PAOLI, Wis. – When Tom and Vicki Sarbacker were approached about being a part of the effort to turn their former milk plant into a lavish hotel, restaurant, café and creamery, they greeted the idea with a bit of skepticism. A proposal that sounded too good to be true at rst, these dairy farmers came to realize it was an opportunity too good to pass up.

Tucked into the quiet town of Paoli, about 15 miles southwest of Madison, Seven Acre Dairy Company is a new one-ofa-kind dairy destination. Here, guests are treated to a delicious escape that puts dairy on a pedestal. Seven Acre Dairy Company is devoted to providing exceptional dining and lodging within the walls of what once was a cheese factory and the building to which generations of Sarbackers shipped their milk. Now, the Sarbackers are helping feed Seven Acre Dairy Company’s customers by supplying both milk and meat to their neighbor across the eld.

“Our milk came here until 1980 when it was Pabst Farms, and now our milk is coming here

once again to make ice cream,” Tom said. “It’s nice to see it come full circle. This is pretty cool.”

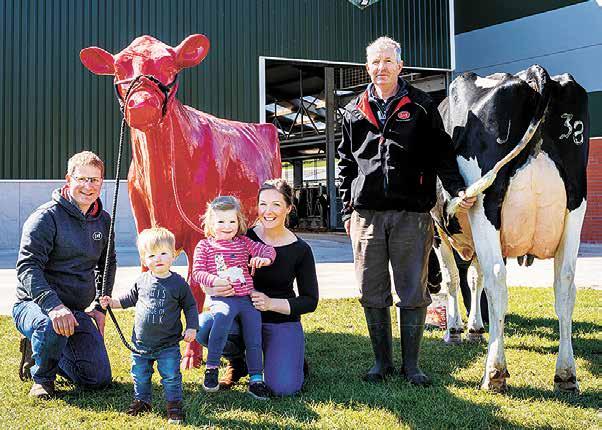

The Sarbackers own and operate Fischerdale Farm near Paoli where they milk 65 cows and farm 180 acres with their son, Joe, and his wife, Sarah. Specializing in registered Holstein genetics, the Sarbackers’ barn is home to 24 Excellent cows and a herd BAA of 110.4. High type and high production are what the family strives for.

“Our herd is mostly homebred, and we’ve taken pride in that,” Joe said.

The farm, which is visible from Seven Acre Dairy Company, was purchased by Tom’s father in 1983. Joe’s and Sarah’s daughters – Payton, Braelyn and Reagan – represent the fth generation at Fischerdale. Sarah also holds a full-time job off the farm as a wedding planner for the business she started with a friend in 2010.

Milk from Fischerdale Farm is the key ingredient in Seven Acre Dairy Company’s soft serve ice cream served in the Dairy Café. Three milkings’ worth, or 6,300 pounds, of milk per week are sent to Seven Acre Dairy Company. Andy Ziegler, one of the partners in the project,

perfected the ice cream recipe at the Center for Dairy Research at the University of WisconsinMadison.

“We knew we wanted to make ice cream from the beginning, but we weren’t sure how,” Ziegler said. “It was important to get local milk and take that milk from the cow and put it into ice cream without much adulteration.”

Soft serve ice cream proved to be the perfect choice.

“Everyone has memories

of eating soft serve ice cream as a kid, and ours is premium soft serve unlike anything else,” Ziegler said. “The milk goes straight into the ice cream with no subtractions or additions of fats, but we do add milk solids.”

Ziegler said ice cream is one of the cornerstones of the business, which will lead to the development of more products.

For example, Ziegler has started doing research on novelty treats.

“We’re so excited to be able to see the farm where our

milk and meat comes from and share that with our customers,” Ziegler said.

The Sarbacker family provides beef to Seven Acre Dairy Company that comes from older, mature dairy cows. The meat is referred to as pasture prime.

“It’s so tender you don’t need a knife,” Tom said.

Joe agreed.

Martin,

“Study the breeding of STELLAR, and see that Triple-Hil Sires is making available a truly rare young sire.”

--Doug Martin, Pleasant Valley Jerseys

able a rare g

“We’ve had a lot of rave reviews about the food,” he said. “The meat is fresh; it’s never frozen.

We’re doing veal too. We thought the milk was great, but it led into doing beef and veal options as well.”

Seven Acre Dairy Company also gets beef from another local dairy farm and other types of livestock meat from farms in the area.

“We’re getting paid a premium for our milk and meat, and that helps us nancially,” Tom said. “I don’t know if all of our milk will ever go to Seven Acre, but it’s a possibility. As more time goes on, I think the ceiling is very high in what they’ll be getting from us. We’re not owners, but we’re feeling pretty involved.”

Nic Mink and Danika Laine are the founders and visionaries of Seven Acre Dairy Company, which they own along with several other investors.

“Nic and Danika are very excited about the building’s story and our farm, and it snowballed from there,” Sarah said. “It’s rare to nd someone who is both business savvy and excited about the dairy industry. That’s the magic in all of this.”

Built in 1888, the 21,000-square-foot building that houses Seven Acre Dairy Company is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Award-winning Swiss cheese and sweet cream butter were made there until the factory closed its doors in 1980. In 2021, a group of local entrepreneurs purchased the factory to preserve a special piece of Wisconsin’s history located steps from the Sugar River.

Keeping the factory’s historic architecture alive, modern amenities are coupled with gentle reminders of yes-

terday at every turn. The concrete oors once traversed on while making butter and cheese more than a century ago are the same oors Seven Acre Dairy Company’s customers stroll upon today. In the restaurant, outlines of where the Swiss cheese tanks once stood serve as visible indicators of the building’s factory days.

“They didn’t take everything away from this place,” Tom said. “I never thought it would be like this. They’re keeping a lot of the old characteristics.”

Vicki agreed.

“So much in here is original; you know you’re in an old creamery,” she said. “It’s beyond our expectations.”

The building’s character and rustic charm lure locals and out-of-towners to immerse in a dairy experience like no other. The Dairy Café – a casual spot for breakfast or lunch – was the rst portion to open in mid-December 2022. The hotel, known as The Inn, followed close behind, welcoming its rst guests Dec. 27. In February, Seven Acre Dairy Company’s upscale restaurant and bar – The Kitchen – will also open for business serving farm-fresh entrees. Much of the food is locally sourced.

The Dairy Café serves specialty sandwiches, soup, coffee, pastries and soft-serve ice cream. The café is open Monday through Friday from 6:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. and also carries merchandise, including apparel, dry goods and artwork.

The boutique hotel features eight rooms, each noted by a special name honoring the past – such as the Milk Haulers Suite, Creamery Room, Swiss

Room and Pabst Room. Black and white canvas prints of the Sarbacker farm and family line one wall of the hotel lobby, and a chandelier made out of glass milk bottles hangs above the front desk. To the Sarbackers’ delight, guests arrive to their room to nd a pitcher of milk and two cookies to enjoy.

“It’s awesome how much they put dairy on the forefront here,” Sarah said. “Dairy is a top priority at Seven Acre.”

Artisan butter is made at the on-site micro-dairy, making Seven Acre Dairy Company one of the few sites in Wisconsin to produce dairy products in three separate centuries. Viewing windows allow visitors to watch the process. Blocks

of butter are available for purchase in the Dairy Café, and the butter will also be used in the restaurant.

The Sarbacker family’s roots run deep in Paoli. Lifetime residents of the area, Tom’s connection to the town’s cheese factory began when he was a boy. Growing up on a farm on the opposite side of Seven Acre Dairy Company from where he currently farms, Tom remembers riding his bike to the factory to buy butter. He used to mow the lawn at the cheese factory and some of his siblings worked there.

“This is super exciting for the farm and its legacy,” Sarah said. “Seven Acre Dairy Company is capturing the nostal-

gia of Fischerdale Farm combined with the nostalgia of ice cream and creating an experience everyone can enjoy. The two businesses are lifting each other up.”

A trail will soon connect Seven Acre Dairy Company to Fischerdale Farm. The Sarbackers plan to give tours to anyone interested in learning more about the farm. Sharing their dairy is nothing new to the family as Vicki has been doing tours for second graders for 35 years.

“Many people don’t know where their food comes from; they don’t know about agriculture,” Tom said. “Everyone at Seven Acre is fully on board with building relationships with the consumer

and explaining and showing them where food originates. This is an opportunity to educate.”

By turning something old into something new and full of promise, Seven Acre Dairy Company is giving a boost to the local economy and expanding the reach of the dairy industry.

“When I think about our small family farm that my grandpa started, it’s hard to believe anything could make you feel as proud as that, but Seven Acre does,” Joe said. “This is where I’ve lived all my life. We love Paoli and giving back to the community that has given so much to us We’re lucky to have this opportunity.”

Reiser Implement, Inc. Waukon • 563-568-4526

SOUTH DAKOTA

Bobcat of Brookings, Inc. Brookings • 605-697-5544

Pfeifer’s Implement Co. Sioux Falls • 605-338-6351

Fergus Falls • 218-739-4505

Farm-Rite Equipment, Inc. Dassel • 320-275-2737

Farm-Rite Equipment, Inc. Long Prairie • 320-732-3715

Things look a little better globally. The second Global Dairy Trade event of 2023 saw its weighted average slip just 0.1% following a 2.8% drop Jan. 3 and 3.8% Dec. 20, 2022. Traders brought 70.3 million pounds of product to market, down from the 73.8 million Dec. 20. The average metric ton price inched up to $3,393, up from $3,365 Jan. 3.

Cheddar buoyed the market, up 4%, after falling 2.7% Jan. 3. Whole milk powder inched 0.1% higher, after falling 1.4% last time. Skim milk powder was down 0.3%, after dropping 4.3%. Anhydrous milk fat led the declines, down 0.9%, following a 5.1% drop, and butter was off 0.6%, after dropping 2.8%.

StoneX Dairy Group said the GDT 80% butterfat butter price equates to $1.9687 per pound, down 1.4 cents, after losing 5.5 cents last time, and compares to CME butter which closed Friday at $2.3225. GDT cheddar, at $2.2097, was up 8.2 cents, and compares to Friday’s CME block cheddar at $1.8350. GDT skim milk powder averaged $1.2891 per pound, up from $1.2874, and whole milk powder averaged $1.4598 per pound, up from $1.4552. CME Grade A nonfat dry milk closed Friday at $1.1750 per pound.

Buyers in North Asia, which includes China, were less engaged in this event, according to Dustin Winston, as volume purchased fell from both the last event and last year. South East Asia, the Middle East and South/Central America were the only regions whose purchases exceeded year-ago levels.

HighGround Dairy said unless there’s massive buying from China post-Lunar New Year, it believes that whole milk powder remains in a quiet state with little volatility ahead. The current freight differential between the U.S. and EU makes European-sourced skim milk powder more attractive, and buyers of U.S. product remain in wait-and-see mode. China’s butter volume dropped to its lowest levels in three months and the contract two price is at lows not seen since July 2021.

StoneX said for now, the expected rebound in demand from China is somewhat more satised by strong domestic production rather than their usual thirst for external sourced product. It is still largely cheaper to import dairy, but it doesn’t advance their agenda. While domestic milk production is strong in

China, domestic demand suffers from COVID-19. And protein margins are weaker heading into 2023.

Chinese imports in December 2022 were actually much better than expected, according to StoneX, up 14.5% from last year. Exports out of the major exporters to China were down 30% during November. Since most of that product lands in China during December, we were expecting Chinese imports to be down at least 20%. But comparing this December-January to previous December-January periods is tricky.

China has a free trade agreement with New Zealand that allows a limited amount of dairy products into China at a reduced tariff rate on a rst-come basis. So in the past we’ve seen New Zealand shipments to China surge in November and December, but then sit in customs and not clear through until January to take advantage of the reduced tariff. However, the volume of product eligible for this reduced tariff is reportedly zero in 2023, which means there is no incentive to clear the product through customs in January versus December, said StoneX.

Chinese importers didn’t sit on product in December like they have in the past, they just pulled it all through customs. That is how we end up with exports to China down 30% and ofcial Chinese imports up 14.5%, or at least we think that is what is going on here. If we’re right, January imports could be down 30%-40% from last year since a lot of product cleared in December and wasn’t held over into January, StoneX said.

One more bit of GDT news; Charlie Hyland has been appointed as independent chair of the GDT Board of Directors, effective Feb. 1. Hyland is head of Europe, Middle East and Asia dairy and food at StoneX.

U.S. dairy exports continue via the Cooperatives Working Together program. Member cooperatives accepted 30 offers of export assistance this week that helped them capture sales contracts for 3.2 million pounds of American-type cheese and 311,000 pounds of cream cheese.

The product is going to customers in Asia, Middle East-North Africa and Oceania, and will be delivered through July. The sales are the equivalent of 32 million pounds of milk on a milkfat basis.

Looking to the last 12 months, CWT-assisted

sales were the equivalent of 1.193 billion pounds of milk on a milkfat basis, according to the CWT.

CME dairy prices headed lower in the shortened Martin Luther King Day holiday week. The cheddar blocks closed Friday at $1.8350 per pound, down 16.50 cents on the week, lowest since Sept. 6, 2022, but 2.75 cents above a year ago.

The barrels nished at $1.58, 12.75 cents lower on the week, lowest since Nov. 29, 2021, 23.25 cents below a year ago, and 25.50 cents below the blocks, which may be reecting actual supply and demand. Sales totaled ve cars of block and 12 of barrel on the week, as the annual IDFA Dairy Forum kicked off in Orlando.

The cheese demand spectrum has widened from week two, said Dairy Market News. Some processors continue to say demand remains quiet, while others, namely retail cheddar and Italian pizza style cheesemakers, said orders have picked up some. Milk availability has not changed, and spot prices were as low as $10 under Class again this week, fourth week in a row. Cheese output is therefore plentiful though some plants say upcoming scheduled maintenance could keep even more downward pressure on available milk. Market tones are a little uncertain, said DMN, but there is plenty of processing going on.

Demand for cheese is unchanged in western retail markets, though some report strengthening food service sales. Football playoffs are contributing to increased demand for mozzarella from pizza makers in the region. Export demand remains steady, though lower international prices may lighten that demand going forward. Sales to Asian markets are strong. Milk is plentiful in the region and cheesemakers are busy, though labor shortages and continued delayed deliveries of supplies is keeping some plants from operating full schedules.

Butter fell to a Friday nish at $2.3225 per pound, lowest since Dec. 27, 2021, down 10.25 cents on the week, and 61.25 cents below a year ago when it jumped 21 cents. There was only one sale on the week at the CME.

Cream is readily available, reports DMN, though cream prices rose somewhat midweek. Churning has been busy. Butter demand is meeting seasonal expectations. Plant management is focused on spring holiday inventory readiness, said DMN. Market tones are holding somewhat rm.

The West continues to see plenty of cream which was outpacing demand in some cases. Butter production remains strong. Unsalted butter stocks remain tighter than salted as availability continues to work toward balancing with demand. Butter demand is unchanged. Some contacts report rst quarter sales being covered, but a lagging start to second, third and fourth quarter sales, as hesitation remains for booking into the remaining quarters of 2023, said DMN.

Grade A nonfat dry milk fell to the lowest level it has seen since March 26, 2021, closing Friday at $1.1750 per pound, down 8 cents on the week and 64 cents below a year ago. There were 20 loads that exchanged hands on the week.

Powder prices in Europe have also been under a tremendous amount of pressure, according to StoneX, as they deal with increasing production and weak demand which has caused concerns over inventory levels.

Dry whey closed Friday at 32.50 cents per pound, 0.75 cents lower on the week, lowest CME price since Aug. 13, 2020, and 47.50 cents below a year ago. There were 16 sales reported for the week at the CME.

The February Federal order Class I base milk price was announced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture at $20.78 per hundredweight, down $1.63 from January, 86 cents below February 2022, and the lowest Class I price in 12 months. It equates to $1.79 per gallon, down from $1.86 a year ago.

Part of the reason the Class I is falling is because uid milk sales continue to ounder. The USDA’s latest data shows November sales of packaged uid products at 3.69 billion pounds, down 2.9% from November 2021.

Conventional product sales totaled 3.5 billion pounds, down 2.7% from a year ago. Organic products, at 230 million pounds, were down 4.9%, and represented a typical 6.2% of total sales for the month.

Whole milk sales totaled 1.3 billion pounds, up 1.5% from a year ago, up 1.4% year to date, and represented 34.1% of total milk sales YTD.

Skim milk sales, at 187 million pounds, were down 8.7% from a year ago and down 8.5% YTD.

Total packaged uid sales for the 11 months amounted to 39.5 billion pounds, down 2.3% from 2021. Conventional product sales totaled 36.9 billion pounds, down 2.4%. Organic products, at 2.6 billion, were down 1.2%, and represented 6.6% of total milk sales for the period.

The gures represent consumption in Federal Milk Marketing Order areas, which account for approximately 92% of total uid milk sales in the U.S.

Checking other demand data, November U.S. total cheese disappearance hit 1.197 billion pounds, up just 0.4% from November 2021, and it was only up that much because of exports. Domestic utilization fell below the previous year for the rst time since July 2022, according to HGD Dairy, off 0.4%, while exports, at 82.6 million pounds, were up 12.8%.

Butter utilization totaled 219 million pounds, down 6.1%, with domestic use down 11.3%. Exports, at 18.6 million pounds, were up 158.3%, highest since March 2014, according to HGD. YTD butter utilization was down 6.7% domestically, while exports were up 52.7%.

Nonfat dry milk utilization, at 191.8 million pounds, remained below a year ago for the sixth consecutive month, down 10.7% from a year ago, due to weak domestic demand which was down 33.1%, and had been poor throughout 2022. Exports totaled 155.2 million pounds, down 3% from a year ago, and down 7.2% YTD.

Dry whey exports amounted to 70.2 million pounds, down 5.3% from a year ago, with domestic

use down 28.3%, and exports totaling 43.8 million were up 17.4%.

Speaking in the Jan. 23 Dairy Radio Now broadcast, HGD’s Eric Meyer referenced the above data and the falling CME product prices, levels not seen in months or years in some cases. He also warned of milk production growth in the northern hemisphere, specically Europe, where he said output has turned positive the last few months.

He said we are still absent November data for a couple countries, but we expect a number that’s going to be close to 2% year-over-year growth. They’re having a signicantly warmer winter season that’s leading to decent milk production growth, he said. So European dairy commodity prices have fallen, and it appears that the U.S. market is following.

Down on the farm, dairy culling in the U.S. was up in December but slightly below December 2021, according to the USDA’s latest livestock slaughter report.

An estimated 266,300 head were sent to slaughter under federal inspection, up 15,400 head from November but 1,500, or 0.6%, above December 2021. Culling for the year totaled 3.05 million head, down 59,100, or 1.9%, from a year ago.

Meanwhile, USDA’s monthly Livestock, Dairy and Poultry Outlook, issued Jan. 19, said based on expectations of lower milk prices and steady to higher feed costs the number of milk cows is projected lower in 2023 at 9,405 million head, down 15,000 from last month’s report.

The USDA cattle report, which will be issued Jan. 31, is expected to provide a better sign of future changes in the dairy herd size, according to the Outlook. The average yield per cow projection for 2023 was unchanged at 24,370 pounds.

Dairy export projections for 2023 were increased as domestic prices for dairy product are expected to be competitive compared to international prices.

The Outlook mirrored milk price and production projections in the Jan. 12 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report, which I previously reported.

Last but not least, the Jan. 13 Daily Dairy Report said a state of emergency has been declared for California as successive, intense storms batter the nation’s largest dairy state. The bomb cyclone slamming the state has brought gale force winds and widespread ooding that have caused vast property damage, evacuations and the loss of human life.

Not even two weeks into the new year, some areas of the state have already received over half their annual rainfall. The weather crisis has put California in the unusual position of simultaneously being under a state of emergency for both drought and ooding, according to the DDR.

By Maggie Molitor Staff Writer

By Maggie Molitor Staff Writer

ST. CLOUD, Minn. – Reliable and proven practices, new ideas and innovative research for organic farming were shared at the Minnesota Organic Conference Jan. 5-6 at the River’s Edge Convention Center in St. Cloud.

Dr. Bradley Heins, professor of dairy management at the University of Minnesota-Morris, spoke about his research on calf raising systems Jan. 5 at a breakout session titled “Putting Dairy Research to Work.”

“How we raise calves is always a hot topic,” Heins said. “Getting out in front of it before the consumer demand is important.”

Heins began a study in the spring of 2020 to research dairy cattle nursing their young while being milked twice daily. As more funding became available, the study expanded to explore individual, pair and group housing as well.

In 2.5 years, the study has accomplished ve sessions, raising almost 100 calves on their dams and about 60 calves each in the other three systems.

While raising calves with their mothers is taboo in the dairy industry, Heins found points of success in this portion of the project.

“Some people are worried that we bred the ability to raise their calves out of dairy cows, but this is simply not true,” Heins said. “We had cows that were 7 and 8 years old raising their calves for the rst time.”

The cow and calf were given a few days to bond together before the cow and calf joined the rest of the herd either in the pasture during the grazing months or in the pack barn in the winter. Calves were weighed, vaccinated and tagged but then were otherwise dependent on their dam. Treatments were given as necessary. Every cow nursed her own calf and began milking twice daily three days after calving.

The nurse calves were only separated from their mothers during milking time.

At day four, all the calves across the study were offered starter. While the calves nursing had free-choice milk from their mothers, the calves in the individual, pair and group housing were fed 10 liters of milk a day.

“How much milk to feed calves is a topic continuously discussed,” Heins said. “I’ve settled at about 10 liters per day, because it is probably optimum from an economic standpoint and a growth standpoint.”

At 3 months of age, all the calves from across the study were weaned.

The study is now coming to a close and some of the rst calves that nursed off their mothers are coming into milk themselves, and as they do, more data will be observed including behavior and production. The economics of the study will be complied within the next year.

Heins’ preliminary results from the study resulted in a few observations.

One of the most notable observations was that blood serum levels in the calves that nursed off their mothers were signicantly higher than those in individual, pair and group housing groups. Heins said this may be due to the calves receiving all of the transition milk therefore absorbing more immunoglobulins than their counterparts.

“This goes against the conventional dairy mentality of trying to pull the calf away from the cow right away because you have to get colostrum in it,” Heins said. “The calf can gure out how to get it from its mother because it’s in its nature.”

Heins did not need to force feed any colostrum to the nurse calves throughout the study.

Heins also found the health of calves across the four systems were all relatively similar with no differences in calf mortality. He said calves in group housing have more incidents of scours but not a signicant enough amount to make it a concern.

The study did shed light on the stressors of weaning.

While all the calves across the study expressed signs of distress while weaning, it was more notable in the nursing calves because the cows were also experiencing distress away from their calves.

“Through all of this, I learned that weaning is way more important than what we have given credit,” Heins said. “It’s stressful. These calves were stressed, but the cows were stressed a lot more.”

After weaning, many of the cows decreased in milk production, but after a few days, most of the cows returned to producing 60 pounds with the exception of a few younger cows.

Heins said he may continue working with nurse cows to identify ways to improve the weaning process.

As Heins weighs the variables of raising systems, he said group housing is his method of choice.

“I think farms should be raising calves in a group housing situation because calves can maintain growth and health in those systems,” he said. “I think that individual housing requires too much labor in today’s dairy industry, and nurse cow systems take a different form of management, so it may not be for everyone.”

ST. CLOUD, Minn. – Organic farmers, gardeners and enthusiasts gathered for the annual Minnesota Organic Conference Jan. 5-6 at the River’s Edge Convention Center in St. Cloud.

Among the wide variety of breakout sessions offered at the conference, Dr. Rebecca Larson, associate professor and extension specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, shared her research on creating a lifecycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions in a session titled, “Organic Dairy Can Store Carbon: Strategies for the Future.”

“A lot of direction and focus is on agriculture when we think of climate change and greenhouse gases,” Larson said. “However, all sectors of industry need to be accountable. My job is to make sure the science is out there so farmers and other people can make informed decisions.”

The model Larson, and the team of scientists she worked with, created considers the many variables effecting carbon outputs and carbon sequestration in order to accurately predict what the carbon emissions are for small organic dairies and how they can improve their carbon footprint.

There are large variables that impact emissions including manure management, feed sourcing, energy and climate, among others. Larson said she and the research team worked hard to ensure the numbers they assessed were averages and accurately represented a wide variety of organic farms.

To account for these variables, the study was split into four regions of interest. The regions group like areas together that have similar climate, herd size and farming practices.

The rst phase of the project was funded by Organic Valley using farms from the cooperative to create the model and build regions.

With the help of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the project continued to its second phase –nding the impact of proposed mitigation practices.

“The lack of data in the organic space is pretty amazing,” Larson said. “The investment from the USDA will hopefully ll some of those gaps so our model can more accurately represent organic dairies.”

Larson said the goal is to give farmers enough information to determine what impact their farm has, where they can go and some strategies for how to get there.

The study shows organic dairies are more carbon neutral than previously thought. Organic dairies are often criticized for being a less efcient way to produce milk compared to conventional dairies, therefore having more carbon outputs. However, the model revealed the importance of taking into consideration grazing and other carbon sequestering techniques to nd the most accurate number.

“Organic farms generally have higher greenhouse gas emissions if they do not include the carbon sequestration number,” Larson said. “Everyone looks at the fat and protein corrected milk, but there are so many other factors to consider, especially how they store carbon.”

Larson said organic farms are often more dynamic, and the model is built to reect the benets that arise from these types of farming systems.

Larson is excited to share her and her team’s ndings as an effort to reduce the carbon footprint.

“Climate change makes me nervous; however, these models will remind people you could remove all of agriculture and still have a problem, but at least we are doing something,” Larson said. “This is meant to be transforming space and not give an end-all solution.”

The research team at UW-Madison includes Larson, Dr. Horacio AguirreVillegas, Dr. Erin Silva, Dr. Michel Wattiaux and Nicole Rakobitsch, director of sustainability at Organic Valley.

Sanborn, MN

Meadowlands

Farmers Co-op 6.7514.63

Almena, WI

Synergy Cooperative 6.0614.27

St. Cloud, MN

ADM 6.4414.77

Westby, WI

Premier Co-op 6.3014.37

Cadott, WI

Cadott Grain Service 6.2514.28

Pipestone, MN Cargill 6.6914.67

Muscoda, WI Riverdale Ag Service 6.3414.32 Wheat 6.61

Gar eld

Pro-Ag Farmer’s Co-op 6.4514.47 Wheat 8.99

Monona, IA

Innovative Ag 6.3114.12

Watertown, SD Watertown Co-op Elevator 6.6014.68 4.10 S. Wheat 9.00 W. Whea t 8.21

Whitewater, WI

Landmark Services Co-op 6.4714.41 Wheat 6.31

Dennison, MN

Central Farm Service 6.5214.34

Belleville, WI

Countryside Co-op 6.4514.41 Wheat 6.31

Glenwood, MN

CHS Prairie Lakes 6.4914.62 S. Wheat 8.89

The last several weeks were rough for some dairies in the Western region of the Midwest. We heard many firsthand stories of milk being dumped on farms. This is always a tough pill to swallow as someone has to absorb this financial pain. Let’s hope this comes to an end soon and plant production schedules return to normal.

Watching the surplus milk trading activity between plants is a good indicator of how tight or loose the milk supply is. Over the past four weeks, spot loads of milk have been selling at steep discounts with prices as low as $10/cwt under class. For plants acquiring these loads, there should be good margins in taking on this milk. Although it beats having to dump it, the price discount is painful for plants on the sell side of these transactions.

The biggest change since the last VisorView commentary has been lower price moves at the CME Group spot market. Recent trading took barrel cheddar back below $1.60/lb. This is pulling block cheddar prices lower, with trades taking place in the low $1.80’s again. The block barrel spread remains near 25 cents. If this spread narrows to normal, Class III prices will move $1.00/cwt. As of this writing February Class III futures

are projecting a cash settle value near $17.09, but spot prices are moving higher as this is going to print.

Nonfat dry milk and whey prices continue to collapse. At this point, the market is searching for demand. Recent spot trading activity has nonfat dry milk trading $1.17 and whey near 32 cents. This is significantly off of the 2022 highs of $1.86 and 85 cents respectively. Global financial challenges with inflation are likely the root cause for the powder market sell off Some of the countries being impacted the worst from inflation, interest rate hikes, and currency fluctuations are emerging economies with exposure to dollar denominated debt.

EU dairy product prices appear to be in a free fall also. Milk supply in the EU has been growing since the fall of 2022 due to record high milk prices. This was met by EU consumers being clobbered by food price inflation and energy prices from the Russian war. Where dairy prices go from here will be highly dependent on how world consumers react to cheaper dairy product values.

*Futures and options trading involve significant risk of loss and may not be suitable for everyone. Therefore, carefully consider whether such trading is suitable for you in light of your financial condition. Past performance is not indicative of future results. DVi is an equal opportunity employer.

Fort Atkinson Hay

Ft. Atkinson, Iowa • 563-534-7513

Small Squares

3rd crop $190/ton 1 load New seeding $150/ton 1 load

Large Squares

1st crop $125-130/ton 3 loads

3rd crop $150-225/ton 4 loads 4th crop $215/ton 1 load

Rounds

1st crop $135/ton 1 load

2nd crop $85-155/ton 17 loads

3rd crop $105-140/ton 12 loads

4th crop $145/ton 7 loads Grass $75-140/ton 1 load

New seeding $120/ton 1 load Baleage $85/ton 1 load

Rock Valley Hay Auction Co.

Rock Valley, Iowa • 712-476-5541

Large Squares

2nd crop $210-240/ton 3rd crop $202.50-252.50/ton Mixed $202.50/ton Straw $135-160/ton

Large Rounds

1st crop $140-215/ton 2nd crop $205-255/ton 3rd crop $220-230/ton Grass $160-215/ton Mixed $202.50/ton Corn stalks $92.50-97.50/ton

WEST LINTON, Peeblesshire, Scotland – Sixteen robots play big roles at Blyth Farms and Blythbridge Holsteins in West Linton.

From milking the cows to cleaning the alleyways, pushing up feed to providing fresh bedding, automation has ushered forward efciency for Colin Laird.

“We are always striving to be more efcient,” Laird said.

Laird, a third-generation dairy farmer, and his parents, Alister and Kathleen, as well as his family – wife, Izzy, and children, Chloe and Gregor –have more exibility and consistency with their operation

since implanting robotic technology.

“We are a family-run business,” Laird said. “We are all involved on the farm.”

Prior to implementing a robotic milking system in 2019, the Lairds milked 540 cows in a rotary parlor three times a day. Now, the herd is milked in 10 Lely Astronaut A5 systems.

The Holstein herd at Blyth Farms averages 93 pounds of milk per cow per day with a 4.1% butterfat and 3.2% protein.

Blyth Farms’ innovation is one reason it was named the 2022 Scottish Dairy Farm of the Year.

Laird and Alister are the primary operators of the dayto-day functions of the farm.

Kathleen takes care of the recordkeeping and paperwork, including registering the calves. Izzy takes care of the calves. They also have four full-time employees.

The robotic technology also includes three Lely Dis-

covery mobile barn cleaners in the freestall barn, two Lely Juno units to push up feed and a Lely Calm for automatic calf feeding.

Scottish farmers are faced with particular challenges including year-round heavy rains, high costs for dairy production, limited dairy processing facilities and the cost of electricity skyrocketing due to the war in Ukraine.

Laird said the robots ease some of the challenges.

Because the freestall barns are never empty, the farm utilizes an automatic bedding machine to spread recycled manure.

“We use green bedding,” Laird said. “We think it maximizes cow comfort.”

Manure is scraped into the slotted oor and stored under

the barn in a 3.5-million-gallon tank. The manure is then separated and recycled.

“The separated manure goes into a trolly that runs along the roof, and it dispenses the bedding above the stalls 24/7,” Laird said. “It’s a small sprinkling all the time.”

Though technology helps Laird and his team, there are issues that persist for them and other farmers in Scotland.

Scottish farmers saw record milk prices in 2022, but the cost of production was also at record levels, Laird said.

“The cost of production has gone up so much that the milk processors had no choice but to pay us more,” Laird said.

Laird said there are not many milk processors in Scot-

land. Companies often ship milk to England for processing. Because of this, Laird said securing a milk contract is difcult.

Laird said the war in Ukraine has also had an impact on farmers and the dairy industry across the United Kingdom.

“Electricity used to be 10 pence a unit; now, it’s a pound,” Laird said. “All of our energy was coming from Russia.”

The soaring electricity costs leave repercussions in Scotland because cows are housed inside year-round due to the amount of rain the region receives each year.

“We get, on average, just under (40 inches) of rainfall every year,” Laird said. “That makes it really hard for us to graze our cows; it makes too much of a mess.”

The climate is mild because the country is surrounded on three sides by the ocean. Temperatures in the summer are generally in the mid-70s and low 80s and in winter rarely dip below zero.

“Very rarely do we get above (86 degrees) in the summer,” Laird said. “And right before Christmas, we dipped down to minus (4 degrees) for a few days, and for us, that is unheard of.”

The freestall barn has an insulated roof and automatic curtains that adjust according to the temperature.

“We do not have fans or cross ventilation,” Laird said. “We don’t get the heat to justify having those.”

Blyth Farms owns 1,650 acres across two farm sites. There are 950 acres at the main site, which is where the cows are milked. The other 700 acres are 50 miles away and surround

the barn where youngstock are housed. All calves are sent to the second site when they are 4 months old. They are then sent back to the main site one month prior to calving.

The family does almost all tasks themselves, including eldwork, A.I. and hoof trimming.

“I love that at the start of the morning, I can bring up a few cows to the robot, then do some hoof trimming, then split a gearbox on a spreader, then check on the cows and ush a few cows and then go onto something different,” Laird said. “No two days are the same.”

Because of the short growing season, the Lairds are not able to grow corn. Instead, they feed grass silage, chopped straw, soybeans, soybean hulls, barley, wheat and a byproduct from a local distillery called draft.

“We are fortunate enough that we have enough land and good enough land to grow our cereals,” Laird said.

The Lairds rarely leave the farm unless to show their registered Holsteins at shows across the United Kingdom and a few shows throughout Europe.

“We went to The (Royal Agricultural) Winter Fair in Canada this year with some friends,” Laird said. “It gets you into a whole new circle of friends, and it’s been incredible.”

Any traveling the family does is most often related to farming.

“Our hobby is our cows,” Laird said. “If we ever leave the farm, it is usually with our cows.”

But when the Lairds do indeed travel, the automation at home ensures the farm can continue operating in their absence.

By Jan Lefebvre jan.l@star-pub.com

By Jan Lefebvre jan.l@star-pub.com

Editor’s note: In the Jan. 14 issue of Dairy Star, a portion of this story was inadvertently omitted. Dairy Star staff regrets this error and includes the full version of the story below.

SCANDIA, Minn. – In 1969, Christine and Vincent Maefsky used a moving truck and a Volkswagen Beetle to move their 17 chickens, two goats, two dogs, a cat and their belongings from Kansas to Minnesota. At the time, they did not know they would someday own one of the largest goat dairies in their new home state.

Today, the couple, along with sons, Stephen and Shane, and daughter and son-in-law, Sarah and Steve Johnson, oversee a herd of 600 goats and milk 275 in a double-24 parallel pit parlor at Poplar Hill Dairy Goat Farm in Scandia. Christine and Vincent’s other son, Seth, lives with his family in Spokane, Washington.

At times, the goat herd at Poplar Hill has numbered 1,000.

“We still have chickens too,” Vincent said.

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the farm’s existence, and Poplar Hill shows no signs of slowing down. The herd today consists of a variety of breeds.

“We have Alpines, Saanens, Nubians and Toggenburgs,” Christine said. “All are registered with the (American Dairy Goat Association).”

Poplar Hill is the only dairy in Minnesota supplying Grade A pasteurized goat milk.

The farm produces enough milk to not only carton and market under the Poplar Hill name but to also sell to

Stickney Hill Dairy for cheese production. Poplar Hill milk is sold in large grocery stores such as Cub Foods, Kowalski’s, Eastside Foods, Lunds & Byerlys and many more. Numerous smaller stores carry their product as well.

The family also sells 13 varieties

of soap made from goat milk and hosts tours by appointment for both large and small groups.

Poplar Hill bucks and does are sold across the United States and in 15 countries. The best bucks are sold for breeding. Others are sold for pets or meat.

Through the years, the demand for goat meat has been increasing.

“One thing that has helped our business is the ethnic diversication of America,” Vincent said. “For us, that’s especially in the Twin Cities area.”

The farm’s success has come from the family’s joyful appreciation of, and careful attention to, their goats.

“We’ve enjoyed the animals,” Christine said. “They are delightful.”

The couple’s journey to owning a goat farm did not begin rurally. Although Christine and Vincent never met as children, both were born in Brooklyn, New York. Christine was raised there while Vincent was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma. In what seems like fate, each attended the University of Oklahoma and met there. Vincent studied philosophy and theology while Christine studied political science.

After falling in love, they moved to New York and married. Christine enrolled at Columbia University to earn a master’s degree in elementary education.

At this time, they joined the Catholic Worker Movement to help serve people in poor urban areas. The movement, co-founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, began during the Great Depression and offered what they called houses of hospitality where the poor and homeless could eat and stay. This branched out to small farms, which Maurin called agronomic universities. The idea was to create communities of self-sufcient farms that could help raise food to share with the poor. Still today, about 200 such urban and rural communities exist across the world.

Drawn to the idea of running a farm in this model, the Maefskys moved to Oklahoma and then to Kansas to establish an agricultural community. They purchased pigs and chickens and looked for a cow to buy for milk.

They also wrote a letter to Day to tell her what they were doing; she published their letter in the Catholic Work-

er newspaper. A reader from the Bronx, New York, wrote to the Maefskys, suggesting they buy goats instead of a cow because of the lower cost and because he thought they were great animals.

The Maefskys took his advice and bought their rst goat.

“We named her Dorothy, of course,” Vincent said.

Then, a job for Christine in the Minneapolis Public Schools led the Maefskys to migrate to Minnesota with their menagerie of animals.

At rst, they stayed on a friend’s property, and Vincent got a job as a realtor.

One day in 1972, Vincent brought a client to an old farmstead in the rolling hills in Scandia. Vincent realized the farmstead’s potential and showed it to Christine. They bought the property themselves. The house on it was 120 years old.

“It had a garden hose inside for water and no central heat, but the barn was magnicent,” Christine said.

The house, restored and updated, is where Christine and Vincent live today.

With the purchase of the farm, Poplar Hill Dairy was born. The farm’s name pays homage to the poplar trees that grew there but later died.

“Never name your farm after a tree with a short life expectancy,” Vincent said. “Sequoia Hill Farm would be all right, but not Poplar. We’re still here, but the poplars are gone.”

Within three years, Poplar Hill’s herd had grown and was producing a lot of milk. The Maefskys needed a plan for selling and moving product.

“In 1975, we bought a home delivery milk truck from Land O’Lakes,”

Vincent said.

They hauled their milk to the North Branch Creamery in Minnesota for pasteurization and then delivered the milk to retailers.

Many other changes have happened through the years as well along with an impressive list of successes and awards.

In 2016, Christine and Vincent became the rst goat dairy farmers to be inducted into the Minnesota Livestock Breeders’ Association Hall of Fame. They are also the Minnesota

Dairy Goat Association founders, and in 2018, their family was awarded the ADGA Pioneer Award, which is given each year to a member or family that has made a signicant contribution to the goat industry.

The Maefskys are also one of only three families that have shown goats at the Minnesota State Fair every year since goats have been shown on the fairgrounds in St. Paul.

“That means we’ve been there for 42 years,” Vincent said.

Poplar Hill goats excelled at the most recent fair in 2022. One was reserve grand champion, another earned best junior doe in show and a third received both grand champion 4-H Alpine junior doe and best junior doe in show.

Other successes have come outside of the farm. Christine worked in Minneapolis Public Schools until 2000 and then spent 10 more years as a consultant for teachers throughout the United States. She has also just begun her fourth term as mayor of Scandia.

“That makes me ‘rst gentleman,’” Vincent said. “All of the glory but none of the responsibility.”

Together, they have long been involved with the University of Minnesota’s veterinary program, allowing their farm to be a place for students to learn and research. Vincent has lectured nationally and internationally, sharing his expertise in dairy goat farming. Both have worked with Heifer Project International and have hosted 33 international agriculture trainees from 19 countries.

Both said the farm has brought joy to them and their family.

“We’ve enjoyed our grandchildren growing up around the farm,” Christine said. “We have made good friends among other goat breeders.”

Vincent said they appreciate the man who advised them to purchase goats all those years ago.

“He said I should forget about cows and buy goats,” he said. “He told me that they were smarter, friendlier creatures and that they made wonderful milk. He was right.”

By Grace Jeurissen grace.j@star-pub.com

By Grace Jeurissen grace.j@star-pub.com

WELCH, Minn. – With technology like genomic testing improving the future of the modern dairy herd quicker than ever before, farms are using beef sires to continue using older cows for production while weaning their genetics out of the herd.

“Beef on dairy isn’t a new thing, but it is changing the way the industry is marketing and utilizing dairy animals during harvest,” Bradley Johnson said.

Johnson, of Texas Tech University, presented information from one of his studies, a partnership with Luke Fuerniss, on the impact of beef on dairy cattle Jan. 12-13 during the Form-AFeed Professional Dairy Conference at the Treasure Island Resort and Casino in Welch.

“Farms can properly utilize their herd of dairy cows to minimize variability in crossed calves and maximize the calf’s feedlot potential,” Johnson said. “No different than a dairy using specic sires on specic cows, they should use specic beef sires to maybe shorten stature on a tall Holstein.”

Johnson said this is not necessarily a concern for farmers who sell bull calves off the farm, but for the producers who raise their own feeder cattle, they can receive better end results by evaluating groups and pairing them with the proper sires.

“Our results didn’t consider the costs of each variation in the study,” Johnson said. “I would say that inseminating a Holstein cow with a beef bull is the way to go in terms of cost and production. Considering the conception rate of embryos versus articial insemination and the prices to do each, the cost-effective route for farms would be articial insemination.”

The study followed ve groups of calves. Each calf in the study was sired by GAR Momentum, an Angus bull in the top 1% of the breed for carcass growth and quality.

The calf groups were comprised of the following: commercial beef cows inseminated with Momentum; Holstein cows inseminated with Momentum; Jersey cows inseminated with Momentum; commercial beef-Momentum em-

bryos placed in Holstein recipients; and commercial beef-Momentum embryos placed in Jersey recipients.

Each group was measured to compare frame size and average daily gain. All of the calves born of a dairy animal were raised in hutches and fed milk and starter grain until weaning. Calves born from the commercial beef cows were raised on their dam until weaning.

“Once calves started hitting the ground and we were measuring birth weight, we expected the Jersey cows’ smaller frames to inhibit the growth of the embryos making birth weight smaller, but in reality, they weren’t far off from the other full beef calves. The smallest birth weight was the Jersey crosses,” Johnson said.

The study measured calves again at 150 days of age. Calves raised on their dams were larger in height and weight while possessing heavier muscling phenotype. The closest in comparison were the Holstein-Momentum calves.

The study then evaluated feedlot performance. Purebred Holstein steers were added to the study to compare. The commercial beef-Momentum embryos implanted in Holsteins had a higher dressing percentage but less average daily gain than the purebred beef calves and the Holstein-Angus crossbreds.

The Holstein-Angus crossbreds showed comparable efciency overall in feeding and carcass performance to the Angus steers. Average daily gain of the Holstein-Angus calves was 3.7 pounds, Angus calves gained 3.8 pounds, beef embryos calved of Holstein cows gained 3.4 pounds, and the Holstein steers gained 3.5 pounds.

Johnson said there are variables to consider when breeding beef on dairy cattle. For example, geographical location of the feedlots the animals are being raised in and the breed being used in the crossbreeding program are of value to a grower.

Black-hided crossbred cattle do not do as well in hot climates like the Imperial Valley in California where a large number of Holstein and Holstein crossbred steers are nished for market. The hot temperatures cause heat stress and effect feed intake. Crossbreeding with lighter colors, like Charolais, were found to be more efcient in hot climates.

“Beef on dairy is a great way to control heifer inventory on your dairy and provide a high value product to the beef industry,” Johnson said.

17.5 years practicing veterinary medicine

Where did you attend veterinary school? I attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine.

What is your background? My parents had a farrow-to-nish hog operation. Later on, they had their own pork business.

What does a typical workday look like for you? Usually, I have pregnancy checks and ultrasounds in the morning and sick calls in the afternoon with emergency calls at night. I am on call every other night and weekend, which is shared with Dr. Lynzie Mlsna.

How much time do you spend each week on various treatment categories? Herd health is about 50%, sick cows and surgeries are 30%, and emergencies are about 20% of my time.

What are your favorite veterinary services to provide? Ultrasounds and reproductive work are my favorite. I like to do things to help make the farm and farmer more protable. I like to work with people who are trying to make improvements and progress on the reproduction of their cows.

Are there any areas you specialize in? I would say I specialize in ultrasounding.

What is the most common ailment you treat on dairy farms during the winter? Pneumonia and displaced abomasums are common because of frozen or inconsistent feed. It’s harder to keep feed consistent when dealing with weather changes.

What are three tools you could not do your job without? My truck, my ultrasound and my stethoscope.

What is the most memorable farm call you ever had or surgery you ever did? Probably the rst cesarean section that Dr. Lynzie and I did together. It was for a show heifer and was later at night. We got a live heifer calf out of it. I also almost broke my wrist when I slipped on the cleanings which also made it memorable.

What is one piece of advice you would give to farmers to help them improve their herd? Being consistent is No. 1 between feed, housing, bedding and timing. Cows love consistency. Also, be proactive on the reproduction side and have fresh cows clean.

How have changes on the farm and in the industry impacted your work? We’re driving farther as more vets are retiring and herds are being sold. I still enjoy the variety of the farm sizes.

What is one of the most important lessons you’ve learned in your career? Try not to get behind and try to stay patient with whoever I’m working with.

Who is someone in the industry you look up to? Dr. Steven Doll who I bought the practice from. He was very helpful to me when I purchased the practice from him seven and a half years ago.

What is the most challenging aspect of being a veterinarian? Working in the elements all winter is challenging. I have learned to work faster.

What is something you have learned from your customers since you have been in practice? Farming requires a lot of perseverance.

What do you nd most gratifying about your work? Seeing farmers improve their operations and seeing cow performance improve.

What do you like to do when you are not working? Spend time with my family and attend my children’s sporting events.

571

Large Rounds 15.04 15.13 108.46 1 20.09 $140.00

572 Large Rounds 10.94 11.98 93.3 1 20.46 $135.00

585 Large Rounds 11.94 13.28 90.27 1 23.8 $140.00

602 Large Rounds 13.58 8.8 84.4 1 19.45 $75.00

609 Large Rounds 14.11 7.75 113.59 1 25.75 $100.00

611 Large Rounds 15.48 17.91 118.24 1 22.55 $115.00

622 Large Rounds 14.33 10.67 71.42 1 20.56 $65.00

629 Large Rounds 15.84 17.33 94.83 1 26.81 $75.00

631 Large Rounds 17.99 18.98 111.44 1 21.94 $85.00

633

635

636

Large Rounds 14.37 18.86 134.31 1 23.42 $85.00

Large Rounds 13.72 8.04 85.56 1 20.54 $85.00

Large Rounds 13.28 16.98 114.3 1 24.72 $125.00

637 Large Rounds 13.89 16.14 113.72 1 22.59 $120.00

639 Large Rounds 14.02 20.94 96.04 1 21.38 $90.00

641

Large Rounds NO TEST 1 5.43 $75.00

642 Large Rounds 18.2 22.04 170.35 1 20.83 $95.00

650 Large Rounds 13.62 7.18 90.3 1 18.23 $85.00

655

659

Large Rounds 17.57 18.48 121.7 1 30.72 $115.00

Large Rounds NO TEST 1 10.22 $95.00

666 Large Rounds 13.29 18.86 113.42 1 25.48 $125.00

677 Large Rounds 11.03 7.79 82.48 1 20.63 $75.00

684 Large Rounds 10.16 7.39 78.94 1 8.21 $70.00

692 Large Rounds 14.22 17.27 122.38 1 14 $50.00

694

Large Rounds NO TEST 1 13.5 $75.00

695 Large Rounds 10.99 8.29 90.04 1 9.37 $75.00

545 Large Rounds 14.37 21.46 132.48 2 24.41 $150.00

568 Large Rounds 12.48 17.38 103.16 2 19.34 $120.00

586 Large Rounds 15.17 19.9 124.28 2 22.6 $120.00

588 Large Rounds 13.96 17.81 125.76 2 26.36 $110.00

593 Large Rounds 16.07 16.63 93.59 2 10.24 $95.00

598 Large Rounds 13.64 18.82 119.02 2 25.86 $130.00

610 Large Rounds 17.23 21.9 124.44 2 20.06 $105.00

612 Large Rounds 15.46 22.25 125.34 2 20.05 $110.00

613 Large Rounds 11.3 17.93 114.82 2 18.29 $90.00

614 Large Rounds 15.56 20.79 122.89 2 20.22 $120.00

616 Large Rounds 13.48 9.86 94.52 2 20.04 $75.00

626 Large Rounds 17.82 15.8 109.73 2 17.8 $75.00

630 Large Rounds 13.54 18.85 125.2 2 16.56 $75.00

632 Large Rounds 17.69 19.85 135.93 2 20.64 $90.00

640 Large Rounds 16.25 23.82 153.97 2 20.72 $100.00

660 Large Rounds 10.43 15.79 91.65 2 32 $50.00

665 Large Rounds 10.41 20.63 130.96 2 22.04 $125.00

671 Large Rounds 13.19 17.06 112.76 2 11.23 $160.00

686 Large Rounds 13.62 20.56 125.46 2 25.53 $125.00

589 Large Rounds 12.32 17.93 172.94 3 25.06 $220.00

619 Large Rounds 19.83 21.04 158.7 3 9.34 $100.00

623 Large Rounds 12.59 15.45 111.54 3 14.25 $120.00

645 Large Rounds 19.09 16.69 119.46 3 25.35 $130.00

646 Large Rounds 16.41 17.37 114.06 3 25.78 $132.50

652 Large Rounds 11.26 16.54 107.35 3 7.19 $160.00

678 Large Rounds 13.67 22.31 141.12 3 27.07 $160.00

681 Large Rounds 16.67 23.3 141.01 3 9.09 $70.00

643 Large Rounds 14.4 16.55 112.3 1&2 17.36 $85.00

597 Large Rounds 17.5 110.83 1&3 23.99 $95.00

596 Large Rounds 13.8 12.47 106.19 19.21 $80.00

663 Large Rounds 12.33 11.77 94.87 18.6 $70.00

689 Large Rounds 14.06 7.21 90.73 27.3 $100.00

696 Large Rounds 12.33 11.77 94.87 18.6 $85.00

550 Large Squares 11.05 17.91 128.15 1 25.55 $150.00

551 Large Squares 11.28 17.8 128.39 1 25.09 $150.00

552 Large Squares 11.05 18.5 135.92 1 25.25 $170.00

561 Large Squares 13.63 19.47 104.45 1 26.45 $135.00

570 Large Squares 12.41 16.84 123.5 1 25.23 $155.00

603 Large Squares 16 19.9 136.8 1 26.19 $110.00

604 Large Squares 14.34 19.43 126.36 1 26.33 $100.00

605 Large Squares 18.58 15.76 99.87 1 24.21 $100.00

606 Large Squares 14.34 19.43 126.36 1 26.1 $110.00 620 Large Squares 16.11 16.3 80.22 1 8.08 $65.00

624 Large Squares 13.88 19.38 140.03 1 22.09 $130.00

669 Large Squares 12.36 12.88 93.46 1 27.74 $125.00 674 Large Squares 8.92 17.73 107.55 1 27.31 $150.00 690 Large Squares 6.63 16.67 95.73 1 21.56 $130.00 691 Large Squares 9.59 16.45 100.39 1 21.42 $120.00 548 Large Squares 14.49 22.82 147.02 2 24.18 $180.00 555 Large Squares 13.64 21.79 116.43 2 25.58 $140.00 559 Large Squares 13.9 20.19 118.06 2 24.69 $145.00 575 Large Squares 14.27 5.95 96.56 2 16.51 $95.00 580 Large Squares 14.34 19.43 126.36 2 26.17 $140.00 590 Large Squares 12.65 19.71 114.36 2 25.97 $145.00 599 Large Squares 14.16 20.15 127.7 2 26.02 $150.00 601 Large Squares 14.67 19.35 117.8 2 23.42 $150.00 670 Large Squares 13.94 19.16 133.4 2 27.12 $140.00 675 Large Squares 13.07 19.37 95.8 2 24.23 $140.00 587 Large Squares 15.33 26.9 200.48 3 23.34 $250.00

661 Large Squares 15.86 24.35 125.37 3 26.38 $150.00

582 Large Squares 15.23 22 184.82 4 25.44 $240.00

546 Medium Squares 12.3 26.23 235.04 1 22.02 $270.00

547 Medium Squares 14.12 19.41 109.57 1 24.21 $140.00

554 Medium Squares 13.3 12.17 90.73 1 22.99 $125.00

557 Medium Squares 14.75 18.48 147.02 1 25.37 $150.00

591 Medium Squares 10.18 16.02 104.46 1 26.28 $150.00

621 Medium Squares 12.93 24.67 161.12 1 26.19 $180.00

672 Medium Squares 14.24 21.83 165.7 1 26.45 $220.00

680 Medium Squares 10.35 18.46 103.82 1 23.64 $110.00

685 Medium Squares 13.06 19.77 124.48 1 24.9 $110.00

693 Medium Squares 16.13 22.9 154.81 1 9.93 $150.00

549 Medium Squares 13.56 16.83 124.03 2 19.78 $145.00

556 Medium Squares 11.59 13.33 105.59 2 25.18 $165.00

562 Medium Squares 12.75 22.92 155.17 2 19.53 $195.00

566 Medium Squares 10.44 13.86 111.06 2 24.35 $160.00

644 Medium Squares 15.24 16.31 101.6 2 19.84 $110.00

658

Medium Squares 14.49 20.26 129.57 2 29.52 $120.00

664 Medium Squares 14.64 17.1 120.11 2 25.4 $185.00

676

Medium Squares 10.62 18.36 90.61 2 23.91 $125.00

565 Medium Squares 17.17 27.01 162.6 3 26.89 $150.00

592 Medium Squares 16.12 25.23 137.92 3 26.98 $140.00

595 Medium Squares 16.37 23.18 135.33 3 27.35 $130.00

600 Medium Squares 14.95 21.09 146.12 3 21.21 $140.00

617 Medium Squares 14.12 23.27 147.61 3 9.73 $140.00

618 Medium Squares 14.75 15.67 103.32 3 9.7 $110.00

653 Medium Squares 14.86 19.85 128.94 3 10.54 $140.00

657

Medium Squares 15.3 20.41 124.32 3 25.19 $120.00

667 Medium Squares 11.89 16.68 117.87 3 23.91 $160.00

668 Medium Squares 13.95 22.15 139.12 3 24.31 $165.00

673 Medium Squares 14.17 22.58 141.85 3 26.74 $180.00

679 Medium Squares 12.45 21.06 159.82 3 24.13 $235.00

683 Medium Squares 13.59 19.37 126.53 3 19.95 $170.00

687 Medium Squares 15.64 21.58 133.81 3 22.45 $120.00

688 Medium Squares 13.59 22.22 140.37 3 10.19 $135.00

543 Medium Squares 12.53 22.69 152 4 24.82 $185.00

544 Medium Squares 14.67 18.91 187.63 4 28.33 $210.00

651 Medium Squares 14.36 22.28 145.21 9.41 $140.00 662 Small Rounds 12.66 8.29 83.21 1 15.8 $100.00

594

Large Rounds STRAW 34 $35.00 615 Large Rounds STRAW 18.57 $95.00

628 Large Rounds STRAW 15.27 $90.00

558

563

Large Squares STRAW 26.38 $110.00

Large Squares STRAW 25.41 $120.00

573 Large Squares STRAW 18.26 $110.00 576 Large Squares STRAW 26.95 $105.00 578 Large Squares STRAW 24.97 $75.00 583 Large Squares STRAW 19.82 $100.00 560 Medium Squares STRAW 76 $37.50 564 Medium Squares STRAW 57 $35.00 567 Medium Squares STRAW 78 $35.00 569 Medium Squares STRAW 78 $35.00 574 Medium Squares STRAW 76 $35.00 577 Medium Squares STRAW 76 $35.00 579 Medium Squares STRAW 16 $32.50 581 Medium Squares STRAW 78 $40.00 607 Medium Squares STRAW 57 $32.50 608 Medium Squares STRAW 57 $32.50 625 Medium Squares STRAW 60 $30.00 627 Medium Squares STRAW 57 $32.50 634 Medium Squares STRAW 25.18 $110.00 647 Medium Squares STRAW 78 $34.00 649 Medium Squares STRAW 36 $45.00 654 Medium Squares STRAW 24 $35.00 656 Medium Squares STRAW 78 $42.50 697 Medium Squares STRAW 72 $32.50 584 Small Rounds STRAW 38 $57.50 682 Large Rounds CORN STALKS 20 $35.00

By Danielle Nauman danielle.n@dairystar.com

By Danielle Nauman danielle.n@dairystar.com

MADISON, Wis. – Reproductive efciency is a paramount factor in productivity and protability on a dairy farm, and decreasing days open is a goal many dairy producers work to achieve.

Dr. Paul Fricke, an extension dairy reproductive specialist and professor with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, spoke about how to optimize the benets of sexed semen in dairy herds during a Jan. 10 Badger Dairy Insight webinar.

“From 1955 through 2000, we saw a decrease in reproductive performance as evidenced by an increase in days open,” Fricke said. “Around 2000, something amazing happened. We saw a couple of major shifts in reproduction, a dramatic reversal in reproductive performance.”

While Fricke said selection for reproductive traits has become more prevalent since about 2005, the data does not correlate for that being the driving factor in the overall improvement in the U.S. dairy herd’s reproductive performance.

“We are putting more emphasis on reproductive traits, which is great,” Fricke said. “But it is not really associated in the improvements we are seeing.”

Instead, Fricke said the development of timed A.I. programs along with increased use of automated activity monitoring systems has led to an increase in the service rate.

Another factor is the improvement in the phenotypic trend for the cow conception rate, raising from 33% in 2005 for rst-lactation animals to 47% in 2020.

“In the last ve to seven years, we have seen a dramatic increase in the conception rate,” Fricke said. “I think that is due to the adoption of fertility programs such as double ovsynch and the concept of a high fertility cycle, which says that if cows get pregnant in a timely manner, they don’t get fat at the end of their lactation, don’t lose a lot of body condition and have poor reproduction in the next lactation.”

All of these factors led to what Fricke calls a reproductive revolution that, in turn, created additional challenges for the industry.

“This caused an oversupply of heifers, and suddenly the industry was looking for ways to rightsize the herd,” Fricke said. “And because fertility was so high, we could adopt sexed semen.”

Sexed semen rst entered the market in 2006 and was primarily used in heifers. As fertility rates began to improve so did the use of sexed semen and ultimately the use of beef semen in those herds as well, according to Fricke.

Fricke said whenever a randomized control trial is done, the results typically show the conception rate of sexed semen to be about 85% of the conception rate of conventional semen.

“That is why we want to optimize fertility when using sexed semen,” Fricke said. “It’s more expensive, and you get a little bit of a fertility drag. We want to make sure we are using it the best way we can to maximize that cost and to get females from the best cows on your farm.”

With these changes in breeding strategy, Fricke said many farms have eliminated the use of conventional semen from their protocols. He also said

Jersey herds were more aggressive in implementing sexed semen due to the lower value of Jersey bull calves than Holstein calves.

“Larger farms use a great proportion of both sexed semen and beef semen than smaller farms,” Fricke said. “Also, farmers are using sexed semen in their most fertile animals in the earliest breedings and using beef semen in their older animals. I think it is an interesting overview of how farmers are using sexed semen.”

When it comes to breeding heifers with sexed semen, Fricke referred to data from 2006, prior to the advent of sexed semen, which showed the average conception rate of Holstein heifers to be 60% with conventional semen, which he uses as his benchmark for normal.

“There is a lot of sexed semen used in heifers, because they are young animals, they have good fertility, and they can tolerate the slight fertility reduction in sexed semen,” Fricke said.

Fricke said synchronizing heifers on a ve-day CIDR fertility program has results that reach his benchmark of a 60% conception rate. One struggle farmers have with using a ve-day program with heifers is that nearly one-third will display early estrus, creating issue with timed breeding.

“They need to be inseminated at that early estrus,” Fricke said. “If you wait until the timed breeding, they will not have normal fertility. I recommend tail chalking them at either of the prostaglandin F2 alpha shots to help detect early estrus.”

Along with Megan Lauber, a graduate student working with Fricke, a study was designed to nd a way to decrease the possibility of early estrus from a fertility program and determine if that would have any impact on fertility in those animals.

The study used a control group that was bred on detection of estrus following an injection of prostaglandin F2 alpha; a group that was administered a ve-day CIDR synch; and a group in which a six-day CIDR synch was used. In the six-day CIDR synch, removal of the CIDR was delayed and pulled after the second prostaglandin F2 alpha injection, with the idea that it would suppress the early estrus.

With the ve-day CIDR synch, approximately one-third of the heifers showed early estrus and were inseminated at that time. The six-day CIDR synch did result in a decrease of heifers showing early estrus, with only one animal in the group

DR. PAUL FRICKE, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN MADISON

DR. PAUL FRICKE, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN MADISON

showing early estrus.

“With conventional semen, that worked,” Fricke said. “There was no difference in fertility, and we suppressed that early estrus. Unlike conventional semen, there was a reduction in fertility with sexed semen between the ve-day and sixday CIDR synch. We don’t want to use the six-day CIDR synch with sexed semen; the ve-day is the way we want to go.”

According to Fricke, the data showed a 52% conception rate for the ve-day CIDR synch versus a 45% conception rate for both the six-day CIDR synch and the control group that was simply bred at estrus after one dose of prostaglandin F2 alpha.

“People are using fertility programs because they are breeding at a 100% service rate and getting about half the cows pregnant versus only about 30% when you only watch for estrus,” Fricke said. “Fertility programs work whether you are using sexed semen or beef semen. Twenty percent used to be the pie-in-the-sky goal for preg rate that we all strived for, and now we see herds hitting 40%; that is just amazing.”

problem with their “years of study” is that they willfully ignore the significant studies. 60 years ago, Dr. Derek Forbes published research proving that liner action forces the staph up the teat canal. 22 years ago, Cornell published research proving CoPulsation™ prevents new Staph infections with CoPulsation™ fixing the problem Forbes identified. 18 years ago, at the NMC annual meeting Univ. of Madison and others reported milk is “pumped” back up into the udder by the closing liner, and the list goes on and on with you losing cows and money. Will 2023 be the year they admit your pulsation is causing...

“That is why we want to optimize fertility when using sexed semen. It’s more expensive, and you get a little bit of a fertility drag. We want to make sure we are using it the best way we can to maximize that cost and to get females from the best cows on your farm.”

1 cup ranch dressing

5 ounces hot sauce

16 ounces cream cheese, cubed and softened

From

2 cups cooked chicken, chopped into small pieces

In a 3-quart slow cooker, add the ranch dressing, hot sauce and cream cheese. Cover and cook on low for two hours, stirring occasionally. Once the cream cheese is melted, stir in the cooked chicken. Cover and cook on low for an additional hour. Turn to warm to serve with your favorite chips or cut up veggies.

1 box brownie mix, not prepared

1 egg

5 1/2 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

1/4 cup milk

French silk layer: 8 ounces cream cheese, at room temperature

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 cups powdered sugar

4 ounces semi-sweet chocolate

1/4 cup unsalted butter, cubed 8 ounces whipped topping

Topping: 8 ounces whipped topping Chocolate shavings or mini chocolate chips

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Grease a 2-quart glass baking dish with nonstick cooking spray. In a medium mixing bowl, combine the brownie mix, egg, melted butter and milk, stirring until smooth. Spread the batter into the prepared baking dish and bake for 25-28 minutes until a toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean. Remove the brownies from the oven and cool completely to room temperature. In a large mixing bowl, beat the cream cheese and vanilla extract with an electric mixer until smooth and creamy. Add the powdered sugar and mix until combined. In a small microwave-safe bowl, heat the semi-sweet chocolate and unsalted butter in 30-second intervals until melted, stirring well between each cooking interval. Add the melted chocolate and butter mixture to the cream cheese mixture and stir until combined. Gently fold in the whipped topping. Spread the French silk layer over the cooled brownies, then spread on the remaining 8 ounces of whipped topping. If desired, sprinkle chocolate shavings or mini chocolate chips over the French silk brownies.