20 minute read

Issue 5: Sustainable land management

The sustainable management of rural land is critical for a range of reasons. Sustainable land management is a term that should be familiar to all rural land holders, whether for biodiversity reasons or to ensure the health of soils and waterways to protect future productive capacity or address a changing climate. In some instances, improvements to land management techniques have also been evolving for generations, ensuring long-term returns for farmers.

With continuous improvement to techniques and technologies, there are however always further gains to be made. This section identifies a number of issues and opportunities to ensure that the Clarence Valley’s rural lands are able to be sustainability managed into the future including:

o Soil health and management, including carbon farming o Adaptation to climate change o Planning for and recovery from natural disasters o Secure water resources for the future o Biosecurity and weed management o Protection of biodiversity and scenic outlooks o Vegetation management o Mining and resource use

Ensuring sustainable land management practices provides for the long term future of rural lands for a variety of outcomes.

50 See for example, https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2021-11-10/soil-solution-to-australias-netzero-climate-commitment/100592298 and https://www.theguardian.com/australia-

5.1 Soil health

Soil heath has been recognised as a key measure of productivity of rural lands. High quality soils are a key component of mapping important agricultural land, and the ongoing care for these soils is often linked to production quality and quantity.

In more recent times, and as captured by Council’s LSPS, there are also trends towards regenerative agricultural techniques, especially to:

increase carbon in soils to improve productive capacity, contribute to reducing atmospheric CO2, increase water holding capacity of soil so reducing drought impact and significantly reducing the effects of runoff and soil erosion on roads, bridges and other infrastructure.

Regenerative agriculture is also integral to many of the current research and education processes being undertaken by (among others) Southern Cross University’s Farming Together Program & Regenerative Agriculture Alliance, Future Food Systems Cooperative Research Centre projects based in Coffs Harbour and soil carbon initiative through the Casino Food Co-op. With a range of soil heath research and programs operating in and around the region, there are opportunities to tap into leading practices into the future.

Over and above the health and environmental benefits, there is also high potential for substantial financial benefits from such processes. Carbon farming and carbon sequestration initiatives would appear to hold great potential into the future. Various reports50 indicate the

news/2021/oct/17/australian-first-farmer-mutual-aims-to-cut-out-carbon-farming-middleman accessed 17 November 2021

potential for rapid change through new farming techniques, changes in modelling regulation and market take-up of carbon farming as market entry become more readily available. This presents opportunities for benefits to both the environment and the farmer as supplementary incomes benefit landowners.

In addition, there are a number of agricultural uses that are moving away from the use of soils, instead relying on above ground substrate materials in the more controlled environment. This is becoming particularly present in the berry industry, where farms are becoming increasingly sophisticated with respect to crop protecting and management of the environment. This has seen a shift from open farms, to nets, tunnels and potentially into the future, glass-house style climate-controlled environments.

Considering existing agricultural uses are generally associated with high quality soils, the continuing emergence of high intensity horticultural activities (which have associated high levels of employment per hectare) is a trend that needs to be considered within the rural lands’ context and planning processes – i.e. agricultural productivity is not only about soil quality and protection of the RU1 Primary Production zone.

5.2 Adaptation to climate change

As identified in Issue 1 relating to the potential loss of agricultural land, climate change has the potential to have significant impacts on the rural lands of the Clarence Valley. Council undertook a Climate Change Impact Assessment in 202151 that recognises more frequent and

51 Clarence Valley Council Disaster Resilience Framework (2021) severe weather events are expected, with agriculture and fisheries being increasingly susceptible to natural hazards.

Potential climate change impacts associated with the region52 include increased risk of fire days in spring and summer, rising minimum and maximum temperatures and variation in historic rain fall patterns. Increased frequency and severity of droughts, floods and storms will be a challenge for many living on rural lands.

The impacts of climate change are already being recognised and responded to by Clarence Valley Council and the community, particularly since the 2019/2020 bushfire season. From a land production perspective, key issues identified include:

o an increasingly hotter and drier climate will mean less access to water than what currently exists o threats to traditional agricultural practices and the ability to sustain certain enterprises o certain forms of agriculture may become more available and more suited to the changing climate of the LGA

Over the next 20 years, raising awareness and building a strong knowledge base about individual, community and government roles in addressing climate change will be important in assisting communities develop resilience to these impacts.

5.3 Natural disasters

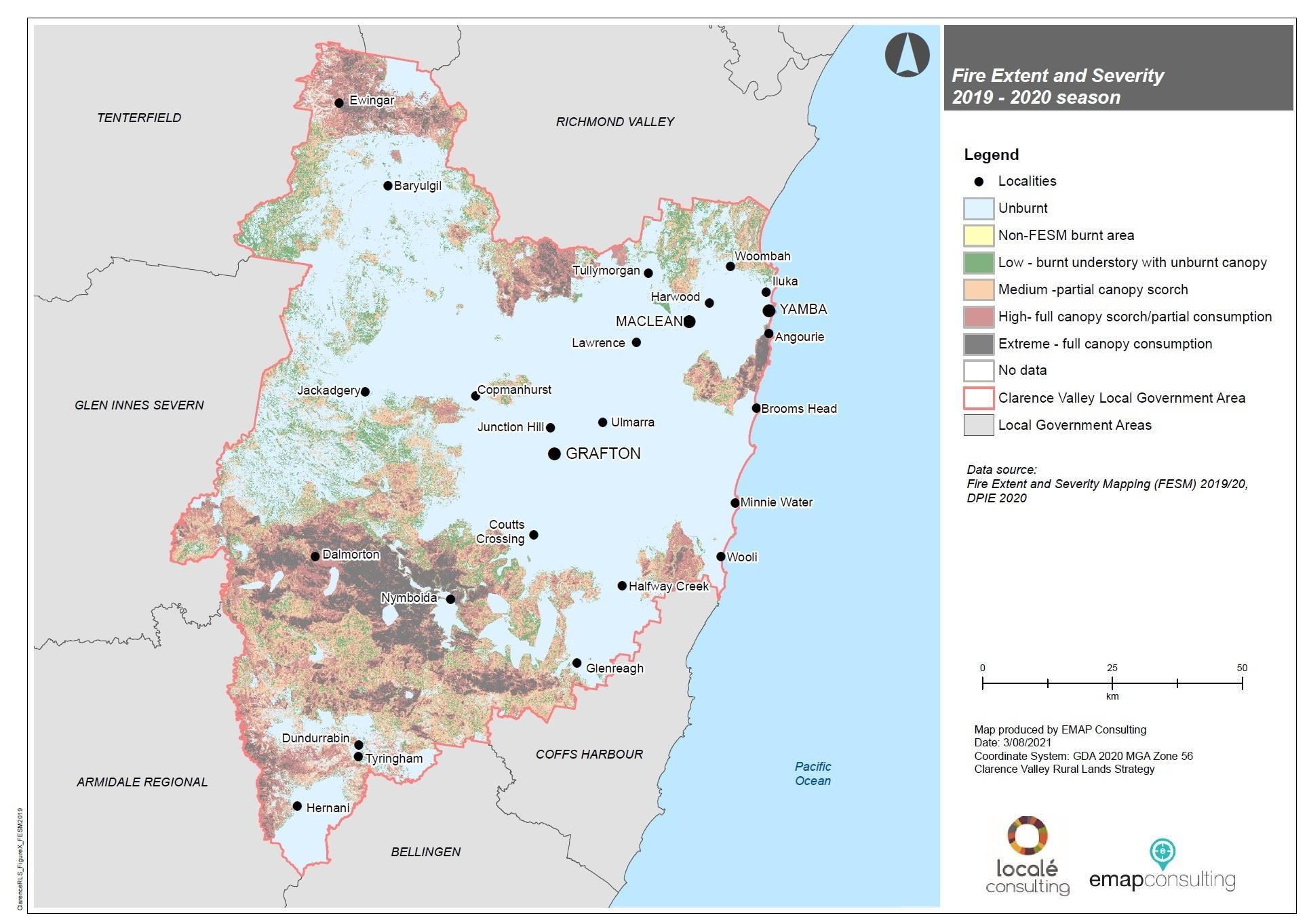

Parts of Clarence Valley’s rural lands are vulnerable to both flooding and bushfires. Both of these have impacted the area in recent times, with the 2019/2020 bushfires being particularly severe, with 59% of the

52 North Coast Climate change snapshot – Adapt NSW 2014

entire LGA being burnt, as shown in Figure 19. These bushfires resulted in 848 properties being damaged / destroyed and ~80% of harvestable forests being affected53 .

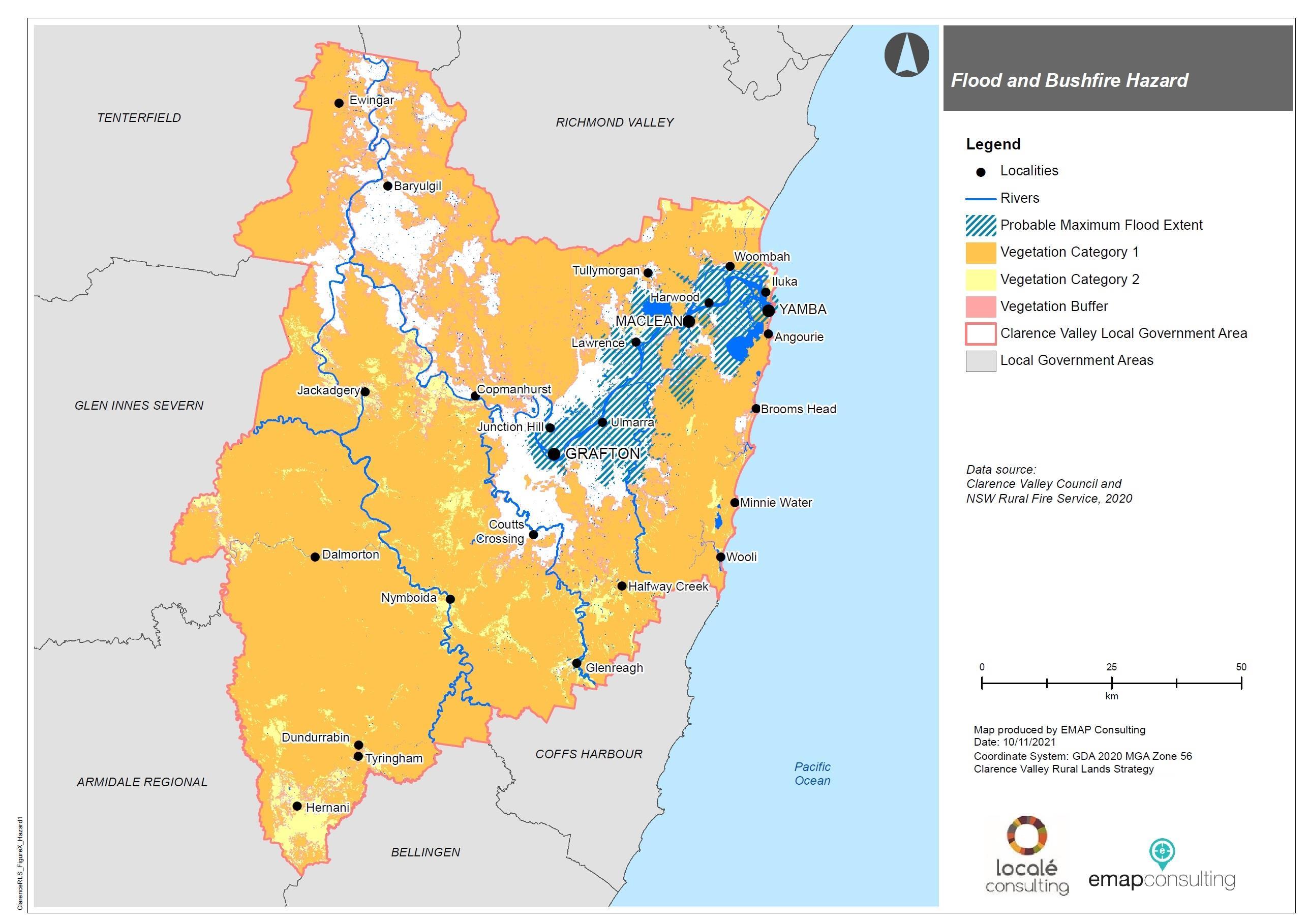

In more generally terms, where large areas native vegetation are not present, flooding tends to be the converse concern (i.e. agricultural areas on the floodplains). In this way, both flood and mapped bushfire prone land represents a significant portion of the land subject to the Rural Lands Strategy as shown in Figure 18.

One core issue in relation to rural land management that exacerbated the extent of the recent bushfires was the mix of public and private vegetated land. Large areas of rural land in the Clarence Valley borders National Parks, State Forest, Crown or Council reserves. Coordination between key agencies responsible for land management surrounding rural land is a concern for many following the bushfires and continues to be a key concern for ongoing land management moving forward.

In addition, local knowledge within these agencies, and particularly within Council and the RFS, is crucial in bushfire preparedness, response and recovery. Creating and improving local knowledge through farmer to farmer and farmer to Council connection is an opportunity to build this understanding. Being prepared for future extreme events as a consequence of a changing climate can assist in avoiding significant losses to stock, property and human life.

Otherwise, land use planning for natural hazards is generally identified in the Clarence Valley LEP 2011 as well as the Clarence Valley Rural Zones DCP 2011. Planning for Bush Fire Protection 2019, developed by the NSW

53 Clarence Valley Regional Economic Development Strategy - Fire impact addendum (May 2020) Rural Fire Service, provides development standards for designing and building on bush fire prone land in NSW. The guidelines now include procedures for strategic planning in bushfire prone lands, as well as for development assessment. The guidelines suggest that for some specific locations that have significant fire history and are recognised as known fire paths, detailed analysis or plans should ‘provide for the exclusion of inappropriate development in bush fire prone areas’.

Key issues identified in relation to hazards including the following:

o The risks of flooding and bushfire are important considerations when identifying potential areas for intensive agriculture o While not all flood areas have been modelled in the LGA, development in flood affected areas needs to be subject to appropriate floor levels or other mitigation measures to minimise flood impacts on property o Bushfire hazard (including bushfire prone land mapping) should be considered in relation to any proposed rural development to ensure that the proposed development is not within a high hazard area.

Council has also developed a Clarence Valley Disaster Dashboard54 that provides emergency updates for a range of natural disasters including bushfire, floods, heatwaves and more.

54 See https://emergency.clarence.nsw.gov.au/dashboard/overview accessed 23.11.21

Figure 18: Bushfire and Flood Prone land map Figure 18: Areas subject to bushfire and flood risk

Figure 19: Bushfire impacted land map Figure 19: Fire extent and severity - 2019/2020 season

5.4 Water security

The Clarence River catchment is a huge 22,716km2 being the largest river on the east coast of NSW and stretches from the Queensland border to the Doughboy Range in the south. It has one of the highest concentrations of marine industry businesses outside of Sydney and Newcastle and the river has a long history associated with agriculture55 . Places along the lower Clarence, including Ulmarra, Brushgrove, Lawrence, Maclean, Harwood and Yamba have played an important role in the historic development of river transport.

Yet the Clarence Valley also covers rural lands that are remote from any significant water sources, and/or have been subject to significant drought in recent years. Water security has therefore been a major concern for many farmers in the Clarence Valley and the extremes between drought and flood in the LGA mean that planning for agricultural activities is challenging.

It is also notable that a large proportion of the Clarence River catchment comprises national park (20%) and state forest (30%), indicating that there are also large areas of the river not used for agriculture. Nonetheless, the main water user within the Clarence River catchment is beef cattle production, particularly on the upper Clarence, with sugarcane concentrated on the floodplain of the Lower Clarence.

56

55 Clarence Valley Local Strategic Planning Statement (2020) 56 See https://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/water/basins-catchments/snapshots/clarence accessed 02.11.21 57 See https://www.coffsharbour.nsw.gov.au/Resident-services/Water-and-sewer/Maintaining-aquality-water-supply/Regional-Water-Supply-Scheme accessed 02.11.2021 The 30,000 megalitre Shannon Creek Dam west of Coutts Crossing provides urban water supplies to both the Clarence Valley and Coffs Harbour regions as part of the $180 million Regional Water Supply Scheme57 . Classified as an off-river storage reservoir, it sources water from the Nymboida River and is designed to be used during dry periods to provide water security. It also reduces the impact of water extraction from the Orara and Nymboida Rivers during low flows. In 2021, Council purchased the Nymboida Hydro Power Scheme and associated water licenses, also further securing domestic water supplies as part of the collaborative Regional Water Supply Scheme58 .

DPI has a Water Sharing Plan for the Clarence River Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources which covers 52 water sources. The plan establishes rules for sharing water between environmental needs of the river or groundwater system and a range of extractive uses such as villages, domestic, stock watering and irrigation needs. Current records indicate that across the North Coast a total of 164,422 ML of water from surface and alluvial water sources is licensed for use across the region with nearly 50% of this volume is licensed from the surface and alluvial water sources within the Clarence River catchment.59

As of July 2016, there are approximately 2,189 water licences in the Clarence River water sharing plan area, totalling 78,154 ML/yr of entitlement divided between unregulated surface water (76,135 ML/yr) and alluvial groundwater (2,019 ML/yr)60 . The highest unregulated

58 See https://www.clarence.nsw.gov.au/News-articles/Nymboida-sale-secures-regions%E2%80%99water-supply accessed 23.11.21 59 See https://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/water/plans-programs/regional-water-strategies/publicexhibition/previously/north-coast accessed 09.11.2021 60 See https://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/166841/clarencebackground.pdf accessed 09.11.2021

river entitlement is in the Mid Nymboida River (29,910ML/yr) with 99% of this allocated for town water supplies. The majority of the unregulated surface water licences are located in the Mid Orara water source. The Clarence water sharing plan does not permit the granting of new unregulated river access licences and any new commercial development must purchase entitlements from existing licence holders. There are also over 450 licensed dams on the North Coast with the greatest number being in the Clarence catchment.

DPIE - Water developed a Draft North Coast Regional Water Strategy that was exhibited in March 2021. The document identifies the overall water security risk in the Clarence Valley as being ‘Very Low’ in 2014, but was expected to increase to ‘High’ by 2040 (albeit still lower than many of the surrounding LGAs). In response, the strategy outlines a number of options that relate to the Clarence Valley. This includes:

o Option 1: Expands the Clarence-Coffs Harbour Regional Water

Supply Scheme o Option 4: Augment Shannon Creek Dam o Option 11: Increase use of recycled wastewater for intensive horticulture

These options, and the finalisation of the North Coast Regional Water Strategy more broadly, will need to be considered in the context of securing water for rural lands in the future.

In addition, and particularly relevant to the rural context, from early 202261, landholders in coastal-draining catchments such as the Clarence River will be able to capture up to 30% (or three times the existing allowance) of the average regional rainwater as harvestable

61 See https://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/water/licensing-trade/landholder-rights/harvestable-rightsdams/increase accessed 23.11.2021 rights. This is captured in dams built on non-permanent minor streams, hillsides and gullies, with the remaining run-off flowing into licensed dams and the local river systems. Water that is captured may only be used for domestic and stock use and extensive agriculture. This is a substantial increase in the extent of water capture available to eligible farmers and provides for substantial increase water security during dry periods.

Further, the Water Management (General) Regulation 2018 allows sugar cane growers in the Clarence valley to use water from drains for irrigation without a licence during crop establishment, provided certain conditions are met62 .

5.5 Biosecurity

Biosecurity risks can have wide ranging impacts on animal and human health, food production, recreational opportunities and the broader economy. With respect to weeds, biosecurity in the Clarence Valley rural lands is managed under Council’s Biosecurity Policy 2021. The Policy outlines Council’s legal weed management obligations under the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015 as the Local Control Authority.

The Policy is guided by LLS’s North Coast Regional Strategic Weed Management Plan 2017-2022 that outlines State and Regional Priority Weeds and the identification of priority weeds to be managed primarily by councils. This is undertaken through a combination of education programs, in conjunction with LLS and DPI, and compliance mechanisms where appropriate and in accordance with the adopted Biosecurity Policy 2021.

62 Refer Schedule 4 – 13 of the Water Management (General) Regulation 2018

One major biosecurity risk in the Clarence Valley is the mismanagement of rural land. One cause is the growing trend of rural lifestylers that are unaware of their responsibilities for managing biosecurity on their land. While new landowners can bring benefits such as renewed enthusiasm and resources, there is also concern from those that spend little time actively maintaining their land. For example, rural lifestylers may reside in the urban areas and treat their rural property as a ‘holiday home’. An absence of continued management can lead to the proliferation of weeds that spread onto adjoining properties, parks, forests and reserves. 63

Another biosecurity risk comes from the level of experience, time and resources (including cost) needed by a landowner to respond. Equipment, as well as herbicides and the like, can be expensive while the energy needed to invest in weed management can be intensive. Increased biosecurity risks can also be amplified from landowners who don’t rely on the land for income and so don’t recognise the importance of weeds management for the health of the land or have the appropriate experience to reduce risks early in an outbreak.

Biosecurity was also raised by a number of stakeholders during consultation. Simple examples such as the sharing of equipment, particularly when shared from outside the region, was a further risk to crop health and production output. Working with industries to have simple and well-informed processes in place, and being educated on their use, was seen as key to mitigating biosecurity risks.

Actions associated with biosecurity are identified in some detail through the adopted Clarence Valley Biodiversity Strategy 2020. This also

63 See for example, Weed Detection and Control on Small Farms - A Guide for Owners - Brian Sindel &

Michael Coleman (2010) includes actions associated with pest animals, including an action to continue to work with LLS in the control of pest species such as wild dogs, foxes, feral cats, deer and wild horses through the Local Pest Predator Plans.

5.6 Environmental and scenic protection

The Clarence Valley features some of the most diverse terrain on the east coast of NSW ranging from pristine unspoiled coastline to Gondwana World Heritage Rainforest. For public land, many of these areas are zoned C1 National Parks and Nature Reserve and managed by NPWS. This accounts for more than 21% or 225,000 hectares of all land in the Clarence Valley.

Private land of environmental significance is generally zoned either C2 Environmental Conservation or C3 Environmental Management. The intent and objectives of these zones is outlined in Appendix A with the C3 zone generally allowing greater land use flexibility than C2.

However, the extent of use of these zones is relatively low, with the C2 zone accounting for just over 0.5% or 6,000 hectares of all land in the Clarence Valley. The zone is applied infrequently, reserved primarily for land identified as coastal wetlands and littoral rainforest – for example larger areas around The Broadwater and Shark Creek. Land zoned C3 accounts for just over 5% or 53,000 hectares. Large parts of this land are located near Jackadgery / Cangai, Dalmorton / Newton Boyd and scattered around low lying areas of Gulmarrad – refer Figure 10 and Page 19 for details.

The application of these zones provides some insights about how land requiring environmental or scenic protection is applied in the Clarence Valley:

o Relatively small areas covered by the C2 and C3 zones could reflect the larger areas of environmental and protected land already captured in the C1 National Parks and Nature Reserves and RU3 Forestry zone (noting that around 50% of the FCNSW estate across the State is understood to be reserved for permanent protection64). Together these two zones cover 21% and 20% of the Clarence Valley respectively. o The RU2 Rural Landscape zone is used as a default scenic protection zone (consistent with the intent of the zone from a

State planning perspective) rather than the C3 Environmental

Management zone that is sometimes be used for this purpose by other Council’s.

Whilst the use of the C2 and C3 zones is relatively low, there is opportunity to further explore lands with strong environmental attributes that may be captured in an environmental protection zone in the future. Examples could include lands that are already, or proposed to be, covered by in perpetuity conservation agreements, biodiversity offsets in perpetuity, or similar arrangements.

Consistent with Council’s adopted Biodiversity Strategy 2020-2025, there is also potential in conjunction with DPIE – BCD, to better identify strategically important biodiversity corridors for inclusion in a more

64 Pers Comm Peter Walters | Protection Supervisor – Far North Coast, Forestry Corporation of NSW (August 2021) 65 Ryder, D. et al. Clarence Catchment Ecohealth Project: Assessment of River and Estuarine Condition 2014. Final Technical Report. University of New England, Armidale. (2014) appropriate environmental zone. Similarly, much of the Clarence River and its tributaries are reported to be highly disturbed and have poor bank condition, both of which directly affect habitat condition and extent of biodiversity65, with protections under Council’s current planning controls being minimal.

As an alternative to rezoning of land, there are also opportunities to use other LEP mechanisms to provide better protection or recognition to these areas. For example, Council may consider the use of local provisions and associated mapping within the Clarence Valley LEP that addresses terrestrial biodiversity, riparian corridors, biodiversity, cultural and scenic values to ensure that these areas can continue to be protected without rezoning. Examples of these types of local clauses are typically found in the more recently adopted planning instruments such as the Coffs Harbour LEP 2013, Lake Macquarie LEP 2014 and Shoalhaven LEP 2014.

5.7 Vegetation management

As outlined in the previous section, a large portion of remnant native vegetation is protected in various areas of public land within the Clarence Valley, including extensive National Parks and State Forests. However, large areas of native vegetation are also located on private land and excessive clearing on these lands can fragment habitats and degrade corridors within the landscape.

Between 2009-2019, and not including loss by bushfire, the Clarence Valley LGA has the highest vegetation loss in the North Coast region66

66 North Coast Region State of the Environment Report Working Group. Regional State of the

Environment Report Summary 2020 – (October 2021)

estimated as between 16,000 and 18,000 hectares. The same report raises questions with respect to approval of Private Native Forestry (PNF). The Clarence Valley has the highest levels of approvals in this area based on data from 2007 to 2015, and typically being 50% or more of the approvals across the region from Port Macquarie to the Queensland border. Further consideration of PNF is provided in Section 6.3.

Clearing of native vegetation on rural land is generally legislated by the Local Land Services Act 2013 and the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. LLS assess and approves the clearing of native vegetation (and PNF) which depends on the purpose, nature, location and extent of the proposed removal. However, the Department of Planning, Industry & Environment are the responsible authority for the clearing of native vegetation and consultation with DPIE identified the Clarence Valley as a current and future ‘hotspot’ for illegal vegetation clearing - with a large number of active cases under investigation at the time of consultation.

Given LLS manage approvals for native vegetation on rural lands and DPIE undertake enforcement, Council’s role in this space may be predominantly related to co-ordination, education and land use planning mechanisms.

5.8 Mining

From December 2014, and again in November 2020, April 2021 and June 2021, Clarence Valley Council has taken a strong position against mining within the LGA. This includes mining and exploration licences within the Clarence River catchment, and previously around coal seam gas (CSG). Recent actions have included writing to State and Federal governments seeking an amendment to the Petroleum (Onshore) Act 1991 (NSW) to make risks or harm to prime agricultural farmland and rural residential areas grounds for suspension or cancellation of a petroleum title.

Three other councils (Glen Innes, Bellingen and Byron) have since resolved to support this position as of October 2021.

Ultimately, the decision of whether mining and exploratory license will occur in the Clarence Valley is made by the State Government. Council has indicated that they will continue to uphold its opposition to both current and future mining activities in the Clarence River catchment.

RELATED RURAL LANDS STRATEGY RECOMMENDATIONS

Note: the recommendation numbers relate to those presented in the Rural Land Strategy document for ease of reference.

Facilitate effective land use planning for rural areas

Recommendation 3: Review the zoning of rural lands that have strong environmental attributes or form part of strategically important biodiversity corridors

Applying appropriate environmental zones is key to ensure land with strong environmental attributes is managed sustainably. Alternatively, if rezoning is not preferred, a local provision for terrestrial biodiversity, riparian land and watercourses or similar map be considered alongside associated mapping.

Recommendation 7: Reinforce existing DCP controls for protection of biodiversity and environmental outcomes through review of buffers and related provisions

Analysing, and amending where required, current DCP controls with respect to protecting biodiversity and environmental outcomes will reinforce biodiversity protections and ensure reduce impacts from adjoining intensive agricultural uses.

Elevate the importance of rural lands within Council and the community

Recommendation 9: Update, maintain and promote Council’s website and associated data as a key resource for rural lands

Education and providing resources online in relation sustainable land management can cover a broad range of issues in a relatively succinct space. Key resources could include establishing an ‘Agricultural Section’ of Council’s website and continually updating Council’s Disaster Dashboard, flood information on the public Intramaps, bushfire prone land mapping and information related to vegetation clearing.

Engage with government and industry to leverage support

Recommendation 17: Provide a range of programs, training and education opportunities for rural landowners and the broader public Through Council’s ‘Sustainable Agricultural Officer’, and in conjunction with government and industry various opportunities within natural disasters, climate change, biosecurity risks, regenerative agriculture, sustainable farming and production methods and land management techniques can be driven.

Recommendation 19: Collaboratively work to ensure appropriate bushfire land management across the Clarence Valley

Ensuring effective management of rural land in preparation of a bushfire requires a cross-agency and multi-cultural approach both in terms to management practices and communications to rural landowners.

Recommendation 20: Facilitate ongoing equitable access and use of water resources

In conjunction with DPI, DPIE - Water and NRAR, Council will continue to monitor and respond to issues to facilitate ongoing equitable access and use of water resources within the Clarence Valley, particularly licencing and including the impacts of changes to water harvesting rights.

Recommendation 21: Lobby government to remove existing, and prohibit new, mining or exploratory licences

Mining can have a significant impact on agricultural practices and the environment of the Clarence Valley. Lobbying of government will occur in alignment with Council resolutions.