CATALINA TUCA

Mentored by Esperanza Mayobre

Presented by CUE Art

137 West 25th Street

New York, NY 10001

CUE Art

All artwork © Catalina Tuca

Photos by Leo Ng

Graphic design by Valentina Améstica

Catalina Tuca

June 20 - August 10, 2024

CUE Art

Exhibition Mentor:

Esperanza Mayobre

Catalogue Essayist: Alexandra Trujillo Tamayo

Writing Mentor:

Aimé Iglesias Lukin

Luma is a solo exhibition by Brooklynbased artist Catalina Tuca with mentorship from Esperanza Mayobre. The exhibition presents new works by the artist informed by the luma—the word used for a police baton in Chile, as well as for a species of evergreen tree that is the source of the dense wood originally used to make them. Tuca explores the paradoxes between these two meanings, positioning the luma as a mediator of geographic identity, cultural heritage, ecological understanding, and systems of power.

Tuca’s work “reminds us that objects are not simply inert products of society, but active agents that participate in the construction and reproduction of social and cultural meaning,” writes catalogue essayist Alexandra Trujillo Tamayo. Through film, sculpture, drawing, and archival material, the exhibition contemplates meaning-making through language and objecthood, reflecting upon the use and transformation of the luma to reveal the blurry boundaries between the local and the global, the personal and the collective.

Amomyrtus luma, the scientific name for a type of myrtle tree now found primarily in the south of Chile, has long been an important resource to indigenous and local communities. Its leaves, berries, and bark have provided food, medicine, and firewood to inhabitants of this land, including the Mapuche peoples, for centuries. The word luma—now also the name of a larger genus of trees in the Myrtaceae family—comes, in fact, from the Mapuche word for this particular species.

As part of the exhibition, Tuca presents a new film-based work that documents her search for the tree, situated in three national parks on the island of Chiloé. The film orients us to the ecosystem of the island, shifting focus in scale from the sweeping landscapes of the forest where the luma lives to the textures of its foliage.

She undertakes a sort of pilgrimage—a metaphorical reversal of the exploitation of the luma for its subsequent use as a weapon of state power.

Tuca’s familiarity with the luma stems from this latter form. Coming of age during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, the wooden baton worn as part of police uniforms represents a distinct period of political unrest for the artist—and has a strong presence in the collective memory of Chileans of her generation. The wood of the luma tree, incredibly hard and resistant to impact, made an ideal material for use by the military police to strike protestors and dissidents. The blows dealt by the baton are still referred to as lumazos, even though the weapon itself is now made of globally produced polycarbonates.

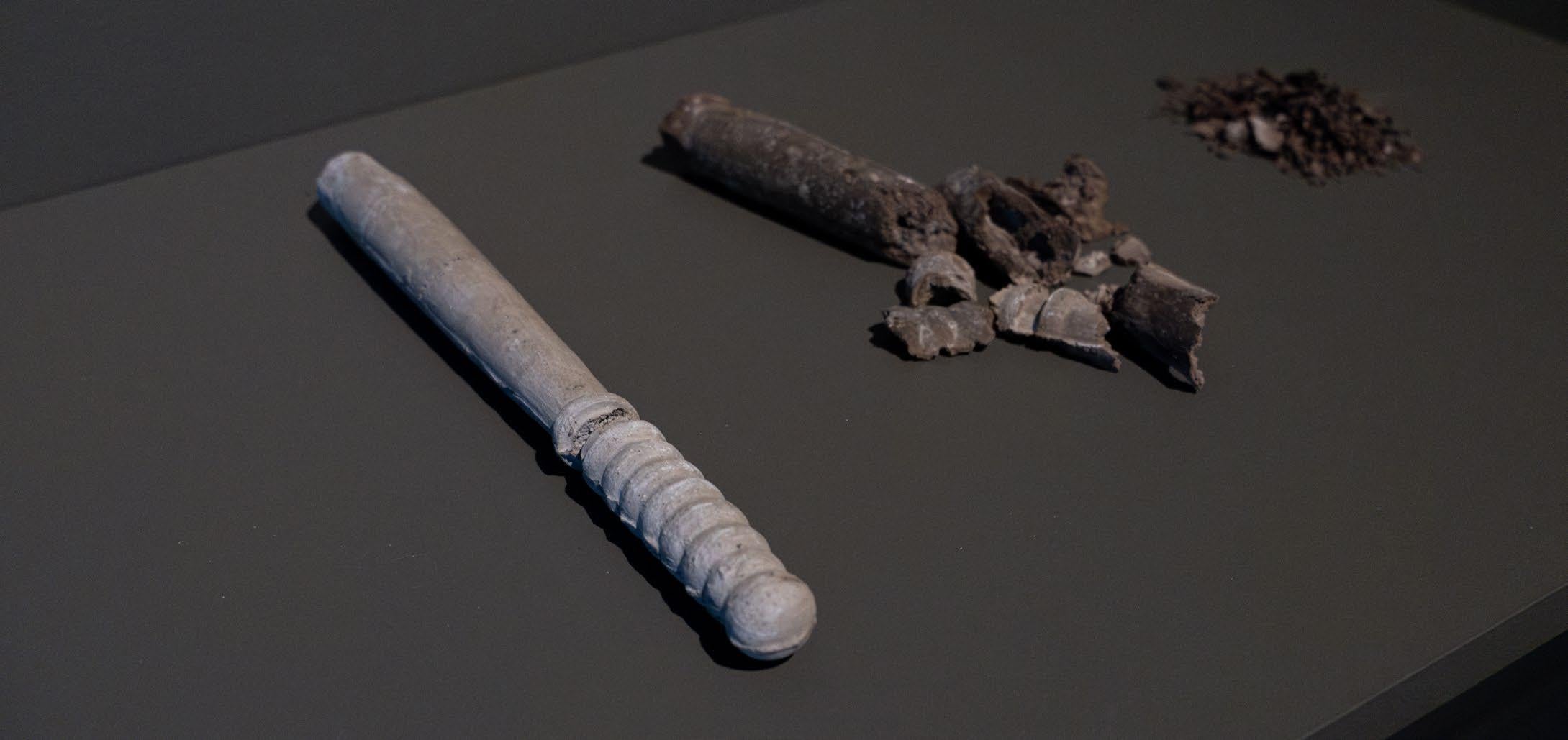

Luma materially intervenes in this complex history. Alongside an original wooden luma from the dictatorship period, Tuca presents her own cast sculpture versions, materially intervening with its form to draw attention to the dichotomy between ecology and violence. Rendering the baton in clay and soil, she softens its impact, allowing it to decompose back into the earth. Further reflecting upon the tree as a natural resource, she presents drawings that contextualize its stories, referencing the illustrations of botanist Adriana Hoffmann. Hoffmann spent her career documenting the flora of Chile, and in the process became a prominent environmental activist and critic of the state’s sustainability and forestry policies.

Luma orients us toward multiplicities of meaning, tracing the many narratives embedded within a seemingly definable symbol of violence and oppression. In uncovering and translating these latent histories, Tuca’s work widens our perception of the ecosystems we inhabit, allowing us to consider their expansive roots.

Catalina

Tuca

I work with found objects and their multiple mediated representations to explore intersections between personal and collective memory. Using media such as installation, photography, and video, I create fictionalized spaces that use the expressive potential of things—and their systems of display—to question notions of identity in relation to culture and territory, and to reveal the blurry boundaries between the local and the global, the personal and the collective.

My practice employs domestic objects as ethnographic tools to examine specific cultural contexts and the intricate geo-socio-political whole we inhabit, in which tradition, globalization, and technology collide and intertwine. My Latin American upbringing informs personal modes of thinking and creating, based on the notions of precarity, vulnerability, and resourcefulness.

To expand the range of my interactions with objects, I often transfer part of the decisionmaking process to others, opting for collaborative staging and processes of translation. These exercises allow me to explore concepts of interdisciplinarity and authorship, creating participative aesthetic experiences in which the uniqueness of each part is the fundament for the whole.

CATALINA TUCA (b. Santiago, Chile) is a multidisciplinary visual artist, educator, and independent curator. After earning a BFA and a degree in Visual Arts Education, she developed her career in Santiago, Chile by showing her work in solo and group exhibitions, teaching visual arts and film, and creating and directing art spaces.

Tuca has had residencies at Youkobo Art Space (Tokyo, Japan); Taller 7 (Medellin, Colombia); and Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (United States). In 2016, she moved to the U.S. to pursue an MFA at Rutgers University, which she received in 2018. She has been a member at NEW INC (New York), a resident at NARS Foundation (New York), a fellow at the Interdisciplinary Art and Theory Program (New York), a resident with Collider Artist Residency at Contemporary Calgary (Canada), and a grantee of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts (New York). She is currently an Adjunct Professor at Pratt Institute. Tuca lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

ABOUT THE WORKS

OBSERVATION

The luma used by the police is known to all Chileans. However, few know that its name comes from a native species of tree. I remember hearing this fact from my father when I was a child. Many years later, I realized that—even though I am keen on observing and learning about the plants of my own and other geographical territories—I did not know anything about this particular tree.

I decided to look for images that could help me identify the luma tree, and I found them in my family home in Santiago, Chile. There, I encountered one of Adriana Hoffmann’s field guides to the flora of Chile. Hoffmann (1940–2022) was a pioneer of Chilean botany and environmental sciences. She wrote many seminal texts in her field of study, and her books were the first—and perhaps remain the only—resources that provide in-depth research and information about the country’s native species.

This book and its illustrations served as my first encounter with the Amomyrtus luma, and Hoffmann’s illustrations became a reference for the drawings I present in the exhibition. The exercise of observing details, parts, and structure of the tree made me one step closer to knowing it. I employed an illustration technique similar to the one Hoffmann used in her guides, but changed the scale and augmented the botanical illustrations with drawings of a congruous style that depict the design and contemporary use of the luma as baton—one of many human extensions of the tree.

EXPLORATION

After studying the luma through drawings, I felt ready to find and meet the tree in its natural environment. I sought to document more contextual information about the temperature, light, and sounds of its environment as well as the flora and fauna that live with and around it. Moving image seemed to be the best form of aesthetic encounter for this purpose, and the result is the film presented in the exhibition.

To document the luma was not an easy task. The Amomyrtus luma is difficult to identify, as it is part of the Myrtaceae (myrtle) family, and other native species of myrtle share similar characteristics. The chequén (Luma chequen), arrayán (Luma apiculata, also known as quetri or temu), and meli ( Amomyrtus meli ) all grow in the southern regions of Chile—in rainforests, near streams, and in other moist habitats.

Amomyrtus luma is also known by the scientific names Myrtus luma, Myrtus valdiviana, Myrtus darwinii, and Eugenia darwinii—the last of which is a reference to Charles Darwin, who spent three years traveling through Chile and conducting explorations that would contribute to his famous theory on the evolution of species. The tree’s common names, aside from luma (a Mapuche word), include; palo madroño, reloncaví, luma colorada, and cauchahue. It has small and glossy leaves and white flowers, and it bears an edible fruit called cauchao, a purplish-black small and round berry, used to make marmalade, juice, and chicha, an alcoholic spirit imbibed by local communities.

The wood of the luma is hard and dense, and resistant to rot. For these reasons, it is used to make tool handles, architectural fittings for stilt houses, and blunt weapons such as the baton most Chileans consider the sole use of the word luma. Due to its high caloric capacity, the wood of the luma tree is widely used as firewood to heat homes, and in many places it has become increasingly scarce and even endangered.

I was led by local experts to the national parks on the island of Chiloé, which are protected and allow the luma to grow undisturbed. In the forest, with many species of trees growing together and entangled in symbiotic relationships, the search seemed as though it may be a failure. However, with guidance from locals who have lived amongst the tree for generations, as well as through modest signage at the entrance to one of the reserves, I was able to find, witness, and document it through this film.

EXCAVATION

I am interested in objects as extensions of our minds, as metaphors for how we relate to the world and to each other. In Chile, the luma—as an object—occupies a prominent place in the collective memory of my generation, regardless of one’s political affiliation or level of engagement. Whether you are on the right or the left, whether active in politics or not, if you were able to form memories during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (from 1973–1990), the luma I present in the exhibition is known to you.

The version of the luma fabricated from wood was widely used by Chilean police officers (carabineros) since at least the 1920s. It was part of the police uniform, with a dedicated slot on a belt around the waist. There were sometimes variations in its size. In the 2000s, it began to be fabricated in new materials (polymers), its design consistent with others found around the world. In Chile, however, it has retained its linguistic connection to its source material. We still call this object luma, but today, the version made from wood is a historical object, long gone from public space and use.

I am interested in the luma as an example of the complex layers of meaning that are contained within an object, in its sociocultural, political, and environmental dimensions. This small baton is a powerful symbol of its context, and suggests a darkness of humanity through the specific violence it was used for during the Pinochet regime. And yet, the narratives it embodies are universal and connect to many other territories and ecologies. How do the objects we use tell us about the worlds we inhabit and the ones we create? The luma is one story of many.

RECOLLECTION

This photograph, presented in the media in 1984 and now in the archives of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile, depicts the luma in action, fulfilling its purpose of violence during one of the longest periods of dictatorship in South America.

Led by Augustio Pinochet, a military coup bombed La Moneda, the seat of governmental power in the capital city, on September 11, 1973. The event, like many other military interventions in Latin America, was spurred in part by the involvement of the United States, its then president Richard Nixon, and the CIA. It led to the death of democratic socialist president Salvador Allende, the first democratically elected Marxist head of state in Latin America.

Pinochet governed until 1990. The legacy of his regime includes the internment of 80,000 people, the torture of tens of thousands more, and the execution or disappearance of an unknown number estimated between 1,200 to 3,200 (and potentially greater than this). Pinochet’s administration enacted violence on people but also the land, giving free reign to corporations over a massive amount of public territory and allowing them the ability to capitalize on and exploit Chile’s natural resources.

This small archival photograph presents a contrast in scale and color to the polychromatic large scale drawings and film with which it sits in conversation. Together, they create a formal dichotomy that reflects the double sided reality of the luma as an object and a tree, and that brings to light the paradoxes of our material culture.

PROJECTION

Through a sculptural gesture, I seek to propose an alternate narrative for the objectbased luma. I cast it in clay and soil, making a reproduction of the original, but one that transforms it from hard—and harmful—to soft, precarious, and fragile. What would it mean for the luma to decompose and return to the earth?

In its native habitat, there are already many other narratives for the luma. In Chiloé, people know it as the most desirable source of heat. “Arde como la luma” (“It burns like a luma”) is a common expression in this cold and rainy region, where firewood stoves ingest pieces of wood—roughly the same size and shape as the baton version of the luma—to provide warmth indoors.

Extraction is a constant threat to the native forests. During her long career, some of which took the form of environmental activism, Adriana Hoffmann exposed paper and logging companies for their role in the destruction of local ecosystems, writing books such as La Tragedia del bosque Chileno (The Tragedy of the Chilean Forest). The cutting of the forest has not yet ceased. Violence is ever present.

And still, the luma continues life through multiple transformations, in a cycle of life and death, from the soil to the air…and perhaps returning once again.

“What color is the spatial infinity? It is the color of air.”

—Clarice Lispector, Agua Viva

After returning from her recent expedition to the island of Chiloé in southern Chile, Catalina Tuca told me “I found the luma. It was a fugitive—hard to identify. Chile has plenty…but what is plenty?”

Tuca plays with forms of exploration, bringing us into the world of the luma. Her drawings, reminiscent of scientific illustrations, share an affinity of sorts with the adventurers, botanists, and anthropologists of the Enlightenment. Through film, she takes us to the forest, documenting her search for the tree and allowing us to experience a romantic evocation of the picturesque landscape that is its home.

And then, she introduces us to the other luma—the one that she did not have to travel very far to find, the one that is viscerally embedded in her cultural memory. This luma, a baton used by police, was omnipresent during the dictatorship of Pinochet and its many years of brutal police repression. In protests, on the street, and behind closed doors, it was used to further a political context that left many people missing, imprisoned and in exile. The violence and power of this luma is palpable. A found version of the object bears the marks of its use; a small historical photograph depicts a police officer—a carabinero —striking a civilian with his baton.

It is through these symbols that Tuca juxtaposes and overlaps multiple meanings. The beauty of nature morphs into a tragic violence of humanity. The romantic notion of ecological exploration through the lens of those such as Alexander von Humboldt becomes a reminder of the mercilessness of civilization, of The Social Contract.

Amomyrtus luma grows near the water in the temperate and humid forests of Chile and Argentina. It has ancestral Mapuche medicinal uses. Its flowers are used for honey production; its wood to kindle fires and heat homes. It is hard and burns slowly.

In the national parks of Chiloé, park rangers have trouble distinguishing the tree from others. Tuca turned to other forms of local knowledge, enlisting a guide and following the signs until she learned its unique indicators—until she could spot its leaves, for example. After that, she encountered it everywhere.

And yet, this luma is endangered. Its remnants are in the air as much as in the forest, as it is constantly being cut down and used for firewood in domestic chimneys, sometimes—in populated areas of the region—making it hard to breathe. The impact of this extractivism, even though primarily local, is profound. The luma is not being replaced or regenerated, either in policy or in practice. The deforestation—itself a cycle of violence—continues.

Tuca is neither a romantic nor an explorer, although she plays with these roles and their histories in her practice. Instead, she serves a facilitator and a translator, bringing forth that which is perhaps empirical—but to whom? Through poetic gestures that seek to interpret the paradoxes of the luma, she makes visible hidden forms of knowledge, and draws out the contradictions of nature—both ecological and human, simultaneously beautiful and violent.

ESPERANZA MAYOBRE is a Brooklyn-based Venezuelan artist who creates fictive laboratory spaces. She inserts herself as a hero, writing a role for herself in the work. She uses light as a metaphor for birth; drawings to create infinite lines; candles to create lines of light; dust to convert illegal to legal aliens. She gives away money to talk about the debt of Third World countries, and makes elegant graffiti to portray urban chaos.

Mayobre has exhibited at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University; the Americas Society; Baxter Street Camera Club; the Fuller Craft Museum; the Museum of Fine Arts Boston; Museo Eduardo Sivori, Buenos Aires; the Queens Museum; The State University of New York Westchester Community College; La Caja Centro Cultural Chacao, Caracas; The Bronx Museum of the Arts; Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center; MIT CAVS; BRIC; the Art Museum of the Americas, Washington DC; the Contemporary Museum of El Salvador; and the Incheon Women Artists’ Biennial, South Korea. She has participated in many residency and fellowship programs and has received numerous awards, including the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, the Lower East Side Printshop Keyholder Residency, the Jerome Foundation Travel Grant, the International Studio & Curatorial Program, Smack Mellon’s Artist Studio Program, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace, and a fellowship at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. Her work has been in Artishock, BOMB, The Brooklyn Rail, Hyperallergic, the New York Times, Creative Time Reports, Arte al Día, and Art in America

Alexandra

Trujillo Tamayo

Catalina Tuca’s practice is situated in a fertile ground of political and environmental interpretation. Interested in the performativity of objects and their relationship to human behavior, Tuca’s works give new dimension to the idea of nature, uncovering layers of ecological, sociological, and psychological meaning embedded in the things we think we know.

It is not surprising, then, that her most recent body of work, presented in the solo exhibition Luma at CUE Art, took her to the national forests of Chiloé, an island in the southwestern part of Chile. This work, at once a process of research and resignification, traces the bodies of the forest and objects that derive from it, and positions them as far more than passive tools to be used, but rather as active agents in the construction and reproduction of identity. Tuca focuses in particular on the paradox of the luma, a police baton in Chilean Spanish, and its origin, a tree of the same name. In bringing awareness to this duality of meaning, she challenges established narratives and promotes a critical awareness of Chile’s political history and the intersections between social and ecological memory.

The capacity of objects to influence the world and social relations through their use and meaning is profound. Judith Butler, for example, researched the ways in which objects can serve to reproduce gender and power identities.1 In Tuca’s work, she relates objects to memories, geography, emotion, and identity. The forest is a site of origin for our embodied violence.

The luma used by police in Chile—and its counterpart in most nation-states throughout the world—is a tool for civilian control. It represents the power of the state and the social wounds that this power inflicts. After the military coup led by Augusto Pinochet in 1973, during the still recent period of history referred to in Chile as simply “the dictatorship,” the country experienced a violent agenda of political repression, human rights violations, and censorship. Until its dismantling in 1990, the military regime implemented authoritarian measures to consolidate its power, including the persecution of political opponents and suppression of the media.

In 2019, twenty-nine years later and just before the pandemic, a series of large-scale protests erupted in Santiago. In that moment, Tuca—and many others of her generation— remembered the luma of the 1970s, constructed of wood. She also recalled something about its materiality: that she had been told by her father that the luma was, in fact, a tree. It was then that she began the poetic search that informs this body of work.

”Many people in Chile know more about the police baton than the tree,” she tells me. And so she began contemplating how to share this duality of meaning, and how it could be a metaphor for the ways in which we change the meaning of things through their use.

The luma tree grows in the southern parts of Chile and has long been known to inhabitants of those areas. It has medicinal uses in Mapuche traditions, where it is a remedy for digestive problems and an anti-inflammatory treatment. Tuca spoke with many local people on the island of Chiloé who told her stories about these uses not encountered in textbooks, such as Luzmira Soto, who recalled her grandmother bringing the leaves home. The tree is a part of the myths and legends of the communities in this region, and many of these stories allude to spectral beings. It is said that the presence of the luma attracts the protective spirits of nature, and that those who respect and care for the tree are blessed with good fortune against the dangers of the forest.

The luma, beyond its existence as a biological entity, serves as a locus of intertwined cultural, social, and ecological meanings. From a phenomenological and semiotic perspective, the tree becomes a node in a vast network of human and natural relationships, where its symbolic and material presence feeds a web of narratives, rituals, and cosmovisions. Tuca mentions in our conversation that local people use the wood of the luma for warmth. The forest enters the house, and the luma takes on a different meaning. Its performativity lies not only in its ability to serve as a material resource, but in its capacity to embody and transmit values, identities, and ontological links between humanity and its environment. The significance of the luma is rooted not only in the materiality of its biology, but extends towards a horizon of shared meaning, where the intersection between the human and the natural is intertwined in a dance of co-creation and constant resignification.

The luma as police baton is an extension of this resignification, and it, in turn, can be resignified by those who hold it in their collective memory. Instead of simply being an instrument of coercion or force, the baton becomes a symbol of violation and repression that many acknowledge as destructive and seek to create distance from. “We inherited

the traumas of the dictatorship,” says Tuca. As a way of healing, she gives voice to the forest, which is also threatened by prevailing extractivism.

In my conversations with Tuca, I come to think of the luma as a manifest image. According to Andrea Giunta, these are images that not only represent an idea or a cause, but that also transform our sense of reality. They go beyond mere visual representation and become tools for political and social action.2 Through Tuca’s sculptural work presented in the exhibition, the luma loses its power, becoming a symbol of fragility by way of new material interventions. The choice of clay for this gesture adds another layer of complexity; the material alters the physical appearance of the baton, and in turn challenges its ingrained meanings. The cast versions are made of something soft that turns brittle and breakable, reminding us of the precariousness of inherited and existing forms of power.

The dichotomy of the luma is made clear by Tuca through this exhibition, and the space of the gallery becomes a site of shared recognition, one that allows us to collectively reflect upon the relationship between nature and culture, between violence and contemplation. The luma—both the baton and the tree—acquire new identities contextualized by their relationship to one another. The resignification of visual symbols is not only an artistic tool, but also a strategy to challenge hegemonic narratives and offer new perspectives. In making visible the origin of the baton in the forest, away from the hegemony of the state, Tuca challenges conventional conceptions of power and resistance, and opens space for a deeper reflection on the relationships between humans and non-humans, between culture and nature.

The paradox of the luma as a symbol of life and death is an undercurrent throughout the show. While the tree is a life-giving being, the baton can serve to extract and diminish life. In repositioning the final narrative of the baton beyond its foregone conclusion— away from one that leads to death—and in referencing the illustrations of pioneering Chilean botanist Adriana Hoffmann (one of the few women in her field), Tuca’s work could also be read as embodying an ecofeminist perspective that rejects the dominance of patriarchal forces and embraces more holistic and interdependent relationships between human and non-human beings.

Through the exhibition Luma, Catalina Tuca further develops an approach that is one of the hallmarks of her artistic practice, inviting us to rethink our relationships with objects and to reposition their meanings. In placing the narrative of the luma that occupies the political memory of her generation alongside that of its ecological source, she subverts its destructive power, giving life-affirming potential to an object rooted in structures of violence and exploitation. Her work reminds us that objects are not simply inert products of society, but active agents that participate in the construction and reproduction of social and cultural meaning—and perhaps can even, through their resignification, become tools of resistance.

Endnotes:

1. Butler, Judith (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge: New York. 2. Giunta, Andrea (2016). “Todas las partes del mundo.” VERBOAMÉRICA. Malba: Buenos Aires.

ALEXANDRA TRUJILLO TAMAYO (b. 1990, Quito, Ecuador) is a transdisciplinary artist, designer, and performer. She is a graduate of Universidad San Francisco de Quito, where she studied performing arts, installation, illustration, and visual arts. She holds a Masters degree in Visual Communication and Diversities from Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar in Ecuador, and also studied at Instituto Mexicano de Curaduría y Restauración in Mexico City. She currently resides in New York City.

Trujillo Tamayo has exhibited at prominent events and institutions worldwide, including the São Paulo Biennial and the New York Latin American Art Triennial, as well as +Arte Galería, Arte Actual FLACSO, and Centro Cultural Metropolitano in Ecuador. She participated in the Cuarto Aparte Bienal de Cuenca in 2018, and her work has been presented in international projects in France, Argentina, Bolivia, the United States, Mexico, Colombia, Spain, and Ecuador. She is a co-founder of CUERPA(S) International Performance Festival, where she led video-mapping projects nationwide. Trujillo Tamayo has held artist residencies in Paris, and she was awarded the Al-Zurich Art Prize for Art and Community in 2020 and the COCOA Art Prize in 2017.

AIMÉ IGLESIAS LUKIN served as a mentor for this essay. She is an art historian and curator. Born and raised in Buenos Aires, she has lived in New York since 2011. Her Ph.D. in art history from Rutgers University, titled “This Must Be the Place: Latin American Artists in New York 1965–1975,” became a show at the Americas Society in 2021. She completed her M.A. at The Institute of Fine Arts at New York University and her undergraduate studies in art history at the Universidad de Buenos Aires. Her research has received grants from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Terra Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the ICAA Peter C. Marzio Award from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Her writing has been presented at conferences internationally and published by prestigious museums and academic journals, including the New Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim Museum. She has curated exhibitions independently in museums and cultural centers, and she previously worked in the Modern and Contemporary Art Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, and Fundación Proa in Buenos Aires.

This text was written as part of the ART CRITIC MENTORSHIP PROGRAM , a partnership between CUE and the AICA-USA (the US section of the International Association of Art Critics). The program pairs emerging writers with art critic mentors to produce original essays about the work of artists exhibiting at CUE’s gallery space. For more information about the program, visit the ACMP page on CUE’s website at www.cueartfoundation.org. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior written consent from the author.

Some of the drawings in the exhibition reference the illustrations of Adriana Hoffmann from Flora Silvestre de Chile: Zona Araucana, Ediciones Fundación Claudio Gay, 1997.

The photograph presented in the exhibition is by Marco Urgate, taken at Plaza de Armas in Santiago, Chile in September 1984. It is in the archive of the Museo de la Memoria.

The film and photography presented in this exhibition and the catalogue are from three national parks in Chiloé, in the Los Lagos region of Chile. They include: Chiloé National Park, Bosquepiedra Reserve, and Tepuhueico Park.

The artist would like to thank the following supporters, advisors, and guides who made this project possible: Angeles Tuca, Dominique Serrano, Rosario Ateaga, Elena Bochetti, Felipe Balmaceda, and Edward Rojas.

CUE Art is a nonprofit organization that works with and for emerging and underrecognized artists and art workers to create new opportunities and present varied perspectives in the arts. Through our gallery space and public programs, we foster the development of thought-provoking exhibitions and events, create avenues for mentorship, cultivate relationships amongst peers and the public, and facilitate the exchange of ideas.

Founded in 2003, CUE was established with the purpose of presenting a wide range of artist work from many different contexts. Since its inception, the organization has supported artists who experiment and take risks that challenge public perceptions, as well as those whose work has been less visible in commercial and institutional venues.

To learn more about CUE, visit us at www.cueartfoundation.org.

STAFF

Jinny Khanduja

Executive Director

Jasmine Buckley Gallery Associate

Keegan Sagnelli Communications Associate

Jocelyn Guzman Intern

Fernanda Cabreja Intern

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Theodore S. Berger, President

Kate Buchanan, Vice President

John S. Kiely, Co-Treasurer

Kyle Sheahen, Co-Treasurer

Lilly Wei, Secretary

Amanda Adams-Louis

Blake Horn

Thomas K.Y. Hsu

Steffani Jemison

Aliza Nisenbaum

Gregory Amenoff, Emeritus

Programmatic support for CUE Art is provided by Evercore, Inc; ING Group; The Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation; The William Talbott Hillman Foundation; and Corina Larkin & Nigel Dawn. Programs are also supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature; and the National Endowment for the Arts.