SPRING 2023

VOLUME XXI NO. 1

SPRING 2023

VOLUME XXI NO. 1

adapting to the information environment: why u.s. internet freedom policy should promote the use of telegram in russia [Pg. 19]

IMRAN KHAN'S REVOLUTION: PAKISTAN'S GREATEST HOPE OR BLEAKEST DANGER? [PG. 38]

THE ROUGH ROAD AHEAD FOR THE REPUBLICAN HOUSE [pg. 13]

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Kaitlyn Saldanha

PUBLISHER

Katerina Kaganovich

CHIEF-OF-STAFF

Reece Brown

MANAGING EDITORS

Jesse Levine

Carmen Vintro

Nicolas Lama

Evelyn Yu

POLICY 360 EDITOR

Michelle Brucker

Columnist EDITOR

Collin Woldt

PITCH MANAGER

Alan Chen

PUBLICITY EDITOR

Amelie De Leon

POLICY 360 CHIEF SENIOR EDITOR

Marla Rinck

COLUMNIST CHIEF SENIOR EDITOR

Avery Lambert

SENIOR EDITORS

Alan Chen | Deepa Irakam | Robert Gao | Charlie Wallace | Benji Waltman | Sebastian Preising | Lochlan Liyuan Zhang | Rachel Krul | John David

Cobb | Carina Layfield | Melissa Yu | Rohil Sabherwal |

Makennan McBryde | Avanti Tulpule | Natalie Goldberg | Max Hermosillo | Layne Donovan | Isabel Randall | Gabriella Chioffi | Aileen Hernandez |

Julia Nash | Andrea So | Roshan Setlur | Carsten Barnes | Ariana Eftimiu |

Tatiana Gnuva | Anna Bartoux | Ryan Safiry

JUNIOR EDITORS

Maryam Abbasi | Daniel Kim | Saniya Gaitonde | Changu Chiimbwe | Joseph Karaganis | Emily Gao | Laila Cruz | Lara Geiger | Lily Sones |

Karun R Parek | Kaitlin Strong | Catherine Li | Isaiah Colmenero | Abby

Sim | Iliana Rios | Martina Daniel | Marla Rinck | Emily Debs |

Giulio Maria Bianco | Monica Vazquez | Devon Hunter | Amelie Ortiz De Leon | Gabriella Frants | Claire Schnatterbeck | Elizabeth Yee

STAFF WRITERS

Ann Mizrahi | Joy Botros | David Eckl | Kira Ratan | Heather Chen |

Makram Bekdache | Adam Kinder | Irene Jang | Kristy Wang | Theodore

Zaritsky | Jackson Weinberger | Nicholas Brown | Rebecca Kopelman |

Emily Swan | Francine Diaz | Alexia Vayeos | Evanna Hasan |

Kyra Chassaing | Eva Atkins | Luis Enrique Monroy | Lokaa Krishna |

Henry Wager | Victoria Gallacher | Max Edelstein | Elise Wilson | Alexia

Pérez | Christian DeMeire Gist | Amelia Fay | Elisha Baker | Carol Davis |

Shiva Yeshlur | Renuka Balakrishnan | Traolach O'Sullivan |

Nia Tomalin | Ada Baser | Fiza Rizvi | Lili Samii | Garrett Spirnock | Alannis

Jaquez | Julianna Lozada | Jack Lobel | Faiza Chowdhury | Andrew Fahey

| Jack Holmgren | Farhan Mahin | Genesis Vanegas Calvo | Moya Linsey |

Luc Hillion | Soenke Pietsch | Lena Barday | Steven Long |

Jonathan Waldmann | Zachary Troher | Adam Rowan | Aleka Gomez-Sotomayor-Roel

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Columbia Political Review, of CIRCA, or of Columbia University. Front cover photo credit: Erica Vega. Back cover photo credit: Scarlet Sappho.

Looking back on the year since our last print edition and looking forward to the year to come, we are faced with continued economic reverberations of the pandemic. We now find ourselves confronting the repercussions of a series of calculated response tradeoffs, witnessing a painful market correction in real-time. But in spells of economic anguish, journalism and free press emerge as more crucial than ever: not just for uncovering truth, but for holding accountable those in power.

At a time of great economic uncertainty, I am empowered by the community of engaged young minds that this publication brings together. It is with this sense of empowerment that I am honored to introduce the Spring 2023 Issue of the Columbia Political Review, our return to print publication after a year of digital content.

The cover piece of this issue draws on perhaps the most poignant political theme of the digital age; that is, the politics of information. In her piece, Amelia Fay proposes U.S. backing of the encrypted messaging platform Telegram as a powerful facilitator of civil discourse in Russia. Carmen Vintro analyzes a new SEC proposal with potential to revolutionize climate accountability on Wall St.. Traolach O’Sullivan explicates the history of racial injustice in U.S. affordable housing policy. David Eckl responds to Kevin McCarthy’s election as Speaker of the House, and Max Edelstein highlights the implications of the L.A. City Council scandal for Latino representation in municipal government.

This issue’s edition of Policy 360 examines the leftist governmental surge, or “Pink Tide,” in Latin America. Led by Managing Editor Michelle Brucker and Chief Senior Editor Marla Rinck, this roundtable brings together the perspective of four writers – and four countries – to assess the implications of Latin America’s harkening back to 2000s-era socialism.

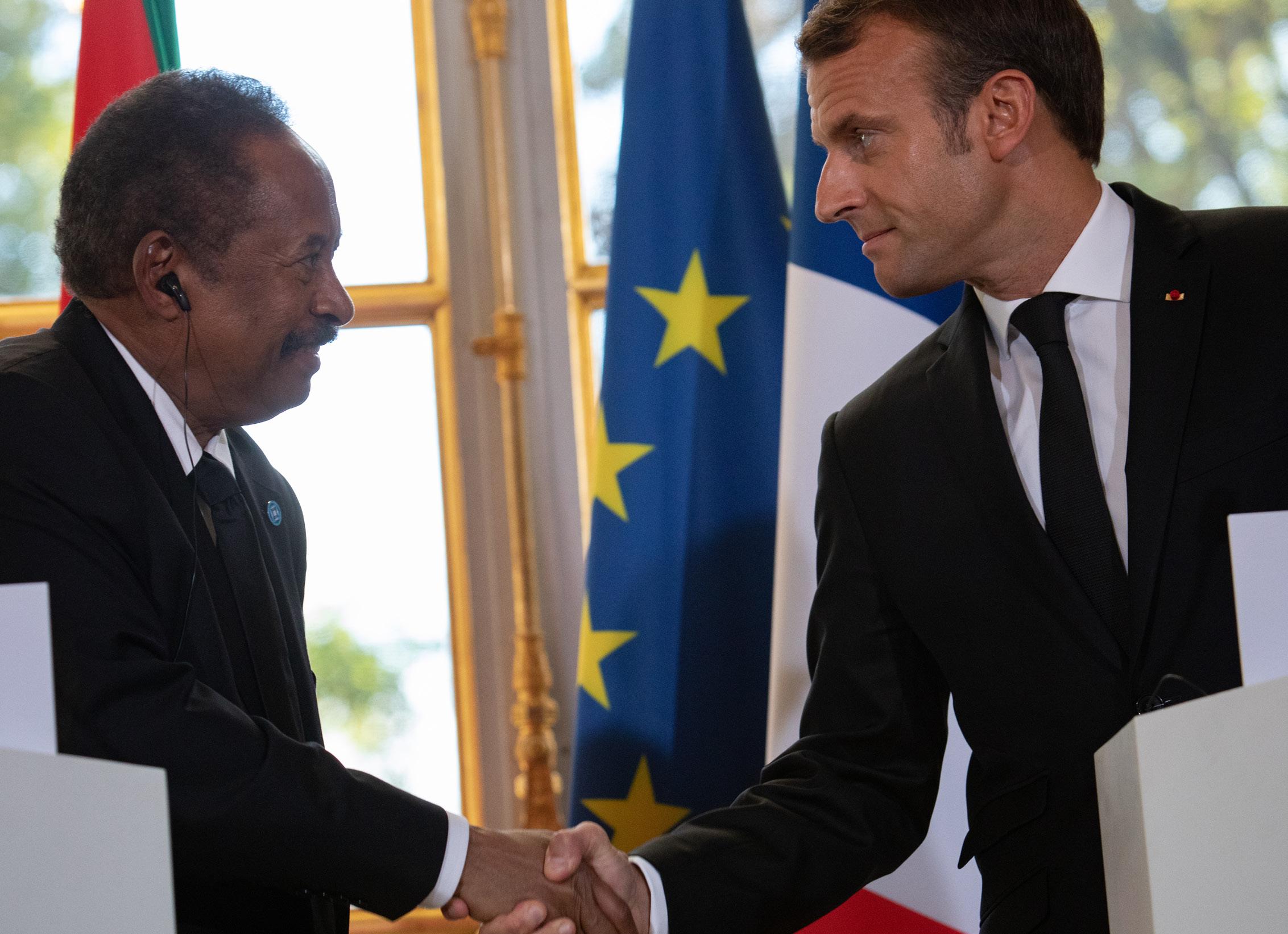

Looking abroad, Eva Atkins assesses the shortcomings of Frontex – the European Border and Coast Guard Agency – in responding to the ever-increasing flow of northern migration guaranteed by the climate crisis. Adam Kinder calls for the abolition of the kafala legal system of the Middle East. Turning to North America, Victoria Gallacher decries the negligence of the Canadian government towards First Nations communities, and Shiva Yeshlur unpacks the international response to Sudan’s post-coup crisis. Finally, Fiza Rizvi takes on the controversial tenure and reformist agenda of Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan.

Collectively, these pieces demonstrate how trying times are survived by the persistence of those who choose to demand accountability. Indeed, in the aftermath of crisis, it is that insistence on discourse – inquiry, prose, the pursuit of knowledge – that brings recovery.

At this moment of intense scarcity, it brings me great joy and immense hope that the Columbia Political Review remains a community dedicated to these values.

THE SEC'S FIGHT TO STANDARDIZE ESG REPORTING IN THE U.S.

Carmen Vintro BC '23

THE NEED FOR RACIAL JUSTICE IN NATIONAL HOUSING POLICY

Traolach O'Sullivan GS '24

THE ROUGH ROAD AHEAD FOR THE REPUBLICAN HOUSE

David Eckl CC '23

EXCLUSIONARY POLITICS VERSUS MULTIRACIAL COALITION-BUILDING: INSIDE THE L.A. CITY COUNCIL RECORDINGS

SCANDAL

Max Edelstein SEAS '25

ADAPTING TO THE INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT: WHY THE U.S. INTERNET FREEDOM POLICY SHOULD PROMOTE THE USE OF TELEGRAM IN RUSSIA

Amelia Fay CC '23

FRONTEX: THE LOOKING GLASS OF EU IMMIGRATION POLICY

Eva Atkins CC '26

KILLING KAFALA: MODERN SLAVERY AND ABOLITION IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Adam Kinder CC '26

THE WATER CRISIS: CANADA'S FAILURE TO FIRST NATIONS COMMUNITIES

Victoria Gallacher BC '24

IMRAN KHAN'S REVOLUTION: PAKISTAN'S GREATEST HOPE OR BLEAKEST DANGER?

Fiza Rizvi CC '24

SHUTDODWNS AND BLACKOUTS: AN INTERNATIONAL FAILURE TO POST-COUP SUDAN

Shiva Yeshlur CC '26

POLICY 360: THE NEW PINK TIDE IN LATIN AMERICA

HOW TO STEER THE TIDE: COLOMBIA'S NEW VISION OF LEFTISM

Steven Long CC ' 24

brazil's dramatic return to a bygone era

Soenke Pietsch CC '23

ARGENTINA'S BALANCING ACT AMIDST A LASTING INFLATION CRISIS

Lena Barday CC '25

LEFT-WING DEMOCRACY IN MEXICO: FUEL FOR CARTEL VIOLENCE?

Luc Hillion GS '24

Over the past few years, a “tectonic shift” to sustainable investing has defined the financial sector. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics, such as carbon emissions, that evaluate company performance based on factors outside of traditional financial accounts are at the core of what it means to invest sustainably in the 21st century. Today, 92% of companies listed on the S&P 500 publish a sustainability report and investors are rushing to integrate ESG considerations into their portfolios, driving the 12-fold increase of money that flowed into sustainable funds from 2016 to 2020. But a lack of reporting standards in the U.S. has let some companies and investors mischaracterize their assets as “green” and caused havoc for investors trying to make decisions using inconsistent and incomparable information.

In March 2022, following in the footsteps of the EU—which already requires robust corporate sustainability reporting—the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued a proposal designed to usher the U.S. public sector into a

new era of climate-oriented disclosures. The proposed rule, expected to come into effect early next year, would require public companies to report climate-related information, such as carbon emissions and material climate-related risks, in their annual financial statements. Though many in the business, political, and nonprofit sectors have voiced support for the proposal, it is far from perfect and will require heavy revision ahead of implementation if it is to survive imminent litigation and succeed in

this proposal, rather than congressional legislation, will be a key factor to achieving the Biden Administration's climate goals.

However, in light of the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that the EPA exceeded its power by regulating carbon emissions, the SEC is concerned that the rule might be struck down by the judiciary. Opponents of the proposal in the corporate world and the Republican party have already threatened litigation, and

its mission to provide consistent climate-risk information to the market. The proposal is a key part of the Biden Administration’s plan to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, and has been praised by investors, companies, NGOs, and academics for formalizing and centralizing the “E” in ESG reporting standards. In the face of a Republican-controlled Congress in the House, executive regulation like

the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a powerful trade group, wrote that the proposed rules “are vast and unprecedented in their scope, complexity, rigidity and prescriptive particularity.”

Others disagree with the entire principle of the government regulation of ESG metrics, arguing that the complexity of ESG means that a one-sizefits-all model will not work on considerations that inherently vary from

company to company.

One of the most substantial objections to the proposal center on the definition of materiality and the legal purview of the SEC, whose regulatory mandate to maintain fair and efficient markets hinges on the requirement that businesses disclose material information. Materiality is a legal concept that serves to determine what information companies are required to make to the public so that they can make an risk-informed investment decision. Drawing from relevant case law, the SEC states its definition of materiality to be information for “which there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would attach importance.” This definition is maintained in the language of the proposal, which points to the impact of California wildfires on farmers and wineries as an example of a material climate-related impact. However, the interpretations of who the “reasonable investor” is and what it is they care about are still up

for debate among legal scholars.

A current commissioner dissented from the proposal, saying that the disclosure requirements were made “without regard for materiality.” Five former commissioners concurred, writing in a dissenting comment that the SEC would be exceeding their legal authority by mandating politically-charged disclosures that are an “unprecedented and unjustified effort beyond financial materiality.” Their arguments imply that a company’s impact on the environment—its carbon emissions—has no bearing on a company’s financial performance and, therefore, are not important to the “reasonable investor” seeking a financial profit. Another group of former commissioners, however, argue that the SEC has used its “authority to require environmental and climate-related disclosures” for decades, and therefore is well within their legal right to propose the new mandates.

Voicing another potential reason why the SEC’s proposal could be in violation of materiality constraints, J.W. Verret, a professor at the Antonin Scalia Associate Law School, suggests that the disclosures are not based on the “reasonable investor,” but rather to appease powerful, vocal, and special-interest investors such as pension and union funds. Thus, he claims, the SEC has exceeded its legal purview because the proposed disclosures are immaterial.

Yet the question as to who counts as a “reasonable investor” is still contentious. A group of law professors commented that disclosure requirements must evolve with a changing market. In a press release, SEC Chairman Gary Gensler illustrated how the market landscape, and thus the “reasonable investor,” have changed with the growing understanding of impending environmental impacts. Gensler said that because investors who represent “literally tens

of trillions of dollars” are “recogniz[ing] that climate risks can pose significant financial risks to companies,” they have a burgeoning need for climate disclosures. Furthermore, it could be argued that the “reasonable investor” is beginning to care more about the environmental and social impacts of their investments beyond financial implications. A recent study by Stanford Business School found that younger investors claim they are willing to sacrifice 6-10% of their retirement savings to “support ESG causes,” hinting at a potential shift in the mindset of the new reasonable investor that broadens the concept of company performance beyond financial profit.

Going even further to expand materiality to include a non-financial dimension, the EU introduced a new concept called double materiality, which looks at materiality from

two perspectives: 1) financial and 2) environmental and social. While the internally-facing financial component is what materiality traditionally considers to be important information, double materiality adds another viewpoint that includes a company’s “external impacts” in its appraisal of company value.

Within this conception of double materiality, London School of Economics PhD student Mattias Täger identified a divide between what he terms “weak” and “strong” double materiality with regard to climate information. With the weak interpretation, non-financial information, such as compliance with strengthening regulation or ability to attract talent, is considered important because of its direct impact to a firm’s bottom line. This weak interpretation finds the environmental and social materiality components to be mate-

rial because they pose financial risk to the firm’s performance. With the strong interpretation, however, the environmental and social components are considered important by the “reasonable investor” for reasons beyond purely financial performance. It is unclear whether the SEC will follow the EU’s lead and adopt this new definition of materiality, let alone if it is legal to do so. Current SEC commissioner Hester Pierce— the only commissioner to disapprove of the proposal—argued that double materiality “has no analogue in our regulatory scheme.” Once the proposal is in its revised form, it will surely face litigation that will determine the future of materiality in U.S. law, and the extent to which the financial sector can participate in the global fight against climate change.

Who deserves protection under the umbrella of the welfare state? Exclusively the destitute? Or does everyone deserve assistance in attaining certain basic entitlements? The relationship of the United States government with housing centers around its response to this question. To that end, American housing policy has been defined by two approaches, each flawed, progressing upon one another historically. First, from 1949 to 1993, the government committed itself to supporting only the most destitute. The approach did not yield positive outcomes, instead being widely characterized by segregation, concentrated poverty, and neglect. When it became apparent that this was a massive failure, Congress attempted to reimagine those fundamental questions about the role of a welfare state in a new policy approach. It launched a new system in 1992; instead of taking on the burden of providing housing itself, it opted to cede as much control as possible to private developers through a grant system. This attempted to fix previous errors that created communities of concentrated poverty by dictating that grants integrate affordable housing into middle class communities. The reforms have been controversial; the problem of creating these new model communities is that it drastically decreases the proportion of affordable housing produced by each dollar of government funding. While it has been said that residents who lived in the neglected communities created by the old government-run model are much better off in new mixed income communities, with access to better employment, education, and quality housing, the prob-

lem is they rarely make it there. The new approach has ultimately proven damaging to most of the low-income residents whom these policies initially claimed to serve.

There is another critical issue to examine with contemporary housing policy, aside from the national government’s decision to step back and attempt to meet the demand for affordable housing through models of privatization; to date, American housing policies have not taken adequate account of race and racism. Whether by deliberately promoting segregation or failing to positively redress long-standing discrimination, national policies have prevented millions of minorities who are statistically most in need of housing from attaining those stable housing outcomes as well as broader economic prosperity.

To understand problems in contemporary housing policy, one must return to decisions made nearly 100 years ago when the national government first became engaged in housing. In the midst of the Great Depression, mass poverty and class-conflict created a unique opportunity for reorganizing society and unprecedented attention was paid to social welfare. However, in response to real estate lobbies fearing competition, government funded housing took on a particular character; Congress committed to serve an exclusively low-income population, plans that optimistically envisioned a “compassionate stopover for the working poor.” The negative consequence of this choice would emerge over time.

In the wake of WWII, as the United States prepared for unprecedented economic boom, the character of public housing was fundamentally altered. Public housing was no longer intended for the downtrodden middle class, as during Depression years. Instead, it was reserved for the most destitute, which–due to a longstanding history of institutional and social discrimination–were predominantly Black Americans. Official policy per the Housing Act of 1949 was to provide “a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family.” But importantly, this was accomplished in different ways for white people than it was for minorities. As Columbia University historian Ira Katznelson explains in his book When Affirmative Action Was White, the G.I. bill propelled white families into middle class homeownership through subsidized loans without requirement for down payments. These opportunities were not extended across racial lines. Subsidized housing was provided for families of color almost exclusively through the sprawling system of public housing, which was far from a path to middle class life. This stratification exerted a natural pressure towards the economic segregation of public housing, though it was also facilitated through an explicit process: the Housing Act of 1949 set a limit on incomes for applicants and accepted only those who “lived in unsafe, insanitary, or overcrowded dwellings, or displaced by public slum-clearance or redevelopment project.” The combination of these shortcomings resulted in a concentration of destitute residents in public housing, isolated from social and economic integration.

A classic example of the practical consequences of the Housing Act of 1949 can be seen in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green, where housing policies created a community marked by racial segregation and concentrated poverty. Cabrini-Green, constructed in 1942, was originally a predominantly white community. But it was transformed over a period of two decades, in no small part by the Housing Act of 1949, into an impoverished and overwhelmingly nonwhite population. Recognizing this shift in the racial diversity is critical to understanding why it failed. It is imprudent and unjust for governments to attempt to concentrate residents it views as undesirable in communities that are out of sight and out of mind. The strategy was not unique to Cabrini-Green or Chicago: it reflects a national mood of developing white communities at the expense of people of color. Underfunding and neglecting “undesirable” communities allowed social crises to blossom, creating challenges that local and national governments continue to grapple with to this day.

It is no exaggeration to say that Cabrini Green was set up to fail. As public housing funds dried up, and Chicago’s overall tax base eroded, in part due to white flight, the City Hall used its available funds to prioritize white neighborhoods. Basic services were withheld from Cabrini-Green such as police, transit, maintenance, and building upkeep. As Cabrini Green grew increasingly isolated from economic opportunities, employment rates plummeted and residents who had previously been responsible for paying a maintenance fee were no longer able to do so. Instead of addressing this, City

Hall and the Chicago Housing Authority simply allowed the community to fall into disrepair. Lawns were paved over to save on maintenance. Broken lights were left powerless for months. The final 1,000 units that were added to Cabrini Green in 1962 were constructed on budgets so thin that their low-quality infrastructure was prone to frequent issues. When those units incurred damages, they were simply left vacant to save money instead of rehabbed and allocated to another resident. Severe economization resulted in a policy of decay and neglect, and a pleasant neighborhood of garden apartments soon became a deteriorating concrete jungle of deep poverty and boarded windows. Crime, gangs, and drugs thrived in a community deprived of economic and educational opportunities. It was textbook structural pov-

While these problems were particularly prevalent in Cabrini-Green, American public housing at-large was increasingly identified with decaying infrastructure, crime epidemics, and social isolation throughout the later 20th century. Troubled by this, Congress established a national commission in 1989 to investigate and respond to the dire circumstances. It noted critical conditions in which residents were “paralyzed by fear of widespread neigh-

borhood crime, incapable of securing meaningful employment, confined to safe and unsanitary units, and unable to access much needed self-sufficiency programs.” To combat these problems it launched a new policy objective in 1992, HOPE VI, to fundamentally redefine its public housing approach. HOPE VI would no longer prioritize housing the extremely poor. Instead, it aimed to revitalize public housing

were successful in some cases, with a number of neighborhoods experiencing growth in per capita income as well as significant decreases in unemployment rates, dependence on government aid, and crime. But there are also undesirable side effects to making mixed-income housing a policy prerogative in order to reduce concentrated poverty: as influxes of higher income residents pour into

pursued: 50% of units were listed at market price, 20% subsidized moderately for the working poor, and 30% designated as public housing. The influx of middle-class families transformed Cabrini from a predominantly Black community to increasingly white. Displacement was a central issue. A small fraction of former residents were granted access to the new townhomes, while most were pushed

through public-private partnerships that would provide homes integrated into surrounding communities where both market-rate renters and public housing beneficiaries would reside. Integration was intended to provide welfare recipients access to pillars of social mobility, including quality education and employment opportunities. Segregated, impoverished, and ill-maintained high-rise projects would be demolished. Importantly, there were no measures to redress the racial inequality that had been nourished through previous housing policies. Reforms treated the housing crisis as a purely economic issue: a decision at the root of its continued ineptitude.

Mixed-income communities

these communities, they gentrify it and resegregate it with a population of upper income, predominantly white residents. The government is then needed to provide deeper and deeper subsidies to keep rent within the bounds of incomes for beneficiaries, and fewer and fewer people are able to be assisted and afford housing.

This was precisely the case with HOPE VI reforms in Cabrini-Green. Owing to its existence atop the national consciousness of disastrous public housing projects, it was one of the first to receive a HOPE VI development grant in 1993. Over the course of 16 years, neat rows of townhomes replaced the old and dilapidated high-rise buildings. A mixed-income resident profile was aggressively

to substandard housing on Chicago’s periphery and denied the opportunity to return.

When “revitalization” becomes equivalent to gentrification, these communities remain segregated: the pendulum merely swings in the opposite direction. Federal audits determined that just 11.4% of former residents return to revitalized HOPE developments, while the majority are displaced to peripheral areas that are equivalently racially segregated and socially isolated.

Thus, the mixed-income approaches only ameliorate problems of concentrated poverty, leaving segregation largely untouched.

”

“

Economic disparities are a symptom of the underlying disease that has pervaded American society: systemic racism. Its ills have been embedded within housing systems across the nation: through redlining, urban renewal, restrictive covenants, disinvestment, and white flight.

Failures in both the specifc case of Cabrini-Green as well as national housing policy at-large are a reminder of America’s persistent racial divisions. Inequalities extend far beyond segregated, substandard public housing, they are apparent in education, employment, healthcare and life expectancy, legal access, law enforcement relations, and prison populations.

Problems rooted in racial inequality cannot be eradicated by solutions designed to curb economic inequality. Eliminating poverty and racial inequality is a much more extensive undertaking than bulldozing dilapidated infrastructure and forcing the residents elsewhere, as if welfare beneficiaries are pieces of dust being swept around a room. Sustainable communities depend on open spaces, reliable public transit, quality schools, robust employment opportunities, community centers, and equitable city services. The aforementioned 11.4% relocation rate of former residents to redeveloped communities is insufficient, and why scholars as-

sert, “the racial pendulum has swung too far from Black to white in many HOPE VI developments.”

Policies that facilitate mixed-income communities provide quality housing resources to wealthy residents at the expense of the displacement of an ever increasing proportion of working class people most in need of housing. While the initial integration of higher income residents into the community may appear to successfully create diverse communities, Northwestern Professor and expert on HOPE VI reforms Thomas Kost proclaims it “inevitably succumbs to the homogenizing force of officially sanctioned gentrification.” Even though the stated goal of these policies is racial integration, the constant pressure of gentrification undermines any kind of long term attainment. Once segregated communities of Black Americans living in concentrated poverty then become gentrified and predominantly white communities. Meanwhile, the root causes of the housing crisis, as well as the widespread need for immediate aid, remain unaddressed.

To tackle today’s salient housing problems, local and national authorities must recognize the strong link between race and class within American society; racial minorities are the most affected by poverty, which is an outcome that came about by deliberate historical processes. Racial segregation and concentrated poverty in public housing did not happen by accident. Economic disparities are a symptom of the underlying disease that has pervaded American society: systemic racism. Its ills have been embedded within housing systems across the nation: through redlining, urban

renewal, restrictive covenants, disinvestment, and white flight. Katherine Gonsalves, who writes on the historical progression and legacies of discrimination in national housing policy, proclaims “the ghetto is not just a place but a structural process.” Racial discrimination in public housing was the source of the ensuing issues of concentrated poverty that Congress faced when it undertook the HOPE VI reforms: but in treating it as purely an economic problem and ignoring the underlying root, policies are utterly incapable of a lasting remedy. Thus, when shaping policy that addresses the combined problems of racial and economic disparities in housing, policies must be oriented around racial justice and integration. Income deconcentration will be addressed as a byproduct, but importantly, whenever there is a policy conflict the race-conscious prerogatives must take precedence. This is the best way to aid those stakeholders to which national housing policy actually is intended to serve, and more broadly remedy root causes of poverty and urban decay. Professor Ulf Torgensen famously declared housing as the “wobbly pillar of the welfare state.” But housing is integral to effective and equitable policies and societies–it cannot be that wobbly pillar. It also must be integrated into a broader welfare strategy, as sustainable housing policy is intimately connected with good employment and educational opportunities. Forging an egalitarian and democratic society depends on ensuring all people have quality access to all these pillars of social mobility: housing, employment, and education.

Legislating–and democracy as a whole–is a collective action problem. In order to create laws and policies that tackle the issues that the United States faces and guide the nation into the future, the 535 members of Congress must cooperate to pass the bills that become law. Under any circumstances, this is a great challenge. Senators and representatives from across the country have their own constituencies, ideologies, and interests, and managing those competing factors makes any success in Congress a huge accomplishment. Add on the existence of two starkly divided political parties who rarely agree with each other, and a management challenge becomes the nation’s hardest juggling act. The leadership teams of each party in the two chambers of Congress exist to take on this challenge, working to corral the members of their caucuses into working together and creating policies that fulfill the party’s priorities. This theory meets reality on Capitol Hill, and as the 118th Congress begins, it is clear that the reality of congressional politics for the next two years will be one where the thin Republican majority in the

House of Representatives makes the collective action problem of legislating all but impossible to solve. Due to Republicans’ poor performance in the 2022 midterm elections, Republican House leadership under the newly elected Speaker Kevin McCarthy will likely struggle to pass mean-

ingful legislation and will be greatly weakened by concessions made to members of the right-wing Freedom Caucus.

To understand the difficulties that await McCarthy and the House Republican caucus in the next two years, it is useful to compare their situation with what Democrats faced over the last four years. The Democratic Party gained a majority in the House in the 2018 midterms, but a large contingent of its members

opposed Nancy Pelosi’s bid for the speakership, seeking a new cohort of younger leaders and changes to how the House operated. After intense negotiations within the caucus, Pelosi was able to secure the speakership through a series of deals on committee memberships and lawmaking priorities that loosened the speaker’s control over the legislative agenda. She also agreed to a limit on how long she would be able to hold the speakership before stepping aside for a younger generation. However, she also set up large obstacles to any efforts to remove her from the position in the meantime by making it more difficult for members to bring up a vote on a motion to vacate: a mechanism by which the Speaker of the House can be forced out of the position.

After making these deals that appeased her opponents within the party’s caucus while eliminating potential avenues to oppose her leadership, Pelosi proceeded to lead House Democrats for four years, including the first two years of the Biden administration, which saw the passage of major legislative initiatives such as the American Rescue Plan, the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment

and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, all while managing a slim majority since Democrats lost House seats in the 2020 election. These victories came despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles in Congress that threatened to derail Democrats’ entire agenda. For instance, the Build Back Better Act, an enormous climate and social policy bill that President Biden campaigned on, was derailed by opposition from Senator Joe Manchin. Following this defeat, though, the bill’s provisions were scaled back and repackaged into the Inflation Reduction Act, a push that Democratic leadership forged in cooperation with Manchin. The example set by Speaker Pelosi over the past few years is one of authoritative leadership in the House, where large pieces of legislation passed despite narrow margins, competing interests, and near-uniform Republican opposition.

Led by Speaker Kevin McCarthy, the Republican House majority of the 118th Congress will struggle to replicate such success. Just like House Democrats after the 2020 election, Republicans now hold a slim majority in the House and can only afford to lose four votes when passing legislation along party lines. This gives each individual member of the Republican House caucus significant leverage over legislation and the ability to influence matters by threatening to withhold their vote. House Democrats under Pelosi were able to walk this tightrope thanks to the deals made between her and her Democratic opposition. McCarthy’s dealmaking has so far failed to effectively manage the disarray within the Republican caucus, with the party

having been gripped by infighting before the new Congress even began.

In November, after the 2022 midterms, when House Republicans elected their leaders, dozens of members of the far-right Freedom Caucus opposed McCarthy’s leadership, seeking fundamental changes to the House’s functioning that would further strengthen the party’s rank-andfile membership. In the weeks lead-

ing up to the speaker election at the opening of the new Congress, McCarthy and his allies failed to reach a compromise with these members of the Freedom Caucus. That failure was brought to the fore in the chaotic, historic, days-long speakership election fight that only saw McCarthy elected as speaker after fifteen ballots and large concessions made to rightwing holdouts. These concessions greatly reduce McCarthy’s power as speaker and all but guarantee that the next two years in the House will be characterized by legislative gridlock and Republican infighting.

The rules under which the House operates can be arcane and

convoluted, but they intimately shape how the chamber and its members behave. In order to gain the support of many members of the Freedom Caucus, McCarthy has had to agree to change the House’s rules in ways that will obstruct swift lawmaking. One cause of Republicans’ discontent with the House’s rules is the recently passed omnibus spending package that Democrats pushed through Congress in December. Individual members had little say in how the package was assembled, and unhappy Republicans saw it as a wasteful abuse of the powers of House leaders. In response, they have pushed McCarthy to institute a waiting period between a bill’s proposal and vote, as well as allow more opportunities for representatives to propose amendments to spending bills when they come up for a vote. This gives individual members a greater say in the legislative process–weakening leaders such as McCarthy who usually have outsized influence over large omnibus packages–but also threatens to hamper lawmaking as each amendment proposed would need time to be debated and voted on. The potential consequences of this shift were summed up by former House Democratic leader Steny Hoyer, who referred to the change as “filibuster by amendment,” since the processing of amendments could dramatically impede legislative action.

In addition, Republicans are moving to restrict earmarks, which are specific provisions in spending bills that route money to representatives’ home states and districts. Earmarks are often criticized as wasteful “pork barrel” spending, but they help accelerate legislation by entic-

ing representatives to support bills that they otherwise might not care to vote for. These changes to earmarks and amendments are two of the most prominent rules changes, but there are others with similar effects that will limit the number of scope of the omnibus bills that leadership often use to push through large amounts of legislation all at once. With Republicans advocating for major changes in government spending and the need to raise the nation’s debt ceiling looming within the year, these changes to amendment, earmark, and omnibus rules will all have major obstructive consequences for the legislative process.

These rule changes give more power to individual members and slow down spending bills, weakening the speaker and House leadership in a time when they tend to dominate fiscal policy in Congress. Some other concessions that McCarthy made to his opponents more directly limit his power. During her speakership, Nancy Pelosi made it very difficult to bring up a motion to vacate and attempt to force her out of office. In negotiations with the Freedom Caucus during the recent speaker election, though, McCarthy agreed to change the rules around the motion, enabling any single member of the House to initiate the vote. This means that if McCarthy’s actions as speaker ever run afoul with those who opposed his speakership bid and tensions boil over, his detractors could easily force the chamber back into the chaos of electing a speaker. With this, McCarthy will be on a very tight rope when attempting to push his party through tough issues: it was exactly this single-member motion to vacate rule that ousted

John Boehner from the speakership in 2015. Aside from the motion to vacate, McCarthy’s powers as Speaker are also eroded by his promise to put three members of the Freedom Caucus on the Rules Committee. The Rules Committee decides which bills get a vote on the House floor, and under what procedures, such as whether and how amendments can be made. The committee is therefore very powerful, and it usually operates under significant influence from the Speaker of the House. The inclusion of three of McCarthy’s harshest critics among Republicans will reduce his control of the legislative agenda and ensure that the Freedom Caucus’ approach to legislation is influential, meaning more conservative legislation comes to a vote, and more time-consuming amendments are allowed.

As the 118th Congress engages in more legislative business in the months ahead, the full implications of these rule changes and concessions will become clear. The divisions within the Republican House caucus have already curtailed Republicans’ early legislative initiatives. Coming into power, Republican leaders planned to quickly vote on a set of resolutions that they described as “ready-to-go.” When the time came, however, opposition within the party–from moderate Republicans on some measures and from hard-right members on others–has prevented some resolutions from being voted on. The biggest substantive matter that Congress has had to deal with so far is the fiscal policy fight caused by the looming debt limit. Republicans are united in their desire to reign in government spending in exchange for raising the debt ceiling, but dif-

ferent factions have different plans for doing so. These divisions have prevented the party from providing a cohesive plan to bring to the negotiating table with President Biden. These examples show that divisions within Republicans’ small House majority are already impeding legislative progress, and as Congress engages in more business in the coming months, the House’s rule changes will likely make the whole process even harder.

The changes made to the functioning of the House with Kevin McCarthy’s election as Speaker will greatly change how the chamber functions. The changes are motivated by a desire among some members of the Republican caucus to empower individuals, weaken leaders, and slow down and open up the legislative process. The ideals that these changes derive from are laudable, but they run up against the political realities of how hard it is to tackle the collective action problem of lawmaking. The weakening of the Speaker, demise of earmarks, proliferation of amendments, and other changes under the McCarthy speakership will all make the work of Congress much slower and more difficult. Add on the facts that the Republican majority is extremely slim, its caucus is divided, and Democrats control the Senate and White House and are united in opposition to the Republican platform, and it is all but certain that the 118th Congress will bring little in the way of major legislation. What it will bring is the spectacle of protracted legislative conflict, with the ordeal of the election of McCarthy as speaker as merely the opening act.

February

21, 2023What does it mean to hold on to political power? And what does it take to get it? What is the value of representation, and how should a marginalized community react when its leaders start to embody the same racist power structure they were elected to challenge?

These are some of the questions being asked in the wake of the appalling anti-Black, anti-indigenous recording that rocked the Los Angeles City Council this past October. In the leaked tape of a secret meeting at the Los Angeles Federation of Labor, three Hispanic councilmembers and the head of a prominent labor group made racist remarks about a white councilman’s 3-year-old Black son, discussed how best to draw districts in order to maximize their political power at the expense of other minority communities, and disparaged Oaxacan Mexicans. The leaked recording led to the resignations of the now ex-City Council President Nury Martinez and ex-LA County Federation of Labor head Ron Herrera, put a nail in the coffin of now disgraced ex-Councilmember Gil Cedillo, and destroyed the once-promising political career of Kevin De Leon. The recording is forcing Angelenos to take a hard look at the corruption

embedded within halls of power and is sparking discussions on reforming power structures in local government.

All but one of the officials involved in the recording have left their positions, and politicians across the political spectrum from local councilmembers to President Joe Biden have denounced the remarks, but one outstanding issue that Latino Angelenos must continue to grapple with is the future of Hispanic political representation in a city where almost half of its residents are Latino, but less than a third of the councilmembers are. This is the issue that Martinez, Cedillo, Herrera, and De Leon were purportedly attempting to solve when they met for their fateful meeting in October of 2021. Between calling a white councilmember’s Black son a “little monkey,” and saying of Cuban-American District Attorney George Gascon, “fuck that guy… he’s with the Blacks,” the solution they came up with was to draw district boundaries in a way that disenfranchised Black councilmembers

in order to increase their own political foothold.

They planned to do this by shifting powerful assets into districts of Hispanic councilmembers, including

the University of Southern California, large public parks, and dowtown Los Angeles, at the expense of Black councilmembers. Having these large assets in a Latino councilmember’s district would allow them to court campaign donations from powerful landowners and allow these politicians to grow their political network to include more influential connections—increasing their political clout and fundraising capabilities. They also attempted to undermine the political stability of more leftwing councilmembers who represent pro-tenant policies. Through gerrymandering, they proposed cutting renter-heavy neighborhoods such as Koreatown out of progressive city councilmember Nithya Raman’s dis-

“the recording is forcing Angelenos to take a hard look at the corruption embedded within halls of power.”

trict, further undermining the voices of poorer Angelenos who are disproportionately Black and Latino by diluting their votes in landlord-heavy districts.

Not only are these shortsighted, racist solutions to a severe problem in Angeleno politics a stain on the Latino political establishment, but these solutions are also the cause of the very problem they are trying to solve. In these councilmembers' minds, anyone who isn’t solely concerned with helping Latino communities in the specific manner in which they think Latino communities ought to be helped is anti-Latino and pro-Black. They mistakenly believe that the interests of Black and Hispanic communities are at odds with each other, and so people like George Gascon, who has lent his support to criminal justice reform, must be “with the Blacks” and therefore anti-Latino. They fail to see that

by viewing other racial groups as foes to be excluded from their assets and separated from their constituents, the Latino political establishment misses out on the ability to form powerful alliances that would increase their clout in city politics.

The alliance these councilmembers are missing out on is built around common priorities. Black and Latino communities have fought together to increase the minimum wage, strengthen labor laws, establish gang intervention programs, improve public transit, and fight discrimination by law enforcement. Black political leaders’ ability to appeal to these shared interests has allowed them to gain power in the three city council districts represented by Black members, all of which have Latino pluralities. In Councilmember Curren Price’s district, for example, the community is 78% Latino and 13% Black, reflecting his ability to appeal

across demographic lines. The same goes for Marqueece Harris Dawson, another Black city councilmember. Martinez, De Leon, and Cedillo miss out on opportunities to further their communities’ interests by attempting to disenfranchise the Black community instead of allying ourselves with them.

Powerful coalitions between minority communities have a long history of success in the city of Los Angeles and California as a whole. After a century of WASP (White-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant) control of the mayor’s office, Black and Jewish communities united in the early 1970s to bring the city’s first Black mayor Tom Bradley into power. This election redefined the city’s political landscape and ushered in a two-decade long restructuring of political power in the city. At the same time, activist groups formed multiracial coalitions, such as the alliance between Cesar

Chavez’s United Farm Workers (UFW) and the Black Panther Party. The Panthers joined the UFW’s boycott against California-grown grapes and the Safeway grocery stores for selling them, and as the Black Panthers were targeted by the FBI, the UFW came to their aid. Together their political power grew, and as the Black Panther Party declined due to the meddling of the FBI, the UFW weakened due to the lack of such a powerful partnership. Coalition building gave them strength in numbers that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise, and the fact that the groups couldn’t survive without each other emphasizes the importance of such alliances.

Of course, coalition building will look different today than it did in the 60s and 70s, and strategies will look different for smaller Black communities and councilmembers than they will for relatively larger Latino ones. But there is still much Latinos must learn from the past and from our fellow Angelenos if we want to evolve past this ugly moment and develop truly sustainable and inclusive political power.

The most recent local elections in Los Angeles seem to reflect this new strategy for increasing the political representation of Latinos in Los Angeles. The progressive former head of the congressional black caucus, Karen Bass, was sworn into the mayor’s office on December 11th, and a new wave of progressive, Hispanic councilmembers joined her in city hall to push the city council to the left. Bass began her political advocacy by founding the now influential Black-Latino advocacy organization Community Coalition. In the

wake of the leaked tape scandal, she positioned herself as the candidate with the decades of experience needed to repair community relations. This strategy apparently paid off, as she was elected by a larger margin than polls anticipated, suggesting Hispanic voters voted for her in larger margins than polls predicted they would.

Hugo Soto-Martinez defeated incumbent councilmember Mitch O’Farrell, supported by the labor movement and the increasingly influential L.A. chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, whose strategy for electoral success relies on looking past racial demographics to unite around the shared challenges that minority communities face. Soto-Martinez said himself that he thinks the scandal will push the city towards a “multicultured, multi-gendered, multigenerational, movement built on shared interests and the uplift of working-class people.”

Last June, self-proclaimed police abolitionist Eunisses Hernandez handily defeated the very same Gil Cedillo caught on the racist tapes several months later. She did this by uniting historically Latino communities with white ones, running on a platform of rejecting the interests of developers and strongly supporting tenants' rights. Before she ran for city council, she co-founded La Defensa, which focuses on uniting Black and Brown people to fight mass incarceration. By creating a multiracial coalition between different communities, Hernandez and Soto-Martinez are able to gain the number of votes necessary to give Latinos another vote on the city council while still representing the interests of other minorities.

This strategy is proving effective outside of City Hall as well; in the California state senate, social worker, veteran, and LGBTQ activist Caroline Menjivar defeated the local Hertzberg political dynasty, a moderate, pro-business, white centrist political lineage. Menjivar’s election brings progressive, working-class Hispanic representation to a heavily Latino district that used to be represented by people who do not share the community’s interests.

These political victories could represent a temporary backlash to a

racist audio clip before a reset into old habits of the Nury Martinezes and Kevin De Leons of our community that continues Latinos' long streak of political underrepresentation and isolation. Or they could signal a new era for Latino political power in Los Angeles, an era defined by multiracial, working-class solidarity that views Black Angelenos as allies in the fight for equity and social justice instead of adversaries. These victories could demonstrate the promise of a future that embraces empathy for those different than us and an understanding that we are stronger united than we are divided.

“we are stronger united than we are divided.”

In 2010, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton remarked that “the spread of information networks [was] forming a new nervous system for our planet.” These technological advances, she reminded her audience, were not an “unmitigated blessing,” but a tool that could be misappropriated to “undermine human progress and political rights.” Clinton’s proposed solution to these issues was internet freedom: the extension of the free web to citizens living under oppressive governments.

Although Clinton’s State Department tenure concluded in 2013, her goal of global internet freedom guides U.S. foreign policy to this day. In May 2022, the State Department announced a new fund for the international dissemination of anti-censorship technology, as well as an initiative to prevent the misuse of technology by authoritarian governments. Unfortunately, these policies represent a well-intentioned yet misguided attempt at democratic

progress and a fundamental misunderstanding of the information environment in many adversarial states.

Traditionally, U.S. internet freedom policy has focused on information access and public media production (in other words, one’s right to

freely consume and share information online). On several occasions, “information access” has meant throwing diplomatic weight behind American companies under pressure from foreign governments to compromise users’ information or to cen-

sor dialogue. For example, in 2010 Secretary Clinton supported Google’s refusal to censor Chinese users’ search results after Chinese hackers compromised the Gmail accounts of numerous activists and U.S. officials. In addition, the State Department has made a consistent effort to identify and to denounce foreign propaganda. Although these policies bring significant international attention to the issues of disinformation and information access, they overstate the importance of traditional news sources and neglect the critical role of secure messaging platforms.

The issue of internet freedom is especially pertinent to the current situation in Russia for multiple reasons. Most obviously, the Russia-Ukraine war demonstrates the potential of fake news to incite violence. In February 2022, Putin justified his invasion of Ukraine with accusations of a genocide against ethnic Russians in Ukraine, claiming

Russian troops were on a mission to "denazify" Ukraine. It goes without saying that these claims were false, but a series of draconian internet regulations made it difficult for Russian citizens to access alternative sources of information.

The second reason why internet freedom is of critical importance in Russia is because it provides an opportunity to shake the foundation of Putin’s power. Since becoming president in 2000, Putin has presented himself as a guarantor of order; yield to him and he provides security, comfort, and stability. The most significant uprisings during Putin’s time in power have occurred when his regime failed to uphold its end of the unofficial social contract (that is, the government curtailed citizens’ rights without providing the necessary stability). Given the ongoing situation in Russia, internet freedom will help citizens come to terms with the disconnect between the Kremlin’s mes-

saging and the reality on the ground. Even if a wide-scale reckoning occurs but does not result in concrete political change, it has the potential to divert significant government resources from the war effort.

To effectively support civil resistance within Russia, the State Department must focus on facilitating private dialogue amongst citizens, rather than on information access. Firstly, most Russians get their news via state television channels (in recent years, independent news outlets attracted a sizable readership, but these outlets’ official sites have been blocked since March 2022). This means the state exercises near total control over traditional media, and that directly accessing international news sources is impossible—not to mention dangerous—for most citizens. In addition, the State Department should be careful not to promote certain sources too passionately, as it risks “tainting” them. As

seen in the Post-Soviet Color Revolutions, the Kremlin has a habit of denouncing legitimate organizations as U.S. agents on a mission to undermine Russian sovereignty. To refrain from playing into Putin’s threat narrative, the State Department should actually maintain a certain distance between itself and any news outlets it seeks to support.

Second, the State Department should prioritize the promotion of secure messaging platforms because doing so is a long-term investment in Russia’s democratic health. Yes, information access is an area of concern, but more important is citizens’ ability to speak freely amongst themselves, to work through conflicting understandings of current events, and to organize on a local level. Enabling these earnest conversations will eventually make the government’s failure a “public fact,” causing the system to crumble organically (the collapse of the Soviet Union is an apt example of this phenomenon). In other words, the State Department should focus not on the immediate gratification

Russian citizens. The app offers users multiple levels of security, including end-to-end encryption, self-destructing messages, and the option to hide one’s phone number. In addition, Telegram can sync messages across devices and allows users to send large files, such as documents or video (this is especially important for reporting human rights abuses). The app is organized via groups and channels, making it easy to share content with large audiences. However, there are four main factors differentiating Telegram from other instant messaging platforms.

First, Telegram offers end-toend encryption, meaning messages cannot be read except on the devices involved. Second, Telegram has a history of denying the Kremlin access to users’ private information. Third, many opposition and international news outlets have an official presence on Telegram; this is currently one of the only ways for citizens to access accurate information. And finally, Telegram became Russia’s top messaging app in March 2022 and

as terrorism and drug trafficking. The reality, though, is that it is impossible to prevent the app’s misuse without monitoring conversations between users, thus compromising the overall privacy of the platform (it is important to note that Telegram has removed public posts inciting violence). Other common concerns include the app’s end-to-end encryption, which is optional but not automatic. This issue, however, could be addressed via a simple educational campaign or clearer messaging by Telegram itself. Telegram is far from perfect, but its status as Russia’s top messaging app shows it has earned citizens’ trust during its years as a platform for human rights activism. Now, Telegram is supporting the dissemination of media from the war in Ukraine, enabling difficult conversations within Russia, and helping Ukrainian and Russian emmigrants communicate with loved ones.

of small internet access victories, but on the long-term strategic benefits of secure civil discourse.

Telegram, a messaging app founded in 2013 “with a focus on speed and security,” is the platform best suited to the challenges faced by

has been downloaded over 4 million times since the invasion of Ukraine. In short, the app is secure and offers users access to countless online communities and topical channels.

Critics have cited the use of Telegram for illicit activities such

In conclusion, Telegram is uniquely suited to support civil discourse in Russia’s closed media environment. Instead of focusing on free access to the traditional internet, the State Department should throw its weight behind Telegram and other secure messaging platforms on which Russians can read independent news and speak freely amongst themselves. To be specific, there is a need for clearer messaging regarding how users can further protect their personal information. Supporting Telegram— in addition to other forms of secure communication—will enable Russian citizens to have the difficult conversations necessary to come to terms with the atrocities in Ukraine, and to process the state media’s misrepresentation of the conflict.

“information access is an area of concern, but more important is citizens' ability to speak freely amongst themselves.”

Intheearly2000s,awaveofleftistgovernmentscametopoweracrossLatinAmerica.The‘PinkTide’promisedsocial andeconomicdevelopmentandrejectedtheneoliberalpoliciesinvogueontherightofthepoliticalspectrumatthe time.ItwasfueledbyaboomincommoditypricesasgovernmentsacrossLatinAmericabrokewiththeirpastand enactedambitiouspolicies.However,despiteprogressinreducingpovertyinmanyofthesecountries,thecombinationofincumbencyfatigueandcommoditypricecrashesbroughtaresurgenceofright-winggovernmentstopower intheearly2010s.Now,inthewakeoftheCOVID-19pandemic,thepoliticalpendulumhasagainshiftedtothe leftintheregion,andnewlyelectedleftistgovernmentshaveanopportunitytoapplylessonslearnedfromthe2000s toimprovetheirpolicies.However,theywillalsohavetocontendwithamuchmoreuncertainglobaleconomicand geopoliticalsituationthanduringthefirstPinkTide.

ThisroundtablelooksatfourimportantcountriesinLatinAmericawhereleftistgovernmentsarecurrentlyinpower: Colombia,Brazil,Argentina,andMexico.Ineach,ourwritersexplorelinksbetweenpastandpresentleftistgovernments,andevaluateopportunitiesandchallengesthesegovernmentswillfacebothnowandinthefuture.Willthe newPinkTidebuildonlessonslearnedanddeliverincreasedprosperityforthepeopleofLatinAmerica? Alternatively,willitbeunabletoovercomethedifficultsocial,geopolitical,andeconomiccontextintheregionand theworld?

On November 7, 1985, a militant guerrilla group known as M-19 sent a message to the Colombian government from inside the Palace of Justice in Bogotá: end the Siege, send in the Red Cross, and begin dialogue. The military then sent a tank into the halls of the Palace. In the ensuing 27-hour military operation, more than 100 civilians were killed. It is surprising then, that Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, is a former member of M-19. But despite his connections with M-19, Petro represents a crucial break with the past.

Petro is an unusual candidate based on his past, and in the context of Colombian electoral history his victory is even more unexpected. Throughout the lifetime of the Republic, the people have never elected a leftist president. Yet, Colombia has also been frustrated by a raft of economic woes, mostly due to inequality and poverty. With a 20 percent youth unemployment rate and 40 percent of the population living in poverty, the country was primed for a shift in leadership. These economic realities, combined in a nation tired of fighting with itself for 70 years, formed fertile ground for Petro’s movement. Faced with an opposition that sought to continue the violence, in 2022, Colombia voted for peace, both physically and economically, with a population exhausted after decades of conflicts with guerillas and drug cartels.

Chile, Brazil, and Mexico are all part of a new wave of leftism and progressivism. This new phenomenon frequently elicits comparison to the older Pink Tide of the early 2000s, which brought to power leaders like Evo Morales in Bolivia and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. Despite this, the older wave quickly fizzled out. Unlike these countries, Colombia did not participate in the previous Pink Tide. This combined with Petro’s mold-breaking election means that Colombia is able to forge a new path, free of the failures of the previous Pink Tide. If the new one seeks greater longevity, perhaps it must also seek an example in Petro.

The surprising thing about Gustav Petro is, for a former guerrilla leader, he’s rather willing to compromise with opposing parties. He appointed a Liberal economist as his minister of finance, a conservative-leaning foreign minister, and another conservative as his minister of education. For Petro, a new leftism is crucial, one which seamlessly blends the revolutionary tendencies of his past with a modern and distinctly democratic form of socialism.

In his first months in office, he has pushed through a sweeping tax reform bill that institutes an inescapable basic corporate tax of 15 percent directed at fossil fuel giants, financial firms, and the wealthy. He has advocated for guaranteed jobs and income for all Colombians, seeking to alleviate the poverty that grips

the country. Petro’s leftism also has a distinct environmental tint: On the campaign trail, he has focused on the conservation of the Amazon, as well as the incursions of oil and gas giants into the rainforest. In fact, against the opinion of foreign economists, he pledged to end new oil exploration in Colombia.

Colombia has shown that it seeks nothing more than to escape the shackles of violence. Gustav Petro has promised “total peace,” forging armistices and ceasefires with cartels and guerillas. He has shown he is able to govern with support across from the opposition, where environmental protection and social progressivism exists simultaneously with economic reform. In a Colombia that now seeks to move past M-19’s siege and the cartels, this is the way forward, at least for now. In the next decade of the left in Latin America, Colombia must serve as an exemplar of this type of Socialism that upholds the ideals of the Pink Tide without bringing the echoes of repression into the future.

“C olombia has shown that it seeks nothing more than to escape the shackles of violence .”

Not everyday is a former-president, turned convict, released due to a supreme court ruling. Very few then also return to the highest office to lead South America’s largest democracy. Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva did the former, and continues to do the latter.

With the election of Lula, the “most popular politician on Earth”, in late 2022, Brazil followed its South American peers in joining the new Pink Tide. Lula’s 2022 campaign rooted itself in a Biden-esque approach of frustration. It was exacerbated by 4 years of conservative, eerily Trump-like politics under former-President Bolsonaro, and reminiscence. Lula served as Brazil’s highest public servant from 2002 to 2010, enacting policies that allowed him to maintain his long-standing popularity. During his first terms, Lula lifted over 20 million Brazilians out of poverty. Buoyed by high commodity prices, the discovery of an immense oil field and favorable U.S. interest rates, he – much like his South American neighbors – enacted cash-transfers, aided small farmers, and reformed labor and pensions. He simultaneously cemented Brazil’s role on the world stage, creating the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) alliance of developing nations. These policies propelled his popularity to a dizzying 87

percent approval rating by the end of 2010, even as global economic catastrophe ensued. Yet even with an infamous headman, the New Pink Tide faces an uphill battle in Brazil – embroiled by a divided government, deep national divisions, and unfavorable global socio-economic conditions. Though Lula clenched (presidential) victory, so did his opposition. In fact, no other party has ever wielded such singular congressional power as Bolsonaro’s Social Liberal Party does in 2023 – not even Lula’s. Such unprecedented opposition poses a threat to successful legislation and a potential government paralysis. Though dissent can strengthen policy by deliberation, the extreme polarization of Brazilian ideology will likely hinder the transformative governance Lula promised. Symbolized by a mere 0.9 percent lead – a far cry from his former popularity – the severity of this problem already revealed itself on the January 8th, 2023 insurrection, during which Bolsonaro supporters stormed Brazil’s capital in a fashion eerily similar to the U.S.’s January 6th calamity. By contrast, however, Brazil is a young, fragile democracy, having freed itself from the shackles of autocracy and military rule in 1988, and still lacks the foundational gravitas of its Northern peer.

Mending Brazil’s divides will be one of the quintessential challeng-

es of Lula’s term. Notwithstanding, he promised to reformulate the economy for the 21st century, protect native groups and environmental spaces, and undo the damage Bolsonaro inflicted. If enacted, these policies will translate the new Pink Tide into a lived reality for Brazilians. If not, the new Pink tide will merely remain a pop of color in the history books of tomorrow.

Yet, Lula does not confront these struggles alone. Neighbors, like Argentina, face many of the same obstacles to true leftist politics. Yet, even in such circumstances, Lula’s term should not be predestined for failure. Political analyst Oliver Stuenkel admits as much. “Since everybody says Lula will get nothing done,” Stuenkel said, “that provides him with some space to surprise the skeptics.” Nevertheless, the occasional surprise does not equate with political revolution. Perhaps this dilemma may be the crux of the threat to Brazil's New Pink Tide. Lula promised a return to normalcy — a return to the ideals from a former time. Still, a return to the norm, even one as dramatic as Lula’s personal journey, can, at its root, hardly be a tidal wave of change. Rather, Lula’s election poses as a familiar wave once more washing up on the shores of Brazil’s political system.

In a new emerging Pink Tide in Latin America, Argentina remains anchored by its crippled economy and immense debts. President Alberto Fernandez’s electoral win in 2019 reflected the residual presence of the Peronist mindset in Argentina, reactive to deepened economic and social inequalities, staggering poverty, and high unemployment rates characteristic of former President Mauricio Macri’s right-wing government. Peronism, championed by former

President Juan Perón in 1940, represents a populist political movement grounded in socioeconomic redistribution and worker rights. During Argentina’s first Pink Tide, Néstor and Cristina Fernandéz de Kirchner adopted Peronist policies in resistance against neoliberal hegemony.

Argentina’s first Pink Tide paved the way for Fernandez’s rise to power. The Kirchner years marked an exciting shift for Argentina as leftist socio-economic reforms were cush-

ioned by the mid-2000s commodity boom and reduction in United States interest rates. Between 2003 and 2007, Nestór Kirchner’s expansion of public expenditure led to drastic improvements in Argentine living standards, with unemployment and poverty rates cut in half since 2002. Considerable economic growth concealed the defective mechanisms at work: state subsidies and devaluation of the peso to nationalize major industries and preserve employment

accumulated expansive fiscal debt. By 2015, Argentina’s economy faced extreme inflation.

In light of this economic struggle, Argentina’s political pendulum swung right, in favor of President Macri’s neoliberal promises of “a shower of foreign investment” and “zero poverty.” This counter-tide, regionally prevalent around the same period— notably in Mexico and Brazil— faced growing discontentment from Argentine society, particularly in response to Macri contracting the largest ever debt with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). By 2018, nearly 40 percent of the population lived under the poverty line. In response to Argentina’s heavily polarized society and a nostalgia for the Pink Tide, Alberto Fernandez’s popularity grew. Meanwhile, Macri’s market-oriented economics failed to sustain economic growth and alleviate inflation.

Fernandez’s bottom-up approach parallels the first Pink Tide, in its appeal to the working class and

minority groups in Argentine society. Nonetheless, the geopolitical and macroeconomic backdrop Fernandez must handle is not nearly as auspicious. The current President faces a balancing act between managing a 44 billion dollar debt to the IMF he inherited from his predecessor, coupled with the damaged socio-economic state of the country, and the challenge to uphold his reformist zeal.

Fernandez and his Vice President, Cristina Kirchner, have had to navigate a global pandemic and macroeconomic crisis whilst attempting to bolster economic growth and negotiate payments and economic plans with the IMF – without breaking their promise of income redistribution and high public spending. Today, Argentina has one of the highest inflation rates in the world. This raises doubts on the sustainability of the current government’s capacity to address economic inequality in the long-term. The government walks on a tightrope. Reflecting internal political polarization in Argentina,

Fernandez’s center-right government faces pressure from radical Peronist factions, especially from his own Vice President. Rather than tightening the staggering budget deficit and reconciling Argentina’s debts, the government expanded its money supply to boost subsidies and public spending. This internal push and pull of economic stabilization and prioritizing social welfare parallels the conflicting ideals of Fernandez and Kirchner. Argentina’s leftist wave must prove its resilience as this new Pink Tide settles in. The government must decide whether to cut back on public spending, thus undermining its political platform, or to commit to the leftist agendas, risking an exacerbation of inflation and a probable economic crisis. Today, Argentina must reconcile its bipartisan agendas and implement cohesive strategies to overcome its political instability and economic fragility.

On January 6, 2023, passengers aboard a plane at Culiacán airport in Mexico threw themselves onto the floor to avoid gunfire that hit the aircraft's fuselage. This commercial flight was caught in a crossfire between the Mexican military and the

Sinaloa cartel, after the arrest of Ovidio Guzmán, son of notorious drug kingpin “El Chapo.” Guzmán’s arrest cost the lives of 10 soldiers and 19 cartel members in gun battles in the Sinaloa Cartel’s stronghold of Culiacán. Such cases of cartel violence have remained unprecedented during

the presidency of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, elected in 2018 from the left-leaning Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (National Regeneration Movement) party.

As Mexico has one of the world’s largest homicide rates, involving the killing of politicians, journalists, and

security forces, Mexican politics has made cartel-related violence a focal point of public discourse. In Obrador’s election campaign, he vowed to prioritize ‘hugs, not bullets’ and tackle violent crime by fighting poverty using social programs. Overall, Obrador promised to radically break away from the confrontational anti-cartel policies first employed under President Felipe Calderón and his War on Drugs declared in 2006. The Mexican government’s open conflict against cartels skyrocketed cartel-related homicides during the 2010s, yielding a murder rate comparable to that of Colombia, another Latin American narco-state.

President Obrador demonstrated his left-wing, conciliatory approach to drug violence in 2019. After Guzmán was arrested, the President ordered his release to prevent civilian deaths as cartel gunmen sieged Culiacán. Nevertheless, the order to release Guzmán in 2019 remains exceptional in Obrador’s wider anti-cartel policy. Until now, his ‘pink’ government has militarized Mexican security forces. In March 2019, Obrador amended the Mexican constitution, legalizing the use

of military units for public security tasks and establishing a National Guard to replace the Federal Police. Since Obrador’s entry into office, he utilized his revamped security forces to capture several cartel leaders, fueling cartel violence. This year, following Guzmán’s definitive arrest, the Mexican military was prepared to handle the Sinaloa cartel’s retaliation, unlike in 2019. Contrary to Colombia's President Gustavo Petro, Obrador's 'pink' counterpart who abandoned the drug kingpin strategy, Obrador has seemingly yet to realize that leaderless cartels often result in fragmentation and internal conflict.

Furthermore, Obrador's militarization of anti-cartel policies has resulted in welfare austerity to finance substantial increases in the military's budget. Shifting priorities, spending for the Army and Navy surpassed the reduced healthcare budget in 2018 for the first time since 2005. In 2021, the Mexican military's financing was 54 percent higher than in 2018 under Obrador's predecessor, President Enrique Peña Nieto.

If Mexican citizens gave Obrador a landslide victory in 2018, hoping that the Pink Tide could

save Mexico from cartel violence, it seems that the President has done the opposite. At the cost of welfare austerity, Obrador’s militarization of security forces has maintained total yearly homicides at around 30,000 to 35,0000 deaths since 2018. Obrador is struggling to reverse the 76 percent increase in homicides from 2015 to 2021 under Nieto’s presidency. Additionally, human rights organizations have criticized the military for extrajudicial killings and human rights abuses that resulted from its confrontational strategies.

Overall, in a state plagued by corruption and violence, Obrador’s promises to depart from the reactionary cartel policies of his more conservative predecessors have not materialized. If Obrador still cares for the Pink Tide’s progressive identity to manifest within his policies, he should instill his ‘hugs, not bullets’ ethos into his newly reformed security forces. Obrador could learn from his Colombian counterpart by implementing social programs to combat poverty and abandoning the kingpin strategy, thereby protecting citizens and preventing the escalation of cartel violence.

All of the leaders of these Latin American countries seem to believe a shift towards leftism will solve the problems afflictingtheirrespectivecountries,fromeconomicinstabilitytocivilconflict.However,itisclearthatthisnewPink Tidewillnotbearepeatofthelast.