Fantasyland

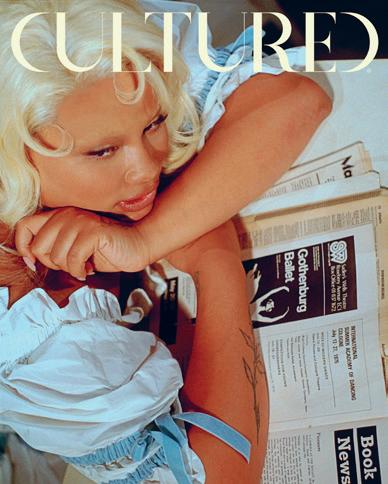

SHYGIRL BY JEREMY O. HARRIS

HANIF ABDURRAQIB / LARRY BELL / CACONRAD / CHRISTINE AND THE QUEENS / SANDRA CISNEROS / DEBBIE HARRY / STEVE LACY /

CALVIN MARCUS / ELLIOT PAGE / BRONTEZ PURNELL / DANEZ SMITH / MING SMITH / MARTINE SYMS / JORDAN WOLFSON

SHYGIRL BY JEREMY O. HARRIS

HANIF ABDURRAQIB / LARRY BELL / CACONRAD / CHRISTINE AND THE QUEENS / SANDRA CISNEROS / DEBBIE HARRY / STEVE LACY /

CALVIN MARCUS / ELLIOT PAGE / BRONTEZ PURNELL / DANEZ SMITH / MING SMITH / MARTINE SYMS / JORDAN WOLFSON

FENDI BOUTIQUES 888 291 0163 FENDI.COM

BEYOND BELIEF

DINING SHOPPING CULTURE

DESIGN

miamidesigndistrict.net/beyond-belief

ORAL REPRESENTATIONS CANNOT BE RELIED UPON

CORRECTLY

THE REPRESENTATIONS

DEVELOPER.

BROCHURE

DOCUMENTS REQUIRED BY SECTION 718.503, FLORIDA STATUTES, TO BE FURNISHED BY A DEVELOPER TO A BUYER OR LESSEE. RIVAGE BAL HARBOUR CONDOMINIUM (the “Condominium”) is developed by Carlton Terrace Owner LLC (“Developer”) and this offering is made only by the Developer’s Prospectus for the Condominium. Consult the Developer’s Prospectus for the proposed budget, terms, conditions, specifications, fees, and Unit dimensions. Sketches, renderings, or photographs depicting lifestyle, amenities, food services, hosting services, finishes, designs, materials, furnishings, fixtures, appliances, cabinetry, soffits, lighting, countertops, floor plans, specifications, design, or art are proposed only, and the Developer reserves the right to modify, revise, or withdraw any or all of the same in its sole discretion. No specific view is guaranteed. Pursuant to license agreements, Developer also has a right to use the trade names, marks, and logos of: (1) The Related Group; and (2) Two Roads Development, each of which is a licensor. The Developer is not incorporated in, located in, nor a resident of, New York. This is not intended to be an offer to sell, or solicitation of an offer to buy, condominium units in New York or to residents of New York, or of any other jurisdiction where prohibited by law. 2023 © Carlton Terrace Owner LLC, with all rights reserved. Future residences located at: 10245 Collins Avenue, Bal Harbour, FL 33154

AS

STATING

OF THE

FOR CORRECT REPRESENTATIONS, MAKE REFERENCE TO THIS

AND TO THE

on s’enrichit de ce que l’on donne, on s’appauvrit de ce que l’on prend Through August 11, 2023 297 Tenth Avenue, New York

Alexis Ralaivao

Alexis Ralaivao, Double date (detail) 2022, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Minimalism and Its Afterimage

Larry Bell

Liz Deschenes

Dan Flavin

Frank Gerritz

Marcia Hafif

Peter Halley

Ralph Humphrey

Donald Judd

Ellsworth Kelly

Jonathan Lasker

Sol LeWitt

Richard Long

Robert Mangold

John McCracken

Howardena Pindell

Robert Ryman

Fred Sandback

Jan Schoonhoven

Sturtevant

Christopher Wilmarth

Through August 11, 2023 509 West 27th Street, New York

Curated by Jim Jacobs and Mark Rosenthal

Marcia Hafif, 27. (detail) , June 1963, lacquer on canvas. © Estate of Marcia Hafif

CONTENTS

June/July/August 2023

CULTURED HOSTS A PANEL ON COLLECTING

In partnership with Louis Vuitton, the magazine hosted a panel of art collectors at the fashion house’s Meatpacking District pop-up in New York.

INSIDE DIOR’S GARDEN OF EDEN

The house’s annual summer capsule collection brings a touch of playful kitsch to Beverly Hills.

STUDIO FREQUENCIES

Six artists reflect on their relationship to music, and share the sounds that keep them company in the studio.

44 46 48 60

SUMMER DISPATCH: PHOTOGRAPHY

Four iconic photographers dig through their archives for an image that conjures a musical era and an intimate moment.

THE STEALTH LUXURY OF SAVETTE

New York–based designer Amy Zurek is transcending the trend cycle to craft heirlooms for a new era.

PLACES TO GATHER

Belgian architect and designer Vincent Van Duysen reflects on his approach to distilling intimate memories into a collection of versatile pieces for the home.

SUMMER DISPATCH: POETRY

To mark the season, three groundbreaking contemporary poets share musings from their summer hideaways.

68 70 73 82

A NEW CHAPTER

Pageboy, Elliot Page’s writerly debut, offers an intimate glimpse into the life of an actor who has grown up alongside his audience.

Clothing and accessories by Dior Autumn/Winter 2023-2024 collection. Photography by Pat Martin.

28 culturedmag.com

CONTENTS

June/July/August 2023

SCOTT SAMPLER’S SECRET SAUCE

For the former filmmaker turned viticulture renegade, natural wine is a form of artistic expression and resistance against a conformist industry.

SEAWATER AND PSYCHEDELICS

Tara Walters’s ethereal painting practice is informed by a fine blend of psychic retreats and spiritualists.

84 86 90 92 94 102 106 116

THE TIMELESSNESS OF TØKIO M¥ERS

The British musician and producer has a slate of collaborations and solo projects on the horizon. They’re pulling him in new and exciting directions.

WELCOME TO THE BALMING TIGER UNIVERSE

As K-pop sweeps the globe, the rising Seoul-based group is adding new dimensions to the genre.

YOUNG CURATORS 2023

The annual list features six practitioners blazing new paths in a crowded field.

LITTLE STUDIO OF HORRORS

Javier Barrios’s practice, rooted in the work that surrounded him in childhood, will be on view this summer for his first solo show with Clearing in Brussels.

STANDING ON THE CORNER

The music collective is heralded for blending sounds of the African diaspora with the raw energy of New York. This summer, they present an avant-garde sonic installation at MoMA PS1.

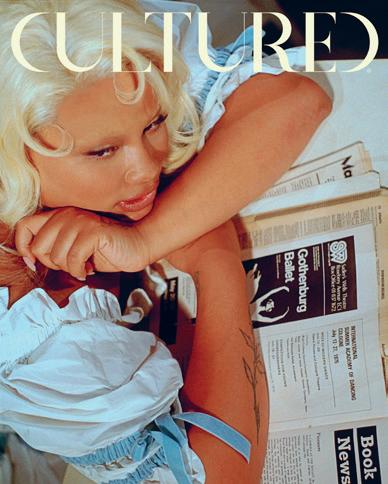

SHYGIRL’S FANTASYLAND

The musician speaks with Jeremy O. Harris about forming her own sultry, silky brand of experimental pop.

30 culturedmag.com

Calvin Marcus photographed in Los Angeles. Photography by Julie Goldstone.

CONTENTS

June/July/August 2023

CAConrad at St. Mark’s Church in New York. Photography by Mary Manning.

160

BRONTEZ PURNELL AND STEVE LACY ON CHURCH CHOIRS AND CLUB RECORDS

124

Brontez Purnell DMs his friend, musician Steve Lacy, for a conversation about gatekeeping, witchcraft, and being the loudest one in the room.

130

MARTINE SYMS AND BEN BABBITT ON CELLISTS AND HYPNOTISTS

The artists dissect their fortuitous meeting, the connection between the human body and technology, and the creative potential of hanging out.

136

THE MAN WHO TURNED BLONDIE’S HAIR BLACK

Blondie’s Debbie Harry and Chris Stein reminisce about their collaboration with the late Swiss artist H.R. Giger.

140

3 RECORDS THAT CHANGED HANIF ABDURRAQIB’S LIFE

Writer and poet Hanif Abdurraqib takes a break from penning his forthcoming book to reflect on the albums that raised him.

146

EVERYONE HAS QUESTIONS FOR CHRISTINE AND THE QUEENS

To mark the release of his latest album, the musician answers questions on life and love from his friends and collaborators.

150

INTO THE WILD

With its Autumn/Winter 2023 collection, Dior pens a billet-doux to three women who subverted the dictums of their time: Catherine Dior, Édith Piaf, and Juliette Gréco.

BILLIE MILAM WEISMAN AND LARRY BELL ON ART IN LOS ANGELES

The pair connect for a conversation about the city that defined their careers.

168

THINKING WITH YOUR HANDS

Five cutting-edge design studios reflect on their processes and inspirations—from road trips to local landscapes.

178

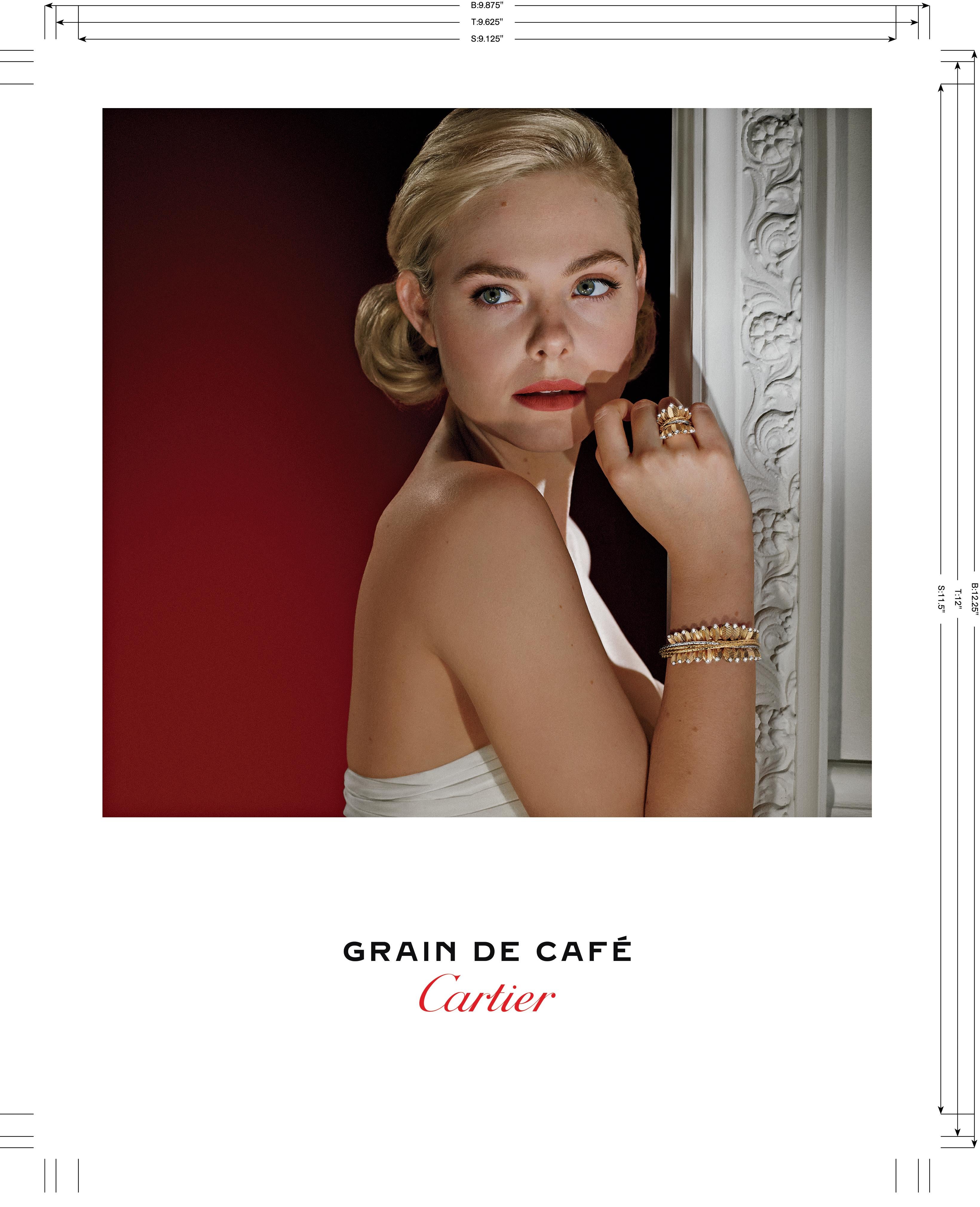

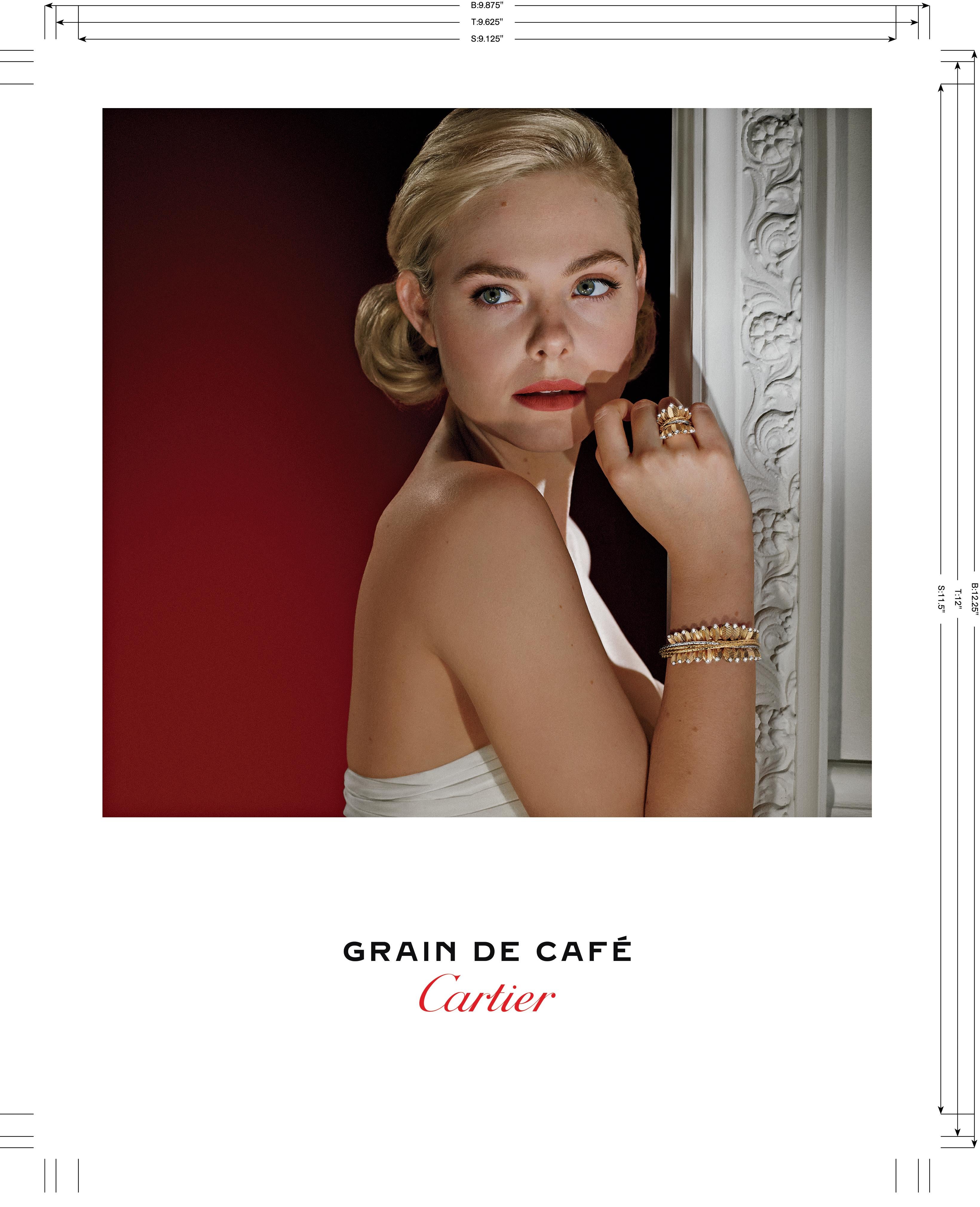

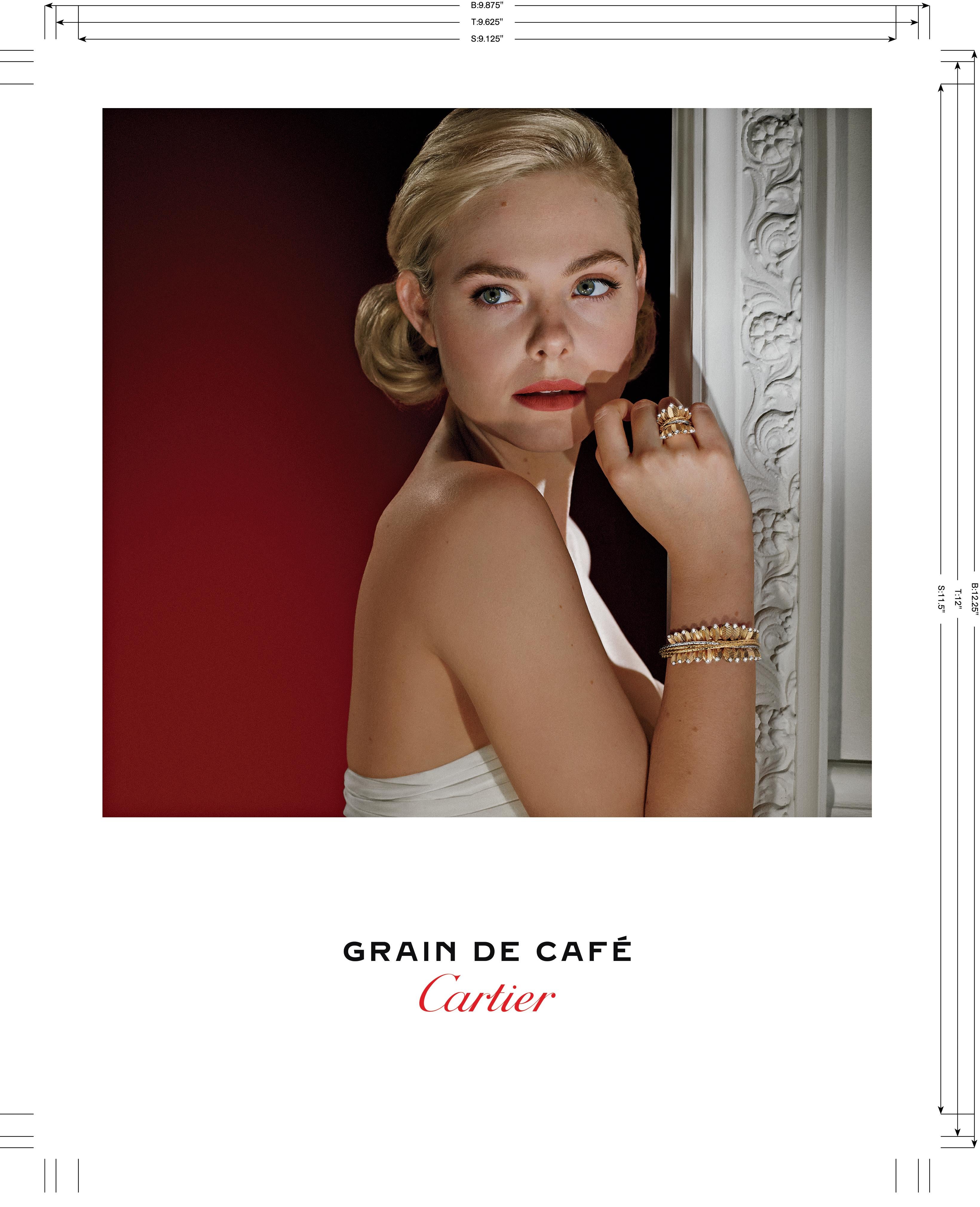

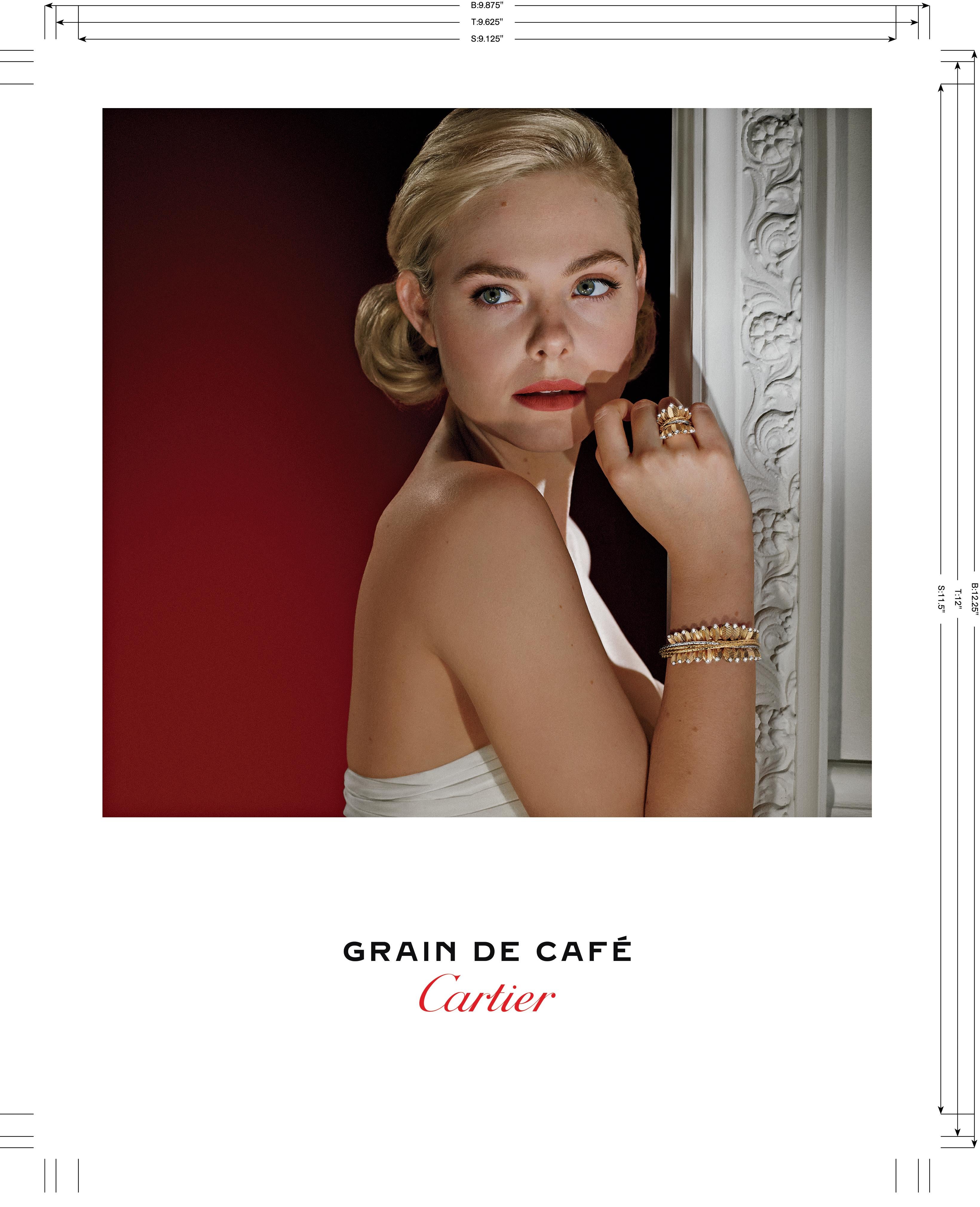

OBJECTS OF AFFECTION

The season’s finest high jewelry unfurls across a verdant botanical wonderland.

32 culturedmag.com

SHOP JILSANDER.COM

ALEC SOTH Photographer

Minneapolis-based photographer Alec Soth has published over 25 books of his work—including Songbook (2015), I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating (2019), and A Pound of Pictures (2022)—and has had over 50 solo exhibitions at institutions including the Jeu de Paume in Paris and Media Space in London. In 2008, he created Little Brown Mushroom, a multimedia enterprise focused on visual storytelling, and in 2013, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He is also a member of Magnum Photos. For this issue, Soth shot poet Danez Smith, a fellow Minneapolis creative, at home. “I’ve been a fan of Danez’s urgent poetry for a long time,” says Soth. “What a pleasure to peek into their world.”

MARTINE SYMS Artist

Martine Syms has captured the art world’s imagination with a practice that combines conceptual grit, humor, and social commentary. She has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, and received a Guggenheim Fellowship this year. Syms has written and directed three feature films: The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto, Incense Sweaters & Ice, and The African Desperate. Ahead of her first solo Sprüth Magers show, she speaks with fellow artist, frequent collaborator, and friend Ben Babbitt.

CONTRIBUTORS

MARY MANNING Photographer

New York–based photographer Mary Manning has had solo exhibitions at Canada gallery and Cleopatra’s, and at Sibling in Toronto. Last year, they curated the exhibition “Looking Back/ The 12th White Columns Annual” for White Columns. Grace Is Like New Music, a book of their recent works, was published by Canada in 2023. The photographer spent an afternoon with poet CAConrad outside St. Mark’s Church for this issue. “Making a portrait with CAConrad in the west yard of St. Mark’s Church was a dream assignment,” says Manning. “When we finished, CA generously gave me a tarot reading with the most beautiful deck I’ve ever seen.”

34 culturedmag.com

ALEC SOTH, PHOTOGRAPHY BY STERRE OTTEN; MARY MANNING, IMAGE COURTESY OF MARY MANNING; MARTINE SYMS, PHOTOGRAPHY BY GABRIELLE DATU.

Ed Clark, Untitled (Midi Series) (detail), 2004, Acrylic on canvas, 70.2 × 79.4 cm / 27 5/8 × 31 1/4 in © The Estate of Ed Clark ESCAPE UNTIL 25 JUNE SOUTHAMPTON, NEW YORK

LÉON PROST Photographer

Autodidact Léon Prost strives to catch what goes unseen. As a French reportage photographer and director, Prost traveled in Romania with his analog camera, documenting his journey through the country. He has shot for publications including L’Officiel Hommes, M le magazine du Monde, and Regain. For this issue, the photographer turned his lens on FrenchLebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh.

KARLA LEYVA Photographer

Karla Leyva is a transdisciplinary artist working to analyze the fantasy around colonized bodies in an increasingly digital world. Implicit in her work is the desire to expand the body beyond the flesh, the desire to leave the periphery, to be seen, touched, felt, consumed, and discarded. Leyva has shown her work in Pereira, Los Angeles; Portland, Oregon; London; and across Mexico, where she currently lives. She entered the world of Javier Barrios, a fellow Mexico City resident, for this issue. “What I like the most about him,” she says, “is that he works very hard to be the great artist he is now.”

JESSE GLAZZARD Photographer

Jesse Glazzard was born and raised in Yorkshire and lives in London, after graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2019. He has documented moments among his close friends over several years, and has shot and directed for brands including Calvin Klein, Ssense, and Adidas, among others. A regular CULTURED contributor, the photographer captured French musician Christine and the Queens for this issue in Paris. “I love working with Chris,” says Glazzard. “It was especially nice this time because I got to see some of the city. We started the shoot with a few push-ups.”

LARRY BELL Artist

Taos, New Mexico–based artist Larry Bell is one of the most noteworthy representatives of abstract art in the postwar period, with a career spanning nearly six decades. Bell’s medium, “light on surface,” often utilizes the technology of thin film deposition of vaporized metals and minerals on glass surfaces. Bell exhibits extensively in museums and galleries across the world, and is the recipient of numerous public art commissions. For this issue, he spoke with collector Billie Milam Weisman about their parallel lives in the arts. “I always enjoy talking with Billie,” says Bell of his longtime friend. “She is a real fixture in the LA art scene.”

CONTRIBUTORS

KARLA LEYVA, PHOTOGRAPHY BY KARLA LEYVA; LÉON PROST, IMAGE COURTESY OF LÉON PROST; JESSE GLAZZARD, PHOTOGRAPHY BY NORA NORD; LARRY BELL, PHOTOGRAPHY BY ERIC SCHWARTZ.

36 culturedmag.com

Curated by Ricky Swallow

Through August 4, 2023

September 5 – October 14, 2023 LOS

Celebrating David Kordansky Gallery’s 20th Anniversary

Through August 19, 2023

SHARA HUGHES

DEANA LAWSON

September 9 – October 21, 2023

LOS ANGELES 5130 W. Edgewood Pl. T: 323.935.3030 NEW YORK 520 W. 20th St. T: 212.390.0079 DAVIDKORDANSKYGALLERY.COM

NEW YORK

DOYLE LANE: WEED POTS

CHASE HALL

ANGELES

20

DAVE HOLMES Writer

Dave Holmes is an editor-at-large and columnist for Esquire whose work has appeared in publications including the Los Angeles Times, Rolling Stone, and New York magazine. He is thrilled to have interviewed the artistic polymath that is TØKIO M¥ERS for CULTURED’s summer music issue. When it comes to his other summer music picks, Holmes will tell you this in confidence, because he feels he can trust you: He still listens to that first Wilson Phillips album about once a week.

CONTRIBUTORS

LEGS MCNEIL Writer

In 1975, Legs McNeil co-founded Punk magazine, serving as the publication’s “resident punk,” which involved drinking, interviewing rock stars, and spreading chaos wherever he went. In 1988, McNeil’s drinking privileges were permanently revoked, and he became a senior editor at Spin before releasing the books Please Kill Me (1996), The Other Hollywood (2005), and Dear Nobody (2013). In this issue, McNeil spoke with Blondie’s Debbie Harry and Chris Stein about making the cover art for KooKoo, Harry’s debut solo album, with artist H.R. Giger.

NELL KALONJI Stylist

London-based Nell Kalonji is senior fashion editorat-large for AnOther Magazine and a guest fashiondirector-at-large at Luncheon. She has collaborated with photographers such as Alasdair McLellan, Collier Schorr, Craig McDean, Jack Davison, and Nadine Ijewere. For this issue, she styled cover star Shygirl for her fantastical 1950s-inspired shoot. “Shy and I love collaborating on editorials like this,” says Kalonji. “It allows us to play with a wider range of characters than we can for stage or carpet looks. Shy was transforming in front of our eyes and getting into character, but it felt really natural— like this is her world.”

madison moore Writer

madison moore is a writer and DJ based in Providence, Rhode Island. He is the author of Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric, a 2018 ode to fabulousness as an act of queer resistance published by Yale University, where he received his PhD in American studies. moore has contributed to The Atlantic, Theater, and the Journal of Popular Music Studies. This summer, he will be the scholar-in-residence at the Sag Harbor arts organization the Church. In this issue, the writer introduces a conversation between the genre-defying musicians Steve Lacy and Brontez Purnell.

38 culturedmag.com

DAVE HOLMES, PHOTOGRAPHY BY LAURA PAVLAKOVICH; MADISON MOORE, PHOTOGRAPHY BY ROME GOD; NELL KALONJI, PHOTOGRAPHY BY FELIX COOPER; LEGS MCNEIL, PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS STEIN, 1976. LEGS MCNEIL, ANYA PHILLIPS, AND DEBBIE HARRY SHOOTING “THE LEGEND OF NICK DETROIT” FOR PUNK MAGAZINE.

Founder | Editor-in-Chief

SARAH G. HARRELSON

Senior Editor

MARA VEITCH

Senior Creative Producer

REBECCA AARON

Fashion Directors

ALEXANDRA CRONAN, KATE FOLEY

Associate Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Editorial Assistant

SOPHIE LEE

Copy Editor

EVELINE CHAO

Junior Art Directors

HANNAH TACHER, ORIANA REN

Contributing Art Directors

MAFALDA KAHANE, SARA PENA

Editor-at-Large

KAT HERRIMAN

New York Contributing Arts Editor

JACOBA URIST

Podcast Editor

SIENNA FEKETE

Contributing Editors

JULIA HALPERIN, LILY KWONG, MARTINE SYMS, FRANKLIN

SIRMANS, SARAH ARISON, DOUG MEYER, CASEY FREMONT, MICHAEL REYNOLDS, DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

Chief Revenue Officer

CARL KIESEL

Publisher

LORI WARRINER

Italian Representative—Design

CARLO FIORUCCI

Interns

LAINE ALLISON

ISABELLA BARADARAN

CAROLINE BOMBACK

MARIA CLARA COBO

ELIZABETH COHAN

SOPHIE COLLONGETTE

MARIANA DE JESUS SZENDREY

AMELIA STONE

Prepress/Print Production

PETE JACATY

Senior Photo Retoucher

BERT MOO-YOUNG

CULTURED Magazine 2341 Michigan Ave Santa Monica, California 90404

TO SUBSCRIBE , visit culturedmag.com. FOR ADVERTISING information, please email info@culturedmag.com. Follow us on INSTAGRAM @cultured_mag.

ISSN 2638-7611

40 culturedmag.com

WALTER PATER, THE 19TH-CENTURY ART critic, once wrote that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” It’s true— when a meal or a painting or a piece of writing comes together perfectly, it sings.

Our summer music issue takes a deep dive into this idea. We turned to artists, writers, musicians, and people who do a little bit of all those things, and set them the insurmountable task of defining their relationship to sound.

Studio Frequencies, our portfolio focused on the music that keeps artists company in the studio, is one approach to this. In it, Jordan Wolfson points out the absurdity of the exercise, responding to a question about his earliest sonic memory with, “Insane question.”

Wolfson is right. Music is so intimately intertwined with daily life and with memory that it’s almost impossible to account for its influence on our lives. We discovered this ourselves while putting the issue together.

The following pages celebrate a group of artists who pull inspiration from across disciplines and channel it into music. Brontez Purnell—novelist, poet, and a musician in his own right—speaks with alt-R&B icon Steve Lacy about “flow, melody, and cadence,” three formal qualities shared by musical composition and narrative form. Martine Syms and Ben Babbitt, frequent collaborators who teamed up to create a soundscape for Syms’s first solo exhibition at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles, discuss music’s centrality to their existence, and their anxieties about and experiments with A.I.-generated vocals. Poet and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib contributed three graceful paeans to the albums that changed his life. Our summer poetry portfolio, curated by Associate Editor Ella Martin-Gachot, sees three of the form’s boundary-breaking contemporary voices share sound bites from their summer hideaways. Shygirl, the issue’s cover star, talks

to playwright and critic Jeremy O. Harris about building the music career that she fantasized about during her early Tumblr days in Southeast London.

Summer is about experimentation and creativity, but it’s also a time of unexpected community. For this reason, we’re thrilled to present our special limited-edition artists cover—shot by William Jess Laird as part of our first of two Hamptons issues guest-edited by Joel Mesler—which spotlights a spectacular group of artists who have found camaraderie together during long summer days out east. The limited release, which will be available in select locations starting in late June, is a testament to coming together and the intimacy of the season, and we’re very proud to see it out in the world.

I hope that this issue provides you with some inspiration—for your summer playlists, dinner table conversations, and beyond.

LEFT: SHYGIRL shot in London, wearing a dress by Molly Goddard

Photography by Rachel Fleminger Hudson. Styling by Nell Kalonji

Creative Direction by Studio& and Rachel Fleminger Hudson

Sarah G. Harrelson Founder and Editor-in-Chief @sarahgharrelson

Follow us | @cultured_mag

Follow us | @cultured_mag

42 culturedmag.com

LETTER EDITOR from the

RIGHT: Rashid Johnson, Sanford Biggers, Sheree Hovsepian, Eric Fischl Mary Heilmann Sarah Aibel, Hank Willis Thomas, and Joel Mesler shot in East Hampton.

Photography by William Jess Laird

MARA VEITCH, ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT, SARAH HARRELSON, HANNAH TACHER, AND REBECCA AARON IN NEW YORK CITY FOR THE SET EVENT. PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAVID BENTHAL.

CULTURED HOSTS A PANEL ON COLLECTING

This April, CULTURED partnered with Louis Vuitton to host a panel of art collectors at the fashion house’s Meatpacking District pop-up in New York.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAVID BENTHAL

TO COMMEMORATE THE RELEASE OF THE SIXTH ANNUAL YOUNG COLLECTORS LIST, CULTURED took over Louis Vuitton’s kaleidoscopic popup space this spring for an evening of conversation and champagne. The magazine presented “The Art of Collecting,” a panel moderated by CULTURED founder Sarah Harrelson, who invited members of the magazine’s extended family—including Hannah Traore, founder and director of Hannah Traore Gallery; Kickstarter CEO Everette Taylor; notable collector and Gagosian liaison Sophia Cohen; and Caio Twombly, co-founder and co-director of Amanita Gallery—to share their collecting stories. Guests such as Jasmine

Wahi, Nina Runsdorf, Sharon Coplan Hurowitz, and Dana Farouki gathered to take in the latest iteration of Yayoi Kusama’s collaboration with Louis Vuitton. The whimsical space was outfitted in bright green polka dots and floral sculptures to welcome the arrival of the spring season. The evening’s panelists, decked out in their Louis Vuitton finest, expounded on their personal collecting philosophies and the principles that have shaped their creative careers. For those onstage, building a collection is an exercise in stewardship, not ownership. “I don’t see myself as a collector,” said Taylor. “I see myself as a caretaker of the work.”

44 culturedmag.com

ABOVE: SARAH HARRELSON, SOPHIA COHEN, CAIO TWOMBLY, HANNAH TRAORE, EVERETT TAYLOR

HANNAH TRAORE

CHARLIE JARVIS, KEVIN CLAIBORNE

GAGE GOMEZ, HENRY BLYNN

SOPHIA COHEN, LILY MORTIMER

SARAH LARSON, SHARON HOROWITZ

DANA FAROUKI, CHASE LEGER, LESLIE FINERMAN

REBECCA REID, CAIO TWOMBLY KATHLEEN LYNCH, JASMINE WAHI

SARAH HARRELSON, CAIO TWOMBLY

Kavi Gupta 219 N. Elizabeth St. Floor 1 Chicago IL 60607 kavigupta.com | 312 432 0708 On view through August 26 Esmaa Mohamoud Let Them Consume Me In The Light

INSIDE DIOR’S GARDEN OF EDEN

BY AMELIA STONE PHOTOGRAPHY BY PAUL VU

THE 18TH CENTURY BROUGHT about a suite of innovations, including the steam engine, the piano, and the establishment of the novel as a literary genre. The period also engendered an aesthetic revolution in Europe, with tides shifting toward frivolous rococo. One of the key elements in this maximalist revolution was toile de Jouy, a traditionally monochrome fabric featuring vignettes of countryside scenes, romantic picnics, and luscious flora and fauna. This summer, the style—the

18th century version of a comic strip—will make its way to beaches and tennis courts with Dioriviera, Maison Dior’s annual summer capsule collection that takes Toile de Jouy Sauvage, a dusty pink and gray interpretation of the classic pattern, as its leitmotif.

Designed by Dior’s creative director of women’s haute couture, ready-to-wear, and accessories collections, Maria Grazia Chiuri, the collection presents a slew of summer necessities adorned with Toile de Jouy Sauvage. Dioriviera will be

available in nine pop-up boutiques in idyllic summer destinations across the world, from Capri to Saint Tropez and Beverly Hills. The maison will take up residence in the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel through the summer season, offering Dioriviera disciples and newcomers alike the opportunity to browse iconic bags like the Lady D-Lite and the Dior Book Tote, along with scarves and satin shirts adorned with the enduring house code.

Channeling the playful kitsch of toile de Jouy, the pop-up’s interior

takes the form of an immersive sandcastle filled with life-sized sand sculptures of wildlife, giving visitors a taste of lighthearted luxury. Surf-inspired cabins line the perimeter, offering Dior parasols, yoga mats, and surfboards. Poolside, guests will recline under Toile de Jouy Sauvage–coated cabanas, where they can schedule boutique relaxation treatments at the Jardin des Rèves Dior Spa. The pop-up experience promises to be a lush summer respite, this year and every year.

46 culturedmag.com

The house’s annual summer capsule collection brings a touch of playful kitsch to Beverly Hills.

134 Madison Ave New York ddcnyc.com

furniture lighting outdoor accessories systems

AN ARTIST’S STUDIO IS A HAVEN—A SOUNDING BOARD FOR IDEAS GOOD AND BAD, A COMPANION ON DARK DAYS AND INSPIRED ONES. THESE SPACES PLAY OCCASIONAL HOST TO CURATORS, COLLECTORS, AND FRIENDS, BUT IN THE DAY-TO-DAY HUM OF CREATION, THEY WRAP THEIR PROTECTIVE ARMS AROUND THEIR ARTISTS, ENVELOPING THEM. CULTURED ASKED SIX MAKERS WHOSE WORK SPANS THE DISCIPLINES OF ARCHITECTURE, PERFORMANCE, PAINTING, AND SCULPTURE TO REFLECT ON THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO MUSIC, AND SHARE THE SOUNDS THAT KEEP THEM COMPANY IN THE STUDIO.

FREQUENCIES

Studio

CLAUDE DEBUSSY JOHN LENNON DRAKE

JORDAN WOLFSON

48 culturedmag.com

The Los Angeles–based provocateur is known for an extensive, uninhibited practice that probes identity politics, pettiness, and the baseness of the virtual-industrial complex. Wolfson’s work, which has taken the form of video, sculpture, installation, photography, and performance, is neither dogmatic nor didactic, opting instead for an uneasy opacity. This summer, the artist’s transgressive streak will be on view through July 22 with “Drawings,” a show that mines the (short) life and legacy of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. at Gagosian’s Basel outpost. In December, the National Gallery of Australia will host a survey of the artist’s work. When it comes to the relationship between music and art-making, Wolfson’s philosophy is simple: Less is more.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF MUSIC IN YOUR PRACTICE? Depends. I used to think pop was radical; now I just like sculpture.

WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE WAY TO LISTEN TO MUSIC? [With] Apple AirPods Max in a La-Z-Boy at my studio, or driving at night.

WHAT’S THE BEST STUDIO SOUNDTRACK? We don’t listen to music at the studio, but probably everyone laughing and enjoying working together.

WHICH MUSICIAN WOULD YOU ASK TO WRITE THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR LIFE? I’d never dare to ask that of another artist, but since you did… Erik Satie.

FIRST SONIC MEMORY? That’s an insane question.

culturedmag.com 49

PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRAD TORCHIA

JIBZ CAMERON

PHOTOGRAPHY

BY CHARLIE GROSS

FUNKADELIC

PINK FLOYD

AUSTRA

THE POINTER SISTERS

CARDI B

LINTON KWESI JOHNSON

PATRICK COWLEY

FEVER RAY

CHARLOTTE ADIGÉRY

PRINCE

YOKO ONO

JANET JACKSON

RAY LYNCH

BRIAN ENO

LEE “SCRATCH” PERRY

NINA HAGEN

GRACE JONES

DONNY HATHAWAY

PENGUIN CAFE ORCHESTRA

LATTO

FREE KITTEN

DICKS

LAURIE ANDERSON

BLACK SABBATH SNEAKS

SONIDO GALLO NEGRO CAN NORMANI

PERE UBU

As a 10-year-old, Jibz Cameron wrote in a poem, “I am the wolf. I run / through the forest. / I howl / back / AND forth / through the forest. / looking for that place / the place where I / can let it all out.” In the nearly four decades since those words flowed out of her, Cameron—better known as her high-camp alter ego Dynasty Handbag—has found myriad pockets and platforms of expression, from her Los Angeles variety show “Weirdo Night,” which will be resurrected this summer, to a topsy-turvy take on Titanic this past May at New York’s Pioneer Works. This fall, the artist’s visual practice will be on view in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial. Cameron’s musical landscape is as riotous and polychrome as her persona.

WHAT’S THE BEST SOUNDTRACK TO GET DRESSED TO? Before a show, I need something mighty, like the Stooges or Megan Thee Stallion, to get me doing air kicks, gnashing my teeth, and stomping about with borrowed confidence. If I need to get grounded, I listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Mass in B Minor.” One of my favorite compositions of all time is “India,” by John Coltrane. I don’t want to sound like a dick. This interview is like, “What music do you like?” And I’m all, “Bach, complex jazz?” But there you have it. I love Bach, and I love John Coltrane. Do I understand it? No, and nary shall I try! Whomst cares!

FIRST SONIC MEMORY? I was obsessed with the radio and never wanted to miss a song, so I would record it at night. Like, I put a tape in the tape deck to record the radio and then flipped it in the middle of the night. I also called the radio a lot and demanded that songs be played. I was about 7 or 8 when “Cum on Feel the Noize” by Quiet Riot (best band name of all time perhaps) was on the Top 40, and I remember calling the radio station telling them to play it again. I remember this really well because it’s also a shameful memory—they laughed at me.

FAVORITE SOUND? I bumped my head into a gigantic wind chime recently, and it was like I was scoring my own cartoon. The sound of an outdoor concert from far away is a great, sad, weird sound. Dogs howling with a siren. Any double bass drums. Frogs. Getting up to pee at 3 a.m. and hearing an owl. Windshield wipers.

WEIRDEST SOUND YOU CAN MAKE? I can do a decent Martha Stewart impression.

50 culturedmag.com

July 8 — August 19, 2023

1700 S Santa Fe Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90021 +1 213 623 3280 vielmetter.com VIELMETTER LOS ANGELES

“Perpetual Portrait”

CALVIN MARCUS

THE BEACH BOYS RADIOHEAD KRAFTWERK

The words “surreal” and “absurd” are thrown around when Calvin Marcus’s name comes up. But the San Francisco–born, Los Angeles–based artist tends more towards the deadpan and discomforting. His deceptively nonchalant paintings, forays into sculpture, and screen-printed works dilate the longer you observe them. This summer, a work of Marcus’s will be included in Clearing’s first Art Basel booth, and the artist will continue to develop his Tuscan TOMATO Residency with the gallery’s Brussels director, Lodovico Corsini. In the midst of these varied projects and practices lies a deep connection to music, which offers the artist both a contemporary catalyst and a time-travel machine.

WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE WAY TO LISTEN TO MUSIC? My studio has wooden floors and a large wooden ceiling, so the acoustics are really nice; it’s the best place to listen to music. It sounds so good and big to be in there with my favorite music of the moment.

WHAT SOUNDS DO YOU ASSOCIATE WITH LA? Cars accelerating. There are also a lot of birds in my neighborhood. Every time I’m on the phone with someone walking my dog around, the person on the line always comments on how loud the birds are.

FIRST SONIC MEMORY? My uncle swimming across a lake on a family camping trip we went on as kids. I still hear his voice and the sound of the water around him.

FAVORITE SOUND? The sound of a skateboard passing by gives me great nostalgia. I’ve been skateboarding since I was 12—less now, but I still love the sound of the hard wheels and loud bearings. It sounds like a snake striking perpetually.

52 culturedmag.com

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JULIE GOLDSTONE

Clay Pop Los Angeles

Curated by Alia Dahl

June 24–August 12, 2023

Diana Yesenia Alvarado

Alex Anderson

Alex Becerra

Genesis Belanger

Seth Bogart

Kenturah Davis

Woody De Othello

Sharif Farrag

Ryan Flores

Joel Gaitan

Melvino Garretti

Lizette Hernandez

Stephanie Temma Hier

Sydnie Jimenez

Grant Levy-Lucero

Candice Lin

Jasmine Little

Amelia Lockwood

Jiha Moon

Ruby Neri

Maija Peeples-Bright

Brian Rochefort

Jennifer Rochlin

Brie Ruais

Stephanie H. Shih

Alake Shilling

Peter Shire

Christopher Suarez

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess

Amia Yokoyama

Maryam Yousif

Bari Ziperstein

JEFFREY DEITCH • 7000 SANTA MONICA BLVD, LOS ANGELES • LA@DEITCH.COM

Sharif Farrag, Stump, 2019–2023

CHASE HALL

ROBERT GLASPER

STEVIE WONDER

CHARLIE WILSON

TYLER, THE CREATOR

FUTURE

A TRIBE CALLED QUEST

JIMI HENDRIX

BLACK SABBATH

Q-TIP

DIZZY GILLESPIE

NIPSEY HUSSLE

CHARLES BRADLEY

TUPAC SHAKUR

ANDRÉ 3000 AND BIG BOI

KENDRICK LAMAR

EARL SWEATSHIRT

ARETHA FRANKLIN

LENNY KRAVITZ

NAJEE

NOEL POINTER

BOB MARLEY

JAY-Z

RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS

THELONIOUS MONK

STEVE LACY

ANTHONY HAMILTON

GENNY!

LAURYN HILL

ELTON JOHN

GIL SCOTT-HERON

B.B. KING

WHITNEY HOUSTON

LYFE JENNINGS

KIRK FRANKLIN

MARVIN SAPP

ESTHER PHILLIPS

BOBBY CALDWELL

EARL KLUGH

ESTHER PHILLIPS

CANDI STATON

This year, Chase Hall developed a relationship with the opera. The New York and Los Angeles–based artist was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera to create a set of paintings inspired by Luigi Cherubini’s Medea last fall, and renewed his ties with the hallowed institution in the spring with a vast painting honoring Terence Blanchard’s Champion —an epic chronicle of boxer Emile Griffith’s life—which was blown up to even more colossal proportions to adorn the building’s facade. This summer, the CULTURED Young Artist 2021 alum confronts another behemoth, Jackson Pollock, in an exhibition at the Aspen Art Museum, the second in a series of artist-led presentations called “A Lover’s Discourse.” For the painter, music is a mirror, a history book, and a portal to transcendence.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF MUSIC IN YOUR PRACTICE? Music has been a father figure, a brother, a mentor, a diary, a Pandora’s box, an ancestor, a journey, and a mirror of my questions and concerns. It has allowed me to locate what art is and to see how it disseminates into real-time culture and humanity. I’m like a poor man’s Rick Rubin—I can’t play a lick, but I know what I like and feel, and what it has showed me of myself, others, and the world.

WHAT SOUNDS HAVE INFLUENCED THE WORK THAT WILL BE ON DISPLAY AT THE ASPEN ART MUSEUM? Free jazz, percussion, samba, freestyle rapping—areas of music that are challenging, intuitive, guttural, spiritual, and informed by the many years prior to their action. The possessive qualities of painting often remind me of someone catching the Holy Ghost, or their eyes rolling back into their skull as they blare through their saxophone. Music is a space, and so is painting—it’s about making that space one you love to come home to.

FIRST SONIC MEMORY? Growing up, my mom always played Elton John and Tupac [Shakur] in her old black Toyota 4Runner, smoking cigarettes. Those two are etched into my memory.

54 culturedmag.com

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LAUREN RODRIGUEZ HALL

The transformative power of art meets the spirit of individuality and ingenuity in one-of-a-kind collectible design and artisan-crafted fine art. Authenticity and uniqueness lie within the exceptional craftsmanship and artistic expression of independent studio artists.

212-673-0531 // www.toddmerrillstudio.com

Tapestry: Gerri Spilka, 2022

Wood and LED Sculpture: John Procario, 2023 Bronze Console: Gary Magakis, 2023

ISHI GLINSKY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

RUBEN DIAZ

NTS MIXTAPES

POWWOW SONGS

PHILIP GLASS

YELLOW MAGIC ORCHESTRA

YVES TUMOR

BEACH HOUSE

Ishi Glinsky’s practice mimics the meticulous virtuosity of a composer. The Los Angeles–based artist is tied to the landscape—and baseball team—of his adopted home, but through his work he digs into the traditions and creative ecosystem of his tribe, the Tohono O’odham Nation, and other North American First Nations. This summer, Glinsky will bring these concerns, and their material articulations, to the fore as part of the Hessel Museum of Art’s “Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-determination Since 1969,” and Tiwa Select’s presentation at the North American Pavilion in London. In the fall, the artist heads back to LA, where he will be featured in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living.”

WHAT SOUNDS HAVE INFLUENCED THE WORK THAT YOU’LL BE SHOWING AT THE BIENNIAL? One facet of my next sculpture is inspired by the stillness and silence of the start of a powwow. It’s about creating a memory of viewing and participating in the Grand Entry of a powwow, while also zeroing in on the regalia and objects that create a roar, [the] concert of sounds mostly meant for healing.

WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE WAY TO LISTEN TO MUSIC? Headphones. I like to keep what I’m listening to private. I have a shared studio space, but even if no one is around, I’d rather crank up my headphones than use a speaker.

FIRST SONIC MEMORY? Quail songs and thunder from the summer monsoons. The sound and smell of desert monsoons are very particular to the Southern Arizona desert and different from anywhere else.

FAVORITE SOUND? My partner’s laugh, gessoing a canvas, the sound of a home run.

56 culturedmag.com

Our rugs lie lightly on this earth. ARMADILLO-CO.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES SAN FRANCISCO SYDNEY MELBOURNE BRISBANE

LINA GHOTMEH

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LÉON PROST

ANA MOURA

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

MILES DAVIS

IBRAHIM MAALOUF

AMÁLIA RODRIGUES

FAIRUZ

OUM KALTHOUM

NINA SIMONE

ARVO PÄRT

DHAFER YOUSSEF

ZIAD RAHBANI

NICCOLÒ PAGANINI

CHILLY GONZALES

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

MARIA CALLAS

The Paris-based architect—whose projects include the Hermès workshops in Normandy, the Estonian National Museum in Tartu, and the Stone Garden apartment block in her native Beirut—grew up wanting to be an archaeologist. Though fate had other plans, she brings from that field a meticulous sensibility regarding landscapes and the passing of time, as well as a fascination with the most humble of materials. This June, Ghotmeh will travel to London to debut her design for the 22nd edition of the Serpentine Pavilion, baptized “À table.” The French dining call is a fitting motto for Ghotmeh, whose connection to music emphasizes the gathering of disparate elements—no matter the origin, generation, or genre.

HOW DO YOU THINK ABOUT SOUND IN THE SPACES YOU DESIGN? I work with sound engineers to study the sound experience within the spaces I design. Each one has a different sound requirement. When working on atelier spaces such as Hermès, the sound of hammers and leather working tools is rendered musical with the acoustic paneling used on the walls. At the Palais de Tokyo restaurant, Les Grands Verres, the high space and the risk of noise reverberation shaped our material choices for the renovation; everything was orchestrated to have the most intimate experience.

WHAT’S THE BEST PLAYLIST FOR GATHERING AROUND A MEAL? The whispers and laughter of people around the table.

WHAT SONG REPRESENTS WHERE YOU’RE AT IN YOUR LIFE AND PRACTICE AT THE MOMENT? “Overture (‘Sinfonia’) in C Major” by composer Marianna Martines.

58 culturedmag.com

DAVID MONTGOMERY

In 1967, the Brooklyn-born, London-based photographer, known for his intimate approach to portraiture, became the first American to photograph Queen Elizabeth II. Four years later, he took on another British heavyweight: the Rolling Stones.

“I WAS MAKING A LIVING AS an advertising photographer, but I also did a lot of editorial work for The Sunday Times. I was shooting plenty of royalty and prime ministers for the magazine. I ended up taking this picture of the Rolling Stones as a favor for a friend of mine. I never went to clubs, I was not on the scene—I was the scene, if you know what I mean. Mick [Jagger] was a couple of hours late; it was summertime and hot. The rest of the band was politely sitting around. By the time Mick came, we were all a bit hungry. There was a fish and chips shop down at the bottom of the road. I thought, Well, since they’re an English band, I’ll shoot it in a fish shop for some nice local color. Everybody eats fish and chips, nothing glamorous about it. There were some teenagers in there, but nobody paid any attention to us. That’s the great thing about London, or England anyway. The band was busy talking amongst themselves, so I had my hands full getting them all to look at the camera. I was starting to get a bit fed up with it. I thought, Let’s just get this done. I want to go home and have supper. Mick was clearly tired, not the most dynamic, but you knew he was ‘the one.’ I’d photographed Jimi Hendrix, who was truly special, the Queen, and even Paul McCartney, but Mick is like electric, you know? Look, they’re the greatest rock-and-roll band in the world. That’s all there is to it. The fish and chips shop is still around, only it moved down a half a block. When I go there, I always think, Did that really happen? Was that really real? ”

60 culturedmag.com

On the following pages, four photographers share an image from a summer day that continues to inspire them.

SUMMER DISPATCH PHOTOGRAPHY

DAVID MONTGOMERY, THE ROLLING STONES, 1970.

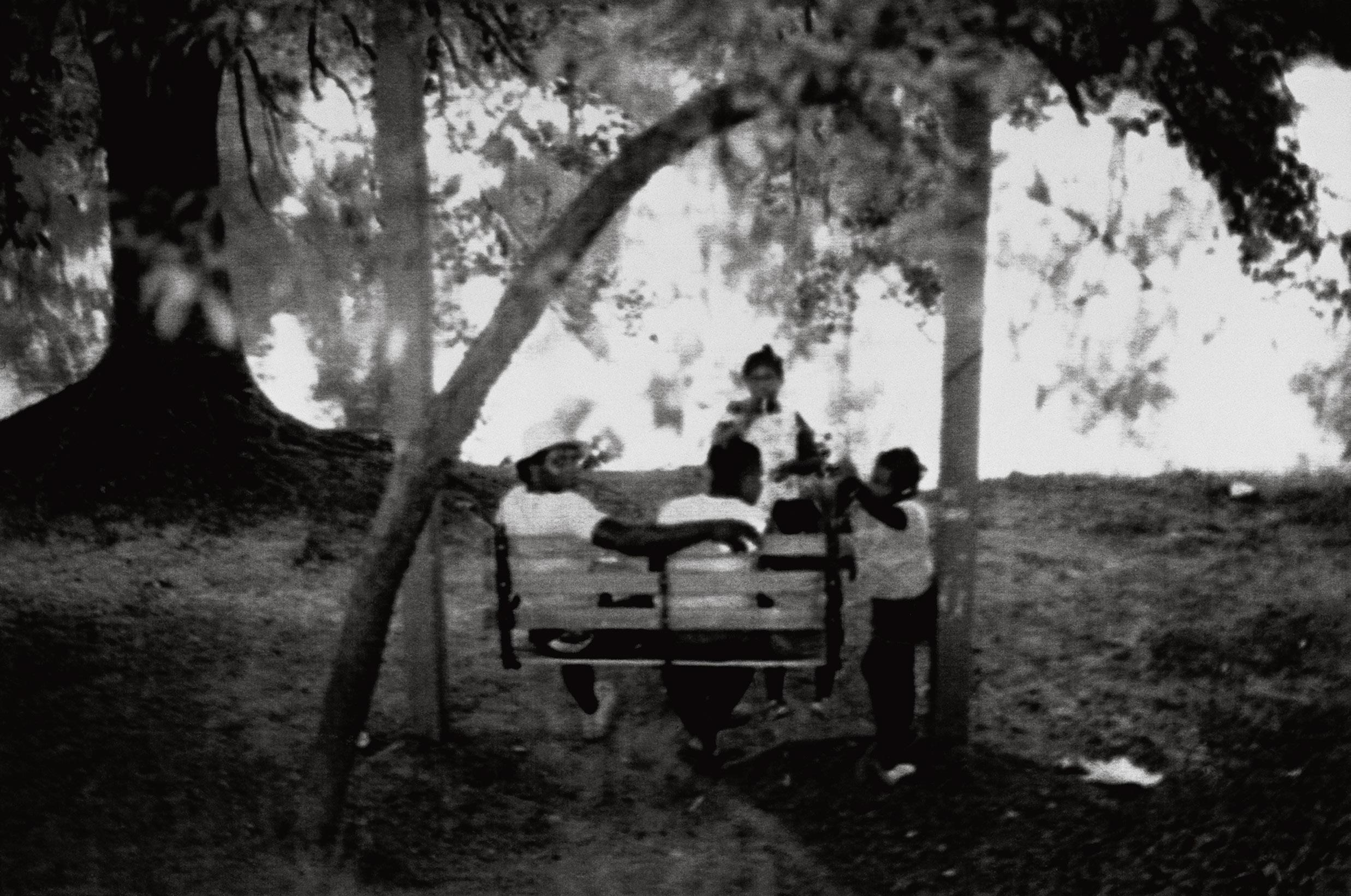

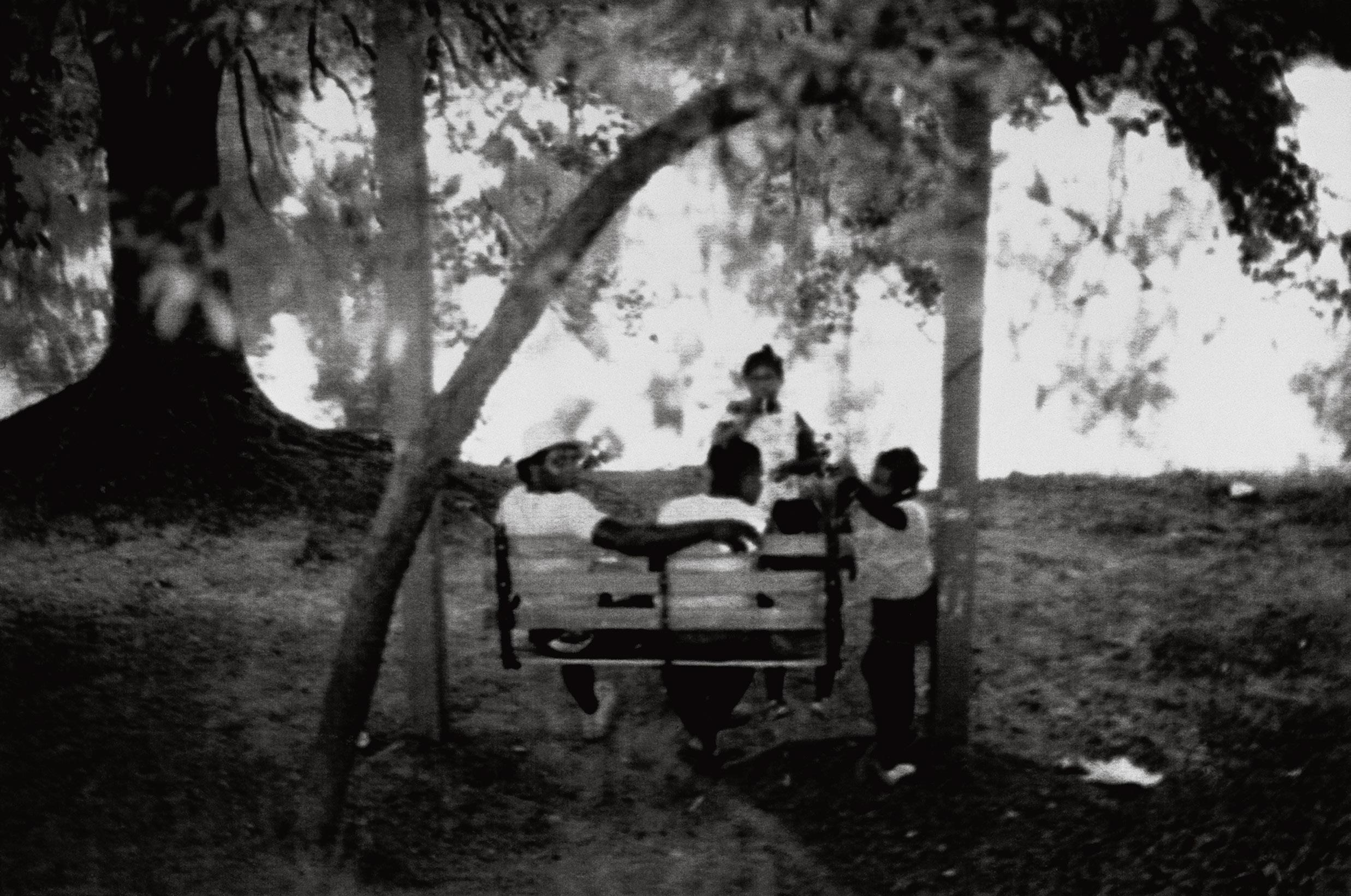

MING SMITH

Over a half-century–long career, the Detroit-born, Harlem-based photographer—and the first Black woman photographer to have a work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art—has captured the auras of music legends like Grace Jones, Sun Ra, and Tina Turner. But for all her stirring portraits, it is a candid summer snapshot that sticks most with Smith, a testament to the resilience and joy of Black family.

“I WAS MARRIED TO WHAT I WOULD call an avant-garde jazz musician. It was a period of lost jazz. Jazz always represented the freedom coming out of Black culture. I was touring with his group, the World Saxophone Quartet, all over the world—and I would work along the way, too. Here, I was attending this cool festival in Atlanta, Georgia, where a long list of musicians, including Kenny G, were performing. I was heading toward the entrance, which was crowded with people ready to celebrate and relax on a nice summer day, and I saw a family. They were just hanging out in the park. The Atlanta Child Murders [of 1979–81] were happening that summer. These were young Black boys—I think there were 28 of them at the time—who had been either strangled or stabbed or shot, and they were found not far from where

they were murdered, in a park. It sent shock waves around the world, but the media was saying, ‘Well, it was tragic and everything, but these children didn’t have fathers.’ What does that have to do with it? So when I saw this family, I was like, Look, there’s a father right there … How beautiful is that family? They were working class folks. There was a father with his arms around his wife, and their two daughters, just swinging back and forth. They were in a private moment, a family moment. You know, I shoot cultural icons—Tina Turner, James Baldwin—but this photograph was expressing something bigger, something totally sincere, something that was political, but beautiful. I love this image. I knew when I took it that it was a winner. Even without the history, it would have been a special one for me.”

64 culturedmag.com MING SMITH, FAMILY FREE TIME IN THE PARK, 1982.

SUMMER DISPATCH PHOTOGRAPHY

WATERFRONT LUXURY IN

LAUDERDALE ORAL REPRESENTATIONS CANNOT BE RELIED UPON AS CORRECTLY STATING THE REPRESENTATIONS OF THE DEVELOPER. FOR CORRECT REPRESENTATIONS, MAKE REFERENCE TO THIS BROCHURE AND TO THE DOCUMENTS REQUIRED BY SECTION 718.503, FLORIDA STATUTES, TO BE FURNISHED BY A DEVELOPER TO A BUYER OR LESSEE. These materials are not intended to be an offer to sell or solicitation to buy a unit in the condominium to be known, while the applicable license remains in effect, as Edition Residences Fort Lauderdale. Such an offering shall only be made pursuant to the prospectus (offering circular) for the condominium and no statements should be relied upon unless made in the prospectus or in the applicable purchase agreement. In no event shall any solicitation, offer or sale of a unit in the condominium be made in or to residents of any state or country in which such activity would be unlawful. All images, designs and views depicted herein are artist’s conceptual renderings based upon preliminary development plans, and are subject to change without notice. All such materials are not to scale and are shown solely for illustrative purposes. Developer makes no representation that such improvements will be built or will be built as depicted. The project graphics, renderings and text provided herein are copyrighted works owned by Developer. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction, display or other dissemination of such materials is strictly prohibited and constitutes copyright infringement. The project is being developed by LV Bayshore SPE, LLC (“Developer”), which has a limited right to use the “Edition” trademarked names and logos. All statements, disclosures and/or representations herein are made by Developer and not the licensor and you agree to look solely to Developer (and not to the licensor and/or any of its affiliates) with respect to any and all matters relating to the marketing, and/or development of the project and with respect to the sales of units in the condominium. No real estate broker is authorized to make any representations or other statements regarding the project and no agreements with, deposits paid to or other arrangements made with any real estate broker are or shall be binding on Developer. FOR MORE INFORMATION + 1 954 355 7116 FORTLAUDERDALEEDITIONRESIDENCES.COM @EDITIONRESIDENCESFTL SALES GALLERY LOCATED AT 3115 TERRAMAR STREET, FORT LAUDERDALE, FL 33304 A COLLECTION OF ONLY 65 RESIDENCES THAT BRING TO LIFE THE SOPHISTICATED GLAMOUR OF THE EDITION IN TWO- OR THREE-BEDROOMS WITH BEAUTIFUL WATERWAY VIEWS.

THE NEW ICON OF

FORT

DEREK RIDGERS

For over four decades, British photographer Derek Ridgers has been capturing the rough edges of concerts, musicians, and their wildest fans. One late night in the ’80s, he turned his lens on the Cramps, and captured the psychobilly band sweating and screaming onstage.

“THIS IS THREE-QUARTERS of the rock band the Cramps harmonizing into one microphone. It was Sunday, April 6, 1986. The weather was overcast in Deinze, which is in Belgium. I remember that day very well because our trip was written up in the U.K. magazine Time Out, and I shot this photograph on commission for them. I’d traveled there early that morning from London with a coach-load of rabid, rockabilly Cramps fans. We headed back to London on the same coach after the gig ended, so it was a round trip of about 26 hours. The headline of the piece was ‘Hell on Wheels.’ It wasn’t really hell for me, but the journalist who wrote it was much less tolerant of spending that long in the company of a lot of overenthusiastic Cramps fanatics.

I was 35 at the time, and I was very lucky to get the job because I’d only been taking photographs professionally for three or four years. If I’d had a camera when I started going to concerts in my teens—when rock was far more fringe—I

could have taken some incredible shots. I saw Jimi Hendrix in December of 1966, and I was so close that I could have operated his pedals for him.

The Cramps were a truly fantastic live band—one of the best I’d ever seen. They didn’t take themselves too seriously, but they took the music very seriously. Poison Ivy was hugely interested in vintage guitars. She was a great rhythm guitarist and, I think, still cruelly underrated. In any case, they certainly weren’t an all-ages band. Lux Interior would sometimes disrobe and wag his weenie at the audience.

I’m not sure a 72-year-old ex–rock-photographer is at all qualified to talk about the music scene today, but for me, the heyday of guitar-based rock was really the ’60s, and the genre properly came of age in the ’70s and ’80s. Since then, it’s been in a slow decline, endlessly repeating itself. I hope I don’t sound like an old curmudgeon, but I suspect I do. So much about life now is better than it was. Just not live rock.”

66 culturedmag.com

SUMMER DISPATCH PHOTOGRAPHY

DEREK RIDGERS, THE CRAMPS, 1986.

Global Partners

31–September 10 Tickets at guggenheim.org

Work in progress by Sarah Sze, 2022. © Sarah Sze. Photo: Courtesy Sarah Sze Studio

March

JAMEL SHABAZZ

The Brooklyn-born Jamel Shabazz has captured the raw alchemy of street life across the world, but the photographer is best known for documenting the birth of hip hop in his hometown. His instinctual style allows him to capture city dwellers at their most confident and expressive—in moments of celebration, uproar, and ennui. On a humid evening in the ultimate crucible of humanity, Shabazz snapped a photo that has stuck with him to this day.

“It was a Saturday night in Times Square during the summer of 1981. It’s just a group of friends enjoying the evening with their boombox. I had just gotten home from Germany, where I’d been stationed, and I took this photograph during a period when I was rediscovering the New York that I had been so homesick for during those years. I used to hear the song “What’s Happening Brother” by Marvin Gaye in my head whenever I photographed the streets. That song is about a Vietnam [War] veteran coming back to America, and he’s trying to understand what’s happening.

As a young photographer who was trying to get better, Times Square was the place to go. Back then, it was like Las Vegas for many young people. People from all five boroughs and the rest of the world would gather there to see a movie,

go to dinner, and just socialize. On this particular evening, I was developing my skills shooting at night, and as you can see from the composition, I was still figuring it out. Technically, this is not a good photo—it’s full of distractions. I spent pretty much the entire afternoon and early evening standing on the corner of 7th [Avenue] and 42nd Street. When the trains came in, hundreds of people would get off who I wanted to photograph; I would pull them over and show them my portfolio and engage with them, and like that I built up a body of work. I found a lot of couples, and focused my lens on love, diversity, [and] people from all over the world. When I saw this group, I thought, Everything is there. The fashion is there, the friendship is there, the hip hop is there. It just represented everything to me.”

68 culturedmag.com JAMEL SHABAZZ, SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, 1981.

SUMMER DISPATCH PHOTOGRAPHY

Gary Simmons (b. 1964, New York, NY; lives in Los Angeles, CA), Double Cinder, 2007. Pigment, oil paint, and cold wax on canvas; 102 × 84 in. (259 × 213.4 cm). The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection. © Gary Simmons. Photo: Ian Reeves. GARY SIMMONS Lead support is provided by the Harris Family Foundation in memory of Bette and Neison Harris, Zell Family Foundation, Cari and Michael Sacks, Nancy and Steve Crown, Hauser & Wirth, The Joyce Foundation, and Karyn and Bill Silverstein. Major support is provided by Ellen-Blair Chube; Jack and Sandra Guthman; Susie L. Karkomi and Marvin Leavitt; Kovler Family Foundation; Liz and Eric Lefkofsky; Gael Neeson, Edlis Neeson Foundation; Carol Prins and John Hart; and the Terra Foundation for American Art. JUN 13OCT 1, 2023 MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO MCA

New York–based designer Amy Zurek is transcending the trend cycle, crafting heirlooms for a new era.

THE STEALTH LUXURY OF SAVETTE

CONSTANTIN BRÂNCUSI SCULPTURES, a plastic tote from New York’s Chinatown, and the sunlit paintings that line the walls of the Whitney Museum of American Art are a few things that have inspired the unconventional handbags designed by Amy Zurek, who founded her luxury brand Savette in 2020. “I absorb the world around me,” she says on a cloudy New York afternoon, “and that impacts the design of the pieces.”

Zurek wants to reframe the narrative around accessories by designing impactful, timeless bags that can be cherished forever by people who celebrate any aesthetic—from Lady Gaga to Emily Ratajkowski, both of whom are devotees of the brand. She doesn’t design with trends in mind, striving instead to create modern heirlooms to be passed down through generations. This is an undertaking that the designer is well-prepared for: After studying fine art and art history at the University of Pennsylvania, Zurek graduated from the fashion design program at Parsons School of Design and landed jobs at luxe, minimalist brands, including Khaite and The Row.

One afternoon, Zurek was taking stock of the gaps in her own wardrobe. “I was looking for a bag that was minimal, clean, and thoughtfully crafted from highquality materials, but wasn’t overly plain or austere,” she recalls. “Something that had a subtle but recognizable element that wasn’t a logo.” Thus, Savette was born—and so was the Symmetry Pochette: a compact, ladylike bag and crowd favorite, with a petite top handle and an oversized turn-lock. “It’s not the most functional everyday piece,” she says, “but there’s a simple sophistication about it.”

Though Zurek’s pieces conjure a vision of pristine, elegant femininity—the kind of thing you’d see in an Audrey Hepburn film—she insists they aren’t meant to be babied. Rather, they’re made with timelessness in mind, and feature resistant materials like woven leather. “Often, women are worried that a bag is going to get scratched, or they’re going to wear it in the rain, and it will be ruined,” says Zurek. “Our bags aren’t bulletproof, but that was definitely something we considered. If you’re investing in an item, you want it to last.” Every piece is made in Italy, in a three-generation family-owned factory, with all materials produced on-site or in neighboring regions of Italy.

True to the Savette ethos, which nods to family heirlooms and fine art, Zurek’s mother and grandmother serve as the designer’s personal style guides, inspiring the shapes and textures of the young brand. “I have a lot of jewelry from my grandmother,” says Zurek. “She collected a lot of Georg Jensen and Elsa Peretti. I really treasure those pieces, and they inspired some of our hardware elements, like our signature locks.”

As the hunt for fresh design trends wages on—Balletcore! Indie sleaze! Barbiecore!—Zurek is carving out a space for herself in a crowded fashion landscape. “I wanted to make handbags that exist outside of the cycle of trends,” she says. “I think that’s an uncommon design philosophy today, when we’re inundated, season after season, with newness.” What’s next for Savette? Zurek sees the brand expanding, perhaps first into small leather goods or a limited collection of homewares. But at the moment, her focus is clear. “I want the bags to be wearable by many kinds of women in all seasons.” she says. “Our guiding principle is timelessness.”

BY KRISTEN BATEMAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY MAEGAN GINDI

68 culturedmag.com

“I have a lot of jewelry from my grandmother. I really treasure those pieces, and they inspired some of our hardware elements.”

culturedmag.com 69 AMY ZUREK IN THE STUDIO SHOOTING SAVETTE’S NEW FALL/WINTER COLLECTION.

Places To Gather

Last year, Belgian architect and designer Vincent Van Duysen partnered with Zara Home to launch Zara Home+, a collection of furniture and accessories for the living room. This year, the duo have partnered for a second collection that takes the dining room—a space of gathering and tradition—as its focus. To mark the release, Van Duysen reflects on his process of distilling intimate memories into joyful, versatile pieces.

WHAT IS THE ETHOS OF THIS COLLECTION? It’s about time and traveling down memory lane. The goal was to translate my DNA into a full program, hearkening back to the last 30 years of my work. The starting point for this challenging exercise was to revisit the key elements that defined my signature, distill [the] shapes and forms, and instill purity into these new creations.

DID YOU FIND INSPIRATION IN OTHER FORMS OF VISUAL ART, FILMS, OR TEXTS? I am like a sponge absorbing the most diverse disciplines. Everything has the potential to inspire me: a documentary, images on Instagram, books, galleries, movies... It’s all filtered through my empathy and my imagination. That’s how I create. But I’m most creative when surrounded

by people. Daily encounters are what inspire me the most. And my travels. And my team!

HOW DO YOU MAKE SURE YOUR PIECES STAND THE TEST OF TIME? At the core, there’s organic material and shapes, tactile and textured pieces, and clean, pure lines.

YOU USED OAK, ASH, JUTE,

COTTON, AND LIMESTONE IN THIS COLLECTION. WHAT DREW YOU TO THESE MATERIALS? First of all, they have texture, warmth, and character, and they age well with time. They are all natural and sourced locally. We like to collect the scraps—solid oak, for example—and upcycle them for smaller pieces such as candle holders or plate servers.

70 culturedmag.comv

Portrait by Zeb Daemen.

SUMMER DISPATCH POETRY

Senses awaken in summer hours, whether they’re spent in stifling cities, sleepy countrysides, or on breezy shores. Soundscapes swell to accommodate the rhythms of outdoor gatherings, and scents waft—a tableau vivant of life in all its forms.

To mark the season, three groundbreaking contemporary poets share their musings on the sounds of summer.

culturedmag.com 73

DANEZ SMITH

How does a life accumulate? How does it write itself on skin, and leave its mark on our insides? Danez Smith reckons with these questions through their explosively present poetry, which mines humor as much as pain. Following their acclaimed poetry collections Homie and Don’t Call Us Dead, their newest compilation of poems, Bluff, will publish in 2024. A scribe of a Black, queer experience, Smith pens a summer dispatch from their Minneapolis home.

64 culturedmag.com

DANEZ SMITH AT HOME IN MINNEAPOLIS. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALEC SOTH.

MORNING, MAY

they’re back! the babies are back! opened the window this morning, as it’s the time of year for opening the windows, and there they are! the babies! laughing! crying! arguing! laughing! cussing! running! getting in line! getting into fights! laughing! singing! singing! the kids singing down the slide or swinging singing a song stitching the same air they slice making half-moons with light-up shoes. they’re singing! laughing! laughing! playing! The children are playing! someone tell the future, tell the earth, tell July, tell the former-children, the number -one enemy of children, that the children are back! they are laughing! we have not killed them all! there are still children! there’s still time! there are babies and they are playing playing playing and the sun is giggling on their faces and the moon hasn’t yet gone her way she’s standing by her door, counting the children so she can balance the books again through their windows tonight. the children! the book of the dead is not yet final. outside, the rabbits are ready to rob the gardens, the squirrels are back on their mess, the dogs have been evicted back to the yards. and the babies are back. don’t tell the country where the children are. please let the babies see September. please tell my country our children are gone. tell the guns and their husbands that we lost the babies in the snow. tell the politicians their prayers worked, they don’t have to think of the children anymore. i hear the babies though the window. lord, let them stay the only sound. the babies are alive! hide them before America finds out. now what will we do about Time?

culturedmag.com 75

SUMMER DISPATCH POETRY

CACONRAD

CAConrad fell for poetry as a child, rummaging through library shelves to absorb the words of Vladimir Mayakovsky and Emily Dickinson. In 2005, Conrad began developing their (Soma)tic Poetry Rituals, structures that instigate an “extreme present” in which to write. Today, they live just up the Connecticut River from the place where Dickinson spent her life: Amherst, Massachusetts. This summer, their work—nearly five decades’ worth—will be honored with a show of poetry as art objects at the Batalha Centro de Cinema in Porto, Portugal. To mark the occasion, they share a poem from their forthcoming book, Listen to the Golden Boomerang Return, a collection of odes to yearning, the weather’s consequences, and the passing of time.

CACONRAD AT ST. MARK’S CHURCH IN NEW YORK. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARY MANNING.

CACONRAD AT ST. MARK’S CHURCH IN NEW YORK. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARY MANNING.

76 culturedmag.com

it was sexy how you politely declined the larger halo ocean waves travel thousands of miles never revealing the source of their power enough poems have been wasted on human cruelty we dig hard to find the other world press pen with everything in us write Gate to open 9 pages at once stay open ignore how much you want to close I love you it must be said I love you can you hear it arriving after countless miles hold my hand as we feel relief with the crashing waves

culturedmag.com 77 SUMMER DISPATCH POETRY

SANDRA CISNEROS

Sandra Cisneros writes from the in-between. The Chicago-born author is a citizen of Mexico and the United States, a maestro of both poetry and prose, and a transgenerational voice. Last fall, she published Woman Without Shame/Mujer sin vergüenza, her first book of poetry in 28 years, and was also awarded the prestigious Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. She is currently adapting her beloved bildungsroman, The House on Mango Street, into an opera with composer Derek Bermel. From the sanctuary of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where Cisneros has lived for the last 10 years, the poet shares a sound bite from a brewing storm.

68 culturedmag.com

SANDRA CISNEROS IN SAN MIGUEL DE ALLENDE. PHOTOGRAPHY BY KEITH DANNEMILLER.

HOUSE ALARM, SAN MIGUEL DE ALLENDE

I can get used to the boom of fireworks at dawn detonating dogs, roosters, donkeys, church bells jolting the faithless awake on holy and unholy days,

Padre Dante’s wobbly hymns warbled from a loudspeaker,

the Otomí procession of armadillo guitars, ocarinas, conch shells, drums thumping a furious beat, but–can’t get used to this: the billionaire’s house alarm wailing like a weary child at el Mercado San Juan de Dios.

Worse, los mexicanos see me as una gringa, think it’s my house alarm. I don’t have one. But, for safety’s sake, can’t say this.

The billionaire’s gone to New Zealand. This the reason his San Miguel house sits vulnerable to local and extranjero rage all season.

Summer simmers the ire of neighbors against all newcomers who have raised the rent and made living in el centro imposible.

Afternoon rains arrive ahead of the hurricanes that straddle both coasts every summer.

Clouds drag a violet shroud of rain across the valley. Beyond the gauzy mountains, strands of lightning crackle louder than the neighbor’s house alarm.

Temperature plummets. Scent of silver.

Pirul trees shiver a drizzle of dust. Palm trees sashay brittle skirts. Basso profundo rumble. Jackpot rush of coins breaking from the heavens.

¡La ropa, la ropa! Housewives rescue rooftop laundry snapping in the wind sweeping in from Celaya, fifty kilometers away, the most dangerous city in the republic, home base to our home state’s cartel.

But we live in the most beautiful city in the world. With nary a worldly care, save a false alarm. Or so our realtors swear.

culturedmag.com 79 SUMMER DISPATCH POETRY

Land Spirit in the On view through

This exhibition is organized by Trevor Schoonmaker, Mary D.B.T. and James H. Semans Director, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. Major support for Spirit in the Land is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. Lead support for Spirit in the Land is provided by the Ford Foundation.

nasher.duke.edu

At the Nasher, Spirit in the Land is supported by the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation; The Duke Endowment; the Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger Family Fund for Exhibitions; the Frank Edward Hanscom Endowment Fund; the Janine and J. Tomilson Hill Family Fund; Katie Thorpe Kerr and Terrance I. R. Kerr; Alexandria and Kevin Marchetti; Parker & Otis; Lisa Lowenthal Pruzan and Jonathan Pruzan; and Caroline and Arthur Rogers.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Under Zim’s Tree, 1998. Oil on canvas, 17 1/4 x 17 1/4 inches (43.82 x 43.82 cm).

Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Gift of Susan and Barkley L. Hendricks to commemorate naming Trevor Schoonmaker as Mary D.B.T. and James H. Semans Director of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2020.6.2. © Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

82 culturedmag.com

“Look at any story about fame. How does it end? It’s strange that these narratives are still so alluring in our society. Literally every celebrity memoir or biopic— it all ends the same.”

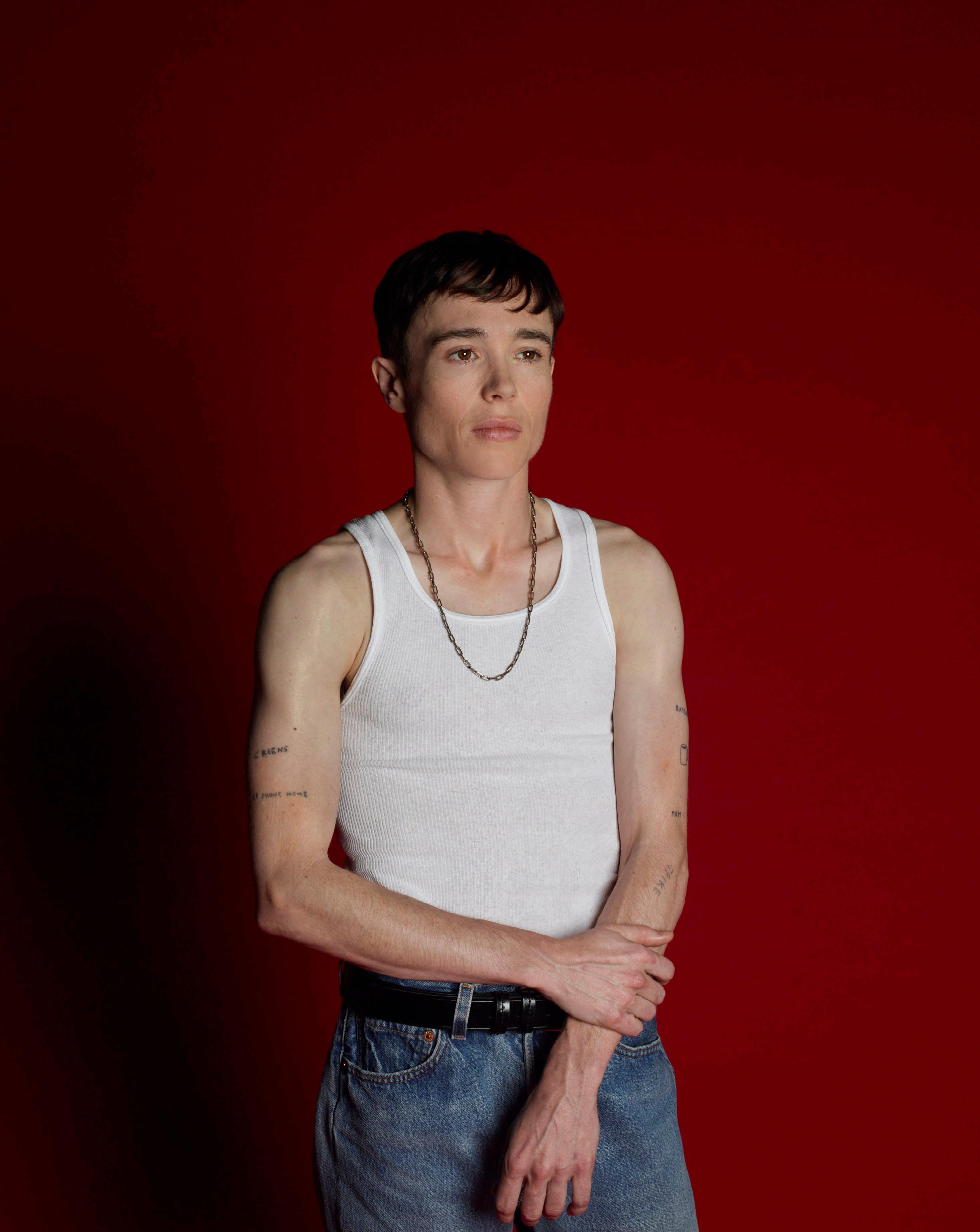

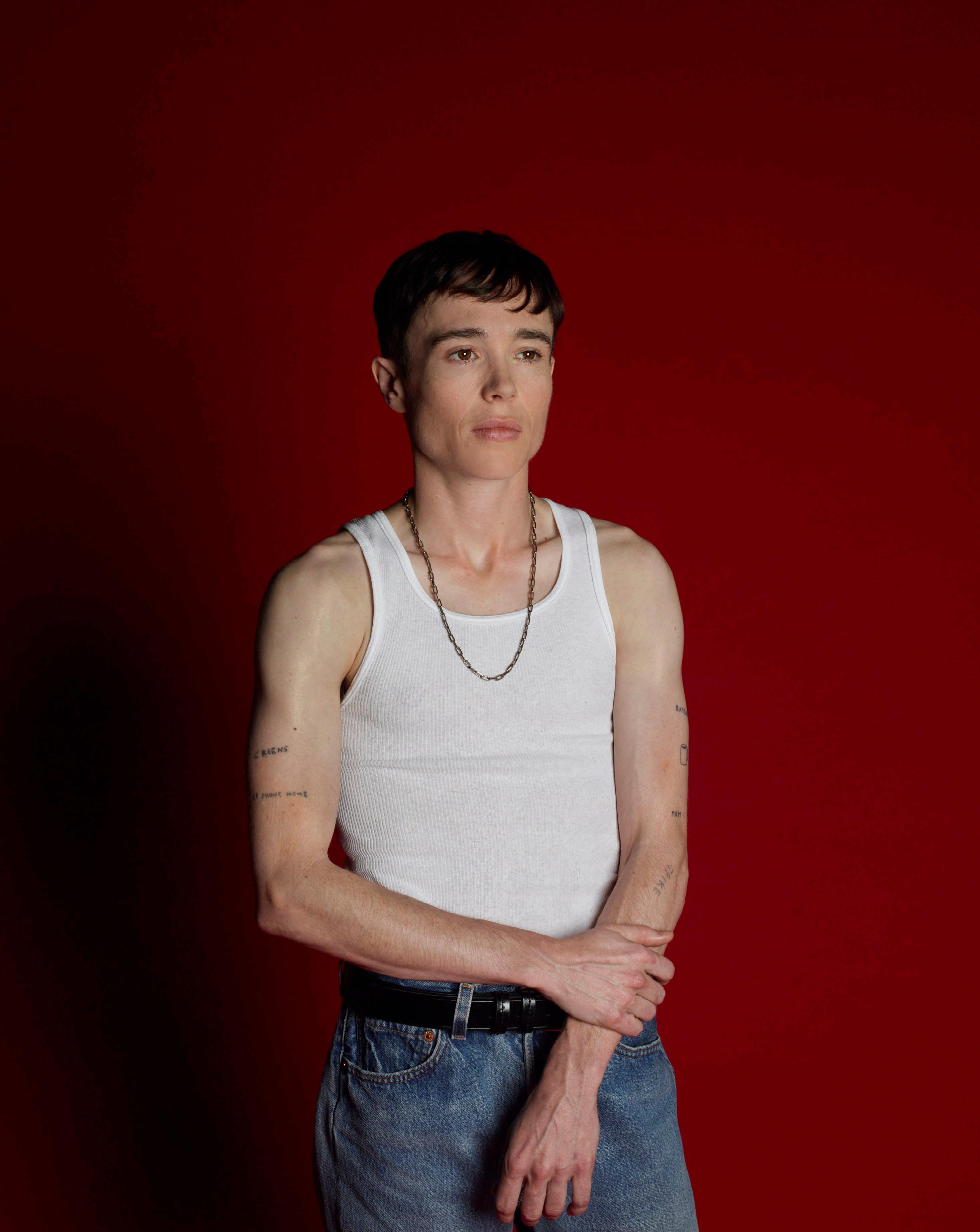

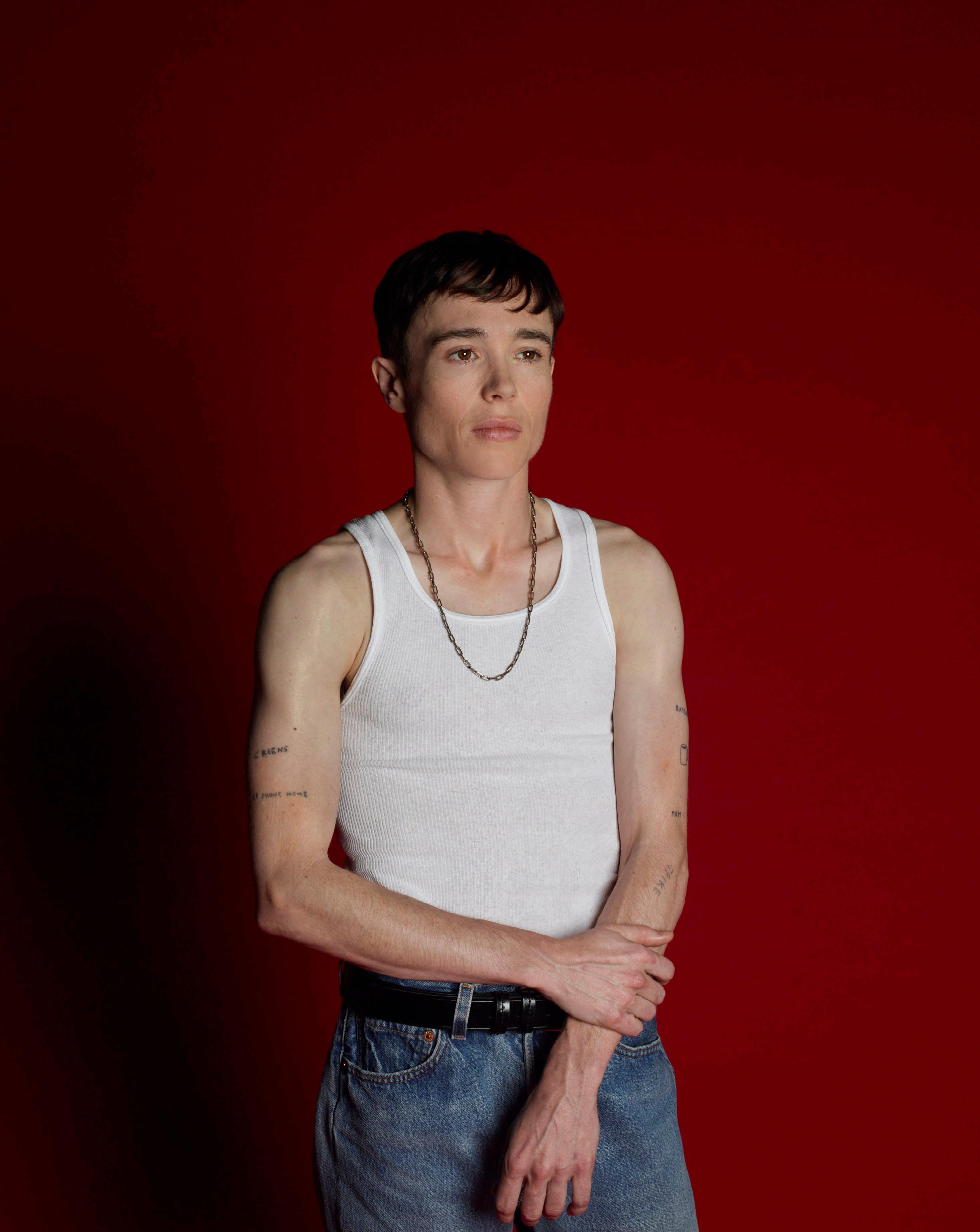

A NEW CHAPTER

BY MARA VEITCH PORTRAIT BY CATHERINE OPIE

ELLIOT PAGE HAS BEEN ACTING since the age of 10. With turns in Juno, Whip It, Inception, and The Umbrella Academy, Page was unmissable, a household name. But the actor was also performing in his personal life—the role of the young starlet, eminently talented and touchingly self-effacing. Until the actor came out as transgender three years ago, he was frozen in place by the bifurcated demands of celebrity: an easily marketable varnish and a smiling face, or a parody of suffering worthy of tabloid coverage. With his new memoir, Pageboy, the actor peels back years’ worth of calcified preconceptions, offering a powerful counternarrative to the ones that have swirled around him since childhood. The memoir—a collection of aching, tender, and raw vignettes that draw on the historic violence, Indigenous erasure, and natural beauty of his hometown of Halifax, Nova Scotia—chronicles moments of furtive, youthful love, isolated Hollywood adolescence, and the lurching process of finding queer community. To mark the book’s release, Page sits down with CULTURED’s senior editor to reflect on the ritual and relief of putting pen to paper.

MARA VEITCH: What was your relationship to writing before taking this on?

ELLIOT PAGE: It was minimal. In the brief moments when I did engage with it, I felt some form of a flow. But I could never sit for long periods or stay with something. It would be a spurt, and I’d move on. I love to read—that’s a big part of my life—but writing to this degree, not so much.

VEITCH: Did any of the writing from those spurts find their way into Pageboy ?

PAGE: A couple did. There were old notes in my phone that I drew from.

VEITCH: The book is full of these tiny, crystal-clear moments. In a life that’s full of tiny moments, how did you decide which ones to hold up to the light?

PAGE: The first time I actually, seriously sat down, I wrote that first Paula chapter, which came out stream-of-consciousness. When the book deal became real, I spent the first couple of weeks feeling, not necessarily overwhelmed, but the acknowledgement of what I’d taken on. At first I focused on whatever came up organically. As I went on, I’d pick an age or a period, and think of a story—or a relationship or a friendship—that covered that period, and build upon it.

VEITCH: Did that overwhelmed feeling come from the pressure of sifting through your own experiences, or was it more like, “I owe pages”?

PAGE: I guess both, and the fear of never having written something to this extent. Every time I read a book I think, How the fuck does somebody do this? That, plus talking about things that, of course, were not easy to talk about. I really felt that in my body as I wrote. It was fascinating, like, I’d hunch over, I’d start to sweat. I would try to strike a balance for myself: Okay, this week I wrote about a rather traumatic incident, so next week I’ll write about getting to wear a Speedo as a kid

VEITCH: How did your work as an actor inform your writing process?

PAGE: I imagine lots of writers do this, but it felt like I could visualize each memory, and translate it on paper in a way might be be similar to translation

from script to screen. It was as if I was watching each moment, which helped me to write it in a more cinematic way.

VEITCH: Who were some of the writers who fueled your writing process?

PAGE: I mean, where do I begin? In terms of memoirs, I love Saeed Jones’s How We Fight for Our Lives; Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and The Argonauts; Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel; Carmen Maria Machado’s In The Dream House; and Tanya Tagaq’s Split Tooth. The way they’re strung together, the way they flow, the way they just keep pulling you forward…

VEITCH: You return often to the history of Halifax—the Halifax Explosion, Indigenous erasure, resource extraction—and how it seeps into the architecture of your family. Why did you decide to make Halifax one of the book’s primary characters?

PAGE: It’s about my fascination with time—all the life that has come and gone, that shapes who we are. Some awful things, some positive things. It’s also about my personal interest in things like the Halifax Explosion. Eventually my editor had to say, “Okay Elliot, that’s enough about that.”

VEITCH: You return often to our insignificance as human beings. Can you elaborate on that?

PAGE: I think often of my own life in relation to grains of sand, the stars, and the sky. I have some days where that thought is quite scary and sad, and other days where that thought is really exciting and liberating. It makes me feel less precious about myself, the things that have happened to me, or the anxiety and stress that I’m dealing with. Like the book coming out, for example. I say to myself, Elliot, you’re a tiny speck. There are a lot of books in the world.

VEITCH: Is that a form of resistance to the pressures of celebrity? I don’t remember many moments in the book where you fully embrace your relationship to fame.

PAGE: It does feel awkward and it always has. I’m finding my love for acting again in such a significant way, which is really special. I loved it as a teen—when I discovered film and art and all these things, and then was able to play all these interesting roles. That was thrilling. What a true gift to get to throw yourself into something like that. The attention—or being told that you’re special because of it—felt very odd and uncomfortable, and I think just simply not true. It can enhance those feelings of emptiness and loneliness. I mean, look at any story about fame. How does it end? It’s strange that these narratives are still so alluring in our society. Literally every celebrity memoir or biopic—they all end the same.

VEITCH: Has your relationship to that uncomfortable side of things changed?

PAGE: Now, everything feels different. Before, when I’d get recognized on the street, I had a difficult time with it. Now, my ability to interact with people when they want to chat, or want a photo, is totally new. I feel present, and I have lovely conversations with people. It’s a significant shift.

VEITCH: How do you want people to feel when they read this book?

PAGE: It’s weird to think—oh my gosh—people are gonna read this, you know? We’re all so pressured to become this narrow version of who we are. We take in all these toxic and unhealthy expectations, and we’re not encouraged to be our full selves. A part of me hopes it allows people to feel seen, to explore internally, investigate, and be who they want to be. I hope it helps people to say, you know, “Fuck you,” to those pressures and fully step into their authentic selves.

culturedmag.com 83

“Pageboy”—Elliot Page’s writerly debut, out this month—offers an intimate glimpse into the life of an actor who has grown up alongside his audience.

84 culturedmag.com

SCOTT SAMPLER AT HIS WINERY IN BUELLTON, CALIFORNIA.

SCOTT SAMPLER’S SECRET SAUCE

THE FORMER FILM DIRECTOR TURNED VITICULTURE RENEGADE CHOSE NATURAL WINE AS HIS FORM OF RESISTANCE AGAINST AN INDUSTRY STUCK IN ITS WAYS.

BY REBECCA AARON PORTRAIT BY HANNAH TACHER

SCOTT SAMPLER HAS FOUND HIMSELF in an industrial complex in Buellton, California. He came to the dusty Central Coast community by way of Beverly Hills and Los Feliz to open his winery, where he makes the “porch pounders” and fine wines that are sipped in some of Los Angeles’s most prestigious restaurants. The winery is more of a creative studio, filled with vestiges of his past lives. His dog, Serge, and cat, Shangy, keep him company in a curated yet cluttered space stacked with crates of vinyls ranging from bossa nova to hip hop, framed works by his artist father, and his own portraits of infamous LA microstars.

Sampler’s upbringing is steeped in Old Hollywood lore—he grew up as a regular at Musso & Frank with Frank Gehry’s daughters as his babysitters, and landed his first job as Quentin Tarantino’s assistant. The proximity to fame never dazzled him—one night, when Tarantino asked Sampler to drive him to a party, he declined. He had a date at a Dizzy Gillespie concert lined up, and plans to make movies of his own.

After studying philosophy and fine art at the University of California, Berkeley, Sampler returned to Los Angeles in 1990, where he wrote screenplays and directed angst-ridden music videos for ’90s rock bands. Along the way, Sampler collected wine obsessively. That’s what happens when your foodie parents sneak you sips at L’Orangerie. “Wine was always in the background,” recalls Sampler. To add some color to days spent writing scripts, Sampler hosted a string of dinner parties that he called “Saucefest,” where collectors, gallerists, and artists gathered for bacchanalian evenings featuring Sampler’s infamous pasta sauce, inspired by his grandmother’s recipe.

While searching for reprieve from heartbreak at a friend’s house in Malibu, something clicked. With his wine collection at critical mass and the vast untouched acreage of the Santa Monica Mountains surrounding him, Sampler decided it was time for a new chapter. “Talking to the producers and agents for the action comedy script I was rewriting was not that exciting,” he recalls, “but talking to the viticulturists and winemakers I befriended was very interesting. It brought me down to earth.”

He was determined to emulate the style of his favorite old school Italian producers, from Barolo to Friuli, who made slow wines with long macerations—

but with no chemical intervention save for minimal sulfurs at the bottling stage. “Everyone thought I was crazy for wanting to make wine this way,” says Sampler, “but it was my calling. The sirens were hurtling me towards the rocks.” While the idea of natural winemaking is increasingly popular among makers and tasters today, the concept of making wine without a laundry list of additives was practically taboo in 2010, the year of Sampler’s first harvest. When the vintners and wine experts in Sampler’s periphery rebuffed his vision, he redoubled his commitment to natural winemaking as a form of artistic expression—and protest against the status quo.

Ultimately, he found a like-minded mentor: a Santa Barbara winemaker who showed him where to source the fruit and shared his own fermenters. The crush facility, where Sampler planned to process his wine, also doubted his non-interventionist philosophy, forcing him to sign a waiver stating that he would pay for the wine even if it tasted like vinegar. He managed to curry favor with the facility’s owner, a zany septuagenarian surfer, who ultimately gave him a key to the place. The first batch turned out exceptionally well.

The result of Sampler’s tireless, meticulous labor spoke for itself. When Sampler placed his first bottles at Spago in Beverly Hills, he realized that by wrangling an unconventional process, he had managed to touch something inside people. “The sommelier [at Spago] broke down in tears of joy in the middle of the tasting,” he recalls. For Sampler, the sommelier’s reaction— along with the art world’s embrace of his bright, funky wines—was proof that his protest was not in vain.

Countless tears, graveyard shifts, and sold-out vintages later, Sampler’s wines can be found in restaurants like Bell’s in Los Alamos, Otoko in Austin, Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, and all the best natural wine shops in-between. Sampler rarely leaves his studio during fermentation, tasting his wines constantly at each stage in his proprietary process. Thirteen years later, Sampler’s operation boasts three flagship lines—the Central Coast Group Project, L’Arge D’Oor, and Scotty Boy!—each with distinct personalities, but all the result of long maceration, skin fermentation, and conscientious objection.

culturedmag.com 85

“THE SOMMELIER AT SPAGO BROKE DOWN IN TEARS OF JOY IN THE MIDDLE OF THE TASTING.”

TARA WALTERS AT HER LOS ANGELES ARTS DISTRICT STUDIO. 86 culturedmag.com

SEAWATER AND PSYCHEDELICS

BY KAT HERRIMAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY ZOE CHAIT

THE DRIVE FROM ARTIST TARA WALTERS’S cornflower blue Malibu hideaway to the parking lot of her sunlit studio in the downtown Los Angeles Arts District takes 25 minutes, if you time it right. It takes closer to an hour and a half if you make an innocent stop at the Palisades Village Erewhon, which ends up being too crowded, so you console yourself with gluten-free, sugar-free brownies from Lauren Conrad’s favorite bakery down the street and then head back to Erewhon to validate your parking ticket with a single cucumber seltzer.

No matter how fast or slow you drive afterwards, the sloshing in the back seat is inevitable. It’s not the seltzer, but the sound of two tall plastic buckets filled with clear seawater Walters collected off the coast of Point Dume yesterday.