22 minute read

How far do you agree that a study of Russian government in the period 1855-1953 suggests that Russia did little more than exchange Romanov Tsars for “Red Tsars” in 1917?

How far do you agree that a study of Russian government in the period 1855-1953 suggests that Russia did little more than exchange Romanov Tsars for “Red Tsars” in 1917?

Felix Williams Upper Sixth

From a theoretical perspective, there are few points of similarity to draw between the late-Tsarist and Soviet regimes. Ideologically, they are opposed – at first glance, the market leaning, highly autocratic hereditary monarchy of Tsardom has nothing at all in common with the collectivised, socialist democracy that was the USSR. However, the de jure ideologies of the two regimes only tell a fraction of the story. In reality, the two eras had a vast amount in common; thus, the phrase ‘Red Tsars’ is an accurate epithet to describe the Soviet rulers. Beneath the superficial ideological differences, there are profound similarities. The actions of the governments in office, and their organisational structures, often suggest continuity, as does the attitude to reform of the regimes. Differences do emerge in the regimes’ use of repression and terror. However, this difference emanates from the Soviets taking a more extreme version of the initial Tsarist tack, rather than the Soviets taking a completely different direction. Therefore, Russia did little more than exchange Romanov Tsars for ‘Red Tsars’ – the primacy of the state over the individual was crucial for every government in this timeframe, and the absolute authority of such a state was similarly preserved. This exchange was not as simple as first glance might suggest. This lack of clarity is partly due to the (admittedly short) interlude of the Provisional Government in 1917; as the Another distinction arises between existence of it certainly dilutes the claim the ideologies on their view of society, that the exchange was a straightforward the economy, and their development. one. Marxists saw the ideal society as one that was classless and stateless – a set of One area of difference is within the decentralised communes with autonomy, ideologies of the two regimes: Marxism for where individuals inside a commune take the Soviets and ‘official nationality’ for the from it what they need and give what Tsarist regime - described by JN Westwood they can in labour, which came into being as ‘orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality’ through the dialectic. Contrastingly, Tsars which ‘provided ideological justification viewed history ‘as the organic development for the…actions of government’. Marxism of authoritarian tradition’ , rather than has boundless confidence in humanity, ‘as a process of class conflict, operating believing that human nature can be dialectically’ as the Soviets did. The Tsarist moulded entirely by circumstance – view of the state informs the Tsarist view of indeed, given the society; the Tsar’s primary right environment, human nature can [T]he primacy of function was to uphold the social hierarchy and ensure be perfected. This the state over the the welfare of the people. view runs in stark contrast to the ideology of the Tsars. The individual was crucial for every The concept of hierarchy is absent from Marxism. Indeed, the entire basis leading thinker who government in of Marxist ideology is to codified the Tsarist ideology is Konstantin this timeframe. destroy it. The Marxist view of the economy is Pobedonostev, that the market, through who took a dim view of human nature, the profit motive, exploits the proletariat particularly Russian human nature, saying by creating ‘surplus value.’ Exploitation is ‘inertness and laziness are generally the justification for the overthrow of the characteristics of the Slavonic nature’. He capitalist system in a revolution. Opposed believed that a strongman ruler was needed to this view is that of the Tsars - it was to control and restrain intrinsically flawed a ‘dream’ of Stolypin to dismantle the humanity, which was fixed regardless of commune. Furthermore, the Tsars viewed situation. the state as an expedient to ‘turbocharge’ the market-driven economy, as opposed to the Marxist view of the market as an expedient in a state-planned economy.

Another difference in the sphere of ideology is the primacy of religion in the Tsarist era, which is virtually non-existent in the Soviet period. The Church ‘never rose in Russia to that commanding height which it attained in the Catholic West’ , but it was nonetheless central to the lives of everyday people. Orthodoxy was one of the main pillars of Alexander III’s ideology. Marxists, by contrast, were passionate atheists who declared organised religion a tool of proletariat repression and that ‘it is the opium of the people’. The two ideologies of the respective periods of government have next to nothing in common with each other.

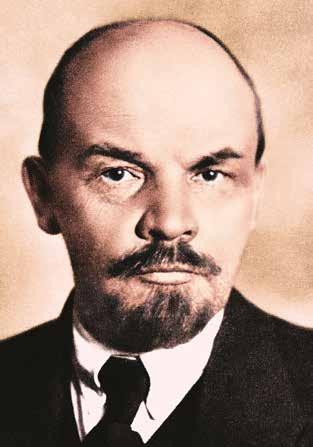

Alexander II

Ideologies begin with assumptions about human nature, and these two have entirely contrasting views. Marxism states the perfectibility of human nature and that society and the economy should eventually decentralise completely in a stateless, classless utopia. There is simply no area of agreement with the Tsarist view that humans are fundamentally bad and need an active state to control them. The Tsars believed in a hierarchical society in a market-driven economy – a far cry from the communist dream. The two regimes also had completely contrasting views on religion, which only helps to widen the gulf in their ideological differences.

While the two regimes were ideologically opposed, they were structurally more similar. Lenin’s regime had two executive bodies: Sovnarkom and the Central Executive Committee; controlled theoretically by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. However, in reality, the executive bodies wholly controlled the legislature with Sovnarkom being the apex of power, under Lenin’s policy of ‘democratic centralism,’ referring to ‘full freedom to express [his] personal opinions’, but that party members should not ‘propose resolutions that are out of harmony with congress decisions’. While the body of Sovnarkom eventually gave way to the Politburo under Stalin, they functioned much the same, and there was little pretence of collective decision making under Stalin. Where Lenin tolerated debate within the party, Stalin sought actively to destroy it. This is evidenced by his policy of centralised unitary states. The Tsars saw ‘purging’ dissenting members of the party – multiculturalism as an unfortunate fact of often by execution and exile. Key to Stalin’s running an Empire and did their best to government was the ‘Cult of Personality’ eliminate it, through Russification. Power which surrounded Lenin and himself. While was centralised in the capital because the Tsars ruled personally, they never created a Russian Empire was a unitary monarchy. By cultish ideation of themselves. contrast, it was Lenin’s 1924 constitution The Tsarist Cabinet national languages and bears similarities Where Lenin nominally the right to to Sovnarkom and the Politburo in the USSR – a single tolerated debate within the party, national autonomy. The 1936 Stalinist constitution expanded the concept of individual surrounded Stalin sought the USSR as federation, by advisers of varying influence. The State Duma under the Tsars actively to destroy it. increasing the rights of constituent nations and adding the right to secede. also bears similarities However, the influence of to the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, the CPSU nullifies much of this notional in that both were ‘controlled by a much ‘decentralisation.’ The CPSU was the only more powerful executive’, thereby making party permitted to operate in the nations, them ineffectual. A notable exception is which was in turn controlled by Stalin in Alexander II, who moved away from a Moscow, making the extra rights of the personal model of rule to a ministerial nations illusory. The concept of the USSR and representative model – indeed, at as a federation is ludicrous. Indeed, due to the beginning of his reign he ‘favoured the machinery of the CPSU, which had a decentralisation’ by ‘strengthening the superior bureaucratic structure compared hands of provincial governors’. However, to the Tsars, the Soviets were able to in both regimes, power was concentrated create a more unitary state than the Tsars in the political zenith; either the Tsar managed. There was no let-up of the tight or the Soviet Premier. Tsars were also centralisation that the Soviets inflicted. dispensaries of patronage, able to give away The same cannot be said for the Tsars. offices and positions, resembling the Soviet Alexander II, for instance, created peasant ‘Nomenklatura’ system which gave the most assemblies known as the Zemstva which loyal members of the party a route into the increased peasant representation. ranks, allowing Lenin to assert personal control of the party membership. Both regimes were in practice that created the USSR, recognising

Despite the ideological differences By contrast, Stalin ‘went a step further by between the USSR and the Tsarist era, they establishing the practice of ‘permanent organised themselves remarkably similarly. terror.’ He adapted the secret police to suit Power was concentrated in the hands of his style of leadership, allowing himself to a single individual. The constancy of a order killings, arrests, and disappearances. unitary state is blatant; where it was the The arrests and executions were completely official policy of the Tsars; it was the de arbitrary – quotas were given to local facto position of the Soviets. officials on the number of arrests and A similarity between the Tsars and the was ‘a calculated wave of mass murder’ Soviets regarding repression and terror is which was ‘extraordinary even by the that both used some form of secret police. standards of the Stalinist regime’. By Alexander II contrast, the employed the Third Section and later the The arrests and executions were completely arbitrary Tsars usually only targeted guilty people, Department for State Police. Alexander III and Nicholas – quotas were given to local officials on the number of arrests and evidenced by the effect of ‘Stolypin’s necktie’ II continued to use the executions in purges. which was a Tsarist policy latter, where it of wiping became known as the Okhrana. The Soviets out dissenters. Another new invention of started with the Cheka, later the GPU – Stalin was the gulag system. This allowed and after the creation of the USSR in 1924, him to exploit political enemies until their the OGPU. This mutated into the NKVD, dying breath. Additionally, the role of then the NKGB and finally the MGB. Beria as head of the secret police cannot be The overarching aims of these agencies overstated. The very fact that the leader of were to remove political opponents the police personally abducted, raped, and and to shut down potential (counter-) murdered targets on a random basis already revolution. Therefore, unity exists between makes the structure of terror a much more the regimes, in that both were partial to unpredictable landscape than existed under repressing and terrorising their population the Tsars. using a secret police. executions in purges. The ‘Great Terror’ The Soviets ‘aimed However, a difference emerges between the to indoctrinate the Tsars and the Soviets over the severity and next generation in sustention of terror and repression. While the new collective a ‘secret police’ did exist at all times, it was way of life’ – a new used in fits and starts. Indeed, for example, innovation compared to ‘Alexander II downgraded the Third the Tsars. This placed Section during the first half of his reign’. the cult of personality The Department for State Police only came and propaganda at the into use due to the rising tide of populism, centre of education, and which does not smack of arbitrariness. ‘schools were instructed How effective the Department was is to establish ‘Lenin unclear, but it cannot have been working Corner’s’, which elevated well, seeing that a populist eventually Lenin to ‘god-like’ assassinated Alexander II. Alexander III status. Children played did consistently utilise the Okhrana, as did games such as ‘Search Nicholas II at the beginning of his reign. and Requisition’ and However, its use became hard to justify ‘Reds and Whites’ which after the 1905 revolution. Alexander III was dichotomised the world the most repressive of the Tsars, especially and forced children into towards Jews, through riots known as a narrow understanding pogroms, which were ‘tacitly tolerated or, of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. on occasion, actively encouraged by the The effectiveness of police forces’. Indeed, late-Tsarist Russia this policy is apparent was ‘probably the most anti-Semitic nation – ‘studies carried out in Europe until the Third Reich’. in Soviet schools in the 1920s showed that children…were ignorant of the basic facts of recent history’, to such an extent that many children did not even know what a ‘Tsar’ was. This is part of the Soviet policy of propagandism, which the Tsars had not the resources or inclination to set up.

The Soviets used repressive techniques far more consistently and savagely than the Tsars did, particularly under Stalin who ‘unlike anyone else in Russian history, made it [terror] the norm rather than the exception’. The similarities of the mere existence of political police outweigh the differences of the purges, gulags, and indoctrination which had not existed to the same extent under the Tsars. The same can be said of the existence of a dominant personality as the head of the secret police, such as Yezhov and Beria. These differences make the concept of the Soviets being ‘Red Tsars’ an inaccurate descriptor regarding the use of repression and terror.

Another area of difference between the two regimes is their attitude to change. The attitude to reform of the Soviets is evidenced well in reality: it was the October revolutionaries that slaughtered the Russian royalty and scrapped most of the existing institutions of the day. The initial surge of reforms that Lenin undertook were as far-reaching as they were radical. It was initially official Soviet policy to ‘fan the flames of the world [socialist] revolution’.

Lower Sixth

Lavrentiy Beria

The conservatism of the Tsars was made the USSR the most democratic nation While they were ideologically opposed, inconsistent. Alexander II had a healthy in the world with his 1936 constitution, the creed of the Soviets often fades into reformist attitude; his most notable by equalising the franchise and lowering irrelevance, as they so loosely adhered to modification was his 1861 Act to the voting age to 18; this was in name only it. Also, while the Soviets were far more emancipate serfs. Some, such as Jason because the USSR was a one-party state, repressive, they were not reinventing the Blum, have said that this impetus came making ‘democracy’ wheel when compared directly from the Tsar, although others have insisted the ‘radicalism’ of the 1860s was more of a pragmatic consideration; it in the ordinary sense a fantasy in Russia. The sham of democracy The Soviets took advantage of new to the Tsars. The Soviets took advantage of new technology and was more advantageous to Alexander to was intensified by technology and chose to apply terror ‘abolish serfdom from above than to wait until it began to abolish itself from below’. The Zemstva and the Dumas of 1864 and the ‘fiction that the legislature controlled the Central Executive chose to apply terror with greater with greater severity and more consistently. This is an area of 1870 respectively were a sincere attempt Committee’. After the severity and more divergence with the to increase representation in Russia. However, this occurred under Alexander Soviet regime was established, change consistently. Tsars, but the two regimes are ultimately II, a notable outlier in the history of and democracy were more similar than Tsardom. A better litmus test to tolerance suppressed to keep things as they were. A different. Having said all this, the exchange of democracy can be seen in Nicholas II’s multi-party system, as had existed in an between them was not straightforward. The reaction to the creation of the State Duma infant format in post-1905 Tsarist Russia, interlude of the Provisional Government in 1906 – he had been forced into a degree was never allowed to develop in the USSR. muddies the waters. They, for the most of reform as he had to make concessions part, scrapped the entire concept of a secret to staunch the flow of instability from the The Tsars and the Soviets were both police, fully embraced a radical agenda wound of the 1905 revolution. It was not conservative, in the sense that preservation including complete toleration for Westerna positive one as he regularly vetoed it or of their regimes was the priority. When style democracy and structured themselves ignored it, eventually they did make changes, they accordingly. However, this intermission emasculating it through the 1907 Electoral Law – [S]chools were instructed to either passed legislation which neutralised such changes, ignored them, was only a matter of months-long – months that were dominated by instability and the war effort. The fact that the period of the indeed, he ‘did all in establish ‘Lenin or tried to frustrate their Provisional Government was so short and his power to restrict the range of parties’ to a narrow array of Corner’s’, which elevated Lenin to workings. They both had a morose view of democracy and representation. There is it thus did not have time to enact many of the changes it otherwise might have wished for makes it an insignificant period within the far-right. Despite ‘god-like’ status. absolute continuity between the grand context of Russian history. The Alexander II’s best the Tsars and the Soviets on existence of it does not diminish the claim efforts, ‘the autocrat as mediator between this matter – both were highly conservative that the Soviets merely represented ‘Red various groups in the Russian polity was in and extremely undemocratic. Tsars.’ no way altered’. In conclusion, Russia did exchange While the reforms of the Soviets were Romanov Tsars for ‘Red Tsars.’ Both theoretically colossal, the influence of the regimes structured themselves in the same CPSU often nullified such changes. Stalin way and were similarly averse to reformism.

The power of 2

Ben Ellett Lower Sixth

In 1943, Thomas J. Watson of IBM famously quickly build up to represent huge numbers disregarded the computer claiming he of possibilities. Imagine you flip two thought there was a global market for coins. This gives you 4 possible outcomes; about 5 of them. Of course he was proved however the addition of a single extra coin wrong spectacularly, with computers far brings this number up to 8, then another exceeding anyone’s initial expectations, brings it to 16, with the total combinations and enhancing our lives in ways people just doubling every time. This leads way to a a century ago could never have dreamed. potentially huge amount of information With this technology, we’ve solved that can be stored and read by a computer, problems, innovated like never before and through only a simple on/off mechanism. even attempted to represent the real world There is a consequence of this however, through the virtual one. as you require many This begs the question; how far can computers go? Will [B]inary can more digits of binary (more commonly known there ever be an end to the quickly build as a bit) to represent 70-year storm that the rise of electronic computing has taken us on? Could we up to represent huge numbers something in say decimal (our 0-9 number system), or through ever hope to create a virtual of possibilities. the alphabet. This very world to challenge our own? sentence uses over representing information through a simple 968 digits of binary (bits) to represent it, In order to answer this, we’ll need firstly compared to the 121 characters it took to to take a look at how a computer works type. Whilst basic and easy for a computer fundamentally, and then what limitations it to process, this is not the most efficient has when representing information. system, and this becomes a problem when Computers are very logical machines, amount of space. trying to fit a lot of information into a small two digit system - binary. Things are either So now onto the potential of computers. on or off, true or false, and whilst the uses How would one go about creating things of this may seem few at first, binary can virtually? Well, like with anything, we need to break the problem down. This technique is called abstraction and is used all the time when solving computational problems. When looking at simulating our own world, we will also first need to get simple. By taking a look at some of the basic rules that help our universe work, we can model objects really well in the virtual world, simulating basic laws such as gravity and motion quite easily. This has already been done, letting architects test their constructions, soldiers, sailors and pilots test their weapons, or even just letting you play around with basic physics. There are even sandbox universes that have been simulated, letting you play with planets, although these planets are no more than simple objects. This attempt at basic modelling is definitely a start, although these simulations are often very focused, and only look at certain aspects of our universe (such as gravity), leaving out nearly everything else.

So can we get any better? In order to get the best representation of our universe, we are going to have to go from the bottom up. If we were to simulate something atom by atom, this would give us quite an accurate recreation of the universe. However, in order to simulate a single atom with our

current computers, it would take more components so far that our wires are mere bits of storage than there are atoms in the atoms wide, and the heat generated puts universe. Consider that for a moment. A our entire circuits at risk of warping and single atom, one of the more basic building breaking, meaning it is virtually impossible blocks of reality, has so many properties to improve performance any further. to it, that it is nearly impossible to model The Bekenstein bound (maximum storage it. All the matter in the universe would limit) and Bremermann’s limit (maximum barely get us there. processing limit) Blame electrons and are two examples of the many-particle [I]n order to limitations that cannot wave function for that one. At a deep level, the strange simulate a single atom with our be exceeded with our current knowledge of physics, a physical wall quantum effects current computers, that we cannot cross, of atoms are just too hard to model with conventional it would take more bits of storage than meaning there will only ever be so much information we can computing. there are atoms in store and a maximum Luckily, there is an alternative. The the universe. processing speed. As this is nowhere near newly developed close to the levels we field of quantum computing gives us need to store data for complex particles another option, allowing us to predict such as atoms, you would be taking up properties of atoms and subatomic particles more physical space and energy than you with great accuracy, meaning modelling could actually simulate, you’re left with small particles like these may not be the a permanent unreachable goal, and this impossible task it once was. This has problem, that leaves you requiring more already been used to great effect, modelling matter in the real world that you can real life particles such as beryllium hydride actually simulate. We straight up will never (BeH2), an impressive success which gives be able to see a perfect copy of reality of great hope for fields such as new drug this size in the virtual world. There are research in the future. simply too many atoms and particles to model. Unfortunately, there is just one problem It appears, at least with current technology, to this quantum solution. To ever dream that our entire reality is a bit of a tall order of replicating something the scale of our for the virtual world, and even a slice of world, we would require huge amounts of reality is a huge struggle, still requiring storage and processing power, which may abnormal amounts of space to store and run not even be possible due to our current your simulation. However, that is not to say understanding of physics. We are rapidly there is no hope. There are workarounds, approaching all sorts of physical limits which may well let us achieve an almost where computers can no longer improve perfect model, such as simply unloading at all. We have shrunk our electrical everything that isn’t needed. Consider the following. Imagine our universe is a simulation. The program would only need to model Earth, and objects near it, in order to create the illusion of a massive universe that does not actually exist. The rest of the observable universe is just that. Observable. We can never actually get close enough to test every single particle, so the simulation just does not need to bother. Nobody knows if the stars in the night sky are actually proper stars until you get closer. All the simulation needs to do is load in the correct stars whenever we get too close. This saves you uncountable amounts of processing power and makes a simulated universe a little more realistic as a goal.

It could get even better than that. We can already model objects with limited accuracy, so why make them more complex if you do not need to? As long as they work as expected, you do not need to overcomplicate your system. We are on a tight budget of storage space after all. The simulation might simply not bother generating atoms unless you look for them, and this would certainly save on processing power. In fact, we are now rapidly approaching the level of virtual reality we currently have today. Granted, this is all just an elaborate illusion, not quite the perfect universe we envisioned, but that does not matter. If it is indistinguishable from reality, does it even matter what is real or not? We’d have successfully made a virtual world which appears the same as our own. So similar, that you would never even realise the difference. This leads us to stop and consider our actual reality and wonder if anything we see here is even ‘real’ at all, and not just some complex simulation. The scary thing is, we have no real way of knowing.

So to summarise, true reality is an increasingly complex mess, with physics and our understanding of our universe never constant, so being able to recreate that in all its chaotic entirety would require perfect understanding of the universe, on top of copious amounts of storage and power that quite possibly cannot be done within the confines of this reality. Whilst this is pretty much impossible, it may not need to be possible for us to create a reality of our own. Technology is advancing in ways nobody can predict, and the only constant in this field is change. Soon, the day may well come where our virtual creations can rival those of nature itself, despite all the challenges standing in our way, and it will be then that we find ourselves grappling with even greater questions. Could it be that our arguably greatest creation becomes a reality we can call our own, and if so, what will we choose to do with it?