DAIRY ST R25

Volume 25, No. 14

Volume 25, No. 14

ST. MICHAEL, Minn.

September 9, 2023

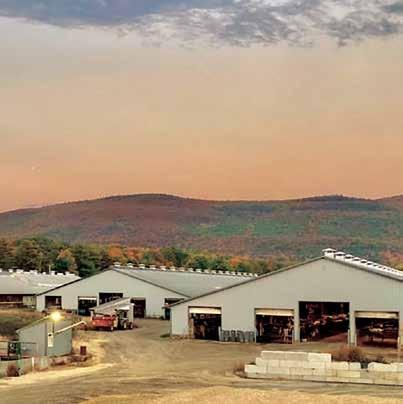

As high school students, Maggie Socha and Grace Volden spent time working together at Green Waves Dairy near St. Michael. Socha, being a year older, soon ventured to South Dakota State University to obtain a degree in dairy production. Volden followed in her footsteps, also attending SDSU to major in animal science.

While at college, the two young agriculture enthusiasts again found themselves immersed in the dairy industry, working together at a dairy farm near their college campus.

Today, having both

graduated with their respective degrees, the two young women have come full circle and returned to the dairy farm they worked at in high school, this time as full-time

employees.

Green Waves Dairy is owned by Mark and David Berning, a father-son duo who milk 480 cows and farm 750 acres. Together with

TAYLOR, Wis. — Tom Olson has an idea. He believes his idea will move a lot of dairy product while putting dairy checkoff dollars to good use. As a result, he is seeking a 2-cent slice of the dairy checkoff. In the Dairy Checkoff Reform Proposal, Olson is asking Congress to amend the Dairy Product Stabilization Act of 1983 to allow dairy producers to divert 2 cents out of the 15 cents per hundredweight they pay to a parent food bank in their state.

Two cents can add up quickly. In 2019, the U.S. produced 218 billion pounds of milk, Olson said. The total checkoff of 15 cents per hundredweight equaled $327 million that was paid in by dairy farmers. Two cents per hundredweight would equal $43.6 million per year that could be spent on dairy products for food banks.

“The checkoff was supposed to help the farmer keep farming,” Olson said. “But when you look at the declin-

Socha and Volden, the four make up the staff of full-time employees.

Turn to SOCHA/VOLDEN | Page 6

By Amy Kyllo amy.k@star-pub.com

By Amy Kyllo amy.k@star-pub.com

ZUMBRO FALLS, Minn.

— Patience has been a dening characteristic of Adam and Sarah Mellgren’s farm from the beginning of their career until today.

Adam and Sarah and their three children milk 70 cows and manage 350 acres of crops on their farm near Zumbro Falls. This year, they are being honored as the Wabasha County Farm Family of the Year.

“All dairy, all the time”™

Online: 2834-6203

Published by Star Publications LLC

Mark Klaphake - mark.k@dairystar.com

320-352-6303 (ofce)

320-248-3196 (cell)

320-352-0062 (home)

Ad Composition - 320-352-6303

Nancy Powell • nancy.p@dairystar.com

Karen Knoblach • karen.k@star-pub.com

Annika Gunderson • annika@star-pub.com

Editorial Staff

Jan Lefebvre - Assistant Editor

320-290-5980 • jan.l@star-pub.com

Maria Bichler - Assistant Editor

maria.b@dairystar.com • 320-352-6303

Stacey Smart - Assistant Editor

262-442-6666 • stacey.s@dairystar.com

Danielle Nauman - Staff Writer

608-487-1101 • danielle.n@dairystar.com

Abby Wiedmeyer - Staff Writer

608-487-4812 • abby.w@dairystar.com

Tiffany Klaphake - Staff Writer

320-352-6303 • tiffany.k@dairystar.com

Amy Kyllo - Staff Writer amy.k@star-pub.com

Consultant

Jerry Jennissen 320-346-2292

Main Ofce: 320-352-6303 Fax: 320-352-5647

Deadline is 5 p.m. of the Friday the week before publication

Sales Manager - Joyce Frericks

320-352-6303 • joyce@dairystar.com

Mark Klaphake (Western MN) 320-352-6303 (ofce)

320-248-3196 (cell)

Laura Seljan (National Advertising, SE MN)

507-250-2217 • fax: 507-634-4413 laura.s@dairystar.com

Jerry Nelson (SW MN, NW Iowa, South Dakota)

605-690-6260 • jerry.n@dairystar.com

Mike Schafer (Central, South Central MN)

320-894-7825 • mike.s@dairystar.com

Amanda Hoeer (Eastern Iowa, Southwest Wisconsin)

320-250-2884 • amanda.h@dairystar.com

Megan Stuessel (Western Wisconsin)

608-387-1202 • megan.s@dairystar.com

Kati Kindschuh (Northeast WI and Upper MI)

920-979-5284 • kati.k@dairystar.com

Julia Mullenbach (Southeast MN and Northeast IA)

507-438-7739 • julia.m@star-pub.com

Bob Leukam (Northern MN, East Central MN)

320-260-1248 (cell) bob.l@star-pub.com

A hearing on possible reform of the Federal Milk Marketing Orders is underway near Indianapolis. “The last time we had a big process like this was about 20 years ago,” said Stephen Cain, director of economic research and analysis, National Milk Producers Federation.

“We’ve developed a big package that we think will help the U.S. dairy farmer, but we’re not the only kids on the block; there’s other groups in there that will have different opinions.” This hearing process is expected to last a few weeks. A recommendation from this hearing will likely happen in February or March, and a nal decision is expected next summer.

Common ground in FMMO hearings

EPA, Corps issue new WOTUS denition

According to Russell Group President Randy Russell, the farm bill is facing a few hurdles before it can cross the nish line. Nutrition programs will likely be a point of contention, especially with House Republicans only holding a four-seat margin. “As you pick up Republicans because you make changes to SNAP, you likely lose Democrats, so it’s a real balancing act,” Russell said. Food security is considered national security, and Russell sees that coming up in the farm bill debate.

Helping to ll the gap

Ag InsiderCoBank released a study that considers how beef on dairy genetics is affecting the supply chain and the beef market. CoBank Lead Animal Protein Analyst Brian Earnest said beef-dairy crosses are helping to ll gaps left by the shrinking U.S. beef herd. “We wanted to explore what it means to utilize more common beef genetics in the dairy industry and the effects on the beef supply chain from the cattle feeders to the packing community,” Earnest said. Earnest is seeing more beef-dairy genetics adopted in recent years.

TurnMOST COMPLETE HAY LINE Cut Dry Harvest

Mower Conditioners

Mowers

Repair Hills, MN

Isaacson Sales & Service Lafayette, MN

Fluegge’s Ag Mora, MN

Northland

Farm Systems

Owatonna, MN

Lake Henry Implement Paynesville, MN

Miller-Sellner-Slayton Slayton, MN

Woller Equipment Swanville, MN

A & P Service Wells, MN

Pfeifer Implement Sioux Falls, SD

Grossenburg Implement Winner, SD

Mark's Machinery Yankton, SD

Nominal change in milk production

Milk production in the 24 major dairy states totaled just over 18 billion pounds in July. That’s down 0.6% from one year ago. In South Dakota, milk production rose 7.5% with an additional 14,000 cows added to the state herd. Minnesota milk output is up 0.3% despite a downward trend in cow numbers.

Hastings Creamery reverberates through dairy community

The closure of the Hastings Creamery has left dairy farmers on both sides of the river without a place to sell their milk. “About 14 or 15 producers that are involved with Hastings are from Minnesota, but the majority, 25 or 26, are from Wisconsin,” said Minnesota Agriculture Commissioner Thom Petersen. The Minnesota Department of Agriculture and Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection are trying to nd a home for the milk displaced by the closure, but most dairy processors are already operating at capacity.

The Personal Consumption Expenditures price index rose 3.3% in July. That’s up from 3% in the June report. This rate is down from the peak of 7% last summer, but it remains well below the 2% growth rate sought by the Federal Reserve Bank. The ination rate is being monitored closely as the Fed considers additional interest rate increases.

As Hurricane Idalia hit the Southeast, cream volumes were redirected away from the southern states. As a result, Total Farm Marketing’s market update suggests cream is more readily available. That could keep short term pressure on the butter market.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has announced the members of its Agricultural Policy Advisory Committee. The list includes Michael Dykes of the International Dairy Foods Association and Jim Mulhern of the National Milk Producers Federation. The Agricultural Trade Advisory Committee in Animals and Animal Products mem-

2X8

bership includes Jaime Castaneda of the National Milk Producers Federation, Cassandra Kuball of Edge Dairy Cooperative, Michael Lichte of Dairy Farmers of America, Ken Meyers of MCT Dairies, Patricia Smith of Dairy America and Chad Vincent of Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin.

Sustainably produced

Canola is grown primarily for the oil, but the Canola Council of Canada is also advocating canola meal as part of the dairy ration. CCC Canola Utilization Director Brittany Wood said cows fed canola meal as the primary protein source produce more milk. Canola meal is also promoted as a sustainably produced dairy feed. “We have done some research to look at methane emission when cows are fed canola meal, and we have ndings that support that canola meal-fed cows are producing less methane than when fed other protein ingredients, say soybean meal, for example,” Wood said.

Jones picked for FDA post

Jim Jones has been appointed as the rst deputy commissioner for human foods at the Food and Drug Administration. Most recently, Jones has led his own environmental consulting rm. He previously spent more than 30 years at the EPA.

Honors for Rugg

Minnesota Milk Producers Association presented its Bruce Cottington Friend of Dairy Award to Brad Rugg Rugg was recognized during the State Fair Open Class Dairy Show for his career of service to the dairy industry and 4-H youth.

Trivia challenge

On average, Americans consume 1.4 servings of dairy products every day. That answers our last trivia question. For this week’s trivia, what is a turophile? We will have the answer in our next edition of Dairy Star.

Don Wick is owner/broadcaster for the Red River Farm Network, based in Grand Forks, North Dakota. Wick has been recognized as the National Farm Broadcaster of the Year and served as president of the National Association of Farm Broadcasting. Don and his wife, Kolleen, have two adult sons, Tony and Sam, and ve grandchildren, Aiden, Piper, Adrienne, Aurora and Sterling.

“The timing for me was perfect,” Socha said. “They were looking; I was looking.”

Socha reected back to her time searching for her dream job after college and said she appreciates her connection that remained with the Berning family.

“I knew what I was getting into here,” Socha said. “I worked here throughout high school and during my college breaks. I had worked with David and Mark before and got along with them; I liked how they managed things, making the position here just a good t overall.”

After Socha had been employed at Green Waves Dairy for roughly a year following her college graduation, Volden graduated and was also seeking employment.

“Our other full-time employee was in the process of leaving, and we were trying to ll the position,” Socha said. “I knew Grace was looking for a job, so I told Grace to talk to David about lling that position.”

Although the open position was not exactly what Volden was looking for, the Bernings were willing to adapt the role and shufe responsibilities and job duties in order for the role to t Volden’s passions.

“They were looking for full-time help, so I came back,” Volden said. “Knowing who I was going to be working with was a huge deal for me and was one of the reasons I ended up back here.”

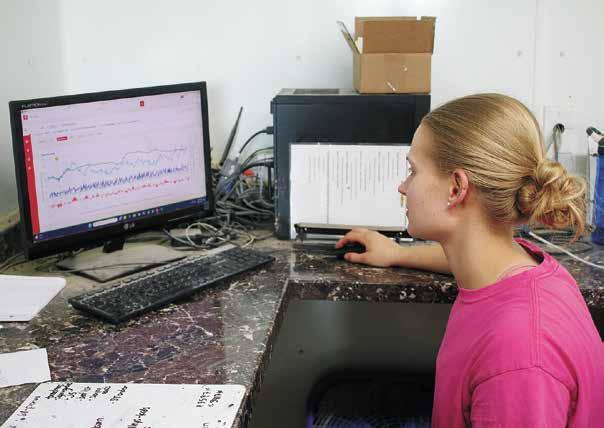

Today, both Socha and Volden work alongside each other on the farm, performing their different responsibilities. Socha manages the cows, milking and the robotic milking system while Volden focuses on calf care and feeding.

“Another reason I came back to this dairy is the size,” Socha said. “The number of cows I get to work with is big enough that I get to work with a variety of cows, but I still get to know all of them.”

The cattle at Green Waves Dairy are milked on eight Lely robots. The youngstock are raised on the farm from birth until roughly 6 months of age. From there, the farm utilizes a local heifer-growing facility where their calves are raised until they are conrmed pregnant at which time they return to the farm.

Volden oversees the care of the young calves up until the point where they are sent to the raising facility.

“Right now, we are kind of on an overll with heifer calves; we have 25 heifer calves this month so far,” Volden said. “They all stay up in the robot barn for about a week, and then they move to the calf barn where they are on automatic feeders.”

Outside of their responsibilities on the farm, the two women have grown a friendship throughout their years of working together.

“We work together, but we are also best friends,” Socha said. “Not many people get the opportunity to work with their best friend every day.”

After having worked together for so many years, Socha and Volden said they truly have grown their friendship alongside their careers.

“Our situation is unique in the aspect that we have worked together in high school, then college and now again after we have graduated,” Socha said.

Volden agreed.

“We truly know each other, maybe even a little bit too well,” Volden said.

Both women are planning to continue their employment at Green Waves Dairy for the foreseeable future and said they are excited to see the continued growth and improvement of the dairy. Socha said she can see the progress the farm has made since she started working there at the age of 15.

“Coming back, it has been so rewarding to see that progress,” Socha said. “When I started, we did not

have any robots, and we milked in a parlor in an old brick barn.”

Socha looks back at that time and remembers the farm’s transition into a robot facility, starting with four units and adding an additional four.

“They have also made a lot of improvements on the calf barn,” Socha said. “They have also made genetic improvements on the cows as well. Watching the herd get better and nding ways to improve and push things to become more efcient and progressive has been truly

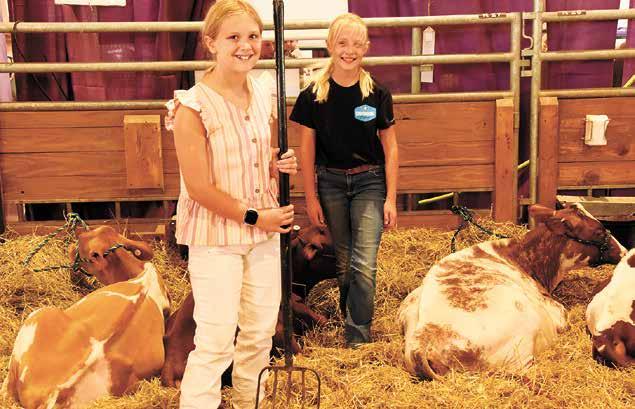

David Berning (from le ), Grace Volden and Maggie Socha gather together June 28 at Green Waves Dairy near St. Michael, Minnesota. The women worked together at Berning’s farm in high school and now work there full me a er gradua ng from college.

rewarding.”

In addition to seeing the progression the farm has made, Volden said she appreciates the opportunities the farm has given her after college.

“The most rewarding aspect of coming back to this farm is being able to apply things that I learned,” Volden

said. “Going to college, sometimes we kind of think we will never use this again, but I have been able to apply a lot of what I learned in school here on the farm.”

In the future, Socha and Volden said they hope to continue to see the farm progress in different aspects.

“We are working to continue improving things on the cows and the calves to raise a more productive and efcient herd,” Socha said. “We hope to continue to be the ones who make the management decisions that would inuence that and keep improving from there.”

Adam moved to their farm with his parents when he was 7. A few years later, his dad passed away, and Adam and his siblings farmed with their mom until 1995. Ten years later, Adam and Sarah purchased the farm.

In 2007, they started milking their cows at Sarah’s parents’, Vince and Sheri Sexton’s, farm because their barn was too outdated.

“We wanted to pay our cows off,” Adam said. “Then we were able to start saving money and nd someone who would work with us who would help us build a parlor and freestall. ... Nobody wanted to loan money to somebody who wanted to milk 70 cows. They thought we were crazy.”

The Mellgrens worked with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Service Agency, and in 2012, they moved their cows home.

Like many other farmers, a low milk price has been the biggest challenge they have encountered. They said they have learned how to ride out price variability.

“It taught us not to borrow money,” Sarah said.

Adam agreed.

“Save, save, save and pay cash,” he said. “Just be patient.”

Daily chores are a family activity at the Mellgren farm. Adam does milking, feeding cows and eldwork. Sarah also does milking. She works with

herd health, oversees calves and does bookwork in addition to her part-time job as a milk inspector for the state of Minnesota.

Emily and Ashley, the Mellgrens’ two daughters, are an integral part of their calf feeding program. They feed calves every day and have developed a keen sense of calf health. Once, when the farm accidentally received incorrect calf feed, it was the girls who identied that multiple calves were sick and that there was a greater problem. Roger, the Mellgrens’ son, also helps feed calves.

Adam said calf care is one of the most important things they do on their farm.

“You don’t take care of your calves right, they are not going to produce for you when they get older,” he said.

The Mellgren daughters have also started becoming involved with sire selection and mating decisions.

“I get them picking out bulls and saying we need this one or that one,” Adam said. “They know how to read a bull book.”

The Mellgrens focus on high-type animals, specically looking at feet and legs and udder as well as making sure the sire’s milk is rated +1,000 pounds or more.

Their herd average for the past seven months has been over 100 pounds of milk per day on two milkings. Through years of focus-

ing on bettering their genetics, Adam said they are starting to see a difference.

“We’ve got some of the best heifers right now that we’ve ever had,” he said. “They look good. They milk good.”

The Mellgrens own Holsteins, which Adam and Sarah grew up showing. Now, their children are carrying on the tradition. Adam said one his favorite things is to relive his showing days through his daughters.

Adam said as soon as the ice is gone from the yard, they may begin walking their animals.

The girls do all their own tting and are good enough that they know their parents are teasing them if they offer to help with a topline. Ashley and Emily even started their own business partnership and own two dairy animals together.

The Mellgrens have extended their delight in showing to lease to other kids as well. Their rst lessee was a teenage employee, and over time, the group has grown. Not only do the Mellgrens lease animals, they also train their lessees with mock cattle shows in their drive-

way complete with cows and a judge. Cattle shows, mock or otherwise, are not the only things the family does together. Adam installed a LED light on the shop by the basketball hoop, so the girls can shoot hoops as long as the weather is above freezing. Many summer evenings nd the family playing catch after chores, driving a mile into town to play baseball in the park or shooting hoops.

“We eat supper late a lot of nights because we’re outside after chores doing something fun instead of working,” Adam said. Adam would like to have the farm acquire more land to set up the children if they would like to farm someday. Currently, the Mellgrens own about 51 acres and rent the rest of the 350 acres they manage.

The girls have dreams of eventually having a show barn and want to take their cows to World Dairy Expo. Adam said their genetics are getting close to the point where they could begin to see a prot from the investments they have made.

Though growth for the show side of their operation is on their minds, Adam also remains committed to the same nancially sustainable, slow growth that has dened the Mellgrens’ career up to this point.

I don’t want to just jump in, borrow money,” he said. “We’re doing it a little bit at a time.”

ing dairy farm numbers since 1983 when the checkoff was started, it is impossible to say this program helped the dairy industry.”

Olson milks 30 cows near Black River Falls and is the president of the Dairy Pricing Association. His proposal is an extension of what DPA does on a regular basis. Based in Taylor, DPA has been buying and donating dairy products since 2011. The money raised by this dairy farmer-funded group comes from approximately 200 members in 10 states.

DPA is a grassroots, voluntary dairy farmer organization that uses producer assessments to purchase excess dairy products from the marketplace. These products are then donated to humanitarian causes that do not displace existing sales. DPA is a regular, active buyer in the daily cash-traded block cheddar cheese market, which the group sees as a benet to milk checks across the nation.

DPA’s mission is to promote domestically produced dairy products and establish the minimum price the dairy industry receives for its production. At the same time, they maintain a level of milk production to meet the needs of the consumer.

“The need for dairy products for use in food banks across the nation is unbelievably large,” Olson said. “The dairy donation program that started during (the pandemic) has ended and left a lot of low-income people struggling to keep dairy in their family’s diet.”

After the program ended, Olson received a call from the Jackson County housing and urban development program which was looking for more donations of dairy products.

“Some of the people they serve are handicapped or elderly, and all are low income,” Olson said. “They’re all on a real tight budget and have to choose how to spend money, whether it be on food or medicine.”

As a result, DPA bought and sent 534 pounds of cheddar cheese to Jackson County in July. The county has 90 recipients who qualify for the HUD program.

“They were really happy to get the cheese,” Olson said. “It made these people’s day.”

When stores remove dated products from the dairy case, Olson said low-fat and non-fat milk is what does not sell and is then donated. Under his proposal, farmers would have the ability to donate 11 million gallons of whole milk or a whole array of dairy products to food banks and soup kitchens annually.

“Food banks have different needs across the nation, but they all have one thing in common and that is the need for dairy products,” Olson said.

“When I look at what food banks receive for donations, the thing I see that is in short supply is whole milk.”

Under Olson’s proposal, the parent food bank would oversee distribution of money to local food banks and soup kitchens with this money earmarked to be used for dairy products only. Producers in every state would choose where the 2 cents is sent and would also have the choice to pull it from their state checkoff or national checkoff.

“Checkoff dollars would be diverted for a better use under my proposal,” Olson said. “It’s going to move a lot of dairy product versus what the money is doing now. Right now, it’s pretty much just advertising. But it’s a form of advertising too when you’re getting milk, cheese, yogurt and ice cream in front of people.”

Olson was invited to the Congressional Agriculture Committee Meeting held in La Crosse Aug. 16. The hearing was a listening session with members of Congress on farm bill priorities to learn what farmers would like to see changed in a farm bill. Olson’s proposal was sent home with members of Congress that day. The proposal is also being sent to all 51 members of the House ag committee.

“This proposal can stand alone,” Olson said. “It doesn’t have to be done through the farm bill.”

DPA is looking for signatures of support for the Dairy Checkoff Reform Proposal to present to Congress. Dairy producers and consumers can sign the proposal on DPA’s website.

“We hope to get as many signatures as we can,” Olson said. “I urge dairy farmers to sign this proposal and help put our checkoff dollars to good use.”

Advanced kernel processing is the secret to a perfect dairy dinner. Experience KP Rolls with square-edged tooth engineering. They serve up the feast—fair and square.

Editor’s note: Dairy Star aims to provide our readers with a closer look into relevant topics to today’s dairy industry. Through this series, we intend to examine and educate on a variety of topics. If you have an idea for a topic to explore in a future issue, send Stacey an email.

HARLAN, Iowa — After nearly two decades of trying to legalize the sale of raw milk in Iowa, supporters of this legislation nally saw success July 1.

On that day, farm-to-consumer sales of raw milk in liquid form became legal in the Hawkeye State.

“It was high time this type of legislation be passed,” said Esther Arkfeld, who owns and operates De Melkerij micro-dairy near Harlan. “Raw milk has nally become a topic that can be openly discussed. Now that laws have changed, this opens things up for us, and our customers are much happier.”

Working closely with Sen. Jason Schultz, who had been leading the raw milk bill for 17 years, Arkfeld played a role from a grassroots perspective in helping that legislation pass.

717.354.5040

“It’s more of a people’s bill allowing that neighbor-to-neighbor transaction; it wasn’t a producers’ bill,” Arkfeld said. “This bill would not cover larger producers, but the law does allow small farms to be able to meet a niche demand.”

The law in Iowa states that a herd can only have 10 active lactating animals. Arkfeld milks four A2A2 Jerseys and has been running a herdshare program for about 1.5 years. Customers buy shares of a cow, and each share entitles a person to 1 gallon of raw milk each week. Customers can purchase multiple shares or half shares. They also pay a monthly boarding fee for every share to pay for the care of their cow.

Arkfeld has more than 20 customers, and each one buys anywhere from 1 to 3 gallons of milk per week. Arkfeld doubled in size from two to four cows around the time the legislation passed.

“We’re very small in the dairy world, but our biggest objective is quality over quantity,” Arkfeld said. “I have a long waiting list and could add to my herd and be up to 10 cows, but I want to make sure our quality doesn’t suffer. I don’t want to overextend ourselves.”

• The highest air ow in a circulation fan - 33,900 CFM.

• Cast aluminum blades have a lifetime warranty.

• Totally enclosed maintenance free, high ef ciency motors have a full two year warranty.

Model VP CA: Belt Drive, 1 HP, 115/230 volt, 9.6/4.8 amps single phase one speed 587 rpm

To ensure the milk she sells is safe for human consumption, Arkfeld follows strict protocols. Under mentorship of the Raw Milk Institute, she has put a risk analysis plan in place and conducts bacteria testing multiple times per month to ensure her processes are working. Yearly health testing of animals and proper veterinary care are also part of the puzzle, she said.

“The Raw Milk Institute is a wonderful resource whether you’re milking just one cow for your family or milking 600 cows,” Arkfeld said.

Arkfeld’s farm is currently the only Raw Milk Institute-certied dairy in Iowa.

“I comply with their certication and testing requirements,” Arkfeld said. “Our Iowa law has incorporated testing requirements, but mine are a little stricter.”

On Aug. 1, on-farm raw milk sales became legal in North Dakota as well. Like in Iowa, farms are free to sell milk directly to the customer for his or her own personal consumption. The bill was sponsored by Rep. Dawson Holle. Holle and his family milk 900 cows on their fthgeneration dairy farm near St. Anthony. Holle believes the new law presents opportunities to North Dakota’s dairy farmers.

“It opens the area of family farms to be scalable once again,” Holle said. “You don’t have to have a 1,000-cow dairy; you can have a 100-or-less-cow facility.”

Holle said he has seen raw milk sell for $15 to $20 per gallon.

“You don’t need that many cows when producing raw milk,” he said. “It cuts out the middleman and just benets the customer and farmer. The farmer gets as much bang for their buck.”

According to the North Dakota Department of Agriculture, as of July 1, there were 33 Grade A dairy farms in North Dakota.

“The number of dwindling farms in North Dakota is another reason I introduced this bill,” Holle said. “We lose one to two farms every year, and we have to do something about it. That’s one of the reasons I decided to get involved in legislation in the rst place.”

Before raw milk sales were legal in North Dakota, the state offered a herdshare program.

“That idea is not really scalable,” Holle said. “You either do a herdshare program or sell your milk to a processor. There was no area for any of those small-town farmers wanting to milk 10 to 40 cows. There was no way to make money.”

When over 50 people came to testify in favor of raw milk at a hearing, Holle said he knew the demand for this product was large.

“These people drank raw milk and thought it was crazy you can’t buy it unless you own a share,” Holle said. “I saw this raw milk movement taking place. The support it had was amazing.”

Holle also sees the legalization of raw milk as a benet to the small-town community.

“When people realize their food is shipped from out of state or from different parts of the state into their local towns, they want to do their part to support the area surrounding them,” Holle said. “If they are supporting local dairy farms, then hopefully the community as a whole will see a rise in economic activity.”

Drinking raw milk comes with potential risks, and many public health experts discourage its consumption.

“There are many different bacteria and parasites in raw and unpasteurized milk, and some can be very serious, even fatal,” said Dr. Joni Scheftel DVM, MPH, DACVPM. “This is why we recommend milk be pasteurized because it kills all the pathogens that can make you sick.”

Scheftel is the state public health veterinarian at the Minnesota Department of Health and supervisor of their Zoonotic Diseases Unit. Scheftel said the most common bacteria people get from drinking raw milk is Campylobacter, which causes fever and diarrhea. About 20% of people with this infection are hospitalized, but deaths are rare.

The most serious bacteria found in raw milk is E.coli O157, Scheftel said. The effects of this bacteria are often most detrimental to children who encounter it.

About 34% of people with E.coli O157 are hospitalized. Approximately 14% of children less than 5 years of age and 9% of children 5 to 9 years of age go on to develop a serious complication called Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. HUS results in destruction of red blood cells and kidney failure, potentially requiring blood transfusions, dialysis and kidney transplants. Some children do not survive.

Parents whose children were in the hospital with HUS infections have told Scheftel statements such as, “I thought I did my homework. I thought I understood the risks, but I never knew how sick my child could get from drinking raw milk.”

“I’ve heard those words many times,” Scheftel said. “No matter how clean a farm is or how careful farmers are with their equipment, these germs are a natural part of cow manure and may accidentally get into milk. This is why we pasteurize milk — to make it safe to drink.”

Although she does not recommend people drink raw milk, Scheftel said she is not against the raw milk law in Minnesota which allows on-farm sales.

“If you want raw milk, you can go to a farm and pick it up,” Scheftel said. “This limits the number of people consuming raw milk, and the law is fair, because there is such a strong demand for it. However, I would be totally against the sale of raw milk at the retail level.”

In both Iowa and North Dakota, raw milk may not be sold at the retail level as it is in some states, such as California and Pennsylvania.

In Iowa, Arkfeld plans to continue with her herdshare program rather than selling direct to the consumer.

“Herdshare allows me to know how much milk to produce because I know how much milk my customers need

each week,” Arkfeld said. “They know it’s going to be as fresh as possible. We always have extra milk, so we might expand and sell a few gallons here and there.”

Arkfeld said many of her customers could not consume pasteurized dairy but found they are able to consume raw dairy.

“By no means is one better or worse than the other,” she said. “I believe there is room for both and a need for both.”

Growing up in Europe, Arkfeld said it was ne to drink raw milk.

“It was no big deal,” she said. “But when we moved to the U.S., we found things are very different.”

In Wisconsin, proposals like those in Iowa and North Dakota have come through over the past 15 years, but they were never passed. Wisconsin does not allow on-farm sales of raw milk, except at the incidental level.

Wisconsin Statute 97.24 prohibits the sale or distribution of non-Grade A milk to consumers, and states that Grade A milk must be pasteurized, which has been the law since 1957.

However, Wisconsin does allow incidental sales of raw milk directly to a consumer at the dairy farm where the milk is produced, for consumption by that consumer (or the consumer’s family or nonpaying guests). But those sales are also illegal if done as regular business or if they involve advertising of any kind.

“Fortunately, lawmakers and governors of two different parties have realized the signicance of Wisconsin’s nearly $50 billion dairy industry and the potential damages a raw milk outbreak could cause that industry,” said Shawn Pfaff, independent contract lobbyist and president of Pfaff Public Affairs.

A former spokesperson for the previously active Wisconsin Safe Milk Coalition, Pfaff was part of the effort to defeat proposed raw milk legislation in the state in 2015. Prior to that, Gov. Jim Doyle vetoed legislation to legalize the sale of raw milk in 2010, which was shot down again in 2013 by Gov. Scott Walker.

“It’s impossible to make an unsafe product safe,” Pfaff said. “There’s a reason we have pasteurization. It kills the bacteria found in milk, making it a safe product to drink.”

Scheftel said that bacteria in milk today is more virulent and resistant to antibiotics compared to bacteria of the past, increasing the likelihood that it will cause serious illness in people. An example is E.coli O157, which did not exist before 1982.

Every year, 60 to 80 cases of sickness caused from consuming raw milk pop up in Minnesota. But Scheftel said this is a gross undercount and only includes people who went to the doctor, had the organism cultured, reported they drank raw milk and agreed to be interviewed.

“The number of people who get sick each day from drinking raw milk is much higher than those we can identify,” Scheftel said.

Of the people interviewed, Scheftel said nearly 40% are less than 10 years of age. Among children less than 5 years of age who got sick from drinking raw milk, she said 76% receive the milk from their own farm or a relative’s farm.

“There is no safe raw milk,” Scheftel said. “My recommendation is to drink pasteurized milk on and off the farm.”

For Arkfeld, her journey into milking cows and drinking their raw milk began six years ago when she discovered her daughter could not consume pasteurized milk.

“Dairy products have wonderful nutritional benets, and when we found that raw milk outlet, we were able to provide my daughter with good nutrition,” Arkfeld said.

Despite the possible dangers that drinking raw milk can present, a demand for this beverage does exist, and Arkfeld said she goes above and beyond to ensure its quality.

“Your end customer is going to consume raw milk the way you produce it, and you have to make sure you do it in the best, most proper and caring way possible,” Arkfeld said.

We utilize the Johnes test, standard plate count, somatic cell count, and mastitis culture tests.

Which is your favorite and why? I like the somatic cell count test to see if there are certain cows that have a chronic high

How does testing with DHIA bene t your dairy operation? DHIA bene ts the dairy by being an independent source helping us make decisions regarding herd health and productivity.

Tell us about your farm. I farm here with my brother, Perry, and my sisters, Brenda and Becky. We are a second generation family farm. We raise our youngstock, nish out our dairy steers, and farm about 900 acres.

father, Melvin; and his father before him.

“I don’t want to give the farm up to somebody else,” Goebel said. “It’s always been in the family name. I’m hoping to hit 100 years here.”

The determined teenager has plans to someday erect a freestall barn with a robotic milking system to expand the herd to include 120 cows.

—

Tanner Goebel was posed the question as a kindergarten student. His answer — a dairy farmer — has never wavered.

“I knew this would be my lifestyle someday,” said the 18-year-old from Freeport. “It gets to be long somedays, but I really enjoy it.”

Goebel, who graduated from Melrose Area High School in June, plans to farm full time alongside his parents, Dale and Brenda, on their 55-cow dairy farm in Stearns County.

While Goebel’s friends from high school might be pursuing a trade in welding or construction, or going off to college, he has found contentment returning as the fourth generation of his family to farm their site. Goebel follows an eight-decade tradition started by his greatgrandfather, Robert; grand-

The Goebels milk in a 55cow tiestall barn. Together, father and son work to complete each day’s tasks. For milking, Goebel washes the teats and applies the pre and post dips, and Dale attaches units. The arrangement has been that way for over a decade.

Afterward, Goebel mixes the herd’s total mixed ration that Dale then feeds. During this time, Goebel cleans the barn and feeds calves. Goebel is also involved with eldwork during the growing season.

“Dad has really taught me to make sure you are keeping up with your cows every day,” Goebel said. “Keep a good milking time schedule, and if you maintain your cows well, they will do good for you. If you don’t comfort them and give them everything they need, they will start going backward.”

Dale’s mentorship has served Goebel well as he plans to work for his parents

before slowly transitioning into ownership of the farm’s livestock and machinery.

“Dad also said don’t

stress out about the crops and the weather,” Goebel said.

“There is nothing you can do about it.”

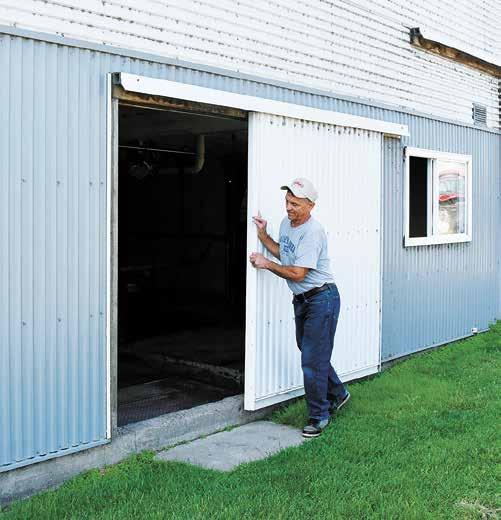

Currently, the Goebels are upgrading their calf barn. Previously, calves were housed as groups in pens, which were pitched out by hand. This fall, the 56- by 50foot barn will be completed and used to house calves up to 5-6 months old.

Goebel is driven by the family’s cows.

“Going out in the morning to milk the cows, see the milk production and knowing the cows are going to make you money just makes me happy,” he said. “I’m happy being with the cows and seeing how they are improving.”

The Goebels breed for milk production but also focus on butterfat and protein content, teat length and spacing, legs and stature.

“We have a family of cows that will always be sticking around,” Goebel said. “They have been good producers over the years.”

Goebel aspires to learn to A.I. so that he can further put his skills to use on the farm.

That mindset to learn has helped shape Goebel’s character.

“I’ve learned a lot in high school with my shop and my ag classes,” he said. “I’ve learned how to build things in woods class and how to weld stuff. I also learned how to identify soil types, how your crops should be rotated and how to put your fertilizers on the eld.”

His main teacher through the years has been his dad. Dale has taught Goebel valuable lessons from a young age, like how to read and balance feed rations as well as analyze feed results. Dale also taught Goebel how to read somatic cell count results, which led to learning how to balance the economics of keeping a cow versus culling those cows that are losing the farm money.

“I check the milk sheet to see if the cows were up or down in milk,” Goebel said. “Usually, I check every other day on my phone to see the butterfat content.”

If Goebel sees numbers going in a negative trend, he monitors the feed in front of the cows to check for moldy corn silage or hay. The inquisitive part of Goebel’s personality helps in his career path as a dairy farmer.

“If I want to get something done, even if it’s going to be a little bit of a struggle, if I put my mind to it, I will get it done,” Goebel said.

Goebel said he is looking forward

to fall on the farm. Hauling boxes full of fresh-cut silage and lling the silo puts a smile on his face.

“It’s rewarding when you are sitting in the tractor relaxing, knowing that you have the harvest done and you can sit back and relax until spring,” Goebel said.

He has also learned to face the challenge of days that do not go as planned.

Last fall, when the Goebels were chopping corn silage, the radiator quit working on a tractor. Goebel was able to repair a few hoses to make it operational. After a time, the fan, belt and all the bearings had to be replaced.

“I told Dad, ‘Let’s see if we can do it ourselves,’” Goebel said. “I put all the new bearings and bolts in, and within four hours, we had the tractor up and going again. That was a really good day, knowing that we xed it and got back to chopping.”

Now, when posed a question about the strenuous workload of a dairy farmer, with work that never quits, Goebel is as enthusiastic as he was as that elementary boy years ago.

“A successful day to me is getting up in the morning to milk cows, then going out in the eld and getting a bunch of work done and coming back to milk the cows and then coming in and eating supper, sitting down with the family and relaxing,” he said. “It’s worth it.”

Health Report

Flags animals falling below optimal health; track condition progress

Breeding Report

IDs animals in heat by Breeding

Window & Heat Index

Tags Maintenance Report Alerts you to tags not read by the system & abnormal readings

Group Routine Report

Provides insight into daily routines & herd activity

Group Heat Stress Report

Displays current status & trends of behavior (panting, ruminating, eating)

Tell us how you became involved in hauling milk. It is the family business. My great-grandpa started the business, Ahrens Trucking, back in 1938. From there, my grandpa did it, my dad did it, and now I am trucking.

Tell us about a typical day. I typically start between 3:30-4 a.m. and stop at anywhere from ve to nine farms. It takes about an hour to get to the plant; then I unload and go back out and get another truckload. I haul to First District Association. I always get two truckloads a day, and my truck has a 6,500-gallon tank. I get home each day between 4-5 p.m.

What do you enjoy about your occupation? I like getting out to the farms and talking to the farmers. I’ve been with the same families for so long that now these guys are like family. I see them all the time; it’s fun getting to know them and their families.

What are the biggest challenges with hauling milk? The biggest challenge for me is the work-life balance. Just like dairy farming, it’s a very demanding job. You have to be there all the time, and it’s hard to get days off.

What is your favorite time of year to haul milk? I would have to say the fall because of the cooler weather and the roads aren’t bad yet. It’s more comfortable to work in.

Tell us about a unique time when you had trouble hauling and how you overcame it. Nothing specic, but the icy roads in the winter are the worst. I am out before the plows and salt trucks are out and drive in the freezing rain and snow. I take a lot of back roads, and there have been a couple of time I am whiteknuckling it while trying to get to these farms.

What things are essential for you to have when there is a busy day ahead? Coffee is the biggest thing; that is essential. I also listen to podcasts, some trucking podcasts, Joe Rogan or whatever I can nd.

What do you enjoy doing in your spare time? When I do get spare time, I like to go snowmobiling, hunting and shing. I also try to spend as much time with the family as I can because I am on the road so much. That would be my favorite thing to do — spend time with the family.

Tell us how you became involved in hauling milk. My father hauled can milk, and I grew up in the business. My father had 50-plus years, I have 50-plus years, and my son Chad has 20-plus years in the business.

Tell us about a typical day. I start my day around 3 a.m. and am done between 2-5 p.m. depending on where I deliver to. I haul 6,500 gallons on a load. I have three to ve stops on a load. I haul for nine producers. I drive a 2018 Freightliner truck with a 6,500-gallon tank.

What do you enjoy about your occupation? I always have been involved in agriculture, and I enjoy seeing my farm friends who I haul for.

What are the biggest challenges with hauling milk? The hours have gotten longer and the miles are further. The Department of Transportation has gotten more involved in running the business. Not many people want to do this because of the commitment of time, hours and days, so it is harder to nd help.

What is your favorite time of year to haul milk? Fall is my favorite time to haul. Winter is too harsh, summer is too hot, and spring is too muddy.

Tell us about a unique time when you had trouble hauling and how you overcame it. I left one morning as usual, but I wasn’t feeling 100%. It was not long, and it got worse. I did some early morning calls, and luckily an old retired milk hauler friend was able to take over for me. It turned out that I had appendicitis and had to stay in the hospital a couple of days.

What things are essential for you to have when there is a busy day ahead? I try and nd a radio station that keeps my interest or talk to someone on my headset to keep my mind awake. I always have water and coffee with me and snacks for the day.

What do you enjoy doing in your spare time? Relaxing and spending time with the family.

Chris Bauer Melrose, Minnesota Millwood TransportFour years of experience

Tell us how you became involved in hauling milk. Chad Stevens, who also works for Millwood Transport, approached me after I got my CDL in 2019. I’ve been driving ever since.

Tell us about a typical day. I leave for work around 11 p.m. and get home normally around noon. I make an average of 12 stops throughout the day and usually bring three truckloads in the plants, averaging about 52,000 pounds of milk. I drive a seven-axle straight truck that can hold around 56,680 pounds.

What do you enjoy about your occupation? Getting to work by myself. I can set my own schedule and start and end when I need to.

What are the biggest challenges with hauling milk? Winter weather and route changes. Driving in the winter, you never know what you are going to get for road conditions. I drive at night, which adds to the difculty of driving in the winter.

What is your favorite time of the year to haul? Summer because the roads are always good. No ice, no snow; need I say more?

Tell us about a unique time you had trouble hauling and how you overcame it. One winter, I slipped into the ditch while backing into a farmer’s yard. I had to go wake up the farmer in the middle of the night to pull me out.

What things are essential for you to have when there is a busy day ahead? For me, it’s a busy night, but a cell phone and Mountain Dew are a must. A phone to connect to other people, friends, co-workers, family and in case of emergency. Mountain Dew to help me stay awake all night.

What do you enjoy in your spare time? Farming. My dad and I own a herd of 180 beef cattle and farm a few acres of hay for the beef cattle near Melrose. This is my home farm, and similar to trucking, I enjoy farming because you can set your own schedule. Trucking and farming are both things that need to get done every day, but I can adjust my timing if needed.

Tell us how you became involved in hauling milk. Calvin Carls asked me to come and drive, and I told him I would give it a shot. It was a truck and pump trailer that held over 50,000 pounds. I liked it because I was home every night. I had previously worked road construction but was gone from home too often. The milk hauling is good because I am home every night.

Tell us about a typical day. Our trailers will hold 55,000 pounds. When I started, I was hauling two loads a day at 52,000 pounds per load, and I had 12-13 farms on each load. Now I only have 11 farms, and I am hauling 8-10 loads, which is over 300,000 pounds a day. When I rst started, it was 5-5:30 a.m. to 6-7 at night, and it’s roughly about the same now. Sometimes I am up at 1 a.m. and haul until 3 in the afternoon. It jumps around a little bit. Right now, I am using three semitrucks that I own. I also own three trailers, and First District Association owns the rest. We park some of the trailers on the farms. We have six trailers that sit on two farms.

Randy Tiedeman

Randy Tiedeman

Flandreau, South Dakota

Leased with Van’t Hof Milk Hauling of Edgerton, Minnesota

Lifetime of experience

Tell us how you became involved in hauling milk. I began to ride in my dad’s milk truck in 1963 when Dad hauled cans of milk for Hull Creamery in Hull, Iowa. We moved from Hull to Lake Benton, Minnesota, in 1973, and I began to drive a can milk truck for Dad when I was a junior in high school. I moved to Flandreau in 1988 and started my own milk hauling business. I now own four trucks and have ve employees including my son, Tyler.

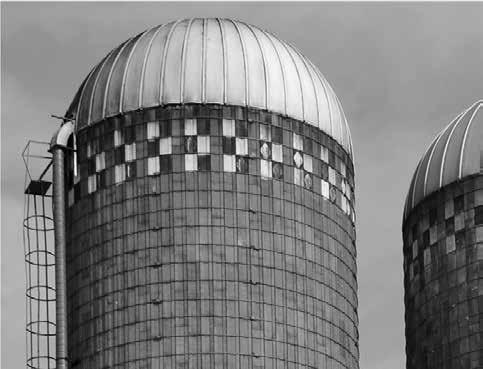

Tell us about a typical day. The time when we start our days can vary quite a bit. The day can begin as early as 6 a.m. or as late as 5 p.m., depending on what we have scheduled. All of our milk pick-ups are one-stop loads. We generally load out of a silo and haul about 7,500 pounds of milk. There are usually about four loads of milk in a silo. I have driven over 3 million miles and have never gone more than 100 miles from home. I am looking forward to breaking in my brand-new Freightliner.

What do you enjoy about your occupation? I have enjoyed making friends with the people we serve. It has been fun seeing dairy farmers’ kids grow up. It seems

What do you enjoy about your occupation? I have always like to truck. I like to talk to the farmers.

What are the biggest challenges with hauling milk? The biggest challenge is the weather in the winter, and nding help is another one. Trying to line up good help is hard now. There are not many guys who will drive weekends. The milk has to be picked up every day, and the young kids don’t want to work the weekends. The state requires you to go to school to get a commercial driver’s license, and it costs $2,000-$6,000. A lot of these kids can’t afford that or don’t want to pay the price.

What is your favorite time of year to haul milk? I like hauling during the summer and the fall because I get to watch the crops grow and be harvested.

Tell us about a unique time when you had trouble hauling and how you overcame it. We tipped a truck over 8-10 years ago. We pumped the milk into another trailer, but it wrecked the whole rig. It totaled out the rig, so I had to go buy a new truck and trailer. Nobody got hurt, so that was the main thing. The driver just got too close to the edge of the road, and the weight pulled the truck in.

What things are essential for you to have when there is a busy day ahead? I listen to the radio and the news, but you have to pay attention to the trafc. The day goes pretty fast. I like coffee, peanuts or Skittles just to stay awake. Skittles are my favorite.

What do you enjoy doing in your spare time? I like going north to go fourwheeling, and I like to ride my Harley Davidson. I don’t get to do much because we are working so much.

like I’ve spent more time with them than my own kids. There’s nothing like being out on the road on a sunny morning in a nice, shiny truck.

What are the biggest challenges with hauling milk? Winter weather is by far the greatest challenge. I can’t remember my wife’s birthday but can clearly recall every blizzard that I have been in. During my rst 28 years of hauling milk, there were only four days when I wasn’t able to go out. When we see a blizzard in the forecast, we will haul milk from our dairy farms ahead of schedule in an effort to make more room for them.

What is your favorite time of year to haul milk? Every season has its pluses. I like spring because it means that winter is over. I like summer because you can smell curing hay when you drive through the countryside. I like fall because everything is crisp and clean. I can’t say much good about winter.

Tell us about a unique time when you had trouble hauling and how you overcame it. One winter day following a blizzard, I went down an unplowed road, thinking that I could open it. I was wrong; I got stuck about 100 yards from the next intersection. Fortunately for me, a friend happened to come along just then with his payloader and was able to get me out.

What things are essential for you to have when there is a busy day ahead? I couldn’t drive without a radio. I like to listen to classic country and the ‘70s on 7 on Sirius XM radio. A radio and a cold Pepsi are all I need.

What do you enjoy doing in your spare time? I like to go shing on the Missouri River near Gettysburg, South Dakota. My wife and I also enjoy spending time with our eight grandchildren. We make a point of attending their school programs and sports activities.

Describe your farm and facilities. We are a fourthgeneration dairy farm. We have a 300 cow freestall barn with slatted oors, and we milk in a double-8 parallel parlor. Our herd is comprised of crossbred cows.

What forages do you harvest? We harvest alfalfa and corn silage.

How many acres of crops do you raise? We have 1,400 acres, and we raise

corn, soybeans, wheat and alfalfa.

Describe the rations for your livestock. Our ration includes 50 pounds of corn silage, 14 pounds of a vitamin-mineral mix, which includes 4 pounds of dry corn; 8 pounds of high-moisture corn, 8 pounds of baleage and 7 pounds of dry hay.

What quality and quantity do you harvest of each crop? We raise 195 acres of

The Gjerdes harvest baleage at 25%-40% moisture on their dairy. They have 195 acres of alfalfa.

alfalfa and take four crops per year. We do baleage and try to harvest that at 25%40% moisture. We harvest

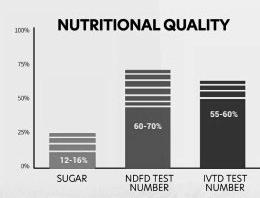

4,500 tons of corn silage, and we harvest at 65%-70% moisture. We also harvest 20,000 bushels of high- Turn to FORAGE | Page 20

moisture corn at 25%-35% moisture.

“We have been using Udder ComfortTM a long time. Today, we use the Udder Comfort Battery-Operated Backpack Sprayer to apply it quickly and easily on all animals in our fresh groups daily,” says Britney Hill (above), herd manager and part of the next generation operating Four Hills Dairy, Bristol, Vermont. They milk 2300 cows, calving 10 animals a day, applying Udder Comfort to fresh groups daily for a 5-day course. They also love Udder Comfort for their award-winning show cows.

“With the Udder Comfort Battery-Operated Sprayer, we can do all in our fresh groups without slowing our parlor throughput,” Britney reports.

“It’s convenient, efficient, easy to maneuver, and the battery charge lasts,” she says.

“With Udder Comfort, our fresh cows are more comfortable, and our fresh heifers adjust to milking much faster with better letdown. Doing all in our fresh groups helps keep our SCC around 130,000,” Britney explains.

“Fresh heifers adjust to milking much

- Britney Hill

Describe your harvesting techniques for alfalfa and corn silage. The corn silage is done with a John Deere self-propelled chopper with a kernel processor. The alfalfa is done with a John Deere round baler with a precutter.

What techniques do you use to store, manage and feed your forages? Our corn silage is on a cement pad and covered with a vapor barrier and a 2-mil tarp. Then it’s covered with tire sidewalls. All the corn silage has inoculant applied. The baleage is precut with the baler and wrapped with a bale wrapper. Our highmoisture corn is run through a hammermill and bagged. The feed is fed with a total mixed ration mixer.

How does quality forages play in the production goals for your herd?

The better quality feed we can put up the easier it is to achieve our goals.

What are management or harvesting techniques you have changed that has made a notable difference in forage quality? It was getting hard to put up good dry hay so we switched to baling wet hay.

The Gjerdes chop corn Aug. 31 near their farm by Sunburg, Minnesota. They chop around 4,500 tons of silage at 65%70% moisture.

Describe a challenge you overcame in reaching your forage quality goals. We’re not hiring for chopping hay, which is nice, but we had to buy more hay equipment, a baler with a precutter and a bale wrapper.

JD

Sep. hrs., #554050 ..................................... $405,000

JD S770 2018, 2261 hrs., 1652 Sep. hrs., #549678 ................................. $259,900

JD S760 2019, 1206 hrs., 871 Sep. hrs., #565714 ................................... $279,900

JD S690 2017, 1433 hrs., 1187 Sep. hrs., #549457 ................................. $280,700

JD S690 2017, 2104 hrs., 1461 Sep. hrs., #552684 ................................. $249,900

JD S690 2017, 2508 hrs., 1605 Sep. hrs., #568113 ................................. $239,000

JD S690 2015, 2400 hrs., 1615 Sep. hrs., #550872 ................................. $232,900

JD S690 2016, 2544 hrs., 1820 Sep. hrs., #547267 ................................. $219,900

JD S690 2012, 2314 hrs., 1645 Sep. hrs., #551148 ................................. $149,000

JD S690 2014, 2280 hrs., 1440 Sep. hrs., #568112 ................................. $139,000

JD S680 2017, 1516 hrs., 1053 Sep. hrs., #273646 ................................. $219,900

JD S680 2014, 2349 hrs., 1668 Sep. hrs., #531966 ................................. $195,000

JD S680 2014, 2328 hrs., 1575 Sep. hrs., #555096 ................................. $169,900

JD S680 2013, 2485 hrs., 1604 Sep. hrs., #551147 ................................. $165,000

JD S680 2013, 2575 hrs., 1906 Sep. hrs., #563909 ................................. $160,000

JD S680 2012, 1493

JD S660 2012, 1643 hrs., 1188 Sep. hrs., #554132 ................................. $179,900

JD 9870 STS 2011, 3650 hrs., 1750 Sep. hrs., #567383 .......................... $109,900

JD 9870 STS 2008, 3261 hrs., 2494 Sep. hrs., #566621 ............................ $97,500

JD 9870 STS 2009, 3579 hrs., 2579 Sep. hrs., #563914 ............................ $94,500

JD 9860 STS 2005, 4528 hrs., 3240 Sep. hrs., #564977 ............................ $59,900

JD 9860 STS 2004, 3924 hrs., 2537 Sep. hrs., #559820 ............................ $55,000

JD 9770 STS 2010, 2058 hrs., 1558 Sep. hrs., #567790 .......................... $120,800

JD 9770 STS 2009, 3095 hrs., 2350 Sep. hrs., #568125 ............................ $99,900

JD 9750 STS 2003, 5105 hrs., 3367 Sep. hrs., #565004 ............................ $37,500

JD 9670 STS 2010, 2525 hrs., 1667 Sep. hrs., #566916 .......................... $114,900

JD 9650W 2000, 3680 hrs., 2665 Sep. hrs., #568122 ................................ $45,000

JD 9570 STS 2011, 2019 hrs., 1231 Sep. hrs., #555820 .......................... $132,500

JD 9570 STS 2009, 2367 hrs., 1597 Sep. hrs., #556547 .......................... $104,900

JD 9560 STS 2004, 4638 hrs., 2982 Sep. hrs., #567094 ............................ $52,500

JD 9600 1995, 4000 hrs., #568110 ........................................................... $28,900

JD 9600 1991, 5313 hrs., 3614 Sep. hrs., #567724 ................................... $24,900

Case IH 2388 1998, 3876 hrs., 2943 Sep. hrs., #549406........................... $34,900

Pickett Twin-Master 2019, #553918 ................................................... $187,000

Has been a quality market for MN dairy farmers for over 100 years. MN producers provide one of the country’s most distinctive brands of cheese that is still made using the same Old World craftsmanship and has been combined with cutting-edge technology to produce cheese that delivers unforgettable taste with unparalleled quality. MN Dairy farmers and Bongards, quality that stands the test of time. We offer a competitive base price, premiums, and the best eld representatives in the industry.

United

Systems, Inc. West Union, IA 563-422-5355

Monticello, IA 319-465-5931

WISCONSIN

Advanced Dairy Spring Valley, WI 715-772-3201

Ederer Dairy Supply Plain, WI 608-546-3713

DeLaval Dairy Service

Kaukauna, WI 866-335-2825

Joe’s Refrigeration Inc. Withee, WI 715-229-2321

Mlsna Dairy Supply Inc. Cashton, WI 608-654-5106

Professional Dairy Services Arlington, WI 608-635-0268

Redeker Dairy Equipment Brandon, WI 920-346-5579

The Scharine Group Inc. Whitewater, WI 800 472-2880

Mt Horeb, WI 800-872-3470

MINNESOTA & SOUTH DAKOTA

Farm Systems

Melrose, MN 320-256-3276

Brookings, SD 800-636-5581

Advanced Dairy Mora, MN

320-679-1029

Pierz, MN

320-468-2494

St. Charles, MN

507-932-4288

Wadena, MN 218-632-5416

By Jan Lefebvre jan.l@star-pub.com

By Jan Lefebvre jan.l@star-pub.com

GREY EAGLE, Minn.

Jerry Pohlmann said it nally hit him when he closed the tiestall barn door after the last of his cows left the farm. He was truly retired from dairy farming.

“For the last couple years, I’d been telling myself that I’d milk one more year,” Jerry said. “I’ve had friends tell me, ‘You’ll know when the time is right.’ And, you know, the time was right.”

Jerry and his wife, Bev, have been milking 60 to 75 Holsteins in a tiestall barn since 1982 at their farm near Grey Eagle. They sold their cows Aug. 11.

“It’s been three weeks now, and it just feels good,” Jerry said. “We want to spend more time with our grandkids.”

The previous night, instead of milking cows, Jerry attended a high school varsity volleyball game in which

three of his granddaughters were playing. Bev had spent the day at a college visit with another grandchild. With ve children and 14 grandchildren, the couple will remain busy in different ways.

“I’m not watching the clock anymore,” Bev said.

“I can go somewhere and not have to think, ‘Ok, I’ve got to be back by 3:30 (p.m.).”

Jerry had planned to retire four years ago, when he was 60. Then he realized the barn would turn 50 years old in 2021. Cows would have been milked there for half a

century. He decided to stick it out until then so that he could hold a celebration to mark the anniversary.

Six months before the party, his dad passed away, but his mother was there to cut a big red ribbon Jerry had tied across front of the barn.

“With 14 kids, 68 grandchildren and many greatgrandchildren that Mom and Dad had at the time, it was a big party,” Jerry said. “The yard was full of cars with just family.”

However, Jerry did not retire.

“A lot of my friends retired at 62 and told me I was nuts (if I’d continue working after that),” Jerry said. “But when I got to 62, I thought, ‘I’m still feeling so good and my cows are smoking guns right now, so I’m going to keep going.”

In addition to milking cows and farm work, Bev began working at a school kitchen and loved it. When sale prices for cows became good, she said the timing seemed right. Jerry agreed. At 64, they sold the cows.

Looking back, both said dairy farming brought rewards to their lives, especially while raising a family. They taught their kids the importance of working hard and being responsible.

“Just the value of doing a good job — our kids have a good work ethic even now (in their current professions),”

Bev said. “We had our meals with the kids. We got up extra early to milk in the morning so that I could get them something to eat and onto the bus.”

The family adjusted times for chores, even milking cows at 4 a.m., to allow the kids to participate in sports but also keep them involved in the aspects of the farm.

“Even our grandchildren are going to have grown up having known the dairy farm because the youngest two are 8 years old,” Jerry said. “They were out here many times, many weekends.”

Still, letting go of dairy farming is hard. One of the Pohlmanns’ sons, Aaron, will continue running the farm as a crop farm. Jerry and Bev are considering raising youngstock with him. Aaron might remodel the tiestall barn into a machine shed, but not yet.

“I want the barn to stay empty for a year,” Jerry said. “We have plenty to do for the rest of this year anyway, so we will gure it out next year. It all started in 1971 when my parents built this barn.”

Jerry is the second generation on the farm. His parents purchased the farm in 1958.

“When Mom and Dad married, they got three cows from my dad’s sister and four cows from my mom’s dad,” Jerry said. “Then they bought a couple more. When they started milking, they had 15

cows.”

Jerry was 12 years old when they built the current tiestall barn with 48 stalls. Before that, his dad worked off the farm, and Jerry and his siblings milked cows with their mom. When the new barn was built, Jerry’s dad began dairy farming full time with the herd size increased to 40 cows.

“I milked cows before school and after school, but my parents let me play all the sports I wanted,” Jerry said. “I came from a family of 14 kids, so we had enough help.”

When Jerry started dating Bev, she lived 20 miles away in the town of Greenwald, but she spent time helping on her aunt and uncle’s farm.

Although Bev had not thought about becoming a dairy farmer, it t into what she wanted in a career.

“I wanted to do something outside, an outdoor occupation,” Bev said.

When the couple married in 1982, she t right into the dairy lifestyle.

“Bev and I milked side by side morning and night since we moved to the farm,” Jerry said.

Both said they enjoyed the feeling of accomplishing something through hard work.

“I liked to be busy all the time, and I liked taking care of calves,” Bev said. “I like to

see them raised from a calf to a cow and to know that I did good work.”

The couple ofcially took over the farm in 1987. It was then that a three-year drought began, the height of it being in 1988.

“The technology of crops, the hybrids we have now, didn’t exist (in 1988),” Jerry

said. “We’ve hardly had any rain this year, and the corn still looks good. If it were the drought year of 1988, 90% of the corn would probably be only knee high.”

In 1988, they received 0.2 inches of rain the morning of Mother’s Day.

“That was it from when the snow melted all the way

to the rst week of August,” Jerry said. “Then, we got 4 inches of rain and had one crop of hay, but it was a nice crop.”

He said it was probably the toughest year of farming he and Bev experienced.

Turn to POHLMANNS | Page 27

Minn. — Carbon credits could be one way for farmers to make more money on cash crop elds. This relatively new marketplace creates opportunities to be paid for incorporation of environmentally friendly practices.

“Carbon Credit Talk” was led by Ryan Stockwell of Indigo Ag and Matt Kruger of Truterra. The seminar was part of Midwest Forage Association’s forage eld day and dairy tour Aug. 8, the afternoon portion of which was hosted at Nate Heusinkveld’s dairy near Spring Valley.

A carbon credit represents 1 ton of sequestered carbon dioxide or avoided carbon dioxide emissions. These credits have value in today’s increasingly climate-aware business culture.

“This a tradeable asset,” Stockwell said. “This is a representation of something that we cannot see.”

Stockwell said carbon credits are important for companies trying to reach environmental goals, especially for those with emissions which are

difcult or costly to eliminate.

Carbon credit buyers include companies like Walmart, Anheuser-Busch, The North Face, Nestlé and Shopify. Stockwell said that products with a sustainability attribute grow 2.7 times faster in market share than their peers.

“This is a market-driven reality, and they are trying to keep up and be competitive in their market spaces,” Stockwell said. “They have emissions that they can’t get rid of, and that’s where carbon credits come into play.”

Though the buyers’ actual emissions may remain the same, their overall balance sheet of carbon emissions is closer to equilibrium thanks to carbon credits purchased from a eld which may be hundreds or even thousands of miles away from their operation.

The value of the carbon credits on a eld depends on individual factors. Stockwell said a carbon credit’s worth on the market is $30 to $50 dollars.

“This is the cherry on top” Stockwell said. “This isn’t the ice cream when it comes to income.”

Kruger said farmers in Minnesota last year made $1.50 per acre to $36 per acre because of carbon credits with an average of $12 per acre.

“Are you going to get rich?” Kruger said. “No, you’re not getting rich off this. ... Is the price going up? Yes, every year the price per metric ton has been going up.”

There are two ways to earn money off of carbon sequestration and avoided carbon emissions: carbon credits and supply chain inset.

Carbon credits function by establishing a baseline of cropping practices on a piece of property. Then, carbon credits can be created by farmers additionally incorporating practices which increase carbon sequestration or avoidance compared to earlier practices.

Supply chain inset is a newer market which gives farmers a premium on crops grown in a way which incorporates carbon sequestration and avoidance management practices. Supply chain inset is a way for farmers who have

established carbon reduction practices to be paid for their efforts.

In the carbon credit sphere, there are two main ways to create additionality to carbon reduction after a baseline has been established. The rst is incorporating cover crops and the second is reducing tillage.

Stockwell said carbon sequestration practices are benecial to a farm beyond the money gained by carbon credits.

“You’re increasing water holding capacity and inltration, and improving your drainage,” he said. “There are so many agronomic values, so this should make agronomic sense for your farm.” Carbon credits are veried through registries. Stockwell said these registries ll a role similar to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s certied organic seal to help buyers understand that they are getting a legitimate product.

Stockwell gave several items to consider when choosing a carbon credit company. First, he said it is important to make sure the company chosen has an adequate customer base so that there will be a market for the carbon credits.

The second thing Stockwell said to consider when choosing a carbon credit company is their prot structure. Some companies buy carbon credits wholesale and sell them at retail while other companies structure it so that the more money a farmer makes the more money the company makes. Choosing a company with the latter structure helps ensure the company has a farmer’s best interest in mind.

The nal three factors to consider, Stockwell said, are a company’s payment rates, making sure that the crop grown and land is eligible, and ensuring that the carbon credits the company issues are registryissued credits.

Kruger, who has family members who dairy farm, said that, currently, carbon credit systems do not function well on dairy farmland. Corn silage elds end up scoring low for carbon credits because of the amount of biomass being removed from the elds. Manure incorporation, depending on how it is done, can also create additional tillage, which is negative for creating additionality.

“But, we were dug in,” Jerry said. “I thought, ‘I’m not giving up; I love dairy farming, so we are doing this thing.’ You go back to my parents’ or my grandparents’ tough times to what we considered our tough times — and Aaron will have something that is a tough time — but you just battle it out.”

Mostly, Jerry said, times have been good on the farm. They are also proud of improvements they were able to make to their herd.

“I took A.I. school and started breeding our own cows to top bulls,” Jerry said.

That led to a lot of change in 41 years. In 1982, their herd was at a 17,500 rolling herd average. In 2023, their herd was at 29,000.

“It was sad to see them go,” Jerry said. “They paved a lot of highway on this farm.”

He said the cows allowed them to buy land, remodel the house, put in tiling and buy farm equipment.

“When it was time (to retire), it was the right herd to sell,” Jerry said. “They were some awesome cows.

The sale was good.”

With their herd gone, Jerry has found a way to maintain freedom with his schedule but still work with cows. His neighbor milks cows in a parlor and needed help. Jerry now milks for him — mornings only, on weekdays and some weekends, but at Jerry’s discretion.

“A lot of my family think I’m nuts, but I love it,” Jerry said.

Both Jerry and Bev said they feel busy but with more freedom. The tiestall barn stands pristinely clean and empty, but Jerry said he sees hope that young families on small farms will nd ways to keep barns like his full, most likely by adapting them with technology.

“The one good thing about robots is, if you want to stay small, you can have one robot and milk your 60 cows, which is nice for a small family, or you can get two robots and milk what might be more nancially (viable), such as 100 to 120 cows,” Jerry said. “That’s going to save a lot of these dairy farms.”

one-stop-shop for all agricultural building, welding, barn parts & equipment needs!

Tell us about your family and farm. I work as the herd manager for a 350-cow dairy in Fennimore, Wisconsin, where my small herd of Brown Swiss cows reside. I currently have eight head of registered Brown Swiss that are expanding graciously this year through my extensive in vitro fertilization program. All of my cows are from elite dairy show families with deep pedigrees. I started by purchasing a single cow online in 2017 that got my feet wet in the national show ring and introduced me to some of the best cow people in the country. My goal has never been to have a large herd but rather to have a few elite females that can produce calves to market and show.

What is a typical day like for you on the dairy? The fun part about my job is there really is no typical day for me. Some might call that a negative, but it denitely keeps things interesting. I have a small group of employees to manage and have the responsibility of ensuring cows are healthy, treating problems, delivering calves, running shot protocols for heats, vaccinations, breeding and parlor management. We also have an extensive IVF program on the farm that I am responsible for, so a lot of planning is done to initiate that. It always is something different each day. My work is never boring.

What decision have you made in the last year that has beneted your farm? The best decision I’ve made all year was to invest heavily in my IVF program. Working with Trans Ova Genetics, I’ve been able to produce additional calves from elite females that have signicant value. I take a lot of pride in my ability to produce fertile embryos that turn into healthy calves and currently run a 90% conception on my Brown Swiss embryos with a 0% death loss in the calves.

Tell us your most memorable experience working on the farm. My most memorable experience isn’t related to just working on the farm but rather developing Arthurst Kade Panda-NP, a 3-year old Brown Swiss cow I pur-

Bridget Achterberg Fennimore, Wisconsin Grant County

Bridget Achterberg Fennimore, Wisconsin Grant County

8 cows

chased as a yearling heifer, into the rst All-American nominated polled Brown Swiss animal. We truly didn’t expect her to get to Madison last fall, much less do as well as she did. After three days on the bedding pack, it was clear that she belonged there. Foreign interest in the cow has certainly made her more fun to deal with as well. Matings by multiple different bulls this year have allowed me to produce more daughters from her.

What have you enjoyed most about dairy farming or your tie to the dairy industry? The most enjoyable part of farming for me is watching a healthy calf be born from our IVF program. Be it an embryo we produce or an embryo we purchased, the anticipation of the calves and the delivery is especially fun. I’ve never been one to desire the average, and this program allows me to stay excited for what’s to come.

What is your biggest accomplishment in your dairy career? My biggest accomplishment goes back to the most memorable one, developing my beloved Panda into an All-American nominated cow. Some strive to develop these elite females their whole lives, and I’ve been fortunate enough to do so in the short ve years I’ve been building my genetics. What’s more exciting is knowing the backstory on Panda and the family that bred her. They have been her biggest fans these past three years, and being able to make them proud is an accomplishment in itself.

What are things you do to promote your farm or the dairy industry? Onfarm promotion is truly done through my Facebook page and just getting the genetics out to shows. Selling calves to other exhibitors has been a huge asset to my breeding program as well. The goal is always to sell the best and watch them succeed for others.

What advice would you give another woman in the dairy industry? My biggest advice for other women in this industry is to not let the idea of being a woman hold you back. I’ve had numer-