By Bruce W. Miller

The North-South Skirmish Association (N-SSA) held its 147th National Competition May 17 through 21, 2023. Member units competed in livefire matches with original or authentic reproduction Civil War period muskets, carbines, breech-loading rifles, revolvers, mortars, and cannon. It is the largest Civil War event of its kind in the country and attracts not only spectators but Civil War enthusiasts and shooting sports media coverage.

Tributes and Targets at N-SSA 147th Nationals

The only bittersweet occurrence at this sun-drenched national was the retirement of longtime executive secretary, Judy Stoneburner. This past winter, health issues plagued Judy who has served the association in this key role for 13 years. A native Virginian, she joined the N-SSA in 1994 and continues to be a member of Mosby’s Rangers. Judy was also the first woman to be the director of a national skirmish. In her own words, she lists her top three duties as “always take care of the members’ needs,

represent the association in a positive and professional manner, and strive for excellence in all of her assigned duties.” Judy was the hub of the organization and will be greatly missed.

It was a big weekend for one of the N-SSA’s founding units, the Washington Blue Rifles. They won medals in five of the seven small arms team matches. They won the musket team match with a time of 514.9 seconds for the five-event program finishing 48.5 seconds ahead of the second place team. One hundred fiftyfive teams participated in this N-SSA signature competition. The 2nd Maryland Artillery (CSA) triumphed in the carbine team match over 121 other sundrenched teams. The Nansemond Guards won the smoothbore musket match, defeating 123 other four-member teams. The Iredell Blues bested 63 other teams to win the fourevent revolver team match by a whopping 77.6 seconds. The

Washington Blue Rifles scored another gold medal in the single shot rifle match, the 1st Maryland Cavalry (CSA) won the Spencer class match and the 2nd Maryland Artillery (CSA) won the breechloading rifle match.

The cannon matches on Saturday afternoon opened with a special tribute to Charles W.

“Charlie” Smithgall. Charlie was one of America’s most renowned collectors of artillery pieces and equipage from the 18th century to modern times. He established The Smithgall Foundation, a 501c3 dedicated to the preservation of

Vol. 49, No. 8 40 Pages, August 2023 $4.00 America’s Monthly Newspaper For Civil War Enthusiasts 14 – American Battlefield Trust 34 – Book Reviews 12 – Central Virginia Battlefield Trust 26 – Critic’s Corner 28 – Emerging Civil War 39 – Events 24 – The Graphic War 18 – The Source 20 – This And That 10 – The Unfinished Fight 16 – Through the Lens H N-SSA . . . . . . . . . . . . see page 4

This is the range officer’s view from the main tower during the musket match of a National Skirmish. Eightperson musket teams fill 65 line positions controlled by one main tower and three sub-towers, which communicate via the range’s PA system, short wave radios, and signal flags. (Ericka Curley)

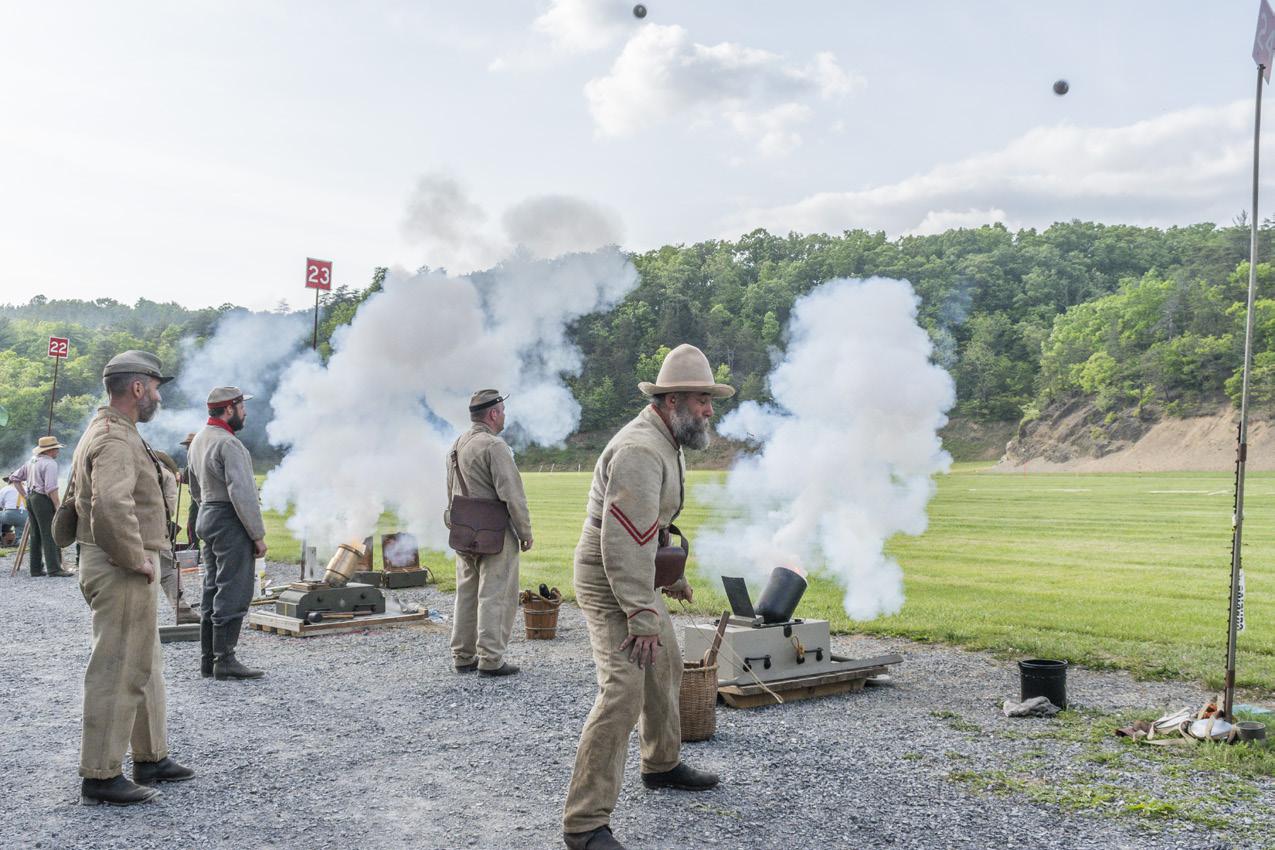

Rob Bethke pulls the lanyard to fire the 3rd Maryland Artillery’s 24-pounder mortar. Crews fire seven mortar balls at target stakes placed 100 yards from the firing line. The distances of the five closest shots are then tallied to determine a team’s score. (Ericka Curley)

Charlie Smithgall smiles as he stands with his 1848 dated Ames 12-pounder field howitzer. His crew had just won the howitzer match at the 138th N-SSA National Skirmish, October 2018. (Ericka Curley)

Civil War News

Published by Historical Publications LLC

2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513 800-777-1862 • Facebook.com/CivilWarNews mail@civilwarnews.com • civilwarnews.com

Advertising: 800-777-1862 • ads@civilwarnews.com

Jack W. Melton Jr. Publisher C. Peter & Kathryn Jorgensen Founding Publishers

Editor: Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D.

Advertising, Marketing & Assistant Editor: Peggy Melton

Columnists: Craig Barry, Salvatore Cilella, Stephen Davis, Stephanie Hagiwara, Gould Hagler, Chris Mackowski, Tim Prince, and Michael K. Shaffer

Contributor & Photography Staff: Greg Biggs, Curt Fields, Michael Kent, Shannon Pritchard, Leon Reed, Bob Ruegsegger, Carl Sell Jr., Gregory L. Wade, Joan Wenner, J.D., Joseph Wilson

Civil War News (ISSN: 1053-1181) Copyright © 2023 by Historical Publications LLC is published 12 times per year by Historical Publications LLC, 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513. Monthly. Business and Editorial Offices: 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513, Accounting and Circulation

Offices: Historical Publications LLC, 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513. Call 800-777-1862 to subscribe. Periodicals postage paid at U.S.P.S. 131 W. High St., Jefferson City, MO 65101.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Historical Publications LLC 2800 Scenic Drive Suite 4-304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513

Display advertising rates and media kit on request. The Civil War News is for your reading enjoyment. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of its authors, readers and advertisers and they do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Historical Publications, LLC, its owners and/or employees. P

:

Please send your book(s) for review to: Civil War News

2800 Scenic Drive Suite 4-304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513

Email cover image to bookreviews@civilwarnews.com. Civil War News cannot assure that unsolicited books will be assigned for review. Email bookreviews@civilwarnews.com for eligibility before mailing.

ADVERTISING INFO:

Email us at ads@civilwarnews.com Call 800-777-1862

MOVING?

Contact us to change your address so you don’t miss a single issue. mail@civilwarnews.com • 800-777-1862

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

U.S. Subscription rates are $41/year, digital only $29.95/year, add digital to paper subscription for only $10/year more. Subscribe securely at CivilWarNews.com

Current Event Listings

To see all of this year’s current events visit our website at: HistoricalPublicationsLLC.com

Terms and Conditions

The following terms and conditions shall be incorporated by reference into all placement and order for placement of any advertisements in Civil War News by Advertiser and any Agency acting on Advertiser’s behalf. By submitting an order for placement of an advertisement and/or by placing an advertisement, Advertiser and Agency, and each of them, agree to be bound by all of the following terms and conditions:

1. All advertisements and articles are subject to acceptance by Publisher who has the right to refuse any ad submitted for any reason. Mailed articles and photos will not be returned.

2. The advertiser and/or their agency warrant that they have permission and rights to anything contained within the advertisement as to copyrights, trademarks or registrations. Any infringement will be the responsibility of the advertiser or their agency and the advertiser will hold harmless the Publisher for any claims or damages from publishing their advertisement. This includes all attorney fees and judgments.

3. The Publisher will not be held responsible for incorrect placement of the advertisement and will not be responsible for any loss of income or potential profit lost.

4. All orders to place advertisements in the publication are subject to the rate card charges, space units and specifications then in effect, all of which are subject to change and shall be made a part of these terms and conditions.

5. Photographs or images sent for publication must be high resolution, unedited and full size. Phone photographs are discouraged. Do not send paper print photos for articles.

6. At the discretion of Civil War News any and all articles will be edited for accuracy, clarity, grammar, and punctuation per our style guide.

7. Articles can be emailed as a Word Doc attachment or emailed in the body of the message. Microsoft Word format is preferred. Email articles and photographs: mail@civilwarnews.com

8. Please Note: Articles and photographs mailed to Civil War News will not be returned unless a return envelope with postage is included.

2 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 2 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

UBLISHERS

Deadlines for Advertising or Editorial Submissions is the 20th of each month. Email: ads@civilwarnews.com Digital Issues of CWN are available by subscription alone or with print plus CWN archives at CivilWarNews.com Advertisers In This Issue: Ace Pyro LLC 31 American Battlefield Trust 22 Artilleryman Magazine 34 Ashley R. Rhodes Militaria 25 CWMedals.com, Civil War Recreations 19 Civil War Navy Magazine 25 College Hill Arsenal – Tim Prince 31 Day by Day through the Civil War in Georgia – Book 18 Dell’s Leather Works 18 Dixie Gun Works Inc. 9 Georgia’s Confederate Monuments – Book 17 Gettysburg Foundation 7 Gunsight Antiques 18 Harpers Ferry Civil War Guns 2 HistoryFix.com 15 The Horse Soldier 5 James Country Mercantile 38 Jeweler’s Daughter 11 Le Juneau Gallery 9 “I thank the Lord I’m not a Yankee” – Book 27 Mike McCarley – Wanted Fort Fisher Artifacts 29 Military Antique Collector Magazine 38 National Museum of Civil War Medicine 22 N-SSA 29 Regimental Quartermaster 15 Richard LaPosta Civil War Books 37 Shiloh Chennault Bed and Breakfast 10 Suppliers to the Confederacy – Book 31 Ulysses S. Grant impersonator – Curt Fields 4 Events: Chicago Civil War Show 7 MKShows, Mike Kent 3, 35 Military Antique Show – Virginia 31 Poulin’s Auctions 40 Southeastern Civil War & Antique Show 15 Rock Island Auction Company 23

Asheville Gun & Knife Show

WNC Ag Center 1301 Fanning Bridge Road Fletcher, NC

Oct. 7 & 8, 2023

Myrtle Beach Gun & Knife Show

Myrtle Beach Convention Center 2101 North Oak Street Myrtle Beach, SC 29579

Nov. 4 & 5, 2023

Charleston Gun & Knife Show

Exchange Park Fairgrounds 9850 Highway 78 Ladson, SC 29456

Nov. 25 & 26, 2023

Mike Kent & Associates, LLC • PO Box 685 • Monroe, GA 30655 770-630-7296 • Mike@MKShows.com • www.MKShows.com Military Collectible & Gun & Knife Shows Presents The Finest Williamson County Ag Expo Park 4215 Long Lane Franklin, TN 37064 Dec. 2 & 3, 2023 Middle TN (Franklin) Civil War Show Promoters of Quality Shows for Shooters, Collectors, Civil War and Militaria Enthusiasts

9

Gun & Knife Show

Exchange Park Fairgrounds 9850 Highway 78 Ladson, SC 29456 Sept.

& 10, 2023 Charleston

H N-SSA

artillery and military antiques. Charlie was a past commander of the N-SSA and frequently wowed members and spectators with the amazing range of guns that he brought to the nationals, including a 30-pounder Parrott rifle that shook the ground when fired. Artillerist Tim Scanlan delivered a stirring eulogy, after which a massive 21-gun salute was fired, followed by a duo of buglers playing “Taps” before the matches began. Charlie leaves behind a great legacy.

Forty-four guns participated in the artillery team matches. The range is reconfigured so that the cannon fire perpendicular to the small arms firing line, and the guns are classified by type: smoothbore, rifled, howitzer, and rifled howitzer. Target frames with paper targets mounted on drywall backers are set at a range of 200 yards for rifled and smoothbore guns and 100 yards for howitzers. Rifled cannon and smoothbore guns fire 12 solid projectiles, with a maximum of seven shots at either of two targets: a bull’s eye and a silhouette of a cannon facing them that represents counter battery fire. The best five shots on each target count for a maximum of 25 points per target, with a perfect score being 50-5V. Howitzers each fire a maximum of 12 projectiles at their single bullseye target, with the 10 best shots counted and a perfect score being 50-10V. In the Smoothbore class, the 1st Virginia Cavalry (gun #1) was the winner with 47-3V. In the Rifled class, the 1st Valley Rangers won with a perfect score of 50-5V. This highly competitive group of 27 had five guns score 50 or better. In the Howitzer class, Hardaway’s Alabama Battery (Baldwin gun) won, shooting an impressive 504V. The 1st Maryland

the Rifled Howitzer class, scoring a terrific 49-5V. Civil War cannon accuracy is truly amazing

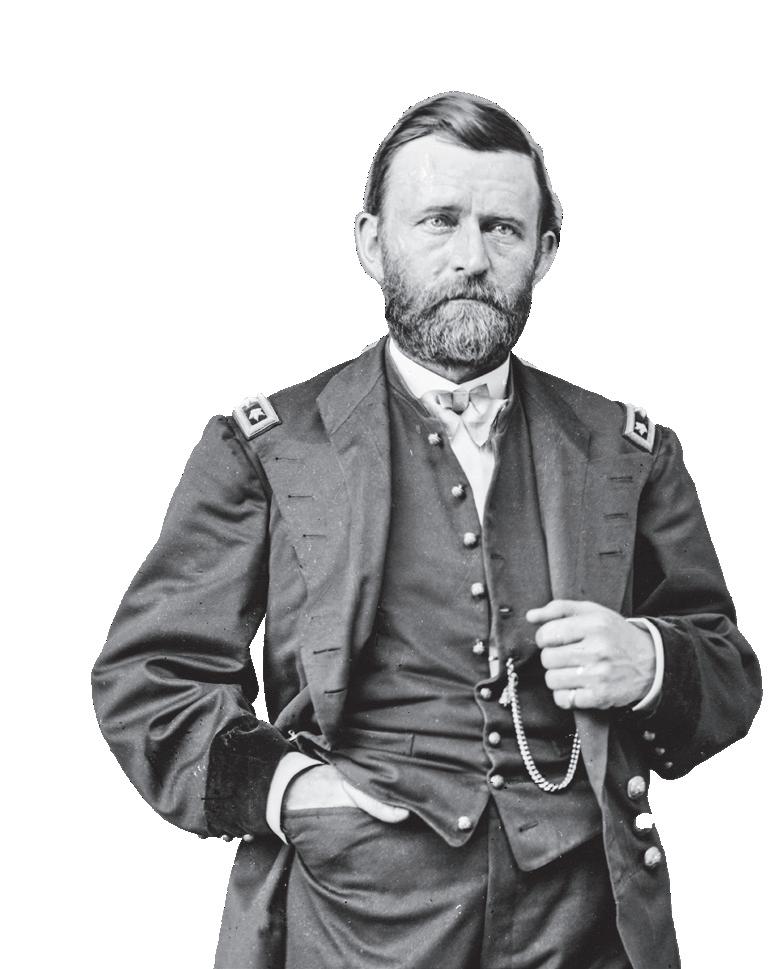

Ulysses S. Grant

E-Telegraph: curtfields@ generalgrantbyhimself.com

Signal Corps: (901) 496-6065 Facebook@ Curt Fields

4 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 4 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

. . . . . . . . . . .

from page 1

Portrayed by

E.C.

Fields Jr., Ph.D.

HQ: generalgrantbyhimself.com

At the start of the Saturday artillery match, cannon crews fired a 21-gun salute for Charlie Smithgall, who passed in October 2022. Following the eulogy and salute, a duo of buglers played “Taps” in tribute to the former N-SSA National Commander, renowned artillery historian, original gun collector, and dear friend to many who were on the field that day. (Ericka Curley)

Cavalry took

Barry Reynolds of the 3rd U.S. Infantry looks on as his daughter Summer fires their family’s 10-pounder Parrott rifle. Many generations of skirmishers have grown up in this sport, like Summer, who has been on a cannon crew since she was a teenager. (Lis Cole)

The lanyard used to fire 3rd Maryland Artillery's Austrian 24-pounder field howitzer is still in mid-air as the gun sends the projectile toward the bullseye target 100 yards down range. (Ericka Curley)

Ray Quinn of the 1st Maryland Cavalry fires Tim Scanlan's Model 1861, 8-inch siege mortar in a blast of flame. Mortars of this model and its 10-inch counterpart were classified as "siege and garrison" pieces, and were used to either defend or attack fortifications. (Ericka Curley)

The 12th Pennsylvania Reserve Volunteers carefully aim at their targets through the thick cloud of smoke raised by the Breechloader match. Skirmishers in this match shoot mostly Henry rifles, and can empty their 16-shot magazines very quickly. But after competitors empty that first full magazine, they must single load for the rest of the relay. (Lis Cole)

Sharleen West mentors a newcomer to the Friday sewing circle. The Costume Committee holds several events and competitions and conducts workshops teaching proper construction of mid-nineteenth century clothing. (Ericka Curley)

and N-SSA artillerists know how to get the most out of them.

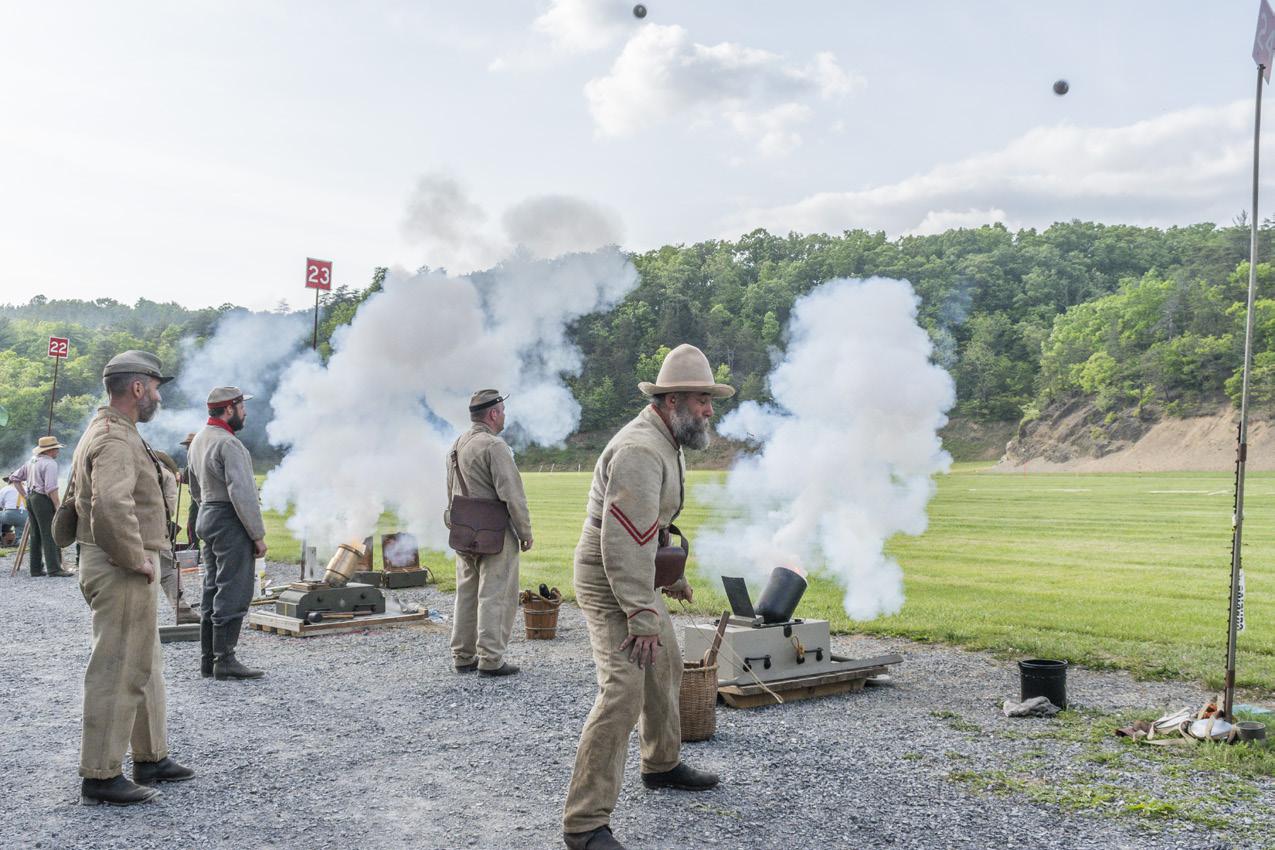

Forty-nine units participated in the Mortar Team match. The mortar teams fire seven shots at a stake 100 yards down range. Officials then carefully measure the distance from the stake and tally the best five shots for score. The overall winner was the Cockade Rifles with a terrific five shot aggregate score of 25 feet-6 inches. This is a particularly fun match to watch because with the mortars’ low muzzle velocity, you can actually see the flight of the projectile.

The N-SSA is the country’s oldest and largest Civil War shooting sports organization with 3,000 individuals that make up its 200 member units. Each portrays a particular unit or regiment and proudly wears a uniform representative of the one they wore over 160 years ago. At the 147th National, 16 members were recognized for 50 years and six for 60 years of membership in the Association: quite an accomplishment. The National Rifle Association award for the top Young Skirmisher (under 19 years of age) went to Emilee Walsh, 2nd Maryland Artillery (CSA), with an aggregate musket and carbine score of 148-0X and the Senior Skirmisher (over 65) award went to Gary Bowling, Nansemond Guards, with a 177-3X.

The 148th National Competition is scheduled for Oct. 6-8, 2023 at Fort Shenandoah, just north of Winchester, Va. For more information about the N-SSA, visit the web site at www.n-ssa.org.

Event

As Fred Bane of the 1st Regiment Virginia Volunteers fires Lars Curley's 24-pounder bronze mortar, you can see the projectile emerging from the burst of fire and smoke. This reproduction gun was very accurately made in 1988 by Paulson Brothers Ordnance Corporation, Clear Lake, WI. (Niki Bethke)

5 August 2023 5 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com Current

Listings To see all of this year’s current events visit our website: CivilWarNews.com Subscribe online at CivilWarNews.com

Emilee Walsh of the 2nd Maryland, Baltimore Light Artillery (CSA) grew up shooting in the "Tenderfoot" BB and pellet gun matches. When she reached 14, the minimum age required to become a full N-SSA member, she joined the team and began to compete in the black powder matches. This National, she won the first place National Rifle Association Young Skirmisher award for the top shooter under 19 years of age. (Ericka Curley)

Chris DeFrancisci carefully loads his rifle musket while Skip Fisher fires at four-inch hanging tiles. Their team, the Washington Blue Rifles, had a successful National Skirmish, winning first place "A" team in the musket match, another gold medal in the single-shot rifle match, and medals in three other small arms team matches. (Ericka Curley)

Brass shell casings fly as Kara and Joel Rogers of the Iredell Blues compete in the Breechloader match. When shooting a Henry repeating rifle, casings can land anywhere, as is evident on the brim of Joel's hat. (Lis Cole)

Left: Two mortar crews with Hardaway's Alabama Battery fire simultaneously. Mortar matches are spectator favorites, because you can follow the ballistic path of the projectiles as they arc through the air toward the stake down range. (Ericka Curley)

Top right: Duncan Bartley, Jack Boyenton, and Rob West of the 1st Regiment Virginia Volunteers load their smoothbore muskets and fire at clay pigeons on a cardboard backer at a distance of 25 yards. One hundred twenty-three fourperson teams participated in the popular smoothbore musket competition, clearing targets at 25 and 50 yards. (Ericka Curley)

Left: Two members of the 9th Virginia Cavalry load and aim their rifle muskets at 32 clay pigeons on a cardboard backer, the first event of the musket match. The eightperson musket teams compete to break all of the clay pigeons in the least amount of time. (Ericka Curley)

Right: Retiring N-SSA Executive Secretary Judy Stoneburner handled any assignment that came her way. Here, she instructs a reporter at a recent media event on the firing of a Smith carbine. (Bruce W. Miller)

6 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 6 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

The Union Guards deftly load and aim their smoothbore muskets and fire at the four-inch hanging tiles at 25 yards down range. National Skirmish targets consist of all breakable targets, hanging or mounted on a cardboard backer. (Ericka Curley)

Above: The 2nd Maryland, Baltimore Light Artillery (CSA) smoothbore team skillfully displays the variety of steps it takes to fire a muzzleloading musket: retrieving a round from the cartridge box, ramming the projectile into the barrel, placing a percussion cap onto the gun's nipple, and aiming at the target. (Ericka Curley)

The percussion cap is about to ignite the main charge as Duncan Bartley, 1st Regiment Virginia Volunteers, fires his original Nathan Starr smoothbore contract musket, made in 1831, a percussion gun converted from a flintlock. (Ericka Curley)

Adding to the period atmosphere of N-SSA Nationals is the authentically uniformed 1st Maryland Infantry fifers and drummers. The unit is composed of skilled musicians and is a crowd-pleaser as they march to the range before commencement of the Sunday morning opening ceremonies. (Lis Cole)

Skirmishers of all ages enjoy shooting in the N-SSA competitions. These two are competing in the rifle musket match along with 155 other eightperson teams. (Ericka

It takes only a fraction of a second for an artillery piece to fully fire once the friction primer is pulled, demonstrated by the position of the lanyard as Hardaway's Alabama Battery fires Jeffery Baldwin's Tredegar 12-pounder field howitzer. Hardaway's won first place in the howitzer class with this gun.

7 August 2023 7 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com Want to Advertise in Civil War News? Email: ads@civilwarnews.com 1,000’s of Civil War Treasures! Plus! Revolutionary War • Spanish-American War Indian Wars • Mountain Men • Bowie Knife Collector Arms • Fur Traders • World Wars I & II Civil War & Military Show 9 - 4 / $10 • Early Buyer’s 8am / $25 • Free Parking September 23 2023 • Fall Show • Saturday

(Niki Bethke)

Curley)

Battle of Perryville Kentucky: the Hankla Farm

By Charles H. Bogart

The Battle of Perryville, Ky., was fought October 8, 1862. This was the largest Civil War battle in Kentucky. While some claim the battle was a tactical win for the South, the fight was definitely a strategic defeat for the Confederacy. The result of the Battle of Perryville was that the Confederate Army, left Kentucky never to return in strength.

Only 24 hours before the Battle of Perryville it looked as if the Blue Grass State was firmly anchored in the Confederacy. Kentucky’s capital city, Frankfort, had been captured and occupied by the Rebels. Richard Hawes Jr, had been inaugurated Confederate governor of Kentucky on the steps of the State Capitol. Confederate officials across the Commonwealth were sworn in to fill state, county, and city offices. John H. Reagan, the Postmaster General of the Confederacy, started organizing routes to provide mail service to the Commonwealth’s citizens.

Within 72 hours following the Battle of Perryville everything the Confederacy had achieved in Kentucky during the previous four weeks was nullified. Federal state government returned and Confederate flags were pulled down within all of Kentucky’s major cities to be replaced by United States stars and stripes.

farm encompasses 311 acres, all covered by an American Battlefield Trust protective easement. The circa 1845 six room farm house is located on the farm, along with five barns that at one time housed tobacco or animals, and some other period farm outbuildings. The Goodknight Family/Confederate Military Cemetery and the site of the Goodknight Confederate field hospital are within the farm boundary. Over a mile of Chaplin River bank and part of the Doctors Fork stream bank, five farm ponds, wood lots, and pastures rich with native grasses, are broken up by thousands of feet of historical dry-stone fencing. The farm also houses vintage farm tractors and equipment, and

various agricultural mechanical tools.

Gen. Braxton Bragg sent units of the Army of Mississippi across this farm. Leading the attack over the farm was Brig. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham’s Tennessee Division. Cheatham’s Division consisted of the three brigades under Brig. Generals Daniel S. Donelson, Alexander P. Stewart, and George Early Maney. These units suffered some 276 killed and 764 wounded.

The farm during the Perryville Campaign saw both Confederate and Federal troop movements before the battle, fighting the day of battle, and afterward. Following the battle, Federal troops camped on the farm. Brigadier General Philip Sheridan's 11th Division

Headquarters was located in the Hankla-Walker House for three days after the engagement. For three months after the battle, a field hospital was located at the Goodnight House. The present owners of the farm, Scott and Ren Hankla, have found and mapped about 2,000 artifacts relating to the battle.

Scott and Ren Hankla have

put the farm up for sale. They are hoping to sell the farm as an intact whole to someone who appreciates Civil War history and has the ability to preserve the historic fabric of the farm. If you have ever wanted to own a Civil War battle site, you could do no better than purchase the Hankla Farm. The email for the Hankla Farm is hshankla@yahoo.com.

8 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 8 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

The Hankla Farm is located in the center of the Perryville Battlefield. The

The Hankla-Walker House was built circa 1845. For three days in 1862 it served as Sheridan’s headquarters. The house exterior is little changed from when built. Heating is still by fireplace. Note the millstone incorporated into the stone wall. The millstones came from the farm’s Prewill Mill, located a quarter mile behind the house. The mill ground grain for use in making whiskey at the Walker Distillery.

This open spot within a new growth of trees was the site of the Goodknight House. For three months following the battle, the area around the house was the location of a Confederate hospital.

During the Centennial Remembrance of the Civil War, family of Francis M. Weems, Co. B, 3rd Florida Infantry, placed this monument in the Goodnight family cemetery. It is not known where Francis Weems is buried.

This stone monument in the Goodnight family cemetery was erected by the U.S. Government in 1912 to mark a Confederate grave site. On the left is Scott Hankla co-owner of the farm and on the right Bryan Bush, Perryville Battlefield Park Manager. Absent from the photo is the farm’s co-owner Ren Hankla. The inscription reads “Erected by the United States to mark the burial place of an uncertain number of Confederate soldiers said to have died while prisoners of war at the Goodknight farmhouse from wounds received at the Battle of Perryville whose grave cannot now be identified and whose names are unknown.”

Mary Todd Lincoln House Falls Victim to Attempted Arson

LEXINGTON, KY—Mary

Todd Lincoln’s teenage home was nearly burned to the ground intentionally by a suspected arsonist the morning of June 16th. The home has operated as a house museum since 1977.

Located in downtown Lexington, Ky., the alarm system of the Mary Todd Lincoln House was tripped around 4 a.m. When police arrived, they found 29-year-old Santosh Sharma pouring gasoline on the structure’s back porch.

The house suffered no damage and was operating on their normal schedule later that day.

The Mary Todd Lincoln House was built as a tavern in 1803–1806. The Todd family bought the residence in the early 1830s. Mary Todd lived in the home with her family from 1832 to 1839, when she moved to Springfield, Illinois.

While living in Springfield, Mary Todd met a young attorney named Abraham Lincoln, and they married in 1842. The couple visited Lexington often.

Sharma has been charged with menacing, criminal trespassing, and attempted arson. His case has been referred to a grand jury.

Submitted by Phillip Seyfrit, Curator of the Battle of Richmond (KY) Visitors Center.

Gun Works, Inc.

Thousands of blackpowder hobbyists and aficionados, from history buffs and re-enactors to modern hunters and competitive shooters, trust Dixie Gun Works for its expertise in all things blackpowder: guns, supplies, and accessories and parts for both reproductions and antique guns. Whether you’re just getting started or you’re a life-long devotee, everything you need is right here in the 2023 DIXIE GUN WORkS’ catalog.

9 August 2023 9 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com DIXIE GUN WORKS, INC. 1412 W. Reelfoot Avenue PO Box 130 Union City, TN 38281 INFO PHONE: (731) 885-0700 FAX: (731) 885-0440 EMAIL: info@dixiegunworks.com VIEW ITEMS AND ORDER ONLINE! www.dixiegunworks.com Major credit cards accepted FOR ORDERS ONLY (800) 238-6785 PROFESSIONAL SERVICE AND EXPERTISE GUARANTEED

TODAY! STILL ONLY $5.00! The tried-and-trusted choice of today’s blackpowder enthusiasts.

ORDER

Buying and Selling The Finest in Americana 11311 S. Indian River Dr. • Fort Pierce, Florida 34982 770-329-4985 • gwjuno@aol.com George Weller Juno

Childhood home of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln located at 578 West Main Street, Lexington, Ky.

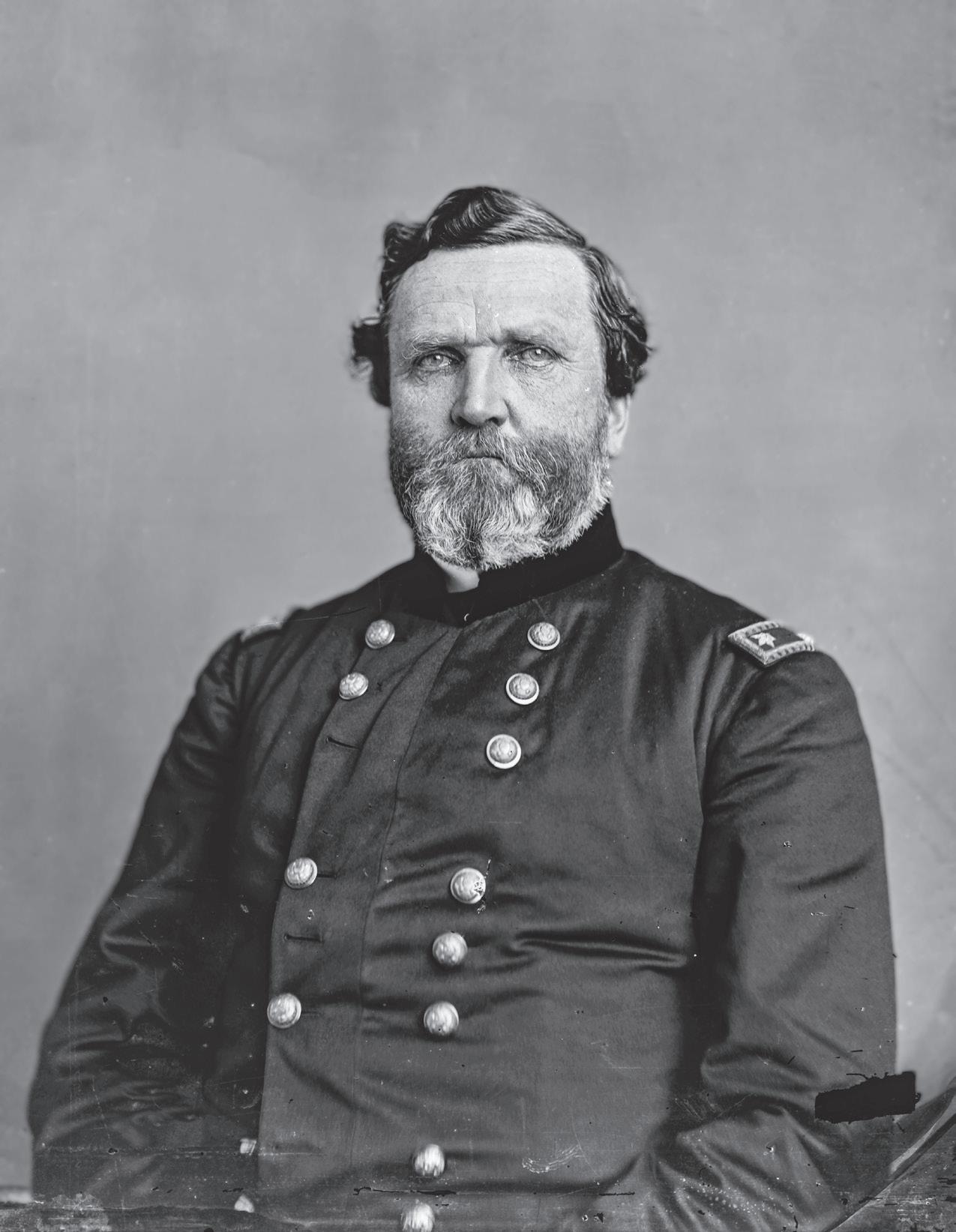

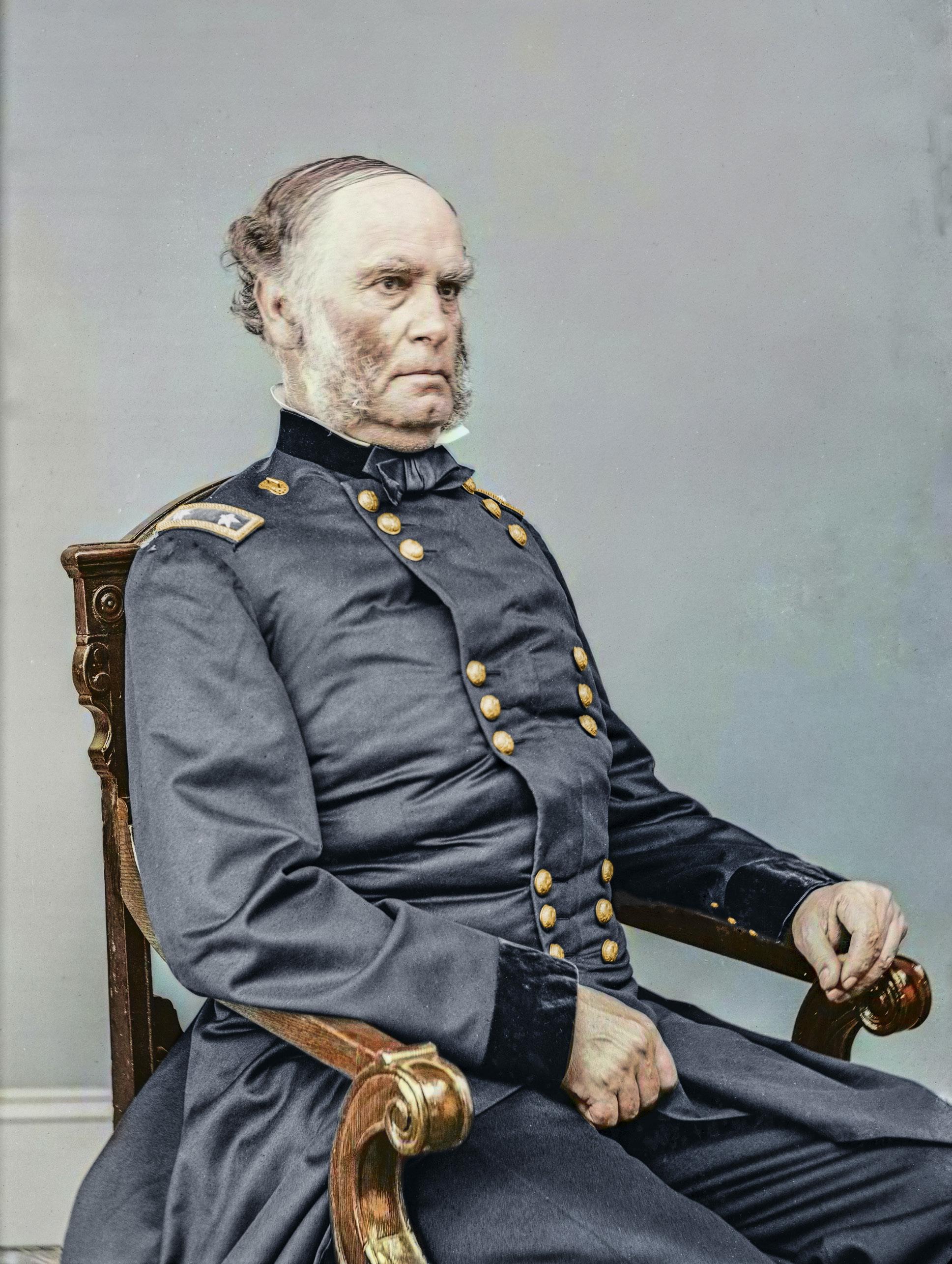

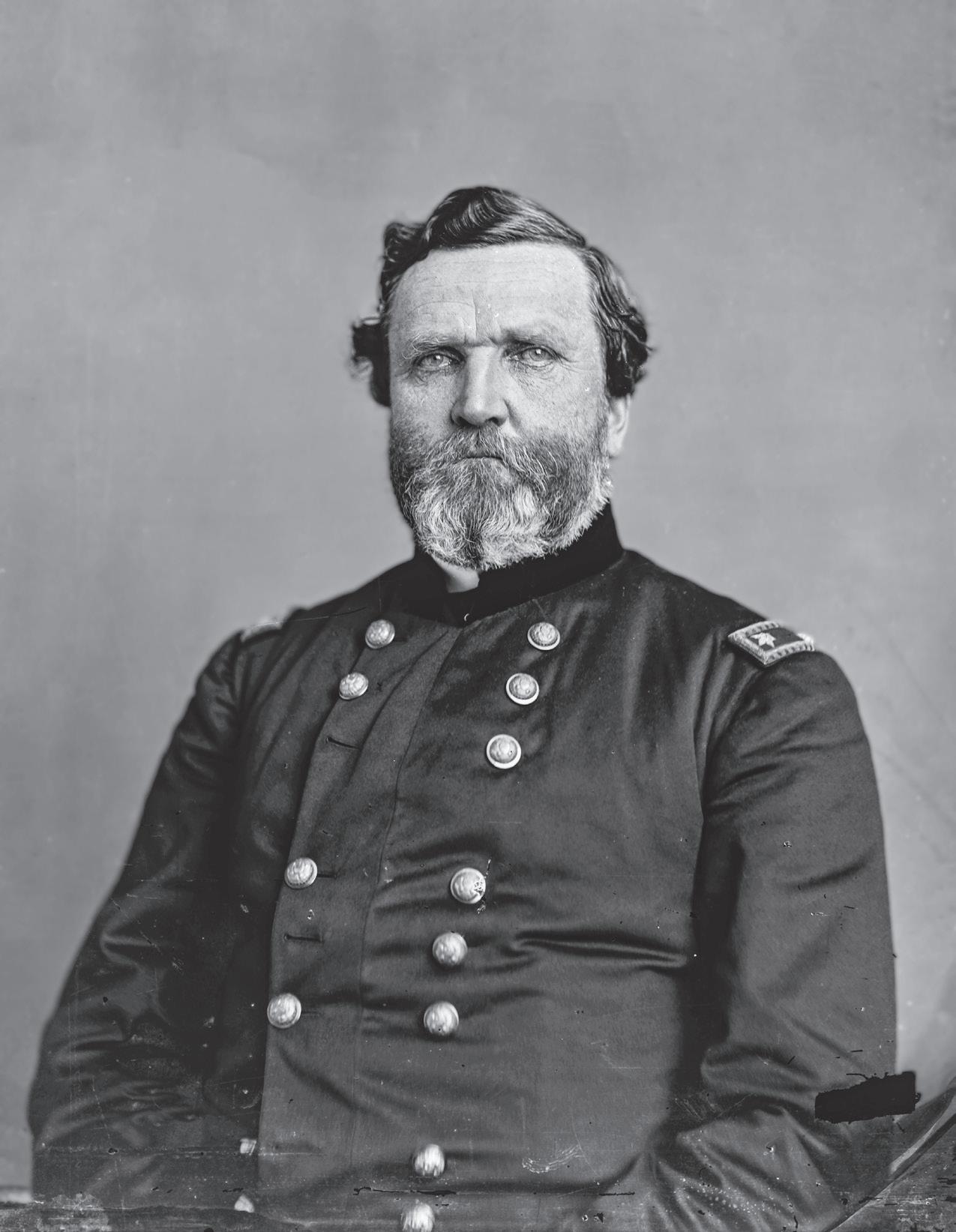

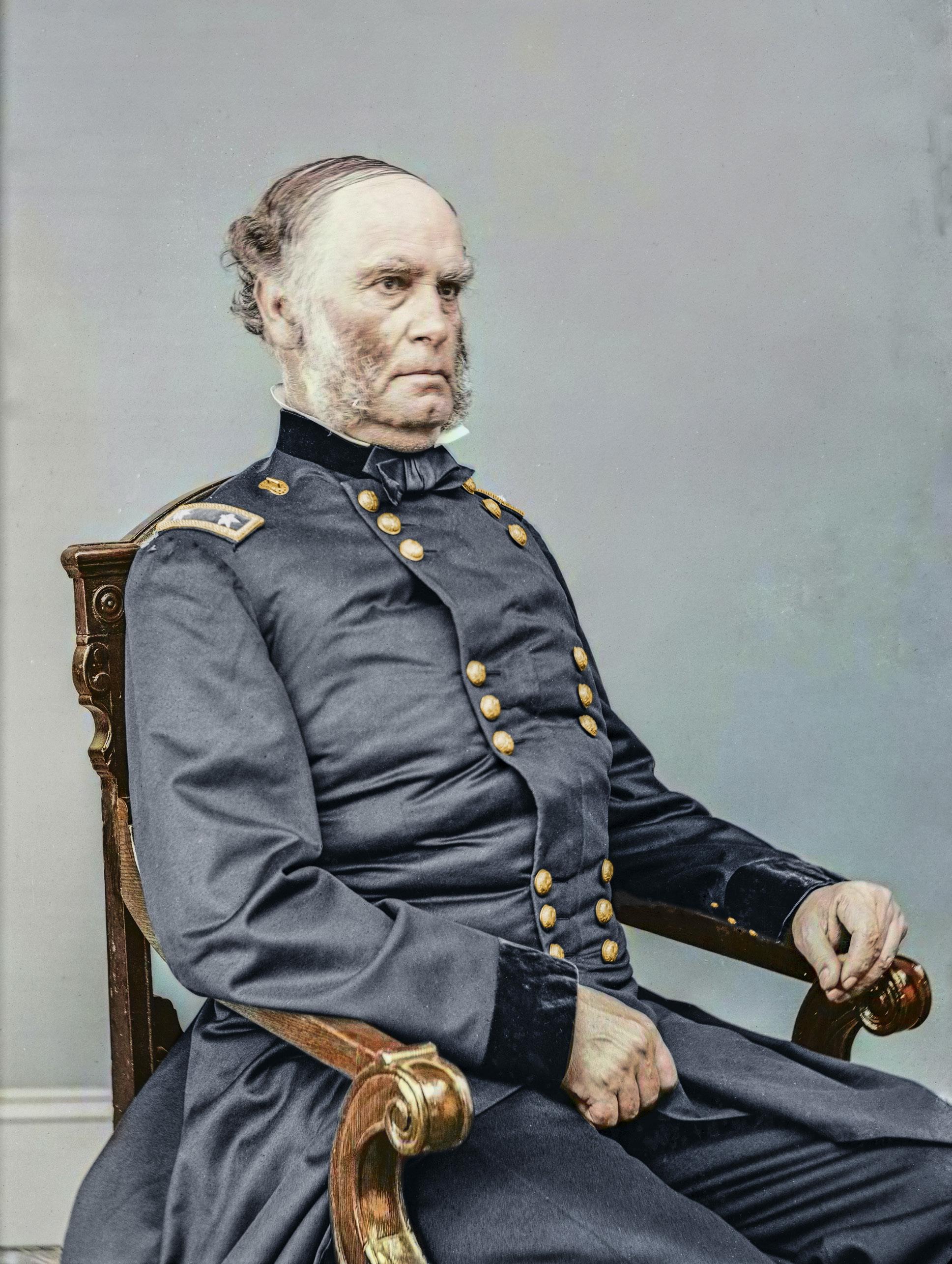

Gen. George Thomas

In May 1865, after fighting in the Civil War had mostly ended, there was a parade in Washington, D.C., featuring all the Union heroes. Ulysses S Grant was there and so were George Meade and William T. Sherman. Missing however was George Thomas of the Army of the Cumberland. The so-called “Rock of Chickamauga,” who had also later demolished John Bell Hood’s forces near Nashville in 1864, Thomas as much as anyone, deserved to be there.

George Thomas grew up in Tidewater Virginia on a plantation in Southampton County just above the North Carolina border. He went to West Point and graduated in 1840. His room mates were William T. Sherman and Stewart Van Vliet. His first assignment was with an artillery crew at Fort Lauderdale, during the 1840’s Seminole Wars. Just before the Mexican War in 1845,

his troops were ordered to Texas. His artillery units served with distinction and Thomas received steady promotions during the Mexican War.

In 1851, based partially on a recommendation from Braxton Bragg, he returned to West Point when Robert E. Lee was Superintendent at the Academy. Thomas was assigned as a cavalry and artillery instructor. The story goes that there was concern about the endurance capabilities of the Academy’s elderly horses. Thomas knew the tendency of cadets was to overwork the horses during cavalry drills. To prevent this he insisted on performing at a pace known as “the slow trot.” Hence, he became known by the unfortunate nickname ”Slow Trot Thomas.” Certainly not slow at everything, while at West Point, George Thomas met his future bride, Frances Kellogg from Troy, New York, and was married in 1852.

In late 1860, Thomas requested

a leave of absence from the from the Army. While traveling to Virginia, he fell off a train platform severely injuring his back. When the Civil War started, Thomas opted to remain with the United States Army. His wife being a New York native probably helped influence the decision. His wife Frances later noted that “whichever way he turned the matter over in his mind, his oath of allegiance to the Government always came uppermost.” In response, his family turned his picture against the wall, destroyed his letters, and never spoke to him again.

While Thomas is often

mentioned for being a Virginian who fought for the Union, there were other Southerners who

remained in the US military as well. Besides George Thomas the list includes Admiral David

10 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 10 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Major General George H. Thomas. (Library of Congress)

Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas on one of his two horses. (Library of Congress)

Farragut, Winfield Scott, John Gibbon, Edmund Davis, and William R Terrill. Nevertheless, when Thomas stayed in the Union Army his true loyalties were questioned and he was always regarded with some degree of suspicion. These concerns obviously proved baseless once the actual fighting got started.

After the Battle of First Manassas, all of Thomas’s assignments were in the Western Theater. In January 1862 he defeated Crittenden and Zollicofer at Mill Springs in Eastern Kentucky. Though not a huge victory, it was an early Union success that turned Confederate forces back into Tennessee.

Arriving after the fighting ended at Shiloh, Thomas successfully led forces at the Siege of Corinth. After Perryville, he was passed over for command in favor of Rosecrans. Although resentful, Thomas successfully held the center of Rosecrans forces at Stones River famously remarking “this army does not retreat.”

Perhaps his greatest moment came at Chickamauga in September 1863. Thomas once again held a desperate position against General Bragg’s onslaught while the Union line on his right collapsed. Thomas rallied broken and scattered units together on Horseshoe Ridge to prevent a significant Union defeat from becoming a hopeless rout while Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga. After the battle he became widely known by a new nickname: ”The Rock of Chickamauga,” for his determination to hold that vital position against continued attacks.

After Chickamauga, Rosecrans was fired and Thomas appointed to command the Army of the Cumberland during the Battles for Chattanooga in November 1863. Missionary Ridge was a stunning Union victory highlighted by Thomas’s troops taking Lookout Mountain on the right and then storming the Confederate line on Missionary Ridge the next day. Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, an eyewitness, called the assault “one of the greatest miracles in military history....as awful as a visible interposition of God.”

Grant for his part, perhaps relying on old grudges from many years past considered George Thomas a defensive general who was slow to attack. Author Bruce Catton noted that Thomas ”comes down in history...as the great defensive fighter, the man who could never be driven away but who was not much on the offensive. That may be a correct appraisal. Yet it may

also be worth making note that just twice in all the war was a major Confederate army driven away from a prepared position in complete rout—at Chattanooga and at Nashville. Each time the blow that finally routed it was launched by (George) Thomas.” While strangely unappreciated in his time, George Thomas was always well prepared, and is now highly regarded among military historians for understanding the role of logistical support in achieving success on the battlefield.

Craig L. Barry was born in Charlottesville, Va. He holds his BA and Masters degrees from UNC (Charlotte). Craig served The Watchdog Civil War Quarterly as Associate Editor and Editor from 2003–2017. The Watchdog published books and columns on 19th-century material and donated all funds from publications to battlefield preservation. He is the author of several books including The Civil War Musket: A Handbook for Historical Accuracy (2006, 2011), The Unfinished Fight: Essays on Confederate Material Culture Vol. I and II (2012, 2013). He has also published four books in the Suppliers to the Confederacy series on English Arms & Accoutrements, Quartermaster stores and other European imports

11 August 2023 11 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com Visit our website at: HistoricalPublicationsLLC.com

Battle of Mission [i.e., Missionary] Ridge, Nov. 25th, 1863, presented by McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. (Library of Congress)

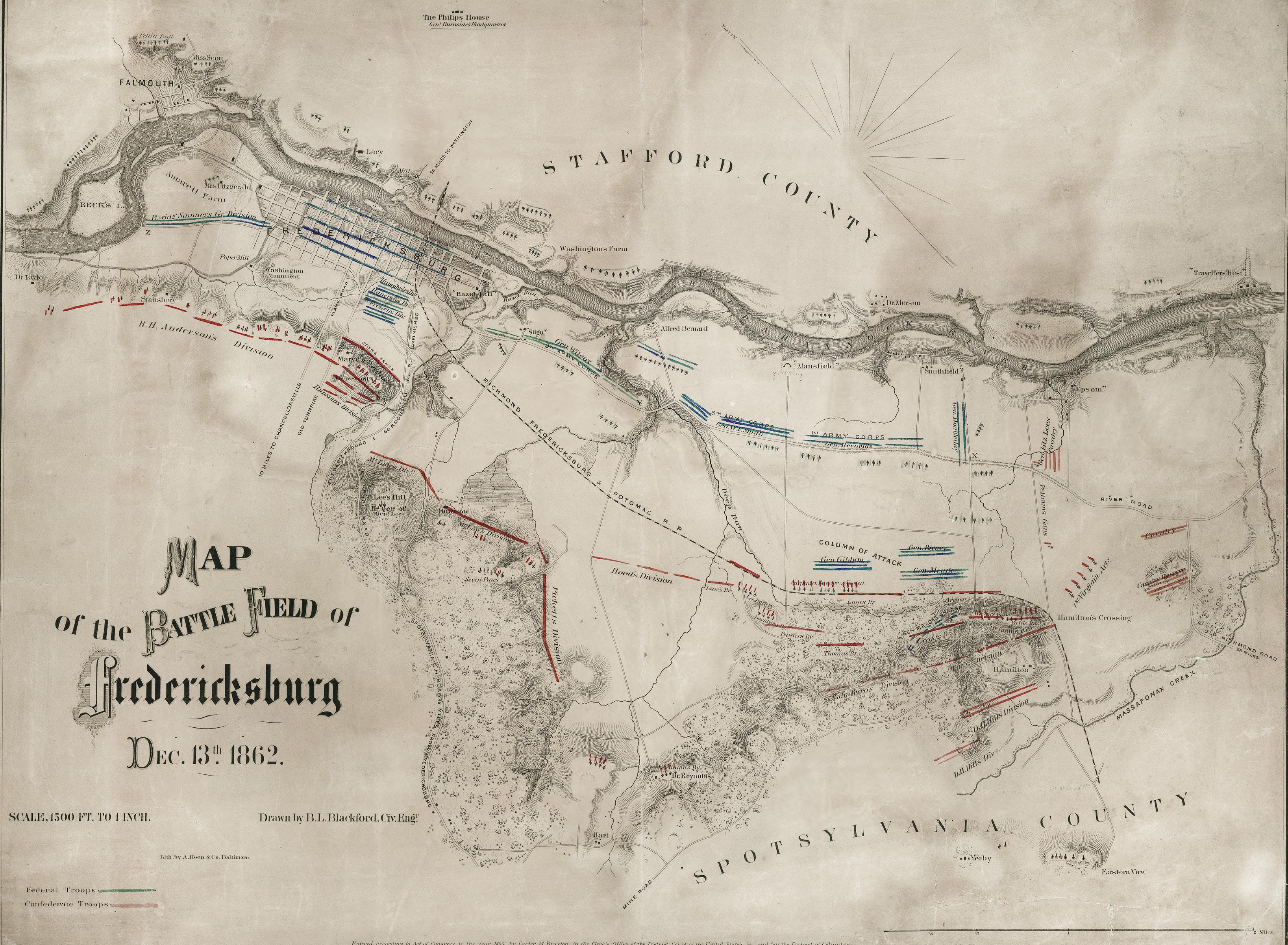

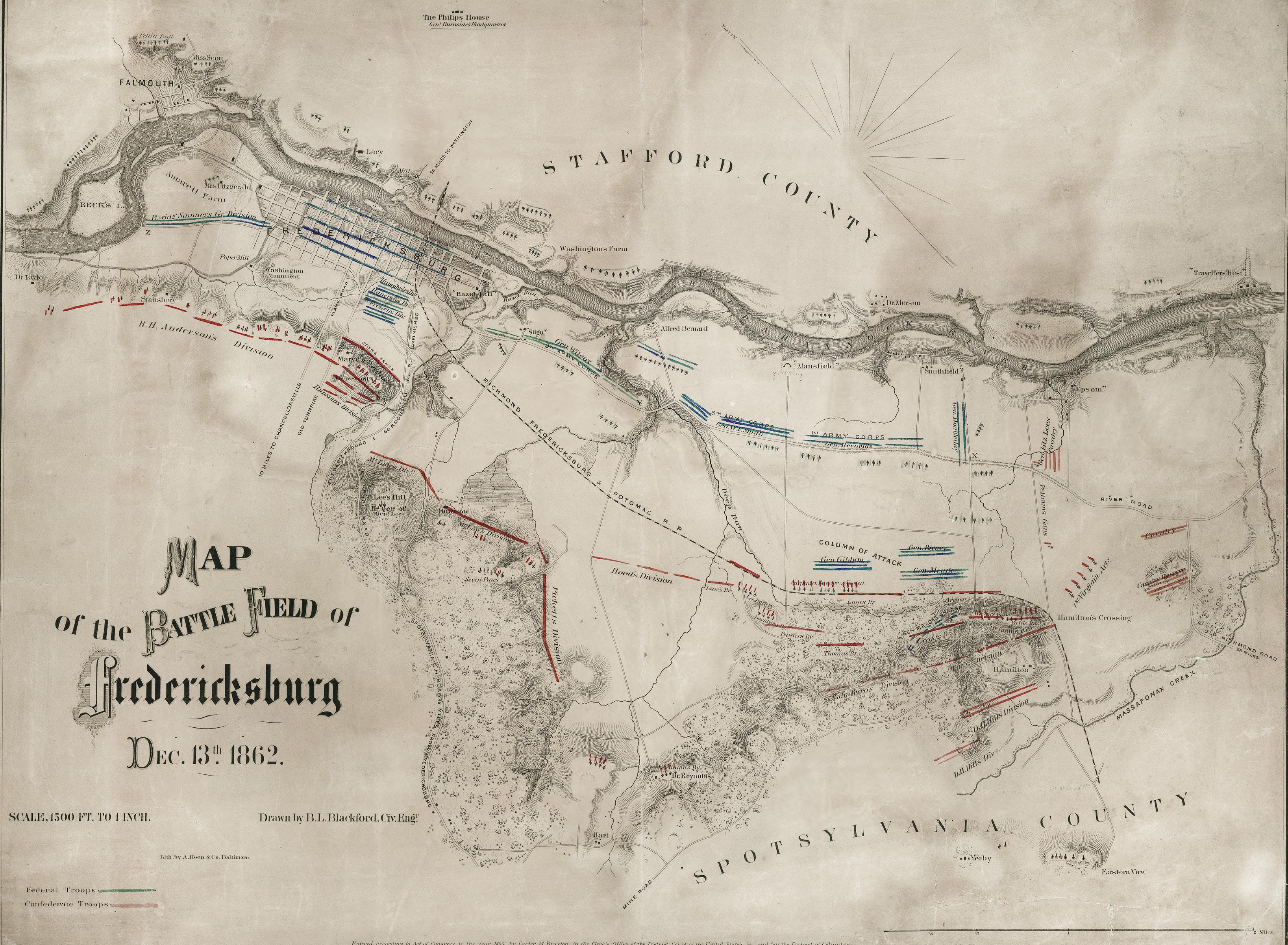

“The Men Fell on All Sides”: Kershaw’s Brigade at Fredericksburg

By Tim Talbott

At Fredericksburg, South Carolinians battled on both ends of the Confederate line. While Brig. Gen. Maxy Gregg’s South Carolina regiments endured a brief Federal breakthrough at Prospect Hill and lost Gen. Gregg to a mortal wound, Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s Palmetto State regiments fought on the opposite end of the long defensive line at Marye’s Heights.

Joseph Kershaw, a lawyer

and Mexican War veteran who served in the South Carolina secession convention, started the war as colonel of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry. He received a promotion to brigadier general in February 1862. At the time of Fredericksburg, most of Kershaw’s brigade were experienced fighters, some having participated in actions as early as First Manassas. The brigade comprised the 2nd, 3rd, 7th, and 8th South Carolina Infantry regiments. The 15th South Carolina Infantry and the 3rd South Carolina Battalion joined the brigade in midNovember 1862.

Just before the Battle of Fredericksburg, Kershaw’s Brigade occupied a position in the center of Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ Division. Kershaw’s line stretched from just south of “Braehead,” the Howison family house on Howison Hill, to Hazel Run and the nearby unfinished railroad bed. On December 11 and 12, the newly joined 15th South Carolina served as the brigade’s

pickets, helping monitor Federal activity around the lower pontoon bridge crossing. The regiment returned to their position in line

“after a night of such intense cold as to cause the death of one man and disable, temporarily, others.”

Kershaw noted the brigade’s other regiments worked “strengthening our defenses nightly without any incident requiring notice until Saturday, the 13th.”

About 1 p.m. December 13, Kershaw received orders from McLaws to send two regiments to Marye’s Heights to bolster Brig. Gen. Thomas R.R. Cobb’s brigade in the Sunken Road. Kershaw immediately sent the 2nd and 8th South Carolina; his other regiments were soon ordered to follow. The 3rd South Carolina Battalion was assigned to guard the Howison Mill location along Hazel Run to protect “a gap in the [unfinished] railroad embankment, and prevent its passage by the enemy.”

and 8th South Carolina appeared. Those two regiments took position in the Sunken Road. Writing to his wife several days after the battle to let her know that he was all right, the 2nd South Carolina’s 1st Sgt. Alexander McNeill noted, “Our Brigade occupied a conspicuous place in the engagement, and for the honor of Carolina, I am glad to say that her sons fought as valiantly as ever men did.” McNeill’s company had seven wounded. “I am at a loss to know how we came off so well, and I can but render thanks to an all wise and ever mercifull God for his kind protection in the hour of danger,” he penned. In total, the 2nd South Carolina lost six killed and 56 wounded in the fighting.

Joseph Kershaw began the war as the colonel of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry. Maj. Gen. Kershaw was taken prisoner at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6, 1865. (Public domain)

Just after putting his brigade in motion, Kershaw learned from McLaws that Cobb was mortally wounded, and Kershaw was to “take command.” He arrived at the Stephens House at the Sunken Road about the same time the 2nd

In his official report, Capt. E.T. Stackhouse of the 8th South Carolina commented that after they occupied the Sunken Road, he received permission from Kershaw to “form my command in four ranks.” Such depth probably helped keep the Federals at a distance. In fact,

12 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 12 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Map of the battle field of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862. (Library of Congress)

Stackhouse reported that evening “the enemy attempted several times to advance on our position, but succeeded only in reaching a defile 200 yards in front, which concealed them from view from our position.” Stackhouse reported that the 8th lost two killed and 29 wounded; 28 of the casualties occurred while moving to the Sunken Road.

Moving to the left along Marye’s Heights, the 15th South Carolina came up behind the Marye House. They soon received orders to shift back to the right, behind the Willis Hill cemetery and support the Washington Artillery of New Orleans. Later, during the evening, the 15th South Carolina moved down into the Sunken Road to support the 2nd South Carolina. The 15th South Carolina lost one killed and 52 wounded.

The 3rd South Carolina received further orders to support troops on the north side of “Brompton,” the Marye house. Urged to hurry, Col. James Nance reported that he led forward several companies already formed. On the hill’s crest, they were exposed to Federal infantry and artillery, and Nance noted that “a severe fire was opened upon us.” The regiment’s other companies soon came up in support and also suffered heavy casualties.

As Colonel Nance moved along the line, he was hit in the left thigh. He remained as long as he could, but the regiment’s officers were falling in quick succession.

Capt. John K.G. Nance, also submitted a report because he led the regiment at the end of the battle, noted Lt. Col. William Rutherford “fell shot through the side, and not long afterward Maj. Robert C. Maffett was disabled with a ball through his arm. Here, too, Capt. Rutherford P. Todd, who was acting as field officer, was disabled by a ball [piercing]

an artery of the right arm.”

Captains William Hance, shot in the leg, and John C. Summer, “killed by a grape-shot through the head,” also went down. The chain of command devolved through at least seven officers in the regiment during the fighting.

Capt. John K.G. Nance was wounded, too, but remained on the field.

Private Taliaferro “Tally”

Simpson wrote his aunt five days after the battle explaining, “I was in the hottest part of the fight and was slightly wounded in the shoulder.” Tally also penned that “Our company suffered severely.

Our gallant Capt [William Hance]

I fear is mortally wounded. His leg has been amputated near the body. Thirty-three of forty-two who were carried into action were killed or wounded.” Noting the fury of the fight, Tally wrote, “The men fell on all sides. The balls came thick as hail, and it is wonderful that every man was not either killed or wounded.”

Suffering disproportionate casualties, the 3rd South Carolina lost 25 killed and 138 wounded. As demonstrated above, casualties among the regiment’s officers were particularly heavy. One officer killed was 25-yearold Capt. Lewis Perrin Foster. Capt. Foster wrote his last letter home three days before the battle. In it, he stated, “Everything here is quiet. I am quite well. All my company well.” How quickly things can change in a time of war.

of CVBT is to preserve land associated with the four major campaigns of: Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Mine Run,

and the Overland Campaign, including the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House. To learn more about this grassroots

preservation non-profit, which has saved over 1,700 acres of hallowed ground, please visit: www.cvbt.org

13 August 2023 13 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

Several of Kershaw’s regiments fought behind the Stone Wall in the Sunken Road below Marye’s Heights. (Tim Talbott)

During the Battle of Fredericksburg, the 3rd South Carolina Battalion guarded the area around Howison’s Mill along Hazel Run. (Library of Congress)

The 3rd South Carolina Infantry suffered heavy casualties fighting near “Brompton,” the Marye House, during the Battle of Fredericksburg. (Library of Congress)

CVBT has helped save over 400 acres of Fredericksburg battlefield land.

Tim Talbott is the Chief Administrative Officer with the Central Virginia Battlefields Trust. The mission

American Battlefield Trust Appeals Controversial ‘Wilderness Crossing’ Development

Alongside local nonprofits and private citizens, the American Battlefield Trust filed a legal challenge in Orange County, Va., against a mega-development proposal this spring. At 2,600 acres, the largest rezoning in county history, the “Wilderness Crossing” proposal would blanket a historic landscape with residential, commercial, and industrial development, including distribution warehouses and data centers. Filed in Orange County Circuit Court, the challenge identified a host of substantive and procedural flaws with the development project and the County’s approval, requiring its invalidation.

Despite overwhelming opposition expressed during the public hearing, the project was voted on and approved the same evening it first appeared on the Board’s agenda. Altogether, the project could result in up to 5,000 residential units, more than 800 acres of commercial and industrial development, and as much as 750 acres of potential data centers and distribution warehouses.

The plan approved by the Board of Supervisors also differed significantly from what had been advanced by the Planning Commission earlier this year. Major changes were submitted during the hearing, which took place at the earliest possible time after the Planning Commission’s action. Freedom of information failings, including a lack of proper notice of Board meetings and a refusal to disclose materials bearing on the rezoning, are amongst the legal flaws in the rezoning approval process. Furthermore, the challenge also identified failures to provide sufficient analysis on several issues, ranging from noise pollution and water quality degradation to traffic impact.

The Trust is joined by the nonprofit Central Virginia Battlefields Trust, Inc. and Friends of Wilderness Battlefield, Inc. in filing the challenge—all three organizations own or steward historic properties in immediate proximity to the rezoned land or stand to suffer significant impacts from the proposed development. Private citizens whose homes are adjacent to the site and face catastrophic consequences also joined as plaintiffs.

To learn more or stay up to date with these developments, please visit www.battlefields.org/ wilderness-crossing.

Play a Part in Restoring Five Battlefields

The Trust has launched a new campaign that will help restore land at six different battlefields— at Gettysburg, Cold Harbor, Fredericksburg’s Slaughter Pen Farm, Lookout Mountain, and New Market Heights. The six battlefield tracts have already been saved from bulldozers, commercial developers, billiondollar tech companies thanks to generous donor and partner

support, but these properties present a special opportunity to restore the land to its wartime appearance before they are transferred to our nonprofit or government partners.

In total, the restoration projects will cost $287,000. With no federal or state matching funds available, every penny counts in our efforts to restore these battlefields.

At Gettysburg, the Trust seeks to tear down the former MacDuffer’s Adventure Mini Golf Park that currently obstructs the view of the battlefield. For an estimated $50,000, concrete, water pumps, and underground pipes will be removed and replaced with grass and native trees. Additionally, the historic James Thompson House across the road from General Lee’s Headquarters would receive overdue repairs and repainting, estimated to come in at $35,000. At Cold Harbor and Lookout Mountain, restoration projects include demolishing non-historic structures, removing trash and debris, and restoring the sites for incorporation into their respective battlefield landscapes.

Especially urgent, at New Market Heights, known for the 1864 Union victory where 14 Black soldiers earned the Medal of Honor, the Trust is facing a late October deadline to remove a 1970s house and restore the land to its wartime conditions. Here, the project is estimated to cost approximately $42,000.

At Slaughter Pen Farm, the Trust recently paid off the hefty loan at the historic farm and now aims to complete restoration of this hallowed ground. Here, a post-war farmhouse will be demolished thanks to the generosity of a former property owner’s relative. After the house is removed, the Trust will remove electric poles and some anachronistic fencing, as well as landscape the area. Following these actions, this land will function as the start of a trailhead with interpretive signs.

To learn more about this restoration campaign, visit www. battlefields.org/restoration2023.

Support Small-ButSignificant Changes to the American Battlefield Protection Program

For more than 20 years, the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) has remained a cornerstone of the Trust’s efforts to preserve our nation’s hallowed grounds. The program, managed by the National Park Service (NPS), is the administrative body overseeing federal matching grants for the planning, acquisition, restoration, and interpretation of battlefields.

Over the past two decades, ABPP battlefield land acquisition grants have aided in preserving more than 35,000 acres across 21

14 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 14 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

The Trust seeks to tear down the former MacDuffer’s Adventure Mini Golf Park at Gettysburg. Photo by American Battlefield Trust.

The Wilderness Battlefield stands to be impacted by a mega-development proposal unless the Trust and its partners are successful in their legal challenge. Photo by Buddy Secor.

Once the postwar farmhouse is demolished, the Trust will begin to restore the land to its wartime appearance. Photo by American Battlefield Trust.

states at places like Gettysburg, Antietam, Princeton, and Vicksburg.

The American Battlefield Protection Program Enhancement Act (HR3448), introduced by Representatives Elise Stefanik and Gerry Connolly, would make small but significant modifications to the program to further increase its impact. The legislation would allow nonprofits and tribes to apply directly for these grants, saving valuable time and ensuring key land acquisitions can move quickly. Additionally, the legislation would widen the scope of ABPP’s restoration grants to all NPS identified battlegrounds and ensure land acquisition grants can be used to preserve significant battlefields from our nation’s founding conflicts. Finally, it would create a mechanism for the NPS to update Congressionally authorized reports identifying key Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War battlefields when there is new research, archaeology, or studies that show a larger battlefield than originally known.

Please join us in supporting the American Battlefield Protection Program Enhancement Act at www.battlefields.org/HR3448.

Save 125 Acres of Civil War Battlefield Land in the Old Dominion

During the Civil War, no other state witnessed as much fierce fighting as Virginia did. Today, thousands of acres of Virginia’s hallowed ground stand protected, but with ever-looming development threats, the Trust has launched a new campaign to save 125 acres of battlefield land in Virginia at Spotsylvania Court House, New Market, and Trevilian Station. Altogether, the cost to purchase these tracts is more than $1.4 million. Thanks to federal and Virginia state grants and the

Shenandoah Valley Battlefield Foundation, every dollar donated will be quadrupled in value to meet our $346,000 need.

These battlefields all share an immeasurable degree of historic significance, connected to both Grant’s Overland Campaign and Sheridan’s Valley Campaign of 1864. However, they are located where land is now considered more valuable than ever—for the development of residential neighborhoods and industrial infrastructure like data centers and distribution warehouses.

At Spotsylvania Court House, the second battle of the Overland Campaign and one of the bloodiest battles ever fought on

assistance to finish the job. To learn more about this preservation opportunity and more, please visit https://www.battlefields.org/ savebattlefields.

15

2023 15

2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

August

August

New Market Battlefield in New Market, Va. Photo by American Battlefield Trust.

Stream history on multiple devices Your favorite videos, wherever you want www.historyfix.com Escape into history through movies, documentaries, docudramas, and how-tos! Available on multiple devices Your favorite videos, wherever you want Try a 7 day free trial today and access exclusive content tailored to history buffs! Southeastern Civil War & Antique Gun Show Cobb County Civic Center 548 S. Marietta Parkway, S.E., Marietta, Georgia 30060 45th Annual Aug. 12 & 13, 2023 Saturday 9–5 Sunday 9–3 Over 190 8 Foot Tables of: • Dug Relics • Guns and Swords • Books • Frameable Prints • Metal Detectors • Artillery Items • Currency Free Parking Admission: $8 for Adults Veterans & Children under 10 Free Inquires: NGRHA Attn: Show Chairman P.O. Box 503, Marietta, GA 30061 terryraymac@icloud.com

Rebel horseman and both sides fired. The Confederates fell back into the trees. Expecting the daily experience that “the enemy would fire only one volley and then seek safety by rapid flight into the depths of the wild woods,” U.S. Col. Charles H. Harris, 11th Wisc., deployed four companies of the 11th as skirmishers and four companies of the 33rd Ill. in a battle line; the cannon was posted in reserve left of the road.

Are You Going To Run Like Sheep?

“I give captured slaves their freedom on the ground that they became captured captives and therefore subject to my disposal instead of a former captor or assignee.” – U.S. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis

At the Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark., March 7-8, 1862, U.S. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, Army of the Southwest, drove C.S. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, Army of the West, off the battlefield in a decisive victory, establishing Federal control of most of Missouri and northern Arkansas. Van Dorn agreed to join his army with C.S. Gen. P.T. Beauregard’s in Corinth, Miss. In his zeal, Van Dorn ordered all arms, ammunition, food, machinery, and stores shipped out of the district, stripping the area of all military manpower and equipment.

Following Van Dorn’s departure, Curtis was ordered to capture Little Rock, Ark. and declare himself the state’s military governor and rule by martial law. Curtis was a West Point graduate, Mexican-American War veteran, and civil engineer. The abolitionist had given up his seat in Congress to fight in the War. On the morning of March 27, Curtis was promoted to major general in a small ceremony. In the afternoon he learned his 20-year-old daughter had died of typhoid fever which she had contracted while visiting the army camps.

On May 20, having gathered sufficient forces to make the march to Little Rock, Curtis was informed that his supply chain was stretched to its limit. It was agreed to establish a waterborne supply chain. The navy’s supply vessels fought past Confederate batteries but were stopped by low water levels on the White River. Undeterred, Curtis announced if the supply boats could not come to him, “I must go to them.”

Curtis left Batesville, Ark. during the last week of June to meet the supply boats at Clarendon, Ark. For the first time

in the War, a Federal army would operate for two weeks without a supply base. In the height of summer, the men marched through the heat and foraged aggressively. According to an Arkansan, “…almost every thing which could not be eaten was destroyed.”

Curtis seized printing presses in every town the army passed through. Before the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was announced on September 22, 1862, and lacking the authority to do so, Curtis printed and issued stacks of emancipation forms. Waving “freedom papers,” over 3,000 refugee slaves left the area.

“No troops—no arms—no powder—no material of war — people everywhere eager to rise, complaints bitter,” wrote C.S. Gen. John S. Roane. Determined to drive out the invaders, Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman assembled a fighting force from nothing. Hindman ordered Gen. Albert Rust to attack James’s Ferry, six miles from Cotton Plant, Ark. He appealed to local citizens to destroy anything that could sustain the Federals. Hundreds of trees were cut to create timber blockades to give Rust time to reach the crossing first. Still, the Federals won the race.

On July 6, the Federals reached James’s Ferry where pioneers cleared the timber blockade. On July 7, the low water level meant the Federals could wade across the Cache River. Col. Charles E. Hovey, the former Illinois Normal College president, sent 400 men, including the 1st Indiana Cavalry with a 3-in. rifled cannon to scout the road ahead. Four miles south they reached a road fork in the middle of Parley Hill’s plantation. They took the southeast road to Clarendon. At Hill’s nearby home, “the command confiscated a ready cooked dinner, and also a couple of wagon loads of bacon and molasses,” and were fired upon. The Confederates trotted back to the fork to take the Des Arc Road. The Federals rushed after them, “to drive the rebels away from the army’s line of march.”

On July 7, the Battle of Cotton Plant began three-quarters of a mile from the road fork amid a swamp. The Federals approached a line of 30 or 40

Waiting in the swamp were about 1,000 cavalrymen, the advance from the force of five Texas cavalry regiments, three Arkansas infantry regiments, one Arkansas artillery battery, a total of about 5,000 men.

These inexperienced men were armed with a variety of single and double-barreled shotguns, squirrel rifles, buck and ball muskets, and “in one thing only were all armed alike, and that was with big knives.”

The surprised Federals fell back. The 12th Texas Cavalry, dismounted, and “yelling like savages and swearing like demons,” advanced. The Federals opened a steady fire with the cannon blasting as fast as could be reloaded. Hovey, at the fork in the road, galloped to find his troops wavering. Hovey grabbed a rifle and cartridge box from a wounded soldier and went to an unoccupied tree, firing

16 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 16 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Col. Charles E. Hovey. Colorization © 2023 civilwarincolor.com, courtesy civilwarincolor.com/cwn. (Public Domain)

towards the enemy. Within two or three shots a spent bullet hit his chest, sending Hovey staggering from the blow. Hovey plucked the bullet out and shouted that the rebellion, “did not seem to have much force in it.” His men cheered.

When the dismounted 16th Texas Cavalry advanced thirty minutes later, the outnumbered Federals gave way. Hovey ordered a retreat. Four of the gun crew had been wounded and their cannon was stranded. “Boys, save the gun,” shouted Capt. Potter. Sgt. Edward A. Pike ran towards the Confederates. He “seized the trail and tore down the road with the cannon as if it had been a baby wagon.” Pike would earn the Medal of Honor for this act. Hovey on horseback caught up with his retreating men in Hill’s cornfield. Waving his sword he yelled, “… Are you going to run like sheep?”

He organized his men into building breastworks out of fence rails, branches, and cornstalks, and positioned others in the heavy timber. The 12th Texas Cavalry, riding four abreast, and yelling Comanche war whoops, charged the breastworks “at full speed and in great force.” The Federals rose and shot at point blank range, then frantically began reloading. Bodies soon covered the ground.

Riderless horses rushed in all directions. The remnants of the 12th led the Confederate retreat.

Two hundred men with two 3-inch rifled cannon from Col. William Wood’s battalion, 1st Ind. Cavalry, arrived. They advanced into the swamp. Spotting the Confederates, the cavalry charged. The Confederates fired a “tremendous volley” hitting the officers in the front. For twenty minutes both sides fired at close range before the Confederates began retreating. The Federals

switched from firing canister to solid shot and explosive shells. Hundreds of Texans raced each other from the field. The Arkansas infantry were surprised to see the Texans stampeding towards them, knocking some men down. The Texans vanished in a cloud of dust. The infantry followed, ending the last serious Confederate effort to prevent Federal control of the state.

Alas, Curtis missed his rendezvous with the supply vessels by a single day. Relinquishing the Little Rock operation, the army marched 45 miles to Helena, Ark., suffering with the heat, bad water, and few rations. Curtis would have the consolation of moving into Hindman’s mansion and flying a large United States flag from the roof. However, Curtis would never receive the credit he earned for his accomplishments in the field.

Sources:

• Shea, William L. “The Confederate Defeat at Cache River.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Summer 1993): 129–155

• Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997

• Way, Virgil Gilman, History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War, 22nd August, 1861, to 7th December, 1865: The [Regimental] association, 1902

• Quiner, E. B.. The Military History of Wisconsin: Clarke & Co., 1866

Stephanie Hagiwara is the editor for Civil War in Color.com and Civil War in 3D.com. She also writes a column for History in Full Color.com that covers stories of photographs of historical interest from the 1850’s to the present. Her articles can be found on Facebook, Tumblr and Pinterest.

Gould B. Hagler, Jr.

This unique work contains a complete photographic record of Georgia’s memorials to the Confederacy, a full transcription of the words engraved upon them, and carefully-researched information about the monuments and the organizations which built them. These works of art and their eloquent inscriptions express a nation’s profound grief, praise the soldiers’ bravery and patriotism, and pay homage to the cause for which they fought.

17 August 2023 17

2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com www.mupress.org 866-895-1472 toll-free

August

GEORGIA’S CONFEDERATE MONUMENTS In Honor of a Fallen Nation

Eward Pike, Medal Of Honor recipient. Colorization © 2023 civilwarincolor. com, courtesy civilwarincolor.com/cwn. (Public Domain)

Gen. Samuel R. Curtis. Colorization © 2023 civilwarincolor.com, courtesy civilwarincolor.com/cwn. (Library of Congress)

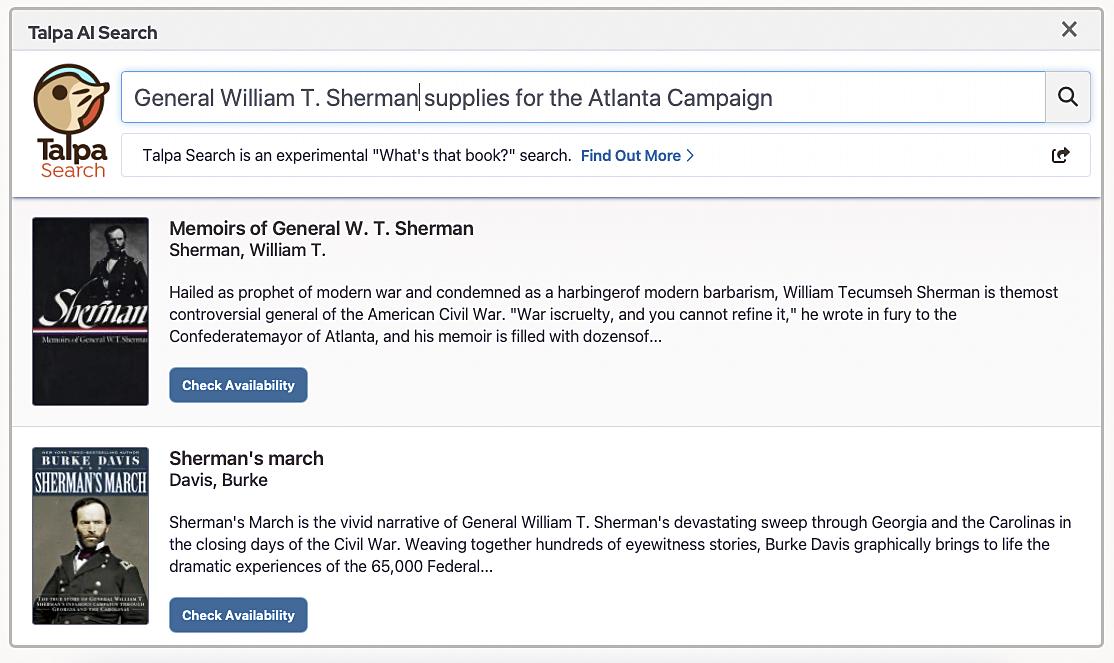

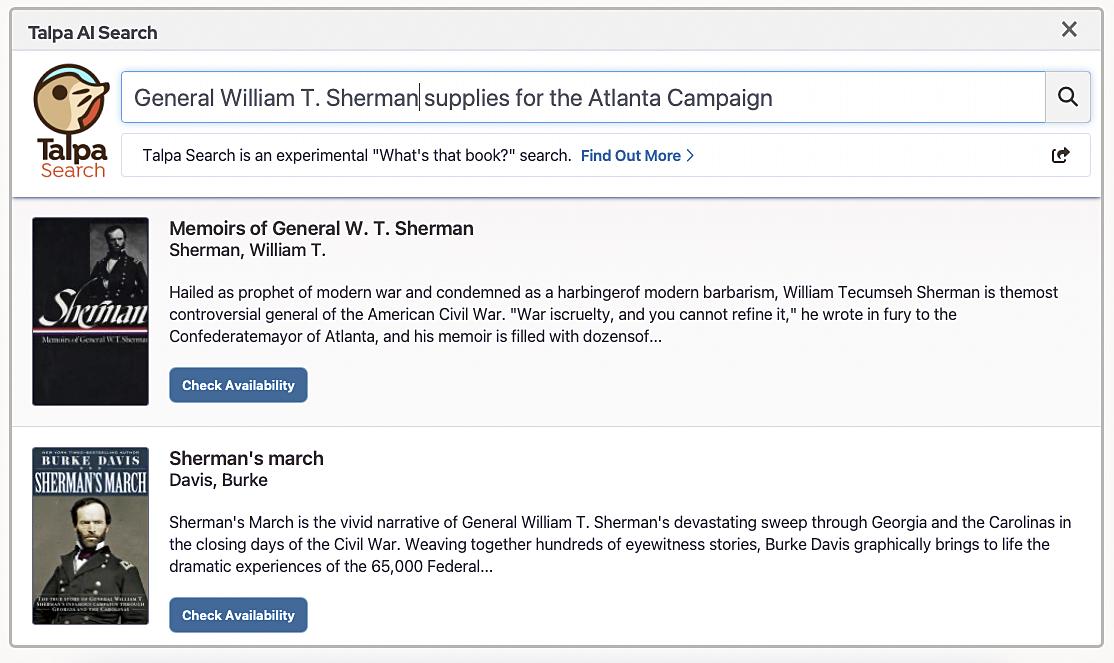

AI as a Civil War Research Tool

This writer admits he can not explain all the workings of the latest buzz in the tech world: ChatGPT, OpenAI, etc. However, one recently developed tool can assist Civil War researchers in locating information found within books on their shelves or at public libraries. Talpa searches sources as described on their website: https://www.talpa.ai. Developers

offered the following details on how AI can comb through books using various search phrases.

“Talpa uses AI technology in two ways: First, Talpa queries large language models from Anthropic and OpenAI for books and other media, validating every item against true and authoritative bibliographic data. Second, Talpa uses the natural-language abilities of large language models to parse and understand queries, which are then answered with

traditional library data. So, for example, a search for ‘novels about World War II in France’ taps into subjects, tags, and character data from LibraryThing.”

Take a few minutes to read the instructions on using this tool at the website mentioned above. Let us put bots to work on Major General William T. Sherman and the Atlanta Campaign!

As shown in the image at the bottom, a search using the phrase ‘General William T. Sherman supplies for the Atlanta Campaign’ netted multiple sources containing pertinent information. Developers note this tool remains in the developmental stage, so do not expect perfect results. Using various search terms, this writer has already benefited from timesavings in locating specific topics under study. Clicking on any of the sources located will not take one to the book or any particular pages within the text; instead, this AI tool simply serves as a quickfind aide for locating key words and phrases.

The Talpa tool currently connects to the Mid-Hudson Library System (NY) database, so remember to use https://www. worldcat.org to find books in a local library. Try using various search phrases with Talpa while researching the American Civil War!

Michael K. Shaffer is a Civil War historian, author, lecturer, and instructor who remains a member of the Society of Civil War Historians, Historians of the Civil War Western Theater, and the Georgia Association of Historians. Readers may contact him at mkscdr11@gmail.com or request speaking engagements at www.civilwarhistorian. net. Follow Michael on Facebook, www.facebook.com/ michael.k.shaffer, and Twitter @ michaelkshaffer. https://www.talpa.ai.

Until now, a daily account (1,630 days) of Georgia’s social, political, economic, and military events during the Civil War did not exist. In Day by Day through the Civil War in Georgia, Michael K. Shaffer strikes a balance between the combatants while remembering the struggles of enslaved persons, folks on the home front, and merchants and clergy attempting to maintain some sense of normalcy. Maps, footnotes, a detailed index, and bibliographical references will aid those wanting more.

February 2022 • $37.00, hardback

Michael K. Shaffer is a Civil War historian, instructor, lecturer, newspaper columnist, and author. He is a member of the Society of Civil War Historians, Historians of the Civil War Western Theater, and the Georgia Association of Historians. Contact the author: mkscdr11@gmail.com

18 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 18 August 2023

CivilWarNews.com

Day by Day through the Civil War in Georgia www.mupress.org

866-895-1472 toll-free Subscribe or Renew Online at CivilWarNews.com

•

– MAKER –LEATHER WORKS (845) 339-4916 or email sales@dellsleatherworks.com WWW. DELLSLEATHERWORKS.COM – MAKER –LEATHER WORKS (845) 339-4916 or email sales@dellsleatherworks.com WWW. DELLSLEATHERWORKS.COM

Sherman search results.

Appomattox 2023 Was a Successful Observation of Lee’s Surrender

By Professor Earnest Veritas Special Correspondent to Civil War News – Western Theater –

Appomattox Court House

National Historical Park hosted the 158th anniversary event on April 7-12, 2023. The commemoration of General Lee’s surrender to General Grant on April 9, 1865, was a successful observation of the event that brought our country back together. More than 2,000 visitors, according to park counts, came to the multiple-day event to experience the park, exhibits, and Lee (Thomas Jessee), and Grant (Curt Fields), and soldiers who came to bring the event to life and enjoy the twenty-plus presentations by park staff. The Living History group, Lincoln’s Generals, provided most reenactors who participated in the event.

An officer’s call and nowannual dinner was held Friday evening at the Babcock House restaurant in Appomattox, a few miles from the park. Some thirty officers, soldiers, and civilians, all contributing to the anniversary observations over the weekend, came to the dinner to kick off the event in a proper spirit. Friendships were renewed across the lines as the evening’s conviviality set the tone for the weekend’s events and demonstrations.

General Sheridan (James Standard) set up a fly and encampment in the yard next to the McLean house. He and other officers and civilians entertained

visitors throughout the weekend. General Joshua Chamberlain (Ted Chamberlain) set up a tent fly on the road where arms were stacked after the surrender. Colonel Ellis Spear (Ray Lizarraga) assisted General Chamberlain. Spear had been one of Chamberlain’s students at Bowdoin College in Maine prior to the war and had raised a company for the 20th Maine regiment. Colonel Spear was sent across the Appomattox River to lead Gordon’s Brigade to the location for “stacking of the arms.” They were the first Confederates to stack arms. It was quite an honor for General Chamberlain to be designated to receive the surrender of the Confederates and equally as much an honor for Colonel Spear to be sent to lead them to where they would surrender arms and flags. The pair of officers talked to several visitors and explained the three-day process of the Confederates stacking of their arms (mainly in the rain) after General Lee surrendered.

On Saturday evening, April 8th, General Lee and General Grant, surrounded by their respective staffs, gave their presentation “Appomattox: The Last 48 Hours” on the front porch of the McLean house to an enthusiastic crowd gathered in the yard. Their presentation recounts and explains the messages exchanged between Grant and Lee from 5 p.m. April 7th to 11:50 a.m. on April 9th. The generals also describe what their respective armies were doing in the final time frame as the war ground to an end. The audience was

privileged to hear, in the generals’ own words, what happened in those last 48 hours of ‘this cruel war.’

The weather for the weekend was mostly chilly, gray, and frequently wet, just as it was in April 1865. Historically, it was wonderful because these same weather conditions were experienced by the original participants. There were more than a few shivers among the participants and the visitors. Complaints were few and goodnatured from both groups!

Several weekend activities

were held at the nearby Museum of the Confederacy. Many Confederate soldiers were encamped, and several Federal troops and an artillery unit joined them. On Thursday, April 6th, Patrick Schroeder gave an informative program at the Museum: “Final Fury and the Last to Die: The Battles of Appomattox Court House and Appomattox Station.” A special treat was the old-time service on Sunday morning by Pastor Scott Strudivant of the United States Christian Commission. The service was very well attended,

with both Grant and Lee there to enjoy the uplifting words of Pastor Strudivant.

Generals Lee and Grant visited the camps of Confederate and Federal troops and enjoyed the fellowship extended to them in both. Several ladies engaged in family life activities and rolling bandages for the troops in the cabin on the premises. The generals toured the cabin and enjoyed learning about what they were doing to keep the home in good shape while their men were away at war. Overall, the American Civil War Museum had a substantial program for the surrender anniversary and plans to have more in the future.

The plans are underway at the park for the 159th anniversary of the surrender in April 2024 and the 160th in 2025. Appomattox National Historical Park and Generals Grant and Lee certainly hope that all who are able will attend both events!

For more information about Appomattox National Historical Park and events held there yearround, contact the park at: Appomattox Court House National Historical Park 111 National Park Dr, Appomattox, VA 24522 Phone 434-352-8987

Professor Veritas would like to extend his gratitude for the assistance and photographs used in this article to Ted Chamberlain, James Standard, Ray Lizarraga, Jacqueline Terzano, and Patrick Schroeder, the Appomattox Court House National Park Historian.

“Simply put: tell the simple truth, simply.” – Professor E. Veritas

19 August 2023 19 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

Lee (Thomas Jessee), and Grant (Curt Fields). (Jacqueline Terzano)

Group of Confederate and Union reenactors that participated in the anniversary

Grant and Lee talking to the crowd about the history of the surrender. (Gene Smallwood)

The War Before the War, Part 2: George B. McClellan

Last month’s “This and That” reviewed the Mexican War experience of an artilleryman, Thomas Jackson. This time we will have a look at the record of an officer who, like Jackson, graduated from West Point in 1846 and almost immediately went into action. Ranking second in his class, George McClellan had his pick of assignments. He chose the Corps of Engineers.

Stephen Sears’s 1988 biography of McClellan devotes the better part of a chapter to his subject’s service in the war with Mexico. Most of the following is based on Sears’s work. I also consulted the 1941 biography by H.J. Eckenrode and Bryan Conrad, which offers a more cursory look at McClellan’s role in the war.

When war erupted McClellan described his excitement in a letter to his sister. “Hip! Hip! Hurrah!” he wrote, delighted at the prospect of entering the fray and battling “musquitoes and Mexicans.” Commissioned on June 1, 1846, the brevet second lieutenant would soon face both enemies.

Lt. McClellan was one of three officers in the elite Company of Engineer Soldiers. He spent two months training recruits in the general duties of a soldier and in the ways and means of building military roads, bridges, fortifications, and other necessary edifices. The company sailed from New York in September and arrived in Texas in October 1846. The warring parties had signed a truce after Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor’s victories in Texas and northern Mexico. McClellan’s first battles, therefore, would be fought not against Mexicans but

against disease, dysentery and malaria.* McClellan was laid up for a month, after which time the engineers worked their way south

400 miles along the coast to Tampico, preparing the road for a division of volunteers that was to take part in Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott’s amphibious landing at Veracruz.

McClellan and his company rode the waves ashore on March 9, 1847, along with the rest of Scott’s army. McClellan wrote of a shot whizzing overhead just before his landing craft was cast off. He expected to be under heavy fire as they were rowed ashore, but to his surprise that single whistle was the only one he heard: the landing was unopposed.

Once on land, the engineers, commanded by Col. Joseph Totten, got to work. McClellan

and other officers oversaw the construction of siege works used to force the surrender of Veracruz. Once, while reconnoitering beyond the lines, McClellan discovered the city’s main aqueduct, which the Americans soon cut. The daytime work was dangerous, as the enemy constantly fired at the workers and their overseers. At night the sand fleas tortured their victims as they tried to sleep.

Starting on March 24, the army’s guns and heavy ordnance borrowed from the navy bombarded the city’s defenses. The Mexicans asked for a truce the morning of the 26th and surrendered on the 27th. Soon Scott’s force moved west on

20 CivilWarNews.com August 2023 20 August 2023 CivilWarNews.com

George B. McClellan. Major General commanding U.S. Army. Fabronius, J.H. Bufford’s lithograph, Boston. (Library of Congress) Bombardment of Vera Cruz. March 25th 1847. Lithograph published by N. Currier. (Library of Congress)

Landing of the American forces under Genl. Scott, at Vera Cruz, March 9th, 1847. (Library of Congress)

the National Road, toward the capital, 250 miles inland.

Fifty miles from the coast the U.S. forces came to Cerro Gordo, where the Mexicans, fortified in a narrow pass, blocked the highway. In his memoirs Ulysses Grant described the difficulty of attacking this position. “The road…zigzags around the mountain-side and was defended at every turn by artillery. On each side were deep chasms or mountain walls. A direct attack along the road was an impossibility. A flank movement seemed equally impossible.”

A way around had to be found. McClellan was on a detail, under Capt. Robert E. Lee, charged

with the task of blazing a trail through the rough terrain. The route was difficult, but a path was made. A force of infantry and artillery reached a position for assaulting the Mexican left. However, when this flank attack was made, McClellan was at the other end of the line, with four regiments of volunteers under Maj. Gen. Gideon Pillow, who had been ordered to make a diversionary attack on the Mexican right. Pillow’s attack was botched, but the main attack by two divisions forced a hasty and disorganized retreat. In his diary McClellan lambasted the inept “parcel of volunteers” and their commander, who displayed

“worse than puerile imbecility.”

After Cerro Gordo the army paused at Puebla. Many volunteers went home when their enlistments expired, so Scott had to wait for fresh troops. McClellan used the down time to study the earlier invasion of Mexico by Cortés. Soon he would continue along the route trod by the conquistadors. Starting in early August, the army headed west, severing communications with Veracruz and living off the land.

Engineer McClellan became an artilleryman pro tem during the Battle of Contreras on August 19. The American troops trudged through the Pedregal lava field,

following a rough path hastily made by the engineers and hundreds of laboring soldiers. As they approached the western end of this horrid landscape (described by Eckenrode and Conrad as “a plain of fire frozen into rock”), the troops were met by artillery fire from a fortified position. Pillow ordered two batteries moved into position to return fire. This order was conveyed by McClellan, who soon found himself in the midst of a lopsided artillery duel. As the Mexican guns took a terrible toll on the outgunned American batteries, Lt. McClellan assumed command of some guns when their officers were seriously wounded. He lost two mounts to enemy fire and was himself hit, but he suffered no serious injury and remained in action.

The following morning American infantry flanked the Mexicans again, forcing another withdrawal. Here, at Churubusco, McClellan was again in action, taking part in an assault which drove the Mexican forces back. For his bravery and leadership, McClellan earned words of praise in the official report and a promotion.

Next came the climactic attack on Chapultepec, the lofty fort protecting two causeways into Mexico City. At Chapultepec the temporary artillery commander went back to engineering, a job not necessarily less dangerous than artillery. On the night of Sept. 11 McClellan and the men he trained, under the direction of Capt. Robert E. Lee, laid out two batteries of siege guns. The following day, while under enemy fire, the engineers placed two more heavy batteries.

After a 14-hour bombardment the infantry assaulted and captured the castle. The American troops pursued the retreating Mexicans toward the city.

According to Sears, “McClellan and the engineer troops took the lead in the house-to-house fighting, breaking through the common walls with pickaxes” as they fought their way along the causeway. American forces took the city gates. The defenders evacuated the city on Sept. 14.

After the American victory at Mexico City the fighting ended under the terms of a truce, which lasted until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. During the eightmonth occupation of the capital McClellan served as his company’s quartermaster. He enjoyed very comfortable quarters in a fine home owned by a highranking Mexican officer. During his off-duty hours he attended the opera, went sightseeing and

In addition to McClellan’s actions in the preparation for and during the fighting, some details not directly related to the battles may be of interest to the reader.

One episode discussed by Sears is McClellan’s disappointment in not being ranked first in his class. To most people, I think, being number two at the United States Military Academy would be a source of great satisfaction. One would expect the secondplace man to offer the top man a sincere and comradely congratulations and keep any disappointment to himself. McClellan, however, thought he was the best and wrote to his family that he had “malice enough to want to show them that if I did not graduate at the head of my class, I can nevertheless do something.”

McClellan showed no more aplomb when he was not promoted early in the war. He had asked his influential father to help him get a captaincy in one of the newly-authorized regiments of regulars. He lost out, and in a letter to his father displayed a fierce resentment, blasting a government so foolish as to be blind to his merit. He started at the top with Pres. Polk and then attacked the new regimental commanders, “deficients of the Mil. Academy, friends of politicians, & bar room blaguards.”