IF YOU:

Feel confused or overwhelmed by social media

Get little or no engagement from your social media posts

Have no idea what you should be doing but...

Know you’re spending way too much time and getting zero ROI from your efforts

I EXPLAIN:

Why getting engagement on your posts is so hard and ways to overcome that

How to build a dynamic social media profile that demonstrates expertise and relevancy, as well as delivers value to your social media followers

How to use our ENGAGED content formula to create the right kind of professional content that attracts the attention of the all-important platform algorithms

Ways in which you can nurture and ‘massage’ these algorithms to increase exposure to your content, in turn increasing engagement and followers

The two sides of the social media coin, without which your social efforts will always fail

While Tor trained as a physical therapist, she has been an entrepreneur now for more than two decades. Her focus is providing resources to help practitioners and therapists develop their businesses and to work more efficiently, a topic that she speaks on regularly at global conferences. The marketing practices and principles that Tor advocates, will help you turn a business that is only just surviving into one that thrives in just a matter of weeks.

Don’t know how to build an audience, or promote your business through social media without being salesy

Feel like your social media efforts are mostly a complete waste of time

...then this is the course for you.

How to use paid social effectively

FAQs around what networks to post to (and why), when and how often

And finally how to generate new clients using social media.

This is a eight part, 2 hour course with a heavy emphasis on practical application so you can walk away and create a social media presence that not only you can be proud of but which engages, adds value, entertains and educates your followers.

CLINIC POSTERS

30-34

2023 PHYSICAL THERAPY CONSUMER SURVEY

14-17

PLANTAR FASCIOPATHY: EPIDEMIOLOGY, RISK FACTORS, DIAGNOSIS AND BIOMECHANICS

26-29

LOADING THE PLANTAR: A COMMENT ON HIGH LOAD EXERCISE

18-25

MANAGEMENT OF PLANTAR FASCIOPATHY AND PLANTAR HEEL PAIN

Publisher/Founder TOR DAVIES tor@co-kinetic.com

Business Support

SHEENA MOUNTFORD sheena@co-kinetic.com

Technical Editor

KATHRYN THOMAS BSC MPhil

Art Editor DEBBIE ASHER

Sub-Editor ALISON SLEIGH PHD

Journal Watch Editor

BOB BRAMAH MCSP

Subscriptions & Advertising info@co-kinetic.com

DISCLAIMER

JULY 2023 ISSUE 97 ISSN 2397-138X is published by Centor Publishing Ltd 88 Nelson Road Wimbledon, SW19 1HX, UK https://Co-Kinetic.com

Facebook www.facebook.com/CoKinetic

Instagram www.instagram.com/co_kinetic/

YouTube www.co-kinetic.com/youtube

Twitter https://twitter.com/co_kinetic

LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/co-kinetic/

Our Green Credentials

Paper:100% FSC Recycled Offset Paper

Our paper is now offset through the World Land Trust

Naked Mailing No polybag used

Plant-Based Ink Used in Printing Process

More details

https://bit.ly/3dAwGwd

CBP006075

While every effort has been made to ensure that all information and data in this magazine is correct and compatible with national standards generally accepted at the time of publication, this magazine and any articles published in it are intended as general guidance and information for use by healthcare professionals only, and should not be relied upon as a basis for planning individual medical care or as a substitute for specialist medical advice in each individual case. To the extent permissible by law, the publisher, editors and contributors to this magazine accept no liability to any person for any loss, injury or damage howsoever incurred (including by negligence) as a consequence, whether directly or indirectly, of the use by any person of any of the contents of the magazine.

Copyright subsists in all material in the publication. Centor Publishing Limited consents to certain features contained in this magazine marked (*) being copied for personal use or information only (including distribution to appropriate patients) provided a full reference to the source is shown. No other unauthorised reproduction, transmission or storage in any electronic retrieval system is permitted of any material contained in this publication in any form.

The publishers give no endorsement for and accept no liability (howsoever arising) in connection with the supply or use of any goods or services purchased as a result of any advertisement appearing in this magazine.

This is a comparison between structural MRI and resting state functional MRI (fMRI) in 108 patients (with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 13–15 and normal CT) and 76 controls. The objective was to see if acute changes in thalamic functional connectivity were early markers for persistent symptoms of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and explored neurochemical associations of the findings as shown by positron emission tomography scans. Inclusion criteria were that subjects had to be aged 18–70 years with no medical history of previous concussion or neuropsychiatric disease.

Of the mTBI cohort, 47% showed incomplete recovery 6 months post-

ACUTE THALAMIC CONNECTIVITY PRECEDES CHRONIC POST-CONCUSSIVE SYMPTOMS IN MILD TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY. Woodrow RE, Winzeck S, Luppi AI et al. Brain 2023;awad056

injury. Despite the absence of structural changes, acute thalamic hyperconnectivity in mTBI, with specific vulnerabilities of individual thalamic nuclei, was found. Acute fMRI markers differentiated those with chronic postconcussive symptoms, with time- and outcome-dependent relationships in a sub-cohort followed longitudinally. Moreover, emotional and cognitive symptoms were associated with changes in thalamic functional connectivity to known serotonergic and noradrenergic targets, respectively.

ADULTS ARE NOT OLDER ADOLESCENTS: COMPARING PHYSICAL THERAPY FINDINGS AMONG ADOLESCENTS, YOUNG ADULTS AND OLDER ADULTS WITH PERSISTENT POST-CONCUSSIVE SYMPTOMS. McPherson JI, Haider MN, Miyashita T et al. Brain Injury 2023;37(7):628–634

This is a retrospective case-control chart review of 481 patients with persistent post-concussive symptoms (PPCS) and 271 non-trauma controls. Physical assessments were categorised as ocular, cervical, and vestibular/balance. Differences in presentation were compared between PPCS and controls as well as between individuals with PPCS in three age groups: adolescents, young adults, and older adults.

All three PPCS groups had more abnormal oculomotor findings than their age-matched counterparts. When comparing PPCS patients from different age groups, no differences were seen in prevalence of abnormal smooth pursuits or saccades (two types of eye movement); however, adolescents with PPCS had more abnormal cervical findings and a lower prevalence of abnormal near point convergence, vestibular and balance findings.

Concussion is very much a hot topic, or the topic from hell if you are the governing body of a contact sport worried about the increasing evidence that concussion symptoms last much longer in some people than thought with the added jeopardy of an increasing number of lawsuits against you. The UK Government has just issued new guidelines for concussion at grassroots level. You can find them at: https://bit.ly/45tWjsd. The title gives an accurate summary of what they recommend, “If in doubt, sit them out.

The study found that even though there is no visible structural injury to the brain the thalamus region goes into overdrive, trying to communicate more as a result of the injury. The more connections it made, the poorer the prognosis for the patient. The big questions are does this move us closer to a pitch-side test for concussion and what are the implications for current return-to-play protocols if even a mild bump on the head can result in concussion symptoms 6 months later? Discuss.

SOCCER. Wentao M. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte 2023;29:e2023_0011

Twenty-two professional footballers were randomly divided into experimental and control groups. Both groups did their normal training but the control group received extra ankle stability training four times a week over a 6-week period. This consisted mainly of low-order training such as anti-resistance hook foot, antiresistance stretch foot, antiresistance ankle varus and highorder training such as valgus, step and balance ball. Data were collected pre- and post-intervention on rear and frontal balance indexes, functional movement assessment and ankle injury cause. The results showed that the intervention groups scores were all better than the controls and they had fewer injuries.

The drawback with this paper is that the experimental exercise regimen is not reported in repeatable detail. However, the overall result is that adding ankle stability training to the programme has benefits in improved balance and fewer injuries. It is reasonable to assume that this would be similar in other sports with high ankle sprain issues such as basketball, handball and volleyball, so coaches get adding those extra drills,

COMPARING THE EFFICACY OF CORE STABILITY EXERCISES AND CONVENTIONAL PHYSICAL THERAPY IN THE MANAGEMENT OF LOWER BACK PAIN: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. Bibi M, Shah A. Northwest Journal of Medical Sciences 2023;2(1):13–17

A total of 60 patients (2 female, 58 male; mean age, 29.70 and 30.86 years, respectively) were randomly assigned to a group receiving core stability exercises for 30min three times a week for 4 weeks or to a group who received conventional physiotherapy for the same time. Data included pre- and post-intervention measures of pain and function using a VAS and a modified Oswestry Disability Index (MODI) questionnaire. There was no significant difference at the baseline between groups in terms of age, pre-VAS and MODI. There was significant improvement of pain and functional status in both groups, but the core stability group was more effective.

Co-Kinetic comment

Sadly, although this paper describes the conventional therapy as including techniques such as heat therapy, manual and/or mechanical traction, short wave diathermy, therapeutic ultrasound and transcutaneous electrical nerve simulation, how much of each is not described and the core stability exercises are not described at all. Would it be too much to ask for an appendix or a link to website to help therapists deal with the massive problem of low back pain. How massive is illustrated by a study published in the British Medical Journal in 2013, which estimated that around 60% of the adult population can expect to have a back problem at some time in their life.

REVIEW

Zhang Y, Qian Y, Huo K et al. Complementary Therapies in Medicine Volume 2023;74:102945

This review used outcome measures of the degree of pain, reported on a VAS, and temporomandibular joint function including maximum active vertical opening, maximum passive vertical opening, and left and right lateral movement. A total of 1032 records were retrieved from the database, with 615 remaining after exclusion of duplicates. Of these, 118 records were selected after reading the title and abstract, and 92 records were excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria after reading the full text. This left 24 studies to be included in the meta-analysis. The overall result was that laser therapy had a more significant effect in terms of VAS as compared to placebo groups but there was no significant difference in improving mandibular movement.

Co-Kinetic comment

The sheer number of research papers found in reviews like this are always a shock – although it shouldn’t be, given that the current total of journal titles that have carried articles of interest to Co-Kinetic readers stands at 427. That’s titles, not editions.

INJURIES AND ILLNESSES DURING THE 2021 SOUTH AMERICA WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS: AN EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDY. Bogado DJ, Martínez Stenger RA, Blajman JE et al. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte 2023;40(1):30–39

The coaching staff of the 11 teams (129 players in total) taking part in the 2021 South America Wheelchair Basketball Championships were asked to report daily all the health problems that occurred (and their characteristics) in a standardised form. Prevalence and incidence rates were calculated. The results showed that 108 health problems were reported, equivalent to 83.7 per 100 players, with 8 time-loss health problems (6.2 per 100 players) and a total of 74 injuries that required medical attention (57.4 per 100 players). Of the illnesses, the most affected organ systems were ophthalmologic, gastrointestinal and genitourinary. More injuries were recorded during matches

( n =43). The most affected regions were shoulder/clavicle (24.7%), hand/fingers (23.7%) and neck/cervical spine (12.9%). The most frequent conditions were muscle contractures/cramps (32.2%), and the predominant mechanism was overuse (53.8%), with concussions during training at 2.2%. Most of the recorded events were without time loss and with return to full participation between zero and one day.

Co-Kinetic comment

If you are thinking of getting into wheelchair basketball you are going to be busy but at least this gives you a heads-up. There is a full breakdown of all the reported illnesses and injuries. You need to be up to speed with illness as well as injury.

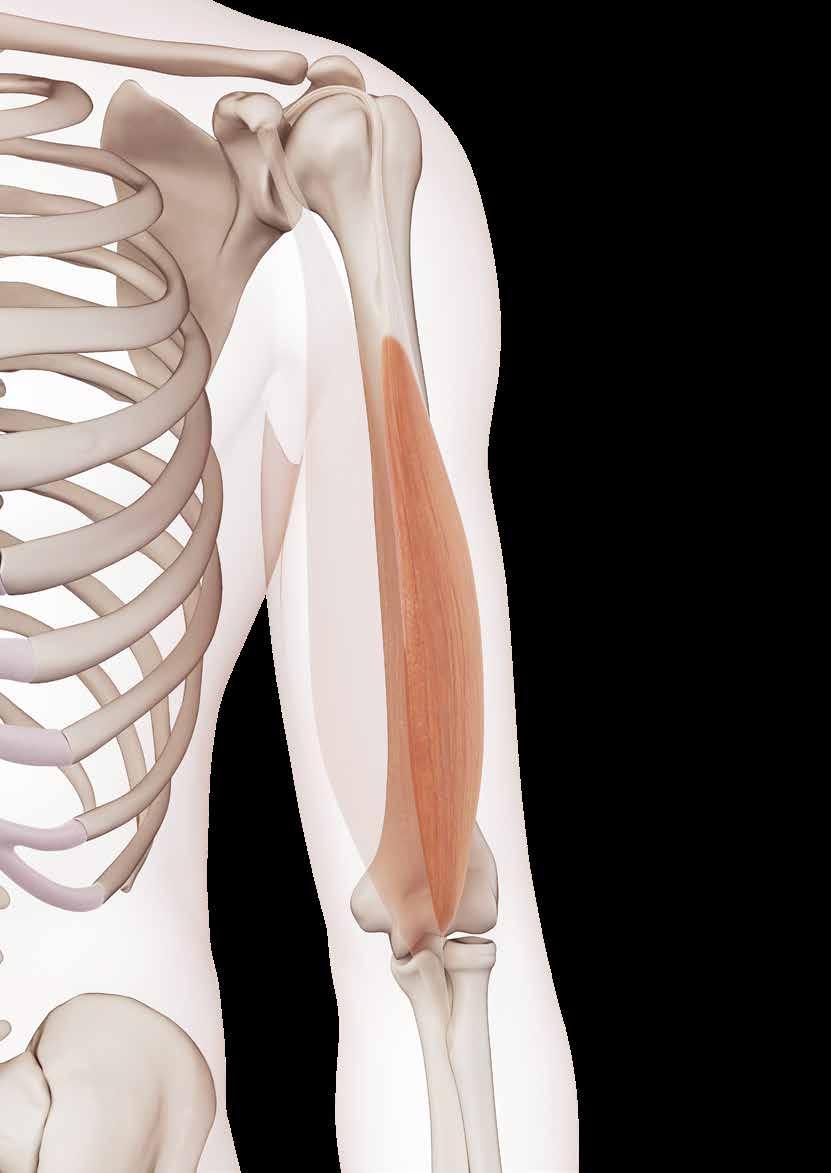

This is a case report on the right arm of a 91-year-old Japanese female cadaver. The complex variations included: (1) the biceps brachii muscle bifurcated at its distal ending; (2) the long head had its own tendon, which divided into two parts, ie. a lateral part fused into the fascia between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi brevis, and a medial part attached to the radius about 1cm ahead of the radial tuberosity; (3) the short head had an accessory origin from the shoulder capsule; (4) the bicipital aponeurosis was of two parts with an anterior superior layer formed by the long head and a posterior deep

BIFURCATED DISTAL BICEPS BRACHII TENDON COEXISTING WITH SEPARATED BICIPITAL APONEUROSIS: A COMPLEX VARIATIONAL CASE REPORT. Zhou M, Ishizawa A, Akashi H et al. Anatomical Science International 2023;doi:10.1007/s12565023-00719-5

one formed by the short head; (5) the musculocutaneous nerve was so underdeveloped that it only innervated the coracobrachialis; (6) the existence of a communicating branch between the musculocutaneous and median nerves, and the median nerve issued muscular branches to the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles; and (7) the brachioradial muscle had two accessory muscular bundles that originated from

EFFECTIVENESS OF AN INJURY PREVENTION VIDEO ON RISKY BEHAVIOURS IN YOUTH SNOW SPORTS: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. Mitra TP, Djerboua M, Mahmood S et al. Paediatrics & Child Health 2023;pxad012

This study is about analysing the role of risky behaviours that contribute to injury to gain an understanding of injury prevention opportunities. The objective was to determine if rates of risky behaviour seen at the ski hill were lower for children and adolescents exposed to an educational injury prevention video. The subjects were students (aged 7–16 years) from 18 Calgary schools who were enrolled in novice-level, school-sanctioned ski and snowboard programmes. They were randomly allocated to either a group who were shown a standard preparation video created by the ski hill, or to an intervention group who were

shown a video that focussed on injury prevention. The Risky Behaviour and Actions Assessment Tool was used by blinded research assistants to observe and record students’ risky behaviours at an Alberta ski hill. In total, 407 observations estimated the rate of risky behaviour. The overall rate of risky behaviour was 23.31/100 person runs in the control group and 22.95/100 person runs in the intervention group. The most commonly observed risky behaviours in both groups were skiing too close to other skiers/snowboarders and near collision with an object/person. So which video they were shown did not make any difference.

In 2015, there were an estimated 13,436 injuries related to snow sports in children younger than 15 years old in the USA, resulting in over 1,300 hospital admissions so anything that seeks to reduce this number is welcome. But wait, snow sports are inherently risky and despite the best efforts of parents who forget that they were once young, risk is part of the fun so no matter what you do you are not going to stop it.

the fascia of the brachial muscle (proximal one) and from the bicipital aponeurosis (distal one).

Co-Kinetic comment

Apparently variations in the biceps brachii muscle are common with accessory head, different origins, variant insertion, and different patterns of nerve innervation. Don’t simply believe everything you read in your anatomy text books.

BREAST INJURY IN THE WOMEN’S FRENCH PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL LEAGUE. Smith LJ, Eichelberger T, Kane E. Journal of Women’s & Pelvic Health Physical Therapy 2023;47(2):90–95

Research on the prevalence of breast injuries in female athletes is sparse. The negative effects from blunt force trauma to the breast outside of sports participation are well documented.

The objective of this study was to report the prevalence, reporting, impact on participation, and the percentage of individuals with a breast injury who received treatment in the French Feminine Professional Basketball League. Subjects were female athletes from six professional basketball teams (50% of the league teams) in France (N=58), and was conducted during the 2020–2021 season. Participants completed a 12-question electronic questionnaire that included demographic information and questions about breast injuries sustained during participation in basketball. The results revealed that nearly one-third of the athletes reported a breast injury. Five athletes reported having three or more separate breast injuries. Four athletes missed practice and/or competition due to the breast injury. Of these, three missed at least 7 days and one missed 1 to 2 days of participation. Only six athletes reported their injury to a medical professional.

There is an interesting discussion in this paper about why a previous study of breast injuries in college athletes reported an injury incidence of 48% and this one is around 33%. Reasons are speculated as being due to bringing attention to an injury that could have obvious financial stakes such as loss of substantial income or other incentives that accompany professional athletics. More specifically, reasons have been the athlete not realising she is actually injured, the athlete not thinking the injury is serious enough to report, the athlete feeling pressure from coaches, teammates, fans and parents, and the athlete reports the injury but the injury is underestimated by the management staff.

INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF PROXIMAL FEMORAL MORPHOLOGY IN NON-CONTACT ACL INJURIES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY. Musliu D, Bexheti S, Kida Q et al. Research Square 2023;doi:https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2821527/v1

The aim of this study was to help identify individuals who are at risk of ACL injury. Fifty-four patients (14 female, 40 male) who had non-contact sportrelated ACL ruptures were identified by MRI and verified arthroscopically by the same surgeon were included. The majority of injuries were caused by football (58.1%), followed by jumping sports (23.8%) and skiing (18.1%). A further 51 patients (10 female, 41 male) with no ACL rupture were matched

by age (15–45 years) and by the side of the injured knee as a control group. To measure their alpha angle, hip radiographs were taken in all the subjects using the modified Dunn view radiograph with patient in supine position, hip flexed 45° and abducted 20°. A mean difference of 5° of the alpha angle was found between the groups. Logistic regression showed a 12–20% risk increase for every degree of alpha angle rise.

ACL injuries are in the British news at the moment because three members of the Women’s Football European Championship winning side have ruptured theirs within 9 months of their triumph. A recent report showed that female footballers are 6 times more likely to suffer an ACL rupture than their male counterparts and there is a race to find out why. This may be one reason. For the non-radiologists among you, the Dunn view is a radiographic projection of the hip that demonstrates and examines the hip joint, femoral head, acetabulum, and particularly the relationship of the femoral head and acetabulum. It is used in the diagnosis of femoral-acetabular impingement and hip dysplasia due to its increased sensitivity for detecting femoral head–neck asphericity. The alpha angle is defined as an angle between the femoral neck and the point at which the femoral head loses its sphericity. Leave that bit to the radiologists, eh! This study equates higher alpha angles to an increased likelihood of ACL injury, with patients who ruptured their ACLs having higher mean alpha angles than those who did not. The authors’ recommendation is that young athletes who are actively participating in sports have their hip alpha angles measured so that those with higher alpha angle can follow special prevention programmes.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN TRAINING FREQUENCY, SYMPTOMS OF OVERTRAINING AND INJURIES IN YOUNG MEN SOCCER PLAYERS. Rodrigues F, Monteiro

D, Ferraz R et al. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023;20(8):5466

The sample consisted of 189 young men soccer players aged 13–17 years old (age, 14.81; SD=1.37). Participants reported that they were training, on average, 5.77 days (SD=1.53) per week. Athletes were competing at a regional ( n =100) or national ( n =89) level. Participants indicated, on average, 2.03 (SD=1.16) injuries since they started practising soccer. The results were a proof of what would be expected: training frequency was significantly associated with overtraining symptoms, overtraining symptoms were significantly associated with the number of injuries. An indirect effect between training frequency and injuries was also observed.

This confirms what all physical therapists know. The more training you do the more likelihood of an injury. The authors make a plea that overtraining warning signs are spotted early to promote young players’ health and safety by customising training regimens to individual needs. Hey coaches, if you break them they can’t play for you!

Gudelis M, Pruna R, Trujillano J et al. The Physician and Sportsmedicine 2023;doi:10.1080/00913847.2023.2170684

The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiology of hamstring muscle injuries in the professional and amateur sport sections of a Football Club Barcelona (FCB) multisport club and to determine any potential correlation between return-to-play (RTP) and injury location, severity of connective tissue damage, age, sex and athlete’s level of competition.

The study included non-contact hamstring injuries sustained during training or competition between September 2007 and September 2017 stored in the FCB database. A total of 538 hamstring injuries were reported, of which 240 were structurally verified by imaging as hamstring injuries. The overall incidence for the 17 sports studied was 1.29 structurally verified hamstring injuries per 100 athletes per year. Of the sports, the highest incidence was in men’s futsal (3.36), followed by men’s football (2.53), and women’s football (2.52). Among amateurs, the highest incidence was found in athletics (1.98), followed by field hockey (1.34), and men´s rugby (0.78). The lowest rate for professionals was found in men’s roller hockey (0.50) and for amateurs in men’s volleyball (0.33). In women’s volleyball, men´s ice hockey and women’s figure skating and ice dancing, no hamstring injuries were reported. Players from sports in which high-speed sprinting and kicking are necessary were at higher risk of suffering a hamstring injury. Notably, the incidence of hamstring injuries in professional sports (2.17) was higher than in amateur sports (0.77).

The muscle most commonly involved in hamstring injuries was the biceps femoris, and the connective tissue most frequently involved was the myofascia. There was no evidence of a statistically significant association between age and RTP after injury, and no statistically significant difference between sex and RTP. The time loss by professionals was shorter than for amateurs, and proximal hamstring injuries took longer to RTP than distal ones.

The motto of FC Barcelona is ‘More than a club’ and it is certainly more than the men’s football section even though they generate most of the publicity worldwide. Over the 10 years studied, they had data on 18,635 players. Within the club structure are athletics, baseball, basketball, cycling, field hockey, futsal, handball, ice hockey, ice skating, roller hockey, rugby, volleyball and wheelchair basketball teams, many of them as successful in their own fields as the footballers so they are an ideal organisation to conduct a multi-sports review. Can we have some more please?

EFFICACY OF THE MYOFASCIAL APPROACH AS A MANUAL THERAPY TECHNIQUE IN PATIENTS WITH CLINICAL ANXIETY: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL. Gozalo-Pascual R, González-Ordi H, Atín-Arratibel MÁ et al. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice

2023;51:101753

Thirty-six adult patients with clinical anxiety were randomised to receive myofascial treatment (n=18) or placebo (n =18). The patients and the evaluators were blinded to this assignation. The treatment consisted of four myofascial sessions of 40min each for 4 weeks. The placebo intervention consisted of four sessions of simulated myofascial intervention of the same duration and frequency as the treatment. Follow-up was at 1, 3 and 6 months. The primary outcome was clinical anxiety measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Secondary outcomes were central sensitisation, general health, somatisation, depression and pain.

The intervention group received 40min of manual myofascial therapy once a week for 4 weeks, in four regions (10min per region) consisting of low load and long duration to the myofascial complex until any tissue restriction disappears or the intervention time ends: (1) transverse planes at the pelvic level, (lumbosacral region and abdomen); (2) transverse planes at the clavicular level (interscapular region and sternum); (3) suboccipital induction; and (4) decompression of the temporals. The control group received a placebo protocol consisting of 40min of simulated myofascial intervention in the same four regions without performing any movement, only maintaining contact.

The results showed that there were significant differences in the behaviour of the groups over time for clinical anxiety, central sensitisation and somatisation in favour of the myofascial group, with a large effect size for anxiety and a medium effect size for central sensitisation and somatisation. There were no adverse events or side effects in either group.

Clinical anxiety occurs when there are high levels of anxiety that interfere with daily life. The extent of this is demonstrated by a couple of previous studies that estimate that the prevalence of anxiety disorders in the USA is estimated to be 18% and in the European Union over 60 million people are affected by anxiety disorders in a given year. The prevalence of performance anxiety in sport, dance and music is high, so anything that helps is a bonus. Try it on your athletes – even if it doesn’t work it shouldn’t do them any harm.

PHYSIOLOGICAL AND NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF SPORTS MASSAGE ON THE ATHLETES’ PERFORMANCE: A REVIEW STUDY. Shamsi H, Okhovatian F, Khademi Kalantari K. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2022;11(5):680–691

This review study aims to investigate the physiological and neurophysiological effects of sports massage on the athletes’ performance, to find out whether the clinical beliefs of sports physiotherapists about the effects of sports massage on sports injuries are supported by scientific evidence or not. A search was conducted in Google Scholar, PubMed and ScienceDirect databases on studies published in English from 1975 to 2020 using the keywords: sports massage, sports injuries, physiological mechanisms, neurophysiological mechanisms, and performance of athletes. Fifty articles about the effects of sports massage were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 14 clinical trial studies and one case report study were included in the review. Analysis of these revealed that few studies have been conducted on the effect of sports massage on the athletes’ performance. The existing studies are

heterogeneous, ie. they have examined the effect of massage on different factors and reported contradictory results. It seems that the effects of sports massage on the athletes’ performance are more due to its psychological effects rather than its clinical effects. The effects of sports massage on athletes’ performance have not yet been supported by scientific evidence.

The trouble with this review is that it uses the term ‘sports massage’ and that is a very general term. As the great Sandy Fritz said in Sports & exercise massage: comprehensive care in athletics, fitness, & rehabilitation, “There is no such thing as Sports Massage, just massage in sport” (https://amzn.to/3MxGXKV).

As you can see from the other massage studies reported in this issue, there are plenty of reports of the efficacy of massage.

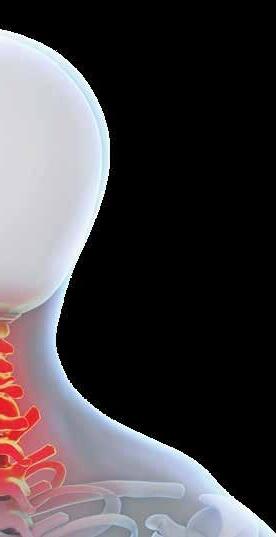

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM AND ENDOCRINE SYSTEM RESPONSE TO UPPER AND LOWER CERVICAL SPINE MOBILIZATION IN HEALTHY MALE ADULTS: A RANDOMIZED CROSSOVER TRIAL. Farrell G, Bell M, Chapple C et al. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy 2023;doi:10.1080/10669817.2023.2177071

This randomised, crossover trial investigated the effects of upper versus lower cervical mobilisation on both components of the stress response simultaneously. The primary outcome was salivary cortisol (sCOR) concentration. Twenty healthy males, aged 21–35 years, were included. Participants were randomly assigned to group A (upper then lower cervical mobilisation, n =10) or group B (lower than upper cervical mobilisation, n =10), separated by a one-week wash-out period. All interventions

were performed in a university clinic under controlled conditions. Statistical analyses were performed with a Friedman’s Two-Way ANOVA and Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. The results showed that there was a statistically significant reduction of sCOR concentration 30min after the interventions.

C-spine mobilisation reduces stress. It will do if it makes an aching neck feel better.

Co-Kinetic Journal 2023;97(July):8-11

Kanpumasatsu is a Japanese custom where one rubs a dry towel along the body to create warmth and friction, to promote good health or ward off disease. This paper is an ‘all you need to know’ essay on the subject, and it quotes research stating positive effects in preventing colds, enhancing immunity, increasing blood flow, activating natural killer cells, and improving metabolism through the autonomic nervous system. The scientific basis for all this is that tactile stimulation to the skin has been known to play a critical role in animal and human growth, influencing DNA expression and having reflexive effects on a variety of physiological functions. The technique is said to have similar effects to other skin stimulation methods, such as acupuncture,

KANPUMASATSU: A SUPERFICIAL SELF-MASSAGE WITH A DRY TOWEL TO ENHANCE RELAXATION AND IMMUNE FUNCTIONS. Komagata S. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 2023;31:100609

massage or application of a hot pack all done with the aim of relieving musculoskeletal pain, reducing soft tissue stiffness by improving blood circulation, and balancing the internal organ functions.

Typically, a soft cotton towel is used to rub the whole body from distal to proximal segments and in slow steady repetitions totalling 5–10min in duration. It can be practised directly against the skin or in a minimally clothed fashion as a self-technique or applied to others. The paper contains a link to a YouTube video showing how

ANALYSIS THE IMPACT OF MASSAGE AND PHYSIOTHERAPY ON THE CONFIDENCE OF CYCLING ATHLETES. Darni DP, Hilmainur Syampurma S. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results 2023;14(3):3284–3289

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of massage and physiotherapy on the confidence of cycling athletes. It is a qualitative study using a case study method. Ten athletes were given massage and physiotherapy following which data was obtained using individual in-depth semi-structured interviews. The results showed that the provision of massage and physiotherapy to the athletes can give them confidence before and after competing. Athletes felt comfortable when given sport massage in a prone position after training. The given physiotherapeutic measures successfully increased functional activity by interpretation in athletes. The authors

speculate that this is because a decrease in self-confidence in athletes is due to the presence of pain, a decrease in the scope of motion of the joints, and a decrease in muscle strength. Therefore, with the successful reduction of the degree of pain, an increase in the scope of motion of the joints, and an increase in muscle strength, functional activity can also increase.

Every therapist in sport knows this but it’s worth having it in writing. Stating the obvious is a theme of this paper. It starts with, “In cycling, athletes are required to be able to pedal a bicycle as quickly as possible.”

to do it: How to practice kanpumasatsu ( ) as a self-care routine https://bit.ly/423QXRR

Co-Kinetic comment

No doubt sceptical Western eyes will view this as something of a gimmick but if you are so inclined it is worth noting that the paper starts with some disturbing facts. Before COVID, the burn-out rate among nurses and doctors in the USA was already between 35 and 54%. The rate among medical students and residents was between 45 and 60%. Obviously the pandemic did not improve the caregiver burden. The laudable aim of this paper is to improve to the health of medical professional. It may be the rub, or it may just be spending 10min of the day alone with your thoughts that reduces stress – if it works, who knows and who cares. Try it.

EFFECT OF MUSCLE ENERGY TECHNIQUE ON HAMSTRING FLEXIBILITY: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND METAANALYSIS. Kang YH, Ha WB, Geum JH et al. Healthcare 2023;11(8):1089

This systematic review aimed to provide clinical evidence for the effectiveness of the Muscle Energy Technique (MET) on hamstring flexibility. Ten electronic databases wee searched (PubMed, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, KISS, NDSL, KMBASE, KISTI, RISS, Dbpia and OASIS) up to the end of March 2022. Only RCTs investigating the use of MET for the hamstring were included. The literature was organised using Endnote. The methodological quality of the included RCTs was evaluated using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool 1.0, and the meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4. In total, 949 patients from 19 RCTs were selected according to the inclusion criteria. During active knee extension tests, the efficacy between MET and other manipulations did not significantly differ. For sit and reach tests, MET groups had higher flexibility compared to stretching and no treatment groups. No significant differences were observed in the occurrence of adverse reactions.

It’s nice to have a review that tells you what tools they have used to help their analysis, such as Endnote and RevMan, which is Cochrane’s own meta-analysis tool. It also tells you that MET works to improve hamstring flexibility.

ACUTE CERVICAL RADICULOPATHY AFTER ANTERIOR SCALENE MUSCLE MASSAGE: A CASE REPORT. Chung SJ, Soh Y. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102(15):e33560

This is a case report involving a 47-year-old Asian woman who had no past history of chronic diseases or medication use; she was 154cm tall and weighed 41kg. The patient’s body mass index was 17.2, which was classified as underweight according to the World Health Organization Asian weight standards. She had previously visited a musculoskeletal pain clinic, was diagnosed with myofascial pain syndrome, and underwent bilateral scalene muscle massage. After a 3min massage to the left anterior scalene muscle, she felt sudden radiating pain and developed shoulder, elbow, and wrist weakness. Cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and showed a right-sided C5–6 disc with mild subarticular protrusion with absence of nerve compression.

Four weeks after symptom onset, nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) were performed. On needle EMG, the left C5 and C6 innervated muscles (including the cervical paraspinal muscle, flexor carpi radialis, extensor carpi radials, biceps, deltoid and infraspinatus) showed recent denervation, increased fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, reduced recruitment, and an interference pattern. The motor NCS showed a decreased (<40%) amplitude at the left axillary nerve (deltoid recording) and left musculocutaneous nerve (biceps recording) compared with that at the right side. Meanwhile, the motor and sensory NCS results and F responses of the median, ulnar and radial nerves were normal. The patient underwent a rehabilitation programme twice a week to improve the ROM in

the left shoulder, elbow and wrist. Four weeks after the first ultrasound-guided selective nerve injection, radiating pain improved by 50% and strength gradually recovered.

The authors point out that to the best of their knowledge, only a few previous case reports of peripheral nerve damage caused by massage therapy have been conducted and this is the first case report on cervical root nerve injury. They speculate that as she was underweight, her skin and muscles were relatively thin, she had less protection and was thus vulnerable to compression injury. The take-home message is that any massage of the scalene muscles should be done very carefully to avoid cervical nerve root injury, particularly in underweight patients.

REDUCING PATIENT’S PAIN WITH POST CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFT (CABG) BY PERFORMING FOOT MASSAGE: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Pamungkas IG, Herawati T, Nova PA. Babali Nursing Research 2023;4(2):278–291

A systematic review was conducted using five databases, namely ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Clinical Key Nursing, and Sage Journal. The total number of subjects in the five papers that met their inclusion criteria was 331, with the majority being male (64.35%). Pooled results showed a significant effect between foot massage and pain in patients after post coronary artery bypass graft.

There is no reason to think that the pain reduction following a foot massage is exclusive to cardiac graft patients.

TENNIS BALL MASSAGE THERAPY IN CLINICAL NURSES: EFFECT ON RELIEVING MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS AND ENHANCING SELF-EFFICACY. Hung YM, Chen SW. Hu Li Za Zhi 2023;70(2):34–44 [in Chinese]

A group of 216 nurses in regional teaching hospitals were screened for neck, shoulder and back pain. From these, 36 were randomly selected to take part in a 4-week ‘fighting pain’ intervention programme. The Pain Visual Scale and Pain Relief Self-Efficacy Scale were used as the assessment tools. The shoulders were the most reported site of muscle pain (94.4%), followed by the neck (88.9%) and the upper back (55.6%). Sadly only the abstract is available in

English so apologies to the authors if the Google Translate version of the methods is not quite right but basically the tennis ball was used to apply pressure on tender spots at the neck (hairline and neck), shoulder pressure points (deltoids), and back (between the shoulder blades and down to the waist). The tennis ball was rolled over the points 5 times on a ‘30s on and 30s off’ rota. The results showed that there were significant reductions in the pain scales.

Simple but effective. Self-applied tennis ball massage is easy to teach, easy to do, takes very little time and – other than a tennis ball – uses no equipment. If you are not sure about how to do it there are lots of instructional videos on YouTube. Employing a trained massage therapist is of course better! The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among nurses is estimated at 1–87.3%, with neck, shoulders and lower back being most affected so the work is there.

This study uses a qualitative methodology to explore professionals’ experiences regarding touch massage (TM) and to identify barriers and facilitators for the implementation of this intervention. The study is part of a larger research programme aimed at investigating the impact of TM on the experiences of patients with chronic pain hospitalised in two units of an internal medicine rehabilitation ward. Healthcare professionals (HCPs) were trained either to provide TM or to use of a massage-machine device according to their units. At the end of the trial, two focus groups were conducted with HCPs from each unit who took part in the training and agreed to discuss their experience: 10 caregivers from the TM group and 6 from the machine group were recruited. The focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed and analysed using thematic content analysis.

Five themes emerged from thematic content analysis: perceived impact on patients, HCPs’ affective

Boegli M et al. PLoS One 2023;18(2):e0281078

and cognitive experiences, patient–professional’s relationships, organisational tensions, and conceptual tensions. Overall, the HCPs reported better general outcomes with TM than with the machine. They described positive effects on patients, HCPs, and their relationships. Regarding implementation of the interventions, the HCPs reported organisational barriers such as patients’ case complexity, work overload, and lack of time. Conceptual barriers such as ambivalence around the legitimacy of TM in nursing care

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF DEEP TISSUE MASSAGE ON PAIN, TRIGGER POINT, DISABILITY, RANGE OF MOTION AND QUALITY OF LIFE IN INDIVIDUALS WITH MYOFASCIAL PAIN SYNDROME. Bingölbali Ö, Taşkaya C, Alkan H et al. Somatosensory & Motor Research 2023;16:doi:10.1080/08990220.20

23.2165054

The study involved patients with myofascial pain syndrome between the ages of 20 and 57 years. They were randomly divided into a control group (n =40) and a study group (n=40). Transcutaneous electrical neuromuscular stimulation, hot pack and ultrasound were applied to both groups. In addition, the study group also had deep tissue massage (DTM) administered for 12 sessions. Neck pain and disability scale (NPDS) for a neck disability, universal goniometer for neck ROM, myofascial trigger point count using manual palpation, Short Form 36 (SF-36) for quality of life and severity of neck pain were evaluated using a VAS. All patients were evaluated before and after treatment. The results revealed that the DTM group had statistically more improvement than the control group for VAS, NPDS and SF-36. Moreover, although there was a significant improvement in favour of the study group for extension, lateral flexion, right rotation and left rotation in the neck ROM, there was no significant difference in flexion measurements between the study and control group.

Another plus for massage and yet there are still people out there who say that there is no evidence for massage. Put them straight!

were reported. TM was often described as a pleasure care that was considered a complementary approach and was overlooked despite its perceived benefits.

Time and time again the Co-Kinetic comment is along the lines of look, massage in its various forms works so spread the word. Here is a paper that shows why those of you wise enough to use massage are often banging your head against a wall of ignorance. The last line says it all, ”TM was often described as a pleasure care that was considered a complementary approach and was overlooked despite its perceived benefits.”

l Weight-bearing foundation: Feet support the body’s weight, acting as primary weight-bearing structures.

l Shock absorption: Feet absorb impact while walking, running, or jumping, reducing strain on joints.

l Balance and stability: Arches, muscles, and ligaments in the feet work together for balance and stability during movement.

l Transfer of forces: Feet transfer weight and forces from the ground up through the body, providing a stable base for movement.

l Alignment and posture: Proper foot alignment promotes overall body alignment, optimising movement mechanics and reducing injury risk.

l Even weight distribution: Healthy feet distribute body weight evenly, minimising pressure on specific areas.

l Adaptability to surfaces: The complex structure of our feet allows for stability and efficient movement on a wide variety of surfaces.

l Choose supportive footwear for good support, cushioning, and stability.

l Do foot exercises to strengthen and stretch your foot muscles.

l Increase activity gradually to prevent overuse injuries and allow your feet to adapt.

l Listen to your feet and seek guidance if you experience pain or discomfort.

l Maintain a healthy weight to reduce strain on your feet.

l Keep feet clean and dry to prevent infections.

l Rest and allow time for your feet to recover after activities, promoting healing.

l Use recommended modifications, like orthotic inserts, for improved foot alignment.

Scan this QR code to access your own copy

Remember, if you have any questions, concerns, or need further guidance, our team is here to provide expert advice and support on your journey to happy and healthy feet.

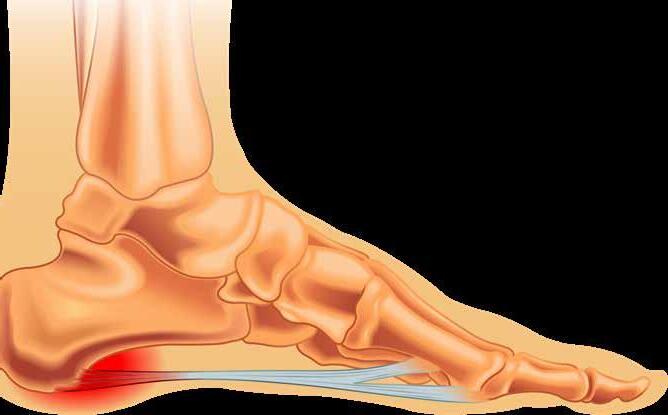

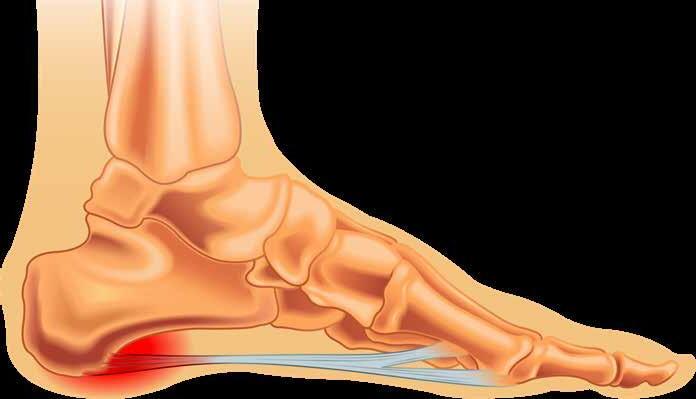

Do you experience pain in your heel or arch area?

If so, you may have plantar fasciopathy (previously called plantar fasciitis), a common foot condition affecting people of all ages and activity levels.

l Heel pain, especially in the morning or after rest

l Pain while walking or standing

l Stiffness in the foot

l Overuse or repetitive stress on the foot

l Obesity or excess weight

l Poor foot mechanics or arch support

l Certain activities or sports

l A healthcare professional will examine your foot and discuss your symptoms. In some cases, imaging tests like ultrasonography may be used.

l Rest, ice, and stretching exercises

l Supportive footwear or orthotics

l Physical therapy

l Shockwave therapy

l Pain medications

l Corticosteroid injections (in some cases)

l Shockwave therapy (in some cases)

l Stretching exercises as advised by a therapist

l Maintaining a healthy weight

l Wearing supportive shoes

l Avoiding activities that worsen symptoms

l If you experience persistent or worsening pain, difficulty walking, or if your symptoms significantly impact your daily activities, consult a healthcare professional.

l Expert advice, exercises, and tips to manage plantar fasciopathy effectively.

l Self-care techniques and preventive measures to keep your feet pain-free.

l Latest advancements in plantar fasciopathy treatment and management.

ASK US FOR MORE INFORMATION!

OUR DEDICATED TEAM IS HERE TO ANSWER YOUR QUESTIONS AND PROVIDE ADDITIONAL RESOURCES.

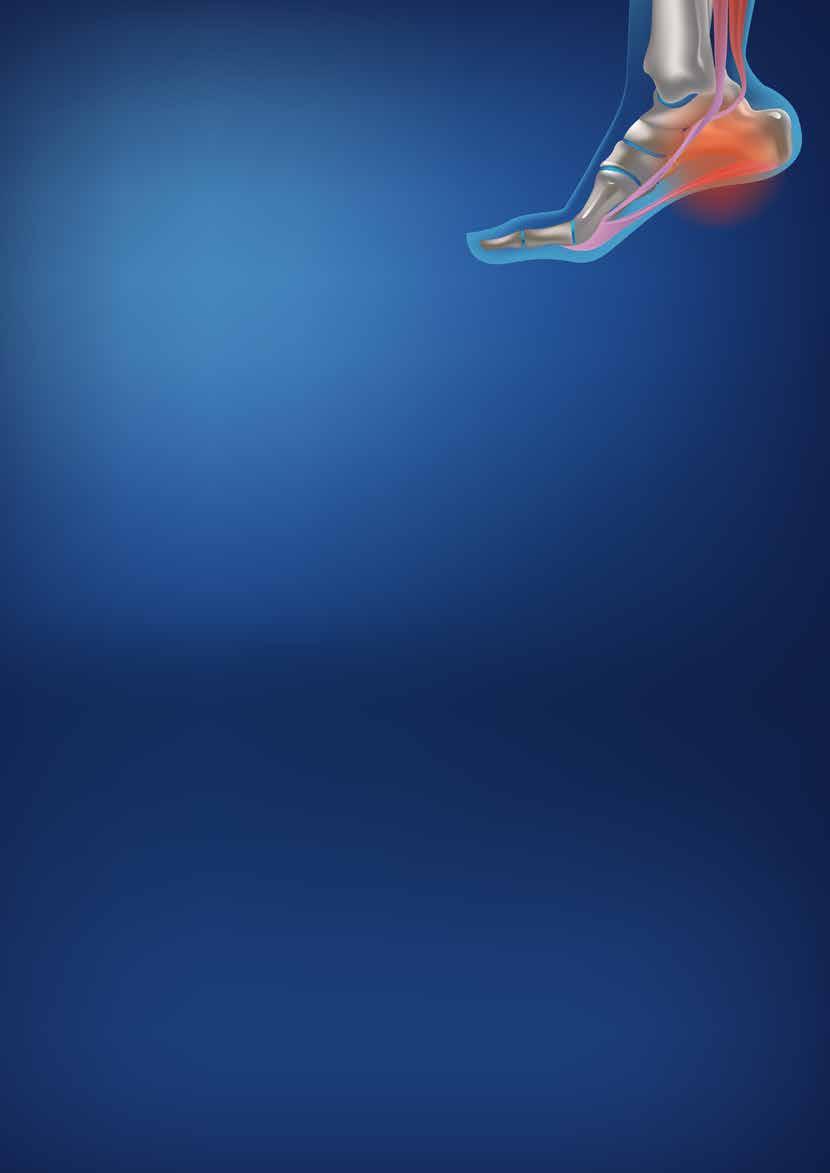

This article is the first of three in this issue of Co-Kinetic that discuss plantar fasciopathy, which has previously and more commonly been known as plantar fasciitis. This articles provides a quick refreshment of your knowledge of plantar fasciopathy and reading it will give you a better understanding of the risk factors for, diagnosis of and biomechanics involved in the condition, before going on to learn more about its management. Read this article online https://bit.ly/3qMUx5S

All references marked with an asterisk are open access and links are provided in the reference list

Feet play an (obviously) critical role in posture and ambulation. In general, the prevalence of foot pathologies ranges between 61 and 79%, and they negatively impact quality of life. Plantar fasciopathy (PF; commonly previously known as plantar fasciitis) is a common musculoskeletal condition affecting individuals across ages and activity levels. PF is most common between the ages of 40 and 60 years and contributes to 15% of foot injuries in the general population without gender difference. The condition may affect both athletic and non-athletic populations, but the incidence is higher among runners affecting up to 17.4% of the population.

Despite the original name,

By Kathryn Thomas BSc MPhilplantar fasciitis, PF is considered a degenerative pathology rather than a primary inflammatory condition. As such, researchers and clinicians increasingly use the terms plantar ‘fasciosis’ or ‘fasciopathy’ in the literature when referring to this condition. Likewise, plantar heel pain is also used interchangeably referring to pain or tenderness under the medial heel or on the sole of the foot extending into the medial arch, exacerbated by weight-bearing activity, as well as after periods of rest or non-weight-bearing. The condition is often chronic, with typical symptoms lasting more than a year (1*). Before considering treatment options for

this condition, let's briefly review the common risk factors and underlying biomechanics that may help guide your management choices.

The association between BMI and PF has been examined in multiple clinical trials and systemic reviews. Interestingly, BMI is not associated with PF in the athletic population; however, there is a strong association in the nonathletic population, where increased body weight is strongly associated with PF.

There is low-quality evidence to support the association of weightbearing activities (such as walking or standing) and PF.

Studies investigating muscle function and size differences between those with and without PF have revealed

THE NAME PLANTAR FASCIOPATHY IS NOW PREFERRED TO PLANTAR FASCIITIS, AS IT IS CONSIDERED A DEGENERATIVE PATHOLOGY RATHER THAN A PRIMARY INFLAMMATORY CONDITION

interesting results. The strength of muscle groups (including those for hallux plantar flexion, lesser toe plantar flexion, ankle dorsiflexion, ankle inversion, and ankle eversion) was lower in patients with PF. Likewise, foot muscle volume was smaller in people with PF. Calf muscle strength and endurance between people with and without PF were not significant. The strength of the evidence assessing muscle strength and PF is very low grade and therefore warrants further investigation.

4.

This aspect of biomechanics and PF requires further research. Some studies have compared the kinematic data of runners suffering from PF with healthy runners and found no significant difference between the two groups. However, another review concluded that decreased ankle dorsiflexion and decreased first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint extension were weakly associated with PF. Increased plantarflexion range of motion is a risk factor for PF, whereas the link with other biomechanical aspects, including ground reaction forces, requires more research.

5.

Studies have shown that the presence of a calcaneal spur was consistently associated with PF. Similarly, PF was more likely to have increased plantar fascia thickness and hypoechogenicity identified on ultrasound.

McMillan et al. investigated the association between subcalcaneal spurs and PF. From clinical trials, patients with PF were eight times more likely to demonstrate radiographic evidence of subcalcaneal spurs than controls (2*). However, other studies show an even stronger association with an odds ratio of 16. A causal relationship has not been established and a better understanding of the role of calcaneal spurs and the development of PF still needs to be investigated further.

Different imaging modalities such as ultrasonography, MRI and plain radiography (ie. X-ray) can be used in

diagnosing PF. Ultrasonography is the most commonly used modality, with a primary diagnostic criterion for imaging being the evaluation of plantar fascia thickness. It has been shown that patients with PF had 2.16mm thicker plantar fascia than controls and tended to have absolute plantar fascia thickness values exceeding 4.0mm. Ultrasound imaging has been confirmed to be an accurate and reliable imaging tool for diagnosing PF, improving accuracy in the delivery of interventions, and monitoring improvement after interventions (2*,3*). Real-time sonoelastography has been used in clinical investigations of tendon disorders including PF (4*). It has been shown that patients with symptomatic PF have measurements indicating a ‘softer’ plantar fascia, and sonoelastography can detect positive findings for PF in symptomatic patients with normal ultrasound findings (4*).

The clinical evaluation of patient history and physical examination is appropriate for evaluating PF. Of the imaging modalities, ultrasound may be most useful when symptoms are equivocal, or to differentiate other possible causes of heel pain and in evaluating treatment outcomes.

Plantar fasciopathy is now the preferred name for plantar fasciitis, as the condition has a lack of inflammatory characteristics and a tendency towards many other ‘opathies’ (like tendons)

for muscle fibres. An aponeurosis is made of layers of delicate, thin sheaths, primarily of bundles of collagen fibres distributed in regular parallel patterns, which make an aponeurosis resilient. The functions of the PA include:

l supporting the foot arch, elevating the foot’s medial longitudinal arch;

l regulating movement about the ankle;

l distributing forces evenly across the foot during loading, the stance phase of running or walking; and

l absorbing energy during movement.

This is a mechanical model that describes the manner in which the plantar fascia supports the foot during weight-bearing activities and provides information regarding the biomechanical stresses placed on the plantar fascia.

Hicks first described the foot and its ligaments as an arch-like triangular structure or truss (5*). The truss’s arch comprises the calcaneus, midtarsal joint, and metatarsals (the medial longitudinal

OF

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION IS APPROPRIATE FOR EVALUATING PLANTAR FASCIOPATHY

arch). The plantar fascia forms the ‘tie-rod’ that runs from the calcaneus to the phalanges. Ground reaction forces travel upward on the calcaneus and the metatarsal heads, resulting in a flattening effect of the truss. Similarly, vertical forces from body weight travel downward via the tibia and tend to flatten the medial longitudinal arch.

Stretch tension from the plantar fascia prevents the spreading of the calcaneus and the metatarsals and maintains the medial longitudinal arch. By virtue of its anatomical orientation and tensile strength, the plantar fascia prevents foot collapse.

A ‘windlass’ is a mechanism that tightens a rope or cable. By analogy, the plantar fascia, therefore, simulates a cable. During the propulsive phase of gait, dorsiflexion winds the plantar fascia around the head of the

metatarsal. This shortens the distance between the calcaneus and metatarsals to elevate the medial longitudinal arch. The essence of the windlass mechanism is thus produced by plantar fascia shortening through hallux dorsiflexion (Video 1).

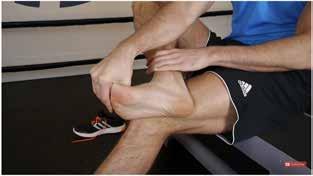

The windlass test achieves a direct stretch on the PA which can be effective in examining the dysfunction of the plantar fascia. This may form a component of the evaluation and treatment monitoring of PF.

A positive windlass test results when heel pain is reproduced with passive dorsiflexion of the toes. Performing the test in a weight-bearing rather than a non-weight-bearing position results in higher sensitivity. De Garceau et al. showed 100% specificity for weight-bearing and a sensitivity of 32% for non-weight-bearing tests (Video 2) (6). This means that this test is not useful to exclude the presence of PF, but very useful to confirm the suspected pathology.

The test is performed as follows.

1. Non-weight-bearing position

Passively raise the toes of the patient while he/she is sitting to see whether this causes pain.

l The patient’s knee is flexed to 90° while in a non-bearing position.

l Examiner stabilises the ankle (with one hand placed just behind the first metatarsal head) and extends the MTP joint while allowing the interphalangeal joint to flex (preventing motion limitations due to short hallucis longus).

l The test is positive if pain was provoked at the end range of the MTP extension.

2. Weight-bearing position

With the patient in a weight-bearing position, the examiner creates a great toe extension.

l The patient stands on a step stool and positions the metatarsal heads of the foot to be tested just over the edge of the step.

l The subject is instructed to place equal weight on both feet.

l The examiner then passively extends the first MTP joint while allowing the interphalangeal joint to flex.

l Passive extension (ie. dorsiflexion) of the first MTP joint is continued

to its end of range or until the patient’s pain is reproduced.

The PA is composed of type 1 collagen, characterised by its elasticity and tensile strength. Type 1 collagen fibres are oriented in a parallel fashion with respect to each other, making them effective in transmitting and distributing forces that are also longitudinal or parallel to the fibre direction. Forces that are perpendicular in nature or compressive cannot be transmitted as effectively and result in the degradation of the collagen fibres (7). Thus, the forces that can cause micro-tearing to the collagen fibres include body weight and vertical ground reaction forces. Having a high BMI can increase the rate at which compressive forces cause microdamage, additionally, the duration of the forces applied increases the rate of collagen degradation. This may be relevant to activities such as prolonged standing or walking, or chronic overuse.

The plantar fascia regulates the movement of the talus and prevents it from moving too far anteriorly during pronation or too far posteriorly during supination. Thus, pronation and supination at the ankle increase plantar fascial tension. These are, however, important movements during the gait cycle. Control of the PA allows for regulated pronation and supination which in turn results in a systematic and efficient gait. During the transition between heel strike and weight acceptance, when maximum ankle pronation occurs, plantar fascial tension is at its highest. The second instance of high tension on the plantar fascia is during the transition between mid-stance and toe-off when maximum ankle supination occurs (8*).

The tibialis posterior muscle functions to reduce tension applied to the PA by eccentrically contracting during weight acceptance. Weakness of the tibialis posterior may result in greater overpronation and increased tensile forces being applied to the PA.

Rigid or high-arched feet decrease the distance between the two attachment points of the PA.

ULTRASOUND MAY BE MOST USEFUL IMAGING MODALITY WHEN SYMPTOMS ARE EQUIVOCAL

This leaves the PA in a continuously shortened state. Reduced elasticity (from a tight and shortened position) can reduce the PA’s ability to absorb energy and respond to ground reaction forces.

A leg-length discrepancy can result in uneven distribution and transmission of ground reaction forces. Compensatory mechanisms include hip and knee flexion, and excessive hip circumduction, which all increase the tensile forces on the PA (8*). PF commonly presents in the longer limb because greater forces are transmitted to the foot on the longer limb.

Old shoes, worn-down from continual use, have a decreased ability to absorb and dissipate ground reaction forces. Thus, the PA will experience more stress as compressive forces are transmitted directly to the plantar fascia, rather than the shoe.

Understanding the biomechanics of the foot system and its impact on the plantar fascia will aid in the identification of underlying muscle imbalances or biomechanical issues that may be contributing to the patient’s condition. This in turn will help guide a personalised treatment plan.

References

1. Rhim HC, Kwon J, Park J et al. A systematic review of systematic reviews on the epidemiology, evaluation, and treatment of plantar fasciitis. Life

2021;11:1287 Open access https://bit.ly/45KGWfi

2. McMillan AM, Landorf KB, Barrett JT et al. Diagnostic imaging for chronic plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research 2009;2:32 Open access https://bit.ly/42p5fMM

3. Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Nakhaee M, Mousavi ME et al. Application of ultrasound in the assessment of plantar fascia in patients with plantar fasciitis: a systematic review. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2014;40:1737–1754 Open access https://bit.ly/43u8nbS

4. Fusini F, Langella F, Busilacchi A et al. Real-time sonoelastography: principles and clinical applications in tendon disorders. A systematic review. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 2017;7 (3):467–477 Open access https://bit.ly/43lskBt

5. Hicks JH. The mechanics of the foot. II. The plantar aponeurosis and the arch. Journal of Anatomy 1954;88(Pt 1):25–30 Open access https://bit.ly/3MS0IN7

6. De Garceau D, Dean D, Requejo SM et al. The association between diagnosis of plantar fasciitis and windlass test results. Foot & Ankle International 2003;24(3):251–255

7. Mienaltowski MJ, Birk DE. Structure, physiology, and biochemistry of collagens. In: Halper J (ed.) Progress in heritable soft connective tissue diseases (Advances in experimental medicine and biology book 802), Chapter 2, PP5–29. Springer 2014. ISBN 978-9402407747 (print £119.99 kindle £113.99). Buy from Amazon https://amzn.to/3NaI04W

8. Yoo SD, Kim HS, Lee JH et al. Biomechanical parameters in plantar fasciitis measured by gait analysis system with pressure sensor. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine 2017;41(6):979–989 Open access https://bit.ly/3NasB4y

l The prevalence of foot pathologies is high, ranging between 61 and 79%.

l The name plantar fasciitis has changed to plantar fasciopathy (PF) as it is considered to be a degenerative pathology rather than a primary inflammatory condition.

l BMI is associated with PF in the non-athletic population but not in the athletic population.

l There is low-grade evidence for a link between PF and low strength of muscle groups such as those for hallux plantar flexion, lesser toe plantar flexion, ankle dorsiflexion, ankle inversion, and ankle eversion.

l Diagnosis of PF is usually through clinical evaluation of patient history and physical examination.

l Ultrasound may be most useful when symptoms are equivocal, or to differentiate other possible causes of heel pain and in evaluating treatment outcomes.

l The windlass test may form a component of the evaluation and treatment monitoring of PF.

l Any biomechanics that result in increased forces on the plantar aponeurosis contribute to the development of PF.

l Plantar Fasciitis: A Pain in the Heel [Article]

https://bit.ly/3sMVKa5

l Spontaneous Rupture of the Plantar Fascia in a Professional Football Player [Article]

https://bit.ly/43GIBk7

l The Core of Your Foot Problems [Article]

https://bit.ly/3u7sOdL

l Management of Plantar Fasciopathy and Plantar Heel Pain [Article] https://bit.ly/3CtkV78

l Loading the Plantar Fascia. A Comment on High Load Exercise [Article] https://bit.ly/3N8LLXo

l Think about your current/previous patients with plantar fasciopathy (PF). Which of the risk factors discussed here did they have? Are some risk factors more commonly represented in your experience than others?

l Which aspects of the biomechanics discussed in this article have broadened your understanding of what contributes to PF and if so how would you change your patient assessment?

l Do you think imaging is useful for diagnosing PF and when might you want to refer your patient on?

Kathryn Thomas BSc Physio, MPhil Sports Physiotherapy is a physiotherapist with a Master’s degree in Sports Physiotherapy from the Institute of Sports Science and University of Cape Town, South Africa. She graduated both her honours and Master’s degrees Cum Laude, and with Deans awards. After graduating in 2000 Kathryn worked in sports practices focusing on musculoskeletal injuries and rehabilitation. She was contracted to work with the Dolphins Cricket team (county/provincial team) and The Sharks rugby teams (Super rugby). Kathryn has also worked and supervised physios at the annual Comrades Marathon and Amashova cycle races for many years. She has worked with elite athletes from different sporting disciplines such as hockey, athletics, swimming and tennis. She was a competitive athlete holding national and provincial colours for swimming, biathlon, athletics, and surf lifesaving, and has a passion for sports and exercise physiology. She has presented research at the annual American College of Sports Medicine congress in Baltimore, and at South African Sports Medicine Association in 2000 and 2011. She is Co-Kinetic’s technical editor and has taken on responsibility for writing our new clinical review updates for practitioners.

Email: kittyjoythomas@gmail.com

Plantar fasciopathy (PF; aka plantar fasciitis) is a common reason for referral to orthopaedic surgeons, physical and manual therapists, podiatrists, doctors and pharmacists. In the general population, its prevalence has been estimated at 7%, predominantly affecting sedentary middle-aged and older adults, and is estimated to account for 8% of all injuries related to running (1*). The condition is characterised by first-step pain and pain during weight-bearing tasks, particularly after periods of rest (1*). Patients may present with pain at varying degrees from slight, irritating, and intermittent discomfort to almost incapacitating pain under the heel and sole of the foot. As suggested in the previous article, ‘Plantar Fasciopathy: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Biomechanics’ (https://bit. ly/3qMUx5S), the importance and/ or presence of a bony spur and inflammation is not conclusive of either diagnosis or prognosis. Although still not fully understood, it has now been demonstrated that pathophysiologically the condition is related to degenerative changes at the proximal insertion of the plantar fascia (especially around its medial band) and micro-trauma to the plantar fascia and plantar aponeurosis (2). A biomechanical fault is often present in these cases. Any factor which is responsible for mechanical overloading of the plantar fascia should be addressed during treatment, including altered foot arch, body mass index (BMI), obesity, decreased

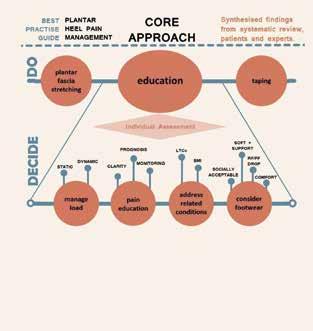

As is often the case, understanding how to best manage plantar fasciopathy (PF) and plantar heel pain (PHP) has been a challenge, because although there is a lot about it in the literature, arriving at a consensus of opinion is difficult: much of the evidence is of low quality and studies involve a mixture of treatment modalities. This second of three articles presents the available evidence for the different treatment options and discusses the best practice guide for these conditions, which gives you a clear plan of how best to approach an individualised treatment for PF and PHP. Read this article online https://bit.ly/3CtkV78

By Kathryn Thomas BSc MPhildorsiflexion range of movement (ROM) and tightness in calf muscles.

The primary approach to the disease is agreed upon worldwide and is based on general non-surgical measures. These include:

l stretching;

l manual therapy;

l local icing;

l exercises to eccentrically strengthen muscles of the posterior chain: in particular, the triceps surae to reduce the amount of mechanical stress transmitted at the plantar fascia;

l dry needling;

l shockwave therapy;

l physical agents:

l electrotherapy

l low-level laser therapy

l phonophoresis

l ultrasound;

l lifestyle counselling;

l anti-inflammatory injections; and

l mechanical treatments such as:

l taping

l rocker shoes

l (ankle-)foot orthoses [(A)FOs] including night splints (3*).

In case of failure of such treatment, some authors advocate the surgical

release of the fascia or fasciotomy. Surgical results are contradictory and the value of fasciotomy is still debated (4*).

In athletes, PF or plantar heel pain (PHP) might significantly affect the level of function, negatively influencing performance and resulting in prolonged periods of rest. Surgery in elite athletes represents a potentially career-ending event, especially in case of rupture of the fascia, which makes the decisionmaking process even more complex for these patients (4*).

The best practice guide (BPG) described in the most recent review by Morrissey et al. (a mixed-methods study synthesising systematic review with expert opinion and patient feedback) suggests the core treatment for people with PHP should include taping, stretching and individualised education (1*). Patients who do not optimally improve may be offered shockwave therapy, followed by custom orthoses. Video 1 gives a brief overview of the paper. Where, you may ask are the exercise and manual therapy components? The published literature is dominated by systematic reviews, guidelines and meta-analyses that include low-quality

THE PRIMARY APPROACH TO THE DISEASE IS AGREED UPON WORLDWIDE AND IS BASED ON GENERAL NONSURGICAL MEASURES

trials with small sample sizes, which may inflate effect sizes and lead to incorrect interpretation (1*). A significant difference in results may not necessarily translate to minimal clinically important difference. That is the smallest change in a treatment outcome that an individual patient would identify as important, indicating a change in the patient’s management or condition. The failure to achieve optimal outcomes in those suffering from PF or PHP is especially true in athletes who experience a median recovery time of 5 months (5*). In fact, a study has shown that 54% of all patients followed for approximately 10 years reported symptoms of approx. 2 years in duration and the remainder were still symptomatic at follow-up (6*).

Owing to their overlap in the literature, clinical presentation and management, this article will detail the management approaches for PF and PHP combined. Focusing on the research, or lack thereof, for physical therapy and mechanical treatment options, without delving into medical and surgical protocols.

PF is the most common musculoskeletal condition of the foot in the general population and in the running community. Even though inflammation may play an important role in the early disease process, PF (similar to tendinopathy) has been characterised by degeneration of collagen. This does not mean that inflammation and degeneration represent a continuum of disease but rather reflect two distinct or often coexisting processes. Mounting evidence suggests that PF is caused by repetitive tensile loads applied to the plantar aponeurosis. This is due to excessive deformation of the foot’s longitudinal arch facilitated by weakness of the intrinsic foot muscles (5*).

A lack of full understanding of the causes, the disease process and pathophysiology may explain why multiple treatment modalities and protocols have been researched in this field, with little homogeneity and even less conclusive outcomes to guide management.

ESWT appears to provide better longer-term outcomes over corticosteroid injection and most interventions studied. There is high heterogeneity across studies, resulting in conflicting evidence regarding optimal type and energy level of ESWT. A recent study showed that similar functional gains were seen between radial shockwave and radial shockwave combined with focused shockwave therapies while using a standardised physical therapy protocol. The standardised physical therapy programme entailed an exercise programme focusing on intrinsic foot muscle strengthening. Collectively, the study suggests that the majority of patients with chronic PF may achieve functional gains using either form of shockwave therapy, with no acknowledgement of the possible contribution from the exercise programme (7).

ESWT has shown greater reduction in visual analogue scores and a success rate of improving heel pain by 60% over placebo when taking first steps and during daily activities. Studies have also shown an overall reduction in PF thickness using ESWT treatment. Authors have found that complications during the first year of follow-up are highly unlikely and concluded that both low- and high-dose ESWT are safe for treating PF (8*).

Although studies using acupuncture therapies have been associated with

symptom reduction, a major limitation is the significant heterogeneity of methods. Myofascial trigger point needling may be associated with a significantly greater reduction in pain at 1, 6, and 12 months. However, poor quality methods and small sample sizes limit the ability to recommend dry needling for PF or PHP (9*).

LLLT has been found to significantly improve pain and function and decrease plantar fascia thickness compared to other therapies, such as exercise. Again the low-quality evidence and large variation in treatment parameters of LLLT limit its use (9*).

Strength training approaches to treating PF and improving intrinsic foot strength come with significant differences in the literature. Huffer et al. classified strengthening interventions into three distinct categories: (i) minimalist running shoe intrinsic foot muscle (IFM) strengthening, (ii) IFM foot exercises, and (iii) plantar aponeurosis loading (10). Although the authors found that these minimalist running shoes and toe flexion against resistance may improve intrinsic foot musculature in asymptomatic populations, high-load

plantar fascia resistance training has not been shown to change plantar fascia thickness. It has not been shown to what extent strengthening interventions for intrinsic foot musculature may benefit symptomatic or at-risk populations of PF. There is limited evidence validating toe flexion exercises against resistance and minimalist running shoes to improve IFM function and what this means to the patient. High-load plantar fascia resistance training had no effect on changing plantar fascia thickness; however, it may aid in reducing pain and improving function (10).

Patients with PF and PHP often present with weaker foot muscle strength and smaller foot muscle volume. Modern footwear use is associated with weaker IFMs, a greater prevalence of flat feet and subsequent changes to the shape of the foot (5*). Over millions of years, the human foot evolved to walk and run barefoot on a variety of natural surfaces. The invention of footwear and artificial surfaces represents a rapid change in the physical environment experienced by the foot. Using this evolutionary perspective, barefoot running on grass has been shown to improve pain associated with PF at 6 and 12 weeks. Participants were required to run barefoot on a grass

field for 15 minutes, at an intensity that represented a rate of perceived exertion of 11, every second day for 6 weeks (21 sessions). It may seem counterintuitive to both patients and clinicians to prescribe or adopt vigorous loading activities (running) on a regular basis – and without shoes – when symptomatic (5*). However, barefoot running was shown to improve symptoms while allowing patients to continue running – often a highly valuable component of mental health to an active individual. Barefoot running may address some biomechanical impairments of the foot associated with PF (5*).

One study compared the use of insoles on all patients, with one group receiving the addition of a plantarfascia-specific stretching programme (10 stretches held for 10 seconds each, 3 times a day), and the other group the addition of a strength training programme (11*). High-load strength training consisted of unilateral heel raises with a towel inserted under the toes to further activate the windlass mechanism. The towel ensured that the patients had their toes maximally dorsal flexed at the top of the heel rise. The patients were instructed to perform the exercises every second day for 3 months. Every heel rise consisted of a 3-second concentric phase (going up) and a 3-second eccentric phase (coming down) with a 2-second isometric phase (pause at the top of the exercise). The high-load strength training was slowly progressed throughout the trial. Patients started at a 12-repetition maximum (RM) for 3 sets. 12RM is defined as the maximal amount of weight that the patient can lift 12 times through the full range of motion while maintaining proper form. By using a backpack with books, patients increased the load after 2 weeks and reduced the number of repetitions to 10RM, simultaneously increasing to 4 sets. After 4 weeks, they were instructed to perform 8RM and perform 5 sets, again increasing the load in the backpacks. If they could not perform the required number of repetitions, they were instructed to start the exercises using both legs until they were strong enough to perform unilateral heel raises. Patients were

instructed to keep adding books to the backpack as they became stronger. This is explained in Video 2.

The results showed a 29-point greater improvement in foot function index (FFI) in patients randomised to high-load strength training at the primary endpoint of 3 months. This difference exceeded the 7 points, which is considered the minimally relevant difference in FFI and suggests clinical relevance. Interestingly, the high-load strength training was not associated with a larger reduction in the thickness of the plantar fascia on ultrasound. By 6 and 12 months there was no significant difference between groups in pain and function. It was suggested therefore that a simple progressive exercise protocol, performed every second day, resulted in superior self-reported outcomes after 3 months compared with plantar-specific stretching. High-load strength training may aid in a quicker reduction in pain and improvements in function (11*). This was the first trial of its kind for PF.