessing the identifiable, physical traits. Meghan Markle is a prime example. She is a mixed woman who could very easily pass as white to some people. She even stated that she didn’t claim to be Black and wasn’t considered Black until she was launched into the spotlight. Yet many Black people adopted her into the community, despite her not

Black. A person is Black because when the world looks at them without knowing their history, what their parents look like, what they experience, it sees a Black person. A person is Black because it is a phenotype, because they exhibit the features and physical qualities that are shared amongst the Black Diaspora.

Story Behind the Story

SYDNEY COOK

originally identifying as Black. Now, she speaks on racism and her experience from the viewpoint of a visibly Black person because she has had a taste of what it’s like (and for that I salute her) and has used this view to build a platform for herself. But the reality of the matter is that her physical appearance hasn’t changed, and it is very likely that she would never have experienced the things she is now dealing with had she never been put under public scrutiny on the basis of her racial background. There are many people today who only claim Blackness for the immediate benefits; no one wants the long-term burden that comes with it.

So while the Black experience is something we share as Black people, that in and of itself is not what makes us Black. A person is not Black simply because one of their parents or grandparents is. A person is not Black because they like things that are stereotypically

Collection of Photos

CYRAH

13

“So while the Black experience is something we share as Black people, that in and of itself is not what makes us Black.”

GAYLE

Black Art Showcase

K al H aile

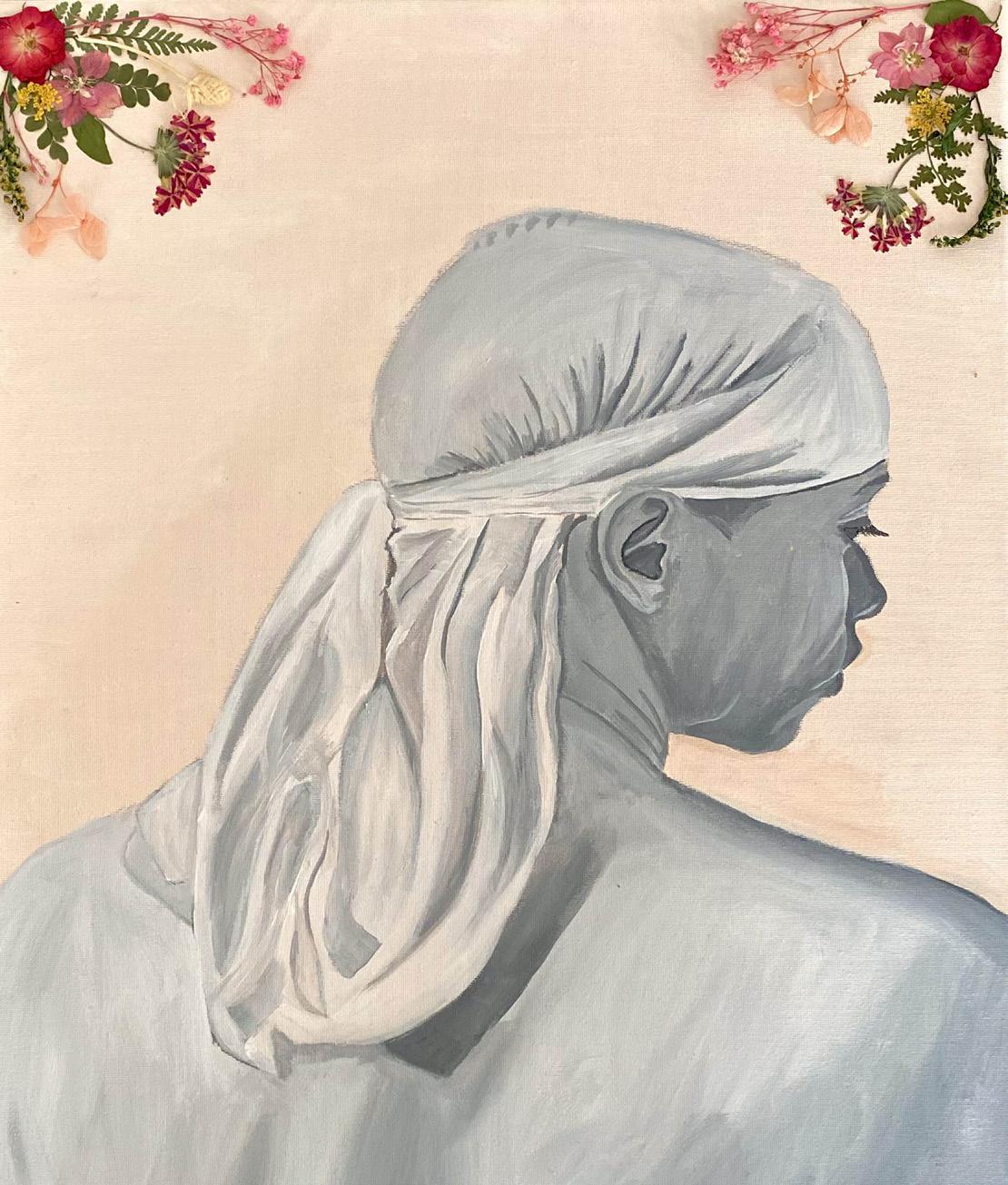

Through every terrain, obstacle, and major event, Black woman will prevail. Every direction we turn our heads they are there, watching, guiding, smiling, crying, and protecting. “H’er Whey” is an ode to our ancestral mothers who look over us then, now, and wherever their children’s head lay.

U r U nna a nyanw U

My piece was done with digital media and the art program Krita. In my piece, a white hand is holding a candle, melting the Black woman’s skin, representative of the forceful removal of Africans centuries ago. Despite the eternal candle continuously melting her skin, she paints it back herself, similar to the ways different Black communities of the diaspora have rebuilt and embraced their individual cultures over the years. Like Sankofa, the many unique Black communities are retrieving strength and beauty for themselves despite the hardships imposed upon them by outsiders.

14

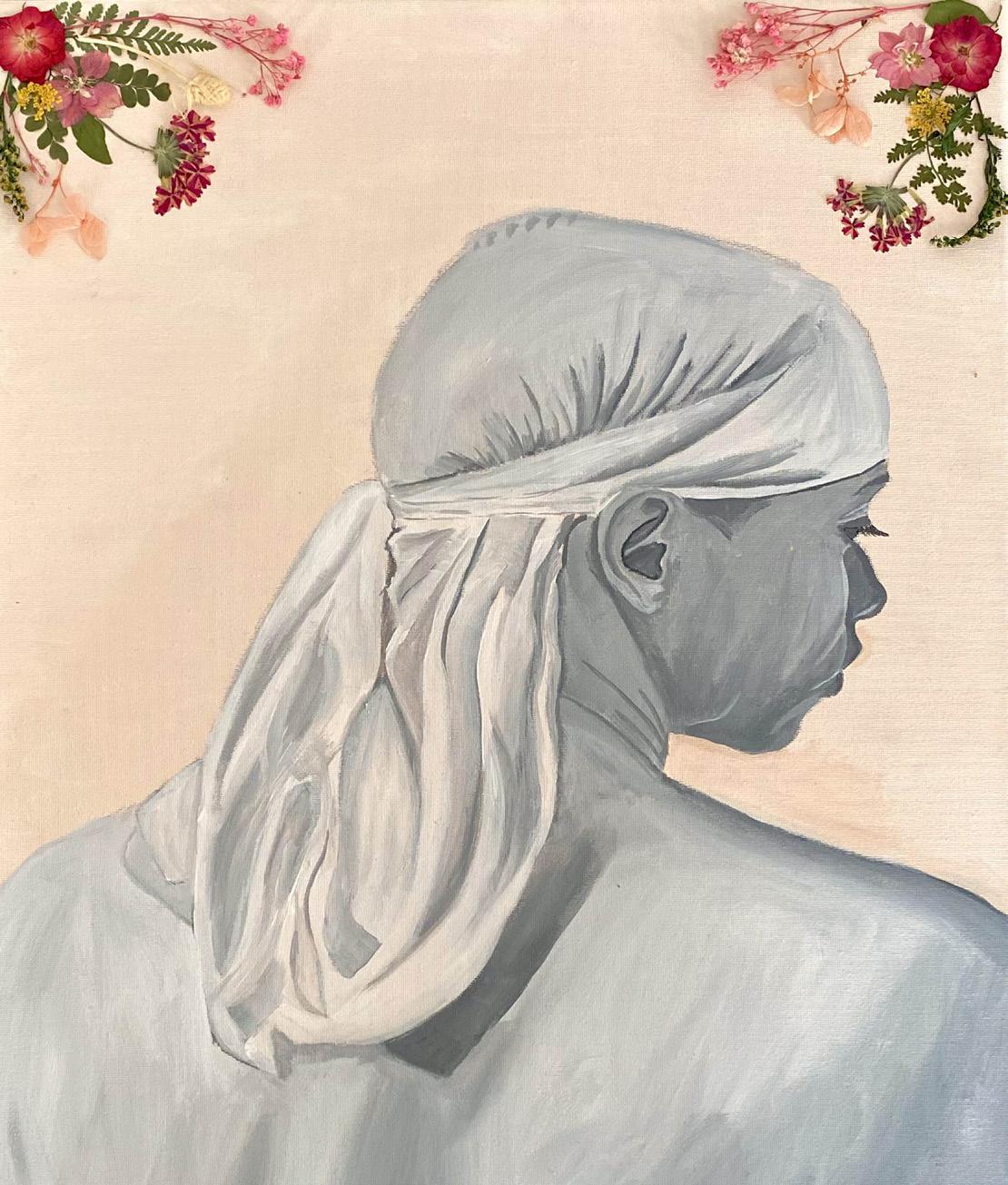

KAL HAILE

S avanna H B owman

“Decriminalization

2020

of the Durag”

Dried flowers and acrylic on Canvas

Pieces 1 and 2 of the “Decriminalizing the Durag” series

These portraits seek to juxtapose the delicacies of nature and the perception of Black men. Simultaneously, it sheds light on a cultural staple: the durag. This is a prominent piece in Black culture with a history that can be traced back to the 19th century.

The pieces use the intimate and unique placement of eyes and flowers to depict our connection to the earth and its influence on our perception of the world. We water our eyes with our lived experiences hoping to grow lush gardens full of culture, beauty, and Blackness but understanding that darkness seeps in from time to time.

15

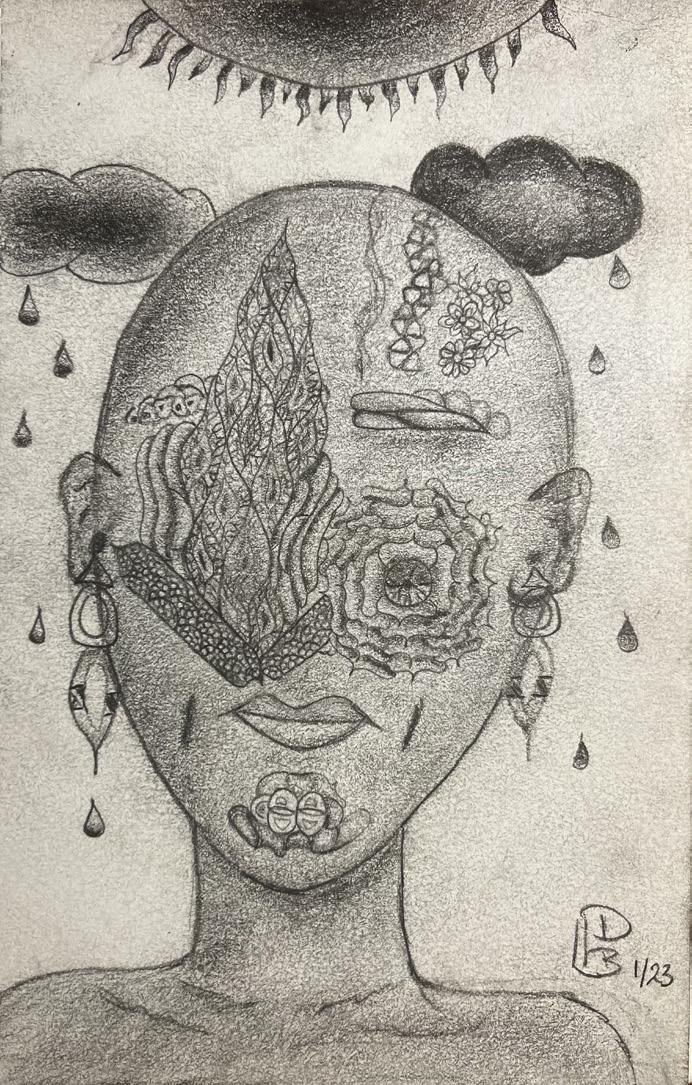

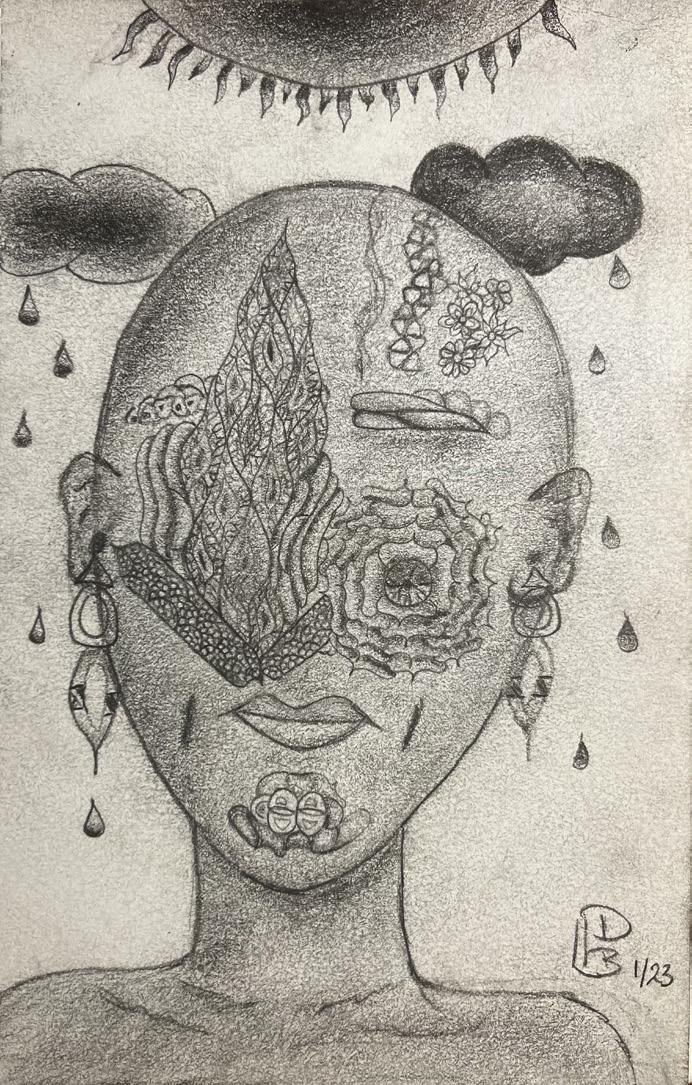

D e S tin B U n DU “Green Eyes”

6x8 2022 Graphite, oil graphite on Cartridge paper

S ara H G aUD ron

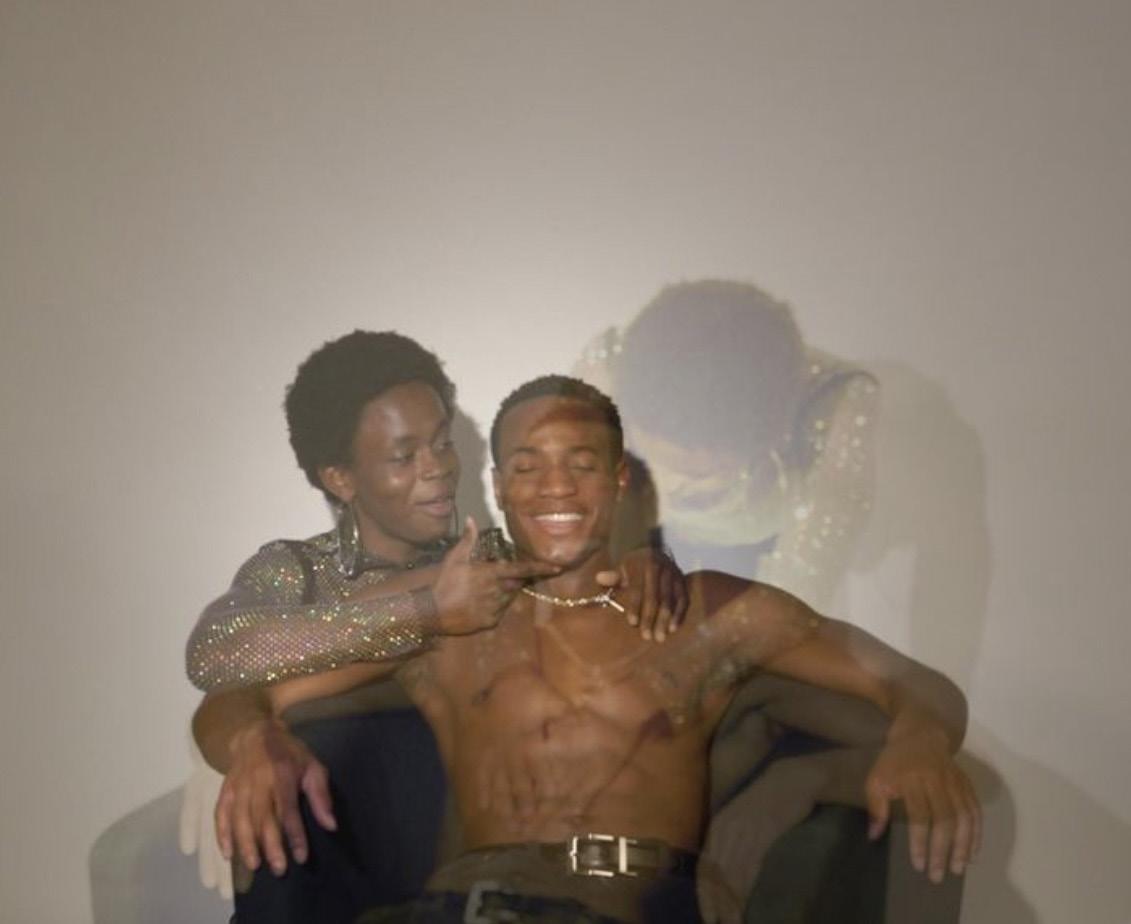

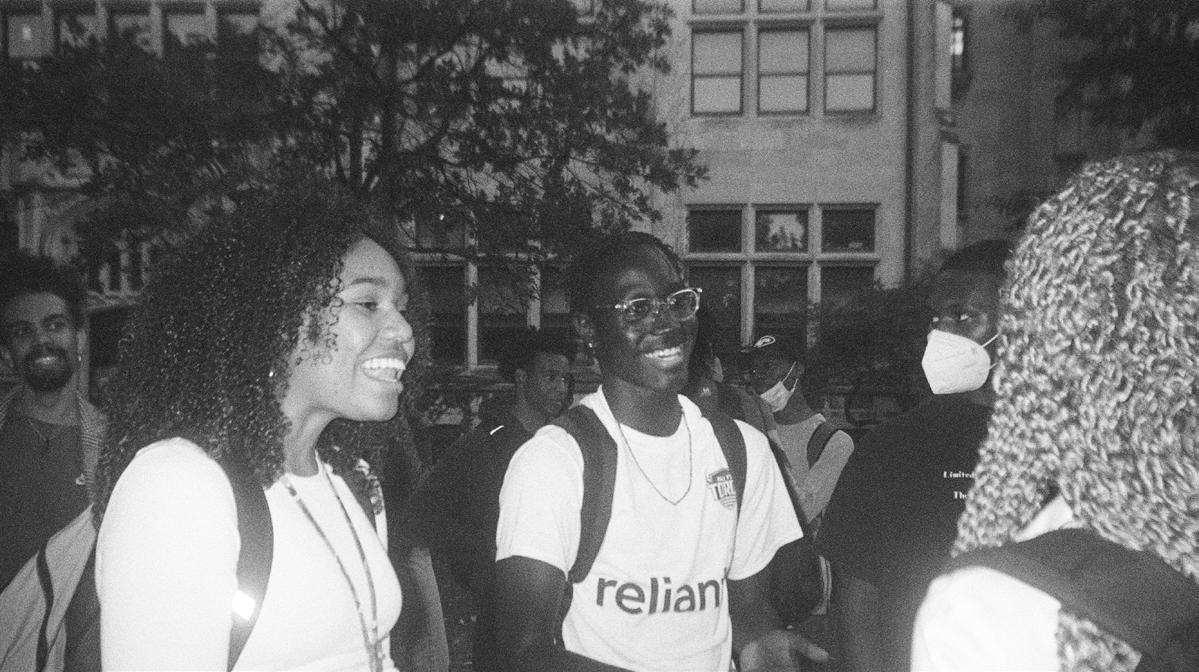

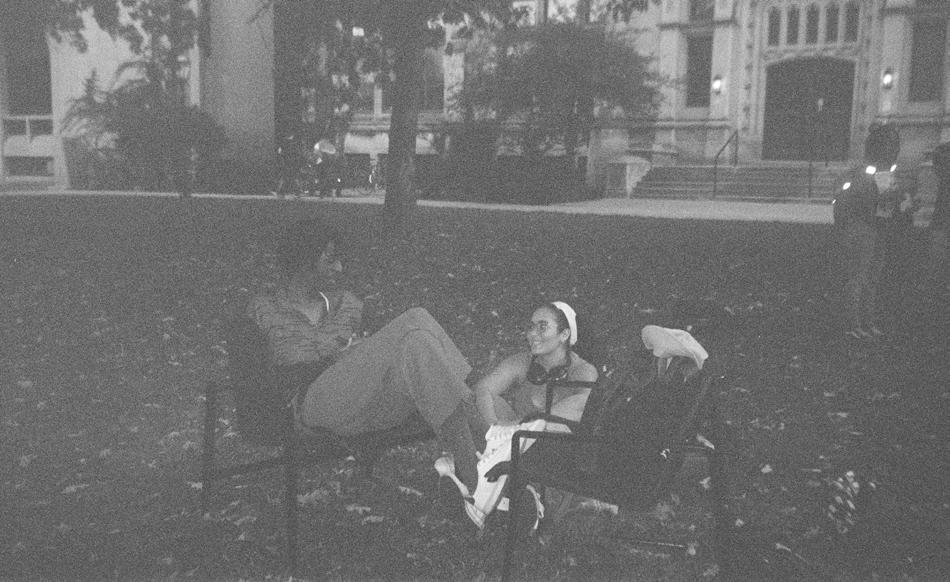

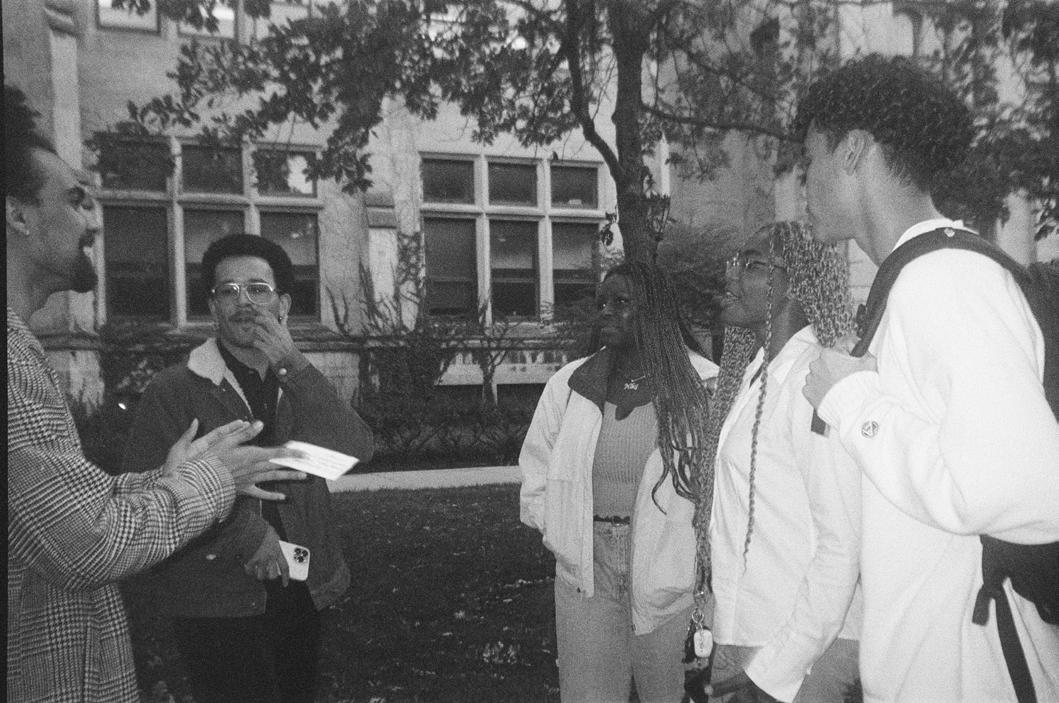

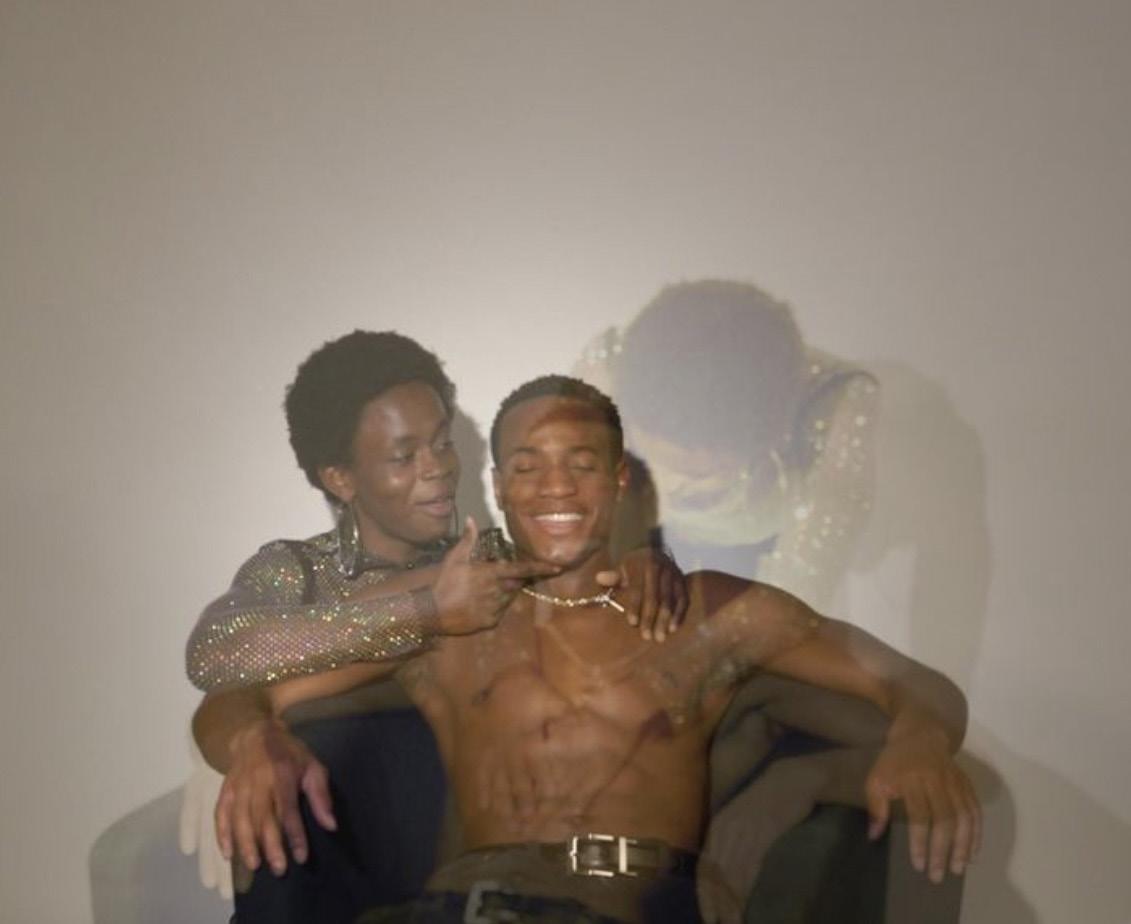

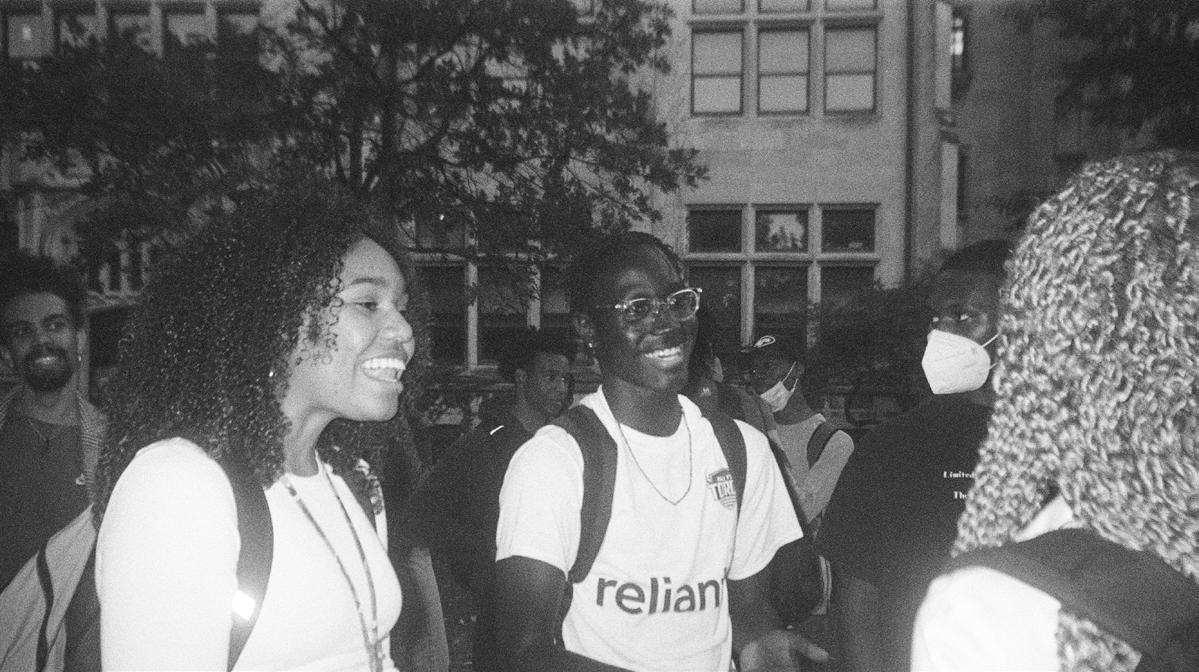

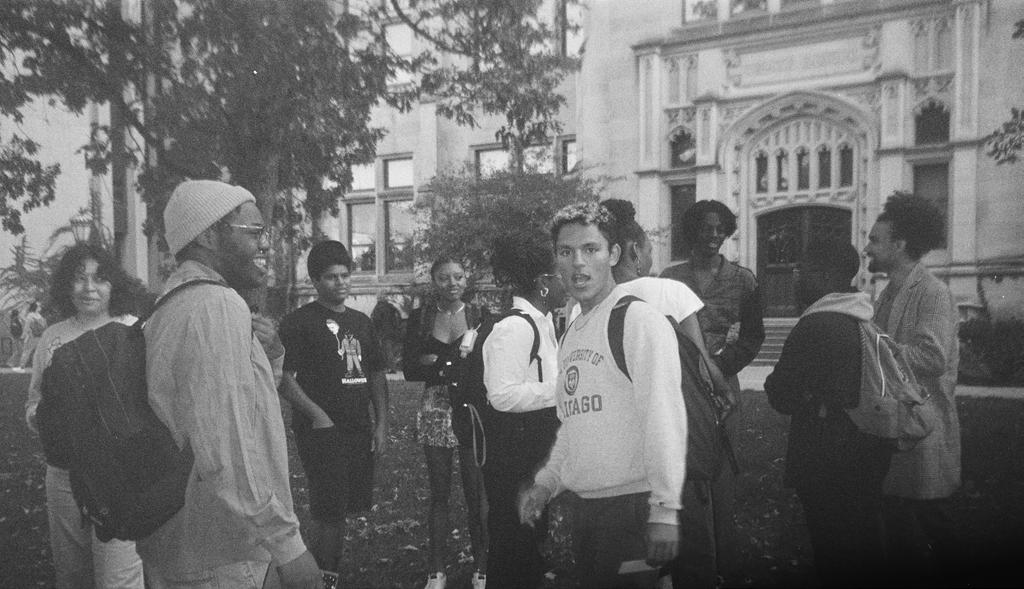

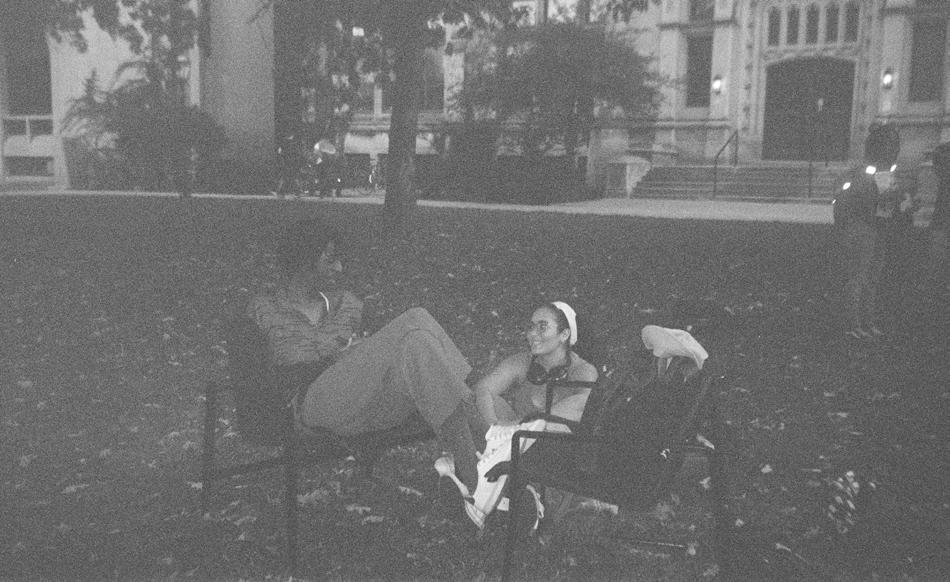

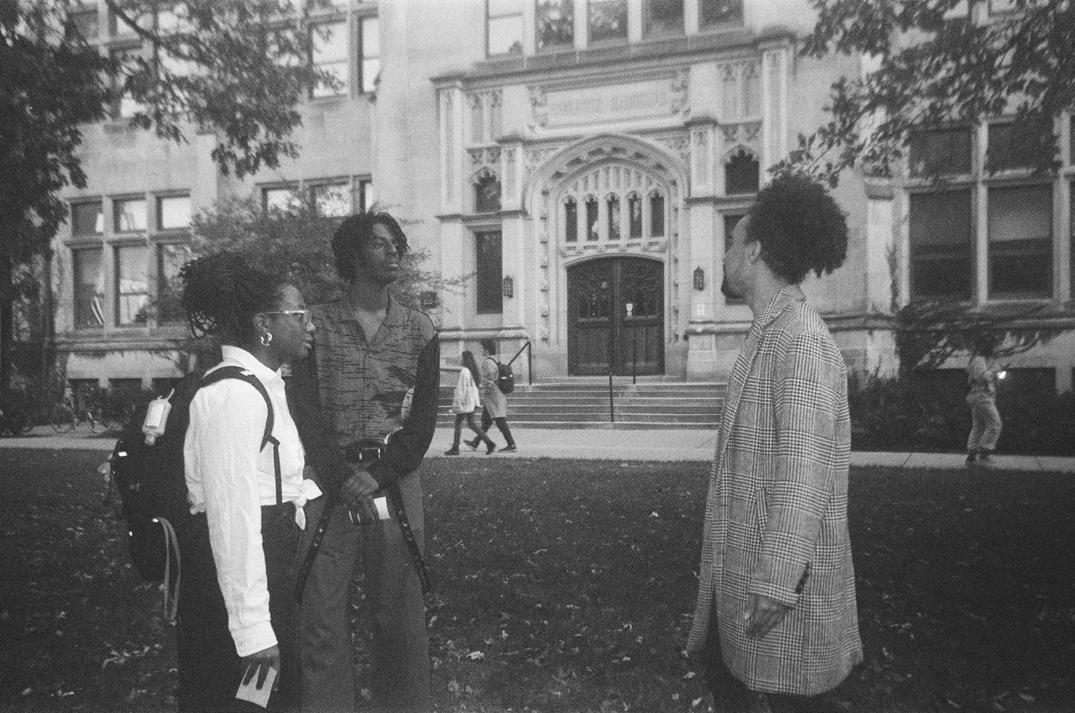

This collection of images serve as hallmarks in my photography journey. For every picture, I can vividly remember what mood I was in and the excitement that I felt to capture the next shot. More importantly, these pictures represent the memories that will connect me with so many beautiful black people I have met on this campus. I have had the privilege of directly engaging with their beauty, talent, and energy in one of the most intimate forms of art. For that, I am grateful that with every step I take further into my artistry, I do it emboldened by the essence of black euphoria all around me.

16

17

A (Sort Of) Nigerian Princess Diary

SOLANA ADEDOKUN them.

A major part of Black History Month is celebrating the achievements of Africans and African people across the diaspora. And there’s a lot of Black excellence–which is the idea that Black people who have a high level of success, achievement, or talent should be highlighted for other members of the diaspora–to celebrate.

Yet there is one aspect connected to Black excellence that is worth emphasizing. We call ourselves kings and queens, yet, for most of us, we do not have any clear-cut connection to any royal African roots. In fact, a joke heard time and time again is a Nigerian prince trying to contact someone, his long-lost family member, to share his wealth. But for me, being contacted by a Nigerian royal, an actual family member, is very real and something that has happened to me.

Now, granted, it wasn’t exactly like The Princess Diaries where I was immediately whisked away to my homeland in order to become an active member of a royal family. That being said, my dad did casually mention over Thanksgiving break two years ago that my uncle we’d be visiting later in Nigeria was a king (and actually had been a king for two years—thanks for sharing late, Dad!)

Once I heard this, I had so many questions. I wanted to know about him, my family, and the specific group of Yoruba people my dad’s family comes from: the Gbagura. When I got to Nigeria and met my uncle after not seeing him for some time, I asked him so many questions that he got one of his head chiefs to come and help him answer

Here is the story of my family, my people, my uncle the king, and why Black African royalty still matters in our celebration of Black History Month and today’s world.

In Nigeria, there are three main tribal groups: the Hausa in the north; the Igbo in the east; and the Yoruba, the one I’m a part of, in the southwest. Within each of these tribes, there are many, many subgroups, and each subgroup usually has its very own

migrated to the present-day area between Ibadan and Abeokuta, both major cities in Yoruba territory. In the early 19th century, the Gbagura people became a major force within the area and attempted to form an Egba Federation. They did this in order to obtain independence from the Ilaris, who were emissaries of the Olooyo, another tribal group.

The Gbagura overtook and fortified Abeokuta, solidifying their independence and remaining a powerful force in Nigerian politics. In fact, the first Agura of Gbagura, Oba Jamolu, ruled from 1870–77 was from my uncle’s—and therefore my—family lineage.

Today, the Oba presides over a dominion of 19 townships. “As the prescribed authority over Gbaguras, my primary responsibilities to my subjects are to ensure peaceful coexistence amongst the citizens and development of the various communities [and]...settlements of land disputes among the citizens as they arise,” Oba Bakre wrote.

specific traditions, including how they traditionally choose their ruler. Because of this, there are a lot of tribal leaders/kings, called obas in Yoruba, around the country.

My uncle’s full name and title is Oba (Dr.) Saburee Babajide Bakre, Jamolu II, Agura of Gbagura. Specifically, he is the king of the Gbagura people, a subgroup of the Yoruba people, in Egbaland in Nigeria. He and I are related on the maternal side of my father’s family.

According to the history told by my uncle and his court, the Gbagura people

Additionally, the Oba can give titles to “deserving” Gbagura people at home and abroad in the diaspora, making the concept of Black kings and queens, at least politically, a reality.

Since Gbagura functions much like other kingdoms, the Oba has the final say on any matter. Despite this, the Oba has a complaints committee that can adjudicate disputes. It is made up of the Oba and five chiefs he has selected. He also meets monthly with the heads of each township to head the Gbagura Council of Baloguns and Chiefs to discuss matters of state.

18

“Here is the story of my family, my people, my uncle the king, and why Black African royalty still matters in our celebration of Black History Month and today’s world.”

With the rise of the concepts of Black kings and queens, one can wonder, what does it mean in this day and age to actually be Black royalty, and what role does it play in the greater Black Diaspora?

Besides many political powers that make him stand out from the other chiefs, the Oba also wears different traditional dress than the other chiefs. An Oba always wears a crown, complete traditional dress, a walking stick, a horse tail, beads, and special shoes. Additionally, because he is forbidden to touch people outside his family, he holds a greeting stick to greet his subjects and others outside his domain.

However, one of the most fascinating parts of the Oba’s rule is how my uncle was chosen. There are only two ruling houses that can produce an heir to become the Agura of Gbagura. They are the Egiri Ruling House, made up of the Jamolu, Ijade, Abolade, and Adeosun families, and the Jiboso Ruling House, made up of the Olubunmi and Shobekun families. My uncle and I belong to the Egiri Ruling House, just like the first Agura of Gbagura.

Once the Agura Oba dies and a 90-day mourning period is observed, the Kingmakers of Iddo Traditional Council of Chiefs, made up of six Ogboni and six Ologuns (chiefs), allow applications to be taken for the position of the Oba. Qualifications are based on criteria coming from a candidate’s respective ruling house, educational qualifications, and work experiences. Then, after a round of interviews, seven out of the 16 candidates are requested to step out of the race, leaving only nine. The nine go through “additional screening”, and the final three are brought to the Ifa Oracle, who determines who will actually be Oba

“Another phase in the Obaship process was the seclusion stage which lasted for ninety days in which I went through the rites of Obaship as Agura of Gbagura. My freedom of movement…[was] curtailed,” Oba Bakre wrote.

Before assuming the throne, the current Oba lived a fairly normal life. He was born in 1960 to Prince Rasaq Olayinka Bakre and Alhaja Latifatu Bakre Adeghite, both from Gbagura. He spent time in Ibadan, Abeokuta, and Isolo for school until 1981, and received a degree in business administration in 1986. He worked for the Nigerian Customs Services and became chief superintendent of customs, leading him to work in various parts of Nigeria. Today, besides ruling, he spends time with his wife and family, along with devoutly practicing his Islamic faith.

This system is interesting because of how differently it operates from the traditional, European monarchies Americans are used to hearing about. In other words, obas, at least in Gbagura, aren’t raised as royalty and have a fairly normal life. This practice is something that ties into and reinforces the idea of Black royalty: Black Americans may not be born into as favorable situations as other American citizens, but instead, they find themselves taking initiative and seizing opportunities given to them to achieve the greatness connoted with Black royalty.

Despite this rich culture and system of governance, the world today is trending more and more towards democracy, putting less of an emphasis, politically and socially, on kings and queens of yesteryear. A notable example of this is former prime minister of the United Kingdom Liz Truss calling for the abolition of the British Monarchy when she was younger. Because of this, what does it mean to be not just a king in our modern world but a Black king?

During British colonialism, much of the power local Obas had, including being

selected by their own people, were transferred to the British colonial government and, subsequently, the Nigerian national government. For the Oba, he believes that it’s important for traditional institutions to play major roles in how Nigerian people are governed.

“Because of the closeness of the traditional institutions to its people it is germane to assign specific duties to them which should be spelt out in the Nigerian constitution. [D]uring the colonial period, Obas were appointed as President of the District Council in their area of locality,” Oba Jamolu wrote. “My people have a crucial role to play in the elections of who to govern them based on the principle of democracy.”

Though on a much larger scale, Oba Jamolu’s actions are similar to that of what we see in African-American culture of the idea of a Black king (similar to a Black queen): a Black man who possesses admirable qualities that makes him not only a great leader, but a person others in the Black community can look up to. In other words, it’s possible to suppose Black royalty serves a much more socio-emotional component than its African counterpart. Royalty connotes a sense of leadership, success, and excellence, an idea that serves as a method for Black Americans to empower themselves.

With many tribal cultures during the slave trade being subsumed into more of a monolith, it is both fascinating and a testament to Black Americans’ resilence keeping that tradition alive to remind ourselves that we are more than what the world may pigeonhole us to believe that we are.

As it relates to Black History Month, I feel it is important to acknowledge and learn about these ancient, yet living, relics of Black culture. It is important to empower ourselves at home but also uplift and educate ourselves on members of our diaspora that have major influences on society.

19

“This practice is something that ties into and reinforces the idea of Black royalty.”

UChicago Black House Campaign

Securing a Physical Black Space at UChicago

ARSIMA ARAYA got the better end of it. However, it is no longer enough—and never was.

“How can we have a Black House if we can’t even have a Black meal,” –Charles

Hendon ’25

This scolding, yet endearing, quote is all I can think about when asked to write a preface to the report on the Black House campaign that I have the honor of forerunning out of two of the premier Black student RSOs: Organization of Black Students (OBS) and the African and Caribbean Student Association (ACSA). Charles Hendon, a brilliant French and Spanish major and aspiring educator, is referring to my not coming to fourth meal. Every night, a significant majority of the on-campus Black students get together late at night to catch up, talk, and just be in the presence of one another. It’s nothing too formal; it’s always “come as you are.” We’ll softly play music, while someone else asks the group ridiculous questions that start the most heated debate, and everyone is in shock when the food is actually good. It is an integral part of our day, and even when I’m busy, it’ll be Charles reminding me to show up. This is about as close as Black students on campus get to having a space for ourselves. We borrow, occupy, and thrive in the rooms of McCormick Lounge and the Center for Identity and Inclusion, but this enjoyment is finite. When the clock strikes or room reservations get canceled, we are left to our own devices. Scrambling to organize nights in our lounge and coordinate party arrivals to make sure we can celebrate the end of midterms together. These temporary homes are what define the Black student experience. This reality precedes us, and alumni will be quick to remind us that we

In April 2022, the OBS Action Committee launched a campaign for the establishment of a Black student house on campus because of the lack of a designated affinity space for Black students. After three failed attempts to do so, the Black UChicago community has organized in unprecedented ways, with the community alongside us providing their narratives and expertise to ensure we are creating a house

Woodlawn residents from even imagining what the interior of a world-class University could offer them. The story as it’s currently written between UChicago and the South Side is entrenched in racist policy and practices.

This house will strive to rewrite this story in our next chapter, burst the UChicago bubble, and restore the fractured relationship with our neighbors in the South Side. It is of utmost importance to us, the Black UChicago community tends to these wounds and gashes done at the hands of the University. However, we cannot task ourselves with this labor without access to the plentiful resources of UChicago. Consistent organizing and advocacy will be required even after the house’s establishment, which is why this campaign is run collaboratively by OBS, ACSA, and the Black UChicago community, as well as our neighbors in the South Side. This project extends beyond academic education to political and critical consciousness to analyze the layers of harm and history that will be undone under the roof of our house.

that serves not only Black UChicagoans but our neighbors in the South Side.

“The UChicago Bubble” is a euphemism for what is the cage of UChicago and a barrier to our neighbors in the South Side. If you take a moment to look at the archive between UChicago and the community, it is as early as 1936 in the Chicago Defender that residents petitioned to have the University bar access to housing for people of color. In 1995, the Law School had a 10-foot barbed wire fence to bar

The story I am telling you today is what the facts are. You cannot dispute the harm done, and it is up to us to reimage and be advocates for a university we can all be proud of. This is and always will be a collective effort that cannot come to fruition or succeed without the investment of our students, faculty, staff, alumni, and community members. The Black House will house the next generation of dreamers, creatives, academics, and they will know this was a labor of love and dedication of so many amazing and empowered Black people. I wish you plenty of laughs, cries, revolutions (small or large), and I know y’all better not leave it a mess either!

20

“This house will strive to rewrite this story in our next chapter, burst the UChicago bubble, and restore the fractured relationship with our neighbors in the South Side.”

21

How the Fun Died: Mental Health and the Black Experience

“Where fun goes to die!”

Probably not something you want to hear in a psych ward.

KHADIJAT DUROJAYE own personal baggage that they had not resolved by the time that they had started raising my younger brother and me. My parents were physically and emotionally abusive when I was a child. This led to me having a harder time forming positive emotional connections with others, a fear of authority figures, cognitive issues, and struggling with depression and anxiety.

These words were spoken by a man wearing a UChicago sweater sitting across the room from me during group therapy. I later learned that he graduated from UChicago 40 years ago and, like me, majored in Physics. He made sure everyone knew that we were both Physics majors at UChicago; he’d bring it up during every group therapy session. After I had left the hospital, I thought about him a lot, and the fact that that was what he chose to say to me after learning that I was a UChicago student.

The phrase has always made me cringe. To me, it’s representative of the culture of romanticizing suffering that exists here at UChicago: bragging about how busy you are, how little sleep you’re getting, competing with other students, and setting unrealistically high standards for yourself. To hear it from someone so much older than me made me realize that that culture has probably existed at this school for decades. All of this, along with stories like Cassidy Wilson’s and Charles Thomas’s, are proof that The University of Chicago is unwelcoming for students with mental health issues, especially if you’re Black.

I believe the mental health services at this institution are inadequate. School administrators and Student Wellness practitioners often shift the blame onto students instead of taking accountability. There are multiple necessary policy changes that need to be made to create a positive environment for all students with mental illness.

My struggles with mental health are deeply rooted in my cultural identity and upbringing. My parents immigrated to Chicago from Lagos, Nigeria in the ’90s. With them they brought the trauma that came with growing up in post-colonial Nigeria. They both had their

Along with the abuse came the struggle to assimilate to American culture while also preserving my parents’ culture. American culture is drastically different from Yoruba culture, and a lot of that has to do with Yoruba’s emphasis on seniority. Parent-child relationships are not at all collaborative. I saw mine more as authority figures and less as people I could rely on for emotional support. They also didn’t make much of an effort to teach me or my brother their language or culture, which I believe contributed to the creation of an atmosphere that lacked love and understanding in my home environment.

Any child of African immigrants knows that mental health can be a difficult topic in our communties, and I’ve been told that my parents are particularly “African.” I was raised with a lot of pressure to perform well academically (you have three options, which all African immigrant children are familiar with: doctor, lawyer, or engineer) along with, “If you don’t listen, I’ll send you back to Nigeria.” I told my parents that I struggled with mental health before college, but they refused to accept that there was anything wrong. I did meet briefly with a (non-Nigerian) therapist in high school, but my parents would either go into the meetings with me and complain about how I wouldn’t assimilate to their culture, or ask me questions about what I discussed in the meetings (it was usually about them) when I got out of them, so I stopped eventually.

When I got to college, I had trouble finding a community in which I felt I could be completely myself. When I first matriculated in 2018, only 8 percent of the students in my class were

Black. I thought college was a place I’d be able to learn to be myself and grow in a positive environment, but instead I had to learn to tolerate racist comments from my peers and cultural isolation. Addition- ally, Nigerian-American and African-American cultures are very different, and I had trouble relating with African Americans because of the cultural divide; I was foreign, and they were not. Growing up, I was “too white” to be a Black person (probably because I was African) and I didn’t feel like I was accepted by African Americans, which I think a lot of Black immigrants can relate to. I did find some comfort with Asian immigrants and international students I had befriended, but every cultural group has their prejudices and I had to deal with microaggressions in these environments as well.

The problems I faced socially were intensified by what I was experiencing in class. I’m studying astrophysics and when I was a first year, there were usually only a handful of Black students (and very few women) in my 100+-person classes, which only worsened the social isolation. I had a lot of support from professors and grad students in the astrophysics department before I had started at UChicago, but this didn’t keep me from internalizing the feelings of not belonging I felt in lecture. I eventually stopped going. I kept telling myself I was too stupid to do the work and I was afraid that if I tried to ask for help, I’d look stupid, so I eventually stopped doing it. A lot of my worth was tied to performing well academically and I wasn’t doing nearly as well as I would have liked. To deal with the depression that came with this, I turned to substance abuse and self-isolation, which only made things worse. I continued to rely on these unhealthy coping mechanisms until the end of spring quarter 2019. I also started over-reporting hours at my lab job that quarter because I couldn’t afford to support myself due to my mom losing her job. I’d known that something was wrong for months and I finally

22

decided to get help when I realized that my lifestyle was not sustainable, so I scheduled an appointment at Student Wellness (then called Student Counseling Services) for the end of May, after finals that quarter.

I had a positive intake appointment experience. The person I met with was sympathetic to my needs, and she recommended a support group for people of color that I decided not to attend. Looking back, I think this support group was exactly what I needed, but at the time I thought I’d be looked down upon for attending the support group. She seemed to care a lot about what I was going through and checked in on me months after I met with her the first time. Since I told her I struggled with race, she told me she’d help me set up an appointment with a Black psychiatrist.

I didn’t know it at the time, but this psych intervention would completely change the course of my academic career.

I first met with the psychiatrist at the end of June 2019, a month after my intake appointment. I went into it optimistically despite what I had heard from other students. Before she evaluated me, she told me she’d ask me questions from a list she had memorized and take notes while I answered them. I thought this was a little unusual, but I had never seen a psychiatrist before, so I figured that this was just how those appointments were supposed to go. I was evaluated for anxiety, depression, and ADHD, but I don’t remember being evaluated for trauma. When we got to the ADHD questionnaire, she started to insert herself into things. At that point, it seemed like she was comparing my experience to her own instead of just evaluating me for an illness. She continued to compare me to herself and her family and share unnecessary facts about her personal life. She told me that all her children were all diagnosed with ADHD and anxiety and told me that her daughter was coming to UChicago next year. She also told me that she had to repeat a year of medical school because she found out that she had ADHD. She spent a lot of the appointment tooting her own horn; she said that she thought late ADHD diagnosis was correlated with high IQ. It was like she was turning a medical diagnosis into a personality trait. I didn’t realize at the time that this was inappropriate. I was honestly just glad I had someone to relate to and was

happy I wasn’t alone in my experience, but the lack of professionalism carried into every other encounter I had with the psychiatric system.

Black women generally have a harder time with misdiagnosis, so I can understand why she was so attached to the ADHD label. She seemed like she wanted to help, but did not seem to consider how being so unprofessional may have affected me. It only took 90 minutes (60-minute intake appointment, and 30-minute second appointment) for her to diagnose me with “ADHD and anxiety.” Later, when I asked her what kind of ADHD and what kind of anxiety I had, she told me it was “just ADHD and anxiety” even though I knew there were multiple types of ADHD. Over the course of the summer, she’d respond to my emails less and less frequently, which I found frustrating, but knew was common with Student Wellness psychiatrists. Because of this lack of accessibility and dismissive approach, I felt that it’d be best to find a new psychiatrist. I didn’t know I could find another one at the University at the time, and I had also heard a few Student Wellness horror stories, so I figured it’d make sense to get help outside of the College. From the recommendation from another student, I was able to see a psychiatrist at a clinic downtown.

Though before this change, I told my psychiatrist I wanted to apply for accommodations with Student Disability Services (SDS). She told me that the school wasn’t very good at accommodating students with disabilities, yet I applied anyway with her notes. When I met with the Deputy Dean of SDS about a month after applying, she informed me that notes from a psychiatrist weren’t enough. I wasn’t familiar with the psychiatric system, and I didn’t know anything about disability accommodations.