1999 2023 ISSUE 95 JANUARY 2023 ISSN 2397-138X HAPPY NEW YEAR HAPPY NEW YEAR HAPPY NEW YEAR

THE JING INSTITUTE – SCHOOL OF MASSAGE AND COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE 28/29 Bond Street, Brighton BN1 1RD • 01273 628942 • info@jingmassage.com jingmassage.com FREE ZOOM FOR THERAPISTS MANUAL THERAPY FOR LOW BACK PAIN Learn the latest research and cutting edge techniques to help improve client pain and mobility. TUESDAY 31 JANUARY 2023 1-2PM Register online: buff.ly/3V2n7tu

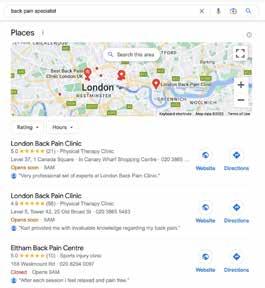

TECHNICAL SHORT LONG PRACTICAL JANUARY 2023 ISSUE 95 ISSN 2397-138X is published by Centor Publishing Ltd 88 Nelson Road Wimbledon, SW19 1HX, UK https://Co-Kinetic.com HOW TO TARGET NICHE MARKETS FOR SEARCH ENGINE OPTIMISATION 42-44 Instagram www.instagram.com/co_kinetic/ Facebook www.facebook.com/CoKinetic Our Green Credentials Paper:100% FSC Recycled Offset Paper Our paper is now offset through the World Land Trust Naked Mailing No polybag used Plant-Based Ink Used in Printing Process Twitter https://twitter.com/co_kinetic LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/co-kinetic/ YouTube www.co-kinetic.com/youtube CBP006075 More details https://bit.ly/3dAwGwd Publisher/Founder TOR DAVIES tor@co-kinetic.com Business Support SHEENA MOUNTFORD sheena@co-kinetic.com Technical Editor KATHRYN THOMAS BSC MPhil Art Editor DEBBIE ASHER Sub-Editor ALISON SLEIGH PHD Journal Watch Editor BOB BRAMAH MCSP Subscriptions & Advertising info@co-kinetic.com what’s inside 4- 11 JOURNAL WATCH SOCIAL MEDIA SUCCESS FOR PHYSICAL THERAPISTS 45- 50 20-26 THE HYPERMOBILITY CONUNDRUM CLINIC POSTERS 12- 13 DISCLAIMER While every effort has been made to ensure that all information and data in this magazine is correct and compatible with national standards generally accepted at the time of publication, this magazine and any articles published in it are intended as general guidance and information for use by healthcare professionals only, and should not be relied upon as a basis for planning individual medical care or as a substitute for specialist medical advice in each individual case. To the extent permissible by law, the publisher, editors and contributors to this magazine accept no liability to any person for any loss, injury or damage howsoever incurred

indirectly, of the use by any person of any of the contents of the magazine.

Limited consents to certain features contained in this magazine marked (*) being copied for personal use or information only (including distribution

shown. No other unauthorised reproduction, transmission or storage in any electronic retrieval system is permitted of any material contained in this

liability

arising) in connection with the supply or use of any goods or services purchased as a result of any advertisement appearing in this magazine. 14-19 SHOULD WE BE TAKING 'GROWING PAINS' MORE SERIOUSLY? 27-32 EVIDENCE BASE FOR INSTRUMENT ASSISTED MASSAGE MANUAL THERAPY AND LOW BACK PAIN 33-41

(including by negligence) as a consequence, whether directly or

Copyright subsists in all material in the publication. Centor Publishing

to appropriate patients) provided a full reference to the source is

publication in any form. The publishers give no endorsement for and accept no

(howsoever

EFFECT

Ansari A, Nayab M, Saleem S et al. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies

OF SOFT AND PROLONGED GRAECO-ARABIC MASSAGE IN LOW BACK PAIN - A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL.

2022;29:232–238

Forty-eight patients with clinically and radiologically diagnosed low back pain were randomised into test and control groups (both n=24). The massage group received soft and prolonged massage at the lumbo-sacral region every alternate day for 20min for up to 3 weeks using a herbal lotion with mainly anti-inflammatory properties. The massage consisted of superficial stroking (10min) followed by tapping (5min) and finally pounding (5min). The

Co-Kinetic comment

control group received shortwave diathermy with a frequency of 27.2Mhz given on every alternate day up to 20min for 3 weeks. The result was that a pain scale score was reduced by 42.14% in the massage group and 13.94% in the control group. Scores on the Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire improved by 37.16% in the massage group and 5.93% in the control group.

You can either accept that the results are influenced by a traditional medicine system similar to Ayurvedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine with its accompanying mysticism or look at this as massage v electrotherapy – and massage won. For the record, Graeco-Arabic medicine is primarily based on the ancient methods taught by Hippocrates (who lived in Greece between 460bc and 370bc) and Galen (who lived in Greece and later in Rome between ad129 and 199) with further contributions by Avicenna (an Arabic scholar who lived in Iran between ad980 and 1037). Treatments include diet, herbal and mineral medicine, massage, manipulation and the application of cold, heat or suction cups.

EFFECTIVENESS OF TREATMENTS FOR ACUTE AND SUBACUTE MECHANICAL NON-SPECIFIC LOW BACK PAIN: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW WITH NETWORK META-ANALYSIS. Gianola S, Bargeri S, Del Castillo G et al. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2022;56:41–50

The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of interventions for acute and subacute non-specific low back pain (NS-LBP) based on pain and disability outcomes. A search of the usual medical databases for randomised clinical trials (RCTs) involving adults with NS-LBP who experienced pain for less than 6 weeks (acute) or between 6 and 12 weeks (subacute) resulted 46 RCTs (n=8765) being included. The risk of bias was low in 9 trials (19.6%), unclear in 20 (43.5%), and high in 17 (36.9%). At immediate-term follow-up, for pain decrease, the most efficacious treatments against an inert therapy were exercise, heat wrap, opioids, manual therapy and NSAIDs. Mild or moderate adverse events were reported in the opioid (65.7%), NSAID (54.3%) and steroid (46.9%) trial arms.

Co-Kinetic comment Bin the drugs, they have side effects. Here you have evidence that movement and a bit of heat and manual therapy work.

A SURVEY OF CANADIAN MASSAGE THERAPISTS EXPERIENCES

OF WORKRELATED PAIN. Barraclough W, Baskwill A, Higgs C et al. International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork 2022;15(3):18–26

This starts with a quote from a study by Statistics Canada which reported that healthcare workers make up 3% of all reported injuries in the country. Another quoted report by the Registered Massage Therapists’ Association of Ontario reported that 51% of practitioners would like to work more hours per week; however, 40.3% of those who wished to work more hours chose not to, owing to the physically demanding nature of the work, and a further 13.4% did not take on more work because they feared physical burnout. The data for the present study came from 42-item questionnaires (n=1103) sent to massage therapists ranging in age from 20 to 73 years, 85% of respondents were female. The majority (85%) had experienced, or were experiencing, work-related pain (WRP) at one or more of five pre-identified, primary locations with the hand/wrist, the most common site (65.5%); followed by the fingers/thumb (60.3%), shoulder (55.0%), lower back (50.1%), and neck (49.2%). Females were significantly more likely to report neck and shoulder pain than males, and were significantly more likely to report WRP at a higher number of body locations, with approximately one in five female MTs reporting WRP at all of the five primary sites. On a 10-point pain-severity scale, females reported significantly higher perceived pain than males. WRP was attributed to the gradual onset of musculoskeletal conditions by 60.3% of respondents, with no other choice of cause being reported by more than 11.1%. Furthermore, 48% reported an impact on activities of daily living, 31% reporting a loss of income, 54.6% working in pain, and 30.5% considering changing (or having changed) their profession.

Various work adjustments to WRP were reported, including altered biomechanics, the use of adjustable massage tables and chairs, and the use of a greater rest period between patients. Respondents believed that some WRP stemmed from what they considered to be ‘bad habits’ developed early in their careers, and that improving techniques reduced WRP. Therapists referred to ‘hiking shoulders’, ‘torquing wrists’, or over-using thumbs/fingers as undesirable.

Co-Kinetic comment

There have been a few similar studies recently. This one has lots of stats and none of them look good for practitioners. It seems that manual therapy is great for the patients but not so great for the therapists; however, the ‘bad habits’ section suggests that some of it is self-induced.

Co-Kinetic Journal 2023;95(January):4-11

4

OPEN

CLICK ON RESEARCH TITLES TO GO TO ABSTRACT = OPEN ACCESS

OPEN OPEN OPEN

Journal Watch

EFFECTIVENESS

OF EXERCISE

This is a clinical commentary on a Cochrane review “Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain” by Hayden et al. [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021;9:CD009790 (http://bit.ly/3AsaHCK)].

It starts with a very simple question: “Is exercise an effective treatment for adults with chronic low back pain?” It then gives a very simple answer: “Yes”. There is low- to moderatequality evidence that exercise reduces pain and improves function in patients with chronic low back pain compared with no treatment, usual care, and other conservative interventions such as education, manual therapy, and electrotherapy. This effect is clinically significant in the short term (6–12 weeks) but less pronounced 6 months after treatment completion. The review does not recommend a specific exercise regimen to treat chronic low back pain.

The latter point is addressed by stating that current guidelines from the American College of Physicians and the National Institute for Health and Care

THERAPY IN PATIENTS

WITH CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN. Lindberg B, Leggit JC. American Family Physician 2022;106(4):380–381

Excellence recommend general exercise with other nonpharmacologic therapies as initial treatment for chronic low back pain. The guidelines quote a recent metaanalysis by Owen et al. published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1279–1287). It compared a specific 4-week exercise programme with varying weekly exercise regimens and found that using Pilates, resistance training, aerobic exercise, and motor control exercises (ie. activation of the deep trunk muscles progressing from simple to complex tasks with an emphasis on functional activities) were overall the most effective exercise treatment modalities for chronic low back pain.

Co-Kinetic comment

This is like playing research pass the parcel. You open one paper hoping for specific help with your long-term low back pain patients and find that you have to open another and then another before you get to something you can use. It may be better to skip the unwrapping and go straight to the Owen et al. paper. You can get it free at [http://bit.ly/3UWRmCC]

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF MASSAGE THERAPY

AND ABDOMINAL HYPOPRESSIVE GYMNASTICS ON CHRONIC NONSPECIFIC LOW BACK PAIN: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. Bellido-Fernández L, Jiménez-Rejano JJ, ChillónMartínez R et al. Disability and Rehabilitation 2022;44(16):4233–4240

Sixty patients aged between 20 and 65 years who had been diagnosed with chronic non-specific low back pain, had mechanical pain for at least 12 weeks, and had no severe complications were randomly divided into one of three groups (each n=20). Each group received 8 interventions of 30min treatment time over a 4-week period.

Group 1 received a massage therapy protocol focused on their spine designed for the soft tissue of the thoracic lumbar and cervical system, the entire fascial system, and the vertebral joints. Group 2 performed a series of six static abdominal hypopressive exercises consisting of postural exercises that decrease the pressure in the abdominal, perineal, and thoracic cavities. These exercises lead to direct activation of the transverse abdominal muscle, which strengthens the abdominal girdle and stabilises the spine. The participants repeated each exercise three times in addition to a previous phase of learning and a minimum rest period. Group 3 received four interventions of massage therapy and another four interventions of abdominal hypopressive gymnastics in alternating sessions.

Outcomes were an Oswestry disability index score, pain intensity using the Numerical rating scale, an SF12 Quality of life questionnaire and lumbar mobility using a Schober’s test. The results showed that both the massage and exercise groups had reduced pain levels, increased mobility of the lumbar spine, and improved disability and quality of life scores in the short term. The combined group had an even better quality of life score.

Co-Kinetic comment

The great Dr James Cyriax, aka the father of orthopaedic medicine, said that all pain has a source and that unless you find the source and treat it directly you will not solve the problem. Non-specific back pain is therefore an anathema to the good doctor’s many followers. It is a lazy diagnosis. On the plus side, the interventions had a positive effect. The authors also deserve credit for saying, “the massage considered the ergonomics of the physiotherapist”.

5 Co-Kinetic.com RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

An experimental group (n=45) received dry cupping therapy, with cups bilaterally positioned parallel to the L1 to L5 vertebrae. The control group (n=45) received sham cupping therapy. The interventions were applied once a week for 8 weeks. Participants were assessed before the first treatment session, then at the mid-point and the end. The sham was that the cups were prepared with small holes <2mm in diameter to release the negative pressure in approximately 3s. On a 0-to-

DRY CUPPING THERAPY IS NOT SUPERIOR TO SHAM CUPPING TO IMPROVE CLINICAL OUTCOMES IN PEOPLE WITH NON-SPECIFIC CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN: A RANDOMISED TRIAL. Almeida Silva HJ, Barbosa GM, Scattone Silva R et al. Journal of Physiotherapy 2021;67(2):132–139

10 scale, the between-group difference in pain severity at rest was negligible at all of the measurement points. Similar negligible effects were observed on pain severity during fast walking or trunk flexion. Negligible effects were also found on physical function, functional mobility and perceived overall effect. No

Co-Kinetic comment

We didn’t report this when it came out but we have included it now because it acts as a counterpoint to the Traditional Chinese Medicine paper. It’s a bit embarrassing for cupping fans.

THE

Fifty-four subjects with low back pain and decreased length in at least one hamstring were randomised to receive either dry needling (DN) or sham dry needling to the T12 and L1 multifidi. Participants underwent regional (fingertip-to-floor) and remote flexibility (passive knee extension, passive straight leg raise) and pressure pain threshold (PPT) testing of the upper and lower extremity before, immediately after and 1 day after treatment. The DN consisted of needles placed using an inferomedial approach approximately

1cm lateral to the spinous process and guided through the muscle to the lamina. Needles were manipulated in a ‘pistoning’ fashion. For the sham, real needles had their sharp end cut off and smoothed. They were kept in the holders and tapped to stimulate the ‘pistoning’.

The results showed that statistically larger improvements in regional flexibility, but not remote flexibility, were observed immediately post-treatment in those who received DN compared to those receiving sham; however, the

EXERCISE AS EFFECTIVE AS SURGERY

IN

IMPROVING

worthwhile benefits could be confirmed for any of the remaining secondary outcomes. OPEN

EFFECTS OF DRY NEEDLING TO THE THORACOLUMBAR JUNCTION MULTIFIDI ON MEASURES OF REGIONAL AND REMOTE FLEXIBILITY AND PAIN SENSITIVITY: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. Clark NG, Hill CJ, Koppenhaver SL et al. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 2021;53:102366

effect did not carry through to the plus 1 day test. Differences between upper and lower extremity PPT were not significant.

Co-Kinetic comment

This is another paper we did not report when it was first published but it also serves as a counterpoint to the Traditional Chinese Medicine paper. This time the sham is not quite as successful in that there is a short-term effect on flexibility but it doesn’t last. This is not the place for an argument about the difference between acupuncture and DN.

QUALITY

OF LIFE, DISABILITY, AND

PAIN

FOR

LARGE

TO MASSIVE ROTATOR CUFF TEARS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW & METAANALYSIS. Fahy K, Galvin R, Lewis J et al. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 2022;61:102597

OPEN

A search was made of the usual medical databases looking for studies about exercise intervention for adults with large-to-massive rotator cuff tendon tears, which are defined as >5cm and involving two or more tendons. Five trials (n=297 participants; average age, 66.7 years; 55% male) were included in the analysis. Three trials compared exercise to another non-surgical intervention and two trials compared exercise to surgery.

At 12 months a significant improvement in pain was found for the surgical group and a significant improvement in shoulder external rotation ROM favoured the exercise group.

Co-Kinetic comment

There are other measures in this study but, based on the available evidence, exercise is as effective as surgery. A caveat is that the authors complain of very low standards of quality of the evidence, and so in reality the jury is still out. We should probably also stress that the success of most surgical procedures, anywhere in the body, depends on the quality of post-surgery rehab so it’s worth trying the exercise approach first.

EFFECTS OF CRYOTHERAPY AFTER SOFT TISSUE INJURY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW.

Mohd Radzi AAA, Mohamad MY. International Journal of Allied Health Sciences 2022;6(2):2625–2631

OPEN

This study aimed to review the effects of cryotherapy on pain reduction and time taken to return to normal activity after soft tissue injury. The Science Direct, PubMed, and Cochrane library were searched. Only 3 articles out of 178 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Significant difference can be seen in terms of pain measured in VAS score when cryotherapy is applied either alone or together with manual therapy. A total of 161 patients who received cryotherapy out of 179 patients from 3 articles reported an average reduction of 2.3 VAS points from their initial score. However, there were no studies that specifically included time taken to return to normal activity as an outcome measure.

Co-Kinetic comment

Cool! [Groan – Ed]

Co-Kinetic Journal 2023;95(January):4-11

6

OPEN

A sports-related concussion (SRC) is most commonly sustained in contact sports. An exercise-induced elevation of core body temperature is associated with increased brain temperature that may accelerate secondary injury processes following SRC, and exacerbate the brain injury. In a recent pilot study, reported here, acute head/ neck cooling of 29 concussed ice hockey players resulted in shorter time to return-to-play. For this study, the clinical trial was extended to include players of 19 male elite Swedish ice hockey teams over five seasons (2016–2021). In the intervention teams, acute head/neck cooling was implemented using a head cap for ≥45min in addition to the standard SRC management used in controls. The primary endpoint was

SHORTER RECOVERY TIME IN CONCUSSED ELITE ICE HOCKEY PLAYERS BY EARLY HEAD-AND-NECK COOLING: A CLINICAL TRIAL. Al-Husseini A, Bakhsheshi MF, Gard A et al. Journal of Neurotrauma 2022;doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0248

time from SRC until return-to-play (RTP). Sixty-one SRCs were included in the intervention group and 71 SRCs in the control group. The median time to RTP was 9 days in the intervention group and 13 days in the control group. The proportion of players out from play for more than the expected recovery time of 14 days was 24.7% in the intervention group, and 43.7% in controls.

Co-Kinetic comment

The authors state a couple of limitations on this study including not having a sham cap for the placebo effect, not knowing for certain that the extent

MANUAL MYOFASCIAL RELEASE AND MUSCLE ENERGY ENHANCES TRUNK FLEXIBILITY AND STRENGTH IN RECREATIONALLY RESISTANCE-TRAINED

WOMEN: CROSS-OVER STUDY. Cunha JCdOM, Monteiro ER, Behm DG et al. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2022;doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbmt.2022.09.011

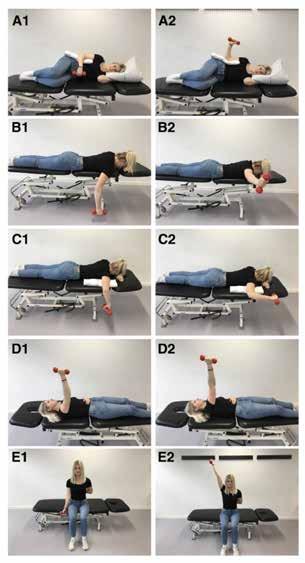

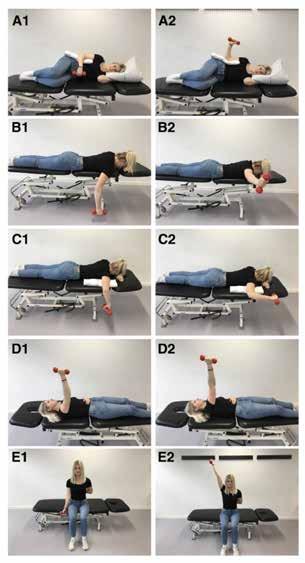

The purpose of this study was to compare the effects of myofascial release (MFR) and muscle energy technique (MET) on acute outcomes in trunk extensors for active ROM and strength. Seventeen apparently healthy women performed three experimental protocols using a cross-over, randomised counterbalanced format, and within-subjects design. The protocols were: l ROM and strength test after MFR; l flexibility and strength test after MET; and l ROM and strength test without MFR or MET to act as a control.

Active trunk ROM was measured via a sit-and-reach test and trunk extension strength via isometric dorsal dynamometer. A significant increase in ROM was found after MFR and MET, and for strength after MFR compared to baseline values.

Co-Kinetic comment

Both are worth doing. The comment about the subjects being ‘apparently’ healthy is worrying in a medical journal. Couldn’t the authors tell?

of the injuries was similar, and not having blind assessors but maybe it is time we re-thought all the randomised control business because – let’s be honest – many of the studies on interventions using ‘healthy’ athletes tell us little or nothing about how real injured ones will react. This does, so the authors shouldn’t be beating themselves up.

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FITNESS MASSAGE AFTER PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SPORT MASSAGE OF LOWER EXTREMITIES IN IMPROVING RANGE OF MOTION AND JOINT FUNCTION SCALE OF FUTSAL ATHLETES. Graha AS, Ambardini RL. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Interdisciplinary Approach in Sports in conjunction with the 4th Yogyakarta International Seminar on Health, Physical Education, and Sport Science (COIS-YISHPESS 2021). Atlantis Press 2022

As the lengthy title states, this is a report from a conference which discusses the difference between sport massage (SM) and fitness massage after physical activity (FMPA) and the effectiveness of both in improving ROM. It used pre-experimental design of two-group pretest and posttest. Treatment was given three times, which were at 2min, 15min and 30min after the game. Forty samples were drawn from the population of 80 students majoring in sport science of the Faculty of Sport

Co-Kinetic comment

Science of Yogyakarta State University using purposive sampling. The ROM was measured with a goniometer and lower extremity functional scale (LEFS) as instruments. Both treatments improved the ROM and the joint function scale of the lower extremities, and the effectiveness of the SM was 0.60 (60%) and that of the FMPA was 0.63 (63%). The effectiveness of the SM in improving the joint function sale of the lower extremities was (73%), and that of the FMPA was (80%).

Sadly the massage protocols were not described which, given that the objective was to compare one to the other, makes it a bit of a waste of time. However, on the plus side, for those of you involved in futsal (according to both FIFA and UEFA it is the fastest growing indoor sport in the world with 115 nations participating) some interesting injury stats are quoted. The WHO states an injury rate of 235 cases per 1000 games. A five-season retrospective study of the aetiology of injuries in the Spanish national futsal male team showed that the majority of the extrinsic injuries resulting from external trauma took place during official training. The thigh was the most injured site (43.3%); followed by the remaining parts of leg (12.6%), knee (10%), back (9.7%), ankle (6.15%), and foot (5.8%). More than 50% of the injuries were diagnosed as resulting from muscle overload and in the most cases (96.6%) the diagnosis was made after clinical assessment. This does raise the question of how were the other 3.6% diagnosed?

7 Co-Kinetic.com RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

OPEN

OPEN

EVALUATION

OF THE

EFFECTS

ON POSTURAL STABILITY IN ACTIVE YOUNG WOMEN. Güler Ö, Bingöl AD, Neşe Şahin F et al. International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology 2020;9(10):44–49

MENSTRUAL CYCLE

OF

The menstrual cycle can be divided into three different phases: the follicular phase (days 1 to ~13, which includes the early menstrual phase), ovulation (~day 14) and the luteal phase (~days 15–28). Postural stability is defined as being able to hold the body centre of gravity within the centre of support to prevent falls and complete desired movements and it is speculated that this together with the systemic hormonal changes that affect tissues such as ligaments, tendons and muscles contribute to an increased injury risk. Hence, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the stability of physically active women during different phases of the menstrual cycle. The phases were estimated from the first day of menstruation with tests on the 2nd or 3rd day (menstrual phase), 14th day (ovulation) and 21st day (mid-luteal phase) of the cycle.

For a limit of stability (LOS) test performed with the Biodex SD System (Biodex, Shirley, NY), a statistical difference was found between the three phases. LOS values decreased in the ovulation phase compared to other phases. No difference was determined between anterior-posterior oscillation, mediolateral oscillation, and postural stability index scores and menstrual phases.

Co-Kinetic comment

If, as these results suggest, menstrual cycle affects balance this is bound to have an impact on injury risk in sports. The big question is therefore what can be done about it? The authors suggest exercises to improve balance performance. There is a PhD out there for someone wishing to find out if it makes a difference.

This study was aimed at looking for risk factors such as characteristics of the participant, environment, structures, and experiences that demonstrate a significant predisposition to burnout. The World Health Organization defines burnout not as a medical diagnosis but as an occupational phenomenon and a ‘syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed’. The most widely used measure of burnout, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, assesses burnout in three constructs: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment.

The usual medical databases revealed 46 studies (8717 participants). The risk of bias assessment

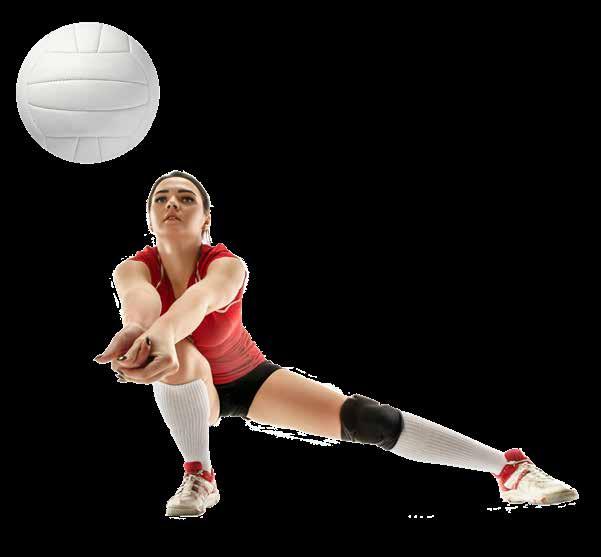

MENSTRUAL CYCLE AND SPORTING PERFORMANCE PERCEPTIONS OF ELITE VOLLEYBALL PLAYERS.

Ergin E, Kartal A. International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology 2020;9(10):57–64

This study aimed to investigate menstrual cycle and sporting performance perceptions of elite volleyball players. The subjects were 130 volleyball players who play in the Turkish Leagues, 45% of whom were internationals. They completed a questionnaire consisting of 25 questions about general and sporting performance before, during and after the menstrual cycle. The results showed that 61.5% of the participants described their general menstruation states as regular and 84.6% of them stated that they had menstrual problems due to sports. In addition, 58.5% of the volleyball players feel bad before menstruation, whereas 52.3% feel good during menstruation. The menstrual periods of 46.2% of the participants sometimes affect their sports/training participation and 99.2% participate in competitions during this period. They listed their problems as irritability (36.2 %) and anger (47.7%); 45.4% think that menstruation sometimes affects their sporting performance, whereas 35.4% consider it does not.

Co-Kinetic comment

This is a great partner study for the one we have reported on balance during menstruation. For those of you involved in women’s sport there is lots of information on training load and the effects on daily activity (not just sport), not the least of which is that nearly 70% of the participants often or occasionally take medication during menstruation which in itself may affect performance.

determined all were of fair or poor quality. Fifty-three risk factors were identified, with 4 being classified as unavoidable and 49 determined as avoidable. The avoidable risk factors were further categorised as: structural/ organisational (32%), psychological/ emotional (19%), environmental (19%), or sociodemographic (13%).

The unavoidable risk factors were: years of professional experience, gender, age, and fewer years of employment. The avoidable ones are too many to list here but some of the major ones are lack of management and supervisor support; boredom or lack of challenge; inadequate staff or

material resources; and poor communication.

Co-Kinetic comment

A number of previous studies consistently suggest that work as a physical therapist is associated with burnout. Everyone in our industry should be aware of the risk factors and note that the vast majority of them are avoidable. Note also that the majority are in the control of management. The paper is published in the journal Physiotherapy so all our Chartered Society of Physiotherapy readers can access it and the rest may be able to get it via Science Direct. Share it with your colleagues. Those of you in management positions should have risk factors framed, put on your desk and you should address them every day.

Co-Kinetic Journal 2023;95(January):4-11

8

OPEN OPEN

RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH PHYSICAL THERAPIST BURNOUT: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Burri SD, Smyrk KM, Melegy MS et al. Physiotherapy 2022;116:9–24

OPEN

OPEN

MEDICAL SERVICES FOR SPORTS INJURIES AND ILLNESSES IN THE BEIJING 2022 OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES. Han PD, Gao D, Liu J et al. World Journal of Emergency Medicine 2022;13(6):459–466

The daily number of injuries and illnesses among athletes reported by Beijing 2022 medical staff in the polyclinic, medical venues and ambulance were recorded. Incidence was calculated as the number of injuries or illnesses occurring during competition or training, respectively, with incidence presented as injuries/ illnesses per 100 athlete-days. In total, 2897 athletes from 91 nations experienced injury or illness. Medical staff reported 326 injuries and 80 illnesses, equalling 11.3 injuries and 2.8 illnesses per 100 athletes over the 17-day period. Altogether, 11% of the athletes incurred at least one injury and nearly 3% incurred at least one illness.

The number of injured athletes was highest in the skating sports (n=104), followed by alpine skiing (n=53), ice track (n=37), freestyle skiing (n=36), and ice hockey (n=35), and was the lowest in the Nordic skiing disciplines (n=20). Of the 326 injuries, 14 (4.3%) led to an estimated absence from training or competition of more than 1 week. A total of 52 injured athletes were transferred to hospitals for further care. The number of athletes with illness (n=80) was the highest for skating (n=33) and Nordic skiing (n=22). A total of 50 illnesses (62.5%) were admitted to the department of dentistry/ ophthalmology/otolaryngology, and the most common cause of illness was

‘other causes’, including pre-existing illness and medicine (n=52, 65%). These findings were similar to the findings during the Olympic Winter Games in 2014 and 2018 despite 2022 still being in the pandemic period.

Co-Kinetic comment Summary papers like this are published after every games. The shear numbers of cases dealt with in a short time is always impressive. If you want to be at the heart of the organisation of the greatest sporting event on the planet and directly contributing to its success, the volunteer portal for Les Jeux Olympiques et Paralympiques de Paris 2024 opens in March 2023 but you can register interest now and receive a newsletter via http://bit.ly/3GIMOf2. They need 45000 people to make it work. It could be you.

Bonne chance.

ICE MASSAGE ON THE CALF IMPROVES 4-KM RUNNING TIME TRIAL PERFORMANCE IN A NORMOTHERMIC ENVIRONMENT. Franco-Alvarenga PE, Cechetti MDS, Barcelos D et al. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 2022:1–7

After familiarisations, 14 recreationally endurance-trained men (age, 21.3±1.2 years; body weight, 67.5±9.2kg; height, 173.0±5.0cm) underwent two 4km time trials on a 400m track in normothermic conditions with or without ice massage before the trial. The time of running, ratings

of perceived exertion (RPE), and pain perception were recorded every 400m throughout the trials. The local cooling with ice massage increased the mean speed (~5.2%) and decreased the time to complete the 4km (~5.5%). Accordingly, ice massage also reduced the exercise-derived pain perception,

although no effect has been found in the RPE during the trials.

Co-Kinetic comment

Just when we are moving away from the use of ice in acute injury management (POLICE to PEACE AND LOVE), it pops up as a pre-match technique. It just won’t be frozen out, will it?

EFFECTS

OF

ACUPUNCTURE, MOXIBUSTION, CUPPING, AND

MASSAGE ON SPORTS INJURIES: A NARRATIVE REVIEW. Zhang H, Zhao M, Wu Z et al. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022;2022:9467002

This is a review of the evidence of four techniques used in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

The results of the World Health Organization’s latest global traditional medicine survey show that acupuncture therapy is recognised by 113 countries worldwide, ranking it first in traditional medical treatment methods. This review includes a table of 14 studies that show that it works for sprains, strains and assorted pains. In summary, it alleviates fatigue, relieves pain, promotes recovery of tissue function, reduces the use of drugs, and has almost no side effects, and so is a viable therapy option for patients and athletes.

Moxibustion is a traditional Chinese method that uses heat generated by burning moxa (mugwort) to stimulate acupoints. Put aside all the stuff about

qi, meridians and balancing yin and yang and it is basically a heat source. Consider it to be the same as infrared or continuous ultrasound. Less scientific support is given for this than for acupuncture with only five studies in the accompanying table. They include it as a treatment for osteoarthritis pain and ligament injury.

Five studies are also cited in support of Chinese massage (tui na), which is a combination of massage, acupressure and other forms of body manipulation. Cited studies are for knee arthritis and plantar heel pain.

Cupping, like the previous techniques is often applied above acupressure points. It has become popular since the Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps appeared at the 2016 games (his fifth) with the tell-tale marks

along his back. The fact that he won four golds to add to his total of 28 Olympic medals helped. For the record that was 23 gold, 3 silver and 2 bronze (even superheroes can have an off day). The table for cupping comprises four studies for low back pain and one for heel pain.

Co-Kinetic comment

OPEN

In the world of evidence-based medicine there is plenty of it here to be quoted to justify the intervention. Whether or not any of it is any good is a different question and you would have to go to the individual papers to make that call; however, let’s not forget that the best evidence is an athlete returning to sports. Does it really matter how they get there as long as they do? As an aside, how annoying is it that when you put a word such as ‘tui na’ into a search engine the first thing that comes up is ‘Buy Tunnia at Low prices’. Stop it please!

9 Co-Kinetic.com

OPEN

EVALUATION OF THE QUALITY OF INFORMATION AVAILABLE ON THE INTERNET REGARDING CHRONIC ANKLE INSTABILITY. Yoon SJ, Kim JB, Jung KJ et al. Medicina 2022;58(10):131

A study quoted in this paper found that almost 90% of patients in Korea search the Internet to obtain information regarding their disease and its treatment. Furthermore, patients who obtain accurate medical information through the Internet tend to enter into good patient–physician relationships, which leads to better treatment outcomes. Therefore, qualitative analyses of the quality of such websites is necessary to ensure that they provide accurate medical information to patients.

The key term ‘chronic ankle instability’ was searched on the three most commonly used search engines in Korea. The top 150 website results were classified into university hospital, private hospital, commercial, non-commercial, and unspecified websites by a single investigator. The websites were rated according to the quality of information using the DISCERN instrument, accuracy score, and exhaustivity score. DISCERN is a brief questionnaire which provides users with a valid and reliable way of assessing the quality of written information on treatment choices for a health problem. The

SURVEY OF PELVIC AND KNEE JOINTS PROPRIOCEPTION AND TYPES OF BALANCE IN ATHLETES AND NON-ATHLETES

FOLLOWING THE FATIGUE PROTOCOL. Moghaddam AM, Ebrahimi Y, Baloochi R et al. Journal of Research in Exercise Rehabilitation 2022;doi:10.22084/ RSR.2021.24483.1583

This study looks at the relationship between core muscle fatigue and joint proprioception with a consideration that this may affect injury incidence.

Thirty men (15 athletes and 15 non-athletes) as a pretest, preformed pelvic and knee proprioception and balance (static and dynamic) tests. In the second session, individuals participated in core muscle fatigue protocol and immediately underwent proprioception and balance tests in fatigue conditions. The findings showed that there was a significant difference between the effect of core muscle fatigue in pelvic proprioception at an angle of 30°, knee proprioception at an angle of 60°, and dynamic balance among athletes and non-athletes. This difference was not significant in static balance.

Co-Kinetic comment

We have not heard much about the importance of ‘the core’ for a while. Is it making a comeback? The suggestion here is that fatigue = changes in the proprioception mechanism = greater injury risk. Another exercise (or set of them) for coaches to embed into their sessions?

results showed that of the 150 websites, 96 were included in the analysis. University and private hospital websites had significantly higher DISCERN, accuracy, and exhaustivity scores compared to the other websites.

Co-Kinetic comment

The Internet is the greatest invention made by man. Discuss. On the one hand, all the information in the world is at your fingertips. On the other, it is full of utter rubbish and the waste tip is bottomless so it’s not surprising that a tool to sort out the wheat from the chaff is useful. The importance of this paper therefore is not that good information on chronic ankle instability has been found but that it brings the tool to your attention. You can download a copy of DISCERN at http://www.discern.org.uk/index.php

SPORT-SPECIFIC REHABILITATION, BUT NOT PRP INJECTIONS, MIGHT REDUCE THE RE-INJURY RATE OF MUSCLE INJURIES IN PROFESSIONAL SOCCER PLAYERS: A RETROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY. Bezuglov E, Khaitin V, Shoshorina M et al. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 2022;7(4):72

Muscle injuries in professional soccer players (n=79; height, 182.1±5.9cm; weight, 76.8±5.8kg; BMI, 23.1±1.4kg/ m2) from three elite soccer clubs from the Russian Premier League were recorded during the 2018–2019 season. The injuries were graded based on MRI, using the British Athletics muscle injury classification. Treatment protocols included the POLICE regimen, short courses of NSAID administration, and a specific rehabilitation programme. The sample group of players (n=34) were given platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections. The average treatment duration with PRP injection was significantly longer than conventional

Co-Kinetic comment

treatment without PRP, 21.5±15.7 days and 15.3±11.1 days, respectively. Soccer-specific rehabilitation and obtaining MRI/US before the treatment was associated with significantly reduced injury recurrence rate. There was no significant difference between the PRP injection protocol applied to any muscle and the treatment duration in respect of grade 2A–2B muscle injuries. The total duration of treatment of type 2A–2B injuries was 15 days among all players. In the group receiving local injections of PRP, the total duration of treatment was 18 days; in the group without PRP injections, the treatment duration was 14 days.

The word ‘might’ is in the title and there are a few mights and maybes in any conclusions drawn from this because it is not clear what criteria were used to choose the players that received the PRP and there were three different protocols for its injection but there is plenty of food for thought. It’s all in the rehab!

10

Co-Kinetic Journal 2023;95(January):4-11

OPEN OPEN

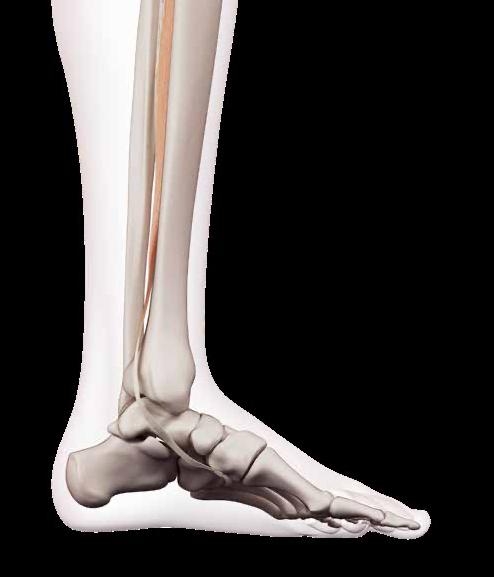

DETERMINE

DORSIFLEXION RANGE OF MOTION, FUNCTIONAL STATUS AND NAVICULAR POSITION IN PATIENTS WITH PLANTAR FASCIITIS. Chouhan D, Joshi S, Kaushik V et al. Indian Journal of Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy 2022;16(4):7–13

Forty subjects with plantar fasciitis (aged 25–60) were randomly divided into an experimental group receiving tibialis posterior strengthening along with conventional therapy and a control group receiving only conventional therapy. All reported pain in their first few steps in the morning, a numerical pain rating scale of 5 to 10, plantar heel pain for more than 3 months, pain on palpation along the proximal plantar fascia, a positive Windlass test, reduced dorsiflexion of ankle joint, and a navicular drop >1cm.

Patients in both groups received iontophoresis with 0.4% dexamethasone drug for 10min, 3 sessions per week for 4 weeks, stretching of calf and plantar surface, self-release of the plantar fascia with tennis ball, intrinsic foot muscle strengthening exercises (heel raises and toe curls). In addition, the treatment group strengthened their tibialis posterior muscle via ankle inversion using elastic bands and emphasising eccentric control, side-lying ankle inversion using ankle weight, emphasising eccentric phase control and single-leg stance balance activities with neutral foot positions twice a day for 4 weeks. Both groups improved but the tibialis strengthening group had the better result.

Co-Kinetic comment

They threw the kitchen sink at this. The authors state that improving overpronation decreased the risk of planter fasciitis. Given that the tibialis posterior is the primary stabiliser of the medial longitudinal arch working it twice a day for 4 weeks is bound to have an effect.

PHYSICAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF BICEPS TENDINOPATHY: AN INTERNATIONAL DELPHI STUDY. McDevitt AW, Cleland JA, Addison S et al. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 2022;17(4):677–694

The purpose of this study was to establish consensus on conservative, non-surgical physical therapy interventions for individuals with long head of biceps tendinopathy using the Delphi method approach.

Twenty-nine experts on shoulder pain were systematically identified as clinicians and/or researchers who had international and nationally recognised training and experience in the physical therapy (PT) management of shoulder pathology or experience in research related to specific PT interventions used to treat individuals with shoulder pain and/or pathology. Once recruited, they rated their agreement with a list of proposed treatment interventions and suggested additional interventions. Agreement was measured using a four-point Likert scale. Descriptive statistics including median and percentage agreement were used to measure agreement. Consensus was defined as an a priori cut-off of ≥75% agreement.

At the conclusion of the study, 61 interventions were designated as recommended based on consensus among experts and 9 interventions were not recommended based on the same criteria; 15 interventions did not achieve consensus. The themes of the interventions revolved around tendon loading techniques, progressive resistance exercises, open and closed kinetic chain exercises and task-specific functional activities (such as reaching, lifting and overhead activity), and occupation and sport-specific activities. In addition there was consensus on stretching/flexibility exercises, non-thrust manipulation and patient education.

Co-Kinetic comment

Not much of a consensus with 61 interventions.

CAN AMERICAN ORTHOPAEDIC FOOT AND ANKLE SOCIETY (AOFAS) SCORE PREVENT UNNECESSARY MRI IN ISOLATED ANKLE LIGAMENT INJURIES? Kandemir V, Akar MS, Yiğit Ş et al. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2022;30(3):10225536221131374

The aim of this study was to validate an algorithm to be used to eliminate unnecessary MRI scans. The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) scale was originally published in 1994 in Foot and Ankle International. It incorporates both subjective and objective information. Patients report their pain, and therapists assess function and alignment. Scores rank ankle trauma from 0 to 100, with healthy ankles receiving 100 points. The score may be used to assess the ankle, subtalar, talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joint levels and may be useful for fractures, arthroplasty, arthrodesis and instability procedures.

For this study, ankle MRI images of 328 patients who had reported ankle trauma followed by persistent problems were taken and compared to their AOFAS scores. As determined by MRI, 21.3% (n=70) of patients had ligament damage and 78.7% (n=258) of patients had no ligament damage. There was a statistically significant difference in terms of AOFAS between the group with ligament damage and the group without ligament damage. Following a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the AOFAS threshold value for MRI request was determined as 80.5 (84.3% sensitivity and 72.3% specificity). Based on the determined threshold value, 73 patients who had unnecessary MRI would have been eliminated, thus reducing the number of MRIs by 42.6%.

Co-Kinetic comment

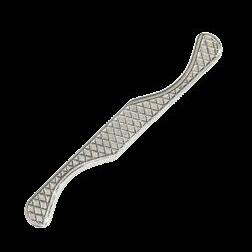

THE USE OF INSTRUMENT-ASSISTED SOFTTISSUE MOBILIZATION FOR MANUAL MEDICINE: AIDING HAND HEALTH IN CLINICAL PRACTICE. Pianese L, Bordoni B. Cureus 2022;14(8):e28623

This informative essay looks at the use of instrumentassisted soft tissue mobilisation (IASTM) tools from the prospective of protection of the clinician’s hands. It points out that such tools were used by the ancient Greeks, Romans and Chinese. They offer a mechanical advantage minimising the forces going through a therapist, especially at the thumbs.

Co-Kinetic comment

In many ways this is a companion piece to the Canadian Massage Association survey and quotes similar stats from an Australian study. To hammer home the message of using tools to prevent hand damage it includes a gory picture of surgery to a trapezius-metacarpal joint. All fair enough, but the Greeks, Romans and Chinese who originated instrument use

Co-Kinetic.com RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

TO

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TIBIALIS POSTERIOR STRENGTHENING ALONG WITH CONVENTIONAL THERAPY ON ANKLE

You can get a free

OPEN OPEN OPEN OPEN

download of the AOFAS from http://bit.ly/3hZvJmy

FACTS

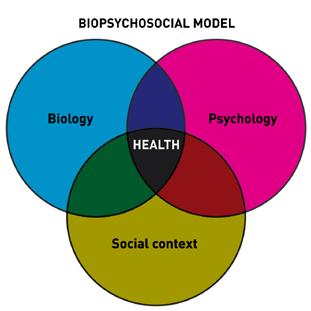

Low back pain is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Treatments can often be costly, time-consuming and may not work. Unhelpful or misleading beliefs about your back pain can cause greater levels of pain, disability and have a damaging impact on your quality of life.

FICTION Here are the 10 most common unhelpful beliefs about low back pain:

It’s always a serious medical condition Gets worse in later life

Pain means tissue damage

Scans and investigations always needed

If it hurts when moving, it’s a signal to stop

It is caused by poor posture

Once any serious pathology has been ruled out, scientifc evidence has shown that understanding these helpful facts below, can bring about a positive mindset change to help you cope better with your back pain:

Scan the QR code to order A1-A3 sized posters

Results from scans or imaging don’t determine your prognosis and won’t improve the outcome of your current back pain Graduated exercise and movement in all directions are safe and healthy for your spine

Your posture and the alignment of your spine while standing, sitting or lifting does not predict low back pain or how long it lasts

For more details talk to your local healthcare professional.

A weak core does not cause low back pain. Although it is good to have strong trunk muscles, it is also helpful to relax them when they aren’t needed Spine movement and loading are safe and build structural resilience when done progressively Painful fare-ups are often related to changes in activity, stress and mood rather than tissue damage

Effective care for low back pain can be relatively cheap and safe and includes education, and optimising physical and mental strength.

Lovingly

planning individual

©Co-Kinetic 2023

produced by The information contained in this poster is intended as general guidance and information only and should not be relied upon as a basis for

medical care or as a substitute for specialist medical advice in each individual case.

Lovingly produced by ASK US FOR OUR BACK PAIN RESOURCES The information contained in this poster is intended as general guidance and information only and should not be relied upon as a basis for planning individual medical care or as a substitute for specialist medical advice in each individual case. ©Co-Kinetic 2023 General Back Pain Resources 10 Facts About Back Pain Acute Back Pain Chronic Low Back Pain Sciatica Understanding Chronic Pain Back Pain in Women Back Pain Triggers and Causes Could My Back Pain Be….? Massage for Low Back Pain Self-Treatment for Back Pain Who Should I See for My Back Pain? Yoga Stretches for Back Pain Back Pain and Sleep Resources Back Pain and Sleep Newsletter 8 Bed Time Stretches Morning Stretch Routine for Back Pain Sleeping Positions for Back Pain Back Pain and Golf Resources Golfer’s Back Newsletter Golf Injury Cheat Sheet 5 Strategies for Sidestepping a Golfing Injury Golfer’s Back Exercise Handout ASK US FOR MORE DETAILS Back Pain Exercise Handouts We also have a wide range of exercise handouts for all types of back pain. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Morning Stretch Routine for Back Pain HIP FLEXOR STRETCH REACH LEGS TWO ARMS Repeat each exercise 3-5 times holding each one for 5-10 seconds l If an exercise causes pain, stop and move onto the next exercise Perform single leg exercises on both legs f BackPain Sleeping Positi Side Lying Y r Fr t SleepingPositiFlatOnBack Ge ingInand OutofBed Back Pain and Pregnancy Resources Pregnancy and Back Pain Newsletter 7 Tips to Relieve Pregnancy Back Pain Pregnancy Back Stretches Pregnancy Back Pain Exercises Back Care with Baby Scan the QR code to order A1-A3 sized posters

‘Growing Pains’

Osgood–Schlatter disease (OSD) is a condition of knee pain in 1 in 10 adolescents. Recent research has shown that it has a greater impact and that its effects can be longer lasting than was previously thought. However, little research has been done on how best to manage it. This article summarises the available evidence and the current thinking about the management of OSD so that you can most effectively help your patients through this condition.

Osgood–Schlatter, also known as Osgood–Schlatter ‘disease’ (OSD), is one of the most common knee-pain conditions in adolescents. It is reported to affect 1 in 10 of the general population; more often in boys between the ages of 12 and 15 years, and also in girls between the ages of 8 and 12 years. Although OSD is more common in boys, as more girls are becoming involved in sports the gender gap is narrowing (1*). OSD prevalence is highest in active adolescents, with early sport specialisation associated with a fourfold greater relative risk of developing OSD (2*). OSD results in knee pain, often severe enough to cause limping. It may be accompanied by swelling or deformity, and frequently results in long-term symptoms with functional impairment. Pain is exacerbated on descending stairs, after prolonged periods of sitting with the knee immobile, while kneeling, and during sports activities. Pain is aggravated by activities that load the quadriceps muscle (and indirectly the tendon attachment), for example, jumping, landing, and running (1*). Although the aetiology is not fully understood, OSD is considered to be an apophyseal

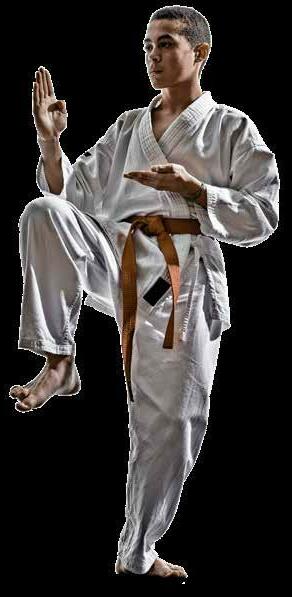

By Kathryn Thomas BSc MPhil

injury of the tibial tuberosity at the site of the patellar tendon attachment. Before maturity of the apophysis, the apophyseal cartilage is thought to be weak and thus susceptible to injury. Apart from pain, characteristics of OSD include cartilage swelling and tendon changes involving thickening of the patellar tendon and increased Doppler activity (3,4*,5*). In football, the statically dominant leg has been shown to be more prone to develop OSD. In other sports (including track and field, basketball, martial arts and handball), however, either leg could be affected by OSD. Age at onset, growth rate, BMI and muscle imbalance is not significantly predisposing. Interestingly previous heel pain (Sever’s disease) is strongly associated with the presence of OSD. It is not clear why or what the pathophysiological connection is apart from possibly exposure to similar levels of physical activity (6*).

Traditionally OSD is reported as a self-limiting growth-related condition that resolves spontaneously within 12 to 24 months with the maturation of the tibial tuberosity, and no residual symptoms in the majority

(~90%) of cases (7). However, there is little data to support this claim. A healing period of even 1–2 years can be a lifetime for an adolescent, especially one that is a competitive athlete. More studies are documenting the fact that adolescents are suffering from long-term symptoms and even adults may present with residual symptoms or sequelae from OSD (8*,9,10*,11). Çakmak et al. also reported on the potential for OSD symptoms to persist into adulthood, thus contradicting the common assumption OSD is innocuous as previously assumed (12). This is problematic, as it may lead clinicians to underestimate the potential burden and impact of experiencing long-standing pain during adolescence. A recent survey of healthcare professionals stated they expected that the majority of patients would return to sport, symptom free within 6 months (13). Thus, children and adolescents complaining of ‘growing pains’ need to be better managed to ensure a favourable long-term outcome. Amusingly, the number of available review articles covering OSD treatment options is even larger than the number of available original studies or clinical trials. Although the problem is starting

All references marked with an asterisk are open access and links are provided in the reference list.

14

THE PREVALENCE OF OSGOOD–SCHLATTER DISEASE (OSD) IS HIGHEST IN ACTIVE ADOLESCENTS

to be recognised, evidence-based guidelines do not exist, which results in treatment recommendations being based on clinicians’ experience and anecdotal evidence (1*,14*). This article will address the concerns of long-term pain and disability following OSD, and what options might exist to better manage our youth. In the best cases, OSD may resolve quickly with no residual symptoms, but this may not be the case for all patients.

The Reality of a Poor Prognosis Following OSD

Research by Krause et al. in the 1990s stated that at long-term follow-up (mean, 9 years) as many as 1 in 4 patients had ongoing symptoms into adulthood (15). Although the severity and impact on sport and lifestyle were not documented, 60% of subjects were unable to kneel without discomfort. A more recent retrospective study (8*) indicated that at a median 4-year follow-up, 60% of OSD patients still experienced knee pain, with an average duration of symptoms being 90 months. Of those still experiencing knee pain, 43% suffered from daily pain. More than half of the subjects reported that the pain reduced their sports participation. The knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score sports/recreation (KOOS) subscale scores were significantly lower in those with knee pain than in those without pain. The lower self-reported function and HRQoL–EQ-5D-3L-Y (health-related quality of life – youth version EuroQol 5 dimensions 3 levels) score in those with continued pain may be a consequence of impaired physical activity due to knee pain (16*). College-aged men (mean, 20 years old) with a history of physiciandiagnosed unilateral OSD have a greater disability compared with agematched subjects without a history of OSD (8*). Research has shown that 79% of the patients still complained of persistent but not impairing pain on kneeling or knee contact at a 4-year

follow-up. However, within this study, 28% of all patients reported having switched their sport activity to other disciplines due to OSD (9).

Kaya et al. found that as many as 50% of adolescents continue to show ultrasound (US) findings consistent with OSD at 24-month follow-up (17). In addition to this, these adolescents demonstrated functional limitations in objective measures of lower limb strength, power and endurance performance at the same follow-up. It is concerning that such functional deficits and resulting disability may persist into adulthood (17).

Interestingly, subjects who stated themselves as ‘recovered’ at followup (ie. no longer experiencing pain), reported mean KOOS and EQ-5D-Y index scores lower than documented for controls without a history of knee pain (18). Again this suggests a potential longer-term disability with functional deficits in patients with a history of OSD (5*,8*,17). A high rate of dropout in sports is seen following OSD. It has been reported that more than 70% of patients with OSD are restricted from sports for more than 10 months on average, and 1 in 3 adolescents when returning to sport after 3 months of being symptom free experience a recurrence (19). There may be a need for greater focus on ongoing management, and rehabilitation as well as a graduated return to sport.

Would Imaging Help the Management of OSD?

The majority of clinicians are confident in making an OSD diagnosis based on patient history and clinical examination without the use of imaging (13). The majority of imaging studies have focused on using imaging to characterise the pathophysiology – despite the fact that the pathology for OSD still

remains controversial. Originally, OSD was attributed to the avulsion of the tibial tuberosity due to forceful patellar tendon contractions. Since then studies have demonstrated that fragmentation may be a normal part of maturation and not necessarily pathologic. Many studies have reported soft tissue changes, such as in the patellar tendon, as being characteristic of OSD. The De Flaviis classification of OSD was developed using US equipment, but the interrater and intrarater reliability is yet to be examined. Baseline De Flaviis categorisation (using US) has been shown to be associated with a worse prognosis for pain, whereas those without identifiable changes (cartilage swelling, bony change, and/ or associated tendinopathy/bursitis) at baseline demonstrate a significantly better prognosis (5*).

PHYSICAL THERAPY

OSD IS CONSIDERED TO BE AN APOPHYSEAL INJURY OF THE TIBIAL TUBEROSITY AT THE SITE OF THE PATELLAR TENDON ATTACHMENT

EVIDENCE SHOWS

Treatment Options Without Scientifc Guidelines

It is possible that owing to the previously assumed innocuous nature of OSD, there is a scarcity of research evaluating interventions to reduce symptoms, improve function and speed up or sustain recovery. Randomised controlled trials are confined to investigating injections and surgical management. No randomised controlled clinical trials have evaluated other management strategies (2*).

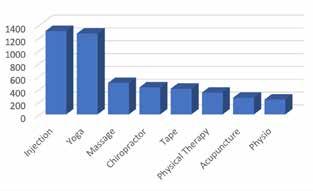

From a recent survey of clinicians, the most common treatments were patient education (99%) and exercise therapy (92%). There was some heterogeneity across pain medication prescriptions (31% for and 34% against). Factors which may influence a clinician’s decision to allow a return

treatment strategies have been proposed (1*,22*):

1. a decrease in physical activity (2*,23);

2 application of cold;

3. use of knee orthoses to apply support or pressure to the patellar tendon thus reducing the tractional load on the insertion;

4. physical therapy (24);

5. warm-up and cool-down exercises before and after training and competition; and

6. stretching of the leg extensor musculature to reduce the tension generated by the extensor apparatus (1*,24,25,26*).

Regarding the final point above, care should be taken not to stretch excessively, as it is essential to

are speculative based on patient symptoms and the understanding of the pathophysiology or have been extrapolated from other knee conditions [including anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury rehab or patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS)]. A recent cohort study by Rathleff et al. reported high rates of successful outcomes among OSD patients (80% at 12 weeks and 90% after 12 months), with 16% having returned to sport after 12 weeks, and 67% after 6 months (2*). This was after a 12-week intervention that included:

1. an activity ladder, designed to manage patellar tendon loading and pain (see the ‘Activity ladder’ on p3 of Appendix 1 “Quit knee pain –Osgood Schlatter” (https://bit.ly/3G8DMYc) from Rathleff et al. (2*));

2. knee-strengthening exercises; and 3. graduated return to sport.

The intervention was structured into 2 blocks: see ‘Table 2: Building blocks of the intervention’ (http://bit.ly/3X271Su) in Rathleff et al. (2*)). Weeks 0–4 included an initial load management strategy with a temporary reduction in sport participation. During this time, subjects were instructed to refrain from pain-aggravating activities and sport participation. Yet knee exercises were performed, including static holds and bridging to avoid loss of muscle strength. The load-based activity ladder and pain monitoring were used as guidance and support at this time

During weeks 5–12, adolescents performed a progressive homebased knee-strengthening exercise programme while still following the activity ladder, and progressing towards a return to sport. Three exercises progressed with increasing difficulty. Subjects were not allowed to move onto level 3 (slow running) on the activity ladder until they were able to perform a squat with a pain rating below 3. The exercises included wall squats that progressed as pain allowed to a 90° knee-flexion wall squat. Then a standing squat progressing to a 90° knee-flexion posture and finally a lunge. Consultation with physical

THAT ADOLESCENTS ARE SUFFERING FROM LONG-TERM SYMPTOMS OF OSD AND EVEN ADULTS MAY PRESENT WITH RESIDUAL SYMPTOMS OR SEQUELAE

therapists during the 12 weeks focused on educating the adolescents and their parents on understanding the benefits of progressive loading and avoiding painful setbacks. Greater detail about the education programme and exercise progression (sets, repetitions, holds) is available in the Appendices of Rathleff et al. “Activity modification and knee strengthening for OsgoodSchlatter disease: a prospective cohort study” (http://bit.ly/3X271Su). This study illustrated that active intervention improved pain and knee function as well as realising a successful return to sport over 12 months. Thus, targeted strength training can offset some of the long-term negative impacts previously documented (2*). Adolescents with OSD have shown approximately 30% lower isometric knee extension strength compared to their pain-free peers (18), and strength deficits may persist after the resolution of symptoms (17). The intervention increased strength to the same level as adolescents without knee pain (18). Strength training should prepare adolescents for return to sport, as they are then better prepared to withstand the physical demands. Treatments such as stretching, rest, and other passive modalities although recommended (22*,25) neglect this objective.

Rathleff et al. highlighted that despite the majority of adolescents reporting that they were improved, one-third still experienced pain and were affected in their sport participation (2*). In addition to this, at 12-month follow-up less than 50% reported that they would be satisfied to live with their current symptoms. It may be prudent to consider this a long-standing condition, which may in some cases need ongoing management (2*). More studies like this are needed to add to the body of evidence and possibly offer a longerterm intervention, follow-up and/or maintenance programme to prevent symptoms continuing into adulthood. Active intervention like physical or exercise therapy may offer an alternative to passive approaches.

Knee rehabilitation and prevention programmes generally cover a component of activity progression combined with progressive

LOAD

strengthening. Within that conditioning element, neuromuscular-training programmes (proven effective through clinical trials) play a vital role. Neuromuscular training may include plyometrics, balance, agility, flexibility and strengthening. Should we not raise the question then why, in the management and prevention of recurrence of OSD, these proven interventions are not considered?

It has been suggested that excessive tractional loads should not be applied through the patellar tendon onto the anterior tibial tuberosity in children aged 9 to 15 years (22*). Any underlying muscle imbalances that favour higher tension (stiffness) in the patellar tendon should be addressed. This may be of particular concern when added to sports activities with acyclic and explosive components. Muscle rebalancing through lengthening (flexibility) and strengthening programmes that contribute to reducing tension at the patellar tendon insertion might be an interesting strategy towards managing OSD (22*). Furthermore, some authors recommend core stabilisation exercises may benefit knee pain and dysfunction. Core stability exercises have become one of the more favoured components in ACL injury-prevention programmes. During physical activities, the knee joint biomechanics are affected by the dynamic motion of the trunk and hip joint. Deficits in neuromuscular control in the trunk and hip joint have been shown to increase ACL injury risk. It has been demonstrated that core stability can predict ACL injury and that hip abduction and external-rotation muscle strength can predict noncontact knee injury in athletes (27*). Simple core muscle training results in changes to neuromuscular control in the trunk and lower limbs, thus increasing trunk and pelvic stability and thereby reducing the risk of a knee injury (27*). These proven benefits should be extrapolated and studied in intervention programmes for OSD in

the future.

EXERCISES

Additionally, it has been seen that trunk muscle activity precedes the dynamic movement of the extremities, implying that the abdominal muscles may engage to provide a stable foundation for production, absorption and force control during the motion to the extremities. Subsequently, insufficient core stability may lead to less efficient movements and possibly musculoskeletal injury. Reduced core stability, tested in runners, has been linked to increased peak torque in knee flexion during the stance phase of running (28*). This, in turn, increases vertical loading and places the individual at risk of injury, specifically in the development of PFPS. Emphasising core stability

17 PHYSICAL THERAPY

AN INITIAL

MANAGEMENT STRATEGY FOLLOWED BY KNEE-STRENGTHENING

HAS SHOWN HIGH RATES OF SUCCESS

OSD IS NO LONGER SIMPLY A ‘REST AND RECOVER’ CONDITION

athletes involved in jumping activities is advocated (27*,28*). Despite these potential benefits, more studies are needed to clarify which type of treatment would be most appropriate for adolescents. As confirmed by Neuhaus et al., no clinical trial comparing specific exercises with sham or usual care treatment exists (1*).

Other treatment modalities could be considered. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy has been proven to effectively reduce tendon pain owing to its analgesic effects and to promote remodelling and repair of soft tissues (29). Magnetic field therapy may effectively enhance cartilage and bone repair by increasing the bone matrix (10*). Again no clinical trial has

been conducted to assess efficacy in adolescents with OSD.

Surgery should only be considered when other types of treatment have previously failed or when bone fragments (intra- or extra-tendon) remain after complete ossification (22*). Surgery may be necessary if nondisplacement fractures are present. Different surgical techniques and approaches have been proposed, each with advantages and disadvantages (22*).

Where Does That Leave Us?

The scarcity of literature pertaining to OSD, particularly in the clinical management of patients is concerning. Future research is required not only to investigate the pathology of the condition but also (and more importantly) any possible preventive measures and long-term management protocols. It is true that investigating and understanding the multiple factors related to this condition is key; however, at this time it is necessary for research to delve much deeper into the treatment options, both at the preventive and recovery level.

For symptom relief, a combination of training load reduction or relative rest, and limitation of movement patterns that generate pain may contribute to the improvement. Progressive muscle strengthening combined with a progressive return to activity appears to produce positive outcomes. Addressing muscle imbalances through exercise therapy and preparing the body for the loads anticipated on return to sport makes ‘rehabilitation sense’. The evidence is telling us that OSD is not simply a ‘rest and recover’ condition. We would be doing our youth an injustice if we did not structure more effective ways of managing OSD.

References

1. Neuhaus C, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Faude O. A systematic review on conservative treatment options for OSGOOD-Schlatter disease. Physical Therapy in Sport 2021;49:178–187 Open access http://bit.ly/3A8oT4z

2. Rathleff MS, Winiarski L, Krommes K et al. Activity modification and knee strengthening for Osgood-Schlatter disease: a prospective cohort study. Orthopaedic

Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;8(4):232596712091110 Open access http://bit.ly/3X271Su

3. Nakase J, Aiba T, Goshima K et al. Relationship between the skeletal maturation of the distal attachment of the patellar tendon and physical features in preadolescent male football players. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2014;22(1):195–199

4. Yanagisawa S, Osawa T, Saito K et al. Assessment of Osgood-Schlatter disease and the skeletal maturation of the distal attachment of the patellar tendon in preadolescent males. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;2(7):232596711454208 Open access http://bit.ly/3AdfN6y

5. Holden S, Olesen JL, Winiarski LM et al. Is the prognosis of Osgood-Schlatter poorer than anticipated? A prospective cohort study with 24-month follow-up. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;9:232596712110222 Open access http://bit.ly/3TBcM71

6. Schultz M, Tol JL, Veltman L et al. Osgood-Schlatter disease in youth elite football: minimal time-loss and no association with clinical and ultrasonographic factors. Physical Therapy in Sport 2022;55:98–105 Open access http://bit.ly/3Gep2qN

7. Circi E, Atalay Y, Beyzadeoglu T. Treatment of Osgood–Schlatter disease: review of the literature. Musculoskeletal Surgery 2017;101:195–200

8. Ross MD, Villard D. Disability levels of college-aged men with a history of Osgood-Schlatter disease. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2003;17(4):659–663 Open access http://bit.ly/3WTIzTz

9. Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Olesen JL et al. Is knee pain during adolescence a selflimiting condition? American Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;44(5):1165–1171

10. Lee DW, Kim MJ, Kim WJ et al. Correlation between magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of the patellar tendon and clinical scores in OsgoodSchlatter disease. Knee Surgery & Related Research 2016;28(1):62–67 Open access http://bit.ly/3EwemT6

11. Circi E, Beyzadeoglu T. Results of arthroscopic treatment in unresolved Osgood-Schlatter disease in athletes. International Orthopaedics 2017;41(2):351–366

12. Çakmak S, Tekin L, Akarsu S. Long-term outcome of Osgood-Schlatter disease: not always favorable. Rheumatology International 2014;34(1):135–136

13. Lyng KD, Rathleff MS, Dean BJF et al. Current management strategies in Osgood Schlatter: a cross-sectional mixed-method study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2020;30:1985–1991

14. Cairns G, Owen T, Kluzek S et al. Therapeutic interventions in children and adolescents with patellar tendon related pain: a systematic review. BMJ

18

Open Sport & Exercise Medicine

2018;4(1):e000383 Open access http://bit.ly/3TxL22T

15. Krause BL, Williams JP, Catterall A. Natural history of Osgood-Schlatter disease. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 1990;10(1):65–68

16. Guldhammer C, Rathleff MS, Jensen HP et al. Long-term prognosis and impact of Osgood-Schlatter disease 4 years after diagnosis: a retrospective study. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;7(10):232596711987813 Open access http://bit.ly/3hH4wVy

17. Kaya DO, Toprak U, Baltaci G et al. Long-term functional and sonographic outcomes in Osgood–Schlatter disease. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2013;21(5):1131–1139

18. Rathleff MS, Winiarski L, Krommes K et al. Pain, sports participation, and physical function in adolescents with patellofemoral pain and OsgoodSchlatter disease: a matched crosssectional study. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2020;50(3):149–157

19. Kujala UM, Kvist M, Heinonen O. Osgood-Schlatter’s disease in adolescent athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine 1985;13(4):236–241

20. Sailly M, Whiteley R, Johnson A. Doppler ultrasound and tibial tuberosity maturation status predicts pain in adolescent male athletes with Osgood-Schlatter’s disease: a case series with comparison group and clinical

KEY POINTS

interpretation. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2013;47(2):93–97 Open access http://bit.ly/3AbmBS0

21. Hirano A, Fukubayashi T, Ishii T et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of OsgoodSchlatter disease: the course of the disease. Skeletal Radiology 2002;31(6):334–342

22. Corbi F, Matas S, Álvarez-Herms J et al. Osgood-Schlatter disease: appearance, diagnosis and treatment: a narrative review. Healthcare 2022;10(6):1011 Open access http://bit.ly/3WTJiUN

23. Nührenbörger C, Gaulrapp H. OsgoodSchlatter disease. Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2018;34(4):393–395

24. Bezuglov EN, Tikhonova AA, Chubarovskiy PhV et al. Conservative treatment of Osgood-Schlatter disease among young professional soccer players. International Orthopaedics 2020;44(9):1737–1743

25. Ladenhauf HN, Seitlinger G, Green DW. Osgood–Schlatter disease: a 2020 update of a common knee condition in children. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2020;32(1):107–112

26. Launay F. Sports-related overuse injuries in children. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2015;101(1 Suppl):S139–147 Open access http://bit.ly/3EwywN8

27. Sasaki S, Tsuda E, Yamamoto Y et al. Core-muscle training and neuromuscular control of the lower limb and trunk. Journal of Athletic Training 2019;54(9):959–969

Open access http://bit.ly/3EEdwEh

28. Chaudhari AMW, Van Horn MR, Monfort SM et al. Reducing core stability

l Osgood–Schlatter disease (OSD) is a sport- and growth-associated knee pathology seen in adolescents.

l OSD is a relevant problem in young athletes, predominantly treated conservatively with a ‘wait and see’ philosophy.

l Research has revealed that adolescents can experience symptoms well beyond the expected 12–24-month recovery timeline.

l Pain, strength deficits and functional disability originating from OSD can persist into adulthood.

l Many adolescents have had to stop their sport, or change their sporting code because of persistent symptoms or recurrence of injury.

l Reviews have highlighted the poor prognosis of OSD and the severe lack of clinical trials investigating treatment protocols.

l Only one study exists that implements an intervention of progressive lower limb strengthening exercises combined with activity modification and a graduated return to sport, and shows positive outcomes in OSD.

l Core muscle strengthening improves neuromuscular control of the trunk and lower limbs reducing the risk of knee injuries, this may be extrapolated to OSD.

l Core muscle training is proven essential in anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention and rehabilitation and could benefit adolescents with OSD.

l A pro-active management strategy of exercise therapy, education, activity modification and graduated return to sport, with a long-term maintenance plan, may be required to ensure a positive outcome.

influences lower extremity biomechanics in novice runners. Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise 2020;52(6):1347–1353 Open access http://bit.ly/3O161dv

29. Lohrer H, Nauck T, Schöll J et al. [Einsatz der extrakorporalen Stoßwellentherapie bei therapieresistentem M. Schlatter.] Sportverletzung Sportschaden 2012;26(4):218–222.

RELATED CONTENT

l Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Practical Treatment Approach [Article] http://bit.ly/3hCalDF

l Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Practical Treatment Approach [Article] http://bit.ly/3WSSSqK

DISCUSSIONS

l What is your current belief and treatment plan for adolescents presenting with OSD?

l Do you believe you have seen knee pain and functional disability in young adults that may be persisting from OSD and why?