26 minute read

by Kenneth L. Smith-Christmas and Owen Linlithgow Conner

The Shoulder Sleeve Insignia of the Fourth Brigade of Marines, 1918–1919

Kenneth L. Smith-Christmas and Owen Linlithgow Conner

Advertisement

In 1982, an article entitled, “Genesis of a Shoulder Sleeve Insignia” by K. L. Smith-Christmas, the then-registrar of the Marine Corps Museum, appeared in the U.S. Army Center for Military History’s quarterly museum publication, The U.S. Army Museums Newsletter. Its publication was preceded by a much-condensed version in the spring 1980 issue of the Marine Corps’ historical quarterly, Fortitudine. Both of these articles had been written without the benefit of being able to examine and analyze original artifacts as, at that time, the registrar’s access to the collection was confined solely to incoming acquisitions and outgoing loans. Moreover, the collections were in need of some serious curatorial attention. Fortunately, however, the insignia on some uniforms in the collection were hurriedly photographed and recorded in what catalog record files were then extant. The article reads as follows:

Genesis of a Shoulder Sleeve Insignia

In World War I the 2d Division first used the Indianhead to identify its transport on the crowded French roads. Many officers and men had a hand in its design By K. L. Smith-Christmas

During the early planning stages for a special art exhibit entitled, “Through the Wheat,” the Marine Corps Museum staff decided some portion of the exhibit should deal with the star and Indian head insignia worn as a shoulder patch by both the 4th Brigade of Marines and its parent 2d Division (Regular Army), American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during World War I. With the rapidly growing interest in World War I uniforms and insignia, this would not only add to the exhibit, but would also clear up some misconceptions regarding the insignia.

The insignia itself is unique in the World War, and the story of its evolution is fascinating, in that so many individuals were involved in its design and application. It was one of the few divisional insignia of the AEF to be used for a tactical purpose.

Luckily, the staff found it had a mass of documentary material upon which to base captions for the exhibit’s artifacts. Richard A. Long, curator of special projects, had “rediscovered” an entire file of documents in the Reference Section of the Marine Corps Historical Center dealing with the evolution of the insignia. Tim Nenninger, an archivist with the Navy and Old Army Branch of the National Archives, who researched the AEF records, discovered many documents that were missing from the files Mr. Long had located. As research continued, all the museum’s “Indian head” uniforms in storage and in the research collection were documented.

With the possible exception of several units during the Mexican War, the AEF’s 2d Division was the only hybrid Army/Marine division ever fielded by the United States. It was composed of two infantry brigades, the 3d (Army) and 4th (Marine), the 2d Field Artillery Brigade, and divisional troops.

Its first commanding general was Brig. Gen. Charles A. Doyen, USMC, the commander of the 4th Brigade and the senior officer on board when the division was organized on 26 October 1917. He was relieved by Army Maj. Gen. Omar Bundy on 18 November 1917. In mid-July 1918, Brig. Gen. James G. Harbord (Army), became the division commander, but less than two weeks later turned over the command to Marine Maj. Gen. John A. Lejeune, and assumed control of all AEF logistical activities. General Lejeune remained as commander of the division until it was returned to the United States and broken up on 3 August 1919.

The evolution of the division’s insignia began in March 1918, when its transport became intermixed with French Army wagons and camions en route to the front lines for the first time near Verdun. On the road through Neufchateau, Gondrecourt, Ligny, and Bar-le-Due, it became apparent some type of distinguishing insignia was needed on the vehicles to prevent the mass confusion which plagued the march.

On 28 March, Lt. Col. William F. Herringshaw, commander of the 2d Supply Train, issued a memorandum outlining the problem and offering prizes to members of his five companies who submitted the best unit insignia. After assessing each officer five francs, he set the three prizes at 40, 25, and 10 francs each.1

Many designs were submitted but the contest committee could not reach a decision. Breaking the stalemate, Colonel Herringshaw superimposed the Indian head design submitted by Sgt. Louis J. Lundy, of Company A, on the white star design submitted by Sgt. John Kenny of Company B. (The committee awarded first prize to Lundy and second prize to Kenney.) Colonel Herringshaw then forwarded a proposal to division headquarters, 12 April, recommending the insignia be stenciled on all 2d Division vehicles and suggesting a blue bonnet and red face on the Indian’s head. Two days later, General Bundy approved the recommendation and requested the design be stenciled on his staff car. This was done while the automobile was undergoing minor repairs at La Ferte-sous-Jouarre, near Chateau-Thierry.2

Throughout the summer of 1918, little thought was given to the use of an insignia for anything else but vehicles. With the battles of Belleau Wood and Soissons, the 2d Division had enough to worry about. However, in the lull before the St. Mihiel offensive, during a conference of 9th Infantry Regiment officers, on 4 September, a system of

FIG 1. Medal of Honor recipient Lt. Louis Cukela (second from left) poses with Capt. Robert Blake (second from right), with Chaplain Mokely and another officer of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines. Both Cukela and Blake are wearing insignia with the Indian head painted on the white star.

unit identification was devised. Following the prevalent British Army system of geometric cloth tactical patches, it was decided regimental headquarters personnel would wear a three-inch square of red and white cloth, divided diagonally from lower left to upper right with the red portion uppermost. The 3d Battalion was to wear a threeinch square of red cloth, sewn three inches down each sleeve from the shoulder. The 2d Battalion decided on oneinch squares of white cloth on the rear of the left shoulder, as its officers believed a large white insignia on each sleeve would draw enemy fire. The 1st Battalion, which was to be the last “over the top,” was to wear three-inch blue squares on each arm. However, it went into action with bare sleeves.3 Maj. Hanford MacNider, the officer sent to Toul to obtain material, could not find any blue cloth.

Obviously, the brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Hanson E. Ely, approved of the scheme, as he directed the officers of both the 23d Infantry and the 5th Machine Gun Battalion to meet on the afternoon of 6 September 1918 and decide on respective insignia for use in the forthcoming offensive. His memorandum, which described the insignia adopted by the 9th Infantry, mistakenly reported the three-inch squares of material as being· four-inch squares.4

Following the action of St. Mihiel, on 22 September 1918, 1st Lt. Oskar E. Youngdahl of Company G, 23d Infantry, sent a letter to his regimental commander recommending the series of distinguishing patches adopted on 6 September be retained, as they had “facilitated regrouping and reorganization of the men at the various stages of the action.” From his letter we learn the system used by the 23d Infantry was a series of isosceles triangles worn on the left sleeve, four inches below the shoulder. The insignia of the 1st Battalion was green, that of the 2d Battalion white, and that of the 3d Battalion blue.

However, the letter is rather confusing, since Lieutenant Youngdahl stated without clarification red patches were also used. He also left unclear what color the regimental headquarters and the supply and machine gun companies used.

In any case, regimental headquarters and Companies A, E, and I wore a triangle of cloth in their particular color with the apex pointing up. Companies B, F, and K wore the triangle with the apex pointing to the front. The regimental supply company and Companies C, G, and L wore the triangle with the apex pointing down. Companies D, H, and M wore the triangle facing to the rear. Youngdahl made the additional recommendation that any unit temporarily attached to another unit be required to wear that unit’s insignia in addition to its own. Although his company commander, Capt. F. F. Hall, favorably endorsed his recommendation, there is no evidence the battle-tested scheme was continued during the Meuse-Argonne campaign.5

As the 2d Division neared the Meuse River after weeks of hard fighting, General Lejeune found time to answer a telegram from AEF Headquarters, asking him to submit a design for a proposed divisional insignia. The general outlined his recommendation on 20 October, but this did not satisfy higher headquarters, which telegraphed again that same day requiring a full written explanation of the proposed system as well as a sample drawing of the Indian head and star design. General Lejeune wrote back the next day saying he proposed to use an Indian head copied after St. Gauden’s sculpture on the American five-dollar gold piece. This was to be embroidered on a white star and would be of better artistic quality than the paper sample enclosed in the letter. He justified the insignia stating “the design has been used in this division for some time, and already [has] been painted on all the transportation of the division.” In anticipation of its approval “steps had already been taken to procure insignia of this design for issue to each officer and enlisted man in the division.” The general asked for full approval as soon as possible so “the insignia could be issued before the division goes into the line again.”6

On 6 November, five days before the Armistice, General Lejeune received approval to use the design submitted the previous month. Insignia instructions were promulgated to the division on 14 November under Order No. 29. The insignia was to be “worn on the left shoulder with the top of the insignia at the shoulder seam of the coat.” The order further noted the star would be of such dimensions as to be contained in an imaginary circle of three and one-half inches in diameter. The Indian head was to be centered on the star and would have a red face and blue bonnet. The head could be either stamped on the white star or,

as was usually the case, embroidered. After specifying the different colors and shapes of the cloth backgrounds for each component unit, the order required all unit commanders to provide the cloth backings to their troops pending receipt of the star and Indian head insignia.7

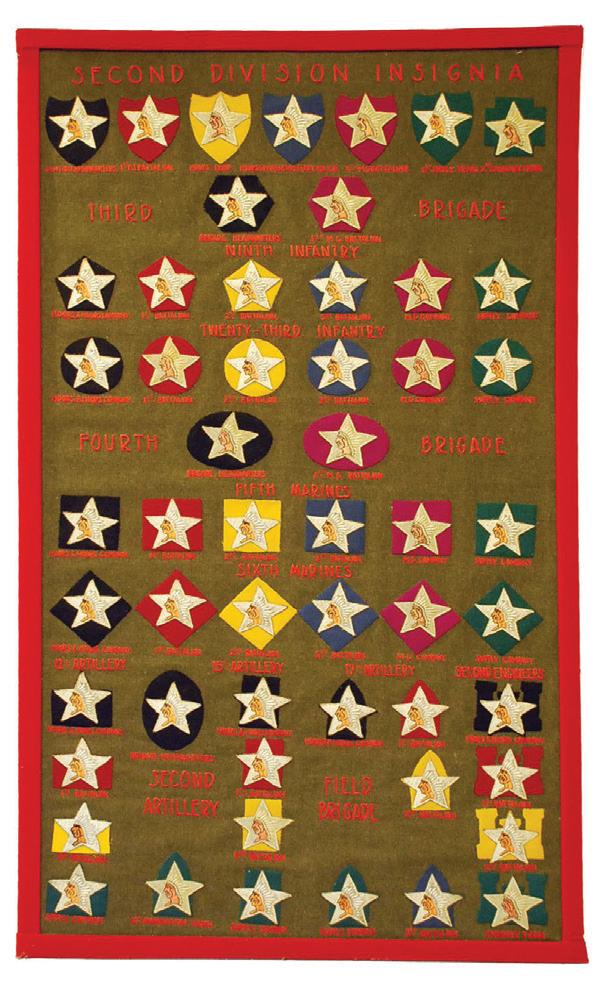

Basically, the overall scheme was to use easily recognizable shapes of varied, but more or less systematically colored, cloth backings. In general, black was used to denote headquarters units and purple machine gun and trench artillery units; most supply units used green. Use of other colors, however, was not as consistent. In most cases, red was used by the 1st battalions of each of the four infantry regiments; yellow by the 2d battalions of the infantry or Marines; and blue by the 3d battalions of the 3d or 4th Brigades. The cloth backing of the patches were as follows:

On SHIELD (Black) Division Headquarters (Yellow) Headquarters Troop (Red) 1st Field Signal Battalion (Blue) Train Headquarters and Military Police (Purple) 4th Machine Gun Battalion (Green) 2d Supply Train On HEXAGON (Black) 3d Brigade Headquarters (Purple) 5th Machine Gun Battalion On PENTAGON (Black) 9th Infantry Regiment Headquarters and Headquarters Company (Green) Supply Company (Purple) Machine Gun Company (Red) 1st Battalion (Yellow) 2d Battalion (Blue) 3d Battalion On CIRCLE 23d Infantry Regiment (used same system as 9th Infantry) On HORIZONTAL OVAL (Black) 4th Brigade Headquarters (Purple) 6th Machine Gun Battalion On SQUARE 5th Marine Regiment (used same system as 9th Infantry) On DIAMOND 6th Marine Regiment (used same system as 9th Infantry) On VERTICAL OVAL (Black) 2d Field Artillery Brigade Headquarters (Purple) 2d Trench Artillery Brigade On HORIZONTAL OBLONG 12th Field Artillery Regiment (used same system as 9th Infantry) On VERTICAL OBLONG 15th Field Artillery Regiment (used same system as 9th Infantry) On UPRIGHT PROJECTILE 17th Field Artillery Regiment (used same system as 9th

Infantry, except that 2d Ammunition Train used same colored backing as Supply Company of 17th Field Artillery

Regiment)

On CASTLE 2d Engineer Regiment (used same system as 9th Infantry, except that 2d Engineer Train used same colored backing as 2d Engineer Regiment)

On GREEK STYLE CROSS (Green) 2d Sanitary Train

Recently retired Marine Lt. Gen. Merwin H. Silverthorn told John L. Stacey, a Washington area historian and

FIG 2 (left). 2d Division Headquarters Insignia—“This insignia of the 2d Division (Regular) AEF headquarters is a finely embroidered Star & Indian Head, as opposed to one of the standard issue embroidered versions. This patch belonged to Marine Lieutenant General John A. Lejeune.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1985.984.1. FIG 3 (right). HQ Co., 5th Marines—“Although it is not now known for certain when the embroidered insignia first appeared, there are several variations to the Indian chief’s face and his war bonnet. This one, on the black square backing (velvet) of the Headquarters Company of the 5th Marines, is one of the most visually pleasing versions. It is associated with Gunnery Sergeant John W. Clark.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2004.104.19.

FIG 4 (left). MG Company, 5th Marines—“This insignia from the Machine Gun Company of the 5th Marines was painted by a talented artist, but not the same artist who painted insignia in other units. It is stitched onto a square of purple felt, and belonged to Corporal Joseph France Foley.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2007.40.1. FIG 5 (right). 1st Bn, 5th Marines—“Contrasting with other beautifully painted Indian Heads, is this one, done in a much cruder style. It is from the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines and was worn by then-Sgt. Albert A. Taubert, a recipient of the Navy Cross, who later had quite a career in the ‘Banana Wars’ in Haiti. The red background was crudely constructed from a civilian quilt.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1994.82.17.

FIG 6 (left). 2d Bn, 5th Marines—“There were several variations of the mass-produced, embroidered version of the Star & Indian Head, with different facial features on the Indian’s face and different colored feathers in his war bonnet. This one, from the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, has white feathers in the bonnet, and the long vertical crease in the Indian’s face. It was worn by Corporal Allen J. Wells, who, at the time, served with the 18th Company (Co E, 2/5).” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2004.102.17. FIG 7 (right). 3d Bn, 5th Marines—“This variation of the massproduced Star & Indian Head, has the feathers outlined in blue, and it has been crudely stitched onto the blue square of the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines. Corporal Allen J. Wells was reassigned to the 3d Battalion in June 1919.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2004.102.18. collector of Marine Corps uniforms, that the star and Indian head insignia were issued embroidered on long strips of cloth tape.8 They were also embroidered on large squares of khaki wool.9 Each soldier or marine was expected to cut off his insignia, trim it, and either sew it on the cloth backing himself or have the company tailor do it.

Although the cloth insignia were completely standardized on uniforms, such was not the case regarding wheeled transport. During the occupation of Germany, an order was issued which specified insignia dimensions to be used on all the division’s transport not already bearing divisional markings. This order, written 12 March 1919, also provided the cross and ribbon of the Croix de Guerre be painted on the transport of those units which had been awarded this decoration.10

Various sized vehicular insignia were based on the diameter of an imaginary circle in which the star was placed. For instance, all motorcycle gasoline tanks were to be painted with a star and Indian head which would fit in an imaginary three and one-half-inch circle. Shapes and colored backgrounds were in compliance with Order No. 29 of 14 November 1918. The 12 March 1919 order is noteworthy as it listed all the different types used by the division at the time. The dimensions and placement of the insignia on the various transport were as follows:

5-inch Insignia

Motorcycle sidecars: in center of front cowl.

Touring cars and staff observation cars (white): centered on both front doors.

Machine gun cars: centered on both middle doors.

Light trucks and motor ambulances: side—on both middle doors centered on first full-sized panel from front; rear— centered on right-hand panel.

Escort wagons—side: centered on second panel from front; rear—centered on right-hand panel.

Ration carts and medical carts: left side only—centered on first panel from front; rear—centered on right-hand panel.

Water carts: sides—centered on the tank; rear—centered on the tank.

Rolling kitchens: sides—centered on first panel from front.

Combat wagons (caisson type): sides—on limber only,

FIG 8 (left). HQ Co., 6th Marines—“This version of the painted Star & Indian Head has the feathers painted in different colors. It is stitched onto the black diamond backing for Headquarters Company, 6th Marines, in black velvet. This insignia was worn by Private Paul Dallas Rust, who served in that unit for the duration of the war and the occupation of Germany.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1996.2.1. FIG 9 (right). 1st Bn, 6th Marines—“Obviously, there were some qualified and talented artists in the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, as this example is one of the best of the early hand-painted insignia. It was worn by Sergeant Charles H. Barnes during his service with the 75th Company (Co B 1/6).” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1987.243.1. FIG 10 (left). 2d Bn, 6th Marines—“Again, the Indian Head has been painted by another artist, this time in the 2d Battalion, 6th Marines, and is painted on a white twilled material. It is in a more orange-hued yellow, and is on the service coat worn by Captain Amos R. Shinkle.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1993.138.1. FIG 11 (right). 3d Bn, 6th Marines —“The 6th Marines also made use of one of the versions the mass-produced Star & Indian Head, and this one, on the blue diamond of the 3d Battalion, 6th Marines, has the feathers outlined in blue, with a short vertical crease in the Indian’s face. It is associated with Sergeant Clarence Baumgartner, who served with the 82d Company (Co I, 3/6).” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1982.55.1.

centered on upper front wing panel; rear—centered on upper right-hand panel. Machine gun carts: rear—centered on rear end of box containing machine gun. Machine gun ammunition carts: rear—centered on rear of left-hand toolbox.

10½-inch Insignia

Heavy trucks: sides; centered on first panel from front; rear—centered on right half of tailgate or bumper.

Engineer tool wagons: sides—centered on third upper panel from front; rear—centered on right-hand panel.

Even as these insignia were being regularized and painted on vehicles, the origin of the insignia was becoming clouded in myth. The divisional magazine, The Indian, reported in May 1919 an unknown truck driver had dreamed up the insignia all by himself and had painted it on his truck without authorization in early 1918. According to the article, his commanding officer liked the idea and directed all the trucks to be painted in that manner.11 Despite the many efforts throughout the years to debunk this fictional account, it is still current.

A variation of the insignia, which is often a point of confusion to historians and collectors, was its use without any colored cloth backing. These insignia, according to General Silverthorn and former Commandant Clifton B. Cates, were worn by the two companies from the 2d Division that were temporarily attached to the 1st Composite Regiment, A.E.F.12 This regiment was formed in the late spring of 1919 as a ceremonial unit and participated in several parades, both in Europe and in the United States, after return from Germany. Marines wore these insignia on Marine dress blue and forest green blouses and on Army khaki blouses.

Unfortunately, the Marine Corps Museum does not have any Army blouses bearing the 2d Division insignia with 4th Brigade cloth backings. These are very rare, although the Marines wore them during the war and later occupation. They all were replaced with Marine Corps blouses when the brigade returned to Quantico in August 1919.13 The men transferred their insignia to their new uniforms and the Army-issue blouses were disposed of.

The star and Indian head is used to this day as the official patch of the 2d Infantry Division, U.S. Army. Its only use left in the Marine Corps is on the unit plaques of the 6th Marines.

FIG 12. 6th MG Bn—“The entire 6th Machine Gun Battalion wore their Star & Indian Head insignia on a purple horizontal oval. This example is one of the variations of the mass-produced embroidered insignia, with the feathers outlined in blue, and with long vertical creases in the Indian’s face.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2012.115.7.

FIG 13 (left). “Lejeune Blanket”—“The men of the 2d Division presented this display, with an example of each U.S. Army and Marine Corps insignia within the division on it, to their commanding general, John A. Lejeune. This remarkable variety of patches was sewn to a wool service blanket.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1975.917.1. FIG 14 (right). “Swatch” of S&I insignia on wool—“At least three, and perhaps more, types of the Star & Indian Head insignia were embroidered onto wool backings, and then cut out by individuals or tailors, and stitched to one of the differently-colored and shaped backgrounds that represented the various units within the 2d Division, (Regular) A. E. F. Further research is needed to discover where these different insignia were actually manufactured.” Courtesy, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 1984.286.1.

Notes

1. Memo for LTC Herringshaw to Second Supply Train, dated 28 Mar 1919, AEF, AG Insignia File, Second Division, Records of the American Expeditionary Forces (World War I), Record

Group (RG) 120, National Archives and Records Administration,

Washington. DC, (hereafter RG 120, NARA). 2. Gordon H. Steele, lLT, QMC, “The Origin of the ‘Star and Indian

Head,’” The Trail, Camp Travis, Texas, 1, no. 11, 1. 3. Letter from CPT C. O. Mattfeld to MAJ A. M. Jones, dated 30

August 1926, AEF, AG Insignia File, Second Division, RG 120,

NARA. 4. Memo from BG El to CO 23d Infantry, dated 6 September 1918,

AEF, AG Insignia File, Second Division, RG 120, NARA. 5. Memo from 1LT Oskar E. Youngdahl to CO 23d Infantry, dated 22

September 1918. AEF AG Insignia File, Second Division, RG 120,

NARA. 6. AEF AG Insignia File, Second Division, RG 120, NARA. 7. Ibid. 8. Telecon between John L. Stacey and K. Smith-Christmas, March 1980. 9. In the collection of James Nilo, a collector of Marine Corps memorabilia. 10. AEF, AG Insignia File, Second Division, RG 120, NARA. 11. Rare Books Collection, U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center

Library, Quantico, VA. 12. Silverthorn Collection, PC 198, National Museum of the Marine

Corps, Quantico, VA. 13. Frank E. Evans, LTC, USMC: “Demobilizing the Brigade,” Marine

Corps Gazette, 4 (December 1919): 309.

Within a few years after this article was published, several new members joined the Marine Corps Museum staff—Anthony Wayne Tommell, J. Michael Miller, John G. Griffiths, and the late John H. McGarry III—and all of them were members of the Company of Military Historians. Together, and under new direction, they, along with other additional staff members, interns, and volunteers, helped the existing museum staff members computerize, regularize, and recatalog the collections over the next decades. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, it was finally possible to conduct comparative studies involving artifacts, especially in the uniform and insignia collections.

The answer to the question, “Who actually made the Star & Indianhead insignia and how were they issued?” was one of the most glaring omissions in the 1982 article. Thankfully, the insignia that were already in the collection in 1982 and all of those insignia acquired since then can now be studied and analyzed to answer those questions— at least in part. The National Museum of the Marine Corps now has examples of nearly all of the insignia worn by the component units of the 4th Brigade, and also has a wide variety of examples that show all the known manufacturing styles. Moreover, all of these insignia have proven provenance from their donors, so the museum’s sampling is free from reproductions, replicas, or fakes, as could possibly be the case with any private collection that depended on acquisitions purchased from dealers or other collectors.

When the approval to use the Star & Indianhead motif on the variously shaped and colored backgrounds was granted on 6 November 1918, the 2d Division was fully engaged in the final assaults into the Argonne Forest and would just be crossing over the Meuse River at the Armistice on 11 November 1918. It is doubtful whether anyone had the time, inclination, or opportunity, to hand-paint portraits of Indian chiefs on white cloth stars during that time. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume the manufacture of the stars did not commence until the division had completed its grueling march into Germany and had gone into occupation billets in the region around Koblenz.

The first stars have hand-painted portraits of Indian chiefs and, while some follow the St. Gauden motif on the five dollar gold piece, there are a variety of styles and colors. This underlines the theory the artists were multiple “soldier artists” involved in the production of the stars— but how many artists and in which units, no one knows for sure. To date, no documentary evidence has yet surfaced that contains phrases such as “being accomplished with an artists’ paint brush, Corporal So-and-So was detailed to paint insignia for the (squad, platoon, company, battalion),” or “ Lieutenant Umptyfratz painted sleeve insignia for the officers’ mess, using the skills he gained from attending art classes at (Yale, Harvard, etc.).” There were numerous skilled artists among the Marine officers, like the famed illustrator John W. Thomason and the cubist Claggett Wilson and from an examination and analysis of the insignia painted on the helmets, there must have been more than a few accomplished artists in the enlisted ranks. Moreover, even local German artists may have painted some of the insignia, in spite of strict nonfraternization policies. At this point, no one really knows. While many researchers have gleaned the personal papers collections in the Marine Corps Archives at Quantico for information on operations in France, few researchers have ever searched the collections for information on material culture. The answers to this question may still be found through further research or may serendipitously become available as a by-product of other research.

After the initial use of the hand-painted insignia, embroidered insignia were acquired for general issue to the entire 2d Division. These stars were embroidered on swatches of olive drab wool cloth, in varying shades of olive drab, and obviously in different contracts. They were then cut out and stitched to the appropriate backing material, of the shapes and colors described in the 1982 article. For Marines, aside from those assigned to 2d Division Headquarters (who wore their stars on

a black shield), they wore a square (for the 5th Marine Regiment), a diamond (for the 6th Marine Regiment), or a horizontal oval (in black for Brigade Headquarters and in purple for the 6th Machine Gun Battalion). For the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments, the system dictated a black background for the headquarters companies, green for the supply companies, and purple for the machine gun companies. The first battalion within the regiment wore red, the second battalion yellow, and the third battalion blue. Purple was worn by all of the companies in the 6th Machine Gun Battalion.

Sadly, no information has yet to surface which would indicate where these embroidered stars were acquired or who was detailed to obtain them. The stars, on their swatches of wool cloth, are most likely of French manufacture, but some, or perhaps all of them, could be German. There are at least three distinctive styles: one with plain feathers on the chief’s war bonnet; one with the feathers outlined in blue; and one with blue feathers, but with a different bonnet headband and depiction of the Indian chief’s face. It could be supposed the outlined feathers may be the last issue, as, from a distance, the insignia is more defined with the outlined feathers—a definite improvement. However, this is pure supposition, as all three (or even more) variations simply could have been concurrent manufacturing runs and arranged by different units within the Brigade or the Division. Again, researchers are urged to avail themselves of the opportunity to delve into the document collections at the Marine Corps University’s new Edwin H. Simmons Historical Center (adjacent to the Alfred M. Gray Research Center) at the Marine Corps’ base in Quantico, Virginia, to find the answers to these questions and then share them with the military history community.

The authors sincerely hope those manufacturers of replicas who insist on producing unmarked copies that “will even fool the curators” will not use the information offered here to make exact replicas for “living history” enthusiasts and reenactors. This reprehensible practice only confuses the field of material culture and further frustrates the preservation and study of actual artifacts by future generations.

Ken Smith-Christmas first joined the Company of Military Historians in 1965 and spent nearly 30 years on the staff of the Marine Corps Museum. Owen Conner joined the Company in 2013 and is now the Curator of Uniforms and Heraldry for the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

vRobert Rucker Charter Member, 1951 Mission Viejo, California

Alfred H. Seibel Oceanside, New Jersey v

New Members Spring 2018

Sumner G. Hunnewell by Jack & Maggie Grothe Lt. Col. Robert J. Driver, USMC (Ret.) by Edwin W. Besch Errol Steffy by Wally Heimbach Brendan O’Shea via CMH Online Charles Kaufman via CMH Online Wesley Dawson via CMH Online Stephen J. Kent by Sam Small Col. Paul R. Rosewitz, USA (Ret.) by Jack & Maggie Grothe John T. Frawner, Jr via CMH Website Joseph E. Schaeffer by Wally Heimbach Janet Wilzbach by Jack and Maggie Grothe Col. Walter W. Davis, Jr by Randy Baehr Errol Steffy by Wally Heimbach Corey King by Paul Lear Ran Maness reinstated by Sam Small Scott W. Radcliffe by Jack & Maggie Grothe Cisco Lopez by Mark Kasal Sam Barnes reinstated via CMH Online Damon Sumpter by Randel Baehr David Ervin by David M. Sullivan Elizabeth A. Malloy by David M. Sullivan Kenneth Osen reinstated via CMH Online Scott Walter by Kenneth Osen Paul Newman via CMH Online