15 minute read

‘Open- air prison’ in southern Mexico traps thousands of migrants

By Taylor Stevens

TAPACHULA, MEXICO – The desperation here is palpable.

I t fills the stifling air as migrants line up in the hot sun outside the National Migration Institute in hopes of receiving an interview, their children close at hand and their visa applications tucked under their arms in colorful protected sleeves so the papers won’t get ruined on the nights their families sleep outside in the rain.

I t strains the voices of the asylum seekers protesting outside a news conference by Mexico’s president, as they chant demands for action before some sew their mouths shut in defiant, gruesome silence.

A nd it wells in the eyes of displaced Haitians – struggling to deal with a system entrenched in anti-Black racism – when they throw rocks and set fires on the streets to bring attention to their plight.

T hese moments unfold day after day in Tapachula, a city of about 350,000 near the border of Guatemala that has long served as a waystation for migrants spurred north by political turmoil, gang violence, discrimination and poor economic prospects in their countries of origin.

B ut as the United States has pressed Mexico to stem the flow of people heading to the U.S. in recent years, tens of thousands of migrants have become trapped here in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state.

T hey now face extreme limitations on their movements, few job prospects, poor living conditions and long waits for immigration hearings in an environment some have labeled an “open-air prison” and others have described as a southern extension of the U.S.-Mexico border.

“You see misery. You see anger. You see desperation,” said Freddy Castillo, a Haitian migrant who arrived in Tapachula last August. “People say, ‘Well, what did I come here for?’ You know, the situation is bad in my country. But that’s supposed to stay there, because I (want to) have maybe a better life someday.”

A s frustrations have reached a boiling point in the city, thousands of migrants set off in the rain Monday for the United States. The group intends to walk the length of Mexico and could grow to as many as 15,000 people, by some estimates – a number that would make this caravan the largest ever recorded in the country, according to The Guardian.

M any of the migrants who end up in Tapachula are from Honduras, El Salvador and other Central American countries, but others started their journeys from such far-flung places as Palestine, Cuba, Nigeria, Brazil and, recently, Ukraine.

A fter escaping the sometimes brutal conditions in their home countries, migrants moving up through South America must pass through the treacherous Darién Gap, a more than 60-mile stretch of jungle that connects Colombia to Panama, where robberies, rapes and encounters with animals are frequent.

T he journey takes multiple days for most migrants. And those who make it out alive sometimes view Mexico as a reprieve, said Yamel Athie, a Tapachula resident and community organizer who has been facilitating dialogue between migrants and locals. I nstead, they face only more challenges.

“I magine if you are from Africa or the Middle East or Haiti and you have spent months fighting to survive, to live, to eat, to pay for your trip,” Athie said. “And when you arrive here, with all of your emotions at the surface because you are reaching your goal, you smash into a wall. And it is a wall that will break your soul.”

The new caravan is yet another sign that although Mexico has stemmed the flow of migrants on their way to the United States, it hasn’t shut it off completely. In April, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported that U.S. officials encountered about 230,000 people attempting to cross the southern border – the highest monthly total in at least the past four years. An encounter is defined as either the apprehension or expulsion of a migrant.

And some analysts predict even more will come because of President Joe Biden’s stated intention to end Title 42 – a policy the federal government used during the pandemic to expel thousands of migrants under the guise of public health protections. Shortly after Biden’s April 1 announcement, groups of migrants took off from Tapachula for the United States, defying local restrictions on their movements. Some fought with police and Mexican immigration officials.

On May 20, a U.S. federal judge blocked the Biden administration from ending Title 42, agreeing with a complaint from 24 states that the move would increase illegal immigration. He also ruled that the administration must provide public notice and a comment period before ending the policy. The administration has announced it intends to appeal the ruling.

Despite migrants’ frequent complaints of poor conditions in Tapachula, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico offered little recognition of and few solutions during his remarks at a news conference in the city March 11.

The best way to help migrants, he said during a brief discussion of the issue, was not to improve conditions in Mexico but to create work programs for them in Central America.

“People don’t hit the road because they enjoy it but because of necessity,” he said. “The majority of the migrants are young people who want to move forward and progress in life – so we have been proposing that there be investment in Guatemala, in Honduras, in El Salvador.”

That approach mirrors the United States’ “root causes” strategy, which seeks to address the forces that push people to leave their home countries as part of an effort to stem migration before it begins. But the strategy would do nothing to help improve conditions for the migrants who protested beyond the white tent set up for López Obrador’s visit.

Wairiuko Samuel Kimani, an asylum seeker who said he fled his home country of Kenya after his family learned he was gay, survived 10 days in the rainforest in Panama. He said being in Tapachula has been worse even than that. At least in the jungle, he saw a way out.

“These people you see here,” he said, motioning around to the mass of migrants nearby, “they are very frustrated because we thought getting out of the Darién Gap was all. We thought that was our living nightmare. But actually Mexico is.”

‘The job of President Donald Trump’

D uring a religious festival in early March, three national flags were posted in the middle of the Suchiate River, which separates Chiapas state and Guatemala –the Mexican flag, the Guatemalan flag and the stars and stripes – a symbol of U.S. influence here, although its border is more than a thousand miles to the north.

U nless they pay a coyote who takes a different route or they have the means to fly over Tapachula, many of the thousands of migrants who make the journey north through Central America each year will cross the Suchiate here.

A bout 70% to 80% of all asylum applications in Mexico are filed in Tapachula, according to the local refugee office. In 2021, that number was 89,000 applicants. And because the city is so close to a main route into the country from Guatemala, Tapachula is “always going to be a place of pressure and then relieving that took root in 2019, after thenPresident Donald Trump threatened to impose tariffs starting at 5% on Mexican imports if the country didn’t increase efforts to “reduce or eliminate the number of illegal aliens” coming to the United States.

F earing the potential impact to its economy, Mexico – whose biggest trading partner is the U.S., and vice versa – struck a deal promising to deploy members of pressure and then pressure again” when it comes to migration, said Rachel Schmidtke, an advocate for Latin America with the global nonprofit Refugees International. B ut the pressures here have felt higher than ever in recent years, thanks to a complicated cocktail of government bureaucracy, politics and pandemic-related challenges that have further exacerbated the difficult conditions for migrants. The same cocktail has strained Tapachula residents, who face great competition for jobs and housing.

“I absolutely believe that U.S. pressure on Mexico has a lot to do with why Mexico has militarized its southern border and is trying to keep migrants out of the country – to stop flows of people coming to the U.S.-Mexico border,” she added.

L ópez Obrador, for his part, has said the shifts in Mexican policy are not a result of his bowing to U.S. pressure. Instead, migrants are being kept in the south to protect them from the powerful gangs that operate near Mexico’s northern border, he said.

“We don’t want them to come to the north where they might become drug addicts or victims of crime,” he said in a press conference in January 2020.

W hatever the motivations, experts say the policy shifts that resulted from the 2019 deal have significantly restricted the movement of migrants.

B efore the agreement, “people were for the most part getting through Mexico,” said Arturo Viscarra, a staff attorney with the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, a nonprofit migrant advocacy and civil rights group that is working in Tapachula.

M ost experts agree that the current situation in Tapachula the National Guard to its border with Guatemala. The deal also expanded the Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as the “Remain in Mexico” program, which requires grants to stay in that country while awaiting immigration processing in the United States. Most applications for asylum or other forms of entry are denied.

S chmidtke said Mexico’s harder line toward immigration has in part reflected its own values, noting that the country doesn’t want “a lot of refugees or migrants.” But the U.S. also plays a “pretty significant role in Mexico’s immigration policies,” she said.

B ut the National Guard’s increased militarization of the southern border has since made it “more difficult” for people to get through the country, he said.

J ust one month after the countries signed their deal, the Mexican National Institute for Migration held more than 30,000 migrants in detention – “the highest number of detentions made in a month in the last 13 years,” according to Refugees International.

I n Tapachula, Kimani, the Kenyan migrant, described the city as a prison, noting that many migrants struggle to leave without proper paperwork.

“I think this, all this you see here, is the job of President Donald Trump,” he said, gesturing to the masses of people gathered outside the National Migration Institute office.

A lthough experts and migrants blame Trump for some of the on-the-ground realities migrants face in Mexico, Kimani said U.S. politics continue to drive changes here even under a new administration.

H e said he’s heard from several migrants who began their journeys after Biden was elected in 2020, in hopes that they might benefit from the Democrats’ softer approach to immigration.

B ut while the rhetoric has changed significantly under the new president, many U.S. immigration policies have remained much the same – and they continue to send ripple effects from the southern border of one country to the other.

“M ost people came because they thought Biden would have a new effort or a better effort toward migration,” Kimani said. “According to what I have read, he hasn’t done much.”

Below: The U.S flag is set up in the Suchiate River, which separates Mexico and Guatemala, during a 10-day religious festival on March 4, 2022. Some observers have called the nearby city of Tapachula, Mexico, the “new U.S. border,” and the flag served as a physical representation of that idea. (Photo by Drake Presto/ Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Rosbalis Parez and her son, Daniel Alejandro, 2, wait in the crowd outside the COMAR office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 9, 2022. The Venezuelan migrants have been living in a tent close to the office while waiting for their immigration paperwork. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

‘I need free movement’

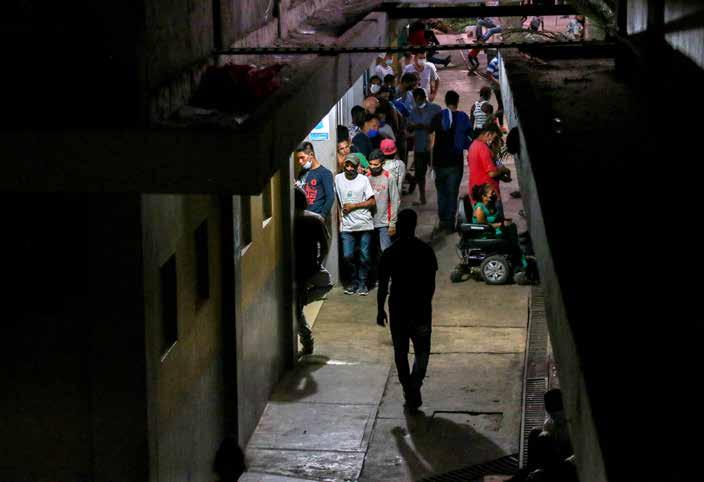

On a muggy day in March, migrants line the wall up and down a colorful mural outside the National Migration Institute office, desperate to obtain an audience with officials who could grant them an earlier immigration appointment. The energy in the air is at once frenetic – as if a protest could erupt at any moment – and listless, as the day gets hotter and they go longer without food and water.

“E very day people are here,” Kimani said, “because they’re trying to reduce their dates. There are people whose dates have been reduced, but I don’t know how they choose who they reduce their dates for.”

N ear the office, National Guard members with shields keep the crowd at bay, avoiding eye contact with the migrants huddled before them.

Am ong the group are Maria Linares and Yandry Mijares of Venezuela, who said they fled the government corruption and violence of their home country in hopes of securing a better life for their son and daughter.

Bu t after they arrived in Tapachula in January, the family found that their struggles were only compounding. Unable to find work, they struggled to pay rent and instead had to sleep on the streets each night. Unable to buy food, their children were facing malnutrition. And without proper immigration documents, they said, their asthmatic son can’t get a prescription for an inhaler.

Li nares spread paperwork out across her hands showing that each family member had a different immigration appointment date – all of which were weeks into the future.

Ev en under normalcircumstances, the process to apply for asylum or a humanitarian visa in Mexico can be long and complex, requiring multiple appointments, interviews and documents. And the stakes are high for people like Linares and Mijares, who are sometimes stuck in limbo for weeks or even months without proper immigration papers.

A s they wait for their applications to be processed, migrants are required to stay in the state where they submitted their claim. In the meantime, they become effectively stuck in Tapachula, with limited housing and job opportunities.

Th ose who try to leave the city without authorization risk detainment in the governmentrun immigration center known as Siglo XXI, and they could be deported to their home countries. Me xico’s already challenging immigration process was further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted the United States to effectively close its borders to migrants under Title 42. Since Title 42 was enacted, Schmidtke said, many migrants became “basically incentivized to stay longer in Mexico.”

Th e number of asylum applications had already been rising in Mexico, doubling “each year from 2015 to 2019,” according to the U.S.

Congressional Research Service. But by 2020, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid, known by its Spanish acronym of COMAR, faced steep backlogs, which it was able to work through only with help from the U.N. High Commissioner. The agency in 2021 again struggled “to meet record demand” for asylum claims.

Al though the number of applications has spiked, not all these migrants want to achieve refugee status in Mexico –particularly because doing so could complicate their efforts to ultimately get legal protection in the United States. And not all the applicants are necessarily eligible for asylum, an international protection available only to people who can prove a “wellfounded fear of persecution” based on their race, religion, political opinion, nationality or membership in a particular social group.

M exico does offer asylum to a broader subset of people than the United States. People whose home countries face “generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive human rights violations, and other circumstances that have seriously disturbed public order” are also eligible for asylum under the Cartagena Declaration, a nonbinding agreement reached in 1984.

I n some cases, migrants apply for asylum in Tapachula as a protection against deportation because they can’t be booted out of the country until their claim has been processed. Others apply so they can obtain a humanitarian visa free of cost, according to Alma Cruz, who is in charge of COMAR’s Tapachula office.

Th e visas, which are issued by the National Institute for Migration and are valid for six months to a year, facilitate access to important government services, including education, health care and permission to work, according to Refugees International.

T hat’s why long waits for humanitarian visas pose such a problem for migrants stuck in Tapachula.

“T he people are coming to us, and if you ask them, they don’t want to be here,” Cruz said.

“They don’t want to be refugees here. The complaint of the people is, ‘I need free movement in Mexico. … I need a humanitarian visa. I need to go out from here as soon as possible.’ And COMAR is not the source of the problem.”

W hile they wait for documentation, masses of migrants in Tapachula spend long days in parks or in the city square, where the men often bide their time playing chess and the women braiding each other’s hair.

So me resell goods on the streets, keeping a watchful eye out for city employees who could shut them down for operating without work permits. Others beg passerbys for money for food or other necessities.

O scar Sierra, who fled Honduras with his wife and three children in early January, looked for formal work when he arrived in Tapachula but found his options limited. He considered a particular job only to learn that it required grueling hours from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., with a daily wage of 150 pesos (about $7.50).

“I t is heavy,” he said, standing with his wife and three children in front of the city steps where they slept their first night in Tapachula. “The people are taken advantage of.”

Si erra said his family had a good life in Honduras and never imagined they would have to leave everything. But as their piñata business became more successful, gangs took notice and began extorting them for money. They were quickly in over their heads, estimating that they owed thousands in protection money. And they feared that they would be killed when the payday came.

Th at’s when they left everything they owned and got on a bus to Tapachula.

Th e family ultimately hopes to make it to the United States to restart their business. In the meantime, they’re trying to pay the bills by churning out piñatas in their small apartment at a rate of four or five per day.

But at 2,000 pesos a month, the apartment isn’t cheap, and they’ve had trouble making rent.

“T he economic situation is complicated,” said Lizeth, Oscar’s wife.

Go vernment jobs programs can help some migrants, but not everyone can take advantage of them.

Af ter finding ways to make money, obtaining shelter is among the biggest challenges migrants face in Tapachula.

La ndlords often charge them exorbitant rents, which some migrants counter by sharing a unit with others to split the cost. Athie, the community organizer, said space was so limited in December that some homeowners began charging people to sleep on their roofs.

“They put up plastic tarps, and people charged them for this,” she said. “It is very sad.”

So me migrants end up in shelters, but space is limited and they often are over capacity, according to a March report from the humanitarian aid organization UNICEF. So those who can’t find work often end up sleeping on the streets; the lucky ones finding an out-of-the-way corner or a thick piece of cardboard to provide some support from the hard ground.

De spite their limited resources and different backgrounds, some migrants do their best to help others.

On one occasion, a group pooled their money together so they could prepare a community meal near the town square – a small act of solidarity within a population that so often ends up fighting for scraps.

“M any of the children were very hungry –not just the Haitian children, but Venezuelan children, all of us,” said Wilnot Devalsaint, a Haitian migrant who has been in Tapachula since late last year. “So what do we do among all of us? We asked, ‘Do you have 10 pesos, 5 pesos, 4 pesos, 20 pesos?’ And so we put it all together to make food. To help each other.”

Fo r all the challenges migrants have faced here, Athie said, their influx also has strained longtime residents of Chiapas state, leaving them with fewer jobs and housing options. Some even see the presence of so many outsiders in the small, poor city of Tapachula as something of an invasion, she said.

“T he local people feel really harmed by the presence of migrants here,” Athie said.

Os car Ulises Sol Diva, a lifelong Tapachula resident, said he has stopped walking his dog at night over fears of violence. He said he understands the obstacles migrants face but noted that many permanent residents in the community don’t have much to give – they’re struggling themselves to find work and to feed their families.

“I don’t know,” he said, “it makes us mad sometimes, with the migrants. They want everything. They say, ‘Give me, give me!’”

A thie, whose family migrated to Mexico from Lebanon, said she has tried to help both sides better understand one another through a community Facebook group she started. On it, she advocates for “a dialogue and a language where we are able to share the co-humanity of everyone and the necessities that we all have.”

Be cause in an area that’s long been shaped by migration, for better and for worse, experts say it’s unlikely that the flow of people through Tapachula will end anytime soon.

Ki mani and other migrants, however, said that if they’d known what awaited them in Tapachula and on their journey here, they would have never left home.

“If you are not in immediate danger, if it’s something you can control, it’s better not to come right now,” Kimani said he would advise other migrants. “Here, people are sleeping out. They don’t have food. They don’t have somewhere to sleep. People are desperate.”

Don’t come, he added, unless “you are willing to be that kind of desperate.”