Coming Soon, 9015 Je erson Highway, Baton Rouge

Since 1978, we have been the cornerstone of St. Francisville, serving our friends and neighbors with a winning combination of community vision and relationship banking. For nearly a decade we’ve been steadily growing in Baton Rouge, always mindful of maintaining the same level of exceptional personalized service. Soon we will break ground on a new Baton Rouge location, and with the help of Cockfield Jackson Architects, Cangelosi-Ward General Contractors and Kenneth Brown Design we will endeavor to duplicate the Bank of St. Francisville aura, elegance and charm that so many know and love.

REFLECTIONS

Spring chickens by James Fox-Smith

Creating a historical record of Afton Villa, seeds at the library & the business of biochar

PLANTING SEEDS

‘tis the season for garden geeks, lucky Irishmen & competitive cooks

Publisher

At Ninth Ward Nursery, bamboo grows as “art you can walk through” by Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

FLEUR D’EDEN

Jeanette Bell’s secret garden in the middle of the city by Kristy Christiansen

TAKE ME TO “LA TERRE”

Building a flower farm from scratch by Mimi Greenwood Knight 28 A LITTLE OASIS

“CATCHING SOME Z’S,” AUGUST 2021. Artwork by Wyatt Waters

There’s nothing quite like fresh-cut flowers, especially when you can get them “grown, not flown,” as the folks at La Terre Flower Farm in Kiln, Mississippi (page 34) put it—that is to say, grown locally. In this year’s “Into the Garden” issue, we spotlight three entrepreneurs meeting their communities’ needs for flora, its beauty as well as its capacity to inspire. We step into Jeannette Bell’s secret rose garden, which has kept New Orleans restaurants flush with flowers for decades now. We wander through the jungle paths of Mark Sanders’ tropical oasis in the Ninth Ward. And we follow the journey of mother-son duo Teri and Connor Wyly, who started their flower farm by watching YouTube videos. Of course, beauty is just the beginning. At Ernie Foundas’s Tiki Food Lab, starfruit grows in the greenhouse and invasive duckweed is fermented into soy sauce. Pollinators flit and fly between all of these verdant sites, some of them ultimately finding a home in Luke Wagner’s hives, where they’ll make the sweet stuff found in the honey houses across Baton Rouge neighborhoods, sparking joy in the wonder of things naturally-made, lovingly-cultivated.

SUIS GENERIS

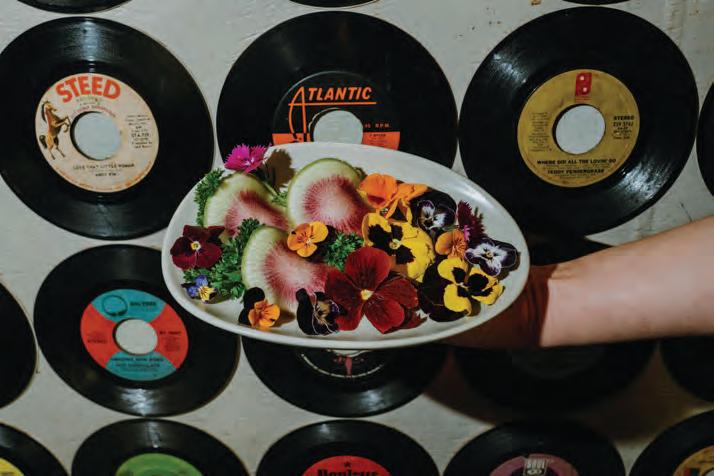

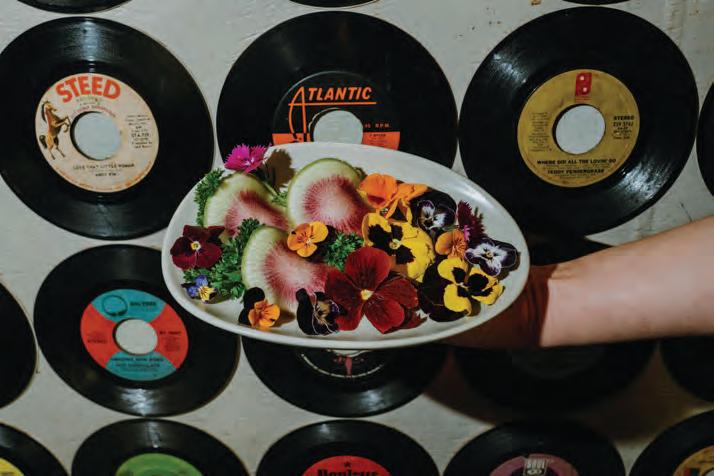

Home to a food lab, a Tiki farm, and a record label by Beth D’Adonno

BEYOND NATIVES

exotics that belong in your garden

Jess Cole

OF

Why milkweed is no longer the answer by Donna Bush

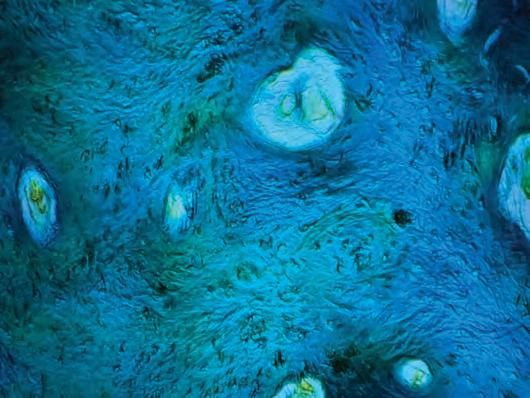

BLEU PERDU An indigo revival in Louisiana by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot THE HOT SAUCE LEAGUE

For more than twenty years, Acadiana was the wild west of the minor leagues by Brian Altobello

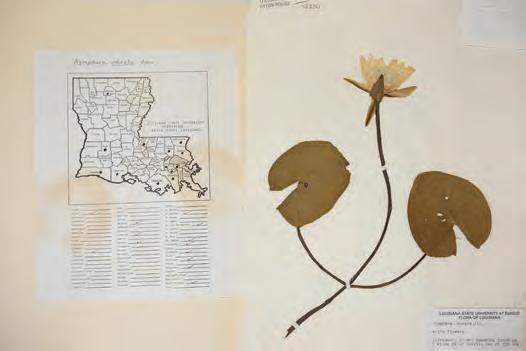

CHASING THE LOUISIANA IRIS A wildflower road trip by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

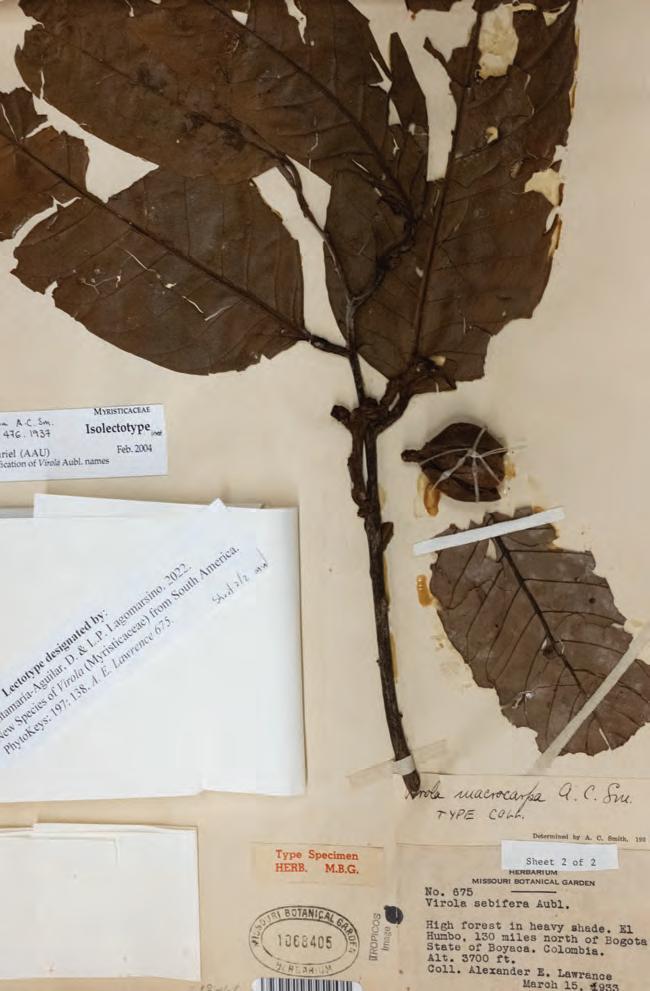

BONTANICA COLLECTANEA

Printmaker Leslie Koptcho is making art from the ecological enemy by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

James Fox-Smith

Associate

Publisher

Ashley Fox-Smith

Managing Editor

Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

Arts & Entertainment

Editor

Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

Creative Director

Kourtney Zimmerman

Contributors:

Brian Altobello, Donna Bush, Kristy Christiansen, Paul Christiansen, Ed Cullen, Beth D’Addono, Jess Cole, Mimi Greenwood Knight, Stephanie Tarrant

Cover Artist

Wyatt Waters

Advertising

SALES@COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM

Sales Team

Heather Gammill & Heather Gibbons

Operations Coordinator Molly McNeal

President Dorcas Woods Brown Country Roads Magazine P.O. Box 490 St. Francisville, LA 70775 Phone (225) 343-3714 Fax (815) 550-2272

EDITORIAL@COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM WWW.COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM

All this talk about America’s egg crisis reminds me that we haven’t talked about hchickens in a minute. With bird flu pushing egg prices to record heights, articles about keeping backyard chickens—usually with dewy photos of plump hens tiptoeing through garden settings—are everywhere. “Doesn’t look that hard,” I imagine America’s omelet-fanciers muttering.

Case in point: last week, Country Roads’ Jordan LaHaye Fontenot revealed that her husband, Julien, had come home with not one but two chicken coops he’d found on Facebook Marketplace. Then, Julien promptly fell down the online chicken rabbit hole, which I know is deep because I’ve been keeping chickens since our kids were small. Our cooking and gardening activities have benefited from the fresh eggs and enhanced compost, and, on warm spring evenings, we’ve loved the simple pleasure of watching the social antics of our ragtag flock from plastic lawn chairs, gin and tonics in hand. We’ve also encouraged a lot of carnivorous wildlife to develop a taste for chicken. So, before the price of eggs has you following Julien down the chicken rabbit hole, I offer six rules of chicken-keeping for your consideration.

Rule 1: Everybody likes chicken. I do mean “everybody.” The variety of wildlife attracted by the prospect of a chicken dinner is matched by the inability of chickens to defend themselves against anything with teeth (or fangs, or a beak). Over fifteen years we’ve lost chickens to raccoons, possums, foxes, coyotes, hawks, owls, snakes, weasels, gnats, our dogs, other people’s dogs, and stupidity—both my own and that of the chickens themselves.

Rule 2: Chickens are stupid. At night, coerced by the sound of something snuffling about outside the coop, a chicken is apt to poke its head out through the wire for a closer look. Raccoons know this, are patient, and will eat whatever they can reach. You can see where this is going.

Rule 3: Don’t name them. When we started out, our kids were little. Our first batch of hens got nursery-rhyme names like “Big Bird” and “Henny-Penny.” After the first few massacres, their replacements got names like “Coq-au-Vin” and “Chicken Nuggets.” Eventually, the kids stopped naming them entirely.

Rule 4: Your coop must be impregnable. Let your chickens free-range at your own (okay, their own) risk. But once the coop door is shut, unless you’re planning to sleep in it with a shotgun, the place needs to be impenetrable. Through years of trial and error, my coop has acquired the layered defenses of a medium security prison, including heavy-gauge floor-toceiling mesh, high perches situated more

from a male one means my flock includes three roosters, and they’re making my hens’ lives miserable. This needs to change. When you get one with a mean streak, make a gumbo. It won’t be very good, because in addition to their other bad character traits, roosters are stringy and tough. But at least you’ll have gotten rid of the problem.

than a paw’s reach from the perimeter

ken-glass-filled trenches to discourage tunnelling. None of this is worth a damn if the predator is already inside. Last spring I got six baby chicks and put them in the special “nursery” coop that you’ll need for raising defenseless things to egg-laying age. Since this boxed-in coop sits on stilts, is screened with layers of wire, and had never been breached, I was confident they’d be fine. In the morning there wasn’t a chick to be found. It took a while to discover the culprit. In a laying box beneath the straw was a sleepy, fivefoot rat snake … with six sad little bumps along the length of its body.

Rule 5: Avoid Roosters. It seems reasonable to assume that for your hens to lay eggs, they’ll require the services of a rooster. This is wrong; hens will lay happily without one, and the feminine energy will make your coop a nicer place. Roosters are handsome, but they’re also noisy, belligerent, violent rapists. Currently, my inability to tell a female chick

Rule 6: Eggs are expensive, but not as expensive as chickens. Sure, the secondhand coop you’ve found online doesn’t cost much. And yes, the adorable chicks at the feed ‘n seed are just a few bucks apiece. But for chicks to survive a single night they’ll need a special coop, special feed, and a heat lamp. You need to keep them alive for six months to get any eggs. Once they do start laying, they eat prodigiously. My eleven chickens get through a 50 lb sack of layer’s pellets ($24) each week. Do the math. It never made sense to me that you could buy a dozen eggs for a dollar, anyway.

If you still long for chickens, then bravo! In my experience, chicken-keeping is neither low-maintenance nor for the squeamish, but if you enjoy cooking, gardening, caring for creatures, and building things, I can’t think of a more rewarding pastime. And if it doesn’t work out, you can always put the coop back on Facebook Marketplace. There’s a chicken-fancier born every minute.

—James Fox-Smith, publisher james@countryroadsmag.com

When she gets home from a day of work at Pennington Biomedical Research Center, the first thing Catherine Carmichael does is visit her garden. “It’s what I do. I’ll always check on it, see what is ready to be picked, what needs to be weeded,” she said. “Sometimes I’ll get my kids to come join me out there.”

As a registered dietitian, Carmichael spends a lot of time thinking about what motivates people to seek out and create more nutritionally dense meals. During National Nutrition Month, which this year explores the theme “Food Connects Us,” Carmichael is highlighting the ways gardening can help us to build direct connections with our food, enabling us to invest in the process, before we enjoy the bounty.

“You see how long it takes to grow, what is required—sun, soil, and water,” she said. “Having a garden can be very inspiring when it comes to changing your way of eating.”

It is also a great way of connecting with others, she pointed out. “It’s an opportunity for a family or group of friends to come and work together.”

Why Grow My Own Food When I Can Find It at the Store?

According to Carmichael, one of the principal benefits to eating from one’s own garden comes from minimizing the distance traveled between your plate and where the food was grown. The greater the distance (and time) a food spends in transit, the higher the likelihood that its nutritional value will have been diminished—by preservatives, chemicals, and other additives required to help it survive the long journey and appear appetizing in a grocery store setting. “If you want more control over what you are putting into your body, then growing some of your favorite fruits and vegetables is a great option to reduce your reliance on the store,” she said.

(Pro tip: If you can’t grow something on your own, or would simply prefer not to, another great way to reduce distance between field and fork is to source your fruits and vegetables from growers at your local farmers’ market.)

Beyond the nutritional benefits, gardening is good for you, too. “It can be terrific for stress relief,” said Carmichael. “And it’s also fun! Gardening can be incredibly satisfying.

We spend so much time looking at screens, it’s an opportunity to put technology down for a minute and step into nature.”

Planning Your Garden

When setting out to establish a garden, the first thing new gardeners should consider is space. “You need space for the plants to grow, you need soil, you need sun, and you need water,” said Carmichael.

Options like container gardening and raised beds can offer more flexibility for people with limited yard space, or limited access to sunlight. Today, she grows her vegetables in raised cinder block beds. “I think a lot of people get overwhelmed by gardening and think you need all this space,” she said. “But you can grow a tomato plant in a five-gallon bucket. And herbs and spices are great, even for apartment dwellers—and can really change the way you prepare your food and eat.”

Once the space is prepped, Carmichael advises sketching out a plan before planting. “I always do that, because I tend to plant more stuff than the amount of space I have will allow. Then it gets crowded and messy. And that can attract pests.”

What Should I Grow?

“I think the thing with being a gardener, whether you’re new or seasoned, is that it all depends on how patient you are,” said Carmichael. There are some plants— like radishes, for instance, or green beans, that produce quickly. Others, like lettuce, should be planted early in the spring, so that you can enjoy the harvest before it gets too hot.

Some of Carmichael’s favorite crops to grow include Tuscan kale, Swiss chard, green beans, cherry tomatoes, and eggplant. You want to plant things you’ll actually eat, Carmichael advised, and things that are versatile. Tomatoes, for instance, can be used in a salad, a tomato sauce, or salsa. Green beans can be cooked or blanched or eaten fresh.

Some great local resources that Carmichael regularly relies on when planning her garden include the LSU AgCenter’s Vegetable Planting Guide and the seed libraries at Central Branch Library, Greenwell Springs Road Regional Branch Library, and the Main Library at Goodwood—which not only share free seeds, but provide information on how to use them, too.

From Seed to Plate

Carmichael’s garden feeds directly into her work as a dietitian at Pennington Biomedical Research Center. The seeds she’s planting inspire the healthy, balanced, and nutritious meals she educates on, and the research she conducts motivates her to get back into the garden as soon as she gets home.

Integrating a garden into your life can be a huge first step in making healthier choices, and Pennington Biomedical has the resources to help you along the journey.

Learn more about the research and initiatives conducted at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at www.pbrc.edu/getinvolved.

THE ST. FRANCISVILLE SPRING GARDEN TOUR IS GOING TO BE BIGGER AND BETTER THAN EVER

“Thhere’s nothing like spring in St. Francisville,” says David Parker, professional florist and chairman of St. Francisville Beautiful.

To celebrate the small town’s historic place as a pinnacle of Louisiana garden-making, Parker and the Feliciana Master Gardeners are expanding St. Francisville’s annual Spring Garden Tour event with a new partnership.

A NEW SEED LIBRARY OPENS IN WEST FELICIANA PARISH

Thhis spring, the West Feliciana Parish Library has announced the launch of its new Seed Library, funded through an LSU AgCenter Healthy Communities Grant. The program allows patrons to share and “borrow” seeds suited to our local climate, to enjoy their fruits at home, and then to bring back more seeds produced from the food or flowers thriving in their gardens. The West Fel Library joins other libraries across the state participating in the seed-sharing trend—an initiative that not only cultivates local plant life and gardens, but also community support. Other seed libraries can be found in libraries of Orleans Parish, Ascension Parish, Livingston Parish, Terrebonne Parish, Lafayette Parish, and East Baton Rouge Parish—which just announced its newest seed library location at the Main Library at Goodwood.

—Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

IN LAKELAND, LOUISIANA, AN EFFORT TO MOVE A MOUNTAIN

In Lakeland, Louisiana, the highest point of land isn’t actually land at all. Covering forty acres at its base hand rising seventy feet above the flatlands, “Mount Bagasse,” as it’s colloquially known, is a monumental pile of sugarcane bagasse generations in the making. Bagasse—the fibrous material left over after cane juice extraction—is the residue of more than a century of sugar production at Alma Sugarcane Mill, which has been processing raw sugar from cane grown at Alma Cane Farm since 1859. Each year the mill processes two million tons of Alma-grown cane to produce around 500 million pounds of

sugar, and generates 600,000 tons of bagasse. Around 250,000 tons are burned to power the mill. The rest goes on the pile. Mount Bagasse is growing by two to three acres per year.

But one industry’s waste is another’s opportunity. Enter Lakeland Biochar, a startup partnering with Alma to turn sugarcane bagasse into high-quality biochar. Biochar is a stable form of charcoal that, when added to soil, enhances fertility, increases moisture and nutrient retention, and promotes beneficial microbial activity while reducing soil emissions of greenhouse gases. Biochar is made in a gasifier, a high-tech process in which

“When you’ve got beautiful homes, beautiful gardens, and you’ve got passionate groups [like St. Francisville Beautiful and the Master Gardeners], it’s kind of a win-win for the community,” said Parker.

The longstanding tradition will continue—opening the front doors and garden gates to some of the town’s most opulent homes and gardens. But this year, the celebration extends into the afternoon, where guests can take advantage of an exclusive plant sale, lectures from master gardeners on topics like “Year-Round Color in Your Garden,” and hands-on workshops. Parker himself will host a lesson in building bouquets “from the grocery store to your dining room table.”

“I want to show people how to easily bring flowers back into the home, which I think has become a dying art,” he said. And it all culminates in a grand, Bridgerton-style coursed feast at the newly renovated home of St. Francisville’s hostswith-the-most, Brandon Branch and Jim Johnson—owners of the St. Francisville Inn.

“Brandon is known for his beautiful gardens and his décor,” said Parker. “This will be an open house, with a special garden tour leading up to the dinner,” which will be prepared by newly returned St.

bagasse feedstock is heated in an oxygen-starved environment. Gasification produces biochar plus a carbon-monoxide-rich syngas, which is burned to power the system—a virtuous cycle that produces very little exhaust. According to Lakeland Biochar founder and CEO Tyler Kerrigan, this makes gasification both efficient and environmentally beneficial, since sugarcane bagasse biochar is not only prized by farmers, gardeners, and soil remediation specialists, but also locks up significant quantities of carbon. So, biochar production generates carbon credits. Kerrigan explained that initially, Lakeland Biochar will build a gasification unit capable of turning 60,000 tons of bagasse into 6,500 tons of biochar while generating 15,000 carbon credits, which the company will sell. Eventually, the goal is to scale the operation to the point at which all the bagasse Alma

Francisville Inn chef, Michael Dardenne. “There will be candles, flowers, a quartet playing pop songs with the strings. It’s going to be a great party.”

Taking place on Mother’s Day weekend, the day-long event is also expanding its philanthropic reach—funding not one scholarship for West Feliciana High students this year, but three. “I think if we plant these seeds with them at a young age, that’s something they’ll carry on for a lifetime,” said Parker. Proceeds will also benefit local school gardens, the 4-H club, and beautification projects around town.

“We in St. Francisville love having people up in town,” said Parker. “The town is really becoming a destination for good restaurants and shopping. But we don’t want to forget what put us on the map, our homes and gardens.”

—Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

The St. Francisville Home & Garden Stroll will take place May 10. The open house & garden tour will take place from 8 am–1 pm ($40); lectures, workshops, and plant sale will take place from 1 pm–5 pm ($40); and the private dinner from 6 pm–9 pm ($250). Purchase your tickets at bontempstix.com.

produces is converted into commercially viable biochar while eliminating a costly waste product. In a state where 550,000 acres of sugarcane is harvested annually, it’s not hard to see the potential. Olivia Stewart, fifth generation owner of Alma Sugar Mill and President of Oxbow Rum Distillery, sees it. “My hope is that this can not only stop the [Alma] pile from growing, but also to begin to eat into the pile,” she said, “and that it can expand beyond Alma to help other mills as well. Because the problem of ever-increasing bagasse is everyone’s problem.” If coming up with a solution to a persistent problem for Louisiana’s sugar industry creates a sustainable, lucrative new state industry into the bargain, everyone wins. And perhaps, after more than 150 years, Mount Bagasse can begin to shrink at last.

—James Fox-Smith

One of St. Francisville’s most enchanting attractions during spring, h Afton Villa Gardens has recently received a federal grant to hfund the continued preservation of the famed nineteenth century garden.

A competitive Historic Preservation Fund Award will enable a team to conduct a Historic America Landscape Survey (HALS) on the gardens, providing a record of the site in decades to come. Awarded by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s National Park Service, the federal funds totalling $58,935 will be used to document the site under the direction of Dr. Lake Douglas, professor emeritus in the LSU Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture.

Douglas, whose background lies in historic landscapes, and who served as editor for Genevieve Trimble’s Afton Villa: The Birth and Rebirth of a Nineteenth-Century Louisiana Garden (LSU Press, 2016), has spent years researching and publishing on historic gardens in Louisiana. So, when he was approached with the opportunity to participate in the survey, he already possessed an abundance of knowledge about Afton Villa and its history. “I was acquainted with a lot of the work, just because of my interest,” Douglas said.

The historic garden, dating from the mid-nineteenth century, is the only element of the Afton Villa estate to have remained intact after the forty-room Gothic Revival mansion burned to the ground in 1963. Trimble and her husband purchased the property in 1972 and spent the next forty years restoring the once-legendary gardens, breathing new life into a formerly derelict landmark. By 2023, the gardens were ranked as the second most beautiful in Louisiana.

HALS is charged with creating a lasting, permanent record of significant cultural and designed landscapes in the country using interpretive drawings, written histories, and images. A team composed of Douglas and Duplantis Design Group of Baton Rouge began late last fall working on the two components of the project: Douglas on the historical narrative portion, and Duplantis on the technical drawings section.

“I thought it was a wonderful opportunity to get this property a little more substantially documented for the record, for future generations, so all of the information is in one place,” Douglas said.

The twelve-month project, when complete, will reside in the Library of Congress. Douglas sees the survey as a reckoning of relevance, noting people often take landscapes for granted and fail to understand the transformative process that created a certain site.

“The evolution of landscapes is an important thing for people to know about. You know, the garden there just didn’t happen. It represents a lot of layers of historically important things,” Douglas said. “I think it tells us a lot about how people responded to the land, and how people were involved with the land.”

Afton Villa’s Spring Season begins March 1 and lasts through June 30. Learn more about the gardens at aftonvillagardens.com.

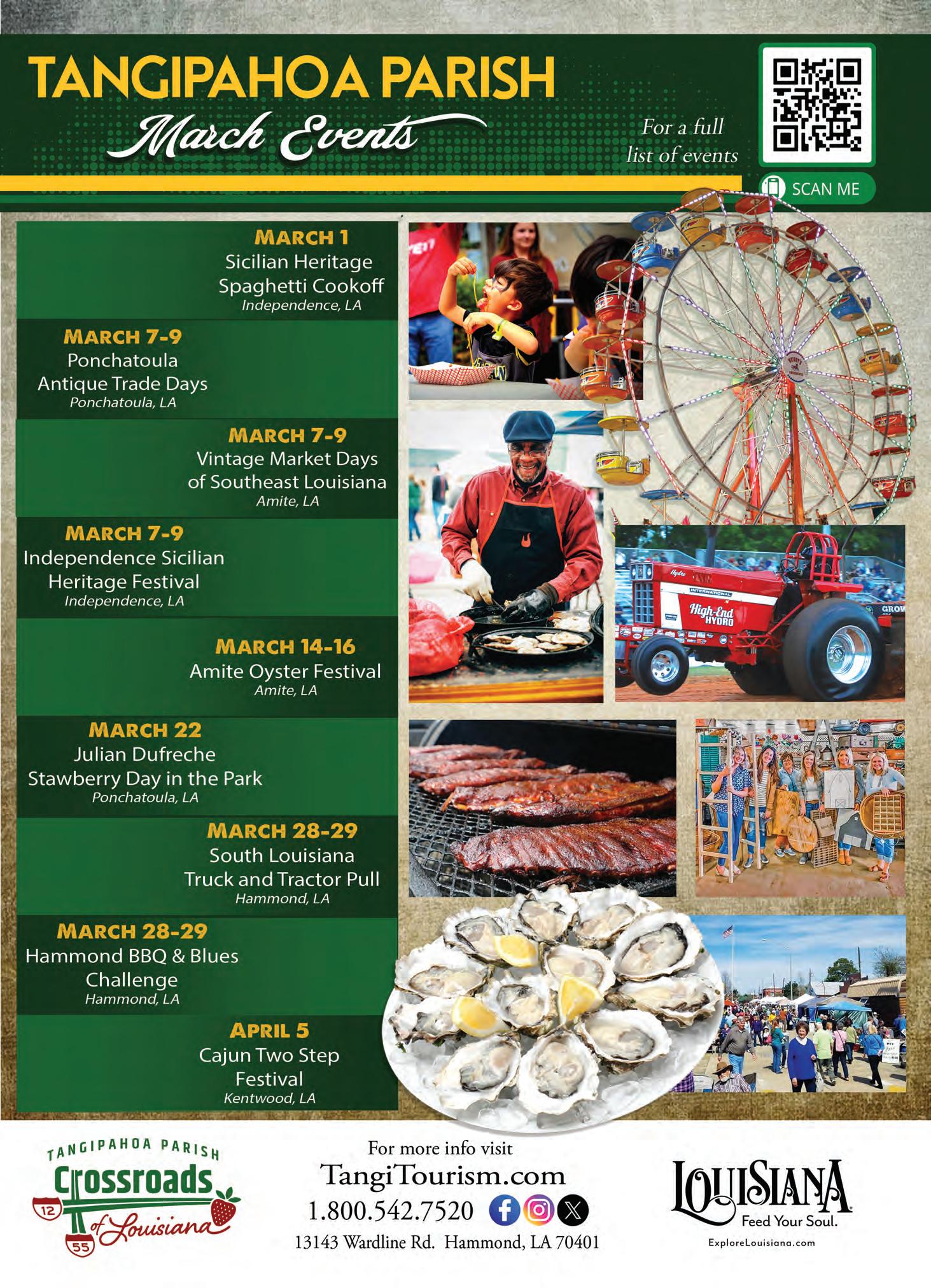

'TIS THE SEASON FOR FLOWERING,BLOSSOMING, AND OPENING UP—FROM PLANT SALES AND GARDENS TO SPRING FESTIVALS AND FUNDRAISERS • MARCH 2025

HISTORICAL FIGURES

THE BIGGEST CELEBRITY OF HIS TIME: GENERAL LAFAYETTE

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Presented by members of Associated Women in the Arts, this exhibition at the Old State Capitol features art inspired by the Marquis de Lafayette—the first foreign general of the Revolutionary War. This exhibition, fittingly, highlights Lafayette's time in Louisiana in 1825. Find more information at the Associated Women in the Arts Facebook Page. 1

REWILDING

PRAIRIE STORIES: ART AND ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION ON LOUISIANA'S PRAIRIES

Lafayette, Louisiana

Prairie Stories: Art and Ecological Restoration on Louisiana's Prairies, on display at the Acadiana Center for the Arts Main Gallery, showcases the work of regional culture bearers in restoring Louisiana's coastal prairies. From Elemore Morgan Jr.’s landscape paintings, to a collaborative installation piece by Rush Jagoe and Maaliyah Symoné, the exhibition will explore the efforts of indigenous groups, artists, and scientists. Rewilding projects, such as

those by the Cajun Prairie Restoration Project, Atelier de la Nature, and the Acadiana Native Plant Project, will be showcased in the exhibition. acadianacenterforthearts.org. 1

7th - MAR 8th

BACKWOODS BEVERAGES

LOUISIANA MOONSHINE FESTIVAL

Leesville, Louisiana

Western Louisiana is embracing its history of "No Man's Land" with this exciting inaugural festival at the Vernon Parish Fairgrounds, honoring the region's history as a place just outside the rules (and proud of it)—along with a celebration of quite possibly the only legal moonshine outfit in the state. The familyfriendly event will feature food vendors (boiled crawfish has been promised), moonshine tastings, and opportunities to meet master distillers from around the country and close to home alike. Live music will keep everyone on their toes throughout the two-day event, performed by musicians like Mike Hughes, Emily Hillman, EV Mae, and more; and a special veterans tribute concert will take place on Saturday night. Gates open at 10 am each day; $15 for Friday; $20 for Saturday; $25 for the whole weekend. louisianamoonshinefestival.com. 1

TOURS OF HISTORIC HOMES AND SITES 2025

MAR 7th - MAR 9th

CULTURAL FESTIVALS INDEPENDENCE SICILIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL

Independence, Louisiana

Celebrate all things Sicilian with the residents of Independence. At the fest, held downtown, you can make spaghetti, eat spaghetti, and even toss meat balls (as far as you possibly can! Yes, we're talking about a meatball throwing contest, friends.). Enjoy carnival rides, arts & crafts, a St. Joseph's altar, pageantry, and even a parade. The live music lineup includes favorites like Peyton Falgoust, Chase Tyler, Kings of Neon, and Rockin' Dopsie. More details at indysicilianfest.com. 1

MAR 7th - MAR 9th

ARTS & CRAFTS

"LIFE'S A STITCH" QUILT SHOW

Abita Springs, Louisiana

Days after Mardi Gras, Abita Springs Town Hall will host a quilt show presented by Ozone Layers Quilt Guild featuring over 100 hand-made quilts, wall hangings, and fiber art projects made by the members. The event will feature daily demonstrations, as well as a Jelly Roll Race, T-Shirt Quilt demo, and a lecture by Mary Green, fiber artist, on

Spring Pilgrimage

Spring Pilgrimage

March 8 - April 19

The Houses

Choctaw Hall

Dunleith

Ellicott’s Hill

Elms Court

Frogmore

Glenfield

Gloucester

Linden

Magnolia Hall

Rosemont

The Stone House

Sunnyside

The Towers

Fall Pilgrimage

Sept. 27 - Oct. 18

Year Round Tours 2025 Christmas Pilgrimage Nov. 22 - Jan. 3, 2026

littleeasytours.com or purchase tickets at houses

The Natchez Garden Club 215 S Pearl Natchez, Mississippi natchezgardenclub.org 601-443-9065

Art Quilts. Three quilts will be raffled. 11 am–4 pm. visitthenorthshore.com. 1

MAR 8th

FAST LANE

NEW ROADS CAR SHOW AND STREET FESTIVAL

New Roads, Louisiana

The City of New Roads & New Roads Main Street present the 16th Annual Spring Street Festival and Car Show, featuring over 300 participants, a raffle benefiting Pointe Coupee Homebound & Hospice, and awards galore. 8 am–3 pm. $40. bontempstix.com. 1

8th

SPRING SHOPPING

SHADOWS-ON-THE-TECHE ARTS & CRAFTS FAIR

New Iberia, Louisiana

Looking for a fun, family-friendly way to celebrate spring? Stroll through the Shadows-on-the-Teche Spring Arts and Crafts Fair in the gardens of the historic Weeks family home. Explore wares made by craftspeople from across the state, shop seasonal items, pantry staples, and clothing—and be sure to fill your belly

with delicious food from local vendors. 9 am–4 p.m. $5 for ages thirteen and above; free for children twelve and under. shadowsontheteche.org. 1

MAR 8th

GOOD EATS

DA CAJUN BURGER COOK-OFF

Morgan City, Louisiana

Chow down on burgers from local chefs and enthusiasts at Da Cajun Burger Cook-Off, held under the Highway 90 bridge in Morgan City as they gather to compete for the title of Best Burger in the Tri City Area. In addition to good eats, there will be live music, alcoholic beverages, and fun for the kiddos. 11am–6 pm. Admission is $10 and includes five sample tickets, plus one People’s Choice token to vote your favorite burger. cajuncoast.com. 1

MAR 8th

GOOD EATS NOT YOUR MAMA'S GUMBO COOK-OFF

Abita Springs, Louisiana

Nothing brings the people together like an old-fashioned gumbo cook off. Head

At NUNU, Anne Crownover and Janelle Hebert present an exhibition celebrating norm-breaking and risk-taking, led by creativity. Falling Out of the Box embraces the extraordinary and urges viewers to honor the unexpected. Opening reception March 14 from 6 pm–9 pm. nunucollective.org. Pictured above is Hebert's piece, "Rain Coming." Image courtesy of NUNU.

out to the Abita Springs Trailhead this weekend, and get lined up as early as 11 am. $10 gets you a wristband and a say-so in the People's Choice Awards. Besides the gallons of gumbo, attendees will also enjoy side items and beverages (adult and otherwise) provided for sale by local vendors and organizations. All proceeds will go towards city beautification projects, glass recycling, liter cleanups, and educational programs. Live music

until 3 pm. Details at the Keep Abita Beautiful Facebook Page. 1

MAR 8th

GREEN THUMBS

GARDEN DISCOVERIES: PLANT IT AND THEY WILL COME

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

“Plant It and They Will Come," hosted by the Baton Rouge Botanic Garden Foundation, is a butterfly-forward event

for gardeners led by Linda Barber Auld— known as the NOLA Bug Lady. Head to the Main Library at Goodwood to learn the ins and outs of crafting an oasis that will increase butterfly activity in your garden. 10 am. Registration available at ebrpl.co/events or call (225)-231-3750. ebrpl.co/garden. 1

SPRING SHOPPING

SPRING MERRY

MARKET

Gonzales, Louisiana

The Merry Market returns to Lamar Dixon Expo Center just in time for spring with a special, seasonally-appropriate market—featuring more than 350 booths offering clothing, jewelry, home décor, candles, toys, Christmas décor, food, bath and body products, art, and more. Saturday from 9 am–5 pm, Sunday from 10 am–5 pm. $10 admission, with a portion of the proceeds going to the Sparrow Foundation. Children under ten are free. $25 for advanced VIP Shopping, which grants early entry from 8 am–noon. There will also be a Kidz Zone to keep the tinies busy while you shop, featuring the Easter bunny, crafts, face painting, and more. Parking is free. merrymarket.shop. 1

BEVVIES

UNCORKED

FOOD & WINE SHOWCASE

Saint Francisville, Louisiana

Enjoy the best of St. Francisville cuisine, courtesy of the West Feliciana Chamber of Commerce, which will host an exciting "Uncorked Food & Wine Showcase" at The Mallory. The event will feature delicious food, fun cocktails, wine, and desserts from local restaurants. 3 pm–7 pm. $50; $40 for Chamber Members. business.westfelicianachamber.org. 1

PARADES

ST. PATRICK'S DAY

PARADE IN SLIDELL

Slidell, Louisiana

Join the festive spirit of the Olde Towne Slidell Merchants Association's beloved

St. Patrick's Day parade, starting at 1 pm. The fiftieth anniversary of this lively procession features over fifty floats, bands, dance groups, and plenty of Irishthemed throws from beads to ingredients for traditional Irish stew (that's right: thousands of heads of cabbage, onions, potatoes, celery, and carrots). Be sure to bring your pots to catch your supper. The excitement departs at City Hall. For inquiries, call (985) 641-1105. 1

MAR 11th - MAR 18th

ART OUTSIDE

SHADOWS-ON-THE-TECHE PLEIN AIR COMPETITION

New Iberia, Louisiana

"Plein air" describes the technique of creating art in the open air—a process that provides dramatically different results as artists adapt to a day's shifting weather patterns and angles of light. Nine years ago, the Shadows honored the artistic tradition that Weeks Hall began by establishing a plein air art competition, which returns to the historic house's grounds this month. In March, dozens of well-known artists from across Louisiana and around the South will come to town to have their blank canvases marked, then will head out into New Iberia and its surroundings to ply their pastels and work their watercolors. Artists' work will be exhibited and available for sale in the Shadows Visitor Center, when the competition winners will be announced on the evening of March 17. Complete details at shadowsontheteche.org. 1

MAR 13th

GREEN THUMBS

EBR MASTER GARDENERS

PRESENTS: POLLINATION AND NATIVE PLANTS

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

For those with green thumbs, or simply

those hoping to get a fresh start with their garden this spring as the weather warms up, stop by Jones Creek Library for an East Baton Rouge Master Gardener presentation. First, Master Gardener Carol Paine will discuss pollination, highlighting plants that pollinators love the most. Then, Master Gardener Gaynelle Wolf will introduce attendees to native plants ideal for a spring garden takeover, sure to help your garden thrive in the coming months. 6:30 pm. Free. ebrmg.wildapricot.org. 1

SPRING SIP, SOW, AND GROW

Mandeville, Louisiana

The St. Tammany Master Gardener Association's Spring Seminar at the Castine Center at Pelican Park in Mandeville brings gardeners together for a delightful morning filled with expert talks on horticulturalist subjects and delicious bites. This year titled “Spring Sip, Sow, and Grow,” the event will feature presentations such as "Louisiana Owns and Blooms," "Little Known Resources for Fruit and Vegetable Gardeners," and others on native plants and vermiculture, among other topics. 8 am–noon. $25. stmastergardener.org. 1

Beginning March 13th - 15th

MAR 13th - MAR 16th

FILM

FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL

New Orleans, Louisiana

The twenty-eighth New Orleans French Film Festival, one of the longest-running foreign language festivals in the country, will once again represent excellence in contemporary and classic Francophone cinema for audiences, this year at the Prytania Theatre Uptown. Live music and lectures will accompany a curated selection of short and feature-length French-films, all of which will be screened with English subtitles. Film passes are $85 and get you free admission into all in person festival screenings. neworleansfilmsociety.org. 1

MAR 14th - MAR 15th

GOOD EATS

JXN FOOD & WINE FESTIVAL

Jackson, Mississippi

Foodies'll be heading north the second they sniff out this new culinary festival in the heart of the up-and-coming food city of Jackson, Mississippi. This year, the festival kicks off on Friday with an exclusive dining experience at Jackson

chef Nick Wallace's restaurant, The Hen & Egg. Saturday brings the fullforce festival, featuring dozens of local and regional chefs offering small plates, samplings of wine, beer, spirits, and mocktails; a demo stage, and live music. Doors open at 6 pm, with early VIP arrival at 5 pm (which also includes an exclusive VIP area with hors d'oeuvres, an open bar, dedicated restrooms, and a celebrity chef meet and greet).

A portion of the proceeds will benefit the Mississippi Restaurant Association Education Foundation. Tickets start at $90. jxnfoodandwine.com. 1

MAR 14th - MAR 15th

BOOKWORMS

FESTIVAL OF WORDS

Grand Coteau, Louisiana

Grand Coteau's annual Festival of Words returns this year with three featured authors and two days of wonderfully wordy events—all for free. On Friday, writers A$iaMae, a Black, non-binary Southern poet, humorist and cultural worker; professor and author Darrell Bourque; and poet Tyler Robert Sheldon

will take part in a community reading with Q&As at the Hive, and then on Saturday will host writing workshops at the Thensted Center. Details at festivalofwords.org. 1

MAR 14th - MAR 15th

CULTURAL CELEBRATIONS

ACADIAN MEMORIAL

HERITAGE FESTIVAL

Saint Martinville, Louisiana

Looking back on more than 250 years of history, this celebration of all things Acadian—or Cadien (Cajun)— centers in Evangeline Oak Park, where there'll be jambalaya, gumbo, cracklin demonstrations, theatre, Cajun dance lessons and music, mask making, storytelling, Longfellow readings, kids’ activities, and more. A re-enactment will take place commemorating the historic arrival of the deported Acadiens into Attakapas Territory. Free. acadianmemorial.org. 1

MAR 14th - MAR 15th

CULTURAL CELEBRATIONS

CELTIC BAYOU FESTIVAL

Lafayette, Louisiana

The annual Celtic Bayou Fest returns, bringing the very best in traditional Celtic music and entertainment to

Lafayette. Downtown will be seeing green with cultural events including an Irish Whiskey Tasting, a Guinness Cook-off, a Pub Crawl, a Bailey's bake-off, a children's area, and more—all of this happening against a background of Acadian & Celtic medleys sparking inner urges to kick up your feet. Green attire encouraged. Friday Pub Crawl starts at 5 pm at the Grouse Room for $25; Kick-Off Party at $10. $20 in advance for Saturday Festival Admission; $25 at the door. $40 for full weekend passes. celticbayoufest.com. 1

GOOD EATS

AMITE OYSTER FESTIVAL

Amite, Louisiana

A staple of the local economy as well as the local palate, oysters have good reason to be celebrated in Amite. The festivities typically start up with the annual Chili Cook-Off and live music on Friday, followed by a full-day on Saturday of parading, oyster-eating, and twostepping, with a headlining performance by Rock Show NOLA. Sunday, get started with a church service and more live music performances, and enjoy a day of carnival rides, local food and drink, and pageantry galore—not to mention a healthy (or maybe not so healthy) portion of fresh oysters, all in Downtown Amite. amiteoysterfestival.com. 1

MAR 14th - MAR 22nd

PERFORMANCES

MARIGNY OPERA BALLET

PRESENTS: DUSK

New Orleans, Louisiana

Marigny Opera Ballet presents the world premiere of DUSK, a contemporary ballet by choreographer Cassi Abranches. The ballet is accompanied by an original score performed live by New Orleans indie rock group, People Museum. Held at the Marigny Opera House in New Orleans, the ballet engages with beginnings, endings, and hope. 8 pm. $60; $40 for students and seniors. marignyoperahouse.org. 1

MAR 15th

PARADES

COVINGTON

ST. PATRICK'S DAY PARADE

Covington, Louisiana

Irish blood runs thick in Covington, Louisiana—and even those who can't claim it have eagerly celebrated the heritage of St. Patrick's patronage in Louisiana since 2018 with the birth of the Covington Celtic Club and annual St. Patrick's Day Parade. The route runs from the Columbia Street Tap Room, and concludes with a block party at the corner of New Hampshire and Rutland Streets, where ladies and leprechauns alike may dance the afternoon away

for a St. Patty's block party. Noon. covingtoncelticclub.com. 1

15th

THE GREAT OUTDOORS

LOUISIANA TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION

SPRING RAMBLE

Covington, Louisiana

Nothing like rambling along the small town roads on a gorgeous spring day. Join the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation for this seasonal tradition, featuring a self-guided tour of historic sites around the Northshore not typically open to the public. This year's ramble includes stops at Villa de la Vergne, Haller-Ward House, Waldheim Gardens/ Jahncke Estate, Otis House at FairviewRiverside State Park, Madisonville Cemetery, Dendinger House, Madisonville Museum, H.J. Smith & Sons General Store and Museum, Covington Presbyterian Church, Mann House, Katz House, and Christ Episcopal Church and Chapel. Start the day at Christ Episcopal Church, where you'll receive an introduction, an informational booklet, and details about each site. 9:30 am–4 pm. $50; $15 for students and teachers, includes a boxed lunch. Register at lthp.org by March 10 to reserve your spot. 1

THE GREAT OUTDOORS

AFTON VILLA GARDENS SPRING SEASON OPENING

Saint Francisville, Louisiana

Celebrate one of the most beautiful corners of Louisiana in full bloom with the Afton Villa Gardens Spring Season Opening, held at Afton Villa Gardens in St. Francisville. Take a stroll, enjoy a self-guided audio tour, and take pictures. Heirloom Cuisine will be on site serving beverages and lite bites. 11 am–2 pm. $40; free for children under 12. aftonvillagardens.com. 1

ART EXHIBITIONS

LAFAYETTE

STUDENT ARTS EXPO

Lafayette, Louisiana

The annual Student Art Expo in Lafayette, hosted by the Acadiana Center for the Arts and the Lafayette Parish School System, is back celebrating the talent of student artists from across the parish. The event pairs schools and businesses to host visual arts exhibits, performances, activities, and more throughout the day all throughout downtown. Expect an art parade, live painting demonstrations, a student artist market, and an interactive dance

HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE GREAT HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE GREAT AMERICAN SONGBOOK II AMERICAN SONGBOOK II

activity. 10 am–6 pm all over town. Free. acadianacenterforthearts.org. 1

CELEBRATIONS

PATTY IN THE PARC Lafayette, Louisiana

One of the biggest Saint Patrick's Day parties in South Louisiana—Patty in the Parc returns to downtown Lafayette starring local favorites DJ Digital, LVVRS, Dustin Sonnier, Wayne Toups, and Cupid. Gates open at 4:30 pm. $20 in advance; $25 at the gate. Visit Patty in the Parc's Facebook Page for tickets. 1

FARM TO TABLE DINNER Saint Francisville, Louisiana

Get ready for some good eats. Bayou Sarah Farms is hosting a farm to table dinner, which includes guest Chef Andy Roberts of Blue Moon Farms cooking over an open fire, and featuring forest-raised pork and grassfed water buffalo. Be sure to sample a complimentary cocktail (Sarah's famous fresh-squeezed margaritas) and take a tour of the farm. 4 pm. $175. Email sarah@bayousarahfarms.org to reserve a space. 1

THURSDAY, MARCH 20, 2025 SONGS OF THE SOUTH SONGS OF THE SOUTH

THURSDAY, MARCH 20, 2025

SATURDAY, MARCH 29, 2025 SATURDAY, MARCH 29, 2025

BB, KING OF THE BB, KING OF THE MISSISSIPPI BLUES MISSISSIPPI BLUES

THE MAGIC FLUTE THE MAGIC FLUTE

SATURDAY, APRIL 26, 2025

SATURDAY, APRIL 26, 2025

FRIDAY, MAY 2, 2025 FRIDAY, MAY 2, 2025 SLAVIC SERENADE SLAVIC SERENADE

THURSDAY, MAY 8, 2025

SATURDAY, MAY 10, 2025 SATURDAY, MAY 10, 2025

THURSDAY, MAY 8, 2025 ALWAYS…PATSY CLINE ALWAYS…PATSY CLINE

THE HEAVENLY LIFE: THE HEAVENLY LIFE: MAHLER- SYMPHONY NO. 4 MAHLER- SYMPHONY NO. 4

WHITNEY HOUSTON… WHITNEY HOUSTON… ALWAYS LOVE YOU! ALWAYS LOVE YOU!

THURSDAY, MAY 15, 2025

THURSDAY, MAY 15, 2025

SATURDAY, MAY 17, 2025 SATURDAY, MAY 17, 2025

Beginning March 15th - 19th

MAR 15th

ARTS & CRAFTS

CRAFTIN' CAJUNS CRAFT SHOW & MARKETPLACE

Houma, Louisiana

Benefit from the outsized ingenuity of a Cajun craftsperson at the HoumaTerrebonne Civic Center. The Craftin' Cajuns indoor craft show and marketplace features over two hundred vendors from 9 am–5 pm. houmaciviccenter.com/craftshow. 1

15th

PARADES

WEARIN' OF THE GREEN PARADE

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Whether it's blue skies or pounding rain, this wildly popular Baton Rouge tradition will roll through the Hundred Oaks neighborhood and Perkins Road overpass area, spreading green goodwill to the thousands who come out in support of the Irish holiday. Come early to claim a spot on the "Wearin of the Green" route; parade begins at 10 am on the corner of Hundred Oaks and Acadian. wearinofthegreen.com. 1

MAR 15th

TREE HUGGERS

FESTIVAL OF LIVE OAKS

New Iberia, Louisiana

Louisiana loves its live oaks, and with good reason. Their beauty inspires, their branches offer shelter from the sun, their roots run deep. The Annual Festival of Live Oaks in live-oak laden New Iberia will offer arts & crafts, music, workshops, barbecue cook-off, and children’s activities—including face painting, pony rides, and more. 9 am–3 pm in New Iberia City Park. iberiatravel.com. 1

MAR 15th

CULTURAL CELEBRATIONS

CLOVER & KILTS FEST

Biloxi, Mississippi

This year, Clover & Kilts Fest— Formally Grillin’ On The Green—will feature award-winning barbecue, live entertainment, contests, craft vendors, and a prize for the best kilt at Biloxi’s Town Green. Be sure to catch the Irish Beard Contest, and Lucky Leprechaun Costume Contest, too. And, in the middle of the festivities, the Hibernia

Society’s annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade will pass by the festival area at 2 pm. 10 am–5 pm. Free. (228)-435-6339 or mainstreet@biloxi.ms.us. 1

MAR 15th - MAR 16th

DIY-ERS

PONTCHARTRAIN HOME SHOW & LOUISIANA FOOD FEST

Kenner, Louisiana

Explore the latest trends in kitchens, remodeling, flooring, outdoor living, and more, while tasting mouthwatering food samples at the 35th annual Spring Pontchartrain Home Show & Louisiana Food Fest, presented by JAAS Productions at the Pontchartrain Convention Center. 10 am–5 pm. $8. bontempstix.com. 1

MAR 15th - MAR 16th

SPRING SHOPPING

BATON ROUGE SPRING CRAFT AND VENDOR MARKET Gonzales, Louisiana

Hop on over to the Tanger Outlets in Gonzales for an all-things-spring market. Local vendors, seasonal treats, and other items for all occasions are sure to please. 10 am–4 pm Saturday; 10 am–5 pm Sunday. Free. See the Baton Rouge Spring Craft & Vendor Market Facebook Page for details. 1

MAR 15th - MAR 30th

THEATRE THEY PROMISED HER THE MOON Covington, Louisiana

In a new production by Playmakers Theater, the first American woman to test for space flight, Jerrie Cobb, steps into an isolation tank for a record-breaking nine hours as her memories unfold before her, from learning to fly a plane as a child in Oklahoma, to testifying in Congressional hearings about the under-the-radar, allfemale Mercury 13 space program. Based on a true story, They Promised Her The Moon is a compelling drama about the challenges of sisterhood and fighting for the greater good. Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 pm; Sundays at 2 pm; Saturday March 29 at both 2 pm and 7:30 pm. $15–$20. bontempstix.com. 1

MAR 19th - MAR 23rd

BOTTOMS UP NEW ORLEANS BOURBON FESTIVAL

New Orleans, Louisiana

Are you known to bend an elbow? Then here's the fest for you. The New Orleans Bourbon Festival (that's the drink, not the street) brings food, spirit, and culture together. Events include

bourbon seminars, dinners, tastings, tours, live music, and beyond—all celebrating brands like Cathead, Four Roses, Maker's Mark, and more. Proceeds from the tickets go toward Kids Can NOLA, a nonprofit organization that benefits the welfare of local children. Single-day, food-only tickets start at $79, seminar-access tickets start at $89, with various bundles and VIP opportunities from there. Location TBD. Visit neworleansbourbonfestival.com for a full schedule and tickets. 1

MAR 20th

PERFORMANCES

"PORTRAIT OF LUDMILLA AS NINA SIMONE" AT THE ACA Lafayette, Louisiana

In this stunning French-language performance at the Acadiana Center for the Arts, Senegalese-Cameroonian singer Ludmilla Dabo tells the story of the life and music of jazz icon Nina Simone. Dabo uses theatrical tributes and musical performances to honor one of music's most legendary figures in a powerful performance. 7:30 pm. $35. acadianacenterforthearts.org. 1

MAR 20th - MAR 22nd

GOOD EATS

IOWA RABBIT FESTIVAL

Lake Charles, Louisiana

Not the state, but the small community of Iowa, near Lake Charles—where bunnies should beware, lest they come the stars of the show in a rabbit gumbo or jambalaya, especially at the Burton Coliseum Complex this weekend. Celebrating the economic and culinary impact rabbits have in Southwest Louisiana, this annual fest is a one-ofa-kind event, from the rabbit gumbo to crowning the new Miss Bunny, who will represent the festival at other state-wide festivals and competitions. Thursday is free admission night, where the carnival and vendors will be open, but Burton will be closed. $10; 12 and younger free. iowarabbitfestival.org. 1

MAR 20th - MAR 23rd

GOOD EATS

LOUISIANA

CRAWFISH FESTIVAL

Chalmette, Louisiana

Celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this

year, the Louisiana Crawfish Festival returns to St. Bernard Parish, where it has sustained a sense of community and generosity for half a century now. Expect hungry festival-goers to arrive by auto, air, bus, and train to enjoy 30,000 pounds of boiled crawfish with all the fixin's, as well as crawfish bread, crawfish pasta, crawfish pies, crawfish rice, and crawfish jambalaya. There's live music galore, arts & crafts vendors, and a carnival midway as well. All the eating takes place at the

Sigur Cultural Center. Free Thursday; $20 Friday; $10 Saturday and Sunday. louisianacrawfishfestival.com. 1

MAR 20th & MAR 29th

SOUND ON NATCHEZ FESTIVAL OF MUSIC

Natchez, Mississippi

Every May since 1991, the Natchez Festival of Music has been making Mississippi musical, staging a month-

long whirlwind of operas, operettas, Broadway musicals, jazz, and special concerts in historic venues around the city. Full schedule and details at natchezfestivalofmusic.com. 1

BEVVIES

WINE DOWNTOWN

Natchez, Mississippi

At Natchez Food & Wine Festival's newest event, Wine Downtown, participants will travel to over fifteen local shops in Downtown Natchez with their passport, which includes one glass of wine or beverage and a small bite at each location. 6 pm–8 pm. $75. bontempstix.com. 1

SPRING SHOPPING

ABITA SPRINGS WHOLE TOWN

GARAGE SALE & FLEA MARKET

Abita Springs, Louisiana

Each year in March since 1994, hundreds of Abita Springs residents have had their garage sales on the same day. If you fancy snatching up a bargain in this small-town celebration, come by Saturday between 8 am and 3 pm and

IS THIS THING ON?

TUNICA HILLS

MUSIC FESTIVAL & JAM

Saint Francisville, Louisiana

Once again, the hills come alive for the annual Tunica Hills Music Festival and Jam. Three stages welcome over thirty bands for concerts, jam sessions, instruction, and celebration of the arts. Bring your blankets, chairs, coolers, and of course your instruments and settle in for a beautiful day. 10 am–10 pm. Free. Details at the Tunica Hills Music Festival Facebook Page. 1

GET-TOGETHERS

WASHINGTON COMMUNITY

FESTIVAL

Washington, Louisiana

For decades, the whiskered fish was the guest of honor every year at the Washington Festival Grounds. Today, the spirit of the old Washington Catfish Festival remains strong, reincarnated into the Washington Community Festival, featuring many of the beloved activities and programming of the old fête, on Washington's Main Street. Expect blocks of vendors, live music, an antique car

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The cups runneth over during the LSU Rural Life Museum's best-lubricated annual event, which definitely calls for designating a driver. The 20th annual Zapp’s International Beer Festival brings tastings of more than two hundred domestic and international beers and ales to the grounds of the museum, plus more than a few home brews, which always end up being a festival highlight. Non-alcoholic beverages will be available for those (heroic) designated drivers. Bottoms up because all proceeds benefit the Rural Life Museum. Don't forget your I.D.—participants must be twenty-one, for obvious reasons. 3 pm–6 pm general admission. $45; $20 for designated drivers; $65 for early admission. Tickets available at bontempstix.com. 1

brings Louisiana's unique stories to a worldwide audience through its annual exhibition of locally-made films. At Parkway Cinema 6, the jam-packed day will include several screenings, Q&As, panel discussions, and an awards ceremony to close out the event. 11 am–4 pm, with a VIP Celebration Party from 6 pm–10 pm at Riverside Reserve. Free. caneriverfilmfestival.com. 1

NATCHEZ FOOD & WINE FESTIVAL PREVIEW DINNER

Natchez, Mississippi

For the second annual Preview Dinner, the Natchez Food and Wine Festival is partnering with Church Hill Variety Restaurant, which boasts an open kitchen with indoor and outdoor seating, combined with a farm store stocked with grab-and-go meals, homemade preserves, produce, farm eggs, and ice cream. The dinner will feature Fan and Johnny’s Restaurant Owner Chef Taylor Bowen Ricketts of Greenwood and Caylen Caldwell of Wishes Bakery in Natchez. Wine and cocktail pairings will be provided with each course, along with domestic beer. 6 pm–9 pm. $125.

Beginning March 22nd - 26th

MAR 22nd - MAR 23rd

SPRING SHOPPING

MARKET AT THE RIVER ARTS & CRAFTS SHOW

Covington, Louisiana

Enjoy the serene, centuries-old riverfront property of The Rivers Retreat Center while stocking up on local, hand-crafted goodies—from pottery to prepared foods to jewelry. Presented by Shallow Water Stalkers, Lindsay Richardson Jones, and the Southern Handmade Crafter, this market will not only make for great shopping, but a beautiful day. 9 am–5 pm. $2. visitthenorthshore.com. 1

MAR 22nd - MAR 23rd

ARTS

ACADIANA OPEN STUDIO TOUR 2025

Lafayette, Louisiana

In perhaps one of the most far-ranging arts events in the region, Open Studio Acadiana annually presents more than one hundred artists and craftspeople, presenting simultaneously at over thirty studios or galleries throughout Acadiana, but with most of the artists concentrated

in the Lafayette area. The event has roots dating to the 1970s, George Rodrigue being the first ever Open Studio Acadiana participant. Many of the galleries and studios will have artists and craftsmen at their sites, and most will have works for sale—some still in progress. 10 am–4 pm both days. A special party to conclude the event will be held at the Sans Souci Gallery on Jefferson Street in downtown Lafayette, at 6 pm on Sunday. Free openstudioacadiana.com. 1

25th

FUN-GUYS

MEDICINAL MYCOLOGY

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The LSU Hilltop Arboretum, partnering with the Louisiana Master Naturalists of Greater Baton Rouge, will offer "Medicinal Mycology" as part of its "Discover Nature" program. The talk, featuring biological engineer Jordan Gros, will introduce Louisiana medicinal mushroom species. Learn how to find and identify the mushrooms, as well as how to incorporate them into a healthy lifestyle.

6:30 pm–8 pm. $15; $10 for members. Register online at lsu.edu/hilltop. 1

MAR 25th - MAR 27th

ART OUTSIDE PLEIN AIR WORKSHOP WITH PEG USNER

New Orleans, Louisiana

This two-day Plein Air Workshop with Peg Usner dives into the spring beauty of Longue Vue's vast estate, allowing participants to set up easels in the gardens to capture the enchanting nature surrounding them. Usner will instruct and guide students through the sessions, which are perfect for beginning or advanced oil painters. Artists are expected to bring oil painting supplies. 9 am–noon. $160; $150 for Longue Vue members. longuevue.com. 1

MAR 25th - MAR 28th

CULTURAL CELEBRATIONS

DEWEY BALFA CAJUN & CREOLE HERITAGE WEEK 2025

Eunice, Louisiana

Learn first-hand from masters of Cajun and Creole music, dance, cuisine, and culture in a very Louisiana setting— Lakeview Park & Beach in Eunice. The Dewey Balfa Cajun and Creole Heritage Week (also known as "Balfa Week"), put on by the Louisiana Folk Roots

organization, is a true cultural immersion experience that includes workshops, jam sessions, featured artist presentations, and evening dances featuring some of the state's finest Cajun and Creole/ zydeco bands. Workshops in accordion, fiddle, guitar, Cajun and Creole vocals, local dance, and Louisiana foodways are on offer, with an instructor roster that features a who's who of Louisiana artists. Find all the details, including up-to-date schedule information, at lafolkroots.org. 1

MAR 26th - MAR 30th

INKLINGS

THE TENNESSEE WILLIAMS LITERARY FESTIVAL

New Orleans, Louisiana

The Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival returns, presenting the thirty-ninth annual celebration of the city's astonishing literary legacy. The five-day fête offers a range of diverse speakers and performers, most of whom will shout "Stella" with enough encouragement. Most events (far too numerous to detail here, but which range from master classes and walking tours to theatre, food, and musical offerings) will take place in the French Quarter. Ticket prices vary depending on the activities or combination thereof. tennesseewilliams.net. 1

Story by Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

Thhis spring, there are plenty of opportunities to join other gardening enthusiasts, newbies included, across the region at plant sales large and small, where you'll surely find inspiration and plenty of new flora for your home garden.

March 7–9: Baton Rouge Spring Garden Show and Plant Sale Green-thumbers (and all the others), rejoice: the 22nd annual Baton Rouge

Spring Garden Show will be held at the John M. Parker Coliseum on LSU campus, featuring a bountiful selection of herbs, flowers, native plants, fruit trees, and more. This year, the AgCenter will also host a speaker series, with topics including “Blackberry and Raspberry Production in Louisiana,” “Edible Plants of the Gulf South," “Conservation Corridors," and more. The talks will be held in the Nelson Memorial Building on the LSU campus just behind the Parker Coliseum, and are free and open to the public. 5 pm–8 pm Friday; 9 am–4 pm Saturday; 9 am–3 pm Sunday. $10; free for children twelve and under, and for students with an LSU and Southern University ID. For more information, call Brayden Echols at 225-578-1890, or email at MEchols@ agcenter.lsu.edu.

March 22: Livingston Parish Master Gardener Spring Plant Sale

Just in time for warmer weather, the Livingston Parish Master Gardener Program will host its annual plant sale at Southeastern Literacy and Technology Center in Walker. Peruse offerings from local plant vendors, including a varied assortment of herbs, vegetables, natives, pollinators, and more. Proceeds support community outreach and educational programs focused on sustainable gardening practices. 8:30 am–2 pm. Find more at the Livingston Parish Master Gardeners Facebook Page.

March 28–29: Southwest Louisiana Garden Conference and Expo

This regional conference and expo is perfect for the gardeners out there ready to jumpstart their yard for spring. Held at the Burton Coliseum in Lake Charles, the event features more than sixty vendors selling a variety of plants and outdoor decor, Master Gardeners with a plant health booth, and a flower show, among other attractions. 9 am–5 pm. $3; free for children twelve and under. swlmg.weebly.com/gardenexpo.html.

March 28–29: Northshore Garden & Plant Sale

Presented by the St. Tammany Master Gardeners Association, the Northshore Garden & Plant Sale is the ideal destination for anyone hoping to get a head start on their spring garden. Vendors specializing in roses, native plants, daylilies, vegetables, shrubs, and trees will be available (among others), and attendees will have the chance to explore garden art, plant material, and outdoor furniture options. Expect activities for the kiddos, educational speakers, and food concessions as well. 9 am–3 pm, both days. $5; free for children and first-responders. stmastergardener.org.

March 29–30: Spring Garden and Pet Show

The third annual Spring Garden and Pet Show, presented by River Road Historical Society in collaboration with the AgCenter and Louisiana Master Gardeners, promises two days of excitement for plant enthusiasts. Held at the Destrehan Plantation, the event features plant nurseries, arts and crafts, small businesses, and more. Animal rescue groups will also be on site for pet adoptions—and don't miss a petting zoo, beekeeping demonstration, and a presentation from the LSU Raptor Rehabilitation Program. 10 am–4 pm each day. $5; free for children under five. destrehanplantation.org. •

MAR 27th

GREEN THUMB

EBR MASTER GARDENERS

PRESENTS: SUPER PLANTS AND PRUNING SHRUBS

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

East Baton Rouge Master Gardeners present two talks at the Bluebonnet Library to prepare for spring in the garden. The first talk, given by Master Gardener Debi O'Neil, surveys Louisiana Super Plants that thrive in our state. Then, stick around for Master Gardener Leo Borders to teach on which plants to prune now, and which ones will keep until later. 6:30 pm. Free. brmg.wildapricot.org. 1

MAR 27th - MAR 29th FILM

NATCHEZ LITERARY AND CINEMA CELEBRATION

Natchez, Mississippi

Back for another year celebrating Southern authors and filmmakers, this year's Natchez Literary and Cinema Celebration will be held at Natchez

Convention Center. Themed, “Follow the Frenchman through Natchez: The Farewell Tour of Lafayette, A Bicentennial Salute,” the festival will feature lectures and panels on topics like the life and contributions of Lafayette, the history of America, and more. Learn more and find the full schedule at colin.edu/ community. 1

TOURS

NATCHEZ SPRING PILGRIMAGE

Natchez, Mississippi

"The most extensive tours of the most extravagant antebellum homes in America." That's the way the Pilgrimage Garden Club describes the Natchez Pilgrimage—the spring and fall tour of homes that has kept visitors coming back to Natchez since 1932. The city has managed to preserve the extraordinary architectural legacy of that wealth, while also paying homage to the enslaved individuals on whose backs that wealth was created. Today, Natchez's streets

remain lined with palatial mansions and filigreed townhouses, and each year the families that occupy them allow guests to nose through two-hundredyear-old homes, meet descendants, learn about the city's history, and generally get a residents' eye view of life in this most genial of Southern cities. Find details on other special events, dinners, and tours at littleeasytours.com, natchezpilgrimage.com. 1

MAR 28th - MAR 29th

GOOD EATS COOKING IN CENTRAL Central, Louisiana Cooking in Central is back, this time

You’re free to live your life out loud! Because you’ve got the compassion of the cross, the security of the shield, and the comfort of Blue behind you.

in partnership with the City of Central to bring plenty of tasty food and entertainment to Amazing Place. The fun begins a 4:30 pm Friday with boiled crawfish and performances by Thomas Cain Plays and Parish County Line. On Saturday, festival gates open at 11 am with kids' entertainment and the carnival. Chris LeBlanc plays at 6 pm, followed by Lauren Lee Band. And of course, at the heart of the thing is the cook-off itself on Saturday, with competitions in categories of brisket, jambalaya, pastalaya, and BBQ chicken. The kids are invited to get involved, too—showing off their own culinary skills. Festival is free. For more information and cook-off entry forms, visit cookingincentral.com. 1

BOOKWORMS

THE SAINTS + SINNERS

LGBTQ LITERARY FESTIVAL

New Orleans, Louisiana

Since 2003, Saints + Sinners LGBTQ Literary Festival has grown into an internationally-recognized event that brings together a who’s who of LGBTQ publishers, writers, and readers from

throughout the United States and beyond. The Festival, hosted by the same folks who bring us the Tennessee Williams and New Orleans Literary Festival and held over three days each spring at the Hotel Monteleone in the New Orleans French Quarter, features panel discussions and master classes around literary topics that provide a forum for authors, editors and publishers to talk about their work for the benefit of emerging writers and the enjoyment of fans of LGBTQ literature. Featured speakers this year include Ezra Adamo, Jan Edwards Hemming, Anne Laughlin, Jeff Mann, and many more. Details at sasfest.org. 1

MAR 28th - MAR 30th

CULTURAL CELEBRATIONS

ITALIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL

Kenner, Louisiana

They gave us cannoli. They gave us marinara. They even gave us St. Joseph's Altars, which are basically piles of beautifully arranged, scrumptious food. So how can we pass up an Italian heritage fest, where these culinary delights will surely be on the menu? This celebration returns to Kenner's historic Rivertown

for its twenty-third year, with live music, local crafters, Italian food and seafood specialties, a historic photo display, St. Joseph’s Altar, and opportunities to talk with genealogical specialists. Details at facebook.com/kenneritalianfest. 1

THEATRE CABARET

New Iberia, Louisiana

Set in a Berlin nightclub at the close of the 1920s, Cabaret delves into the chaotic life of Berlin's natives and expatriates against the backdrop of the emerging Third Reich. Don't miss this classic performance at the Iberia Parish Performing Arts League. 7 pm; 2 pm Sunday. $22.58. ipaltheater.com. 1

MAR 29th

FUNDRAISERS

CRAWFISH

COOKIN' FOR A CAUSE

Mandeville, Louisiana

For the fifteenth year, Crawfish Cookin' for a Cause will host its popular headsucking fundraiser at Mandeville's Lakefront Splash Park, benefitting local families affected by catastrophic illness. This year's beneficiaries are Grant's Gift Foundation and HARK. Tickets are $40 in advance, which gets

you a ton of crawfish. 11 am–5 pm. crawfishcookinforacause.com. 1

MAR 29th

THE LONG WAY HOME

BRITISH MOTORING FESTIVAL

Covington, Louisiana

Hold onto your hats, chaps. The British Motoring Club of New Orleans returns for the 33rd annual British Motoring Festival at the Tammany Trace Covington Trailhead and Firehouse Event Center for a day dedicated to British cars and motorcycles. Interested parties can enter their car or bike, or stop by to view the automotive excitement. bmcno.org. 1

ART EXHIBITIONS

ST. LANDRY PARISH STUDENT ARTS EXPO

Opelousas, Louisiana

Head to Opelousas's Courthouse Square for a celebration of area student artists, featuring performances by local school bands, choirs, and theatre groups, as well as visual arts exhibitions and an artist market. The event is a partnership between the St. Landry Parish School Board and the Acadiana Center for the Arts. 10 am–3 pm. Free. acadianacenterforthearts.org. 1

MAR 29th

GET-TOGETHERS

COMMUNITY

HISTORY FESTIVAL

Pride, Louisiana

The Pride-Chaneyville Branch of the East Baton Rouge Parish Library hosts this community history festival for the fifteenth year. It's a day of fun, food, and games. This year's theme is "Country Crafts." There will also be a marketplace with a variety of local vendors. The Louisiana Lagniappe Dulcimers and the Upbeats will provide music, and once an hour it's time for the ever-popular oldfashioned Cake Walk. 10 am–1:30 pm. ebrpl.com. 1

MAR 29th

BLOOMS

GARDEN WORKSHOPS: SPRING FLOWER ARRANGING

New Orleans, Louisiana

Head to Longue Vue for this Spring Flower Arranging gardening workshop, directed by greenhouse operations lead Leigh Gradiz. Sip prosecco while arranging springtime blooms—ideal for a creative afternoon with friends or family. Open to all ages, but children must be accompanied by a ticketed adult, with a two-children maximum. 1 pm–3 pm. $85; $75 for Longue Vue members. longuevue.com. 1

MAR 29th

HOOK, LINE, SINKER

BIG BASS FISHING RODEO & FISHTIVAL

New Orleans, Louisiana

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) and New Orleans City Park will host the 76th annual Big Bass Fishing Rodeo and Fishtival in New Orleans City Park. The tournament is catch-and-release, with anglers vying to land the largest bass of the competition. The Battle for the Bass competition is also open to students in seventh through twelfth grades, offering an opportunity for them to represent their schools.

Kayakers and other paddlers can compete in the Boats on the Bayou competition on Bayou St. John. After the competition, the Fishtival will commence with live music, jambalaya for sale, exhibits, and activities for kids. Fishing competitions begin at 6:30 am, Fishtival is from 9 am–noon. Find more information at bigbassfishingrodeo.com. 1

MAR 29th

GOOD EATS

LOUISIANA CRAWFISH BOIL CHAMPIONSHIPS

Marrero, Louisiana

For twenty-three years now, Louisianans have clambered over one another to prove themselves as the best crawfish boiler

in the state at the annual Crawfish Boil Championships, held at the Immaculate Conception School in Marrero. The event is sanctioned by the State of Louisiana as the official competition for boiling, and this year it's looking like over sixty teams will be heating up their pots to serve an estimated 40,000 pounds of mudbugs.

A $30 ($18 for students) wristband gets you all the crawfish you can eat, with options to purchase other food, beer, and refreshments onsite. Details at the Louisiana Crawfish Boil Championships Facebook Page. 1

MAR 29th

GOOD EATS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP CRAWFISH ÉTOUFFÉE COOK-OFF

Eunice, Louisiana

The étouffée extravaganza has Eunice simmerin' again this year with crawfish and good times galore. And though we're pretty sure places like Germany, Thailand, or Chile aren't competing in the cook-off, we like the sound of world championship, too. The Cook-Off kicks off at the Northwest Pavilion at 10 am. While live Cajun and zydeco music play in the background, get to tasting. And don't miss the arts and crafts vendors, live music, and family fun while you're out there. Free. etouffeecookoff.org. 1

MAR 29th - MAR 30th

RETAIL THERAPY

SLIDELL SPRING STREET FAIR

Slidell, Louisiana

In the heart of Olde Towne Slidell, upwards of two hundred vendors gather to peddle antique furniture, glass, vintage clothing, jewelry, collectibles, handmade crafts, and things to eat. It's a colorful, walkable opportunity to find a wide range of merchandise, and typically draws around 10,000 people each year. 10 am–5 pm. Free. slidellstreetfair.com. 1

MAR 30th

SOUND ON ABITA SPRINGS

BUSKER FESTIVAL

Abita Springs, Louisiana

If you brake for buskers, don't miss the Abita Springs Busker Festival at the Trailhead. This festival showcases the talents of young musicians honing their craft on Louisiana's street corners and far beyond. Plenty of food, and of course Abita beer, will be available at the event. 11 am–7 pm. Free. louisiananorthshore.com. 1

For more events, visit countryroadsmag.com/eventsand-festivals.

Mbecoming a New Orleans bamboo icon, but paying off student debt can lead to unexpected vocations.

It began with a two-storey house that loomed over Sanders and his then-wife’s backyard, removing any semblance of privacy for the couple when spending time outside. Sanders, who already had an affinity for gardening, remembered there was a type of non-invasive, clumping bamboo that could provide a natural screen when planted in a line. He found a supplier and purchased $100-worth of bamboo—an amount that

“So I decided to sell a few plants and upcharge them a little bit, and then make a bit of my money back,” Sanders recalled. “As soon as I posted an ad for those plants online, they sold out. And I thought, ‘Wow, that was an easy way of making money.’”

He turned his initial $100 investment into $200, which he turned into $400. “And then I scaled up, and started learning about propagating bamboo,” he said. “I learned that I could take one plant and turn it into two plants. So instead of doubling my earnings, I would start making vastly more on each sale.”

Selling bamboo from his backyard turned out to be a convenient way to pay off his student loan debt—with the added bonus that propagating bamboo was something he actually enjoyed. After a few months, his thenwife suggested he officially start a business, since he seemed to derive so much joy from the venture.

In December 2015, he purchased an inexpensive property in the lower 9th Ward, which was still reeling from Hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic flooding a decade before. Sanders, a journalist by profession with no formal horticultural training, then set about learning to grow and maintain a plant nursery.

It was just the beginning of what would become an unlikely gardening destination in the city—not just for those seeking guidance on different types of bamboo, but also for anyone searching for a little peace, greenery, and shade amid the chaos of everyday life.

“I can be somewhat compulsive, by which I mean I'll get an idea, and no matter how impossible it seems, I cannot let go of it until it happens,” Sanders said. “There is really no practical business reason why I should spend so much time trying to create this sort of urban jungle in an infrequently visited part of town.”

Sanders’s childhood was idyllic, filled with memories of lush outdoor adventures. He grew up in northern Alabama—a city child, but one who lived on the edge of a forest.

“Ever since I can remember I've always loved spending a lot of time outside,” he said. “My mother is a master gardener, and so being outside, being with my mom in the garden, was just … my ideal way to spend the day.”

Those youthful experiences forged within him a dedicated, constant yearning for physically and intellectually stimulating endeavors, and a drive toward careers that would push him outdoors (he has a master’s degree in archaeology). According to Sanders, he has spent time in about a dozen states and traveled extensively, even traveling to New Zealand as a teenager. This urge to explore, coupled with apparently boundless energy, would serve Sanders well as a journalist. And his eagerness to learn about new subjects and delve more deeply into every facet of them would also ultimately contribute to his passionate escapades as a gardening guru.

“When I was a child, I was never very good in school, but I was always somewhat proficient at learning things on my own,” he said. “If I found something that I liked, I would get hyperfixated on it.”

For the past ten years, the something has been bamboo—and that interest has grown into a larger captivation with horticulture and landscape design.

Now the editor of BAMBOO Magazine, the official publication of the American Bamboo Society, Sanders immerses himself full-time in the nuances of the plant and spends his time talking to experts who gladly fuel his interest. He doesn’t expect everyone who visits the nursery to know everything (or even anything) about bamboo, and he has a spiel prepared for hesitant buyers.

“Not all bamboo is invasive,” Sanders said. “There are over 1,400 species of bamboo in the world and counting, because new species are still being discovered all the time. And many of them do not become invasive.”

Those non-invasive varieties grow in a clump, a clus ter of contained shoots ideal for privacy screening pur poses. Say you wanted a twenty-foot privacy screen; five plants, about four feet apart from each other, would cre ate a wall of soaring greenery. For his purposes, Sanders searches for diversity in the bamboo he carries, though he primarily focuses on the types that will best flourish in South Louisiana and the Gulf Coast environment.

Once you account for climate zones and humidity, things get more interesting. Sanders carries some plants that only reach twelve feet tall, while others tower at six ty feet when fully mature. Some of his bamboo is pow der blue, some yellow, some green, some variegated; some are thick and robust, others are thin and stately. The clear favorite among his customers is called, some what whimsically, graceful bamboo ( gracilis)—ideal for smaller yards and urban settings.

Apart from a successful business venture, the nursery also quiets what Sanders describes as an active mind, creating a haven for contemplative thought and the relief of something real, tangible, and present.

“I always have these monkeys in my brain that are just doing somersaults and running around and playing,” Sanders said. “And being in a garden helps calm down those monkeys. Being in a plant nursery also helps calm down the monkeys. Being in people's yards and beautiful spaces helps do that.”

In many ways, Sanders has always been dreaming about someday-plants and their homes. He cites a litany of sites that have inspired him visually over the years, from temperate forests in New Zealand to botanical gardens he has sought as a refuge on his many travels: Denver Botanic Gardens, Marie Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota, and Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, among others.

These are the gardens that danced through his mind, in riotous color, when the coronavirus pandemic stilled the world in 2020 and early 2021. He had already expanded his initial operation, incorporating tropical plants in addition to the thousands of varieties of bamboo, in 2018. But now, Sanders decided his nursery would morph into “a botanical garden where the plants are for sale.” That became his mission during lockdown—to build out the nursery, drawing on landscape design that inspired him.

“I think of landscape design as art that you can walk through,” Sanders said. “It's multi-dimensional. It's multi-sensory. You can smell it, you can see it, you can hear it, things on the tree you can taste, you can touch things. There's so many different tactile things in a garden, and that's what really continues motivating me.”

Arranging plants in a pleasing, interesting way has stirred Sanders’s imagination for decades. As far back as 2003, when he first bought a house in South Florida, Sanders would spend large blocks of time sitting in

a lawnchair in his backyard, studying the blank stretch of grass (save a lonely kumquat tree) and envisioning his future garden.