Feeling Green, 2014 (detail below)

Cups

Chine-collé photogravure and etching on magnani pescia

After Bar Close, 2014

Video Still from Red Quantum inititiation, 2014

Dimensions variable

A Second Attempt at a Partial Taxonomy of the Irrational, 2015 Ink on polypropylene 17.5 x 22.25”

Pointing Eyes, 2015

this side up, (Pedro’s Flag), 2014 Oil

Glazed ceramics, metal bracket

8.5 x 40.5 x 6.5”

A bit of nostalgia, 2014 Installation

General view wooden structure

All that is left is this rock to sit on, 2014 Installation Islands for chilling and windows

A bit of nostalgia, 2014 Installation

Detail inside structure

A bit of nostalgia, 2014 Installation

General view wooden structure

All that is left is this rock to sit on, 2014 Installation Islands for chilling and windows

A bit of nostalgia, 2014 Installation

Detail inside structure

Open System (in progress), 2015

Dissect Facade

Cipher

Humanness

Aporia Gaze

Narrative

Woman

Grasp Layers

Resurrection

Missing

Quixotic

Zig Apostrophe Manifest

Lightness

Becoming Circle

Oops

Agency

Everything

Romanticism

Shelter

Time

Cell

Cristina Camacho (b. 1987, Bogotá, Colombia) earned a BFA in Design and Fine Arts from Universidad de los Andes. In 2010, she moved to New York where she studied at the School of Visual Arts, NYU, the Art Students League, and Parsons. She participated in the Summer Residency Program at SVA. Her work has been shown in Bogotá and New York.

Cuts. Layers. Weight. Gravity. Experiential. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic. Personal narratives. Musical illustrations. Deconstruction. Construction. Dissections. Textures. Asymmetry. Symmetry. Color. Form. Structures. Grids. Materiality. Body. Shadows. Space. Volume. Process based. Geometry. Light.

www.cristinacamacho.com

What do you intend when you layer and cut canvas? In my paintings, I reimagine the materiality of the canvas through the cut and the juxtaposed layers. I push its logic to transform it into three-dimensional anthropomorphic and zoomorphic entities, personal narratives, architectural spaces, and musical illustrations. Through the deconstruction and construction of the piece, I create structural and spatial changes, where gravity, shadows, and color re ections evoke a physical and tactile experience. Without planning or sketching, I paint, cut, and juxtapose layers of multicolored stretched canvases. The cut is a line, a drawing, while the canvas as the paint, is used to create the image. I dissect each layer as if it were skin, shaping it to reveal hidden secrets. The process is always evident; my tracks remain for the viewer to see.

The pieces are always intuitive and autobi-

ographical. All of them are informed by lived moments, people I know, and places I have been to. The passion for textiles that runs in the family, an extremely talented aunt who unconsciously taught me everything about color and painting, an old man who comes to life in etchings and drawings, a dictionary of imaginary places, a series of notebooks of doodles by my mother, the music my father listens to while appreciating a garden in the dark.

Contemporary painting is a vampire, feasting from bones torn o the corpse of history. I fear my paintings are only skeletons born as ghosts, equally of discontent and love -- I hate paintings that hide behind critical ambiguity, and yet I make them. The distance placed between ourselves and our world is poisonous, for me the antidote is deepened sincerity; painting animals.

Sam Cockrell, NYC, NY.title can be categorized. I give them names of Simpson’s episodes. I think I accidentally painted the same cat twice.

Please write about your work and what it means to you.

My art is not about nature, and barely about archiving. I see the archive as no longer rooted in Euclidian space, existing within an indeterminate seam between everyday life and a sort of pansophical, virtual [on-line] presence. How does ART t in there? Should I be addressing this shift didactically, or does simply producing work now Hegelian-ly worm these ideas into the work? Something I’ve been thinking about a lot recently is the (perhaps fraught) task of creating a body of images that is waiting to exist or be introduced into the Larger Body of All Images, which seems to be parallel to the ‘2015 archive.’ I started painting animals because I wanted to paint something that meant something -- I paint them now because I’m more interested in where and how they belong. Any collection of images under one

Kelsey Elverum grew up on an island north of Seattle. She received her BFA in Painting and Drawing from the University of Washington in 2009 and a Post-Baccalaureate Certi cate in Studio Art from Brandeis University in 2012. Her work combines printmaking, painting, drawing, sculpture, and installation.

www.kelseyelverum.com

What is your history?

I grew up on an island north of Seattle. My fragmented family lived above the water, 500 ft. up on the edge of a cli in a hidden forest. I watched eagles y and whales swim by my window. I hiked mountains and combed beaches. I tended gardens and gathered e s. From a child to adult, I hunted for fossils in sand and dirt and rain and sun. The moun-

tains and water and green are as much a part of me as esh and blood. It was seductive to reinvent the turbulence of people and events that surrounded this insular world.

Does this factor into your work?

My work is my history, nature’s history, excavation, my equal heritages of Norwegian and Filipino, mythology, recreation, fantasy, totemism...

And your colors re ect this?

My colors come exclusively from nature. So yes. The neon pinks, the hot blues, the deep lavenders...they are as readily found as browns and blacks. It is easy to dismiss them as unnatural and arti cial but I see the skin of frogs, scales of sh, the petals of owers, the green of trees against a grey sky. Natural. And very human.

John Ganz was born in New York in 1985. What does your work mean to you?

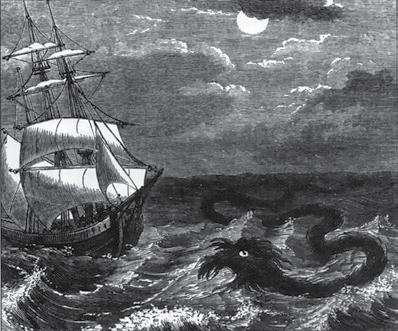

“I hate to be near the sea, and to hear it roaring and raging like a wild beast in its den. It puts me in mind of the everlasting e orts of the human mind, stru ling to be free, and ending just where it began.” — William Hazlitt, 1823

“There is something in being near the sea like the con nes of eternity. It is a new element, a pure abstraction. The mind loves to hover on that which is endless, and forever the same. People wonder at a steam boat, the invention of man, managed by man, that makes its liquid path like an iron railway through the sea--I wonder at the sea itself: that vast Leviathan rolled round the earth smiling in its sleep waked into fury fathomless boundless a huge world of water drops--Whence is it, whither goes it, is it of eternity or of nothing? Strange ponderous riddle that we can neither penetrate nor grasp in our comprehension ebbing and owing like human life and swallowing it up in thy remorseless womb,—what art thou? What is there in common between thy life and ours who gaze at thee? Blind deaf and old thou seest not hearest not understandest not neither do we understand who behold and listen to thee! Great as thou art, unconscious of thy greatness, unwieldy, enormous preposterous twin-birth of matter rest in thy dark unfathomed cave of mystery, mocking human pride and weakness. Still is it given to the mind of man to wonder at thee, to confess its ignorance, and to stand in awe of thy stupendous might and majesty and of its own being that can question thine. But a truce with re ections.” William

Hazlitt, 1826“Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down? Canst thou put an hook into his

nose? or bore his jaw through with a thorn?

Will he make many supplications unto thee? will he speak soft words unto thee?

Will he make a covenant with thee? wilt thou take him for a servant for ever?

Wilt thou play with him as with a bird? or wilt thou bind him for thy maidens?

Shall the companions make a banquet of him? shall they part him among the merchants?

Canst thou ll his skin with barbed irons? or his head with sh spears?

Lay thine hand upon him, remember the battle, do no more.

Behold, the hope of him is in vain: shall not one be cast down even at the sight of him?”

Job 41

Patrice Aphrodite Helmar (b. 1981 in Juneau, Alaska) is a photographer who lives and works in New York City. Patrice’s work is driven by a wearing your heart on your sleeve approach to life. Helmar’s photographs are currently on display at the Anchorage Museum, as part of the Alaska Biennial. In 2014, she was a nalist in the New York Photo Festival, and for the Gordon Parks Prize. In June 2015, Patrice will be showing at BOSI Contemporary in the Lower East Side.

www.patricehelmar.com

Instagram & Twitter: @patchop

How has cinema in uenced your work?

I’m in uenced by the work of Fellini, John Cassavetes, Tru aut, Les Blank, and others. One of the lms I remember watching with my family growing up was Fellini’s Amarcord. The title is a word from an Italian dialect, which means, “I remember.” The act of taking a photograph is in part an act of trying to recall - or making something last. Fellini’s casts and characters were often people who lived in his memories or subconscious.

I have faith in chance, fate, or maybe the better word is luck. If I go out in the world with a camera, my photographs are often better than anything I could ever construct. When I choose someone to photograph, they have something. I’ll notice them in the street, or on the train with this something. It’s almost like I recognize them, like they have a spark that I’m compelled by. I get a gut feeling, almost a heart sickness and I usually always go with it—even though it’s awkward.

Stephen Paul Jackson worked as a visual artist based in Alaska as Stron Softi, with solo exhibitions at the Alaska State Museum and the Anchorage Museum, and exhibiting in Zurich and Brussels, before pursuing his undergraduate education in New York. He obtained a BA in Art History and Visual Arts from Columbia University in 2013.

From land back, ground back, to background? We hold these.1 Evidently, there aren’t very many of us left, i testify, but who are we? Forensics.2 Sick of homesick, ingestion discourse3 we swallowed you. Who can consume who? Hello Indigenati4. Now.5 What? Looking Glass6 is rising. Red Quantum7 I hear you. My8 people, let us return our9 gift, we can share. You. You can put us on again.10 Bite us. But with love.

“When it kept on, kept on, kept on, kept on happening, [negotiators] went between them with their masterless atóow.”11

1 Je erson et al. in the Declaration of Independence, continues: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” King George. Outside brought the inside.

2 Vs. Testimony. Least of all Possible Evils. Weizman are we convinced?

3 Beyond assimilation policy.

4 To be determined.

5 What time is it?

6 Looking Glass, died in battle. Complicity. Not referring here to Glass “A Cannibal in the Archive” 2009, but I’d like to now. George Hunt awé.

7 Formerly Blood Quantum.

8 Possesive non exclusionary Property, beyond a Lockean proviso. A nity.

9 Sharing, Scaring? Eagle down.

10 Improved Order of Redmen. redmen.org, and Louis Henry Morgan. Wear us.

11 Anóoshi lingít aaní ká= Russians in Tlingit America: battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804 / edited by Nora Marks Dauenhauer, Richard Dauenhauer, and Lydia T. Black. (Sally Hopkins p. 361)

12 “This is not my story… That is why it’s like I know it … Yes, that’s how.” Anóoshi lingít aaní ká, (Alex Andrews p. 346)

“Tlél xát ax sh kalneegée yé … Ách áwé xwasikuwu yáx yatee … Aaá yéi.”12 We are preparing

Bora Kim is an interdisciplinary artist and sociologist from Seoul, Korea. Her process is based in cultural research revolving around the spectacle and performance of Asian femininity, particularly in the context of global media. Kim’s work addresses the public gaze and occupies the sphere of popular culture.

How did this project of yours begin?

I was interested in researching the phenomenon of the Korean Wave, and the commercial success of K-pop especially, on a global scale. It was almost an overnight explosion with PSY’s Gangnam Style, and the way that the Korean press and public dealt with this phenomenon intrigued me. I thought it was very important and poignant that, as a post-colonial country, Korea had successfully managed to export cultural goods to other Asian countries and soon after, “the West.” The Korean pop industry has always appropriated its concepts from the West, and also the West through Japan, until now, and the reverse of this cultural ow was a shock for the Korean public. “Idol Groups” became national heroes and K-pop became part of a proud national identity. But there is a double standard at play here. The criticisms that K-pop usually receives from the Korean public, that “it’s overrun by highly produced idol groups targeted towards teenagers; it’s too visually driven; it doesn’t have anything originally ‘Korean’ in its contents; or, it’s too commercial,” are precisely the reason why it gained such international popularity. K-pop had been looked down upon until outsiders started to consume it and its related products as well. The Korean government has found that for every $100 made in K-pop exports, there’s an increase of $400 pro t in Korean IT product sales, for example, things like mobile

phones. And in fact the bi est bene ciaries of the Korean Wave are companies like Samsung and LG. I was interested in K-pop and Idol Groups on this level initially as I was thinking about cultural ow, or the relationship of dominant culture and peripheral culture, and how that is interwoven with one’s identity or one’s national identity. I wanted to see what would happen if I made American boys into K-pop performers, by teaching them how to sing in Korean and act like Korean boys, and complicate this ow/appropriation even more, since I’m in New York, where so many talents are just one online recruitment ad away.

I needed a team that could help me, and I rst asked Karin, a friend whom I knew from my studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her focus was primarily photography, sculpture, fashion, and art criticism. I found Samantha through an artist friend. She studied Arts Administration at Maastricht University, Netherlands, and she was intrigued to help me execute this crazy project with her experience in arts administration, and knowledge of curating and cultural theory. Through the nature of the project though, our roles began to interconnect more, as it was just the three of us, and we began syncing more as a collaborative and creative team.

Why boy band? Tell me about your experience in this project.

It was somewhat determined from the beginning without discussion that we should make a boy band and not a girl group. We wanted to objectify the idea of boys or young males and take charge of the gaze towards them, through the perspective of three Asian females, even if that is a very arti cial setting and not how the real world operates. Sometimes it feels like we are playing with dolls, and sometimes we just have fun surrounded by six charming guys, but most of the time we are very stressed and annoyed by them and think our job description should be changed into babysitters.

I have with Sam and Karin after our sessions (which we document incessantly) with or without the boys. We talk about how masculinity is performed in such a di erent way according to class, race, ethnicity and culture, especially comparing America and Korea, and also Japan, Taiwan and Netherlands since Karin and Sam have lived in those countries.

Tell me more about your comment on masculinity being performed in a di erent way?

We were amazed how the concept of gender operates in K-pop boy bands. These boys are tailored to attract straight young females, originally, but the presentation of their sexuality is very complicated. A lot of people in the U.S., when encountering K-pop idol groups for the rst time, express their confusion about the gender role and sexuality that these boys convey. For example, a young group of pretty boys with great skin start rapping in a hip-hop music video while wearing a lot of make-up. What does this mean? Who is the target audience? It is totally gender-bending and experimental, but, at the same time, it is very typical, mainstream K-pop. And the acceptance of this strangeness (in the eyes of Western audiences) started to happen when Korean economic prosperity reached a point where it was enough for the entertainment industry to produce high-quality pop culture products. Cultural barriers or mistranslation are overcome by the shiny framing/packaging of pop. And that’s where I want this project to go in the long run. The bi est obstacle is funding, of course, but I do want to have the language of the commercial in order to convince people and to get people’s attention and start the dialogue on the politics of our cultures.

On a related note, we also wanted our project to examine what the fandom among young girls means, as well as among older women (over 40). Boy band fandom used to be the domain of

teenagers, but now the age group has expanded because the societal weight of Idol groups and their surrounding culture in Korean society is very substantial. And their taste in uences the production of the boy bands including their beauty. As a result, I think, these endless K-pop boy bands (according to Mnet TV Korea, there were 144 working idol groups in 2014) have created a new ideal type of Asian male in the global media, and of course that translates naturally to our daily lives and has an e ect on us in an actual and physical way. They are young and fresh, cute, “pretty” rather than handsome, gender ambiguous, non-threatening, humble, obedient (to their labels, managers or companies, as well as towards the fans), docile, hard-working, but at the same time very powerful, because they not only have the support from the Korean public and Korean Government, but they are also the main contributors and valuable assets to the whole Korean Wave, and consequently, the country’s economic surge. Maybe it’s too early to judge what this entails in terms of feminism or gender studies, since the industry de nitely deserves criticism in many ways, but I have to say boy band culture and the fandom surrounding it, plays a crucial role in creating a space in Korean society where it is safe and acceptable for females (both younger and older) to express sexual desires in public, and in general.

On a global level, Asian masculinity as a concept has been equated to being: feminine, weak, nerdy and asexual. K-pop boy bands still have those qualities, but because of the capital and the glamorization that is inherent to the commercial pop industry, all these characteristics become attractive and desirable. We wanted to experiment and play with this idea by teaching our boys how to act and embody what it means to act like K-pop boy bands. For example, we held something we called “Cuteness Workshop” and saw how they interpreted foreign cultural cues that interfered with their own ideas of masculinity.

Who are the team members behind IMMABB? Tell me about your experience in this project as well. Karin Kuroda: When Bora and I met at SAIC, we began a dialogue around femininity and Asian pop culture. Our perspectives seemed to align, clash, and intersect in a way that continued to present itself in my studies of postcolonial theory and pop culture (mainly tourism and fashion/photography). With this in mind, I originally came on board as a research consultant to the project to continue this realm of questioning. Between the three team members, this project manifests in many ways but ideally aims to utilize the form and material of “Boy Band” in a complex and subversive way. By analyzing the idea of intentionality in pop culture as well as in art, I think that we have managed to create and explore, while still remaining critical and rooted in our motives as artists.

The “I’m Making a Boy Band” project aims to examine critical aspects of pop/business culture through the lens of an artist. By asking oneself what it means to assimilate or twist the rudimentary formula in K-pop “idol” culture, this project highlights societal issues on a global and personal level.

As a team we are consistently forcing ourselves to analyze what K-pop looks like and how it materializes, while also comparing to see if we are living up to this standard. However, as the project goes on I’m nding it harder for myself to analyze whether or not we t that mold because we’re getting to know the boys a bit more. In knowing their idiosyncrasies, it becomes more di cult to have an objective/ industry view. This is what really forces us to wrestle with the act of irting with these ethical boundaries that exist within the K-pop industry. By doing so we continue to question what it means to then recreate them, produce them, and disseminate them into the world again. While our main aim is to consistently present the boys as intentional subjects, we often nd ourselves re ecting and questioning

our roles as team members, bosses, collaborators, Asian women, and ultimately global citizens and makers.

Samantha Shao: When Bora f irst mentioned the project to me, the rst thought that came into my mind is, “she is crazy,” and then I thought, what if we could really pull it o ? And that thought excited me. We talked a lot about the differences between Asian (Taiwanese and Korean particularly) and American pop culture, and how should we translate messages back and forth in both popular culture and ne art settings. I believe it is the ambiguity of this project that interested me the most.

IMMABB is a massive project, from both the production and conceptual perspectives. The process of making pop music is business-oriented, but the team tries not to allow the project to become a machine, as it is not entirely a part of the pop music industry. Yet, the structure of our working process is somewhat institutional. For example, my role among the IMMABB team is mostly related to administration and development, despite my title. We need that structure to make this project run smoothly, at the same time, we try even harder to protect its autonomy as an artwork.

By changing the working process (of making “art”), we intend to re-think and re-de ne what it means to communicate with the art world and its audience. Since the main character of this work is people - not only band members, but also collaborators - we try to challenge ourselves by giving up authorship from time to time. Just like Bora authorizes Karin and me to be deeply involved in her thesis project.

I consider contemporary art as more of a way of communication rather than an expression. I imagine IMMABB to be something that welcomes interactions, encourages questions and provokes confrontations. If an artwork is the outcome of making, our product is denitely not the outcome, but rather, everything that sits in-between our actions.

Karin Kuroda (School of the Art Institute of Chicago, BFA and BA in Visual and Critical Studies, Class of 2013) serves as editorial content manager on the IMMABB team and oversees the coordination of production, social media, theoretical research and critical analysis.

Samantha Y. Shao (Maastricht University, Netherlands, MA in Arts Management, Class of 2013) serves as the marketing and communications director on the IMMABB team. She oversees all budgeting, production, administrative and communications directives. ----

As a member of such a unique boy band setting, what do you guys think of this project, and how do you envision pop music could exist in the art world? (an excerpted conversation between the IMMABB team and EXP band members)

Frankie: I certainly believe that pop music can exist in the ne art world when it’s presented in that form. Today most music is released on the radio and on TV and very rarely, if ever, is it introduced in an art exhibition or museum. When you give the ne arts world a chance to look at pop music as a ne art, they can see it in a more literal art form.

David: I would place this project on movie screens around a museum. No sound needed.

Bora: Why no sound?

David: I want people to guess what we are doing and why we are doing it, and silence allows the people who are viewing us to use their own imagination and form their own opinion.

Koki: I like this project because we are not

Korean boys, it presents the contract of cultural di erences in a pleasing package.

Sime: It would be an interesting concept to non-Koreans because we are talking about Korean culture here, but not a lot of people understand it. For instance, when we talked to Yoahn (Han), he was saying there are so many small things that surprise people. It also must be interesting for you guys to see how we are taking up that culture.

Samantha: That is how di erent cultures communicate with each other.

Karin: Or don’t communicate with each other.

Hunter: Boy bands are so manufactured and machine-made. It would be very interesting to do what ‘N Sync had (that whole no strings attached thing), we have strings attached to us at certain points, and they show that a lot of these are forced or made, an idea of what should be.

Koki: Not only manufactured, boy bands are also imagining “a perfect version of male”, somehow we are like gurines. We should make a line of action gures. (Laughter)

Tarion: What if we are these gurines in the center that have strings attached to us, and when people come in there are these di erent buttons they could press, and we will learn 3 or 4 songs to do when they press the buttons. You know like Power Rangers when they all morph together, they become this huge machine, but they are di erent parts of that machine. So we are separate, but we come together.

Hunter: Or we could put six samples of our semen, and people need to taste them and guess which belongs to whom. (Laughter)

Bora: That could actually be a good art piece.

Yujin Lee works with video, drawing, and printmaking. She is interested in microhistorical narratives that revisit themes such as war, globalization, and collective identity. In 2012, Lee started a biannual curatorial project, the “Drawing Show,” where she invites emerging artists from around the world. She has also participated in collaborative projects with dancers, cinematographers, writers, and other visual artists. Lee was born in Korea, received her BFA from Cornell University, during which she studied abroad in Rome and Shanghai. She lived in Berlin for three years before moving to New York to pursue her MFA at Columbia University. Lee has exhibited throughout Europe, Korea, and the US.

What is the motivation of making work based on your autobiography?

I am a being. I am a human being. I am female human being. I am Asian female human being. I am Korean Asian female human being. I am South Korean Asian female human being. I am Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being. I am middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being. I am 29-years-old middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being. I am heterosexual 29-years-old middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being. I am educated heterosexual 29-years-old middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being.

middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being.

middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being. I am an artist American educated heterosexual 29-years-old

middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being.

middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being.

I am American educated heterosexual 29-years-old

I am cynical artist American educated heterosexual 29-years-old

middle-class Buddhist South Korean Asian female human being. I am shy stubborn cynical artist American educated heterosexual 29-years-old

I am stubborn cynical artist American educated heterosexual 29-years-old

Nicole Maloof (American, b. Seoul, S. Korea) received her BFA in Painting and BA in Chemistry from Boston University. Her work draws upon a diversity of interests—interests that also led her to pursue chemistry research at Harvard and a Fulbright teaching grant in South Korea. Her current practice includes drawing, animation, printmaking, and video as she layers narrative imagery with text, numbers, and science puns.

www.nicolemaloof.com

How do you use the body as a means of representing age, gender, race, etc.?

I am not looking to portray or point to particular demographics of people solely for the sake of representation. For instance, I do not draw female bodies simply to represent women. I am more interested in the cultural role/space that particular bodies have historically inhabited, and so drawing gives me the freedom to play with, mimic, or break these structures. I prefer to draw bodies en masse, where I can get into a mindset of storytelling that lies somewhere in between the individual and the a regate.

Why is drawing relevant to your work as your main medium?

Even though being in school has allowed me to expand my practice, drawing still remains central to how I approach and create images. Line gives me everything that I need: a direction, form, immediacy, and I nd it close to the gesture of writing. Drawing is so directly connected to how I think about the world that the act is almost compulsive. One word. Layers

“The visual field is not neutral to the question of race; it is itself a racial formation, an episteme, hegemonic and forceful.”

— Judith Butler, “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia,” in Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising, edited by Robert Gooding-Williams (New York: Routledge, 1993), 17.

“Up to the end of the sixteenth century, resemblance played a constructive role in the knowledge of Western culture.”

— Michel Foucault, The Order of Things, (New York: Random House, Inc., 1970), 17.

“The gap between overall structure and underlying components is the symptom of a lack of information: the elements are too numerous, their exact whereabouts are unknown, there exist too many hiatus in their trajectories, and the ways in which they intermingle has not been grasped.”

Bruno Latour, “Tarde’s idea of quantification,” in The Social After Gabriel Tarde, edited by Matei Candea (New York: Routledge, 2010), 146

Hi there, I’m Talia Link and I run a YouTube channel called Talia Link. From my Monica Lewinsky Nails DIY video, to the livestreamed performance Have You Ever Had Sex With Your Boss?, my channel is all about the con icted experience of being a woman in a capitalistic era of publicized privacy; It’s about being a feminist at a time in which Beyoncé sings about feminism while wearing almost nothing.

Come visit my bed without leaving your own bed at youtube.com/talialink

Why are you so fascinated with American pop culture? I’m all about the mainstream. And I like shiny stu .

Dana Lok’s paintings and drawings play with language, sequence, illusion, and material in compositions that tease out subtleties of pictorial perception. Dana grew up in Berwyn, PA, a suburb of Philadelphia, and currently lives and works in New York. She received her BFA from Carnegie Mellon University and attended the Vermont Studio Center in 2011. Dana’s work has been exhibited across the North East in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and New York City.

Tell me about the references you use in your work. I entered this program making primarily abstract paintings. I worked through a structure I called “Slow Frames,” which o ered you two sequential views of an abstract scene, like two frames lifted from an animation. Seeing a second view of the scene implies that even an abstract painting promises some other, continuous world inside its frame. When I began to very carefully let imagery seep into my work, it came from a source already essentially

temporal, constructed, and graphic: a cartoon.

The Fleischer Studios of the 1920s and 30s created a at world with rhythms that travel on the surface of the picture plane. People, animals, objects, and environment are made of one uni ed, rubbery substance. Everything in this world bounces with life, and everything has the potential to return your gaze. Betty Boop occupies a land at once sweetly inviting and menacing (1).

Disney, on the other hand, set out to achieve a high degree of naturalism. With the use of his patented “Multiplane Camera,” he attained a stunningly realistic illusion of three-dimensional space in his feature length animated lms, including Pinocchio, Bambi, and Sleeping Beauty (2). Traditionally, animations have two layers, one, a stationary background, and two, a series of overlaid transparent cels for animated elements. Instead, Disney created multi-layered backgrounds with several glass panels that could be manipulated individually to create the illusion of parallax as a camera panned across the scene: glass panels with foreground features moved faster, while the panels with the furthest elements of the background moved slowly (3).

I’m charmed by what great lengths Disney went to in order to make a shallow space look deep, but I’m drawn to use his work to tease out the strange threshold between the surface of an image and the deep space it depicts. In one scene of his Multiplane Camera Documentary, a background painter demonstrates how a painting is irritatingly flat by rotating the picture and showing you an oblique view of the panel (4). The rotation makes the atness explicit because you can no longer suspend your disbelief about what is on the other side of the forms in the picture- there’s no backside of the hand, far side of the tree, no bulk to the boulder. Our tacit assumption that we might be able to hop inside the scene and see the other side of the tree is undermined by the demonstration that there’s simply no more informa-

tion there. I’m fascinated by the prospect of distilling this demonstration and reinserting it into a painting. I have the power to slip new, unexpected information into the space where you assumed there might be the backside of a tree.

***

Depicting an image within an image is like nesting a story within a story. This structure is ripe with potential for meta- ctional interplay across levels of the painting.

Such meta- ctional, cross-level play is most succinctly and comically utilized in Wile E. Coyote’s classic gag of painting the continuation of the road on a canvas at the edge of a cli . In the collapsed and graphic world of the cartoon, for a few moments the road in the painting is a real road, and then, sure enough, Wile E. Coyote demonstrates the pesky atness and falsity of the scene by bursting through the canvas (5). It can’t be a historical coincidence that you could take a select a still from almost any Warner Brother’s Looney Tunes, frame it, and have showcased the same paradoxical play of signs and symbols de nitive of the best Magritte paintings (6).

Ioana Manolache investigates the possibility of materiality and illusion within a at plane through observation of found detritus. Ioana completed her BFA studies at The Cooper Union (2011). She was nominated for the Rema Hort Mann Foundation Artist Grant (2011, 2012), and has exhibited in New York City. She was awarded a residency at the Contemporary Artists Center at Woodside (2014) and recently curated a group exhibition

“Stirring Still” at the LeRoy Neiman Gallery at Columbia University. Her work was included in the publication of New American Paintings MFA Annual Edition (2015). Ioana was born and raised in Romania.

One word.

Resurrection, mundane, time, rectangle, place, spiritual, perception, history, sacri ce, materiality, realism, eld of vision.

How do you choose the objects you use as subject matter in your paintings?

The “sweet scent of freshly picked strawberries” is still faintly present on the weathered and discarded tree cardboard cutout. The tree’s fuzzy interior contrasts with its hard asphalt resting place, and yet, despite being completely contrasting solids, the two objects share a warm toned, gray color and visual density.

Little Trees is the name given to the car deodorizers in the stylized shape of an evergreen tree. Designed to camou age scent in a small, enclosed, and usually private space where one would expect company, Little Trees come in many shades, but just one shape.

The sense of smell is closely linked with memory, evoking powerful and vivid recollections more than any of our other senses. Trees are objects with the ability to transport one back in time to memorable conditions.

Color is the symbolizing agent for scent – red for wild cherry, yellow for lively lemon, blue for new car, and mint for bayside breeze. The shape of the Tree is an iconic symbol for ‘landscape’, while its color is indexical of a fruit or atmosphere, all while being cardboard. Perpetually complicating its content with its structure, a Little Tree is an object, a representation, and a material at all times. Similarly, a painting captivates both an individual and a collective, as it attempts to convey a view outside its own materiality and structure. A deodorizer attempts to camou age its space despite its physical shortcomings, and a painting can be understood to do the same to its viewers. Advertised as an “escape to another place” or o ering the chance of “bringing childhood to life,” this cardboard cutout is aspiring, but designed to fail. The illusion of ease, the illusion of cleanliness, and the promise of luxury are all resting within this object which is failing to meet its own illusion – that of a freshly picked strawberry, that of an evergreen tree, that of cardboard, and that of possibility.

What is your relationship with children’s drawings? It’s their stubborn simplicity and levity while dealing with something complex. Outer space, family, and animals are my favorite themes in children’s drawings. They are not afraid of not knowing. It may seem that they embrace this feeling. Not knowing does not weigh them down. Most importantly it’s their insistence that what they draw exists and is real. They believe it, an imagination that grounds gravity. I approach abstraction as creating something real that carries parts and pieces of the known, ambiguous parts that prompt to some recognition while giving them di erent rules of existence.

Which painters are in uences in your work?

There were few painters who created a world to which I felt so close to at certain times of my life. I was so fascinated by them; I would paint exactly like them. When I was 16 or 17 I would paint so similar to Georg Baselitz that you would not know the di erence. The same happened when I saw paintings of Antoni Tapies or the works of Pierre Alechinsky. You are always nding yourself through others.

Born in Levoča, Slovakia, Jakub Milčák currently lives in New York and Halifax, Nova Scotia. He devotes his time to painting, writing and illustrating books. He also translates American and British poetry into Slovak. In 2012, he established a small publishing house named Shift Fox Press.

“There is always…between words and the meaning of words, an area which is not to be penetrated…. the region of magic, the place of the priestly interpreter of nature, the man who identifies himself with all things and with all beings, and who suffers and exalts with all of these”

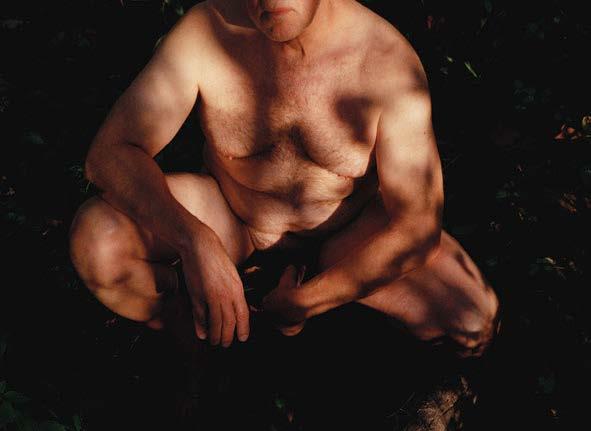

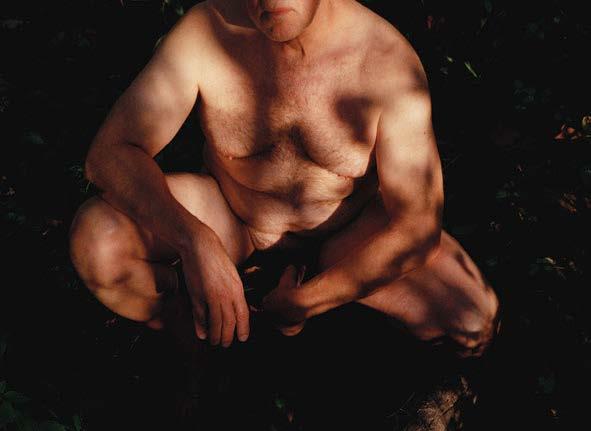

— Kenneth PatchenMatthew Morrocco is a photographer concerned with history, aging, sexuality, isolation, and intimacy. After graduating from New York University’s Gallatin School he was awarded a year-long fellowship with a blade of grass, an organization dedicated to artists working with social practice. He is the 2015 winner of Project Basho’s Onward Compé photography competition, chosen by Elinor Carucci. He has shown internationally in the United States and Germany.

How do you relate to the characters in your work?

The men I photograph become a part of my life the way any companion for a long journey might—Dante and Virgil, Don Quixote and Sancho, Huck Finn and Jim, Batman and Robin, Harry, Ron, and Hermione. It is not an instant connection but a long slow process involving mutual trust and a slight libidinous undercurrent. The project of my life balances tediously on the precipice between a Wildean sense of propriety and wit, and a Wojnarowiczian sense of vulgarity and frustration. I seek to express an emotional sensibility that is at once sexual in nature, expansive in dimension, and self-a rming in politics. It is this, the unapologetic narcissism, emotional vulnerability, and dynamic self-e acement that we, the people I photograph and myself, invite you, the viewer, to take part.

Early life: vines, sewers, soft pretzels.

Address transformation in your work

I’ve been known to enjoy answering a question with a question. Yet here a question hasn’t strictly been posed. A question-as-answer has the chance to be an answer. It can be and do many things. You look at me like: why did you answer my rhetorical question? And Gertrude Stein declares, “To me when a thing is really interesting it is when there is no question and no answer...” (Everybody’s Autobiography).

“At any moment when you are you you are you without the memory of yourself because if you remember yourself while you are you you are not for the purposes of creating you.”

– Gertrude Stein, “What Are Master-pieces and Why Are There So Few of Them” (1936)

“I’ll be down in a minute, I’m drinking a Snapple.”

– Lil’ Kim, “Revolution”, The Notorious Kim

short for Jean-Pierre Mot, is a Cambodian artist born in Montreal. An apostle and a stone make up my given name… I am a saintly sinner who could not cast away the rst rock without losing a part of my rst name. My surname, in French, means word… In the Ugaritic language, I am God of Death of the land of Canaan. As an omen, shades of darkness surround me much like a nameless crow. In La Fontaine’s tale’s, I lose to the trickery of the fox. As the village’s idiot my loving caw bedazzles the failure of an alchemist.

In your work, what is the link between mytholo and technolo ? MOT might be...

In Ugaritic, Mot is personi f ied as a god of death, who lives in a city named Hmry. His appetite is that of lions in the wilderness, like the longing of dolphins in the sea and he threatens to devour Baal himself a god of thunderstorms, fertility and agriculture, and the lord of Heaven.

The curse of Ba’al:

I, MOT the God of Death, have cursed Ba’aL; the God of Life. The mere Ba’al is spellbound to my laziness. At my dawn, it is ONLY after my glorious daily 10000 steps that the miscreant shall receive LIGHT... Until my dusk leading to my slumber!”

Recipe of the curse

Mandatory: One (1) Plant One (1) Home*

Recipe:

One (1) step counting device ($70)

One (1) smartphone ($500)

One (1) modem ($30)

One (1) smartswitch ($55)

One (1) UV lightbulb

One (1) home internet subscription ($30/ month)

One (1) cellphone service with data plan ($40/month)

Optional:

Two (2) running shoe ($50/pair)

One (1) god of death onesie ($20 after Halloween)

* Project presupposes access to a location with electricity available.

1 Con f igure the modem using the home internet

2 Con gure the stepcounting device to your smartphone

3 Con gure smartswitch to the modem

4 Con f igure the smartswitch to the smartphone

5 Install UV lightbulb over the plant and plug it into the smartswitch

6 Program the minimum steps necessary in order to receive a noti cation on your smartphone through your stepcounter

7 Select 10000 steps

8 Begin walking

If the UV bulb lights up after 10000 steps— congratulations... Welcome to the world of contemporary alchemy.

Every time I write the city that I was born in I have to think about the spelling.

www.ginaoconnor.com

Who are the people in your work?

I often paint strangers

how’s your mother?

I am drawn to people who spend a lot of time in one place

dry mouth

who sit in the same chair

wet eyes and are xed in a tight space

gentle hums percolating from wrinkled lips

I am lured to the accumulated weight of the domestic

tiny foreheads mashed against the window pane I experience their bodies through the painted body and its impressions

bowed ngernails tapping on woodgrain

pursuing crucial lines quivering television glow tracing and disputing the quotidian on rosé wine lips

I negotiate with the characters watch the weather oscillating between exclusion and a rmation sitting still I make su estions curling toes under the carpet moments of emergence repeat how’s your mother?

Faces and gestures from older work sometimes haunt and contaminate the new do you want to hear my story or not? resurrecting emotional content of the moments we shared

It’s all the same to me.

Ilaria Ortensi was born in Rome in 1982 and completed her BA in Cinema Studies there. She is a visual artist that mainly works with photography and sculpture. Her work has been exhibited in group shows throughout the US, London, Berlin and Italy. She currently lives in New York.

One word. Lightness.

What role does photography play in your work?

In my artistic practice I use photography and sculpture dialectically to create works of art with an open structure. While photography does claim a central role in my work, I constantly question its de nition and status as a medium.

Born and raised in Casazza, northern Italy. She received her BFA in Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice (IT) in 2010. She works with painting, drawing, and animation.

www.lorellapaleni.it

Why are you interested in the animal? It always surprises me when someone asks me that. “Why shouldn’t I?” I think. Why would anyone not be interested?

The question of the ‘animal’ is a question that has been met with indi erence throughout the course of human history, and not for nothing, since it is out of this ignorance that man has built a world, created truths, scales of values, categories, and priorities. The question of the ‘animal’ is the question of the Other, of Truth/Untruth, of what Human is. The other’s eyes, the other’s face, the other’s world. Not a generic other, nor a generic animal, but this speci c animal, this unique form of life and being. It’s an epistemological problem, it undermines society’s structure, hierarchies, and oppression systems; it questions the validity of language. Man is afraid of the ‘animal,’ rightly, because it is the animal that can shake the ground on which man’s castle is built.

“Man is not the center of animal life, just as earth is not the center of the universe. The human is but a momentary blip in a history and cosmology that remains fundamentally indifferent to this temporary eruption. What kind of new understanding of the humanities would it take to adequately map this decentering that places man back within the animal, within nature, and within a space and time that man does not regulate, understand, or control? What new kinds of science does this entail? And what new kinds of art?”

—Elizabeth Grosz, Becoming Undone

“…how miserable, how shadowy and fleeting, how aimless and arbitrary the human intellect appears in nature. There are eternities in which it did not exist, and when it has vanished once again, it will have left nothing in its wake. For the human intellect has no further task beyond human life. [...] If we could communicate with a mosquito, we would learn that it, too, flies through the air with this same pathos, feeling itself to be the moving center of the entire world.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche, On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense

Ruth Patir works with lm, performance/ action and writing.

Patir locates the hidden quality of subjectivities within the sharing and re-telling of stories.

She graduated from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design Jerusalem 2011 (BFA), and has been showing in various venues including The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA, 2014), The Petach Tikva Museum of Modern Art, Kav-16 community Gallery for contemporary Art (2012, 2013). Collaboratively, Patir has also founded and taken part in several art spaces including “Mazeh 9” and other participatory art spaces in Tel-Aviv-Yafo.

Please write about your work. In this new work, I engage the subject of cliché that surrounds dreams, reevaluate it, and place it in new focus. It began with a dream I had about President Barack Obama, a story I began retelling until the image of our meeting transformed from ction to fact. Realizing the power of this retelling, the work expanded into a documentary voyage, wearing many forms and concluded at a ceramicist’s wheel with a presidential look-a-like.

I took the role of the documentarist, capturing the evasive qualities of the dream narrative and celebrating the agency each dreamer possesses within her own story. In doing so, the work illustrates the dream as a site of political intervention.

Our sense of time is post-traumatic, suspended in the continuous present of dreams this work demonstrates the lack of ability to di erentiate between past, present, and future in both dream world and within our contemporary society. Its documentary character

emphasizes the hidden quality of subjectivities within the sharing and re-telling of stories.

Lauren Lawrence, the celebrity dream interpreter I work with writes in her book Dream Keys for the Future that even “the ordinary dream may be considered as a possible vehicle of prophecy.” Lawrence elaborates that the narrative of dreams can be a universal key connecting us with our unconscious by accessing an otherwise unreachable plane, realm of perception, or experience. It is from this unconscious realm that collective, universal remembrances emerge.

“Confronting scientific reasoning, the majority of paranormal experiences or phenomena, such as prophesy, clairvoyance, astral projection, and ESP, remain either unverifiable, inconsistent, or unexplainable – and at best, in the realm of the hypothetical. Prophetic dreams, however, in that they come packaged in narrative form, may for the most part be interpreted and understood in conventional psychoanalytic terms. But after everything is dreamt and discussed, even the ordinary dream may be considered as a possible vehicle of prophesy- a universal key that connects us with our unconscious by accessing an otherwise unreachable plane, realm of perception, or experience. For it is from this unconscious realm that collective, universal remembrances emerge.

Universal remembrance is very different from individual remembrance. To be sure, whereas an individual remembrance is concerned with one’s

exclusive, personal, private past preserved in unconsciousness, the universal remembrance is concerned with the Jungian collective unconscious: one’s shared, impersonal, world memory, in which lies the accretion of knowledge of past events. While it is certain that our unconscious contains the past, it is entirely a matter of conjecture whether it contains future as well. As a dream, and particularly the uncurious, in non linear, it has neither temporal knowledge of past or present nor knowledge of spatial boundaries, because there is no contrast or distinction of time. This characteristic allows the opposite sides of the spectrum, past and future, to chase each other’s tail such that the future appears in the past and the past appears in the future.

If time is no significant to the unconscious mind, why are prophetic dreams difficult to believe, understand, or accept?

If we can conceptualize Einstein’s view of the circularity of time, we can conceptualize an oxymoron: the previous future.“

b. 1986, Perth Amboy, NJ

sondraperry.com

mothermothermother.org

Expound upon your interest in video and new technologies.

Video artist Nam June Paik said, “Skin has become inadequate in interfacing with reality. Technology has become the body’s new membrane of existence.”

This may be true; though I’ve always thought of me and my ancestor’s bodies as technologically advanced.

----

“I am going through hard times. In the shadow of real recent converging, passing, pressing, milling, swarming, pulsing, changing in the country, formalized choreographic gestures seem trivial.

In recent performances I have allowed for elements to emerge that pertain to actual ways in which we engage with each other. But like any group we will lose our vitality if these ‘engagements’ remain on the level of fun and games.

I am not interested in group therapy as performance, but I am still interested in performance.

I experience a strong sense of risk when I think about what lies ahead. I never did before. My conditioning-with its powerful imperative of history, ambition, imagination, quality, and control - lurks ever in my peripheral vision.

— Yvonne Rainer “Information”, 1971, MoMA, Statement in the catalogue

Letters Editor

The New York Times Weekend Section

229 West 43rd St. New York, NY 10036

27 October 2001

To the Editor:

When I first saw Ken Johnson’s review of my New Museum retrospective last November 17, 2000 (“Art in Review: Adrian Piper”), the first thing I noticed was how similar in tone and tactics it was to many reviews of my Alternative Museum retrospective in 1987 and exhibitions I had immediately thereafter. That retrospective marked the beginning of my professional rehabilitation, after approximately fifteen years of obscurity following the art world’s discovery of my race and gender in the early 1970s. But in 1987 I enraged even more people than I had in 1972, and many of the reviews showed it. They had three features in common:

(1) rampant factual misrepresentation of my work and artistic motives,

(2) a hostile tone, and

(3) the use of these misrepresentations as an excuse for the hostility.

I made the decision at that time to communicate to the community of art critics that I would not tolerate rampant factual misrepresentation of my work. I replied in writing to each such review with a list of factual corrections and/ or factual assertions made by the critic for which no factual basis had been supplied. For about three years, I wrote a lot of letters. It was a very depressing and demoralizing task. But I felt it was important to try to set a minimum standard of respectful treatment of the work of African American women artists, below which no critical review would dare to sink. At the time I was the first and only African American woman artist given serious and sustained recognition by the mainstream art world. So I recognized the necessity of this task as part of the price of breaking new ground.

I thought that task had been long since completed. In recent years I have felt relatively secure that critical reviews of my work could be relied upon to get at least most of the facts right, whether the critic liked

my work or not. Even when I first saw Johnson’s review, I tried to dismiss it as an anomaly. Johnson had reviewed my work twice before (for Art in America), and had demonstrated the ability to write thoroughly and judiciously about it despite his evident personal antipathy toward it. I respected him for that, as a critic and an intellectual. So I tried to explain away his New York Times review as motivated by a bad mood, or perhaps an attempt to impress his new employer, and remained silent.

I now understand that Johnson’s review was not an isolated case, but part of an emerging pattern among some mainstream publications—the same pattern I fought against so hard over a decade ago. I now understand how little has changed, and that I will now have to fight this battle all over again. So in the remainder of this letter I am going to list the factual misrepresentations in Johnson’s review of my work (I enclose a copy for your recollection), and close with some comments as to their significance.

(1) I do not want to “make people behave better.”

(2) I do not work to “force” anyone into anything.

(3) I do not view “the system” as “pervasively racist, xenophobic and unjust.”

(4) I do not “more or less tacitly” take the “art-world audience to be white and liberal.”

(5) I do not presume the viewers of Cornered to be white.

(6) I do not make “attempts at psychological manipulation.”

enough in print – by me as well as by others – as to my actual beliefs, motives, and assumptions that Johnson has read. So he knows that (1) –(7) are false. What they add up to, however, is nevertheless coherent: a picture of me as trying to pressure and manipulate white viewers into shedding their racism, and of my work as a footnote to Barbara Kruger.

As usual in reviews of this sort, these distortions then serve as the foundation for Johnson’s overt antagonism – less toward my work than toward me personally. To Johnson, I am “hectoring;” “bitterly sarcastic;” “nothing if not intelligent;” “have the touch of a sledgehammer;” have “an off-putting, morally bullying tone;” and am “heavy-handed and calculating.” These characterizations, too, amount to a coherent and very familiar picture: that of an angry, overbearing, pushy, manipulative black woman.

Now since (1) – (7) are false, they do not provide any foundation for this familiar picture. So what we – or, I should say I – am left with is Johnson’s picture of me, and his obvious antagonism toward this picture of me (which I do not take personally because, like all racial stereotypes, it doesn’t have much to do with me).

— Adrian Piper(7) My Decide series, which includes How to Handle Black People: A Beginner’s Manual, is not a response to any work by Barbara Kruger.

All of these factual mistakes purport to report my beliefs, motives, and assumptions. There is

Julia Phillips was born and raised in Hamburg and is a citizen of Germany and the US. Phillips graduated with her Diploma at the Academy of Fine Arts Hamburg in 2012 and is the recipient of two DAAD scholarships and several grants including the Dean’s Travel Grant from Columbia University, School of the Arts. She has shown her work internationally, e.g. in Berlin, London, Vienna, Warsaw, Los Angeles and New York. Beyond her individual work, Phillips engages in collaborative publications, performances, panels and translates art-related texts from English to German.

www.juliaphillips.org

What is the overall intention behind your objects?

Omar, I am so glad you are asking me that. How great it would be to answer this question. I have a few thoughts that might give an impression of what could be an answer.

The idea for my tool-reminiscing objects starts with the title. It usually describes an interactive function and a character at once, like Bender or Regulator.

Acknowledging the nature of ceramics, the tools are not functional on a physical or mechanical level, but rather on an imaginary one. I intend for the objects to steer the imagination into a direction where ideas about desire and physical power dynamics might exist. Ideas that in the society that has shaped me seem to be located in a private mind space and seep into a public representation that I often nd to be normative, limited, and lled with misrepresentations and stereotypes.

The traces of the body in my objects, such as hand embossments, torso-casts, or footprints are an attempt to represent what is not shown,

leaving it open to viewers to complete the work in their mind and add their imagined representation of the body and the action that is missing to the work.

When I was about seven or eight years old, my mother Gwendolyn Phillips told me that I do not need to say everything: “You have your mind for a reason, use it for everything that does not need to be said or acted upon.” That was such a liberating thought. A space of existence was created for anything that did not have a language or a shape through which it could properly be expressed. And in that space di erent rules seem to apply, where facts, actions, images, and feelings live in another dimension, do not become manifested, and remain in a constant state of potential transformation.

The negative space in my objects is what I intend to be the site for the unsaid and unshaped. It is meant as an invitation for imaginations to meet, not knowing what the imaginations of others are.

Xiaoshi Vivian Vivian Qin (b. 1989) was born and bred in Guangzhou, China. She studied History and Art at the A liated High School of SCNU, Guangzhou, earned a BA in Communication Theories and Art in Denison University, Ohio. Her works were shown or presented in The Jewish Museum, New York (2014), HB Station of Times Museum, Guangzhou (2014), Wallach Art Gallery of Columbia University, New York (2014) and ROY G BIV, Columbus (2012). She received the Lotos Foundation Prize of 2014.

www.xiaoshiqin.com

IG:artbeastartbreast

Can you talk about your research?

Research for me means organizing and reorganizing things, making and breaking connections, looking and mostly looking away. I research a lot because I am very afraid to make art, or making art is making me very afraid, so I research all the time as a procrastination strategy. I think sleeping helps a lot with my research. When I am half asleep and half awake I always get strange ideas: for example, I heard a voice saying “past is present is future” once. I think it is because we are so addicted to information nowadays and don’t have time to process it. Only in between dreams does your brain start to work on the digestion. A part of my research is to predict the near future. For example, I would write about what will happen tomorrow, and write down again what had actually happened when the day has passed. But because you wrote it down before, it has already changed what will happen in the

future. If I wrote down “tomorrow I will get a mint- avor ice cream,” whether I get it or not it is still a response to the decision of the day before. So, where does future begin?

Write something about something.

THE EXISTENTIAL RISK OF MATHEMATICAL ERROR

Mathematical mistake or error-rates limit our understanding of rare risks (philosophy, transhumanism, statistics)

created: 20 Jul 2012; modified: 26 Feb 2015; status: draft; belief: likely

Angelica Teuta (1985) is a nomadic Colombian artist. She creates site-speci c installations that immerse the visitor in a ctional ambience that talks about the context or needs that she and her surroundings experience. Inspired by 19th century ghost imagery, she uses light projections, low-tech machines, recycled resources, and sound. In her current project, she started blending her surreal ambiences with new interests in architecture by designing spaces inside others and ambient rooms.

See also “Confidence levels inside and outside an argument”

Mathematical error has been rarely examined except as a possibility and motivating reason for research into formal methods; Gaifman 2004 claims.

An agent might even have beliefs that logically contradict each other. Mersenne believed that 267-1 is a prime number, which was proved false in 1903, cf. Bell (1951). [The factorization, discovered by Cole, is: 193,707,721 × 761,838,257,287.]…Now, there is no shortage of deductive errors and of false mathematical beliefs. Mersenne’s is one of the most known in a rich history of mathematical errors, involving very prominent figures (cf. De Millo et al. 1979, 269-270). The explosion in the number of mathematical publications and research reports has been accompanied by a similar explosion in erroneous claims; on the whole, errors are noted by small groups of experts in the area, and many go unheeded. There is nothing philosophically interesting that can be said about such failures.

- Gwern, http://www.gwern.netTeuta has shown large installation projects in the United States, Canada, Norway, Costa Rica, Brazil, and Colombia, and has been published in Artforum and ArtNexus . angelicateuta.com

What previous work triggers your current project? FROM DECORATION FOR CLAUSTROPHOBIC SPACES (2009– ) TO EMOTIONAL ARCHITECTURE (2013– ).

I used to put light windows in enclosed places. The windows showed b&w analogue moving landscapes that were made with paper cutouts, acetate layers, slow motors and computer fans on top of overhead projectors. The lack of land/scapes in living spaces radically a ects our emotions. With my projections, I have been creating outdoor environments inside for people to interact with. Nowadays, I’m more interested in building spaces or structures where people can also have a physical experience. These constructions are located inside other spaces in a symbiotic relationship. They provide a release situation from an issue that the host space was experiencing. I like to play with constructions in the same way kids build forts in their bedrooms in order to make spaces that better t their bodies and imaginations.

My art-pieces are contained within overarching projects that allow for the possibility of never ending. My research usually starts with the combination of leisure time, some travelling, and work and is guided by always being aware of the situation that my friends and I are living in. Then, I get more speci c into what things I can learn and produce on my own. Lately, I have been stimulated by nomadic architecture and furniture books, emergency constructions for surviving situations, DIY manuals, history about shelters and how people develop skills to make themselves at home.

The walls of my studio are full of images that I take from di erent resources, and from time to time, I pause my no-ending research and organize the puzzle. In my emotional architecture project, I’m focusing on studying “nostalgic” outdoors structures and the idea of making shelters. I am also concerned about the interior situation of each structure that I build, and I see how I can misplace other ideas in it. I am interested in how spaces a ect emotions and vice versa. The di erence with an architect or interior designer is that I do not aim for a result that solves immediate problems to society, but I am looking for visitors to develop thoughts about their memories and actual life, and hopefully they can bring or imitate some idea at home.

August Vollbrecht was born in 1988 in St. Charles, IL.

Drawing is intrinsic to painting. I do not make preparatory sketches. I draw within the works. I am a romantic. My paintings are resolved when the con ict between instinct and “institutionalism” reconcile in peace, no compromise. I repudiate all ideas of ground, depth, and form turning my back on formalism. Painting cannot escape painting but my romanticism leads to conclusion without script.

A mosquito lands on Hunters forearm. “Oh look at that little cutie!”

We burn our tattoos o with cigarettes.

Jonathan Bruce Williams invents photographic, retinal and perceptual systems that display enigmatic narratives, while attempting to collapse the history of archaic and emergent technologies. He received a BFA in Photography from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 2008, and has been awarded grants from the Minnesota State Arts Board and the Jerome Foundation. Recent projects include solo exhibitions for Franklin Art Works and the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts. jbw2149@columbia.edu, 651-246-8918, Instagram (@cellularcinema)

One word.

Cage. Cage is related to a set of ideas I have been working from, although to me the captivity implied by the word cage is broadened in its meaning by the word “cell.”

A cell can be a prison or the building block of life, a reproductive struct re that divides, multiplies, self or____ganizes. It cleans itself. Your exi stance is cellular, your body is a /

\cell, an amoeba under the microsco pe. This is your home, a monas____/

\____tic cell. It grows and then i t dies; dissolved and then tr/

/

\

\ansformed. Now it is turning into something else. This is/

\____/

\

\also alive. It will also di e. Now it is turning into so\

/mething else. It is made ou t of cells. It has metastisiz\____/

/

\____/ed, infecting everything aro und it, an invasion, unstoppa/

/

\

\ble. Soon it is mineralizing its own tissue, making image/

\____/

\

\in its own image, structure out of its own structure, in\

/telligence with its own int elligence, spreading into the\____/

/

\____/cosmos. It thinks that it is in control. It isn’t in control, a\

/tiny little cell, dividing, multi plying, self organizing. It isn’t g\____/od, but it thinks it is. Suddenly, it is, inspiring awe and amazement. Now it can build a path out of the cell.

There is no greater pleasure in my role as Dean than attending the thesis events for the four programs that comprise the School of the Arts—Visual Arts, Writing, Theatre, and Film.

The School of the Arts o ers our students the depth and breadth of Columbia University’s intellectual traditions, as well as access to New York City’s multifarious cultural events. We invite you to join us for a theatre production, lm screening, poetry, ction, creative non ction, theatrical reading, or a visual arts exhibition such as this—a spectacular showcase for our graduating MFA students working in all forms of visual production.

This year we are thrilled once again to partner with the Fisher Landau Center for Art as the venue for this exhibition. We are very grateful to the Center and to the Fisher Landau family for their generous support of our students and for sharing such a professional museum space with the graduating class of 2015.

The Thesis exhibition in Visual Arts is the culmination of two years of hard work. It is the moment at which the students (soon to be alumni) choose how to represent their creative time at the School of the Arts. 27 artists will graduate this month. Their work will be varied, unexpected, often profound, and full of exuberance. Friends, family, and the art world at large will turn out in multitudes for the opening and for the run of the exhibition to see what the next generation of artists is working on today.

We hope you too will visit the show as well as attend the varied events that will take place at this site in celebration. I know you will nd access to this new work exhilarating.

Carol Becker Dean of Faculty Columbia University School of the ArtsWhen I started collecting art 40 years ago, I never dreamt that it would lead to something as extraordinary as this! From the time I was a young girl I have always had a great interest in the arts—attending many art classes and considering myself quite the amateur. After I married Martin Fisher (a founding partner at the real estate rm Fisher Brothers), we were given the unique opportunity to meet some of the late 20th century’s most in uential artists, including Jasper Johns, Georgia O’Kee e, Mark Rothko, Ed Ruscha, Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, and many others. Of course, this was before they were as renowned and appreciated as they are today. Meeting them, discovering their work, and getting to know some as close friends was and always will be among the greatest thrills of my life. I collected their work early on, much of which is now displayed at the Fisher Landau Center for Art in Long Island City.

Getting to know these artists so early in their careers was very important. As a line in a movie I recently saw says: “One of the hardest things we will ever have to do in life is defend the new.” Young artists face a di cult situation: they must take concepts and methods of the past and combine them with emotions and perceptions of the present to create the art of the future.

The Fisher Landau Center for Art is proud to co-host Columbia University School of the Arts’ Visual Arts Program Thesis Exhibition. In many ways it feels as though this show brings home the ideals that made this Center possible. Much of the artwork in the Center’s permanent collection was purchased or commissioned while the now-renowned artists were in similar positions in their careers as these graduating students are today. As those masters did then, these students show a great deal of promise, ambition, and piercing originality. I encourage everyone to come see this show, to meet these artists as I did those years ago, and to enjoy some fantastic work.

Emily Fisher LandauOn behalf of the Visual Arts Program faculty and Dean Carol Becker, I would like to thank Emily Fisher Landau and the entire Fisher family for hosting the MFA Thesis Show for Columbia University School of the Arts for a sixth year. This gesture of generosity provides our graduating students with an amazing jumping o point for their future lives as artists. Twenty years ago Emily Fisher Landau showed an enviable prescience in choosing Long Island City for the home of her family’s remarkable collection of art. L.I.C. is now a vibrant art center with thriving non-pro t institutions, museums, and dozens of artists’ studios. It is very exciting to locate our thesis exhibition within this community. The gift of the three stunning oors of the center speaks to the special vision of the Fisher family and their commitment to supporting young artists poised to make substantive and imaginative contributions to world culture.

I would also like to thank Nicholas Arbatsky and the patient and dedicated sta , Matt Marello, David Walker, Dean MacGregor, and Monica Erausquin, for supporting this leviathan undertaking. We are thrilled to have enlisted the experienced curatorial sensibility of Ruba Katrib for this exhibition. In partnership with Nicholas, Ruba has worked tirelessly to satisfy the needs of 26 disparate artists, and more importantly, to create a show with a owing and vibrant choreography. I thank each of our supporters for the faith they have shown in the artists that pass through Columbia’s gates. Their help is essential in maintaining the vitality of our visual arts community.

We have an amazing and diverse faculty. Thanks to each of them. The sta and administration, both in our program and in the School of the Arts, make Visual Arts percolate and coordinated all aspects of this show. Thanks to Carrie Gundersdorf, Madelyn Sutton, Peter Clough, Rider Urena, Frank Heath, Anders Rydstedt, Ronnie Bass, and all our Visual Arts sta , who contributed long hours and focused judgment to this undertaking. Dean Carol Becker and Dean of Academic Administration Jana Wright have given the School of the Arts six years of visionary leadership and in a real sense, made possible the success

of this partnership. I wish to thank the architect of this project, Moss Cooper, and in turn Roberta Albert and Werner Orellana who spirited this adventure along from day to day.

My last words are reserved for the amazing artists in this MFA Thesis Exhibition. A walk through the show is clear evidence that these 26 areready for the next phase of their lives. Over this brief two-year period they have read, listened, argued, and learned; but most of all they have created, remaining steadfast in their commitment to their own practice. They have also formed a community—an interdisciplinary community—that includes the MFA classes ahead and behind them, and the full faculty. That community is the real treasure they take with them. This show will soon vanish but their bonds will never fade.

Shelly Silver Chair, Visual Arts Associate Professor of Visual Art Columbia University School of the ArtsThe Visual Arts Program attracts emerging artists of unusual promise from around the world. They comprise a vibrant community studying with an exceptional faculty at a renowned research institution in the global center that is New York City.

Contemporary art has become increasingly interdisciplinary. To that end, the Visual Arts Program o ers an MFA degree in Visual Arts rather than in speci c media. The two-year studio program, taught by internationally celebrated artists, allows students to pursue digital media, drawing, installation, painting, performance, photography, printmaking, sculpture, and video art.

arts.columbia.edu/visual-arts

Columbia University School of the Arts awards the Master of Fine Arts degree in Film, Theatre, Visual Arts and Writing and the Master of Arts degree in Film Studies; it also o ers an interdisciplinary program in Sound Arts. The School is a thriving, diverse community of artists from around the world with talent, vision and commitment. The faculty is composed of acclaimed and internationally renowned artists, lm and theatre directors, writers of poetry, ction and nonction, playwrights, producers, critics and scholars. Every year the School of the Arts presents exciting and innovative programs for the public including performances, exhibitions, screenings, symposia, a lm festival, and numerous lectures, readings, panel discussions and talks with artists, writers, critics and scholars. This year, the School marks the 50th Anniversary of its founding. For more information, visit arts.columbia.edu.

Omar López-Chahoud has been the Artistic Director and Curator of UNTITLED. since its founding in 2012 and will lead the curatorial team of UNTITLED. 2015. As an independent curator, López-Chahoud has curated and co-curated numerous exhibitions in the United States and internationally. Most recently, he curated the Nicaraguan Biennial in March 2014. López-Chahoud has participated in curatorial panel discussions at Artists’ Space, Art in General, MoMA PS1, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. He is currently a member of the Bronx Museum Acquisitions Committee. LópezChahoud earned MFAs from Yale University School of Art and the Royal Academy of Art in London.