C Transit Voter Guide

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

In just a few weeks, Cobb County voters will choose one of two paths.

A countywide referendum will ask: should Cobb raise its sales tax by 1%, for 30 years, to fund public transportation?

It’s one of the biggest decisions in the history of Cobb, which voted against joining MARTA in 1965, voted to authorize the creation of CobbLinc, an independent bus system, in 1987, and has historically been skeptical of mass transit.

If approved, Cobb’s sales tax would increase from 6% to 7%. Over three decades, the estimated $11 billion in collections would overhaul transit in the county.

Combined with anticipated federal grants, Cobb expects to spend $14.5 billion over the life of the tax.

The main elements of the Mobility Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax (M-SPLOST) are 108 miles of rapid bus routes, half a dozen new transit centers and a countywide system of on-demand “microtransit” service.

The M-SPLOST’s new transit would be operated by the county’s own CobbLinc, and not be part of MARTA. The proposal does not include rail.

To help voters decide, the MDJ has dedicated this voter guide to the transit tax proposal. In it, you can find:

♦ Background and history of SPLOST referendums;

♦ Specifics on the proposed projects;

♦ An analysis of the economics of sales taxes;

♦ The stories of people who rely on Cobb’s existing transit;

♦ A critical look at CobbLinc’s ridership and financing;

♦ A review of another major effort to curb congestion — interstate express lanes;

♦ Q&As with the transit tax’s architect and her opponents;

♦ Opinions from readers on both sides of the issue.

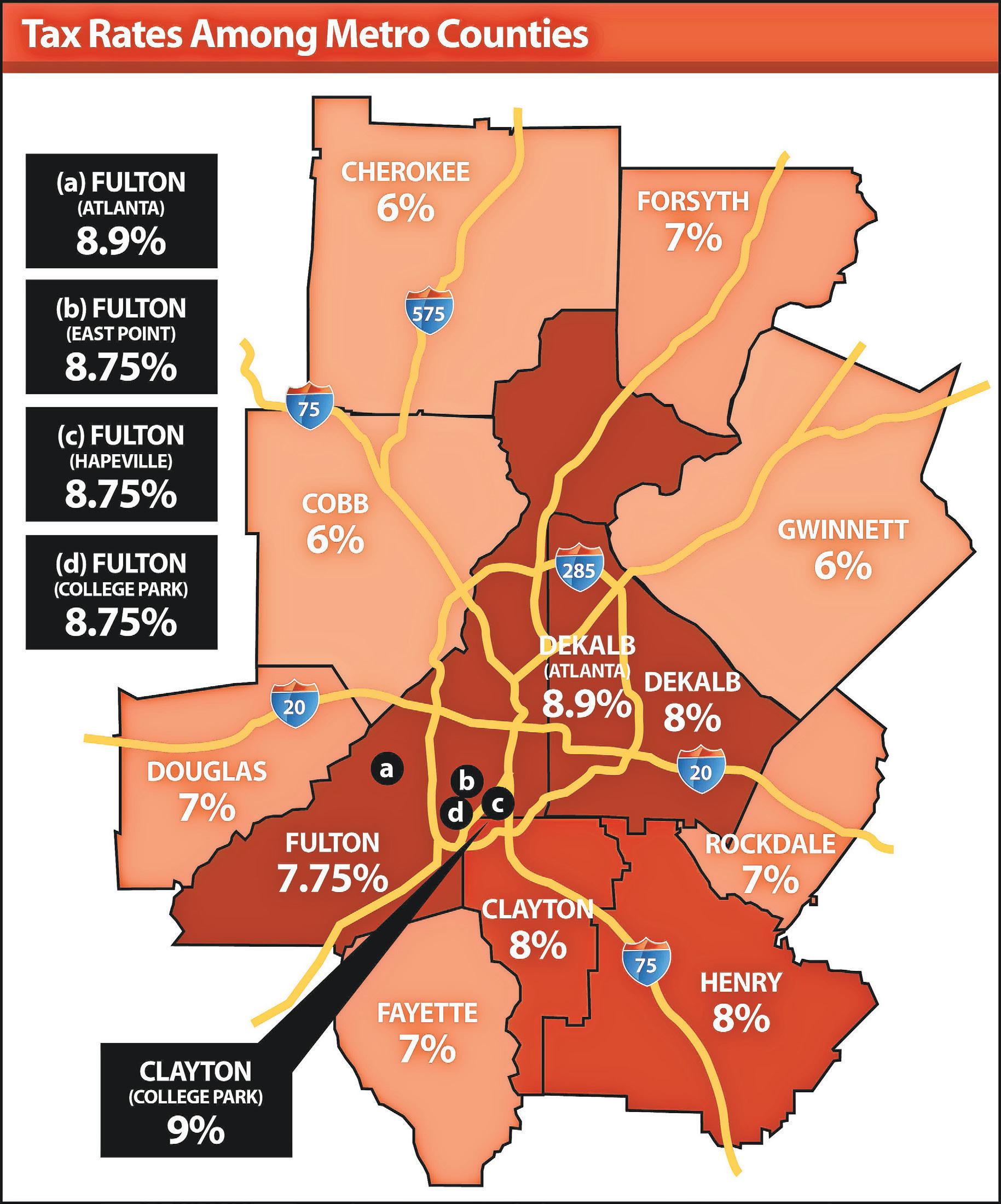

Presently, Cobb’s sales tax has a base rate of 4%. Two SPLOST taxes, 1% each, are already in place. One funds the county government and six of its cities, the other funds Cobb’s two school systems. County sales tax rates range from 6-9% in Georgia. At the moment, Cobb is tied for the lowest sales tax in the state

— only three other counties have a 6% rate.

The transit tax has been spearheaded by the Democratic members on the Cobb Board of Commissioners. Republican officials and conservative groups are working to defeat it.

M-SPLOST supporters say transformational change is needed to accommodate population growth, provide more transportation options, ease congestion and spur economic development.

Opponents, meanwhile, criticize the tax for its length and cost, unprecedented in the history of Cobb’s SPLOST referendums, and have questioned whether the system would be widely used.

CobbLinc now offers nine local routes, five express routes, two circulator routes, one flex route, and paratransit service within threequarters of a mile of the 11 local fixed routes.

The M-SPLOST would fund the construction of seven bus rapid transit (BRT) routes and three arterial rapid transit (ART) routes.

BRT would operate mainly in new dedicated travel lanes. ART would operate in some dedicated lanes, but would otherwise mix with traffic.

Those routes would cost an estimated $6 billion to build, while $5 billion more would be split between local transit expansion and vehicles, facilities and amenities.

Just over $3 billion is estimated to cover transit technology; more localized, on-demand transit known as microtransit; and improvements to roads, sidewalks and trails.

Both BRT and ART would stop at stations featuring off-board fare collection, sheltered stops, lighting and other amenities; and would operate at a frequency of every 15 to 20 minutes.

BRT stops would be approximately every half-mile; ART stops would be every quar-

ter- to half-mile.

BRT and ART buses would both enjoy signal priority at intersections — use of technology or “queue jumper” lanes which give buses priority at red lights.

The “high-capacity transit” routes — BRT and ART — would connect places like Town Center and Kennesaw State University, Marietta, Cumberland, Wellstar Cobb Hospital, Mableton and Smyrna. They would also connect to the Arts Center, Dunwoody and H.E. Holmes MARTA stations.

The cities of Austell, Powder Springs and Acworth, as well as the west Cobb area, would have little access to high-capacity transit. Downtown Kennesaw would also not be on a high-capacity transit route. The only highcapacity route that would go into the heart of east Cobb would be along Roswell Road.

The BRT connection to Midtown Atlanta would use Interstate 75. BRT would also run on I-285, from I-20 in the south to Georgia 400 in the east.

Additionally, the project list includes a countywide system of “microtransit,” which would bring connectivity to areas with little or no access to the fixed routes.

The county envisions microtransit — ondemand, localized transit vehicles — as providing “curb to curb” service within 14 defined zones.

Cobb plans to use up to $950 million in revenue bonds to frontload spending and build the majority of the transit within the first decade of the tax. In the next two decades, the county would use M-SPLOST revenue to finish the system, pay off the bonds and maintain operations.

To view all of our coverage on the transit tax, including the full project list, visit mdjonline.com/transit.

For the better part of a year, much of my job has been reporting on Cobb’s looming transit tax vote.

We’ve spilled a lot of ink trying to educate voters on the tax — projects proposed, how it will impact you, what both sides think. It’s a big decision for Cobb: a 30-year, 1% sales tax, projected to collect $11 billion, intended to overhaul public transportation in the county. That reporting’s involved riding the buses to get a feel for the system and its users.

Earlier this year, to cap a series we ran about CobbLinc’s ridership and funding, I was assigned to write a column about my experience on the buses. So what’s new?

In the last column, I started with an anecdote about a dysfunctional robot bathroom at the Cumberland transfer center. I’m pleased to report that on my last visit, the bathroom was clean, and the sink was working. And how about those fareboxes?

When reporting the aforementioned series, we learned CobbLinc fareboxes were frequently malfunctioning, leaving an unknown amount of fare revenue on the table.

In my last column, I tried and failed to pay with my Breeze card on five trips, saving myself — or costing the taxpayer, depending on your perspective — $12.50. Cobb recently spent $1.4 million to replace the fareboxes. Since then, I’ve taken six trips and been able to pay four times.. So from my limited experience, the new tech is an improvement, though not perfect. And occupancy? It matches what the data says, as far as I can tell. Routes 10 and 30 are popular, and the buses are pretty full. The other routes I’ve tried — Routes 15, 40 and 50 — were a little more sparse. What about timing?

In a recent MDJ column, Smyrna resident Stephen Mattson told his story about a bus he waited for, after leaving a Braves game, which never came. I’ve also made a frustrating attempt to catch a circulator bus in the Battery after a game, only to give up after waiting too long. Maybe it’s the postgame traffic. But for the most part, the buses run on time. Last time around, I found the buses to be clean and comfortable, and drivers friendly. That remains true. Even when you’re paying the fare, they’re cheap to use — the standard $2.50 fare hasn’t changed in 13 years. Since then, the cost of everything else has gone up by 40%.

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

SPLOST stands for Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax, a financing method used by local governments across the state.

These sales taxes are approved in countywide referendums. In Cobb, that means all registered voters in the county vote on a SPLOST, which when approved raises the sales tax across the entire county.

Regular SPLOSTs are used to fund capital projects, which can include road resurfacing, parks, government buildings, vehicles and more.

Typically levied at a rate of 1%, regular SPLOSTs in Cobb County provide funding to the county government and the county’s city governments.

Education SPLOSTs, also taxed at 1% which are developed and voted on separately, benefit Cobb’s two public school systems — Cobb

County School District and Marietta City Schools. Funds have been used to build and renovate schools, among other expenses. In general, county government SPLOSTs can be levied for periods up to five years, after which they end or must be re-approved by the voters. If the county and municipalities enter into an intergovernmental agreement, however, the tax may be imposed for up to six years, as is the case in the current Cobb County SPLOST cycle.

Education SPLOSTs, meanwhile, can be imposed for up to five years.

Before a SPLOST is placed on the ballot, the Board of Commissioners must create a list of projects for which proceeds will be used. The county is also required to provide the estimated cost of each project and the estimated revenues the tax will collect.

If local governments plan to create debt and issue bonds

backed by the SPLOST, it must indicate its intentions to do so on the ballot.

SPLOST revenues are collected into a separate account than the county’s general fund.

The legislation enabling the creation of SPLOST was enacted in 1985. Since then, SPLOSTS have become widespread in Georgia. Cobb voters have regularly approved new regular and education SPLOST cycles for years.

The Association of County Commissioners of Georgia has attributed the popularity of SPLOST referendums to the “unpopularity of property taxes and the simplicity and perceived fairness of sales taxes.”

What is the ‘M-SPLOST?’

The proposed Mobility Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax would create an additional 1% countywide sales tax in Cobb to fund public transit projects.

Presently, Cobb’s sales tax

has a base rate of 4%. Two SPLOST taxes, 1% each, are already in place. One funds the county government and six of its cities, the other funds Cobb’s two school systems.

If the M-SPLOST is approved, Cobb’s sales tax would rise from 6% to 7%.

Aside from funds being explicitly dedicated to transit projects, the M-SPLOST is distinguished by its proposed length of 30 years.

The unprecedented timeframe of the M-SPLOST also means that more revenue is at stake in a single referendum.

The current regular SPLOST is estimated to collect $750 million for the county and its cities, and the current education SPLOST is estimated to collect $966 million for Cobb’s two school systems.

The M-SPLOST, meanwhile, is estimated to collect $11 billion.

If approved, the M-SPLOST would be used to construct 108 miles of rapid bus routes, half a dozen new transit centers and a countywide system of on-demand “microtransit” service.

Staff reports

When to vote on Election Day

The M-SPLOST will be on the ballot in the general election on Nov. 5. Polls will be open from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Voters must bring a photo ID. Where to vote on Election Day

To find your voting precinct, visit the Georgia My Voter Page at mvp.sos.ga.gov.

When and where to vote early

Early in-person voting is available from Oct. 15 through Nov.

1. Hours are 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., Monday through Saturday, at all 12 locations.

Anyone registered to vote in Cobb can vote at any of the early voting sites. Early voting will be offered noon to 5 p.m. on Sundays at five locations.

Early voting locations are listed below. The first five locations have Sunday voting, the others do not.

1. Elections Main Office: 995 Roswell St. NE, Marietta

2. North Cobb Senior Center: 3900 South Main St., Acworth

3. South Cobb Community Center: 620 Lions Club Drive, Mableton

4. East Cobb Government Service Center: 4400 Lower Roswell Road, Marietta

5. Boots Ward Recreation

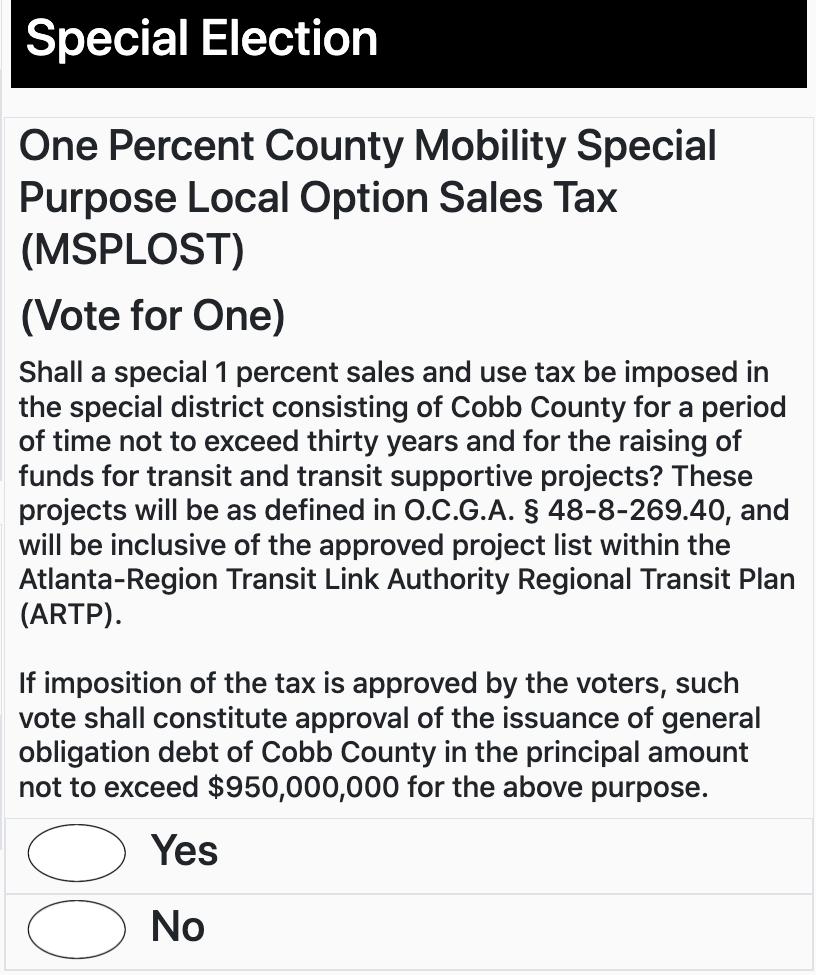

The referendum as it appears on the voting machine.

Center: 4845 Dallas Highway, Powder Springs 6. Smyrna Community Center: 1250 Powder Springs St. SE, Smyrna 7. Collar Park Community Center: 2625 Joe Jerkins Blvd., Austell

8. Tim D. Lee Senior Center: 3332 Sandy Plains Road, Marietta

9. West Cobb Regional Library: 1750 Dennis Kemp Lane, Kennesaw

10. Ben Robertson Community Center: 2753 Watts Drive, Kennesaw

11. Fair Oaks Recreation Center: 1465 West Booth Road Extension, Marietta

12. Ron Anderson Recreation Center: 3820 Macedonia Road, Powder Springs

When to vote absentee

Cobb began mailing ballots out on Oct. 7. The last day to request an absentee ballot is Oct. 25.

Editor’s note: Below is a list of terms related to Cobb County’s upcoming M-SPLOST referendum

ART — Arterial rapid transit. Rubber-tire buses run on fixed routes through major thoroughfares, connecting to regional destinations. Uses both dedicated lanes and regular lanes, as well as “queue jump” lanes, and transit signal priority.

BRT — Bus rapid transit. Rubber-tire buses run on fixed routes through major thoroughfares, connecting to regional destinations. Used primarily on dedicated lanes. Stops are anticipated to be a half-mile to 1 mile apart, with service frequency every 15-20 minutes. CobbLinc — Cobb County’s bus system, operating since 1999. CobbLinc would operate new transit systems funded by the M-SPLOST. Commuter buses — Rubber-tire buses that serve long-distance routes, targeted toward commuters. Current CobbLinc commuter routes connect riders to midtown and downtown Atlanta via the I-75 and I-20 corridors. CobbLinc currently consists mostly of local and commuter buses, and paratransit, plus a limited microtransit program.

Dedicated lanes — New traffic lanes built for and used solely by transit vehicles. In some cases, will be grade-separated and include flyover lanes.

Heavy rail — In the public transit context, passenger trains, in exclusive, grade-separated right-of-ways. Designed to carry a heavy volume of passengers on high-speed electric railways. In metro Atlanta, MARTA is the only heavy rail transit operator.

High-capacity transit — In the context of M-SPLOST, an umbrella term referring to BRT and ART.

Light rail — Passenger trains, on gradeseparated or street-level right-of-ways, designed to carry a lighter volume of passengers at lower speeds than heavy rail.

Local buses — Rubber-tire buses that mix with other traffic, with frequent stops every quarter-mile. Serve local destinations. CobbLinc currently consists mostly of local and commuter buses, and paratransit, plus a limited microtransit program.

Microtransit — On-demand transit service to provide “first and last mile mobility” in lower-demand areas, connecting riders to the high-capacity transit. The M-SPLOST would create 14 microtransit zones across the county. M-SPLOST — Mobility Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax. A voter-approved sales tax over a set period of time to fund transit capital projects. In the case of the M-SPLOST, the tax would be 1% and last for 30 years.

Absentee ballots will begin being mailed out Oct. 7.

Completed ballots are due back by close of polls on Election Day (7 p.m. on Nov. 5). Request an absentee ballot

To download an absentee ballot application, visit cobbcounty.org/elections/voting/ absentee-voting

To send in the completed application:

♦ Fax: 770-528-2458

♦ Mail: Cobb County Board of Elections and Registration, P.O. Box 649, Marietta, GA 30061-0649. If using a shipping service that doesn’t deliver to a P.O. Box, use the office address: 995 Roswell St. NE, Marietta, GA 30060

♦ In-Person: Cobb County Board of Elections and Registration Office, 995 Roswell St. NE, Marietta, GA 30060

♦ Email: Absentee@cobbcounty.org

Submit an absentee ballot

To submit a completed absentee ballot:

♦ Mail: Cobb County Board of Elections and Registration, P.O. Box 649, Marietta, GA 30061-0649. If using a shipping service that doesn’t deliver to a P.O. Box, use the office address: 995 Roswell St. NE, Marietta, GA 30060

♦ Hand-deliver in person: Cobb Elections Office, 995 Roswell St NE, Marietta, GA 30060

Paratransit — CobbLinc’s paratransit service provides shared-ride, curb-to-curb service for customers with disabilities or other limitations which prevent them from accessing the regular bus service. Paratransit is currently offered within a one-mile radius of bus routes.

Queue jump lanes — Extra lanes for transit installed right before and right after intersections, allowing buses to jump the queue of cars waiting at a red light.

SPLOST revenue bonds — Municipal bonds, issued by local governments to raise money for capital investment. Lenders purchase the bonds by loaning the government money. Governments pay back the bondholders over a period of time, with interest, using SPLOST revenue.

Transit signal priority — Use of technology to give transit the priority at intersections and stop lights.

Transit supportive projects — Various transportation infrastructure projects which would be funded by the M-SPLOST in order to facilitate construction and access to the transit system. Includes bridges, grade separation, road widening, sidewalks, intersection improvements, bike lanes and trails. Transfer center — Transit hubs where riders can switch routes and access connections to MARTA and other transit systems. Cobb currently has two transfer centers — one on South Marietta Parkway in Marietta and one on Cumberland Boulevard in Cumberland. If approved, the M-SPLOST would fund the rebuilding of the two existing centers, and add transit centers in south Cobb, east Cobb and north Cobb.

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

On a daily basis, 424,000 Cobb Countians commute to work. On average, it takes them 30 minutes.

In this sprawling, suburban county, most households have a car, and only 44% of residents live within a quarter-mile of a bus route. Those buses, should you choose to take them, usually come on a half-hourly or hourly basis.

In that system, transit can’t compete with the speed of driving. The result is that 70% of Cobb drives to work, alone, and just 0.7% takes transit. Some 20% now work from home.

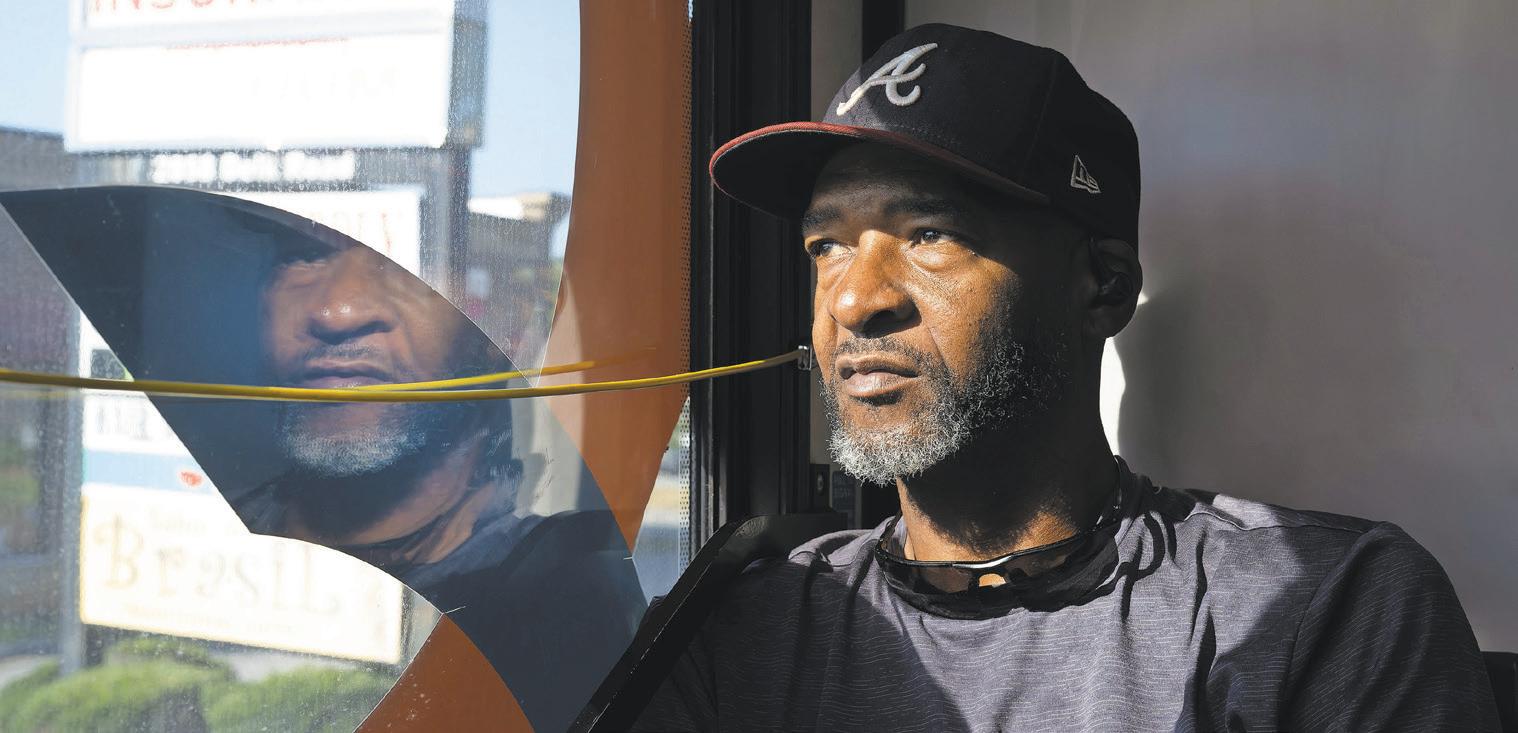

But for those 30,000 or so who commute via transit, the CobbLinc bus system is crucial to their paycheck.

“It’s a great option to have,” said Derrick Thompson, who lives off Delk Road in Marietta. “… Some people don’t want to take it because it’s inconvenient, sometimes it might be raining, sometimes it might be too cold. … But at least it’s a way to work and home. … And the fare is not bad.”

In a few weeks, Cobb will consider a historic investment in transit. On the Nov. 5 ballot, residents countywide will vote on a 30-year, 1% sales tax to fund public transportation projects. The centerpiece of the proposal is bus rapid transit.

(Learn more: mdjonline. com/transit)

If approved, the transit system Cobb plans to build would be vastly superior to what exists today: faster and more frequent service, more extensive routes, dedicated bus lanes, high-quality stations and more.

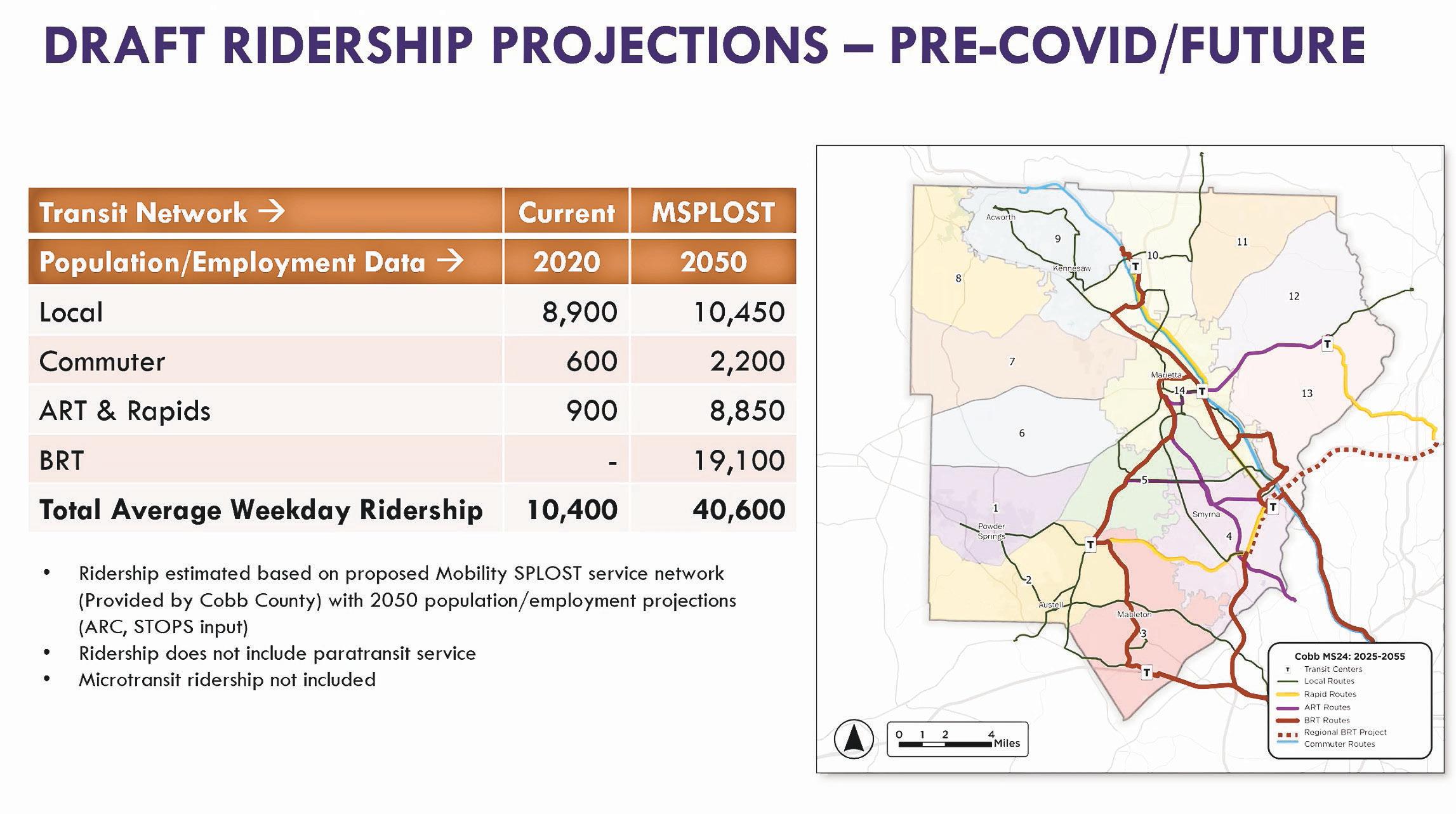

If that enhanced system can match the speed of driving, it could attract many more riders, though supporters and opponents of the tax disagree on how many. The county, for its part, projects there would be 40,600 weekday rides by 2050, up from 10,400 in 2020.

For now, the conventional wisdom in Cobb is that transit is an option used mostly by people who have no other choice.

In interviews, CobbLinc users said the same thing — they would drive themselves if they could. “I wouldn’t normally do it,” said Thompson, who is taking the bus because his truck broke down. “... I get tired of it when I don’t have a car, and while I have a vehicle I never take it.” Riders, however, also said they were grateful to have the buses, and had few complaints about how CobbLinc is run.

If the transit tax is approved, Cobb’s sales tax would increase from 6% to 7%.

Known officially as the Mobility Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax (M-SPLOST), the tax would collect $11 billion to construct 108 miles of rapid bus routes, half a dozen new transit centers and a countywide system of on-demand “microtransit” service.

None of the riders who spoke to the MDJ had heard of the transit tax referendum. But all were intrigued about the possibility of better transit in Cobb.

Who rides transit?

Much of the federal funding CobbLinc receives — which paid for 48% of operating costs in 2022 — is contingent on the system serving its most vulnerable passengers.

“A lot of the folks that utilize our system are transit-dependent,” Cobb Transportation Director Drew Raessler previously said. “… A lot of the (federal) funding requires it, but we make sure that we’re operating a system that takes care of those that absolutely need it.”

Greg Erhardt, a civil engineering professor at the University of Kentucky, told the MDJ earlier this year that transit has two main benefits: taking cars off the road, and providing transportation to those who don’t have a car or can’t drive.

“That tends to be low-income people,” Erhardt said. “In particular, it’s disproportionately minorities, and maybe someone who’s in a wheelchair, this sort of thing.

“Even though it’s a relatively small share of the population in a lot of places in the U.S., those are important trips to serve, in part because it

enables people to work. … If you don’t have a car, and you can’t get to work, there’s costs both to that person, and to society as a whole.”

County assessments of CobbLinc have found the “transit-oriented” population is most concentrated along existing bus routes: along the Interstate 75 corridor from Cumberland to Kennesaw, along the Austell Road corridor from Marietta to south Cobb, in the Fair Oaks area west of Dobbins Air Reserve Base, and near I-20 in Mableton.

“I am adamant about us optimizing transit here, for particularly those who are dependent on transit,” Cobb Chairwoman Lisa Cupid previously told the MDJ, in an interview about the tax.

Antonio Johnson has lived with his mother in Cumberland since moving to Cobb from Louisiana five years ago. He works at a Wendy’s near the Big Chicken.

He used to have a car, but lost it in April because he couldn’t pay $5,000 for a new transmission. And while his mother has a vehicle, she needs it to commute to her job at the Atlanta airport.

So every work day, Johnson takes CobbLinc’s Route 10 up Cobb Parkway to work. Occasionally he’ll use rideshare apps, but that can run him $15, compared to a $2.50 bus fare. He likes that it’s a straight shot, and his only real complaint is dealing with “crazy people.”

“It’d probably be nice,” he said, upon learning about the M-SPLOST. “I’m going to definitely look into it.”

Another transit commuter is Jerchari Clark of Mableton, who works at a liquor warehouse off Fulton-Industrial Boulevard. He owns a car but lost his license, so he relies on CobbLinc and MARTA buses for his 30-minute commute.

After his 10-hour shift, which runs from 6 p.m. to 4 a.m., he takes rideshare home, since the buses aren’t running.

Nahiam Burden, a CobbLinc driver of 20 years, drives the 50 Route.

“Just regular everyday people, going to work, trying to

take care of their families,” Burden said, describing his passengers. “... Common, working class people.”

Burden has always been a transit fan. As a kid in New York City, he loved taking the bus. He memorized the routes and would ride for fun, befriending drivers. He’d heard of the M-SPLOST, but didn’t know many details.

“That would be great, that would be nice,” he said. “… Not everybody can get around. There’s a lot of people with disabilities. … It would definitely improve traffic. But it all depends on if the people really want it. Because there’s a big stigma about buses.”

‘Yin and yang’

One of those disabled people is Shawn Creecy, who lives off Riverside Parkway in Mableton, and takes transit everywhere.

On a recent weekday, Creecy was taking the 30 Route to the H.E. Holmes MARTA station, then planned to take the train to downtown Atlanta for a medical appointment. The bus driver extended a ramp, allowing him to board in his wheelchair, before the driver folded up seats and used straps to secure the chair. As the bus began moving, the wheelchair lurched a bit, before stabilizing.

Creecy, 31, was shot in the back at 16 in Clayton County, an innocent bystander to a drive-by shooting. He’s been paralyzed from the chest down ever since.

Creecy used to have a car he operated with hand controls, but it was stolen. He lives with his brother and often visits family, but doesn’t like asking people for rides. Transit enables him to get around independently.

“I don’t like to depend on people anyway,” he said. “The buses, they help me out.”

Victoria Baucum lives in Atlanta’s Adamsville neighborhood, but previously lived in Cobb. She recently rode CobbLinc to get to a doctor’s appointment in Cumberland.

Baucum had a 15-year career in live events and worked at the Georgia World Congress Center. Then COVID-19 hit, and the convention business went up in smoke. She

lost her job and wound up homeless. She was ticketed for driving without car insurance and spent time in jail.

After that, “I refused to drive for a year,” she said. “It was like this experiment I did. … It was the best and the worst year of my life, but it was interesting.”

During that year, she relied on bicycling and public transportation. While she enjoys biking, she’ll opt for driving when she can.

“You just sit in traffic here all the time,” Baucum said. “And on a bike, I’ve got my music, I’m out in the fresh air, I get in good shape. … But at the same time, if I have a car, I don’t bike at all.”

Baucum has an apartment now, and a resale business, picking up free items listed on the internet and selling them for a profit.

A recent car issue, however, led to her getting back on the bike.

Baucum was skeptical the M-SPLOST would pass — “nobody likes buses, people like trains.” But she resents the suggestion, made by some, that transit brings crime to communities.

“It’s yin and yang,” she said. “With all good things come a couple rough things. But there’s more good than bad.”

Wanda Billingslea of Mableton is a mother of five and doesn’t have a car. She relies on the bus when she needs to get to Marietta.

“It’s all right,” she said of the system. “It gets me where I need to go. It’s a lot of walking … before you catch the bus.”

Billingslea knows there are many in Cobb who never take the bus. But if the system were upgraded significantly, she could see that changing.

“Since they’re building up in Mableton and this area anyway, I think that’d be great,” she said. “… I think they (wealthier people) would be riding the bus a little bit more if it was upgraded.”

How many rely on it?

It’s not entirely clear how many people in Cobb are considered “transit-dependent.”

Cobb transportation officials said the county does not know how many people use CobbLinc on a weekly

or monthly basis. The system only records passenger volume — the number of rides taken.

Some statistics help paint the picture, like the 30,000 workers who use transit to commute. There are others who use it to run errands, visit family, get to school or doctor’s offices. The Census estimates that 3.5% of Cobb households — 12,000 households — have no vehicle. Another 31% — 98,000 households — have one vehicle.

The county has studied who lives near transit, and what percentage of them fall into certain groups. Cobb estimates that 33% of impoverished residents, 40% of zero-vehicle households, 14% of seniors and 27% of minorities live near a bus line.

If the M-SPLOST projects are built, those numbers would increase — 41% of impoverished residents, 50% of zero-vehicle households, 24% of seniors and 36% of minorities would live near bus lines.

Plus, the entire county would have access to the on-demand microtransit.

For transit tax opponents, the transit-dependent population is too small to justify the length and cost of the M-SPLOST.

“Is it right to do a massive taxpayer subsidy to reduce the amount of money that you spend to get from point A to point B?” said anti-tax activist Lance Lamberton. “Isn’t that responsibility in the hands of the individual to take care of? … To pay for it themselves.”

For Cupid and her supporters, the M-SPLOST can serve the transit-dependent, while also reducing congestion and spurring economic development.

“I would love to see us collectively have a different shift in the work that we do … in thinking about how we are investing and making Cobb County as great as it can be for everyone,” Cupid said. “… At some point, we’ve got to look forward in how we do things. And this is a great opportunity that we have to do so.”

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

When it comes to solving transportation headaches, officials often turn to two options: more roads or more transit.

On Nov. 5, Cobb County voters will consider increasing the sales tax they pay to raise billions of dollars for more transit.

Heretofore, officials’ solution to Cobb’s traffic woes, especially at the state level, has mainly been to invest in roads.

No project in recent history illustrates that better than the Northwest Corridor Express Lanes on Interstates 75 and 575. When they were built, the nearly 30 miles of reversible toll lanes were the largest transportation project in Georgia history, costing $834 million.

Nearly six years after opening, the express lanes have been effective at providing faster trip times, according to the state.

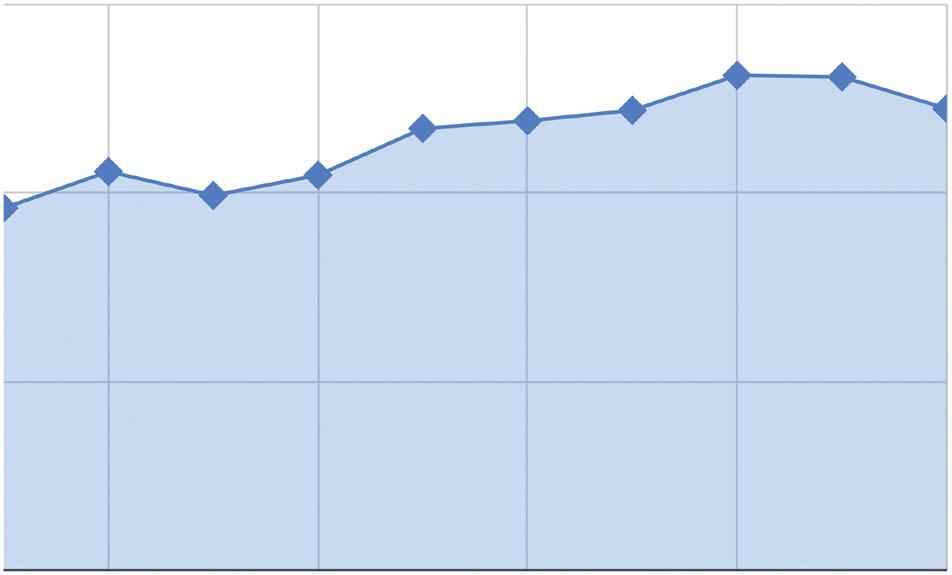

Over time, the lanes have become more popular and more expensive to use, state data shows.

The Georgia Department of Transportation is doubling down on toll lanes as an answer to metro Atlanta’s infamous congestion. Construction on 16 miles of express lanes for State Route 400 is expected to start next year. Even more ambitious are plans to add two barrier-separated lanes in each direction along the “top end” of I-285. Eventually, GDOT hopes to create a “hub-and-spoke” system of interconnected express lanes across metro Atlanta.

History Plans to use express lanes to ease metro Atlanta’s traffic started developing in the early 2000s as interstates were running out of room, and the region kept growing.

“We realized that we were running out of available right of way along the interstate corridors in the region, and that any expansions of the interstate network, it was going to be very important that we manage those as much as we could to get increased, improved mobility,” said John Orr, managing director of transportation planning for the Atlanta Regional Commission.

Adding more free lanes hasn’t reduced congestion, said GDOT program manager Tim Matthews.

“We’ve been widening it for years and years and years, and every time we widen it, it just fills back up,” he said.

In 2011, high-occupancy vehicle lanes — free to use for cars with two or more occupants — were converted to paid Peach Pass express lanes on the northeast side of metro Atlanta on I-85. In 2017, express lanes opened on I-75 on the south side. The following year, the state opened an extension of the I-85 Express Lanes, as well as the Northwest Corridor Express Lanes.

GDOT had previously indicated the 285 Express Lanes would be complete by 2032, though the timeline is now less clear. The project just wrapped up another public comment period as part of its environmental process. The next phase, procuring a developer to lead the project, could take more than a year. The first phase to be built will be on the northeast side of the perimeter, the northwest side in Cobb will come after.

Going forward, the biggest metro Atlanta road projects in the state’s pipeline will be more express lanes, as well as redoing major highway

Opened in 2018, the northwest Corridor express lanes are 29.7 miles of reversible lanes from akers Mill Road to Hickory Grove Road on i-75 and on i-575 to Sixes Road

8,321,286 trips

2.05% non-tolled trips

$2.65 average toll fare

693,000 average monthly trips

$20,287,667 toll revenue for northwest express lanes

$63,689,715 toll revenue for all metro atlanta express lanes

$48,383,937 operating expenses for all express lanes

35,852 highest one-day total express lanes were 4 mph faster than regular lanes in the morning express lanes were 18 mph faster than regular lanes in the evening

Source: State Road and Tollway authority Fy2023 annual Report

I-75-I-285 interchange in Cobb was ranked the 18th worst truck bottleneck in the U.S. last year by the American Transport Research Institute. But motorists using the Northwest Express Lanes on their commutes often save 15 to 30 minutes, per GDOT.

Speeds in general purpose lanes are 10-15 mph faster than before the express lanes opened, GDOT officials have said. A year after opening, the average northbound speed on I-75 at peak rush hour doubled from 20 mph to 40 mph. The lanes also led to the morning and evening rush hour periods shrinking by an hour, the state says. In fiscal year 2023, express lanes were about 4 mph faster than regular lanes in the mornings, and 18 mph faster in the afternoon/evening, according to SRTA.

A 2022 Georgia State University study, with support from GDOT, surveyed people living along the Northwest Corridor.

Among all respondents, commutes shortened by about two minutes from pre-opening to 2022.

Randall Guensler, a Georgia Tech professor who has studied the impact of the express lanes on behalf of SRTA, said the number of vehicles on the I-75 corridor increased in the years after the express lanes opened. There are several theories as to why. One is that people avoided I-75 and I-575 during construction, then returned once it finished. Another is that commuters who previously used Georgia 400 or I-20 started using the I-75 corridor once the express lanes opened.

Others may have switched from using arterial roads like Cobb Parkway to using the interstate. Guensler said there’s truth to the concept of induced demand — if you build more lanes, more people will use the interstate and fill them. But determining where new traffic came from is difficult.

Source: State Road and Tollway authority The tolls on the Northwest Express Lanes rise and fall with demand. In the lanes’ first month September 2018, the average toll was just 94 cents. Tolls grew steadily to over $2 before taking a dip at the onset of the COVID pandemic in early 2020, before rising again and growing over time. The average toll has been higher than $3 since May 2023.

Source: State Road and Tollway authority Usage of the Northwest Corridor Express Lanes, measured in monthly trips, increased steadily from the lanes’ debut in fall 2018 until the onset of the COVID pandemic in early 2020. Usage has since recovered — every month from March 2022 to March 2024 saw more than 600,000 monthly trips.

interchanges to try to alleviate bottlenecks, Orr said. The Northwest Express Lanes, the longest of metro Atlanta’s four express lane segments, run for 29.7 miles through Cobb and Cherokee counties. On I-75, they run from Akers Mill Road in the south to Hickory Grove Road in the north. They split off from 75 where it meets I-575, continuing until Sixes Road. On weekdays, the lanes run southbound into the city from 1 a.m. to 10:30 a.m., and northbound from 1:30 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. The roadway is owned and operated by Georgia DOT, while Peach Pass pricing is operated by the State Road and Tollway Authority. The lanes were built mostly

with a mix of state and federal funds, including a $275 million loan through the U.S. Department of Transportation and $233 million in state gas tax funds.

In a first, the state leveraged roughly $60 million in private financing from the company selected to design and build the lanes.

The state is also using a public-private partnership to build the I-285 Express Lanes. Officials say it allows the state to free up public funds for other projects.

Toll revenue is used to service debt and pay for lane operations and maintenance.

The lanes are not without critics. Some skeptics view them as “Lexus lanes” for the rich, or question the fairness

of charging residents to use a taxpayer-funded road. Others say they’re nothing more than an expensive stopgap, calling for the state to invest in transit.

The express lanes use dynamic pricing, with tolls increasing with demand. There is a minimum rate of 10 cents per mile. During periods of very low demand, that is sometimes replaced with a fixed toll of 50 cents per trip.

Tolls are displayed on electronic signs with two rates. One is the cost to use the lane until the next express lane exit; the other is the cost to use the lane for its remaining length.

Large trucks and trailers are banned. Registered transit vehicles, vanpools and emergency vehicles use the lanes for free.

According to the state, the Northwest Express Lanes offer faster speeds not just in express lanes, but in general purpose lanes, too.

“We found that not only are folks getting reliable trip times in that corridor, but the folks who are not using the express lanes are getting better trip times in the GP (general purpose) lanes, because we freed up room in the GP lane,” Matthews said. Both interstates, 75 and 575, still have their regular slowdowns and jams. The

“It’s hard to know what’s new demand and what’s been shifted around,” he said. The express lanes have also led to a decrease in carpooling, Guensler said.

“I guess that’s not surprising,” he said. “There’s less incentive to form a carpool when you have reduced congestion and improved speed.” But despite a higher throughput of vehicles, the lanes have been successful in tempering congestion, he said.

To understand why, you have to understand what causes congestion in the first place.

“Once the vehicles get too close together and the separation between the cars is uncomfortable, then somebody pumps their brakes, and the flow breaks down,” he said. “It essentially drops into a congested condition.”

The queue builds up and doesn’t release until demand drops, or in the case of a crash, the blocked roadway is cleared. Congestion, Guensler said, is “nonlinear.” A simple increase in cars doesn’t necessarily cause a jam.

“It doesn’t take much,” to cause a jam, Guensler said. “Once you get to a certain tipping point, and the flow breaks down, you go immediately from operating at 45, 40 mph down to 20, 25 mph. … And it takes a long time for that congestion to go away.”

Managed lanes, by taking some cars out of the

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

Purchase a No. 1 meal at the Marietta Chick-fil-A on Roswell Road today, and you’ll pay 55 cents in sales tax. If Cobb increases its sales tax by 1%, as voters may authorize Nov. 5, that chicken sandwich, fries and drink would cost nine cents more. The difference, of course, stands out more with big-ticket items. Purchase a $9,990 engagement ring at the D. Geller & Son in Cumberland today, and the sales tax is almost $600. Add 1%, and you’ll pay nearly $100 more.

But what will the average Cobb resident pay over the course of a month, or a year, or 30 years, if the sales tax goes up? What will those 1% increments add up to when applied to all of the items, small and large in price, a consumer purchases?

The answer isn’t clear. Cobb County does not have any such estimates, its communications office told the Marietta Daily Journal.

On Election Day, Cobb residents will vote on approving a 30-year, 1% sales tax to fund public transit projects. Cobb’s sales tax would increase from 6% to 7%.

The Mobility Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax (M-SPLOST) would collect $11 billion to construct 108 miles of rapid bus routes, half a dozen new transit centers and a countywide system of on-demand “microtransit” service.

Georgia levies a 4% sales tax statewide. If the M-SPLOST is approved, it would be the third additional 1% sales tax on the books in Cobb. Residents already pay a 1% SPLOST for general government, split between the county and its cities, and a 1% SPLOST to fund education, split between Cobb’s two school districts.

Cobb expects to collect $10.87 billion from the M-SPLOST over 30 years. That works out to, on average, $30.2 million in collections per month.

The county SPLOST on the books now generated, on average, $18 million per month over the last 12 months for which data is available.

Cobb an outlier

At the moment, Cobb is tied for the lowest sales tax in the state. Only three other counties have a 6% rate — Cherokee, Gwinnett and Glynn.

The sales tax rate ranges from 6-9% across Georgia. A 7% rate would put Cobb closer to the average.

Forty-six of Georgia’s 159 counties have a 7% rate. The state’s average sales tax rate is 7.38%, putting it at 19th highest in the nation, according to an analysis by the Tax Foundation, a conservative-leaning think tank.

The prospect of raising Cobb’s sales tax has led some to wonder whether consumers will respond by, say, choosing to shop in a different county, thereby hurting local merchants.

Scott Baker, a professor of finance at Northwestern University, has studied the effects of state and local taxes on businesses and households, including how consumers respond to changes in tax rates.

In some cases, people do go elsewhere to make purchases.

“Households … they’re behaving in fairly sophisticated ways,” Baker said. “They do a lot of things that you might think. … If it (the sales tax) increases, they start shopping more cross border, where they can.” The effect depends on what people are purchasing, and where they live. People are more willing to make an effort to avoid taxes on big-ticket items, Baker said.

The effects are also greater for items with high tax rates, such as cigarettes and alcohol. Consumers may drive to other jurisdictions to purchase large quantities of those items.

Baker’s research also indicates that households may “pull forward” or “push back” spending.

“If taxes were going to increase, they would pull forward spending to the month before the tax went into effect,” he said.

The long-term effects, however, are much more muted, Baker said. In general, people going to the store are stocking up on all sorts of goods, whether they’re subject to sales tax or not.

Cobb residents wouldn’t have many options to seek lower taxes. Gwinnett County voters are also set to vote in November on a 1% transit sales tax. And three neighboring states — Alabama, Tennessee and South Caro-

lina — have higher average sales tax rates than Georgia, according to the Tax Foundation.

Clint Mueller, director of governmental affairs for the Association County Commissioners of Georgia, is skeptical that many consumers will travel in search of lower tax rates when weighed against other factors, like convenience.

“I just don’t think people, for a penny or so, unless it’s a really big ticket item, they’re not worried about driving to a cheaper place,” Mueller said.

Kyle Wingfield, president and CEO of the conservative Georgia Public Policy Foundation, believes there could be an effect.

“It’s going to have an effect on consumer behavior,” Wingfield said.

“And you see people will maybe go elsewhere to make certain purchases.”

Jonathan Geller, president and CEO of jeweler D. Geller & Son, said the transit tax would hurt his business.

“When we left Midtown and we moved to Cobb 50 years ago, my dad picked Cobb for a reason. ... It was strong leadership and it was tax advantages,” Geller said at a recent rally for M-SPLOST opponents. “...

Let’s say this goes through — my engagement ring budget’s just dropped by 1%. And that’s not nothing for a purchase that you’re going to shop around for, and you might shop for in a county that didn’t get hit with an increase.”

What is taxed?

Some high-end items subject to sales tax include jewelry, art, guns and clothing.

Other purchases have their own special tax in Georgia, instead of being subject to state and local sales tax. For home sales, there’s the real estate transfer tax. For most cars purchased after 2013, there’s the title ad valorem tax.

Most groceries aren’t subject to the 4% state sales tax, but they are subject to local sales tax. Prepared foods, such as at restaurants, are fully taxed.

There are also sales tax exemptions in Georgia for prescription drugs, glasses, contacts and insulin, as well as certain machinery and chemicals.

Most services are not subject to sales tax in Georgia, but there are exceptions, including taxis and limos, event tickets, and participation in games and amusements.

Gasoline is taxed by the state using a formula — which currently sets it at 32 cents per gallon — and is also subject to a federal gas tax.

When Georgia’s sales tax was es-

tablished in 1951, it quickly became the state’s largest revenue source, said Danny Kanso, director of legislative strategy and senior fiscal analyst at the left-leaning Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

Over time, its capacity has diminished as services became a larger share of the economy. Now, it makes up about 23% of state revenue, compared to the 52% that comes from income tax.

And state lawmakers have, over the years, continued to add exemptions to the sales tax, further limiting what it applies to.

The share of services which are subject to sales tax in Georgia is likely in the bottom five among all states, Kanso said.

“We’ve seen just steadily … that capacity diminish in comparison to the economy,” he said.

In the case of the M-SPLOST, it would function mostly like the other local sales taxes do. But there are a few special exemptions to the transit tax laid out in the law, such as jet fuel, gasoline, fuel used for off-road heavy-duty equipment, and motor vehicles.

Who pays most

Flat sales taxes are considered regressive by economists, because people with lower incomes spend more of their earnings on the tax.

By contrast, progressive taxes, like the federal income tax, tax people more heavily if they earn more.

The regressive nature of sales taxes can be seen clearly in the data, said Kanso.

The lowest 20% of earners in Georgia pay 6% of their family income in sales tax. For the second-to-bottom 20%, it’s 5.5%, and for the middle 20%, it’s 4.6%, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

“Low-income and middle-income folks are going to be the most sensitive to those tax changes,” Kanso said.

The top 1% of Georgia earners, meanwhile, pay just 1% of their family income in sales tax.

Kanso said counties and cities, however, shouldn’t be blamed for relying on sales taxes to build infrastructure, since it’s the legislature which determines what options localities have. They’re not allowed, for instance, to levy income tax.

“Preemption laws in Georgia are extremely restrictive, and limit local governments to a range of extremely regressive options that they have to raise revenue for essential services, like infrastructure and transit,” Kanso said.

ing fuel, and the proceeds are used to fund the state’s roads.

Kanso’s GBPI doesn’t typically take positions on local referendums, but Kanso noted, “infrastructure generally does benefit the economy as a whole, (and is) certainly something that is necessary as a function of government.”

“It’s just about how we pay for it and how we look at the overall distribution,” Kanso said.

A politically palatable tax

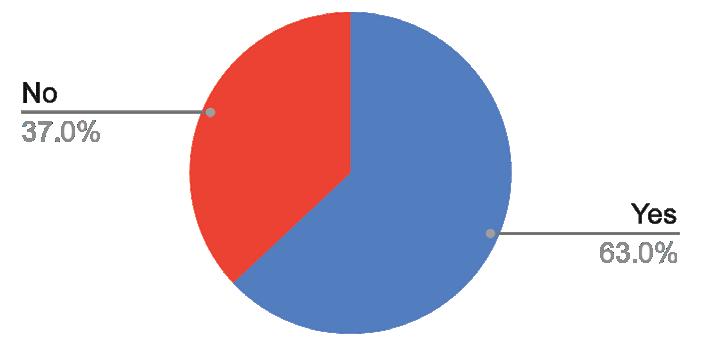

Roughly 90% of local sales tax referendums in Georgia are approved, said the ACCG’s Mueller.

“They (voters) like to know what they’re voting on,” said Mueller, referencing the project lists that are published ahead of SPLOST referendums.

In most referendums, however, voters aren’t making a 30-year commitment.

Sales taxes are generally more popular than income or property taxes, Mueller said. Georgia has more types of local sales taxes than most other states.

“The counties like them, and therefore we’ve (ACCG) advocated over the years for these different types of local sales tax options,” Mueller said. “… Whether they’re good or bad, it’s kind of up to the citizens to make that decision.”

In a 2016 guide to SPLOSTs, the ACCG attributed the popularity of sales taxes for financing capital projects to “the unpopularity of property taxes,” as well as “the simplicity and perceived fairness of sales taxes.”

SPLOSTs are often sold in part by arguing that much of the taxes will be paid by nonresidents — tourists, visitors and non-local commuters.

Hall

The argument that sales taxes are regressive is typically made by those on the political left. But that hasn’t stopped opponents of the M-SPLOST from employing it. At Cobb commission meetings, conservative public commenters have told the commission that its transit tax would hit the poorest families hardest.

“It impacts lower-income people more than upper-income people,” anti-tax activist Lance Lamberton told the MDJ. “If you have a lot of money, you’re probably not going to notice it. … If you’re kind of just getting by … you’re going to feel it.”

Lower-income people are also more likely to be users of public transit, though.

It’s difficult for the average citizen to estimate how much they’ll be taxed by an extra 1% over the course of a year, though Lamberton believes most people will pay hundreds of dollars more in sales taxes annually. He also called for the county to produce projections to answer that question.

The group Lamberton leads, the Cobb Taxpayers Association, is generally opposed to all SPLOST referendums. In recent years, he said, they’ve shifted to picking and choosing which taxes they’re going to campaign aggressively against.

But for Lamberton and his allies, the unprecedented 30-year tax, and its billions of dollars for transit, is the most egregious proposal yet.

“It’s a huge waste of money and resources,” he said.

Whatever one thinks of the sales tax as a funding mechanism, the need for better public transportation is clear, said pro-transit activist Matt Stigall.

“That’s kind of the only option, really, the state allows … It’s hard to sit there and wish for better when we kind of have our hands tied,” said Stigall, one of Cobb Chairwoman Lisa Cupid’s appointees to the county’s Transit Advisory Board.

The county already uses millions in sales tax revenue for road infrastructure, Stigall added. If that’s the way Cobb builds, then the county should also be investing in pedestrian and bike infrastructure, and public transportation.

“What type of county do we want to see for ourselves in 10, 15, 20 years?” Stigall said. “… We’re kind of at the fork in the road of, do we want to continue to pour money into more and more cars, or do we want to give people the option?”

Wingfield’s GPPF tends to advocate for user fees to fund transportation. The gas tax is one example — motorists pay it when purchas-

Cobb estimates that more than $2 billion of the $11 billion in MSPLOST collections will come from nonresidents.

“There’s some truth to that. It’s less true when everybody has the sales taxes,” Wingfield said. “It just means that when you cross the county line, you’re paying someone else’s SPLOST.”

With the exceptions of 1990 and the years between 1999 and 2005, there has been a county SPLOST on the books in Cobb every year since 1986.

“People just really hate the property tax,” Wingfield said. “Not so much that they enjoy paying sales taxes, but they intensely hate paying property taxes.”

Local governments like SPLOSTs, Wingfield said, because the referendum gets citizen buy-in.

“We’re letting you, the people, vote on this tax, and the people almost always vote to approve it, and the officials get the money that they wanted to spend,” Wingfield said.

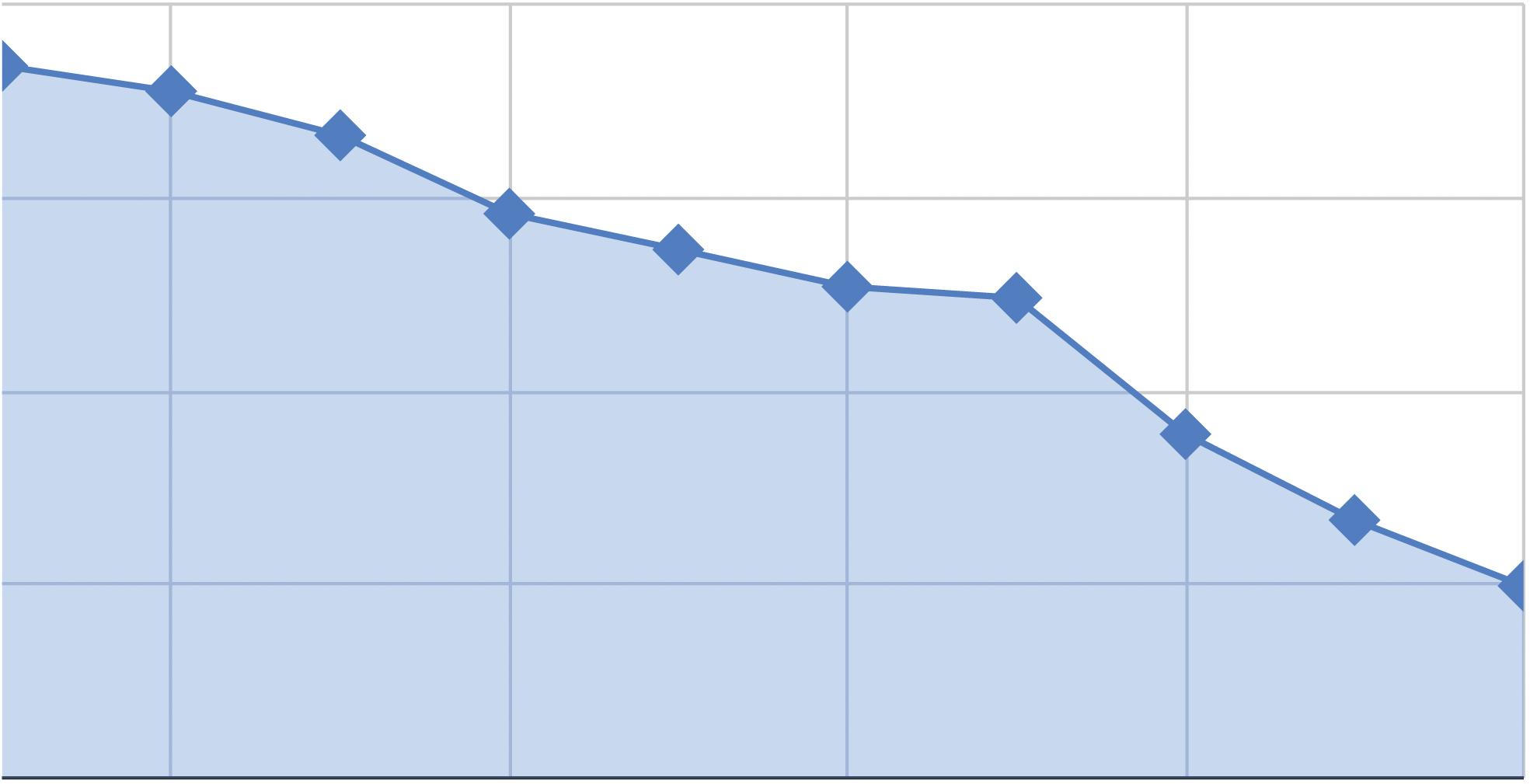

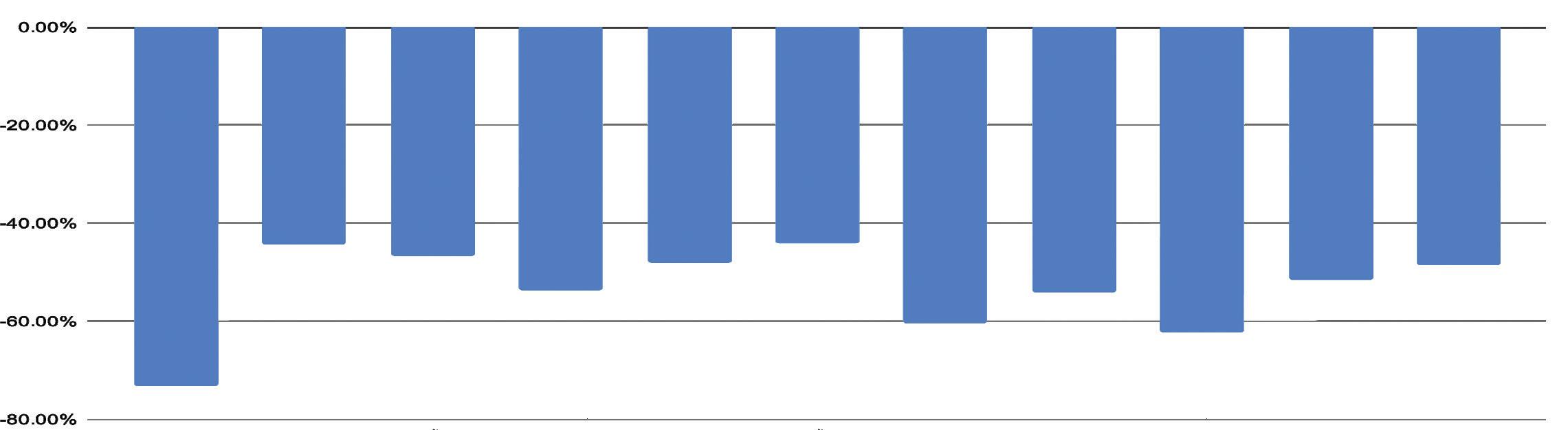

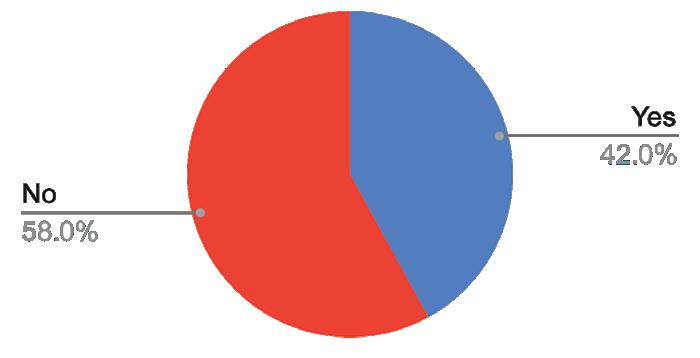

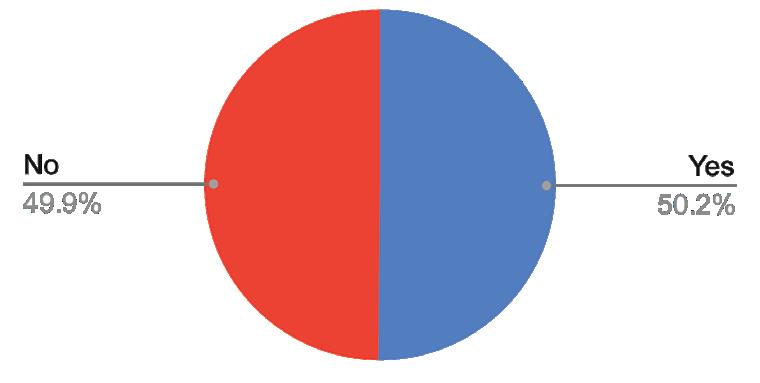

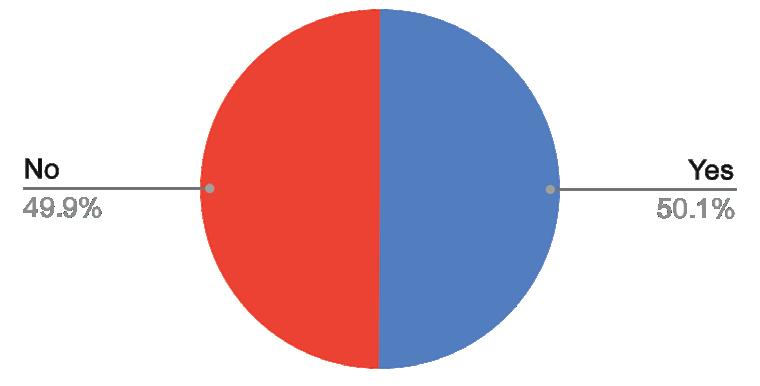

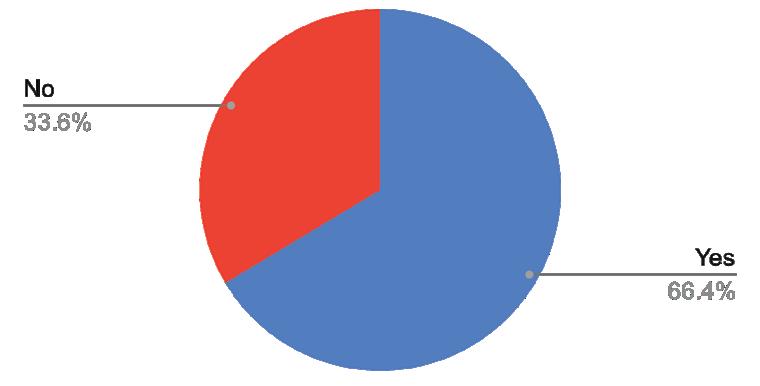

Cobb voters have approved the past four general SPLOSTs, going back nearly two decades. And the margin of approval has increased over time. There were bare majorities in 2005 and 2011, but SPLOST won by six points in 2016, and by a 33-point landslide in 2022.

Six education SPLOSTs, meanwhile, have been approved by voters consecutively since 1999.

Governments which have become reliant on sales taxes start planning their budgets with the expectation the taxes will continue. In some cases, Wingfield said, it becomes the tail wagging the dog.

“There’s some evidence that they’ve increased the size of their general budgets to meet their general revenues,” Wingfield said. “And then they turn around and say, ‘Well, we don’t have money for construction or capital improvements or whatever, we need (to renew) this additional sales tax.’ … They put themselves in that position, because they came to count on that sales tax always being there.”

If the M-SPLOST is approved, residents won’t have the chance to vote on it again for three decades. Supporters argue the length is necessary in order to compete for federal grants. The federal government wants to know that its investment will be protected by a steady local revenue stream.

The referendum, if approved, will set Cobb on a course for many years.

“They’re essentially deciding to increase this tax, for all intents and purposes, on a permanent basis,” Wingfield said. “And that’s just something to keep in mind as they’re weighing the cost versus the benefit of this particular tax.”

Historically, county government Special Purpose local Option Sales Tax referendums have done well in Cobb County. excluding education SPlOSTs, of the 10 SPlOST referendums held in Cobb, seven have been approved by a majority of voters. Some were approved by razor-thin margins of a couple hundred votes. Others, like the 2022 SPlOST approved in the 2020 election, won about two-thirds of the vote. in the early days, SPlOST was mainly used to fund road improvements. The 1985, 1989, 1990 and 1994 referendums focused on road projects; three out of four passed. an unsuccessful 1998 referendum was also transportation-focused, but included a monorail transit proposal from Cumberland to Town Center. One referendum in 2000 focused on parks and sidewalks, but failed at the ballot box. The 2005 SPlOST, meanwhile, mainly funded transportation and public safety projects.

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

When Lisa Cupid led Cobb County to move forward on a proposed 30-year sales tax to fund transit, the Democratic county commission chairwoman called it “a moment of transformation,” on par with the Atlanta Braves moving to Cumberland, or the construction of sewer lines which enabled the development of east and west Cobb.

When Commissioner Keli Gambrill weighed in, however, her first critique of the proposal concerned Cobb’s existing transit system.

“Folks pretty much don’t ride the buses currently,” said Gambrill, a Republican.

At that December 2023 meeting, over the objections of Republican commissioners, the board’s three-member Democratic majority set the course for raising the sales tax consumers pay by 1% for 30 years. The new revenue will fund transit.

If approved by voters, the Mobility Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax (M-SPLOST) would pay for construction of 108 miles of rapid bus routes, half a dozen new transit centers and a countywide system of on-demand “microtransit” service. Voters will decide Nov. 5. Conservatives have criticized the proposed MSPLOST for its length, unprecedented in the history of Cobb SPLOST referenda, and its size, with projected revenue of $11 billion.

But Gambrill’s comment exemplified another theme around which the debate has crystallized: whether people use Cobb’s existing public transportation, and whether they would use a much-enhanced system.

Critics charge the county’s CobbLinc buses are running without passengers, a drain on taxpayers which provides little public benefit.

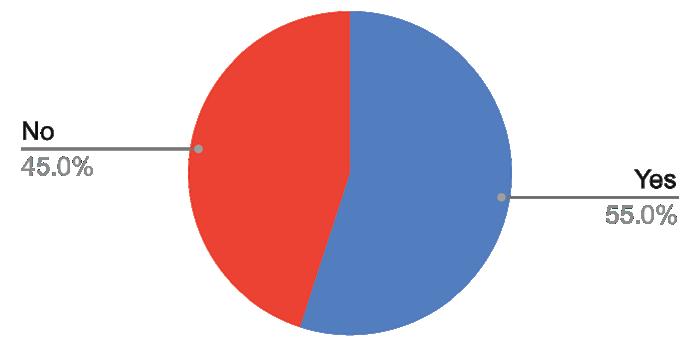

CobbLinc buses are not “empty,” as is sometimes said. The system recorded nearly a million trips in 2022, according to county data submitted to the federal government.

But the same data shows that, over the past decade, ridership dwindled every year, before taking a nosedive at the onset of the pandemic. Ridership is still only at 38% of pre-pandemic levels.

That decline mirrors a national trend which experts have attributed to a range of causes. Over the past decade, however, CobbLinc’s declining popularity has been steeper than that of peers around the state and nation.

As ridership has dwindled, so too has fare revenue. In 2022, just 7% of CobbLinc’s operating cost was covered by fares.

Supporters of the tax argue that misses the point of the SPLOST: a vastly enhanced system will attract more riders.

How many more riders?

Cobb did not originally plan to produce projections estimating how ridership would increase under the program. But following criticism, a state agency forced

the county to do so.

By 2050 — 25 years into the 30-year tax — the county expects an average of 40,600 rides on weekdays. That would represent a twelvefold increase over the average weekday ridership of 3,180 trips in 2022.

RIDERSHIP WOES

From 2013 to 2022, CobbLinc recorded a 73% drop in annual unlinked passenger trips, a commonly used ridership metric.

(Unlinked passenger trips refers to the number of passengers who board transit vehicles; passengers are counted each time they board.)

The trend is not unique to CobbLinc. Transit systems around the state — in Atlanta, Gwinnett County, Savannah and elsewhere — and in some of the nation’s largest cities — like Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. — have also seen declines. None of the aforementioned agencies, however, saw ridership fall as far as CobbLinc. CobbLinc’s decline persisted despite the county’s population growing by 8% over the same period.

“You’re looking at something that, because of changing demographics and technology, the demand for transit, especially in a suburban community like Cobb County, we anticipate, is going to be very low,” said Lance Lamberton, a conservative critic of the tax.

Data also indicates ridership declined even as the county increased bus service. Two metrics used to measure transit service — vehicle revenue miles and vehicle revenue hours — have both risen over that period, by 6% and 28%, respectively. CobbLinc also expanded service in 2019 by adding Sunday service for the first time.

Still, given the overall quality of Cobb’s service, low ridership shouldn’t be surprising, said Matt Stigall, a local pro-transit activist.

“How many bus stops around the county don’t have a shelter, and you’re waiting for the bus for 30 minutes or an hour?” Stigall said. “And we wonder why a lot of people aren’t taking transit.”

WHAT CAUSED IT?

Declining transit ridership has been attributed to a variety of causes, experts told the MDJ, COVID-19 chief among them.

“The pandemic upended everything,” said Greg Erhardt, a civil engineering professor at the University of Kentucky.

Drew Raessler, Cobb’s transportation director, cited the impact of COVID and believes CobbLinc has seen its low ebb.

A 2023 report from the American Public Transportation Association, a nonprofit industry group, attributed low ridership nationwide, more than anything, to “persistent telework.”

“COVID really decimated the transit industry … And it has been slow to come back,” said Candace Brakewood, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Tennessee who studies transit ridership.

A 2023 study co-authored by Brakewood found transit ridership hit a 100-year low in 2020.

U.S. Census data on commuting patterns also demonstrates COVID’s impact.

In recent years, the biggest change in how Cobb County commutes has been the rise of those with no commute at all.

From 2019 to 2022, the share of Cobb residents working from home more than doubled, according to Census estimates, climbing to 19%.

The state agency which manages the Xpress commuter bus service is planning to reduce service due to low ridership, which is still only at 30% of prepandemic levels.

Nationwide, transit ridership has recovered to 79% of pre-pandemic levels, according to the APTA. Recovery has been slower in Cobb. In the 12 months preceding the pandemic, CobbLinc averaged 206,000 rides per month. In the last 12 months for which data is available (through July 2024), the system has averaged 79,000 rides per month — 38% of pre-pandemic levels. That figure, however, is up from the spring, when it was 33% of pre-pandemic levels. The Census estimates a

tiny fraction of Cobb, less than 1%, uses public transportation to commute, and that nearly all households have access to at least one vehicle. Two-thirds have more than one.

More broadly, researchers have attributed lower transit ridership to a litany of factors — rising incomes, lower gas prices, service reductions, a resurgence in bicycling, the dissemination of electric scooters and the rise of ride-sharing apps.

Erhardt spoke about the benefits transit provides, even if many residents don’t use it regularly, or at all. In many cities, it’s people who have no other option who are still using it. “Even though it’s a relatively small share of the population in a lot of places in the U.S., those are important trips to serve, in part because it enables people to work,” Erhardt said. Raessler said much of the federal funding CobbLinc gets is contingent on the system serving its most vulnerable passengers.

“A lot of the folks that utilize our system are transitdependent,” Raessler said.

“… A lot of the (federal) funding requires it, but we make sure that we’re operating a system that takes care of those that absolutely need it.”

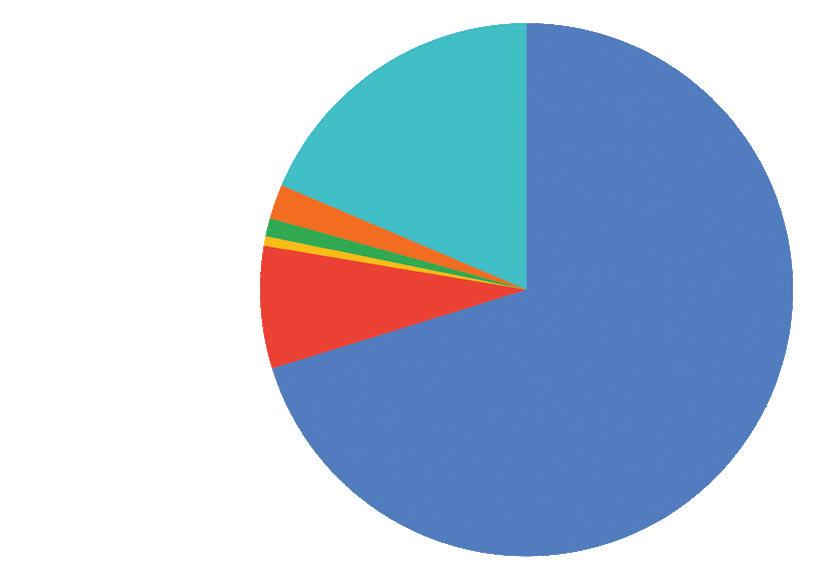

REVENUE DECLINE As ridership drops, so does revenue. Fare revenue for CobbLinc totaled $5.9 million in 2013. By 2022, it had fallen to $1.9 million.

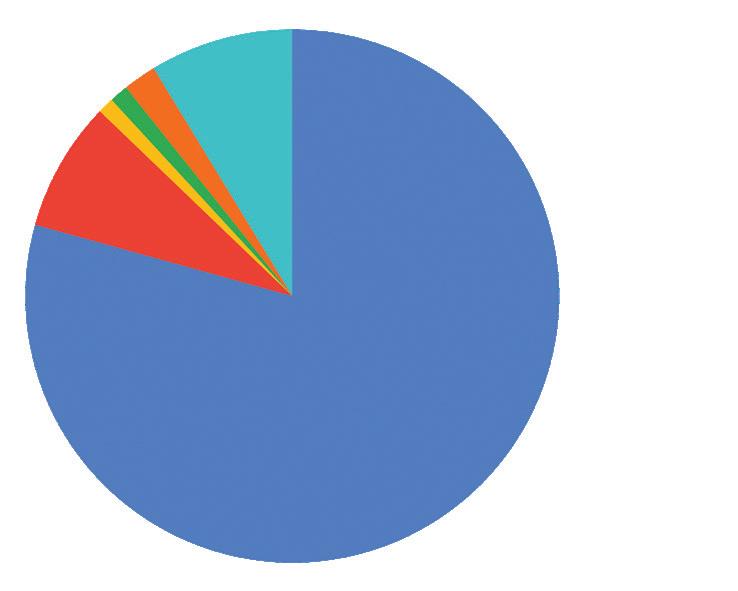

CobbLinc cost the county $27.6 million to operate in 2022. Of that, $13.2 million came from federal dollars, $11.5 million came from the county government and $2.9 million was generated by fares and other direct revenue.

Like ridership, fare revenue was declining preCOVID, before taking a nosedive at the pandemic’s onset.

Dwindling ridership and fare revenue can spell doom for transit systems, producing negative effects on traffic, the environment, and people who rely on transit, said Erhardt.

“Financial viability is important because well, either you have to continue to provide some level of service for the people who need it, or you throw up your hands and you say, ‘You’re out of luck.’ And if you don’t have your own car, or you can’t drive … you’re on your own,” Erhardt said.

From 2013 to 2022, CobbLinc’s operating expenses rose from $18.1 million to $26.3 million.

Raessler said the pandemic not only affected ridership, but contributed to rising expenses, such as a tighter labor market driv-

IF YOU BUILD IT, WILL THEY COME?

Should voters approve the tax, the transit system Cobb could have in a decade or two would be scarcely recognizable to the county’s system today. CobbLinc now offers nine local routes, five express routes, two circulator routes, one flex route, and paratransit

ing up wages. CobbLinc did go completely fare-free from April 2020 to January 2021. Part of the federal funding CobbLinc received early in the pandemic went toward replacing that lost revenue. The share of operating costs paid for by fares is known in transit circles as the farebox recovery ratio. Most agencies have a recovery ratio of 20-30%, said Candace Brakewood, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Tennessee who studies transit. In 2022, Cobb’s was 7%, down from 20% in 2019. Amid dwindling fare collections, CobbLinc has become more reliant on its other two funding sources — subsidy from the county general fund, and especially federal funds. In 2022, the lion’s share of funding — 48% — came from the federal government. The bulk of CobbLinc’s operating expenses are payments to Transdev, the private company which operates CobbLinc. Cobb commissioners voted 3-2 along partisan lines in August 2023 to approve a new three-year contract with Transdev, at a cost of $29.8 million for the first year.

If the M-SPLOST passes, Raessler said, the general fund subsidy will be eliminated.

If voters reject the transit tax, and federal dollars diminish, Cobb will eventually have to increase the general fund subsidy or consider cutting service, he said.

Brakewood said transit systems which scale back service can end up in a “death spiral.” Fewer vehicles and routes means worse overall service. In response, fewer people use it. Governments sometimes then increase fares to raise revenue, further alienating riders.

“You really don’t want to enter into that spiral if you can avoid it,” she said. CobbLinc hasn’t raised fares since 2011, when local one-way trips went from $2 to $2.50, and one-way express fares went from $4 to $5. Seniors, youth and paratransit passengers are eligible for reduced fares or free rides. Low fare collections, and the local and federal subsidies, are proof to critics that the transit system isn’t efficient. But Erhardt noted transportation is always subsidized one way or another, citing the huge costs of building and maintaining roads for private vehicle use. In fiscal year 2023, Cobb County’s transit operating budget was $29.7 million, just 2.6% of the

20 minutes, and enjoy signal priority at intersections.

“With BRT, it is a dedicated lane, it is a much faster trip, it is a much more reliable trip in terms of knowing exactly how long it’ll take, whether or not there’s a crash in some of the general purpose lanes,” Raessler said. “So it is a very different system than what exists today.”

Additionally, the project list includes a countywide system of “microtransit.”

The county envisions microtransit — on-demand, localized transit vehicles — as providing “curb to curb” service within defined zones. The tax would upgrade existing local routes to BRT and ART, and also add traditional local bus routes to unserved areas. BRT routes would add transit to Interstate 285, from I-20 in the south to Georgia 400 in the north. If Cobb builds a new, much revamped system, “it’s likely that people will use it,” said Brakewood, as attracting riders is all a function of speed, frequency and reliability.

Cobb’s plans to use dedicated lanes, signal priority and other methods would increase speed, she said. When it comes to frequency, the “magic number” is a vehicle that arrives every 10 minutes. That allows riders to head out on their journey without planning it around an infrequent bus schedule, Brakewood said. If Cobb can build a system that competes with driving yourself, people are likely to reconsider their travel mode.

“If you’re sitting in traffic on the highway, and you see a lane next to you, and you see a transit vehicle speed by you, well, you might be more likely to get on the bus or the train the next time,” Brakewood said.

PROJECTING

Democratic Commissioner Monique Sheffield said faster trips and a bigger network can entice new riders.

“Once we can connect some dots,” Sheffield said, “then there will be an increase in ridership.” Gambrill is skeptical ridership will increase much,

By Hunter Riggall hriggall@mdjonline.com

The transit tax has been spearheaded by Cobb Chairwoman Lisa Cupid and her fellow Democrats on the Board of Commissioners.

The MDJ sat down with Cupid for a Q&A on the transit tax. Topics covered include the tax’s purpose, length and goals, the projects proposed, ridership and more. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marietta Daily Journal: In a nutshell, why should Cobb citizens vote for this M-SPLOST?

Lisa Cupid: OK, well, I can share with you that I’m in a tough position in answering that question, leading on the side of advocacy versus education. But I can share with you that generally, for our SPLOST programs, they provide significant investment in our county that enable us to better serve our citizens. And I believe that if we were to look at transit investment similarly, it’s going to augment transportation services for our citizens beyond what we have today.

We’re fortunate that we’ve had a transit system operate in Cobb County for the past 30 years that has helped to get citizens through the county and throughout the region, but we know that there’s opportunity to make that existing system more efficient, as well as to add additional transit investment that will augment that experience for our citizens.

In addition to doing that, there’s opportunity for us to add additional projects, I think, that will help to improve transportation for everyone. … My phrase is “being all in,” and I look at this as being an M-SPLOST for all. Whether or not you’re taking transit or not, our goal is to provide transportation, is to improve transit options and the transportation experience for everyone here.

Now, I’ll be very specific for the rider. I am adamant about us optimizing transit here for particularly those who are dependent on transit. I was not in Cobb County government in 2011 when we had the budget cuts, but I was in the audience when we made those cuts, and I know the hurt that it has caused many of our citizens to have a service that they’ve depended on, to see it removed.

And so there’s opportunity to reestablish Cobb County as a place where everybody has access to opportunity throughout the county. And when you don’t have access, not just via roads, but through a robust transit system, you’re basically cutting off people’s opportunity to experience the same levels of opportunity and enjoyment of this county that others have, because they have a vehicle. So that’s something that’s very near and dear to me.

Also, back in 2017 there was an assessment of our riders here in the county, and it found that 80% of our riders were utilizing transit to go to work or to go to school. And in a county where we pride ourselves in being a very educated county, and a county where we perceive ourselves as being very business-friendly and economically focused and thriving, it would only make sense to ensure that there is a reliable way for people to have economic and academic advancement in this county. So transit, to me, it’s a definite tie-in to that.

And then again, looking at economic development. Economic development is largely buoyed by travel and tourism here in this county, and also by retail. And a lot of those positions have persons who are not as robustly paid as others, and who are not only having a more difficult time of living near their place of employment, but getting to their place of employment, because of traffic. And we have the opportunity to make work more proximate and accessible to them, and to make employees more accessible to our businesses, so they can have a reliable workforce.

So for me, that’s important. I can continue to go on. So those, again, are for the transit-dependent. And then I’ll go a little bit deeper into looking at demography for what I perceive transit-dependent populations are, which are always perceived to be low-income persons here in the county. I look at our young people who are looking to get to work. I think of people like my son, who just got his first job, who calls me and my husband during our work day to figure out how he’s going to get to his next day’s work or next day’s training. And we have to be creative in how he gets to work. And sometimes when we can’t take time off of work to get him there, he depends on Uber. By the time that he pays for his Uber rides, he’s barely making any money from that job. And we know that the experience of him working is more valuable than the money that he gets, and transportation costs are a cost that we can eat, as a family. But for those families that depend on those types of service-oriented jobs, they are making very tough decisions about how they’re going to pay to get to work, because they don’t have access to, not only reliable, but affordable ways to get to work. And you know, we can go from the younger end of the spectrum to the older end of

the spectrum, and look at our seniors who are approaching ages where driving is not as easy as it used to be. And where they’re having to make decisions about how they can get to things that they used to freely be able to get to, whether it’s for essential services or for recreation or just to even connect with their friends or relatives. And having a more robust transit system like the one that’s being contemplated in our program, particularly on-demand transit, I think helps to make those opportunities possible, so that they can continue to fully participate in Cobb County.

So those are just a few of the reasons. There are many others that I could list. Reducing congestion by having more people get out of their cars. The example of on-demand transit, you have more people depending on one vehicle, as opposed to everybody having their own vehicle. I also think from an environmental perspective, again, getting people out of their vehicles is something that can help reduce our carbon footprint over time.

And you know, just the practicality of it and the cost of it, Cobb County is expected to grow about 25% to 2050, a population of over a million people. And can you imagine having cars for that growth with our current road system? I just don’t think we’re going to build our way out of making congestion any less of an issue than what it is today. At some point you have to start looking at other options.

With our zoning hearings, I remember there was a day where our zoning hearings used to last all day because we were constantly building. Those days are few and far between, because most of Cobb County is built up already. But yet, people continue to move here and live here. And our young people, they’re aging, they’re driving, and they need a reliable way to get to work.

Then I think there’s a transit-choice rider. So, I lived in the Six Flags area, my husband was an attorney working in Midtown, and he would sometimes choose to take transit, whether or not we had a car that was in the shop, I think that was often the reason why he did it. But I remember having an internship when I was in law school in the Five Points area. It was quicker, less stressful and less costly for me to take transit. I didn’t have to deal with crossing I-285, and I didn’t have to pay to park once I got to work. So to me, I had a car, and I could have chosen to take it, but taking transit was a more attractive option for me, and I think that there are other reasons why transit could be a more attractive option for some people. It may not be their sole use of getting around the county and the metro region, but it could be something that they choose to do.

MDJ: I think one of the biggest concerns people have is the length. Could you briefly make the case for why 30 years makes sense, and not five or 10?

Cupid: So 30 years ago was … 1994, which perhaps for some people may have seemed like a lifetime ago. For me, it still very much feels like yesterday. And I share with you the example of some of our citizens that were transit-dependent, who were significantly impacted when we decided to shift money away from our transit system. These are people who’ve made life decisions on where they’re going to live and where they are going to work based on the network that they thought would be readily available to them.

Yesterday, even somebody who was in opposition to transit yesterday at our BOC meeting, said “transportation, or transit, is like infrastructure.” It is. We can build a house or move to an apartment and pick a job based on the road network that gets

them there. Many people have chosen to live, move, and create their life around a system that they thought would be readily available. So not having that dependency over a reasonable amount of time can create a significant amount of instability for people that utilize transit.

Also, I think when there’s opportunity to leverage federal dollars, if we are not showing that we’re committed to sustaining an asset, it makes us less attractive for investment, when there are other communities that have indicated that commitment. And why put millions and millions of dollars investing in something that you know is only going to be there for a short amount of time?

Again, if we are getting to the point where we recognize transit as infrastructure, you don’t think I’m going to put in million dollars towards a road, and then that road’s not going to be there five or six years from now. People are making life decisions on connecting from point A to point B, and it makes sense to make sure that that’s stable. Not just from an accessibility perspective, but from a funding perspective. And we truly limit ourselves to access dollars that will help sustain our system over time if we are not considering a serious time frame of maintaining that system.

MDJ: The centerpiece of the project list is bus rapid transit, arterial rapid transit, microtransit. Why go with those instead of rail, for instance?

Cupid: That’s a good question. I think a lot of it comes down to dollars, and what you can get with those dollars. So rail could be considered, but the cost of rail would have really limited our options when it came to this SPLOST. And I think one thing that we grappled with initially was, do you want to create a program that provides coverage throughout the entire county, or connection through the region? And if our focus was on connection through the region, then we could have invested money perhaps in looking at rail. But that would have limited all of the other options.