In all that it does, the nonprofit organization seeks to support emerging filmmakers by bringing their vibrant, urgent work to life. That’s why I chose to partner with the organization in celebration of the Independent Spirit Awards—a night dedicated to celebrating the relentless optimism of the film community. 40 years on, the Awards are a bright spot on the industry’s whirlwind calendar. After a rocky start to 2025, we need as of those as we can get.

“The reputation of an awards show host is that you come in there … with your bazooka of hot takes and satirical burns,” two-time Independent Spirit

Awards host Aidy Bryant tells her fellow comedian Nick Kroll in this issue. “But I’m really thrilled to be there. I really believe in the ethos.”

That ethos—of making a movie at all costs, of highlighting stories that stay with audiences long after the credits roll—is encapsulated in the work of Sean Baker, the issue’s cover star and a nominee for Best Director at this year’s Independent Spirit Awards. Known for wrenching microbudget films that honor life at society’s margins—like Tangerine (shot on an iPhone), and The Florida Project (featuring primarily first-time actors)—Baker is a beacon of hope for independent filmmaking in an

ALI ABBASI’S NERVES OF STEEL

The Danish-Iranian director is no stranger to challenging subjects. But The Apprentice tested his resolve.

IGNORANCE IS BLISS—UNTIL IT’S NOT

In her latest film, Magic Farm , artist Amalia Ulman takes Chloë Sevigny and Alex Wolff down to Argentina. 05

LOVE ME, LOVE ME NOT

industry with sky-high budgets and even higher barriers to entry. His latest opus, Anora, is a testament to this commitment. Elsewhere in the issue, you’ll find profiles of equally awe-inspiring filmmakers and actors, each of whom is dedicated to making work that stops us in our tracks.

We hope you’ll spend time with this

This limited-edition issue of CULTURED pays tribute to the people committed to keeping Hollywood—its fantasy and lore as well as its daily machinations—alive. Few organizations better embody that spirit than Film Independent.

Filmmaker Cazzie David’s latest project, a romantic comedy run amok, examines the dark side of modern relationships. 14

THE 2025 NOMINEES

This year’s Film Independent Spirit Awards nominees, broken down by category.

TEAM SPIRIT

As comedian Aidy Bryant prepared to host the 40th annual Film Independent Spirit Awards, she called up fellow hosting alum Nick Kroll for some last-minute advice.

16

NATASHA ROTHWELL BARES IT ALL

A decade into her career, the White Lotus actor and How to Die Alone creator is renewing her commitment to challenging herself—and the film industry.

CALL HER DADDY

In her zeitgeisty follow-up to 2022’s Bodies Bodies Bodies, director Halina Reijn skewers the sexual topography of middle age. 20

WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE

Following the breakout success of his latest film, Anora , Sean Baker has solidified his status as the consummate outsider-insider.

HOLLYWOOD’S NEW GUARD

In a culture quick to dole out attention, true fame—that alchemic mixture of mystique and staying power—feels more elusive than ever.

By Elissa Suh

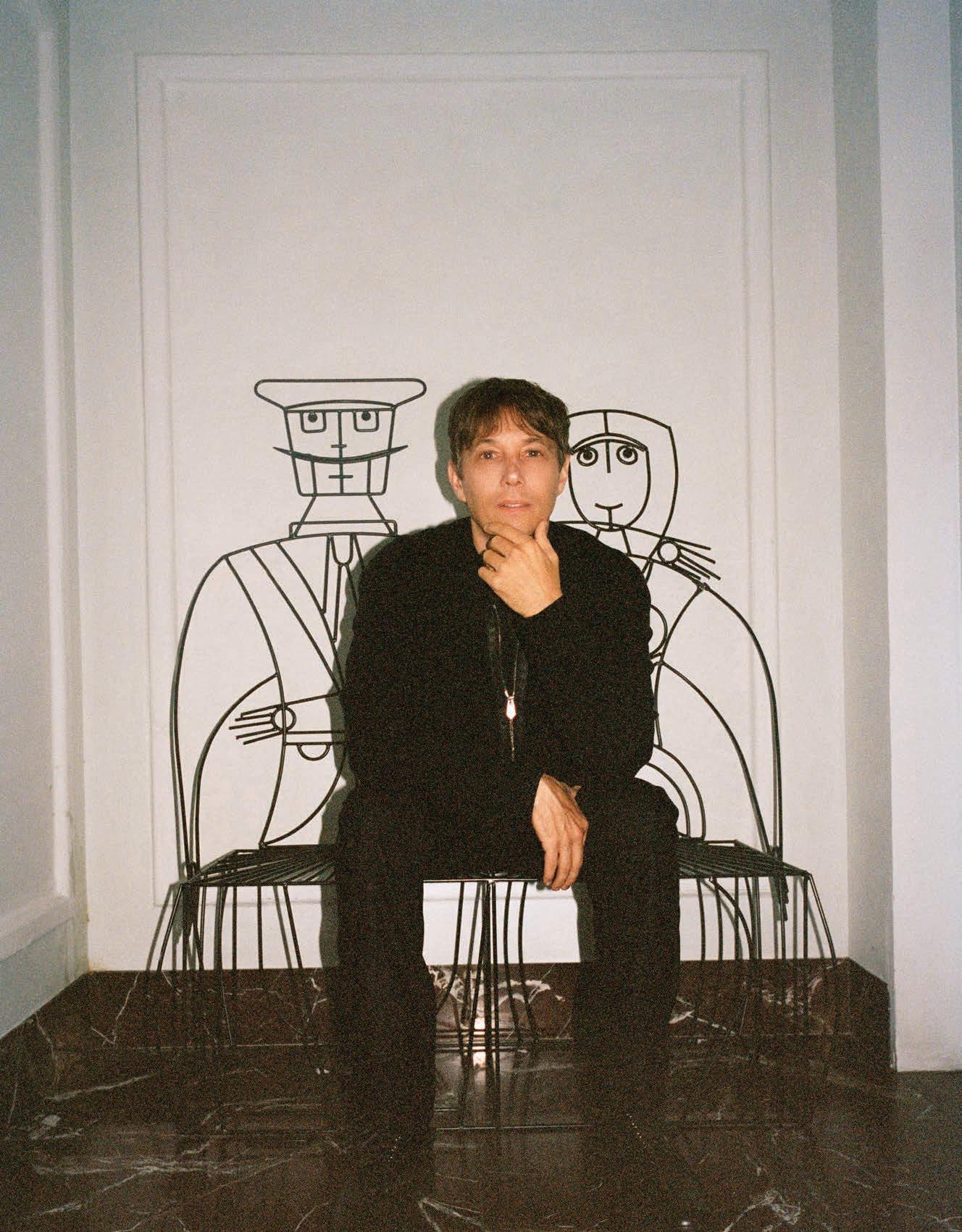

“There’s no upside to making a film like this,” Ali Abbasi says of his latest feature, The Apprentice, a biopic chronicling Donald Trump’s rise to prominence under the mentorship of Roy Cohn in the 1970s and ’80s. “If I were an American director, I might have passed [on it], too.”

Initially, the script, written by the journalist Gabriel Sherman, made the rounds among high-profile filmmakers like Clint Eastwood and Paul Thomas Anderson. Both declined, deeming it a business risk. Without any direct ties to the U.S., the Danish-Iranian Abbasi was a fitting choice. He first became aware of Trump in June 2015, on the day the infamous real-estate mogul descended the escalator of his Fifth Avenue skyscraper to announce his bid for president.

“I didn’t grow up in the U.S.,” says Abbasi, “but living in Iran, you can’t help but have a relationship to [American] politics.” The filmmaker was initially drawn to Trump’s candidness before his rhetoric took a divisive turn—the president’s “Muslim ban” had a personal impact on Abbasi, who at the time held an Iranian passport and had difficulty traveling to the Telluride Film Festival for a screening of his 2018 film Border. It was at the festival that he first encountered Sherman’s script.

The Apprentice represented a departure from the outlandish thrillers and supernatural horror films for which Abbasi had become known. This story, the filmmaker notes, was defined by its “real agenda in understanding this person without bashing or praising him.” It reminded him of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. In the 1975 film, the titular Irish striver ascends the ranks of society only to confront the consequences of his ambition and deceit. “Barry is a social climber who doesn’t know where he’s climbing. Donald is similar. He’s not sympathetic, but you begin to understand him,” he says.

“I DIDN’T GROW UP IN THE U.S., BUT LIVING IN IRAN, YOU CAN’T HELP BUT HAVE A RELATIONSHIP TO AMERICAN POLITICS.”

Another aspect of Barry Lyndon that resonated with Abbasi was Kubrick’s ability to immerse viewers in the past through aesthetics atypical for the film genre. (The minimal electric lighting and wide angles created a painterly effect that was entirely Kubrick’s own.) The distinctiveness of that approach served as a foundational inspiration for Abbasi and Director of Photography Kasper Tuxen, who shot 2021’s The Worst Person in the World. “Recreating a past era with pristine detail always felt a bit too fetishistic and inauthentic to me,” Abbasi explains. Instead, the film begins with a lived-in texture reminiscent of 16mm footage before transitioning into the cruddier appearance of broadcast video. This visual shift mirrors not only the temporal transition but a narrative one, coinciding with the themes at play: the early construction of Donald Trump’s

mythological image, followed by its deconstruction.

Unexpectedly, The Apprentice eschews sarcasm and cynicism, opting instead to present Trump’s narrative as a human drama. “Every time I make a movie, I ask myself the same questions,” he says. “Do I like the script? The dynamics? The movement? ” Some critics have argued that the film, which initially struggled to find a distributor, fails to deliver a sufficiently hard-hitting portrayal of its subject. Meanwhile, Trump has dismissed it as a “disgusting hatchet job.”

Abbasi is less interested in the film’s political impact than its artistic merit—whether audiences think it’s good or bad. The Canadian filmmaker Mary Harron (best known for I Shot Andy Warhol, American Psycho, and The Notorious Bettie

Page) sent him a note of support. “She felt it was absolutely the right decision not to make these people monsters—because that would have let what she called ‘vulture capitalists’ off the hook,” Abbasi explains. “The underlying point is not the humanity of these characters but the system at work. With looser checks and balances, that system can turn anyone into a monster.”

Since its premiere at Cannes last May, where it received an eight-minute standing ovation, the film has elicited enthusiastic reviews of its stars, Sebastian Stan (as Trump) and Jeremy Strong (as Cohn)—both of whom were nominated for Academy Awards. Abbasi—nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for Best Director himself—adopts a notably hands-off approach when collaborating with actors. “I’ve gotten a reputation for being good with [them],” he remarks, “which isn’t really true. At this level, you’re dealing with very dedicated professionals. It’s not like I can give them any technical tips. In fact, I could make them worse by telling them shit they don’t need to hear.” He feels that his role on set is to cultivate a sense of spontaneity— coordinating a seamless flow between takes and allowing the creative process to unfold naturally.

For the first time in a decade, Abbasi doesn’t have his next project lined up. After a relentless stream of films, which overlapped in their making, he finally has a moment to pause and reflect. “It’s been like dominoes. I want to stop and look at the world around me,” he says, noting that in the past 10 years, the political landscape and what we define as truth has shifted dramatically. “Now, anything with enough likes on X can become reality. Conspiracy theories can rival rational narratives. There is no hierarchy of realities,” he concludes. “Our world has fundamentally changed—and we need to address it.”

In her latest film, Magic Farm, artist Amalia Ulman takes Chloë Sevigny and Alex Wolff down to Argentina.

In Amalia Ulman’s new film, Magic Farm, a Vice -like crack team of documentary filmmakers—incarnated by the likes of Chloë Sevigny, Alex Wolff, and Ulman herself—land in rural Argentina to shoot a piece about a local musician, only to realize they’re in entirely the wrong country.

In the midst of our protagonists’ frenzied reaction to the news, little thought is dedicated to the locale they’ve come to in their search for viral content: a community suffering the consequences of harmful crop spraying. So absorbed is the film crew in their city slicker woes that they fail to notice the turmoil around them— children are born with chemically induced physical defects; agricultural planes zoom overhead, sending the locals running for cover; and coughing fits are shrugged off like spring allergies. This trick, of backgrounding the foreground of a narrative, is one that Ulman, an Argentine-Spanish video and performance artist, previously employed in her 2021 directorial debut, El Planeta

That film premiered at Sundance Film Festival, and last month, Magic Farm followed in its footsteps. Ahead of its wide release later this year, the artist spoke to CULTURED about her approach to skewering our collective sense of moral detachment.

Did you think much about the parallel between making a film about a crew traveling to Argentina to shoot a movie, and doing the same thing yourself?

In a way, I enjoy making fun of myself. The crew and everyone involved in the

“THE CRITIQUE OF HIPSTERISM IS ALSO A CRITIQUE OF MYSELF, WHICH I THINK MAKES IT MORE ACCESSIBLE AND RELATABLE.”

story reflect elements of people I know and love. The critique of that style and hipsterism is also a critique of myself, which I think makes it more accessible and relatable.

Tell us about the cinematography of the film. There are a lot of scenes shot with unusual lenses, saturation, and other editing techniques.

I’m inspired by a lot of the beautiful things happening online and on TikTok, especially concerning editing.

We even used CapCut for some of the editing and transitions. The animal camera footage was inspired by a YouTube account I love, where someone in China attaches a camera to their cat.

Filmmaking is still a young art, even though the rules often feel rigid. The Internet today can feel like a dumpster, but there are beautiful things if you know where to look. I’m especially drawn to moments when people are unaware they’re making art—that’s when something magical happens.

What do you hope audiences take away from the film?

The film shows how superficial this hipster culture is when compared to the larger, looming problems that affect everyone. At some point, we’ll all have to face those deeper issues. That’s the message of the film: There’s something more significant happening beneath the surface, and it’s something that connects us all.

David’s latest project, a romantic comedy run amok, examines the dark side of modern relationships.

After captivating audiences at SXSW last year, Cazzie David’s I Love You Forever was released in theaters on Feb. 14—darkly comedic timing befitting a darkly comedic film that plumbs the murky depths of emotionally abusive relationships.

A writer, actor, and essayist, David has honed a distinctive voice that blends wit with poignant, often uncomfortable truths. Her 2020 essay collection, No One Asked for This, further cemented her status as a writer with a keen eye for the absurdities and nuances of modern life, relationships, and the messy contradictions of adulthood. Whether dissecting the pitfalls of romance or the chaos of quotidian interactions, David’s work is equal parts biting and reflective, with a refreshingly unflinching slant.

In an exclusive conversation with CULTURED, David reflects on the personal and creative forces behind I Love You Forever. She opens up about the challenges of creating multidimensional characters, navigating the fine line between humor and heartbreak, and why this film, in all its complexity, is her most intimate and daring project to date.

How did we get this movie?

I experienced something in this vein and there wasn’t a lot to turn to in the aftermath. I wanted to make something that felt like a grounded, realistic portrayal of the feelings that swirl around emotional abuse. I talked to many people, and as I learned more, it became clear that it’s a kind of epidemic. I thought it was so crazy that there weren’t any movies that could help people to either feel seen or prevent themselves from getting into something like this.

At the same time, my writing partner

and I wanted to write something that felt like a rom-com for our generation. It came together perfectly, because the textbook emotionally abusive relationship starts out feeling like a fairy tale or a once-in-a-lifetime love story.

Was there catharsis for you in making this film?

I think that will come when and if people can relate to this movie. I’m kind of waiting for that moment. It’s strange to have an experience and then direct that same experience on a set, but in the end, the film was an amalgamation of so many stories. We wanted there to be a glimpse of every manipulation tactic a person could have experienced in an emotionally abusive relationship— even a friendship—so that there’s something that almost anyone could relate to.

So many of the relationships in the film are heavily mediated by technology. That’s always

“My writing partner and I wanted to write something that felt like a rom-com for our generation. It came together kind of perfectly, because the textbook emotionally abusive relationship starts out feeling like a fairy tale.”

— CAZZIE DAVID

something I’m wary of—it’s challenging to pull off a hypercontemporary story in that way.

Hyper-contemporary movies, they’re such a bummer. Sometimes I’ll see a character in a show take a photo and be like, “La di da—posted!” No one has ever done that—come on! You take 300 photos, you craft a caption, and hours later you post it and delete it. I find those nuances to be really funny and touching, and they’re rarely portrayed accurately. But in the film, the phone has a major role—it becomes a leash linking Mackenzie to her boyfriend.

You seem interested in the idea of this film educating people. Many directors shy away from that.

I don’t want it just to feel informative—because that’s not a movie, it’s a PSA. But since I feel confident in the story—it has a lot of humor in it and it’s relatable to my generation—I’m happy if it also manages to teach you something. I think it has that educational potential because this is a subject that we have really inaccurate conversations about. If I had seen something like this when I was in high school, it could have helped.

(Award given to the producer)

ANORA

Producers: Sean Baker, Alex Coco, Samantha Quan

I SAW THE TV GLOW

Producers: Ali Herting, Luca Intili, Dave McCary, Emma Stone, Sarah Winshall

NICKEL BOYS

Producers: Joslyn Barnes, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, David Levine

SING SING

Producers: Clint Bentley, Greg Kwedar, Monique Walton

THE SUBSTANCE

Producers: Tim Bevan, Coralie Fargeat, Eric Fellner

SCOTT BECK, BRYAN WOODS Heretic

JESSE EISENBERG A Real Pain

MEGAN PARK My Old Ass

AARON SCHIMBERG A Different Man

JANE SCHOENBRUN I Saw the TV Glow

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

DINH DUY HUNG Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell

JOMO FRAY Nickel Boys

MARIA VON HAUSSWOLFF Janet Planet

JUAN PABLO RAMÍREZ La Cocina

RINA YANG The Fire Inside

(Award given to the director and producer)

DÌDI

Director / Producer: Sean Wang

Producers: Valerie Bush, Carlos López Estrada, Josh Peters

IN THE SUMMERS

Director: Alessandra Lacorazza Samudio

Producers: Janek Ambros, Lynette Coll, Alexander Dinelaris, Cynthia Fernandez De La Cruz, Cristóbal Güell, Sergio Alberto Lira,Rob Quadrino, Jan Suter, Daniel Tantalean, Nando Vila, Slava Vladimirov, Stephanie Yankwitt

JANET PLANET

Director / Producer: Annie Baker

Producers: Andrew Goldman, Dan Janvey, Derrick Tseng

THE PIANO LESSON

Director: Malcolm Washington

Producers: Todd Black, Denzel Washington

PROBLEMISTA

Director / Producer: Julio Torres

Producers: Ali Herting, Dave McCary, Emma Stone

JOANNA ARNOW The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed

ANNIE BAKER Janet Planet

INDIA DONALDSON Good One

JULIO TORRES Problemista

SEAN WANG Dìdi

HIS THREE DAUGHTERS

Director: Azazel Jacobs

Casting Director: Nicole Arbusto

Ensemble Cast: Jovan Adepo, Jasmine Bracey, Carrie Coon, Jose Febus, Rudy Galvan, Natasha Lyonne, Elizabeth Olsen, Randy Ramos Jr., Jay O. Sanders

(Award given to the best feature made for under $1 million; award given to the writer, director, and producer)

BIG BOYS

Writer / Director / Producer: Corey Sherman

Producer: Allison Tate

GHOSTLIGHT

Writer / Director: Kelly O’Sullivan

Director / Producer: Alex Thompson

Producers: Pierce Cravens, Ian Keiser, Chelsea Krant, Eddie Linker, Alex Wilson

GIRLS WILL BE GIRLS

Writer / Director / Producer: Shuchi Talati

Producers: Richa Chadha, Claire Chassagne

JAZZY

Writer / Director / Producer: Morrisa Maltz

Writer / Producer: Lainey Shangreaux

Writers: Andrew Hajek, Vanara Taing

Producers: Miranda Bailey, Tommy Heitkamp, John Way, Natalie Whalen, Elliott Whitton

THE PEOPLE’S JOKER

Writer / Director: Vera Drew

Writer: Bri LeRose

Producer: Joey Lyons

LAURA COLWELL, VANARA TAING Jazzy

OLIVIER BUGGE COUTTÉ, OLIVIA NEERGAARD-HOLM The Apprentice

ANNE MCCABE Nightbitch

HANSJÖRG WEISSBRICH September 5

ARIELLE ZAKOWSKI Dìdi

ALI ABBASI The Apprentice

SEAN BAKER Anora

BRADY CORBET The Brutalist

ALONSO RUIZPALACIOS La Cocina

JANE SCHOENBRUN I Saw the TV Glow

BEST DOCUMENTARY

(Award given to the director and producer)

GAUCHO GAUCHO

Directors / Producers: Michael Dweck, Gregory Kershaw

Producers: Christos Konstantakopoulos, Cameron O’Reilly, Matthew Perniciaro

HUMMINGBIRDS

Directors: Silvia Del Carmen Castaños, Estefanía “Beba” Contreras

Co-Directors / Producers: Miguel Drake-McLaughlin, Diane Ng, Ana Rodriguez-Falco, Jillian Schlesinger

Producers: Leslie Benavides, Rivkah Beth Medow

NO OTHER LAND

Directors / Producers: Yuval Abraham, Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Rachel Szor

Producers: Fabien Greenberg, Bård Kjøge Rønning

PATRICE: THE MOVIE

Director: Ted Passon

Producers: Kyla Harris, Innbo Shim, Emily Spivack

SOUNDTRACK TO A COUP D’ETAT

Director: Johan Grimonprez

Producers: Rémi Grellety, Daan Milius

AMY ADAMS Nightbitch

RYAN DESTINY The Fire Inside

COLMAN DOMINGO Sing Sing

KEITH KUPFERER Ghostlight

MIKEY MADISON Anora

DEMI MOORE The Substance

HUNTER SCHAFER Cuckoo

JUSTICE SMITH I Saw the TV Glow

JUNE SQUIBB Thelma

SEBASTIAN STAN The Apprentice

YURA BORISOV

Anora

JOAN CHEN Dìdi

KIERAN CULKIN A Real Pain

DANIELLE DEADWYLER The Piano Lesson

CAROL KANE Between the Temples

KARREN KARAGULIAN Anora

KANI KUSRUTI Girls Will Be Girls

BRIGETTE LUNDY-PAINE I Saw the TV Glow

CLARENCE “DIVINE EYE” MACLIN Sing Sing

ADAM PEARSON A Different Man

ISAAC KRASNER Big Boys

KATY O’BRIAN Love Lies Bleeding

MASON ALEXANDER PARK National Anthem

RENÉ PÉREZ JOGLAR In the Summers

MAISY STELLA My Old Ass

ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT

France, India, Netherlands, Luxembourg Payal Kapadia

BLACK DOG

China

Guan Hu

FLOW

Latvia, France, Belgium

Gints Zilbalodis

GREEN BORDER

Poland, France, Czech Republic, Belgium

Agnieszka Holland

HARD TRUTHS

United Kingdom

Mike Leigh

EMERGING FILMMAKER AWARDS

The Producers Award, now in its 28th year, honors emerging producers who, despite highly limited resources demonstrate the creativity, tenacity and vision required to produce quality, independent films.

ALEX COCO

SARAH WINSHALL ZOË WORTH

The Someone to Watch Award, now in its 31st year, recognizes a talented filmmaker of singular vision who has not yet received appropriate recognition.

NICHOLAS COLIA

Director of Griffin In Summer

SARAH FRIEDLAND

Director of Familiar Touch

PHAM THIEN AN

Director of Inside The Yellow Cocoon Shell

The Truer Than Fiction Award, now in its 30th year, is presented to an emerging director of non-fiction features who has not yet received significant recognition.

JULIAN BRAVE NOISECAT, EMILY KASSIE

Directors of Sugarcane

CARLA GUTIÉRREZ

Director of Frida

RACHEL ELIZABETH SEED

Director of A Photographic Memory

TELEVISION CATEGORIES

BEST ENSEMBLE

HOW TO DIE ALONE

Ensemble Cast: Melissa DuPrey, Jaylee

Hamidi, KeiLyn Durrel Jones, Arkie Kandola, Elle Lorraine, Michelle McLeod, Chris “CP” Powell, Conrad Ricamora, Natasha Rothwell, Jocko Sims

BRIAN JORDAN ALVAREZ English Teacher

RICHARD GADD

Baby Reindeer

LILY GLADSTONE

Under the Bridge

KATHRYN HAHN

Agatha All Along

CRISTIN MILIOTI

The Penguin

JULIANNE MOORE

Mary & George

HIROYUKI SANADA

Shõgun

ANNA SAWAI

Shõgun

ANDREW SCOTT Ripley

JULIO TORRES Fantasmas

JESSICA GUNNING

Baby Reindeer

DIARRA KILPATRICK

Diarra from Detroit

JOE LOCKE

Agatha All Along

MEGAN STOTT

Penelope

HOA XUANDE

The Sympathizer

TADANOBU ASANO

Shõgun

ENRICO COLANTONI

English Teacher

BETTY GILPIN

Three Women

CHLOE GUIDRY

Under the Bridge

MOEKA HOSHI

Shõgun

STEPHANIE KOENIG

English Teacher

PATTI LUPONE

Agatha All Along

NAVA MAU

Baby Reindeer

RUTH NEGGA

Presumed Innocent

BRIAN TEE

Expats

(Award given to the Creator, Executive Producer, Co-Executive Producer)

ERASED: WW2’S HEROES OF COLOR

Exec Producers: Idris Elba, Johanna Woolford Gibbon, Jamilla Dumbuya, Jos Cushing, Khaled Gad, Matt Robins, Chris Muckle, Sean David Johnson, Simon Raikes

Co-Exec Producers: Annabel Hobley

HOLLYWOOD BLACK

Exec Producers: Shayla Harris, Dave Sirulnick, Stacey Reiss, Jon Kamen, Justin Simien, Kyle Laursen, Forest Whitaker, Nina Yang Bongiovi, Jeffrey Schwarz, Amy Goodman Kass, Michael Wright, Jill Burkhart Co-Exec Producers: David C. Brown, Laurens Grant

PHOTOGRAPHER

Exec Producers: Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, Jimmy Chin, Pagan Harleman, Betsy Forhan

Co-Exec Producers: Anna Barnes, Brent Kunkle

REN FAIRE

Exec Producers: Ronald Bronstein, Benny Safdie, Josh Safdie, Eli Bush, Dani Bernfeld, Lance Oppenheim, David Gauvey Herbert, Nancy Abraham, Lisa Heller, Sara Rodriguez

Co-Exec Producers: Abigail Rowe, Christian Vasquez, Max Allman

SOCIAL STUDIES

Creator / Exec Producer: Lauren Greenfield

Exec Producers: Wallis Annenberg, Regina K. Scully, Andrea van Beuren, Frank Evers, Caryn Capotosto

(Award given to the Creator, Executive Producer, Co-Executive Producer)

BABY REINDEER

Creator / Exec Producers: Richard Gadd

Exec Producers: Wim De Greef, Petra Fried, Matt Jarvis, Ed Macdonald

DIARRA FROM DETROIT

Creator / Exec Producers: Diarra Kilpatrick

Exec Producers: Kenya Barris, Miles Orion Feldsott, Darren Goldberg

Co-Exec Producers: Ester Lou, Mark Ganek

ENGLISH TEACHER

Creator / Exec Producer: Brian Jordan Alvarez

Exec Producers: Paul Simms, Jonathan Krisel, Dave King

Co-Exec Producers: Kathryn Dean, Jake Bender, Zach Dunn

FANTASMAS

Creator / Exec Producer: Julio Torres

Exec Producers: Emma Stone, Dave McCary, Olivia Gerke, Alex Bach,

Daniel Powell

Co-Exec Producers: Ali Herting

SHÕGUN

Creators / Exec Producers: Rachel Kondo, Justin Marks

Exec Producers: Edward L. McDonnell, Michael De Luca, Michaela Clavell

Co-Exec Producers: Shannon Goss, Andrew Macdonald, Allon Reich, Jamie Vega Wheeler

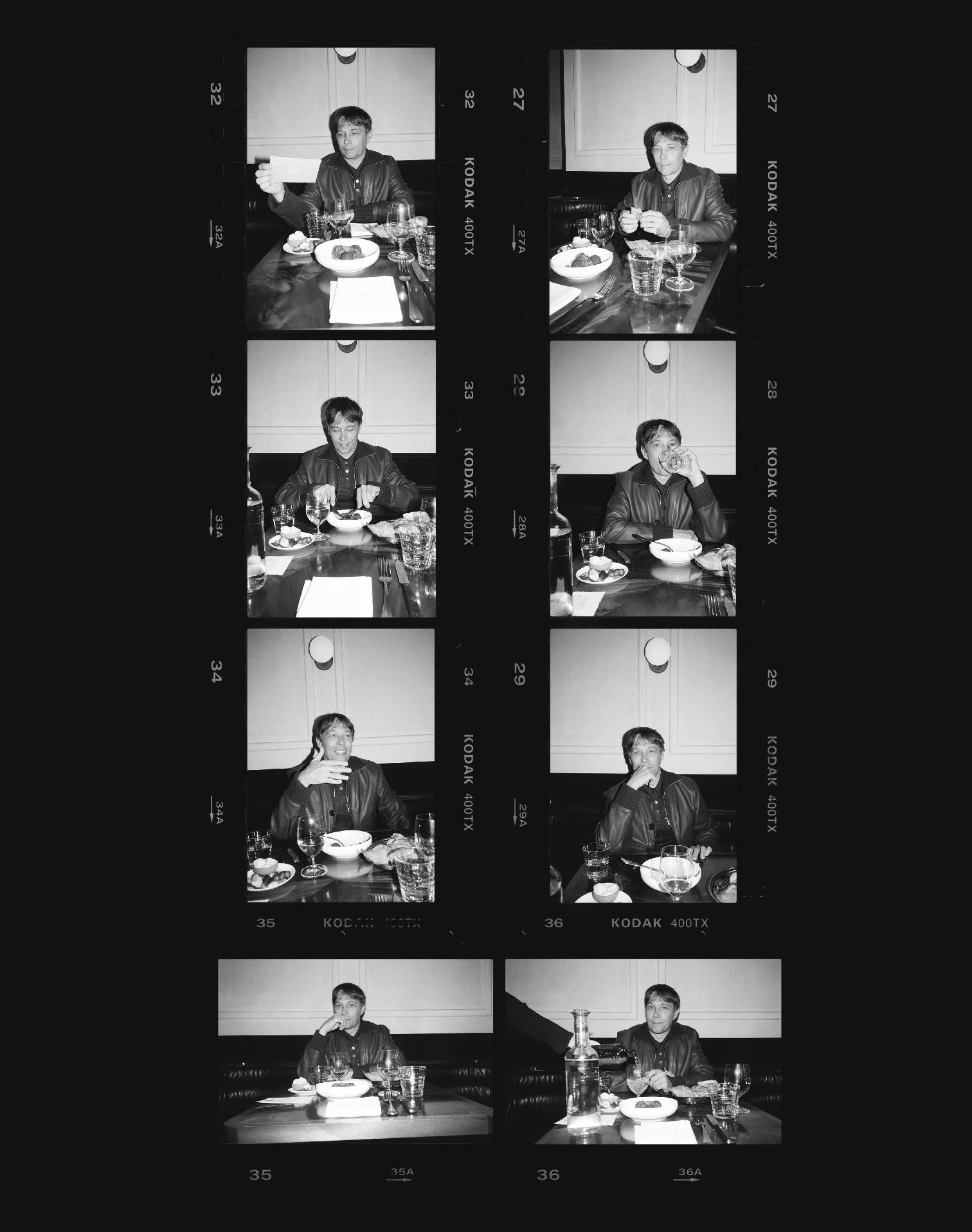

“AIDY, MY INSTINCT IS THAT I MET YOU WHEN YOU GOT ON SNL. UNTIL YOU’RE ON SNL, YOU’RE INVISIBLE TO ME.”

—NICK KROLL

At most awards shows, hosts have earned a reputation for being thinly veiled roast emcees. Cameras pan to A-listers hiding behind their co-stars or opera gloves, and all manner of jabs are fired off liberally. But the Film Independent Spirit Awards demand a different touch. The annual event has cemented itself over the past four decades as a highly anticipated and refreshingly lighthearted celebration of rising and indie filmmakers. That crowdpleasing reputation has drawn a roster of buzzy hosts, including two of Hollywood’s most affable celebrities: Aidy Bryant and Nick Kroll.

Bryant will return on Feb. 22 for her second run on the Spirit Awards stage, while Kroll has helmed the festivities twice himself—alongside his sometime comedy partner John Mulaney—in the late 2010s. Ahead of the show, Bryant and Kroll took a break between rehearsals at New York’s Hudson Theatre (where the pair were among the cast of the live comedy reading series All In: All About Love) for a run-through of her forthcoming hosting appearance, where she’ll celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the Spirit Awards and entertain the creators and fans of 2024 favorites Anora, Sing Sing, The Substance, and more.

Nick Kroll: We have a lot in common—and not just hosting the Spirit Awards. We also share a love of big cups.

Aidy Bryant: I love drinking from my big cup.

Kroll: Mine is an Erewhon mason jar. No big deal. I am in constant fear of being dehydrated, so I drink out of these. Anytime I drink out of a regular glass, I’m embarrassed—like for the cup.

Bryant: Agree. If it’s not big, I don’t rock it. I also want to say I’ve never been to Erewhon.

Kroll: It is so funny how expensive it is. And we can find that funny because we’re America’s two biggest celebrities, and because we get paid the big bucks to host things like the Spirit Awards.

Bryant: How and when did we first meet? I don’t remember. Feels like I’ve just known you for a long time now, maybe 10 years.

Kroll: My instinct is that I met you when you got on SNL. Until you’re on SNL, you’re invisible to me.

Bryant: And since I’ve left, I’ve been

invisible to you. I’m so grateful for this time together.

Kroll: Until you hosted the [Spirit Awards] last year. Then you became a central voice on Human Resources, my animated show.

Bryant: It was the honor of my life to be your employee.

Kroll: Thank you, as it was written in the contract for you to say so in any future engagements.

Bryant: You hosted the Spirit Awards with John [Mulaney] both times, right?

Kroll: Yeah, and he was later offered the chance to host the Oscars without me. I think that’s for the best.

Bryant: I wouldn’t want to do those. Would you?

Kroll: That was the fun of doing the Spirit Awards. I felt quite free, like we could kind of do whatever we wanted.

Everyone is happy to be there; it’s a little more relaxed. The first year we hosted was 2017. The second time was in 2018, right after #MeToo.

Bryant: They said, “We need to put a voice to this. Who should host? Nick and John.”

Kroll: “Let’s get those two white guys back up there.” Both experiences were equally fun, but it felt more complicated the second year. How do you feel going into the second year?

Bryant: I had so much fun the first time that I guess that’s my only goal this time: to have fun again. The reputation of an award show host is that you gotta come in there and blow those fuckers away with your bazooka of hot takes and satirical burns. But I’m really thrilled to be there. I also really believe in the ethos of Film Independent.

Kroll: In that room, you really do feel a shared value system. Our job is to make lots of jokes but also, in this particular case, you’re not like, “I’m gonna fucking shred these people and their movies.” It’s such a big day for people—these are independent filmmakers who have spent years toiling to get their very niche films in front of people. Diminishing what they’ve done doesn’t sound like much fun.

Bryant: If you’re hosting the Oscars and the biggest celebrities in the

world are there, you want to take them down a peg. I know one of the movies this year was shot in 11 days in the woods for like $10. I don’t need to be swinging a bat at that.

Kroll: We hosted the year that Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri was nominated. Frances McDormand was there, who absolutely rocks. Later at the after-party I saw her trying to sneak out with a jacket over her head. Normally, I’d think, Oh my God, that’s Frances McDormand, just leave her be, but since I’d been hosting, I felt a little entitled, like I was part of the scene. I was like, “Franny! Franny!” She stopped, looked at me, and said, “Okay, I will talk to you.” I replied, “Great. I need you to know that you look so much like my therapist.”

Bryant: Do you remember how you prepared to host with John?

Kroll: We ran it a lot. I’m blown away and mystified by people who host these things and don’t run it. For you at SNL or for me with stand-up, you’re like, “I need to hear from an audience what’s working and what’s not working.”

Bryant: I can’t even fathom just looking at a piece of paper and then being like, “Great, this is what I will do.” Even if I’m selling myself out by testing material, it’s worth it to me. I just want them to have a good time. I’ll show hole if I have to.

Kroll: Do you plan to show hole at the show?

Brant: I’m thinking about it for sure—toying with the idea, toying with which hole.

Kroll: It’s a terrible turn we’ve taken here.

Bryant: Do you have constructive feedback for me based on my last performance?

Kroll: Picture the audience absolutely naked. But no, honestly I loved being in that room with people who spent a lot of their life force to make something that they really believe in. It’s a big day, and you just want to show them a good time. Plus, you can hit the Santa Monica boardwalk immediately afterwards.

Bryant: As soon as I finished hosting the awards last year, I hopped on my skateboard, got a corn dog, and just started cruising the beach for guys. Do you know how to skateboard?

Kroll: I do not. Do you?

Bryant: No.

Kroll: Fuck, next year.

“WE HAVE A LOT IN COMMON—AND NOT JUST HOSTING THE SPIRIT AWARDS.

WE ALSO SHARE A LOVE OF BIG CUPS.”

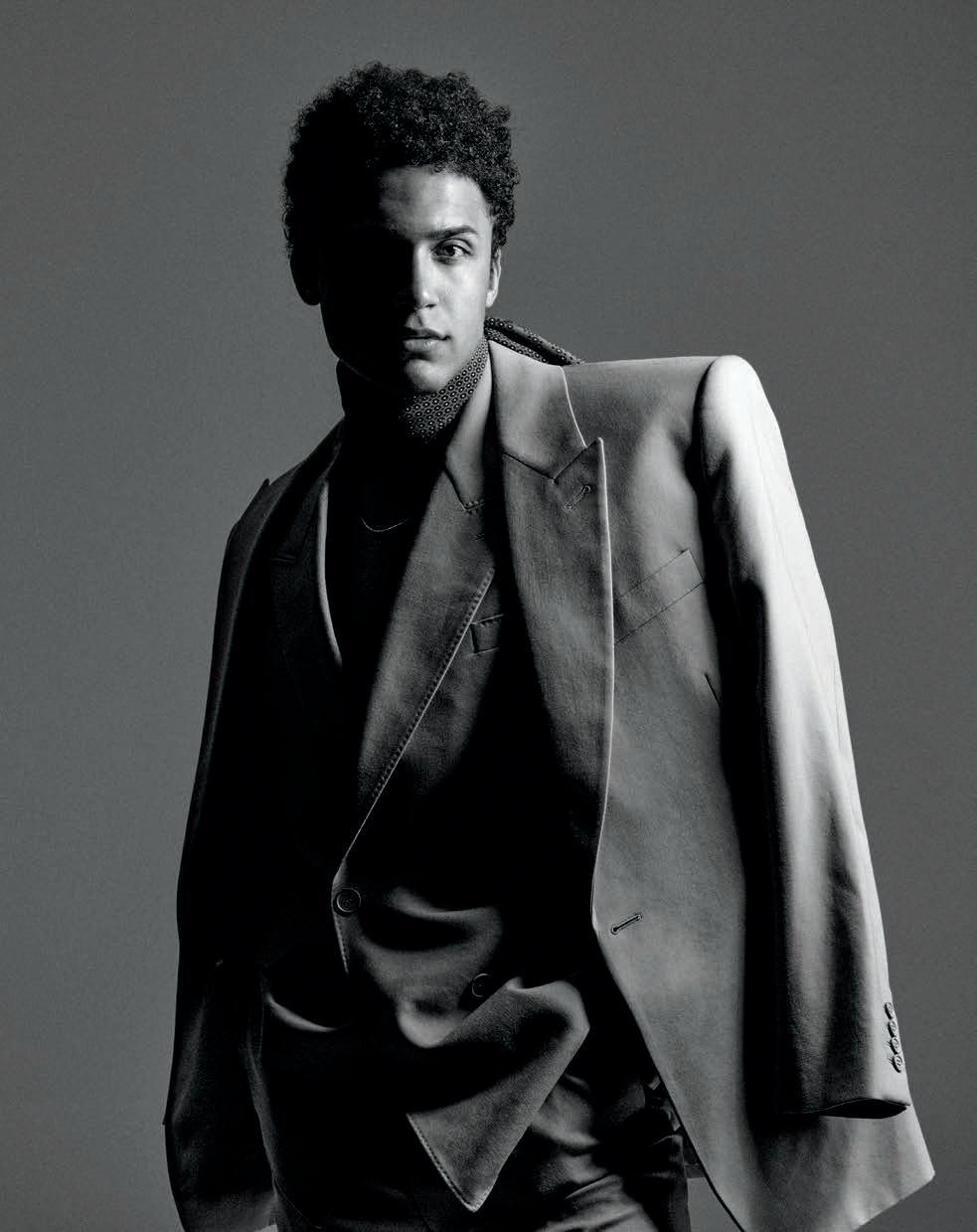

Photography by Brandon Hicks Styling by Meaghan O’Connor

A

By Rachel Cargle

While the world catches up to the brilliance of Natasha Rothwell, she’s been “10 toes down” in developing characters and taking on roles that offer her, and her audience, a 360-degree view of what it means to be “whole” onscreen.

Since 2014, we’ve caught glimpses of Rothwell’s wit and wisdom as a writer on SNL and as Issa Rae’s hilarious friend Kelli on HBO’s Insecure. In recent years, her star has reached new heights with roles like Belinda, the loving and striving spa manager on the hit Max show The White Lotus, and Mel, a broke JFK airport worker who sets out on a journey of self-discovery in the Hulu series How to Die Alone, which Rothwell created.

“It feels like an expansion that I’m now allowing others to witness,” she shares over a recent afternoon Zoom. She apologizes as her black goldendoodle skitters by, leaning down to ruffle the puppy’s ears. Rothwell’s soft curls and deep brown skin glow on my laptop screen.

She exudes the ease and intention of someone who has found their footing. “I’ve been feeling that growth for some time, and I think it does, in fact, feel like my moment,” she reasons.

Rothwell smiles as she speaks, but impostor syndrome seems to creep

up on her midsentence. “I say that with a lot of trepidation because, despite my vocation, I can be pretty shy,” she admits. “It’s ultimately thrilling to be in this place where I’m garnering so much respect in my industry and having so many more people exposed to my work. But taking up space as a fat, Black woman; as a creator; as someone who has, for her whole life, desperately wanted to be seen—

finds that her Emmy-nominated role as Belinda on The White Lotus is another opportunity to be a more expansive version of herself. As she heads into season three alongside a star-studded cast that includes Parker Posey and Carrie Coon, Rothwell challenges what audiences might expect from her screen presence. “When you walk through the world as a Black, plus-size woman, there are a lot of expecta-

“WHEN YOU WALK THROUGH THE WORLD AS A BLACK, PLUS-SIZE WOMAN, THERE ARE A LOT OF EXPECTATIONS PEOPLE HAVE BASED OFF OF THEIR PRECONCEIVED NOTIONS OF FILM AND TELEVISION.”

that’s equally terrifying.” Rothwell hasn’t let those feelings overwhelm her. As she developed How to Die Alone (a seven-year dream come to life), she let her full self show up— even the “unhealed parts,” as she puts it. In one scene in the season finale, her character strips down to her bra and panties on a public beach—a level of public exposure Rothwell has never faced in her personal life. Doing it on television added new layers of vulnerability, but she pushed through, feeling powerful and new when she emerged. “It’s painstaking,” she says. “You can only be as honest as you’ve been with yourself.” She

tions people have based off of their preconceived notions of film and television,” she explains. “The mischievous side of me really delights in subverting those expectations.”

Rothwell was born in Wichita, Kansas, but spent her childhood on military bases around the world. Her father, who was in the Air Force, and her mother, who worked in health care, fostered a sense of pride in whatever work she chose to pursue. Ultimately, it was theater, then the comedy circuit, that beckoned Rothwell. But it was never just about the stage. Her occupation

as an actor has always been accompanied by a role as an advocate for the issues she feels are worth the fight: mental health care, voting, and media representation.

Those values pulled Rothwell into developing a production company of her own, Big Hattie Productions, named after the late Wichita-born actor Hattie McDaniel, who is best known for her Academy Award–winning role as Mammy in Gone with the Wind. Rothwell stumbled upon the film as a teenager working at Blockbuster.

For the first time, she saw someone onscreen who looked like her. “I saw the deference the other actors gave to her in each scene, and how she demanded the attention of every person that she engaged with in that film, and I saw very clearly why she won the Academy Award,” Rothwell says. “My production company is about subverting expectations, demanding that attention, and centering the voices that are often marginalized in the industry.”

When I ask Natasha where her inspiration is taking her next, she carefully avoids specifics but makes one thing clear: “I’m very picky about what I do; I’m very deliberate about the projects that I take on. [But] each one channels the spirit of Hattie McDaniel—the spirit of being so good they can’t ignore you.”

By Durga Chew-Bose

Maloney

For years, Halina Reijn was the muse. “Now, I’m sitting in the chair where I saw all these men sit all of my life,” says the acclaimed Dutch actor turned director, whose second English-language film, last winter’s Babygirl, received a feverish response to its unflinching investigation of power and desire. Romy, a perfectionseeking CEO embodied by Nicole Kidman, finds herself adrift at middle age—struggling to navigate the gulf between the fairy tale family life she shares with her husband (Antonio Banderas) and a growing sense of shame at her own dissatisfaction. She falls into a smoldering affair with Samuel, an intern with an easy grin and a deep reserve of confidence, played masterfully by Harris Dickinson.

The fallout is an explosive yet redemptive unraveling of Romy’s carefully manicured identity.

Right now, Reijn is living her own fairy tale—promoting the rare film that is both a critical darling and a hit with general audiences, and attending a whirlwind of dinners, parties, and Q&As with Kidman, Hollywood’s most ubiquitous star, on her arm. The demands that come with striking cinematic gold can be intense, but Reijn—who was “raised by hippies completely off the grid”—is fairly unflappable. “It’s all great, of course, but it’s tiring,” she says of the awards hubbub. “I’m always afraid to do something wrong or forget a dress in a certain country.

You’re constantly borrowing these beautiful clothes that are not yours, and you have to give them back.”

Reijn’s candor gives me a sense of what she might have been like on set, and why her collaborators often note the director’s uncanny ability to build the trust required to explore thorny topics. “It’s very important to show [my actors] that I’m not above them. I’m not some dictator telling them to undress, crawl around, cry,” she explains. “I’ve experienced that myself. Even a scene that looks very

“I’M SO CONFUSED ABOUT BEING A WOMAN, I REALLY AM. I FEEL SO MANY CONTRADICTIONS INSIDE OF ME.”

simple from the outside can be incredibly vulnerable and scary when everybody around you is standing around wearing a North Face jacket and eating pizza.”

The filmmaker approaches our conversation with a similar level of salt-of-the-earth sincerity. The relentlessly inquisitive and fast-talking 49-year-old listens attentively and speaks passionately, but she does not orate. She wants a dialogue, I’d venture, because she is not interested in making art that serves as a final word—on the representation of beauty and aging in media, on the contradictory expectations of men and women as directors, on the invisible trip-wires of motherhood, partnership, and pleasure, any of it. “My primary urgency [creatively] is my confusion,” Reijn says, looking directly at me. “I’m so confused about being a woman; I really am. I feel so many contradictions inside of me.”

That sense of disorientation was only amplified by a successful decades-long career as a stage and screen actor in the Netherlands. Reijn worked with directors like Paul Verhoeven and performed countless plays by Shakespeare, O’Neill, and Ibsen, which she also credits as her writing education.

“These roles became part of my DNA, and they were all written by men,” she says. “The female

characters are searching for liberation, but they end up either killing themselves or going crazy. For better or for worse, everything I do is informed by those women. They hold me like ghosts.” The role she created for Kidman was, in part, an exorcism of these characters, but also a challenge: “What would I want to play? What would my dream role be, where I could show my full range?” Contradiction in its many forms—between expectation and reality, desire and expression, and among the suppressed parts of ourselves—is at the heart of Babygirl. In one scene, a large dog appears, charging at Romy in the New York streets before being tamed (by Samuel). In another, Romy meets Samuel for a hotel room rendezvous that leaves both characters’ vulnerabilities exposed. Briefly, reality gives way to a fable about suppressed desire, dominance, and the beasts buried

deep within. Embodying the hound, Romy releases her power, overtaken by a full-body rush—forgetting the children, the boardrooms, the Botox—and becoming the incarnation of her long-dormant arousal, finally awakened amid the trappings of a seedy hotel room. You can almost smell the carpet and feel the walls closing in as Romy disentangles shame from pleasure.

This primal encounter is one of many glittering exchanges—across a bar over a glass of milk, or in a soundproofed meeting room—that fuel the film’s sensual undulations. Each is set against an eerie sonic landscape of breathing, grunting, and panting, an aide-mémoire of the body’s needs and natural rhythms. When I ask Reijn about her relationship to rhythm, she nods emphatically. “It’s everything. When I’m writing, I’m pacing it all like I

hear it—that’s my theater background. I love big scenes with just a table and two people talking, like it’s a chess game. It’s all music.” In fact, it was music (the song “Father Figure”—a satisfying George Michael needle drop, to be specific) that was the genesis of Babygirl. “I had that [song] as an idea before anything. I knew I wanted to make a movie about a powerful woman and a younger man dominating her. With ‘Father Figure,’ I could spin that on its head.”

I ask Reijn how she knows when an idea has become a movie. “Everyone is asking me, ‘What’s next?’” she concludes. “I don’t know. I have all these embryos. Some I don’t even like—they feel like demons. Some I love, and they’re angels.”

FOLLOWING THE BREAKOUT SUCCESS OF HIS LATEST FILM, ANORA, SEAN BAKER HAS SOLIDIFIED HIS STATUS AS THE CONSUMMATE OUTSIDER-INSIDER.

Around 2000, just after Sean Baker got clean from opioids, he had to rebuild his life from scratch. He had been tossed from Greg the Bunny, the TV show he helped create that had been picked up by Fox. He lost most of his contacts and had stuck around New York while others from his early film escapades went west. But he thought he could survive one last attempt at becoming a filmmaker. “I did everything I could not to get a nine-to-five,” Baker tells me. “I wanted to stay connected to the industry, even if I was on the farthest fringes.” He edited corporate videos; he duplicated VHS tapes for actors’ reels. And—whether you’re a palm reader or a lawyer or a filmmaker—there is always work in weddings. “I worked for the high-end wedding video company,” he recalls. “Martha Stewart–type stuff.”

Most of the weddings he filmed were in ethnic enclaves of New York. One took place in Brighton Beach, where the Moscow satellite elitism and shitty weather stuck with him. It was an early seed for Anora, his latest movie, which was nominated for a whopping six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director,

By Elena Saavedra Buckley

Photography by Quil Lemons at Le Rock at Rockefeller Center

Styled by Rebecca Ramsey

and Best Actress (along with an Independent Spirit Awards Best Director nomination for Baker himself). It also took home this year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes—the first time an American filmmaker has won the award since Terrence Malick in 2011. The film is about an exotic dancer and escort—the titular Anora, better known as Ani—who grew up in Brighton. After meeting Vanya, the son of a Russian oligarch, she becomes his girlfriend for the week in exchange for $15,000. She then marries him in Las Vegas and is clumsily taken hostage by his parents’ goons while they try to find Vanya, who has fled, so they can annul the union before their bosses arrive on American soil.

You could call Baker’s work “neo-neo

realism,” the term coined by A.O. Scott in 2009 to describe Great Recession–era films that focused on outsider characters, first-time actors, and bare-bones depictions of socioeconomic struggles. But he’s been at it for longer than that. (Longer, in fact, than one might expect—he looks good for 53, like he could do a kickflip if you asked.) Nevertheless, his attempts at that realism, no matter how vérité his shots or how shoestring his budgets, are forever complicated by the simple fact that he is the ultimate insider-outsider: at once fluent in the hustling, addiction-adjacent lives he depicts, and something of a Hollywood voyeur. When we spoke, Baker was in his New York apartment, jet-lagged from events in London and rubbing his eyes as his dog crawled

“IF I PICK UP ANYTHING HARD IN THE OPIOID WORLD AGAIN, IT’S SUICIDE. SO IT IS DANGEROUS. BUT I CAN’T BE WRITING MY WORLDS SITTING IN WEST HOLLYWOOD.” — SEAN BAKER

into his lap. He was bracing for the film’s New York premiere, which he accented with scare quotes—“the ‘premiere’”—as if the pomp was a little embarrassing. Anora’s box office numbers prove that Baker has reached a kind of escape velocity. It doesn’t hurt that Zoomer appetites for chaotic and brash New York fare have been whetted by the Safdie brothers.

Anora is the rare film that features cell phones and vape pens—the key accoutrements of its 20-something characters’ lives—successfully (which is to say, constantly and without much interest). But Baker’s eye developed back in the 1970s, when he would drive into the city from New Jersey with his dad, a time when porn was still shown in theaters. “We would come out of the Lincoln Tunnel and head down 42nd Street. It was a ‘Welcome to the Jungle’ moment every single time,” he told me, with ads for Marilyn Chambers and Deep Throat lighting the way. He has visited various corners of the sex work industry in most of his films since. Tangerine focuses on Black trans sex workers in LA; Red Rocket is about a

washed-up male porn star on the Gulf Coast. Baker consistentently, if dutifully, speaks out for decriminalization, but he’s allergic to preachiness and politics. “A lot of our media speaks to the left. I happen to be left-wing, but I think it’s important for everyone to be talking,” he says. “I’m trying to make a universal story that has fleshed-out, three-dimensional, human characters who allow audiences to have empathy. They can apply their own thoughts and ideologies.”

Baker calls Anora “high-concept,” since its plot can be summarized in a sentence, but it’s also his most planned movie. Its budget was reportedly $6 million—three times the estimate of The Florida Project—and while his other films achieve their heady tenor through the rough-and-ready chaos of first-time actors, Anora’s central performers are all pros (he was even willing to wade through Russian visa complications to bring a couple of them over).

“With me taking more money this time, the risk is higher. I didn’t want to fool around, basically,” Baker muses. “In the future, I’m sure I’ll always have a portion of the cast that’s brand-new, off-the-street faces, but being able to work with professionals changed my game.” Fourth-wall breaking in Anora is

“WHEN YOU BUILD A CAREER ON THE HUSTLE MINDSET, THE ETERNAL QUESTION IS, WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU BECOME SUCCESSFUL?”

mostly self-referential: This is the second movie in which the actor Karren Karagulian, a frequent Baker collaborator, drives a car while someone pukes in the back seat. (Other tears in the fabric, like using t.A.T.u.’s “All the Things She Said”— also the Red Scare podcast theme song—in one climactic sequence, made people audibly groan in the theater where I watched it.)

When you build a career on the hustle mindset, the eternal question is, What happens when you become successful? Baker hasn’t “made it” in any consequential sense, since doing so in American independent cinema is essentially impossible—although he’ll probably never have to

edit another wedding video.

But whether higher budgets and buzz will bring him more scrutiny, or make his art suffer, is another matter. Most important to Baker is whether he’ll be able to dip back into the jungle for inspiration again. When I asked him about avoiding creative atrophy amid growing resources and comfort,

he answered with the frankness of someone who has found himself, at times, in dire straits. “You have to get embedded a bit. Sometimes it gets to a risky place, whether that’s drugs or something else,” he said. “If I pick up anything hard in the opioid world again, it’s suicide. So it is dangerous. But I can’t be writing my worlds sitting in West Hollywood.”

After seeing Anora in downtown Brooklyn. I cued up “Greatest Day,” the smarmy pop anthem by Take That, which soundtracks the fragile joy that blossoms in the movie right before everything goes to shit. I got on the Q train and headed in the direction of Brighton Beach. But I got off before I could get there.

“WHEN YOU BUILD A CAREER ON THE HUSTLE MINDSET, THE ETERNAL QUESTION IS,

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU BECOME SUCCESSFUL?”

By Mara Veitch

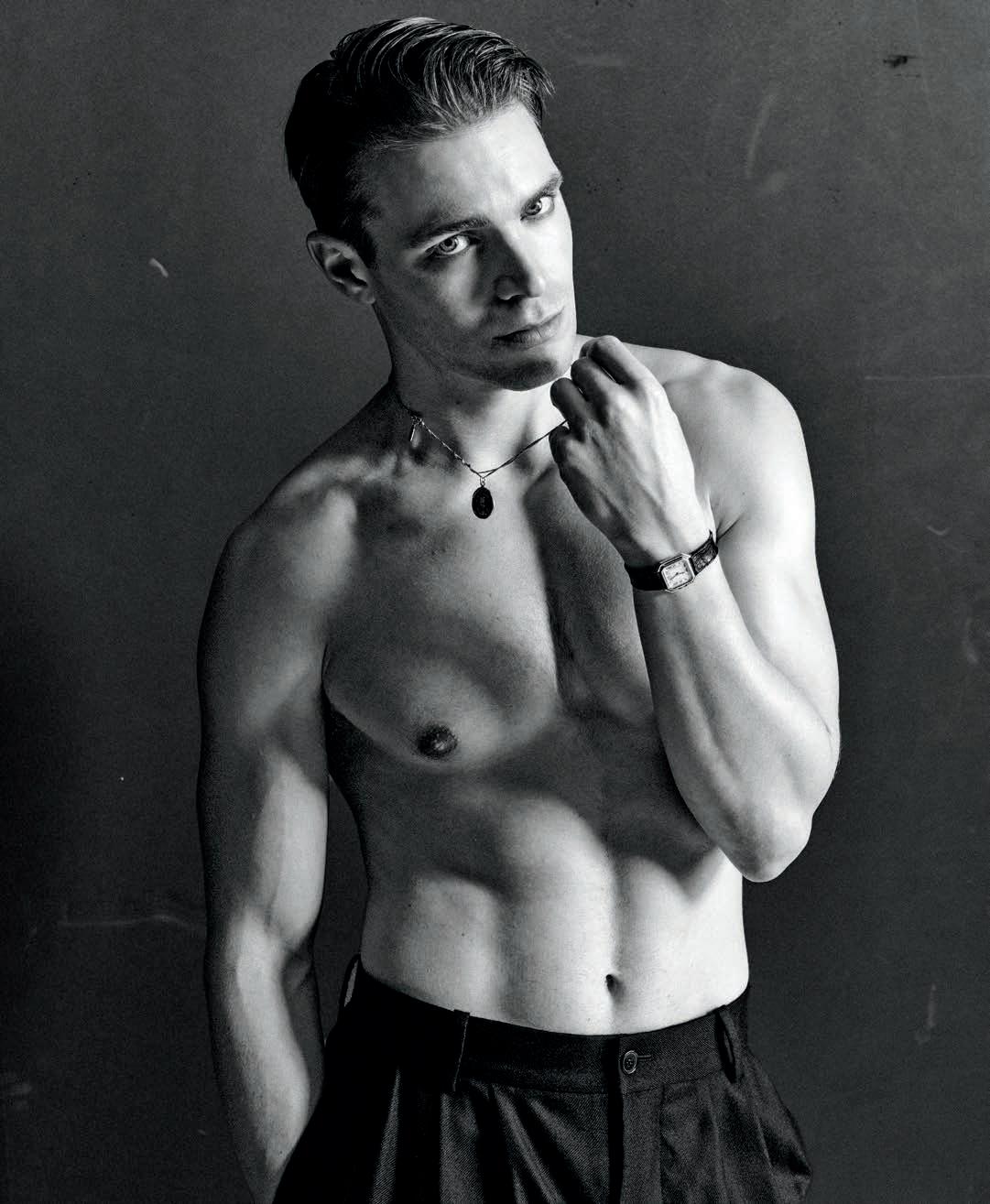

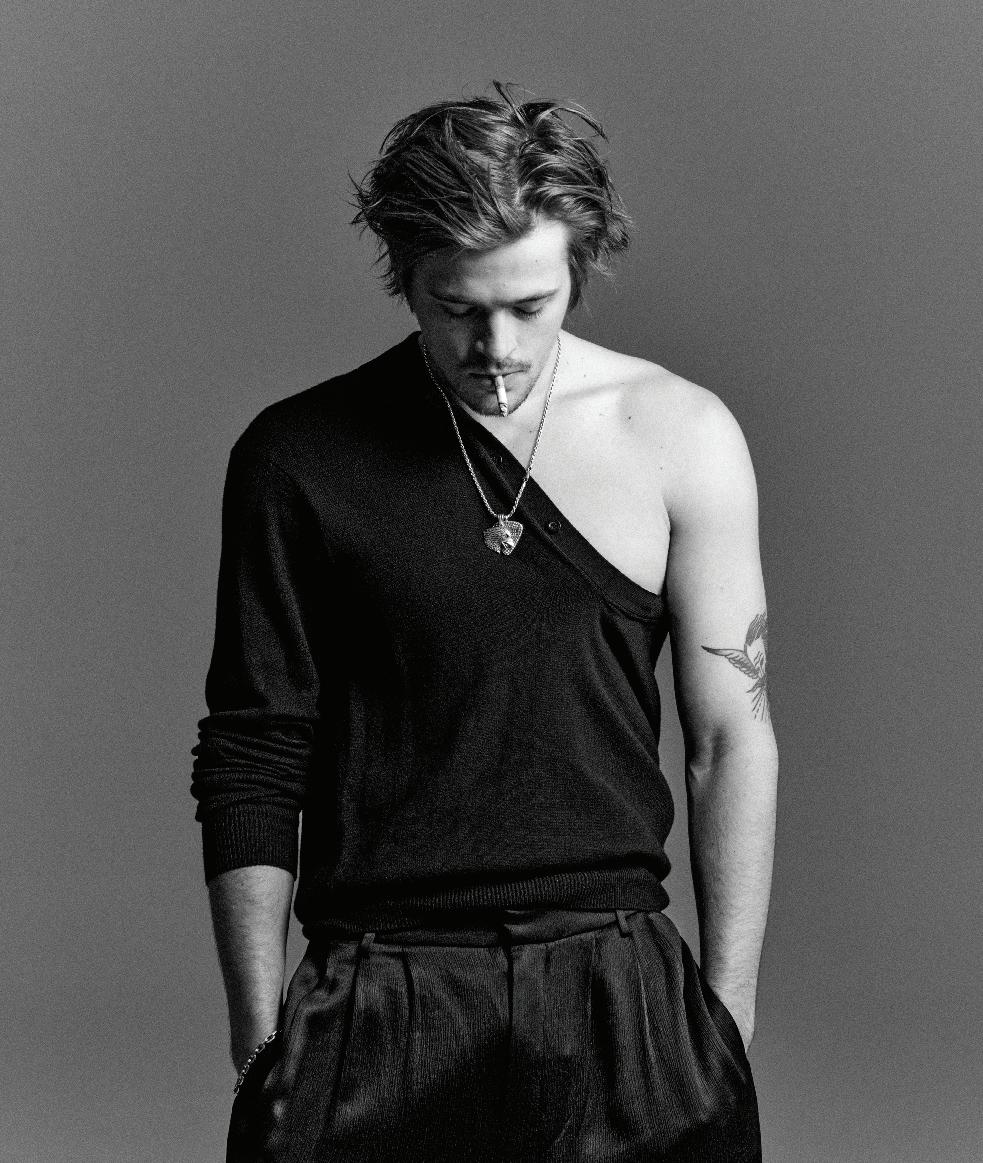

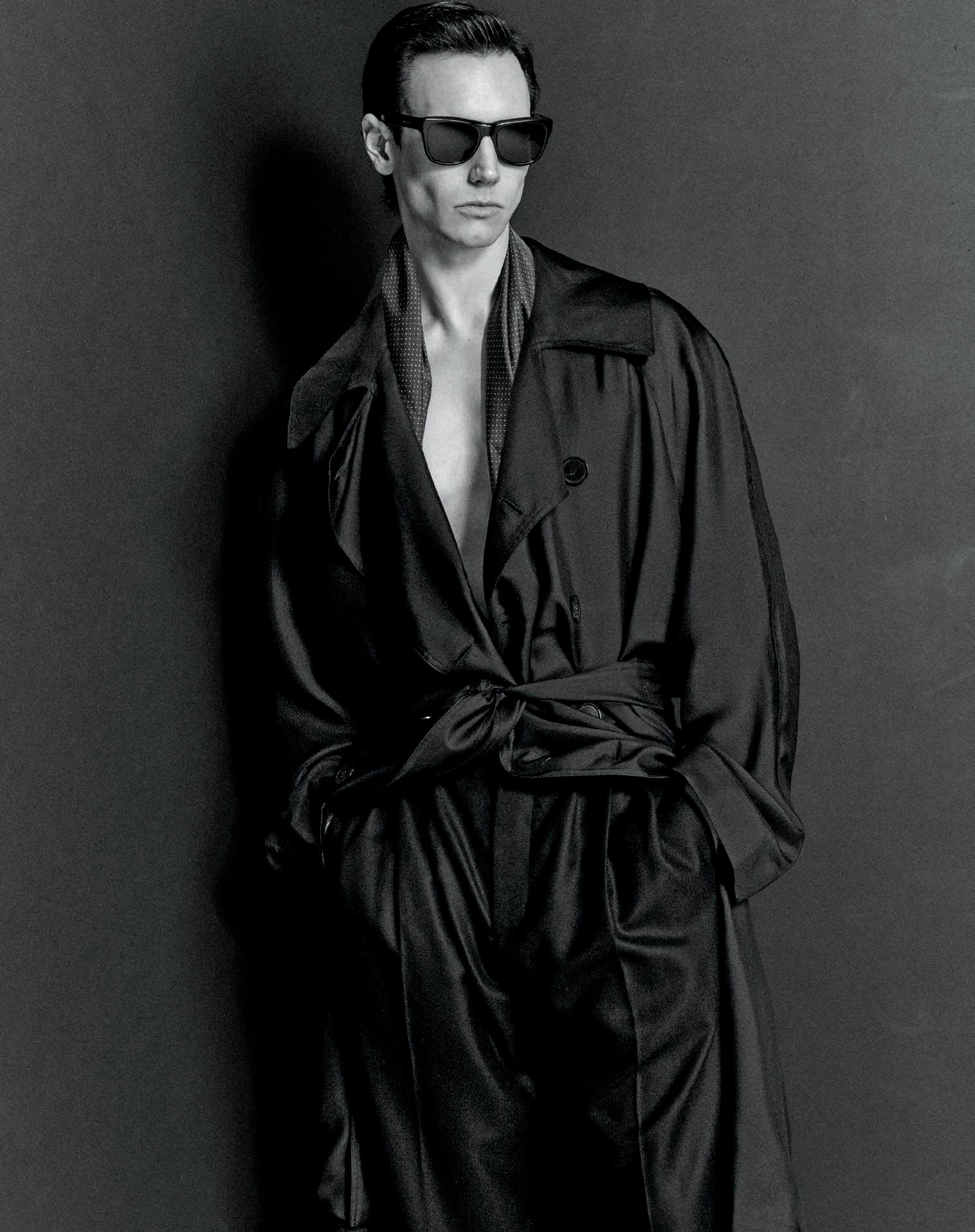

In a culture quick to dole out attention, true fame—that prized mixture of mystique and staying power—feels more elusive than ever. The film industry, rocked by strikes and streaming platforms, has grown ever more gun-shy, retreating from original material in favor of more bankable fare. For Hollywood hopefuls, star-making moments are harder than ever to come by.

Yet, for those tireless (perhaps delusional) enough to persevere, there’s still magic to be found in the pursuit. On a winter day in New York, CULTURED shot seven of the industry’s most promising names on the eve of career-making projects, from indie features to blockbusters. Some of them cut their teeth on their hometown’s local theater stages, while others learned their craft at the knee of Hollywood greats. All of them maintain a fierce dedication to what cinema can be—a dream that, in the blink of an eye, can become reality.

“I TRY TO GRAVITATE TOWARDS SOMETHING NEW EACH TIME. I WANT TO WORK IN EVERY GENRE AND CHALLENGE MYSELF WITH THE ROLES I PLAY.”

Following a number of film roles—both solo and alongside her father, Ewan—Clara McGregor set her sights on the other side of the camera. Deux Entertainment, the production company she co-founded, is currently developing a number of projects focused on the stories of women. This year, the British-born multihyphenate will appear in Xavier Palud’s horror film Noon

“SIR IAN MCKELLEN CAME TO A PLAY I WAS IN AT THE YOUNG VIC IN LONDON. I GREW UP WATCHING EVERYTHING HE EVER DID, ADMIRING HIM, LEARNING FROM HIM. I WALKED OUT AFTER THE SHOW AND THERE HE WAS. HE TOOK MY HAND AND WHISPERED, ‘YOU CANNOT LET ANYONE ELSE PLAY THIS PART.’ I WAS OVERCOME. WE SPOKE FOR A WHILE AND SAW EACH OTHER A FEW MORE TIMES AFTER THAT. I WROTE IT DOWN IN MY JOURNAL THAT NIGHT AND RETURN TO IT IN MOMENTS OF NEED.”

The Rhode Island native and Tony Award winner made his name with acclaimed performances in award-laden plays like The Inheritance and Aaron Sorkin’s Camelot. Next, he’ll appear opposite Rachel Zegler in the Greta Gerwig–penned live remake of Snow White, as well as the high-octane thriller The Up and Comer

“I SAW KILL BILL VOL. 1 WHEN I WAS 18 AND IT BLEW MY MIND. I COULDN’T TAKE MY EYES OFF OF UMA THURMAN. SHE GALVANIZED ME; SHE BROKE MY HEART. I DESPERATELY WANTED TO BE HER. I WAS FEVERISH WITH THE NEED TO BE INSIDE OF A FILM LIKE THAT. SHORTLY AFTER, I SAW HER INFAMOUS YELLOW SNEAKERS IN A SALE BIN SOMEWHERE. THEY WERE A SIZE TOO SMALL BUT I WORE THEM FOR MONTHS, EVEN THOUGH THEY HURT. I FELT LIKE I WAS PART OF HER TEAM, LIKE I COULD LOOK DOWN AT THEM AND TAP INTO HER COURAGE.”

“I’M DRAWN TOWARD DEEPLY FLAWED CHARACTERS, ESPECIALLY FEMALE ONES, WHO BEHAVE IN WAYS NOT ALWAYS ALIGNED WITH THE MORALS OF THE AUDIENCE. ALL OF THOSE DARK HUMAN QUALITIES—SELFISHNESS, JEALOUSY, ANGER, MANIPULATION—COMPEL ME TO ROOT FOR A CHARACTER.”

In her breakout role as the magnetic lead in Netflix’s Ginny & Georgia, Antonia Gentry achieved the elusive alchemy of teen angst and biting wit. With her first feature-length comedy, Prom Dates, under her belt, the Atlanta-born actor is preparing for the next season of her hitmaking series.

“I’M NOT SURE I HAVE ENOUGH EXPERIENCE YET TO NOTICE A PATTERN IN [THE CHARACTERS I PLAY]. HOWEVER, NO MATTER THEIR CIRCUMSTANCES, I LIKE TO THINK THEY ALL HAVE SOME SECRET THAT IS BURNING THROUGH THEM FROM THE INSIDE, NEVER LETTING THEM FEEL TOTALLY AT EASE.”

“MY SECOND-EVER FILM JOB WAS A LIMITED SERIES OPPOSITE FRANCES MCDORMAND. MY CHARACTER STRUGGLES WITH SCHIZOPHRENIA AND SUICIDAL IDEATION—SERIOUS EMOTIONAL TERRITORY. BUT WHEN I SHOWED UP TO REHEARSAL, I WAS SO OVERWHELMED AT MEETING ONE OF MY FAVORITE ACTORS THAT I COULDN’T STOP SMILING. BEAMING! NERDING OUT! IT WAS SO INAPPROPRIATE. I WAS EXPERIENCING THE INSANE REALIZATION THAT—NOT TO BE TOO CORNY—MY DREAMS WERE COMING TRUE IN REAL TIME.”

“REJECTION IS A TOUGH ONE FOR ME. I’M A VERY CONFIDENT PERSON; I MANEUVER THROUGH MY LIFE AS IF I CAN DO ANYTHING IN THE WORLD. BUT EVERY NOW AND THEN I GET COMPLETELY ROCKED BY A ‘NO’ AND IT TAKES A WHILE TO RECOVER. WHEN THAT HAPPENS, I’LL GO TO THE MOVIES. NO MATTER WHAT I SEE, I ALWAYS LEAVE FULL OF INSPIRATION TO KEEP PUSHING FORWARD.”