Opens After Four Year Restoration

ATLANTA, Ga.—On Feb. 22, 2019, the Atlanta History Center opened The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama after a four-year, $35.8 million relocation and restoration project. The 360-degree painting is the centerpiece of the Center’s 25,000-square-foot multi-media exhibition Cyclorama: The Big Picture.

In 2017, The Battle of Atlanta and the locomotive Texas were moved from a 1921 building in Grant Park, Atlanta, to the newly-constructed Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building at the Atlanta History Center. Both artifacts have undergone complete restorations.

Created by the American Panorama Company in Milwaukee during 1886, the cyclorama portrays the U.S. victory of July 22, 1864, when General William T. Sherman’s armies repulsed a determined Confederate attack directed by General John B. Hood along the Georgia Railroad east of Atlanta.

A team of 17 mainly German artists painted the 18,000-squarefoot painting in less than five months. Using sketches made

on the battlefield, they re-created the moment at approximately 4:45 p.m. when General John A. “Blackjack” Logan led a counterattack against Confederates who had captured the DeGress Battery at the Troup Hurt House. The entire scene was composed from a Northern perspective so that it would appeal to Northern audiences. Only in large Northern cities were there enough paying customers to make the massive paintings profitable.

The Battle of Atlanta was shown in Minneapolis and Indianapolis through 1890. There was also a second copy of The Battle of Atlanta exhibited in Detroit and Baltimore. This second copy fell into disrepair and disappeared around 1900.

In 1891, Georgia entrepreneur and showman Paul Atkinson purchased The Battle of Atlanta in Indianapolis after it had gone bankrupt. He moved it to Chattanooga and then Atlanta, where he advertised it as the “Only Confederate victory ever painted” to appeal to Southern audiences.

After going bankrupt again, The Battle of Atlanta was donated to the city of Atlanta in 1898. After nearly thirty years in a “temporary” wooden building, where it suffered considerable damage, the painting was enshrined in the 1921 steel, concrete, and marble structure in Grant Park, where it remained through 2017.

Of at least 40 cycloramas that toured the United States depicting battles, biblical scenes, and disasters, only The Battle of Atlanta and The Battle of Gettysburg survive. One inspiration for The Battle of Atlanta project was the move and restoration of The Battle of Gettysburg cyclorama between 2004 and 2008.

In the 127 years that The Battle of Atlanta has been on display in Atlanta, the cyclorama has been the subject of periodic re-interpretation. At times, it was seen as a proud symbol of the capital of the New South rising from the ashes left by Sherman. It has also been criticized as an anachronism

meant to glorify the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy. Perceptions of history, and the painting itself, have depended on the eye of the beholder, as audiences viewed it in different times and places.

In 2012, a task force convened by Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed recommended moving The Battle of Atlanta from its outdated ninedecades-old building to a new one to be built at the Atlanta History Center. On July 23, 2014—one day after the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta, Reed announced a 75-year licensing agreement with the non-profit Atlanta History Center for the relocation and restoration of The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting and the Texas

A $10 million endowment pledge from Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker initiated fund-raising

for the project. The Center raised an additional $25.8 million in private funds to design and construct a new building, relocate the painting, restore it to its original 1886 size and appearance, and create new interpretive exhibitions. From July 2014 through February 2019, a team of more than 200 architects, engineers, riggers, construction workers, and art conservators worked to bring The Battle of Atlanta back to life. The most significant challenges were erecting the building and engineering the move of the 10,000-pound painting as well as the 53,000-pound Texas

Today, three once missing sections of the painting have been restored: a 54-inch-wide vertical strip to the left of the Troup Hurt House (damaged and removed in 1893), a 22-inch-wide

vertical strip along the Decatur Road (excised in 1921 because the new Grant Park building was too small); and seven feet around the upper edge of the painting (removed incrementally as the painting was moved in the late 1880s and early 1890s).

The sky, overpainted in 1922, has also been restored to its original appearance. Today, The Battle of Atlanta stands at its original size of 49 feet tall and 371 feet in circumference, just as visitors first saw it in 1886.

Entering the new exhibition, Cyclorama: The Big Picture, guests are greeted by an introductory video and a 10-foot-tall animated map illustrating the course of the Civil War in Georgia. Two levels of exhibitions examine the

Civil War News

Published by Historical Publications LLC

520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412

800-777-1862 • Facebook.com/CivilWarNews

mail@civilwarnews.com • www.civilwarnews.com

Advertising: 800-777-1862 • ads@civilwarnews.com

Jack W. Melton Jr. C. Peter & Kathryn Jorgensen

Publisher Founding Publishers

Editor: Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D.

Advertising, Marketing & Assistant Editor: Peggy Melton

Columnists: John Banks, Craig Barry, Joseph Bilby, Matthew Borowick, Stephen Davis, Stephanie Hagiwara, Gould Hagler, Tim Prince, Salvatore Cilella, John Sexton, Michael K. Shaffer

Editorial & Photography Staff: Greg Biggs, Joseph Bordonaro, Sandy Goss, Gordon L. Jones, Michael Kent, John A Punola, Bob Ruegsegger, Gregory L. Wade, Joan Wenner, J.D.

Book Review Editor: Stephen Davis, Ph.D., Cumming, Ga.

Civil War News (ISSN: 1053-1181)

Copyright © 2018 by Historical

Publications LLC is published 12 times per year by Historical Publications LLC, 520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412. Monthly. Business and Editorial Offices: 520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412, Accounting and Circulation

Offices: Historical Publications LLC, 520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412. Call 800-777-1862 to subscribe.

Periodicals postage paid at U.S.P.S. 131 W. High St., Jefferson City, MO 65101.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Historical Publications LLC 520 Folly Road Suite 25 PMB 379 Charleston, SC 29412

Display advertising rates and media kit on request. The Civil War News is for your reading enjoyment. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of its authors, readers and advertisers and they do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Historical Publications, LLC, its owners and/or employees.

P UBLISHERS :

Please send your book(s) for review to:

CWN Book Review Editor, Stephen Davis

3670 Falling Leaf Lane, Cumming, GA 30041-2087

Email cover image to bookreviews@civilwarnews.com

Civil War News cannot assure that unsolicited books will be assigned for review. We donate unsolicited, unreviewed books to libraries, historical societies and other suitable repositories. Email Dr. Davis for eligibility before mailing.

ADVERTISING INFO:

Email us at ads@civilwarnews.com Call 800-777-1862

MOVING?

Contact us to change your address so you don’t miss a single issue. mail@civilwarnews.com • 800-777-1862

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

U.S. Subscription rates are $38.50/year, $66/2 years, digital only $29.95, add digital to paper subscription for only $10/year more. Subscribe at www.CivilWarNews.com

TO THE EDITOR:

I enjoy the Civil War News and find it most informative. The piece on Hiram Roosa’s collection was especially timely, as I had been asked to give a book report in February to the San Fernando Valley [Los Angeles area] Civil War Roundtable on The Rest I Will Kill: William Tillman and the unforgettable story of how a free black man refused to become a slave by Brian McGinty (Liveright Publishing Corp, New York, 2016). However, I believe that Roosa’s and Leon Reed’s statements that the captain and officers of the SJ Waring were set free in Cuba may be in error. McGinty (page 92) asserts that on July 9, two days after capturing the Waring near New York City, the Confederate privateer Jeff Davis intercepted the Mary Goodell off Rhode Island and transferred all her prisoners, including those taken from the Waring, to the Goodell. The Goodell promptly returned to Portland, Maine. So the citizens of New York had word of the Waring’s capture before that ship returned.

Given the relative distances between New York and Charleston, and New York and Cuba, the release of prisoners in the North seems far more likely.

“Let Them Rest” by Gould Hagler was also very good.

Nancy Martsch Sherman Oaks, Calif.Correction:

In the March issue we neglected to give credit for four photographs published with the “This and That” column. The photos were provided by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association and were published with the Association’s permission. We regret the oversight and wish to express our thanks to Association and its CEO, Bill Stephens.

Completely overpainted in 1922 to hide water stains, the sky was returned to its original light blue color. Plastic sheeting protected the rest of the painting during this work. Included as a salute to Wisconsin soldiers, “Old Abe,” the War Eagle, still soars above the scene, despite his absence during the battle.

Nancy Livengood retouches the figure of Captain Frederick Whitehead, Assistant Adjutant General of the XV Corps, using high-resolution copies of 1886 photographs of the painting. There are 24 U.S. officers identified by name in the cyclorama but no Confederate officers are identified.

April 2019

untold stories of the painting, consider the role visual entertainments have had in shaping perspectives of the Civil War, and provide a look at the fleeting entertainment sensation of cycloramas.

Among the key artifacts exhibited are: the sword carried by Confederate Brigadier General Arthur M. Manigault during the assault on the DeGress Battery,

Civil War News

the sword used by Captain Francis DeGress to defend his battery, a Henry rifle used by Private Enos Tyler of the 66th Illinois near the Troup Hurt House, and a wooden chest and other personal effects of U.S. Major General James B. McPherson, who was killed during the Battle of Atlanta. Also on display are original artists’ sketches and oil studies for The Battle of Atlanta, a

preliminary sketch for a competing cyclorama of the Battle of Atlanta that was never made, and original cyclorama advertising brochures, photographs, and memorabilia from the collection of Sue Boardman, historian of The Battle of Gettysburg cyclorama.

In the 1880s, cycloramas were an immersive experience; they were the IMAX of their time. Every step in the extensive twoyear restoration process has been choreographed to revive that original viewing experience, albeit with visitor accessibility and safety in mind (cyclorama buildings of the 1880s were firetraps!). Visitors enter The Battle of Atlanta through a 7-foot-tall tunnel—passing underneath the diorama—before ascending an escalator to a 15-foot-tall stationary viewing platform. Here they get a full 360-degree view with the horizon at eye level, exactly as intended by the artists. There are no timed tours; you can stay as long as you want. The view is enhanced by LED lighting technology and a 12-minute largerthan-life theatrical presentation projected onto the painting at the top of every hour.

Visitors can also walk underneath the viewing platform, different from cycloramas of the 1880s. Seeing the diorama from

ground level reveals how the illusion above you works. It is all about tricking the eye. There is also a series of computer kiosks on this lower level that explain specific scenes in the cyclorama. Here you can learn about the battle and its famous personalities while sorting out what is historically accurate in the painting versus what is artistic license.

All cycloramas of the 1880s were meant to have a diorama, or artificial terrain, in the foreground. At the time, however, none were made with human figures because it was thought they might detract from the painting. Between 1934 and 1936 two Atlanta sculptors created 128 plaster soldier figures to enhance the three-dimensional illusion of The Battle of Atlanta. Today these figures, including one later adorned with the face of Clark Gable, are considered integral to the artifact and have also been restored.

Even if you have seen The Battle of Atlanta before, you have never seen it like this; and if you have never seen it, you are in for a spectacular treat!

The Atlanta History Center is open 10 a.m.–5:30 p.m. MondaysSaturdays and noon–5:30 p.m. Sundays. For more information, please call 404.814.4000 or visit AtlantaHistoryCenter.com.

Preserving the military history of the Western Hemisphere since 1949. Membership includes a scholarly quarterly magazine with an annual twelveprint uniform series. Join us!

Contact: David M. Sullivan Administrator

Email: cmhhq@aol.com Visit our website at www.military-historians.org

Sculptors of the 1930s only molded the parts of the figures visible from the viewing platform. As seen here, the front legs of this figure were left hollow to save weight and materials. The blanket roll is simply a rolled-up sheet.

Visitors entering the cyclorama rotunda see the back of the cyclorama painting. A weighted ring at the bottom edges revives the original hyperbolic, or curved, shape. Without this suspension, the painting in its old building hung like a wrinkled curtain.

In an exhibit gallery under the viewing platform, interactive computer kiosks allow visitors to explore various figures, landmarks, and scenes. For example, here you learn the real story behind General John A. Logan, who did not sponsor the painting as was often claimed in the past.

Whoever weds himself to the spirit of this age will find himself a widower in the next. — William

IngeFew realize that Florida was so committed to The War Between the States that she gave more soldiers to repel Northern invaders than she had registered voters. Gainesville was among the towns that responded. As a result, the local United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) chapter later erected a statue of an ordinary infantryman honoring the hometown boys who had fallen, including many buried anonymously far from home. When erected in 1904, most of the living veterans were in their sixties and seventies. In May 2017 the county commissioners voted to remove the monument, which had become fondly known to most residents during the previous 113 years as Old Joe. After the vote, one audience member raised her hand to ask a question. The Chair recognized Nansea Markham, President of the local UDC chapter. She asked, “What will you do with the memorial?” The county attorney explained that the statue would be sold at auction if it was worth over $2,000. Otherwise Joe would be scrapped.

Nansea stood and held an old document at shoulder height before saying, “I’m sorry. You cannot do that.” Motioning with the papers she added, “This is the

Rescuing Old Joe

original 1903 document pertinent to Old Joe’s legal status. It shows that he remains the property of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.”

The commissioners held an impromptu conference as the audience looked on. Afterward the Chair announced that the commission would give the UDC sixty days to accept the return of Old Joe. He added that if the offer was accepted the UDC would be responsible for all moving expenses and must complete the move within sixty days of acceptance.

One commissioner who voted to remove the statue had previously announced that he would not allow the county to spend a single dime to move the memorial. He would rather see it destroyed.

Although Nansea was relieved for one last chance to save Old Joe, her chapter had less than $1,000 in the bank. Given the security requirements and care required to safely relocate so old an object, she worried the task might be too difficult. The next morning, however, she began to get supportive phone calls and emails. Many previously silent sympathizers recognized her from earlier Old Joe hearings before the commission and other local organizations during the preceding two years.

One phone call from a Vietnam vet lit a fire in her heart. He explained that the American soldier’s creed requires that a warrior

will “never leave a fallen comrade.” He told Nansea, “That’s how I see Old Joe’s situation. You are rescuing him. He is a veteran and I cannot leave him fallen on the ground to be scrapped. I will send you money.” Realizing that many older Americans now cringe with shame at how they treated returning Vietnam vets in the 1960s and 70s, Nansea reasoned that the same might apply to Old Joe in the years ahead. Thereafter she took every phone call and replied to every email. Many originated beyond Florida’s borders, including states above the Mason-Dixon Line. She took suggestions such as creating a FaceBook page and a GoFundMe Internet site. But she never directly asked for money. It started arriving anyway. She mobilized the UDC chapter members to send a hand-written “thank you” note to every donor. On July 20, 2017, she notified the county commission: “We [the UDC chapter] accept the Confederate Soldier Statue.”

Her laconic acceptance prompted repeated media inquiries including from national organizations such as The Washington Post and National Public Radio. She took the phone calls but politely declined to be interviewed or quoted. “Why?” asked one NPR reporter. “An interview would add publicity to help you raise money to move the statue.” “That’s true,” said Nansea, “but it might also attract unwanted attention. My job is to get Old Joe safely moved. I don’t want publicity that might trigger vandals.”

By mid-August the Gainesville UDC chapter had raised $30,000 and secured a site for Old Joe on private property adjacent to a cemetery containing the bodies of some Confederate veterans. The county attorney required Nansea to sign a twelve-page agreement that held the UDC chapter liable for any damages caused by Old Joe’s removal. Her group was also responsible for security in the event of interference from protesters.

Unfortunately, violent anti-Joe demonstrators were a genuine threat. They realized that the county government would do nothing to protect the memorial. As a result, they eagerly awaited the moving day when they assumed the media would be present. But Nansea fooled them. In the days leading up to the move she organized theatrics in which volunteers pretended to be dissembling Old Joe but did little

actual work. Rain arrived on the true moving day. It was enough to keep the protesters away until the moving crew was ready to drive off.

Although a dubious zeitgeist drove Old Joe from public grounds, his valor remains intact. The Kirby Smith Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy rescued it. Note: Nansea’s name is pronounced Nancy.

Phil Leigh has authored five books on the Civil War and Reconstruction: Southern Reconstruction, Trading With the Enemy, The Confederacy at Flood Tide, Lee’s Lost Dispatch, and an annotated version of Sam Watkins’s memoir Co. Aytch. A sixth, U.S. Grant’s Failed Presidency will soon be released. During the Sesquicentennial he also authored twenty-four Civil War articles for the New York Times.

Reenactment History, Dixie Gun Works Catalog

In my December column, I wrote about the confusion at the Civil War Centennial reenactment of the Battle of Antietam. In doing so I ventured an opinion that that reenactment was the last one to take place on the actual original battlefield it was commemorating. I was incorrect. A reenactment of “Pickett’s Charge” the following year was held on the original field at Gettysburg. Reader and Gettysburg resident Mike Strong advised me that he “attended a dress rehearsal of Pickett’s Charge in 1962 that was staged on the Gettysburg Battlefield.” Unfortunately, he missed the actual reenactment the following year due to being hospitalized with mononucleosis. The early dress rehearsal was no doubt an attempt to avoid the confusing preparations that subsequently occurred at Antietam. Some classified the rehearsal for the Gettysburg Centennial as a commemoration of the ninety-ninth anniversary of the battle, and I suppose you could term it so if you wish. Did the rehearsal result in an excellent show in 1963? Apparently not.

On July 4, 1963, a newspaper reported that: “Some 30,000 persons, happy under a mellow sun, saw Pickett’s Charge launched almost on schedule yesterday.” The report went on to state that “there were some 500 buffs on each side.” The charge reenactment ended on a rather bizarre note, because when the opposing sides were 100 feet apart, the shooting stopped and both “lowered their arms, marched together to a spot behind the Bloody Angle, formed hollow squares, and pledged allegiance to the national government and raised the Stars and Stripes on a tall staff while a US Navy band played the National Anthem.” “Some problems” occurred, with spectators sitting atop the stone wall adjacent to the Bloody Angle, a helicopter buzzing over the assault, and a mongrel dog that had to be “shooed out of the line of fire by State Troopers.”

There were antics in reenactor ranks as well, as “carloads of patent medicine, heavily laced with alcohol, were sold to preserve the health and bolster the courage of the troops.” Mike recalled that “the circus atmosphere surrounding the 1963 event led to the Superintendent deciding that no more re-enactments would take place on the Gettysburg National Military Park grounds. The 115th event took place across from Howe Avenue on land that was privately owned and was subsequently acquired by the NPS.”

Dixie Gun Works New Offerings

Dixie Gun Works, the iconic black powder retailer, has published its 2019 catalog, with some new items of interest to the Civil War shooter. The catalog lists new Pedersoli rifles, including a reproduction of the

by Joe Bilby

by Joe Bilby

1854 Austrian Lorenz rifle. The Lorenz, in both original .54 caliber and reamed out to .58 caliber, was widely used by both sides during the Civil War. The Fifth New Jersey Infantry was originally equipped with Lorenz rifles. The rest of the Second New Jersey Brigade shouldered smoothbores, so the men of the Fifth were permanently assigned to skirmish duties, most notably during the brigade’s first big fight at Williamsburg, Va., in 1862. Dixie also sells a special Pedersoli mold for the .54 caliber gun. It casts a .547 diameter slug weighing 430 grains and features two deep grease grooves and two rifling bands. Another new rifle in the Dixie catalog is the Pedersoli remake of the famed Whitworth sharpshooter rifle. This .45 caliber gun, designed by British inventor Joseph Whitworth with hexagonal rifling, was perhaps the most accurate small arm of

the era. Queen Victoria reputedly fired one and hit a target at 400 yards. Small numbers of Whitworths were used to equip select Confederate marksmen in sharpshooter units during the last years of the Civil War.

Sticklers for historical accuracy see some faults in the Pedersoli Whitworth, as Pedersoli apparently used a shortened standard P53 stock rather than a Whitworth specific stock and equipped the gun with Enfield brass mounts, although the original Whitworths had iron mounts. One thing everyone agrees on, however, is the Pedersoli Whitworth’s shooting qualities are excellent. One friend of mine critical of the gun’s historical details added that “Pedersoli arms have great bores and can shoot well.” Dixie offers a .451 hexagonal bullet mold and hexagonal wads, which are sold separately. Traditional six-gun

shooters should be happy with Dixie’s new “Revolver Reload Kit.” The kit has everything you need, except the powder, to reload your percussion ignition revolver, including round balls, felt Wonder Wads, and the new Wonder Seals. The kit has enough material for 24 rounds, or four complete reloads. Some shooters use the seals above the ball to eliminate the possibility of a chain or cross fire. A snug fit bullet would suffice for that, but the Wonder Wad is great because it sweeps fouling out of the barrel behind the ball. Most chain fires are ignited by an ill-fitting cap that has fallen off the nipple (cone), but shooting folklore from the 1950s, when revolver shooters used to smear Crisco on the cylinder chambers above the bullet, persists in some quarters, and seals are easier to apply. With blanks it might be a good idea to use both seals and wads, just to be on the safe side, however. Among the other new Dixie offerings for hand gunners are a traditional “slim Jim” style holster designed for the massive Walker Colt revolver and a revolver loading stand adaptable to both .36 and .44 caliber guns.

Revolver Reload Kit: Each kit contains everything you need, except powder and caps. Round balls, felt Wonder Wads, and the new Wonder Seals. Provides enough for 4 complete loads (24 rounds). .36 and .44 calibers.

MA6006 Reload Kit - .36 cal

MA6007 Reload Kit - .44 cal

Deadlines for Advertising or Editorial Submissions is the 20th of each month.

Email to: ads@civilwarnews.com

Joseph G. Bilby received his BA and MA degrees in history from Seton Hall University and served as a lieutenant in the 1st Infantry Division in 1966–1967. He is Assistant Curator of the New Jersey National Guard and Militia Museum, a freelance writer and historical consultant and author or editor of 21 books and over 400 articles on N.J. and military history and firearms.

He is also publications editor for the N.J. Civil War 150 Committee and edited the award winning New Jersey Goes to War. His latest book, New Jersey: A Military History, was published by Westholme Publishing in 2017.

He has received an award for contributions to Monmouth County (N.J.) history and an Award of Merit from the N.J. Historical Commission for contributions to the state’s military history. He can be contacted by email at jgbilby44@aol.com.

The original pair of brass raking spurs featured here are, to the trained eye, easily recognized as Confederate. The raking style spur (rowels sideways) is a distinctly Confederate military design. It allowed the rider to roll the rowels against the horses’ flanks rather than just giving a poke. I have often read of battlefield courier’s horses’ flanks being bloodied and torn by the rider’s spurs, and though the writer never mentioned the type of spur that did the damage, I think it very likely that it was done by severe application of the raking spur.

This particular pair of spurs is one of the rarest of all Confederate spurs; so rare in fact, that to my knowledge, another matched pair does not exist. The only published examples are excavated specimens. The existence of this non excavated pair allows us to see that the previously held opinion that the CS was cast into the spur is incorrect; the letters

CS Marked Raking Spurs

are actually stamped, but this could not be discerned when examining excavated examples. In hindsight, we should have recognized that the varied spacing gave proof that the CS was not part of the molding process.

This pair of spurs uses two 1860, New Orleans mint quarters as rowels. The spurs did not come from the manufacturer this way; perhaps the owner changed them out to go easy on his steed. Regardless of why, it is apparent that they have been this way for a long, long time. The leather keepers are original.

Shannon Pritchard has authored numerous articles relating to the authentication, care and conservation of Confederate antiques, including several cover articles and is the author of the definitive work on Confederate collectibles, the widely acclaimed Collecting the Confederacy, Artifacts and Antiques from the War Between the States, and is co-author of Confederate Faces in Color.

Improvements for the Reproduction

U.S. Model 1861

“Gettysburg, Penn. July 3, 1863. We went out and picked up Springfields and left our Enfields. Nearly everyone did so.”– Diary of William Livermore, 20th Maine Infantry.

The U.S. Model 1861 rifle musket occupies a unique niche in Civil War history. The quote in the heading is based on instructions given by Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain to Union soldiers deployed on Little Round Top during a lull in the battle of Gettysburg. Is this a form of latent provincialism on his part or was there another reason why Chamberlain would tell his fellow Maine-men to discard their issued arms and glean the battlefield for “Springfields”? The most obvious conclusion you might draw is that the machine made, parts interchangeable M1861s were more desirable than the handmade (mostly not parts interchangeable) imported English P 1853 Enfields.

Another quote that reinforces this preference for the M1861 is from Pvt. Orrin Cook of the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry, Co. B. Cook hailed from Springfield, Mass., and served in the Army of the Potomac. He was engaged in most major Eastern Theater battles including Antietam, Sharpsburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Courthouse. Cook was injured at the Wilderness in 1864, but it did not keep him down for long. When the regiment mustered out later in 1864, he transferred to the 32nd Massachusetts for the duration of the war. In his memoirs, Cook notes the following about the arms they were issued: “Some of our boys got Austrian rifles, some Enfield and others Springfield. I got the Enfield and (my comrade) Bob got the finest arm of the whole lot, a fine United States Springfield rifle.” The term “Springfield” was a

catch-all phrase used by soldiers for what the U.S. Government officially referred to as the U.S. M1861 rifle musket, whether they were manufactured at the National Armory in Springfield, Mass., or by one of about twenty private companies that produced them on contract as pattern arms. There were 756,567 M1861 rifle muskets manufactured during the Civil War. Springfield Amory produced 265,129; government contractors produced the remaining 491,438. William B. Edwards notes in Civil War Guns (Stackpole Publishing 1962 p. 25) that had Lincoln’s first Secretary of War Simon Cameron not committed the United States Government to procuring these private contractor produced U.S. Model rifle muskets, “there would have been little chance for the North in the latter stages of the war.” The U.S. rifle muskets made by contractors were marked with the year of manufacture and an identifying name while those produced by the National Armory were marked “US Springfield” with the year of manufacture. This all seems straightforward enough. Hence, if a Union soldier was fortunate enough to be issued “a fine United States Springfield rifle” the odds were about 2:1 that it would have been manufactured by a private contractor rather than the National Armory. Soldiers don’t seem to have cared, as long as they got one. In fact, oddly enough, there is anecdotal evidence that Union soldiers who captured the C.S. Armory variation called them “Richmond Springfields.”

If you happen to favor the reproduction M1861, every current reproduction comes marked one way only…”US Springfield” with a date of 1861. This by itself is somewhat problematic as less than ten percent of Springfield Armory’s total output was manufactured during 1861. For those of who care about such details, there is some good news to report. There are new options to lend a bit more historical accuracy to your reproduction

M1861. Gunsmith Todd Watts, email wattsdefarbs@gmail.com,

is now offering several government contractor variations for the M1861. Watts is perhaps best known for his work on reproduction Enfields and U.S. M1841s (Whitney and Harpers Ferry). Some years ago, he de-farbed my ancient mid-1970s vintage Parker-Hale Enfield as a LACo dated 1862. The case colors are still vivid on the lock plate. I also have an equally ancient (mid-tolate 1970s) U.S. M1861 made up of original and reproduction parts with a custom barrel made by Mike Yeck. It had one of the aforementioned “US Springfield 1861” reproduction Miroku lock plates that was always a sore point for me and it seemed time for an upgrade. I selected the “Philadelphia” variation, based on the initial government contract with John Rice that was actually filled by Alfred Jenks.

John Rice has an interesting story. He wrote Secretary of War Cameron on Oct. 2, 1861, offering to supply muskets for the Union. Rice was not himself a gun maker. He was actually a contractor for stonework at the U.S. Capitol building and a carpenter by trade, but he had many contacts “in the mechanical industries of Philadelphia.” He wrote in his correspondence to Secretary of War Cameron that “I can organize the manufacture of (US rifle muskets) at various places in Philadelphia and furnish from ten to twelve thousand by July 1, 1862…and furnish employment to a large number of workmen who are now idle.” Despite the apparent philanthropy, his offer was not accepted but, after “checking about in Philadelphia,” Rice came back with a new proposal to make 3,000 to 4,000 per month for twelve months commencing in Feb. 1862. This offer was accepted and on Nov. 21, 1861, he received a contract for 36,000 “Springfield pattern rifle-muskets.” The deliveries were to begin with 3,000 in Feb. 1862 and an additional 3,000 per month afterwards. The catch was that “in case of any failure to make deliveries to the extent and within the times specified all obligations of

the United States to receive and pay for any muskets…shall be cancelled and become null and void.” This meant that Rice, who never made arms in his life, had two and a half months to supply 3,000 M1861 rifle muskets. The U.S. government was also curious and inquired where his operation was to be located? He did not own a factory to manufacture parts or even a workshop to assemble the arms. He hoped to find premises near the Springfield Armory, so he could more easily deliver arms for inspection there.

Rice seems to have been somewhat unconcerned about these details and set about to have several lock assemblies made up that were delivered to Springfield Armory and passed inspection with gauges, as well as several ramrods which did not. He was also unsuccessful in his initial attempts at getting his iron barrels made before July 1862, and he sought an extension to the initial deadline. Rice entered contracts with at least ten subcontractors to provide various parts, at least some of whom had their own government contracts to fill, in addition to supplying any parts to John Rice. It appears he finally realized there was more to manufacturing parts interchangeable M1861 rifle muskets than making kitchen cabinets and sought in April 1862 to have the Government take the contracts off his hands or as Rice phrased it, “…be relieved of the liabilities.”

Did John Rice ever get any finished M1861s out the door? There are existing examples found with the lock plate marked “Philadelphia” and dated 1862. Claud E. Fuller notes in The Rifled Musket (Stackpole 1958) that the Philadelphia marked M1861s were fully produced by Alfred Jenks of Bridesburg Machine Works, but at a separate shop located in Philadelphia. William B. Edwards states in Civil War Guns that there is some evidence that Alfred Jenks (Bridesburg) took over the John Rice contract and supplied “Philadelphia” marked M1861s as a part of his government contract for 98,000 arms. Undoubtedly that was the case;

Jenks was already one of the subcontractors initially providing gunstocks and stock tips to John Rice, as well as parts to many other contractors. Claud E. Fuller states that the “Philadelphia” marked M1861s were all finished and provided by Alfred Jenks, while Edwards allows that “Rice was able to get a few arms finished…before defaulting on his contract.”

Alfred Jenks was not only the highest producing individual contractor but also one of the two private contractors with the fewest rejects after the rigorous U.S. government inspection with gauges at Springfield Armory.

Craig L. Barry was born in Charlottesville, Va. He holds his BA and Masters degrees from the University of North Carolina (Charlotte). Craig served The Watchdog Civil War Quarterly as Associate Editor and Editor from 2003–2017. The Watchdog published books and columns on 19th-century material and donated all funds from publications to battlefield preservation. He is the author of several books including The Civil War Musket: A Handbook for Historical Accuracy (2006, 2011), The Unfinished Fight: Essays on Confederate Material Culture Vol. I and II (2012, 2013) and three books (soon to be four) in the Suppliers to the Confederacy series on English Arms & Accoutrements, Quartermaster stores and other European imports.

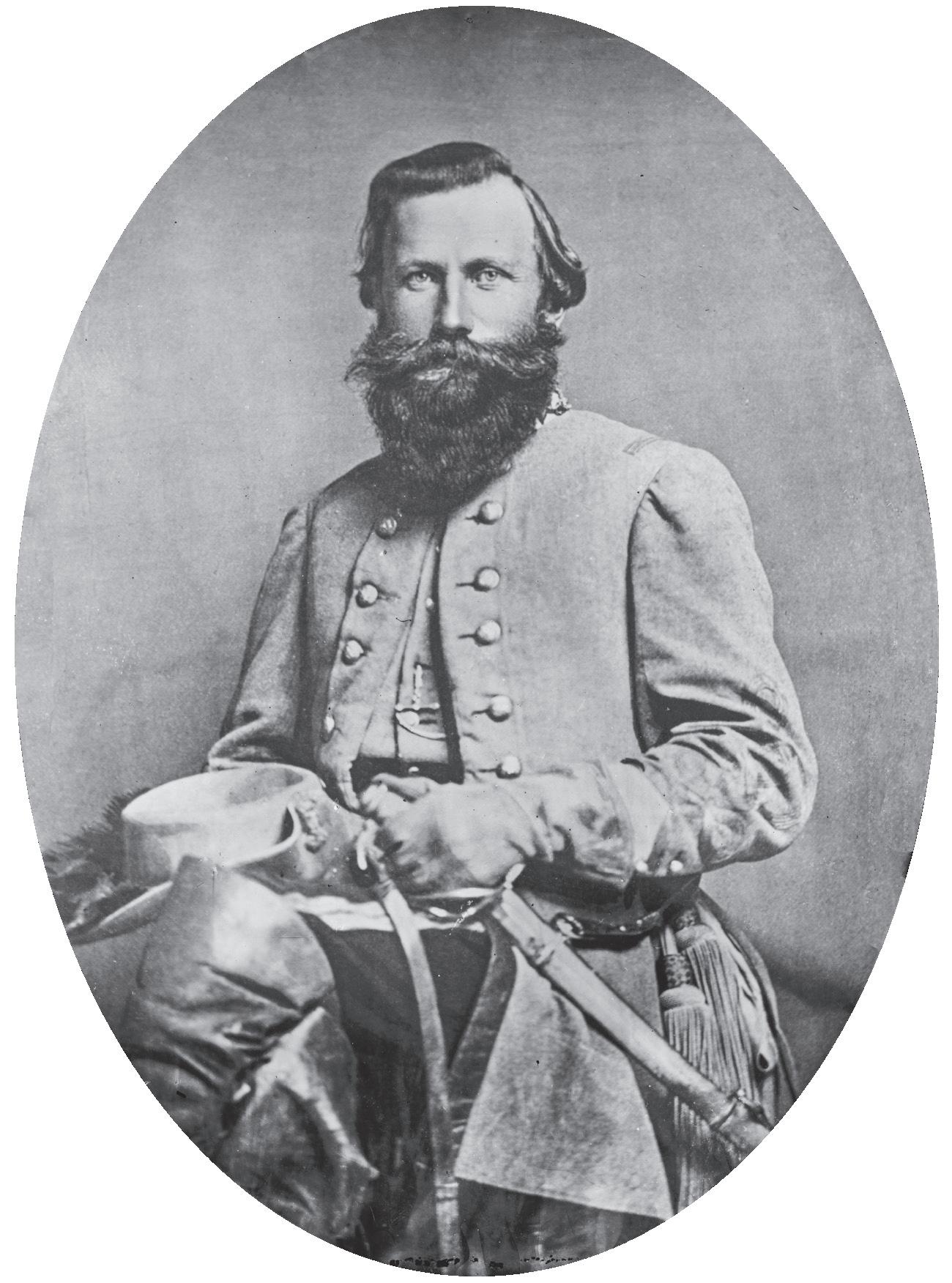

This article, “Atlanta and Nashville,” is in the Augusta Constitutionalist of February 5, 1865. It is signed “G. W. Y.” On the 7th the paper issued a correction, “G. W. Y. should have been G. W. S.,” leading us to conclude that the author was Gustavus W. Smith, who was living in Augusta at the time. General Smith was John Bell Hood’s distant cousin, whom Hood visited in early February as he passed through Augusta on his way to Richmond after his resignation from army command.

We believe Hood was already writing his report of the Atlanta and Tennessee campaigns, and may have shown a draft of it to Smith, or at least talked with him about its contents. Together the two men apparently decided upon planting this article in the Southern press as a means of conveying Hood’s narrative of events. As such it is very one-sided and self-serving for Hood, but it is possibly the clearest and most succinct articulation of his viewpoint in print. We therefore present it in full, for the first time, we think, in the historical literature.

The “G. W. Y. article” was

Clippings from the Past

reprinted in the Richmond Sentinel of Feb. 17, 1865, which is the text reproduced here.

From the Augusta Constitutionalist, Feb. 5. Atlanta and Nashville.

Generals are often deprived of commands by the chief executive officers of their country, because public opinion sometimes demands it, and it may be that the Executive is opposed to the plans of the General. Sometimes they are not properly supported by the government and retire from the service, satisfied that others who are more fortunate in possessing the confidence and good will of the Executive, would be far more likely to achieve success in war. At other times generals voluntarily retire from commands, although strongly supported by both the government and their own army, because public opinion is expressed through the newspapers severely censuring the plans and movements devised by them.

General Bragg commanded the army of Tennessee lying in front of the enemy at Chattanooga, covering Atlanta. The army was

in great part opposed to him; the press and the people were opposed to him. His removal was demanded. The President yielded to this after a long struggle; Bragg was removed and Joseph E. Johnston assigned to the command.

About the 7th of May Sherman advanced upon Johnston then lying at Dalton. It is conceded by all that Johnston’s army at that time was in the highest effective fighting condition in every respect. After Polk joined him, the army numbered about 65,000 effective men. Johnston on the 14th of July had been forced back across the Chattahoochee, having lost all of North Georgia, and over 20,000 of his men without bringing on a general engagement. The spirit of the army was almost ruined by constantly retiring—always on the defensive, fatigued almost beyond endurance by digging trenches for personal security, its morale was not only badly injured—it was almost lost. The enemy holding their own in numbers, were every day becoming more energetic and defiant.—When Johnston crossed the Chattahoochee, beaten back to the very suburbs of Atlanta, he

was relieved of his command by Mr. Davis, and General Hood was placed in command of the army on the 18th of July.—Never, probably, was a young officer promoted and assigned to the command of any army under more difficult and trying circumstances.

We are informed that General Hood has been relieved of the command at his own request. This, no doubt, was caused by the fact that the press and the people were censuring his operations with great severity, calling loudly upon the Executive to replace General Johnston [SIC Hood], and fast creating in the minds of all his sick and absent soldiers as well as upon many subordinate officers and privates in his army, the impression that Hood is a good fighter but has no head.

The enemy, too, join in depreciating his capacity as a military leader. This may be for a purpose, as well as they may be especially meaning in the violent opposition manifested towards this young General by certain parties in our own country.

Before entering upon the following statement of facts and opinions, it is proper to state the writer of this article is no friend of

Jefferson Davis. Hood took command of the army near Atlanta on the 18th of July. He immediately changed the policy of the campaign from the defensive to the active offensive.

On the 20th, he attacked the enemy in position, and if Hardee’s corps had executed the part assigned to it, what was only a partial success, would have resulted in a complete victory. This, Hardee himself admitted, and stated that he could not get his orders obeyed.

Again, on the 22d, Hood attacked the enemy and the partial success of Hardee demonstrated conclusively, what the result would have been had Hardee executed the orders given him by General Hood, by which he was required to completely turn the position of the enemy—if to do this he should have to march as far as Decatur or even beyond.

The fortifications of Atlanta were of little if any strength, at the time Hood took command of the army, and the position was by nature very far from being advantageous—still he held Sherman at bay for more than forty days, twice during that time attacked and would have beaten

the enemy had his orders been executed. This was the state of affairs on the 30th of August. Hood lost during this time less than seven thousand men, but not one inch of ground. His army in the meanwhile was regaining much of its former spirit and morale.

Nothing could as yet be said against Hood’s practical generalship. Johnston in seventy days had lost the strongly fortified position between Dalton, all the strong defensible positions between Dalton and Atlanta, and with them all North Georgia—he had lost more than twenty thousand men, and the fighting spirit of his army had been materially impaired—so far certainly there was nothing to indicate that Johnston in his campaign showed any superiority over Hood. On the 30th of August, Hardee, with his own corps and that of Lee’s, was ordered to attack that portion of the enemy which had crossed Flint river, in the direction of Jonesboro.’ He was ordered not to cross the Flint river for the purpose of attacking, but on his arrival to attack and beat back whatever forces he might find between Flint river and the Macon and Atlantic railroad. The enemy had two small corps in position. Had they been badly beaten, it was supposed that Sherman would move to their support, and leave his fortifications, thus

enabling Hood, with a large portion of the forces under Hardee, and Stewart’s corps from Atlanta, to strike between Sherman’s army and the river, without having to strike his strong fortifications, which already extended from the river to West Point railroad. The fact was impressed upon General Hardee that upon the success or failure of this attack depended the fate of Atlanta. Hardee had more men on the decisive point than Sherman had.

His attack failed most signally. Our troops, after a short contest, retired from the field, with a loss of only about 1,400 men in the two corps. Thus, for the third time, was Atlanta played for and lost. Every time the orders of the commanding general were right, and the want of success was due to failure in their execution. At least such are known to be the opinions of Lieutenant General Stewart and Lieutenant General Lee, and other separate commanders under Gen. Hood.

The complete failure of Hardee’s attack at Jonesboro, placed Sherman’s army in position to destroy Macon and Columbus, and release 34,000 prisoners at Andersonville, turning them loose to incite rebellion amongst the slaves in Southwest Georgia, leaving the women and children, the non-combatants and the property of all that section a prey to the released prisoners, and

Vin Caponi Historic Antiques

We carry a very large inventory of Colt and Civil War firearms including muskets, carbines, rifles and accoutrements. Our inventory of historic antiques and firearms begin at the early collectors level and range all the way up to the advanced collector and investors level.

negroes, acting at their instigation. To prevent this Hood had to place his army between Sherman and Macon. Atlanta had, therefore, to be evacuated. But its fall is not fairly attributable to want of capacity and military ability on the part of Hood. Immediately after Hood took his new position at Lovejoy’s, Sherman retired to Atlanta, thus clearly proving that the enemy was not at that time in condition to continue the contest any further. This was the first retrograde movement forced upon his [sic him] between Dalton and Lovejoy’s. Sherman commenced to fortify Atlanta for permanent occupation, and he proclaimed that through this “Gate City” he would subdue and hold all Georgia.

The first great problem for General Hood to solve was how best to prevent this. Let any man in Georgia, be he soldier or not, ask himself what would have been the probable result had Hood fortified his position, and awaited Sherman’s preparations and reinforcements? Had he done this, in all human probability the enemy would at this time not only have held Atlanta and all North Georgia, but Macon, Columbus, Augusta and Savannah would have been taken and strongly fortified, with lines of communication in every direction made perfectly secure by works which the enemy knew perfectly well how to construct, and garrisoned in such way that their power would have been fastened upon us.

North Georgia is ours. The enemy have given up the almost impregnable fortifications which they constructed at Atlanta.—‘Tis true, they occupy the city of Savannah, but that port was closed to us already.— He marched through the State, but did not conquer and could not hold it. Who compelled Sherman to abandon Atlanta and left him to choose only between the sea coast, or retiring into Tennessee?

Gen. Hood believed that if he acted strictly upon the defensive, the enemy, strengthened and reinforced as all knew he soon would be, could compel him at any time to fall back, and this policy would inevitably result in the ultimate loss of the whole State by piecemeal. There was still another and very serious consideration which induced him to assume the active offensive, one which no commander can safely disregard. The morale and esprit de corps of the best army in the world can be ruined by retreating and digging. No one understands this better than General Hood. The public mind was prepared for the fall of Atlanta when Johnston’s army crossed the Chattahoochee.—But

after Hood had succeeded in holding the place for more than a month, they seem to have concluded he could and ought to hold it forever. When it did fall, with [sic without] stopping to inquire into the causes, he was at once charged with incompetency by the press; and this was so general and oft repeated as to cause serious doubts in the minds of many of his men in regard to his capacity as a leader. Hood had two objects in view; one was to get Sherman’s army out of the stronghold of Atlanta, the other to bring the army back to the highest point and spirit which it possessed in the beginning of the campaign at Dalton.

He, therefore, determined to take the initiative, and moved upon Sherman’s rear, destroying thirty miles of his railroad communication between Marietta and and [sic] Tunnel Hill. This compelled Sherman to withdraw his main army to the vicinity of Dalton.—Hood then moved by way of Gadsden to the Tennessee river, intending to cross in the vicinity of Gunter’s Landing, which would have forced Sherman to withdraw into Middle Tennessee. Before crossing, Hood considered it necessary to have the assistance and co operation of the great cavalry leader of the West for the protection of the trains of his army. By some mischance the orders to General Forrest did not reach him

in time. This rendered it necessary for Hood to move his army to Florence, in order to effect the required junction with Forrest. This movement caused sufficient delay to enable Sherman to repair his railroad, and crowd through from Nashville provisions sufficient to enable him to move from Atlanta to the coast with a large portion of his army. But for this compulsory movement of Hood upon Florence, Sherman could not have placed in Atlanta provisions enough to have justified his attempt to move a large force from this point to the coast. Sherman promptly availed himself of the opportunity, pushed provisions into Atlanta, divided his army and commenced his movement through Georgia. Gen Hood had then to decide which portion of this divided army he would attack. To turn back and pursue Sherman in Georgia would in the minds of his soldiers have been a compulsory retreat. They were by this time fully up to the highest fighting standard. A large portion of his army were Tennesseeans, and as seeming retreat without a fight might well have produced a very depressing effect upon the army. Besides, Hood knew that Sherman had barely sufficient provisions with which to make the march to the coast and a very short supply of ammunition. He therefore inferred that Sherman would not

stop to besiege the fortified cities of Georgia before reaching the coast and that a march through the State, beyond damage to railroads, would produce no important military result.

Thomas had in Tennessee the smaller portion of Sherman’s army. If Hood could not beat that he had a poor chance for coming up with and beaten [sic beating] Sherman. Thomas beaten, Nashville in our possession, the road to the Ohio river would be open, and Sherman would not be able to remain in the swamps of the Southern coast, with Hood’s army largely increased by recruits from Tennessee and Kentucky on the Ohio river, threatening the heart of the Northern country. Hood, for these reasons, determined to attack Thomas—moreover, he believed if he attacked Thomas and failed—it would be better than to have Thomas to follow him either into Alabama or Georgia without a battle. Certainly in his mind, it was better than having the combined armies of Sherman and Thomas, with uninterrupted railroad communications behind them slowly and surely fastening their hold upon all the vital points in the interior of Georgia, which he could not have prevented by acting upon the defensive. In his opinion the only possible way of preventing this result, was to possess himself of the railroad between Atlanta and Nashville.

We have yet to examine the question, how the campaign against Thomas was conducted by Hood from Florence. He moved upon Columbia, (and forcing the enemy to abandon it,) turning the fortified position of Pulaski. They crossed Duck river and took position upon the north bank and fortified themselves. Hood crossed higher up, and succeeded in gaining position near their line of communications at Spring Hill. The reason why this masterly and successive movement did not result in the destruction or capture of eighteen thousand of the enemy’s infantry, and all their artillery and trains, is well known in Hood’s army, and it is not necessary to allude to it further. The soldiers who were there know well whose head conceived and caused the movement to be executed, and who failed to inflict the fatal blow when all was ready prepared for it. The enemy, after making this narrow escape, retreated rapidly to Franklin. Captured dispatches indicated that the enemy contemplated fortifying Franklin, and holding the line of Franklin and Murfreesboro’. It being inexpedient to attempt a flank movement, and this being the last chance to

crush the enemy before he could reach the strong fortifications at Nashville, it was necessary to attack as soon as the troops could be put in position. The courage and conduct of the army in this fiercely contested struggle proved, beyond a doubt, that its old fighting spirit was restored, and stands in marked contrast with the conduct of the same troops at Jonesboro.’

After this decisive victory, Hood pushed forward to Nashville and fortified his position for the purpose of cutting off Thomas’ army from the garrisons of Murfreesboro, Knoxville and Chattanooga, thus forcing him to abandon these fortified positions, giving up that whole section of the country, or coming out to attack Hood in position.—Thomas did attack, and whilst all was going on well along Hood’s whole line, one division unaccountably gave way, which resulted in the retreat of the whole line in disorder.—In this struggle before Nashville, Hood was beaten by a giving way of a division—producing an almost immediate panic which could not be remedied. Notwithstanding the confusion and disorder, in which the troops left the field, they were soon rallied, and though the enemy made a vigorous pursuit, the army with its material safely crossed the Tennessee river—and the campaign ended.

This was not the first offensive campaign attempted by us during the war. Lee has made two, one into Maryland, ending with the battle of Sharpsburg; another into Pennsylvania, which culminated in defeat at Gettysburg. What great results were gained by either? Hood is charged with being a reckless fighter. In his record there is no Malvern Hill, or any approach to the like of it. It is no part of the present purpose to criticize General Lee’s military operations, or comment upon the mistakes or misfortunes of the leader battling so courageously in the suburbs of the Capital of the Confederacy.

Lee is, above all others, the favorite General, both with the Executive and the people, has been vested with almost plenary powers in regard to officers, men and materials, and stands first in the estimation of the armies of the country. Notwithstanding all this, there are those of high position competent and proper judges, too, who know Hood best, and are acquainted with the facts connected with his campaign, who believe that Hood in high capacity for active offensive war and characteristics of a great General, is fully equal to Lee himself—and that when their campaigns are made the subject

of fair military criticism, the facts in regard to those known, the records will show that not only in tangible and advantageous results, but in management and generalship Hood’s will compare favorably with either of Lee’s. It is true that some of the railroads in Georgia have been broken up by the enemy. But suppose Hood had not made his movement upon Sherman’s rear, and had allowed the combined armies of Sherman and Thomas, with railroad communications uninterrupted between Nashville and Atlanta, to move upon Central and Southern Georgia.—The chances all are those that the whole of Georgia would have been occupied by the enemy.

But whatever may be the differences of opinion in regard to Hood’s capacity, his management of the campaign and its results, the army under him, after all its hardships, fatigues and battles, has returned in fine spirits and effective condition, and may all be justly proud of their achievements, saving only the unfortunate few who, in an evil moment,

gave way, or failed to do what was justly and fairly expected of them.

When Lieutenant General Stewart, Lieutenant General Lee, Major General Forrest, and other commanders under Hood, express their unqualified conviction that the campaign failed in producing all the great results which could have been expected under the most favorable circumstances, not from any mistake upon

the part of their general, it is not unreasonable to ask the press and the people not to condemn, at least until they know something of the facts. The sentiments of a commander, and the officers and men of an army, are certainly better judges of the capacity of their leader than outsiders, be they presidents, legislators, soldiers, citizens, correspondents, or editors.

G. W. Y. Author Publisher’s Award of Literary Excellence

Steal My Dog I Steal Your Cat

“I little thought, when I faced the storm of bullets at Edwards’ Ferry, [Va.] and escaped a soldier’s death upon the field, that it was only to be left by my country to die upon the gallows.” – U.S. Col. Milton Cogswell

On April 17, 1861, C.S.A. President Jefferson Davis issued a proclamation, “inviting all those who may desire, by service in private armed vessels on the high seas,” to apply to become legal pirates for the Confederacy. Lacking a navy, Davis decided to combat U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s blockade by authorizing private ships to attack Union shipping and warships for profit. Several captains seized the opportunity to turn privateer. On

May 16, the Ocean Bark, at the mouth of the Mississippi River, became the first ship captured. The Federal Navy in turned captured privateers. The privateers expected to be treated as POWs. To their horror, they were put on trial as that scourge of all mankind – Pirates! Davis vowed to treat Federal prisoners the same as the captured privateers. Soon he had his chance. On July 18, the 13th N.Y. Volunteer Infantry had engaged in a fight at Blackburn’s Ford, Va. As the men included volunteers from his congressional district, the Hon. Alfred Ely considered it his duty to visit them. Ely obtained a pass from U.S. Gen. Winfield Scott, hired a carriage and set off to visit the men near Manassas, Va., on July 21. Ely had the bad timing of his visit coinciding with the First Battle of Bull Run.

On October 22, in Philadelphia,

Penn., the courtrooms were packed with the national political elite for the separate trials of five men from the privateer Jefferson Davis. The fate of the privateers was of avid interest around the nation and across the pond. Three days later, Capt. William Smith was sentenced to death by hanging. Three more men were sentenced to the same.

On October 23, in New York City, the dean of the New York bar, Daniel Lord, teamed up with renowned criminal defense lawyers James T. Brady and Algernon Sullivan, to defend the 12 crew members of the privateer Savannah. Lord had a personal interest. The first mate of the Savannah was the son of Lord’s Yale classmate. Before the trial began, Sullivan had corresponded with Confederate officials on his clients’ behalf.

U.S. Secretary of State William Seward had Sullivan thrown in the Ft. Lafayette, N.Y., prison for seditious contact with the enemy. Sullivan was released on an oath of loyalty shortly before the trial began.

From the start, Lincoln wanted to treat the secessionists as criminals. His decision to “blockade” instead of close Southern ports was “to avoid complications” that might result in a foreign war. U.S. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens had protested that by doing so, the United States was being committed, “to conduct the war, not as if we were suppressing a revolt in our own States, but in accordance with the law of nations.” Now the decision to “blockade” was being used to the privateersmen’s advantage.

The Savannah’s defense team argued that the dispute wasn’t over the essential facts. It was over how to characterize them. Were the men legitimate privateers like the American privateers of the War of 1812? Or were they high sea robbers? “Lord fumed about a government that claimed to treat southerners ‘as enemies, for the purpose of confiscation’ but ‘as traitors and pirates, for the purpose of execution.’” After six days of listening to the lawyers’ arguments, the jury came back

deadlocked. Another attempt to reach a decision failed. In the end, the government simply couldn’t convince the jury that the past six months of fighting was not a war.

Meanwhile, in Richmond’s Libby Prison, Ely was held in the officer’s quarters. Both residents and tourists flocked to see the “Yankee Congressman,” inspiring jokes to charge for tickets. On November 10, Ely was in the officer’s quarters as C.S. Gen. John Winder entered. Winder had been ordered to select by lottery, men of the highest rank, to be treated as felons and to be executed if the privateers were executed.

Slips of paper with the names of the six Federal colonels in Confederate custody were placed “in a tin case nearly a foot in depth, and only large enough to admit the hand. After shaking up the ballots,” Winder requested the only non-military man, Ely, draw the name of the colonel “who should stand as a hostage for privateer Smith now condemned to death in Philadelphia.”

The attention of 75 Federal officers was fixed on Ely as he fulfilled his “painful duty.” The first name drawn was Col. Michael Corcoran, Ely’s “mess mate and intimate friend.” Thirteen more names were drawn from the tin. Davis had the names of

the selected officers widely published. The men were marched off to the county jail, “confined in one small room, about twelve by sixteen feet.”

On November 21, newspaper publisher turned privateer John P. Calvo, wrote a protest letter to Lincoln. Calvo had been captured on August 3 and had grown weary of languishing in a NYC prison. Calvo’s position was that if the War continued it would be a “dog eat dog”—“steal my dog I will steal your cat” situation. The men on both sides, “should be considered and treated the same. … if you still think and will have it that I am a Pirate for serving my country, in God’s name have me indicted, tried, sentenced and hung instead of having me imprisoned. … Do you suppose dragging us from pillow to port in irons as have been done, and confined and fed as we are now will make us loyal subjects under the Stars and Stripes any quicker? If so, you and those in power are and will be deceived!”

After over five months in captivity, Ely was exchanged for the Hon. Charles Faulkner, former U.S. Minster to France. On December 29, Ely arrived in Washington, D.C., and spent the evening at the White House. Ely described to Lincoln and Seward his experiences at Libby Prison, including pulling the names out of the tin.

At this point, Lincoln had to have realized that his efforts to portray secessionists as criminals

had failed. The privateers were quietly redesignated as POWs and eventually exchanged. The Confederacy did the same with their “hostages.” However, the strategy’s failure was a small price to pay. Lincoln would use international law to avoid the pit falls that could result in having “two wars on our hands at once.”

Sources:

• Fabian, John, Lincoln’s Code: The Laws Of War In American History

• Ely, Alfred, Journal of Alfred Ely, a prisoner of War in Richmond

• Clavo, J.P.M. Letter to Abraham Lincoln, Nov. 12, 1861

• Daly, Charles P. L.L.D., the Southern Privateersmen Pirates, Letter to Hon. Ira Harris, US Senator

Stephanie Hagiwara is the editor for Civil War in Color.com and Civil War in 3D.com. She also writes a column for History in Full Color. com that covers stories of photo graphs of historical interest from the 1850’s to the present. Her articles can be found on Facebook, Tumblr and Pinterest.

Gun Works, Inc.

The Atlanta Papers (cont.)

This month, we march on with our look into Sydney C. Kerksis’s The Atlanta Papers; a collection of Federal accounts from the Atlanta Campaign. Major W.H. Chamberlin of the 81st Ohio Volunteer Infantry delivered Paper No. 18—‘Recollections of the Battle of Atlanta’—to the Ohio MOLLUS Commandery. Chamberlin, who served on the staff of Major General Grenville Dodge (XVI Corps), provided a detailed account of the July 22, 1864, battle. Colonel Robert N. Adams, D.D., led the 81st Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the Battle of Atlanta and recalled ‘The Battle and Capture of Atlanta’ in Paper No. 19. Adams

stated the fighting proved “…the bloodiest and most decisive battle of the campaign,” then avowed, “General McPherson did take and hold that position, which proved to be the ‘key to Atlanta,’ but at the sacrifice of himself and thousands of his brave men.”

Continuing to focus on the fighting east of the city on July 22, Major General Dodge authored Paper No. 20, ‘The Battle of Atlanta.’ Dodge addressed a lingering question at the time, 1895, as to why the battle “…was never put ahead of many others its inferior, but better known to the world and made of much greater comment?” The general surmised the loss of Major General James McPherson in the fighting “… counted so much more to us than victory, that we spoke of our battle, our great success, with our loss uppermost in our minds.”

Lieutenant Colonel William E. Strong of McPherson’s staff, remembered his fallen chieftain in Paper No. 21, ‘The Death of General James B. McPherson.’

Strong opened his account with a strong statement: “Numerous accounts have been published, but none of them go into details, and none that I have seen are entirely correct.” Details indeed! Within the following 32 pages, researchers can glean valuable information about the general’s

death. Strong cites wartime reports, newspaper accounts, and other documents in his attempt to clarify when, where, and how the general fell. The writer numbered among the first to arrive at McPherson’s side after the fatal shot struck the officer, and recalled, “Raising his body quickly from the ground, and grasping it firmly under the arms, I dragged it…through the brush to the ambulance….” Shifting away from July 22, 1st Lieutenant Granville C. West, who served in the 4th Kentucky Infantry (mounted during Atlanta Campaign) penned ‘McCook’s Raid in the Rear of Atlanta and Hood’s Army, August 1864,’ Paper No. 22. West offered a general history of his regiment before detailing McCook’s attempts to break the rail lines servicing Atlanta. The writer criticized Major General George Stoneman, scheduled to meet McCook’s force near Lovejoy Station. Stoneman decided to liberate the prisoners at Camp Sumter in Andersonville; the cavalry general and a sizable portion of his command ended up prisoners themselves after the Battle of Sunshine Church. West suggested had Stoneman joined McCook, “our united forces would have been masters of the situation;” instead, they “remained there [Lovejoy] nearly all

day expecting him [Stoneman], and wasted some precious hours….”

The Chicago Board of Trade Battery made an appearance in Paper No. 23, ‘With Kilpatrick Around Atlanta,’ as 1st Lieutenant George I. Robinson of the battery recounted the attempt to break the Macon & Western Railroad, and the resultant engagements near Jonesboro. Robinson, a gifted writer, weaves an engaging narrative, one occasionally laced with dry humor. Recalling when he first learned Major General William T. Sherman had requested Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick to lead his cavalry during the campaign, Robinson remembered even greater surprise “…when at about the same time the battery under my command was ordered to report to Gen. Kilpatrick.” Capturing more of the action covered in the previous chapter, 1st Lieutenant William L. Curry of the 1st Ohio Volunteer Cavalry provided Paper No. 24, ‘Raid of the Union Cavalry, Commanded by General Judson Kilpatrick, Around the Confederate Army in Atlanta, August, 1864.’ Like Robinson, Curry wrote a fluid-prose, and among his various accounts of the raid, he gave a thorough explanation of how cavalrymen damaged rail lines. “The men then

form along one side of the track in close order, and at command grasp the rails and ties and turn the track over, and sometimes a half mile of tracks is turned before a joint is broken.” Next, “… the men move along rapidly, and many rods of the track will be standing up on edge. If there is time, the rails are then torn loose from the ties by picks and axes, carried for that purpose; the ties are piled up and the rails on top of them, and the fires are fired; thus the rails are heated in the middle and bent out of shape…twisted around trees or telegraph poles.”

Concluding his lesson on cutting the rails, Curry added the final ingredient to the recipe “…the rails are left to cool.” In closing, he suggested, “…no doubt some of them are there yet [Curry wrote in 1898] to mark the trail of the cavalry raiders.”

Remember to check WorldCat http://www.worldcat.org for help in finding this source in a local library; search The Atlanta Papers + Kerksis. Researchers may also have luck in securing a copy of this 1980 Morningside Press publication from an online bookseller. Next month, we will complete the review of The Atlanta Papers. Until then, continued good luck in researching the Civil War!

Nobody even comes close to building a Civil War tent with as much attention to reinforcing the stress areas as Panther. Our extra heavy duty reinforcing is just one of the added features that makes Panther tentage the best you can buy!

PANTHER Catalog - $2 Web: www.pantherprimitives.com 160 pages of the best selection of historical reenactment items from Medieval era to Civil War era. Includes over 60 pages on our famous tents and a 4-color section. Your $2 cost is refundable with your first order. SEND for copy TODAY

Michael K. Shaffer is a Civil War historian, author, lecturer, instructor, and a member of the Society of Civil War Historians, the Historians of the Civil War Western Theater, the Georgia Association of Historians, and the Georgia Writers Association. Readers may contact him at mkscdr11@ gmail.com, or to request speaking engagements, via his website www.civilwarhistorian.net. Follow Michael on Facebook www.facebook.com/michael.k.shaffer and Twitter @michaelkshaffer.

Fort Donelson Anniversary Programs

By Craig Barry

By Craig Barry

The battle at Fort Donelson was an early turning point in the US Civil War that took place in mid-February 1862, right around St. Valentine’s Day. General Grant received national recognition for the victory, the first major Union success of the War. The capture of Fort Donelson and its garrison by the Union led directly to the capture of Nashville, Tenn., the capital and industrial center of the state.

Nashville remained in Union hands from Feb. 25, 1862, until the end of the war and, along with the victory at Stones River later in 1862, gave the Union effective control over much of Northern and Middle Tennessee. These two defeats struck a major blow to the Confederacy early in the war.

The annual anniversary programs at Fort Donelson National Battlefield commemorating these events are the unofficial start of the historic weapons demonstrations and living history schedule of events in Tennessee. The recent U.S. government shutdown forced cancelation of the Stones River anniversary programs late last year and left the programs at Fort Donelson up in the air until a week or two before the event.

Fortunately, the staff at Fort

Donelson was able to not only get back and running in time, but also get the necessary ground work done to put programs together on a very tight time line. Kudos go to park ranger Susan Hawkins and her staff for their work in that regard. For those of us who enjoy participating in these programs, we were very grateful for their efforts. The dates selected were Feb. 9-10, 2019, …among the last possible just in case the U.S. government shut things down again as had been threatened when the park temporarily reopened a few weeks ago.

The weather was the usual mix of clear, very cold, and sunny on Saturday with slightly less cold but rainy and wet on Sunday. On Saturday morning, the weather channel reported temperatures of about 20 “that feel like 8 degrees.” This is seasonable for those parts in mid-February but this much can be said for certain, no matter what your winter kit may include to keep your body warm, fingers struggle with the dexterity needed to place a percussion cap on a musket under such conditions. There were about two dozen volunteers from the 9th Ky. Inf. (U.S.) on hand for the programs and the area around tour stop five (the site of Smith’s

attack) was cleared for the camp. The historic weapons and living history programs were held behind the original visitor’s center (closed for renovation for about three years now).

There were demonstrations of drill, marching in formation, loading in nine times, and historic weapons (musket) firing. For participants in the programs, it was an excellent chance to re-connect with friends who have not been together since late last year. Whatever challenges may have been with the cold and winter weather, a nice crowd of visitors braved the conditions and

the programs were all successfully completed as scheduled. Interest in the American Civil War remains strong in that part of Tennessee.

Craig L. Barry was born in Charlottesville, Va. He holds his BA and Masters degrees from the University of North Carolina. He writes Civil War News column “The Unfinished Fight.” He is the author of several books including three books in the Suppliers to the Confederacy series on English Arms & Accoutrements, Quartermaster stores and other European imports.

National Civil War Memorial Gains Local Support

By Leon Reed Sculptor

By Leon Reed Sculptor

Gary

Casteelhas been advocating development of a National Civil War Memorial for two decades. He feels he may be closer to the project’s go-ahead than ever before. “If you go to the National Mall in Washington, you’ll find monuments to the soldiers who fought in World War II, the Vietnam War, the Korean War, even World War I,” said Casteel. He noted “They’re even developing one for Desert Storm.” “But, “he observed, “there has never been a national memorial to the Civil War,” but he thinks his latest proposal may be on course.

The city of Taneytown, Md., about 12 miles south of Gettysburg sits on one of the three main routes used by the Army of

the Potomac to get to the battle. Since an October presentation to the Borough Council and a visit by most of the Borough officials to Casteel’s studio on Baltimore Street in Gettysburg, Casteel has gained the support of the mayor and most of the town council. A site on the edge of town has tentatively been selected.

“The Memorial is intended to educate the present generation about the war by telling stories about important events and participants,” said Casteel. “It is a Civil War memorial and is only concerned with the events from April 1861 to April 1865.” He believes the memory of the Civil War and the sacrifices of millions are in danger of being lost. “This generation is the last chance to

get this monument built.”

The memorial will consist of a monumental circle with walls containing scenes of the war and portraits of key individuals who were important during the war. In the center of the circle is a bench with two old soldiers speaking to a child about their experiences.

Key events include the firing on Fort Sumter, Gettysburg, and Appomattox. Individuals portrayed include military figures such as Lee, Grant, Stonewall Jackson, and Meade while civilians portrayed include Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, diarist Mary Chesnut, and poet Walt Whitman. Some eyebrows have been raised by the portrayal of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth. But Casteel

argues that the memorial is depicting individuals who played a leading role and that there is no suggestion that he is being honored.

Casteel is one of the most prominent sculptors of Civil War subjects. Among his Civil Warrelated projects are the statue of General Longstreet at Gettysburg National Military Park, two smaller sculptures in Gettysburg; one honors Wesley Culp and his brother, the other honoring Civil War musicians; a statue in Lexington Park, Md., honoring African American soldiers who fought in the war; a Confederate

POW memorial at Point Lookout, Md.; and a monument to soldiers from North Carolina at South Mountain, Md.. He also recently prepared sculptures of a World War I doughboy and Lady Liberty at Carlisle Barracks, Penn., and has undertaken a project to create high quality miniature versions of Civil War monuments at Gettysburg and elsewhere.

Leon Reed is a former congressional aide, defense consultant, and U.S. History teacher. He lives in Gettysburg and writes military history books.

Passing on a Passion for the Past

By Joe BordonaroScattered throughout communities across the United States are small groups of dedicated individuals who strive to preserve our nation’s history. One such is the Lawrence Township Historical Society in Cedarville, N.J. On the evening of Feb. 19, 2019,

members of the local reenacting community gathered together to make a presentation on Civil War history to the LTHS. They were led by local resident, Dan Casella, who made his passion for passing on the past literal by bringing his son, Sebastian, to the event. The presentation was very well

received and a new link between local historians and living historians has been forged. Perhaps other reenactors will consider doing the same, especially those who may be stepping down from an active participation in reenactments. Sharing your passion with people in your community,

Shenandoah Civil War Associates Civil War Institute

The Seven Days Campaign

June 14-16, 2019

Saturday:

• Lee’s Headquarters

• Beaver Dam Creek/Mechanicsville

• Gaines’s Mill

• Lunch at the Cold Harbor picnic area

• After lunch, finish up Gaines’s Mill and Savage’s Station

• Yellow Tavern Battlefield

Sunday:

• Savage’s Station

• White Oak Swamp

• Glendale/Frayser’s Farm

• Malvern Hill

Friday and Saturday evening dinners included with dinner speakers Frank O’Reilly and Jeff Wert. Includes two nights lodging at the picturesque Virginia Crossings Hotel in Glen Allen, Virginia.

For information:

Total cost $495.00