GettysburG

inside PaGes: 1 GettysburG to 40 GettysburG

GettysburG

inside PaGes: 1 GettysburG to 40 GettysburG

MANSFIELD, Ohio—Guests

were very pleased and commented about the many rare displays and memorabilia on display; “

I’ve never seen so many rifles and weapons at one show.” “It takes two days to see the entire show and I never want to miss any of the demonstrations and educational presentations.” “A quality show of this kind will entertain and educate interested history buffs about their passion and stimulate youngsters to learn more about our history and what happened during such difficult times.”

The Annual Ohio Civil War and WWI & II Show is held at the Richland County Fairgrounds in Mansfield, Ohio, each year in May. Almost 4,000 visitors attended over the two days this year. Exhibitors were very happy to see so many guests; diehard history buffs were excited to see rare memorabilia, weapons, books, prints, jewelry, and sutler materials, many of them unique

items in the educational displays. The added outdoor attractions are definitely crowd pleasers and get lots of attention from young and old. The Ohio Civil War Show offers these outdoor features to educate and entertain the visitors. Guests enjoyed period music by the Camp Chase Fife & Drum Corps, Abraham Lincoln presented the Gettysburg Address, members of the Society of Civil War Surgeons preformed a limb amputation on a wounded soldier, and the Brigade of the American Revolution, along with Confederate and Union Infantry, fired weapons and marched in line as the cannon roared. Special Civil War and World War II Living History Encampments showed visitors how the soldiers lived and survived.

A dream came to life 27 years ago when the show’s founder, Don Williams, decided to add the Artillery Show. The only show of its kind in the United States, it showcases artillery field

pieces from the Revolutionary War through World War II. Visitors enjoyed seeing full-scale cannon, limbers, caissons, and artillery shells along with an eight cannon firing line. Reenactors in full dress gave an impressive educational and entertaining presentation of artillery firing on line. The cannon fire could be heard miles away as the guns sent out flames and smoke billowed across the grounds with that unique burnt powder smell.

In addition to celebrating the Civil War, the World War I & World War II exhibitors were added to the Show due to the greater interest in our history. German soldiers walked through the crowd answering questions from guests who wanted to learn and understand more about the “other side.” A rare encampment set-up within the large barn in conjunction with a separate WWII tent exhibit on the grounds showed complete living quarters, uniforms, weapons,

and ammunition. WWII GI’s and German soldiers blank fired various military weapons in demonstrations.

The organization and personal attention to the Show comes from the Williams family who manage the many details. The Show is thriving after 42 years, all due to the family’s passion and dedication for keeping history alive. Donald B. Williams of Ashland, Ohio, started the Show with just 60 tables in 1978. Don had the passion to share his love of the Civil War and give history buffs and the interested general public an opportunity to learn more about wars the U.S. has fought. Today, his three children and their dedicated committee of family and close friends continue their Don’s tradition. They are proud to say that respecting our history is simply how they were raised. The family hopes to continue the Show for many, many years to come.”

Exhibitors were invited to participate in a display competition, in which 25 dealers showcased unique items with

their historical facts in displays. We are excited to note that three award winners this year were women. The ladies definitely seized the opportunity to share their knowledge in creatively displayed exhibits.

Award winners this year included Elizabeth Topping for Best Educational with her photographic display “Mystic of Death.” James Brenner received Best Arms or Equipment for his display “Changing Of The Guard – Ohio Volunteer Militia and National Guard 1830–1874.” Ken Knoll received Best Artillery for his display of a “Macon 10-Pounder Parrott #8.” Matt Switlik received Best World Wars for a great display entitled the “French 75 In American Service 1918.” Three different Judges Awards were presented; one went to Cathy Spencer for her presentation on the wrecked USS Shenandoah Rigid Airship “Lighter Than Air.” A second Judges Award went to Ingrid

see page 15

While there are serious and legitimate disputed interpretations and reinterpretations of history, the past, especially in the popular view, has produced an overabundance of myths and near myths over the years, some based in duplicity, but most in a simple lack of understanding, There are probably more of these errors in the field of firearms development and tactical use, usually disregarded as being of less importance by academic historians, than other topics. The Civil War concept of what constituted a “sharpshooter” is one for sure.

Although many people today seem to view “sharpshooter” as a synonym for “sniper,” that was not the case in 1861. Unfortunately, the term was often randomly used by units hoping to elevate their military credibility. In truth, trained sharpshooters could be considered the ultimate Civil War infantrymen, screening advances and withdrawals as skirmishers.

Although the Army of Northern Virginia developed some very effective sharpshooter battalions

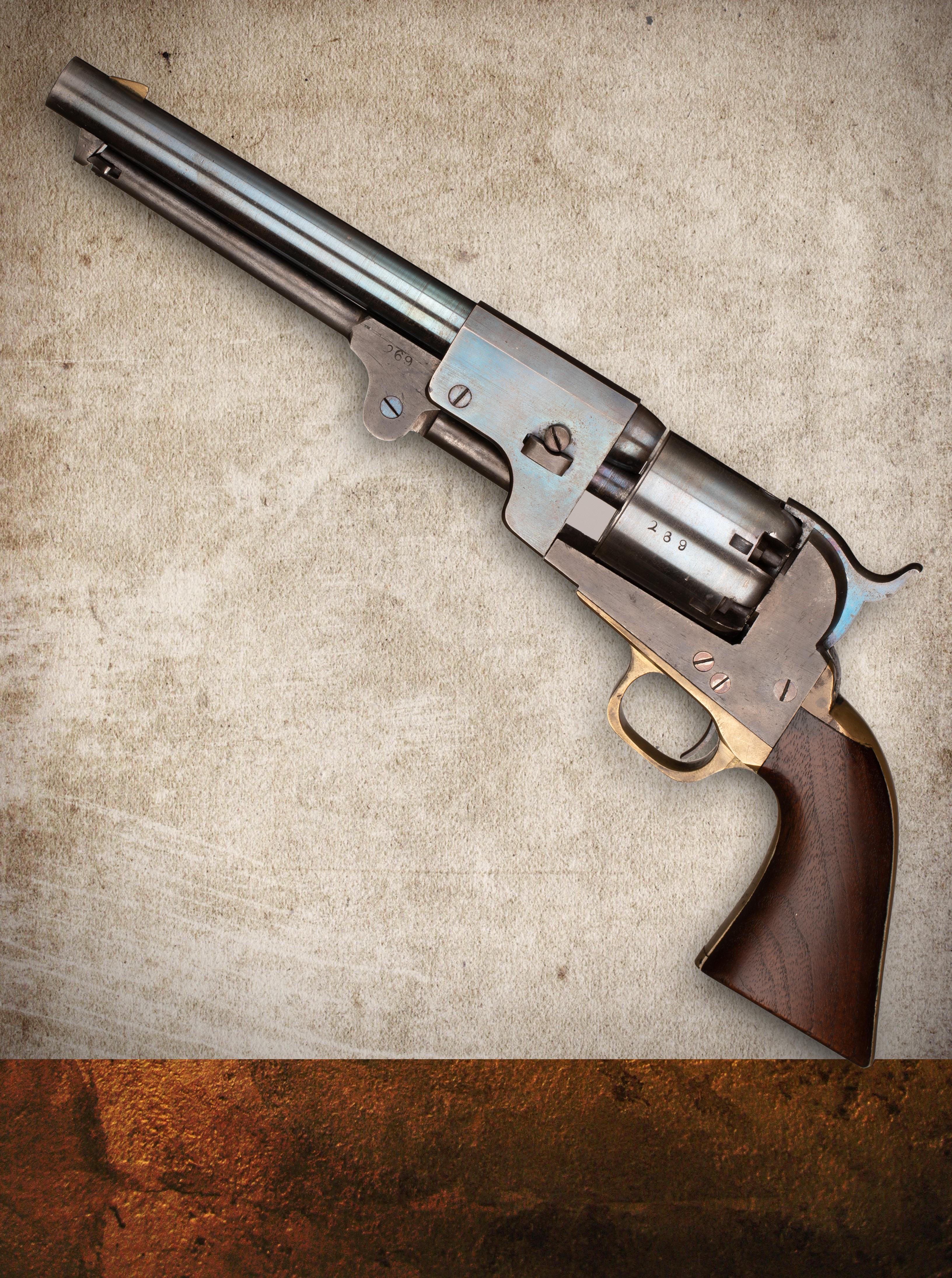

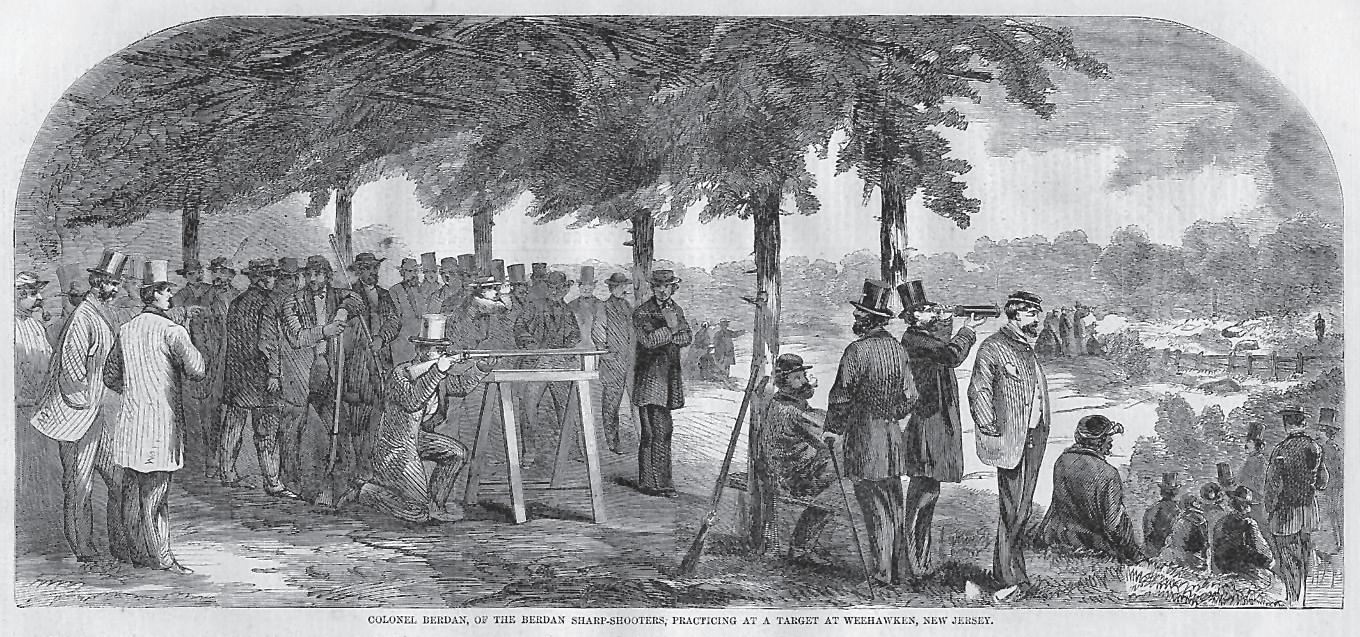

in the war’s final years, perhaps the best known such units were Colonel Hiram Berdan’s 1st and 2nd US Sharpshooter Regiments. Initial admission into the regiments involved competitive target shooting with heavy specialized rifles but, once in service, Berdan’s men were largely reequipped with, initially, Colt revolving rifles, and then Sharps rifles, with a few telescopic sighted target rifles in reserve for use in static situations. The famous Winslow Homer painting and the widely circulated print it gave rise to tended to make the soldier portrayed a typical “sharpshooter.’ I always wondered how he could reload that gun in the tree, but then again that sort of thing is my “thing.”

Although the US Sharpshooters performed well, both regiments were mustered out of service when their original enlistments expired in August 1864 and the following February. Recruits with service time remaining were transferred to line outfits from their respective states, taking their Sharps rifles with them. Sharps rifles were scattered throughout

Featuring a large assortment of Civil War and Indian War autographs, accoutrements, memorabilia, medals, insignia, buttons, GAR, documents, photos, & books.

Please visit our fully illustrated online catalog at www.mikebrackin.com

252-565-8810

by Joe Bilbythe army in other units, usually for use in skirmishing.

Berdan’s regiments were not the only Union units bearing the “Sharpshooter” title. The 66th Illinois, which performed so well at Atlanta, began as “Birge’s Western Sharpshooters,” armed with civilian target rifles. By Atlanta their initial armament had been largely replaced by Henry repeating rifles, short range rapid fire arms. Most “Sharpshooter” units found their target rifles largely unsuitable for combat. Several companies of Ohio sharpshooters recruited in 1862 were initially issued rifle-muskets, later replaced by Spencer rifles, which like the Henry, were more suited to skirmishing than long range work.

The 1st Michigan Sharpshooters, recruited in 1862 and 1863, did not enter combat until 1864, when they were armed with standard rifle-muskets. The 1st suffered heavy casualties in Virginia fighting as line infantry during 1864, but there is evidence that some Native Americans from the regiment would camouflage themselves with cut corn stalks and roam the lines seeking targets of opportunity. Although effectiveness varied, arguably the best sharpshooter units by 1864 were those in the Army of Northern Virginia, where brigades were authorized to form three to five company sharpshooter battalions. After

testing all available arms, these battalions adopted the two-band .577 caliber muzzleloading Enfield rifle, as its five-groove fast twist rifling provided better long-range accuracy, and were also issued high quality British manufactured ammunition. They also received extensive marksmanship training and drill in small unit skirmish tactics, based on Confederate General Henry Heth’s manual, plagiarized from the British one. These sharpshooter battalions had specific tactical assignments whenever their brigades were in action—to aggressively lead in the advance and provide an effective rear guard in withdrawal.

Each company in a sharpshooter battalion was issued one or two .451 caliber hexagonally bored fast twist Whitworth rifles. The British Whitworths, some of equipped with side mounted Davidson telescopic sights, weighed about the same as rifle muskets, and were far more portable than the heavy target rifles usually deployed by Federal snipers. Perhaps the most famous long- range kill of 1864 was credited to a Whitworth. On May 9, at Spotsylvania, Va., seconds after proclaiming “they couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance,” Union Major General John Sedgwick fell to a bullet fired from more than 600 yards away. That Sedgwick was singled out by the shooter is unlikely in the smoke and confusion of the battlefield as well as the distance of the shot. He had dismounted to assist an artillery battery positioning its guns, and the battery itself was the likely target. Still, his death graphically demonstrated the long-range effectiveness of the Whitworth.

In the west, Confederate sharpshooter units, the best of them in General Patrick Cleburne’s Division, were armed with a mix of rifle muskets, Whitworths, and British-made .451 caliber Kerr rifles, as well as some heavy

barreled target rifles converted by the Atlanta arsenal to fire standard rifle musket ammunition. Perhaps influenced by Cleburne’s interest in long range shooting, western Confederate sharpshooters seem to have concentrated on sniping more than skirmishing. Sharpshooters from Kentucky’s Orphan Brigade were instructed to never approach within 400 yards when engaging Federal artillery batteries with their Kerr rifles. The batteries were the targets, not individual soldiers.

Joseph G. Bilby received his BA and MA degrees in history from Seton Hall University and served as a lieutenant in the 1st Infantry Division in 1966–1967. He is Assistant Curator of the New Jersey National Guard and Militia Museum, a freelance writer and historical consultant and author or editor of 21 books and over 400 articles on N.J. and military history and firearms. He is also publications editor for the N.J. Civil War 150 Committee and edited the award winning New Jersey Goes to War. His latest book, New Jersey: A Military History, was published by Westholme Publishing in 2017. He has received an award for contributions to Monmouth County (N.J.) history and an Award of Merit from the N.J. Historical Commission for contributions to the state’s military history. He can be contacted by email at jgbilby44@aol.com.

As soon as we had stacked arms, I left for the city to replenish my haversack, which had become rather flat…On entering town I passed by the abandoned Confederate Commissary department, and seeing a great abundance of food stuffs, I thought that I would go down into town for a while, and then on my way back would fill up my haversack. But when I returned, I found the building in flames and all the food which we could have put to good use was in ashes before daylight. – Civil War diary of Alexander Dowling, February 1865.

Term: Haversack (Civil War)

Haversack provided through the U.S. Quartermaster Department began to display the characteristics that would be common throughout the Civil War-era and on into the late 1870s. The first post-1851 change was that the haversacks were painted black and treated with linseed oil for water resistance. The dimensions still varied slightly, but the official size appears to have been between twelve inches square, or thirteen inches across by eleven inches deep. In any event, the haversack was not supposed to be longer than it was wide, although some no doubt were. There was a top flap secured with a leather strap and a japanned (painted) roller buckle. Inside the haversack was (a smaller) white cotton drill “rice bag,” officially called the pocket, held in place by three buttons. The rice bag was supposed to hold the actual field rations. It could be unbuttoned and removed for

Definition: “Linen or canvas bag about one foot square, which was slung over the shoulder and used to carry a soldier’s rations when on the march.” (Dictionary of Civil War History: Wisconsin Historical Society)

The haversack was a key piece of equipment for the Civil War soldier in the field. Without it there were very few options for the soldier to carry several days’ worth of rations, except in his stomach, which was sometimes done whether a haversack was available or not. The term haversack actually derives from the 18th century German word hafersach or “oat bag,” a canvas bag used by the Prussian cavalry troops to feed their horses. Perhaps by outward resemblance to the hafersach, the English etymology of the word evolved during the 19th century to indicate a single strap shoulder bag used by any branch of the military to carry marching rations.

In America prior to 1851, haversacks with shoulder straps appear to have been made from plain white linen in a variety of sizes; there was a lack of standardization. It was not until May 1865 that the U.S. Quartermaster Manual addressed “official specifications” for the haversack which was too late to have any impact as far as what was used during the preceding years.

After 1851 the haversack

cleaning, a necessity due to the messy nature of the usual ration of greasy salted meat.

The rest of the mess kit (plate, knife, fork) were to fit in the haversack around (but not inside) the rice bag. This includes the tin cup, if there was room for it inside. Tin cups were not automatically hung from the outside strap as they clanged around noisily when placed there and could get snagged. Soldiers make mention of this in their diaries. For example, a New Jersey soldier noted, “besides this (three days rations) I have in my haversack a plate, tin cup, knife and fork…” When soldiers make note of attaching the tin cup to the outside of the haversack, it frequently includes a mention of the din caused by its banging against the bayonet scabbard or canteen.

Although much has been written about foraging for food to supplement the rations, an activity

which may not always work out well as noted if the diary entry from the heading is to be believed; it is a simple fact that the vast majority of the sustenance a soldier consumed during his enlistment was furnished through the Commissary Department and carried in his haversack. One Union soldier noted that

…one shoulder and the hips support the ‘commissary department’—a haversack with its odorous mixture of salt pork, salt junk, sugar, tea, coffee, rice and leftover bits of yesterday’s dinner.

This description brings up a good point. Used as intended, painted cloth haversacks would not last long, they wore out and were replaced on a regular basis through the Quartermaster Department much like clothing or shoes. Very few issued items were replaced on a fixed schedule; the replacement of the haversack was not automatic or at any particular interval. Replacements were ordered on the basis of individual need. Note the following

from the diary of a soldier in late 1862:

The men drew new clothing today just as fast as the quartermaster could receive the supply from the general quartermaster. We were pretty hard on our clothes in the Army…Nearly every man in the regiment is drawing a full suit, out and out. Some of the men will need new knapsacks, canteens and haversacks, while others are getting new shoes. I drew a pair of pants and a fatigue blouse (sack coat), a pair of drawers and a pair of socks.

As time went on, U.S. Army Regulations even added procedures for returning a damaged haversack for repair or even for a return to stock if there was any excess supply. Note the following:

SURPLUS AND DAMAGED STORES

3044. On arrival of recruits at their destination, the clothing-bags and haversacks which they turn in as unnecessary, unsuitable, or unserviceable, will be

$39.95

Available online at http://booklocker.com/books/9403.html

Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble. Hardcover, 534 pages.

properly packed and turned over to the Quartermaster Department for transportation to Watervliet Arsenal.

There are two accepted variations of the Regulation Federal Civil War-era haversack. Without making things overly complicated, the types are broadly defined as “Early War” and “Late War.” The two styles are almost indistinguishable except for the leather closing strap, or rather how the leather strap is attached to the outside of the bag. On “Early War” haversacks, the strap and the buckle are sewn to the outer surface of the haversack. On the “Late War” haversacks, the strap is reinforced with a copper rivet. The inside seams were flat felled, like the seams of an unlined Union sack coat. Sometimes the haversack appears to be sewn after the material was painted black and other times before. Sometimes main seams are machine sewn while others show evidence of being hand-sewn throughout. A variety of different contractors supplied haversacks to the various U.S. Arsenals over the course of the war. It is a safe estimate that millions were produced. The cost to the Quartermaster Department

was about 56 cents each. The shoulder straps were between 42-48 inches long and were often shortened on the haversack. The average Civil War soldiers were as a rule smaller, but even allowing for a height/weight differential, the shortened straps suggest the bag was worn fairly high up on the soldier’s hip. This is for comfort, so it did not bounce off the thigh while on the march. As a final point, the cloth used on original haversacks is surprisingly thin compared to most reproductions which are produced from heavier (almost tent thickness) canvas. On some surviving haversacks the material used for the outside bag is only slightly thicker than the rice bag (about as thick as a cotton shirt), although the coating of black paint and linseed oil on the surface did reinforce it.

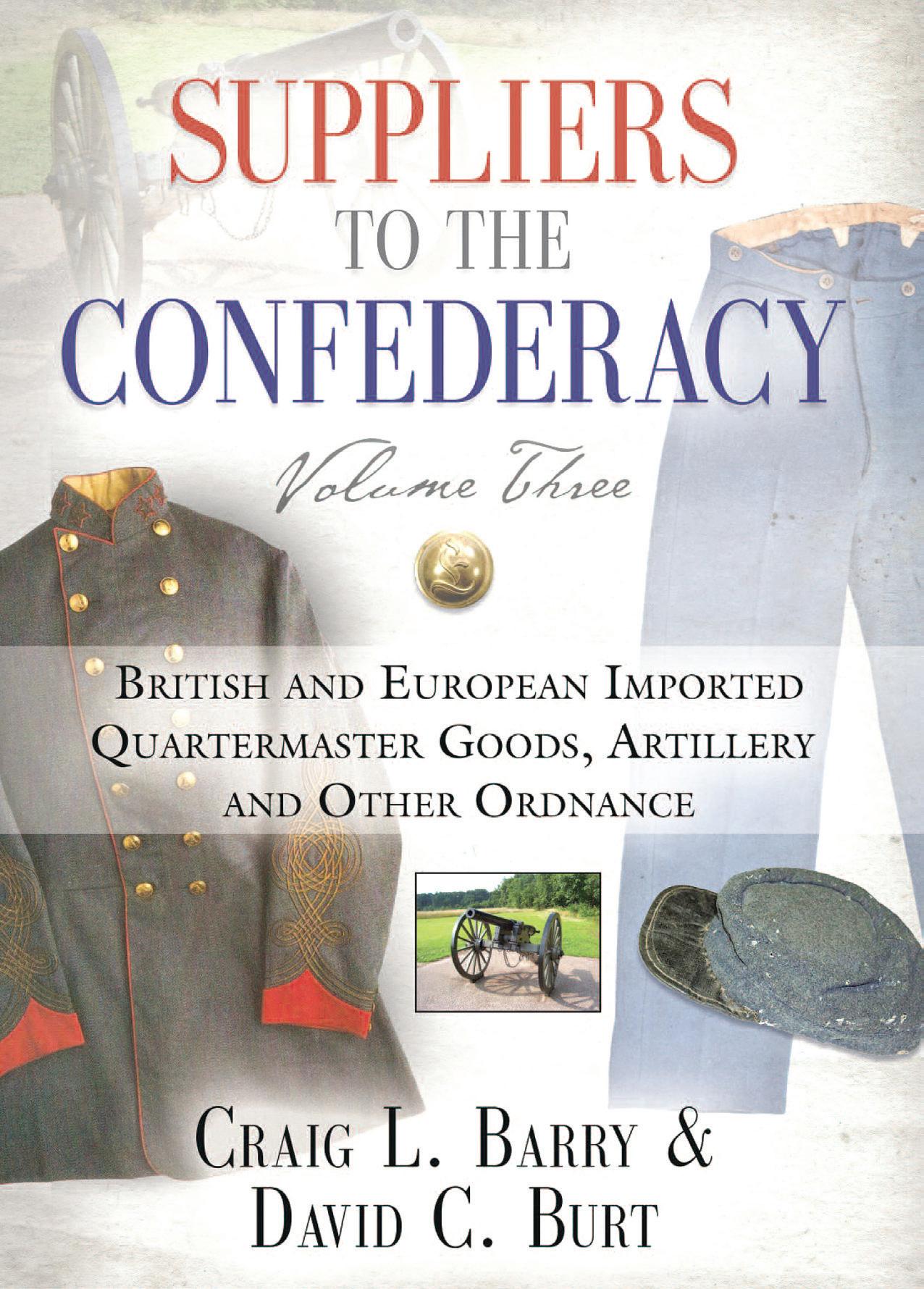

Craig L. Barry was born in Charlottesville, Va. He holds his BA and Masters degrees from the University of North Carolina (Charlotte). Craig served The Watchdog Civil War Quarterly as Associate Editor and Editor from 2003–2017. The Watchdog published books and columns on 19th-century material and donated all funds from publications to battlefield preservation. He is the author of several books including The Civil War Musket: A Handbook for Historical Accuracy (2006, 2011), The Unfinished Fight: Essays on Confederate Material Culture Vol. I and II (2012, 2013) and three books (soon to be four) in the Suppliers to the Confederacy series on English Arms & Accoutrements, Quartermaster stores and other European imports.

The N-SSA is America’s oldest and largest Civil War shooting sports organization. Competitors shoot original or approved reproduction muskets, carbines and revolvers at breakable targets in a timed match. Some units even compete with cannons and mortars. Each team represents a specific Civil War regiment or unit and wears the uniform they wore over 150 years ago. Dedicated to preserving our history, period firearms competition and the camaraderie of team sports with friends and family, the N -SSA may be just right for you.

For more information visit us online at www.n-ssa.org.

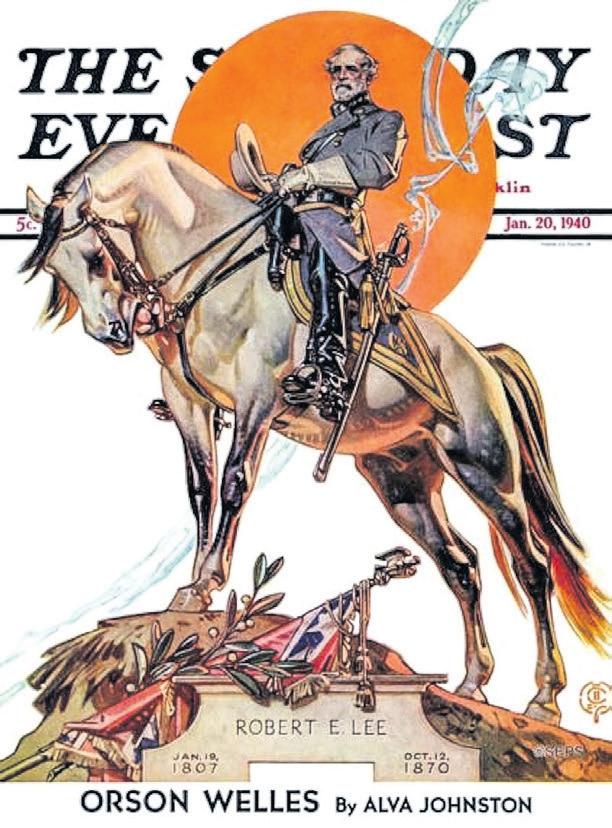

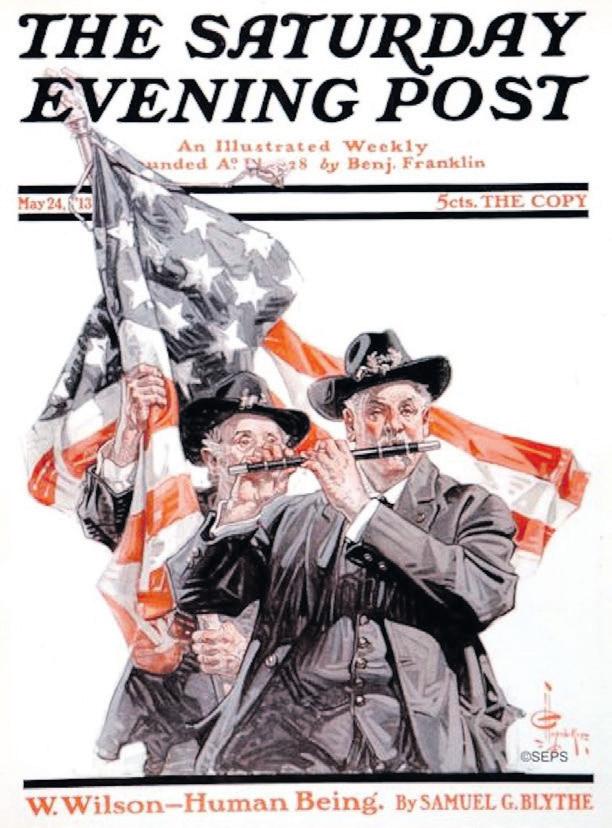

Beginning print in 1821 out of Philadelphia, on the same press Benjamin Franklin used to rollout his The Pennsylvania Gazette in 1728, the Saturday Evening Post has covered many stories from throughout American history, including the American Civil War. Recently, the publisher digitized all issues of the magazine and archived them on their website. Researchers can access these archives, with an affordable $15 print/digital subscription to the magazine, at https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/issues/ page/4/?issue-year=1860s. The archives hold every weekly issue from 1862, 1864, and 1865; two from 1863; and none from 1861. This writer awaits word from the Post on the missing 1861 items and will update readers in a future column. Navigating the archive website takes a little practice, but

soon, researchers will gain comfort and can quickly locate various articles through keyword searches.

The following provides a couple of examples found when keyword searching, first, ‘U.S. Grant’ in the June 11, 1864, edition. “Our readers will remember the old anecdote – ‘If you are a

great general,’ said one famous warrior of antiquity to another, ‘come out of your intrenchments and fight me.’ ‘If you are a great general,’ replied his wise adversary, ‘make me come out of my intrenchments, and fight you.’” This editorial continued, “Lee has said, in effect, the same to Grant – and Grant has made him leave one fortified position after another until both are now near Richmond. And whatever may be the future of the campaign, it will not alter the great fact that Grant has forced his way to the fortifications of the rebel capital….” Searching “Sherman” in the July 30, 1864, edition yielded the following result. “General Sherman has done much fighting since crossing the Chattahoochee, and lost General McPherson. Sherman appears to hold a part of Atlanta…all communication with Atlanta, excepting from Macon, was closed at the last advices…. General Hooker thoroughly whipped the rebels on Wednesday [Peach Tree Creek] in the open field, and forty-four hundred were killed and wounded.”

The pages of the Post during the war also contain various reports from Federal soldiers. Publishing in Philadelphia, the Post typically focused on Northern accounts from the war, and printed letters from Federal soldiers. The March 5, 1864, edition carried one such message, entitled ‘Heroic Capture of a Rebel Colonel.’ The writer, Private Charles Philbrick

Jr. of the 3rd Massachusetts Cavalry, recounted his exciting capture of a Confederate colonel outside Baton Rouge. Writing in third-person, Philbrick noted, “Quietly fastening his horse, he crept to the front door, burst it open, and, pistol in hand, astonished the assembled party with the sight of a Union soldier on the rampage.”

Expanding your search beyond the Civil War years will produce many additional results, as the magazine continued to publish various articles on the war, although most fall within the secondary-source category. Several Civil War-themed covers

occurred during the early decades of the 1900s, like the 1913 Memorial Day cover featuring veterans, and a 1940 cover with General Robert E. Lee.

In 2018, the Post published a collector’s edition—Untold Stories of the Civil War—which researchers may find helpful as an offline index to aid in searching the online archives. Copies of this issue remain available from the publisher for $10; order at https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/product/the-saturday-evening-post-untold-storiesof-the-civil-war/. Next month, we will explore another primary source. Until then, continued good luck in researching the Civil War!

Michael K. Shaffer is a Civil War historian, author, lecturer, instructor, and a member of the Society of Civil War Historians, the Historians of the Civil War Western Theater, the Georgia Association of Historians, and the Georgia Writers Association. Readers may contact him at mkscdr11@ gmail.com, or to request speaking engagements, via his website www.civilwarhistorian.net. Follow Michael on Facebook www.facebook.com/michael.k.shaffer and Twitter @michaelkshaffer.

Cobb County Civic Center

548 S. Marietta Parkway, S.E., Marietta, Georgia 30060

Free Parking

$6 for Adults

Veterans and Children under 10 Free

Over 230 8 Foot Tables of:

• Dug Relics

• Guns and Swords

• Books

• Frameable Prints

• Metal Detectors

• Artillery Items

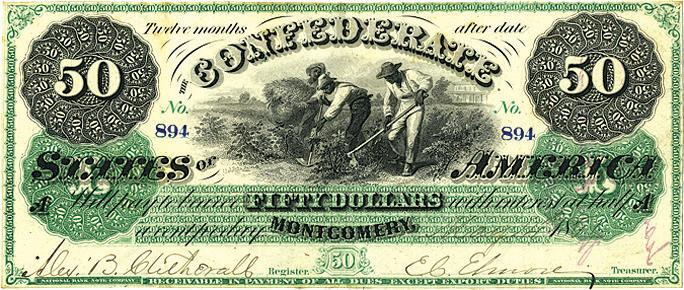

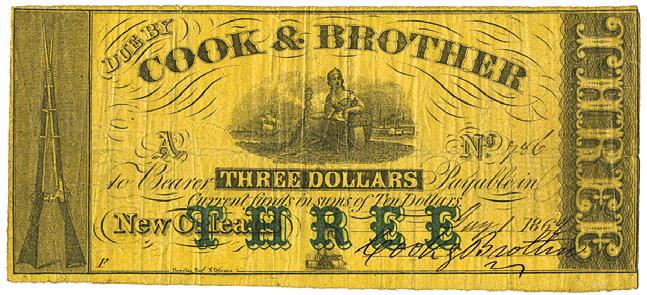

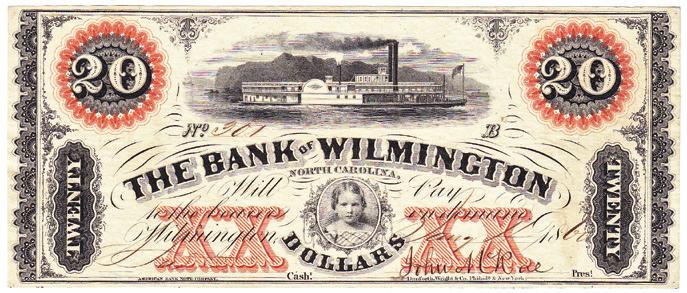

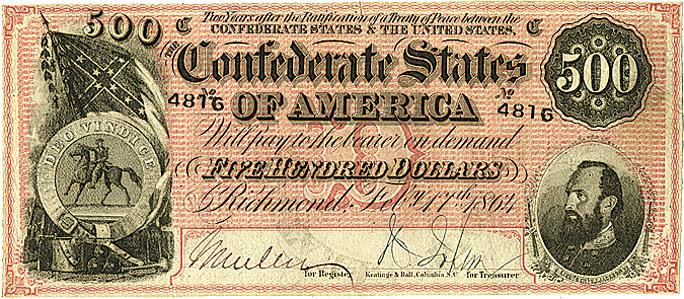

• Currency

August 10 & 11, 2019

Saturday 9–5

Sunday 9–3

Inquires:

NGRHA Attn.: Show Chairman P.O. Box 503 Marietta, GA 30061 terryraymac@hotmail.com

www.NGRHA.com

Digital Issues of CWN are available by subscription alone or with print plus CWN archives at CivilWarNews.com

10. Fort St. Philip, from which 52 guns fell into Federal hands:

21 twenty-four-pounders

9 thirty-two-pounders

6 forty-two-pounders

5 eight-inch Columbiads

5 ten-inch siege mortars

1 eight-inch mortar

1 seven-inch rifle

1 six-pounder

1 twelve-pounder

1 twenty-four-pounder howitzer

1 thirteen-inch seacoast mortar (Battles & Leaders, vol. 2, 75)

Digital Issues of CWN are available by subscription alone or with print plus archives from 2012 to present at www.CivilWarNews.com

9. Yorktown. “We captured 53 guns in good order; 3 guns burst. Total number of guns, 56.” (J. G. Barnard, OR, vol. 11, pt. 1, 337).

8. Nashville, where Gen. John B. Hood’s Army of Tennessee was routed on Dec. 16, 1864. “Our loss in artillery was heavy—54 guns,” Hood admitted in his report (OR, vol. 45, pt. 1, 655).

7. Fort Donelson. “Of the sixty-five captured artillery pieces that had not been spiked, most were generally new and in good order” (Kendall D. Gott, Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, 263).

6. Chickamauga, Sept. 19-20, 1863. O. T. Gibbes lists the Confederates’ artillery haul in their rout of Rosecrans’ army (OR, vol. 30, pt. 1, 40-42):

12 twelve-pounder howitzers

10 twelve-pounder bronze howitzers

10 3.8-inch bronze rifled guns

8 six-pounder bronze guns

5 three-inch iron rifled guns

4 twelve-pounder mountain howitzers

3 twenty-four-pounder bronze howitzers

3 twelve-pounder iron howitzers

3 twelve-pounder bronze mountain howitzers

2 twelve-pounder bronze guns

1 twenty-four pounder Parrott

1 twenty-four-pounder howitzer

1 six-pounder howitzer

1 twelve-pounder rifled gun

1 three-inch rifled gun

1 six-pounder bronze rifled gun

5. “Harpers Ferry yielded 73 pieces of artillery” (Dennis Frye, “Harpers Ferry in the 1862 Maryland Campaign” in Gary W. Gallagher, ed., Antietam: Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign, 15).

4. Fort Jackson. The Federals’ artillery haul included, according to Battles & Leaders, vol. 2, 75:

25 twenty-four pounders

17 thirty-two pounders

10 twenty-four-pounder howitzers

6 forty-two-pounders

5 eight-inch Columbiads

3 ten-inch Columbiads

2 eight-inch mortars

2 eight-inch howitzers

1 ten-inch siege mortar

1 seven-inch rifle

1 six-pounder

1 twelve-pounder

3. Island No. 10. Pope had boasted of 158 cannon captured (123 heavy guns and 35 field pieces). Recent scholarship has whittled that number down to 109 (Larry J. Daniel and Lynn N. Bock, Island No. 10: Struggle for the Mississippi Valley, 144-45).

2. Vicksburg, July 4, 1863. Grant “captured 172 pieces of artillery” (Terence J. Winschel, Triumph & Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign, 185).

1. Gosport Navy Yard, where Southerners took fully 1,195 artillery pieces of all types, including 662 thirty-two-pounders, 63 forty-two-pounders, 52 nine-inch guns and 79 eight-inch guns (Message from the Executive of the Commonwealth, Transmitting a Report of Wm. H. Peters, Commissioner, Appointed by the Governor to Make an Inventory of Property Taken from the United States Government, at the Navy Yard, Gosport, and in and Near Portsmouth, Virginia [Richmond, 1861]. Copy courtesy of Greg Biggs, Clarksville Tenn.).

The topic of this article was recently suggested by one of my customers. I appreciate the suggestion and welcome them from the readership.

The U.S. Model 1858 Cadet rifle musket was the direct result of an 1857 inquiry by the state of New Jersey about the availability of cadet muskets for issue to the state. In response, the Ordnance Department noted that there were not any “Cadet” pattern muskets available in stores, and there were no plans to continue manufacturing the M1851 cadet musket, as it was now deemed obsolete.

The M1851 was essentially a scaled down. .57 caliber version of the U.S. M1842 .69 caliber smoothbore musket currently in service. In 1855, the U.S. M1842 had been superseded by the

U.S. Model 1855 rifle musket, a .58 caliber rifled arm with the Maynard patent automatic tape priming system. Once the new pattern rifled arms had been adopted for general issue to the military, the Ordnance Department decided to rifle a small number of the U.S. M1851 cadet muskets in inventory, add long range rear sights, and issue these arms to the Corps of Cadets at West Point. It was deemed a necessary modification to acquaint the cadets with the principles of rifled arms and adjustable rear sights, since their current smoothbore arms were obsolete. At best, this was a stop gap measure. The rifled and sighted M1851 was still styled like the earlier flintlock pattern arms that the M1842 originated from, and the new M1855 incorporated an automatic primer

system that was to be standard in U.S. military small arms. As such, the Ordnance Department was at least cognizant that a new pattern of cadet musket needed to be developed.

The New Jersey request for “Cadet” arms set the wheels in motion for adopting a new pattern cadet sized musket. In January 1858, a representative of the Ordnance Department visited

West Point to find out what form a new cadet musket should take. The recommendation from the Board of Ordnance after reviewing the West Point requests read in part:

It appears to the Board that the improvements in regard to the weight and length of the arm as stated in Captain Benton’s letter may be attained by reducing the length of the barrel to 38 inches, and altering its form, and that of all other parts of this arm to correspond in shape with the pattern of the new Rifle-Musket, using (for the Cadet Musket) if practicable, either the same lock as for the Rifle-Musket, or the pistol lock with the comb of the hammer lengthened.

The board further recommended that the new arm be “precisely similar” to the model then in production and that the new musket should be fabricated with as little additional new machinery,

fixtures, and parts as possible. Since the Board offered the opportunity to utilize the standard M1855 lock, the National Armory at Springfield designed a rifle musket with the appropriately shorter barrel that was 2-inches shorter than the standard M1855’s 40-inch barrel. The new design had an overall length of 53 inches instead of the standard rifle musket overall length of 56 inches. Both the cadet variant and the standard version M1855 rifle musket were completely identical in dimensions between the front edge of the comb of the stock and the rear barrel band. The buttstock was 1-inch shorter on the cadet musket, and the barrel was 2-inches shorter. Like the slightly larger U.S. M1855 rifle musket, the barrel was secured by three flat, spring retained bands. The barrel band spacing was also proportionally adjusted for the shorter overall barrel length. In fact, Captain Benton noted that “All parts of the new arm should be

615-972-2418

precisely similar to those of the new Service Rifle-Musket.” The board also recommended issuing the 40 grain cartridge for the M1855 pistol carbine for use by the cadets when they were issued the cadet rifle musket. A specially designed, scaled down socket bayonet was designed for use with the guns, and a proportionally shorter, swelled-shank, tulip-head ramrod of the same pattern used on the U.S. M1855 rifle musket was carried in the channel under the barrel.

Research by George Moller indicates that the pattern cadet musket was manufactured prior to June 30, 1858, and that it was officially adopted prior to August 19 of that year. It is well documented that 2,501 of the muskets were produced at Springfield, with the “1” musket being the pattern gun. It appears the production was divided into three groups, with 1,500 produced during the last quarter of 1858, another 1,000 produced during the 2nd quarter of 1860. The anomaly is a report that 500 were produced during fiscal year 1866 (July 1, 1865–June 30, 1866) (see Moller Volume III, page 282). This would suggest that either 3,001 of the guns were manufactured or that only 1,000 were manufactured in 1858.

The muskets were produced in two “variants” or “types,” with the guns produced during 1858 having long-base, long range M1855 pattern rear sights and brass nose caps (Type I) and the later production guns having the M1858 pattern short base rear sight and iron nose cap (Type II). Although not widely known, thirty new M1858 cadet muskets were issued to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and another two hundred forty-six were issued to the U.S. Navy. These were delivered to the Bureau of Ordnance & Hydrography and were requested by Captain (later Admiral) James H. Dahlgren of “Plymouth Rifle” and “Dahlgren Bowie-Bayonet” fame.

According to Moller’s research, additional M1858 cadet rifle muskets were issued to the states of Illinois, Kentucky, Georgia, Maine, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Tennessee prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. However, the numbers issued to each state are not provided. I was able to find a reference to eleven “Cadet Muskets” (model not noted) in the inventory of the Atlanta Arsenal during FebruaryMarch 1863. By March 18, 1863, these guns were no longer listed in the arsenal’s inventory. The total number of U.S. M1858 cadet muskets issued to the states was 1,624. When combined with the

thirty sent to West Point and the two hundred forty-six that ended up with the Navy, that leaves six hundred of the known “2,500” production guns, so it is possible that the fiscal year 1866 reference to five hundred guns might really be a note of how many were IN stores, not DELIVERED into stores. As these muskets were .58 and could fire the standard issue .58 ammunition used with the M1855 and M1861/63/64 rifle muskets, it is quite likely that the M1858 cadet rifle muskets issued prior to the Civil War saw service during the war, along with their full sized brethren.

Markings for both the Type I and Type II U.S. M1858 cadet musket were the same. The locks were marked with the usual horizontal two-line legend: U.S. / SPRINGFIELD forward of the tape primer compartment, with the standard U.S. Spread-Winged Eagle on the tape primer door and the date of production in a horizontal line at the tail of the lock. The left angled flat of the breech was marked with the usual U.S. arsenal V (view), P (proved) and Eagle-Head markings and the barrel’s date of production was stamped on the top of the breech. The tang of the buttplate was stamped U.S. and the barrel bands were stamped with a “U” for “up” on their obverse. As with all arsenal produced arms, numerous small inspection marks are found on various parts with a final inspection and acceptance cartouche(s) on the counterpane, opposite the lock. Some examples are known with rack markings, applied during their cadet service, as well as with state ownership markings, most often the “NJ” of New Jersey. All the guns were manufactured with the “National Armory Bright” polished finish, with all iron furniture, with the exception of the brass nose cap of the Type I variants. Stocks were American black walnut. At least one New Jersey surcharged variant appears to retain traces of a period applied

blue finish, but why or when the gun was blued is unclear.

An entire family of U.S. military long arms would be adopted based upon the M1855 rifle musket and the Maynard tape priming system. These included not only the rifle muskets, but a 33-inch barreled rifle, a shorter percussion carbine (without the Maynard system), and a pistol-carbine. All these arms were manufactured in numbers exceeding the M1858 cadet rifle musket, with the exception of the M1855 carbine, of which only one thousand and twenty were produced.

For collectors, M1858 is one of the harder U.S. arsenal produced arms from the immediate pre-Civil War period to find for sale. When these are encountered on the market, they often show

heavy use, particularly those with any southern provenance. In addition to being a fairly scarce gun, the U.S. M1858 cadet rifle musket also holds the distinction of being the last of the muzzleloading cadet arms produced by the Ordnance Department, as all subsequent cadet rifles would be metallic cartridge guns manufactured in the post-Civil War period.

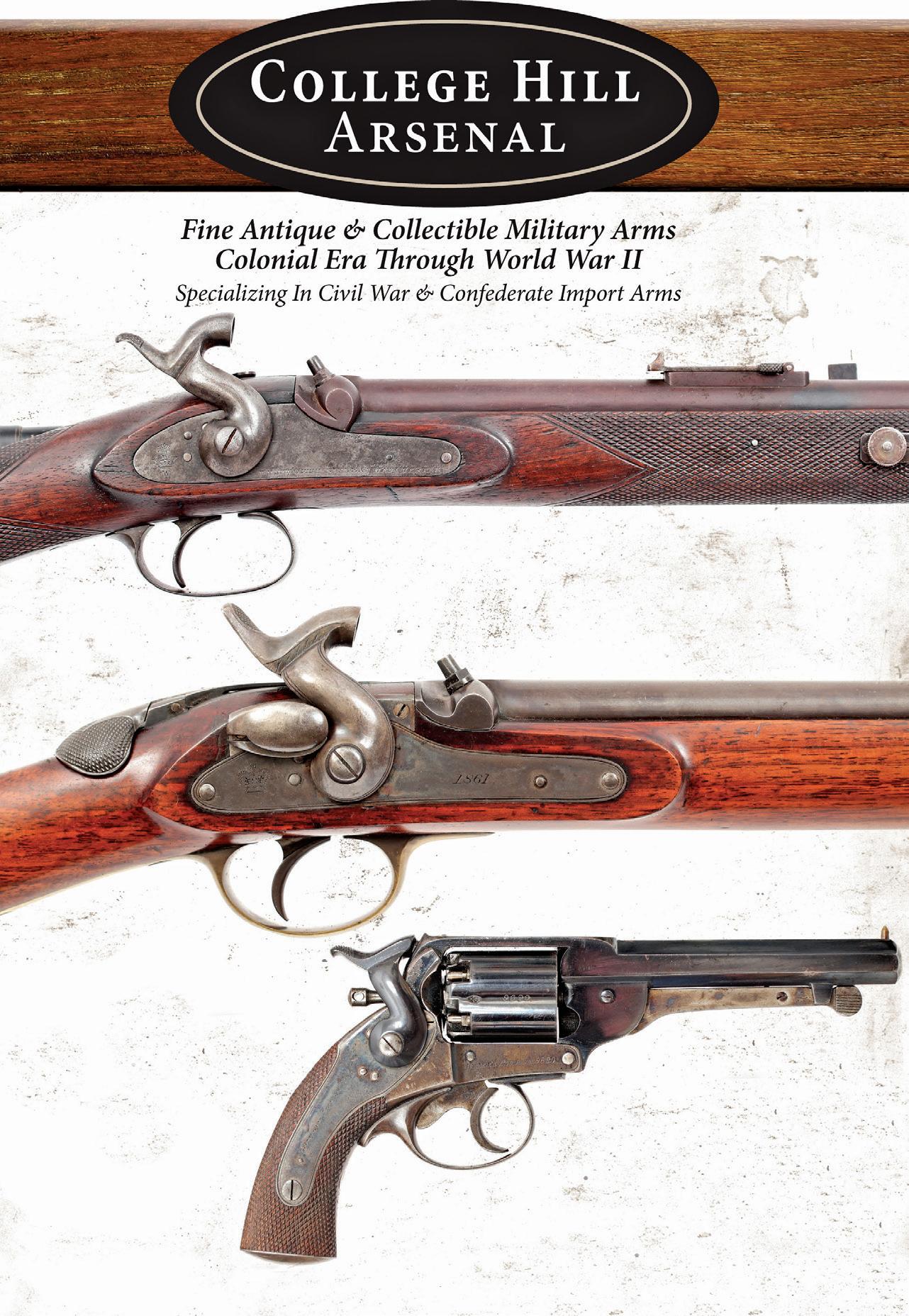

Tim Prince is a full-time dealer in fine & collectible military arms from the Colonial Period through WWII. He operates College Hill Arsenal, a web-based antique arms retail site. A long time collector & researcher, Tim has been a contributing author to two major book projects about Civil War era arms including The English Connection

and a new book on southern retailer marked and Confederate used shotguns. Tim is also a featured Arms & Militaria appraiser on the PBS Series Antiques Roadshow.

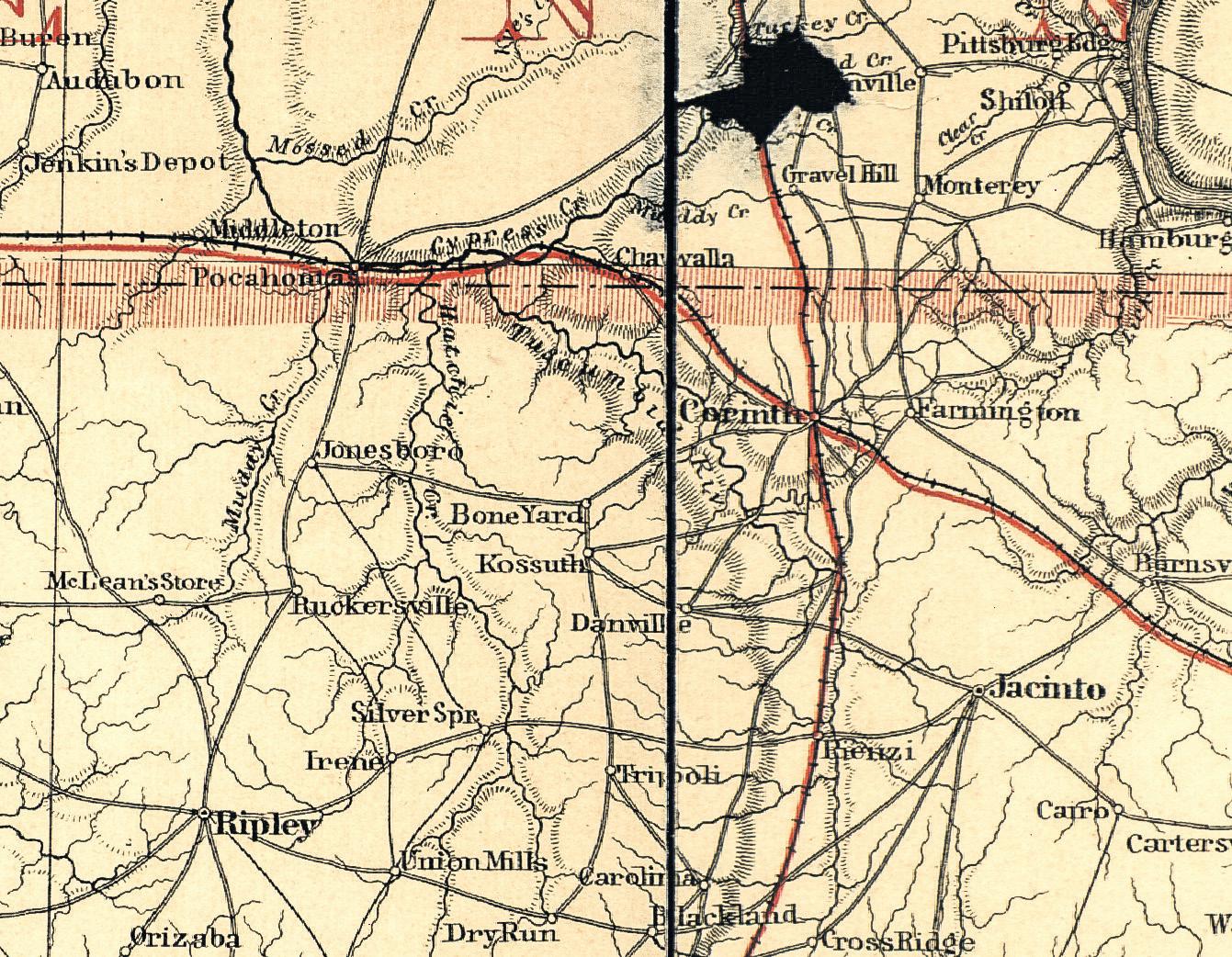

In May 1862, seven weeks after Shiloh, the Confederates were compelled to evacuate Corinth, Miss. Four months later they tried to take back the important railroad junction, but failed in a two-day battle ending the afternoon of October 4.

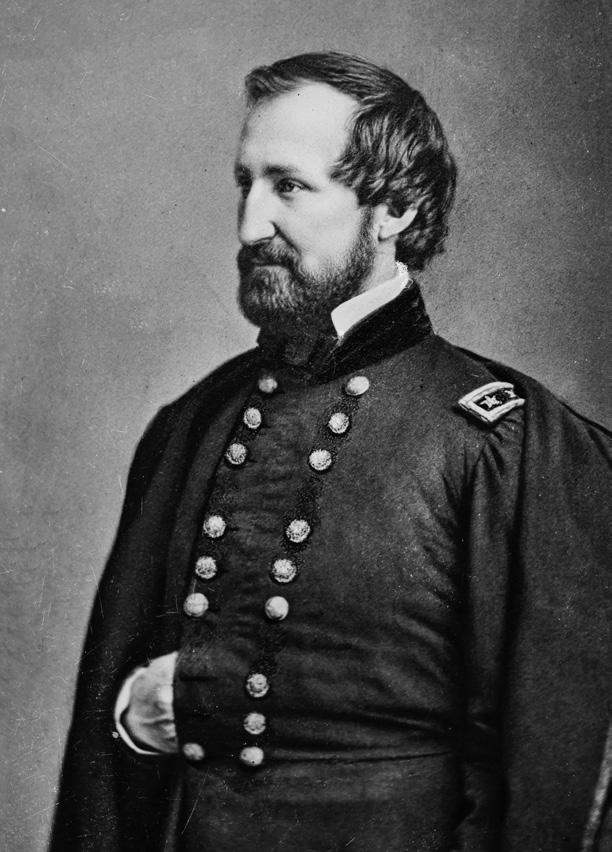

Under Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, the Southern forces withdrew to the northwest, the direction from whence they came; aiming to cross two rivers, then head south toward Ripley and Holly Springs. The Federals, commanded by Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, followed, hoping to destroy the defeated Confederate army.

In this column we will march with Rosecrans’s men in their pursuit and, in addition, take a look at the controversies that arose in this aftermath of the Battle of Corinth.

Rosecrans was subordinate to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who commanded the Department of

the Tennessee from his Jackson, Tenn., headquarters 58 miles north of Corinth.

In his report dated Oct. 30, Grant states: “As shown by the reports [of subordinate officers] the enemy was repulsed at Corinth at 11 a.m. and was not followed until the next morning. Two days’ hard fighting without rest probably had so fatigued the troops as to make earlier pursuit impracticable.”

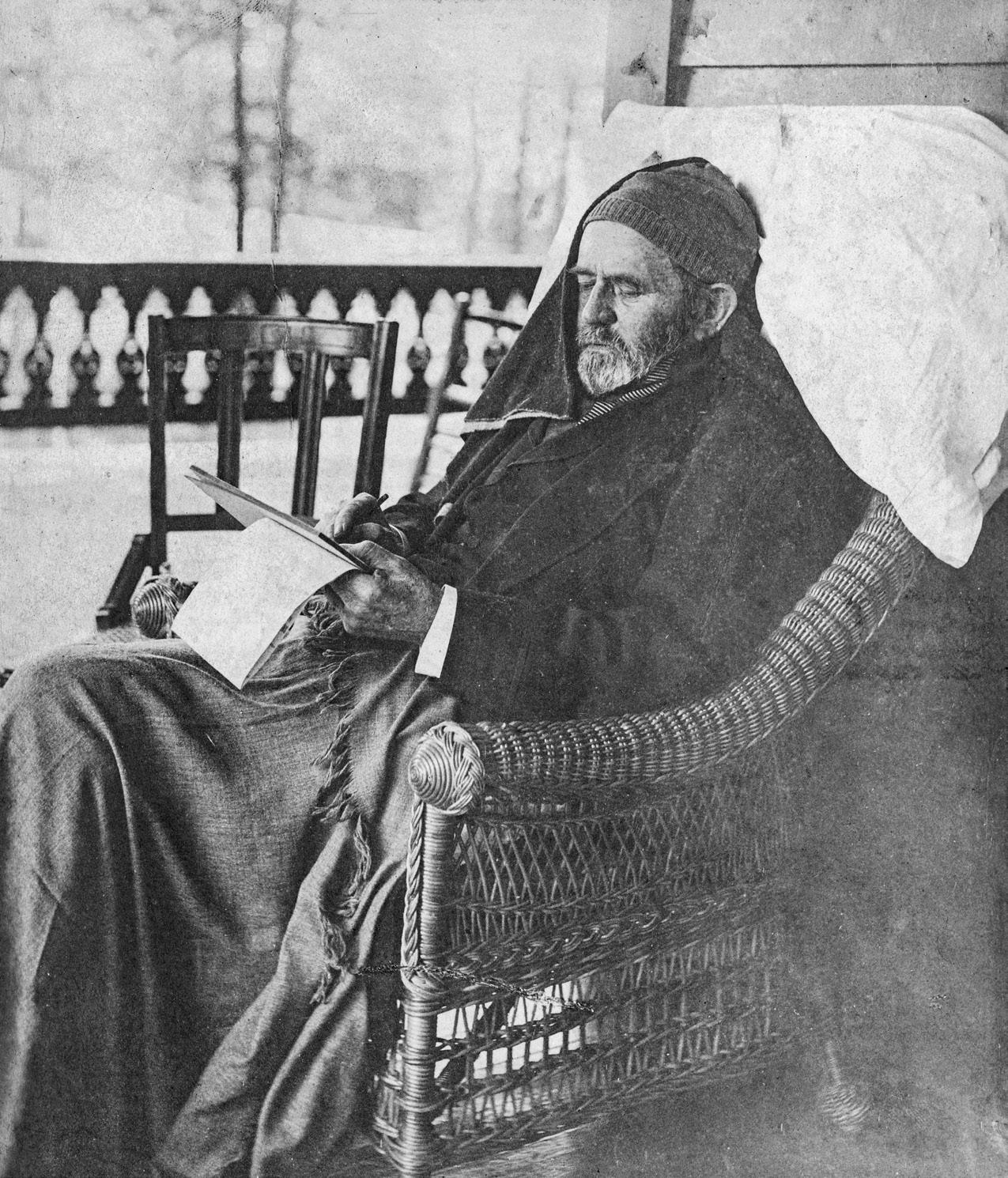

Grant says that he “regretted this,” as swifter pursuit would have been more damaging to the enemy, but he assigns no blame for the delay. His memoirs tell a different story.

“General Rosecrans…failed to follow up the victory,” Grant writes, “although I had given specific orders in advance of the battle for him to pursue the moment the enemy was repelled. He did not do so, and I repeated the order after the battle.” Continuing

his criticism of Rosecrans’s performance, Grant provides more detail. “Rosecrans did not start in pursuit till the morning of the 5th and then took the wrong road. Moving in the enemy’s country he travelled with a wagon train to carry his provisions and munitions of war. His march was therefore slower than that of the enemy, who was moving toward his supplies. Two or three hours of pursuit on the day of the battle, without anything except what the men carried on their persons, would have been worth more than any pursuit commenced the next day could possibly have been. Even when they did start, if Rosecrans had followed the route taken by the enemy, he would have come upon Van Dorn in a swamp with a stream in front and [a Federal force under Maj. Gen. Edward] Ord holding the only bridge; but he took the road leading north to Chewalla instead of

west, and, after having marched as far as the enemy had moved to get to the Hatchie, he was as far from the battle as when he started.”

So, according to Grant, the enemy was repulsed at 11 a.m.; Rosecrans disobeyed an order to pursue “the moment the enemy was repelled;” he marched on the wrong road and burdened himself with an unnecessary wagon train; and after a long march he was as far from Van Dorn’s army as when he started.

Let’s start with the time of the repulse, a minor but significant question. The earlier the repulse, the longer the gap between the battle’s end and the pursuit’s beginning; moreover, longer fighting would mean more casualties and wearier troops. No report other than Grant’s mentions a time as early as 11 a.m. Most state no time at all, and those that do range from noon until 2 p.m. One Union report states that the Confederates broke through the works and into the town at 11:30.

A Confederate brigade commander mentions that he was ordered forward at 11 a.m. The discrepancy is not great, but 11 a.m. is clearly incorrect and the records provide no basis for Grant’s assertion.

We next examine the claims that Rosecrans took the wrong road and impeded his progress with a wagon train.

A glance at the map shows that the road to Chewalla goes not north from Corinth, but to the northwest. At Chewalla the road bends to the west toward Memphis, crossing the Tuscumbia River at Young’s Bridge and then the Hatchie River at Davis’s Bridge. This is the route taken by Rosecrans, and it is also the route taken by the army he was pursuing.

Numerous reports confirm this. In his Oct. 25 report Rosecrans writes that “The enemy blew up several ammunition wagons between Corinth and Chewalla,

and beyond Chewalla many ammunition wagons and carriages were destroyed, and the ground was strewn with tents, officers’ mess-chests, and small arms.”

A detachment commanded by Brig. Gen. James B. McPherson led the pursuit. McPherson’s report states that his command “shortly after daylight on [Oct. 5] started in pursuit of the enemy on the road north of the railroad to Chewalla…when about 6 miles from Chewalla heavy firing was heard in the direction of Davis’ Bridge across the Hatchie River….” (This was Ord’s force that Grant’s memoirs allude to, coming from the north to block the Confederates at Davis’s Bridge.)

The report of Capt. Joseph Smith, commanding the 5th Ohio Cavalry, states that he was pressing on Van Dorn’s rear. “At Chewalla,” Smith writes, “I had a severe skirmish with the enemy’s rear guard…. He soon left upon the approach of the main column, and we again pursued him, coming upon him near the Tuscumbia, at Young’s Bridge.” This column could be lengthened unnecessarily with quotes from other accounts. The Confederates took the road to Chewalla. Rosecrans followed. What of the wagon train?

The reports contain no reference to any train except the one belonging to a single division. Rosecrans dealt with this problem on the first day of the pursuit. “Halt your train, turn it out, and park it,” read the order from Rosecrans’s chief of staff. “I am told it is a mile long. Take nothing with you but ammunition and ration wagons. You have left our advance force without a support by your tardy movements. You are in the way of other divisions.” Hours after the start of the pursuit Rosecrans learned of the trouble and ordered it fixed.

The Union force was pursuing on the right road, slowed for a time by one division’s wagon train. What was the nature of this pursuit? Federal reports tell of a harried Confederate army with an enemy nipping at its heels.

Col. John Mizner commanded the cavalry division. His report, dated Oct. 19, states that his brigades “formed two flanking columns, [with one] moving on the north side [and the other] on the south side of the Chewalla road, making frequent dashes at the enemy’s flanks, harassing them, hanging continually on their skirts, and impeding their retreat….”

From McPherson’s report: “After crossing the Tuscumbia and the Hatchie…, the evidences of a most rapid retreat, almost a rout, were apparent. The road was strewn with tents, blankets, clothing, wagons, small-arms, ammunition, six caissons, and a battery-forge, some of them blown up and partially destroyed and others in good condition.”

Brig. Gen. John McArthur’s Division marched behind McPherson’s force for much of the pursuit. McArthur’s description is similar to McPherson’s. He writes of “capturing many prisoners and causing the enemy to abandon and destroy much of their property in arms, artillery, ammunition, and camp equipage,” as he followed the route to Ripley before his return to Corinth.

Return to Corinth? Yes, at 8:30 p.m. on Oct. 7 Grant ordered Rosecrans to halt the pursuit and return to Corinth.

In a midnight dispatch Rosecrans exhorted Grant to reconsider. “We have defeated, routed, and demoralized the army which holds the Lower Mississippi Valley…. All that is needed is to continue pursuing and whip them. We have whipped, and should now push to the wall and capture all the rolling stock of their railroads….. If…you still consider the order to return to Corinth expedient I will obey it and abandon the fruits of

a victory, but I beseech you bend everything to push them while they are broken and hungry, weary and ill-supplied.”

Grant did reconsider, and told Rosecrans to stay in place until he consulted with General-inChief Halleck.

On the morning of Oct. 8 Grant sent a dispatch to Halleck advising him that “Rosecrans has followed the rebels to Ripley…. I ordered Rosecrans to go back [to Corinth] last night but he is so averse to returning that I have directed him to remain still until you can be heard from.” Later that same day Grant changed his mind, telling Halleck “On reflection I deem it idle to pursue farther without more preparation, and have ordered for the third time his return.” Halleck’s reply has an incredulous tone: “Why order return of our troops? Why not re-inforce Rosecrans and pursue the enemy into Mississippi…?”

Grant sent Halleck his reasons: inability to subsist on the country; the expected arrival of Confederate reinforcements; and the troops’ exhaustion. Grant told Halleck that there was a possibility of “partial success…from farther pursuit” but predicted that “disaster would follow in the end.” Grant added: “If you say so, however, it is not too late to go on….” Halleck, quite naturally, deferred to Grant’s judgment.

In his Oct. 30 report, Grant says this about his order to halt. “When I ascertained that the enemy had succeeded in crossing the Hatchie I ordered a discontinuance of the pursuit…. This I regarded, and yet regard, as absolutely necessary to the safety of our army. They could not possibly have caught the enemy, before reaching his fortifications at Holly Springs, where a garrison of several thousand troops were left that were not engaged in the battle for Corinth. Our own troops would have suffered for food and suffered greatly from fatigue.”

We conclude with a discussion of the order referred to in Grant’s memoirs, “specific orders in advance of the battle for him to pursue the moment the enemy was repelled.”

No such order is to be found in the records, nor is there any reference to this order in after-action reports or correspondence.

The silence in the records is all but conclusive, but beyond that we should ask whether an order of this kind makes any sense, and whether such an order is likely to be issued by a commander 58 miles from the scene with communication slowed because of a broken telegraph line. Specific orders. In advance of the battle.

The moment the enemy was repelled. The battle had not yet begun. Neither Grant nor anyone else knew how long the fighting would last, what time of day or night it would end, how heavy the losses on each side would be, what condition the opposing forces would be in when the battle ceased, or even if the Confederates would be the ones retreating.

On Apr. 22, 1865, Rosecrans appeared before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. He testified on the Confederates’ condition after the Battle of Corinth and the subsequent pursuit. “The enemy was exhausted; his cavalry, eighteen regiments strong, gave way everywhere to our four little [cavalry] regiments. Numbers of deserters and stragglers were scattered through the woods in all directions, and were constantly being picked up by our men….” Numerous indications led Rosecrans to the conclusion that “the enemy considered himself thoroughly whipped…. Mississippi was in our hands.”

“Mississippi was in our hands,” said Rosecrans, when Grant ordered a halt.

Irony abounds. Grant, known for his aggressiveness, was critical of Rosecrans for not being sufficiently aggressive in failing to pursue “the moment” the Confederates were repulsed. On Oct. 8, over his subordinate’s strong protests that continued aggressive pursuit would reap great benefits, he ordered Rosecrans to return. Furthermore, Grant tells Halleck, “your call,” but phrases the choice in such a way that Halleck really had no choice. If the man on the scene (or at least close to the scene) predicts disaster how can a commander in Washington say “go ahead”? At the same time Grant does not defer to the judgment of the general who is in immediate command of the troops chasing Van Dorn. Rosecrans judged his men too tired to begin the pursuit on Saturday afternoon. He was wrong. Four days later, Rosecrans reckoned his men fit for continuing the chase, and judged the Confederates unable to stop the Federals. Wrong again.

As time passed and Grant was writing his memoirs, Rosecrans got even wronger.

Further reading: The reports and dispatches referenced— and much else that is relevant to the topic—are in the Official Records, Series I, Vol. XVII, Parts I and II. Rosecrans’s testimony on the battle and pursuit is found on pages 20-24 of “Rosecrans’s Campaigns” in Joint Committee on the Conduct

Gen. U.S. Grant writing his memoirs, Mount McGregor, June 27, 1885. (Library of Congress) of the War at the Second Session Thirty-Eighth Congress. His article “The Battle of Corinth” is in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. All of these documents are easily found online. There are two biographies of Rosecrans: The Edge of Glory: A Biography of General William S. Rosecrans, U.S.A. by William M. Lamers (Louisiana University Press, 1999) and William S. Rosecrans and the Union Victory: A Civil War Biography by David G. Moore, (McFarland & Company, 2014). General Grant and the Rewriting of History, by Frank P. Varney (Savas Beatie, 2013) was reviewed in the February 2019 issue of Civil War News. The subtitle of Varney’s book best describes its contents: “How the Destruction of General William S. Rosecrans Influenced Our Understanding of the Civil War.”

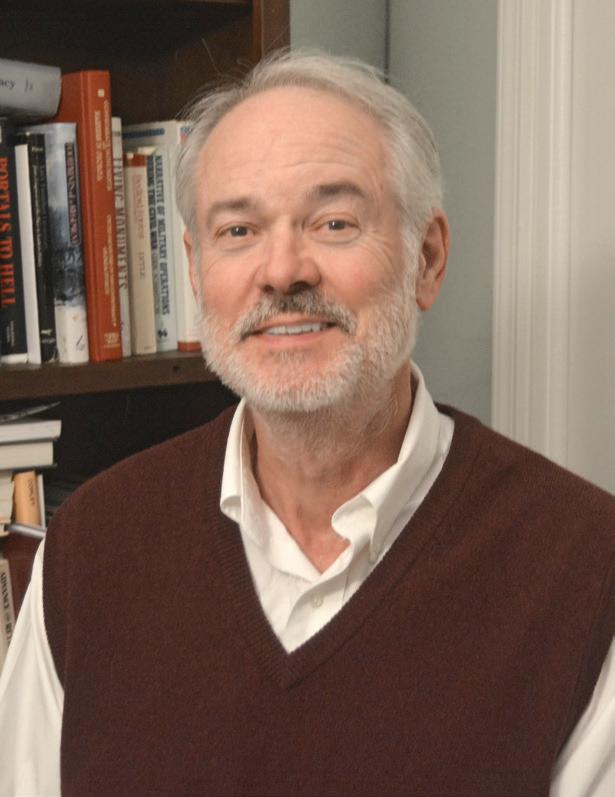

Gould Hagler is a retired lobbyist living in Dunwoody, Ga. He is a past president of the Atlanta Civil War Round Table and the author Georgia’s Confederate Monuments: In Honor of a Fallen Nation, published by Mercer University Press in 2014. Hagler speaks frequently on this topic and others related to different aspects of the Civil War and has been a regular contributor to CWN since 2016. He can be reached at gould. hagler@gmail.com. Hagler is a distant cousin of General Grant’s (sixth cousin five generations removed).

This unique work contains a complete photographic record of Georgia’s memorials to the Confederacy, a full transcription of the words engraved upon them, and carefully-researched information about the monuments and the organizations which built them. These works of art and their eloquent inscriptions express a nation’s profound grief, praise the soldiers’ bravery and patriotism, and pay homage to the cause for which they fought.

weeks. While mowing earlier today, I came across a four-leaf clover. It’s my ninth one this month. (Seriously!) If you saw the first day of our Facebook LIVE with the Trust, I found one during our broadcast from Germanna Ford, and then I found seven the next day in the Widow Tapp Field (live on camera, so there are witnesses).

From the Editor

To the east, a full moon is about to lift itself above the horizon. Already, the thin cloud cover glows with pregnant light, signaling an imminent arrival.

I recently re-watched The Wolfman—not the great Lon Chaney Jr., version but the lessgood Benicio Del Toro version— so on some unconscious level, this full moon is the source of mild alarm to me. The cigar I’m smoking to ward away the bugs is apt to do me little good against a werewolf should one come prowling. I’m sitting on my back porch, enjoying this smooth Macanudo and a bourbon barrel-aged Allagash beer, in an attempt to carve out a little quiet time in what has already been an insanely busy month, and it’s only 2/3 over. May always brings so much to do because the anniversaries of Chancellorsville (1863) and the Overland Campaign (1864), keep me particularly busy; some of my other colleagues focus on the opening of the Atlanta Campaign, the battle of New Market, or the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. No one gives the Red River Campaign any love, I guess, poor Nathaniel Banks! ECW has so much already this month that I can barely think in bullet points, let alone full sentences. For me, May also marks the ending of a semester with all its attendant grading. No matter how well-prepped I try to be going into the home stretch, I always have a ton to do. And, of course, to add one final insult to injury, the lawn, “the green demon,” as my colleague Dan Welch refers to his, somehow needs mowing about thirteen times in the month’s first three

What better reminder could there be of how lucky I am to be able to get to do what I love, every single day, whether that be mentoring young writers in the classroom, sharing stories of the Civil War with so many interested people, or writing, writing, writing.

I may not really be superstitious about the full moon, but I can’t deny my great good fortune. I am a lucky man, indeed.

– Chris Mackowski, Ph.D. Editor in Chief

We have twelve tickets left for our upcoming ECW Symposium, Aug. 2-4, 2019, at Stevenson Ridge on the Spotsylvania Battlefield. Yep, just twelve.

Tickets are $155 each and include ten speakers, a keynote address by A. Wilson Greene, and a Sunday tour of the North Anna battlefield with Bert Dunkerly and Chris Mackowski, plus all the other usual cool fun we always have at the Symposium!

You can find more details, and order one of the last tickets, at https://emergingcivilwar. com/2019-symposium/.

Sarah Kay Bierle hunkered down at the Library of Congress for a few days at the end of May following a successful series of appearances related to the launch of her new book (see the ECW Bookshelf for details). She signed books at the Virginia Military Institute Museum on Remembrance Day (May 15), spoke to the Powhatan Civil War Roundtable, then gave a series of talks at the New Market battle reenactment, where she also signed books, May 18-19.

James Brookes has an article in the most recent edition of The Journal of American Studies, published by Cambridge University Press: “Images in Conflict: Union Soldier-Artists Picture the Battle of Stones River, 1862–1863.” You can read that article here: https://tinyurl.com/y246acjk

Meg Groeling surprised everyone when she showed up at Manassas National Battlefield on May 11 with a walker, but she made it most of the way through the woods “In the Footsteps of the 69th NY.” Of course, she straggled, but she was such a good sport about it all that no one complained within her hearing distance. Meg reports, “Historian Damian Shiels was just as charming as possible, as was Harry Smeltzer. John Hennessey was a true gentleman.” Meg says she’s thrilled at the opportunity to write about 11th New Yorker (and Ellsworth aide-de-camp) John Wildey for Mr. Shiels’ blog, “The Irish in the American Civil War.” She hopes to use Shiels’ methods of examining government documents to piece together stories of some men in the 11th New York, adding to her already copious interest in “Ellsworth’s Lambs.”

Kevin Pawlak spent a couple of days in the National Archives recently researching miscellaneous Army of the Potomac files. We can’t wait to see what he has found.

Dan Welch will be heading

service to help Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge’s forces stop a Federal advance by Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel.For more information, check out the publisher’s website: www.savasbeatie.com.

Also, new in audio this month: Let Us Die Like Men: The Battle of Franklin by Lee White and Fight Like the Devil: The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863 by Chris Mackowski, Kris White, and Dan Davis. Both books are available at Audible.com.

back to Gettysburg this summer as a seasonal Park Ranger with the National Park Service. Look for him on the battlefield or at the visitor center.

Did you catch ECW’s teamup with the American Battlefield Trust to commemorate the 155th anniversary of the Overland Campaign? If not, you can still see the videos on the Trust’s Facebook page (even if you don’t belong to Facebook). Kris White hosted the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and North Anna, while Garry Adelman hosted Cold Harbor. Among familiar ECW faces who joined in the fun were Doug Crenshaw, Dan Davis, Phill Greenwalt, Steward Henderson, and Chris Mackowski.

The 33rd book in the Emerging Civil War Series is now out: Call Out the Cadets: The Battle of New Market by Sarah Kay Bierle. The book features a foreword by Col. Keith Gibson, director of the VMI Museum in Lexington, Va.

Sarah’s book tells the story, among others, of the VMI cadets called into Confederate

By day, Todd Arrington is the site supervisor for the James Garfield National Historic Site in Mentor, Ohio; by evening, he helps manage ECW’s social media. You can read his full bio here: https://emergingcivilwar. com/author-biographies/authors/ todd-harrington/.

As ECW’s social media manager, you do a lot of behind-thescenes work. What do you like about social media?

I think it’s a great way to get historical information out to people, whether they’re professional historians or just casually interested in the Civil War era. The reach of social media allows us to communicate information to people everywhere. The number of people who will go out and buy a book (or check it out of the library) or attend a symposium is small, but tools like Facebook and Twitter give us the potential to reach millions. Even if only a handful of them end up reading an article at EmergingCivilWar. com or getting interested in doing their own research, we’ve still made a major impact.

How did you get interested in social media in the first place?

By necessity, really. About ten years ago it was becoming clearer and clearer that social media was a powerful force in how people received and consumed information, be it about what’s going on in the world, popular culture, or even history. We needed someone to start working with Twitter and Facebook at my workplace, and I just started playing around with it and seeing what worked and what didn’t. That eventually led to Instagram and blogging as well. Surely there are many other social media platforms out there by now that I really don’t know anything about, so I’m far from an expert. But I’ve definitely had fun with it and had at least some success.

You’ve also been blogging for a while (prior to ECW, you

blogged with We’re History). What do like about blogging?

Blogging is a great way for historians of all levels of education, experience, qualifications, etc., to put their research and ideas out there for the world to see. In academic history, there is so much pressure to regularly publish (“publish or perish,” as some often say) books and articles. For people working in academic history, blogging is a great forum to try out ideas and theories and see if they’ve got legs. Even for non-academic historians, amateur historians, and history enthusiasts, blogging is a perfect way to get your work out there and have people read it, evaluate it, and ask questions about it. It has given everyone a forum to publish pretty much whenever and whatever they want. Not all of it is good, of course, but I’ll also say that some of the best original research I’ve ever read has been on blogs. I’m thrilled to blog with Emerging Civil War and am excited to be working to get We’re History back up and running as well.

You work by day at the James A. Garfield National Historic Site in Mentor, Ohio. What do you find fascinating about Garfield?

So much about James Garfield is fascinating. He lived through some of the most trying times in our nation’s history and played a significant role in them. But he’s largely forgotten now and usually written off as unimportant because he served so briefly as president before being assassinated in 1881, in office just four months before being shot. But his presidency is really just a tiny part of his life. He lived almost 50 years, and for only 200 days of that was he President of the United States. So learning more about him every day and communicating that information to the public is something I really enjoy. I joke with our staff all the time that by the time I’m finished with Garfield, they’ll be adding him

Civil War?

Stonewall Jackson.

Favorite Trans-Mississippi site?

Homestead National Monunmet of America in Beatrice, Neb. Not a place many people expect to find Civil War history, but it’s hugely important there! (Full disclosure: I worked there for 10 years!)

Favorite regiment?

Right now it’s the 42nd Ohio since James Garfield commanded that regiment for a time.

Symposium focusing on the American Revolution.

to Mount Rushmore. That might be a stretch, but I’ll keep trying anyway.

You’re working on a book about the election that put Garfield in the White House. What discoveries have you made along the way that have been particularly exciting for you?

The thing that has most impressed me about Garfield is how dedicated he was as a congressman during Reconstruction to protecting the civil and political rights and physical safety of African Americans in the South. Garfield was a pretty reliable Radical Republican for most of Reconstruction. And though there are many people who even today choose to believe that slavery had little or nothing to do with the Civil War, Garfield had it pegged from the beginning. Two days after Fort Sumter in 1861, he wrote, “The war will soon assume the shape of Slavery and Freedom. The world will so understand it, and I believe the final outcome will redound to the good of humanity.” And then he put his money where his mouth was and joined the Union Army. For the rest of his life, as a soldier, congressman, and president, he was usually on the right side of history when it came to civil rights. By 1880, when he was a somewhat unexpected presidential nominee for the Republicans, even many of the most radical Republicans were moving on to issues other than civil rights. But not Garfield. In fact, he even addressed civil rights in his inaugural address. What I’ve learned about him during my book research makes me convinced that he was absolutely the right man for the presidency in 1880. Of course, this just compounds the tragedy of his assassination. I think he could have been a truly great and important president.

Lightning Round (short answers):

Most overrated person of the

What is the one Civil War book you think is essential?

Hard question! I’ll say Battle Cry of Freedom by James M. McPherson but also Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels. The latter is the book that hooked me on the Civil War, so I’d be remiss not to mention it.

What’s one question about the Civil War no one has ever asked you that you wish they would?

I don’t know about that, but instead I’ll share a question that I once WAS asked that I still can’t believe. This happened almost 25 years ago when I was working at Gettysburg. A guy asked me, “Why were Civil War battles always fought in national parks?” I hope he was kidding, but I don’t think so.

Our Emerging Civil War Podcasts for May featured a pair of programs about battles with May anniversaries.

Our first podcast of the month featured an interview with Sarah Kay Bierle about her new book, Call Out the Cadets: The Battle of New Market.

Our second podcast featured part two of a conversation between Chris Mackowski and Kris White about the battle of Chancellorsville.

Each episode is only $1.99. You can subscribe here: https://www. patreon.com/emergingcivilwar.

Alexandria is George Washington’s hometown and we feel it is a great place for us to start this new endeavor. Historic “Old Town” Alexandria is home to dozens of museums and historic sites as well as great pubs, restaurants, and shops. Gadsby’s Tavern Museum is the premier 18th century tavern museum in the country and hosts the famous annual George Washington Birthnight Ball. The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum will be our host location. Today The Lyceum serves as the City’s history museum and is a center of learning through lectures, demonstrations,

and exhibits. This year’s theme is “Before They Were Americans” and will highlight several topics about the years leading up to the American Revolution. Our speakers include: Phillip Greenwalt, Katherine Gruber, William Griffith, Stephanie Seal Walters, and Dr. Peter Henriques as the keynote.

Registration will open on July 1, 2019, through AlexandriaVA. gov/Shop or by calling 703746-4242. For more information about this symposium and get your American Revolutionary Era fix, continue to check out the Emerging Revolutionary War blog at www.emergingrevolutionarywar.org.

Deadlines for Advertising or Editorial Submissions is the 20th of each month.

Email to: ads@civilwarnews.com

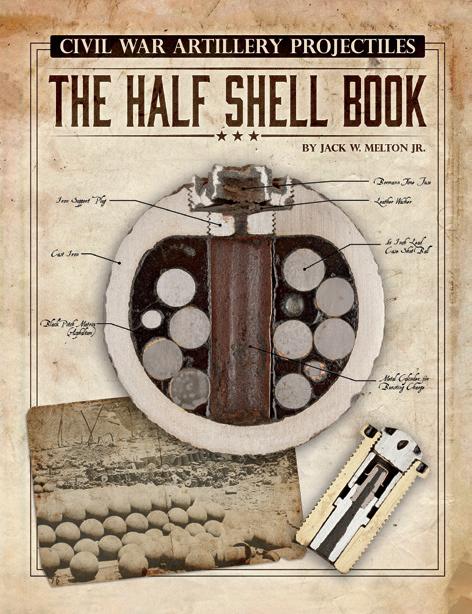

New 392 page, full-color book, Civil War Artillery Projectiles – The Half Shell Book.

For more information and how to order visit the website www.ArtillerymanMagazine. com or call 800-777-1862. $89.95 + $8 media mail for the standard edition.

Mark your calendars for September 28, 2019! Emerging Revolutionary War is excited to announce that we are partnering with Gadsby’s Tavern Museum and The Lyceum of Alexandria, Va., to bring to you a day-long

SUBSCRIBE NOW 4 quarterly issues, $24.95

Online: MilitaryImagesMagazine.com

Since 1979, MI has been America’s only publication dedicated to historic photographs of soldiers and sailors. By check payable to: Military Images PO Box 50171 Arlington, VA 22205

Want to try before you subscribe? Visit MI’s website to sign up for a 2 issue trial.

(1952), turned to the genre of alternate history. I mentioned his book two years ago when I wrote in this space about fictional renditions of Confederates’ victory at Gettysburg.

As you may recall, the counterfactual bookshelf offers quite a few scenarios. Pickett’s Charge cracks the Yankee line wide open (Winston Churchill, 1930). Stuart stays with Lee and the battle never happens (Otto Eisenschiml and E. B. Long, 1948). Ewell boldly takes Culp’s and Cemetery Hills (MacKinlay Kantor, 1960).

learned in MacKinlay Kantor’s If the South Had Won the Civil War). In Moore’s novel, the North American map was redrawn when Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri were included in the Confederate States. Dixie generously gave away western Virginia, but negotiators drew the Confederacy’s borders westward from Kansas to California, incorporating the southern reaches of that vast territory into the nascent nation.

world in book publishing.

I think I learned the word funky from Rockford (James Garner) back in the ‘70s.

Well, something definitely funky is going on when one reads the first sentence of Ward Moore’s novel, Bring the Jubilee: “Although I am writing this in the year 1877, I was not born until 1921.”

Ward Moore (1903–1978) was an American science fiction writer who, with Bring the Jubilee

Lee takes a defensive position and Meade launches disastrous attacks (Mark Nesbitt, 1980; Newt Gingrich and William R. Fortschen, 2003).

In Moore’s “What if?” the key to Lee’s victory at Gettysburg is the Confederate seizure of the Round Tops following their rout of the Union I and XI Corps on July 1. They bring artillery up the commanding heights that, on the second day, supports the Southern infantry’s savage attacks on Meade’s army. With Pickett’s charge on July 3, “the disorganized Federals were given the final killing blow in their vitals.”

The protagonist in Bring the Jubilee is Hodgins McCormick Backmaker, the grandson of a Union Civil War veteran. On the very first page of the novel Backmaker refers to Lee’s victory, the Army of the Potomac’s “Great Retreat to Philadelphia,” and the fall of Washington. The Union’s western forces bristled at the idea of surrender, but after they were defeated at Chattanooga, the Lincoln government sued for peace and formally recognized Southern independence.

Military counterfactualism in itself can be fun, but so can imagining America in the years after Confederate victory (as we

As would occur in the Treaty of Versailles, the Peace of Richmond imposed a huge reparations bill upon the defeated North. Disgusted Northern voters threw the Republicans out, so Democratic presidents Clement Vallandigham and Horatio Seymour had to contend with the weakened U.S. economy. Rampant inflation made even life’s necessities unaffordable for most people; food riots broke out in Northern cities during 1873–74. Things got so bad in the U.S. that for thousands of men and women, the only way to escape poverty was to sell themselves as indentured servants.

To resurrect a two-party system in U.S. politics, the Whigs experienced a rebirth; in 1876 Benjamin F. Butler was elected the first Whig president since Zachary Taylor. He remained hobbled, though, by the widespread economic slump that had no end; the enormous reparations payments to the South had to be paid annually and in gold.

Hodgins Backmaker, as a lad in the 1920s and ‘30s, recalled how his parents talked bitterly of how the War of Southron Independence “still, nearly seventy years later, blighted what was left of the United States.”

The North’s bleak economy even affected U.S. population numbers. Many people left the country; foreigners ceased to come, as northern America was no longer a “land of opportunity.” Unable to support large families, most Northerners married late in life, often raising only one child.

U.S. economic woes extended in every direction. While the Confederate States, like other prosperous nations (e.g., the German Union) had plenty of automotive cars (“minibiles”), they were rare in the North. Transcontinental railroads offered another index: the Confederacy had seven, British America one, and the United States zero.

As for educational and cultural benchmarks, Confederate and European universities towered over decaying Northern institutions like Harvard and Yale. Together with England, the Confederacy also led the western

In 1938 the largest Northern city, New York, had a mere 1.5 million people, much smaller in size than Confederate metropolises such as Washington (grown so large as to now take in Baltimore), St. Louis, and Leesburg (formerly Mexico City). C.S. president Robert E. Lee, who succeeded Jefferson Davis, had opposed the Confederate conquest of Mexico, but he had bowed to a determined Congress before dying in office in the 1870s. Confederate colonialism also extended into South America, so that ca. 1944–52 the Confederacy had 50 million citizens and 250 million subjects.

After the war the Confederacy also emancipated its slaves, but did not give them citizens’ rights, including the vote, the same status imposed upon Latinos after annexation of Mexico. Eventually full rights of citizenship were granted only to the posterity of citizens in the Confederacy as of July 1, 1864.

In the North, blacks fared little better and in an economy of scarce resources, were encouraged to emigrate. Many moved westward to places like Idaho and Montana, where unconquered Sioux and Nez Perce Indians still roamed.

Such is the world as described by Hodgins Backmaker after Robert E. Lee won the battle of Gettysburg.

…or maybe not. I won’t divulge the surprise ending of Ward Moore’s delightful novel. I’ll just say that it’s a trip.

P.S. Clio is the Greek muse of history. Moore terms her the

“most enigmatic of the muses.” That we can totally rewrite history in novels—and articles like this—makes the point.

Note

Ward Moore, Bring the Jubilee was originally published in 1952 by Farrar, Straus and Young, New York. A paperback edition was printed in 1997 by Ballantine Publishing Group, New York.

Stephen Davis’ article, “Simply Criminal,” on the battle of Pickett’s Mill, appears in the May 2019 issue of America’s Civil War. Civil War News of January 2019 also carried Steve’s article about an incident of that battle—how Union soldiers complained that all the bugling from Willich’s brigade alerted Confederates of their march to Pickett’s Mill. He and Bill Hendrick are working on a book on the Atlanta Daily intelligencer, leading wartime newspaper in the city.

Quick! What was the largest single-event capture of enemy artillery pieces in the entire Civil War? The answer may surprise you….

Here, based on my research (tell me if I’m wrong), are the “top ten” cannon-captures of the war. I list them in ascending numerical order of guns taken.

10. Several days after the fall of New Orleans, this Confederate fort on the Mississippi was surrendered on April 28, 1862. Can you name the fort, originally built in 1792 by the Spanish, who named it Fort San Felipe?

9. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate forces abandoned this point on the lower Peninsula of Virginia on May 3, 1862. Union officers counted 53 workable guns captured.

8. In arguably the Confederacy’s worst rout of a battlefield army, fifty-four cannon were lost in a Tennessee battle fought in December 1864. Which battle?

7. The fall of this Confederate fort on the Cumberland River opened the way to Union forces’ capture of Nashville within a week. It also gave U.S. Grant’s forces sixty-five captured cannon. Which fort?

6. Perhaps the Army of Tennessee’s greatest victory was this battle in

northwest Georgia, September 1863, which led to the Confederates capturing sixty-six Northern artillery pieces. Which battle?

5. When Stonewall Jackson captured a U.S. arsenal just before the battle of Sharpsburg, his troops captured seventy-three artillery pieces. Which arsenal?

4. This Louisiana fort, across the Mississippi from that referred to in question #10, was also surrendered by Confederates on April 28, 1862. Federals captured seventy-four cannon. What was its name?

3. The surrender of this Mississippi River island on April 8, 1862 netted Federal forces under John Pope 109 cannon. Which island?

2. When Confederate Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton surrendered this Mississippi River fortress in July 1863, he turned over 172 cannon. Which garrison?

1. The largest single-event capture of artillery occurred on April 21, 1861, when Virginia state troops seized which U.S. naval base near Norfolk?

Answers found on page 7. Steve Davis is the Civil War News Book Review Editor.

He can be contacted by email at SteveATL1861@yahoo.com.

Holzwarth for her display entitled “The Chaplain in WWI.” George Reese put out a great display called “Ohio Was There.” The Best Photographic award went to Richard Wolfe for his display “West Virginia Mourns Her Dead.”

The 2019 Best of Show Award went to Dave Gotter for his display of canister and grape shot entitled “A Withering Hail of Iron.” This display was a hit for artillery collectors and guests were pleased to see such a complete presentation of Civil War anti-personnel artillery weaponry.

Thanks to all the dealers who were generous in displaying their collections, memorabilia, and educational materials.

The Ohio Show is happy to have such a variety of quality displays for all to enjoy.

Make the Ohio Civil War Show your travel destination each year.

TitlesTake time to step back in time! Mark your calendars for May 2 and 3, 2020. The show will be held in the same location, the Richland County Fairgrounds, located in Mansfield, Ohio. Visit us on Facebook – Ohio Civil War Show and find out more on ohiocivilwarshow.com.

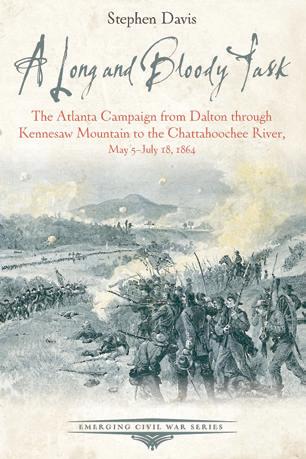

Stephen Davis

Stephen Davis

The Atlanta Campaign from Dalton through Kennesaw Mountain to the Chattahoochee River May 5–July 18, 1864

Davis’ narrative history of the Atlanta Campaign is divided into two paperbacks from Savas Beatie’s Emerging Civil War Series. Volume One, A Long and Bloody Task, carries Sherman’s forces from Dalton in northwest Georgia to the Chattahoochee River. There the Confederate government was forced to relieve its army commander, Joseph E. Johnston, and replace him with Gen. John B. Hood.

Paperback, 192 pages. $14.95 + $4.95 shipping

The Atlanta Campaign from Peachtree Creek to the City’s Surrender July 18–September 2, 1864

With the Yankee army five miles outside of Atlanta, Hood promised not to give up with city without a fight— which is all President Jefferson Davis asked. Davis’ companion volume, All the Fighting They Want, describes Hood’s efforts to defend Atlanta. Its fall in early September 1864 was a mortal blow to Confederate hopes for independence and a big boost to Lincoln’s hopes for presidential reelection.

Paperback, 192 pages. $14.95 + $4.95 shipping

To order a signed copy from author Stephen Davis call 404.735.8447 or email SteveATL1861@yahoo.com

Since 1981, I have traveled over 5 million miles buying, selling, appraising, brokering, cataloging and researching over $100,000,000 in value of historical memorabilia, including the most expensive and valuable Confederate arms in most every category over the past 25 years. These items included the finest firearms, swords and textiles to ever come to the market.

I still travel over 100,000 miles a year attending all major antique arms and Civil War shows as well as all major auctions of historical arms and Civil War. I provide services in securing the finest items with guaranteed authenticity to the most discerning Institution or collector. My fees are reasonable and well worth the "peace of mind" of having qualified written authenticity report on valuable objects.