EXCHANGE

ISSUE 04 2023

AN IWI PUBLICATION

Published annually at Columbia University (New York, NY)

Books printed o set and bound by Bookmobile Cra Digital (Minneapolis, MN)

Cover art by Kellen Stuhlmiller

Layout Design by Colleen Reynolds

is publication would not have been possible without the generosity of the Mark R. Robin Memorial Fund for Creative Writing.

EXCHANGE 04 STAFF

MANAGING STAFF

Editor in Chief

Leah Silverman

Director of IWI

Chyana Marie Sage

Correspondence Team

Christiana Deverets

Haley Glover

Nonfction Editors

Joe Bubar

Donna Lee Davidson

Zoe Hardwick

Fiction Editor

Jessica Sun

Poetry Editors

Jonathan Fletcher

Jude Misick

Joel Sedano

Social Media Manager

Jude Misick

Outreach Manager

Gigi Blanchard

Art Directors

Colleen Reynolds

Jessica Sun

And a thank you to

Anastasia Walton

EDITORIAL BOARD

Miranda Mazariegos

Issa Taseen Spencer

Damien McClendon

Jillian Damiani

Zoe Maya Engels

Wyonia McLaurin

Wally Suphap

Sophia Lind Mautz

Destiny Hall

Christiana Drevets

Marissa Yoo

Addison Schoeman

Robert Gold

Abigail Eastman

Caleb Knight

Gigi Blanchard

Meghan Fay

Braudie Gabriella Blais-Billie

Meredith Charlene Aristone

Alexandra Rose Banach

Diana MacLaren Heald

Xinle Hou

Matthew Kimball

Kai-Lilly Kane Karpman

Leah Silverman

Jessica Sun

Jude Misick

Alexandra Kukoff

Haley Jordan Glover

Liv Waite

CONTENTS

ANATOMY OF A CELL: FOUR WAYS - EMILIO FERNANDEZ

UNTITLED - ADRIENNE MARCH

THE DEINDIVIDUATION OF INNER-CITY YOUTH -

SHAWN HARRIS

BIRTHDAY - ABIGAIL COOK

INSIDE BLUE - LINDA DOLLOFF

TINTINNABULATIONS - JACOB ROWAN

THE PACK - WILL MORGAN

SECRETS IN THE TREES - JAMES PEARL

THE POWER OF THE PEN - L.T. HENNING

MR. BOX - LARRY N. STROMBERG

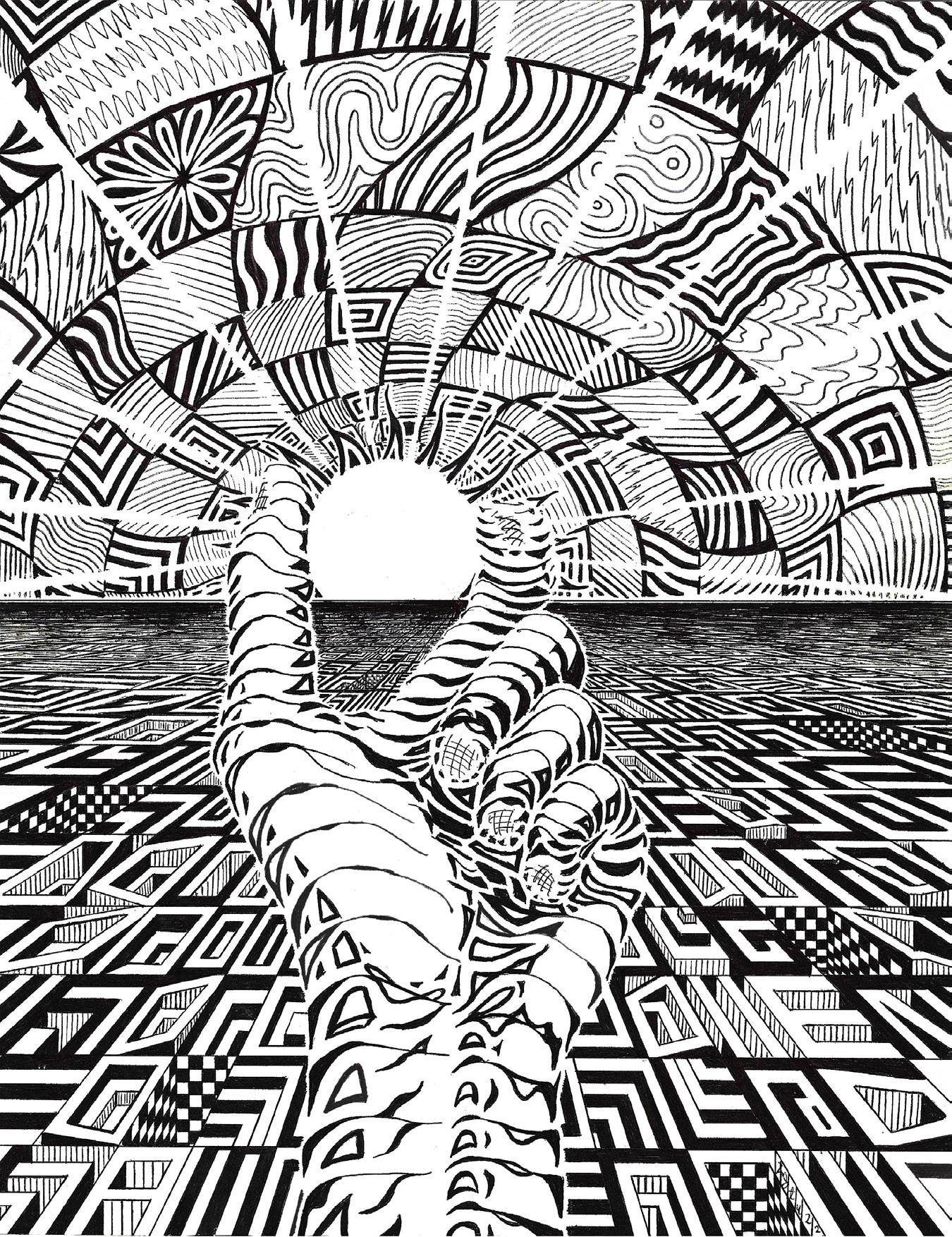

UNTITLED - KELLEN STUHLMILLER

SOMEONE - WILLIAM PEEPLES

BODY - ABIGAIL COOK

’TWAS THE NIGHT BEFORE - JEFFERY A. SHOCKLEY

UNTITLED - JAKARRI JONES

AN INTERVIEW WITH AMERICAN BOOK AWARD

RECIPIENTS, REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS & DR.

RANDALL HORTON

LIFELINE - KAMAKAZI MERGATROYD

THE MAGPIES AND THE WIND - EMILIO

FERNANDEZ

PRISON WORLD - LARRY N. STROMBERG

PUBLIC SECRETS - BEN WILKINS

AS A MATTER OF BLACK - MARCUS JACKSON

DESIGN YOUR BLUEPRINT FOR YOUR LIFEMARCUS ISREAL

AUTHOR & ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES

UNTITLED - KELLEN STUHLMILLER

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

WELCOME to the fourth issue of Exchange, a literary magazine of poems, essays, stories, and artwork exclusively by individuals who have faced imprisonment.

Exchange is a part of the Incarcerated Writers Initiative, an effort launched in 2016 to open the gates of academia and publishing to this historically overlooked and underserved community of creators. Each submission to IWI is given a thoughtful feedback letter and considered for publication in both Exchange and the Columbia Journal. It is our pleasure and privilege to be able to engage with this work.

In these pages, you will be transported to man’s primordial era and back, led by idealists, autodidacts, and deep thinkers. These works question our nature, grapple with the cycles of violence and tyranny, and answer the call to create with an intentional and driven hand. Exchange is a project of reciprocity and solidarity: it gives voice to those intentionally silenced, while the creators in these pages offer readers the opportunity to expand, to be challenged, and to be moved.

As one of the writers in this edition so keenly declared, “Brick by brick, we dismantle injustice by the power of the pen.” Indeed, this is exactly what Exchange seeks to do. We believe writing is a means of seeing oneself and seeing each other. And in a system that thrives on isolation, participating in this exchange of ideas is an act of love and respect.

Leah Silverman Editor-in-Chief, ExchangeANATOMY OF A CELL: FOUR WAYS

Based on Anne Panning’s Vietnam: Four Ways

Emilio FernandezI’m afraid of spiders. Well not anymore. Sort of. I’ve come to realize their usefulness. Tucked into high corners of my cell, webs waiting to snare the unsuspecting gnat, they devour that which annoys me, leaving a oating cemetery lled with arthropod exoskeletons. It pains me now when colonels or wardens command us to wipe away those webs during inspection. Don’t they see their beauty? eir bene t? If only those on the other side of the fence wouldn’t fear me, but recognize my usefulness instead of wiping me away like trash.

2. Made in India

55% Poly / 30% Acrylic / 10% Co on / 5% Other. e other consists of a spectrum of thread combined with strands of golden tinsel and snippets of shing line. is blanket bleeds charcoal gray hues that make the swamp summer sizzle, yet teams up with a twin to keep me warm when I can’t shut the window in winter. It has drunk tears tinged with sweat as minutes, hours, days, months,

years have piled atop a steel slab. e tag says it’s authorized for use at homeless shelters. A perfect match, as home is still so far away.

3. Closet Space

ree pressed, Facebook-blue uniform sets consisting of a cardboard-thick nurse-style shirt and elastic waistband pants with white lines down the outer seams; six co on white t-shirts; four boxers made from old sails; six socks, three of which have the heels and toes grayed out; a backup clear plastic garbage bag ready with cutouts for air conditioning; a set of frayed o -white long johns; one gray sweatshirt mismatched with a pair of sweatpants made from a lighter gray sweatshirt; two white dri- t t-shirts; one stateissued pair of prison blue gym shorts; one pair of dark blue jersey basketball shorts; one donated bar of Irish Spring from last winter; one long, far-from-over sentence in a laundry bag.

4. Stitches

My sneakers are scarred. A size ten, six-year-old pair of New Balance that no longer live up to their name. ey have persevered even as I have subjected them to a soccer eld with more rocks than weeds. ey have been sewn and patched using paperclip needles, waistband elastic threads, and a plethora of pieces from discarded Crocs and boots. ey’ve recently lost their soles and been dubbed Frankenstein. Maybe if I was free I would throw them away. But I’m not and I won’t. Not just out of necessity, but because they remind me of me.

UNTITLED

Adrienne March

Clock tic tocking/ watch the way I pop out rocking/ watch the way I count that pro t/ stop with the nonsense/ I’m just honest/ moving in the room like its no contest/ looking like a bag i know I ex/ next on my list is a li on a private/ trip on a island/ real one I am/ dri ing I’m wild in/ get you a bag/ be happy wit that/ be careful wit me, I’m gi ed and black/ li ed and trapped/ the studious mack/ I’m killing this rap/ if hip hop dead I’m bringing it back/ coming for me/ I’ll give you a map/ freeing my mind/ my body is trapped/ sky’s the limit/ I’m aiming for that/

Now I’m really feeling its time to rise / I’m really feeling its time to shine/ can u not see the time is now/ do you not hear the underground/ who can u trust/ who do u love/ who u gone rock wit/ real recognize real so meeting you here feels awkward/

I stayed loyal to guys but they did not ride/ I wave em’ goodbye its easy as pie/ inside of my mind/ I can not nd one of those times where le ing you slide kept you disguised/its best I decide/ I’m le ing you y/ unlimited sky/ I stay out the way/ avoiding the snakes/ I’m counting the days/ I’m breaking these chains/ I’m feeling strong/ screaming her name Breonna live on/ I’m dreaming alone/ seeing the change/ its giving me hope/ me in a plane/ its making me oat/ love on the brain/ its

keeping me broke/ mirrors of pain/ its keeping me ghost/ invisible man like Ellison wrote/ End of my rope and I hand em’ a quote

Now I’m really feeling its time to rise / I’m really feeling its time to shine/ can u not see the time is now/ do you not hear the underground/ who can u trust/ who do u love/ who u gone rock wit/ real recognize real so meeting you here feels awkward/

You go a know that I ain’t wit the chit chat/ big fact, big facts/ all of the mis-steps /regret, re ex/speak less, re ect/ wake up, sleepless/ relax, deep breaths/ three hs, we less/ fresh out, what’s next/ I don’t really know yet/ stayed down, respect/ mask o / faces/ people protest/ lootin’ hopeless/ be strong, focus/ stay up, be blessed/ peace out/speak less/

THE DEINDIVIDUATION OF INNER-CITY YOUTH

Shawn HarrisDeindividuation is de ned as the loss of a person’s sense of individuality and the reduction of normal constraints against deviant behavior. I talk about these issues from my personal experience growing up as a child of trauma in the inner-city. Social Psychologist Philip Zimbardo (1969) observed that arousal, anonymity, and reduced feelings of individual responsibility contributes to deindividuation. Other psychologists add additional cues which make deviant behavior more possible. But none of this has been measured in the context of traumatized individuals growing up in the inner-cities.

If we use Philip Zimbardo’s observation, the arousal in this instance would be, the drug-infested, high-crime, prevalent violence of the inner-city. en we can add to that the trauma, the poverty, and the feeling of oppression born of the confrontational presence of law enforcement. e list of potential arousals for deviant behavior, in the inner-city, are endless. e second aspect of the observation is anonymity. e examples which social psychologists used involved individuals

wearing masks, with the exception of situations where thousands of people had gathered, thus creating relative anonymity. But in the inner-city, the anonymity is established the moment we assume one of three archetypes. e three archetypes of the innercity are the victor, the victim, and the victimizer.

In addition to this new standing, within the inner-city, you take on a new name. is name may be an abbreviation of your actual name. If your name began with an ‘S’, or ‘B’, or an ‘H’, you would now be known as “S”, “B”, or “H”. Sometimes your actual name is altered in a way that sounds cool and urban as was the situation in my case where my name became “Shiz”. And other times, you may be given or take on a name that sounds intimidating like, Killer, Beast, Blood, and so on. e anonymity occurs when we take on a name other than our given name, in which case we feel obscured beneath this virtual mask.

For many young boys in the inner-city this is where the selfdiscrepancy kicks in, and where the cognitive dissonance picks up. Self-discrepancy is a theory put forth by E. Tori Higgins (1989) in which he states that there occurs a con ict between one’s actual self and one’s ought self. Basically, it means that the person one is and the person one wants to be are at odds. ere are fundamental values that we possess and there are standards that we would like to uphold. When those two things are in con ict, that is called self-discrepancy.

According to another Social Psychologist, Leon Festinger (1957), this discrepancy can give rise to what he calls cognitive dissonance theory. is theory states that a powerful motive to maintain cognitive consistency can give rise to irrational, sometimes maladaptive behavior. He states that discrepancy doesn’t always produce dissonance. What really causes dissonance is the knowledge that you commi ed yourself to an a itudediscrepant behavior freely, and with some knowledge of the consequences. When that occurs the dissonance manifests itself, and you become motivated to reduce it. e inner-city youth increase their drug use and abhorrent behavior because of the con ict which exists within their selves. Allow me to explain further with an account of my personal experience.

One very nice summer day, I was out on the block, selling

crack-cocaine. ( e con icting imagery is purposeful.) A young, beautiful woman walks up to me. She was in the advance stages of pregnancy. She asked, “Are you holding?” (A term used to refer to the action of selling drugs.) I became so enraged, so beside myself in response to this lady. At the time I believed it was because of this woman’s blatant disregard for the life of her unborn child. I was eating a hamburger at that moment, and I hurled it into her face with as much force as humanly possible. I went on to verbally assault her with expletives and threats, along the lines of, “If I nd out that you are using drugs while you are still pregnant, I am going to do such and such to you!”

e incident lasted no more than ve minutes. I remember feeling gallant, proud, and virtuous a erwards, as if I had slayed a dragon. Later that night, I used more drugs than I had ever before. In retrospect, my rage wasn’t towards her. It was towards me.

ere I was engaging in an act which was in complete opposition to my values, who I was at my core. e young, pregnant addict approaching me for drugs was just a reminder of how far I had strayed and how at odds my life was. She was a mirror of my own discrepancy and deviant behavior. My outburst towards her was a veiled a empt to reconcile, reduce that con ict.

at’s the reality of cognitive dissonance. At the end of the day, my behavior did li le to dissuade my feelings of discord and internal friction. e behavior continued, the con ict continued, and I ended up where I found myself. irty-something years later I still remember that incident, which lasted no more than ve minutes, with a clarity of presence as though it were happening in the now.

e third observation of Philip Zimbardo in the occurrence of deindividuation is the reduced feeling of individual responsibility. It is a result of the previous two (arousal and anonymity). In the context of the inner-city, personal responsibility is mute. It is like the Yeti or Aliens: People talk about it, but there’s no real proof of its existence.

Let’s take the environmental landscape of the inner-city. ere are dilapidated buildings, pavements cracked in bits and shards, streets with so many holes and irregularities that driving through them is like riding through an obstacle course. Someone

is supposed to be responsible for this, right?

e inner-city child learns, through the grievances of the parents and adults around them, that the all-mighty government is not responsible. Especially when it comes to the needs of the innercity. en there are the parents and the adults around them. ey speak to the child about responsibility, yet they are the greatest example of irresponsibility a child has. You bring a child into the world when you do not have adequate nancial means to support yourself and them! You then further, make no e orts to improve said conditions! You enter into relations with partners who abuse you, your children, and leave you emotionally wrecked. All in the purview of your child! You expose them to the truth of your fears, hopelessness, and trauma, thereby robbing them of their virtuous innocence!

And then there is the community at large. e fatherless homes. e uneducated and uncared-for children that crowd the playgrounds and sidewalks! e drug addicts, dealers, and opportunists who seem to own the streets! Someone is supposed to be responsible for this, right?

Yet to the inner-city child, all that he has are examples of irresponsibility. We inner-city children learn irresponsibility early in life. And that sad education predisposes us to being able to carry out acts of malice and violence.

Another point about this lack of responsibility in the inner-city that are based on my experiences: To be responsible, you must rst be in a position to ful ll certain rights to yourself and others. e rst and second generations of freed slaves were not in a position to ful ll those rights. eir concept of responsibility was tied more to their religious faith than to any societal norms or duties. ey passed along (in words and deed), the institution of responsibility as it relates to religious practice to their children. And their children passed it one to theirs, and so on, until it became the way people of the Ghe o understood responsibility.

As later generations began to pull away from religion, so too was there a diminishment of responsibility. e institution of responsibility (which was rooted in the church) that our ancestors put forth was replaced by the convenience of relative responsibility. You are only responsible if it suits your immediate needs. It is easy

for an inner-city child of trauma to reduce feelings of individual responsibility, since there has always historically existed a diminished capacity for personal responsibility in those places. e crisis of young Black men in the inner-city is a crisis of identity and this identity has nothing to do with the father, or his absence, but has everything to do with their identity being rooted in humanity. When young African American children of the inner-city assume one of the three archetypes therein, they lose any sense of self and become desensitized to deviant behavior. e illness is a lack of an identity rooted in humanity, and deindividuation is one of its symptoms.

Birthday

©2023/Abigail Cook

INSIDE BLUE

Linda DolloffShould I wear Blue or Blue today?

What about the periwinkle Blue of a new tee? Or, a 30-wash baby Blue. And of course, the coveted Old Lady Blue Hair, Blue as it’s nearly white.

Ah, Blue.

I’m Blue. My roommate’s Blue. How could we not; living in Blue? Even if you work here – you must be Blue.

Some are dark as navy been here too long, or su er the agonizing Blue of trauma.

Some are light Blue; they fake it till they make it. Some are icy Blue with buzz-o wri en across their foreheads.

Some cover up their Blue, they try to be pink. ey’re not fooling anyone.

ere are those who don’t know they’re Blue. Shhhh, let’s not wake them up.

Even the walls are Blue. ey’re white but they’re Blue.

ey don’t want to be here either.

So, the choice remains should I wear

Ba’ lue; the in-your-face kinda Blue. or, maybe blue so no one notices me or, Bluuuuuue hoping someone will notice and share their Blue.

Together, we can lighten our Blue or wear it without shame, fear, or contempt. at’s the Blue I’m looking for a triumphant, owning, courageous Blue. I’m proud of my Blue. How about you?

TINTINNABULATIONS

Jacob Rowan

DING Life subjectively speaks DING People subjectively speak DING Reality though is objective

DING You feel an importance pull in life

DING Abandon your prized “IQ”

DING e tongue nothing but spirit speak

Heart

DING Ho ho! Aha!

DING Nice try! Nice guy!

DING You Bless God, he said

DING God Bless You, she said.

Heart

DING Soul consciousness is it

DING Ah! but it is love

Love it is Love it is

DING

DING

Now silence Just think

THE PACK

Will MorganYou toss another stick onto the re as it burns low. You’d prefer a bigger blaze the night is cold and most of the skins you were able to grab in your ight from the raiding party have gone to your mate and children as they sleep. e fuel you were able to gather as the sun set is limited, and you dare not venture out of the circle of ickering light in search of more. ere are worse dangers than men, howling from the darkness beyond the feeble illumination provided by the burning wood.

You struggle to stay awake, but someone must keep watch. Someone must be prepared to ght should a predator nd you. You hold no illusions that you’d win, you’re too exhausted for that, and equipped with only a sharp rock and desperation. But the beasts you face now are not men. You need not win, only delay as your family escapes.

A twig snaps nearby, and the chemical your descendants will one day know as adrenaline oods through you, wiping away your exhaustion. Your pitiful human ears strain to locate the source.

Your eyes sweep from side to side for a moment before locking on two glowing spots low to the ground, a short distance away. Eyes, but not eyes belonging to any human. Human eyes don’t re ect relight like that. You rise slowly, gripping the sharp rock that is your only weapon, the only thing between you and the rending claws and teeth of whatever predator this is that has decided you smell supremely edible tonight. e moment seems to stretch for eternity, as your eyes remain xed on the monster in the dark. You dare not break its gaze, even as you sense another beast approach from behind. It pads so ly closer until it’s right beside you, so close you feel the brush of its shaggy fur. When its growl starts, it is felt much more than heard. A low vibration that could shame the smoking mountain far to the west. Without taking your eyes from those glowing specks, you know the beast’s lips have pulled back and bare fangs longer than some of your ngers.

You reach down and place your hand between its shoulders, the feel of its coarse hair washing away the fear those bright eyes brought. Now you have more than just a bit of sharp rock between you and the terrors of the night. You have a monster of your own. He stands beside you, rumbling like distant thunder, shoulders coming nearly to your waist, snarling a challenge into the darkness beyond the re. He will ght at your side, spend his life if need be, to protect his pack. His family. Your family.

Slowly the bright orbs fade into the darkness, deciding to try for an easier meal. e growls of your companion fade as well, but his eyes and ears remain vigilant, making sure the threat is truly gone before relaxing.

As you come down from the adrenaline, a vision ashes before your eyes. More beasts like yours, yet di erent. All di erent sizes, shapes, and colors. Some smaller than your hand, some bigger than you. Glossy and sleek, or shaggy like your friend. Red, brow, black, white, gray as a storm, and golden as the gun. Leading familiar bands of fur clad hunters through a forest, at the head of strange men searching through smoke and rubble. Si ing proud and tall next to kings on gilded thrones, and curled up next to an emaciated master in a stinking gu er. Ripping with sharp teeth

and razor claws at warriors during a bloody ba le, and healing with so fur and gentle licks on a crying child in a sterile room.

As the vision fades, you crouch next to your best friend and quietly thank him and all his kind for giving your family the simple gi of another day. For protecting your ancestors ten thousand years ago, and your descendants for twenty thousand years to come. For standing rm in the face of the howling dark, and howling right back.

Your hand moves to just behind his ears, and begins a ritual as old as the bond between your kind. He nally relaxes, and his tongue lolls out as he gently pants with contentment. You u er a few sounds which your distant descendants, could they hear them through the mists of time, would hardly recognize as a language at all. But their meaning is clear.

Good dog.

SECRETS IN THE TREES

James Pearl

It’s amazing how life puts us in spaces occupied by people who came before us. Yet we grapple with the same moral dilemmas from another space and time. It was the spring of nineteen seventy-six. My friend Mary, who was white, invited me to spend the day at Wakulla Springs State Park with her parents.

I’d heard the tales about what happened there in the late of night to the poor Black souls who ran into the swamp never to return to the broken-down cabins with rust-eaten tin roofs.

Si ing beneath old, lifeless cypress trees slumped over by the weight of the dead souls they carried. I ascend into something silent shocked by the jungle of oaks and palme os where Black men were chased in moonlight, caught and hung naked in one of the moss bearded trees.

A truth not spoken of buried in the depths of the springs. My eyes close as I see them running in the blackness of night because of lies told. Because they refused to be owned ever again. Risking death because in it they found freedom. ey ran to escape the hunter only to be betrayed by the moon.

My eyes opened to the stares as I sat with Mary and her parents. Eyes burned through my shoe-black skin with the hatred of their ancestors. A touch of my hand and a smile from Mary reminding me that we can ascend from the past with forgiveness, hope, and healing.

THE POWER OF THE PEN

L.T. Henning

A er the steel doors clang shut, you trudge down the shiny cement corridor with your state-issued clothing, in between two towering correctional o cers, to the tune of the clackety black-bulb, spi le-cleaned boots, harmonizing with the jinglejangle of the keys and cu s, while static from the radio drowns out your thoughts, as you trip over the silver jewelry on your ankles you know then, your goose is not only cooked, but it’s burnt. You’ve been buried so deep in the prison system that it will take an engineering crew with earth-movers and lidar topography scanners just to reach you deep within the con nes of a maximum-security penitentiary. e criminal justice system1, designed to convict and punish, uses the coarseness and abrasiveness of the prison uniform scraping against your raw esh as a gentle reminder of the might of the prosecutor’s pen.

1 e Public Defenders are placed under the purview or oversight of the Justice Department, whose purpose is to prosecute and convict. I was told by my own Public Defender that the state had no money for my defense. erefore, I would be denied DNA expert witnesses for one of the largest D.N.A. cases in the state’s history. e state would falsify the DNA report, with the help of the police (case documents available online).

Your procedural due process rights will be denied as o en as the ambitious prosecutor can conveniently do so. You turn your life over to an indi erent Public Defender, while the state hides exculpatory evidence and in zero to sixty, you accelerate down the highway to justice, careening out of control with a public defender at the wheel complaining about the low-pay only to crash and burn with a life sentence conviction. Your chance of overturning a life sentence is less than 2 percent. I had a death penalty trial, and jurors in such trials have been found to be more likely to convict than jurors in trials in which the death penalty isn’t an option.2 My a orney failed to defend me as he represented the state’s witness against me before trial, and my J & S (judgment & sentence) with a sentence of 73 years tells me I can be paroled when I turn 119 years-old, if I can a ord the parole costs. Heck, I could barely a ord to maintain myself in a cell, without heat or plumbing for the entire winter with temps hovering around zero degrees.

at’s the situation I found myself in almost 24 years ago. I knew next to nothing about criminal law. In college, I had taken one business law class, which was one more than the rest of the 600 inmates. Yet, everyone came to me for legal advice. I had a reputation to live up to, so I volunteered as the jailhouse lawyer, who would defend inmates at their disciplinary hearings to prevent them from being thrown into the dungeon or having street charges which would extend their stay.

In the pink jungle, or the women’s prison, most of the women’s disciplinary reports involved either drugs, tobacco, or sexual misconduct those reports reading like so porn. Over ten years, I had every major misconduct report either dismissed or lowered to “failure to follow published rules.” is was due in part to my writing skills. As the appeals process overturned major and sometimes minor reports, I learned how to organize my thoughts and arguments into a logical and compelling narrative. My pen became my newest and best friend. Among the inmates, my reputation grew, but so did the administration’s hostility towards me. I walked around “campus” with a bulls-eye target on my backside. Cells tossed, law books burned or destroyed, my hygiene

tossed in the trash during serious shake-downs, and worst of all, the potato chip bags and the prison currency, the ubiquitous ramen soups brutally crushed right before my eyes. I cried. But I continued to win in disciplinary proceedings despite the onerous and pe y prison o cials. Every book burned (waste disposal unit outside the prison) resulted in acquiring two more. I studied criminal law by ordering the free jailhouse lawyer’s manual3 given out by advocacy groups and o en by reading others’ legal pleadings, court opinions and decisions. Ordering every case in legal le ers, decrees, or memorandum opinions, including the “Order Denying Petition,” I began to see the logic and sometimes, even the beauty, of the American judicial system. It reminded me of being a kid: First you go to Dad. If you can’t nagle what you want from him, you go to a higher power Mom but if that doesn’t work, you address the Supreme Court of the Family Unit Gramma or Gramps. Eventually, you’d win if you had the patience to persevere, similar in concept to the judicial system.

At night, while prisoners played spades for big bucks ten ramen chili soups and the pods reeked of cannabis smoke (brought in by entrepreneurial o cers), I spent every evening reading U.S. Supreme Court decisions, like Strickland v. Washington and Cuyler v. Sullivan. I memorized every signi cant passage, writing it over and over again, in a green-colored composition book with dog-eared pages. I deconstructed the holdings, the dicta, and used a borrowed Black’s Law Dictionary to understand legal terms such as, “Motion for Summary Judgment,” “Dismissed without Prejudice,” and “Habeas Corpus.” I dreamt of the Sixth Amendment. e Due Process Clause. e Equal Protection Clause. I borrowed a Latin book from the prison library. I learned that a court could, of its own accord, sua sponte, take corrective action in criminal or civil rights cases. I read all night, each night, until the blood vessels in my eyes burst. A er dissecting no less than 3,000 cases, I understood how jurists think, beginning with the most commonly-used claim to overturn a criminal conviction, the “Ine ective Assistance of Counsel,” or simply, the “ine ectiveness” claim. Over time,

I mastered the subject ma er. e law, through the biological process of osmosis, seeped into the darkest recesses and lobes of my brain, illuminating the most salient arguments, and with the power of the pen, I had the knowledge now to write arguments in a compelling manner that would sway judges. e pen I wielded, so artfully during disciplinary proceedings, and a er years of arduous work, became the device to not only set me on the path to freedom, but others, wrongfully charged, or su ering under an illegal sentence.

In 2007, I began with the state courts, securing early releases for inmates based upon good, very good behavior, and personal achievements. e rst judge returned my motion, with suggestions as to how to succeed with early release motions. Six months later, he granted the request, allowing one woman to leave six months early. Chalking up successes over the years, I carved each one into my bunk, a permanent tribute to the power of the pen, a er I fed the feral cats in the yard. Night classes at the prison helped me relearn the art of creative writing. Learning how to cra a creative defense, not another formulaic murder mystery, became my focus.

My skills grew exponentially, until I easily defeated the two managing directors from the Law O ce of the Public Defender in arguments to the courts; the L.O.P.D. fought against the court appointing counsel to represent two inmates on their issues of competency and ine ectiveness. Pleased to see some of my e orts result in women walking out of prison thrilled to resume their lives, I continued to bring about changes in the local criminal justice system, as hundreds of other jail-house lawyers or prison advocates do daily, across America, in some of the worst, substandard housing and prison conditions, su ering, as I have, under racist and sexist management.

In the famous case of Gideon v. Wainwright, a jail-house lawyer’s power of the pen changed the Constitution. A semi-literate prisoner in the 1930s would scribble his objections about his onesided trial in Florida onto thin tissue paper, eventually reaching the United States Supreme Court Justices revolutionizing the criminal justice system in the process, ensuring that every indigent defendant be appointed defense counsel at their trial. Brick by brick, we dismantle injustice by the power of the pen.

MR. BOX

Larry N. Stromberg

A cool cat gliding with soul, Immense wisdom his demeanor, Loved grooving to a tune, Cherished every family member, never forge ing a name, Incarcerated severely by a condemning system, Never gave up the ght for freedom, Even with no light on the horizon, Faith and education his only escape, Diagnosed terminal with the cankerworm, Hospice in an in rmary prison cell, Praying for compassionate release, Forty-seven years in, denied on his deathbed, No mercy for a lifer with remorse in his heart, He nally made it home.

SOMEONE

William Peeples

Ebony Stone is awakened from sleep, ashbacks from the recurring nightmare invading her waking consciousness in strobe light-like images. As always, she sees the li le boy with a face like her’s: big light brown eyes, bu on nose, sandy red hair. Ebony frowns; that boy no longer exists. Why can’t she put her distant past to rest and live fully in the reality of now? She looks around in admiration of her tastefully decorated bedroom. e mahogany wood of the hand-carved headboard and matching nightstands cost her a mint, but the African wildlife motif spoke to her Afro-centric soul. Her gaze moves to the beautiful handwoven Afghan rug that Camille sent her while stationed in Afghanistan. Camille, her best friend since third grade, worked intelligence and interrogation but lost her faith in what America was doing in a country that hadn’t produced the majority of those blamed for the horrible a acks on 9-11. So when her tour was up, Camille quit, came home, and used what Uncle Sam had taught her to start her own anti-espionage company in

the corporate sector, making more money than some Fortune 500 CEOs.

As Ebony swings her legs out of bed, she stops to appreciate the two paintings on her bedroom wall, Impressionist-style works created by her multi-talented aunt Anne. Her eyes misted as she thought about how dearly she missed auntie, without whom she’d probably have died long ago. She mu ers to herself, “Yep, because of you I’m the woman I was destined to be. I wish you were here to see how far I’ve come.” ough she lives alone she is not lonesome, not looking for someone to make her feel complete, yet wanting someone to share her life with. Educated at the prestigious HBCU Spelman, she went on to get her Masters at Northwestern University in psychology. By all outward appearances, she is a smashing success. She is educated and owns her own therapy center bringing mental health and healing to underserved Black and Brown children in Chicago, as well as a lucrative consulting position at a high-end law rm. Ebony is beautiful, smart, and healthy. e one thing she lacks is someone to love and be loved by. She has done all the dating sites, even submi ed to blind dates set up by her close friends, with plenty of dating but no connection beyond physical a raction. ough she is stunningly gorgeous, standing at ve feet eight inches and 145 pounds with a Rubenesque gure, dark chocolate skin, and the visage of an African Goddess so exquisite it would make Aphrodite weep, she is not particular about looks. She has her own money and she is not a snob when it comes to how much education a man has, or even what he does for a living provided he is not a criminal. What a racts her is intelligence, a keen sense of humor, good grooming and hygiene, and spirituality. She can’t stand a man who doesn’t believe in something greater than himself.

She faces the full-length mirror with a gilt-edge frame. She purchased it for $50 at a thri shop in Bronzeville three years ago. She appraises her curvaceous form. A lifetime of tennis, skating, and yoga has toned and tightened her small waist, ample bosom and a bu , hips, and thighs that some women spend thousands of dollars to get. A smile its across her luscious lips, then she thinks, “You’re a hot girl, but who gets to enjoy the view except you?” Just then her cellphone plays her ringtone, Jodey Watley’s I’m lookin’

for a new love.

“Hello,” she answers.

“Hey boo, are you up yet?” her BFF Camille’s melodically resonant voice chimes.

“You know I don’t sleep past 4:30A.M., so tell me why you’re really calling,” Ebony replies.

“Well, I was online last night and I saw this website for men in prison seeking female pen pals. Now before you say no, listen to this ad and you’ll see why it piqued my interest. Here it says: ‘Could you be my someone? I don’t mean my girlfriend, but my soulmate. I’m not talking about romance. e best relationships germinate from a seed of friendship. I am a man drowning in a sea of testosterone in search of an estrogen refuge to engage in mental, emotional, and spiritual intercourse. e carnal satiation will come later a er we’ve achieved a higher love.’” Having nished her recitation of the ad, Camille asks, “Now, ain’t that some shit to stimulate your mind and your nether regions?”

Ebony had to admit that despite herself, she was intrigued. “First of all, why in God’s name were you, a happily married woman, on a damned prisoner’s pen pal site, and secondly, what makes you think I’m so hard up I’d even consider this man a potential mate?”

Camille laughs. “I’m happily married but I’m also insatiably curious. My sister’s coworker met her husband on this site two years ago, and I wanted to see what kind of man could compel a woman of her stature to ever consider writing to him. It’s also my mission to nd my homegal a man.”

Ebony chuckles. “ anks but no thanks, I don’t have time to dumpster dive for a man. I don’t do criminals.”

Camille sighs. “Girl, you don’t have to ‘do’ criminals to appreciate the guy who wrote this ad. Hell, if I wasn’t already boo’d up, I might check him out. You are alone with no real prospective mates, what could hurt to see what’s really to this guy? I’ll give you his information and pro le picture and you can decide from there, okay?”

Before Ebony can say “not okay,” Camille hangs up. Nonplussed, Ebony sets her phone down. While showering, she thinks to herself, “Camille’s ass is a trip! What could possibly

come from a prison romance except heartache and me possibly becoming his next victim?” As she gets out of the shower, her phone chimes. Sure enough, it’s Camille’s email. Curiosity compels her to open the le as she thinks, “What would it hurt to look, it’s not like I’m going to contact him.” e face of the author of the ad is not exceptionally handsome, he’s no Idris Elba or Denzel Washington, but he has the most soulful eyes Ebony has ever seen. ey almost seem to speak to one’s heart and soul on a non-verbal, visceral level. Before she has time to really think about it, she types a message to him and sends it. e reply is “Your contact info and message have been sent to the prisoner. ank you.” Ebony puts down the phone and gets ready for work.

e work day passes in a blur. She saw three of her patients, one a Latina girl who tried to hang herself a er her mother’s new husband and his son took turns raping her. en Ebony went to court and testi ed before a judge that a 13-year-old Black girl who set her stepbrother on re by drenching him in ngernail polish remover was su ering from PTSD from molestation by the stepbrother since she was 10. ank God she could put that one in the “win” column since the judge agreed, and instead of prison he sent her to Ebony’s in-patient treatment center until Ebony cleared her for release. Of course the prosecutor had a t, she wanted the girl to do hard time since the brother was burnt on 85% of his body. In the end Ebony convinced the judge the girl’s actions were not premeditated, but were the classic responses of a teenage girl victimized and made to feel she had no other way out of the abuse since neither the girl’s mother nor stepfather believed her when she told them what was happening.

Ebony returns home exhausted. On impulse she checks her emails as she soaks in the tub. She sees a message from Mr. Raheem Akbar. e message reads, “Greetings Goddess, thank you for this blessed opportunity to commune with you soul-to-soul, heart-to-heart. You said in your message that you’re a therapist which is kismet because I’m a student of the mind and trauma. I am an erudite scholar, not formally trained, but self-taught like Malcolm X. As you’ve no doubt gured out from my name, I am a Muslim, but more spiritual than religious. I believe there are many paths to God and that our purest form of worship is not the strict

observance of precepts and tenets, but our love, kindness, and compassion shown to the creatures of Allah whom we profess to serve. Tell me more about yourself, where did you go to school? Have you ever been married? What spiritual path do you follow? If you’re comfortable, I’d also like a photo of you, nothing racy, just a headshot will su ce. You can acquaint me with your body a er you’ve introduced me to your heart, mind, and spirit. Bye for now. Warmly, Raheem.”

Ebony had to admit that line about “acquainting him with her body a er she’d introduced him to her heart, mind, and spirit” really got to her. She’d heard from other women how men in prison could talk a sista out of her panties, not to mention her money, in a heartbeat! Guys in prison had li le or nothing to do all day but hone their tools of seduction, discovering what women wanted or needed to hear, and then regurgitating rhetoric they’d worked on and perfected. And yet, something about Raheem did not seem contrived or disingenuous. He came o as organic and sincere, like the words emanated from his very heart and soul. Laughing at her own naivete, she thought, “Girl, you don’ drank Kool-Aid. You literally just met this man, how could you possibly gauge his level of sincerity?” Still, in her heart, something told her Raheem Akbar was indeed a rare nd.

She woke up in a cold sweat at 2 A.M. e recurring night terror was the same. is time she got as far as seeing the boy’s lips smeared with lipstick, dressed in a sundress too big for him. en a booming voice and huge scarred hands pummeling the boy’s face, screaming, “I told you you ain’t no girl! You’re a boy and boys don’t wear lipstick and dresses. No boy of mine is gonna be a faggot, I’ll kill you dead before I let you shame me!” Ebony’s breathing is shallow and rapid, her hands ailing, trying to block the blows from the hands in her dream. She reminds herself, “ at boy died long ago and I buried that pain and loss, why can’t I just forget him?” Unable to go back to sleep, she reaches for her laptop and pulls up Raheem’s email. Reading it over and over again, she replies.

Two months later she and Raheem have been emailing 3-5 times a day. She is still not sure where this love a air is headed, but like a moth to the ame, she’s drawn to this man. She also has not

yet “introduced” Raheem to her body, but she has sent him plenty of headshots, some with makeup on, some with nothing except lip gloss. Raheem says he loves her face unadorned, as he puts it. Inevitably they’ve discussed her coming to visit him to spend oneon-one time together. is weekend she plans to y to New Jersey to see him for the rst time. ough Raheem has said nothing more about her body, she nevertheless wants to show him what “her momma gave her” and she’s nervous about what to wear, and how much to reveal. ey’ve “video visited” but this is their rst in-person date, so she wants this to be special.

Saturday morning, Ebony struts into the visiting room dressed to kill in an eggshell white sheer blouse with a matching camisole underneath, a turquoise ed skirt with a daring slit up the thigh, black shnet stockings, and black stile os. e visiting room o cer, a strikingly beautiful Latina with almond-shaped, almost jet-black eyes, burnished brown skin, and a symmetrical contoured mestiza face, catches Ebony’s a ention. e o cer points out the assigned table and asks her to take a seat. A minute later, Raheem strolls in wearing dark blue khakis and a light blue denim shirt. He isn’t overly muscular, but it’s clear he exercises daily. ey haven’t discussed how they’ll greet one another so she doesn’t know if they’ll hug, kiss cheeks, or shake hands. It feels perfectly natural when Raheem enfolds her in a loving embrace and kisses her painted lips. Despite there being no tongue, the kiss still sets her heart racing. When he releases her, he holds her at arm’s length and gazes into her eyes. He says, “I think I’ve fallen in love.”

e visit is less like a rst date and more like a continuation of a lifetime of intimate rendezvous. Raheem informs her that the visiting room o cer and him are friends so they’ll have the room to themselves. Because Ebony came from out of state, they have eight hours of visiting time that day and eight hours on Sunday before her ight back to Chicago. At one point Raheem takes her hand and pulls her into his lap. e o cer smiles and says nothing. She expects Raheem to try and feel her up, maybe even reach under her skirt. But he simply pulled her forward until her head rested on his shoulder, then he strokes her hair. At the end of the visit, Raheem holds her again and stares not at her, but into her. He kisses her cheeks, rst one side then the other, punctuating it with a kiss

on the lips. Not once did he grope or try to fondle her. She can’t believe how valued that made her feel. He whispers in her ear, “See you tomorrow, insh’Allah. at means if it be the will of ALLAH.”

at night in her hotel room she does not dream at all. For the rst time in 15 years, she does not wake up screaming.

e next morning at 9:30 A.M. sharp she sees Raheem being escorted into the visiting room. e same o cer sits at the desk, and this time she even greets Ebony with an hola.

Far too quickly the visit is almost over. Just like the day before, Raheem has made no sexual advances. She expected him to at least rub her legs, especially a er he remarked on how sexy they are. Instead he put her feet in his lap and massaged them for two hours. She hates to admit it but this is by far the best any man has ever treated her. Most men have an agenda, ge ing you naked and sexed as soon as possible. Fla ering compliments, romantic gestures, and a ne meal were all part of the strategy to get between a woman’s legs, and here this brother in jail had treated her not like a potential lay, but like a human being. Ebony looks Raheem in the eye and says, “I think I may be in love too.”

Within two years Raheem and Ebony are engaged. She has no clue how he pulled it o , but he managed to get her a 2.5-carat diamond engagement ring that t her perfectly. New Jersey law permits them to be married while he is still in custody, and though Ebony was willing to do that, Raheem insisted on waiting until his parole hearing in October. “See, honey bee, if they grant me parole we can have a December wedding,” he explains. She says, “I thought Muslims didn’t celebrate Christmas.” Raheem laughs. “We don’t, but if it’s good enough for Jesus (peace be upon him), surely it’s good enough for me to marry the woman of my dreams!”

Since the night of their rst visit, Ebony has been nightmarefree. She tells Camille about it and she says, “I guess Love does indeed conquer all.” She pauses before asking, “Have you told him about your dreams, about your past?” Ebony confesses that she has not. “I’m scared that if he knows my past he won’t want me anymore. For the rst time someone accepts me for who I am. I don’t want to lose that.” Camille does not judge nor condemn. She only says, “Baby, I know this is all you ever wanted but if you don’t

tell him, it’s not acceptance. It’s deceit.”

In her heart Ebony knows this is true, so she promises to tell Raheem at their upcoming visit.

Saturday morning Ebony wakes up in her New Jersey hotel room with her stomach in knots. Today is the day. She will not shy away from the truth. She dresses to impress. Raheem loves to see her legs, though to this day he still has never fondled or groped her. When she asked about his self-restraint he said, “Baby, I want to touch and explore every inch of your sacred frame, but I wanna do it as your husband in our bedroom, not our here in the open like you’re a cheap thrill.” e day he said that was the day she knew that if he asked, she would marry him without hesitation.

When Raheem walks into the visiting room, he greets the o cer. Ebony once asked Raheem what their history was, and he told her how three years ago the Latina o cer was running showers for the men in his cell block. ere were supposed to be two o cers, one male and one female. But her coworkers thought it would be funny to make her do it by herself. On his way to the shower, Raheem saw another convict grab O cer Laraza by her hair and drag her into his cell. In prison, the rst thing you learn is to mind your own business, but Raheem has sisters and loves the heck out of his momma so he couldn’t let this go down. He entered the cell and told the convict that Laraza was his, so if he wanted her then he’d have to ght Raheem. ough Raheem is Muslim and una liated with the prison gangs, he is known for his penchant for violence and revenge. e guy let O cer Laraza go and from that day on, she vowed to do anything to show her gratitude. He never had her bring him guns, drugs, or alcohol. Raheem only asked her for small favors that didn’t jeopardize her job or her freedom.

Raheem greets Ebony with his signature hug and kiss. Feeling the sti ness in her body he asks, “What’s wrong honey bee, ain’t you happy to see me?”

Ebony looks him in the eye. “Raheem, I’m happier than I’ve ever been in my life, but I have something to tell you. Something I should’ve told you a long time ago.”

He jokes, saying, “I think we be er sit down for this.”

Once seated she takes his hand. “ ere’s something about my past you need to know. Something that may change the way you see

me and think about me.”

Raheem squeezes her hand reassuringly. “Whatever happened in the past is behind us. I’ve done terrible things and you haven’t held them against me. I was 17 when my burglary turned into a home invasion, ending in the death of a precious human being. When I told you my past, you found a way to forgive me and love me. How could anything you’ve done be worse than murder? Whatever happened has nothing to do with our future.”

Ebony prays he means those words as she takes a deep breath and tells him. “I was born male, but I always always knew I was in the wrong body. When I was 7, I began trying to show people who I was. My mom sensed it all along, but my daddy was a man’s man and he beat me. He swore he’d ‘beat the faggot’ right out of me. I le home at 15 to live with my paternal aunt Anne. She was the only family member I had who accepted me. She found a doctor willing to give me the hormonal injections to begin my transition. At 17 I tried to cut my penis o and damn near bled to death. at’s when my aunt sent me to Europe to have my surgery. High school was a living hell. When my classmates found out, I got beat up. Once, a group of boys pretended to like me only to get me alone, gang rape me, and beat me almost to death. A er that I moved to a di erent school where I registered as female and had my name changed. Since then I’ve lived as a woman. I am a woman. I am not a gay male. I am a woman inside and out, I was just born in the wrong body.”

Raheem just sits and stares at her. Finally he says, “I’m not gay, I don’t like men.”

“Aren’t you listening? I’m not a man who likes men, I am a woman. I’m your woman if you still want me!”

Raheem looks away. “You should’ve told me this from day one. I can’t process this.” He stands and leaves the visiting room. Ebony screams his name but he doesn’t look back.

A year passes. Raheem called the engagement o so she mailed him the ring back. All of her emails have gone unanswered, and the one time she went to New Jersey to visit him she was told that she had been removed from Raheem’s visiting list.

e nightmares returned, the rejection she’s known all her life. Tonight she sits in her living room with beautiful teak furnishings,

expensive sectionals and a Lazyboy, complete with the latest audiovisual equipment. She watches Empire, trying to drink herself to sleep. e doorbell rings. She looks into the peephole and gasps. It’s Raheem, but how is he here? Why is he here? She knows he can’t see her, but nevertheless she feels his soulful eyes pierce her heart. Ebony opens the door.

“How did you get here?” she asks.

“I took the bus. It cost me all the money they gave me upon release.”

“But why are you here? You told me you couldn’t accept me.”

“I know what my stupid mouth said, Ebony. But my heart led me here to you, and where my heart is, is where the rest of me belongs. I don’t know how, but we’ll get through this together. I know two things without a doubt: one is that I love you with all that I am, and two is that I can’t see a life of happiness without you in it. If you’ll still have me, I want you to be my wife.”

With that Raheem kneels, ring in hand. “Ebony Stone, will you let me spend the rest of my life loving only you?”

Tears stream down her face. She says, “I can never give you children.” Raheem smiles, taking her into his arms. “ ere’s more to family than biology. Our children will be born of our love for one another. We’ll be a family of the heart and spirit.” at night Ebony sleeps in Raheem’s arms. She found her someone.

©2023/Abigail Cook

‘TWAS THE NIGHT BEFORE... Jeffery A.

Shockley

’Twas

e Night

Before Christmas

And all through the prisons

Not a prisoner was stirring

Just paying the price

For decades-old decisions

Some

Mended socks

Hung on makeshi

Clotheslines for those who’d dare

In hopes they’d dry in the nigh ime, Circulated, arti cial air e

Inmates were restless

Still locked in their beds

As visions of freedom

Did dance in their heads

Each In eir

Brown T-Shirts

And state-issued briefs

Some making promises, changing for keeps

While I, on the other hand, Unable to sleep

Sending another submission for PJP

When out on e the upper tier ere arose such a cla er I set down my tablet to see What was the ma er

e 10-6 shi Corrections O cer Unlively and thick

I thought for a second Is that St. Nick? While Most still Asleep throughout e compound

Just another day for many Here living in [prison] browns

On Corrections O cer, the occasional Sergeant to see Making sure the prisoners Secure in their keep Be er for all em not hearing a peep

Pepper spray and handcu s On the ready abound

In plain sight as the O cer’s Routinely Do their rounds

Along the top tier now Some changing their pace eir mind would wander

As the count they did take e count lights

Came on signaling the day

Excited in His Love

To my Lord I now pray Standing to our feet Many without a cheer I’m hoping others could be free Notwithstanding Being here.

I exclaimed in joy

As the guards changed their shi s Merry Christmas to all We’ve been given a gi Happy Birthday to Baby Jesus It doesn’t get any be er Nothing greater than this.

UNTITLED

Jakarri Jones

So now her emotions are running high and she is panicking because of what her future son had told her li le apa. So now in her head she is wondering, what now? Am I even good enough for him, what is he going to think about me? And in her head she thinks, am I crazy, I mean he is 31 and she is in her 40s. But she knows that he is the one. She knows that she wants to spend the rest of her life with this man. But she already told apa about the dreams and visions and apa said ok, sounds good, but he didn’t give her anything else a er that, so she doesn’t know how to feel or to keep pushing along with it. How was she supposed to compete with a 25-year-old woman? But li le apa said, if she doesn’t have him it will change the future. Secretly, apa is 31 but he likes older women. She doesn’t know that because they have only known each other for a few weeks. She felt a lot deeper in love with him than he felt and she knows it but didn’t want him to know. She made that secret doctor’s appointment without him knowing and while she was at

work, she started to think am I crazy because we never even fully had a talk if we are even together. Is he my boyfriend? Am I his girlfriend?

Everyone at her job knows she loves him to death but apa and her never had never talked about it. But everyone knew if you even bring up her apa, or talk about him around her, she would get emotional and defensive over him.

She thought, how do I stop the future from changing? Because she knows she’s in her 40s but she wants to be with this 31-year-old sexxxy handsome smart intelligent exquisite man with a beautiful forehead for the rest of her life. And for the past few weeks she has been watching him, the way he is, the way he acts with his kids, the way he calls his family the forehead family like the addams family.

But she loved it.

She wanted to be his queen of the family. She wanted to be a part of the family. If he would just give her a chance, she would never mess it up. She would be his addams family queen or his forehead queen even though she is older.

She had never been so sure or wanted something so much in her life. She didn’t judge her apa because he made a few mistakes and has been in prison. He’s di erent, like no man she has ever been around before. Her heart never felt this way ever in her life.

She thought, I really do love this man, how do I get him to see it or know it? en she thought, maybe I should get some advice from one of my friends.

So she explained all of it to her friend the next morning. It sounds crazy but I can’t help it, the heart wants what the heart wants. And her friend sees and understands and tells her, you’re in love, I can see it in your eyes. She said, what do I do? Her friend says, well. But before her friend got a chance to answer, her eyes light up and she says, I really want to be his forehead queen, his addams family queen.

AN INTERVIEW WITH AMERICAN BOOK AWARD RECIPIENTS, REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS & DR. RANDALL HORTON

Hosted by the incarcerated duo, The Mundo Press & Ghostwrite Mike

If you don’t already know who Be s and Horton are, Google them, and swim in the sma ering of keyword-thirsty descriptors about their dated transgressions commi ed before they became vaunted literary creators, accomplished academics, and dogged prison reform advocates. Be s did eight years in Virginia as a teenaged youth o ender, got out, graduated as an Honors Academy scholar from Prince George’s Community College, and applied to Howard University a prestigious HBCU while having had to check a box admi ing he’d been convicted of a felony. Howard never even acknowledged his application.

Horton served less than two years a er having dropped out of Howard as an undergrad, and upon his release he reapplied as a returning student. Howard rejected him on the basis of his felony record.

As incarcerated writers, journalists, and multimedia content creators, we neither support the prison abolition movement nor seek to defund the police; rather, we observe those particular philosophical nuclear wargames happening and admire the respective intellectual jousting between those opposing factions. We invited Be s and Horton to discuss with us the obstacles we’ve faced as incarcerated creators.

1. Mundo: Right now in California, you can’t even get a barber’s license with a felony, absent a Governor’s rehabilitation certi cation - the equivalent of a commutation/pardon action. So, when a youth o ender does every day of his term, completes the entirety of his parole, and has thereby literally paid his societal debt, if rehabilitation is the objective, shouldn’t his felony be wiped for the purposes of reintegration?

DB: We should have a far more robust use of the pardon power. We also need to eradicate some of these senseless collateral consequences. ough, maybe saying

collateral consequences is also a bit of a euphemism these are the consequences and we have to keep making the case that they are not legitimate.

RH: Yes, especially when we talk about paying this debt that is never repaid in the minds of those who only hear the word prison or felon. It becomes the anvil, that dead weight which many cannot and will not overcome.

2. Ghost: What role do you both think creative outlets like poetry, spoken word, narrative essay, podcasts, audio books, or hip-hop can play in the rehabilitative process of youth o enders?

DB: We all know that writing is that thing, the arts is that thing, that helps you know and understand not just yourself be er but the world be er. Art will turn an enemy into a friend far quicker than any slogan and it’ll reveal something as unexpected to you as a full moon to a two year old. You know them fat blood moons that seem so close that you can touch it? A kid sees that the rst time and it feels like a kind of magic. Books and art have been the only thing I’ve encountered that always carry that magic with it. In fact, I’m reading Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross’s new book Your Brain on Art where they elegantly make that case that art is essential to our lives and to our well-beings. Sadly it’s only in hardback now, but when the paperback it’s out, I got y’all some copies.

RH: A er installing our rst creative space at the Youth Detention Center in Birmingham, Alabama, the Director of the YDC revealed that our space is a haven where kids drop their masks shed that falsehood of what I like to call hardism that is so o en fatal for these young people. We have seen rsthand how art can transform a person’s moral compass, make them believe that rst, they are human beings, and secondly, if they can create, then they can do for themselves.

3. Mundo: Do either of you believe ‘prisoners’ are capable of creating media that can compete in retail as content that doesn’t at all associate with or relate to the prison experience?

DB: I’m not even sure how relevant I think that question is. Of course we can and some of us do. But I don’t think we’d want to push Milton not to write about religion. We’d not want to push Jonathan Franzen to abandon his exploration of that very particular frame of American life he gets at. We don’t o en choose our subjects, but even within the narrow constraints of prison as theme, in prison as subject, I nd there are still vast areas of substance I still lack the skill to get at. Whatever the case, I don’t think anyone should feel boxed into a particular topic,

but also don’t think they should be afraid of it.

RH: I think when we engage in this question we are engaging in perception versus reality, as in the stereotypes that are produced from being detained within the carceral state. I mean, you know, like I know, there are some very intelligent people on the inside, who read widely and can discourse with the best of them. I know I do. For context I did not write about that place they call prison in my rst two books, and only sparingly in my third. It was not until my memoirs that I delved more extensively into that space in my life. e reality of this is that the prisoner and the criminal justice system are envogue and organizations are ge ing funded to be associated with said population. is is something we at Radical Reversal encourage, allowing those on the inside to take control of what they create/produce while being able to learn from various art forms in a collaborative manner.

4. Mundo: What would you say to policy makers in California that have yet to say yes, haven’t enabled us, & read this interview?

DB: Truth be told, I think that the support is always just around the corner. at we show up and press and reconvene and gure out how to adjust our approach, that we constantly make the work we’re doing the only calling card we need. And then folks say yes, because they want to say yes at the end of the day. I have to believe that there are folks running and working within these facilities that want to see us ourish and ourish with us, in the same way that when I was sixteen and scrawny and in a state that wasn’t my home, I had to believe that there were cats around me that wanted to see me be somebody.

RH: I would tell them to read, even if you don’t understand read. e words, the language, what they mean in concert and the echoes will become clear over time. I promise. Recidivism is real. is is why I love Freedom Reads and the idea of beginning with access to books. As a Literary Ambassador to FR, I’ve seen what bringing those work-of-art bookcases to a facility can do.

THE MAGPIES AND THE WIND

Emilio Fernandeze gavel knocks on the front door

Guilty rings the rap of wood on wood

My dreams drop dead to the tiled oor

Satan smiles, obviously he would

Guilty rings the rap of wood on wood

Desperate to hold my mother near Satan smiles - of course the bastard would

As I sit drenched in my mother’s tears

Impossible to hold my mother near Razor wire fences keep her at bay

ere is no life in my mother’s tears

Only fake smiles and empty words to say Swamps and concrete keep my mother away

Daily wondering how long she will last ere are no smiles or words today

I decide not to put on my mask

Who knows how long she will last?

I ask the magpies and the wind

ey don’t mind me without my mask

ey don’t judge me again and again

I ask the magpies and the wind

Will I one day hold my mother free?

ey stare and squawk what’s on their mind

Yes, but we have no idea when that will be

Will I one day hold my mother free?

My dreams rise up o the oor

Yes, but will I still be me?

When the guard unlocks the heavy door

PRISON WORLD

Larry N. StrombergTrapped in the bars of my mind

Addiction has feasted on my soul

Obsession controlling my thoughts

A dark cloud hovers over me

I’m searching for the light

My prefrontal cortex on lockdown

Welcome to Prison World

I go a break free, plan my escape

Release myself from bondage

Riot my emotions

Next stop, Death row, if I don’t break the chains of oppression

Accept rehabilitation, embrace my recovery

Learn to forgive all, including myself

Accountability, responsibility my mo o of truth

A heart of remorse

Atonement lays at my feet

Freedom calls my name

PUBLIC SECRETS

Ben Wilkins

His blood geysered into the air, creating bright red pa erns on the oor like a Rorschach ink blot test. Four emergency response guards lumbered on scene screaming, “lockdown! lockdown!” with red dot tasers and mace canisters drawn before the victim was half carried, half dragged down a ight of stairs to a waiting stretcher.

During lunch in our overcrowded housing unit, the twentyyear old man had been clobbered by the vicious a ack. Fresh blood streaked the oor next to our lunch table. We inhaled the remainders of our meal. I commented to my tablemates, asking them if they thought we should have lost our appetites.

“I don’t see why we should. I mean it’s hotdog day, Bro. I could go for seconds.”

“Not our problem,” shrugged another.

Unfortunately, this was not an uncommon spectacle for a Friday a ernoon at Anchorage Correction Complex-West. Turn on the TV or scroll through social media and you’re not likely to nd another prison story as real as this. I was nearing my h

anniversary inside and a harsh new reality was se ing in. To survive in this crowded cage, we must learn to thoroughly suppress our feelings and emotions. Heaven forbid anyone would care to talk (let alone write) about expressing emotions. ey would be shunned as a pariah in all but the rarest emotional support situations. at’s another story. I wondered how bad the emotional desensitization would become. My favorite emoji has always been the winking smiley face. Will I have to change that too? Only time will tell, but for now: suppress and survive.

e three most ravaging concerns of Alaskan prisons are overcrowding, lack of rehabilitation, and sta shortage. is trifecta can push us to the breaking point causing us to become irritable, tense, paranoid or antisocial even violent. e clamor of an overcrowded prison incubates stress and violence. Case in point: the youngster described above took a weeklong eld trip to the ICU on taxpayer’s dollars.

Because of overcrowding the guard wouldn’t allow a routine cell change. e two combatants had both asked the unit guard for a cell change, “Before something bad happens,” they plead. e o cer’s reply was curt. “We’re too crowded, I’m not doing any cell moves period so try asking the next shi when they come on duty.”

Next shi was six hours away, the assault happened within an hour.

To be fair, many guards are more accommodating; they get it and don’t want to see excess violence any more than we do. One guard recently voiced his opinion:

“I don’t like it [overcrowding] any more than you guys do. It makes my days seem way longer and more stressful for sure.”

For once we agreed on something.

Due to tough new sentencing laws and guidelines, stories like this become common as droves of younger o enders are packed in tighter and tighter alongside seasoned convicts. For example, a misdemeanor facing a three-day sentence for his/her rst DUI o en may be placed in the same unit as an accused or convicted murderer.

“I didn’t realize how bad it is in jail,” a newb squawked to me a er he moved into our unit and was celled with two other men in a twelve-by- eight concrete box. His designated sleeping area is the cell oor where his head is barely two feet from the toilet that all

three cellmates share.

When the facility at ACC-West opened for business, every cell was single man, one bed per cell-by design. e larger units contained 24 cells and housed 24 men max capacity. e medium sized units had 18 cells, 18 men max. Fast forward forty years. Now those same units cram up to 60 men and 45 men respectively, making them burst at the seams with two and a half times the original capacity. is extreme overcrowding makes the guards’ job more than twice as di cult. When the sta stresses out, we feed o their negativity and repeat. It’s the circle of life, prison style.

e overcrowding is even worse in the adjacent ACC- East building. e herds still pra le like lost ca le as they roam the crowded pasture of con nement. However, the rec rooms are lined up with rows of boats. (A giant soap dish shaped piece of plastic that serves as a oor bunk) ese boats take up the space intended for prisoners to walk laps or exercise to burn o steam.

Traditionally, rec has been one of our only long standing “rights” and now it’s quietly being squelched. is sequestering fosters the development of frosty coping mechanisms. e extra tension then rubs o on the sta making them act mean and snappy. A rookie female o cer expressed concern.

“You can’t get away from the noise and the crazies they mix in here with you guys. It a ects everyone here and gets downright hostile, especially when we’re overcrowded,” she said with her brows raised.

e overcrowding tends to push us closer to mischief and further from self-improvement. Racial segregation, deception, and depressions grow rampant. ese are not the characteristics anybody would want a person to bring back into society. For be er or for worse, 99% of prisoners will return to the streets one day. Drug overdose deaths surpassed 100,000 for the rst time in U.S. history in 2021. Yet we have allowed Covid and budget cuts to e ectively kill rehabilitation. By canceling the much-needed drug abuse programs, classes, religious services, and visitations, we are set up to fail. It’s like stacking a row of dominos in front of a toddler and saying, “now don’t touch that!” ey get touched and the rows fall like fate against a busted poker hand.

Behind the scenes some cons cope by ge ing together to cook pruno (homemade prison wine) seeking relief from the mayhem of overcrowding one sip at a time. Imagine a weak merlot paired with a hint of moldy orange peel a whi of swirling sour apple and a fermented wine-cooler nish. at’s the smell of a cooking batch of pruno. In similar fashion, drug users band together and conspire ways to get a x. Others gamble or deal in black market “state” goods, smuggled food from the kitchen. It’s the economy unseen from people who tour prisons. When the big wig o cials walk through it’s a total dog & pony show. Clean up and act calm or get thrown in the hole for months on end that’s your two options. Even the guards don’t see much of the prison underground unless they stumble upon trouble or have a snitch bitch.

When men are con ned in a small cell there is no escape from one another’s presence. Whether you are reading, ahem…trying to write, cha ing, trying to relax, or using the toilet for a deuce, you are one with your cellies. us, escapism becomes a cold hard fact of prison life. Some nd temporary relief from the madness by accepting free pills at med line. ey shu e around like zombies while the latest experimental psychotropic drugs are tested on them. It’s a sad sight to behold for those of us who refuse that route of insanity. e nurses do a great job, taking studious notes on the zombies to be passed along to whichever doctor or big pharma company the facility is under contract with. e melee created by Covid’s peak astounded prisons worldwide, Alaska included. It must be noted that the nurses were overworked big time and held it down like champs as dozens, hundreds, then thousands tested positive throughout AKDOC. (Shout out to Nurse Sonya and C.O. Hodges! You two are awesome professionals!) Some sta was helpful and went out of their way to nd us cleaning supplies or request medical treatment. ey tried to help with countless other Covid related problems. Other sta was extremely unhelpful; I’ll avoid details here because it would likely keep this from seeing print. And so it goes.

Outside the cell isn’t much be er than inside. Long lines form for chow thrice daily, di o for med line. Now that’s to be expected,

but what’s not rational is how o en we are locked down 23-24 hours a day, multiple times per week.

“We’re on lockdown again today because we’re short sta ed, sorry guys I know it sucks,” the cool guards will say.

Same 23-24 hours a day lockdowns when Covid quarantine hits but those can last months on end. One hundred and six days straight was the worst stint I endured. e excess lockdowns create an energy of darkness as the ame of rehabilitative hope is snu ed out with a heavy pinch.

A er we’re nally released to our normal schedule, all those bo led-up lockdown frustrations resurface. Fights over the phones break out and potential violence can come from any number of perceived disrespects. For instance, someone was stabbed repeatedly with a toothbrush shank because he ate an apple that had been le out on a dayroom table.

Anyhow, it’s a shame the state has been cu ing anger management classes for years now. Evidently, we could really use them.

My friend Brian looked super stressed a er breakfast one morning, so I asked him, “What’s up man?”

He was a wreck because his Mom was dying from cancer at Alaska Native Medical Center and his visitation requests had all been denied. She had been sick a long time; doctors had recently given her six months, best case. His relationship with her was close and it was eating him up inside. He paused to swallow the lump in his throat, then spu ered.

“I don’t know what to do, this is bullshi*, how can they get away with being so heartless?”

His anguish was palpable as I struggled to console him. Normally (A) she would have been allowed to visit him at prison or (B) he could be approved for a one-time escorted “death bed visit of a direct family member”. Covid canceled any chance of her visiting him at prison. And the escorted visit option was denied by the higher ups in admin, citing, “we don’t have enough personnel at this time.” When she died four months later he became a bi er husk of a man. If that wasn’t bad enough, Brian didn’t even get to pay his nal respects to his Mother. His routine funeral visit was denied because of sta shortages and failed Covid protocols.

RIP indeed.

I’ve seen rsthand what prison overcrowding does to the psyche of the people who live and work here. Our prisons have the good side of bad, the bad side of good and everything inbetween. e public has a strong First Amendment right to know what really happens behind the barrier of prison walls. American prisoners don’t have much but they do have a constitutional right to shed light on these places which are famously secretive and inaccessible. Taxpayers are entitled to an accurate viewpoint of how our prisons are under-sta ed, overcrowded, and under rehabilitated. ey should also be allowed to hear the thoughts, feelings, and views of the men and women in those prisons.

Nearly 7,000 prisoners die in custody each year in the United States. Arguably, most violent a acks could have been avoided if overcrowding wasn’t so unrestrained. I’ve lost count of how much senseless violence I’ve seen. e medical costs alone add up to untold millions. is is a true story about a broken system and the real people who su er because of it. I am determined to let their voices be heard, by continuing to paint pictures with brushstrokes of perseverance. Best case scenario, I’m hopeful to open any proactive discussion to reconsider how we can together build a more equitable and humane society, both inside and out.

As many a great artist has said, “the paintings are up for individual interpretation.” How might you interpret this one?

Poetry AS A MATTER OF BLACK Marcus Jackson