Mentored by Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Presented by CUE Art

New York, NY 10001

CUE Art

All artwork © Tsohil Bhatia

Photos by Leo Ng

Graphic design by Anamika Singh

September 5–December 14, 2024

CUE Art

Exhibition Mentor: Puppies Puppies (Jade

Catalogue Essayist: Swagato

Writing Mentor: Alpesh Kantilal Patel

Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Chakravorty

This Fire That Warms You is a solo exhibition by Tsohil Bhatia with mentorship from Puppies Puppies. The show imagines the gallery as a kitchen, activating and recontextualizing its furnishings, ingredients, methods, and labor. Bhatia engages in transmodal ways of making that consider the everyday and the ephemeral. Their studio and kitchen practices converge, revealing excerpts and observations of their daily life through sculpture and installation-based works.

The exhibition sets a stage for something that is yet to happen—or perhaps that has already taken place. Bhatia constructs a scenography that serves as a backdrop to study and reperform domestic and emotional labor. Repurposed kitchenware hangs from the ceiling; dried fruits and vegetables are self-actualized through decay; pressure cookers erupt with sound and steam; surfaces bear evidence of cuts, spills, and burns. Remnants of labor hint at the presence of a body and its ghost. In its absence, however, time becomes a central character— measured in odor, hissing, running water, and discoloration. Abstracted rituals unfold without instruction, enabling a form of mourning that both facilitates memory and anticipates loss.

In the work, fire becomes a metaphor and a vector. Bhatia explores its multiplicities, from anger and rage to passion, desire, comfort, care, danger, violence, and destruction. In the kitchen, fire is disciplined; its functional uses abound. This domestication, however, gives way to moments of unpredictability, to instances in which its latent qualities become visible. Through the work, Bhatia evokes movements and processes that embody the dynamic potential of fire, calling for an embrace— but also a warning—of the paradoxes it contains.

This Fire That Warms You is Bhatia’s first solo exhibition in New York City. The show extends beyond the gallery walls with Untitled (Rano), a sculptural work at NADA House on Governors Island. Through the works presented in these projects, a queer domesticity takes hold, one that is deeply personal to the artist. Bhatia sets alight the forms, movements, and spaces we think we know, allowing for transformative action in the kitchen and beyond.

Untitled (Cacerolazo ii), 2024 Pots, pans, metal and wood utensils, pine, wire, wire mesh, chain Dimensions vary with installation

Three Simple Fountains, 2024

Steel sinks, metal utensils and plates, ceramics, glassware, 660 lph pumps, buckets

Dimensions vary with installation

In my practice, I have always considered my body. I have made photographs and performances that study its form and its interaction with space, objects, and the viewer. I’ve become curious about what remains of bodies when we don’t see them, when we are discouraged from ascribing to them vocabularies of identification and classification. I value materials, movements, and gestures that evidence the personal history of my body and its relationship with objects, memory, and action.

My work studies time—its representation, its abstraction, and the mourning of its inevitable loss. I explore the anticipation of losing this moment, of the passing of my mother, and of the fading of my memory. In preparation for these losses, I engage in forensic observation and documentation of my immediate surroundings, inhabiting rituals of domestic practice. These rituals become an embodied archive, an incessant form of remembrance.

I work with methodologies that construct time within time—through acts of counting and waiting, of decay and disappearance. I am drawn to modes of making that embrace the unresolvable and the ephemeral, allowing for the sustenance of paradox.

A significant part of my artistic practice is my work with Red Flower Collective, based in New York City. This project treats the kitchen as an open studio and a lab. With an emphasis on care and communal eating, the collective aims to uplift and acknowledge often devalued reproductive labors of the kitchen. My most recent work bridges my studio practice with my domestic practice, moving toward a productive amalgamation of the two.

—Tsohil Bhatia

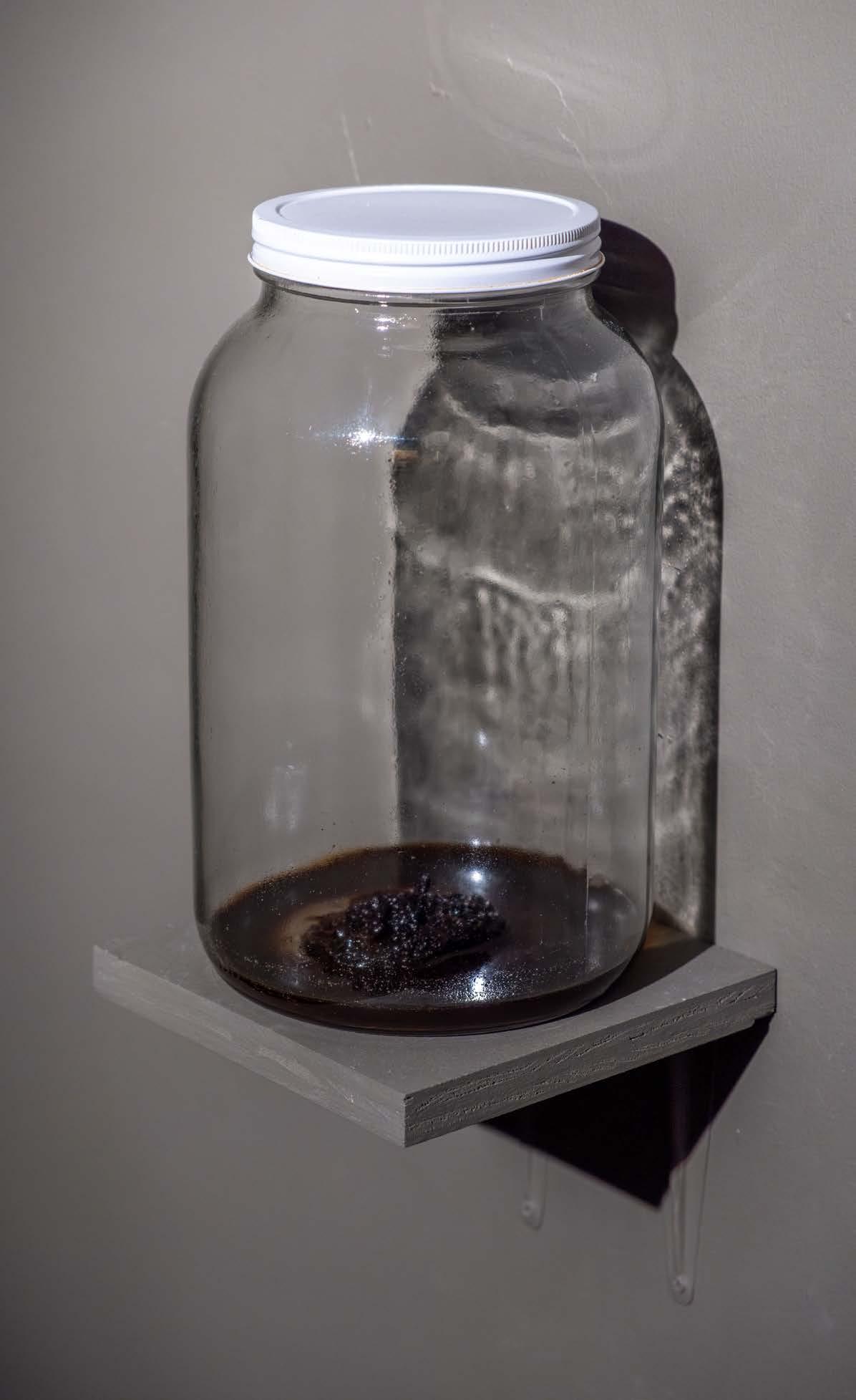

21 September 2022 – Ongoing, 2022

Two-year-old apple, glass jar, customised pine shelf 10 x 6 in

Tsohil Bhatia (b. New Delhi, India) is an artist, homemaker, and educator currently based in Lenapehoking, now known as New York City. They received an MFA at the School of Art at Carnegie Mellon University (2020). Their practice thinks through sculpture, performance, and the kitchen. Bhatia’s work emerges from contemplations about the latencies of mundane objects, rituals, and images—bringing together the complexities of the everyday, and of the body’s relationship with time and the space it inhabits. In some of their recent work, they have counted their breath, measured a

Untitled (Cacerolazo ii), 2024

Pots, pans, metal and wood utensils, pine, wire, wire mesh, chain Dimensions vary with installation

day’s worth of water from a leaky faucet, mapped light from a window, collected and evaporated water from the five oceans, intuitively counted the seconds of a clock, and swum towards a setting sun.

Bhatia is a co-founder of Red Flower Collective, a food research collective that hosts communal meals in NYC. They have been awarded residencies at Fire Island Artist Residency (2024), Center for Book Arts (2022), Oxbow Summer Residency (2021), Chautauqua Artist Residency (2021), HH Art Spaces (2017), and 1 Shanthi Road (2016). Their work has been shown at the University of British Columbia, Twelve Gates Arts, Queer Arts Festival, Franconia Sculpture Park, Hair+Nails, and the Warhol.

Banana flower, ginger, potato, rambutan, onion, okra, eggplant, carrot, cucumber, strawberries, melon, celery leaf, celery root, endive, lemon, lime, mandarin, navel orange, blood orange, garlic, pomegranate, cabbage, apple, watermelon, bottle gourd, bitter gourd, mermaid’s purse, banana, mamey, lichi, driftwood, wheat flour cat, breadfruit, cauliflower, dried bougainvillea leaf, horseshoe crab skeleton, mango, mango pit, apricot, black grapes, brussel sprout, jackfruit, baby eggplant, buddha’s hand, papaya, mamey pit, banana peel, turnip, orange peel, avocado skin, mangosteen, dragonfruit, quenepas, dried rose, tamarind spine, wheat dumpling, pomegranate skin

Fruits of passing (Remains from home), 2022-2024

Dried fruits, vegetables, and found objects on packed earth

Dimensions vary with installation

Notes on Resistance, 2024

Electric cooking range, four pressure cookers (3L, 4L, 5L, 8L), water

40 x 36 x 25 in

The steam evaporating into the air and filling the viewer’s lungs • a mold spore drifting away

• with the current of the ventilation system • an apple contained • going through stages of a sealed ecosystem • a snare drum roll • as the water hits the metal pan • greeted with seasonings and spices • aromas • asking you to breathe in • there’s spirits leaving the kettles • left in a space that seems frozen • as if someone vanished • and you’re witnessing what was suddenly • left behind

• what you can’t see at first is the giving heart and spirit behind the moments • a spirit that serves nourishment to the people around them • a giving spirit • responsible for every water-induced beat • for every whisper and exhale • for every crash and collision • responsible for warm food in your mouth

• responsible for the thoughts that emerge • there’s a gentle whisper in their expression • and moments that are louder • like the rapids of a river • there’s reminders of humanity in these moments • poetic reminders • there are things that • unite our existence as humans • a need for nourishment • a need to feel the warmth of love from those around • Tsohil reminds me to love • and give • Tsohil reminds me of the fleeting moments Félix González-Torres conveyed • Tsohil reminds me of the existential convos around warm bowls • under the kitchen light • with clouds of weed smoke • late into the night • Tsohil reminds me that sometimes • I lay on my bed • and it feels like death is there next to me

• reminding me to express • every emotion • every feeling of the pressure cooker steam in my lungs

• like an FTG • piece of candy • it stays with you

• starts to break down in the stomach • enters the bloodstream • and everything leads so beautifully • so intensely • to the heart

—Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Untitled (Latent tension), 2024

Glassware, customized pine shelves, paint, sea salt

Dimensions vary with installation

Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo (b. 1989, Dallas, TX), widely known by the moniker Puppies Puppies, expands ideas around the readymade by imbuing ubiquitous and everyday objects, signifiers, and actions with a personal and political charge. She has, for example, reconfigured antibacterial gel dispensers, toilet bowl liquid, and the color green, as well as the acts of sleeping, peeing, and taking a pill in installations and performances that challenge ableist frameworks of artistic and capitalist production.

Untitled (Concrete Codex), 2017-2024

Pantry items in various containers, on customised shelves

Dimensions vary with installation

Many of Puppies Puppies’ exhibitions have also included actionable components: a GoFundMe campaign to support a friend’s transition fund, free HIV testing and counseling, and a working shower available for use by the public. Kuriki-Olivo asserts that life can be viewed as its own form of endurance practice, especially for those whose very survival is at stake, including trans, nonbinary, and gendernonconforming people of color.

Untitled (Concrete Codex), 2017-2024

Pantry items in various containers, on customized shelves

Dimensions vary with installation

Peanuts, red wine vinegar, liquid aminos, apple cider vinegar, screwpine flower water, rosewater, olive oil, rose syrup, vetiver syrup, pomegranate molasses, kokum syrup

Kidney beans, black lentil whole, black lentil split, pili pili (Morocco), chickpeas, mung beans

Four honeys (Mexico City), hot honey from Pragya, date syrup, maltose, cane jaggery, honey

Almond extract, banana flavoring, baking soda, cornstarch, baking powder, bengal gram, blackeyed peas, yellow lentil split, red lentil, red beans small, pigeon peas, deshelled black lentil split, dried peas, roasted gram, popcorn kernels from Keioui

Peanut butter, black lava salt from Furqan (Hawaii), scorpion salt (Mexico City), worm salt (Mexico City), grasshopper salt (Mexico City), hibiscus salt from Thomas (Mexico City), black pepper powder, Old Bay, black salt, dried sage, dried butterfly pea flower, dried chrysanthemum, cacao beans, black cumin, dried birds eye chili, Tajín, peperoncino from Erin (Italy), chili pepper from Saloni (Tanzania), ground cinnamon, ground thyme, chinese five spice, italian seasoning, dry basil, merken from Marianne (Chile), red pepper flakes

Deep frying sieve

Dried limes, fennel seed, dried wood ear mushroom, dried white mushroom, dried porcini mushroom from Erin (Italy), guajillo pepper, dried hibiscus flower, dried paan, sambar powder from Vijaya, dried bamboo shoot, fried onions

Woodfired garlic powder, black sesame powder, stone flower, annatto seeds, homemade chaat masala, gochugaru, fish powder, dried oregano, allspice, dried mint, dumpling maker from Huidi, lime salt, shrimp powder, chili powder (Sri Lanka), basil seed

Sumac, nigella seed, cloves, licorice, chaat masala from mom, whole chili round, goan sichuan pepper, mint powder, fenugreek seed, fenugreek seed powder, red chili coarse, fish powder (South Korea), black peppercorn, poppy seed, red mustard seed, white sesame seed, ghost pepper from Saurav, za’atar, black cardamom

Himalayan salt, sugar

Cumin seed, veg garam masala from mom, turmeric powder, carom seed, red chili powder hot, dry mango powder, mace, kokum, dried red chili whole, star anise, black mustard seed, sichuan peppercorn, green cardamom, veg garam masala (Sri Lanka), mustard seed powder, dried fenugreek, cumin powder, non-veg garam masala from mom, anise from Jenna, kashmiri chili powder, yellow food coloring, chaat masala, black pepper powder, red food coloring, coriander powder, red chili powder, asafoetida, ginger powder, coriander seed, saunf mix, yellow mustard seed, chaat masala

Latent Energies

Swagato Chakravorty

This Fire That Warms You highlights new directions in Tsohil Bhatia’s conceptual, multidisciplinary practice, articulated through sculptural installations. The works in this exhibition, some of which are variations upon works shown previously at Blueprint.12 Gallery in New Delhi, comprise an extended investigation into process and transformation. Inside CUE’s theatrically spotlit gallery, one finds decay and desiccation [21 September 2022 – Ongoing, 2022; Fruits of passing (Remains from home), 2022–24], the cumulative force of small gestures [Three Simple Fountains, 2024; Untitled (Latent tension), 2024; Untitled (Cacerolazo ii), 2024], simmering energies and the occasional volatile release [Notes on Resistance, 2024], and—permeating it all—the promise (or threat) of an event, a happening— something yet to be, or maybe already bygone. Bhatia self-identifies as a homemaker as well as a working artist, conceiving of care-work and domestic labor—particularly relating to cooking and the kitchen—as forms of creative practice, and vice-versa. Here, however, labors of care and domesticity seem withdrawn. The artist-caregiverhomemaker is not present; only their traces endure. This absent presence haunts the works, making ordinariness newly strange by revealing the materiality of time’s passing. Bhatia extends and occasionally disrupts the narratives of these works through activations, interventions, and a related public sculpture-performance presented at NADA House on Governors Island.

This Fire that Warms You reimagines the art gallery as a kitchen; a creative reworlding that undoes hierarchies of artistic and domestic spaces. Notably, there are no wall labels. Stepping into CUE’s spaces, you encounter Bhatia’s kitchen shelves, laden with condiments and jars of grains, lentils, and spices. During installation, the artist had shown me these shelves in their own kitchen. Here, transposed to another context, they appear as a wall-mounted installation of found objects titled Untitled (Concrete Codex) (2017–24), implicitly quoting—in its serial regularity—Minimalism with

a difference. These everyday items, reassembled as an artwork completed over a specific duration, also document Bhatia’s culinary practice; the differing quantities of ingredients index a chronicle of cooking. Some ingredients are unlabeled, but those with a working knowledge of South Asian cooking will identify many staples of the desi (and diasporic) kitchen. If the seriality of Untitled (Concrete Codex) evokes histories of Euro-American modernism, its presentation of ordinary cooking ingredients (some more culturally-specific than others) suggests what the artist calls an “abstracted biography”—a way of contesting (raced, gendered) visibility through the strategic withholding of information.1 Bhatia’s use of abstraction, in this sense, doubles as an assertion of what Édouard Glissant calls the “right to opacity.”2

Bhatia’s work is formally rigorous. Untitled (Cacerolazo ii) organizes the artist’s pots, pans, and utensils into a hanging chandelier. Three Simple Fountains presents three steel sinks set in a row, each with carefully piled up metal plates, ceramicware, and glassware, onto which tap continuous streams of pumped water. Notes on Resistance comprises four pressure cookers simmering on an electric cooking range, with a Palestinian keffiyeh draped over the oven door handle, doubling as an ordinary kitchen towel. In Untitled (Latent tension), some fifty pieces of glassware neatly arrayed on five shelves rest precariously atop each other, balancing on just the bottom shelf with the rest set apart from the wall. Fruits of passing (Remains from home) is a large square of packed soil on the floor. Upon its surface is strewn—in an orderly chaos—a large number of dried, decayed, and rotted fruits, vegetables, and plant matter seemingly drawn from around the world (the banana flower, common across South and Southeast Asia, is rare in the US; mangoes and okra evoke expansive diasporic histories).

Five repetitions of a singular form along the wall, “one thing after another.”3 A square sculptural form placed on the floor. Three “fountains” lined up in a series. I see Bhatia queering episodes from a (mostly straight, white, and male) history of modern and contemporary art: Judd, Andre, Duchamp, Nauman….Across their seriality, with iterations upon the line and the grid, one senses the ghosts or afterlives of Minimalism. We never quite grasp the fullness of these installations; they are in flux, at temporal

Three Simple Fountains, 2024

Steel sinks, metal utensils and plates, ceramics, glassware, 660 lph pumps, buckets

Dimensions vary with installation

Notes on Resistance, 2024

Electric cooking range, four pressure cookers (3L, 4L, 5L, 8L), water

40 x 36 x 25 in

scales that sometimes escape human perception. It’s difficult to adequately describe what the work of some of Bhatia’s artworks is—that is, at what point in time (if ever) it is completed.

Untitled (Cacerolazo ii), true to the history of noisy protest it names, erupts into clamor whenever the artist vigorously shakes the chandelier of pots and pans, setting the whole thing swinging and swaying, and casting fantastical shadows onto the wall. Thus activated, the work suddenly reaches across historical and geographical contexts, tracing unexpected affinities—from the intimacies and labors of Bhatia’s South Asian diasporic kitchen to popular protests worldwide: France in the nineteenth century, French-colonized Algeria in 1961, Chile in the 1970s and 80s, Argentina in 2001, Lebanon in 2019, and rallies for Palestinian liberation since late 2023. Three Simple Fountains seems poised on the edge of catastrophe, as the cascading streams of water—with their subtly distinct acoustic pitches that disrupt the installation’s seriality— threaten to unbalance the delicate heaps of plates and glassware. This precarity, a latent potential for structural failure that would instantly transform order into chaos, recurs in the title and the just-so balancing act of Untitled (Latent tension)

Notes on Resistance and Fruits of passing (Remains from home) most clearly evince the tensions contesting aesthetic formalism in Bhatia’s practice. Take the Palestinian keffiyeh in Notes on Resistance that, through its strategic placement within the installation, doubles as an ordinary kitchen towel. In the present context, it risks overdetermining the work, even as it highlights Bhatia’s commitments to forging community and solidarities with the minoritized and the dispossessed everywhere. One must work through these initial recognitions to also apprehend this object as the artist offers it—as a kitchen towel— and to more closely read the installation’s titular notes on resistance. The four pressure cookers, of an older design familiar to generations of South Asians (and indeed much of the global majority), are of various sizes and contain differing levels of water. They are continually heated upon their respective cooktops, inexorably building pressure that results in explosive releases of steam. This is not a quiet or gentle work. Walk around the installation and you hear the simmering of its water as a sustained grumble.

Get too close during a steam release and you could get hurt. Pressure cookers of this design have sometimes been modified into explosive devices, weaponized toward various ends. They have even exploded in ordinary use. Here, in the exhibition, the release of steam by each pressure cooker—a furious hiss—sometimes occurs together as a chance synchronization, a cacophony of pent-up energies rushing forth. At other times, one of them may produce a lone sound. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang tell us that decolonization is not a metaphor.4 See the keffiyeh. See it as a kitchen towel. Repeat until time doubles your perception.

“We never quite grasp the fullness of these installations; they are in flux, at temporal scales that sometimes escape human perception.”

It recalls nineteenth-century optical illusions, in which two images each signify something on their own, yet also combine to signify a third thing. Third meanings, third spaces,5 Third World solidarities. Often in Bhatia’s practice, formal rigor gives shape to materially-grounded concerns. Notes on Resistance brings them together with precision, asking us to hold space for a multiplicity of meanings as well as for the global multitude. Fruits of passing (Remains from home) is a work of somber tenderness. Eschewing the sterility of Minimalist histories of sculpture such as that in the work of Carl Andre, it offers soil as a material support for organic matter. The work’s double gesture of citation and (historical) transformation becomes a refusal of violent white masculinity, especially considering Bhatia’s use of earth—a material central to, for example, Ana Mendieta’s “earth-body” performances and her Silueta series. The varied organic material, meanwhile, recalls seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas still life paintings. These richly detailed paintings,

Untitled (Latent tension), 2024

Glassware, customized pine shelves, paint, sea salt

Dimensions vary with installation

Untitled (Butcher’s Lament), 2024

Inkjet print on Hahnemühle satin photo rag

44 x 31.5 in

their emergence entangled with the global reach of Dutch colonial enterprises, offered viewers sumptuous visions of global biodiversity as well as sobering moral lessons on the impermanence of life through depictions of rotting fruit and flowers, complete with those lifeforms—flies and other insects—that continue cycles of life after human beings cease to be.

The presence of dried and decaying fruit also evokes the queer histories and fleshly ephemerality of Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (1992–97), itself born out of the 1980s–90s HIV/ AIDS crisis. Leonard created Strange Fruit to mourn the passing of a friend, the artist David Wojnarowicz (1954–92). Over five years, she sewed back together the peels from approximately 300 bananas, oranges, lemons, and other fruits. These mended skins, emptied of the flesh they once contained, continue to decompose at the artist’s own insistence. The inevitability of their transformation over time poses an enduring challenge to institutional tendencies toward preserving objects in a fixed state.

Among the organic matter in Fruits of passing (Remains from home), there is a solitary rose—dark red, complete with its stem. It reminds me of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince (1943), a picaresque tale of a young prince who wanders through space and travels to various planets, touching on existential themes of friendship, love, loneliness, and loss. But it is the little prince’s (ultimately frustrated) relationship with a rose that returns us to care-work, its withdrawal, and the concerns with time that animate Bhatia’s practice. Seeking closure, the little prince realizes that what makes his rose distinctive is not necessarily its unique beauty but rather the labor and time that have shaped his care: “it is she that I have watered…it is she that I have listened to, when she grumbled, or boasted, or ever sometimes when she said nothing. Because she is my rose.” And he is reminded (by a wise fox that has become his companion): “It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important.”6

Fruits of passing (Remains from home) is rich in complexity; it offers art historical transformations and refusals, earthly sculpture, an archive of ephemerality, and as the title suggests, a

grave marker of sorts. The questions it, like other works in the exhibition, poses are deceptively simple: how might we apprehend time in the act of its passing? How do we relate to it from the tenuousness of our bodily existence? This Fire That Warms You offers propositions constructed around abstraction, opacity, precarity, and community— imagined and otherwise. In the process, Tsohil Bhatia goes a long way toward unburdening representation.7

Endnotes:

1. “Thinking Through Flower Box 3D,” a conversation between Alpesh Kantilal Patel and Tsohil Bhatia in The thing that happens when the thing that is supposed to happen does not happen, eds. Elizabeth Chodos, Jon Rubin, Charlie White (Pittsburgh: Miller ICA at Carnegie Mellon University, 2022), 72.

2. Édouard Glissant, “For Opacity,” Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 189-194.

3. Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” Complete Writings 1959–1975 (Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975).

4. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1:1, 1-40 (2012).

5. Homi Bhabha defines a “third space” as that “which gives rise to something different, something new and unrecognizable, a new area of negotiation of meaning and representation” in contexts of anti-colonial cultural resistance. See Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994).

6. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, trans. Katherine Woods (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971), 48.

7. Kobena Mercer, “Black Art and the Burden of Representation,” Third Text, 4:10 (1990).

Fruits of passing (Remains from home), 2022-2024

Dried fruits, vegetables, and found objects on packed earth

Dimensions vary with installation

Three Simple Fountains, 2024

Steel sinks, metal utensils and plates, ceramics, glassware, 660 lph pumps, buckets

Dimensions vary with installation

Swagato Chakravorty (he/him) is an Indian American curator and critic whose work ranges across modern and contemporary art and visual culture, focusing on cross-cultural and diasporic contexts, especially in relation to the Global South. He is currently completing his PhD at Yale University. Most recently, he was the Daniel W. Dietrich II Curatorial Fellow in Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), where he co-curated Isaac Julien: Lina Bo Bardi — A Marvellous Entanglement (with a newly-commissioned performance) and organized Day With(out) Art 2022: Being and Belonging (with Visual AIDS), as well as several time-based media installations. Previously at MoMA, the Jewish Museum, and the New Museum, he assisted with numerous exhibitions, including Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done; Jonas Mekas: The Camera was Always Running; and Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel. He has published work on the reception of Ritwik Ghatak’s cinematic radicalism in Western contexts, high-speed photography and the history of performance art at MoMA, Anthony McCall’s light installations, and the lens-based practice of Alfredo Jaar.

Alpesh Kantilal Patel served as a mentor for this essay. Patel is an associate professor of global contemporary art and LGBT*Q theory at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University. Their art historical scholarship, curating, and criticism reflect their queer, antiracist, and transcultural approach to contemporary art. They organized a series of exhibitions under the theme “Forever Becoming: Decolonization, Materiality, and Trans* Subjectivity” at UrbanGlass, Brooklyn, where they were curator-at-large in 2023. They are the author of Productive Failure: Writing queer transnational South Asian art histories (2017) and co-editor of a special issue of Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art (2021) commemorating Okwui Enwezor, as well as the anthology Storytellers of Art Histories (2022). They recently contributed to the volumes Routledge Companion to Decolonizing Art History (2023) and A Companion to Contemporary Art in a Global Framework (2023). Their research has been supported by grants and fellowships from the Fulbright Foundation, Arts Council England, NEH, Cranbrook Academy of Art, and New York University. Their book Multiple and One: global queer art histories is forthcoming in 2026.

This text was written as part of the Art Critic Mentorship Program, a partnership between CUE and the AICA-USA (the US section of the International Association of Art Critics). The program pairs emerging writers with art critic mentors to produce original longform essays about the work of artists exhibiting at CUE’s New York City gallery space. For more information about the program, visit the ACMP page on CUE’s website at www.cueartfoundation.org. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior written consent from the author.

Untitled (Rano), 2024 Daybed; whole wheat flour and water (146 lbs) 71 x 40 x 21 in

In conjunction with This Fire That Warms You, CUE Art presents Untitled (Rano), a sculptural work by Tsohil Bhatia on Governors Island as part of the sixth edition of NADA House.

Untitled (Rano) is sits on the lawn of Nolan Park House 17, extending the language of the domestic into the public realm. 146 pounds of kneaded dough is placed upon a charpai (daybed), reflecting the weight of the artist’s body.

This act is a reverent reperformance of Rano, a family elder. As a memorial to her departed presence, the work considers the fleeting and the unresolvable. Left to ferment in the elements and to be fed on by the creatures of the island, Untitled (Rano) contemplates the artist’s decaying body, mourning the inevitable loss of time and its bodily manifestations.

Untitled (Rano), 2024

Daybed; whole wheat flour and water (146 lbs)

71 x 40 x 21 in

CUE Art is a nonprofit organization that works with and for emerging and underrecognized artists and art workers to create new opportunities and present varied perspectives in the arts. Through our gallery space and public programs, we foster the development of thought-provoking exhibitions and events, create avenues for mentorship, cultivate relationships amongst peers and the public, and facilitate the exchange of ideas.

Founded in 2003, CUE was established with the purpose of presenting a wide range of artist work from many different contexts. Since its inception, the organization has supported artists who experiment and take risks that challenge public perceptions, as well as those whose work has been less visible in commercial and institutional venues.

Exhibiting artists are selected through two methods: nomination by an established artist or selection via our annual open call. In line with CUE’s commitment to providing substantive professional development opportunities, each artist is paired with a mentor—an established curator or artist who provides support throughout the process of developing their exhibition.

To learn more about CUE, visit us online or sign up for our newsletter at www.cueartfoundation.org.

STAFF

Jinny Khanduja

Executive Director

Jasmine Buckley

Gallery Associate

Keegan Sagnelli

Communications Associate

Kota Khan

Gallery & Production Intern

Zain Latif

Gallery & Production Intern

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Theodore S. Berger, President

Kate Buchanan, Vice President

John S. Kiely, Co-Treasurer

Kyle Sheahen, Co-Treasurer

Lilly Wei, Secretary

Amanda Adams-Louis

Blake Horn

Thomas K.Y. Hsu

Steffani Jemison

Aliza Nisenbaum

Gregory Amenoff, Emeritus

SUPPORT

This Fire That Warms You is supported, in part, by a Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grant.

Programmatic support for CUE Art is provided by Evercore, Inc; ING Group; The Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation; The William Talbott Hillman Foundation; and Corina Larkin & Nigel Dawn. Programs are also supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature; and the National Endowment for the Arts.

CUE Art