Vicksburg 160th

Celebrations to Observe the Union Victory were Memorable

By Professor Earnest Veritas Special Correspondent to Civil War News – Western Theater –

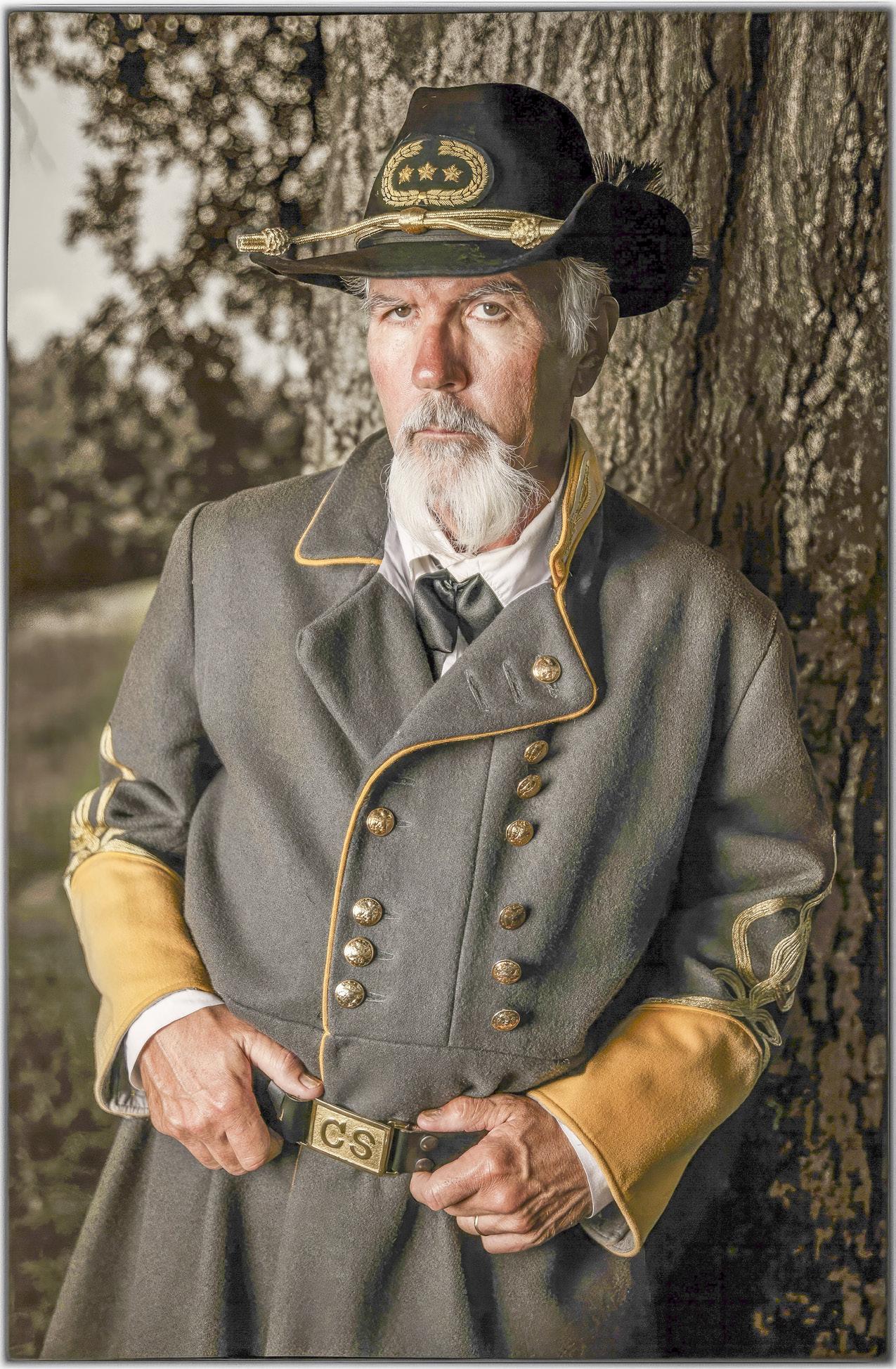

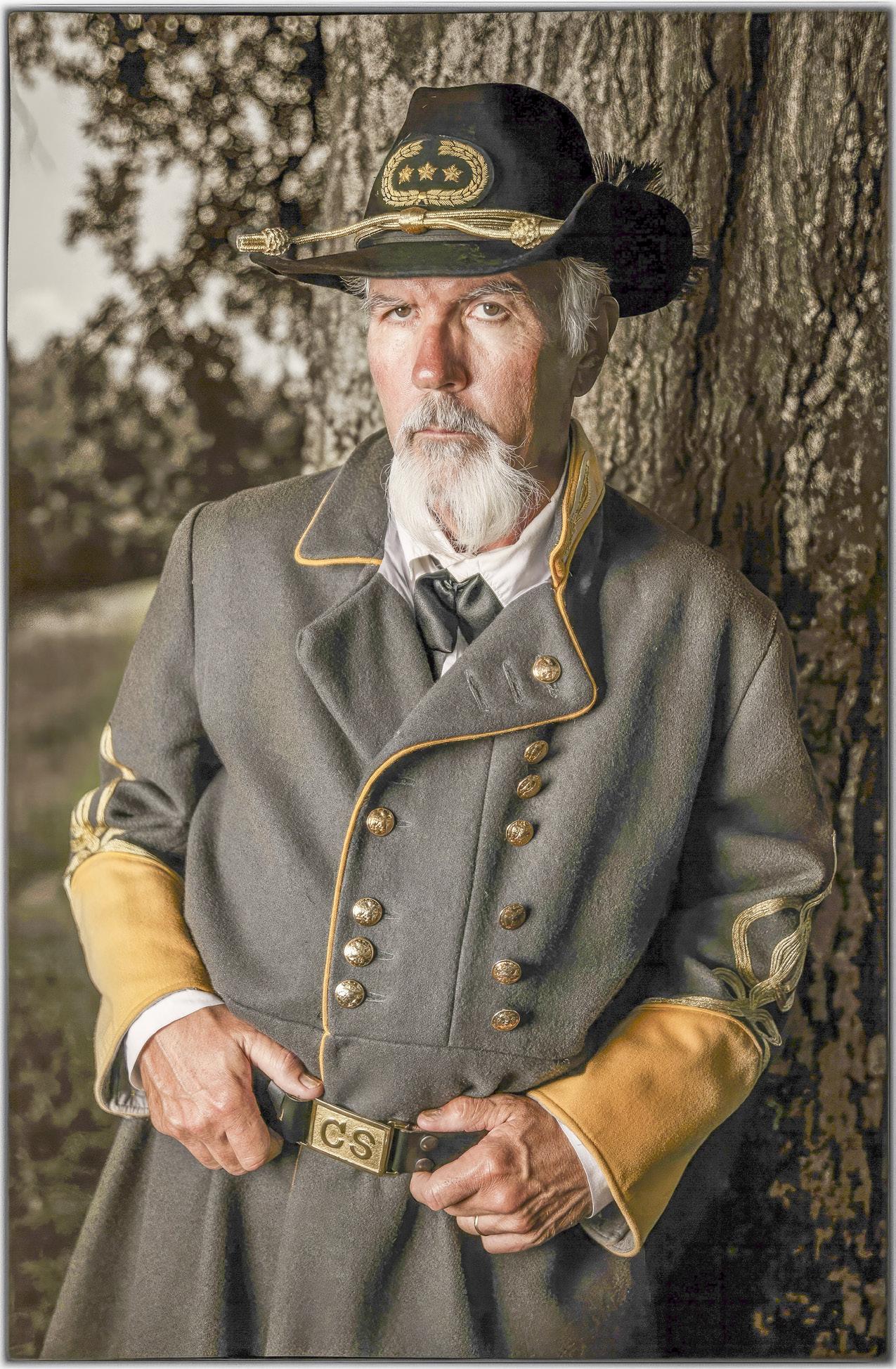

The 160th anniversary of the surrender of Vicksburg, Miss., by General John C. Pemberton to General Ulysses S. Grant was observed on July 1st and 2nd, last, at the National Military Park with the paradox of roaring cannon, contrasted with quiet talks from the soldiers camped on the battlefield around the Shirley house in the sweltering heat of a Mississippi July. Visitors to the park that weekend were also treated to the dynamic story of how the siege came to a quick and merciful end without a final assault on Confederate lines as was planned. That very brief sequence of events was told in the visitor center auditorium in presentations from the two opposing commanders, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (Curt Fields) and John C. Pemberton (Morgan

Gates). The generals came together and explained how the surrender was worked out in less than one day in their presentation “Vicksburg: Just 24 Hours,” which was given in the morning and afternoon of both days.

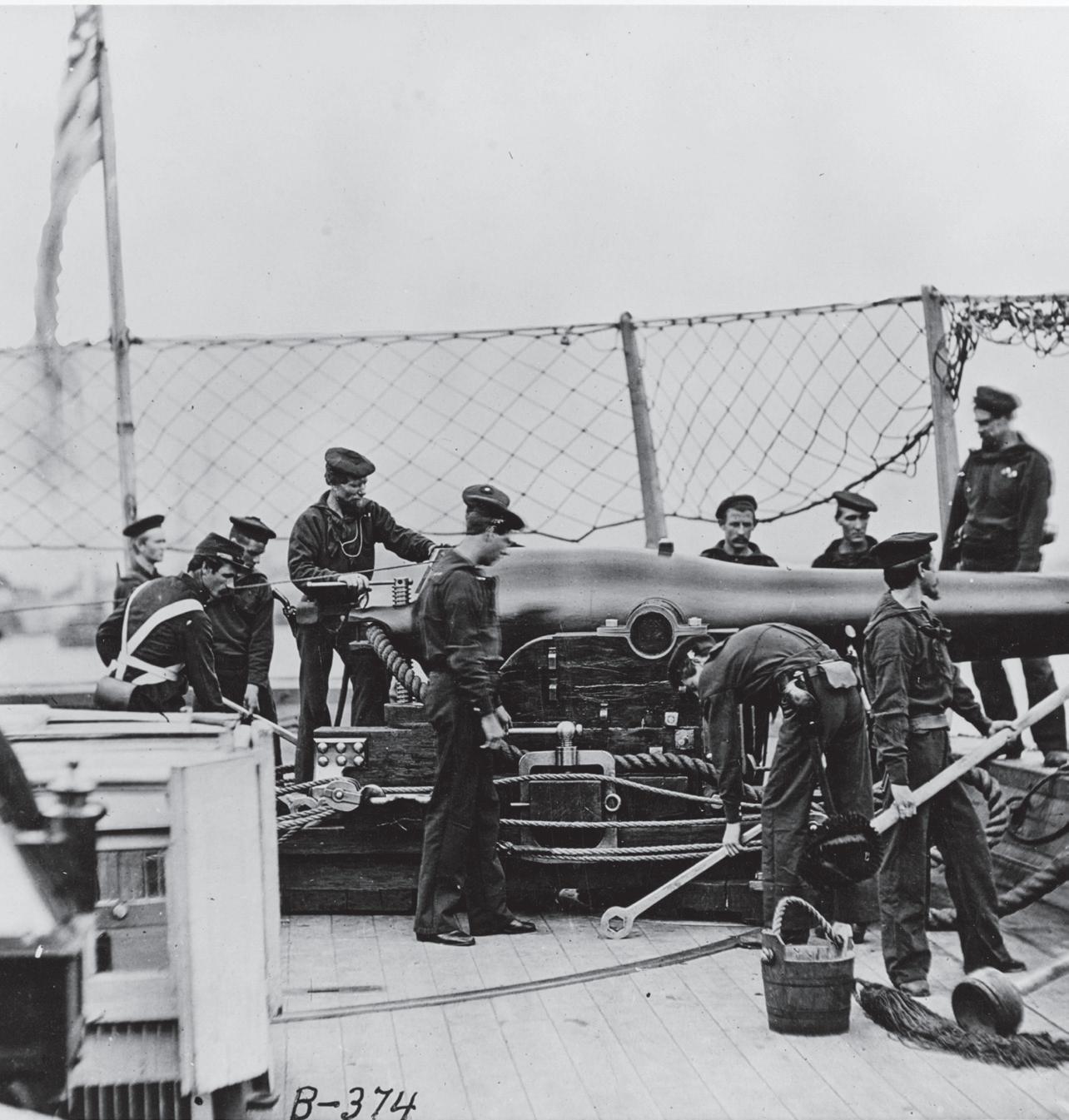

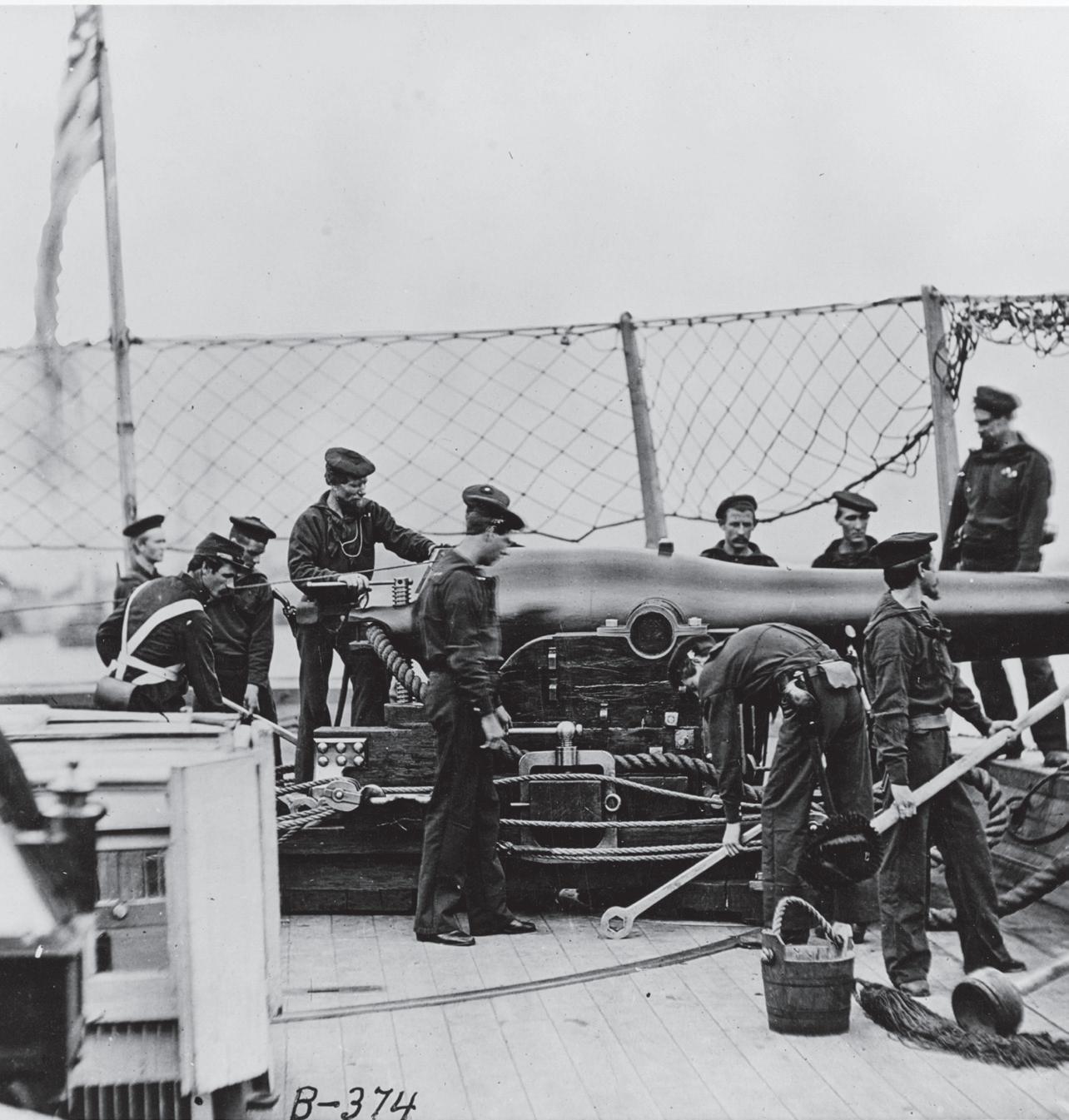

Cannon firing demonstrations were given throughout both days by a Federal gun crew at the visitor center and a Confederate gun crew at the 2nd Texas Lunette (at tour stop 12). They had alternating schedules to accommodate the visitors to the park for the 160th observations.

At the visitor center, the Federal gun crew fired at 9, 10, and 11 a.m. on Saturday and Sunday.

The Confederate gun crew could be viewed firing their cannon at Tour Stop #12 (2nd Texas Lunette): 9:15, 10:15, and 11:15 a.m. on Saturday and Sunday. The Confederate crew was visiting from Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield.

The hardy troops of the 45th Illinois Infantry were encamped

on the grounds around the Shirley House on the battlefield. Their encampment was authentic and most impressive. While they were involved in normal camp-life duties, they talked with various visitors to the park that weekend. In an overview of the Vicksburg

Campaign, a soldier of the 45th explained the importance of Vicksburg, the campaign from 1862–1863, emphasizing the role of the common soldier in camp and combat.

They talked of the particular uses and importance of the equipment they carried as they showed their weapons, uniforms, backpacks, blanket rolls, and other equipment they used.

A soldier spoke of the challenges and hardships faced by Union soldiers as they besieged Vicksburg.

Several soldiers talked about the typical rations they were issued and demonstrated methods for cooking.

Some of the 45th talked about the June 25th mine explosion at the 3rd Louisiana Redan and the desperate attempt to break through the Confederate lines, emphasizing the role of the 45th Illinois in that battle.

Doug Baum brought his Texas Camel Corps to the park for both days of the anniversary observation to represent Old Douglas, the vaunted mascot of the 43rd Mississippi Infantry.

Doug had two camels available for the young (and not so young) visitors to admire, pet, and look at up close. Doug also talked about the story of Old Douglas, the Camel mascot of the 43rd Mississippi Infantry.

Douglas was a hold-over from the 1850’s Texas Camel Experiment. During the War, he carried the regimental band instruments and other camp equipment for the 43rd Mississippi. Sadly, Douglas was killed by a sniper while at Vicksburg. He was buried in the old city cemetery.

For an added treat for visitors to the park, Generals Grant and Pemberton spent time conversing on the famous ‘Surrender Knoll’ where they were on July 3rd, 1863.

For more information about Vicksburg National Military Park, visit www.nps.gov/vick/ index.htm.

Morgan Gates is a licensed Vicksburg battlefield guide and may be reached on his Facebook

Vol. 49, No. 9 40 Pages, September 2023 $4.00 America’s Monthly Newspaper For Civil War Enthusiasts 18 – American Battlefield Trust 34 – Book Reviews 13 – Central Virginia Battlefield Trust 38 – Civil War Trails 30 – Critic’s Corner 32 – Emerging Civil War 39 – Events 28 – The Graphic War 22 – The Source 24 – This And That 10 – The Unfinished Fight 20 – Through the Lens H Vicksburg . . . . . . . . . . . . see page 4

Reenactors of the 45th Illinois Infantry at Vicksburg’s 160th anniversary. (Buddy Secor)

Union artillery fire their 12-pounder Napoleon during the event. (Buddy Secor)

Civil War News

Published by Historical Publications LLC

2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513 800-777-1862 • Facebook.com/CivilWarNews mail@civilwarnews.com • civilwarnews.com

Advertising: 800-777-1862 • ads@civilwarnews.com

Jack W. Melton Jr. Publisher C. Peter & Kathryn Jorgensen Founding Publishers

Editor: Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D.

Advertising, Marketing & Assistant Editor: Peggy Melton

Columnists: Craig Barry, Salvatore Cilella, Stephen Davis, Stephanie Hagiwara, Gould Hagler, Chris Mackowski, Tim Prince, and Michael K. Shaffer

Contributor & Photography Staff: Greg Biggs, Curt Fields, Michael Kent, Shannon Pritchard, Leon Reed, Bob Ruegsegger, Carl Sell Jr., Gregory L. Wade, Joan Wenner, J.D., Joseph Wilson

Civil War News (ISSN: 1053-1181) Copyright © 2023 by Historical Publications LLC is published 12 times per year by Historical Publications LLC, 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513. Monthly. Business and Editorial Offices: 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513, Accounting and Circulation

Offices: Historical Publications LLC, 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513. Call 800-777-1862 to subscribe. Periodicals postage paid at U.S.P.S. 131 W. High St., Jefferson City, MO 65101.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Historical Publications LLC 2800 Scenic Drive Suite 4-304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513

Display advertising rates and media kit on request. The Civil War News is for your reading enjoyment. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of its authors, readers and advertisers and they do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Historical Publications, LLC, its owners and/or employees. P

:

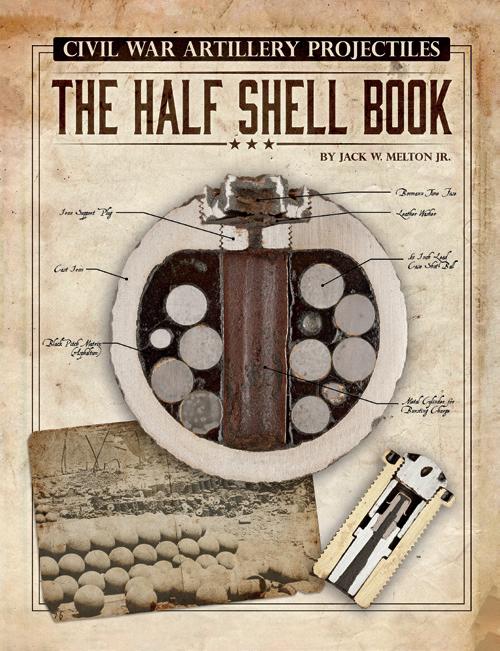

Please send your book(s) for review to: Civil War News

2800 Scenic Drive Suite 4-304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513

Email cover image to bookreviews@civilwarnews.com. Civil War News cannot assure that unsolicited books will be assigned for review. Email bookreviews@civilwarnews.com for eligibility before mailing.

ADVERTISING INFO:

Email us at ads@civilwarnews.com Call 800-777-1862

MOVING?

Contact us to change your address so you don’t miss a single issue. mail@civilwarnews.com • 800-777-1862

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

U.S. Subscription rates are $41/year, digital only $29.95/year, add digital to paper subscription for only $10/year more. Subscribe securely at CivilWarNews.com

Current Event Listings

To see all of this year’s current events visit our website at: HistoricalPublicationsLLC.com

Terms and Conditions

The following terms and conditions shall be incorporated by reference into all placement and order for placement of any advertisements in Civil War News by Advertiser and any Agency acting on Advertiser’s behalf. By submitting an order for placement of an advertisement and/or by placing an advertisement, Advertiser and Agency, and each of them, agree to be bound by all of the following terms and conditions:

1. All advertisements and articles are subject to acceptance by Publisher who has the right to refuse any ad submitted for any reason. Mailed articles and photos will not be returned.

2. The advertiser and/or their agency warrant that they have permission and rights to anything contained within the advertisement as to copyrights, trademarks or registrations. Any infringement will be the responsibility of the advertiser or their agency and the advertiser will hold harmless the Publisher for any claims or damages from publishing their advertisement. This includes all attorney fees and judgments.

3. The Publisher will not be held responsible for incorrect placement of the advertisement and will not be responsible for any loss of income or potential profit lost.

4. All orders to place advertisements in the publication are subject to the rate card charges, space units and specifications then in effect, all of which are subject to change and shall be made a part of these terms and conditions.

5. Photographs or images sent for publication must be high resolution, unedited and full size. Phone photographs are discouraged. Do not send paper print photos for articles.

6. At the discretion of Civil War News any and all articles will be edited for accuracy, clarity, grammar, and punctuation per our style guide.

7. Articles can be emailed as a Word Doc attachment or emailed in the body of the message. Microsoft Word format is preferred. Email articles and photographs: mail@civilwarnews.com

8. Please Note: Articles and photographs mailed to Civil War News will not be returned unless a return envelope with postage is included.

2 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 2 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com

UBLISHERS

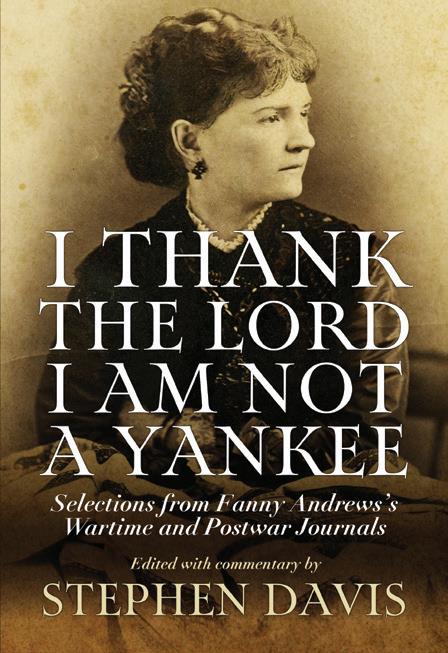

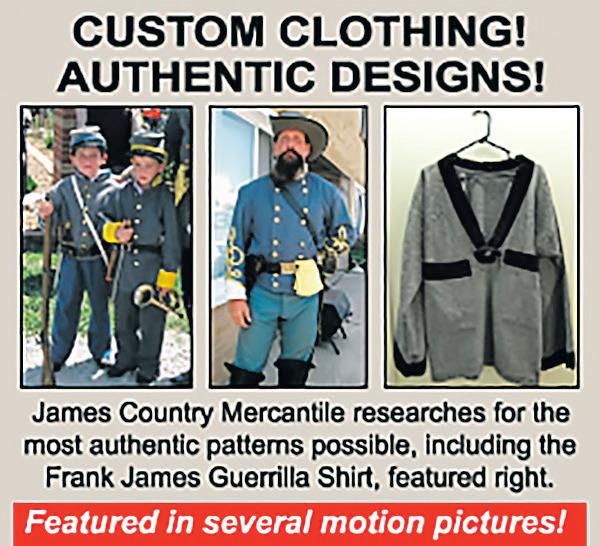

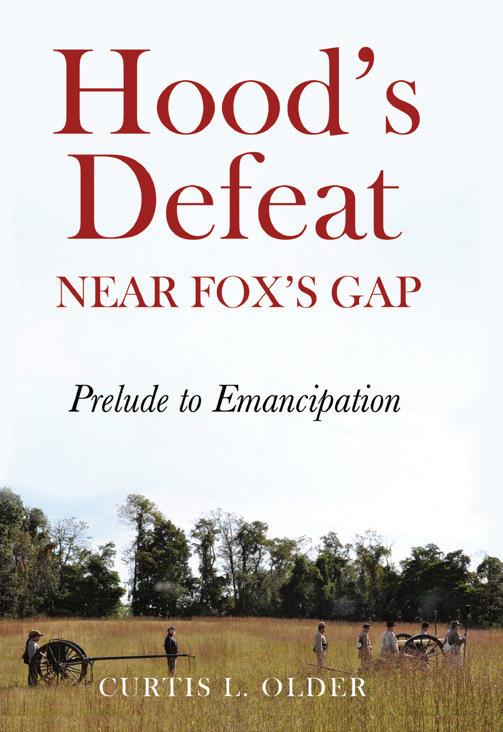

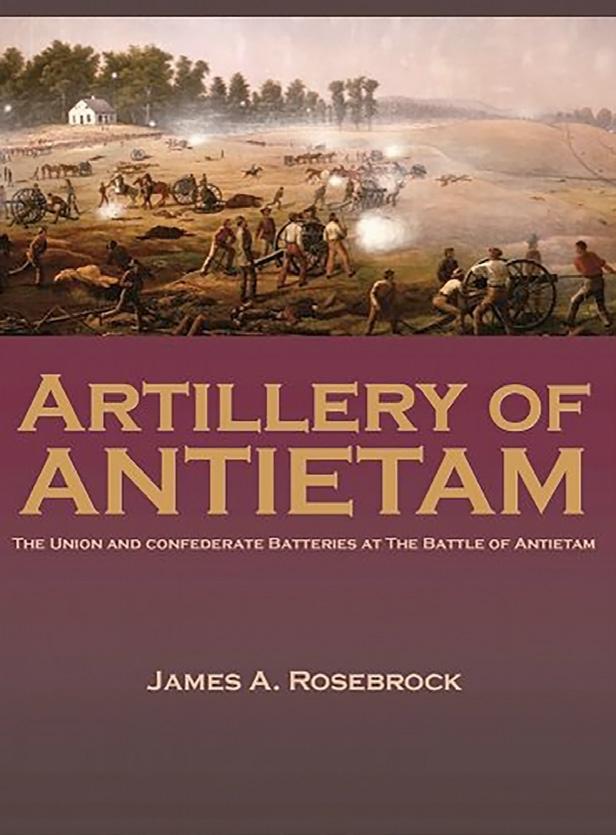

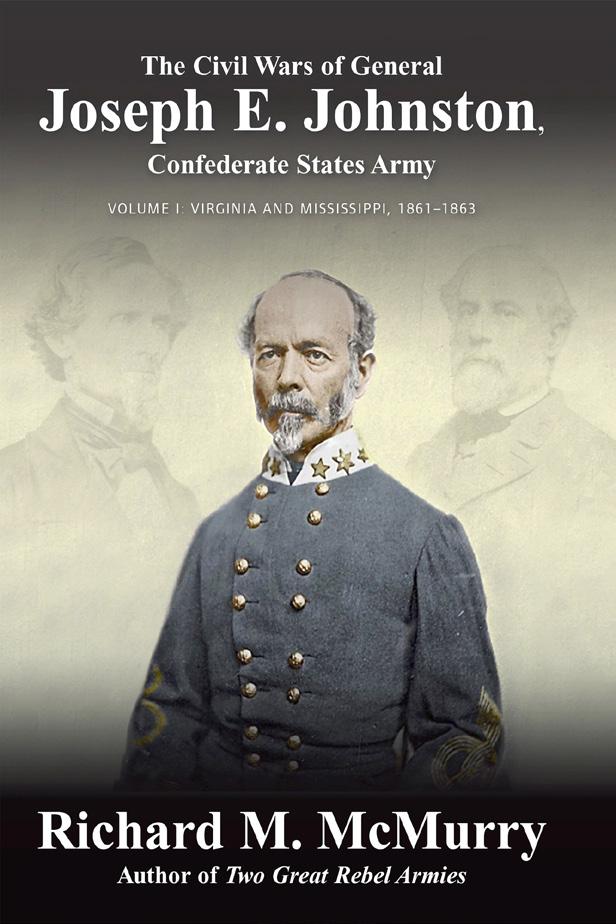

Deadlines for Advertising or Editorial Submissions is the 20th of each month. Email: ads@civilwarnews.com Digital Issues of CWN are available by subscription alone or with print plus CWN archives at CivilWarNews.com Advertisers In This Issue: Ace Pyro LLC 27 American Battlefield Trust 26 Artilleryman Magazine 12 Ashley R. Rhodes Militaria 28 CWMedals.com, Civil War Recreations 19 Civil War Navy Magazine 29 College Hill Arsenal – Tim Prince 26 Day by Day through the Civil War in Georgia – Book 23 Dell’s Leather Works 23 Dixie Gun Works Inc. 12 Georgia’s Confederate Monuments – Book 17 Gettysburg Foundation 9 Gunsight Antiques 17 Harpers Ferry Civil War Guns 2 Hood’s Defeat Near Fox’s Gap – Book 35 The Horse Soldier 5 James Country Mercantile 38 Jeweler’s Daughter 11 Le Juneau Gallery 5 “I thank the Lord I’m not a Yankee” – Book 31 Mike McCarley – Wanted Fort Fisher Artifacts 23 National Museum of Civil War Medicine 33 N-SSA 23 Regimental Quartermaster 19 Richard LaPosta Civil War Books 35 Shiloh Chennault Bed and Breakfast 12 Suppliers to the Confederacy – Book 26 Ulysses S. Grant impersonator – Curt Fields 12 Events: Chicago Civil War Show 4 Elite Collectors Civil War Show 23 MKShows, Mike Kent 3, 17 Military Antique Show – Virginia 27 Poulin’s Auctions 40 Remembrance Day Ball in Gettysburg 8 Rock Island Auction Company 23

Asheville Gun & Knife Show

WNC Ag Center 1301 Fanning Bridge Road Fletcher, NC

Oct. 7 & 8, 2023

Myrtle Beach Gun & Knife Show

Myrtle Beach Convention Center 2101 North Oak Street Myrtle Beach, SC 29579

Nov. 4 & 5, 2023

Exchange Park Fairgrounds 9850 Highway 78 Ladson, SC 29456

Mike Kent & Associates, LLC • PO Box 685 • Monroe, GA 30655 770-630-7296 • Mike@MKShows.com • www.MKShows.com Military Collectible & Gun & Knife Shows Presents The Finest Williamson County Ag Expo Park 4215 Long Lane Franklin, TN 37064 Dec. 2 & 3, 2023 Middle TN (Franklin) Civil War Show Promoters of Quality Shows for Shooters, Collectors, Civil War and Militaria Enthusiasts Exchange Park Fairgrounds

SC 29456

9 & 10, 2023 Charleston Gun & Knife Show

9850 Highway 78 Ladson,

Sept.

Show

Nov. 25 & 26, 2023 Charleston Gun & Knife

page: Morgan Gates. One may also contact him directly through the park.

Also, visit Friends of Vicksburg National Military Park and Campaign.

Professor Veritas would like to thank the Vicksburg National Military Park staff and the park website for the valuable assistance of both for information in the preparation of this report.

“Simply put: tell the simple truth, simply.” – Professor E. Veritas

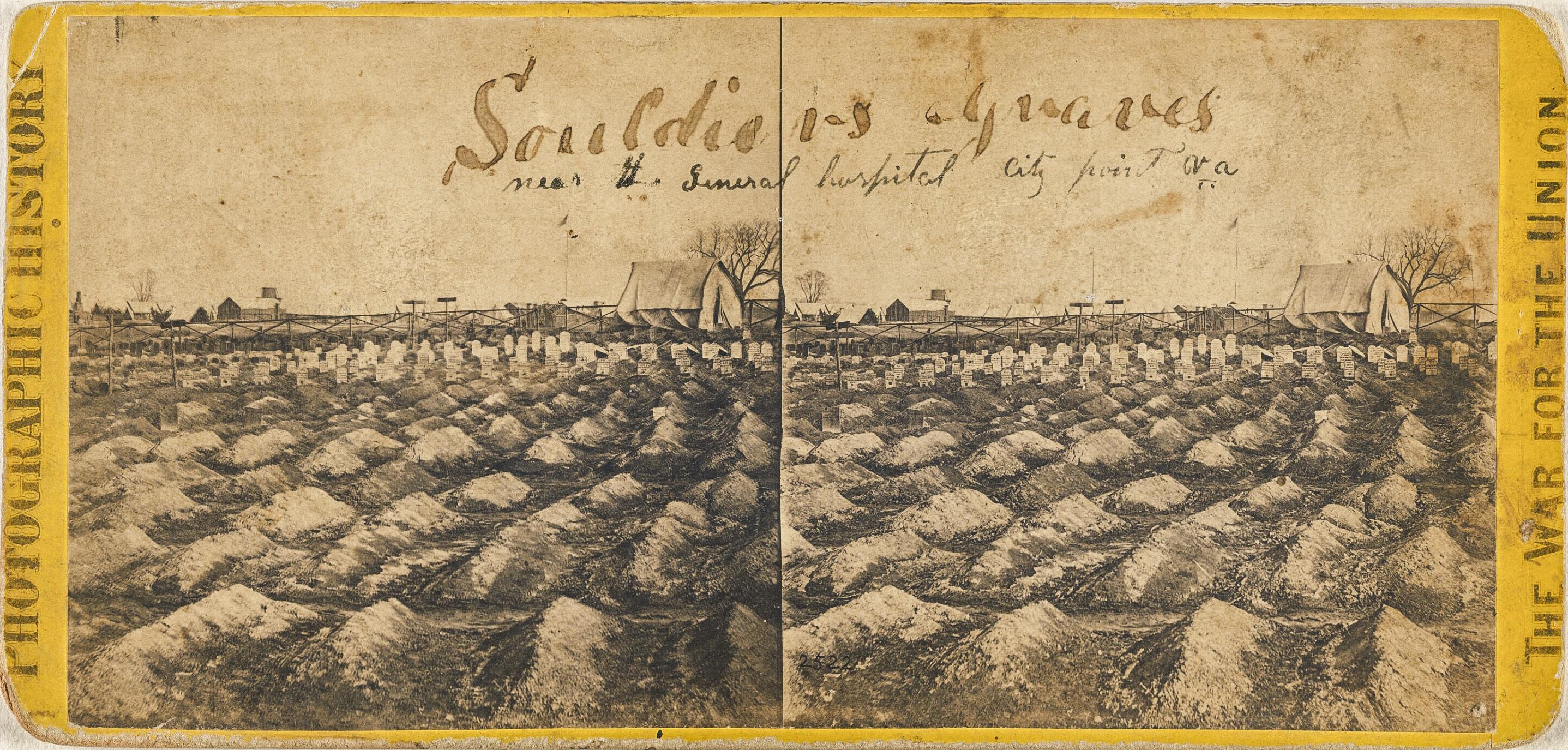

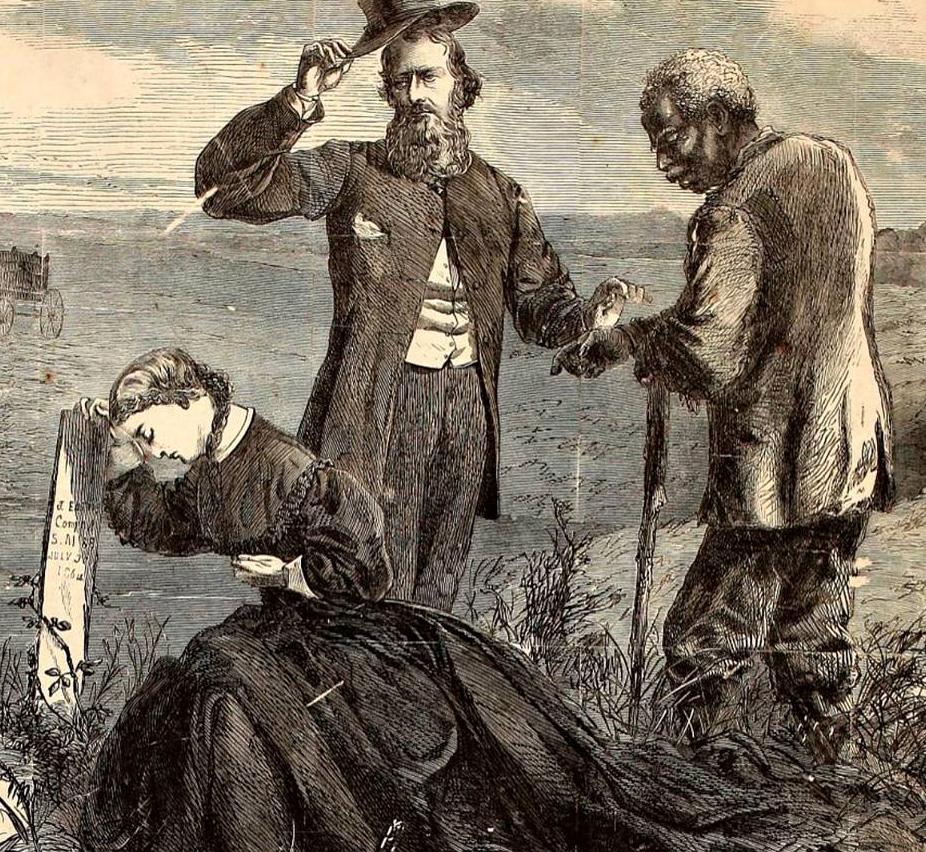

About the Surrender

The Surrender at Vicksburg, which took place during the American Civil War, was a pivotal

event that significantly impacted the outcome of the conflict. It marked a turning point in the war and had profound implications for the Union’s ultimate victory.

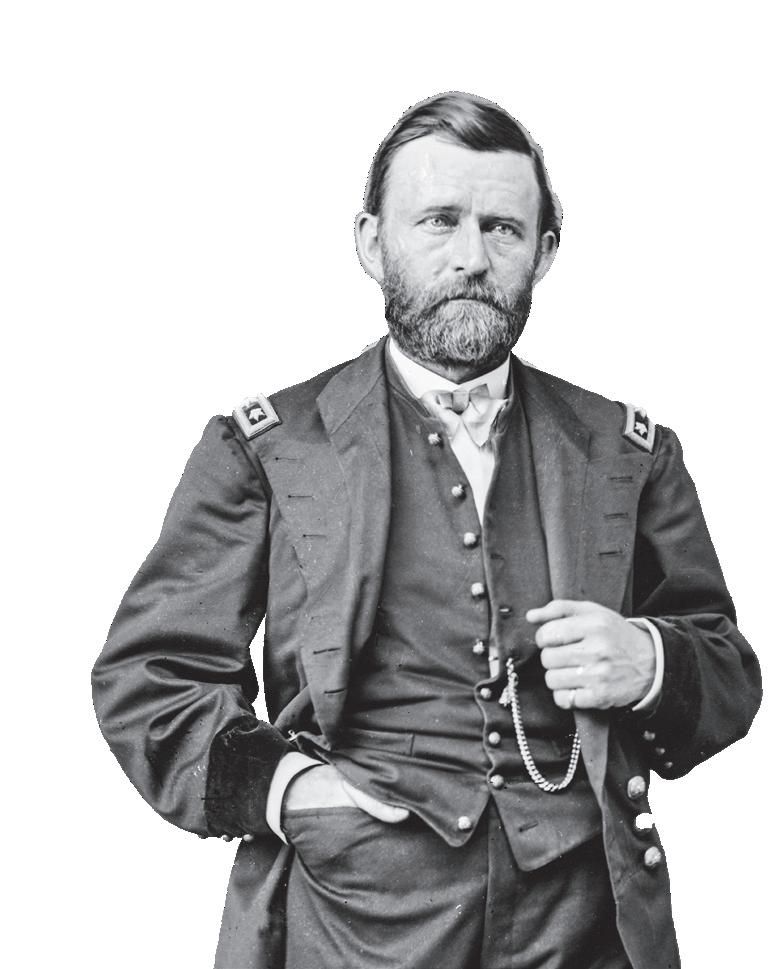

Vicksburg is located on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, was a strategic stronghold for the Confederacy. The city’s location made it a critical point of control over the river, and its capture became a top priority for the Union forces. General Ulysses S. Grant was determined to take Vicksburg as part of his broader plan to gain control of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy in two.

The siege of Vicksburg began in May 1863 and lasted for over six weeks. The Confederate forces,

led by General John C. Pemberton, held out bravely, but they were ultimately overwhelmed and surrounded by the Union army. The relentless bombardment and lack of supplies took a toll on the Confederate defenders, leading to their eventual surrender on July 4, 1863.

The fall of Vicksburg was a significant blow to the Confederacy. It effectively cut off their access to the Mississippi River, severing vital supply lines and dividing the Confederacy geographically. This victory also boosted Northern morale and solidified General Grant’s reputation as a skilled military leader, eventually leading to his promotion to Lieutenant General

and command of all Union forces.

The surrender at Vicksburg came one day after the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, making the 4th of July a doubly joyous day for the Union. The combined victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg bolstered Northern support for the war

effort and further demoralized the Confederacy.

In conclusion, the surrender at Vicksburg was a critical moment in the American Civil War. It significantly weakened the Confederacy and helped pave the way for the Union’s ultimate triumph. The capture of Vicksburg

4 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 4 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com 1,000’s of Civil War Treasures! Plus! Revolutionary War • Spanish-American War Indian Wars • Mountain Men • Bowie Knife Collector Arms • Fur Traders • World Wars I & II Civil War & Military Show 9 - 4 / $10 • Early Buyer’s 8am / $25 • Free Parking September 23 2023 • Fall Show • Saturday

The Confederate gun crew from Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield. (Mike Talplacido)

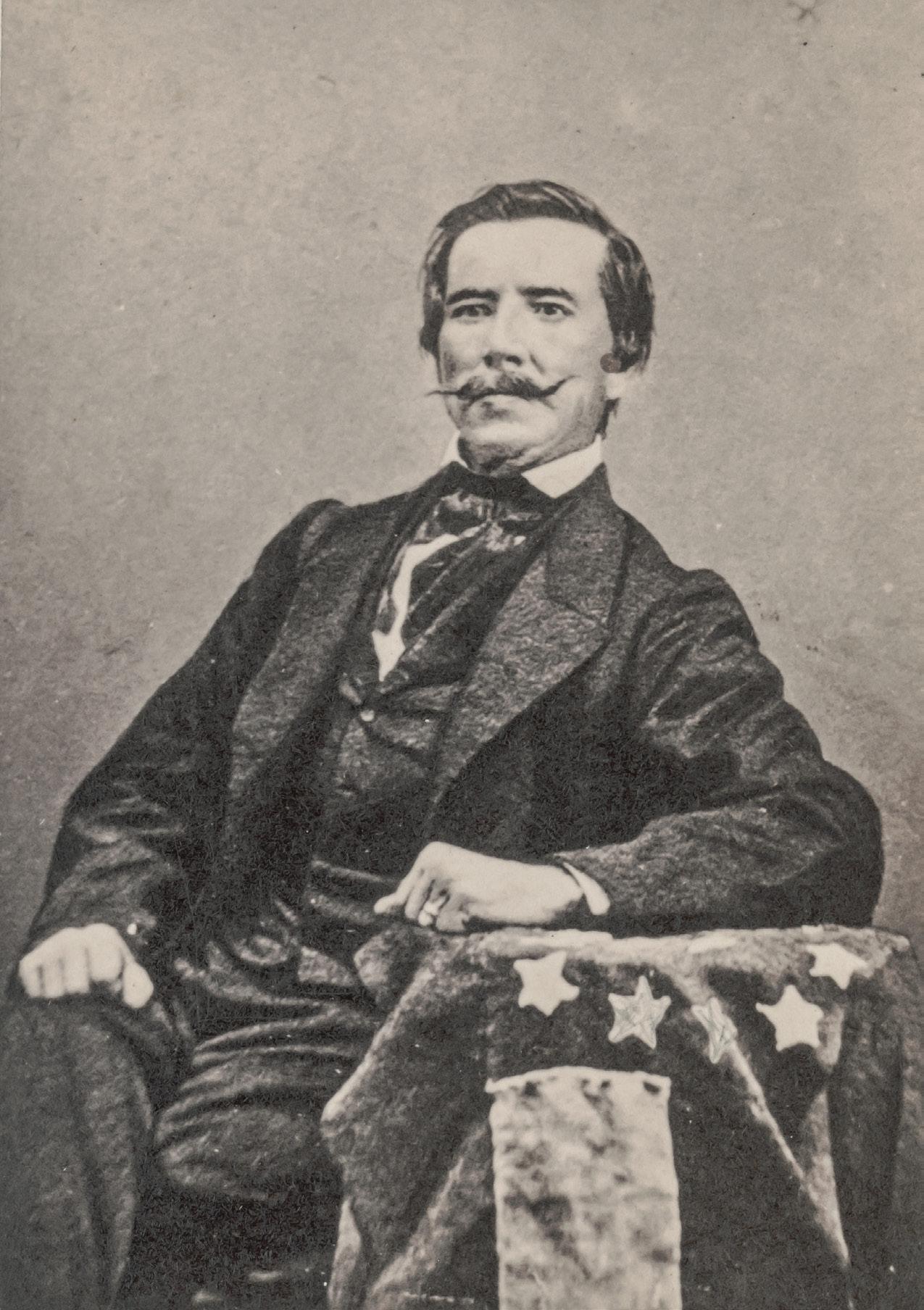

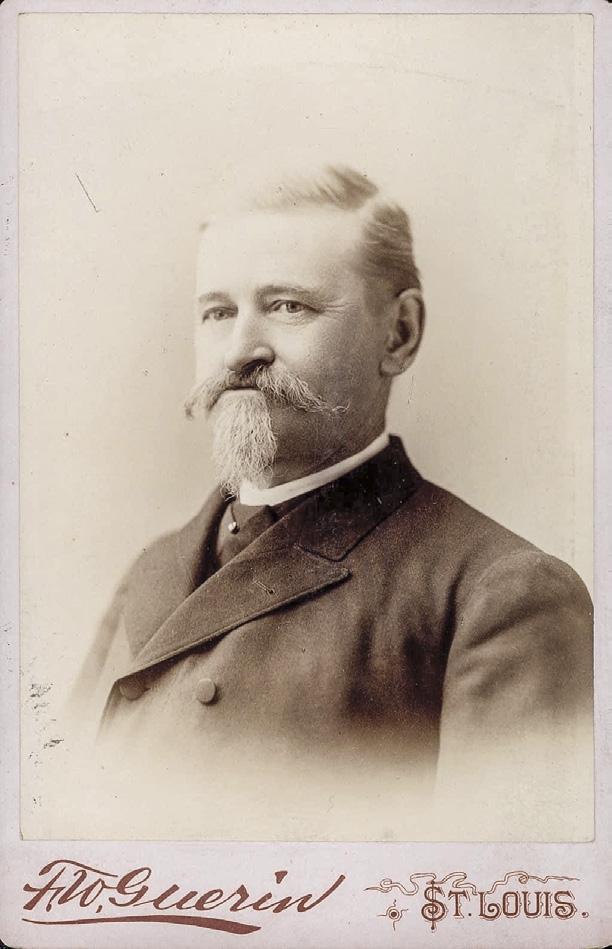

Confederate General John C. Pemberton portrayed by Morgan Gates. (Buddy Secor)

General Grant and Pemberton discuss the terms of surrender on “Surrender Knoll.” (Buddy Secor)

by General Grant’s forces was a strategic and symbolic victory that turned the tide of the war in favor of the Union.

Grant at Vicksburg

Union General Ulysses

S. Grant led the assault on Vicksburg with the intention of gaining control of the Mississippi River and cutting off Confederate supply lines. The campaign was a challenging one, as the city was heavily fortified and protected by skilled Confederate forces under General John C. Pemberton.

Grant’s troops initially attempted to take Vicksburg by direct assault, but they faced fierce resistance and suffered heavy casualties. Recognizing the difficulty of a direct approach, Grant shifted his strategy and decided to lay siege to the city. His forces encircled Vicksburg, cutting off its supply lines and subjecting its inhabitants to relentless bombardment.

During the 47-day siege, both sides endured harsh conditions and constant danger. Civilians sought shelter in caves and endured food shortages, while soldiers on both sides faced the physical and psychological tolls of war. Despite the hardships, Grant’s determination and strategic acumen prevailed.

Pemberton at Vicksburg

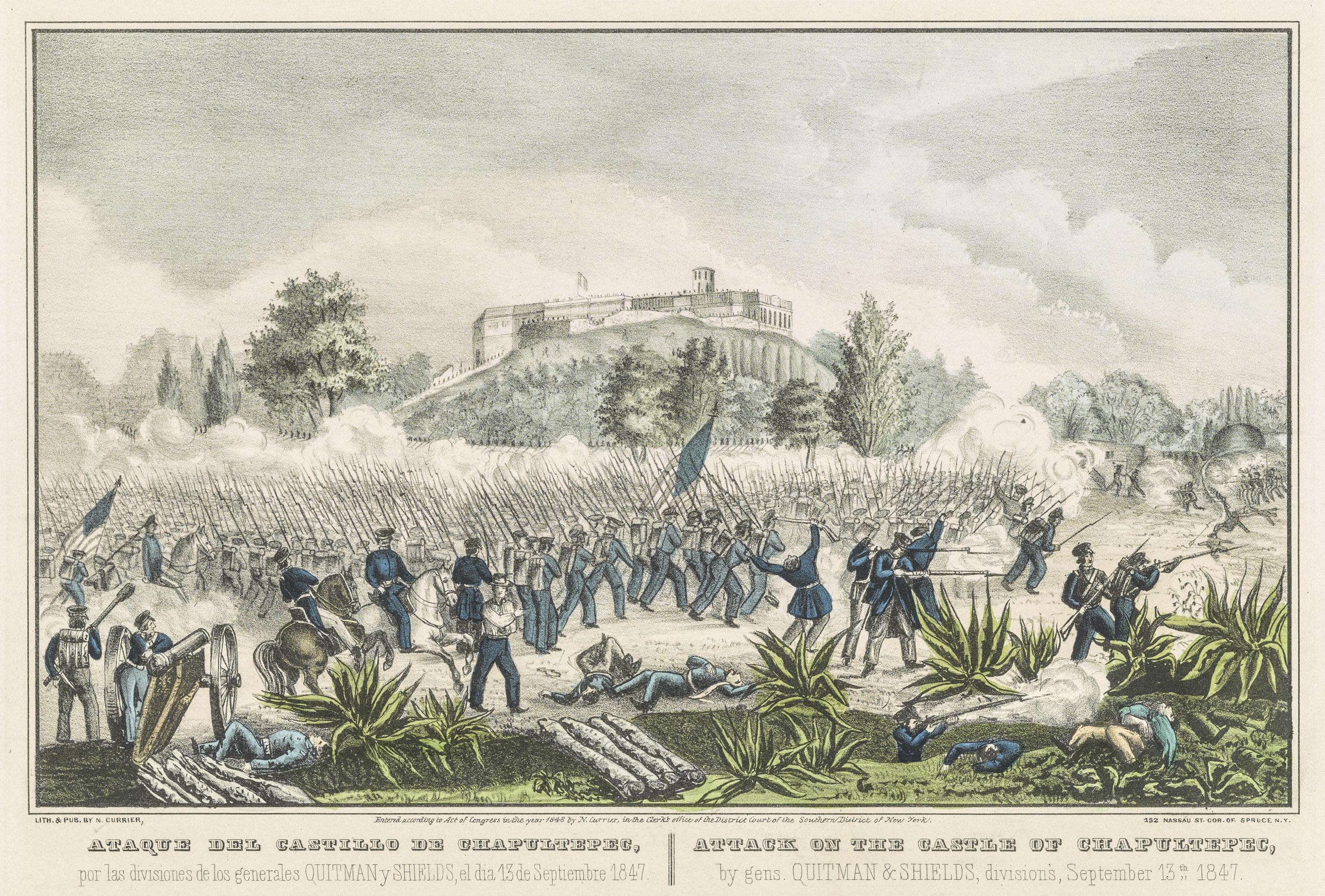

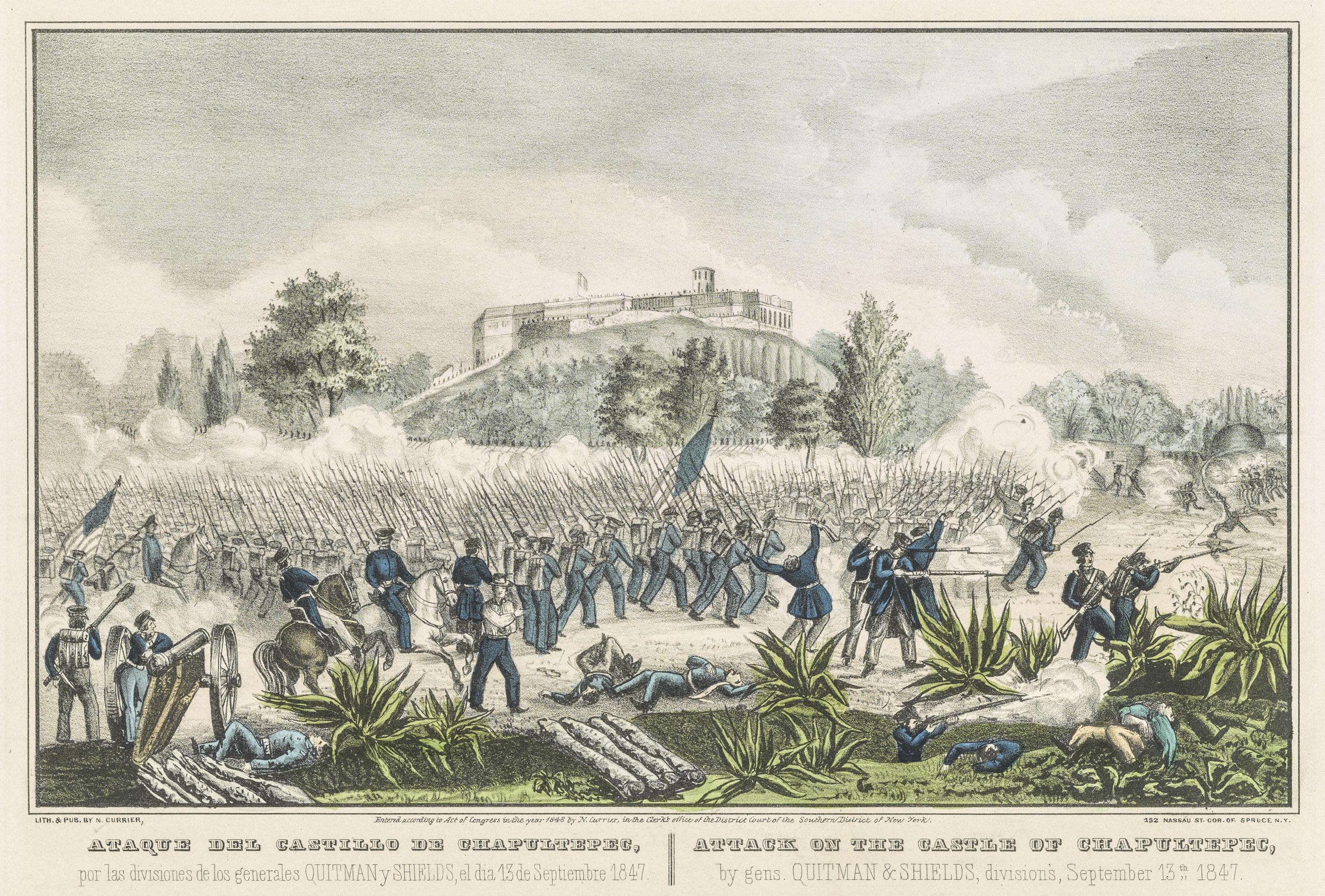

John C. Pemberton’s role at Vicksburg during the Civil War was significant, as he found himself in command of a crucial Confederate stronghold that held strategic importance in the Mississippi River region. Born in 1814, Pemberton was a West Point graduate and a veteran of the Mexican-American War, possessing military experience that would prove valuable during the impending conflict.

In May 1863, Pemberton was appointed to command the Confederate forces at Vicksburg. He faced immense pressure from Union forces, led by General Ulysses S. Grant, who sought to gain control of the Mississippi River, cutting the Confederacy in two. The city’s high bluffs and formidable defenses made it a formidable obstacle for the Union army.

Pemberton, however, faced numerous challenges during his tenure. He struggled to maintain morale among his troops, as they faced shortages of food, supplies, and ammunition. Additionally, his relationship with his subordinate officers was often strained, leading to communication issues and coordination problems within

the Confederate ranks.

During the 47-day Siege of Vicksburg, Pemberton’s men valiantly defended the city against relentless Union assaults. Despite their resilience, the Confederate forces were ultimately overwhelmed, and

Vicksburg fell to the Union on July 4, 1863. This pivotal loss was a severe blow to the Confederacy, as it not only granted the Union control of the Mississippi River but also boosted Northern morale and further weakened Southern resolve.

After the defeat at Vicksburg, Pemberton’s military career suffered a setback, and he was reassigned to less prominent roles for the remainder of the war. Following the Confederate surrender in 1865, he returned

to civilian life and later moved to Virginia. John C. Pemberton’s legacy remains tied to his command at Vicksburg, where he faced enormous challenges and contributed to shaping the outcome of the Civil War.

5 September 2023 5

2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com Buying and Selling The Finest in Americana 11311 S. Indian River Dr. • Fort Pierce, Florida 34982 770-329-4985 • gwjuno@aol.com George Weller Juno

September

Union General Ulysses S. Grant portrayed by Curt Fields. (Buddy Secor)

By Jeffry D. Wert

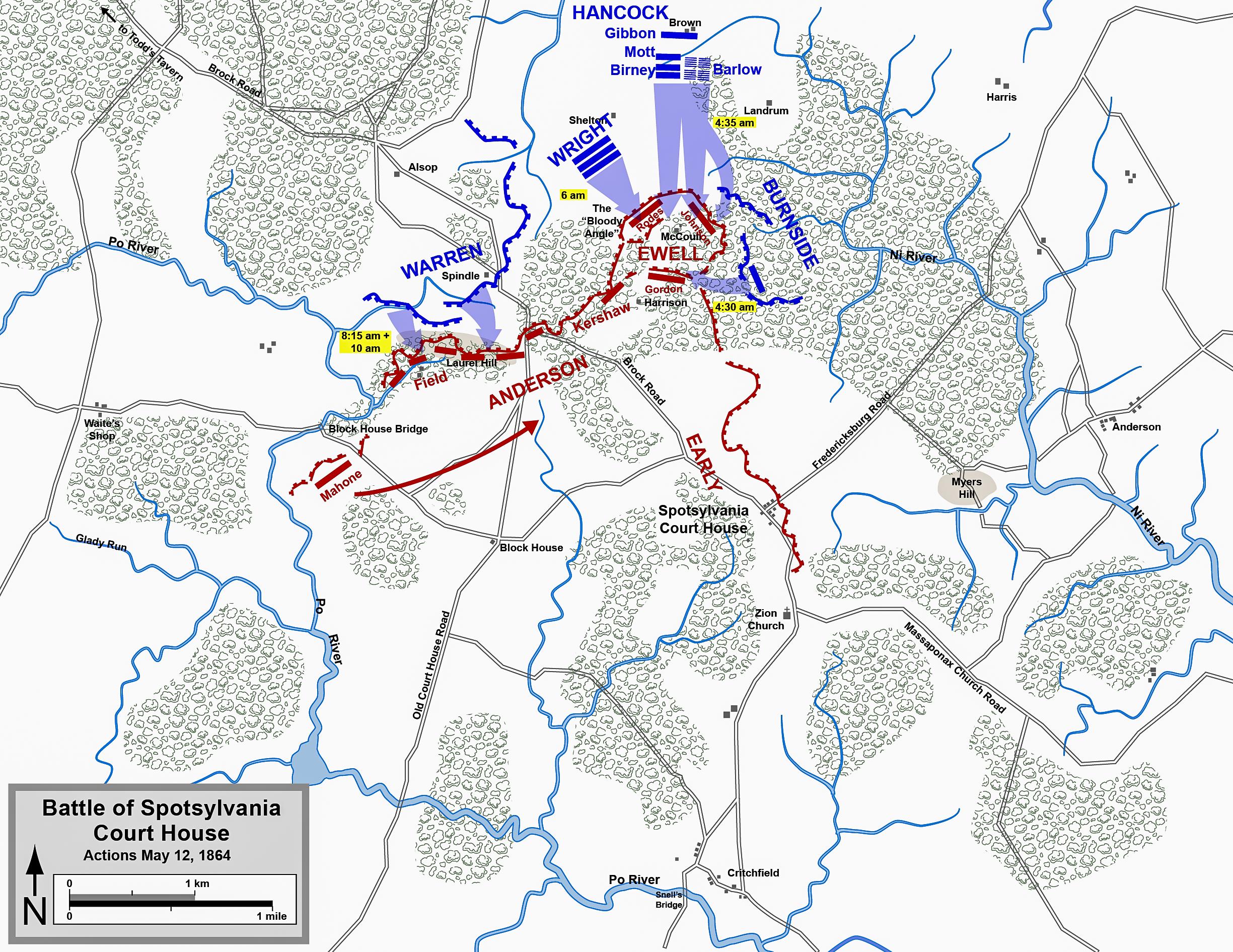

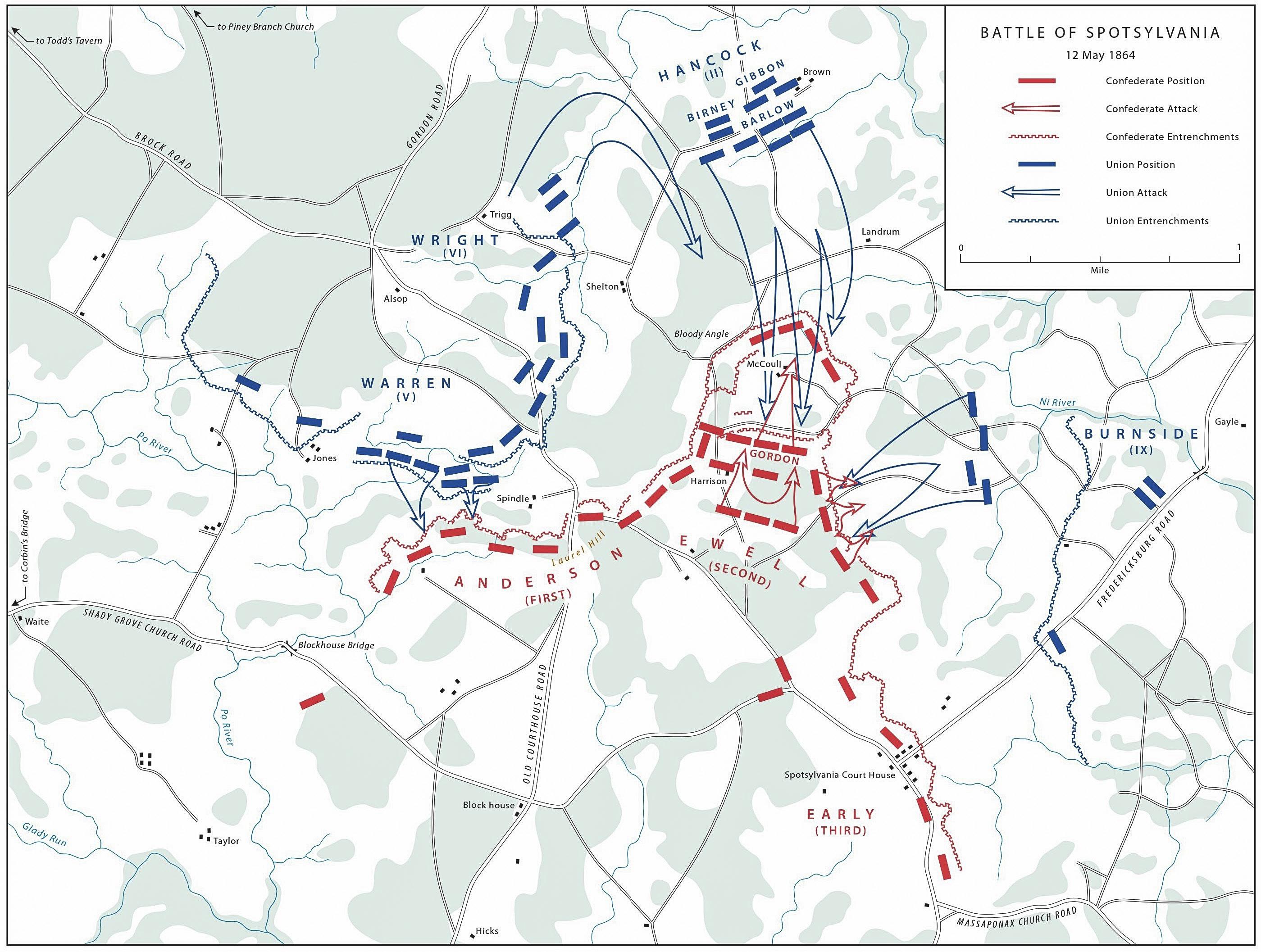

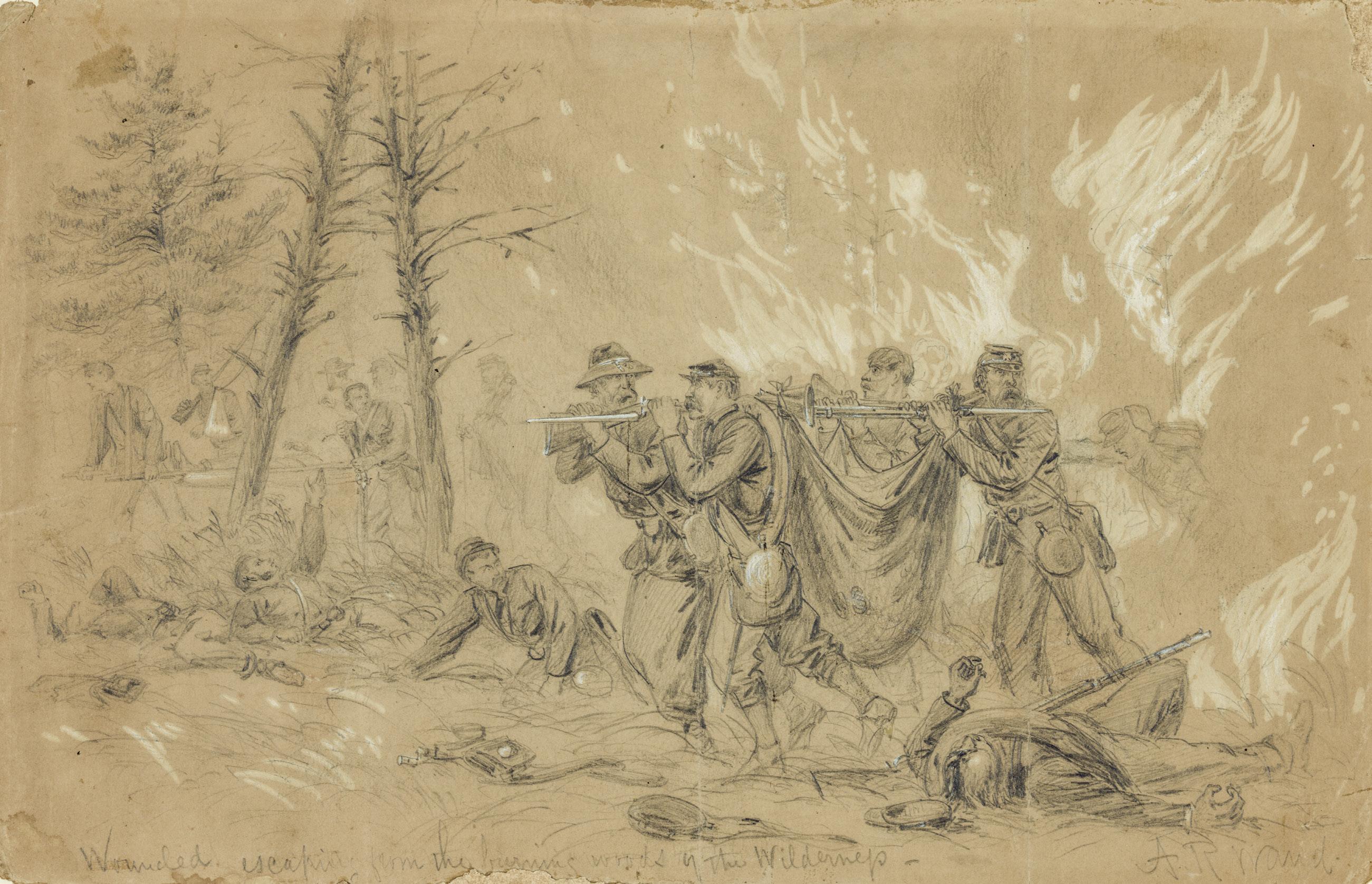

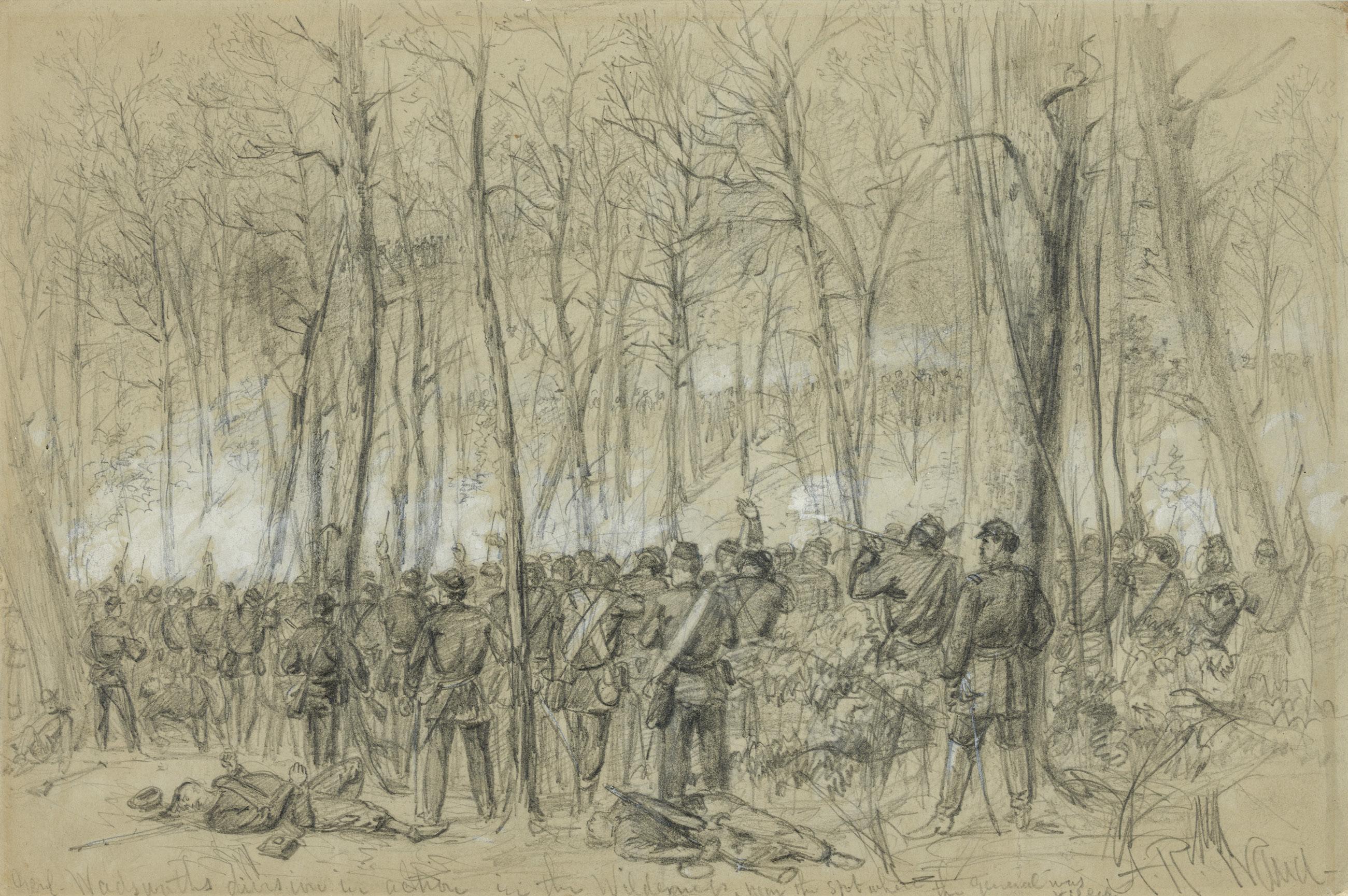

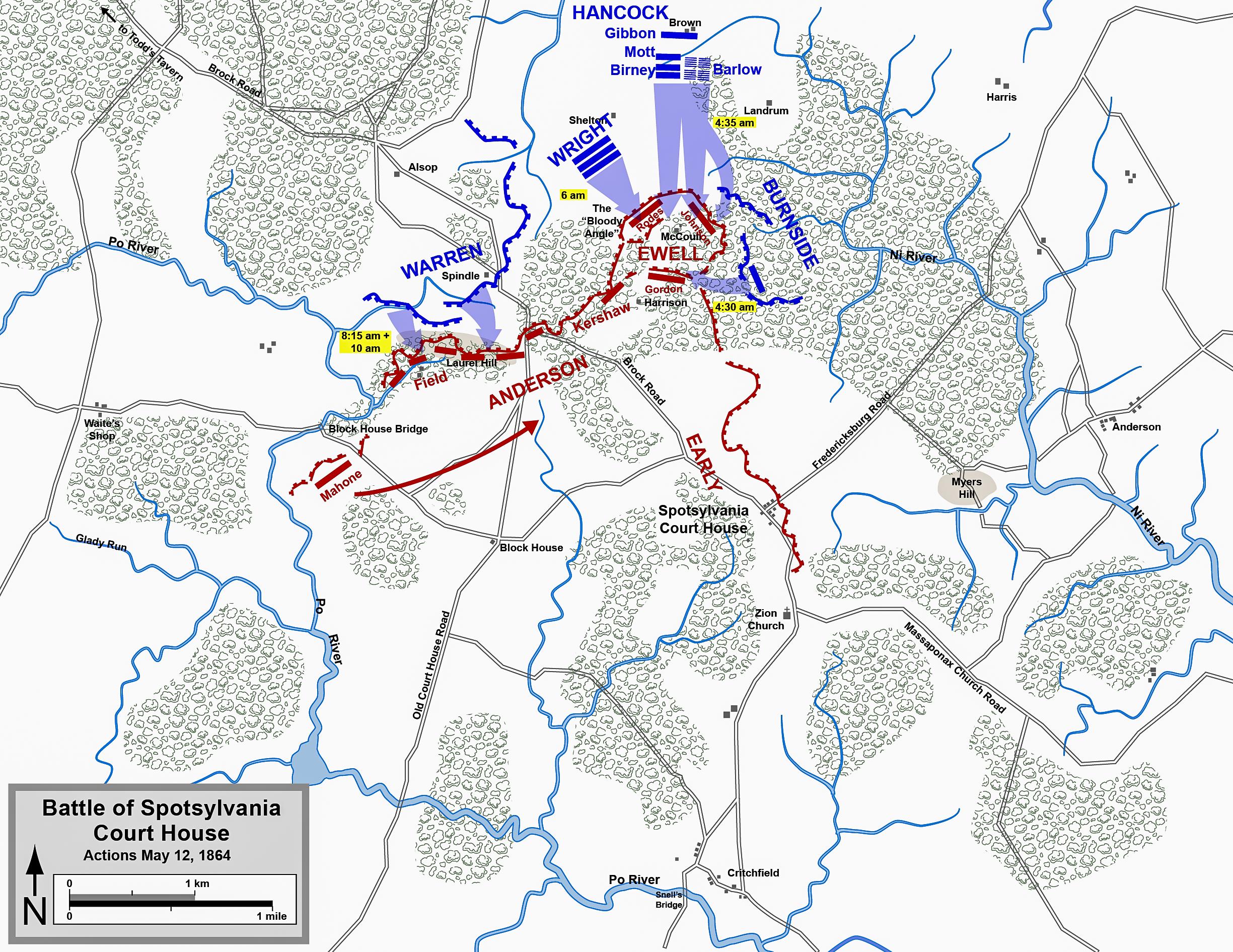

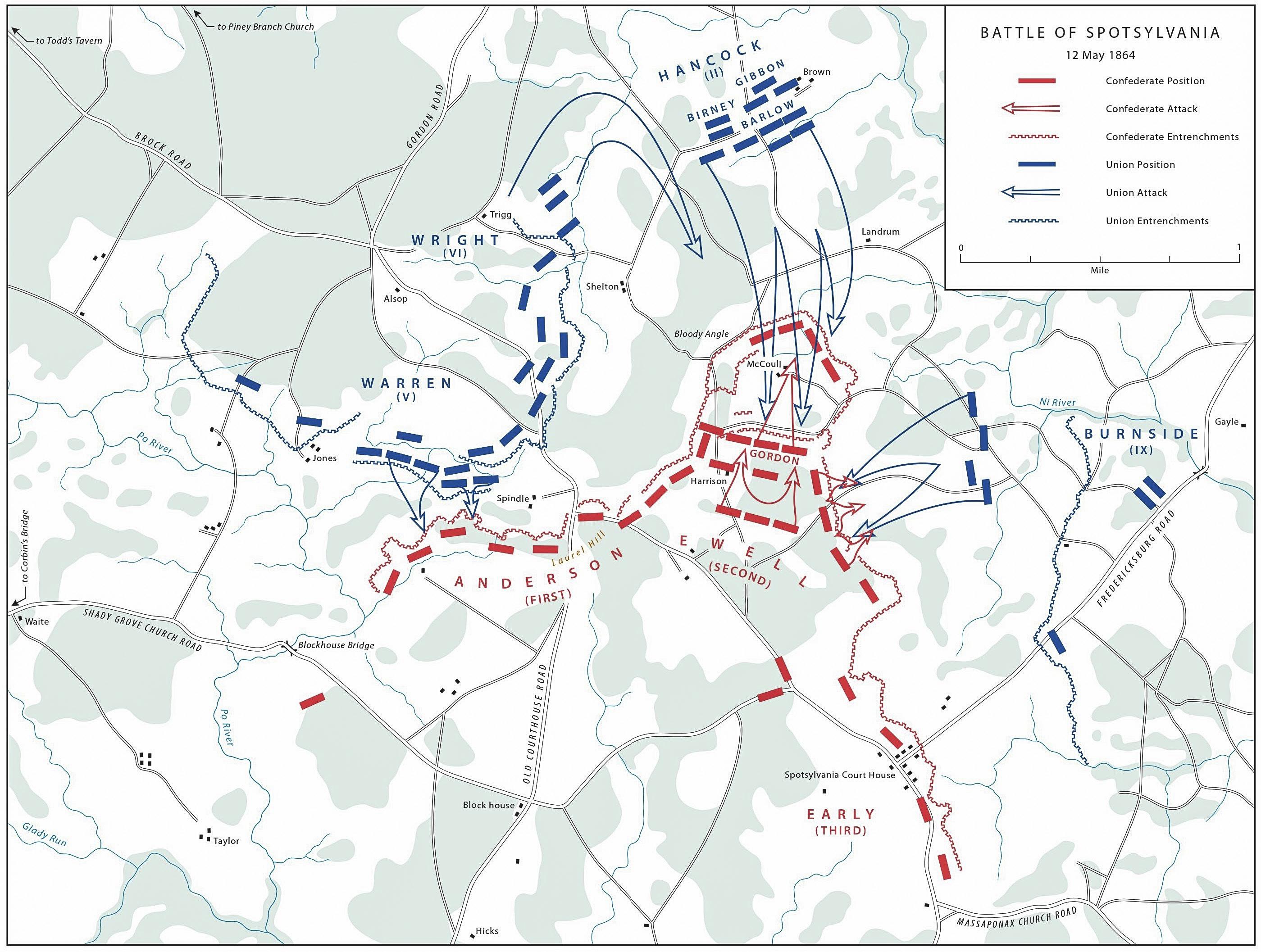

The Union assault on the Confederate position known as the Mule Shoe near Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, on May 12, 1864, began a hellish ordeal without parallel in the four-year conflict. The Federals charged at 4:35 a.m., pouring over the salient’s breastworks and routing the Rebel defenders. What ensued after the breakthrough was relentless combat between the foes at the length of a rifle barrel amid downpours of rain for some twenty-two hours.

For these veteran troops on both sides, the fearful struggle surpassed anything in their collective experience.

The fighting around the crossroads village of Spotsylvania Court House was the second major engagement of the Overland Campaign. The renewal of active operations in the war’s fourth spring began when Union General-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant ordered the 119,000-man Army of the Potomac across the Rapidan River against General Robert E. Lee’s 66,000-man Confederate Army of Northern Virginia on

The Mule Shoe Struggle

May 4. It was a bright spring day that heralded darkness.

The ensuing two days, May 5 and 6, witnessed a furious engagement between the old nemeses in the “demonic” Wilderness, as a Yankee soldier called the forbidding landscape.

Another soldier described the fighting as “a blind and bloody hunt to the death, in bewildering thickets, rather than a battle.”

The Confederates held the battlefield after two days, with total casualties exceeding 29,000.

On May 7, Grant ordered the army southeast toward Spotsylvania Court House and more open terrain. Both armies raced throughout the night and the next day. The Confederates arrived first by the narrowest of margins, seized Laurel Hill, and began repulsing the initial Federal attacks. Throughout May 8 and into the night, the armies converged on what became a sprawling 12-day battlefield.

One of the final Confederate units to arrive on the field was the 4,000 officers and men of Edward Johnson’s Division. Johnson halted his veteran infantrymen in the darkness on a slight

ridge. This position was part of Neil McCoull’s “Woodshaw Farm.” Johnson instructed his men to erect fieldworks, but the exhausted infantrymen lay down and slept.

Lee visited Johnson’s position the next morning as the troops were constructing log and dirt breastworks. A Georgian depicted the crescent-shaped defenses as “an awkward and irregular salient to the northward.” When finished, the “horse shoe” or “mule shoe,” in the words of its defenders, covered some 250 acres, a half mile deep and roughly 1,160 yards, less than three-fourths of a mile wide. The completed works stood four feet high, with a head log and firing slot, and a twofoot-deep trench on the inside. The Rebels built steps to stand on whten firing from the position.

When Lee saw the trench line’s shape, he knew the salient could be subjected to enemy fire from three sides, he allegedly declared: “This is a wretched line. I do not see how it can be held.” The army’s Second Corps commander, Richard S. Ewell, argued with Lee that Johnson’s men held the higher ground and, if the position were abandoned, it

6 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 6 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com

One of a series of seven maps depicting the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House of the American Civil War. Drawn by Hal Jespersen, http://www. posix.com/CWmaps/.

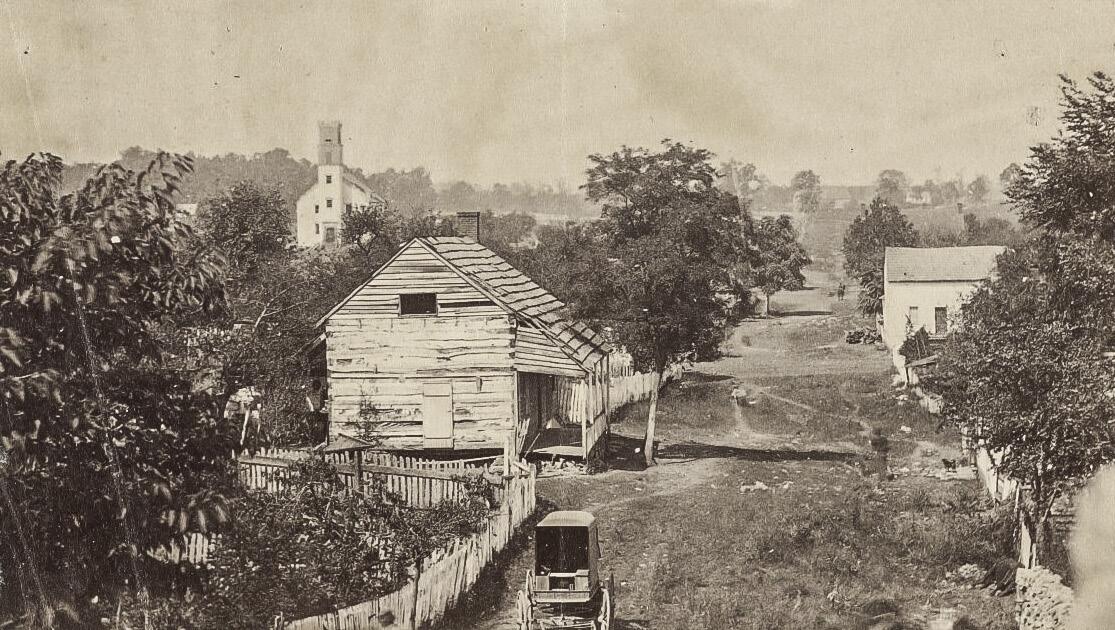

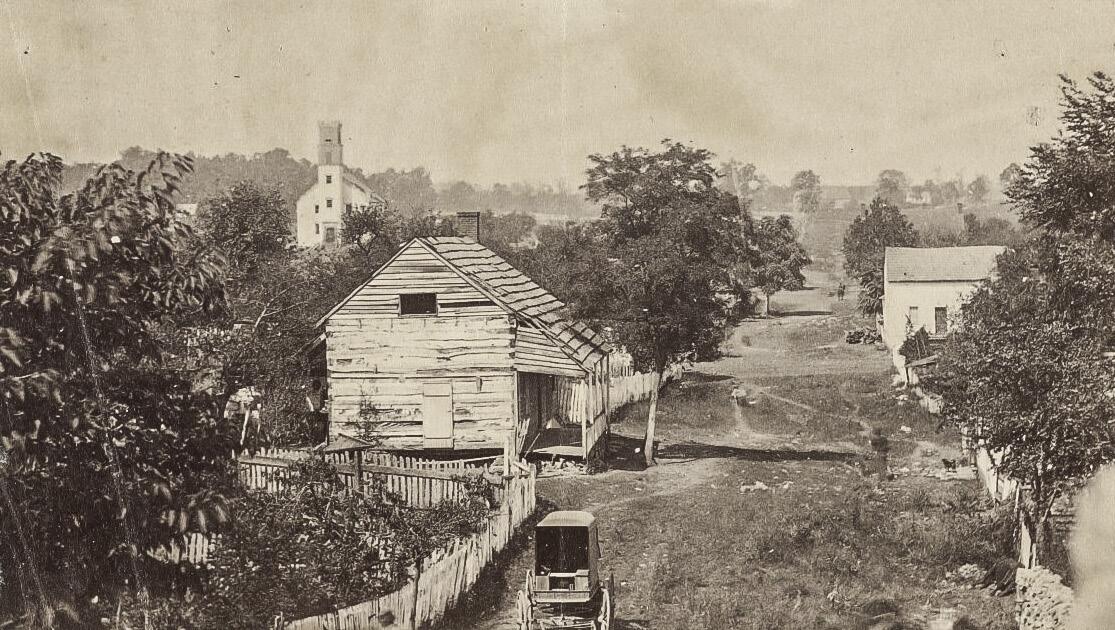

Three African American men at the water pump in front of the Spotsylvania County Court House. (Library of Congress)

would be seized by the Yankees. Lee relented reluctantly, directing twenty-nine cannon into the salient as support for the infantry.

The Federals knew about the Confederate position but never learned the vulnerable shape of the defenses or how many enemy troops and artillery batteries manned the works. Nevertheless, when Union Colonel Emory Upton proposed an attack on the enemy lines, Grant and army commander George G. Meade approved. Upton requested a dozen regiments to be formed in four lines, three regiments abreast, with the support of an infantry division and artillery batteries.

Georgians of George Doles’ brigade charged at 6:30 p.m. on May 10, striking a slight bulge in the Mule Shoe’s western face known as Doles’s Salient for the Georgians George Doles’s brigade. The Yankees penetrated the salient’s main works and overran a Rebel battery. Upton’s 4,500 officers and men clung to

the captured works for an hour before Confederate reserves drove them back across open ground. The expected support from the reserve infantry division failed to appear.

When Grant learned of Upton’s initial success, he thought an assault on a larger scale might break Lee’s lines. He ordered attacks across the army’s front, with a renewal of attacks on Laurel Hill and an advance by Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps on the Mule Shoe’s eastern face. Grant assigned the 20,000 officers and men of Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps to the main thrust against the Mule Shoe. He designated the offensive to start at 4 a.m., Thursday, May 12.

Lee, meanwhile, received a message from his son, cavalryman William H. F. “Rooney” Lee. Referring to Burnside’s units, the younger Lee reported: “There is evidently a general move going on. Their trains are moving down the Fredericksburg road, and their columns are in motion.” If his

opponent were marching south again, Lee wanted to pursue, either interdicting the movement or barring its route. Lee could not know if the intelligence was correct, but he needed to prepare a counter-movement.

Lee ordered the twenty-nine cannon removed from the Mule Shoe to expedite a possible march. His willingness to hold the salient had been predicated on these guns posted within the defenses. E. Porter Alexander, artillery commander of the army’s First Corps, observed later, “The withdrawal of these guns was the one fatal Confederate blunder of this whole campaign.”

To be sure, Lee miscalculated, but his decision was based on intelligence he had received. He left the infantry divisions of Johnson and Robert E. Rodes in place until the next morning and ordered a pair of four-gun batteries into the salient.

Hancock’s blue-coated officers and men marched overnight toward their assembly point on

7

2023 7 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

September

8-21,

Situation May 12.

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May

1864).

General Emory Upton. (Library of Congress)

the farm of John and Elizabeth Brown, located three-fourths of a mile north of the Mule Shoe’s apex. “Of all our many night marches,” grumbled an enlisted man, “this one took the cake.” Rain fell, and another soldier remembered, “It was so dark that it could almost be felt.” A dense morning fog settled in, delaying the assault until 4:30 a.m. All Hancock and his division commanders knew was that “a large white house [McCoull’s] known to be inside the enemy’s works.”

To the south, meanwhile, Confederate pickets lying along the Willis Landrum farm lane heard the Yankees gathering on the Brown farm. They alerted Johnson, reporting that the enemy was preparing to attack. Johnson ordered his veterans into the trenches an hour before daylight. Union bands had been playing songs for hours, the sounds filtering through the rain and fog to the Confederates. At last, the music ceased. Before long, a staff officer reported to Johnson,

“General, they are coming!”

Hancock’s infantrymen struck the Mule Shoe’s eastern face and 300-yard-long apex, overwhelming the defenders. The Confederates had built numerous traverses inside the salient to protect their inner flanks if an enemy breached the works. Described as twelve to fifteen feet three-sided works, the Rebels likened them to “pig pens” or “horse stalls.” Along the trenches and in the traverses, Johnson’s veterans resisted briefly before being overwhelmed by the many Yankees, who captured upwards of 3,000 officers and men, including Johnson and Brigadier General George Steuart.

The enemy had gouged a threequarter mile gap in Lee’s lines northwest of Spotsylvania Court House. A disorganized mass of Federals began penetrating deeper into the Mule Shoe. In front of the surging Federal attack stood 4,600 Rebels, the three brigades of John B. Gordon, who admitted later “that the situation was critical.” An instinctive

fighter, Gordon counterattacked with one brigade and advanced the other two brigades toward the salient’s base, where a second line of works had been built earlier on Lee’s orders.

Before the Virginians and Georgians stepped forward, Lee joined Gordon. The army commander appeared as if he might want to lead a counterattack, but Gordon promised that his men would not fail. A Virginia sergeant took the reins of Traveler, Lee’s horse, and led the general to the rear. Gordon’s men surged toward the works, arriving almost simultaneously with the Yankee host. The Rebels triggered volleys of musketry; the Federals staggered, and then turned rearward. Gordon’s veterans pursued and, joined by the third brigade, reached the eastern side of the original salient. The momentum of the assault had been blunted.

The Federals held the apex, the east and west angles where the works bent slightly south, and the traverses. Lee decided the

broken lines had to be retaken while a second line of works was being erected by fugitives from Johnson’s Division farther south. He ordered counterattacks by Confederate brigades drawn from other defensive sectors. Lee needed a tactical stalemate in the Mule Shoe, but for those already there and for those who would be drawn in, ahead loomed a testing unlike any before in the conflict.

During the next three hours, six Confederate infantry brigades entered the struggle, which became in a Union private’s words, “a seething, bubbling roaring hell of hate and murder.”

Two brigades from Rodes’s Division, Cullen Battle’s Alabamians and Stephen Dodson Ramseur’s North Carolinians, led the counterattack. While Gordon’s troops fought along the Mule Shoe’s eastern face, the Alabamians and North Carolinians angled toward the western face. “This was a serious time with us,” recalled one of Ramseur’s veterans, “and would have been more so, if we would

have really realized our position.” The Confederates crossed a reserve or inner line of works, then charged into the trenches along the main breastworks. They drove the Federals in a handto-hand melee over the works, where the foes continued to kill and maim each other on opposite sides of the parapet. The Yankees lunged over the works, trying to retake the trenches. “We pitched many of them with the bayonet right over the ditch,” declared a North Carolinian.

William Wofford’s Georgians and Abner Perrin’s Alabamians came up next, filing into the trenches to the left or south of Battle and Ramseur. Like their comrades before them, Wofford’s and Perrin’s veterans charged into a wall of musketry from Yankees holding the apex and some traverses. The rifle fire struck Perrin as he leaped his horse over the inner works, mortally wounding the general. The musketry was relentless, coming in waves like a “very river of death,” according to a Rebel.

8 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 8 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Outside the entrenchments, brigades from the Union VI Corps joined in the fury.

Finally, the last pair of Confederate brigades, Nathaniel Harris’s Mississippians and Samuel McGowan’s South Carolinians, charged into the fray, a clawing advance from traverse to traverse. They reached the breastworks along a section of the apex and where the entrenchments bent south at the west angle. By roughly 9 a.m., the fighting had dissolved into a bloody stalemate. “The deathgrapple of the war,” claimed a Yankee.

So, it would continue without cessation, hour after hour into the afternoon and evening. The combat was, thought a New Englander, “so bloody, and had such an aspect of savagery about it.” A lieutenant in a South Carolina regiment admitted, “The question became, pretty plainly, whether one was willing to meet death, not merely run the chances of it.” A North Carolinian declared, “At noon the water so bloody in the ditches, that one inexperienced would have taken it for blood entire.”

Men on both sides leaped onto the breastworks, firing down into their enemy faces while

comrades passed them loaded rifles. Few survived such acts.

A lieutenant in a Pennsylvania regiment remembered these men and wrote, “I never during over four years of active service in the army witnessed so many individual acts of daring and foolhardiness on the part of soldiers as on this day.”

Thunderstorms rolled in late in the afternoon, adding to the misery. Still, the butchery continued. Union regiments and brigades rotated in and out of the fearful struggle, but the graycoated defenders were trapped. Reports reached the Confederates that the new line of works should be completed by 6 p.m. when they could begin withdrawing. The hour passed, however, with no orders to abandon the Mule Shoe. A Mississippi private described the shared ordeal better than anyone when he declared: “I don’t expect to go to hell, but if I do, I am sure hell can’t beat that terrible scene. Indeed I am sure that the hell on earth is a pledge for the hell after death.”

About midnight a red oak tree behind the west angle crashed to the ground. The hours of musketry and artillery fire sawed it off five feet above the ground. The stump measured 22 inches

in diameter and 61 inches in circumference. No place in this carnage-steeped field was the area grislier than around the west angle, which the Confederates were already calling the “Bloody Angle.”

At three o’clock on the morning of May 13, the Mule Shoe’s defenders began quietly evacuating, retiring to a new position. On a ridge nearly threefourths of a mile south of the Bloody Angle, pioneer troops and Johnson’s fugitives had finished a new line of fieldworks. The Federals never detected their enemy’s withdrawal. One of the Rebels noted: “We looked like a lot of painted devils. We could hardly tell one another apart.” When he and his comrades halted, many of them lay down and slept. When daylight revealed the empty trenches, a Union brigade conducted a reconnaissance, halting when it came upon the new Confederate works. Details began collecting the wounded and burying the dead. The Federals finished the gruesome work that day, followed by Confederate details on May 14. Upwards of 55,000 Americans, 38,000 Northerners; 17,000 Southerners, had fought at the Mule Shoe. The killed, maimed, and captured

amounted to 17,500, the most casualties on a single day of fighting in the East between July 3, 1863, at Gettysburg, and April 9, 1865, at Appomattox.

Grant’s army-wide offensive failed, except for the initial penetration at the salient. On Laurel Hill, more Federals fell before the rifle and artillery fire of its defenders. On the Mule Shoe’s eastern face, Burnside’s attack went forth hours late and succeeded in briefly occupying a small section of the Confederate works before being repulsed. In the afternoon, Rebel troops attacked Burnside’s flank, nearly capturing a Union battery.

In turn, Lee had been spared a possible crippling defeat by the stalwart defense of his

battle-tested officers and men. Thursday, May 12, had been unlike any other during the war both for the proximity of the foes and the duration of fighting. Years later, an Ohioan visited the battlefields around Fredericksburg. Guided by a Confederate veteran, the fellow eventually stopped at the Bloody Angle, remarking, “It is a dark spot.” The former soldier replied, “It is the heart of hell.”

Jeffry D. Wert is a retired high school history teacher and award-winning Civil War historian, whose most recent book is The Heart of Hell: The Soldiers’ Struggle for Spotsylvania”s Bloody Angle.

Loyal Legion of the Confederacy

9 September 2023 9 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

National Defense Medals & other banned internet items Civil War Recreations WWW.CWMEDALS.COM cwmedals@yahoo.com

Smithbridge Rd., Unit 61,

CSA

1

Chester Heights, PA 19017

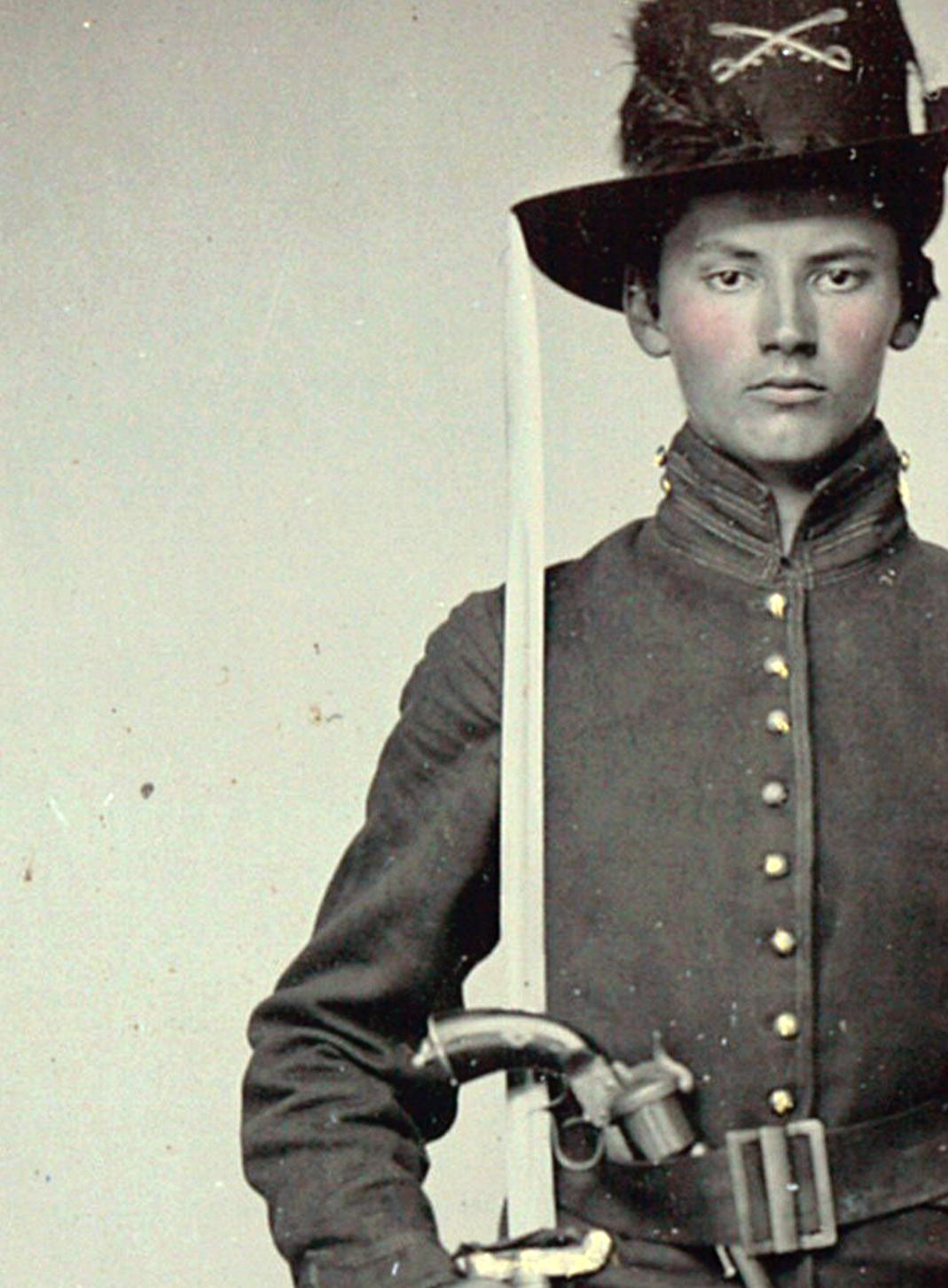

Private Orrin Cook, 22nd Massachusetts Company B

“Some of our boys got Austrian rifles, some Enfield, and others Springfield.

I got the Enfield, and Bob got the finest arm of the whole lot, a fine United States Springfield rifle. Training in the use of these weapons was startlingly belated and haphazard.” – Diary of Pvt. Orrin W. Cook, Company B. 22nd Regt. Massachusetts Volunteers, November 1863.

Orrin W. Cook was a lumberman in western Massachusetts when the U.S. Civil War began. He

later worked as a billing clerk for Robinson, Marsh & Company, a lumber yard in Springfield, Massachusetts. Cook avoided volunteering for military service until he was drafted during July 1863. Cook’s father offered to pay for a replacement but Cook declined and mustered in to the 22nd Massachusetts and was assigned to Company B. Cook was badly injured in both legs at the 1864 Battle of the Wilderness, then captured by the Confederates, and spent five months recuperating at the hospital in Lynchburg, Va. He was lucky to have survived his injuries.

Cook was also lucky in that he was paroled in one of the

last 1864 prisoner exchanges before General Grant stopped the practice. Pvt. Cook got a surprise though when he learned upon his return that “…the authorities are sending to the field all men that are fit to go.” Cook notes in his diary with a sense of relief that the Assistant Surgeon at the hospital ruled that “…my legs were hardly fit for field duty.” Pvt Cook served out the remainder of the Civil War as a clerk with the Navy in Annapolis, Md., and mustered out in November 1865. The 22nd Massachusetts Regiment entered the war in 1861 as ninety-day recruits. They were assigned to the Army of Potomac (AoP) and fought in the Peninsula Campaign

at Gaines Mills, followed by Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, including an illfated charge at Marye’s Heights, and the remaining men were at Chancellorsville although largely held in reserve. Whatever the case, by Gettysburg in July 1863, the 22nd Massachusetts Regiment was down to 127 active soldiers. Rather than create entirely new regiments composed of all new recruits, the AoP command structure began refilling existing regiments. This policy was in effect when Orrin Cook and his fellow recruits arrived during November 1863. The theory was that by mixing new recruits in with seasoned veterans, the learning curve for

the newer soldiers would be greatly reduced. Instead, Cook found the veterans were resentful and largely dismissive of the “fresh fish.” He notes in his diary that he felt somewhat “ill at ease” among them and wonders why he is “so generally regarded with aversion.” It is another good observation recorded by Pvt. Cook and a worthwhile subject for another day.

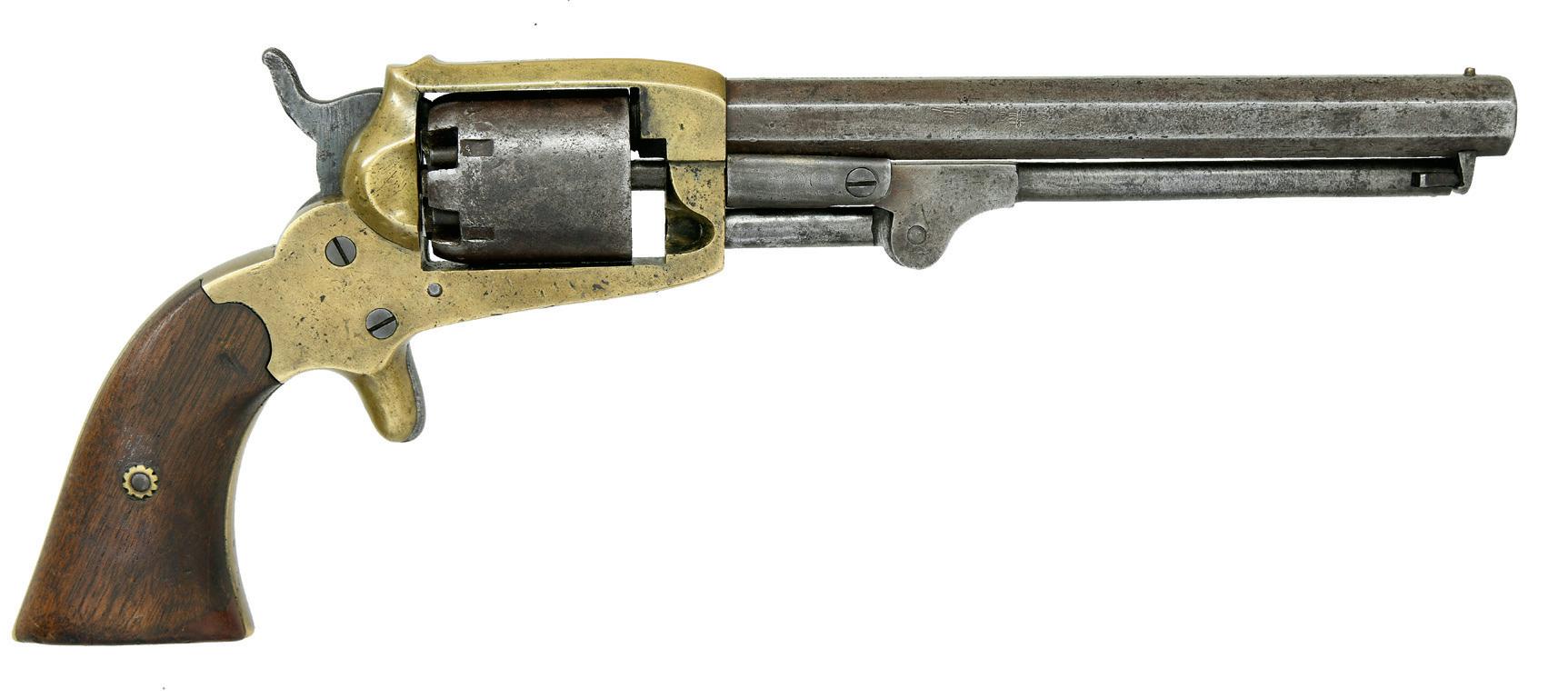

Also of interest is what Pvt. Cook notes about infantry arms issued to the 22nd Massachusetts, compared to what the records indicate for U.S. and C.S. units in 1864. The appendix of Earl Coates & Dean Thomas, An Introduction to Civil War Small Arms, was compiled by William O. Adams who is extremely reliable. Here is a graphic representation of the totals to summarize the distribution of Union arms in the ranks by 1864:

The table paints a surprising picture, particularly the large number of Union regiments still outfitted entirely with the imported Enfield P53 long rifle as late as 1864, about a year after the U.S. government contracts with Birmingham Small Arms Trade were canceled. The contracts were canceled because of the newly manufactured U.S. M1861s were available in sufficient quantities to replace them. If many still harbor the impression that M1861s were issued en-masse to Union troops as replacements during 1863, it appears this is not the case. This chart also supports the observations of Pvt. Cook in terms of the variety of rifled arms potentially issued to the 22nd Mass Regt in late 1863.

It is understood that due to shortages early in the Civil War, most small arms were issued as they became available. For example, the U.S. Ordnance Department shipped 114 cases to Michigan units, which arrived in on Nov. 4, 1861. If the records are to be trusted, 30 of these cases contained new Enfield P53 riflemuskets and the remainder held what were broadly described as “Prussian muskets.” In all likelihood these “Prussian muskets” were older, large

10 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 10 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Firearm Regts Percent Enfield P53 431 39% U.S. Model 255 23% Austrian Rifle (Lorenz) 9 9% U.S. M1842 musket 69 7% Mixed P53 and U.S. M1861 59 6% U.S. M1841 rifle 4 3% Enfield short rifle 13 1%

Five soldiers, four unidentified, in Union uniforms of the 6th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Militia outfitted with Enfield muskets in front of encampment. (Library of Congress)

caliber, smoothbore weapons from a number of sources, including Belgium.

Hence, regiments armed on or after Nov. 4, 1861, received a mix of infantry arms consisting of some modern rifle-muskets, and some clunkers. However, to make amends, by mid-February 1863, the U.S. Ordnance department re-issued to these same Michigan units 50,000 new Model 1861 rifle-muskets. As might be expected, those still armed with the obsolete second (or third) class “Prussian muskets” received the new M1861s and those with previously issued Enfield P53 rifle-muskets would have retained them if they were still serviceable. These regiments are no doubt included on the above chart listed among the 6% armed with “mixed P53 and M1861s.” Also, depending on availability, the replacements were not always exclusively M1861 or U.S. model 1863 rifle-muskets until well into the year 1864.

According to Pvt. Cook’s diary, in November 1863, the 22nd Massachusetts Company B was issued a mixture of various type rifled arms including the Austrian rifle Model 1854 (Lorenz), M1861s and P53 Enfield long rifles. The only attempt at standardization if there is any, appears to be a rifled arm in the bore diameter of the U.S. standard .58 (or the close approximate .577) caliber. While the Lorenz could be found in a multitude of bore diameters, most U.S. contracts by 1863 specified .58. At least the same size ammunition would work (in theory) for all these arms, which was something the Confederacy struggled with for the entire war.

It is important to consider the system in place for issuing small arms during the Civil War, and it appears to be virtually the same system for both the U.S. and C.S. Ordnance. When a soldier was injured, killed, or disabled he did not retain his weapon or accoutrements or have them buried with him. These items were government property and returned to the Ordnance Department for reissue. If an injured soldier recovered and subsequently returned to a line unit, he would be issued another stand of arms at that time. In modern parlance, Ordnance was “recycled.”

The decision to re-issue arms was based on two factors. First, the field command had to complete a requisition to the Ordnance Department for replacements. This is the opposite of the Quartermaster Department where items such as jackets, coats, trousers, socks,

boots, tents, and rations were issued on a semi-regular basis. The Ordnance Department did not automatically issue new arms or accoutrements as replacements on any regular basis. Second, the Ordnance Department had to determine whether they could fill the requisition and to what extent. An order for M1861s which had

been previously promised as an inducement to a group of new recruits was sometimes filled with whatever was on hand. John M. Gould noted in History of the First-Tenth-Twenty-ninth Maine Regiment:

“Oct. 21st, muskets were delivered to the men, and this

furnished another excuse for a hearty growl from the 1st Mainers. “Had we not been promised new blue uniforms and new [U.S. Model 1861] Springfield muskets…look at these Enfield muskets with their blued barrels and wood no man can name.”

In another such instance, an order for new M1861s from General Irvin McDowell received the following response from Chief of Ordnance General James Ripley: “We have no Springfield arms but will send the best of what is in the Washington Arsenal in fifty-eight calibre… the best foreign arms in depot and

11 September 2023 11 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

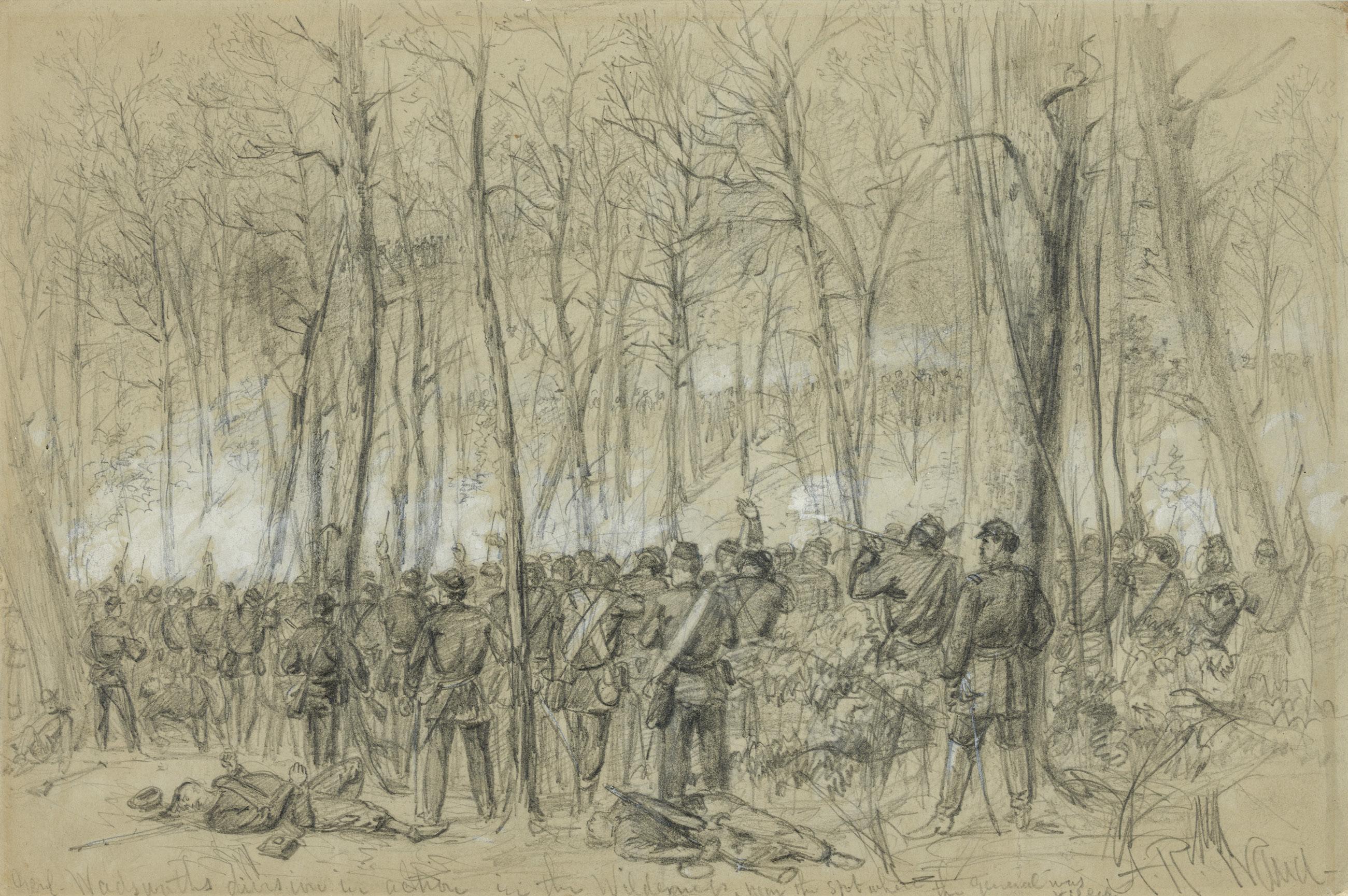

Genl. Wadsworths division in action in the Wilderness, near the spot where the General was killed. (Library of Congress)

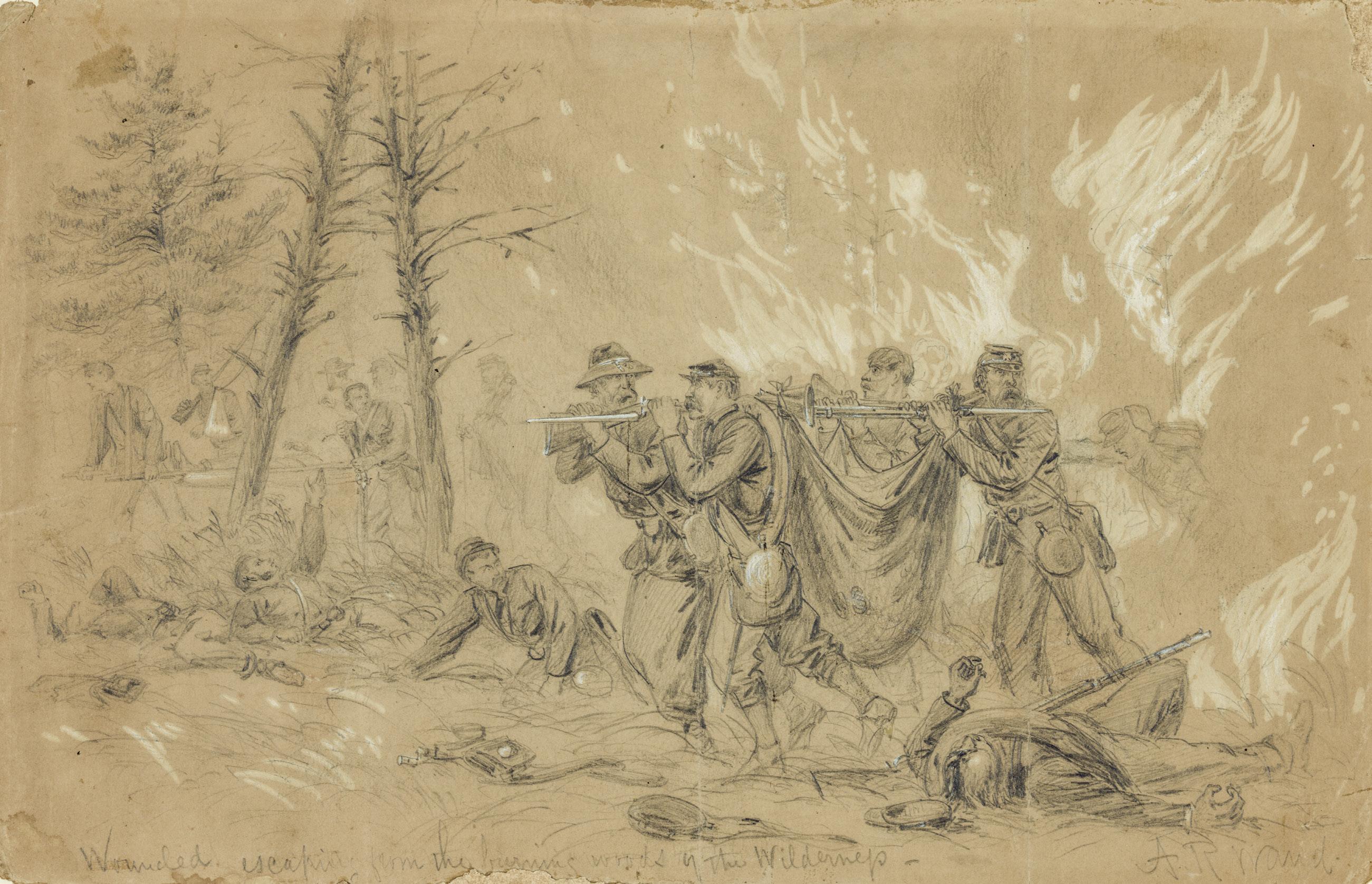

Wounded escaping from the burning woods of the Wilderness. (Library of Congress)

in New York have been ordered to you.”

Accoutrements were also filled through the Ordnance Department and there are many recorded instances of mismatched sets. For example, a soldier who turned in his .69 caliber

smoothbore musket for a newer model .58 caliber rifle-musket would not simultaneously receive a new matching set of .58 sized U.S. accoutrements. The soldier was expected to keep his old set until it was no longer serviceable, never mind if the smaller size

ammunition fit in the box or the different bayonet fit properly in the scabbard. Hence, we don’t know if all new U.S. model rifle-muskets were requisitioned for the 22nd Massachusetts recruits in late 1863, but most likely it would not have mattered. Pvt Orrin Cook and his comrades ended up with whatever mixture of serviceable weapons were available, some of which would have likely already seen previous action and some which may have been refurbished. Only after the existing stockpiles of returned serviceable small arms were back in the ranks, would recruits in the 22nd Massachusetts receive new arms, the coveted prize which Pvt. Cook refers to as the best arms of the whole lot, “a fine United States Springfield rifle.” There are no documented examples during the Civil War of any soldier on either side discarding a serviceable U.S. M1861 rifle-musket in favor of something else.

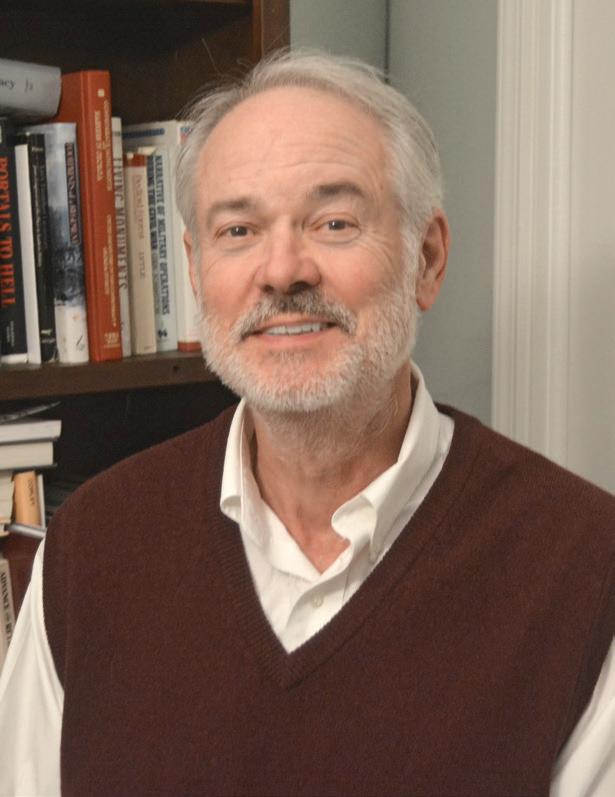

Craig L. Barry was born in Charlottesville, Va. He holds his BA and Masters degrees from UNC (Charlotte). Craig served The Watchdog Civil War Quarterly as Associate Editor and Editor from 2003–2017. The Watchdog published books and columns on 19th-century material and donated

Gun Works, Inc.

The tried-and-trusted choice of today’s blackpowder enthusiasts.

Thousands of blackpowder hobbyists and aficionados, from history buffs and re-enactors to modern hunters and competitive shooters, trust Dixie Gun Works for its expertise in all things blackpowder: guns, supplies, and accessories and parts for both reproductions and antique guns. Whether you’re just getting started or you’re a life-long devotee, everything you need is right here in the 2023 DIXIE GUN WORkS’ catalog.

ORDER TODAY! STILL ONLY $5.00!

PROFESSIONAL SERVICE AND EXPERTISE GUARANTEED

www.dixiegunworks.com

Major credit cards accepted FOR ORDERS ONLY (800) 238-6785

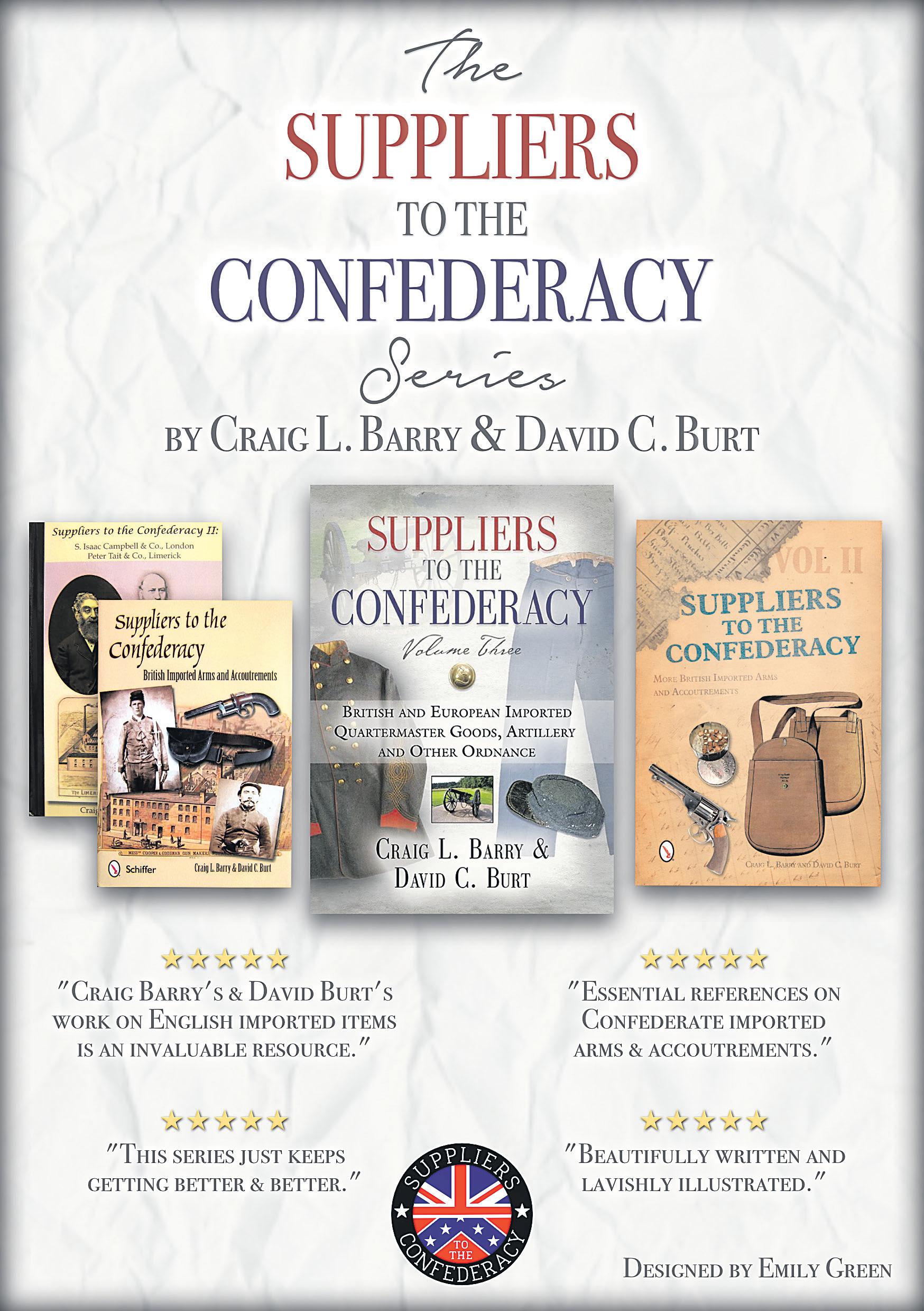

all funds from publications to battlefield preservation. He is the author of several books including The Civil War Musket: A Handbook for Historical Accuracy (2006, 2011), The Unfinished Fight: Essays on Confederate Material Culture Vol. I and II (2012, 2013). He has also published four books in the Suppliers to the Confederacy series on English Arms & Accoutrements, Quartermaster stores and other European imports.

12 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 12 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com Want to Advertise in Civil War News? Call 800-777-1862 or email ads@civilwarnews.com The Artilleryman is a quarterly magazine founded in 1979 for enthusiasts who collect and shoot cannon and mortars primarily from the Revolutionary War, Civil War to World War II. The Artilleryman Magazine 2800 Scenic Dr, Suite 4 PMB 304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513 • 800-777-1862 • mail@artillerymanmagazine.com www.ArtillerymanMagazine.com FOUR INCREDIBLE ISSUES A YEAR

DIXIE GUN WORKS, INC. 1412 W. Reelfoot Avenue PO Box 130 Union City, TN 38281 INFO PHONE: (731) 885-0700 FAX: (731) 885-0440 EMAIL: info@dixiegunworks.com VIEW ITEMS AND ORDER ONLINE!

S. Grant

by E.C. Fields Jr., Ph.D. HQ: generalgrantbyhimself.com E-Telegraph:

generalgrantbyhimself.com

Facebook@

Fields

Ulysses

Portrayed

curtfields@

Signal Corps: (901) 496-6065

Curt

Brig. Gen. William H. Morris: A Forgotten Casualty of Spotsylvania

By Tim Talbott

By Tim Talbott

The opening three days of fighting at Spotsylvania Court House proved deadly for several general officers in the Army of the Potomac. On May 9, 1864, VI Corps commander Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick fell victim to a sharpshooter’s bullet. The following day, Brig. Gen. James C. Rice received a mortal wound while commanding his V Corps brigade. In addition, Brig. Gen. Thomas G. Stevenson, who led a division in the IX Corps, still technically independent from the Army of the Potomac at this time, fell on May 10 as well. Interestingly, each of these men killed in action was later honored by the naming of three forts at Petersburg for them that were all in close geographical proximity to each other.

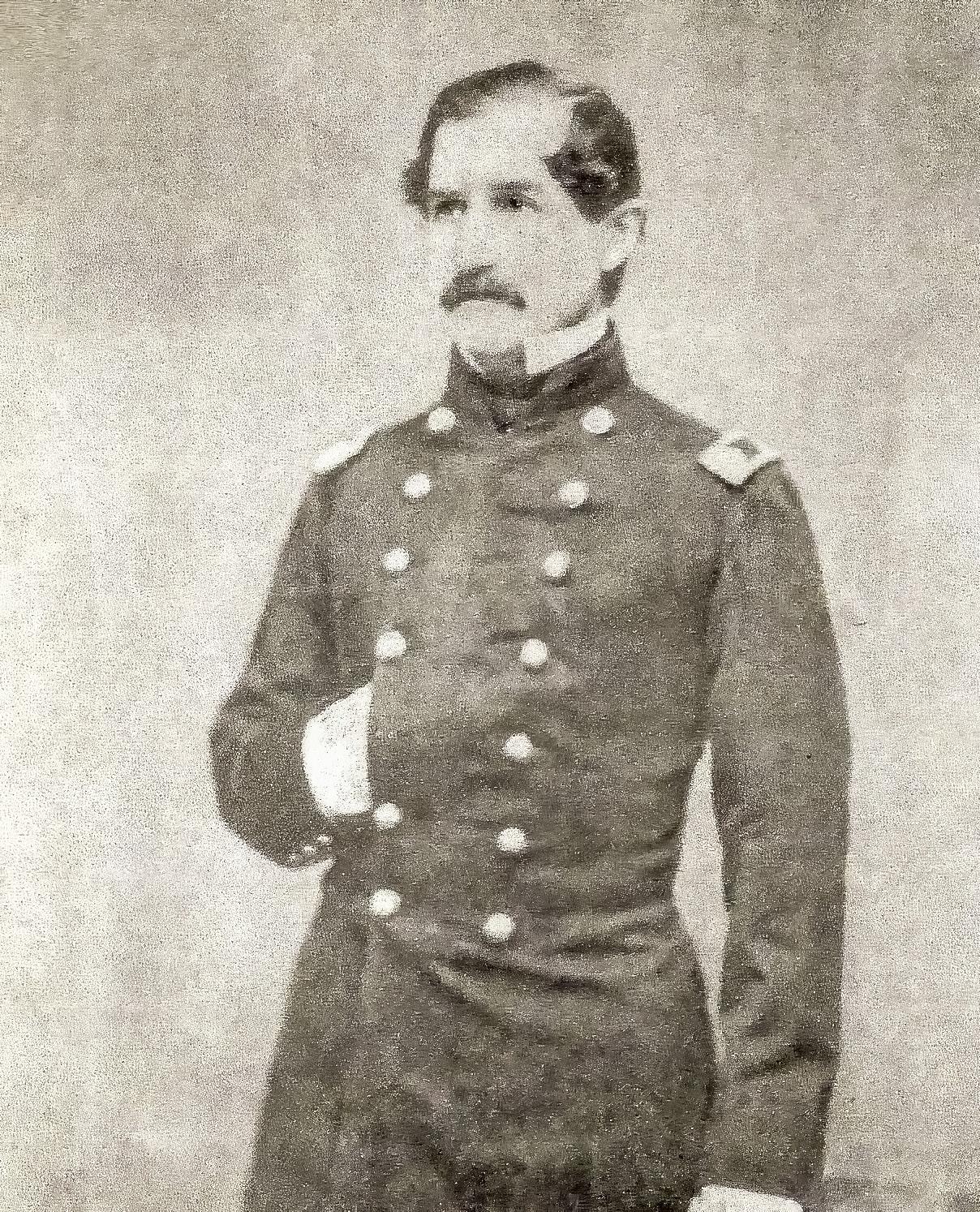

In addition to those killed or mortally wounded during the opening days at Spotsylvania were the woundings of V Corps divisional commander Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson on May 8, and Brig. Gen. William Hopkins Morris, who commanded a brigade in James Ricketts’ division in the VI Corps on May 9. Morris is probably the least remembered of these five general officer casualties.

Born in New York City in 1827, William Hopkins Morris came from a family with deep ties to American history. His lineage included two ancestors who signed the Declaration of Independence. As a young man, Morris seemed to have an affinity for military matters. He enrolled as a cadet at West Point in 1846 and graduated 27th out of 51 in his class of 1851.

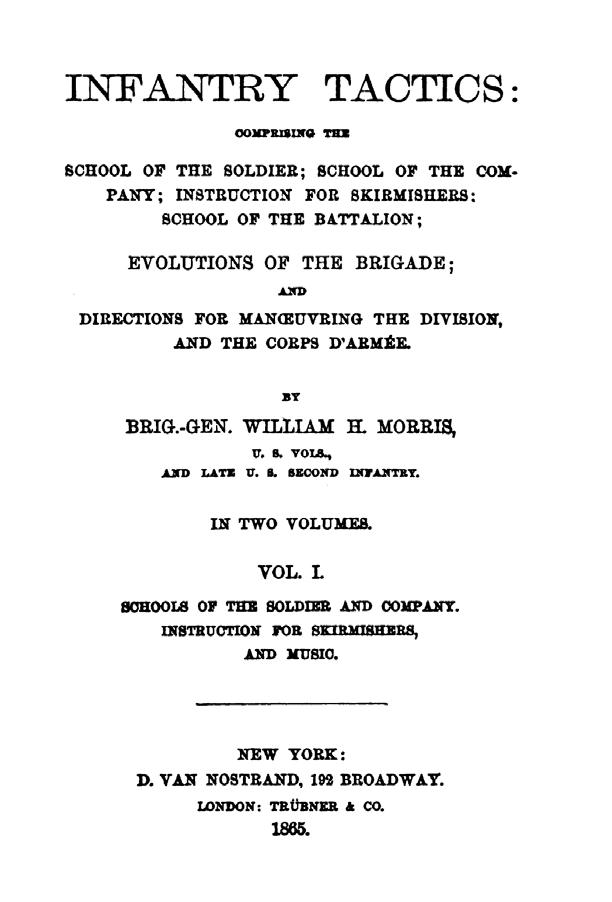

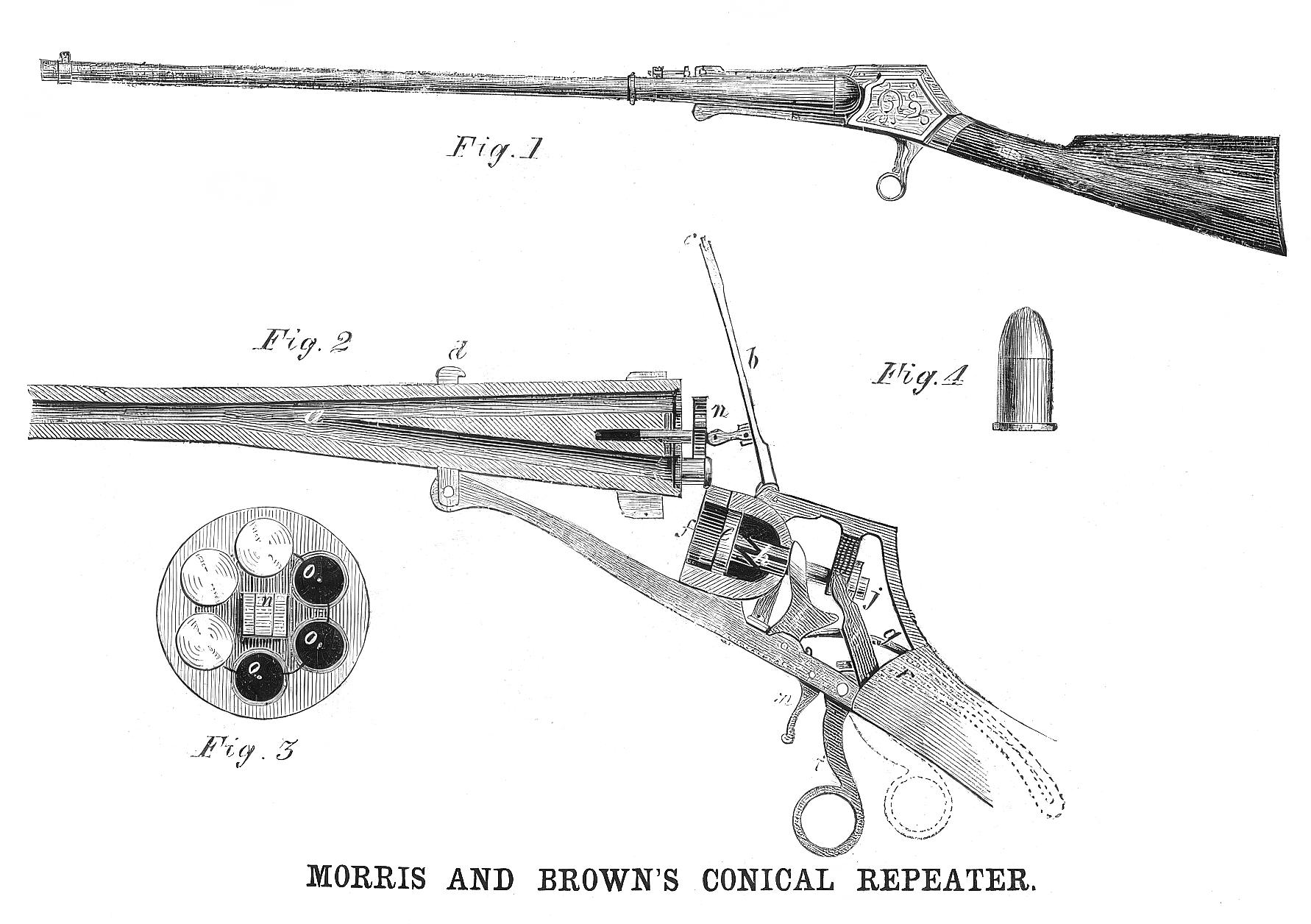

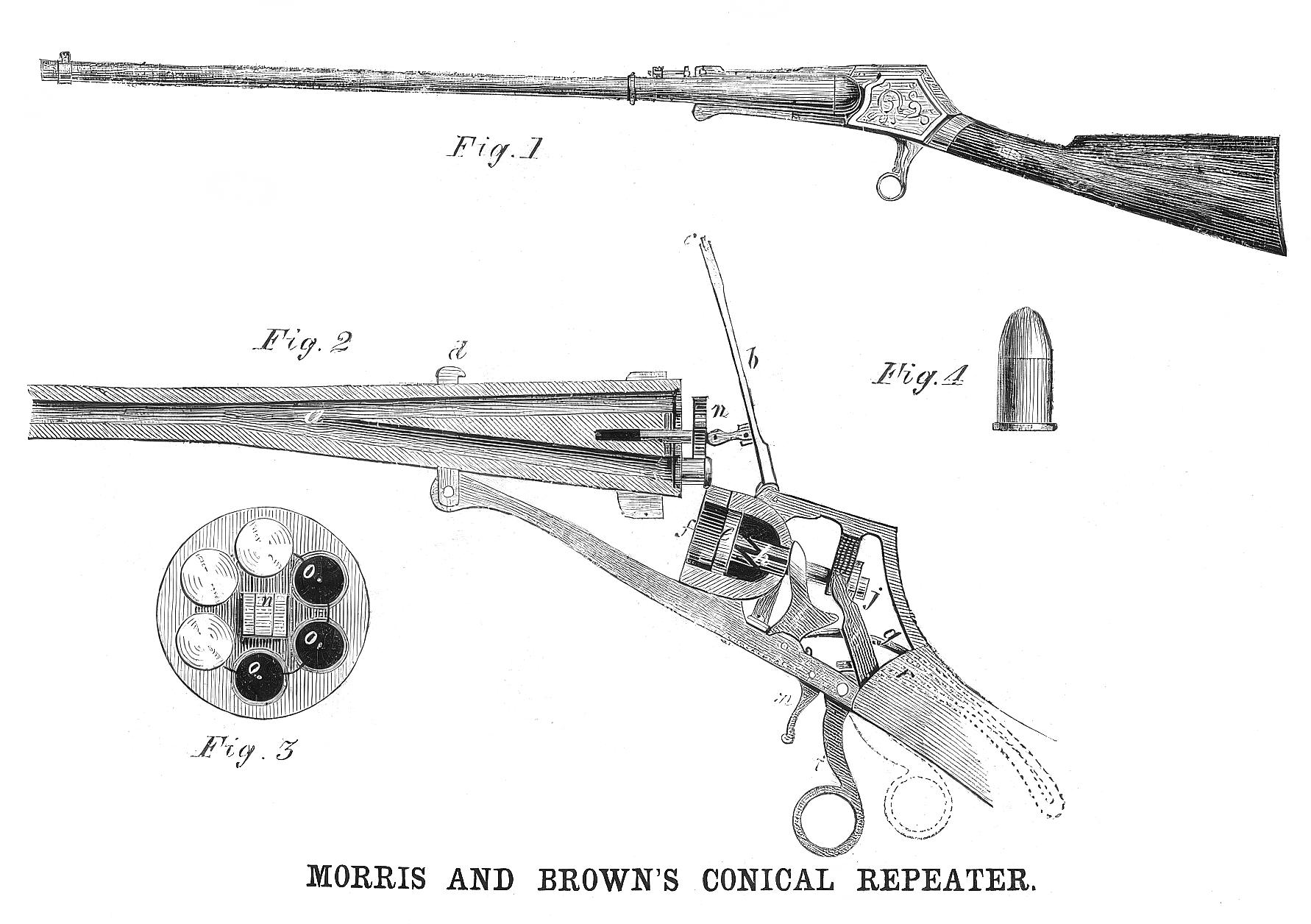

Serving in the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant, Morris spent time at Fort Columbus and Fort Wood in New York and then transferred west to Fort Yuma, California, until he resigned his commission in 1854. That year Morris returned to the Empire State to help his father edit the New York Home Journal newspaper. Morris also copatented the Conical Repeating Rifle with partner Charles L. Brown in 1859, which proved to be an unsuccessful attempt as an inventor.

When the Civil War erupted, Morris enlisted and initially helped man the defenses of Washington D.C., serving on the staff of Gen. John J. Peck as assistant adjutant general. Peck’s brigade eventually received orders to participate in the Peninsula Campaign. As part of the IV Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keys, Peck’s regiments fought at Yorktown, Williamsburg, and Fair Oaks. Their limited role in the Seven Days’ Battles occurred at Malvern Hill.

On September 1, 1862, Morris became colonel of the 135th New York Infantry, later redesignated as the 6th New York Heavy Artillery. Morris led this unit while stationed at Baltimore until December 1862. Moving to the Harper’s Ferry area that month, Morris received promotion to brigadier general in March 1863, and commanded a mixed infantry, artillery, and engineer brigade there. Although a participant in the Gettysburg Campaign, Morris’ brigade remained in a reserve role. That fall, they were involved in the Army of the Potomac’s movements between the Rapidan River and northern Virginia and back.

also added, “The enemy made repeated attempts to advance in front of the brigades of General Morris and Colonel Keifer, but were repulsed each time with heavy loss.”

Fighting in the Wilderness, but now in one of two brigades in James Ricketts’ Third Division of the VI Corps, Morris’ brigade saw little action on May 5. After being shelled early in the day and losing three killed and 19 wounded, Morris received orders from Sedgwick to support the right end of the corps line that had been flanked, “I changed front so as to face to the right, in order to injure the enemy as much as possible with my fire as he advanced,” Morris reported. Later, while repositioning after a discussion with Sedgwick, Morris noted that in doing so, “The shells of the enemy were severe upon us...” May 7 and 8 were primarily days of movement and maneuvering for the brigade. They left the Wilderness battlefield on the night of May 7, marching toward Spotsylvania. Morris noted their route as “along the pike and plank road to Piney Branch Church, through Chancellorsville. We were on the march fifteen consecutive hours.” They arrived at Spotsylvania on the afternoon of May 8 and went to support the V Corps. Being positioned and reposited several

Morris wrote several books on tactics, including the second volume of his Infantry Tactics, published in 1865. (Public domain)

Later transferred to the Third Corps, Morris’ brigade participated in the fighting at Mine Run. Morris did not file an official report on his brigade’s actions at Mine Run, but they did receive mention in division commander Joseph Carr’s report. Carr explained that he ordered Morris’ brigade “to charge and drive them from it [fence], which he did, driving the enemy through the fields beyond.” Morris and his brigade performed well, as Carr

13 September 2023 13 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

This photograph shows Morris as colonel of the 6th New York Heavy Artillery. (National Archives)

Capt. William Hopkins Morris began his Civil War career on the staff of Brig. Gen. John J. Peck. Morris appears third from the right in this photograph of Peck and his staff. (Library of Congress)

times during the day must have annoyed Morris and his men.

On May 9, following orders to realign a couple of his regiments and while riding along his line, Morris “was wounded by a rifleball and rendered unfit for service in the field.” The shot apparently struck him near the right knee. Morris was still at the divisional field hospital the following morning, May 10, where he wrote his brigade’s official report

that covered the Battle of the Wilderness to his wounding at Spotsylvania.

A Confederate sharpshooter, or sharpshooters, made life along the VI Corps line particularly miserable on May 9. The marksman, or marksmen, made it dangerous for Battery H, 1st New York Artillery to operate their guns. A soldier in the 15th New Jersey noted that, “a rebel rifleman was posted on our right,

in a tree. He seemed to kill at almost every shot and was said to have taken twenty lives.” One of the victims was the color sergeant for the 15th New Jersey, Samuel Rubadeau, who was shot through the chest. The same bullet also wounded Sgt. Israel Lum in the thigh.

Was the harassing Confederate marksman who shot Brig. Gen. Morris the same one who shot these men and soon after killed

Sedgwick? It is difficult to know definitively, however, Sgt. Berry Benson, a sharpshooter in the 1st South Carolina Infantry, hinted in his memoirs of who he thought it was. Benson explained that a soldier named Ben Powell (officially a member of the 12th South Carolina), who was also in Gen. Samuel McGowan’s brigade but operated independently as what we would today call a sniper, came in from his day’s work on May 9 and said that “he had killed (or wounded) a Yankee officer.”

Powell utilized a long-distance shooting Whitworth rifle with a telescopic sight for his work. Benson noted that “[Powell] had fired at long range at a group of horsemen he recognized as officers. At his shot, one fell from his horse, and the others dismounted and bore him away.”

Benson speculated that Powell’s officer victim was Sedgwick and left it at that. However, several pieces of evidence indicate that Sedgwick was standing, not mounted, when killed; but Morris was riding, and his staff probably helped carry him to get medical attention. McGowan’s brigade was not in the area on May 9, but if Powell operated independently, as Benson explained, Powell might have wounded Morris.

the field, serving instead on court martials in Washington D.C. until he formally left the service in August 1864. A doctor’s report on January 1, 1865, noted that Morris’ wound still “has not healed, and the limb remains swollen and painful.”

After leaving the army, Morris stayed busy writing. He published Infantry Field Tactics in 1864 and Infantry Tactics (two volumes) in 1865. He also served in the New York Constitutional Convention in 1866. Morris received a brevet major general of volunteers rank from Congress in 1867. In addition, Morris continued editing the New York Home Journal. In 1879, Morris published another tactics book for troops using breechloading and repeating weapons. Dying at age 73 in 1900, Morris rests in Mountain Avenue Cemetery in Cold Spring, N.Y.

The repeating rifle that William Morris and Charles L. Brown developed before the Civil War never went into production. Charles L. Brown became major of the 34th New York Infantry and was killed at Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862. (Public domain)

Morris spent several months recuperating from his painful wound. Although not requiring an amputation, he did not return to

CVBT has helped save over 150 acres of Spotsylvania battlefield land. The mission of CVBT is to preserve land associated with the four major campaigns of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Mine Run, and the Overland Campaign, including the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. To learn more about this grassroots preservation non-profit, which has saved over 1,700 acres of hallowed ground, please visit: www.cvbt.org.

General Sedgwick A Short Note

On May 9, 1864, during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in Virginia, General Sedgwick met his untimely end. He was standing with his staff and troops when Confederate sharpshooters began firing at them from a distance of about 1,000 yards. As the soldiers sought cover, Sedgwick reportedly showed characteristic bravery and dismissed the danger, declaring, “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” Tragically, those were his last words, as moments later, a bullet struck him just below the left eye, killing him instantly.

The news of Sedgwick’s death spread rapidly, sending shockwaves throughout the Union ranks and eliciting profound grief from soldiers and civilians alike. He had been a highly respected and effective leader, known for his calm demeanor, strategic acumen, and genuine concern for his men’s welfare.

14 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 14 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Tim Talbott is the Chief Administrative Officer of the Central Virginia Battlefields Trust.

This sketch by Alfred Waud shows the spot where Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick was killed. Morris was wounded nearby on the same day, May 9, 1864. (Library of Congress)

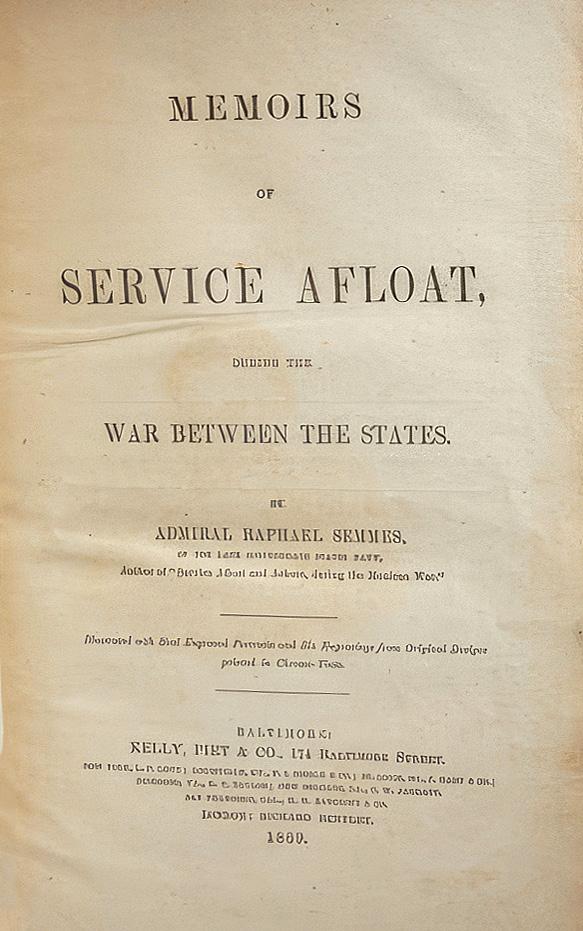

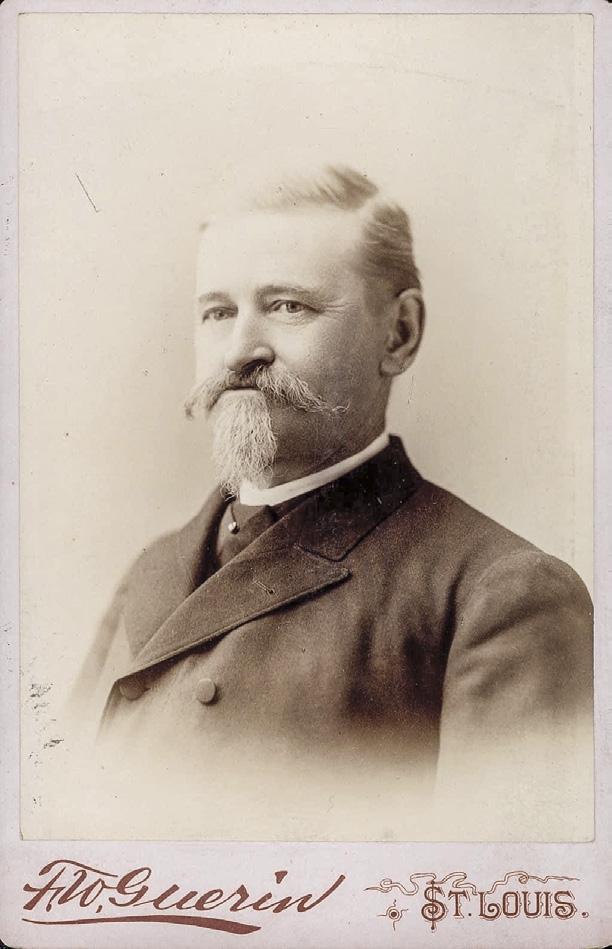

Col. Abraham Charles Myers, CSA and the Quartermaster Service of the Confederacy

by Lloyd W Klein

Abraham C Myers was the first quartermaster general of the Confederate States Army. He is not as well-known as Lee nor as illustrious as Stuart, but for the first three years of the War, no one had a more critical job, acquiring supplies necessary for the army and conveying them to the front. As the Quartermaster General, Myers was responsible for managing and supplying the Confederate Army with provisions, food, clothing, and equipment.

Background

Myers was born in Georgetown, South Carolina on May 14, 1811. He was the son of Abraham Myers, a Charleston attorney who had fought in the South Carolina Militia during the Revolutionary War.1 Myers was accepted to the United States Military Academy and entered in 1828; after repeating his freshman year, he graduated in the 1833 class.2 During the Second Seminole War (1841–1842) he served as an assistant quartermaster in the United States Army, and was promoted to captain in 1839. He then was in service at Fort Moultrie. During the Mexican

War he was brevetted to lieutenant colonel for “gallant conduct,” which is highly remarkable for someone in the quartermaster service. General Taylor was so impressed that Myers rose to command all quartermaster operations in his army.3 From 1848 to 1861, he served in the Quartermaster Department under Quartermaster General Joseph E. Johnston. He held numerous important administrative posts in several forts throughout the Southern United States.4 Myers was the quartermaster for the Army’s Department of Florida5 in 1850; Fort Myers, Fla., was named after Abraham Myers.

The Onset of the Civil War

In January 1861, Myers was stationed in New Orleans as chief quartermaster of the Southern Department.5,6 When Louisiana passed the Ordinance of Secession, several Federal officers immediately resigned.

Maurice Grivot, Adjutant General of Louisiana, carrying out orders issued by Governor Moore, moved to sequester the remaining Federal property in the state.7 Myers, a secessionist and man of Southern heritage, promptly resigned his commission from

the United States Army and personally turned the supplies over to Confederate authorities. He was immediately named Quartermaster General of Louisiana.8

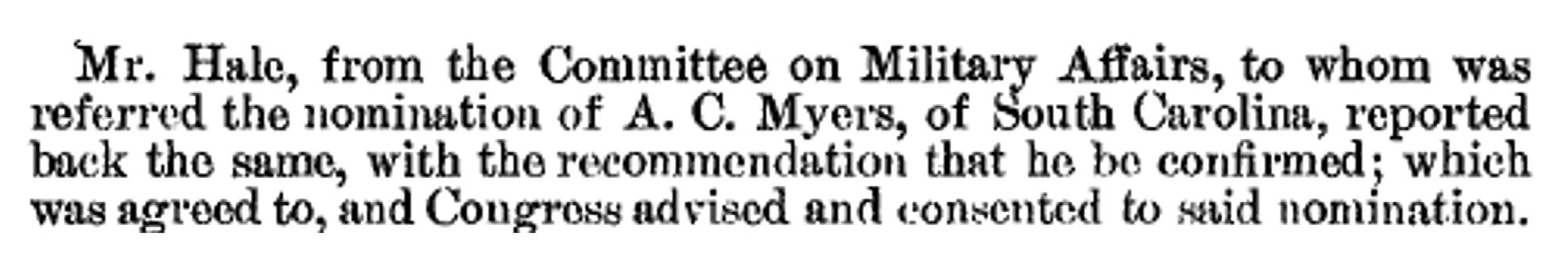

The Confederate Quartermaster Department

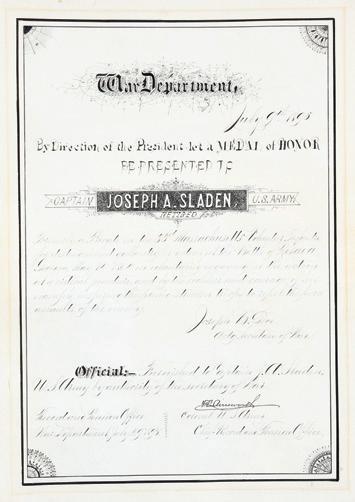

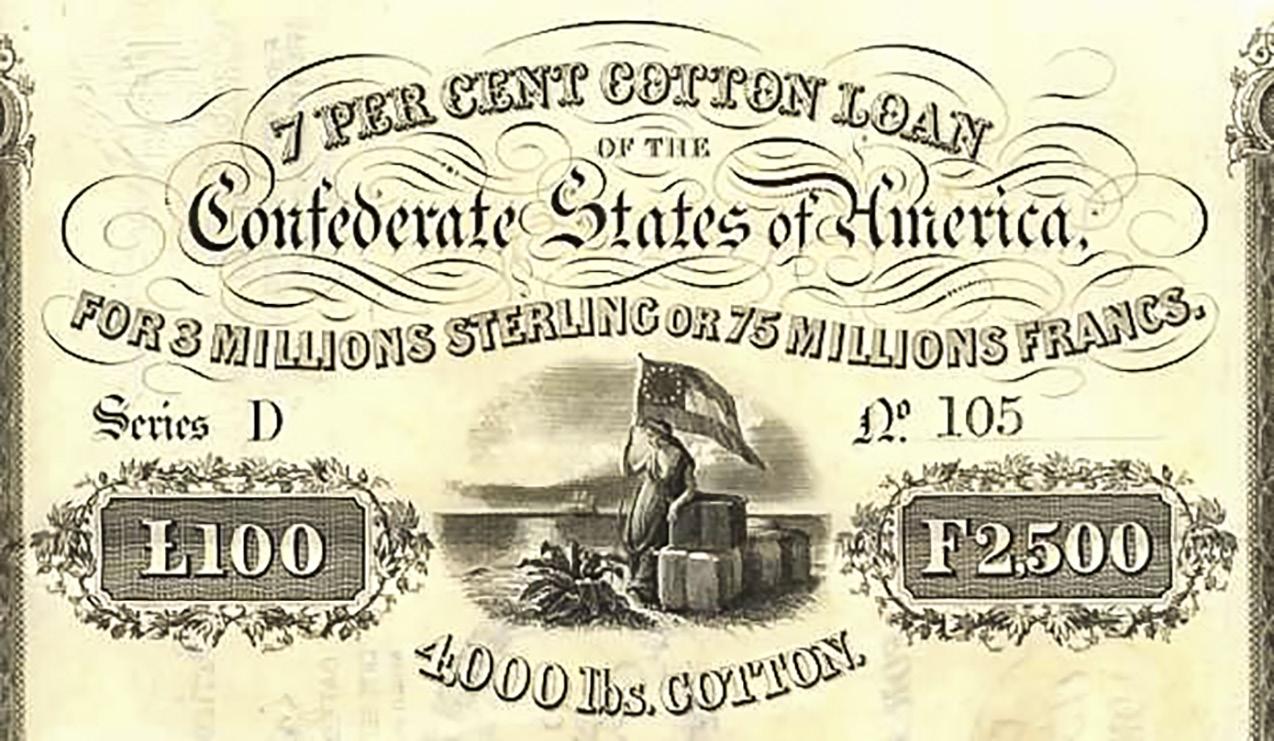

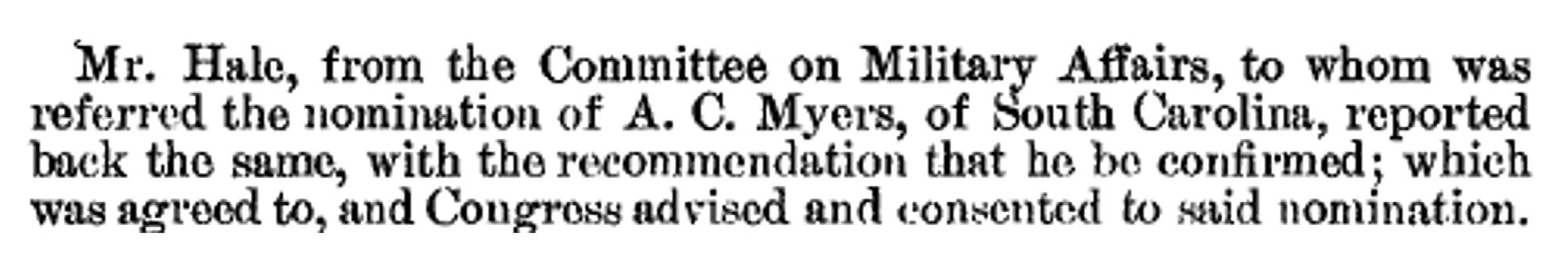

Myers actively sought the position of Quartermaster General of the Confederate Army. After the Confederate Congress created the position of Quartermaster General, Myers made his official nomination February 15, 1862. It was passed February 17 (see figure 1).9 Myers served as the first Quartermaster General for the Confederate States of America.

When the Confederate capital moved from Montgomery to Richmond, Myers’ bureau grew into an extensive administrative arrangement. The Quartermaster Bureau had its offices on the second floor at the southwest corner of 9th and Main Streets. The staff would eventually become the largest in the Confederacy’s supply administration, including 88 members.

The role of the Quartermaster General was crucial in maintaining the logistics and efficiency of the Confederate military operations. Abraham Myers played a significant part in ensuring Confederate forces were adequately equipped and provisioned throughout the war. The CSA faced numerous challenges due to limited resources; blockades imposed by the Union impacted their ability to sustain their war effort. The Confederate government lacked nearly all manufactured production and had little capacity to generate them. Most industry and transportation facilities in the United States were in the North. Along with its lack of manufacturing, the South had to contend with a formidable blockade of its ports, which severely hampered the Southern economy. Myers, who like most Southerners thought the war would be a short one and that the South would prevail, did not initially believe these were insurmountable problems.

His experience prewar southern postings and his prewar contacts were especially valuable. Myers sent agents into

the domestic market, contracting with local manufacturers, and paying competitive rates. The department bought cotton, woolen cloth, and leather goods. He also established shops for making clothing, shoes, tents, wagons, and other equipment, and purchased livestock at market prices for as long as possible. During the first few months the South had sufficient supplies to cobble together a supply chain.10

A quartermaster department is responsible for creating a supply network for the army; in particular, the procurement, maintenance, and transportation of military materiel, facilities, and personnel. It is the functional bridge between economics and tactical operations. To operate optimally, the logistical network must connect the combat forces with the strength and capabilities of the society it defends. It is not merely an administrative task; it is an enterprise in itself that requires using technological and economic resources to overcome an enemy and sustains military forces by supporting its warfighting readiness.11

The South lacked the infrastructure required to produce and manufacture the required huge quantities of food, shoes, and clothing, and it further was incapable of transporting them long distances in a timely manner. The Confederacy also lacked the machinery and personnel to maintain its existing railroad network, or build new locomotives and railroad cars to replace equipment that wore out.

Settling in for what would be a long war they had not planned for, the supply deficits developed into a crisis as the financial weakness of the country led to runaway inflation. Perhaps even more problematic than limited resources was the “pervasive ineffectiveness that characterized every aspect of Confederate administrative life, especially its logistical and supply arrangements.”12 Creating a new country with a new financial system, revamping its rail system, and developing an industrial capacity posed inconceivable and perhaps impossible problems for a state oriented government system. Trying to accomplish these tasks while being invaded by a much larger, resource rich country bordering its most critical strategic areas was likely beyond anyone’s capacity.

Myers immediately began advertising for tents and other camp equipment from Southern vendors.13 As president of the military board, Myers helped design the first Confederate Army uniform: “a blue flannel shirt, gray flannel pants, a red flannel undershirt, cotton drawers, wool socks, boots, and a cap.”14 Blankets, shoes and wool remained scarce. Quartermaster depots were created at Richmond and Staunton, Va.; Raleigh, N.C.; Atlanta and Columbus, Ga.; Huntsville and Montgomery, Ala.; Jackson, Miss.; Little Rock, Ark.; Alexandria, La.; and San Antonio, Texas.15

Supplying uniforms in bulk in 1861 was a huge problem.16 Myers estimated that he needed 1,600,000 pairs of shoes for the first year, but he could only locate 300,000.17 He also estimated that he would need hundreds of thousands of blankets, socks, and shirts, and almost no industry was present in the South to manufacture them. They would have to be purchased in Europe and brought through the blockade.

It was not enough to purchase these items; they had to be transported to the armies. He devised a system of supply depots; Richmond and Nashville would be the main depots for the two theaters, with multiple satellite storage areas closer to the front.18 Railroads were the primary means of transport; overland wagon routes were slow, roads were bad, and draft animals were required by the military. River traffic provided some relief but the armies did not operate along navigable rivers very often.

Despite a very large department, Myers was hampered by a lack of funds, inflation, and poor railroads, over which he had no control. His department was criticized by field commanders because the South could not obtain supplies to outfit the Army. His inability to provide shoes and uniforms was an especially serious problem.

He set goals and controls for Southern manufacturing throughout the war. By commandeering more than half the South’s produced goods for the military, the quartermaster general, in a counterintuitive drift toward socialism, appropriated hundreds of mills and controlled the flow of Southern factory commodities, especially salt.19

15 September 2023 15 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com CivilWarNews.com

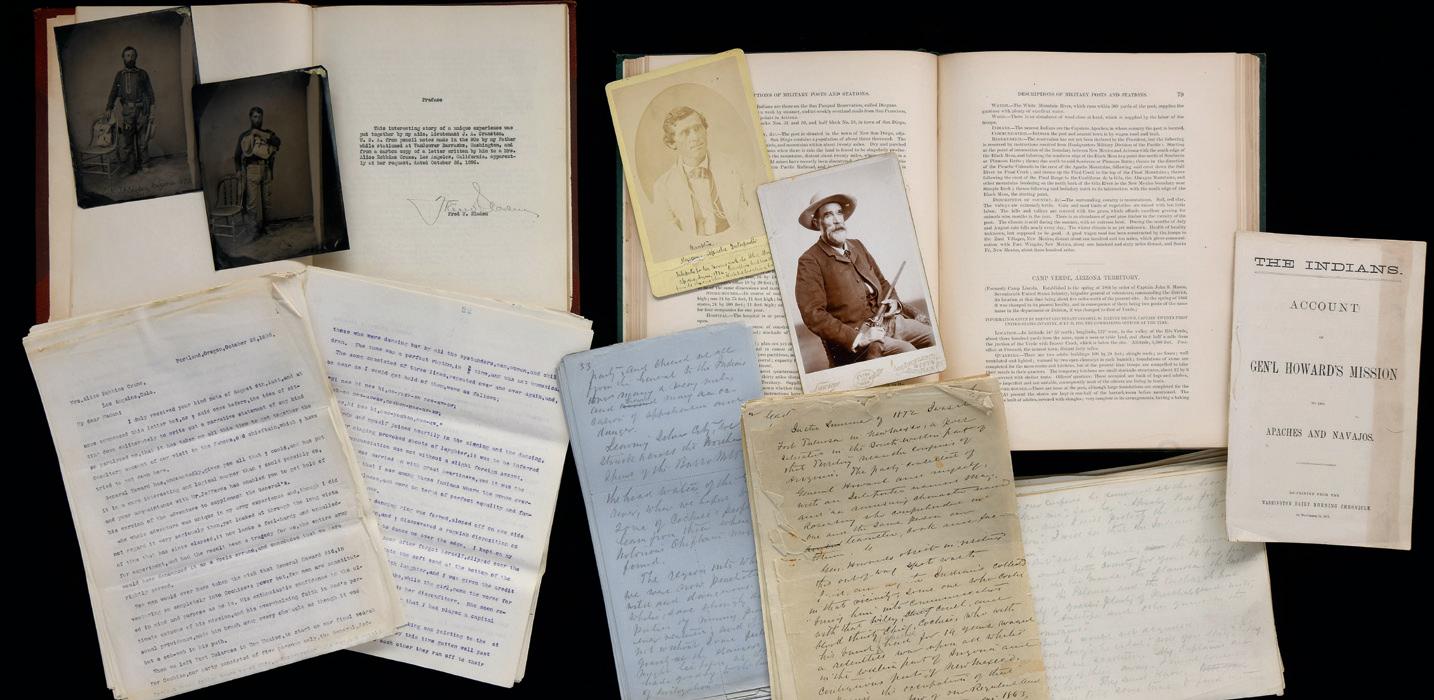

Figure 1. The Acts of the Confederate Congress Establishing Myers as Chief, CSA Quartermaster Department.

Cost of Supply

Understanding the problems that confronted Myers requires a comprehension of the costs of Confederate supply and how the Confederate inflationary spiral altered the War. As a comparison, the U.S. dollar has experienced on average a 2.18% inflation rate per year since 1860. Hence, $1 in 1860 is roughly equivalent to $32.43 in 2023 dollars.20

The inflationary spiral of the Confederate dollar during the War increased costs exponentially: every six months, the value of the Confederate dollar decreased so much that costs were almost incomparable to the previous time frame. The total expenditures of the Confederate government, nearly all of which were for the War Department, increased from $70 million in November 1861 to $329 million in August 1862. That is a dizzying figure to contemplate in retrospect, and impossible to imagine what it was like for Myers, whose job was to administer and develop budgets for his department a year in advance. One example is that the $199 million allocated for the war budget for 1862 ran out by September.21 It’s impossible to operate a functional war machine with inflation at that unsustainable rate.

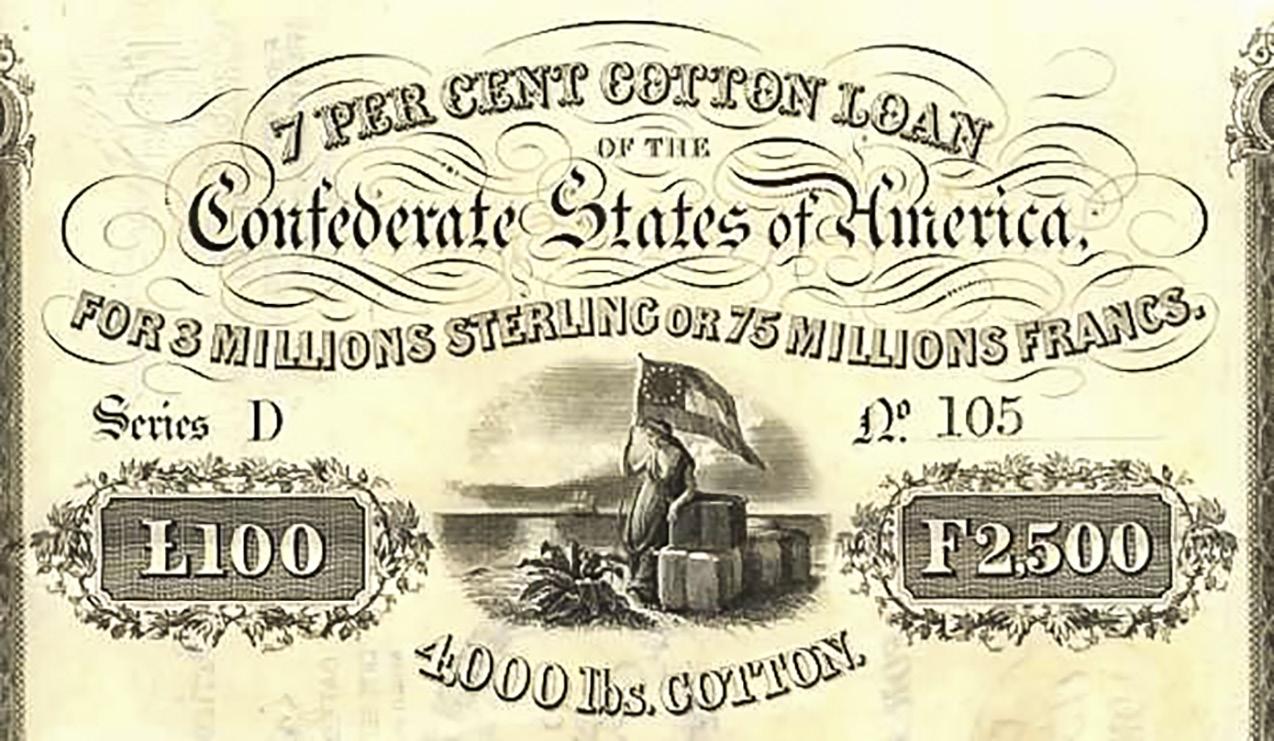

How did this happen? On April 29, 1862, Commander David Farragut captured the South’s largest port city, New Orleans.22 The fall of New Orleans was a powerful financial disadvantage. For a nation composed of rebellious states to wage war, it must have capital with which to pay for war supplies; weapons, armaments, horses, food, clothing, soldiers’ salaries, etc. The way the Confederacy raised cash to finance the war was to sell bonds to its citizenry. The Confederates issued one round of bonds for $15 million and a second for $100 million. With only six million citizens, and even fewer with real wealth and flexible cash, public financing through bonds sales was a limited prospect. The Confederate

government knew only foreign trading and investment could save it. Foreign investors thought conventional Confederate bonds were a poor investment and would not buy them. Moreover, the Confederacy itself was a poor credit risk. What products did they manufacture? What collateral did they own?

To spark interest in their bonds, the Southern treasury came up with an innovative solution. It involved exploiting the South’s most abundant and important crop, cotton. They would issue 20-year bonds; should they fail to make payments on the 7% coupon, the bondholder could convert them into cotton at the pre-war price of 6 pence/pound (figure 2.) To try and run the price of their bonds up even more, as well as compel Great Britain to recognize the Confederacy, the South imposed an embargo on cotton shipments. British imports of Southern cotton fell from 2.6 million bales in 1860 to just 72,000 in 1862. By late 1862 what the British called “The Cotton Famine” was laying waste to its industry and causing so much unemployment in the textile regions in the north of England that civil unrest was bubbling to the surface. Meanwhile, as the Southerners hoped, the price of cotton soared, from 6.25 pence/ pound to 27 pence, making their cotton-backed bonds more valuable. This sequence of economic events succeeded in attracting investors in London and Amsterdam, which initially provided some cash to finance the war. The value of the bonds was underpinned by the holders being able to take delivery of physical cotton at the discounted price should the South fail to make interest payments. Collateral is only good if a creditor can take control of it.

That’s why the Union Navy’s capture of New Orleans was so critical. It choked off a major Southern cotton export gateway. By 1863, after Britain had found new sources of cotton in India, Egypt, and China, investors lost faith in the Southern bonds. The

effect on the Southern economy was catastrophic. With the domestic market exhausted, and no European buyers of their bonds, the Confederacy was forced to print unbacked paper money. Eventually the South printed at least $1.7 billion in paper money. The North did too, but at war’s end their “greenbacks” were still worth 50¢ in gold, whereas the “graybacks” were worth just 1¢. Making things worse, Southern states and municipalities printed paper money of their own adding to the supply of unbacked bills. The resulting budgetary pressure had consequences all along the administrative path. In 1862, Myers saw his estimated budget cut from roughly $27 million/month to $19 million. He informed the cabinet that the current actual expenditure was $24.5 million/month, and with rising inflation would clearly become much higher. Myers lobbied Congress for more appropriations to keep the war effort on track. The Congress then passed a supplementary expenditure of $127 million to pay for just the three months of December 1862 to February 1863.23

Increasing Problems as the War Continued

By the spring of 1862, Myers was forced to resort to impressing necessary supplies. The scarcity of goods in the domestic market drove up prices, and combined with the insufficient funds provided him, made purchases to supply the war effort ineffectual. Added to this was the devaluation of currency and poor railway transportation of those supplies that were available. As the war progressed, Southern armies became short of all supplies. Many troops were barefoot or relied on boots taken from dead soldiers. Food, horses,

and supplies of all types were woefully inadequate.24

The spring 1862 battlefield setbacks had a catastrophic effect on the Quartermaster Department. Loss of cities like New Orleans, Nashville, and Memphis, with their river access, warehouses, and manufacturing, was irreplaceable. Surplus stocks were lost in the storage. Even more deplorable were supplies wasted by soldiers who discarded them in critical amounts.25

The loss of the Virginia Peninsula resulted in losing several depots with supplies that could not be replaced easily. Although the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days battles are considered great strategic victories, implications of the supply system impacts are overlooked. By moving to meet McClellan’s threat in the east, Johnston had to abandon his position in northern Virginia, which opened territory east of the Shenandoah north of the Rappahannock to Union control. This was prime flour and beef farming land, all lost to Union operations.26

By mid 1862, Myers was unable to fulfill requisitions for 40,000 uniforms. Commanding generals of both major armies blamed Myers for the lack of supplies. Bragg dismissed the chief quartermaster assigned to his army and replaced him with someone untrained in the business; Myers protested to Secretary George W. Randolph.27 Although nothing was done then, later that fall orders from the Secretary of War ruled that transportation and distribution of supply was under the command only of the quartermaster service. The 1862 losses in the west were devastating to the Confederate cause, not just from a strategic perspective, but from the logistics viewpoint as well. While 1862 is generally thought of as being

the peak of Rebel strength, the loss of the border states and the Mississippi Valley would have severe logistical repercussions for the next two years. The South lost many reserve supplies in retreats and a left behind large swath of food crops.28 This is a frequently overlooked feature of the war: as the Confederate army retreated, not only was it losing strategic ground but its supply resources as well, further impacting its strategic situation. In many retreats, supply depots and stores were often burned or abandoned, leaving unused, difficult to procure supplies.

Two years into the war, the initial measures taken to allay stresses on the supply chain had long been utilized. Attendant economic and supply consequences had strained the South’s economy and become perceptible both to citizens and the army, with substantial political and military consequences. In 1863, the interconnected economic effects of scarce resources and lost food producing territory had become an irresolvable conundrum.

The Union blockade decreased imports, reducing the amount of collectable customs duties. The blockade also limited Southern agricultural exports; thus, farmers and planters had less income to pay taxes. State’s rights made the central Confederate tax collections ineffective, even as the states were unable to contribute enough to support national war costs. The existence of slavery in the South and the diminishing likelihood of Confederate victory made foreign governments generally reluctant to loan money to the Confederacy.

General Lee felt that his army was never adequately supplied and experienced numerous problems due to the lack of supplies.29 Resort to impressing shoes by Lee’s soldiers became necessary. The

16 CivilWarNews.com September 2023 16 September 2023 CivilWarNews.com

Figure 2. A 7% Confederate Cotton Bond.

Proposed February 15, 1862. Passed Feb. 17, 1862.

inefficient redistribution system compounded the depletion of supply. The disparate groups granting contracts, submitting requisitions, and having a central authority, with no actual control or presence in the army units were conspicuous flaws in the process.

Myers was given permission to send his own agent, Major J.B. Ferguson, overseas to purchase stores. He also assumed some control over domestic leather, wool, and textile industries. By mid-1863, Myers had established an extensive organization of purchasing agents, local quartermasters, shops, and supply depots. It was still insufficient, and the Confederacy soon resembled a rag-tag army, particularly in clothing and footwear. The quartermaster department soon became the target of much criticism, and in spite of his personal efficiency, he was unable to overcome the laxity and carelessness of remote subordinates. There was a considerable black-market operation, as well.30

Removal from Office

Complaints about Myers, some of which were based on his religious background, led to him being replaced in the summer 1863. Inadequate supplies, especially clothing and shoes, had reached a crisis point. Tents, uniforms, blankets, shoes, horses, and wagons remained

scarce, requiring scavenging and impressment throughout the war. Although manufacturing improved during this time, it remained woefully inadequate.31

Myers was an excellent administrator but he could not create supply lines without purchasing power. Despite these supply problems, he was well regarded among his colleagues and contemporaries, who understood that the supply deficits were not due to his malfeasance.

Conclusion

Abraham Myers’ role as the Quartermaster General was important in supporting the Confederate war effort by overseeing army supply and logistics. His successor was even less successful than Myers in supplying the Confederate armies as the war went on, territory was lost, and the blockade took

Endnotes:

1. Burke, Walter E. Quartermaster: A Brief Account of the Life of Colonel Abraham Charles Myers, Quartermaster General C.S.A. W.E Burke Jr, 1976. Rosen, Robert N. (2000). Chapter 3: Hebrew Officers and Israelite Gentlemen. The Jewish Confederates Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. https:// muse.jhu.edu/book/85577. 2021, pp. 89–161. Kabakoff, Jacob. The Tombstone of the Reverend Moses Cohen. Accessed at https:// kevarim.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Rev-Moshe-HaCohen.pdf

2. Burke op cit. Allardice, Bruce S. Confederate Colonels. A Biographical Register. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. 2008. Goff, Richard D. Confederate Supply Durham: Duke University Press. page 8. Warner, E. J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Loui-

increasing effect.

siana State University Press, 1959.

3. Elliot, Ellsworth Jr. West Point in the Confederacy. New York: G. A. Baker & Co., 1941. Page 401.

4. The Twiggs-Myers Family Fix Bayonets Blog. (hereafter: Fix) https://fixbayonetsusmc. blog/2019/03/29/the-twiggs-myersfamily-part-iii.

5. Colonel Abraham Charles Myers Jewish Military History Blog. https://jewishmilitary.org/f/colonel-abraham-charles-myers.

6. Goff op cit page 8.

7. Edwin C Bearrs. The Seizure of the Forts and Public Property in Louisiana Louisiana History 2:401-409, 1961). http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/ Louisiana/_Texts/LH/2/4/Seizure_of_the_Forts*.html. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. I, 495. Washington: Government Printing Office (Hereafter: OR). https://ehistory.osu.edu/ books/official-records/001/0495.

8. Rosen op cit. Chapter 1: The Free Air of Dixie. pp. 9–55. Bearrs op cit and OR pages 492-3. https:// ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/001/0492. Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865 [Volume I] THURSDAY, February 21, 1861] accessed https://www.loc. gov/item/05012700. Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865 [Volume I] THURSDAY, February 21, 1861. https://www.loc.gov/ item/05012700. Nomination in congress March 16, 1861, page 154. Hereafter: JCCSA. Wilson, Harold S. Confederate Industry Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War. Town: University Press of Mississippi. 2005.

9. Pages 841, 844 JCCSA; Wilson op cit.

10. Goff op cit pages 15-17 and Fix, op cit.