Civil War News 2022 Gettysburg Edition

THE OFFICIAL START TO YOUR GETTYSBURG VISIT

New Exhibit Opens

July 1

See the Film. Experience the Gettysburg Cyclorama. Explore the Museum.

Tour the Battleeld with a Licensed Battleeld Guide.

Connect with National Park Service programs.

Tour the home and grounds at Eisenhower National Historic Site.

Visit the David Wills House and the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Journey to our historic sites and experiences.

Commemorating the 159th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg • July, 1 – 3, 2022

SACRED TRUST

Talks & Book Signings

Join renowned authors, historians and National Park Service Rangers for book signings and featured talks on the American Civil War. Visit GettysburgFoundation.org for the schedule and required evening program tickets.

Battle Anniversary Guided Programs

Join National Park Service Rangers for daily guided programs. Visit nps.gov/gett for the complete schedule of Gettysburg National Military Park programs.

Programs and talks are free and open to the public.

For tickets and current hours, call 877-874-2478 or visit GettysburgFoundation.org

Proceeds from tickets and other purchases in the Museum & Visitor Center benet Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Site.

The best surviving example of a corps-level eld hospital from the Battle of Gettysburg

Living historians make history come alive at this family farm suddenly transformed into a Civil War eld hospital in July 1863. Open summer weekends and for special events.

Summer Season Opens: June 10 – 12, 2022

Gettysburg’s most family-friendly NEW interactive children’s history museum

Explore the stories of Gettysburg through experiences of children who lived here during the battle. Engaging rst-hand accounts and interactive exhibits bring stories to life.

The NEW virtual reality experience at the Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad StationTM Travel back to 1863. Meet some unlikely station occupants. Hear stories of their experiences during the aftermath of the battle.

Now Open

When Maj. Gen. Jubal

A. Early’s Confederates smashed Union defenders here at 3 p.m., the Federal line north of Gettysburg collapsed.

East Cavalry Battlefield Site

Here on July 3, during the cannonade that preceded Pickett’s Charge, Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg intercepted and then checked Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry. For more information, ask for the free selfguiding tour brochure at the park visitor center information desk.

The complete 24-mile auto tour starts at the visitor center and includes the following 16 tour stops, the Barlow Knoll Loop, and the Historic Downtown Gettysburg Tour. The route traces the threeday battle in chronological order. It is flexible enough to allow you to include, or skip, certain points and/or stops, based on your interest. Allow a minimum of three hours to complete the tour.

July 1, 1863

McPherson Ridge

The Battle of Gettysburg began about 8 a.m. to the west beyond the McPherson barn as Union cavalry confronted Confederate infantry advancing east along Chambersburg Pike. Heavy fighting spread north and south along this ridgeline as additional forces from both sides arrived.

Eternal Light Peace Memorial

At 1 p.m. Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes’s Confederates attacked from this hill, threatening Union forces on McPherson and Oak ridges. Seventy-five years later, over 1,800 Civil War veterans helped dedicate this memorial to “Peace Eternal in a Nation United.”

Oak Ridge Union soldiers here held stubbornly against Rodes’s advance. By 3:30 p.m., however, the entire Union line from here to McPherson Ridge had begun to crumble, finally falling back to Cemetery Hill.

When the first day ended, the Confederates held the upper hand. Lee decided to continue the offensive, pitting his 70,000-man army against Meade’s Union army of 93,000.

July 2, 1863

North Carolina Memorial

Early in the day, the Confederate army positioned itself on high ground here along Seminary Ridge, through town, and north of Cemetery and Culp’s hills. Union forces occupied Culp’s and Cemetery hills, and along Cemetery Ridge south to the Round Tops. The lines of both armies formed two parallel “fishhooks.”

Virginia Memorial

The large open field to the east is where the last Confederate assault of the battle, known as “Pickett’s Charge,” occurred July 3. Pitzer Woods

In the afternoon of July 2, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet placed his Confederate troops along Warfield Ridge, anchoring the left of his line in these woods.

Warfield Ridge Longstreet’s assaults began here at 4 p.m. They were directed against Union troops occupying Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, and Peach Orchard, and against Meade’s undefended left flank at the Round Tops.

Little Round Top Quick action by Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, Meade’s chief engineer, alerted Union officers to the Confederate threat and brought Federal reinforcements to defend this position.

The Wheatfield Charge and countercharge left this field and the nearby woods strewn with over 4,000 dead and wounded.

The Peach Orchard

The Union line extended from Devil’s Den to here, then angled northward on Emmitsburg Road.

Federal cannon bombarded Southern forces crossing the Rose Farm toward the Wheatfield until about 6:30 p.m., when Confederate attacks overran this position.

Plum Run

While fighting raged to the south at the Wheatfield and Little Round Top, retreating Union soldiers crossed this ground on their way from the Peach Orchard to Cemetery Ridge.

Pennsylvania Memorial Union artillery held the line alone here on Cemetery Ridge late in the day as Meade called for infantry from Culp’s Hill and other areas to strengthen and hold the center of the Union position.

Spangler’s Spring

About 7 p.m., Confederates attacked the right flank of the Union army and occupied the lower slopes of Culp’s Hill. The next morning the Confederates were driven off after seven hours of fighting.

East Cemetery Hill

At dusk, Union forces repelled a Confederate assault that reached the crest of this hill.

By day’s end, both flanks of the Union army had been attacked and both had held, despite losing ground. In a council of war, Meade, anticipating an assault on the center of his line, determined that his army would stay and fight.

July 3, 1863

High Water Mark

Late in the afternoon, after a two-hour cannonade, some 7,000 Union soldiers posted around the Copse of Trees, The Angle, and the Brian Barn, repulsed the bulk of the

A

12,000-man “Pickett’s Charge” against the Federal center. This was the climactic moment of the battle. On July 4, Lee’s army began retreating.

Total casualties (killed, wounded, captured, and missing) for the three days of fighting were 23,000 for the Union army and as many as 28,000 for the Confederate army.

National Cemetery

This was the setting for Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered at the cemetery’s dedication on November 19, 1863. Use the Soldiers’ National Cemetery parking area on Taneytown Road.

Historic Downtown Gettysburg Tour

David Wills House Home of the prominent Gettysburg attorney who oversaw the creation of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Abraham Lincoln finished his Gettysburg Address here the night before the cemetery dedication. Under renovation. Will reopen November 2008.

Gettysburg Train Station

Abraham Lincoln arrived here on November 18. This structure was also a vital part of the recovery efforts after the battle, as a depot for delivery of supplies and evacuation of the wounded.

Look for these signs as you drive the battlefield. They identify the Auto Tour Route.

by George H. Lomas

by George H. Lomas

This 3-inch Ordnance rifle, serial no. 1, was part of Lieutenant Wilber’s section, Reynolds Battery L, First New York Light Artillery, assigned to the I Corps Artillery Brigade, under the Command of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright.

Serial no. 1 was manufactured by Phoenix Iron Company, Phoenixville, Penn., in the fall of 1861, under the U.S. Ordnance Contract of July 24, 1861. It was delivered to the government in November and issued from Washington Arsenal to Reynolds’ Battery at Camp Barry.

In May 1862, the battery was sent to join General Banks in the Shenandoah Valley. It was first assigned to General McDowell’s command. It was in reserve, though under fire, at Cedar

Mountain. The battery’s first engagement was at Rappahannock Station, where two were wounded; White Sulphur Springs, Grovetown, and Second Manassas followed. In the latter engagement, the battery bore a prominent part; had a number of men wounded, and eight horses killed. It was assigned to a position opposite a Rebel battery; another Federal volunteer battery stood on their immediate right. Owing to the severe firing of the Rebels, the other battery withdrew. Battery L retained its position, returning the sharp fire of the Southern artillery, and also repulsed an infantry charge using canister, while still holding their position until directed to retire by a general officer.

The battery was ordered to join the I Corps, and fought under General Hooker at Antietam, South Mountain, and Fredericksburg. It fought at Chancellorsville, and made the memorable march from Virginia to Gettysburg.

Around 3:30 p.m. July 1, 1863, Capt. Gilbert H. Reynolds, Battery L, First New York Light Artillery, now armed with six 3-inch rifled guns was directed by Col. Charles S. Wainwright, I Corps Chief of Artillery, to take position between Gettysburg and the seminary, then move still farther forward. It was too hot there. Rebel cannon swept their position with a deadly crossfire

So the gun was abandoned. I was terribly grieved when I heard of it, for I had begun to look upon our getting off from that place as quite a feat, and wished that it could have been without loss of a gun. The more I think of it, the more I wonder that we got off at all. Our front fire must have shaken the rebel lines badly or they would have been upon us. The gun lost was No. 1, the first three-inch gun accepted by the ordnance department.

from the right. Captain Reynolds was wounded in the side and lost an eye. Lt. George Breck took over the battery. Now Rebel infantry came storming in on the battery’s left, while Union infantry masked its fire, and the battery was compelled to give ground. They opened fire again but not for very long, as its infantry support melted away under terrible shellfire and a hail of bullets, leaving the guns exposed to the full weight

of the attack. The guns were quickly limbered to pull out but the Chambersburg Pike was jammed with a mass of retreating infantry, neither to be threaded nor skirted. The battery was

“Reynolds”

Battery L

1st N.Y. Light Artillery

Artillery Brigade 1st Corps

Back of the monument reads:

Casualties July 1st, 1863 near Chambersburg Pike, 1 killed, 15 wounded, 1 missing. July 2nd and 3rd engaged with enemy from position on Cemetery Hill.

Organized at Rochester, N.Y. Sept. 17, 1861. Mustered out June 17, 1865.

The monument to Battery L of the 1st New York Light Artillery is west of Gettysburg on the east side of Reynolds Avenue about 1/3 mile north of Fairfield Road and 250 yards south of Meredith Avenue. Reynolds Avenue is one way northbound at this point.

The following is taken from final report on The Battlefield of Gettysburg (New York at Gettysburg) by The New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1902.

COMRADES OF BATTERY L:

It is exactly twenty-eight years ago to-day since this organization was formed in the city of Rochester, and more than a quarter of a century since we fought here, as Lincoln declared on this historic field that, “A government of the people, for the people, and by the people, should not perish from the earth.” In this long interval of nearly a generation, I believe that few, if any, of us have ever set foot on this scene where for three days raged one of the fiercest battles of modern times, and where our desperate, courageous, but misguided foes fought for their last great stake on Northern soil. As you recall your activity amid the death throes and din of that tumultuous strife, you may well feel proud that Battery L was permitted to do its appointed share in securing the great victory which settled the fate of the Republic. You may well reflect too that this triumph was not easily purchased nor cheaply won; and had we suffered a reverse here of the magnitude of some of those which overcame the Army of the Potomac in its earlier history the face of modern civilization might have been changed.

Suppose, for instance, the army of General Lee, with its sullen resolve and impetuous daring to strike panic into the Northern heart, and hence to secure influential political allies in our rear,

had successively occupied Harrisburg, Philadelphia, and New York,— what might not have been the termination of, the war?

It is perhaps idle to speculate upon such a contingency. Yet we, who passed through the greatest civil war in all history, all know that there is no such thing as certainty in the result of the clash of conflicting armies, such as we witnessed here. But the victory was priceless all the same; and the survivors of this field, remembered by a grateful people, have written over this undulating surface, in granite, and marble, and bronze, the story of that three days’ triumphant struggle, making this battlefield unique for all time. Pass over the fields of Waterloo, of Austerlitz, of Sadowa, or Gravelotte, and you behold nothing to mark the gigantic strife of nations on those famous theatres of war. It has remained for America to remember her sons who fell, as we see them, commemorated on these diversified acres; and certainly we cannot feel otherwise than proud that not the least among the commands who have a monument here is our veteran battery, which I had the honor to command during the latter part of the battle.

In keeping with the proprieties of this occasion I have prepared, with the assistance of Lieutenant Shelton, a sketch of the part which this battery took in the action. I have also prepared a brief sketch of Battery “L,” and a complete roster of the command from the date of its organization until it was finally mustered out of service at Elmira, June 17, 1865.

Most of the data for the following sketch of Reynolds’ Battery at Gettysburg are taken from the official report of General Wainwright to General Hunt, chief of artillery, and bearing date July 17, 1863. We are indebted to the politeness of Major Cooney, at the New York headquarters of the Gettysburg Monuments Commission, for access to the advance sheets of a government work on Gettysburg not yet

published, and which contains the report aforesaid.

On the night of June 30, 1863, Reynolds’ Battery was encamped with the batteries and troops of the First Corps, about two miles from Emmitsburg, along the Pike leading to Gettysburg. Marching orders were received about 8 o’clock on the morning of the 1st of July. We were soon apprised of the presence of the enemy by the sound of skirmish firing ahead, and between 10 and 11 o’clock the battery was drawn off the road and parked in a field, but a short distance from the Seminary Grove. Those of us who were present at that time, will remember the clouds of cavalry skirmishers which, having been relieved by the infantry, were falling back down the hillsides which

Wadsworth for some guns in his front, I posted Lieutenant Wilbur, with a section of Company L, First New York, in the Orchard on the south side of the Cashtown Road, where he was sheltered from the fire of the enemy’s battery on his right flank by the intervening houses and barn, and moved the remaining four pieces around to the south side of the wood on the open crest.”

Some confusion about the Seminary and Cemetery Ridges seems to have prevailed at this stage of the battle, and Colonel Wainwright, understanding the former instead of the latter was to be held at all hazard, proceeded with his usual tenacity of purpose to post his batteries at this end. The enemy’s infantry, meanwhile, in two columns, having outflanked us to the left,

No. 1 has US marked in crisp lettering on top of the barrel between the trunnions. Note the small sight, to the right in this photo, used for aiming the cannon.

forced to move at an agonizing walk. Close behind it came the Rebel yells; bullets whistled past. At last the pike was cleared; the infantry had swung off to take cover in the railroad cut, a ready-made trench.

Army of the Potomac, speaking of this engagement, said, “There were occasions when a gun could be lost with Honor, and Battery L’s loss after its gallant stand was such an instance.” From this time on the gun was used by the Confederates until its recapture the following spring at Spotsylvania Court House when it was recognized by its muzzle number (No. 1).

New York (State) Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga. Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, 3 vol. Albany, N.Y., J.B. Lyon Co., 1900.

The Guns at Gettysburg, by Fairfax Downey, McKay Co., Inc., New York, 1958.

A Diary of Battle, The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861–1865, edited by Allen Nevins, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, 1962.

“The 3-Inch Ordnance Rifle,” by James C. Hazlett, MD, published Civil War Times Illustrated, December 1968.

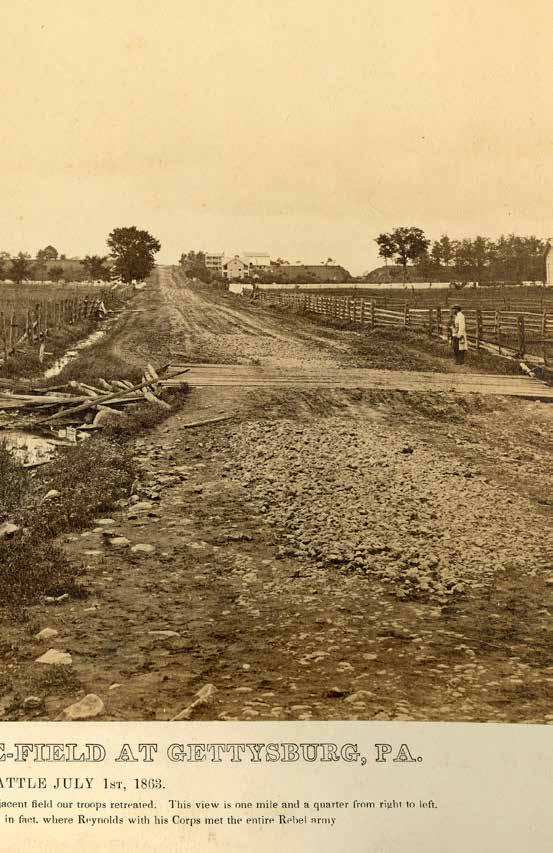

Title page caption: Wartime photograph of Chambersburg Turnpike, Gettysburg, Penn. Mathew Brady is standing on the right side of the road.

In Memoriam

George Henry Lomas was born September 7, 1942, exactly, as he would

recount with a twinkle in his eye, nine months to the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Born into a working class family in Germantown, Penn., he was the fifth and last child born to Anna and William Lomas.

His influence could be felt throughout the hobby as more attention to the details of event production became a standard. George recognized the importance of both the reenactors’ experience and safety as well as creating an environment where spectators and visitors could learn more, and better appreciate, the vibrant and transforming events of 1861 to 1865 in the United States.

As the “big” anniversary years grew nearer, George transitioned from participant to event organizer. The

Note: 3-inch ordnance rifle no. 1 is on display in the Lomas Center & Museum, 50 Mayor Alley, Gettysburg, PA 17325 https://lomascenter.org.

135th Gettysburg Reenactment was the product of conflict, compromise, and cooperation. Several groups vied for the opportunity to produce this reenactment. The Civil War Reenactors Alliance wanted one event. Their determination to bring the factions together to produce the most rewarding experience for the reenacting community succeeded. Civil War Heritage, led by George Lomas, and Gettysburg Living History, joined forces to stage the largest and most successful Civil War reenactment ever. Over 22,500 reenactors participated during the event commemorating the 135th anniversary of that pivotal Civil War battle. The 135th created the gold standard for Civil War reenactment event production.

Establishing the Regimental Quartermaster retail shop in Gettysburg solidified George’s commitment to the town that would become his home.

George’s story would not be complete without mentioning his avid and voracious need to learn more and become more knowledgeable. He was not an academically educated man, but he was an extremely smart, self-educated man. From his younger years helping unload Bannerman’s Island, handling original Civil War artifacts, to visiting museums and historic sites, and learning minute details regarding lock plates, artillery shells, muskets, and cannons, George became a walking encyclopedia of Civil War knowledge.

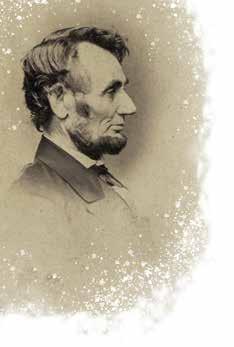

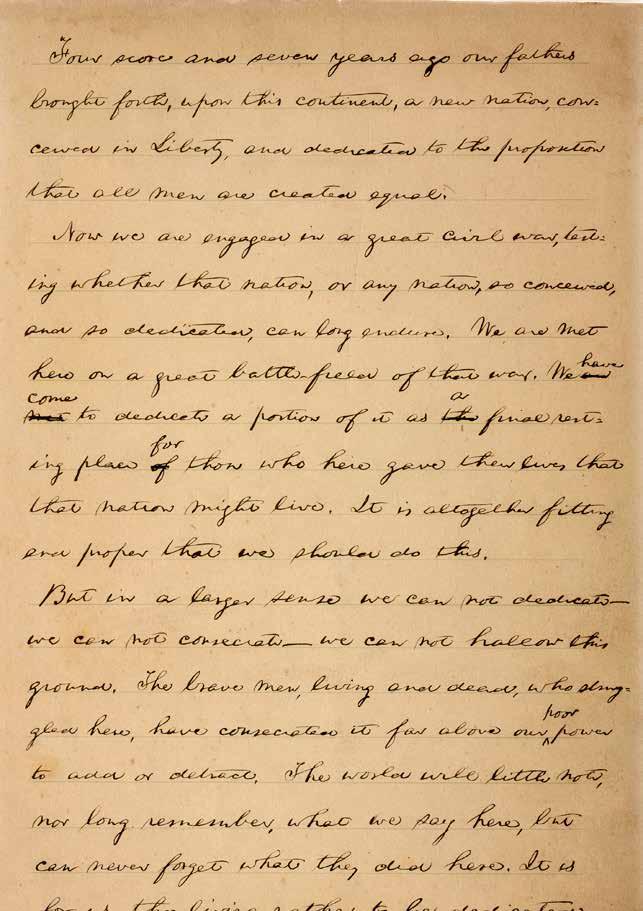

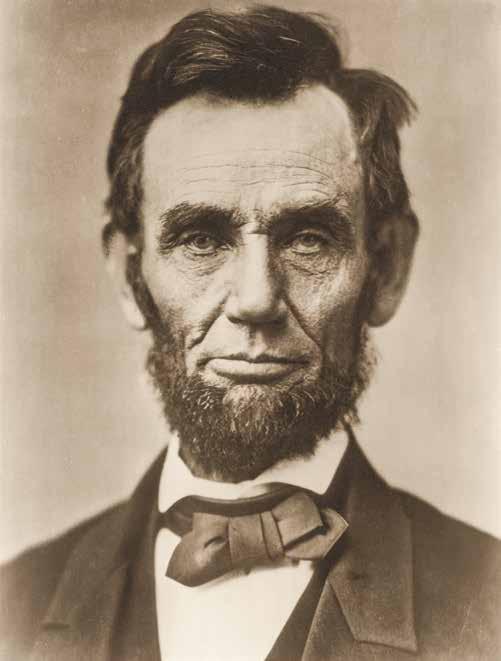

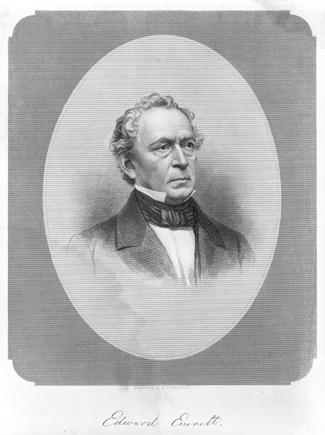

Imagine it: a recently defeated vice-presidential candidate invited to give the main speech at the dedication of a new cemetery for soldiers who died for their country; the President of the United States asked to the same event only later and half-heartedly, to deliver just “a few appropriate remarks” on the same occasion.

Can anyone imagine a current president ceding the spotlight to an opponents former running mate, after the election should a similar opportunity arise today? Call it implausible; and could anyone imagine a president later congratulating his onetime rival for his effort?

Yet that is exactly what transpired seven score and nineteen years ago, when Abraham Lincoln accepted second-billing at Gettysburg in deference to Edward Everett, a veteran Massachusetts politician who had run for Vice President just three years earlier

on a third-party ticket. As the President well knew, Everett’s supporters had campaigned on the idea that Lincoln lacked the capacity to handle the mounting national crisis over slavery.

So it happened that on November 19, 1863, Everett delivered a long, orotund, quickly-forgotten stem-winder at Gettysburg. Lincoln followed with what he called a “short, short, short” statement that eventually attained the status of American scripture.

All but forgotten is the humility Lincoln had demonstrated in accepting a minor role in the first place. True, Everett was the nation’s most distinguished speechmaker, and could be relied upon to offer a crowd-pleasing performance; but Lincoln was commander-in-chief and author of the recent Emancipation Proclamation. His armies, after all, and not Everett’s, had won the Battle of Gettysburg the previous July.

Lincoln decided it was more important to consecrate the “honored dead”

The most famous of Alexander Gardner’s November 8, 1863 photos, this closeup came to be known as “The Gettysburg Lincoln,” but was in fact produced at the request of a sculptor who needed new pictures to serve as models for her proposed Lincoln bust. (Library of Congress)

of that victory than to obsess about his own status. He raised no objections to the insulting arrangement. He said nothing when the event was postponed to November fit Everett’s schedule. He reverently toured the battlefield after he arrived and shunned the liquor-fueled celebrations that erupted on the streets the night before the dedication. He tried to put aside lingering worries about the health of his little boy, Tad, sick in the White House with smallpox just a year after his older brother, Willie, had died there of typhoid fever. Somehow Lincoln closed out the noise, the pomp, and all other outside

concerns to concentrate on writing a final draft of his talk.

After riding to Cemetery Ridge, Lincoln endured yet another ordeal: three hours of prayers and dirges, not to mention the Everett marathon, before taking center stage so briefly that photographers on the scene neglected to take a close-up picture.

Lincoln’s only false step at Gettysburg, another self-effacing gesture unimaginable in today’s boast-riddled political culture, was to suggest that the world would “little note, nor long remember” what he said. In fact, Lincoln did nothing less than consecrate a new nation of, by, and for a people still only at the midway point in a bloody civil war.

According to one legend, Lincoln himself initially judged his Gettysburg performance “a flat failure.” But even if he first doubted that his speech would “long endure,” he soon learned otherwise, and from a source equally impossible to imagine in today’s house divided: his podium rival.

Edward Everett quickly sent a compliment pithier than anything he had said at the cemetery: “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

There the matter might have rested, had

Orator Edward Everett as he looked in 1863, engraved by H. Wright Smith. (Library of Congress)

the recipient of this generous, and accurate, appraisal not been Lincoln. After digesting Everett’s kind words, Lincoln reciprocated in kind: “In our respective parts yesterday, you could not have been excused to make a short address, nor I a long one. I am pleased to know that, in your judgment, the little I did say was not en tirely a failure.” As for Everett’s oration, Lincoln affably exagger ated that it was “of great value…. transcended my expectation.”

Enveloped in military and political crisis, the President might understand ably have demanded both center stage and ample time to deliver the one and only official message at an event certain to be covered widely by the national media. In a timeless lesson to modern leaders who make such somber occasions more about themselves than the casualties of war, Lincoln swallowed his pride and fit himself

elegantly into a pageant that history would ultimately recall solely for his magisterial contribution.

He did so not only by crafting a masterpiece, but making sure his audience joined him in reverencing the achievements of others: those who “gave their lives that the nation might live.”

Paying tribute to the “honored dead” is agonizingly difficult. Sharing the honor of doing so is harder still. Appropriately, Lincoln’s words at Gettysburg have not perished from the

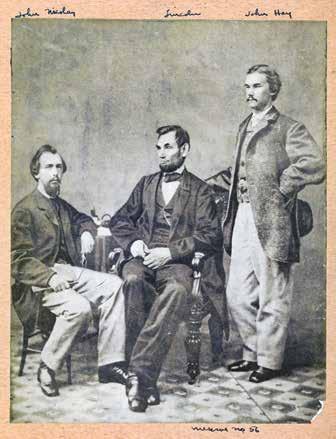

Eleven days before the Gettysburg Address: Abraham Lincoln, Sunday, November 8, 1863, by Alexander Gardner. The sheet of paper lying on the table may be an advance, typeset copy of Edward Everett’s address, sent to the President so he would not repeat the principal orator’s main points. (Library of Congress)

earth. His modesty before the event, and his graciousness after, deserve to be remembered as well.

In truth, Lincoln bore no great respect for Edward Everett and thought him “very much overrated,” but he shared that dismissive, tweet-length critique with only one confidant. He never revealed his disdain widely or cruelly.

The following year, onetime opponent Edward Everett not only enthusiastically endorsed the president for re-election, he persuaded Lincoln to send him a new, handwritten copy of his Gettysburg Address to sell for the benefit of wounded soldiers. Lincoln’s words and modesty had united them in common cause.

Everett died on January 15, 1865.

Three months later to the day, the President with whom he had exchanged speeches and compliments at Gettysburg succumbed to an assassin’s bullet.

Harold Holzer, Chairman of the Lincoln Forum, won the 2015 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize for his book Lincoln and the Power of the Press.

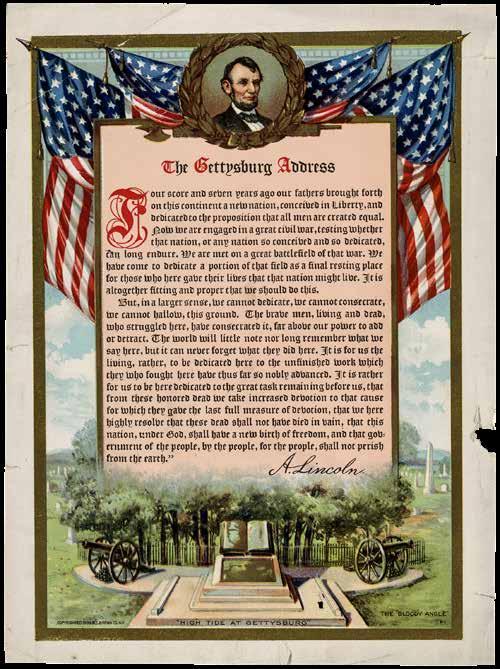

M. C. Brown copy of the Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. (Library of Congress)

by Sue Boardman

by Sue Boardman

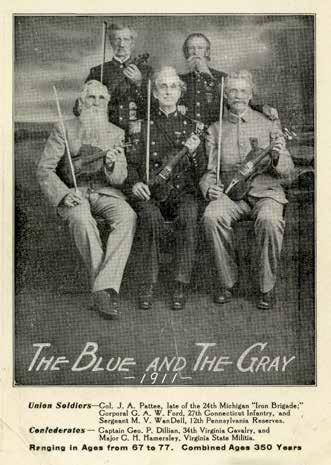

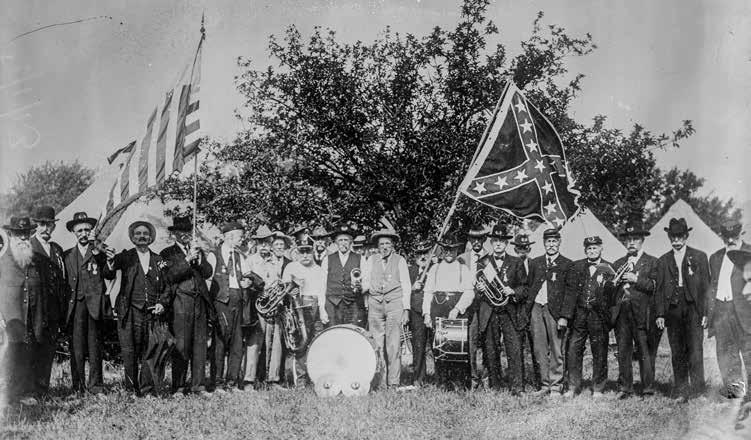

When the Civil War ended, most veterans went home to rejoin or start families, find steady work, and eventually retire. For one veteran, though, a late-in-life opportunity gave him a second career and made him famous. John Artimus Pattee became the founder, manager, and lead player in the Old Soldier Fiddlers, a vaudeville act in which two Southern and two Northern fiddlers played antebellum and Civil War music while touring the United States and Canada between 1910 and 1922.

John was born June 5, 1844, in Huron Township, Wayne County, Mich. Although Detroit was the county seat, John grew up on a farm in a rural part of the county. In fall of 1862, the 24th Michigan was raised in his home county and John, age 18, enlisted in the regiment’s Co. K. Shortly after enlistment, he volunteered to man the ranks of the “Iron Brigade Battery,” also known as Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, and was with the guns at Gettysburg. After 18 months with the battery, John returned to the infantry and served the 24th until the end of the war.

In 1866 John married Eliza Maes and by 1880 the couple had five daughters and a son. He tried his hand at farming and later worked as a hotel keeper. At some point, John and Eliza divorced. By the 1890s he was working as a life insurance agent and temporarily living in Wilkes-Barre, Penn. In 1896 he married his second wife, Samantha, in Richmond, Va., whom he met while traveling for his job. When she passed away in 1904, he married his third wife Ella Winona and resided in Huntington, W.Va., still selling insurance and leading an unremarkable life. However, an unsolicited request was about to change his life forever.

Huntington is located along the Ohio River at the point where West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky meet, and was home to both Union and Confederate veterans. In 1910, the Huntington Chapter #150, United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) planned an evening of entertainment for Confederate veterans living in

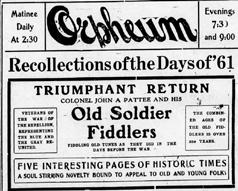

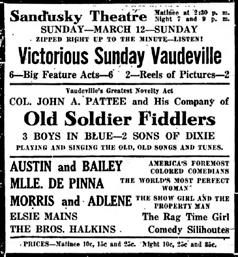

Newspaper ad for a return performance of the Old Soldiers Fiddlers to the Orpheum Theater in Altoona, Penn., October 1913. (Public Domain)

soldiers, North and South, to take part in a fiddling contest. The result was a gathering of military veterans from West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Kentucky, all able to grind out war-time tunes with great gusto. The idea occurred to him that he had the makings of a Blue and Gray quartet that could tour the country with him. Like many veterans, John gave himself a promotion; he had mustered out of the service as a corporal but dubbed his act “Colonel Pattee and his Old Soldier Fiddlers.”

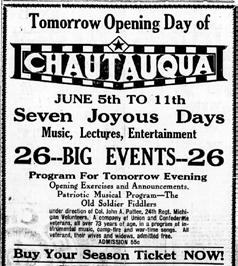

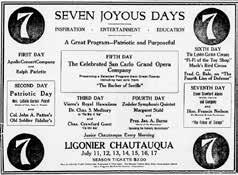

Newspaper ad for Ligonier, Penn., Chautauqua showing schedule for the week of June 11, 1916. The second day’s entertainment featured Col. John A. Pattee’s Old Soldier Fiddlers and Mrs. LaSalle Corbell Pickett. (Public Domain)

the vicinity. John Pattee had come to their attention as a life-long fiddler and a good entertainer. Fiddling was a popular tradition where John grew up in Michigan and was usually selftaught and played by ear, even among the best fiddlers. His mother gave him a fiddle when he was a youngster and he used it his entire life.

John agreed to play as requested but suggested an ad be placed in local newspapers asking all old-time

The first year on the road saw them perform in a half dozen cities across the country, sometimes opening for and sharing billing with other traveling shows. Eventually the fiddlers’ reputation as unique entertainers came to the attention of national theater agents who signed them to the B.F. Keith vaudeville circuit. The Keith circuit had large auditoriums in some of the leading cities across the United States and Canada. Over the next decade, Pattee and the Old Soldier Fiddlers played in Keith and Orpheum theaters to full houses, sometimes as the featured act with top billing, and

Iron Brigade Headquarters tent during the 50th reunion at Gettysburg showing a banner advertising entertainment by the Old Soldier Fiddlers. (wedgwoodinseattlehistory website)

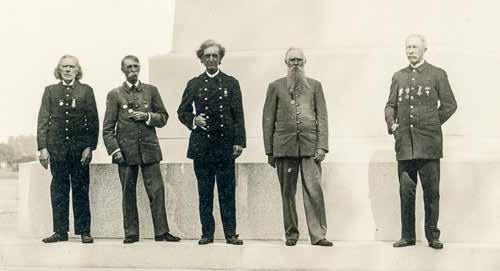

often as popular return engagements. They played in over a dozen major cities a year between 1911 and 1919, sometimes doing side shows for veterans’ reunions and at old soldiers’ homes along the way. During the 1913 50th reunion at Gettysburg, the Iron Brigade set up a headquarters tent and invited veterans of the 26th North Carolina to come and enjoy special music provided by Pattee and

his fiddlers. Several photos were taken of the troupe at the unfinished Virginia Monument and in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

Just before a November 1915 show in Lincoln, Neb., Ella became ill and died unexpectedly. John tearfully performed the scheduled act that evening, not wishing to disappoint the audience, then accompanied her remains to Cincinnati the following day while the rest of his troupe continued with their engagements.

The shows were always popular, whether in northern or southern locales, and among civilians and veterans alike, probably because John, the consummate entertainer, changed the program to suit the audience, but certain elements were universal. The program would start with some antebellum songs sung “back ‘fore de War” which usually precipitated foot stomping and hand clapping among

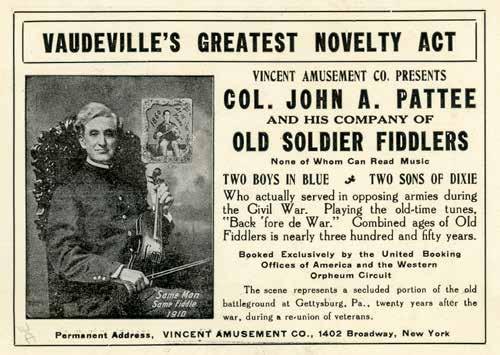

Newspaper ad for vaudeville show in Sandusky, Ohio, March 1917, featuring Col. John A. Pattee’s Old Soldier Fiddlers. The act is billed as “Vaudeville’s Greatest Novelty Act.”

the audience. Pop Goes the Weasel, Devil’s Dream, Money Musk, The Mockingbird, and other old-time jigs were interspersed with light banter between the veterans of the Blue and Gray. As the show progressed into Civil War songs, Goober Peas was a favorite, the banter became a bit strident as the men in blue and the men in gray taunted one another about their playing, their songs, and their states of origin. At that point, John, clearly the manager and self-imposed ranking “officer,” would admonish them with reminders that they belonged to one country now and they were to put the past behind them. Then the fiddlers would play Dixie, followed by the Star-Spangled Banner during which the audience was invited to participate. Then the former Yankees would clasp hands with the former Rebels as the program closed to rousing cheers. Per

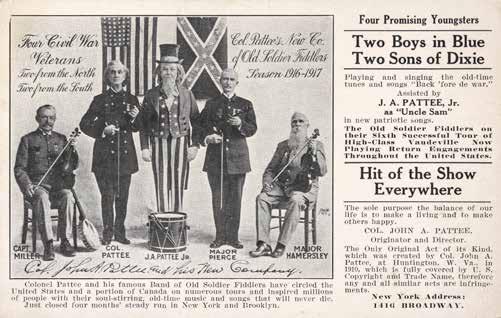

Postcard ad for John A. Pattee and his company of Old Soldier Fiddlers, circa 1915. (Author’s collection)

Pattee’s directive, veterans, their wives, and widows were always admitted free to his shows.

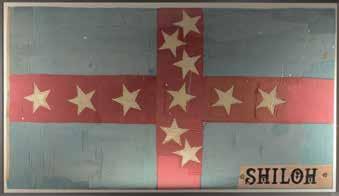

Stage props usually included Union and Confederate flags. After the 1913 veteran’s reunion, a large backdrop was added, depicting the July 3rd battlefield at Gettysburg as it looked twenty years after the battle which John described in vivid terms. Over the years, fiddlers would change as former players passed away or quit, but all who played were billed as veterans of the late war “who fought on opposite sides at Gettysburg.” Though not entirely true, a few were indeed Gettysburg veterans.

Of the twenty different names offered in the newspaper advertisements over the years, two served in the 34th Virginia Cavalry (Witcher’s Battalion), and several Union fiddlers served with New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania regiments at Gettysburg. Some however, such as an 11th Illinois veteran and one from the 147th Ohio, were not. A few of them do not appear on soldier rosters at all. In any case, Pattee’s service at Gettysburg was legitimate and he boasted he was “within a stone’s throw of General Reynolds when the latter was shot from his horse.”

Preceding each engagement, publicity notices ran in local newspapers often describing the troupe in endearing and sometimes corny terms. Quotes from Pattee about the group were humorous: “Give us a crowd and we’ll show you some fiddling,” and “we’re not as young looking as we were in the sixties but we’re just as full of ginger.” Pattee insisted theirs was not violin playing but just old-time turkeyin-the-straw fiddling. He also stated they were “promising youngsters, none of whom can read music,” often sharing that they were all grandfathers between 70 and 78 with a combined age of over 300 years. Theater critics wrote, “They don’t attempt to break any records in technique” and “they make no pretension

of artistry in their playing but there is something sweet and pathetic about their performance that appeals to everyone.” Others said they were sincere and refreshing, humorous with an old-fashioned flavor. From 1915 on, they were always billed as “Vaudeville’s Greatest Novelty Act.”

The years 1916-18 were by far the busiest for the Old Soldier Fiddlers with 80 engagements that took them

from New York to California, Texas, and Washington State. 1918 was also the year John married his fourth wife, Fannie Berdan, when he returned home to Detroit from his successful tour season.

There were two reasons for the sharp increase in the Old Soldier Fiddlers’ stage appearances; America’s growing involvement in World War I and the Chautauqua movement. Chautauqua was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which sought to bring learning, culture and, later, entertainment, to the small towns and villages of America. Former President Theodore Roosevelt said that Chautauqua is “the most American thing in America.”

Tipton photograph of the Old Soldier Fiddlers at the unfinished Virginia Monument during the 50th reunion at Gettysburg, July 1913. (Author’s collection)

In 1916, President Wilson used this platform to inspire patriotism and unite the country. Newspaper articles across the land announced, “While President Wilson and his associates are bending every effort to the mobilization of the physical resources of the nation

for prosecution of the war, an army of trained performers in 5,000 Chautauqua tents and auditoriums will do their bit in mobilizing the minds of America.” The article went on to say, “An America of one mind regarding the war is invincible…there is no more effective way of reaching the people and effecting a solidarity of opinion than is offered by Chautauquas of America.”

In response, Pattee wrote a letter to President Wilson “hereby offering our services to you to go wherever directed, either with our muskets or our fiddles and drums.” Pattee and his Old Soldier Fiddlers joined the Chautauqua movement. Some of the major personalities who took the stage with them were Mrs. George Pickett, the governors of several states, former President Taft, the Honorable Leslie M. Shaw, the Honorable Elmer Burkett, and Dr. Russell H. Conwell, the founder of Temple College, now

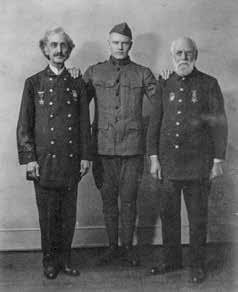

Pattee altered his fiddlers’ program to include his son, John Pattee Jr. who initially dressed as Uncle Sam and later as a “modern soldier,” in a khaki uniform standing between the Civil War veterans, holding a banner that proclaimed, “One County and One Flag.”

The Old Soldier Fiddlers disbanded about 1920, chiefly due to the passing of most of the fiddlers who played

Pattee, his son John Jr. and Major E.W. McIntosh reformed the group as Col. Pattee’s New Company of Old Soldier Fiddlers briefly in 1921. They disbanded for good in the fall of 1922. (Military Images magazine, Vol. 35, No. 4, Autumn 2017, p. 21.)

with Pattee. They briefly reformed the following year with just Pattee, Major E.W. McIntosh, and John Jr. By mid-1922 John was back in Detroit, performing weekly on radio station WWJ which reached audiences in Michigan, Indiana, and Canada. During the show, John played many of the old-time tunes from his vaudeville act and included barn dances for which he also called the steps. The following year, he did shows for Springfield, Massachusetts, radio station WBZ. From September through December 1924, John did a radio show for New York station WEAF.

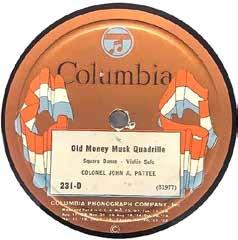

To document the old fiddling traditions that were becoming lost to society, on September 6, 1924, Pattee made several recordings of fiddle playing with accompanying dance calls for Columbia Records. Pattee was one of only three confirmed Civil War veterans to make a ‘country music’ recording. He was about 80 years old when he cut four sides at the session, but only one record was released. The two tracks on this record, “Old Catville Quadrille” and “Old Monymusk Quadrille” can be heard on the MichiganFiddle.com website at this link: http://www.michiganfiddle. com/recordings.

John died in Manhattan just a few weeks after making the recordings, on December 10, 1924. His passing was shared in an on-air announcement:

“Colonel John A. Pattee, old soldier fiddler and favorite of WEAF’s radio audience, will never stand before a microphone again. This unfortunate news came with word of his death which canceled his radio barn dance from WEAF scheduled for Saturday Evening…”

He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Sue Boardman, a Gettysburg Licensed Battlefield Guide since 2001, is a twotime recipient of the Superintendent’s Award for Excellence in Guiding. Sue is a recognized expert on not only the Battle of Gettysburg but also the National Park’s early history including its many monuments and the National Cemetery.

Beginning in 2004, Sue served as historical consultant for the Gettysburg Foundation for the new museum project as well as for the massive project to conserve and restore the Gettysburg cyclorama, and served on the advisory committee during the restoration of the Atlanta Cyclorama (2017–2019). She has authored a book on the history of the Cyclorama titled The Gettysburg Cyclorama: A History and Guide and co-authored The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas. Sue has also authored Elizabeth Thorn: Wartime Caretaker of Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery and has published articles in a number of Civil War periodicals.

Sue is Director Emeritus of the Gettysburg Foundation’s Leadership program, “In the Footsteps of Leaders,” which has been well-received by corporate, government, non-profit and educational groups. Sue is on the design committee to install a children’s museum in the Rupp House History Center. She serves on the board of the Adams County Historical Society, where she is a member of the committee to build a new museum scheduled to open in 2022. Sue also served as President of the historic Evergreen Cemetery Association and is currently on the Board of Trustees. She has worked as an adjunct instructor for Harrisburg Area Community College and Susquehanna University. She and her husband Ken live in Bonneauville with their two dogs.

Observe Daily Battles

• Watch Ongoing Skirmishing

• See Live-Fire Cannon Demonstrations

• Observe Period Medical Demonstrations

• Shop for Period Items in the Sutler Village

• Visit Union and Confederate encampments

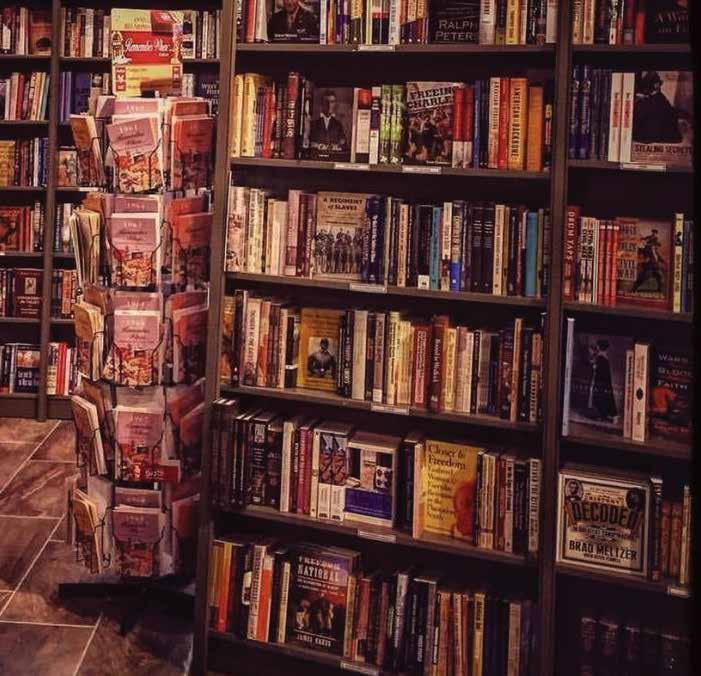

• Attend Oral Presentations on Civil War Topics

• Meet Published Authors and Purchase Their Books

• Attend the 73rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment Band Concert

• Participate in Protestant and Catholic Period Services

Sunday morning

For additional information:

www.sidneycivilwar.org

Gettysburg Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides

September 23 - 25, 2022 Gettysburg PA

“Do

With 10 Licensed Battlefield Guides from the Nation’s Premier Guide Organization

BATTLEFIELD TOURS:

Attack of the Irish Brigade • Caldwell Strikes the Wheatfield • The Philadelphia Brigade at the Angle• Willards Brigade & the Attack of the 1st Minnesota Guns of the Second Corps: Woodruff

• Cushing • Rorty • Rhode Island Batteries

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Friday deluxe seafood / steak tips buffet dinner at the historic Dobbin House.

• Saturday night cigar firepit at Rupp House garden, detailed map book, commemorative pin, and ID lanyard.

• Special hotel room rate at 1863 Inn of Gettysburg!

Reserve a room BEFORE August 9 by calling 866-953-4483 or 717-334-6211.

Mention A.L.B.G. 2022 Fall Seminar. Online booking will not apply discount.

REGISTER NOW!

https://gettysburgtourguides.org/ albgseminar/

Within two years of the Battle of Gettysburg, no fewer than eight photographers recorded more than 170 outdoor, documentary photos of the battlefield and the town. Dead soldiers, destruction, landscapes, and famous structures dominated the various series. Only a small portion of these photographs include the living and most of these show photographers’ assistants, posing to make a scene more interesting or to provide more depth to a photo. Still, some few wartime photos include identifiable people; photographers, journalists, soldiers, and Gettysburg’s civilians.

Here are eight photos by five different photographers; four were taken in

July 1863, three in November that same year, and one in July 1865. Instead of razor-focusing upon the battle and battlefield, let’s zoom into the people who were captured on glass plates for all time and examine who they were and how they related to America’s greatest battlefield. For more information, see William A. Frassanito’s books, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time and Early Photography at Gettysburg . In these masterpieces, Frassanito dates and discusses all the early Gettysburg photographs and identifies or details most of those known by name in postwar images. These two book provide the crucial contexts surrounding those in the photographs.

The humanity involved in and

affected by the Civil War is an often overlooked but essential part of studying the conflict. Somehow, seeing their faces and stances help us sympathize with and better understand the people of the past.

Garry Adelman is Chief Historian of the American Battlefield Trust, vice president of the Center for Civil War Photography, the author, co-author or editor of more than 50 books and articles concerning the Civil War, and a longtime licensed battlefield guide at Gettysburg.

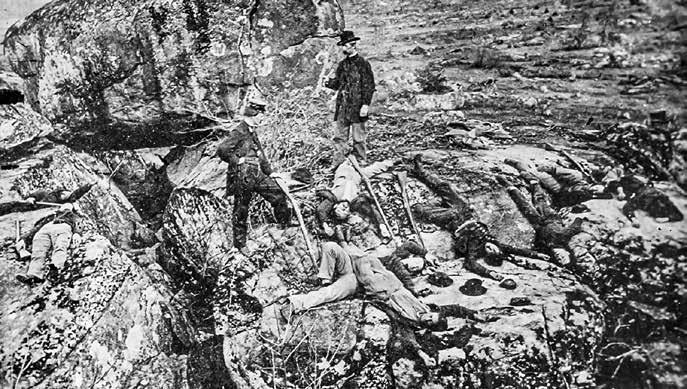

November 11, 1863. At first glance this scene may seem especially gruesome until one considers the lifelike appearance of the “dead” and the complete lack of foliage on a summer battlefield. As detailed by Frassanito, these soldiers are posing at Devil’s Den for Peter S. Weaver’s camera just eight days before the consecration of Gettysburg’s Soldiers National Cemetery, when President Abraham Lincoln would deliver one of America’s most-famous speeches. At dead center—no pun intended—lies 23 year-old Jacob Shenkel, who noted in his diary that he accompanied the artist to the area take some battlefield scenes, which included views of men both alive and posing as dead. Just 60 feet to the right of the camera’s position is the Alfred Waud Rock. (Library of Congress)

Left: July 6, 1863. Alfred Waud was an artist who traveled to Gettysburg during or just after the battle to sketch battlefield scenes. These sketches could be improved and even colored for sale as art but their most prolific use was as engravings, or “woodcuts,” in Harper’s Weekly or other publications. Waud created dozens of Gettysburg scenes including at least one at Devil’s Den, where photographer Alexander Gardner recorded this photograph. Gardner’s work demonstrates that there were numerous Confederate corpses only steps away when Waud was captured on glass at Devil’s Den. The boulder on which he sits, now popularly known as the “Waud Rock,” is easy to locate today; it sits just off the road in front of the largest boulder known as the Table Rock. (Library of Congress)

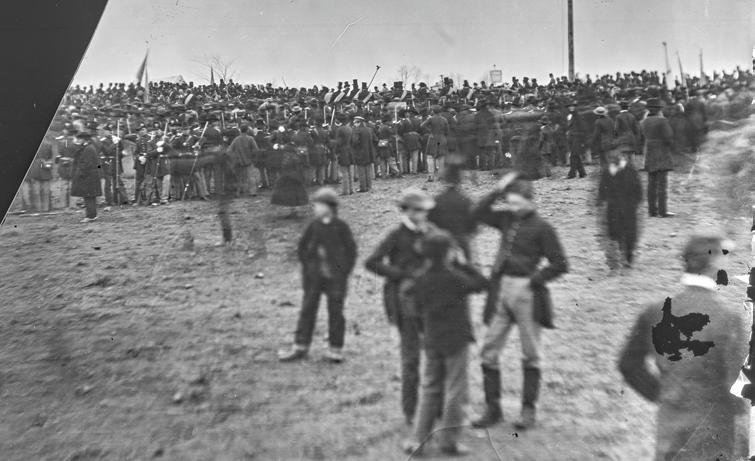

November 19, 1863. Proceedings surrounding the consecration of the Soldiers National Cemetery were captured by several photographic firms. It seemed that everyone had come to town, including governors, cabinet members, senators, orators, and other dignitaries. Here, in this tight detail, a bareheaded President Abraham Lincoln can be seen just above the crowd at center left. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin is at far right. Historians have various opinions about the identification of others on the platform in this detail; see Frassanito’s books as well as the mostly online work of Christoper Oakley and Craig Heberton. Historians agree that this photo, probably taken by David Bachrach, depicts Lincoln but still disagree on whether this is the only photo depicting Lincoln at Gettysburg. (LOC)

November 20, 1863. One of the men who remained in Gettysburg after Lincoln’s departure on November 19, was Benjamin French, who had served as a marshal during the ceremonies. He had supervised the funeral arrangements for President Lincoln’s son, Willie, and, seventeen months after this photo was taken, would also do the same for Abraham. French poses here at center for Gardner’s firm on the porch of the home of the Widow Lydia Leister, also known as General Meade’s Headquarters during the battle. On the right are two children. (Library of Congress)

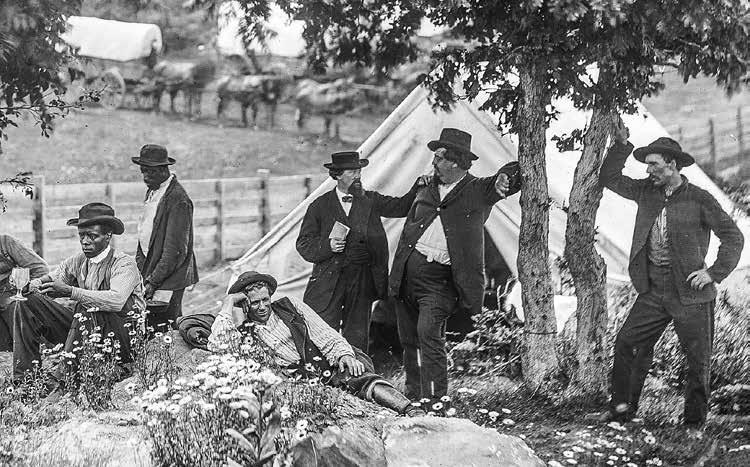

July 4, 1865. Crowds assembled once again at Gettysburg at the end of the war to commemorate the laying of the Soldiers National Monument cornerstone in the cemetery. Frustratingly, there is no known photo of these proceedings, but at least twelve photos, are known to have been taken by Alexander Gardner’s firm on or around the date of the commemoration, July 4, 1865. Five photos were recorded in the camp of Captain John J. Huff, who served as a commissary officer throughout the Civil War. At Gettysburg he was apparently supporting the hundreds of soldiers on hand for the event. In this detail the portly Huff is seen leaning against a tree on Stevens Knoll just west of Culp’s Hill. With him are mostly civilians who were apparently part of his team. (Library of Congress)

Gettysburg National Cemetery is the final resting place for more than 3,500 Union soldiers killed in the Battle of Gettysburg. At the cemetery’s consecration on November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln rose to deliver “a few appropriate remarks,” now known as the Gettysburg Address. His two-minute speech served as a reminder of the sacrifices of war and the necessity of holding the Union together.

(August 24, 1834 – May 24, 1901)

Known as “French Mary” she was a French-born vivandière who fought for the Union army during the Civil War. Tepe served with the 27th and 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiments. Tepe was awarded the Kearny Cross for her courageous service at Fredericksburg, and she is wearing it on her jacket. She carried a small keg of whiskey for medical purposes, and a pistol to protect herself.

ca. July 10, 1863. The 114th Pennsylvania vivandière, known as French Mary, leans against a fence post along the Baltimore Pike near the crest of East Cemetery Hill. Tepe is behind lunettes used to defend Stewart’s Battery B, 4th United States Artillery just days earlier. The photographer, Frederick Gutekunst hailed from Philadelphia just like the 114th Pennsylvania. (Special Collections and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College)

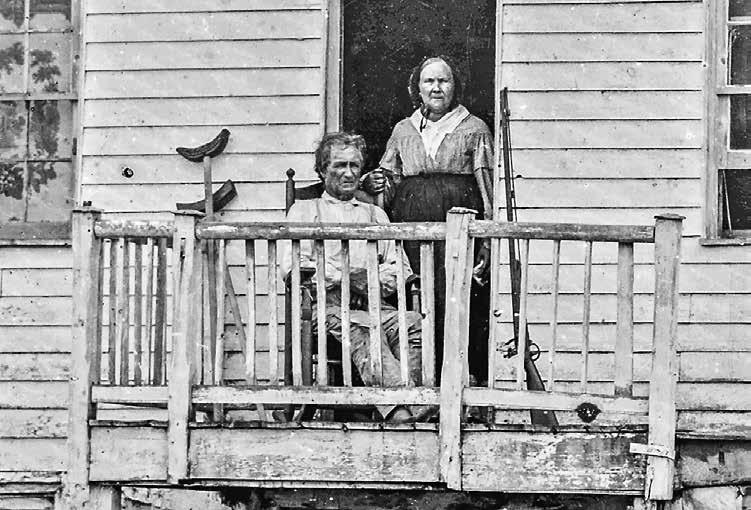

ca. July 15, 1863. Because his home was located on the same road as the Thompson house, it would have been a simple task for Brady’s crew to secure photographs of Gettysburg’s most famous living civilian, John Burns, seen here with his wife Barbara on the porch of their Gettysburg home. When Confederates were known to be approaching Gettysburg, on July 1, 1863, Burns famously grabbed his old musket and left home to fight alongside Northern soldiers. Leaning against the doorway is his half-stock flintlock fowler, a cut down military musket. His wife strongly opposed his decision to no avail. Wounded three times, Burns soon became known as the Hero of Gettysburg for his heroic defense of the town. He and his house were among the most-photographed subjects in Gettysburg during the War. In this Brady detail, you can clearly see the crutches, necessitated by his wounding. (Library of Congress)

From the tablet on John Burns’s monument:

My thanks are specially due to a citizen of Gettysburg named John Burns who although over seventy years of age shouldered his musket and offered his services to Colonel Wister One Hundred and Fiftieth Pennsylvania Volunteers. Colonel Wister advised him to fight in the woods as there was more shelter there but he preferred to join our line of skirmishers in the open fields. When the troops retired he fought with the Iron Brigade. He was wounded in three places.” –Gettysburg report of Maj-Gen. Doubleday.

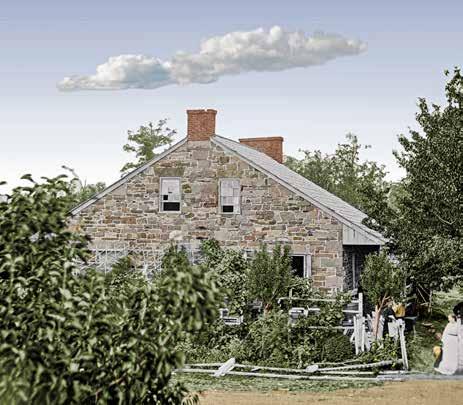

ca. July 15, 1863. The famed photographer Mathew Brady arrived in Gettysburg after the dead had been buried and therefore chiefly recorded photographs of battlefield scenes and structures that played a role in the conflict. He and his team secured four photos of the Widow Mary Thompson’s stone house on the Chambersburg Pike. This structure is commonly known today as Lee’s Headquarters. In this detail, Brady (standing) and one of his assistants pose with a woman thought to be none other than the nearly 70-year-old Widow Thompson herself, seated in a chair in front of her now-forever-famous house. The assistant is perched on one of Thompson’s damaged fences. (Library of Congress)

The Mary Thompson house and acreage around it was purchased by the American Battlefield Trust in 2016 and restored to its wartime appearance, including the rebuilt fences and the arbor visible in the background.

There are many tales associated with the Battle of Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. The following is an abridged “photo album” capturing a few events that occurred in Gettysburg, Penn., between July 1-3, 1863.

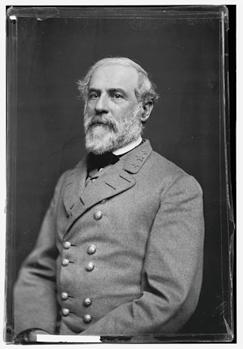

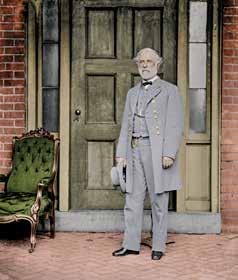

Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, Commander, Army of Northern Virginia

“An invasion of the enemy’s country breaks up all his preconceived plans, relieves our country of his presence, and we subsist while there

on his resources. The question of food for this army gives me more trouble than everything else combined.” –Robert E. Lee

On June 16, fear spread in the North as Gen. Lee’s army crossed the Potomac River at Point of Rocks, Md. Lee was not attacked as he marched through Maryland, but he had not heard from Gen. James “J.E.B.” Stuart on the whereabouts of the Union Army. On July 1, Lee arrived at Gettysburg in the late afternoon.

U.S. Gen. George Gordon Meade, Commander, Army of Potomac

“General I am the bearer of sad

news.” – Staff officer with news of Meade’s appointment

About 3 a.m., on June 28, Meade was unceremoniously awakened to be informed he was the new commander of the Army of the Potomac. His protests that there were generals better qualified and more senior were ignored. On June 29, Meade’s army marched 25 miles after Lee. At 1 a.m. on July 2, Meade caught up with his army at Gettysburg. The generals in his army were a mix of factions. Despite their personal conflicts, Meade would become the only general to defeat Lee in a clear victory.

“The Devil’s to pay” – U.S. Gen. John Buford, Cavalry Corps.

Buford’s 2,700 cavalrymen had been sent to search for the Confederates. At 7 a.m. the first shot was fired. Soon the cavalry were fighting against Rebel infantry more than twice their number, trying to hold high ground, waiting for their own infantry to arrive. About

10 a.m., Gen. John Reynolds asked if Buford could “hold out until his corps came up.” Buford, as he climbed down the ladder from the cupola of the Lutheran Seminary replied, “I reckon I can.” Both men believed they could buy time until the rest of the Army of Potomac arrived. By 11 a.m., Reynolds was dead.

“I am going out to see what is going on.” – John Burns, 68-year old Gettysburg resident Burns grabbed his flintlock musket and powder horn. He volunteered his services to the nearest Union regiment while wearing a swallowtail coat with brass buttons, yellow vest, and a tall hat. The soldiers replaced his gun with a modern rifle and cartridges. They expected Burns to run when the firing became heavy. Instead he slid behind a tree, experienced the intense fighting with the Iron Brigade, and suffered three wounds. Burns was captured,

and then released by the Confederates. During his November Gettysburg trip, Lincoln requested to meet the famous Burns.

“We could see only that the oncoming lines of the enemy were encircling us in a horseshoe.” – U.S. Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes, 6th Wisc. Inf.

By 3:30 p.m., the entire Union position began to crumble. To support their infantry, Federal artillery was placed within yards of the stone home of 69-year-old (Widow) Mary Thompson. Thompson, her daughter-in-law, and day-old granddaughter, sheltered in the basement as the battle roared above them. The Confederates followed the retreating U.S. Army, “yelling like demons, in a mad charge for our guns.” From her building, selected for his headquarters, Lee” was able to watch his men chase Federals through the town, heading for Cemetery Hill.

“How splendidly they march. It looks like a dress parade, a review.” –U.S. Maj. St. Clair A. Mulholland, 116th Penn.

Meade had laid out his line in the shape of a giant fishhook. Assigned to the left flank, U.S. Gen. Daniel Sickles, III Corps, moved his divisions forward to higher ground of the Peach Orchard; isolating his men in front of the army while exposing the left flank of II Corps. His front became the target of the Confederates’ primary attack. Sickles would be carried off the field, “with his right leg amputated and lying there, grim and stoical, with his cap pulled over his eyes, his hands calmly folded across his breast, and a cigar in his mouth!”

“Little Round top, crowned with artillery, resembled a volcano in eruption.” – C.S. Col. W.F. Perry, 44th Ala. Inf. U.S. Gen. Gouverneur Warren realized that the high ground of Round Top and Little Round Top, the “key of the whole [Union] position” was wide open for capture. Col. Strong Vincent, not knowing he had just been promoted to general, heard the call for reinforcements, and got there first. As the battle raged below at Devil’s Den, Vincent selected a ledge, known afterwards as Vincent’s Spur, as the spot to place his men. On Vincent’s far left, the rebels surged towards his collapsing line. Vincent waving his riding crop, leaped onto a rocky perch yelling, “Don’t

give an inch boys. Don’t give an inch!” Vincent dropped, shot in the thigh, mortally wounded.

“Forward men to the ledge!” –Confederate Col William Oates, 15th Ala.

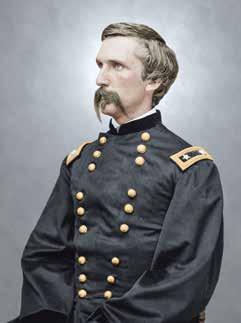

Into the breech arrived the 140th N.Y. “Commence firing,” yelled Col. Patrick O’Rourke. The lines erupted as both sides opened fire. The 140th swarmed in, energizing the entire Federal line. “The front surged backward and forward like a wave.” On the far left, Col. Joshua Chamberlain, 20th Maine, had already extended his line into a reverse “J” to counter Oates’ flanking move. With his men firing their last cartridges, Chamberlain’s desperate shout, “Bayonets,” was passed down the line. Chamberlain yelled, “Charge!” and the Maine men flew downhill. “We ran like a herd of wild cattle,” recalled Oates.

“The clashing of sabers, the firing of pistols, the demands for surrender Gen.

and cries of the combatants now filled the air.” – Union. Capt. William E. Miller, 3rd Penn. Cavalry

After 1 p.m., Gen. James “J.E.B.” Stuart’s 5,000 cavalrymen rode up York Pike. Protecting the crossroads was newly minted Gen. George Custer with his Michigan Brigade. Both sides charged, the collision sounding “like the falling of timber … horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them.” Custer would lead counter charges yelling, “Come on, you Wolverines!” In the fight against a larger force, the 5th Mich., armed with Spencer repeating carbines, gave the Union the advantage.

“The air [was] filling with the whirling, shrieking, hissing sound

of the solid shot and bursting shell … nearly 150 guns belched forth messengers of destruction.” – Pvt. Joseph McDermott, 69th Penn.

About 1 p.m., Lee’s artillery began bombarding Cemetery Ridge. Gen. Alexander Webb, holding the center of the Union line, knew “that an important assault was expected.” He seized the time to prepare for the upcoming battle. He replaced his artillery with fresh batteries. The 71st Penn. Inf. were positioned behind a stone wall and began loading up some 300 abandoned firearms they collected from the field.

“Charge the enemy and remember old Virginia.” – C.S. Gen. George Pickett

In silence the Confederates advanced with “the appearance of being fearfully irresistible.” As Gen. Richard Garnett’s Brigade came within 250 yards of the stonewall, the 71st Penn. unleashed Alexander

their firepower. Gen. Lewis Armistead, twirling his hat on his sword, led the way to his death as men followed him over the wall. Webb’s position was being overwhelmed. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock ordered the 19th Mass. and 42nd NY into the breach, pushing the Confederates out of the clump of trees and back to the wall.

The fighting turned into pandemonium. As more Federals poured into the area, the Confederates realized the fight was futile. The men held up their hands as a token of surrender. The “sharp, quick huzza of the Federals told of our defeat and their triumph,” wrote Lt. George Finley, 56th Va.

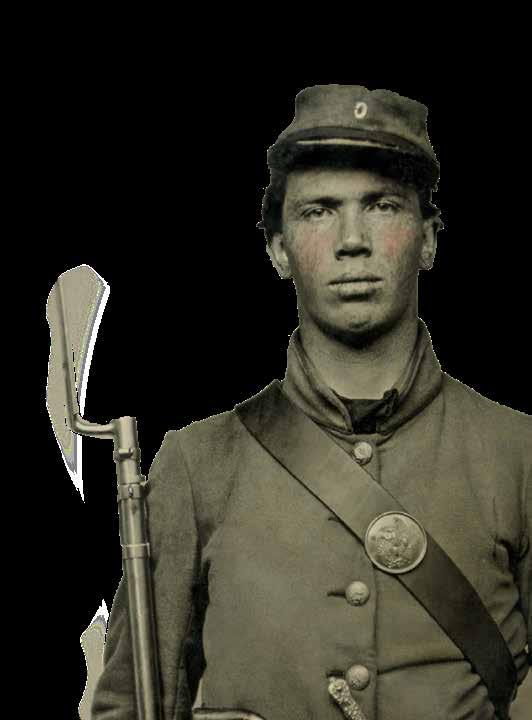

After the battle, both armies departed, and the photographers arrived. In a lane across the street from Lee’s Headquarters, three Confederate prisoners posed for posterity.

Stephanie Hagiwara is the editor for Civil War in Color.com and Civil War in 3D.com. She also writes a column for History in Full Color.com that covers stories of photographs of historical interest from the 1850’s to the present. Her articles can be found on Facebook, Tumblr and Pinterest.

“... I do not think ...there was such a thing as regiments. The men were fighting pretty much at will.” – U.S. Capt. Andrew Cowan, 1st NY Independent BatteryGeneral George E. Pickett. Three Confederate prisoners. Photograph taken after the Battle of Gettysburg.

55 Mayer Alley

Gettysburg, PA 17325

717-360-8805 • cwheritage@aol.com

https://lomascenter.org

The George Lomas Center is a non-profit museum and education center dedicated to sharing America’s rich history through the interpretation and preservation of the George Lomas Collection. Providing unique access to small arms and artillery, hard-to-find artifacts and research materials in an environment that appreciates collectors and living historians and their contributions to the preservation of American History.

The George Lomas Learning Center seeks to deepen the understanding of the American Civil War and the greater story of the United States, support the community in exploration of the past and facilitate learning and exploration for all ages.

Built on the foundations of the incredible private collection of George Lomas, founder of the Regimental Quartermaster Inc. Our collection is the result of a life time of collecting, impressive in scope and quality.

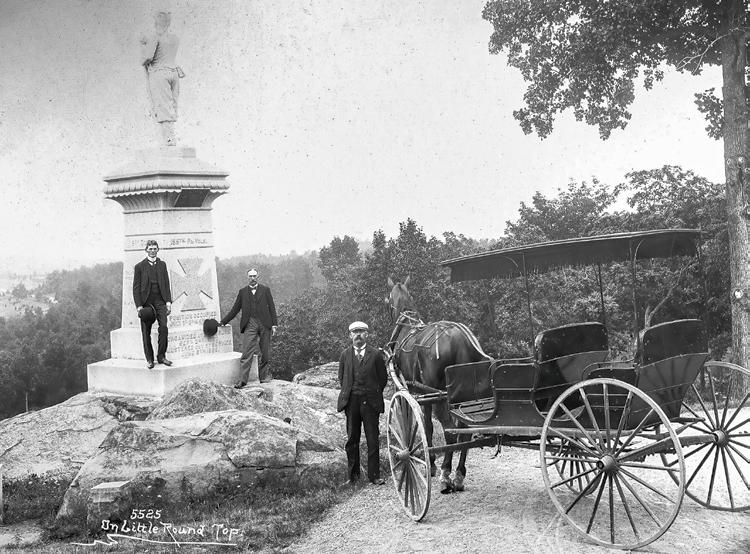

Guiding on the Gettysburg battlefield has a longstanding tradition. Almost as soon as the armies pulled away in July 1863, shocked local citizens were called on to conduct a variety of grieving family members and confused visitors around the area. The first individual to emerge in the post-war period to act as a professional guide was a former Union soldier, Sergeant William David Holtzworth.

Holtzworth became the era’s prototype battlefield guide. Part owner of a Gettysburg livery company, he and his fellow hackmen played a key role in providing the transportation and narration for post-war visits by veterans of all ranks from both armies. During the monumentation era of the 1870s and 1880s, livery hackmen, day laborers working with construction crews, and other Gettysburg citizens who had experienced the terrors of battle became sources of valuable information for returning veterans and non-veteran visitors alike. Veteran reunions and monument dedications, and the stories told therein, added to the body of guide lore.

The spring 1884 completion of the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad and the 1894 building of the Gettysburg Electric Railroad economically made it possible for thousands to travel to and around the field providing another great boon to guiding. Others took advantage of the opportunity, joining nationally prominent individuals already guiding, such as Luther W. Minnigh and Capt.

James T. Long. By the late 19th century, it is estimated fifty individuals made all, or a substantial part, of their living from guiding; those who wanted to guide, did. This unregulated approach led to concerns about quality and consistency in practice, such as not covering all battlefield sites during a tour and telling wild, unsubstantiated, and generally inaccurate stories.

The 1895 establishment of the Gettysburg National Park Commission under the auspices of the U.S. War Department led to the first written evidence of a requirement that anyone intending to conduct tours of the field had to receive authorization to do so from the commission. Despite being granted this early authority to regulate

Top Left: Original LBG “Star Badge” from 1915–1927.

Left: Battlefield Guide Charles Sheads (top right) with a car tour at Devil’s Den, circa 1906. At the time of his death, local newspapers remembered that he was “one of the few remaining battlefield guides who was a resident of Gettysburg during the time of the battle.” Sheads was also a wounded veteran, surviving a gunshot wound to the face at the Battle of Monocacy, July 1864. (Adams County Historical Society)

guiding, the War Department and its commission in the late 19th and early 20th centuries focused more on the myriad projects designed to improve the Park itself, including developing the Confederate army’s lines, building and improving the Park’s road system, and improving visitor infrastructure. Activities of local guides were not a priority.

The passing or retirement of the first true battlefield guides, as well as the advent of the automobile and subsequent decline of the livery system, led to the entry of unqualified individuals guiding at the Park. Complaints of guide quality and shoddy solicitation practices began to pour into the offices of the commission. By the 50th Anniversary in 1913, an estimated 100 men and boys were actively guiding. To stem the flood of complaints, Park Commissioner and

battle veteran John Page Nicholson, working with the Assistant Secretary of War Henry S. Breckinridge, developed a procedure to implement a written examination. Passing the exam was considered an absolute prerequisite of obtaining authorization, or “a license,” to practice guiding on the battlefield of Gettysburg.

The goal of Nicholson’s licensing procedure: to protect the public and those eminently qualified to be guides by refusing to license anyone obviously unfit and by revoking the license of those who failed to perform or did not comply with guiding regulations. Throughout September and October 1915, 91 individuals sat for this new written examination. Some proved they were qualified and scored high enough to earn what were called first-class licenses. Others, scoring less than a set percentage, were granted second- and

third-class licenses but were required to complete additional study under the auspices of a “Guide School” and retake the exam to earn an acceptable score.

The era of licensed guiding officially began October 17, 1915. The courts upheld the newly enhanced War Department guiding regulation when unlicensed individuals were arrested for conducting tours on the battlefield after that date. As a direct result, the quality of guide services improved.

Newly licensed battlefield guides (LBGs) were issued an official ninepointed guide badge as evidence of their status. Fees were standardized at $3 for a basic tour of the battlefield. Shortly afterward a group of guides led by J. Warren Gilbert requested the adoption of a formal uniform for the LBGs. On October 24 the following year, the Battlefield Guide Association was established to serve as the guides’

official representative in dealing with both the Park commission and Gettysburg Borough authorities. Its name was changed to Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides in the early 1980s and today enjoys its status as the oldest professional guide organization in the United States.

From 1915 to the onset of the Great Depression, the Gettysburg LBGs continued as the visitor’s sole source of interpretation on the Gettysburg battlefield. Exams were held periodically to license replacements for those who passed away or simply gave up the profession for a more stable income. The War Department appointed a “guide supervisor,” William Storrick, to oversee the guide service. Guide methods of tour solicitation at various locations in the town became something of a challenge. Lincoln Square was a hotbed of activity for many guides, although hotels and

certain key outposts around town were also regular places of acquiring tours.

Two changes came to the guiding profession in 1929: the last exam administered under the auspices of the War Department and the retirement of the original guide uniform in favor of a more modern military one in khaki. Park Superintendent Colonel E.E. Davis (Ret.) also retired the guide badge in this period, thus halting its use by some as a means of stopping visitors via the flashing of the badge in the manner of a policeman. A numbered wreath cap badge replaced it.

A low point in licensed guiding began in 1930. The onset of the Great Depression quickly led to a sharp dropoff of visitation. To entice visitors to hire guides, a “twister” or short, one-hour tour at a reduced price was adopted. This tour survived into the mid-1960s. Fewer visitors meant less business for existing guides. Consequently, no new guide exams were offered, and no new guides were licensed for many years

resulting in a slow decrease in the roster of LBGs.

President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order August 10, 1933, transferring the War Department military parks, including Gettysburg, to the National Park Service (NPS). In existence less than 20 years, NPS leaders inherited a system they neither understood nor wished to control, leaving the Gettysburg guide system somewhat adrift.

Even though less than 40 guides remained working by the early 1940s, the NPS began making changes affecting the tour experience. The opening of visitor contact facilities initially staffed by Park “RangerHistorians” in the spring of 1937 at the West End and South End stations was an attempt to control the solicitation practices of the few remaining guides. Guides also viewed the implementation of a self-guided auto tour route the year before as a direct attack on their business.

Perhaps to settle fears that the NPS planned to eliminate LBGs, the Park Superintendent announced in 1942 that Park Historian Dr. Frederick Tilberg would offer a required 12part training session followed by a mandatory retesting of all current guides. Clearly an effort to ensure the quality of guides licensed under the old War Department, this move allayed guides’ fears of elimination. A soon-tofollow Park attempt to place remaining guides on the Civil Service rolls as paid employees did not meet with the same success, as guides overwhelmingly voted to remain independent.

The post-war period saw the NPS now firmly committed to the continuation of the long-entrenched private guide service. A rapid increase in visitation led to the realization that the guide force was woefully small with perhaps no more than half the number working that had been licensed in 1929. On August 15, 1951, the first NPS guide examination was administered purely for the purpose of adding additional guides to the roster. These new candidates also faced a new challenge, the requirement of a partial oral exam in the presence of Dr. Tilberg. Compensation improved with the first increase in authorized guide fees from the original $3 per tour that had been in effect since the turn of the century!

Concerted efforts to improve quality and increase the quantity of guides continued. Though initial Park efforts were aimed at creating lists of qualified candidates and maintain an active guide list of 55, the next three decades saw the steady increase of guides up to nearly 100 with guide exams again offered on a more regular basis.

The 1962 opening of the Park’s first true Visitor Center, the Richard Neutra

designed “Cyclorama Building,” led the NPS to begin encouraging guides to work there as the primary location for tour distribution. At the same time, some guide stations around town, including the North End, South End, and East Cemetery Hill stations, were closed. Although up through the mid-to late 1980s, some guides were permitted to continue soliciting their own tours from outlying sites, such as Lincoln Square and the West End station, the process of centralizing guides continued. By 1975, all newly licensed guides were informed they could only work out of the Visitor Center.

Despite the changes in solicitation methods and where guides picked up tours, one thing had held constant; licensed guiding was an exclusively male occupation. Even NPS

Superintendent J. Walter Coleman had publicly stated “...licenses were to be restricted to men,” when reintroducing the guide exam in 1951. This changed in spring 1968, however, when Park policy was relaxed and Barbara Schutt applied for and then passed the guide exam, becoming the first female LBG.

A few years later, Supervisory National Park Technician Nora Saum was appointed guide supervisor, a post she held until her retirement in 1980. During her tenure, the requirement for a full, two-hour, individual oralexamination tour of the battlefield was implemented. Although guiding remains primarily a male profession, fifty other women have earned guide

licenses since Schutt first donned her guide uniform.

In 1972, the NPS purchased the National Museum and Electric Map from the Rosensteel family. This building became the Park’s Visitor Center and the headquarters for the licensed battlefield guides. During the nation’s Bicentennial in 1976, the LBG uniform changed again, this time to the blue/gray uniform still in place today. As part of the 75th anniversary commemoration of licensed guiding in 1990, a reduced version of the traditional guide badge was reintroduced. That same year, the PBS/Ken Burns documentary series on the American Civil War, coupled with the release of the Ron Maxwell movie Gettysburg in 1993, led to a spike in visitation and the rapid increase of the guide force. In 1995 alone, 30 individuals were tested and licensed; the most guides licensed in a single year since the original 1915 class.

Today, there are over 140 licensed battlefield guides still working

under the direct supervision of the National Park Service. It remains the oldest professional guide service to be tested and licensed by the NPS under regulations set down in the Code of Federal Regulations Title 36, Chapter 1, Part 25. Two other Civil War parks today allow guides to operate that have been tested. Guides at Vicksburg National Military Park in Mississippi are licensed by the National Park Service and operated by the Vicksburg Convention and Visitors Bureau. Antietam National Battlefield also has a guide service with individuals certified via an NPS-written exam but run through the Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association. Modern battlefield guides are required to be completely familiar with all Park rules and

regulations and are to ensure that their clients comply with such regulations. Guides are not salaried but receive a fee for each tour completed based on the length of the tour. The basic tour still consists of two hours as it has for more than 100 years, with additional hours added at the request of the visitor. Since 1915 guide fees are established by the Superintendent of Gettysburg National Military Park and a guide may not charge any more than that. Currently, fees are based on the number of people a vehicle can safely hold.

At present, the park’s managing partner, the Gettysburg Foundation, schedules guides. Visitors may call to reserve a guide in advance or simply walk in to the Visitor Center and see if an LBG is available. To ensure an adequate force of guides to serve the visiting public, the National

The latest group photograph of LBG’s taken in 2019.

The latest group photograph of LBG’s taken in 2019.

Park Service periodically administers written and oral examinations, licensing new guides as needed. Today, the licensed battlefield guides still retain the motto established in 1915 by their predecessors: “A Good Battlefield Trip is the Best Advertisement for Gettysburg.”

Fred spent four years serving as an Intelligence Analyst with the United States Air Force during the latter stages of the Vietnam War. Following service Fred earned university degrees in American History and another in Secondary Education. He went on to acquire an advanced degree in Colonial American History and Historical Archaeology. Fred, a LBG since 1981, served as president of the Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, Inc. – the oldest professional guide service in the United States dating back to 1915.

by Carl L. Sell Jr.

by Carl L. Sell Jr.

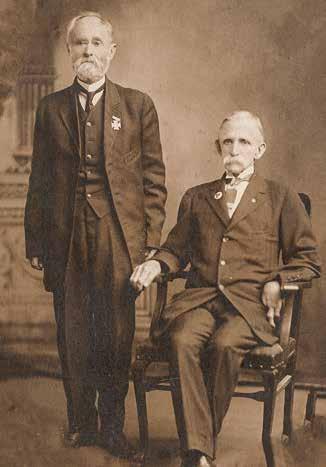

There were more than 53,000 reasons why veterans attended the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913, but none were more personal than those of the 40th Virginia’s Timothy H. Edwards and William P. Hagadorn of the 125th New York. They were looking for each other.

Edwards and Hagadorn first met on July 3, 1863, as Confederate and Union forces clashed on Cemetery Ridge in the climactic final major episode of the three-day battle. It was a fleeting encounter; Edwards was captured and Hagadorn’s unit regrouped and began to move south on the heels of the retreating Confederate army.

It remains a mystery as to what drew the pair together in 1863, but they did admit that they went to the 1913 reunion specifically with the hope they would reunite. Fate put them together in the large crowd of veterans. Edwards then moved to Baltimore from Lancaster, Va., to be close to Hagadorn and the pair became inseparable for the rest of their lives. Edwards died in 1915 and Hagadorn in 1921.

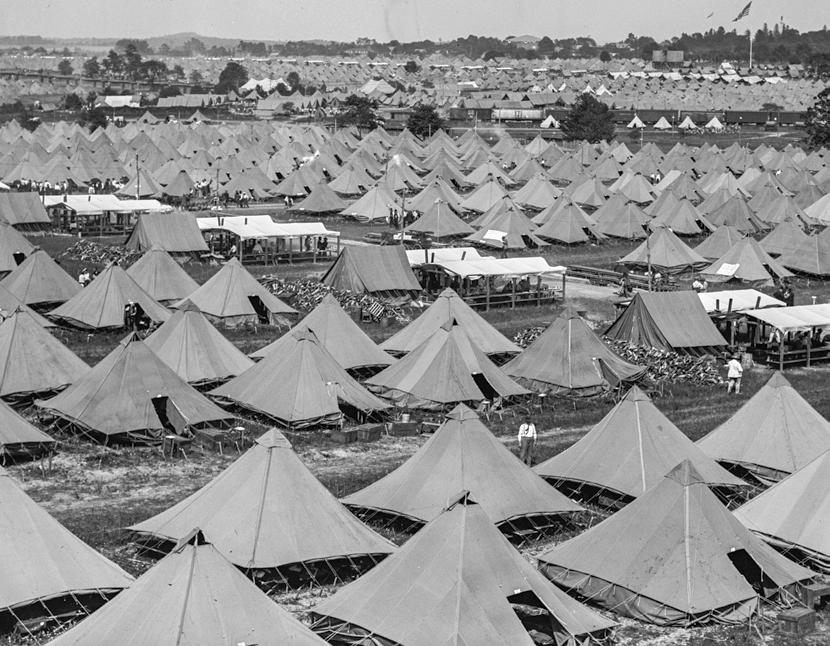

The old battlefield became a tent city as hotels were filled in Gettysburg and nearby towns in 1913. Veterans also were lodged at the Lutheran Theological Seminary and Pennsylvania College (which became Gettysburg College in 1921). The weather ranged from bright sunshine

and high temperatures to cool rains, just as it had in 1863. Even though it was the middle of the summer, 105, 262 blankets were issued to veterans ranging in age from their late 60s to beyond 80. More than 3,000 Boy Scouts were on hand to help with baggage and make sure the men found their assigned tents or place of lodging. All was organized by the United States

Timothy Edwards (standing) and William Hagadorn became unlikely friends at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. Right: The 1913 reunion at “Bloody Angle.” – Confederates to the right;, Union veterans on the left; the Outer Angle’s stone wall stands between them. (Library of Congress)Above: Now the “Friendly” Angle. One of the most affecting sights witnessed during the present [1913] reunion of Confederate and Federal veterans at Gettysburg is depicted in this photograph. Across the stone wall, which marked the boundary of the famous “Bloody Angle” where Pickett lost over 3,000 men from a force of 6,000, these old soldiers of the North and South clasped hands in fraternal affection. (Library of Congress)

and ran to avoid further carnage. Left behind were ten wounded; Edwards was one of some 60 captured Brockenbrough men.

War Department, the Army, and the Battle of Gettysburg Commission. Many veterans arrived by train so the platform at Gettysburg had to be enlarged to handle the crush.