CARNIVAL’S

CARNIVAL’S

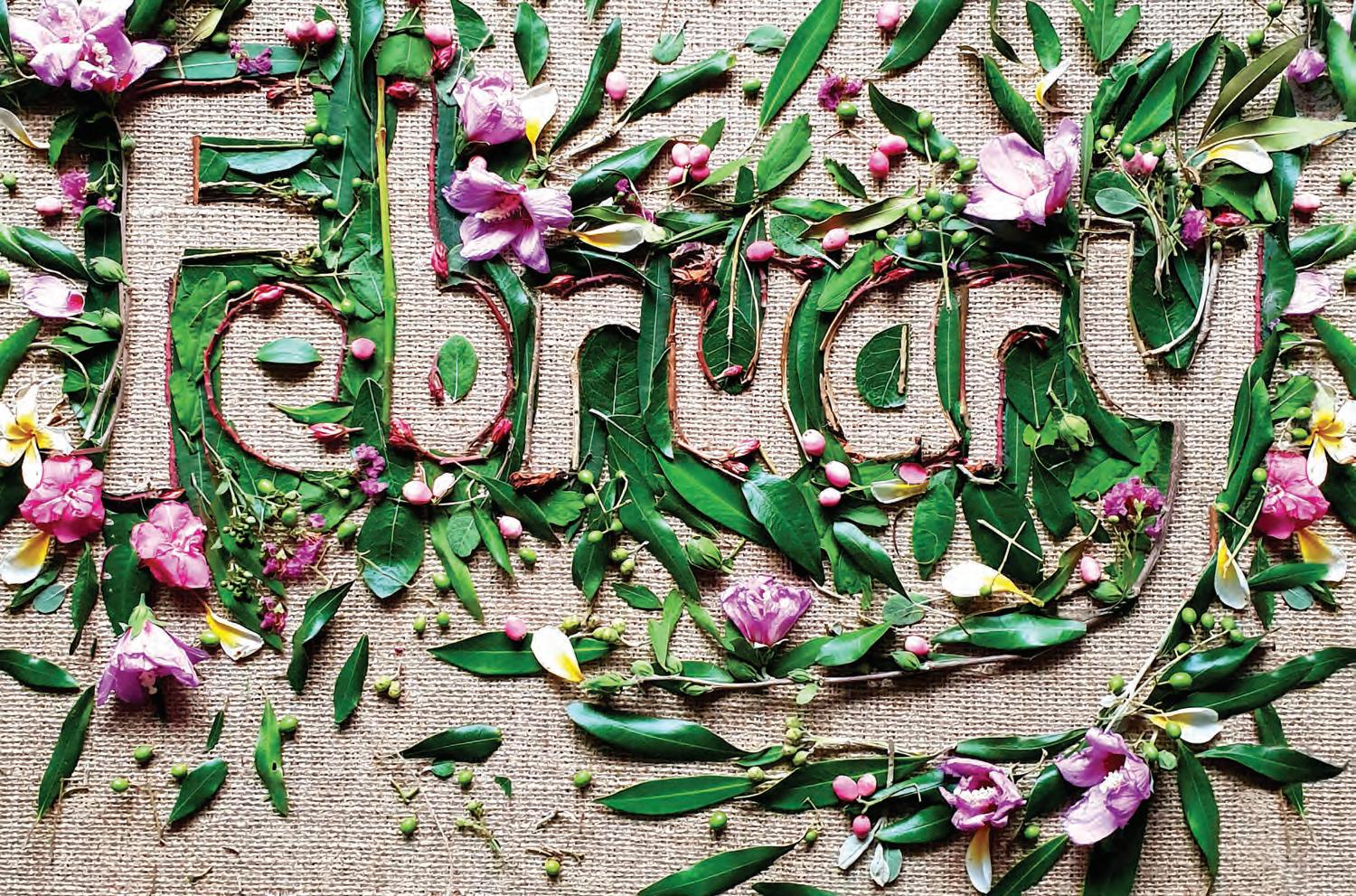

From Morocco to New Orleans, a musical odyssey by Alexandra Kennon

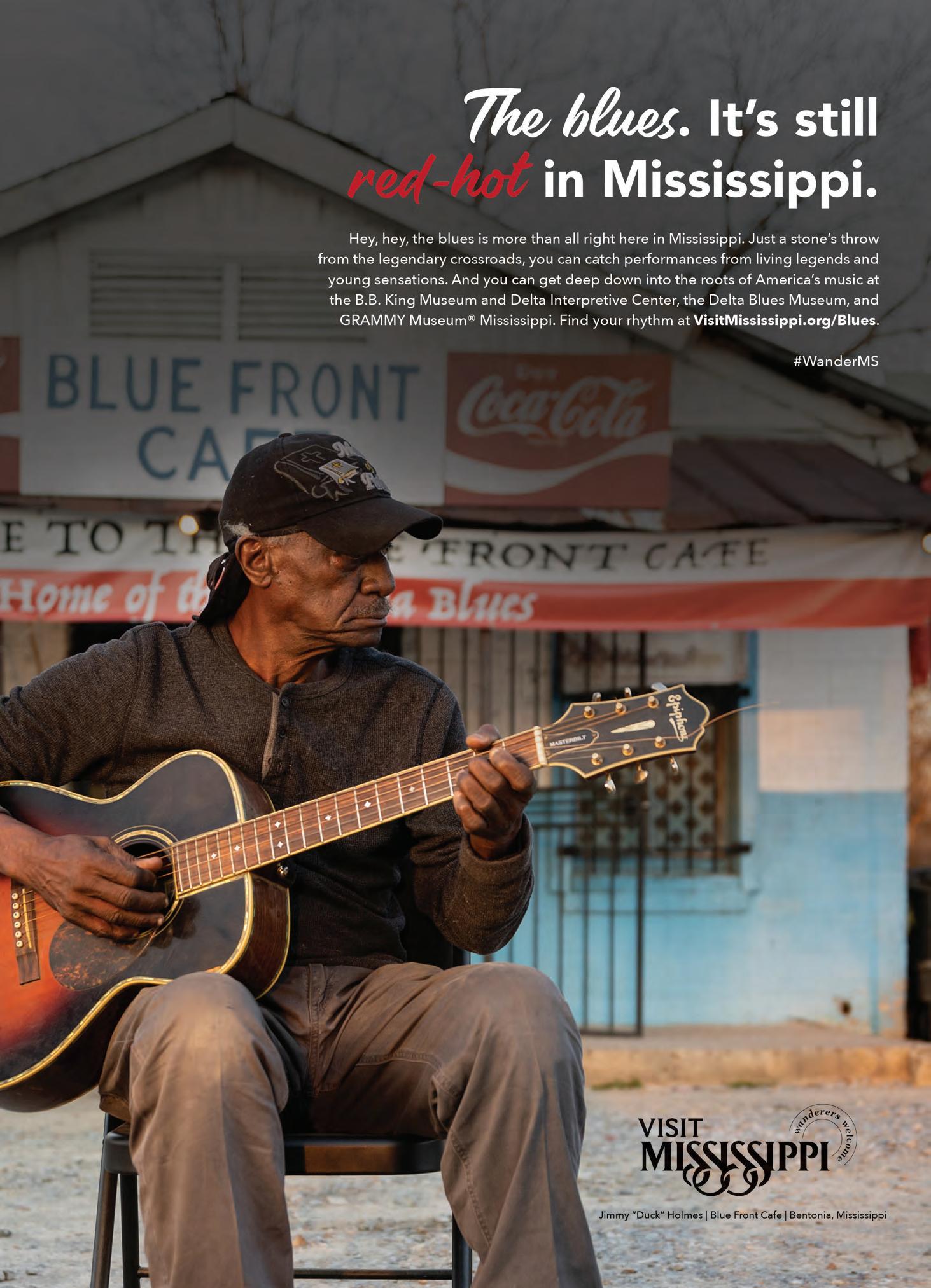

From the new guard to the old, the Baton Rouge bluesman is stepping up by John Wirt

The five young women taking over Acadiana’s music scene by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

Cover image by Brei Olivier

“I’m a New Orleanian,” the Moroccan guitarist and oud player Mahmoud Chouki declares, to his audiences and to his interviewers. He’s now been here for five years, following a lifetime of appearances on international stages in over thirty countries. But New Orleans, and the music made here, is where he has made his home.

It’s a tale as old as jazz itself. Our region has long enticed musicians from far away places—drawn as though by magnets to our vibrant indigenous music scenes, fostering genres steeped in history and local legacy, but bursting with vitality, always transforming and evolving as musicians of new generations and new locales step in to reverently offer their own interpretations.

For this year’s Music Issue, we look at the ways the places we’ve come from and the places we’ve been shape us—as people, and as artists. In our features besides Chouki’s odyssey, we turn to the young women picking up accordions and fiddles as torches of Cajun music and adding their own flare; and to Baton Rouge bluesman Kenny Neal as he continues in the path of greats like Buddy Guy. We hold our ear to our subjects’ pasts, and listen closely for the sounds that come from their own ancestors, or from across the world.

LA BOUCHERIE DE QUARTIER The historic evolution of

WHEN ELVIS WENT BACK TO CHURCH

The Mississippi songwriters behind The King’s most famous gospel hits. by William Browning

RITUAL PBS puts a spotlight on Southern tradition in its new docuseries by Alexandra Kennon

PRETTY, PRETTY, PRETTY An insider look at Big Chief Lil’ Charles Taylor’s creative process by Grete Viddal

100 MEN HALL The iconic Chitlin Circuit venue lives on by Poet Wolfe

INTO THE PASCAGOULA

BD Markey’s paddle excursions foster reconnections with nature by Jason Christian

PERSPECTIVES

Jean Luc & Vanessa Toussaint’s Mask Making Traditions by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

Publisher James Fox-Smith Associate Publisher Ashley Fox-Smith

Managing Editor Jordan LaHaye Fontenot Arts & Entertainment Editor Alexandra Kennon Creative Director Kourtney Zimmerman

Contributors:

William Browning, Laura Carbone, Jason Christian, Brei Olivier, Jonathan Olivier, Olivia Perillo, Chris Turner-Neal, Grete Viddal, Jo Vidrine, John Wirt, Poet Wolfe

Cover Artist Brei Olivier Advertising

SALES@COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM Sales Team Heather Gammill & Heather Gibbons Advertising Coordinator Melissa Freeman

President Dorcas Woods Brown

Country Roads Magazine

758 Saint Charles Street Baton Rouge, LA 70802 Phone (225) 343-3714 Fax (815) 550-2272

EDITORIAL@COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM WWW.COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM

$21.99 for 12 months $39.58 for 24 months

ISSN #8756-906X

Copyrighted. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in Country Roads magazine are those of the authors or columnists and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, nor do they constitute an endorsement of products or services herein. Country Roads magazine retains the right to refuse any advertisement. Country Roads cannot be responsible for delays in subscription deliveries due to U.S. Post Office handling of third-class mail.

The other day while watching the opening round of the Australian Open tennis tournament, I realized that the first live music concert I ever saw took place on the same patch of ground where Novak Djokovic was at that moment making life miserable for his opponent. Today, that ground is occupied by Melbourne’s Rod Laver Arena, where the Australian Open has been played since the stadium was built in 1988. Prior to that, the site was known as the Melbourne Sports & Entertainment Centre, which as the name suggests, served as a venue for live music concerts when it wasn’t hosting sporting events.

The year was 1986 and the concert was by the British band Dire Straits. A friend and I were taken to it by his father—a man I considered one of the “cool” dads, because he did things like taking his kids to rock concerts, something my own father was about as likely to do as he was to sprout antlers. Our seats were in an altitude-sickness-inducing second balcony, so we spent most of the concert squinting to make out the antlike band-members strutting about the distant stage, bathed in a (for 1986) pretty spectacular light

show. But even from that great height, the event made a powerful impression on sixteen-year-old me. I was awestruck by the energy and showmanship, and transported by the tide of communal goodwill washing through this sea of sweaty strangers.

The experience turned me into a concert junkie, and through the rest of my high school and college years I spent much of my meager disposable income on getting closer to that distant stage. As Australia’s second-largest city, Melbourne was a good town for live music: large enough to justify a stopover whenever a big band set out on a world tour. So, in the late eighties and early nineties, I was fortunate enough to see concerts by iconic performers like Pink Floyd, Bruce Springsteen, The Eurythmics, INXS, the B-52’s; and later, as college sent my musical taste down various esoteric rabbit holes, scores of other acts whose names and song catalogs have long since been consigned to the second-hand record bin of history.

I’m writing this on the verge of flying back to Melbourne to visit my parents—English expats who have called Australia home since a working holiday in 1975 turned into an accidental immigration. Dedicated worshipers of the classical music canon, my parents wore their devotion to the music of the European enlightenment like a shield against the unfamiliar popular culture of the strange new country in which

they found themselves. Consequently, they often seemed dismayed by their teenaged son’s musical taste, which my mother was fond of describing as “a man shouting over the roar of heavy machinery.” And while dad’s record collection did stretch to include the occasional album by a jazz heavyweight like Dave Brubeck or Artie Shaw, I couldn’t imagine any scenario in which he would voluntarily attend a concert by Dire Straits, let alone any of the other, more obscure bands in my obsessively curated catalog.

Often the transition from childhood to adulthood seems set to a soundtrack sure to be considered puerile, unintelligible, or morally repugnant by one’s parents. But perhaps that was the point. When you’re young, music plays a vital role in defining your identity, so loving

songs that your parents can’t stand is a rite of passage—one with the added benefit of keeping them out of the places where you and the rest of your generation are getting on with the business of becoming adults on your own terms.

Here in Louisiana, though, I’m not sure that conventional wisdom holds true, because so many of our most enduring musical genres unite, rather than divide, audiences across the generations. Last spring I went back to New Orleans JazzFest, after a several-year hiatus that was only partially attributable to COVID. It was one of those idyllic late April days—warm and breezy and devoid of the energy-sapping humidity that summer would soon bring. The lineup was classic JazzFest: a few big stars, orbited by a constellation of lesser-known but phenomenally talented acts playing zydeco and blues and jazz and gospel and rap and reggae, and mashups of all the above. The music flooded forth from the stages and tents to an ecstatic reception from fans aged eight to eighty. It was joyous and inclusive and, not for the first time during a Jazzfest afternoon, I found myself wishing my father could be there to see it—certain that he, too, would love this extraordinary demonstration of music’s power to move, regardless of whether or not that music was his own.

—James Fox-Smith, publisher james@countryroadsmag.com

It’s doubtful there’s a more Louisiana way to celebrate finishing a PhD thesis than by choreographing a dance for a Mardi Gras parade, especially when there is an opportunity to use your now-official expertise to infuse new cultural influences into New Orleans’ vibrant traditions.

Soon to complete her English PhD at LSU in Bollywood and Indian Fiction, Ankita Rathour is heading a group of dancers as part of the recently-formed Krewe da Bhan Gras—who will debut

New Orleans Carnival’s first traditional Bollywood performance through the streets as part of the Krewe Bohème Parade on February 3.

Krewe da Bhan Gras was formed with a mission to, “represent the South Asian diaspora in New Orleans,” while “entertain[ing] and inspir[ing] parade-goers with vibrant, upbeat, traditional Indian dance.”

The group of dancers and auxiliary support people (among them Rathour’s husband, Jason Christian, who some-

times contributes to Country Roads), have been taking time from their individual busy schedules to rehearse the Bollywood-style dance twice a week in a St. Claude Avenue space leading up to the big night. “It’s been going really fantastic, to be honest,” Rathour gushed. “How quickly everybody is just grasping the steps has been very impressive for me.”

And as for finishing her thesis, Rathour agrees that a Bollywood-inspired celebration wrapped into a Mardi Gras parade couldn’t be a more fitting conclusion.

IN 2015, SAM IRWIN STARTED A BAND, A BLOG, AND A BOOK

The day after New Orleans Rhythm and Blues icon Allen Toussaint died in November, 2015, musician and author Sam Irwin heard a rendition of Toussaint’s “The Bright Mississippi” played by Grammy-winning trumpeter Nicholas Payton. The music struck Irwin, who hadn’t picked up his own trumpet in thirty years.

This is the story of how Irwin started his band the Florida Street Blowhards, but it is also the story of how he started writing his latest book, The Hidden History of Louisiana’s Jazz Age (History Press)—which began as a collection of blog posts he wrote to promote his new band, and has now emerged as a fully-fledged exploration of jazz music’s history in his home state.

We at Country Roads have had the great pleasure of sharing excerpts from this project over the past year, including the stories behind Louis Armstrong’s first visit to Baton Rouge, and his much-debated birthday. In his book, Irwin deep dives into similarly tantalizing topics, such the biography of Crowley trumpeter Evan Thomas—who was murdered on the bandstand; the history of how jazz found a home miles away from New Orleans in rural Acadiana; and the legacy of Baton Rouge musician and bandleader Toots Johnson.

—Jordan LaHaye FontenotAutographed copies of The Hidden History of Louisiana’s Jazz Age can be purchased at samirwin.net. The book can also be found at arcadiapublishing.com/the-history-press.

Imagine a music streaming platform with the ease and functionality of Spotify—except entirely hcurated by a team of music scholars, with the goal of uplifting New Orleans’s rich collective of artists and providing a listening experience that transmits a tapestry of the city’s one-of-a-kind music scene.

The New Orleans Public Library has done it, launching Crescent City Sounds last fall with a collection of thirty locally-produced albums culled from submissions from New Orleans musicians spanning genres. The curatorial team

included Alison Fensterstock, music journalist and WWOZ DJ; David Kunian, Curator of the Jazz Museum; Holly Hobbs, music consultant and ethnomusicology expert; local rapper Alfred Banks; and Tavia Osbey, co-founder of MidCitizen Entertainment.

From brass band anthems by the Grammy-winning New Orleans Nightcrawlers and the moody funk of Sandra Love & the Reason, to rhymes by rising hip hop star Kaye the Beast and vintage blues originals by Sao Paulo-born guitarist T. Guy—Crescent City Sounds emulates the feeling of walking past a

collection of this music city’s nightclubs, poking your in head each one, and opting to stay awhile.

Local listeners with an interest in getting to know the music created by their neighbors and further supporting it have found a ready-made landing place; while artists enjoy a new avenue for sharing their work right here at home. Artists featured on the platform enjoy a spot there for at least five years, and are paid an honorarium for non-exclusive licensing rights. On the other hand, listeners can enjoy access to the platform free of charge.

“This is like, the best way to graduate,” she laughed. “And I can’t imagine a better culture than New Orleans and a better place than New Orleans to do a Bollywood kind of a fusion dance … I think just, you know, the city is absolutely perfect for like a melting pot of cultures and people just coming and having a good time.” —Alexandra Kennon

Look for the Krewe da Bhan dancing as part of the Krewe Bohème Parade on February 3 at 7 pm. kreweboheme.com

Heather Riley, Circulation and Customer Experience Librarian at the New Orleans Library, said that in addition to the thirty inaugural artists selected for inclusion in 2022, later this year the library plans to add another sixty.

“Crescent City Sounds was the library’s push to sort of start preserving our culture, our current culture,” she said, “as well as our history.”

—Jordan LaHaye FontenotStream music by New Orleans artists for free at crescentcitysounds.org.

Pest control will take on a festive air February 24-25 in Venice during the 2023 Swamp Safari Shootout Nutria Rodeo, where the marsh-destroying nibblers will be the target of squadrons of hunters competing to bag cash prizes for bringing in the most and the biggest nutria. Those who come up short in these categories can still hope for prizes in “best team name,” “best team costume,” and the nutria toss (judged by distance). In 2022, sixty-two teams removed 1,934 nutrias from the Delta, and organizers hope to meet or match that tally this year. After weigh-in, many of the late nutria will be provided to the Audubon Zoo to allow their resident alligators a taste from their wild cousins’ menu.

According to publicist James Haik, while the event is fun, it also draws attention to the swamp and efforts to keep Louisiana’s wetlands intact. Most people know about the damage the invasive nutria population causes, but it’s important to realize that there are ways of addressing the issue. It’s unlikely that Louisiana will ever eradicate the nutria, but keeping the population suppressed can still benefit the swamps and the people who rely on them—which if you count their role in flood control, is effectively everyone south of Alexandria.

Non-hunters are welcome at the event and will have plenty to do—though to keep in the spirit of things, if you see a nutria, give it a dirty look. Cajun music will play both nights and vendors will sell alcohol, crawfish, and other food. The adventurous can sample the products of the nutria cook-off, which appears for the first time in an official capacity after some dabbling in jambalaya and gumbo in previous years. (Per Haik, the meat has the slight gaminess people will recognize from all wild meat, along with the chickeny-but-not-quite-chicken texture of water animals—think frog legs.) Plus, you’ll know you’re cheering on efforts to save Louisiana’s wetlands, one not-so-cuddly critter at a time.

—Chris Turner NealEarly registration is $35 per boat, with day-of registration $45. There is no limit to the number of team members per boat; it’s one boat per team, so no pulling together an armada. Hunters will be required to follow all Louisiana hunting rules and regulations, and those competing for most nutria must get a trapper’s license. (At a bounty of six dollars per tail, the trapper’s license will pay for itself in a half-dozen nutria.) Also of note: all winners will have to pass a polygraph test (visible to the public), so no showing up with nutrias hidden in your waders to pad your figures. Regulations, details, and more information online at nutriarodeo.com.

Frombluestorap,andfromcountrytoclassical,home-grownmusicisaculturalassetthat’softenunderappreciatedinBatonRouge.Butlookcloserand it’seasytoseethatmusicisapowerfulthroughline,withcountlesssongwriters,vocalists,andmusicianscreatingatapestryofexperiencesateveryturn.

In 2019, Newsweek listed Baton Rouge as one of nine “Music Meccas Around the World You Need to Visit,” singling out the Red Dragon and other listening rooms as intimate venues that attract top talent. Baton Rouge is home to a distinct brand of the blues, celebrated annually at the popular Baton Rouge Blues Festival. And Red Stick is the birthplace of scores of rappers who have risen to international fame.

“We have an incredible music culture in Baton Rouge that could place us on the map among the country’s great music cities,” said Renee Chatelain, president and CEO of the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge.

One of the clearest examples of this is the Capital City’s jazz heritage, thanks in part to the legacy of jazz icon Alvin Batiste. The pioneering clarinetist performed worldwide, but chose to spend most of his time as a music educator, teaching at Southern University for more than 30 years.

“We learned about music, but we also learned about life,” said musician and recording artist John Gray, who studied jazz trumpet under Batiste. “And while he was teaching, he was always in a state of learning.”

Gray and renowned saxophonist Roderick Paulin, another Batiste student, were recently appointed directors of Southern’s Alvin Batiste Jazz Institute for the Spring 2023 semester.

“It’s a full-circle moment,” said Gray.

Before his death in 2007, Batiste helped found the River City Jazz Coalition, which sparked the creation of the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge’s River City Jazz Masters series, now in its 16th season. A prized gig among international jazz performers, the annual series attracts top talent to the city. Some performers also deliver workshops to young musicians.

“It’s on par with Jazz at Lincoln Center,” said Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge Executive Vice President Jonathan Grimes. “Musicians around the country really aspire to be part of it.”

Batiste would be proud. Over the course of his career, he was recognized for his commitment to music education, earning fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities and winning the International Association of Jazz Educators’ Lifetime Achievement Award and the Louisiana Governor’s Award for Outstanding Contribution to Arts Education, among many others.

Scores of students who trained under Batiste still attest to the power of his teaching style.

“I was actually a student at LSU, but I spent more time at Southern playing with him,” recalls Baton Rouge-based Grammy awardwinning composer Mike Esneault, music instructor at Baton Rouge Magnet High School. “Being introduced to him was a life-changing experience. He made you think about music organically, and I still find myself using the one-liners with my students that he used on us.”

Along with Gray, Paulin and Esneault, the lengthy list of Batiste students includes Branford Marsalis, Michael Foster, Randy Jackson, Troy Davis, and dozens more. They form a kind of club of “Bat” disciples, said Esneault.

Baton Rouge Area Chamber President and CEO Adam Knapp says Baton Rouge’s music scene is an important asset in the city’s cultural portfolio that needs to keep growing.

“One of the best ways to keep and attract people is an amazing music scene, grown locally and with lots of great concerts and more venues,” said Knapp. “To grow more artists, it helps to support those music venues where they can earn a living doing what they love.”

“How do we help?” Knapp continues. “See more live shows!”

FROM BIG CITY PARADES TO RURAL PRAIRIE COURIRS, CATCH THESE FESTIVITIES ACROSS THE SOUTH THIS ROWDY, WONDERFUL CARNIVAL SEASON W

Peruse the following pages for Carnival camaraderie in all its forms as we gear up for Fat Tuesday. Laissez les bons temps roulez!

Krewe Bohème: Presided over by the intoxicating Green Absinthe Fairy, Bohème will march through the Marigny and French Quarter under the theme “Love Letter to New Orleans”. 7 pm. kreweboheme.com.

February 4

Krewe du Vieux: This is New Orleans’ only Mardi Gras parade featuring traditional mule-drawn floats, each with its own satirical theme. 6:30 pm. kreweduvieux.org.

‘tit Rex: Miniature size, maximum fun, this walking parade with the petit, handmade floats marches down the median in St. Roch. 4 pm. titrexparade.com. krewedelusion: One of the weirdest parades of the season, krewedelusion is on a mission to save the universe, starting at its center— New Orleans’ French Quarter. 7 pm. facebook.com/krewedelusion.

Krewe of Cork: New Orleans’s wine krewe will be sippin’ and steppin’ through the

French Quarter. 3 pm. kreweofcork.com.

Krewe of Oshun: This krewe includes marching Baby Dolls, a band contest, peacocks, and the goddess of love—all making their way down St. Charles. 6 pm. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe of Cleopatra: The first all-female organization on the Uptown route will roll again. 6:30 pm. kreweofcleopatra.org.

Krewe of ALLA: One of the oldest of the New Orleans krewes, ALLA has been marching in Uptown since the Great Depression. Step out to catch one of their signature genie lamp throws. 7 pm. kreweofalla.net.

Magical Krewe of Mad Hatters: This recently-founded Metairie krewe aimed at capturing the imagination brings Alice in Wonderland to life with colorful lights, costumes, and dance troops on Veteran’s Boulevard. 5 pm. madhattersparade.com.

Knights of Nemesis: The krewe of St. Bernard Parish will make its annual, unforgettable appearance coming down Judge Perez Drive. 1 pm. knightsofnemesis.org.

Krewe of Pontchartrain: Famous for its history of celebrity Grand Marshals, this St. Charles Avenue parade is one of New Orleans’ longest-standing. 1 pm. kofp.com.

Krewe of Choctaw: Starting their eightyyear history on mail wagons as floats, this krewe will march down St. Charles. 2 pm. kreweofchoctaw.com.

Krewe of Freret: This krewe has a focus of preserving New Orleans Mardi Gras tradition, and will march down St. Charles. 3 pm. kreweoffreret.org.

Knights of Sparta: This all-male krewe has been around since the fifties. 5:30 pm down St. Charles. knightsofsparta.com.

Krewe of Pygmalion: This parade founded by Carnival veterans in 1999 rolls down the St. Charles route around 6:15 pm. kreweofpygmalion.org.

Mystic Krewe of Barkus: This one has gone to the dogs—see them all, including the four-legged royalty, this year with the theme “Top Dogs: Barkus Comes to the Rescue”. In the French Quarter, starting at 2 pm. kreweofbarkus.org.

The Mystic Krewe of Femme Fatale: The first krewe founded by African American

Parades and more in Greater New Orleans & Acadiana

women for African American women, their signature throw is a designer compact. 11 am down St. Charles. mkfemmefatale.org.

Krewe of Carrollton: The fourth-oldest parading krewe of New Orleans, known for throwing shrimp boots. Noon down St. Charles. kreweofcarrollton.org.

Krewe of King Arthur and Merlin: One of the largest New Orleans krewes, Arthur and Merlin’s signature throw is the King Arthur Grail——hand-made goblets that are bestowed upon the most esteemed parade-goers. Follows Carrollton at 1 pm. kreweofkingarthur.com.

Krewe of Druids: This secret society is known for its wit and tendency to ruffle feathers. One year it featured a float saying: “Seriously...The Parade Behind us is not Worth the Wait.” 6:15 pm down St. Charles. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Knights of Babylon: Traditional to the max, this Uptown krewe designs their floats exactly as they were drawn up over eighty years ago. The king’s identity is never revealed to the public. 5:30 pm. knightsofbabylon.org.

Knights of Chaos: Chaos carries on the grand tradition of satire, following Babylon on the Uptown route at 6 pm. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe of Muses: Let’s get some shoes—one of the most coveted throws of the season comes from this incredibly popular allfemale parade. 6:45 pm. kreweofmuses.org.

Krewe of Bosom Buddies: This French Quarter walking parade celebrates women of all walks of life, and throws out hand-decorated bras. 11:30 am. bosombuddiesnola.org.

Krewe of Hermes: Every year, the Hermes captain leads the Uptown procession in full regalia on a white horse, followed by innovative neon floats and 700 male riders. 5:30 pm. kreweofhermes.com.

Krewe d’Etat: Led by a dictator instead of a king, this secret society gets a kick out of throwing blinking skulls at its audience. Pick up a copy of the D’Etat Gazette, a bulletin with pictures and descriptions of the floats. 6:30 pm down St. Charles. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe of Morpheus: Looking through the chaos and tomfoolery for an “old school” parade down St. Charles? This one’s for you. 7 pm. kreweofmorpheus.com.

Krewe of NOMTOC: The Krewe of New Orleans Most Talked of Club was founded in 1969 by the Jugs Social Club. The all-

Black krewe tosses out ceramic medallion beads, jug banks, and signature Jug Man dolls. Starts on the Westbank at 10:45 am. nomtoc.com.

Krewe of Iris: One of the oldest and largest female Carnival organizations for women, Iris members continue to follow tradition with white gloves and masks. 11 am down St. Charles. kreweofiris.org.

Krewe of Tucks: This one’s developed a reputation for its potty humor, including toilet paper throws draping St. Charles’s live oaks. Noon. kreweoftucks.com.

Krewe of Endymion: If you’re heading to

parade, and evolved into the over 250-rider krewe it is today, traveling on the traditional Uptown/Downtown route. 11 am. kreweofokeanos.org.

Krewe of Thoth: This year, the theme of this inclusively-routed parade that goes by healthcare facilities is “Thoth’s Diamond Jubilee.” Noon on the Uptown route. thothkrewe.com.

Krewe of Athena: Jefferson Parish’s newest all-female krewe will be tossing out hand-decorated fedoras down Veteran’s Memorial Boulevard. 5 pm. kreweofathena.org.

Krewe of Atlas: This Metairie Krewe was founded on the principle of equality for all. 5:30 pm down Veterans. mardigrasneworleans.com.

parades. 8 am on St. Charles. kreweofzulu.com.

Krewe of Rex: Elaborately decorated, handpainted floats, masked riders in historic costumes, and a rich and colorful history make Rex one of the cultural centerpieces of Mardi Gras. Rex was formed in 1872, making it the oldest continually-operating krewe. The identities of Rex’s king and queen remains secret until Lundi Gras. 10 am down St. Charles. rexorganization.com.

Black Masking Mardi Gras Indians: See the intricate hand-beaded-and-feathered suits—traced back to the Native Americans who helped Africans enslaved in New Orleans escape—when dozens of tribes take to the streets Uptown, usually around 2nd and Dryades streets; and downtown, often near the Backstreet Cultural Museum in the Treme late morning to mid-day. Free.

Elks, Krewe of Orleanians: The world’s largest truck parade features over fifty individually designed truck floats and comprises of over 4,600 riders. Follows Rex at 10:30 am. neworleans.com.

Krewe of Crescent City: Each truck in the Crescent City Truck Parade represents a different Carnival organization. This parade signals the official “beginning of the end” of Carnival. Follows ELKS Orleanians at 11 am. crescentcitytruckparade.com.

One of Jefferson Parish’s largest and most family friendly parades, Argus draws over a million revelers to the Veterans Memorial Parade Route in Metairie. Past celebrity guests include Barbara Eden, Phyllis Diller, and Shirley Jones. 10 am. kreweofargus.com. Elks, Krewe of Jeffersonians: Featuring more than ninety trucks and 4,000 riders, this krewe shares the Elk mascot with its sister krewe, the Krewe of Elks-Orleanians. 11 am on the Veterans Memorial Boulevard route. neworleans.com.

organization and largest all-female krewe, the Metairie Egyptian-themed parade features marching bands, dance teams, and spectacularly-attired maids. Starts at the Esplanade Mall at 6 pm. kreweofisis.org.

Krewe of Bacchus: Revered as one of the most spectacular krewes in Carnival history, this parade is known for staging celebrities Bob Hope, Dick Clark, WIll Ferrell, and Drew Brees as its namesake, Bacchus. The parade ends inside the Convention Center for a black-tie Rendezvous party of over 9,000 guests. 5:15 pm. kreweofbacchus.org.

Krewe of Mid-City: This one is famed for its foil-covered floats and children-oriented themes. 11:25 am along the St. Charles Route. kreweofmid-city.com.

Krewe of Okeanos: Back in the fifties Okeanos started as a small neighborhood

established as a super krewe immediately after its debut, which rolled out 700 riders, and celebrates forty years this year. This year, monarchs include Golden Globewinner Darren Chris and pop icon Joey Fatone. Fatone will headline Orpheusapade, the post-parade gala which is open to the public. Rolls on the Uptown route at 6 pm. kreweoforpheus.com.

Krewe of Centurions: The family-friendly Centurions parade is comprised of over 350 men, and rolls on the Metairie route. 6:30 pm. kreweofcenturions.com.

Krewe of Zulu: A parading krewe since 1909, Zulu was the first and for many years the only krewe representing New Orleans’ Black community. Its extraordinary costumes, float designs, and history distinguish it from other Mardi Gras

Featuring trucks and unique throws, the Krewe of Jefferson follows the Elks Krewe of Jeffersonians to signal the “beginning of the end” of Carnival in Jefferson Parish. 11:30 am. kreweofjefferson.com. k

Bayou Mardi Gras Association Parade: This family-oriented parade runs along Bayou Teche in historic New Iberia, energized by community leaders committed to building on past traditions while creating new ones. 7 pm. bayoumardigras.com.

La Danse de Mardi Gras: The Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette celebrates rural Cajun Mardi Gras traditions with this country dance, including commentary about local traditions by American Routes Host Nick Spitzer, lively music by Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys, Cedric Watson,

and Jeffrey Broussard, as well as dinner by Tony Chachere’s chefs. $35-$500. 5 pm. acadianacenterforthearts.org.

Krewe de Canailles: Celebrating inclusivity, creativity, and sustainability, this walking parade down Jefferson Street in Lafayette does allow for floats—if you drag them yourself. Tossing out eco-friendly throws and joining together groups of sub-krewes, these carnival crusaders have found a way to party their way to a better Lafayette. This year’s theme is “There’s Something in the Water”. 7 pm. krewedecanailles.com.

Lakeview Park & Beach Children’s Mardi Gras: Immerse your tots in the traditional Mardi Gras experience at Lakeview in Eunice, where chickens will be set loose for chasing, and live music will usher in a two step. lvpark.com.

Lebeau Mardi Gras: It starts with an old-school courir that includes the addition of a greased pig, and zydeco tunes. Then the Lebeau Mardi Gras Parade welcomes participants on horse, ATV, automobile,

wagon, or a traditional float. Festivities start at 8 am, parade departs at 1 pm and ends at a music fest at the Immaculate Conception Church. cajuntravel.com.

Courir de Mardi Gras de L’anse: Come for the run, stay for the fais-do-do and gumbo afterwards at a home on Lafosse Road, which the public is invited to enjoy. Courir begins at 8 am, Fais Do Do at 4 pm. $5. acadiatourism.org.

Krewe Des Chiens: The least we can do for our dogs is to parade them, in all their grandeur, through the streets of Lafayette. Noon on West Vemilion Street. krewedeschiens.org.

Lake Arthur Mardi Gras Run/Parade: Bringing the extravagance of Carnival right up beside the old Acadiana traditions, Lake Arthur’s celebration includes both floats and riders on horseback. The courir-style run begins at 9 am from Lake Arthur Park, followed by the float parade at 2:30 pm. jeffdavis.org.

Krewe of Carnivale en Rio: Known for its vibrant floats, dazzling lights and the jubilant accompaniment of maracas, the Parada—which honors Brazil’s first emperor Dom Pedro I and his granddaughter Dona Isabel—has become

Lafayette’s premier Mardi Gras event. 6:30 pm down Johnston and Vermilion. riolafayette.com.

Courir de Mardi Gras at Vermilionville: Vermilionville and the Basile Mardi Gras Association host a traditional Cajun Mardi Gras run in the historic village. Begins at 10 am with a screening of Pat Mire’s documentary Dance for a Chicken, followed by a presentation on the traditional “Chanson de Mardi Gras” at 11 am. The run kicks off at 11:30 am. $10; $8 for seniors; $6 for students; and children younger than five are free. bayouvermiliondistrict.org. Scott Mardi Gras Parade: This small town parade is one of Acadiana’s largest, and a favorite for families city-wide and beyond. Floats and costumed riders will vie en fete for the title “Most Original Float.” 1 pm. scottsba.org.

Greater Southwest Louisiana Mardi Gras Kick-Off Parade: Getting things started for the slate of events that makes up the Association’s celebration of Mardi Gras in Lafayette, this parade travels through the Downtown area to land at Cajun Field. This year’s theme honors Lafayette’s Bicentennial with a celebration of the city’s festivals. 6:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

Le Festival de Mardi Gras à Lafayette: Head to Cajun Field in Lafayette for Carnival rides and games, and live music like Wayne Toups, the Chee-Weez, Three Thirty Seven, and more. gomardigras.com.

Eunice Cajun Mardi Gras Festival: In the days leading up to Eunice’s historic courir on Mardi Gras Day, the city convenes downtown for five days of fais do-doing. Some of the acts to look forward to include Wayne Toups, T’Monde, Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys, and Geno Delafose & French Rockin’ Boogie. Don’t miss the open jam session Saturday morning, or the traditional boucherie by the Pa Ta Sa Krewe on Sunday. Expect to watch the end of Eunice’s courir come through town at 3 pm Tuesday afternoon. eunicemardigras.com.

Cankton Courir de Mardi Gras: A chicken run, trail ride, gumbo cook-off, live music, and more at Landon Pitre Memorial Park. 7 am. $10 to participate in each event; proceeds benefit the Special Olympics of Louisiana. facebook.com/cccdmg.

Mamou Street Dance: Saturday mornings are always a riot in Mamou, but the Saturday before Mardi Gras is something

else entirely. Find traditional music in Fred’s Lounge, then step outside and find it in the street, too—along with a crowd of eager and dedicated locals who will show you how it’s all done. 9 am. evangelineparishtourism.org.

Church Point Children’s Courir & Parade: A children’s chicken run, with all the trappings, at Saddle Tramp Clubhouse. For children younger than fourteen. Starts at 10 am. churchpointmardigras.com.

Jennings Mardi Gras Festival & Parade: Strolling along since 1994, this parade is marked on both ends by festive food and family-style activities, including live music, home-style food, and crafts. Starts at 11 am in Founders’ Park with the Squeezebox Shoutout Cajun Accordion Championship; Parade on Main Street begins at 4:30 pm. louisianatravel.com.

Sunset Mardi Gras Parade: Sunset Mardi Gras has continued on as a Carnival classic with beads, doubloons, and live music— along with children’s activities. 11 am. sunsetmardigras.com.

Lafayette Children’s Parade: The city’s tiniest krewes will head down Johnston at 12:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

Eunice Parade of Paws: Come see the pups parade through Downtown Eunice, then catch Fred Charlie & the Acadiana Cajuns on the bandstand. 3 pm. eunicemardigras.com.

Rayne Mardi Gras Parade: Everyone is invited to be in Rayne’s annual parade— walkers, drivers, and floaters alike. Starts at American Legion Drive, ends at the Frog Fest Pavilion. 3 pm. raynechamber.net.

Lafayette’s Krewe of Bonaparte: A hallmark since 1972, this krewe infuses excitement and youth into the city’s traditions. See them roll from Jefferson to Johnston, to the Cajun Dome, starting at 6:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

Courir de Mardi Gras Church Point: Once named “The Best Traditional Mardi Gras,” this run features costumed horseback riders, wagons, buggies, floats, and live music along with all your characteristic chicken chasing and greased pig capturing. 8 am–1:30 pm. $40, must be in costume to participate. Main Street parade begins at 1 pm. churchpointmardigras.com.

Eunice Lil’ Mardi Gras: Watch the lil’ costumed runners race after the courir’s mascot—fueled by the promise of a chicken-shaped trophy. $10 per child; $10 per vehicle to follow along the route. Begins at 9 am at the Eunice Recreation Complex, followed by the official chicken chasing competition at 1:15 and the children’s parade through downtown at 3 pm. facebook.com/ eunicelilmardigras.

Sunset Kids Wagon Parade & Family Fun Day: This inaugural parade begins and ends at the Sunset Community Center, featuring decorated wagons and children decked out for theme of “Alice in Wonderland” 1 pm. Stick around from 2 pm–4 pm for live music

and food behind the Community Center. Free. sunsetmardigras.com.

Grand Marais Mardi Gras Parade: Admire costumes from the artistic to the repulsive—all elaborate, plus floats and dance troops at this family-friendly Jeanerette parade, which begins at Grand Marais Park at 2 pm. iberiatravel.com.

Lundi Gras at Lakeview: Lakeview Park & Beach know how to throw a party, and their free Lundi Gras pig roast is no different. Get your fill, then stick around for live music by Jamming with Bird and Cajun Fire, then the traditional barn dance with Geno Delafose & French Rockin’ Boogie from 4:30 pm and Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys at 7 pm. lvpark.com.

Lafayette’s Monday Night Parade: Evangeline LXXXII and LXXXIII will reign over the city’s most regal krewes, rolling down the Southwest Louisiana Mardi Gras route at 6 pm. gomardigras.com.

Courir de Mardi Gras de Grand Mamou: One of the most raucous and famous chicken runs on the prairies gets its start at 6:30 am, and travels throughout the country roads collecting goods for that end-of-theday gumbo. Catch the parade at the end of the day in downtown Mamou around 3 pm. evangelineparishtourism.org.

Faquetaigue Courir de Mardi Gras: Founded in 2006 by friends Joel Savoy, Linzay Young, Jesse Brown, Lucius Fontenot, Lance Pitre, and Dave Johnson— this courir celebrated on the outskirts of Eunice holds values of tradition, as well as inclusivity, at its heart. Designed to be appropriate for all ages and to emphasize culture—the run takes place on horseback, on foot, and via trailer, journeying throughout the Faquetaigue community. Dancing, begging, and singing are aplenty, all leading up to a traditional gumbo and concert at the day’s end. Begins at 8 am; full costumes with hats and masks are required. $20. faquetaigue.com.

Le Vieux Mardi Gras de Cajuns de Eunice: Dating back to the city’s earliest days, Eunice’s Courir de Mardi Gras features riders on horseback in masks, conspiring in chicken-chasing, revelry, general silliness, and an effort to make a community-wide gumbo. Costume-clad trailers follow behind—and all join together in downtown Eunice for a final fais do do at 3 pm. The day starts at 8 am at the Northwest Community Center. facebook.com/eunicemardigras.

Tee Mamou-Iota Mardi Gras Folklife Festival: Featuring all your favorite traditions, the handmade costumes, the medieval capuchins, and the unbridled chaos—the Folklife Festival also celebrates with live music, folk crafts, and local food booths on the prairie. 9 am–4 pm. acadiatourism.org.

Carnival D’Acadie: Run into the heart of

Parades and more in the Capital Region & Cajun Coast

the Cajun Prairie to celebrate Fat Tuesday, Rice City Style. Crowley’s Fat Tuesday festival includes carnival rides, live music by Wayne Singleton, Swampland Revival, Adam Leger Band, and Dustin Sonnier— plus a grand parade at 2 pm. Music starts at 10 am. acadiatourism.org.

King Gabriel’s Parade: Lafayette’s grandest of parades, honoring the King of Carnival and the hundreds of volunteers who make the vibrant showcase down Johnston possible. 10 am. gomardigras.com.

Opelousas Imperial Mardi Gras Parade: Floats, beads, and reigning royalty make up this Opelousas parade. Rolls from East Landry Street to Liberty Street beginning at 11 am. cajuntravel.com.

Lafayette Mardi Gras Festival Parade: Emitting the spirit fueled by the Carnival atmosphere at Cajun Field, this parade will run down Johnston at 1 pm. gomardigras.com.

Lafayette’s Mardi Gras Indians: Replicating the better-known Black Masking Indians of New Orleans, Lafayette’s tribes have cultivated their own distinct traditions since the 1950s. See the elaborate costumes and the invigorating spirit of the tradition on display at “Pontiac Point” (the corner of

Simcoe and Surrey Streets) at 1 pm, and again at the Judging Contest at Clark Field at 3 pm. lafayettetravel.com.

Independent Parade: Anyone can participate in this parade, which closes out Mardi Gras day in Lafayette. Take part, or enjoy the show of “independent” floats rolling down Johnston, starting at 2:30 pm. gomardigras.com. k

Krewe of Oshun Parade and Festival: Find Carnival games, eating contests, and other free family fun at BREC’s Scottlandville Parkway Conservation Park for this third annual festival and parade—which features bands, dance teams, schools, businesses, and non profits in addition to entertainers and krewe members’ floats. Rolls at noon, festival carries on from 2 pm–6 pm. visitbatonrouge.com.

Mystic Krewe of Mutts: Bark your calendars for the CAAWs Mystic Krewe of Mutts parade, held in downtown Baton Rouge. Bark in the Park events begin at 10 am, and the parade rolls at 2 pm. caaws.org.

Krewe of Artemis: The first all-female krewe in Baton Rouge begins and ends at the corner of St. Philip Street and Government Street. Revelers will be treated to the Krewe of Artemis’ signature highheeled shoe. 7 pm. kreweofartemis.net.

Krewe of Diversion Boat Parade: Set sail in sin for Livingston Parish’s parade on the Amite River/Diversion Canal. Noon. Live auction at Manny’s after the parade benefitting St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. (225) 939-2135.

Krewe Mystique de la Capitale: Baton Rouge’s oldest parading Mardi Gras krewe continues its mission to uphold Carnival season in the Capital City. Fun for all ages, it starts at the River Center and winds downtown. 2 pm. krewemystique.com.

Krewe of Tickfaw Mardi Gras Boat Parade: Mardi Gras comes to the Tickfaw River with boats decked out in ways unimaginable. 2 pm. Details at the Krewe of Tickfaw-Mardi Gras on Tickfaw Facebook Page.

Krewe of Ascension Mambo Parade: Prepare to be awed as the creative masterpieces that are Ascension Parish’s Mardi Gras floats pass down Irma Boulevard to the corner of Highways 44 and 30. 2 pm. Details at the Krewe of Ascension Mambo Facebook Page.

Krewe of Denham Springs: The Antique Village comes to life with people throwing trinkets at each other at noon from Denham Springs High School, and ends at Veteran’s Boulevard. Stick around for the first-annual Mardi Gras Mambo celebration in the Village, featuring food trucks and artists Clay Cormier, Chase Tyler Band, and Thomas Cain. 3 pm. Free. livingstontourism.com.

Krewe of Orion: A Carnival-themed tractor pull through downtown Baton Rouge. Begins and ends at the River Center, where the after-party masquerade will be held. 6:30 pm. kreweoforion.com.

Mid City Gras: Baton Rouge’s freshest Mardi Gras parade returns to Mid City. The one-afternoon revel down North, from 22 Street to Baton Rouge Community College, invites locals to “get nuts,” featuring Mid City artists, musicians, and more in a neighborhood strut. 1 pm. midcitygras.org.

Krewe of Southdowns: Catch this nighttime parade glittering and glaring along its usual route from Glasgow Middle School through the Southdowns neighborhood. 7 pm. southdowns.org.

Baton Rouge Mardi Gras Festival: An incredible line-up from Henry Turner Jr.’s

Listening Room in North Boulevard Town Square is the highlight of this familyfriendly Mardi Gras celebration This year catch acts including Pastor Leon Hitchens, Eddie “Cool” Deemer, The Soul Revival Band, and Henry Turner Jr. & Flavor. 10 am–7 pm. Free. ultimatelouisianapar. wixsite.com/brmardigrasfest.

Spanish Town Parade: Spanish Town’s annual parade of miscreants rolls from Spanish Town Road and Fifth Street, to Lafayette Street and Main. The krewes dole out dozens of infamously-irreverent floats, with marching bands, dance troupes, and waves of pink throws. This year’s theme is “Man I Love Flamingos.” Noon. mardigrasspanishtown.com.

Krewe of Good Friends of the Oaks Parade: Residents of the Port Allen community “The Oaks” established this krewe in 1985, and it has been rolling right along ever since. 1 pm. westbatonrouge.net.

Krewe of Comogo Night Parade: See Plaquemine like you never have before when Comogo rolls, sure to dazzle. 7 pm down Bellevue Drive. kreweofcomogo.com.

Lundi Gras at Circa: Circa 1903, the event center associated with Morel’s in New Roads, continues its tradition of hosting a Lundi Gras bash. 7 pm. $100. bontempstix.com.

Community Center of Pointe Coupee Parade: Every year for 101 years now the population of New Roads multiplies tenfold as parade-goers searching for a more laid-back time flock to the “Little Carnival Capital”. Rolls at 11 am through downtown New Roads.

New Roads Lion Club Parade: This beadheavy annual parade follows right behind the Community Center of Pointe Coupee Parade. 2 pm. pctourism.org. k

Bayou King Cake Festival: A sugary new Carnival celebration is making it’s way to Downtown Thibodaux this year, bringing together local bakeries to present a tasting tableaux of local king cakes—introduced by a children’s parade. Enjoy live music from Nonc Nu and Da wild Matous, and cast your vote for the best king cake. All funds benefit the Lafourche Education Foundation. 1:30 pm. $10 facebook.com/ lafourcheeducationfoundation.

February 10

Krewe of Hercules: A favorite along the traditional West Side Route in Houma, Hercules celebrates its thirtysixth anniversary this year. 6 pm. kreweofhercules.com.

Krewe of Shaka: Noted for its

contributions to the community, the King and Queen of this parade are annually presented with the Key to Thibodaux. 12:30 pm in downtown Thibodaux. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Ambrosia: A funky Thibodaux time, this parade has floated through town for over thirty years. 2 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Hyacinthians: The Ladies Carnival Club, Inc. is the largest carnival club in Terrebonne Parish, and surely not a force to be reckoned with. Kicking off at 12:30 down Houma’s West Side Route. hyacinthians.org.

Krewe of Titans: Also dubbed the “Terrebonne Family Carnival Club,” this parade welcomes festivalers of every kind. 1 pm down Houma’s West Side Route. Details at the Krewe of Titans “Terrebonne Family Carnival Club” Facebook Page.

Krewe of Adonis: St. Mary’s first parade of the season is this historic night parade in downtown Morgan City. 7 pm. louisianatravel.com.

Cypremort Point Boat Parade: Spend the day at Cypremort Point State Park, watching the iconic boat parade pass by. 1 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Cleophas: Thibodaux’s oldest parade will march again, featuring over fifty floats, bands, stilt walkers, dance teams, and more. 12:30 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Chronos: One of Thibodaux’s most celebrated parades of the season, Chronos believes in the slogan “Every Man a King,” and “Every Woman a Queen.” 1:30 pm. kreweofchronos.com.

Krewe of Galatea: St. Mary’s first female Krewe has been rolling the streets of Morgan City since 1969. Begins on 2nd Street, through downtown, and lands at the Morgan City Auditorium. 2 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Cleopatra: The six hundred plus ladies of Cleopatra steal the night for the only Lundi Gras parade in Terrebonne Parish. 6:30 pm down Houma’s West Side Route. houmatravel.com.

Krewe of Hera: One of the Cajun Coast’s newer parades, this Morgan City procession is all excess and excitement. See them heading down Second Street to Onstead to the auditorium on Myrtle. 7 pm–9 pm. louisianatravel.com.

Krewe du Gheens Celebration and Parade: Kicking off Mardi Gras day in

Parades and more in North Louisiana & beyond

the Cajun Bayou region, the Krewe of Gheens will roll at 11 am, beginning on Gheens Shortcut Road. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Ghana: Fun floats and dancers will make their way through downtown Thibodaux on Mardi Gras Day. Noon. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Houmas: This historically-rich krewe was the first to ever parade down Houma’s West Side Route. On each float, family is honored with at least one fatherson duo or pair of brothers. 1:30 pm. kreweofhoumas.wildapricot.org.

Krewe of Hephaestus: The oldest krewe in St. Mary Parish dates back to 1914, rolling on Mardi Gras day from Sixth and Sycamore to the Morgan City Municipal Auditorium. 2 pm. cajuncoast.com. k

February 4

African American History Parade: This thirty-fourth annual parade celebrating the many contributions of Black Americans starts at the Shreveport Municipal Auditorium at 11 am. sbfunguide.com.

Krewe de Riviere Children’s & Pet Parade: This parade includes a bunch of

fantastic beasts and little ones, too. 10 am starting at South Grand Street in Monroe. monroe-westmonroe.org.

Krewe de Riviere Mardi Gras Parade: Enjoy a traditional feel with floats, walking groups, riding groups, and plenty of goodies. Starts at West Monroe High School and ends around the Ouachita Parish Courthouse. 5 pm. monroe-westmonroe.org.

Krewe of Centaur: The largest parade in the Ark-La-Tex area, Shreveport’s “Fun Krewe” is known for its celebration of the regional gambling industry. 3:30 pm starting downtown and traveling down the Shreveport-Barksdale Highway, to E. Kings Highway, ending just before Preston. kreweofcentaur.org.

Krewe of Janus Children’s Parade: A cute parade with even cuter riders at Pecanland Mall’s Center Court in Monroe. 9:30 am. kreweofjanus.com.

Krewe of Janus: Celebrating forty years, Northeast Louisiana’s oldest parade joins the Twin Cities by parading through West Monroe and Monroe, mostly down Louisville Avenue. 6 pm. kreweofjanusonline.com.

Krewe of Paws Parade: Furry friends of all shapes and sizes will be in West Monroe dressed in their Mardi Gras best, beginning on the 100 block of Commerce Street. 1 pm. monroe-westmonroe.org.

Krewe of Barkus and Meoux: The crowd acts like animals for this Shreveport favorite, themed “Krewe of Barkus and Meaoux Gets Geek’d”. 11 am at the Louisiana State Fairgrounds. facebook. com/theanimalkrewe. Parade takes off at 11 am. barkusandmeoux.com.

Krewe of Gemini: Shreveport and Bossier City’s first modern krewe. Downtown Shreveport at 3 pm. kreweofgemini.com.

Krewe of Highland: Lunch will be supplied at this eclectic Shreveport parade in the form of grilled hot dogs and packaged ramen noodles hurled off of floats. After, enjoy live music, crawfish, and more at the Mardi Gras Bash at Marilynn’s. Rolls at 2 pm through the Highland neighborhood. kreweofhighland.org.

East Bank Golf Cart Parade: Golf carts will be decked out when this fun parade (with prizes for the best-decorated carts) returns to Bossier City. 7 pm in the East Bank District and at the Plaza. shreveport-bossier.org. k

Krewe of Bilge: For the Northshore’s marine-Mardi Gras, the boats of the Krewe of Bilge travel down the waterways of Slidell, starting at the Marina Cafe and ending at the Dock of Slidell. Noon. kreweofbilge.com.

Krewe of Poseidon: Themed “Carnivals, Around The World,” this year’s parade will feature around twenty-five floats traveling down Ponchartrain Drive in Slidell. 6 pm. poseidonslidell.com.

Krewe of Pearl River Lions Club: Celebrate the season with floats, the Pearl River High School Band, dance groups, cheerleaders, churches, and families. 1 pm starting at Pearl River High School, heading south on Highway 41 then east to Highway 11, and ending at Town Hall. louisiananorthshore.com.

Krewe of Eve: It began with six women, and now has over five hundred members. With Blaine Kern floats, this parade begins on LA-22 and continues down West Causeway Approach above Monroe Street, crossing 190 and ending on East Causeway Approach. 7 pm. kreweofeve.com.

Krewe of Push Mow: A group of artists in Abita Springs decided it would be

Card. The Right Care.

Childhood comes and goes in a blink. We’re here through the stages of your life, with the strength of the cross, the protection of the shield. The Right

a hoot if they decorated lawn mowers for a parade (spoiler alert: it is). Noon starting on Main Street. facebook.com/ abitaspringspushmowparade.

Krewe of Tchefuncte: This boat parade celebrates maritime life on Madisonville’s historic Tchefuncte River. 1 pm. kreweoftchefuncte.org.

Krewe of Olympia: For the oldest parade in St. Tammany, King Zeus’s identity is kept secret until the parade, which starts on Columbia Street in Covington. 6 pm. kreweofolympia.net.

Krewe of Dionysus: Named for the Greek God of wine, Slidell’s first all-male krewe will set out at 1 pm on Berkley Street. kreweofdionysus.com.

Krewe of Selene: Slidell’s only all-female krewe tosses out one-of-a-kind handdecorated purses. Rolls at 6:30 pm down Pontchartrain Drive and Front Street. kreweofselene.net.

Carnival in Covington: Covington’s main parade includes full-sized floats, hand-built floats, marching bands, dancers, walking groups, horses, cars, and a kids’ costume contest at the mid-point of the parade route through the downtown area. 10 am. carnivalincovington.com.

Tammany Gras: This free party immediately follows the Carnival in Covington parade at the Covington Trailhead. Features live music, food trucks, drinks, a “Little Jesters” area with crafts, costume contests, and more until 4 pm. louisiananorthshore.com.

Krewe of Folsom: An eclectic parade invites all to join in on the fun with the citizens of Folsom. 2 pm. Begins and ends Magnolia Park. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe du Pooch: Dogs for days out on the Mandeville Lakefront with the theme “Great Gatsby by Krewe du Pooch”. Noon. krewedupooch.org.

Mystic Krewe of Mardi Paws: This dog parade in downtown Covington is a lot more bark than bite, with a theme of “Tails from the Barkside”. 2 pm. mardigrasneworleans.com. k

February 10

Pineville Light of Nights Parade: This parade glows and shimmers through the streets of Pineville, beginning at Louisiana Christian University and ending at Alexandria City Hall. 7 pm. mardigrascenla.com.

February 17

Classic Cars & College Cheerleaders

Parade: The name of this parade really says it all, and will cheer and roll through the streets of Downtown Alexandria. 4:30 pm. alexmardigras.net. Taste of Mardi Gras: Area restaurants offer their top-tier Carnival flavors, all at the Randolf Riverfront Center in Alexandria. 7:30 pm. $30; $10 for children ten and younger. 7:30 pm. mardigrascenla.com.

Children’s Parade: Alexandria’s kiddo parade brings loads of festive cuteness to the streets of Downtown. 10 am. alexmardigras.net.

February 19

Krewes Parade: Alexandria’s Krewes Parade is one of CenLA’s biggest, and honors local celebrity Chris Chelette as Grand Marshal, and Miss Louisiana Gracie Reichman as its special guest. Rolls at 2 pm from Texas Avenue to the Mall. alexmardigras.net. k

February 18

World Famous Cajun Extravaganza and Gumbo Cook-off: Teams compete for the best chicken & sausage, seafood, and wild game gumbos. 8 am–2 pm at the Lake Charles Civic Center. $10, kids ten and younger free. visitlakecharles.org.

Mystical Krewe of Barkus Parade: Furry and fabulous, costumed pets parade down Gill Street in Lake Charles for one of the most highly-attended parades of the season. 1 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

Krewe of Omega Parade: Omega celebrates the African American community of the Southwest Louisiana region. Rolls at 2 pm through the streets of Downtown Lake Charles. visitlakecharles.org.

Lake Charles Children’s Day & Parade: Held in the Lake Charles Civic Center’s Exhibition Hall, Children’s Day features interactive exhibitions, crafting, and games. At 3:30 pm, it all culminates in the Children’s Day Parade Downtown. Free. visitlakecharles.org.

Iowa Chicken Run: Even if you don’t catch a chicken, you can have some gumbo after the chase. Departs from the Iowa Knights of Columbus Hall at 8 am. $10 for adults and $5 for children twelve and younger. visitlakecharles.org.

Second Line Stroll: Skipping the floats, area groups strut their Mardi Gras spirit down Lake Charles’s Ryan Street to Mardi Gras music. 1 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

Krewe of Krewes: Over a hundred floats from a variety of local krewes roll through downtown Lake Charles starting at 5 pm. visitlakecharles.org. k

LITERATE OCCASIONS

ST. FRANCISVILLE WRITERS & READERS SYMPOSIUM

St. Francisville, Louisiana

West Feliciana Parish invites accomplished authors to present readings and discuss works, this year in Jackson Hall at Grace Episcopal Church. The goal of this annual symposium is to offer audiences a wellbalanced appreciation for the art of literature in all its forms through a focus on the work of Louisiana writers. This year’s featured authors include: Ronlyn Domingue, Susanne Duplantis, Wayne Flynt, Maurice Ruffin, and F. Wayne Stromeyer. Readings and discussions about their work and the creative process will be conducted throughout the day from 9 am to 4 pm. $65. bontempstix.com. k

STEPPIN’ OUT KICK IT OUT... THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT!

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge’s contemporary dance company, Of Moving Colors, continues

bringing professional dancers together with young talent from ages five through eighteen for their yearly community production. Celebrate four decades of OMC inspiring and entertaining audiences with this high-energy show at the Manship Theatre. 4 pm and 7 pm. $13–$35 at manshiptheatre.org. k

GOOD EATS (& CAUSES)

WILD GAME COOKOUT 2023

Port Allen, Louisiana

A full day of cooking by teams from all over East and West Baton Rouge parishes, all for the good cause of supporting St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. They’ll be grilling, stirring, and frying wild game—followed by dinner, a silent auction, and a rowdy live auction. Entertainment will be provided by Passing-Outlaws from 11 am–3 pm. 7 am–8 pm, dinner at 4 pm. Free, but dinner is $15—which will take place in the Pavilion next to Sandy’s Daiquiris. dreamdayfoundation.org. k

ARTFUL DISGUISES MASK-MAKING MARTINIQUE STYLE WORKSHOP RETREAT Arnaudville, Louisiana

Join traditional Carnival mask-makers Jean-Luc Toussaint and Vanessa GayeToussaint for a four day workshop exploring mask-making techniques from Martinique, as well as those in Acadiana and other parts of the world. All materials will be provided, and students will have access to sewing machines, a laser cutter, 3D printer, and more. $150 for NUNU Members; $450 for non-members (who have the opportunity to become members for $25/year). Begins at 6 pm Friday. nunuaccollective.homesteadcloud.com. Read more about this Martinique-Louisiana Carnival cultural exchange in Jordan LaHaye Fontenot’s Perspectives profile on page 54. k

Denham Springs, Louisiana

The magical, the two-dimensional, the dangerous, and the mysterious all come alive at Livingston Parish Library. Costumes encouraged. 10 am–2 pm at the Denham Springs-Walker Branch. Free. mylpl.info. k

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Join Chef John Folse for his annual Fête des Bouchers, where he’ll be joined by approximately seventy butchers and chefs from around the country to preserve this time-honored tradition. For Folse, the event is dedicated to keeping Cajun food heritage alive by focusing on the educational aspect of the boucherie and teaching others how to make delicacies such as hog’s head cheese, andouille, boudin, smoked sausage, cracklins, and other spoils of the event. 8 am–3 pm. $85; $15 for children younger than twelve. whiteoakestateandgardens.com.

Read more about the history of the contemporary boucherie in Jonathan Olivier’s story on page 36. k

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Peruse the beautiful blooms, which should be at their seasonal peak, when The Baton Rouge Camellia Society sets up its show at Burden Museum and Gardens. Approximately 1,500 blooms will be on display, and plants will be available for sale, as well. Saturday

from 1 pm–4 pm, Sunday from 10 am–3 pm. Free. lsu.edu/botanic-gardens. k

Natchez, Mississippi

Back for another year celebrating Southern authors as well as filmmakers, this year’s Natchez Literary and Cinema Celebration will be held at the Natchez Convention Center. The festival feature lectures and panels from scholars including Drs. Rebecca Hall, Jonathan White, Joan DeJean, and beyonde; and authors including Julie Hines Mabus and Diane McPhail. colin.edu. k

Alexandria, Louisiana

Meet twelve versions of Elvis at the Coughlin-Saunders Performing Arts Center during a weekend full of performances by the best impersonators, touching on every era of The King’s life. 7:30 pm Thursday–Saturday and 2 pm on Friday–Saturday. $25 at louisianaelvisfestival.com. k

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The Baton Rouge Garden Club’s annual Tablescapes Flower Show features displays interpreting artworks painted by members of the The Louisiana Water Color Society. 1 pm–4 pm on Saturday and Sunday at the Baton Rouge Garden Center. $5. Find the Baton Rouge Garden Club on Facebook for more information. k

New Orleans, Louisiana

The Marigny Opera House’s ballet company presents Tennessee Williams’ most famous play in the form of a two-act ballet, choreographed by Diogo de Lima and accompanied by an orchestral score from New Orleans composer Tucker Fuller. $35–$55. All performances begin at 7 pm. marignyoperahouse.org. k

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

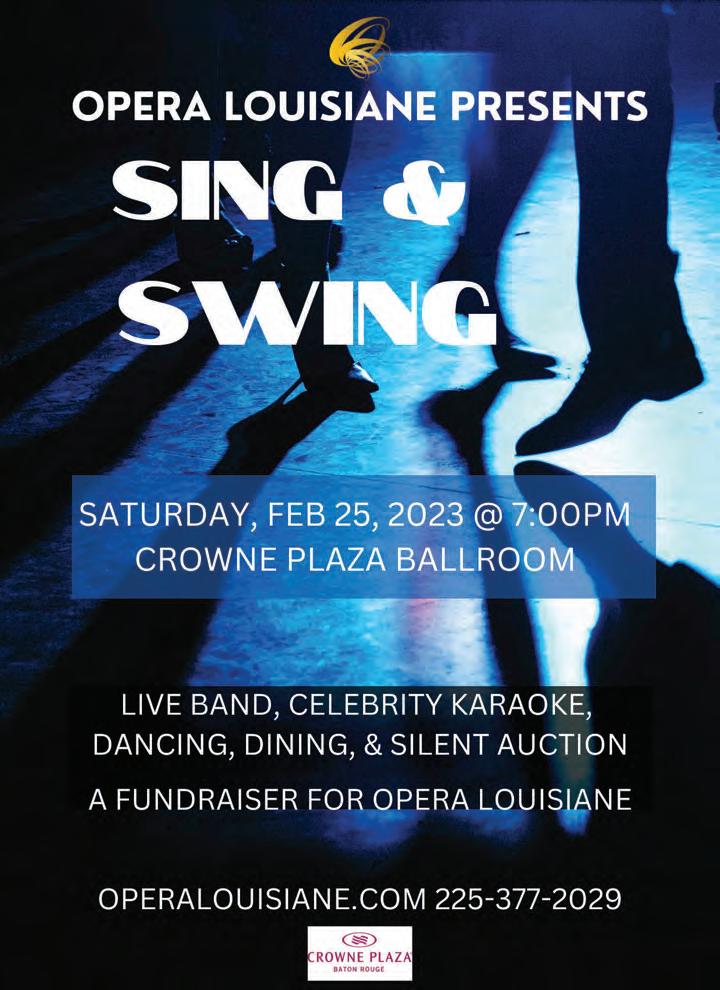

This month sees Opéra Louisiane’s fan-

favorite fundraiser ready to ignite some friendly competition. 7 pm–10 pm. Tickets start at $100 at bontempstix.com. operalouisiane.com. k

Lacombe, louisiana

From 1935-1956, Bayou Gardens was a must-see horticultural attraction on the northshore of Lake Ponchartrain. Now the headquarters of the Southeast Louisiana National Wildlife Refuges, the gardens showcase an impressive variety of camellias and azaleas. Celebrate the historic garden with free garden tours, camellia growing tips, workshops, arts and crafts, and more. Explore the historic gardens on your own or with a guided tour, and enjoy free refreshments provided by the Friends of Louisiana Wildlife Refuges. 9 am–3 pm at the Southeast Louisiana National Wildlife Refuges’ Bayou Lacombe Center. Free. See a full schedule at fws.gov. k

GREEN THUMBS HERB DAY AT BURDEN Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Herb Day at Burden Museum &

Gardens, led by the Baton Rouge Unit of the Herb Society of America, promises hundreds of herb plants for sale, classes and demonstrations, and more. 8 am–1 pm. Free. lsu.edu/ botanic-gardens. k

Find our full list of events, including those we couldn't fit into print, by pointing your phone camera here.

Istage with three New Orleans musicians, Mahmoud Chouki deftly removes his brimmed hat, hliberating a few animated dark curls as he raises his guitar behind his head, his wiry fingers never once faltering in his swift, intricate, and pleadingly-emotive picking of the complex melody. He completes the phrase, triumphant, and lowers the instrument back to his knee, laughing and flashing a broad smile to bassist Noah Young, then back to his rapt audience. In a bit, after the set was technically billed to have finished, he will excitedly tell them, “Let’s go to Morocco!” as he trades his guitar for an oud, the lute-like Middle Eastern stringed instrument, and begins to sing in Arabic.

Chouki’s is not an act you expect to find in a neighborhood bar in the Riverbend, yet that Thursday night, he plays to a full and fully-captivated audience for three hours—alternating between improvising with the other musicians and playing his original music, Young’s original music, covers of songs by progressive American jazz artists, and by the end, the Moroccan folk tunes. In between songs and sips of IPA, he shares anecdotes from his global travels. “I was supposed to come to New Orleans for four days. I stayed for two weeks,” Chouki laughs, then proudly announces, “Now, I’m a New Orleanian.”

mance at the Station, he told three-hours-worth of stories to another rapt audience, of one. The two of us were settled in a red velvet booth at the Columns Hotel & Bar on St. Charles Avenue—his suggestion—as he shared the remarkable tale of how he went from a Moroccan guitar prodigy to calling Louisiana home, his guitar and oud cases resting at our feet.

Chouki’s life began in a port city nearly 8,000 miles from New Orleans. In 1984, he was born in Kenitra—a place he hardly recalls because at the age of two, he moved with his parents up Morocco’s Atlantic coast to Larache.

In Larache, which was formerly colonized by Spain, Chouki’s early memories were underscored by the sounds of Spanish radio programming—especially the music, particularly flamenco.

His parents loved music, too, and their collections of Arabic and Middle Eastern classics filled their son’s young ears, supplementing the flamenco and Spanish songs with music closer to that of his own roots—like the Lebanese superstar Fairuz, Egyptian vocal icon Umm Kulthum, and Egyptian singer and composer Mohammed Abdel Wahab. His uncles also played music, though not professionally, and would sometimes travel from Casablanca with a full band to play for special occasions. And, even in northern Morocco, Chou-

ki’s early influences were rounded out by his father’s affinity for western hits by the Beatles and the Eagles.

“So, growing up in the north of Morocco was kind of lucky because it was like, on a crossroad of cultures— between north, south, east, and west. And so very open to all kinds of music,” Chouki explained. As a young child, he was always tapping away with his fingers, singing, and dancing. At seven years old, Chouki’s parents enrolled him in the Moroccan Ministry of Culture’s after-school music conservatory program, housed in a historic church. About a year into his schooling, he was still searching for an instrument when, like fate, he found the guitar.

“It was kind of a dreamy thing. I walked, and then the door opened, and there’s like, lights. There’s a guitar teacher, surrounded by kids and having fun and laughing, and I said—” here Chouki gasped dramatically, his eyes wide under his round double-rimmed glasses, emphasizing childlike wonder, “‘—I want to do this!’ That’s why I switched to guitar. It was not because I loved guitar. It’s just, I saw that fun moment, with the teacher and the kids, and that’s what attracted me.”

After a year of study with that guitar teacher, at age nine, Chouki and his family moved to the coastal town of Temara, in pursuit of the opportunities that came from being so near to the nation’s capital of Rabat— which included the chance for Chouki to study at the

Conservatoire National de Musique et de Danse in the capital city, a much more serious learning environment than that of the music school in Larache. “It was very strict. And it had a lot of kids,” he remembers. By the time Chouki was in middle school, he was performing with the conservatory’s kids’ orchestra.

In 1998, at age fourteen, Chouki was chosen as one of four young musicians to represent Morocco in a Meeting of the United Arab Emirates in Sharjah. He came in second-place for his singing and playing. When he returned to Morocco, the whirlwind of his first international performance continued. He was invited on Moroccan television programs, and demand to see him perform was high. “I was kind of a little star. And it just kind of started being problematic, because I have school also.” His parents started turning down the invitations for their son to play, to prioritize his life and education beyond music. “I remember people coming to the house, like begging my parents,” Chouki said. “It was very hard. And then, yeah, everything starts being harder in high school. Because … I love music. I want to do music. I want music to be my life.”

In an act of rebellion against his parents’ desires for him to focus on school, Chouki took up the electric guitar and started a band with some friends. He quickly learned that his peers were far less interested in complicated works of classical guitar than they were contemporary Western music. “In high school I discovered that, like, I can’t seduce the girls with a classical guitar,” he tells me, a laugh bubbling up again. “So, I needed to learn more modern stuff.” Chouki accepted the challenge, and taught himself Metallica’s “Nothing Else Matters” in its entirety in a single night. He didn’t stop there, quickly mastering songs by Nirvana and the

had a show, he would practice on his classical guitar, then borrow his friend’s electric guitar for the concert.

Western rock wasn’t the only genre Chouki branched into during that time—he began playing more North African music, and attributes his strict teacher at that time, Ibrahim Iabloul, with helping him to greatly improve his hand technique on the guitar.

Ultimately, Chouki discovered a particular affinity for Spanish guitar music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. “Because at this moment, I knew that I loved melody. I love the melody. I love hearing something beautiful, I want to play something beautiful to my ear first,” Chouki told me. “For me, it’s very important to

bered. “And that was the moment for me to say like, ‘Okay,’ I had the confirmation that I can play whatever I want … From that moment, I said like, I will listen to my heart, and what I want to do, and I will do it. And nothing will stop me. From this moment, everything’s changed in my life.”

After graduation, Chouki went on to participate in the Moroccan Minister of Education’s new program offering education degrees with a specialization in music. While engaging in his studies at the university in Rabat—learning piano, Arabic music history, psychopedagogy, and more—he was also gigging, often playing for only around $15 a set, happy it would afford him a pack of cigarettes.

me to enjoy music, so I can share it … if you like what you do, it’s easy to share it with everyone. You don’t need any force.”

At eighteen he traveled with the conservatory’s guitar ensemble on a two-week trip to Andalusia, Spain to play. “I was always the youngest, I was always like, hanging with older people and older musicians.” The last day was the international guitar competition, for which Chouki played a piece of Spanish music on the guitar. When they announced that he won first prize, he burst into tears. One of the judges told him, “You know why

While still gigging and enrolled in the university program, he accepted an invitation from friends to teach a group of young guitarists in Tangier. He spent nearly a year traveling between the two cities every few days. “I lived my whole life in trains in Morocco,” Chouki said. “It was awesome. And I’d discover other people that would give me another opportunity, and that’s like how actually my life is …” In each new place, at each new gig, with each new student, he made connections that opened more doors and opportunities.

When he graduated, the government sent him to Northeast Morocco to teach music to middle schoolers “which was a big shock for me because I am young. And I am like a government employee, like I’m a teacher. And this wasn’t the dream I had. I just was like, ‘Oh, shit. No.’ I love teaching, I love the kids— but like the system in general is like, ‘Okay, you’re done. You’re good. You have a salary. You have benefits. Do your life.’”

For him, it wasn’t enough. Within a year, he left his teaching job to travel across Morocco, in pursuit of learning more about his own musical heritage. His parents could not understand why he would leave such a

“I ARRIVED TO NEW ORLEANS, AND I WAS HEARING JAZZ. SOMETHING I’D JUST HEARD ON YOUTUBE AND CDS, AND NOW I AM IN FRONT OF IT. FOR ME, IT’S BLOWN MY MIND.”

respected and stable job. “My family was very proud for me to be a teacher …and then I said, ‘I’m leaving. I can’t—I want to be a musician, I want to be an artist.’ So, it was very hard. And it was kind of like a separation.”

But he knew his calling was to travel, and to play music. So he set out, seeking masters who could teach him to recreate the sound of the loutar on his guitar, to harmonize in different ways, and to imitate sounds from various regions. “I want to be kind of an ambassador of my music,” Chouki explained. “So, I can make my music accessible to the occidental ear.” He says that following the creative restrictions of his classical training, this period of traveling and connecting with Moroccan folk music “unchained” his soul. “And then I became like, a machine of composing, of playing music, of having fun.”

With this freedom, he found himself able to return to the concept of teaching, offering guitar lessons for a time in Casablanca—Morocco’s bustling economic capital—to a whole group of kids he proudly tells me have since grown up to become doctors, lawyers, writers, and even some professional musicians themselves, living around Europe. “When I’m touring in Europe, they come to see me.” During this time, he was also hired as the casting director for the 2007 film Whatever Lola Wants, and was tasked with hiring dozens of international musicians for big concert scenes. “That’s when I found my thing: Connecting people.”

In 2012, these connections led to one of Chouki’s most exciting and enduring projects. Assaad Bouab, a French-Moroccan comedian and actor, called. Bouab had recently crossed paths with someone in search of a Moroccan guitarist for a project.

The project was an international music collaboration called Rencontres Orient Occident, held in the hâteau Mercier in Switzerland. Over a decade since, Chouki has remained involved in the annual event, returning to the Chateau each year to participate in, curate, and even serve as music director for the nowfamed cultural exchange.

Before that, though, back in Casablanca, Chouki started spending time at a club that played Latin music from Chilé, Peru, and Columbia. He started going for drinks and to listen, but before long he was regularly on stage, which led to a tour, and then to other tours with other artists from other places. Which led to recording sessions. “So then, my life was—“ here Chouki makes the sound of an explosion, creating the effect with his hands, his long fingers bursting out from each other.

To show an example of the way various connections, from all over the world, have come together to enrich his career every step of the way, Chouki pulled out his phone to show me a photo, pointing to someone he identifies as “the friend of the composer” who scouted him for a 2011 symphonic performance at the opening of the Qatar Art Museum. This friend currently lives in Indonesia, and they’ve played in Bali together before. “Music is so crazy,” he said.

At this point in our conversation, jazz pianist and composer David Torkanowsky approached our table, greeting Chouki with “I know a rockstar when I see one!” before hurrying off to play a show with Stanton Moore and James Singleton in the other room. Interactions with well-established locals like this pepper our lengthy interview, exemplifying how—after a lifetime spent playing music all over the the world—Chouki today is fully enmeshed in New Orleans. And how, in turn, the city has embraced him with its signature warmth.

On his first trip to the United States in 2015, he embarked on the obligatory American road trip: trav eling from Asheville, to Nashville, to Memphis; jamming with musicians and checking out the scene for a few nights in each city. When he arrived in New Orleans, his plan was to stay for four nights. The first night, he attended a show at Maison, a favorite Frenchmen Street venue, that featured jazz guitarist and University of New Orleans professor Brian Seeger with A.J. Hall on drums, Oscar Rossignoli on keys, and Nathan Lambertson on bass. “I had never heard music like this in my life. I was just like—“ he gasped, clutching a hand to his chest. “I was like, ‘I would love to play this music one day. I want to play it so bad.’”

When the gig was over, Chouki, who didn’t yet speak English, had his girlfriend at the time translate a brief conversation with Seeger, and he gave Seeger his business card. Seeger went home, looked Chouki up, and immediately sent Chouki an email inviting him to speak to his jazz students at UNO, followed by a home-cooked meal of crawfish étouffée. Shortly after, Chouki got to join Seeger to play the same music he’d heard at Maison: New Orleans jazz. “And for me, that was like a dream became true.”

I asked him, after hearing and playing so many styles of music in over thirty countries across the world, what was so different about the set he heard at Maison that night. Without any hesitation, he said, “It’s the quality of the musicians of New Orleans. With all respect, I’d never heard that before. I’m talking about jazz now—I’m used to European jazz. I was in Nashville and Memphis, there’s mostly country, blues, Americana. But now, I arrived to New Orleans, and I was hearing jazz. Something I’d just heard on You tube and CDs, and now I am in front of it,” Chouki said. “For me, it’s blown my mind.”

That four days in New Orleans turned into two weeks, then Chouki left the United States for two years. When he returned, he did so to make New Orleans his home. He began workshopping with students at UNO, thanks to Seeger, and playing shows at Frenchmen Street’s intimate jazz club Snug Harbor. “I am grateful that I came to New Orleans by the big door,” he told me, referring to Seeger’s influence, even despite their language barrier.